[ 1 ]

AS TOLD BY

Edited by Elizabeth Grinnell

Author of "How John and I Brought Up the Child," "John and I and the

Church," "Our Feathered Friends," "For the Sake of a Name," etc.

Dedicated to Disappointed gold=hunters the world over

David C. Cook Publishing Company

ELGIN, ILL., AND

36 WASHINGTON STREET, CHICAGO

[ 2 ]

ALASKA.

Copyright, 1901,

By David C. Cook Publishing Company.

[ 3 ]

The following story was originally written in pencil on any sort of paper at hand, and intended merely for "the folks at home." It is only by a prior claim to the manuscript that the young gold-hunter's mother has obtained his consent to publish it. The diary has been changed but little, nor has much been added to make it as it stands. The narrative is true from beginning to end, including the proper names of persons and vessels and mining companies. It is offered to the David C. Cook Publishing Company with no further apologies for its sometimes boyish style of construction. It will give the reader, be he man or boy, a hint as to how a young fellow may spend his time in the long Arctic winter, or in the whole year, even though he be a disappointed gold-hunter. It may afford suggestion to mining companies continually going to Alaska as to their responsibility to each other and to the natives of the "frozen North." It may give "the folks at home" some intimation as to possible "good times" under trying circumstances. Blue fingers may not necessarily denote a blue heart.

ELIZABETH GRINNELL.

Pasadena, Cal., Jan. 15, 1901.

WE ARE a company of twenty men bound for Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. It is needless to say we are gold-hunters. In this year of our Lord 1898, men are flying northward like geese in the springtime. That not more than one of us has ever set eyes on a real, live nugget passes for nothing; we shall naturally recognize "the yellow" when we see it. It is our intention to ransack Mother Nature's store-houses, provided we can unlock or pry open the doors without losing our lingers by freezing.

Why we have selected Kotzebue Sound as the field of our maneuvers it would be difficult to give a rational reason. It may be nothing more nor less than the universal rush to the gold fields of Alaska, which rush, being infectious, attacks all grades and conditions of men. That all grades and conditions are represented in our company will be demonstrated later on, I believe.

The instigator of the Long Beach and Alaska Mining and Trading Company is an undertaker by trade, a sometime preacher by profession and practice when not otherwise engaged. His character is not at all in keeping with his trade; he is a rollicking fellow and given to much mirth.

We have also a doctor, as protection against contingencies. His name is Coffin. He and the undertaker have been bosom friends for years. The combined influences of these are sufficient to insure proper termination to our trip, if not a propitious journey. The eldest of our company is rising fifty, the youngest twenty-one. The oldest has lived long enough to be convinced that gold is the key that unlocks all earthly treasures; his sole object is the key hidden somewhere in the pockets of the great Arctic. The youngest cares little for the gold, being more concerned about certain rare birds which may cross his devious path. The most of us have never met before, but are now an incorporated mining company, like hundreds of ship's crews this year. Each intends to do his share of work and to claim his portion of the profits, if profits come.

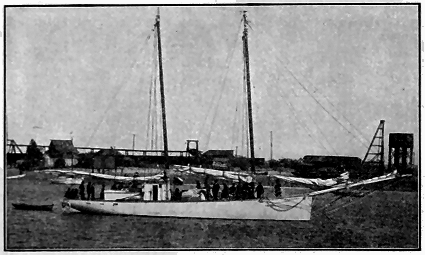

We have a two years' outfit of every comfort possible to store away on a little schooner seventy-two by eighteen feet. Her name is "Penelope;" you can read it in plain type half a mile away. She was built for Japan waters and has never set keel in Arctic seas. There are numerous prophecies concerning her: "She will never reach her destination;" "Impossible that she is built for a stormy coast;" "You may as well make your wills before you embark." And many other cheering benedictions are tossed to the deck by friends on shore who watch us loading the freight into her hold.

We make no retort. Of what would be the use? Our hearts, our hopes, ourselves, are [ 4 ] on board of her for better or for worse. We wave our handkerchiefs in a last "good-by." They are the only white handkerchiefs in our possession, brought and shaken out to the winds for this very purpose. From henceforth the bandana reigns on occasions when any is required. Old Glory floats above us; the "Penelope" is bright with new paint and trimmings and masts; she is towed out of San Pedro Harbor, and heads for San Francisco for more supplies.

Out of San Pedro Harbor! The very same of which R. H. Dana wrote in 1840 as a "most desolate looking place," frequented by coyotes and Indians, but "altogether the best harbor on all the coast."

We have a copy of his "Two Years Before the Mast" on board, and shall be complimented by what he says about the Englishmen and Americans whom he met. "If the California fever (laziness) spares the first generation, it always attacks the second." Did Dana mean the crew of the "Penelope"? We shall see.

Having made a dutiful promise to my mother to "keep a faithful diary" of our cruise, which, in event of disaster, shall be duly corked in a large bottle and sent adrift, I now enter my first date since April 8, 1898, the day on which we set sail from San Pedro. California.

North Pacific Ocean, June 5.—We are seventeen days out from San Francisco, and have made a little over twelve hundred miles: that is, in a direct line on our course to Unamak Pass through the Aleutian Islands, for we have had many unfavorable winds against which we were compelled to tack. We have sailed two thousand miles, counting full distance. We have experienced two storms which, put together, as the captain says, makes "a good half a gale." While the "Penelope" rides the highest billows like a duck, at times she pitches and rolls in a terrific fashion. Her movements are short and jerky, unlike those of a steamer or larger vessel. When the wind blows hard on her quarter, the rail is often under water. This makes locomotion difficult, especially if the waves are rolling high, and everything is bouncing about on deck. It is my duty to carry "grub" from the galley to the cabins, and I can never handle more than one thing at a time, as I am obliged to keep one hand free. I wait for my opportunity, else a heavy sea starts at the same time and we go down together, "grub" and all. However, I have had few accidents. Once I landed a big platter of mush upside down on the deck, and at another time a gust of wind took all the biscuits overboard, while a big sea filled the milk pitcher with salt water. This was not so bad as Dana's experience with the "scouse," which "precious stuff" came down all over him at the bottom of the hatchway. "Whatever your feelings may be, you must make a joke of everything at sea," he wrote just after he had found himself lying at full length on the slippery deck with his tea-pot empty and sliding to the far side. We are better off than the crew of the "Pilgrim" in 1840, for there is plenty more, if half the breakfast goes to feed the fishes.

Down in the cabin there is the most fun. The table is bordered by a deep rail, and several slats are fastened crosswise over the surface to hold the dishes, besides holes and racks for cups; yet when things are inclined at an angle of thirty-five degrees it is almost impossible, without somebody's hand on [ 5 ] each separate dish, to keep the meal in sight. We have some trouble in cooking at times, but the stove has an iron frame with cross pieces on top to keep the kettles from sliding, which, in rough weather, can never be filled more than half. We usually get up very good meals; that is, for such of the crew as have an appetite. For breakfast, rolled oats mush, baking-powder biscuit, boiled eggs or potatoes, and ham. For dinner, light bread or milk toast, beans or canned corn, salt-horse, creamed potatoes, and often soup with crackers. For supper, canned fruit, muffins or corn bread, boiled ham and baked potatoes. Of course tea or coffee with each meal. The cook makes fine yeast bread, ten loaves a day. There are twenty-three men on board. Including the hired sailors who are not of the company, and even with five in the hospital we make way with a good deal of food.

Our fare differs somewhat from that of the crew of the "Pilgrim." whose regular diet, Dana wrote, was "salt beef and biscuit," with "an occasional potato." But it must be remembered that we had several articles, such as eggs and ham and fresh potatoes, the first days of our cruise, which we never saw later on when we were confined to bacon and beans for staple supplies, with dessicated vegetables and some canned goods for extras.

We left San Francisco May 10, after taking on board the parts of a river boat, to be put together when needed, and much more Arctic clothing than we can possibly use in two or even four years. The Sea was very rough. Our captain had not been on board ship for two years, and the result was that he, with every one of the party except the sailors, was very sea-sick. The doctor was pretty well in a couple of days, but the undertaker fared not so well, he stayed on deck and sang and jumped about and did his best to keep jolly as long as nature could hold out. Presently one could tell that he was feeling rather uneasy about something, when all of a sudden quietness reigned and only an ominous sound from over the rail gave indication of what was passing.

We have some fine singing. "The Penelope Quartette" has been formed and practices every evening, making voluminous noise, but there is no fear of disturbing adjoining meetings or concerts. The quartette is composed of Reynolds (the undertaker). Foote, Wilson and Miller. There are other singers of less renown. We have a "yell." which is frequently to be heard, especially at getting-up time in the morning. It is "Penelope, Penelope, zip, boom, bah! Going up to Kotzebue! rah! rah! rah!"

We are very much crowded and have many discomforts, as anyone can imagine we should have in so close quarters; but we are a congenial crowd. I was sea-sick for a week, but am all right now and capable of eating more than anyone else, a symptom which the doctor fears may continue, as I make it a rule to eat up all there is left at both tables. There are eleven men in the after cabin and twelve in the forward cabin, including the forecastle, and each set have meals served in their respective cabins. Having been chosen as "cook's assistant," I have ample opportunities.

We have seen but few things of interest outside the boat, and that makes us more interesting to one another. We have sighted no vessels for two weeks. I saw two fur seals. They stuck their heads above the water just behind us, eying us curiously for a few minutes, and then vanished. We have seen one shark, but no whales. Petrels, or Mother Cary's Chickens, are almost always to be seen flitting over the waves. Black-footed albatrosses, or "goonies." as the sailors call them, are common, following the boat and eating all kinds of scraps thrown to them. We caught two with a fish-hook, but let them go, as there is now no suitable place to put the skins. One of the albatrosses measured seven feet three inches from tip to tip of the outstretched wings. We fastened upon his back a piece of canvas, giving the "Penelope," with the date and longitude and latitude. I wonder if he will ever be seen again, and, if seen, if this will be the only news of us the world will ever receive!

There are several "goonies" which seem to follow us constantly. We have named them Jim. Tom and Hannah. They know when meal time arrives, and then come close alongside within a few feet.

Tuesday, June 7.—The past two days have been stormy, but we have made good time and are only four hundred and sixty-seven miles from Unamak Pass. We saw several pieces of kelp this morning, which gives evidence of land not far off. This morning the sun came out several times, and every one is feeling quite jolly, which makes even the sea-sick ones better. One of the most popular songs on deck these cloudy days has been the familiar one. "Let a little sunshine in." Everyone was singing it to-day, when [ 6 ] suddenly the clouds broke as if by impulse and the warm sunshine flooded the damp decks.

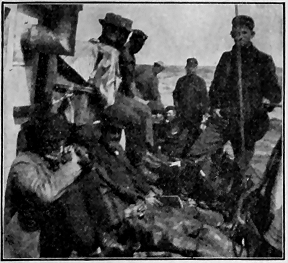

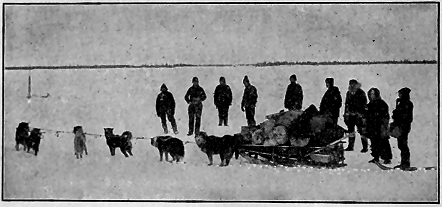

The sun doesn't set now till nearly nine o'clock, and the whole night long it is scarcely dark at all. To-day Clyde took the pictures of the party in groups, or "unions." There is the "Sailors' Union" (six of the boys besides the regular sailors, who go to the watch along with them and take their tricks at the wheel), the "Dishwashers' Union," the "Doctors' Union" (Dr. Coffin, and Jett, who is a druggist), the "Cooks' Union" (Shafer and myself), and the "Crips' Union" (the cripples, or those who are sea-sick, and do no work; they are Fancher, Wyse. McCullough. Wilson, Reynolds and Shaul). If the winds are favorable we expect to rest in Dutch Harbor for a few days, as we are no doubt too early to get into Kotzebue. From all accounts we cannot hope to reach the Sound until July 14.

This sort of experience is, so new to me. I thought I knew something of life on a schooner, during the trip to San Clemente and San Nicholas last year, but this is more and better. Nearly everyone save myself is longing for land, and they watch our course each day as it is traced on the chart with more interest than anything else. Just now I am sitting alone on a bench in the little galley, watching the potatoes and salt-horse boiling. The sun has come out and everyone is on deck, the "crips" lying against the stern rail or along the side of the cabin. By orders of the doctor all the bedding is airing on the deck and rails amidships, and some of the boys are taking advantage of the fair weather to do their washing. I did my own yesterday, although it was raining, and, as I have a "pull" with the cook, I dried the clothes in the galley at night. Of course all washing has to be done in salt water and it is scarcely satisfactory, to say the least. This necessary laundry work of ours is destined to occupy a good deal of our time and patience, and I suspect that before our cruise is over we shall long for a glimpse of a good, faithful washerwoman with her suds, and her arms akimbo, and her open smile.

Cooks' Union.

|

Sailors' Union.

|

Dishwashers' Union.

|

Crips' Union.

|

June 12.—We are in Bering Sea and all's well. It is partly clear, but cold, with a sharp wind. We went through Unamak Pass in the night. The captain thought it dangerous as well as delaying, to stop at Dutch Harbor, so we gave it up with disappointment. After beating for several hours, we are now well on our way straight northward to St. Lawrence Island. There is no ice in sight, but we can smell it distinctly. As we went through the Pass it was raining. and we could see but indistinctly the precipitous shores. The Pass is not usually taken by sailing vessels, as it is quite narrow, but our captain brought us through all right in spite of fog and storm. He has not slept for forty-eight hours. The shortest time ever made by a sailing vessel from San Francisco to Unamak Pass, 2,100 miles, was eighteen days; and we made it with the "Penelope" in twenty-three days. Hurrah for the "Penelope"!

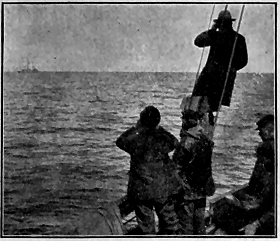

This morning we passed within hailing distance of the ship "Sintram," of San Francisco. She had taken a cargo to St. Michaels and was on her way back. Her captain promised to report us, and he also told us that the ice was yet packed north of St. Michaels and that several ships were waiting. Clyde took a snap shot of the "Sintram."

There are plenty of birds to be seen now. If I had faith enough to warrant my walking on the water I would go shooting. Our small boats are all lashed [ 7 ] to the dock of the "Penelope," but the captain says that in a few days we can put a skiff overboard if it is calm, and then ho! for murre pot-pie! Everyone is hungry for fresh meat. We try fishing with no luck. Saw a fur seal to-day, the first in two weeks.

June 19. Bering Sea, latitude 63 degrees, longitude 172 degrees, 38 minutes.—For the past few days we made good time, one hundred miles to the day, but on this date we are becalmed. Clyde has gone out in the boat to catch a snap shot of us. He need not hurry, for never was mouse more still than the "Penelope" at this moment. The thermometer registers 38 degrees on deck. We have sighted no ice yet, and hope the Bering Straits are open.

I am sitting in the galley, as my fingers get too cold to write outside. We have just cleared off supper, and the boys are pacing the deck for exercise. Some of them are below, where an oil stove in each cabin takes the chill and dampness from the air. It is seldom that the galley is not crammed full, but just now the cook and the others have gone below for a game of whist, so I embrace the opportunity to write. My diary is always written after I have finished my daily bird notes, which I make as copious as possible. I have some good records already. We were becalmed three days in sight of the Prybiloff Islands, and at the time were so close to St. Paul Island that we could hear the barking of thousands of seals, and, by the aid of a field glass, could see them on the beaches. A few were seen about the "Penelope," and one came so near to the boat that it was touched with an oar. We unlashed the smallest boat and rowed out with her during the calmest days, so we had some much-needed exercise. Frequent fogs kept us near the "Penelope's" side, as we should easily become lost. We saw no ducks or geese, but we had murres in plenty and pot-pie for several days. For a change they were served up in roasts, being first boiled, and were finer than any duck I have tasted, though some of the squeamish crew composing the "Crips' Union" declared they were "fishy."

Of course I improve every opportunity during pleasant days to collect, and the result is thirteen first-class bird skins. These sea birds are almost all fat and the grease clings to and grows into the skin so firmly that it is almost impossible to put them up. Among the good things which I have secured are the crested auklet, red phalarope, pallas, murre and horned puffin, but it will be difficult to preserve the skins in this damp climate. Dr. Coffin is becoming interested already, and talks of putting in his spare time collecting with me. He has been taking lessons in skinning, and so far has put up two specimens. We have rigged up a cracker-box for our bird-skins and try to keep it in the dryest place, though it is so crowded on shipboard that a convenient place for any particular thing is scarce.

The currents in Bering Sea are quite strong, tending northward toward the straits, so that even when the wind fails [ 8 ] us we are drifting towards our destination at the rate of fifteen to twenty miles a day. On board we are all happy and in good spirits, notwithstanding the fact that some have never before known a hardship, and their eight hours watch per day on deck, especially when it is stormy, is calculated to make them think longingly of their pleasant homes. Besides, many of the boys have salt water sores on their hands and chilblains on their feet.

Yesterday the sea was choppy and several were sea-sick again. Even I felt that peculiar indescribable sensation, but I ate a hearty dinner of beans and salt pork and felt better. C. C. is suffering from what he declares is "indigestion" a weakness to which he has always been subject. He feels a reluctance to owning that he has the common ailment. "C. C." is our abbreviation for Reynolds, the undertaker and sometime preacher. He makes so much fun for other people that we cannot help amusing ourselves at his expense sometimes.

We passed St. Matthew Island and caught a glimpse of its rugged shores through the thick fog. We can generally tell the proximity of land by the increased number of sea-birds. It is not often that the sun appears now, but occasionally it shows itself long enough for the captain to take his observations. It is light all night and seems like a dream of childhood to have to go to bed before the lamps are lighted.

I must pay a compliment to our captain. Besides knowing his business thoroughly, he Is a jolly, agreeable man, always cutting jokes except during a storm. He has been created the "Penelope's" laureate, and has written a couple of poems that would make good his rank anywhere.

There was one day when we all had an attack of the poetic fever and wrote verses. They will be found in the ship's log.

To-day is Sunday, and as usual we all attended services, which consist of songs and a short talk from C. C. The rest of the day is like any other.

Last night an exhausted sandpiper flew on board and was caught. I was asleep and the boys came and laid it on my breast. He Is now safely wrapped in cotton wadding and laid to rest in the aforementioned cracker-box. The boys declared they would whip me for not letting him go, and yet when they get a chance they shoot at birds from the boat for "sport," with no other purpose in view. I am doing my best to educate them in bird lore, but whenever I get off the long Latin names they give me the "ha-ha." By this time and after many lessons the most of them know a murre by sight, and a fork-tailed petrel, and a kittiwake; but when it comes to distinguishing the different species of anklets at a distance they think I am fooling them, and laugh at me until I show them the bird at close range. I never realized before the vastness of the sea as when a solitary little bird dips his wings and flies skyward.

JUNE 1.—Yesterday the fog cleared and disclosed to us the snowy peaks of the Siberian coast far to the northwest, and in front to the north of us the long coast line of St. Lawrence Island. We headed for the west end of the island, intending to pass up the channel between it and the Siberian coast. Saw two vessels in the distance returning from that direction. After we had beat against a bad wind all day we found ourselves almost surrounded by icebergs. With the field glass we could see the whole horizon a solid mass of ice. Our way was blocked. Turning eastward, we tried the passage between St. Lawrence Island and the Alaskan coast. The wind was blowing bitterly cold from the Siberian shore. Beating eastward along the south side of the island, we have now left the ice behind. This afternoon a two-masted schooner spoke us on her way to try the passage we had just abandoned. She turned and sailed with us. She carried a pretty tough-looking crowd of miners. They, like ourselves, are bound for Kotzebue. We gave them the "Penelope" yell, which they returned with three cheers. In sizing up their piratical appearance we forgot to look in the glass.

June 25.—Seventy-five miles southeast of Bering Strait. The Alaskan mainland north of Norton Sound in plain view. Have spent five days trying to get around St. Lawrence. Are still in sight of the east end. It is calm. [ 9 ] We need more wind. Entered Boring Sea two weeks ago, and the days have been like a yachting cruise. Everyone is in good spirits. Several of the boys are witty and jokes fly. And the singing!—we exhaust the words we know and then make up as we go along, like plantation negroes. Are playing several tournaments in games. Only one so far has been concluded—the domino game. Dr. Coffin and Jett were the unlucky ones, and last night they entertained the crowd. Captain was master of ceremonies and dressed in a most ludicrous manner. He made a mock speech and read a poem. The two unlucky victims were treated to burnt cork and wore great Eskimo muckluks (sealskin boots), murre-skin hats, and red calico decorations. Doctor beat the big tin washpan and Jett blew the foghorn. The captain's wand was a boat-hook with a shining red onion on the tip and bearing a red pasteboard banner with the motto. "On to Kotzebue." They were to march fifty times around the deck. Casey, our Irishman, was appointed policeman by the captain "to keep the small boys and the carriages off the street." And so, to the tune of the foghorn and the dish-pan, they tramped their penalty. Then the captain gave an exhibition of clog dancing, with a fife and harmonica accompaniment. So one can see there is always something going on to break the monotony and keep the blues away. We suffer little from dull times. Whales are now as common as seals. One we saw looked as large as the "Penelope." Clyde took its picture. I got out our Winchester to-day. Am on the lookout for polar bears, which are expected to frequent the ice packs. The cook has just yelled "Supper!" and everyone is singing "Beulah Land."

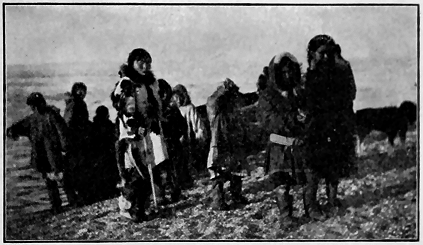

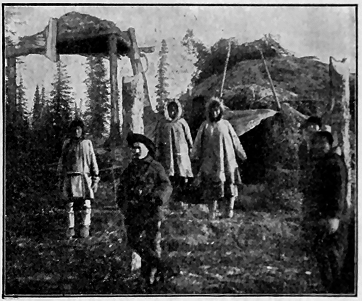

Arctic Ocean, July 7.—The next morning after my last date we sailed to within a mile of King's Island. This is a precipitous point of rock scarcely a mile in diameter, and yet more than two hundred Indians live upon it. Before we were within three miles of the island the natives began to come alongside of the "Penelope" in their skin canoes, or kyaks, wanting to trade. These were the first natives we had seen, and our interest in them was unbounded. Fully fifteen canoes, some singly, but mostly lashed together in pairs, reached us, and their occupants came on board with their sealskin bags full of articles to trade. They had a large quantity of walrus tusks, some of large size, weighing probably ten pounds, and very valuable. There were polar bear skins and fox skins beautifully tanned, also sealskin coats and muckluks (skin boots).

They wanted in exchange clothes, flour, tobacco, knives, etc, and, if we had prepared ourselves, we could have obtained many valuable things. Most of us saved what things we had to trade with later on.

Beyond King's Island our way was again blocked with ice. We then turned east towards Port Clarence, but in a couple of hours encountered the ice pack extending out full twenty miles from the Alaskan shore. We thought our way was blocked, but the captain thought we could keep along the shore ice, and did so, the passage opening as we advanced. After skirting the ice all day we entered the straits at midnight [ 10 ] June 26, and found ourselves between the Diomede Islands and Cape Prince of Wales. Everyone was on deck enjoying the scene until 2 a. m. The sun loitered along the horizon four hours and at midnight barely disappeared. The clouds and water were gorgeously tinted in the manner so often described by Arctic travelers. No words can do the scene justice. To the right rose the mountains of Alaska, extending far back from Cape Prince of Wales, the shores broken by their blue-tinted ice pack. Dark blue shadows stood the mountains out in beautiful distinctness. On our left were the precipitous Diomede Islands and Fairway Rock, with the snowy mountains of the Siberian shore rising further in the distance.

Ahead, our progress would soon be stopped by the long line of ice extending under the Arctic horizon, where the sun was vainly endeavoring to set. Just at midnight a spot of blazing light appeared at Cape Prince of Wales, fully eight miles away. It was the reflection of the fiery red sun on the window of the mission which has been established at that point. These shores are not inviting, and yet we know that here on this bleak coast are living, the whole year through. American missionaries, whose purpose is as eternal as the icebergs.

Everyone was happy and exerting himself to express what he felt. Some yelled wildly, and, taking off their shoes and stockings, threw them into the ocean. Others sang with might and main. "Beulah Land" and "Nearer, My God, to Thee" were followed by "Yankee Doodle" and "My Country, 'tis of Thee." with every body dancing and running about like a lot of Indians. "Penelope, Penelope, zip, boom, bah! Going up to Kotzebue, rah! rah! rah!" was yelled till all were hoarse. Finally, about 3 p. m., we began to quiet down for a little sleep.

In the night a small schooner like our own, the "Acret," caught up with us, having found the passage we had followed. We passed through scattering ice and sailed about fifteen miles beyond the straits, but here were confronted by the solid ice pack of the Arctic which extended on all sides. After sailing about in circles in this limited area of water all day, the "Acret" was seen to be heading through a break in the shore side of the ice, and we followed. Both boats dropped anchor about a mile from the Alaskan shore in shallow water, where the ice had left a clean anchorage. The "Acret" and "Penelope" were so far the first boats to pass through the straits.

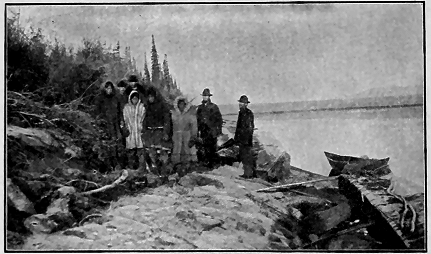

We were all eager to land. As soon as the dinky was overboard, five of the boys, with little thought for anyone else, as was quite natural under the circumstances, jumped in and moved for shore. And what was exasperating beyond description to us who were obliged to wait our turn, they did not bring the boat back for two hours. We have forgiven them, but they'll have to pay for it.

At 6 p. m., Dr. Coffin and I, and others, landed and started on our first tramp. Our feet were for the first time on Alaskan soil. But we saw none of the soil. Moss everywhere, and flowers and wild strawberries. It was a queer sensation to set one's feet down on what looked like substantial ground and sink a few inches to solid ice, crushing the flowers beneath.

I was all eyes and ears for what new birds might cross my path. Almost the first thing a flock of Emperor geese flew past me and were out of range. These are the rarest geese in North America and found only in Alaska. I saw but one land bird, a species of sparrow, but there were large numbers of water birds. I obtained some rare eggs, such as phalarope, western sandpiper, etc. A snowy owl was flushed, the first I ever saw alive, and it was at once mobbed by a dozen Arctic terns which had their nests near by. The land here is low and rolling, with little knolls and lakes. The ground in places Mas thawed about a foot—that is, taking the depth from the top of the spongy moss. On the dryer knolls several kinds of flowers were blooming and the grass was luxuriant in places. I searched for insects, but found only two bumblebees, which I could not catch, having no net with me.

We stayed on shore until midnight, tramping over the tundra and collecting birds and eggs. At 1 a. m. rowed back to the schooner. A canoe load of Indians had come alongside, and they had one Emperor goose. I coveted it. Tried to trade for it, offering several [ 11 ] articles, but failed to offer the right thing. Afterwards one of the "Acret" men obtained it for an old tin tomato can. The "Acret" fellows had also been on shore and succeeded in shooting another goose, so they now had a pair of them, which they allowed me to have for the skinning, provided I returned the bodies in time for breakfast. I was happy. I immediately went to work, having the usual experience in skinning sea birds with the enormous amount of fat which must be peeled, rubbed, scraped and picked off. It took me until three o'clock in the morning, and I was then glad to crawl into my bunk for a little sleep. By night the next day the water seemed almost clear of ice, so we heaved anchor and started northeast along the shore towards Kotzebue. Soon came to the ice again, scattered and in blocks. Keeping right on between the blocks, we came to a big, fatherly iceberg which had run aground. The water here was very shallow, and we had to be careful not to run aground ourselves. The "Penelope" draws eleven feet of water, and a mile from shore it is often scarcely three fathoms, and of course shallower towards shore.

It was very exciting sometimes when the ice blocks became too Thick. And they choked and moaned and snored and heaved against each other in a fit of passion, and challenged one another to "come on." and ground their teeth in rage, and swished calmly, and chuck-a-lucked through the water. It was a grand sight to remember.

At times several of the boys had to take poles—driftwood which we had taken possession of for just such an emergency—and, standing at the bow, push off the ice. Even then several of the larger blocks got the better of us and would stop our progress by a sturdy crunch against the "Penelope," scraping along her side and taunting her with piratical intention. But she was firm and answered not a word, giving only a few scales of her weather-beaten paint as a sort of peace-offering.

The "Acret" was all the while accompanying us, most of the time ahead, for she drew only eight feet, so she could sail nearer shore than we could, where the water was clearer of ice. We anchored two nights and a day, again sheltered behind a grounded iceberg.

The "Acret" and "Penelope" were tied up side by side, and we exchanged calling courtesies. This crew was intending to prospect in couples, each two men having a boat. Each person was independent of any other man, unless they should choose to form partnership among themselves. That is, they were not formed into a regular company as we were. We are no doubt better off individually as we are, though this remains to be proved.

After spending several days slowly making our way along the Alaskan coast towards Kotzebue, through the still breaking ice, on July 2 we found ourselves really in a dangerous position. The wind began to blow from out to sea, thus crowding the ice towards shore, making our sailing quarters more and more limited. We were already running too close in, from two to three fathoms, when suddenly the schooner ran aground, and we found ourselves stuck on a sandy bottom, with the ice rapidly moving down on us. An anchor was quickly towed out and dropped, so that by heaving in on the anchor chain the boat could be dragged out into deep water. This was slowly being accomplished, when a mass of ice too large to pole off caught against the schooner, causing a tremendous strain on the anchor chain.

Another ice cake floated against the first, and the "Penelope" would have been crowded deeper and deeper aground had not, after much chopping and prying, a crack opened up across the ice on our port bow. The two pieces swung apart, leaving the "Penelope" free. Again we tried to heave into deeper water, and finally with all sails set and all hands pulling on the chain, the boat slid off in time to escape another big [ 12 ] sheet of ice. Of course this was one of the few times we did not feel like shouting and singing. We held our breath. It was an unpleasant experience, but one upon which we can look back with a sort of quiet satisfaction. We shall-at least have one hair-breadth escape to narrate to our friends at home. After dodging and threading our way, the captain finally sailed us into an open tract of water outside the ice.

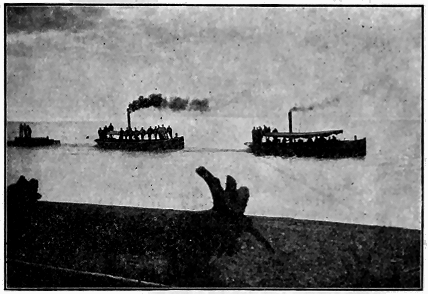

We have made little progress these last days. We have been sailing about in circles, at times coming within forty miles of Cape Blossom, but still blocked by the line of ice that closes the mouth of Kotzebue Sound. It is now rapidly breaking up and melting, and as soon as an off-shore wind sets in, the ice will be surely driven out to sea and our path will be clear. We are fifty days from San Francisco, and the majority of us are longing for land. Vessels are constantly coming In sight.

Last night twelve vessels besides our own were seen waiting for the ice to open. What a mad rush this is to a land nobody knows anything about, and whose treasure-trove, if she holds any, is far in the interior! There is plenty of country, if not of gold, for us all, and we can take our chances.

We have spoken the bark "Guardian" from Seattle with 130 on board. The barkentine "Northern Light" from San Francisco with 120 on board; the bark "Leslie D." with 58 on board, besides the "Catherine Sudden," and others whom we have not been near enough to speak.

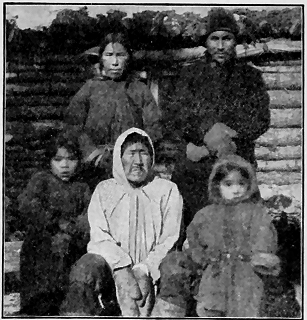

While we were near shore natives. Eskimos, came on board in their skin canoes nearly every day, and often stayed several hours with us. Indeed they would remain with us all the time if allowed to. They are very greasy and not at all desirable in their present condition, dressed entirely in skins, and owning few civilized implements. Some were on summer hunting trips from as far as the Diomede Islands and the opposite Siberian shore. We have made some fine trades with them. Rivers, one of the boys, got a good skin kyak for a pair of overalls, a match safe and a few other trinkets. I got some nice seal (not the fur seal) skins for an outing shirt, and about one hundred yards of strong raw-hide rope, for soiled socks, undershirts, etc.

It is a good opportunity for obtaining spears, toys, implements, and clothing of Indian manufacture, etc., if only I could spare the stuff to trade. With all the hundreds of people coming to the coast this year, the trade will be spoiled by next year, or I would send home for a box of articles for trade.

These natives really require very little outside of their own resources, so it is hard to tell what articles would be likely to strike [ 13 ] their fancy. Load, powder, tobacco, calico and clothes would be the best things.

The prince or chief of this tribe of Indians was an intelligent young man about twenty-five years old. He could not speak our language, but, strange to say, his wife, who accompanied him, was educated and refined. She had received some schooling at Port Clarence. It was she who interpreted for all of us during our trading hours.

The natives came in families, and the children were not uninteresting. Not a baby was heard to cry, although in the canoe for hours at a time, nor would they try to move. These canoes or kyaks are very strange boats, and prove quite treacherous to the novice. It looks easy rowing in one of them. I had learned the trick during my hunting about Sitka two years ago, and could not be induced to try my hand in a hurry. Not so Casey, who went out by himself in Rivers' new kyak. He started out all right, shouting that it was like riding a bicycle, "very hard to keep balanced in." He was getting along finely, keeping near the vessel, when he grew over-confident, and a misstroke with the paddle set him out of balance, and boat and poor Casey went rolling over together in the water. He struggled and kept to the surface long enough for a rope to be thrown out to him, but he could not get his legs out of the hole in the kyak for several seconds. Seconds are hours in this blistering ice-water, and had he been further from home he could not have survived the chill.

No one has tried kyaking since, but as soon as we reach shallow water I mean to practice until I have revived the lost art.

We are now inside the Arctic Circle, about 67 degrees north latitude. That is pretty well north for Southern Californians who, at home, rub their ears when the frost nips the tomato plants in January.

CAPE BLOSSOM, July 13, 1898.—The voyage is behind us. What is floating ice to a ship's crew safe on shore! We can laugh at whales, and unfriendly breezes that whisper tales of shipwreck on barren coasts. And we can walk at all hours of the day and night without holding on to the rail, and we don't have to cook breakfast and supper and dinner in an S x S galley. Oh, the charm of being on land again, a land without visible limit; a land where we are not crowded, and where we are not hindered from our work by newspaper reporters!

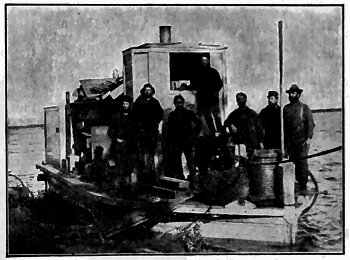

I am sitting at the camp-table in the dining-tent near the new "Penelope" ship-yards, and the sounds that greet my ears are varied. The incessant pounding gives evidence of vigorous work on our river boat; the hum of the forge and the ring of the anvil where Casey and Stevenson are making fittings for the engine, the wash of the surf close at hand, and last, but not least, the low, irritating, depressing, measly whine of the mosquito—this last word to mean the race. I would not intimate that there is one mosquito, or twenty: there are millions! We wear bobinet masks which protect our heads very well. To-night the wind is blowing fresh, and the winged plagues are using most of their force to keep their land legs. It is very warm, and a little exertion brings out a copious perspiration, but it is less fatiguing to keep hard at work with a will than to stop and think about it. No ice now in sight. Within two rods of camp is a deep snowdrift, where we obtain nice drinking water. Ice may be seen anywhere in Alaska all the hot days, but it is so mixed and grown in with the everlasting mosses that it is not fit to melt for drinking save in rare cases. Our ship-yards are located on the pebbly beach, and it all seems so roomy and clean after our long stay on the little "Penelope." though on account of the mosquitoes we still sleep on shipboard. The boat is anchored a mile from shore on account of the shallow water. As I look out to sea I bethink me that in all probability Kotzebue, the Russian explorer, stood on this exact spot and looked about him as long ago as July, 1816. And the mosquitoes were biting him, too!

I can afford to sleep only every other night these days. There will be time enough to sleep when the sun goes to bed. The landscape is beautiful—grassy meadows, green, bushy hillsides, and, over all, thousands of wild-flowers of a dozen kinds; dandelions, daisies, sweet-peas, and many other varieties. I have found a few beetles and have seen some butterflies, but get little time for collecting either insects or birds. My duty is to the company, and any time in which I may do what I love best to do must be taken out of my sleeping hours. Everyone is working with might and main, as the missionaries tell us that winter sets in by the last of August.

By the way, we surprised these missionaries, who been located at Cape Blossom [ 14 ] some two years or more, and in that time have seen few fellow-countrymen. C. C. Reynolds and Clyde and Dr. Coffin were old acquaintances, and waked them up one day all of a sudden. The three were told by the natives of the best way to approach the mission building, and, as they did so, the first thing that met their eyes were little boxes of lettuce and radishes and onions set on the sunny side of the cabin to steal the breath and smile of Old Sol, while he has his eye on the place. This is a Friends' Mission, and the three missionaries are from Whittier, California.

They are Robert Samms and wife, and a Miss Hunnicut.

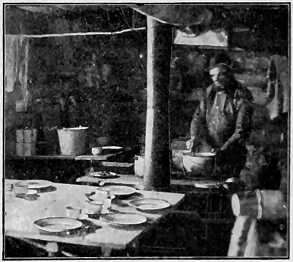

The boys are working on the river boat in two shifts from twelve to twelve. This makes time for four meals a day, the largest meals being at the two twelves, and I have one of these to get. I also have the 6 p. m. and the midnight meals to get; Shafer gets the others. Of course we have our assistants who wait on table and wash dishes. Who would have thought I would become a mess cook!

I have just dressed three salmon weighing about fifteen pounds each. We traded ten gingersnaps to an Indian for them. They will make fully two meals for all of us.

July 10, 2 p. m. In the dining-tent at "Penelope" ship-yards.—Yesterday was a great day for us. We received our first mail from home. The revenue cutter "Bear" brought it, and it will probably be our last. It is sweltering hot. We find our most congenial employment in drinking ice-water and taking cold baths. And no one suffers from it. The river boat is nearly done and we have been here only a week. To-day our first prospecting party starts out, one of two, to go up the Kowak River in advance of the main party. They are taking a month's provisions, and, besides prospecting for gold, are to locate our winter quarters. We hope to make two trips with supplies up the river before it freezes. There are so many vessels of every description here that it looks like a seaport harbor. The natives are "catching on" to trading schemes, and are asking exorbitant prices for everything. We offered sixty dollars worth of flour and other things for a canoe and failed to get one. I doubt the things being of much use to us if we had them. The skins soak up water rapidly and are then easily torn or worn. The Indians keep them in water only a few hours at a time before taking them up on the beach and turning them over to dry.

Shafer went with our first party as cook, and that leaves me with seventeen men to feed. I want to get in some collecting this fall and am willing to work hard now. Of course everyone of the party is industrious; we expected to work. The mosquitoes do not like me and so I have the advantage of the others. I keep a smudge burning in the tents so the boys may eat in peace.

Penelope Ship Yards, July 17.—Oh, how hot it is to-day! And the mosquitoes are rushing business, as if aware time is nearly up with them, I slept on shore last night. We had a small tent and banked it up all around tight, and then made a smudge and shut ourselves in. We killed all the mosquitoes in sight and finally got to bed for a good seven hours' sleep. There is plenty of driftwood along the beaches, and we shall not be obliged to draw on our supply of coal for a good while. Several tons of it is coming on the "Mermaid." The vessel has not yet arrived, neither have several others whose crews warned us before we left San Francisco last spring that we would not reach Kotzebue this year. And here we are a week ahead of them, and one party prospecting up the river already.

July 19.—This morning the "Helen," as we have named our river boat, was towed out to the "Penelope," where the boiler and engines were hoisted on. She is back again now, and all is well save Rivers, who had his Angers smashed.

[ 15 ]

There must be a thousand people now in the Sound, and more are coming. These first-comers are respectable men, with few exceptions. A drunken white man shot an Indian up near the mission, and now there will be trouble. The Indian law dates far back—"An eye for an eye." A good many accidents are happening. Some men are lost, and so are whole loads of provisions. We are safe; have lost nothing. Birds are numerous now. I went up the slough last night and got three ducks. This noon I served up a hot duck pie. This is the summer home for many birds that spend their winters south. Every morning I hear the plaintive song of the Gambel's sparrows from the bushy thickets on the hillsides, just as we hear them from the hedges at home in winter. Other familiar birds now rearing their broods here are the barn swallow. Savannah sparrow and tree sparrow. Insects are common as the warm weather continues. I caught a bumblebee this morning and bottled him. As fast as the snowdrifts melt, grass and flowers spring up, crowding the snow, so to speak, into more and more limited quarters, and finally replacing it altogether. The brightest and greenest spots are where the snow has the most recently disappeared. This is a beautiful country. Some day when the speedy airship shall make distance trivial, it will be a popular summer resort, except that the water is too icy for the average bather.

JULY 23. Penelope Ship Yards.—The "Helen" is at last ready. Three of the boys have cut up several cords of wood into proper lengths for the boiler.

I cannot help mentioning the flowers again. New kinds appear every day without so much as sending up a leaf in advance. There are dandelions, and purple asters, and cream cups, and bluebells, and big daisies, and buttercups, and tall, blue flowers like our garden hyacinths. There are acres of blue-grass as smooth and green as if newly mown, birds and bumblebees are abundant. I should like to collect more of these, but still have a hungry mob to feed. The boys are working hard at shifting the cargo, and chopping wood and doing other things, and of course are hungry as bears. My work gives me some half-hours which I spend collecting. We have good stores. For supper to-night my menu is baked navy beans—Boston baked beans away up here at Kotzebue Sound!—corn bread, apple sauce, fricasseed salmon eggs, fried salmon, duck stew, tea, etc. It will be appreciated to the last crumb by the Arctic circle.

The days are growing shorter. The sun now sets before eleven at night, leaving only a short semi-twilight. The doctor has just come in from a visit to the mission. He reports ships still arriving, and prospectors having all sorts of luck. Flour is three dollars for fifty pounds. Liquor is being sold to the natives without stint. It is against the law, but what is law without a force to back it? Dr. Sheldon Jackson is expected soon, and he is the man who will not be afraid to hunt out the rascals who are spoiling the natives. I am so nearly related to the American Indians myself that I naturally take sides with these natives. You know I was born on the Kiowa, Comanche and Wichita reservation, when those Indians [ 16 ] were savages or nearly so, and I learned to love them before I could speak. Here and now it is the old familiar story of the white man's abuse of the redskins. It makes me indignant. We found these people confiding, generous, helpful, simple-hearted, without a shadow of treachery except as they have learned it from the whites, who are invading their homes and killing them as they will, with little or no excuse. Many of these gold-hunters that I hear of have already done more harm in a few days than the missionaries can make up for in years. I could write the history in detail, but desist. It will never all be written or told. The natives are worked up to the last point of endurance and will surely kill the whites. Whisky is doing its share of havoc, although a few of the faithful mission Indians are trying to keep the others quiet.

Sunday. July 24.—We are now waiting for the tide to take the "Helen" out of the creek. Steam will soon be up.

July 29, Dining Tent.—We are still here and the rains have begun. The "Helen" made her trial trip and works well. We have discovered that she cannot transport all our goods up the river, so have delayed in order to build a barge. It is two feet deep, ten feet wide and eighteen feet long, with a capacity of ten tons.

August 1.—The storm washed the sand up and locked the "Helen" into Penelope inlet. The only thing to be done was to dig a channel and float her out. From ten in the morning until ten in the evening we worked. We had to pry her out as the tide kept failing. We could not have succeeded had it not been for some kind Indians who helped us. They are always ready to help when they see us in trouble. Of course we treated them to a good supper and they were happy.

After steaming out to the "Penelope," we started north around the peninsula to the inlet, arriving about two in the morning, after the hardest day's work we have had yet. Here at Mission Inlet Dr. Coffin. Fancher and myself are left with the camp outfit and a load of provisions. After three hours' sleep and a hot breakfast the rest went back to the schooner with the "Helen" for another load, and to bring the barge, which by this time should be finished. Soon after they left, yesterday, a stiff breeze sprang up and we were very anxious. The "Helen" is little better than a flat-bottomed scow and cannot stand much of a sea. An inlet near us is, we think, deep enough to float the "Penelope," if we could get her in, and here she would be safe all winter. The missionaries tell us that no boat like her can stand the crushing ice in the open sea during the winter, and that this inlet is the only protected place for miles around.

The mission and village are two miles west of us. There are four frame houses and a hundred tents. A Mr. Haines of San Francisco, took supper with us last night and gave us the shipping news. Men are left with nothing save the clothes on their backs; others are drowned; many are homesick. Rumor reaches us that gold has been found on the Kowak. But rumor is not to be relied upon when it is gold that sets it afloat.

If there is gold on the Kowak we shall find it. Our present care is to get our supplies up there in safety, but we are going at a slow pace. Six of our party are already up the river, six are on the "Helen" en route to the "Penelope" headquarters, two are at the ship-yards, and four are on the schooner. Dr. Coffin. Fancher and myself are here at Mission Inlet. This accounts for all of us as at present divided. We expect the return of the "Helen" to-night.

We three have been living high since the others left. For supper, with the help of our San Francisco visitor, we got away with three ptarmigan, two curlew, twelve flapjacks with syrup, stewed prunes, etc. After supper we went to sleep and did not awake until nine this morning, when we had ptarmigan broth, fried mush, ham and flapjacks. The other day we picked three quarts of salmon berries. They are very fine eating, something like a blackberry in size and shape, but are red like a raspberry and grow flat on the ground like a strawberry vine. They seem a combination of the three.

Two other kinds, inferior to the salmon berries, also grow on the ground. We want [ 17 ] to eat everything in sight. If there were rattlesnakes I believe that I should cook them. I have broiled a good fat rattlesnake when hunting in the Sierras, and found it a dish for an epicure—that is, if the epicure happened not to see it until served. I put up nine bird-skins this morning. They are two redpolls, one Siberian yellow wagtail, three ptarmigan, one tree-sparrow and two curlew. I have put up seventy-five skins so far. I have also saved quite a number of insects, but these are scarce since the rains set in. Last night I heard the beautiful song of the fox-sparrow from a hill on the opposite side of the inlet. A raven, the first I have seen, flew high overhead with ominous croaks. "Evil omen," say the natives.

Mission Inlet, Aug. 5, 1898.—The "Helen" has returned after a perilous trip. She had the barge in tow and both were heavily loaded. It took ten hours to cover twelve miles, so rough was the sea. She ran aground twice, and the boys were indeed "tired" on their arrival, but were wonderfully refreshed in a short time by flapjacks and bacon, which I served to them piping hot, after which they slept for eight hours. It has taken a good deal of hard work to get ready to make our start, and a good storm is in order. "Indian Tom" is guide, and he knows everything about the river and country. He says, "Wind too much; bimeby all right," and we take his advice. The "Helen" and the barge in tow are to carry two-thirds of the year's supplies up the river, and the "Helen" will alone return for the rest. We cannot get the "Penelope" into Mission Inlet, as we hoped, hence it has been decided to leave the captain and two men with her all winter. The provisions not needed this winter are stored on the schooner, and she will be anchored down in Escholtz Bay, in as sheltered a place as can be found, where she will freeze in. It looks dangerous, but it is our only alternative. It would not take much ice pressure to crush her, and then good-by to our provisions! They will try lifting her by windlass and other means, and the captain shows his pluck in the emergency. Pluck is what is needed in these Arctic regions, besides plenty of flapjacks. Jett and Fancher remain with the captain on the "Penelope." They hope to shoot polar bear and have other winter sport, but I guess they will have a monotonous time. Perhaps some of us will take a sledge journey down to them in winter.

Dr. Coffin, Wyse, Rivers and myself are to stay here until the "Helen" returns for us and the remainder of the stuff. I always volunteer to stay at camp when a person is wanted, for in this way I get in some collecting. The rest don't see so much fun in staying at camp. It may be two weeks before the boat gets back and, outside of my camp duties, I shall have considerable leisure for my favorite pastime. Doctor and I went out and got thirteen ducks, which made a good meal for the crowd before they started. We also had a large mess of stewed salmon berries which, though very tart, proved a most acceptable change from our dried fruit.

Mission Inlet. Aug. 9.—The "Helen" left for the Kowak yesterday and the weather has been perfect, so we hope she has safely crossed Holtham Inlet. Until she returns we four are to keep camp and finish up some work for the winter. We are becoming acquainted with the natives. Like those I knew in Dakota and the Indian Territory, they are very superstitious. They make us pass in front of a tent in which is a sick person, and if we are towing a boat past along the beach, we must get into the water and row around the camp so as not to walk past. Many of them are ill, and they lay It to the gold hunters: but it is really from exposure in following the whites around. The [ 18 ] doctor has treated several, and if they recover he is "all right;" but if they die, it is his fault. Not so very unlike other folks! The doctor makes the natives pay for medicine, as this, he says, "is the better policy." He charged a salmon for some pills last night, and in another case where more extended services were required, he charged a nickel and two salmon. He does not intend to infringe upon any existing fee bills in the States, but if any "medicos" thereabouts pine for a more profitable field, there is plenty of room at Kotzebue Sound.

Some of the prospectors who went up the river earlier are now returning broken-hearted, and are going home.

Mission Inlet. Aug. 11.—The "Helen" came in last night with all safe aboard. They got about one hundred miles up the river, and concluded it better to get us all up that far before going on. We expect to start to-night. Our folks met two of our first prospecting party, who reported going as far as Fort Cosmos, three hundred miles up the Kowak, and who announced that place to be our best winter harbor. They had found some "colors," but nothing definite as to gold.

This will prove my last entry on the Kotzebue, but the winter's record will not be dull. I am thinking, by the time we thaw out in the spring of 1899. C. C. and the doctor, whose proclivities are well known to be of a semi-religious type, have a whole library of good books, such as "Helpful Thoughts." "The Greatest Thing in the World." Bible commentaries, and so on, with which we may enliven the winter evening that knows no cock-crowing. However, we shall have games and lighter reading.

I have now more than one hundred bird-skins, some of them rare, such as Sabines' gull. Point Barrow gull, etc. I believe I am the only one of the party who could get the smallest satisfaction out of a possible disappointment as to gold.

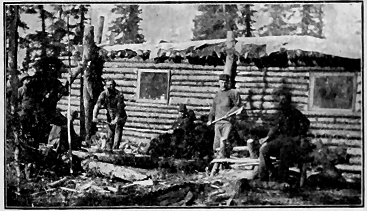

PENELOPE CAMP, Kowak River, Aug. 28.—Here we are, one hundred and seventy miles from the mouth of the Kowak River and hard at work on our winter cabin. The "Helen" is almost a failure, else we should have been much farther up the river. The river is swift and has many rapids which we could not stem. The boat is slow. Her wheel is too small. She will be remodeled this winter. It took five days to come this far, and, as there are two more loads to bring up, we thought it best to halt. We have been here a week and the walls of the cabin are nearly done, so that we are on the eve of owning a winter residence on the Kowak. We are expecting the "Helen" back soon with her second load.

The Kowak River, though scarcely indicated on good-sized maps, is as large as the Missouri. At our camp it is nearly a mile across, and very deep on this side, with sand bars in the middle. Other folks are having a harder time than we. Only three out of the dozen or more river steamers are a success. One is fast on a sand bar, and it looks as if she would stay there.

Some of our crowd think we had a hard time, but when we compare our lot with that of others we see it differently. Hundreds are toiling up in the rain, towing their loaded skiffs mile after mile along muddy banks. We have not had an accident worth mentioning unless it be the loss of a water pail. We took the wrong channel once coming up and steamed twenty-four hours up a branch river. It was the Squirrel River, and although but a tributary to the Kowak, is as large as the Sacramento and San Joaquin combined. It was so very crooked that at one point where we stopped to wood up. I climbed a hill and could see its route for several miles. Our course went around the compass once and half way again. When we got back to the Kowak we made good time until we reached the first rapids, where our trouble began. The "Helen" would swing around and lose all she had made every few minutes when the current struck her broadside. Finally a squad of us took to the river bank with a long tow-rope, and foot by foot she was towed past the critical points. There were six of these rapids. When the wind blew there was fresh trouble; it would catch on the side of the "house" and blow the boat around in spite of us. She almost got away from us once, and we were in danger of being dragged off the bank, in spite of the fact that we dug our heels into the ground and braced with might and main. It was a tug of war. And such is gold hunting in the Far North!

Many others had a still harder time. We passed thirty of these parties in one day towing their provisions, while many lost their boats. There must inevitably be great suffering here this winter. Men have not [ 19 ] realized what a long winter it will be and are poorly provisioned.

Our crowd is becoming a trifle disappointed as to the gold proposition, and of course the general discontent is infectious. Hundreds are going back down the river every day, spreading defeat and failure in their path, and yet they have done no actual prospecting. This is a large country and a year is none too long to hunt; but with many parties the result is that after panning out a little sand the job is thrown up.

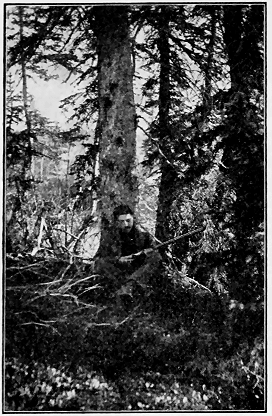

Birds are all right here, if there isn't any gold. I have been into the woods only twice so far, but secured another rare specimen of Hennicott's Willow Warbler. There is a bear in the woods back of camp. I have "laid" for him three times, but he is very shy.

Sept. 1.—The "Helen" came with her last load yesterday, and our whole crowd is together again excepting the three men with the "Penelope."

After a big pow-wow it has been decided to divide for the winter. Ten men are to take the "Helen." with supplies, and push up the river as far as possible. They think they can do some mining during the winter. We who are destined to live together here for eight mouths are Dr. Coffin, C. C. Reynolds. Harry Reynolds, Clyde Baldwin, Cox. Brown. Rivers, Wyse and myself. Time will prove if this is a congenial combination. We shall resemble California canned goods in our narrow limits, and the winter will show our "keeping qualities." Andy and Albert, our Swede sailors, leave us to-day. They were hired and do not belong to the company, and will return to Kotzebue, where they hope to ship for St. Michaels.

Camp Penelope, Kowak River, Sept. 13.—Our cabin is done. It measures 25 × 30 feet. We moved in on the 7th. The river rose very high and threatened to inundate our tents. The place where they were is now under water. Our cabin roof was not a success. It was too flat. On the night we moved in it rained heavily, and about 2 a. m. we were roused by the water pouring in on our beds and our precious supplies. We got to work without delay. The roof could not be repaired without rebuilding it, so we spread it all over with flies and tent cloth, which froze stiff for the winter, and now we are dry. When the cabin was started it was intended for our whole party, but there is no room to spare even now with only nine occupants. The foundation was leveled on the side of the knoll, so that the top of the hill is nearly as high as the roof and the earth is banked the rest of the way over the wall. That leaves no point for the north wind to strike the house. We made a lean-to on the west and the door from the cabin opens into it. We have two windows, which we brought with us, fitted on the south. The interior of the cabin is a single room seven feet high. It has a gable a foot or two higher, which gives "ample breathing space." as I told the boys, but which I have my eye on as a storeroom for my collection. The roof above this structure is fearfully and wonderfully made. If it had a trifle more pitch to it, to make it shed water, it would be better. A heavy ridge-pole and stringers run lengthwise, and over these are closely laid poles, the butts at the eaves along the sides, and the slender tops bent over and clinched on the opposite side of the roof. Above the [ 20 ] poles is packed a thick layer of moss. Above the moss is a layer of heavy sod with the dirt side up. Above all is a layer of spruce boughs like shingles. These boughs grow thick and flat, with needles pointing the same way, so they make good roofing.

The logs of the walls are chinked tightly with the moss. The floor is the natural sand. We did not cut the timber from near the house on account of the protection it gives us from the north winds. Trees large and long enough for building purposes are not very numerous, and we had to carry them a good ways. A few are as large as twenty inches at the butt, but mostly they are from ten to fifteen inches. It is all that eight of us can do to struggle along with one of these logs, they are so heavy, and we put them on rollers sometimes. Four of the men can easily carry one of the twenty-four foot logs, but a green spruce log of any size is always heavier than it looks.

I have initiated "Brownie" into the secret mysteries of the cook stove, and am one of the regular laborers now, working hard ten hours a day. But yet it is fun; for we are working for ourselves, with but the clean woods all about us, and there is a fascination in chopping up the spruces, their delightful fragrance permeating everywhere.

Sept. 19.—Six of us have just returned from a trip up the Hunt River—Harry Reynolds, Wyse, Cox, Rivers, Clyde and myself. I was culinary officer as usual. We had the eighteen-foot sealing boat, and It was loaded pretty heavily. The whole of us had to work for it, one in the stern of the boat to steer, one wading at the tow-line as near the boat as possible, to lift it over snags, and the other four tugging at the tow-line. We wore hip boots and outside of them oil-skin trousers tied around the ankles. Even with this outfit we were constantly getting into the water all over. Rivers got a soaking the first day. He shot a duck and jumped out of the boat in pursuit. The bottom is so plain through the water that it is deceptive, and he went in up to his waist, but he grabbed the side of the boat to keep from going under. He got his duck—and a ducking thrown in. We had to pull him in and to the shore, where we got him out of his wet clothes. In the afternoon Wyse also got a ducking by falling into a pool as he was scrambling up a steep bank. We found good camping-places. We had two tents, which we put up facing each other, with a flap left up on the side of one of them for a door. The two were heated by the sheet-iron camp-stove. At noon we did not put up the tents, but got dinner in the open—flapjacks, coffee and bacon. I shot two geese the first day out, which gave us a couple of meals. They were young and so fat I could not save their skins. But I made a drawing of one of them so that I could be positive of their identity. Looking them up when I got home where my books are, I found them to be the Hutchins goose. The doctor and I shot two white-fronted geese on the banks of the Kowak. We see a good many, but they also see us and we have to do a good deal of sneaking through the bushes to get any.

We had some narrow escapes, especially Cox, who fell into a whirlpool. He was dragged off his feet by the rushing water, but we pulled him into the boat after a frightful struggle.

On the fourth day out Clyde and I thought we would explore a little canon. Harry Reynolds had washed out several pans of sand from different bars on the way up, but had not found a trace of gold. Clyde and I hoped to have better luck, and started out in high spirits with spade and pick and gold-pan to do our first prospecting.

We found a brook in the cañon where we panned some without success. Finally we found a place where the stream ran over bed-rock. The rock had cracks and fissures running crosswise with the stream, so we reasoned that if there was gold above, particles would have been caught in these cracks. We dammed the brook and turned the stream to one side, exposing the fissures in the rock. We then gathered several pans of sand from the niches, examining it with [ 21 ] wistful eyes, but no trace of gold did we find. So we gave it up on that stream. We found nothing save Fool's Gold. We kept on up the cañon and, as it was yet early, decided to climb the mountain peak. As we went up the spruces grew smaller and finally disappeared. The sides were barren save for a thin covering of moss and lichens and patches of stunted huckleberry bushes. These bushes, not more than three or four inches high, bore hordes of luscious ripe huckleberries, and nearly every hundred feet in our climb we would drop on our knees on the soft moss and till ourselves, so often could we find room for more. Another little black spicy berry growing in crannies was good. Just as we were toiling up the last slope a flock of twenty white ptarmigan flew up in front of us, and circled down to another ridge. They, too, had been feeding on the huckleberries.

As we rested ourselves, sheltered in a niche of the summit crag safe from the chilling wind, a little red-backed mouse ran from a crevice and scampered through the moss straight to a huckleberry patch, his own winter garden. Clouds began to gather on the highest peaks, and we started down, leaving them behind.

The moss was slippery and we found that we could slide down the steep pitches easier than we could walk or jump. I remembered seeing the little Sioux slide down the hills of Dakota in government skillets, and immediately sat down on my shovel, steering with the handle just as I had seen the Indian boys do, and made terrific progress. I was soon able to pick myself up, feigning to examine a ledge of quartz while I rubbed my posterior, and looked back for Clyde.

He tried sitting in the gold-pan and started all right, but soon found that he couldn't steer. He went at a frightful rate, tearing down the steep slide backwards, until he, too, found himself examining the geological strata while giving some attention to his anatomy. And then we had to hunt for the gold-pan which, from the musical sounds which grew fainter and fainter and finally died away altogether, must have got switched off into the bottomless abyss. Will it be found some day generations hence and borne off in triumph as proof of a prehistoric race? It was a race. Such is gold-hunting in far-away Alaska.

At camp that evening we were joined by a native, "Charley." who told us by signs and by what few words he could speak, that he had come part way up the Hunt River behind us, but had left his birch-bark canoe several miles below, roaming off to hunt in the neighboring hills.

He told us that he had shot a bear the day before and had cached it down the river, his boat being too small to take it. He wanted us to go and get it. Sure enough, a few miles down, we found the bear as Charley had said. It was all cut up, the skin being stretched on poles and fastened in a tree. The carcass was also divided and hidden in a pole-box raised high on a slender scaffold. Charley had expected to come on his sled later on and take it home. After loading on this prize we continued down the river, the Indian accompanying us in his canoe. The rapids were furious and many, and we shot them as if we had been behind a locomotive. It took a cool head to steer a boat under these conditions, and Cox did it. At one place the stream had washed under a bank above and trees had fallen over, making a complete set of rafters. The current rushed the boat under a series of these, like city roofs, and it kept us busy to duck our heads.

We arrived home yesterday, making in seven hours a distance that had taken us three days to go up. Charley gave us bear meat to last a month. It tastes fishy, as the bears live mostly on salmon in summer, but it is a welcome addition to our larder. During the trip I obtained two hawk owls and an Alaskan three-toed wood-pecker, both species being new to my collection.

OCT. 15. 1898.—In looking over my diary I find that I have recorded no "bad weather." This comes of my having inherited a tendency to look on the bright side [ 22 ] of things. I hear such complaints as "bad weather," "disagreeable day." "awfully cold." etc. Days when some are grumbling about its being "too hot" or "too cold," "too wet" or "too windy," I find some special reason for thinking it very pleasant. It is no virtue of mine, as I said. It is natural. Up till to-day there has been warm weather mostly. Now there is a sudden drop in the temperature. Seven degrees above zero this morning. The north wind is blowing and makes one's ears tingle. All standing water is frozen and the Kowak has begun to show patches of ice floating down with the current. The great river is choking. It is being filled with ice which can move but slowly, grinding and crunching and piling up into ridges where opposing fields meet. Suddenly it is at a standstill. In a day or two the ice will support us, as it does now on the margin.

So quickly does the cold of winter close its grip. All these achievements of nature are new and interesting to me. I ran down to the river bank a dozen times to-day to note how the process is going on. It is very low now on account of the dry weather of the past weeks, but, as the choking goes on, a flow of water comes down from above over the ice, making a double fastness. The only fish that can survive will be those that seek the deeper places. There will be no more passing of boats. We hear that the steamer "John Riley" has been left high and dry on a sand-bar, and has broken in two in the middle by her own weight. Two other boats are aground on sand-bars, and must be taken to pieces if ever rescued.

Since the Hunt River trip I have been at home mostly. I have been cook, of course, a part of the time. There is no special work to be done outside.

I have collected some birds, but they are growing very scarce. I went into the woods to-day for a couple of hours, and saw only two redpolls.

Redpolls look and act very much like our goldfinches in the States. Rivers made me a bird-table. It is strange, but everybody declared they would "fire" me bodily if I continued to skin birds on the dining-table; that is why Rivers took pity on me and made me the finest table I could wish for, and a chair to match.

We have the saw-mill. Dr. Coffin and Harry Cox, with the aid of others, ran that for several days, and enough boards were ripped out to cover the cabin floor, besides library and cupboard shelves. They declare "whipping" is hard work. I didn't try it myself, as I was cooking at the time. I prefer to run a cross-cut saw. The saw-mill worked "relays," working five minutes, talking fifteen minutes, resting a half hour before the next took its place. Whip-sawing is an interesting process, especially to the man who stands below and looks up into the shower of sawdust. The doctor advised the plan of wearing snow-glasses, so that the sawdust difficulty was obviated, but the hard work was still there. The doctor tried his best to get me into the business, for he said it would surely tend to straighten my back, which stoops from constant skinning of birds at the table. He got such a "crick" in his back from whip-sawing that he could scarcely sleep for several nights.

Besides the saw-mill, there was the furniture factory. C. C. and Harry Reynolds and Dr. Coffin were engaged in that enterprise. As a result the cabin is supplied with double bedsteads, with spring-pole slats and mattresses. And there are lines of wooden pegs in the wall for hanging clothing, and carpets for the bed-rooms made of gunny-sacking stuffed with dry moss.

A partial partition runs lengthwise of the cabin. At the kitchen end this partition is composed of a tier of wood, then an entrance space, and then a series of shelves from top to bottom for pantry, medical department and library, which latter is extensive. At the farther end is another open space communicating with the "bed-rooms." The whole inside of the cabin is lined with white canvas tenting, which brightens us up ten times better than dark logs. On the south side of the partition is the "living-room," "dining-room" and "kitchen;" all in one apartment to be sure, but yet with their recognized limits. On the north side of the partition is the bed-room. There are three double beds and three single ones, according to the wishes of the occupants. A pole runs crosswise of the apartment, and on each side of this is a line of pegs hung full of clothes. This forms a wall dividing the apartment into "bed-rooms." Carpeted alleys run between the beds, and the walls are hung with clothing. What we are to do with all this clothing I do not know.

[ 23 ]

Oct. 21.—Just through supper and everyone has settled down to read, excepting several who have gone out to "call at the neighbors'." C. C. Reynolds, our president, undertaker, preacher, all-around-man, has taken to cooking. He started in well. For supper he gave us some fine tarts. I am glad to be relieved from the cooking, and do not intend to engage in the business again. We shall see.

I am skinning mice now, little red-backed fellows which swarm in the woods and around the houses. I set my traps every night. This morning I had a dozen. Wolverines and foxes are common about here, but they are too cute for me and decline to be caught in the steel traps which I keep constantly set for them. An Indian shot two deer in the mountains and brought them to the village. The doctor traded for some venison, which is better than the bear meat, though I have no craving for either. The boys think me a baby because I prefer "mush" to meat.

Last Sunday the temperature fell to even zero. The trees were heavily covered with hoar frost, and the scene, as the sun rose upon it, was magnificent.