INDIAN YOUTH AT “SCHOOL” (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

BY JOHN M. DOUGLASS

The author, a member of the History Division of the Milwaukee Public Museum, died January 26, 1951, shortly after completing the manuscript of this handbook.

POPULAR SCIENCE HANDBOOK SERIES NO. 6

DESIGNED AND PRINTED AT

THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM

PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF

THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

MAY 1954

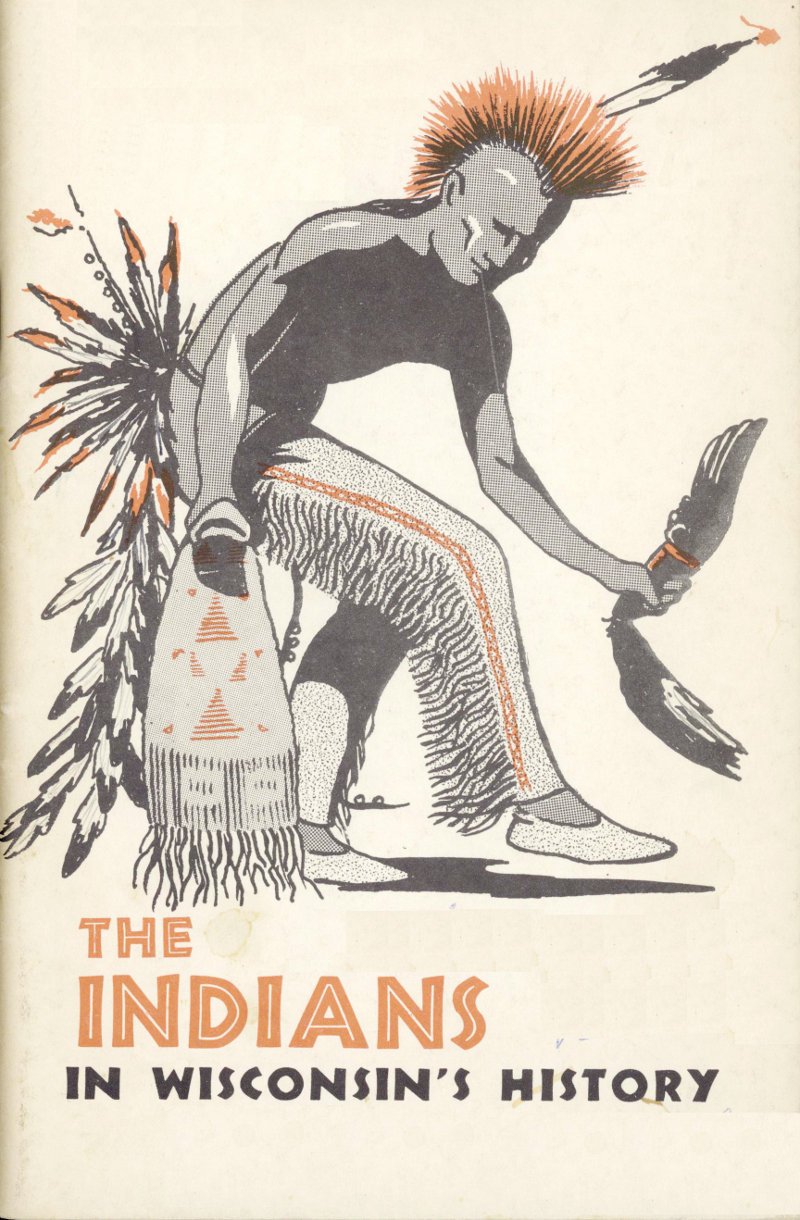

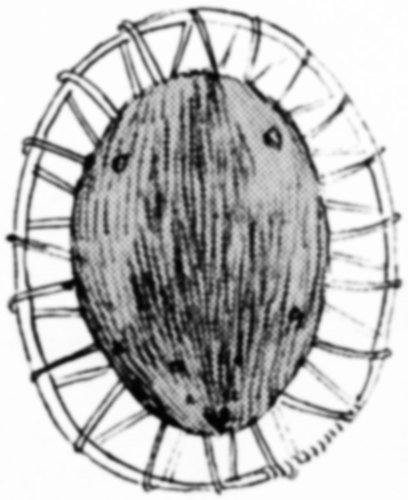

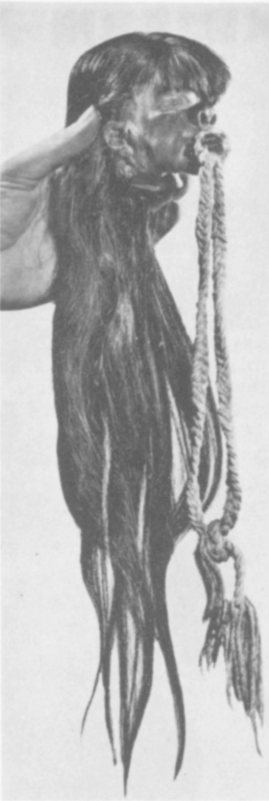

ROACH HEADDRESS (MUSEUM EXHIBIT).

It is difficult now to realize that Wisconsin, famed as a dairy state and rich in farm land and thriving communities, was once a great wilderness. Before the land was cleared for the farmer’s plow and with its dense forests yet to hear the lumberjack’s axe, the thick timberland of the north and even the rolling prairies of the central and southern portions of our state teemed with a great variety of wild life, including animals no longer occurring in Wisconsin, such as the woodland caribou, moose, elk, and buffalo or bison, as well as the more familiar deer, bear, and many smaller varieties.

Before the arrival of the Europeans, this Wisconsin wilderness was the home of Indians who were wonderfully adapted to a life in the forests. They depended almost entirely on hunting and the gathering of natural products for their food, shelter, clothing, tools, and weapons, although most of them raised some garden crops such as corn, squash, beans, and possibly tobacco.

Let’s pretend that we can travel backwards in time about 350 years and visit a typical Indian family of that period. As we arrive on the scene the tribe is preparing to set up a new camp. The women are busy unpacking their household gear, including reed mats used to cover the outer sides of the wigwam. The women themselves have carried the loads during the journey. This is not done because of any laziness on the part of the men, a common error of white observers, but simply because the men need their hands free to ward off a sudden enemy attack, or to kill any game they might chance upon during the journey.

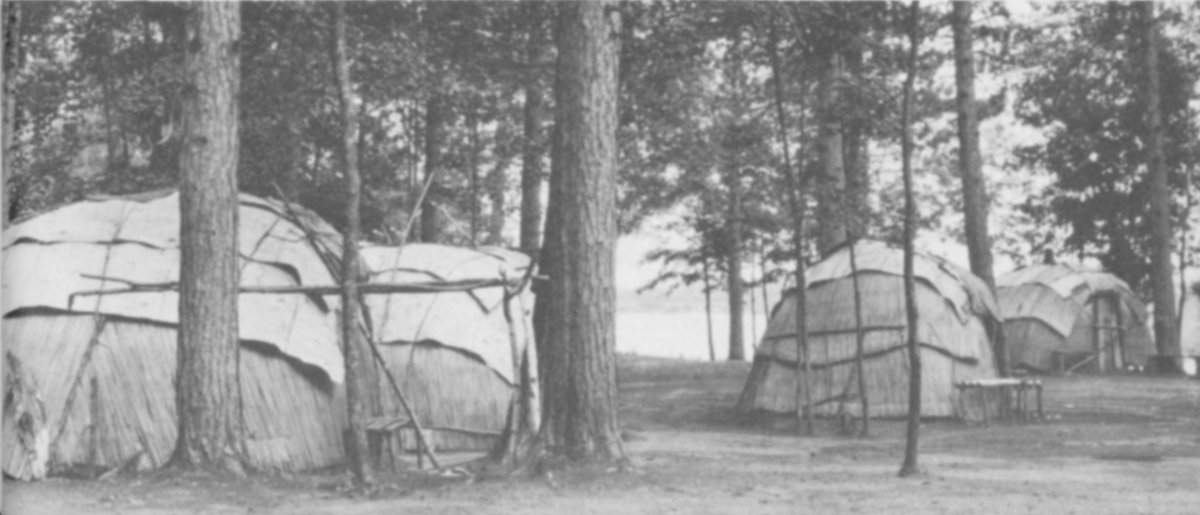

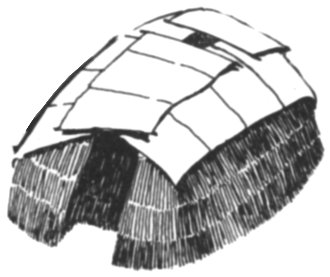

While the women unpack, the men enter the woods to cut poles for the framework of the wigwams, and collect birch bark for the roofs. After the poles are set into the ground to make an oval enclosure, they are bent and tied together at the top to form a rounded roof. The women then tie on the reed mats, and roof the hut with the rolls of bark. This is the typical Wisconsin Indian winter lodge. Although it is the latter part of March, the weather is still too cold to live comfortably in a summer lodge.

If we lift the bearskin covering the entrance and step into the lodge, we may see the simple furnishings and personal possessions of the family we are going to visit. A hole in the middle of the roof serves to carry off the smoke from the fire burning in the center of the floor. This fire serves the double purpose of heating the lodge and cooking the family meals. We find the hut almost too smoky to endure, accustomed as we are to our modern homes, but our Indian friends seem quite comfortable.

Since our Indian family is fairly large, including the father’s parents as well as the mother, father, two boys, and two girls, the wigwam is proportionately large in order to accommodate all of them.

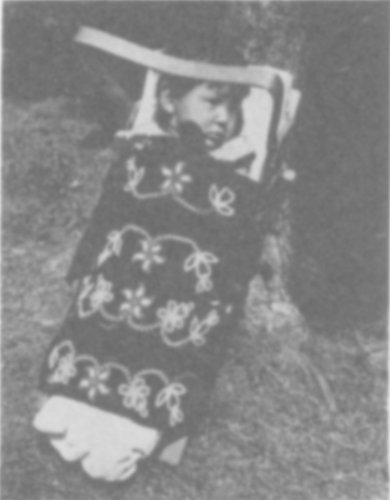

We look about the inside of the lodge and see the sleeping mats and furs. The family’s spare clothing, breechclouts, shirts, leggings, and moccasins of tanned deerskin for the men, and skirts, blouses, and moccasins for the women, are in one corner. The garments are beautifully decorated with designs grandma embroidered on them with dyed porcupine quills. The work is quite fine and it takes many hours to do a small portion of the embroidery. Father is especially fond of his headdress, a roach made of deer and porcupine hair, and an eagle feather which indicates that he has killed an enemy in battle.

WIGWAMS, OR WINTER LODGES.

As we step outside again and look about, we can see why this particular spot has been chosen as the campsite. A small lake and several springs are only a short distance away, but the most important reason for camping here at this season is a large grove of sugar maple trees immediately to one side of the camp. March is the proper time to tap the trees for their sap.

The next two or three weeks are spent tapping the trees, and boiling the sap down until maple syrup, and finally only maple sugar is left. This sugar keeps indefinitely and provides a very nourishing as well as a delicious source of food for the entire family. The children are especially fond of it.

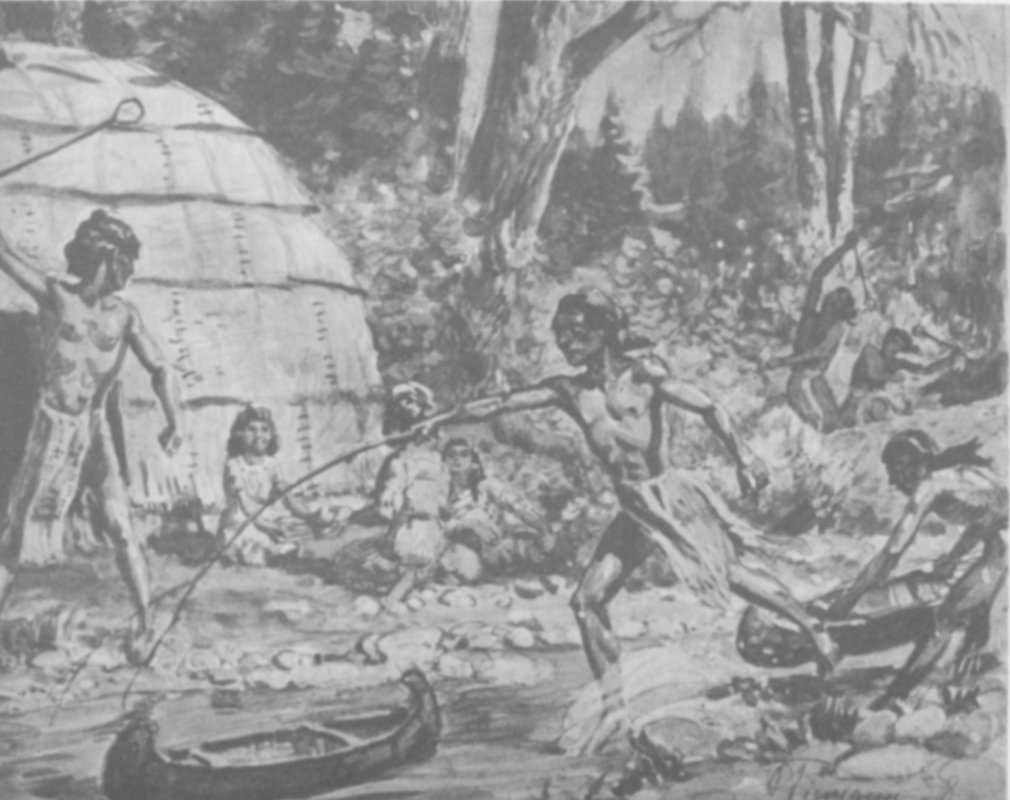

It is not a case of all work and no play during this period, for the children, Morning Star, White Fawn, Blackbird, and Little Otter, play games when their tasks are finished, and gambling games are popular with the men and women. Here we see mother and some neighbor women playing the cup and pin game. Each player in turn tosses into the air small cone-shaped cups made of antler tips or bear-toe bones, and tries to catch one or more on a bone pin. The men are enthusiastic gamblers, too, using marked sticks which are thrown and scored somewhat like our own familiar dice games.

When the sugar making is finished, the tribe breaks camp and travels by birch-bark canoe to a new location. The canoes are wonderfully light boats and can be paddled very swiftly. Their light weight makes them relatively easy to carry or portage from one stream to another. Our canoe has eyes painted on the bow and stern. The father explains that these eyes enable the canoe to “see where to go.”

INDIAN CHILDREN AT PLAY (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

BIRCH-BARK CANOE.

At the new summer camp we watch our friends build summer lodges. These are rectangular in shape with inverted-V-shaped roofs much like our own houses. The entire lodge is covered with strips of elm or other bark.

As is often the case, the new campsite is near a river, and springs nearby furnish cool, pure drinking water. There are also open clearings closeby which will be utilized for gardening. The next few weeks, however, will be used for making necessary utensils and equipment needed by the tribe.

SUMMER LODGE.

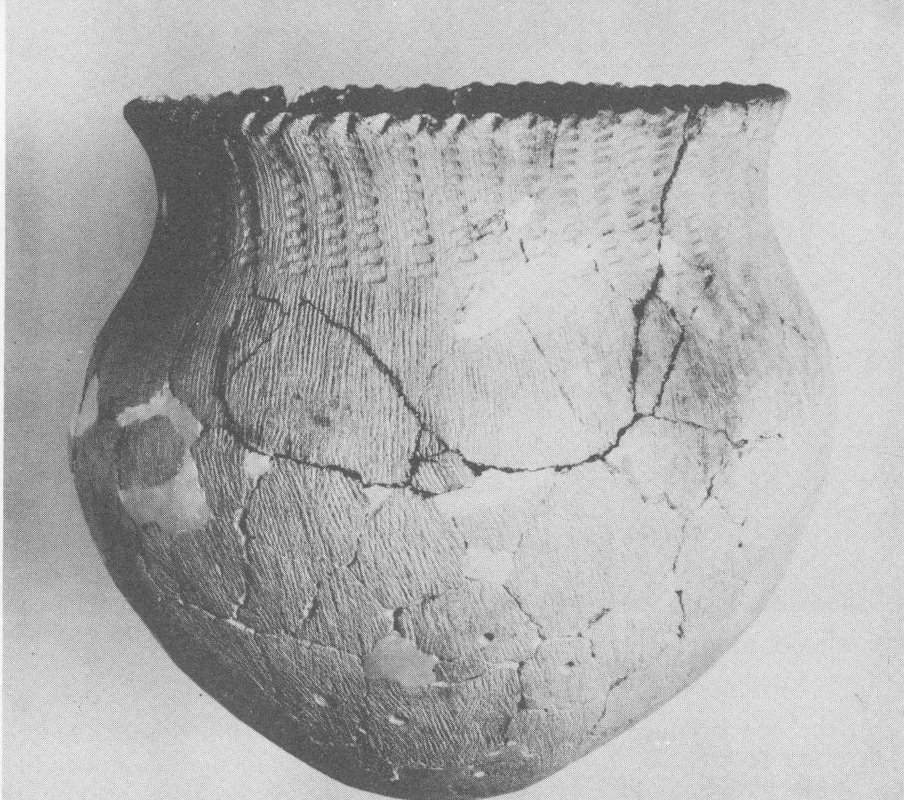

ANCIENT WOODLAND POTTERY VESSEL.

One day we are interested observers of pottery making. Grandma goes to a clay bed near the river and selects suitable materials including some coarse sand for tempering the pottery paste, which is made of both clay and sand. The paste is worked into long cylinders which are finally coiled about into the desired shape. After the vessel has assumed final shape it is paddled with a cord-wrapped tool and allowed to air-dry for several days, and finally baked in a large outdoor fire. The finished pot can be used to boil water or cook food, and has the advantage of being easily replaced in case of breakage.

May soon arrives, and as this is the time to plant corn, our Indian family selects a suitable clearing for their garden. The men burn out the underbrush and the women and girls prepare for the planting itself. Grandma informs us that it is always best to soak the grains in water several days before seeding. After the seeds have been properly softened, the women and girls dig holes in the ground, place six or seven grains of corn in each hole, and then heap up the dirt over the seeds in a little hillock. Squash and beans are planted in the clearing, too.

One day we are told that the tribe is going to have a game drive, since considerable meat is needed by the village. We go along into the forest and watch the men chop down trees with their stone axes. These are all felled in one direction, the cut incomplete so that the tree is still attached to the stump, and in two rows so as to leave a gradually narrowing corridor more than a mile long. The deer are then driven towards the corridor where men stationed with bows are able to shoot them easily as they approach the narrow opening between the barriers.

A number of the animals are killed in this way and taken back to the village where their flesh can be preserved by being cut into strips and smoke-dried. We are all too hungry, however, to wait until we return to the village before eating. The chief says we can have some boiled venison stew. We are puzzled at this, for no utensils have been brought along, but we soon learn how resourceful our Indian friends are.

One of the men obtains some edible roots; another cuts the stomachs from several of the deer. Each one of the stomachs is cleaned and tied to form a pouch. The venison, roots, and some wild rice which some of the men brought along, are placed in the prepared deer stomachs, water added, and the ingenious “kettles” suspended over a slow fire. In a relatively short time a delicious stew is set before each of us, served in birch-bark dishes prepared in a few minutes by another of the hunters.

While we are eating we ask the father of the Indian family we are visiting how the chief of his tribe obtained his position. We are told that his ability as a warrior and leader has led to his being chosen war chief, and his ability as an orator and his power to make people like him has kept him in authority. He says that in a nearby village the chief is also a great war leader, but he is not well liked otherwise. For that reason he sometimes finds it difficult to make his warriors obey him and he is therefore not nearly as powerful as our leader. We soon realize that the Indian chiefs depend primarily upon personal prestige and influence to keep them in power. We are informed, however, that in some other tribes the chief is always selected from a certain clan.

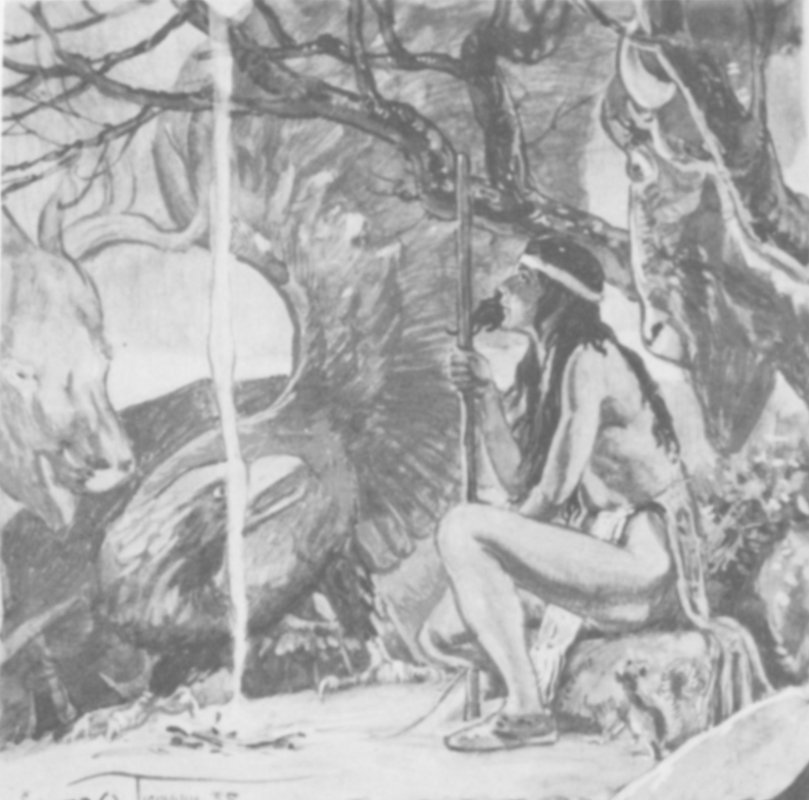

YOUTH FASTING FOR A VISION (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

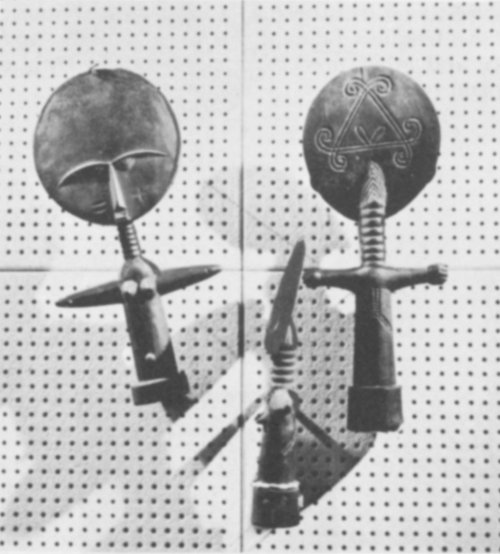

One morning we witness a curious ceremony. Grandfather offers Blackbird, the older boy, some charcoal as well as his food. The father seems very proud when his son rejects the food, applies the charcoal to his face, and leaves the village to enter the forest alone. Grandfather 7 explains that Blackbird, by accepting the charcoal, automatically agreed to fast alone in the forest for one day. This one-day fast will be good training for the day when he will feel ready to go on the long fast of four or five days. Every man has taken this long fast in the hope of seeing a vision of a guardian spirit who would then be his lifetime protector.

The girls, too, must fast, but in a somewhat different fashion. Soon Morning Star, the older girl in our friend’s family, will reach womanhood and be segregated for a number of days in a secluded lodge, and during this period no men may approach her.

The summer season rapidly nears an end. We have enjoyed ourselves watching the activities of our friends at work and at play. We have learned, too, some of the beliefs of our friends. Grandfather has told us stories about the great white bear with the copper tail who dwells underground and is the greatest power for evil. He has told the children how the “Indian Sandman,” a good-natured elf, would put people to sleep at night by hitting them on the head with a soft war club. We have learned, too, of the many spirits for good and evil who control the sun, moon, stars, winds, rain, thunder, and all the other phenomena of nature. One evening he pointed out the Milky Way and told us that this was the road over which the dead travelled to the land of the spirits. He also warned us about entering the woods alone at night because of the evil, living skeleton which haunts the forest paths seeking unwary men.

TALES OF THE SPIRIT WORLD (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

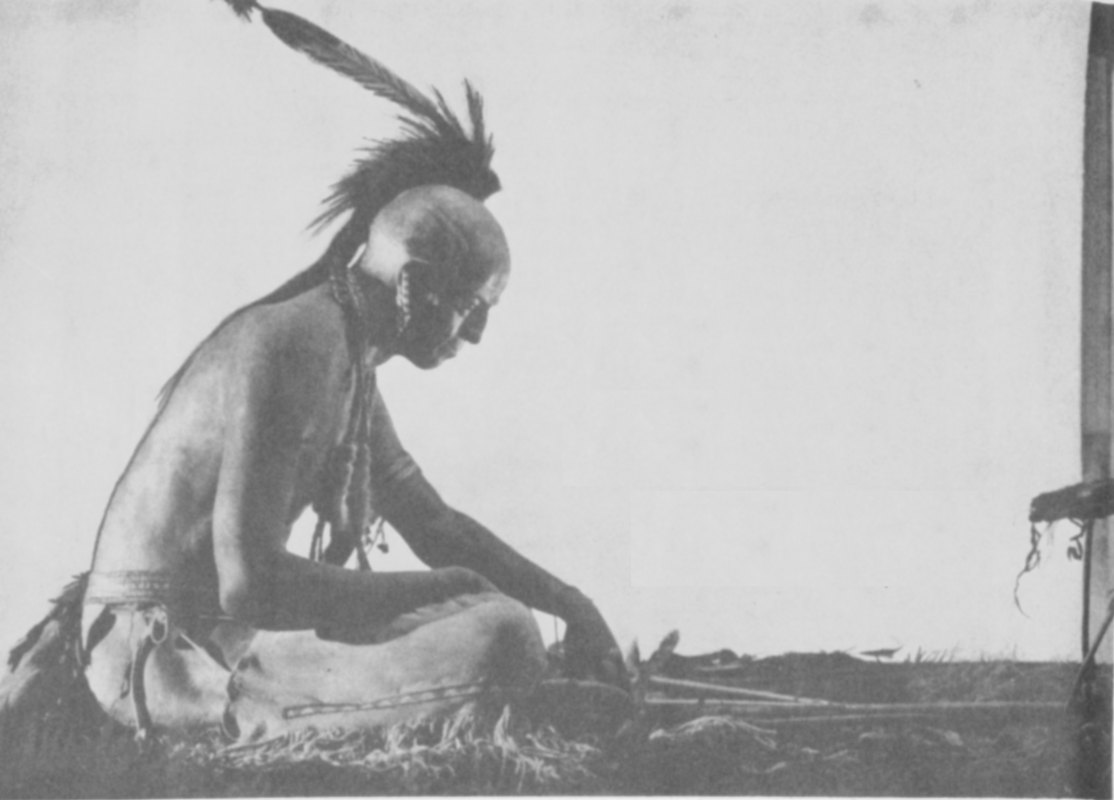

THE RICE GATHERER.

Autumn, the time for harvesting garden crops as well as various wild vegetable foods, is a season of hard work for all. Corn is the most important garden crop, and from time to time we have sampled the ripe grain. The women have served us some roasted on the cob, or the fresh kernels ground with a wooden mortar and pestle and served as a sort of porridge. The ripe corn is now gathered and the ears will be allowed to dry. The dried kernels can then be ground into a meal, as needed, since the dry corn will remain edible for a long time.

Wild rice is the most important vegetable food provided for the Indians by nature. One day, in the middle of September, we all go a short distance up the river in our canoes and enter a small lake. Here the wild grain grows in great quantities. The men selected by the chief to determine when the rice is ready to be gathered have already given us the signal that the grain is ripe. We learn, however, that one more function is required before we can proceed with the harvesting of the rice.

The chief medicine man of our village approaches the edge of the water and blows tobacco smoke towards the heavens as an offering to his “Grandfather,” the “Master of the Rice.” He then buries a small portion of tobacco in the ground, and we are ready to proceed.

In each canoe, as the man poles the boat slowly through the rice, the woman, who sits facing the man, pulls the stalks over the canoe with one cedar stick, while with another stick she beats the ripe grain into the boat. When the canoes are full, we head back for camp where the rice is spread out to dry.

Then the women heat the unhusked kernels in a pot over a slow fire until all have partially popped open. Next a small pit is dug and a stake set into the ground beside it. The depression is lined with buckskin and filled with the parched grain. The father then takes hold of the stake, steps into the grain-filled pit, and begins treading the grain with his feet to loosen the husks from the kernels.

The women take the grain from the pit and toss it up and down in bark winnowing trays. The wind blows away the light chaff as the grain is tossed into the air, and allows only the kernels to fall back into the tray.

The time soon arrives for our friends to break camp and seek a winter campsite where the hunting is known to be good. Hunting and fishing will be the main source of food during the winter season.

At the new campsite, storage pits lined with birch bark are dug in the ground to be used for storing the nuts, dried berries, dried corn, and rice that have been gathered and prepared during the Autumn. If hunting is poor, or if a severe winter threatens famine to the village, this stored food may be the sole means of preventing starvation.

It is now time for us to leave our Indian friends, but before we go we learn that the winter season will be spent not only in the pursuits of fishing through the ice and hunting, but also, in the telling of stories, singing, and playing many different games. When the snows are deep, the tribe will don snowshoes for their hunting trips. We will miss seeing them play snowsnake. In this game the Indians compete with each other to see who can hurl the wooden “snake” the greatest distance across the 10 snow or ice. We are sorry to miss all these things, but the time has come for us to end our visit.

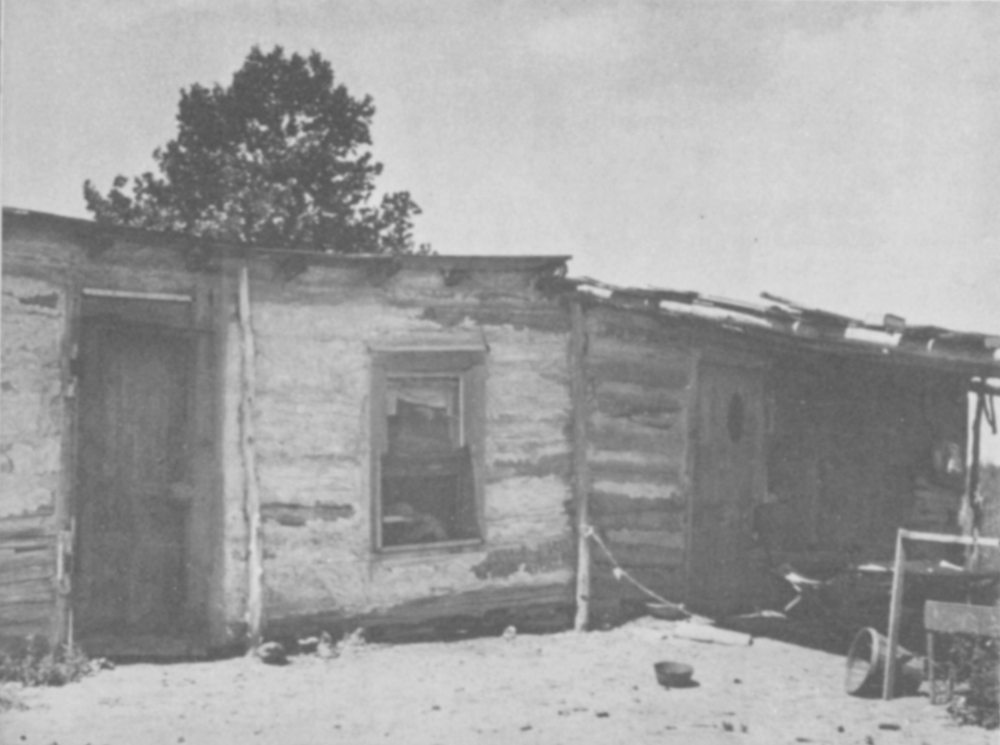

As we say farewell to our friends from the distant past, we reflect regretfully that the coming of the white man will change the old ways of life for these people of the forests, and soon their independence and freedom will vanish forever. The Indians seem destined to become largely dependent upon the whites for their livelihood, and even for the few remnants of land to be left them for their homes.

THRASHING RICE (MUSEUM EXHIBIT).

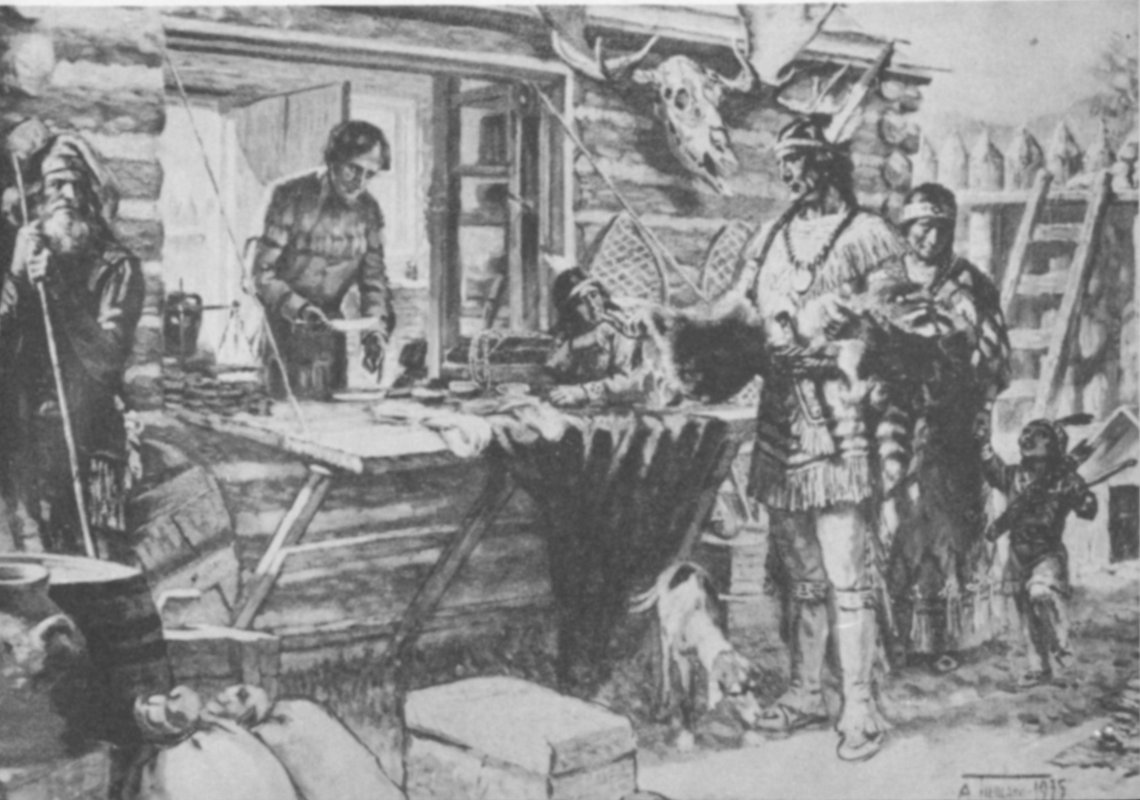

THE FUR TRADERS (MUSEUM MURAL BY A. O. TIEMANN).

Few of us realize that the early history of Wisconsin is as romantic as any our eastern seaboard states can boast. The area that is now the State of Wisconsin became the gateway into the Middlewest and the meeting place for the French and the Indian tribes of what was then regarded as the West. This early period of French control was an era in which Jesuit missionaries carried the doctrine of Christianity from village to village, often visiting tribes that had never before seen white men. It was a time when the French traders, lured by the love of adventure and romance as well as the wealth to be obtained in the fur trade, pushed through the forests and followed strange rivers until they reached the villages of unknown Wisconsin Indians. It was in these villages that such traders, including the “noblest” youth of New France, lived with the Indians, sat in their councils, took part in their war dances, accompanied their war parties to battle, and often married their women.

It was in this early French Regime that Wisconsin’s Indian tribes underwent great changes in their manner of life due to contacts with the white man’s civilization, It was a time of warfare and a struggle for supremacy in North America between the British and the French, and 12 their Indian allies, with Wisconsin’s tribes espoused to the cause of the French. It was the heyday of the fur trade with literally millions of beaver and other skins being taken from Wisconsin to enrich the trader and obtain white man’s goods for the Indians.

Despite the fact that Wisconsin’s Indians all lived in pretty much the same manner, most of us are aware that there were different tribes in our state at various times, and that they spoke different languages in some instances. If we use a comparison from European languages, we might better understand the character of these Indian languages. German, English, and Swedish all originated from the same parent tongue and belong to the same basic language division. English and Chinese are unrelated tongues belonging to different basic language stocks. Thus, while many words are very similar in English and German, in English and Chinese no apparent similarity exists.

Three basic language divisions, Algonkian, Siouan, and Iroquoian, were represented by Wisconsin’s Indians. Algonkian was represented by such tribes as the Menomini, Potawatomi, Chippewa, Mascouten, Sauk, Fox, Ottawa, and Kickapoo. Relatively late arrivals to Wisconsin (in the 1800’s), also speaking Algonkian tongues, were the Munsee, Brotherton, and Stockbridge tribes. The Siouan group included the Winnebago, and the Santee division of the Dakota Sioux. The Huron and the Oneida (the latter also arriving in the 1800’s) were Wisconsin representatives of the Iroquoian language stock. The differences become more apparent when we realize that languages in the Iroquoian division would be as different from those in the Algonkian stock as English is from Chinese.

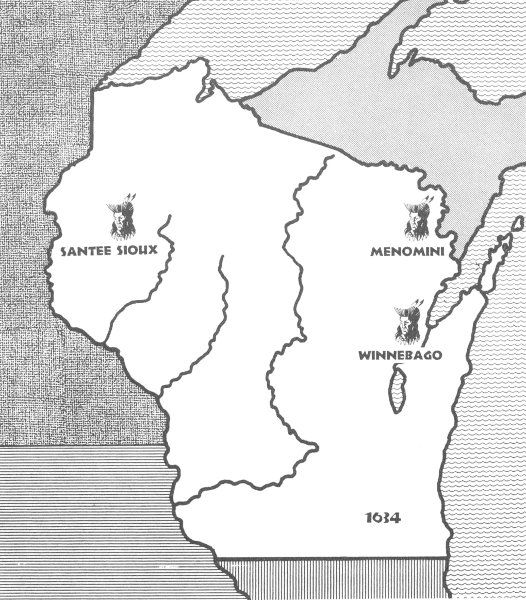

The historic period in Wisconsin began when Jean Nicolet, the first known white man to visit Wisconsin, landed near what is now Green Bay, in 1634. Nicolet’s mission was to arrange a peace between the powerful Winnebago tribe, or Puans, as they were known to the French, and the Ottawa who were then acting as middlemen between the French and the Indians of the unknown Middlewest.

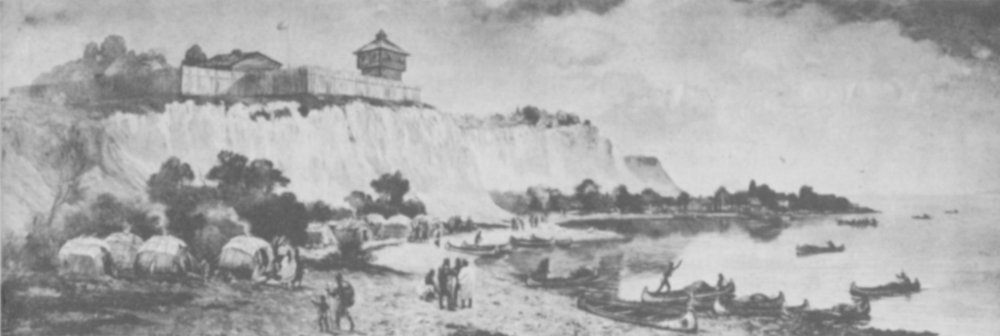

THE LANDING OF NICOLET (MUSEUM MURAL BY GEORGE PETER).

Nicolet’s journey into the Wisconsin wilderness, a mere fourteen years after the landing of our pilgrim forefathers at Plymouth Rock, was the beginning of the period of French exploration and rule in Wisconsin which is as romantic and fascinating a story as any in our country’s 13 history. Imagine Nicolet’s emotion as he approached his destination, a lone white man with seven Indians for companions, in a country which, as far as was known, had never before been visited by a white man. He had no idea as to what sort of reception he would receive from these strange people he was to visit. Their friendliness or enmity would be determined upon arrival. Fortunately he was hailed as a great visitor, and feasted and entertained accordingly.

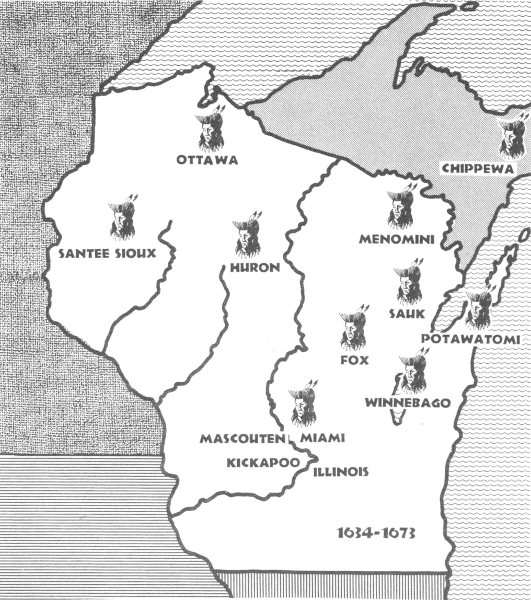

Only three Indian tribes are definitely known to have been residents of Wisconsin when Nicolet visited here in 1634. These were the Winnebago; the Menomini, who resided along the shores of the Menominee River above Green Bay; and the Santee Sioux, whose villages were scattered along the upper reaches of the Mississippi River in northwestern Wisconsin and eastern Minnesota.

Documentary evidence strongly suggests that some other tribes, often mentioned as early residents, as, for example, the Mascouten, did not arrive until a generation later. Archaeological findings conclusively show the prehistoric occupation of Wisconsin by the Santee Sioux and the Winnebago, and support the probability of prehistoric occupation by the Menomini. Thus Wisconsin was controlled primarily by Siouan speaking peoples in 1634. The peaceful Menomini were far outnumbered by their powerful neighbors, the Winnebago, but this situation was soon to change radically.

WINNEBAGO VILLAGE (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

Events occurring far to the East, in what is now New York State and eastern Canada, were to profoundly affect and change the Indian population of Wisconsin. When the French began permanent settlement along the St. Lawrence they found the Huron and the Iroquois Confederacy engaged in a death struggle for supremacy in the area. The French espoused the cause of the Hurons who quickly became the middlemen in the fur trade between the French and the western Indians.

The Iroquois, who were farmers and hence controlled less land than hunting tribes who were their neighbors, soon depleted their land of fur bearing animals and began to plan acquisition of land held by nearby tribes. At about this time the Dutch considerately gave the Iroquois guns, and by this act unleashed what was probably the most potent Indian military confederacy in North America upon the Hurons, who were practically exterminated in an amazingly short time. The Erie, Tobacco Nation, and Neutrals soon suffered the same fate as the Hurons.

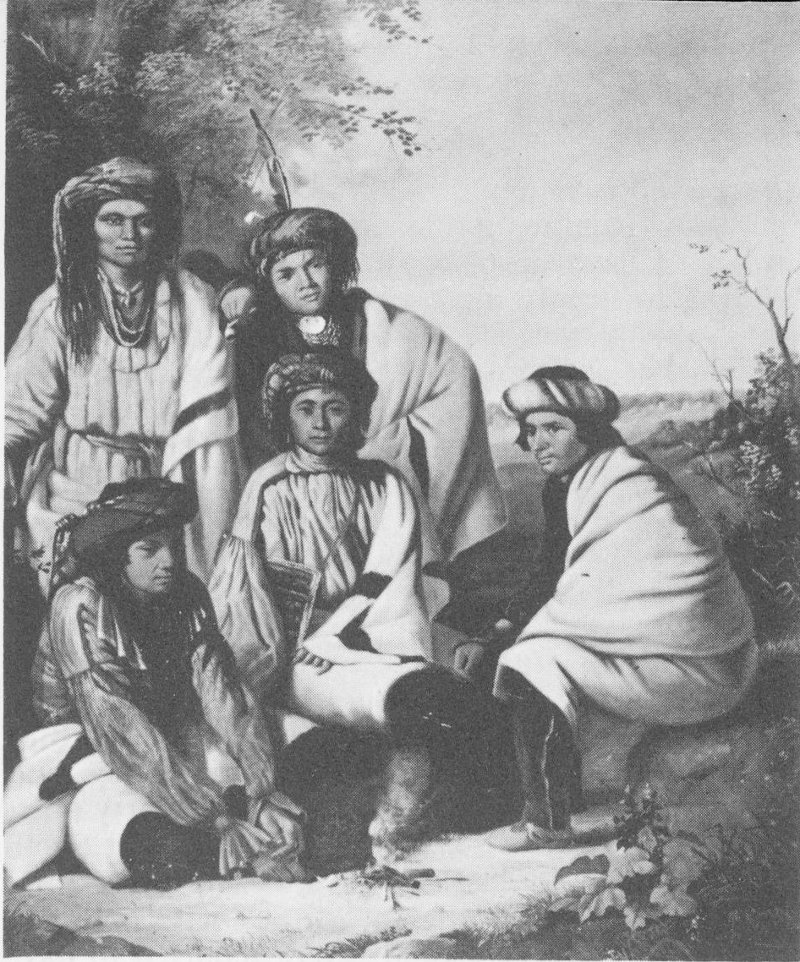

The Algonkian tribes, attacked first by the Neutrals and then by the victorious Iroquois, fled pell-mell into eastern Michigan and the Sault area. Eventually most of these tribes either went around the southern or the northern extremity of Lake Michigan to arrive in the relative security of wilderness Wisconsin.

The exact dates for the arrival of these various dispossessed eastern tribes are not certain. We do know that they probably came to Wisconsin sometime after Nicolet’s visit in 1634. The Mascouten, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Sauk, and Fox were coming into Wisconsin before 1654. Some Huron and Ottawa settled here temporarily at this time, but by 1678 were compelled by the Sioux to flee back to the Sault. The Chippewa stayed around and west of the Straits of Mackinac and actually did not settle in Wisconsin until about 1670.

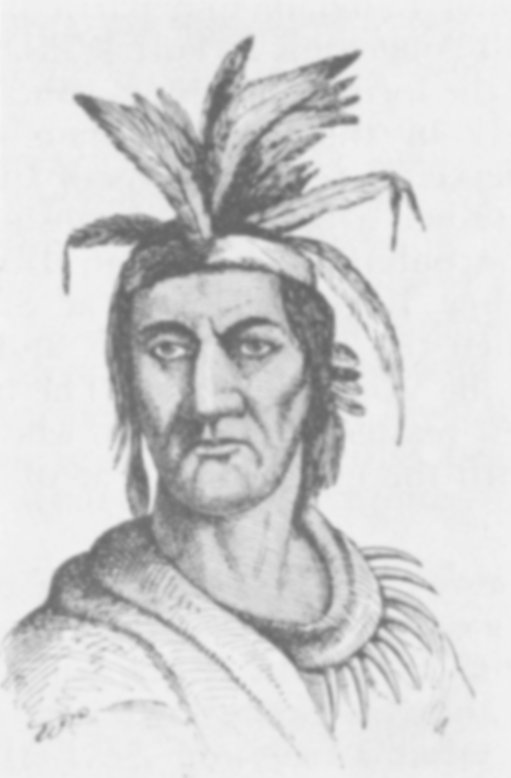

SAUK AND FOX INDIANS (FROM MAXIMILIAN).

CHIPPEWA INDIANS (FROM GEO. CATLIN).

The Winnebago at first defended themselves vigorously against the invading refugee tribes; however, this constant warfare greatly reduced their numerical strength. Further decimated by plagues, probably smallpox introduced by the whites, and by famine, the Winnebago were compelled to make peace with the invading Algonkians who eventually settled in great numbers along the Upper and Lower Fox rivers, the lower reaches of the Wolf River, and in the vicinity of Green Bay.

Fur trade with the western Indians was successfully blocked by the rampaging Iroquois for twenty odd years after Nicolet’s voyage of exploration into the Middlewest, but with the establishment of a brief peace, the Ottawa, who had assumed the position of middlemen in the fur trade, sent a large canoe fleet to the western Indians and soon returned with large quantities of furs which had been accumulated by the Indians during the Iroquois War.

On the return journey two young Frenchmen, Radisson and Groseilliers, went into Wisconsin with the Ottawa and became the first known white traders in the area. Other traders quickly followed their example, and by 1670, the fur trade in Wisconsin was proceeding at a good pace.

The Indians, even before actually being visited by the whites, had received European implements by trade with other Indians and soon learned the superiority of iron knives and axes over those of stone. The arrival of the white traders with their guns, kettles, cloth, brandy, and many other trade items was eagerly awaited by the Indians of what is now Wisconsin.

As early as 1668, Perrot and traders with him had brought furs to Green Bay (La Baye). Great activity in the fur trade was quick to follow with the French traders using guns and brandy particularly as an inducement to increase the tempo of fur trapping by the Indian. The Indian was as anxious to obtain the white man’s goods as the trader was to obtain the Indian’s furs. This formed the basis for an understanding mutually agreeable to Indian and trader alike.

The fur trade, during the French Regime, went through many changes due to changing circumstances, and the issuing of different regulations from time to time. The discovery of new western lands and tribes spurred literally hundreds of Canadian youths to seek these virgin territories and the riches in furs to be had there. At first traders persuaded the Indians to make the long trip to Montreal with their furs. The presence of so 16 many traders in the forests, however, soon made these long trips unnecessary. By the time Perrot began trading in Wisconsin the traders were carrying their goods to the Indians in their own country.

Regulations required that all traders must be licensed, or buy Conges as they were called. Twenty-five of these were issued each year and permitted the trader to take a designated load of goods into the interior to be traded for the Indian’s furs. The presence of great numbers of unlicensed traders in the woods was responsible for an edict from the king declaring such illegal traders to be outlaws. The punishment for such activities was death. These outlaw traders were known as coureurs de bois and were actually never hampered too much by the stringent laws passed against them.

During the latter part of the 17th century outposts were built to help control the trade. Nicolas Perrot built posts at Mt. Trempealeau, at Lake Pepin, and at the mouth of the Wisconsin River. The Sieur DuLhut (Duluth) built posts in the Lake Superior region.

Since these terms are often misused, it might be best to briefly describe the following occupations: A bourgeois, was an owner of goods and a license; the hired men were called engages; those hired men who only carried the goods and paddled the canoe for a stipulated daily hire were called voyageurs. The coureurs de bois and sometimes the voyageurs were usually the ones who often remained in the forests and “went native.”

PIERRE RADDISON (COURTESY OF WISCONSIN STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY).

The impact of the white man’s civilization was bound to profoundly change the life and geography of the Indians, and, particularly in the early French period, this change was extremely rapid. Three groups were actively working to institute changes in the Indian pattern of life. These were the fur trader, whose goods revolutionized the material culture of the natives, the Jesuit missionaries who hoped to convert the tribes to 17 Christianity, and the French government itself, which attempted at various times to relocate the tribes, form confederacies, and even to “civilize” them.

The fur trader was the only one of the three groups who really succeeded in materially changing the Indian’s way of life, although his success was unintentional. So completely did the materials of the white man replace those of the Indian that within a few short generations almost no one knew how to make stone tools and weapons, pottery vessels, bows and arrows, and many other aboriginal products which were abandoned as rapidly as superior goods of the whites were made available.

The change in tools and weapons naturally changed the Indians’ pattern of life in many ways, but the entire economy of the tribes was affected greatly by the fur trade. The Indian’s need for the white man’s goods was great and he became more and more dependent upon the trader. As the tempo of fur trading increased, the Indian began devoting almost all of his time to hunting and trapping until, in a sense, he became an employee in a great “fur-trade factory” with the goods he received from the trader representing his wages. Much of the Indian’s old life of freedom gradually disappeared, since failure to obtain guns or powder and bullets meant starvation for the Indian and his family.

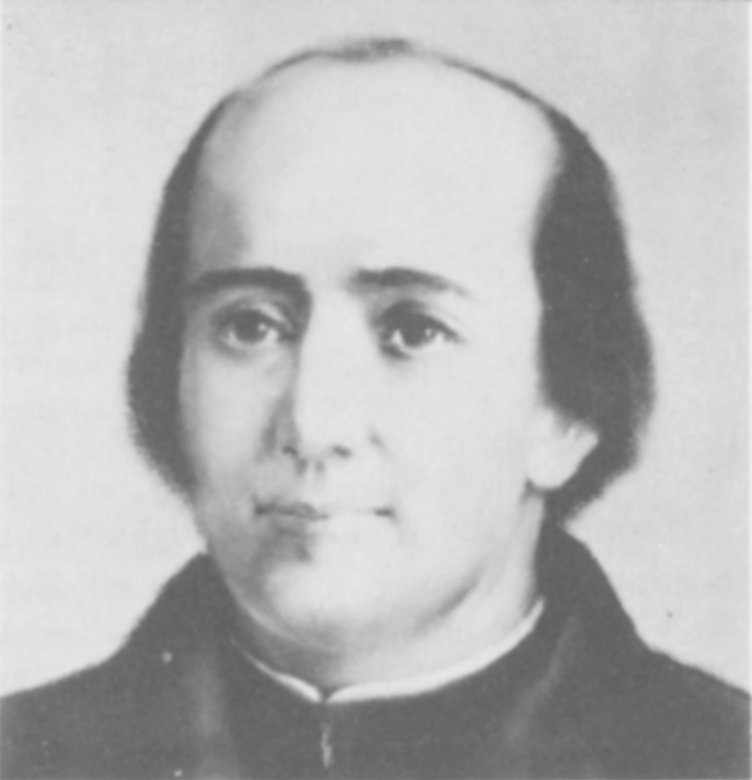

JESUIT MISSIONARY.

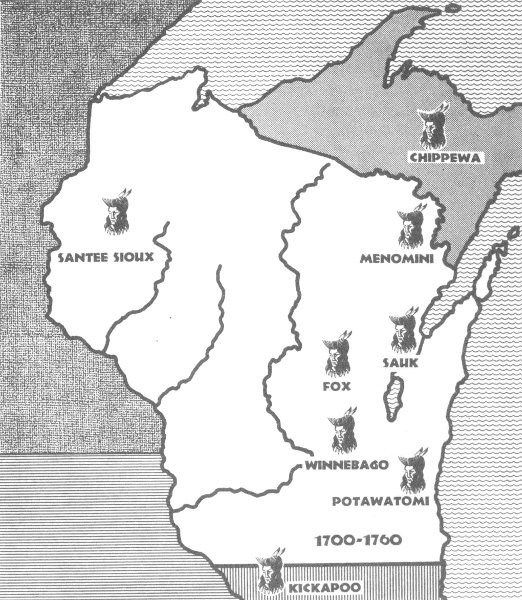

Perhaps the worst effect of the contact between the Europeans and the Indians was the introduction of brandy, always an effective persuader 18 in bargaining, and the introduction of European diseases, particularly venereal disease and smallpox, the latter in some instances wiping out entire tribes. The tendency for tribes to congregate around fur-trade areas at the behest of the traders also had a detrimental effect upon the Indians. In the Fox River valley and around Green Bay this overpopulation resulted in famine and the voluntary exodus of some tribes before 1700, among them the Miami and some of the Kickapoo and Mascouten.

It should be noted that the adoption of new materials and living habits was not entirely one-sided. The white man learned how to use the Indian’s birch-bark canoe, many of his foods, tobacco, moccasins, snow shoes, and often buckskin clothing.

Both the Jesuits and the French military deliberately aimed at changing the Indian’s way of life but their aims were in direct opposition to one another. The Jesuits were not interested in “civilizing” the Indians. They desired to see these simple people maintained in their original ignorance except for their belief in the “One True God,” and such simple improvements in agriculture and other techniques as would improve their lot as mission Indians. The Jesuits, not without some justification, regarded contact between their charges and the French traders and soldiers as having a demoralizing influence.

MENOMINI INDIAN MEDICINE LODGE CEREMONY (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

Despite great heroism and prodigious efforts on the part of the missionaries, permanent effects on the Indians by the Jesuits was to prove almost negligible. The Wisconsin Indian was highly war-like and found it difficult to appreciate the humility preached by the missionary. The 19 Indian regarded such behavior as effeminate.

FATHER JACQUES MARQUETTE (COURTESY OF MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY).

Nevertheless, the story of their efforts to Christianize the tribes, and the valor of these missionaries in exploring unknown territory, makes a fascinating story in our state’s history. Not the least among such heroic deeds was the great voyage of exploration by Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet. Traveling up the Fox River, crossing over on foot at what is now Portage, Wisconsin, and proceeding down the Wisconsin River, the two explorers entered the Mississippi River on the seventeenth of June, 1673. They explored the great river as far south as the Arkansas River and then returned, by way of the Illinois River. This great discovery made known a continuous water route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, and opened to the French the interior of a vast continent.

It was the desire to exploit and unify this vast wilderness empire that led the French leaders to attempt deliberate changes in the Wisconsin Indian geography and political structure. This was necessary in order to strengthen the Wisconsin tribes and keep them fighting the Iroquois who consistently raided the western Indians and the French settlements along the St. Lawrence.

LaSalle conceived the idea of a great Indian confederacy which, it was hoped, would be able to successfully oppose the mighty Iroquois, and so built forts in the Illinois country to help defend the area. The Wisconsin Mascouten and Kickapoo left this area, partly because of their desire to join the confederacy and partly because of population pressure in the Fox River valley.

The year before the Iroquois invasions of 1680, DuLhut helped to strengthen the French cause by negotiating peace between the Dakota Sioux and their enemy of long standing, the Chippewa, and also reconciling the Dakota Sioux and Assiniboine, who had been warring for thirty years.

Nicolas Perrot probably was the most influential French officer ever to have worked with the Wisconsin tribes. It was mainly through his constant efforts that they were kept from going over to the Iroquois when the tribes felt that the French had abandoned them. Perrot was probably the only Frenchman to remain consistently on friendly terms with the Foxes, who eventually were to engage the French in the bloodiest Indian war 20 ever to be fought on Wisconsin soil. Perrot constantly travelled from village to village organizing raids against the Iroquois, raids which eventually assisted in forcing the Iroquois to sue for peace. The French, through the efforts of men like LaSalle, Perrot, and DuLhut, had once again secured a firm hold on the western tribes, but the Iroquois warfare of the 1680’s had caused a slump in the fur trade. The trade was, moreover, soon to receive a blow which was to almost completely kill all official commerce between the Indians and the French for a number of years. This was the issuance of a royal edict by the French King, May 21, 1696, revoking all fur trade licenses and prohibiting all colonials from carrying goods to the western country.

There were really two main causes for the issuance of this edict. One was a slump in the beaver market caused by the great flood of furs into France and a decline in beaver hat production, due partly to the emigration of the Huguenots who were the main hat felters; the other cause for the edict was the anger of the Jesuits, aroused by the sale of brandy to the Indians by the traders and soldiers.

It was hoped that the Indian tribes would make the journey to Montreal themselves to trade their furs, but it was soon discovered that most tribes either would not or could not make such a journey for purposes of trade. The result, of course, was severe hardship for the Indians of Wisconsin. Lack of gunpowder and lead restricted their hunting abilities and made it more difficult for them to defend themselves against the Iroquois and other hostile tribes. The Indians were becoming increasingly dependent upon the French to the extent that they had lost much of the freedom they had enjoyed as a self-sufficient people.

The rapid abandonment of the western posts followed the fur trade ban. The commanders of these outposts, for the most part, did not consider it worthwhile to stay on in that capacity if they could not enrich themselves by means of the Indian trade.

Peace was finally arranged between the Iroquois and the French and their Indian allies in 1700. The Iroquois had suffered heavily from the raids by the western Indians. They claimed to have lost more than half their warriors. With the fear of Iroquois raids ended, the confederacies of western tribes quickly fell apart, and the latter turned to fighting among themselves as they had always done in the past.

The French military now decided on a concentration policy. The western posts were to be restricted to three main centers. These were to be at Detroit, New Orleans, and near Tonty’s post in the Illinois country. Fairly large numbers of troops were stationed at these posts to provide adequate defense, and the western tribes were to be concentrated in these areas. This would facilitate the fur trade by permitting the Indians to trap their furs and bring them directly to the trading centers. The French government also hoped to “civilize” the Indians, teaching them to farm the land, learn the French language, and eventually even participate in the colonial economy.

The concentration policy was foredoomed to failure. The Wisconsin tribes, of whom many were hereditary enemies, only needed a spark to set them at one another’s throats. This led to trouble at Detroit which resulted in the bloody Fox Wars, long, costly fighting for the French which contributed much towards their final downfall in the New World.

SAUK AND FOX WARRIORS (FROM MAXIMILIAN).

Events occurring in Wisconsin during the first half of the Eighteenth Century were to bode little good for the French, and were to contribute towards the final downfall of New France at the hands of the British. For a good share of the years between 1701 and 1738 the French were to be largely occupied with the attempt to subjugate the Fox Indians and their allies.

Not only were the expeditions against the Fox to prove costly to the French, but the enmity of the Fox required shiftings of trade routes. As an inevitable result, friction between the French and English traders developed, since the Fox at times blocked both the Fox River in Wisconsin and the Illinois River to the French traders. The determined resistance of the Fox also prevented the fruition of French hopes to dominate the western tribes and influence them to espouse the French cause. Furthermore, the difficulty experienced by the French military in conquering a relatively small group of Wisconsin Indians did little to further French prestige among other western tribes.

The First Fox War was actually the result of the French concentration policy. Within a few years after the founding of Detroit in 1701 by the Sieur de Cadillac there were almost 6000 Indians in the vicinity of the fort. The Fox, meanwhile, determined to prevent the carrying of guns to their enemy, the Dakota Sioux, were halting French traders attempting to proceed up the Fox River on their journey to the Sioux country on the Upper Mississippi. A French fort in the Sioux country was also abandoned after the loss of several men due to attacks by the Fox.

Cadillac, realizing the need for some measure to bring these warlike tribesmen under control, in 1710 invited the Fox, along with the other tribes resident around Green Bay, to come and reside near Detroit. At this crucial time, when so much depended on the leadership of a Frenchman experienced in handling the tribes, Cadillac, probably the most capable Colonial officer of the times, was sent to Louisiana as governor of that colony. The new commandant at Detroit had none of Cadillac’s ability with the Indians.

The arrival of the Fox and their allies, the Kickapoo, Sauk, and Mascouten, was the signal for trouble. These tribesmen were feared as well as hated by the other Indians about Detroit. After a band of Mascouten were attacked by the Ottawa near the St. Joseph River, during the winter of 1711-1712, the Fox, in revenge, immediately attacked the Ottawa and Huron at the Detroit post.

The Detroit commandant sided with the Ottawa and Huron and permitted them to seek refuge in the French fort. Shortly after, the Fox erected a stockade of their own and made preparations for a long fight. The French and their allies were reinforced by a large band of Illinois, Missouri, Osage, Potawatomi, and Menomini. This greatly superior force laid siege to the Fox fort and the latter soon offered to surrender. The French and their Indian supporters, however, were now determined to completely exterminate their enemies.

After a siege of nineteen days, the Fox attempted to escape by taking advantage of cover offered on a dark, rainy night. They were pursued, overtaken, and the great majority of them were slaughtered. This was a victory for the French, but a very costly one, for the Fox and their allies still had a great many warriors in the forests of Wisconsin. These, in retaliation, began a war of extermination against the allies of the French who had participated in the Detroit massacre and the hunted tribesmen soon complained that their people were starving because they dared not hunt in the forests lest their men be slain by the vengeful Fox.

The summer of 1716 saw the first white army ever to invade the forests of Wisconsin. The Sieur de Louvigny, in May of that year, left Montreal with an army of several hundred French and a force of mission Indians determined to compel the Fox to sue for peace. He arrived in Wisconsin with his army augmented by western tribesmen, and coureurs de bois who had been granted pardons for joining the expedition at their own expense. With this total force amounting to about 800 men, Louvigny besieged the fortified Fox village, situated near Little Lake Butte des Morts. While the French kept up a fire with two small cannon and a grenade mortar, they sank a trench towards the Fox fort determined to mine the place and blow it up.

The Fox surrendered after three days of fighting and agreed to accept terms which Louvigny thought very severe, but which his Indian allies regarded as overmild. The terms included the requirement that the Fox pay for the costs of the expedition against them by means of furs yet to be gathered, to give up prisoners taken from the allies of the French, to furnish a number of hostages to guarantee their future good behavior, and to cede their territory to the French King.

The peace temporarily halted the bloody warfare of the four preceding years and permitted the fur trade to be resumed. The concentration policy had proven to be a failure, and shortly after the death of Louis XIV, in 1715, the posts were once more occupied and the licensing system for the fur trade was restored. A fort was built at La Baye (Green Bay) in 1717, and a post was occupied at Chequamegon Bay to keep the Chippewa from attacking the Fox and causing a resumption of war, and also to regulate the fur trade in that area.

EARLY FORT AT MICHILLIMACKINAC (MUSEUM MURAL BY GEORGE PETER).

The quite considerable friction between the colonies of Canada and Louisiana provided the background for the events which led directly to the Second Fox War. There was considerable argument as to the exact boundaries of Illinois which now was annexed to Louisiana, although originally settled by Canadians. The Fox took advantage of these feelings of hostility by attacking the Illinois in the vicinity of Kaskaskia, even killing Frenchmen in this area. The Fox claimed the Illinois would not return Fox prisoners as they had promised according to treaty. The Canadian governor, Vaudreuil, tended to side with the Fox in the argument.

After the death of Vaudreuil, his temporary successor, Baron de Longueuil ordered the Sieur de Lignery, commandant at Mackinac, to enforce a peace between the Fox, Kickapoo, and Mascouten, and their enemies, the Illinois. The Fox promised to obey this demand, and in order to ensure their obedience, a new post was built in the Sioux country. This was rendered necessary by the fact that the Dakota Sioux had now become allies of the Fox, and the French intended to make sure that no aid would be coming to the Fox from that warlike tribe. The three forts in the northwest, at Chequamegon Bay, La Baye, and on the upper Mississippi in the Sioux country were to be maintained rather steadily until near the end of the French regime.

Meanwhile the Fox chief Kiala had succeeded in forming an alliance against the French between the Fox and their long-time allies the Kickapoo and Mascouten, and a series of other tribes including, in addition to the nearby Winnebago, such far distant tribes as the Abnaki and Seneca in the East, and the Dakota Sioux, Missouri, Iowa, and Oto in the West. Kiala hoped by this means to form a hostile circle about the French which would end in their complete defeat, a plan similar to that later attempted by Pontiac, and Tecumseh.

The Marquis de Beauharnois, appointed governor of Canada to replace Vaudreuil, was determined that the raids on the Illinois and the French at Kaskaskia must be stopped. A French army once more was sent against the Fox. This time, headed by the Sieur de Lignery, the 25 expedition numbered about four hundred French and approximately one thousand Indians. Warned by the Potawatomi, the Fox escaped from their villages and the army arrived at each to find it deserted. At Little Lake Butte des Morts the soldiers refused to go farther and Lignery had to be satisfied with the burning of the Fox and Winnebago villages and their stores of food.

Despite the poor showing of Lignery’s expedition against the Fox, Kiala’s confederacy began to fall apart. Even their old allies, the Mascouten and Kickapoo, were persuaded by the French to turn against them, and the Sioux, closely watched by the French, no longer could give the Fox refuge in their country. Discouraged by these losses and defeated by the French under the capable Paul Marin, the Fox decided to flee to the Iroquois country. The Fox had long been secretly treating with the English and the Seneca, a member tribe of the Iroquois Confederacy and hoped to find a friendly reception in their country.

Warned by the Mascouten and Kickapoo regarding the plans of the Fox, French officers from nearby posts hastily gathered together Indian allies and prepared to attack their fleeing enemies. The Fox, warned by their scouts of the force advancing against them, hastily erected a stockade and prepared to fight for their lives. They managed to fight off the besiegers for twenty-three days. Then on a stormy night they attempted flight but were quickly overtaken. Almost all of the band were either slaughtered or taken as slaves.

After the few survivors of this disaster, seeking refuge in their village near the mouth of the Wisconsin River, were attacked by Detroit Indians, Kiala and three other chiefs offered to give themselves up, asking mercy for themselves and the fifty surviving warriors, supposedly all that were left of the entire tribe. De Villiers accepted the surrender and hastened to Montreal with his prisoners. De Villiers was ordered to return and kill off the rest of the Fox, taking only the women and children as prisoners. These were to be sold into slavery, like Kiala, who was fated to end his days as a slave in the West Indies.

De Villiers returned to the Sauk village at Green Bay and demanded that the Sauk release the remnant of Fox survivors. The Sauk declined to release warriors with whom they had strong blood ties, and in an attempt to force an entrance, one of de Villiers’ sons was killed. The French quickly retaliated and in the exchange of fire de Villiers himself was killed by a twelve year old boy, who later became renowned as the Sauk Chief Blackbird. In the battle that followed, the Sieur Duplessis, the Sieur de Repentigny, and six other Frenchmen quickly met the same fate. The Sauk and Fox, too, lost heavily and fled to the vicinity of the present-day city of Menasha. The bloody battle that ensued there, it is said, accounts for the name Butte des Morts, or Hill of the Dead.

As a result of this battle, the remainder of the Fox and the Sauk amalgamated and for all practical purposes became one tribe. They fled into Iowa where they erected a new fort, and gradually their ranks were swelled by Fox released from captivity by tribes now secretly in sympathy with the Sauk and Fox. One more expedition was sent against them, led by the Sieur de Noyelles, but although he followed the Sauk and Fox to the vicinity of the Des Moines River, they were so well entrenched that it 26 was impossible to dislodge them and the expedition returned home without success. Eventually the Fox Wars were brought to an end through a policy of conciliation inaugurated in 1740 by Paul Marin, the new commandant at La Baye. Force had, in the long run, proven a failure in the campaign to completely subjugate the Fox.

SAUK AND FOX CHIEF (FROM GEO. CATLIN).

Throughout the first half of the Eighteenth Century the French, as we have seen, had been occupied with more or less constant warfare with the Fox. This warfare was the dominant note in the history of Wisconsin for this period, and in general, the role of other Wisconsin tribes during this era was that of serving as allies either of the French or of the Fox.

The failure of Noyelles’ expedition against the Fox had helped to lower French prestige among the western tribes, and in 1736 the Sioux, angered by French friendship for the Chippewa and Cree, murdered a French officer, a priest, and a party of nineteen voyageurs. From this 27 time on the Sioux could no longer be numbered among the allies of the French. By 1739, the Sioux-Chippewa War flamed into action and the Sioux were driven westward from the areas in Wisconsin now held by the Chippewa.

Warfare between the English and the French in America again was to seriously affect the western tribes. This conflict, lasting from 1744 to 1748, saw the fur trade with the western tribes reach extremely low proportions. Goods were very scarce due to the loss of French ships at the hands of British fighting vessels, and this failure to produce sufficient goods for the Indians, in addition to the already declining prestige of the French, encouraged some of the western tribes to seek more favorable relations with the British. Most of the Huron, under Chief Nicolas, began trading with the British, and many other western tribes exhibited the same inclination.

The end of the current conflict with the English enabled the French to regain control of these tribes, but the Miami had moved into Ohio and established a large village called Pickawillany which became a fairly permanent camp for a number of English traders. Several expeditions against this village by the French failed. In 1752, however, Charles de Langlade, later famed as one of Wisconsin’s pioneer French settlers at Green Bay, who was part French and part Ottawa and who thus had tremendous influence among the Indians, led an expedition against Pickawillany which enjoyed remarkable success. The village was destroyed, the English traders captured, and the Miami returned to French allegiance.

For a while France again enjoyed supremacy in the West. In 1755, Langlade and his contingent of Wisconsin and Mackinac braves participated in the famous battle culminating in “Braddock’s Defeat”. Chippewa, Menomini, Potawatomi, and Winnebago were said to be present at this engagement, and for many years thereafter trophies of this battle were to be found in Wisconsin Indian lodges. Despite this severe defeat of the British and American Colonials, the fortunes of the French were destined to take a turn for the worse. By 1761, Wisconsin was under British control, and in 1763, France formally surrendered the rest of her American possessions to England. She had ceded Louisiana to Spain the year before.

Much had happened to Wisconsin’s Indians during this period, roughly from 1700 to 1760. The long and bloody Fox Wars had wrought hardship on the other tribes as well as on the Fox. The Sioux-Chippewa war had resulted in the Sioux being forced to relinquish most of their Wisconsin territory to the Chippewa. The Potawatomi Indians, who had fought 28 under Langlade and participated in the killing of the unarmed English and Americans at Fort William Henry, were visited by a grim vengeance in the form of smallpox, contracted from the English soldiers and brought back by the tribes to their own country where it raged virtually unchecked. Great numbers of Indians lost their lives as a result.

Other tribes left Wisconsin, some never to return. The Kickapoo and Mascouten were now in Illinois and Indiana. The Potawatomi were below Lake Michigan at St. Joseph. Thus many of the tribes here when the French traders and missionaries first arrived, no longer were in the Wisconsin scene. The tribes remaining here were destined to know new masters, the British, who were to control the fur trade in Wisconsin until the end of the War of 1812.

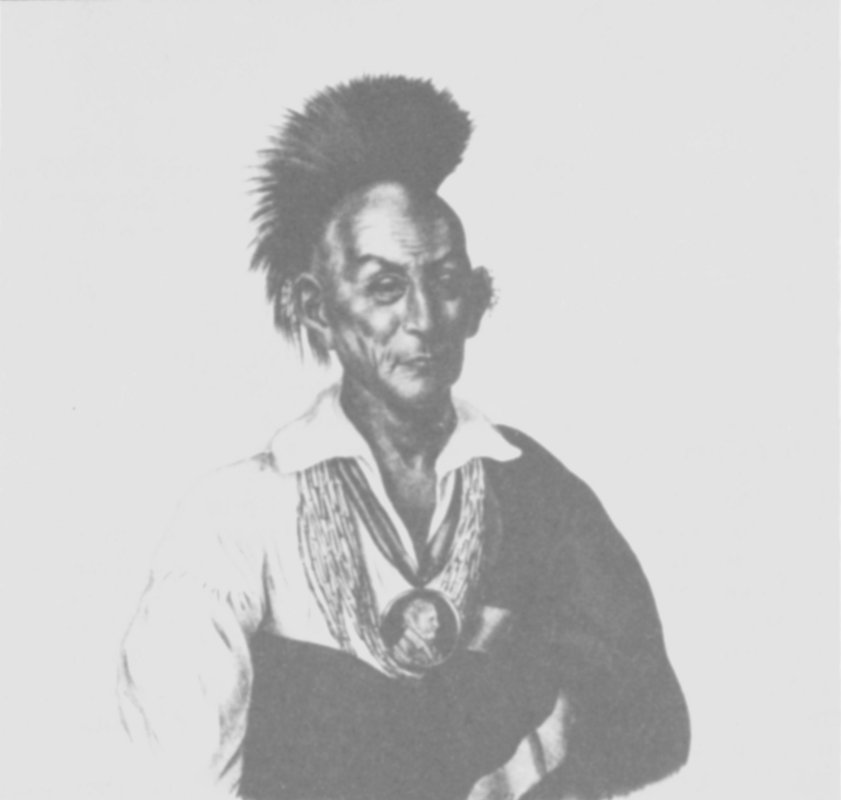

PONTIAC.

British military control of Wisconsin was ushered in with the arrival of Ensign James Gorrell at Green Bay on the twelfth of October, 1761. With the aid of his two non-commissioned officers and fifteen privates, Gorrell set about to restore the old French fort which he renamed Fort Edward Augustus, in honor of the Duke of York. His next task was to win over the French habitants about the fort and to gain the sympathy of the Indians in the area for the British cause. Apparently Gorrell was quite successful in both tasks.

The French habitants about the posts taken over by the British found it rather easy, for the most part, to transfer their allegiance to the British Crown since they were given the same privileges they enjoyed under French authority. Moreover, the British traders found it more advantageous to form partnerships with the more experienced French traders than to attempt to supersede them.

British success with the Indians varied according to local conditions at the different forts. The British were not inclined to give presents as liberally as the French had done, and it was not British policy to fraternize or intermarry with their savage allies. The feeling of inferiority 30 prompted by this treatment caused resentment among many tribes.

TRADERS PORTAGING (PAINTING BY T. LINDBERG).

In central Wisconsin, however, Gorrell’s diplomatic treatment of the Indians, added to the fact that the Sauk, Fox, Winnebago, and Menomini held a certain amount of resentment towards the French, swung these tribes over to the British. The promises of medals and commissions to the Indian chiefs, and the fact that the British trade goods were cheaper by far than those offered by the French, also tended to offset the more arrogant treatment of the tribes by the British.

Gorrell’s success with the Indians of central Wisconsin was very important to Wisconsin history, for in 1763 the British were compelled to deal with a widespread Indian uprising largely led by Pontiac, chief of an Ottawa tribe from around the Straits of Mackinac, and one of the most able Indian leaders who ever lived. It was Pontiac’s plan to drive all the British and Colonials into the sea by means of an alliance of Indian tribes from the Alleghenies to the Mississippi River, and from the Ohio River to the Great Lakes. Pontiac’s chief claim to greatness lies in his remarkable feat of keeping a number of tribes together for a seven-month 31 siege of Detroit, a unique event in Indian warfare.

In addition to the attack on Detroit, concerted attacks were made on other British posts, of which a number fell, including the one at Mackinac. The failure of the Indians to take Forts Detroit, Pitt, and Niagara assured defeat for Pontiac’s campaign.

On June 2, 1763, the Chippewa Indians took Fort Mackinac by a clever subterfuge. They faked a game of LaCrosse in front of the stockade and pretended accidentally to knock the ball into the fort. As the players rushed after the ball they seized guns from the watching Indian women who had concealed the weapons under their blankets. Most of the garrison was massacred before they had a chance to defend themselves.

The loyalty to the British of Wisconsin’s Sauk, Fox, Winnebago, and Menomini Indians, and the timely arrival of a delegation of Sioux, sworn enemies of the Chippewa, probably saved Green Bay from a similar fate.

Etherington hastily summoned Gorrell to his assistance. Gorrell abandoned Fort Edward Augustus at Green Bay and with the aid of 90 men of the Sauk, Fox, Menomini, and Winnebago tribes succeeded in obtaining the prisoners’ release from the Indians. The party then proceeded on to Montreal. British military occupation of Wisconsin was not resumed until the War of 1812.

The Pontiac rebellion also served to bring the problems relating to the Indians home to the British Government and probably helped as an incentive to the issuance of the Proclamation of 1763. British subjects were now forbidden to purchase lands west of the Appalachian mountains without special license. It was hoped that this would prevent further encroachments by white settlers upon Indian lands. Trade with the Indians was to be permitted where licenses with the various colonial governments had been procured. Moreover, since Wisconsin was not included in the limits of any of the colonies, Wisconsin was left without any government other than that exercised by the military at Mackinac. This matter was not rectified until 1774 when the Quebec Act placed Wisconsin under the authority of the Governor of Canada.

Mackinac became the seat of Wisconsin’s fur trade when the fort was rebuilt there in 1764. It was the only fort northwest of Detroit with government officers and Indian agents. By 1767, large numbers of traders were coming into the Wisconsin area. The Indians by this time were so dependent on the white trader that any interruption in the supply of goods flowing to the Indians worked severe hardships upon them.

Wisconsin’s fur trade was still largely controlled by Montreal investors, mostly British. The actual traders, however, who contacted the Indians were still primarily Frenchmen, and this was to remain so throughout Wisconsin’s fur-trade period. Some competition in Wisconsin was given to the British by Spanish and French traders from Louisiana, which had become Spanish territory by the peace treaty in 1763. But the British managed to retain the bulk of the northwest fur trade with the Indians.

Wisconsin’s Indians did not participate strongly in the American Revolution, but they did take part in some action. Charles de Langlade, half French, half Ottawa Indian leader who helped the French so efficiently during the French and Indian War, now espoused the British cause as ardently as he had the French. Langlade’s tremendous influence over 32 the Indians was well known, and the British hoped to persuade him to obtain Wisconsin Indian help in fighting the Colonists. Langlade did succeed in leading Chippewa and Ottawa east to help Burgoyne in 1777, and in 1778 Wisconsin Indians went to Detroit to help General Hamilton. On the whole, however, Wisconsin’s Indians were too disinterested in the white man’s war to be enthusiastic about long trips east to aid the British.

MICHILLIMACKINAC, RESTORATION OF LAST FORT.

The American Revolutionary War hero, Major George Rogers Clark, whose capture of Vincennes and Kaskaskia, and the French villages of the Illinois country, provided the basis for United States claims to the Northwest Territory during the peace negotiations between the British and the United States, called together a great assembly of Indians at Cahokia, Illinois, in 1778, and succeeded in obtaining their pledges of allegiance to the United States. Many Wisconsin Indians attended the meeting, including the noted Blackbird, chief of a Milwaukee village composed of Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi. Blackbird apparently remained loyal to the American cause. Major Clark’s influence with the Wisconsin Indians tended to nullify the efforts of Charles Langlade, and other French officers in the service of England, to mobilize the Wisconsin Indians against the United States.

In 1780, England utilized some Wisconsin Indians in an attack on the Spanish with whom she was then at war. Twelve hundred warriors were assembled at Prairie du Chien, and marched on St. Louis. Aided by the fact that they had advance knowledge of the enemy movements, that some of the tribesmen were more or less sympathetic with the American cause, and that the Indians showed no enthusiasm for attacking in the face of cannon fire, the Spanish and Americans succeeded in routing the attackers. After this action Wisconsin’s Indians were not involved in any important campaigns during the remaining years of the American Revolution.

CHIEF OSHKOSH (PORTRAIT BY S. M. BROOKS, COURTESY OF THE WISCONSIN STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY).

British control of Wisconsin’s Indians did not cease with the end of the Revolutionary War. Despite the British agreement in the Treaty of Paris, in 1783, to turn over their posts at Niagara, Detroit, and Michillimackinac, they continued to hold these forts until after the Jay Treaty of 1794. It was not until October, 1796, that Mackinac, the last post to be turned over by the British, was officially occupied by American troops. The British, however, still maintained their control over Wisconsin’s Indians through the fur trade now operating from posts just across the Canadian border.

Within a month after the declaration of war against England by the American Congress in 1812, Mackinac was retaken by the British and 34 Menomini and Winnebago Indians from Wisconsin. Among the Menomini were chiefs Tomah and Oshkosh, the latter destined to become a famous Menomini leader and friend of the Americans. Within another month Fort Dearborn (at Chicago) was attacked by Indians and most of its civilian and military inhabitants massacred. Menomini, Potawatomi, and Winnebago Indians from Wisconsin took part in this attack.

MENOMINI WARRIOR (FROM INDIAN TRIBES OF NORTH AMERICA).

The Americans were well aware of the strategic importance of Prairie du Chien in any attempt to control Wisconsin’s Indians. In June, 1814, Fort Shelby, probably the first building over which an American flag ever flew in Wisconsin, was erected at this strategic location. Lt. Perkins and sixty men were left in charge at the fort.

The British quickly determined to drive out the Americans and succeeded in forcing Perkins to surrender the fort on July 19, 1814. About 500 Indians, mostly Menomini, Chippewa, Winnebago, and Sioux, took part in the assault on the American post.

The British renamed the post Fort McKay and managed to hold it against the Americans until, in agreement with the Treaty of Ghent, they finally abandoned the fort in May, 1815, and British control of Wisconsin’s Indians was finally at an end. The fate of Wisconsin’s Indians was now in the hands of the United States Government.

Wisconsin’s Indians, under the French and British had become increasingly dependent upon the white man. Without the invaders’ tools, weapons, utensils, and various other things which the Indian had come to depend upon, he found himself unable to supply himself with the necessities of life. The French and British traders, of course, were interested almost exclusively in procuring furs from the Indians, and as long as the aborigines could obtain furs for them, the traders would supply their needs.

The Americans, however, were primarily interested in exploiting and settling the Indians’ land; fur trading was secondary. As they pushed into the new territory in ever increasing numbers, first to exploit the lead mines of southwestern Wisconsin, and then to farm the fertile soil, the Indian was doomed to be relentlessly pushed aside. He had lost his independence. Now he was to lose his land and the very means of his livelihood.

The arrival of the Americans upon the Wisconsin scene pleased neither the Indians nor the French traders. Both relied to a great extent on the fur trade, and they knew that the clearing of land by the settlers would hasten the end of this activity. Many of the French, too, had Indian blood and considered their cause as one with the Indians. The United States 36 government first showed poor judgment in its attempt to make these people conform to American standards. For example, the French and Indians were warned that common-law marriages between the two races would no longer be tolerated, but must be legalized by either a civil or church ceremony, and violators would face punishment. Both the French and Indians bitterly fought what seemed to them oppression, and eventually later decisions recognized the legality of common-law unions of earlier regimes.

Wisconsin’s Indian agents were for a time under the authority of two superintendents of Indian affairs. Lewis Cass, Governor of Michigan Territory, of which Wisconsin was a part from 1818 to 1836, was in charge of the Indian agent at Green Bay. The agent at Prairie du Chien worked under the direction of William Clark who, as Superintendent of St. Louis from 1807 to 1838, had authority to the source of the Mississippi River. These agents distributed annuities and payments due the Indians and attempted to keep white settlers from squatting on Indian land. The settlers, however, rudely took over Indian land and, in the inevitable conflict that followed, the militia and army would be called out to protect the whites. In the ensuing “peace treaty” the Indians would be forced to cede their lands and move westward.

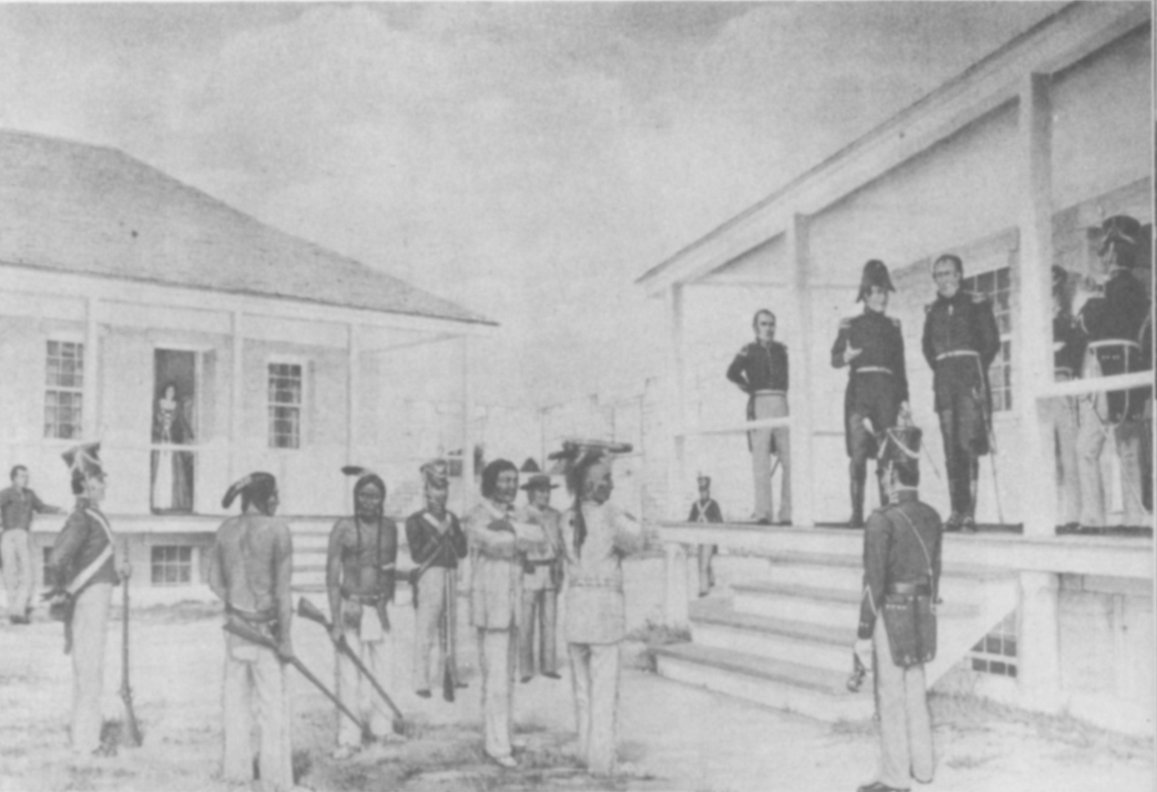

INVADING SETTLERS (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

Wisconsin’s early territorial period was also the era of the frontier fort manned by the regular U. S. Army. Since the pay for the ordinary soldier was very small, the army attracted men who could not succeed elsewhere, or immigrants who wished to desert at the first opportunity and travel westward. The officers, however, were of different character entirely. Educated at West Point, they were by far the most educated 37 and cultured men in the frontier settlements. With their wives, they represented the cream of Wisconsin society of this period.

THE ENFORCING OF LEGAL MARRIAGE (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

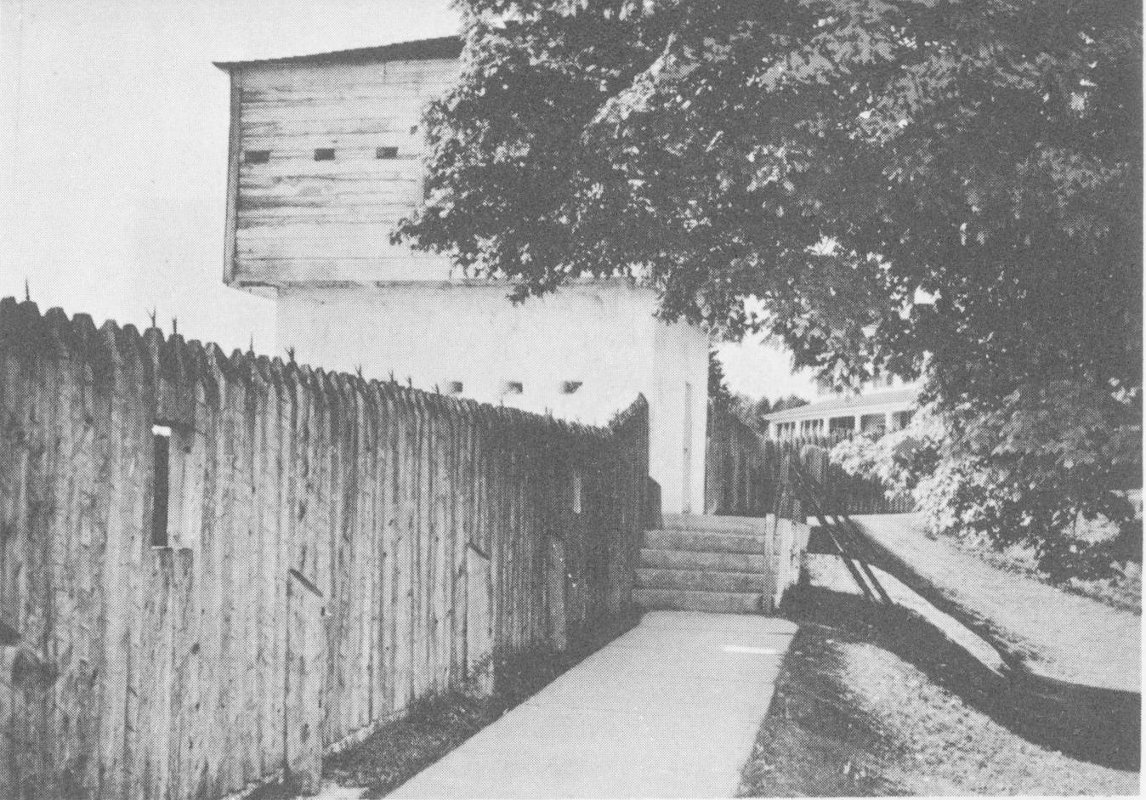

Wisconsin had three main forts along the Fox-Wisconsin waterway. Fort Howard was erected at Green Bay in 1816, the same year that Fort Crawford was established at Prairie du Chien. Fort Winnebago was built at what is now Portage in 1828, shortly after the Red Bird rebellion. The United States army did its best to maintain peace between the Indians and whites, and to protect the Indians from unlicensed traders, and sometimes legitimate ones, who illegally sold whiskey to them. In their efforts in this direction they often found themselves in conflict with civil authorities who sometimes protected the traders apprehended in such violations.

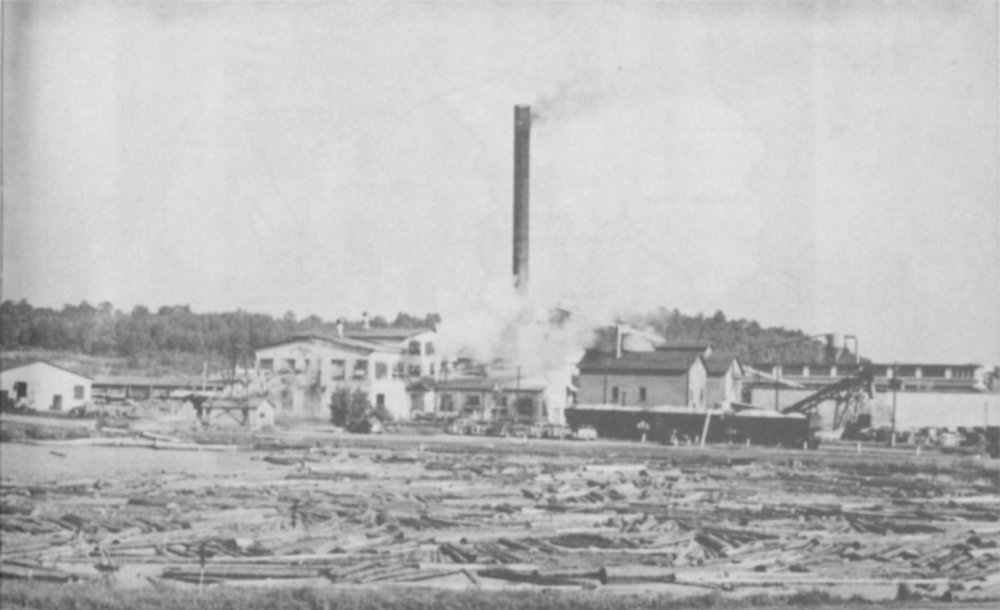

The fur trade continued in Wisconsin while the population was primarily Indian, but by 1835 it was no longer of any significance in this area. Following the War of 1812, the United States Government set up fur trade “factories” at Prairie du Chien and Green Bay, hoping by this means to control some of the evils, one of the most vicious of which was the peddling of whiskey to the Indians. The whiskey was usually diluted with water, and adulterants such as turpentine, or even corrosive acids, added to restore the “bite.”

The government entry into the fur trade was unsuccessful. The factors, as the proprietors of the trade “factories” were called, lacked experience in dealing with the Indians. They did not give credit advancements to them as did the other traders, and the American Fur Company applied pressure on Congress to end this system. Gradually this Company acquired the fur trade monopoly in this area; Solomon Juneau, 38 Milwaukee’s famous founder, was one of the American Fur Company’s agents in what is now the State of Wisconsin. The gradual decadence of the fur trade, of course, increased the hardships of Wisconsin tribes.

OLD FORT WINNEBAGO (COURTESY OF THE WISCONSIN STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY).

THE SECOND OR STONE FORT CRAWFORD (COURTESY OF THE WISCONSIN STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY).

THE FIRST OR LOG FORT CRAWFORD (COURTESY OF THE WISCONSIN STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY).

As settlers began encroaching on the Indians’ land, conflicts were inevitable. John C. Calhoun, the Secretary of War in 1825, sponsored a plan for the removal of eastern tribes across the Mississippi to the western 39 plains. It was believed that by furnishing them with equipment for hunting and farming they could survive readily and would be safe from further pressure by white homesteaders. No one realized at this time how soon these western lands would be overrun by the relentless pressure of the American pioneer. The land purchased from the Indians was to be made available to American settlers. The lands of certain tribes of Wisconsin Indians were to be included in this overall plan.

SOLOMON JUNEAU, AGED 60.

Unfortunately for the smooth functioning of this operation, the Indians did not care to leave the land on which they and their ancestors had hunted for so long a time, and travel to new hunting grounds. In many instances they were not removed without a show of force, sometimes with considerable blood being shed by both whites and Indians.

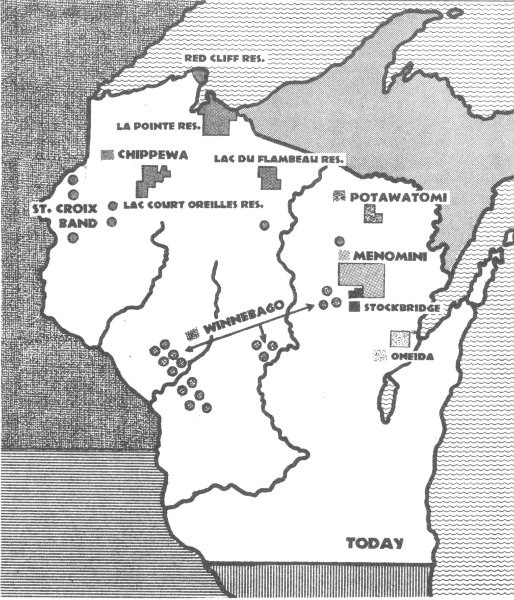

In 1825, Lewis Cass and William Clark held a conference of Wisconsin tribes at Prairie du Chien. They hoped to establish definite boundaries for the holdings of the different tribes in order to eliminate friction between them. This would also facilitate future land purchases from the Indians. Roughly these boundaries were recognized: the southwest and southeast corners of Wisconsin were allotted to the southern Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi; the Winnebago held the remainder of southern Wisconsin; the Menomini kept the northeast part of the state from the Milwaukee River up; and the Chippewa held all of northern Wisconsin west of the Menomini. These Indian territories were not to be respected for very long by white squatters, however, and the Winnebago were to be among the first to encounter trouble from this source.

The fact that southwestern Wisconsin was very rich in lead was discovered 40 quite early in the French regime, and it is probable that the French taught the Indians how to mine and smelt the ore. By 1811, the Sauk and Fox are reported to have devoted almost all their attention to lead mining, only hunting to supply themselves with meat. They exchanged the metal with Canadian traders for the goods they needed. Some early American traders who attempted to get in on this trade were killed by the Indians, who feared that once the Americans learned of the value of the lead deposits their cupidity would be aroused and the Indians would lose their land. Later events were to prove the excellence of this reasoning.

Aroused by the rich deposits, Cornish miners, particularly, began to arrive in force by 1827. The Indians were rudely expelled from their diggings and their mines appropriated by armed whites. In the same year, Red Bird, a young Winnebago chief, killed two settlers and scalped a baby who, interestingly enough, survived to become the mother of a large family and live to a ripe old age. Following this attack Red Bird and his warriors, about forty in number, celebrated the scalp taking with a drunken carousal at the mouth of the Bad Axe River, about forty miles north of Prairie du Chien. Two keelboats on their way from Fort Snelling to St. Louis were fired upon by the drunken Winnebago braves, and after a battle of about three hours, the keelboats escaped with a loss of four men dead and several wounded. The Indians were reported to have suffered losses of seven dead and fourteen wounded.

JUNEAU’S TRADING POST, MILWAUKEE (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

MENOMINI INDIANS OF THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY (PORTRAIT BY S. M. BROOKS).

THE PIONEERS (PAINTING BY A. O. TIEMANN).

United States troops rapidly arrived at the scene, and after fleeing up the Wisconsin River, Red Bird found himself and his tribe surrounded. The Americans agreed to forget the matter of the keelboats providing the murderers of the settlers would give themselves up for trial. On Sept. 3, 1827, Red Bird, rather than engage his people in a hopeless war against the whites, voluntarily surrendered to Major Whistler at Portage. Arrangements were made for the Americans to use the lead mines until a treaty could be arranged, and in July, 1829, another Grand Council was held at Prairie du Chien. The Winnebago, southern Potawatomi, Chippewa, and Ottawa agreed to cede their land. The United States Government now owned the rich lead mining country of southwestern Wisconsin.

WINNEBAGO CHIEF (PORTRAIT BY S. M. BROOKS).

During this period of American settlement, beginning as early as 1821 and lasting through 1834, a migration of Indians from New York occurred which was to add some permanent residents to Wisconsin’s Indian population. The Oneida and Munsee settled near Green Bay, and the Stockbridge and Brotherton Indians settled along the eastern shore of Lake Winnebago. The Menomini ceded 500,000 acres of their land to these tribes in 1831.

Meanwhile the stage had been set for what was to become the most famous, and also, perhaps, the most infamous Indian and white conflict in the Wisconsin area. This was the so-called Black Hawk War, although it was more of a systematic extermination of Indians by whites, hardly deserving the term “war.”

Black Hawk was leader of the “British band” of the Sauk with a large village, said to number about 500 families, situated near the mouth of the Rock River in Illinois. His people were known as the “British band” because of their known sympathies with the English, and also since Black Hawk and his warriors had fought with Tecumseh and the British against the Americans in the War of 1812.

White settlers began squatting on Black Hawk’s land as early as 1823, despite the fact that according to treaty the Indians were not required to give up their land until land offices had been set up, an event which had not occurred. The Indians’ cornfields were fenced in, wigwams were burned, and the women mistreated. Black Hawk went to the British agent in Canada, near Detroit. He was advised that the treaties of 1804 and 1816 were being violated and that he rightfully could resist the settlers and expect the backing of the United States Government. Black Hawk returned and warned the settlers that they would be attacked unless they left at once.

I-TWA-KU-AM, MOHICAN LEADER (PORTRAIT BY HAMLIN).

The alarmed settlers sought help from the Illinois militia which was rapidly called to arms in 1831. This show of force compelled Black Hawk to retire to the west side of the Mississippi River with his people, and 44 promise not to return without government permission. Chief Keokuk, head of the combined Sauk and Fox tribes, had already taken all of his people, except the rebellious Black Hawk and his band, into what is now Iowa in 1830, realizing the futility of fighting the tremendously superior white forces.

BLACK HAWK (FROM INDIAN TRIBES OF NORTH AMERICA).

On April 6, 1832, Black Hawk crossed back into Illinois with approximately 1000 of his people, about 400 of whom were warriors. He had been promised aid by emissaries of the Potawatomi, Winnebago, Ottawa, and Chippewa, but before a month had passed Black Hawk realized he would get little aid either from these tribes or from the British in a war against the settlers. The militia had been called out again in the meantime, and Black Hawk now only desired to make peace and get his people back to Iowa. He sent messengers under a white flag to Major Stillman who was encamped nearby with about 400 volunteers. The white flag was ignored, and three of the Indians were killed. Black Hawk had only forty warriors with him at the time, but angered by this treachery, he attacked Stillman’s men in what he himself called a “suicide charge.”

The tremendously superior force of volunteers, upon seeing Black Hawk’s charging braves, fled frantically with the first volley fired by the Indians. As they fled they spread the alarm over most of northern Illinois, and maintained that Black Hawk had ambushed them with 2000 warriors. Following this event Black Hawk removed his women and children to the Lake Koshkonong area in Wisconsin, so that they could forage for desperately needed food and be relatively safe from attack. Black Hawk and his warriors spent the following two months attacking settlements along the Wisconsin-Illinois frontier. Two hundred whites and possibly as many Indians were killed in these border skirmishes.

Black Hawk soon found himself pursued by a greatly superior force of militia and regular U. S. Army troops. He and his band fled through the Madison, Wisconsin, area and were overtaken attempting to cross the Wisconsin River, where the Battle of Wisconsin Heights took place on July 21, 1832. Black Hawk’s braves succeeded in holding back the Americans while the tribe crossed the river, and the following morning one of his men made a surrender speech in the Winnebago language. No one in the American camp understood the plea for surrender terms, since the Winnebago followers of the Americans were not in their camp at the time. The Indians were again compelled to flee.

Black Hawk then divided his people into two groups, one of which obtained rafts and canoes from friendly Winnebago, and proceeded down the Wisconsin River, hoping to reach the Mississippi River and cross back to Iowa. Soldiers from Prairie du Chien captured or shot most of them. Some others were hunted down in the woods by Menomini Indians led by white officers. As the rest of Black Hawk’s band fled overland toward the Mississippi River, they were pursued by the combined forces of General Atkinson, General Henry, and Major Dodd, a total force of some four thousand men.

When Black Hawk’s band arrived at the Mississippi River, they were met by the steamboat “Warrior.” Black Hawk again attempted to surrender, but the “Warrior’s” captain preferred to believe this a trick and opened fire on the Indians. The infantry then arrived and attacked the Indians from the rear. Men, women, and children were forced into the river at bayonet point. Many were drowned as they attempted to swim the river, and others were picked off by American sharpshooters from the shore. This was the massacre of the Bad Axe River, which lasted three hours, and in which 150 Indians were killed and as many more drowned. A band of Sioux, brought there for the purpose by General Atkinson, set upon the 300 Indians who reached the other bank and killed about half of them.

Only about 150 survivors remained of the thousand Indians who had crossed with Black Hawk into Illinois in April only four months before.

Black Hawk fled to the Winnebago, who later surrendered him to the Americans. He was then taken on a tour through the eastern states to impress him with the power of the American Government, and released in June, 1833. His tribe was given a small reservation in Iowa on the Des Moines River, where he died October 3, 1838. The treatment of Black Hawk and his people in the so-called “Black Hawk War” will always remain a blot on American history and a discredit to the Government.

From the time of the “Black Hawk War” on, Wisconsin Indians were rapidly deprived of their land. In September, 1832, the Winnebago ceded the rest of their holdings south and east of the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers. Upon promise of payment of about one million dollars to the Indians and their creditors, the southern Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi, in a treaty at Chicago, Illinois, turned over their holdings in southern Wisconsin in 1833. The Menomini ceded almost four million acres between Green Bay and the Wolf River to the United States Government in 1836. In 1838, the Oneida ceded most of their land in this same area to the 46 United States. The Chippewa, Sioux, and Winnebago, in three separate treaties, ceded the western half of Wisconsin, above the Wisconsin River, in 1837. With the final cession of some small holdings of the Menomini in the east central part of the state, in 1848, the United States Government now had possession of all Indian land in Wisconsin.