BRAVE BRITISH SOLDIERS

AND

THE VICTORIA CROSS.

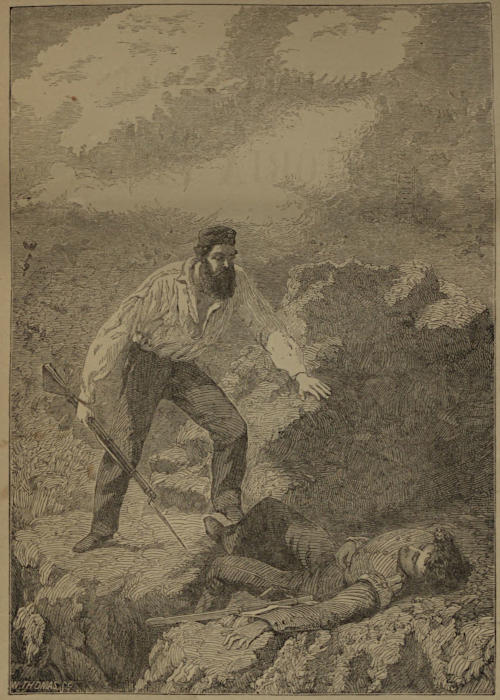

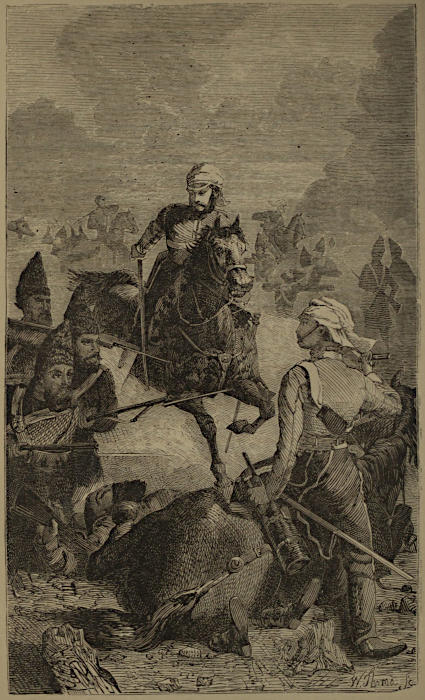

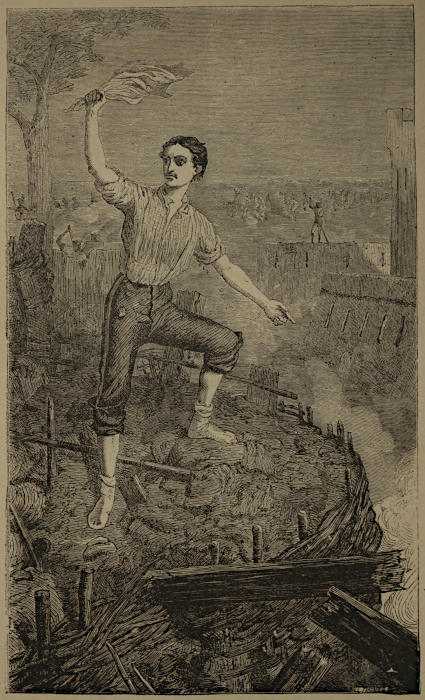

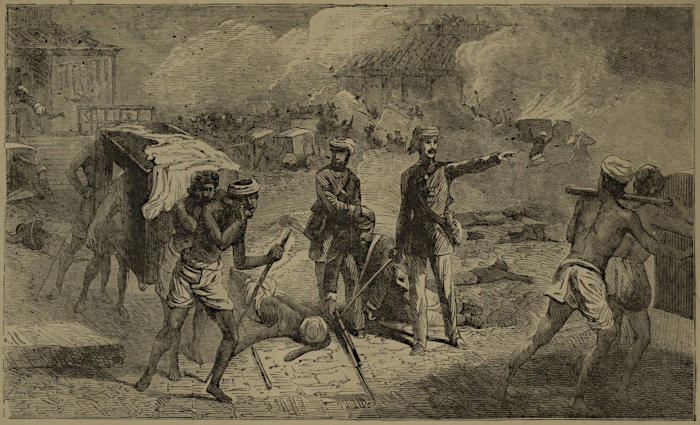

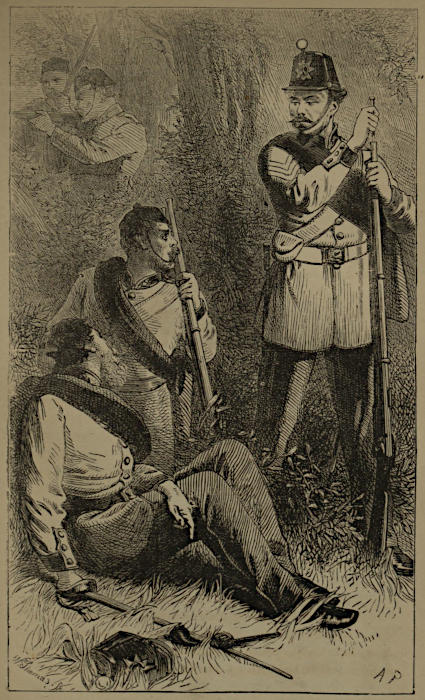

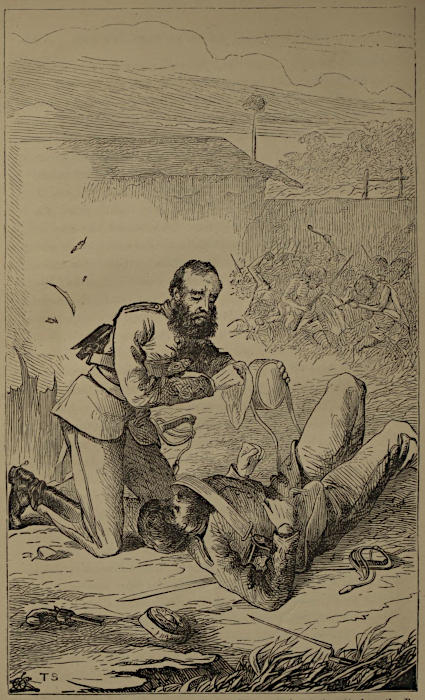

Corporal Robert Shields, 23rd Regiment (Royal Welsh Fusiliers), finding the Body of his wounded Adjutant, Lieut. Dyneley.

BEETON’S BOY’S OWN LIBRARY.

BRAVE BRITISH SOLDIERS

AND

THE VICTORIA CROSS.

A General Account of the Regiments and Men

of the British Army.

And Stories of the Brave Deeds which Won the Prize

“for Valour.”

Edited by S. O. BEETON.

With Sixteen Full-Page Engravings and Illustrations

in the Text.

LONDON:

WARD, LOCK AND TYLER,

WARWICK HOUSE, PATERNOSTER ROW.

BEETON’S

BOY’S OWN LIBRARY,

COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS.

Handsomely-finished bindings in cloth, plain edges, 5s.; gilt edges, 6s.

The best set of Volumes for Prizes, Rewards, or Gifts to English Lads. They have all been prepared by Mr. Beeton with a view to their fitness in manly tone and handsome appearance for presents for Youth, amongst whom they enjoy an unrivalled degree of popularity, which never flags.

LONDON: WARD, LOCK, AND TYLER.

This book is written for Boys. The majority of the articles were expressly prepared for the “Boys’ Own Magazine,” and the interest which their appearance excited, coupled with the favourable notices they won, encouraged the Editor to publish them in a connected form.

Boys—worthy to be called Boys—are naturally brave. There is not, so far as we are aware, any etymological connexion between the words boy and brave; but there is an association of ideas, which if it does not make the terms interchangeable, is still strongly suggestive of their being one and the same. The expression brave man is easily understood, but to us, brave Boy looks like a pleonasm. A man has experience. He has tested—if there be any good thing in him—his courage in the rough exploits of the world’s campaign. He has tilted, mayhap, with Quixotic chivalry against windmills, and in the encounter has been discomfited; he has awakened from his bright dream to a sad reality; he has been tempted to turn prosaic—inclined sometimes to beat his sword into a sickle, to gather in for his own special use the golden wheat from anybody’s cornfield, and to make those late foes of his—the windmills—grind up the corn to make his bread. Now he is no longer brave. His views of life are taken from a new point of sight. He smiles at the boy’s enthusiasm, and counts himself wise in his man’s selfishness. But a man who has done battle, who has been thrown in the lists, who has been ready to mount and splinter lance again, who in the gaining of experience has lost nothing of the Boy’s boldness—such a man is brave.

The drift of these remarks is that experience may ruin a Boy’s “pluck”—may give him the vulpine sagacity of Reynard in place of the courage of Leo Africanus.

But a Boy is brave. Youth is the season of confidence. “Your young men shall see visions” while our “old men shall dream dreams.” What visions are those which rise up before the young—what brave words to speak, what brave actions to do—how bravely—if need be—to suffer! “The young fellows,” said an old soldier to the writer, “are always pushing forward in a battle charge—they are in a mighty hurry to smell powder—the veterans fall into the rear!” Do they?—ah, well, ’tis the lesson, perhaps of experience! But is it better than the Boy’s eagerness to be foremost?—is it not—answer brave hearts—better to die planting the colours on the wall, than to share the spoil which others have won?

This is the leading thought in this book about Soldiers—it is meant to keep alive the bravery of youth in the experience of manhood. The editor of the book is very sensible of the incompleteness of the work. He knows that it is defective in many places, but it is honest. A good many of the papers were written by one who was then far away on a foreign station doing brave service; some of the papers are the work of dead hands. The articles have been put together as carefully as circumstances would allow, but there has been an anxious care on the Editor’s part to retouch as little as possible the work of absent contributors. He offers the book to the Boys of England—not as the best piece of work that can be done—but as a volume they will read with delight and keep as a souvenir of pleasant hours. He is of opinion that anything which helps to make Boys more in love with true courage is good work done—he believes that bravery excites bravery, just as iron sharpeneth iron; and so he has confidence in this book being useful—a record of brave deeds that shall make its readers echo the words of King Harry—

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | OUR SOLDIERS AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 1 |

| II. | THE GUARDS, OR HOUSEHOLD TROOPS OF ENGLAND | 14 |

| III. | THE ENGINEERS | 24 |

| IV. | THE ROYAL WELSH | 40 |

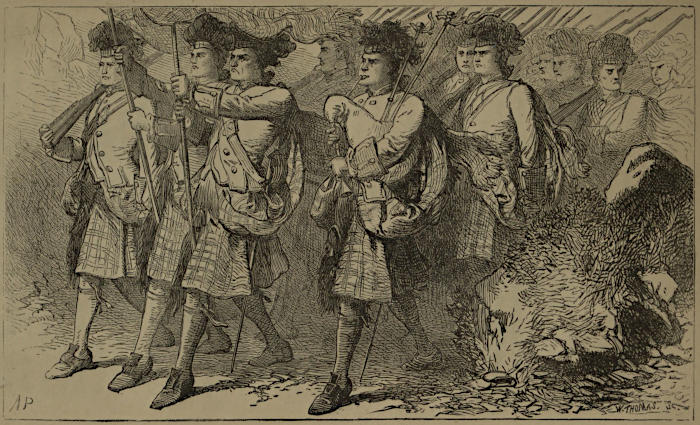

| V. | OUR HIGHLAND REGIMENTS | 54 |

| VI. | OUR HIGHLAND REGIMENTS—(continued) | 64 |

| VII. | OUR HIGHLAND REGIMENTS—(continued) | 84 |

| VIII. | OUR HIGHLAND REGIMENTS—(continued) | 93 |

| IX. | OUR HIGHLAND REGIMENTS—(continued) | 107 |

| X. | THE PIPERS OF OUR HIGHLAND REGIMENTS | 123 |

| XI. | COLONEL BELL AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 139 |

| XII. | COMMANDER (NOW CAPTAIN) FIOTT DAY, R.N., AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 149 |

| XIII. | LIEUTENANTS MOORE AND MALCOLMSON AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 158 |

| XIV. | CAPTAIN W. A. KERR, SOUTH MAHRATTA HORSE, AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 168 |

| XV. | PRIVATE HENRY WARD, V.C., 78TH HIGHLANDERS | 176 |

| XVI. | LIEUTENANT ANDREW CATHCART BOGLE, V.C., 78TH HIGHLANDERS (NOW CAPTAIN 10TH FOOT) | 193 |

| XVII. | DR. J. JEE, C.B., V.C., SURGEON; ASSISTANT-SURGEON V.M. M’MASTER, V.C.; AND LIEUTENANT AND ADJUTANT HERBERT J. MACPHERSON, V.C. | 207 |

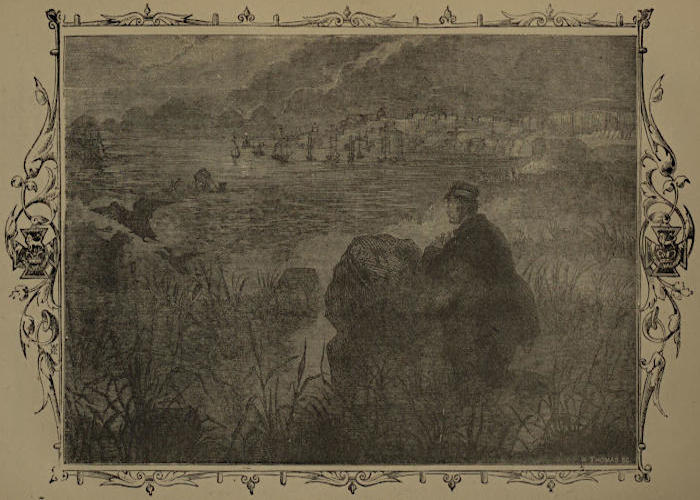

| XVIII. | “LUCKNOW” KAVANAGH AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 221 |

| XIX. | LIEUTENANT BUTLER AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 236[viii] |

| XX. | DR. HOME AND DR. BRADSHAW AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 244 |

| XXI. | ROSS L. MANGLES, ESQ., V.C., BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE ASSISTANT-MAGISTRATE AT PATNA | 257 |

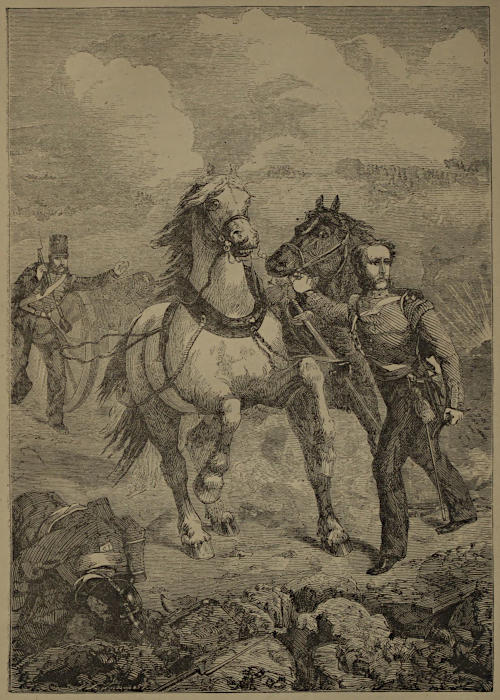

| XXII. | CAPTAIN HENRY EVELYN WOOD, 17TH LANCERS | 272 |

| XXIII. | SAMUEL MITCHELL AND THE VICTORIA CROSS; OR THE GATE PA AT TAURANGA | 285 |

| XXIV. | ENSIGN M’KENNA AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 299 |

| XXV. | SERGEANT MAJOR LUCAS, OF THE 40TH REGIMENT, AND THE VICTORIA CROSS | 313 |

| XXVI. | THE HEROES OF THE VICTORIA CROSS IN NEW ZEALAND | 322 |

| XXVII. | THE NAVAL BRIGADE IN INDIA | 334 |

| XXVIII. | THE VARIOUS RANKS IN THE BRITISH ARMY, AND HOW TO DISTINGUISH THEM | 347 |

| XXIX. | A GRAND REVIEW | 362 |

| XXX. | A SOLDIER’S FUNERAL | 376 |

| PAGE | |

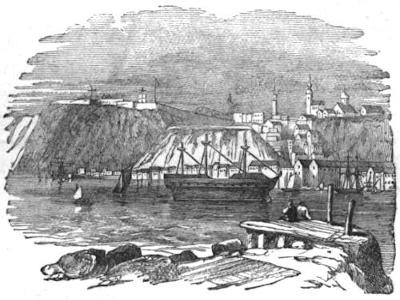

| BUSHIRE | 167 |

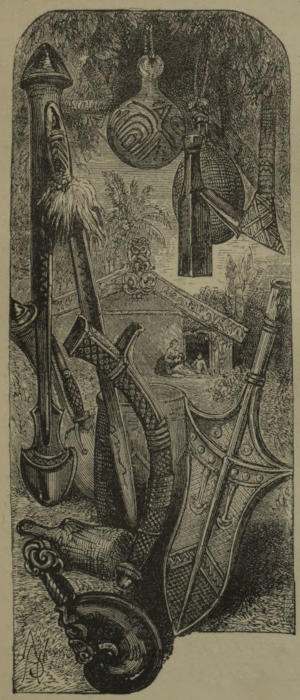

| FINIAL, DEATH DEFENDING THE RAMPARTS | 53 |

| GIBRALTAR | 24 |

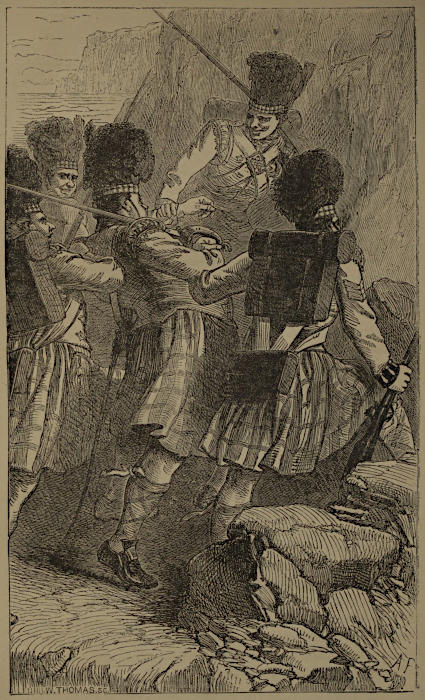

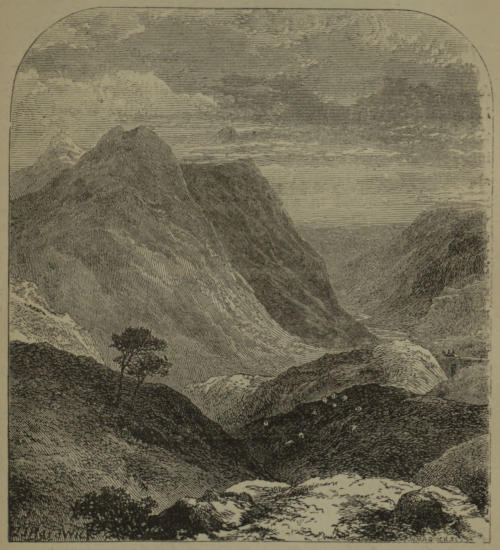

| GLENCOE | 113 |

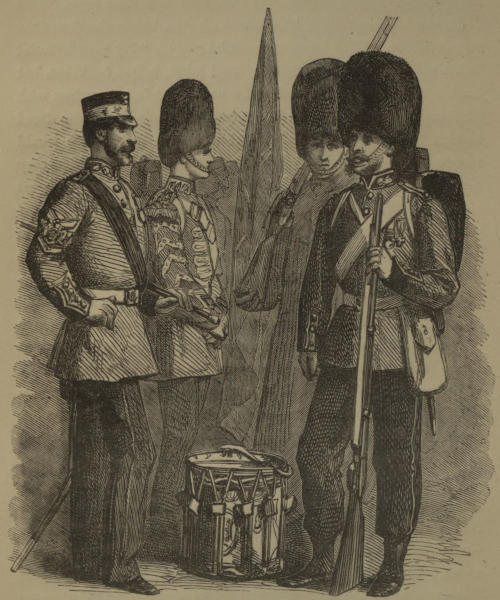

| GRENADIER, COLDSTREAM, AND SCOTS FUSILIER GUARDS | 23 |

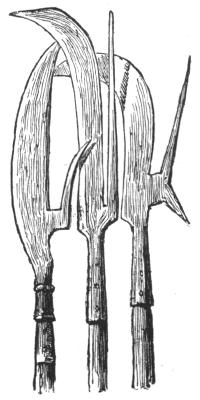

| NEW ZEALAND ARMS | 285 |

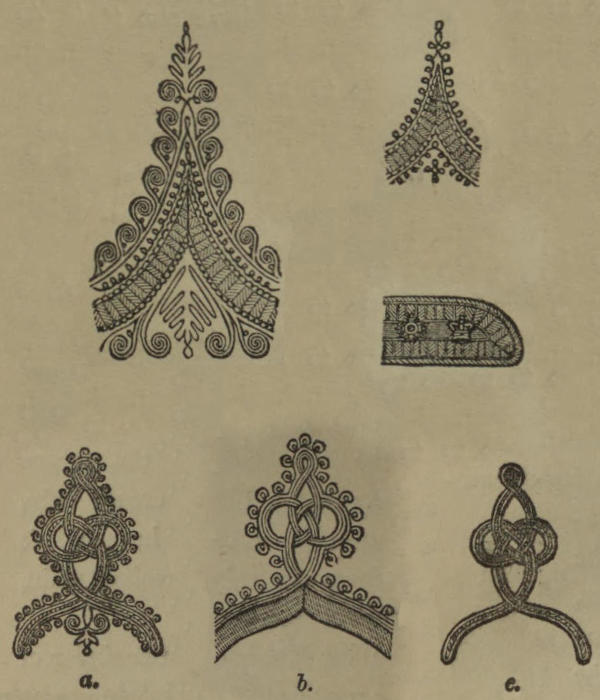

| OFFICERS, EMBROIDERY ON UNIFORM OF | 349, 350 |

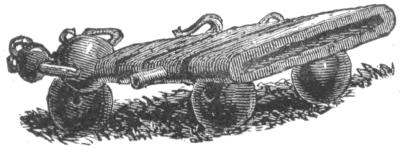

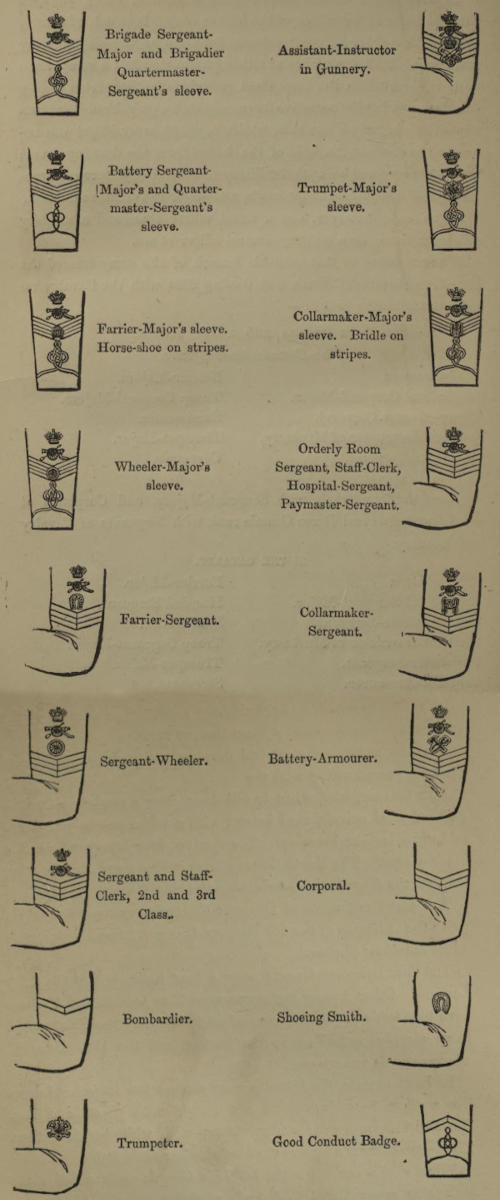

| ROYAL ARTILLERY, BADGES OF NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICERS OF THE | 356, 357 |

| ROYAL WELSH, INITIAL LETTER TO THE CHAPTER ON THE | 40 |

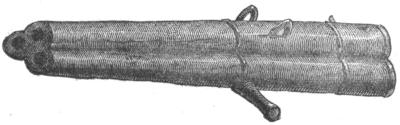

| VICTORIA CROSS, THE | 1 |

It has been our lot in life to live very much among soldiers, and we like to write and talk about them. We hope that our readers will not be averse from hearing something of a class in whom we have all a common interest. It is true that English boys are not quite so warlike in their tendencies as French; they neither worship la gloire nor dress like manikin soldats. Swords and guns are not their only playthings, nor are feeble imitations of sanguinary contests their only pastimes. We here delight in all manly games and sports, for which French men and boys have little taste, and we thus acquire a muscular development and hardiness of frame which enable us to bear any amount of fatigue. It was a saying of the grand old Iron Duke that all his battles were won on the playground at Eton; by which we suppose[2] he meant that his officers, most of whom were Eton boys, received there such a physical training as fitted them to be heroes in the strife. Still, it is one of those epigrammatic sayings in which truth is sacrificed for effect; for what could the duke, with all his officers, have done without the brave privates who composed his forces, and to whom he rendered justice on another occasion by saying that with such an army he could go anywhere and do anything?

A chaplain belongs, of course, to the non-combatant class in the army. It is not his duty to appear in the field, or to take part in battles. He has to remain at the hospital, and to administer the consolations of religion to the wounded and the dying; but he is precluded by his profession from being present at, or taking part in, any battle.

It is for this reason, perhaps, that we have always had a certain pleasure in listening to soldiers as they fought their battles over in hospital, and recounted their experience to one another. It was all strange and new to us, as, we dare say, it will be to most of those who read this book.

The soldiers of whom we speak all took part in and survived the Crimean war. Their manly breasts are all adorned with the different medals awarded to them; two of them wear the Victoria Cross. One early object of our curiosity was to ascertain what are the sensations or feelings of a soldier on entering battle, or being exposed to fire for the first time. Now, the answer we invariably received will, perhaps, take some of our readers by surprise. They felt nothing of that warlike intoxication ascribed to the old Vikings on the eve of the combat; they had none of that strange joy ascribed by the patriarch to the war-horse at the sound of the trumpet, nor were they exactly afraid; but there was a certain uneasy sensation experienced by all as the bullet whizzed past the ear, and comrade after comrade dropped, sometimes with a sharp cry of pain, sometimes giving no sign.

This feeling some of them graphically described as similar to that which a bather experiences before plunging into the water; ce n’est que le premier pas qui coûte; after the first dip Richard is himself again. But our readers are not to suppose that the soldier[3] shows the same hesitation in advancing to charge as the bather on the brink of the stream. If he did he would be a coward, and be scorned by all his comrades. To make the two cases parallel, we must suppose a thousand bathers rushing forward to the stream at once. Now, though an individual bather standing alone might stop short on reaching the water, and pause before taking a header, a thousand bathers rushing forward at once, would plunge into the water without hesitation. The dread of shame, of exposure, of ridicule, would nerve the least courageous for the final leap. There is, moreover, such a strong feeling of sympathy diffused among large bodies of men acting in concert that the strength of the stronger is imparted to the weaker. Now, it is the same with soldiers advancing to the charge. All of them feel the cold shiver like that of the bather approaching the water, but they march shoulder to shoulder, and with them are some old soldiers who have been under fire before. The younger ones are encouraged by their example, and many a lad who has trembled on first smelling powder has proved himself a hero in the fight.

We have read in books that soldiers sometimes weep while fighting hand to hand and sorely pressed—not tears of cowardly terror by any means, but such tears as the strongest of men will shed in hours of fierce excitement. Wellington wept as he embraced Blucher after the Battle of Waterloo. This, indeed, has been denied, but it is not difficult to believe it true. There are moments in the lives of all men, even the most reserved and self-contained, when the hidden fountains of feeling well over and find an outlet through the eyes, and we should not think a whit less highly of our soldiers did they shed a few tears of valiant rage while victory was still doubtful. But these tears, we suspect, are purely imaginary. For ourselves, we never met with a single soldier who confessed that he had shed tears himself, or seen others weep. We are sure that they would not have denied it if they had yielded to any such weakness, for, as a class, soldiers are the most truthful of men. All with whom we conversed agreed in affirming that our men were very quiet while fighting hand to hand with the enemy. There would be occasionally a shrill cry of pain from the wounded, or a short cry of triumph from the man who struck down his opponent,[4] but generally, all the dread work of the battle-field was done in silence. All admitted that the most fearful sound during a battle was the cry of a wounded horse; it was so like that of a human being in his death agony—shrill, piercing, heartrending. The horses seem to become almost human in the hour of battle, to share in all the wild passions of the combatants, and to exult equally in the hour of victory.

But while our men fought in silence, the Russians were very noisy both in advancing and in fighting. They uttered the most savage yells, as if they thought to inspire our men with terror by the mere noise they made. They soon discovered that Englishmen are not so easily frightened; but they still continued to shout from mere habit. Their officers also encouraged them in this custom, giving them, moreover, drink to make them pot-valiant. Notwithstanding this, we have always heard our soldiers frankly speak of the Russians as “foemen worthy of their steel.” Brave men, we know, learn to respect one another even in the field, and the Russians are certainly one of the bravest nations in Europe. They still retain, however, many of the characteristics of savage life; they have not yet learned to act on the old Roman maxim, “Debellare superbos, parcere victis.” They often bayoneted our men when left defenceless and wounded. It is but just to add that they expected no mercy when left in the same condition, and seemed overwhelmed with surprise when our men treated them with the same generous tenderness as though they had been comrades instead of foes.

There are sometimes strange traits of character exhibited during the excitement of battle. Men may have been living under restraint for years, and come to believe themselves to be very different from what they are. Xenophon relates a story of a Greek soldier who, in consequence of a wound which had affected his brain, forgot the language he had spoken for many years, and began to express himself in his native tongue, which, before this accident, seemed to have entirely faded from his memory. Something analogous to this occurred at the Battle of the Alma, in the case of a sergeant of the Guards. He had once been much addicted to swearing, but had been enabled to vanquish this and other evil[5] habits, and for many years had been looked up to by his comrades as a man of exemplary character. His company, while charging up the heights of the Alma, was surrounded by the enemy, and, after suffering severe loss, was obliged to retreat. In vain the poor sergeant endeavoured to rally them. He was borne along with the current. Overpowered with shame and rage, he gave way to a sort of madness, and swore such fearful oaths that we have often heard the men of his company say that it was something awful to hear him. Those who occupied the same tent with him relate that he spent most of the night after the battle in prayer, and was often heard sobbing like a child. He never spoke of the strange outburst of that day to any of his comrades, and they had the delicacy to avoid all allusion to the subject; but it was observed that he was more humble, kind, and considerate in his bearing towards them than he had ever been before. He survived the war and returned to England, where he enjoyed the respect of all who knew him, and was never known to indulge in the habit which gained the mastery over him at the Alma. He is now dead, but his surviving comrades speak with a sort of awe of the incident we have related.

One soldier of the Guards became raving mad at the Alma. It happened in this way:—The Russian fire struck down several of the men as they were advancing. The soldier of whom we speak was a young lad who had never smelt powder before. By his side was a comrade who belonged to the same district, and had enlisted at the same time. The latter was hit by a cannon-ball, and his brains were bespattered over the face of his friend, who became frantic, roaring and shouting like a madman. He imagined that his comrades were the enemy, and that he was fighting hand to hand with them. The whole company was thrown into confusion, and he wounded some of his comrades before he could be disarmed. He was conducted to the rear, fighting and struggling the whole way. The surgeons pronounced him to be a dangerous lunatic, and he was strapped down upon one of the beds in the hospital, with a sentinel to watch over him. That sentinel told us that he was never entrusted before or since with such an unpleasant duty. Owing to the shock which the brain had received, the poor madman[6] could not rest for a moment. He fancied himself in the thickest of the combat, fighting with all the energy of despair, and swearing that his comrades should be avenged. He continued in this raving condition for about twenty-four hours, when, with the exultant cry of “Victory!” he expired. A similar incident occurred at Inkermann: in this case, also, the soldier survived only twenty-four hours.

Soldiers rarely feel much pain at the moment they receive their wounds, unless these be very severe, in which case they suffer much from thirst. There is one very gallant friend of ours—a non-commissioned officer—who was shot through the ankle in crossing the stream at the Alma. He knew not that he was wounded till the battle was over, but thought that his foot had got entangled among the vines in crossing the valley, and that he had sprained the joint. A good soldier never likes to go to hospital when there is any hard fighting, and our friend kept “a quiet sough,” as they say in the North, about his wound, and marched at the head of his company as if nothing had happened to him. His courage and endurance were rewarded: he was present at, and took part in, the Battle of Inkermann, where his gallantry attracted the notice of the commanding officer, on whose recommendation he obtained the medal and pension for distinguished conduct in the field. He was wounded also on this occasion, but his hurt was of a far more serious character. He was shot through the head: the bullet literally entered at one side, and came out at the other. He felt a sharp, stinging pain, and remembered nothing more till he regained his consciousness in hospital, and was surprised to learn that he had been some weeks under the doctor’s hands. He suffers no inconvenience from his wound now, except occasional dizziness and half-blindness after any excitement or exposure to the sun. Such a man in the French service might have risen to the rank of field-marshal, and obtained a name in the page of history. Well, after all, the great thing is to do our duty well in the position we occupy; and our friend, as sergeant-major of his distinguished regiment, is happier, probably, than if he had had greatness thrust upon him.

Though soldiers recover from their wounds at the moment, they are often very dangerous afterwards. The brain is often injured, and the disease goes on till the man loses his reason, or drops down dead. A poor fellow was hit on the crown of the head by a piece of shell in one of the trenches before Sebastopol. He was stunned at the moment, but thought so little of it that he did not even report himself wounded. For eight years he felt no pain, but one day, while on guard, he was seized with a sudden giddiness, and became insensible. He was conveyed to hospital in a cab, and on recovering his consciousness he found that he was suffering the most intense pain on the crown of his head. His sufferings were very great; the only relief he could obtain was through the application of chloroform.

We write all this knowing that English boys feel deep sympathy with, and profound admiration for, our soldiers, and to show that their powers of endurance, when disabled, equal in heroic worth their gallantry upon the field.

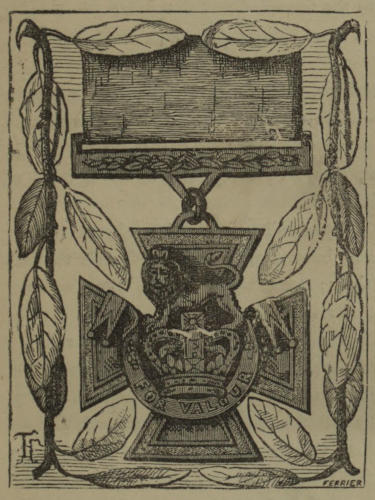

Not all our readers, perhaps, have seen the Victoria Cross. It is not very beautiful nor very valuable in itself. A fac-simile of it appears at the commencement of this chapter. It is a simple piece of bronze, shaped like a cross, and its intrinsic value may be about threepence. Its intrinsic value! but who can tell the price a soldier puts upon it? He had rather have that piece of bronze on his breast than be made a Knight of the Garter, and have his banner hung up with those of the other K.G.’s in the Chapel of St. George at Windsor. To obtain that small piece of bronze of the value of threepence he will lead the forlorn hope, be the first to storm the breach, and ever ready to expose his life to any danger. The Victoria Cross is as much to a soldier as the gage d’amour the knight-errant in the days of chivalry received from his lady-love, and swore never to part with. The pledge of her affection might be a soiled and tattered glove, worth even less than the cross “For Valour,” but it was dearer to her lover than life itself. O that the day may never come in this country when we shall judge of things by the Hudibrastic principle—

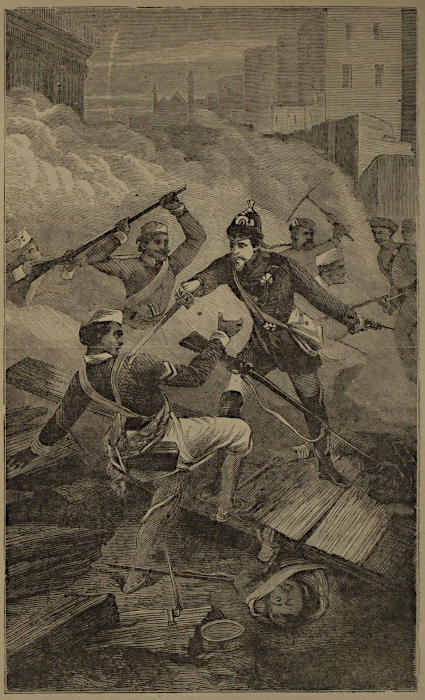

for badly then will it fare with Old England. When our soldiers come to value their crosses at threepence each, the price they will fetch at a marine store, we shall not long survive as a nation. But there is little danger of such an eventuality. There are things—God be thanked—which we do love and value more than life itself—things which gold can not purchase. The Victoria Cross is one of them; and we are about to relate how three gallant officers of one of our most distinguished regiments came to be decorated with the priceless meed “For Valour.” One was a commissioned officer; the other two were sergeants. Though different in rank, they were equal in bravery; their bravery was equally rewarded. Most people—thanks to Mr. Kinglake’s history, and other sources of information—are now tolerably familiar with all the details of the Battle of the Alma. They know how the gallant Welsh Fusiliers, after forcing their way to the heights, and seizing the colours on the Russian battery, were so cut up by the enemy that they were forced to retire. They fell back in obedience to orders. It so happened, however, that as the word, “Fusiliers, retire!” was given, the Scots Fusilier Guards were charging up the heights, and the officer in command of them, hearing the order, thought that it was intended for his own men, and commanded them to fall back. This fact is not mentioned by Mr. Kinglake, but there are many witnesses still alive who heard this second order given, and acted upon it. Now, it is very difficult to retire before an enemy without falling into confusion; and it so happened that the Welsh Fusiliers came rushing down like a torrent. One gallant regiment opened their ranks, allowed them to pass through, and then closed again; but the Scots Fusiliers were not so fortunate. They did not open their ranks, because they received no order to do so, and were already falling back, when the crowd of Welsh Fusiliers came rushing upon them, broke through their ranks, and threw them into disorder; and, in the midst of this, the Russians made a dash at the colours of the regiment.

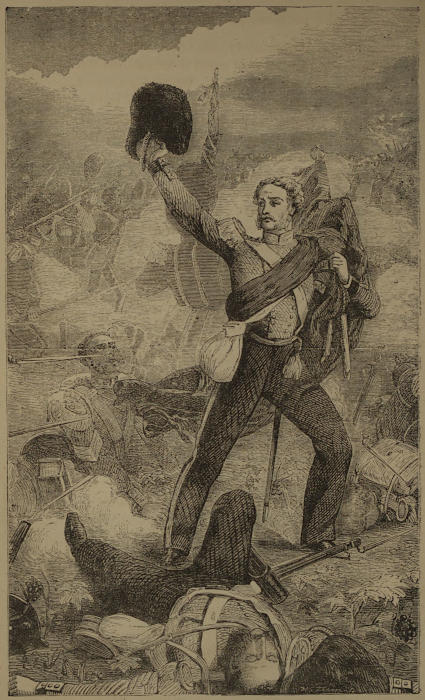

Captain Lloyd Lindsay, Scots Fusilier Guards, saving the regimental colours at the Alma.

Now, it is not needful to dwell on the fact that it would be as disgraceful for an English regiment to lose its colours as it would have been for an old Roman centurion to have lost his shield. The[9] colours are usually intrusted to one or two subalterns and several sergeants, who form a sort of guard of honour over them, and are held responsible for their safety. When they are in danger the bravest men in the regiment rally round them, and it is held unworthy not to follow them wherever they are seen. They are the same to our soldiers as the white plume of Henry of Navarre was to his men, or the bronze eagles to Rome’s Tenth Legion. Knowing this, officers have sometimes thrown the colours into the very midst of the enemy, sure that their men would die rather than lose them. No sooner, therefore, was it known that the colours were in danger than the bravest men of the regiment tried to reach them, but only a few succeeded. They did not come too soon; the men intrusted with the colours fought like lions, but one officer was struck down, and only two sergeants survived the fearful contest. But the colours were safe, and the men might proudly say, with Francis I. after disastrous Pavia, “Tout est perdu, hors l’honneur.” The regiment wiped out the memory of the misfortune at the Alma (it was no disgrace to obey orders) on the bloody field of Inkermann, and a grateful country did not forget the men who loved their colours better than their lives. The officer who was struck down died of his wounds on the voyage home; Death was envious of the honours that awaited him. The other officer still survives, and wears on his breast the cross his sovereign bestowed upon him. He is, or will be, one of the wealthiest men in England, but we are sure that he values that small piece of bronze of the value of threepence more than all the money he has at his banker’s.

but the memory of a brave action has never perished.

But gallant deeds are the same whether they be done by officers or by men; and the two sergeants demand notice who were also, for the part they took in this affair, decorated with the Victoria Cross. We should not dwell upon their history if it were not that it points a moral, though it does not adorn our tale. Both of these sergeants were fine, handsome fellows; one of them is six feet two inches in height. When they returned to London, and walked[10] forth in the streets, decorated with the memorials of their bravery, their appearance naturally attracted much attention. Foolish people stopped them in the street, and invited them to drink. Now, no man of sense or good-breeding will drink in this way with soldiers, and no man of good feeling will tempt soldiers to drink. Those who thus invited our sergeants, we believe, meant no harm, but only wished to give the sergeants a cheerful glass, and to make them light their battles o’er again. But soldiers who know how to resist the enemy in war are not always proof against temptation in times of peace. These two Victoria Cross men fell into irregular habits, such as could not be tolerated in the case of non-commissioned officers; every effort was made to save them, but in vain; their irregularities became so glaring that they were reduced to, and have ever since remained in, the ranks. They are steady enough now, but it is felt that they cannot be trusted, and they are not likely ever to regain their former rank. It seems very hard that brave men should lose their position through the mistaken kindness and thoughtlessness of their admirers, and we hope that those who feel sympathy with soldiers will find some better way of expressing it than by giving them drink. These two men, though serving in the ranks, have still much influence over their comrades, and that influence, we are glad to say, is generally exercised for good. The possession of the Victoria Cross carries with it a pension of 10l., which cannot be forfeited through misconduct; the pension for distinguished conduct in the field is 15l. per annum.

Many small pledges of affection were found on the persons of our soldiers who fell on the battle-fields of the Crimea. Sometimes a lock of hair, or a photograph, or a last letter from home, or a small Bible or Testament, was found concealed beneath the tunic of a dead soldier. Many of them carried their Bibles with them to the field as a sort of talisman to protect them from danger; and there is a well-authenticated case of one soldier having had his life saved from the bullet, which would otherwise have reached his heart, having lodged in his Bible. We should think that book would become a precious relic in his family, ever to be prized, never to be parted with, for it was literally the Word of Life to[11] him. Another was found with his right hand so firmly clenched that it was difficult to open it. He had allowed the blood from his wound to flow upon his hand, so that, on closing it, his fingers became, as it were, cemented together. Inside the hand were found several sovereigns he had saved from his pay with the intention of remitting them to his wife at home. His last thought was, probably, of her, and her heart must have been touched when she received the money he had saved for her with his heart’s blood. Another man, who died of his wounds in hospital, had recourse to a singular expedient to save his watch, which he wished to be sent to his father in some remote country village. It was known that he was possessed of a watch, and there was no small uneasiness among the hospital orderlies when it could not be found after his death. Search was made for it in vain, and suspicion naturally fell upon the orderly who had been with him when he died. As this man, however, had always borne a good character, and there was no direct evidence against him, he was allowed to retain his situation, which must have been anything but a comfortable one. About ten days after the death of the soldier the mystery was cleared up. The effects of a dead soldier are usually sold by auction, and the proceeds, after paying all demands, remitted to his relations at home. It so happened that this man was possessed of a pair of good boots (a rare piece of good fortune in the Crimea), and these were purchased by a comrade for a few shillings. The purchaser, in trying on the right boot, found some obstacle in the toe which he imagined to be a pebble; on shaking it out he discovered the missing watch. The dying man, in the delirium of his last struggle, had contrived to secrete it in the place where it was found. It would be difficult to assign any reasonable motive for such an act; it was probably done in a moment of unconsciousness.

Commodore Wilmot has told us a good deal in his book about the King of Dahomey’s Amazons. These female warriors form his body-guard, and are three times as numerous as the men, whom they surpass in strength and bravery. They are very skilful in the use of firearms, and carry gigantic razors for shaving off[12] heads—a very unladylike amusement, as all will allow. Now, in this country we have no regularly organized army of Amazons, though there is no saying what we may soon have in these days, when there are so many suggestions for the employment of female labour. It may be a prejudice on our part, but we confess we should not like to see nice young ladies firing off blunderbusses, or shaving off people’s heads. Still, women have been found serving in the ranks, both in France and in England, without their sex being discovered, and a good many soldiers’ wives accompanied our forces to the East. It is painful, but truthful, to add that most of these adventurous females had to be sent home, for reasons which we had rather not specify; four only were allowed to remain. These well-conducted Amazons weathered all the dangers of the campaign, watched over their husbands in the field and the hospital, did all the marketing, without knowing a word of “the foreign lingo” spoken by the natives, passed through many perils, and returned to relate their “accidents by flood and field” to their admiring friends.

Soldiers, as we have said, are very patient while enduring physical pain. A hospital presents a fearful scene on the day after a battle. It is surprising that no artist has selected such a subject to illustrate the horrors of war. Our army surgeons are brave men, or they would lose their presence of mind amid such scenes, for it requires less courage to kill than to heal. Every form of physical suffering is to be seen there; but a groan is rarely to be heard. It is only during the amputation of a limb, or the probing of a wound, that a sharp cry of pain is sometimes wrung from the sufferer, who generally turns aside his head, as if ashamed of such unsoldierly weakness. Wounded and dying soldiers like to be visited by their chaplains; they often say, “We have led a bad life; can there be any hope for us now?” They may have been bad men, but they are always truthful: they never try to make themselves out to be better than they really are. Their last thought is generally of home. Often in India and the Crimea a dying soldier has said to his chaplain, “You will write and tell them all about it. I hope I have done my duty, and[13] nothing to disgrace my name.” If our chaplains did nothing but soothe the last hours of our soldiers, their mission would not be altogether in vain; and no class of men are more grateful for kindness, as our nurses in the East will testify. And here we detract not from the excellent intentions of those ladies in saying that, from want of previous training, they were, as a class, disqualified for the work they undertook; yet we have always heard them spoken of by the men with the deepest respect. We have baptized many a Florence Nightingale, and the feeling cherished towards this lady in the army is almost analogous to the Mariolatry of the Italian peasantry: it borders on idolatry. “Shure she is not a woman, but an angel of mercy,” said a poor Irishman whom she had nursed. “I could kiss the very earth she threads.” There are many others equally grateful, though less demonstrative and poetical in the expression of their gratitude. Florence Nightingale and the Queen are the two patron saints of the British Army. Our soldiers have not yet forgotten how her Majesty visited them in hospital on their return from the Crimea, and showed her sorrow and her sympathy as a woman best can show it—by her tears. And, after all, be we queen or soldier’s wife, drummer-boy or commander-in-chief, we are all members of the same family, with the same great heart beating within our breasts. One touch of nature makes the whole world kin. Our Queen wept for her wounded soldiers, and there was many a soldier wept for our Queen when the great sorrow overtook her. Such tears are not lost; they bind us all together, and give us a deeper insight into that great law of love taught by Him who did not esteem it a weakness to weep at the grave of a friend.

From the earliest times, when standing armies were needless, inasmuch as every human unit that made part of a nation’s total was more or less a soldier, and was ready and willing to buckle on his harness and fight at the beck of the ruler to whom he owed allegiance, to the present day when the army and navy estimates are the bêtes noirs of every would-be politician who prefers money-grubbing to national honour, the chosen head or chief magistrate of every nation—no matter what his style and title may have been, or may be—has always had a select body-guard at his command, partly as a mark of distinction and honour, and partly for the special defence of his person against malcontents at home and enemies abroad.

To this rule Victoria, by the Grace of God, Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and Empress of Hindostan, is no exception, and could our eyes be gratified with a review in which the “household troops” of all nations took part, from the Cent Gardes of Napoleon III. to the Amazons of His Brutality of Dahomey, it would be seen that there are none superior to the British Guards.

The Guards, or Household Troops of England, consist of six regiments, three of cavalry and three of infantry. The three regiments of cavalry are styled respectively, the First Life Guards, the Second Life Guards, and the Horse Guards, or Oxford Blues; while the three regiments of Foot Guards are known as the First, or Grenadier Guards, the Second, or Coldstream Guards, and the Third, or Scots Fusilier Guards. These six magnificent regiments of cavalry and infantry are—and it is just and right to say so,[15] though it be said with the pride of an Englishman—unequalled in the world, whether it be in appointments or soldierly bearing, in physical strength or majesty of stature, in dash or discipline, unflinching endurance of hardships or superb indifference to death—which last, by the way, are qualities common to all British soldiers and sailors at all times and under all circumstances.

The First and Second Life Guards owe their origin to a troop of eighty Cavalier gentlemen who were enrolled in Holland, on May 17, 1660, as a body of Life Guards for the protection of the person of Charles II. against the conspiracies that were said to be forming in England to assassinate him as soon as he set foot once more on English soil. The number of this body-guard was raised to six hundred before the king quitted Holland; but after the Restoration had been effected, several gentlemen retired from the service to return to their homes in the country, and it dwindled down to two troops—one of which remained with the king in London, while the other went into garrison under the Duke of York at Dunkirk. The attempt, however, of the “Fifth Monarchy Men” to overthrow the king’s authority in 1661 led to the recall of the Duke of York and his troopers, when the corps of Life Guards was raised to five hundred men, and divided into three troops—the first being called His Majesty’s Own; the second, the Duke of York’s, as before; and the third the Duke of Albemarle’s.

No change was made in the constitution of the Life Guards, with the exception of the addition of a fourth troop after the Duke of Monmouth’s rebellion in 1685, until October, 1693, when the Horse Grenadiers, who had hitherto been attached to each troop of Life Guards—just as a company of grenadiers formed part of almost every infantry regiment in the British service until a few years ago—were embodied and formed into a separate troop, distinguished by the title of the Horse Grenadier Guards. It should also be stated that the Scots Life Guards and Horse Grenadier Guards, which had been raised after the Restoration to act as a guard of honour to the Lord High Commissioner and the Scottish Parliament, were marched to London, and incorporated with the English Life Guards shortly after the union of the two kingdoms.

In 1745, after the defeat of Prince Charles Edward—otherwise styled the Pretender—at Culloden, the four troops of Life Guards were reduced to two; but the establishment of the Horse Grenadier Guards, which now consisted of two troops, remained on the same footing. This continued until June 25, 1788, when the two troops of Life Guards and the two troops of Horse Grenadier Guards were embodied into two regiments, the former bearing the title of the First Regiment of Life Guards, and the latter that of the Second Regiment of Life Guards; and no further alteration has been made to the present day, except in the number of companies in each regiment, and the numerical strength of the companies.

The third cavalry regiment of the Household Troops—the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards, or Oxford Blues, as it is familiarly called—was originally a body of horse that had been raised by Cromwell as a body-guard, and had been retained after his death to act as a guard of honour to the Parliament and General Monk, who then bore the title of the Lord General. After the Restoration the whole of the troops that had been in the service of the Parliament were disembodied; but the officers and men of the Lord General’s troop of horse were immediately formed into a new regiment, which received the title it now bears, and was placed under the command of the Earl of Oxford. With the exception of alterations at various periods in its numerical strength, no change has taken place in the constitution of this regiment from the time of its enrolment for the service of Charles II. until the present time.

Of the three infantry regiments of the Household Troops, the First, or Grenadier Guards, although it takes precedence of the other two regiments in point of rank, yields to the Coldstream Guards in priority of enrolment. This regiment was incorporated at Brussels in 1657, having been raised at that time by the Duke of York for the service of the Spanish crown in the Netherlands. It consisted of about four hundred men of all ranks, the majority of whom were gallant, reckless, royalist gentlemen, who had fought and bled for Charles I. and his son Charles II. in the Civil War, and had followed the fortunes of the latter and his brother, the Duke of York, when they were driven from England, and obliged to take[17] refuge in France, from which country they were also expelled when peace was made between Louis XIV. and Oliver Cromwell in 1655. The regiment was cut to pieces before Dunkirk in 1658, when that town was taken from the Spaniards by the French troops and the soldiers of the Commonwealth; but it was reorganised two years subsequently by Lord Wentworth, who then assumed the command. In 1662 it was ordered to repair to England, where it was incorporated with a regiment known as the “King’s Regiment,” commanded by Colonel Russell, under the title of the “First Regiment of Foot Guards.” It did not receive its present appellation of the “Grenadier Guards” until after the battle of Waterloo, when it was thus distinguished in commemoration of the glorious charge in which its officers and men broke and routed the veteran Grenadiers of the far-famed French Imperial Guard—the last charge of the British line on June 18, 1815, which decided the terrible struggle of that eventful day in favour of the English arms, and crushed for ever the power and prestige of Napoleon I.

The regiment known as the Coldstream Guards derives its origin from a regiment of the Commonwealth that served against the king in the Civil War under the command of General Monk. It takes its name from Coldstream, a small border town in the south of Berwickshire on the left bank of the Tweed. This town formed the head-quarters of General Monk for some time before he set out on his march for London with the view of effecting the restoration of Charles II., and it was here, indeed, that this movement was projected and matured. During his sojourn in this town in 1659, Monk may rather be said to have reorganised and recruited his old corps, originally called “Monk’s Regiment,” than to have raised a new one, as it is commonly stated, and, having surrounded himself with a body of troops on whose fidelity he could rely, he commenced his march towards London on January 1, 1660. On his arrival his soldiers were employed in repressing the tendency which was evinced by the citizens of London to dispute the authority of the Parliament then sitting. Immediately after the Restoration the forces of the Commonwealth were disbanded by Act of Parliament, but Charles had resolved to add “Monk’s Regiment” to the[18] Household Troops that were then forming for the defence of his person against the attempts of the more desperate republicans who still cherished a bitter hatred to the monarchical form of government, and the soldiers, having laid down their arms on Tower Hill as a mark of obedience to the king’s authority, and in token of their dissolution as a regiment of the Commonwealth, immediately took the oath of allegiance, and sprung into existence anew as an English regiment, under the name of “The Duke of Albemarle’s, or Lord General’s Regiment,” which appellation was changed to that of the “Coldstream Guards” about 1670, after the death of Monk, in remembrance of the place where he had prepared for the enterprise which it was his good fortune to bring to such a happy issue.

The precedence of the Grenadier Guards over the Coldstream Guards was established by a general order, dated September 12, 1666, in which it was directed “that the regiment of Guards (composed of the two regiments of Foot Guards, commanded by Colonel Russell and Lord Wentworth) take place of all other regiments, and the colonell take place as the first foot colonell; the General’s Regiment (the Duke of Albemarle’s, or Coldstream Guards) to take place next.”

The Scots Fusilier Guards were placed on the roll of the English army, and first shared the duties and privileges of the Household Troops, shortly after the union had been effected between England and Scotland, in 1707, and it was found unnecessary to retain them any longer in Edinburgh, where, in conjunction with the Scots Life Guards, they had acted as a guard of honour to the Lord High Commissioner and the Scottish Parliament, besides rendering efficient service in the various continental wars in which England had been involved during the latter part of the seventeenth century.

The Scots Life Guards were established in Edinburgh in 1661, a single troop having been enrolled in that year, to which a second was added about two years after, to assist in the maintenance of order and the enforcement of the Episcopalian form of worship, which the covenanting Scotch, especially the Lowlanders, cordially hated. It is probable that the Scots Foot Guards were enrolled at the same time, as it appears that after the suppression of the risings[19] in Scotland in 1667, and the peace that was concluded in that year with Holland, all the regular Scottish forces were disbanded, with the exception of the two troops of Scots Life Guards above mentioned and the regiment of Scots Foot Guards.

Space would fail us entirely if we attempted to notice even a tithe of the thousand and one battles and exploits in which our Household Troops have signalized themselves. We can, indeed, only mention the few hard-fought fights, the names of which are blazoned in scrolls of glowing gold on the regimental colours of these regiments, in memory of the battle-fields in which they have won such a glorious meed of honour and renown at the priceless cost of life and limb and liberty; and we must abstain from making more than the briefest mention of the services rendered by detachments of the Life Guards and Coldstream Guards, who acted as Marines on board the English fleet in 1665 and 1666, under Prince Rupert and the Dukes of York and Albemarle (some fifty years prior to the addition of the splendid and distinguished corps that is now known as the “Royal Marines” to the British army), and at the battle of Solebay in 1672; the gallant deeds of the same regiments before Maestricht in 1673, under the Duke of Monmouth and John Churchill, afterwards Duke of Marlborough, the services of the Grenadier and Coldstream Guards in Flanders, in 1678, under the same generals; the share that these regiments had in the occupation of Tangiers in 1680, in conjunction with the Spanish troops, and the subsequent battles with the Moors; the battle of Bothwell Bridge, in Scotland, with the rebel covenanters, in which the Scots Life Guards and Foot Guards bore a conspicuous part under the Duke of Monmouth; the frustration of the attempt of the same nobleman to wrest the crown from James II., by the untoward battle of Sedgemoor, in which all the regiments of English Life and Foot Guards were engaged; the campaigns against France in the Netherlands, in 1689 and 1691, the last of which was followed by the loss of Namur; and the long list of battles and sieges in which these regiments took part during the latter part of the reign of William III. and Mary, those of Queen Anne, George I., and George II., and the early part of the reign of George III., including[20] the battles of Steenkirk, Landen, Blenheim, Ramilies, Almanza, Oudenarde, Malplaquet, Dettingen, Fontenoy, Minden, Warburg, the American campaigns, and the battle of Valenciennes in 1793.

The First and Second Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards all bear the words “Peninsula” and “Waterloo” on their guidons. The Grenadier Guards bear the memorable names of “Lincelles,” “Corunna,” “Barossa,” “Peninsula,” “Waterloo,” “Alma,” “Inkerman,” and “Sevastopol” on their colours; and in addition to these, Corunna only being excepted, the Coldstream Guards and Scots Fusiliers have the words “Sphinx,” “Egypt,” and “Talavera.”

To speak further of the achievements of the Household Troops in Belgium, Egypt, Spain, and Portugal, would be to write a military history of the reign of George III., or to tell again the oft-told but never tiring tale of the Peninsular War, the disastrous retreat on Corunna, the battle fought there on the eve of embarkation, the death and burial of Sir John Moore, the triumphs of Talavera, Vittoria, Salamanca, and Barossa, and the “crowning mercy” of Waterloo, in which battle the Household Cavalry and the First Dragoon Guards broke and utterly routed Napoleon’s magnificent Cuirassiers, and won the right to bear the word “Waterloo” on their standards and appointments for ever.

From 1815 a long rest from war’s alarm fell to the lot of the Household Troops until the outbreak of the Crimean War, in the hardships and glories of which the three regiments of Foot Guards participated. As the honour of the battle of Balaclava belongs peculiarly to the “six hundred,” who were set face to face with sure and sudden death when they were launched against the Russian batteries, and rode, like heroes as they were, into the graves that yawned to receive them, so the glory of Inkerman adds especial lustre to the laurels of the British Foot Guards.

Amid the cold grey mists of that dark November morning they bore the brunt of an almost hopeless struggle, as line after line of Russian soldiers, maddened with drink, swarmed up the hill from the valley of the Tchernaya to recoil with broken ranks from the base of the little battery that the Guards held with desperate courage. It was the key of the position: to have been forced from[21] it would have brought destruction on the entire British camp. They knew this, and officers and men would all have died there gladly, like Leonidas and his three hundred at the pass of Thermopylæ, rather than have quitted the earthwork alive, though not dishonoured. Tears trickled down the cheeks of their royal leader as he saw his men falling, like autumn leaves, before the fire of the infuriated foe. With bleeding heart he gasped, “My poor Guards! What will they say in England?” Ay! what, indeed? What, but honour to the men who esteemed life as nothing in comparison with England’s reputation? What, but honour to the Duke who dared to sigh for his maimed and slaughtered men as a father would sorrow for his dying son? Even when ammunition failed them they did not abandon the post they had held so long, and at so great a cost. No! if they could no longer pour a shower of lead into the advancing masses of the Russians, they could at least rain stones upon them, and many a Russian soldier fell to the rear that day with loosened teeth and shattered jaws, smarting under the blows of the rough missiles that the Guards tore from the banks and mould around them. But succour was at hand: the red-breeched Zouaves of France came leaping to the rescue at the pas de charge; and, as they advanced, the Guards sprang, with a cheer, over the parapet of the earthwork, and drove the blades of Bayonne to the very muzzles of their muskets into the backs of the running foe, who left behind them more killed and wounded than the British numbered at the commencement of the battle.

It may have been noticed that all officers in the Guards are entitled to hold that rank in the army which is immediately above the rank which they hold in their own regiments: an ensign in the Guards being styled “ensign and lieutenant” in his commission, and so on. The privilege of holding the rank of lieutenant-colonels and captains in the army was granted to captains and lieutenants in the Guards in 1691, when the allied armies, under the command of William III., were encamped on the plain of Gerpynes, in the Netherlands, near the French frontier, a few weeks before the battle fought between the Allies and the French on the banks of the little rivulet near Catoir; but the rank of lieutenant in the army was not[22] held by ensigns in the Guards until after the battle of Waterloo, when this privilege was conceded to them by the Prince Regent, in an order from the War Office, dated July 29, 1815.

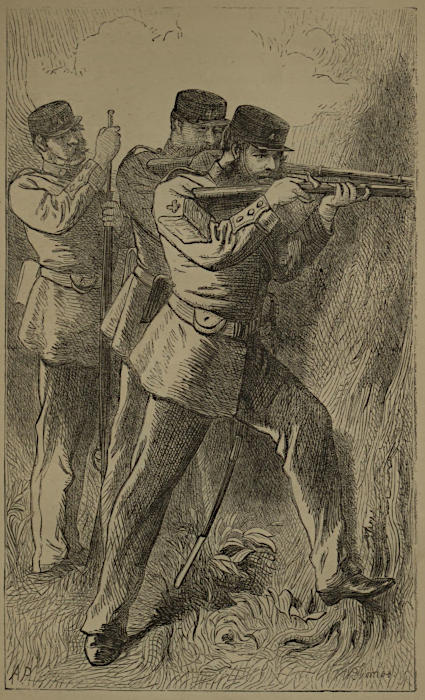

The illustration that accompanies this chapter gives the present costume of the three regiments of Foot Guards—a scarlet tunic, lately introduced, with blue facings, white cross-belt and waist-belt, and black trousers, with a scarlet cord down the seams in winter, and white in summer. When in full dress, the whole wear bearskin caps, but each regiment has distinctive ornaments on the collar[23] of the tunic, etc.; and when in undress, the men belonging to each may be distinguished by the band round the cap—the Grenadier Guards wearing a red band, the Coldstream Guards a white band, and the Scots Fusiliers a band chequered with red and white.

The two regiments of Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards all wear corselets—consisting of a breast-plate and back-piece—and helmets of polished steel, with breeches, sword-belts, cross-belts, and gauntlets of white leather. They are, however, to be distinguished by the colour of their coats, and the plume that they wear in their helmets—the Life Guards being clad in scarlet coats, and having white plumes, while the Horse Guards wear blue coats, and scarlet plumes. They are all armed alike, with sword and rifled carbine, and carry pistols in the holsters of their saddles, which are covered with white sheep-skin for the Life Guards, and black sheep-skin for the Horse Guards Blue. In undress the former wear a scarlet shell-jacket with blue facings, while the latter wear a blue shell-jacket with scarlet facings. The cap—black, with a scarlet band—is the same for each regiment.

Apropos of this subject, it may not be generally known that the First Royals, or First (Royal) Regiment of Foot, are a corps of Foot Guards by regimental tradition, if not by authority from the Horse Guards.

The writer of this chapter once knew an old Devonshire pensioner, John Sculley by name, who belonged to the “Fust Ry-uls,” as he used to style his old regiment, who had fought in almost every one of the principal battles of the Peninsular war, and had escaped without a scratch.

“John,” I would sometimes say to the old fellow, as he stood leaning on his spade, “what regiment did you belong to?”

“Why, Sponshus Pilut’s Guards, to be sure,” he would curtly reply. “I’ve told ’ee so often enough, I reckon.”

“No, I think not. But Pontius Pilate’s Guards—what a queer title! Why in the world were you called so?”

“Why, you see, the ridg’ment was raised in Sponshus Pilut’s time, and that’s how us got the name.”

And this he implicitly believed.

Gibraltar is well named the Key of the Mediterranean. In peace it protects our commerce and our fleets, in war it affords equal facility for harassing our foes; by its position and its strength its possession is of the utmost importance to the English, and it has excited for the last century and a half the suspicion and the jealousy of other nations. The rock of Gibraltar projects into the sea about three miles. Its northern extremity, owing to its perpendicular altitude, is inaccessible; its[25] southern extremity is known as Europa Point; and the southern and eastern sides are rugged and steep, affording natural defences of a very formidable character. It is only on the western side fronting the bay that the rock gradually declines to the sea; but the town of Gibraltar is so built that an attack upon it, however well planned, however strong or long continued, is almost certain of failure. The bay formed by the two points already named is more than four miles across. The depth of its waters, and the protection afforded by the headland, render the harbour remarkably secure, and it is well adapted for vessels of every description. The extreme depth of the water within the bay is a hundred and ten fathoms. The security of the harbour has been still further increased by two moles, one extending eleven hundred feet, and the other seven hundred feet into the bay. The bold outline of the rock is conspicuous and striking, as it lifts its colossal proportions into the sky, and against the intense blue of that sky every crag is sharply defined. From the water to the summit, from the land forts to Europa Point, the whole rock is lined with formidable batteries. Like a crouching lion it looks out to sea, and every foe is daunted by its aspect.

Gibraltar is essentially military. Sentinels, gateways, drawbridges, fortifications, guns pointing this way, that way, and the other, looking as if—supposing them to be fired—they would inevitably blow up one another; narrow streets of stairs which it is hard work in the hot sunshine to ascend; nothing to see when you reach the top but a line of ramparts, and another street of stairs in perspective. Excavated passages in the rock lead from point to point; every new position seems more impregnable than the last; awful heights rise above, terrific depths yawn below; guns peer—at the most unexpected points—from the sides of the rock, as if they were natural productions; tunnelled galleries open to the right and to the left, inviting or deterring the visitor. There is one huge chamber cut out of the solid rock, and serving as a battery or a banquet room as occasion may require; it is called St. George’s Hall, and is the most formidable and singular cutting of Gibraltar. There is another excavation of the same character[26] christened by the name of Cornwallis, but it is neither so spacious nor so elegant as that of St. George.

The people one meets in Gibraltar are a mixed multitude—the familiar English uniform is of course conspicuous, but for the rest it is only what we have read of, or heard of, or dreamed of in connexion with Gil Blas and Don Quixote. There is so much that is Spanish that you might fancy yourself in Barcelona; so much that is Moorish that you might fancy yourself in Morocco; so much that is English, Italian, Greek, Polish, Jewish, African, and Portuguese, that you might conceive yourself to be in the midst of an animated Ethnological museum on a large scale, opened at Gibraltar, regardless of expense.

The rock of Gibraltar, forming with Abyla in ancient times the far-famed pillars of Hercules, was captured from the Spaniards by Sir George Rooke in 1704. During the nine following years the Spaniards in vain tried to recover it, and in 1713 its possession was secured to the English by the treaty of the peace of Utrecht. But treaties are liable to be broken. When the men of the pen have finished their work the men of the sword may undo it. To hold the rock of Gibraltar by treaty was one thing, to hold it by strength was another. The fortifications required for its defence were necessarily on a gigantic scale, and the men of the pick and the shovel were in request. When we glance at the subterranean passages cut in the rock, the huge caverns scooped out of it, the long lines of rampart making the place impregnable, even though attacked by an enemy having the command of the sea, we may readily understand how important was the service rendered by the engineer and labourer. So important indeed was their work, that it added a new division to the British army—a division, that wherever our flag waves has done good service—namely, that of the Engineers.

Previous to the year 1772 all our great engineering works in connexion with military operations were mainly executed by civilians. The works at Gibraltar were entrusted to ordinary mechanics obtained from England and the Continent. These operatives were not engaged for any term of years, neither were they amenable to military discipline; they worked when they[27] pleased, they idled when they pleased; they were wholly regardless of authority; received good wages; and their dismissal was in all instances more injurious to the Government than it was to the men.

The hindrance and inconvenience of this system led to the formation of a corps of military artificers. The idea was suggested to Lieutenant-Colonel Green by the useful result of the occasional occupation of soldiers who had learned mechanical trades previous to enlistment. He thought it possible that a sufficient number of these men might be banded together for the carrying on of all necessary engineering works, and that their employment would lessen the cost while it secured the completion of any engineering operation, and at the same time, that the men so employed would at any period be ready to participate in the defence of the place.

Lieutenant-Colonel Green submitted his suggestion to the Governor of Gibraltar. The governor approving the plan, it was recommended to the attention of the Secretary of State, and royal consent was given to the measure in a warrant dated March 6th, 1772: thus originated the corps of Royal Sappers and Miners.

The warrant authorised the raising and forming of a company of artificers, to consist of a sergeant-major, as adjutant, who was to receive 3s. a day; three sergeants, each of whom was to receive 1s. 6d. a day; three corporals, whose pay was 1s. 2d. a day; and sixty privates, and one drummer, each of whom was to receive 10d. a day.

The rank of adjutant attached to that of sergeant-major was not adopted, but it appears to have been taken by Thomas Bridger, who so describes himself on his wife’s tombstone at Gibraltar, adding thereto a touching tribute to her charity, and a sneer at the end—like the sting in the tail of the serpent—at the parsimony of the Government.

Recruiting for this company was a service of but little difficulty, as permission was granted to fill it with men from the regiment then serving in the garrison. The whole of the civil mechanics[28] were not discharged from the department on account of this measure; a few, on the score of their merit, were retained in the fortress; the foreign artificers were dismissed; most of the English “contracted artificers” sent home; permission, however, was given to any “good men” who chose to enlist; but not one availed himself of the privilege.

Before the close of the year 1772, the ranks of the company were almost full, and the system was found to work so well, that on the recommendation of the lieutenant-governor a fresh warrant was issued for the increase of the corps, and no sooner was it completed than the engineers proceeded with great spirit in the execution of the King’s Bastion. On laying the foundation of this work, General Boyd, in his speech, desired that the bastion might be as gallantly defended as he knew it would be ably executed, and that he might live to see it resist the united efforts of France and Spain. His desire was fully realised. He not only lived to see what he wished, but materially to assist in the operations of the siege.[1]

In October, 1775, the company of Soldier Artificers was still further augmented, and consisted of one hundred and sixteen non-commissioned officers and men.

Gibraltar, ever since its capture by the English in 1704, had been a source of jealousy and uneasiness to Spain; as soon as ever an opportunity offered for the commencement of hostilities, Spain assumed an aggressive attitude, and in 1779 sat down before the place at St. Roque with a powerful camp, and sent out a fleet to cut off supplies. The gallant old General Elliot, and the no less gallant veteran Boyd, defended the rock nobly, and found their best help in the Soldier Artificers. The sufferings of the undaunted garrison were great—the price of mutton or beef being 3s. 6d. a pound, eggs sixpence each, and mouldy biscuit crumbs 1s. a pound; but the indomitable energy of the men never slackened; they laboured night and day, piercing the rock with subterranean passages, and forming vast receptacles for stores and ammunition in the solid stone. Failing in their efforts to reduce the garrison by[29] famine, the French and Spaniards, after three years’ beleaguering, began a terrific bombardment. Fire was opened with unexampled fury, and continued incessantly for days and weeks. The battering flotilla was warmly received by the “dwellers in the rock.” But for a long period the battering ships seemed invulnerable. At length red-hot shot was employed by the garrison, and sheets of resistless flame burst in all directions from the flotilla: the whole of the batteries were burnt; the magazines blew up, one after another; and it was a miracle that the loss of the enemy by drowning did not exceed the number saved by the merciful efforts of the garrison.

The contest was still prolonged: the enemy were bent on reducing their invincible opponents at all cost. The British were in no mood to yield; red-hot shot was their grand specific; the Artificers were instantly employed in erecting kilns in various parts of the fortress, each kiln capable of heating a hundred shot in an hour.

The struggle continued for some time; from one thousand to two thousand rounds were poured into the garrison in the twenty-four hours, and this was kept up for months. During the cannonade, the Artificers under the engineers were constantly engaged in the diversified works of the fortress, and they began to rebuild the fortification known as the Orange Bastion, on the sea line, and in the face of a galling fire completed their work in three months. The number of the Artificers had been augmented by the arrival of one hundred and forty-one mechanics, under Lord Howe; but, even taking this into account, the erection of such a work in solid masonry, and under such circumstances, is unprecedented in any siege.

Failing to obtain the submission of the garrison either by famine or bombardment, the enemy attempted to mine a cave in the rock, by which to blow up the north front, and thus make a breach for their easy entrance into the fortress. The secret was revealed by a deserter; but very little attention was paid to his statement, until the discovery of the enemy’s proceedings was made by Sergeant Thomas Jackson, who, making a perilous descent of the rock by[30] the help of ropes and ladders, ascertained beyond all doubt the work in which the Spaniards were engaged. The ratification of peace put an end to all military operations, and terminated a siege which extended—with circumstances of unparalleled difficulty and danger—over a period of four years.

During the whole of this memorable defence, the Company of Artificers proved themselves to be good and brave soldiers, and no less conspicuous for their skill, usefulness, and zeal in the works—works, as the commander of the hostile forces [Duc de Crillon] remarked, “worthy of the Romans.”

At the close of the siege, there were twenty-nine rank and file wanting to complete the number of Soldier Artificers. The deficiency was speedily supplied, and the company was never allowed to sink beneath its established number. A force of more than two hundred and twenty non-commissioned officers and artificers were employed in restoring the work which had suffered during the bombardment; and to expedite the labour, the Soldier Artisans were excused from all garrison routine, as well as from their own regimental guard and routine, and freed from all interference likely to interrupt them in the performance of their working duties. Still, to impress them with the recollection that their civil employments and privileges did not make them any the less soldiers, they were paraded, generally under arms, on Sundays; and to heighten the effect of their military appearance, wore accoutrements which had belonged to a disbanded Newfoundland regiment, purchased for them at the economical outlay of seven shillings a set. Perhaps no body of men subject to the articles of war were ever permitted to live and work under a milder surveillance; and it may be added, that none could have rendered service more in keeping with the indulgences bestowed.

In the summer of 1786 the company was divided into two, the chief engineer still continuing in command of both companies. About the same time, those men who were disqualified in any way for service were removed from the corps, and the enlistment of labourers, in addition to skilled hands, was authorized by the Government. Five batches of recruits were sent to the Rock in[31] rapid succession. The second party of recruits, comprising fifty-eight men, twenty-eight women, and twelve children, were destroyed in a storm off Dunkirk. Only three persons escaped.

The valuable services rendered by the corps, and the hearty good-will with which they invariably laboured, led to a still further extension of their privileges. They were allowed to pass in and out of garrison on Sundays and holidays without a written pass, and to wear at pleasure whatever dress suited their inclination. It was not uncommon, therefore, for the non-commissioned officers and the respectable portion of the privates to stroll about garrison or ramble into Spain, dressed in black silk and satin breeches, white silk stockings, and silver knee or shoe buckles, drab beaver hats and scarlet jackets, tastefully trimmed with white kerseymere.

In 1787 the king’s authority was granted “for establishing a corps of Royal Military Artificers.” It was to consist of six companies, of a hundred men each. Officers of the Royal Engineers were appointed to command the corps; and when required to parade with other regiments the corps was directed to take post next on the left of the Royal Artillery. The companies were ordered to serve at Woolwich, Chatham, Portsmouth, Gosport, Plymouth, and one company was divided between Jersey and Guernsey. The companies at Gibraltar, although similarly constituted, remained a distinct and separate body until their incorporation with the corps in 1797. The recruiting was carried on by the captains of companies; there was no standard as to height fixed, but labourers were not enlisted over twenty-five years of age nor any artificer over thirty, unless he had been employed in the Ordnance Department and was known to be an expert workman of good character. The bounty given at first to each recruit was five guineas, but during time of peace it was reduced to three. Labourers promoted to the rank of artificers received a bonus of two guineas, an additional 3d. a day, and were privileged to wear a gold-laced hat.

By the operative classes some opposition was offered to the enrolment of the Royal Artificers, and on more than one occasion a serious outbreak took place between the civilians and the military;[32] the jealousy, however, at last died out, and the old animosity was forgotten.

In 1791, a vessel bearing several recruits to Gibraltar encountered a terrific storm in the Bay of Biscay. The wreck and its circumstances gave rise to a song called “The Bay of Biscay O!”

The declaration of war with France, 1793, put an end to the comfortable and easy life which the Royal Artificers had been leading. They were, as soldiers, liable to be sent to any part of the world where the British Government might require their services. The idea of this liability ever being insisted upon seems to have been foreign to the minds of the corps. When it was known that their services would be required in the Low Countries and in the West Indies, many of them eluded service by providing substitutes, and some resorted to the very dishonourable alternative of desertion. Of the finest company sent out to the West Indies, not a man escaped the ravages of “yellow Jack.” Those who served in Holland distinguished themselves by their bravery, especially at the famous siege of Valenciennes. The continuance of the war rendering it essential that the artizan companies should be kept in foreign stations, while the necessity for increased vigilance at home was each day becoming more urgent, led to the extension of the corps, and four new companies were enrolled—two to serve in Flanders, one in the West Indies, and one in Upper Canada.

The special company destined for service in the West Indies sailed from Spithead, November, 1793, and arrived at Barbadoes early in the following year. From thence they proceeded to Martinique, where their spirited conduct in the field commanded the admiration of the whole army. The companies which were sent both to Toulon and Flanders behaved also with much gallantry, proving that the Royal Artificers were not only skilled workmen but efficient soldiers.

In June, 1797, the Soldier Artificers Corps at Gibraltar were incorporated with the Royal Military Artificers; by this incorporation the latter corps were increased from 801 to 1075, of all ranks; but its numerical strength only reached 759 men. Detachments[33] of the corps served with credit under Sir Ralph Abercrombie at Trinidad, and also in the unsuccessful attack on Porto Rico.

Among the measures suggested for reducing Porto Rico was one for taking the town by forcing the troops through the lagoon bounding the east side of the island. In order to ascertain whether the lagoon was fordable, David Sinclair, one of the Military Artificers, picked his way across at dead of night, reached the opposite shore in safety, and picked his way back again to report. He was rewarded for this daring act, but the fording of the lagoon presented so many difficulties as to be given up.

The memorable mutiny of the Fleet at Spithead was followed by the rising of some unprincipled men, who by every means endeavoured to shake the allegiance of the soldiery. The Plymouth Company of Artificers in an especial manner distinguished itself by its open and soldier-like activity against these disloyal exertions; in a printed document, bearing date May, 1797, they avowed at that momentous crisis their “firm loyalty, attachment, and fidelity to their most Gracious Sovereign and to their Country.” The declaration was well timed, and had the desired effect.

Throughout the war in the Low Countries the Corps of Artificers rendered eminent service. One of their most important achievements was that of the total destruction of the Bruges canal.

About the same time a company of Artificers was sent to Turkey to operate with the troops of the Sultan against Napoleon, in Egypt. There also they distinguished themselves alike by their active service and good conduct. A Turk having attempted to stab one of the men, was sentenced by the Turkish governor to death; this punishment, at the earnest entreaty of the commanding officer, was mitigated, the culprit being sentenced to receive fifty strokes of the bastinado, to be imprisoned twenty years, and to learn the Arabic language.

In the West Indies the Artificers were exposed to worse than human foe. There the yellow fever decimated their ranks, but the conduct of the men throughout was both intrepid and humane, and in the despatches reference is frequently made to their exemplary conduct. When the mortality was at its height, three privates[34] voluntarily devoted themselves to the burial of the dead, and worked on with unflinching ardour; surrounded by the pest in its worst form, inhaling the worst effluvia, never for a moment forsaking their frightful service, they laboured on inspiriting those about them by their example, until the necessity for their exertions no longer existed.

In 1806 a company of Military Artificers was established at Malta, and remained a distinct and separate body.

The necessity for an efficient body of trained artizan soldiers became, indeed, every day more obvious; and no expedition of any consequence was undertaken without a body of these men being included in the forces sent out. In America, in the Indies, East and West, on Mediterranean service, in the Peninsula, in the Low Countries, they were alike needed, and rendered excellent service. At home, also, they were continually employed in erecting new and strengthening the old fortifications, for it was anticipated that Bonaparte would visit our shores, and that stone walls as well as wooden walls would be required for our defence.

Throughout the Peninsular war the services of the corps were invaluable; in sap, battery, and trench work, in the making of fascines and gabions, in repairing broken batteries and damaged embrasures, in constructing flying bridges over the Guadiana, the Artificer vied with the regular engineers. Major Pasley, R.E., on his appointment to the Plymouth station, began regularly to practise his men in sapping and mining. He was one of those officers who took pains to improve the military appearance and efficiency of his men, and to make them useful, either for home or foreign employments. He is believed to have been the first officer who represented the advantage of training the corps in the construction of military field-work. After the failure at Badajoz (1811) the necessity of this measure was strongly advocated by the war officers. Then it was recommended to form a corps under the title of Royal Sappers and Miners, to be composed of six companies, chosen from the Royal Military Artificers, which, after receiving some instruction in the art, was to be sent to the Peninsula to aid the troops in their future siege operations.

In April, 1812, a warrant was issued for the formation of an establishment for instructing the corps in military field-work. Chatham was selected as the most suitable place for carrying out the royal orders, and Major Pasley was appointed director of the establishment. Uniting great zeal and unwearied perseverance with good talents and judgment, Major Pasley succeeded in extending the course of instructions far beyond the limits originally assigned, and he not only filled the ranks of the corps with good scholars, good surveyors, and good draughtsmen, but enabled many, after quitting this service, to occupy, with ability and credit, situations of considerable importance in civil life.

At Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz, and other places made famous in the Peninsular war, the Military Artificers won the praise of Wellington, conducting themselves with the greatest gallantry and coolness.

On the 5th of March, 1813, the title of the corps was changed from that of Royal Military Artificers to that of Royal Sappers and Miners. A change of equipment was also introduced. In this respect many irregularities had crept in, the members of the corps in various parts of the world being variously armed, rather to suit their own fancy than to meet the exigencies of the work. Uniformity in the matter was of great importance, and this was gradually and effectually introduced.