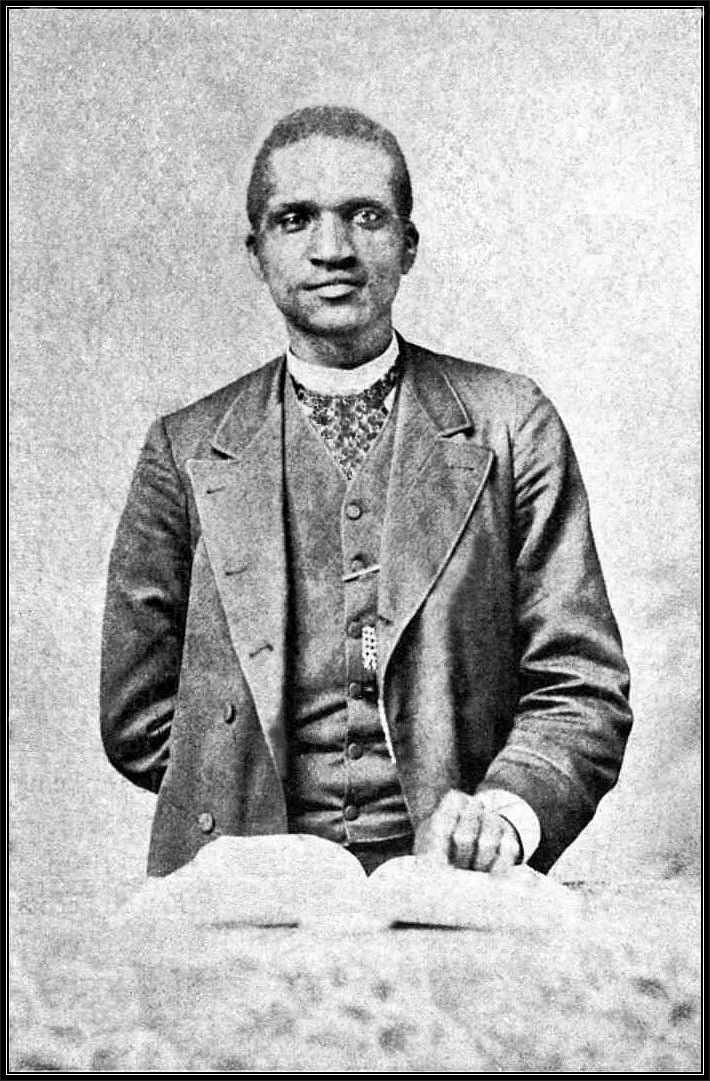

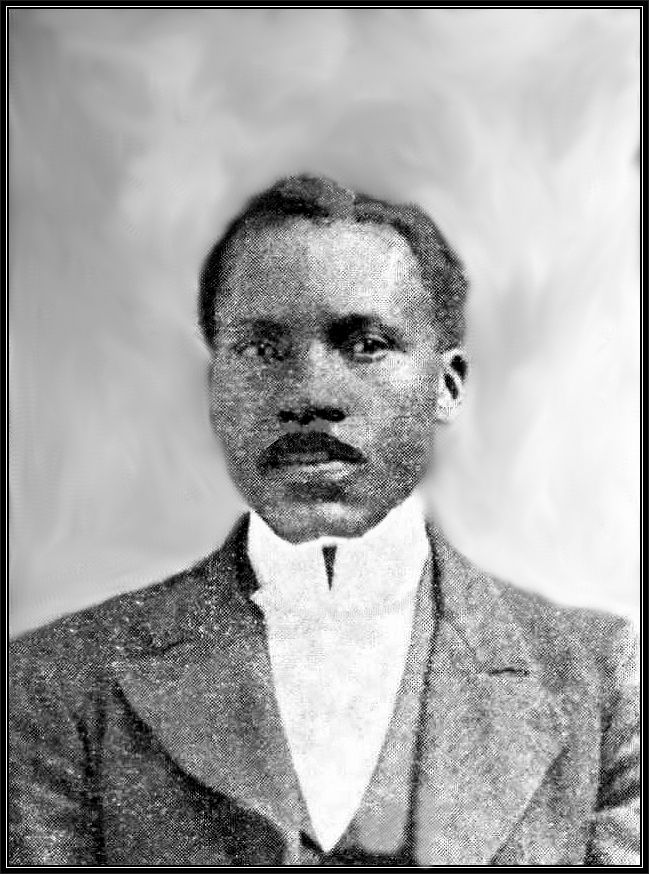

(“THE BLACK SPURGEON.”)

PASTOR MT. OLIVET BAPTIST CHURCH, NEW YORK CITY.

BY

SILAS XAVIER FLOYD, A. M.

WITH AN

INTRODUCTION

BY

ROBERT STUART MacARTHUR, D. D.

NASHVILLE, TENN.:

NATIONAL BAPTIST PUBLISHING BOARD.

1902.

Copyrighted 1902,

By Silas Xavier Floyd, A. M.

There is no species of literary composition more difficult than the writing of a good biography. Biographers are under a great temptation at times to create, or at least to magnify, the virtues of their subjects; and the temptation is not less on other occasions to deny, or greatly to minify, their vices. The biographies of Holy Scripture are models of biographical literary production. Inspired writers neither extenuate the defects nor magnify the excellencies of their subjects; extenuating nothing on the one hand, they do not, on the other, set down aught in malice. The excellence of the inspired writings in this regard differentiates them from the uninspired writings of any country or century.

But while to biographize is a confessedly difficult task, it is at the same time universally admitted to be a form of literary production of great value, when properly executed. A biography is generally understood to be the history of the life, actions and character of a particular person; it is that form of history proper whose subject is described in the facts and events of his individual experience. Carlyle, in his “Sartor Resartus,” says: “Biography is by nature the most universally profitable, universally pleasant of all things.” He also elsewhere says: “There is no heroic poem in the world but is at bottom a biography, the life of a man.” He has frequently expressed the idea that history is biography; that the history of any nation is the story of the lives of its great men. In a profound sense this statement is literally true. We thus see that peculiar ability is required accurately to write the life of any representative man. His forbears for many generations ought to be accurately known; his environment, in all its essential characteristics, ought to be thoroughly mastered. The times partly make men, and men partly make their time; each acts and reacts upon the other. Neither can be exhaustively described independent of the other.

The difficulty of writing good biographies is so great that comparatively few great biographies have been written. All the world is familiar with the unique biography of Johnson by Boswell. It has excited hearty laughter, while it has imparted valuable information. Lockhart’s Life of Scott and Lady Holland’s Life of Sydney Smith, fill almost a unique place in biographical literature. G. Otto Trevelyan’s Life of Lord Macaulay and Hallam Tennyson’s Life of his father are among the more recent and valuable illustrations of the biographical literature of modern times.

The word biography comes from two Greek words, bios, life, and graphein, to write. In order that there should be a good biography, it is necessary, therefore, that there should be a life nobly lived, and a writer competent to describe it in fitting terms. In the biography of Rev. Charles T. Walker, D. D., by Rev. Silas X. Floyd, D. D., both these conditions are excellently met. By his careful literary training, his wide experience as a writer, and his intimate knowledge of the history of Dr. Walker, Dr. Floyd is eminently fitted to write a readable account of Dr. Walker’s life and work. He has been associated in newspaper, pastoral and evangelistic work with Dr. Walker for the past twenty years. When Dr. Walker was business manager of the Augusta Sentinel, Dr. Floyd was its editor; and when Dr. Walker resigned the pastorate of the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Augusta, Ga., Dr. Floyd became his successor. He thus has had unusual opportunities to study Dr. Walker’s public and private life day by day for nearly a quarter of a century. Dr. Floyd is a graduate of Atlanta University, Georgia, from which institution he received the degree of A. M., three years after his graduation. For three years he was employed by the International Sunday School Convention as one of its Field Workers in the South. He is at present in the employ of the American Baptist Publication Society as a Missionary for Georgia and Alabama. The degree of “Doctor of Divinity” was conferred upon him by Morris Brown College, Atlanta, Ga., June 4, 1902.

There is probably no other Negro in the United States, and perhaps no other in the world, who is a better subject for a biography than Charles T. Walker. Many will affirm that Booker T. Washington is the most prominent representative of his race in America; doubtless, in his special department of effort for his people, he is the representative Negro. But all intelligent men, black or white, familiar with the facts, will say that Dr. Walker is the ablest Negro preacher and pastor in the United States. His racial characteristics are so strongly emphasized that the most bitter opponent of his race cannot attribute his acknowledged ability as thinker, writer and preacher to any interfusion of white blood in his veins. He is a Negro in every drop of his blood. Dr. Walker had careful training as a preparation for the work of the gospel ministry. Too many men, both white and black, rush into the ministry with quite inadequate preparation. The time has come when the apostolic injunction, “Lay hands suddenly on no man,” must be literally obeyed. This injunction is especially important in its relation to preachers and pastors of Negro churches. They are the natural and powerful leaders of their people. This is a transition period for the millions of the Negro race in America. Tremendously important racial problems are now demanding solution. Whites and blacks, both North and South, must have great patience with one another in the presence of these pulsing problems. Right solutions will eventually come; and all men must remember that no question is settled truly until it is settled rightly.

Dr. Walker has been an earnest student ever since his school days. He has traveled widely, read extensively and thought profoundly. In all these respects he has set a good example to all preachers and pastors. There is no standing still in professional life. If a man does not advance, he must retrograde; if he does not grow up, he must grow down. Every preacher is like a man on a bicycle—he must go on constantly or go off speedily.

Dr. Walker’s ministry in New York has been remarkable for pulpit power and for practical results. His ministry in this city is a distinct accession to the pulpit force of the entire church, irrespective of denominational divisions and creedal distinctions. Perhaps in the entire history of the city no pastor of any church ever had so many accessions to the membership of his church in the same length of time as Dr. Walker has had.

A great future still awaits his ministerial labors. Marvellous possibilities are before his race in America. Booker Washington, Dr. Walker, and a few great Negroes, are wisely training their people for a noble future; they are teaching their people that the time for pitying them, and coddling them, as well as for abusing, not to say lynching, them has passed, never to return. They must take their place as men and women among the men and women of the hour. They are to be neither babied nor bullied; neither petted nor pampered; they ought only to expect and demand simple justice; on their behalf these great leaders demand nothing more, and they will be satisfied with nothing less. To deny them simple justice would be an unspeakable reproach to the dominant race in America. Dr. Walker’s greatest days as preacher and pastor are still in the future. That he and his race may worthily perform their whole duty, and grandly attain their high destiny is the sincere desire of every true man, earnest patriot, and devout Christian.

This volume ought to be widely circulated and generally studied. It will give genuine inspiration to all men, white or black, who are struggling for higher and better things for time and eternity. Its general circulation will greatly help the Negro toward the realization of his laudable ambitions as a man, a citizen and a churchman.

Robert Stuart MacArthur.

Study, Cavalry Baptist Church, New York.

To THE YOUNG MEN OF THE NEGRO RACE IN AMERICA

This Volume Is Respectfully Dedicated by

THE AUTHOR.

For the combination of shrewd common sense, fine executive ability, ready speech, genial acceptance of conditions, optimistic faith in the future of his race and self-sacrificing zeal in their behalf, Booker T. Washington stands easily first among the nine million Negroes of America. The greatest claim that has yet been made by the Negro in English Literature, according to the most competent critics, has been made by Paul Laurence Dunbar, who, for the first time in our language, has given literary interpretation of a very artistic completeness to what passes in the hearts and minds of a lowly people. The greatest claim that has been made by the Negro in the field of scholarship has been made by W. E. Burghardt DuBois, Ph. D., the eminent sociologist. But not more certain is it that Washington stands first in the list of Negro educators, and Dunbar first in the list of Negro poets and literary men, and DuBois first among scholars, than that the Rev. Charles T. Walker, D. D., who is popularly called “The Black Spurgeon,” stands first among eminent and successful Negro preachers.

Dr. Walker’s father died the day before Dr. Walker was born. His mother died when he was only eight years old. The first seven years of his life he was a slave. Becoming an orphan one year after emancipation, the years of his youth and young manhood were years of great hardship and privation. In this respect, his early life resembled that of other distinguished men of humble origin who have been a power in the world, and whose names have an honorable place on the pages of history. The prophetic reference to Christ, “Though thou be little among the thousands of Judah, yet out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel,” has been paralleled in human lives by a host of men whose names and deeds are recorded in history, sacred and profane. From the anointing of the Bethlehemite shepherd boy as King of Israel to the present time, history has furnished innumerable illustrations of the providential selection of men from obscure localities and unpretentious surroundings for great responsibilities and important fields of influence. Again and again, in the history of our own country, we have had memorable examples of men who have left an undying influence, whose early life was without friends, and whose heritage was void of patrimony. Abraham Lincoln, James A. Garfield, Benjamin Franklin, Frederick Douglass, George W. Childs, Henry Wilson, Stephen Girard, Horace Greeley, and a host of others were such men.

One of the most profitable uses of history is the narrative of such lives. Having this in mind, it is safe to say that there is no species of writing of more value than biography. It inspires the young to nobler purposes, develops higher resolves, and proves an incentive to the laudable imitation of men who in prominent positions have proved true to principle and duty. It is in this spirit and with this thought in mind, that I undertake to write the story of the life of Dr. Walker. I confess to a great degree of admiration for the man; I glory in his career; I thought that the story of his life ought to be told; I believe that the telling of his life story will do much to encourage, inspire and incite to new endeavor thousands of young colored men all over the land, who need to be encouraged and inspired, and who, because of the peculiar environments of American civilization, find so little to incite them to high resolves, honest endeavors and upright lives. If, therefore, the story of Dr. Walker’s life as told by me shall encourage, inspire or incite one single human being, I shall have my reward.

Silas Xavier Floyd.

Augusta, Ga., February 1, 1902.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Parentage and Birth | 19 |

| Ancestry—Character of Dr. Walker’s Father—Dr. Walker’s Uncles—Dr. Walker’s Birth—Character of Dr. Walker’s Mother—W. A. Clark’s Tribute—A Generation of Preachers—Dr. Walker the Greatest of Them All. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Early Childhood | 25 |

| Richmond County During the Slave Period—The Hardships of Slavery—The Evils of Slavery—Dr. Walker Becomes an Orphan—His Strange Conversion—Joins Franklin Covenant Baptist Church. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Student Period | 29 |

| First Taught by His Mother—Yankee Teachers—Enters the Augusta Institute—Dr. Joseph T. Robert—Dr. Walker’s Struggles—Ready to Leave School—Students Come to Rescue—Others Interested—Mr. Bierce’s Narrative—Dr. Walker’s Failure to Graduate—His Ordination. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Early Pastorates | 35 |

The Call to Franklin Covenant Baptist Church—Other Calls—Strange Custom of Negro Preachers—Dr. Walker Teaches School—Some of His Early Pupils—His Marriage—The Work at LaGrange. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Work at Augusta | 39 |

The Call to Central Baptist Church—The Unholy Wrangle Prior to His Call—His First Sermon—New Life for a Time—The Troubles Renewed—Central Baptist Church Sold—Tabernacle Baptist Church Organized—New Church Dedicated—Wonderful Record—The Pastor Goes North—Justin Dewey Fulton’s Commendation—Dr. Walker’s Report on His Return. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Other Work at Augusta | 47 |

Business Manager of the Augusta Sentinel—Founder of the Walker Baptist Institute—A Dream for the Future—Director-General of the Negro Exposition—The Exposition—Lends a Helping Hand to Many. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Influence in Georgia | 55 |

Offices Held—Public Addresses—Interest in Public Affairs—As an Evangelist—Securing Competent Leaders for Churches and Schools—Dr. Walker’s Unselfishness. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Visit to the Holy Land | 59 |

Provision for the Trip—Traveling Companions—Itinerary—Preaches at Mount Olivet Baptist Church on His Way—His Return—His Account of the Journey—On the Lecture Platform. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| A Colored Man Abroad | 69 |

Extracts From Dr. Walker’s Writings—Tribute to the Sea—First Sabbath at Sea—Spurgeon’s Tabernacle—A Storm on the Mediterranean—Manners and Customs of the East—The Testimony of the Mountain—Drifting on Life’s Ocean—Anarchy—Warning. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| As a National Figure | 77 |

First National Baptist Convention—Dr. Walker one of the Founders—His Reply to Rev. H. C. Bailey—Resolutions Adopted—A National Leader—At Indianapolis—“A Strong Man in a Crisis”—Receives His Degree—Offices Held in National Baptist Convention—Chaplain U. S. V.—Vice President International Sunday School Convention—Calls to Other Churches. | |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Chaplain U. S. V. | 83 |

At San Luis, Cuba—Great Crowds Hear Account of Experiences—Resolutions Passed. | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| As an Evangelist | 88 |

Sphere Limited—Powers as an Evangelist—The New York Campaign—At Atlanta—In Kansas City. | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Leaves Augusta—Goes to New York | 98 |

Resignation of Augusta Church—Efforts to Retain Him—Last Sunday Night in Augusta—Mt. Olivet Church—His Success—Officers of Mt. Olivet Church. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Colored Men’s Branch Y. M. C. A. | 108 |

Movement Started—Adopted by City Association—Secretary Coles—Obituary—Board of Management—Mr. Dugas—Miss Connelly—A Perpetual Monument to the Founder. | |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Called to Augusta Again | 115 |

The Recall—Mass Meeting in New York—Letter of Dr. Bitting—Speech of Col. Powell—Mass Meeting at Augusta—Dr. Walker’s Decision. | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Extracts from Sermons | 125 |

What Hath God Wrought—Go Forward—Infallible Proofs of the Resurrection. | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Extracts from Orations and Addresses | 138 |

Eulogy on President McKinley—Reply to Hannibal Thomas—The Golden Rule as an Individual Motto—An Appeal to Cæsar—Colored Men for the Twentieth Century. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Extracts from Newspapers | 155 |

The Examiner—Sun—World—Journal—Tribune—Times—Augusta (Ga.) Chronicle—Fall River (Mass.) Evening News—Georgia Baptist—Augusta Chronicle—Georgia Baptist. | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Anecdotes | 171 |

“The Black Sturgeon”—Reading and Counting for Negroes—Praying for Money—Praying for Converts—About Jay Birds—Early Religious Impressions—Electing a Church Treasurer—Dr. Walker’s Complexion—The Negro a Novelty. | |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Appearance, Manners, Habits | 178 |

Description—Still a Rustic—Democratic—Remarkable Memory—Shy—His Sermons—The Bible and the Newspaper—Hunting and Fishing—Love for Little Children. | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Traits and Characteristics | 184 |

Patience—Motto of Dr. Walker’s Life—The Faithful Minister and His Trials—Humility—Gratitude—Other Characteristics—Not a Perfect Man. | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Conclusion | 191 |

God’s Best Gift to Man—The Magnetism of Goodness—Scope of Influence—Goodness is Communicable—The Real Forces of Life. |

It has long been a mooted question as to which State in the Union produces the best class of Negroes. Though there are no scientific data from which to draw definite conclusions, it is very generally agreed that the best Negroes—the most intellectual, most industrious, wealthiest, and the best behaved Negroes—come either from Virginia or Georgia. If that be true, then, if one is so fortunate as to be a native Georgian with Virginia ancestors, or vice versa, he ought to be considered a Negro of superior birth, to say the least. Viewed in this light, Charles Thomas Walker was born to superiority. In 1773, a family of Negroes was brought from Virginia to Burke County, Georgia, by the grandfather of the late Col. A. C. Walker, who was a prominent Georgia planter and politician and who for many years was a member of the Georgia legislature. In 1880, Col. Walker, writing of the Negro Walkers who had descended from the family brought to Georgia by his grandfather, said: “As slaves, they were noted for their admirable qualities, and as freedmen they have sustained their reputation.”

Charles Thomas Walker was the fourth in descent from this family. His father was a man of the name of Thomas Walker, and was one of three brothers. Thomas Walker was his master’s coachman—a position which only the best and most trustworthy slaves were allowed to hold, and a position which the slaves themselves always considered as a place of honor. The fact, also, that he was a deacon in the church of which he was a member attests the esteem in which he was held by the other slaves. Two of Charles T. Walker’s uncles, Joseph T. Walker and Nathan Walker, were both Baptist ministers. The Franklin Covenant Baptist Church, about five miles from Hephzibah, Ga., and only a short distance from the Burke County line, was organized for the colored people in 1848. In 1852 or 1853, this church, though its membership was made up of slaves, raised the necessary amount and purchased the freedom of the Rev. Joseph T. Walker, at that time their pastor, in order that he might devote himself entirely to his church work and to the preaching of the gospel in the counties of Richmond, Jefferson and Burke. In this work, Rev. Joseph T. Walker continued until the close of the war. The Rev. Nathan Walker, though a licensed preacher before the war, was not ordained to the ministry until 1866, when he succeeded his brother as pastor of the Franklin Covenant Baptist Church.

In 1848, Thomas Walker was married to a young woman of the name of Hannah Walker. To them eleven children were born—six females and five males. On the 5th day of February, 1858, near Hephzibah, Richmond County, Ga., about sixteen miles southwest of Augusta, their youngest child—Charles Thomas Walker—was born. Thomas Walker, the father, was buried the day before Charles was born, having died of pneumonia. Mrs. Hannah Walker survived her husband eight years, dying in Augusta, Ga., in 1866. It is related of her that she was a woman of unusual piety and strength of character, being a devout member of the Franklin Covenant Baptist Church, of which her husband was a deacon. She had high hopes and fond expectations for her youngest child, and longed to live to see him make a great and good man of himself, and especially so, because of the sad death of his father which occurred only two days before the child was born. God willed otherwise, and took her home to be with him and to watch from the “high and uplifted” battlements of glory the career of her son.

The following tribute to Mrs. Hannah Walker is taken from “Under the Stars and Bars; or Memories of Four Years’ Service with the Confederate Army.” This book was written by Mr. Walter A. Clark, Treasurer of Richmond County, Ga. Mr. Clark was a prominent officer in the Confederate Army; he is a graduate of Emory College (Georgia), and a literary man of great merit; he is a nephew of the late Col. Walker, already quoted in this book, was reared along with the black Walkers and knows whereof he speaks. His tribute to Mrs. Walker is no less a credit to the memory of the deceased than it is a testimony of the goodness of heart and magnificent manhood of the writer.

“My heart prompts me to pay its earnest tribute to one whose memory the sketch above recalls—dear old Aunt Hannah. How her name brings back to my heart and life to-day the glamour of the old, old days that will never come again—days when to me a barefoot boy, life seemed a long and happy holiday! I can see her now, her head crowned with a checkered handkerchief, her arms bare to the elbows, her spectacles set primly on her nose, while from her kindly eyes there shone the light of a pure white soul within! She was only an humble slave, and yet her love for me was scarcely less than that my father and mother bore me; and when, on a summer’s day in 1861, my brother and myself left the old homestead to take our humble places under a new born flag, there was not a dry eye on the whole plantation, old Aunt Hannah wept in grief as pure and deep as if the clods were falling on an own child.

“Long years have come and gone since she was laid away in the narrow house appointed for all the living. No marble headstone marks the spot, yet I am sure the humble mound that lies above her sleeping dust covers a heart as honest and as faithful, as patient and as gentle, as kindly and as true, as any that rests beneath the proudest monument that art could fashion or affection buy. She reared a large family of children, the Rev. Charles T. Walker, ‘The Black Spurgeon,’ among them, and transmitted to them all a character for honesty and virtue marked even in those, the better days of the Republic.

“Wisely or otherwisely, in the order of Providence, or in the order of Napoleon’s ‘heavier battalions,’ we have in this good year of our Lord (1900) not only a New South, but a new type of Aunt Hannah. The old is, I fear, a lost Pleiad, whose light will shine no more on land or sea or sky.”

The Walker family produced a number of able and successful preachers—some say more, some say less. As already shown, two of Dr. Walker’s uncles—Joseph T. Walker and Nathan Walker—were ministers. The latter is still living, venerated and honored, at the good old age of 85. He was one of the founders of the Walker Baptist Association, and was for more than twenty years its moderator, retiring about ten years ago on account of the infirmities of old age. The Association was named in honor of the Rev. Joseph T. Walker. The Walker Baptist Institute at Augusta, named also for the Rev. Joseph T. Walker, was founded by this Association and has been for many years supported by it. In all respects the Walker Baptist Association is to-day the leading Association in Georgia. An older brother of Dr. Walker, the Rev. Peter Walker, now retired on account of age, was, in his day, a man of great force and power in the pulpit. A nephew of Dr. Walker, the Rev. Prof. Joseph A. Walker, son of Rev. Peter Walker, was up to the time of his death, about eight years ago, the honored and successful Principal of Walker Baptist Institute. Besides these, there are two first cousins of Dr. Walker who are among Georgia’s most distinguished clergymen—the Rev. W. G. Johnson, D. D., Pastor of the First Baptist Church, Macon, Ga., who is Secretary of the Walker Baptist Association, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Walker Baptist Institute, and a member of the Board of Trustees of the Atlanta Baptist College; and the Rev. R. J. Johnson, Pastor of the First Baptist Church, Millen, Ga., and Treasurer of the Board of Trustees of the Walker Baptist Institute. Other cousins in the ministry are the Rev. Samuel C. Walker, Augusta, Ga., Rev. A. J. Walker, Millen, Ga., Rev. T. W. Walker, Wrightsville, Ga., Rev. Solomon Walker, Savannah, Ga., Rev. Matthew Walker, Savannah, Ga., an elder in the C. M. E. Church, and Rev. Nathan Wilkerson, Waynesboro, Ga. In addition to these, there are many of this family who were once in the ministry of earth, but who have long since gone to join the ministry on high.

Descended from a generation of preachers, Dr. Walker towers above them all like Saul among his brethren. So great is his fame and so celebrated has he made the name of Walker that the other members of the family find it a passport in many places for them to make it known that they belong to the generation of Walkers.

The first seven years of young Walker’s life were spent under the hard tuition of slavery, though, of course, he cannot have any very vivid recollections of the hardships of those days. It is fair, nevertheless to assume that his lot was not different from that of thousands and thousands of other black children in different parts Of the South. Richmond County, one of the large “Black Belt” counties of Georgia, which had then, and which has to this day, a larger black than white population, was in no respect different in its slave customs and regulations from other slave communities, excepting possibly the religious privileges enjoyed by the slaves. They had their own churches and enjoyed for the most part the ministrations of colored preachers, such as they were. They had their own houses of worship, their own church officials, and held regular and stated religious meetings. This was true in only a very limited number of places in the South during the slave period. In this respect, Richmond County was somewhat in advance of other localities. But only in this respect. In other matters, it was the same in Richmond County as elsewhere. The slaves received regular rations or allowances. The monthly ration consisted of eight pounds of pickled pork or its equivalent in fish. The pork was often tainted and the fish of the poorest quality. With this, they had one bushel of unbolted Indian meal, of which quite fifteen per cent. was fit only for pigs, and one pint of salt. This was the entire monthly allowance for a full grown slave. The children had no regular allowance, and often were compelled to dispute with dogs and cats and pigs over the scraps thrown into the yard or into the swill tub. Children not large enough to work in the field had neither shoes, stockings, jackets nor trousers given them. Their clothing consisted of two coarse tow linen shirts per year, and when these were worn out, they were literally naked until the next allowance day. Flocks of children from five to ten years old might be seen on the plantations as destitute of clothing as any little heathen in Africa, and this even in the cold and dreary months of winter. These children had no school advantages—certainly not. It was made a misdemeanor by law to teach a colored person to read or write. These children had no home life. The night for the slave—male and female—was shortened at both ends. The slaves worked as long as they could see, and were usually up late cooking and mending for the coming day, and at the first gray streak of the morning were summoned to the fields by the driver’s horn. Young mothers working in the field were allowed to go home about ten o’clock in the morning to nurse their children. Sometimes they were compelled to take their children with them and leave them in the corners of the fences in order to prevent loss of time. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, who got his knowledge of slavery while sojourning in the colony of Georgia, did not err when he denounced slavery as “the sum of all villainies.”

In such a school as this, Charles Thomas Walker received his early training. How different from the early training of such men as Henry Wilson, Abraham Lincoln, William McKinley, James A. Garfield, Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and other white men who were born to poverty. Though these men were born in humble circumstances, yet they were born to freedom. Charles Thomas Walker was born poor, and—what was worse—he was born a slave. These men owned at least themselves; they were free to go wherever they desired or to pursue any course of study or line of work that they wished. Charles Thomas Walker owned nothing—not even himself—and was compelled to go wherever his master ordered and do whatever his master commanded.

As to this slave system, the ancient question might well be asked, “Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?” And the reply is,

And how we thank God that we can write of this dreadful system of iniquity in the past tense. It did crush and cower so much of genius and intellectual strength and moral grandeur, and did send to their graves without opportunity and without chance thousands and thousands who, under any just and equitable scheme of civilization, might have proved God’s noblest friends and humanity’s strongest helpers!

By the exigency of war and the interposition of Jehovah, slavery in America was brought to an end in 1865. One year later young Walker’s mother died. From this time on young Charles was left to his own resources. Moving about as best he could from one relative to another, finally, in 1873, he went to work as a farm hand for his uncle, the Rev. Nathan Walker. This uncle had by this time come to be a large planter in his own right, and was renting hundreds of acres of land from his former masters.

Wednesday before the first Sunday in June, 1873, while young Walker was hoeing cotton, he decided to seek the Lord. When he reached the end of the row, without saying a word to anybody, he jumped over the fence and went into the woods. Without eating or drinking, and without seeing any one, he remained in the woods until the following Saturday afternoon, when he was happily converted. He had remained in the woods three days and three nights. How like the blessed Christ, who laid in the grave three days and three nights and then rose triumphant over death, hell and the grave! This strange way of seeking the Lord, this strange conversion, as it might be called, was all the more remarkable when it is understood that there was no great wave of religious revival sweeping over Richmond County. A short time before this there had been special prayer services in which there had been numbers of conversions; but young Walker’s conversion was the result of quiet and serious meditation on his own part and an earnest desire to be a meek and lowly follower of the Lamb.

Young Walker joined the Franklin Covenant Baptist Church, near Hephzibah, and was baptized into the fellowship of that church the first Sunday in July, 1873. The ceremony was performed by his uncle, the Rev. Nathan Walker, the pastor of the church and the man by whom he was at that time employed. This was the same church of which another uncle, the Rev. Joseph T. Walker, had been pastor during the days of slavery, and of which young Walker’s father was once a deacon. At the time of his baptism, young Walker was fifteen years old.

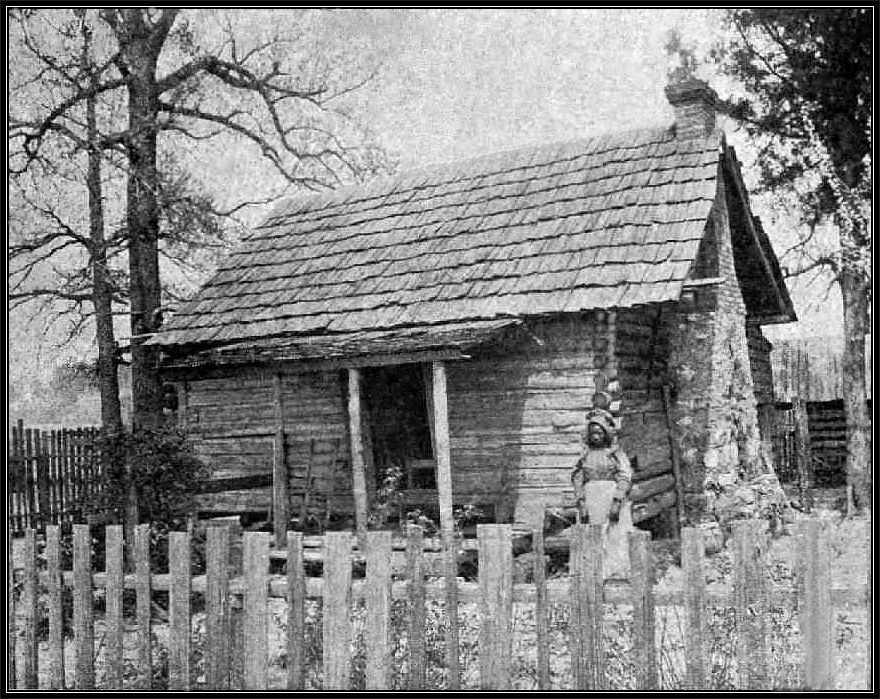

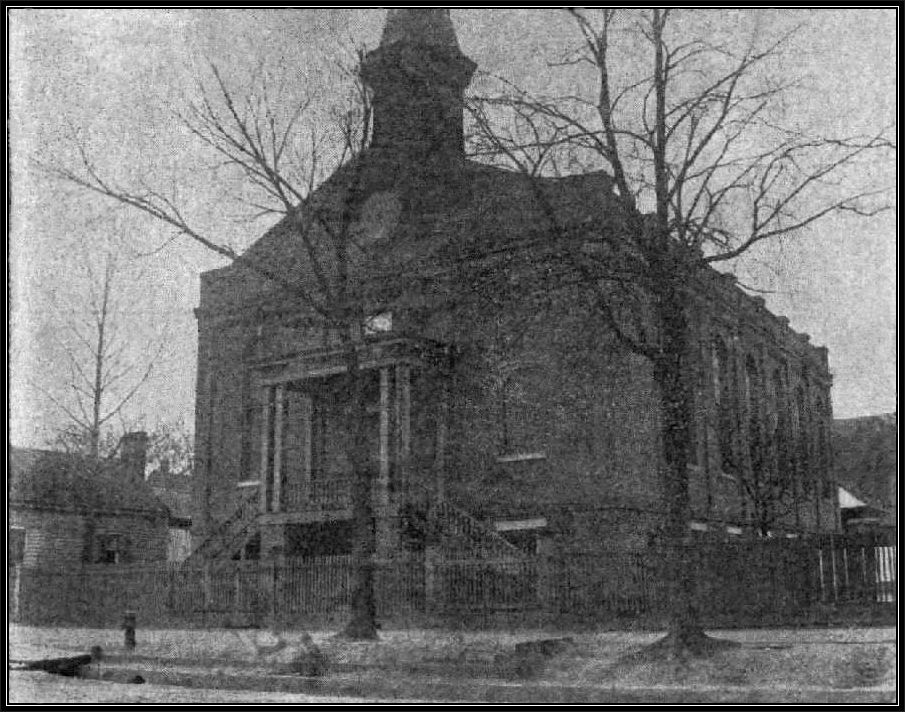

HOME OF PETER WALKER, NEAR HEPHZIBAH, GA., WHERE CHARLES T. WALKER LIVED DURING THE FIRST EIGHT YEARS OF HIS LIFE.

From the time of his conversion, young Walker was an active and zealous Christian, and at once became prominently identified with every branch of church work—the prayer meeting, the Sunday school and the preaching service. He had not been long converted before he was deeply impressed with the thought that he was called of God to preach the gospel. He felt, nevertheless, that he must restrain this desire until he had acquired some education. He had been taught his A, B, C’s by his mother. She had also taught him to read the fourteenth chapter of John. He has preserved to this day the old Bible from which his mother taught him to read. It is needless to say that his mother’s Bible is to him a priceless treasure. Subsequently his entire schooling had been confined to two terms of five months each in the schools conducted in Augusta, Ga., by the Freedman’s Bureau. His first teachers were two Northern young ladies, Miss Hattie Dow and Miss Hattie Foote. In order to secure better school advantages, and in order to fit himself for his life work, he came to Augusta in 1874 and entered the Augusta Institute, a school which was specially designed for colored preachers. This school was presided over by the late Rev. Joseph T. Robert, LL. D. Dr. Robert was a native of South Carolina and had been a slaveholder. After emancipation, he felt moved of God to take up the work of training Negro young men for the Christian ministry. He wrought well in his day and generation; he made the Augusta Institute a great school; no man, before or since his time, has left a deeper impress upon the history of the Negro Baptists of Georgia; and there is no man whose name is more honored and revered among them. He was a polished and scholarly gentleman of the old school; he possessed a great degree of what is called personal magnetism; and, by his upright living and Christian fervor, he had the power of inspiring his pupils to higher and nobler things. In the autumn of 1879, Augusta Institute was moved to Atlanta, and the name was changed to Atlanta Baptist Seminary. More recently the name has been changed to Atlanta Baptist College. It is still the largest and most influential school for young men in Georgia, and is regarded as the headquarters of the Negro Baptist ministers in the State.

In school young Walker was soon celebrated for his thoroughness, his exemplary deportment, and for his native talent. He had only six dollars in money when he entered school. With this he rented a room in a private family, for which he paid two dollars per month. In this room he lived during his first year in the Augusta Institute. He did his own washing and cooking—cooking only twice a week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. He did this in order to save time for study and to keep down expenses. He had only one suit of clothes, which he used on Sundays as well as on week days. When he had exhausted his six dollars, he picked up his little bundle, and was on the verge of leaving school, having decided to walk back to the country and find work to enable him to re-enter school at the opening of the next school year. Some of his friends among the students, finding out the reason for his proposed departure, remonstrated with him and, presenting him a small sum of money, urged him to be patient a day or two longer. One of his fellow students, the late Rev. E. K. Love, D. D., of Savannah, Ga., went so far as to agree to provide for Mr. Walker until other arrangements could be made. In the course of time this same Dr. Love came to be, all things considered, one of the brainiest and most brilliant Negro preachers in America, and as an organizer of men in religion, education, politics or business, he was probably unequaled by any of his contemporaries. For fourteen years he pastored the largest Negro church in the world—the First African Baptist Church, Savannah, Ga. At the time of his death in 1900, Dr. Walker, who came all the way from New York to Georgia to speak at his funeral, referred with much feeling and tenderness to the strong ties of personal friendship which had so closely bound them for years, and spoke with gratitude of Dr. Love’s ready assistance to him during his student days.

Through some of the students, Dr. Robert, the President of the Augusta Institute, was informed of young Walker’s sad plight, and, through Dr. Robert, three gentlemen in Dayton, Ohio—Mr. G. N. Bierce, Mr. A. B. Solomon, and Mr. E. B. Crawford—became interested in him, and, through the kindness of these three men, he was enabled to prosecute his studies at the Augusta Institute for five years. Two of these three gentlemen—Mr. Bierce and Mr. Solomon—are still living. Both are still very wealthy, and are among Ohio’s most successful business men. In November, 1901, Mr. Bierce went to New York to attend the Jubilee Dinner of the International Y. M. C. A. While in New York, he visited Dr. Walker at his home, went with him to the church which he serves as pastor, and also to the Colored Branch of the Y. M. C. A., 132 W. 53rd St., which was founded by Dr. Walker. In his speech at the Colored Men’s Branch, Mr. Bierce, among other things, said that he had made many investments in his life, but he believed that the money he had invested in Dr. Walker’s education had yielded the largest and best returns of any investment that he had ever made. He also told how he came to be interested in the elevation of the colored race. He said that during the late Civil War he was a soldier in the Union Army, and had drifted with his regiment into Kentucky. While there he was seriously wounded and left for dead on the battlefield. After many hours he managed to make his way to the house of a white Southerner, and asked for shelter and food. Seeing that Mr. Bierce was a Union soldier, the white Southerner denied him both, but called one of his colored servants and told him that he might take charge of the man and care for him, if he desired to do so. The colored man took charge of Mr. Bierce, and, in their lonely cabin, the colored man and his wife carefully watched and nursed the wounded soldier, and in a few weeks brought him back to health and strength. After the war, Mr. Bierce made many efforts to find these faithful Good Samaritans and reward them for their kindness. Failing in this, he decided that, as he owed his life to the attention and care of two members of the Negro race, he would let no opportunity pass to help any of the race who might need assistance. And true to his pledge, Mr. Bierce has been the steady and consistent friend of the colored people from that day to this. Dr. Walker is only one of many beneficiaries of his kindness, and Dr. Walker is a conspicuous example of what a little money, wisely placed in the education of one colored man, can do toward the elevation of an entire race.

Though Dr. Walker finished the prescribed course at the Augusta Institute, he was not graduated from that institution. No graduates were sent out from that school until long after it had been moved to Atlanta, the first class being regularly graduated in 1884. Subsequently, by vote of the trustees, it was decided that the names of nearly fifty young men who had finished the prescribed course prior to 1884, should be placed in the catalogue and marked “entitled to rank as graduates.” Dr. Walker’s name is in this number. But whether graduated or not, Dr. Walker easily excels any man who was graduated there, and no man, living or dead, has ever heard him express any regret that he does not hold a diploma.

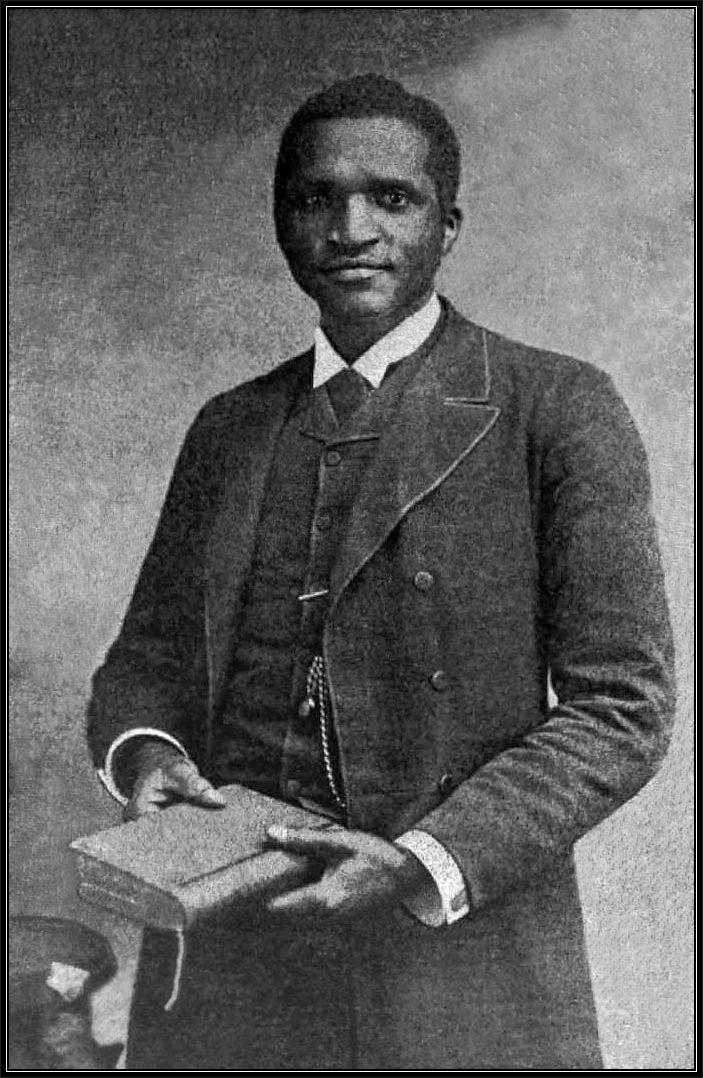

In September, 1876, after two years in the Augusta Institute, and in the eighteenth year of his age, young Walker was licensed to preach. The first Sunday in May, 1877, he was ordained to the sacred office of the Gospel ministry.

The Rev. Mr. Walker soon became noted as a preacher in and around Augusta. Possessing a fair knowledge of the Bible, and at all times an earnest and enthusiastic speaker, the people literally crowded to hear the “boy preacher,” as the Rev. C. T. Walker, on account of his age and youthful appearance, was called for a good many years after he entered the ministry. October 1st, 1877, he was called to the pastorate of the Franklin Covenant Baptist Church, near Hephzibah, and assumed the duties of the office on the first day of January, 1878. This was the church of which he was a member, of which his father had been a deacon, and of which, before him, two of his uncles had been pastors. Calls to other churches followed in rapid succession, and by the time he reached his twenty-first birthday, February, 1879, he was pastor of the four following churches: Franklin Covenant Baptist Church, near Hephzibah, Ga.; Thankful Baptist Church, Waynesboro, Ga.; McKinnie’s Branch Baptist Church, Burke County, Ga., and Mount Olive Baptist Church, in the suburbs of Augusta, Ga. If it seem strange that one man should be the pastor of so many churches, it may be stated that it is customary in the country districts of the South for one preacher to be in charge of several churches. He will give about one Sunday in every month to each church. Sometimes the churches served by one pastor are all in the same county. Sometimes they are separated by many miles. Of course, no real pastoral work can be done in this way. Of necessity the people suffer; no continuous, well-organized spiritual training can be kept up. But, as a rule, the country churches are unable to properly pay their pastors, and but for this system which allows one minister to pastor several churches, there are many churches which would be without any pastor. Even under the present system it is very difficult for the majority of pastors to secure anything like proper remuneration.

The Rev. Mr. Walker, nevertheless, was not to be doomed to the drudgery of pastoring several churches at one and the same time. After a little more than one year’s service, he resigned all of his other churches to become pastor of the First Baptist Church at LaGrange, Ga., in the early part of 1880.

It was with very great regret that the churches which he had been serving consented to his withdrawal. Two of them voted to increase his salary if he would decide to continue to serve them. He had done good service, and these struggling churches felt that it would be difficult to find any one who would be able to serve as well, as faithfully, and as acceptably as he had done. Hence, they objected to his removal. Especially was it hard for him to withstand the entreaties of his home church. The members of the Franklin Covenant Baptist Church held a mass meeting protesting against the withdrawal of their pastor and urging him to remain with his own people. When he announced to them his final decision, to the effect that he felt that the Lord was calling him to the new field of labor and that he would obey what he believed to be the call of the Holy Spirit, the whole congregation broke down in tears. It was a sad and trying experience in the life of the young preacher.

During the summer months of 1876, 1877, 1878 and 1879, the Rev. Mr. Walker taught school in the Franklin Covenant Baptist Church building. That is another thing that is peculiar to the rural districts of the South. In many places, perhaps in the majority of places, the public schools are conducted in church edifices, the States having no funds for buildings for schools and the people, as a rule, the white people as well as the colored people, being too poor to erect separate school buildings, find it convenient to use the church building for school purposes. As a school-teacher he was successful, so far as the conditions of the time and his own attainments warranted. It must be confessed, none the less, that he taught school as a means of support and to help him in paying his own expenses while attending the Augusta Institute.

June 19th, 1879, Rev. Mr. Walker was married to Miss Violet Q. Franklin, of Hephzibah, Ga. To them four children were born. Three children are dead. One son is still living—Master Jonathan Walker, a lad yet in his teens. One daughter, Mrs. Alberta Walker Hughes, left a daughter at her death, and this grandchild is pet of Dr. Walker and wife.

Dr. Walker remained in LaGrange for nearly three years. While there he was a busy, active, energetic, influential and successful pastor. It was while there that he gave promise of his future eminence as a soul-stirring, soul-saving evangelist. He conducted two of the most eventful revivals ever held in Western Georgia. More than four hundred souls were savingly converted, and more than three hundred were added to the church which he pastored. After these meetings, he received many invitations to conduct series of meetings in the leading Georgia cities, and accepted as many as he could well afford to accept without injury to his own work at LaGrange. At LaGrange he also established a school for Baptists, and was instrumental in having a large frame building erected for this purpose. The school finally grew into the LaGrange Academy, a large and influential Baptist High School. It was at LaGrange, also, that he read law for nearly two years under Judge Walker, one of the ablest members of the Georgia bar, and, though he was never admitted to the bar, it is evident that his legal learning has stood him in good stead in the exposition of many a Scripture passage, and, though the law may have lost a brilliant expounder, it is certain that a great leader and teacher was saved to the church and religion.

The Rev. Charles T. Walker was called to the pastorate of the Central Baptist Church at Augusta, Ga., in 1883, and resigned the First Baptist Church at LaGrange to enter upon the work at Augusta. Central Baptist Church is one of the oldest churches in Augusta, and was the first colored church in the city to erect a brick building. The edifice was very large and was a credit to the city. But for nearly twelve months before the Rev. Mr. Walker was elected pastor, the church had been engaged in a very unfortunate wrangle. The Rev. Henry Jackson was the predecessor of Rev. Walker, and he had been the pastor of the church almost from its organization in 1858. A daughter of Rev. Jackson was the organist of the church, and it seems that the pastor wanted her salary increased. The majority of the deacons and trustees did not agree with the pastor; but the pastor called a business meeting of the church, and, by high-handed methods, so it was claimed, succeeded in having a vote passed favoring the proposed increase in the organist’s pay. From that day the wrangle started in good earnest. There were charges and counter-charges. There were plots and counter-plots. The faction favoring the pastor was called “Jacksonites,” and the opposing faction was called “Ramrackers.” The deacons were divided; the trustees were divided; the membership was divided. There was scarcely a meeting held at the church for any purpose but that there were harsh words passed on both sides, and sometimes there were fisticuffs. Many police trials resulted from these disgraceful occurrences. Once the lights were put out during a meeting. In the darkness, some miscreant sent a pistol ball crashing through one of the windows. Pandemonium reigned within. The church was locked up several times by injunctions sued out before the courts—sometimes by one side, sometimes by the other. Finally, the trouble became so acute that it was positively unsafe for any one to attend the church. There came a temporary lull in the warfare of the saints (?) when the Rev. Henry Jackson resigned and left the city. For a time the factions seemed to have settled their differences. The church came together and extended a unanimous call to the Rev. C. T. Walker to take up the pastorate. After much deliberation and prayer, the Rev. Mr. Walker accepted the call. He was twenty-five years old at the time, but looked to be much younger. From the beginning he made a favorable impression. His first sermon was preached the fourth Sunday in August, 1883, from these words: “For I am determined not to know anything among you, save Jesus Christ, and him crucified” (1 Cor. 2:2). Those who were present on the occasion of this introductory sermon remember vividly the preacher’s sermon and his appearance. A youngish looking man of medium height and rather slim, with frank, open features; face very dark; quiet of demeanor and graceful in movement; with a sweet, clear, orotund voice, enunciating every word distinctly. With the man and the sermon, the church and congregation were alike delighted and encouraged; and never did they seem to sing before with such thrilling effect and such depths of meaning, “Blest be the tie that binds.”

But church wars never end. Whatever may have been the outward appearances, those on the inside knew that, though all said that they had buried the hatchet, some of them at least had left the hatchet’s handle sticking a good way out of the ground. None knew this better than the new young pastor, and none grieved more because of it. “The Jacksonites” wanted to direct the policy of the new minister, and so did the “Ramrackers.” Each side was jealous of the other, and, although siding with neither, the new pastor found himself at every stem of his journey between two fires. Consequently, though earnestly desiring to do the Lord’s work and praying daily to learn God’s will, he was an unhappy man. The troubles continued. By and by the church reached the point where it felt that to discipline a few of the recalcitrant officers might help matters some. The action of the church not suiting the “Jacksonites,” the church was again closed by injunction, and the whole affair was dragged again into the courts. By the advice of lawyers on both sides, since it seemed impossible to harmonize the differences, it was agreed that the church should be sold and the proceeds equally divided between the representatives of the two factions. Accordingly, the church was sold at public outcry. It was bid in by the “Jacksonites.” The “Ramrackers,” so-called, received something over $2,000 for the sale. The “Jacksonites” took charge of the old church, reorganized and called the Rev. Henry Jackson as pastor. The other side, under the leadership of the Rev. Mr. Walker, worshipped temporarily in the hall of the Union Waiters’ Society on Ellis Street, the hall being generously donated by the Society for that purpose. Friday night, August 21st, 1885, this body was formally organized at the Union Baptist Church, under the name of Beulah Baptist Church. The enrolled membership at the time of organization was 310—115 males and 195 females. At a special business meeting at the close of the service Sunday night, August 23, 1885, at the suggestion of the pastor, the name of the church was changed from Beulah Baptist Church to Tabernacle Baptist Church. Plans were at once set on foot for the erection of a house of worship. Proper committees were appointed. A lot was secured on Ellis Street, above 10th Street, and work was commenced on the new building September 1st, 1885. September 10th, the corner stone was laid with appropriate ceremonies, the address being delivered by the late Rev. E. K. Love, D. D., of Savannah, Ga. The building was opened for worship and formally dedicated to the Lord the second Sunday in December, being the 13th day, 1885. The dedicatory sermon was preached at the morning service by the Rev. E. R. Carter, D. D., of Atlanta, Ga., from this text: “But will God indeed dwell on the earth? Behold the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain thee; how much less this house that I have builded?” (1 Kings 8:27.) The afternoon sermon was delivered by the Rev. Lansing Burrows, D. D., the well known Secretary of the Southern (white) Baptist Convention and for a long time editor of the American Baptist Year Book. The sermon at night was delivered by the late Rev. Dr. E. K. Love.

The Tabernacle Baptist Church edifice is built of brick, two stories high. The basement is used for the prayer meetings, the Sunday School, the pastor’s study, and closets. The auditorium upstairs is used for the preaching services and for lectures. It will seat comfortably about 800 persons. It cost (for ground and building) $13,500. Dedicated within three months after it was commenced and paid for within less than two years after it was completed, including a new pipe organ costing $1,500, is a record which has probably not been surpassed by any colored congregation in the South, and speaks well for the ability and zeal of the leader. With a new church building and with a sterling and brilliant young pastor, Tabernacle Baptist Church soon became the leading colored church in Augusta, a city noted for its splendid churches and its able pastors. It was while he was with this church that the Rev. C. T. Walker made his reputation as a pulpit orator, a sound theologian, a soul-winning evangelist, and a resourceful pastor. At the close of fourteen years of hard labor, Oct. 1st, 1899, it was found from the records of the church clerk that more than 2,000 souls had been converted during his ministry, and that more than 1,400 had been baptized by him into the fellowship of the Tabernacle Baptist Church.

It was in connection with the work at Tabernacle Church that the pastor made his first extended tour throughout New York and New England. The members of the church had by their own efforts paid nearly $10,000 of the $13,500, which was the total cost of their ground and building. In the autumn of 1886, the pastor, armed with numerous testimonials and letters of introduction, went North to solicit funds to assist in completing the payments on the church property. He found ready acceptance and willing ears everywhere he went. It was at this time that he preached for the first time in Mt. Olivet Baptist Church, 161 W. 53rd Street, New York city, of which years afterwards he became pastor. Of his visit to the Centennial Baptist Church, Brooklyn, the pastor, the late Rev. Dr. Justin Dewey Fulton, wrote: “My people who heard him pronounce him a preacher of more than ordinary ability. His voice is good, his bearing modest and impressive, his language excellent, and the aim of his preaching is to glorify Christ.” In other churches and in other cities, the Rev. Mr. Walker found similar warm friends, who listened eagerly to his exposition of God’s word or to his appeals for aid in his work at the South. He returned to his work in Georgia, satisfied with the financial results of his trip, but more gratified with the moral support and encouragement he received. In reporting his labors to his members on his return, the Rev. Mr. Walker said, among other things: “The Lord went with me, and opened up for me many places which were considered very hard, and enabled me to approach some persons who were at first apparently not at all friendly toward the colored people. When I got on the grounds and learned the true situation, I was not at all disposed to criticise the people of the North for being cautious about distributing their money to irresponsible persons. I found out that numbers of colored people go up North every year begging for money for churches and schools and orphan homes and the like, which have no existence at all, except in the imaginations of their impostors or on paper. When members of my own race will do such things they make it hard for a worthy person soliciting for a worthy and legitimate enterprise and you cannot blame people for being careful about giving their money when they know that there are many little schemes being worked by colored men to rob them. ‘A burnt child dreads the fire,’ and the good have to suffer on account of the conduct of those who are dishonest and speculative. But God was with me and directed me, and I secured a hearing and received contributions in some places where others were denied. We should all be thankful for this, as much as any thing else. It pays to be honest, sincere and straightforward, and I have no patience with those hypocrites who are systematically robbing the good people of the North, who are very willing to give of their means for the uplift of my downtrodden race.”

Not only was the Rev. Mr. Walker notably successful as a pastor while he lived in Augusta, but he was also a very active citizen, taking a prominent part in all enterprises looking to the betterment of the people along educational, religious and business lines. It may be said with truth that his public spirit, his generous concern for the welfare of all the people, was one of the things that gave point and power to his preaching and caused “the common people” to hear him gladly.

In 1884, the Augusta Sentinel, a weekly paper, was established by Prof. R. R. Wright, A. M. (afterwards Major R. R. Wright, LL. D.), who was at that time Principal of the Ware High School. The Rev. Mr. Walker was one of its largest stockholders and was elected Business Manager. In 1891, Prof. Wright left the editorship of the paper to become the first President of the Georgia State Industrial College, near Savannah, Ga., a position which he still holds. Major Wright was and is one of Georgia’s leading educators and most representative citizens. He has represented his State four or five times in Republican National Conventions, and was appointed a “Major and Additional Paymaster” in the U. S. V. by the late President McKinley during the Spanish-American war. When Prof. Wright left the editorial chair, he was succeeded by the late Rev. E. K. Love, D. D., of Savannah, Ga. Dr. Love retired in 1892, and was succeeded by Prof. Silas X. Floyd. But, through all these changes, the Rev. Dr. Walker remained in charge of the business department of the paper until it died a natural death in 1896. In 1891, while Dr. Walker was traveling in Europe and the Holy Land, he sent a weekly letter to the Sentinel, and these letters did much in adding to the popularity of the paper. On his return, these letters were compiled and published in a volume of 148 pp. 16mo. under the name and title of “A Colored Man Abroad.” The book had a wide sale and found many readers.

The Walker Baptist Association in 1880 passed a resolution to establish a high and normal school for colored children. Dr. Walker was the author of that resolution. The school was at first located at Waynesboro, Ga., where it remained for about three years. Dr. Walker became convinced that the school would thrive better if it was moved to Augusta, and he was specially anxious to have the school removed to that place, because he desired to see a good school conducted by Baptists in Augusta, a city of Baptists, and in which the Methodists and Presbyterians were already conducting creditable normal schools. It was mainly through Dr. Walker’s efforts that the school was finally moved to Augusta in 1891, and even the most doubtful have been led by subsequent events to appreciate the wisdom of his suggestion. The school is now a large and flourishing institution, occupying a commanding site, the chapel, class rooms, dormitory and grounds being valued at something over $5,000. The school is unencumbered, owned and controlled by the colored Baptists, assisted to a very limited extent by the American Baptist Home Mission Society. From the beginning, Dr. Walker has been the Financial Agent of the school, which position he still holds. He has succeeded in bringing to its support a large number of friends, both white and black, North and South. It is one of his fond dreams for the future to establish in connection with this school a large Industrial School and Business College. His friends believe that it will not be difficult for him to accomplish this, because the work already done by the colored people themselves in connection with this school, the excellent showing they have made in the direction of self-help, will commend itself to a generous public wherever it is told.

In 1893, the colored people of Augusta organized an exposition company. This company held an exposition that year, commencing December 18 and running through one week. The officers of the company were Bishop R. S. Williams, of the C. M. E. Church, President; Prof. Silas X. Floyd, Editor Augusta Sentinel, Secretary; Mr. Charles J. Floyd, Assistant Secretary; Mr. George J. Scott, a grocer, Treasurer, and Dr. C. T. Walker, Director-General. Exhibits were on hand from colored undertakers, colored cabinet makers, colored harness makers, shoemakers, contractors, carpenters and brick masons, printers, wheelwrights, carriage and wagon makers, farmers, who exhibited farm products, cattle, swine, poultry and the like, dressmakers, needle and fancy work by colored girls and young women, colored artists, who exhibited oil paintings, landscape paintings and sketches in charcoal and crayon, colored bakers, tailors, electricians, school-teachers, and the like. In his address to the public, Director-General Walker said: “Primarily, the basic principle upon which the Negro Exposition is founded is a desire to show to the world the advancement and progress made by the American Negro, especially the Southern Negro, and most especially the Georgia Negro, within the past thirty years. But no such exposition can be held in Augusta without also resulting in a general advantage to the interests of the city.” Evidently, the city council of Augusta, composed entirely of white Southern men, took the view held by the Director-General, for, upon request for aid from the Directors of the Negro Exposition Company, the city council appropriated $200 from the city treasury for the promotion of the enterprise, and gave six policemen and all fire protection free. The exposition was a creditable display of the Negro’s progress, and did much to illustrate the purposes for which it was organized. The Director-General was present every day and had charge of the program. The welcome address was delivered by the mayor of the city, Major J. H. Alexander, to nearly 5,000 colored people and many hundreds of white people on the opening day, Monday, December 18, 1893. At the conclusion of the address of welcome, the formal opening address was delivered by the Rev. E. R. Carter, D. D., of Atlanta, Ga., one of the most popular Southern Negro orators. Tuesday, December 19, was Educational Day. All the public and private schools of the city had a general holiday in honor of the event. More than 2,000 school children marched early in the morning of that day behind brass bands to the Exposition Grounds, where appropriate exercises were held. Speeches were delivered by Prof. Lawton B. Evans, Superintendent of Schools, Augusta, Ga., and Prof. R. R. Wright, A. M. Music was furnished by a trained choir of 500 voices of public school children under the direction of Prof. A. R. Johnson. Wednesday, December 20, was Military Day. The address of the day was delivered by Congressman George W. Murray, of South Carolina, after which there was a spirited prize drill by the various companies. Thursday, December 21, was Firemen’s Day. A mammoth street parade of twelve fire companies took place in the forenoon, and, in the afternoon, there were reel races, foot races, bicycle races, and a base ball game. Friday was Vaudeville Day. Mason and Johnson’s Ethiopian Minstrels gave performances afternoon and evening. Saturday afternoon the exhibition closed with a grand industrial parade on the Exposition Grounds. The like had never been seen before in this country, and probably has not been seen since. To no one was more credit due for the success of the entire affair than to the indefatigable Director-General, the Rev. Dr. Walker. He gave himself to the work both night and day without receiving one cent of pay.

In these public ways and in others, Dr. Walker made his presence in Augusta known and felt. But not alone for his public spirit is he known, honored and loved by the people of Augusta, as is no other man who has labored there, but also for the rendering of many private acts of sympathy and help and encouragement, which the world does not know about, and which the world cannot know about. The number of those whom he has been instrumental in saving from the jails, chain gangs and penitentiary; those he has had released from imprisonment, whose fines he has paid out of his own pocket; the number whose house rent he has paid, and furnished food, and clothing, and fuel; the number of unhappy husbands he has reconciled to unhappy wives, thereby making both happy again; the young people he has sent to school and has helped to educate; the men and women for whom he has secured employment; those he has brought to Christ by private ministrations; the number he has encouraged and cheered by a kind act or a “word fitly spoken;” the number he has helped and inspired in one way and another, will reach far into the thousands. The number cannot be known

Dr. Walker did these things as if by second nature, and, though now and then friends remonstrated with him and told him that he ought not to allow others to impose upon him, he went straight ahead, quietly and unostentatiously, spending and being spent for the Master, and his heart filled with the milk of human kindness, he lent a listening ear and an outstretched arm to every cry for pity and every appeal for help.

In spite of his arduous labors and duties at Augusta, Dr. Walker yet found time to be interested in all matters which concerned the welfare of all the people throughout the State of Georgia, and was an active participant in many State gatherings of various kinds, aside from the large number of evangelistic meetings he found time to conduct in many Georgia cities. For several years he was Moderator of the Western Union Baptist Association; for four or five years he was Chairman of the Executive Board of the Missionary Baptist Convention of Georgia; for two years he was Vice President, and for eight years Secretary of the same body; he was Treasurer for several years of the Sunday School Workers’ Convention of Georgia; he was at one time Vice President of the Georgia Interdenominational Sunday School Convention; he was for a number of years a member of the Republican State Executive Committee; he has been, from the beginning, a member of the Board of Trustees of the Walker Baptist Institute, and was also a member of the Board of Trustees of the Atlanta Baptist College. The filling of these various offices of trust and responsibility indicate in a small way the immense activity which he has displayed in the general welfare of the State, and particularly the welfare of the Baptist denomination.

In addition to these things, there has not been a convention of any kind called by the colored citizens of Georgia, as has frequently been the case during the past twenty years, which he has not attended, anxious always to do something to advance the Negro in the scale of civilization. He has many times visited the annual meetings of the State Teachers’ Association of Georgia and, by invitation, has addressed them, trying to show what part the teachers ought to take in solving the so-called “Race Problem.” He has been a favorite commencement orator at many of Georgia’s schools and colleges, and has never been able in any one year to accept all the numerous invitations which have come to him to deliver baccalaureate sermons. On the first day of January each year, it is customary for the colored people throughout the South to hold public meetings, where addresses are delivered by distinguished men, in commemoration of the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln, Jan. 1st, 1863. Dr. Walker’s addresses, delivered at different places in the State on Emancipation Day, would alone make a very large and interesting volume. Nor has he felt that his duties as a preacher have of necessity absolved him from active participation in public affairs, or what is more generally called politics. He was for years a member of the Richmond County Executive Committee of the Republican Party, and also a member of the Republican State Committee. He has believed and has taught that it is the duty of every citizen to be interested in the political welfare of his city, State and country, and, in his judgment, no man is entitled to be called a good citizen who allows the vicious and corrupt to do all the voting and all the dictating, and then sits down and sighs for what is called “the better and purer days of the Republic.” Of his work as an evangelist, mention will be made in a later chapter. But let it be said now that no one man in Georgia has held a larger number of special meetings throughout the State, nor has had a larger number of conversions to be attributed to his preaching, than has Dr. Walker. It is not exaggeration to say that he is the best known Negro minister of the State of Georgia, and that more people will go to hear him preach than will go to hear any other colored man. Not the celebrated, plain-spoken, claw and hammer preaching of Sam Jones, nor the Holy Ghost preaching of the pious Dwight L. Moody, of sainted memory, drew larger crowds to the auditorium at Exposition Park, Atlanta, Ga., than did the thunderous proclamation of the gospel by Charles T. Walker.

Perhaps in no way has his influence been felt in Georgia more than in the selection of competent men for Baptist pastorates and in the appointment of competent men and women as teachers at many places in the State. Dr. Walker’s reputation as a safe leader and wise counsellor, his extensive travels and consequent wide acquaintance with men and women throughout the State and nation have proved to be very helpful to all concerned in the recommendations he has been asked to make. No one in Georgia who knows of these things can recall a single instance in which the recommendation of Dr. Walker, in the case of a church or school, has been turned down. So interested has Dr. Walker been in the welfare of others, and so eager has he been to see competent leaders set over the people, that he has been known time and again to go 500, 600, and sometimes 1,000 miles at his own expense to assist those who needed and asked his opinion and advice, or to help some person to secure a position. Not all of those whom he has helped have been grateful; not all of them will admit their obligation; only a few of them remember the bridge that carried them over. When told of the ungratefulness of different ones, Dr. Walker only laughs and says: “I do not help anybody with the expectation of being thanked. It is my duty to do my duty toward my fellow men, whether they thank me or not.” Thus he dismisses the subject, and goes to talking about something else. Several times larger churches in Georgia, that could pay him more money than Tabernacle Baptist Church, extended calls to him to occupy their pulpits, but he always replied that Tabernacle Church was good enough for him, and then would assist the churches in securing good men. Such unselfishness is rare, and has helped very much to perpetuate the hold which Dr. Walker has had on the people of Georgia for so many years.

Tabernacle Baptist Church, Augusta, Ga., was the first colored church in this country to send its pastor on a trip to Europe and the Holy Land. This it did in the Spring of 1891. The church voted Dr. Walker a vacation of three months, with full pay, and the church and friends in Augusta, white and colored, furnished money with which to enable him to take the memorable journey. His church was supplied during his absence by the Rev. L. B. Goodall, at that time of Augusta, Ga., now of Charlottesville, Va.

He left Augusta Thursday afternoon, April 9th, 1891, and sailed from New York City on Wednesday, April 15th, at 11 o’clock, a. m., on the steamship City of New York, bound for Liverpool. He was accompanied as far as London by the Rev. E. R. Carter, D. D., of Atlanta, Ga., and Prof. M. J. Maddox, at that time, of Gainesville, Fla., now of Savannah, Ga. He visited Liverpool, London, Paris, Turin, Genoa, Pisa, Rome, Pompeii, Alexandria, Cairo, Ismailia, Port Said, Joppa, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Hebron, Jericho, Bethany, Mount of Olives, Gethsemane, Calvary, Beirut, Cyprus, Smyrna, Ephesus, Pierus, Athens, Corinth, Venice, Patras, Corfu, Brindisi, Basle, Heidelberg, Mayence, Cologne, Coblenz, Brussels, Antwerp, and some few other places. Dr. Carter accompanied him during the entire journey. He returned to New York on Saturday, June 27th, 1891, and reached Augusta on the fourth day of July.

Before leaving New York on his way to the Holy Land, he preached twice on the Sabbath at the Mt. Olivet Baptist Church, and, at the request of the pastor and officers, he preached again on Monday night, April 13th. The church gave him a liberal contribution to help him on his way, and he departed with their best wishes and with many prayers for a safe journey and a safe return.

The following account taken from the Augusta Evening News, of July 6th, 1891, will give some idea of Dr. Walker’s reception on his return to Augusta:

“The impressions of an intelligent, zealous and popular colored minister about the Holy Land are well worth hearing and recording.

“The Evening News has already announced the return of the Rev. Chas. T. Walker from his three months’ trip abroad, and, indeed, has kept up with him pretty well in his great journey in Europe, Asia and Africa. The paper was glad to commend him on his departure, and welcomed his return, and these courtesies are both deserved and appreciated. A man who is so highly regarded by his congregation and friends that he is given such a trip, and whose influence is all for good among his people in this community, certainly deserves consideration and courtesy. Hence, more space than ordinary is given to this prominent and popular leader among his people.

“A genuine and hearty welcome was given Mr. Walker by his congregation, and yesterday he preached to his church for the first time in three months. Last night he gave an outline of his trip through the Holy Land, and promised half hour talks about places, scenes and customs for every Sunday evening.

“After reading of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to Solomon, he took his text from the famous words, ‘the half has not been told,’ and declared that those words expressed his ideas about the Holy Land. He did not go into details about his journey, but with a wonderful power of seizing upon leading scenes and incidents and putting them before his audience, with their vivid illustrations and comforting lessons, the preacher held his vast congregation spellbound for about an hour. It was in itself a scene well worth witnessing, to behold this earnest and really eloquent man, with his deep and resonant voice, and genuinely magnetic manner, telling his story to breathless and sympathetic listeners, who crowded every inch of sitting and standing room in the church. This ovation was a great compliment to the humble man of God, who spoke in grateful terms of those who had sent him on his memorable journey; and every one of his people must have felt fully repaid when, in summing up the results of his trip and the analysis of his observations, he declared that, after seeing and investigating the Holy Land for himself, he felt more than ever that God’s word was true. If any one is sceptical about the Bible, its history and its sacred truths and traditions, said this preacher, let him go to Palestine, and he will be sceptical no longer.

“He also went to Egypt, which is scriptural land, where Moses, the greatest law-maker of the earth, was born, and where Joseph and Abraham, and even Jesus went, and he followed their footsteps back into Palestine, through Joppa, the gateway to Jerusalem, as it also became, through Peter’s vision, the doorway of the Gentiles to God’s kingdom. The preacher then described the great astronomical miracle performed by Joshua on the plain of Ajalon, when he commanded the sun and moon to stand still; he made graphic references to his journey along the famous highway over which the Roman Emperors and the Christian Crusaders traveled to the Holy City, Jerusalem, with its four mountains, its old walls, its eight gates, its well-remembered streets, was particularly dwelt upon, and the speaker declared that it was hard for him to realize that he was actually in the great city where the prophets walked, which was blessed by the Saviour’s presence and consecrated by his crucifixion. He went straight to Calvary, he said, and his description of Calvary, as the greatest battle field the world ever saw, was very interesting, and was one of the most eloquent and vividly touching portions of his discourse. The effect on the audience was realistic and remarkable. The people leaned forward, and as the preacher alluded to Calvary as the greatest battlefield the world ever saw and said that the cross was its eternal monument, murmurs and shouts of approval went up all over the house.

“The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Tomb of the Saviour, Gethsemane, the Brook Kedron, and the Mount of Olives, were in turn dwelt upon; and the minister said that as he bowed and wept at the Saviour’s Tomb, he arose refreshed and wrote in his note-book: ‘Thank God, he is a resurrected Jesus.’

“In describing the River Jordan, in which he bathed while he was there, and which he visited at the points where Joshua passed over, where Elijah ascended in the chariot, where Naaman was healed, and where Christ was baptized by John, the preacher was again inspired, as he described what he said was the most glorious convocation that ever took place on earth—when the Trinity met at the Saviour’s baptism.

“In impressing the truth of the Scriptures, Mr. Walker used several striking illustrations. He said that the old prophecies were coming true, and that even the Turks, in their ignorance, were fulfilling prophecy. They keep the Golden Gate—the Gate Beautiful—always closed, the only one entering Jerusalem which is never opened, because the superstitious believe that if the Christians ever enter by it, they will retake the city; but the minister declared that the real reason was that it was a fulfillment of Ezekiel’s prophecy found in the forty-fourth chapter of his writings. Again, Jeremiah said, twenty-five hundred years ago, that ‘Zion shall be ploughed like a field.’ The people of a then rich and powerful city came near stoning him for his madness, and yet the speaker declared, with his own eyes he had seen the fulfillment of this prophecy. Jeremiah also declared that Zion should be rebuilt, and on the unearthed ruins of the very towers indicated by Jeremiah, the rebuilding of Jerusalem had been begun. To-day, they are rebuilding, as the prophet said. In Jerusalem and all through Palestine, the record speaks in solemn, sacred and rock-ribbed confirmation of the blessed and everlasting truth of God’s word.