{161}

Vol. VIII.—No. 363.

Price One Penny.

DECEMBER 11, 1886.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

GREEK AND ROMAN ART AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

MERLE’S CRUSADE.

CHRISTMAS IN A FRENCH BOARDING-SCHOOL.

LACE-MAKING IN THE ERZGEBIRGE.

“NO.”

THE SHEPHERD’S FAIRY.

VARIETIES.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

By E. F. BRIDELL-FOX.

THE BIRTH OF ATHÉNÉ.

(From a Vase in the British Museum.)

All rights reserved.]

{162}

THE ELGIN MARBLES.

“Abode of gods whose shrines no longer burn.”

I have now to complete my account of the sculptures of the Parthenon, that wonderfully beautiful temple to Athéné (or Minerva), at Athens, which has never ceased to be the centre of attraction for all visitors to Greece from the time it was first built—namely, about 435 years B.C.—even till the present moment, when it stands a shattered wreck on its rocky height.

My first article dealt chiefly with the long, sculptured frieze that ran continuously the whole length of the walls of the building (protected by the outer colonnade), and the ceremonials which that frieze represented. The present article will be devoted chiefly to the fragments of the external frieze, and to the figures of the eastern and western pediments, which represented the chief legends connected with the goddess.

I will, before proceeding, here pause a moment to account for the shattered condition in which those fragments now are.

In 630 A.D. the Parthenon was consecrated for use as a Christian church. Like the famous church at Constantinople, it was dedicated to Santa Sophia, the Divine Wisdom. The older temple, that stood near the Parthenon, called the Erecthium, which had been far more venerated by the early Athenians than the Parthenon itself, was about the same time also consecrated. This latter was dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

Long before this date, Christianity had happily become the religion of the Roman Empire by law established—that is to say, of the whole civilised world. It is evident that in adapting the Pagan temple for Christian worship it was impossible to allow the fables of Paganism to remain depicted over the chief entrance, however splendid as works of art. Accordingly, we find that the entire centre group in the pediment facing the east was completely done away with, a plain surface of blank wall filling the space whereon, in all probability, the inscription of the Christian dedication was placed. The subordinate figures at the two extremities were left, as, without the central group to explain their object, they could have had no intelligible meaning.

Our business for the moment is to show what means exist for restoring the lost central group, which was the key of the subject. The evidence is two-fold. There is, first, the Homeric hymn which gives the legend of the birth of Athéné; and, secondly, there is the description given of the Parthenon by the ancient author, Pausanias.

Pausanias was a Greek gentleman, native of Lydia, in Asia Minor, a geographer and traveller, who visited noted sites in Greece with the express purpose of seeing and describing all that was most beautiful and interesting in Greek art. He lived about one hundred and fifty years after the Christian era. His travels or “Itinerary” has come down to us, and a most curious and interesting work it is. He saw and described the Parthenon with much enthusiasm, with all its beautiful statues and works of art, as “still perfect,” though they were, even in his day, already considered as ancient art. He refers to the Homeric hymn as suggesting the subject of the group on the eastern pediment over the principal entrance to the temple.

This Homeric hymn to Athéné gives the account of her fabled birth, full grown and fully armed, from the head of her father, Zeus (or Jupiter). It describes her, first as the goddess of war, and afterwards, when she has thrown off her arms, as the goddess of the peaceful arts. I give the hymn in full.

Homeric Hymn to Athéné.

Such is the famous hymn. And from Pausanias we learn that it afforded to the sculptor, Pheidias, the subject for his chief group on the eastern pediment. But, exactly how he treated it we have no precise or definite knowledge.

The Eastern Pediment.—“Doubtless, in this composition, Jupiter (Zeus) occupied the centre, and was represented in all his majesty, wielding the thunderbolt in one hand, holding his sceptre in the other; seated on his throne, and as if in the centre of the universe, between day and night, the beginning and the end, as denoted by the rising and the setting sun.

“It is probable that the figures on his right hand represented those deities who were connected with the progress of facts and rising life—the deities who preside over birth, over the produce of the earth, over love—the rising sun; whilst those on the left of Zeus related to the consummation or decline of things—the god of war, the goddess of the family hearth, the Fates, and lastly the setting sun, or night. Whilst the divine Athéné rose from behind the central figure in all the effulgence of the most brilliant armour, the golden crest of her helmet filling the apex of the pediment.”

I quote this glowing description from Sir Richard Westmacott’s “Lectures on Sculpture.”

This, however, is all conjecture, for the space is a mere blank. As some little aid to the imagination to help to fill the blank, I give a sketch of the same subject, viz., the birth of Athéné, copied from a painting on a vase now in the British Museum. The artist may have probably seen the Parthenon, and may have taken a free version of the subject, from memory, to decorate his vase. We find the same subject repeated, with variations, on other vases. Zeus (Jupiter) occupies the centre, a small Athéné springs forth from his head, Hephaestos (Vulcan) stands by with his axe (with which he has split open the thunderer’s head to let forth the infant deity), Poseidon (Neptune), with his trident, behind him; and Artemis (Diana), with her bow, and a nymph, on the other side, look on. The figures on the vases are so extremely stiff and formal as compared to the grand, life-like statues of the pediments, that I hesitate to give my illustration. But it shows the probable arrangement of the group. The figures on the vase are red on a black ground, treated perfectly flat, without the slightest modelling.

To return to the pediment of the Parthenon itself, the space immediately surrounding the blank, on each hand, is filled with different gods, who appear to look with wonder and admiration towards the central group. At the extreme end on the left the rising sun, Phœbus-Apollo, drives the car of day out of the ocean; while Seléné, goddess of night, plunges downward with her team of steeds, into the waves, at the end on the right.

Of the figures referred to, we may identify the following fragments:—First, we note a fragment of the sun-god, his powerful throat and extended arms emerging from the waves, as he shakes the reins to urge on his prancing steeds; before him, a splendid head of one of the horses of his car, the head flung back, as if he tossed his mane in eager movement to rush up into the daylight. Next comes a recumbent figure, of heroic manly proportions, the most perfect of the Elgin collection. A lion’s skin on which he reposes, leaves little doubt but that it was intended to represent the youthful Hercules, the god of strength. It is popularly, but erroneously, known as Theseus. Then come two grand, matronly, seated personages. The attitude and beauty of proportion in these two stately figures is considered no less admirable than the subtle arrangement of their flowing draperies. They probably represent Demeter and her daughter, Persephone (the Ceres and Proserpine of the Roman mythology). The younger one leans her arm lovingly on the shoulder of her mother. The mother, Demeter, raises her arm, as if in astonishment at the news communicated by the next figure, who comes rushing towards them, her drapery flying far out behind her, from the rapidity of her movements. This is doubtless Iris, the messenger of the gods, sent to announce the wonderful events transacting in the central group. Three fine dignified female figures, on the further side of the pediment, equally distant from the centre, appear to have balanced this last group of Iris, Ceres, and Proserpine. These were the three Fates, who spun the thread of human life, named by the Greeks, Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropus. Two are seated, a little apart; the third reclines, half leaning on the lap of the second. These three figures are equally well preserved, and equally noble and beautiful with the group to which they correspond on the further side.

The subject of this eastern pediment is evidently supposed to have taken place on Mount Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece, the fabled home of the gods, and the figures were intended to represent a conclave of the gods.

The Western Pediment.—The subject of the west end, on the contrary, may be supposed to have taken place in Athens itself, on the Acropolis. The subject here was the contest between Athéné and Poseidon (or Neptune) for supremacy in Athens. Here we find local personages, such as the river deities (the rivers personified), and the legendary kings and heroes of Athens. These statues, with the exception of Athéné and Poseidon, are a size smaller than those on the eastern pediment, being not at all more than life size. The object for which this assembly has met is to see which of the two deities could present the best gift to the Athenians. Poseidon struck the earth; the horse appeared, so the story runs. Athéné did the same; the olive tree grew before them. Both were most useful gifts; but the olive tree, on account of its fruit and the oil which it yields, was considered to have the higher claim.

Athéné was proclaimed the victor. The gods bestowed the city upon the goddess, after whom it was named Athens; and Poseidon was so enraged, continues the legend, that he let loose the waters of the angry sea{163} (which, as monarch of the waves, of course obeyed his behests), and straightway it overflowed its banks and deluged the plain round Athens.

Such is the story, and in the times of Pausanias were shown the three great dents on the rock, the marks of the trident of Poseidon, where he had struck the earth, as well as a small pool of salt water. The Greek traveller mentions having seen these things.

Strangely enough, these two same old-world curiosities were re-discovered not many years ago when excavations were being made on the Acropolis, in the very centre of the older temple, near to the Parthenon, where Athéné and Poseidon were once jointly worshipped. Athéné and Poseidon were the two central figures in the midst of their assembled votaries, the legendary kings and heroes of Athens, and the local nymphs and river gods.

This group is terminated at each end by recumbent figures, supposed to represent the two streams that water the plain round Athens—the Illissus and the Cephissus. The figure of Illissus is scarcely second to the so-called Theseus for beauty of manly proportions; it is perhaps more graceful and less vigorous. “Half reclined, he seems, by a sudden movement, to raise himself with impetuosity, being overcome with joy at the agreeable news of the victory of Athéné. The momentary attitude which this movement occasions is one of the boldest and most difficult to be expressed that can possibly be imagined. The undulating flow given to every part of the drapery which accompanies the figure is happily suggestive of flowing water.” Next to the Illissus is a broken fragment of the nymph Callirrhoë, who represents the only spring of fresh water in Athens; while next to the Cephissus, on the other side, sits King Cecrops, the mythical first king of Attica, with his wife, Agranlos (her name means a “dweller in the fields”), and his daughter Pandrosus (whose name means “the dew”).

Of the two heroic figures in the centre, Athéné and Poseidon, whose contest is the subject of this western pediment, the only fragment now existing is the muscular, finely-developed back and chest of the sea-god; and of Athéné, the upper half of the face (the sockets of the eyes intentionally hollow, that they might be filled in with precious stones), also one of her feet, and the stem of the famous olive tree.

A careful model of the Parthenon in its present condition is placed in the Elgin Room, and by reference to that we can identify the fragments on the pediments, and can also see the position of the various sculptures. The sculptured figures on it are copied from drawings made from the Parthenon itself at Athens in 1674, by a French artist, Jacques Carey by name, before Lord Elgin had removed those which we now possess, and when many of the figures were far less damaged than they now are. The Parthenon had been used as a powder magazine by the Turks when they conquered the city in 1687. It was during the siege that a bomb from the enemy fell into the edifice, igniting the stored gunpowder, and the whole centre part of the ancient temple, with a part of its lovely frieze, was blown into the air. Again, a similar misfortune occurred in the Greek struggle for independence and freedom in 1827. Yet, in spite of the terrible gap, enough of the building is still left for us to admire the wonderful beauty of proportion, and simple, yet grand, lines of the outline; and more than enough to recognise the general plan and places of most of the sculptures that adorned its walls.

The Metopes.—These are panels in alto, or high-relief, in the frieze which ran above the colonnade of the Parthenon. They pourtray the struggle between the youth of Athens and the centaurs—monstrous creatures, half horse, half man. This struggle is supposed to have been intended to typify the contest between intelligence and moral order on the one hand, against the power of lawlessness and brute force, as represented by the monsters, on the other—a contest, the result of which was in that day acutely realised.

There were originally ninety-two of these Metopes, fourteen on each end, and thirty-two along each side wall. We possess seventeen out of the ninety-two. So many having been destroyed, it is impossible to judge with any greater certainty of the subject.

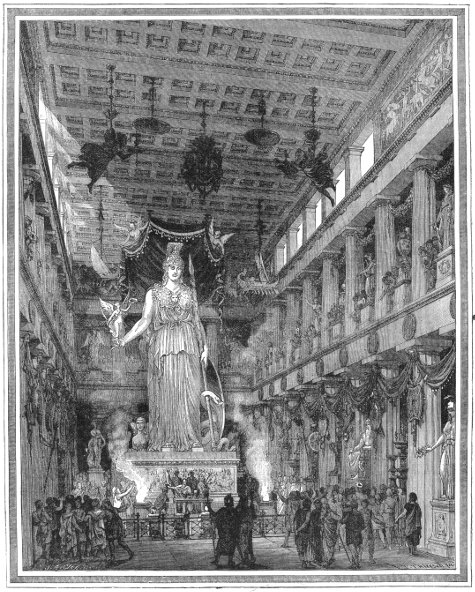

The Statue.—My account would be incomplete did I not add a few words descriptive of the beautiful statue of Athéné that originally stood within the temple, facing the east. For, although all trace of the statue itself has long vanished, we know its form by copies in marble in several of the museums and galleries in Europe. The one at Naples is considered the best. We have also, in the Elgin Room, two small rough copies of it.

The grand original, which Pausanias saw and describes as “perfect,” “a thing to wonder at,” was of gold and ivory. Its robes were of gold, its flesh was of delicately cream-coloured ivory, its eyes flashed with precious stones.

“Lovely, serene, and grand,” its gigantic form filled the centre of the temple, and the golden griffins on its helmet reared themselves against the very roof.

This statue, with that of the Olympian Jove, was undoubtedly the exclusive work of the master, Pheidias, who, though he may have allowed his pupils to assist him in some of the labours of the other figures of the Parthenon, assuredly hoped that his fame would be secured by these works. Their fame now, alas! rests solely upon copies and description. I give a sketch of the best of the two small rough copies in the Elgin Room. Like the grand original, she holds the figure of Victory in her extended right hand, and grasps the spear in the left, while her shield, together with the snake (type of the native soil of Athens) lie at her feet.

The art of presenting figures in gold and ivory, for which Pheidias is peculiarly famous, is a lost art. A special name was given to these statues. They were called Chrys-elephantine.[2] The combined richness of the gold with the soft hue of the ivory must have produced a wonderfully fine and mysterious effect when seen in the recesses of a dimly-illumined temple. The golden robes of the goddess were considered as part of the State treasury, and were between the times of the great festivals unfixed from the statue, and stored in the treasure house at the back part of the temple. They were from time to time carefully weighed, and were looked upon in the light of national wealth, which might, in time of need, be drawn upon for the country’s requirement. The gold of the robes was said to have been worth as much as £100,000. It is supposed that this part of the goddess was melted down, and finally reduced to Byzantine coin about the time of the Roman Emperor Julian—viz., about A.D. 360.

As Athens sunk from her high position among the Greek States, her processions and ceremonies fell into decay; but while she flourished, none were more brilliant.

Other festivals there were in Greece besides the one at Athens in honour of Athéné, where similar athletic games and feats of skill were performed before the altars of other tutelary gods. There were the far-famed Olympic games in honour of Zeus (Jupiter), in which all the Greek States competed. The Odes of Pindar have immortalised the Olympic chariot races. There were also the Delphic games in honour of Apollo, the sun god, the god of poetry. The practice of these games lasted in Greece, and were in use in Rome, till long after Christian times. How popular they were in those times we may infer from the many references to them in the Epistles and Acts of the Apostles.

Professor Jebb observes, in one of the admirable series of Shilling Primers now publishing, the one on “Greek Literature:” “The Greeks were not the first people who found out how to till the earth well, or to fashion metals, or to build splendid houses and temples. But they were the first people who tried to make reason the guide of their social life. Greek literature has an interest such as belongs to no other literature. It shows us how men first set about systematic thinking.” And, he proceeds, “neither the history of Christian doctrine, nor the outer history of the Christian Church, can be fully understood without reference to the character and work of the Greek mind. Under the influence of Christianity, two principal elements have entered into the spiritual life of the modern world. One of these has been Hebrew; the other has been Greek.”

Of all the many beautiful things which the Greeks produced, the Greek language itself is considered to have been the first and most wonderful; and “no one,” continues the professor, “who is a stranger to Greek literature, has seen how perfect an instrument it is possible for human speech to be.”

We may remember that the whole of the New Testament was given to the world in this beautiful and expressive language; that St. Paul was well versed in Greek philosophy, and that many of his Epistles were to Greek cities, and many of his first disciples among the Gentiles were Greeks.

We can also be sure that he must often have been present at Greek games such as we have been describing. The frequent references and metaphors referring to them prove this. In the first Epistle to the Corinthians the references to the foot-races run in the Isthmean games, celebrated at Corinth, occur again and again. “Know ye not that they which run in a race run all, but one receiveth the prize? So run that ye may obtain” (ch. ix. 24); and in the following verse, “They strive for a corruptible” (or perishable) “crown, but we an incorruptible”—referring to the fragile crowns or garlands of fresh leaves awarded to the victors in the games we have been describing.

And again, in the Epistle to the Philippians, iii. 14, “I press towards the mark” (or goal) “for the prize.” In the first Epistle to Timothy, vi. 12, “Fight the good fight before many witnesses.”

The first preaching to the Gentiles was to Greek-speaking peoples, either noted Greek cities, as Athens itself and Corinth, or Greek colonies in Asia Minor. We find (Acts xii.) how St. Paul actually visited this same beautiful City of Athens, whose early legends, like quaint fairy stories, we have been describing; how he stood on the Areopagus (the Hill of Mars) facing the Parthenon, and must have seen all its lovely statues and grand monuments still perfect; and how he “thought it good to be left at Athens alone,” when he there preached to her wise men and philosophers, and found followers and disciples from among them, whose hearts were opened to a higher wisdom than any that the worshippers of the famed Athenian goddess knew.

{164}

THE INTERIOR OF THE PARTHENON.

(The Giving of the Prizes. Conjectural Arrangement.)

{165}

By ROSA NOUCHETTE CAREY, Author of “Aunt Diana,” “For Lilias,” etc.

“I TRUST THEM TO YOU, MERLE.”

ith the early summer came a new anxiety; Joyce was growing very fast, and, like other children of her age, looked thin and delicate. She lost her appetite, grew captious and irritable, had crying fits if she were contradicted, and tired of all her playthings. It was hard work to amuse her; and as Reggie was rather fretful with the heat, I found my charge decidedly onerous, especially as it was the height of the season, and Mrs. Morton’s daily visits to the nursery barely lasted ten minutes.

Dr. Myrtle was called in and recommended change for both the children. There was a want of tone about Joyce: she was growing too fast, and there was slight irritability of the brain, a not uncommon thing, he remarked, with nervous, delicately organised children.

He recommended sea air and bathing. She must be out on the shore all day, and run wild. Fresh air, new milk, and country diet would be her best medicine; and, as Dr. Myrtle was an oracle in our household, Mr. Morton at once decided that his advice must be followed.

There was a long, anxious deliberation between the parents, and the next morning I was summoned to Mrs. Morton’s dressing-room. I found her lying on the couch; the blinds were lowered, and the smelling salts were in her hand. She said at once that she had had a restless night, and had one of her bad headaches. I thought she looked wretchedly ill, and, for the first time, the fear crossed me that her life was killing her by inches. Hers was not a robust constitution, and, like Joyce, she was most delicately organised. Late hours and excitement are fatal to these nervous constitutions, if only I dared hint at this to Dr. Myrtle, but I felt, in my position, it would be an act of presumption. She would not let me speak of herself; at my first word of sympathy she stopped me.

“Never mind about me, I am used to these headaches; sit down a moment; I want to speak to you about the children. Dr. Myrtle has made us very anxious about Joyce; he says she must have change at once.”

“He said the same to me, Mrs. Morton.”

“My husband and I have talked the matter over; if I could only go with you and the children—but no, it is impossible. How could I leave just now, when our ball is coming off on the eighteenth, and we have two dinners as well? Besides, I could not leave my husband; he is far from well. This late session tries him dreadfully. I have never left him yet, not even for a day.”

“And yet you require the change as much as the children.” I could not help saying this, but she took no notice of my remark.

“We have decided to send them to my father’s. Do you know Netherton, Merle? It is a pretty village about a mile from Orton-on-Sea. Netherton is by the sea, and the air is nearly as fine as Orton. Marshlands, that is my father’s place, is about half a mile from the shore.”

I heard this with some trepidation. In my secret heart I had hoped that we should have taken lodgings at some watering-place, and I thought, with Hannah’s help, I should have got on nicely; but to go amongst strangers! I was perfectly unaware of Mr. Morton’s horror of lodgings, and it would have seemed absurd to him to take a house just for me and the children.

“I have written to my sister, Merle,” she continued, “to make all arrangements. My father never interferes in domestic matters. I have told her that I hold you responsible for my children, and that you will have the sole charge of them. I laid a stress on this, because I know my sister’s ideas of management differ entirely from mine. I can trust you as I trust myself, Merle, and it is my wish to secure you from interference of any kind.” It was nice to hear this, but her speech made me a little nervous; she evidently dreaded interference for me.

“Is your sister younger than yourself?” I faltered.

“I have two sisters,” she returned, quickly; “Gay is much younger; she was not grown up when I married; my eldest sister, Mrs. Markham, was then in India. Two years ago she came back a widow, with her only remaining child, and at my father’s request remained with him to manage his household. Domestic matters were not either in his or Gay’s line, and Mrs. Markham is one who loves to rule.”

I confess this slight sketch of Mrs. Markham did not impress me in her favour. I conceived the idea of a masculine, bustling woman, very different to my beloved mistress. I could not well express these sentiments, but I think Mrs. Morton must have read them in my face.

“I am going to be very frank with you, Merle,” she said, after a moment’s thought, “and I do not think I shall repent my confidence. I know my sister Adelaide’s faults. She has had many troubles with which to contend in her married life, and they have made her a little hard. She lost two dear little girls in India, and, as Rolf is her only child, she spoils him dreadfully; in fact, young as he is, he has completely mastered her. He is a very delicate, wilful child, and needs firm management; in spite of his faults he is a dear little fellow, and I am very sorry for Rolf.”

“Will he be with us in the nursery?” I asked, anxiously.

“No, indeed: Rolf is always with his mother in the drawing-room, to the no small discomfort of his mother’s visitors. Sometimes he is with her maid Judson, but that is only when even Mrs. Markham finds him unbearable. A spoilt child is greatly to be pitied, Merle; he has his own way nine times out of ten, and on the tenth he meets with undesirable severity. Adelaide either will not punish him at all, or punishes him too severely. Children suffer as much from their parent’s temper as from over-indulgence.”

“I am afraid Rolf’s example will be bad for Joyce.”

“That is my fear,” she replied, with a sigh. “I wish the children could be kept apart, but Rolf will have his own way in that. There is one thing of which I must warn you, Merle. Mrs. Markham may be disposed to interfere in your department; remember, you are responsible to me and not to her. I look to you to follow my rules and wishes with regard to my children.”

“Oh, Mrs. Morton,” I burst out, “you are putting me in a very difficult position. If any unpleasantness should arise, I cannot refer to you. How am I to help it if Mrs. Markham interferes with the children?”

“You must be firm, Merle; you must act in any difficulty in the way you think will please me. Be true to me, and you may be sure I shall listen to no idle complaints of you. I wish I had not to say all this; it is very painful to hint this of a sister, but Mrs. Markham is not always judicious with regard to children.”

“Will it be good for them to go to Netherton under these circumstances?”

“There is nowhere else where they can go,” she returned, rather sadly; “my husband has such a horror of lodgings, and he will not take a house for us this year—he thinks it an unnecessary expense, as later on we are going to Scotland that he may have some shooting. All the doctors speak so well of Netherton; the air is very fine and bracing, and my father’s garden will be a Paradise to the children.”

We were interrupted here by Mr. Morton.

“Oh, are you there, Miss Fenton?” he said, pleasantly (he so often called me Miss Fenton now); “I was just in search of you. Violet, your sister has telegraphed as you wished, and the rooms will be quite ready for the children to-morrow.”

“To-morrow!” I gasped.

“Yes,” he returned, in his quick, decided voice; “you and Hannah will have plenty of work to-day. You are looking pale, Miss Fenton; sea air will be good for you as well as Joyce. I do{166} not like people to grow pale in my service.”

“I have been telling Merle,” observed his wife, anxiously, “that she is to have the sole responsibility of our children. Adelaide must not interfere, must she, Alick?”

“Of course not,” with a frown. “My dear Violet, we all know what your sister’s management means; Rolf is a fine little fellow, but she is utterly ruining him. Remember, Miss Fenton, no unwholesome sweets and delicacies for the children; you know our rules. She may stuff her own boy if she likes, but not my children,” and with this he dismissed me, and sat down beside his wife with some open letters in his hand.

I returned to the nursery with a heavy heart. How little we know as we open our eyes on the new day, what that day’s work may bring us! I think one’s waking prayer should be, “Lead me in a plain path because of mine enemies.”

I was utterly cast down and disheartened at the thought of leaving my mistress. The responsibility terrified me. I should be at the tender mercies of strangers, who would not recognise my position. Ah! I had got to the Hill Difficulty at last, and yet surely the confidence reposed in me ought to have made me glad. “I trust you as myself.” Were not those sweet words to hear from my mistress’s lips? Well, I was only a girl. Human nature, and especially girl nature, is subject to hot and cold fits. At one moment we are star-gazing, and the majesty of the universe, with its undeviating laws, seems to lift us out of ourselves with admiration and wonder; and the next hour we are grovelling in the dust, and the grasshopper is a burthen, and we see nothing save the hard stones of the highway and the walls that shut us in on every side. “Lead us in a plain path.” Oh, that is just what we want; a Divine Hand to lift us up and clear the dust from our eyes, and to lead us on as little children are led.

These salutary thoughts checked my nervous fears and restored calmness. I remembered a passage that Aunt Agatha had once read to me—a quotation from a favourite book of hers; I had copied it out for myself.

“Do as the little children do—little children who with one hand hold fast by their father, and with the other gather strawberries or blackberries along the hedges. Do you, while gathering and managing the goods of this world with one hand, with the other always hold fast the hand of your heavenly Father, turning to Him from time to time to see if your actions or occupations are pleasing to Him; but take care, above all things, that you never let go His hand, thinking to gather more, for, should He let you go, you will not be able to take another step without falling.”

Just then Hannah came to me for the day’s orders, and I told her as briefly as possible of the plans for the morrow. To my astonishment, directly I mentioned Netherton, she turned very red, and uttered an exclamation.

“Netherton—we are to go to Netherton—Squire Cheriton’s place! Why, miss, it is not more than a mile and a half from there to Dorlecote and Wheeler’s Farm.”

“Do you mean the farm where your father and your sister Molly live?” I returned, quite taken aback at this, for the girl’s eyes were sparkling, and she seemed almost beside herself with joy. “Truly it is an ill wind that blows no one any good.”

“Yes, indeed, miss, you have told me a piece of good news. I was just thinking of asking mistress for a week’s holiday, only Master Reggie seemed so fretful and Miss Joyce so weakly, that I hardly knew how I could be spared without putting too much work upon you; but now I shall be near them all for a month or more. Molly had been writing to me the other day to tell me that they were longing for a sight of me.”

“I am very glad for your sake, Hannah, that we shall be so near your old home; but now we must see to the children’s things, and I must get Rhoda to send a note to the laundress. I had put a stop to the conversation purposely, for I wanted to know my mistress’s opinion before I encouraged Hannah in speaking about her own people. How did I know what Mrs. Morton would wish? I took the opportunity of speaking to her when she came up to the nursery in the course of the evening. Hannah was still packing, and I was collecting some of the children’s toys. Mrs. Morton listened to me with great attention; I thought she seemed interested.

“Of course I know Wheeler’s Farm,” she replied at once; “Michael Sowerby, Hannah’s father, is a very respectable man; indeed, they are all most respectable, and I know Mrs. Garnett thinks highly of them. I shall have no objection to my children visiting the farm if you think proper to take them, Merle; but of course they will go nowhere without you. If you can spare Hannah for a day now and then I should be glad for her to have the holiday, for she is a good girl, and has always done her duty.”

“I will willingly spare her,” was my answer, for Hannah’s sweet temper and obliging ways had made me her friend. “I was only anxious to know your wishes on this point, in case my conduct or Hannah’s should be questioned.”

“You are nervous about going to Netherton, Merle,” she returned, at once, looking at me more keenly than usual. “You are quite pale this evening. Put down those toys; Hannah can pack them, with Rhoda’s help; I will not have you tire yourself any more to-night.”

“I am not tired,” I faltered, but the foolish tears rushed to my eyes. Did she have an idea, I wonder, how hard I felt it would be to leave her the next day. As the thought passed through my mind she took the chair beside me.

“The carriage has not come yet, Anderson will let me know when my husband is ready for me; we shall have time for a talk. You are a little down-hearted to-night, Merle; you are dreading leaving us to-morrow.”

“I am sorry to leave you,” I returned, and now I could not keep the tears back.

“I shall miss you, too,” she replied, kindly; “I am getting to know you so well, Merle. I think we understand each other, and then I am so grateful to you for loving my children; no one has ever been so good to them before.”

“I am only doing my duty to them and you.”

“Perhaps so; but then how few do their duty? How few try to act up to so high a standard. I am dull myself to-night, Merle. No one knows how I feel parting with my children; I try not to indulge in nervous fancies, but I cannot feel happy and at rest when they are away from me.”

“It is very hard for you,” was my answer to this.

“It is not quite so hard this time,” she returned, hastily; “I feel they will be safe with you, Merle, that you will watch over them as though they were your own. I know you will justify my trust.”

“You may be assured that I will do my best for them.”

“I know that,” returned my mistress, gently. “You will write to me, will you not, and give me full particulars about my darlings. I think you will like Marshlands; my sister Gay is very bright and winning, and my father is always kind.”

“Mrs. Markham?” I stammered.

“Oh, my sister Adelaide; she will be too much occupied with her own boy and her own affairs to trouble you much. If you are in any difficulty write to me and I will help you. Now I must say good-night. Have I done you any good, Merle? Have the fears lessened?”

“You always do me good,” I answered, gratefully, as she put out her slim hand to me; and, indeed, her few sympathising words had lifted a little of the weight. When she had left the nursery I sat down and wrote a long letter to Aunt Agatha, bidding her good-bye, and speaking cheerfully of our intended flitting. When the next day came I woke far more cheerful. The bright sunshine, Joyce’s excitement, and Hannah’s happy looks stimulated me to courage. There was little time for thought, for there was still much to be done before the carriage came round for us. Mrs. Morton accompanied us to the station, and did not quit the platform until our train moved off.

“Remember, Merle, I trust them to you,” were her last words before we left her there alone in the summer sunshine.

(To be continued.)

{167}

Christmas morning of more than twenty years ago is breaking over a picturesque old town of fair France. The cold wintry sun touches upon the masts of the ships in her harbour and upon the crowded houses of the Lower Town, creeps up to the leafless trees upon the ramparts, and glints upon the steep roofs and stately cathedral of the Upper Town.

From the dormitory windows of a large boarding-school some dozen or more of girlish heads are peering into the feeble light, in the hope of seeing across the narrow “silver streak” the white cliffs of their English home. In vain. A cold, grey fog is rising from the sea, and baffles even their strong young eyes. The casements are closed, and as the big school-bell sends forth its summons, the English boarders hasten into the class-room below. It does not look very inviting at this early hour; there is no fire and little light, while the empty benches and the absence of the usual chattering throng of schoolgirls serve only to make those of them who remain the more depressed. They gather, from force of habit, round the fireless stove, and wish one another a “Merry Christmas”; but they neither look nor feel as if a merry Christmas could be theirs. With hands swollen with chilblains and faces blue with cold, they stand, a shivering group, comparing this with former anniversaries, and increasing their discomfort by reminding one another of the warm firesides, the ample Christmas cheer, and the lavish gifts with which the day is being ushered in at home.

At length the welcome sound of the breakfast-bell is heard, and our small party descends to the réfectoire. Here excellent hot coffee and omelettes, with the best of bread and butter, somewhat reconcile us to our hard lot, while the different mistresses are really very kind to les petites désolées, and do their best to enliven the meal. We are told that during the ten days’ holiday now begun we shall be entirely exempted from the necessity of talking French, and shall be allowed to get up and go to bed an hour later than during the school terms; moreover, that after service in our own church that morning (for, to their credit be it said, these ladies, devout Catholics themselves, never tampered with our belief), we should have a good fire lighted in the small class-room, where we could amuse ourselves as we pleased for the rest of the day.

After such good news we set off, under the escort of the English governess, in revived spirits for church. It was a plain little building, but we always liked to go; it seemed a bit of old England transplanted into this foreign town; and to-day the holly and flowers, the familiar hymns, and our pastor’s short and telling address, made the service particularly bright and cheery.

We were very fond of our good, gentle little clergyman, and always lingered a while after the services in the hope that he would speak to us, as he often did, especially upon any Church festivals; and to-day we had quite a long talk with him before, with many and hearty good wishes, we parted in the church porch.

As usual, after service, we went for a walk on the ramparts which encircle the Upper Town. The view was very fine, comprising on one side the Lower Town, the shining waters of the Channel, and, on very clear days, the houses as well as the cliffs of Dover; on the other, the hills and valleys, watered by the Liane; if we went further still, and passed the gloomy old château—now a prison—we could trace the roads leading to Calais and St. Omer; while on a bleak hill to the left rose Napoleon’s Column.

This rampart walk was a great favourite with us all, and we generally liked to make two or three turns. To-day, however, we were to have an early luncheon, and, besides, were yearning for our letters; so we contented ourselves with le petit tour, and hurried home. Here we found an ample mail awaiting us, whilst among the pile each girl found a neat little French billet from mademoiselle, inviting us formally to dinner and a little dance that evening. Of course we sat down at once to write our acceptances, then, with a cheer for mademoiselle, turned our thoughts to the absorbing topic of what we should wear. Dinner was fixed for 5 p.m., so that after luncheon there was really not very much time left, especially as each girl, besides the difficulty of choosing and arranging her most becoming costume, had also to have her hair “done.”

Hair-dressing was an elaborate science in those days, puffs and frisettes, curls and plaits, being all brought into requisition on state occasions, and if this—a dinner and a dance given by mademoiselle, the rather awe-inspiring though extremely kind mademoiselle, who reigned an undisputed autocrat in our little school-world—if this, I say, was not a state occasion, I appeal to every schoolgirl throughout the kingdom to tell me what was.

The dortoir was a gay and animated scene as we English girls repaired thither after luncheon to “lay out” (rather a dismal phrase, but one we always used) our best frocks and sashes, our open-worked stockings and evening shoes, and our black or white silk mittens. One of the girls was a capital hairdresser, as everyone else allowed, and as her services were eagerly entreated by the less skilful in the art, I can tell you her powers and her patience were put to the test that afternoon.

Oh, the plaiting and waving, the padding and puffing, the crimping and curling, that we gladly underwent on that memorable occasion! How openly we admired one another, and—more secretly—ourselves; and then how very funny it seemed to be walking into the drawing-room as mademoiselle’s visitors!

Kind mademoiselle! how handsome she looked in her dark satin dress, with a little old French lace at her throat and wrists! How pleasantly she welcomed us all, while she gave extra care to the one child amongst us, who could only wear black ribbons even for Christmas Day.

Of course, all the under-mistresses were there, and one or two of the non-resident ones. I particularly remember the pretty singing mistress, and the head music mistress, whose brother I hear of nowadays as the first organist of Europe; whilst last of all to arrive was Monsieur l’Abbé, who was a frequent and honoured guest, and for whose coming we had all been waiting.

The dinner bell rang a few minutes after this important arrival, and we all descended to the réfectoire. How good that dinner was! A soup such as one never tastes anywhere but in France; the bouilli, which we were too English to care for; the turkey stuffed with chestnuts—delicious, but so unlike an English turkey; the plum pudding, very good again, but still with a foreign element about it somehow; and, as a winding up delicacy, the delicious tourte à la crême, a real triumph of gastronomy.

Then our glasses were filled with claret, and we drank the “health of parents and relations,” a rather perilous toast for some of us, whose hearts were still tender from a recent parting; and finally coffee was served—not the coffee of everyday life, but the real café noir, which we girls drank with an extra dose of sugar, but which to seniors was served with a little cognac. Then, as we sat over our fruit and galette, mademoiselle and her mother, a charming old lady, with bright, dark eyes, and soft, silver hair, combined with Monsieur l’Abbé to keep us merry with a succession of amusing stories of French life and adventure, until the repeated ringing of the hall bell announced the arrival of some of the old pupils, who had been asked to join our dance. Tables were quickly cleared, superfluous chairs and benches removed, violin and piano set up a gay tune, and then we danced and danced away until nearly midnight, when the appearance of eau sucrée and lemonade, with a tray of tempting cakes, concluded the fun, and gave the signal for retiring.

{168}

By EMMA BREWER.

Annaberg is a bright, thriving little town in Saxony, and, from its pleasant situation, is known to the people round about as the Queen of the Erz Mountains.

Its attractions are enhanced by the character of its population, whose kindness, cleanliness, and industry are known to all.

Like many another old town, it has a history, and boasts of chronicles which record many memorable facts concerning it, one of which is peculiarly interesting to us, viz., that a great service was rendered by a woman, in return for which a great benefit was received, and in its turn given out again to women, among whom it brought forth fruit a hundredfold; but this we will explain presently.

This cheery little town is surrounded by pine forests, to which many of the poor inhabitants of the upper mountains come in the hot summer months to pick berries and gather mushrooms, and so add to their scant means. The highest point of the Erzgebirge is only two hours distant, or about six miles, and it is quite worth while to climb to it, for from it you get a view which does your heart good. Not that the character of these mountains is either romantic or wild, like that of the rugged rocks in the Bavarian Highlands; on the contrary, it is soft and gently undulating, conveying rest and peace to the heart.

And what of the inhabitants? Are they as attractive as the mountains? I cannot be quite sure. Of one thing, however, I am certain, that they would interest you. They are simple-hearted and good tempered. By incessant industry they manage, as a rule, to gain a scant livelihood, although there are bad times when, in spite of constant toil, many suffer hunger.

Potatoes, and a suspicious kind of drink which these people call by the name of coffee, form the chief means of support. Those dwelling high up in the mountains consider themselves quite happy if they are able to place a dish of steaming potatoes on their well-scrubbed pinewood table. If, however, night frosts and long rains spoil these, they have little else to live on than the clear water from the spring and the fresh air of the mountains. The result of this is that about Christmas, which should be a happy time, the ghost of Typhus may be seen stalking abroad over the mountains, pausing here and there to knock at one or other of the little snowed-up huts of the weaver, the toy-maker, or the lace-worker, and the gravedigger finds more than enough to do digging graves down through the ice and snow.

Necessity has taught these simple people not only to live sparingly and to exercise self-denial, but it has given them a wonderful cleverness and readiness in taking up any new industry.

Just as in great towns the fashions are continually changing, so the demands of the markets of the world create new trades, and give a variety to the occupations of even these remote dwellers of the mountains. In the very poor huts, with shingle roofs scattered about in out-of-the-way corners of this mountain district, you would scarcely expect to see the inhabitants working a thousand various and tasteful patterns of glistening, sparkling pearl articles, which, when finished, go forth out of those poor huts to adorn the dresses of grand ladies in Berlin, Paris, and London; yet this is the fact.

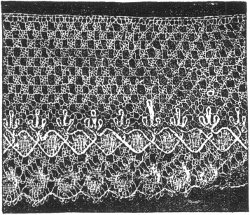

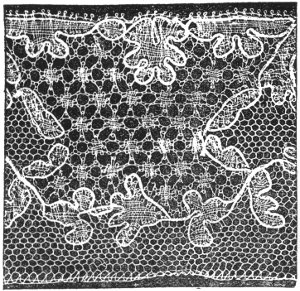

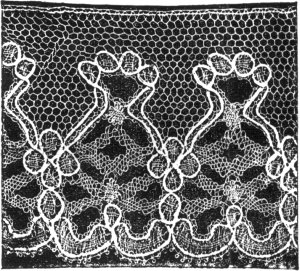

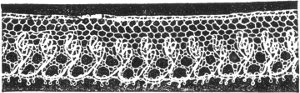

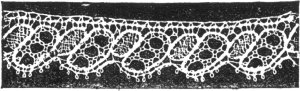

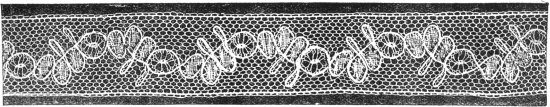

In like manner and in like houses{169} you may see the inhabitants busy with the beautiful art-industry of pillow lace-making, which brings us to the interesting fact recorded in the chronicles of Annaberg—interesting to us because it refers to woman and woman’s work.

The middle of the sixteenth century was a hard time for the people of the Erz Mountains. Yearly the population increased, and yearly the means of support grew less; for the productiveness of the mines, which up to that time had been great, fell off to such an extent that even the new tin industry failed to make up the loss.

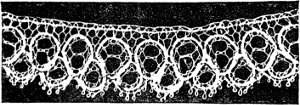

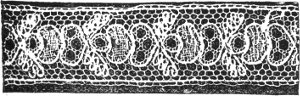

It was just when the need was greatest that the good Frau Barbara Uttman, a rich patrician lady of Annaberg, came to the rescue of the inhabitants by teaching the poor women and girls[4] an entirely new industry—one that had never been known in Germany. It was the rare art of making exquisitely soft and costly texture with the hand by means of dexterously intertwining and knotting single threads of silk or cotton; in fact, to make what is known as bobbin or pillow lace.

Barbara Uttman (born in 1514, died in 1575), as the story goes, learnt it from a fugitive Brabantine whom she hospitably received into her house. If this be so, then was her hospitality rich in good fruit.

Although pillow lace does not hold so high a place in fashion at the present time as in the good old days, yet the memory of Frau Barbara is kept in affectionate and pious remembrance by the good and simple people of the Erz Mountains.

A venerable avenue of lime-trees leads to her tomb in the “Gottesacre” of Annaberg. It is one of the most simple in style and execution. It points her out as the founder of the bobbin art, seated at a lace cushion.

A good action is the most beautiful memorial, just as gratitude is the highest of virtues.

Past neglect has been in a manner atoned for by erecting a worthy memorial of her exactly opposite the ancient grey town-hall in the market-place of Annaberg.

There is a possibility that this memorial may be the means of reviving the industry which has been so good a friend to the inhabitants; and yet it is scarcely possible that{170} it can ever compete with the machine-made lace of Nottingham, which is comparatively cheap, and, to the uneducated eye, scarcely to be distinguished from the hand-made cushion lace. During the last thirty years the poor bobbin villages would have starved on the ever-decreasing profits had not other industries sprung up to give them work.

Many attempts have been made to give the pillow lace a fresh start, a new life; but without any permanent good result. Standing out from among many noble ladies who have made the attempt, is the Queen Carola of Saxony, who has done her utmost to keep it going.

She maintains model bobbin schools, wherein children are taught the industry under skilful supervision. It was she who gave the order to the poor lace-makers for the bridal veil of the Princess Maria Josepha, as well as for the lace dress.

It is the object in all the schools to ward off the threatened downfall of the hand-made lace industry, by the production of patterns full of taste and style; but this only goes a short way, the markets of the world must do the rest.

Ladies might do much for the industry if they resolved to wear real lace instead of cheap machine lace.

A committee of ladies in Vienna have already determined to do this, which may be the beginning of better things.

Quite apart from its practical purpose of maintaining for the poor mountaineers a branch of business peculiarly theirs, we must remember that, should the cushion lace-making fail, an ancient and noble house industry will have its fall—an industry which is even now able to turn out beautiful works of art, worthy of high praise, one for whose success three centuries have laboured.

The effect of this industry among the people who earn their bread by it is to make them scrupulously clean; their huts have, as a rule, but one floor, but the boards are always freshly scrubbed, the walls are spotlessly whitewashed. The kitchen utensils, which are hung on the walls, are like looking-glasses, so bright are they, and you would look in vain for dust on the poor furniture of the little room.

The costly lace requires the most particular cleanliness, as well in the lace-maker herself as in her surroundings.

The manners of these people are those bequeathed them by their forefathers, and their work is carried on as in former days.

Even little children of four years old earn a few pence weekly at the cushion towards the housekeeping, by making common wool lace. To produce tasteful hand lace requires not only great patience, but also such a high perfection in the art that it must be regularly practised from childhood, and this explains the reason of such young children being placed at the cushion.

The bobbin lace-making industry has never brought even a moderate competency to the cleverest and most industrious worker. How could it, when, if she work from early morning till late at night, the highest she can possibly earn is 5s. a week, and in less busy times not more than two to three shillings?

In the hard winter days no morsel of meat is seen on the table; and if the potatoes are all consumed, then dry bread, and not much of it, is all the nourishment they get.

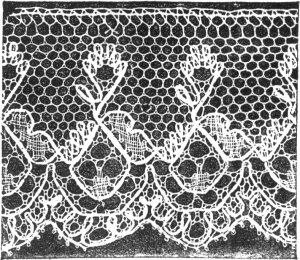

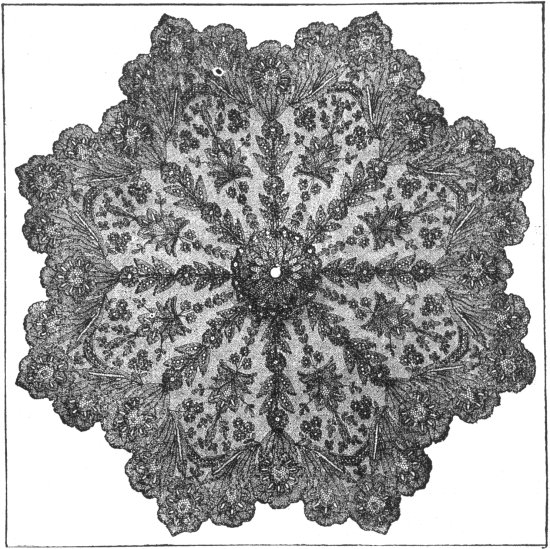

How does it happen that such valuable work fails to give a fair return? This, with a little knowledge, is easy to answer. It takes a very long time indeed to produce the most simple lace, and as to costly patterns of rich and tasteful designs, such as we give here as a cover to a lady’s sunshade—well, it would require for its production six to twelve months, or even longer, according to the pattern and the ability of the worker. This lace-cover is bought in the shops of our great towns for the ridiculously cheap sum of £5—perhaps £7 10s.—or, at the very highest, £15.

If you take into consideration the high duty on these articles, the worth of the raw material, which is generally the best silk, and the fee to the middle-man, you will see how much remains for the industrious artist at her cushion—never more than 2s. 1d. a day.

Supposing that a yard of pillow lace cost 7½d. in the shops, you must take off quite 2½d. for the purchase of material and the fee for the middle-man, which leaves the worker 5d. as the price of a day’s hard work, for she cannot make more than a yard a day.

The poverty of the pillow lace-maker is no doubt due also to the low market price of the lace, and this cannot be remedied, for lace being not an article of necessity, but only of luxury, the desire to buy will decrease with every rise in price, especially as the machine-made lace is produced so easily and in such perfection that it is difficult often to tell the true from the false.

For the last ten years it has seemed useless to think of bettering the position of the lace-maker, male or female. Any effort made is rather to prevent an excellent and artistic industry from dying out. The population has turned itself to other industries which pay somewhat better, merely taking up the lace-work when others fail.

For example, men who in summer seek their bread on the plains, either as bricklayers, labourers, or artisans, join the family circle in the winter in making lace, and it is wonderful to see what soft and delicate work is turned out by those hard hands. It is pleasant to see the wooden stools drawn round the table behind the glass globe filled with water, through which the lamplight falls sharp and clear on the spotless work, and watch the family, from the aged grandmother down to the toddling grandchild, take their places at their cushions or pillows. For those who have never seen pillow lace made, we will give a few words.

The pillow or cushion is of cylindrical form, and tightly stuffed. On this a number of pins are stuck, according to the pattern to be worked. The threads, fastened to small bobbins, are thrown across the cushion and placed round these pins; the threads, traversing from left to right, or vice versâ, often weave at once the pattern and the ground. There is a line in one of the Volkslied which runs—

We echo the wish, but fear it will never be realised.

By MARY E. HULLAH.

o you like this part of London?” asked Horace, by-and-by.

Embrance had taken off her bonnet and ulster, and was sitting by the side of the fire. It was one of her characteristics, owing, perhaps, to the need of rest after long hours’ work, that she could remain perfectly still for a considerable length of time. She had no desire to busy herself with fancy work or to twirl her watch-chain; she did not throw herself into picturesque attitudes, but sat with clasped hands, listening to her visitor’s easy flow of conversation. A curl of her dark hair had escaped from the stiff plait, and her lips were parted with a smile.

“Not half so alarming as I imagined she would be,” was Horace Meade’s thought, as he pursued his inquiries as to her liking for Bloomsbury, “but why, in the name of all that’s wonderful, does she wear such a frightful garment? It requires beauty to carry off a Cinderella garb of that kind.”

“I find it convenient to live here,” explained Embrance, while her visitor’s fancy had soared far away, and was drawing her hair high on the top of her head, putting pearls in her ears, and a mass of crimson roses in the lace round her throat. “She would make a good study for the ‘ugly princess,’” he thought.

“I know that you are one of the busy folk,” he said, “Joan has told me about you and your hard work. I only hope—” with a certain kindliness that went straight to her heart—“that you are not overdoing it. Joan ought to look after you.”

Just for a second, Embrance’s dark eyes looked up at him with a flash of inquiry: could it be that this polite, soft-voiced man was making fun of Joan and of her? As if ashamed of her suspicion, she replied gently—

“It is a great pleasure to me to have Joan’s company; we have been friends for a great many years, ever since we were little schoolgirls.”

“And you helped her with her sums after hours,” said Horace, twisting the end of his moustache. “I have heard a great deal about you and your doings, Miss Clemon, but seriously, I should be glad to talk to you about my cousin, if you will let me.”

“Please do; she has been so looking forward to your coming; will you be able to suggest any line for her to take up? She doesn’t much like teaching; she was not very happy at home, and (with a slight hesitation) her grandfather makes her no allowance while she is here.”

“Poor girl!” exclaimed Mr. Meade, “I expected how it would be; he is a regular old miser. As for Joan, with all her talent, she’s had no proper teaching herself, and hasn’t an idea what real work means. What has she been doing lately?”

Embrance, conscious that Joan had been spending the last fortnight in making herself a charming terra-cotta walking dress, looked towards the window, and said that there had been so many fogs, it was bad weather for artists. Mr. Meade nodded, then marched up to the easel, and examined the drawing—a study of roses, white and pink—that Joan had begun a month ago; but even before the roses (which had cost as much as a week’s{171} rent) withered, she had got tired of the drawing, and had put it on one side for a copy of a landscape, intended for the good of her pupil, and also left unfinished.

For some minutes he stood there in silence, took the drawings nearer to the light, and carefully replaced them on the easel.

“Well?” asked Embrance, anxiously.

“What do you think of them?”

“I am not a judge; I know so little about it.”

“Very likely, but look here” (she came closer to the easel), “you are accustomed to observe. Do you see the grouping of the roses is pretty enough, but there, look, that is quite out of drawing, and the stalk is an absurdity.”

Embrance could not stay there any longer in mute acquiescence: “But she is so quick,” she remonstrated, “and has a real love”—for painting, she was about to say, but her sense of truth turned the sentence into: “for anything that is beautiful!”

He turned away from the window with a sigh. “As an amateur, it is all very well, but otherwise, I don’t see what is to be done. Poor little Joan! It’s a bad business; how is she looking, Miss Clemon?”

“Prettier than ever, I think.”

“I am glad to hear it. She is a charming companion, and I am very glad that you like her. It is a comfort to know that she has got such a good friend in you.”

Embrance blushed, feeling very uncomfortable, and half inclined to resent his remarks. It was rather late in the day for a complete stranger to interfere in such an old friendship as hers and Joan’s. “However,” she reflected, “I am sure he is very fond of her; I wish she would come in.”

“Perhaps,” continued Horace Meade, “you think that I have no business to say this; but the fact is, that I had expected to find, at least I had not expected to find—that is to say——”

He stopped abruptly, and Embrance could not refrain from laughing: “You had imagined that Joan had set up housekeeping with a strong-minded woman of the most extreme type, who didn’t care what became of her.”

“No, no, indeed!” began Horace, but she would go on.

“Please let me explain to you that I would do anything, anything in the world to make Joan happy. I have been looking forward to your visit; I hoped that between us we could find some way of helping her.”

It occurred to Horace that this would be an advantageous moment to say something complimentary, and get himself out of an awkward predicament, but he did not avail himself of the opportunity. He was a person who believed in his own insight of character, and Miss Clemon (who was so widely different from his preconceived notion of Joan’s learned friend) interested him very much; he was quite sure that she was open and honest as the day. Better be straightforward, too.

“Thank you very much,” he said, almost as if she had conferred a favour on him personally, “I will think over what you have said; we will try and help her; and may I come again soon?”

Embrance answered that she would be very glad to see him, and when, after a little more chat, he took his leave, she went singing into the next room, feeling lighter of heart than she had done for days. She liked Horace Meade very much, and how pleased Joan would be to hear of his arrival!

Joan was, indeed, delighted to welcome her cousin; Mrs. Rakely invited him to the hotel, and there were many happy days spent in his society. His own rooms and studio were in a distant suburb, but he found time to make himself very agreeable to the ladies, and to show them the sights of London. Joan was in her element, but too soon there came a period of reaction. Mrs. Rakely went back to the country, and Horace began to work regularly; he was slowly making his way as a portrait painter. Joan fell into low spirits again, she wrote a great many letters, and received bulky communications from Mrs. Rakely, about which she maintained a silence, strangely unlike her usual talkativeness. Now and then she would turn wistful glances on Embrance, as if longing for sympathy, but she made no confidences. And Embrance treated her with great tenderness, believing that some slight squabble with Horace was the cause of her despondency. “Better not to worry her with too many questions,” she thought, “she will tell me in her own good time.”

Horace came to the little second floor parlour, generally timing his visits so as to arrive about seven o’clock. He had dined at his club. If he might be allowed, it suited him best to drop in at this time. He hoped he wasn’t in the way. Embrance bade him heartily welcome, while Joan would forget her melancholy, and brighten into fresh beauty under the influence of her cousin’s pleasant talk. More than once Embrance, busy as she was, had attempted to leave the cousins to themselves, while she laboured at a side table; but Horace had a knack of coaxing her back to the fireside, asking her opinion on some interesting topic, or referring to her laughingly as a competent authority. And she had been enticed away to listen to his account of his travels, or description of his housekeeping failures in his own rooms. He set Joan hard at work painting menu cards and photograph frames, saying that he knew a man who would dispose of them at a fair price, and now and then he brought a drawing for her to copy, but he showed no sign of being impressed with the progress that she made.

“Do you expect your cousin this evening?” asked Embrance, one afternoon, about a month after Christmas; “he has not been to see you for some time.”

“No,” said Joan, wearily. She was lying full length on the hearthrug, with her head on a pillow, while Embrance arranged the ornaments on the mantelpiece to her better satisfaction; “but I have heard from him.”

“What did he say?” asked Embrance, fancying that in Joan’s manner she could trace a desire to be further questioned; “is it a secret, Joan, or may I know all about it?”

Joan fixed her great eyes upon Embrance, and raised herself from the ground with one arm: “I have got a secret, but I am not to tell you. Did you guess that I had?”

Embrance nodded. She had finished putting the ornaments to rights, and now came and sat on a low chair by the fire. “You would rather not tell me about it just yet, Joan?”

“Not yet,” said Joan, excitedly. “You will know soon. Mrs. Rakely knows. But, but”—she hesitated, “I don’t know when Horace will come here again; he is very inconsiderate sometimes. What do you think he proposed I should do? I met him one day and asked his advice—you are so busy, Embrance, there seems to be no time to talk to you. He says that I had better go back to Doveton!”

“He wants to take her away from me,” thought Embrance, with a pang; “perhaps he is right, and I ought never to have kept her.” She took Joan’s hand and patted it softly. “There is no occasion to fret about it,” she said. “Would you like to go back, Joan?”

“I don’t know,” said Joan, half crying. “I’m sorry I quarrelled with Horace. I was very disagreeable to him. He doesn’t think I ought to stay with you much longer.”

“I am sorry,” began Embrance, humbly; but Joan was too much taken up with her own grievance to listen. She went on: “He offered to speak to the head of a firm he knows where they make furniture and employ people (artists, Horace calls them) to decorate rooms and paint panels. He said I should have to be taught to do it; and, oh! Embrance, I should hate to be shut up all day; I should feel as if I were in a prison; so I said I wouldn’t go and see his friend—that I would rather go on the stage. And then he advised me to go back to Doveton.” Joan was sitting bolt upright now, and her eyes were sparkling. “Do you think I behaved badly?”

“It was very hard for you, my poor dear; but I dare say you were not so disagreeable as you imagine. He would make allowance for your not being accustomed to keep such regular hours.”

“It’s you who make allowance,” cried Joan. “You are very good, Embrance; and I am keeping so much back from you. But don’t think hardly of me; promise me you won’t. Have patience with me, whatever I do.”

A sharp east wind was blowing across the park; the chestnut-trees stretched their bare branches grimly towards the sky. Embrance Clemon was walking home after her day’s work; the dead leaves swept rustling and dancing towards her. A party of noisy children were racing after their hoops a few yards in front of her. She had just been told by the mother of a pupil, with many expressions of regret, that her services would not be required any more after Easter. Her head was full of plans, by which she could contrive to manage her slender resources, so that Joan should not be made to feel that she was in any way increasing the household difficulties. In truth, she could ill afford to lose a lesson just now. She had heard no more of Joan’s quarrel with Horace Meade; she imagined that that was made up long ago; the two had met more than once, she knew, at a friend’s house, but he had left off coming to call. Embrance missed his visits; it was clear to her now, looking back to the last few months, that Horace Meade had brought a great deal of happiness into their quiet lives—hers as well as Joan’s. And yet, try as she would, she could not but feel hurt that he should be so anxious to remove Joan from her influence. “It doesn’t matter, after all,” she reflected, walking faster and faster in the grey twilight, “what he thinks of me.” Nevertheless, it mattered so much, that Embrance grew sad at heart; there came over her a great longing to throw up the present occupation and go away, anywhere, and begin again; to shut up her past life tight and firm and to start afresh. And Joan? She almost smiled at her own folly, as she recollected how impossible it would be to leave Joan in such an unceremonious fashion.

(To be continued.)

{172}

A PASTORALE.

By DARLEY DALE, Author of “Fair Katherine,” etc.

If it had not been for his anxiety about Fairy, this would have been an excursion quite after Jack’s own heart. He delighted in anything unusual which varied the monotony of his daily life, and if it partook of the nature of an adventure he was all the better pleased. As he and his father tramped along the Oatham-road, one walking on the extreme right, the other on the left hand side, it was natural that John should beguile the way with reminiscences of other fogs.

“The worst fog I ever remember was when I was courting your mother, Jack. It was just after Lewes sheep fair, and a Saturday night, and it came on quite suddenly, so that I saw it was impossible to attempt to get the sheep home that night, for I was on Mount Caburn, and I did not know the mount so well then as I do now. But I always spent Saturday evening and the best part of Sunday with your mother, and I did not feel inclined to be done out of my weekly treat by the fog, so, though I could not get the sheep into fold, I thought I would leave them to take their chance till the fog lifted, and then come after them; I knew I should soon find them by the help of the bell-wethers and Rover, so I left the sheep, and set off to try and find my way home through the fog. I knew there were one or two nasty places where I might fall and break my neck, so I went pretty carefully, you may be sure. I had no lantern with me, and it was a darker night than to-night, and I think I must have wandered round and round the top of Mount Caburn for three or four hours before I even began to descend. At last I found I was actually on a downward track, though I had not the least idea which side of the hill I was, and I think if I had not been in love I should have remained where I was till the morning, or at least till the fog cleared. As it was, I determined, at all hazards, to go on, though I guessed I should get a scolding from your mother for my pains; so on I went, on my hands and knees, feeling my way before me, for I was afraid to walk upright lest I should step over a precipice, and at last I reached the bottom in safety. Then I had no idea where I was till, luckily for me, I met a man with a lantern, and he put me in the road, but it was too late to go to your mother’s that night, and the greater part of Sunday was spent in looking after the sheep, who had wandered for miles. But this fog won’t last much longer, Jack; the wind is rising,” said the shepherd.

“Yes,” said Jack. “I wish it would blow those children home safely. I do hope nothing has happened to them; but Charlie is so careless, he leads Fairy into danger without thinking.”

“She does not want much leading into danger; she is apt enough at running into that, I am thinking, Jack. But what is become of Rover?” said the shepherd, stopping and whistling.

“Bow-wow-wow,” replied Rover, in an excited tone, from the depths of the fog.

“Where are you, sir? Come here,” cried the shepherd.

“Bow-wow-wow-wow,” answered Rover, in a still sharper key.

“Come here, sir; what are you at?” cried John Shelley.

“I hope he has not found the children in that chalk-pit. See, we are near the first one,” said Jack, crossing over to his father, and moving with him to the chalk-pit, which was at the side of the road.

“I trust not, Jack. Here is Rover; he has found something, that is clear. All right, I am coming, good dog,” said the shepherd, as Rover now emerged from the fog, and, by dint of many barks and wagging of his tail, gave his master to understand that he had discovered something.

The shepherd throwing the light of the lantern in the direction the dog indicated, followed{173} him, while Jack, with his heart in his throat, dreading at every step that the next would bring him face to face with Fairy stretched lifeless at his feet—a picture his quick imagination had but little difficulty in conjuring up—brought up the rear.

They were at the mouth of a large chalk-pit, but, owing to the density of the fog, the lantern did not enable them to see more than a yard before them; moreover, they were obliged to go very carefully, as huge pieces of chalk were scattered over the centre of the pit. Suddenly Jack kicked against something, and stooping, picked up a large gingham umbrella, which, to his joy, he saw at a glance did not belong to Fairy.

“See, father, an umbrella; can this be what Rover is making all this fuss about?” asked Jack, handing the huge thing to his father to examine.

“I doubt not; I am afraid we shall find the owner of the umbrella next, Jack, by Rover’s ways. But look, there is a name cut on the handle, and it looks as if it had been cut quite recently, too. See if you can make it out, I can’t; seems a foreign name to me,” said John Shelley, holding the umbrella close to his lantern for Jack to read.

“D-e-t—No, it is a capital t; De Thorens, that is the name, plain enough. A foreign one, too, as you said. It must belong to some stranger, then; perhaps someone has lost his or her way and taken shelter in this pit. Let us shout, father, they may hear us,” and Jack shouted, but in vain.

Rover now became more excited than ever, and seizing John Shelley by the skirts of his smock-frock, dragged him forward, until suddenly he came to a standstill, and loosing his hold of his master, sniffed round and round something which was lying a step or two further on. John Shelley stooped, and, lowering his lantern, turned the light on the object, and saw to his horror the apparently lifeless body of an old woman, which was lying huddled together in a shapeless mass. Gently and reverently the shepherd straightened the limbs, which were already getting cold and stiff, and then looking at the face, which was not disfigured by the fall, the old woman having fallen on her back, he recognised his old acquaintance Dame Hursey.

“Is she dead, father?” asked Jack, in an awe-stricken voice, as he clutched his father’s arm, for it was a ghastly sight these two were gazing on in the cold, dark, foggy night, by the weird gleams of their lanterns.

“Yes, Jack, yes; do you see who it is? Poor old Dame Hursey, the last person I ever thought to find here, for if anyone knew the Downs it was she. She is dressed in her best, too; she was not out wool-gathering, that is clear,” said the shepherd, slowly.

“But what are we to do, father? We can’t leave her here, and we have not found Fairy and Charlie yet.”

“We must leave her here for the present, Jack; she is dead, and must have been killed on the spot; I expect Rover will watch by her till we come back. We must separate; you go back to the police station for a stretcher and some men, while I go on and look for these children. I hope and trust they won’t come across this sight; it would give Fairy a terrible fright. Be as quick as you can, Jack, for if the children are not on the Race Hill we shall have to go in another direction. I’ll meet you at the police-station; I shall be back there by the time you have got the poor old dame carried there. Rover, stay here till Jack comes back.”

No need to tell Rover twice; he laid down by the body at once, and there he would have remained till doomsday if Jack or his master had not returned before; and Jack, though he by no means liked his task, and would far rather have gone on to look for Fairy, obeyed as promptly as Rover.

And where were Fairy and Charlie on this cold, dark November evening in this thick fog? They had not gone to Mount Harry after all, though they had set out with that intention, for as soon as they reached the Brighton-road Fairy had suggested they should go to Brighton instead, and though Charlie, who was rather lazily disposed, hesitated and raised objections, Fairy overthrew them all, and finally succeeded in persuading him to take her.

The object of their walk was to pay a visit to a bird-stuffer in Brighton, and find out the price of an eared-grebe which had lately been shot in the neighbourhood, and which this man, as Jack, who had been over two or three times to look at the bird, had told Fairy, was stuffing and mounting. If only the price were reasonable, a better Christmas present for Jack could not be thought of. He would be wild with joy at possessing this bird, which Fairy described to Charlie from a picture Mr. Leslie had of it. Charlie did not care much what the price was, but he was curious to see this wonderful grebe with the ruff round its neck, so he consented to take Fairy.

“How much do you think it will be, Charlie?” asked Fairy, as they trudged along the muddy road in the mist.

“I don’t know; Gibbons will let us have it ever so much cheaper than anyone else, because Jack so often gives him birds and eggs, and all manner of curiosities. How much can you afford, that is the question?”

“Well, mother will give me something, and John and Mr. Leslie will give me five or ten shillings, and I have got seven myself; I think I can afford a sovereign altogether. You must give something, too, Charlie, you know.”

“That’s all the money I have,” said Charlie, putting his hands into his pockets and producing twopence halfpenny. “That won’t go far,” he added, ruefully.

“Never mind, it will help. I do hope Gibbons will let us have it for a pound,” answered Fairy; and buoyed up with this hope, she walked into Brighton, a good eight miles, without once complaining of being tired.