Why would a Space Officer lead an android

rebellion? Even Lieut. Mannion believed he was

guilty as they gave him the supreme penalty....

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

October 1957

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Lieut. Dan Mannion of the Earth Space Patrol stood in the prisoner's dock in the courtroom, gripping the rail of his cubicle so hard his fingers hurt.

Comdr. Edward Harkness of the SP, who was presiding, glared at him sternly. "Lieutenant Mannion, the charges against you are severe. You face the risk of total mnemonic erasure if found guilty. Is there anything you care to say in your own defense before we proceed with the trial?"

Mannion glanced around the military courtroom, seeing the pale, tense, anxious face of his wife Virginia, the stern countenance of Dubrow, his former commanding officer, the interested eyes of half a hundred onlookers.

"No," he said. His voice was thin and dry. "There's nothing I can say. Nothing at all."

He saw Virginia's pleading eyes. She was telling him silently, Please, Dan. Tell them you're innocent. At least put up a defense!

"Call the witness," Commander Harkness ordered.

"Base Commandant Lee Dubrow will please take the witness stand."

While Dubrow was being sworn in, Mannion studied him. His former commander on the Iapetus base was a tall, icy-faced man with close-cropped gray hair and a stiff military mustache. Mannion had never been particularly friendly with his commanding officer.

"Commander Dubrow, will you relate the events leading up to Lieutenant Mannion's actions in the Android Rebellion?"

Dubrow cleared his throat. "Very well. As you know, the Space Patrol established its base on Iapetus last year—no, two years ago, at the end of 2365—as part of its program of preparing Saturn's moons for colonization."

"How many members of the patrol were with you?"

"Fifteen, altogether. I was in command, naturally, and for most of the period we were there Lieutenant Mannion was my second-in-command."

"Isn't it fairly unusual for a Lieutenant to hold such a high position?" the prosecutor asked.

"Major Dunphy was killed by a rebellious android seven weeks after we arrived," Dubrow said. "Lieutenant Mannion was the next highest ranking officer in my squadron and he took over."

"How many androids did you have with you?"

"Over a hundred," said Dubrow. "It was quite a time we had when they mutinied."

"Had you any knowledge of the mutiny beforehand?"

"No."

"Did any member of your staff know about the mutiny before it took place?"

"Yes."

"Who?"

"Lieutenant Mannion. He was in conspiracy with VZ-1972, the ring-leader of the mutiny."

Mannion felt his face go bright red. He wanted to stand up and shout, "That's a lie! I never knew anything about the mutiny!"

But he couldn't. Somewhere in the back of his mind lay a shadow of doubt. He could not remember anything that had happened at the time of the mutiny—and perhaps he had—perhaps—

The judge said, "Tell us about Lieutenant Mannion's part in the mutiny."

"Yes, sir. The first we knew about it was on the morning of November 9, 2366, when the androids we used to keep the atmosphere-generators running refused to perform their regular tasks. I ordered Lieutenant Mannion to go outside and discover what the trouble was. He refused. I ordered him a second time, and he struck me and threw open the airlock. All of the androids rushed in."

"What happened then?"

"I found myself wrestling with Lieutenant Mannion while the androids destroyed all of the Project's equipment and apparatus. In the struggle all 12 of my men were killed by the androids. Finally I succeeded in subduing Lieutenant Mannion and bringing the androids back under control—"

"How was that done?"

"The androids respond automatically to a direct command from the superior officer, no matter what they're doing. Had I been free to give that command the mutiny would never have taken place. But Lieutenant Mannion prevented me from giving the command until it was too late. All of our men were dead and the Project set back more than a year. I placed Lieutenant Mannion under detention, put the androids in permafreeze, and returned to Earth. And here I am."

"Is that the extent of your testimony?"

"It is."

"You may step down, then. Lieutenant Mannion?"

Mannion rose and faced the judge. "Sir?"

"You've now heard your commander testify that you wilfully obstructed his attempt to end the android mutiny ... a mutiny which cost 12 human lives and did over $5,000,000 worth of damage to the Iapetus Project. Is there, again, anything you care to say in your own defense?"

Mannion shook his head. "No, sir."

"Very well, then. The court will adjourn for 15 minutes while data is programmed and fed to the computer, after which the verdict will be announced and the sentence read."

Mannion left the stand and felt his wife Virginia come up to him and hold him tightly.

"Dan, Dan, why don't you say something? Dubrow's testimony is damning if you don't speak up!"

Mannion frowned. "But I don't remember, Virginia! My mind is a blank for the entire period of the mutiny! For all I know I did do as the Commander says!"

"Impossible, Dan! You were always so loyal to the Patrol—"

"I still am," he said. "And if I committed this crime I deserve to be punished for it."

"Do you know what the punishment is?"

"Mnemonic erasure," Mannion said.

"No! Do you know what mnemonic erasure means? They'll strip away all your memories, everything but the basic pattern of your reflexes and reactions. Everything that is Dan Mannion will be erased, discarded, thrown away." Tears appeared in the corners of her eyes. "I'll be declared a widow, officially. And your body will be given a new name, a different identity. You'll be re-educated as someone else."

Mannion nodded bleakly. "I know. What can I do? Dubrow's my Commander; he has to be telling the truth. I don't remember anything. Perhaps I went temporarily out of my mind, did an insane thing, and now my consciousness has blanked out that period. It doesn't matter. I killed 12 men by my actions, Ginny."

"No! No!"

"I'm afraid so," Mannion said. "And I'll take my punishment for it now."

He turned away, not wanting to see his wife's tearstreaked face. A torrent of conflicting emotions raged within him despite the calm exterior he maintained. All his life he had dreamed of the Patrol and its glory; he had worked toward that one end. Four years at the Academy, two more in apprentice-work, then finally the commission and the assignment to Iapetus.

And what happened? A moment of insanity, perhaps—or downright conspiracy with an android to overthrow the Project by violence? He didn't know. He would never know. All he knew was he had done some mad act and now he would pay for it. His marriage, his career, even his identity itself, would be taken from him.

An orderly touched his arm. "The court's returning to order, Lieutenant Mannion. Please resume your place."

"Sure. Sure, I'm going." He kissed his wife tenderly and started up the row of steps to take his place in the prisoner's dock.

Commander Harkness was staring grimly at him. The verdict, when it came, would be no surprise; from the nature of Mannion's lack of defense, it would be a foregone certainty.

"Lieutenant Mannion, you're aware of the nature of the crime you're charged with?"

"Yes, sir."

"The only witness against you has been your former Commander, Lee Dubrow. You have not made any statements in your own defense."

"No, sir."

"In view of this situation, the court has no recourse but to find you guilty of insubordination in the highest degree, conspiracy, malicious attack upon an officer with intent to aid in mutiny."

Mannion bowed his head. "Yes, sir," he said in a half-audible tone.

"The punishment for these crimes in necessarily severe," the judge went on. "Naturally, we're unable to put into effect what would normally have been the penalty 300 years ago. The death penalty is obsolete. However, I hereby pronounce a sentence amounting to execution upon the personality, mind, and accumulated memories of the man formerly known as Daniel Mannion."

"You mean mnemonic erasure, sir?"

"Obviously. This sentence automatically carries with it loss of all privileges, pensions, and honors that go with your high rank in the Space Patrol. Your name will be wiped from its roster. After the erasure, you will never have existed, Lieutenant Mannion. Your body will be restrained under a new name and will make a fresh start in life. It will even be possible for your new personality to enter the Space Patrol, if it so chooses. No prejudice against your body will be entertained for your mind's previous acts."

In the background, Mannion heard his wife's faint sobbing. "I hear and accept the sentence, sir," he said quietly.

"The act of erasure will be carried out immediately, in the Space Patrol's mnemonic laboratories on the 14th level of this building." The gavel rapped three times. "The case of Earth versus Daniel Mannion is hereby considered closed."

"No!" Virginia suddenly shouted. All eyes in the courtroom swivelled to focus on her as she rose from the audience to protest. "No, don't close the case yet!"

"This is highly irregular," said Judge Harkness. "Do you have additional testimony, Mrs. Mannion?"

"Not—testimony, your honor. But can't you see that Dan's obviously insane? He's allowing himself to be sentenced without even a protest! Can't he enter a plea of insanity?"

"The plea of insanity would not alter the judgment in any way, Mrs. Mannion. Rest assured that your husband's—ah—disturbed mental state has been taken into account in the decision. Whether he was insane or criminally possessed at the time of the mutiny makes no difference; the crime has been committed, obviously, and the guilty person is of no further value to society. Mnemonic erasure is not merely a punishment, Mrs. Mannion. It's the gateway to rehabilitation for a sick person."

"I—see. May I say goodbye to my husband before you—erase him?"

Going down in the lift tube from the courtroom on the 60th floor of Patrol headquarters to the lab on Level Fourteen, Mannion felt strangely numb inside.

Two Patrol members stood behind him, ready to go for blasters if he made the slightest move toward escaping. But Mannion had no idea of escaping.

He was on his way to be erased.

He wondered what erasure was like. Did it hurt? Did you feel the pain as they stripped away layer after layer of your memory like peelings from an onion? First 2367 would go, but the new year was only two weeks old and he'd spent those two weeks in prison. Then 2366 would vanish—but 2366 was partly gone, at least for the few hours of the Mutiny. Next would go 2365, the year they first landed on Iapetus.

And so, ever backward, they would tear away more and more of the accumulation of memories and experiences that was Dan Mannion. 2364, 2363.

2362. That was the year he met Virginia. They would take away his courtship, his wedding, those wonderful early days of marriage—

The two years as a Patrol Apprentice would go. The four years at the Academy.

Adolescence. Boyhood. Childhood.

Soon there would be nothing left of Dan Mannion but a few vague memories of babyhood, and then even those would be gone. He would emerge from the lab wiped blank, a fresh unmarked slate ready to be given its new identity.

Suddenly, he found himself quivering.

I'm not guilty! I didn't do it! I couldn't have done it!

Too late, a voice said. He saw again the faces of Virginia, of Commander Harkness, of stern-faced Dubrow giving the testimony that damned him.

Too late. Too late to defend yourself.

"Fourteen," the robobrain of the elevator announced. The door slid back. Mannion felt light pressure behind each of his arms as his two guards shoved him gently forward.

A frosted glass door loomed up ahead of him. The sign on the door read Mnemonics Laboratory.

Cold sweat drenched his body. Now that he was but feet away from the room where the erasure would take place, he wanted out desperately, wanted some chance to prove that he hadn't conspired with the androids, hadn't aided in the revolt, hadn't helped to murder 12 fellow Patrolmen and wreck the Iapetus project.

"You go in here," someone said to him.

The door marked Mnemonics Laboratory was swinging open to receive him.

There was no way out.

Four gray-smocked technicians waited inside for him. One of the guards with him said, "This is Mannion. He was just sentenced upstairs."

"I know. The order came down the pneumotubes a minute ago. Total erasure."

"That's right," the guard said. "He gets wiped clean."

"Will you lead him to the machines, please?"

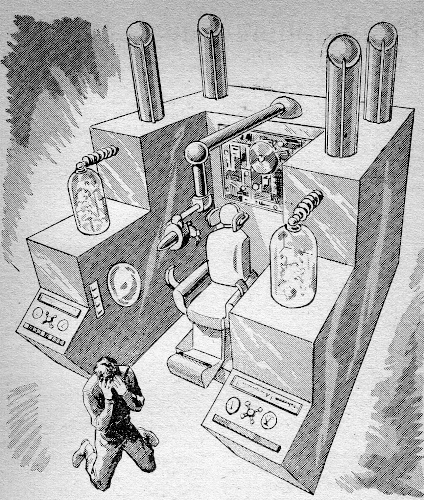

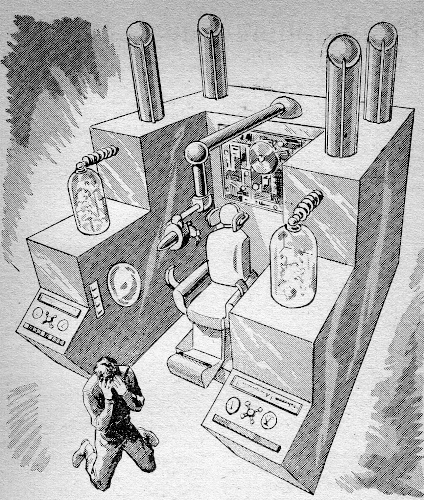

Dan went forward and faced a complex angle of probes and dials, "Is this the machine that does it?" he asked uneasily.

"That's right. It'll be over in a minute, Lieutenant Mannion. We clamp the electrodes to your scalp and run preliminary tests with an electoencephalograph—and then we use the Eraser."

"Will it be painful?"

"It'll be quick. There won't be anything more than a faint tickling sensation, and then—"

"Then Dan Mannion ceases to exist." He stared appealingly at the technician in charge and said, "Listen—does the sentence have to be carried out at once?"

"The order says immediately. We have the machine all ready for you."

Dan felt perspiration trickling down his body. "Can you wait a few minutes? There's something I'd like you to do for me?"

"What's that?"

"Probe my mind. I'm suffering from amnesia—a short-range blockage of the critical era around the time the android mutiny took place. Couldn't you—?"

"Impossible. Not without a court order, at any rate. And the trial's over."

Dan scowled. "But my life depends on it! My identity is going to be taken away. The least you could have done was look!"

"Come on, Mannion," one of the guards growled. "The time to make your pitch is during the trial, not after the sentence has been pronounced." Dan felt himself shoved forward.

The machine loomed up before him—gigantic, monstrous, a mindless instrument of horror. Within minutes he was going to undergo mnemonic erasure, to have his mind blanked, his identity removed—

For a crime I didn't commit!

Suddenly he felt sure of his innocence. Despite the evidence, despite the testimony, he knew in his heart that he was innocent.

It was a frameup of some sort. It had to be.

He allowed himself to be led up to the machine. But abruptly, as they were unhinging some apparatus to strap to his head, he spun away from the guards who held him lightly, dove, grabbed at a blaster that protruded from a black leather holster—

"Okay," he said. "Get against that wall, all of you. One move I don't like and I'll destroy the whole lab."

His fingers were shaking with inner tension. All his life he had been raised to obey authority, to accept the commands of his superior officers—

And now he was rebelling. He was threatening the destruction of one of Earth's most expensive pieces of equipment.

The threat worked. The four technicians and the two guards backed against the wall.

"What do you want?" the head technician asked.

"I told you before. I want you to probe my mind, to look into that period that's a blank for me. If you find that I'm guilty, I'll—I'll submit to the erasure. If not, I'll demand a new trial. But I won't allow myself to be wiped out without at least a look!"

"All right. We'll probe you," said the technician. "You'll have to be under anesthetic, of course."

"How can I trust you? How do I know you won't put me through mnemonic erasure the moment I submit to being anesthetized?"

The technician had no answer. "I'll tell you," Mannion said. "You're all doctors, aren't you? All four?"

They nodded.

"All right, then. I'll rely on your oaths as medical men not to put me through erasure until you've probed that mutiny fully. Well?"

"Okay, Mannion. We'll take a look. But if it's not as you say—"

"I'll take my chances," Mannion said. He felt cold and uncertain inside. He didn't know what they'd find. He didn't even know whether they'd keep their word and probe him before the erasure.

He put the gun down on a lab table. "Here," he said. "Here's my gun. Now let's see how good your oath is."

The only trouble with that was he might never see how good it was.

"Just relax," the technician said. "The probe is entering your mind, now. Just relax...."

Mannion sank downward into the soft, warm darkness that enfolded him. He was moving back into his own past now, gently guided along by the mind-probe—

WHAM!

It was like walking full-tilt into a mountainside. Some obstruction in his mind, no doubt.

But the probe bored its way through, drilled through the hard barrier of amnesia in his mind.

And suddenly he was back on Iapetus, in Project Headquarters.

He was saying, "Commander Dubrow, the androids running the atmosphere-generators are lying down on the job. They don't seem to be working."

Dubrow glared at him coldly. "Stick to your own job, Lieutenant Mannion. Coleridge is supervising the androids out there."

"No, he isn't! Coleridge isn't there."

"He must be there, Lieutenant."

"Commander, I'm going out there to see what's wrong. Those androids have been acting up strangely all day and I don't like it."

"I order you to stay here!" Dubrow snapped.

"But—"

Hesitantly Mannion took a few steps toward the airlock. The androids outside were sauntering casually around like unemployed thieves. It wasn't a natural way for androids to behave.

"Sir, I request special permission to go out there and investig—sir!"

Dubrow was throwing open the airlock—and the androids came rushing in!

He's crazy, Lieutenant Mannion thought. I've got to take charge—keep those androids from wrecking the Project—

"Get away from there, sir! Close the lock!"

"Don't give me orders, Mannion!"

Dan shook his head and started to run toward his superior officer. But suddenly Dubrow charged him.

The abrupt assault bowled him over. Dan ducked and tried to land a punch but Dubrow had his blaster out. A blow crashed into Mannion's forehead. He tried to clear away the cobwebs but Dubrow hit him again and all went dim.

He had a vague memory of Dubrow's directing the androids in a methodical destruction of the Project. Then it was all over and the androids were back where they belonged. Dubrow was holding a hypnomech in front of his eyes, spinning around and around, a dizzying sleep-inducing confusing blare of many colors, around and around, around and around....

And then he was asleep.

"We owe you a great apology, Lieutenant Mannion," the technician was saying. "If you hadn't forced us to probe your mind we would have sent an innocent man to mnemonic erasure. But now we have the record of what actually happened—"

"Hang on to it," Mannion said. "I've got to get upstairs and find Dubrow before he gets out of here."

Without waiting for a word of protest, Dan threw off the mind-probe apparatus, jumped off the table, and raced out into the hall.

He caught the lift tube going up. In all likelihood Dubrow, Virginia, and the judge would still be in the courtroom, working out some settlement of the former Lieutenant Mannion's private property.

He was right.

"Mannion! What are you doing—"

Dan ignored the judge's outcry. "Hello, Dubrow. I just had some of my amnesia removed. That was a pretty clever story you told, wasn't it?"

"I don't know what you're talking about, Mannion."

"The hell you don't! You don't know anything about the hypnomech you used to block my mind and—"

Dan ducked suddenly as a spurt of energy from the proton-gun in Dubrow's hand seared through the wall behind him. Dubrow was aiming the gun, readying to fire again—

And Judge Harkness rose from the bench and hurled a heavy law-book at him.

It struck Dubrow squarely on the side of the head; the bolt of proton-force squirted toward the ceiling and Dan leaped forward.

He crashed into Dubrow and knocked the tall officer sprawling; the proton-gun clattered to the floor. Dubrow squirmed and kicked but Dan's fists thundered against his body.

"Hypnotize me, will you? And try to frame me for that mutiny? I'll—"

"All right, Mannion," a calm voice said from somewhere above him. "You can get off him now. He's out cold."

Judge Harkness faced Dan and Virginia Mannion. "I don't understand why you didn't speak up, son."

"I—I assumed I was wrong, sir. I've always been trained to respect the word of an officer. If Commander Dubrow said I was guilty and I didn't remember—well, sir, he had to be right!"

Harkness chuckled. "You know differently now. We've had a mind-probe run on Dubrow. It seems he was bribed by a group of private contractors to wreck the Patrol's project on Iapetus so they could get the job instead. He figured he'd have you tried for the crime, leaving him in the clear. So all he did was switch the action around and then hypnotize you into forgetting it."

"What's going to happen to him now?" Mannion asked.

"What else? He's being erased now. Commander Dubrow no longer exists."

Mannion shuddered. He remembered vividly that complex pile of machinery on the 14th Level.

"I guess I'm free, then," he said.

Harkness nodded. "I guess you are, young man. And next time don't be so ready to believe your own guilt."

"No, sir! I mean—yes, sir! I mean—"

It didn't matter. Mannion smiled at Harkness and took his wife in his arms. The case was closed and he was a free man and an officer in the Space Patrol.

And he was still Dan Mannion.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.