As the greatest detective in the galaxy, Len

Zitts could easily arrest the murderer. His

main interest was in analyzing the weapon used!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

April 1951

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Len Zitts wiggled his big toe and gently pressed it against the velvet-covered button, and the couch on which he was lying began easing from beneath the desk to shape itself into a lounging chair. In the process, a pair of mechanical arms slipped a pair of flexible plastic moccasins on his feet and another pair of arms buttoned his shirt collar and straightened his maroon cravat. At the same time a mechanical comb and brush straightened the part in his thick chestnut hair and smoothed it neatly.

Rising from behind the desk to a sitting position, without any effort on his part, Len Zitts blinked brown eyes and looked again at the vision of blonde loveliness which stood with full mouth agape just inside the doorway.

"Oh!" The slender woman drew a deep breath, causing her bosom to swell alluringly. "You scared me. Popping up like a jack-in-the-box!"

Moving his little finger an eighth of an inch, Zitts touched a button on the arm of the chair and a mechanical hand put a cigaret in his mouth and another tubelike arm moved beneath the cigaret and squirted flame against its tip. "Sit down," Zitts invited. "Have a cigaret." He pressed another button and an arm on the far side of the desk extended a tray of assorted cigarets toward the woman.

A little breathless, she sat down and smoothed her diaphanous cerise skirt along her thighs. "I—I'm still a little scared," she said tremulously.

Zitts arched a chestnut brown eyebrow, significantly glanced at the desk and the mechanical equipment, and said, "Don't be alarmed. Just a few little inventions of my own. Desks were originally intended as a resting place for the feet. I've merely modernized the idea. Slip under the desk to relax. People can't spill drinks and ashes down your collar while you sleep."

The woman nodded, smiled, revealing even teeth and a wide mouth with upturned corners. "I suppose you want me to tell you why I came?"

Zitts shook his head almost imperceptibly. "I know why you came," he said. "You want to offer me a ton of gold to investigate your husband's death. Sorry! Afraid we can't do business."

"B-but—but—how did you know?" The woman leaned forward and lifted a slender hand and looked at it as though to test her eyes.

Zitts eyed the round arm with interest. "Elementary," he said. "People are always wanting me to investigate something, and they always try to palm off that trash called gold. They never offer anything worthwhile, such as a dozen genuine bacteria for my collection, or a scuttle of coal—that almost priceless black stuff from which so many things are made. Ever seen any coal?"

The woman shook her head, swinging the shoulder-length blonde hair from side to side, and her deep blue eyes opened wide in wonder. "Heard of it. Glossy ebon substance of which ornaments are made. A princess on Mars is said to own a chunk of it as big as my thumb, set in a pendant. It was captured in the Martian war with Saturn."

"It's probably a phony," Zitts pointed out. "The Martians are too smart to let a woman wear that precious stuff. A piece that big could be made into the nucleus of a webbing which would trap enough sunlight and moisture from the orbit of Mars to turn every sandy plain on that planet into fertile land."

The subject seemed beyond the grasp of the woman. "But you haven't told me," she said softly, "how you knew it was my husband's death, not something else."

Zitts turned slightly in his chair. The turning itself seemed to serve as a signal. The door on his right opened noiselessly and a dusky Venusian female glided into the room, came and sat down on a seat which was remarkably like a man's knee.

"My confidential secretary," Zitts said by way of introduction. "Miss Xuren Claustinkelwickwellopiandusselkuck. I streamline that a bit and call her Zoo. Zoo, this is Mrs. Elmer-Brown Jake-Smith."

"What?" The blonde woman's eyes snapped from Zoo to Zitts. "How did you know my name? And how did you know I had two husbands?"

"One husband," Zitts corrected. "Mr. Jake-Smith was done to death in some mysterious manner yesterday morning at daylight just as he was going to bed for the day. But you're still entitled to both names, having been legally wed to both men. The beyondlaws, I believe, are bidding Elmer-Brown."

"Beyondlaws? Isn't that an outmoded term? Its meaning has slipped me."

"Outmoded, yes, but still appropriate. Coined to replace the term congressmen. They once made the laws, I believe, but they were beyond the laws themselves. Then the people got stirred up and demoted them to ratcatchers and put responsible men in their places. They worked up from ratcatchers to jobs then known as policemen. The term ratcatchers stuck, but it seems more dignified to call them beyondlaws. These people are holding your other husband, leaving you husbandless. But that shouldn't be so bad. With your shape you ought to be able to snare a hundred husbands."

The woman dropped her eyes and blushed. "You shouldn't flatter a poor widow at a time like this," she said coyly. "But how do you know all these things about me?"

Zitts turned to the Venusian. "Show her, Zoo," he said.

Zoo uncrossed her graceful legs and leaned forward on the mechanical knee.

"Why," the blonde woman broke in, "does she sit on a thing like that? It—it's so suggestive of sitting on a man's lap."

Zitts smiled indulgently. "Miss Claustinkelwickwellopiandusselkuck," he said, "attended an oldfashioned secretarial school. The reason for their training to sit on a man's lap is lost in antiquity. But I have a feeling there was a good reason for it. In the twentieth century when bandits stalked the cities, when detectives were popping in and out of every second doorway in pursuit of murderers, and wiping off fingerprints in their wake, it is to be presumed that a man and his secretary undertook many things of a confidential nature. As a preliminary to such confidential things, a session of lap-sitting might've been just the thing. Of course we'll never know for certain. But it is an honored custom in the old schools, and, of course, we cannot go against the dignity of the past.

"Now, with your permission, I'll have Zoo go ahead."

The woman nodded assent and the Venusian girl touched a lever on the side of the desk which Zitts could not reach without stretching. Instantly a round white globe, lighted by a faint yellow glow at its center, rose out of an opening in the desk. The blonde woman, sitting close, drew back with a gasp.

"That's me," she said. "Inside the globe."

"Of course." Zitts cocked an eyebrow at Zoo who pointed at the vision. "Notice closely," Zitts went on. "Right there at the tip of Zoo's claws. You are standing on the moving carpet in a lower corridor of this building. As I lay beneath this desk I was looking into that globe which was then visible below. It is now reproducing exactly what I saw."

The woman had somewhat recovered her poise and now leaned close and watched herself glide along the corridor on the moving carpet. "But I still don't see—" she began.

"You will when I explain," Zitts informed her. "Look closely at your features. They are beautiful!"

"Yes. But—"

"It has been known for centuries," Zitts declared, "that every thought has a physical reaction. Sometimes it is only glandular. But it is a short step from observing the reactions to reading the thoughts. The reactions, of course, differ in different people. It would be necessary to catalogue your reactions before I could specifically read your every thought. But certain key reactions are fairly common, such as grief, fear, love, hate. In a glance you can tell whether a person is grieving, fearing, loving, hating. A study of reactions advances this talent remarkably. A little intelligent deduction, judgment, putting of two-and-two together, and it is possible to come fairly close to what anyone is thinking without knowing the catalogued reactions. Am I making myself clear?"

"Go on," the woman urged with interest. "But don't read my exact thoughts. I wouldn't want anyone to do that."

"I probably haven't the language to read your exact thoughts," Zitts assured her. "Shall I tell you how I knew your purpose in coming here?"

"By all means."

"Look closely at the vision. It is smiling serenely to itself. That's you a few minutes before you entered this office. That pleased expression means you have just conceived a bright idea, probably thinking you could palm off a ton of gold on me."

"But I never—"

"Observe there where Zoo's claws are pointing. A man approaches. Now look at your own face. You have suddenly remembered that one of your husbands is dead and the other is in the hands of the ratcatchers, and you are supposed to register sorrow. You do but it's feigned. Your thoughts are more on the way the man is staring at your figure. Watch! Now you're swaying your hips gracefully. Very nice! Now look! The man has passed you, glanced back once to see if you are still waving your hips, and gone on. You are no longer waving your shape. You're thoughtful again. Oh, oh! You've turned on the waves again. Another man must be approaching. There he is, sure enough. That's why you're blinking your eyes now, to call attention to your long lashes. That will stop as soon as he passes, but your hips will wave a trifle more until you're certain he's out of range."

"Stop! Stop this minute," the blonde cried. "You're just making up all that."

Zitts shrugged. "My dear Mrs. Brown and Smith, if you do not care to know how I learned of the purpose of your visit here, it is quite all right with me. No charge whatever for this interview. Zoo will show you to the corridor."

"B-but—but I do. But you don't have to go into all of a woman's secrets."

"Secrets?" Zitts lifted his hand a trifle, then let it fall, which inadvertently plunged the room into darkness and caused a grim voice to growl, "Don't move! I'll burn you in your tracks!" He corrected this at once, reassured the woman and briefly explained: "I often interview desperate characters in this room, Martians, Saturnians and even politicians. Have to protect myself."

"What were you saying about secrets?" the woman prodded with curiosity which had not evolved very much in ten thousand years.

"Secrets?" Zitts repeated. "I wonder! Most actions and reactions are as obvious as the thoughts behind them. Secrets? I sometimes doubt there is such a thing. Shall I tell you what you are thinking now?"

The woman blushed, shook her head. "Please don't. I'll try not to wish I could claw your eyes out anymore. Just go ahead and investigate my husband's death."

Zitts rolled his eyes and looked at Zoo without moving. Zoo put her arms around the back of her seat, which slightly resembled a man, kissed it lightly and leaped nimbly to her feet. She glided smoothly to a corner, her figure undulating gracefully, and set in motion a four-wheeled machine which rolled to the center of the room and paused. Panels began to slide back from the machine, revealing its insides. Meanwhile Zitts explained:

"The news of your second best husband's death was on teleview," he said. "I was interested in the case purely from an academic standpoint. With the machine you see on your left I watched the ratcatchers tearing up your apartment. The machine is called a key-skeleton. There isn't another like it in our solar system. With this key-skeleton I can enter any apartment or domicile no matter how well it is locked. Not in the flesh, no. That would be far too much trouble. I simply bring your apartment into this room. Not materially, but three-dimensionally to all effect. I have already gone over your apartment thoroughly and can describe the man who killed your husband."

The woman's curving mouth popped open. "Why don't you tell the ratcatchers?" she wanted to know.

Zitts shrugged. "I haven't the evidence to prove my theory. Besides, there is another phase of the case in which I am interested. The weapon which killed your husband was a strange, unearthly thing. Nothing like it is known to modern science. It is a hand weapon with a tube about six inches in length. Behind this tube is a six-chambered cylinder which appears to revolve when certain mechanisms are set in motion. Inscribed on it in ancient lettering is this legend: Colt. It is not known how this weapon works nor which end of it destroys. But the ratcatchers are going to experiment with it, and when they asked my advice I suggested that they hold the tube end of it toward their bodies. That seems the most harmless part of it. I also suggested that they line up behind one another when they do this, and stay away from the butt end of it. I expect to learn the results soon. Zoo! Turn on the machine."

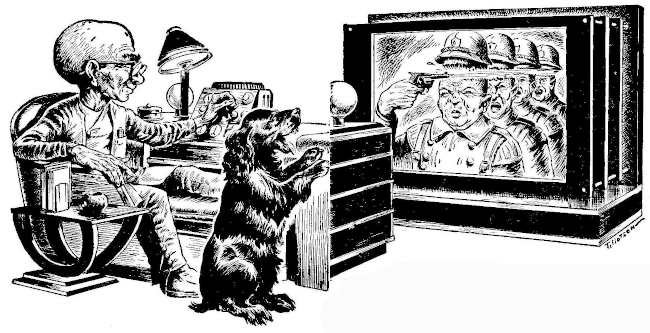

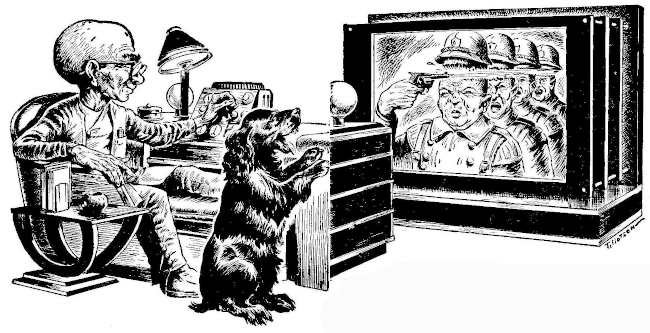

Just as the machine was turned on a loud bang sounded in the room, and the woman gasped as the view lit up and showed four uniformed ratcatchers sprawled on the floor of what was obviously the ratcatchers' lair. Zitts snorted in disgust.

"Zoo!" he called. "Get in touch with the chief rat of the ratcatchers and tell him I said those men have clearly ignored my advice. Tell him I said to caution the next men who experiment with that weapon. Tell him to see that they hold the tube next to their bodies, and tell him for the sake of safety to have six men line up behind one another. Better yet, he had better undertake the experiment himself. His men are careless. Like idiots they have been pointing the tube away from themselves and holding the butt near their bodies. Turn off the machine. The sight of those dead men and the smell of blood is offensive."

Zitts sat in gloomy silence until the woman spoke again. "Then you'll bring the murderer to justice?" she ventured quietly.

Zitts shook his head. "I'm interested in the weapon, not the murderer. Such a weapon is far beyond our science. We have only rays which kill without noise. That weapon makes a terrific bang. Seems far more fitting than silence, especially in murders resulting from hate. We might in another hundred years be able to duplicate it and put them on the market and sell them literally to millions who have a right to expect some entertainment as well as wind from their politicians. When a fellow felt in an ill humor he could destroy a politician with that weapon. The bang of it would immediately cheer him up."

The woman leaned across the desk and tears came into her eyes. "If you don't catch the man who killed my almost best husband," she sobbed brokenly, "I won't be able to get married more than a couple more times. Suspicion would fall on me and I don't know but two men who would marry a murderess."

Zitts softened somewhat. "And if I do catch the murderer?" he said.

The woman brightened, blew her nose and brushed away the tears. "I'll be the happiest person in our galaxy," she said, smiling. "I can marry six men tomorrow and probably twelve or fourteen the next day. You don't know how wonderful it will be to have so many husbands that the loss of a few now and then won't matter."

Zitts nodded sympathetically. "I can well understand," he said. "But you shouldn't expect me to use my training and intelligence for nothing. After all, I have ninety-six wives to support—partially—that is. Their other husbands contribute a bit now and then."

"I could give you a uranium mine," the woman offered.

"Uranium? Nonsense. It's used only to flush sewers when they get gummed up. Haven't you anything valuable?"

"Platinum."

Zitts shook his head. "Used for ballast in deep-sea diving and then dumped in the ocean. Have you any humorous writings, such as an ancient Congressional Record?"

"Never heard of anything like that," the woman replied. "Heard once there was some sort of record of congress which was destroyed because so many people died laughing over it."

"Exactly! Very dangerous," Zitts went on. "But I could trade it to the Martians to use in their war against Jupiter. Even a Jovian, who can endure so many more gravities than we, couldn't endure the weight of a Congressional Record. And if he could, he would either die laughing or become an epileptic. Have you got one?"

"No!" The woman shook her head sadly. "I have a private atmosphere-runabout, a house with seventeen rooms in Florida, a ranch in California with ten thousand domesticated descendants of movie stars grazing on it, a plantation on Venus where I keep a herd of poets, a million acres of arable land on Uranus, a crater on the moon, and a chunk of what's left of the ice at the North Pole. But I have nothing whatever valuable."

"No property on Mars?"

"A single canal, but it's worthless. It's filled with billions and billions of barrels of oil. Have tried to give it away, but no one is fool enough to take it."

"H—m." Zitts studied the woman with pity and understanding. "There should be some sort of charity to aid people in your poverty-ridden condition. I suppose I'll have to handle the case for nothing. I wouldn't do it for anybody else for less than a star of the sixth magnitude, but I do not believe in imposing on the poor."

"I have a nickel in ancient money," the woman said softly.

"What? A nickel? Good God, woman! For half of that I would solve every murder since the beginning of time and commit some of my own. Give me that nickel. Where did you get it? Don't you know there are people who would cut ten thousand throats for a sum like that?"

"I—I didn't know it was valuable."

"It's priceless! People will sell their souls, commit perjury, betray their friends, cheat their neighbors, buy and sell votes, and even do some good things for money."

"But such a little piece—"

"Woman, you have no idea of values. Since money has become replaced by credit and barter, such pieces as this have become invaluable collectors' items. Even before that it was valuable. You could buy a lead dime with it. And if you were clever enough you could use the lead dime to buy a tin half-dollar. Then you could change the half-dollar into wooden quarters and begin all over again. A shrewd man could amass a fortune in counterfeit dollars by such trading. Of course, he couldn't buy anything with the counterfeit dollars, but reflection on the trading would strengthen his mind while he rested behind bars. At least that's the way history relates it. Zoo! Take this precious nickel, handle it carefully and with due reverence, seal it in a tube, send it through the pneumatic to the armored transport, have them place a hundred men armed to the teeth about it, and escort it solemnly and without undue ostentation to the Universal Bank, that institution which covers eight square miles and towers ten thousand feet into the air, and deposit it with proper ceremony to my account. I shall be the wealthiest man on this planet and the envy of every creature in the galaxy. But don't worry, Mrs. Brown and Smith! I shall not overcharge you. You have two cents change coming, a tidy sum—nay a fortune—and your case is as good as solved. Zoo! Sound the alarm. We go into action at once."

Bells clanged, a siren screamed, a series of red lights flashed on and off and on and off, and a distant rumble shook the building. The blonde woman caught her breath, gripped the arms of her chair to steady herself, waited until the noise and the shaking had subsided, then asked, "Do you always go into action like that?"

"Invariably," Zitts affirmed serenely. "Seismographs all over the world register when Len Zitts launches himself in pursuit of a criminal, and the underworld trembles in despair. But," he added a trifle wistfully, "it doesn't register on Mars and Venus and they never send reporters and photographers. I'm thinking of installing a heavier vibrator. Zoo! You may inform the inquirers who will be hounding you in a moment that the nemesis of crime has plunged forth to strike death and terror to the heart of criminals. You may elaborate that a bit. Mention my towering figure, nearly five feet tall, and the bulging muscles which back up my eighty-six pounds of weight. You may also speak of my handsome features, but not in a manner to attract more than a few thousand women. I have enough wives already. Now! Clear the deck! Here we go."

The blonde woman gathered her small feet under her, preparing to leap out of the way, and she took a deep breath for fear all of the air would be sucked out of the room in the wake of his rush; but to her astonishment he merely slumped down in the chair and, to all appearance, went to sleep.

"He's in action now," Zoo explained softly and musically. "Concentrating. He'll come up with a plan in ten seconds."

The prophecy proved true. Zitts opened his eyes with a start, rose an inch in the chair and winked three times at the Venusian girl. Instantly the girl sprang to the door on the right and swung it open, and a four-legged creature, with its tongue lolling out, waddled into the room and squatted on its haunches.

"See!" Zoo cried in delight. "His plans always begin with Pupsie. The ancients called him a bloodhound. His species is almost extinct, but he's smart and he claims his ancestors pursued criminals thousands of years ago."

"Claims?" the blonde woman exclaimed, aghast. "You mean, that four-legged creature can talk?"

"Whaddya think?" said Pupsie. "Living generation after generation around windbags who did nothing but talk, wasn't it to be expected that dogs would eventually evolve to that stage themselves? Not that it is an improvement, mind you. Dogs had to learn in self-defense. Even back in the twentieth century hundreds of people everyday were asking questions of animals. 'Ain't oo the pretty little thing?' 'Does oo want a tiss, oo lovey dovey?' The first words my ancestors learned to speak in answer to such questions were 'Go to hell!' The meaning of the phrase is lost in our modern language, possibly because my ancestors overworked it, using it every time a human opened his mouth to ask a question of an animal, until at length it had no meaning whatever."

"And you catch criminals?"

"Catch anything," said Pupsie, "that I can smell, if it deserves catching."

"Quiet!" Zitts roared, displaying his customary impatience when another usurped the floor. "Zoo! Fetch forth the Longsnozzle. And while you're at it you can bracket this case as 'The Longsnozzle Event.' Mark that word 'Event!' I have a suspicion this is an insignificant case with not more than eight or ten murders involved."

"Eight or ten murders!" The blonde woman became deathly pale. "You mean, there is more than one murder?"

Zitts looked at the woman with pity in his brown eyes. "Woman, you evidently do not understand the psychology of murder. One always leads to another. It's always been that way. Look at the murder stories of even the blind age of the twentieth century! Thirteen murders, ordinarily, on the first page. Seven on the second, and the balance strung out through the book. It is the aspiration of every collector to find a book with only one murder in it. Personally, for such a work I would offer seventy-five interstellar giant transports each loaded to bursting with ton upon ton of diamonds, emeralds, pearls, sapphires, oyster shells, and even those rare gems called kidney stones that come from the galaxies of innerspace—and, yes, even those magnificent broke-stones found only in a single planetary system in a galaxy on the very rim of outer space. These latter are practically untouchable, and the more you try to touch them the more broke-stone they become."

Zitts drew a deep breath and went on: "If a solitary genius of the latter half of the twentieth century had had the godlike stature to create a work with only one murder in it, instead of dozens, he would be immortal and today worshipped by the protagonists of moderation and hated by the antagonists who maintain, and not without reason, that all of the characters in such stories, and especially the detective, should come to a violent and horrible end on page three."

The blonde woman wiped her eyes, glanced into a small mirror and tried to compose herself. "Very well," she murmured half to herself. "I shall prepare myself to endure whatever I must and view as many murders as necessary."

"It won't be bad at all," Zitts assured her with feeling. "May even be boring, with so few murders. Personally, I rarely take a case which doesn't offer the prospect of at least a hundred. They generally murder my suspects one after another, and for that reason I try to suspect as many as possible to keep the case interesting.

"Now, if you are prepared—"

The woman, fearful but dry-eyed, nodded in response.

"Pupsie! On your mark! Zoo! Switch on the machine."

In fear and wonderment the woman watched Pupsie don the longsnozzle which appeared to be a mechanical nose two-feet in length with its other measurements in proportion. This extra nose did not appear heavy or to handicap Pupsie in any way. Its nostrils flared and the Venusian girl produced some six square yards of white linen, held it significantly at the proper place, and the beast blew its extra nose, making a honking sound which made the windows rattle.

"That clears the way for smelling action," Zoo said in explanation.

Just then the view lit up and the bristles along Pupsie's back suddenly stood on end. The scene in the viewplate was familiar. Six ratcatchers were lined up, one behind another, with the foremost pointing the Colt at his own midriff. Through the adjoining wall, which was transparent on the viewplate, a man in the uniform of the chief rat of the ratcatchers, was visible holding his fingers in his ears and with a terrified and painful expression on his face.

The blonde woman jumped when the bang sounded and the six ratcatchers reeled and then collapsed. The chief beyond the wall looked a trifle relieved to find himself still alive, but Zitts snorted with audible disgust.

"Bunglers!" Zitts growled, then looked at Pupsie. "That weapon, Pupsie," he said. "Get a good whiff of it."

The huge nostrils flared and sniffed in a way that stirred a strong breeze in the room and sent prickles along the blonde woman's spine. Then Pupsie looked up and winked.

"Now trace it to the murderer," Zitts ordered.

Pupsie gathered himself for a leap at the chief rat, but Zoo sprang between him and the viewplate and shut off the machine.

"No, no," Zitts cautioned. "His smell is on the weapon, of course. But he merely examined it. Use your head now and tune in the machine yourself and find the murderer."

Nodding, Pupsie moved close to the machine, switched it on and began tuning radarlike by sniffing and twisting the dials. Almost at once his eyes lighted and his tongue lolled out and his muscles stiffened for action. The blonde woman held her breath, expecting to view the murderer.

The view lit up faintly, became brighter, became a dark alley with a cat inspecting a garbage pail.

"No, no!" Zitts cautioned. "This is no time for sport. Get down to business."

Pupsie continued tuning and suddenly began panting and gasping and twitching in every muscle.

Recognizing the emergency, Zitts thundered "The treadmill, Zoo!"

Zoo stamped on the floor and started an endless carpet moving under Pupsie's feet. It was just in time, for Pupsie was running like the very devil in order to remain in the same place. He was in pursuit of a female dog which appeared on the viewplate.

Features darkening and eyes blazing, Zitts waited for Zoo to turn off the machine. Then in a thunderously quiet voice he called Pupsie to book.

"I warned you this is no time for sport!" Zitts glanced at Zoo who produced a dogcatcher's net and held it threateningly above Pupsie. The poor dog shuddered. "For the last time," Zitts said ominously, "I'm warning you."

The blonde woman felt so sorry for the creature she turned tearful eyes to Zitts in mute appeal. Zitts appeared to relent.

"When you find that murderer," he said, temporizing, "I shall order you a special nine-foot bone from one of those Martian tyrannasauraplexus creatures. Now, keep your mind on your work!"

At the mention of a tyrannasauraplexus bone Pupsie's jaws slavered and a look of rapture came over his ungainly features. Clearly he had been reformed.

Setting to work immediately, Pupsie sniffed and tuned by twisting the dials, and suddenly the blonde woman gasped and almost fainted.

"That's my lover's apartment," she said in horror. "I recognize the bed. Surely he can't be the murderer."

"Your ex-lover," Zitts pointed out. "That's a corpse in the bed."

The blonde woman fainted, for it was true. The man was dead, or should have been, for he neither breathed nor gave any sign of heartbeat.

"Examine that room," Zitts ordered Pupsie, "until you get a whiff of the second murderer."

Soon Pupsie was off again, sniffing and tuning, and just as another scene came in the blonde woman opened her eyes, gasped, "Another of my lovers," and fainted again.

"Ex-lover," Zitts corrected and directed Pupsie to pursue this murderer also.

They ran through three more murders before the woman recovered, and Zitts deducted, which subsequently proved correct, that these were also ex-lovers. Then, as the woman recovered and was composing herself and straightening her mouth and re-making her face, they came upon a scene with a live person in it.

"No, no! No!" the blonde cried. "He's my next to the best lover. He wouldn't murder anybody."

The man, about ninety years old, gray and stooped, sat placidly on what appeared to be the railing of a balcony and contemplated the rolling countryside a hundred stories below. At a signal from Zitts, Zoo switched the machine to two-directional view.

"All right, murderer," Zitts snarled. "Confess!"

The man looked up, started, then almost fell over the rail as he caught sight of Mrs. Brown and Smith.

"No, no! I don't want him brought to justice," the blonde woman cried. "If he loved me enough to commit all those murders I want to marry him."

Zitts pondered this briefly, then said, "That ought to be punishment enough. What have you got to say, murderer?"

The man cowered back, trembled. "I'll confess," he said quaveringly. "But I ask for a reasonably humane punishment like being boiled in oil. Marrying that woman would be more than I can bear."

Zitts nodded understandingly. After all, he was humane even with criminals. And although he was not a man to compromise with crime he could not bear the light of horror in the man's eyes. "I'll take the matter under consideration," he said. "But I promise nothing. If you confess promptly and clear up the mystery, your chance of being boiled in oil will be somewhat improved. I'm waiting."

"It's like this," the man began, wiping perspiration from his brow. "On my ninetieth birth anniversary I decided to have one more fling and retire until I had reached my second youth-hood at the age of a hundred. I visited seventeen of my best sweethearts that day and night, and twelve of my wives. It was rather exhausting."

"I can imagine," Zitts said encouragingly. "Go on."

"Mrs. Brown and Smith was among those I visited," the man went on tiredly. "She was the most exhausting of all, actually insisting that I kiss her hand before I left. It took a lot out of me."

"Go on," Zitts urged impatiently.

"I swore off then and there," said the nonagenarian with a sigh, "and that left Mrs. Brown and Smith with only five lovers and two husbands. That increased the load on these remaining seven and they began to urge me to come back and do my duty. I refused.

"That," the man went on, "brought things to a crisis. In desperation Smith made another appeal to me. Again I refused, but I gave him some sound advice, to wit: that he should make the other lovers carry a little more of the burden. This he tried without success, and again I advised him, this time arming him with an ancient weapon. In turn he went to each of the other lovers and offered them their choice, and each chose suicide in preference to fulfilling more than their normal obligations. When he realized what he had done, and what a tremendous burden would now fall on him, he turned the weapon on himself."

The man paused, wiped away the tears and added, "I am guilty of six murders," he said dolefully. "And Brown, who is being held by the ratcatchers, will naturally make a false confession and ask to be put to death at once—when he realizes that his wife has neither lovers nor another husband. It is sad, and if you'll just boil me in oil as quickly as possible—"

"No, no!" the blonde woman screamed. "I want to marry you."

Startled, the man whipped out a strange, unearthly weapon, on which was inscribed, it was learned on later investigation, this legend: S&W. He placed the weapon against his temple and a bang resulted. Then he toppled over the rail and disappeared.

"Which end of that weapon did he place nearest him?" Zitts demanded as Zoo switched off the machine and the view faded.

"The tube end," Zoo replied.

"I knew I was right," Zitts exulted. "Get in touch with the chief rat and tell him the case is solved, wrapped up. He can release Brown and forget it. Also tell him I have learned the secret of that weapon. I was right all along. Tell him personally to place the muzzle of it against his temple and finger that little lever underneath. I am sure that is the way it is done. Tell him to try it at once and let me know the results."

Zitts sighed in satisfaction, glanced once more at the lovely curves of the blonde woman, and pressed the button which set in motion the machinery to ease the lounging chair beneath the desk and shape it into a couch.

"Ssh—h!" The Venusian girl signaled silence. "After he's been in action for a few seconds," she whispered, "he always rests for a week or so."

The blonde woman rose quietly and marched wavily to the door, opened it. Then, with tears of thankfulness in her limpid blue eyes, and a last worshipping glance at the place where Zitts had disappeared, she stepped into the corridor and went in search of replacements for her used up husbands and lovers.

Pupsie waddled over to a corner and curled up to dream of a tyrannasauraplexus bone.