Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. VIII, No. 360, November 20, 1886

{113}

Vol. VIII.—No. 360.]

[Price One Penny.

NOVEMBER 20, 1886.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

THE SHEPHERD’S FAIRY.

NOTICES OF NEW MUSIC.

EVERY GIRL A BUSINESS WOMAN.

VARIETIES.

A WIFE’S WELCOME.

THE INCORRIGIBLE.

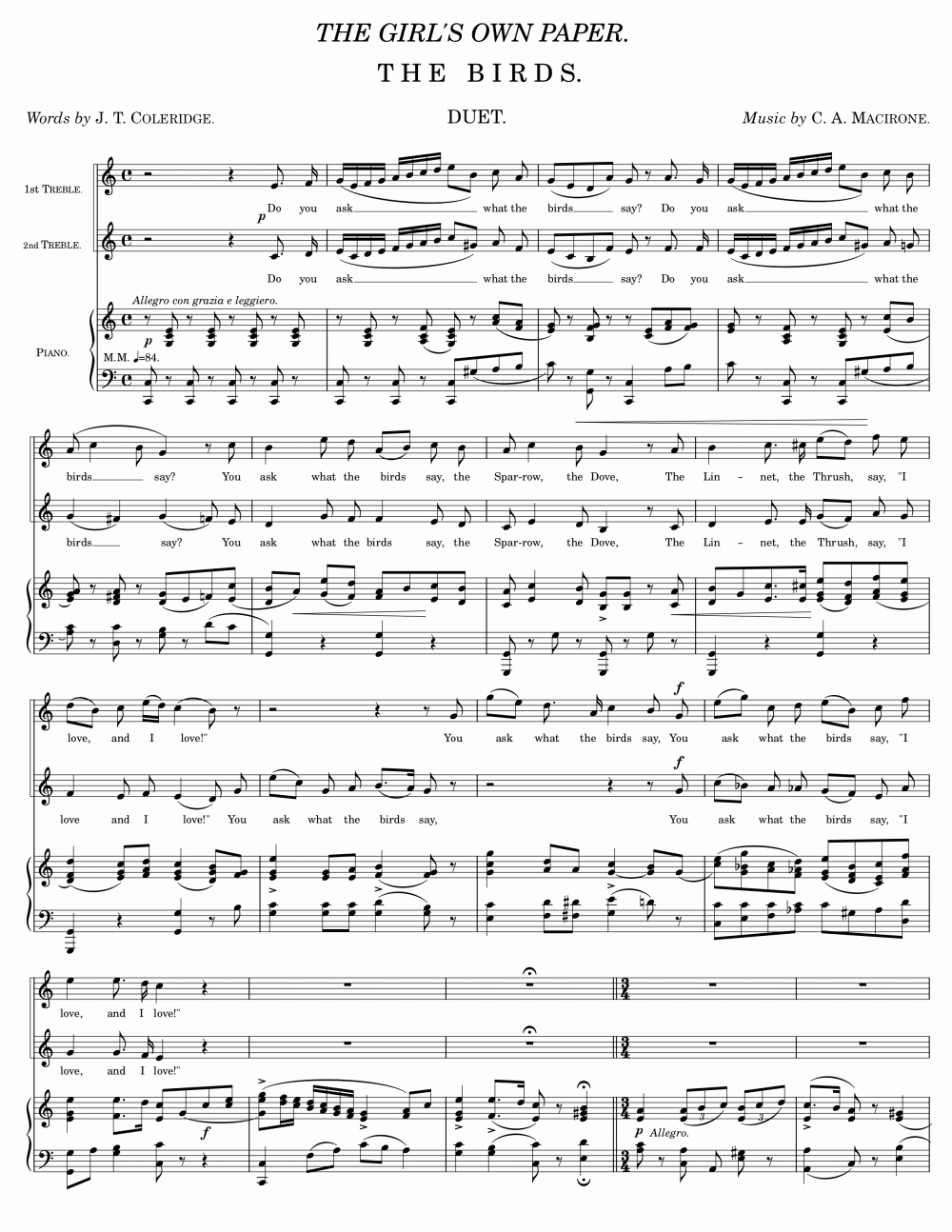

THE BIRDS.

MERLE’S CRUSADE.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

A PASTORALE.

By DARLEY DALE, Author of “Fair Katherine,” etc.

“AND READ IT ALOUD.”

All rights reserved.]

TWELVE YEARS LATER.

In the early days of the present century, during which period the events of this story took place, the education of the lower classes was of the meagrest description; boys like Jack Shelley, with intellectual capacities above the level of their own class, had none of the opportunities afforded at the present day of rising from their humble position. Jack, indeed, was fortunate in getting hold of Fairy’s books, which he very soon mastered; but in those times young ladies were taught very little besides history and geography, and a little French, and Fairy was not fond of study; she liked French, and she was fond of poetry; history she hated, and but for Jack her ignorance of arithmetic would have been pitiable. Her taste for poetry hence fitted Jack indirectly, for Mr. Leslie gave her a Shakespeare on her tenth Christmas Day, and from the first day Jack caught sight of it he never rested till he had saved up enough money to buy himself one, which was his constant companion on the downs. He was an{114} intense lover of nature as well as of poetry, and his shepherd’s life helped him in this respect; for during the long hours he passed daily on the lonely downs, he had plenty of time for observation of all the birds and animal life he came across. Sussex is a famous county for rare birds, and the neighbourhood of Lewes in particular is celebrated in this respect; and by the time Jack was seventeen he was quite an authority on birds; he knew all about them, what kinds visited the neighbourhood and at what seasons; which remained all the year round, and which were only rare and occasional visitors; which bred there, where their nests were to be found, how they were made, and how many eggs and of what kind each species laid; the habits and very often the characters of different birds—all this he knew.

His drawback was he could not afford to buy any good book on birds—they were all far beyond his means; but Mr. Leslie had “Bewick,” and one of Jack’s greatest treats was to go and fetch Fairy, when she spent an evening at the Rectory, and be allowed half an hour’s study of this most fascinating book.

But besides natural history and Shakespeare, Jack studied mathematics on the downs; he bought an old Euclid and an algebra in a book-shop at Lewes, and these, with his Shakespeare and one or two other books, he kept in a hole in a chalk-pit on one of the downs; and winter and summer alike, while the sheep grazed he studied. In winter he walked up and down to keep his blood in circulation, for it was sometimes so cold that he would have been frozen had he sat still; but in summer he stretched himself full length on the short turf in some grey hollow, where he was in shadow.

In some ways a shepherd’s life suited him; it gave him plenty of leisure for study; he was his own master from the time he left home in the grey dawn till he returned at sunset; his duties were light, he had but to follow the sheep, and his dog did all the hard work; moreover, he had none of the responsibility—that all fell on John’s shoulders. Then he liked the loneliness of it. Often for days he met no one except, perhaps, his father, with the rest of the flock, or Dame Hursey gathering wool, or some other shepherd; but yet, for all this, Jack hated the life. He hated it because he felt he had the capacity in him for doing higher work; he hated it because, though his father was content to live all the year on the chalky slopes, visiting Lewes at the two sheep fairs, and occasionally on market days, and on the fifth of November to see the carnival, he was not; he longed to go beyond those round-topped mountains, to cross that silver streak of sea he caught a glimpse of on clear days, to see some of the cities and places he had read of. Above all, he hated it because he felt it was an insuperable obstacle between him and Fairy; for whom, from that day when, as an infant, she had clutched hold of his finger, he had entertained a romantic and ardent affection.

And then he was very proud; and though it was doubtless very foolish pride, he was ashamed of being a shepherd. He would not have had his father, for whom he had the greatest respect, suspect the real secret reason of his dislike to his occupation for worlds, but there it was all the same. He knew to have refused to become a shepherd would almost have broken John Shelley’s heart; and so, for his sake, Jack had never demurred when it was proposed, but he cherished hopes of some day rising to a higher calling.

Poor Jack! could he but have known how that longing was to be fulfilled! But Jack no more than the rest of us could afford to look into the future, neither had he the power—it was as mercifully veiled from him as from others. To look back on past sorrows is sad enough; to look forward to coming ones with the same certainty would be insupportable.

Jack’s seventeenth birthday was a glorious day, and before the sun was high in the horizon, he, and Fairy, and the two other boys were on their way to the seaside, with their dinners in a basket. They were all in high spirits, for a holiday was a rare thing indeed for Jack, and Willy was nearly always at sea, so it was a treat to have him with them, especially to Jack, whose favourite brother Willy was. Moreover, when Willy was there, he would be sure to take Charlie away for part of the day, and leave Jack and Fairy together, and this was a thing to be very thankful for in Jack’s opinion, for he considered Charlie a little nuisance, and had always been very jealous of his brotherly affection and friendship for Fairy. One thing in particular annoyed Jack; Charlie always kissed Fairy every night when he went to bed—a thing neither he nor his father ever ventured to do, nor had Willy ever done so since he came back from sea; but Charlie kissed her every night in the coolest way; and when Jack remonstrated with his mother, as he sometimes did about it, Mrs. Shelley only laughed and said as they were foster brother and sister, and both still mere children, it was quite natural.

But this day was destined to be a very happy one for Jack; he was the hero of it, and Fairy gave herself up to making it as pleasant for him as possible. Her present had delighted him greatly, so he started in his happiest mood. He was lucky, too, and found a nest of a Cornish chough in the chalky cliffs, with five little birds, one of which Jack took home alive and made a great pet of; then, as they neared Newhaven, he shot a water-ousel with his catapult, to add to his collection of stuffed birds found in the neighbourhood. Jack was a charming companion on a country walk; he knew every bird they came across, and his delight and excitement when they saw a rare or scarce bird was charming to witness. A flight of crossbills, or a ring-ousel, was a delightful incident to Jack; and when, in the evening at Newhaven, he actually descried a stormy petrel skimming over the surface of the sea in its usual business-like way, as if all the affairs of the nation depended on it, his delight was unbounded. He had had a glorious birthday, he declared—only one little shadow was cast across it on their way home, when, as they reached the top of the down, at the foot of which lay the shepherd’s house, they met Dame Hursey. Now Jack never could bear Dame Hursey to approach Fairy! He always connected her in some way or other, how, he did not exactly know, with Fairy’s arrival, and he had a very shrewd suspicion that the old wool-gatherer knew far more than anyone else about Fairy’s parentage. One thing was certain—she was most curious about the child, and never met either Jack or his father without talking about her, and trying to find out something about her; and if she could only speak to Fairy herself, she was quite happy; but this Jack never suffered her to do if he could prevent it; and seeing her coming he now tried to hurry Fairy home before Dame Hursey could catch them up.

“Hi, man, Jack Shelley, stop a minute, will you, and let me have a look at the little lass?” shouted Dame Hursey in her broad Sussex brogue, and Jack, much against his will, was obliged to stop.

“Poor old woman, Jack; she can’t do us any harm; why shouldn’t we stop and speak to her?” said Fairy, who did not keep her pretty manners for the other sex only, but was just as anxious to charm an old woman like Dame Hursey, and be as courteous to her as she would have been to Mr. Leslie or any of the people she met at the Rectory.

“Well, you are fair enough for a princess. We shall have the prince coming one of these fine days and carrying you off,” said Dame Hursey, holding the little slender fingers Fairy tendered her in her horny old palm, and gazing with her piercing black eyes, bright now in spite of her seventy odd years, at the child’s fair face.

“I hope not; I am very happy here,” said Fairy, laughing.

“But you don’t belong here for all that; you look as much out of your place here as a black-faced horned sheep would among John Shelley’s flock of Southdowns.”

“We must be going, Fairy. See, the sun is setting,” said Jack, impatiently.

“Ah, it is no use your frowning about it, Jack Shelley. You may take her away now, but you mark my words, as sure as my name is Hursey, the prince will come and carry the fairies’ child away one of these days, in spite of all you can say or do to the contrary,” persisted the old woman, as Jack led Fairy off, feeling very much annoyed at her words.

“Old witch,” muttered Jack.

“Poor old thing! she means well, Jack,” laughed Fairy.

“I almost think she has meant mischief to you, Fairy, ever since that day after you first came to us, and I was left at home to watch Charlie, while mother took you to Mr. Leslie. I remember as well as if it were yesterday; she came in while you were gone, and ransacked the place to look for your clothes and things. If you had been in the cradle instead of{115} Charlie, I am sure she would have stolen you.”

“Oh, Jack, how absurd you are! Well, at any rate, I am too big to be stolen now, so you might let me be civil to her.”

“Civil you can be, but, Fairy, promise me you will never go to her cottage, nor stop talking to her when you are alone,” said Jack.

“Well, I promise. I am not at all anxious to go to her very dirty hut, and mother very seldom lets me go out alone, except to and from the Rectory.”

“I only wish she did; here I have to go out with Fairy whenever she chooses, whether I like or not,” put in Charlie.

“But you always do like,” said Fairy, at which Jack frowned ominously.

The next week Willy went to sea, and the others were left at home for the summer, except Fairy, who went to the seaside with the Leslies for a fortnight in September, the longest fortnight Jack ever spent. While she was away, Mrs. Shelley took the opportunity of warning Jack about his growing jealousy of Charlie, which was daily becoming more apparent, and she flattered herself when Fairy came back that her words had had some effect, until a little incident occurred to show her she was mistaken.

One evening in November, as Jack was coming down the High-street of Lewes, whither he had had to accompany his father, much against his will, to the last sheep fair, he saw a large bird flying slowly overhead. He followed it down a by-street, and saw it was getting lower and lower, evidently tired, until at last it sunk exhausted on the ground, a few paces from Jack, who secured it without much difficulty. It was a wild goose come southwards for the winter, and, being exhausted either for want of food or by its long journey, had become separated from its companions. By its black, snake-like head and neck, and the smallness of its size in comparison with other geese, Jack recognised it at once as a Brent goose, and taking it up in his arms he ran home in triumph with his prize, which soon revived after being fed. He clipped its wings and put it with the rest of the poultry, where it soon became quite at home, and attached itself to Charlie, who always fed it, and constantly followed him about the premises, sometimes even into the house.

For some reason or other Fairy took a dislike to this bird; she declared it looked like an evil spirit, and she was sure it would bring ill-luck to them. She could not bear to see it about the garden, and often begged Charlie in Jack’s hearing to keep it shut up with the rest of the poultry. Charlie, however, delighted in having found a way of teasing Fairy, and partly on that account, partly because he was really fond of the bird, he encouraged it to follow him wherever he went.

One morning Charlie came in to breakfast in the greatest distress—the Brent goose was gone; he had searched the premises, but could not see a sign of it.

“I am very glad of it. Horrid bird, with its snaky head and neck! I hated it,” said Fairy.

“Have you done anything with it, Fairy? Do you know where it is?” asked Charlie.

“Ask Jack,” laughed Fairy; and that was all Charlie could get out of her.

Jack was on the downs with the sheep, and would not be home till evening, so Charlie spent the day in searching the neighbourhood for the Brent goose, but in vain; and when Jack came home Charlie’s first words were, “The Brent goose is lost, Jack.”

“No, it isn’t,” said Jack.

“I tell you it is; I have been all over the country looking for it, and I can’t find it anywhere.”

“You didn’t go to the Pells, I suppose, did you?” asked Jack.

The Pells is the public garden of Lewes—a paddock, with a piece of ornamental water, on which live a beautiful collection of wild ducks, belonging to the town.

“No, I forgot that; how stupid of me! It is too dark to go now,” said Charlie.

“And no use either, though the goose is there; I have given it to the town,” said Jack.

“What a shame, when I was so fond of it! you only did it to spite me,” cried Charlie, ready to burst into tears, only he was too big to cry about a goose.

“I didn’t do it to spite you; I sent it away because Fairy hated it, and you were always teasing her about it. If you want to see it you can go to the Pells every day if you like and look at it, but I won’t have Fairy teased about it.”

“You won’t have Fairy teased, indeed! Why, she is much more my sister than yours; you have nothing to do with her; I am her foster-brother,” broke out Charlie.

For a moment Jack hesitated, and Charlie put up his arm to ward off the blow he seemed to expect, but on second thought Jack only turned on his heel, and with a bitter laugh muttered contemptuously, “Get out of my way, and don’t talk such stuff, you little idiot.”

They never understood each other, these two brothers. While Charlie thought Jack a book-worm who encroached upon his relationship with Fairy, Jack thought Charlie an idle little boy, not over clean, who would never be anything more than a labouring man to the end of his days, and who had the impertinence to consider himself on an equality with Fairy. With Willy Jack got on much better, though Willy was no cleverer than Charlie, nor any fonder of study; but then he never roused his eldest brother’s jealousy in the way Charlie did. Mrs. Shelley, who understood her eldest son better than anyone else did, always tried to ward off any collisions between the boys, and if that were impossible, took Jack’s part, which always had the effect of mollifying him at once. On this occasion she had heard the squabble between the boys, and as Jack went upstairs to change his clothes before helping Fairy with her lessons, she persuaded Charlie, who had been tramping about the country the whole day, to go to bed before Jack reappeared, promising to bring him up some supper.

But Mrs. Shelley could not be always at her boy’s heels to keep the peace between them, and as Jack grew into manhood she watched with anxious heart his growing passion for Fairy, and his increasing jealousy of his youngest brother. Under any circumstances his love for Fairy would have made her tremble for him, though at present Fairy was such a child it was impossible to say how she might feel in the future with regard to Jack; but Mrs. Shelley thought it far more probable the child would meet someone at the Leslies than that she would choose Jack, whom she had known all her life, and whom she seemed to regard as an elder brother. But when added to this Jack’s jealousy of Charlie grew side by side with his love, like an ugly poisonous weed by the side of a beautiful flower, Mrs. Shelley, in spite of the comfort and joy Fairy was to her, often regretted having taken her in, though, as she told herself, she really did not know what else could she have done.

A few days after the Brent goose was sent to the Pells, Fairy, on coming back from the Rectory at four o’clock, found she had left one of her books behind her, and as Charlie was not to be found, being in all probability at the Pells, paying an afternoon visit on his goose, Fairy with some difficulty persuaded Mrs. Shelley to let her go back to the Rectory alone, declaring she would be home again before dark.

She reached the Rectory safely, got her book, and was just passing the Winter-bourne, about ten minutes’ walk from the shepherd’s house, when, rather to her annoyance, Dame Hursey suddenly appeared from a by-lane and stopped her.

“Good-evening, Mrs. Hursey; I must not stop, it is getting so dark; mother will be frightened,” said Fairy, trying to pass the old woman, mindful of her promise to Jack, and secretly rather nervous at her encounter with the old wool-gatherer in this lonely spot, and in the gathering gloom of a November evening.

“Mother, indeed! You have a grander lady for your mother than Mrs. Shelley ever saw the like of, proud as she and her son Jack may be, I am thinking; but never mind that—one of these fine days Dame Hursey may tell you some news that will open those pretty eyes of yours, till they will look bigger than ever. Tell me, child, you can read writing, of course, can’t you?” said Dame Hursey, pulling aside her coarse apron, and fumbling among the folds of her tattered linsey skirt for her pocket.

“Yes, I can read and write too; but I really must be going home; it is getting so late,” said Fairy.

“Wait a minute, child; I am not going to keep you long. I want you to read a letter for me I had from my son this morning; maybe there is something in it I should not care for just everyone to know; I have been on the look out for John Shelley or gentleman Jack all day, but I have missed them somehow, and I can’t read writing myself. Ah! here it is at last,” producing a letter from the bottom of a very capacious pocket filled with some very incongruous articles—a few coppers, a piece of cheese, a thimble,{116} a sock she was knitting, some corks, and various other odds and ends too numerous to mention.

Fairy took the letter, and by Dame Hursey’s instructions read it aloud. It ran as follows:—

“Dear Mother,

“I am just home from Australia, but I am going back there again at once. First, I want to see you, as I think you can tell me something I want to know, so will you meet me on the top of Mount Harry at three o’clock next Saturday afternoon? I shall be there, and, if you are living, I shall expect you. Till then I am your affectionate son,

“George.”

“Is that all? Every word of it?” asked Dame Hursey, fixing her black eyes on the child.

“Yes. Shall I read it again?” said Fairy.

“No. Next Saturday afternoon at three o’clock, on the top of Mount Harry. I shall be there safe enough. Thank you, my pretty one; I shan’t forget that one good turn deserves another. Good-night,” and the old wool-gatherer dived into a lane, and was out of sight before Fairy had recovered her astonishment, when she took to her heels and fled breathless to Mrs. Shelley, who was anxiously watching at the gate for her.

(To be continued.)

Beethoven’s Songs. Vol. I. With both the German words and an English version. By the Rev. Dr. Troutbeck, to whom we are indebted for so many excellent translations of words to music.—This truly valuable collection, including such specimens as “Adelaide,” “The Glory of God in Nature,” popularly known as “Creation’s Hymn,” will be eagerly sought for by all singers; particularly when we mention that the twenty-six songs may be purchased for eighteenpence.

Liederkreis. The opus 39. By Schumann.—A circle of twelve songs, many well known to you. Amongst them we find the “Frühlingsnacht,” “Mondnacht,” “In der Fremde,” and other lovely poems.

Six Duets. For soprano and contralto. By F. H. Cowen.—Form a most charming volume, and are published at the same moderate price and in the same excellent form, with clear type and careful editing.

Six Vocal Duets, for the same voices. By Oliver King, a rising composer, may also be warmly recommended.

Ten Songs. By George J. Bennett, a youthful Academy student. Settings of words by Robert Burns. Are all most fresh and delightful, and add to a reputation which this hard-working young composer has already firmly established.

Three volumes of Piano pieces, by Fritz Spindler, a well-known pianoforte teacher and composer in Dresden (forming numbers of Novello’s Pianoforte Albums), are most useful and artistic contributions to our store of light piano music. The transcriptions of subjects by Wagner are very good.

Scales and Arpeggios. By Harvey Löhr.—These excellent studies are systematically fingered, and contain many useful hints towards improving the pianist’s technique.

The Star of our Love. By F. H. Cowen.—A graceful, well-written song, to words by the late Hugh Conway, whose little books have created so much excitement lately. Compass D to E or F to G.

Clouds, and I love you too well. Two more songs by the same eminent composer. Published in one or two keys.

Three Songs. Words and music by W. A. Aikin.—Very simple and effective.

The Ride of Fortune (founded on Shakespeare’s lines, “There is a tide in the affairs of men,” &c.). By Charles A. Trew.—An excellent contralto song.

Operatic Fantasias. For violin, with piano accompaniment. By F. Davidson Palmer Mus.Bac.—Judging from Il Trovatore, the number before us, these fantasias should be often used for concerts and other entertainments, where a faithful transcription of operatic melodies is required, untrammelled by too many cadenzas and fireworks for the solo instrument.

La Figlia del Reggimento.—This selection is also to be commended. It is for two violins and piano, and arranged by John Barnard.

Sarabande (ancien style). Pour piano. Par Henri Roubier. Idée Dansante. For piano. By Percy Reeve.—Two dances above the average, graceful and musicianly.

{117}

Partita, in D minor. For violin and piano. By Hubert Parry.—A scholarly work, made up of six sections:—Maestoso, Allemande, Presto, Sarabande, two Bourrées, and a Passepied in Rondo form. One might almost call it a Sonatina of many movements. The partita differs from the suite in not being restricted to dances only.

Je l’aimerai toujours. An easy piano piece for beginners. Composed by François Behr.

Intermezzo-Minuet. A short entr’acte for piano. By G. Bachmann.—This smoothly-written morceau is included in Czerny’s orchestral series as a string quartett.

Adoration. A meditation upon Bach’s 7th “Small Prelude.” By Oscar Wagner.—Arranged for piano and violin, or flute or violoncello, with organ and additional strings, upon the model of Gounod’s similar work, but scarcely so interesting, and certainly not so spontaneous in melodic treatment. It is also arranged as an “O Salutaris Hostia” for voice, violin, piano, and organ or harmonium.

Stars of the Summer Night. By Edouard Lassen.

My All-in-all. By Theodor Bradsky.—Both these songs have violin obbligatos, in which the chief fault appears to be that the violin never rests, not even for a bar.

Happy Days. A touching song. By poor Max Schröter. Compass C to F.

For ever with the Lord! Sacred song. By Gounod.—A new song by Gounod needs only to be mentioned to engage the attention of our readers. Gounod has been happier in his setting of other English hymns, such as the “Green hill far away” and the “King of Love my Shepherd is.” But there are some lovely points in this. It is published in keys suitable to all voices, both as a solo and a duet, and it also appears in anthem form for four voices and organ.

She Noddit to Me. A song that bids fair to become most popular. The words by A. Dewar Willock.—Describe the delight of a Scotch body at receiving a “special bow” from the Queen as she passed her cottage on the Deeside. The music is by J. Hoffmann, and it is dedicated by special permission to Her Majesty.

The Crusader. A stirring baritone song. By Theo. Bonheur.

The Goblin. A cynical poem, set to music by Gustav Ernest, whose clever works we have before noticed.

The Winged Chorister. The music by Pinsuti.—The chorister in question (although there is a harmonium part) is not a dying choir boy, but a robin which has got into the church by some means, and whose “pure, clear notes,” it is suggested, “would harmonise our coarser tones, and bear them straight to Heaven.” Our recollection of the robin’s note, easily imitated by tapping two pennies together, hardly carries out this lofty idea!

Let us Wander by the Sea, and The Merry Summer Time. Two duets for soprano and contralto. By our much lamented countryman, Henry Smart, whose delicate fancy has in so many ways enriched English music.—The edition before us is ruined, as far as outward appearance goes, by vulgar drawings on the covers.

Aubade Française. A most elegant serenade in the purely French style. By M. de Nevers.—Very suitable for a light tenor voice.

Gavotte des Oiseaux. A bright little dance for pianoforte. By G. Bachmann.

The Musical Monthly.—This last year’s number is as extraordinary a shillingsworth as ever, containing, in the midst of much that is unworthy, several good old English airs, some of Mendelssohn’s songs without words, five songs from the Bohemian Girl, of Balfe’s, some good Scotch songs, etc., etc.

We have also received an advance copy of No. 1 of the “Violin Soloist,” well got up, and containing ten or twelve good solos. It is to be brought out monthly at a penny per number.

Canadian March. For Piano. Solo and duet, and for every other imaginable combination. Composed by Carl Litolff.

150 Exercises and Questions in the Elements of Music. By I. L. Jopling, L.R.A.M.—Most thorough and searching test questions, systematically and exhaustively treated. This little book will prove of great help in preparing for the elementary examinations of the various colleges and academies. It is to be used after studying Mr. Davenport’s primer.

Six songs by Erskine Allon to words by Sir Thomas Wyatt, who died in 1542.—All that Mr. Allon writes is interesting. In these songs the accompaniments are as full of charm as the melodies are of quaint character and grace.

Shakesperian Sketches, for Pianoforte, by Frank Adlam.—Clever illustrations of passages and scenes in Shakespeare’s plays.

The Choralist: 269, “Waiting for the Spring.” 270, “A Winter Serenade.”—Two capital four-part songs by J. S. Mitchell.—267, “Come, Lassies and Lads.”—A masterly arrangement in four parts of the good old seventeenth-century ditty.

Cavendish Music Books.—In No. 101 we have a selection of American pieces. To those who wish to know what our cousins on the other side of the Atlantic are doing in musical composition, we advise a perusal of this selection. It proves that, at any rate in this kind of art work, we are more “go-ahead” than they are.

The Sweet old River. Song by Sydney Smith.—A smoothly written song, published in C and E flat.

Dreams. Song by Cecile S. Hartog.—Miss Hartog’s compositions are exceptionally good, and far above the average ballad.

The Wide, Wide Sea.—One of the best songs that Stephen Adams has written. Compass, B flat to E flat, or C to F.

In the Chimney Corner. By F. H. Cowen.—A song of the Behrend type, but higher in conception, and rather more hopeful in tone.

Go, Pretty Rose. Duet in canon. By Marzials.—We recommend this duet to all who have sung and admired his other canon, “My true love hath my heart.” It is a most elegant canon, and very melodious and bright withal.

Grave and Corno. By Joseph Gibbs (1744), and air and jigg by Richard Jones (17th century). All for violin and piano.—These really good and interesting relics of old English composition have been revived by Herr Peiniger, who has arranged a piano part from the figured basses. Just as we admire the case of an organ, so may we speak of the admirable covers to these pieces. They are in excellent taste.

Five Pictures on a Journey. By F. W. Davenport.—Well written and suggestive piano pieces.

Episodes for the Piano. By Frederick Westlake.—We have received No. 1, Prelude, and feel sure that the others equally well sustain the reputation of this esteemed professor of the Royal Academy.

A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO THE WORLD OF INDUSTRY AND THRIFT.

By JAMES MASON.

e come now to speak about the receiving and the paying away of money. These are things which, by common consent, are always done in a certain way. If they are done otherwise it shows either a want of sense or a want of education.

When money owing to any person is paid, a receipt for it should always be given—that is to say, it should be acknowledged in writing that the money has changed hands. If the receiver merely takes it and puts it in her pocket, she who pays will have no security, except the receiver’s good faith and good memory, against being called on to pay the sum a second time.

A receipt may be given in any form of words, but the following are correct forms for business purposes—

London, 15th September, 1886.

£17 4s. 6d.

Received from Miss Rose Hastaway, Chester, the sum of seventeen pounds four shillings and sixpence in payment of account rendered (or of annexed account.)

Flora Malcolm.

Guildford, 12th July, 1886.

Received from Mrs. Trundle the sum of six pounds seven shillings and ninepence, in payment of account to this date.

£6 7s. 9d.

Elizabeth Badger.

On all receipts for money amounting to £2 or upwards you must put a penny stamp. Not long ago there was a stamp sold expressly for the purpose, but now a penny postage stamp is used, which is much simpler. The stamp may be placed anywhere, but is best where the signature is, the signature being written across it. If the receipt of money is acknowledged in a letter, the stamp should be put at the end, just where you sign{118} your name. It is always better, however, to give a separate and formal receipt.

The Government require that either the name or the initials of the person giving the receipt be put on the stamp, together with the true date of writing, the object being to show clearly and distinctly that the stamp has been used. Ordinarily the date is given in a contracted form, for instance, the two receipts given above would have “15. ix. 86” under the name of Flora Malcolm, and “12. vii. 86” under that of Elizabeth Badger. Figures representing the amount for which the receipt is given are often added also.

Whoever gives the receipt pays for the stamp, and the penalty for refusing to give a duly stamped receipt in any case where the receipt is liable to duty is £10.

When you receive money as a loan, you may acknowledge it by what is called an I O U, which is in this form:—

Carlisle, 3rd October, 1886.

To Miss Alice Golightly,

I O U three pounds ten shillings.

Anne Winkle.

I O U’s are not much in favour in business; they are rather friendly documents than business ones.

An I O U does not need a stamp, whatever the amount may be, as it is simply an acknowledgment of a debt, and neither a receipt nor a promissory note—that is, a note giving a promise to pay at a particular time. Suppose Miss Winkle had written, “I O U Three pounds ten shillings to be paid on the 2nd of January, 1887,” she would have changed her I O U into a promissory note, which would have required a stamp.

But “neither a borrower nor a lender be”—which is another way of saying that I O U’s are to be avoided. When the money is repaid, the I O U, of course, is returned to the person who gave it.

In cases where money is received in payment of an account, and the acknowledgment is put on the account itself, the account is “discharged,” as it is called, in any one of the following ways. The person to whom the account is due writes on it her own name, and, preceding her name, the words, “Paid,” “Received Payment,” “Received,” or “Discharged,” or—if such be the case—“Same time paid,” or “Paid by cheque.”

Or this form may be used. Suppose the amount to be £25 10s. and the discount five per cent.

| 21st September, | ||

| By cash | £24.4.6 | |

| ” Discount, 5% | 1.5.6 | |

| £25.10.0 | ||

| Marion Featly. | ||

Should you be receiving payment for somebody else, you sign as you would a letter in similar circumstances. Thus:—

Same time paid,

for Margaret Bell,

Ellen Chapman.

or,

Paid by cheque,

Mary G. Grove,

per Ina Meadows.

Some polite people, in discharging accounts write “with thanks” in the left-hand bottom corner or under their signature. In the case of tradespeople, it is a courteous phrase that sometimes goes a long way towards securing another order.

Receipts of all kinds should be kept for at least six years. After that time you may either continue to keep them or make a bonfire of them. The reason for your being then free to please yourself is that actions for unclaimed debt arising out of a simple contract are limited to six years from the date of the cause of action. After six years you are safe against being called on to pay the money a second time.

Bills are occasionally rendered a second time after being paid, not the least, perhaps, from an intention to defraud, but simply from carelessness. People omit to enter the money they receive in their books, and forget they have got it; and to keep all receipts is a way of protecting oneself against such a happy-go-lucky style of doing things.

Receipts should be folded in the same way as letters, and marked on the outside with all necessary particulars. Thus:—

12th August, 1886.

Griffin and Constable,

Manchester.

Washing Machine

£3 15s.

If you have a set of pigeon-holes, receipts should have a pigeon-hole all to themselves; if not, keep them tied up in a bundle and arranged in alphabetical order.

When you have to make out accounts always do it as neatly as possible. A neat account has a well-to-do air, and may do as much good to one’s credit sometimes as a handsome balance at the bank. Hard-up people are seldom neat either in accounts, or correspondence, or anything else.

Accounts or invoices in business are usually made out on ruled and printed forms, and are headed with the address of the seller. After that come the names of the buyer and seller, thus:—

Miss Rachel O’Flinn,

Bought of Leigh, Goldhawk, and Still.

Or the wording may be,

Miss Rachel O’Flinn,

To Leigh, Goldhawk, and Still,

which mean that Miss Rachel O’Flinn is debtor to the firm named, the word “debtor” being dropped in practice.

Below the names of the parties the terms of sale are sometimes put: “Nett Cash” or “Cash in 14 days,” or “Accounts rendered monthly,” or whatever the conditions are. Then follow the particulars of the goods sold, the dates when they passed into the hands of the purchaser being put in the left hand margin.

People who have any money transactions at all, and do not wish their affairs to get into hopeless confusion, must keep books of some sort—that is to say, they must adopt a plan of writing down their transactions in regular order for easy reference.

It may be a primitive method or a very elaborate one—that depends on the nature and requirements of the business—but some system there must be, and of book-keeping in at least its general principles every business woman should make a study. By its means we gain an exact knowledge of how we stand, we see what comes in and what goes out, how much we owe and how much other people owe us, and whether we are putting any of our money into bags with holes.

There are many good books published on the subject of book-keeping, and by all means study the best treatise you can get; but better than all books is actual practice. The experience of keeping an account of one’s own transactions for a week gives more insight than all the books that have ever been written. In a book, things seem sometimes exceedingly puzzling, whilst in reality they are simple enough.

The main fact to be grasped in book-keeping is the distinction between debtor and creditor; you must get it well into your head that the person or thing represented by an account is “debtor to” what he, she, or it receives, and “creditor by” whatever he, she, or it gives or parts with.

The simpler business books are the better, so long as they answer the purpose for which they are intended. They must be clear to the person who keeps them, and clear also to any who have to consult them. The utmost care should be taken with them, so as to have no blotting, no scraping out of figures, and no tearing out of leaves.

There are two ways of keeping books, known as single entry and double entry. Single entry is called so because each item is entered only once in the accounts of the ledger, which is the principal book. In double entry, on the other hand, it is entered twice, to the debtor side of one account and to the credit of some other account.

In this way, when books on the double entry system have all the sums on the debtor side and all the sums on the creditor side added up, the total amounts in both cases are the same. That is, if the books have been rightly kept and no mistake has been made in addition, like that of the man who spent a long time trying to make them come right, and found at last he had made the slight mistake on one of the sides of adding in the figures of the current year.

The object of double entry is to establish a series of checks so that mistakes are not likely to occur, and in all establishments of any importance this is the system adopted. Books kept by the other and simpler system of single entry afford no check upon themselves. “Errors in addition,” says Mr. A. L. Lewis, “which are as easy to make in hundreds of pounds as in pence, errors and omissions in posting or in carrying forward balances, any or all of which may entail serious loss, can only be prevented in single entry books by the most careful checking and rechecking every item, and no one, however sharpsighted, can always avoid making an error, and even failing to discover it when made.”

What is called posting in book-keeping is the operation of transferring items from one book to another, and arranging them there under their proper heads. The difference between the Dr. and Cr. sides of an account is known as the balance.

Transactions are entered in their books by business people at once. They never put off making an entry till to-morrow, for they are well aware that there is no putting any dependence on memory.

They are constantly turning over their books, too, so as to keep their affairs fresh in their minds, and see in a general way how they are getting on. Then every little while they go particularly into all their accounts and strike a balance as it is called—that is to say, make out a statement of their assets and liabilities, and arrange things for a fresh start. The word assets, we may as well mention, stands for property or sums of money owing to anyone, and liabilities means just the reverse.

There are two mistakes often made in balancing books which a business woman must take care never to fall into. The first is to include bad debts—debts of which you are never likely to get a farthing, or, at best only a few shillings in the pound—on the same footing as if they were good ones. The second is to calculate that property we possess is worth what we paid for it, never considering that as a general rule things decrease in value every year through use and change of fashion and other causes. The only wise plan is to subtract from the first cost, every time we balance, a certain sum to represent what is termed depreciation of property. All such deductions should be made with a liberal hand; no harm is done by estimating ourselves poorer than we really are, but many a one has been ruined by mistaken calculations, showing property to be worth a good deal more than it would fetch in the market.

When one person acts for another in money{119} matters, a statement, called an account current, should be sent at regular intervals—say once a half year or once every twelve months—showing the transactions. Here is an example. For convenience in printing we shall place the Cr. side below the Dr.; but in practice the two sides should be placed alongside of each other—the Dr. side to the left, and the Cr. side to the right.

Miss Winifred Holt, Edinburgh, in account current with Nathaniel Evans, London.

| Dr. | |||||

| 1885. | |||||

| June | 30. | To balance of last account | £9 | 4 | 2 |

| Aug. | 3. | Cash paid M. Perry on your account | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| Sept. | 27. | Cash paid J. Short on your account | 4 | 12 | 7 |

| Dec. | 12. | Cash paid you | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| £95 | 19 | 6 | |||

| Cr. | |||||

| Aug. | 1. | By cash received from B. Green on your account | £50 | 0 | 0 |

| ” | 12. | Cash received from W. Rae on your account | 35 | 0 | 0 |

| Dec. | Balance of account carried to your debit in new account | 10 | 19 | 6 | |

| £95 | 19 | 6 | |||

Errors Excepted.

Nathaniel Evans.

London, December 31st, 1885.

Here on the Cr. side we have all the sums received by Nathaniel Evans for Miss Winifred Holt, and on the Dr. side all the payments made to her or for her by him. Instead of “Errors Excepted,” before the signature, “E. E.” might have been written, or “E. & O.E.,” which last means “Errors and Omissions Excepted.” These guarded phrases, however, may be omitted. You may correct errors afterwards, whether they are there or not. If accounts of this kind, or, indeed, any accounts, are thought to be incorrect, the fact should be intimated to the persons sending them at once.

Book-keeping and the making out of accounts requires ability in calculation. Indeed, no one can succeed in getting a character for business capacity who has not all the rules of arithmetic at her fingers’ ends. The use of “Ready Reckoners,” “Interest Tables,” or such-like compilations, often saves, however, a great deal of trouble, even when people are quick at figures. Some pretend they can do without such helps, but they would be better to use them. We ought to avail ourselves of all the help we can get, and it is absurd to take roundabout ways of doing things when short cuts will answer the same purpose.

Besides understanding about the right method of keeping books and making out accounts, the thorough business woman will know well about the art of buying. Here we see how a knowledge of business ways may assist in the upbuilding of happy homes. One who understands the art of buying will return triumphant from marketing expeditions, and when she goes shopping there will be no fear of her wasting the contents of the family purse.

The good buyer does not spend much time in going her rounds. She has made herself familiar beforehand with the qualities of things, the methods by which they are adulterated, and the seasons when they are cheapest, and if the goods shown her are not what she wants, she says so, and no persuasive tongue can induce her to take them. “Much comment on the part of the seller,” says an American writer, “she regards as an incentive to be wary; and all pretences to confidential favours, unless proved to be such by undoubted documentary evidence, as a reproach to her understanding.”

She makes it a rule to deal with respectable people only, knowing that by that course she is best served, and you never find her very sharp-set on bargains. She knows better.

On the subject of bargains Mr. Charles Dickens, in his “Dictionary of London,” has some wise remarks. They specially refer to the metropolis, but they are applicable to all large towns over the country. Everywhere skilfully-baited traps are set for the unwary, though it is in London that the traps catch most victims and rogues reap the best harvest.

Bargains, Mr. Dickens points out, are to be met with, of course, but only by those who know very well what they are about. The numerous “bankrupts’ stocks,” “tremendous sacrifices,” and so forth, are just so many hooks on which to catch simpletons.

“One of the commonest tricks of all is that of putting in the window, say, a handsome mantle, worth eight or ten guineas, and labelled, say, £3 15s., and keeping inside for sale others made up in precisely the same style, but of utterly worthless material. If they decline to sell you the actual thing out of the window, be sure that the whole affair is a swindle. See, too, that in taking it from the window they do not drop it behind the counter and substitute one of the others—an ingenious little bit of juggling not very difficult of performance.

“Another very taking device is the attaching to each article a price label in black ink, elaborately altered in red to one twenty or five and twenty per cent. less. This has a very ingenuous air. But when the price has been—as it commonly has—raised thirty or forty per cent. before the first black ink marking, the economy is not large.

“Of course, if you do buy anything out of one of these shops, you will take it with you. If you have it sent, be particularly careful not to pay for it until it arrives, and not then till you have thoroughly examined it.

“When a shop of this kind sends you ‘patterns,’ you will usually find a request attached not to cut them. Always carefully disregard this, keeping a small piece for comparison.

“There are, however, some houses where, if you at all understand your business, real bargains are at times to be had.”

The business woman is not often to be seen at auctions either, and if ever she does go, she makes sure beforehand that the sale is to be conducted on strictly honourable principles, and presided over by an auctioneer who is above suspicion. She is well aware that there are many unscrupulous individuals who, under cover of an auctioneer’s licence, lend themselves to transactions the reverse of honest.

For example, in company with a band of “followers,” as they are called—back-street brokers and “general dealers” of shady character—auctioneers of this sort take a dwelling-house, and cram it with worthless furniture. Then, after a month or two, the whole is seized under a fictitious “bill of sale,” to give the affair an appearance of genuineness, and the trashy goods are disposed of by auction to the unsuspicious public, the rogues dividing the spoil.

Another plan is to get possession of a shop in a frequented thoroughfare, and, day after day, beguile innocent folk to enter the premises, and then wheedle and bully them into bidding for and buying a lot of rubbish at four or five times more than its actual worth. It is quite a mistake to suppose that goods disposed of “under the hammer,” as it is termed, must necessarily sell for less than their real worth.

These mock auctions are swindles pure and simple, and what the initiated call “rigged sales” are not much better. These take place at auction rooms of more or less legitimate position, are usually held in the evening, and consist chiefly of articles vamped up or made expressly for the purpose. No one should go to them who wants to get value for her money.

In all dealings with tradespeople, a good business woman will do her best to pay cash. As she does this, she always goes to ready-money shops. Shops that give credit must charge higher prices, for they must have interest for the money out of which they lie; and, besides, they must add to the price of their articles to cover the risk that some of their customers will not pay. Those who do pay, pay not only for the credit they get themselves, but for the failure of others.

Now and again, however, to postpone paying one’s debts has an advantage, as was the case with a merchant whom Southey, the poet, once met at Lisbon. “I never pay a porter,” said this merchant, “for bringing a burden till the next day; for while the fellow feels his back ache with the weight he charges high; but when he comes the next day, the feeling is gone, and he asks only half the money.” But it is not often that one has the chance of getting a reduction in this way.

The cash buyer has many advantages, not the least being an easy mind and a knowledge at all times of what she is worth. Let every girl, then, keep in mind for the rest of her days the remark of the American writer, who said, “I have discovered the philosopher’s stone. It consists of four short words of homely English—‘Pay as you go.’” The easiness of credit has been the ruin of many people, by inducing them to buy what they could not hope, unless by a miracle, ever to pay for.

So much for the business woman in her dealings in a private capacity with business people. In a business capacity, however, one must sometimes both give and receive credit. But, it cannot be said with too strong an emphasis, the less of it the better.

The Composer and the Sea-Captain.

When Haydn, the composer, was in London, he had several whimsical adventures, and the following is one of them:—A captain in the Navy came to him one morning, and asked him to compose a march for some troops he had on board, offering him thirty guineas for his trouble, but requiring it to be done immediately, as the vessel was to sail next day for Calcutta.

As soon as the captain had gone, Haydn sat down to the pianoforte, and the march was ready in a few minutes. Feeling some scruples, however, at gaining his money so very easily, Haydn wrote two other marches, intending first to give the captain his choice, and then to make him a present of all the three, as a return for his liberality.

Next morning the captain came and asked for his march.

“Here it is,” said the composer.

{120}

The captain asked to hear it on the pianoforte; and having done so, laid down the thirty guineas, pocketed the march, and walked away.

Haydn tried to stop him, but in vain—the march was very good.

“But I have written two others,” cried Haydn, “which are better—hear them and take your choice.”

“I like the first very well, and that is enough,” answered the captain, pursuing his way downstairs.

Haydn followed, crying out, “But I make you a present of them.”

“I won’t have them,” roared the seaman, and bolted out at the street door.

Haydn, determined not to be outdone, hastened to the Exchange, and, discovering the name of the ship and her commander, sent the marches on board, with a polite note, which the captain, surmising its contents, sent back unopened.

The composer tore the marches into a thousand pieces, and never forgot this liberal English humourist as long as he lived.

Table-Talk.—Welsh rabbit is a genuine slang term, belonging to a large group, which describes in the same way the special dish or product or peculiarity of a particular district. For example, an Essex lion is a calf; a Fieldlane duck is a baked sheep’s head; Glasgow magistrates or Norfolk capons are red herrings; Irish apricots or Munster plums are potatoes; and Gravesend sweetmeats are shrimps.

A Foolish Investment.—It is foolish to lay out money in the purchase of repentance.—Franklin.

Ruling and Serving.

A Hard Task.—It is often difficult to control our feelings; it is still harder to subdue our will; but it is an arduous undertaking to control the contending will of others.—Crabb.

The Art of Authorship.—The great art of a writer shows itself in the choice of pleasing allusions.—Addison.

Affectation.—Affectation is an awkward and forced imitation of what should be genuine and easy, wanting the beauty that accompanies what is natural.—Locke.

The Happy and the Discontented.

Some people, not to be copied, live in a perpetual state of fret. The weather is always objectionable; the temperature is never satisfactory. They have too much to do, and are driven to death, or too little, and have no resources. If they are ill they know they shall never get well; if they are well they expect soon to be ill. Their daily work is either drudgery, which they hate, or so difficult and complex that they cannot execute it.

In contrast to these, we meet sometimes with men and women so bright and cheery that their very presence is a positive pleasure. They discover the favourable side of the weather, of their business, of home surroundings, of social relations, even of political affairs. They will tell you of all the pleasant things that happen and give voice to all the joy they feel. Of course, they are sometimes annoyed and worried by petty troubles, but the very effort they make to pass them over silently diminishes their unpleasant effect upon themselves and prevents the influence from extending.

The Good-tempered Wife.

A man in Sussex whose wife was blessed with a remarkably even temper went over the way to a neighbour one evening and said—

“Neighbour, I just should like to see my wife cross for once. I’ve tried all I know, and I can’t make her cross no way.”

“You can’t make your wife cross?” said his neighbour. “I wish I could make mine anything else. But you just do what I tell you, and if that won’t act nothing will. You bring her in some night a lot of the crookedest bats you can get, them as won’t lie in no form, and see how she makes out then.”

The bats (or pieces of wood) were accordingly brought in, as awkward and crooked and contrary as could be found. The man went away early to work, and at noon returned to see the result of his experiment. He was greeted with a smiling face and the gentle request—

“Tom, do bring me in some more of those crooked bats if you can find them; they do just clip round the kettle nicely.”—Rev. J. C. Egerton.

Choosing a Wife.—Benjamin Franklin recommends a young man in the choice of a wife to select her “from a bunch,” giving as his reason that when there are many daughters they improve each other, and from emulation acquire more accomplishments, and know more than a single child spoiled by parental fondness.

Without Religion.—Friends who have no religion cannot be long our friends.—Mozart.

Refreshing Sleep.—“Sound sleep” is usually considered a healthy state of repose; but it is an observation of Dr. Wilson Philip that “no sleep is healthy but that from which we are easily roused.”

Masters and Servants.—There is only one way to have good servants; that is, to be worthy of being well served. All nature and all humanity will serve a good master and rebel against an ignoble one.—Richter.

Beware of Bad Habits.—Let players on musical instruments beware of bad habits. Mozart, speaking of a girl whom he heard at Augsburg in 1777, says, “She will never master what is the most difficult and necessary, and, in fact, the principal thing in music—namely, time; because from her infancy she has never been in the habit of playing in correct time.”

Culpable Carelessness.—It is more from carelessness about truth than from intentional lying that there is so much falsehood in the world.—Dr. Johnson.

Marrying for Money.—A strong-minded woman was heard to remark the other day that she would marry a man who had plenty of money though he was so ugly she had to scream every time she looked at him.

A Foolish Mouse.

Received for The Princess Louise Home.

Mona and Mila, 2s.; Lizzie Smith, 2s.; Mary, Maggie, and Ada, 3s.

Work for the bazaar to be held (D.V.) next summer, from Miss E. N. Nixon, Fanny Gough Pope, Caroline M. M. Hog (second contribution), Little Dot, Gretta, E. G., E. Morgan, E. Stroud, Cornie Trevena, Lucy, Madge S., Mona and Mila, A Servant in Torquay, A Welsh Maiden, A Village Maiden; W. C. Newsam, 100 pieces of music.

For the Home, The South Hampstead High School for Girls, 22 valuable articles of clothing; Anon, a parcel of books.

By RUTH LAMB.

{121}

{122}

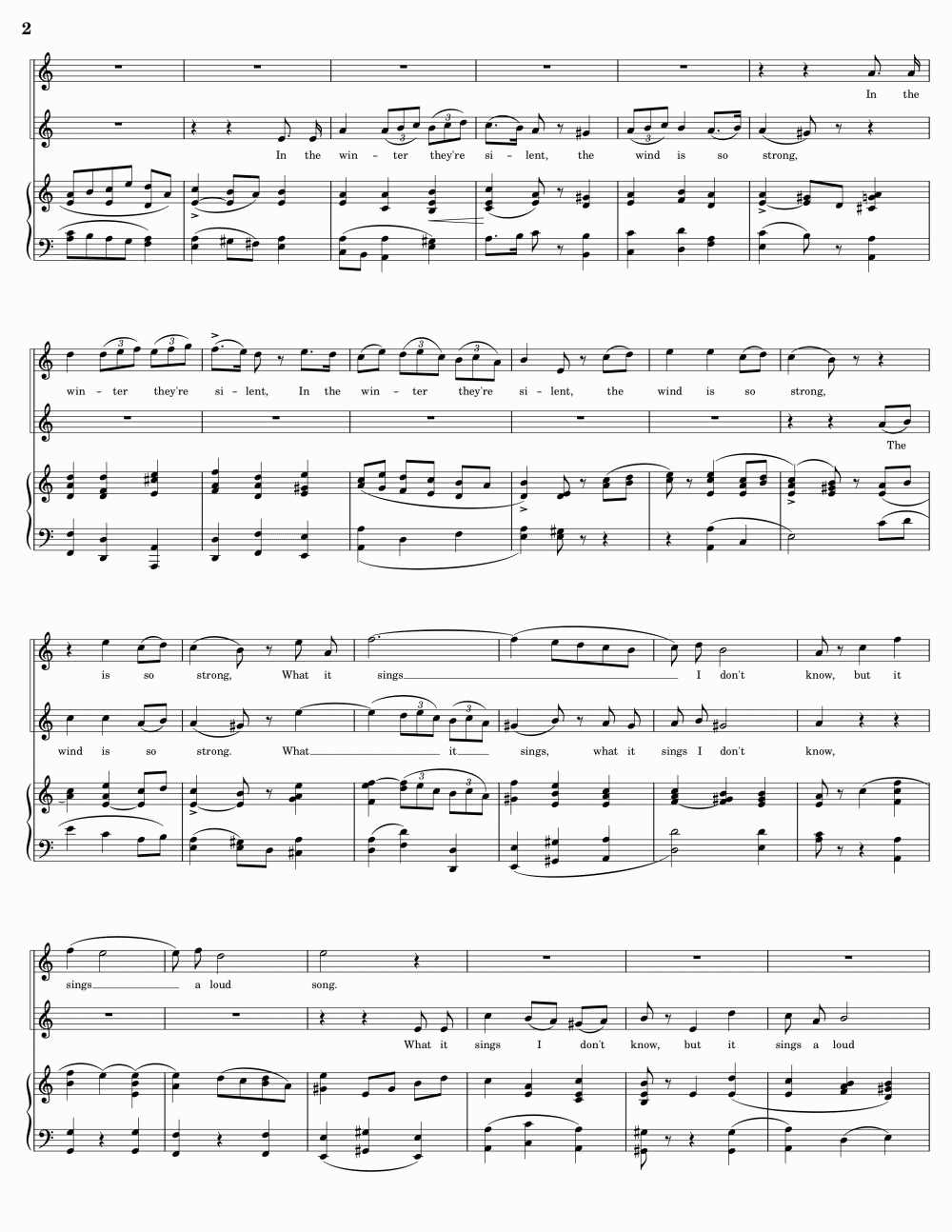

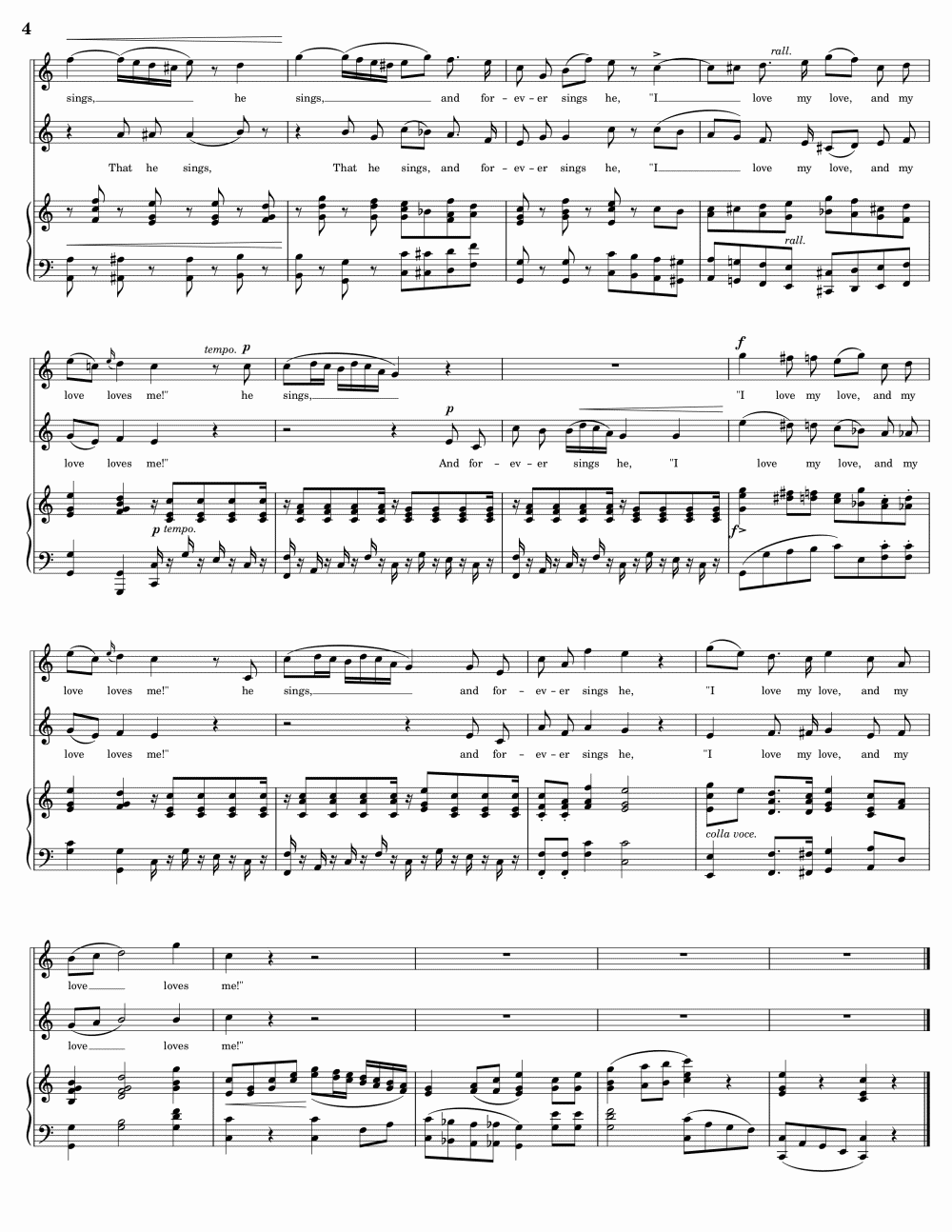

Words by J. T. Coleridge.

Music by C. A. Macirone.

DUET.

{126}

By ROSA NOUCHETTE CAREY, Author of “Aunt Diana,” “For Lilias,” etc.

THE FASHION OF THIS WORLD.

have said that from the first moment I had felt a singular attraction towards my new mistress. As the days went on, and I became better acquainted with the rare beauty and unselfishness of her nature, my respect and affection deepened. I soon grew to love Mrs. Morton as I have loved few people in this life.

My service became literally a service of love; it was with no sense of humiliation that I owned myself her servant; obedience to so gentle a rule was simply a delight. I anticipated her wishes before they were expressed, and an ever-deepening sense of the sacredness and dignity of my charge made me impervious to small slights and moved me to fresh efforts.

I was no longer tormented by my old feelings of uselessness and inefficiency. The despondent fears of my girlhood (and girlhood is often troubled by these unwholesome fancies), that there was no special work for me in the human vineyard, had ceased to trouble me. I was a bread winner, and my food tasted all the sweeter for that thought. I was preaching silently day by day my new crusade. Every morning I woke cheerfully to the simple routine of the day’s duties. Every night I lay down between my children’s cots with a satisfied conscience, and a mind at rest, while the soft breathings of the little creatures beside me seemed to lull me to sleep.

It was a strangely quiet life for a girl of two-and-twenty, but I soon grew used to it. When I felt dull I read; at other times I sang over my work, out of pure lightheartedness, and I could hear Joyce’s shrill little treble joining in from her distant corner.

“I wish I could sing like you, Merle,” Mrs. Morton once said to me, when she had interrupted our duet; “your voice is very sweet and true, and deserves to be cultivated. Since my baby’s death my voice has wholly left me.”

“It will come back with time and rest,” I returned, reassuringly, but she shook her head.

“Rest; that is a word I hardly know. When I was a girl I never knew life would be such a fatiguing thing. There are too many duties for the hours; one tries to fit them in properly, but when night comes the sense of failure haunts one’s dreams.”

“That is surely a symptom of overwork,” was my remark in answer to this.

“Perhaps you are right, but under the circumstances it cannot be helped. If only I could be more with my darlings, and enjoy their pretty ways; but at least it is a comfort to me to know they have so faithful a nurse in my absence.”

She was always making these little speeches to me; it was one of her gracious ways. She could be grateful to a servant for doing her duty. She was not one of those people who take everything as a matter of course, who treat their domestics and hirelings as though they were mere machines for the day’s work; on the contrary, she recognised their humanity; she would sympathise as tenderly with a sick footman or a kitchen-maid in trouble as she would with any of her richer neighbours. It was this large-mindedness and beneficence that made her household worship her. When I learnt more about her former life, I marvelled at her grand self-abnegation. I grew to understand that from the day of her marriage she had simply effaced herself for her husband’s sake; her tastes, her favourite pursuits, had all been resigned without a murmur that she might lead his life.

She had been a simple country girl when he married her; her bees, her horse, and her father’s dogs had been her great interests; to ride with her father over his farms had been her chief delight. She had often risen with the lark, and was budding her roses amid the dews.

When the young rising politician, Alick Morton, had first met her at a neighbouring squire’s house, her sweet bloom and unconscious beauty won him in spite of himself, and from the first hour of their meeting he vowed to himself that Violet Cheriton should be his wife.

No greater change had ever come to a woman. In spite of her great love, there must have been times when Violet Morton looked back on her innocent and happy girlhood with something like regret, if ever a true-hearted wife and mother permits herself to indulge in such a feeling.

Mr. Morton was a devoted husband, but he was an autocrat, and, in spite of many fine qualities, was not without that selfishness that leavens many a man’s nature. He wanted his wife to himself; his busy ambition aimed high; politics was the breath of his life; unlike other men in this, that he lived to work, instead of working to live.

These sort of natures know no fatigue; they are intolerant of difficulties; inaction means death to them. Mr. Morton was a committee man; he worked hard for his party. He was a philanthropist also, and took up warmly certain public charities. His name was becoming widely known; people spoke of him as a rising man, who would be useful to his generation. If he dragged his wife at his triumphal chariot wheel, no one blamed him; these sort of men need real helpmeets. In these cases the stronger nature rules: the weaker and most loving submits.

Mrs. Morton was a submissive wife; early and late she toiled in her husband’s service; their house was a rallying point for his party. On certain occasions the great drawing-rooms were flung open to strangers; meetings were held on behalf of the charities in which Mr. Morton was interested; there were speeches made, in which he largely distinguished himself, while his wife hovered on the outskirts of the crowd and listened to him.

He kept no secretary, and his correspondence was immense. Mrs. Morton had a clear, characteristic handwriting, and could write rapidly to dictation, and many an hour was spent in her husband’s study.

This was at first no weariness to her—she loved to be beside him and share his labours. What wife begrudges time and work for her husband? But she soon found that other labours supervened that were less congenial to her.

Mr. Morton was overworked; the demands on his time were unceasing. Violet must visit the wards of his favourite hospitals, and help him in keeping the accounts. She must represent him in society, and keep up constant intercourse with the wives of the members of their party during the season. She worked harder even than he did. Her bloom faded under the withering influence of late hours and hot rooms. Night after night she bore, with sweet graciousness, the weary round of pleasures that palled on her. It was a martyrdom of human love, for, alas! in the hurry of this unsatisfactory life, the Divine voice had grown dim and far off to the weary ear of Violet Morton; the clanging metallic earth bells had deadened the heavenly harmonies.

Sometimes a sad, pathetic look would come into her eyes. Was she thinking, I wonder, of the slim, bright-eyed girl budding roses in the old-fashioned garden, while the brown bees hummed round her? Was the fragrance of the lilies—those tall, white lilies of which she so often spoke to me—blotting out the perfume of hothouse flowers, and the heavy scents of the crowded ball-room?

It was a matter of intense surprise to me that Mr. Morton seemed perfectly unconscious of this immense self-sacrifice. He could not be ignorant, surely, that a mother desires to be with her children, and that a woman’s tender frame is susceptible to fatigue. Selfish as he was, he loved her too well to impose such intolerable burthens on her strength, if he had only known them to be burthens. But her cheerfulness blinded him. How could he know she was overtasked, and often sad at heart, when she never complained, when she sealed her lips so generously?

If she had once said, “I am so tired, Alick; I cannot write for you,” he would at once have pressed her to rest;{127} but men are so dense, as Aunt Agatha says. Their great minds overlook little details. They take in wide vistas of landscape, and never see the little nettles that are choking up the field path. Women would have noticed the nettles at once, and spied out the gap in the hedge beside.

I had not been many weeks in the house before I found Sunday was no day of rest to my employers, and yet they were better than many other worldly people. Mrs. Morton always went to church in the morning, and, unless he was too tired or busy, Mr. Morton went too. They were careful, too, that their servants should enjoy as far as possible the privilege of the day. The carriage was never used, so the horses and the coachman were able to rest. They dined an hour earlier, and invited only one or two intimate friends to join them, and there was always sacred music in the evening. But there was no more leisure for thought on that day than on any other. In the afternoon Mr. Morton wrote his letters and read his paper, and Mrs. Morton had her share of correspondence; the rest of the afternoon was given to callers, or Mrs. Morton accompanied her husband for a walk in the park. She was always very careful of her toilet on these occasions, and if it were Travers’s Sunday out, my services were in requisition. I had once offered to assist her, and I suppose I had given satisfaction. More than once Mr. Morton had found fault with some part of her dress, and she had gone back to her dressing-room with the utmost promptitude to change it.

“I have not satisfied my husband’s taste, Merle,” she would say, as cheerfully as possible; “will you help me to do better?” And she would stand before the glass with such a tired look on her lovely face, as I brought her a fresh mantle and bonnet.

I hate men to be over critical with their wives, but I suppose it is a greater compliment than not being able to see if they are wearing their best or common bonnet. I confess it must be trying to a woman when a man says—and how often he does say it?—“What a pretty gown that is, my dear. Have I seen it before?” when the aggravating creature must know that she wore it all last summer, and perhaps the previous summer too.

I found out that Mrs. Morton was ill-satisfied with the way they spent Sundays.

I remember one Sunday evening I was sitting in the twilight with Reggie on my lap and Joyce on her little stool beside me. I had been teaching her a new verse of her hymn, and she had learned to say it very prettily. We were both very busy over it, when the door opened, and Mrs. Morton came in.

Joyce jumped up and ran to her at once.

“I know it, mother—my Sunday hymn—it is such a pretty one.”

“Is it, my darling? Then, suppose you let mother hear it.” And Joyce, folding her hands in her quaint, old-fashioned way, began very readily:

“Very pretty indeed, Joyce,” observed Mrs. Morton, rather absently, when the child had finished. But Joyce looked up in her face wistfully.

“Do you ever say hymns, mother dear?”

“I sing them in church, my pet.”

“But you never teached them to me, mother; they are all nurse’s hymns, the little one and the long one, and the little wee hymn I say with my prayers. Would you like to hear my little wee hymn, mother dear?”

“I will hear all you know, my darling.” But there were tears in the beautiful eyes as she listened.

“How nicely she says them! I am glad you teach her such pretty hymns, Merle,” as the child ran off to fetch Snap, who was whining for admittance. “Somehow it seems more like the Sunday of old times up here—so quiet, so peaceful. We must do as the world does, I suppose; but these secular, bustling Sundays are not to my taste.”

Her words jarred on me, and I replied rather too quickly, considering my position, “Are we obliged to follow a bad fashion? That is indeed going with the crowd to do evil.”

She looked up in some surprise. It must have been a new thing to the petted mistress of the household to hear herself so sharply rebuked.

“Oh, I beg your pardon,” I exclaimed, penitently; “I had no right to say that; I forgot to whom I was speaking.”

“Do not distress yourself, Merle,” she returned, in her sweet way; “it is good for all of us to hear the truth sometimes. It was foolish of me to say that. I only mean that in our house it is very difficult not to follow the world’s custom.”

“Very difficult indeed,” I acquiesced; but she continued to look at me thoughtfully.

“Do not be afraid of saying what is in your mind; you may speak to me plainly, if you will. You are my children’s nurse, but I cannot forget that in many ways we are equals. You never intrude this fact on my notice, but it is none the less apparent. I know our Sundays are terribly secular,” as I continued silent; “sometimes I wish it were not so, for my children’s sake.”

“Not for your own sake, Mrs. Morton?”

A distressed look came over her face.

“I seem to have no time to wish for anything.”

“I could well believe that; but, Mrs. Morton, it seems to me as though we owe some duty to ourselves. If we neglect the highest part of ourselves we are committing a sort of mental suicide. How often has Aunt Agatha told me that!”

“How do you mean?” she asked, anxiously.

“We all need a quiet time for thought. It always seems to me that on Sunday one lays down one’s burthens for a time. It is such a rest to shut out the world for one day in the week, to forget the harass of one’s work, to take up higher duties, to lift one’s standard afresh, and prove one’s armour. It is just like abiding in the tents for shelter and rest in the heat of battle.”

I had forgotten the difference in our station, and was talking to my mistress just as though she were Aunt Agatha. Something seemed to compel me to speak; I felt a strange sort of trouble oppressing me, as though I saw a beautiful soul wandering out of the way. She seemed moved at my words, and it was several minutes before she spoke again.

“Your words recall the old Sundays at my own dear home,” she observed, presently. “Do you not love Sundays in the country, Merle? The very birds seem to sing more sweetly, and the stillness of which you speak seems in the very air. My Sundays were very different then. We lived near the church, and we could hear the chiming of the bells as we walked through the village. I taught in the Sunday-school; I recollect some of the children’s names now. Father always liked us to go to the evening service. I remember, too, we invariably sang Bishop Ken’s evening hymn. One evening a little robin found its way into the church. I remember Mr. Andrews, our vicar, was just reading that verse, ‘Yea, the sparrow has found her a house, and the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young,’ when we looked up and saw the little creature fluttering round the chancel. Oh, those sweet old Sundays!” And here she broke off and sighed.

I thought it best to say no more, and leave her to those tender memories. A word in season may do much, but I was young, and had no right to teach with authority. I suppose she understood my reticence, for she looked at me very kindly as she rose from her seat.

“It does me good to come up here, Merle; I always have a more rested feeling when I go down to my duties. If I did not feel that they were real duties that called me I should be very unhappy.”

She bade her children good-night, and left the nursery. What made me take up my Bible, I wonder, and read the following verse! “In this thing the Lord pardon Thy servant, that when my master goeth into the house of Rimmon to worship there, and he leaneth on my hand, and I bow myself in the house of Rimmon, the Lord pardon Thy servant this thing.”

(To be continued.)

{128}

Chatterbox.—Your acquirements are satisfactory, and might gain for you perhaps £30 per annum. But these are to be weighed against two serious drawbacks—extreme youth, and consequent lack of weight and authority with your pupils, and complete lack of experience in reading their several characters and bodily condition, and the modifications and changes of method requisite to suit these different subjects under your training. Teaching lessons is but a small part of the duties of a governess. The characters of her pupils have to be carefully read and moulded, their manners and habits trained according to those of polite society, and she should discover what natural gifts should be cultivated and what studies should be remitted, more or less. At sixteen you are scarcely more than a child yourself, and quite such in inexperience. Thus, you are really only fit for a visiting governess, teaching under the direction of the mother; and if you take a residential situation, it could only be at a low salary.

Desiree.—If you wish to prepare yourself for being a nurse at home, we recommend you a careful study of a small manual, often named for the purpose, “Sick Nursing at Home” (L. U. Gill, 170, Strand, W.C.). When you could be examined on that you will have made great progress towards efficiency. You do not name your age. Had you done so, we could have advised you further.

Daughter of Gentleman Farmer (Dublin).—If you have artistic taste and can design, and, in addition, have a delicate touch, write either to the City and Guilds Technical Institute, Exhibition-road, South Kensington, S.W., or to the Polytechnic, Regent-street, W., where classes for wood-carving are held. Address the secretary in both cases. If you think of training for the teaching of children under the Kindergarten system, there are many schools for the purpose. Write to the Misses Crombie, 21, Stockwell-road, S.W., with a view to entering the college established by the British and Foreign School Society. Or else to the secretary, Home and Colonial Training College, in Gray’s Inn-road, W.C.

M. L. P.—It is to be regretted on your own account, if not on that of others, who might be glad to avail themselves of your musical society, that you should contemplate giving it up without first inducing someone to take your place. Your society, we imagine, is already entered in a directory of girls’ clubs, shortly to appear, and too late now to be omitted.

Old Man’s Darling.—You will often find songs in our paper. It is sad to hear that you “get wild with your nose,” which at seven or eight o’clock p.m. “gets puggy.” What can that mean? As we cannot hope for the pleasure of witnessing such a phenomenon, we advise you to consult your mother about it. If an hereditary “pug,” we do not understand why it should be otherwise during the day.

Courtleroy.—We are obliged to you for the information you give respecting the tonic sol-fa system. It was invented by Miss Glover, of Norwich, and afterwards improved upon by John Curwen, in about the year 1847; but the Tonic Sol-fa College was established a year earlier than that.

Romola.—The class of music known us the “cantata” was invented by Barbara Strozzi, a Venetian lady.

A Greek Girl.—1. The song you name is one in the Christy Minstrels’ collection, and is, we believe, one of the late Stephen Foster’s, who died in March, 1864. He was the originator of that class of music. You write English so well, that we should have thought you a countrywoman. 2. If you wish to see the prettiest parts of England, you should visit some parts of Surrey, Devonshire, Derbyshire, Cumberland, Westmoreland, and portions of Wales. We are glad you are partial to the English, and that you appreciate our series of articles on good breeding and etiquette. Your writing is good, and thoroughly English.

Popsey.—Perhaps Blackwood’s “holdfast” would prove satisfactory in securing the scraps on your screen. We imagine that you are not very careful in brushing the gum or paste quite over the corners that you complain curl up. Very little of the above-named “holdfast” will be required to make the scraps adhere firmly.

Tennyson.—The precise origin of the office of “Poet Laureate” does not appear to be known. There was a Versificator Regis in the reign of Henry III. Chaucer was Poet Laureate by his own appointment, and he subsequently received an annuity from Richard II. Some twenty-one poets succeeded him in the office. The immediate predecessor of Tennyson was William Wordsworth, and he was succeeded by Dr. Robert Southey. Tennyson, who was born in 1809, received the appointment in 1850.

Alice Grey.—See page 519, vol. vi., for description and illustration for a supper table. Add some chickens and a ham, and you could make it do for your plain wedding breakfast. The bride and bridegroom sit together and lead the way to the dining-room, and place themselves in the centre of the long table opposite the wedding cake. The father of the bride takes the bridegroom’s mother, and seats himself next his daughter, and the bridegroom’s father takes the bride’s mother, who sits next the bridegroom. The bridesmaids generally sit opposite the bride and bridegroom.

Marcelle’s question was answered on page 704, vol. vii. The poem, “Pleasures of Memory,” is by Samuel Rogers.

A Delicate Country Lassie.—1. We have read your nice little letter with much interest and sympathy. It is pleasant to hear that our advice has been helpful to you, and we only wish your health would improve. But we think you might lay the matter before God in faith, and ask Him to cure you and raise you up, according to the promise, “the prayer of faith shall save the sick.” See St. James v. 15, and Matt. viii. 17. 2. The 26th June, 1874, was a Friday. Write to the secretary, Lifeboat Institution, 14, John-street, Adelphi, W.C.