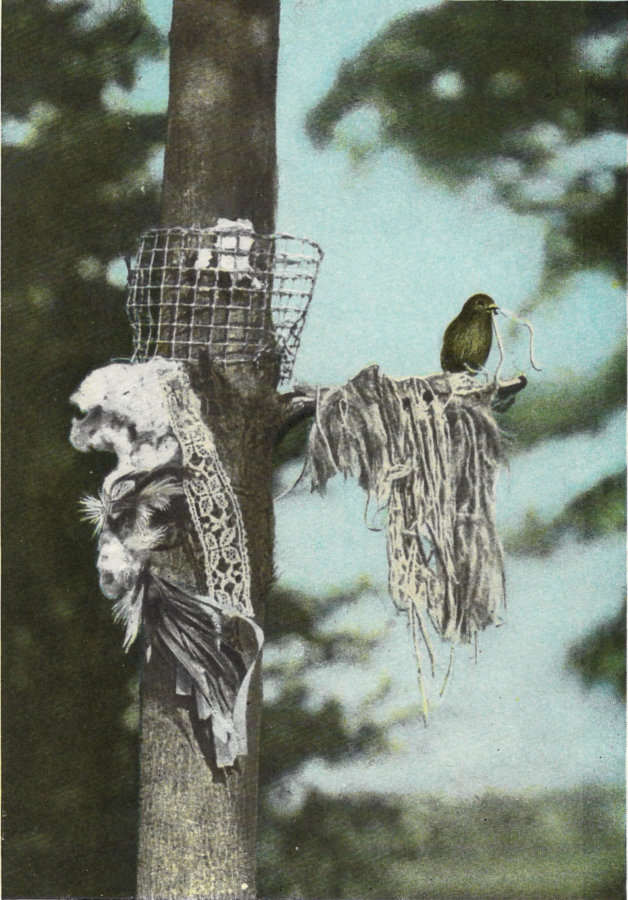

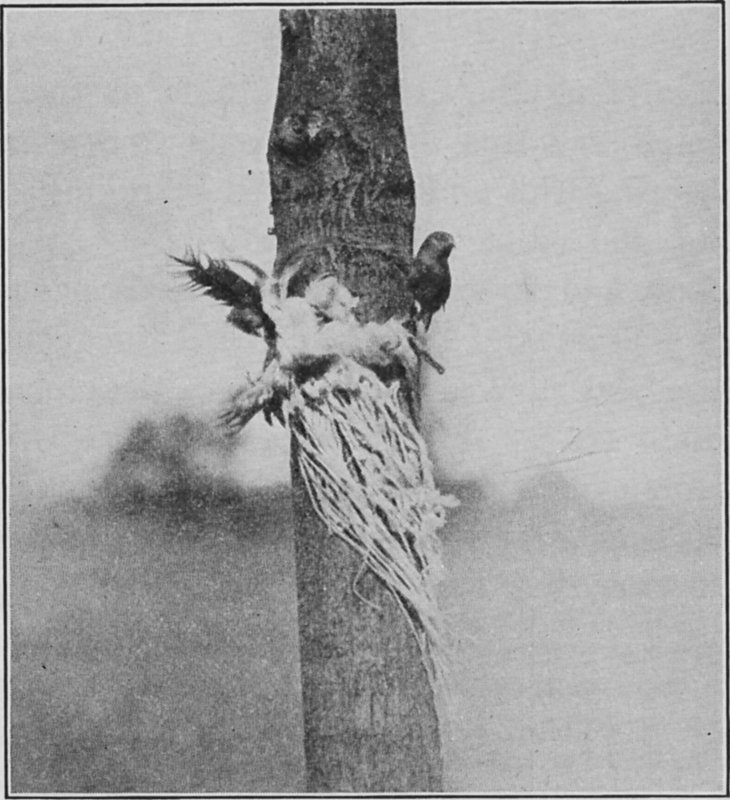

STRINGS AND COTTON AND CHICKEN FEATHERS FOR THE BIRDS’ NESTINGS (See page 56)

BY

S. LOUISE PATTESON

AUTHOR OF “PUSSY MEOW, THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A CAT”

AND “KITTY-KAT KIMMIE, A CAT’S TALE”

PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR

COVER BY HELEN BABBITT AND ETHEL BLOSSOM

D. C. HEATH AND COMPANY

BOSTON NEW YORK CHICAGO

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY

S. LOUISE PATTESON

118

DEDICATED TO

BOYS AND GIRLS

This narrative of neighborship with birds is suggestive rather than exhaustive. It aims not so much to inform the reader, as to instill in him the desire to learn from the outdoors itself, to know at first hand about the charms and the benefactions of birdlife. The observing reader will supply what has been left unsaid, and so experience the zest of initiative, the joy of discovery, in our mysterious and manifold bird-world.

S. L. P.

Waldheim,

East Cleveland, Ohio,

October, 1917.

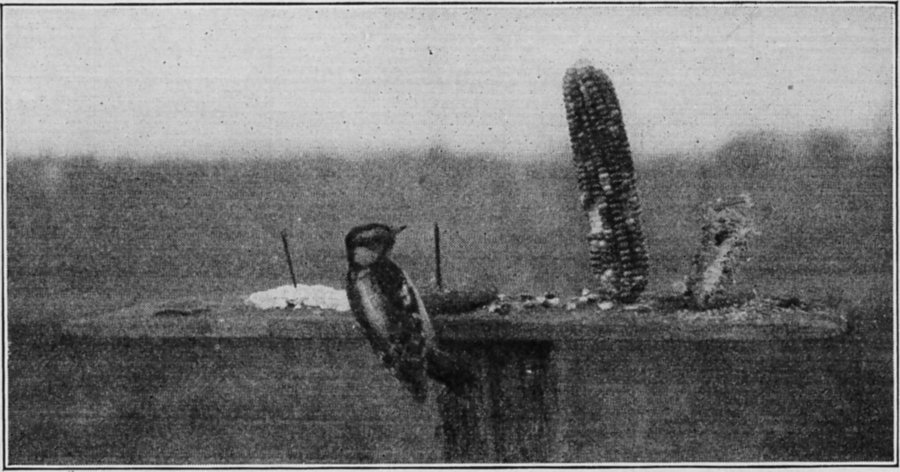

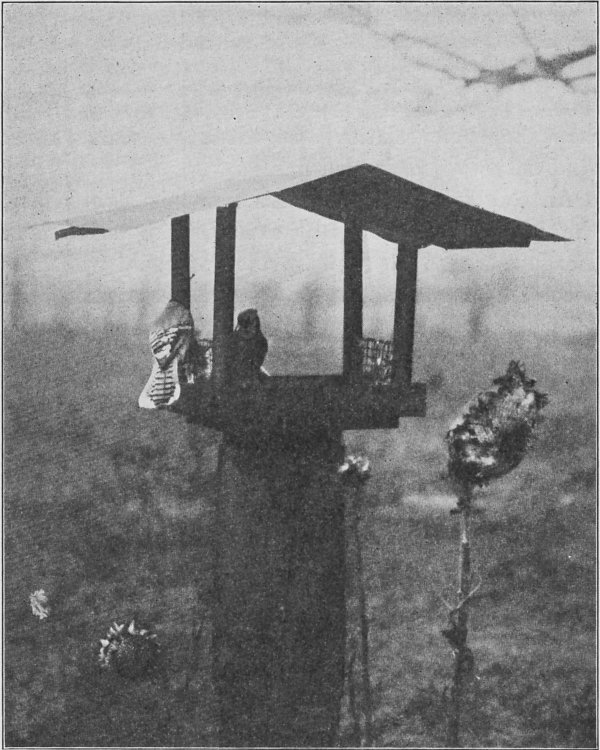

SUET AND DOUGHNUTS FOR DOWNY, CORN FOR THE CARDINAL, CEREAL FOR THE SONG SPARROW

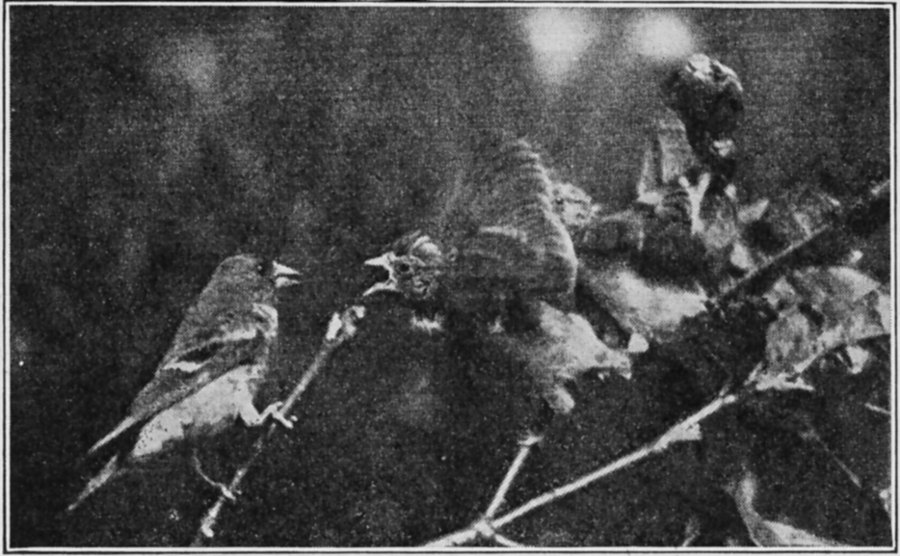

GOLDFINCH FEEDING BABIES

“OH, WHERE IS MOTHER?”

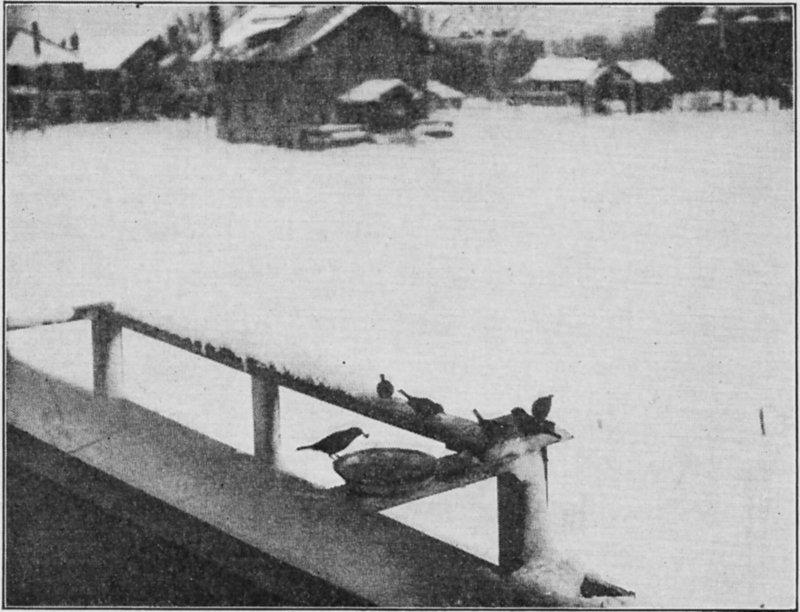

THE BASIN ON THE PORCH RAILING

The birds that live in my yard are the loveliest of all my neighbors. During the springtime and summer they awaken me every morning with their sweet songs. Then all the day long their pretty ways make me wish I had nothing to do but to watch them.

Now I can imagine someone saying, “If I had a yard, I, too, would try to have bird neighbors.” Listen! Before I had a yard I had bird neighbors on my porch.

How did I get them?

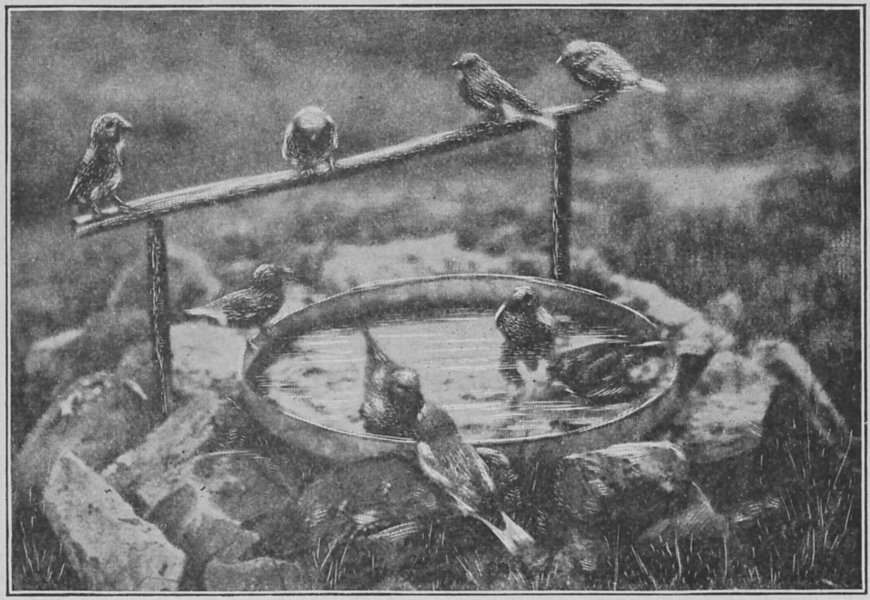

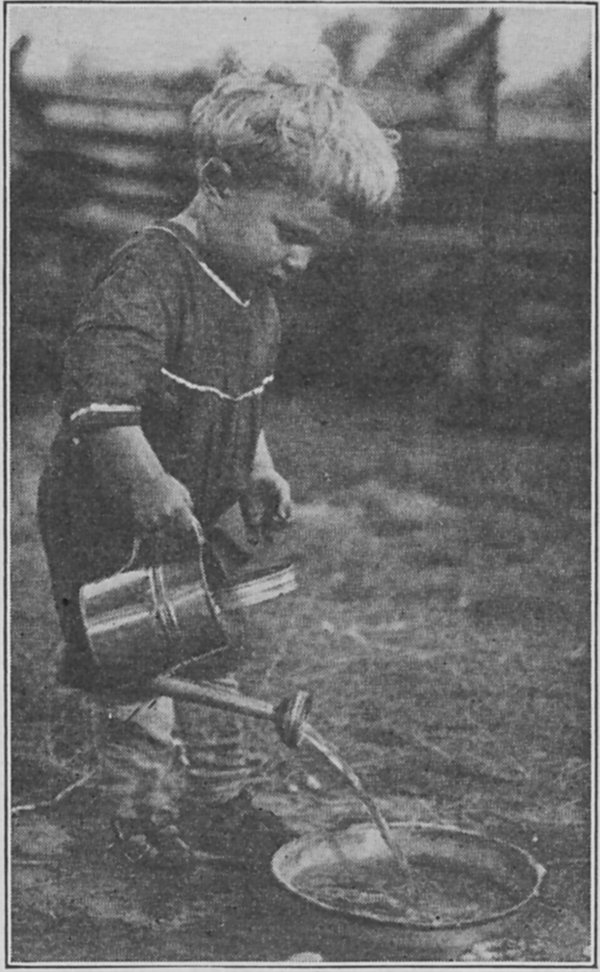

In summer, a basin of water on the porch railing, and in winter, the basin filled with table scraps—this is what did it. On the porch of that apartment house I learned how to neighbor with birds.

A kind lady in the next house tied suet and strings of peanuts to one of her trees. During winter and spring the woodpeckers enjoyed the treat, while we enjoyed the woodpeckers! Pigeons and bluejays came too, and, yes, English sparrows, those birds that are nowhere welcome. But they didn’t have it all their own way there, as they do where nothing is done to attract other birds.

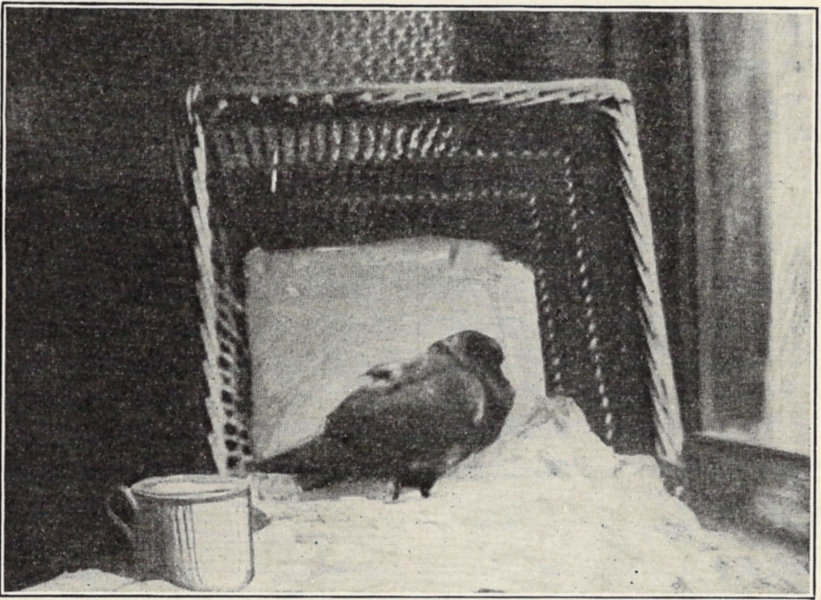

One winter day a beautiful blue and white pigeon with rose-colored neck came in at an open window. The streets were covered with snow. It was hard for birds to find anything to eat. This pigeon ate some rolled oats that I scattered before it, drank some water, and walked into a corner. After a nap it ate some more; then took another nap. When it awoke again I set it in a waste-paper basket by the open window, so it could go away when it pleased. It took several more helpings of oats. Toward evening it flew away.

Among the pigeons that used to come often to my porch was my little guest of a day. As the pigeons ate they always cooed. Perhaps they were remarking how good it tasted.

In early spring the robins came. They liked little 3 scraps of meat. Chopped raw beef was to them the greatest treat. At the basin they not only drank, but spread their wings over it and splashed the water all around, trying to bathe in that shallow dish. It was only a big flower-pot saucer. While the weather was still cold, they began to sing mornings before daylight. It was like listening to Christmas carols to hear them.

On mild and thawing days they could be seen hopping over my neighbor’s lawn. Most cunningly they would turn their heads to one side, then to the other. It is said that they do this so they can hear the worms and insects move about in the ground. I believe it; for often I have seen a robin, after listening intently at some spot, stop to scratch and dig, then pull out a worm.

The robins often pulled and jerked at the morning-glory vines on our porch. Whenever they got one loose they would gather it up in loops with the bill and carry it away. They also tore strings off our mop and flew away with them.

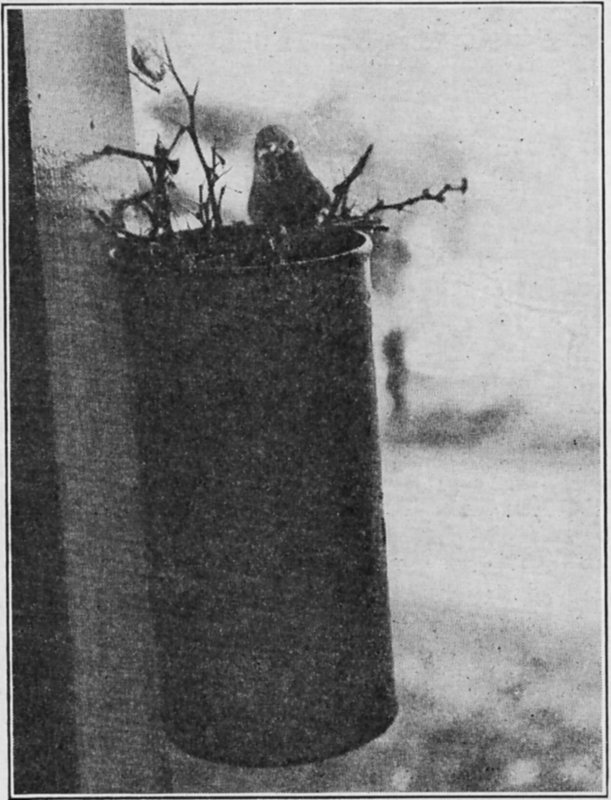

On a pillar of our porch there hung a can in which we sometimes put flowers. One rainy April day a little wren alighted on the edge of that can and looked in. The can was empty at the time, so the bird went inside, but came out again quickly and flew away.

Pretty soon two wrens came, and both went inside. Then for several days they made frequent visits to 4 that can, and there was almost constant trilling of the merriest bubbling songs. Sometimes there was just a chatter back and forth, as if they were talking or arguing. These wrens were so much together that I concluded they were mates.

THEY WERE MAKING THAT CAN INTO A BIRD HOME

They fetched little twigs of all kinds and dropped them into that can. They also fetched bits of cloth and chicken feathers, as if they actually intended to make a feather bed. Mr. Wren could carry things in his bill and sing at the same time. Once in a while, when he brought something, Mrs. Wren chattered louder than usual. It sounded as though she wasn’t pleased with what he had brought. Sometimes she wouldn’t even let him in, and, after carrying his burden around for a while, he would drop it. But he sang on just as happily, and entertained her while she did most of the work. This went on for several days. At last they fetched 5 grasses, too. It was a joy to see how happy they were at their work. They were making that can into a bird home.

When the little home was finished, Mrs. Wren loved it so well that for about two weeks she stayed in it nearly all the time. Mr. Wren brought her many kinds of bugs and worms to eat, and sang to her all the day long.

Soon there were some baby wrens in that little home. Again Father and Mother Wren worked hard from daylight until dark, fetching worms and bugs for their babies to eat. Whenever one came home with a bill full, he glided right in among those thorny twigs. How they could do it without getting pricked was a wonder!

One day all this was changed. Instead of going into their little home with provisions, both Father and Mother Wren stayed out on the edge, and held a worm or a bug where the little ones could see it. After a while, one of the baby birds came up a little way to receive a helping of the food. But the big outdoors must have frightened him; for he ducked right down again. The next one that came out had more courage, or else he was more hungry. He received a helping; then gazed about him a little. Evidently the world looked pleasant to him. He shook his feathers, flapped his wings, and didn’t go back into the little home at all. This was just what Father and Mother wanted him to do, and each gave him a 6 whole worm, although the birdies inside were calling for some too.

The day was fine. It was still early. The babies would have all day in which to get used to the outdoors if they would come out now. To-morrow it might rain, and the next day, and the next. The babies were quite old enough to live outside of that stuffy can. They must come out to-day,—so Father and Mother Wren had decided.

After the little venturer had received several helpings, another birdling came scrambling up. He got all of the next helping. Mother Wren was among the porch vines, chirping. Every little while she flew to the little ones, fluttered her wings before them, and then flew back to the vines. In this way she was coaxing them to follow her.

Before Number Three came out, the mother had Numbers One and Two safely among the vines. Number Four came close behind Number Three. It wasn’t very pleasant to stay down in the can all alone. The mother kept up her coaxing until she managed to get them all in nice, shady places.

It was now about nine o’clock. The rest of the day was spent quietly among the vines. After they had rested a little from the excitement of their first flight, Mother tried to keep them moving from vine to vine. One was more clever than the others. He learned everything quickly.

The Wren family lived in the vines all the next 7 day. On the third day Mother Wren began to coax them farther away. Back and forth she flew between the porch and my neighbor’s tree, and around in circles, to show the babies how to do it. Father Wren coaxed them on with a white worm in his bill. He was not singing much now, because these growing birds needed more and more food. Also, father-wisdom bade him keep quiet lest his babies be discovered and come to harm.

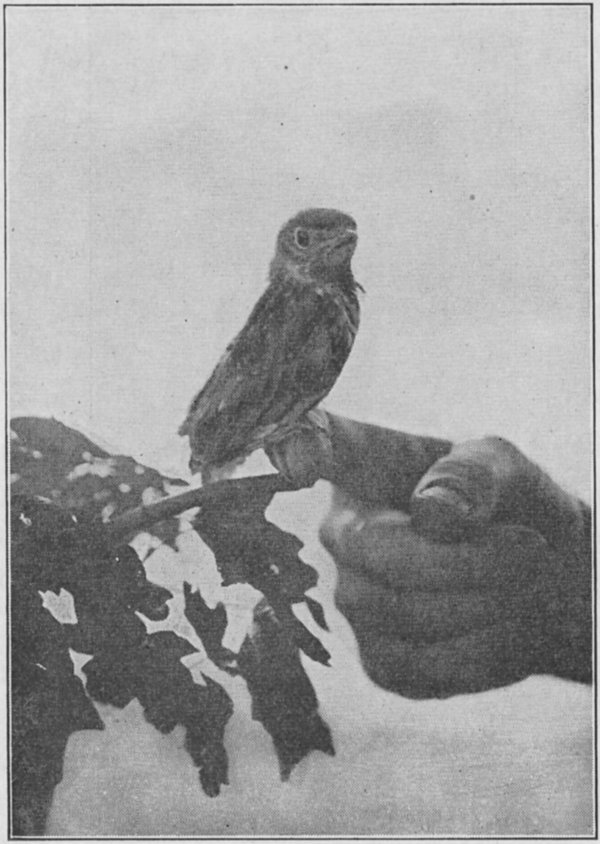

The cleverest of the four was also the biggest; so it was easy to tell him from the rest. Again, he was always the first to venture. But as he neared the tree, when he had almost reached his goal, he began to drop; and he fell to the ground. Fearing some harm might come to him, I went down quickly with the long-handled dust mop. It was fuzzy, and soft for him to rest on. With it I hoisted him to a low branch. Mother and Father Wren scolded, but went to the young bird as soon as my back was turned. Birds do not like to have people meddle with their affairs; but sometimes when they are in trouble we can help them.

Maybe this little mishap showed Mother Wren that her babies were not yet strong enough to fly so far. Anyway, she waited until the next day before she urged the others to go. Even then she was not quite decided. At dinner time the three were still on the porch. They had reached the highest rung of the trellis. In the afternoon, when I returned from 8 school, they were gone. Father Wren was again singing his cheery songs. He had kept pretty quiet while the little ones were learning to fly. Why? Because he did not want anyone to find out where they were.

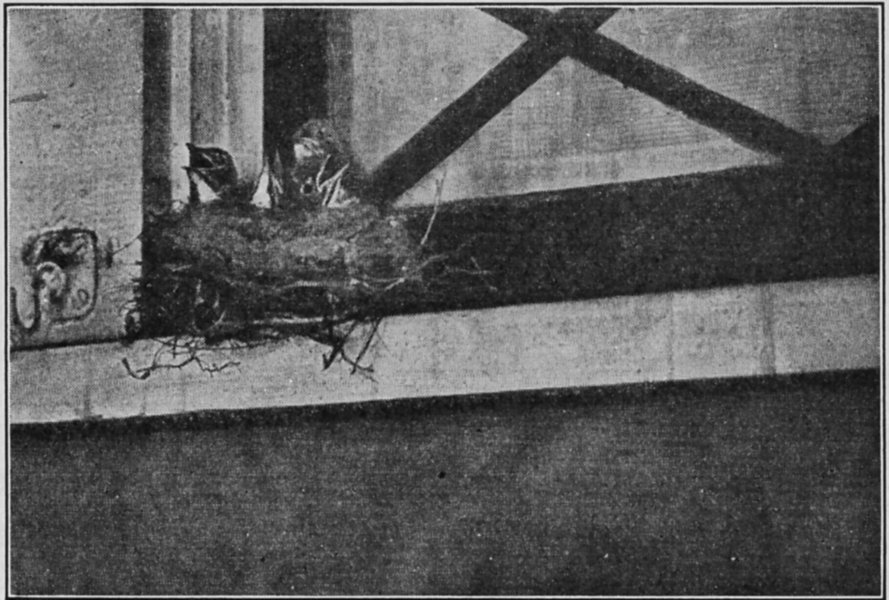

My robins, meanwhile, had made themselves a nest on a high window sill at the far end of the porch; but not until the wrens began nesting did I discover it. Already there were three blue eggs in it. The robins seemed so distressed at being found out that we kept away from that end of the porch until they got well used to us. The wrens didn’t fear us at all. They came to their nest no matter how many people were on the porch.

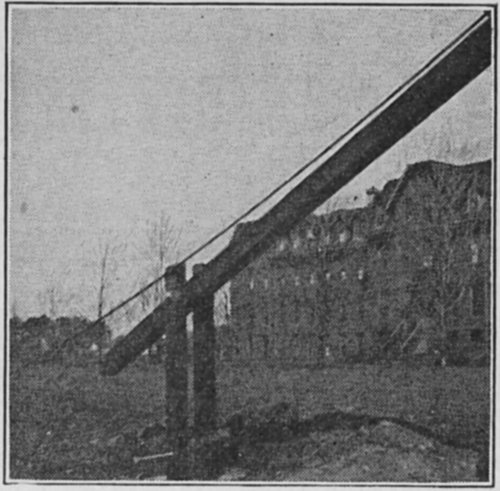

I had now learned what the wrens and the robins like for their nestings; so I fastened strings, shreds of cloth, some cotton, and small chicken feathers to the low branches of my neighbor’s trees, and also on my porch. I had read somewhere that some birds will pull feathers out of their own bodies, if they can find none elsewhere, with which to line their nests. After the wrens had cleaned out the can, they helped themselves to cotton and feathers, and made ready for their second nesting.

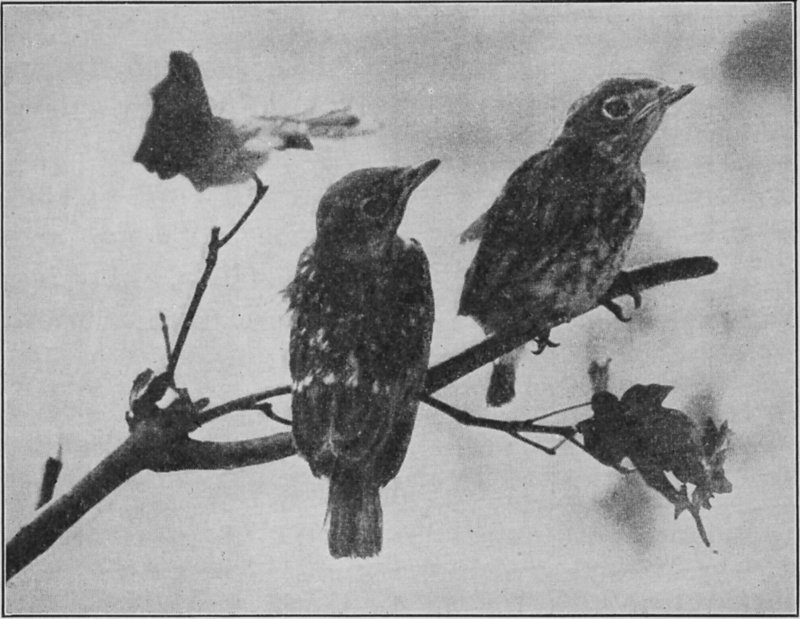

Father and Mother Robin were such devoted parents, it seemed as if they couldn’t do enough. Their babies always craned their necks and opened their bills wide as soon as they heard anyone near. As they grew older they also chattered and flapped 9 their wings. Sometimes they fluttered over the sides of the nest so far that I feared they would fall off the high window sill.

THE BABY ROBINS

One morning the robins’ nest was empty, and the young were over on my neighbor’s lawn. For convenience I will call this neighbor Mrs. Daily. She lived on our right. The neighbor to our left was Mrs. Cotton.

A birds’ bath at Mrs. Daily’s and the tree with nesting materials on it showed the birds that they were welcome there. So the parents coaxed their young in that direction.

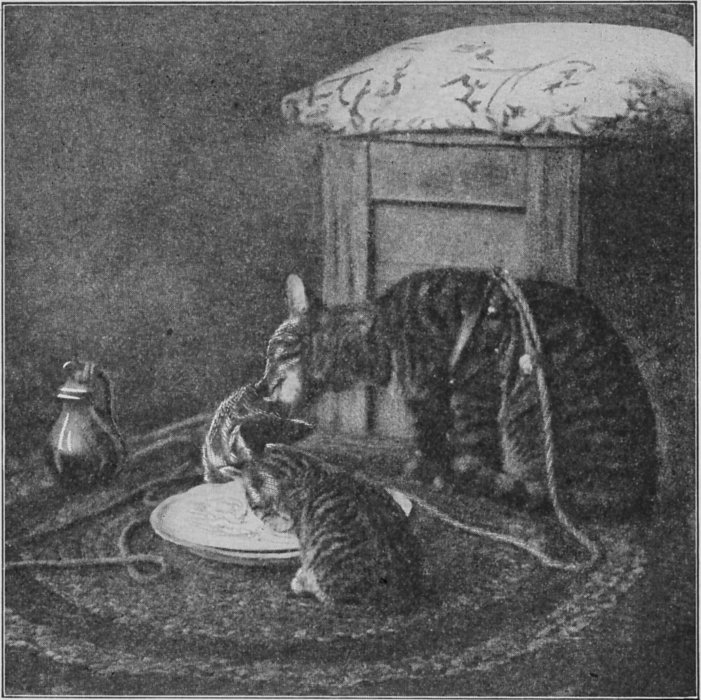

Mrs. Cotton also tried to attract birds. But her basin sometimes went dry for days. Also, she had a big, beautiful cat that was usually somewhere in the 10 yard. It was not so inviting there, according to birds’ ways of thinking, nor so safe for their young, as over at Mrs. Daily’s, where the cat was kept in.

I kept our kitty locked up night and day, and asked my neighbors to keep their cats in, too, until these young robins could fly up into trees. At first they could only fly sideways. It is more than just a kind act to save young robins from harm: it is saving birds who will be useful and pleasing all their lives, and who will spread happiness wherever they go.

When I saw how my birds left me as soon as their young could fly, I began to wish that I, too, had a yard and trees, like my neighbors. I longed to have more birds, and birds of different kinds.

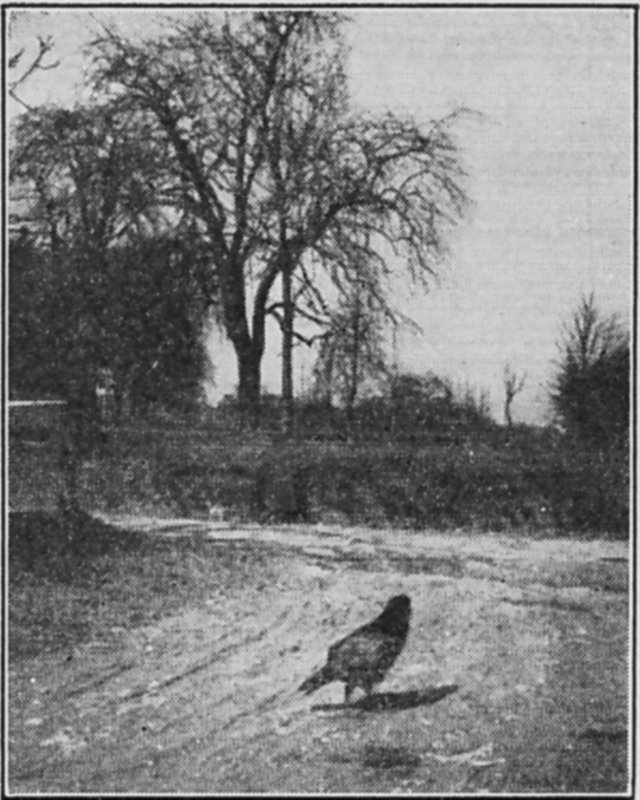

ONE WINTER DAY A PIGEON CAME IN AT AN OPEN WINDOW

VACANT LOTS ATTRACT BIRDS

I got my wish: Our present home is a whole house, with a yard. We have big trees and little ones, and on one side there is a grape arbor. All around us are vacant lots, where thornapple bushes, dogwood trees, and tall sunflowers grow. These attract birds. Behind the vacant lots there is a ravine with wild cherry trees, elder bushes, wild grape tangles, and other attractions for birds.

The wrens and the robins had gone to their winter homes when we moved, and the woodpeckers had come. I had bought a bird guide with colored pictures, and a pair of field glasses which brought those black and white birds very near to me. Some had red on the back of the head. They were the 12 downy woodpeckers. A bird very much like the downy, but larger, was the hairy woodpecker. And there were birds just like the downy and hairy but without the red patch on the head. They were the mates of the downy and the hairy.

Whenever I heard a brisk “chsip,” I could see downy approach in graceful, curving flight toward some tree. Usually he perched near the bottom and climbed up, pecking and scratching as he went. Sometimes he alighted higher up and came down cat-fashion, but always busily pecking at the bark. The hairy did the same. This must be why these birds are called woodpeckers.

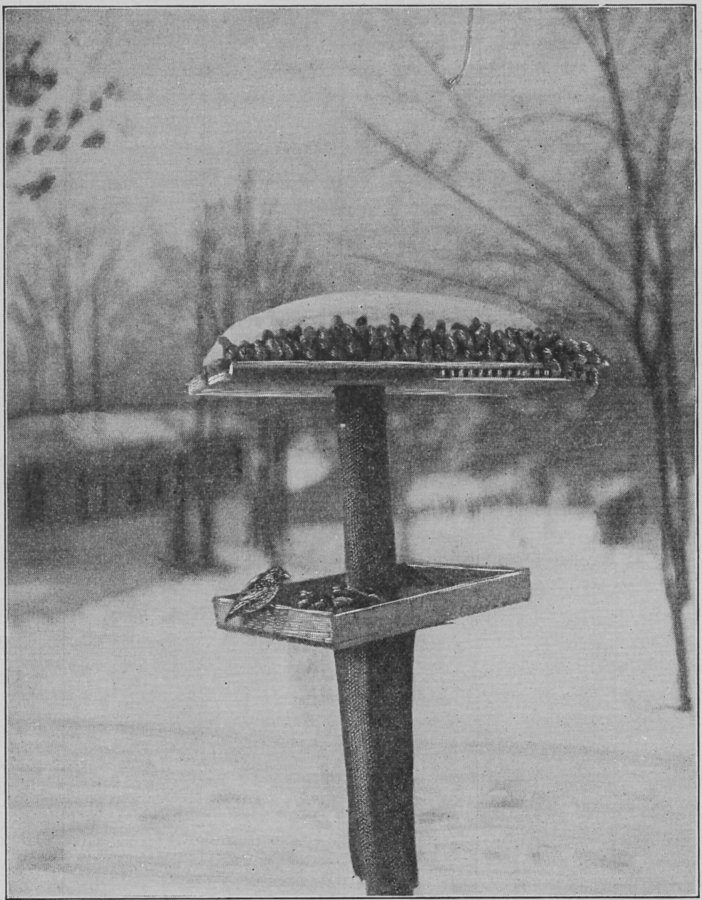

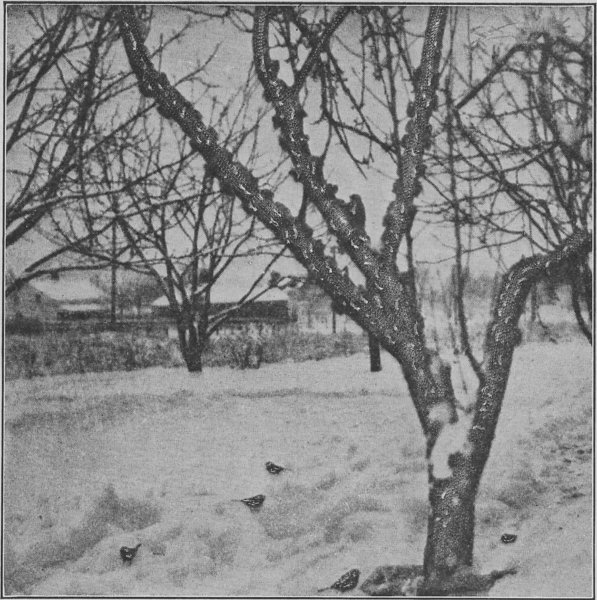

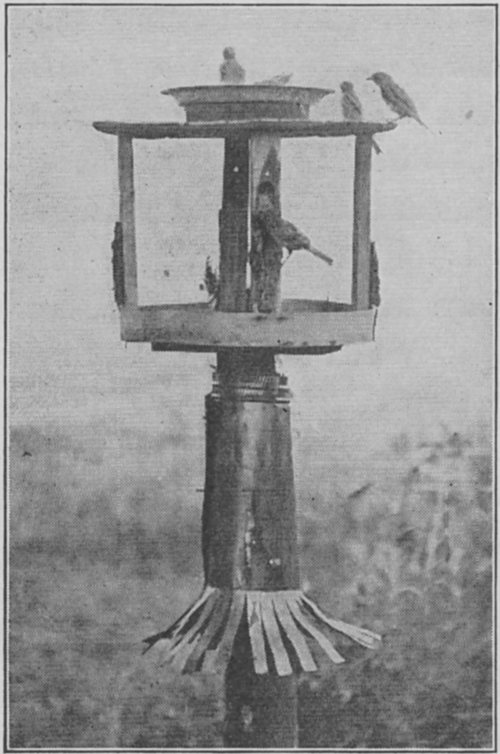

Knowing how well the winter birds like peanuts and suet, I fastened strings of peanuts across a bird table that I had made, and in the tray below I kept suet. I also scattered chickfeed on the ground beside a tree, and added to it buckwheat and sunflower seeds. But I soon learned better than to put anything for birds near a tree behind which a cat could hide!

It was great fun to watch the different birds select their favorite food. The woodpeckers liked the suet so well that, while it was on hand, they hardly ever touched the peanuts. Downy also liked the chickfeed; but he did not like to step down to the ground. In trying to get it, he would back down the tree until his tail touched the ground. Then, without leaving the tree and while propped on his tail, he reached 13 over to the right or left and picked up kernels. In this way he could eat without stepping on the ground.

THE WINTER BIRDS LIKE PEANUTS AND SUET

And downy had good eating manners. He never 14 hurried, never fidgeted. Sometimes he stayed twenty minutes at a meal and ate slowly and quietly, like a well-bred person.

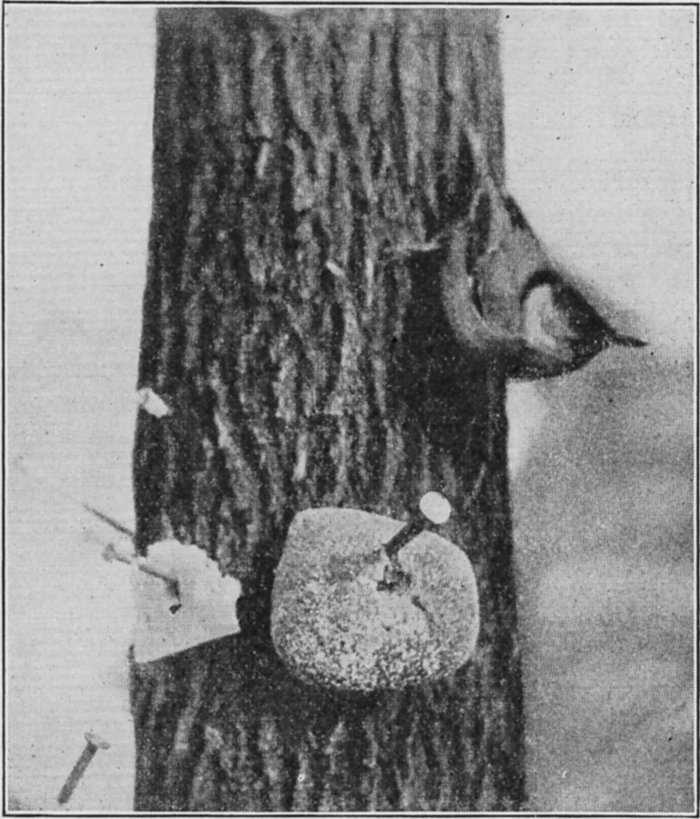

WHEN I DID NOT HAVE PEANUTS I GAVE THE NUTHATCH DOUGHNUTS

Another bird that came to my place in winter had a light blue back and a white front. His wings and tail were dark blue, and so was the top of his head. I always knew he was near when I heard a sound like “gack” or “yack.” He liked the peanuts better than anything else. With his sharp bill he would punch a nut, then hold down the shell while 15 he pulled out the kernel. Maybe this is why he is called the nuthatch. Sometimes, when I did not have peanuts, I gave him doughnuts. He liked them just as well. He would nibble at a doughnut until it dropped from the nail, then go to the ground and forage there. He liked cheese also.

I soon found that somebody else, too, liked suet and peanuts. This was the red squirrel, and when he was on the table the birds would not come near. However, it was birds I wanted and not squirrels,—especially not the red squirrel, who is said to bother birds in many ways. To keep him away I nailed tin sheeting around the post of the bird table.

I am sorry to say that the nuthatch was not at all polite to other birds. He always wanted all the food himself, no matter how much there was on hand. He would flit from one feeding place to another and chase the other birds away. I stopped putting peanuts on the table, so that he would have no excuse to go there and the birds who liked the suet might eat in peace. I put all the peanuts on the tree farthest back in the vacant lot and made the selfish nuthatch eat there by himself.

Another thing that was not nice about the nuthatch was his way of eating. He was always in a hurry. He would take the kernel out of a nut, walk up the tree with it, and fly away. Then he would come back quickly and do the same thing again, as if afraid another bird might get something. 16 Sometimes he kept this up for an hour or more. Even after all the peanuts were moved to his tree, he would bluster around at the other feeding places and try to drive those peaceable birds away.

The dearest of all my winter birds were some that came singing in all sorts of weather. I called them my little minstrels.

“Chicaday, chicaday, chicaday-day-day-day,” was their song. Somebody has named them chickadees, and the name just fits. If you should see a little gray bird with a black cap and bib, who comes singing that song, you may know that you have seen a chickadee.

The chickadees were not at all particular what they ate. They sang just as cheerily when they had only breadcrumbs as they did when they found suet and peanuts and sunflower seeds. They never wasted their food. If any fell to the ground they picked it up. They were the politest of birds and, like the downy and the hairy, they worked at the trees most of the time.

These winter birds are some of nature’s best house-cleaners. They work all through the cold and stormy season when the other birds are away in their sunny winter homes. Should we not remember to give them a treat once in a while, and so brighten the cold days with good cheer?

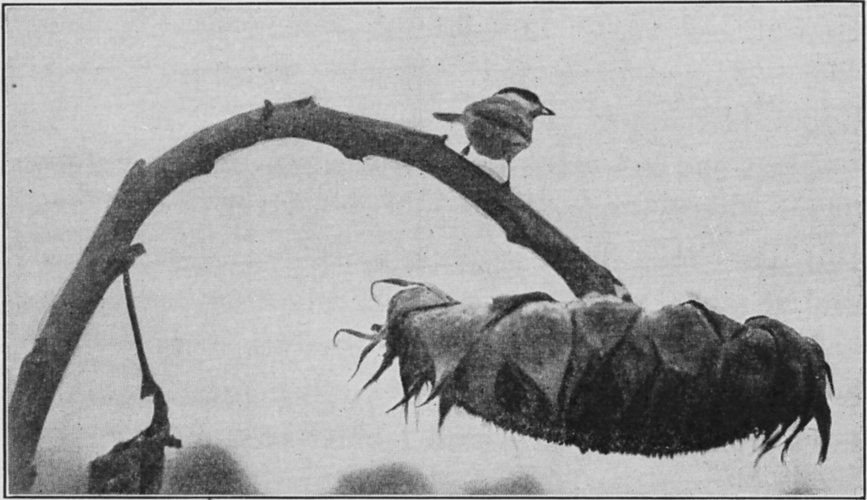

From the very first, I heard many bird voices coming from the ravine. So one morning I took 17 a walk out that way. Scattered all along were tall sunflowers, now gone to seed. Foraging on some were the noisy bluejays, on others the dear happy chickadees. The trees were bare, so that I could see as well as hear the birds. Woodpeckers were tapping, pecking, delving. All along I heard this pleasing, friendly music, as if the birds were following me. So pleasant was my walk that I did not realize how far I was going until I was at the end of the city, where the country begins.

THE DEAR HAPPY CHICKADEE

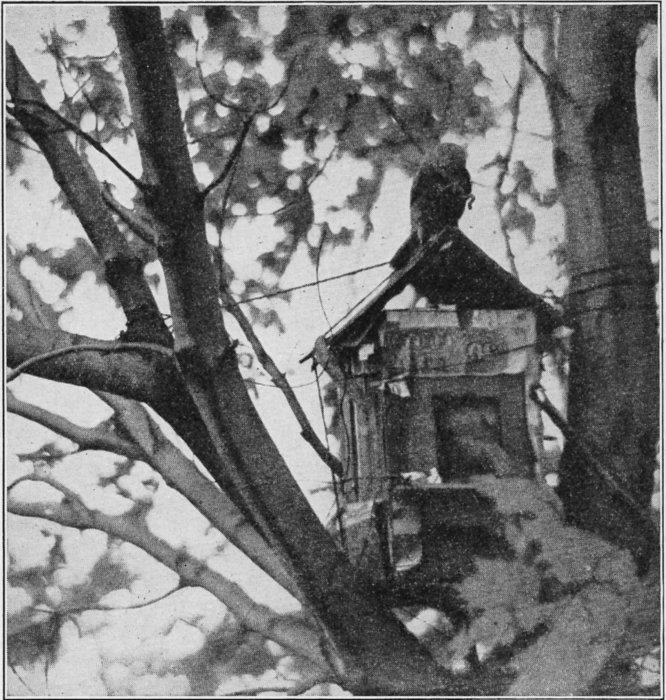

A good way off were some widely scattered houses. On a tall pole near the first house was a very large bird house. As I drew nearer, three small bird houses came in sight.

I made up my mind to get acquainted with the 18 people in that home. A pleasant lady opened the door and invited me in.

“Who put up those bird houses?” I asked, the first thing.

“That’s my boy,” said the lady. “He just loves to tinker with his tools.” She pointed with pride to a clock shelf which she said he had made for her birthday.

“And he made that big bird house, too?” I asked.

“He made every one,” answered the lady, “and he is making more. He is learning it in the manual training school.”

I told her I wanted to make some bird houses, but didn’t know just how to go about it.

Then she led me into a tiny room off the kitchen. There by the window stood an old dry goods box that had been fitted up as a work bench, with a vise and a rack for small tools. Larger tools were hanging on the wall. On some shelves were wooden boxes and boards. On the work bench lay a bird house. I picked it up and looked at it.

“He says that’s to be for wrens,” explained the lady. From a chest she produced another bird house which she said was for bluebirds.

“He makes them out of these boxes that he gets from our grocer,” she added, “and I save the starch boxes for him.”

The lady had much to do, so I made ready to go. But she went on talking:

“At first, I couldn’t bear to give up this little storeroom. But since I have seen how happy it makes Laddie to have this little ‘shop,’ as he calls it, I am glad I gave in to him. Would you believe it: from the time he begins to work with these tools until he lays them down again he whistles and sings like a bird himself! I think anything that makes a boy so contented must be good for him.”

The lady then went about her work, telling me not to hurry. So I stayed to take some measurements of the bird houses. Both were made so that they could be opened in front.

“He makes them that way so they can be easily cleaned,” explained the lady.

On the way home I stopped at our grocer’s and got some small wooden boxes. Two were yeast foam boxes, and one was a cocoa box. I, too, had learned in manual training school how to use simple tools, so I bought also a saw, plane, shaving knife, brace and set of bits, and a small vise. Then out of an old sewing machine stand I made a work bench, and a light corner of the basement became my “shop.” I made those yeast foam boxes into wren houses, and out of the cocoa box I made a bluebird house. The boy’s mother had told me that his manual training teacher was a lady, and that she was “just as good as a man,” so I felt quite proud of my new fancy work.

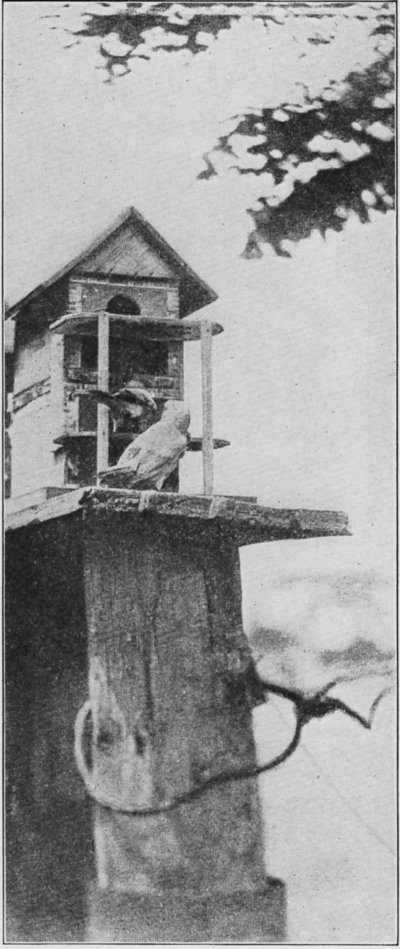

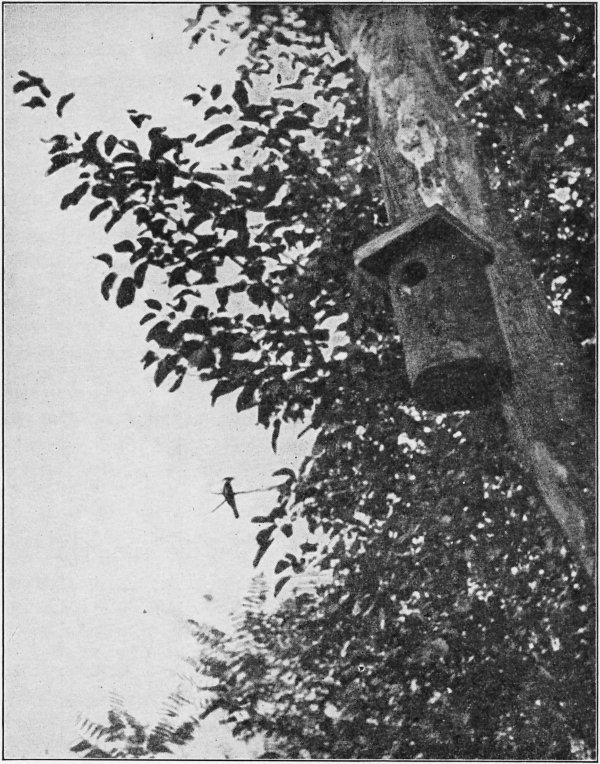

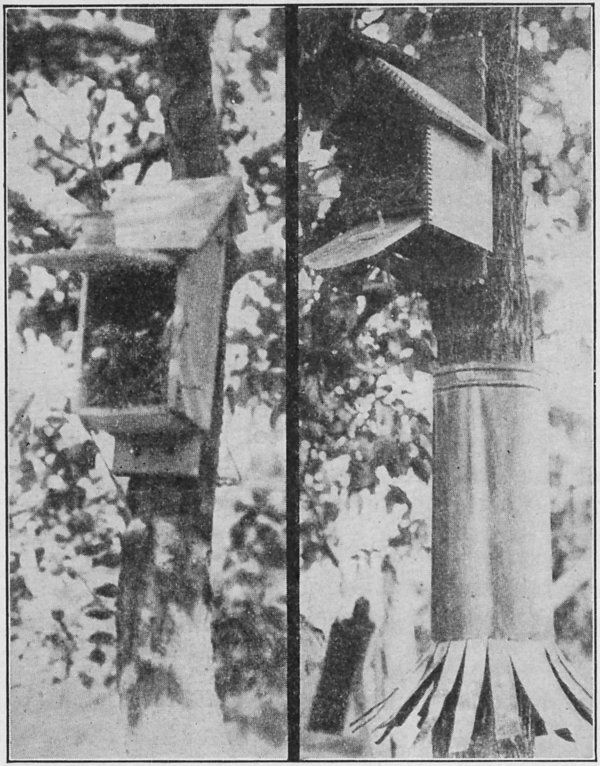

The house for bluebirds and one for wrens were put 20 up in trees. The other wren house was mounted on a post above the grape arbor. But it did not stay there long, for I soon found that a grape arbor is no place for a bird house. Can you guess why not?

It was while waiting for the wrens and the bluebirds to come that I had such delightful times with the woodpeckers, the nuthatches and the chickadees.

THE SELFISH NUTHATCH

CATS BELONG ON THEIR OWN PREMISES

I said that birds were lovely neighbors. So are some other animals. At my new home I soon became acquainted with a wild rabbit. Two dogs roamed around in the vacant lots and in the ravine a great deal. Often when I heard them barking, the next thing I saw would be Bunny, running as fast as he could toward our place, with the dogs 22 after him. Bunny could glide through under the garden fence, and that was lucky for him. The dogs were too big and couldn’t.

I was glad when Bunny came to our place for safety. He liked slices of apple so well that he would come nearer and nearer to get them, until finally he ate out of my hand.

THE BASIN WAS BUNNY’S LOOKING-GLASS

One hot day while Bunny was in our yard, he saw the birds’ basin, and went there to drink. He had 23 been accustomed to drink at the brook in the ravine, where the water always runs, if there is any. But the brook was dried up at this time of year. The clear, still water in the basin was a new thing to Bunny. He took a long look at it. Seeing himself pictured in the water was another new thing to him, and he looked again and again. Evidently he thought himself quite handsome, for even after it rained and the brook filled up again, he still kept coming. The basin was his looking-glass.

I am sorry for what I have to tell about some other animals. One day our neighbor’s cat lay crouching near the tree under which the chickfeed was scattered. A downy woodpecker was just coming down the tree. Kitty’s eyes glared. Her teeth chattered. But evidently the downy did not see her. I scolded Kitty and drove her away. This disturbed the downy, and he flew away too. But that was better than to let him come down where Kitty could jump on him. She could easily have done so while he was reaching over to the ground for a kernel.

After this experience I covered up all the chickfeed beside the tree, and scattered some in more exposed places, away from any trees and from bushes. I also laid suet on low branches of trees and tied it on firmly, and poked some into small holes of old trees, and under the bark.

Soon afterward I saw the same cat again. This time she was on a branch, eating suet. That set 24 me to thinking: “If the cat can get to the suet in the tree, she will also be able to get to the bird houses. Some day she might find some baby birds in there, not yet able to fly.”

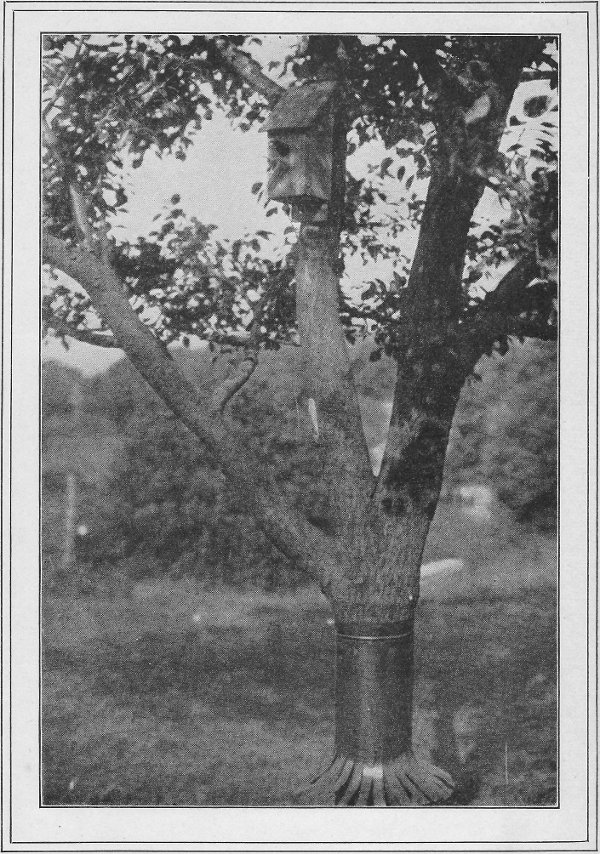

I did not take away the suet which the birds liked so well. I got some tin sheeting and tacked it around the tree. The cat could not climb over the smooth sheeting.

Imagine my surprise when I saw her up there at the suet again! “How did she get there?” I wondered to myself. Day after day I watched Kitty before I found her out.

One morning, who should go climbing up that tree but a red squirrel? When he reached the tin, he looked around and made a loud chatter. Seeing no one, he took one big jump over the sheeting and went to the suet. After tasting it, he wiped his mouth on the bark as if he did not like it. Then he went over to the bluebird house. The entrance to this little house had been nicked by somebody with sharp little teeth. Now I found out who that somebody was. This squirrel was even now nibbling at the entrance, trying to make it still bigger. At the wren house somebody had broken off the little porch, which was probably the squirrel’s doing also.

I wondered what I should do to keep this squirrel from spoiling my bird houses. Some more tin sheeting, I thought, would fix it so he could not jump over. I put another sheet just above the first one. 25 That made the tin protection thirty-six inches deep. When the squirrel came the next time, he climbed as far as he could, then looked up at the tin. That was too high a jump. He turned, jumped to the ground, and scampered away.

The pilfering red squirrel is not to be confounded with the genial gray squirrel of our parks, who loves to take peanuts out of our hands.

I still wondered how Kitty had made her way to the suet, with the tin around that tree. Surely she could not jump over the tin! As a jumper the squirrel can beat Kitty any time. One day I heard a scratching noise. Kitty was sharpening her claws on the bark of the next tree. Every little while she climbed a few steps up that tree; then sharpened her claws again. There was nothing in that tree that she could harm, so I let her go on. She walked along on one of the branches, and jumped across to a branch on the other tree, the one that held the bluebird house, and smelled around there. It was early spring. There were no young birds in the house yet; so I let her go on, just to see what she would do. Some English sparrows had started to nest in the little house. Kitty pulled out grasses and feathers, and spoiled the nest.

Now just think how wise she was to plan that all out so nicely! And all she gets for it is scolding! Why should we blame Kitty for liking birds? We like our chicken dinners. We praise Kitty when she 26 catches a mouse or a rat. Some people even entice her to catch English sparrows. How can she know it is good to clean out a mouse nest and naughty to clean out a bird nest?

Two things can be done to lessen the loss of birds by cats. First, to safeguard in every possible way every bird house, feeding place, and bath. Second, to compel the owners of cats to keep them on their own premises, and to lock them up nights. It is at night, when there is no one to interfere, that cats do the most damage to birds.

I knew that if Kitty could jump from that tree to the next one, the squirrel could do it, too; so I put double tin sheeting on that tree also.

But such a clever cat and such a nimble squirrel would also know how to climb the grape arbor, I thought; so I took the wren house off the arbor. This house also had been nibbled and the entrance made much larger. I concluded that the worst of all places for a bird house is a grape arbor, a pergola, or a garden arch.

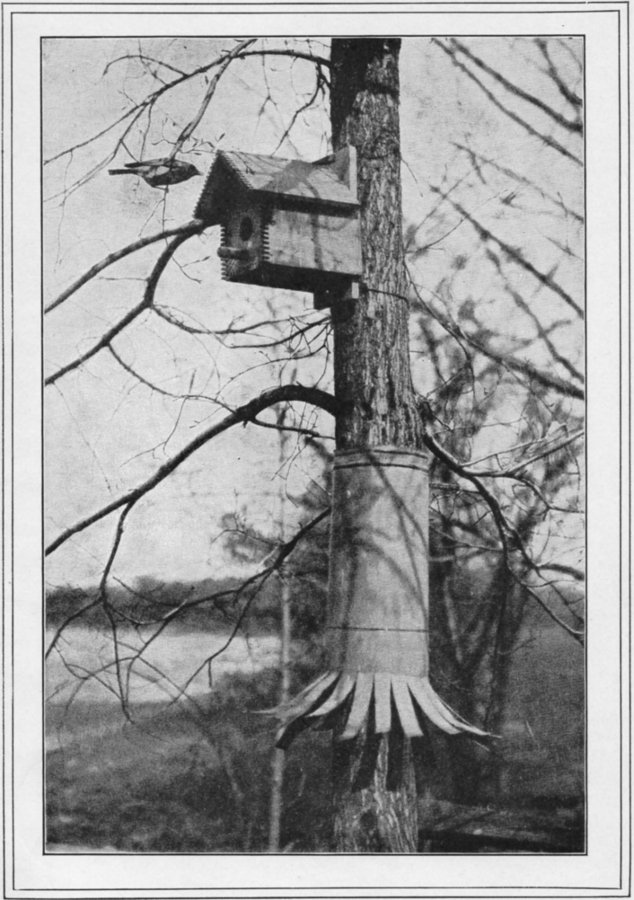

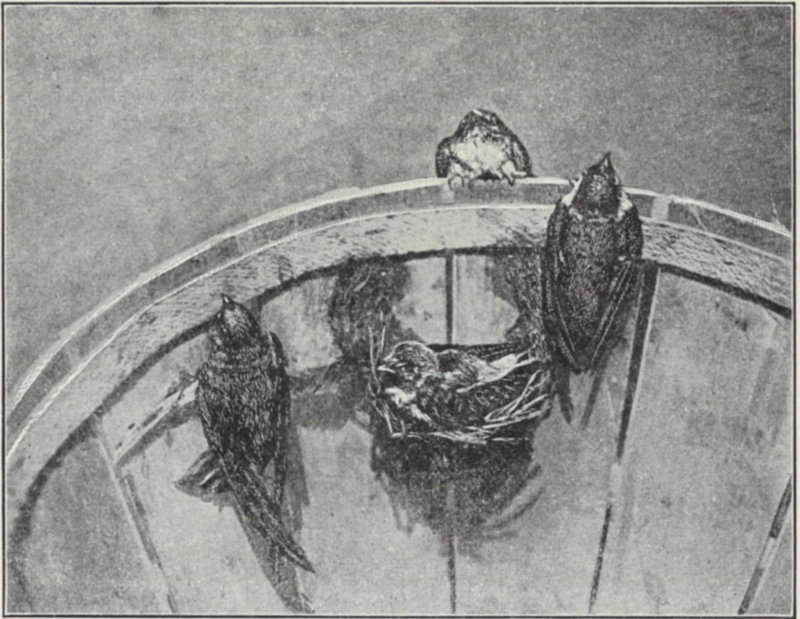

A friend had sent me a beautiful wren house. It was shaped like a small barrel, and had four rooms. I called it the apartment house. Fortunately, it was made of such hard wood that no squirrel could bite through. I had this house put on a tin-sheathed post on the north side of the house where it would be in shade.

For the bluebirds I put up two new houses. The 27 one that had been up all winter was so smelly of squirrels and English sparrows that I knew the dainty bluebirds would not like it. The time was near for the birds to return from their winter homes. I wanted everything clean and safe for them.

THE GENIAL GRAY SQUIRREL

THE RETURN OF THE BLUEBIRD

I love the springtime because it brings my birds back from their winter homes.

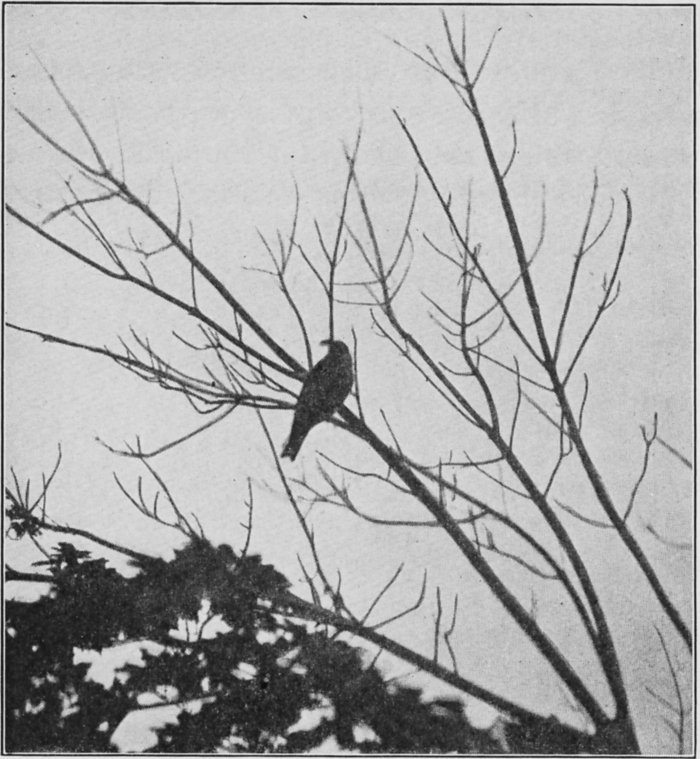

One cold March day I saw something blue flash across the sky.

“Can that be the bluebird I have been waiting for?” I thought.

It flew into a tree; then alighted on a clothesline post. I could plainly see the blue on its back and the red on its front. Yes, it was the bluebird. His song was as beautiful as his plumage, but in a minor tone:

“De-ary! De-ary!”

Next he flew to the top of the wren house, tripped along the roof, leaned over and looked at the little porches. Then he went down on one of them and looked into the room. That was as far as he could go. The entrances to these apartments had been made for the tiny wrens and not for bluebirds. When he saw the bluebird house in the tree, he flew to a branch just in front of it and looked at it a while. Then he flew back to the wren house and tried that again; he liked it so well, he couldn’t bear to give it up.

After a week or so another bird came, of much paler hue, but with the reddish breast. The song of my bluebird now became long and pleading: “Deary! dear, dear, deary!” But it still remained subdued and minor. Together he and his newly arrived companion visited the bird houses, so I concluded that they were mates. They could hardly make up their minds which house to take, so pleased were they with all of them. Mrs. Bluebird tried the wren house, too. But when she saw she could not get inside she did not go there any more.

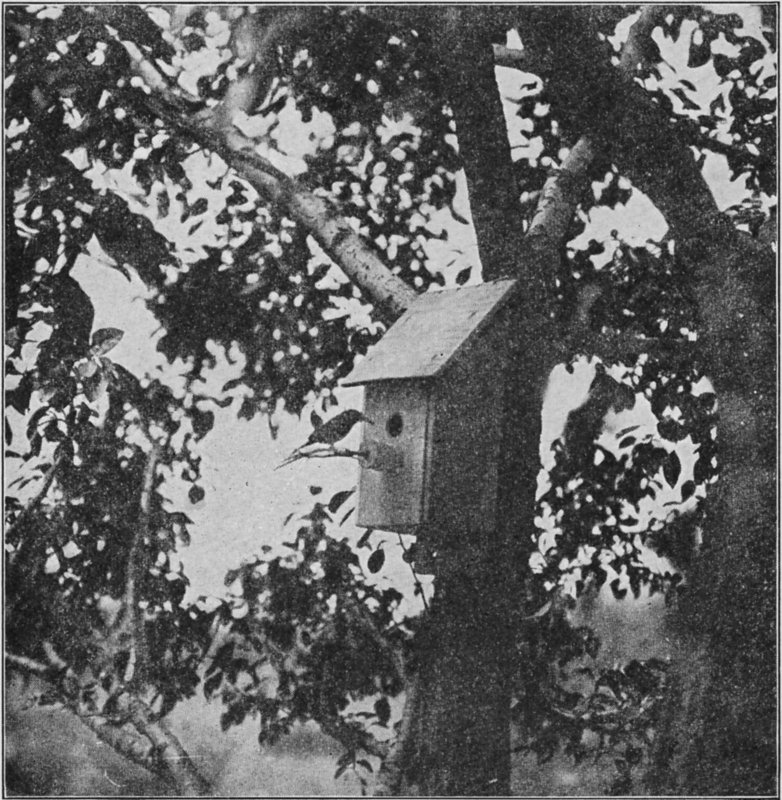

My prettiest bluebird house was on our hammock post, well shaded by our biggest tree. I had read somewhere that bluebirds like to have one house for spring and another for summer. So this house was made with two rooms, one above the other. I thought the bluebirds would surely like this double house better than the single one, for they went inside it many times, and always stayed there long.

The other house, which was mounted on a young maple, was not nearly so pretty. It was made out of cigar boxes and I had forgotten to take off the labels. After the bluebirds had visited it I did not dare touch it because, if their houses are interfered with, birds are liable to go away. Both the maple and the hammock post were well protected with tin sheeting.

One day Mrs. Bluebird fetched some grasses in her bill. To my great joy she alighted on the perch in front of the double house. Twice she poised to fly, but did not. At last she flew—and where do you think she went? Why, to that ugly little house with the labels on it!

SOMETIMES SHE WAS JUST GLIDING THROUGH THE ENTRANCE AS HE ALIGHTED ON THE HOUSETOP WITH A CHOICE MORSEL FOR HER

While she was in the house, Mr. Bluebird alighted on the porch, looked in, and sang a little song. Mrs. Bluebird flew out past him and almost brushed him off. Then he went inside, and just as Mrs. Bluebird returned with some more grasses he came out with a chip in his bill. Some chips had fallen inside when I made the entrance, and he did not like that. The little house must be clean, since Mrs. Bluebird was going to make her nest in it. Sometimes he brought a grass or two; she brought whole wads of grasses. But he made up in attentions to her. Wherever she might be working, he perched near by, on a fence 32 post or a low branch, and kept his eyes on her. As she went from place to place to find the right kind of grasses, or to the little house to throw them in, he always followed her. Sometimes she was just gliding through the entrance with a load as he alighted on the housetop with a choice morsel for her to eat.

One day our neighbor’s cat was hiding behind an evergreen near where Mrs. Bluebird was hunting grasses. Mr. Bluebird’s bright eyes saw her just in time.

“Dear-dear-dear!” he cried, quickly and jerkily.

Mrs. Bluebird knew that that meant, “Danger! Fly quick!!” Up she flew, and away.

The cat jumped high and almost caught her.

After that I chased the cat away every time I saw her. There certainly should be a law to make people keep their cats at home.

When Mrs. Bluebird had her house all furnished she stayed at home about two weeks and took a good rest. Mr. Bluebird continued to bring her meals and to entertain her. When he was not hunting bugs and worms, or chasing English sparrows, he was sure to be somewhere near home, singing his sweetest songs.

When Mrs. Bluebird was able to be out again she and Mr. Bluebird were busier than ever. Both were carrying food to the little house. I knew then that they had babies in there, so I called him Father, and her Mother.

BLUEBIRD BABIES TO FEED AND CARE FOR

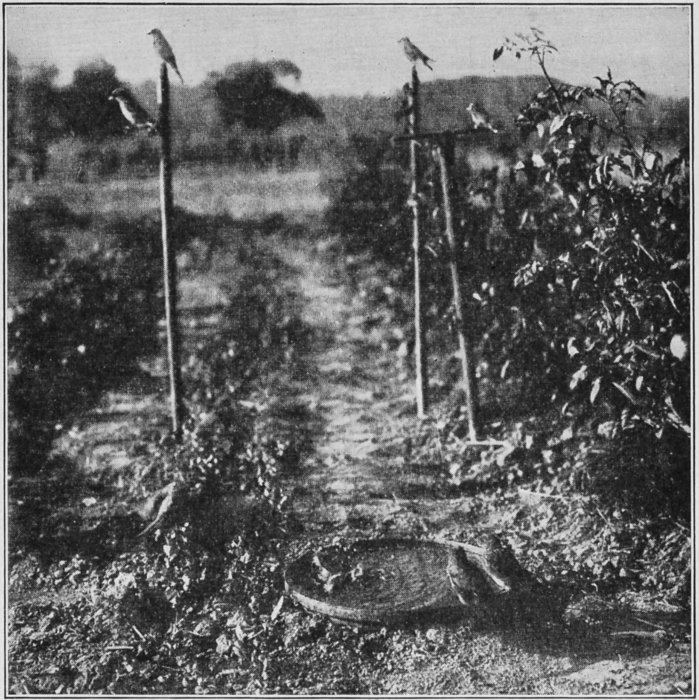

The bluebirds caught some of their food in the air, but a good deal of it they picked up in my garden. I had some low stakes there expressly for them. They perched on these and on the bean-poles, and from there pounced on many a luckless worm or bug that their sharp eyes espied. I am sure the bluebirds are great helpers in a garden.

After two busy weeks of baby-tending, Father and Mother Bluebird did just what the little wrens had done. They made the babies come outside for their food, or go hungry.

I think the first little bird to leave a nest must be 34 very courageous. The others usually follow close after him. It was so with these bluebirds. And as they came out, one after another, Mother coaxed them over to the thornapple bushes. She did it by calling, “Dear dear,” and flying back and forth between the little house and the bushes.

THE BLUEBIRDS MOVED INTO THE PRETTY DOUBLE HOUSE

Some of the baby bluebirds were quite obedient and flew after the mother. Two liked it so well on a branch in front of their house that they stayed there a while; then flew to other branches in the same tree. Father looked after these, and Mother stayed with the other three. What a chatter they always made when food was brought to them! It seemed 35 as if each one said: “Come to me! Come to me!”

While Father and Mother Bluebird had those babies to feed and to care for, they started another housekeeping. This time they moved into the pretty double house and took the lower story. In the second coming-out party there were four more little bluebirds.

All through this second housekeeping the English sparrows tried repeatedly to get into the upper story, and Father Bluebird had to spend much time chasing them away. In the one-story house he had that much more time to get food, or to sing.

I did not clean the bungalow house after their first nesting, because I did not want the bluebirds to nest in it again. After the double house was vacated, I cleaned both houses, and found that the bluebirds had used only grasses and a few feathers for their nesting. In each case they had covered the entire floor with grasses, but the cup-like nest was back against the rear wall, as far from the entrance as it could possibly be.

What could this mean but that the bluebird likes a house with depth so she can bed her young as far back from meddling paws as possible? This much I learned from examining the deserted bluebird nests.

RENTED FOR THE SUMMER

A four-room house which had been sent to me was very much liked by a pair of wrens. Again their lively, rippling notes filled the air, as these wrens went from room to room of this “apartment house,” as I called it. It was three days before they made up their minds which room they liked best.

Then they brought little twigs and bits of rag, and leaves, and other things, and poked them into one 37 of the rooms. It was as good as saying, “We will take this apartment for the summer.”

Some English sparrows wanted that same room. We always shooed them away, of course, if we could without frightening the other birds. The wrens jabbered and hissed at the sparrows, and stayed, pecking them and being pecked by them. There were four sparrows and only the two wrens; so the poor little wrens finally gave up and went away.

But, try as they would, the sparrows could not get inside of the house. After a while, they, too, went away. Then the wrens returned. It seemed as if they had been watching for the chance.

The wrens soon fetched more twigs, some of them several inches long. They poked them in as far as they would go; then went inside and pulled them in as well as they could. But some of the longest ones remained partly outside and so blocked the entrance to any birds except the tiny wrens.

Again the English sparrows came and, although they couldn’t even get their heads in now, still they bothered the wrens. They couldn’t have that room themselves, and they didn’t want anybody else to have it.

With such a mean spirit is it any wonder that nobody likes these birds? I cannot bear to call them sparrows any more, because so many good birds go by that name, and are therefore in danger of being disliked. Or, I wish that all the good sparrows could 38 have a different name, and let the English sparrow alone keep the name he has dishonored.

The boy has told me that, to keep English sparrows from increasing around his place, he destroys their eggs wherever he can find them. He said that one pair of sparrows seemed to blame the bluebirds for it, and in revenge destroyed the bluebirds’ nest.

We kept up the shooing and handclapping whenever English sparrows visited the wren house. After a while the wrens began to understand that we were trying to help them, and went on with their nesting. They put tiny sticks and twigs into other rooms of their house also,—and now there was a perfect concert of wren music all the time. Before night two more entrances were blocked. Some of the twigs that these wrens brought had such long thorns on them that they would not go inside at all. But this did not discourage the plucky wrens. They just dropped them to the ground and fetched others.

The next day another pair of wrens came. It seemed as if wrens had a way of letting their friends know where some nice apartments could be had. I was so eager to accommodate as many wrens as would come that I had made some one-room houses for them. One was mounted in a pear tree; another under the overhang of the garage roof.

THE SMALL WREN HOUSE IN THE PEAR TREE

This last wren pair seemed quite bewildered with so many houses to choose from, and all of them different. Whenever Mrs. Wren showed preference for one house, Mr. Wren would go to another one and with his singing try to coax her there. She was seen oftener about the house under the garage roof, than the others. Mr. Wren seemed to like the apartment house best. He was such a jolly little fellow, it is no wonder he liked to have company. But Mrs. Wren did not care for that at all. A small cottage was her choice. After making us believe that she liked the 40 one under the garage roof, she came with a stick about three inches long and flitted about with it.

Mr. Wren had already put some nesting material into the apartment house. But hard as he tried, by singing and by soft chatter, which I suppose was coaxing, and by frequent visits to the apartment house, he could not win her over. Her mind was made up, and it must be—what? Well, it was the small house in the pear tree. When Mr. Wren saw that he couldn’t have his way, why, of course, that small house became his choice too.

Each of these pairs of wrens raised some babies. But with all their work and family cares, and the English sparrows to bother them at times, they were always a happy company. They could sing just as beautifully when carrying twigs or worms or bugs as at any other time. Their happy music made a continuous open-air concert. And their manners, whether at work or at play, were so entertaining that I could not bear to take my eyes off them.

This went on through late April and part of May. One morning the wrens were all excited. Two of their little ones were on the ground. Our kitty had been tethered to a hitching weight; but now, fearing one of the little wrens might fly near her, I locked her up. The parents were coaxing their little birds over toward the vacant lot where the thornapple bushes are. These bushes start even with the ground and are so dense, and have such long, sharp needles, 41 that a cat would get her eyes scratched out if she tried to go in. I shall always plant thornapple bushes wherever I may live, especially for the protection of young birds. And I shall plant several close together, so as to make a dense thicket. These bushes will provide food for birds, as well as protection.

The way these wrens coaxed their little ones to follow was very clever. They would go near them; then walk away trailing their wings. This made a soft, rustling, coaxing sound. But it was over an hour before they succeeded in getting the little ones where they wanted them. They had to come back to them again and again and keep up the coaxing. I was glad when they finally had them safe under those thorny branches, where I could not see them any more for the leaves.

By this time two more young were ready to leave the house. One was already on the little porch, the other peered out of the entrance. These were wiser than the first two. Instead of going to the ground, one flew to the kitchen roof which was near and almost even with the wren house. It was a flat roof covered with gravel. Pretty soon the second baby also flew to the roof.

It must indeed be a wonderful event in the life of a bird when first he steps out of the crowded little home and looks around him at the big outdoors. Then what courage it must take to venture on his 42 wings! He has fluttered them a few times over the nest, of course, but that is not to be compared with just bouncing out into the air and trusting to his wings to bear him up.

The two stayed on the kitchen roof all the rest of the day. I put a potted plant out there for them to perch on. In the morning one of the baby wrens perched for a little while on a window sill, but Father Wren coaxed him back to the roof. I put several more plants out on the roof in order that the fledglings might exercise their wings and strengthen them for the long flight they would have to make to the nearest tree. After a while they did fly from plant to plant. In this way they spent the rest of the day and they liked it so well that they stayed another day, and perhaps longer.

I was absent from home a few days. On my return the apartment house was empty of baby birds; so also was the small house in the pear tree. The wrens were pulling out the feathers and grasses of the first nestings, and getting ready to nest again. One pair had already begun nesting in an unoccupied apartment. Can anyone imagine the hustle and bustle of those busy wrens, cleaning house and nesting at the same time, and the joy with which they did it?

The one-room house in the pear tree was so made that the front could be raised after turning a small screw-eye on the side. This made cleaning it easy.

Now, aside from furnishing their rooms all over again, these wrens had their babies to care for. But they seemed the happier the more work they had to do. They were just bubbling over with happiness all the time; and they made everyone about them happy, too.

I should think everybody would put out wren houses and get these jolly little fellows to live near them. Wrens are not particular whether they live on a porch, in a city yard, or on a farm. They are just as happy in one place as another, as long as they have a safe little home; and they will rid a place of bugs and flies and other unpleasant things.

So cheery was that summer with those wrens around me, that I hope always to have them as my neighbors.

A BABY WREN ON THE WINDOW SILL

BLUEBIRDS ARE GREAT HELPERS IN A GARDEN (See page 33)

One day in early April I was in the ravine getting hepaticas. Before I knew it I was near the boy’s house again. His mother called to me from her garden.

“The boy is at home now,” she said; “maybe you would like to see him at work.”

I thanked her, and went with her to the little shop. There beside his work bench stood a boy about twelve or thirteen years old. He was painting the wren house a dark green. The bluebird house was finished, ready to put up.

I told him I had put up my bird houses long ago, and that the bluebirds had been house hunting for some weeks. He said that there were so many English sparrows around his place that he feared they would nest in his houses if he put them out early. But he had just learned of a way to keep the sparrows from nesting in bluebird houses. He said his manual training teacher had advised him to mount his houses for wrens and bluebirds only about eight feet from the ground, since the English sparrows seldom nest lower than ten feet from the ground, and will not be likely to take a house that is lower.

The boy put up the bluebird house while I was there, on a young maple that afforded plenty of shade. His bluebirds were house hunting too, and visited the house right away.

I told him about the tin sheeting to keep cats and squirrels down. He said he had been using tangle-foot, the sticky stuff that is sometimes put on trees to keep bugs down. But he said that cats and squirrels didn’t mind climbing over it, and he was going to try the tin.

I fear that the boy was not wise in delaying so 46 long to put up his bird houses. When I saw him again, in mid-April, he said that one pair of bluebirds had nested in a house that he had intended for chickadees; that another pair were in an old hollow tree; and that a pair of wrens were visiting the new bluebird house.

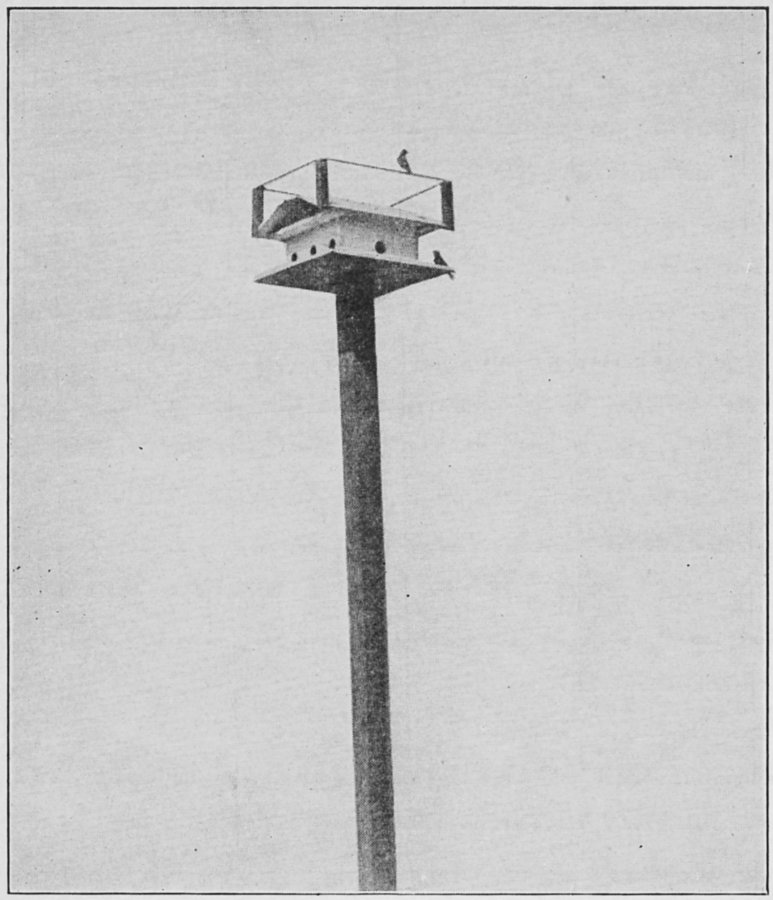

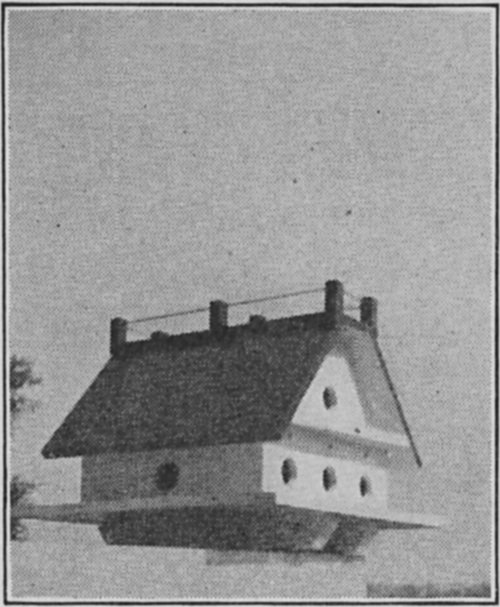

Two of his other houses were for woodpeckers, and a beautiful new one for purple martins already had some tenants.

“It is two years now that the first martin house has been up, and yet I have never had any martins to stay!” said the boy. “They would come, go into the house and twitter, and then fly away.”

He began talking again about his manual training teacher: how she called one day, and told him that the martin house was mounted too low, and too near trees; that martins want to be fifty feet away from a tree or building, and sixteen feet up from the ground; also, that it pleases martins to have openings near the ceiling of their rooms so they can have a change of air.

I remarked that this ventilation would make their rooms more comfortable.

“Yes,” said the boy; “and this new martin house is made according to teacher’s directions.”

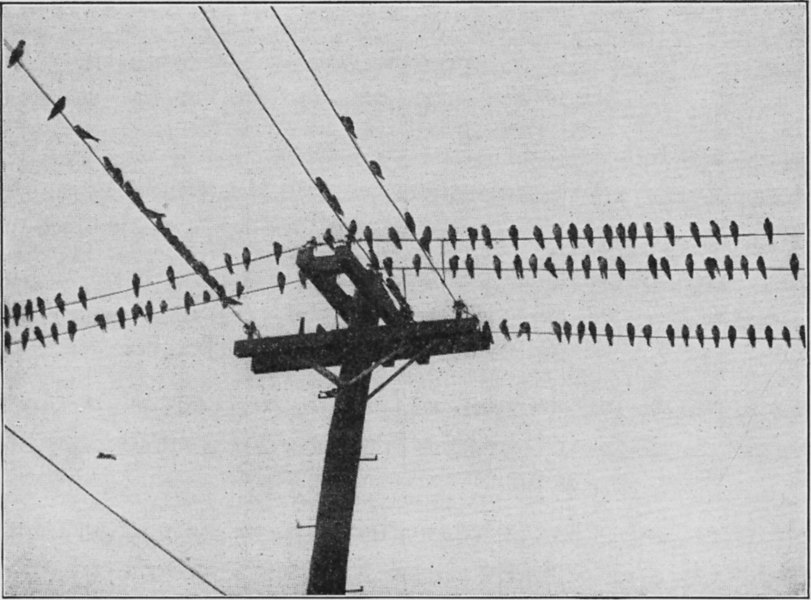

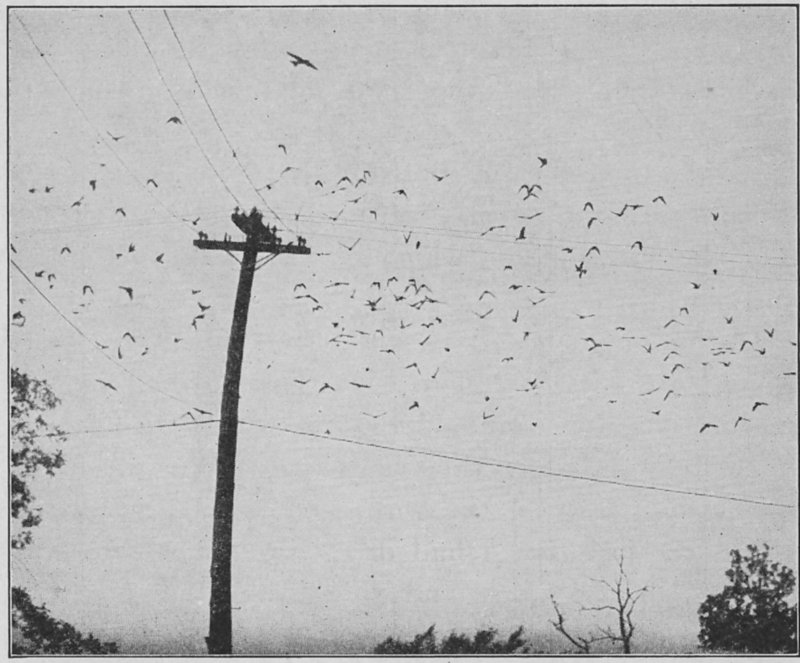

As we stood there, martins were flying about, twittering, singing, perching on the telephone wires near by and on the roof and the porches of their house. The pole had hinges so that the house could 47 be brought down and cleaned, when necessary, or closed.

One lovely June day found me again at the boy’s home. I remarked the large number of young robins on the lawn.

“The young have just left their nests in that tree,” answered the boy, pointing into a big cherry tree. “Robins have nested in that tree every year since I can remember.”

I guessed that perhaps the cherries were the attraction.

“Well,” he said, “we think birds earn all the cherries they eat; we never pick those on the top branches at all, but leave them for the birds.”

During that visit the boy showed me several bird homes. First he apologized for doing it. “Every bird home is a secret between mother and me,” he said; then added, “but I know I can trust you.”

One of these little homes belonged to bluebirds. The others belonged to the flicker, the wood thrush, and the killdeer.

We walked slowly and talked low, as we went from one place to another. Loud talk and running frighten birds. And to go very near to a bird nest is harmful because, every time the mother is frightened away, the eggs or young are liable to get chilled if the weather is cool. If hot, and the nest is exposed to the sun, the eggs or young are liable to get overheated.

The boy told me of a marsh hawk’s nest which a gentleman came to photograph. He said that this gentleman brought a lad along to hold his hat over the young to shield them from the sun, during the mother’s absence. The two were there only about ten minutes. But evidently that boy told other boys; for soon the nest was being visited at all times of day. At every visit, the mother flew away, and in a few days all the young were dead.

I remarked that photographing nests should be done with the greatest care; that if any screening foliage was pushed aside, it should be replaced, and the nest left just as the mother bird had planned it. It is indeed fortunate that bird photography is so difficult that only few people attempt it. Exposing a nest to the camera is very apt to result in disaster unless it is done by one who has the highest interests of birds at heart.

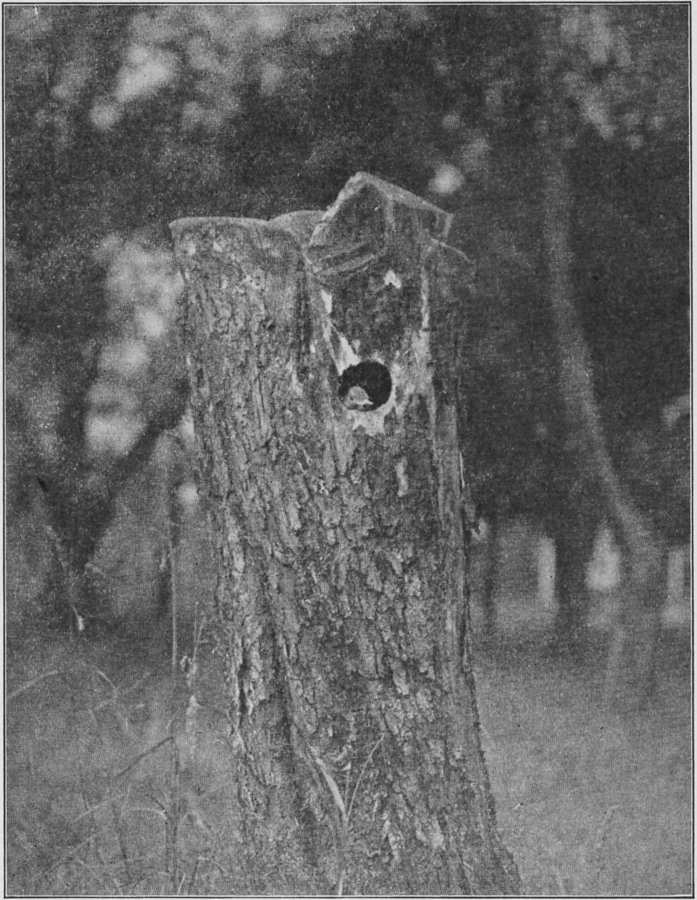

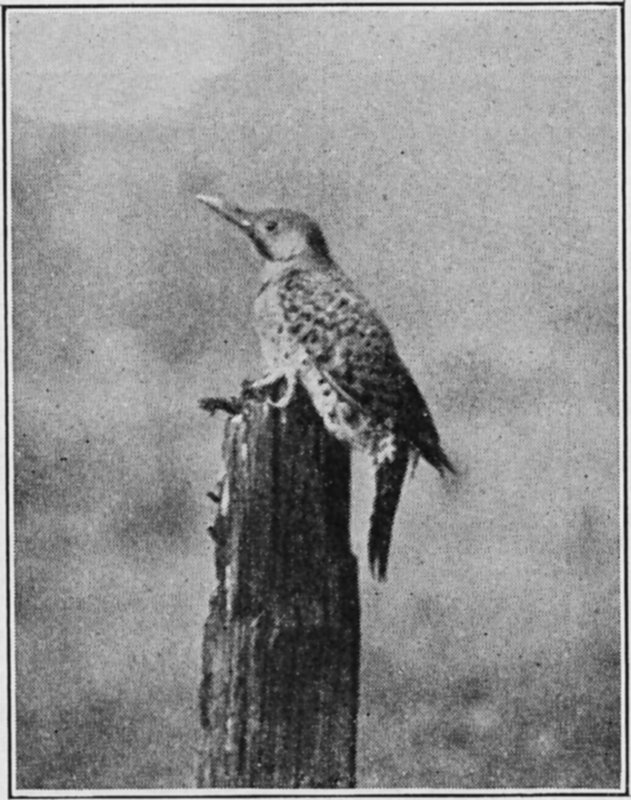

The flickers had their home in a stump of a tree. The entrance was so low I had to stoop in order to look in; but the nest was down deep, out of sight. Whenever Father or Mother Flicker came with food they called softly, “Ye quit! ye quit!” Then the babies could be heard making a hissing sound. Sometimes when the parents were gone longer than usual, a baby flicker could be seen taking a peep at the outside world.

BABY FLICKER PEEPS AT THE OUTSIDE WORLD

One day during the previous spring while walking along the ravine I had seen three of these large brown birds, and had learned their name from hearing them sing, “Flicka flicka flicka.” It is easy to get acquainted 50 with birds who are named after their song. One of these birds on that spring day was constantly spreading his wings and his tail before the others, as if he wanted to show the beautiful yellow feathers underneath. Because of these yellow feathers the flicker is also called golden-winged woodpecker. Nearly all birds have a scolding word. When the flicker wants to scold he says, “Queer,” as plainly as a person can say it.

Of course, we never went near enough to any bird’s nest to frighten the brooding birds, nor did we stay long enough to keep the parents from feeding their young. We always found a convenient place fifty feet or more away, and through our field glasses watched the birds without annoying them.

I had long known the wood thrush by his yodeling song. It usually came out of the thickets and tangles in the ravine back of our place, so the singer could not easily be seen. At sunrise and sunset, the music of the thrushes, singing and answering one another, was like bells calling to prayer. From early May until mid-July I always wanted to be out mornings and evenings to attend the matins and the vespers of the wood thrushes.

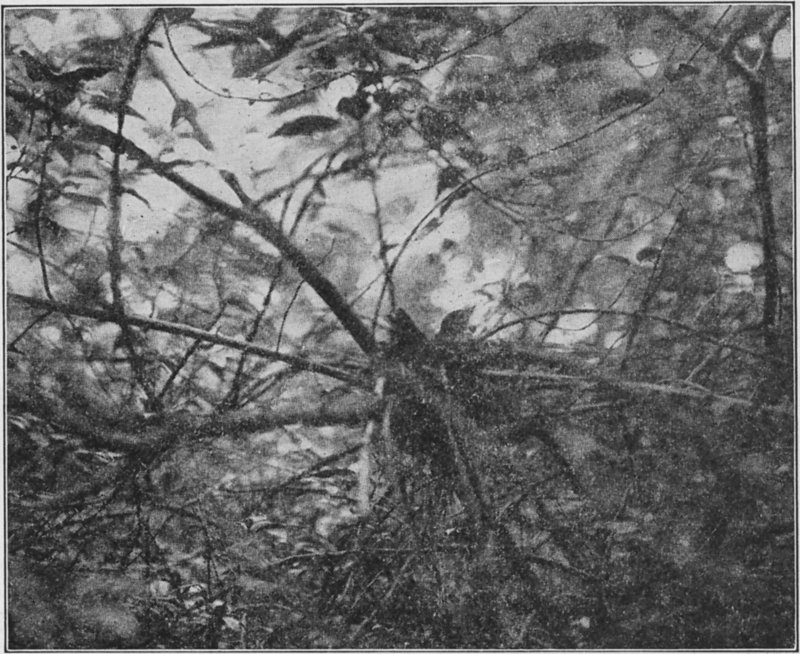

Mrs. Wood Thrush tried hard to hide her nest; it was completely surrounded by thornbushes. “Wit-a-wit-a-wit,” said her mate as we went near; then he came out of his hiding place. He had a brown back and a white and brown speckled front just like 51 Mrs. Wood Thrush, who sat serene on her nest all this time. She was trusting in something to protect her fully; whether it was her brave companion, or those bushes bristling with thorns that surrounded her nest, I do not know. Maybe she thought we didn’t see her at all. We pretended not to see her.

MRS. WOOD THRUSH ON HER NEST

Always, when I find a nest, I turn away and try to keep the birds from knowing they have been discovered. I look out of the corners of my eyes, and go away humming a tune. After a while I return and walk near by, again singing the same tune. 52 I do this as many times as I can during a day or two. Before long the birds seem to know that the person who comes singing that tune has never harmed them. They remain quiet when I am near, and this affords opportunity to observe them more closely.

Some bluejays were flitting about. Bluejays are everywhere, and at all times of the year. The bluejay is that big blue and white bird with handsome crest. In early spring he sings some pleasing notes, but in autumn and winter he is just noisy. Now he was very still. I could just see Mrs. Bluejay’s head between two branches of a poplar tree. She had a nest there, for there were tell-tale twigs hanging over on both sides. Mr. Bluejay did not want anybody to find her, nor the nest. This was why he kept so still.

The boy had scattered some peanuts on a bald spot in the yard. I asked why he did this during the summer time.

“It keeps the chickadees and woodpeckers coming here all summer,” said he.

As we sat there a bluejay came for a peanut and went under a tree with it. There he punched a hole in the ground with his bill and poked in the nut. Then he went to a currant bush and got a leaf. Returning to the spot where he had buried the peanut, he patted the leaf neatly over it.

A brown and white bird about as big as a robin flew overhead singing, “Killdeer killdeer” as loud and as fast as he could.

A KILLDEER’S NEST IN A POTATO FIELD

“There goes a killdeer,” said the boy.

So the killdeer is another bird that is named after his song! How easy it would be to know birds if all were named after their song, like the chickadees and the killdeers and the flickers, or after their colors, like the bluebirds, or after their actions, like the woodpeckers!

The boy’s father had found a killdeer’s nest in a potato field when he was plowing. We went to see that, too. It was in a patch of ground overgrown with weeds because the man had kindly plowed around it. Mother Killdeer sat dutifully on the nest while Father Killdeer guarded the premises and told 54 us by his various shrieks and somersaults that he wished we would not go near enough to disturb her.

On the farm that day I saw the golden-throated meadowlark. He is another yodeler. His favorite tune is:

“Le-o- lee-o-loo”

His songs ring so clear and flute-like that I can hear him away over at our place. He is a brown bob-tailed bird. Over a beautiful yellow front he has a black band, pointing down in the middle, V-shaped. A large company of these birds were in the meadow, happy as larks; so they are well named meadowlarks.

But think of a dear little bird and such a sweet singer as the song sparrow, bearing the same name as the odious English sparrow! It seems unjust, and in this the boy agreed with me. We got to talking about the song sparrow because one was on a fence post near by, singing over and over this lively ditty:

“Twee twee twee/twe-e\twe-e\\jejejejejejejejeje jay.”

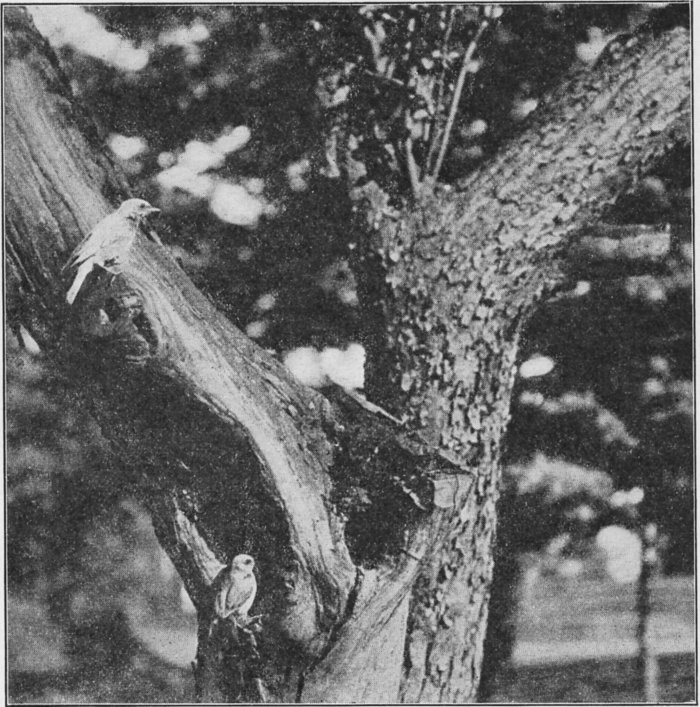

THE BLUEBIRDS IN THEIR PRIMITIVE HOME

The bluebirds’ home that the boy had mentioned at the beginning of my visit was in a hole of an apple tree. By standing on tiptoe I could look in and see four light-blue eggs lying on a nest of grasses that looked like a cunning little basket. It was a hot day, too hot for Mother Bluebird to stay in that hollow tree all the time. She was out playing tag with Mr. Bluebird. Perhaps she thought the hot air would keep her eggs warm. After she went in again he visited her often with food. Before going after 56 more he usually perched on a little knob just above the entrance and sang. Sometimes she came out on the ledge to listen. It was a winsome sight to see the bluebirds in their primitive home.

This was the bluebirds’ second nesting on the farm. Their first one had been destroyed by the English sparrows. The boy said he had tried in every way to help the bluebirds, and that, whenever he saw any sparrows near, he gave a sharp whistle—his confidential whistle, he called it—and that Mrs. Bluebird got so she understood what it meant; that as soon as she heard it she would come up on the ledge and call, “Dear, dear-dear.” Immediately Mr. Bluebird would appear and drive the intruders away.

These bluebirds were also annoyed by a red squirrel who climbed the trees in the orchard and peered into the nest holes. Mr. Bluebird dashed for him whenever he saw him, especially if he found him near the home tree. Sometimes both the bluebirds chased the red squirrel, who would run off barking like a little dog.

The boy had seen how I put out strings and cotton and chicken feathers, for the birds’ nestings, and he had fixed up a “store”—as he called it—on a tree, where they could “buy without money.” Every little while a goldfinch came and got some string. Always on coming he sang out, “Perchikatee,” as if to say, “By your leave.” Downy woodpeckers, chickadees, and nuthatches were there at this time of 57 the year, although ordinarily they are seen only in winter and early spring.

EVERY LITTLE WHILE A GOLDFINCH CAME TO THE “STORE” TREE AND GOT SOME STRING

The boy said it was the ravine, with its trees and thickets and tangles, that attracted so many birds. He was always praising that ravine. He thought so much of it that he had asked the neighbors not to throw rubbish down there, and not to disturb the underbrush, which shelters so many birds. He had also asked them please to keep their cats indoors at 58 night, because so many birds had nests and helpless little ones on the ground, or in low bushes.

“Mother put me up to that,” he said; and added, “we are trying to keep that ravine as a sanctuary for birds, where they and their little ones can be safe.”

Another thing that attracted birds to that place was a mulberry tree. Though only two years old, it was bearing fruit and was visited by robins, orioles, thrashers, and redheaded woodpeckers.

The boy had so many kinds of birds never seen near our place that I began to wish I, too, could live on a farm and have so many more of these charming neighbors.

A storm came up. Soon the shallow places in a cornfield near by were turned into puddles. The baby martins that had been lounging on the porch went inside. The old ones came flying home in a hurry. We went to the garden house, which the boy had fitted up as a workshop because he didn’t like to deprive his mother any longer of her little storeroom. When it stopped raining the sun came out and the clean earth fairly glistened. A flock of robins came to hunt for worms in the drenched field. Some bathed in the puddles. It was amusing to watch them chase one away if he stayed in long.

As we were enjoying the robins, the boy’s mother called out: “Come here, you bird people, and see what has happened.” She took us to the living room 59 and told us to listen at the chimney. A rasping twitter came from within.

“It must be those chimney swallows,” guessed the boy.

He stepped upon a chair and took off the chimney cap. There, scrambling around in soot, were some black looking birds.

“One, two, three, four,” he counted, as he reached in and handed them out on a newspaper.

Three were young birds, and one was an adult bird with long wings. Their nest was also there. The heavy rain had loosened it and made it fall.

The little ones screeched in chorus, and tried constantly to get hold of something with their claws. The older bird gave no sound at all. She seemed to be hurt. We called her the mother.

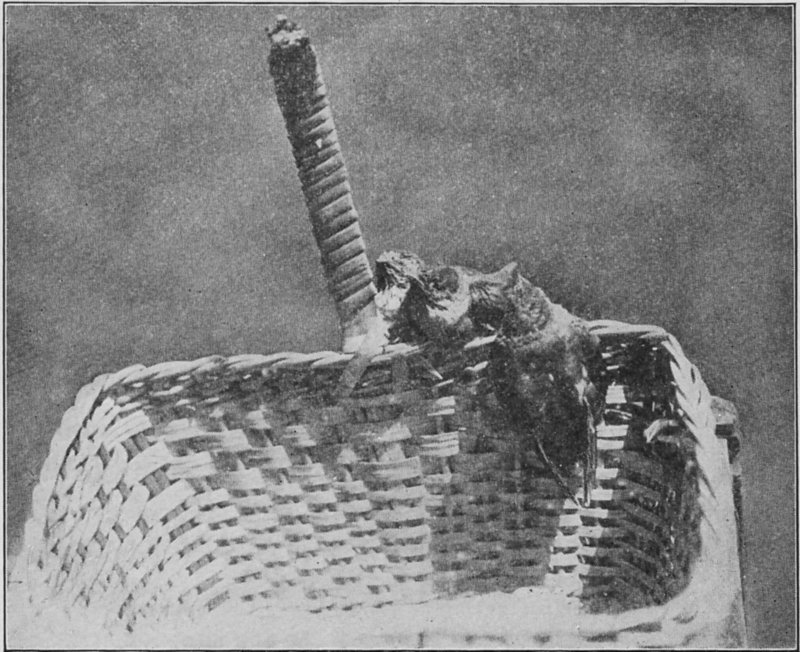

The lady looked at their little nest. Then she went and fetched a basket, and, as soon as the birds were removed to it, they began to clamber up the sides. When they got to the top, where they could hang at full length, they stopped their screeching. Only now and then they still gave a rasping sound. Perhaps they were hungry, and scolded because nobody brought them any food. Some crossed over the rim of the basket and tried the other side.

I stayed there the rest of the afternoon. Every ten or fifteen minutes the little birds gave a call, like, “Gitse gitse.” Thinking that they must be almost choked with the soot, I tried to give them 60 water, but they would not open their bills. I forced them open with a manicure stick, and gave them a drop at a time. They swallowed it when it was dropped far down in their throats; otherwise they would jerk their heads and throw it out.

I also moistened a cracker with some egg yolk, and mixed into it about fifty flies out of the flytrap; then tried to feed the birds with the little stick. By prying up their upper mandible I got some flies down each bird’s throat. The lower mandible was very soft and would not bear handling.

THE CHIMNEY SWIFTS’ TEMPORARY HOME

I became so attached to these birds, I hated to leave them, but the time came for me to go home. The boy and his mother seemed distressed at the prospect of having birds as boarders. There was canning to do, besides cooking for extra farm hands; and Laddie had to help his father with the haying,—so his mother said.

I offered to take the birds and do the best I could with them, if the lad was willing. He was; so I took the birds and the nest with me in the little basket, which was their temporary home.

THE FLICKER IS ALSO CALLED GOLDEN-WINGED WOODPECKER

CHIMNEY SWIFTS’ NEST

The correct name of these birds whose home life was so rudely broken up is chimney swift. According to the bird books, they have been known to fly a thousand miles in a day, and they live in chimneys. Could any name fit them better? Chimney swifts are sometimes called swallows, probably because they resemble them somewhat, and twitter like swallows. But they are not swallows at all.

I thought if the birds could have their nest near them, it would seem more like home to them. It was a tiny nest, a bracket made of twigs which were woven together basket fashion and tightly glued. I have preserved it as an art treasure. On each side is a flat, gluey extension. Wetting this extension made it sticky; but it would not stick to the rough 63 surface of the small basket. I laid it on the smooth surface inside a peach basket and put weights on it. When it became dry, the nest was stuck fast.

ONE OF THESE SWIFT BABIES WAS PUT TO REST IN THE NEST, BUT HE DID NOT STAY THERE LONG

Then I transferred the swifts from the small basket, which had been their temporary home, to the peach basket. They perched around the nest. One of these babies was put to rest in the nest, but he did not stay there long. They all clambered up to the edge and from time to time they changed places, sometimes crossing over the edge of the basket from one side to the other.

It was fortunate that this happened during my vacation, because the care of a baby bird demands much time. He has to be fed regularly and often. Having several birds to feed is about enough to take up all one’s time.

If they only had opened their bills when they were hungry, it would have been much easier to feed these swifts. Their very short but wide bills had to be pried open every time and the food poked down their throats. I tried to feed them every fifteen or twenty minutes. It took so long to feed each one, that usually, by the time I had finished with number four, it was necessary to begin feeding number one again.

The food I gave them was bread soaked in warm milk, with plenty of flies mixed in. For a change I mixed the bread with a raw yolk. I gave them warm water occasionally. It seemed to me they needed it after having come through that mass of soot.

At the end of the first day the young were as chipper and bright as any young birds. Instead of screeching they began to twitter, “Gitse gitse.” The mother was very still. She did not seem to care for her babies at all, and did not go near to keep them warm. She just hung in the one position. Several times she tried to fly, but she could only fly a few feet; then she fell to the floor.

During the second day the young seemed to be doing well. They preened themselves, and their 65 blackish breasts were changed to gray. It was a cool day, and I set the basket where the sun would shine on the birds. They fluffed their feathers as if they enjoyed the warmth. Once in a while one tried to fly, but he always fluttered to the ground and had to be brought back. The mother tried her wings again and again. She got so she could fly a little farther at every attempt, before she went to the ground. At about five o’clock she flew far enough to get out of sight.

All the next day I kept the peach basket with these swifts in it outdoors, hoping the mother would return and feed them. But she did not return.

On the following day these birds began to look feeble. I went to the telephone and called up a gentleman[1] who is an authority on birds, and asked him what I should do. He said the main thing was to keep the birds evenly warm; that more young birds die from chill than from hunger. To revive them he said I should put a few drops of whiskey in a glass of water and give them each a few drops; then I should try to get them some gnats, or a grub from the garden, mince it well, and feed it to them. Flies, he said, had not much nourishment in them.

On returning I found that two of the little birds had died. I determined to try hard to save the remaining one. It was impossible to get whiskey 66 because I live in a temperance town. I gave the little bird a weak solution of baking soda because he had a big lump in his craw. Then I wrapped him in a silken scarf, and warmed him beside the cook stove as I have seen baby chicks revived when they have been chilled by a sudden rain. The lump disappeared. He brightened up. I could find no grubs; but a few grasshoppers, some ant larvæ, and several juicy green cabbage worms were food enough for the rest of that day. I kept the bird in his wrappings all day, but fixed it so he could clamber on to the basket. At night I put him away warm and snug, and seemingly happy. The first sound I heard the next morning was “Gitse gitse.”

The little bird was ready for a meal. From an ant hill near by I got more ant larvæ, something which all young birds like. For the first time now he swallowed food just as soon as it got inside his bill. Up to this time he had jerked it out unless it was poked down. But he still refused to open his bill.

He did not care for the nest and never would stay on it. So I fixed him again in the little basket where he would be more snug. I had lined it with cotton batting and woolen cloth so his breast would be against a soft, warm surface. I also kept him at an even temperature, and fed him regularly. The little basket was on my work table. He seemed to enjoy being near me and being talked to. Sometimes he flew over on my shoulder. I fed him more cabbage 67 worms and grasshoppers, and also gave him water occasionally.

I could not forgive myself to think I hadn’t asked for advice sooner. I felt sure that, had I done so the first day I took charge of these birds, and then followed instructions, the two would not have died.

Again at the close of the day Baby Swift was put away in his warm wrappings. In the morning I did not hear the usual, “Gitse gitse.” Baby Swift had gone to the bird heaven.

It had been a big undertaking to adopt those homeless birds; but I am glad for several reasons that I did it.

First, I am glad that I helped them in their trouble.

Second, I am glad I relieved the boy and his busy mother of caring for them.

Third, I am glad because I have since read in the bird books that the chimney swift is a very useful bird; that he feeds wholly on troublesome insects.

Fourth, I am glad because it gave me opportunity to get acquainted with one more bird. I consider that something worth while.

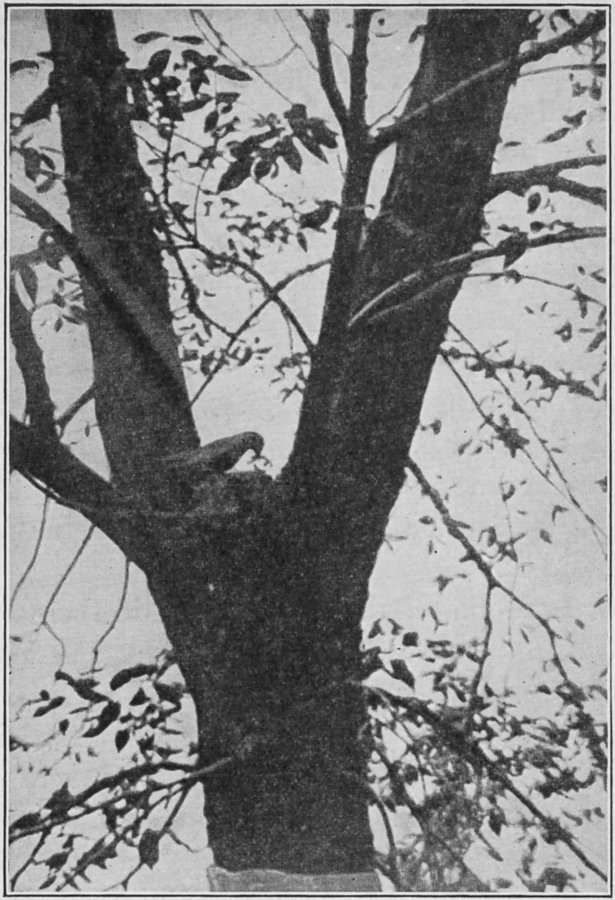

A ROBIN’S NEST

One day, on looking up into a tree in the vacant lot, what should I see there? A mother robin just dropping a worm into her baby’s open beak.

The nest was right in the crotch where the trunk 69 forks into two main branches. So many robins’ nests are blown off the branches by the wind, or washed off by heavy rains, that I was glad to see this nest firmly saddled on that strong trunk. But a second thought told me that it was easy for cats and squirrels to get at, so I studied how to make it safe.

All the tin sheeting had been used up; but I knew where there was some old stove pipe. A kind neighbor ripped it open. One piece was not wide enough to go around the tree, so I had to use two. Mrs. Cotton, who had again become my neighbor, having built a bungalow on one of the vacant lots, came to help me. She said it wasn’t good for the tree to drive nails into it, and fetched some wire. Meanwhile, I got the stepladder; for the sheeting must be high enough so that cats and squirrels cannot jump from the ground to the trunk above it. We used only two small nails, to keep the wires from slipping.

Of course, the robins scolded while we were doing this. They never liked to have anybody near their tree.

After a week the young ones were sitting on the edge of the nest. I knew then that they would soon leave it, and I began to keep a close watch on them, and on the cats of the neighborhood.

If all cats belonged to people, and had to be kept on their own premises, little birds would be much 70 safer. As it is, cats may roam wherever they please. They can crouch in tall grasses, flower beds, shrubs, and other places, ready to pounce on any bird that comes near enough. Homeless cats who have to hunt their living are the greatest menace to birds, especially to young birds who are not yet wise to the dangers that surround them. Now who is to blame? Surely not the cats. Instead of continually berating the cats, let the friends of birds secure laws to license cats, to compel people to keep their cats on their own premises, to punish people for putting cats astray, and to put homeless cats out of their misery.

One June day, while walking along the ravine, I saw three robins on the ground. I went to the tree to see if the young had all left the nest, and found that one was still there. He looked down, as if he would like to go to join his brothers; but he seemed to be afraid to leave the safe little home. The parents brought food to him and also to those on the ground. Whenever the parents went to the one on the nest, they urged him to come over to some of the near branches; but he stayed on the nest as if glued to it. Finally, one of the parents got behind him and just politely pushed him off. He spread his wings to fly, but fluttered to the ground. Instead of continuing my walk that morning I stayed with the robins. About a hundred feet away I could see them well with my field glasses. My neighbor, 71 Mrs. Cotton, was just as much interested in these birds as I was. They could not fly well yet. Between us we saw to it that no harm befell them that day.

Towards evening the robins also sought the protection of those bristly thornapple bushes. One by one they coaxed the young in that direction.

During that night a great storm came up of lightning and thunder and rain. I was sorry for the young robins, but had no doubt that their parents shielded them. I have seen a mother bird sit faithfully on the nest when the rain was pelting her mercilessly. Mother love knows no discomforts.

I think all birds enjoy a good shower; they always sing joyously as soon as it clears again, and sometimes while it is still raining. Some also enjoy a shower bath. Sometimes they finish it with a ducking in the basin. Those that do not care for the shower usually know where to find a comfortable place during a heavy downpour. On such occasions, I have seen them take refuge in trees, close to the trunk where it is steady and where the foliage is dense over them. And I have seen them go for shelter under rail fences, such as there are in the country, where the rails are broad enough to protect a little bird. I have also seen birds come out from under a corn-crib after a rain, so I presume they had gone under it for shelter.

After the robins had left their nest I took the sheeting off the tree. It is said that the bark of a 72 tree is its lungs through which it breathes. I want all the trees around me to breathe deeply of the precious air, so I try always to save the bark. It is much easier to take off the wires than it is to take nails out of a tree. Already some insects had made nests and cocoons under this sheeting.

My way of getting acquainted with birds was by keeping a notebook. In it I wrote everything I saw any bird do: what he ate, how he sang, what he looked like, where he was generally seen, etc. I always watched a bird as long as it stayed in sight. When it left I observed its flight and its shape. Then I looked at the colored pictures in my bird books, to see if I could find a bird similar to mine. If I did find him, then I read all about him to see whether that bird ate the kind of food, and acted, and flew, and sang, in the way my strange bird did. If he did, then I knew I had made the acquaintance of a new bird.

For instance, I had written about one bird:

“Rather plump, head pointed, bill long. Head and back olive. Front yellow. Wings dark with white bars. Tail brown with dark marks. Is on the fence getting strings. Also visits the basin. Never sings. Likes bread crumbs. Nearly as large as robin.”

Sometimes there came with this bird a beautiful black and orange bird. In a little pocket guide I found both these birds pictured as mates. They were the Baltimore orioles. She was the bird I had 73 described in my notebook. While she was getting strings, her mate was usually up in a tree somewhere near, singing:

“Hee\ho/hee, hee\ho ho/hee.”

It was no wonder that the orioles needed so many strings. They made a baglike nest on the tip end of a branch in Mrs. Cotton’s elm. The wind used to swing that nest like a hammock. I often thought how nice it must be for those baby orioles to be rocked by the wind and to have such a fine musician for their father.

Mrs. Cotton was keeping her cat housed during those days. Moreover, she threw bread out on her lawn every day for any birds that might want it. The orioles were among the birds that went there; they preferred graham or entire wheat bread to white bread.

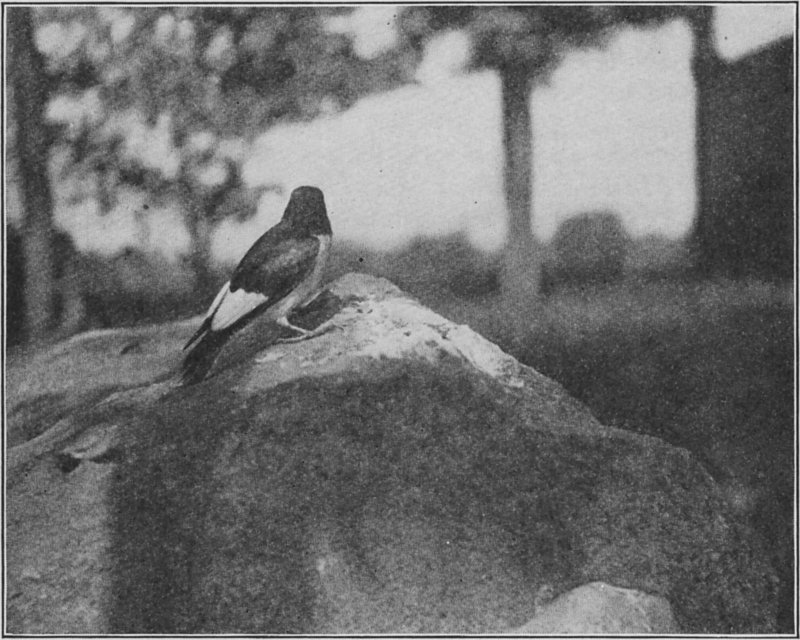

Other birds that came to my yard were the brown thrasher, the goldfinch, and the redheaded woodpecker. They had their nests along the ravine.

The redheaded woodpeckers’ home was in a hole of an old tree near the ravine. Their call was a guttural “Chr-r-r,” which was pleasant to hear. Near the nest tree was a big stone which they used as a convenient perch. The woodpecker babies did not have the showy red head and neck of the parents; theirs were of a rusty color, and the white on their wings was barred with black. During the summer, Father Woodpecker often brought the babies to the food station. They could help themselves pretty well 74 to suet; but the peanuts were a puzzle to them. They just pecked into the shell and tried to eat that. Usually, before the babies arrived, the father came and perched on some high point and looked all around. If all was to his liking, he sounded his rattling tattoo. The babies always came so promptly that it was evident he had hidden them somewhere near, probably with orders to await his signal before venturing farther.

NEAR THE NEST TREE WAS A BIG STONE WHICH THE REDHEADED WOODPECKER USED AS A PERCH

I think the brown thrasher must have had a large family; he used to tear off pieces of bread and carry 75 them away from the bird table. Once he carried off a piece of cheese that kept him trailing near the ground, it was so heavy. A blackbird followed and tried to take it, but the thrasher got away from him.

A queer thing about the brown thrasher is his song. It is made up of real words and sentences, and he sings everything twice or more times. If you should ever hear a big brown bird, with a long reddish tail and speckled breast, sing, “Beverly Beverly,” “Peter Peter,” “Tell it to me! Tell it to me!” “Come here! Come here!” and such things, then you have heard the brown thrasher. If you will look high enough you can almost surely see him too, in the top of a high tree. He loves to be seen as well as heard.

Mrs. Brown Thrasher looked just like her mate. She had hidden her nest so well that I did not find it until it was empty. It was in a dense thicket. I knew it was hers because she was still near. “Io-it! io-it!” she scolded, until I went away. One little baby thrasher was on a branch of the thicket. The mother was guarding him.

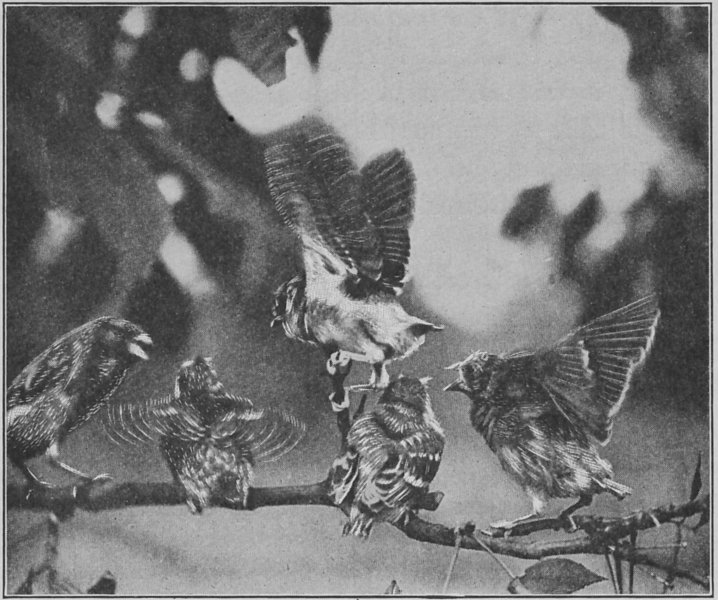

The goldfinches were very late with their housekeeping. In July they were still gathering strings and cotton for their nesting. They are just as polite and gentle as the chickadees. Their name fits so well that anybody who sees these yellow birds, just like canaries with black wings and tail, ought to know them at once. Their song usually starts with 76 “Sweet sweet sweet,” and the rest is a regular canary song. They are sometimes called wild canaries.

EACH LITTLE GOLDFINCH CALLED AS LOUD AS HE COULD

The young goldfinches loved to sit on the edge of their nest as soon as they were old enough. As they sat there they chattered to each other, “Ze bebe, ze bebe,” and fluttered their wings a great deal. When I found their nest I was surprised that I hadn’t seen it before; it was low on a buckeye.

When the young goldfinches left their nest it seemed as if they wanted to get acquainted with people. They came down on the lowest branches, 77 and quite near the house. One alighted on the clothesline. Whenever Father or Mother came with food there was the greatest fluttering of wings. Each one called, “Ze bebe ze bebe,” as loud as he could, and opened wide his bill to catch what the parents tossed or squirted out to him. It was no living, squirming thing, but a pulpy mass.

The young were yellow in front, olive on the back, and they had black wings with brown and white bars. The black tail was edged with white.

Goldfinches like sunflower seeds. But the main reason why they are so useful and so well liked is that they eat large quantities of thistle seeds and dandelion seeds.

When cold weather came the parent goldfinches were no longer so beautifully yellow, for they had put on their gray autumn coats.

A YOUNG GOLDFINCH ALIGHTED ON THE CLOTHESLINE

THIS MARTIN SCOUT BROUGHT A LADY WITH HIM

The purple martins like a house with many rooms, so they can live together in a large company. Since the martins belong to the swallow family, to call them purple swallows would, it seems to me, be more informing.

My friend who had sent me the wren apartment 79 house was so pleased with its success that he sent me also a martin house. It is four stories high and has twenty-six rooms. Around each story are porches, some of them several inches wide.

It pleases birds to have their houses look, before they occupy them, as if they had been out in all sorts of weather. So, for several weeks before this martin house was set up, it lay out in the yard to be rained and snowed on.

One cold March day a purple bird came in at my window. He perched on picture frames, twittered a little, and went out again. According to the bird books, my little visitor was a purple martin. Maybe he had seen the martin house on the lawn, and came to ask me to put it up. Anyway, the next day it was mounted in the farthest corner of the garden. For, according to the directions that came with the house, martins want their houses to be fifty feet away from any building or tree, and on a pole at least sixteen feet high.