Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The illustrations may be enlarged for better legibility and visibility by clicking them (may not be available in all formats).

The cover image has been created for this text, and is in the public domain.

Crown 8vo, price 6s. 6d.

TEACHING AND ORGANISATION.

With Special Reference to Secondary Schools.

A MANUAL OF PRACTICE.

Edited by P. A. BARNETT, M.A.

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | The Criterion in Education. By P. A. Barnett, M.A., late Principal of the Isleworth Training College. |

| II. | Organisation and Curricula in Boys’ Schools. By A. T. Pollard, M.A., Head Master of the City of London School. |

| III. | Kindergarten. By Elinor Welldon, Head Mistress of the Kindergarten Department, The Ladies’ College, Cheltenham. |

| IV. | Reading. By Arthur Burrell, M.A., Assistant Master in Bradford Grammar School. |

| V. | Drawing and Writing. By I. H. Morris, Head Master of the Gleadless Road Board School, Sheffield. |

| VI. | Arithmetic and Mathematics. By R. Wormell, D.Sc., Head Master of the City Foundation Schools, London. |

| VII. | English Grammar and Composition. By E. A. Abbott, D.D., late Head Master of the City of London School. |

| VIII. | English Literature. By the Editor. |

| IX. | Modern History. By R. Somervell, M.A., Assistant Master in Harrow School. |

| X. | Ancient History. By H. L. Withers, M.A., Principal of the Isleworth Training College. |

| XI. | Geography. By E. C. K. Gonner, M.A., Professor of Political Economy in University College, Liverpool. |

| XII. | Classics. By E. Lyttelton, M.A., Head Master of Haileybury College. |

| XIII. | Science. By L. C. Miall, F.R.S., Professor of Biology in the Yorkshire College, Leeds. |

| XIV. | Modern Languages. By F. Storr, B.A., Chief Master of Modern Subjects in Merchant Taylors’ School. |

| XV. | Vocal Music. By W. G. McNaught, Mus.Doc. and H.M. Assistant Inspector of Music in Training Colleges. |

| XVI. | Discipline. By A. Sidgwick, M.A., Fellow and Tutor of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. |

| XVII. | Ineffectiveness in Teaching. By G. E. Buckle, Master of Method in the Isleworth Training College for Schoolmasters. |

| XVIII. | Specialisation. By M. G. Glazebrook, M.A., Head Master of Clifton College. |

| XIX. | School Libraries. By A. T. Martin, M.A., Assistant Master in Clifton College. |

| XX. | School Hygiene. By C. Dukes, M.D., Lond. Medical Officer in Rugby School. |

| XXI. | Apparatus and Furniture. By W. K. Hill, B.A., late Head Master of Kentish Town High School. |

| XXII. | Organisation and Curricula in Girls’ Schools. By M. E. Sandford, Head Mistress of the Queen’s School, Chester. |

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON;

NEW YORK, AND BOMBAY.

WORK AND PLAY

IN

GIRLS’ SCHOOLS

BY

THREE HEAD MISTRESSES

DOROTHEA BEALE

LUCY H. M. SOULSBY

JANE FRANCES DOVE

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK AND BOMBAY

1898

[v]

The book is divided into three Sections, and each of the writers is responsible only for her own part, and yet I hope it will not be merely a composite book; all the contributors are members of the teaching staff of the Cheltenham Ladies’ College, or have at some time formed part of it, and now, as then, there is I believe a unity of purpose, which will give harmony to the work.

The book is intended to be a practical one, helpful chiefly to teachers in our large Secondary Schools; the limits imposed compel us (1) to deal more with methods than the underlying principles; (2) to isolate more or less the influences of the school from those of the manifold environment, which are at the same time forming the body, mind and character of the child, and which seem to make the school-life of relatively small moment; (3) we have to treat only of a few years of life; for, like the bird of the fable, the soul of the child comes to us often from some unknown region, stays for a while in[vi] our banqueting hall, and then passes again into the darkness.

Yet I suppose the experience of most of us bears witness to the great importance of the school-life as one of the factors in the “development of a soul”. “The atmosphere, the discipline, the life” of the school is so potent, that the word education has been often limited to the school period, and the pupils of an Aristotle, an Ascham, an Arnold, speak of their teachers as having given them a new life. Our work is not insignificant, and our earnest study must be by instruction and discipline, by what Plato calls music and gymnastic, to promote the harmonious development of the character; to bring our children into sympathetic relations with the noble and the good of all ages; to lead them into the possession of that good land, “flowing with milk and honey,” the spiritual inheritance of humanity.

I would fain hope, that one day all teachers will endeavour to spend at least some time, before entering on professional work, in studying the art, the science, the philosophy of education. In this little book we have had to restrict ourselves almost to the first, but we have referred to works which deal with the higher aspects of the subject. I would earnestly press on all my readers, that their own education must[vii] never be regarded as finished; if we cease to learn, we lose the power of sympathy with our pupils, and a teacher without intellectual and moral sympathy has no dynamic, no inspiring force. Especially should all teachers be students of psychology, of that marvellous instrument, from which it is ours to draw forth heavenly harmonies. To many a teacher might the words of Hamlet be addressed by her pupils:—

How unworthy a thing you make of me! You would play upon me; you would seem to know my stops; you would pluck out the heart of my mystery; you would sound me from my lowest note to the top of my compass; and there is much music, excellent voice in this little organ; yet cannot you make it speak. Do you think I am easier to be played on than a pipe? Though you can fret me, yet cannot you play upon me.

Dorothea Beale.

| SECTION I. | |

| INTELLECTUAL EDUCATION. Edited by DOROTHEA BEALE, Principal of the Cheltenham Ladies’ College; formerly Mathematical and Classical Tutor, Queen’s College, London. | |

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| A Few Practical Precepts | 37 |

| PART I. HUMANITIES. | |

| English Language Generally—Reading, Writing, Grammar, Composition | 44 |

| Classical Studies | 67 |

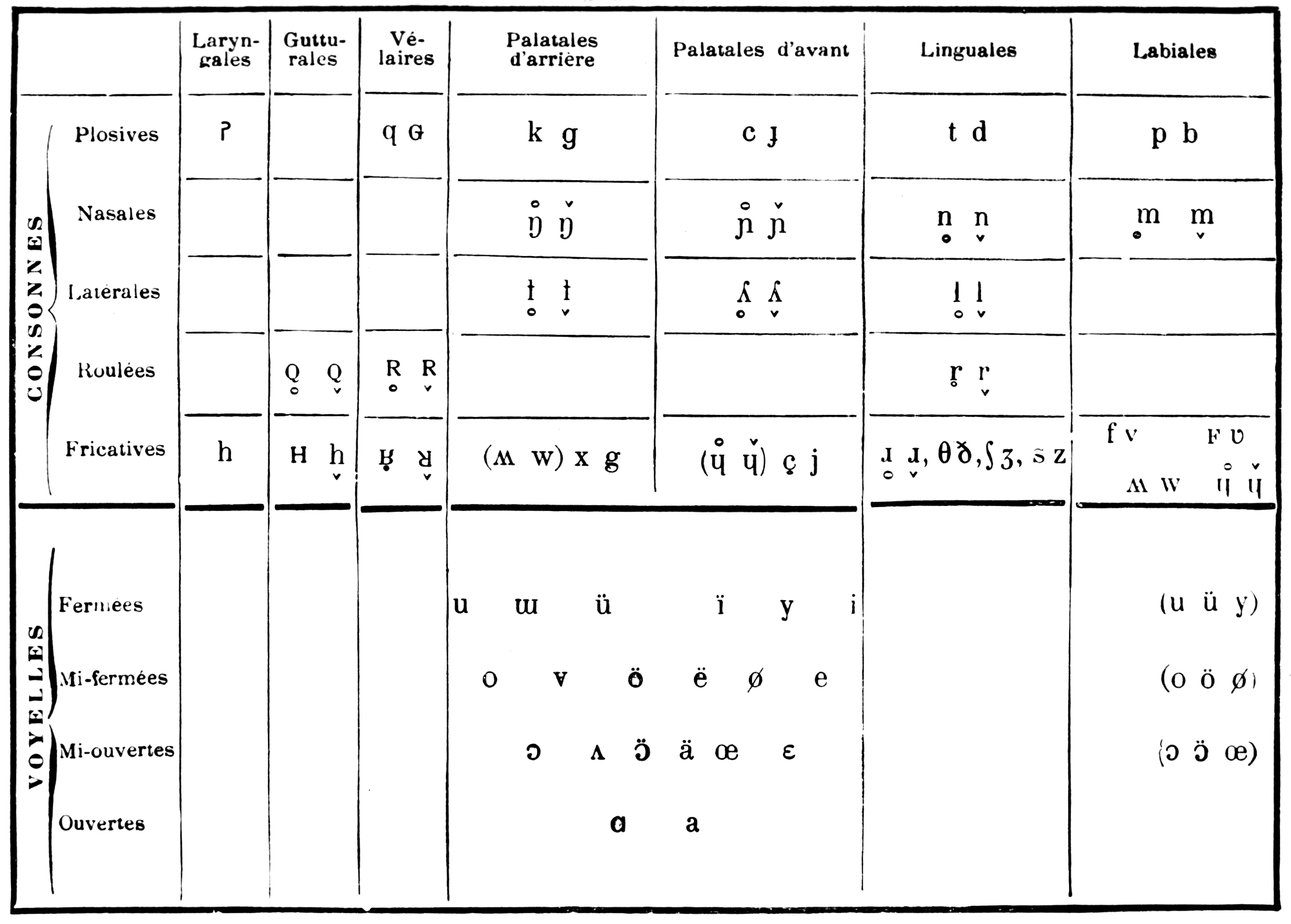

| Modern Languages | 94 |

| Spelling Reform | 106 |

| History as an Educational Subject | 114 |

| Teaching Modern History to Senior Classes | 124 |

| The Teaching of Ancient History | 159 |

| Time-Maps | 168 |

| Economics for Girls | 186 |

| English Literature | 192 |

| Philosophy and Religion | 202 |

| PART II. MATHEMATICS. | |

| Arithmetic | 216 |

| Mathematics | 239 |

| PART III. SCIENCE. | |

| Introduction—Psychological Order of Study with Special Reference to Scientific Teaching | 251 |

| The Teaching of the Biological Sciences | 260 |

| Geography | 275 |

| Physics | 291 |

| The Teaching of Chemistry [x] | 307 |

| PART IV. ÆSTHETICS. | |

| Introduction—Art | 320 |

| Pianoforte Teaching | 326 |

| The Violin | 338 |

| Class-Singing | 340 |

| Singing. Tonic Sol-fa | 344 |

| Elocution | 346 |

| Drawing, Painting, etc. | 348 |

| Brush Drawing | 354 |

| Painting | 356 |

| Fresco | 358 |

| China Painting | 360 |

| Art Needlework | 361 |

| Wood-Carving, etc. | 362 |

| Modelling | 363 |

| Sloyd | 366 |

| Conclusion—Relation of School to Home | 367 |

| SECTION II., p. 374. | |

| THE MORAL SIDE OF EDUCATION. By LUCY H. M. SOULSBY, of Manor House School, Brondesbury, N.W.; late Head Mistress of the Oxford High School. | |

| SECTION III., p. 396. | |

| CULTIVATION OF THE BODY. By JANE FRANCES DOVE, of Wycombe Abbey School; late Head Mistress of St. Leonard’s School, St. Andrews, N.B. | |

| INDEX | 425 |

[1]

Subject.I have been asked to undertake one section of a book on the education of girls, and to confine myself, as far as possible, to the intellectual aspects of education, leaving to others the task of dealing with the physical and moral aspects. I shall try to keep within the assigned limits—abstain from any systematic treatment of the laws of hygiene, and write no formal treatise on school ethics—but all the intellectual work must of course be conditioned by the necessities of the physical life, and the final cause of all education must be the development of a right character.

Education of girls in secondary schools.I am to treat the subject too with special reference to the large secondary schools which have come into existence during the last fifty years, and in doing so, I must dwell briefly upon the changes which have taken place in the ideals and theories regarding the education of girls, which have found expression in these schools, and in the Women’s Colleges. I shall speak of what has yet to be accomplished, for we are still in a period of transition, and I shall consider by what means we may best realise our ideals.

[2]

Aim of educationNow in education there is always a twofold object. Bacon tells us the furthest end of knowledge is “the glory of the Creator and the relief of man’s estate”—in other words, the perfection of the individual, and the good of the community. In some periods, indeed in pre-Christian times generally, the latter was emphasised,[1] men were to live for the commonwealth; the individual was regarded as an instrument for accomplishing certain work—he was not thought of as an end in himself. Thus even the most enlightened among ancient writers have spoken of slaves, as if they were mere chattels. Our moral sense is shocked by much that we read in Plato and Aristotle, and still more by what the laws of Rome permitted. Christianity on the other hand taught that the primary relationship of each was to the All-Father, the primary duty of each to realise God’s ideal for His children, to become perfect, and by glorifying human nature to glorify God. This was the first commandment, but the second was implied in the first—self-love was not selfish, the love of God descending from heaven became the enthusiasm of humanity.

[1] Even Milton writes: “I call a complete and generous education that which fits a man to perform justly, skilfully and magnanimously all the offices to the public and private, of peace and war”.

as regards the individual,“Education,” writes Mr. Ruskin (Queen’s Gardens), “is the leading human souls to what is best and making what is best out of them; and these two objects are always attainable together, and by the same means; the training which makes men happiest in themselves, also makes them most serviceable to others.” “The only safe course,”[3] writes Miss Shirreff (Intellectual Education), “is to hold up individual perfectness as the aim of education.”

as regards the commonwealth.And so the task of the educator is in the first instance to develop to the highest perfection all the powers of the child, that he may realise the ideal of the All-Father. But the perfection of man “the thinker,” the anthropos, “the upward looker,” can be attained only when as a son he enters into, and co-operates with the Divine purpose in thought and act: therefore to know God and His laws for His children’s education and development, is the beginning and the end. These laws man reads (1) in the world of Nature with which science has to do; (2) in human history and institutions; (3) in the hidden life of the soul—of which philosophy and religion and ethics treat. He has to seek first to know truth, to bring his will into conformity with the Divine thought, and then to utter what is true and right in word and deed; only thus will the kingdom of righteousness be set up, and the perfection of the whole—the well-being of the commonwealth—of “man writ large” be secured. The most civilised nations are devoting their best energies to the work of education, realising that upon this depends their very existence—that it is not by starving the individual life, and merging it in the general, but by developing each to perfection, that the common good will be secured. They trust less to the power of laws and institutions, more to the power of a right education—less to external restraint, more to the wisdom that comes of a wisely directed experience.

Reforms since 1848.These principles have guided the new movement for women’s education, and those who have followed the changes in public[4] opinion, since people have thought more of each individual as an end in himself, are full of confidence and hope. The reformers said: “Let us give to girls an invigorating dietary, physical, intellectual, moral; seclusion from evil is impossible, but we can strengthen the patient to resist it”.

Such were, I believe, the feelings and the thoughts of those who initiated just fifty years ago the great movement, which found its first visible expression in the foundation of Queen’s College by Maurice and Kingsley and Trench and others like-minded and less known. This was soon followed by the opening of Bedford College, 1849, and the Cheltenham Ladies’ College, 1853. Miss Buss and her brothers, in association with Mr. Laing, established the first great High School, and Mrs. Grey and Miss Shirreff carried on the movement in that direction; from the Union founded by them grew up the G.P.D.S. Co., while Miss Davies with far-seeing wisdom won over Cambridge professors (amongst whom I may specially mention Professor Henry Sidgwick and James Stuart) to offer the highest culture to women.

The leaders had to ask and answer many questions. What direction, what shape should the new movement for higher education take? Should there be two sorts of education for girls and boys? The Schools’ Inquiry Commission had shown that a specially feminine education had not produced very successful results, and the leaders said: Let us give to girls the solid teaching in languages and mathematics and[5] science, which are found to strengthen the powers of boys, and prepare them to do good work of many kinds. If it was objected that women were to rule in the home, and men in the larger world, they argued, that for girls as for boys, the right course was to give a liberal education. The boy does not learn in the school the things which will be required in his future business or profession, but he brings to these the cultivated mind, the power of work, the disciplined will.

And the world is more and more recognising that the leaders were right, and schools have arisen in all our great towns. Fifty years ago there were dismal prophecies—an outcry that study would ruin health. Results physical and moral.Now it is a common remark that there is a general improvement in physique. Women too are more conscious of their responsibilities in the life of the family, as well as in that of the country, especially in social and church life. They feel, that though they may have but the “smallest scruple” of excellence, they must render for it “thanks and use”. Besides, another good has been more and more realised; as Mrs. Jameson, in her beautiful lecture,[2] set forth, girls taught on the same lines, and women who can enter into the subjects of study and thought which occupy the minds of their fathers, husbands, sons, have more understanding, more sympathy, more power to make the home what it should be; the only healthy intellectual companionship is communion between active minds, and the highest purposes of marriage are unfulfilled, if either husband or wife lives in a region[6] of thought which the other cannot enter. Besides, those many women who remain unmarried can, if well educated, find in some form of service the satisfaction of their higher nature. Surely women trained in good schools and colleges have as wives and mothers shared the labours and entered more fully as companions into the lives of husbands and children. The names of many will occur to my readers, but one cares not to name the living. We see every year at the Conference of Women Workers, that the seed sown in faith has brought forth fruit; that the whole aspect of the woman’s realm has changed since the days of Evelina and Miss Austen.

[2] “Communion of Labour.”

But none of us may rest in that which has been attained. We ask for the “wages of going on and not to die”. There is earnest endeavour on the part of all engaged in the work of education, which has found expression in such societies as the Parents’ Educational Union, the Child Study Society, and the Teachers’ Guild. Teachers are not content with the school year, but holiday courses are the order of the day, and many are seeking training, and others ask for a year or a term to improve, and books on education are pouring from the press, and some of us, who have gained experience which may be helpful to others, feel bound, though much hindered by the calls of active life, to share those experiences, and say what we can about the ideals, the principles, the methods, which, we trust, have already, in spite of the gloomy portents of years gone by, improved the physical, the intellectual and moral vigour of those who have shared the larger life, entered into the higher intellectual interests, and undergone the strengthening discipline of our large schools.

[7]

CurriculumWith these preliminary remarks, I enter upon the subject of the curriculum; I have drawn up a table which I shall proceed to discuss. I have classed the subjects of education under five heads, and divided the pupils in a general way also into five classes. But before I deal with the practical, let me speak of the ideal. There is nothing so practical as ideas—these are the moving power of all our acts.

If what I have said is true, the subject cannot be treated in reference to girls only; not because I would assimilate the teaching of girls to that of boys, but because the teaching of both should aim at developing to the highest excellence the intellectual powers common to both. The teaching of modern science tells us that both pass through the same lower stages, that they may rise into the higher, and all history tells us that men and women

So we ask generally what is the Education of Man? Fröbel has rightly emphasised the last word. It is the development of that which distinguishes man from all the lower forms of life “summed up” in him, that can alone be properly called the Education of Man: other creatures can live, as he does, the nutritive or vegetable life, which goes on of itself—other animals live the conscious life, they see and know, but to man alone it is possible to objectify all things by transcending them, and even that lower self, which is part of his dual nature; he is able to know himself both as “I” and “me”; he brings to sensation the formative power of his own thought, makes, as Kant has said, the[8] universe which he did not create. And so man does not merely perceive, but apperceive, takes into his own being ideas, thoughts; combines, associates these,—and indeed it is difficult to speak of these ideas otherwise than Herbart does, as entities, by which the mind grows, fashioning them to its own uses, as the body does, the food on which it lives. Because he can objectify thus, language is possible. Man gives to thoughts, these “airy nothings, a local habitation and a name”; he is able to plan, to project and therefore to form judgments.

But if he is related to that world to which the senses reach, he is also in relation, through an inward feeling which we call sympathy, with other “subjects,” able to recognise in others that which he knows in himself as mind; if he finds himself so related to the world of sense, that he responds to its touch, much more nearly is he in relation with other personalities; these he knows, before he recognises objective nature; through other minds his own is educated, and so the humanities take the first place; he enters into relations through the communis sensus with a world of thinking beings. These persons communicate thoughts, specially through (a) language immediate, and through written language. By written speech the limitations of space and time are abolished, and we are able to speak not only of men, but of man, for not only is his physical life continuous, but his mental and moral life through the ages is one. So from language we pass to (b) history and literature and historic act, the record of what men have done and suffered and thought and recorded, not in books only but in all material things; for man the dead live; and as the actors pass from the stage, history, no less than philosophy and science, tends upwards to those[9] higher regions of thought, where we ponder on the (c) mysteries of man’s self-conscious life, on his relation to other minds, and to the One whose offspring we are, and in Whom all things live and move and have their being.

The subjects of study then may also be classified under five headings:—

I. The Humanities: which have to do with man, known objectively through word and deed, in language and literature, in history and art; subjectively, as in ethics, religion, philosophy.

II. Mathematics: embracing three divisions relating to space, number, energy in the abstract—these have to do with necessary truth.

III. Science: which rests not on a basis of thought only, but on facts given through sense objectively.

IV. Æsthetics: which may be classed under the three heads, as music, painting and the other arts—considered subjectively.

V. The exercises suitable for the physical development.

It is with the first section that every teacher has to do; though he may be a specialist for science or mathematics or music, he has always to do with man in his manifold relations, he has ever to do with the humanities. It must be the constant study of the teacher to find the best means of developing the powers of thought, of calling forth right motives of action, developing right habits, and so forming noble characters, which is the final cause of all his labours. Ever throughout life he will by study and experience deepen and extend his knowledge, but it is earnestly to be desired that he should have some leisure for definite preparation by the study of education as an art, a science, a philosophy, before entering on his responsible work. In this, as in everything else, only those who have gained the knowledge are really judges of its value. The man who knows no foreign tongue, supposes he understands English, but we know in how poor and faulty a way. A study of the mysteries of our own being, of the fundamental basis of philosophy and psychology, personal knowledge of and sympathy with the great thinkers and philosophers and martyrs of education, must move us to more purposeful and thoughtful and devoted lives, and give us a joy that we cannot feel when we are working blindly and mechanically, without the faith which works by love.

[10]

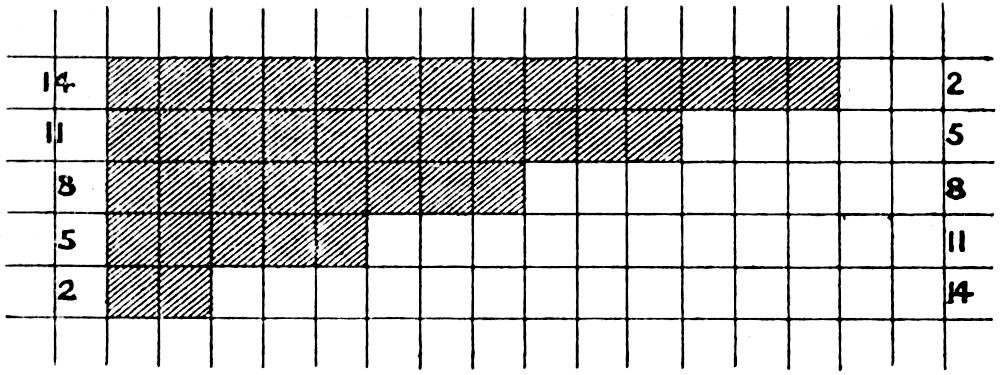

HOURS OF STUDY INCLUDING PREPARATION PER WEEK.

| Subjects. | A. Under 8 years. | B. 8 to 12 years. About 24 hours. |

Hrs. B and C. | C. 12 to 16 years. About 30 hours. |

D. 16 to 18 years. About 36 hours. |

E. Over 18 years. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Hu- mani- ties. |

- | 1. Language. | English reading and French v. voce. | Elementary ideas of grammar, French v. voce, and reading and translation into English, learning poetry, dialogues, etc. | - | 12 | Grammar; increasing attention to philology; French, with German, or Latin. | French, German or Latin. In some cases one other language. | An additional language, Greek or Italian. | ||||||||||

| 2. Man objectively. | - | History. Literature. Art. |

Mythological tales and stories from history. Learning poetry. |

Time maps and epochs in world’s history. English history treated biographically. Stories from ancient history. Learning poetry. | English history in periods and corresponding literary periods with special books. Outlines of general history, ancient and modern, with time maps. | English constitutional history. Special period of English. Also of ancient or modern. Difficult books in English. | Ancient classics in the original or translations. Foreign classics and view of European literature. | ||||||||||||

| 3. Man subjectively. | - | Ethics. Religion. Philosophy. |

Bible stories, simple hymns and prayers. | Bible lessons selected. Learning simple passages from New Testament, hymns and collects. | A gospel. Instruction in the prayer-book, etc. | St. John or epistles. Doctrinal teaching. |

Fundamental ideas of philosophy. Christian dogmatics and ethics. | ||||||||||||

| II. Math- emat- ics. |

- | 4. Arithmetic and Algebra. | Arithmetic, chiefly with concrete objects. | Arithmetic in some cases generalised to algebra for older children, for younger still much concrete. | - | 3 to 5 |

Arithmetic and algebra to quadratics. | Advanced pure and mixed mathematics. | |||||||||||

| 5. Geometry. | Simple ideas of form. | Elementary practical geometry. Many problems. In some cases a beginning of logical demonstrations. | Euclid I. and II., or equivalent. | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. | - | Kinematics. Mixed Mathemats., e.g., Mechanics. |

Elementary mixed mathematics. | ||||||||||||||||

| III. Sci- ence. |

- | 7. Natural Science.[11] | Object lessons. | Botany, zoology, astronomy, laws of health—in succession. | 2 to 4 |

Botany, zoology, astronomy, laws of health—in succession. | Physiology and one or more branches of physical science. | ||||||||||||

| 8. Physiography. | Making map of school and near places; modeling in clay or sand. | Erdkunde, physiography, natural phenomena. | Erdkunde, physiography or natural phenomena. | ||||||||||||||||

| 9. Molecular Science. | Chemistry, heat, light, electricity—in succession. | ||||||||||||||||||

| IV. Æs- thet- ics. |

- | 10. Music. | Sol-fa singing. | Instrumental music, singing, elocution. | 7 to 9 |

Instrumental music, singing, elocution. | - | Some one branch. | |||||||||||

| 11. Drawing, etc. | Drawing with pencil and brush. | Drawing and painting. | Drawing and painting. | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. Plastic Arts, etc. | Modelling in clay. Basket making, cardboard sloyd, etc., etc. | Various kinds of handwork. | Various kinds of handwork. | ||||||||||||||||

| V. Ath- let- ics. |

- | 13. Gymnastics, etc. | Systematic drill. | Systematic drill. | |||||||||||||||

| 14. Games. | Kindergarten games and drill. | Games. | Games. | ||||||||||||||||

| 15. Country Excursions. | Field clubs. | Field clubs. | |||||||||||||||||

[12]

I have mentioned at the close of the introduction some books not too large or difficult which will be helpful to those who desire to begin the serious study of the subjects included under the general heading of pedagogy.

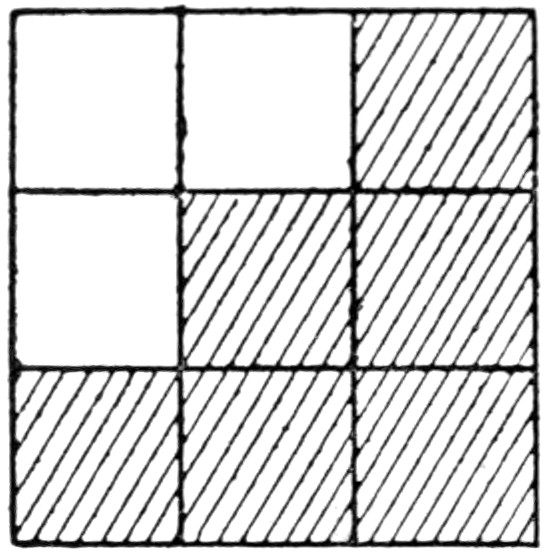

In the table (p. 10) I have arranged courses of study and grouped pupils according to age, but only for those called B and C have I attempted to give the time each week, which might be allowed on an average for serious study. I think the Bs generally and the Cs almost always should follow a fixed course, though some variation should be permitted to the Cs. The Ds and Es should take special directions, dropping some subjects and giving much time to others. Under the head of B, I have given what is perhaps the nearest approach to the normal type in my own school. Those who do not learn music, can of course take an extra language, or otherwise cultivate a special subject; those who are but slightly pervious to mathematical ideas are allowed to drop Euclid, after having done[13] enough to profit by the wholesome discipline of writing out propositions say up to Euclid I. 26. These may perhaps add another musical instrument or some manual work.

The principle I would insist on is that our curriculum should, to use a sensible figure, be pyramidal, having a broad base and narrowing; the total cubic content might be the same each year, but in proportion as the subjects taken were fewer, there would be greater depth. Thus the Cs would specialise to a slight extent, the Ds should do so still more, and the Es have found out their vocation, so that for these last no time-table can be given.

In drawing up a time-table I have given only the general lines, and assigned an average time for each section; the case of every individual must be separately considered, and there should always remain some hours of leisure—in the highest classes I have arranged for school work about eight hours out of the twenty-four. If we give four hours to meals and outdoor exercise, and eight to sleep, we have a margin of four hours—a considerable amount of time, if multiplied by six; part of this may be given to general reading, part to social and family life, but for the growing and developing mind there must be time for solitude, for entering into the secret chamber, and listening for the voice heard only in the stillness. We read much in praise of “Eyes” and much in dis-praise of “No-eyes,” but there are times when great thinkers are blind to outward things, and deaf to earthly voices; it is at such times there rise before the mind’s eye ideals which fashion the whole life. I am sure that in these days the[14] young lose much for want of more quiet on Sundays. There may have been over strictness in the past—there is now a surprising ignorance of the Bible and the grounds of faith. Silence.The silence rules of a good school tend to produce a spirit of repose, and a library where no speaking is allowed is a help. Rules which hinder idle talk in the bedrooms are a great boon to those who find the value of quiet at the beginning and end of the day, and I earnestly hope that the excitement of the playground may never supersede the country rambles which have been fruitful of spiritual health to many of us.

In considering how I shall best make this small volume of use to teachers in high schools, I propose to adopt the following plan. First to treat of a few general matters which belong to organisation and the methods of management—e.g., distribution and economy of time, corrections, marks, etc.

Then to deal with the subjects of the curriculum in order, in a series of papers by myself and my colleagues.

In Part I. I have written first of language generally, embracing reading, speaking, grammar, composition, foreign tongues. It will be clear to all that I could not possibly, in the few pages assigned to each subject, treat the matter exhaustively, but I hope I may strike out some lines of thought which will be helpful, and the lists of books may assist teachers in their studies. In most subjects I have been able to get a few papers from members of my staff, past and present. Under the head of Language I have one from Mr. Rouse, a most able teacher, who had many years’ experience with our elder pupils, specially those reading for classical honours in the University of London.

[15]

In History and Literature I have papers by Miss A. Andrews, Miss Hanbidge and Miss Lumby, the very successful teachers who take these subjects in the London and Higher Cambridge class; there is also a paper on Economics by Miss Bridges.

In Part III. I have papers by four specially able and experienced teachers—Miss de Brereton Evans, D.Sc. Lond., Miss Reid, B.Sc. Lond., Miss Leonard, B.Sc. Lond., and Miss Laurie.

In Part IV. I have a number of short papers by members of our teaching staff.

Section II. has been assigned by the publishers to another hand, and for that I am not responsible. Upon the basis of this classification, I have drawn up a table showing how the methods of teaching these subjects will vary with the age of the pupil, and what is, I consider, the best order of subjects. I have also added some chapters on various subjects—as Spelling Reform and the Relation of School to Home.

Time available.Before proceeding further it will be best to consider what is the amount of time at our disposal for school teaching. The division of the year into three terms of about twelve weeks, consisting of five or six days each, is so generally adopted that we may take that for granted. The years of school life are at the utmost about ten—in the case of most girls far less.

For day schools in large towns, attended by pupils from considerable distances, two attendances are impossible, and the morning has to last from about 9 or 9·30 to 1 or 1·30. Of the four hours about three and a half are available for lessons, the remaining half-hour being taken up with the general assembly for prayers and a brief[16] interval for recreation; but these twenty-one or twenty-four hours are not spent, as parents are apt to imagine, in poring over books, but are varied by lessons in gymnastics, drawing, singing. Some pupils in large towns remain to dine at the school, and have afternoon teaching in accomplishments. In small towns they return. Thirty hours a week should, I think, be the limit of time given to study for girls of school age. Students fully grown may study six hours a day. Eight should, I think, not be exceeded by any.

Length of lesson.In arranging the time-table, several things have to be considered. (1) A, the youngest children, would have no lessons of more than half an hour, and not more than two hours of definite instruction, the remainder being occupied with games, drill, singing and various hand occupations. Those under eight would have a larger proportion of these last, and perhaps attend for a shorter time. The elder children can have a reading lesson before the general assembly, and the little ones might leave half an hour before the morning closes. If they wait for elder sisters, amusements may be devised. (2) In the case of all, an endeavour should be made to place those studies which make the heaviest demands on the attention as far as possible in the early morning hours. (3) The lessons for Sections B and C would average about fifty minutes, some being thirty minutes, others an hour, the drawing lesson being perhaps longer, whilst religious instruction following upon prayers would occupy half an hour, as would drill and singing. (4) Care should be taken to vary the subjects, so that if possible two lecture lessons should not follow one another, nor two on language, nor two mathematical lessons.

[17]

Order of study.We have next to consider the order of study, what subjects are best adapted to the state of development of the child, or in what different ways the same subject may be treated to make it suitable at different ages. In this matter fatal mistakes are still made.[3] Happily the teachings of educational reformers have brought before us the evils of the neglect of psychological principles. Dietary.We are shocked when we hear of mothers ignorant of physiology, feeding infants on bread and tea, and giving soothing syrups; we recognise the danger of too many sweets, and of cigars for growing boys—these have their parallels in the mental dietary. But it is not so much giving wrong things as the deprivation of right things at the right time that is fatal. It is wonderful how much unwholesome food can be disposed of by a vigorous child—there is a fit of sickness and it is gone; but we see in the adult bodily framework, the stunted skeleton, the decaying teeth, etc., the effect of starvation during years of growth. To deprive the child of the mental food and exercise necessary for his development at each period of his growth is a fatal error, the consequences of which are irreparable. This has been forcibly put by Dr. Harris, Chief Commissioner of Education, U.S.A. Speaking of the prolongation for man of the period of infancy required for his development,[18] that he may be adapted to the spiritual environment of the social community into which he is born, he writes: “Is it not evident that if the child is at any epoch inured into any habit or fixed form of activity belonging to a lower stage of development, the tendency will be to arrest growth at that point, and make it difficult or next to impossible to continue the growth of the child into higher and more civilised forms of soul-activity? A severe drill in mechanical habits of memorising, any overcultivation of sense-perception in tender years, may arrest the development of the soul, form a mechanical method of thinking, and prevent the further growth into spiritual insight—especially on the second plane of thought, that which follows sense-perception, namely, the stage of classifying or even the search for causal relations, there is most danger of this arrested development. The absorption of the gaze upon the adjustments within the machine, prevents us from seeing it as a whole. The attention to details of colouring or drawing may prevent one from seeing the significance of the great works of art.... To keep the intellect out of the abyss of habit, and to make the ethical behaviour more and more a matter of unquestioning habit, seems to be the desideratum.”

[3] “The logical order of a good course of instruction,” writes Compayré (Psychology Applied to Education), “must correspond to the chronological order of development of the mental powers.” “If,” writes Herbert Spencer, “the higher faculties are taxed by presenting an order of knowledge more complex and abstract than can be readily assimilated, the abnormal result so produced will be accompanied by equivalent evil.”

Tradition furnishes those who have made no formal study of the subject of mental growth with some empirical rules for a healthy dietary,—as Mr. Barnett has shown,[4] or our children would fare badly; but the evils of misplacing subjects in the order of study, of neglecting to teach the right subjects at the right[19] time, and of partial starvation, are too apparent. Let me conclude with an illustrative anecdote—an object lesson. At school I always kept caterpillars; they were regularly fed, and seldom failed to come out in perfect condition. Once some “woolly bears” escaped; they were found after a few days, and again provided with ample food; but it was too late, they came out with only rudimentary wings.

[4] Teaching and Organisation, p. 5.

But not only have we to provide the right subjects at the right time, we have to consider how the manner of teaching the same subject may be adapted to the age of the pupil. In an excellent Report on the Schools of St. Louis some years ago, Dr. Harris expounded the spiral system. In studying say botany in the lowest class, the children would learn to observe the forms of plant life, and become familiar with the main facts of classificatory botany, the observing power being chiefly called into action. Then the subject would be dropped, and taken up years after from the physiological point of view, when the learners would be able to understand the chemical changes, the process of development, etc., as they could not in earlier years. Similarly all Herbartians know how the teaching of history proceeds from the mythological story, through biography to history, and some of us have seen the bad results of giving little children formularies which have no meaning for them, instead of seeking to develop in them through the discipline of home, and Bible teaching regarding the lives of the good, feelings of filial trust and reverence and obedience. For examples of this I may refer to Miss Bremner’s book on the Education of Girls.

In the accompanying time-table I have endeavoured[20] to make a double classification in reference to the subjects taught, and the age of the learners. In discussing it I shall continue to use the word faculty, in spite of Herbartian protests, meaning thereby the power of doing certain special acts, which vary in character. We have the power of directing our attention to the objects of sense, or of withdrawing it from these, and becoming conscious only of the working of our own mind; we have, i.e., the faculty of observation and of reflection; by the use of the word faculty—etymologically, the power of doing—we need not dismember the Subject, but think of the One person as acting in different ways.

Part I., the humanities, should throughout the whole course be represented in all its branches; to it belong specially the cultur-studien. I think of some miserable starved specimens of girls I have known, fed upon an almost unmixed diet of either classics or mathematics; their physique had suffered, and they had no mental elasticity, their one idea being to win scholarships: they did this, but never flourished at the university, for want of all-round culture. Others I have known, who thought they could be high-class musicians by practising their fingers, without cultivating their minds; the results were lamentable; whereas those who gave half the time to music and half to cultur-studien, did more in the limited time. Is not the overwork of which many complain later, due to the too undivided work at one subject during the undergraduate period at the university? Mathematics relieves the strain of classics; specialising may be comparatively harmless to the full-grown man, but the child-specialist will grow up deformed.

[21]

Class teachers and specialists.Shall teaching be by class teachers or by specialists? Once every teacher was expected to take all the subjects with her class, now the tendency is towards specialisation. In junior classes the class mistress has many advantages over the specialist, for she knows what the children can do, the character and difficulties of each, and can adapt her teaching to her pupils. In any case she must exercise control over specialists, each of whom is inclined to think her subject the most important. She can get hold of children, and exercise a stronger influence than an occasional teacher, and the more subjects she teaches, the more intimate will be the relation to her pupils. On the other hand, it is not good for children to be shut up to one personality, though it is not well for them to be under too many, and there ought always to be one predominant; for this reason special arrangements are made in some boys’ schools for a tutor to follow the boy’s career all the way up the school. A class teacher too can correlate the different subjects, and make one help the other; being always at hand, she can give such help as is needed at odd times, to bring up laggards, and generally bring the intellectual to act upon the moral.

On the other hand, a specialist can attain to greater excellence, throw more life into the subject, keep up with new discoveries and methods; the best plan is perhaps for the class teacher, at least in junior classes, to hear and help to bring home to her pupils the teaching of specialists; this is desirable with some foreign teachers, who fail to understand the exact difficulties of English children. It can, however, only be done when the staff is large. The case is different with upper[22] classes, which should be taught almost entirely by specialists, though there should be always some one person responsible for each class.

Head mistress.There seems to be a great difference between the kind of influence and control exercised by a Head Master, and a Head Mistress. The government of a boys’ school approaches more nearly to a republic, of a girls’ school to a constitutional monarchy; whilst classes and teachers change for the child each year, the head mistress is permanent, and follows each through all the classes, knowing her in all her phases. She reads marks, gives encouragement and admonition, and is in immediate relation with the other controlling influences, parents and teachers. Then—owing possibly to the fact that many women have not degrees—the head mistress permits herself to criticise and advise her teachers in a way that no young master fresh from the Honour Schools would permit. “I hear you go and listen to your teachers,” said the head of an Oxford College to me—his face, on my admitting it, expressed more than his words. Again, the head mistress considers herself responsible for good order in every class, whereas in boys’ schools the entire responsibility seems to rest on the individual master; this must always be the case to a certain extent; head mistresses try to avoid indiscipline by insisting on the training of teachers, and resorting to various devices, e.g., a junior teacher is made assistant to a senior, and entrusted with a class of her own, only when she has shown herself able; or—until she has well grasped the reins—she is set to teach in a large room in which there may be the head mistress and some other teacher capable of overawing[23] the restless; or if she is a specialist the class teacher may be in the room. If the class is insubordinate owing to the bad teaching they get, there is of course no alternative but to change the teacher, or to improve her.

Economy of time.Here let me touch on some of the chief perplexities of modern teachers. Professor Miall (Thirty Years of Teaching) writes: “No one can write on education without insisting on new subjects; and yet the old claims are not relaxed. We must have science in several branches, modern languages (more efficient than heretofore), drawing and gymnastics, but classics and mathematics and divinity must be kept up and improved. Increased hours are not to be thought of, fewer lessons, shorter lessons, and not so much home-work, are the cry. More potatoes to carry, and a smaller basket to carry them in.... I believe the problem is not an insoluble one after all.”

The remedy, or perhaps I ought to say rather the mitigation of the teacher’s difficulties, is to be found in four directions. (1) In increasing the number of school years. The well-trained kindergarten child comes with an interest in lessons, a power of attention, a considerable amount of knowledge, and a clear understanding of much that formerly children knew nothing about, so that we gain time at the beginning. (2) Then if girls come earlier to school and stay later, if we have a girl from eight to eighteen, we can give many things in succession, which we once had to attempt simultaneously, when girls came “to finish” in a year, or at most two years. (3) If the hours are shorter, we can get more work done than was the case when children were wearied out with long hours; when[24] I began my teaching life at Cheltenham, children came back sleepy for two hours of afternoon lessons, and returned to do home work, when they should have been in bed. (4) Better methods economise time, but this matter is so important that I shall insist on it at some length.

Economy of time in school.(a) First let me beg a teacher to think how easy it is to waste half an hour in one minute. You have thirty girls before you and you say: “Now, girls, I am going to give you a lesson, and you must be very attentive,” and so on for one minute. Let every teacher use as few words as possible. Let there be no preambles, no repetitions: “Now, my dear child, I wonder whether, if I asked, you would be able to tell me at once,” etc. Let the question be direct. “As I have said just now,” then do not say it again.

Wordiness must be avoided. We all know how wearisome it is to hear the same thing repeated in the same or different words. If we see this in a book, we skim; if it is done in lesson or lecture, we let our thoughts wander. Children do the same. I once heard a mistress of method recommend teachers to repeat themselves!

(b) Learn what not to say, e.g., a name that you do not want remembered. I knew some boys who were set to learn the names of the “Do nothing” kings; the memory must not be loaded with useless luggage.

(c) In giving a dictation, some teachers will habitually repeat twice; the consequence is that many do not listen the first time, and a third repetition is often asked for. Let it be understood that the sentence will be given distinctly, and not repeated.

[25]

(d) In English dictations do not ask that every word should be written, but emphasise those required—“Each separate parcel was received”. “I did not perceive his meaning.” “He did not succeed in persuading her to secede.”

(e) If a lesson has been set, we must ascertain that every one has learnt it, but there should be no questioning round and round a class. If a question and answer take one and a half minutes in a class of thirty, the whole time is gone, and the teacher has no distinct impression of which pupils have answered well; but if two questions in succession are asked of each and are promptly answered, the whole lesson may be considered to be known. Suppose there is a French dialogue to be heard, or an exercise has been learned, the teacher should not read the English; the sentences should all be numbered, the teacher call the number, and the child read the French from the English. The sentences in some books are not numbered, and some dialogue books are so printed, that the French cannot be covered; these are time-wasting books. A prompt reply must always be given; since we speak at the rate of over a hundred words in a minute, three children could say two short sentences each in half a minute. Thus a class of twenty could be heard in ten minutes, or if the class teacher is assisting, and takes half the class, five minutes only would be necessary, and time saved for oral composition, or reading exercises at sight, or training in pronunciation, etc. Some teachers, if unanswered, repeat a question. A girl who is not sure will often give an indistinct reply; one who does this robs her companions; the time of the class cannot be wasted thus, she must come in the afternoon and say it by herself;[26] it will generally be found that her vocal powers are improved by this exercise.

(f) In many subjects a so-called written viva voce may be properly substituted—say six questions written on the blackboard with numbers, the answers promptly written in class, the papers of different girls exchanged, the faults underlined and the name of the corrector signed. The answers can be quickly marked by the class teacher at home. This has been dwelt on in Miss Andrews’ paper.

If French verbs have to be heard, table should be suspended, and the teacher point to a tense and a number. Here is a portion of one:—

| Sing. | Plur. | |

|---|---|---|

| Indic. Pres. | 1, 2, 3. | 1, 2, 3. |

| Imperf. | ||

| Passé défini, etc. |

Of course this rapid questioning is suitable only when we wish to ascertain whether a lesson has been learned, not to such viva voces as are dialectic, intended to elucidate a subject and make pupils think.

Note-taking should never be allowed in junior classes; a syllabus may in some cases be profitably supplied, or the lesson may be an amplification of a text-book which the pupils have read, or questions may be set calculated to bring out the main points of the lesson. It should be an invariable rule that whatever is written is looked over and corrected; if this is not done, we shall certainly get bad writing, slovenly work and general inaccuracy. Should this not be possible without over-working the staff, the written work of the[27] pupils must be diminished, or the number of teachers increased.

Corrections.The work of correcting is not mere drudgery, and it is essential, not for the sake of the pupil only, but of the teacher. Without written exercises she may imagine she is teaching, whilst her pupils are not learning. A lesson she felt to be good, she will find perhaps has been ill-adapted to the class, and therefore relatively bad. She will find she has not emphasised the important matters, she has given a confused picture in which one fails to see the wood for the trees. There are no teachers like one’s own pupils if one will learn of them: they convict us of disorder, inaccuracy, vagueness, etc.

It is important however that the teacher should be spared as much as possible unnecessary labour and waste of time. It is one of the most urgent duties of the head mistress to see that the teachers have not so much to do in the way of correcting, as to stupefy them, and deprive them of the time required for preparing lessons. The work of correcting should be reduced as far as practicable for the teacher, and made as profitable as possible for the pupil.

Suppose the teachers to be free after one o’clock, an hour may be given in the afternoon to correcting, and one in the evening. Language teachers, whose preparation is light, might do more, those who give lectures less; the work of correction must be fairly distributed, and a junior teacher trained to correct, by taking books first, and having these revised and given out in class, in her presence by a senior teacher.

Giving up books.Very strict rules must be made regarding the giving up of books at the right time by the pupils, and their[28] being returned punctually in class by the teacher with explanations and comments. The books should always be in uniform, and some rules, e.g., respecting French being red, German, blue, etc., are very useful. Outside should be a label with the name of the pupil, the class and the boarding-house. This is important in the case of derelicts. All corrections should be made in red ink, and the exercise signed with the initials of the corrector.

Giving out books.Suppose we have a foreign language exercise to be given out. The teacher should come into class with memoranda of faults which have commonly occurred, and mention these to the class generally. Faults of mere carelessness should have a special indication in the book of the offender, and need not be spoken of further to the class. Each pupil should, before writing the next exercise, divide the page, write on one side correctly the sentence in which the fault occurred, underlining the words that were wrong, but on no account writing the mistakes again, and on the other explain why it was wrong.

When an arithmetic paper has been set the teacher may read out the answer, and each girl write W or R. The papers may be then collected, and it will only remain for the teacher to see whether the method was good. If not, she can write L W for “long way,” give explanations at the next lesson, and have the sum done again. Slates should not be used, nor loose papers, for such exercises.

If the paper is an essay, or answers to questions, the teacher should make notes of the subjects in which the class generally has gone wrong, and explain these. She may select specimens of broken[29] figures, bad grammar, etc., but it is very profitable to read out good specimens; it is a great help to us to see others succeed, when we have tried and failed, and there is nothing that many need more than a word of encouragement to make them feel able to try. One who has done well may be requested to enter good paragraphs in a book (what I think Dr. Kennedy called a “Golden Book”) for the benefit of the class, and the worst writers desired to copy it; this would have done them no good, had they not tried and failed, but afterwards it helps us much to see how well another can express what we could not. The teacher may herself write in the book of the most painstaking pupil, things which she has failed to make clear, and ask her to copy that into the aforesaid book; it will do her good and help others. Certain conventional marks may be agreed on, e.g., L would stand for wordiness, C P for commonplace, S for satisfactory, G for good, Fig. for broken metaphors, etc.

Apparatus.Diagrams and apparatus may be reckoned amongst time-saving things, but like ready-made toys these may be less profitable to children than very simple things, which they put together themselves, and the more they make for themselves, the more they appreciate and profit by the labours of others. Fergusson, lying on his back with a brown paper roll for a telescope, and watching the movement of the stars, learned more than many who are provided with an elaborate orery, and the Edgworths learned more about the reason of a rainbow from their glass of water, than many from the lens. As Miss Leonard has said in her paper, many things are not necessary in teaching elementary science, and it is a great[30] pleasure to children to make anything for themselves. Here the kindergarten training will tell. For higher work well-equipped laboratories are good, but these are an expensive luxury, especially as new things are being constantly invented.

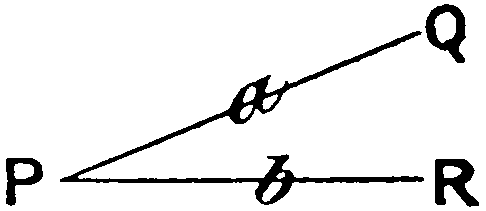

Physiological models are almost indispensable for class teaching, and excellent botanical ones are obtainable. A museum in which lessons can be given, and specimens referred to, is very desirable for natural science, but children should have their own private ones. Maps of physical geography should be constantly before the eye, but wall maps of political and historical geography cannot be so well seen; the teacher should be able to draw on the board or on paper, maps bringing out the special features of the lesson. It is understood that no class on history or geography is given without large maps both of space and time.[5]

[5] And here let me protest against the mischievous practice of having a round roller at the bottom, but a flat piece of wood at the top of maps. They are sure to be rolled on the latter and the map cut to pieces.

Working models of pumps, archimedean screws, mechanical powers, and steam engines are within the reach of most, and some simple forms of orery. There is an inexpensive one with the world inside a glass globe, on which are engraved a few circles, and this removes the difficulty which most children feel on seeing a pair of globes.

Marks, reports, prizes, place-taking.In former times when lessons were made less interesting, many ways were employed to keep up attention. Place-taking, by which each child took down all above her who failed to answer a particular question. This was most distracting; and so much depended on accident, that[31] it was impossible by means of it to arrive at any trustworthy conclusions. Except for small children it has wholly gone out. The giving of counters has found more favour on the Continent, but this lends itself to barter, and anything which fosters the habit of considering what we can get by knowledge, is destructive of that calmness, that “wise passiveness” which is as necessary for mental, as for physical assimilation; it is equivalent to playing games, or running about during dinner-time. Some record there should be of each exercise, some “stock-taking” at intervals, and these intervals should for little ones be short, for time passes more slowly with them. If the head mistress each week looks over the mark-book in the presence of the class and the teacher, she is kept in touch with all, comes to know if there are girls who are wasting their time, and is able to give encouragement or reproof, and strengthen the hands of teachers. If there are a great number of lessons returned, she may find that a specialist is making unreasonable demands; she sees if corrections have been omitted by the teacher—in fact, notices things which, if left to the end of the term, might have resulted in considerable mischief. It is undesirable, however, to take up much of the teacher’s time in adding up marks, and placing pupils in order of merit; it may be left to individual class teachers to do as they think best; there is no need in this for uniformity of practice, and it is always well to give every teacher as much liberty in following her own methods, as is consistent with the general management.

In language exercises the number of faults can be written at the end, and classified as mere careless ones, and those for which there is at least some excuse—the[32] former being counted double. In these and other exercises a maximum say of ten marks may be given; in many the teacher can give only a general estimate, but when returning books, she can show why she puts a higher estimate on one than on another. In junior classes the marks may be added, read with comments, and perhaps sent home each week. A sort of weather chart is used by us in the youngest classes—showing for each week whether they have risen or fallen in the number of marks.

Prizes, in part determined by work done at home, are dangerous, the temptation to get undue help is great; a conscientious child will reject such assistance as would be really good for her, lest she should gain an unfair advantage. Prizes given on the result of examinations, provided they are given not to the best, but to all who have attained a certain standard, are less objectionable; we cannot make it too clear that good may be better than best, and that the only praise we should desire is to hear: “She hath done what she could”.

[33]

Public prize-givings seem to me very undesirable. A terminal report parents may reasonably look for, and words of blame or encouragement may be made very helpful to the child. Punishments in the shape of doubled lessons, lines, etc., are objectionable; if a duty has been neglected, or badly done, it has to be done at an inconvenient time—say in the afternoon. A fine may be required for untidiness and damage—in order to compensate others for trouble and expense, but to inflict a fine for breaking rules is altogether wrong. At a school I knew, where this was done, girls would deliberately break rules, e.g., talk at prohibited times, and say they were going to have “three pennyworth”. Into a matter of right and wrong, money cannot enter; so also conduct prizes should, I think, never be given; the proper reward for doing right is a good conscience, and the trust, friendship, respect of others.

Use of examinations.Having lived through the pre-examination period, and seen the great evils which resulted from there being no test, I cannot join in the popular condemnation. There is no unmixed good, and many mistakes, which we learn to avoid later, are made when a system is new. I shall regard examinations only from the point of view of their value educationally. (1) They are useful as a test of what we really know; preparation for them enables us to find out what are our permanent possessions; (2) competitive examination compels us to set these in order, and estimate their relative importance. (3) Examinations tend to produce presence of mind, mental self-control, (4) to suppress wordiness and abolish a florid style, and (5) to make us feel the supreme importance of clearness and accuracy.

[34]

Examining is a difficult art, and examiners have to learn their métier. All are not perfect; the process of reading papers is exhausting, and after reading ninety-nine, an examiner may fail to appreciate the exquisite thought and philosophic insight of the hundredth. It is possible he may form an erroneous opinion regarding some unusual performance—there have been reviewers who failed to appreciate the early volumes of Wordsworth, Tennyson and Browning; there are examiners, however, really sympathetic, laborious, and anxious to see what has been done (which is limited) rather than find out what has not been done (which is unlimited), and these may give much help both by their criticisms and their encouragement. It is good for all of us to have our work tested by a competent critic.

An internal examination, if well conducted, is most valuable, as it can better follow the work, but on the other hand, many teachers feel that an internal examination places them too much at the mercy of caprice, or personal feeling, and hence prefer a central one, such as the University Locals.

Regular attendance.Schools must insist on punctuality in returning, and no unnecessary absences should be allowed. Children who are absent cannot follow the teaching in the next lesson, and laggards demoralise the class and distract the teacher, who feels she is not understood.

Rapport with the class.In conclusion let me say the teacher must have the power of holding the class. She must be sensitive to the least inattention, quick to discern whether it is her fault or that of the pupil, and take her measures accordingly, acting always upon the wholesome maxim (which should never be[35] heard outside the common room), certainly never whispered to parents, that it is always the teacher’s fault, if pupils do not learn. When she fails to establish the rapport between herself and her class, she must try to discover the cause of her failure. Young children, like wild animals, are tamed by the eye, and a class is controlled by a teacher who sees everything that goes on. If a teacher when using the board turns away and writes in silence, a restless child is almost sure to play some amusing trick, and it may take a considerable time to recover attention. If experiments are performed, the teacher, like the conjurer, should never cease talking or questioning. If she cannot manage to do both, she must have an assistant.

Dress, manner, etc.She must avoid awkward tricks. I knew two very distinguished teachers whose lectures were admirable, but one had a habit of pulling a tuft of hair, and another would stuff his handkerchief carefully into his folded hand, and then draw it out again—to the great distraction of the class. We have all heard of the parliamentary orator and his button.

A study of the Pedagogical Seminary for August, 1897, would be profitable to teachers careless about externals. The article is called “A Study in Morals”. The question was put in writing and answered by twenty-three boys and one hundred and sixty girls: “Reflect which teachers, from kindergarten to college, you have liked best, and been influenced most by, and try to state wherein the influence was felt. Account if you can for the exceptional influence of that particular teacher. Was it connected with dress, manner, voice, looks, bearing, learning, religious activity, etc.? Four out of five mentioned the manner of the teacher[36] as exerting an influence. One in three speaks of the voice, one in four speaks of dress.” These externals, as we are apt to call them, are the outcome of the personality, or they would not exert influence. We must therefore so order our inner being that manner, voice, dress, should express self-respect and unselfishness, right feeling, love of order, good taste.

If I were writing a treatise on psychology, I might insist on the teacher’s gaining an insight into the contents of the child’s mind—what Herbart calls apperception-masses, but in this short introduction I can only touch on the subject. I subjoin a short list of books not too difficult for teachers. I conclude with a few common rules derived from psychological observation and a few practical hints for the schoolroom.

[37]

This is not a treatise on psychology but a practical hand-book for young teachers. Before entering on the special subjects, it may be well to say something of the application of the principles which are familiar to all who are trained, and dwell upon a few of the most important.

(1) There is the fundamental precept, awaken interest. Have you seen the Medusa spreading its tentacles idly on the waves? Have you watched the change as it fastens on its prey? So does the mind grasp that which is suitable for its nourishment. As the intelligence of the child awakens, it no longer perceives in the lazy, dreamy way in which the infant is conscious of a light; it apperceives, takes into itself the object, the word, the thought, and grows thereby.

(2) Avoid distractions. The senses and the mind must be fixed on the subject of instruction. When a bird is to be taught to speak, he is placed in a dark room, shielded from the distractions of sight, until the words are acquired, then the use of other senses than hearing is permitted; so little children require more quietness and isolation than older ones.

Distractions are not all of sense. The mind is distracted by fear. How dreadful are the old pictures of the dame, teaching rod in hand, or the master with his cane; some may remember the music teacher ready to rap the knuckles, and know how all sense of harmony was[38] destroyed. And it is so also with the seeking of rewards. I hope place-taking and prizes and scholarships will one day follow the rod and the cane, and children be led from their earliest years to feel, what is really natural to them, that knowledge is in itself a pleasure and a good.

(3) Proceed from the known to the unknown. Observe the laws of association; for this a teacher must be in intellectual sympathy with her pupils—know and feel by an inner sense, when mind is responding to mind. I have heard some so-called teachers, who spoke like a book, who were lecturers; they saw their own thoughts, but not those of their pupils, and were therefore unable to lead them on. E.g., if a sum was wrong, they would say, “Do it thus,” instead of inquiring into the cause of the mistake. In questioning they would not try to see into the child’s mind.

It is more difficult to enter into intellectual sympathy with very little ones, hence we need specially able teachers for them. It is also better for class teachers not to change too often, as it takes time to get into sympathy with a new class. Of course specialists have to do this; it is one reason why cæteris paribus they are less successful than class teachers.

(4) Proceed in classifying by noticing first the likenesses, then the differences—in other words, proceed from the genus to the species. There are some excellent chapters on this in Rosmini’s Method of Education, translated by Mrs. Grey, p. 15.

(5) Make lessons pleasant. This does not imply that the act of learning should be always easy or amusing. Children like to feel they are making progress, and a teacher wearies them who is always trying to be amusing, but does not really get them[39] on. Porridge has a very plain taste, but for everyday fare even children prefer it to tarts for breakfast. A London confectioner was asked, if he did not find the many boys he employed make depredations. “No,” he said, “when first they come I tell them they may eat what they like; in a few days they make themselves sick and eat no more.” There was a book called the Decoy, a story mixed with conversations on grammar; children always managed to get the story without the grammar. They like sums and history for regular meals, fairy tales for dessert.

(6) Teaching must be adapted to the mental state of the pupil, and be just a little above his unassisted intelligence. It is a worse fault to teach below than above the powers of the child. I shall never forget my indignation at having a book given me, which was below my powers, nor the stimulus of trying to do what was hard. One who was afterwards a distinguished teacher, told me how the Maurice lectures helped him, by making him feel there were regions of thought on which he had not yet entered. Knowledge quite within reach does not promote progress. A friend who had a night school was told by its members, “We want to be taught something as we can’t understand”. They meant something they could not learn without help; they wanted to overcome difficulties.

(7) Form right habits. We should as far as possible prevent the making of mistakes even once. A child when reading the Bible miscalled the word patriarch, reading it partridge; when an old man, he never saw the word without recalling his error. Hence we should not give children misspelt words, or bad grammar to correct, or let them write exercises before[40] the ear has been cultivated to know what is right. I knew a music master who would anticipate mistakes, and stop the pupil, saying: “You shall not play that wrong note”.

On the other hand each repetition of a right action makes it easier, and the prime work of the educator is to form right habits; these should become instinctive, and so set free thought for ever higher and more perfect performance.

(8) Awaken and sustain the spirit of inquiry. We need, however, to be very careful not to ask questions, which the child cannot possibly answer. This encourages mere guessing, and the habit of deciding upon insufficient data. We should question the pupils, and build on their knowledge, but as they get older the viva voce questioning may be overdone—and for the highest classes it would be simply a distraction. For these it is well to give questions to be thought out, and answered in writing. Pascal’s father shut him up alone to find out the translation of a classical author; there are so many helps now, that people rely upon them when they might gain vigour by grappling with difficulties. No intellectual habit is more essential than the habit of patient, sustained inquiry, that described by Newton when he said: “I keep the subject of my inquiry continually before me, till the first dawning opens gradually by little and little to the perfect day”.

(9) Foster intellectual ambition. Help the child to feel the joy of surmounting difficulties, of climbing the heights. This invigorates the intellectual life. Some can remember how, e.g., they grappled with the dull work of early mathematical study, that they might one day learn to solve the problems of astronomy, or went[41] through the labour of learning irregular verbs, that they might read the poetry and philosophy of Greece.

(10) Put before pupils the highest ideals which they can appropriate. These are not the same at each stage of development. The little child desires first to have something, and this is not wrong. Later it feels more the need of love, of approbation, and this is a legitimate and right motive; it is generally his best guide, until he can exercise himself, irrespective of the outward voice, to have a “conscience void of offence”. We have to teach him to discriminate voices which are in harmony with, from those in discord from, that inward voice, and to make this ultimately his supreme law.

(11) The ultimate ideal or final cause should be implied in all that we teach, viz., the attainment of the perfect development of the individual, through bringing each into harmony with the environment, the universal, and thereby on the other hand helping to perfect the whole. For this, wisdom and self-denial and sympathy with the noblest and the best are to be sought, and above all with the One, the Infinite Wisdom revealed in Nature, in the world of thinking beings and in the self-conscious mind. All should feel in their inmost soul what Milton has expressed:—

[42]

| Name of Work. | Author. | Pages. | Price. | Publisher. | Remarks. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Foundations | W. Harris | 400 | 6s. | Appleton | An excellent book by the Commissioner of Education, U.S.A., showing the correlation of the Philosophy of Education with Psychology and Ethics. | ||

| Philosophy of Education | Rosenkranz | 280 | 6s. | Appleton | Well translated. Notes by Dr. Harris add much to its value. | ||

| Handbook of Psychology | Sully | 400 | 6s. 6d. | Longmans | |||

| Education of Man | Fröbel | 330 | 6s. | Appleton | Well translated by Hailmann. | ||

| Educational Laws | Hughes | 300 | 6s. | Arnold | Should be read by all teachers. A very clear exposition of the ideas of Fröbel and other reformers. | ||

| Pedagogy of Herbart | Ufer | 120 | 2s. 6d. | Isbister | Not too difficult for beginners. | ||

| Herbart and Herbartians | De Garmo | 270 | 5s. | Heinemann | A clear account of Herbart’s thoughts and application of his principles by others. | ||

| Essentials of Method | De Garmo | 130 | 2s. 6d. | Heath | |||

| Herbart’s ABC of Sense-Perception | Eckhoff | 300 | 6s. | Appleton | Not an easy book. Gives much insight into Herbart’s theories and practice, especially in mathematics. | ||

| Application of Psychology to Education | Mulliner | 360 | 4s. 6d. | Sonnenschein | Introduction gives a full exposition of Herbart’s psychology. | ||

| Apperception | Lange | 120 | Isbister | Very clear. Suitable for beginners. On Herbartian lines. | |||

| Herbartian Psychology | Adams | 200 | 2s. 6d. | Isbister | Excellent for beginners. Full of apt illustrations. | ||

| Primer of Psychology | Ladd | 5s. 6d. | Longmans | ||||

| Leading Principle of Method | Rosmini | 360 | 5s. | Heath | A thoughtful, religious, sympathetic writer. Translated by Mrs. Grey. | ||

| Vocation of the Scholar | Fichte | 130 | 2s. 6d. | Chapman | Will kindle enthusiasm and lift the thoughts to the higher aspects of learning. | ||

| Metaphysica Nova et Vetusta | Laurie | 300 | 6s. | Williams & Norgate | Clear and full of interest. | ||

| Outlines of Pedagogics | Rein | 200 | 6s. | Sonnenschein | |||

| Educational Theories | Oscar Browning | 192 | 3s. 6d. | ||||

| Elementary Psychology | Baldwin | 300 | Appleton | Very systematic. Not a book for the general reader, but for the serious student. Many good diagrams. | |||

| Psychology[43] | Kirchner | 350 | Sonnenschein | A very thorough book, suitable for those who have some knowledge of philosophy. | |||

| Psychology Applied to Education | Compayré | 220 | 3s. 6d. | Isbister | Useful and well arranged. | ||

| Education as a Science | Bain | 450 | 5s. | Kegan Paul | - | Contains much of value to teachers. With a good deal the editor is not in sympathy. | |

| Education | Herbert Spencer | 170 | 2s. 6d. | Williams & Norgate | |||

| L’Education des Femmes | Gréard | 300 | Hachette | A very interesting book. | |||

| Rousseau’s Emile Extracts | Worthington | 160 | 3s. 6d. | Heath | |||

| Les Pères et les Fils | Legouvé | 350 | 3s. | Hetzel | Short chapters giving in the narrative form the way a father deals with his son. Delightful reading. | ||

| Hist. Critique des doctrines de l’Education | Compayré | 500 | Hachette | Several volumes. Very judicious and interesting. | |||

| Educational Reformers | Quick | 330 | Longmans | Very good. | |||

| L’Education Progressive | Necker de Saussure | 7s. | Three vols. A mine of original observation. Rosmini depends much on it. | ||||

| Home Education | Mason | 3s. 6d. | Kegan Paul | A very helpful book for parents and teachers. | |||

| Lectures on Teaching | Fitch | 430 | 5s. | Camb. Univ. Press | Should be in the hands of all teachers. | ||

| Teaching and Organisation | Barnett | 420 | 6s. 6d. | Longmans | A very valuable book. Contains 23 papers on different subjects. | ||

| Aims and Practice of Teaching | Spenser | 280 | Camb. Univ. Press | Very good. Contains 12 papers by various writers. An excellent one on modern languages by the editor. | |||

| Thirty Years of Teaching | Miall | 250 | 3s. 6d. | Macmillan | A series of brightly-written practical essays, which all teachers may read with pleasure and profit. | ||