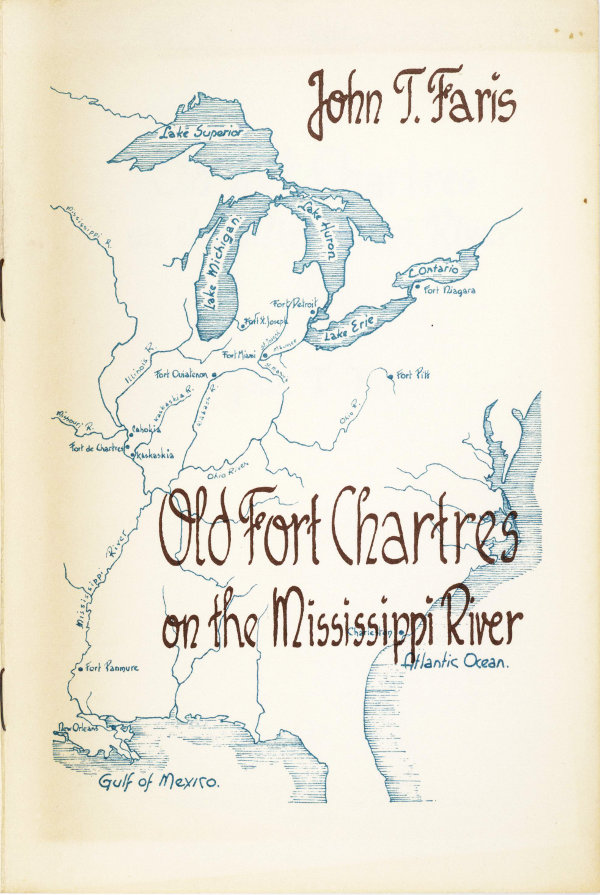

John T. Faris

Prepared by the Staff of the

Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County

1955

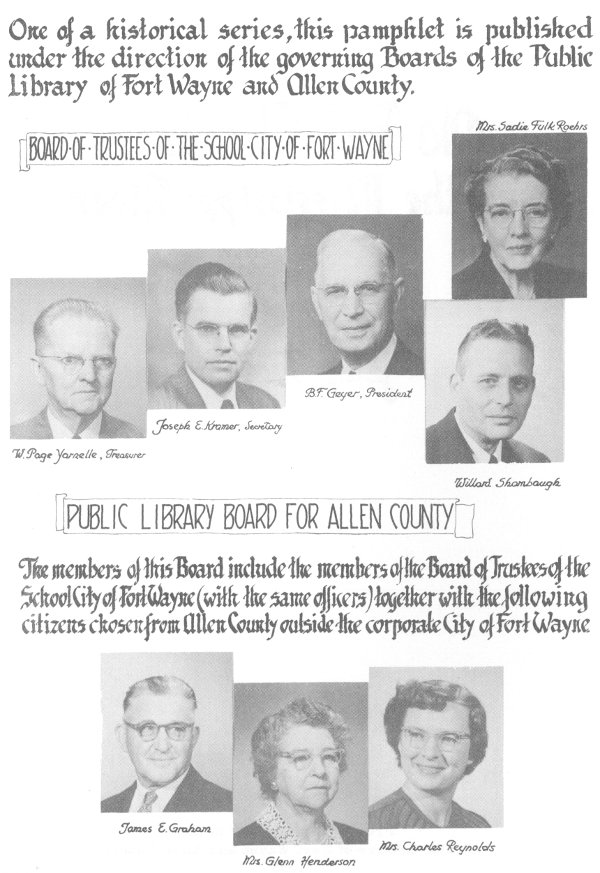

One of a historical series, this pamphlet is published under the direction of the governing Boards of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE SCHOOL CITY OF FORT WAYNE

PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD FOR ALLEN COUNTY

The members of this Board include the members of the Board of Trustees of the School City of Fort Wayne (with the same officers) together with the following citizens chosen from Allen County outside the corporate City of Fort Wayne:

The following publication, which narrates the fortunes of Fort Chartres in Illinois, originally appeared as chapter XII in THE ROMANCE OF FORGOTTEN TOWNS by John T. Faris. The publishers, Harper & Brothers, have graciously granted permission to reprint the chapter.

The Boards and the Staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County present this account with the feeling that it is an important part of our heritage and with the hope that it will be interesting and informative to Library patrons.

More than two centuries ago there was an astonishing bit of feudal France on the banks of the Mississippi River. It was called Fort Chartres by those who chose the location near the southern extremity of the fertile American Bottom, which extends from a point nearly opposite the mouth of the Mississippi River nearly to Chester.

On the Bottom there were a number of French villages noted both for the military prowess of the residents and for the sleepy, Old World life of these residents among the Indians, with whom they were on friendly terms.

The present Fort Chartres was occupied in 1720 by Philippe François de Renault, the French director-general of mining operations, who brought with him up the river for the purpose two hundred white men and five hundred Santo Domingo negroes, thus introducing slavery in what became Illinois. The purpose of the fort was to protect against the Spaniards the servants of John Law’s famous Company of the Indies, whose startling scheme for curing the financial ills of France was later known as the Mississippi Bubble. Law’s plan was to set up a bank to manage the royal revenue and to issue notes backed by landed security. In selling shares in his Company of the Indies, which was to accomplish financial wonders, “large engravings were distributed in France, representing the arrival iv of the French at the Mississippi river, and savages with their squaws rushing to meet the new arrivals with evident respect and admiration.”

Promises of great dividends from mountains of gold and silver, lead, copper, and quicksilver were made. Shares rose rapidly and soon were selling for 20,000 francs. For three months the French people believed in Law. Then the Mississippi Bubble burst and there was sorrow in the homeland.

In the meantime the work at Fort Chartres was continued. Within the stockade of wood, which had earth between the palisades for purposes of strength, were received many wandering savages who brought their furs for barter. The French residents felt secure in the presence of their protection.

Various expeditions were sent out against the Indians. One of these went out against the Chickasaw Indians, on the Arkansas River. Disaster overtook the company of French soldiers, and fifteen were captured and put to death with savage barbarity.

In 1753 the fort was in such bad condition that it was decided to build anew, this time of stone, brought from the bluff. When completed, the new structure was one of the strongest forts ever built in America.

An English traveler who visited the new fort in 1765, when the British were in control, told of finding walls two feet two inches thick, pierced with loopholes at regular distances, and with two portholes for cannon in the faces, and two in the flanks of each bastion. There was a ditch, but this had not been completed. The entrance was a handsome rustic gate. Within the fort he found the houses of the commander and of the commissary, the v magazine for stores, and the quarters of the soldiers. There were also a powder magazine, a bunk house, and a prison.

The visitor told how the bank of the Mississippi was continually falling in, and so was threatening the fort. In the effort to control the destructive current a sand bank had been built to turn it from its course; the sand bank had become an island, covered by willows. Yet it was realized that the destruction of the fort was sure.

“When the fort was begun, in the year 1756,” he wrote, “it was a good half mile from the water side; in the year 1766 it was but eighty paces; eight years ago the river was fordable to the island; the channel is now forty feet deep.”

In the year 1764 there were about forty families in the village near the fort and a parish church served by a Franciscan friar. In the following year, when the English took possession of the country, they abandoned their houses, except three or four poor families, and settled at the village on the west side of the Mississippi, choosing to continue under the French government.

An English visitor who saw Fort Chartres in 1766, when it was still in its prime, wrote of his impressions:

“The headquarters of the English commanding officer is now here, who in fact is the arbitrary governor of the country. The fort is an irregular quadrangle; the side of the exterior polygon is 490 feet. It is built of stone plastered, and is only designed as a defense against the Indians, the wall being two feet two inches thick, and pierced with loopholes at regular distances, and with two portholes for cannon in the face and two in the flank of each bastion.

“It is generally agreed that this is the most commodious and best built fort in America.”

In 1772 a flood washed away part of the fort, on which a million dollars had been spent—a large amount for that day. The garrison fled north to Kaskaskia, where another fortress was built.

More than sixty years later the Illinois Gazetteer said:

“The prodigious military work is now a heap of ruins. Many of the stones have been removed by the people of Kaskaskia. On the whole fort is a considerable growth of trees.”

But the Mississippi relented in its approach to Fort Chartres. A bit of the old fort still stands—the powder magazine and bits of the old wall.

Fortunately, in 1778, Congress withdrew from entry or sale a tract of land a mile square, including the site of the fort. Thus the way was opened for the acquirement of the property by Illinois, which has made of it a state park. The fort is to be rebuilt in accordance with the original plans, which have been discovered in France.