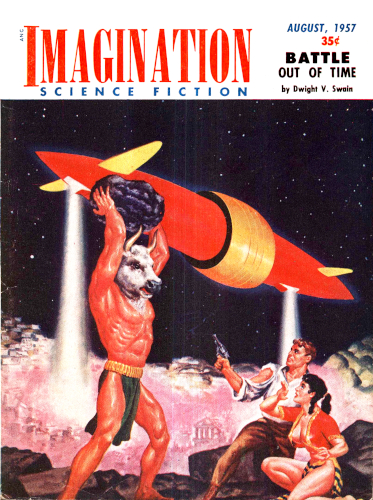

Burke knew of the ancient Bronze Age and

its legend of the dread Minotaur. But he didn't

know he was about to become a vital part of it!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

August 1957

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

An utter dark lay upon the hills outside the palace now, moonless and with clouds drawn heavy all across the Cretan sky.

Wind, too, had come with the night, rising till Burke found himself fearing for the shutters. The lamps flared on their stands with each new gust and draft. Light flickered orange and yellow on Ariadne's lovely face, eddying through the shadows so that the tentacles of the frescoed octopi on the walls seemed to writhe and twist and turn....

Burke laughed without mirth. It was that mad a moment.

And that dangerous.

For while he might find temporary cover here with Ariadne, in these private quarters beyond the Queen's Megaron, death yet bayed at his heels.

Already, bearded King Minos himself no doubt paced some other palace hall—thirsting for Burke blood; raging in jealous fury that any outlander should dare aspire to his lovely daughter.

That slavering Greek lecher, Theseus, too—it was lucky he lay dead drunk there in the corner. Sober, and confronted with a rival, he'd kill just to salve his wounded ego.

And then, as if that were not enough of peril, there was ... the other.

Involuntarily, Burke shuddered.

What chance did a mere human have, pitted against the dark craft of the alien? Where could he hope to find the strength and skill and insight to win over the strange horror from beyond the void?

Yet with Ariadne's life at stake, Earth's whole future in the balance, how could he turn back?

No; he had no choice but to press on; seek out and challenge the might of that nightmare monster men called the Minotaur.

He couldn't help find it surprising, though, that in the face of such he still had it in him to notice the play of light on decorative motifs. Truly, the strange twist of mind that seemed to pervade this weird Mediterranean realm had claimed him for its own!

But to dare the Labyrinth, the Minotaur....

Almost without thinking, Burke rested a hand on the worn Smith & Wesson in his belt; then, bleakly, laughed again.

Ariadne moved uneasily beside him. Her words came halting and uncertain: "You—you are amused, my lord Dionysus...?"

Irritation boiled up in Burke—quick anger that he should have let himself forget even for a moment the desperate urgency of his task. How could he play the fool so—here, now, at a time when every breath, every second, brought inevitable disaster closer?

It added up to tension that had to find an outlet. Savagely, he lashed out at Ariadne: "For the hundredth time, girl: I'm not Dionysus, not a god. I'm Dion Burke, that's all. A man, like any other—"

Hurt came to the great dark eyes. A tear-mist veil blurred the glow of awe and adoration. The soft lips quivered.

But only for a moment. Then, contritely, the girl bowed her head. Jet ringlets glistened in the lamplight. Bringing up slim hands, she crossed them upon the firm young breasts that she wore bared in the traditional Minoan style. "Your pardon, my lord...."

Burke breathed in sharply. As swiftly as it had come, his anger died. Of a sudden he wanted nothing so much as to take the girl in his arms and draw her to him ... solace her, soothe her, hold her with a thousand tender caresses through the endless hours of this long, black night.

Why was it always so between him and Ariadne? What was there about this slim Minoan princess that the very sight of her should make his firmest resolves melt? The women he'd known in his own world—they'd been wiser, wittier; more beautiful, even, perhaps, by an objective standard. Yet not even the one who'd hurt him most and helped to precipitate him onto this fool's mission had stirred him a tenth as much as Ariadne.

With a curse, he reached out, pulled her to him.

She came willingly, nestling against him, her lithe body soft and warm.

For a long moment, Burke held her close.

Only then, over in the corner, brawny, bull-necked Theseus stirred and shifted. A noisy, wine-sodden snore broke from his open mouth.

Burke stiffened.

Like an echo, Ariadne's lovely oval face lifted from his shoulder. "My lord! You do not still feel anger—?"

Burke shook his head. "Forget it, princess. It's just I'm all on edge. There's not much time—"

He broke off; brought up his wrist and strained to read the watch-face.

And that was good for another wry, twisted shadow of smile: a watch, here in Bronze Age Crete ... product of the United States of America, vintage 1954 A. D., wrenched 5,000 miles and 3300 years out of its place and time. An anachronism to end all anachronisms.

Or no, that wasn't quite true.

For surely he himself was a greater anachronism than the watch, even.

The bare facts alone would drive an obituary writer crazy: "Dion Burke, archaeologist extraordinary without portfolio; born, Erie, Pa., August 9, 1929; disappeared April 14, 1957; died at Knossos, in the Great Palace of Minos, mightiest sea-king of Crete, on some vague, early spring date in the vicinity of 1400 B. C."

Only no obituary writer would ever hear those facts. The watch, the gun, the lighter—they'd all have sifted away to rusty dust long before Sir Arthur Evans and his fellow-scholars came this way.

Not that that mattered. Not now; not while he still had a job to do.

He moved his wrist closer to the nearest of the flickering lamps, and strained again to read the watch.

Almost 10:30. Little more than an hour-and-a-half till midnight and the moment of Knossos' doom.

Sometime between now and then, he had to meet the Minotaur.

For a moment he held the slim girl in his arms even closer than before. Then, ever so gently, he moved her back away a fraction; lifted her small, satin-smooth chin. "Ariadne...."

"Yes, my lord?"

"There's a thing I must do now, Ariadne. An important thing, for both of us." A pause. "I need your help to do it."

"My help—?" The dark eyes widened. "My lord knows he has only to command. What must I do?"

Carefully, Burke picked his words; strove to hold the tension from his voice: "Among the people of this palace, there's one called Daedalus. You know him?"

"Daedalus the Smith, you mean?" The jet ringlets danced as the girl laughed. "Of course I know him. He's chief of all my father's craftsmen. What is it you seek of him?"

Again, Burke weighed his words. "Some talk, that's all. A chance to ask a few questions."

"Talk—at this hour?" Ariadne stared.

"I have no choice," Burke shrugged. "To see him by daylight would be as much as my life is worth."

"Oh."

"Yes." Time for a smile now, Burke decided. His most engaging smile. "You see, there are things the man knows, things his skill's taught him—"

Ariadne stiffened in the same instant. "Things Daedalus knows—?" For the first time, her voice held an edge, dark shadows of suspicion. "How could a smith know anything that means so much? What might he say that my lord Dion had not already heard a thousand times?"

"What—?" Burke felt his smile go stiff. "Why—why, many things—his skills, his artifices—" He groped and fumbled.

"No!" In a flash all Ariadne's humility of manner vanished. She thrust Burke's restraining arm aside, defiance in the gesture. "Do you think me a fool, my lord Dion? Daedalus the Smith holds but one secret that such as you might seek to learn. One only!"

Burke stood ever so still.

Ariadne spat like a cat. "You seek the secret of the Labyrinth, my lord! You would stalk the Minotaur in his very lair! Waste no breath trying to lull me with denials!"

Burke sighed. A weary sigh, heavy with the knowledge of all the things he could not change.

And, from Ariadne: "What makes you think you're destined to succeed, where each year fourteen others fail? How dare you hope to live, when the monster that is the Minotaur has slain the mightiest warriors of all Athens?"

How, indeed? Of a sudden, Burke wanted no more of such questions.

He cut in flat and hard: "Shut up, wench!"

The girl stopped as short as if he'd slapped her. Her face paled with anger.

Only then, as she stared up at Burke, that too passed, and a mask of sudden fear came to replace the fury. Her naked breasts lifted with a quick, indrawn breath. She fell back an uncertain step ... another ... another.... "My lord—Dionysus—"

Burke laughed harshly. "All right. Call me that if you want to." And then, tight-lipped: "Because make up your mind to it, you're going to do what I say as if I were your whole damn' pantheon!"

He closed in.

The girl pressed back against the wall now—white to the lips, dark eyes distended. "Dion—Dion Burke—"

Burke gripped her wrist. "Is it agreed, then? You'll do what I tell you?"

His lovely captive winced as he twisted. "But—my lord—the Minotaur—Dion, it will slay you!"

"Maybe. And then again, maybe not." Burke brushed a hand against the revolver in his waistband. "You see, I won't be on quite the same spot as those others who died, Ariadne. I've reserved a couple of special Dionysan thunderbolts to try out on your monster, patent of two subsidiary gods named Smith & Wesson."

"But Daedalus—he's my father's man, Lord Dion, chief of all the palace craftsmen. He'd never help you, even if you could reach him."

"I'll reach him. And he'll help me."

"But why, my lord? Why risk it?" A sudden taut, eager note crept into Ariadne's voice. With her free hand, she smoothed the fabric of Burke's shirt. "Don't you see? There's no need—not when you've the power to come here as you have tonight, in spite of all my father's guards! Under his very sword, we can be lovers—"

Burke smiled bleakly. "I'm sorry, princess. I wish it were that simple."

"But it is!" Now Ariadne's lithe young body once more was tight against his. "I want you to come, my lord Dion! I welcome you—"

"I know. And ... I love you too." For the fraction of a second Burke let his arms tighten around her.

Then, abruptly, he pushed back; gripped her shoulders. "You see, I can't just come and go at will, the way you seem to think I can. And even if I could, it wouldn't help."

"It would not—?" Blank bafflement spread across Ariadne's lovely face.

"Not after tonight."

Puzzled eyes. A wordless question.

Burke said tightly, "By tomorrow there won't be any Knossos. The Great Palace here, the shrines, the other buildings—as of midnight tonight, less than an hour-and-a-half from now, they'll all be destroyed."

Tension, spiraling higher with each passing second.

Burke said, "Now you know why I came tonight, Ariadne: because this is the last chance I'll ever have. I've got to get you out of here, now or never. That's why I have to see Daedalus, and go into the Labyrinth, and meet the Minotaur and kill it."

Still the silence echoed.

A numb despair seeped through Burke. Bleakly, he wondered how he ever had been fool enough to think his words might spark response in a Bronze Age mind, or that any such mad enterprise as this could possibly end otherwise than in disaster.

Only then, while he watched, once more Ariadne bowed her head and crossed her hands upon her breasts. Her words came low, submissive: "The quarters of Daedalus the Smith lie close at hand, my lord."

She turned as she spoke.

Heart pounding, Burke walked with her towards the doorway....

There was a guard in the corridor beyond the Queen's Megaron.

Wordless, Burke flicked a glance at Ariadne.

Her dark eyes flashed a daredevil acceptance of the challenge. Sliding past him, she swung the heavy door back so it hid him, then leaned against it, body arched in practiced coquetry.

The spearman outside straightened just a fraction. His chest swelled and his belly drew in.

Slowly, Ariadne's full lips curved in a smile that was all invitation. Her hand came up to smooth her hair as she turned, twisting and preening. Then, still unspeaking, and with one last lingering glance over her shoulder, she drew back into her own apartment.

The guard's head swiveled as his eyes followed her.

Ariadne laughed softly from the shadows. Her long skirt swirled and rustled.

The guard's breath rasped in the stillness. For an instant he hesitated, peering down the hall in both directions. Then, eagerly, he crossed the threshold and moved with swift steps towards the princess.

Burke waited till the man was clear of the door. Then, savagely, the Smith & Wesson flat on the palm of his hand, he stepped forth from his hiding place and smashed a blow to the back of the other's neck.

The guard's knees hinged. He spilled to the floor.

Burke snapped, "Quick! Cords! A gag!"

The shrill, nerve-jangling squeal of cloth tearing echoed. Deftly, Ariadne thrust strips from a drape into his hands.

Burke bound and gagged the guard, then straightened and strode across the room to where bull-necked, snoring Theseus lay, the stench of sour wine still thick about him.

Ariadne came close. "More cloth, my lord?"

Burke prodded the Greek ungently with his toe, without response; then once more glanced at his watch.

Ten forty-five now.

And that left only an hour-and-a-quarter more, at best.

The back of Burke's neck prickled. "Forget it," he clipped. "The Hero of Athens is too drunk to turn over, even, let alone give us trouble."

"This way, then," the girl said. Her voice all at once was not too steady, and the hand that gripped Burke's showed a tendency to tremble.

Together, they made their way from the apartment, down the corridor past a row of great painted jars and, finally, out onto the long ascending ramp that led to the palace's central court.

Now Ariadne turned right, keeping to the shadows of the colonnaded buildings past which they moved.

Close behind her, gun in hand, Burke tried to watch all ways at once. Every rattling stone, every wind-tossed branch against the cloud-blocked sky, became for him a trigger for new tension. Once, when the shadows behind him flickered, he almost persuaded himself that Theseus must be on their heels. Or perhaps, somehow, they'd caught the attention of another of old Minos' guards....

Again Ariadne veered right. A door creaked as she put her shoulder to it.

This corridor was so black Burke had to grip the girl's hand to keep contact with her.

More doors. More halls. More rooms. The place was like a maze—the very Labyrinth itself.

Yet not once did Ariadne hesitate. Swift, sure, she led Burke on and on through one murky chamber after another.

Then, as they rounded a final corner, a block of greyness came to mark the end of a passage. In seconds, they were once more out into the open and the night.

Ariadne paused and pointed. "That's the place," she whispered.

"Daedalus' quarters?"

"Yes."

Narrow-eyed, Burke studied the looming bulk a moment. Then, tight-lipped, he strode towards the geometric shadows that marked the entrance.

But now Ariadne caught his arm. "Please, my lord Dion—let me be the one to talk to Daedalus."

"Let you—?" Burke stared. "But why?"

"You wish him to speak, do you not—to tell you the things you seek to learn?"

"Do I want him to talk—?" Burke spoke between clenched teeth. "Believe me, it's more than that, Princess. He's got to!"

The girl laughed softly in the darkness; and somehow there was a ring of steel beneath the velvet. "That's why I must be the one to face him, Lord Dion!"

Without waiting for further word from Burke, she stepped forward and knocked upon the door.

No answer. After a moment, she knocked again.

This time, a faint stir of sound rose from within. Then, abruptly, the door opened, framing a brawny, bearded man who glowered out at Burke and the girl from below a sputtering, hand-held lamp.

Uncowed, without hesitation, Ariadne stepped forward. "Come, Daedalus!" she chided smoothly. "Would you leave your master's daughter standing here wind-whipped on your threshold in the night?"

The belligerence vanished from Daedalus' face, replaced by an impassive, noncommittal mask. For an instant his eyes flicked to Burke. Then he stepped back heavily; opened the door wider. "Enter, my princess. What brings you to my poor quarters at this hour of the night?"

Uninvited, ignoring the hostility that gleamed in their host's deep-set eyes, Burke followed Ariadne in and closed the door behind them.

Simultaneously, the girl said, "It was a terrible thing for you to do, Daedalus! Did my father know it, he'd have you flayed alive!"

Even Burke rocked back on his heels: the words were that much of a shock, that unexpected ... cool, conversational, without preliminary.

As for the smith, he stood very still. The deep-set eyes seemed to retreat yet further into the broad, high-domed skull.

"And what is this terrible thing of which you speak, Princess Ariadne?" he asked finally.

"What is it—?" Ariadne's eyes distended, then narrowed. Her voice took on a taut, dangerous note. "Do you think to mock me, artisan? Me, daughter of Minos, favored beyond all women of this realm?"

Daedalus' hairy chest rose and fell in heavy, almost deliberate rhythm. Turning, he crossed with short, clumping steps to the nearest stand and set down his lamp, then made a small business of straightening the wick.

"What black slander is this, princess?" he asked coldly, eyes still on the flame. "What are you trying to say I've done?"

"Would you deny it, then?" Like a sleek cat stalking, Ariadne moved round him in a long, slow arc. "Or do you seek perhaps to saddle poor Icarus with the blame?"

"Icarus—!" The smith's head lifted sharply. "Whatever this deed is that you speak of, my son had nothing to do with it!"

"Do you count it nothing for a youth to enter secretly into my apartment, then assault a guard when he's surprised?" Ariadne's lovely face fixed into a mask of scorn. "Ambition ill becomes you, Daedalus. For a man who'd plot such a thing, risk his own son's life to gain power over me, you show little courage and less sense."

Before Burke's eyes, sweat came to the smith's broad forehead. A tremor ran through the heavy hands. "May the gods bear witness, Ariadne, you know I've done no such, and so does your father!"

"And of course he'll take your word over his own daughter's." Ariadne laughed without mirth. "Tell me, smith, are you such a fool as to think your fiend's work with my mother, Pasiphae, is so soon forgotten?" And then: "Besides, you know all the secrets of the palace—a dangerous knowledge. My father will leap at an excuse to slay you!"

Daedalus rubbed at his beard with thick, scarred knuckles. His lips had a dry, parched look, and his breathing was ragged and uneven.

Coolly, Ariadne turned and walked away from him, to Burke. "Come, my lord Dion! Let us waste no more time on this numb-skull."

Daedalus' head seemed to sink down between his great shoulders. Through clenched teeth, he said, "All right, curse you! What is it you want?"

"What do you mean, smith?" The girl stayed remote as some slim statue. "Are your wits slipping? You know I've asked for nothing."

Head high, a picture of poise, she moved towards the door. Stiffly, Burke fell in behind her.

For a moment, Daedalus stood flat-footed, rigid.

Then, abruptly, he too was moving towards the door. For the first time, his voice held a raw, uncertain edge, as if touched with panic. "Princess—most favored of Minos—please—"

Ariadne paused. Her dark eyes glinted soaring triumph in the instant that they touched Burke's. "Please indeed, Daedalus! After all, I came here tonight but to satisfy a whim. This outlander,"—a gesture to Burke—"vows there's no access to the Labyrinth, the Minotaur, save by the Shrine of Oracles.

"For my part, I argued that you, who laid out that whole area of the palace, could enter any chamber, no matter how well the doors were guarded." A shrug. "All the talk—it ended in a wager. So, now, I count on you to prove me right, show some secret way by which, if necessary, a determined man could invade even the Minotaur's most secret precinct undetected."

The beads of sweat on the smith's broad forehead began to merge into rills and trickle down into his eye-brows. "Princess, were I to tell this outlander such a secret—believe me, you ask me to gamble with my life!"

"Yet if you do not tell," Ariadne retorted calmly, "what will happen will involve no gamble!"

Seconds ticked by while the heavy-thewed chief of craftsmen stared at her. Then, bleakly, he said, "Very well, princess."

Another long pause, with Daedalus frowning and tugging at his lower lip.

At last: "The only unguarded way to the Minotaur leads through the drainage system, the great sewer-pipes that lie beneath the palace."

Burke frowned. "You mean, you'd drop through a manhole here—anywhere on the grounds—and then come up again inside the Labyrinth?"

"Exactly," the smith nodded.

"But how would you know when you reached the right exit?"

"Only one connects with the Labyrinth. A cage of bars cuts off the pipe at that point, so no workman may by accident come up within the Labyrinth and thus meet his doom."

Narrow-eyed, Burke brooded on the things the smith had told him.

But now Ariadne broke in; and all the poise she'd shown brief moments earlier had vanished: "Dion—you mustn't! Don't you see? This is a trap. Even though you were to slay the Minotaur, you'd never find your way back to safety through all that maze of pitch-black tunnels!"

"On the contrary, princess." Burke smiled thinly. "This is one advantage of coming here from another time. It tells me in advance so many of the things that are scheduled to happen."

Ignoring her obvious blank bafflement, he again spoke to the smith: "Daedalus, do you have cord here—light, strong line such as you use in laying out the walls of each new building?"

"Yes."

"Then get some for me."

The brawny craftsman crossed to a chest against the wall; brought out a thick skein of twine. "Will this do?"

"Is it long enough to guide me to the Labyrinth?"

"Yes."

"Then that's all I need from you." Burke turned to go.

"Wait!" This from Ariadne. Her dark eyes pinned their host's deep-set orbs. "Daedalus, I've a promise to make you."

"A promise—?"

"A vow, if you will." Never had Ariadne looked more beautiful—or more deadly. Her smile held the shadow of impending doom. "For if there's any trick to this, smith, or if word should reach my father of what's happened here tonight, I swear an hour will come when you'll pray for death to end your agonies!"

Then she and Burke were out in the night again, silent as shadows, feeling their way back through the murky maze of alleyways and corridors and buildings to the central court.

Burke pulled the girl to a halt there, in the narrow slot between two pillars. "Where are we going?" He held his voice low; spoke with his mouth close to her ear to compensate for the buffeting of the wind. "We can't chance your rooms, you know. That guard's snapped out of it by now."

"Of course. I've a place in mind across the court, closer to the shrine."

"All right, then."

But again, as before, tension rose within Burke. A guard's shouted challenge somewhere far off started him sweating. When the low, mingled laughter of a man and a woman drifted from a nearby window, he froze in his tracks.

The role of hero, he decided, ill became him. He thought too much of consequence and peril; found it too difficult to lose himself in an emotional haze of recklessness.

Yet here, now, he had no choice—not feeling the way he did about Ariadne; not knowing the things he knew from that brief session before the inverter's scanning screen.

And the time remaining was so short ... less than an hour, as of this moment.

"This way, my lord Dion."

Wordless, once more Burke fell in behind the girl.

Their destination proved to be an ornate suite where Burke stumbled over furniture in the darkness.

Ariadne squeezed his hand. "No one will disturb us here—those who occupy this apartment are visiting at Phaestos." And then, changing position: "I've a lamp. Give me fire."

Burke fumbled out his lighter; flicked the wheel.

The flame showed his companion close beside him. In seconds, the lamp she held was sputtering to life.

The girl turned quickly. "There's a manhole back here, in the ante-room to the bath."

She led Burke to it as she spoke; held the lamp low so he could see the cover-slab.

Dropping to his knees, he heaved the heavy stone aside.

Instantly, new air-currents swirled about him. A mustiness assailed his nostrils.

Somewhere, along that black tube below or another like it, the Minotaur was waiting.

A knot drew tight in the pit of Burke's stomach. Rising, he tossed Daedalus' thick skein of cord down by the base of the nearest lamp-stand, then faced Ariadne.

"Thank you for your help, my princess," he said gently. "Now, though, it's time for you to go."

"To go—?" She stared at him, dark eyes suddenly wide. "What byplay is this, my lord Dion? Surely you'd not ask me to leave you now, in the hour when your worst danger is upon you?"

Burke forced a wry smile. "Do you remember what happened the other time when you refused to carry out my orders?"

"You mean—when you hit me?" Gingerly, the girl's fingers moved along her bruised jaw as she spoke.

"Precisely."

"But my lord Dion—"

Burke stopped smiling. "I'm sorry, Ariadne. You're not going with me. That's final. If you try, if you won't promise to go back to your own apartment, I'll knock you out and tie you up. Is that clear?"

He started forward as he finished—face set, fist doubled.

But the girl gave not an inch before him. Stepping in, instead, she stood very close, face upturned to his.

"My lord Dion," she said softly, "I tell you now: you're the bravest man I've ever seen."

It threw Burke off balance. He could find no words with which to answer.

The girl said, "I promise you, you needn't worry for me; a warrior should not have to think of women, or fear for them. I'll await you at my own apartment."

Burke groped. "Ariadne—"

It was as if he hadn't spoken: "Remember, you have my promise. But if anything should go wrong, if I'm missing when you reach my quarters—Lord Dion, do you know the River of Amnissus?"

"Yes, of course."

"To its left, where it meets the sea, a headland rises. So, if fate decrees that I must flee from Knossos, you can expect to find me there."

Her slim, soft arms were round his neck, then; her lips on his for a long, pulsing moment.

When it ended, she was sobbing, her cheeks tear-streaked.

"Dion ..." she choked. "Please my Lord Dion, come back to me! Without you—"

She broke off; whirled and fled.

For a long, long moment, Burke stared after her, straining his eyes against the black encroachment of the night.

Then, abruptly, he dropped to one knee and set to looping one end of Daedalus' cord around the lamp-stand—tying it tight; tugging and testing it.

Sound stirred behind him, a faint whisper.

Burke bit down hard. "Damn you, Ariadne!"

No answer.

Another fragment of sound. A footstep.

A footstep far too heavy to be Ariadne's.

Burke went rigid; started to turn.

Only before he could even bring his eyes up, something clouted him a terrific blow to the side of the head, so hard it knocked him clear off his feet and against the wall beside him.

Desperately, he tried to roll clear, get his gun out.

But his eyes blurred. His head rang. A sandaled foot kicked the Smith & Wesson out of his fumbling fingers before the weapon had hardly cleared his waistband.

And now, a tremendous weight crashed down upon him. Blows rained to his face, his rib-cage, his belly. A knee drove for his groin. Cable-muscled fingers clutched his windpipe.

Burke choked on his own tongue. The fingers cut off his breath. His head spun. His chest heaved—lungs aflame, convulsing in agony.

Then spidery tendrils of blackness seeped into his brain. His will to fight ebbed. He felt himself drifting away, as on a swift-flowing stream that plunged into a cave's dark, swirling shadows.

Cautiously, the fingers relaxed on his windpipe.

Burke fought for breath in short, tremulous gasps. He didn't have the strength in him even to fill his lungs fully, let alone try to renew the battle.

The fingers left his throat and fumbled at his wrists; then his ankles.

Burke began to get better control of his breathing. Forcing himself to ignore his aching head and battered body, he pried his eyes open.

Bull-necked Theseus squatted by his side, leering down at him. The Greek gripped the Smith & Wesson in one hand, and every line of his face and stance mirrored gloating triumph.

Cold with rage—or was it partly panic?—Burke stared up at his captor. But when he tried to move his arms to lift himself, he found that they were bound together.

Beside him, the Athenian chuckled unpleasantly. "That Minos is smart, isn't he?"

Burke stared. "Minos—?"

"Sure. He told me I'd catch you if I just played drunk long enough." The other's smirk broadened. "That's how much he hates you, see? He said he'd let me and the others go, forget all that crazy stuff with the Minotaur. All I had to do was grab you before you could sneak away someplace with Ariadne."

It was all Burke could do to keep from groaning.

If Theseus noticed, he ignored it. "Me, I've got a better idea. Something really clever. You'll love it."

A small chill ran through Burke. He still didn't speak.

Theseus said, "You want to get at the Minotaur so rotten much—well, I'm just the boy to help you do it, now you've worked all the details out with that Daedalus and Ariadne." A leer. "We'll handle it just the way you planned it: drop into the sewer-tunnel here, then hunt till we find the manhole into the Labyrinth."

The burly Greek got up as he finished. "All right. On your feet!"

By way of emphasis, he kicked Burke in the stomach.

Retching, Burke lurched over to a face-down position and tried to rise.

Stumbling erect proved difficult enough. Then, on his feet at last, he discovered that his captor had hobbled his ankles also, so he could move only in short, awkward steps.

Now the Athenian gestured to the open manhole that led into the sewer. "Hurry it up! Get down there!"

Awkwardly, Burke shuffled towards the opening.

Apparently he moved too slowly for his captor's tastes, for a sandaled foot took a leg from under him and he spilled to the floor and half-fell through the hole.

Then he was down in the cool, drafty blackness of the great drain. A moment later, Theseus joined him, a lamp in one hand, Daedalus' cord in the other. The revolver he'd taken from Burke was thrust into his loin-band.

Together, with Burke pushed into the lead, they moved along the tunnel.

It was a nightmare, after that—a nightmare of slime and smells, sudden winds and water. Snakes slithered across Burke's feet. Cobwebs brushed his face. The lamp's gleam was a pinprick in an infinity of darkness. A dozen times they struck dead ends; retraced their steps out of blind alleys. And each time Theseus raged with greater fury, till Burke's back and hips were numb with blows and kicks and buffets.

And then, suddenly, they came to a place where a cage of bars blocked off the passage.

Burke's heart leaped. A tight band seemed to constrict his chest.

But before he could even speak, Theseus elbowed him aside with new blows and curses. The Hero of Athens was breathing hard; even by the lamp's feeble light, his eyes showed distended.

Looping the heavy skein of twine over his shoulder, the Greek now gripped the nearest bar in a brawny hand and shook it.

It didn't even quiver.

Snarling, Theseus stepped back and, lifting the lamp, scrutinized the terra cotta of the tunnel wall till he found a crack-formed ledge wide enough to hold the light. Then, returning to the bars, he seized one in both hands and heaved on it while he braced a foot against another.

Still nothing happened.

Again the Athenian heaved, and this time every muscle along his back and arms and legs swelled. His belly drew into heavy ridges. Veins stood out at throat and temple.

For the instant, even Burke couldn't help but watch fascinated at the picture of sheer physical strength displayed.

And now, ever so slowly, one of the bars began to bend ... the merest fraction ... an inch ... a hand's breadth....

Then, suddenly, with a dull metallic twang, the piece tore loose from its fitting.

The sound broke Burke's spell. Convulsively, he strained at the bonds that held his own wrists.

They only cut deeper into the flesh.

And there was so little time....

Warily, Burke cast a sidewise glance at the revolver, still hanging at the other's waist. Then, as casually as he could manage it, he started moving closer.

Now, panting with exertion, Theseus turned his attention to a second bar.

This time, he had more room to maneuver. Almost from the first moment, the metal showed signs of twisting.

Burke took yet another sidling step—a step that brought him within arm's reach of the Smith & Wesson. Clumsily, he poised, readying himself to spear out for the butt with both hands as one.

A groan escaped Theseus as he wrenched at the reluctant bar with all his might. Little by little, the heavy metal bent.

Burke snatched for the gun.

Only as he did so, incredibly, the weapon wasn't there. His hands slapped Theseus' sweat-greased side instead.

Simultaneously, a fist like a maul smashed him full in the face: The Athenian's harsh laughter rang in his ears. He crashed back against the sewer-pipe's wall like a doll flung aside by an angry child. Words hammered at him; Theseus' words: "I wondered when you'd try that, you outlander dog!"

It was all Burke could do to keep his feet, let alone answer.

The Greek snarled, "Now's a good time to tell you the rest of it, too, rack you!"

Burke tried to blink away the haze between them. "The rest of it—?" he mumbled.

"That's right; the rest." His captor gloated openly now. "You didn't think I dragged you through this hell-hole just for entertainment, did you, when all I needed to do to get rid of you was hand you over to Minos?"

Burke didn't answer.

Theseus scowled, spoke almost as if to himself; "That slut Ariadne—I'll teach her to scorn me for an outlander! Once I've shoved you up through this manhole into the Labyrinth, where there's no chance for anyone but the Minotaur to find you, alive or dead, I'm going to go explain to Minos all about how you took me unawares and almost killed me, back there in Ariadne's quarters. He'll believe me, because it fits right in with what that guard you tricked will tell him.

"Then, while Minos has everyone out hunting for you, I'll take Ariadne down to where my ship lies anchored at the mouth of the Amnissus. By the time Minos realizes what's happened, I'll be gone, with his daughter with me; and she'll be good for nothing but to be queen of Athens, so he'll have no choice but to make peace with my father, no matter how it galls him."

The hair along the back of Burke's neck prickled. Of a sudden he saw how he'd vastly underestimated Theseus. Because the man looked like a handsome, stupid, dissipated block of beef, Twentieth Century intellect had sneered at him.

Only Theseus had a schemer's brain, as well as a Greek God's face and physique. And what looked like stupidity came out as an almost oriental taste for the un-prettier types of vengeance.

All of which added up to nothing less than disaster.

Keeping his voice level with an effort, Burke said, "Theseus, you hate me, and I don't blame you for it. For that matter, I hate you too.

"But right now, there's no time for either of us to indulge his feelings. This is too big for that. Knossos falls tonight. It's going to be destroyed—soon now, within the hour.

"Unless we kill the Minotaur, Ariadne dies too. There'll even be other Minotaurs, not just here but all over the world. That's why I wanted to get into the Labyrinth—"

Laughter exploded in Burke's face.

It was a better answer than words. Tight-lipped, Burke groped frantically for some new plan, some trick, some lingering straw of hope to cling to.

Theseus said, "Don't worry, outlander. You'll get your chance at the Minotaur."

He stalked forward as he spoke; poised a doubled fist close by Burke's jaw. "Just remember, though: while you're taking care of the monster, I'll be taking care of Ariadne!"

The poised fist lashed out. When Burke tried to jerk his head aside, Theseus' other hand came up in a casual, almost lazy arc and slapped it back into place.

Fist and jaw met. Burke's brain exploded inside his skull. The flickering lamp seemed to burst into a blaze of dazzling, kaleidoscopic stars.

Then, one by one, they faded. Blackness closed in....

The feeling, Burke decided, basically was one of frustration—a moiling, roiling, boiling tension that crept higher and higher as his own helplessness became the more apparent.

Well, what else could he expect, in a situation sprung from monomania's loins? From the beginning, everything about this business had had the spell of madness on it. Success, when the cards were down, had always been too much to hope for.

Now, thinking of it, Burke could only sigh bleakly and shake his head.

Only that wasn't quite true, either. For his head wouldn't shake, and his sigh held neither sound nor breath.

How had it all come about, this nightmare? Where had it started, really?

With the Research Professor?

With The Girl?

With The Director?

But no. In his heart Burke knew that none of them held the answer.

Because the beginning lay farther back ... so much, much farther....

... All the way back to the old, dormer-windowed house amid the elms, and his childhood, and the Bowl of Minos.

The bowl....

He could still remember the first time he saw it, lying in a litter-heaped trunk up in the attic.

Fascinated, he'd picked it up and run stubby fingers over the stylized Minoan octopus that stood out in bold relief upon its surface, till it seemed he could almost feel the twining tentacles' pressure.

It brought a queer sense of excitement to him ... a sort of paradox of feeling that made him thrill to the bowl's beauty even while he stared at the creature that served as its decoration with a strange, shuddery sensation close akin to horror.

Then his mother saw what he was doing, and took the pottery vessel from him, explaining the while about the footloose, adventuring uncle who'd brought it here all the way from Crete.

A lump formed in Burke's throat as he recalled her patience ... how when she'd found him returning again and again to the attic and the trunk, she'd brought the bowl down and given it a place on the livingroom table, where he could examine it all at will.

Someone even told him about Minos and Theseus and Pasiphae and Ariadne and the Minotaur, and all the rest of the legendry that went with Bronze Age Crete.

Yet the legends were never quite enough. They raised too many questions; left too much unsaid.

The fragments of fact he picked up proved even less satisfactory.

How had a civilization rich and powerful and advanced as that of the Minoans ever risen on a sea-isolated island such as Crete?

Where had the Minoans learned their skills, their arts?

Above all, why had their culture vanished? What brought about Great Knossos' fall?

Questions without answers, all of them. Mysteries like the Cretan's strange, undeciphered writing, and the final fate of lovely Princess Ariadne, Minos' daughter, and how Theseus, bare-handed, could have slain the mighty Minotaur.

It was all enough to drive a seven-eight-nine-ten-year-old boy to distraction!

Then a careless visitor's elbow knocked the bowl to the floor. It shattered into shards.

At ten, a boy's too old to cry—before company, at least. So he'd clenched his fists behind his back, and blinked back the tears, and held his mouth to a stiff white line till he could be alone, face pillow-muffled, behind the closed door of his room.

And from that moment he'd known that sometime, somehow, he himself would find his way to Crete.

School became a place where he greedily snatched up crumbs of mythology and history between dreary hours spent battling his way through all the other subjects his teachers demanded that he learn.

High school brought a broader view. He began to see the interrelatedness of learning. Literature, chemistry, physics, Latin—of a sudden he found he loved them all.

Yet always, always, there ahead lay Knossos, beckoning.

How old had he been when, avidly, he plowed his way through Sir Arthur Evans' "Palace of Minos", groping his way by context past all the unfamiliar words? Thirteen? Fourteen?

By high school commencement time, he no longer cared that his parents couldn't understand his passion for things Cretan.

College, then. Major in anthropology, minor in classics. Greek now, as well as Latin. Linguistics, too. Comparative cultures, technical photography, ethnological methods, archaeological methods, museum methods. Year after year, course after course.

And always, the same goal. Let others weigh and choose between Yucatan and Oceania, Murdering Beach and the Valley of the Kings. For him—ever; always—there was only Minos and Knossos and Bronze Age Crete.

Dion Burke, B.A., now, Dion Burke, M.A.

Then, the last step; the final goal: the onward, upward march to Doctor of Philosophy, Ph.D.

Or rather, not quite: not quite Ph.D.

And that was where The Director came in.

Burke cursed the day he'd met him.

A kindly soul, The Director, by his own statement, in spite of his scowl and beetling brows and jutting, heavy-boned, prognathous jaw. So fascinated by all things Minoan. So happy such a brilliant student had selected this most benign of all universities as the one at which to work for his doctorate.

It was only a step from there to casual acquaintance with The Research Professor.

The Professor was the first universally-acknowledged-as-authentic genius Burke had even known. Even the man's colleagues on the staff of the university's Science Institute agreed that he knew more about certain aspects of electronics than anyone alive.

The Professor, it developed, wanted Burke's collaboration on a project—a device he termed a "computational translator" which he felt might solve the riddle of the mysterious Minoan language, if only its hieroglyphics could somehow be reduced to sound.

That was when Burke brought out his own idea, his madman's dream for the ultimate archaeological tool.

An inverter, he called it; a time inverter, designed to carry researchers back bodily into the past.

The Professor scoffed openly when Burke first told him about it.

The second time, he frowned and tugged at his pointed chin.

The third found him already at work.

The computational translator, and the time inverter. Two lunatic concepts, born of monomania and genius.

Two concepts that, it appeared increasingly, just might work.

Time out for Korea ... Chinese communists in quilted coats ... blood and iron and freezing death.

Well, at least it would pay for the rest of the doctorate, under the GI Bill.

If he lived through it.

The notice of the car crash reached him at Heartbreak Ridge.

No mother now, no father. Just an inheritance.

More courses, more digging, more Professor's letters, pulsing excitement and jubilation for all their veiled language.

Home again. Back to the university. The shock of seeing at first hand just how far The Professor had gone; how short a distance there remained to go.

And then, at last, The Girl, and the old line about passes and glasses turning out not always to be true after all.

More courses, more digging, more months slipping by. The discussions, increasingly acerbic, as it developed that The Director was a stiff-necked, belligerent bigot who classed Sir Arthur Evans and God in that order when it came to authority on matters Minoan.

The Girl, encouraging, all intellect and well-bred adoration. The Professor, designing a new-type radiation detector to help search out the truth about Knossos' fall, just in case they never did get the time inverter to work properly.

The Director, adamant.

The inverter, failing again and and again.

The faint, nagging disappointment of discovering that The Girl could discuss the courtship customs of Papua and Parthia and Patagonia in detail, yet still hold a man at arm's length here on the campus.

But still, there was his dissertation to sustain him, his long-planned trip to Crete to cling to. Even if it took every penny of his inheritance, even if The Girl wouldn't marry him and go along because he still lacked his degree, the journey couldn't help but prove worthwhile.

By air, to London. Then to Athens and the British School, to complete contacts.

Finally, down across the Aegean to Crete itself.

He had to shove his hands deep into his pockets to hide their trembling when first he stepped from the car at Knossos. Even seeing the reconstructed palace with his own eyes shook him that much.

The British, polite and helpful as they tried to hide their amusement at the use of the detector. The Cretan workmen, exchanging glances that said openly that he was surely mad.

And then, the needle, going crazy—trying to bounce clear off the dial. The headphones, buzzing till his ears hurt.

Endless hours of aching to talk to someone, yet not daring. Long days when the right words for the dissertation just wouldn't come.

And the words had to be right, exactly. He couldn't content himself with anything less. The whole dissertation—every page, every sentence, must be logic-grounded, solidly-documented, overwhelming evidence to prove his hypothesized explanation of the fall of Knossos.

He finished it, finally ... came home again ... turned in the first draft....

Then came that day in The Director's office. That ugly day, the last Burke was to spend in his own time and place.

The argument; the tempers, rising.

The Director—face flushed, jaw outthrust: "You young whelp, how dare you contradict Sir Arthur Evans? Would you set yourself up on a level with Hogarth? Pendlebury? Wace?" And then, the final knife-thrust: "Very well; have it your way. But so far as I'm concerned, I'll not accept this dissertation, now or ever. And so long as I'm here, you'll receive no doctorate, let alone a recommendation of any sort!"

Exit The Director. Forever.

Then, The Girl: "But Dion! Why did you have to be so stubborn? You could at least have kept your opinions to yourself till later. Now—well, how much of a field is there for an archaeologist with only an M. A. degree? You might as well forget Crete right now. And for my part, I must admit the idea of being the wife of an instructor in some second-rate college, at four thousand a year hardly appeals to me."

Exit The Girl. Forever.

The Research Professor, finally: "Damn it, Burke, I just don't dare to back you on it! Old Ape-Jaw's got the president's ear. If I even let it be known I designed that detector, I'll be operating this laboratory on a negative budget next biennium."

Exit The Professor. Forever.

In spirit, at least.

In body, though, he still might have his uses.

Burke held his voice carefully level. "In other words, then, you won't even let me use your name as supporting authority for my statement that the ruins at Knossos still show radiation traces?"

The Professor: "I'm sorry, Dion."

"But the time inverter—"

"Are you completely insane, boy? I built that thing with university funds. If anyone should find out about it, and that I didn't have proper authorization for it—well, all I've got to say is that I'm going to junk it first thing in the morning, before The Director has a chance to snoop around."

What happens to a man when he plunges into that deep a pit? How many blows can he take before he cracks?

Burke didn't even recognize that it was raining when he stepped out into the street.

Dully, he tramped through the gathering dusk. Block after block, mile after mile, hardly aware that his clothes clung to his body, soaked, or that water sloshed in and out of his shoes with every step.

Slowly, then, his thoughts began to sort themselves into some sort of order. A little at a time, conclusions took form and gave strength.

When it came right down to it, he didn't give a hang whether he ever achieved a Ph. D. degree or not.

So to hell with The Director!

As for security, a job, he'd lived through Heartbreak Ridge; and after that, any more economic peril came out as strictly anticlimax.

Losing The Girl—well, he had no choice but to admit it bruised his ego. Yet, on the other hand, it relieved him of all the gnawing inner doubts, the secret hesitations at her coolness.

The Professor? Another disappointment. But the mere fact that an idol's feet turned out to be of clay hardly rated as a unique discovery.

At any rate, he'd survive it.

So, what did that leave of his losses?

He cringed.

That was the way with dreams. They were so hard to give up.

And he'd worked towards this one for so long.

Now, there was nothing left to do but face the facts: he'd never have a chance at Crete; never really know for sure why Knossos fell.

Unless—

Burke stopped short.

What had The Professor said? That he'd destroy the time inverter first thing tomorrow morning?

Which still left tonight, didn't it?

It was a thought to appall any man in his right mind. For while The Professor admitted to small progress with the machine, he also said frankly that he was completely stymied in the most vital area: while he had succeeded in transporting objects from present to past on an experimental basis, he couldn't move them even an instant into the future.

Carrying this a step further, anything sent into the past stayed there. It couldn't be returned to the present.

And that meant that if anyone named Dion Burke should prove so mad as to send himself back to Bronze Age Crete, there he'd stay, with no chance ever of return to Twentieth Century United States.

It was a thought to numb a man.

Yet, was it really so insane?

After all, what was more important to him than that he learn the truth about the fall of ancient Knossos? What else could satisfy him, after all these years?

Even if he died, it wouldn't matter too much. His parents were already gone, his friends mostly on the casual side.

For the first time, now, it dawned on Burke that rain was splattering in his face. It felt good. His clothes and shoes—he didn't even care that they were ruined.

Pivoting, he started the long tramp back to his apartment.

There, for comfort, he took a hot shower; then put on a clean, dry outfit.

It seemed like a good idea, also, to check his watch, fill his cigarette lighter, and stow the old five-shot Smith & Wesson thirty-eight he'd inherited from his father in the waistband of his trousers.

By the time he'd completed all such arrangements, the rain had stopped. Here and there, stars shone amid the thin clouds overhead.

Head up, shoulders back, Burke strolled along the wet, glistening walk towards the campus. He felt somehow detached, apart from the world about him, and it was a good feeling, even though he also enjoyed the smell of the rain-soaked earth, and the way leaves had piled up in little dams along the gutter, and the hissing, whispering sound of tires on wet pavement every time a car went by. Once he even caught himself smiling a little, a small, quiet, secret smile, over the way The Director and The Girl and The Professor each in turn had looked as they took their stands and walked out of his life.

The main door of the Science Institute was still unlocked, so Burke went on in, pausing only to nod pleasantly to a campus policeman who happened to pass by at the moment.

The laboratory had a glass-paned door. Without hesitation, Burke rapped a hole in it with the butt of his revolver, reached in long enough to turn back the bolt, then stepped inside and locked the door again behind him.

Now he turned to the inner room where The Professor dealt with his most private matters.

The first thing he noted upon entering was a cluttered desk, on one corner of which lay a flat box perhaps five by eight by two inches in size.

That pleased him, for by its grilled front he recognized the thing as the incredible, transistor-packed device The Professor described as a "computational translator." Experiments with assorted foreign students and American Indians of various tribes indicated that it would enable a man to conduct a successful two-way conversation in any language.

Strapping the box in place flat against his belly, Burke moved on past the desk.

Beyond it, around a corner, loomed the time inverter.

It was a cumbersome-looking thing, a cramped platform suspended amid grids of wire. Each grid, in turn, fitted within a larger framework appropriately equipped with calibrated spindles, so that the grids' relative position to each other and to the inner platform could be adjusted at will.

To one side, a neat control-board occupied a wall-space. A larger area was given over to a screen somewhat like that of a television set.

Warily, Burke picked his way over to the screen. Now that he was here, his stomach showed a strong tendency to quiver. Despite all the long nights he'd spent in this room with The Professor, he found himself doubting his own ability to operate the inverter. As for the theory of the thing, that was completely beyond him.

But it was no time for doubt. Switching on the power, Burke carefully set about adjusting the control dials.

Latitude and longitude came first, down to minutes and then seconds. A moment's tuning, and Crete and then the Great Palace of Knossos lay before him on the scanner screen.

Falling back a step, Burke rubbed the nape of his neck where it ached from strain.

Time adjustment, now. A new set of dials.

The screen changed before his eyes. The work of excavation and reconstruction vanished. Off to one side, olive groves appeared. Then a building with unmistakably Byzantine architecture flashed on.

Again Burke twisted the dial. Again.

Now whole towns came and went. One moment, the screen showed neat huts and cultivated fields; the next, ruins or no buildings at all.

But never a trace of people. People moved too quickly for even the finest settings of the time-spindles to show them.

Farther back ... farther ... farther....

And now there was only a great, dark ring on the hillside to mark the palace. Wall-blocks and pillars lay strewn like scorched blocks in all directions. It was as if lightning had blasted the very earth. The few huts to be seen stood far off, as if the site of Knossos were a place accursed, to be avoided under pain of death.

A chill touched Burke; and though he'd seen this sight a dozen times before, his fingers trembled.

Back farther ... farther....

As swiftly as it had darkened, the screen came bright. The palace rose again, white gypsum walls and columns aglisten in the sunlight.

Skillfully, Burke adjusted the detail dial, working forward again to the moment when the palace had crumbled.

The disaster came at night; that was plain to see. And so fast that the screen could not record the instant when it happened. One second, the buildings were there, solid as only rock could make them.

The next, there were only dark, blighted ruins.

Of course, the destruction could conceivably have taken hours, yet still show as instantaneous on the scanner.

But if a man were to go back to a time, say, twelve hours before the cataclysm....

He'd need to choose the right place, too ... somewhere out of the line of palace traffic—that apartment off the Queen's Megaron, for instance.

Not too steadily, Burke set the dials; then straightened.

The realization of his own folly flooded through him in the same instant.

How could anyone be so mad as to sacrifice his life on the altar of sheer intellectual curiosity? What did it matter if he never knew why Knossos fell? To go through with this because he'd been intrigued by an octopus-decorated Minoan bowl as a child of seven—it was absurd. His place was here—in his own time, his own land. To think otherwise could only be evidence of gross imbalance.

He started to reach for the main switch; to turn off the inverter.

Simultaneously, a hand rattled the knob of the laboratory's outer door.

Burke froze.

Now a key clicked in the lock. A voice—the voice of the campus policeman—called, "All right, you! Come on out! We know you're there!"

And then, not quite so plainly, the voice of The Professor: "Be careful, officer. He's been acting queerly—thinks I've some kind of strange machine in there. What he needs is a psychiatrist. But till we can get him to one, he may be dangerous."

The Professor, coppering his bets ... taking no chances on trouble over having misused university funds to finance a private project.

Not even if it involved proclaiming a friend insane.

The final straw, piled on the camel's back.

And only one way out.

Savagely, Burke whipped the Smith & Wesson from his belt; then, tight-lipped, flicked a quick glance along the dials.

The inverter was as ready as it ever would be.

Breathing hard, Burke slid between the wire grids; stepped up onto the cramped central platform.

From the outer room: "Come out, now, Burke! You'll have a chance to prove you're sane—just a few tests, a month or two of observation—"

Burke gripped the activating switch, the lever that would throw full power into the grids.

Again, then, he hesitated.

The campus policeman's head appeared around the corner, peering. To one side, The Professor cried out. "The inverter—! Stop him!"

It was like a wire snapping in Burke's brain. He fired a single shot, high, and simultaneously threw the activating switch in one swift, coordinated flow of motion.

The grid-wires glowed. A tingle of energy pulsed through Burke's body.

The laboratory disappeared....

Burke heard the voices first—strange voices, speaking in a strange language.

The room came clear a moment later, cool and shadowy. Burke recognized it by its shape, and by the distinctive relief in painted stucco on one wall.

So his calculations had been correct. He'd landed in the apartment off the Queen's Megaron.

Cat-like, he moved towards the room's doorway, the voices.

The speakers were man and woman, apparently. And when Burke flicked the switch of the computational translator strapped tight to his belly, he found he could understand them almost as well as if they'd been talking English.

"... and you're a pretty thing, you know," the man was saying. "As a matter of fact...."

His voice trailed off, the last words lost in a rising feminine giggle. "Master Theseus! You're here to see my mistress, not me—"

Warily, Burke peered through the grating of a sort of grilled divider that helped to separate room from room.

The chamber beyond was larger than the one in which he stood. Brighter, too—a typical Minoan light-well spilled noonday sun clear along one side. The furnishings and the octopus frescoes on the wall showed an opulence that spoke of nothing less than royalty.

As for the man and the woman, they were alone in the room, and playing a game as old as time. That is, the man was trying to catch the woman—girl, really—while she strove to stay out of his reach.

Burke decided he could have taken her efforts more seriously if she hadn't kept giggling—not to mention slowing whenever the man gave any sign of pausing in his pursuit.

Then, abruptly, the man leaped across a low table, cutting her off.

The girl promptly tripped, and fell into his arms.

The embrace that followed was a trifle too prolonged for Burke's tastes. When it ended, the girl sighed, starry-eyed, and ran long, supple fingers through her companion's short black hair. "How can a warrior such as you, a hero, even look at a serving-wench like me, Master Theseus?" she murmured.

The man straightened and swelled out his chest; and now Burke saw that he was not only a good six feet tall and powerfully built, but handsome in a somewhat coarse, heavy-featured way.

"I'll deny no wench my favors just because she's of a lower station," he proclaimed pompously. "I've no doubt you'll keep a man as warm as this Princess Ariadne who's your mistress."

The girl giggled. "You mustn't say such things, Master Theseus! Ariadne's the loveliest woman in all Knossos."

"What—?" Theseus' broad brow furrowed, and he stood with mouth half open, looking more than a little stupid. "Are you trying to confuse me, wench? If this Ariadne's such a beauty, why must she send secretly for prisoners from her father's dungeon in order to find lovers?"

An uneasy shadow seemed to fall across the maid's pretty face. She moved restlessly. "It—it's the curse of Pasiphae, Master Theseus."

"The curse of Pasiphae—?" Theseus looked blank. "What's that, wench? Tell me of it."

"Of the curse?" The girl's smile grew suddenly stiff, and her hands moved in a small, nervous gesture.

Then, quickly, she came close to her barrel-chested companion and slipped her arms about him. "No wonder you're the pride of Athens, Master Theseus! Close to you this way, I feel your strength. It brings a woman all sorts of thoughts—"

Belligerently, Theseus scowled and pushed her back. "None of that, wench! This curse—tell me about it!"

The girl drew a deep, unhappy breath, "If you must, then—" And, after a moment's pause: "You know, of course, that Pasiphae is King Minos' wife; Ariadne's mother?"

"Yes."

"And also that she lusted after the sacred bull of Zeus—"

"—and so gave birth to the monster in the Labyrinth, the Minotaur? Of course. Who hasn't heard it?"

The maid looked round almost fearfully. "Do you not see, then, Master Theseus? There's the curse! Ariadne's daughter of a woman who's defied all the laws of gods and men. Who knows what evil may befall the child? So, no youth dares even look at Ariadne, no matter how great her beauty."

Theseus' jaw sagged for a moment. Then he bristled. "It's not because of my fame, then, my prowess as a lover, that she sent you to bring me here in secret?"

The maid bowed her head. But from his vantage-point, Burke could see her hidden smile—quick, minx-like. "She seeks only to escape her destiny, Master Theseus. In you, hero that you are, she sees one who might slay the Minotaur and take her away from Crete and the scorn and loneliness that so long have been her lot here."

"So!" grunted Theseus. "She'd use me, would she! Me, hero of Athens!"

His scowl grew even blacker. Then, abruptly, it faded. Sweeping the girl up bodily in his arms, he bore her to the nearest couch. "Enough of this empty talk, wench! We've wasted too much time already on your precious mistress!"

The couch groaned with their joint weight. Throwing the maid back, tilting her face up, Theseus strove to kiss her.

But now the girl drew away, struggling in obvious earnest. "No, Master Theseus, no! We dare not! Ariadne may come at any moment—"

"Let her come!" Athenian pinned maid with hands and body. "Let her see for herself who I prefer—"

Across the room, a door opened. A slim young girl, proud-faced and beautiful and poised, stood framed within the entry.

On the couch, the maid gave a little shriek. "Princess Ariadne!" Frantically, she tried to writhe free of Theseus.

He clutched at her as she spun erect. Cloth ripped as her whole skirt tore away, leaving her standing well-nigh naked.

The maid's face flamed. Whirling, she darted for the grill-masked doorway where Burke stood hiding.

It took him off balance; it was that unexpected. Before he could even get clear, jump back, she dodged behind the grating; crashed into him full-tilt.

Burke reeled back against the door-frame.

The maid screamed.

Like an echo, Theseus tore away the screening grillwork.

After that, for Burke, there was no choice. Instinctively, he knew that no matter what the cost, he must gain command of the situation.

Snatching the Smith & Wesson from his waistband, he leveled it at Theseus. "Stand back, you!"

Apparently the computational translator put words and tone into language the bull-necked Athenian could understand. He stopped short.

Catching the maid by the shoulder, Burke shoved her, stumbling, over to join her playmate.

Next, Ariadne, still standing frozen beside the far door:

"You, princess!" Burke clipped tightly. "Over here, on the double!"

The slim girl didn't move a muscle.

Burke snapped, "Come here, I said! Now! Do you hear me?"

Coldly, the great dark eyes took in Burke and his so-different garments. Then, in a voice edged with scorn, the princess asked, "And who are you, to command the daughter of Minos in her own chambers?"

Sweat slicked Burke's palms, his forehead. "That doesn't matter. It's enough that I hold the power of the thunderbolt in my hand here." He gestured with the Smith & Wesson.

"Indeed?" Now, coolly, Ariadne strolled in his direction. "Perhaps, then, you're a god; is that it?"

Burke groped. "Perhaps."

"Or more likely, you're just a thief from some far country." The girl stood very erect before Burke, oval face even lovelier for her anger. "What brought you to my chambers, dog? Or must I have you flayed alive to get an answer?"

The trouble with taking command of a situation, Burke decided, was that you had to be willing to go all out. And he wasn't.

At least, not with this slim young beauty.

Desperately, he tried a final gambit. "You, Theseus! Seize her!"

But now the Athenian's eyes had narrowed. His head came forward, just a fraction. It had the effect of making his body loom even larger than before. He looked belligerent and dangerous.

Burke tried again. "Theseus—"

"No."

Without volition, Burke found his finger tightening on the Smith & Wesson's trigger.

Beside Theseus, the maid whimpered. "Master Theseus—the thunderbolts—"

The Athenian snorted. "He's no god; he's a man. But if he reaches Minos with a tale of having found me in the Princess Ariadne's quarters, I'll be a long time dying." He licked thick lips. "No. Better that he should die. Here. Now."

He lunged at Burke.

Leaping aside, Burke thrust a foot between his charging adversary's legs.

The Athenian lurched wildly, clawing at the air.

Gun high for a quick blow, Burke leaped in close behind him.

Only then, incredibly, the other was whirling on one foot, with all the grace and skill of a ballet dancer.

Simultaneously, the other foot whipped up, kicking for Burke's groin.

With a desperate effort, Burke caught the blow on his forearms.

But now it was he who'd been feinted off balance. Before he could recover, a left-handed blow sent him tottering backwards.

Then he hit a couch. His knees hinged. He sprawled belly-up exposed and helpless.

Like lightning, Theseus seized a great stone jar, a pithoi. Muscles bulging, with unbelievable strength he swung it high above his head, poised to dash down on Burke.

Burke jerked his revolver up and fired in one spasmodic movement, straight at the pithoi.

Gun-thunder echoed through the chamber. The great jar shattered, cascading slack-jawed Theseus with shards and oil.

Burke rolled from the couch and stumbled to a new defense-point against the nearest wall.

But one shot had been enough for the Hero of Athens. He still stood blank-eyed, looking more stupid than ever as he stared in a sort of numb fascination at the shattered stoneware about his feet.

As for the maid, she'd fainted. And the expression lovely Ariadne now wore was beyond Burke's power to read.

But already, feet were pounding in the corridor outside. Guards poured into the room, half-a-dozen of them—great, strapping blacks with spears and swords and shields.

Six guards ... and only three shots left in the revolver.

Now the Cretan who seemed to be in command of the Negroes looked about uncertainly. "What happened, princess?" he asked. "Who are these men, these strangers?"

For a moment, Burke thought, a smile almost flickered at the corners of Ariadne's mouth.

Then, coolly, she said, "They're strangers to me, too, warrior. I only know that when I came in, this one"—a gesture to Burke—"was tearing the clothes from my maid. Then, he swore he'd possess me, also, and would have, had it not been that this other,"—the gesture was to Theseus this time—"fought to save me."

The Cretan's nostrils flared. He spat an order to the guards: "This dog is yours. Slay him!"

Burke's stomach churned. It was all he could do to breathe.

Was this the way his dream must end—here, now, before he'd even learned the secret he'd come after?

Only then, as the blacks started forward, Ariadne spoke again: "No, guards! Don't kill him!" And slowly, calculatingly, dark eyes strangely brooding: "For this man says he's a god, and for such a blasphemer a quick death is too good.

"So, let him live—to face my father, Minos!"

The place was called the Shrine of Oracles, Burke gathered. It featured distinctively Minoan pillars—of cypress, and so tapered as to be smaller at the base than at the top.

Also, it stank with a peculiar, acrid odor.

But beyond that, to Burke, it seemed disappointingly ordinary ... hardly colorful enough to rate the trial of a man accused of playing god.

That is, so it appeared until his captors dragged him into a central room ... and there, black-browed and haughty, sat bearded Minos on his throne.

A chill ran through Burke. Never had he seen such malevolence staring out of human eyes.

For his own part, it would be the supreme test of his skill and daring if he even left this room alive. With all his heart, he wished he had the Smith & Wesson back.

Lacking it, he'd have to rely upon his wits and play the scene by ear.

And that brought up another nagging question: why had Ariadne insisted on possessing herself of the weapon? And why did she take such pains to stay well separated from him, with others of his captors always in between?

Studying her now, it once again came home to Burke that she was indeed a strange, a tragic figure, for all her loveliness. For even here, in the presence of the mighty sea-king who was her father, her isolation showed up all too clearly. The guards, the priests, the nobles—as one, they walked wide around her, as if some mark of shame and menace were blazoned on her forehead.

Perhaps—

But now Minos leaned forward upon his carved gypsum throne. "Well, blasphemer? How do you choose to die?"

The monarch's voice echoed the black hatred of all mankind that gleamed with such intensity in his eyes.

Burke forced himself to boldness. "Who says I blaspheme?" he demanded.

"Do you deny it, then, dog?" King Minos came up from his throne in blazing fury. "Do you dare to say that the Princess Ariadne, my own daughter, lies?"

"When she says I claim to be a god? No." Burke laughed harshly. And then, with sudden inspiration: "It's only the blasphemy I deny; not the godhood."

"Not the godhood—?" Now Minos' eyes distended. A note of uncertainty crept into his voice. "You mean, you stand before me claiming kinship to the mighty ones, the lords of earth and sea and sky who rule men's destinies?"

"Do you doubt it?"

"Then name yourself, mocker! Who is it you claim to be?"

With a strange sort of detachment, Burke found himself mentally flicking through the pantheon for some name that would fit well with his own.

"Well, blasphemer?"

Burke twisted his mouth into a thin, wry smile. "Would you disown mighty Dionysus?" he queried coolly. "Would you drive from your midst the giver of grapes and wine and joy?"

"Dionysus—!" In awed whispers, the name ran round the crowded room.

For the fraction of a second, Minos' gaze flickered.

Only then, a new storm of belligerence seemed to shake him. He strode forward, shaking his fist. "We'll see, dog! We'll see! The oracle shall decide!"

The whole throne-room quivered with sudden hushed fear.

"Make way!" roared Minos. "Make way to the shrine, that the oracle himself may judge this mocker!"

Then, to Burke: "—And if he declares you false, you dog, you'll wish I'd thrown you to the Minotaur before you die!"

He pivoted; stalked down an aisle formed by the onlookers.

Roughly, Burke's guards shoved him along behind. A stone-walled well loomed, with broad steps leading down.

—The lustral area! The sacred place of purification that Sir Arthur Evans first had assumed to be a bath!

Only now, it was turning out in reality to be for revelation, not purification; a holy of holies where Man could receive the pronouncements of the gods.

The guards let go of Burke when he reached the steps. Apparently they had no intention of following him down into the pit itself.

Of a sudden he felt strangely nervous. His knees showed a tendency to shake.

But he couldn't let that happen, and he knew it. Not if he wanted ever to leave this weird place alive. So he straightened his shoulders and clenched his teeth and strode boldly after King Minos.

With every step, the biting, acrid smell grew stronger. Burke almost choked on it. He found himself wondering if perhaps the oracle spoke in trances induced by vapors; if maybe this pit were outlet for a pocket of some sort of natural gas.

Not even a whisper rose from the watchers in the throne-room. The only sound was the scrape of his own shoes upon the stone.

Then, at last, he and Minos reached the bottom of the stair. Dramatically, the sea-king threw wide his arms. "Mighty oracle of Zeus, it is your chosen one who calls!" he thundered. "Speak to me! Tell me—tell all of us—if this creature here beside me is a god!"

Silence.

"Speak, oracle! Give us your answer! Is this truly Dionysus? Or is it but a man, a blasphemer we should slay?"

More silence.

Burke choked on a sudden impulse to laugh. To think of it—a twentieth century man and a Bronze Age sea-king, together in this dank, smelly hole, calling on the gods for a revelation!

And what if the oracle's secret really turned out to be gas? Might it prove his own salvation—or at least give him a quick and easy death?

For instance, suppose he were to flick the wheel of his pocket lighter—would the all-pervasive smell explode or burn?

"Oracle, I am your chosen one, King Minos! I command you—"

Quietly, Burke palmed the lighter.

"Speak, oracle; speak!"

A sudden recklessness surged through Burke. He opened his mouth to laugh.

And stopped stone cold.

Because suddenly, out of nowhere, another mind was probing in his brain!

Instinctively, he strove to force out the invader.

The very effort gave him new insight. For now, as he fought, he knew that the mind which he had joined in combat was not human, but alien. Its whole quality and mode of thought were of another order, another realm.

Feeling that mind, fighting it, Burke all at once understood the malevolence he'd seen in Minos' eyes.

In the sea-king, he faced a man possessed.

Now, the alien thing sought to possess him, too.

Savagely, Burke met its probings. Sweating, straining, he fought it, hate for hate, and turned it back, and drove it from his brain.

Then, as quickly as it had come, the pressure was gone.

But in the same instant, Minos cried out, "This is no god! This is but a man!"

And from the crowd above, a thunderous echo: "Yes, yes! He's but a man!"

The bearded king turned on Burke. His sword-point scraped the grillwork of the translator case still strapped flat against Burke's belly beneath the clothes. "Up, dog! Up from this holy shrine and meet your doom!"

Bleak, dry-lipped, Burke started up the stair.

At the top, directly ahead of him and in the front row of those waiting, stood Ariadne.

As he climbed, now, her eyes caught his and, burning, held them for a moment. Then her hands moved in a quick, restricted gesture that momentarily pulled her stylized apron to one side.

The Smith & Wesson hung beneath it.

Burke drew a shallow, unsteady breath.

Six steps more and he'd be at floor level. That left no time to question motives.

Casually, he flipped back his lighter's lid.

Three steps more, now.

Another quick, shallow breath. Then, spinning the lighter's wheel with his right thumb, he knocked Minos' sword from his back with his left forearm and thrust flame straight at the sea-king's eyes.

The monarch gave a choked, incoherent yell and jerked back. A shove, and he was crashing down the stair.

Whirling, Burke charged like a battering-ram straight into the crowd at the head of the steps.

Screams, scrambling, panic. Burke dived across two fallen priests, at Ariadne.

The next instant he had the revolver, and his free arm was locked about her waist. When a thick-shouldered noble started towards him, swinging a great double-axe, he fired by sheer reflex.

The axeman stopped short, a shocked expression on his face and a hole in his chest. When he fell, the whole throne-room sounded with the hiss of breaths sharply indrawn.

Burke rapped, "I'm leaving. Your princess goes with me. Try to stop me and she dies!"

Out the door, then. Down a corridor.