| Title: | Our Little Tot’s Own Book |

| of Pretty Pictures, Charming Stories, and Pleasing Rhymes and Jingles |

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

There was once a very happy little girl who spent her childhood on an old green farm. She had a little sister, and these two children never knew what it was to possess toys from the stores, but played, played, played from dawn till dark, just in the play-places they found on that green farmstead. I so often have to tell my children “how mama used to play”—for I was that very happy little girl—that I think other “little women” of these days will enjoy knowing about those dear old simple play-times.

One of my pet playhouses was an old stump, out in the pasture. Such a dear, old stump as it was, and so large I could not put my arms more than half way round it!

Some of its roots were partly bare of earth for quite a little distance from the stump, and between these roots were great green velvety moss cushions.

On the side, above the largest moss cushion, was a little shelf where a bit of the stump had fallen away. On this little shelf I used to place a little old brass candlestick. I used to play that that part of the stump was my parlor.

Above the next moss cushion were a number of shelves where I laid pieces of dark-blue broken china I had found and washed clean in the brook. That was my dining-room.

There were two or three little bedrooms where the puffy moss beds were as soft as down. My rag dolly had many a nap on those little green beds, all warmly covered up with big sweet-smelling ferns.

Then there was the kitchen! Hardly any moss grew there. I brought little white pebbles from the brook, and made a pretty, white floor. Into the side of the stump above this shining floor, I drove a large nail. On this nail hung the little tin pan and iron spoon with which I used to mix up my mud pies.

My sister had a stump much like mine, and such fine times as the owners of those two little stump-houses used to have together, only little children know anything about.

THE STUMP PLAY-HOUSE.

Two little girls went shopping with their mamma. While she was at the end of the store, Julie, the youngest, ran to the door. Her mother was too busy to notice her, but Julie’s sister Mattie was watching her. She saw a tall woman pass the door, and snatch up little Julie. Without a word to her mother, Mattie ran after them.

Away they went down the street. The woman would soon have outrun Mattie, but her screams attracted the attention of a policeman. He followed too. They came up with the woman as she was darting into a cellar. Mattie told the policeman that the bad woman had stolen her sister Julie. He soon took both children home. Their mother was overjoyed to see them, and praised Mattie for being such a brave little girl. She never let Julie go out of her sight again, when she took her out on the street.

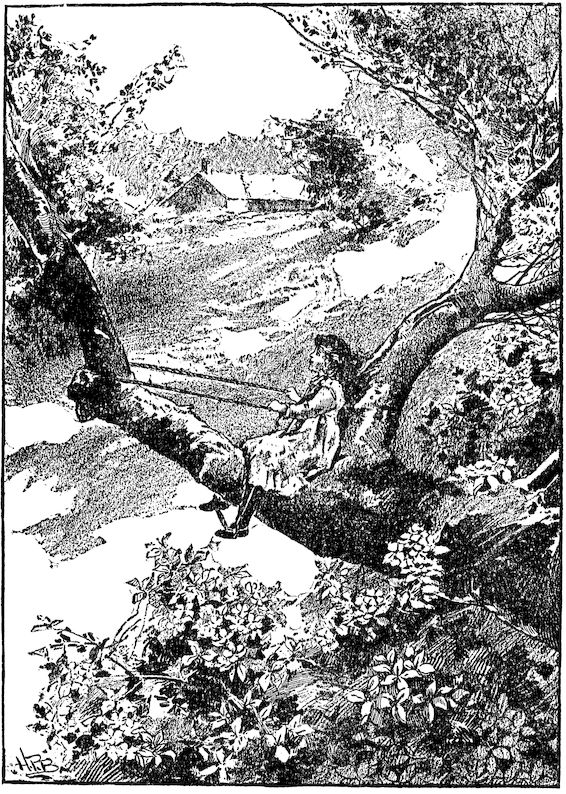

There was an old apple-tree in the orchard that was the oldest tree in the town. It overtopped the house, and the trunk was very big and brown and rough; but O, the millions of fine green leaves, as soft and smooth as silk, that it held up in the summer air!

In the spring it was gay with pink and white blossoms, and then for days the tree would be all alive with the great, black-belted bees. A little later those sweet blossoms would fall off in a rosy rain, and Myra and I would stand under the old apple-tree and try to catch the little, fluttering things in our apron! And then, later still, came little apples, very sour at first, but slowly sweetening until it seemed to me that those juicy, golden-green apples tasted the best of any fruit in all the world! My apron-pockets were always bursting with them!

There was a famous horse up in the old tree. It could only be reached by means of a ladder placed against the old tree’s stout trunk! A strange horse, you would call him, but O, the famous rides that I have had on that horse’s broad, brown back! The name of the horse was “General.”

Up among the leaves where the sunshine played hide-and-seek was one dear bough that was just broad enough and just crooked enough to form a nice seat. Another bough bent round just in the very place to form a most comfortable back to that seat. A pair of stirrups made of rope, some rope reins tied to the trunk of the tree, and there was my horse, “all saddled and all bridled!”

I put my feet into the stirrups, shake my bridle-reins and cry, “Get up, General!”

The bough would sway a little, and I and the birds would be off together, swinging and singing, up in a fair green world where there was no one to disturb nest or little rider! The birds would sing to me, and I would sing to them, and which of those little singers was the happiest, I do not know!

But I do know that my little heart was full of glee and joy to the brim!

RIDING “GENERAL.”

Little Mary had had a volume of Hans Andersen’s Fairy Stories given her at Christmas. The story she liked best was “The Princess and the Pea,” for, like all little girls, little Mary had a natural desire to be a Princess.

When she went to bed at night with her doll little Mary would think to herself, “Oh, how beautiful to be a real princess of such very fine blood as to feel a little bit of a pea under twenty mattresses!”

One morning a comforting idea came to little Mary. “Who knows,” she said to herself, “with all my very many great grandfathers and grandmothers, but p’raps I am related to some King or Queen way back?”

Thereupon, she went to her mother’s pantry and took a bean from the jar—as large a one as she could find—and, going to her room, put it carefully under the hair mattress. That night she went to bed happy, with joyful hopes.

In the morning little Mary’s elder sister found her with her head buried in her pillow crying. “Oh,” little Mary sobbed, “I did think I might have just a little speck of royal blood in my veins, but I couldn’t feel even that big bean under just one mattress!”

Nothing would comfort little Mary until her mama explained to her that even princesses were not happy unless they had good hearts; and she could have, if she tried, just as good and royal a heart as any Princess under the sun.

Out in the pasture, was a little pond. This little pond was quite deep in the time of the spring and autumn rains. At such seasons Myra and I would take our little raft made of boards, and by means of some stout sticks would push the raft around on that little pond for hours. The wind would raise little waves, and these waves would splash up against the sides of our little raft with a delicious sort of noise.

We used to dress a smooth stick of wood in doll’s clothes. We used to call this wooden dolly by the name of Mrs. Pippy. We would take Mrs. Pippy on board our ship as passenger. Somehow, Mrs. Pippy always contrived to fall overboard. And then, such screaming, such frantic pushing of that raft as there would he, before that calmly-floating Mrs. Pippy was rescued!

Just beyond the further edge of the pond was a little swampy place where great clumps of sweet-flag used to grow. Sweet-flag is a water-plant whose leaves are very long and slender and their stem-ends, where they wrap about each other, are good to eat. In summer this little sweet-flag swamp was perfectly dry. But when the rains had come and the little pond was full, this little sweet-flag swamp was covered with water.

Right between the pond and the swamp lay a big timber, stretching away like a narrow bridge, with the pond-water lapping it on one side and the swamp-water lapping it on the other. Such exciting times as we used to have running across that little bridge after sweet-flag!

“Run! run!” we would cry to each other; and then, away we would go, running like the wind, yet very carefully, for the least misstep was sure to plump us into the water!

When the water in the swamp had nearly dried up, a bed of the very nicest kind of mud was left. Taking off our shoes and stockings, we would dance in that sticky mud until we were tired. Then we would hop over the timber and wash our small toes clean in the pond.

“You like clever cats, Arthur,” said Laura; “and I am sure this is one. See how funnily he is drinking the milk with his paw. Did you know this cat, mamma?”

“Yes, my dear, I was staying at the house when his mistress found him out. We used to wonder sometimes why there was so little milk for tea, and my friend would say ‘They must drink it in the kitchen, for the neck of the milk jug is so narrow, Tom could not get his great head in.’

“But Tom was too clever to be troubled at the narrow neck of the milk or cream jug, and one day when his mistress was coming towards the parlor through the garden, she saw Tom on the table from the window, dipping his paw into the jug like a spoon and carrying the milk to his mouth. Did he not jump down quickly, and hide himself when she walked in, for he well knew he was doing wrong.”

“And was he punished, mamma?”

“No, Laura, although his mistress scolded him well, and Tom quite understood, for cats who are kindly treated are afraid of angry words.”

“Did you ever see Tom drink the milk in this way?”

“Yes, for his mistress was proud of his cleverness, and she would place the jug on the floor for him. When she did that, Tom knew he might drink it, and he would take up the milk in his paw so cleverly that it was soon gone.”

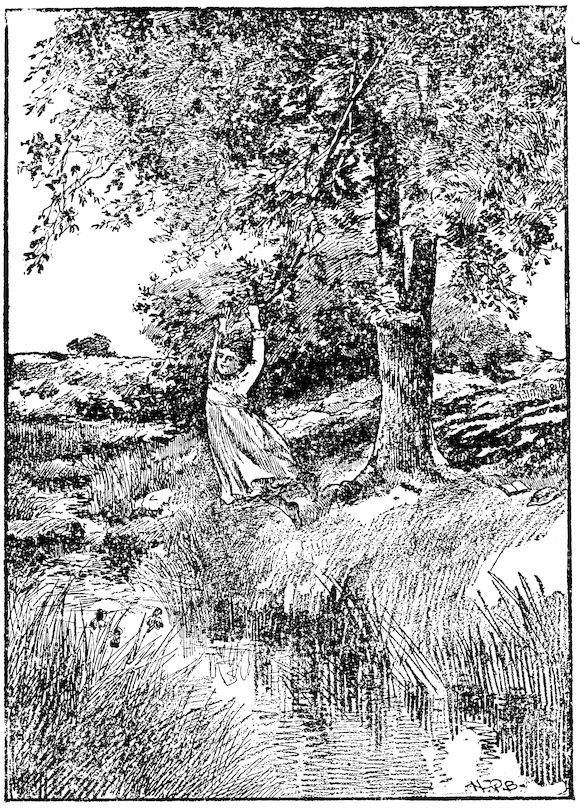

We had a merry playmate in a little brook that ran down through the sunny meadows! It slipped and slid over little mossy pebbles and called to us, “Follow, follow, follow!” in the sweetest little voice in the world!

Sometimes, I would kneel down on the little low bank, and bend my head down close, and ask, “Where are you going, little brook?”

It would splash a cool drop of spray in my face, and run on calling, “Follow, follow, follow!” just as before.

Wild strawberries grew red and sweet down in the tall grass, and great purple violets, and tall buttercups nid-nodding in the wind.

Very often Myra and I would take off our shoes and stockings, and wade. The roguish little brook would tickle my small toes, and try and trip me up on one of its little mossy stones. Once I did slip and sat right down in the water with a great splash! And the little brook took all the starch out of my clothes, and ran off with it in a twinkling.

Now and then, I would fasten a bent pin to a string and tie the string to the end of a stick and fish for the tiny minnows and tadpoles. But, somehow, I never caught one of the little darting things. I used to believe the brook whispered them to keep away from that little shining hook.

Sometimes, I would take a big white chip and load it with pebbles or violets and send it down stream. The sly little brook would slip my boat over one of its tiny waterfalls just as quick as it could! If my little boat was loaded with pebbles, down would go my heavy cargo to the bottom! But if it were loaded with violets, then a fleet of fairy purple canoes would float on and on, and away out of sight.

A great green frog with big, staring eyes watched from the side of the brook. Now and then, he would say, “Ker-chug!” in a deep voice. I used to ask him in good faith, what “ker-chug!” meant. But he did not tell, and to this day I have not found out what “ker-chug” means.

“WILD STRAWBERRIES GREW RED AND SWEET DOWN IN THE TALL GRASS.”

Another place where I played was out on the meadow-rocks. Right down in a level spot in the meadow were three great rocks. Each one of these rocks was as large as a dining-room table. Right through this little flat place ran the brook I have told you about, bubbling round our three great rocks.

0, what splendid playhouses those rocks were! We each owned one. The third was owned by that wooden doll, Mrs. Pippy. In order to get to either one of the houses you had to cross a little bridge that spanned a tiny river. Also there were dear little steps up the sides of the rocks which it was such a pleasure to go up and down.

On the top of the rocks, which were almost as flat as the top of a table, were little closely-clinging patches of moss that we called our rugs. There were queer-shaped hollows in the tops of these rocks. In one little moss-lined hollow I used to cradle my baby-doll. Another hollow was my kitchen sink. I used to fill up my sink with bits of broken dishes, turn on some water from the brook, and then such a scrubbing as my dishes got!

At the rocks, kneeling down on the planks that formed our bridges, we used to wash our dollies’ clothes. Then we would spread them on the grass to dry. Didn’t we use to keep our babies clean and sweet!

Afterwards, pinning our short skirts up about us, we would wash the floors of our little rock houses until they shone. When everything was spick-and-span, we would unpin our skirts, pull down our sleeves, rub our rosy cheeks with a mullein leaf to make them rosier, and with a big burdock leaf tied on with a couple of strings for a bonnet we would go calling on our lazy neighbor, Mrs. Pippy, and give her a serious “talking-to.”

Or, perhaps, we would call on each other and talk about the terrible illnesses our poor children were suffering from. Or, perhaps, we would go to market. The market consisted of a long row of raspberry bushes along the meadow fence.

WASHING-DAY AT THE ROCK-HOUSES.

There was skating on the ponds where the snow had been cleared; there were icicles on the trees, nice blue, clear skies in the daytime, cold, bright, wintry moonlight at night.

Lovely weather for Christmas holidays! But to one little five-year-old man, nothing had seemed lovely this Christmas, though he was spending it with his Father and Mother and his big sisters at Grandpapa’s beautiful old country house, where everybody did all that could be done to make Grandpapa’s guests happy. For poor little Roger was pining for his elder brother, Lawson, whom he had not seen for more than four months. Lawson was eight, and had been at school since Michaelmas, and there he had caught a fever which had made it not safe for him to join the rest of the family till the middle of January. But he was coming to-morrow.

Why, then, did Roger still look sad and gloomy?

“Stupid little boy!” said Mabel. “I’m sure we’ve tried to amuse him. Why, Mamma let him sit up an hour later than usual last night, to hear all those funny old fairy tales and legends Uncle Bob was telling.”

“Yes, and weren’t they fun?” answered Pansy. “I did shiver at the witch ones, though, didn’t you?”

Poor little Roger! Pansy’s shivering was nothing to his! They had all walked home from the vicarage, tempted by the clear, frosty moonlight and the hard, dry ground; and trotting along, a little behind the others, a strange thing had happened to the boy. Fancy—in the field by the Primrose Lane, through the gateway, right in a bright band of moonlight, he had seen a witch. Just such a witch as Uncle Bob had described—with shadowy garments, and outstretched arms, and a queer-shaped head, on all of which the icicles were sparkling, just as Uncle Bob had said. For it was a winter-witch he had told the story about, whose dwelling was up in the frozen northern seas—“the Snow Witch” they called her.

Cold as it was, Roger was in a bath of heat, his heart beating wildly, his legs shaking, when he overtook his sisters. And the night that followed was full of terrible dreams and starts and misery, even though nurse and baby were next door, and he could see the night-light through the chinks. If it had not been that Lawson was coming—Lawson who never laughed at him or called him “stupid little goose,” Lawson who listened to all his griefs—Roger could not have borne it. For, strange to say, the little fellow told no one of his trouble; he felt as if he could only tell Lawson.

No wonder he looked pale and sad and spiritless; there was still another dreadful night to get through before Lawson came.

But things sometimes turn out better than our fears. Late that afternoon, when nursery tea was over and bedtime not far off, there came the sound of wheels and then a joyful hubbub. Lawson had come! Uncle Bob had been passing near the school where he was, and had gone a little out of his way to pick him up. Every one was delighted—oh, of them all, none so thankful as Roger.

“Though I wont tell him to-night,” decided the unselfish little fellow, “not to spoil his first night. I sha’n’t mind when I know he’s in his cot beside me.” And even when Lawson lovingly asked him if anything was the matter, he kept to his resolution.

But he woke in the middle of the night from a terrible dream; Lawson woke too, and then—out it all came.

“I thought she was coming in at the window,” Roger ended. “If—if you look out—it’s moonlight—I think p’r’aps you’ll see where she stands. But no, no! Don’t, don’t! She might see you.”

So Lawson agreed to wait till to-morrow.

“I have an idea,” said Lawson. “Roger, darling, go to sleep. I’m here, and you can say your prayers again if you like.”

Lawson was up very early next morning. And as soon as breakfast was over he told Roger to come out with him. Down the Primrose Lane they went, in spite of Roger’s trembling.

“Now, shut your eyes,” said Lawson, when they got to the gate. He opened it, and led his brother through.

“Look, now!” he said, with a merry laugh. And what do you think Roger saw?

An old scarecrow, forgotten since last year. There she stood, the “Snow Witch,” an apron and ragged shawl, two sticks for arms, a bit of Grandpapa’s hat, to crown all—that was the witch!

“Shake hands with her, Roger,” said Lawson. And shake hands they both did, till the old scarecrow tumbled to pieces, never more to frighten either birds or little boys. “Dear Lawson,” said Roger, lovingly, as he held up his little face for a kiss. And happy, indeed, were the rest of the Christmas holidays.

May they never love each other less, these two; may they be true brothers in manhood as they have been in their childish days!

Well, first of all, I must tell you that I am a Brownie, and although I am ever and ever so old, I look as young to-day as I did when I was but one year old. Well, it was about seven hundred years ago, and I used to be a great deal with some other Brownies, cousins of mine, visiting at the same farm-houses as they did, and helping them with their work. And it was in this way that I got to know the Three Blind Mice,—Purrin, Furrin, and Tod.

Pretty, pleasant little fellows they were; and they were not blind then,—far from it. They lived up in the loft of Dame Marjoram’s room, over at Fiveoaks Farm.

Such merry supper-parties as never were, I think, before or since, we used to have then. We would think nothing of finishing a round of apple and a walnut-shell full of honey between us, in one evening, to say nothing of scraps of cheese-rind and the crumbs we stole from the birds. Purrin had a most melodious voice, and could sing a good song, while Tod was never at a loss for an amusing story. As to Furrin, he was almost as quaint as our Mr. Puck, and, though perhaps it is not for me to say so, when those in high places do encourage him, not one-tenth as mischievous.

When Angelina, the old stable cat, had kittens, he would get into all sorts of out-of-the-way places, and imitate their squeaky little voices, so that she was always on the fidget, thinking she must have mislaid one somewhere, and never able to find it. For you see, as she could not count, she never knew whether they were all beside her or no. Often he would coax a whole hazel-nut out of Rudge, the Squirrel, who lived on the Hanger, just above, and whom every one believed to be a miser. And then his Toasting-fork Dance was so sprightly and graceful, it did your heart good to see it. Ah, me! those days are gone, and Furrin is gone too; and the Moon, when she looks through that chink in the barn roof, no longer sees us feasting and making merry on the great beam.

And this is how they became blind:

They were very fond of Gilliflower, Dame Marjoram’s little daughter, and after the nurse had put her to bed, Furrin, Purrin, and Tod used to creep up into her room, and read her some of the funny little tales from Mouse-land till she went to sleep. She would lie there with her eyes shut, and perhaps imagined that it was her own thoughts that made her fancy all about the fairy tales that came into her head; but really it was the mice who read them to her, but in such a low voice that Gilliflower never thought of opening her eyes to see if any one was there. I must tell you that the print in Mouse-land is very, very small and hard to read. This did not matter so much during the long Summer evenings, when there was plenty of light to see to read by; but when the Winter came on, and the mice had only the firelight to read by, then reading the small print began to tell its tale. You know how bad it is for the eyesight to read any print by firelight, and it must be very much worse when the print is very small; and so Furrin would say to Purrin, “My eyes are getting quite dim, so now you must read;” and before Purrin had read a page he would say the same thing to Tod, and then Tod would try; but after a time their eyes became so dim they couldn’t see at all, and so they had to invent stories to tell little Gilliflower; so the poor little mice went quite blind, trying to amuse their little girl friend.

I took what care of them I could; but their blindness was very sad for them. No longer had Purrin the heart to sing or Furrin to dance and jest. Only they would sit close together, each holding one of Tod’s hands, and listening to his stories, for he kept his spirits best, and did all he could to cheer the others. All the marketing fell to me then, and it gave me plenty to do; for, poor souls, the only amusement left them was a dainty morsel, now and then.

And, by and by, they became so tired of sitting still, when Tod had exhausted all his stock of stories, that they got reckless, and would go blundering about the house after Dame Marjoram, whom they knew by the rustle of her silken skirt, and the tapping of her high-heeled shoes. They all ran after her, forgetting, that although they could not see her, still she could see them, and trying to follow her into her store-room, where the almonds, and raisins, and sugar, and candied-peel were kept.

I told them she would get angry, and that harm would come of it; but I think their unhappiness and dulness made them quite foolhardy, for they still went on, getting under her feet, and well-nigh tripping her up; clambering into the lard-pot before her very eyes; in short, doing a thousand irritating and injudicious things day by day, until her patience was quite worn out. And at last, when they scrambled on to the dinner-table, thinking it to be the store-room shelf, and sat all in a row, quietly eating out of Miss Gilliflower’s plate, Dame Marjoram, who had the carving-knife in her hand, thought it high time for them to have a lesson in manners. So, thinking the knife was turned blunt side downwards, she rapped them smartly across their three tails. What was her horror and their dismay, to find them cut off quite cleanly. The little tails lay still on the table, and the three little mice, well-nigh crazed with terror and pain, groped their way off the table and out of the room.

I was returning from the cheese-room, and met them crossing the great hall.

Of course, I took in at a glance all that had occurred, and I must say that I felt but little surprise, though much sorrow. I guided them to our old haunt in the loft-roof and then sat down to prepare a Memorial for Dame Marjoram, giving a full account of all that they had suffered for the sake of her family.

This I placed on the top of the key-basket; and while she was reading it, with my usual tact I silently brought in Purrin, Furrin, and Tod, and pushed them forward in front of her.

The tears stood in her eyes as she finished reading my scroll, and from that time forth nothing was too good for the Three Blind Mice. The good wife even tried to make new tails for them.

But they did not live long to enjoy their new happiness. The loss of their sight, followed by the shock of having their tails cut off, was too much for them. They never quite recovered, but died, all on the same day, within the same hour, just a month afterward.

Their three little graves were made beneath the shadows of a lavender bush in the garden.

Sometimes I go there to scatter a flower or two, and to shed a tear to the memory of Purrin, Furrin, and Tod.

There was a great clump of lilac bushes out by the garden wall. These lilacs grew close together and made a thick hedge nearly around a little plot of ground, where the grass grew so thick and velvety that it was like a great green rug, and they bent their tall heads over this little green plot, and so formed a lovely summer-house.

Here we used to sew for our dolls, and here we used to give tea-parties. Raspberry shortcake was one of the dainties we used to have. This is the way we made it: Take a nice clean raspberry leaf, heap it with raspberries, and put another leaf on top. Eat at once.

In this lovely summer-house I used to keep school. I had a row of bricks for scholars. Each brick had its own name. Two or three of the bricks were nice and red and new. I named those new bricks after my dearest little school-friends.

The rest of the bricks were either broken or blackened a little. Those bricks were my naughty, idle scholars. I used to stand them up in a row to learn their lessons. The first thing I knew those bad bricks would all tumble down in a heap. Numbers of little lilac-switches grew about my schoolhouse, and I fear I was a severe teacher.

When the lilacs were in bloom, that dear little summer-house was a very gay little place. The great, purple plumes would nod in every little wind that blew. The air was full of sweetness. Butterflies made the trees bright with their slowly-waving wings. There was a drowsy hum of many bees. Sometimes we would catch hold of one of the slender trunks of the lilac trees, and give it a smart shake. Away would flash a bright cloud of butterflies, and a swarm of angry, buzzing bees!

Pleasant Sabbath afternoons, we used to take our Sunday-school books out under the lilacs to read. And as we read about good deeds and unselfish lives, our own choir of birds would sing sweet hymns. Then we would look up and smile, and say, “They have good singing at the lilac church, don’t they?”

I HAD A ROW OF BRICKS FOR SCHOLARS.

That sand-bank in the pasture was one of the nicest of our playhouses. There was neither dust nor dirt in it—nothing but clean, fine sand, with now and then a pebble. It was not high, so there was no danger of a great mass of sand falling down on us two children.

The sand-bank was not very far from the little brook. Myra and I would carry pailful after pailful of water from the brook to it, until we had moistened a large quantity of sand. Sometimes we would cover our little bare feet with the cool, wet sand, packing it just as close as we could. Then gently, O, so gently, we would pull our feet out from under the sand. The little “five-toed caves” as we used to call them, would show just as plain as could be, where our little feet had been! We used to catch little toads and put them into those little damp caves, but they would soon hop out.

We used to make the nicest pies and cakes and cookies out of that lovely wet sand. We used to wish our sand-dainties were fit to eat!

Oftentimes, when we were tired of cooking, we would go to work and lay out a wonderful garden with tiny flower-beds and winding paths, out of that wet sand. Some of those flower-beds were star-shaped, some were round as a wheel, and some were square. We used to gather handfuls of wild-flowers and stick them down in, until every tiny bed blossomed into pink and blue and white and gold!

We used to make sand-preserves out there. The time and the patience that we used up in filling narrow-necked bottles with sand! After a bottle was well-filled and shaken down, we would catch up that bottle and run down to the brook. We would wash the outside of that bottle until it shone like cut-glass, and then we would pack it away in a hollow stump that we called our preserve-closet.

We used to play a game that we called “Hop-scotch” out in the old sand-bank. In this game, you mark the sand off into rather large squares. Then hopping along on one foot, you try with your toe to push a pebble from one square into another.

THE SAND-BANK GARDEN.

I used to play a great deal out in the old pasture. It had a clump of cradle-knolls in it. A cradle-knoll is a little mound of moss.

On these mossy little cradle-knolls, checkerberry leaves and berries used to grow. How delicious those spicy young checkerberry leaves tasted! And we hunted those red plums as a cat hunts a mouse!

The pasture had two or three well-beaten paths in it, that the cows had made by their sober steady tramping back and forth from the barnyard lane to the growth of little trees and bushes and tender grass at the back. At sunset-time, two little barefooted girls would “spat” along those cool smooth winding paths after those cows.

As long as we kept in the paths our little feet were all right. But sometimes a clump of bright wild-flowers tempted us, and then two sorry little girls with thistle-prickles in their feet would come limping back. But out where the tender grasses grew there were no thistles, and such fun as hide-and-seek used to be among the bushes!

Sometimes we could not find the cows very readily; and then we would climb up on a smutty stump and call, “co’ boss! co’ boss!” until the woods rang.

In the spring, we would go a-maying out in the old pasture, and O, such great handfuls of the sweet mayflower as we used to bring home! Later on, we would gather great bunches of sweet-smelling herbs that grew wild out there, and carry them home to hang up in the shed-chamber and dry.

If one of my schoolmates had been unkind to me, I would go out into the old pasture, and there I would plan out for myself a lovely future wherein I should be very rich and very good to the poor. And my unkind schoolmate would be one of the humble receivers of my gifts, and so it would come about that before I got through building air-castles I would actually feel sorry for the poor schoolmate who had ill-used me. And then home I would go, singing and skipping!

“CO’ BOSS!! CO’ BOSS!”

Out in one of the meadows was a big elm-tree. It was very tall, and in summer it looked like a monster bunch of green plumes.

It stood on the bank of our little brook. Right where the old elm stood, the bank was quite high, six feet almost. The boughs on the old tree grew very low. I would catch hold of one of those low-hanging boughs. Then, I would give a little run and jump. Away out over the bank and over the brook I would swing!

Oftentimes I would take my patchwork out under the old elm. But soon the patchwork would be on the ground, forgotten, and an idle little girl would be lying flat on the grass, with her hands clasped under her head, looking up into the clear blue sky!

I used to make believe that the white clouds were my ships, coming into harbor under full sail. And I used to make up fine names for my ships, and O, such splendid cargoes as they would be loaded with, all for me—their rich young owner—the idle dreamer in the grass!

O, it was such fun to lie there in the midst of funny daisies with their high white collars, and buttercups with their yellow caps! The roguish little winds would make them bend over and tickle the rosy face of the little girl whom the birds and the brook had almost hushed off to sleep. There would be a soft little touch on my forehead, and then another on my chin, and yet others on my cheeks. Then I would open my eyes and laugh at those funny little white and gold heads, soberly wagging up and down. But once I was rather frightened out under the old elm. I had been lying flat on my back for an hour or two, when I was called. I half raised myself up and answered. My hand was on the ground just where I had been lying. I felt something squirming around my thumb. It was a tiny brown snake! Of course, it was as harmless as a fly, but didn’t I spring to my feet!

When I had to recite a little piece in school or at a church concert, I always used to rehearse that little piece out under the old elm, over and over again.

SWINGING ON THE ELM-TREE BOUGH.

Tic-tac-too was a little boy; he was exactly three years old, and the youngest in the family; so, of course, he was the king. His real name was Alec; but he was always known in the household, and among his wide circle of friends generally, as Tic-tac-too. There was a little story to account for this, and it is that story which I am now going to tell.

There are very few children who do not know the funny old nursery rhyme of “Tic-tac-too;” it is an old-fashioned rhyme, and in great vogue amongst nurses. Of course Alec enjoyed it, and liked to have his toes pulled, and the queer words said to him. But that is not the story; for it is one thing to like a nursery rhyme very much, and another to be called by the name of that rhyme, and nothing else.

Now, please, listen to the story.

There was no nicer house to live in than Daisy Farm: it was old-fashioned and roomy; there were heaps of small bedrooms with low ceilings, and heaps of long passages, and unexpected turnings, and dear little cosey corners; and there was a large nursery made out of two or three of the small rooms thrown together, and this nursery had casement windows, and from the windows the daisies, which gave their name to the farm, could be seen. They came up in thousands upon thousands, and no power of man and scythe combined could keep them down. The mowing-machine only suppressed them for a day or two; up they started anew in their snowy dresses, with their modest pink frills and bright yellow edges.

Mr. Rogers, who owned Daisy Farm, objected to the flowers; but his children delighted in them, and picked them in baskets-full, and made daisy-chains to their hearts’ content. There were several children who lived in this pleasant farmhouse, for Tic-tac-too had many brothers and sisters. The old-fashioned nursery was all that a modern nursery should be; it had deep cupboards for toys, and each child had his or her wide shelf to keep special treasures on; and the window-ledges were cosey places to curl up in on wet days, when the rain beat outside, and the wind sighed, and even the daisies looked as if they did not like to be washed so much.

Some of the children at Daisy Farm were old enough to have governesses and masters, to have a schoolroom for themselves, and, in short, to have very little to say to the nursery; but still there were four nursery little ones; and one day mother electrified the children by telling them that another little boy was coming to pay them a visit.

“He is coming to-morrow,” said mother; “he is a year younger than Alec here, but his mother has asked us to take care of him. You must all be kind to the little baby stranger, children, and try your very best to make him feel at home. Poor little man, I trust he will be happy with us.”

Mother sighed as she spoke; and when she did this, Rosie, the eldest nursery child, looked up at her quickly. Rosie had dark gray eyes, and a very sympathetic face; she was the kind of child who felt everybody’s troubles, and nurse said she did this far more than was good for her.

The moment her mother left the room, Rosie ran up to her nurse, and spoke eagerly—

“Why did mother sigh when she said a new little boy was coming here, nursie?”

“Oh, my love, how can I tell? People sigh most likely from habit, and from no reason whatever. There’s nothing to fret anybody in a sigh, Miss Rosie.”

“But mother doesn’t sigh from habit,” answered Rosie; “I expect there’s going to be something sad about the new little boy, and I wonder what it is. Harry, shall we collect some of our very nicest toys to have ready for the poor little new boy?”

Harry was six; he had a determined face, and was not so generous as Rosie.

“I’ll not give away my skin-horse,” he said, “so you needn’t think it, nor my white dog with the joints; there are some broken things down in that corner that he can have. But I don’t see why a new baby should have my best toys. Gee-up, Alec! you’re a horse, you know, and I’m going to race you from one end of the nursery to the other—now trot!”

Fat little curly-headed Alec started off good-humoredly, and Rosie surveyed her own shelf to see which toys would most distract the attention of the little stranger.

She was standing on a hassock, and counting her treasures over carefully, when she was startled by a loud exclamation from nurse.

“Mercy me! If that ain’t the telegraph boy coming up the drive!”

Nurse was old-fashioned enough still to regard telegrams with apprehension. She often said she could never look at one of those awful yellow envelopes, without her heart jumping into her mouth; and these fears she had, to a certain extent, infected the children with.

Harry dropped Alec’s reins, and rushed to the window; Rosie forgot her toys, and did likewise; Jack and Alec both pressed for a view from behind.

“Me, me, me, me want to see!” screamed baby Alec from the back.

Nurse lifted him into her arms; as she did so, she murmured under her breath,—

“God preserve us! I hope that awful boy isn’t bringing us anything bad.”

Rosie heard the words, and felt a sudden sense of chill and anxiety; she pressed her little hand into nurse’s, and longed more than ever to give all the nicest toys to the new little boy.

Just then the nursery door was opened, and Kate, the housemaid, appeared, carrying the yellow envelope daintily between her finger and thumb.

“There, nurse,” she said, “it’s for you; and I hope, I’m sure, it’s no ill-luck I’m bringing you.”

“Oh, sake’s alive!” said nurse. “Children, dears, let me sit down. That awful boy to bring it to me! Well, the will of the Lord must be done; whatever’s inside this ugly thing? Miss Rosie, my dear, could you hunt round somewhere for my spectacles?”

It always took a long time to find nurse’s spectacles; and Rosie, after a frantic search, in which she was joined by all the other nursery children, discovered them at last at the bottom of Alec’s cot. She rushed with them to the old woman, who put them on her nose, and began deliberately to read the contents of her telegram.

The children stood round her as she did so. They were all breathless and excited; and Rosie looked absolutely white from anxiety.

“Well, my dears,” said nurse at last, when she had spelt through the words, “it ain’t exactly a trouble; far from me to say that; but all the same, it’s mighty contrary, and a new child coming here, and all.”

“What is it, nurse?” said Harry. “Do tell us what it’s all about.”

“It’s my daughter, dears,” said nurse; “she’ll be in London to-morrow, on her way back to America.”

“Oh, nurse!” said Rosie, “not your daughter Ann?”

“The same, my love; she that has eight children, and four of them with carrotty hair. She wants me to go up to London, to see her to-morrow; that’s the news the telegraph boy has brought, Miss Rosie. My daughter Ann says, ‘Mother, meet me to-morrow at aunt’s, at two o’clock.’ Well, well, it’s mighty contrary; and that new child coming, and all!”

“But you’ll have to go, nurse. It would be dreadful for your daughter Ann not to see you again.”

“Yes, dear, that’s all very fine; but what’s to become of all you children? How is this blessed baby to get on without his old Nan?”

“Oh, nurse, you must go! It would be so cruel if you didn’t,” exclaimed Rosie.

Nurse sat thinking hard for a minute or two; then saying she would go and consult her mistress, she left the room.

The upshot of all this was, that at an early hour the following morning nurse started for London, and a girl, of the name of Patience, from the village, came up to take her place in the nursery.

Mrs. Rogers was particularly busy during these days. She had some friends staying with her, and in addition to this her eldest daughter, Ethel, was ill, and took up a good deal of her mother’s time; in consequence of these things the nursery children were left entirely to the tender mercies of Patience.

Not that that mattered much, for they were independent children, and always found their own amusements. The first day of nurse’s absence, too, was fine, and they spent the greater part of it in the open air; but the second day was wet—a hopelessly wet day—a dull day with a drizzling fog, and no prospect whatever of clearing up.

The morning’s post brought a letter from nurse to ask for further leave of absence; and this, in itself, would have depressed the spirits of the nursery children, for they were looking forward to a gay supper with her, and a long talk about her daughter Ann, and all her London adventures.

But this was not the real trouble which pressed so heavily on Rosie’s motherly heart; the real anxiety which made her little face look so careworn was caused by the new baby, the little boy of two years old, who had arrived late the night before, and now sat with a shadow on his face, absolutely refusing to make friends with any one.

He must have been a petted little boy at home, for he was beautifully dressed, and his curly hair was nicely cared for, and his fair face had a delicate peach bloom about it; but if he was petted, he was also, perhaps, spoilt, for he certainly would not make advances to any of his new comrades, nor exert himself to be agreeable, nor to overcome the strangeness which was filling his baby mind. Had nurse been at home, she would have known how to manage; she would have coaxed smiles from little Fred, and taken him up in her arms, and “mothered” him a good bit. Babies of two require a great lot of “mothering,” and it is surprising what desolation fills their little souls when it is denied them.

Fred cried while Patience was dressing him; he got almost into a passion when she washed his face, and he sulked over his breakfast. Patience was not at all the sort of girl to manage a child like Fred; she was rough in every sense of the word; and when rough petting failed, she tried the effect of rough scolding.

“Come, baby, come, you must eat your bread and milk. No nonsense now, open your mouth and gobble it down. Come, come, I’ll slap you if you don’t.”

But baby Fred, though sorrowful, was not a coward; he pushed the bowl of bread and milk away, upset its contents over the clean tablecloth, and raised two sorrowful big eyes to the new nurse’s face.

“Naughty dirl, do away,” he said; “Fred don’t ’ove ’oo. Fred won’t eat bekfus’.”

“Oh, Miss Rosie, what a handful he is!” said Patience.

“Let me try him!” said Rosie; “I’ll make him eat something. Come Freddy darling, you love Rosie, don’t you?”

“No, I don’t,” said Fred.

“Well, you’ll eat some breakfast; come now.”

“I won’t eat none bekfus’—do away.”

Rosie turned round and looked in a despairing way at her own three brothers.

“If only nurse were at home!” she said.

“Master Fred,” said Patience, “if you won’t eat, you must get down from the breakfast-table. I have got to clear up, you know.”

She popped the little boy on the floor. He looked round in a bewildered fashion.

“Let’s have a very exciting kind of play, and perhaps he’ll join in,” said Rosie, in a whisper. “Let’s play at kittens—that’s the loveliest of all our games.”

“Kittens” was by no means a quiet pastime. It consisted, indeed, in wild romps on all-fours, each child assuming for the time the character of a kitten, and jumping after balls of paper, which they caught in their mouths.

“It’s the happiest of all our games, and perhaps he’ll like it,” said Rosie.

“Patie,” said Alec, going up to the new nurse, “does ’oo know Tic-tac-too?”

“Of course I do, master Baby—a silly game that.”

“I ’ike it,” said little Alec.

He tripped across the nursery to the younger baby, and sat down by his side.

“Take off ’oo shoe,” he said.

Fred was very tired of being cross and miserable. He could not say he was too little to Alec, for Alec was scarcely bigger than himself. Besides he understood about taking off his shoe. It was a performance he particularly liked. He looked at Baby Alec, and obeyed him.

“Take off ’oo other shoe,” said Alec.

Fred did so.

“Pull off ’oo ’tocks,” ordered the eldest baby.

Fred absolutely chuckled as he tugged away at his white socks, and revealed his pink toes.

“Now, come to Patie.”

Fred scrambled to his feet, and holding Alec’s hand, trotted down the long nursery.

“Patie,” said Alec, “take F’ed on ’our lap, and play Tic-tac-too for him?”

Patience was busy sewing; she raised her eyes. Two smiling little baby-boys were standing by her knee. Could this child, whose blue eyes were full of sunshine, be the miserable little Fred?

“Well, master Alec,” she said, kissing the older baby, “you’re a perfect little darling. Well, I never! to think of you finding out a way to please that poor child.”

“Tic-tac-too!” said Fred, in a loud and vigorous voice. He was fast getting over his shyness, and Alec’s game suited him to perfection.

But the little stranger did not like the game of kittens. He marched in a fat, solid sort of way across the nursery, and sat down in a corner, with his back to the company. Here he really looked a most dismal little figure. The view of his back was heart-rending; his curly head drooped slightly, forlornness was written all over his little person.

“What a little muff he is!” said Harry; “I’m glad I didn’t give my skin horse to him.”

“Oh, don’t,” said Rosie, “can’t you see he’s unhappy? I must go and speak to him. Fred,” she said, going up to the child, “come and play with Alec and me.”

“No,” said Fred, “I’se too little to p’ay.”

“But we’ll have such an easy play, Fred. Do come; I wish you would.”

“I’se too little,” answered Fred, shaking his head again.

At that moment Rosie and her two elder brothers were called out of the room to their morning lessons. Rosie’s heart ached as she went away.

“Something must be done,” she said to herself. “That new little boy-baby will get quite ill if we can’t think of something to please him soon.”

She did not know that a very unexpected little deliverer was at hand. The two babies were now alone in the nursery, and Patience, having finished her tidying up, sat down to her sewing.

Patience lifted him on her lap, popped him down with a bounce, kissed him, and began,—

When the other children returned to the nursery, they heard peals of merry baby laughter; and this was the fashion in which a little boy won his name.

We used to play a great deal about the pasture fence. It was a high rail fence and we used to take a little pole in both hands as a balancing pole, and run along on the top. Carefully we balanced ourselves as we ran! But finally we would tip first one way and then the other, and then, with a little laughing scream, off we’d topple!

Sometimes we would put a board through the fence and have a fine time at “seesaw.” Up one of us would go, high in the air, and down would go the other with a thud!

We used to play that the pasture fence was a huge cupboard. Each rail was a shelf. Many of those rail-shelves were loaded down with bits of broken dishes, shining pebbles, bits of green moss that we called “pincushions,” and white clam-shells full of strawberries, or raspberries, or little dark juicy choke-cherries. The contents of the clam-shells were for the birds. If we found a clam-shell lying on the ground, we believed with all our little hearts that a little winged creature had been fed from our cupboard.

Sometimes we would carry on a thriving millinery store out at the pasture fence. We would make queer little bonnets out of birch-bark. Then we would sew wildflowers on the bonnets and lay them on the rails of the fence for sale. Such a number of those funny little bonnets as would be on exhibition on our rail-counters!

One of the big upright posts of our rail fence was hollow a little way down. One day we found on the ground a nest full of birdlings; one of them was dead, and a little green snake had almost reached the nest. The mother-bird was flying about crying pitifully. I snatched the nest away and carried it O, so carefully to the pasture fence and put it down in the hollow of the fence-post. Then we went a bit away and waited. Pretty soon there was a little rush of wings; and soon the mother-bird settled down in that hollow post just as cunning as could be. And that dear little family staid in that hollow post until the baby-birds grew up and flew away.

Lulu was six years old last spring. She came to make a visit at her grandfather’s, and stayed until after Thanksgiving.

Lulu had lived away down in Cuba ever since she was a year old. Her cousins had written to her what a good time they had on Thanksgiving Day; so she was very anxious to be at her grandfather’s at that time. They do not have a Thanksgiving Day down in Cuba. That is how Lulu did not have one until she was six years old.

She could hardly wait for the day to come. Such a grand time as they did have! Lulu did not know she had so many cousins until they came to spend the day at her grandfather’s. It did not take them long to get acquainted. Before time for dinner they felt as if they had always known each other.

The dinner was the grand event of the day. Lulu had never seen so long a table except at a hotel, nor some of the vegetables and kinds of pie.

Lulu had never tasted turkey before. Her grandmother would not have one cooked until then, so she could say that she had eaten her first piece of turkey on Thanksgiving Day.

After dinner they played all kinds of games. All the uncles and aunts and grown-up cousins played blind-man’s-buff with them.

We had a number of rainy-day playhouses. When it did not rain very hard, Myra and I would scamper out to our little playhouse made of boards, and listen to the patter of the drops.

It was not a very costly playhouse. It was built in a corner made by the shed and the orchard fence. One side of our playhouse was the shed. Another side was the fence; this open side we used to call our bay-window. A creeping hop vine twined around the rough fence-boards and made a green lace curtain for our bay-window. The third side was made of boards. Across this side stretched the wide board seat, which was the only furniture of our playhouse. The fourth, or front side of the playhouse consisted mostly of a “double-door,” of which we were very proud. This double-door was two large green blinds. Did not we feel like truly little housekeepers when we fastened those two blinds together with a snap!

When the rain came down in gentle showers we used to go out to the little playhouse and have a concert. First Myra would step up on to that wide board seat and recite a little piece. Then I would step up on to the seat and sing a little song. Perhaps while I was singing a robin in the orchard would begin to sing, O, so loud and sweet that all the orchard just rang with that sweet music! We would stop our concert and listen to the robin. When he had finished, we used to clap our little hands. And all the time the rain kept up a fairy “tinkle, tinkle,” as if some one was keeping time for us on a tiny piano.

Spat-t! Spat-t! would come the little drops through a tiny hole in the roof of our little house. We used to hold our faces up towards that little leak in the roof. Oftentimes a drop would strike us fairly on the tip of our small noses! Then how we would laugh!

Sometimes we would take hold of hands and repeat together, over and over again: “Rain, rain, go away, come again, another day!”

And if we said those words long enough, the rain would go away!

THE RAINY-DAY PLAYHOUSE.

In winter we played everywhere! The whole white world was a lovely playground! We had no skates, but we wore very thick-soled boots that took the place of skates very well. At least we thought so, and that was all we needed to make us contented. When the little pond was frozen over, we would take a quick run down its snowy banks and then we would skim clear across that little pond’s frozen surface just as swift as a bird would skim through the air.

Sometimes a thick frost would come in the night-time. The next morning a fine blue haze would be in the air and everything would be clothed in soft white frost-furs. As the sun rose higher and higher we would watch to see the trees and bushes grow warm in the sunshine and throw off their furs. Then we would try and catch those soft furs as they fell. But if caught they melted quickly away.

If the surface of the snow hardened enough so that we could walk on the crust without breaking through, our happiness was complete. High hills were all about us, and it seemed to us as if every shining hill would say if it could, “Come and slide!”

And O, the happy hours that we have had with our clumsy old sled! Away we would go, the wind stinging our faces until crimson roses blossomed in our cheeks, and the shining crust snapping and creaking under our sled, and the hill flying away behind us!

If a damp clinging snow came, it made lovely snowballs; and it was such fun to catch hold of the long clothes-lines and shake them and see little clumps of snow hop like rabbits from the line into the air.

And if instead of warmth, and great damp feathery snowflakes, there came a bitter wind and an icy sleet that froze as it fell—what then? Never mind! Sunrise would set the whole world a-sparkle. Every tree and bush would be gay with splendid ice-jewels! And in the great shining ice palace, we could run and laugh and shout, watching the ice-jewels loosen and fall, all day long.

“AWAY WE WOULD GO!”

It was Uncle George who called her “Gran’ma” when she was only six, and by the time she was seven everybody had taken to the name, and she answered to it as a matter of course.

Why did he call her so? Because she was such a prim, staid, serious, little old-fashioned body, and consequently her mother laughingly took to dressing her in an old-fashioned way, so that at last, whether she was out in the grounds, or round by the stables with Grant, in her figured pink dress, red sash, long gloves, and sun-bonnet, looking after her pets, or indoors of an evening, in her yellow brocade, muslin apron—with pockets, of course, and quaint mob cap tied up with its ribbon—she always looked serious and grandmotherly.

“It is her nature to,” Uncle George said, quoting from “Let dogs delight;” and when he laughed at her, Gran’ma used to look at him wonderingly in the most quaint way, and then put her hand in his, and ask him to take her for a walk.

Gran’ma lived in a roomy old house with a delightful garden, surrounded by a very high red-brick wall that was covered in the spring with white blossoms, and in the autumn with peaches with red cheeks that laughed at her and imitated hers; purple plums covered with bloom, and other plums that looked like drops of gold among the green leaves; and these used to get so ripe and juicy in the hot sun, that they would crack and peer out at her as if asking to be eaten before they fell down and wasted their rich honey juice on the ground. Then there were great lumbering looking pears which worried John, the gardener, because they grew so heavy that they tore the nails out of the walls, and had to be fastened up again—old John giving Gran’ma the shreds to hold while he went up the ladder with his hammer, and a nail in his mouth.

That garden was Gran’ma’s world, it was so big; and on fine mornings she could be seen seriously wandering about with Dinnywinkle, her little sister, up this way, down that, under the apple-trees, along the gooseberry and currant alleys, teaching her and Grant that it was not proper to go on the beds when there were plenty of paths, and somehow Dinnywinkle, who was always bubbling over with fun, did as the serious little thing told her in the most obedient of ways, and helped her to scold Grant, who was much harder to teach.

For Grant, whose papa was a setter, and mamma a very lady-like retriever, always had ideas in his head that there were wild beasts hiding in the big garden, and as soon as his collar was unfastened, and he was taken down the grounds for a run, he seemed to run mad. His ears went up, his tail began to wave, and he dashed about frantically to hunt for those imaginary wild beasts. He barked till he was hoarse sometimes, when after a good deal of rushing about he made a discovery, and would then look up triumphantly at Gran’ma, and point at his find with his nose, till she came up to see what he had discovered. One time it would be a snail, at another a dead mouse killed by the cat, and not eaten because it was a shrew. Upon one occasion, when the children ran up, it was to find the dog half wild as he barked to them to come and see what he was holding down under his paw,—this proving to be an unfortunate frog which uttered a dismal squeal from time to time till Gran’ma set it at liberty, so that it could make long hops into a bed of ivy, where it lived happily long afterwards, to sit there on soft wet nights under a big leaf like an umbrella, and softly whistle the frog song which ends every now and then in a croak.

Grant was always obedient when he was caught, and then he would walk steadily along between Gran’ma and Dinny, each holding one of his long silky ears, with the prisoner making no effort to escape.

But the job was to catch him; and on these occasions Gran’ma used to run and run fast, while Dinny ran in another direction to cut Grant off.

And a pretty chase he led them, letting them get close up, and then giving a joyous bark and leaping sidewise, to dash off in quite a fresh direction. Here he would perhaps hide, crouching down under one of the shrubs, ready to pounce out on his pursuers, and then dash away again, showing his teeth as if he were laughing, and in his frantic delight waltzing round and round after his tail. Then away he would bound on to the closely shaven lawn, throw himself down, roll over and over, and set Dinny laughing and clapping her hands to see him play one of his favorite tricks, which was to lay his nose down close to the grass, first on one side and then on the other, pushing it along as if it was a plough, till he sprang up and stood barking and wagging his tail, as much as to say, “What do you think of that for a game?” ending by running helter-skelter after a blackbird which flew away, crying “Chink—chink—chink.”

That was a famous old wilderness of a place, with great stables and out-houses, where there was bright golden straw, and delicious sweet-scented hay, and in one place a large bin with a lid, and half-full of oats, with which Gran’ma used to fill a little cross-handled basket.

“Now, Grant,” she cried, as she shut down the lid, after refusing to let Dinny stand in the bin and pour oats over her head and down her back—“Now, Grant!”

“Wuph!” said Grant, and he took hold of the basket in his teeth, and trotted on with it before her round the corner, to stop before the hutches that stood outside in the sun.

Here, if Dinny was what Gran’ma called “a good girl,” she had a treat. For this was where the rabbits lived.

Old Brownsmith sent those rabbits, hutch and all, as a present for Gran’ma, one day when John went to the market garden with his barrow to fetch what he called some “plarnts;” and when he came back with the barred hutch, and set the barrow down in the walk, mamma went out with Gran’ma and Dinny, to look at them, and Grant came up growling, sniffed all round the hutch before giving a long loud bark, which, being put into plain English, meant, “Open the door, and I’ll kill all the lot.”

“I don’t know what to say, John,” said mamma, shaking her head. “It is very kind of Mr. Brownsmith, but I don’t think your master will like the children to keep them, for fear they should be neglected and die.”

“’Gleckted?” said old John, rubbing one ear. “What! little miss here ’gleck ’em? Not she. You’ll feed them rabbuds reg’lar, miss, wontcher?”

Gran’ma said she would, and the hutch was wheeled round by the stables, Grant following and looking very much puzzled, for though he never hunted the cats now, rabbits did seem the right things to kill.

But Gran’ma soon taught him better, and he became the best of friends with Brown Downie and her two children, Bunny and White Paws.

In fact, one day there was a scene, for Cook rushed into the schoolroom during lesson time, out of breath with excitement.

“Please’m, I went down the garden, ’m, to get some parsley, and that horrid dog’s hunting the rabbits, and killing ’em.”

There was a cry from both children, and Gran’ma rushed out and round to the stables, to find the hutch door unfastened, and the rabbits gone, while, as she turned back to the house with the tears running down her cheeks, who should come trotting up but Grant, with his ears cocked, and Bunny hanging from his jaws as if dead.

Gran’ma uttered a cry; and as Mamma came up with Dinny, the dog set the little rabbit down, looked up and barked, and Bunny began loping off to nibble the flowers, not a bit the worse, while Grant ran and turned him back with his nose, for Gran’ma to catch the little thing up in her arms.

Grant barked excitedly, and ran down the garden again, the whole party following, and in five minutes he had caught White Paw.

Dinny had the carrying of this truant, and with another bark, Grant dashed in among the gooseberry bushes, where there was a great deal of rustling, a glimpse of something brown, and then of a white cottony tail. Then in spite of poor Grant getting his nose pricked with the thorns, Brown Downie was caught and held by her ears till mamma lifted her up, and she was carried in triumph back, Grant trotting on before, and leading the way to the stable-yard and the hutch, turning round every now and then to bark.

The rabbits did not get out again, and every morning and evening they were fed as regularly as Gran’ma fed herself.

On reaching the hutch, Grant set the basket down, leaving the handle rather wet, though he could easily have wiped it with his ears, and then he sat down in a dreamy way, half closing his eyes and possibly thinking about wild rabbits on heaths where he could hunt them through furze bushes, while Gran’ma in the most serious way possible opened the hutch door.

There was no difficulty about catching White Paw, for he was ready enough to thrust his nose into his little mistress’s hand, and be lifted out by his ears, and held for Dinny to stroke.

“Now let me take him,” she cried.

“No, my dear, you are too young yet,” said Gran’ma; and Dinny had to be content with smoothing down White Paw’s soft brown fur, as it nestled up against its mistress’s breast, till it was put back kicking, and evidently longing to escape from its wooden-barred prison, even if it was to be hunted by Grant.

Then Bunny had his turn, and was duly lifted out and smoothed; after which, Brown Downie, who was too heavy to lift, gave the floor of the hutch a sharp rap with one foot, making Grant lift his ear and utter a deep sigh.

“No,” he must have thought; “it’s very tempting, but I must not seize her by the back and give her a shake.”

Then the trough was filled with oats, the door fastened, and the girls looked on as three noses were twitched and screwed about, and a low munching sound arose.

Three rabbits and a dog! Enough pets for any girl, my reader; but Gran’ma had another—Buzz, a round, soft-furred kitten with about as much fun in it as could be squeezed into so small a body. But Buzz had a temper, possibly soured by jealousy of Grant, whom he utterly detested.

Buzz’s idea of life was to be always chasing something,—his tail, a shadow, the corner of the table-cover, or his mistress’s dress. He liked to climb, too, on to tables, up the legs, into the coal-scuttle, behind the sideboard, and above all, up the curtains, so as to turn the looped-up part into a hammock, and sleep there for hours. Anywhere forbidden to a respectable kitten was Buzz’s favorite spot, and especially inside the fender, where the blue tiles at the back reflected the warmth of the fire, and the brown tiles of the hearth were so bright that he could see other kittens in them, and play with them, dabbing at them with his velvet paw.

Buzz had been dragged out from that forbidden ground by his hind leg, and by the loose skin at the back of his neck, and he had been punished again and again, but still he would go, and strange to say, he took a fancy to rub himself up against the upright brass dogs from the tip of his nose to the end of his tail, and then repeat it on the other side.

But Gran’ma’s pet did not trespass without suffering for it. Both his whiskers were singed off close, and there was a brown, rough, ill-smelling bit at the end of his tail where, in turning round, he had swept it amongst the glowing cinders, giving him so much pain that he uttered a loud “Mee-yow!” and bounded out of the room, looking up at Gran’ma the while as if he believed that she had served him like that.

In Gran’ma’s very small old-fashioned way, one of her regular duties was to get papa’s blue cloth fur-lined slippers, and put them against the fender to warm every night, ready for him when he came back tired from London; and no sooner were those slippers set down to toast, than Buzz, who had been watching attentively, went softly from his cushion where he had been pretending to be asleep, but watching all the time with one eye, and carefully packed himself in a slipper, thrusting his nose well down, drawing his legs right under him, and snoozling up so compactly that he exactly fitted it, and seemed part of a fur cushion made in the shape of a shoe.

But Buzz was not allowed to enjoy himself in that fashion for long. No sooner did Gran’ma catch sight of what he had done than she got up, went to the fireplace, gravely lifted the slipper, and poured Buzz out on to the hearth-rug, replaced the slipper where it would warm, and went back, to find, five minutes later, that the kitten had fitted himself into the other slipper, with only his back visible, ready to be poured out again. Then, in a half-sulky, cattish way, Buzz would go and seat himself on his square cushion, and watch, while, to guard them from any more such intrusions, Gran’ma picked up the slippers and held them to her breast until such time as her father came home.

Those were joyous times at the old house, till one day there was a report spread in the village that little Gran’ma was ill. The doctor’s carriage was seen every day at the gate, and then twice a day, and there were sorrow and despair where all had been so happy. Dinny went alone with Grant to feed the rabbits; and there were no more joyous rushes round the garden, for the dog would lie down on the doorstep with his head between his paws, and watch there all day, and listen for the quiet little footstep that never came. Every day old John, the gardener, brought up a bunch of flowers for the little child lying fevered and weak, with nothing that would cool her burning head, and three anxious faces were constantly gazing for the change that they prayed might come.

For the place seemed no longer the same without those pattering feet. Cook had been found crying in a chair in the kitchen; and when asked why, she said it was because Grant had howled in the night, and she knew now that dear little Gran’ma would never be seen walking so sedately round the garden again.

It was of no use to tell her that Grant had howled because he was miserable at not seeing his little mistress: she said she knew better.

“Don’t tell me,” she cried; “look at him.” And she pointed to where the dog had just gone down to the gate, for a carriage had stopped, and the dog, after meeting the doctor, walked up behind him to the house, waited till he came out, and then walked down behind him to the gate, saw him go, and came back to lie down in his old place on the step, with his head between his paws.

They said that they could not get Grant to eat, and it was quite true, for the little hands which fed him were not there; and the house was very mournful and still, even Dinny having ceased to shout and laugh, for they told her she must be very quiet, because Gran’ma was so ill.

From that hour Dinny went about the place like a mouse, and her favorite place was on the step by Grant, who, after a time, took to laying his head in her lap, and gazing up at her with his great brown eyes.

And they said that Gran’ma knew no one now, but lay talking quickly about losing the rabbits and about Dinny and Grant; and then there came a day when she said nothing, but lay very still as if asleep.

That night as the doctor was going, he said softly that he could do no more, but that those who loved the little quiet child must pray to God to spare her to them; and that night, too, while tears were falling fast, and there seemed to be no hope, Grant, in his loneliness and misery, did utter a long, low, mournful howl.

But next morning, after a weary night, those who watched saw the bright glow of returning day lighting up the eastern sky, and the sun had not long risen before Gran’ma woke as if from a long sleep, looked up in her mother’s eyes as if she knew her once more, and the great time of peril was at an end.

All through the worst no hands but her mother’s had touched her; but now a nurse was brought in to help—a quiet, motherly, North-country woman who one day stood at the door, and held up her hands in astonishment, for she had been busy down-stairs for an hour, and now that she had returned there was a great reception on the bed: Buzz was seated on the pillow purring; the rabbits all three were playing at the bed being a warren, and loping in and out from the valance; Grant was seated on a chair with his head close up to his mistress’s breast; and Dinny was reading aloud from a picture storybook like this, but the book was upside down, and she invented all she said.

“Bless the bairn! what does this mean?” cried nurse.

It meant that Dinny had brought up all Gran’ma’s friends, and that the poor child was rapidly getting well.

Miss Myrtle read to the children this afternoon an Account sent by her married cousin, Mrs. Pingry. Mrs. Pingry wrote: “I spell it with a big A, just for fun, because it is of so small a matter, but it was a sunshiny matter for it caused some smiling, and it brought out real kindness from several persons.

“Mr. Pingry goes in on the 8.17 train and attends to his furnace the last thing, allowing twelve minutes to reach the station. When about half-way there, yesterday, it occurred to him that he forgot to shut the drafts. Just then he met Jerry Snow, the man at the Binney place, and asked him to please call round our way, and ask for Mrs. Pingry, and say Mr. Pingry had left the drafts open. Jerry said he would after going to the post-office, but Mr. Pingry, fearing Jerry might forget, called hastily at the door of Madam Morey, an elderly woman who does plain sewing, and said he forgot to shut the furnace drafts; if she should see a boy passing would she ask him to call at our door, and ask for Mrs. Pingry, and tell her? Madam said she would be on the lookout for a boy, while doing her baking.

“Now as Mr. Pingry was hurrying on, it came to him that he had not yet made a sure thing of it, and at that moment he saw the woman who does chore-work at the Binney’s, coming by a path across the field. He met her at the fence, and asked if she would go around by our house and say to Mrs. Pingry that Mr. Pingry had left the drafts all open. She agreed, and Mr. Pingry ran to his train, a happy man.

“Now Madam Morey felt anxious about the furnace, and stepped often to the window, and at last spied a small boy with a sled, and finding he knew where we live, told him Mr. Pingry went away and forgot to shut the furnace drafts and wished to send back word, and would the boy coast down that way and tell Mrs. Pingry? The boy promised, and coasted down the hill.

“Madam Morey still felt uneasy about the furnace, and not being sure the boy would do the errand kept on the watch for another; and when the banana-man stopped and made signs at her window ‘would she buy?’ she wrote a few words on a bit of brown paper and went with him far enough to point out the house and made signs, ‘would he leave the paper there?’ He made signs ‘yes?’ and passed on.

“Now at about half-past eight, our front doorbell rang and I heard a call for me. I hurried down, and received the chore-woman’s message and acted upon it at once.

“Sometime afterwards, as I was in the back-chamber, I heard voices outside and saw six or eight small boys trying to pull their sleds over a fence, and wondered how they happened to be coasting in such a place. Presently I heard a commotion on the other side and went to the front windows. All the sleds were drawn up near the steps, and the small boys were stamping around like an army come to take the house. Seeing me they all shouted something at me. They seemed so terribly in earnest, and came in such a strange way, that I flew down, sure something dreadful had happened—perhaps Willy was drowned! and I began to tremble. At sight of me at the door they all shouted again, but I did not understand. I caught hold of the biggest boy and pulled him inside, and said to him, in a low, tremulous voice, ‘Tell me! What is it?’ He answered, in a bashful way, ‘Mr. Pingry said he left the drafts open.’ ‘Thank you all!’ I said.

“Next, the banana-man, bobbing his head, and making signs, though I shook my head ‘no.’ Finally up came Bridget with a slip of brown paper having written on it, but no name signed: ‘Your furnace drafts are open.’ Such a shout as went up from us!

“Grand company coming, I guess! exclaimed my sister, a short time afterwards. Sure enough there stood a carriage and span. Jerry Snow, it seems, forgot our furnace until he went to look at his own. He was then just about to take Mrs. Binney out for an airing. He mentioned it to her and she had him drive round with the message.

“By this time we were ready to go off, explode, shout, giggle, at the approach of any one; and when Madam Morey stepped up on our piazza we bent ourselves double with laughter, and my sister went down upon the floor all in a heap, saying, ‘Do—you—suppose—she—comes—for that?’

“Even so. She had worried, thinking the hot pipes might heat the woodwork, and half-expected to hear the cry of ‘fire!’ and bells ringing, and could not sit still in her chair, and in the goodness of her heart she left her work and came all the way over!

“Oh! we had fun with Mr. Pingry that evening. But now, my dear Miss Myrtle, the funniest part of all was that Mr. Pingry did not forget to shut the drafts!”

Sammy Swattles wasn’t a bad boy, you understand; he was simply thoughtless. He thoughtlessly did things which robbed him of peace of mind for some time after he did them.

When Sammy was ten years old he had to leave school, to go to work for Mr. Greens, the grocer, in order to help support his mother.

He did a great many things for the grocer, from seven o’clock in the morning till six at night, but his principal work was to place large paper bags on the scales and fill them with flour from the barrel.

When the bag weighed twenty-three pounds, Sammy had to seal it up and take it to the family it was ordered for. The grocer allowed him two cents for every bag he carried, over and above his wages, which were $2.50 per week. Some weeks Sammy made over $3.00 which helped his mother to run their little house quite comfortably.

Now, Sammy, in his thoughtlessness, used to sample quite a good deal of the grocer’s preserved ginger. Every time he would pass the tin boxes of ginger, he would thoughtlessly take a piece, and it would disappear in the recesses of Sammy’s rosy mouth.

One night, after he had locked up all but the front door of the store, he helped himself to quite a large piece of the ginger, and walked home.

He did not care for any supper that night. He felt as if bed was the best place for his troubled little stomach.

He hadn’t been in bed two minutes when a little fierce man, with a white cloth round his black body and a huge grin on his ebony face, bounded into his room.

With a scream Sammy leaped out of bed and bounded out of the window. With a yell the Indian was after him. Sammy flew down the road like a runaway colt, the black man in his rear yelling like thunder and lions. Sammy never ran so fast in his life, but the little black man gained on him, and finally caught him!

Sammy pleaded hard to be spared to his mother, but the little man grimly took him by the collar, and with one leap landed him on the island of Ceylon, in the Indian Ocean, at a place called Kandy. Then he led Sammy out into the country, and blew a whistle. In an instant they were surrounded by hundreds and hundreds of men, women and boys, all as black as Sammy’s captor. Sammy cried:

“What have I done! what have I done!” and they all cried:

“You have taken the ginger that we have gathered by hard work, without permission, and you are condemned to live here for the rest of your life on ginger alone!”

Then Sammy began to cry real hard, for he thought of his poor mother, off there in Massachusetts, wondering day after day, “What has become of my Sammy!”

And then to be compelled to eat nothing but ginger all his life! It was awful! He already hated ginger. He looked so woebegone that they all cried:

“If you will promise to be good, and think before you do things, we will let you go! But if you don’t keep your promise we’ll get you again, and then, look out!”

So Sammy promised, and ran for home. But the black people seemed to regret having let him off so easily, and they all came trooping after him!