| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/headgearantiquem00wadl |

WADLEIGH’S

474 Washington Street,

BOSTON, MASS.

CONSTANTLY ON HAND,

Untrimmed Chip and Straw Hats and Bonnets,

French, English, and American.

THE CORRECT STYLE

IN

Trimmed Dress Bonnets, Round Hats, Travelling

and Riding Hats.

DAILY RECEIVING THE VERY LATEST NOVELTIES.

FEATHERS, FLOWERS, RIBBONS,

VELVETS, AND SILKS,

In all the Extreme and Exclusive Shades and Tints,

A SPECIALTY.

Misses’ and Children’s Hats, Trimmed and Untrimmed.

Illustrated.

COMPILED AND EDITED

BY

R. H. WADLEIGH.

BOSTON:

COLEMAN & MAXWELL, Stationers and Printers,

58 and 60 Federal Street.

1879.

Copyright, 1879.

R. H. WADLEIGH.

My recent publication on Head-Gear, Antique and Modern, will be delivered to all our customers. Should there be any who do not receive a copy, they will do me a favor by making application at the store where they will be supplied. I take great pleasure in presenting the only work exclusively devoted to this subject ever published, trusting a perusal of its pages will be at least interesting, if not instructive. I have used every effort to make it a correct description of styles, beginning with Egypt in the days of the Pharaohs (dating back nearly six thousand years) and ending with modern Paris, giving some twenty pages of beautifully executed illustrations, and thirty pages of descriptive essays and quotations from ancient and modern writers.

We solicit continuance of your patronage this coming season, and feel confident that with a rich and varied assortment of millinery goods and perfect artists we shall be able to sustain our motto “CORRECT STYLES.”

Respectfully yours,

R. H. Wadleigh.

FASHIONABLE MILLINERY AND CAP ROOMS,

474 WASHINGTON STREET BOSTON.

MARCH 24th, 1879.

A special importation of novelties in HEAD-DRESS ADORNMENTS. At prices to suit the times.

The object of this work is to give an idea of the fashions in head-gear of ancient and modern times, which to most people are very interesting. To obtain anything like a correct description thereof, it is necessary to consult not only history, but also laws, poems, and biographies. For this, few have opportunity or inclination; and this work is an earnest endeavor to supply in a condensed form what I have found to be a desideratum; and I believe it contains a correct description of styles not to be found in any other work, and no statement is made without the most patient study and research.

As civilization and mental improvement advance in any country, a laudable curiosity is awakened to inquire into, and become acquainted with, the appearances, manners, and opinions of other nations and times. To gratify this curiosity, and to assist in this effort to be informed respecting[6] the individual manners and customs, the external appearance, and the general fashions of different peoples and periods, this work is issued, presenting to the eye a series of judiciously selected and well executed representations of the original and ancient head-dress, and quotations and facts gleaned from ancient history to verify their correctness.

Trusting this work will interest, if not benefit, its readers,

I remain, respectfully,

R. H. WADLEIGH.

Millinery Rooms, 474 Washington St.

Boston, March 1, 1879.

Catching all the oddities, the whimsies, the absurdities, and the littlenesses of conscious greatness by the way.

Perhaps the most ancient head-dress that we find mentioned in history is the tiara. Strabo informs us that it was in the form of a tower.

It is often seen carved upon ancient medals, and Servius calls it a Phrygian cap. The kings and heroes of Homer and Virgil wore this head-dress:—

Woman is defined by an ancient writer to be an “animal that delights in finery”; and it is to be feared the annals of dress in every land, the most savage as well as the most civilized, will but prove the truth of the assertion.

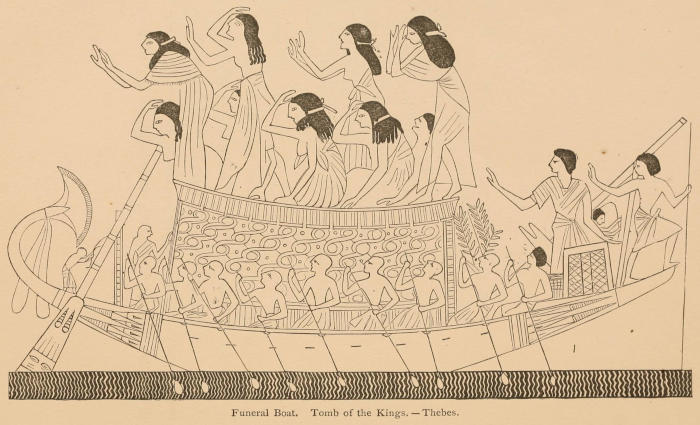

1

Funeral Boat. Tomb of the Kings.—Thebes.

A caul is a very ancient head-dress; it is mentioned in the Bible, and by many old writers; it was usually made of net-work, of gold or silk, and enclosed all the hair. Some were set with jewels, and were very heavy and of great value. In the time of Virgil cauls were much worn:—

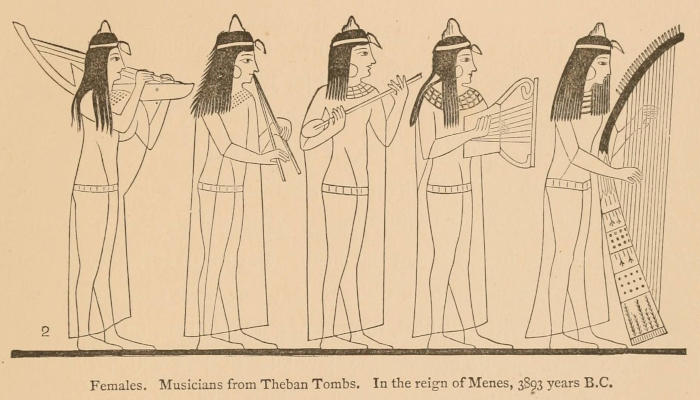

2

Females. Musicians from Theban Tombs. In the reign of Menes, 3893 years B.C.

It appears that females were the chief musicians, and these were probably ladies of rank, for they are robed in that delicate texture which was then called “Woven Air.”

The figures on the opposite page give an illustration of Chinese women in full dress. Fig. 3 represents a married lady with her hair tied on top of the head. A quantity of false hair was used to make a tuft as large as possible, filled with gold or silver pins, the ends of which were highly ornamented with jewels. Artificial flowers were often used to ornament the head. But the favorite coiffure—the object of a Chinese lady’s greatest admiration—was an artificial bird, formed of gold or silver, intended to represent Fong-Whang, a fabulous bird of which the ancients relate many marvellous tales. It was worn in such a manner that the wings stretched over the front of the head; the spreading tail made a kind of plume on the top, and the body was placed over the forehead, while the neck and beak hung down; and the former, being fastened to the body with an invisible hinge, vibrated with the least motion.

3 4

The recorded history of China begins 2697 years before Christ.

The above figures, Nos. 3 and 4, represent the head-dress and costumes of a later date.

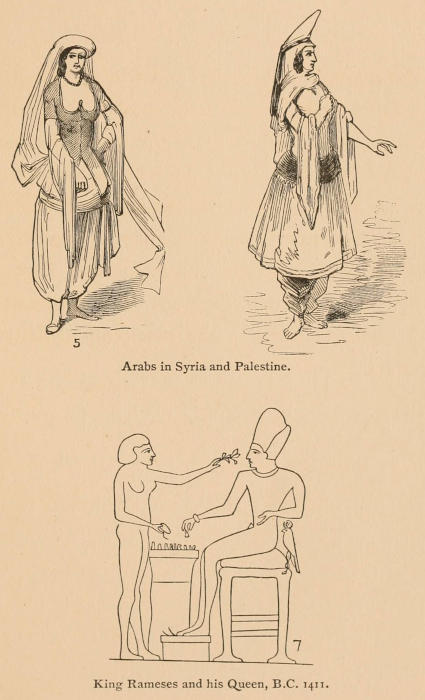

The researches of scholars and critics which have been so generously and successfully lavished, for the last two centuries, upon the ruins of Egypt, are perfectly marvellous, and only increase our desire to be more acquainted with its customs, of which we can find but little in the way of head-dress to ornament these pages. Figure 7, on the opposite page, represents King Rameses First and his queen, who reigned through the most illustrious period of Egyptian history, in the nineteenth dynasty, about 1411 B.C.

5 6

Arabs in Syria and Palestine.

7

King Rameses and his Queen, B.C. 1411.

In the early history of Rome, 550 years B.C., in the reign of Servius Tullius, there seems to have been nothing whatever of head-dress.

Thus we read in the “Æneid”:—

Ribbons or fillets were a very general head-dress.

Thus Virgil says:—

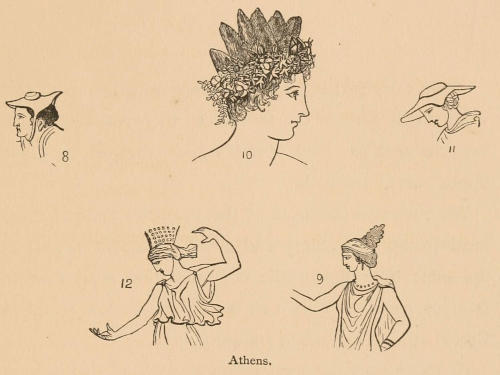

Strabo says, that in Athens it consisted of a wreath of myrtle leaves and roses around the head, forming a corobulus.

The hair over the forehead of Apollo Belvidere is an example of a corobulus. And the hair was twined or spun around a spindle, in the shape of a cone, and one or more of these projected from the crown of the head, with a golden grasshopper for ornament, as seen in Fig. 10.

Four hundred and eighty years B.C., hats were not worn as a rule, and dress was in simple style. It was considered[17] improper for women to be seen on the street, and their appearance there occurred only on exceptional occasions.

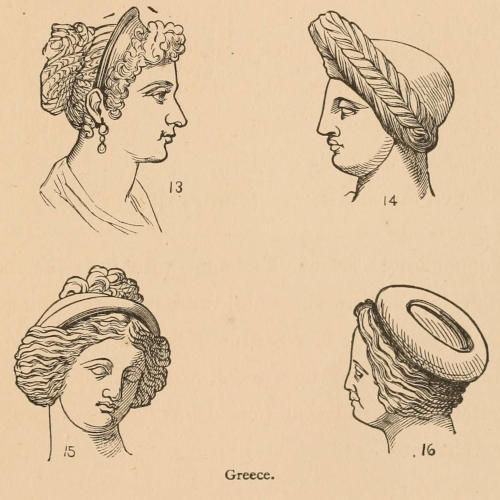

8 9 10 11 12

Athens.

On journeys, women wore a light, broad-brimmed petasos, which Figs. 8 and 11 represent, as a protection from the sun. At a late period the head-dress of Athenian ladies, at home and for the street, consisted, in addition to the customary veil, chiefly of different contrivances for holding together their plentiful hair.

At an early period, Greek women wore longer or shorter veils, which covered the face up to the eyes, and, falling over the neck and back in heavy folds, covered the whole upper part of the body.

We often find instances of the exquisite taste of these head-dresses in statuary and gems of ancient origin; at the same time it must be confessed that most modern fashions, even the ugly ones, have their models, if not in Greek, at least in Roman antiquity.

A ribbon used to be worn around the head, tied in front with an elaborate knot. The net—after it the ’kerchief—was developed from the simple ribbon, in the same manner as straps on the feet gradually became boots.

The head-dress of the women, as well as their costumes, were different at different periods, as figures on preceding page illustrate.

13 14 15 16

Greece.

Homer frequently mentions the veil as a part of the attire of the Grecian and Trojan ladies.

Of Helen, he says:—

The ancient head-dress of the Irish appears to be but little known till the twelfth century, when it is said to have been much the same as that worn by the Southern Britons.

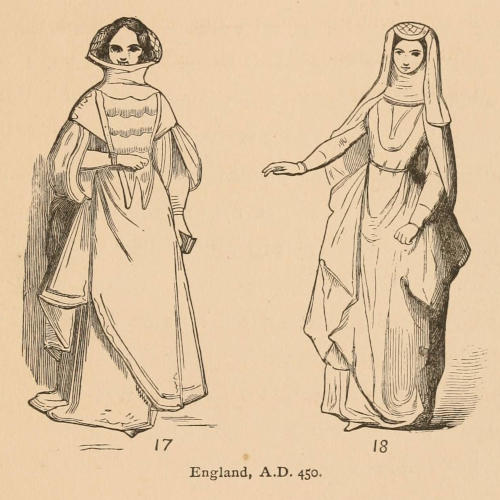

17 18

England, A.D. 450.

In ancient Britain, from the earliest time to the arrival of the Saxons, A.D. 450, we can find no mention made of ladies’ head-dress, and but little is mentioned until about 1066, and even at this date not any style existed, although[22] Anglo-Saxon females of all ranks wore a veil, or long piece of linen or silk wrapped around the head and neck. This part of their dress was exceedingly unbecoming, perhaps partly owing to the want of skill in the artists, and this head-dress was seldom worn except when they went from home (see figures on preceding page), as the hair itself was cherished and ornamented with as much attention as in modern times.

In an Anglo-Saxon poem the heroine is called, “The maid of the Creator with twisted locks.”

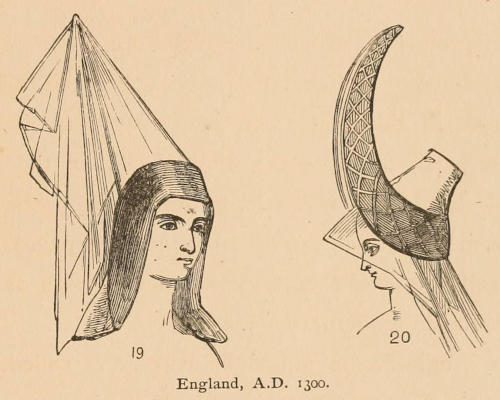

About this time the fashions began to travel northward from Italy, through Paris to London, and caps, hats, and bonnets of various and fantastic shapes were introduced.

(See figures opposite.)

As Shakspeare said:—

19 20

England, A.D. 1300.

In England, artificial flowers were unknown till the reign of Edward III., A.D. 1041.

Artificial flowers, those beautiful imitations of the “stars of the earth,” are brought to such perfection that they almost rival the blossoms they are intended to imitate.

In France, during the reign of Charles VIII., in 1483, it is recorded that head-dresses were lowered considerably; but in the portrait of Mary of Burgundy, we find that she still wore the favorite towering cap that had been fashionable for two hundred years before her time, with the veil hanging to the ground and a square piece lying upon the neck and shoulders.

It is a hard thing to say, but the women might have carried the Gothic building, this steeple head-dress, much higher had it not been for a famous monk, Thomas Conects by name, who attacked it with great zeal and resolution.

This holy man travelled around to preach down this monstrous style, and succeeded so well, that, as the magicians sacrificed their books to the flames upon the preaching of an Apostle, so many of the women threw down their head-dresses in the middle of his sermon, and made a bonfire of them within sight of the pulpit. He was so renowned, as well for the sanctity of his life as his manner of preaching, that he would often have twenty thousand people at a time to listen to him. The men placed themselves on one side of the pulpit and the women on the other, and the latter appeared (to use the similitude of an ingenious writer) like a forest of cedars with their heads reaching to the clouds, but, like snails in a fright, drew their horns in, to shoot them out again as soon as the danger was gone.

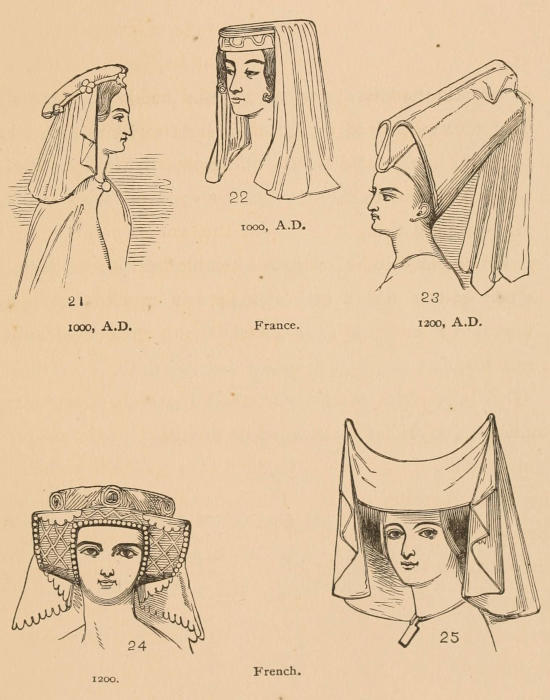

21 1000, A.D. 22 1000, A.D. 23 1200, A.D.

France.

24 1200. 25

French.

Whenever they wore them in public, they were pelted down by the rabble with stones; but, nevertheless, they mounted them again after a short time. The customs of the Norman peasants in many respects differ from those of Britain. The head-dress called Burgonin is the most remarkable and conspicuous part of their attire.

The weaving of gold and silver threads into ribbon and cloth, which is now in use, is no new idea; it was ascribed by Pliny to King Attalus, about sixteen hundred years ago.

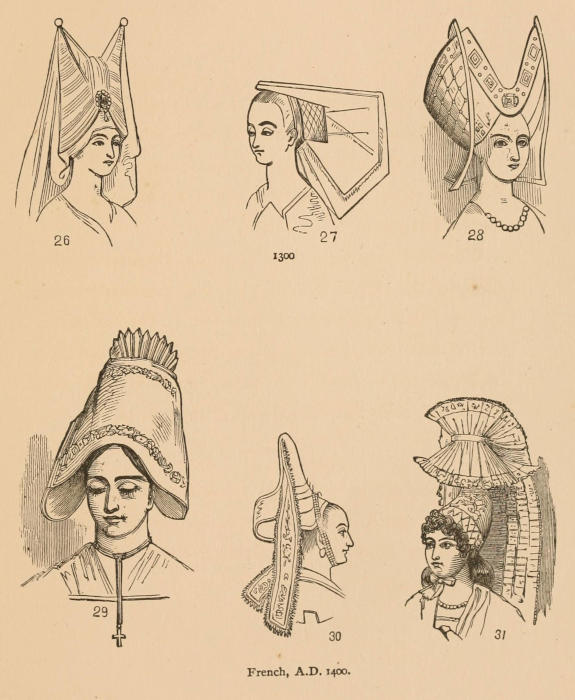

26 27 28

1300

29 30 31

French, A.D. 1400.

In the same poem we read:—

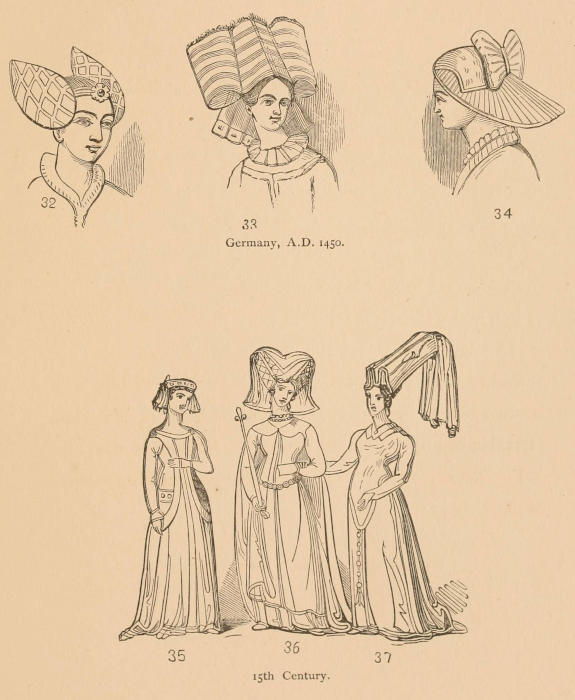

In Germany the styles seem to have differed but little from those of France, as, no doubt, France at that date furnished the styles for the world, as she does to-day.

Fig. 32 was copied from the “Nuremberg Chronicle” of A.D. 1493.

32 33 34

Germany, A.D. 1450.

35 36 37

15th Century.

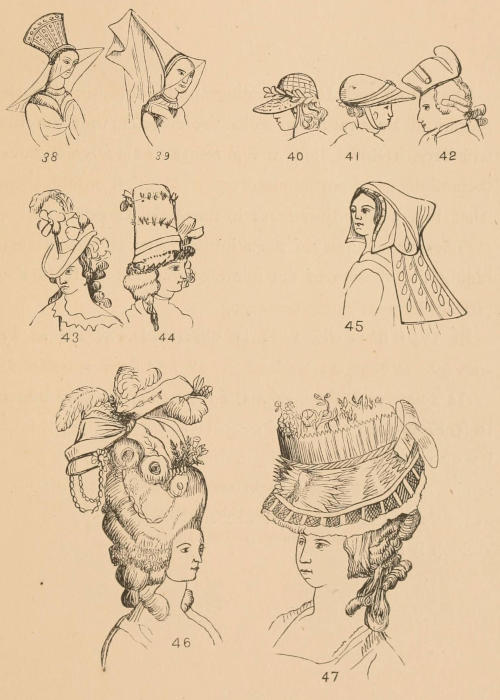

As we advance in these pages one would suppose we ought to be exhibiting styles more quiet; but, on the contrary, when we look at Figures 38 and 39, which have been selected from miniatures in MSS., it would seem that improvement was made in the wrong direction.

The caps shown on the opposite page, in Figs. 40, 41, and 42, were worn in the reign of William and Mary in 1688, and were quite becoming.

In 1750 there was a change for the worse, and as we advance to Figs. 43, 44, and 45, we find them ridiculous.

In 1789, as in Figs. 46 and 47, there is nothing added to their beauty.

38 39

40 41 42

43 44

45

46 47

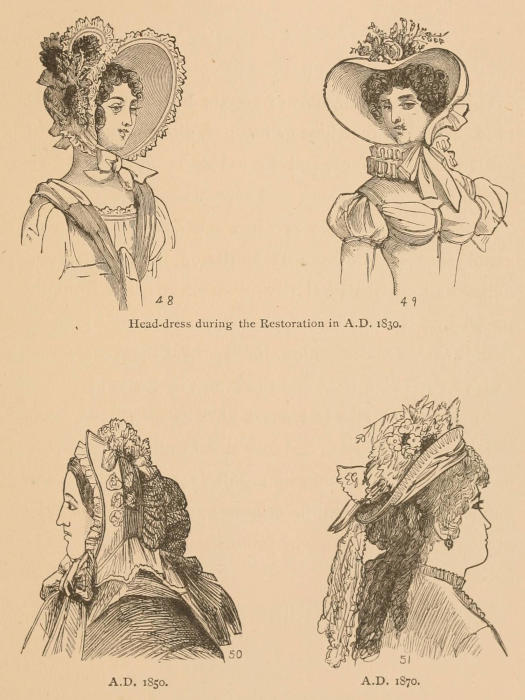

Figures 48 and 49, illustrating the Restoration of A.D. 1830, indicate a reaction against the Voltairean philosophy and French Revolution, and a return to chivalry and devotion.

At this period they were heart-shape in front, in remembrance of Mary Stuart, imitating an open carriage, hiding the charms of the fair face underneath from the passer-by.

In 1850 a modification is observable, as shown in Fig. 50.

As we arrive at the fashions of 1870 (Fig. 51), we begin to feel more at home. Of course each generation thinks its own styles are just right, but in centuries to come modistes, no doubt, will look back upon our present styles as we do on the fashions of centuries past.

Such is life.

48 49

Head-dress during the Restoration in A.D. 1830.

50

A.D. 1850.

51

A.D. 1870.

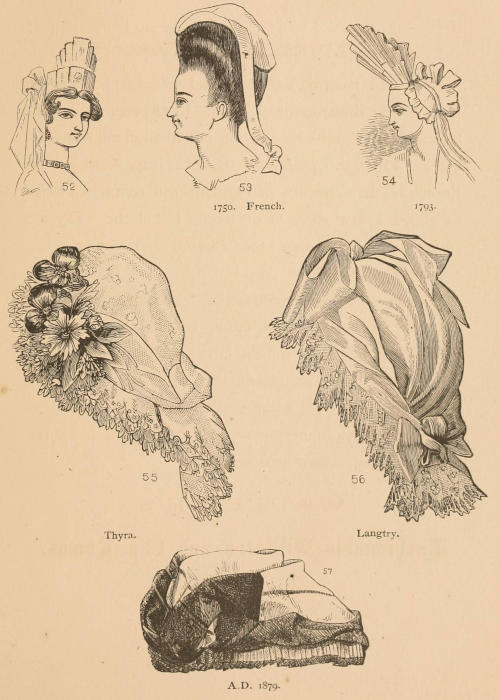

As yet no mention has been made of caps, but a great many of the illustrations of simple head-covering resemble caps more than hats or bonnets, although not so designated. Figs. 52, 53, and 54 are dress caps worn by the French in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Fig. 55 shows a new style of dress cap called the “Thyra,” composed of Bretonne lace, ribbon, and flowers; the crown being of dotted lace.

Fig. 56 is a muslin breakfast cap called the “Langtry,” made of Valenciennes lace, falling over the front, finished with an Alsatian bow, and the crown of Swiss muslin.

Fig. 57 is a new and novel idea called the “Turban,” composed entirely of a large silk handkerchief. This is much worn for a dinner or evening toilet. The last three styles are taken from the originals at

WADLEIGH’S

BOSTON.

52 53

1750. French.

54

1793.

55

Thyra.

56

Langtry.

57

A.D. 1879.

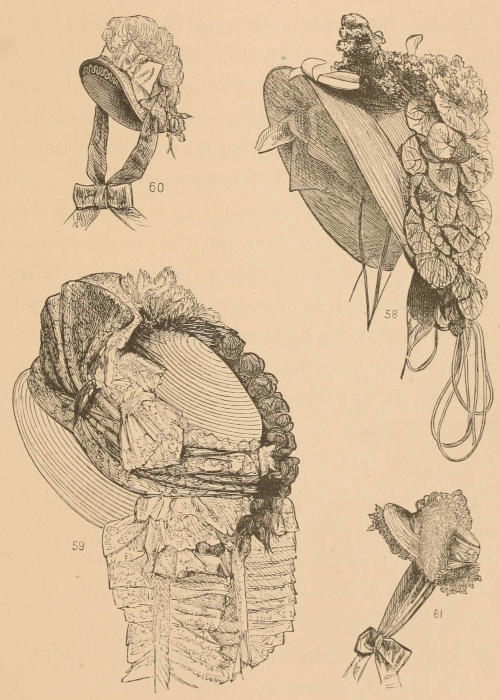

On the opposite page (Fig. 58) is an illustration of the very latest Paris bonnet by Madame Magnièr.

The foundation is heavy corded silk of cream-color, with an immense wreath of Mignonette covering the front of the crown and drooping gracefully to the left, with face-trimming of a simple knot of Bretonne lace.

Fig. 59, designed and executed at Wadleigh’s, is a white French chip. The face of the bonnet has alternate pipings of light-blue and cardinal satin, with a shirring of the latter. The outside is composed of a knot and twist of Sultan silk mingled with Bretonne lace, a fine wreath of forget-me-nots, and drooping cardinal buds, with Bretonne lace ties. Figs. 60 and 61 are also copies of the latest spring designs.

Fashion now assumes a most important place in the domestic economy of nations.

58 59 60 61

Fashion is the only tyrant against whom modern civilization has not carried on a crusade with success, and its power is still as unlimited and despotic as ever. There is no part of the body which has been more exposed to the vicissitudes of fashion than the head, both as regards its natural covering of hair and the artificial covering of hats and bonnets.

For a long period the world has acknowledged the French to be leaders of fashion. We look to Madame Virot, and other leading modistes of Paris, from season to season, for what might be termed first ideas, but still in all we are obliged to soften down and modify them to suit the more simple taste of American ladies.

the outward signs of woe and sorrow, have always been demonstrated by some peculiarity in color in all nations.

The Roman women under the Republic wore black; under the Emperors white was adopted.

Grecian women covered their faces and wear black.

The Chinese, Siamese, and Japanese wear white.

Turks wear blue or violet.

Ethiopians wear gray.

Peruvians wear mouse-color.

Spaniards formerly wore white serge.

Italian women formerly wore white, the men brown.

Syria and Armenia wear blue.

In France, mourning apparel was formerly white.

The following explanation has been given of the cause of the adoption of different colors for the symbol of mourning:—

White is the emblem of purity; celestial blue indicates the space where the soul ranges after death; yellow (or dead leaf) exhibits death as the end of hope, and man falling like the leaf in autumn; gray is the color of the earth, our common mother; black—the color of mourning now general throughout Europe—indicates eternal night. “Black,” says Rabelais, “is the sign of mourning, because it is the color of darkness, which is melancholy, and the opposite to white, which is the color of light, of joy, and of happiness.”

The first thing that a woman should consider in preparing for the great work, her toilette, is the shape of her head, which she must also compare with her stature. The art of dressing the head and the art of fashion are connected without being identical, and in spite of their close union we can readily distinguish them. Whatever may be the material, it is important not to forget that variety is the enemy of severity.

A single color freely used by itself would be more severe than several colors. Let there be no mistake: there are many things in the bonnet which do not depend upon fashion, which are released from its absolute yet limited control. We must be clearly understood: the suitableness of a bonnet may vary.

A bonnet which would appear smart in the city may be elegant and suitable for the country or for the sea-side, provided the rest of the dress is in keeping. At such times a little liberty is allowable. Flowers have a great deal of character, also feathers, ribbons, lace, and[41] gauze. It is only a slight thread that connects these with our feelings, but that slight thread is never broken.

In closing with these few suggestions, it would be well to remark that it is very important when ladies are making their selections for head-dress, and are not fully decided in their wants, it is generally well to yield to the judgment of those who make it a study, providing they are sure that they are in the hands of such of experience. An observing person, in attending our fashionable churches, operas, or even promenading the streets, cannot fail to notice how comparatively small the number of ladies who wear a suitable and becoming style head-dress. It has often been remarked by some of our leading modistes, that only one lady in twenty has the head becomingly dressed, showing that in selecting they have not studied their complexion, stature, and general style, when the expense would really have been no greater had they done so.

One of God’s eternal laws is that nothing stands still. A nation is always changing for better or worse. A people either marches towards perfection or retrogrades. Every bud that blossoms seemingly throws out some new delicate fragrance; every day, every hour, something new and startling falls upon the ear. Every fresh thought that rushes into the mind of the inventor marches with electric speed to further development. Those who have carefully studied the subject of this work well know what grand and noble strides fashion has taken towards perfection, without reaching it, however, as the result of one day’s delay in going to press necessitates a still later style. (See following page.)