PHOTOGRAPH BY MARCEAU, NEW YORK

Merrily Yours

Marshall P. Wilder

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARCEAU, NEW YORK

Merrily Yours

Marshall P. Wilder

THE SUNNY SIDE

OF THE STREET

BY

MARSHALL P. WILDER

Author of “People I’ve Smiled With”

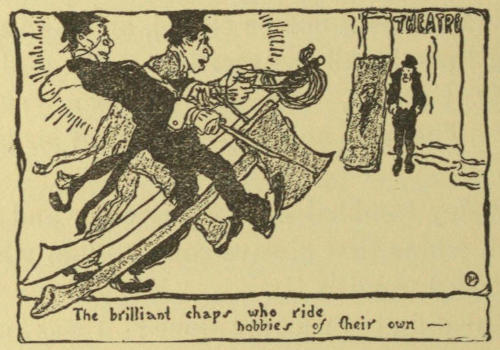

WITH TEXT ILLUSTRATIONS BY BART HALEY

AND COVER DECORATION BY

CHARLES GRAHAM

FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY

NEW YORK AND LONDON

1905

Copyright, 1905, by

FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY

[Printed in the United States of America]

Published, June, 1905

Affectionately Dedicated

To

My Father

In this little volume are offered recollections of the sunny side of many people. I have plucked blossoms from the gardens of humor and pathos, which lie side by side, and in weaving them into a garland, claim only as my own the string that binds them together.

| I. | Sunshine and Fun | 23 |

| The Sunny Side of the Street.—Jests and Jesters.—The Force of a Joke.—Lincoln’s Way.—Kings and Their Joke-makers.—As They do It in Persia and Ireland.—“Chestnuts.”—Few Modern Jesters but no End of Jokers.—Entertainers and Their Ways. | ||

| II. | Sunny Men of Serious Presence | 31 |

| Richard Croker.—A Good Fellow and Not Hard to Approach, if One is not in Politics.—Croker as a Haymaker.—Does not Keep Opinions on Tap.—He and Chauncey Depew on New York City Politics.—Croker Bewilders a London Salesman.—His Greatest Pride.—Recorder Goff.—Not as Severe as His Acts.—Justice Tempered With Mercy.—Two Puzzling Cases. | ||

| III. | At the White House and Near It | 41 |

| My Prophecy to “Major” McKinley.—President McKinley Becomes “One of the Boys” of My Audience; His Attention to His Wife.—How He Won a Vermont City.—A Story of the Spanish War.—My First Meeting with President Harrison.—A Second and More Pleasing One.—A Chance Which I Gladly Lost.—Some of President Harrison’s Stories.—I Led a Parade Given in His Honor.—Vice-Presidents Morton and Hobart. | ||

| IV. | Story-Telling as an Art | 57 |

| Different Ways of Story-Telling.—The Slow Story-Teller.—Lincoln’s Stories.—Bad Telling[10] of Good Stories.—The Right Way to Tell a Story.—The Humorous, the Comic and the Witty Story.—Artemus Ward, Robert J. Burdette and Mark Twain as Story-Tellers. | ||

| V. | Actors’ Jokes | 68 |

| All of Them Full of Humor at All Times.—“Joe” Jefferson.—J. K. Emmett.—Fay Templeton.—Willie Collier.—An Actor’s Portrait on a Church Wall.—“Gus” Thomas, the Playwright.—Stuart Robson.—Henry Dixey.—Evans and Hoey.—Charles Hoyt.—Wilson Barrett.—W. S. Gilbert.—Henry Irving. | ||

| VI. | A Sunny Old City | 81 |

| Some Aspects of Philadelphia.—Fun in a Hospital.—“The Cripple’s Palace.”—An Invalid’s Success in Making Other Invalids Laugh.—Fights for the Fun of Fighting.—My Rival Friends.—Boys Will Be Boys.—Cast Out of Church.—A Startling Recognition.—Some Pleasures of Attending Funerals.—How I Claimed the Protection of the American Flag. | ||

| VII. | My First Trip to London | 93 |

| Large Hopes vs. Small Means.—At the Savage Club.—My First Engagement.—Within an Ace of Losing It.—Alone in a Crowd.—A Friendly Face to the Rescue.—The New York Welcome to a Fine Fellow.—One English Way With Jokes.—People Who are Slow to Laugh.—Disturbing Elements.—Cold Audiences.—Following a Suicide. | ||

| VIII. | Experiences in London | 108 |

| Customs and Climate Very Unlike Our Own.—No Laughter in Restaurants.—Clever Cabbies.—Oddities in Fire-Fighting.—The “Rogue’s Gallery.”—In Scotland Yard.—“Petticoat Lane.”—A Cemetery for Pet Dogs.—“Dogs Who Are Characters.”—The Professional Toast-Master.—Solemn After-dinner Speakers.—An Autograph Table-cloth.—American Brides of English Husbands.[11] | ||

| IX. | “Luck” in Story-Telling | 121 |

| The Real Difference Between Good Luck and Bad.—Good Luck with Stories Presupposes a Well-stored Memory.—Men Who Always Have the Right Story Ready.—Mr. Depew.—Bandmaster Sousa’s Darky Stories.—John Wanamaker’s Sunday-School Stories.—General Horace Porter’s Tales That go to the Spot.—The Difference Between Parliament and Congress. | ||

| X. | Journalists and Authors | 133 |

| Not all Journalists are Critics, Nor are all Critics Fault-finders.—The Most Savage Newspapers not the Most Influential.—The Critic’s Duty.—Horace Greeley.—Mark Twain’s First Earnings.—A Great Publisher Approached by Green Goods Men.—Henry Watterson.—Opie Reid.—Quimby of the “Free Press.”—Laurence Hutton, Edwin Booth and I in Danger Together. | ||

| XI. | The Unexpected | 146 |

| Robert Hilliard and I and a Dog.—Hartford’s Actors and Playwrights.—A Fit that Caused a Misfit.—A Large Price to Hear a Small Man.—Jim Corbett and I.—A Startled Audience.—Captain Williams and “Red” Leary.—“Joe” Choate to the Rescue.—Bait for a Dude.—Deadheads.—Within an Inch of Davy Jones.—Perugini and Four Fair Adorers.—Scanlon and Kernell. | ||

| XII. | Sunshine in Shady Places | 164 |

| On Blackwell’s Island.—Snakes and Snake Charmers.—Insane People as Audiences.—A Poorhouse That was a Large House.—I am Well Known by Another Profession.—Criminals are Not Fools.—Some Pathetic Experiences.—The Largest Fee I Ever Received. | ||

| XIII. | “Buffalo Bill” | 177 |

| He Works Hard But Jokes Harder.—He and I Stir Up a Section of Paris.—In Peril of a[12] Mob.—My Indian Friends in the Wild West Company.—Bartholdi and Cody.—English Bewilderment Over the “Wild West” People.—Major “Jack” Burke.—Cody as a Stage Driver.—Some of His Western Stories.—When He Had the Laugh on Me. | ||

| XIV. | The Art of Entertaining | 190 |

| Not as Easy as It Would Seem.—Scarcity of Good Stories for the Purpose.—Drawing-room Audiences are Fastidious.—Noted London Entertainers.—They are Guests of the People Who Engage Them.—London Methods and Fees.—Blunders of a Newly-wed Hostess from America.—Humor Displaces Sentiment in the Drawing-room.—My Own Material and Its Sources. | ||

| XV. | In the Sunshine with Great Preachers | 199 |

| I am Nicknamed “The Theological Comedian.”—My Friend, Henry Ward Beecher.—Our Trip Through Scotland and Ireland.—His Quickness of Repartee.—He and Ingersoll Exchange Words.—Ingersoll’s Own Sunshine.—DeWitt Talmage on the Point of View.—He Could Even Laugh at Caricatures of His Own Face.—Dr. Parkhurst on Strict Denominationalism. | ||

| XVI. | The Prince of Wales, Now King Edward VII | 211 |

| The Most Popular Sovereign in Europe.—How He Saved Me From a Master of Ceremonies.—Promotion by Name.—He and His Friends Delight Two American Girls.—His Sons and Daughters.—An Attentive and Loving Father.—Untiring at His Many Duties.—Before He Ascended the Throne.—Unobtrusive Politically, Yet Influential. | ||

| XVII. | Sir Henry Irving | 222 |

| A Model of Courtesy and Kindness.—An Early Friend Surprised by the Nature of His[13] Recognition.—His Tender Regard for Members of His Company.—Hamlet’s Ghost Forgets His Cue.—Quick to Aid the Needy.—Two Luck Boys.—Irving as a Joker.—The Story He Never Told Me.—Generous Offer to a Brother Actor-manager.—Why He is Not Rich. | ||

| XVIII. | London Theatres and Theatre-Goers | 236 |

| Why English and American Plays Do Best at Home.—The Intelligent Londoner Takes the Theatre Seriously.—Play-going as a Duty.—The High-class English Theatre a Costly Luxury.—American Comedies too Rapid of Action to Please the English.—Bronson Howard’s “Henrietta,” not Understood in London.—The Late Clement Scott’s Influence and Personality. | ||

| XIX. | Tact | 247 |

| An Important Factor of Success.—Better Than Diplomacy.—Some Noted Possessors of Tact.—James G. Blaine.—King Edward VII.—Queen Alexandra.—Henry Ward Beecher.—Mme. Patti.—Mrs. Ronalds.—Mrs. Cleveland.—Mrs. Langtry.—Colonel Ingersoll.—Mrs. Kendall.—General Sherman.—Chauncey M. Depew.—Mrs. James Brown Potter.—Mme. Nordica. | ||

| XX. | Adelina Patti | 263 |

| Her Home in Wales.—Some of Her Pets.—An Ocean Voyage With Her.—The Local Reception at Her Home-coming.—Mistress of an Enormous Castle and a Great Retinue of Servants.—Her Winter Garden and Private Theatre.—A Most Hospitable and Charming Hostess.—Her Local Charities are Continuous and Many. | ||

| XXI. | Some Notable People | 278 |

| Cornelius Vanderbilt.—Mrs. Mackey.—The Rockefellers.—Jay Gould.—George Gould and[14] Mary Anderson.—Mrs. Minnie Maddern Fiske.—Augustin Daly.—Nicola Tesla.—Cheiro. | ||

| XXII. | Human Nature | 292 |

| Magnetism and Its Elements.—Every One Carries the Marks of His Trade.—How Men Are “Sized Up” at Hotels.—Facial Resemblance of Some People to Animals.—What the Eye First Catches.—When Faces Are Masked.—Bathing in Japan.—The Conventions of Every Day Life That Hide Us From Our Fellows.—Genuineness is the One Thing Needful. | ||

| XXIII. | Sunny Stage People | 302 |

| “Joe” Jefferson.—I Take His Life.—His Absent-Mindedness.—Jefferson and General Grant.—Nat Goodwin, and How He Helped Me Make Trouble.—Our Bicycling Mishap.—Goodwin Pours Oil on Troubled Dramatic Waters Abroad.—George Leslie.—Wilton Lackaye.—Burr McIntosh.—Miss Ada Rehan. | ||

| XXIV. | Sunshine is in Demand | 313 |

| Laughter Wanted Everywhere.—Dismal Efforts at Fun.—English Humor.—The Difference Between Humor and Wit.—Composite Merriment.—Carefully Studied “Impromptus.”—National Types of Humor.—Some Queer Substitutes for the Real Article.—Humor is Sometimes “Knocked Out,” Yet Mirth is Medicine and Laughter Lengthens Life. | ||

| XXV. | “Bill” Nye | 321 |

| A Humorist of the Best Sort.—Not True to His Own Description of Himself.—Everybody’s Friend.—His Dog “Entomologist” and the Dog’s Companions.—A Man With the Right Word for Every Occasion.—His Pen-name was His Own.—Often Mistaken for a Distinguished Clergyman.—Killed by a Published Falsehood.[15] | ||

| XXVI. | Some Sunny Soldiers | 330 |

| General Sherman.—His Dramatic Story of a Trysting-place.—The Battle of Shiloh Fought Anew.—Sherman and Barney Williams.—General Russell A. Alger on War.—General Lew Wallace.—The Room in Which He Wrote “Ben Hur.”—His Donkey Story.—General Nelson A. Miles and Some of His Funny Stories.—A Father Who Wished He Had Been a Priest. | ||

| XXVII. | Some First Experiences | 348 |

| When I was a Boy.—One Christmas Frolic.—How I Got on One Theatre’s Free List.—My First Experience as a Manager.—Strange Sequel of a Modest Business Effort.—My First Cigar and How It Undid Me.—The Only “Drink” I Ever Took.—My First Horse in Central Park.—I Volunteer as a Fifer in School Band, with Sad Results to All Concerned. |

The Sunny Side of the Street.—Jests and Jesters.—The Force of a Joke.—Lincoln’s Way.—Kings and Their Joke-Makers.—As they do it in Persia and Ireland.—“Chestnuts.”—Few Modern Jesters but no End of Jokers.—Entertainers and Their Ways.

I live on the sunny side of the street; shady folks live on the other. I always preferred the sunshine, and have tried to put other people there, if only for an hour or two at a time, even if I had to do it after sunset from a platform under the gaslight, with my name billed at the door as entertainer.

As birds of a feather flock together, it has been my good fortune to meet thousands of other people on the sunny side of the street. In this volume I shall endeavor to distribute some of the sunshine which these fine fellows unloaded on me.

Nature has put up many effective brands of concentrated sunshine in small packages; but the best of these, according to all men of all countries, is the merry jest. As far back as history goes you will find the jest, also the jester. The latter was so important that kings could not get along without him. Some kings more powerful than any European sovereign is to-day are remembered now only by what their jesters said.

All these jesters are said to have been little people. I am doubly qualified to claim relationship with them, for I am only three and a half feet high, and I have been jester to millions of sovereigns—that is, to millions of the sovereign American people, as well as to some foreign royalties.

The reason for little people taking naturally to sunshine and good-natured joking is not hard to find, for it is a simple case of Hobson’s choice. It is easier to knock a man out with a joke than with a fist-blow, especially if you haven’t much height and weight behind your fist. It is the better way, too, for the joke doesn’t hurt. Instead of the other man’s going in search of an arnica bottle or a pistol or a policeman, he generally hangs about with the hope of getting another blow of the same sort. One needn’t be little to try it. Abraham Lincoln had a fist almost as big as the hand of Providence, and as[25] long a reach as John L. Sullivan, but he always used a joke instead, so men who came to growl remained to laugh. I’m not concerned about the size of my own hand, for it has been big enough to get and keep everything that belonged to me. As to reach, as long as my jests reach their mark I shan’t take the trouble to measure arms with any one.

It is a Simple Case of Hobson’s Choice.

There’s always something in a jest—for the man who hears it. How about the jester? Well, he is easily satisfied. Most men want the earth, so they get the bad as well as the good, but the best that the world affords is good enough for the jester, so I shan’t try to break the record. It is[26] often said that the jester swims near the top. Why shouldn’t he? Isn’t that where the cream is? And isn’t he generous enough to leave the skimmed milk for the chaps dismal enough to prefer to swim at the bottom?

I am often moved to pride when I realize how ancient is my craft. Adam did not have a jester; but he did not need one, for he was the only man—except you and I—who married the only woman in the world. Neither did old Noah have or need one, for he had the laugh on everybody else when the floods fell and he found himself in out of the rain. But as soon as the world dried out and got full enough of people to set up kings in business, the jester appears in history, and the nations without jesters to keep kings’ minds in good-working order dropped out of the procession. The only one of them that survives is Persia, where John the Jester is, as he always was, in high favor at court. When trouble is in the air he merely winks at the Shah and gets off: “Oh, Pshaw!” or some other bon mot old enough to be sweet; then the monarch doubles up and laughs the frown from his face, and the headsman sheathes his sword and takes a day off.

Speaking of old saws that are always welcome reminds me to protest against the unthinking persons who cry “Chestnut!” against every joke that is not newly coined. In one way it is a[27] compliment, for the chestnut is the sweetest nut that grows; but it does not reach perfection until it has had many soakings and frosts, and has been kicked about under the dead leaves so many times that if it was anything except a chestnut it would have been lost. Good stories are like good principles: the older they are, the stronger their pull.

There is not a more popular tale in the world than that of Cinderella. It is so good that nations have almost fought for the honor of originating it. Yet a few years ago some antiquarians dug some inscribed clay tablets from the ruins of an Asiatic city that was centuries old when Noah was a boy. Some sharps at that sort of thing began to decipher them, and suddenly they came upon the story of Cinderella—her golden slipper, fairy godmother, princely lover and all. But do children say “Chestnut!” if you give them this, and then tell them the story of Cinderella? Not they!—unless you don’t know how to tell it. A story is like food: it doesn’t matter how familiar it is, if you know how to serve it well.

Why, the story-teller, of the same old stories, too, is as busy in Persia to-day as he was thousands of years ago, and one of the most important of his duties is the passing of the hat. You will find him on the street corners of the towns[28] with a crowd about him. When he reaches the most interesting part of the story he will stop, like the newspaper serial with “To be continued in our next.” Then he passes his fez. The listeners know well what the remainder of the story will be; but instead of “Chestnut!” he hears the melodious clink of coppers.

Not only the Shah, but many a wealthy Persian keeps a jester for the sole purpose of being made to laugh when he feels dull. Some of the antics of these chaps would not seem funny to an American—such, for instance, as going about on all fours, knocking people down and dressing in fantastic attire—but there is no accounting for tastes, as the old woman said when she kissed the cow. The Shah’s jester has a great swing—he has twelve houses, and not a mortgage on one of them. He also has all the wives he wants. Who says that talent is not properly appreciated in Persia?

If you will run over to Europe you will find the Irish prototype of the Persian story-teller on the streets of Dublin and Limerick. Many a time I have seen him on the street corner telling the thrilling story of how O’Shamus was shot, or some similarly cheering tale—for fighting seems the funniest of fun to an Irishman. And just before first blood is drawn, the story-teller pauses to pass the hat, into which drop hard-earned[29] pennies that had been saved for something else. It is the old Persian act. The manner is the same, though the coat and hat are different, so I should not be surprised to learn that the Irish are direct descendants of the ancient Persians.

The Irish Prototype of the Persian Story-Teller.

It would be easy to follow the parallel and to show how from the ancient jester was evolved the modern comedian; but of the “true-blue” jesters of to-day—the men who evolve fun from their own inner consciousness—I am compelled to quote: “There are only a few of us left.” Of these “entertainers,” as they are called in modern parlance, I shall let out a few of the secrets which admit them to the drawing-room[30] of England and America to put a frosting, as it were, on proceedings that otherwise might be too sweet, perhaps too heavy. The modern jester comes to the aid of the queen of the drawing-room just as the ancient one did to the monarch of old, so he is still an honored guest at the table of royalty.

Richard Croker.—A Good Fellow and Not Hard to Approach.—If One is Not in Politics.—Croker as a Haymaker.—Does Not Keep Opinions on Tap.—He and Chauncey Depew on New York City Politics.—Croker Bewilders a London Salesman.—His Greatest Pride.—Recorder Goff.—Not as Severe as His Acts.—Justice Tempered With Mercy.—Two Puzzling Cases.

One of the privileges of a cheerful chap without any axes to grind is that of seeing behind the mask that some men of affairs are compelled to wear. Often men whom half of the world hates and the other half fears are as companionable as a hearty boy, if they are approached by a man who doesn’t want anything he shouldn’t have—wants nothing but a slice of honest human nature.

Such a man is Richard Croker, for years the autocrat of Tammany Hall and still believed, by many, to have the deciding word on any question of Tammany’s policy. With most men it is a serious matter, requiring much negotiation, to get a word with Mr. Croker, and they dare not expect more than a word in return.

While at Richfield Springs, a few years ago, I drove out to call on Mr. Croker at his farm. I met Mrs. Croker on the piazza and was told I would probably find her husband in the hay-field; so I went around behind the stables and found the leader of Tammany Hall in his shirt-sleeves pitching hay upon a wagon. At that time an exciting political contest was “on,” and New York politicians were continually telegraphing and telephoning their supreme manager,—the only man who could untangle all the hard knots,—yet from his fields Richard Croker conducted the campaign, and with so little trouble to him that it did not keep him from making sure of his hay-crop, by putting it in himself.

In later years I saw much more of Mr. Croker, for I was often his guest at Wantage, his country home in England, and I could not help studying him closely, for he was a most interesting man. In appearance he suggested General Grant; he was of Grant’s stature and build, his close-cropped beard and quiet but observant eyes recalled Grant, and his face, like the great general’s, suggested bulldog courage and tenacity, as well as the high sense of self-reliance that makes a man the leader of his fellow men. Few of his closest associates know more of him than his face expresses, for he is possessed of and by the rarest of all human qualities—that of keeping his[33] opinions to himself. Most political leaders say things which bob up later to torment them, but Croker’s political enemies never have the luck of giving him his own words to eat. He can and does talk freely with men whom he likes and who are not tale-bearers, but he never talks from the judgment seat. Even about ordinary affairs he is too modest and sensible to play Sir Oracle. One day he chanced to be off his guard and gave me a positive opinion on a certain subject; when afterward I recalled it to him he exclaimed: “Marshall, did I tell you that?” It amazed him that he had expressed an opinion.

During one of my visits to Wantage Mr. Croker and I were together almost continually for a week; he not only survived it, but was a most attentive and companionable host. His son Bert was fond of getting up early in the morning to hunt mushrooms, and in order to be awakened he would set an alarm clock. “Early morning” in England and at that season of the year was from three to four o’clock, for dawn comes much earlier than with us. His father did not wish him to arise so early, so he would go softly into Bert’s room and turn off the alarm, to assure a full night sleep for the boy. The fact that he could not hear the alarm worried Bert so greatly that he placed the clock directly over his head, hanging it to a string from the ceiling. But even[34] in this position Mr. Croker succeeded in manipulating it, and he gleefully told me of it at the time.

One day, in London, Mr. Croker called for me and took me to see Mr. Depew, who had recently arrived. We drove to the Savoy and found Mr. Depew on the steps, just starting for Paris. He exclaimed:

“Hello? What are you two fellows doing together?—fixing up the election?”

This was just before Van Wyck was elected mayor; Mr. Strong’s enforcement of the liquor law had been so vigorous as to enrage many bibulous voters. As he bade us good-bye Mr. Depew found time to say to Mr. Croker,

“All your party will have to do will be to hold their hats and catch the votes.”

At the time of the Queen’s Jubilee we were invited to view the procession from Mr. Jefferson Levy’s apartment in Piccadilly, but Mr. Croker declined; he told me afterward that he would have offended many Irish voters in America had he appeared in any way to honor the Queen.

Before starting from London for Wantage one day, Mr. Croker asked me to go to a furniture dealer’s with him; he had some purchases to make. As we entered the place he said to me, “We’ve only half an hour in which to catch the train”—but the way he bought furniture did[35] not make him lose the train. He would say, pointing to a dresser,

“How much is that?”

“Six guineas, sir.”

“Give me six of them.”

Pointing to another,

“How much is that one?”

“Five guineas, sir.”

“Well, seven of those”—and so on.

With such rapid fire, even though he expended more than a thousand dollars, and not at haphazard either, there was ample time to catch the train. The incident, though slight in itself, is indicative of his quickness of decision; but it so utterly upset the dealers, accustomed to English deliberation, that he begged permission to wait until next day to prepare an itemized bill.

Mr. Croker’s quiet unobtrusive manner, which has so often deceived his political enemies into believing that he was doing nothing, dates back a great many years—as far back as his courtship. The future Mrs. Croker and her sister were charming girls and their home was the social rendezvous of all young people of the vicinity. Their father was a jolly good fellow and as popular as his daughters; when the latter went to a dance he was always their chaperon, and a most discreet one he was for he always went up-stairs and slept until the time to go home. Mr. Croker[36] was at the house a great deal but was so quiet and devoted so much time to chat with the father that no one suspected that one of the daughters was the real attraction, but with the quiet persistence that had always characterized him he “won out.”

Great soldiers delight in fighting their battles o’er and no one begrudges them the pleasure. Mr. Croker has been in some desperate fights and won some great victories. Hoping for a story or more about them I one day asked him of what in his life he was most proud. His reply indicated the key-note of his nature, for it was:

“That I have never gone back on my word.”

Another man who has kept many thousands of smart fellows uncomfortably awake and in fear is Recorder Goff. When he conducted the inquiries of the Lexow Committee he extracted so much startling testimony from men whom no one believed could be made to confess anything, that a lot of fairly discreet citizens were almost afraid to look him in the eye, for fear he would ferret out all their private affairs. I had never seen him, but I had mentally made a distinct picture of him as a tall, thin, dark-browed, austere, cold character, rather on the order of a Grand Inquisitor, as generally accepted. When we met it was at a dinner, where I sat beside him and had to retouch almost every detail of[37] my picture, for, although tall and thin, he was blonde and rosy, of sanguine temperament, with merry eyes, a genial smile and as talkative as every good fellow ought to be.

The acquaintance begun at that dinner-table was continued most pleasantly by many meetings in Central Park, which both of us frequented on our bicycles. One day, while we were resting in the shadow of Daniel Webster’s statue, I made bold to ask him how he came by his marvelous power of extracting the truth from unwilling occupants of the witness-box. He murmured something self-deprecatory, but told me the following story in illustration of one of his indirect methods and also of how truth will persist in muddling the wits of a liar.

“A man was brought before me accused of killing another man with a bottle. He had a friend whose mother was on the witness stand and she tried to save her son’s friend, though she perjured herself to do so. She swore she had seen the murderer and could describe him. I was convinced of the accused’s guilt and the woman’s perjury, and I determined to surprise her into confession.

“I got seven men of varying appearance who were in the court-room to stand up, which they did, though greatly mystified, for they were present only as spectators. I asked the woman[38] if the first man was the murderer. She promptly answered ‘No,’ to his great relief.

“‘But,’ I said, ‘he resembles the murderer, doesn’t he? He is the same height?’

“‘Oh, no,’ she answered, ‘he is much taller.’ Motioning the first man to sit down, I pointed to No. 2, and asked:

“‘This man is the same height as the murderer, is he not?’

“‘Yes, exactly.’ I asked the man his height, and he said ‘five feet seven.’ He was told to sit down, and No. 3, who had a head of most uncompromising red hair, was brought forward.

“‘You said the murderer had red hair like this man, didn’t you?’

“‘Oh, no—brown, curly hair.’

“‘Were his eyes like this man’s?’

“‘No, they were brown.’

“Number four, who had fine teeth, was asked to open his mouth, greatly to his embarrassment.

“‘Were the murderer’s teeth like this man’s?’

“‘No, he had two gold teeth, one on each side.’

“Number five was rather stout and the woman thought the murderer about his size; he weighed one hundred and sixty. Six and seven were looked at and sent back to their seats, nervous and perspiring. Then I said:

“‘We find from this woman’s testimony that the murderer was about five feet seven in height, weighed one hundred and sixty, had dark curly hair, brown eyes, two gold teeth and a habit of keeping his hands in his pockets.’

“By this time the prisoner was white and shaking, for bit by bit the witness had described him exactly. When the woman realized what she had done she broke down and confessed that the prisoner was the real criminal.”

It was charged that a man brought before Recorder Goff for theft was an old offender and had served a term in states prison, but the accused denied it and no amount of cross-questioning by the prosecution could shake his denial. Mr. Goff noticed that he had lost a thumb; as prisoners are generally given a name by their comrades, signifying some physical peculiarity, the Recorder said:

“While in prison you were known as One-Thumbed Jack.” Taken off his guard, the man asked:

“How did you know that?”

“Then you are an ex-convict?”

“Well, yes, sir, but I had honest reasons for not wanting it known and I’d like to speak to you alone, sir.”

Mr. Goff granted the request and they retired to a small room where the prisoner after telling[40] his real name, related a touching story of devotion to a young sister whom he brought up and educated with the proceeds of his earlier crimes. While serving his prison term he had written her letters which his pals posted for him in different parts of the world to make her believe he was traveling so constantly that any letters from her could not reach him. This sister was now married and had two children and it would break her heart to find out that her brother was a convict or had ever been one. So he wished to be sentenced under another name. Mr. Goff said:

“I will suspend sentence.”

Later the man’s statements were investigated and found to be true. So his request to be sentenced under an assumed name was granted. Farther, he got but two years, although he would have been “sent up” for ten years had it not been for his story—a fact which shows how in Recorder Goff, the city’s greatest terror to evil-doers, justice is tempered with mercy.

My Prophecy to “Major” McKinley.—President McKinley Becomes “One of the Boys” of My Audience; His Attention to His Wife.—How He Won a Vermont City.—A Story of the Spanish War.—My First Meeting With President Harrison.—A Second and More Pleasing One.—A Chance Which I Gladly Lost.—Some of President Harrison’s Stories.—I Led a Parade Given in His Honor.—Vice-Presidents Morton and Hobart.

It had been my good fortune to meet several presidents of the United States, as well as some gentlemen who would have occupied the White House had the president died, and I learned that, in spite of their many torments and tormentors, they all liked to get into the sunshine and that they had done it so much that the sunshine had returned the compliment right heartily, as is its way “in such case made and provided.”

Some years ago while entering a New York hotel to call on Madame Patti I chanced to meet in the corridor William McKinley, who was then governor of Ohio, though his New York acquaintances still called him “Major.” His was one[42] of the big, broad natures that put all of a man’s character in full view, and there was a great lot in McKinley’s face that day,—thoughtfulness, self-reliance, strength, honesty, as well as some qualities that seldom combine in one man—simplicity and shrewdness, modesty and boldness, serious purpose and cheerfulness, that I became quite happy in contemplation of him as a trusty all-around American. He greeted me very cordially and as I was smiling broadly, he asked:

“What pleases you, Marshall?”

“The fact that I am shaking hands with the future president of the United States,” I replied.

Some years afterward, when Mr. McKinley had fulfilled my prophecy, I was the guest of D. A. Loring, at Lake Champlain, and the president and most of his cabinet were at the same hotel. Besides Mr. and Mrs. McKinley there were Vice-President and Mrs. Hobart, Secretary of War Alger and Mrs. Alger, Postmaster General Geary and Mrs. Geary, Cornelius N. Bliss, Secretary of the Interior, and others. Every one at the hotel treated the distinguished guest with the greatest consideration, by letting him entirely alone, so that he got the rest he sorely needed. He walked much about the grounds, enjoying the bracing atmosphere and peaceful, beautiful surroundings.

One day I went into the bowling alley to spend half an hour or more with the boys who set up the pins; boys are always my friends, and I was going to do some card and sleight-of-hand tricks for these little fellows. Just as I had gathered them about me and started to amuse them, Mr. McKinley came to the door and looked in, smiled, came over to us and asked what was going on. I replied:

“Well, Mr. President, I was just doing some tricks to amuse the boys.”

“Then I’m one of the boys,” said the president of the United States. He sat down in the circle and was one of my most attentive auditors. When I had finished he walked apart with me and said:

“Marshall, do you remember meeting me in the Windsor Hotel, New York, and saying you were shaking hands with the future president of the United States?”

“I recall it very distinctly,” I replied.

“I have just been thinking,” he said, “of that—to me, strange prophecy. You must be possessed of some clairvoyant power.” There are some things you can’t tell a man to his face, so I didn’t explain to him that a man with a character like his couldn’t help becoming president, when the whole country had come to know him.

I shall never forget what I saw of his lover-like devotion to his invalid wife, nor her evident gratitude for his every service, nor the sweet solicitude and pride with which she regarded him. One day his brother Abner arrived, went to the portion of the hotel reserved for the president, met Mrs. McKinley and asked:

“Is William in?”

“Yes,” was the reply, “but I shall not let you see him for an hour. He is resting.”

A little incident that was described to me by an eye-witness brought out one of the qualities which endeared President McKinley to his fellow countrymen. While on a brief visit across the lake, in Vermont, he was driving through a small city, followed by a great procession of people who had turned out in his honor. While passing through the main street he noticed an old man seated on the piazza of a modest dwelling, and asked the mayor, who was beside him in the carriage,

“Who is that old gentleman?”

“That is Mr. Philip, father of Captain Philip, of the battleship Texas,” was the reply.

“I thought that must be he,” said the president. “Will you kindly stop the carriage?”

The carriage stopped and so did the mile or more of procession, while the president jumped out, unassisted, ran up the steps, grasped the[45] hand of the astonished and delighted old man, and said:

“Mr. Philip, I want to congratulate you on having such a son as Captain Philip, and I feel that the thanks of the nation are due you for having given the world such a brave, patriotic man.”

The old man, tremulous with gratification, could scarcely find words with which to thank the head of the nation for his appreciative attention, but the president’s simple, friendly manner quickly put him at his ease and the two men chatted freely for several minutes, the president evidently enjoying it keenly. Then after a hearty invitation to visit him at the White House, Mr. McKinley got into his carriage and the procession again started.

Mention of the Texas recalls a visit I made to her when she was at the New York Navy Yard for repairs, after the fight with Cervera’s fleet, in which the Texas was the principal American sufferer. A young officer took me about the ship, showed me her honorable wounds, repeated Captain Philip’s historic remark, made after the battle,—“Don’t cheer, boys; the poor fellows are dying,” and told me the following story:

One of our Irish sailors was very active in saving the Spaniards in the water, throwing them ropes, boxes and everything floatable he could[46] find. But there was one Spaniard who missed everything that was thrown him. Just before the battle we had had religious service and the altar was still on deck, so our Irishman grabbed it, heaved it overboard and yelled:

“There, ye haythen! If that won’t save ye, nothin’ ever will.”

While Mr. Harrison was president I became pleasantly acquainted with his son Russell, who, having read of President Cleveland’s very kind treatment of me when I went to him with a letter of introduction from Henry Ward Beecher, wanted me to meet his father and gave me a letter to that effect. My visit to the White House was quite impressive—to me. Soon after I reached Chamberlain’s, at Washington, a messenger arrived and informed me that the President had received my letter of introduction and desired me to call the next morning at ten o’clock, which I did.

After passing the sentinels at the door I was taken into the room of Mr. Private Secretary “Lije” Halford, who greeted me cordially and said: “Mr. Wilder, the president will see you.” I was ushered into Mr. Harrison’s presence, and the following conversation ensued:

“Mr. President, this is Mr. Wilder.”

“How do you do, Mr. Wilder?”

“How do you do, Mr. President?”

A profound silence followed; it seemed to me to be several minutes long; then I said:

“Good-day, Mr. President.”

“Good-day, Mr. Wilder.”

After leaving the room I turned to Mr. Halford, raised my coat-tails and asked:

“Won’t you please kick me?”

Of course I had to refer to the incident in my monologue that season, for it isn’t every day that a professional entertainer is invited to call at the White House. But I did not care to tell exactly what occurred, so I adopted an old minstrel joke and said:

“I called on the president the other day. I walked in, in a familiar way, and said, ‘How do you do, Mr. President?’ He said, ‘Sir, I cannot place you.’ ‘Well,’ I replied, ‘that’s what I’m here for.’”

I afterward heard that President Harrison was very cold and lacked cordiality; still later I discovered, with my own eyes and ears, that he had a kind heart and genial nature. One summer while I was at Saratoga I was asked by Mr. W. J. Arkell to Mount McGregor, to meet President Harrison at dinner and to become a member of a fishing party. The occasion was the president’s birthday, and the invitation was the more welcome when I learned that a list of the people at the Saratoga hotels had been shown[48] the president, who had himself selected the guests for his birthday celebration. At Mount McGregor I found, as one always finds, wherever the President of the United States is staying a few days, thirty or forty newspaper correspondents, all of whom I knew and most of whom professed to doubt my ability to make the president laugh. This did not worry me, for I don’t love trouble enough to look ahead for it, and dinner time, when the laughing was to begin, was a few hours distant.

We all went by carriage to a stream about five miles away and all helped fill the president’s basket with fish,—for which he got full credit, in the next day’s newspapers. My own contributions were few and small, for I never was a good fisherman. So I was grateful when Russell Harrison took me to a little pool where he was sure we would have great luck. But not a bite did either of us get. Then I recalled something that a veteran fisherman played on me when I was too young to be suspicious; it was to beat the water to attract the attention of the fish. Russell kindly assisted me at beating the water, but the fish beat us both by keeping away.

When we got back to the hotel and to the banquet it was announced that there were to be no speeches, but the president would make a few remarks and I would be called on for a few[49] stories. Consequently I had no mind or appetite for dinner, for most of the guests were newspaper men who had been surfeited with stories ever since they entered the business, and the most important listener would be the president, who the boys had said I couldn’t make laugh.

I was still mentally searching my repertoire, although I had already selected a lot of richness, when the president arose and made some general remarks. But it was impossible for him to forget that at this same place—Mount McGregor, Ex-President Grant breathed his last, so Mr. Harrison’s concluding remarks were on the line that any other whole-hearted American would have struck in similar circumstances. As I am a whole-hearted American myself, they struck me just where I live, and I am not ashamed to confess that they knocked me out.

So, when I was called upon, I declined to respond. Several friends came to my chair and whispered: “Go ahead, Marsh.” “Don’t lose the chance of your life; don’t you know whatever is said at this dinner will be telegraphed all over the United States?” But I held my tongue—or it held itself. There is a place for every thing; a table at which the President of the United States had just been talking most feelingly of the pathetic passing of another president was no place for a joke—much less for a budget[50] of jokes, so instead of making the president laugh I allowed the newspaper men to have the laugh on me. In the circumstances they were welcome to it.

“I allowed the newspaper men to have a laugh on me.”

Nevertheless I succeeded, for the president succeeded in breaking the strain upon him, and later in the day at his own cottage he transfixed me with a merry twinkle of his eye and said:

“Marshall, what’s this story you’ve been telling about your visit to the White House?”

I saw I was in for it, so I repeated the minstrel joke, already recorded. He laughed so heartily that there wasn’t enough unbroken ice between us to hold up a dancing mosquito, so I made bold to tell him that some men insisted that he did not appreciate humor. Then he laughed again; I wish I could have photographed that laugh, for there was enough worldly wisdom in it to lessen[51] the number of cranks and office seekers at the White House for years to come. But I hadn’t much time to think about it, for we began swapping yarns and kept at it so long that I suddenly reminded myself, with a sense of guilt, that I was robbing the ruler of the greatest nation on earth of some of his invaluable time. Never mind about my own stories that evening, but here is one that President Harrison told me, to illustrate the skill of some men in talking their way out of a tight place.

There was a man in Indiana who had a way of taking his own advice, though he generally had to do things afterward to get even with himself. He was a hog dealer, and one season he drove a lot of hogs to Indianapolis, about a hundred miles distant, though he could get nearly as good a price at a town much nearer home. Arrived at Indianapolis, he learned that prices had gone down, so he held on for a rise, but when offered a good price he stood out for more, and insisted that if he did not get it he would drive the hogs back home, which he finally did, and sold them for less than was offered him in the city. When one of his friends asked him why he had acted so unwisely he replied:

“I wanted to get even with them city hog-buyers.”

“But did you?”

“Well, they didn’t get my hogs.”

“But what did you get out of the transaction?”

“Get? Why, bless your thick skull, I got the society of the hogs all the way back home.”

I had long been puzzled as to the origin of the word “jay,” as applied to “easy marks” among countrymen, and I told the president so. He modestly admitted that I had come to the right shop for information; then he told me this story:

“Winter was coming on and a blue jay made up his mind that he would prepare for it. He found a vacant hut with a knot-hole in the roof, and he said to himself, ‘Here’s a good place to store my winter supplies,’ so he began to collect provender. His acquaintances who passed by saw what he was doing; then they laughed and took a rest, for they knew how to get in by the side door. Whenever he dropped a nut or a bit of meat through the knot-hole they would hop in below and gobble it. So, Marshall, next time you hear any one called a ‘jay’ I’m sure you’ll know what it means.”

The next morning, when we all met on the president’s special train en route to Saratoga, my newspaper friends twitted me anew on not having made the president laugh, but I said: “Now, boys, you wait.” Then I was so impudent as to approach the president and say:

“Mr. President, I am very glad to have had you with me on this fishing trip, and I hope whenever you want to go off on a similar affair you will let me know it. At the foot of the mountain a band of music and escort of troops are waiting for me, and in the hurry I may not be able to say good-bye to you, so I say it now.” But not one eyelash of the president quivered as he shook hands with me and replied: “Glad to have met you, Mr. Wilder,” so the newspaper boys certainly did have the laugh on me.

But the day was still young. Arrived at the Saratoga depot, all hurried into carriages. Waiting until all were seated and started in procession, I found an open landau and gave the driver the name of my hotel. “All right, Mr. Wilder,” was the reply, which did not startle me, for I am pretty well known in Saratoga by the cabbies—and the police. I said:

“Make a short cut, get out of the crowd and get me to the hotel as soon as possible, so I may avoid the parade.” He endeavored to get out, but he got in; and in trying to extricate himself he succeeded in driving through the band and past the troops and finally beside the carriages of the president and his guests. I took advantage of the occasion; as I passed the president I stood up (though it made little difference whether[54] I sat or stood, for not much of me was visible over the top of the carriage door) and I bowed my prettiest. The president raised his hat, as did the other guests, and I led that procession down Saratoga’s Broadway, the sidewalks of which were crowded with New York and Brooklyn people who knew me and to whom I bowed, right and left, to the end of the route, where one of the newspaper men said:

“Marsh usually gets there.”

In Mr. McKinley’s first term I fell in conversation at a hotel with a gentleman of manner so genial that I never forgot him. We exchanged a lot of stories, at which I got more than I gave, but suddenly the gentleman said:

“I can see, Mr. Wilder, that you don’t recognize me.”

“Well, really, I don’t,” I replied, with an apologetic laugh. “You must pardon me; I meet so many. May I ask your name?”

“Certainly. It is Garret A. Hobart.”

“The Vice-president of the United States! Well, that isn’t anything against you”—for I had to say something, to keep from collapsing. He seemed greatly amused, and I could not help wondering if in any other country of the world a high official of the government could be picked up in a hotel corridor, be chatted with, then be compelled to introduce himself, and throughout[55] all conduct himself as if he were no one in particular.

Levi P. Morton, ex-vice-president, has been out of politics for some years, yet he is remembered as a man who could tell good stories to illustrate his points. Here is one of them:

“The General doubled on his tracks.”

“Not far from my country place is a farmer noted for his fine, large cattle. People come from everywhere to look at his Durhams and Alderneys, but they have to be careful how they venture into the pastures, for some of the bulls are ferocious. A certain major-general, who was very proud of his title, was visiting near by, and one day while walking he cut across the[56] fields to shorten distance. Before he knew of his danger a big bull, bellowing and with tossing head, began to chase him. The general was a swift runner, and made good time, but the animal too was lively, so when the general reached a fence he dared not stop to climb for the bull was near enough to—well, help him. The general doubled on his tracks several times, but the bull kept dangerously near. Suddenly a gate offered a chance to shut off pursuit. Near the gate stood the farmer, who had been viewing the chase; the panting general turned on him fiercely and asked, between gasps:

“‘Sir—sir—did you—see your bull chasing—me?’

“‘Ya-as,’ drawled the farmer.

“‘Is that all you have to say, sir? Do you know whom that bull was chasing?’

“‘You, I guess.’

“‘But do you know who I am, sir? I am General Blank.’”

“‘Wa-all, why didn’t you tell that to the bull?’”

Different Ways of Story-telling.—The Slow Story-teller.—Lincoln’s Stories.—Bad Telling of Good Stories.—The Right Way to Tell a Story.—The Humorous, the Comic and the Witty Story.—Artemus Ward, Robert J. Burdette and Mark Twain as Story-tellers.

The ways of story-tellers differ almost as widely and strangely as the ways of politicians—or women—yet every man’s way is the best and only one to him. I know men who consume so much time in unloading a story that they remind me of a ship-captain who had just taken a pilot and was anxious to get into port. The pilot knew all the channels and shoals of the vicinity, and being a cautious old chap he wasn’t going to take any risks, so he backed and filled and crisscrossed so many times that the captain growled: “Hang him! He needs the Whole Atlantic Ocean to turn around in.”

Yet a lot of these long-winded story-tellers “get there”—and they deserve to, not only because a hearty laugh follows, but because hard work deserves its reward. As to that, Abraham[58] Lincoln, long before he became president, and when time was of no consequence, had some stories almost as long as old-fashioned sermons; but nobody left his seat by the stove at the country store, or his leaning place at the post-office, or his chair on the hotel piazza until “Abe” had reached the point. But there never was more than one Abraham Lincoln. To-day a long-winded story-teller can disperse a crowd about as quickly as a man with a bad case of smallpox.

But it isn’t always length that troubles the listener—the way in which a tale is told is the thing, whether the tale itself be good or bad. It is never safe for some people to repeat a good story they have heard, for they may tell it in a fashion that is like being bitten to death by a duck.

I do not claim originality for my own method and material. I simply tell a story, using whatever material comes my way. Often a friend will tell me of something he has seen or heard; I will reconstruct his narrative, without tampering with the facts, yet so that the people of whom he told it will not recognize it.

There is nothing, except advice, of which the world is more generous than stories. Everybody tells them. They mean well; they want to make you laugh, and they deserve credit for their intention. Yet when neighbor Smith or Brown[59] calls you aside, looks as if he was almost bursting with something good, and then gets off a yarn that was funny when he heard it, but in which you can’t discern the ghost of a laugh—why, you can’t help wondering whether Smith’s or Brown’s funny-bone hasn’t dropped off somewhere, without its owner’s knowledge; you also can’t help wishing that he may find it before he buttonholes you again.

It seems to me that the supreme art of telling a story is to tell it quickly and hide the nub so that the hearer’s wits must find it. But it is possible for some people to tell it quickly at the expense of the essential parts, either through forgetfulness or by not knowing them at sight. For example, here is a tale I heard not long ago:

“The other night Ezra Kendall told about an Irishman who had a habit of walking in a graveyard about twelve o’clock at night. Some boys of the neighborhood planned to so dig and conceal a grave that the Irishman would fall into it; another man was to drape himself in a sheet, to scare Mike. The night arrived, the Irishman took his customary walk and fell into the hole prepared for him. A boy in a white sheet arose, and said in a sepulchral voice:

“‘What are you doing in my grave?’

“‘What are you doin’ out of it?’ Mike replied.”

Soon afterward an amateur gave me the story as follows:

“I heard a story the other day by a man named Kendall about a man who went out in a graveyard at night to walk, about twelve o’clock. He fell into a ditch, and another fellow happened along and said, ‘What are you doing out of it?’—or something like that. I know I laughed like the deuce when I heard it.”

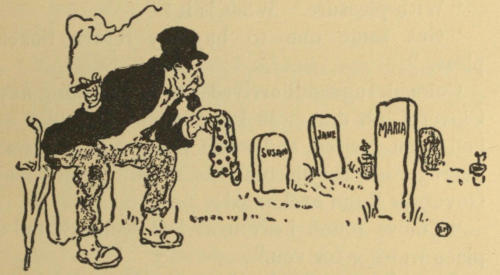

“What are you doing in my grave?”

But even when a story has been committed to memory or written in shorthand on a shirt-cuff, to be read off without a word lost or misplaced, much depends upon the teller. Some people’s[61] voices are so effective that they can tell a story in the dark and “make good”; others can’t get through without calling all their features to help, with some assistance from their arms and legs. One man will lead you with his eye alone to the point of a story; another will drawl and stammer as if he had nothing to say, yet startle you into a laugh a minute.

Of course a great deal depends on the story itself. People are too grateful for a laugh to look backward and analyze the story that compelled it; they generally believe that fun is fun, and that is about as much as any one knows of it. The truth is that while there are all kinds of stories there is only one kind of humor.

As a rule, humorous stories are of American origin, comic stories are English, and witty stories are French. The humorous story depends upon the incidents and the manner of telling; comic and witty stories depend upon the matter. The humorous story may be spun out to any length; it may wander about as it pleases, and arrive at nowhere in particular; but the comic or witty story must be brief, and end in a sharp point. The humorous story bubbles along continually; the other kinds burst. The humorous tale is entirely a work of art, and only an artist can tell it; while the witty or comic story—oh, any one who knows it can tell it.

The act of telling a humorous story—by word of mouth, understand, not in print—was created in America, and has remained at home, in spite of many earnest endeavors to domesticate it abroad, and even to counterfeit it. It is generally told gravely, the teller doing his best to disguise his attempt to inflict anything funny on his listeners; but the man with a comic story generally tells you beforehand that it is one of the funniest things he ever heard, and he is the first one to laugh—when he reaches the end.

One of the dreadfulest inflictions that suffering humanity ever endures is the result of amateur efforts to transform the humorous into the comic, or vice versa. It reminds one of Frank Stockton’s tearful tale of what came of one of the best things in Pickwick by being translated into classical Greek and then brought back into English.

The Rev. Robert J. Burdette, who used to write columns of capital humor for The Burlington Hawkeye and told scores of stories superbly, made his first visit to New York about twenty years ago, and was at once spirited to a notable club where he told stories leisurely until half the hearers ached with laughter and the other half were threatened with apoplexy. Every one present declared it the red letter night of the club, and members who had missed it came around and[63] demanded the stories at second-hand. Some efforts were made to oblige them, but without avail, for the tellers had twisted their recollections of the stories into comic jokes; so they hunted the town for Burdette to help them out of their muddle.

The late Artemus Ward, who a generation ago carried a tidal wave of humor from Maine to California, with some generous overflows each side of its course, had a long serious face and a drawling voice; so when he lectured in churches, as he frequently did, a late-comer might have mistaken him for a minister, though not for very long. He would drawl along without giving the slightest indication of what was coming. When the joke was unloaded and the audience got hold of it he would look up with seemingly innocent wonder as to what people were laughing at. This expression of his countenance always brought another laugh. He could get laughs out of nothing, by mixing the absurd and the unexpected, and then backing the combination with a solemn face and earnest manner. For instance, it was worth a ten-mile walk after dark on a corduroy road to hear him say: “I once knew a man in New Zealand who hadn’t a tooth in his head”—here he would pause for some time, look reminiscent, and continue, “And yet he could beat a base-drum better than any other man I ever knew.”

Mark Twain is another famous humorist who can use a serious countenance and hesitating voice with wonderful effect in a story. His tale of “The Golden Arm” was the best thing of its kind I ever heard—when told as he himself told it—but everything depended on suddenness and unexpectedness of climax. Here it is, as he gave it:—

“Once ’pon a time dey wuz a mons’us mean man, en’ he live ’way out in de prairie all ’lone by himself, ’cep’n he had a wife. En’ bimeby she died, en’ he took en’ toted her ’way out da’ in de prairie en’ buried her. Well, she had a golden arm all solid gold, f’om de shoulder down. He wuz pow’ful mean—pow’ful; en’ dat night he couldn’t sleep, ’coze he wanted dat golden arm so bad.

“When it come midnight he couldn’t stan’ it no mo’, so he got up, he did, en’ tuk his lantern en’ shoved out troo de storm en’ dug her up en’ got de golden arm; en’ he bent his head down ’gin de wind, en’ plowed en’ plowed en’ plowed troo de snow. Den all on a sudden he stop” (make a considerable pause here, and look startled, and take a listening attitude) “en’ say:

“My lan’, what’s dat? En’ he listen, en’ listen, en’ de wind say” (set your teeth together, and imitate the wailing and wheezing sing-song of the wind): “‘Buzz-z-zzz!’ en’ den, way back[65] yonder whah de grave is, he hear a voice—he hear a voice all mix up in de win’—can’t hardly tell ’em ’part: ‘Bzzz-zzz—w-h-o—g-o-t—m-y g-o-l-d-e-n arm?”’ (You must begin to shiver violently now.)

“She’ll fetch a dear little yelp—”

“En’ he begin to shiver en’ shake, en’ say: ‘Oh, my! Oh, my lan’!’ En’ de win’ blow de lantern out, en’ de snow en’ de sleet blow in his face en’ ’most choke him, en’ he start a-plowin’ knee-deep toward home, mos’ dead, he so sk’yeerd, en’ pooty soon he hear de voice again, en”[66] (pause) “it ’us comin’ after him: ‘Buzzz-zzz—w-h-o—g-o-t m-y g-o-l-d-e-n—arm?’

“When he git to de pasture he hear it agin—closter, now, en’ a comin’ back dab in de dark en’ de storm” (repeat the wind and the voice). “When he git to de house he rush up-stairs, en’ jump in de bed, en’ kiver up head en’ years, en’ lay dah a-shiverin’ en’ a-shakin’, en’ den ’way out dah he hear it agin, en’ a-comin’! En’ bimeby he hear” (pause—awed; listening attitude) “—at—pat—pat—pat—hit’s a-comin’ up-stairs! Den he hear de latch, en’ he knows it’s in de room.

“Den pooty soon he knows it’s—standin’ by de bed!” (Pause.) “Den he knows it’s a-bendin’ down over him,—en’ he cain’t sca’cely git his breaf! Den—den he seem to feel somethin’ c-o-l-d, right down neah agin’ his head!” (Pause.)

“Den de voice say, right at his year: ‘W-h-o g-o-t m-y g-o-l-d-e-n arm?’” You must wail it out plaintively and accusingly; then you stare steadily and impressively into the face of the farthest-gone auditor—a girl, preferably—and let that awe-inspiring pause begin to build itself in the deep hush. When it has reached exactly the right length, jump suddenly toward that girl and yell: “‘You’ve got it!’”

If you have got the pause right, she’ll fetch a[67] dear little yelp and spring right out of her shoes; but you must get the pause right, and you will find it the most troublesome and aggravating and uncertain thing you ever undertook.

All of Them Full of Humor at All Times.—“Joe” Jefferson.—J. K. Emmett.—Fay Templeton.—Willie Collier.—An Actor’s Portrait on a Church Wall.—“Gus” Thomas, the Playwright.—Stuart Robson.—Henry Dixey.—Evans and Hoey.—Charles Hoyt.—Wilson Barrett.—W. S. Gilbert.—Henry Irving.

Actors are the most incessant jokers alive. Whether rich or poor, obscure or prominent, drunk or sober, prosperous or not knowing where the next meal is to come from, or whether there will be any next meal, they have always something funny at the tips of their tongues, and managers and dramatic authors as a rule are full of humorous explosives that clear the dull air and let in the sunshine.[69] They are masters at repartee, yet as willing to turn a joke on themselves as on one another, and they can work a pun most brilliantly.

Joseph Jefferson one day called on President Cleveland with General Sherman, and carried a small package with him. All his friends know that dear old “Joe” is forgetful, so when the visitors were going the general called attention to the package and asked: “Jefferson, isn’t this yours?”

“Great Cæsar, Sherman,” Jefferson replied, “you have saved my life!” The “life” referred to was the manuscript of his then uncompleted biography. Jefferson delights in telling of a new playmate of one of his sons, who asked another boy who young Jefferson was, and was told:

“Oh, his father works in a theatre somewhere.”

“Pete” Dailey, while enjoying a short vacation, visited a New York theatre when business was dull. Being asked afterward how large the audience was, he replied: “I could lick all three of them.”

On meeting a friend who was “fleshing up,” he exclaimed: “You are getting so stout that I thought some one was with you.”

J. K. Emmett tells of a heathenish old farmer and his wife who strayed into a church and heard[70] the minister say: “Jesus died for sinners.” The old man nudged his wife, and whispered:

“Serves us right for not knowin’ it, Marthey. We hain’t took a newspaper in thirty year.”

Fay Templeton tells of a colored girl, whose mother shouted: “Mandy, your heel’s on fire!” and the girl replied: “Which one, mother?” The girl was so untruthful that her discouraged mother said: “When you die, dey’s going to say: ‘Here lies Mandy Hopkins, and de trufe never came out of her when she was alive.’”

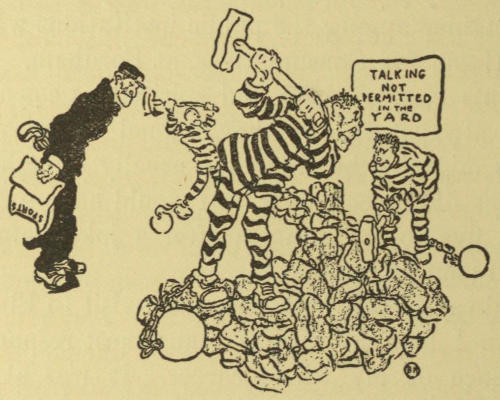

“Actors are the Most Incessant Jokers Alive.”

I have been the subject of some actors’ jokes, and enjoyed the fun as much as any one. May Irwin had two sons, who early in life were susceptible to the seductive cigarette, against which[71] she cautioned them earnestly. I entered a restaurant one day where she and her sons were dining, and she called me over and gave me an opportunity to become acquainted with the little fellows. After I left them, one turned to his mother and asked:

“What makes that little man so short?”

“Smoking cigarettes,” she replied. And they never smoked again.

He Smokes Cigarettes.

Willie Collier invited me one summer to his beautiful home at St. James, Long Island. He was out when I arrived, and when he returned, Mrs. Collier said to him:

“You’re going to have Marshall P. Wilder for dinner,” and Willie replied:

“I’d rather have lamb.”

There is a colony of theatrical people near Collier, and they have a small theatre in which[72] a dazzling array of talent sometimes appears, although the performances are impromptu affairs. On Sundays this theatre serves as a church for the Catholics of the vicinity. At one side hangs a large lithograph of Willie Collier, concerning which the following conversation between the two Irishmen was overheard:

“I wint into the church this mornin’ airly, while it was pretty dark, an’ I see a picture hanging there, an’ thinkin’ it must be one av the saints I wint down on me knees an’ said me prayers before it. When I opened me eyes they’d got used to the dark, an’ if I didn’t see it was a picture av that actor-man beyant that they call Willie Collier!”

“An’ what did’ you do?” asked the other Irishman.

“Sure, I tuk’ back as much av me prayers as I cud.”

Augustus Thomas, the playwright, who is always “Gus” except on the back of an envelop or the bottom of his own check, was chairman of a Lambs’ Club dinner at which I was to speak. When I began, he joked me on my shortness by saying:

“Mr. Wilder will please rise when making a speech.”

I was able to retort by saying: “I will; but you won’t believe it.”

When an acquaintance said to him after being wearied by a play: “That was the slowest performance I ever saw. Strange, too, for it had a run of a hundred nights in London!” Thomas replied:

“That’s the trouble. It’s exhausted its speed.”

He was standing behind the scenes one night with Miss Georgia Busbey, who while waiting for her cue, said: “Tell me a story, Mr. Thomas, before I go on.”

“It must be a quick witty one then, Miss Busbey.”

“I know it, but I’ve come to the right place for it.”

Stuart Robson was present at a Lambs’ Club dinner of which Mr. Thomas was chairman; but he endeavored to hide when called on for a speech. Thousands of successful appearances on the stage never cured him of his constitutional bashfulness.

Thomas said: “Is Mr. Robson here? If he has not gone, we should like to hear from him.”

Robson said: “Mr. Thomas, will you kindly consider that I have gone?”

Thomas replied: “While the drama lasts, Mr. Robson can never go.”

Robson had been a close neighbor and friend for many years to Lawrence Barrett. His bosom friend Marshall Lewis fell in love with Barrett’s[74] charming daughter Millie, and Robson pretended to think it was the greatest joke in the world.

“Why don’t you go in, and win and marry her, Marshall?” he used to say in the squeaky voice which was not for the stage alone. “I’ll tell you what I’ll do—the day you marry Millie Barrett I’ll give you five thousand dollars.”

This went on for some time, until to Robson’s astonishment and chagrin Miss Barrett accepted Lewis.

By the way, when Barrett learned of it he exclaimed: “My dear boy, you don’t know what you’re doing. You are robbing me out of my only remaining daughter.”

“Not at all,” Lewis replied, with a slap on the back of his father-in-law elect. “I’m merely giving you another son.”

When the marriage day came Robson did not attend the ceremony; but he sent his daughter Alicia in his place, and gave her a check for five thousand dollars, drawn to Lewis’ order, but with emphatic orders not to part from it until Lewis and Miss Barrett were pronounced man and wife. When Alicia returned her father asked her if she had given Lewis the check.

The girl replied: “Yes, father.”

“What did he do and say?” Robson inquired impatiently.

“Why, father, he was so overcome that he cried for a minute after I gave it to him.”

“Egad!” squeaked Robson, “was that all? Why, I cried for an hour when I wrote it.”

Henry Dixey is an adept at the leisurely tale, which is a word picture from start to finish. Here is a sample:

In one of the country stores, where they sell everything from a silk dress and a tub of butter to a hot drink and a cold meal, a lot of farmers were sitting around the stove one cold winter day, when in came Farmer Evans, who was greeted with:

“How d’do, Ezry?”

“How d’do boys?” After awhile he continued: “Wa-all, I’ve killed my hog.”

“That so? How much did he weigh?”

Farmer Evans stroked his chin whiskers meditatively and replied: “Wa-all, guess.”

“’Bout three hundred,” said one farmer.

“No.”

“Two seventy-five?” ventured another.

“No.”

“I guess about three twenty-five,” said a third.

“No.”

Then all together demanded: “Well, how much did he weigh?”

“Dunno. Hain’t weighed him yet.”

Other men kept dropping in and hugging the[76] stove, for the day was cold and snowy outside. In came Cy Hopkins, wrapped in a big overcoat, yet almost frozen to death; but there wasn’t room enough around that stove to warm his little finger.

But he didn’t get mad about it; he just said to Bill Stebbins who kept the store: “Bill, got any raw oysters?”

“Yes, Cy.”

“Well, just open a dozen and feed ’em to my hoss.”

Well, Stebbins never was scared by an order from a man whose credit was good, as Cy’s was, so he opened the oysters an’ took them out, an’ the whole crowd followed to see a horse eat oysters. Then Cy picked out the best seat near the stove and dropped into it as if he had come to stay, as he had.

Pretty soon the crowd came back, and the storekeeper said: “Why, Cy, your hoss won’t eat them oysters.”

“Won’t he? Well, then, bring ’em here an’ I’ll eat ’em myself.”

When Charley Evans and Bill Hoey traveled together, they had no end of good-natured banter between them.

Once when Hoey saw Evans mixing lemon juice and water for a gargle, he asked: “What are you doing that for, Charley?”

“Oh, for my singing.”

“Suppose you put some in your ear; then maybe you’ll be able to find the key.”

While they were crossing the ocean, Evans came on deck one day dressed in the latest summer fashion—duck trousers, straw hat, etc.—and asked Hoey: “How do you like me, Bill?”

“Well, all you need to do now is to have your ears pierced,” was the reply.

At the ship’s table the waiter asked Hoey what he would have.

“Roast beef.”

“How shall I cut it, sir?”

“By the ship’s chart.”

Evans always carried the money for both, and the two men had a fancy for wearing trousers of the same material, though of different sizes, for Evans was slighter than his partner. One day Hoey fell on hard luck. He had been to the Derby races, where a pickpocket relieved him of his watch and his money too. They were to start for America next morning, and Evans had plenty of money and return tickets also, yet Hoey was so cut up by his losses that he went to bed early and tried to drop asleep. This did not work, so after tossing for several hours, by which time Evans had retired, he got up and began to dress himself. But to his horror his figure seemed to have swelled in the night.

This was the last straw; he woke his partner and with tears in his eyes and his voice too, he said: “Charley, beside all my hard luck to-day I’m getting the dropsy.”

“Bill,” said Evans after a glance, “go into the other room and take off my pants!”

A certain diamond broker called on the late Charles Hoyt with a large bill.

While Hoyt was drawing a check the broker said: “Charley, a dear friend of mine was robbed yesterday.”

“Is that so? Why, what did you sell him?”

The English stage is as full of jokers as ours. Wilson Barrett tells that at a “First night” his play did not seem to suit the pit, so he came before the curtain at the end of one act and asked what was the matter. The “Gods” have great freedom in English theatres, so there was much talk across the footlights between the stage and the audience; but it was stopped abruptly by a voice that said:

“Oh, go on, Wilson! This ain’t no bloomin’ debatin’ society.”

W. S. Gilbert, although not an actor, is a playwright and extremely critical. A London favorite had the best part in one of Gilbert’s pieces, but the author thought him slow. Going behind the scenes after the performance, Gilbert noted that the actor’s brow was perspiring, so he said:

“Well, at all events, your skin has been acting.”

Gilbert can give evasive answers that cut like a knife. A player of the title part of Hamlet asked Gilbert’s opinion of the performance.

“You are funny, without being vulgar,” was the reply.

Forbes Robertson, who essayed the same part, asked Gilbert: “What do you think of Hamlet?”

Gilbert answered: “Wonderful play, old man; most wonderful play ever written.”

E. S. Willard tells the following story of Charles Glenny, of Irving’s Lyceum Company. “The Merchant of Venice” was in rehearsal, and Glenny did not repeat the lines: “Take me to the gallows, not to the font” to the liking of Irving, so the latter said in the kindly manner he always maintained at rehearsals:

“No, no, Mr. Glenny; not that way. Walk over and touch me, and say: ‘Take me to the gallows, not to the font.’” The line was rehearsed several times, but unsuccessfully.

Finally Irving became discouraged and said: “Ah, well; touch me.”

Irving witnessed Richard Mansfield’s performance of “Richard III,” in London, and by invitation went back to see the actor in his dressing-room. Mansfield had been almost exhausted,[80] and was fanning himself, but Irving’s approach revived him, and natural anticipation of a compliment from so exalted a source was absolutely stimulating.

But for the time being all Irving did was to slap Mansfield playfully on the back and exclaim in the inimitable Irving tone: “Aha? You sweat!”

“Aha! You Sweat!”

Some Aspects of Philadelphia.—Fun in a Hospital.—“The Cripple’s Palace.”—An Invalid’s Success in Making Other Invalids Laugh.—Fights for the Fun of Fighting.—My Rival Friends.—Boys Will Be Boys.—Cast Out of Church.—A Startling Recognition.—Some Pleasures of Attending Funerals.—How I Claimed the Protection of the American Flag.

A hospital is not a place that any one would visit if he were in search of jollity, yet some of the merriest hours of my life were spent, some years ago, in the National Surgical Institute of Philadelphia. I was one of about three hundred people, of all ages, sizes and dispositions, who were under treatment for physical defects. Most of us were practically crippled, a condition which is not generally regarded to be conductive of hilarity, yet many of us had lots of fun, and all of it was made by ourselves. I was one of the luckiest of the lot, for Mother Nature had endowed me with a faculty for finding sunshine everywhere.

Yet part of my treatment was to lie in bed, locked in braces, for hours every day, and each of these hours seemed to be several thousand[82] minutes long. So many other boys were under similar treatment that an attendant, named Joe, was kept busy in merely taking off our appliances. These were locked, for between pain and the restiveness peculiar to boys, we would have removed them for ourselves or for one another. Joe was not a beauty, yet I distinctly remember recalling his appearance was that of an angel of light, for I best remember him in the act of loosening my braces. Whenever the surgeon in charge was absent, we would beg Joe to unlock us for “Just five minutes—just a minute”—and sometimes he would yield, after making us promise solemnly not to tell the doctor. The result recalls the story of the old darky who was seen to hammer his thumb at intervals. When asked why he did it, he replied,

“Kase it feels so good when I stop!”

To keep from thinking of my pain and helplessness, I kept looking about me for something to laugh at, and it was a rare day on which I failed to find it. When there came such a day, I had only to close my eyes and look backward a few months or years; I was sure to recall something funny. Then I would laugh. Some other sufferer would ask what was amusing me, and when I told him he would also laugh, some one would hear him and the story would have to be repeated. Soon the word got about the building[83] that there was a little fellow in one of the rooms who was always laughing to himself, or making others laugh, so all the boys insisted on being “let in on the ground floor”—which in my case was the fourth floor. I made no objection; was there ever a man so modest that he didn’t like listeners when he had anything to say? So it soon became the custom of all the boys who were not absolutely bound to their beds to congregate in my room, which would have comfortably held, not more than a dozen. Yet daily I had fifty or more around me; the earlier comers filled the chairs, later arrivals sprawled or curled on my bed, still later ones sat on the headboard and footboard, the floor accommodated others until it was packed, and the belated ones stowed themselves in the hall, within hearing distance.

’Twas a hard trip for some of them, poor fellows for there were not enough attendants to carry them all, and three flights of stairs are a hard climb for cripples. So, to prevent unnecessary pain while I was outdoors taking the air, I hung a small American flag over the stair rail opposite my door, whenever I was in; this could be seen from any of the lower halls. I learned afterward that it was the custom of royalty and other exalted personages to display a flag when they were “at home,” but this did not frighten me; in memory of those hospital days, I always[84] display a flag at my window when I am able to see my friends.

Boys are as fond as Irishmen of fighting for the mere fun of it, so we got a lot of laughing out of fist fights between some of the patients. The most popular contestants were Gott Dewey from Elmira, N. Y., and a son of Sheriff Wright of Philadelphia. Both were seriously afflicted, though they seemed not to know it. Wright was a cross-eyed paralytic, while Dewey had St. Vitus’s dance and was so badly paralyzed that he had no control over his natural means of locomotion. He could not even talk intelligibly, yet he had an intellect that impressed me deeply, even at that early day. He could cope with the hardest mathematical problem that any could offer; he read much and his taste in literature and everything else was distinct and refined.

Yet, being still a boy, he enjoyed a fight, and as he and Wright were naturally antipathetic by temperament, they were always ready for a set-to. These affairs were entirely harmless, for neither could hit straighter than a girl can throw a stone. The result of their efforts was “the humor of the unexpected,” and it amused us so greatly that we never noticed the pathetic side of it.