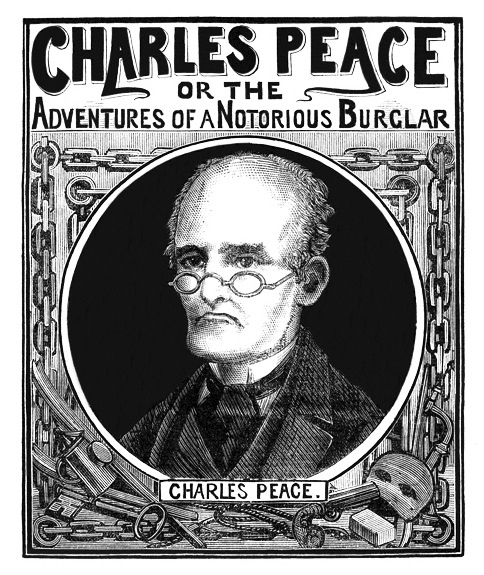

CHARLES PEACE

OR THE

Adventures of a Notorious Burglar

CHARLES PEACE.

This book was originally published in 100 weekly installments. The volume number of each issue is provided as a sidenote, highlighted in light grey, occasionally mid-paragraph. Illustrations that appeared at the beginning of each issue were moved to the nearest paragraph break. Additional notes are at the end of the book.

OR THE

Adventures of a Notorious Burglar

CHARLES PEACE.

No. 1.

Charles Peace alias John Ward, whose life and adventures form the subject-matter of our story, has gained for himself a reputation equal, if not superior, to the lawless ruffians, Jack Sheppard, Dick Turpin, and others of a similar class. He is a union of various elements.

In more senses than one he was a local character. Born in Sheffield he was, in early days, trained according to the customs of the day, and when about eight or ten years of age was one of the foremost amongst his companions in any game of audacious fun.

He was always considered a “rough,” even amongst his earlier associates, and it is said that he was dreaded by the children with whom he played. At ten years of age he had to assist his father who was named Joseph Peace, in the earning of the daily bread for the family.

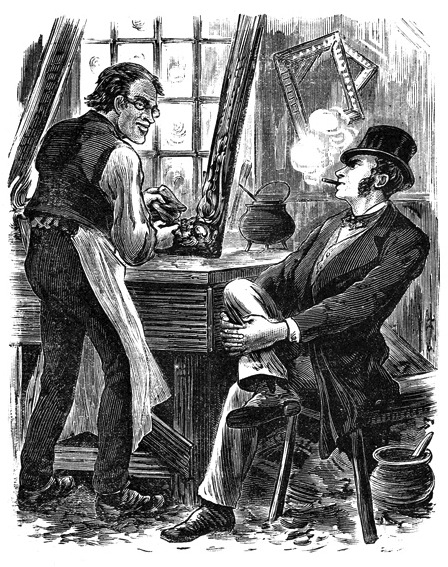

Mr. Joseph Peace was a man well respected. He was what is known in Sheffield as a “little master,” but in commercial terms would be placed as a “file manufacturer.” He had a large family, and amongst his children was this lad, who has achieved such notoriety in the world.

Charles Peace, from his very boyhood, was wild. It is said that there was no adventure to be undertaken in regard to which he had any fear; neither did he require twice telling when he was requested to lead the way in any mischievous plot.

Mr. Joseph Peace was a man of religious inclinations, and was a member of the Wesleyan body. He occupied a house in George-street, Langsett-road, a thoroughfare which is now known as Gilpin-street.

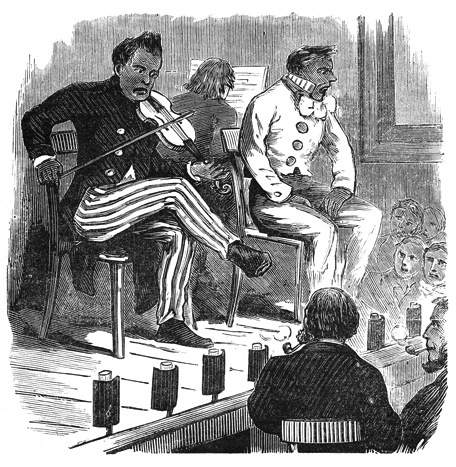

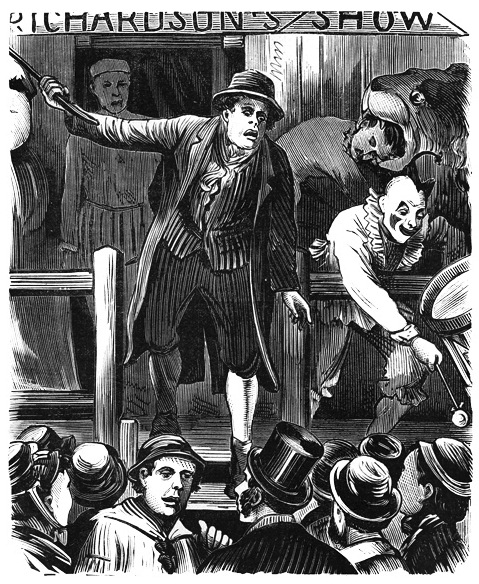

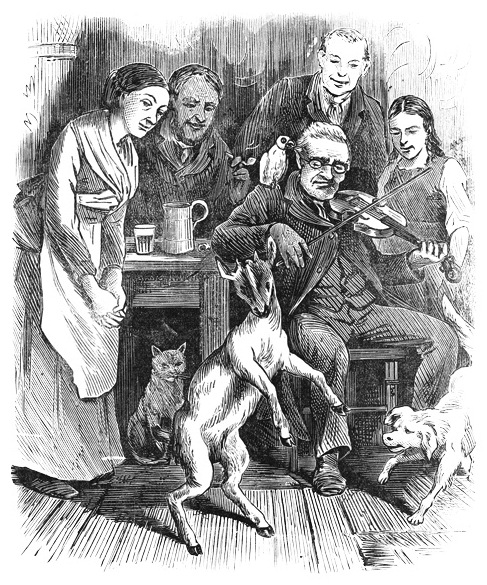

He had a taste for music, and played the “bass” at the Wesleyan Chapel, Owlerton. When ten years of age Charles Peace commenced to take lessons on the violin, his instructor being his father, who rather prided himself on the way he could play the double-bass.

His son Charles was a diligent pupil, and ultimately, having acquired a proficiency in the instrument, he started in life as a sort of successor to Paganini—fiddling most successfully on one string, and only failing to achieve some distinction because he lacked the patience which was necessary to make the stage his “field of fame.”

Yet he was always an artist.

If he did not discern for himself a sufficiently splendid career in art, amateur violinists who lived in the neighbourhood of Greenwich, Peckham, or Blackheath had sufficient reason to regret Mr. Charles Peace’s devotion to music.

They found that some undiscovered burglar was abroad who had a good taste in the selection of fine instruments.

Mr. Peace indeed had a passion for violins; and if he spared a service of plate sometimes, he was never known to leave a really good fiddle behind.

He was distinguished, too, by his general cultivation and by his devotion to the fair sex. As his good fortune grew, so did the number of inamoratas increase, yet he never seems to have really deserted the wife whom he married.

In housekeeping his taste was luxurious, and he invariably moved into more aristocratic neighbourhoods as he prospered in the art and mystery of burglary. And here comes out the singular phase of his character.

There is no doubt his fame and fortune as a housebreaker culminated in the period between the Bannercross murder and his apprehension at Blackheath; but he appears to have previously enjoyed a reputation as a cracksman.

How does it happen, then, that he could settle down to the life of a picture-frame maker at Sheffield?

The circumstances would not be so mysterious if he had not really made picture-frames; but it appears that he actually worked at the trade. There is some mystery here which requires to be explained. It is difficult to believe Peace turned honest in a fit of repentance; he would, in all probability, have some other object, which has not yet been made clear.

But, indeed, Peace’s character in Sheffield is altogether in singular contrast with his character as exhibited elsewhere. His behaviour to the Dysons, as it was described in Mrs. Dyson’s evidence, was very much like that of a lunatic.

There appears to have been a singular absence of motive, both for his general conduct and the murder which he is said to have committed. Instead of being the ingenious and cautious Charles Peace of the London burglaries, he is simply an indiscreet and violent criminal.

Equally in contrast was his behaviour on the two occasions when he appeared in the prisoners’ dock. In London he was whining and supplicatory; in Sheffield he was reckless and defiant. This change may, perhaps, be accounted for on the grounds that he had a chance in one case, and no chance in the other; but other contradictions in his character are not so easily explained.

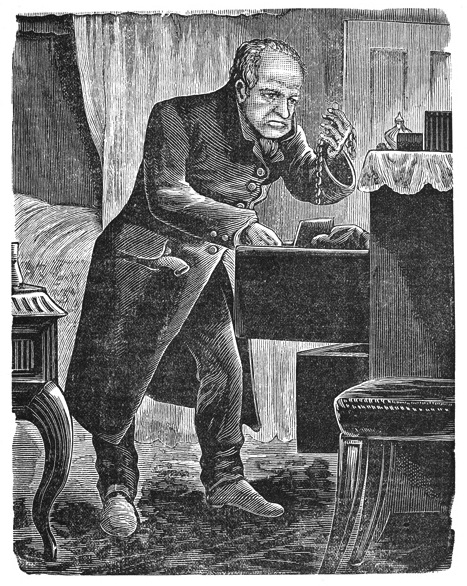

Without doubt he was a cunning, bold, and fearless scoundrel of the old heroic type. The history of his many exploits, of his clever disguises, of his extraordinary escapes from punishment, and of the success with which for many years he contrived to live on burglary, even in these days, when we have a large and well-organised police force, cannot fail to excite surprise in the minds of every citizen.

His career is almost unique in the annals of crime. Not only the boldness and skill which he showed in committing his depredations, but his remarkable success in eluding the vigilance of the police, must be regarded as being altogether uncommon. Working entirely alone in his burglarious course, he seemed to command success.

We are told that even dogs felt the influence of his power, and failed to give any alarm on his approach. As for locks, bolts, and other means of security, Peace simply laughed at them. If he made up his mind to get into a house he got into it, and the booty which he appropriated was exceedingly valuable.

Probably many of the stories which are told of his exploits have only an element of truth, but the sub-stratum on which they rest is doubtless constituted of actual facts. Scarcely less remarkable than his success as a burglar was the skill with which he contrived to escape detection by the police.

Although he had been living openly in London, walking even into Scotland-yard itself, he was not recognised as Mr. Dyson’s murderer; and his eventual detection was owing to the accident of his capture at Blackheath.

Peace certainly possessed remarkable ability in effecting an almost impenetrable disguise. He has boasted of his contempt for the police, and his confidence seems to have been abundantly justified.

The history of his life presents a combination of passion, craft, cruelty, great spite, and audacity, such as is rarely to be found in any single being.

But Peace has boasted of his ability to deceive the most astute constable or detective. As a proof of this we quote the following personal narrative of one of his old pals. We give it in the words of the narrator:—

“Once on a time, no matter where, no matter when, Charley Peace told me the whole story of his life after that little indiscretion which resulted in the death of Mr. Dyson, at Bannercross.

“It is a narrative of events which have never yet been made known to the public. It presents points of uncommon interest, for everybody has wanted to know how he escaped on that fatal night—how he was disguised, where he went, and how he has lived, down to the days when he reappeared at Peckham, and spent his days and nights after the manner now familiar to the public through the special commissioner of the Independent.

“I shall not trench on the latter well-known period. But I shall fill up the blank in his biography with these autobiographical episodes, for they are almost entirely his own words. I give to you, Mr. Editor, ample credentials to convince you that this is a genuine narrative, for I know, by the way you have stood former tests, that wild horses will not make you break confidence.

“So nobody need take the trouble to come fishing about either you or me for further ‘information.’

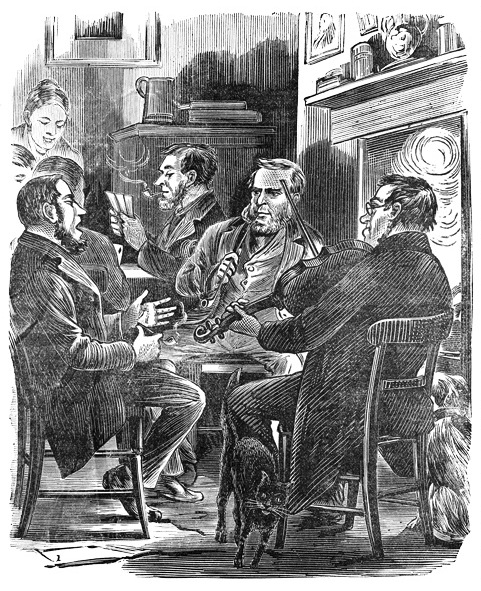

“Imagine, then, a circle of choice spirits assembled round Charles Peace, under circumstances calculated to make him loquacious.

“‘They talk,’ said he, ‘about identifying me! Why I could dodge any bobby living! I have dodged all the detectives in London many a time. I have walked past them, looked them straight in the face; and they have thought I was a mulatto.’

“Then he asked us if we knew how he did it; and said ‘Just turn your faces away a minute, and I’ll show you.’

“We turned our heads away, and when we looked again we found he had completely altered the expression of his countenance, and so entirely distorted and disfigured it—save the mark!—that he did not look like the same man.

“He threw out his under jaw, contracted the upper portion of his face, and appeared to be able so to force the blood up into his head as to give himself the appearance of a mulatto.

“Then he laughed heartily at his cleverness; went through pantomimic gestures that would have done credit to ‘Quilp,’ and again boasted of the many times he had ‘put on that face,’ and walked past the cute detectives in London and elsewhere.

“We then made allusion to the clever way in which he dodged the police and got away from Sheffield on the night of the murder; and he at once went off into a long story of his escape, telling it with almost fiendish glee, and occasionally laughing joyously at his exploits. He said:—

“‘After that affair at Bannercross I went straight over the field opposite, and through Endcliffe Wood to Crookes, and round by Sandygate. Then I doubled and came down to Broomhill, and there I took a cab and was driven down to the bottom of Church-street.

“‘I got out and walked into Spring-street, to the house of an old pal. There I doffed my own clothes and disguised myself. I stopped there a short time, and then I went boldly through the streets to the railway station, and took train for Rotherham. I walked from that station down to Masbro’, where I took a ticket for Beverley.

“‘On reaching Normanton I left the train, retaining my ticket, and took a ticket for York, where I put up that night. The next morning I went to Beverley, and then walked on to Hull.

“‘I got in an eating house near the docks, where I stopped a considerable time, and did a ‘bit of work’—(meaning, of course, committed a few robberies).

“‘Then I went to Leeds, and from Leeds to Bradford; and from Bradford I went to Manchester. I was there a short time and then I went to Nottingham; and in a lodging house there I picked up Mrs. Thompson.

“‘Whilst we were together one night, an inspector, who had heard I was there and suspected I was a “fence,” came and said to the landlady—“You have got a lodger here—have you not?” She said, “Yes, he is upstairs.”

“‘He said he wanted to see me, and upstairs he came into our bedroom. When I saw him I said, “Hullo!” He answered, “Where do you come from?” and I told him from Tunbridge Wells. “What is your name?” he asked. “John Ward,” said I. “Well,” he said, “what trade are you?”

“‘At that I let out and said, “What’s that to you what trade I am? What do you want to know for?”

“‘He told me he wanted an answer. “Then,” said I, “if you do I’ll give you one—I am a hawker!” “Oh,” said he, “a hawker. Have you got any stock?”

“‘I told him my stock and licence were downstairs, and if he would step down my wife and I would come and show him all. He was as soft as barm and went down.

“‘I said to Mrs. Thompson, “I must hook it,” and, hastily dressing myself, I bolted through the window and dropped into a yard, where I encountered a man, who was surprised to see me. I told him there was a screw loose, and the bobbies were after me with a warrant for neglecting my wife and family. I asked him not to say I had gone that way. He promised he would not.

“‘To leave the yard I had to go through the passage of a public-house, and at the door stood the landlady. She was frightened to see me without stockings or boots on; but when I told her the same tale as I had told the man in the yard she said it was all right, and I passed on.

“‘I took refuge in a house not forty yards from that I had left, and in a short time I got the woman who kept it to go for my boots, and she brought them.

“‘Soon after that I did a “big silk job” in Nottingham, and then, finding the place was getting too hot for me, I left it and went back to Hull. I had made several visits there before, and had given my wife money to maintain her.’

“Peace then told us how he paid no less than three visits to Sheffield after the murder, and more than once encountered one of the most astute and experienced inspectors of the force, but his disguise was so perfect that he passed unnoticed.

“Whilst in Sheffield he committed, he said, several robberies, and he particularly called attention to his adventures in a house at the corner of Havelock-square. ‘Do you mean,’ we asked, ‘at Barnascone’s,’ and he said, ‘Yes, that was the place. The family were out, and there I did very well. I got several rings, and brooches, and £6 in gold. The policeman said he saw me, but he didn’t. I saw him and blocked him, and he never saw me.’

“Peace declared to us that he was in Sheffield when the inquest was held on Mr. Dyson. Afterwards he returned to Nottingham, picked up with Mrs. Thompson, and went on to London with her, where his life and exploits are now matter of history.

“Peace went on to mention the names of several Sheffield people whom he met at different periods in London; and that part of his astonishing story has been confirmed in a remarkable degree by one of the persons himself.

“More than a quarter of a century ago he worked in Sheffield with Mr. William Fisher—in those days known as Bill Fisher—and they remembered each other very well. One day Mr. Fisher was walking across the Holborn-viaduct, when he saw the well-remembered figure approaching him.

“Their eyes met, and Mr. Fisher exclaimed—‘That’s Peace!’ He turned to look again, but Peace had disappeared as if by magic, and was nowhere to be seen. About a week after, Mr. Fisher was going down the steps leading from Holborn to Farringdon-street, and about midway he again encountered Peace.

“Mr. Fisher gave information to the Sheffield police, and the news was sent to Scotland-yard that Peace was in London.

“‘But what,’ said Peace, ‘was the use of that, when I could walk under their very noses and not be recognised?’

“Again a demoniacal grin overspread his face, and again he went through a series of pantomimic gestures, and set us all laughing.

“It has been conceded that he could be exceedingly good company when he liked, and we assure you he had our attention whilst he related these, the most extraordinary chapters in his history.”

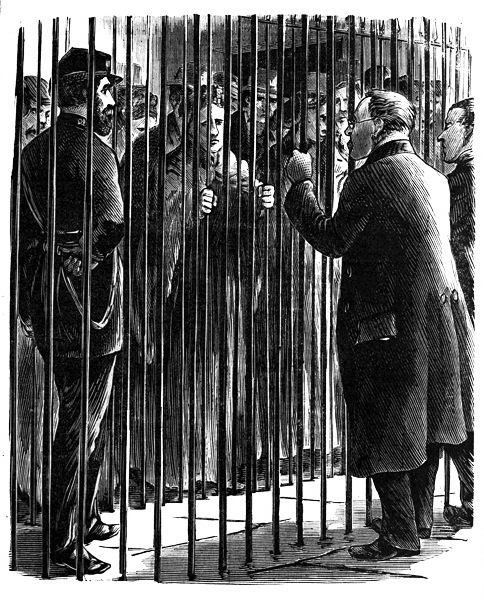

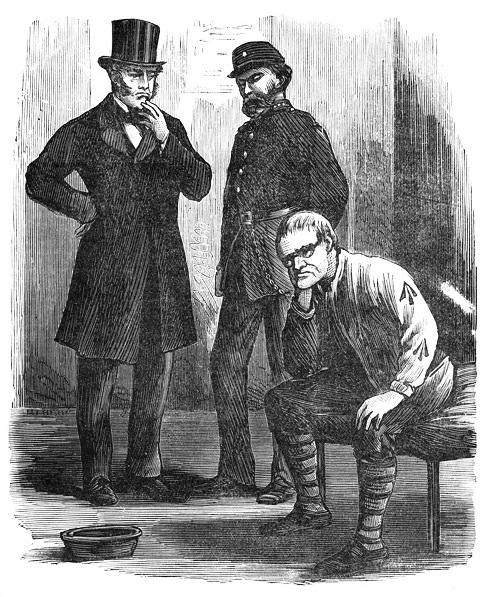

The personal appearance of Peace is thus described by one who paid a visit to Newgate while the burglar was awaiting his trial. He is a man about 5 ft. 3 in., with white hair on his head, cut very close, and bald in front of the head; but the razor had lately done this.

His eyebrows are heavy and overhanging the eyes, which are deeply sunk in their sockets; a chin standing very prominently—and, as if to make it more so, the head was thrown back with an air of half self-assertion, yet half-caution.

The lower part of his cheek-bones protruded more than was their wont in years gone by; but he had apparently some bruises recently, and had had his whiskers shaven off since he was last seen at Sheffield.

In addition he wore a pair of large brass-rimmed spectacles. Peace was professedly a religious man. The neighbourhood thought him so, and probably he thought so, too; so he associated with the good folk who congregated in the edifice, but never made himself conspicuous.

He trifled with Fate. She had made him rich in worldly goods, although they were not his own. Some idea of the magnitude of his operations may be gathered from the fact that there is evidence in the hands of the police that would convict him of no less than fifty burglaries.

The property he obtained is valued at several thousand pounds, but the burglar as a rule does not realise even one-fourth of the value of the property he appropriates.

The charges of “receivers” in every branch of the profession are of an unusual character, but it has been asserted upon reliable authority that he was a burglar years before the events which have made him so notorious.

It is quite twenty years since he worked at a rolling mill at Millsands, and it was while following this employment that he broke his leg. This accident appears to have thoroughly disgusted him with hard work, and as soon as the injuries were cured he went to Manchester.

Here he appears to have fallen into bad company, and to have been the leading spirit of a gang of burglars. In the small hours of the morning Peace and his confederates were tracked to a lonely house at Rusholme, and the police succeeded in obtaining an entrance.

After a desperate struggle Peace was secured, and a great quantity of the stolen property was recovered, but not before the officers had been severely handled. At Old Trafford he was sent to penal servitude, but he played the “good boy” and was let out on a ticket-of-leave.

After his Old Trafford sentence he returned to Sheffield and took a small shop in Kenyon-alley. Here he used to amuse his acquaintances by showing them the dexterity with which he could pick the most stubborn lock. He soon resumed his old courses, and made the acquaintance of Millbank.

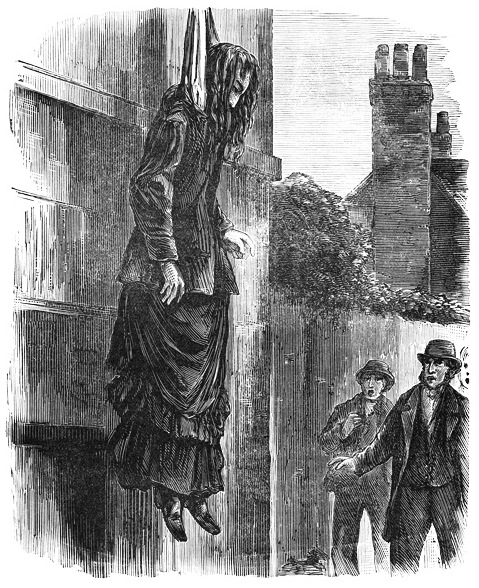

The career of the notorious culprit whose doings are chronicled in this work furnishes the novelist with a moral. It will be clearly demonstrated to those who peruse these pages that, sooner or later, justice overtakes the guilty, and that it is impossible for the most astute and cunning scoundrel—such as Peace has proved himself to be—to escape punishment.

A life of crime is always a life of care, for the hearts of the guilty tremble for the past, for the present, and for the future. The author of the “Life of Peace” reprobates in the strongest degree that species of literature whose graduates do their best to cast a dignity upon the gallows, and strive to shed the splendour of fascinating romance upon the paths of crime that lead to it—to make genius tributary to murder, and literature to theft, to dignify not the mean but the guilty.

Let crime and its perpetrators be depicted as conscience sees them, as morality brands them; let them stand out in prominent but repulsive relief. There is yet wanted a picture of crime and its consequences true to nature and conscience, and it is hoped that the present serial will, in some measure, supply that want.

The author proposes to present to his readers the felon as he really is—to describe facts as they were found—to present pure pictures of guilt and its accompaniments.

He does not desire to make use of artificial colouring, believing that the interest in the work lies in its reality. The felon appears just as he is, as crime makes him, and as Newgate receives him—successful, it may be, for a season, but arrested, condemned, scourged by conscience, and cut off from society as unfit for its walks.

Of all the members of the family of man few have been so rapidly forgotten as those who have been swept from the face of the world by the fiat of the law and the hands of the public executioner. Yet the guilty and the unfortunate have left biographies behind them that speak to future generations in awful and impressive tones.

If they were inflictions on the past generation, they may be made useful in the present age as beacons to the reckless voyager—voices lifted up from the moral wrecks of the world speaking audibly to listening men “of righteousness, and temperance, and judgment.”

Our first scene opens at a picturesque-looking farmhouse situated on the outskirts of a pretty little village within a few miles of Hull. Oakfield Farmhouse—so called from a number of patriarchal oaks poising their lofty heads in the rear of the establishment—was in the occupation of two substantial yeomen named respectively John and Richard Ashbrook, their only sister Maude being mistress of the bright and cheerful abode.

In the earlier portion of the day our two Yorkshire farmers had been out on a shooting expedition. They brought back with them two friends—fellow-sportsmen. They were driven home by the rain, which fell in torrents, and rendered further sport impracticable.

“I knowed how it would be,” said Richard Ashbrook to his companions. “These beastly river fogs always bring wet, and the clouds have been as ‘bengy’ (full of rain) for some time—as bengy as could be.”

When the party reached Oakfield their garments were saturated with wet, and clung to them like a second skin.

“I have got a fire in the big bedroom—a good blazing fire—for I guessed how it would be,” said Maude Ashbrook, as she received her guests at the door. “You’ll all of you have to change your things. Mercy on us, you are dripping wet, John!” she exclaimed, placing her hand on her brother’s shoulder.

“Our friends will stop and have a morsel of something to eat and drink for the matter o’ that,” observed Richard.

“Indeed no—I think not,” said Mr. Jamblin, one of the farmer’s companions.

“Ah, but he will,” returned the farmer. “None of yer think nots. Come, friends, get thee in. We don’t intend to part with thee so easily.”

Mr. Jamblin smiled, shrugged his shoulders, and obeyed. The other friend of the farmer’s, a Mr. Cheadle by name, followed Jamblin.

After dinner had been served, “clean glasses and old corks” were festively proposed by the host. Some bottles of genuine spirits and a box of Havannas were placed on the board; an animated discussion on things agricultural and political followed, while ever and anon Jamblin and Cheadle would rise from their seats, repair to the window, and, flattening their noses against the panes thereof, would endeavour to distinguish a star in the sky, or the first beams of the rising moon.

But the sky remained black and gloomy, and continual pattering of the rain was distinctly heard.

“It’s no good, my fine fellows,” observed Richard Ashbrook. “You are in for it. The rain has set in for good, so you had better make up your minds to stop where you are. ‘Any port in a storm,’ as my uncle the captain used to say. Nobody will ever expect you home, such a night as this.”

“You are very kind, Ashbrook, but——”

“Oh, bother your buts! I tell you I’ve got a couple of beds for ye. They are small iron bedsteads, both in the same room; but you don’t mind roughing it for one night, surely.”

The farmer’s two friends accepted the offer, and prepared themselves to pass the hours merrily. This they had no difficulty in doing.

Several games of whist were played, after which the host was called upon for a song. He was not quite in tune, but that did not matter. The other singers were equally deficient in that respect; but what was wanting in skill was made up by noise.

Most of the ditties had a good, rattling chorus, which each singer interpreted according to his own fancy. After sundry libations, and much protestation of friendship and good-fellowship, the hour arrived for repose, and the two farmers, their visitors, and Maude betook themselves to their respective sleeping apartments.

As Richard, who was the last, was about to ascend the stairs, he was touched gently on the elbow by a tall long-haired young woman, who was one of the domestics in the establishment.

“Well, Jane, what’s up now, lass?” inquired the farmer.

“Hush, master. This way.” She drew him back towards the entrance to the kitchen, and said in a low, mysterious tone of voice, “Are the guns loaded?”

“Two of them are. But what of that?”

“Load the others.”

“Why, dash it—what ails thee, girl?”

“Nothing, master. I can’t tell why, but I feel timmersome like, and fancy something bad is going to happen.”

“If loading the other guns will do thee any good the remedy is easy enough,” observed the good-natured farmer, who at once proceeded to charge the other weapons.

“Thanks, Mr. Richard, thanks!” exclaimed the girl, in a tone of evident satisfaction.

The farmer repaired to his bedroom, taking the two guns—his own and his brother’s—with him. At his suggestion his two friends had carried up their weapons into their bedroom in the earlier portion of the evening. This might appear a little singular, but John Ashbrook had playfully observed to Cheadle and Jamblin that there was sometimes a hare to be seen out of the bedroom window, feeding on the orchard grass of a morning.

“And so,” he observed jocosely, “if you see one to-morrow morning you will of course be able to knock him over.”

“We will do our best should there be one,” said both gentlemen.

In less than half an hour after the party had broken up all the inmates of Oakfield House were soundly sleeping.

All save one.

This was Jane Ryan, the girl who had exchanged a few parting words with her master, or, more properly speaking, with one of her masters, for John and Richard Ashbrook were partners.

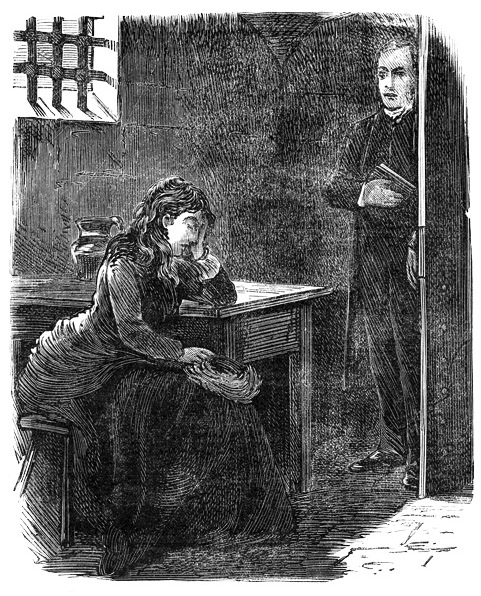

A strange sense of coming evil had taken possession of the girl, who sat moodily and dejected in the kitchen long after the other members of the household had retired to rest. Jane did not feel disposed to seek repose; she was restless and disturbed, albeit she was quiet, moving from place to place in a stealthy way, in direct variance with her usual manner.

“I cannot sleep,” she murmured; “and so I will e’en keep watch for one hour or more.”

She put some fresh coals on the kitchen fire, before which she sat for some time absorbed in thought.

Leaving her there, we will take a survey of the exterior of the house and its surroundings.

It was two o’clock in the morning. The rain had ceased; the moon was shining brightly, and covered the fields with a pale, lustrous light; the stars sparkled in the rain-drops which were hanging from the leaves, and so clothed the trees with a mantle of diamonds.

All was silent in the fields, for the birds and insects of the night were torpid till summer came once more.

All was silent in the yard—the cattle sleeping on their beds of straw, and the fowls upon their wooden perches.

Seen by the pale moonlight the old farmhouse was a picture worthy of an artist’s pencil.

On the northern side of Oakfield ran a narrow lane, skirted by a dense mass of foliage, which threw the lane into sombre darkness. The lane itself rose abruptly as it neared the farm, which stood on the upland.

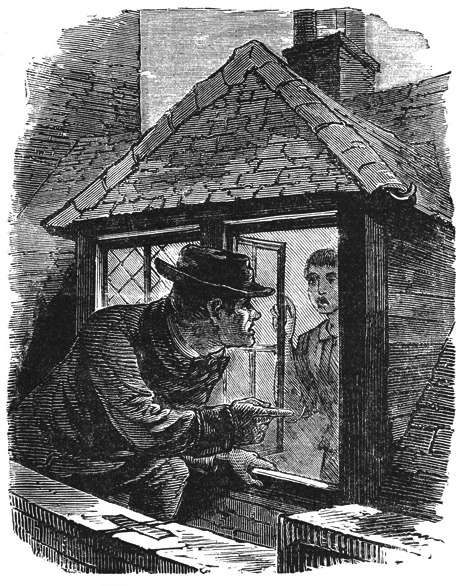

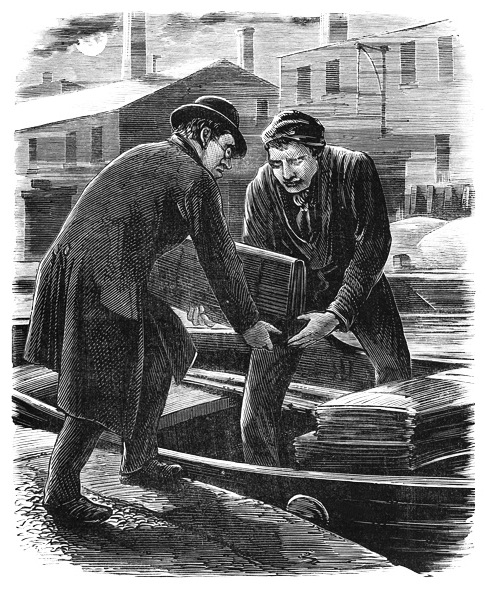

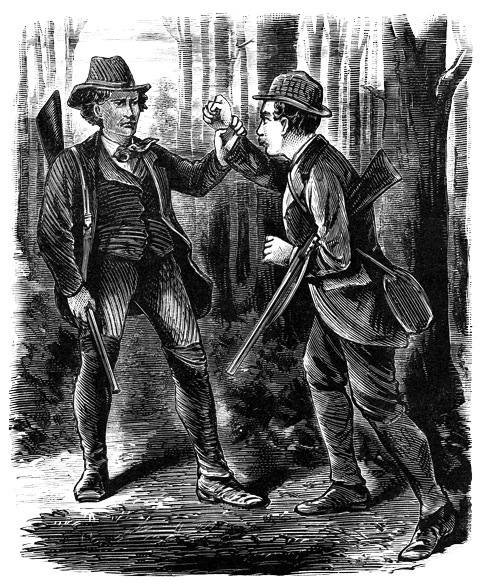

In this lane the forms of three men might be seen. The first of these is Charles Peace. Standing facing him is the notorious “cracksman” Ned Gregson, better known by the name of the “Bristol Badger.” The last of the three is known as “Cooney;” he is a tinker by trade, but he is a sort of jackal to rogues of a greater degree than himself.

The three men are in close converse. They had come suddenly to halt, as if doubtful as to their course of action.

“I tell yer it’s right as the mail,” observed the tinker, in a tone of confidence. “The farmers have sold their wheat, and there’s a mighty good ‘swag’ in the house. Only yer see, Ned, old boy, yer must not be too rash. Be keerful—be very keerful.”

“What do yer mean?” inquired the Badger.

“Well, it’s just this, old man, the farmers—leastways so I heerd at the ‘Six Bells’—have had two blokes with ’em to-day, a poppin’ at the blessed birds, bad luck to them; and from what I could gather from Tim, the two blokes are a stoppin’ there to-night.”

“What matters about that?” said Peace. “We don’t intend to wake the gentlemen.”

“All right—so much the better,” answered the tinker. “I’m for doing things in a quiet sort of way, I am.”

The Badger uttered an oath, and his ill-favoured countenance wore an expression of disgust.

“Do you know where they keep the shiners?” he asked.

“Oh, yes; I think that’ll be all right. I haven’t been in the house to mend the bell wires without a keeping my eyes open. Ah, ah!”

“Stow that, yer fool!” exclaimed the Badger. “Wait till yer out of the wood afore yer laugh.”

“All right, Ned, I’m as silent as the grave.”

“When were you at ‘The Bells,’ then?” inquired Peace.

“I had a game of skittles this afternoon.”

“At what time?”

“Between three and four o’clock; or it might be a little later. Can’t say to half an hour or so.”

“And that’s how you came to know about these two sporting chaps?”

“Right you are. Tim gave me the tip.”

“You haven’t been fool enough to push your inquiries too far?” said Peace. “Tim, as you call him, might suspect.”

“He suspect?” returned the tinker, indignantly. “Not he. I was as good as gold.”

“It’s no use making a long palaver about the matter,” ejaculated Gregson. “Let’s to business.”

The three burglars made direct for Oakfield House. In the space of a few minutes they were busily at work to effect an entrance, but they found this by no means so easy a task as they had imagined. The windows and doors of the habitation were carefully secured, and, although they knew it not at the time, there was one inmate of the establishment keenly alive to every movement.

This was Jane Ryan, who was aroused from her lethargic reverie before the kitchen fire by a sound which was new to her ears.

Jane started and rose from her seat.

“I said something was about to happen,” she murmured, pressing her hand against her side. “I could have taken a Bible oath of it.”

She paused for a few moments, apparently in doubt as to what course to take; presently she appeared to have decided upon her line of action. She glided from the room with long, stealthy, and noiseless steps, carrying her shoes in her hand.

A sudden surprise awaited her two young masters.

They were awoke from their sleep by a hand placed upon their shoulders. They stared around them sleepily, as yet not realising the real state of affairs. It was dark in their bedroom, for the moon was behind a cloud.

When it gleamed out, they saw Jane Ryan standing before them. Her arms were naked to the shoulder; her eyes glistened with a strange light.

She held a loaded gun in her hands.

The Ashbrooks were perfectly bewildered when they beheld this strange apparition awaking them in the silent hours of the night.

“Jane!” exclaimed Richard Ashbrook, suddenly calling to his mind the warning given him in the earlier part of the night by his faithful and devoted servant. “Jane—what’s the matter? Speak, girl.”

“Hush!” she murmured, placing her finger on her lips; “make no noise, or it may be fatal. Listen.”

Both the farmers listened till their ears tingled, but they could hear nothing.

A thought crossed the minds of both almost simultaneously, that the girl was (to use the expression they made use of afterwards) off her head.

The brothers stared at each other in mute astonishment.

“I can’t hear anything,” said John Ashbrook.

“Don’t speak, master, but watch and wait; you will hear,” said Jane, in a low whisper.

She was standing as if in anxious expectation—one hand raised to her ear, the other grasping the fowling-piece.

The two Ashbrooks listened again, and as the moonlight ebbed slowly from the room like a great white wave streaming back towards the sea, they heard a thin scraping sound, which was unlike anything they had heard before. This mysterious sound was followed by deep and heavy blows.

“Are you satisfied now?” said the maid.

“What is it?” they inquired.

She answered in a low, horse voice—

“Robbers, burglars, assassins!”

The two farmers stole hastily but silently from their beds.

Jane immediately left the room.

They at once proceeded to arouse Mr. Cheadle and Jamblin. All this was done as noiselessly as possible. When the four men were up and dressed, Maude Ashbrook joined them, declaring that she would not leave the side of her brothers upon any consideration.

They left the door wide open, and all crouched together in a corner.

The sound of the burglars’ tools soon ceased—a sign that they were worked by practised hands.

Indeed, no more skilful “cracksmen” existed at this time than Charles Peace, the Badger, and Cooney—the two first-named men have never been surpassed.

The farmers and their friends silently awaited the movements of the robbers, who had without doubt, by this time, effected an entrance into the house.

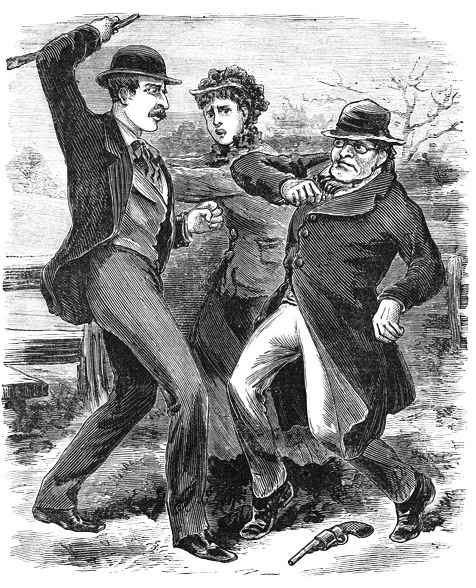

The party in the bedroom stood prepared for any emergency—they all cocked their guns.

“Let us have no firing, except in self-defence,” said Mr. Cheadle. “There are four able-bodied men here, and it must go hard with us if we cannot hold our own.”

“I shan’t be at all particular about peppering the scoundrels, whoever they may be,” returned John Ashbrook. “A set of lawless, midnight marauders—fellows of their stamp do not deserve pity or consideration.”

They now heard muffled footsteps in the room beneath them, and immediately afterwards similar sounds were heard on the stairs.

They began to breathe a little quicker, and grasped their guns more tightly.

A gleam of light fell across the threshold.

They could see a slipper lying there—one that Maude had dropped.

The burglars had probably perceived this, and thence argued that people were afoot, for the light disappeared, and they could hear whisperings outside the door.

The big bedroom, as it was called, was a square chamber, barely furnished. The two bedsteads had been placed close to the window on the left-hand side.

Round and about these beds the six besieged persons were crouched or seated.

The moonlight poured in at the window in such a manner that while the whole of the opposite side, except one corner, was as light as day, the little nook by the beds was buried in impenetrable darkness.

The one dark corner on the opposite side was formed by the chimney, which jutted out some little way into the room.

They listened breathlessly for some moments, till they fancied that they heard a board creak inside the room close to the door; and at that moment, as if by magic, a voice issued from the corner of the chimney.

“We are armed with loaded revolvers; if you come a step nearer we fire!”

The lurid flash of a pistol flamed within the room, and they heard a ball strike sharply against the wall.

Maude betrayed their hiding-place with a shriek, and fell fainting in her brother John’s arms.

A loud report rang in their ears, and the room was filled with a thick, sulphurous smoke.

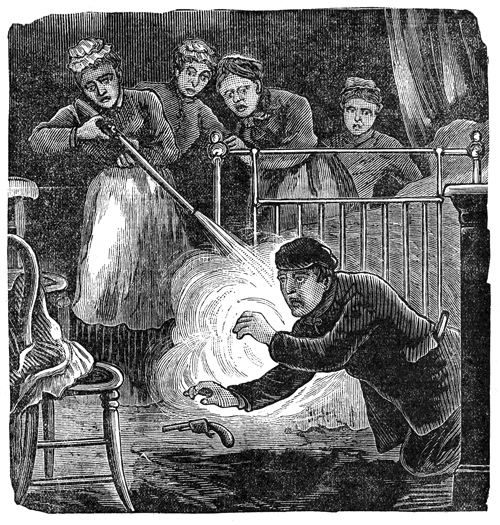

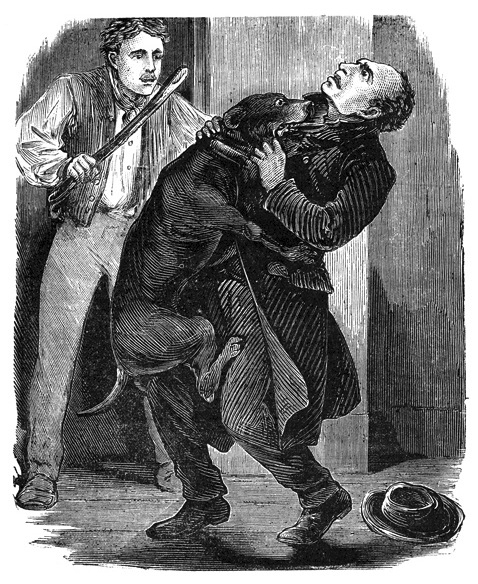

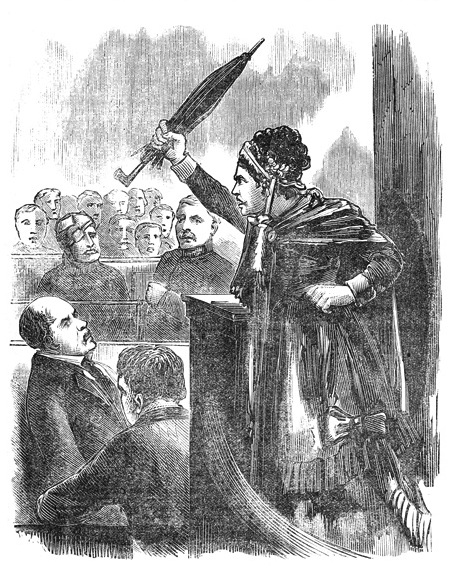

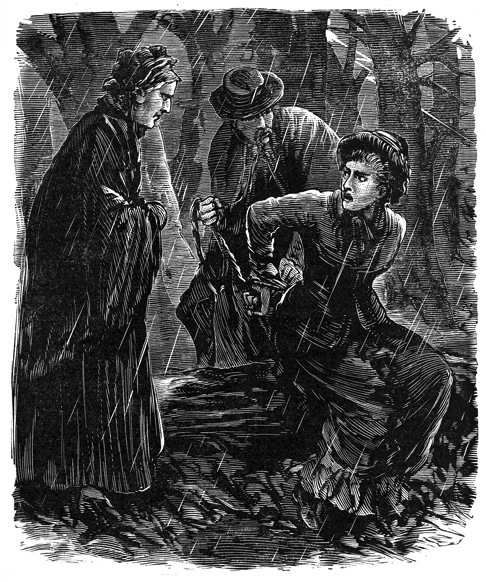

By the light of the powder’s flame when the first shot was fired, there was one who had seen the robber’s face—a face, once seen, not soon to be forgotten. The dark cavernous eyes of the “Badger” had been distinctly visible to Jane Ryan, who gave a scream of triumph and revenge.

It was but momentarily that she had caught sight of the forbidding features of the miscreant; but it was enough for her purpose.

She levelled her master’s gun at the supposed spot where the robber was; and as she fired, something fell heavily upon the floor.

A shudder passed over them like a cold wind. They drew their breath and heard the same whisperings outside the door.

John Ashbrook placed his sister behind himself and his brother. There was an interval of silence; they began to hope that the burglars had gone, when presently they perceived something on the opposite wall.

They watched it with fascinated eyes. It was a small, dark shadow, creeping towards them along the wall.

It was the shadow of a man’s hand.

Then they heard a harsh, rustling sound, as if something was being dragged along the floor.

The robbers were taking away the dead body of their comrade.

They did not dare to move, for they knew the burglars were armed to a far greater extent than they were, and exposure might prove fatal.

Ten minutes passed thus; ten minutes of frightful suspense to these farmers—who were brave but not phlegmatic—who now fought men for the first time, and fought them in the dark.

They could not possibly tell how many there were of their enemies. To fire the only three remaining charges they had would have been an act of madness; they therefore thought it prudent to keep these in reserve for the grand or final conflict.

But the worst was over, as far as the Oakfield housebreakers were concerned.

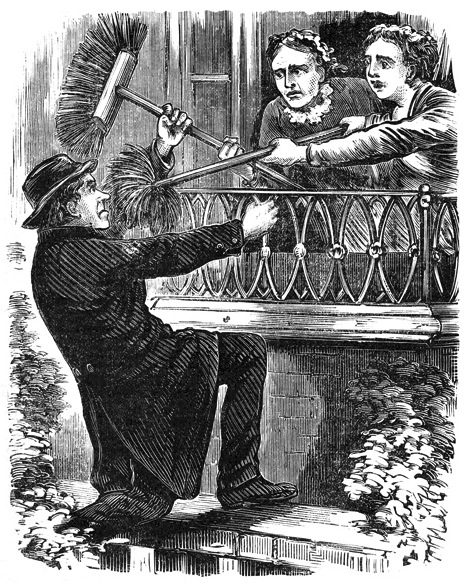

Presently the eager tramp of men’s feet echoed from the road before the farm, and a dozen rough voices were heard bawling to each other.

The besieged party rushed to the window, and saw in the front of the house one of the village constabulary force, who was accompanied by a posse of strong-bodied youths of the immediate neighbourhood. In addition to these there were shepherds armed with crowbars, stablemen with their pitchforks, bird-keepers with their rusty fowling-pieces, woodmen with their billhooks, and a tall relation of Jane Ryan’s with a substantial kitchen poker.

The reports of the gun and pistol in the dead hour of the night had aroused the whole neighbourhood.

As may be readily imagined, the strong reinforcement at once dispelled all anxiety or doubt in the minds of the farmer’s household.

Three men were instantly mounted, and started off in the dark to the three nearest railway stations. The rest were invited into the kitchen to wait till daybreak.

There had been an unprecedented number of burglaries committed at several houses in the neighbourhood within the space of a few months—hence it was that the rustic population were so keenly alive when any signal of alarm was given.

To capture the robbers was the wish of everyone assembled at Oakfield on that eventful night.

With the first streaks of dawn the party congregated in the yard, and took counsel on the best means of pursuit.

“If they have been carrying a body with them they can’t be very far off,” said Mr. Jamblin.

“They are lurking about somewhere hard by, I dare say,” said the police-officer.

“Where’s Jarvis?” cried Will, the carter. “He’d be the boy to find ’em for us. He’d ketch ’em if they burrowed underground like a rabbit.”

“Would he?” ejaculated the policeman. “He must be a clever chap.”

“Aye, that he be,” returned another rustic.

“Have you got any more of his sort in this neighbourhood?” asked the officer.

The rustics made no reply.

“Who is this Jarvis you were speaking of?” inquired John Ashbrook.

“Jarvis, sir? Why, him as ’listed some years ago, and fought under Lord Clyde in the Injies. Arter that they sent him to the other Injies, where the red men be, and they’ve taught him a power of strange tricks. He came here wi’ us, but he’s got lost since, or summat.”

“No, I baint lost, Joe,” said a tall young man, whose left cheek was one great red scar, and whose face had been bronzed by no English sun.

“Why, sure enough, it is Jarvis!” exclaimed Mr. Ashbrook. “Give us your hand, lad. Sure enough I shouldn’t ha’ known ye, they’ve knocked ye about so.”

“Aye, that they have, Master Ashbrook,” returned the soldier. “But tell us, neighbour, what you can about this night’s business.”

“You shall know all I know,” answered the farmer; who thereupon put the soldier in possession of all the facts with which the reader is already acquainted.

When he had finished, the soldier said, “I’ll be bound for it that the body of the dead or wounded man is not very far from here.”

“You think not?”

“Ah! that I do. We came up so soon that they’d have no time to get far away with that load upon their backs; and most likely they’ve been forced to hide it in a slovenly way.”

The sudden disappearance of Charles Peace and his two companions upon the arrival of the villagers excited surprise in the minds of all who had assembled at the farmhouse. The police officer did not choose to commit himself by any expression of opinion. He was not a man given to loquacity where silence was requisite. He did not, however, attempt to deny the assertion made by soldier Jarvis—namely, that the robbers were not far off.

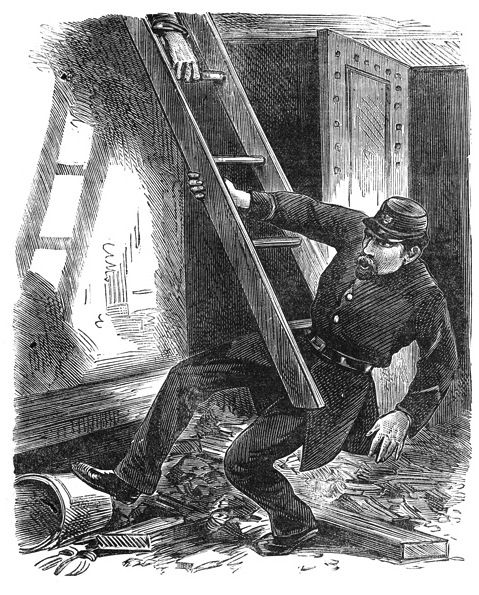

Enjoining the villagers to stay where they were and to carefully avoid treading over more ground than was absolutely necessary, the young soldier accompanied Mr. Ashbrook to the kitchen window, where the entrance had been forced by removing the glass with a diamond—or “starring the glaze,” as it is termed in the burglar’s phraseology—and after this had been done panelling the shutter. It was this last process that aroused Jane Ryan to a sense of danger.

Jarvis carefully examined the ground beneath the window, and pointed to some footprints in the wet earth which led towards the straw yard. In one place they were so plain that every nail in the soles could be distinguished.

“They are the impressions of a strange foot—that’s certain sure,” observed Ashbrook.

“We are on the trail of one of them,” returned Jarvis. “I dare say they thought they could do as they liked among yokels, but we’ve got the trail and I mean to keep it.”

The speaker walked slowly across the yard, following the tracks with his eye as a bloodhound would have followed them with his nose.

“They’re in this barn, Master Ashbrook,” he said, stopping before one of the doors. “No, they baint, though, they’re come out agen and gone along the wall. But they’ve left their dead mate behind ’em. See how different their track is now; they tramples quite close alongside of each other, while afore they carried the body from shoulder to shoulder, and so were forced to walk one behind and a little way apart.”

The villagers gave a murmur of astonishment.

“Ah, he knows how many blue beans make five,” said the carter, as he took out the peg by which the folding doors were kept dosed.

“I don’t feel quite so sure about the footsteps,” remarked the policeman; “they don’t appear to me to tally with the others.”

“If I’m mistaken, we shall have to try back,” answered Jarvis. “Of course, it is just possible we are on a false scent. Ah! what is this?” The speaker pointed significantly to some drops of blood upon the straw in front of the barn. “What say you to that?”

“Blood, without a doubt,” observed the constable.

“That’s where they laid him down when they opened the barn door.”

“Ah!—dare say—most likely.”

The villagers were open-mouthed with wonder. They, one and all, voted the soldier a necromancer.

The doors were flung wide open, and they sprang over the rack into the body of the barn. There had been some threshing done the day before, and there was a vast heap of chaff just outside.

While they were gazing around, a low moan, as of one in pain, fell upon their ears.

“Keep quiet, lads,” exclaimed Jarvis; “leave this matter to me and the constable. Keep where you are. We can none of us tell what next will happen.”

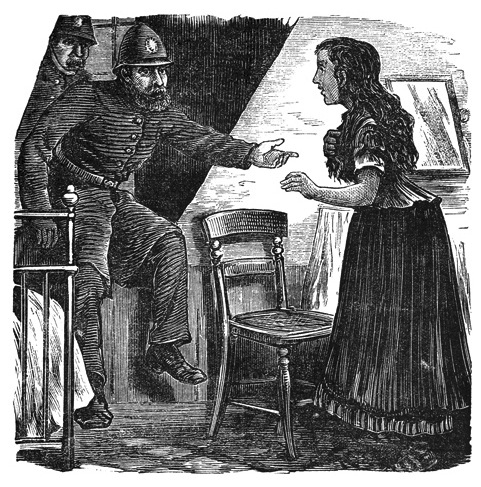

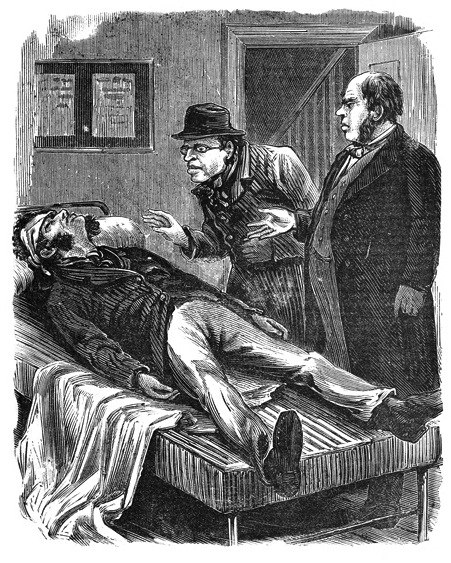

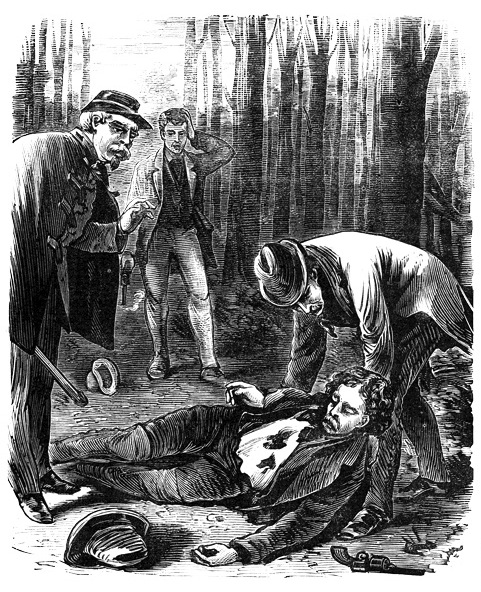

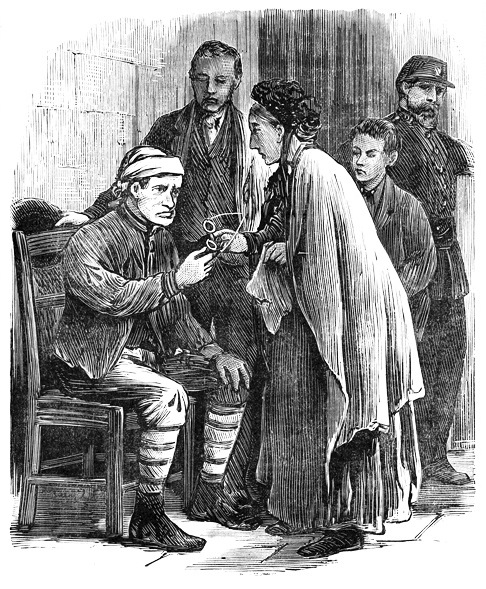

“Here’s footmarks on the chaff, and blood on it also,” said the constable, who took a few steps further inside, whereupon his eyes lighted on the prostrate figure of a man lying in the corner on a heap of straw.

He flashed his bull’s-eye on the face of the wounded burglar, and uttered an exclamation of surprise.

The Bristol Badger lay helpless, and bathed in blood.

Jane Ryan, who had followed the constable and Jarvis, gave a slight scream.

“Don’t take on so, woman,” said the constable. “He’s only got his deserts.”

Heedless of this observation, Jane went close to the wounded burglar and peered into his face.

“Dost know who this here is? I’ll tell ye!” she exclaimed, in a voice of concentrated rage; “he’s the murderer of my sweetheart. I should ha’ known him out o’ ten thousand.”

There was a murmur of unmixed surprise at this observation.

“What beest thee saying, Jane?” said the farmer, scratching his head. “Hast ever seen ’im afore?”

“Aye, sure enough I have, master. It was not for nothing that I sat up this night. I knew summut was about to happen, but never guessed it would turn out like this.”

Gregson endeavoured to rise to his feet, but the attempt was a futile one; he was too weak from loss of blood.

“What has that false, wicked woman been saying?” he inquired of the policeman.

“She accuses you of murder,” was the brief rejoinder.

“She’s mad. I never saw her before.”

“What’s to be done wi’ this man?” inquired the farmer of the constable.

“He’s my prisoner, anyway,” answered the latter. “Best see and have his wounds attended to, and then we will take him to the lock-up. You charge him, I suppose?”

“Yes, with burglary.”

“Attempted burglary,” chimed in the cracksman.

“And I charge him with wilful murder!” exclaimed Jane Ryan.

Having said this, she folded her arms upon her breast and relapsed into gloomy silence. There she stood, colossal as an Amazon, in her sublime strength, beautiful as a Judith in her just and fearful vengeance.

A hurdle was brought by some of the villagers, and upon this the ill-fated Badger was placed; he was then carried into the farmhouse, not, however, before the constable had taken the precaution to handcuff him, for he was known to that astute officer as a ruffian of no common order. He was, however, run to earth, having been, in a manner of speaking, hunted down by a woman.

A doctor was sent for, who bandaged his wound, which, although severe, was not likely to prove mortal—certainly not unless some unfavourable symptons set in.

While all this clatter had been going on, Charles Peace had contrived to conceal himself in a neighbouring coppice, from which he durst not emerge while the village folk were prowling about.

When Gregson was conveyed into the house the majority of the villagers wheeled off; at the same time Jarvis, however, was still endeavouring to trace out No. 2. the Badger’s companions. He came too near to the coppice where Peace was concealed to be at all pleasant to a gentleman of his retiring habits, so Peace was fain to avail himself of a neighbouring hedge, on the other side of which he crept along on all fours.

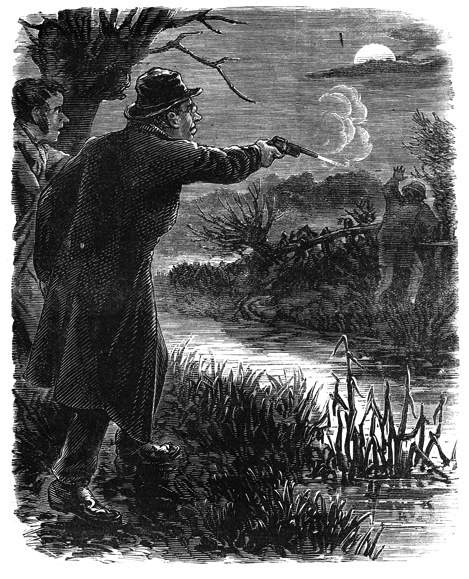

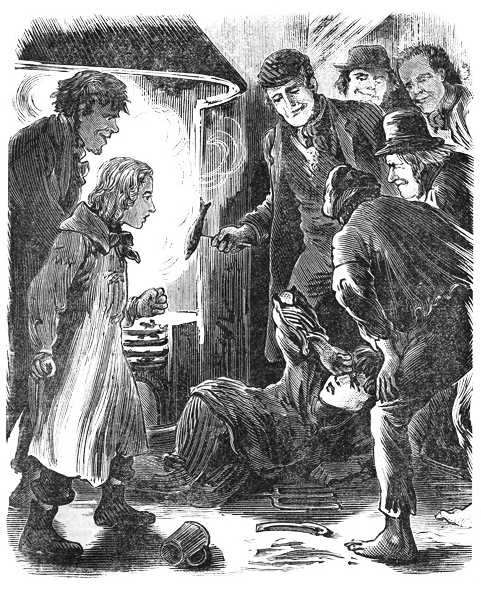

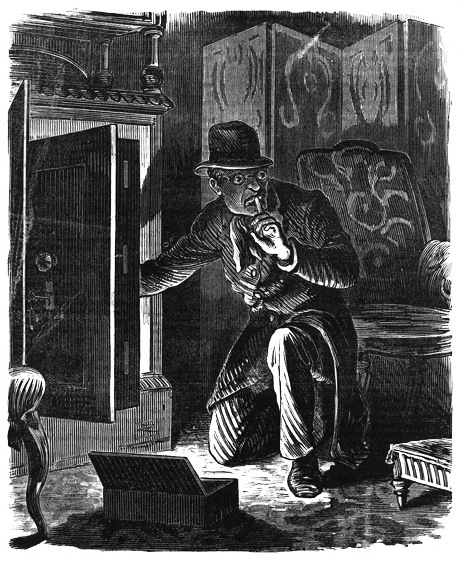

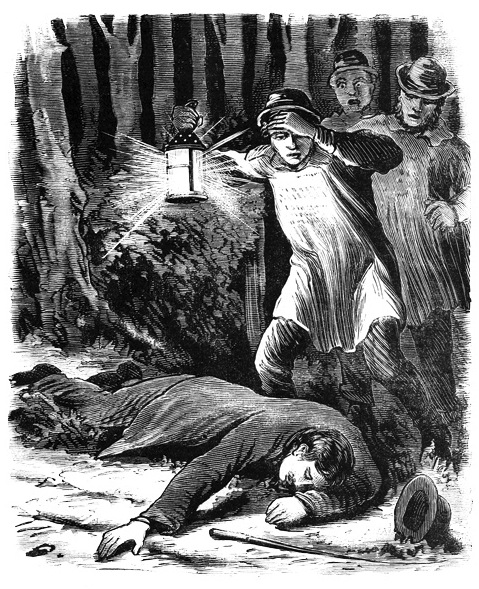

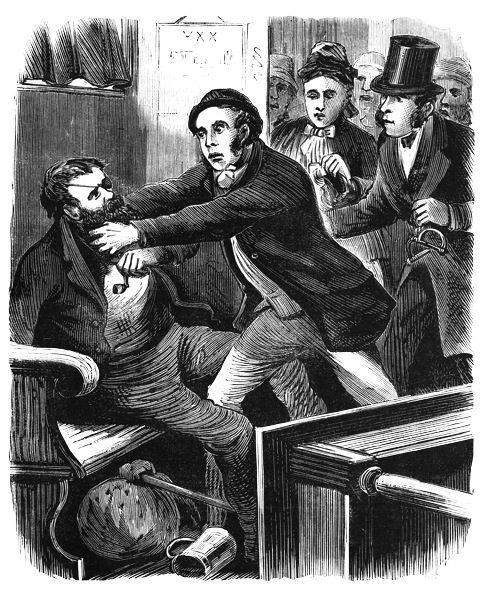

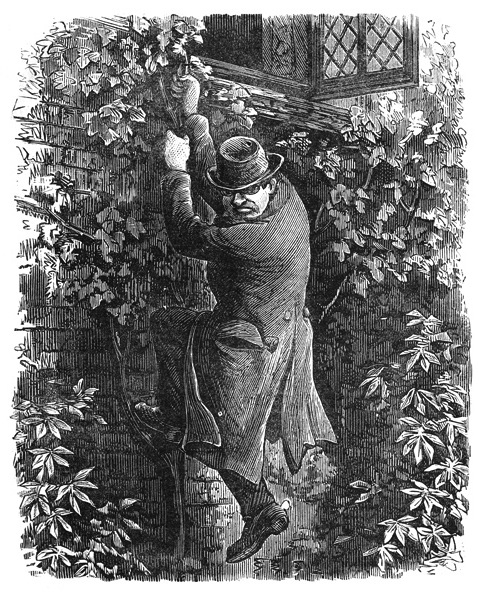

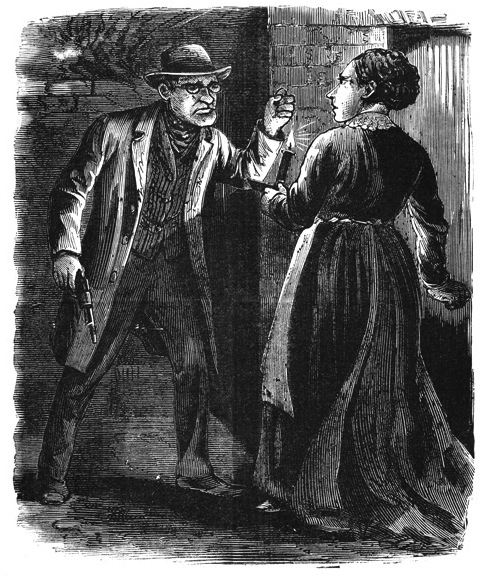

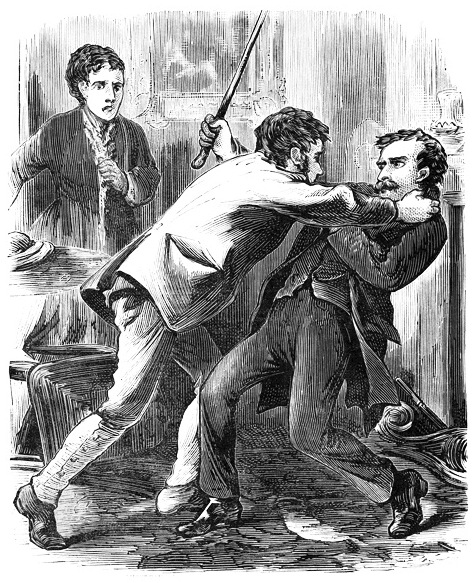

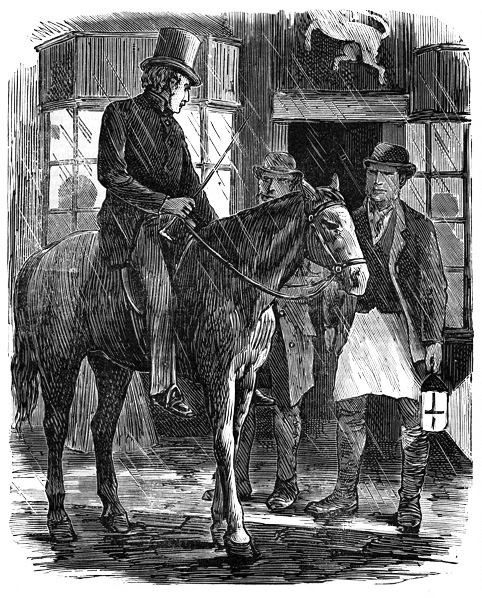

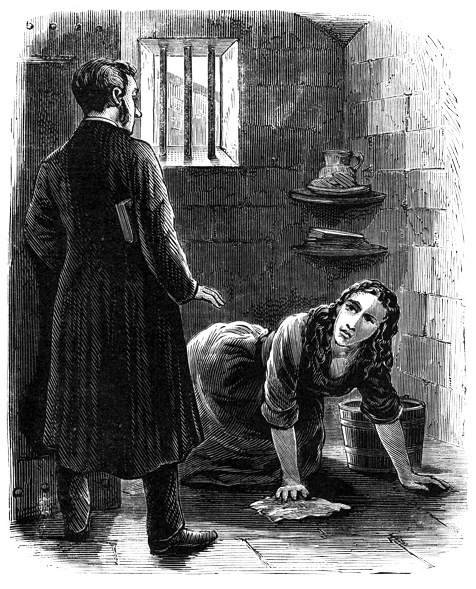

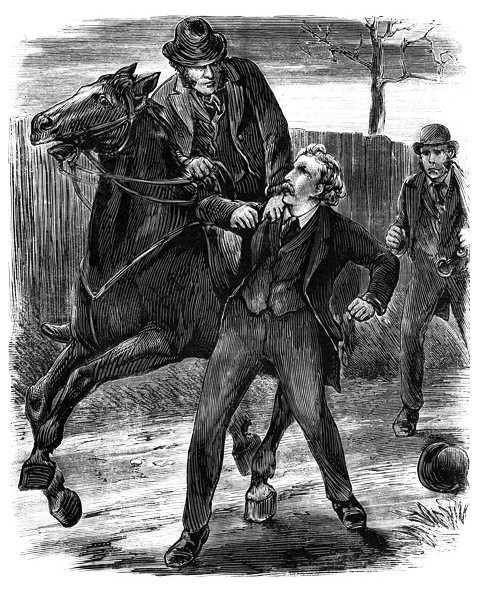

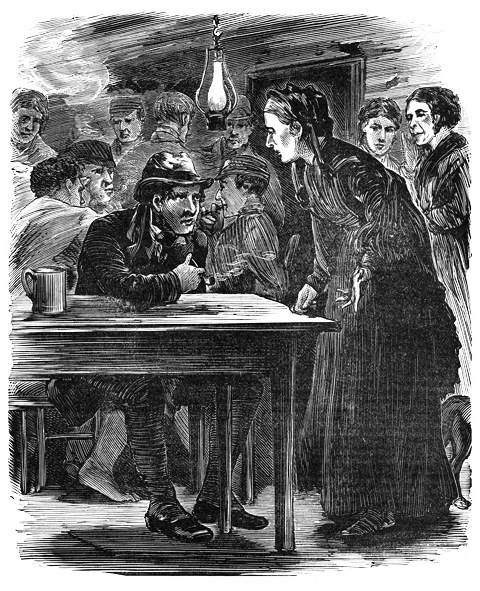

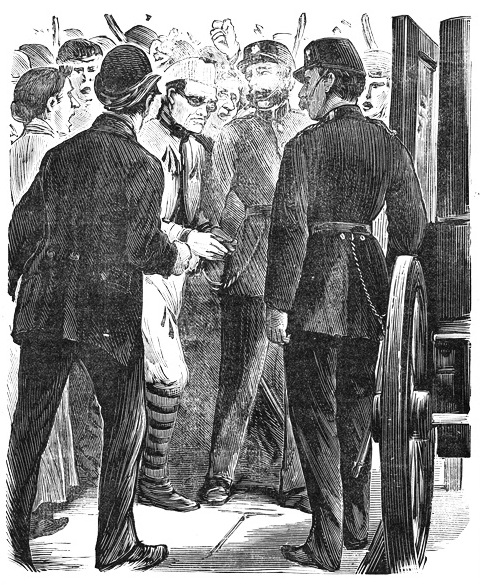

THE “BRISTOL BADGER” SHOT BY JANE RYAN.

Having gone some considerable distance by this means of progressive, he imagined that he was out of sight, and betook himself to the open field, across which he ran at the top of his speed. His movements were however not unobserved by Jarvis.

The latter caught Mr. John Ashbrook by the leg. The farmer was mounted on his bay mare, and said: “There goes one of them; ride down the lane and intercept his flight, while I run across the field. We shall have him yet.”

The farmer needed no second bidding. He rode at the hedge which skirted the lane. With one stroke from the long corded whip, and one cry from the rider’s lips, the gallant animal bounded over the hedge like a flying deer.

“Wouldn’t ’a brushed a fly off the top twig,” exclaimed Ashbrook, triumphantly. “Now, for my gentleman. Dall it, if this won’t turn an eventful night, especially if I catch that rascal.”

While the farmer was riding down the lane, Jarvis and several others were in hot pursuit of the fugitive.

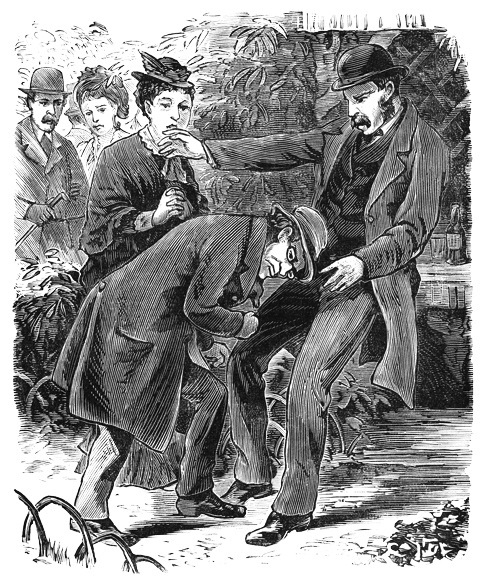

Peace became aware, much to his discomfiture, that every movement he made was plainly visible to his pursuers, and he deeply regretted having taken to the open field.

He ran his hardest, and had the satisfaction of getting into the lane before any of the pursuing party had even reached the field.

Ashbrook, as he was trotting down the lane, saw the fugitive jump through a gap in the hedge. The farmer urged on his steed, being now under the full impression that the capture of Peace was reduced to a certainty.

In a brief space of time he came within a hundred yards of the enemy.

“I’ve got him now!” exclaimed the farmer. “He’s mine as sure as my name’s Jack Ashbrook.”

But there’s an old adage “that it is as well not to reckon your chickens before they are hatched.”

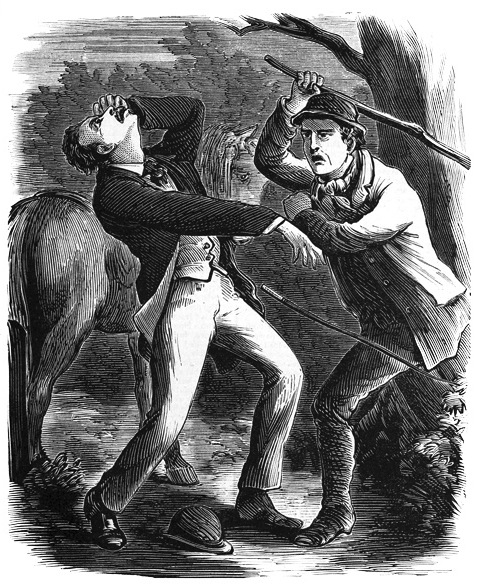

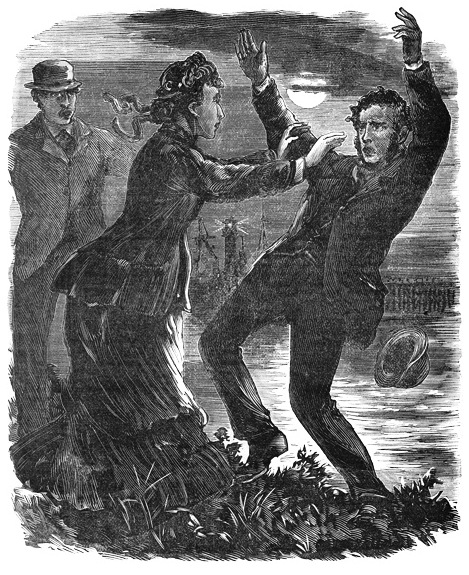

Peace was in imminent danger, but he was an astute, cunning rascal, who was up to every feint and dodge in all cases of emergency. He, nevertheless, was fully impressed with the fact that matters were growing serious—much too serious to be pleasant. He turned round and boldly faced the horseman.

Drawing a revolver from his pocket, he watched till Ashbrook came within range of the shot, then he fired. At this time he could not have been more than twenty paces from the horse and its rider.

A bullet was lodged in Mr. Ashbrook’s right shoulder. The wound was not a very serious one certainly—not enough to place the farmer hors de combat, but the effects of the shot proved more disastrous in another way.

The mare, who was a high-spirited animal, became restive from the pistol’s flash. She reared, then stumbled, and threw her rider heavily to the ground. Peace rushed forward and struck Ashbrook two blows on the head, which produced insensibility.

He then made for the mare’s head. Turning her sharply round, he led her some paces from the scene of action. He patted her on the neck, and strove as best he could to overcome the effects of the fright caused by the flash of his weapon. The mare became comparatively quiet and tractable.

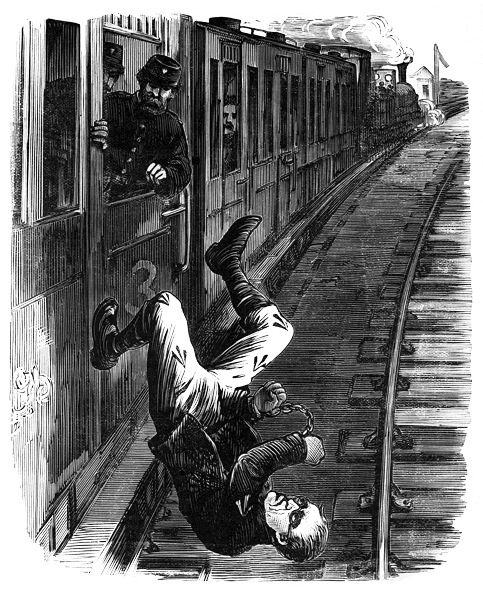

Peace jumped on her back, and rode off at headlong speed.

While all this had been taking place in the lane the mob of persons in the field had increased considerably in numbers; but the foremost of them were a long way from that part of the lane where the short but decisive struggle had taken place.

Two other horses had been brought out from the stables at Oakfield, but some time necessarily elapsed before they could be saddled; and when Mr. Cheadle and Mr. Jamblin mounted them for the purpose of giving chase, Peace was so far ahead that the chances were remote of finding him.

He knew the bye-roads of the neighbourhood perfectly well, and took very excellent care to choose a circuitous route. As he was riding along he listened every now and then to ascertain if there were any sounds of horses’ hoofs to be heard, but none were as yet audible. He felicitated himself upon this fact, arguing therefrom that his pursuers had gone another road.

“I shall give them the double; they are on the wrong scent,” he ejaculated, in a tone of satisfaction; “but even when the worst comes to the worst all that will be left for me will be to make a stout fight of it.”

He had unlimited faith in his own power, skill, and address in confronting and overcoming difficulties; and his confidence did not desert him on this occasion.

Presently he came to three cross roads, and was hesitating which to take—calculating the while the chances of detection with his accustomed coolness.

While thus engaged he descried a mounted patrol on a formidable-looking horse, coming at a measured pace towards him.

To turn and fly was his first impulse, but upon second consideration he thought it better to put a bold face on the matter.

The mounted policeman came forward, and regarded him with a look of doubt and mistrust.

“Good morning, friend,” said Peace, in a cheery tone. “Better weather than it was a few hours ago.”

“Yes,” returned the other. “Where might you be journeying to this early hour?”

The speaker regarded him with a searching glance. This, however, did not in any way discompose Peace, who, throughout his career, plumed himself upon being able to throw dust in the eyes of the constabulary.

“Ah, I’m sorry to say my errand, or rather the cause of it, is one of a painful nature. A poor gentleman is at death’s door, and I have been sent off for the doctor. In cases of this sort minutes are precious. Let me see, yonder’s the nearest way to Hull, isn’t it?”

“Yes, the right-hand one. But who is in such extreme danger?”

“A farmer—Mr. Ashbrook. Poor fellow, it is a chance if he recovers, so they seem to think.”

“I know both the Mr. Ashbrooks perfectly well. Which one is it that’s so bad; they were right enough yesterday?”

“Mr. John Ashbrook.”

“Umph! that’s strange. What’s the matter with Mr. John?”

“He was thrown—horse reared and fell upon him. His injuries are very serious.”

“I’m sorry to hear this, but—” and here the speaker regarded Peace with a still more searching look, “it’s his horse you are riding.”

“Yes, that’s right enough; it is.”

“Then who are you going for?”

“Dr. Gardiner.”

While this conversation was taking place, Peace had so distorted his features that recognition was almost impossible. He was an adept at this. By constant practice he was enabled to throw out his under jaw, lift up his eyebrows, and so alter the expression of his features that he defied detection. This is now pretty generally acknowledged.

“Well, I must not let anyone detain me very long in a case like this,” he observed, carelessly. “So farewell for the present.”

The patrol made no reply. He did not, however, feel quite satisfied that all was quite right; at the same time he did not consider it his duty to offer any obstacle to Peace’s passage along the road, which led directly to the town of Hull.

Peace trotted along till the patrol was lost to sight, then he pulled the bridal rein of the mare, and turned her into a narrow lane which ran at right angles with the road.

“That fellow suspects something,” he murmured; “and for two pins he would have collared me there and then. The sooner I part company with the mare the better it will be for both of us, I’m thinking.”

He dismounted, opened a gate which was at the corner of a meadow, and led the mare into the field; then he took off the saddle and bridle, which he threw into a ditch, gave the animal a sharp crack with his whip, shut the gate, and left her to herself. This done, he proceeded merrily along on foot.

Messrs. Cheadle and Jamblin had meanwhile been riding to their hearts’ content, but they did not catch the most distant glance of the man of whom they were in search. No wonder, seeing that they had lost all traces of the fugitive, and had been journeying in an opposite, or very nearly in an opposite direction to the one taken by Peace. They had, therefore, the gratification of riding many miles upon a bootless errand.

They returned, vexed and dispirited, to Oakfield House, where they found John Ashbrook in bed, with his sister and the village surgeon in close attendance upon him.

The latter had extracted the bullet, and strapped up the head of the sufferer, who was, he said, doing as well as could be expected. Certainly there was no immediate danger.

The farmer had an unimpaired constitution, and, although sadly bruised and knocked about, would in all probability soon get the better of his wounds.

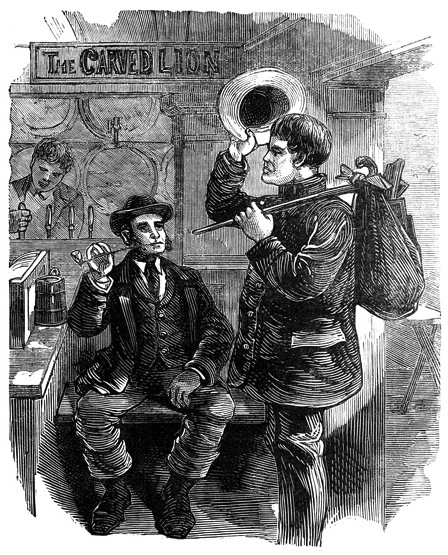

Peace, when he came to the end of the lane, turned into a road, where stood a small beerhouse, of a primitive character, with a good dry skittle-ground at the back.

He knocked several times at the side door of this establishment, but received no answer to his repeated summonses. It was evident that all were asleep within.

He called the landlord by name, with no better result. While thus engaged, a man came forward from the opposite side of the road, and said—

“Why, what’s up now, Charley? Want to get in?”

Peace turned round in some alarm, but was a little reassured upon finding the speaker was a friend of his.

“Hang it! I’m as tired as a dog, and wanted an hour or two’s rest,” said Peace.

“Tired! where have you been to?”

“Playing the fiddle to a party some miles away from here. They could not accommodate me with a shake-down, so I’ve had to trudge it.”

“Come along wi’ me, my lad,” said the good-natured groom. “You shall have an hour or two’s rest in my little crib over the stable.”

Peace gladly availed himself of his friend’s offer.

A hue and cry would be raised throughout the neighbourhood of the attempted burglary at Oakfield House and the surrounding districts, and Peace, young as he was at this time—he had only just turned twenty—was fully impressed with the necessity of using caution.

No one would dream of his being in the groom’s sleeping apartment. The latter informed him that he had to take the carriage up to London, and that he should not return from the metropolis for several days.

“But that aint of no kind o’ consequence,” said the groom. “You can sleep away to your heart’s content, only when you do leave mind and lock the door. You can give the key to the stable-boy.”

“I’m sure I do not know how to sufficiently thank you, Jim,” observed Peace in his blandest tone and manner.

There’s no call for thanks, lad. You’ve done me a good turn afore now, and one good turn deserves another.”

Peace was conducted by his companion into the small sleeping chamber.

“There you are,” said the latter, pointing to the bed. “In less than half an hour I shall be at the station; make yourself comfortable. We shan’t meet again for some days, that’s quite certain, and so good-bye for the present.”

“Good-bye, Jim, and many thanks.”

Then, as the man was about to pass out, Peace said, quietly—

“Oh, by the way, there is no occasion for you to say you have seen me, or, indeed, I’ve been here. It’s a little private matter I’ve been about. You understand.”

“A nod’s as good as a wink to a blind horse,” returned the other, with a chuckle. “No one will know anything from me, Charlie.”

After the departure of his friend, Peace was too disturbed in his mind to sleep. He watched from the little window of his dormitory the carriage and pair, driven towards the railway station by his friend, the groom.

When the vehicle was lost to sight, he walked towards the door, took the key out of the lock, and fastened the door on the inside. In a few minutes after this he stretched himself on the bed, and sank into a deep sleep—the village clock had struck eleven before he awoke.

He now began to consider his course of action; he felt perfectly secure from observation in his present quarters. No one would for a moment imagine that he was safely ensconced in one of the apartments of the stables adjoining a gentleman’s house.

He thought it best to watch and wait; it would not do to be too precipitate; in the dusk of the evening he might creep out and get clear off.

He found in the groom’s bedroom some bread and cold meat, which served him for a meal, and he prepared himself to pass the lonely hours as best he could. The day wore on tediously enough, but the longest day must have an end. And when the grey mists of evening began to encircle the objects seen before so distinctly from the window, Charles Peace prepared to take his departure.

He disguised himself in so complete a manner as to almost defy detection. He made himself up as a hawker. He took the precaution to always carry a hawker’s licence, made out in a fictitious name; the licence itself, however, was genuine enough.

He heard, as he descended the creaking stairs, the boy whistling in the stable. Agreeably to the directions he had received, he handed the key to the lad, at the same time dropping a shilling in his hand.

The lad stared with astonishment, which was not unmixed with alarm.

A few words from Peace soon reassured him.

“But ye’ve been ’nation quiet all the day though,” said the lad, with a broad grin.

“People generally are quiet when they are asleep, my lad,” was the ready rejoinder.

“Ugh! ’spose so.”

Peace did not want to have further parley. His purpose was served, and he therefore proceeded on his journey.

The most celebrated cracksman of his day, Ned Gregson, alias the Bristol Badger, was certainly the least fortunate of the three ruffians who contrived to effect an entrance into Oakfield House. He was run to earth. After he had been carried on the hurdle into the farmhouse the village surgeon made a superficial examination of his wound, which was of a fearful nature; the whole of the charge from the gun fired by Jane Ryan had entered the burglar’s chest, and the loss of blood was enormous. The only wonder was, that Gregson had not been killed outright; but he was not the sort of man to be so easily disposed of. As far as physical strength was concerned he was a perfect giant; this he had proved on many occasions.

He was more than double the age of Peace, with three times his strength. Nevertheless, as far as the guilty and lawless lives of the two men were concerned, there was not much difference between them; they were both criminals of the worst type, their whole career being one of profligacy and crime.

Gregson was taken away to the lock-up in charge of the constabulary, who procured an ambulance from the hospital. The divisional surgeon was sent for; every care was taken of the prisoner; and all that skill and attention could do to preserve so valuable a life as the burglar’s was, as is usual in such cases, not wanting.

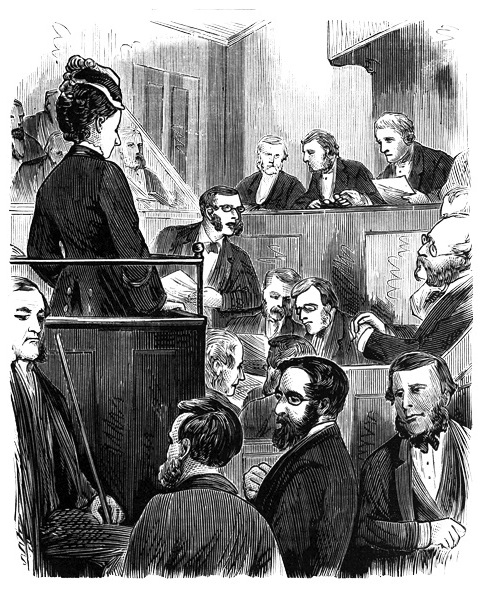

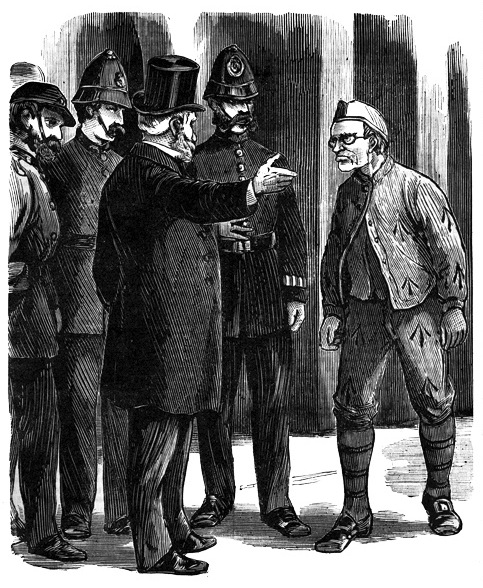

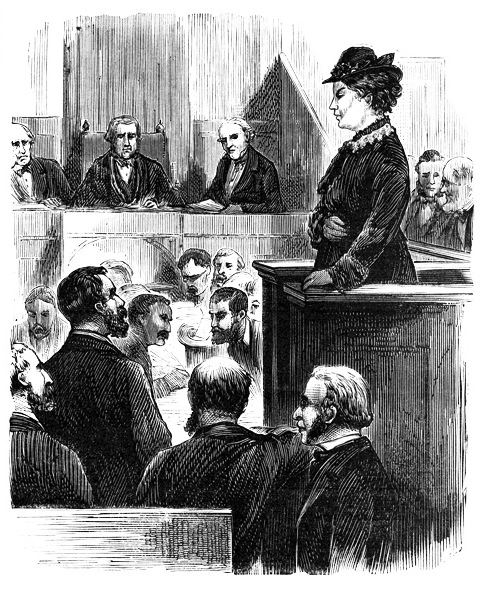

When sufficiently recovered Gregson was examined before the stipendiary magistrates. The facts deposed to were plain enough, and the prisoner was committed for trial upon two distinct charges—namely, murder and burglary.

Mr. John Ashbrook had by this time sufficiently regained his strength to leave his room and look after his farming stock, but he was not as yet up to his usual form.

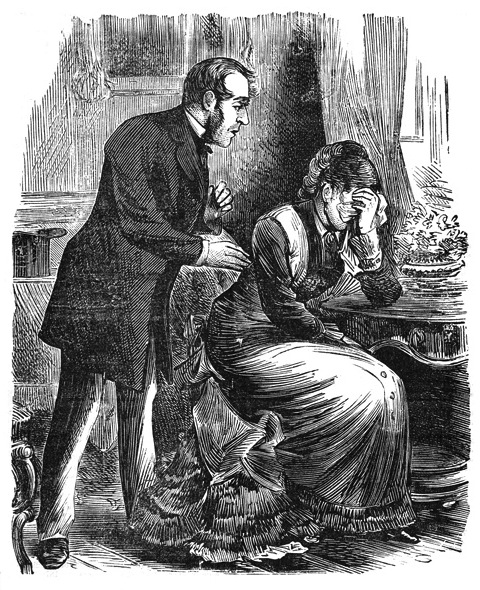

“This extraordinary charge of murder,” said the farmer to Jane, one afternoon, as he reclined upon the sofa in the front parlour, “it seems just like a romance. Strange that you should have recognised the ruffian by the pistol’s flash on that eventful night.”

“I should have known him out of ten thousand. His face was as familiar to me as if I had seen him but yesterday.”

“Tell us all about it, Jane.”

“Well, master, it’s a sad and sorrowful tale, which I have kept locked up in my own breast for ever so long, but it is but right you should know all about it.”

“Right lass, right you are; go on. What made you imagine that the house was likely to be attacked? You asked me to load the two other guns.”

“I did, because I felt assured that danger was at hand.”

“Why so?”

“I had a dream—twice I dreamt the same thing—and then I went over to Mother Crowther and consulted her. She can read the future—being—being a wise woman.”

“She is a wise woman indeed if she can do that,” remarked the farmer, with a smile; “what did she say?”

“She consulted a book, cast my nativity, and told me that in less than three days I should see here or hereabouts the murderer of James Hopgood.”

“And who might he be?”

“He is dead now; he was my sweetheart,” answered Jane, hanging down her head.

“Oh, your sweetheart—eh?”

“Yes, before I came here I lived at Squire Gordon’s. A kinder master never lived. James Hopgood was a carpenter by trade; he had been doing some work for the squire—building some outhouses, and while the work was going on he slept in the house.”

“How long ago was this?”

“Aye, it must be nearly six years.”

“You’ve been here over four.”

“That’s true. Indeed, it must be more than six years. I cannot say to a certainty; but they’ve got the date—the pleece have.”

“No matter, that’s quite near enough—six years or a little more. What happened then?”

“I will describe all to you, just as it occurred. James Hopgood was in the kitchen; he and Mary, my fellow-servant, were having supper together. I was in the back kitchen, when all of a sudden we heard a scuffle in the passage, and my master cried, ‘Murder!’ James rushed past me, and flew up the kitchen stairs. Then we heard a heavy fall in the passage; this was followed by some low moans. I went up to see what was the matter, and found my master stretched on the floor of the passage, with blood flowing from a wound in his left temple. I endeavoured to raise him, but was unable to do so. He was a stout, heavy man, and I had not strength enough to lift him.”

“Was he killed?”

“No—oh, dear, no; he recovered afterwards. But the worst remains to be told. Oh, master, these be tears that are a flowin’ from my eyes. I can see it all now, as if it occurred but yesterday.”

“Yes, your master, the squire, you found him senseless. There’s no hurry, girl, take your time—don’t flurry yourself.”

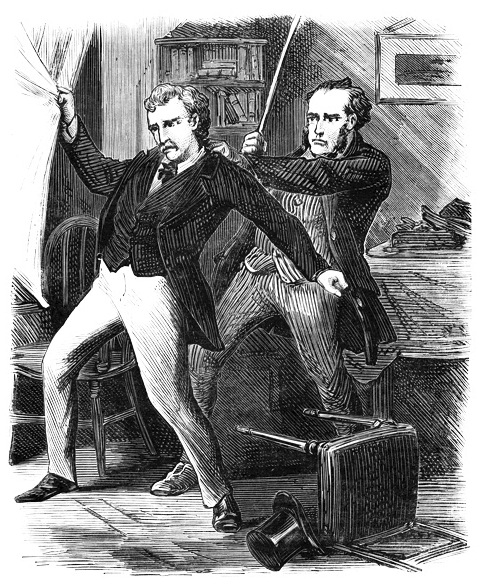

“While I was looking at my poor master, I caught sight of James Hopgood and the burglar—him as I shot down in the big bedroom. James had closed with the ruffian, who, as far as I could judge, was striving to shake James off; but he was not able to do this so easily; they wrestled like two serpents. I felt sick and faint; but, notwithstanding, I had sufficient strength left to hasten to young Hopgood’s assistance. I saw the flash of an open knife in the pale moonlight, saw the gleaming of the desperate wretch’s eyes, and in another moment the knife was buried up to the hilt in James’s breast. He fell with a deep groan, and never stirred hand or foot afterwards.

“I rushed forward, and caught his murderer by the handkerchief which encircled his throat. After this I lost all consciousness. When I came to I found myself on the wet grass of the lawn—the ruffian’s handkerchief was firmly grasped in my right hand.”

“Why, Jane, my girl, this is indeed a horrible story, and have you kept this all to yourself for these last six years?”

“Indeed I have; but, waking or sleeping, one burning thought has been in my brain. It is this—to avenge the death of my dear and true-hearted James.”

The farmer was bewildered—partly dazed by the fearful tale he had been listening to. He turned his eyes towards his sister, who had crept into the room to listen to the appalling narrative.

“Did you know of this?” inquired Ashbrook.

“I knew a shocking affair of some sort took place at Squire Gordon’s when Jane was there, but I never knew till now its precise nature. I understood that some young man was murdered—that is all. How and by whom I was never told.”

“And was the man never discovered? An attempt was made to find him, I s’pose?” asked the farmer of his servant.

“Government offered a reward of a hundred pounds; a description of the man was printed on handbills, which were sent, so they said, to every police-station.”

“With what result?”

“With none, except the arrest of a poor harmless fellow, who never set foot in the squire’s house, and who had no more to do with the crime than you or I have.”

“And the handkerchief?”

“That I have kept. The knife also with which the murder was committed was picked up on the lawn; that, too, I have preserved. They are both now in the possession of the pleece. Ah! we shall bring it home to the deep-dyed villain. I felt certain that, sooner or later, he would be caught, the murderin’ thief.”

“What became of the squire?”

“He left England for good, and settled in Brittany. He has a daughter who is married there.”

“Is he still alive?”

“I believe so. I never heard of his death—oh! I’m pretty sure he’s alive.”

“Do you think he could identify the man?”

“He told me after his recovery that he saw his features distinctly, and that he would be able to swear to him. It appeared that Gregson was making his escape from the house with the things he had stolen, when he was suddenly and unexpectedly confronted by the squire, who had come over the fields, crossed the lawn, and entered by the back door of his residence.”

“We’ve all of us had a narrow escape,” said Maud Ashbrook, “and it will be a warning to us for the future.”

“I’m glad Jane shot the fellow down,” observed the farmer. “She’s a true-hearted, brave girl—not, mind ye, but it would ha’ bin better for him to have fallen by the hands of one of us men.”

“No, master, no,” cried Jane, in a deprecating tone. “I am the most deeply injured, sick and sore of heart—I who have sworn to devote the remainder of my life to discover the slayer of James Hopgood—I was the most fitting person to hunt him down. It has been done, and he will not escape now.”

Jane had given her evidence before the stipendiary magistrates in the clearest and most lucid manner. She swore positively to the prisoner Gregson, whose features she declared had not changed since she saw them so distinctly on that fatal night. Her fellow-servant also identified the prisoner, whom she saw, so she averred, through the back-parlour window at the time Jane had hold of him by the handkerchief.

He was also recognised by several of the police as a well-known burglar, who had been convicted several times.

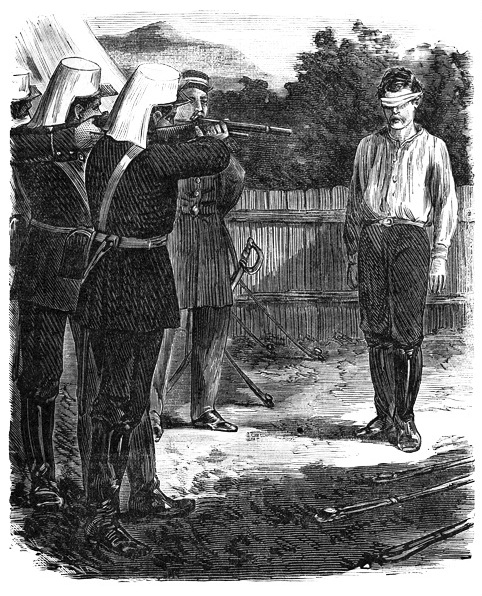

Gregson, who was about as hardened a ruffian as it was possible to conceive, knew and felt that his game was up; nevertheless he clung to the hope, as most criminals do of his class, that he might escape the last dread sentence of the law—perhaps his life might be spared.

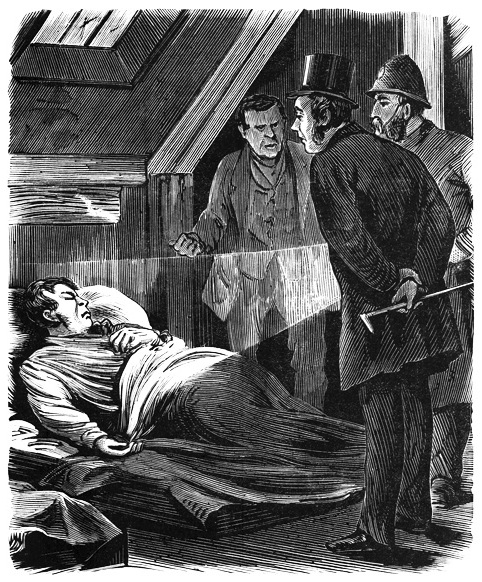

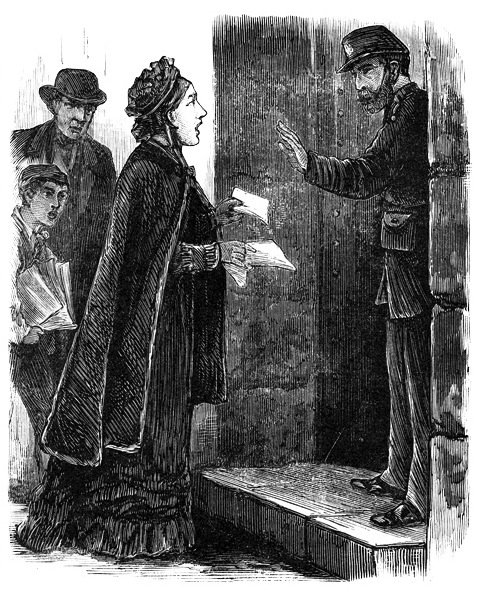

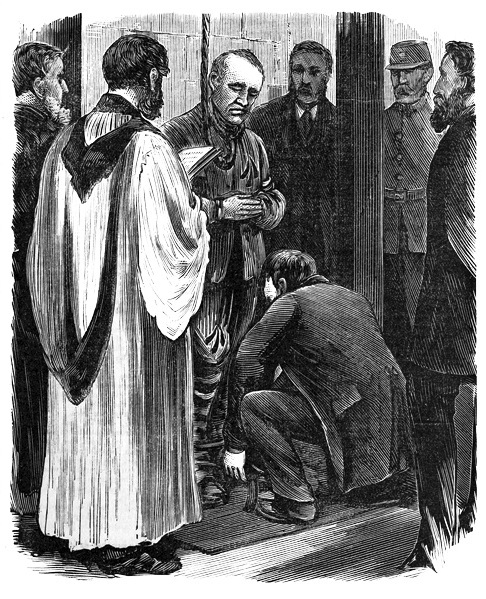

He was taken to Broxwell Gaol; his custodians conducted him through the lodge, then he passed through a square with a green plot of grass in the middle, encircled by a gravel walk.

It was like a college quadrangle.

Gregson looked at the grass and the turnkeys who came out to meet him. He was conducted up a flight of stone steps, and one of the turnkeys who had joined him and the constabulary who had him under their charge tapped at a thick oak door, which was covered with iron nails and secured with a gigantic lock.

They were admitted immediately into a little room, which was almost entirely filled by a clerks’ desk and stool.

Upon this stool was seated an old man, with a pair of iron-rimmed spectacles on his nose, making entries in an account-book.

The turnkey who had opened the door to them now closed it with an ominous sound.

The key clanked loudly in the lock.

The Bristol Badger was in prison.

The turnkey unlocked another door and disappeared. In a few moments he returned, dismissed the constable, and ordered the prisoner to follow him.

They entered a snow-white corridor, which was lined with iron doors, and above with galleries, also of iron, bright and polished.

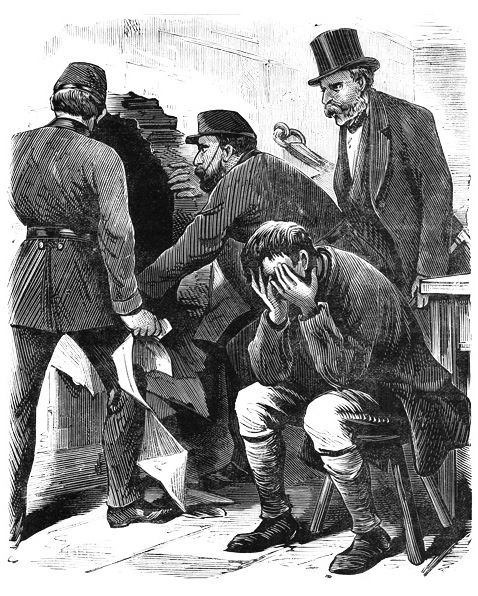

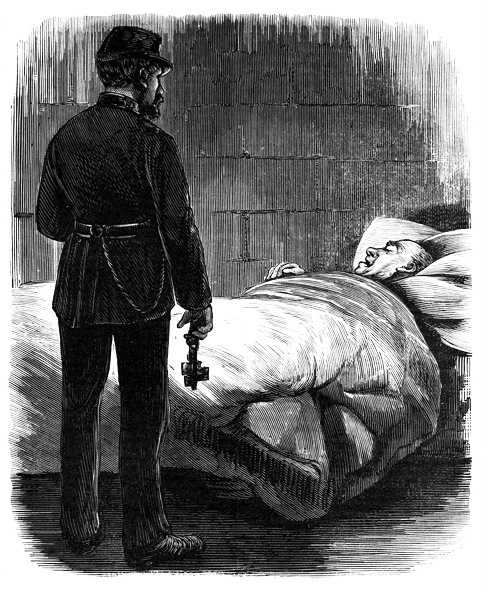

Gregson was placed in a cell, for some time in the company of a single turnkey, who stood by him, rigid and voiceless as a statue, watchful as a lynx.

The “cracksman” assumed an air of dejection, and kept his eyes fixed upon the ground.

He had only partially recovered from his wound. From this a vast number of shots had been extracted; but several more, it was thought, still remained in the flesh.

The burning pain in his chest had not entirely left him, although it was not nearly so insupportable as at first.

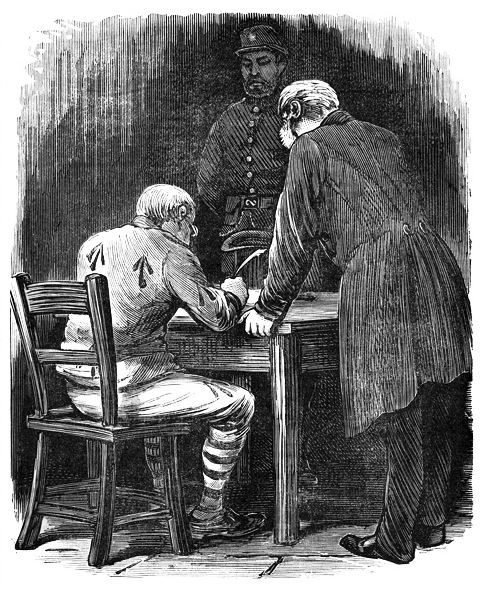

Presently the door of the cell opened, and a gentleman in plain clothes came in. He had a ruddy complexion, with a brown moustache and beard.

Gregson recognised him immediately. He was the governor.

The recognition was mutual.

“So,” he said, “you have come here again?”

“They’ve brought me here,” muttered the cracksman.

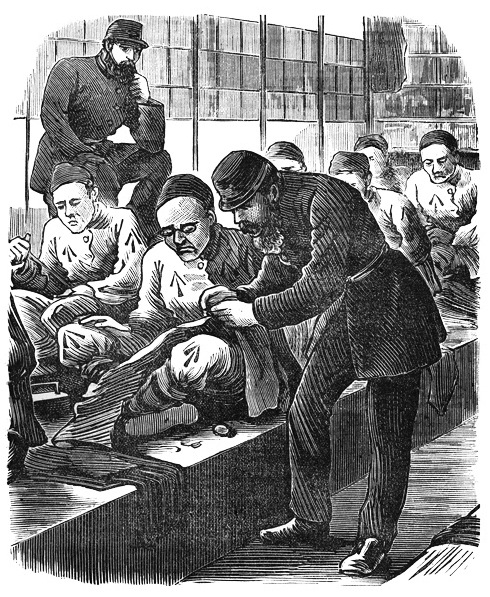

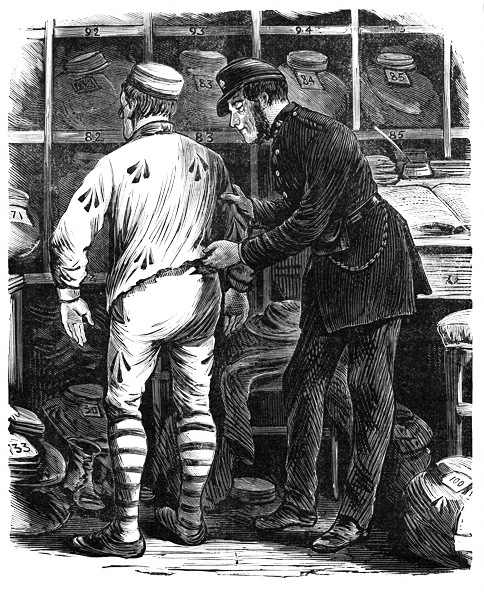

“Precisely. Of course you know the usual forms prescribed by the authorities. We must put you through the ordeal of a warm bath.

“Turn on the tap, Wilson,” said the governor; and in a few minutes the bath was filled with hot water.

They took off his handcuffs, and then stood by him as he undressed.

“Do you know, governor, that I’ve been wounded—well-nigh to death? It’s too bad to put a cove in hot water in my state.”

“Wounded, eh? We’ll send for the doctor.”

The prison surgeon was brought into the room.

He glanced at the wound, which still presented an angry appearance.

“The bath won’t hurt you. There is no necessity for you to immerse your chest or shoulders in the water. In my opinion you will be better for it.”

“All right,” returned Gregson; “you shall have your way. I’m not one to make things disagreeable.”

And forthwith he jumped in.

The governor paced the corridor for the next ten minutes or so under pretence of superintending the arrangements of the prisoners’ dinners, which ascended from the kitchen on a great tray by means of mysterious machinery.

On his return he called another turnkey, and ordered him to have the prisoner’s clothes brushed and cleaned.

“You have got plenty of money,” he said to Gregson. “You are suffering from a severe wound. We don’t wish to deal harshly with you.”

“I’m much obliged, I’m sure,” returned the Badger.

The governor took no notice of this last observation, which, to say the truth, was half conciliatory and half sarcastic.

“We will therefore allow you to wear your own clothes, and to procure your own meals from an eating-house if you prefer it.”

“Yes, I do prefer it, if it makes no difference.”

“So be it, then. You will see by the printed copy of the rules which is hung up in every cell that you are not allowed more than one pint of wine or one quart of malt liquor daily, and that, if you undertake to board yourself, you must do so altogether. Besides this you will be allowed books to read and paper to write upon, and other little comforts, under my supervision, as I have no desire to treat you with unnecessary severity during the brief period that will elapse while you are awaiting your trial. I hope you will conduct yourself in a proper and becoming manner.”

The cracksman nodded, and seemed by his demeanour to appreciate the lenity which the governor displayed.

“You are very good, sir, I’m sure,” he muttered. “I wish all gentlemen in your position were equally kind and merciful.”

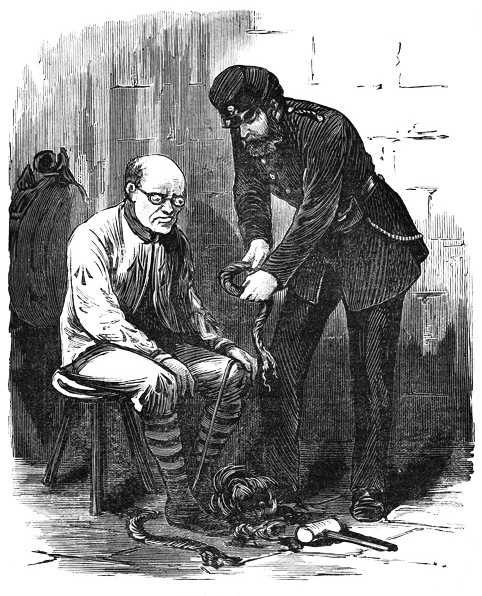

The governor bowed in a dignified manner, and then left the cell. The turnkey returned with Gregson’s clothes, and stood by him as he dressed. He was then conducted to Cell No. 15.

There they showed him how to ring the bell, how to pull the slide from the grating when he wanted fresh air, and how to manage the water taps and the bed furniture.

They also informed him that when he wanted anything from the town there was a prison servant attached to the establishment whose office it was to run errands for the prisoners who were waiting for trial.

The turnkeys made these explanations with a courteous accent, for turnkeys have a sort of veneration for great criminals.

And Ned Gregson, in this respect, was a man of mark.

The prison officials went out of the cell backwards, as if they were retiring from a royal presence; they locked the door with an ostentatious noise that they might thereby strike a wholesome awe into the mind of their prisoner.

Gregson sat himself down upon the wooden stool in his cell without moving.

The bitterness of his thoughts it would not be so easy to describe.

He remembered with harrowing distinctness the most remote incident of the night upon which the ill-fated James Hopgood fell beneath the fatal blow.

“And that cursed woman!” ejaculated the Badger. “Who would have dreamt of her being an inmate of the farmhouse? And the oily-tongued Peace, he has got clear off, I’ll dare be sworn; and the chances are that he is now playing that old fiddle of his—whilst I—I—”

Here he uttered an impious oath, and then lapsed into silence again.

He sat for two hours a prey to the most agonising thoughts.

At the expiration of that time he uttered curses loud and deep. He ran frantically round his narrow cell.

One of the turnkeys opened the door, and told him that he must make less noise. There was a punishment for making an outcry of that nature, and he pointed to one of the printed rules.

The “cracksman” answered with a howl of rage, and squatted abjectly on his stone floor.

The turnkey, who was pretty well used to scenes of this nature, and who, therefore, made due allowance, repeated his warning and shut the door.

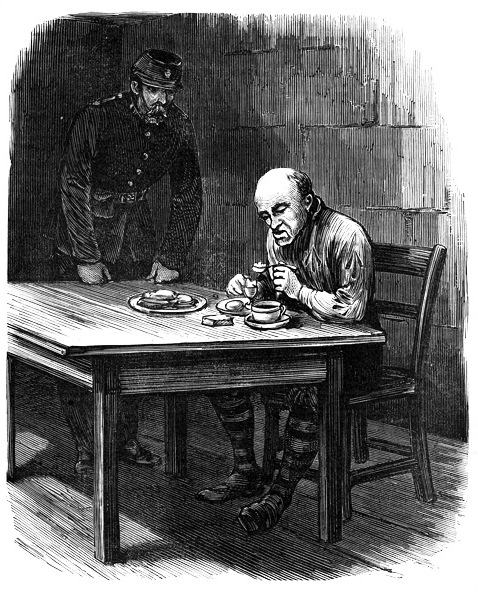

Soon after this the prison servant brought a wooden tray in.

There were two dishes, each surrounded by a pewter cover. One contained three slices of roast mutton, floating in lukewarm gravy; the other contained four good-sized potatoes.

Gregson, who was still on the floor, looked at them supinely.

“Governor! thought you would like a little dinner,” said the man kindly; and he propped up a slab which was hanging from the wall, placed the tray on it, reached down a salt dish from a shelf in the corner, where it had grown dusty, in company with a bible and two hymn books.

“Will you take beer or wine?”

“I want wine,” said the Badger, sulkily.

“Very good, I will bring you a pint; it’s against the rules to have any more.”

He drank some of the eating-house sherry, which, bad as it was, encouraged him to eat a few mouthfuls. This awoke him from the stupor into which he had fallen, and which had been almost akin to madness.

Leaving the guilty man to his reflections, we will now return to the hero of our story.

Charles Peace, after he left the groom’s little bedroom, succeeded in getting clear out of the neighbourhood, without attracting any observation.

As he trudged along he reflected that it would be advisable not to return to Hull. The hue and cry raised in consequence of the events already described would reach Hull, and search would be made by the police in that town.

What had gone of Cooney Peace had not the remotest idea. Whether he had escaped or been captured it was not possible for him to say; neither did he concern himself much about the fate of the tinker. In cases of this sort he felt that self-preservation was the first law of nature.

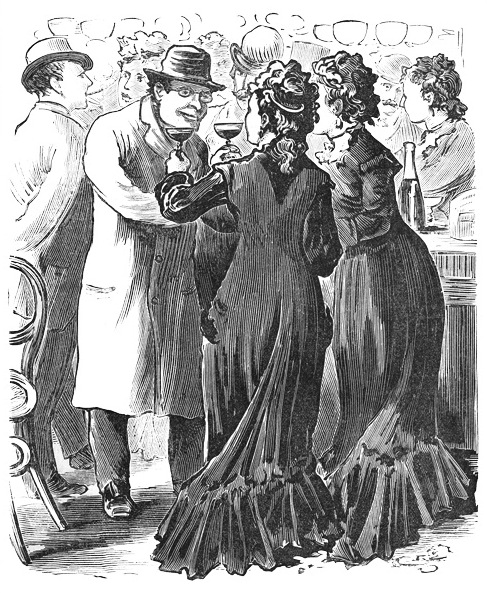

As he was proceeding along he was overtaken by a covered cart. He persuaded the driver thereof to give him a lift on the road. By this means he managed to get many miles on his journey. Having made up his mind to take up his quarters at Bradford, he, on the first opportunity, took the train to that town. He was acquainted with a girl at Bradford, who was, to a certain extent, attached to him. She was a mill-hand. She was possessed of a considerable share of personal attractions.

It was evening when Peace arrived at Bradford, and in the streets were throngs of persons. The factory hands had knocked off work; some were hastening homewards, others were making for some favourite house of entertainment, and groups of inveterate gossips were to be seen in various parts of the town.