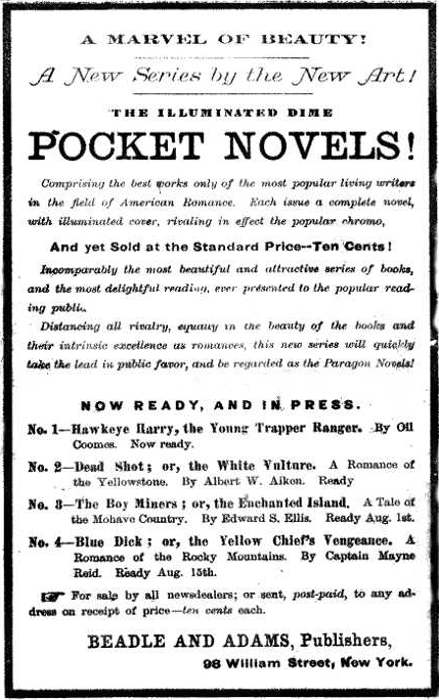

Transcriber’s Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

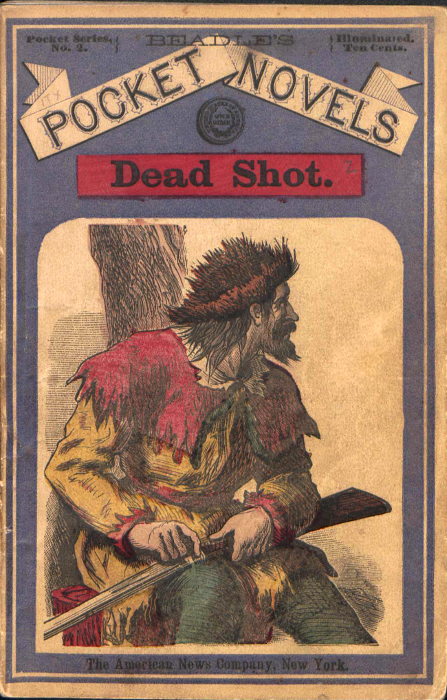

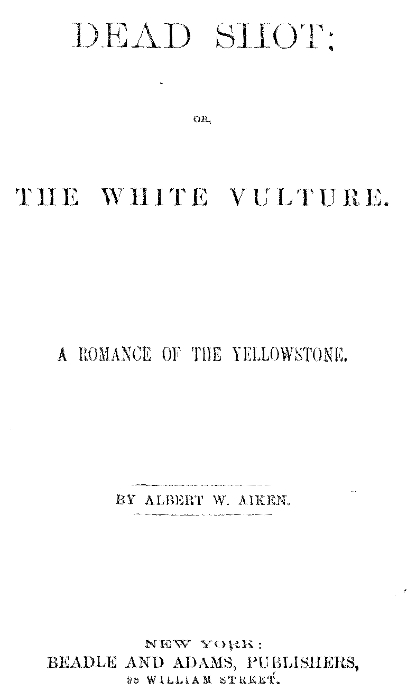

OR,

THE WHITE VULTURE.

A ROMANCE OF THE YELLOWSTONE.

BY ALBERT W. AIKEN.

NEW YORK:

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

BEADLE AND ADAMS,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

(P. N. No. 2.)

THE

WHITE VULTURE

It was at the close of a bright May afternoon; the last rays of the sinking sun shone down gayly upon the broad prairie, through which, like a great yellow serpent, rolled the turbid waters of the Yellowstone river—a river that took its rise at the base of the Rocky Mountains and then flowed eastward, until it poured its current into the great Missouri. Just at the junction of the Yellowstone and the Powder rivers, the sun’s rays shone down upon the whitewashed walls of Fort Bent, a frontier post, located at the confluence of the two rivers, to guard the wagon-trail to Montana. The advance of civilization has now caused the fort to be removed, but at the time at which we write it was the last halting-place for the wagon-trains bound for any of the small settlements nestled here and there upon the golden-streaked rocks of Montana. After leaving Fort Bent, the trail run by the banks of the Yellowstone, two hundred miles or so, then turned abruptly north toward the Rocky Mountains. This was called the southern trail. The northern route was by the bank of the Missouri.

Fort Bent was garrisoned by a single company of United States troops—a hundred men or so. Under the shelter of the fort, a few trading-houses had sprung up, designed to supply the wants of the emigrants in powder, ball, blankets, or any of the little articles necessary for a journey of three hundred miles through the wilderness. For, as we have said, after leaving Fort Bent, the way led through the fertile valley of the Yellowstone, a valley abounding in rich grasses, the little clumps of timber that fringed the river being filled with game, the stream itself well stocked with fish—a country that[Pg 10] only needed the strong right arm of civilization to bloom and blossom like a fruitful garden.

The wagon-trail through this lovely country was not without its dangers. Near Fort Bent, the fierce Mandan tribe of Indians flourished; their hunting-grounds stretching from the Big Horn river to the little Missouri. Sometimes, too, wandering bands of the Sioux, the ruthless marauders of the Missouri, extended their forays as far as the Powder river. Deadly foes were they of the Mandan tribe.

And then, after following the wagon-trail along the bank of the Yellowstone, passing where the Big Horn river emptied its waters, swollen always by the melting snows of the Rocky Mountains, into the first named stream, we enter upon the dominion of the Crow nation, the Indian kings of the north-west—the tribe whose warriors wear the claws and teeth of the grizzly bear as necklaces around their necks, sign and symbol of their prowess—the greatest fighting men of all the tribes that roam the great wilderness of rock and prairie from the Gulf of California in the south, to the Columbia and Missouri rivers in the north—the warlike tribe that has fought the powerful “Blackfeet” for ages, and yet more than held their own against them—the tribe whose war-cry is a terror to the gold-diggers of Southern Montana.

And so, after passing the junction of the Big Horn and the Yellowstone rivers, the old mountain men, the prairie guides, prepare for danger; and few wagon-trains, unless large in numbers, pass through the valley and turn northward to Montana, without losing stock or men on their passage.

Now that we have described the scene of our coming story, we will return to Fort Bent, where a wagon-train is at the moment resting, preparatory to daring the dangers of the march through this wilderness.

The fort and its vicinity presents a lively scene. The soldiers are chatting with the members of the train, inquiring the news from the East and eagerly perusing the newspapers that have been brought by the emigrants.

The train was composed of some twenty wagons, containing, perhaps, sixty souls all told, men, women, and children. There were twenty-three men in the party, besides the two guides, a force sufficient to beat off any ordinary Indian[Pg 11] attack, if handled skillfully, of which there could be but little doubt, for the two guides—the captains of the train—were men skilled in Indian warfare, and had a reputation as Indian-fighters second to none on the upper Missouri.

The two guides stood together by the foremost wagon, leaning on their rifles, surveying the scene before them with a listless air. They were known as Abraham Colt and David Reed—called Abe and Dave, commonly, by their friends. Abe was the elder of the two, a man of about forty-years of age. Tall and straight, he stood nearly six feet high; but weighed not more than a hundred and fifty pounds—all muscle, bone and sinew, no useless flesh about him. A professional prize-fighter would have looked at him in admiration. From his earliest boyhood he had been accustomed to the wild life and dangers of the prairie. His father had been a guide before him, and had reared his son to his calling. The father had died on the prairie, shot through the temple in a Crow attack on a wagon-train—had died in his son’s arms, almost instantly after receiving the ball. From that hour Abe had sworn an oath of vengeance against every red-skin in whose veins ran the blood of the Crow nation.

The story of the death of Abe’s father, and of the oath of vengeance of the son, was of course well known to all the frontier-men; and he was looked upon as a sort of a hero, for, since his father’s death, which occurred some twenty years before the time at which we write, Abe had encountered the braves of the Crow nation in many a desperate fight on the prairie trail by the Yellowstone; and in every contest the guide had been victorious; every time the Crows had attacked a train in which Abe acted as guide, they had been repulsed with great slaughter; his presence seemed to be fatal to them.

Abe would never have been taken by a stranger for the famous Indian-fighter; there was no sign of the desperado about him. His face was well browned by the prairie winds and the rays of the sun; his eyes were large, and gray in color; his chin was shaven as smooth as a young girl’s; his features were strongly marked and the deep wrinkles about the eyes and mouth told of hard service and troubles. He was dressed Indian fashion, in a hunting-shirt of deer-skin,[Pg 12] trimmed with porcupine-quills; leggings of the same material, fitting tightly to the leg; moccasins, ornamented with little leaden tags, curiously shaped; upon his head he wore a cap, formed of a portion of a coyote’s skin, with the tail hanging down behind. His hair, black as an Indian’s, was worn short and curled in little ringlets tight to his head. He was a picture worthy the pencil of the artist as he stood leaning carelessly upon his rifle, gazing upon the little groups before him. One approaching him from the rear would have taken him from his dress to be an Indian chief.

His companion, the other guide, was a young man, probably not over twenty, called David Reed. His history was a strange one. A party of United States troops, some nineteen years before the time of which we write, had surprised a party of Blackfeet Indians encamped near the head-waters of the Missouri. The savages had been on a raid against the white frontier settlements on the upper Missouri, and the soldiers had followed in pursuit. They surprised the Indians and a bloody fight ensued; the Indians were outnumbered and nearly exterminated. After the fight, the soldiers found a baby boy snugly wrapped in a blanket near the Indian camp. From his dark complexion and from the outline of his features, they concluded that he was a half-breed, possibly the child of one of the Indian braves by a white wife, because it is a very common thing for the Indians to carry off white girls in their frontier raids and force them to become their wives. Why the child should have been carried with the war-party contrary to the usual custom of the savages puzzled the old Indian-fighter, who acted as guide to the soldiers. He carefully examined the encampment, and finally discovered the footprints of a woman. It was evident, then, that there had been a squaw with the party, and possibly that squaw was one of the white wives that the great chiefs sometimes have; though why the chief should carry her on a marauding expedition was a mystery.

The soldiers took the child back with them to their post; the infant was apparently a year old. The captain in command of the troops acted as sponsor to the child thus strangely found in the desert, and called it David Reed.

The infant grew apace. Years passed on: the child[Pg 13] became a man and adopted the profession of prairie guide, and was noted on the upper Missouri as one of the surest shots and best guides in all the upper valley.

In appearance, he was a fine-looking fellow, standing about five feet nine, well proportioned and well built; his face was pleasing; there was something noble about it—an air of native dignity, akin to that of the red-skins; his eyes were large, jet-black and full of fire; his nose long and straight; the chin, square and well formed, firm-set lips, that showed resolution and strength of purpose; his bronzed face, the high cheek-bones and jet-black hair, that slightly curled at the ends, worn long and floating down over his shoulders, alone showed the Indian blood.

He was dressed roughly. A red shirt, thrown open carelessly at the neck and exposing his finely-formed throat; a pair of dark butternut homespun pantaloons that had been cut open at the side and fitted into the leg, Indian fashion; a pair of moccasins, which, from the peculiar trimming, an old Indian-fighter would have pronounced to be of Sioux manufacture; a belt of untanned deer-skin girded around his waist, supporting a broad-bladed hunting-knife and a serviceable-looking revolver, and we have the pen-picture of Dave Reed.

Reed had met the “Crow-Killer” in Montana, some three years before the time at which we commence our story. A singular friendship had sprung up between the two men, and from that time they never had separated. Lucky was the wagon-train that obtained the services of the “Crow-Killer” and young Dave Reed, as his friends called him, for a trip across the upper plains!

“Does that fellow there belong to our train?” asked Dave of the “Crow-Killer,” directing his attention to a man who stood apart from all the rest near the bank of the river.

“Whar?” asked “Crow-Killer,” turning his eyes in the direction indicated.

“That one there, wrapped up in the blanket as if he had the chills,” and Dave pointed to a man standing near the river, with his back to the two guides. The stranger was wrapped in a dirty red blanket which completely covered him. On his head he wore a common black felt hat, from under which[Pg 14] long black locks fell down over his shoulders, forming a striking contrast to the red blanket.

Abe took a long look at the motionless figure.

“Well, do you know him?” asked Dave.

“Nary time!” answered Abe. “He looks like an Injun, durned if he don’t. He’s a powerful big feller, I should judge.”

Just then the stranger turned round and exposed a face a few shades darker than that of Dave’s, but not dark enough to proclaim the owner to be an Indian, or, if he was one, one much lighter in color than the generality of his race. The face of the stranger was an odd one; high cheek bones, the dark color, the flashing black eyes, no sign of a beard—all these would proclaim him an Indian; yet, the long black hair curled slightly at the ends, and was much finer than the usual coarse locks of the red-skin.

As he faced toward the two guides, the eyes of the stranger wandering listlessly over the talking crowd, Abe got a good full view of his face and started in astonishment.

“What’s the matter?” questioned Dave.

“That man’s face!” answered Abe, still staring intently upon the stranger.

“Well, what of it?”

“Why, he’s the perfect image of you!”

Dave now started in surprise, and turned his keen glance upon the stranger. As Abe had said, save that the unknown was darker in color, there was, indeed, a wonderful resemblance between the two men—the same long black hair, curling at the ends—the same flashing black eyes, the same expression on the face, almost the same size, and features marvelously like those of the young guide.

“Yes, he does look like me,” said Dave, surveying the stranger with a puzzled air.

“Like you! You couldn’t be more alike if you were run in the same mold,” said the “Crow-Killer.”

“It is very strange, to say the least.” Dave spoke thoughtfully.

“Strange, you bet!” answered Abe, tersely.

And yet, at this very moment, to a close observer, there was something else stranger than all, and that was the resemblance[Pg 15] in the general expression of the features that both Dave Reed and the stranger bore to Abe, the “Crow-Killer.” Their eyes were black and his were gray, and yet they looked alike. Had they been clad alike, a stranger would have taken the three for father and sons.

“He looks like an Injun, and yet he is too light colored for one,” said Dave.

“Yes,” responded the “Crow-Killer,” watching the unknown with a keen glance, “he ain’t one of our party I know. I guess he’s a stranger hyar too, for he don’t seem to know any of the folks round. He don’t look exactly like an Injun, but he may be one with white blood in him; that would account for his light color.”

“I’ll go over and find out who he is,” said Dave.

“Go it, young hoss!” answered the “Crow-Killer,” “that’s a good idea.”

One of the corporals attached to the post at this moment approached the two guides.

“Who is that chap over thar? do you know him?” asked the guide.

The corporal took a good look at the motionless figure, wrapped in the gaudy blanket.

“I don’t know him; a stranger in our ranche, I reckon.”

“You have never seen him before then?” said Dave.

“I think not. I guess he’s one of the Mandan Injuns come in to get some whisky or something of that sort.”

“He ain’t no Mandan,” said Abe, after another good look.

Dave bent his steps toward the stranger.

Although the stranger was apparently indifferent to all that passed around him and seemed half asleep, yet his quick eye had noticed the two guides in conversation, noticed the glances they had cast toward him, and had rightly concluded[Pg 16] that they were speaking of him; then, when he saw Dave walk toward him, he quietly turned his head in the direction of the river as if seeking an avenue of escape in case of danger. As if satisfied, he turned his attention again to the crowd near the fort. Dave came up to him.

“How are you, stranger?” said the guide.

“Well,” answered the unknown, in a deep, guttural voice that instantly proclaimed its owner to be a red-skin.

“Is the chief a Mandan?” questioned the guide.

“No,” was the laconic answer of the stranger.

“Sioux?”

“Yes.”

“What tribe?”

“Yancton!” responded the stranger, who, Indian fashion, was sparing of his words.

“What brings the chief to Fort Bent, so far away from his home?” asked Dave.

“Ah-ke-no is a chief of the Sioux; he fought the Mandan braves on the Powder river. In the dark he lost his brothers, he traveled north to the wigwams of blue-coated braves. He is at peace with his white brothers; he is hungry and would eat; he is thirsty and would drink. Ah-ke-no is a great chief of the Yanctons!”

The savage uttered his story with a stolid face, while the quick flashing of his eyes changed into a dull gleam.

“Did my brother come on foot?” asked Dave.

“The chief is not a mud-turtle,” answered the savage; “he does not crawl when he can fly like the eagle. My white brother will look,” and the chief pointed to a small, open space between the fort and the river, where a white horse, strangely marked with small patches of black in the flanks, and of matchless beauty, tethered to a stake, lay upon the ground.

The guide gazed upon the steed with unbounded admiration. He had seen many a horse of wondrous beauty, but never one to compare with that milk-white steed of the chief.

“My brother’s horse is handsome,” said Dave.

“The chief is a great brave among his warriors; he rides on the wind. The mustang never lived that could overtake the “White Vulture”!”

“Your horse?” questioned Dave, wondering at the name.

“The chief has said,” responded the Indian, with savage dignity.

“If my brother is hungry, come to the fort and eat,” said Dave.

“My brother is good; the blue-coats have fed the Sioux chief; his hunger is gone.”

“Will you return to your people now?” questioned the guide.

“As fast as the crow flies to his nest; his braves mourn him as dead and gone to the happy hunting-grounds, but the scalp of the Sioux chief will never hang in the smoke of a Mandan lodge,” and the savage drew his tall form up proudly. Then, bending his eyes on the train, he asked: “Does my white brother hunt with the white wigwams, that go to the setting sun?” and with his eyes he indicated the emigrant-wagons as he spoke.

“Yes, I am their guide,” answered Dave.

“And the tall chief, who wears the hide of the coyote,” indicating Abe, who was in conversation with the corporal, as he spoke, “does he hunt with my brother?”

“Yes; we are the chiefs of the train,” said Dave, wondering at the curiosity of the Indian.

“What is my tall white brother called?” asked the red-skin, pointing to Abe.

“Abe Colt.”

“Crow-Killer?” questioned the savage, with a slight uneasiness perceptible in his manner.

“Yes,” answered Dave, secretly wondering that his companion’s name should be so well known to the Yancton Sioux; “you have heard of the ‘Crow-Killer’ then?” he asked.

“The deeds of a great brave on the war-path travel like the white clouds, when the winds blow over the prairie. The ‘Crow-Killer’ is a great chief,” answered the Indian, a peculiar gleam in his dark eyes, as he looked upon the famous Indian fighter.

“Does my brother go soon?” asked Dave.

“When the moon comes, the Sioux chief rides like the wind for the Big river, (Missouri); his warriors wait for him,[Pg 18] and the singing bird that sings for the chief, sings not when the wigwam is empty and the nest is cold.” Then the Indian gazed upon the crowd with the same stolid glance as before.

Dave having gained all the information that he could, rejoined Abe and the corporal.

“Wal, who and what is he?” asked Abe.

“He says he’s a Sioux of the Yancton tribe, separated from the rest of his braves in a fight with the Mandans on the Powder river; and that he came here for food and drink,” answered Dave to Abe’s question.

“Well, now I think of it,” said the corporal, “I remember hearing the boys saying something, this morning, about an Indian coming in, hungry, and they giving him food.”

“A Yancton Sioux, eh?” said Abe, half to himself.

“Yes; what do you think of him?” asked Dave.

“Wal, I don’t exactly know,” replied the “Crow-Killer,” thoughtfully; “but ef I were to meet that Injun, a hundred and fifty miles west from hyar, I’d say he was a Crow an’ be willin’ to bet my life onto it.”

“A Crow!” cried Dave.

“That’s so, hoss; though I noticed he’s ripped off the trimmings of his moccasins and leggins, so as to make ’em plain and disguise his tribe. Now, if he were a Sioux, why does he come skulking hyar in disguise—that’s what I want to know?”

Just then the “Crow-Killer” was interrupted by a horseman dashing into the little village from the upper trail leading up the bank of the Yellowstone. The horse was covered with lather, showing that he had been ridden hard; the horseman, a sturdy-looking fellow but pale as death in the face, drew rein in the center of the little square formed by the fort, the trading-houses and the wagon-train; then tumbled from his horse exhausted. A crowd gathered around him.

“What’s the matter?” “What is it, stranger?” were the questions poured in upon him by the bystanders.

“The devil’s to pay!” gasped the stranger. “The Injuns are up again on the Yellowstone trail, thick as grasshoppers in summer.”

“What Injuns?” yelled half a dozen excited voices.

“The Crows!” replied the stranger, who thereupon proceeded to tell his story. He had left Montana with a party, composed of two wagons loaded with furs, and ten men; they had not seen signs of Indians until after passing Great Falls and striking across to the Yellowstone; then they came across an Indian trail, which one of the trappers pronounced to be that of a war-party and about three days old; but, as the trail led directly southward across their line of march they did not anticipate any danger. But, on the first night after striking the Yellowstone river, they were attacked by a large party of Crow Indians; the trappers fought bravely but they were overpowered and forced to leave their wagons and seek safety in flight. How many of his companions had escaped he knew not; but he, possessing a very swift horse, had succeeded in passing the line of the encircling savages and in escaping by reason of the fleetness of his horse; but, in escaping from the Indians, he had been compelled to leave the lower trail and go northward, and had been five days in reaching the fort, which, had he come straight by the bank of the Yellowstone, he might easily have made in four.

Dave and Abe had listened intently to the tale.

“Stranger, I believe you said the red devils were Crows?”

“Yes,” answered the trapper.

“What chief mought be at the head on ’em? Do you know?” asked Abe.

“Yes; Dick Sawyer, my partner, recognized one of the chiefs, an’ he seemed to be the head one of the party. He said it was the ‘White Vulture,’” said the trapper.

“You don’t say so!” and the “Crow-Killer” indulged in a low whistle of astonishment. “Why, he’s the biggest fighting man in all the Crow nation. They do say he’s a perfect ‘painter’ on the war-trail. I never see’d him yet, but I’d like to!” and there was a strange tone in the old hunter’s voice, and a strange glitter in his eyes, as he uttered the words. His fingers, too, clenched tighter around the long barrel of his rifle, and there was an expression upon his face which boded danger to the Crow chief.

“I didn’t see much of him,” said the stranger, “’cos I were in pretty considerable hurry to git for the open country, but he’s a heap on fight, I should say for he cleaned us out in[Pg 20] about twenty minutes, an’ we made a tough old fight of it, too.”

“Do you think any the rest of your friends escaped?” asked the captain in command of the fort, who had been an attentive listener to the trapper’s story.

“Wal, I don’t exactly know,” said the trapper, scratching his head thoughtfully. “I guess my partner, Dick Sawyer, would get shet of them, if any in the party would, ’cos he had a powerful running hoss—an animal that was jist chain-lightning on the go. It were a hoss from the south. Dick give a couple of hundred for him, an’ that’s a fancy price, you know; but he were awful fast, an’ jist as handsome a critter as I ever laid eyes on. An’ I kinder think that if any of the party got away ’sides me, it were likely to be Dick an’ his white hoss.”

“A white horse?” asked Dave, a sudden suspicion coming into his mind.

“Yes,” answered the trapper, “a hoss jist as white as milk, ’cept it had a patch or two of black upon its flanks, an’ the prettiest beast you ever saw.”

Could it be possible, that the Crow chief had the bravado to come into the fort in disguise, and right after his attack upon the trappers? Dave looked around for the Indian; he had disappeared! The guide quietly left the little knot of people and went toward the bank of the river. The white horse was gone; the Indian as well. Far in the distance, on the trail leading up the river, Dave saw the stranger mounted on the white steed, riding at full speed.

“Curse you, red-skin!” he muttered; “you’ve been after no good. I’ll meet you one of these days, and I’ll put a bullet through you, though you do look enough like me to be my brother.”

The young man rejoined the little knot of people around the trapper, who were eagerly discussing the particulars of the late attack.

Dave drew Abe aside, and told him his suspicions. Abe heard all with a grave shake of the head.

“I had an idea that that Injun was a Crow,” he said. “Some way or other I can generally tell ’em: but, though I hate the whole nation and never yet spared a Crow that I got[Pg 21] within rifle range of, yet I should dreffully hate to put a bullet through this fellow, for he looks so much like you.”

“You think then that I am right in my suspicions?”

“Sart’in, you’ve hit the right nail on the head. That Injun was the ‘White Vulture,’ the greatest fighting-man of all the Crow nation, though he’s a mighty young brave.”

“He can’t be older than I am,” said Dave.

“No, I should say he wasn’t. I first heard tell on him about three years ago, when I were up trading in the Blackfoot country. A party of Blackfeet made a raid down into the Crow region, an’ at the first on it, they whipped the Crows right out of their moccasins; they took this ‘White Vulture’ prisoner, tied him to a tree to torture him a little, but, before they lit the fire under him they amused themselves by seeing how near they could come to his head throwing hatchets and scalping-knives at him in their devilish fashion. Well, some way they hadn’t tied him very strong and one of the hatchets, thrown carelessly, cut one of the thongs that bound him. In a twinkling he burst the rest of the bonds, seized one of the hatchets, laid about him right an’ left, killed five of the Blackfeet braves almost instantly and then made a rush for life and escaped, although the whole party gave chase. Then, after he got back to his tribe he collected a few warriors and hung about the rear of the retreating Blackfeet, picking off a man hyar and there, until at last their retreat became a rout and they hurried north as if the devil himself was at their heels. Well, I were in the Blackfeet country when the party got back, an’ of course I hearn all about it. The next year, the ‘White Vulture’ returned the visit of the Blackfeet and raided all through their country, with a small party too, hardly losing a man. From that day to this his fame as a great brave has been increasing; the Crow Indians themselves regard him with superstition; they think he’s a great medicine-man; they don’t believe that the bullet was ever run that can kill him; in fact, to-day he’s the head-chief and the greatest fighting man in all the Crow nation.”

“I’m afraid that if he ever comes again within range of my rifle I shall convince the Crows that there’s a bullet in my pouch that will settle him,” said Dave, with a grim smile, tapping the butt of his rifle.

“Do you know, Dave, that I don’t want to meet the ‘White Vulture’?” said the “Crow-Killer” solemnly.

“Why not?” asked Dave, in amazement.

“Because I should have to kill him, and that I don’t want to do. Strange, too, that up to to-day we have never met. The last time he attacked a wagon-train between here an’ Fort Benton, I was to go as guide with that same train, but at the last moment, just as we were starting, I had a sort of feeling which said, ‘don’t go!’—a sorter voice that seem to whisper, ‘don’t go,’ right in my ear. I didn’t go, but got another man in my place; I thought I was acting like a fool at the time; wal, that train was attacked an’ the stock all run off; an’ the Crows were led by this same ‘White Vulture.’”

“Well, that was strange,” said Dave.

“It were more than strange,” replied the old guide, in a solemn tone, “I’ve got a notion somehow that it isn’t fated that we shall ever meet in fight, an’ then ag’in, I get the idea that if we ever do meet, it will be the death of one of us.”

“It’ll be the ‘White Vulture’ then that’ll go under. I’ll bet my life on it,” cried Dave.

“I don’t know that, Dave, I don’t know that; he’s a good fighter, quick as a cat an’ savage as a painter. They do tell me that he’s the best runner in his tribe an’ a sure shot with the rifle. If we meet in a fair fight, I think he’s got the advantage of me. The Indian owes me a debt of vengeance for I killed his father.”

“You did?” said Dave.

“Yes.” By this time they had reached the open prairie, just beyond the wagons; there they paused.

“Sit down,” said Abe, “and I’ll tell you all about it.”

The two guides sat down upon the grass. Abe closed his eyes for a moment thoughtfully, as if striving to remember the past. After a moment of silence he spoke:

“Of course you’ve heard, Dave, that my father was killed out here on the Yellowstone trail by these Crows, and died in my arms?”

“Yes,” said Dave, “I have heard the story.”

“An’ I suppose hearn, too, how I swore to be revenged upon all the red devils of the Crow nation?”

“Yes, I heard that also.”

“Wal,” said the guide, “I did a good deal in wiping ’em out in fair fight, but the bitterest revenge that I took wasn’t in fair fight. It were about two years after my father’s death, an’ the border folks an’ the Injuns had already begun to call me the ‘Crow-Killer,’ that a large lot of the Crows came into Fort Benton to sign a treaty and have a big talk with the Injun agents. I was at the fort at the time an’ the Crows were mighty anxious to get a look at their devil as they called me. Of course as they were there on a peace-mission, I couldn’t very well take their top-knots, but I wanted to, for the blood were hot in my veins in those days. Being on a peace-talk, they had brought their squaws with them, an’ among the squaws was the prettiest Injun I ever saw. She were called ‘Little Star,’ an’ she were a star! Although she were a Crow, I fell in love with her, an’, as it ’bout always happens in just such cases, she fell in love with me. She was to be the wife of one of the young braves, named ‘Rolling Cloud’; the ‘White Vulture’ is his son. Wal, the ‘Little Star’ an’ I used to meet nights, outside the fort; she were dead gone on me—I were called a handsome feller then—an’ were willin’ to leave her tribe an’ go with me. Wal, I loved the gal, Injun though she was, an’ I took her. One morning both she an’ I were missin’. We went down the river, an’ I married her, Injun fashion, for thar wasn’t no minister nigh. Wal, my takin’ the gal riled the Crows awfully. I pitched my shanty with a little settlement on the Missouri, an’ for two years I were happy. There were some things happened in those two years, but I don’t care to speak of them. At the end, about, of those two years I came back one night an’ found my cabin destroyed an’ my wife gone, an’ from that day to this I have never hearn word of her; but in an Injun fight out hyar, I met the ‘Rolling Cloud.’ We had a fair tussle an’ I downed an’ knifed him, an’ as he died he muttered something ’bout the ‘Little Star,’ which makes me think the Crows know something of my wife’s fate.”

For a moment or two after Abe finished his story there was silence. The old guide closed his eyes and leaned back upon the grass. It was not often that he spoke of the past, and the remembrance of that past brought a flood of bitter memories to his mind.

Dave, too, was thinking. He had heard some of the particulars of the life of the “Crow-Killer,” which were current topics in Southern Montana and along the Missouri; but that the great enemy of the Crow nation had married a daughter of that tribe was news to him. The “some things” that had occurred during the married life of the “Crow-Killer,” which he had not explained and barely mentioned in his story, puzzled Dave; it was evident that there was a mystery connected with the past life of Abe Colt, and that the “Crow-Killer” imagined that the Crows held the threads of that mystery, which one day they might unravel.

The thoughts of the two guides were interrupted just then by the approach of two members of the wagon-train. The two men were father and son; their names were, respectively, Eben and Richard Hickman. Eben was a man probably forty-five years of age, large and powerfully built, with an ill-looking, treacherous face, shifting, light-blue eyes, yellow hair and beard, his cheeks thin and hollow, and an expression of greed and cunning upon his features. The son, Richard, resembled the father in looks and build, only with a far better-looking face. His hair was cut short, and the expression upon his features was not an unpleasant one.

The father, Eben, was in business in a little mining town in Southern Montana, known as Spur City; the son had just come from the East, to join the father, who had met him at St. Paul.

“When do we start?” asked Eben Hickman, of the guides.

“To-morrow morning at four,” answered Dave.

“Do you think there is danger from Indians on the way?”

“I can’t say; you heard the news the trapper brought, didn’t you?” asked Dave.

“Yes,” answered Hickman.

“The red devils are on the war-path, but I don’t expect that they can trouble us much, because we’re too many for them. They’ll probably try it, but we’ll flax ’em if they do,” said Dave.

“You think there is danger of an attack then?” questioned the elder Hickman.

“Sart’in!” answered Dave, “jist as sure as we are hyar at Fort Bent to-day.”

“The Indians always attack at night, I believe?” said Eben.

“Yes, generally,” answered the guide, curtly. He had taken a dislike to the Hickmans, both father and son, a dislike he could not well explain.

Eben Hickman stood for a moment as if in thought, then turned to his son. “Come, Richard, we may as well look after our ammunition.” So the two walked back toward the fort.

“Ammunition, blazes!” said Abe, emphatically. “If thar’s any fighting to be done, I guess both of those chaps will be more likely to be behind a wagon than facing the Injuns.”

“That’s what I think,” cried Dave; “I hate the sight of both those fellows, I don’t exactly know why, but I s’pose it’s because I think they’re a couple of cowards.”

“I think thar’s another reason, Dave,” said Abe, in his quiet way; “a pretty good reason, too, an’ that reason’s a female.”

“Eh?” stammered Dave, getting as red in the face as a blushing girl.

“Jus’ so!” responded the “Crow-Killer.” “Guess I ain’t blind yet, Dave. It’s a mighty suspicious sign when a young gal likes to leave the wagons an’ ride alongside of the guides, an’ hear stories ’bout buffler huntin’ an’ Injun fightin’ an’ sich like.”

“Why, you don’t think that Miss Leona cares any thing ’bout me, do you?” asked Dave, anxiously.

“Wal, it’s hard to say; thar’s no tellin’, sometimes, ’bout these gals. I’m death on readin’ Injun sign, but a woman[Pg 26] gits me. But, I look at it in this way: when I see the print of a moccasin on the prairie, it’s nat’ral to conclude that some one’s been thar; when I see a young gal likes to be in the company of a young feller, an’ seems to take pleasure in being with him, I don’t think I’m fur off from the trail to say that she likes him. Now that’s just the way this case stands, as near as I can fix it.”

“But, I say, Abe, you’ve forgot one thing: she’s a well brought-up girl, been educated and all that sort of thing, an’ my bringin’ up has been rough; mighty little schooling I’ve been through,” and the young guide shook his head thoughtfully.

“You’re a durned sight better educated than I am,” said Abe, “an’ I reckon I can hold up my head with any man on the upper Missouri; besides, that ain’t every thing; a man must have brains too. This Miss Leona is a sensible gal, I take it; she wants a man to fall in love with—a man with muscle an’ nerve, fit to fight his way through the world, not a dandy chap that would faint at the sight of an ax or at the smell of gunpowder, but a man she can look up to, one that can protect her, care for her an’ love her all at the same time.”

“Yes, I think you are right there; she seems to be a very sensible girl,” replied Dave.

“That’s so,” responded Abe. “I’ve had my eyes open ever since we left St. Paul; she can’t bear the sight of that Dick Hickman, though he’s been trying to be mighty sweet on her. I’ve seen it! She gits out of his way as much as she can, though he’s always arter her. I should think the feller would have sense enough to see that she can’t bear him, but there’s some men in this world haven’t got as much sense as an owl. You see, as I haven’t had any Injun sign to look arter, I’ve been amusing myself by watching the humans round me.”

“You think, then, that the girl likes me?” asked Dave, anxiously.

“Sart’in, I’d go my pile onto it, an’ I ain’t got much to go an’ can’t well aford to lose that little, but I’d bet high on it.”

“But I’m a poor man,” urged Dave.

“Jus’ so, but ’arter we get to Montana we’ll try the gold-diggin’s, an’ who knows we mought make a big strike thar.[Pg 27] If the gal does love you, why she’ll wait a little while for you, an’ if she won’t wait, why she don’t love you an’ the quicker you forget her the better; that’s sense, now I tell you.”

“Well, Abe, I believe it is; I have not tried to make the girl love me, but I will try now, and if she does love me, that’s all I ask for in this world”—and the young guide’s face shone with a smile of happiness as he leaned upon his elbow and thought of the golden locks of the pretty Leona, to him the prettiest girl in all the world.

“You’re right, Dave,” said the “Crow-Killer,” thoughtfully, “a good woman’s love is a treasure in this world; years have gone by since I lost my little Injun wife, but I haven’t forgotten her. Thar’s a mystery about her death, for I suppose she was killed when the red-skins burnt my cabin, but I ain’t sure of it. She may be alive, even now, up in the Crow nation. One of these days I’m goin’ to take a party up thar an’ see if I can’t diskiver the truth. Thar’s something else, too, that I want to know; thar’s a sort of suspicion in my mind that thar’s a reason why I an’ the ‘White Vulture’ shouldn’t come together. I want to capture a Crow Injun, an old chief, one as old as myself, if I can, an’ if he’ll only speak the truth to me, he can tell me of some things connected with the Crow nation that I want to know.”

We will now leave the two guides and follow the Hickmans, father and son, as they walked toward the fort.

“That fellow Dave is not over civil,” said the son.

“No,” responded the father, “I don’t think that he bears either of us any great love.”

“I think I can guess the reason,” said Richard, with a sneer.

“That is not difficult to guess,” responded the father, a sneer also upon his lips. “The fellow has a fancy for Leona.”

“Exactly what I think,” said Richard.

“And from what I have seen, I rather fancy that the girl is not indifferent to him,” continued the father.

“I know that she likes him,” responded Richard, savagely, “I see it plain enough. Don’t she ride by his side nearly every day at the head of the train? Hasn’t he been bringing her flowers from the prairie, and don’t she always stick tight[Pg 28] in the wagon whenever he’s out on a scout or a hunt, and the moment he returns, don’t she always get tired of being in the wagon and want to ride? Why, it’s as plain as the nose on my face. I tell you, father, what little sense Dave Reed has got is all tangled up in Leona’s red hair. Curse him! for I’ve taken a fancy to the girl, and she don’t seem to care any thing more about me than she does of the dirt under her feet.”

“I am sorry to say, my son, that I think you have spoken the truth. I’m very sorry for it, for I wanted the girl to fall in love with you,” said the father, a crafty smile upon his thin features.

“Well, I know that,” responded the son, moodily. “It was you that put it into my head to make love to her. I shouldn’t have thought of her as a wife but for you. What did you want me to make love to her for?”

“Ah!” and the father shook his head, “that requires an explanation.”

“Well, suppose you explain; I’m tired of working in the dark. I’d like to know what you are driving at.”

“Very well,” and then the father looked carefully around him to see if any one was within hearing, but no one was near. “You know that I left the East a year ago to try my fortunes in Montana. In going across the plains, I made the acquaintance of a man named Daniel Vender—”

“Vender! Why that is Leona’s name,” interrupted the son.

“Exactly; Daniel Vender was her father. On the march we shared the same wagon, and became very intimate. He told me all about himself and his plans. He came from the town of Greenfield in Massachusetts; he had left a daughter behind him there—he had been seized with the Western fever, as they call it; had converted all his valuables into cash, and was going to Montana to embark in mining. If he succeeded and liked the country, it was his intention to send for his daughter and make Montana his home. He took quite a liking to me—we were both about the same age—and proposed to me to join with him in a claim. Well, you of course know, Dick, that I had very little money; so I was glad to join with him. We arrived in Montana safe, and as we[Pg 29] couldn’t find a claim to suit us at first, we bought out a trader’s stock and started a store at Spur City. We did first rate, and in a few months had doubled the money we put into it. Then there came a chance to buy a claim in a new mine, just struck, about twenty mile west of us, in a place called Rattlesnake Gulch. The way we worked the store was that Vender put in nine parts of the money and I one. We bought the claim in the same way; so you see that I only had one-tenth interest in it. Well, about two months ago Vender was suddenly taken sick. His sickness did not last long, for in four days from the time he was taken down he died. This would have been a very bad thing for me, for the store and the mine were both making money, but Vender left a will, deeding to me all his property.”

The son looked at the father with a peculiar glance.

“He forgot his daughter in his will entirely then?” he asked.

“Yes.” The tone of Hickman’s voice was hard and dry.

“Wasn’t that rather strange?” questioned the son.

“Perhaps some people might think so,” was the reply, a sly but furtive look appearing in the shifting blue eyes.

“What did the people around there think of it?”

“Oh, nothing was said about it. There wasn’t any one in the whole place except myself knew that he had a child; and besides, as he distinctly said in his will that he left all his property to his cousin, Eben Hickman, what could people say?” asked the father.

“His cousin?” cried the son, in astonishment.

“Yes, that was me, of course. Vender and I came to the town together; he was a quiet sort of a fellow, kept himself to himself, made very few friends and spoke not at all of his private affairs; therefore no one knew any thing about him; no one disputed the will, and I came into possession of all his property,” and the cunning eyes twinkled with delight as he spoke.

“Let me see. I believe you’re quite clever with the pen, ain’t you?” asked the son, with a grin.

“Oh, tolerably clever!” and the old villain chuckled with delight as he thought of the wrong he had done the dead man.

“But, how did you fix it about the witnesses? I should have thought that would have bothered you.”

“Oh, no! I got two drunken miners to affix their names to it; things in the law way are rough out here; no one made any objection to the will, or, in fact, made any inquiry about it at all. I took possession, and of course hold the property now.”

“How much is the whole thing worth?” asked Dick.

“About fifteen thousand dollars,” answered the old man.

“Then this girl, this Leona Vender, is the real heir to—”

“The mine known as Rattlesnake Gulch—exactly,” said the father. “As soon as I had the estate fixed up and properly made over to me, I wrote East for you to come on; and the very same day that I received your letter telling me when you would start, I received a letter from this girl Leona, of course directed to her father, telling him when she would start to join him; and she was to come just one week after you. By her letter, I guessed that Vender had sent her money to come on with—perhaps told her of his success and of his prospects. Now, this letter struck me cold. Of course if she ever arrived at Spur City, she would instantly expose me, and the chances are that, if she ever does get there, proclaims her relationship with Daniel Vender and denounces me as an impostor, the citizens of Spur City will give me a taste of Judge Lynch, for justice is very speedy in the mountain region when they once get their hands in.”

“What do you think of doing?” asked the son, anxiously.

“In the first place, let me see what I have done, so as to make the case all complete,” said Eben. “I wrote you that I would meet you at St. Paul. I did so. The girl, in her letter, said that she also would come by that route. That was the reason why we waited a week there; you remember you wondered at my delay. Well, I was waiting for her. I kept close watch. At last she came; I found out all about her, and made arrangements to come in the same wagon-train. Now, then, this was my calculation. I was pretty sure that Vender had never written his daughter any thing about me. I took pains to be introduced to her. I noticed that she manifested no surprise at the mention of my name, which convinced me that my suspicions were right and that she had[Pg 31] never heard of me. If you remember, I cautioned you not to say any thing about Spur City, or that I knew any thing of the place, to any of our companions. My first plan was this: I thought that the girl on the journey might take a fancy to you; if she would only fall in love with and marry you, why then every thing would be all right, for, of course she wouldn’t want to prosecute her father-in-law for forgery, and the whole affair would be settled forever.”

“Yes,” responded Dick, dryly, “but she isn’t a-going to take a fancy to me. I think, father, that she would be just as likely to fall in love with you as with me. That cursed guide has got her eye; his copper-colored skin and Indian-looking head have taken her for all she’s worth.”

“He might be got out of the way,” suggested the father, a treacherous gleam in his eyes.

“Yes, but not by violence; he’s an ugly customer to handle. Besides, I don’t think the girl would like me any way, the little red-headed minx—”

“Gold! golden hair, you know,” interrupted the father.

“It’s near enough to red, any way, but that of course ain’t neither here nor there; the girl don’t like me; there’s no use beating about the bush in this matter. We might as well fix it out straight, and I don’t think she would ever like me, even if this guide, Dave Reed, was out of the way altogether.”

“As you say, we might as well understand the matter,” rejoined the father. “One thing is certain—that girl must go into Spur City your wife, or not go into it at all.” There was menace in this speech of Eben Hickman, which boded no good to the orphan girl.

The two walked on thoughtfully for a few moments, the father watching the son’s face from under his yellow eyebrows. At last, Dick spoke:

“I don’t see very well how you can make the girl marry me, unless she wants to, and if she don’t want to, as is very evident, I don’t see how you’re going to keep her from going to Spur City.”

The elder Hickman looked around again carefully; no one was near; then lowering his voice almost to a whisper he asked:

“You heard my conversation with the guide, didn’t you?”

“Yes, what of it?” asked Dick. “What has that to do with us?”

“A great deal! You heard him say that there was danger of an Indian attack, and that the Indians generally attack at night?”

“Yes, I heard that too; but, come to the point; what do you mean?” asked Dick, impatiently.

“Why, Indian bullets respect no one. If the savages attack us in the night, they are just as likely to kill her as any one else.”

The son did not fully read the father’s language.

“Yes, but she will be in a wagon, protected somewhat, and she may escape unharmed.”

The father put his mouth close to his son’s ear.

“If the Indians attack us, she will be killed!”

Dick started in surprise; he understood his father now.

“But the danger of detection!” he cried, in a low tone.

“None at all. In the confusion of a night attack, who can tell whether a shot is fired outside the camp or within it?” asked the father.

“Very true; but, suppose the Indians do not attack us?”

“Then I’ll think of some other way before we reach Montana.”

The precious pair of villains walked back to the fort, having come to an understanding.

The glowing sun had set in the west—a huge ball of fire that seemed to sink into the ground. The shade of night had fallen and darkness veiled in the distant prairie. Supper had been prepared and eaten by the emigrants and some had begun to arrange to retire for the night.

The moon, three-quarters full, was rising slowly, casting its clear, pure light over the vast plain, chasing the darkness[Pg 33] away and dancing in little waves of light on the yellow and swift-flowing waters of the Yellowstone.

The fires of the emigrants threw out their uncertain and flickering light upon the faces of the little groups that surrounded them. All were speaking of the dangers of the journey before them, and many a tale of Indian warfare and border peril were rehearsed around the watch-fires of the wagon-train.

By the wagon that stood nearest to the river’s bank a little group of four people were seated; three women and one man. The man was called Grierson; one of the women, the elder one, was his wife; the other, who resembled her strongly in features, was her daughter, Eunice by name. The mother and daughter were dark eyed and dark haired, presenting a decided contrast to the last of the group, who was a young girl, who did not look over sixteen. She had one of those sweet, innocent, childish faces that win favor at the first glance—a face once seen, never to be forgotten—there was something so odd, so striking about it. The face was little, but a perfect oval, with a high, white forehead, dark-blue eyes, full of life and expression, dimpled cheeks, slightly tinged with a crimson flush, that relieved the white, pearly skin, a little chin exquisitely shaped, full, pouting lips, red as ripe cherries, a long, straight nose, and then, the great charm of the head—the red-gold hair that hung in profusion, in little tangled ringlets, clinging elfishly together almost down to her little shapely waist. In figure she was a little sprite of a girl, exquisitely proportioned, with the daintiest little feet and hands. In brief, she was innocence and grace personified. Such was Leona Vender, the fairy, who had tangled up the honest heart of Dave Reed, the guide, in the silken meshes of her red-gold hair.

The Grierson family were neighbors of the Venders in Greenfield, and hearing how well Daniel Vender had made out in the Far West, had determined to try their fortune in Montana and had made preparations so as to set out at the same time as Leona. Leona of course was very glad of their company, particularly as Eunice, the daughter, had been her school companion and was her dearest friend.

Leona, although looking like a mere child of fifteen, was[Pg 34] in reality nineteen years of age. Eunice, her friend, was one year older.

“Well, wife,” said Grierson, rising from his seat near the fire, “I guess I shall go to bed. We start at four in the morning, and as we make a long march to-morrow, we shall need all the rest we can get. Girls, don’t sit up late.”

“No, father,” answered Eunice, speaking for both.

Grierson and his wife retired to the shelter of the wagon.

Leona was gazing dreamily out upon the surface of the rolling river, whereon the moonbeams danced like so many silver sprites. Eunice noticed her abstraction.

“A penny for your thoughts, Leona!” she cried, stroking down the curling locks of her friend’s hair.

Leona started a little; a faint smile came to her lips, as she answered in a low voice:

“Perhaps my thoughts are not worth a penny.”

“Oh, Leona!” cried Eunice, “what a little humbug you are! Not worth a penny! Well, now, if I were thinking of what you were thinking of, and you should say what I did, I should have answered that my thoughts were worth a great many pennies.”

Leona smiled again, then looked shyly at her friend.

“How can you know what I am thinking of? I hardly believe I know myself,” said Leona.

“Let me word your thoughts, then, for you. A tall, manly figure; long black hair, curling, oh! so romantically down over his shoulders; a pair of jet-black eyes; an honest, handsome, earnest face—and the—the—well, the wish that he might think of somebody as somebody thinks of him. Come, confess, ain’t I right?” and Eunice put her arms around the slender figure by her side and drew the shapely little head with the silken curls down upon her shoulder.

“Yes,” came in a whisper from the lips of Leona.

“There!” cried Eunice, triumphantly, “I knew that I was right, and, you little cheat, to try to deceive me!”

“But, Eunice,” rejoined Leona, “I don’t know that he cares any thing for me.”

“Then you must be blind!” exclaimed Eunice, impulsively. “Why, I can see that he worships the very ground you walk on. When we are riding with him at the head of the train,[Pg 35] he never takes his eyes from you for a single moment. Now, he’s something like a lover; he’s never obtrusive, yet always near at hand to do you service. If he don’t love you, then you will never be loved by mortal man, and your fate will be to die an old maid.”

“Are you sure that he loves me?” asked Leona, dreamily, her fingers pushing the little curls back from her forehead.

“Of course I am! I only wish some such nice-looking fellow would fall in love with me. I wouldn’t let him grieve himself to death for want of a loving word.”

“But, he has never said that he loves me, although I own from his actions that I thought he did,” replied Leona.

“Very likely. He’s bashful; he’s not one of your city chaps, that have such a good opinion of themselves that they think every woman they meet is in love with them. He’s an honest fellow—as brave as a lion and as true as steel. I tell you what it is, Leona, if you don’t give the poor fellow some encouragement, I shall set my cap for him myself, for I give you fair warning that I am half in love with him already.”

“Why, Eunice!” and Leona looked into her friend’s face, half in reproach.

“There now, don’t be frightened. I shan’t take your lover away from you—probably for the best of all reasons, and that is, that I couldn’t get him if I wanted him!”

“But, if he loves me, why don’t he tell me so?” demanded Leona.

“Why?” cried Eunice. “Because he’s a bashful goose like you are. When we are riding at the head of the train, you and he say scarcely a word to each other, while the other guide, the one they call Abe, and I, have had fine chats together.”

“Why, no!” said Leona, in her earnest way, “you are quite wrong; he has told me all about his life—how he was born here on the frontier and has always lived on the prairie—how he has hunted buffalo, and some dreadful stories about the Indians.”

“And I dare say that you listened to him with those large eyes of yours opened to their widest extent, and that, with every word he spoke, you loved him more and more.”

“Yes,” murmured Leona, softly. “I do love him, and I know I shall never love any one else as I love him.”

“Well, then, the sooner you understand one another the better; but, Leona, do you think that your father will consent?”

“Oh, yes!” answered Leona, “I am sure of it; he loves me too well to refuse. Besides, when he sees Mr. Reed, I feel sure he can not help liking him.”

“Oh! you poor little kitten!” cried Eunice, twining Leona’s red-gold ringlets around her fingers; “because you like him, you think everybody else must.”

“Here is Mr. Reed coming,” added Eunice, quickly. “Now you have a fine chance for a walk along the bank of the river—a moonlight walk—and if you are not both great gooses, you ought to be able to find out whether you like one another or not.”

The manly figure of Dave came into the circle of light thrown out from the fire.

“Good-evening,” he said, as he advanced.

“Good-evening,” replied both the girls.

“Oh, I’m glad you have come, Mr. Reed. Leona has been wanting an escort for a walk up the bank of the river in the moonlight, and I am too tired to go.” Eunice cast a merry glance at Leona’s scarlet face as she spoke. Dave did not notice Leona’s confusion; he was only too happy to be able to enjoy the society of the fair young girl, to him the dearest girl in all the world.

“I shall be happy to offer myself for an escort,” he answered.

“And she would be happy to accept the offer,” cried Eunice, “and you too,” she added, mentally, “if you would offer yourself.”

“There is no danger, I suppose?” Leona said.

“Oh, no!” replied Dave, “we will only go a little way beyond our picket-line, and then we can return.”

Abe, as captain of the train, had thrown out regular pickets, as though on the prairie.

Leona got a cloak of dark cloth from the wagon, wrapped it around her, took the offered arm of Dave, and the two walked off in the path leading up the river.

“Now, if they don’t discover whether they love each other or not, before they come back, then they ought to be ashamed of themselves!” cried Eunice to herself, as she looked after their retreating figures.

Leona and Dave walked on arm in arm; they passed the picket-guard by the river, and got beyond the limits of the camp.

Dark clouds had begun to gather on the hitherto clear sky, and every now and then one would sail across the moon, shading the earth in darkness for a few moments; then the moon would shine out clear again till another cloud followed.

No sounds were stirring on the still night-air save now and then the shrill cry of some little earth insect, burrowing beneath the feet of the lovers.

“Do you think there is danger of the Indians attacking us before we reach Montana?” asked Leona.

“It is difficult to say,” replied Dave. “We are a large party, and the Indians seldom attack unless three to one. They don’t care about fighting if they can help it. If a large war-party should happen to come across our trail, why then of course they would trouble us; but we are not likely to meet any large parties; and the small ones will try and run off our stock if they can, but they’ll keep out of rifle-range.”

“If there should be an attack, you would be exposed more to the savages than any of the rest, would you not?” asked Leona.

“Of course, my partner Abe and myself, being captains of the train, are expected to front all the danger—that is what we are paid for,” returned the guide.

“It is a terrible risk you run,” said Leona, with a half-shudder at the thought of the possible danger.

“Well, Miss Leona,” said Dave, in his honest, straightforward way, “we must all die some day, and from what little I have seen of the world, I should say that we were always in danger. When a train is attacked that I’m with somehow I never think of the chance of my getting killed. The fact is, I’m always too busy looking out for the safety of the train. And if there’s anybody got to die by the hands of the red devils, why, better me than a man who has wife, sisters and daughters that love him. You know, for I[Pg 38] have told you, that I am alone in the world, and if I should go under and these red heathen take my top-knot, there wouldn’t be any one in the world to grieve for me.”

A cloud at the moment was passing over the moon, which shaded the earth in darkness, or Dave, if he had looked at Leona’s face, would have seen that her eyes were filled with tears.

“You are wrong,” Leona said, in her low, sweet tones. “There is some one in the world that would mourn for you.”

Dave thought for a moment, then he spoke:

“Yes, I forgot the ‘Crow-Killer.’ I believe he does love me like a brother, although he is old enough to be my father, and until a short time ago we had never met.”

“Then there are two that would mourn for you, for there is another besides him.” Leona was blushing scarlet at her own boldness. Dave detected a meaning in her tone and words that sent a thrill of joy to his heart; and Leona, feeling his arm tremble within hers, knew that she was understood. When two people love each other, and wish each to know of that love, as a general thing it don’t take very long for them to discover the truth, and so, as they walked on in the darkness, walked on beside the winding river, Leona and Dave knew that they loved. Oh, happy moment, when the first love fills the heart, that before had been vacant!

Dave was the first to break the silence.

“Leona,” he said, “I’ve wanted for a long time to tell you how much I cared for you, but I never found the courage to do so until now. I’m only a poor guide, but if you’ll give me your love, I’ll work hard and build up a home for you that one day you won’t be ashamed to share.”

“I should never be ashamed of any home where you are, David,” replied Leona, looking up into her lover’s face, with those trusting blue eyes, so full of innocence and love. “I can not give you what you ask, for it is not mine to give—it is yours already.”

David Reed had never felt so happy, and so the lovers walked on, weaving bright hopes for the future—that future which always looks so bright to those who love.

Dave, so engrossed by the sweet girl at his side, had not noticed a dark figure that moved when they moved, and[Pg 39] halted when they halted; and now, as the lovers sat down by the river-bank, hand in hand, and whispered low words of love and of eternal faith, the shadowy figure extended itself flat on the prairie a hundred yards or so from them, and became invisible in the gloom.

A few hundred feet from where the lovers sat was a little thicket of dwarfed oak trees. Concealed behind the thicket from the view of the fort and the wagon-camp, stood a white horse, spotted on the flanks with patches of black. ’Twas the horse of the Indian who had called himself a chief of the Yancton Sioux. As the moon was again obscured by clouds, forth from the little thicket came the Indian himself. Snake-like he crawled toward the lovers, who, listening only to each other, did not dream that danger was nigh. On came the savage, noiseless as a cat. In his hand he carried a long scalping-knife; his face was bedaubed with war-paint, vermilion and white. Every second brought the creeping savage nearer and nearer to the unconscious pair. He had accomplished half the distance between the thicket and the lovers, when for a few moments the moon again struggled forth and threw its beams over the prairie; the savage sunk down in the grass. When the moon was again obscured, he recommenced his onward passage. But if his approach had been unnoticed by the lovers, ’twas not so with the shadowy form on the prairie. That watcher evidently had seen the Indian, for, imitating his motions, he made his way noiselessly through the grass, also toward the lovers. When the savage got within ten feet of Leona and Dave, he paused for a moment, gathered himself together like a cat—he had not noticed the dark form in his rear, so intent was he on his prey—sprung upon Dave and aimed a lightning stroke at his back; but, at that very moment, Dave moved a little to the right, to kiss, for the first time, the upturned lips of Leona—a movement that saved his life, for the knife of the Indian, missing his body, only cut through the loose red shirt. The force of the shock, though, sent Dave headlong off the bank into the river. In a moment the Indian seized Leona, raised her in his arms and was about to fly across the prairie, when the dark shadow which had trailed him in the grass, and which was none other than Abe, the “Crow-Killer,” sprung[Pg 40] upon him. The Indian relinquished Leona, who sunk to the ground, to grapple with the “Crow-Killer.” His only object now was to escape, but the grasp of the old Indian-fighter was not easily shaken off. They closed in a fearful struggle; the moon once more shone forth, and they beheld each other’s features; the surprise was mutual.

“The ‘Crow-Killer’!” cried the savage, in the Crow tongue.

“White Vulture!” exclaimed Abe.

“Yes, son of ‘Little Star’,” cried the Indian.

For a moment the grasp of the “Crow-Killer” relaxed; the savage tore himself away and fled across the prairie toward the thicket, where stood his horse. Abe drew a revolver and leveled it at the flying Indian; a moment he covered him with the shining tube; he was in easy range, and the “Crow-Killer” was a dead shot; a moment he held the life of the White Vulture at his mercy; then he slowly dropped the revolver from the poise, muttering:

“Not by my hand! his blood must not be on my head!”

Dave speedily gained the bank, nothing hurt by his involuntary bath, and they all returned to the camp. Abe charged both Leona and Dave to say nothing of the attack as it would only create useless alarm. The Indian having gained his white steed fled in the darkness.

Early on the following morning the emigrants broke camp and started on their march up the Yellowstone trail. Abe and Dave rode on before.

“That was a bold move of the Injun last night,” said Dave.

“Yes,” answered Abe; “I expected that he might be lurking nigh our camp, arter I saw him in the afternoon. That was the reason that, when you and the gal headed for the prairie, I followed. I kinder thought that you would be so took with the gal’s bright eyes that you wouldn’t be able to[Pg 41] look out for yourself,” and the old hunter indulged in a dry chuckle.

“I own that it was careless, but I didn’t think that the red devils would ever dare to come so near our camp and the fort.”

“Jus’ so; but this ’ere ‘White Vulture’ has got a white man’s head on his shoulders as to judgment and dash, combined with the deviltry and cunning of the Injun. Why, if it hadn’t been for me, he’d have carried off the gal as sure as my name’s Abe Colt. It was a bold thing an’ it would have been successful if luck hadn’t ’a’ gone ag’in’ him.”

“One thing, Abe, puzzles me,” said Dave.

“An’ what is that?” asked the “Crow-Killer.”

“How he escaped after you clinched with him?”

The old hunter paused for a moment before he answered but after a little while, he spoke:

“Wal, he said something that staggered me. I let up on the grip an’ then he slipped through my fingers jus’ like an eel.”

“What did he say?” asked Dave.

“Not much; only that he was the son of ‘Little Star,’” replied Abe, a peculiar expression appearing upon his features.

“And ‘Little Star’ was the Crow girl that you married!” cried Dave in astonishment.

“Jus’ so. If you remember, I told you I had a kind of a sort of a feelin’ that it was ag’in’ my nature to hurt the ‘White Vulture,’ although he belonged to the tribe, not a red sucker of whom I ever spared when I got within rifle-range of ’em.”

“Then the ‘Little Star’ must have been carried to the Crow nation and married to one of their chiefs,” said Dave.

“That air likely; but a Crow warrior that I met onc’t at Fort Benton on a peace talk, a brother of the ‘Rolling Cloud’—that’s the father of the ‘White Vulture,’ that I killed—walked up to me an’ asked if I were the ‘Crow-Killer.’ Wal, I expected a tussle thar an’ then, but he only looked at me, an’ said in the Crow language: “The ‘Crow-Killer’ is a great chief; he is as strong as the white bear; he killed the ‘Rolling Cloud,’ but the Crow chief has a son, the ‘White Vulture,’ an’ he will take the scalp of the ‘Crow-Killer’; it will dry in the smoke of his lodge, an’ the Crow nation will[Pg 42] be glad. The ‘Crow-Killer’ is a great brave, but when he is tied to the torture-stake, the Crows will speak words in his ear that will make him howl like a dog—words that will burn like fire;” then the chief walked away. Now, I’ve puzzled considerably to know what those words air. I s’pose it’s something ’bout my Injun wife, the ‘Little Star,’ but I hadn’t any idea then that the ‘White Vulture’ was her son, an’ it kinder considerably started me when I hearn he was. I’ve a sort of suspicion now what them words air a-goin’ to be, that’s goin’ to make me squeal. But then ag’in, thar’s another thing that gits me: I never hearn of this chief—this ‘White Vulture’—having any brother, but still t’other one mought have died. Anyway, one of these days I shall find out all about it.”

“Yes, you’ll find out easy enough; just let the Crows get hold of you—”

“Jus’ so!” interrupted Abe, with a shrewd smile, “but I ain’t in a hurry to have that happen. My top-knot is well enough as it is, an’ I don’t intend that any Crow shall lift my ha’r if I can prevent it. I’ll give ’em pretty considerable of a tussle first. But, I say, you took a long walk last night; did you an’ the little gal come to an understanding?”

“Yes,” answered Dave, a smile lighting up his features.

“Wal, I thought it probable that you settled matters; but, I say, Dave, don’t give the red devils a chance at you ag’in.”

“Don’t fear; but I did not think that there was the slightest danger. I don’t believe that there’s another red-skin on the plains that would have dared to attempt it.”

“We ain’t seen the last of him yet,” said Abe, gravely. “If we don’t have a big fight afore we reach the head-waters of the Yellowstone, then I’m a sucker an’ no Injun-fighter.”

“I agree with you,” said Dave, “but it will take a big party to clean us out. We ought to be able to whip a couple of hundred red-skins at the least.”

“That’s so, Dave. This fellow being around the fort looks mighty suspicious; he was on a spying expedition to see how big a party we were. He’s a long-headed Injun, is this ‘White Vulture’; he knows if he can only flax out the ‘Crow-Killer,’ it will be a big feather in his cap among his nation. An’ my opinion is, that he’ll try mighty hard to do that; so[Pg 43] we must keep our eyes open. I reckon they won’t trouble us until after we get past the Big Horn river, but, arter that time look out for lightning. In about two days, if I don’t miss my calculations, we’ll have Injuns all around us, thick as fleas in a Mexican ranche.”

So, on went the wagon-train—Abe and Dave keeping a sharp look-out over the rolling prairie.

At noon the train halted for a couple of hours for rest and food. At two o’clock, the train was again in motion, the vigilance of the guides increasing as they progressed further into the prairie waste.

During the noon halt, Dave had found time to exchange a few words with Leona. He frankly and without reserve told her that danger was at hand, that the train was liable to be attacked at any moment, and that at the first sounds of alarm for herself and companions to lay down in the wagon, the sides of which would afford some protection. Leona’s cheeks paled a little, more, though, at the thought of her lover’s danger than at her own.

“You will be careful, Dave,” she said; “be careful for my sake.”

“Yes,” he responded; “don’t fear, Leona. I shall come through all right; only look out for yourself, that’s all, because it I thought that you were needlessly exposed, it would take away half my courage.”

Leona, like a good girl, promised to be careful.

The danger of an Indian attack was known now to all the emigrants, and as the train rolled on, the men looked carefully to their weapons and prepared for the expected encounter.

Abe and Dave were ahead as usual, their keen eyes eagerly and carefully scanning the broad expanse of the prairie before them.

So far, even the watchful glance of the old Indian-fighter had not detected a single sign of Indians being near. No fresh trails were upon the prairie.

Early that morning, before the march, he had carefully examined the hoof-prints left by the horse of the Indian chief, commencing at the little thicket; the trail led across the river and off in a south-western direction, but this did not relieve the mind of the guide; he knew the Indians too well; he[Pg 44] conjectured that the party under the lead of the ‘White Vulture’ were probably encamped somewhere near the Big Horn river, and that their intention was to follow the river north and thus strike the course of the train.

At six that afternoon the train halted for the night; they had made forty miles since leaving the fort. Fires were kindled, the river-bank supplying plenty of fuel. Then arrangements were made for passing the night; the wagons were drawn up in a semicircle, the ends of which rested on the river-bank; the beasts of burden were unharnessed and brought within the circle—a wise precaution, for the first attempt on the part of the Indians in an attack is always to stampede the cattle. These once dispersed and scattered over the prairie, the emigrants of course can not advance or retreat, and if the savages are unsuccessful in their attack on the wagons and are beaten off, at least they have the satisfaction of gathering in the stampeded stock.

The wagon-train “packed,” the next movement of the guides was to throw out pickets and divide the men into “watches” for the night. Arms were looked to and all preparations made to resist a night attack. Instructions were given to the pickets, who were relieved every two hours, to fire their rifles at the slightest alarm. The guides slept by turns, and one was always on the alert, passing from picket to picket, noiselessly as a panther, and ever and anon gliding like a ghost through the darkness of the prairie beyond the picket-line, watching to detect the presence of the foe.

The night passed slowly away without a single signal of danger.

As the first gray streaks of dawn began to appear, Abe, returning from a prolonged scout on the prairie, met Dave who had just woke from an hour’s nap.

“Well, any sign?”

“Nary sign. Thar hain’t been a red devil within a mile of us last night, I’ll bet,” replied Abe.

“Can they have thought we are too strong for them and given us up?”

“No, I don’t think that,” responded Abe, thoughtfully. “I tell you, this ‘White Vulture’ is jist as smart as they make ’em. He knows that we of course suspect that an attack[Pg 45] would be made, ’cos we saw him. Now, of course, he knows that we’ll be on our guard ag’in’ the attack; so he just waits; he lets two or three days go by; we don’t see any Injun sign; we git careless—don’t keep up our watch—don’t look for an attack—an’ then he comes down onto us like a panther, claws an’ all. Two days more, at the rate we are going at, will bring us to where the trail crosses the Yellowstone an’ strikes off to the north-west to Codotte’s Pass. Wal, now, in ’bout three days, when we’re between the Yellowstone an’ the Missouri, heading for the Missouri, he’ll go for us.”

“There is sense in what you say,” said Dave.

“Sartain, I’m a nigger if thar ain’t; but though I think I’ve got the Injun’s plan down to a p’int, I ain’t a-going to be caught napping afore we leave the Yellowstone, ’cos he may go for us at any moment; therefore I shall keep my eyes open.”

Breakfast was prepared and the emigrants, after partaking of it, again took up their line of march.

We will now return to the “White Vulture” we left flying for his life across the prairie. Mounted on the milk-white steed, that was indeed a horse of matchless action, he crossed the Yellowstone and rode in a south-western direction. His way lay across a rolling prairie dotted here and there with little clumps of timber. Ever and anon he turned in his saddle and listened for the sounds of pursuit. Satisfied at last that no one was on his trail, he drew rein beside one of the little clumps of timber; dismounted, tethered his horse to a stunted oak, then taking from his pouch some dried buffalo-meat, cured in the sun, he made a scanty meal, then after a careful scout around his immediate neighborhood, he laid himself down upon the prairie and slept. The white steed, that had evidently been reared among the Indians and understood their customs, slept calmly by the side of its master.

As the first cold gray streaks of light appeared in the east, the Indian chief awoke, mounted his horse and rode off, this time shaping his course almost directly west. On he rode, from the early dawn until the sun’s warm rays showed the noon at hand; then he halted by the side of a little hollow in the prairie from which a spring gushed forth, gave his horse water, partook again of the buffalo-meat, let his horse graze[Pg 46] for an hour or so on the fresh young grass and then again pursued his way.

Two hours more of hard riding brought the “White Vulture” to the bank of the Big Horn river, to an Indian encampment.

Some hundred warriors of the Crow nation had there tethered their horses, while the braves themselves lay upon the grass, or walked listlessly up and down by the turbid stream, now swollen high by the spring rains.

From the fact that no squaws were with the party, nor lodges, nor dogs—those usual accompaniments to stationary Indian encampments—one acquainted with their customs would instantly have pronounced them to be on the war-path. And if further evidence was wanted, the gayly-painted faces of the warriors, bedecked with crimson, yellow, black and white tints in all the hideous fashions of the savages when on the war-trail, would have confirmed it.

The “White Vulture” dismounted from his horse, tied him to a shrub, and with stately steps walked to the river’s bank, where, under the shade of an oak tree, sat ten warriors, evidently the principal chiefs of the party. The “White Vulture” sat down in the circle.

“My brother is late,” said an old chief, who was known among the Crows as the “Thunder-Cloud,” probably from his dark color; he was one of the oldest and best warriors in all the Crow nation.

“Yet the ‘White Vulture’s’ horse is like the wind; he could not come before.”