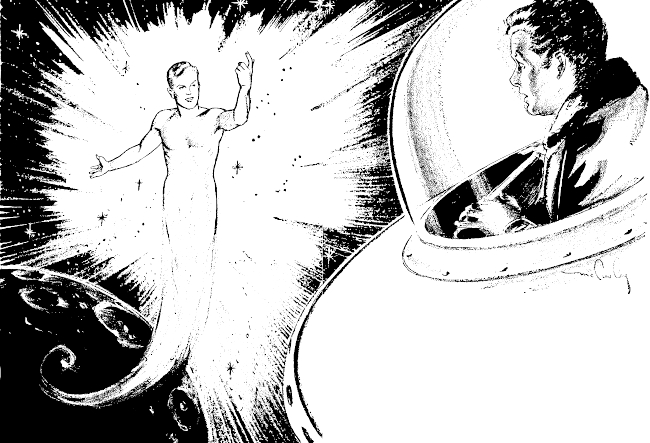

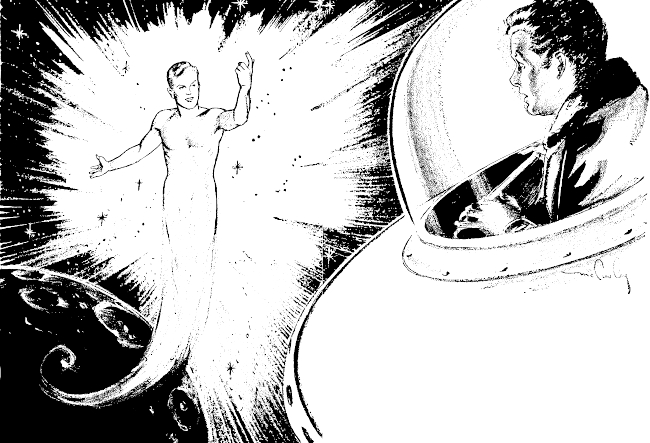

As he looked through the glassite hull of the space ship at the surface of the Moon a strange thing happened. A shimmering figure appeared in a halo of light.

The major problem in achieving space flight lay in

overcoming gravity. That had been done and men had

reached the Moon. But strangely, they never returned!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

November 1951

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

They took a thousand days to build the great, gleaming monster, and another two hundred to groom it for its trip around the moon. All this they did with an air that made a trip to the moon seem quite natural and sure, even though three other rockets had gone before and not one had returned.

"This one will," they said, as though convincing themselves.

But they were not sure. They were stubborn, perhaps proud, but not sure at all. All the world had watched three other such rockets, with men in them, go screaming off moonward. All had waited for them to return. And all had seen nothing come back down from the sky. Not even a small scrap of metal. This one might return, and, if it did, the men in it just might be alive to tell. But that was not being sure.

"A military base on the moon!" the leaders had cried. And that had been that. Robot rockets had gone first. They had landed on the moon. They could do that, but they could not establish the desired base. So men had started on a round trip, around the moon, first to prove that men could do it. The only thing they proved was that whatever goes up need not come down.

Now the fourth rocket waited, leaning over against its heavy launching rack, ready to face whatever unknown danger lay out there beyond.

On a certain night, a night long appointed, one overshadowed with heavy clouds that brought a threat of rain, there were lights about the rocket and in the low, concrete buildings that cowered back a ways from the upright metal giant. Around the base of the rocket men scurried like ants, making last minute preparations and seeing that everything was just so and not being satisfied with "good enough".

In one building, a little nearer the rocket than the others, two men lounged, talking of the coming trip and other things that concerned last night's women, and smoking endlessly, the last smokes they would have for four days. These men would soon climb into a long, metal thing and try to do what others had failed to do.

In other buildings were men with great ideas held firmly in their minds, doing things with pencils and paper and adding machines. These checked back over figures and charts, knowing all the time that everything was flawless, but checking just the same. Some were Army men and some were not.

The feeling that seemed to grow over everything was one of waiting and suspense, and one might know without asking, without seeing the many glances at watches and clocks, that it would soon be time.

Strangely, the two men waiting and speaking mostly of wine, women and general good times, knew very little of the import of what they were about to do. In fact, they had no real concept of even the size of the earth, let alone the magnitude of space, the moon and the stars. This, however, was as intended.

The men who had gone in the other rockets had been scientists, greatly skilled men, men of high I.Q.'s. So the brass and the brains had gotten together and reasoned, and pooled data, and considered statistics, and finally decided that the strain of being completely out of one's natural element, exposed to the terrible, thought-twisting blankness of space, might be greater than had been supposed. And the high-strung, sensitive, sometimes slightly neurotic minds of the highly intelligent might well be expected to crack under the strain.

This, of course, was at most a poor explanation. But it served, at least, as an excuse for retaining the great minds and sending those more expendable. These, not knowing, would probably consider the whole thing nothing more than a slightly unusual adventure.

So when the Army officers came, very stiff and orderly, and opened the door to the little building, the two men came out laughing and pushing at one another playfully. They followed the little group of officers toward the gleaming rocket, not at all worried, like men going off for a happy spree at some local bar.

The rocket seemed to loom higher as they neared it. It was now bathed in the light of many spotlights, reflecting back the light in such a way that one might think he would go blind if he looked too long. Only when they stepped on to a platform, with two of the higher officers, and were lifted swiftly upward, did they give a thought to what was going on.

The platform halted its climb just below a round hole near the nose of the rocket.

"You men should know exactly what you are to do," said the higher officer, "and that is not much. You are not, under any circumstances, to touch anything until you near the moon. Up to that time, the rocket will be guided by at least one control station here on Earth." The officer paused and tried to see understanding in the eyes of the two. He was one of those who did not agree with sending such dense fellows.

"You have been trained for months," he continued, "to read a few instruments and to perform the fairly simple tasks required to take you around the moon and start you back. Do only what you have been taught. Do nothing more. You must remember that certain conditions near the moon, which interfere with radio reception, and which we have been unable to overcome, will put you entirely on your own until you start back."

One of the men, a little uncertain, acted as if he wished to speak.

"Yes?" said the officer.

"Didn't they send rockets once without no men in 'em at all?" he asked. "Then, how come they can't do like we wasn't even there?"

"My dear fellow," said the officer, perplexed, "to aim and fire a rocket at so near and so large a target as the moon is a simple matter. To guide one around the moon in a precise orbit is a matter entirely different." He paused. "Any more questions?"

"No sir," said the men.

"Very good." The officer seemed glad there would be no further conversation. "In you go now."

The men went into the opening, helped by the officers, like olives being put into a bottle. In a moment the officers had gone and a cover had been placed into the opening and screwed firmly into place.

There was lead-glass, very heavy, in the windows of all the buildings. The thick cement walls and doors were covered with sheets of lead.

Inside the most distant buildings, at the small windows, men stood with black looking glasses over their eyes, watching. Each time a rocket went into space it was exactly thus. The atomic drive was new and not completely perfect. Always there was a chance that something might go wrong. The radiation grids could go haywire, there could be an explosion, or the ship could falter and slip on the way up.

So the men waited and watched in their little buildings, with fingers crossed, hoping for the best.

Now it was very quiet. The spotlights had been extinguished because every bit of electric power was needed to start the amazing rocket motor. Only enough was spared for lighting, where needed, in the buildings, and for the P.A. system. And over the P.A. system voices spoke.

"Trackers ready?"

"Trackers ready."

"Control station ready?"

"Control station ready."

"Radio room, report!"

"Radio reporting. All tracking and control stations reported or relayed in."

There was a pause. Then: "Stand by." The silence seemed to grow even more intense. The ticking of clocks and watches could be heard. The unreal atmosphere of a dream settled over the clustered buildings on the plain.

"Activators!"

Out on the plain, the rocket came to life. It surged and clattered against its launching rack, nearly leaping, pawing the ground with hot explosive blasts. Now it became a living wild thing, a bound monster surging against its chains, fighting to be free and away.

The voice, in a short while, came again, a little strained. "Ready.... Ready.... Ready.... ROCKET AWAY!"

The great, gleaming monster lifted up from the plain, bellowing its defiance of space with the voice of ten thousand waterfalls. It rode up from the center of a tremendous flower of glowing dust on a pillar of intense blue flame, slowly gathering speed, like a whale rushing up from the depths of the ocean.

For a while it lighted up miles of rolling plain with its glare, and sent its thunder out to crash against distant hills. Then it was gone beyond heavy clouds, leaving only a smear of light above and a hollow, boiling rumble, muted by distance.

In the thin, cold air above the clouds the rocket pointed its sharp nose eastward. It raced across the sky, a blue streaking and a stuttering scream. It crossed a nation with amazing speed and moved over the Atlantic.

In an instant the moon and the stars were gone and the rocket was looking at the sun. Clear morning fled away in fear of this flaming beast and it was noon within minutes after sunrise. In an hour the night returned, the stars and the moon with it.

"Brother, we're in!" cried Pfc. Walter Jones, in the head of the rocket. "Boy, the babes'll mob us after this. Real big shots, that's us. The men in the moon! Hah!"

"If we get back," Pvt. Robert Moore shouted over the roar. "Remember, we gotta get back yet."

"Chicken!" shouted Jones. "Chicken's what you are!"

"Oh yeah? So what happens to them guys what went before?"

"Nuts to that," Jones sneered. "I hear they's a lot of places up in space we don't know nothin' about, where there's maybe a lot of nice babes and buildings made out of gold and stuff like that."

"Scientists don't go much for babes," Moore said.

Jones kicked back in his seat, roaring laughter. "Hah! Don't kid yourself, son. Anyway, so what? So they get a chance to be kings, or somethin', on account of being from Earth. What do they do? They stay an' be kings, natch'!"

"It ain't for me," said Moore, moodily. "I know babes on good ol' Earth. An' who wants to be king?"

"That's what I'm tellin' you," Jones shouted. "We ain't got no worry at all. All we gotta do is not let them guys up there sidetrack us."

"I hope you're right," said Moore.

They fell silent, looking down at the reeling Earth. On the ground, two hundred miles below, at every tracking and control station around the world, men worked without pause, trying to make their tired minds outrace a speeding rocket. Night side and day side, messages flashed through the ether. They reported in: position, time, corrections made, passing the rocket quickly, from one to another like a hot potato.

On its last lap around the world before flinging itself moonward, the rocket screamed across the much worn boot of Italy. It climbed swiftly up the sky of the Holy Land and plunged down in the east, drawing a blue pencil line across the heavens that faded slowly.

At last it turned upward, and breathing streamers of fire and light, shot into airless space, a silver arrow gone from the bow and dead on its mark.

"It sure seems quiet," said Moore.

They looked through the glassite port into the great distances.

"Quiet, and empty."

"Yeah!"

"Do you feel different?" Jones asked suddenly.

"I don't know. Maybe. In a way."

"Like you can think a lot better?"

"Something like that," Moore said.

They sat and thought about it. The rocket was now fifteen hundred miles up, climbing swiftly.

"For one thing," Moore said, "we are lighter. What do they call it? Gravity? Gravity is less."

"I don't like it," cried Jones. "I don't like it at all!"

"What?" Moore looked at him.

Jones stared back, frightened. "It's nothing like I thought it would be. Maybe we'll get so light there won't be anything left! Where is everything? It's so empty it don't make sense. Something's wrong, Bob. Let's try to turn back before we die like the others! I don't want to die! I want—"

Moore reached over and slapped the other's face, hard. Jones focused glassy, unsteady eyes, surprised and hurt. "Why did you do that?"

"You called me yellow a while ago," Moore said, disgusted. "Now it's you who are acting like a woman or a child. You would really kill us, trying to turn back at this velocity."

"I'm still afraid," Jones said, but not wildly. "I don't know what's happening to me. I can remember things that happened years ago; things I hardly noticed. I'm starting to understand things I never understood before, and some of the things are hard to take."

"Don't you think I feel it, too?" Moore looked out at space in a new way, understanding.

For a while there was silence, a little strained, while the rocket sped another thousand miles. After that it was not so strained. It was more an atmosphere of concentration, of two men, thinking within themselves. There was no more fear.

"So this is what happened to the others," Moore said finally. "But what do we have to fear?"

Jones shrugged. "I'm not afraid anymore, but maybe I should be." He leaned back and looked at Moore. "Have you any idea what is happening to us?"

"I'm not sure," Moore frowned.

"It's as if some great obstacle to clear thinking has been removed. Have you noticed how we have been speaking? Our memory has so improved that we are able to use words we may have seen or heard used only a few times. And the new sharpness of mind that enables us to use these words properly also makes us able to grasp quickly new ideas and to reason logically. As to what causes the change, I do not know."

"I have been thinking about gravity," said Jones, reflecting. "It seems to me that the change in mental power is just about inversely proportioned to change in gravity. That might, in some way, have something to do with it."

Moore sighed, frowning. "You may be right. But, granting that you are, we are still in the dark as to the nature of the danger we must face."

"I think I'm beginning to get some idea," said Jones. "I wouldn't be surprised if my first crude idea, in a way, was very nearly right."

Moore showed surprise. "You still think those others found someone out here who made them kings, or some such?" He laughed.

"Not exactly," Jones said. "But there may be even stranger things." And he would say no more.

At fifty thousand miles they had lost all thought of danger. They spoke of space and the unseen medium that must be there. After forming the only logical conclusion about the nature of this, they passed on to matters of relativity and the nature of time and of life itself, understanding each in its turn.

They became so absorbed in conversation they did not even notice when they stopped talking and conversed in pure thought. Not even did they realize that a golden glow had come to their faces and bodies that was not simple light. And they were content in knowing they would never return to earth, knowing also that they would not die.

The rocket carried them one hundred thousand miles through space before it happened.

"There is someone behind us," Jones said, simply.

As he looked through the glassite hull of the space ship at the surface of the Moon a strange thing happened. A shimmering figure appeared in a halo of light.

They looked, and beheld a man standing in space. He was hardly a man anymore, as men are called, but one like themselves. A golden glow seemed to blend with him. He smiled.

"Welcome!"

"We have been expecting you," said Moore, smiling in return. "Your voice, your thoughts reached us. We know you are one of those who came out in a rocket before us. But your name is not clear."

The being seemed mildly surprised. Then he laughed; a thing that was as the tinkle of small bells, as the dew of a cool meadow before the rising sun or the joyous song of a nightingale.

"I am one of them," he said, "and all of them. We who have overcome the chains of gravity, who have become one in thought and find it impossible to do otherwise, have no need for individuality."

"But you have a body," said Jones. "Surely that gives you some sort of individuality."

"Yes, if one's mind is bound, controlled by matter. But the mind working without resistance is a perfect machine. It is able to control matter in every respect. We take this form or that form as a matter of expedience."

"We have reasoned that all this is due to release from gravity," Moore reflected. "But we do not understand completely. Will you tell us?"

"Even those on Earth know that gravity hampers the mind," the being said. "This they have learned through observation of mental factors in relation to the gravitational pull of the sun and moon. But look into my mind and you will see more clearly."

They looked, and saw a copper disk turn before a powerful magnet. And they saw resistance caused by electric currents induced in the copper, so that a great deal of power was required to turn the disk, even slowly. This, the thoughts indicated, was a principal well known to those yet on Earth.

Next came the relationship between magnetism and gravity, clearly demonstrated.

They then saw a human brain, locked in the powerful embrace of gravity. And the tiny pulsations and complex motions, the processes of thought, were, as with the disk, sluggish—in large portions not even present. They watched a brain come alive as gravity decreased. It bulged, the tempo of motion rising, parts long dormant surging with power. They saw and they understood.

"If only we could go back and help them," sighed Jones. "If we could overcome that gravity on Earth!"

Again the being smiled his kind smile. "If you returned it would be to the same mental prison. You could not, in your crude manner, convince them."

The two knew what they must do, even before the being spoke again.

"The others, the rest, wait beyond the light of universes," he said. "We think. We learn. Soon, we will find a way of helping those on Earth, and we will return. Come with me."

They replied together. "We are ready."

On the dark side of the moon, where they had been projected by identical velocities, lay the battered wrecks of four gleaming rockets. And in all the wreckage, among all the bits of twisted metal, there was not a single drop of human blood.