[Pg 1]

PLANS AND SUGGESTIONS

BY A. F. HUNTER

PUBLISHED BY

F. W. BIRD & SON

Established 1817

Mills and Main Office

EAST WALPOLE, MASS., U.S.A.

| Branch Offices | ||

| NEW YORK | ||

| CHICAGO | ||

| WASHINGTON | ||

| HAMILTON, ONT. | Canadian Factory at | |

| WINNIPEG, MAN. | HAMILTON, ONT. |

COPYRIGHT, 1905, F. W. BIRD & SON,

EAST WALPOLE, MASS.

[Pg 2]

The very cordial appreciation which has met the first edition of our book, “Practical Farm Buildings,” makes it seem wise to prepare a larger and more complete book, and we hope you will find some of these plans and suggestions adapted for your own particular requirements.

Farm-building plans are as variable, almost, as is the individuality of those building and using them, and in making this selection, we have been guided by the practical merits of the designs, including only such as have proved their value by constant use on the farm. In poultry buildings it has been our special purpose to present plans which illustrate the marked tendency of recent years, which has been to open up the houses to sunshine and fresh air; a tendency which makes conditions more wholesome and promotes the good health and greater profitableness of the flocks.

Our editor, Mr. Hunter, wishes here to fully acknowledge his indebtedness to Bulletin No. 16 of the Cornell Reading Course for Farmers, entitled, “Building Poultry Houses,” also Farmers’ Bulletin No. 141 of the U. S. Department of Agriculture, entitled, “Poultry Raising on the Farm,” from which he borrows many of the hints and suggestions here given. Some of the poultry plans are taken, or adapted, from several poultry periodicals and Experiment Station Bulletins, and for their kind courtesy our thanks are tendered.

East Walpole, Mass., U. S. A.

[Pg 3]

Practical Farm Buildings

Farmers’ Bulletin, No. 141, says: “Poultry houses need not be elaborate in their fittings or expensive in construction. There are certain conditions, however, which should be insisted upon in all cases. In the first place, the house should be located upon soil which is well drained and dry. A gravelly knoll is best, but, failing this, the site should be raised by the use of the plow and scraper until there is a gentle slope in all directions sufficient to prevent any standing water even at the wettest times. A few inches of sand or gravel on the surface will be very useful in preventing the formation of mud. If the house is sheltered from the north and northwest winds by a group of evergreens, this will be a decided advantage in the colder parts of the country.”

In “Building Poultry Houses,” Professor Rice says: “Poultry keeping is an exacting business. The four corner-stones upon which success rests are:

Here we find that “suitable buildings, properly located,” is the first, hence most important, of the four corner-stones upon which success with poultry rests, and in giving the buildings this prominence we believe the professor is entirely right. No one thing does more to promote, or hinder, success with poultry than the buildings, hence the importance of a wise decision as to which of the many different patterns of houses is best adapted to your purpose.

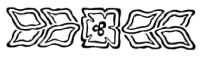

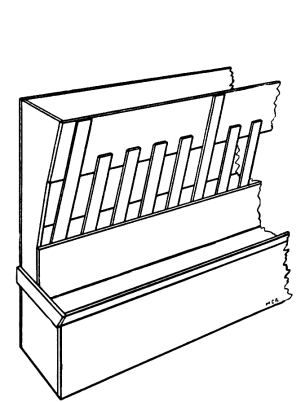

Fig. 1—A plan to secure dryness.

Select a dry location; if the ground is not naturally dry make it so by draining it. The first illustration gives a plan for making the interior of a poultry house absolutely dry, if the ground is fairly well drained. The foundation walls are built up about eighteen inches above the ground level; about twelve inches of this space is filled in with small stones or coarse gravel, and the balance with fine sand or dry, sandy loam; on the outside the ground is sloped up to the level of the bottom of the sills, and thus all surface water is effectually turned away.

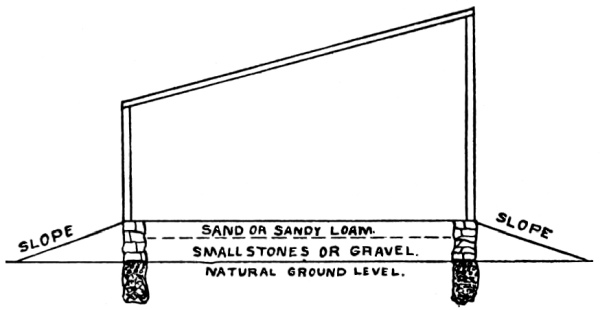

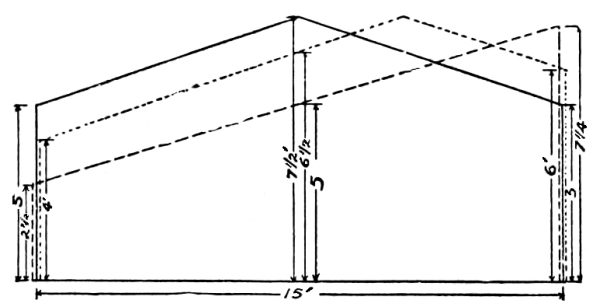

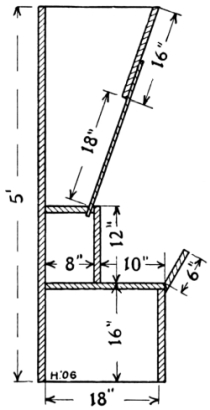

Fig. 2—The shape of the roof influences the cost.

[Pg 4]

Fig. 3—Each of these houses require the same material.

In building a hen-house the working unit is the floor and air space required for each hen. A safe working rule is about five to six square feet of floor space, and about eight to ten cubic feet of air space for every fowl. Foundation walls should be built deep enough to prevent heaving by the frost and high enough to prevent surface water from entering. Where large stones are scarce sometimes grout walls may be made with gravel or small stones and cement; or the building may be set upon posts set well into the ground, in which case hemlock or hard wood boards should be securely nailed to bottom half of sills and extend down to natural ground level, to exclude rats.

Dampness is fatal to hens; build or drain so as to secure dryness. It is better by far to have a cold, dry house than a warm, damp house. The warmer the air the more moisture it will hold; when this moist air comes in contact with a cold surface condensation takes place, which is often converted into hoar-frost. The remedy is to remove the moisture as far as possible, by first cutting off the water from below which comes up from the soil. The water table is the same under a hen-house as it is outdoors; dirt floors, therefore, are liable to be damp. Stone filling covered with soil is sometimes difficult to keep clean and may only partially keep out dampness. Board floors are short lived if the air is not allowed to circulate under them, and in a cold climate a free circulation of air under the floors makes them very cold; in either case they are likely to harbor rats. A good cement floor is nearly as cheap as a good matched-board floor, counting lumber, sleepers, nails, time, etc. When once properly made it is good for all time. It is practically rat-proof, easily cleaned and perfectly dry, cutting off absolutely all the water from below. If covered with a little soil, or straw, or both, as all floors should be, it will be a warm floor.

A low house is easier warmed than a high one. Solid walls radiate heat rapidly. The best way to make a poultry house warm is to build it as low as possible without danger of bumping heads. There will then be ample air-space for as many fowls as the floor space will accommodate. Too much air-space makes a house cold; it cannot be warmed by the heat given off by the fowls.

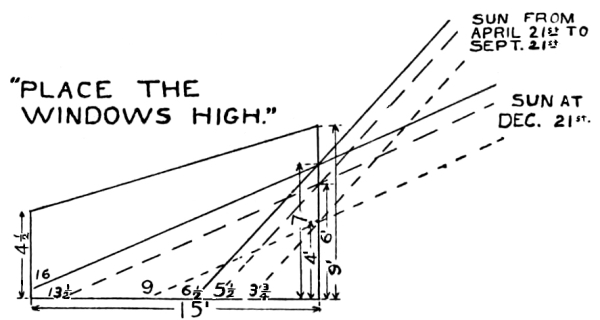

Sunlight is a necessity to fowls; it carries warmth and good cheer, and tends to arrest or prevent disease. Too much glass makes a house too cold at night and too warm in the daytime, because glass gives off heat at night as readily as it collects it in the daytime. Much glass makes construction expensive; allow one square foot glass surface to about sixteen square feet floor space, if the windows are properly placed. The windows should be high, and placed up and down, not horizontally and low (Fig. 4). In the former the sunlight passes over the entire floor during the day, from west to east, drying and purifying practically the whole interior. The time sunshine is most needed is when the sun is lowest, from September 21 to March 21. The lines in Fig. 4 represent the extreme points which the sunshine reaches during this period, with the top of a four-foot window placed four feet, six feet, and seven feet high, respectively. With the highest point of the window at four feet, the direct sun’s rays would never reach farther back than nine feet; at six feet it would shine thirteen and one-half feet back, and at seven feet it would strike the back side of the house one foot above the floor.

Fig. 4—Showing extent of sun’s rays.

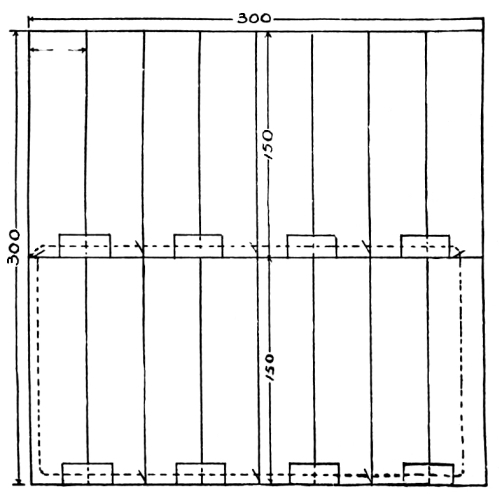

Make the yards long and narrow (Fig. 5). Double yards are desirable where space can be given for them; they allow a rotation of green crops, which cleanses and sweetens the ground, and converts the excrement which would become a source of danger into a valuable food crop. The shape of the fields, the slope of the land, and the location of other farm buildings will have much to do with the shape of the yards [Pg 5] and mode of access to the poultry buildings. Generally the yards should be long and narrow, so as to make cultivation easy. Two rods wide and eight rods long is a good size yard for forty or fifty hens, although more room would be better. This size permits a row of fruit trees in the center for shade, which is a necessity.

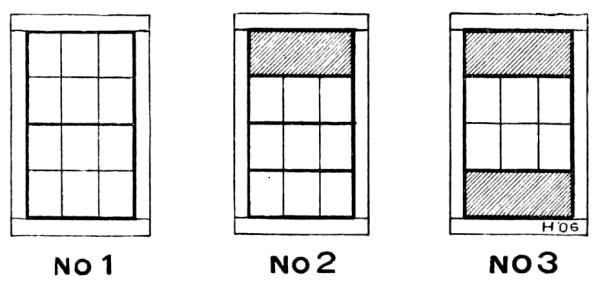

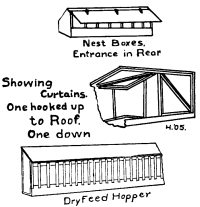

Much of the dampness in poultry houses in winter is due to the condensation of the breath of the fowls. The warm air exhaled from the lungs is heavily charged with moisture, and this, coming in contact with the cold roof and walls, is condensed into hoar-frost, which melts and drops to the floor when the house is warmed up by the sun. In recent years considerable success has attended efforts made to prevent this moisture by ventilating the pens through muslin curtains set into the tops of doors, or forming a part of the front wall (see plans of Dr. Bricault’s poultry house, page 12, and of the Maine Experiment Station House, page 18), also by setting the curtains into part of the window spaces. In Fig. 6 is given an illustration of an experiment tried on the Lone Oak Poultry Farm, Reading, Mass., in the winters of 1904-6. Being much annoyed by the moisture which collected on the roof and walls in the night and, melting, dropped to the floor when the sun warmed the roof and walls during the day, frames the size of one fourth of each window were made and common muslin tacked on. To better ascertain the effect of the curtains the windows in house No. 1 were left closed, as formerly; in house No. 2 the top sash was dropped the length of one light and a curtain set into the space; in house No. 3 the windows were dropped from the top and raised from the bottom, curtains being set into both spaces. In house No. 1 the dampness and “chill” remained as before; in house No. 2 there was some improvement; in house No. 3 there was a great improvement, and the temperature, in the coldest days of the winter, was about six degrees warmer in house No. 3 than in house No. 1 where the windows were all kept closed tight. The two curtains, making half the space of each window, were not quite sufficient to dry out the moisture, which had already got well established, but by installing the curtains both top and bottom as soon as the weather dropped below freezing the next fall, they were found to be ample to keep the pens well ventilated and quite dry.

Fig. 5—Make the yards long and narrow.

Fig. 6—An experiment with curtains in the windows.

Secure shelter and warmth by building in the lee of a windbreak or a hill, or of other farm buildings. Buildings that face the south, or about two points east of south, will get the largest amount of exposure to the sun’s rays and protection from the cold northwest and west winds of winter; other things being equal they will be warmer, dryer, and more cheerful. An eastern exposure is usually preferable to a western exposure, barring prevailing winds being from the east; because, like flowers, hens prefer morning to afternoon sun.

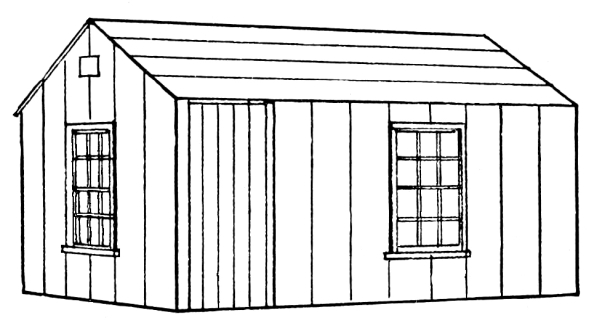

The shape of the roof of a poultry house greatly influences the cost, and, generally speaking, the preference should be for houses with single-span (or “shed”) roofs. See Figs. 2 and 3. These houses are the easiest and cheapest to build, they give the much-desired vertical front, with room for the windows to be placed high to distribute the winter sunshine (Fig. 4), and with the drip of the roof all carried off [Pg 6] to the north the ground in front of the house is dry. It also is cooler in summer, as it is not exposed to the direct rays of the sun, and is warmer in winter because it gets the direct rays of the sun.

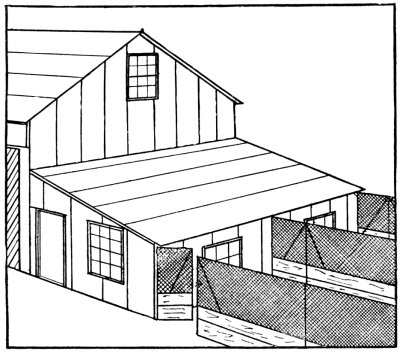

Fig. 7—An implement house adapted for poultry.

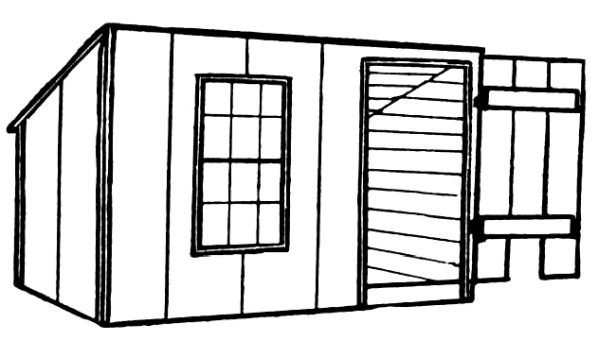

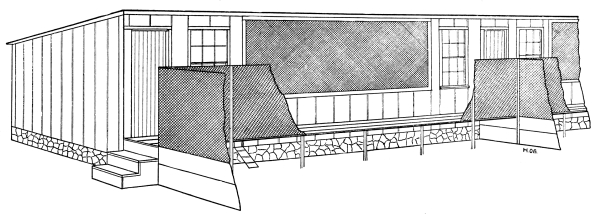

Not infrequently there are small buildings on the place which can be easily and economically adapted to poultry use; as, for example, an old implement house, or grain house, or tool shed, which can be altered into a one or two pen-house, as desired, by arranging windows and doors and adding one or two open-front scratching-sheds for exercise and fresh air (Figs. 7 and 10). In case there is no building suitable for remodelling into a poultry house an inexpensive lean-to may be built onto the south end of the stable (Fig. 9). A house of this kind can be simply, economically, and conveniently built, and well supplies the conditions for successful poultry keeping; we recently visited a dairy and poultry farm in Connecticut where house room for one hundred and fifty head of laying-breeding stock had been built in the lee of and annexed to the dairy barns and sheds. A good prepared roofing, such as “Paroid,” makes quite shallow and low lean-to roofs easy of construction, both air and water-tight, and very durable.

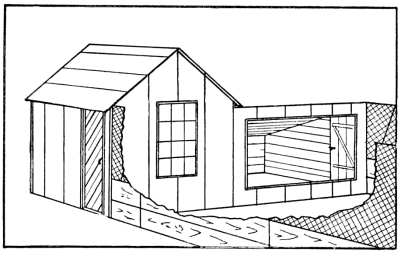

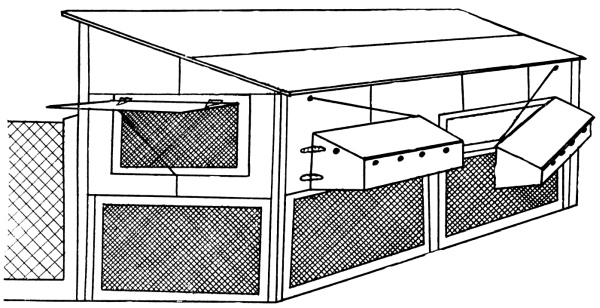

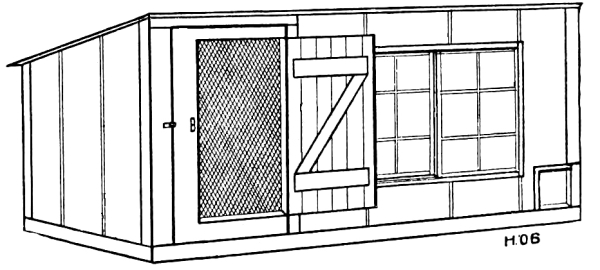

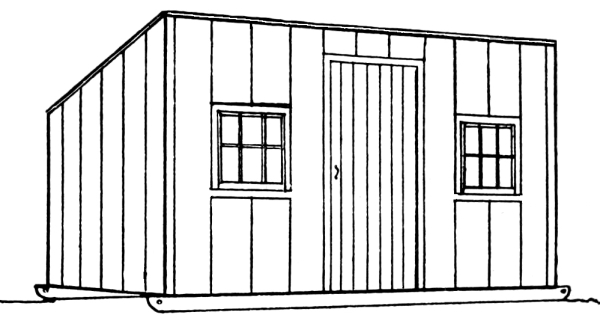

Sometimes a dweller in the suburbs, or one living on a small, rented place, wants to keep a flock of fifteen or twenty head of fowls, to supply the family with fresh-laid eggs during the fall, winter, and spring, and then fresh poultry meat for the table; these are all disposed of before the family goes away to the country or seashore for the summer, and another flock of well-matured pullets is bought in the fall. For such purpose the small portable house shown in Fig. 12, or one of the several patterns of “colony-houses” given herein, will serve excellently; all of these colony-houses are portable. A good size of house of this kind is ten feet long by seven feet wide, six feet high in front and four feet six inches high at the back; or for a flock of eight or ten fowls eight feet long by five or six feet wide will answer well. Houses of this type are built of a size to suit the builder, and they can be easily moved to a new location at any time.

Excellent patterns of small poultry houses, well adapted to the suburban lot or for moving out into the orchard on a farm, are shown on pages 8 and 9; these “colony” houses have proved their merits in many different localities. They are especially valuable on a farm, where it is desired to locate a flock of half-grown chicks out in the stubble of a newly-cut grain field, or colonies of chicks along the border of a cornfield, or on a poultry farm where extra room is needed for surplus stock and cockerels which are to be sold for breeding purposes. A solid board floor enables shutting the birds in at night and keeping them in until the team has drawn them to the new location in the morning; it also secures the birds against marauding animals at night, if the slide door has been closed. For convenience of drawing to a new location it is best to have them mounted on low runners.

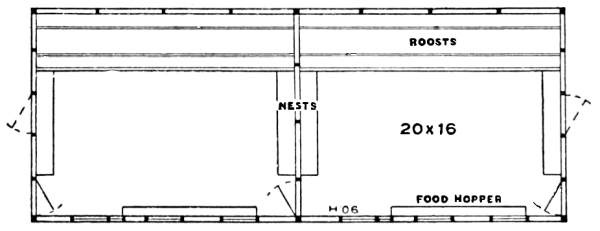

Fig. 8—Ground Plan.

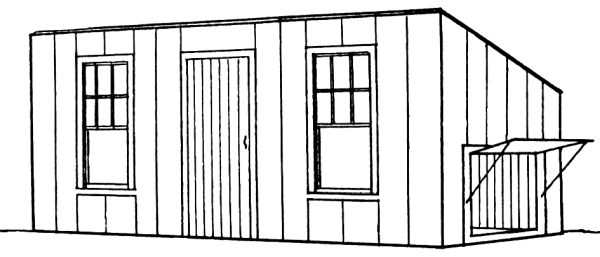

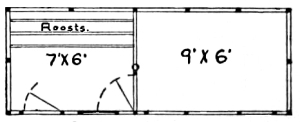

An excellent plan of colony-house is given in Figs. 14 and 15, and comes from the Connecticut Experiment Station; this combines the advantages of the curtained-front scratching-shed with that of the small colony-house. This house is sixteen feet long by six feet wide, [Pg 7] is six feet high in front and four feet high at the rear; the roosting apartment being 7 × 6 feet and the scratching-shed 9 × 6 feet in size. A muslin curtain 4 × 8 feet, tacked to a light frame which is hinged to the top of open space, closes the front on cold nights and is kept closed in stormy weather.

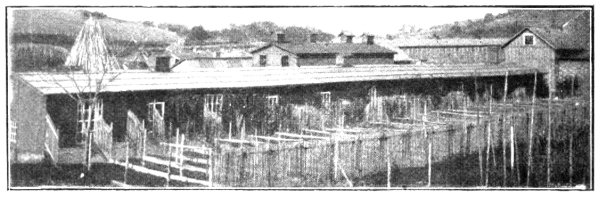

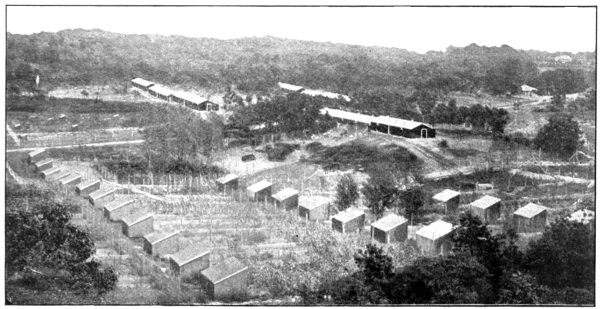

On page 17 we show a type of colony-house which is well adapted for a portable brooder house, an “in-door” brooder being placed in each end and fifty to seventy-five chicks being put in each brooder. When the chicks are large enough to do without artificial warmth the brooders are removed, the chicks being left till such time as it is well to separate the sexes, when the cockerels can be removed and the pullets left to grow to laying maturity. On page 42 we show an illustration of thirty of this pattern of colony brooder house in use on the “Gowell Poultry Farm,” Orono, Maine; a few over four thousand chickens were put into these thirty portable houses in the spring of 1905, nineteen hundred and eighty-five cockerels were sold off as broilers, some sixty more raised for breeding males, and a few over two thousand mature pullets taken from them in October and moved into the 400 feet long poultry house which had been erected during the summer. When the pullets were occupying them, in midsummer, they were turned about to face north and lifted up to about a foot and a half height above the ground by stones about a foot in height being put under the ends of the runners; this gave the pullets the much-needed shade of both the inside and underneath the house, a simple device, but decidedly helpful.

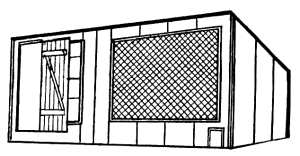

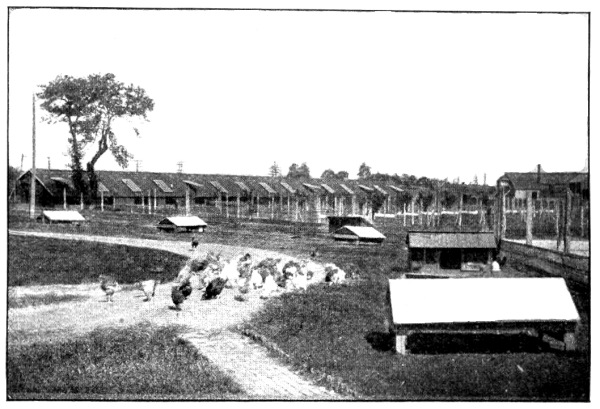

In Fig. 11 we show a type of colony-house such as used on the large colony poultry farms about Tiverton and Little Compton, R. I. These are usually about ten by sixteen feet in size, six feet high to the eaves when built with double-pitch roof, seven feet high in front and five feet at back when shed roof. These houses are very simple in plan and construction, there being three roost-poles about three feet above the ground at the back, five or six nest boxes, food trough, water dish and hopper for shells and grit. The houses hold about forty fowls, are placed about a hundred and fifty to two hundred feet apart in locations convenient to drive to with the feed and water-wagon, and on some of the large farms as many as fifty to a hundred of these colony-houses may be seen. The capital needed to equip a colony farm of this kind is very much less than where long houses and yards are erected; the labor charge of caring for the flocks is very much greater, however, so that what is saved in capital is expended in labor.

Fig. 9—A lean-to poultry house.

Fig. 10—Implement house with scratching-shed attached.

Poultry farmers in America have generally preferred the continuous-house plan of keeping fowls, and the resulting poisoned ground of the yards has no doubt been the cause of many a failure in the poultry business. An eminent English lecturer is authority for the [Pg 8] statement that the portable-house plan has been the saving of the poultry business in England, and bringing the small (portable) houses together near the other small buildings in winter, then moving them to convenient locations out in the fields in the spring, has solved the difficulty of extensive poultry farming over there. It would be well to carefully consider these points while taking up the continuous-house plans which we give in following pages.

An objection to the scattered “colony-house” plan, as seen on the large poultry farms in Tiverton and Little Compton, R. I., has been the great labor of feeding two or three times a day—one of the feeds being a cooked mash. By adopting the modern method of feeding the food dry and keeping a supply of food constantly before the fowls a considerable saving in labor is effected, and it is practicable to successfully keep a large number with but one visit a day to the several flocks; this would be an afternoon visit, for rinsing and refilling the water fountains and collecting the eggs. By having the food-hoppers sufficiently capacious to hold a supply of food for a week but one visit a week would be made for filling them.

This is the method adopted on the Vernon Fruit and Poultry Farm, Vernon, Conn., where some three thousand head of layers are kept, the food-hoppers being refilled once a week; as there is a little brook and numerous springs convenient to the houses no watering whatever is done, each flock of fowls having but fifty to two hundred feet to journey to find an abundant supply of running water.

Fig. 11—Type of house on Rhode Island colony poultry farms.

On the Gowell Poultry Farm, Orono, Maine, there is an excellent example of the continuous-house, and by the partial adoption of the dry-feeding method the labor is so far reduced that one man can do all the work of feeding and caring for two thousand head of layers, kept in a house four hundred feet long by twenty feet wide, which is divided into pens twenty feet square and one hundred birds kept in each. The double-yard system is in use here, there being one tier of yards one hundred feet long by twenty feet wide extending south from the house, and another tier of yards the same size north of the house; when the south-yards have been denuded of green food the birds are turned into those north of the house, and the south-yards are plowed and sown (or planted) to a quick-maturing crop. By this method poisoned ground is avoided and the conveniences of the continuous-house retained; the safety of such a plant would lie, of course, in the intelligent handling of the work. It is worthy of note that on the Gowell Farm the portable colony-house method is in use in growing the young stock (see page 42), while the continuous-house method is used with the laying-breeding stock. This is true of practically all of the large poultry farms, it being conceded that free range over farm-fields, or through orchard and woodland, promotes good growth in the young stock. When, however, it is desired to develop the physical energies towards egg-production the semi-confinement of houses and yards is brought into play; in this manner the greatest egg-yield, and consequent profit is obtained.

Here are three different methods of avoiding the evil of ground-poisoning: First, the continuous-house with double-yard system, one set of yards being used while the other is being sweetened by a growing crop; second, the colony-house plan with houses located a hundred and fifty to two hundred feet apart and convenient to drive to for feeding and watering; third, the “portable-house” plan, which is the colony method with the houses changed from one location to another, and brought together near the group of farm buildings for the winter months. Convenience, amount of capital available, and other considerations, will influence the choice of a method.

Fig. 12—A small “portable” poultry house.

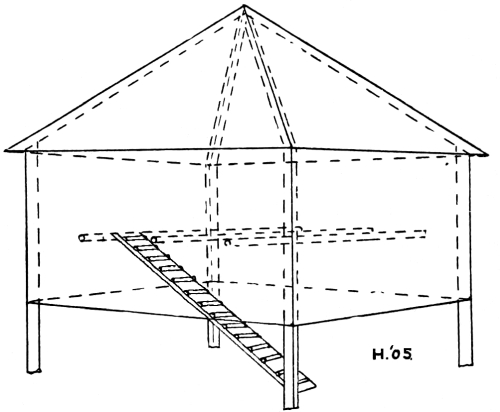

[Pg 9] In Fig. 14 we give an illustration of an elevated poultry house used in Florida, which was published in the “Poultry Standard,” of Stamford, Conn., and described as made of Neponset Red Rope Roofing, both top and sides; a better construction would be Paroid Roofing for roof and sides, or Paroid for roof and Neponset Red Rope Roofing for the ends and sides. This house is built upon posts set in the ground at the back and six feet high in front; the six posts, three front and three back, are all the frame required. The light furring to sustain the roof and sides is nailed to the posts, and the roofing securely nailed to the strips of furring.

The open space below the house is enclosed by one-inch mesh wire netting; there is no floor, and a narrow platform along the rear, inside, gives the hens access to the nest boxes, which are hinged at one end, and swing out as shown in the drawing. The roost-poles should be a foot above the open bottom, to be quite sheltered from winds.

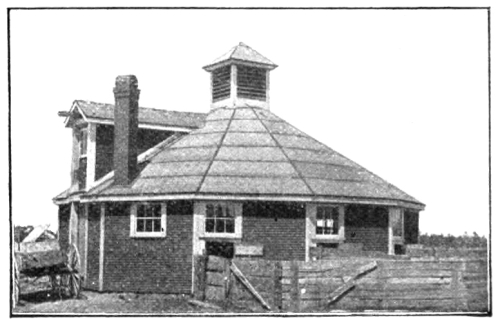

Of similar pattern is the “Mushroom Poultry House,” from Southern California. These houses may be built any size, but are usually made four or five feet square. They set up from the ground about eighteen inches, and the closed sides are three feet, the posts being four and one half above the ground. There is no floor used, the air circulating freely beneath. When built of boards no frame is needed, the boarding being nailed to the posts. The roof goes up from all four sides, in pyramid form, and is made water-tight. The roosts are placed about fifteen or eighteen inches above the bottom, as shown by the dotted lines, and a walk or ladder is provided which leads from the ground to the rear roost. This is made movable, so that it can be taken down at night, thus protecting the fowls from marauding animals.

Fig. 13—A California “Mushroom” poultry house.

Fig. 14—A Florida poultry house.

Some of the houses are built of iron advertising signs, and have the common double-pitch roof; in some cases the sides are made of burlap tacked on to furring, which is nailed to the posts. This burlap is then painted with crude oil, distillate, and Venetian red, to make it wind-proof. Lumber is very expensive in that section, and the burlap, when water-proofed, makes a cheap and quite desirable house.

A much better wind and water-tight construction would be Paroid for the roof, and Paroid or Neponset Red Rope Roofing for the sides. [Pg 10]

When fowls are kept in the confinement of houses and yards an important question is how to keep the yards sweet. The ground becomes tainted in a couple of years or so, and then is a fruitful source of disease. Unless grass can be kept growing so as to keep the ground free from the poison of the droppings there is no alternative but to change the ground. It is well to have two runs, using each alternately, and by planting the one vacated with some quick-growing crop it can be made ready for occupancy again in a few weeks. An excellent crop for this purpose is Dwarf Essex Rape, which makes one of the best summer-green foods for fowls confined to houses and yards; or such garden crops as squashes, melons, etc., can be grown. After these rye or oats can be sown, to furnish green food in the fall.

It is a comparatively simple proposition to have the yards divided into two sections, by setting the house in the middle, having half (or two-fifths or three-fifths) of the length of yards north of the house; these north yards being used three or four months in summer, a crop of some suitable kind being grown in the vacant yards south of the house in the meantime.

Fig. 15—Illustrates double yards for a continuous poultry house.

In Fig. 17 we give a plan for such house and yards. In this plan we suppose the yards to be one hundred and twenty-five feet long by eighteen wide, and have placed fifty feet of length of yards north of the house and seventy-five feet of length south of it. There are lift-off gates next to the house in the fence south of the house, the second gate in illustration being shown as lifted off and leaning against the next panel of fence. These gates give access to all the yards, for plowing, harrowing, and cultivating a crop; also for driving up to the front of the pen with a cart to haul away the fouled earth of the floor of the house. The usual access to these yards is through the house itself and a gate opening out of the scratching-shed; for ordinary visits to the north yards there are small, swinging gates next to the house, and then lift-gates which will admit a team for plowing, etc. There should be a row of fruit trees set in each yard, to give the needed shade, and the trees give the owner a second source of profit. [Pg 11]

Fig. 16—Dr. Bricault’s “New Idea” poultry house.

Desiring a poultry house which would give closed pens or could be opened up to admit the air and sunshine at will, Dr. C. Bricault, Andover, Mass., adapted the well-known “Dutch Door” to his purpose, putting the door in the middle of the front of each pen, and so arranging it that the whole door could be open day and night, in warm weather, or the lower half of the door shut and the top half open, or the top half could be closed by a curtain in quite cold weather, and in severe storms the whole door closed. The size of the pens are ten by twelve feet, the frame and building plan being substantially the same as in the preceding house-plan, the doors in the front of each partition giving a passage through the entire length of the house. There are two windows in the front of each pen; the roosts are set up against the partitions between the pens, and the trap-nests are set on a platform against the north wall. The building is covered with a cheap sheathing paper, then with sheathing quilt, then Neponset Red Rope Roofing; a better construction would be Paroid Roofing on the roof and Neponset on the sides.

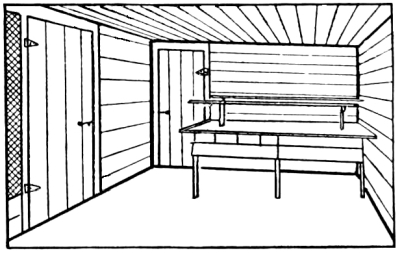

Fig. 17—Interior of pen.

Fig. 17 gives an interior view of one of the pens showing roosts and trap-nests. [Pg 12]

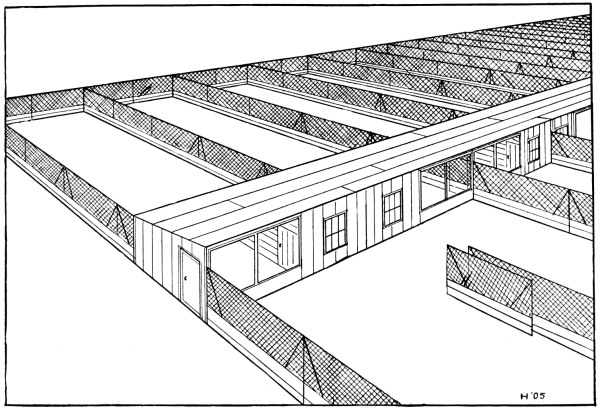

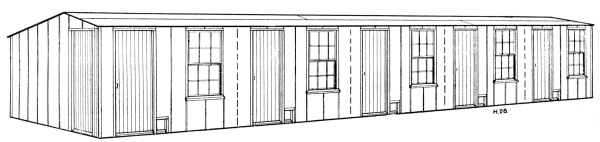

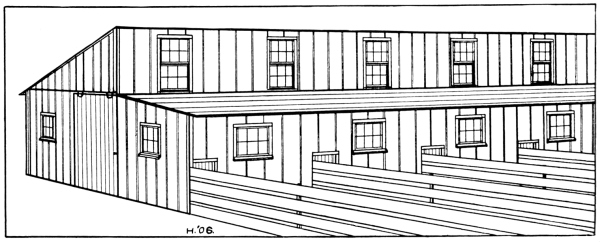

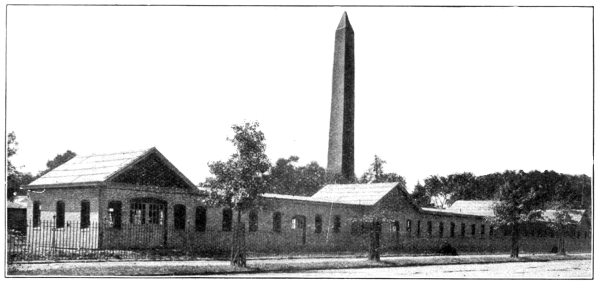

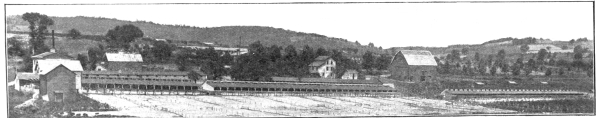

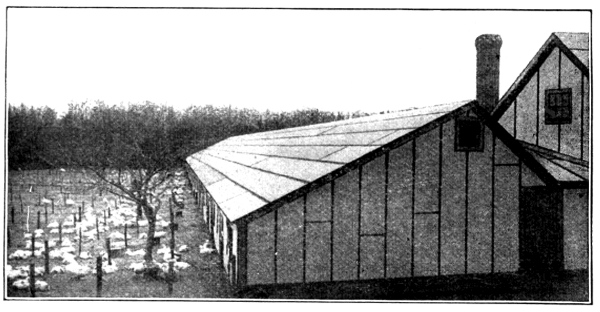

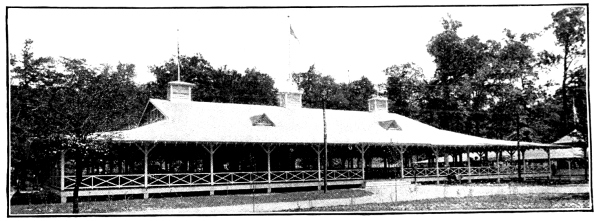

Fig. 18—A long

poultry house on the White Leghorn Poultry Yards,

Waterville, N.Y.

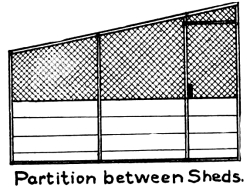

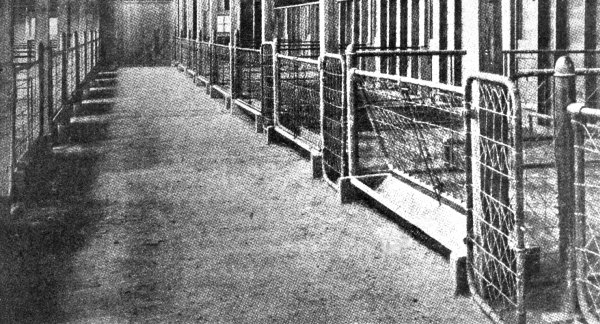

In New York State it has been thought desirable to have warm houses for the Single Comb White Leghorns so largely kept there, and we give illustrations of one of the long poultry houses of the White Leghorn Poultry Yards, Waterville, N.Y. This house is two hundred and forty feet long by sixteen feet wide, divided into pens twelve feet square and a walk three and a half feet wide along the north side. It has a floor of seven-eighths inch matched boards throughout. The outside walls are first boarded, then covered with sheathing and clapboarded. The inside of the building is boarded up with matched boards on the inside of the studs, making a four-inch dead air space between the walls. The ceilings are made of matched boards laid at the level of the plates. In this ceiling, over the centre of each pen, is a small trap door, two feet square, opening up into the attic space above, which is designed to give diffusive ventilation.

Three ventilating cupolas cap the roof, and there are full-sized windows in each gable end. This attic space is storage room for straw, which is drawn upon from time to time, to furnish scratching material for the pen floors and opening the trap-door into the ceiling, it gives excellent ventilation without drafts. A door opens from the alleyway into each pen, and doors in the partition between the pens permit passing through from pen to pen. The roost platforms with nest boxes beneath are against the partition between the walk and pens and the plan of partitions between pens as shown in Fig. 19. The roof is covered with Paroid Roofing. A fault here is the wire netting in these partitions; a better plan would be matched-board partitions throughout.

The twelve feet square pens have one hundred and forty-four square feet of floor space each, giving ample room for twenty-five head of layers, and while a long house of this description is somewhat expensive to build, it has many advantages, which, on a large and permanent poultry plant, will more than make up for the first cost in the ease and economy of feeding, etc., and the warmth of the house and the simplicity of the ventilation. This style of poultry house has been in use on the White Leghorn farm for several years, and it has been found to be both practical and economical; it combines very completely the laying and the breeding house. On this plant they practise the alternate system of males in the pens, a small coop for the extra male being set against the partition in one corner of the pen, four feet up from the floor. One male bird is cooped up while the other runs with the hens and they are exchanged every two or three days, the change being effected at night, on occasion of the shutting-up visit.

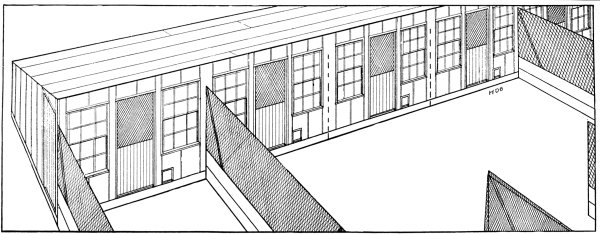

Fig. 19—Interior, showing partitions between pens.

Fig. 20—Interior of pens, showing roosts.

[Pg 13]

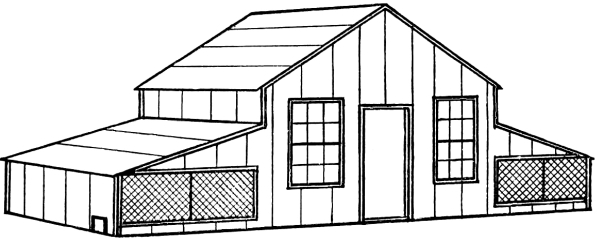

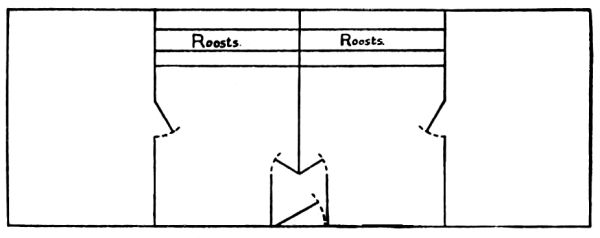

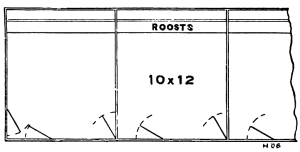

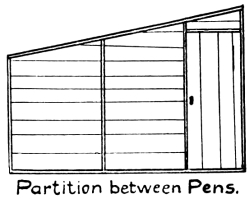

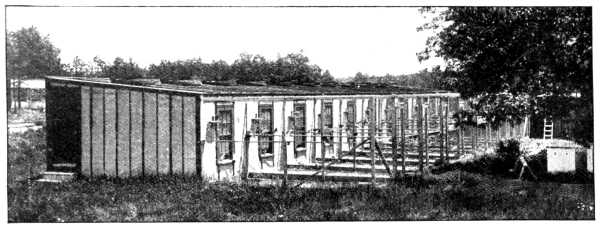

Fig. 21—Mr. A. G. Duston’s five-pen breeding house.

One of America’s most successful poultrymen is Mr. Arthur G. Duston, South Framingham, Mass., and as he has recently established himself on a new farm, to secure necessary room, the type of poultry houses he decides are the best for him is of interest. He is building seventeen houses of five pens each, and uses some thirty odd of his well-known colony-houses (Fig. 23). The five-pen houses are raised from the ground from two to three feet, the space beneath being utilized as scratching room. Each house is fifty by twelve feet, the pens being ten by twelve feet each, and there is a window and door in the front of each pen; doors in the front of partitions allow passing through from pen to pen. The roosts are at the back, with nest boxes beneath the roost platforms.

This house has a short hip-roof sloping south, which is open to the objection of carrying part of the roof-drip to the front of the house,—a fault which can be mitigated by a gutter along the front, but that increases the cost without always giving complete relief from the drip; we decidedly prefer the single-slope roof.

Fig. 22—Ground plan and cross-section.

Fig. 23—Mr. Duston’s “colony” house.

Mr. Duston’s “colony,” or portable, houses are justly favorites, the distinctive feature of them being the double door, or wire netting door covered with a second door. These “colony” houses are ten by five feet on the ground, five feet high in front, and four feet high at the back, and have board floors. [Pg 14]

Fig. 24—The straw-loft poultry house.

In New York state, especially, the Single Combed White Leghorns have long been the preferred variety, and, as they have rather thin single combs, which are considered to be susceptible to frost in cold weather, it has been a problem to house them so that they shall be protected from freezing. Many different types of houses have been tried, some of them with a stove in one end and a long pipe running through to the chimney at the other, thirty or forty feet away; a decided disadvantage with this was the having to keep the house shut quite tight to conserve the heat, and the consequent dampness from the moisture of the breath of the birds.

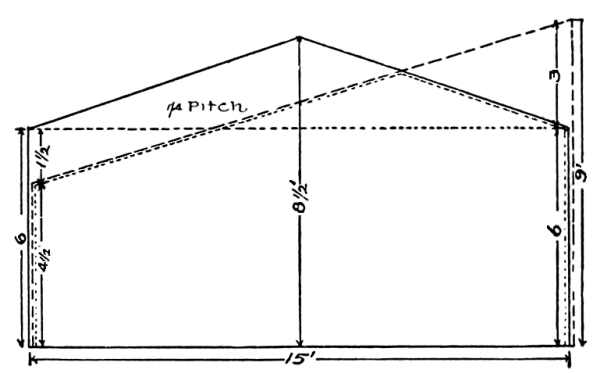

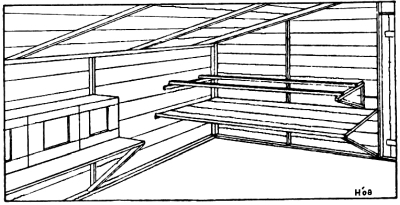

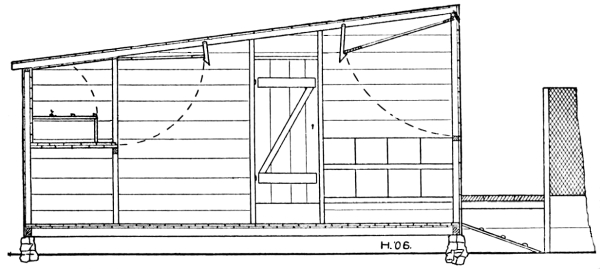

To get over this difficulty diffused ventilation was devised by Mr. H. J. Blanchard, of Fairview Farm, Groton, N. Y.; this ventilation was obtained by stowing straw (or swale hay) in the loft in the gable, and this permits a slow diffusion of air upward through the cracks of the floor and out of the small doors in each end of gable. This straw-loft poultry house has been widely adopted all over the United States; a good example of a long house of this type is shown in the illustration on page 12.

Fig. 25—Ground plan.

Mr. Blanchard’s houses are forty feet long by sixteen feet wide, and divided into two pens twenty by sixteen feet each; about fifty birds are wintered in each pen. The walls of the house are made double, boarded on both sides of the studs with a dead air space between; in some cases the walls are packed with saw dust or planer shavings, at the well-known Van Dresser farm, in Cobleskill, N.Y., they are packed with straw. The floor is double boarded, with a good sheathing paper between. Overhead, on the plates, two by six inch stringers are laid, and a loose floor of rough boards, with inch to inch and a half cracks between, is laid. A one-third pitch roof is laid on shingle laths nailed [Pg 15] to the rafters six inches apart, and on this a good sheathing paper covered with two-ply Paroid. In each gable a door is cut, as large as will swing under the roof. On the attic floor is put some twelve to fifteen inches of loose straw.

In very cold weather, when the house is tightly closed save for a muslin curtain in one or two windows of each pen, the vapor thrown off in the breath of the fowls will pass up through the cracks in the loft-floor and be absorbed in the straw above, instead of being condensed on the walls and roof in the form of frost. On mild days in winter the doors in the gable may be opened wide, or if it is very windy the door in the leeward end may be opened, which permits the air to draw through over the straw, drying it thoroughly, without any draughts upon the birds on the floor below.

In warm weather the gable doors may be left open night and day, and the draught through the loft, together with the ventilation through open doors and windows in the house below, keeps the birds cool and comfortable. These houses are thoroughly practical in every way and will be found very desirable for use on any large farm. A few such scattered in convenient localities will give good opportunity to rotate crops and poultry, and so gain a two-fold profit from the land and at the same time avoid all danger of the soil becoming poisoned by accumulation of the droppings. At Fairview Farm Mr. Blanchard combines fruit growing with poultry keeping, a combination which it would be difficult to better for double profits, and a combination which should be better understood by poultry growers. The advantages of combining fruit and poultry growing are many, not the least of the advantages being furnishing the shade which Prof. Rice tells us is so essential in summer. For the permanent yards there is nothing to equal apple trees, but as they are of somewhat slow growth and need large space when full grown, it is well to set apple trees about forty feet apart and set plums or peaches (or both) in the spaces between; the plum and peach trees will mature, produce a few crops of fruit and break down, before the apple trees will have grown to a stature to require all the room. A few years ago plum trees were strongly recommended for poultry yards, but experience has demonstrated that they cannot be depended upon for but a half dozen years or so, hence the wisdom of setting apple trees for permanent shade.

Fig. 26—West Virginia Experiment Station Colony-house.

Plantations of small fruits, such as grapes, blackberries, and raspberries, serve admirably for range and semi-shade for growing chicks, and it is a mistake to imagine that the chicks damage the crops of fruit; if they touch any it will only be the lower (and always inferior) stems that they reach. There are such substantial benefits accruing from the presence of little chicks about the small fruit plantations, or the mature birds about the apple, plum, and peach trees—such as the destruction of hosts of worms and insects and keeping the surface of the ground stirred, that every consideration urges the combination of fruit and poultry growing. At the Vernon Fruit and Poultry Farm, Vernon, Conn., we saw last summer Baldwin apple trees that were six inches through at the butt, yielded an average of a barrel of choice apples each in the fall, and had been set only six years. They began bearing the second year after setting, had borne increasing crops every year, last season averaged to be about six inches through and gave their owner a barrel of apples each. These apple trees were part of an orchard which was occupied by colony poultry houses having fifty layers each, and set sufficient distance apart so that there were about two hundred birds to the acre; the owner told us he had never seen a borer or any evidence of borers about those trees.

Fig. 27—Colony poultry house

at Connecticut Experiment Station.

Fig. 28—Ground plan.

[Pg 16]

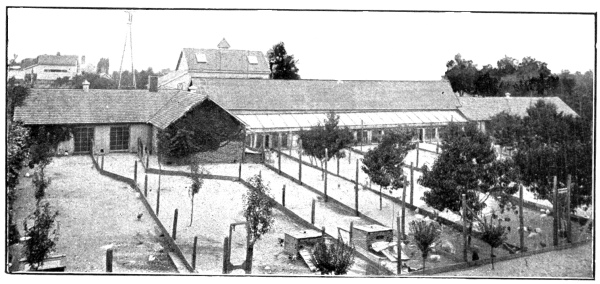

Fig. 29—The curtain-front,

curtained roosting-closet, poultry house.

Maine Experiment Station.

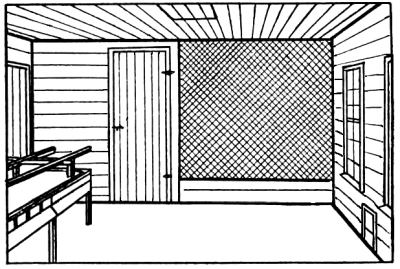

As stated elsewhere, the tendency in poultry house construction today is to more and more open up the houses to fresh air and sunshine, and the most advanced type of the fresh air poultry house has been developed at the Maine Experiment Station, Orono, Maine. This consists of a house-front about half open, a little more than a fourth of each pen-front being closed by a cloth curtain only, two windows and a door making with the curtain about half of the whole front of each pen.

At the rear of each pen, and elevated three feet above the pen-floor, is a curtained-front “roosting closet,” as it is called; this roosting closet is the “bed-room” and the whole pen the “living-room,” in this type of house.

Fig. 30—Cross-section.

It seems almost like cruelty to animals to put hens in such houses, where they have but the two cloth curtains between them and all outdoors in the very cold winters they have up in central Maine; the [Pg 17] Maine Station is very nearly up to forty-five north latitude, about the same as Ottawa, Ontario, St. Paul, Minn., and Portland, Oregon. One of the Station bulletins, however, says: “These curtain-front houses have all proved eminently satisfactory. Not a case of cold or snuffles has developed from sleeping in the warm elevated closets with the cloth fronts, and then going down into the cold room, onto the dry straw, and spending the day in the open air. The egg-yield per bird has been as good in these houses as in the warmed one.” In a letter written by Prof. Gowell, just after an extremely cold period, he says: “This is the ninth day of weather all the way from zero to twenty-five degrees below, still the fifty pullets in the ten by twenty-five feet curtained front house with its curtained-front roosting-room have fallen off but little in their egg-yield, and both the house and scratching material on the floor are perfectly dry. There is no white frost on the walls and there will be no dampness when the weather moderates and a thaw comes.” There could hardly be a stronger indorsement of fresh, pure air in a poultry house and good ventilation without draughts. If such good results can be attained in cold Maine they can be attained anywhere in the United States and southern Canada.

Fig. 31—Maine Station Colony Brooder House.

The Maine Experiment Station has now three of these curtain-front houses, of which one is one hundred and forty feet long by twelve feet wide, divided into pens twenty by twelve feet in size, in each pen being housed fifty birds; the other is one hundred and twenty by sixteen feet, divided into pens thirty by sixteen feet, and one hundred hens are kept in each. On Prof. Gowell’s farm, two miles distant from the Station, he erected last year a house of this type four hundred feet long by twenty feet wide, divided into pens twenty by twenty feet each, and a hundred birds are kept in each pen; in the thirty by sixteen feet pens there is a floor space of four and eight-tenths feet per bird; in the twenty by twenty feet pens the floor space is four feet per bird. It is of interest to note that the one hundred birds, Barred Plymouth Rocks, penned on this four hundred square feet of floor space, do not go outdoors from the time they are put in the house in October till the ground of the yards is well dried off in spring, say about May first; this suggests the practicability of housing laying-stock in suitable convenient buildings in winter, pains being taken that ample sunshine and fresh air (through curtains) be supplied, and in the spring the birds be moved out to portable colony houses scattered about the orchard, or a wood-lot, or other convenient place, where they would be pushed for a liberal egg-yield through the summer and sold off to market before molting time in the fall. This plan supposes the rearing of another generation of pullets for layers during the summer, and these pullets go into the winter-laying-pens in October, to be removed to the colony-houses in May, to be in turn, sold off to market in September. This plan of an annual rotation of laying-stock will undoubtedly give the best financial returns from egg-farming, and as by the adoption of the dry-feeding method of handling the fowls the labor is reduced to the minimum, the results, with intelligent management of the business should be quite satisfactory; the profits will be liberal for amount of capital invested and labor engaged.

In Fig. 29 we give a single pen of the one hundred and twenty feet long house, with a door opening into each pen from the board-walk along the front. Each pen has two windows, which light the interior when the weather is stormy and it is necessary to keep the curtain closed; the curtain is open every day when the weather is fair. There are banks of nest boxes at each end of pens, and coops for breaking up broody birds above the nest boxes. The twelve by four feet curtain in the pen-front is hinged at top so it may be swung up against the roof and hooked up there; the roosting closet is up three feet from the floor, the platform is three feet wide, and the curtain which closes the front is the whole length of the pen, and also swings up against the roof, where hooks secure it up out of the way. The whole floor of the pen is open for exercise, and is an enclosed out-of-doors pen all the time. [Pg 18]

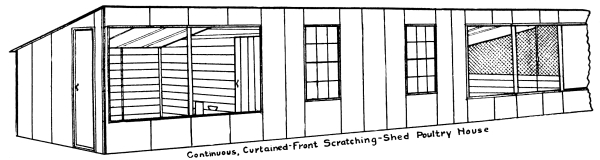

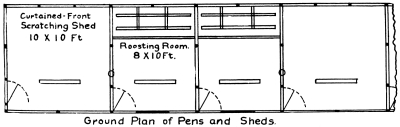

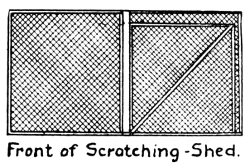

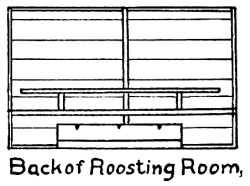

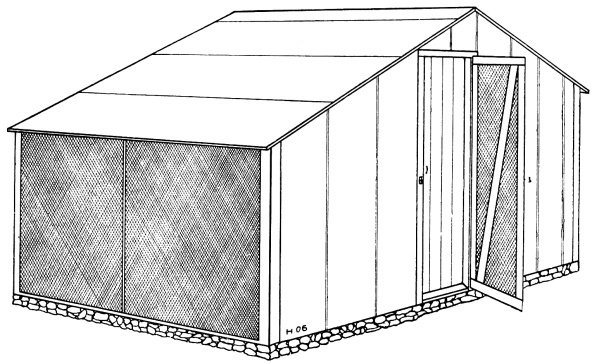

The tendency in poultry house construction in recent years has been to more and more open up the house to fresh air and sunshine, and this opening up of the houses, and getting more and more fresh air and sunshine into them, has been a decided step in advance in poultry work. There are many modifications and adaptations of the scratching-shed plan of house, perhaps the best known of them being the “scratching-pen” plan, and the enclosed-roosting-closet plan, the latter being the one evolved at the Maine Experiment Station and illustrated on page 16. In this enclosed-roosting-closet house we see the entire floor of the pen a curtained-front scratching pen and the roosting apartment lifted up and enclosed by another curtain-front; in the one we have the shed one department and the roosting-laying department another (one a “living-room” and the other the “bed-room”), with wide range of adaptability in the way of opening up the roosting-laying room; in the other the enclosed roosting-closet, or “bed-room,” and scratching-shed, or “living-room,” are in the one apartment. Certain it is the curtained-front scratching-shed type of house that has been growing very rapidly in favor with practical poultrymen, and probably combines more advantages with fewer disadvantages than any other one style of poultry house.

Each combined pen and shed covers eighteen by ten feet, the curtained-front shed being ten by ten feet, and the roosting-room adjoining being eight by ten feet, room sufficient for twenty-five to thirty fowls of the American or thirty-five to forty of the Mediterranean varieties. No “walk” is required because the walk is through gates and doors, from shed to pen and pen to shed, and so on to the end of the house and out the other end. The much-desired ventilation of the poultry house is very varied in this plan, at the discretion and according to the judgment of the operator, and can be adapted to the different seasons in half a dozen different ways. In summer the doors and windows are all wide open and the curtains are hooked up against the roof out of the way. (It is to be remembered that the doors between two pens are never to be left open when there are birds in the pens, they are always kept closed except when opened for the attendant to pass through from one pen to another). When the nights begin to be decidedly frosty in the fall close the windows in the fronts of the roosting pens, but leave shed-curtains hooked up and doors between pens and sheds open. When it begins to freeze nights close the curtains (at night) in fronts of sheds, but still leave doors between pens and sheds open. These doors (including the slide door) are never closed excepting on nights of solid cold, say when the thermometer runs five to twenty degrees below zero; and for real zero weather, from five above to away below zero, close the curtains in front of roosts and all doors and windows are closed. An additional protection against cold in extremely cold latitudes would be to double-wall the back of the roost-pen, from the sill up to plate and then up the roof-rafters four feet, packing the spaces between the studs and rafters with planer shavings, straw, swale hay, or seaweed (the latter is vermin-proof), then have a hinged curtain to drop down to within about six inches of front of roost platform, and extending a foot below it; this curtain we would close only on the very coldest nights.

We would build this house seven feet high in front and five feet high at the back. Sills and plates are all of two by four scantling, halved and nailed together at joints. The rafters, corner studs, and studs in centers of fronts of sheds are all two by four; the intermediate studs are two by three. Set the sills on stone foundation a foot and a half above the ground level, or on posts set into the ground below the usual frost line, the posts being set five feet apart excepting in front of roosting pens (where they come four feet apart)—there being a post at corner of each pen and shed, with one between. The rafters should be two feet between centers; as lumber comes twelve, fourteen, or sixteen feet in length, and two-feet-apart rafters allow the lumber to be used with almost no waste. The sills we would set a foot and a half above average ground level. When set on posts put hemlock (or some hard wood) boards from bottom half of sill down to ground, nailing them firmly to sill and foundation posts; then fill up inside to bottom of sills and slope the ground outside to same height, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Toe-nail studs to sills firmly, plates to studs ditto, and rafters to plates. Set the studs in front of roosting pens to take the window frames (or the window sash, if no frames are used), and in partitions a stud should be set to take the two and one half feet wide doors and gates. All of the framing is simple and easy, and any man who can saw off a board or joist reasonably square and drive nails straight can build this house; the slight bevel at each end of rafters being perfectly simple. All boarding is lengthwise, the boards firmly nailed and good joints made all over. Cover the roof and sides with Paroid, and the house will be wind and waterproof. [Pg 19]

Fig. 32—The Continuous, Curtained-Front Scratching-shed Poultry.

[Pg 20]

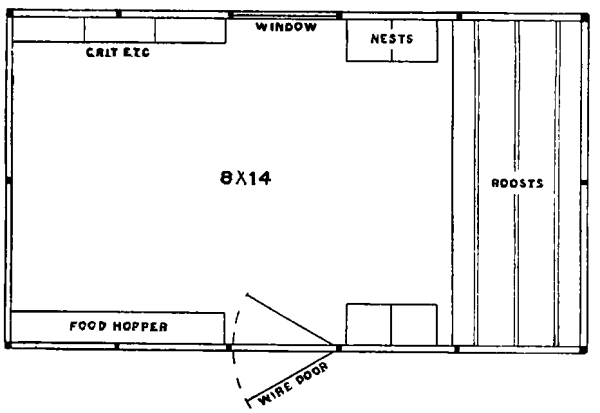

This “Fresh Air Poultry House” has been evolved by Mr. Joseph Tolman, a practical poultryman of eastern Massachusetts, some twenty-five miles south of Boston, and differs from most other plans in that the front is wide open night and day all the year around; the south front is always open, being closed by one-inch mesh wire netting only.

Fig. 33—The All-Open-Front Poultry House.

The roof and sides are one inch boards nailed to two by four inch rafters and studs, and covered with sheathing paper and two-ply Paroid; this makes a tight roof, and east, west, and north walls, excepting that there is a window in the center of the west side and a door opposite it, in center of east side. In operating this house in summer both the door and window are removed and wire netting tacked to a light frame set in the places; for convenience we recommend that the door-screen be hinged to outside of door frame, and when not in use hooked back against the wall. There are many nights in spring and fall when it is desirable to leave the door open excepting that the opening is closed by the wire screen, and possibly the very next night it is better that the door be closed; having the door-screen hung to the wall enables adapting to weather changes at will.

Fig. 34—Ground plan.

The house here shown is made eight by fourteen feet in size, four feet to eaves and seven feet to apex of roof, and makes a fine home for twenty-five fowls; a larger size of this house is recommended to be made twenty-one by fourteen feet on the ground, with five feet posts in north and south ends and eight feet to apex of roof; this would comfortably house fifty head of layers.

[Pg 21]

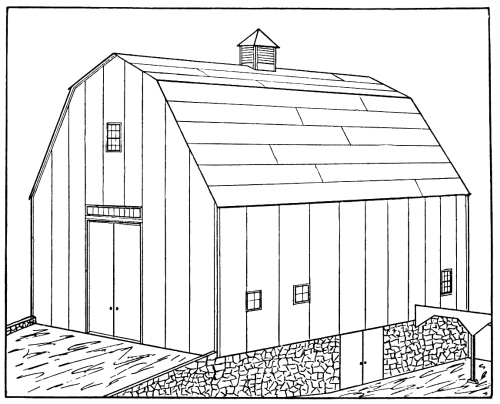

There is a very great diversity in plans of barns and stables, the taste of individual owners seeming to favor this or that plan, which they think is best adapted to their needs. Observation of various types of farm buildings, however, will convince the thoughtful man that too often a single point of convenience is magnified till other points are wholly obscured, and to secure the one advantage several decided conveniences are sacrificed; in a study of conveniences all possible points should be considered and a decision arrived at which will give the greatest and sacrifice the least number.

Talking with a dairy farmer living in central New York, who had just completed a dairy barn which cost him about three thousand dollars, he told that he had waited a dozen years to build that barn, and had studied and figured to get the two most important conveniences of a cement floor to preserve the liquid manure and a drive-way onto the main floor; to get those he had let go one or two others which he considered of far less importance, and had at last got a barn exactly to his liking. One of the conveniences which he had let go was a covered-way to the barn, and this one point is considered of so great importance by many that almost everything else is sacrificed to gain it. We were discussing this point with a farmer whose barn was about a hundred and fifty feet away from his house, and he was positive that the advantage of having the barn near to and connected with the dwelling house was over-estimated; that there were but a very few days in a year when the covered-way was of so great advantage, and there were decided advantages in having the barn a little distance from the house,—among them absence of barn-odors, flies, and noises. With the barn off a little distance he avoids those, and gains the (to him) great advantage of a drive-way onto the main floor, a fine basement for composting the manure and housing the farm carts, etc., and a drive-way out of the basement with only an insignificant rise to the level of the fields.

This same farm-barn had one defect, to remedy which we offered the suggested shed shown in Fig. 35. The barn extended very nearly east and west, consequently the linter door was exposed to the cold west and northwest winds of winter, and during the winter the farmer wanted his cows to have the exercise-room of the barn yard on the south side of the barn. To overcome the difficulty we suggested an open-front shed along the west side of the barn yard, and a covered-in walk down from the linter door to the shed; as subsequently built the shed was extended five feet beyond the corner of the barn, so as to cover the linter door, and a broad door in the shed-end gave out to the lane leading to the pasture. By closing that broad door in the end of the shed and opening a gate to the barn yard a covered-way was made for the cows to pass from the linter to the barn yard, without being exposed to the cold winds of winter, and gaining the complete shelter of the shed on the west; a simple expedient, and yet a very decided convenience.

Fig. 35—A convenient shed-shelter for west end of barn yards.

Driveways onto two or more different floors of a barn or stable are most substantial aids to the economical doing of the farm work. On a large Essex county (Mass.) farm which we recently visited a new hay-barn was being erected, the site for it being especially selected so that an easy grade could be built to the top floor, permitting the hay wagons being driven into the top of the barn, under the high roof, and all the hay was pitched off and down into the twenty-feet deep mows. A recent letter says: “The new barn is practically done, and already some twenty loads of hay are in one corner of it. We find it a great saving of labor; four men in the barn will take better care of the hay and keep ahead of the gang in the field easier than seven men and a horse could put it into the top of the barn with a fork.” A second drive-way leads out of the ground floor of this barn to the high road, practically on a level, and a third out of the west end of the basement, whence an easy grade rises to the farm roads. By these convenient driveways much hard work is eliminated—a most important [Pg 22] point in these days of growing scarcity of farm help. Because of this great scarcity of help, especially of dependable help, it is a necessity that the farmer take advantage of every convenience, or labor-saving device, which will aid him in his work; it is both good economy and good business policy for him to do so.

We have thought it wise to give here a few simple, practical plans, which have approved themselves in everyday use. Barns and stables need not be expensive in construction nor elaborate in fittings; the important considerations are the comfort of the animals, the convenience of the owner and the adaptability of the building to its purpose.

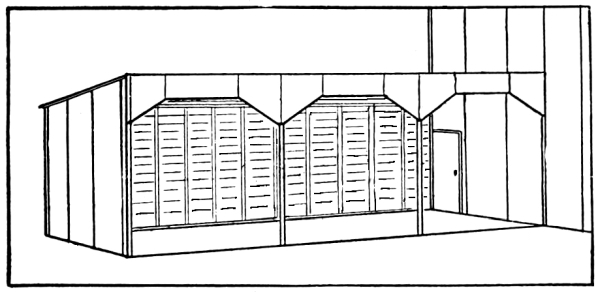

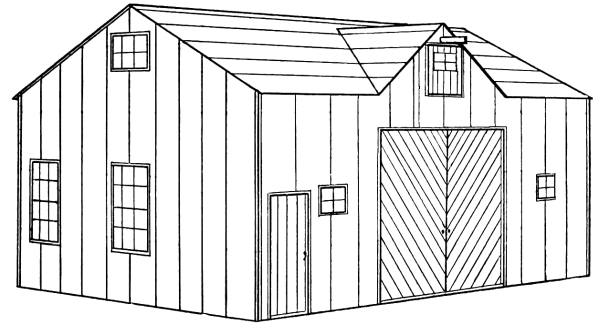

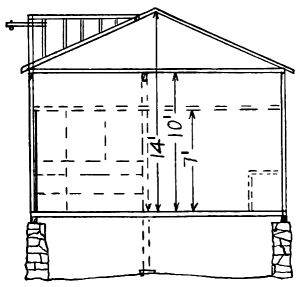

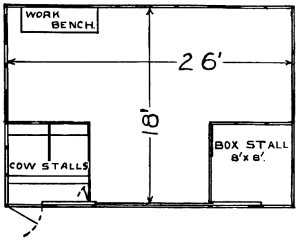

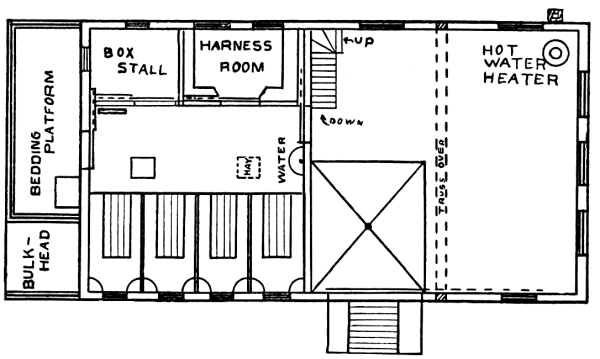

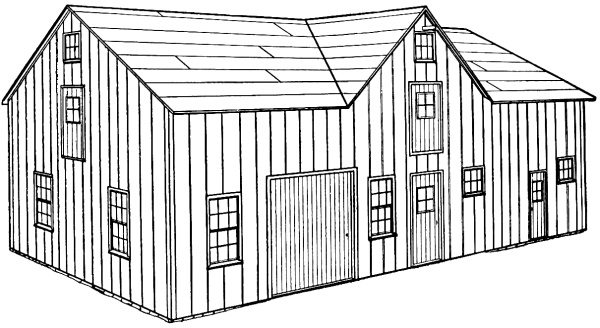

In Figs. 36, 37, and 38 we give a plan for a village stable, for the man who keeps a horse and one or two cows, and the ground floor also provides room for the work-bench (which is most desirable where there are boys in the family), besides standing room for the carriage, wagon and sleigh.

Fig. 36—A village stable for a horse and cow.

Fig. 37—Cross-section.

Fig. 38—Ground plan.

This stable is planned to be twenty-six feet long by eighteen feet wide, is ten feet from floor level to eaves, and fourteen feet from floor to ridge of roof. More pitch can be given to roof if desired, but with a good roofing like Paroid the roof slope may be slight. It would be better to make the walls two feet higher if more storage space is desired above the scaffold floor. The doorway is eight by eight feet, and stall space eight by eight feet is made in each front corner; a box stall is provided for the horse and two cow stalls in the left-hand corner, with a small door opening into the cow linter. Hay scaffolds seven feet above the floor extend across each end and may be joined at the rear if desired; a scaffold floor above the large doors extends from front to rear, or to the drop-scaffold walk connecting the two side scaffolds at the rear. A basement six or seven feet deep under the whole is a valuable addition to such a stable, making room for storing and rotting the manure, and a storage room for roots, etc., in one corner.

Six-inch-square sills, posts, and floor stringers are amply strong for the strain usually put upon a small stable, and the center posts, set at corners of box stall and cow stalls, help carry the main floor and the storage floor above. If preferred, the intermediate posts may be set in the center and the stall-spaces extended a foot, making them eight by nine feet. With the roof covered with Paroid Roofing, and the sides with Neponset Red Rope Roofing battened on laps and halfway between laps, a very neat and economically constructed stable is made. If desired a richer appearance may be given to the roof by adding the ornamental battens shown on page 28 and painting the whole a dark red. [Pg 23]

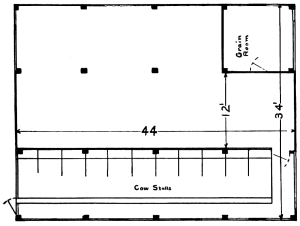

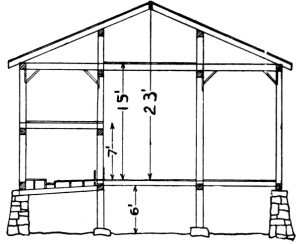

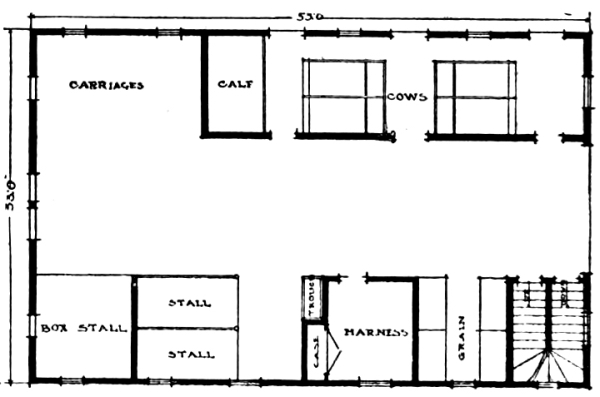

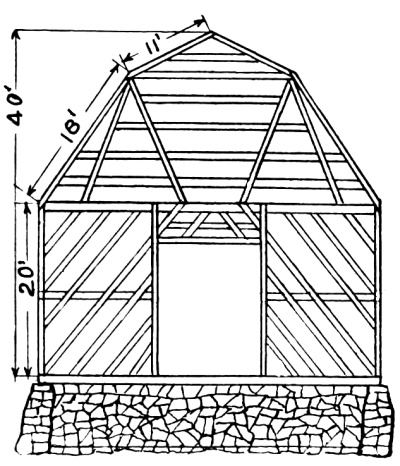

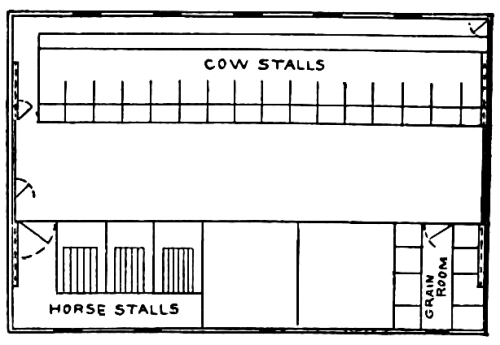

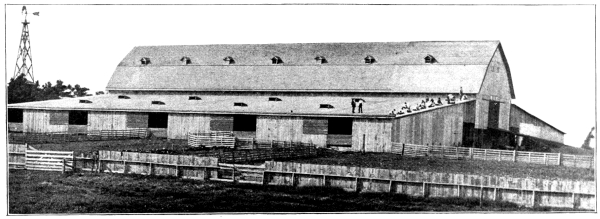

The farm-barn is a most important aid to economy of labor, if rightly planned, and we give on this page the plans of a small barn, for a farm where eight or ten cows are kept, such as is quite common in New England and the Middle States, and which gives excellent satisfaction everywhere. On the farm where this plan was studied the pair of horses were housed in a small horse barn nearer the dwelling house, the Democrat wagon, canopy top carriage and sleigh, etc., being under the same roof.

Fig. 39—A barn for a small dairy farm.

Fig. 40—Ground plan.

Fig. 41—Cross-section.

This barn is forty-four feet long by thirty-four feet wide, and is built in four “bays” of eleven feet in length each. The main floor is twelve feet wide, and hay wagons drive in at either end and out at the other. The cow stalls occupy all of the linter on the south side, a door at the end opening into the lane to the pasture. The first bay on the north side is ceiled up with tongued and grooved boards, has a tight floor overhead, and is used as a grain storeroom; the other three bays on that side are hay mows from floor to roof.

Over the main floor and fifteen feet above it is a floor for hay, or corn, or used for general storage at different seasons. There was no floor on the collar-beams when the present owner bought the farm. Strong poles had been laid across the space and surplus hay thrown on them; since being floored over the owner says it is the best part of the barn, and invaluable for drying out crops not fully cured. A basement about six feet in depth receives the manure from the cows, and three or four logs have the run of the cellar and manure heaps, thoroughly rotting and “fining” the manure for the next season’s crops.

The frame of this barn is of eight-inch square hemlock timber, the braces three by four inch hemlock mortised into posts and stringers, the floor stringers three by nine inches, two feet apart and well cross-bridged, the floor of three-inch plank. The scaffold floor is of inch boards laid on two by six inch stringers three feet apart, and is amply strong for any load put upon it.

Grain bins along two sides of the grain room may be four feet wide, and, fitted with drop fronts may be five feet high and divided into two or more compartments. Two small bins may be fitted in each side of the window; the window may be in the end if preferred. [Pg 24]

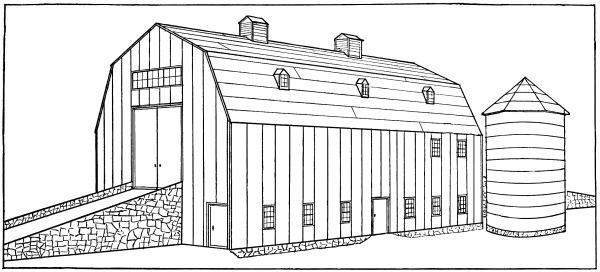

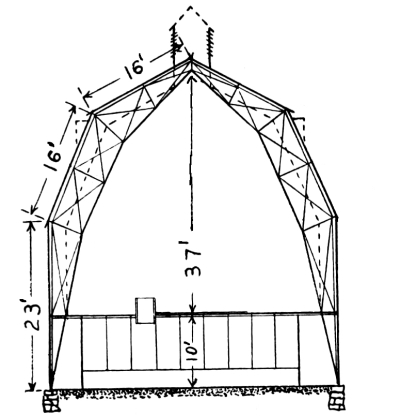

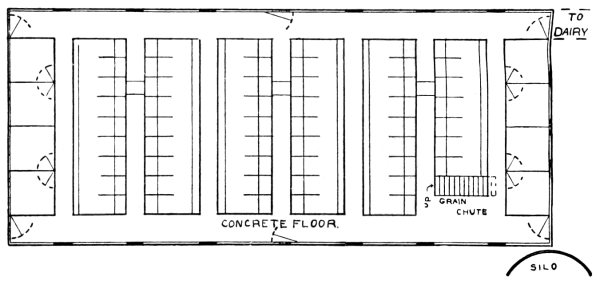

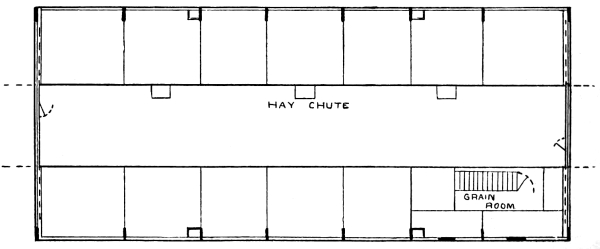

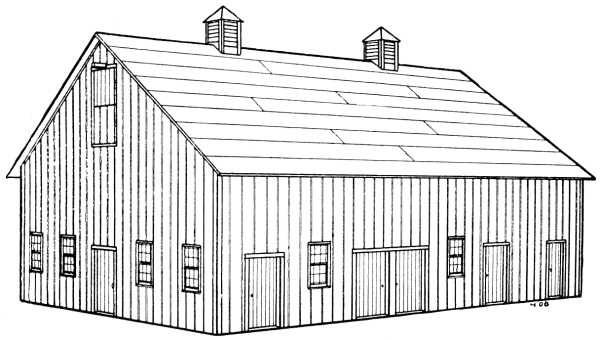

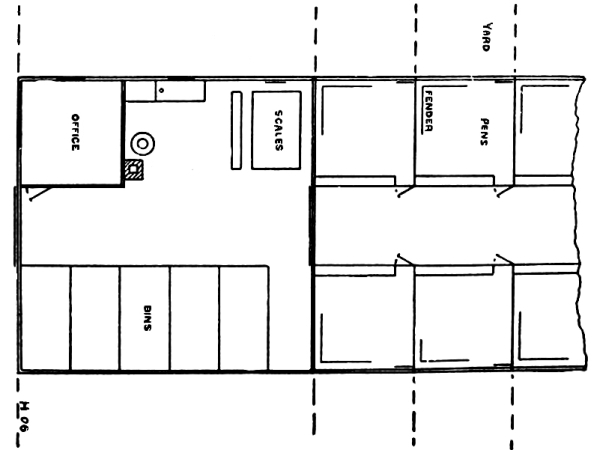

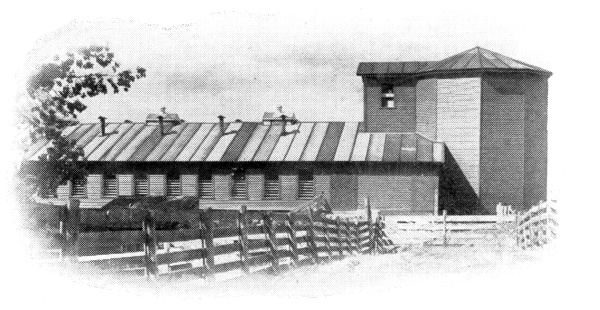

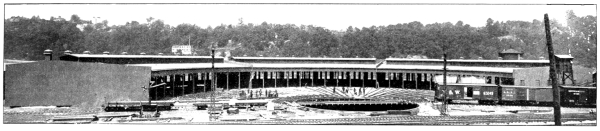

Fig. 42—A complete dairy barn, with silo.

Modern dairy farming means an up-to-date dairy barn, and we give herewith the plans of one which is warmly endorsed by the owner and carries fifty cows in perfect comfort. This is a truss-frame barn, ninety-three feet long by forty feet wide, the basement (or ground) floor being wholly occupied by cow stalls and calving pens, the main floor being a hay-storage room. Two bays on one side are used for grain storage, all the remainder of the bays on both sides being for hay; a drive-way fifteen feet wide extends through this floor, and inclined driveways at each end give access from the fields in either direction.

The ground floor is concrete throughout. A walk five feet wide extends along each side and cross walks three feet wide are between each row of stalls at both front and rear, one for breeding and the other for the cows and the milkers. A shallow gutter, eighteen inches wide by six inches deep, extends along the rear of the stalls to receive the droppings and urine, which is removed twice a day and drawn at once to the fields or heaped for tramping over and rotting under wide-roofed sheds. The calving stalls, four at each end of this floor, are eight by seven and three quarters feet in size, and one or two of them can be occupied by bulls, if desired. [Pg 25]

The watering system may be either a wooden gutter extending along the front of each row of stalls or a cast-iron semicircular pan set between each pair of stalls so as to supply a cow on either side. Whether troughs or pans are used there should be an automatic cock and tank, which keeps the water always at the desired level, and check valves which prevent the water once in the trough or basin returning to the pipe and contaminating others.

Fig. 43—Cross-section showing truss-frame plan.

All the food is stored on the main floor, whence convenient chutes convey it to feeding troughs or push-carts on the walks below. The ensilage from the silo is loaded directly into the push-carts just outside the door, or could be chuted to the walk inside. The soiling crops fed in summer are cut up on the main floor and sent down to the waiting push-carts in the walks below. The roof and sides of this barn are covered with Paroid roofing.

Fig. 44—Ground floor plan of basement story.

Fig. 45—Floor plan of main floor.

The tying arrangement may be either chains, straps, or swing stanchions as desired, and all three methods are in use on up-to-date dairy barns. The stock kept may have an influence upon the length of the stalls; those given are seven and one half feet long by three feet three inches wide. [Pg 26]

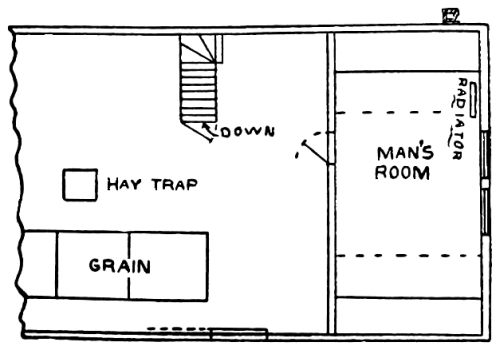

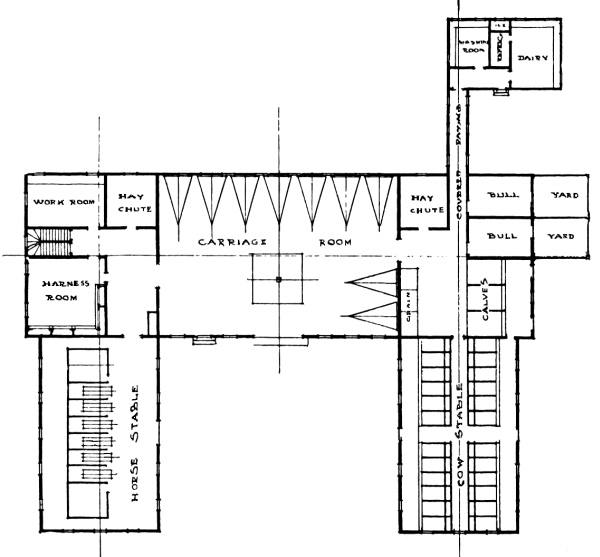

Fig. 46—A stable for a suburban place.

A convenient and well-arranged stable is greatly appreciated, and we present plans for a stable for four horses, with carriage room, harness room, man’s room, etc., hay-loft, platform for drying the bedding, and other accessories of a modern stable for a suburban home. It is built without cupola or other ornamental features, is just a plain, simple stable.

This building is forty-four by twenty-four feet in size, the sides and roof rough boards covered with Paroid Roofing. There is a basement under the whole.

Fig. 47—Second story plan.

Fig. 48—Floor plan.

The walls and ceiling of the entire lower floor are sheathed with hard pine, a wooden partition separating the stalls from the carriages, and abundant windows give light and air to all parts. The ventilation of the horse room is such that no gases reach the carriages, and “Hydrex” waterproofing felt between the floorings of the carriage room cuts of the steam and gases from the manure pit. The iron gutter along the rear of the stalls is covered with maple or birch plank, and the stall floors are either maple or birch. Running water is piped to the water basin in the horse room, and a hose cock on the other side of the partition receives the hose for washing carriages, or a revolving, overhead hose-fixture can be installed, just above the washing floor, if desired. A hot-water heater may be installed on the main floor, but better be in the basement, where the coal bin would be; radiators may be set as desired, with one at least in rear of the box stall and one on the carriage floor, and a small one in the man’s room on second floor. The roof is drained by galvanized iron pipes emptying into blind wells. The carriage room floor is concreted, and a drain pipe leads from the depression where carriages are washed to a blind well. At one end is a platform for drying the bedding, and ventilation is so well provided for there are almost no odors. As it is planned this is a practical, convenient, well-arranged stable, adapted to the needs of a family of moderate means on a suburban place. [Pg 27]

AS DESIGNED FOR C. H. LINVILLE, ESQ.,

BALTIMORE, MD.

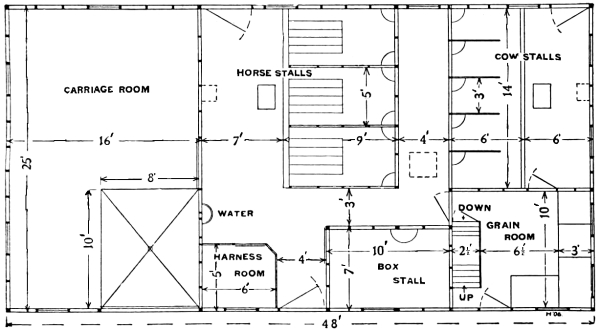

Desiring a stable which would give him room for four cows, three horses and carriage room under one roof, Mr. C. H. Linville, of Baltimore, Md., wrote and asked about enlarging the plan of a stable for a suburban place, and wished to place the carriage room at the other end of the stable, because the slope of the ground was such as to favor getting the basement under that end in the location on which he desired to build; the result was a re-drawing of that plan and presenting it as given herewith. A comparison of these two plans will aid any intending builder to change and adapt to his especial purpose such plan as he prefers, but which may not be, as here presented, the best for him.

Fig. 49—A combined horse and cow stable.

This stable is planned to be forty-eight feet long by twenty-five feet wide, outside measure, and the space is so divided there is a good seven by ten feet box stall and a good harness room in the horse apartment; in the west end a grain room ten by twelve feet gives space for four grain bins and the stairway up to loft opens out of this room. The carriage room is sixteen by twenty-five feet, and the manure pit is in the basement beneath this room; to prevent the escape of ammonia from the manure pit into the carriage room a good cement floor should be laid down.

This building is planned to be fourteen feet high to the plates and twenty feet to the ridge, which gives liberal hay-lofts; should more hay space be thought desirable we would carry side walls to sixteen or eighteen feet height, six feet, or even five feet of height from plates to ridge gives ample slope to roof where Paroid is the roof covering. An ornamental cupola could easily be placed at the junction of the roof of the gable with the main roof, and would aid in the ventilation of the hay-loft.

Fig. 50—Floor plan.

The partitions between the different divisions and about the stalls give ample opportunity for studs to be set to support the hay-loft floor excepting in the clear span over the carriage room, and the floor stringers there should be doubly heavy to support the weight over so large a space. Another way to gain the desired strength here would be to tie the roof-rafters securely and carry the strain on hangers dropped from the ridge; the three or four hangers necessary would interfere but slightly with the hay storage space. [Pg 28]

FRONT ELEVATION

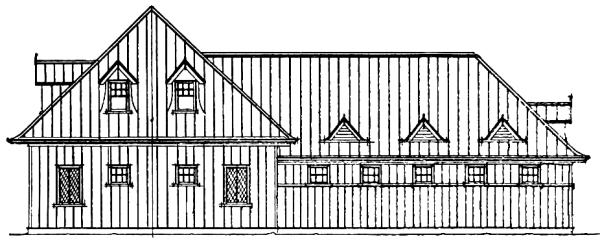

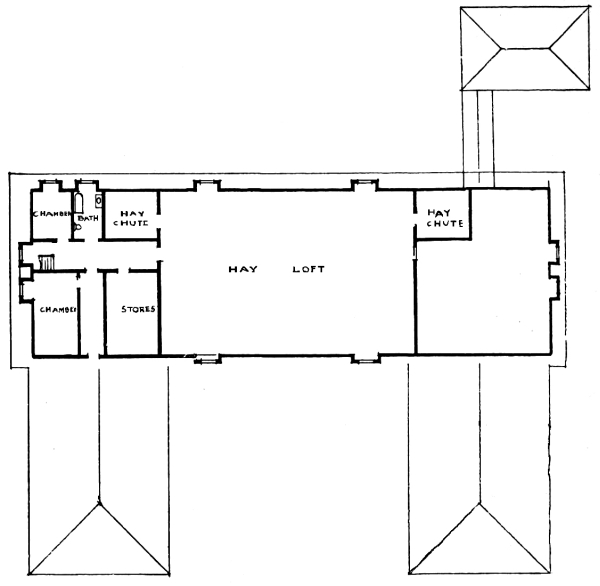

Fig. 51—An attractive dairy barn.

Sometimes it is desired to have more attractive looking buildings than the severely plain ones seen on many farms, and to illustrate the decidedly attractive appearance which can be given to buildings which are covered with Paroid roofing, we have had prepared plans of a dairy barn and a village stable, with the roofs treated with ornamental battens and the whole roof painted with a dark green or red paint, which gives the rich effect of copper sheathing and is most pleasing to the artistic eye. A cross-section of the battens we recommend are given here. Paroid can be laid more rapidly when battens are used, and enough labor is saved to pay for the slight extra cost of the battens.

SIDE ELEVATION.

Fig. 52

Fig. 53—Ornamental battens.

The same idea may be carried out on the sides of all kinds of buildings, and especially farm and poultry buildings, at a less expense than clapboards and shingles. Parine Paint, which is made especially for Paroid Roofing, is a dark brown and produces very neat results. Paroid one-ply is the best weight for the sides and we would recommend two-ply for the roof.

This dairy barn is spread out extensively, instead of being built up into the air, the front being eighty feet long by twenty-six feet wide, and there being two wings twenty feet wide extending forward thirty-two feet, enclosing three sides of a quadrangle. A dairy room is set out in [Pg 29] rear of the end containing the pens and yards for the bulls, and is connected with the cow stable by a covered walk; this semi-detached dairy room avoids having the stable odors contaminating the milk, and aids to cleanliness of dairy utensils by ample equipment for washing and refrigerating.

FIRST FLOOR PLAN.

Fig. 54.

SECOND FLOOR PLAN.

Fig. 55.

The second floor of the main building is utilized for hay and grain storage, and in one end are rooms for the stablemen, including a bath-room; this latter is a most important adjunct of a good dairy stable, it having been demonstrated that facilities for cleanness promotes cleanness, and absolute cleanness of men, animals, and all utensils is demanded in the up-to-date dairy. [Pg 30]

Fig. 56—A suburban stable.

Fig. 57—Ground plan.

The smaller stable, designed for a modest suburban residence, or country summer home, gives space for a pair of horses and three or four cows. It is planned to be built fifty-three feet long by thirty-three feet wide, the end being planned to be the front, with a drive-way onto the main floor in the front. The hay is pitched into the storage loft through a trap-door in the ceiling, or, as some might prefer, a hay-door could be set in place of the window over the drive-way doors. The dormer windows and ornamental cupola combine with the copper sheathing effect of the Paroid-covered roof to make a most attractive stable building and at comparatively moderate cost. If it was desired this plan could be altered to give a more roomy hay-loft by adding either two or three feet to the length of the posts, and correspondingly flattening the roof, carrying the dormers very nearly out to the eaves. The added height of the posts could be added to the height of the stable, keeping the roofs as steep as at present, if preferred, but it is one of the many advantages of Paroid covering for a roof that the roof need have but slight pitch, when a shallow pitch is desired. The ground plan can be arranged differently; an improvement might be to place the harness room where a calf-pen is indicated, making the space gained into a clothes and wash-room for the stableman. [Pg 31]

The plank-frame barn has been very popular in several sections of the country; the considerable saving in lumber and ease of building recommending it to practical men. Less men and time are required to build one of these barns; they are stronger, the excellent “bracing” of the frame making them effective to stand the pressure of hay and grain within or strong winds without.

Fig. 58—A plank-frame barn.

In some sections a solid frame foundation is used, in Maine the entire structure is of plank; the barns are built either with or without basement, according to the taste of the owner. A good, firmly built stone and cement foundation is advisable; with this foundation to rest the plank upon the frame is raised. Do not be sparing of spikes, they are an essential feature.

Fig. 59—Cross-section.

Fig. 60—Ground plan.

No sills are used, and the upright studs take the place of posts. Two for each post are set on the foundation on each side, between these is placed and spiked the cross-plank, which extends the width of the barn and ties the two sides together. The scantlings on each side of barn floor, forming center posts, are then raised and spiked in place. Upon outside of each upright is spiked a plank of same size as, and parallel with, the first cross-plank; this gives three 2 × 8’s for cross sills through center of barn, each joint or band being fixed in this way. End joints, using boards instead of plank on outside, give the bedwork of the barn. At the sides, between uprights in place of sill, a plank is firmly spiked; this holds the uprights firmly in place and prevents working sideways, while the thoroughly spiked cross planks prevent all movement in other directions.

Some barns are boarded diagonally, some horizontally; both methods give excellent satisfaction. Many of these barns are built with a hip-roof, as in the illustration given, and these give a great amount of storage room in the loft. The steeper single-slope roof gives equally good results, looks well, and is a little more economical to build.

Paroid on roof and sides make it wind and waterproof. [Pg 32]

(FROM A WISCONSIN FARM-INSTITUTE BULLETIN)

Fig. 61—Perspective of sheds.

Fig. 62—Frame plan.

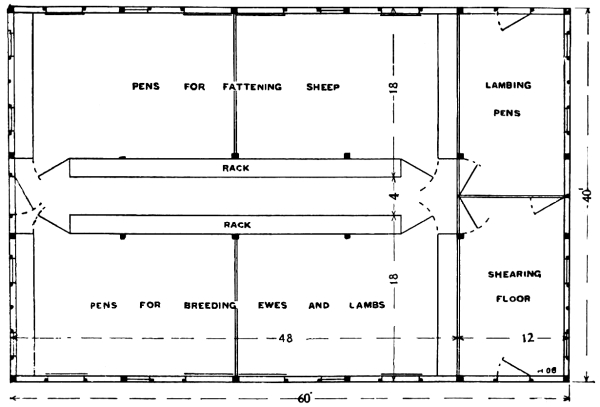

It is in the nature of sheep to dislike dampness. In the pasture they will fold at night always on the high and dry elevations. In selecting the site of a sheep shed these facts should determine the choice of a site that is drained and dry throughout the year. Dryness is one of the essentials of a good foundation for a healthy shed; second only to this in importance is the ventilation. Warm, close sheds mean the downfall of the sheep that are folded in them. A sheep is warm in body, as its blood temperature is high, and then the nature of the fleece is such as to be very retentive of the body’s heat. The cause of most failures to keep sheep profitably has been from housing them in warm, close buildings.

Fig. 63—Ground plan.

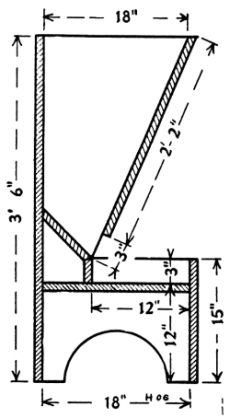

Closely connected with the question of ventilation is the size of the shed. The amount of room required by a sheep will vary considerably, ranging from ten square feet for the Merino and Southdown to fifteen square feet for the larger breeds, including the Cotswolds and larger Downs. It is not advisable to crowd breeding ewes into a small area. The crowding is most injurious when it results from restricted room at the feeding rack and when it occurs through narrow doors. A breeding ewe weighing one hundred and fifty pounds will require fully one and one-quarter feet of space at the fodder rack.

A desirable attribute of a shed is the entrance of sunlight; this particularly encourages the growth of the lambs, and it is to them that [Pg 33] the shed will do the most good. To further the entrance of sunlight the windows should be higher than they are wide, which will materially assist in diffusing the rays over the greatest amount of inside space. In addition to these a shed should be large enough to supply storage space for sufficient fodder to feed the sheep while they must be sheltered. Estimating that a ton of hay requires five hundred cubic feet, and that a sheep will not eat over three pounds of hay per day, it would require about one hundred and twenty-five cubic feet of space to contain the hay needed to maintain a sheep during six months. There should also be room available for a root cellar and for the storage of straw.

Fig. 64.

Fig. 65.

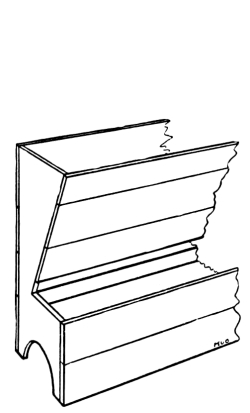

Rack for inside feeding.

Fig. 66.

Fig. 67.

Rack for outside feeding.

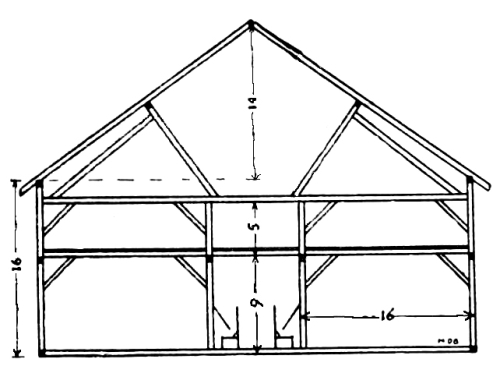

The plan here given is of a building forty feet wide and sixty feet long. It has two stories, the first being nine feet high and the second six feet from the floor to the eaves. It is advisable to make the height of the lower story nine feet to secure the best results in ventilation. The sills are six by eight inches, resting preferably on stone foundation, and if set on posts they should be heavier. The ground both on the inside and outside should come close to the sills, so that no obstruction is offered by the sills to the free passage of the sheep through the doors. The doors are all four feet wide, and those that are used by the sheep should be sliding; the windows are three feet wide and four and one-half feet high. In the center of the sheep apartment there are double doors ten feet wide. When both are opened and the center post removed a wagon can be driven through to remove the manure from the pens.

The arrangement of the lower floor has been adjusted so as to give the sheep the smallest amount of space and yet have easily accessible feed racks that would give sufficient room to the sheep for feeding. The feed racks are all permanent, as there is no necessity for their removal, and they form a wall for the passage way which runs through the center. In this way it is easy to put hay in them, and it is very easy to put grain into the troughs in front of them. As will be seen in the ground plan there are two chutes at each end, down which the hay is thrown from the loft. From where it falls it is easily distributed into all the racks. [Pg 34]

(Adapted from Bulletin No. 109.

Illinois Experiment Station.)

Fig. 68—Individual

hog house.

Individual Houses.—Individual hog houses, or “cots,” as they are sometimes called, are built in many different ways. Some are built with four upright walls and a shed roof, each of which (the walls and roof) being a separate piece can easily be taken down and replaced, making the moving of these small houses to another location an easy matter. Others are built with two sides sloping in towards the top so as to form the roof, as shown in Fig. 68. These are built on skids and when necessary can be moved as a whole by being drawn by a horse. They are built in several different styles: some have a window in the front end above the door, while all may have a small door in the rear end, near the apex, for ventilating purposes. These houses are built in different sizes; indeed, there are about as many different forms of cots as there are individuals using them.

The arguments in favor of this type of house for swine are that each sow at farrowing time may be kept alone and away from all disturbance; that each litter of pigs may be kept and fed by itself, consequently there will not be too large a number of pigs in a common lot; that these houses may be placed at the farther end of the feed lot, thus compelling the sow and pigs to take exercise, especially in winter, when they come to the feed trough at the front end of the lot; that the danger of spreading disease among a herd is at a minimum; and in case the place occupied by the cot becomes unsanitary it may be removed to a clean location.

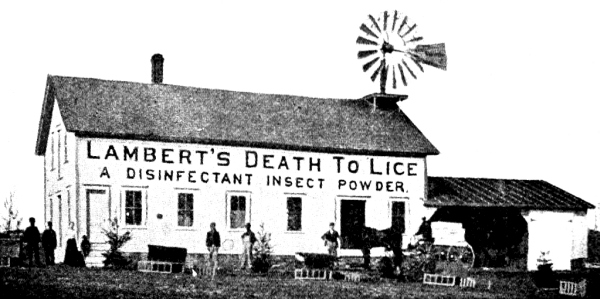

Large Houses.—Individual hog houses have certain advantages in their favor, and large houses, if properly planned and built, have many points of advantage; among them being good sanitation, serviceability, safety in farrowing, ease in handling hogs, and large pastures involving little expense for fences. In order to be sanitary a hog house should admit the direct rays of the sun to the floor of all the pens and exclude cold drafts in winter, be dry, free from dust, well ventilated, and exclude the hot sun during the summer.

Fig. 69—Large hog house.