| Title: | Hindu Magic |

| An Expose of the Tricks of the Yogis and Fakirs of India |

A few minor typographical errors were silently corrected.

The cover image was produced by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

AN EXPOSE OF THE TRICKS OF THE

YOGIS AND FAKIRS OF INDIA

BY

HEREWARD CARRINGTON

Author of “Handcuff Tricks,” “Side Show and Animal Tricks,” “The Boys’ Book of Magic,” “The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism,” Etc., Etc.

ILLUSTRATED

PUBLISHED BY THE SPHINX

Kansas City, Missouri

1913

TO

SIDNEY LENZ

(With Warmest Regards.)

3

| Page | |

| The Mango Tree Trick | 5 |

| The Basket Trick | 19 |

| The Dry Sands Trick | 26 |

| The Coloured Sands Trick | 27 |

| The Diving Duck | 29 |

| The Jumping Egg | 30 |

| The Beans and Scorpion Trick | 32 |

| The Basket and Birds Trick | 33 |

| The Ball of Cotton Trick | 34 |

| The Brass Bowl Trick | 37 |

| Snake Charming | 38 |

| Voluntary Interment | 41 |

| The Rope Trick | 44 |

5

HINDU MAGIC

In this pamphlet I propose to consider the phenomena which are presented by the fakirs and yogis of India, and to inquire into their nature and the method of their production.

The feats performed by Indian fakirs are numerous, but I shall describe those most commonly witnessed: the mango-tree trick, the basket trick, the bowl of water trick, the dry sands trick, the rope and dismembered body test, levitation, snake charming, burial alive, etc.

As so much is heard of Indian magic, and the powers of the Oriental performer, it may be well to examine their performances somewhat critically, and to see how far we are entitled to assume that there is anything in them suggesting the supernormal, anything calling for explanations that necessitate the operation of laws “other than those known to Western science.”

I shall begin by describing the famous mango-tree trick—perhaps the best known of all the feats performed by the Indian conjuror. I shall first of all describe the performance as it would appear to the uninitiated witness, afterwards explaining the secret.

As the trick is usually exhibited, it is some 6what as follows: The native comes forward, almost nude, being covered only with a small loin cloth, of such small compass that the onlooker can see clearly that there is nothing hidden in or about it or the performer. As the trick (like almost all Indian tricks) is performed in any locality—on the deck of a ship, in one’s own room, etc.—all idea of pre-arrangement, trap-doors, etc., is precluded. The performer advances, carrying in his hands a little earthen or tin pot containing water, and another containing a quart or so of dry sand. He also has with him some seeds of the mango-tree, and a large cloth, about four feet square. This is shaken out and both sides are shown to the spectators, so that they may see that nothing is concealed within it.

All this having been gone through, the fakir proceeds to build up a little mud pile of his earth and water, mixing the two together with his fingers, and dexterously moulding them into a 7 pyramid of muddy earth. This may be done in some previously examined vessel, or on the bare earth or floor. The mango-seed is now inserted in the soil, and covered on all sides with earth. The fakir then covers the mound of earth with the shawl or large handkerchief, and places his hands and arms under the shawl, manipulating the seed and the earth for some time; placing his hands over the seed; making passes above the seed, etc. As his hands and arms are bare, and can be seen bare throughout this process of manipulation, and as his hands never once approach his body, no one has any objection to his handling the seed and the earth in this manner, or to his placing his hands beneath the cloth. After a few minutes of this manipulation, the conjuror withdraws his hands, and proceeds to make passes over the cloth and above it, at the same time muttering semi-articulate incantations, etc. Sometimes a tom-tom is beaten, or other instrument is played upon, and, after a while, the conjuror removes the cloth, and the seed is seen to have sprouted—a couple of tiny leaves appearing above the surface of the earth. If the onlooker is especially skeptical, the fakir sometimes removes the seed, and shows the skeptic a couple of minute roots, sprouting from the lower end of it. It (the seed) is then replaced in the earth, the manipulations and incantations repeated, and, after a while, the fakir removes the cloth a second time, and the mango is seen to have sprouted still more—now being 8 several inches in height. This process is repeated five or six times, or even more, at the end of which time the mango-tree is two feet or more in height. It is even asserted that, in some cases, the tree has been known to bear fruit.

So much for the effect of the trick. Now for the explanation.

There are numerous ways of performing this mango-tree trick—for trick it is.

In the first place, it will be noticed that it is always a mango-tree that is made to grow, and no other shrub. Now, why is this? Surely it is not because the mango is the only tree in India which is ready to the hand of the fakir, for we know that there are numerous others that might be made to grow. And yet it is always the mango! The conjuror, S.S. Baldwin (from whose book, Secrets of Mahatma Land Explained, I shall have occasion to quote later on), asked a native conjuror if he would make a young palm, a tea plant 9 or a banana tree, grow for him, and received the response: “Nay, sahib, cannot do. Mango-tree the only one can make.” I repeat, why is this?

The reason is that it is the peculiar construction of the mango leaf that renders the trick, as presented, possible at all. The leaf and twigs of the mango-tree are exceedingly tough and pliable, almost like leather, and can be folded or compressed into a very small space without breaking the stems and the leaves, and, when this pressure is released, the leaves will resume their former expanded condition very rapidly, without showing any traces of the folding process. The leaves can be turned upon themselves and rolled into a tight ball, in which folded condition they occupy very little space, and yet will resume their extended condition when this pressure is released. And this brings me to the heart of my explanation.

The mango seed that is placed in the mound of earth is especially prepared before the performance, by the fakir, in the following manner: He splits the seed open, scoops out its contents, dries it somewhat, then places within it a shoot of a mango-tree folded and compressed so as to fit into the mango seed. It must be remembered that the mango seed is no small thing, but is about two inches long (sometimes more) by an inch to an inch and a half broad. It resembles slightly the mussel shell found on the seashore. It will be obvious that a seed of this size might contain a 10 good deal of material, and if the mango leaves were folded into a small compass, would hold a good-sized twig. The leaves are folded very carefully, and are prepared in a special manner. The upper surface of the leaf must be folded on itself, and that surface, skillfully treated and watered, will scarcely show a crease on a superficial examination. The creasing which the under surface would show is, of course, concealed from the spectator’s view.

When the fakir places his hands beneath the cloth the first time, then, he gets hold of the seed, and proceeds to manipulate it in such a manner as to extract from the upper end of the seed about an inch or so of the plant it contains. He may extract the seed altogether from the earth for that purpose, and replace it in the earth again at the conclusion of this manipulation, banking up the earth around the seed again before removing his hands. The fakir then removes both hands, and proceeds with the playing of his tom-tom, and whatever other mummeries he may see fit to perform, in order to impress his onlooker. After a while the cloth is removed, and the seed is found to have sprouted, and an inch or so of the stem and the first green leaves are seen to be sprouting from the earth. The illusion is perfect, and the onlookers are more taken up with gazing in wonder at the miraculous growth and discussing it one with another than with critically examining the seed and the sprouting plant. If the conjuror 11 wishes to show the roots sprouting from the lower end of the seed, he merely has to place these roots in the seed before the performance begins, and extract them in the course of his manipulation of the seed, previously explained. The preparation of the seed is concealed by the fact that a duplicate seed is first exhibited to the spectators, and that seed is frequently examined by them. Before the seed is placed in the ground, however, the conjuror finds occasion to change it for another, prepared in the manner described. No one thinks of examining the seed after the performance is concluded.

To return, however, to the method of working the trick. After the conjuror has shown the growth from the seed the first time, he covers the seed with a shawl and again places his hands beneath the cloth and works out a little more of the mango; then repeats his incantations and his tom-tom playing; finally showing the shoot a second time, when it is found to have grown a considerable amount in the interval. Amazement is correspondingly great! This performance is gone through several times, until the folded mango shoot is all worked out of the seed, the growing tree being covered each time by the shawl. When the shoot is all worked out of the seed, there is a fair-sized shrub standing before you.

But there are some cases in which the mango-tree is reported to have grown to a height of several feet, and even to bear fruit; and the explanations offered would not explain such cases, 12 it may be said. That is admitted; and I shall now endeavor to explain how these more marvellous feats are performed.

It must be remembered that Hindu fakirs seldom or never travel singly, but always in troupes of threes and fours; and, during the performance of one of the fakirs, the others assist him by passing him the articles he uses in his performance—jars, water, earth, etc. Now, every time the conjuror moves the shawl from the growing plant, he tosses the shawl to his assistant, and shows his hands empty. When receiving the shawl back from his assistant, he also shows his hands empty; then shakes out the shawl and shows both sides of it—showing, in this way, that nothing is concealed in the shawl, and that he introduces nothing under cover of the said shawl. To all appearances, nothing could be fairer. And, indeed, nothing is fairer at first; but the conjuror shakes the shawl less and less vigorously every time he places it over the mango-tree, until, towards the end (the seventh or eighth time, let us say) he hardly shakes it at all. The spectators, having seen it empty so many times, get into the habit of mind of thinking it is empty as a matter of course, and pay no attention to this part of the performance, after the first few times. Their thoughts and attention are centered upon the mango-tree and its growth. So, when the conjuror has worked out all the shoot from the seed, he must perforce introduce a fresh shoot of larger proportions; and he does this in 13 the following manner: He passes on word to his assistant, by means of a secret sign, that he has reached the end of his present stock of “occult vitalizing influence”—in other words, the mango shoot—and the assistant, in passing him back the shawl or cloth this time passes him back another cloth, which he has secretly exchanged for the original one—the one the conjuror began operations with. This second cloth is double, and contains a very large mango shoot, more or less doubled up in the manner of the first shoot that was placed within the mango seed. A slit in the cloth enables the conjuror to extract the second shoot, and place it in the mound of earth, working this shoot out to its natural size with his fingers. When this large shoot is worked out to its full limit it is a very large tree, and the conjuror has only to remove the cloth to display it to his astonished onlookers. The cloth just employed is exchanged for the original while the eyes of the spectators are fascinated by the huge tree just exhibited to them, and when the trick is concluded this cloth is handed for examination; and, of course, no trickery is discovered in connection with it. The whole performance is a very pretty chapter in the psychology of deception.

As to the cases in which, it is asserted, fruit grows upon the tree grown in this manner, I have no exact explanation of that fact, and I frankly confess my disbelief in its occurrence. I have diligently searched for any first-hand account of 14 this fact, and have never found one; nor have I been enabled to meet anyone who could assert that he had seen it himself. It seems to rest on the same hazy foundation as the famous rope exploit, to be discussed later on.

I may say that my father was an old Anglo-Indian, having lived ten years in Calcutta, but he never saw this finale to the trick, though he had many times seen the mango-tree trick performed, as described above. Nor had he ever met anyone, in all that time, who could state that he had witnessed the feat with his own eyes. It would seem, therefore, to be one of those “grand finale” flourishes which happened to be placed at the end of some magazine writer’s description of the mango-tree trick, in order to make it appear as wonderful as possible—and gained wide credence on that account!

There is then, so far as I have been enabled to discover, no first-hand account of fruit growing upon the mango-tree, that has been made to grow in the manner described; and until such evidence be forthcoming, I think we are entitled to say that it has never been done. However, there are certain considerations which might make us admit that such was the case—and yet the fruit might be obtained and placed there by fraudulent means! One such method would be for the fruit to be introduced under the cloth, in the act of covering the mango-tree. The introduction of the fruit would be comparatively easy if some of 15 the methods about to be explained were employed. At all events, this feat is no more difficult—certainly no more “miraculous”—than that performed by Kellar, in which roses are made to grow from empty flower pots—which roses are cut and distributed to the audience immediately. In this instance, two empty flower pots are shown (they may be examined, if desired) and filled with earth. Seeds are then sprinkled over the earth, and watered. A tube, open at both ends, is then shown empty, and examined by the audience. It is made of card-board, and everyone can see that it is quite unprepared. First one flower pot and then the other is then covered with this tube, and upon removing the tube, the seeds are found to have sprouted into full-grown bushes, fully eighteen inches in height, and covered with roses—at least fifty, on both plants. These roses are cut off immediately, and distributed among the audience, who testify to their genuine character. In a very similar illusion, on a small scale, a glass tumbler is filled with earth, and covered for a moment with a borrowed hat; upon removing which it is found that the seeds have blossomed into a plant about six inches high. If flowers can be made to grow under such circumstances, therefore, why not fruit upon mango-trees, grown under similar conditions, and before far less critical audiences, who have already had their critical faculties blunted, moreover, by a succession of unexplained marvels?

16

So far, I have described only one method of performing this mango-tree trick, and there are several other methods, which I shall now briefly enumerate—since the method above described is the one in general use, without a doubt. Another very good method, however, is the following, which was first made public, if I remember rightly, by Mr. Charles Bertram, the conjuror, to whom I am indebted for the secret, in this instance.

In this case the conjuror makes his mound of earth as in the last instance, and has a prepared seed, which he exchanges for an examined seed at a convenient moment. The seed in this case is, however, prepared in a slightly different manner. It is split in two, and emptied of its contents. Then one end of it is wedged open by means of a small wedge of wood, and several small pieces of string are inserted into the other end, which, when hanging down from the seed, after being placed in the mud, exactly resemble roots. The seed is then fastened together, so that the two sides or halves will not fall apart. This seed the conjuror exchanges for the examined seed at some convenient moment, and this is the one placed in the ground.

The juggler then hands round for inspection four bamboo sticks, and a piece of thin cloth. After the sticks are handed back to him, he places them in the ground, slanting towards a common centre, and ties the tops of the sticks together 17 with a bit of string. Around these sticks is now stretched the cloth, thus making a sort of tent, about three feet in height and open at the back. The thinness of the cloth allows the interior to be dimly seen through it. The mound of earth, containing the seed, is within this tent, it having been built round it, in fact. The juggler suddenly appears to notice that the cloth is too thin, allowing the interior to be seen through it, and proceeds to cover the tent with a thicker piece of cloth. The conjuror in this case has a rag doll, which he uses very much as our Western magicians use their wands; and with this he proceeds to make passes over the tent, about the seed inside the tent, etc. He also waters the seed several times. After a time, the cloth is lifted up, and the spectators see that the tree is several inches in height. This performance is repeated several times, the passes, waterings, etc., being gone through each time, and generally a wait of several minutes is necessitated, during which waits the conjuror performs some other trick, such as the diving duck, the cups and balls, or the colored sands, all of which I shall explain later on. At the conclusion of the performance the juggler removes the cloth, and the mango is found to have grown to a very respectable height.

Now for the explanation:

In the first place, the rag doll which the conjuror uses is hollow, and contains, folded up within it, a shoot of the mango-tree. In the course of 18 making passes over the seed he extracts this shoot, and inserts it in the wedged-open end of the seed, where it remains until removed. The conjuror could now show this shoot, but it would lose in effectiveness to show it so soon, and for that reason he performs the minor tricks in the interval. When he returns to the tent and raises the cloth, this shoot is seen sprouting from the ground. The conjuror then lets the cloth fall to the ground again, and proceeds to make more passes over the seed. During these passes he manages to extract the small shoot from the seed, and replace it in the rag doll again. He then places a much larger shoot of the tree in the slit end of the mango seed. This larger branch was concealed in the second cloth which the conjuror placed around his tent, after discovering, apparently by accident, that the first cloth was so thin as to be semi-transparent. Within the folds of this second cloth was contained the mango-tree shoot of larger size. The tree is now grown to its full size and might be shown immediately, but, for effect, the conjuror again waits for several minutes before showing the growth to his onlookers. Sometimes the tree is made to disappear altogether at the end of the performance, like the palace in the Arabian Nights. When this is the case, the conjuror has extracted the branch from the seed, and managed to conceal it under the carpet on which he was sitting. This is gathered up and removed at the close of the entertainment.

19

There are, doubtless, other methods of performing this mango-tree trick. Kellar describes a method in which the performer concealed several shoots of the tree of various sizes within his sleeves, and produced them in turn, under cover of the cloth. As, however, Hindu fakirs seldom wear robes of the kind, I think we may say that this is a method seldom used. Some conjurors cover the growing seed with a basket; and when this is the case there is probably room for concealment of shoots of the tree within secret compartments of the covering basket.

I now come to the “basket trick.” For this trick the juggler brings forward a large, oval basket, peculiarly constructed, being much larger at the bottom than at the top. Probably nearly every one is familiar with the shape of these baskets. The lid is perhaps 30 inches by 18 inches, and is oval, while the basket itself spreads out to about 4 feet 7 inches by 2 feet 6 inches at the bottom.

Roughly, the basket may be said to resemble a huge egg, with an opening in one side. This is shown to the audience empty, and a man or boy is brought forward by the conjuror. This boy wears some conspicuous article of clothing—a scarlet turban or jacket. He is placed in the basket, into which he apparently just fits, occupy 20ing the whole of it. The lid is placed upon his head, and a large blanket is thrown over it, completely covering him and the basket. He is seen to sink down gradually until he finally disappears into the basket altogether, and the lid resumes its natural position over the opening.

The performer now removes the cloth and proceeds to run the basket through and through with a sword he has in his hand. Every part of the basket is pierced in this manner, and it appears as though the boy must be killed, even if he somehow managed to conceal himself within it. The juggler now replaces the blanket over the basket, places his hands under it, and removes the basket lid, throwing it to one side. He then places his hand into the basket itself and removes the turban and the jacket, which he throws to one 21 side. The body has apparently disappeared! To make matters more certain, however, the juggler suddenly jumps right into the basket, stamps about with his bare feet, and ends by sitting in it himself.

As it was formerly seen that the basket was only large enough to contain the boy, it seems impossible that he can now be concealed in or about it. The conjuror then replaces the turban and the jacket in the basket, replaces the lid, and removes the blanket. Suddenly he darts forward, carrying with him the blanket, and snatches in the air with the latter as if catching a body, and goes back with much excitement and much jabbering to the basket, which he covers with the blanket; when suddenly something is seen to be moving under the cloth! Immediately the lid of the basket goes up. In another moment the boy, clad in his jacket and turban, emerges from the basket, none the worse for his recent trying experience.

I shall now explain this apparent marvel.

The instant the boy is covered with the blanket he proceeds to divest himself of his jacket and turban, which he deposits in the bottom of the basket. He now gradually sinks into the basket until he is completely inside it and the lid is even with the top of the basket. Now comes the chief portion of the trick—the method of concealment of the boy within the basket—for he does not escape from within it, in the version of the trick now described, but remains within it throughout 22 the performance. It will be remembered that the lower portion of the basket is much larger than the top portion. The boy within the basket manages, then, so to curl his body round the basket, eel-wise, that he is occupying the entire outer rim of the basket, so to speak, thus leaving the centre of the basket (the part of the basket directly under the opening) empty. When the juggler runs his sword through the basket he takes special pains to run it through this unoccupied space, almost exclusively; and, by the concealed boy wriggling from place to place within the basket, the juggler is enabled to run his sword through almost every portion of it in turn, and so give the appearance of its complete emptiness. It will now be seen that the juggler can place his hand inside the basket and remove the discarded jacket and turban at any time; also the lid, and to stamp and sit in the basket, since the space he occupies is that left unoccupied by the boy in the 23 basket. So long as the blanket is over the opening in the basket, the boy can never be seen. The magician then replaces the jacket and the turban in the basket, and replaces the lid—all this before removing the blanket. As soon as the lid is again placed upon the basket the boy inside slips on his jacket and turban, and is ready to emerge from the basket as soon as the lid is withdrawn. The snatching in the air with the blanket is to distract the attention of the sitters away from the basket while the boy is donning his clothes—since some slight movement of the basket might be noticed and the spectators thus suspect that the boy is already inside.

Sometimes the boy is seen to be outside the basket at the conclusion of the performance, and in some distant tree, etc. How is this to be explained? (1) There may be two boys, exactly alike, the first of which remains in the basket, while the second, dressed like him, hails the onlookers from the tree-top and comes down among them. During the instant that everyone’s attention is directed to the boy in the tree and his approach, the original boy makes good his escape, aided by a confederate, who stands close by the basket, and in whose hands is a large blanket, partially covering the basket. The boy escapes behind this confederate’s body. (2) There is also a method of causing the boy to disappear and appear in a tree-top, without employing any duplicate boy or confederate. In this case, the 24 basket is placed within a few feet of some convenient wall or hiding place, and the trick is performed on that spot. Matters proceed very much as before until the time comes for causing the boy to vanish and re-appear in the tree. When this time comes the juggler brings forward four poles, four or five feet in height, and these are stuck in the ground around the basket, and the conjuror has two or three assistants stationed on each side of the basket, assisting him, and standing a few feet from the basket. In this case the boy wraps up his turban and jacket in a cloth, while in the basket, and this the conjuror manages to get hold of and pass out to one of his assistants earlier in the trick, while the basket is being constantly covered and uncovered.

Presently the conjurors begin to quarrel among themselves, and at the same time others begin to play upon tom-toms, etc., making an awful noise and distracting the attention of the spectators away from the basket containing the boy. Meanwhile the conjuror has procured a large piece of cloth, and has attached one end of this strip to one of the poles—one of those nearest the onlookers. He then proceeds to attach it to each of the other four in turn, thus enclosing the basket in a roofless tent, the front side—the side nearest the audience—being enclosed last. At least, so it appears. What has really happened, however is this. At the moment when the noise was created, and the conjuror’s assistants began 25 quarreling among themselves, and the spectators’ attention was accordingly distracted as much as possible, the conjuror crosses in front of the basket for a moment, as though to ascertain the cause of the disturbance, and for an instant conceals the basket from view. In that instant the boy leaps from the basket, darts between the legs of one of the assistant conjurors, and is lost behind them before the cloth is withdrawn that had concealed his escape. It has taken only a second or two, and the interval is so short no one remarks upon it—especially as they were distracted by the noise, etc., at that instant. The careful enclosure of the basket subsequently also tends to convey the impression that the boy is still within it. But he has now escaped; he has turned the corner, and is hidden from the view of the spectators. He carries with him the cloth containing his jacket and turban, which he proceeds to don. Then, climbing a near-by tree, he is ready to cry out to the spectators whenever he receives the signal from the conjuror to do so.

Another method of escape is the following: The conjuror wears a thick strap under his loin cloth. The boy, under cover of the enveloping blanket, reaches up and grasps this strap, and by its aid he draws himself from the basket, and round, behind the juggler. He is hidden for the moment by the conjuror’s body and the blanket, which the juggler has removed from the basket. 26 The boy slips away into the crowd, through confederates, as in the manner last described.

Perhaps one of the best known tricks performed by the Hindu fakirs, after the two just enumerated, is the “dry-sands trick.” In this case, the juggler brings forward a little pail, some eight or nine inches high, and perhaps six inches across the top. This the conjuror proceeds to fill with water. There is no trick about the pail, and the water is ordinary water, which may be supplied from any source. The conjuror then extracts a handful of dry sand from a bag and blows it hither and thither, showing it to be exceedingly dry. A handful of this sand is then carefully deposited in the bottom of the pail, in the water, and everyone can see it, resting peacefully at the bottom of the pail. The conjuror then carefully washes and wipes his hands, and shows them perfectly clean and empty. Then, placing one hand in the water, he extracts from the pail a handful of the sand, and shows it to be just as dry as when it was placed in the pail. Blowing sharply into his hand, the sand flies in every direction, showing it to be still perfectly dry.

This is a very ingenious trick, and could never be discovered unless its secret were explained. There is no trick about the pail or water, as stated: it all consists in the preparation of the 27 sand. In order to prepare this sand for the experiment, the juggler procures some fine, clean, sharp sand, gathered from the seashore preferably. This is washed carefully a number of times in hot water, so as to free it from adhering clay or soil of any sort. It is then carefully dried in the sun for several days.

About two quarts of this sand is then placed in a clean frying pan, and a lump of fresh lard the size of a walnut is placed into the pan with it. It is now thoroughly cooked over a hot fire until all the lard is burned away—the result being that every little grain of sand is thoroughly covered with a slight coating of grease, which is invisible to the sight and touch, and at the same time this renders the sand impervious to water. When the little handful of sand is placed in the bottom of the bucket, to be shortly afterwards brought out, it is squeezed tightly together into a little lump, the grease making it adhere. Thus, when it is brought out it is nearly or quite as dry as when placed within the pail. Brick dust is sometimes treated in a similar manner.

This is another trick very popular with Indian jugglers, known as the “coloured sands trick.” The conjuror eats a small quantity of sand or sugar, apparently swallowing it. He then eats sugar coloured variously—black, red, yellow, 28 green and blue, as well as the usual white sugar. These are chewed and swallowed by the conjuror each in turn. The conjuror then asks his audience to select whichever colour they prefer of those swallowed, and, upon the choice being made, the conjuror immediately blows from his mouth the coloured sugar requested. This is repeated until all the colours have been called for in turn. Sometimes the juggler dissolves all the coloured sugars in water and drinks the compound. Sometimes, again, chalks are used instead of sugar; but these are merely variations of the same trick, and are worked on the same principle exactly.

For this trick, the conjuror has secretly prepared beforehand six small packages or capsules, each one containing one of the coloured sands. These are enclosed in thin, parchment-like skin, and are secreted in the conjuror’s mouth, three in each cheek, in a pre-arranged order. The conjuror can easily reach any one of these packets with his tongue, bring it to the front of the mouth, break the skin by pressing it against his teeth, and blow the sand, sugar or chalk out in a perfectly dry condition. This is repeated until all six have been exhausted, when the trick is said to be concluded. If some skeptical investigator wishes to examine the juggler’s mouth, he merely swallows the skins. The sugars or chalks were also swallowed in the first place. Hindu jugglers will frequently swallow far more disagreeable things than skins for the sake of a few rupees.

29

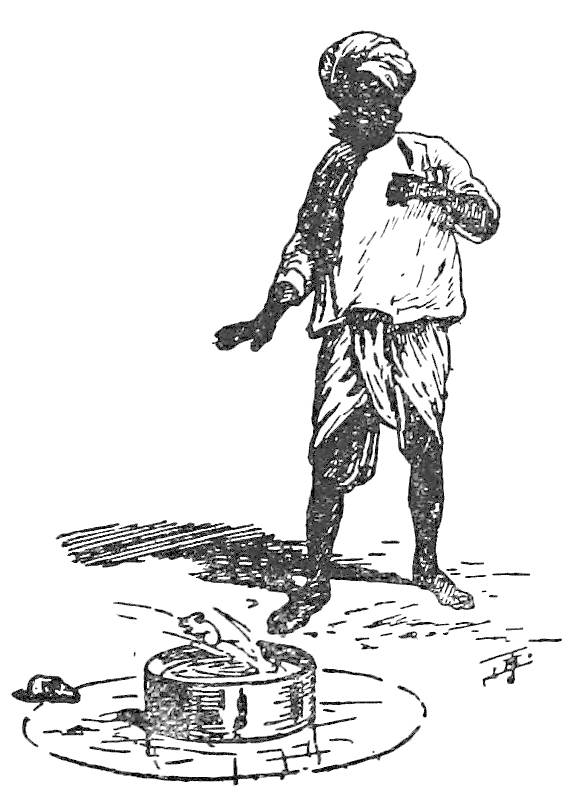

There is a very simple, and yet a very puzzling, little trick known as the “diving duck.” The juggler places a shallow bowl upon the ground, which he proceeds to fill with water. When this is done the conjuror places a miniature artificial duck in the water, then retires from the bowl about two feet, and begins to play upon his tom-tom, etc. Soon the duck is seen to move, and very soon it dives in a very natural manner. Whenever the hand of one of the onlookers approaches the duck it dives out of sight, reappearing as soon as the hand recedes. Finally, the duck is taken out of the water, and immediately handed for examination, when it is found to be perfectly free from trickery or preparation of any sort. The bowl is also emptied of its water and again shown to the onlookers.

The secret in this case is, again, simplicity itself. In the bottom of the shallow pail or pot 30 there is a miniature hole bored, and through this is passed a thread or hair. To the inner end of this hair is attached a small dab of wax. The other end extends along the ground, and the trick is always performed on soil the colour of which will make the hair invisible. The duck is fastened to the inner end of the hair by means of the bit of wax; and it can readily be seen that, when the pail is filled with water, the duck will dive beautifully every time the hair is pulled by the conjuror, and will rise to the surface when this pressure is released. This is the complete secret of the diving duck. In order to conceal the fact that the pot leaks, the conjuror first sprinkles some water on the ground; or fills the bowl so full (apparently by accident) that it overflows. This conceals the fact that water is gradually running away through the small hole in the bottom of the pail.

In another trick sometimes exhibited the reverse method may be said to be employed—since the egg or small rabbit employed jumps out of the water, at the word of command, and lands on the ground, right outside the pail. No thread or hair is used in this case, however, as might be supposed, and onlookers sometimes come right up to the pail and stand over it while the rabbit makes his marvellous leap. The juggler may be 31 any distance from the pail at the time, and even held by onlookers to prevent any action on his part.

The conjurer begins by filling the little pail with water. After he has done this he pours into the water some coloured sand, and stirs it up with a stick, when the sand rises to the top of the water, forming a sort of curtain, and preventing anyone from seeing what is within the pail. In the act of stirring the water, pouring in the sand, etc., the juggler has secretly introduced into the pail a thin but broad spring, bent over so as to form an almost complete circle. The two ends of the spring are kept apart by means of 32 a piece of sugar, so that, when this sugar melts, the spring will be released and will spring open with a sudden jerk. It is upon this spring that the egg or little rabbit is placed. The juggler goes through various incantations, playing the tom-tom, etc., until the sugar melts, when the spring will fly uncoiled, and the little rabbit will be ejected from the water precipitously. If the pail is emptied later on, the juggler simply turns the pail upside down, thus allowing the water to escape, and retaining the spring by means of his finger.

The trick that is sometimes seen of changing three beans into a scorpion or a snake is simplicity itself—is so simple, in fact, as to be seldom exhibited. It is sometimes seen, however. The juggler has a box, containing two compartments. In the upper one the beans are kept, while the lower one contains the scorpion or the little snake. These compartments are separate, and either can be opened at will. The conjuror puts the three beans into the hand of one of the audience and tells him to hold them. He then asks him to open his hand again to see if they are still there. The conjuror takes them out of this person’s hand, exhibits them to the audience, and puts them back in the box. He asks the spectator to again hold his hand out; and, when he has done so, the 33 conjuror deftly opens the lower box and allows the snake or scorpion to fall into his hand. Naturally this person jumps back, and, in the excitement, the conjuror has ample opportunity to exchange the box used for another, without preparation.

Another trick sometimes seen is the following. The conjuror exhibits a basket, some 18 inches in diameter and 14 inches high. A stone is placed under the basket, which is then inverted over it. Soon the basket is lifted, and a snake or scorpion is found beneath it, while the stone has disappeared. The snake is thrown into a bag which the conjuror carries with him, and the basket replaced on the ground. After some manipulation the basket is again raised, and this time 34 some ten or fifteen little birds walk out from beneath it. Apparently nothing could be more extraordinary!

And yet the explanation is simplicity itself. In the act of inverting the basket the first time the conjuror introduced the snake or scorpion and removed the stone—very much in the same way as Western conjurors extract and replace the cork balls in the cups-and-balls trick. The little birds are all contained in a black cloth bag; and are introduced into the basket when everyone’s attention is called to the snake or scorpion, left on the ground, after the basket is raised the first time. The conjuror introduces his hands beneath the basket and opens the cloth bag; when the little birds are free to make their escape. The bag can be disposed of at any convenient moment.

Mr. Charles Bertram, writing in Mahatma (a conjuror’s magazine) for February, 1900, said:

“The most startling trick I ever saw was done by a man who was performing some of the little tricks while the mango-tree was growing. He took a little ball of rough cotton, about the size of a walnut, and threw the ball to a woman who formed one of the party of those who were assisting him. The jerk unravelled about two 35 yards, and she broke the end off and kept the ball. The conjuror placed the end which he held into his mouth, and by a deep breath the cotton flew into his mouth and he appeared to chew it. Then he borrowed a penknife from me, and with a big blade made as though he would stab himself in the throat, the woman preventing him with some show of excitement; but presently, turning her back, the man seized the opportunity to plunge the knife into his stomach, and that he did very well. He then put his hand under the loose linen shirt he was wearing and began to draw out the piece of cotton.

“When he had drawn out nearly as much as the length of the piece which had been broken 36 off, he lifted his shirt slightly and showed the end of the cotton apparently embedded in the skin. He then took the knife and moved it upward against the skin as if he were pressing out the last bit of thread, which was tinged with red, as if with blood.

“This was really an admirably executed little trick, although by no means difficult. The sucking in of the cotton is skilful, but with a very little practice I was able to do the same thing, and so can anyone else, the only precaution to be taken being to prevent the end coming into contact with the back of the throat, for if it did it would bring on an attack of coughing.

“Of course the chewing of the cotton is merely a method of secreting it, and another piece of cotton of similar length is rolled up previously and put in its place with the end coloured with some paint. A little brown material is put over the skin with a scrap of cotton, perhaps a quarter of an inch attached to it, so that it really looks as though it were sticking up out of the skin, and the upward movement of the knife scrapes this off, and it can easily be gotten away at a convenient time. This is hardly a trick for an English drawing-room.”

Frequently we see an Indian juggler remove his turban, double it, cut it into two pieces, and finally join them together again. I think it will be a sufficient explanation if I state that this feat is performed precisely in the same manner as the 37 familiar string trick—in which a piece of string, cut in halves is restored to its original condition. As every schoolboy knows this trick, I shall not dwell upon it here.

Mr. S. S. Baldwin describes a very ingenious trick he once saw performed.[1] A juggler brought forward a brass bowl, which he showed empty. He filled this with cold water, placing a little piece of ice in the water, to show it was really cold. He then covered the bowl for a few moments with a borrowed handkerchief, made passes over the bowl, played on his tom-tom, etc. Soon he removed the handkerchief, and the water was found to be scalding hot, as was verified by placing the fingers in the water.

In this case the bowl was of a peculiar construction. The sides of the bowl were double; and so also was the foot upon which it stood. When brought forward the space between the two sides of the vessel was filled with the boiling water, while the lower space was empty. While covering the bowl with the handkerchief the juggler found occasion to scratch off a wax pellet, covering an air-hole, this allowing the cold water to run down into the empty space in the foot of the bowl. By scratching off a second wax pellet on the side of the bowl the hot water is made to 38 run into the body of the bowl until it finds its own level. It is difficult to explain this on paper, but the principle upon which it rests is well known to Western conjurors, and is the basis of several good illusions performed by them.

There are several minor tricks that I should like to consider, but cannot for lack of space. Thus, M. Jacolliot states that he saw a small stick, placed upon the top of a vessel of water, move in all directions, and finally sink to the bottom of the vessel at the command of the fakir. He suggests that “the fakir, upon charging the small piece of wood with fluid, might perhaps have increased its weight so as to make it heavier than water.”[2] Personally I should be inclined to think that the piece of wood was manipulated by means of a hair, somewhat after the manner of the “diving duck,” described above. Baldwin saw a somewhat similar trick in Zululand. In this case the conjuror threw a branch of wood upon the surface of the river, which promptly proceeded to swim upstream! He afterwards discovered that, in this case, the trick was effected by means of long black threads, in the hands of hidden assistants.

I now pass on to consider, very briefly, the feats of snake-charming that are so frequently exhibited. I do not doubt that much—perhaps the 39 majority—of that which is exhibited by snake charmers is genuine, with one exception; the fangs of the serpent are invariably extracted.

Hindus are exceedingly ingenious in extracting fangs, stings, etc., and I have heard from many independent sources that snakes are never exhibited in public unless their fangs are first extracted. It may interest the reader to learn that my sister, when a little girl, took a great liking to bees, and desired to play with them. My father and mother were in Calcutta at the time, and bees were plentiful. Accordingly, my father commissioned one of the servants to extract the stings from a number of bees, which he did with great skill, and apparently with no lasting injury to the bee. My sister then had a whole room full of bees to play with, while quite free from danger herself. I mention this to show how ingenious Hindus are in handling reptiles and insects of the sort, thus proving that it would be quite possible for them to extract the fangs from any serpent. The fangs once extracted, and the snakes fed upon milk, and perhaps more or less drugged and charmed by the music, we can very readily see that it would be no very difficult feat for the snake charmer to handle them in any manner desired.

It is a well-known fact that snakes and many other animals may be hypnotised and rendered more or less cataleptic by means of passes and various manipulations. Sextus, in his Hypnotism, 40 devotes many pages to this subject. It is probable that, when a snake is stiffened out to its fullest extent, and remains stiff, it cannot be distinguished from a stick at a first casual glance. Perhaps this may bear some resemblance to the priests who performed before Pharaoh, “changing their rods to serpents” before his eyes. At all events, I quote the following passage, which seems to bear a distinct resemblance to that incident, and has the advantage of being “recorded at first hand,” and is by no means so “remote” as the other tale! It runs as follows:

“Sitting one morning on the verandah, an aged magician approached and asked permission to perform some of his tricks. As I was in a humor to be amused, I told him to go ahead. He asked me to loan him the walking-stick which I carried. He waved this over his head two or three times and exclaimed: ‘No good; too big; can’t do,’ and handed the stick back to me, which, as I grasped it, changed into a loathsome, wriggling snake in my hand. Of course, I immediately dropped it. The magician smiled, picked up the snake by the middle, whirled it around in the air, and handed it back to me. As I refused to take it, he said, ‘All right, no bite,’ and behold it was my stick.”[3]

I think the similarity of narrative should at least prove suggestive and interesting.

41

Let us now turn to a consideration of those feats of “voluntary interment” so often referred to.

Take, e.g., the famous case of the Fakir of Lahore, who, at the instance of Runjeet Singh, and under the supervision of Sir Claude Wade, was interred in a vault for a period of six weeks. Doubtless the details are familiar to most of my readers. The fakir’s ears and nostrils were filled with wax, and he was then placed in a bag, then deposited in a wooden box which was securely locked, and the box was deposited in a brick vault which was carefully plastered up with mortar and sealed with the Rajah’s seal. A guard of British soldiers was then detailed to watch the vault day and night. At the end of the prescribed time the vault was opened in the presence of Sir Claude and Runjeet Singh, and the fakir was restored to consciousness.

Now, though I shall not say that a feat of this kind is impossible, far better evidence will have to be forthcoming than an account such as the above, in order to gain credence. How was the bag tied in which the fakir was placed? Who made the box? What guarantee have we that there was no outlet from the vault than by means of the door? In short, there are so many methods of escape that such a badly recorded account as the above should carry no weight with us what 42ever. What makes me skeptical of such accounts is the fact that, in one instance of which I know the details, it was discovered that a fakir, after being buried in a grave several feet beneath the ground, managed to make good his escape by means of a tunnel especially built, leading into a hollow tree, through which the fakir escaped under cover of the darkness. In this case, the grave was well sealed, and it was certain that the fakir did not escape in that manner. He was however, discovered that night in the hut of a relative of his, quietly sleeping. Investigation showed that the grave had been dug in a certain spot, and that there was only a thin wall of earth between the end of the coffin, which hinged inwards, and the other tunnel, which communicated with a previously prepared tunnel, leading to the hollow tree, and so to air and freedom. Every interment was made in the same spot, and Europeans were being constantly taken in by the same trick. In the face of this piece of evidence I may be excused for being somewhat skeptical as to genuine feats of the kind.

And when we turn for analogy to cases of induced hypnotic trance, lasting over a number of days, we find that here, too, there is much fraud—much more than the public supposes—though I must not be understood as saying that trances of this character are not well authenticated. But I do assert that in the majority of public tests, in which the “professor” keeps his subject asleep 43 for seven days, etc., much fraud enters into the case. I do not say that it is all fraud from beginning to end, but there is an element of fraud in the case, which it might be as well to make plain in this place. The average method of procedure would be about as follows:

A good somnambule is selected who is in good physical health, and he is prepared by giving him a good dose of castor oil or rhubarb the day before the test. But little must be given the subject to eat or drink for a few hours before he is put to sleep. He is hypnotized several times daily before the test and suggestions made that he will not wake, that he cannot wake until permission is given him to do so, etc. He is then put to sleep carefully, and forcible suggestions given—that he cannot awaken, etc. The subject is then placed in his coffin, plenty of fresh air being allowed to get to him, and he is covered with mosquito netting if the test is in the summer-time, and flies, mosquitoes, etc., are numerous. The subject is turned over from side to side frequently, especially after the second day, and repeated suggestions are given him to sleep, that he cannot wake, and so forth. The subject will not be in an equally deep sleep all the time. Some of the time he will be actually asleep, of course, but he will be very near to waking much of the time, after the first two or three days, and must be kept asleep by constant suggestion. When the night comes on and it gets cold and there are fewer 44 persons watching, the performer makes this the excuse for covering the subject with a blanket. Under this blanket is concealed a rubber bottle containing water, and a sandwich or two are dropped in the coffin at the same time. These the subject invariably eats. I am not asserting this here for any other purpose than to show that these so-called “seven-day sleeps” bear no real resemblance to the cases in which men have been interred for days and weeks at a time, and throw the other cases into stronger relief in consequence. In view of the facts above noted, and of the fraud that is known to exist in some of these cases, I think we are entitled to ask for a considerable amount of first-hand evidence before we need consider seriously these cases of long-continued interment.

There remains for our consideration only one other well-known feat performed by Hindu fakirs or yogis, and that is the famous “rope exploit,” before referred to. I looked up the evidence for this performance with great care when writing my Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism, contrasting the evidence for hallucination in this and kindred tests with certain of the seances with D. D. Home, to ascertain if there were any similarity between the two. I think that I cannot do better than to quote the case as therein given. I accordingly quote from pp. 389-93 of that book. 45 After referring to Dr. Hodgson’s article in Proceedings, S.P.R., Vol. IX., pp. 354-66, the account goes on:

“But the most interesting part of Dr. Hodgson’s paper is his consideration of the alleged feats of levitation and the famous rope-climbing exploit, both of which are probably too well known to my readers to need describing here. The nature of the former of these phenomena is explained by its title; the second is the famous feat in which a rope is thrown into the air by the performer, where it stays—suspended by some unknown power—and gradually stiffens, allowing a small boy, the fakir’s assistant, to climb up it, and finally disappear in the clouds. Soon, the legs and arms of the boy are seen to fall to the ground, then the head, and finally the trunk falls to earth, all before the astonished and horrified gaze of the onlookers! These pieces gradually join themselves together, and re-form the boy’s body, whole as it was at first, and the boy goes on his way rejoicing!

“Of the levitation I shall not speak now, beyond stating that it is recorded in several of the books mentioned, as previously stated. The value of the testimony will be variously estimated by individuals, partly according to their preconceived ideas of the limits of the possible, and partly according to their familiarity with the evidence that has been collected in various works on the subject. As I have considered this question of 46 levitation elsewhere I shall dismiss it for the time being, and turn to the feat that most particularly interests us in relation to this question of hallucination and its possibilities.

“It need hardly be pointed out, I believe, that if this feat were ever witnessed by Europeans at all (i.e., if the whole thing is not a myth), and certain individuals imagined they actually witnessed it, the effect was the result of an hallucination, and not the result of seeing what actually took place. It need scarcely be said that the nature of the trick, if trick it is (the suspension of the rope by some unknown power, the ascent of the boy into the clouds, the tumbling down to earth of the separate members, and, finally the joining together of these into a live form again), would forbid any such performance taking place in reality—except on the stage, e.g., when appropriate apparatus can be arranged to perform this feat—an illusion of this sort being mentioned in Mahatma, Vol. III., No. 5, November, 1899. If such a performance were even witnessed, therefore, it must have been the result of some sort of hallucination, possibly hypnotic, which the onlooker was experiencing at the time. The question, therefore, narrows itself down to this: was the onlooker hallucinated?

“Several reported instances seemed to show conclusively that such was the case, it being stated that (particularly in one case which the writer quoted from his own experience) the photographic 47 plate of a camera revealed that nothing of the sort had transpired. The person witnessing the performance had actually seen it, as described, while the photographic plate, which cannot be hypnotised and so share in the hallucination supposedly induced, showed that the performance had not taken place at all. Such was the story, at least, which reached a very large portion of the reading public—so large, indeed, that this is the explanation that is given of this illusion whenever it is mentioned, as if it were a fact past all questioning!

“Dr. Hodgson, in criticising these articles, pointed out that the illustrations reproduced to back up the story (supposedly photographs) were in reality, woodcuts, and consequently were not what they purported to be at all, and served to throw a grave suspicion on the story in toto. Later, it came to light that this story was concocted by its author, and had no basis in fact whatever.[4] Dr. Hodgson actually doubted if the phenomenon had ever been witnessed at all, or even if any person thought he had witnessed it, rather inclining to the belief that these stories were invariably made up ‘out of whole cloth,’ and had no real basis in fact, even that the sitters were hallucinated, as it is stated they were. Several cases have lately come to light, however, particularly a recent and well recorded one,[5] which would 48 seem to show that the stories have at least some basis in truth. I shall accordingly consider the cases as if they actually existed, merely pointing out that such performances are extremely rare, even if they exist at all. Dr. Hodgson never witnessed the illusion, nor could he find anyone who had a first-hand account to offer him. ‘Even Colonel Olcott,’ says Dr. Hodgson, ‘a faithful servant of Mme. Blavatsky ... told me, after several years’ residence in India, he had never witnessed the rope-climbing performance.’[6] At the same time Dr. Hodgson was willing to admit that the story might have originated because of some hypnotically induced hallucination, akin to those induced by our Western hypnotists. The evidence, as it stands, is certainly inconclusive, in any case, and though there is a certain analogy between these performances and those of D. D. Home, e.g., the inaccuracy in recording, the doubt surrounding these phenomena can be said to offer no direct support to the theory of hallucination in Home’s case, which must stand or fall on its own merits. It can derive no real support from the performances of Oriental conjurors.

“On the subject of Oriental magic generally I cannot do better than to conclude this summary 49 in the words of Dr. Hodgson, to be found in the article so frequently referred to already. In summing up the evidence for the supernormal in these performances, he says:

“‘I conclude, therefore, that, in spite of the strong assertions of a distinguished conjuror, we have before us no real evidence to the manifestation by Indian jugglers or fakirs of any marvels beyond the power of trickery to produce.... The conjuror’s mere assertion that certain marvels are not explicable by trickery is worth just as much as the savant’s mere assertion that they must be so explicable—just as much, and no more.’”

From all that has been said, I think we shall be justified in concluding that the vast majority of feats performed by the Hindu fakirs present no evidence whatever of the supernormal, but are, on the contrary, clearly due and traceable to trickery. It is highly probable that every one of their well-known tricks are such only, and involve no occult powers, nor do they warrant our belief in the operation of any forces “other than those known to physical science.”

Are we to conclude, therefore, that nothing is to be gained by a study of the East and its phenomena? I think we should scarcely be justified in doing that, since there seem to be many phenomena witnessed there that are well worthy of serious consideration. The snake charming is one of these; the cases of prolonged 50 trance probably present many interesting phenomena, from any point of view; the rope exploit has at least its psychological interest; and there are many cases of levitation reported, which are worthy of serious consideration. “Baron Seeman,” a conjuror, describes in his book, Around the World with a Magician and a Juggler (pp. 54-6), a case of levitation; and various other conjurors have described the same thing. M. Jacolliot, in his Occult Science in India, before referred to, has recorded a number of most interesting experiences with a Hindu fakir. He obtained raps, telekinetic phenomena, independent writing, levitations, materialisations, playing upon an accordion, etc. Strange to say it was through the instrumentality of the very same fakir that Seeman obtained his experiences in levitation (Covindasamy).

And it will be noticed further that all these phenomena—so different from the usual tricks of the Hindu fakir—bear a close resemblance to the mediumistic phenomena witnessed in our countries.

That is a most striking fact, and at once places them on a different level from most of the tricks exhibited by Hindu fakirs, which are certainly tricks and nothing more. There may be genuine mediums among the Hindus; but the phenomena witnessed in such cases are of a very different type from those usually observed. This fact at once tends to discredit the ordinary tricks 51 exhibited, and strengthens the evidence for the phenomena that so closely resemble the occurrences witnessed in the presence of occidental mediums. It shows us, at all events, that some, and perhaps much, good may come from a close study of these wonder workers; and that, in investigating them, “we must not,” as Mr. Frank Podmore expressed it, “for the second time throw away the baby with the water from the bath.”

[1] Secrets of Mahatma Land Explained. pp. 45-46.

[2] Occult Science in India. p. 236.

[3] Secrets of Mahatma Land Explained. p. 49.

[4] Journal S. P. R., Vol. v., pp. 84-86; 195.

[5] Journal S. P. R., Vol. xii., pp. 30-31.

[6] Proceedings S. P. R., Vol. ix., p. 362. I do not at all agree with Mr. J. N. Maskelyne’s “Explanation” of this feat, however (see his pamphlet “The Fraud of Theosophy Exposed, and the Miraculous Rope Trick of the Indian Jugglers Explained” pp. 23-24).

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.