Lowndes didn't like Nestor. For Nestor

was a robot—managing his finances. And Nestor

had only one thought in his brain: save money!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

October 1958

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The old robot was one of the few remaining hand-made productions of the Rotulian era—an era which had seen each individually constructed robot reach the zenith in the various professional fields. An era totally unlike present-day Cornusia and its slip-shod electro-assembly line robotic productions. And indeed slip-shod were these productions, many Cornusians agreed. Loudly and indignantly they howled that the stupid Cornusian robots, conspicuous by their dress (multicolored sport coats, striped trousers, curling shoes and brightly feathered hats) did nothing but prance around all day and engage in horseplay.

Not so the old robot....

From that long-ago day when his final bolts had been lovingly tightened by grimy machinists and tabac-chewing electronicians, he had been fabulous. Even the Rotulian elders, accustomed as they were to robotic achievements, had been stunned by his rapid rise in the fields of finance and economics. And even the irascible bearded banker, Tesmit Lowndes, after an eighty year association with the robot in investment circles, would admit, although grudgingly if questioned, that the robot was "sharp with a kredit."

Upon the early demise of the elder Lowndes (at age ninety, and there were raised eyebrows in Cornusian society at such an early departure) his will, officially striped in red and green and properly opened in the presence of the required seven witnesses was found to state unequivocally: "It is my last testament, under the laws of Cornusia, that my longtime and good friend Nestor shall operate the finances of my estate for my son Harry, sole survivor, until...." And there followed, set down in tiny multitudinous lines of legal terminology peculiar to the age, the conditions and the length of the operation of the estate.

So it was that the robot Nestor became involved, through no fault of his own, with certain people who—

"Nestor," said Harry Lowndes to the robot who had entered the study in answer to the pull on the bell cord, "I must have an advance on my allowance."

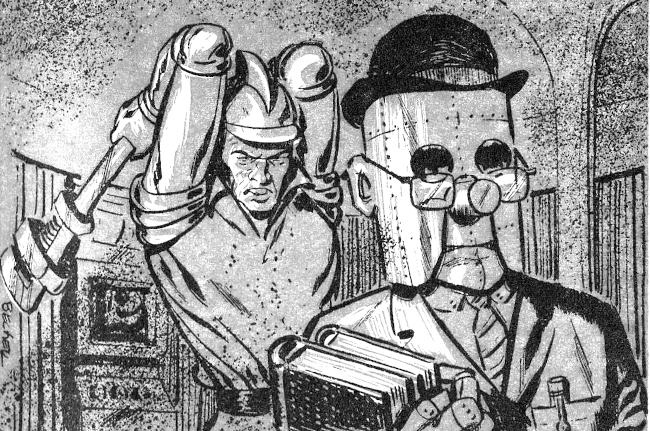

Nestor stopped just inside the door. He was a small and chunky robot, much older than the slender six-tube types presently in use. His somber clothing, unlike the gaily clad, stupid Cornusian robots, gave evidence that he was a production of the Rotulian era. A blue-serge suit decked his blocky metal frame. A conservative black and white zebraic tie, a type popular with professional men, was knotted neatly into his spotlessly white button-down collar and draped in graceful folds over his aud screen. Thick, horn-rimmed focals perched on his stub nose and magnified his magenta eye sockets.

He was carrying two bulky ledgers, a huge well-worn legal-looking volume and half a dozen much-thumbed copies of the Uni-Worlds Financial Journal. As Lowndes finished speaking Nestor shuffled toward the desk, set the armload down and stepped back, removing his black bowler and exposing to Lowndes' view a worn, blue-gray pate from which tiny specks of aconium flaked—a sign of rapid aging in the Rotulian robot.

"Master Lowndes," said Nestor, "an advance will be impossible. According to the terms of your late father's will—"

Lowndes interrupted, red-faced. He slammed his fist down on the desk top. "All right. All right, Nestor," he growled. "So my father left you, his financial adviser, in charge of the estate. I'm not complaining. You're making kredits. But can't you loosen up a little bit? All I need is a five hundred advance on next month's allowance."

Nestor leaned forward to place the black bowler on the corner of the desk. "I'm sorry, Master," he said, straightening back up slowly. "The will allows you one thousand kredits."

"I know what the will allows me," yelled Lowndes.

"Master," said Nestor, "I am trying to preserve the estate. Your interests are paramount with—"

"Nestor, I've got to have five hundred kredits!"

The robot did not answer. His aud lights flickered.

Lowndes cooled down. "Nestor," he asked, "can't you find a loophole in the terms of the will?" He pointed to the legal-looking volume setting on the desk. "How about digging through that?"

Nestor did not answer. His aud lights still flickered fitfully.

"Nestor, I am sorry I spoke shortly to you."

Silence.

Lowndes stared at the motionless robot. "Now look here Nestor, you heard me apologize."

Still silence.

"Please, Nestor," Lowndes pleaded. "I know you can figure out a way. Just this once. Please Nestor."

Suddenly Nestor's cranial lights lit up. His aud lights flashed on. He looked like a Christmas tree. His relays began to click-clack. His aud box hummed. He sounded like a swarm of bees.

Lowndes stared in amazement. Nestor's deep thought processes never failed to fascinate him. As he watched, abruptly all the lights cut out. The relays gave a final "clack." For a minute there was silence. Then Nestor spoke: "Master, I have converted a majority of the holdings ... yet five hundred cash kredits remain in Central National Repository. Under provisions of section four, paragraph seven, sub-paragraph eighteen of the Quarto Code, this amount could be carried to the ledgers as a gift to you, deductible. Your signature would not be required for the cash transfer."

Lowndes eyes gleamed. "I'm proud of you, Nestor. How long will it take to get the kredits?"

"Master, as I mentioned, I have converted all but—"

"For pete's sake Nestor, I've got to have those kredits by seven tonight!"

"Master, please! Allow me to explain the disposition of the converted assets. I am certain that we are facing a recession comparable to that suffered by the ancients in the twenty-ninth year of the twentieth century. Therefore, I have withdrawn—"

Again Lowndes broke in. "Look, Nestor, tell me later. Let's get the five hundred!"

"Perhaps we should reconsider, Master. Even though legal, this action is irregular."

"Reconsider! Whadya mean, reconsider! You figured it out, didn't you? Nestor, someday you'll blow your tubes from worry. Now how about getting those kredits!"

"All right, Master. I shall go." The robot shuffled from the study, his tempite joints creaking with age.

Lowndes stared after him. So Nestor was converting assets, he thought. He'd bet a herd of two-headed Venusian horses that the robot would more than quadruple any investment. He'd probably buy into some new uni-space enterprise. Even though it rankled to have the robot controlling the finances, still he had to admit that old Nestor was a financial wizard. Under the terms of the will of the departed elder Lowndes, Nestor was to control the estate investments until Harry reached the age of thirty—or until Nestor ceased operating. And in the meantime, though it was at times galling to have to live on the allowance—Harry termed it a dole—of one thousand kredits a month, he consoled himself by reflecting that Nestor couldn't possibly last much longer—he'd already had several major overhauls. Besides, he, Harry, would be thirty in three more years. Anyway, Nestor wasn't too hard to get along with. He was just too conscientious. But he was making kredits by the barrelful. Harry thought, I've been pretty lucky talking Nestor out of the five hundred. Maybe I've found the secret of handling him. Anyway, I'd better watch myself. If I couldn't pay Sliman, I'd really be in the soup. At the thought of Sliman, he scowled. Too bad I can't take Nestor down there and clean out that sharp-suited gambler. Too bad the law forbids calculators like Nestor to enter establishments such as Sliman's Snake Eyes Club. Wow! What Nestor wouldn't do to Sliman's roulette wheel. And as for the dice game—! Well, he'd pay Sliman the five hundred and that'd be all! He was through!! From now on he'd better devote his time to Judy. Of course, he reflected, she was a trifle expensive for his one thousand kredit allowance, always wanting jewelry and those cute Martian minks, but—His thoughts shifted. She'll be plenty burned, he thought, because I didn't show up at the Krinkled Worlds Club last night. I should never have stopped in at Sliman's when I had a date with her. Apologies are definitely in order. I'd better talk to her and get out of the dog—

The video-screen hanging on the wall shrilled. He got up from the desk, walked over to press the "On" switch.

The head and shoulders of an attractive female appeared on the screen. Her shoulder length auburn hair framed a face dominated by green eyes and sulky red lips.

"Judy," said Lowndes enthusiastically, "I was just thinking of you."

"Don't 'Judy' me, you beast," she flung back at him.

"Why, sweets, what's wrong?" he asked innocently.

"You know well enough what's wrong," she flared. "I waited for you at the Club last night. But you never showed!" Her temper, clued by her auburn hair, was showing. "And I waited for my birthday present! But I suppose it never occurred to you"—she stressed the you nastily—"that last evening was also my birthday!"

"Sweets, I'm sorry." He sidled away from the green eyes glaring at him and added, "I'll see you tonight at eight-thirty."

She snorted. Then, noticing his furtive movement away from her she yelled, "Harry Lowndes, you come right back here in front of this screen where I can see you. I want to know where you were last night!"

He came back, a sheepish grin spread over his face. "I stopped in at Sliman's," he said.

Her carmined lips tightened. "Sliman's! All right, Harry Lowndes, how much did you lose?"

"Five hundred."

Her green eyes flashed. "Lost five hundred!" she screamed. "That five hundred would have bought me a birthday present!" Her voice dropped several octaves. "I'm through, Harry. I'm sending your ring back in the morning."

He was shaken. "Sweets, it'll never happen again. I'm paying Sliman off tonight and, believe me, sweets it is the last time."

"I mean it, Harry."

He groaned. "Judy, please! What of our plans?"

"Plans! Did you think I'd marry you on a pitiful one thousand kredits a month?"

He was desperate. "Judy, you can't do this. I'll speak to Nestor. I'll get him to increase the allowance."

She laughed at him, biting, sarcastic laughter. "Speak to Nestor! You couldn't get Nestor to do anything. He controls your estate. Or didn't you know?"

"Judy, please listen. I will—"

"Good-bye Harry. Your ring will—"

He tried desperately to hold her on the screen, cutting in with, "Judy, it will be only a year or two until Nestor quits operating. Then we will have the estate."

She was furious. Her anger, smouldering till now, erupted white-hot. "You actually expect me to wait for that senile walking adding machine to run down?" She was raging now, whiplashing him with abuse. "Why, you spineless worm! You cheap excuse for a man! If you were half the man you pretend to be, you'd make that stupid robot quit operating! Good-bye!"

The impact of her words had stunned him. He walked to the desk, slumped limply, held his head in his hands. Unseeing he stared at the ledgers, the much-thumbed journals. His eyes were bleak. Even now, still reeling under her scorn and smarting under her abuse, he thought of her. Recalled his last glimpse of her, auburn-haired and red-lipped. Flinched at the memory of her green eyes, glittering with rage, boring into him.

He groaned, ran his hands through his dark hair, then rose. His face was grim. He walked to the garage, rummaged in the trunk of the little ground scooter, pulled out the three pronged ironite wheel wrench. He carried it back to the study, laid it beside the desk and sat down to wait for Nestor....

The old robot shuffled into the study, his diaphragm tubes pulsing under the strain of the four square trip to Central National. He pulled a thick roll of orange colored kredits from the pocket of his blue-serge coat, and handed it to Lowndes. "There you are, Master," he wheezed.

"Thank you, Nestor," Lowndes replied. He walked toward the study windows, glanced out into the sunlighted patio, then turned back to face the robot. "Nestor," he said, "a problem has come up. Do you think it could be possible to increase the allowance. You see, I am planning marriage."

Nestor's magenta eye sockets flickered slightly after Lowndes had finished speaking. "Might I offer a suggestion, Master?" he asked.

"Go ahead."

"Master, it is rumored in the city that you have been frequenting the establishment of Sliman, the gambler."

Lowndes glared at the robot. "Whadya talking about? What's Sliman got do with all this? I asked you if you couldn't work out a liberal increase. I want to get married!"

"I have an answer for you, Master. But I thought it politic to mention that the odds at Sliman's are definitely against you."

"Forget about Sliman!" snarled Lowndes. "How about the increase?"

The robot's words thudded into Lowndes brain. "An increase is impossible. Master!" he said. He went on, his aud tones crackling, "Indeed, I may have already overstepped in gifting you the five hundred kredits. The testament and tort attorneys may never allow it, especially since it was in payment of a gambling debt! Good day!" Nestor reached for the black bowler he had placed on the desk and set it neatly in the center of his worn pate. He picked up the armload of books and journals, and headed for the door. He turned back for a moment to face Lowndes and add "And Master, if you will forgive my impertinence, I should like to say that I do not believe a marriage with Miss Judy would be prudent."

In that moment Lowndes' face turned livid with anger. Seizing the heavy wheel wrench, he lunged for the blue-clad robot. He brought the wrench down squarely in the center of the black bowler.

SSSSSSSSSSS ... SSSSSSTTTTT ... CRACKLE ... SSSSSSTTTT....

The heavy pronged ironite wrench crashed into Nestor's cranial tubes, drove through the blue-gray worn pate, sliced into the fragile old-style gretile metal, battered and shredded the robot's upper works into a twisted mass.

Again and again, in maniacal fury Lowndes slammed the ironite prongs down. Nestor crashed to the floor in a final hiss and crackle.

Lowndes stared at the robot's smashed remains, stared at blue-gray old-fashioned gretile metal scattered in a twisted heap of powdered tubes, shredded relays and curling tensit wires. Off to one side the ledgers lay where they had fallen. He reached out and picked up one of them. He thumbed through the pages, ran his eyes over the lists of holdings set down in Nestor's precise hand. What was this? The page titled Central National showed withdrawals. Where was the balance? His eye riveted on the final figure.... Zero! He threw the ledger down, reached hurriedly for the other. Hah! here were further listings. He flipped rapidly through page after page, intent on the balance. Page after page—One-World Banking—Coxcomb Trust—Martian Financial Institute—Venusian Investors—Cornusian Tex Fund—But—But what was this? All showed withdrawals. All showed balance Zero!

BALANCE ZERO!

He sagged against the corner of the desk, his face pale. His hands shook. Where were the kredits? What had Nestor done with them? Sweat broke out on his forehead. Steady, Steady—he dragged himself back from panic. His mind worked. Let's see. Central National is the biggest of the repositories; Nestor held the working capital down there. If he converted the kredits, they'd know. He'd tell them; he's dealt with them for over eighty years. I'd better go down and find out. I'll tell them.... He was busy, his mind churning and twisting, concocting a story....

He felt much better as he walked toward the study door. Thoughts intent on Judy, green-eyed, red-lipped, curvaceous Judy, and on the kredits certain to be invested somewhere in the maze of holdings, he stepped over the pile of smashed tubes, twisted relays and scorched tensit wires that had been Nestor. He eyed the pile. Nestor, he reflected, has met with an unavoidable accident. An accident, coincident with a tube failure on Nestor's part, whereby the ground scooter broke its electronic control and ran over the robot. And in the same line of thought ... I shall have to drag him over and stack him in front of the garage and use the wheel wrench on the fenders and head lamps of the scooter. They shall have to be battered to show that....

He was smiling as he started for the big, eight-sided structure, Central National.... A four square trip, and one which Nestor had made earlier in the day....

Vice-president Milligan, a thin, narrow-shouldered man who affected a pince-nez greeted Lowndes. He offered a cool hand: "Mr. Lowndes, this is indeed a pleasure. We don't see you down here very often. Have a seat."

"No, not very often," said Harry, dropping the hand and sitting down, "Nestor handles the accounts."

"Well, Mr. Lowndes, what can we do for you?"

"Mr. Milligan, Nestor has suddenly blown a tube and has decided to turn in for an overhaul."

"Sorry to hear that. These tube failures can be so sudden. Matter of fact, I believe I saw Nestor in our investment department an hour or so ago."

"That's right, he was," said Lowndes. "But after the tube blew, he became very concerned as to whether the balance he showed in the ledgers was correct." Lowndes smiled, "I told him I'd find out, Mr. Milligan. Sort of humor him, y'know."

Milligan rose, pulled his pince-nez out of his suit pocket and placed it squarely on the tip of his nose. He looked over at Lowndes and said, "Mr. Lowndes, you are fortunate to have Nestor handle the financial affairs for the estate. Your father showed exceptional judgment in the selection. Naturally, we at Central National were elated—why, we've held your family's finances and dealt through Nestor for over eighty years. In fact, ever since your father organized Lowndes Methodical Investments." Milligan started for the door, "Now," he said, "if you'll excuse me, I'll go and check on the accounts balance."

He came back frowning. He removed the pince-nez from his nose and held it in his hand. He appeared concerned. "Mr. Lowndes," he said, "Nestor has closed out the accounts. Every kredit has been withdrawn—not only here, but in all our correspondent repositories." He paced back and forth in front of Lowndes. He stopped, peered down and added, "A five hundred thousand withdrawal, Mr. Lowndes."

"Five hundred thousand," repeated Harry. He reached for his handkerchief. His forehead was beginning to bead with sweat.

"We have explicit confidence in Nestor's ability, Mr. Lowndes but—" Milligan looked sharply at Harry. "Are you sure he hasn't had an unreported tube failure during the past few days? After all, withdrawing five hundred thousand kredits—" he broke off.

"Five hundred thousand kredits!" said Harry.

"I agree with you, Mr. Lowndes. Indeed a sizable amount." Milligan gave a weak laugh. "Naturally," he continued, "we are loath to lose an account of this size. That is the reason I inquired as to possible failure on Nestor's cranial range. His actions certainly have been strange—"

Lowndes interrupted, "What? What's strange? He was all right this morning."

Milligan was agitated. "Are you sure, Mr. Lowndes? First of all, Nestor told Farrell, our investment man that we Cornusians were headed for a recession of even greater severity than that experienced by the ancients in the twenty-ninth year of the twentieth century."

Lowndes' hands were shaking. He fumbled for a Martian rolled plovur, lit it and inhaled the greenish fumes. "Why," he said, "Nestor told me the same thing this morning. What does that prove?"

Milligan stared at the greenish fumes with distaste. He did not smoke. He said shortly, "Allow me to continue, M. Lowndes. I am as distressed by this affair as you are. After all, five hundred thousand kredits." He broke off, eyed the green fumes curling from the tip of Lowndes' plovur, then continued, "Frankly, Mr. Lowndes, I never heard of anything so fantastic."

Lowndes couldn't control his hands. He dropped the plovur on the carpet. He stood. He couldn't control his shaking legs. He grasped the edge of Milligan's desk. "What-dya mean, you never heard of anything so fantastic?" he croaked weakly. "What'd Nestor tell Farrell he was going to do with the kredits?"

Milligan's face blanched. His voice in turn quavered. "What? You mean you don't know? Why, Nestor told Farrell he was going to tell you—in case an emergency came up. Farrell says Nestor walked out of here with a great big grip jammed full of the kredits. Said he was going to bury them. Said he'd be back and redeposit them after the recession was going good—when a kredit would be worth a kredit!"