Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

A MERCHANT

FLEET AT WAR

By

ARCHIBALD HURD

Author of “The British Fleet in the

Great War,” “Command of the Sea,”

“Sea-Power,” etc. etc.

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1920

All rights reserved

vii

During a war, which was at last to draw into its vortex practically the whole human race—the issue depending, first and foremost, on sea power—there was little time or opportunity or, indeed, inclination on the part of British seamen to keep a record of their varied activities. The very nature of many of the incidents recorded in the following pages precluded the preparation of detailed reports at the time. Nor can we forget that many of the officers and men, to whose resource, courage, and devotion this volume bears testimony, have joined the great silent army of the dead to whose exploits the freedom of conscience of every man and woman in the British Empire, as well as their state of material comfort, bear witness.

This book has been written under not a few difficulties, and it owes whatever merit it possesses to many individuals—captains, officers, engineers, pursers and other ministers to British sea-power—who have assisted in its preparation, whether by recounting incidents in which they took part, by placing written records at my disposal, or byviii lending photographs from which the illustrations have been prepared. I would especially emphasise that the illustrations have been made from photographs of all sorts and shapes, taken by all kinds of cameras, though for the most part of pocket size. Many of the pictures were snapped under dull and forbidding skies, and some were secured in the very presence of the enemy in mad pursuit of his piratical policy. Some of these pictures were soaked with sea water, and other were recovered from destruction at the last moment. The value of the illustrations lies not so much in their perfection as in the knowledge that they were taken “on active service.”

Finally a word should be said, perhaps, of another difficulty which confronts any one who endeavours to tell the story of what merchant sailors did during the Great War. These men dislike publicity and their modesty disarms the inquisitor. Like their comrades of the Royal Navy, they are content if they can feel that they have done their duty. They would leave it at that. But were silence to be maintained, later generations would be robbed, for the progress of humanity depends, in no small measure, onix the manner in which the memory of great deeds is preserved, and handed down from age to age. No man can live unto himself.

The story of the contribution which British seamen have made to the happiness and well being of the world can never be half told, and these pages form merely a footnote to one of the most glorious epics in human annals. They go forth in the hope that they may help to perpetuate those sterling virtues which find increasing expression in the British race throughout the world. James Anthony Froude once declared that all that this country has achieved in the course of three centuries has been due to her predominance as an ocean power. “Take away her merchant fleets; take away the navy that guards them; her empire will come to an end; her colonies will fall off like leaves from a withered tree; and Britain will become once more an insignificant island in the North sea.” So I hope this book may be regarded not merely as a footnote to history, but may remind all and sundry of the priceless heritage which our seamen of all classes and degrees have left in our keeping.

ARCHIBALD HURD.

xi

| PAGE | ||

| Foreword | xvii | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | Mobilisation | 1 |

| II. | Combatant Cunarders | 12 |

| III. | Carrying on | 38 |

| IV. | The Ordeal of the “Lusitania” | 58 |

| V. | The Toll of the Submarines | 87 |

| VI. | Shore Work for the Services | 119 |

xiii

| In Colour | |

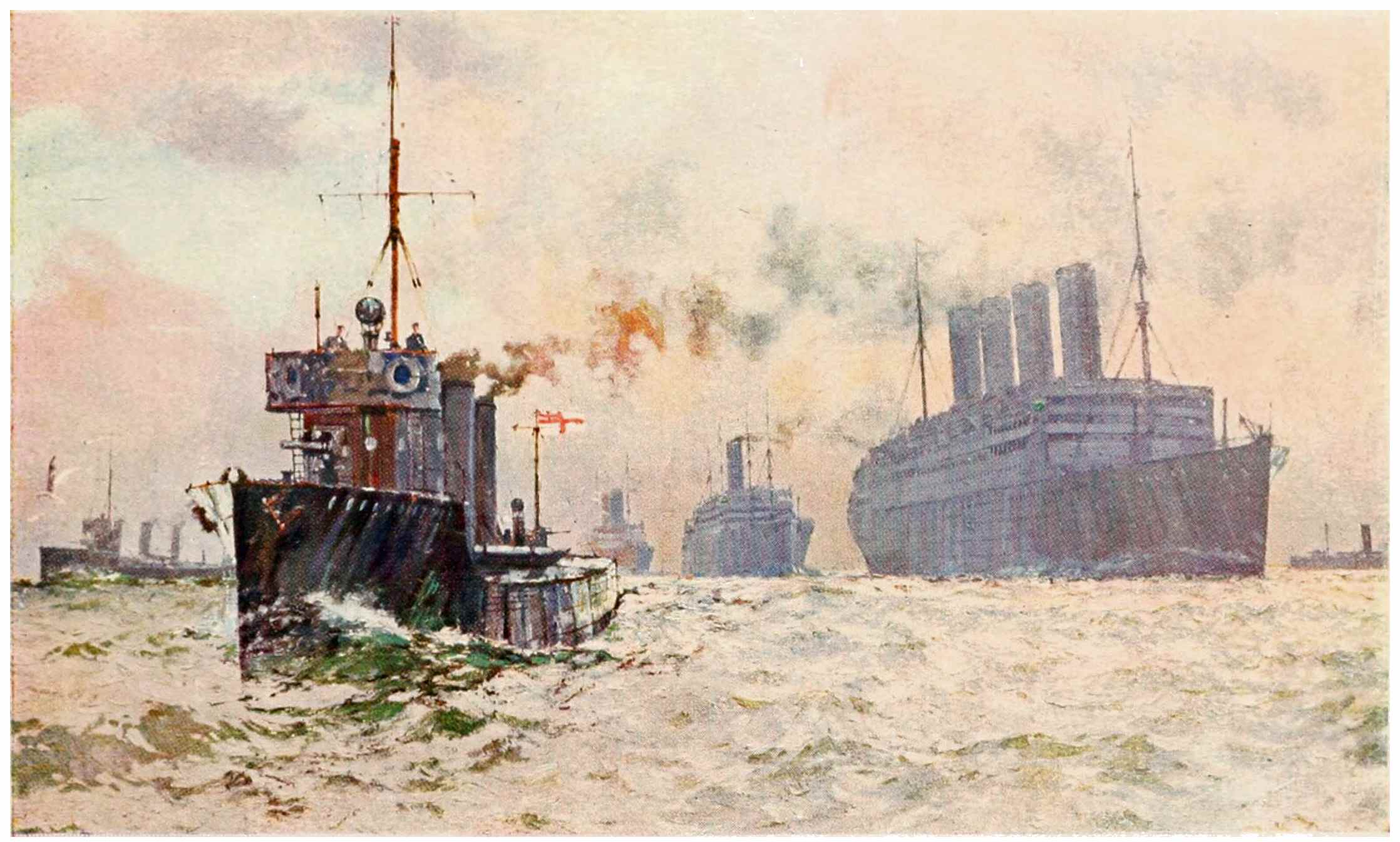

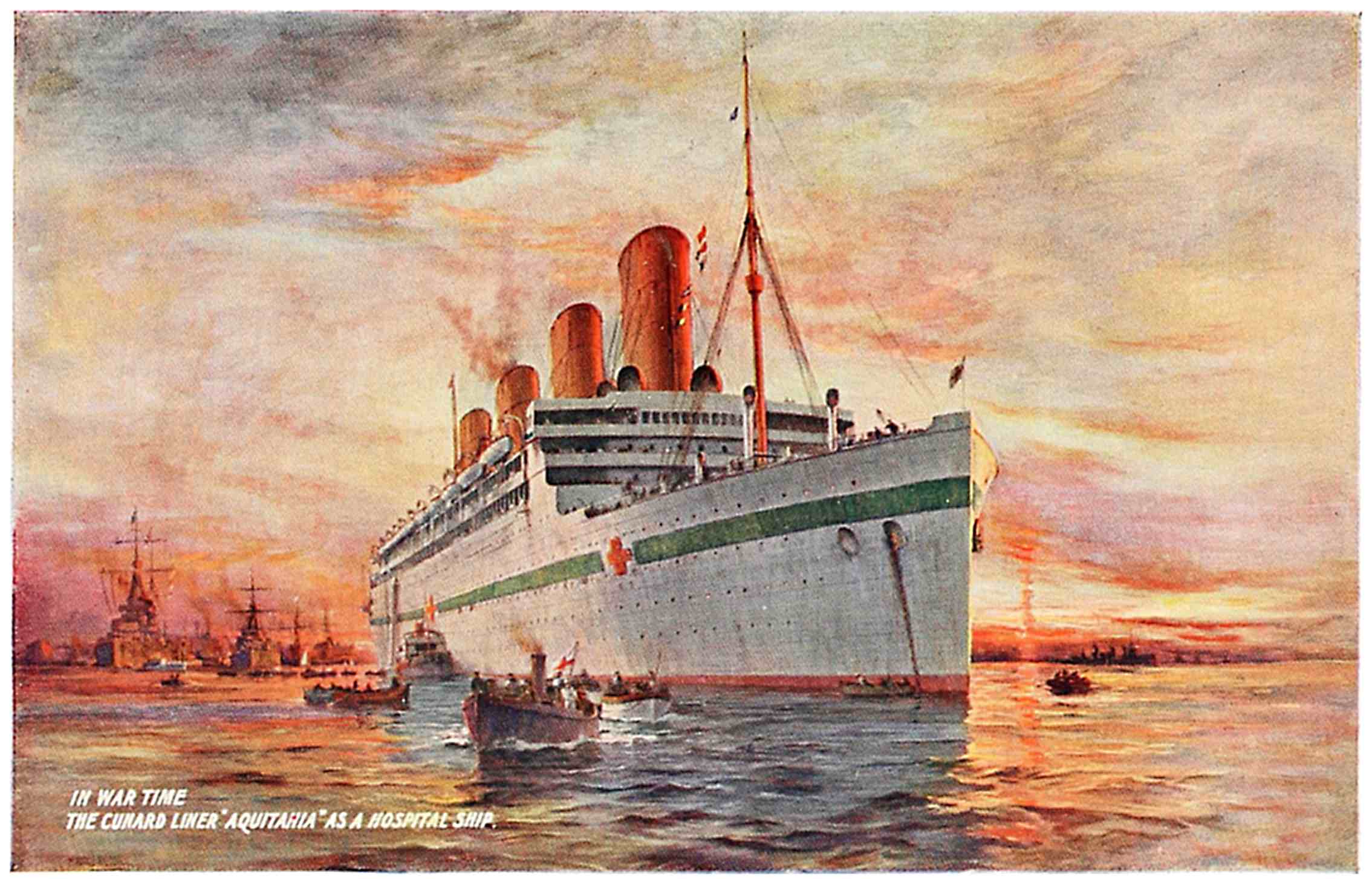

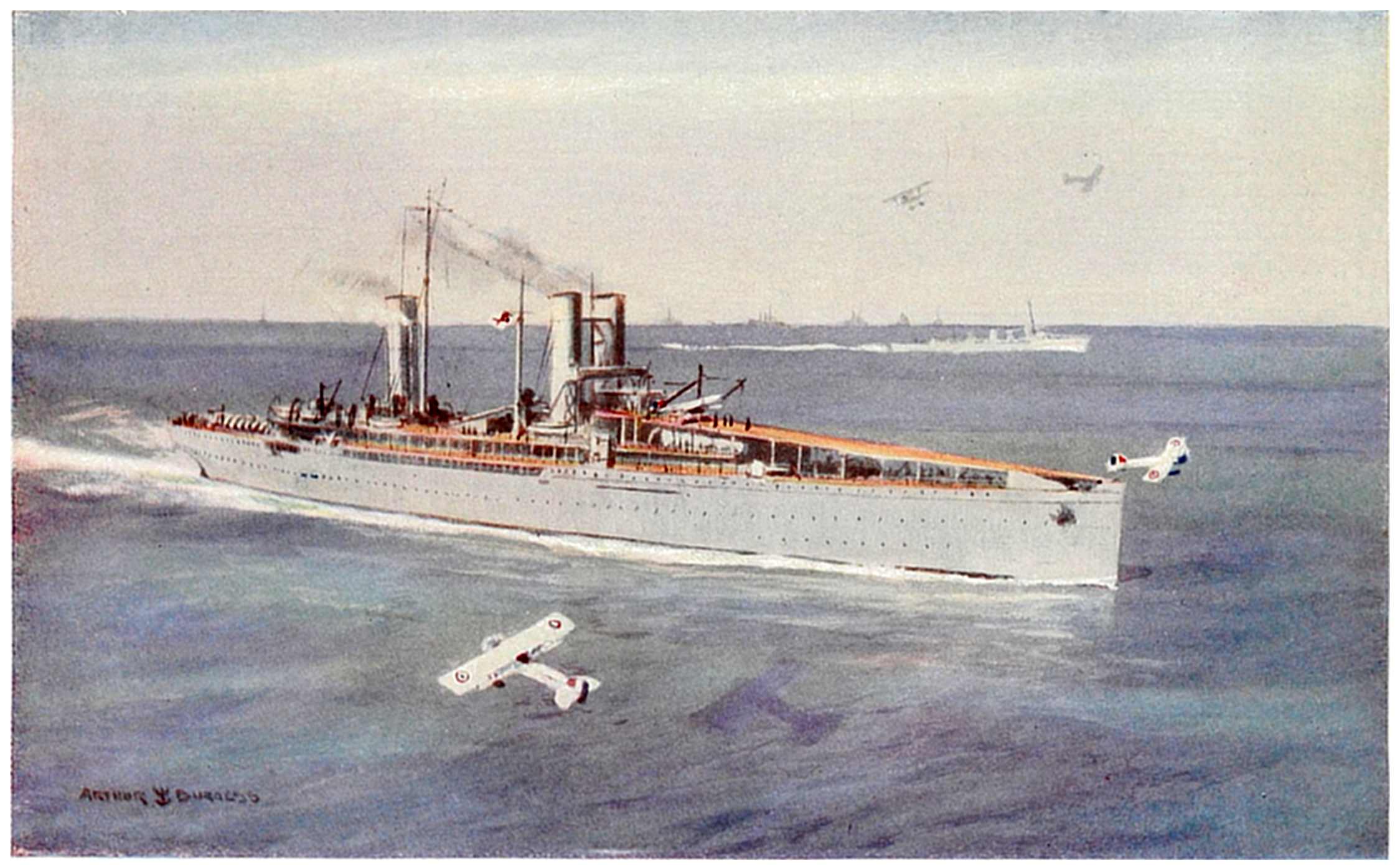

| “Aquitania” leading the transports | Frontispiece |

| To face page | |

| “Aquitania” escorted by destroyers | 4 |

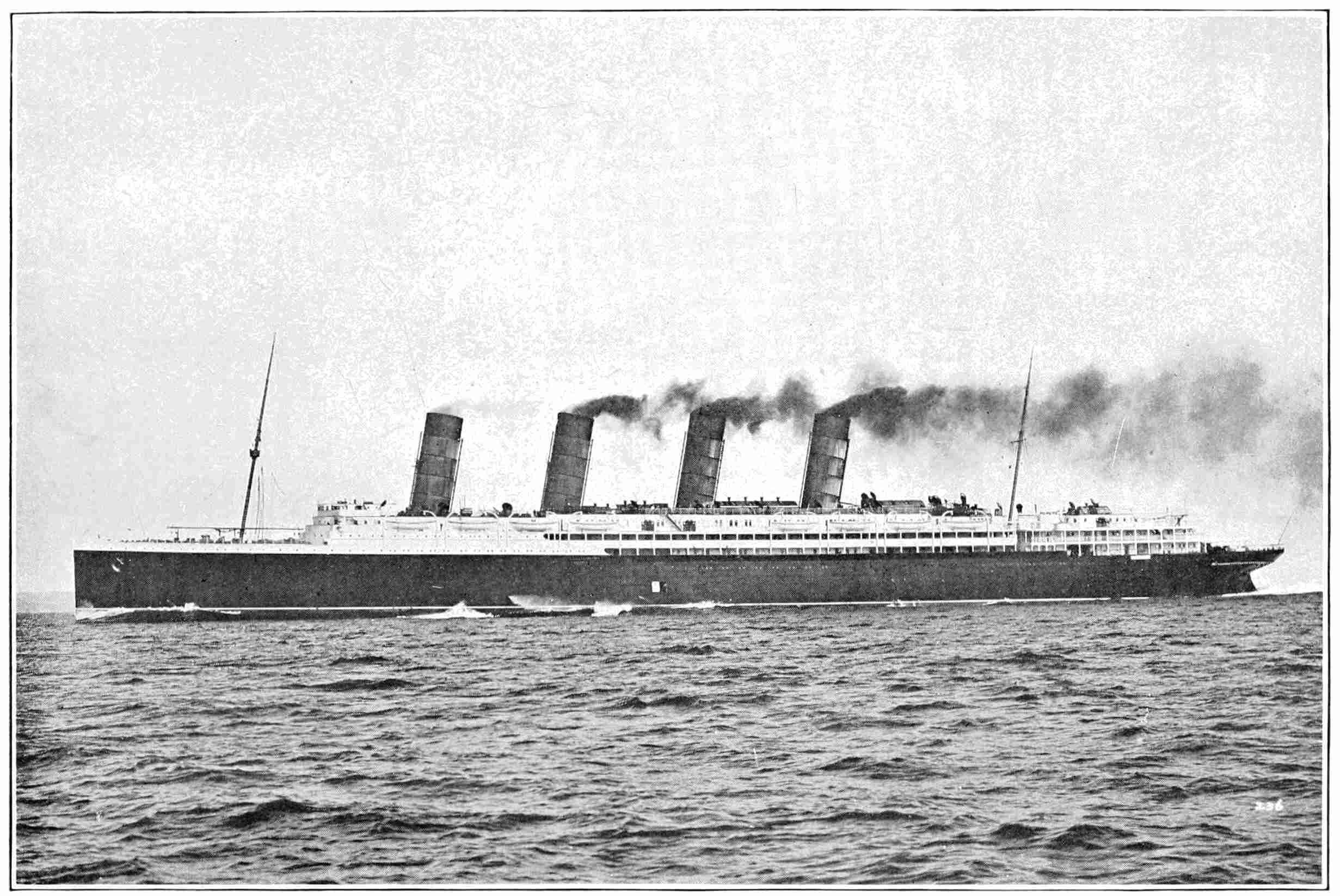

| “Mauretania” escorted by destroyers | 12 |

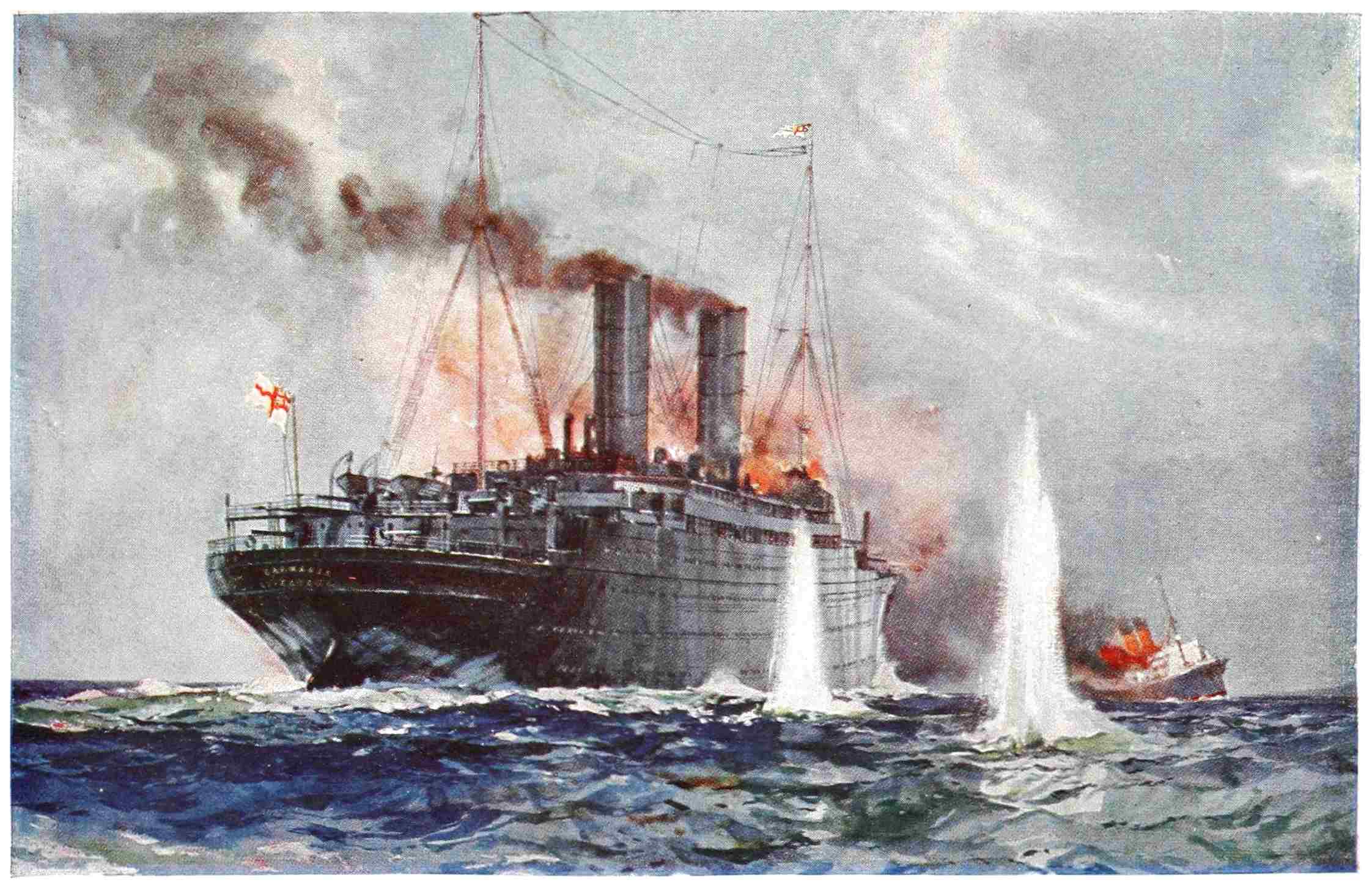

| Torpedoing of the “Ivernia” | 28 |

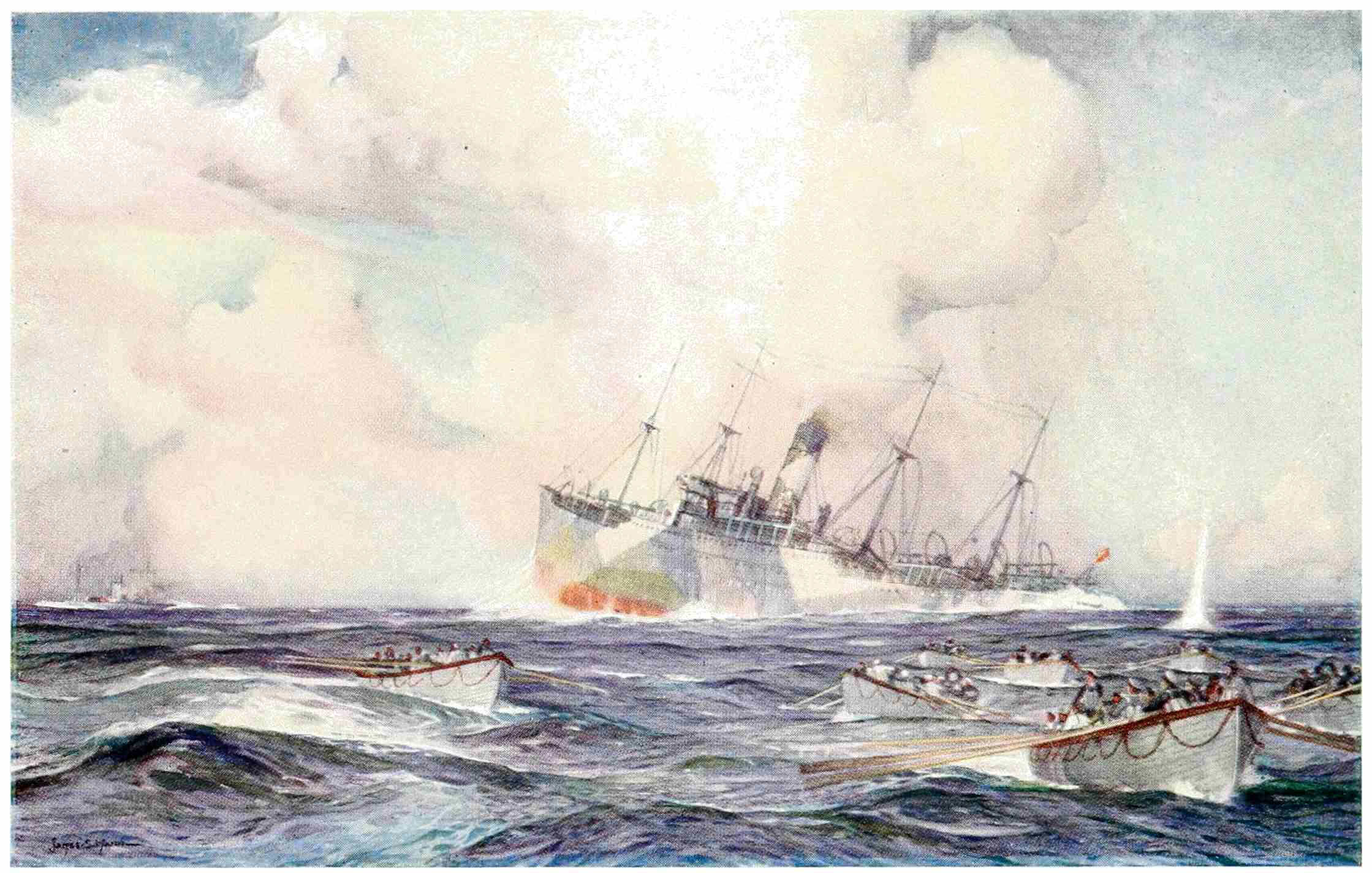

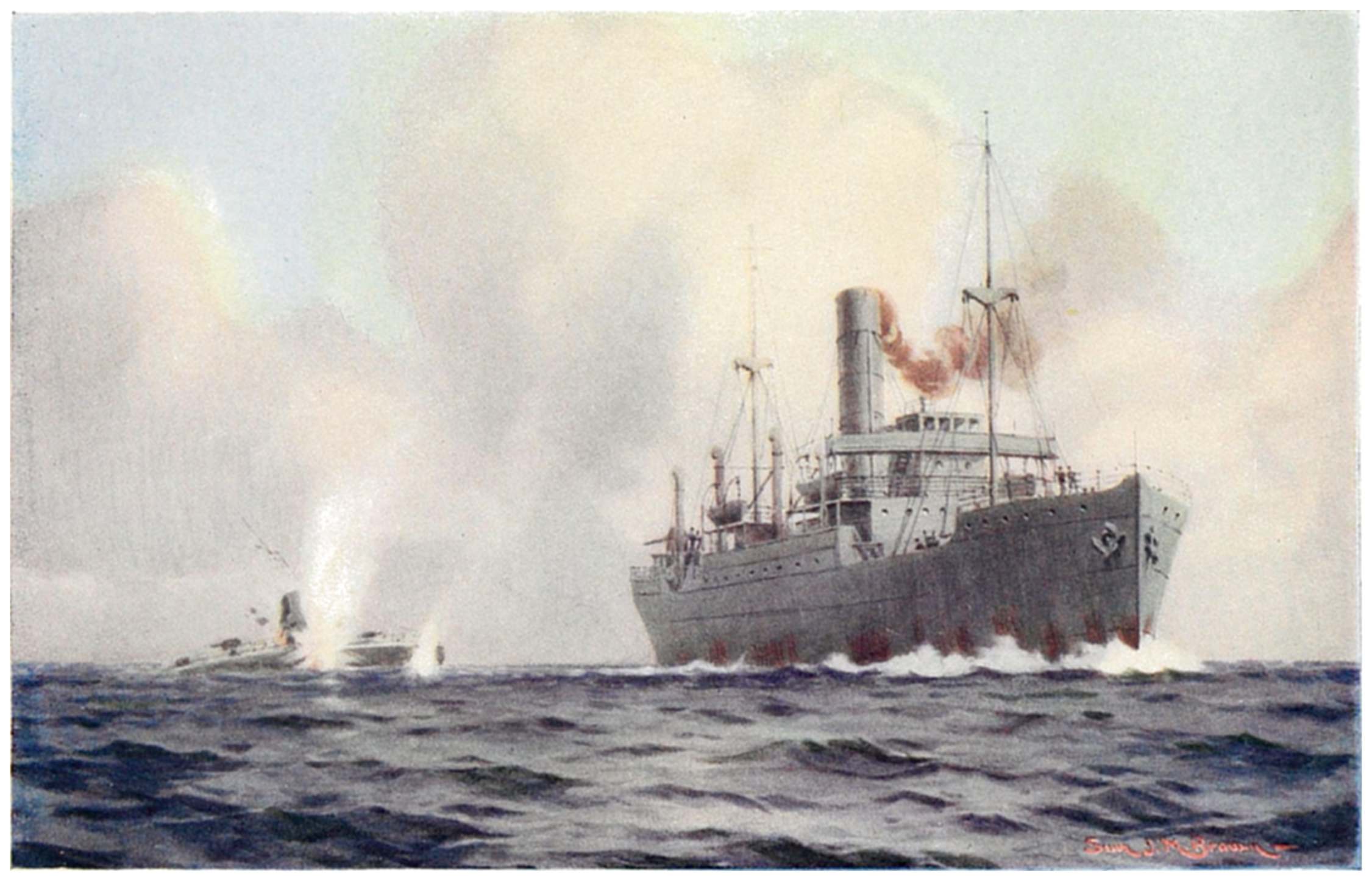

| “Carmania” sinking “Cap Trafalgar” | 36 |

| Torpedoing of the “Ausonia” | 44 |

| Torpedoing of the “Lusitania” | 52 |

| “Phrygia” sinking a submarine | 60 |

| Torpedoing of the “Thracia” | 68 |

| “Valeria” sinking a submarine | 84 |

| Torpedoing of the “Volodia” | 92 |

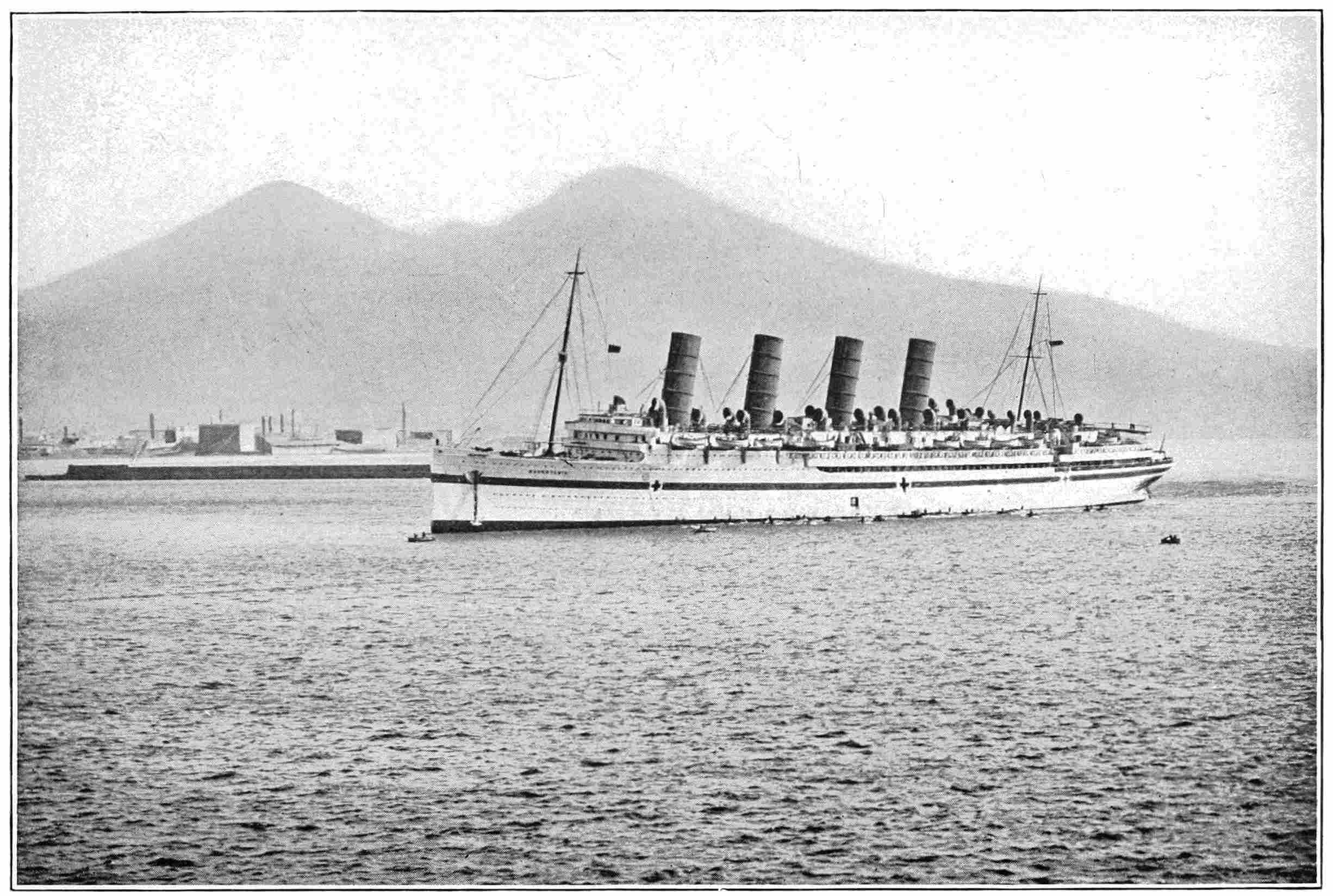

| “Aquitania” as hospital ship | 108 |

| “Campania” as seaplane ship | 124xiv |

| In Monochrome | |

| To face page | |

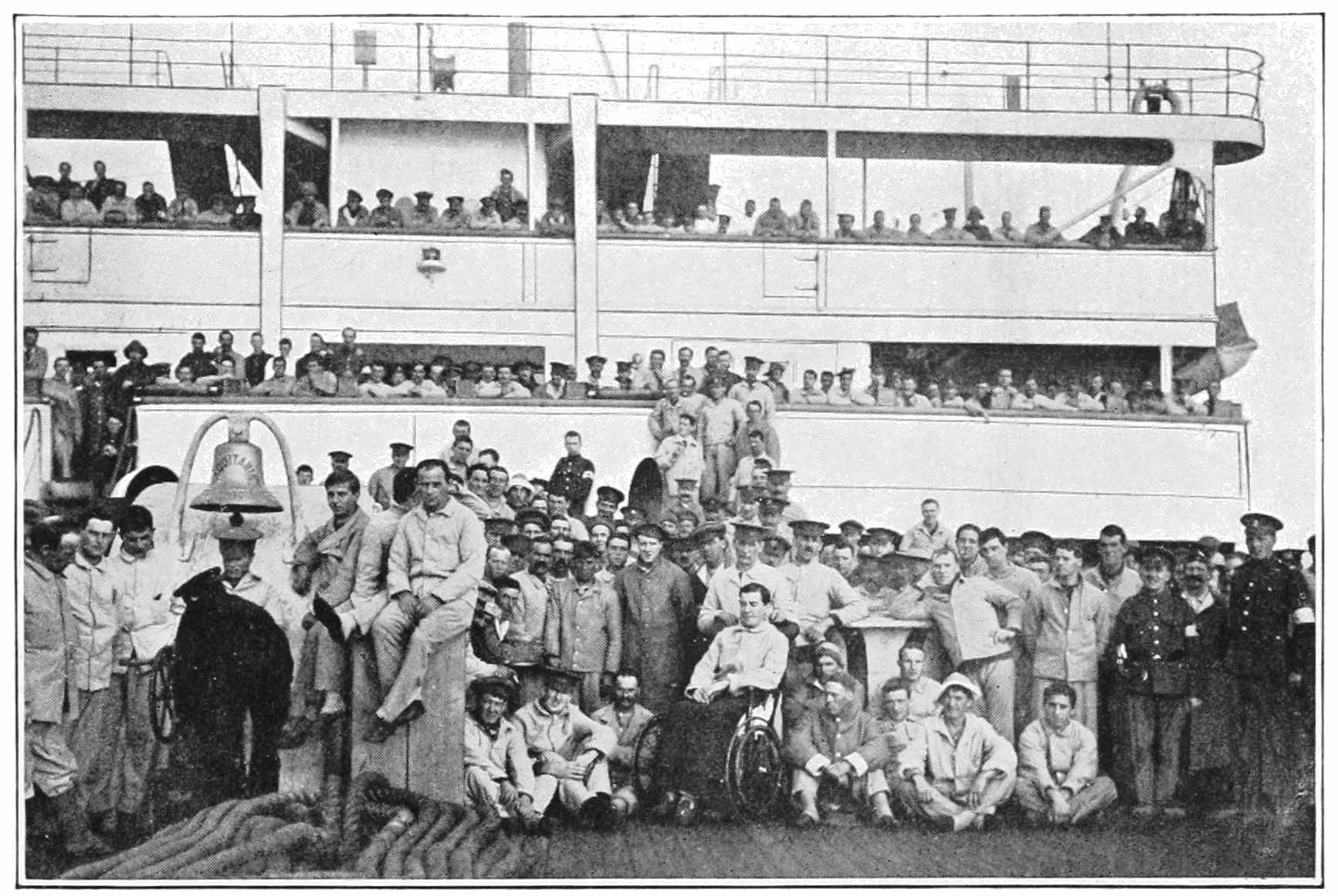

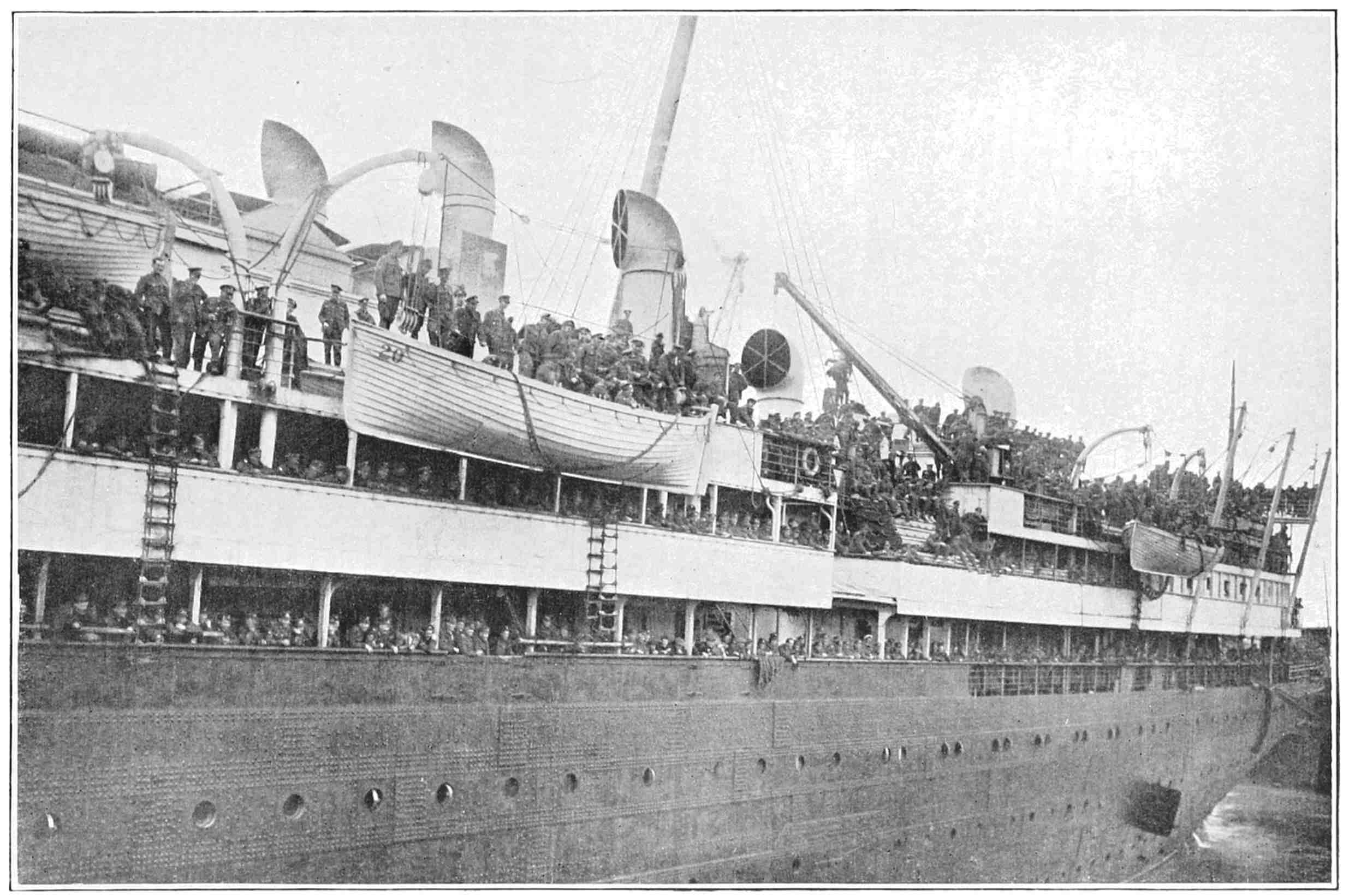

| “Aquitania” at Southampton with Canadian troops | 2 |

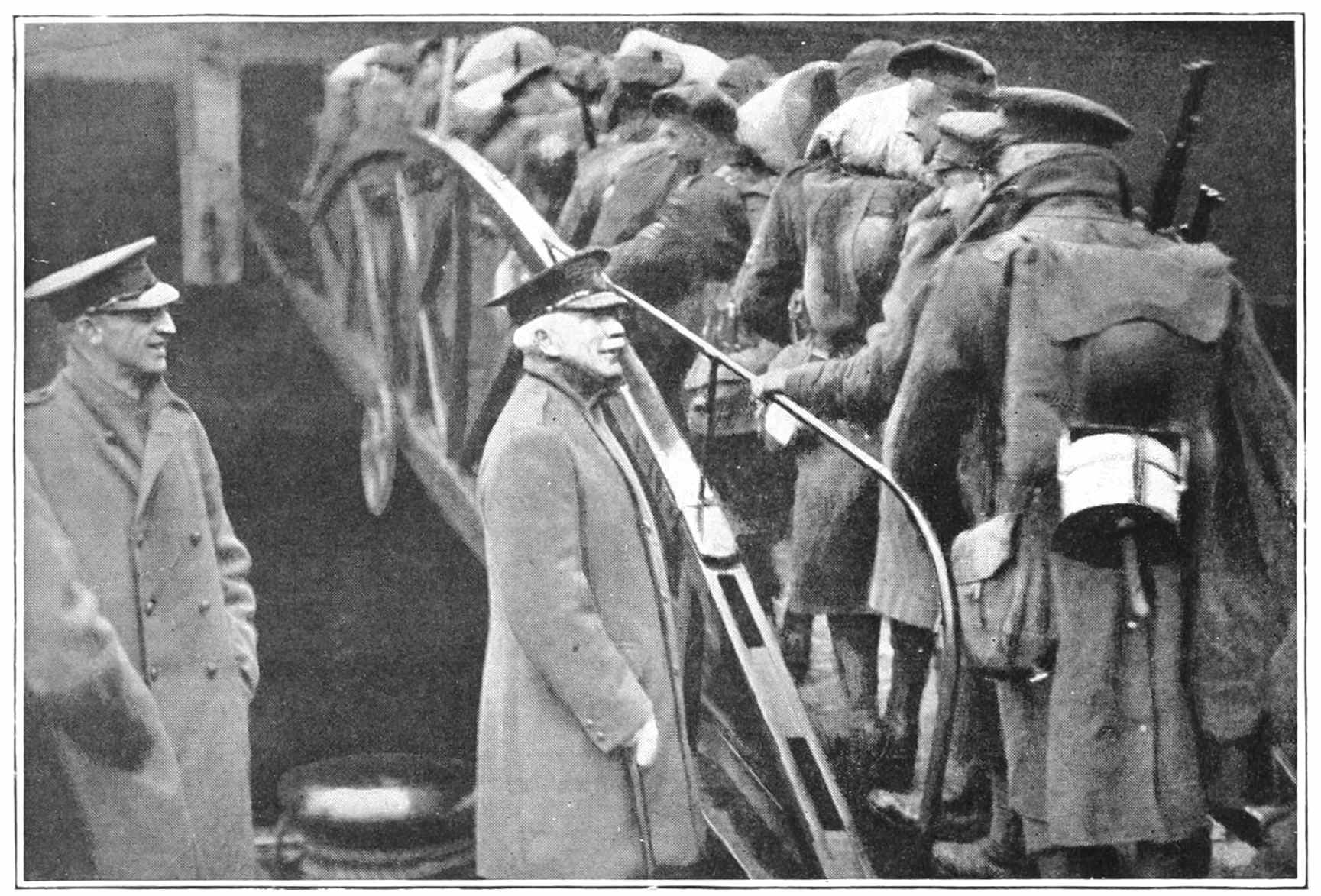

| Embarkation | 6 |

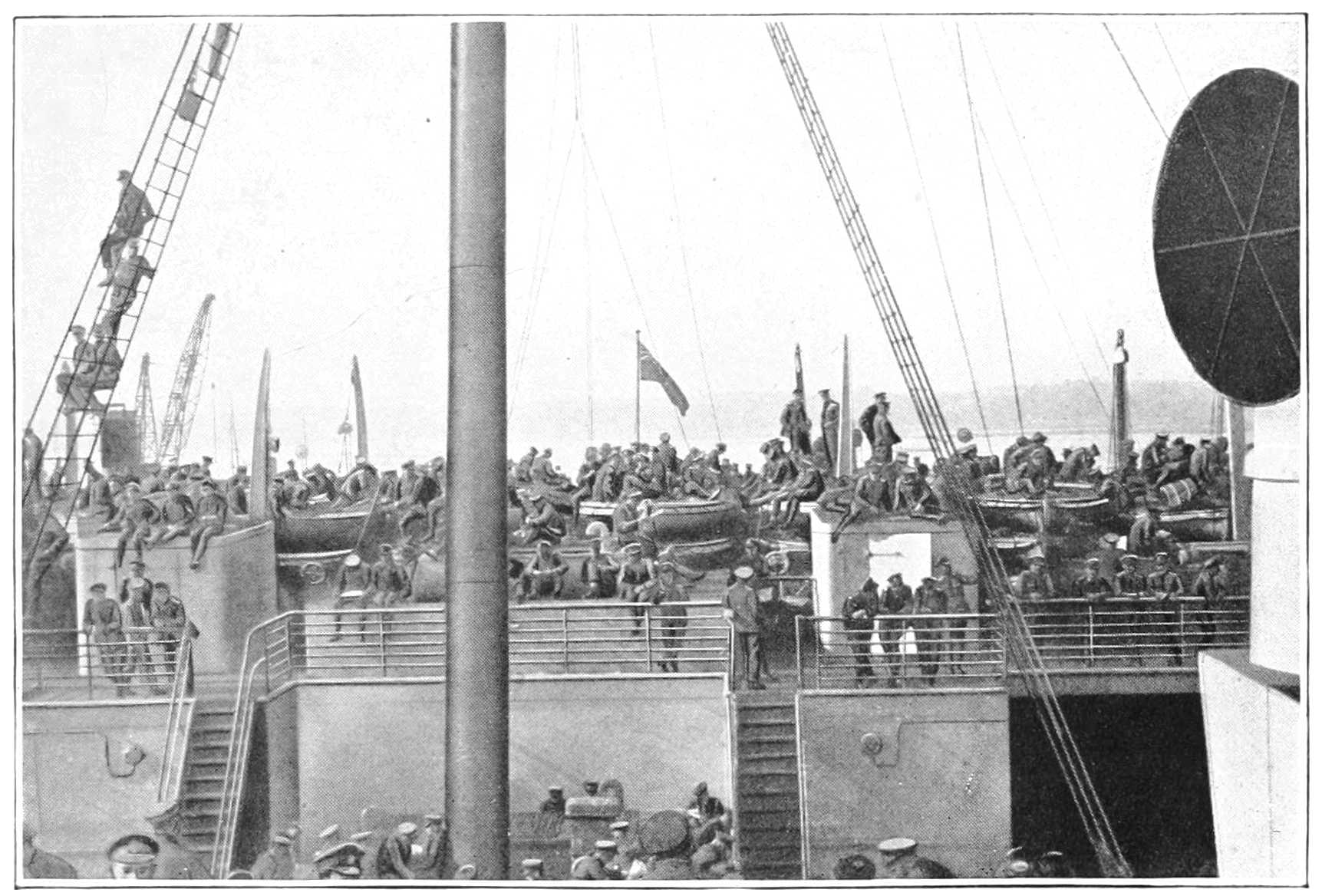

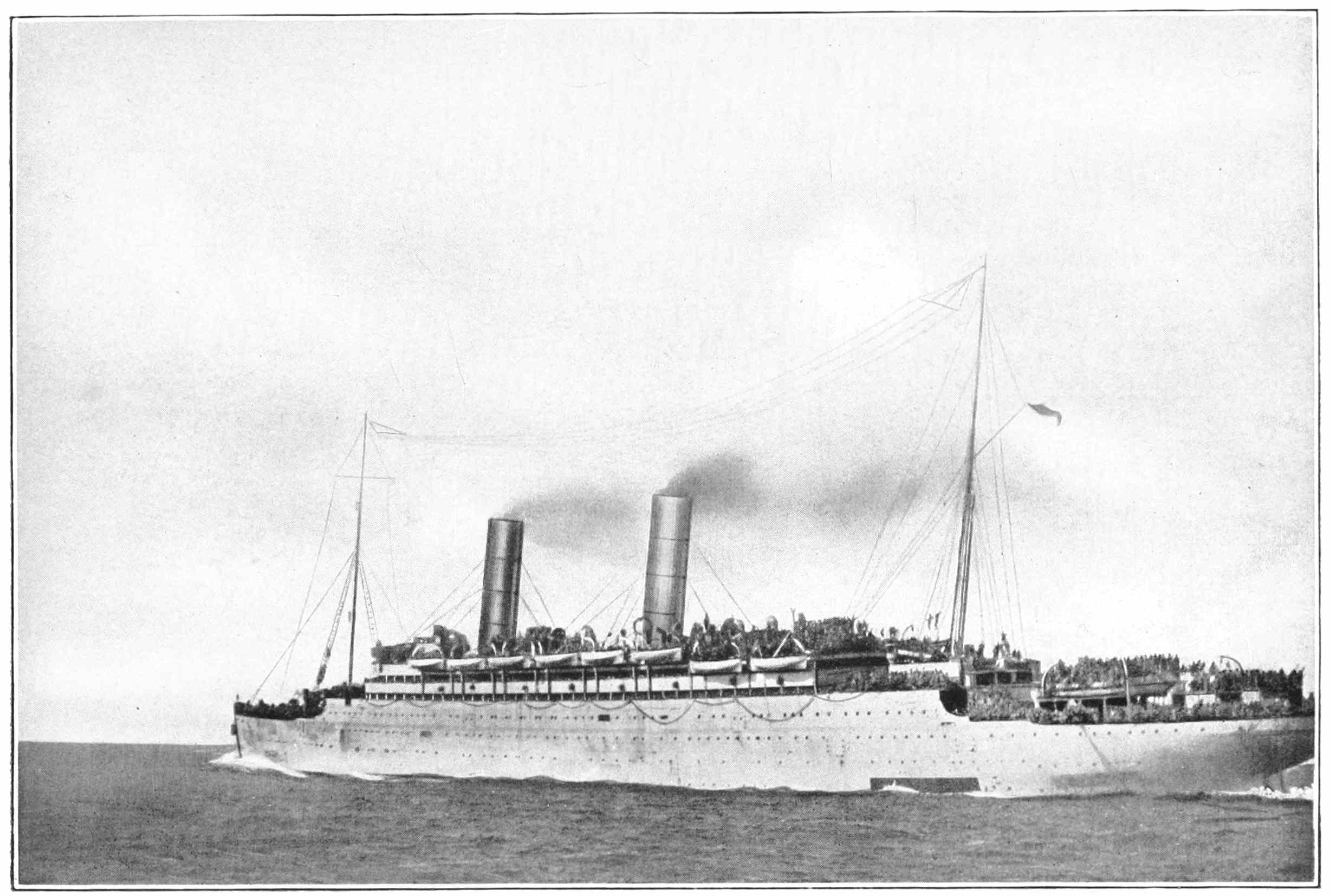

| Transport in Southampton Water | 6 |

| Canadian troops on “Caronia” being addressed by their commander | 8 |

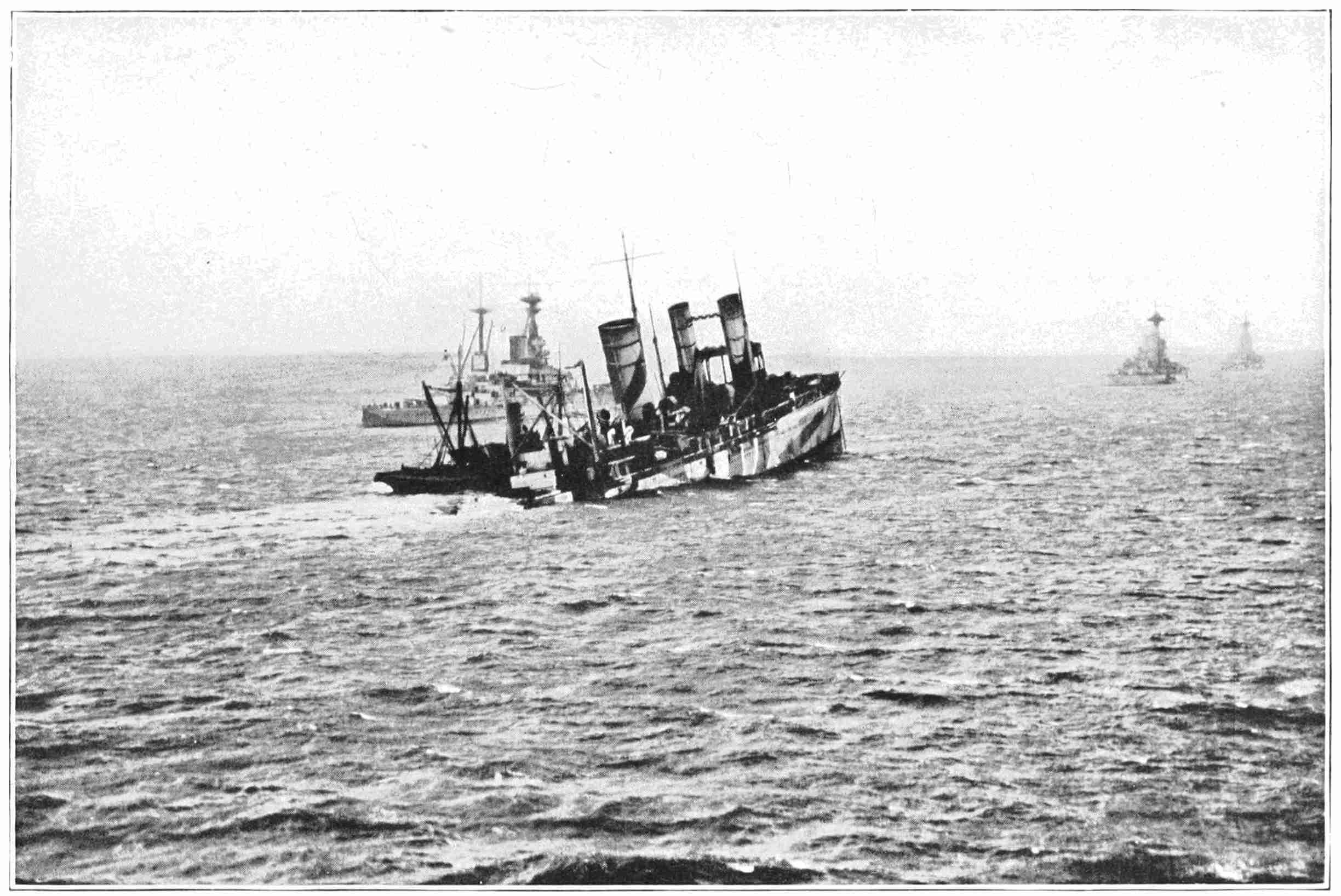

| The “Campania” sinking in the Firth of Forth | 10 |

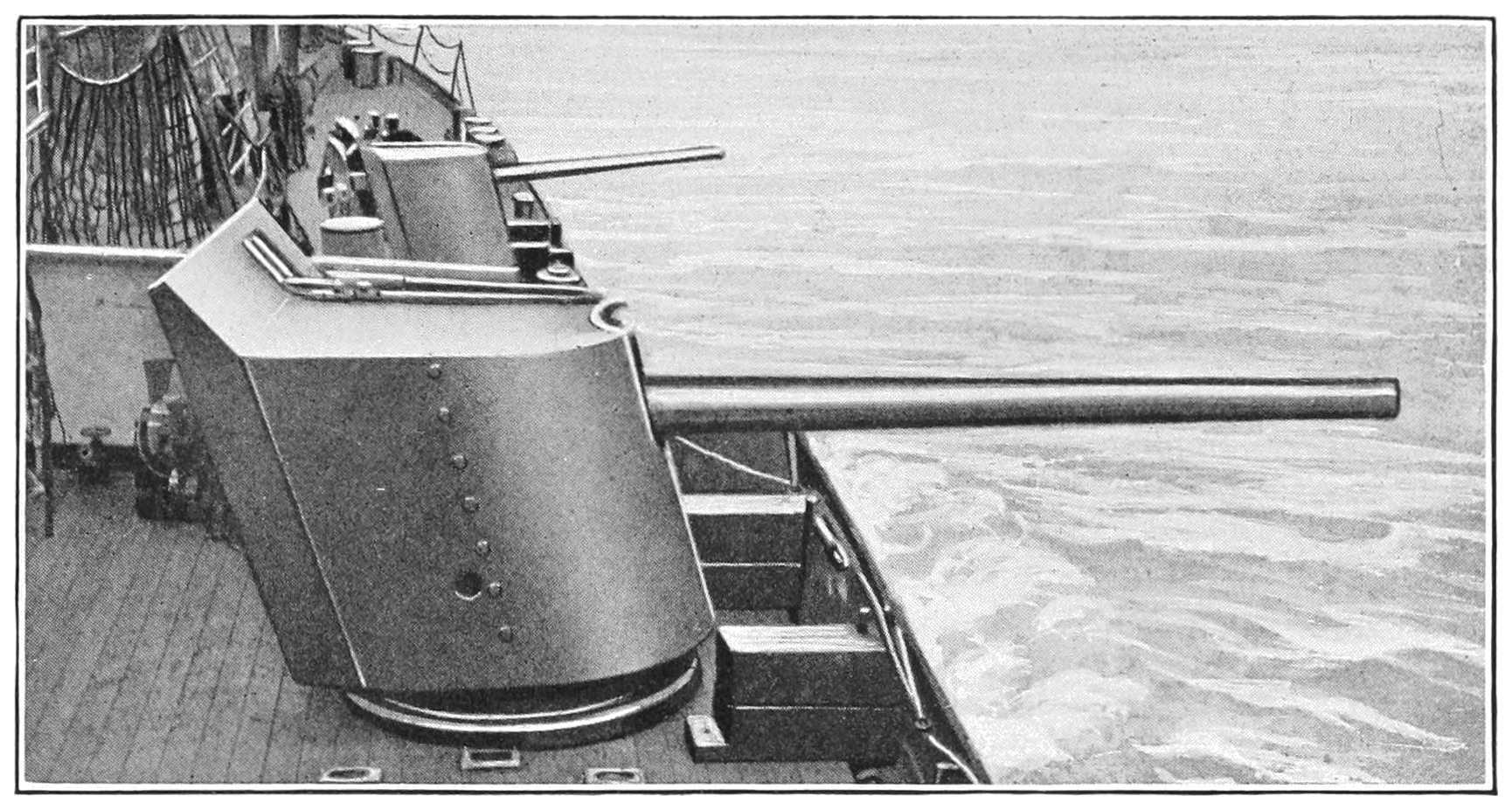

| The “Carmania” starboard forward guns | 14 |

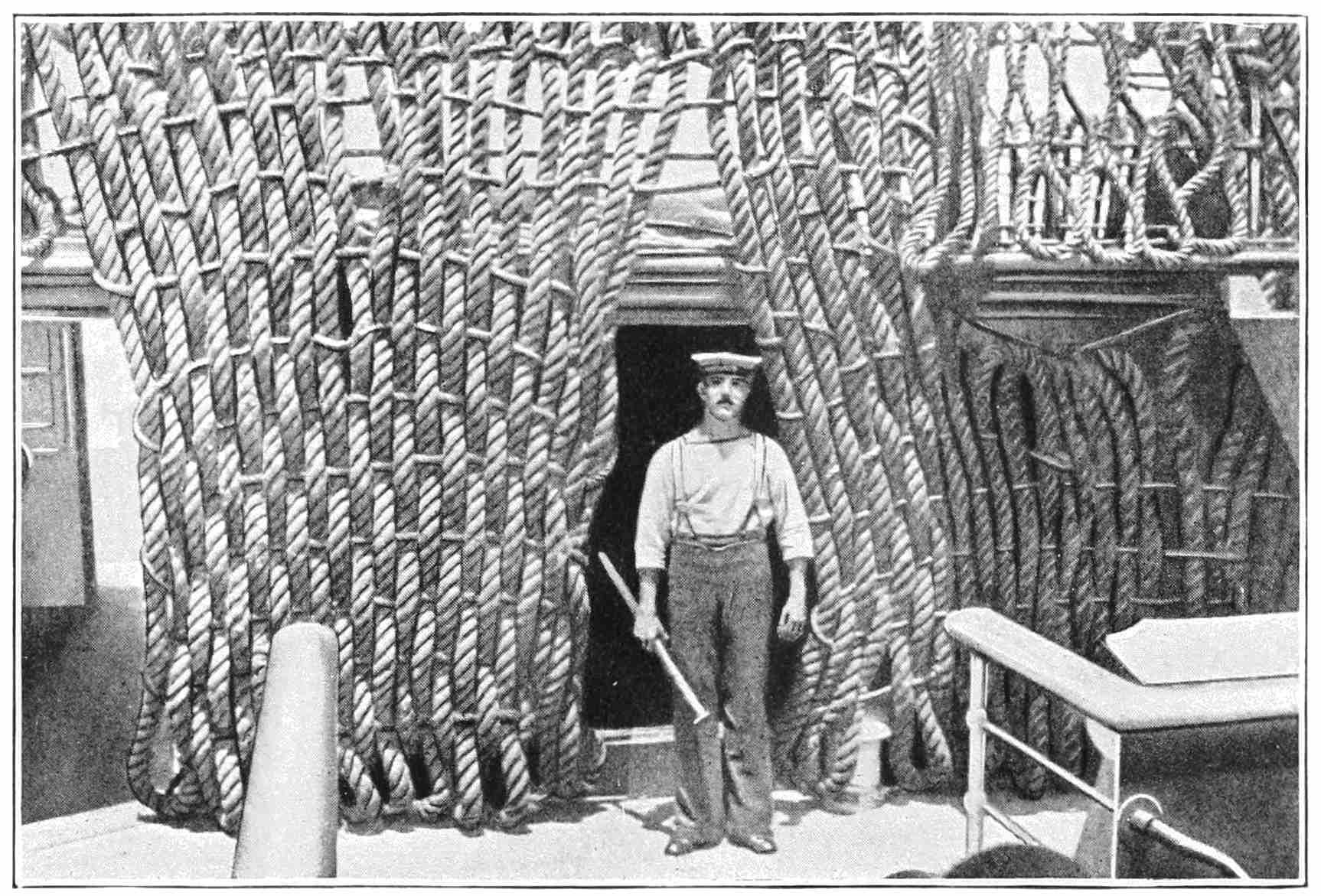

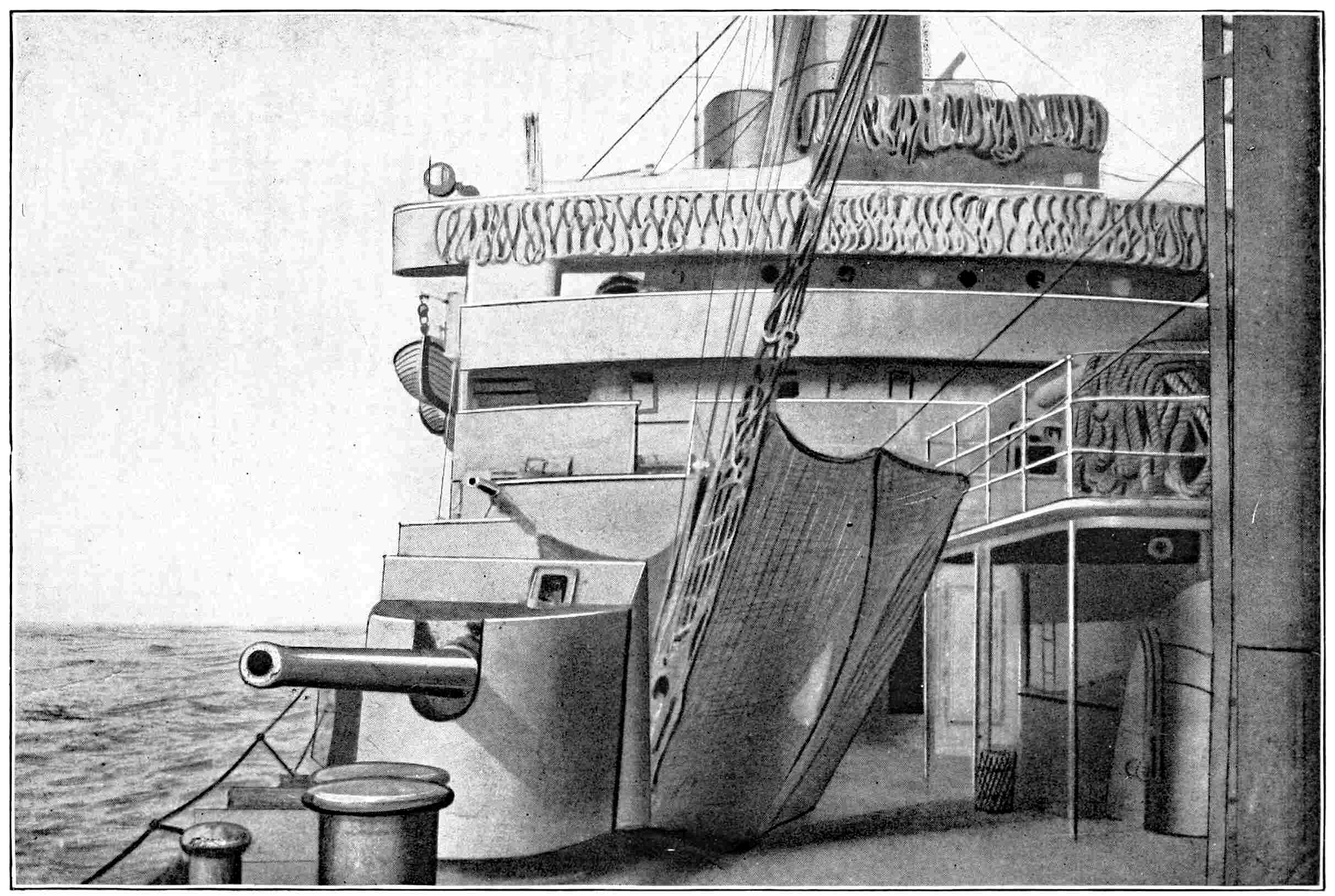

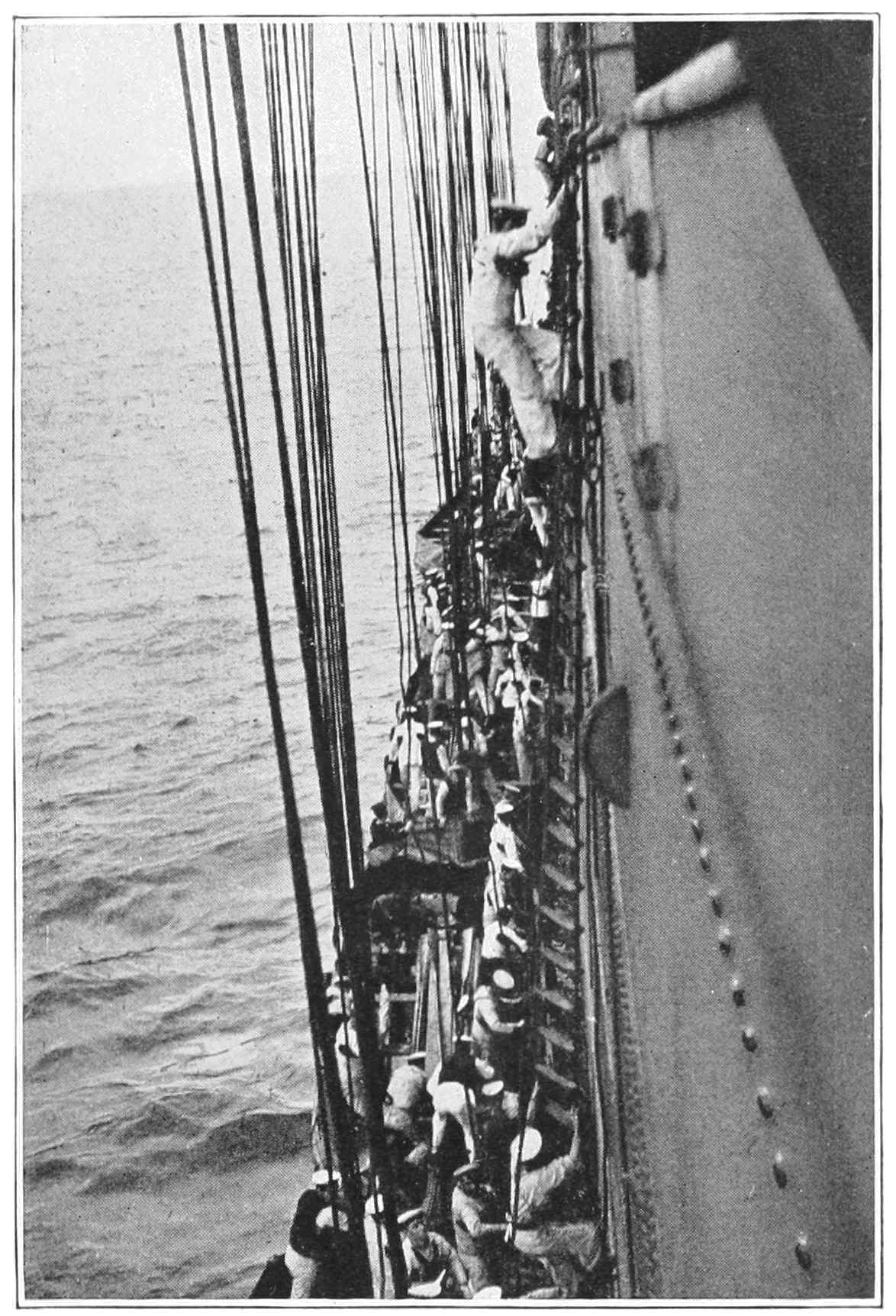

| Rope protection on “Carmania” against shell splinters | 14 |

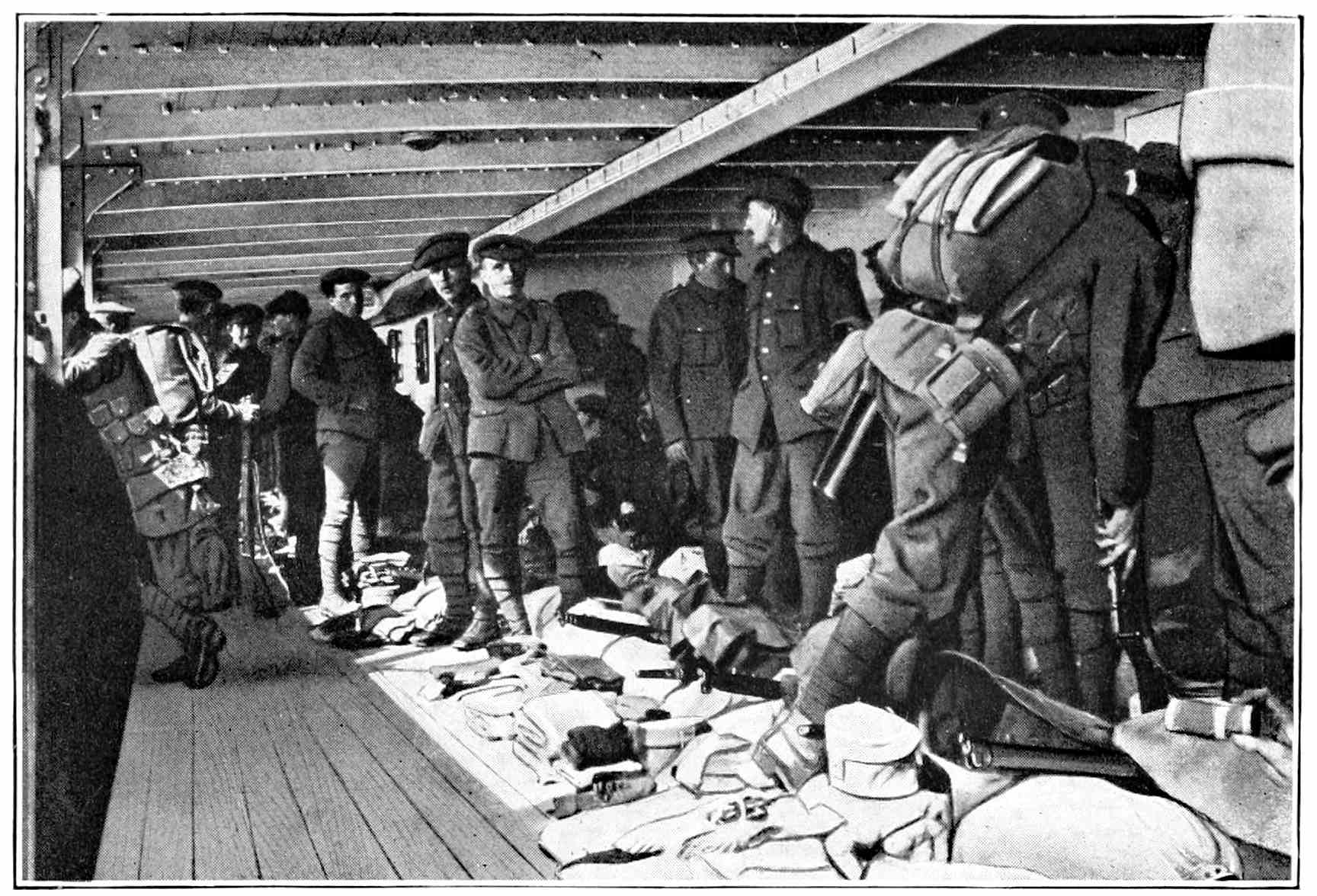

| Life on a transport (i): Kit inspection | 16 |

| Life on a transport (ii): Rifle drill | 16 |

| The “Carmania” ready for action | 18 |

| South African infantry on board the “Laconia” | 22 |

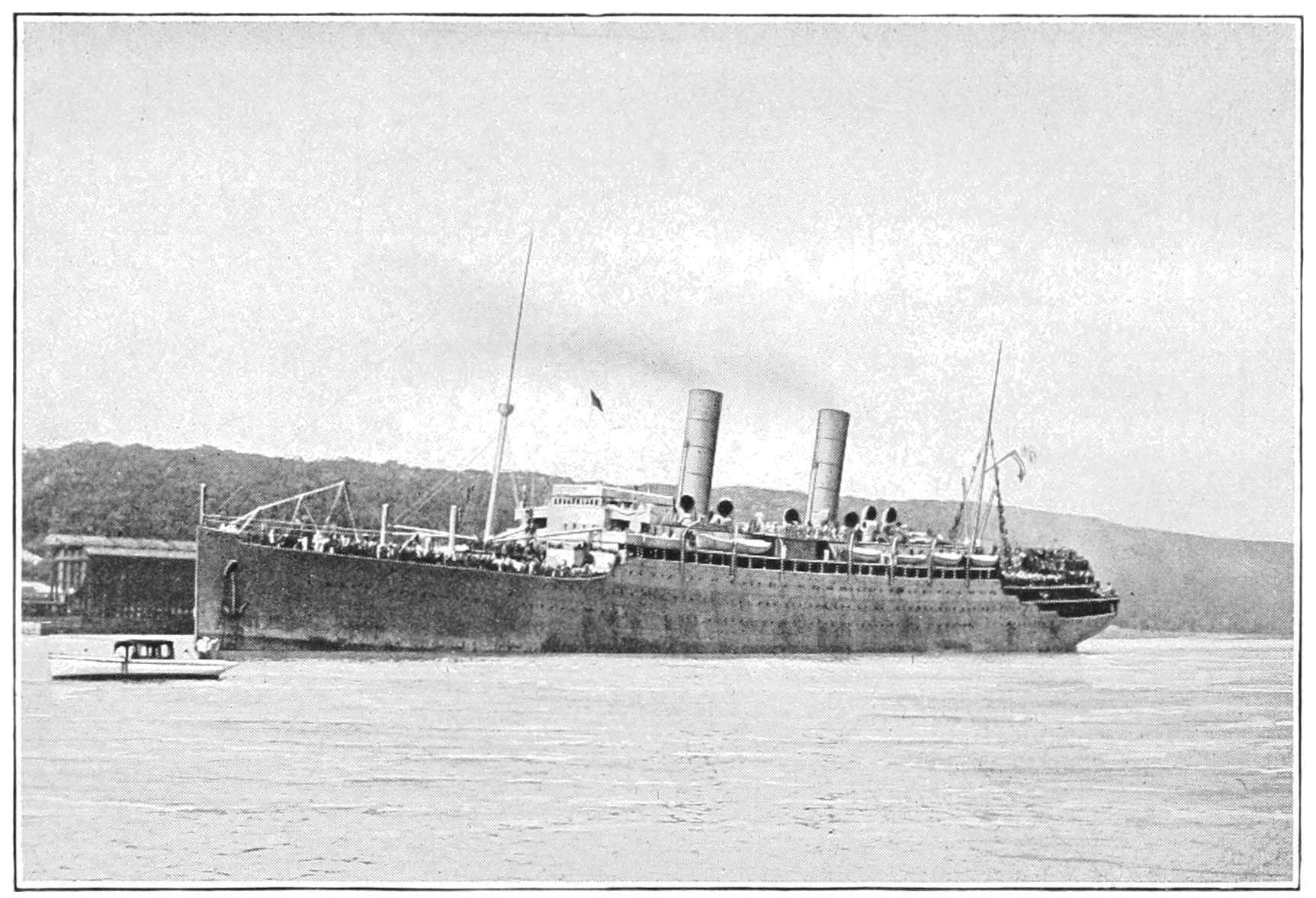

| The “Caronia” leaving Durban | 24 |

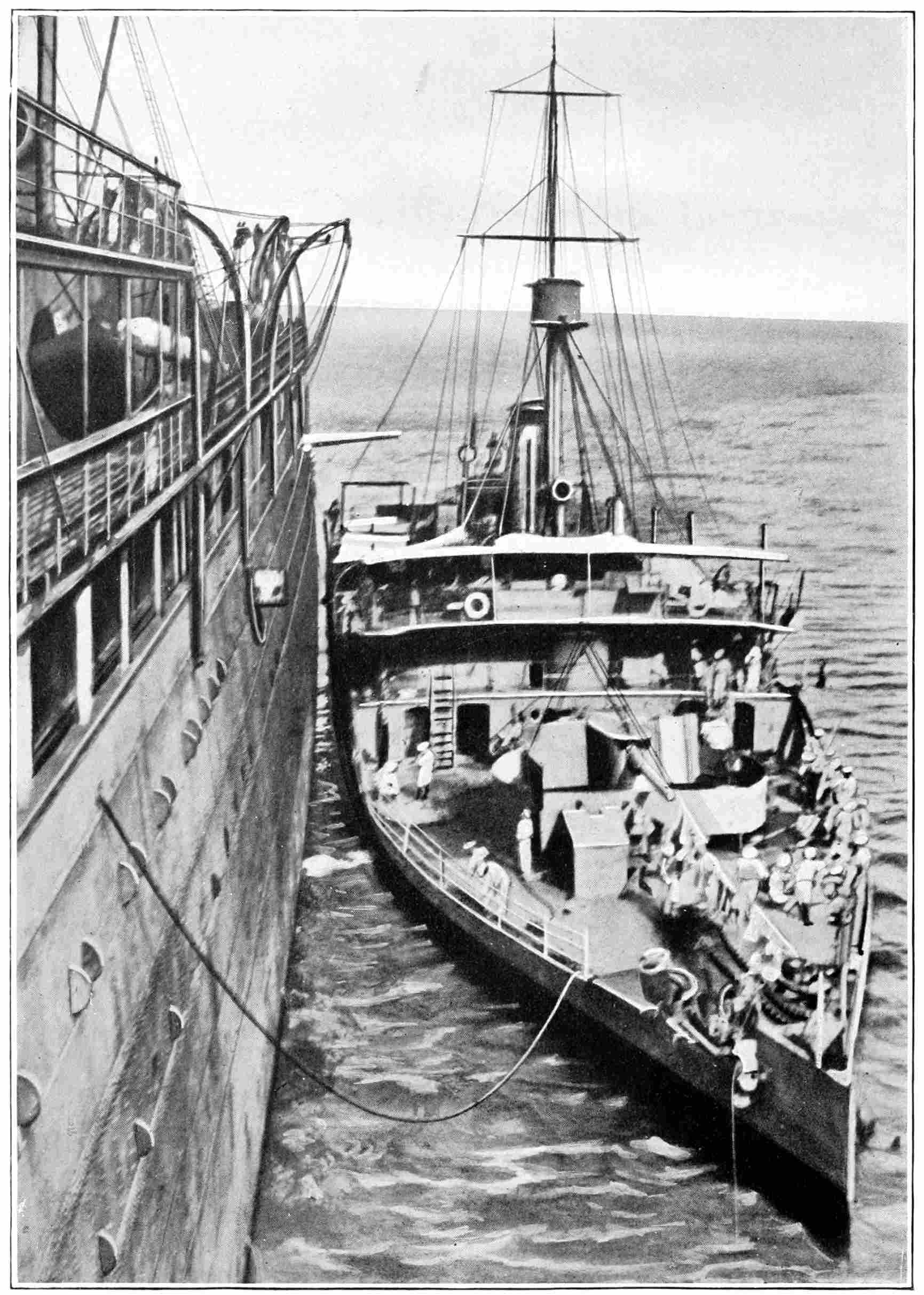

| H.M.S. “Mersey” alongside the “Laconia” off the Rufigi River | 26 |

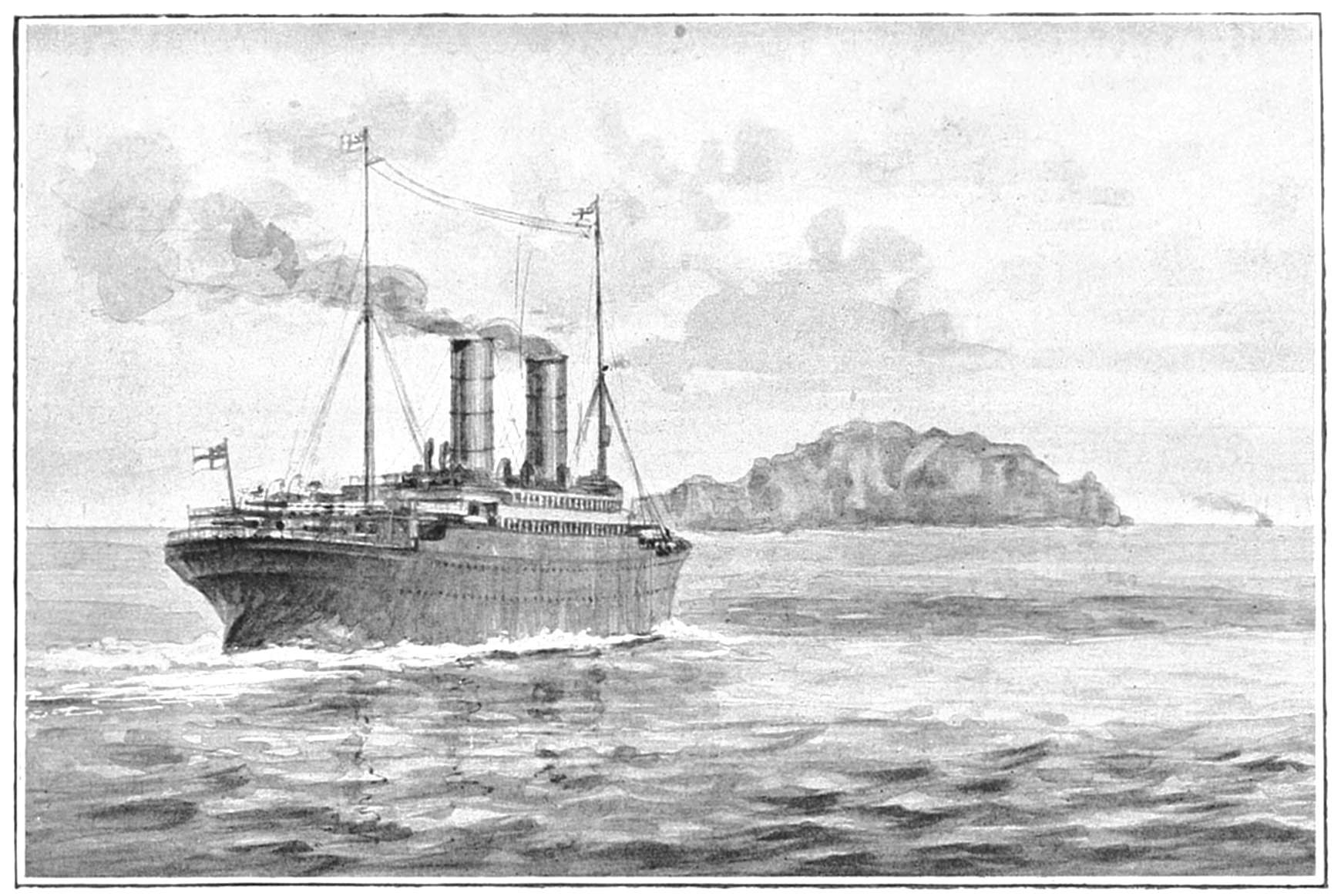

| The “Carmania” approaching Trinidad | 30 |

| One of the “Carmania’s” guns | 30 |

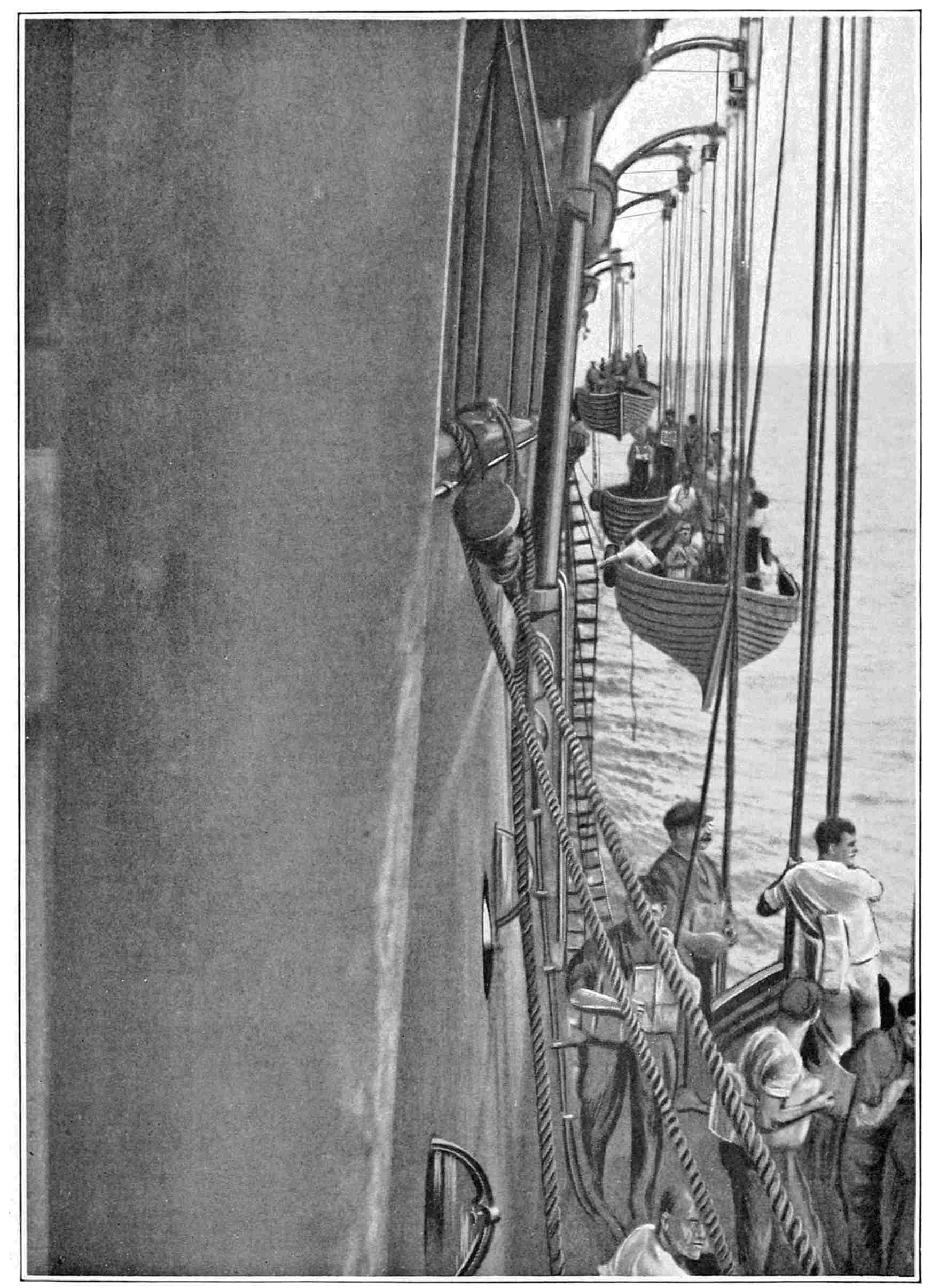

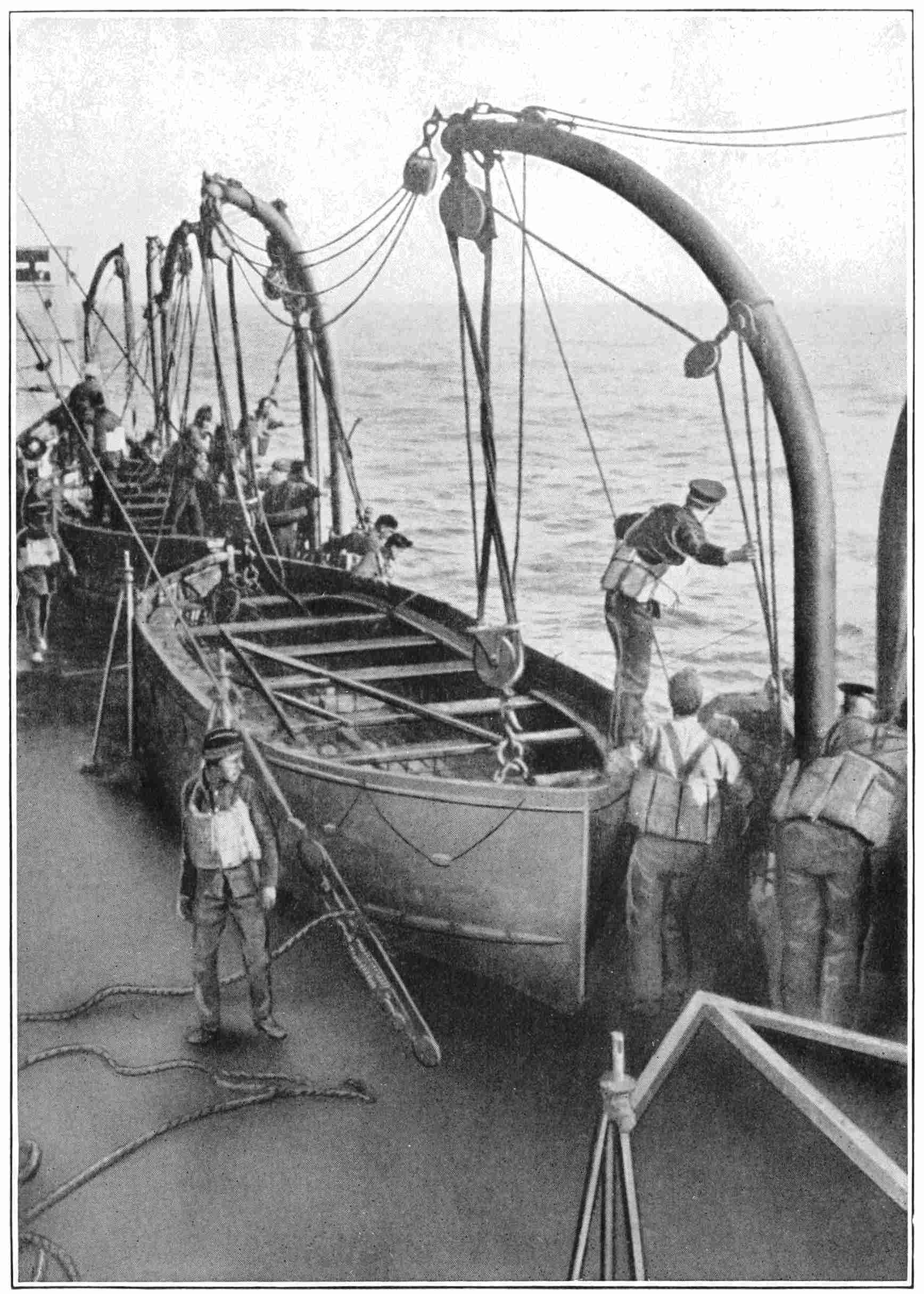

| “Abandon Ship” drill at sea | 32 |

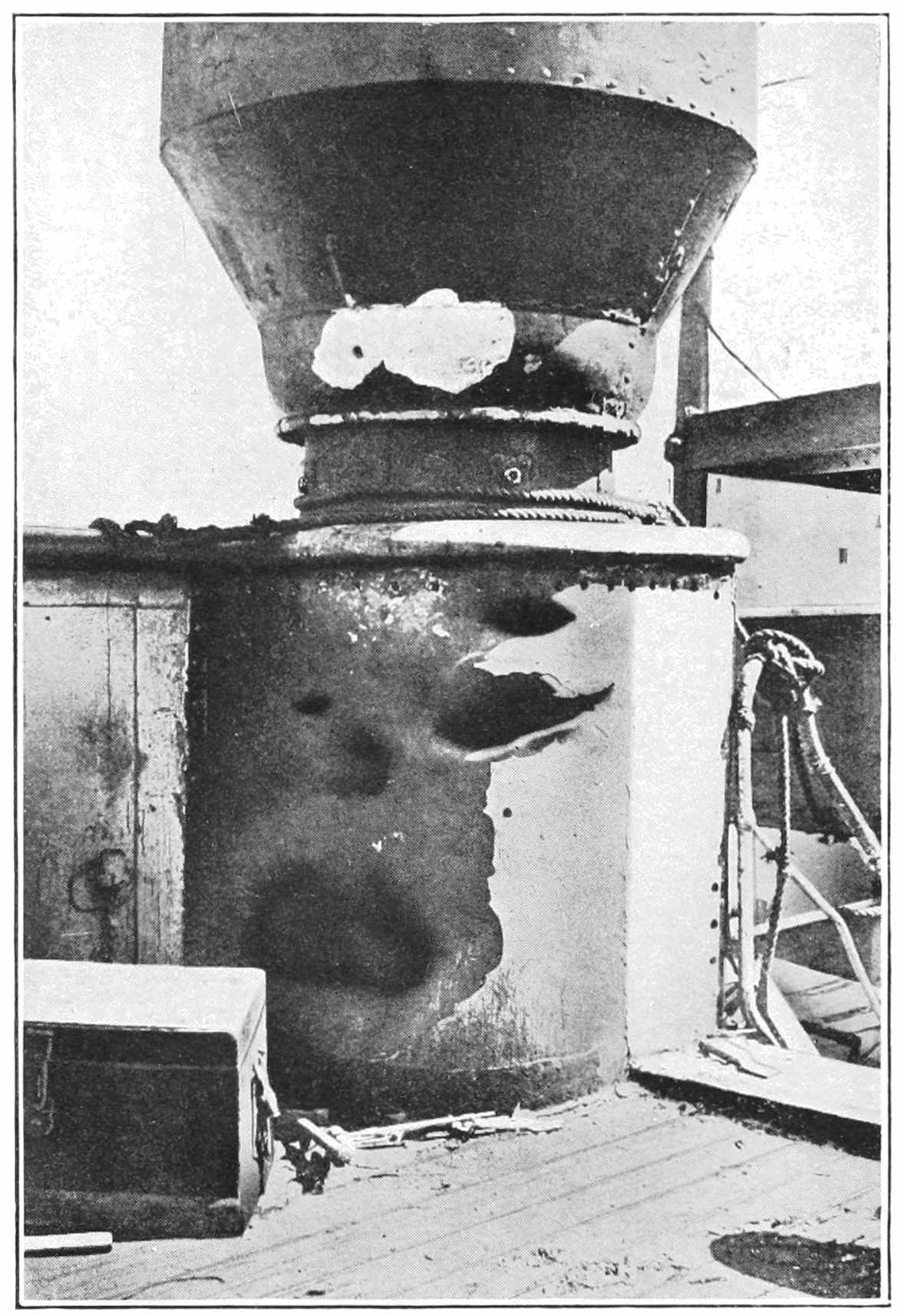

| After the fight | 32 |

| Chart-house and bridge of the “Carmania” after the fight | 34 |

| The “Laconia” at Durban | 38 |

| Final of the S.A.I. heavyweight championship on the “Laconia” | 38 |

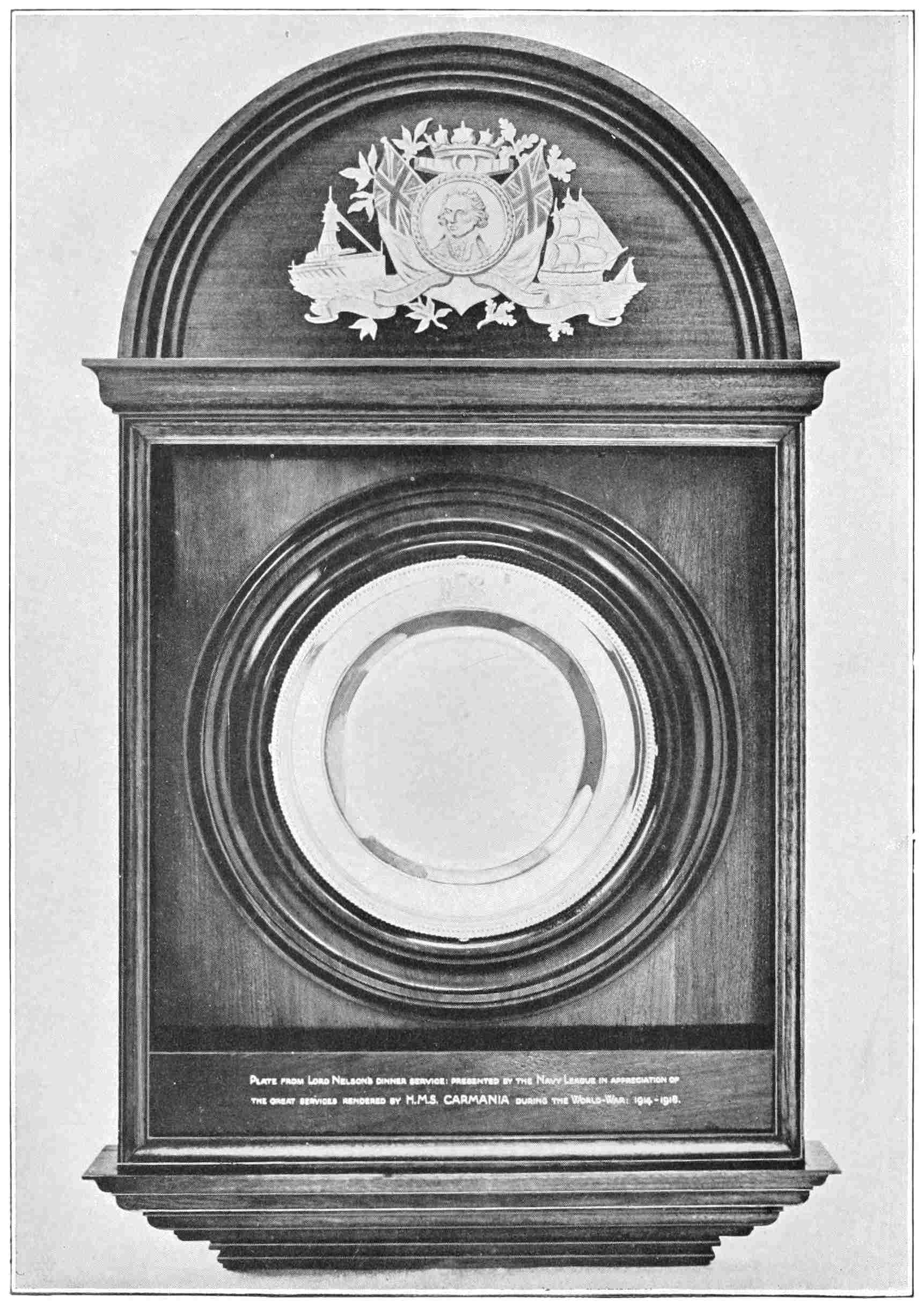

| The Nelson Plate presented to the “Carmania” | 40 |

| Crew leaving the “Franconia” after she was torpedoed | 42xv |

| Scene on board after the torpedoing of the “Ivernia” (i) | 46 |

| Scene on board after the torpedoing of the “Ivernia” (ii) | 48 |

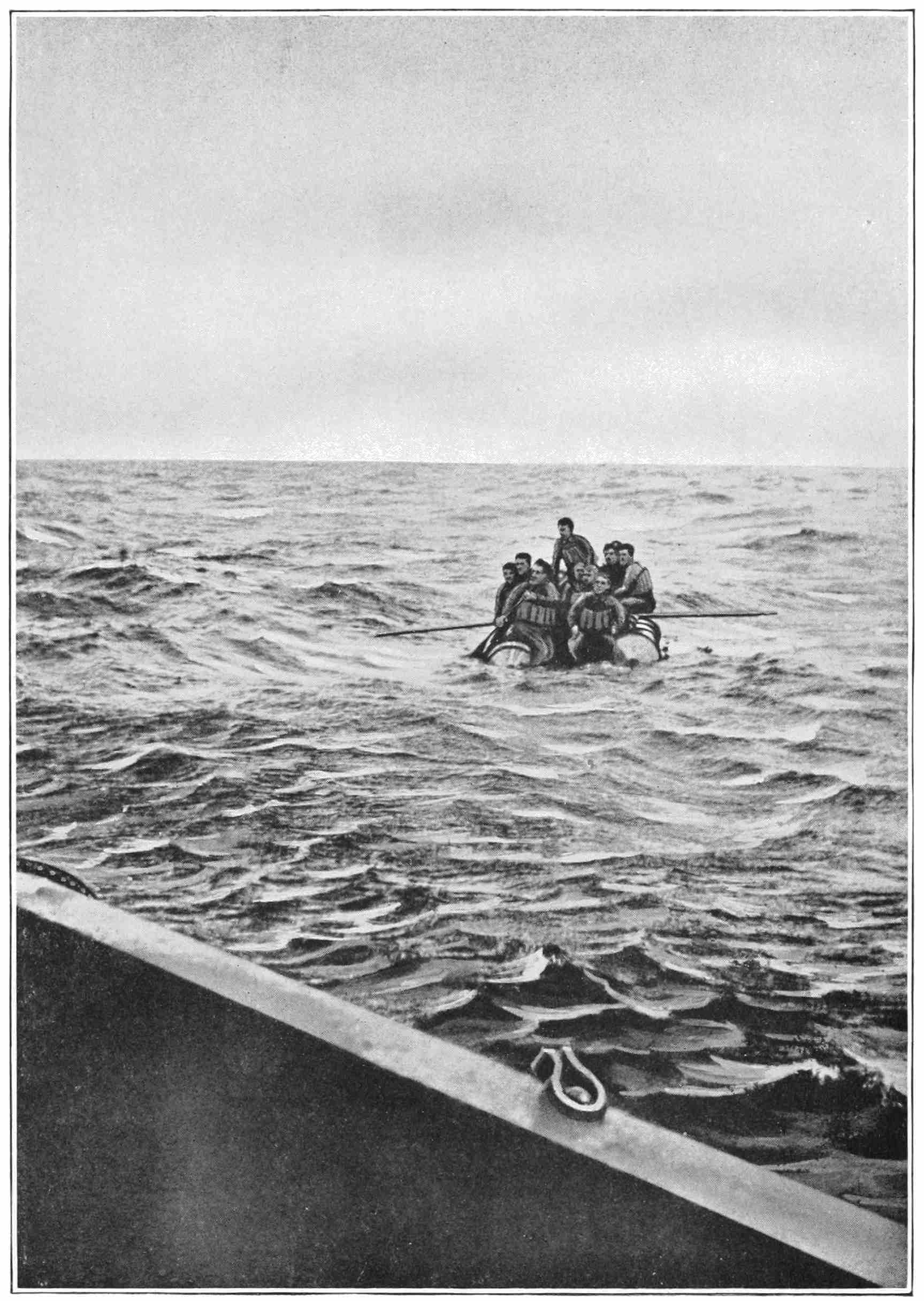

| The torpedoing of the “Ivernia”: Survivors afloat on raft | 50 |

| The torpedoing of the “Ivernia”: Survivors being taken in one of the boats | 54 |

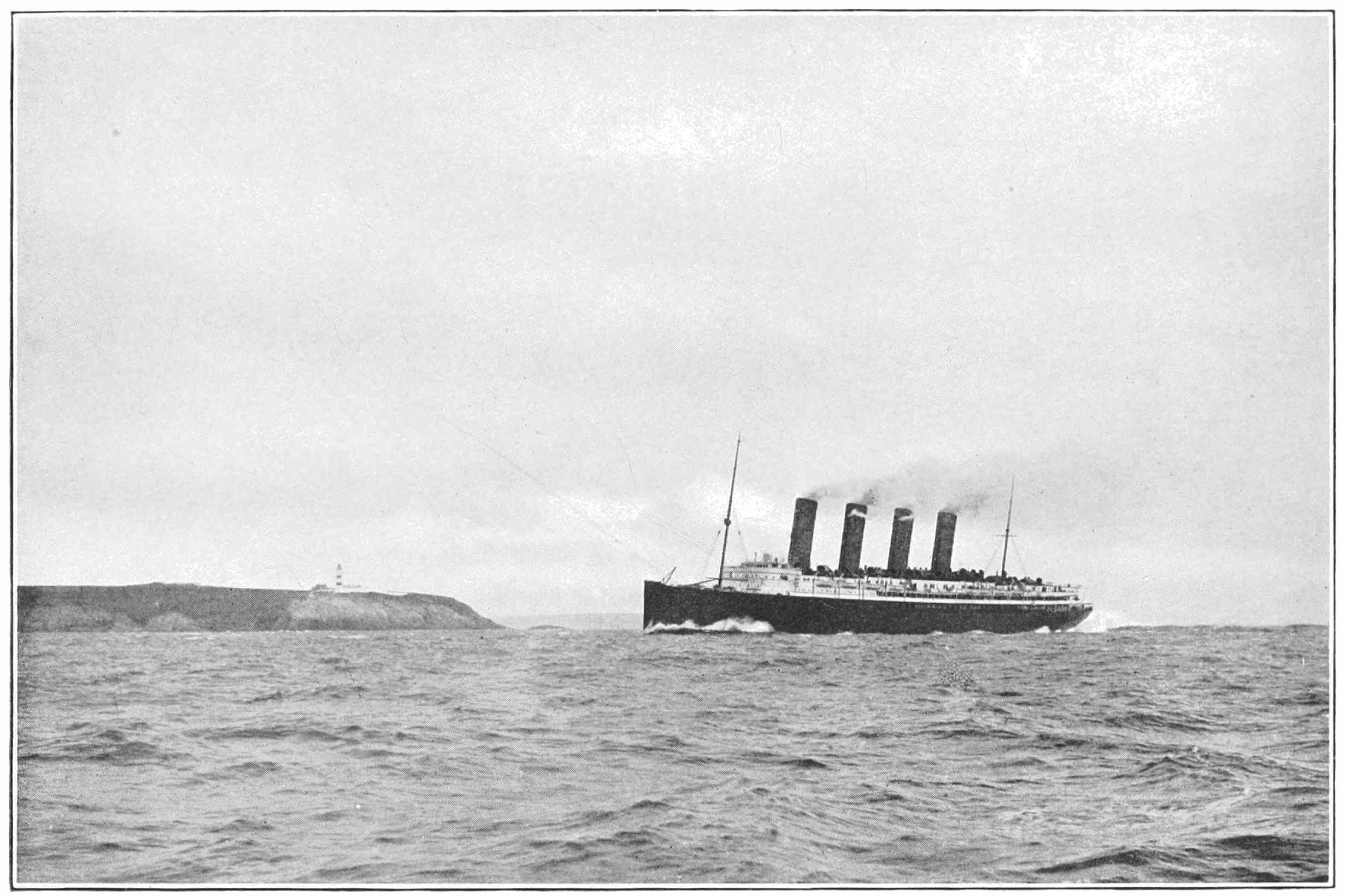

| The “Lusitania” | 56 |

| The “Mauretania” as a hospital ship off Naples Harbour | 58 |

| The “Alaunia” as an emergency hospital ship | 62 |

| The “Lusitania” passing the Old Head of Kinsale | 64 |

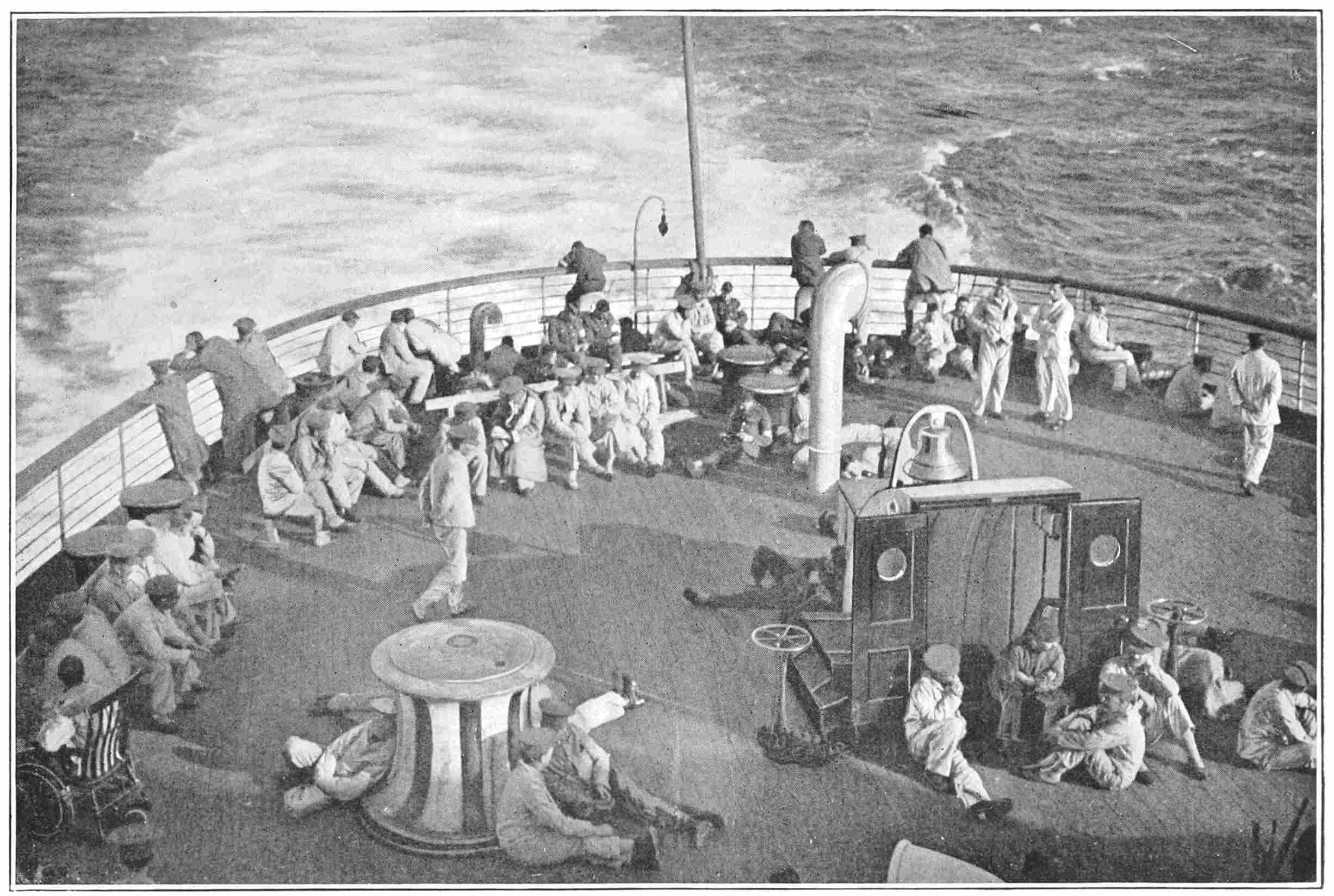

| The “white wake” that stretched to the beaches of Gallipoli | 66 |

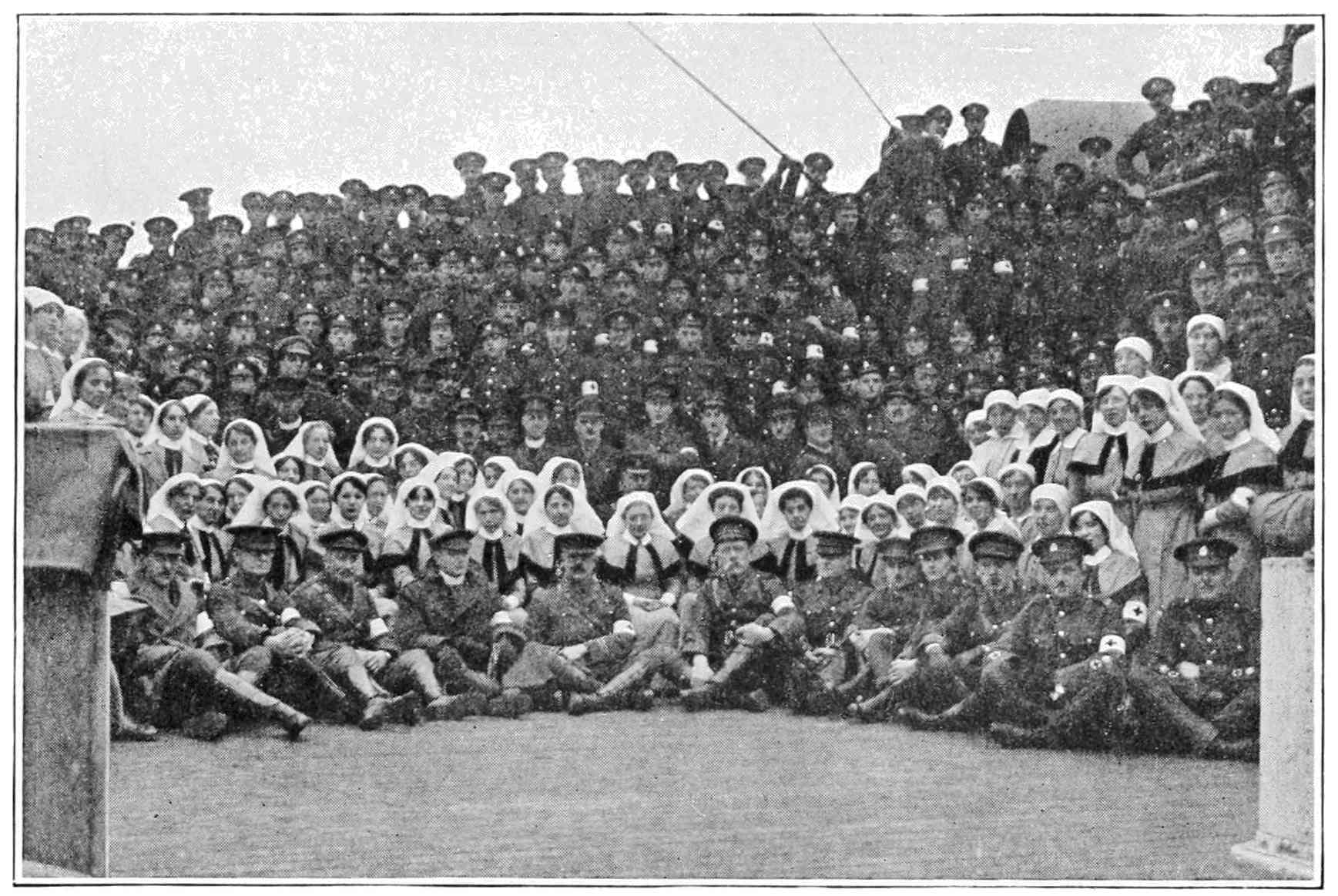

| Officers, nurses and R.A.M.C. orderlies of H.M.H.S. “Aquitania” | 70 |

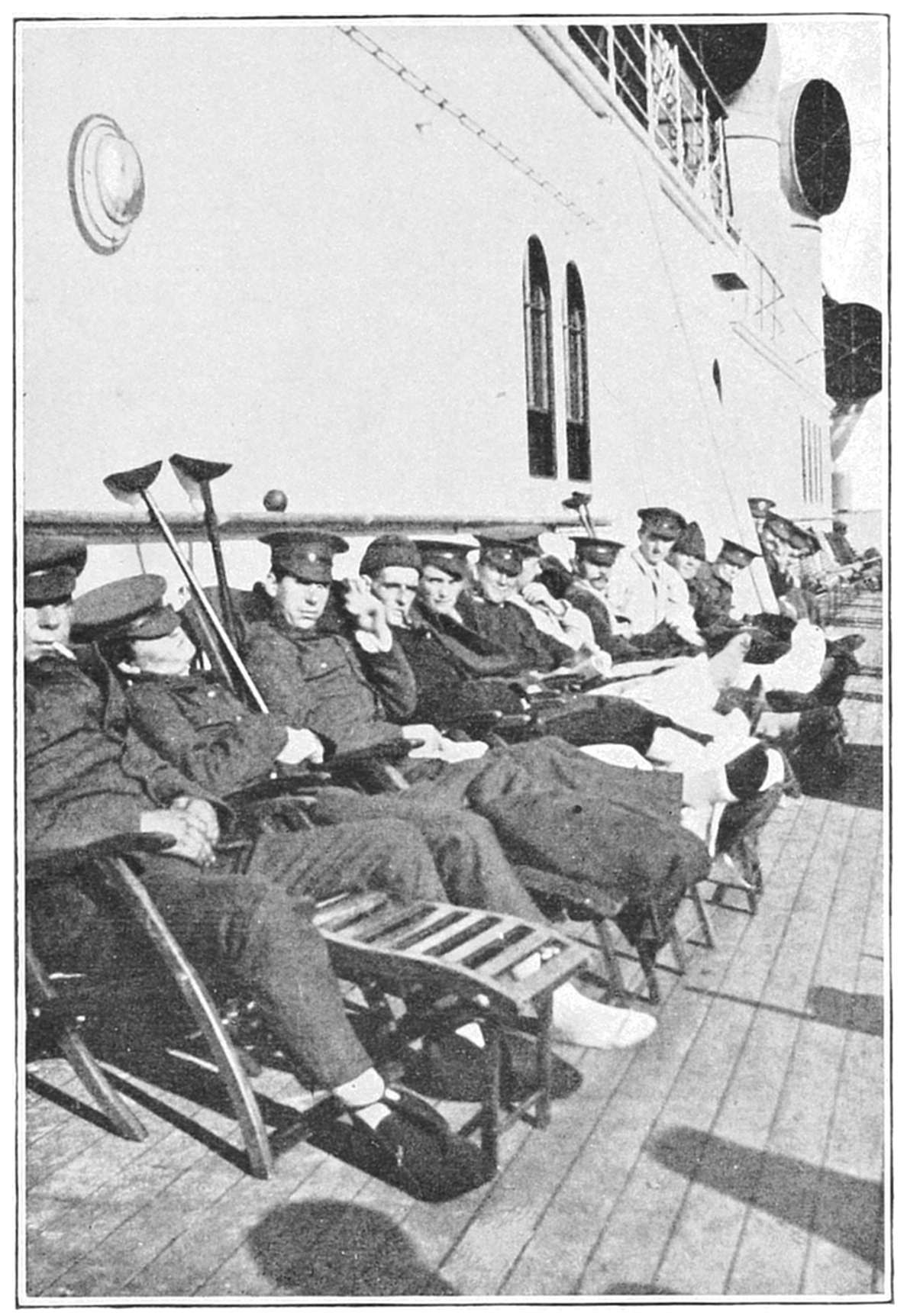

| “Homeward Bound.” | 70 |

| The sun-cure | 72 |

| The “Franconia” passing through the Suez Canal | 72 |

| American troops never forgot the “Lusitania” | 74 |

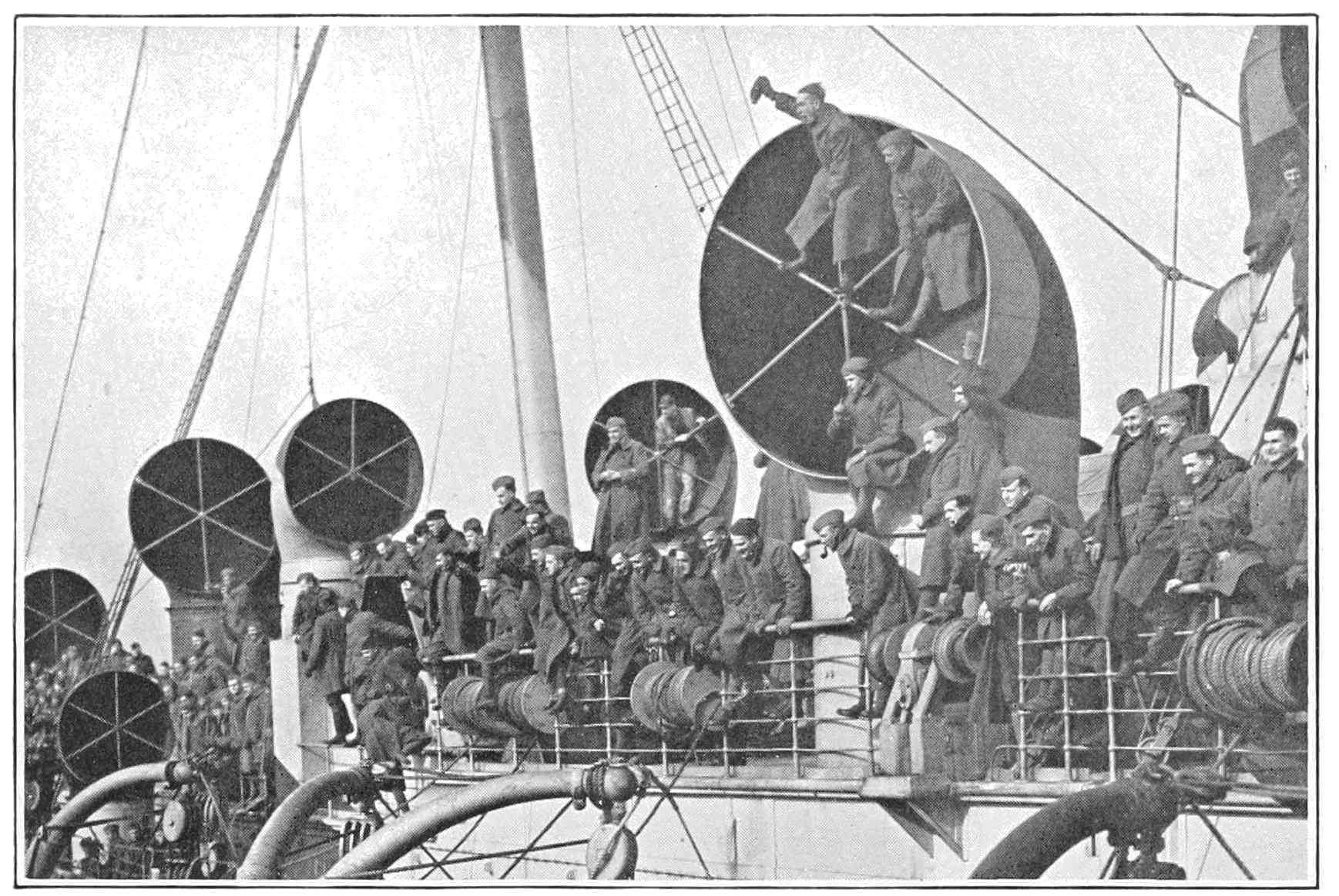

| In the Spring of 1918 the “Mauretania” brought 33,000 American soldiers to Europe | 78 |

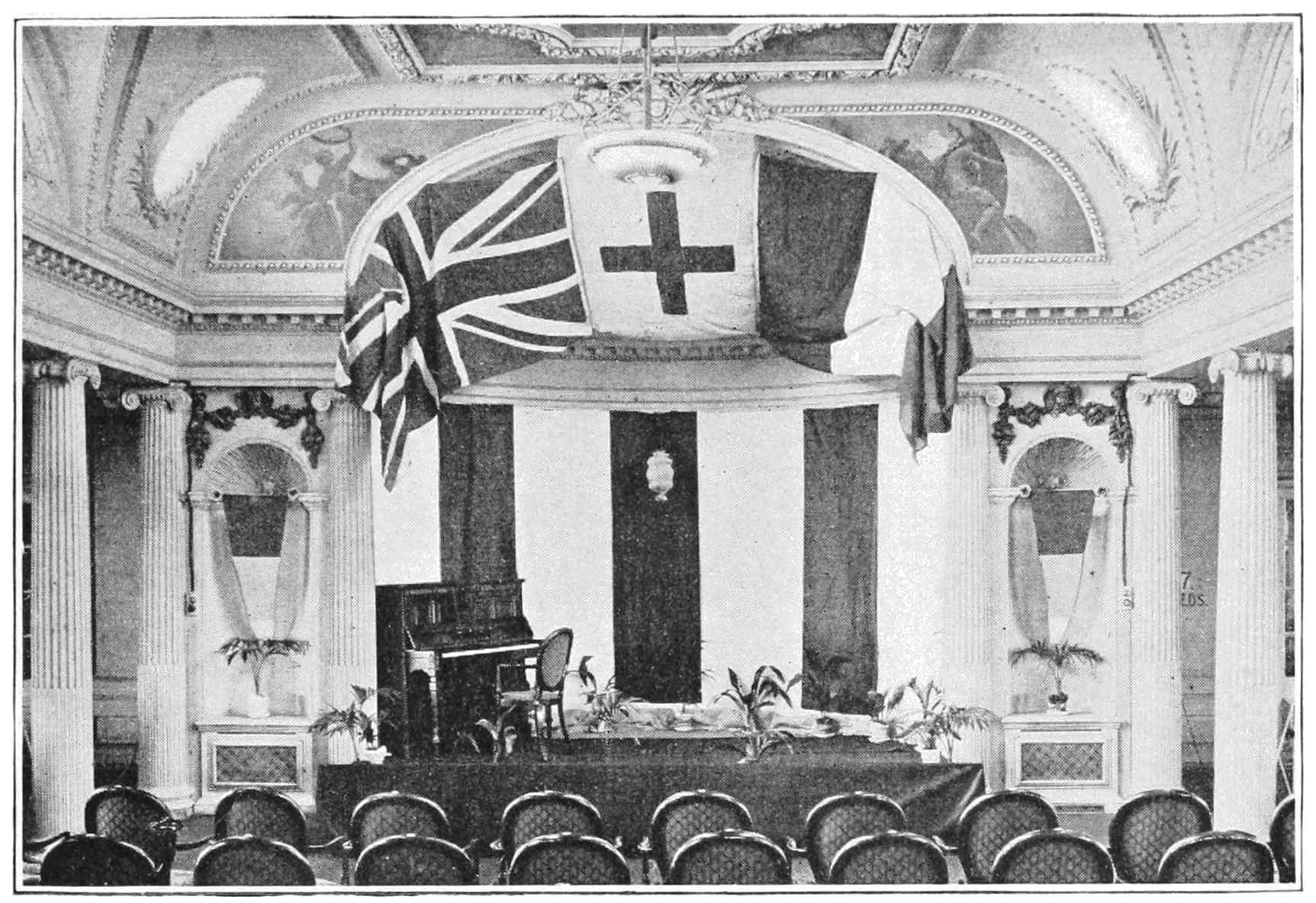

| The “Aquitania’s” stage | 80 |

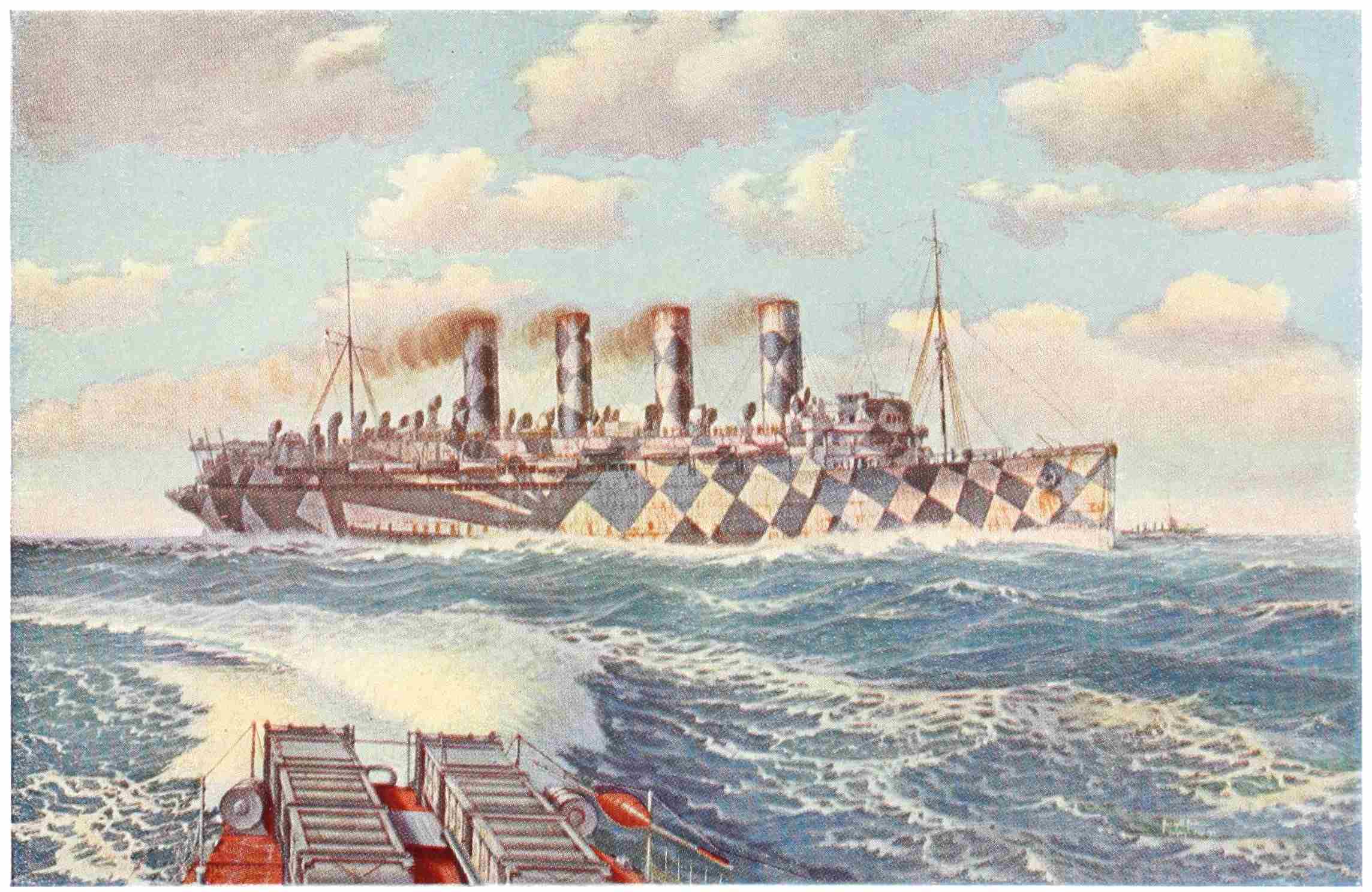

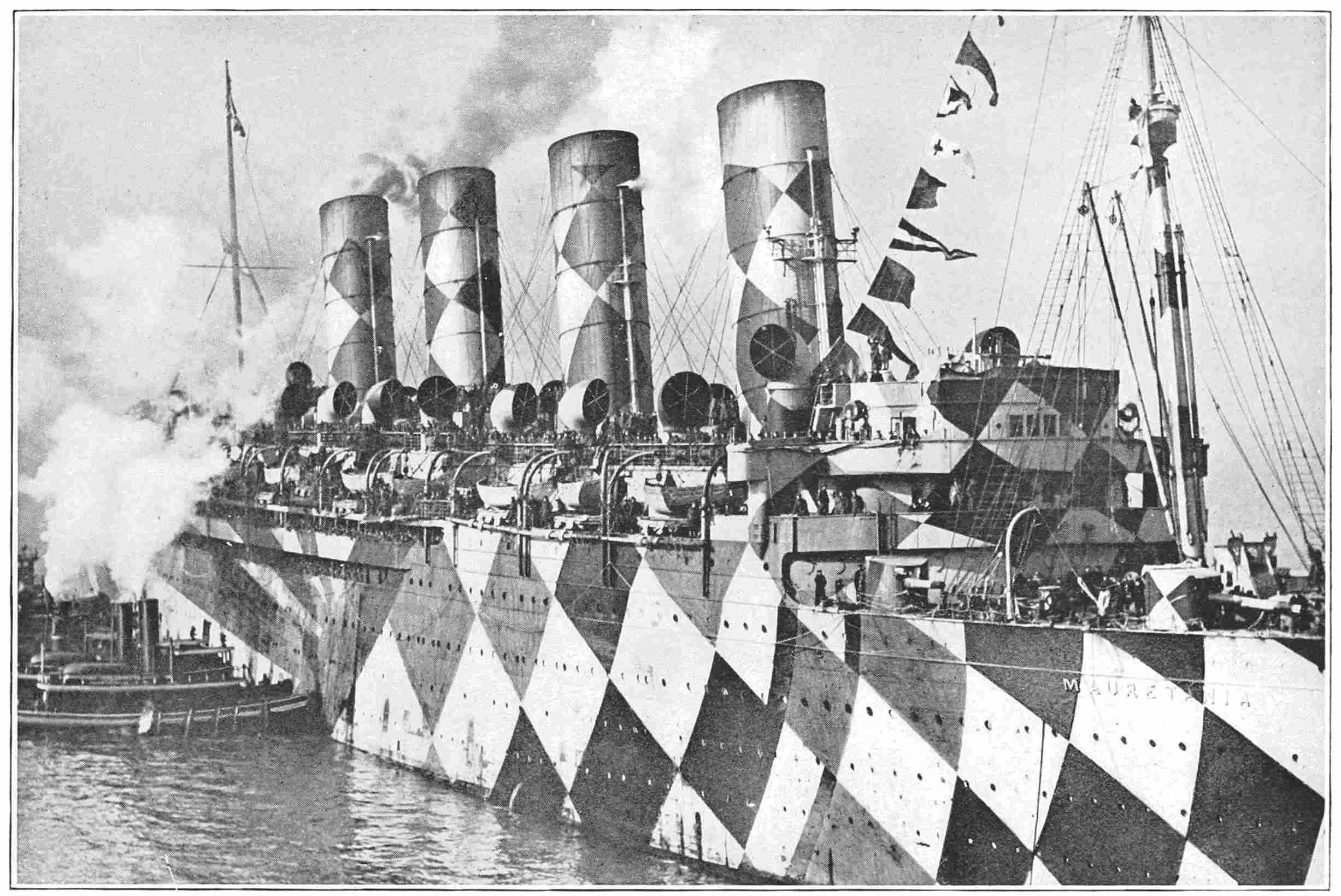

| The “Saxonia,” camouflaged, leaving New York with American troops for Europe | 80 |

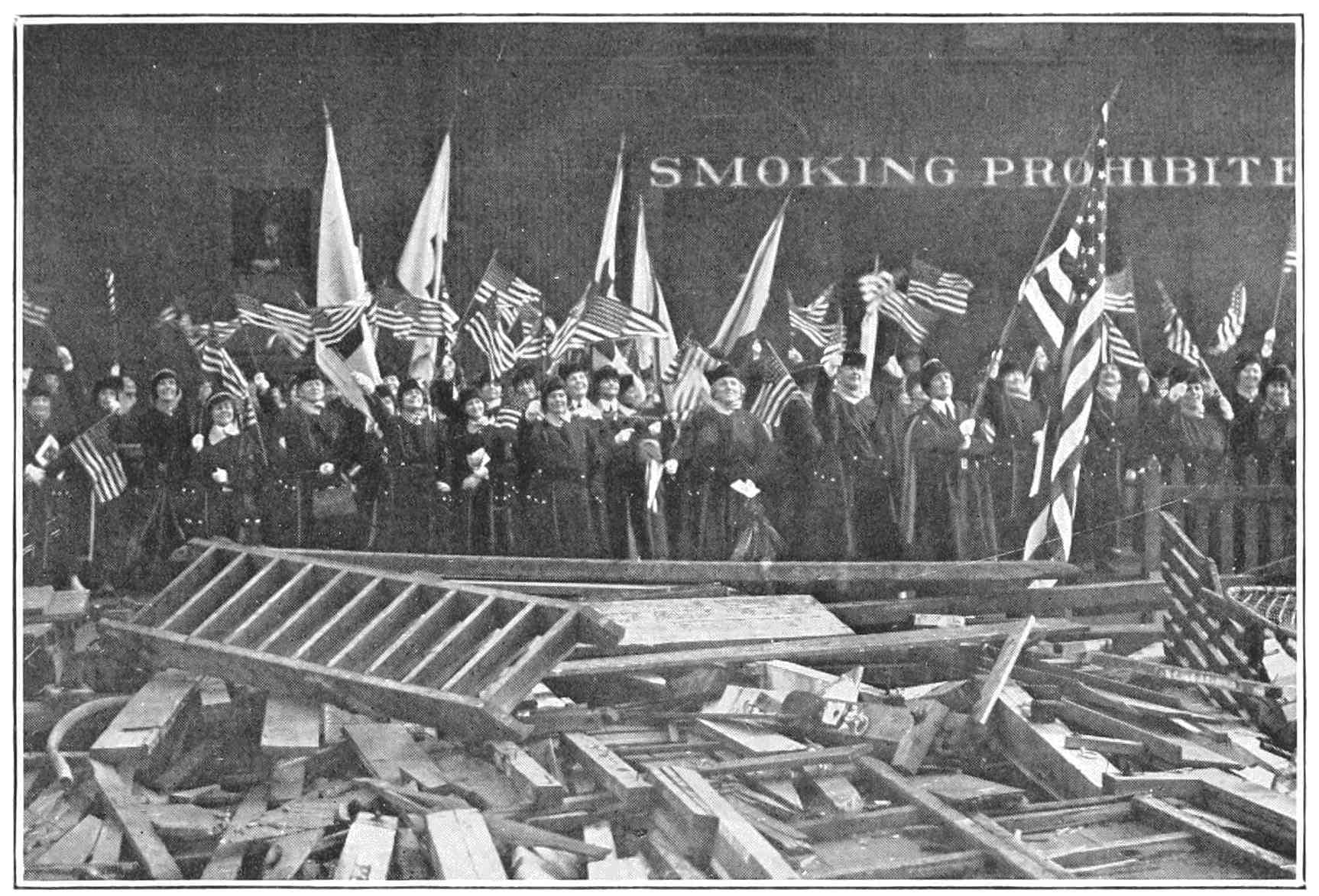

| Welcoming the first contingent of returning American troops, New York, December 1918 | 82 |

| The “Mauretania” arriving at New York, December 1918 | 82 |

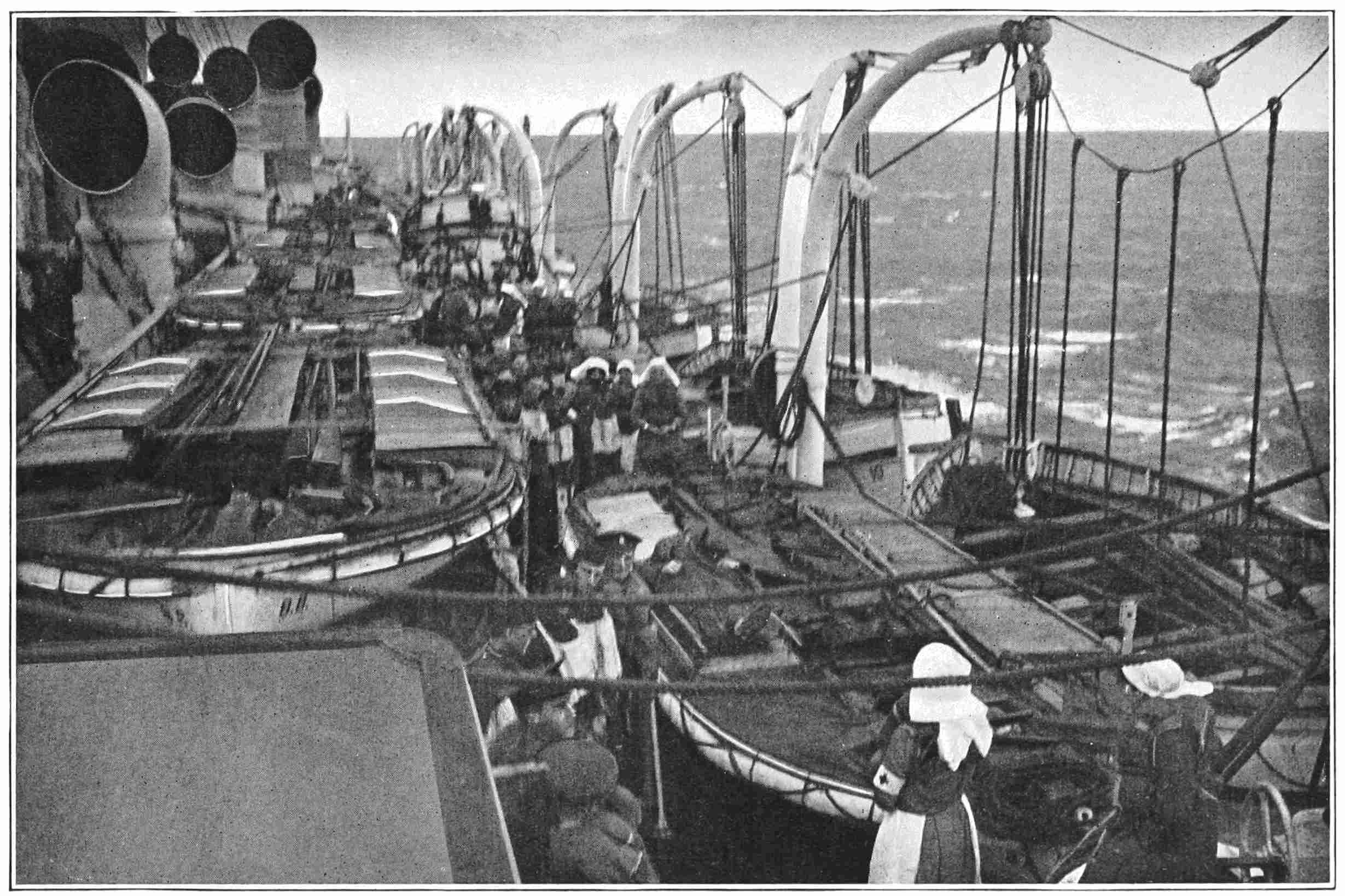

| Boat drill on a Cunard hospital ship | 86 |

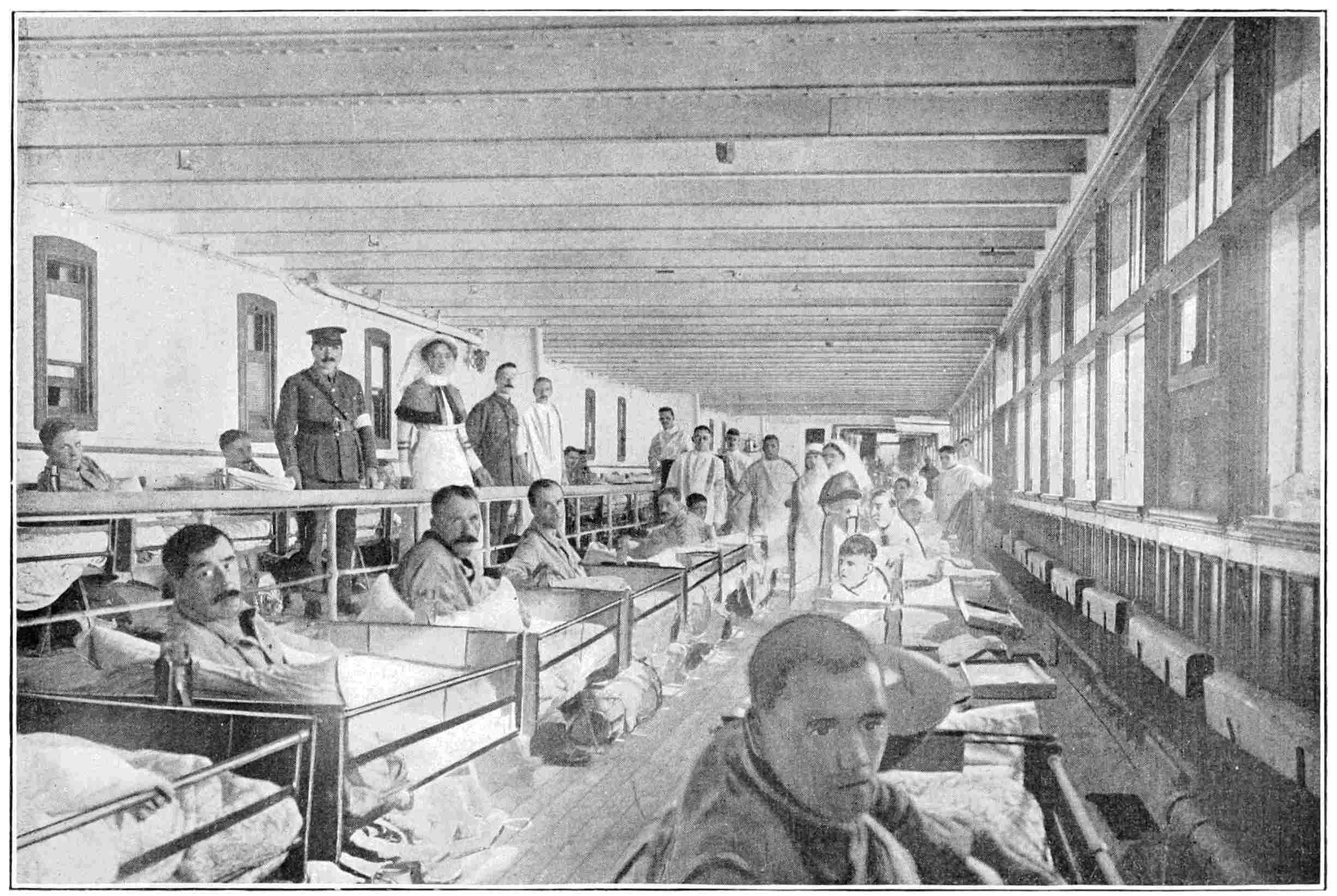

| The “Aquitania’s” garden lounge as hospital ward | 88 |

| The “Aurania” ashore after being torpedoed | 90 |

| The “Ivernia” settling down | 90 |

| The “Ivernia” survivors arriving in port | 94 |

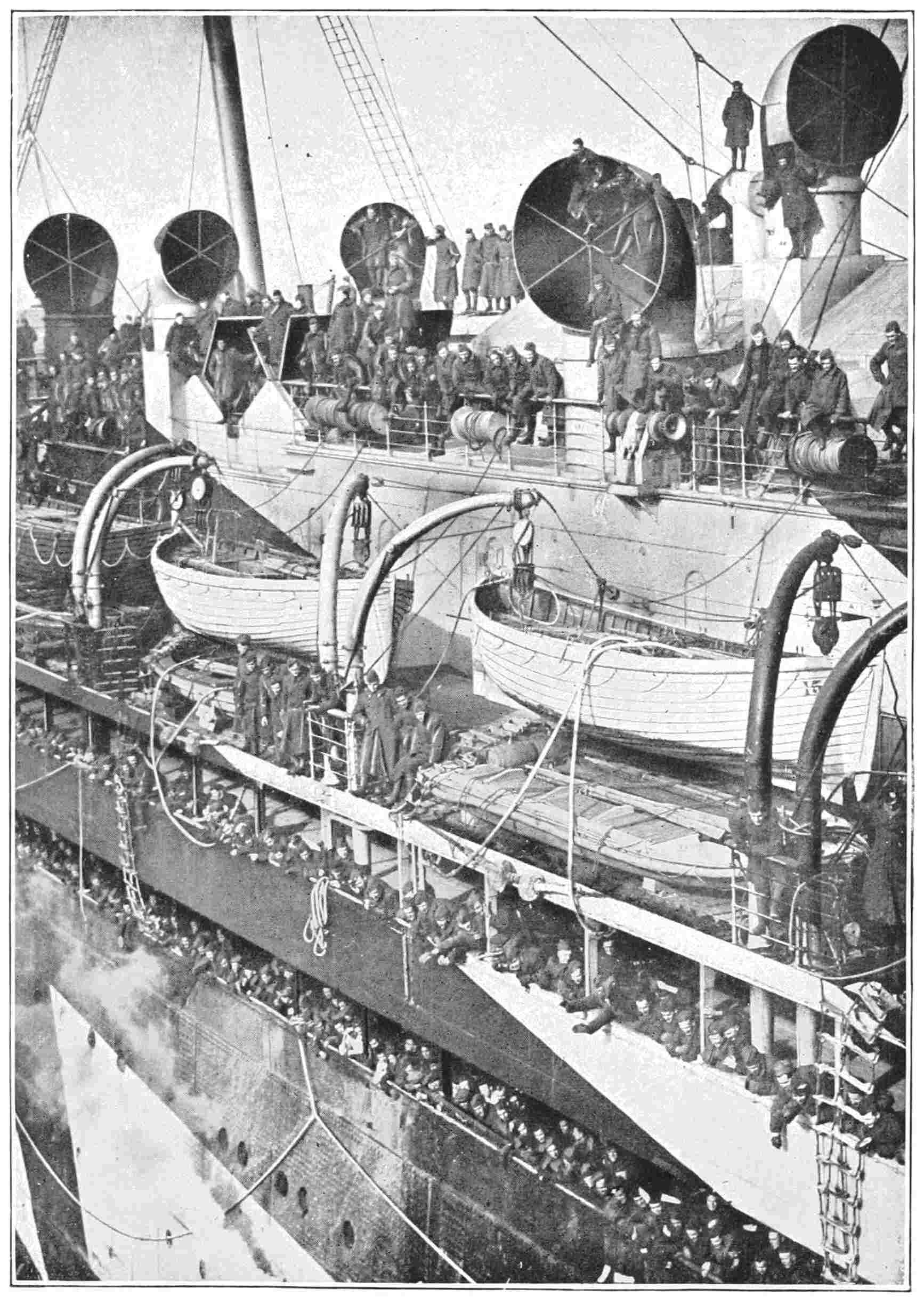

| Troops landing from the “Mauretania” | 94 |

| The “Dwinsk” settling down after being torpedoed | 96xvi |

| Survivors from the “Dwinsk” after eight days in the lifeboat | 96 |

| The “Mauretania” leaving Southampton | 98 |

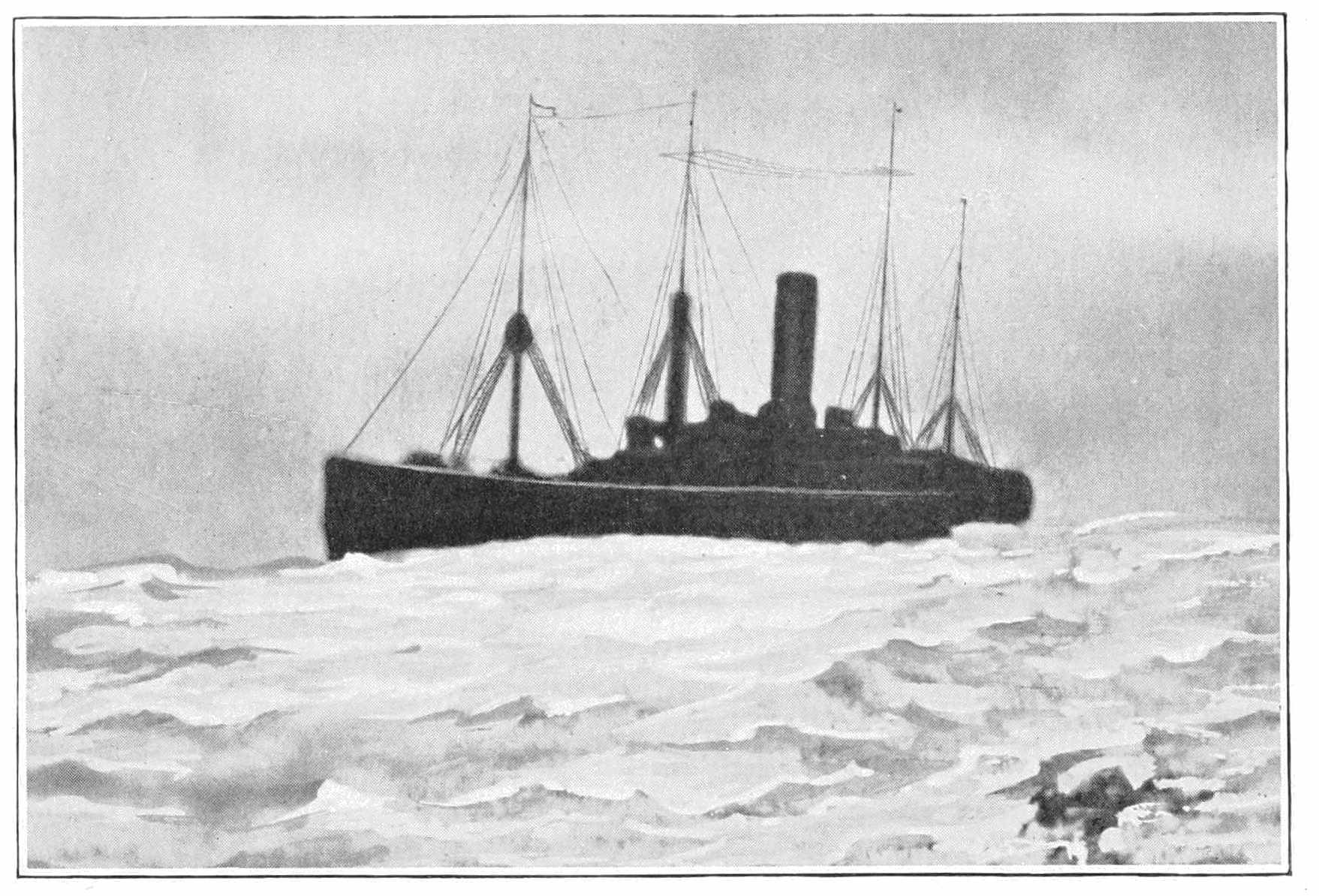

| “Father Neptune” cared little for the preying submarines | 102 |

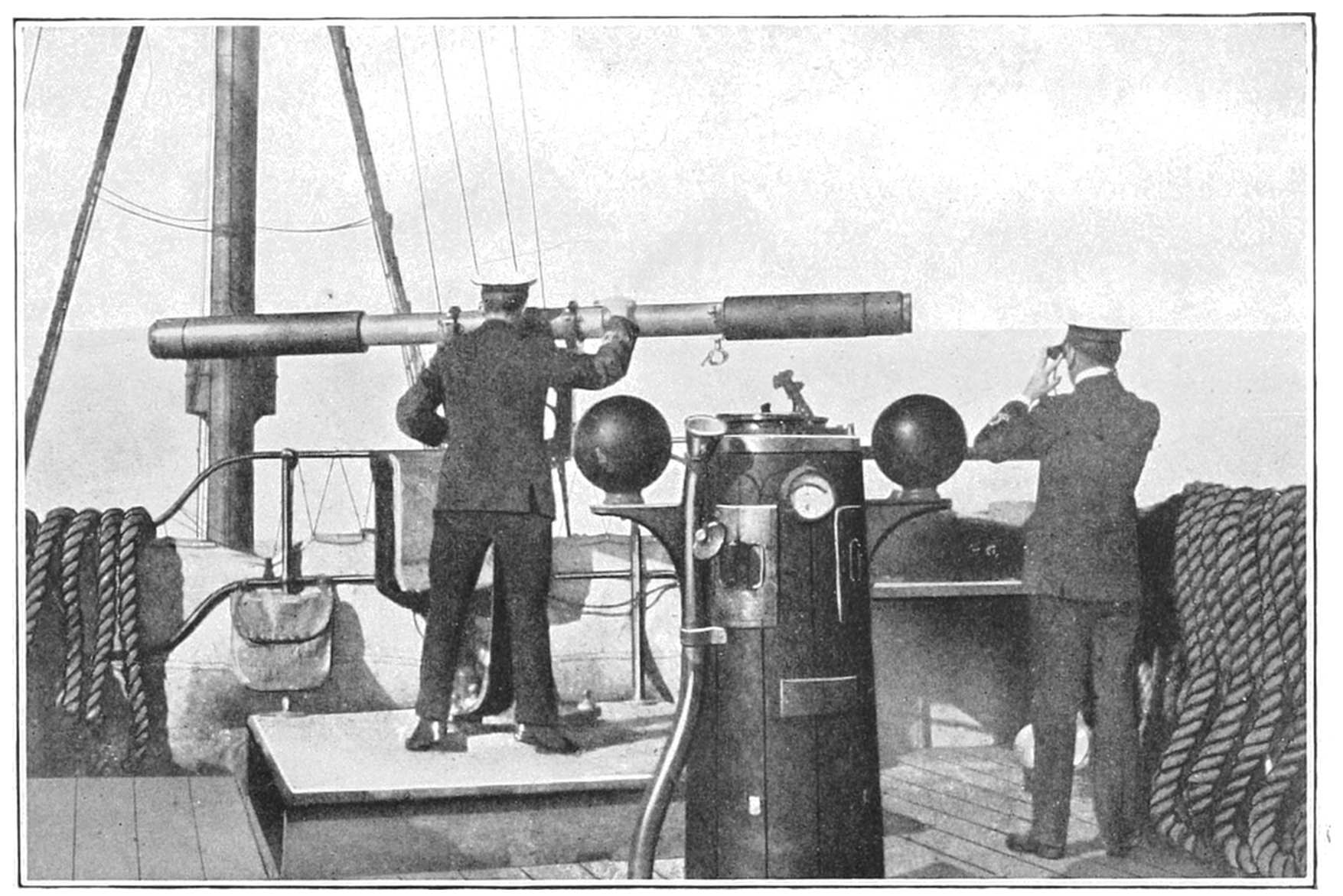

| An armed cruiser’s range finder | 102 |

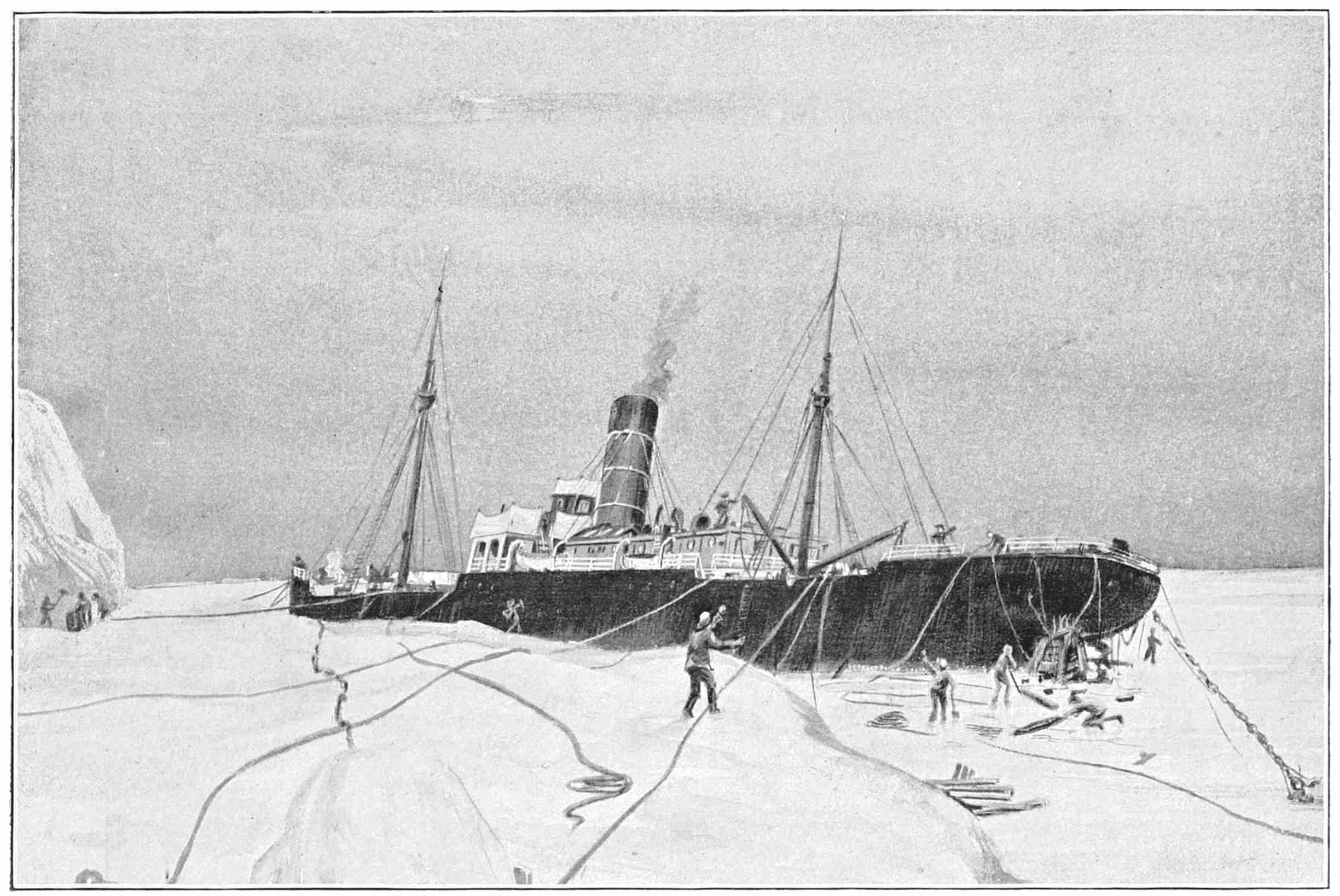

| The “Thracia” fast | 104 |

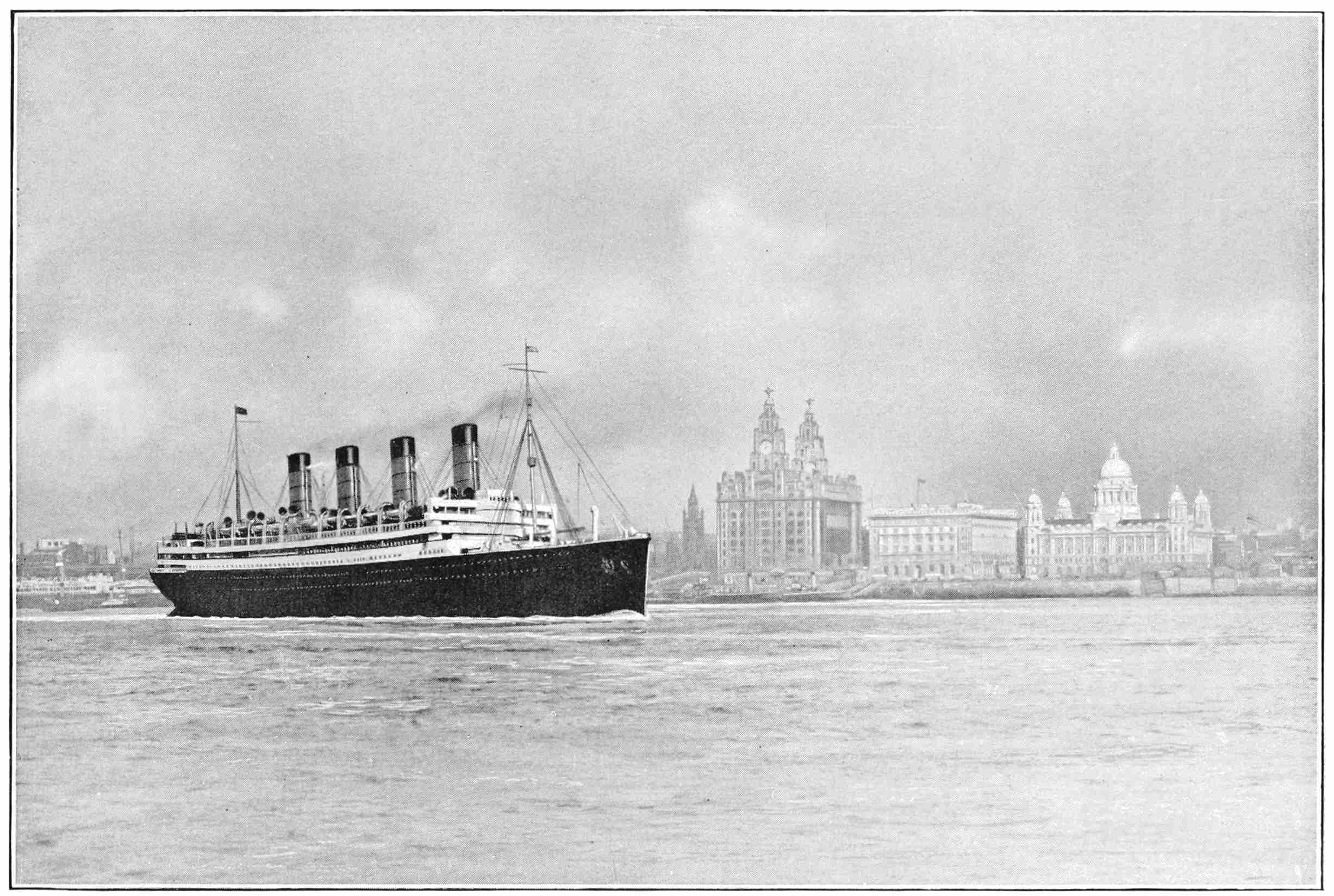

| The “Aquitania” re-appears in the Mersey | 106 |

| Officers of the torpedoed “Franconia” | 110 |

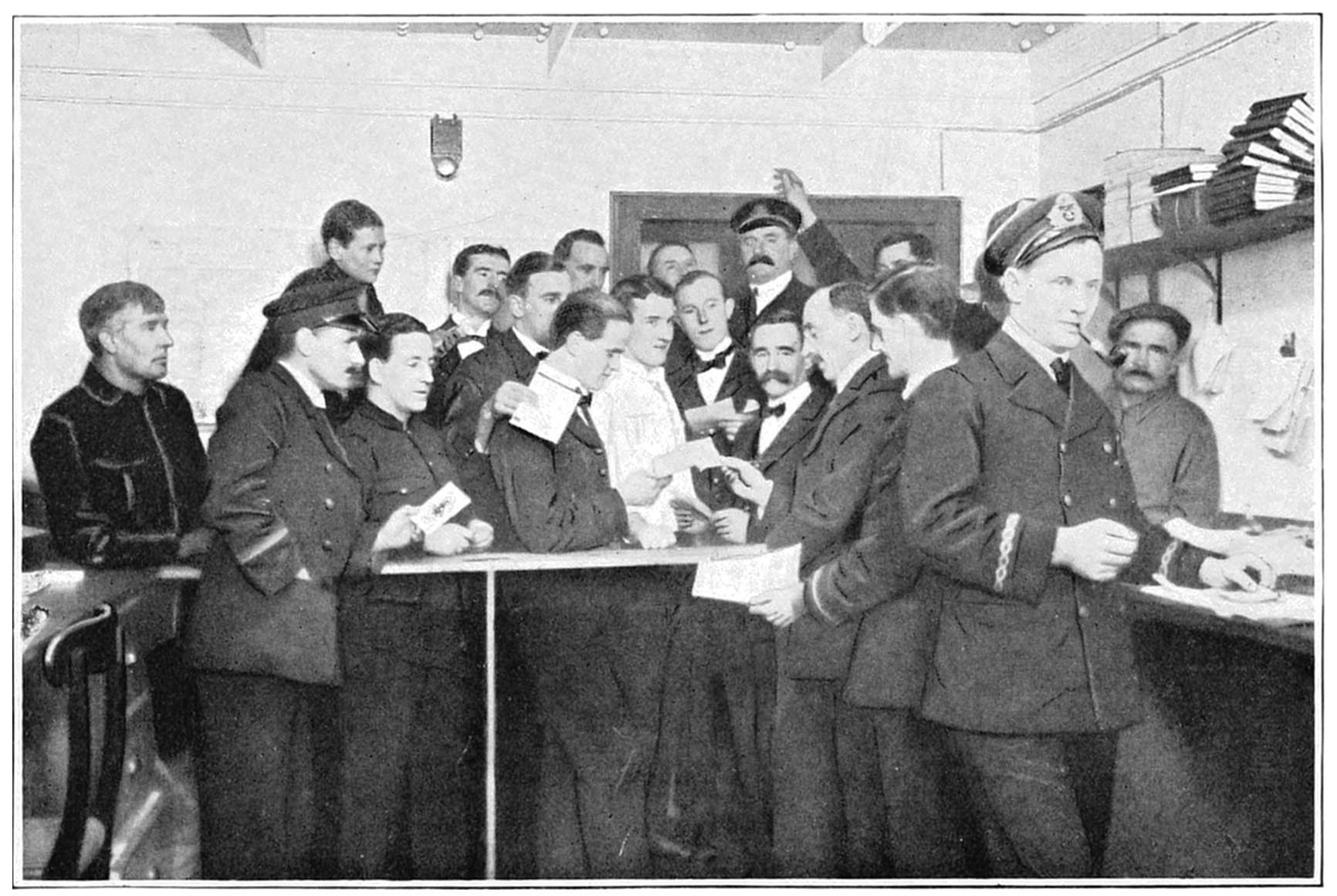

| A Cunard crew buying war savings certificates | 110 |

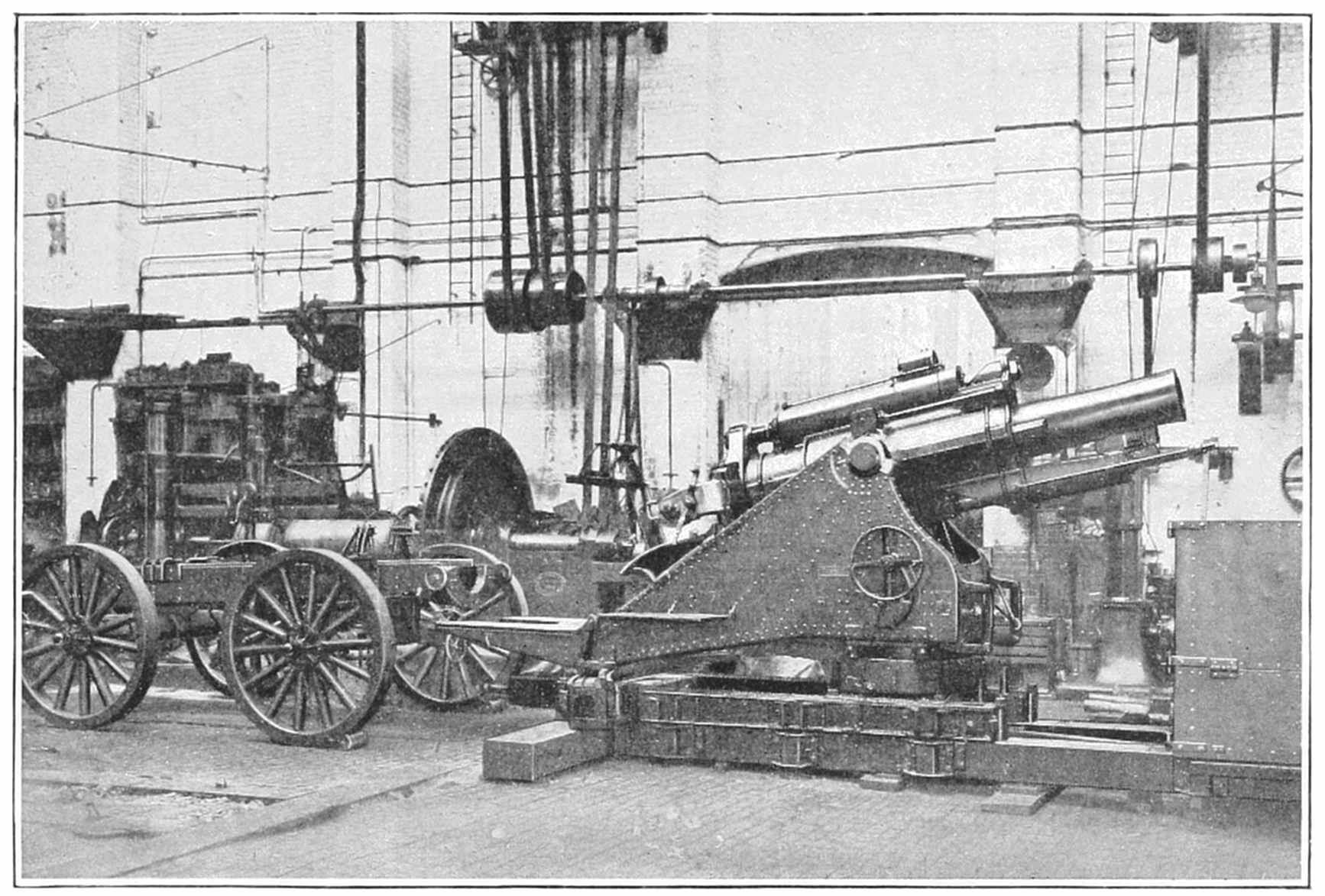

| One of the American howitzers, assembled at the Cunard works | 112 |

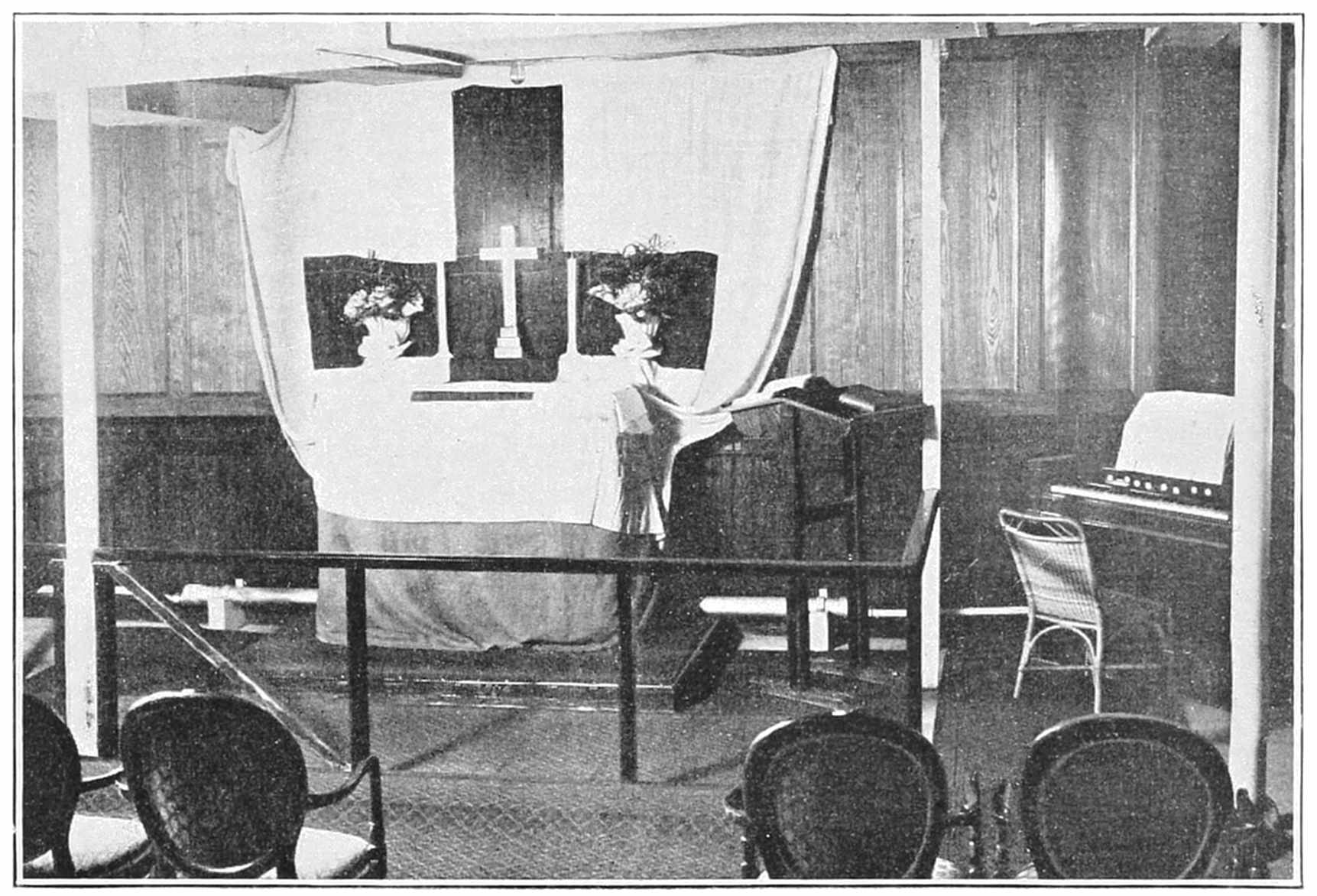

| The “Aquitania’s” chapel | 112 |

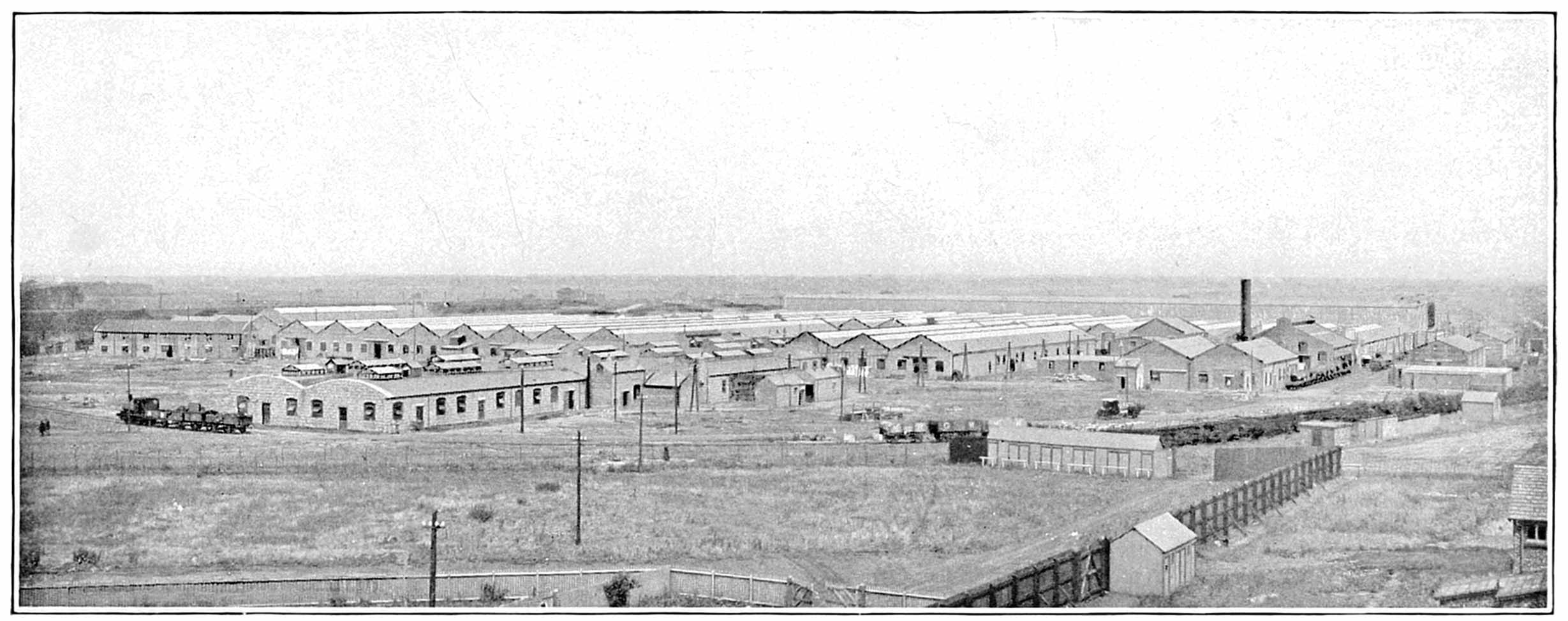

| Cunard national aeroplane factory | 114 |

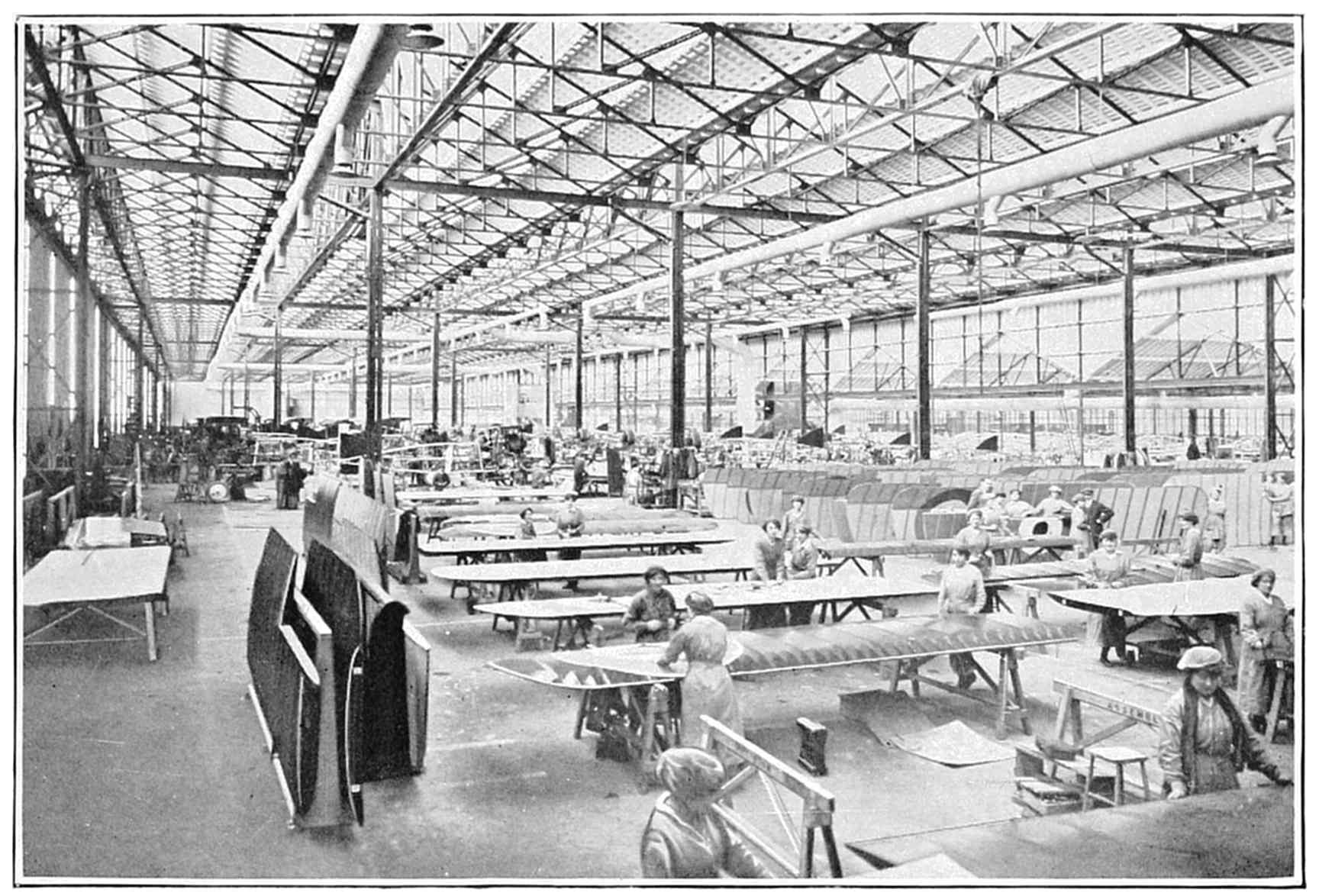

| Interior of the aeroplane factory (i) | 118 |

| Interior of the aeroplane factory (ii) | 118 |

| Interior of the aeroplane factory (iii) | 120 |

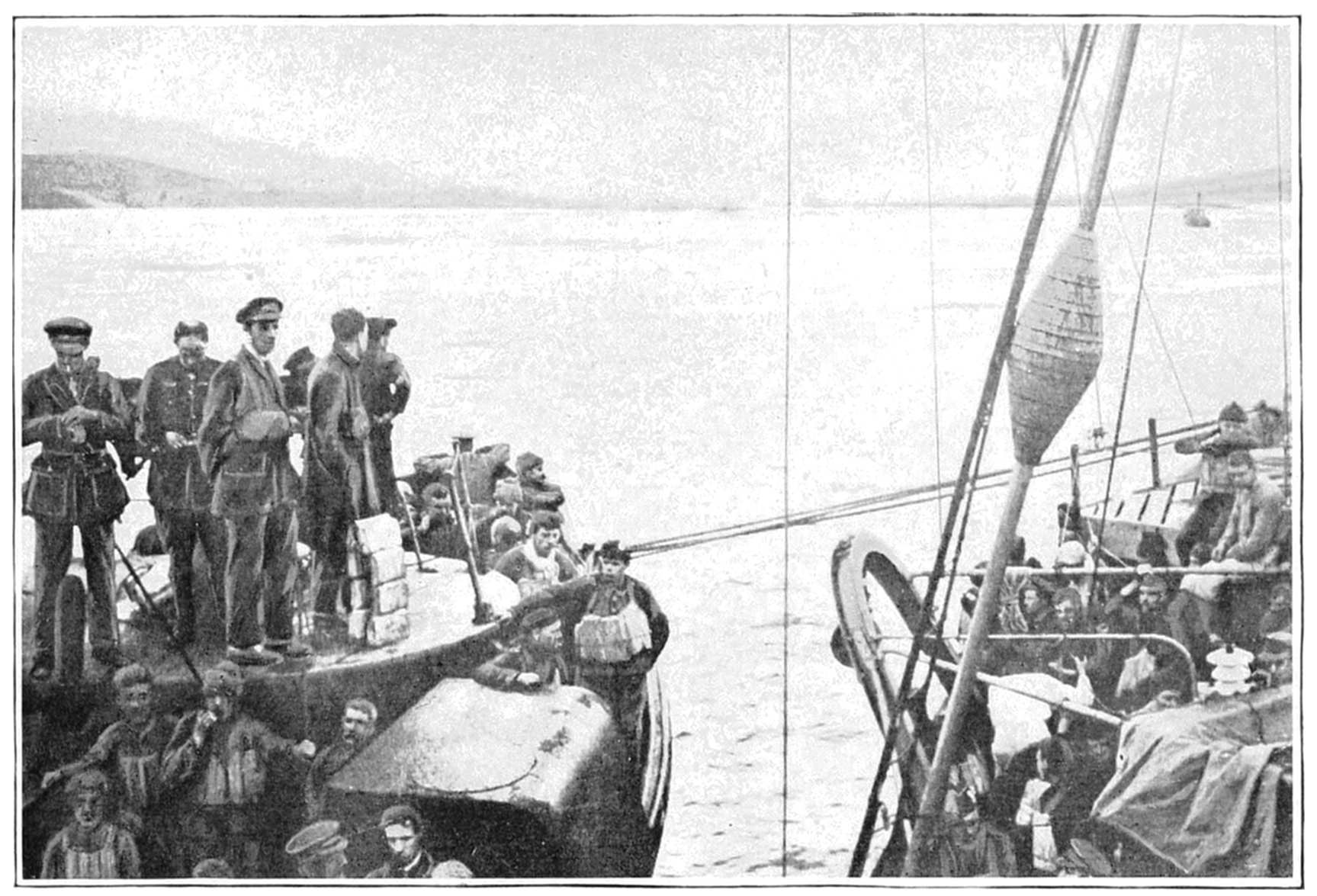

| Russian refugees on the “Phrygia” | 120 |

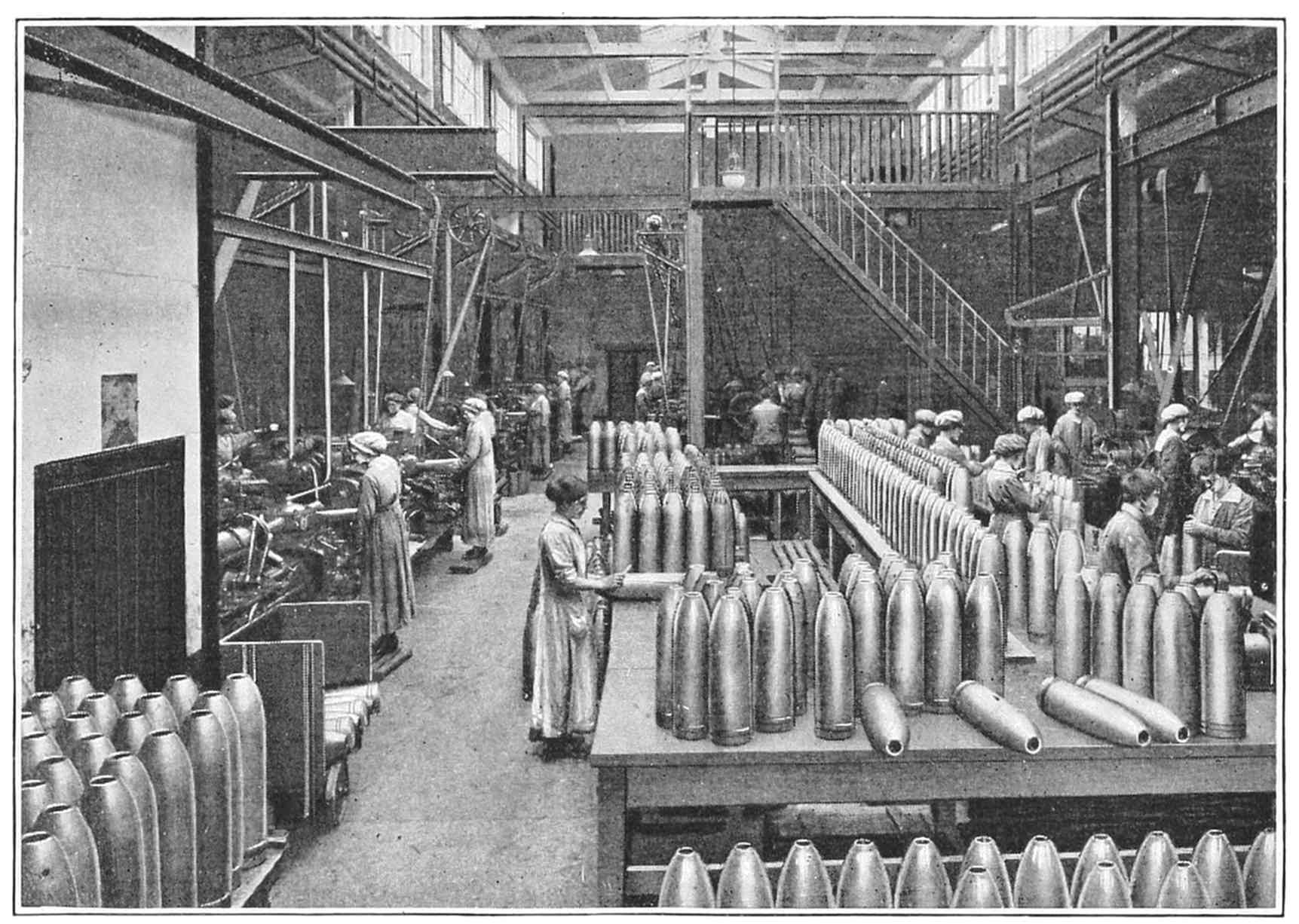

| One of the rooms in the Cunard shell works | 122 |

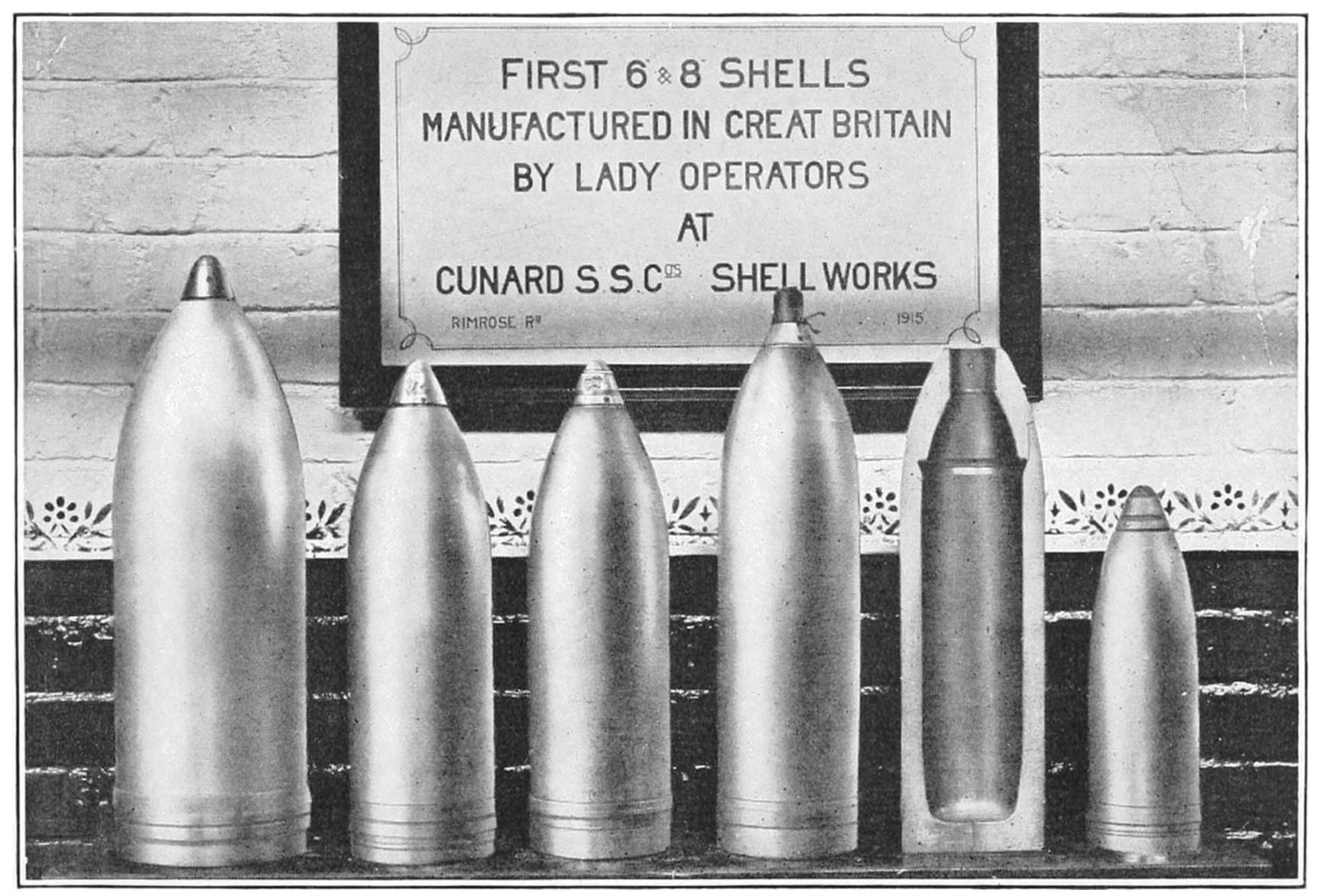

| A Record of “striking” value | 122 |

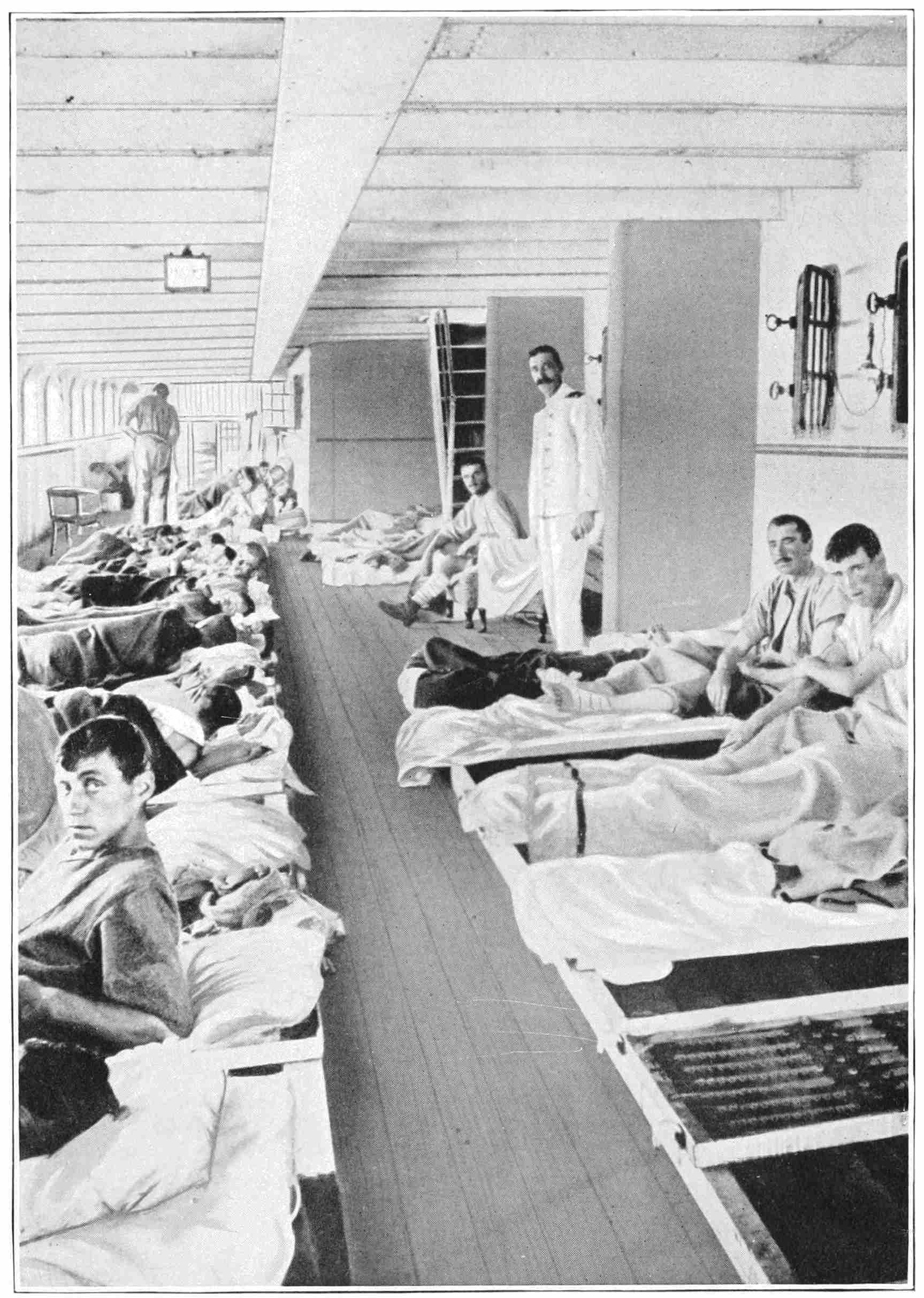

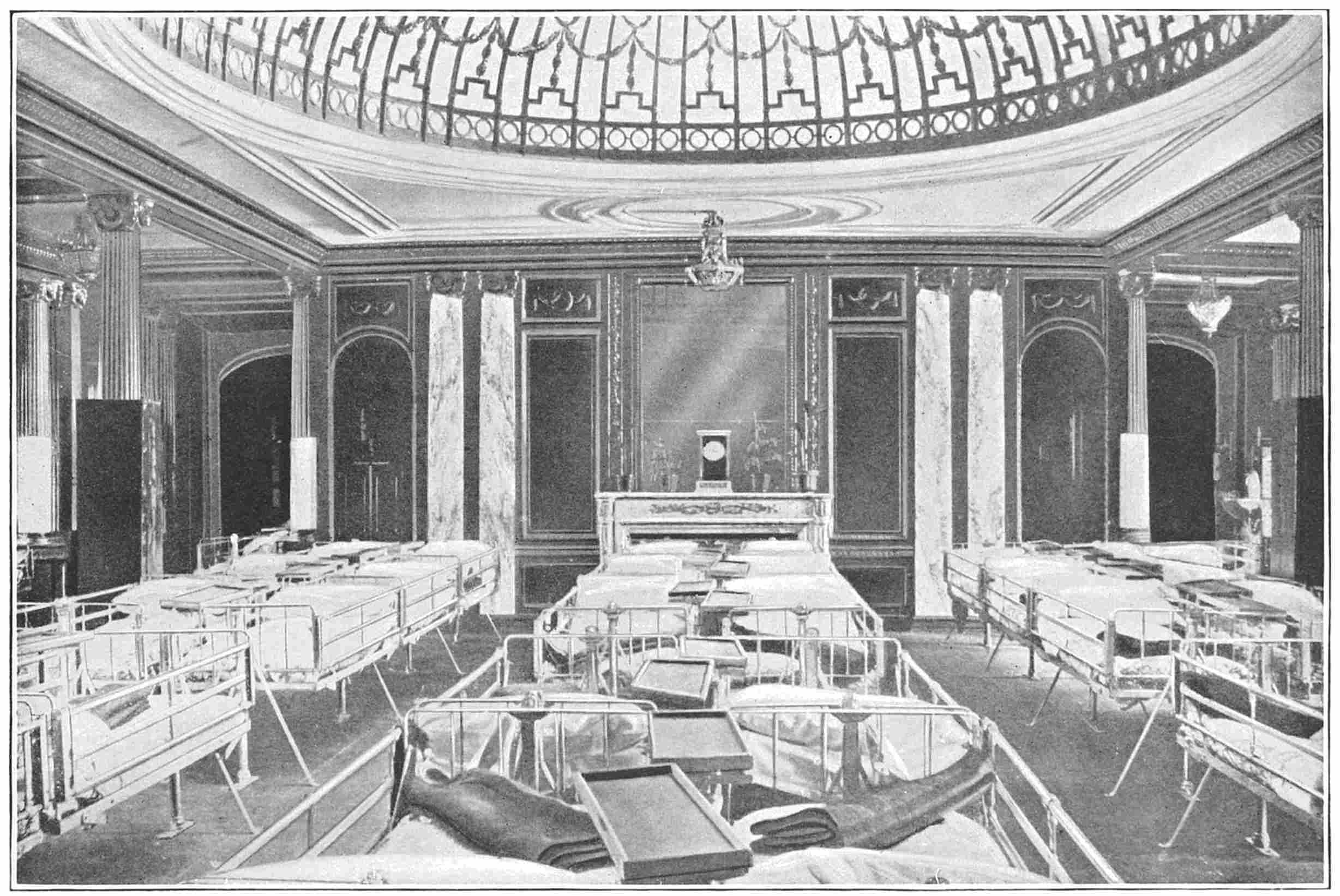

| A hospital ward in the lounge of the “Mauretania” | 126 |

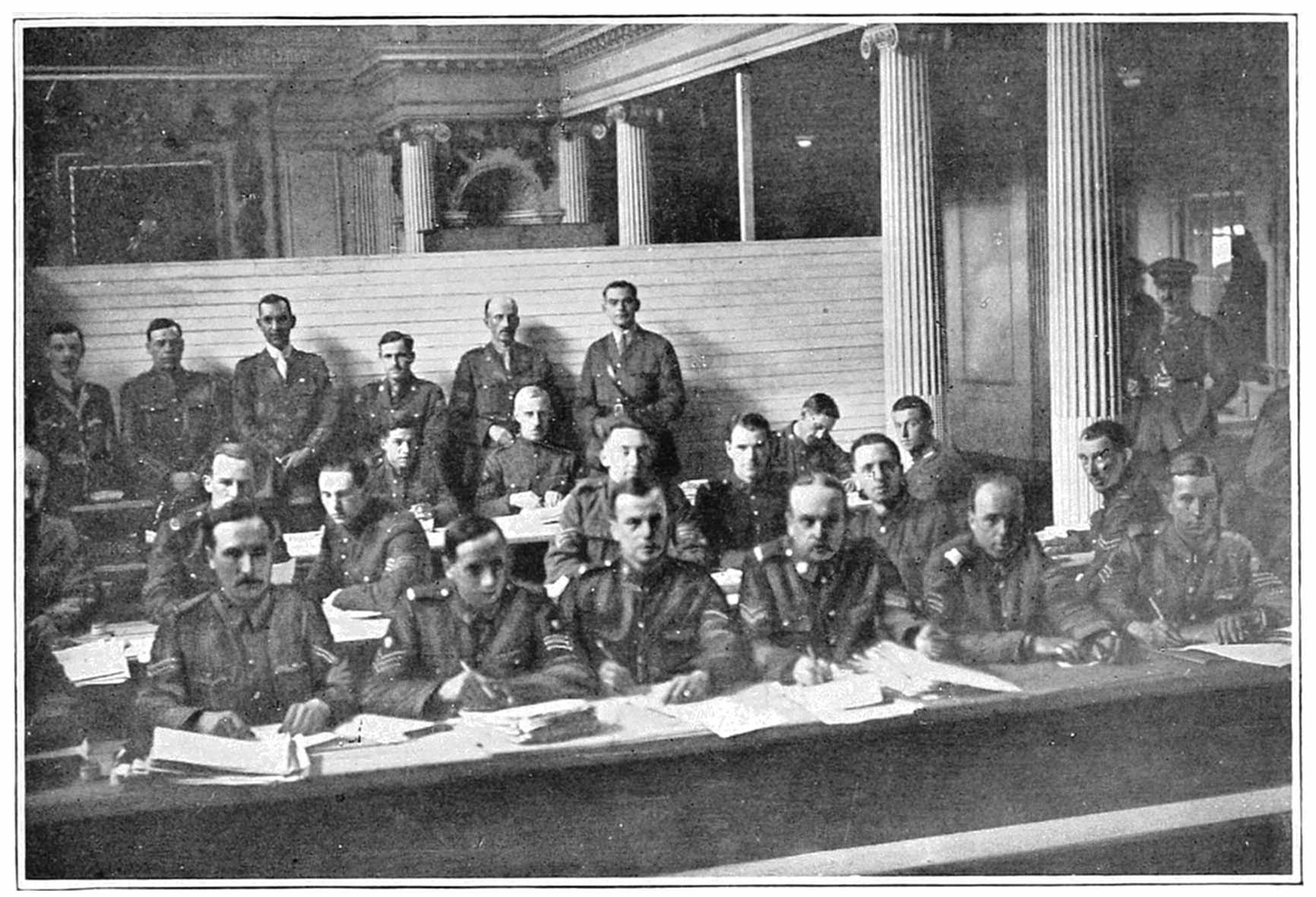

| The “Aquitania” lounge as orderly room | 128 |

| Officers’ ward in the smoking room of the “Aquitania” | 128 |

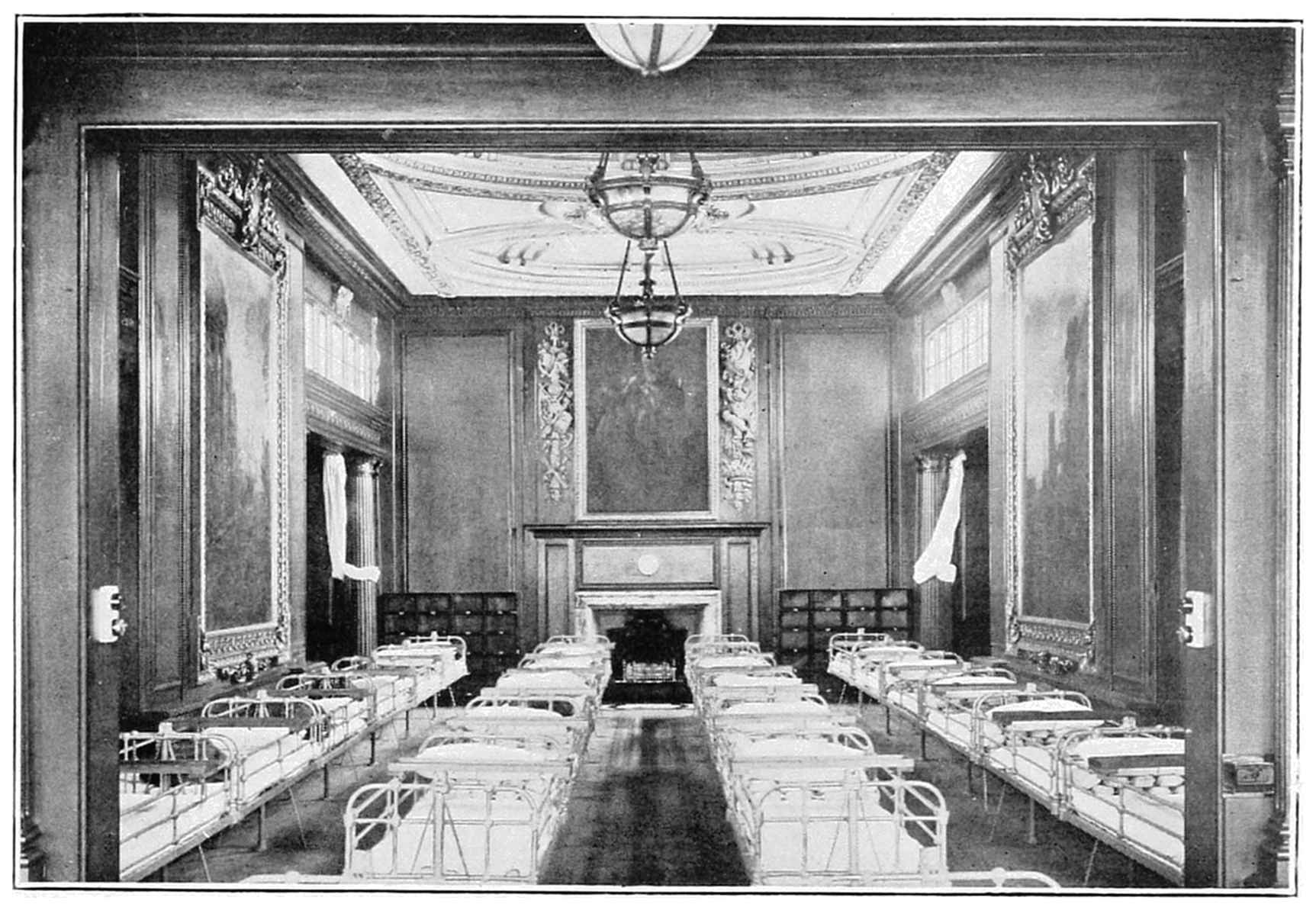

| Men’s ward in the lounge of the “Aquitania” | 132 |

| The “Franconia” sinking | 136 |

xvii

There was never a time in our history when the value of the Mercantile Marine to our national life was as apparent as it is to-day. After passing through the crucible of war, we are what we are, mainly, because we are the possessors of ships.

When the Great War came, we possessed only a small, though highly trained, Army, and the guns of our Navy extended little further than high-water mark. How could we, a community of islanders, in partnership with other islanders living in Dominions thousands of miles away, hope to make our strength felt on the battlefields of the Continent of Europe, where the military Powers were mobilising conscript armies counted not by thousands, but by millions? The original Expeditionary Force, as finely tempered a fighting instrument as ever existed, was at once thrown across the Channel in merchant ships and it held in check the victorious army of Germany, saving by a miracle, the Channel ports; then, having mobilised on the eve of the declaration of war, the Royal Navy, the great protective force ofxviii the British peoples, we mobilised also the Merchant Navy, their essential sustaining force, bridged the oceans of the world, and concentrated on the conflict the enormous and varied powers of the 400,000,000 inhabitants of the Commonwealth. In Belgium and France as in the Pacific, in Gallipoli as in Eastern Africa, in Salonica as in Mesopotamia, and in Italy as in Palestine, British troops were soon confronting the forces of the Central Alliance; every ocean was dominated by British men-of-war. The enemies had the advantage of interior military lines, but by the aid of ships—carrying troops, munitions, and stores—we gradually forged a hoop of steel round them and slowly but irresistibly drew it tighter and tighter until, their economic power having been strangled by sea power, their naval and military power was weakened and they were compelled to sue for peace. If it had not been for our ships—ships of commerce drawing strength from the seas, and ships of war, efficiently policing those seas—the Allies could not by any possibility have won the Great War and Germans would to-day be the dominant race, not only in Europe, but in both hemispheres.

xix

It is a common error to think of sea power in terms only of battleships, cruisers, destroyers and submarines. The secret of the spread of Anglo-Saxon civilisation, with its ideals of fair play, tolerance and personal liberty, its hatred of tyranny and love of justice, is not to be found as much in these emblems of organised violence as in merchant ships. Out of our island State the Merchant Fleet, a purely individualistic institution, developed by the compulsion of geographical necessities; the British people could not exist without ships even in days when their numbers were small and the standard of living was relatively low. The population has trebled in the last hundred years and the level of comfort of all classes has risen, and to-day the very existence of the 45,000,000 people of the British Isles, as well as their commercial and social relations with the other sections of the Empire, depends on the sufficiency and efficiency of the Mercantile Marine.

We possessed a trading Navy, with fine traditions of peace and war, long before we had a Fighting Navy. The owners of merchant ships for many centuries defended this country fromxx raids and invasions, just as it was the early merchant-adventurers who laid the foundations of the Empire. Thus as far back as the reign of Athelstan, we find this Saxon king granting a Thaneship—or, as one might say, a knighthood—to every merchant who had been three voyages of length in his own trading vessel. It was largely with the ships of merchant owners that in 1212 the English, by raiding France, prevented a French invasion, and that in 1340 one of the greatest British naval victories was won over vastly superior forces at the battle of Sluys. And though, by the time of the Armada, merchant ships were but as it were the core of the fleets that fought and destroyed the threatened world domination of Spain, they played an exceedingly important part in that epoch-making struggle, which marked the emergence of this Island as a world power. Similarly the Indian Empire, the early American Colonies, and many other British Possessions all over the world, were founded by merchant shipping enterprise alone. From time immemorial, the British merchantman has carried the flag to the outermost parts of the world and thus helped to maintain its prestige.

xxi

The Mercantile Marine and Navy have always been so closely knit that it is often difficult to separate their histories. The Mercantile Marine was in reality, as has been said, the parent of the latter. As the State grew, and civilisation became more complex, a process of separation between the ships of commerce and the ships of war was inevitable, and the Navy became more and more a distinct Royal Service. The increasing difficulties of the problems of defence, armament, and so on, led to a process of specialisation, and could only be adequately studied and the Empire’s growing needs supplied by a State Department. On the other hand, the Mercantile Marine remained, and still remains, individualistic, each merchant ship-owner, or company of ship-owners, building the sort of vessel best adapted to the particular enterprise in hand. Thus we have sailing from our ports, ships of all descriptions, ocean-going liners carrying passengers, cargoes and mails, as well as tramps, colliers, cold-storage vessels, and an infinity of other types.

But while this process of separation, or specialisation, has been both inevitable and fruitful, the Mercantile Marine has, in every war, beenxxii called upon by the Navy to provide transports, auxiliary cruisers, hospital and munition ships, and, in the recent Great War, minesweepers, submarine chasers, ‘Q’ ships, and many other equally vital subsidiaries. Similarly, in the personnel of the Mercantile Marine, the Navy has always had a powerful reserve, not only of experienced sailors, but of actual navally-trained officers and men. Without these, it is safe to say that the Navy could never have undertaken, or accomplished, those vast and world-wide, and many of them unforeseeable, tasks, so magnificently and successfully carried out; and it is equally true that but for the Mercantile Marine, the armies of the whole Alliance would have been paralysed.

In no history, however long and laboriously compiled, would it be possible to do full justice to the war-work of the British Mercantile Marine, but the present volume supplies, at any rate, an index to the scope and value of what it performed. In the re-action of one unit, of one old, honourable, and successful merchant shipping Company to the demands of the world war, it is perhaps possible to realise more clearly than byxxiii making a wider sweep of research, the amazing accomplishments of the whole; and where all rose, with magnificent unity, to heights of service never surpassed in our annals, none excelled either in the prescience or organizing ability of its directors, in the courage and resource of its captains and crews, or in the loyalty and ingenuity of its skilled and unskilled employees, the record of the Cunard Steamship Company.

1

In order to obtain the truest conception of what the Cunard Company stood for in 1914, it will be well not only to consider very briefly its first origin and steady growth, but to refresh our memories by recalling one or two of the tidemarks of ocean-going navigation. Thus it was in 1802, in the year, that is to say, following Nelson’s great victory at Copenhagen, in the year of the2 Peace of Amiens, and three years before the Battle of Trafalgar, that the first successful, practical steamer was launched. This was the Charlotte Dundas, built by William Symington on the Forth and Clyde Canal, and fitted with an engine constructed by Watt, which drove a stern wheel. This vessel proved to be an inspiration to Robert Fulton, who in 1807 built the Clermont at New York, a wooden steamer 133 feet long, engined by Bolton and Watt. In the autumn of that year, this vessel made a trip from New York to Albany, a distance of 130 miles in 32 hours, returning in 30 hours, and thenceforward maintained the first continuous long distance service performed by any steam vessel. Five years later Bell’s famous steamer, the Comet, began the earliest, regular steamer passenger service in Europe.

In 1814 the Marjory, the first steamer to run regularly on the River Thames, began her career; but it was not until 1819 that the Savannah, a wooden sailing ship of American construction, but fitted with engines and a set of paddles amidships, crossed the Atlantic, arriving at Liverpool after 29½ days. In the following year3 the Condé de Palmella was the first engined ship to sail across the Atlantic from east to west, namely from Liverpool to the Brazils.

These were but tentative experiments, however, and the Transatlantic Steamship Service, as we see it to-day, did not really begin till the year 1838, when the steamers Sirius and Great Western sailed within a few days of each other from London and Bristol respectively. Both ships crossed without mishap, the Sirius in 17 days, and the Great Western in 15. In the same year, the Royal William and the Liverpool crossed from Liverpool to New York in 19 days and 16½ days respectively.

It was now clear that a new era in transatlantic navigation had dawned, and the Admiralty, who were then responsible for the arrangement of overseas postal contracts, and had hitherto been satisfied to entrust the carrying of mails to sailing vessels, invited tenders for the future conveyance of letters to America by steam vessels. One of their advertisements, as it happened, came into the hands of Mr. Samuel Cunard; he was the son of an American citizen of Philadelphia, who had settled in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in4 which city he had been born in 1787. For some time the idea of developing a regular service of steamers between America and England had been simmering in Mr. Cunard’s brain. He was already in his 50th year, a successful merchant and ship owner; and he now resolved to visit England with the intention, if possible, of raising sufficient capital to put his ideas into practice. Armed with an introduction to Mr. Robert Napier, a well-known Clyde shipbuilder and engineer, he went to Glasgow, after having received but little sympathy in London. Through Mr. Napier he became acquainted with Mr. George Burns, a fellow Scotsman of great ability and long practical experience as a ship-owner, and through him with Mr. David McIver, also a Scotsman of sagacity and enterprise, then living at Liverpool. Between the three of them the necessary capital was obtained, and Mr. Cunard was able to submit to the Admiralty a tender for the conveyance of mails once a fortnight between Liverpool, Halifax, and Boston, U.S.A. His tender was considered so much better than that offered by the owners of the Great Western that it was accepted, and a contract for seven years was5 concluded between the Government and the newly formed British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, as it was then called.

Such was the beginning of the Cunard Company in the shape of four wooden paddle-wheel steam vessels, built on the Clyde, the Britannia, Acadia, Caledonia, and Columbia; and its history from then until 1914 was one of steady and enterprising, cautious and daring, development. This is not the place to linger in detail over the technical strides made since 1840 by the Cunard Company’s directors, but one or two of the more important milestones should perhaps be noted. In the year 1804, John Stevens in America had successfully experimented with the screw-propeller, and in 1820, at the Horsley Iron Works, at Tipton in Staffordshire, Mr. Aaron Manby had designed and built the first iron steamer. It had always been the policy of the Cunard Company to keep in touch with every new marine experiment, but at the same time it had been their wise habit, both from the commercial point of view and that of the safety of their passengers and crews, to move circumspectly in the adoption of new devices. It was not, therefore, until6 1852 that the first four iron screw steamships were added to their fleet, namely the Australian, Sydney, Andes, and Alps, four vessels that were also the first belonging to the Company to be fitted with accommodation for emigrants. For the next ten years, however, it was found that passengers still preferred the old paddle-wheel system, and side by side with their iron screw steamers, the Company continued to build these until, in 1862, the Scotia proved to be the last of a dying type. Meanwhile, in 1854, the Government was to realise another side of the value to the nation of the Cunard Company. During the Crimean War, in response to a strong Government appeal, the Company immediately placed at the Admiralty’s disposal, six of their best steamers, the Cambria, Niagara, Europa, Arabia, Andes, and Alps; later adding to these their two most recent acquisitions, the Jura and Etna. Throughout the campaign these eight vessels were continuously employed upon various important missions, supplying the needs of the military forces.

Perhaps the next most important era began with the invention in 1869 of compound engines,7 and in 1870 the Batavia and Parthia were fitted with these, and proved extremely successful, maintaining good speeds, with a reduced consumption of fuel. The Company was now sailing one vessel under contract with the General Post Office every week from Liverpool to New York, calling at Queenstown, and from New York to Liverpool, also calling at the South Irish port, and receiving a certain subsidy for so doing. They were also maintaining services between Liverpool and the principal ports in the Mediterranean, Adriatic, Levant, Bosphorus, and Black Sea, and between Liverpool and Havre. In 1881 the first steel vessel, the Servia, was built for the Cunard Company. This was the most powerful as well as the largest ship, with the exception of the famous Great Eastern, that the world had then seen. She was followed in 1884 by the Etruria and Umbria, the former of which in August, 1885, set up the record for speed from Queenstown to New York, the journey being accomplished in 6 days 6 hours and 36 minutes. In the meantime, research work, in the construction of marine engines had been continued, and Dr. Price had invented the triple expansion engine,8 which effected further considerable economies in the consumption of fuel; and these were fitted by the Cunard Company into the two great twin-screw vessels, the Campania and Lucania, built in 1893. With the Campania we shall deal again, as she performed valuable services in the late war, and it is interesting to note that it was on board the Lucania in 1901 that Mr. Marconi carried out certain important experiments in wireless telegraphy, this vessel being the first, under the Cunard management, to be fitted with a wireless installation.

Through all these years the Cunard Company had of course been submitted to very great competition in the transatlantic trade, not only by British lines, but by American and Continental shipping companies also; and in the year 1900 with the Deutschland and in 1902 with the Kaiser Wilhelm II, what has been called the “blue ribbon” of the Atlantic passed to Germany, these vessels having an average speed of 23½ knots. It was then decided that the supremacy in this respect, should, if possible, be regained by Great Britain, and, with Government help, and in return for certain definite prospective services if required,9 the Cunard Company laid down the Lusitania and the Mauretania. In 1907, these vessels making use of Sir Charles Parsons’ turbine engines, were put into service and soon afterwards attained a speed of over 26 knots, and the mastery, in respect of speed, of the Atlantic.

Enormous as were the proportions, however, of these huge vessels, they were yet to be eclipsed by the Cunard Company’s later and most recent giant, the Aquitania, a vessel that might more fitly be described as a floating city of palaces, libraries, art galleries, and swimming baths, than the steamship child of the little Britannia of 1840. Let us for a moment compare them, remembering that only the ordinary span of a human life-time intervened between them. The Britannia was 200 feet long, a wooden paddle-wheel steamer of 1,154 tons, 740 horse-power, and a speed of 8½ knots. The Aquitania is 902 feet long, of 46,000 tons, with quadruple screws driven by turbine engines of a designed shaft of 60,000 horse-power, maintaining a speed of 24 knots. With her Louis XVIth staircase, her garden Lounge, her Adams drawing-room, her frescoes, her Palladian lounge, her Carolean smoking-room, and her10 Pompeian swimming bath, she can carry in the comfort of a first-class hotel more than 3,200 passengers, together with a crew of over 1,000.

Such then has been what one may best call, perhaps, the technical advance of the Cunard Company, and in 1914, at the commencement of hostilities, it had in commission 26 vessels, apart from tugs, lighters, and other subsidiaries. Of these, since we shall presently deal with their individual adventures, the following list may be found convenient:

| Name of Ship. | Tonnage. Gross. |

| Aquitania | 45,646 |

| Mauretania | 30,703 |

| Lusitania | 30,395 |

| Caronia | 19,687 |

| Carmania | 19,524 |

| Franconia | 18,149 |

| Laconia | 18,098 |

| Saxonia | 14,297 |

| Ivernia | 14,278 |

| Carpathia | 13,603 |

| Andania | 13,404 |

| Alaunia | 13,404 |

| CampaniaA | 12,884 |

| Ultonia | 10,402 |

| Pannonia | 9,851 |

| Ascania | 9,111 |

| Ausonia | 8,152 |

| Phrygia | 3,353 |

| Brescia | 3,235 |

| Veria | 3,228 |

| Caria | 3,032 |

| Cypria | 2,949 |

| Pavia | 2,945 |

| Tyria | 2,936 |

| Thracia | 2,891 |

| Lycia | 2,715 |

A This vessel was sold for breaking up a few weeks prior to the outbreak of war. Her career as a warship is referred to in these pages.

11

From this it will be seen that the total tonnage possessed by the Cunard Company in 1914 was considerably over 300,000, and the Company was operating services not only between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and Canada, but also between the United States of America and the Mediterranean, as well as from Liverpool and other British ports to the Mediterranean and France.

12

With the war now over, and after five years, during which the public mind has been accustomed to emergency arrangements of all sorts, nothing is more difficult than to reconstruct the enormous and unprecedented activities that were called so suddenly into being in the first war weeks of 1914; and in these the Cunard Company had a typical and vitally important part to play. Of the number of navigating officers in their employment, namely 163, no fewer than 139 were in the Royal Naval Reserve, and as such were immediately mobilised, being instructed to report themselves for naval duty upon their arrival in13 a British port; and by the end of the year 131 of these officers had actually done so. Nor was this the least of the problems that the Company had to face, in that, at a time when not only every reliable officer and man was worth his weight in gold to them, so large a proportion of their best and most highly trained servants had thus to be yielded up to the senior service.

In the latest agreement arrived at with the Government in 1903, the whole of the Cunard Fleet was, in time of war, to be placed at its disposal, and there was considerable uncertainty at first as to the various purposes to which the ships might be allocated. In the present chapter we shall confine ourselves to dealing with those of the Cunard vessels that were commandeered by the Admiralty for strictly combatant purposes, of which the more important were the Aquitania, Caronia, Laconia, Campania, and Carmania; and since the Campania had only just passed from Cunard control, it may be well, perhaps, in view of her distinguished and lengthy service under the Company’s flag to deal with her first. She became a seaplane carrier; after having at first however, taken a large share in repatriating14 Americans stranded in the British Isles owing to the exigencies of war. Her after funnel was removed and a smaller one put abreast of the forward funnel; and this alteration, together with the dazzle paint with which she was at a later date covered, rendered her almost unrecognisable even to the old Cunarders who had been familiar with her for many years. Throughout the war she was fortunate in escaping injury both from enemy gunfire and submarine attack, and her honourable career only came to an end at the conclusion of the armistice, when she was accidentally sunk in collision with H.M.S. Revenge in the Firth of Forth.

Turning now to the other vessels, the Aquitania and Caronia, these were fully dismantled and fitted out as armed cruisers in the first days of August, 1915. This, of course, meant the ruthless stripping out of all their luxurious fittings and those splendid appointments to which reference has been made in the last chapter; and for all these articles storage had to be found on shore at the shortest notice. Some idea of the work involved in this conversion can best be gathered perhaps, by realising that no less than 5,000 men were employed upon this herculean task, and15 that more than 2,000 waggon loads of fittings were taken ashore from these two liners. While these two ships were thus being fitted, yet a third, the Carmania, arrived in port to be similarly transformed; and a brief account of what took place on board this famous vessel may be taken, perhaps, as typical of what occurred in all three.

Arriving at Liverpool landing stage at 8 o’clock in the morning of August 7th, 1914, she was almost immediately boarded by Captain Noel Grant, R.N. and Lieutenant-Commander E. Lockyer, R.N., who were to be respectively her Captain and First Lieutenant under the new conditions. At that moment she looked about as unlike a man-of-war as she could well have done. From half a dozen gangways, baggage was being landed at express speed, while first and second class passengers were also going ashore from the overhead gantries. Owing to the fact that there were known to be Germans amongst the passengers on board, a considerable number of police and custom officials were present upon the vessel; and this necessitated the detention of a large number of third-class passengers, who had to be carefully scrutinised and sorted out.

16

While all this was going on arrangements for the new equipment and personnel of the vessel were already being discussed, and the proportions of Cunarders and Naval ratings for the Carmania’s future war service being determined. It was decided that the engine staff was to be Cunard, the men being specially enrolled for a period of six months in the Royal Naval Reserve, while the Commander of the ship, Captain J. C. Barr, was to remain on board as navigator and adviser to Captain Grant, with the temporary rank of Commander R.N.R. The Chief Officer, Lieutenant Murchie, with certain other officers, also remained on board, Lieutenant Murchie, owing to his special knowledge of the ship, ranking next to Lieutenant-Commander Lockyer for general working purposes. The ship’s surgeon, her chief steward and about 50 of the Cunard ratings for cooks, waiters, and officers’ servants, were also retained, as well as the carpenter, who was kept on board as Chief Petty Officer and given six mates, the cooper, blacksmith, plumber, and painter, being also retained with the same rank.

Leaving the stage about noon, the Carmania was immediately docked at Sandon, where after17 some further delay the third-class passengers were landed. Owing to the fact that the Caronia was already in the Carmania’s proper berth, being fitted out as an armed cruiser, and that both she and the Aquitania were already well on the way to completion for their new task, the Carmania could for the moment neither discharge her cargo nor bunker owing to the shortage of labour. As many painters, however, as could be assembled began at once to alter her hull and funnels, blackening out her well-known red and black tops, while a gang of shipwrights started to cut out the bulwarks fore and aft on the ‘B’ deck, in order to allow of the training to suitable angles of the guns that were to be placed in position there. Other Cunard stewards and joiners also concentrated at once upon the task of clearing out passenger accommodation from the vessel. During Saturday and Sunday the Carmania remained in the basin, and it was on this day that her future midshipmen turned up, and had to be provided with accommodation in the midst of the existing confusion. On Monday she was able to get an empty berth, where she began at once to discharge her cargo, and to18 bunker at express speed. Armoured plates were now being put in position upon all her most vulnerable parts, and these were also being re-inforced with coal and bags of sand by way of extra protection. All the woodwork in the passengers’ quarters was being taken away; two of her holds were being fitted with platforms and magazines were being built on them; while means for flooding were also being installed, speaking-tubes fitted in the aft steering gear room, control telephones being run up, and her eight guns placed in position.

These were all of 4.7 inch calibre and with a range of about 9,300 yards. In addition a 6 ft. Barr and Stroud range-finder was being fitted, together with two semaphores. Two searchlights were being mounted on slightly raised platforms on the bridge ends, while two ordinary lifeboats and eighteen Maclean collapsible boats were retained for war purposes. By Wednesday all the coal was in, all the bunkers being full, and the protection coal was in place. At 5 o’clock the next morning, the Naval ratings in charge of Lieutenant-Commander O’Neil, R.N.R., arrived from Portsmouth, most of them being19 R.N.R. men, but a good many belonging to the Royal Fleet Reserve, while the Marines on board were drawn in equal proportions from the Royal Marine Artillery, and the Royal Marine Light Infantry. The able seamen were for the most part Scotch fishermen of the finest type.

On the same day messing, watch, and sleeping arrangements were made, ammunition was taken aboard and stored in the magazines, together with a limited number of small arms, in addition to the marines’ rifles: and so unremitting had been the work of all engaged, and so efficient the organisation evoked by the crisis, that the Carmania was actually at sea as a fully equipped armed cruiser by Friday, August 14th, only a week after she had entered port as an ordinary first-class Atlantic liner. With her later adventures we shall deal in a moment, but before doing so let us follow the adventures of the other three vessels that were converted into armed cruisers.

The Aquitania, fitted with 6-inch guns, sailed on August 8th, but unfortunately was damaged in collision and on returning to port was dismantled at the end of September. From May to August, 1915, she was employed in carrying troops, when20 she was fitted out as a Hospital Ship, in which capacity she continued to work until April of the following year. She was again requisitioned as a Hospital Ship in September, 1916, plying between England and the Mediterranean until Christmas. She was then laid up by the Government for the whole of 1917, and in March, 1918, was again put into commission by the Admiralty as a transport, and played an important part in bringing American troops to Europe at that critical time.

The Caronia had a somewhat longer career as an armed cruiser. She was commissioned on 8th August, 1914, by Captain Shirley-Litchfield, R.N., with Captain C. A. Smith, Cunard Line, as navigator. She sailed from Liverpool on August 10th, for patrol duties in the North Atlantic, being attached to the North American and West Indies Station, under the command of Rear-Admiral Phipps-Hornby, with Halifax (N.S.) as base.

She was employed on the usual patrol duties, stopping, boarding and examining shipping. In the very early days of the war, she captured at sea and towed into Berehaven the four-masted barque Odessa, and, some little time after, she21 took over from a warship and towed to Halifax a six thousand ton oil tanker.

Eight 4.7-in. quick-firing guns were originally mounted in the Caronia, but, on her return to England for refit in May, 1915, they were replaced by a similar number of six-inch.

She was at sea again in July, 1915, for another commission on the same station, with Captain Reginald A. Norton, R.N., in command, and Captain Henry McConkey, Cunard Line, as navigator. She remained away until August, 1916, when she returned to this country to pay off.

The Caronia was then employed in trooping between South and East Africa and India until her return to the Company’s service.

During the whole of this time, she was manned chiefly by mercantile marine ratings, enrolled for temporary service in the R.N.R. for the duration of hostilities.

The Laconia, for the first two years of the war was also used as an armed cruiser, seeing special service on the German East African Coast, and taking part in the operations which ended in the destruction of the German cruiser Konigsberg in the Rufigi River. She was then taken out22 of commission, and returned to the Company’s transatlantic service. She was finally sunk by a German submarine on the 25th February, 1917, American lives being lost aboard her. There is no doubt that this was the “overt act” that helped to confirm the decision of America to enter the war on the side of the Allies.

It is safe to say that all these vessels maintained in their new naval roles, not only the best traditions of the Cunard Company itself, but those of the Mercantile Marine of which they had once been so distinguished a part, and the British Navy of which they became not the least useful and honourable units. To the Carmania, indeed, fell the singular honour of being the only British armed auxiliary cruiser to sink a German war vessel in single armed combat; and the five years war at sea produced few more kindling and romantic stories than that of her duel with the Cap Trafalgar in September, 1914, near Trinidad Island in the South Atlantic.

Leaving the Mersey, as we have seen, on Saturday, August 15th, she first went up the Irish Channel examining merchant vessels, on her way to the Halifax trade route; where she23 was to carry out her first patrol duties. Having kept this track, however, for twenty-four hours without adventure, she received orders to sail for Bermuda, and on her way there seized the opportunity of dropping a target and carrying out some practice, firing which not only proved that her gun-layers were exceptionally skilful, but which gave all on board considerably greater confidence in the ship as a fighting unit. On the evening of August 22nd, she sighted the searchlights off St. George, Bermuda, and early next morning performed the difficult task of navigating a channel that no vessel of anything like her great size had ever before been through. Here for the next five days she coaled, while officers and men were able to obtain certain articles in the way of tropical clothing, that they had not had time to procure at Liverpool.

On August 29th she left the Bermudas, and on September 2nd passed through the Bocas del Dragos, at the mouth of the Gulf of Paria. Here, amidst scenery new and entrancing to many on board, she approached the Port of Spain, whence after a couple of days’ coaling, she left to join Admiral Cradock’s ill-fated squadron, which was24 then searching the coast of Venezuela, and the mouths of its rivers, for the German cruisers Dresden and Karlsruhe. To this squadron she became attached about a week later, and soon received orders to investigate Trinidad Island in the South Atlantic. On September 11th, however, while on her way there, she received orders to try and intercept, in conjunction with the cruiser Cornwall, the German collier Patagonia, which was supposed to be leaving Pernambuco that night; but she was not found, and, as a matter of fact, did not sail for another three days, when she succeeded, in the absence of the Cornwall, in getting away. Before this, however, the Carmania had received orders to continue on her original mission, namely the examination of Trinidad Island, and she accordingly headed down for it. This is a small and lonely piece of land, about 500 miles distant from the South American coast, rising to a height of some 2,000 feet, and being only some 3 miles long by 1½ miles broad, but with a good anchorage on its south-west side. Though often sighted by sailing vessels homeward bound from Cape Horn, this island was well out of reach of any ordinary steamer,25 and was thus an extremely likely place for an enemy vessel desiring to coal in a convenient and unobserved position. Moreover, although both Great Britain and Brazil had at various times attempted to form small settlements there for the purpose of cultivating the castor oil plant indigenous to the island, these attempts had never been successful, and the island was uninhabited.

It was at nine in the morning of Monday, September 14th that the Carmania sighted the island ahead; and soon after 11 a.m. a large vessel was made out, lying on the island’s westward side. It was a bright clear day, with a gentle north-easterly breeze blowing, and the mast of the unknown vessel showed distinctly above the horizon, two funnels becoming visible a little while later. It was at once concluded that she must be an enemy, since it was known that there were no British war vessels in the neighbourhood, and that no British merchant vessel was at all likely to be here. Her exact identity, however, remained a problem that was not to be solved, as it happened, until several days afterwards. The only enemy vessels that might possibly be in the neighbourhood according to the knowledge of those on board26 the Carmania, were the Karlsruhe, with four funnels, the Dresden with three funnels, the Kron Prinz Wilhelm with four funnels, and the Konig Wilhelm, an armed merchant cruiser which had one funnel. Even had the funnels been altered it could not have been any of these, since the outlines of all these vessels were known to one and another of the experienced and widely travelled observers on board the Carmania, and this uncertainty added to the excitement of a peculiarly thrilling occasion. The sudden pouring out of smoke from the strange vessel’s funnels showed at once that the Carmania had been sighted and that the enemy was getting up steam, while the position of the island added further to the thrilling possibilities of the situation.

It was true that there were no other vessels in sight, but the Carmania had approached so as to head for the middle of the island, in order that any observer who might be on the look out should be unable to tell on which side the armed cruiser meant to pass. This meant, however, that the greater part of the island’s lee side was out of sight, and behind its shelter other enemy vessels such as the Karlsruhe or Dresden, might well be lying in27 wait—the visible vessel merely acting as a decoy to the approaching Britisher. That other ships were indeed present, became manifest almost at once, as a smaller steamer, a cargo vessel, as it appeared, of about 1,800 tons, was now seen backing away from behind the enemy ship. This vessel at once began steaming away to the south-east, probably in order to discover whether or no the Carmania was accompanied by consorts at present hidden by the land. There were also to add to the anxiety of the Carmania’s commanding officer, two more masts appearing above the side of the unidentified ship that obviously belonged to a vessel still out of sight. Fortunately, however, this proved to be only another small cargo boat, who very soon detached herself and steamed away to the north-west.

This left them up to the present only the one big vessel as an opponent, a vessel of some 18,500 tons, and an armed cruiser like the Carmania. It promised, therefore, as regards numbers at least, to be an equal fight, and in preparation for it dinner was ordered for all hands that could be excused duty, for the hour of 11.30, in accordance with the old naval principle—food28 before fighting. Meanwhile every endeavour was being made to identify the mysterious enemy, and the conclusion arrived at was that she must be the Berlin, a German vessel of 17 knots. She was, as a matter of fact, although those on the Carmania were not to learn this for several days, the Cap Trafalgar, the latest and finest ship of the Hamburg South American Line—a vessel of 18 knots that had as yet only made one voyage. She had been built with three funnels, one of them being a dummy one used only for ventilation, and this had been done away with, reducing the number to two. She had been in Buenos Aires when war broke out, and had left that port, as it chanced on the very day that the Carmania had sailed from Liverpool, her destination being unknown and her cargo one of coal.

The Carmania had by this time gone to “General Quarters,” and all on board were ready for the encounter. The largest ensigns floated both from the flagstaff aft and the mastheads, and the Cap Trafalgar now ran up the white flag with the black cross of the German Navy. It was still, however, not quite certain that the enemy was armed, and it was therefore necessary that29 the usual formalities should be attended to. Well within range, Captain Grant ordered Lieutenant Murchie to fire a shot across her bow, and the shell, very skilfully aimed, dropped about 50 yards ahead of this. The reply was immediate, the enemy firing two shells which only just cleared the Carmania’s bridge, and dropped into the water about 50 yards upon her starboard side.

The fight had now begun in earnest, and the firing on both sides was of a high order, although the first round or two from the Carmania fell short, while those of the Cap Trafalgar erred a little in the opposite direction. Quite soon, however, hits were being made by both sides, and soon one of the Carmania’s gun layers lay dead, his No. 2 dying, and almost the whole of the gun’s crew wounded.

For the first few minutes of the duel, only three of the Carmania’s guns could be brought to bear, but soon by porting a little she was able to bring another gun into action, and some very successful salvoes at once followed. The British gun-layers, firing as coolly as if they had been at practice, were now hitting with nearly every shot, and the vessels were closing one another rapidly,30 when at about 5,500 yards the new and sinister sound of machine-gun firing began to thread the din of the bursting shells. By this time a well placed enemy shell had carried away the Carmania’s control, so that it was no longer possible for ranges to be given from the bridge to the guns by telephone, and it was evidently the Cap Trafalgar’s intention to disable the bridge entirely, shell after shell hitting its neighbourhood, or only just missing it. It was at once clear to those on board that if the enemy’s machine-gun could now get the range, the guns and ammunition parties on the unprotected decks of the Carmania would be inevitably mown down. The order was therefore given to port, and the Carmania wore away in order to increase the range. This brought the enemy astern and another of the Carmania’s guns into action, and for a brief moment she had five guns bearing upon the Cap Trafalgar. Still porting, however, the guns on that side ceased to fire, and the turn came for the starboard gunners to take their hand. The enemy now also ported, and as she did so, it became clear that she was visibly listing to starboard; she had already been set on fire foreward, but this fire seemed to have been extinguished.

31

The Carmania’s gunners, on the soundest principles, were steadily aiming at the Cap Trafalgar’s water line, and there was no doubt that as a result of this policy she was already beginning rapidly to make water. It was by no means, however, the case of the honours resting with one side entirely, and the enemy was constantly registering hits on the Carmania’s masts, ventilators, boats, and derricks, and it is an amazing fact, considering that at one time the range was not more than 1½ miles, that her casualties should have been so few. The Carmania’s gunners were now firing so fast that the paint was blistering off the guns, and at the same time she herself was on fire to an extent that might have proved very serious. The main pipes having been shot away, no water could be got through the hose pipes and brought to play upon this fire, and reliance had therefore to be placed upon water buckets handled under the most difficult conditions of smoke and heat.

It was now evident that the Carmania’s bridge would in a very short time be untenable, and her Captain therefore ordered the control to be changed to the aft steering position, and this was accordingly32 done, the enemy being kept at about the same bearing. The bridge was now well alight, and the flames were licking upward with increasing ferocity. The port side of the main rigging was hanging in festoons from the only remaining shroud. The wireless gear had been shot away in the first moment of the action. Many of the ventilator cowls were in ribbons, and a large hole yawned in the port side of the aft deck.

Battered as she was, however, it was now clear that the Cap Trafalgar was in a far worse case. She was listing heavily, and her firing, though still rapid, was becoming wild. She was badly on fire, and almost wholly wrapped in smoke. Suddenly she turned abruptly to port and headed back for the island, leaning right over with silent guns, and already beginning to get her boats out.

Upon this all the Carmania’s hands, except the gun layers, were employed in trying to extinguish the fire. Bucket gangs were formed, and at last a lead of water was arranged from the ship’s own fire main once more. It was, of course, hopeless now to attempt to save the bridge and the boat deck cabins, but there was still a hope of preventing the fire from spreading, and33 in order to stop the draught the engines were slowed down. It was a fierce task, and one that demanded every energy on the part of all on board, but it was one in which they were encouraged, as they toiled and sweated, by the sight of their heeling enemy, from whose sides half a dozen boats had already cleared, pulling towards one of her smaller colliers who was standing about 3 miles away.

More and more the big liner fell over until at last her funnels lay upon the water, and then, after a moment’s apparent hesitation, with her bow submerged, she heaved herself upright and sank bodily. It had been a good fight and she had fought honourably to the end and gone down with her ensign flying, and when, as she vanished, the men of the Carmania raised a cheer, it was hardly less for their own victory than as a tribute to the enemy.

By now, thanks to their unremitting exertions, the crew of the Carmania had overcome the fire, but a new danger was already reported and necessitated prompt action on the part of her Commander. Smoke had been reported on the northern horizon, and soon afterwards four funnels34 appeared, the new comer being undoubtedly another enemy, probably summoned by wireless by the Cap Trafalgar. Crippled as she was, and with nearly a quarter of her guns’ crews and ammunition supply parties either killed or injured, it would have been the sheerest madness for the Carmania to risk another action at that moment, and she accordingly increased her speed, shaping a course to the south-west, and steering by sun and wind, until she could assemble what was left of her shattered navigating gear. Afterwards it was learned that the enemy sighted was the Kron Prinz Wilhelm, who, on learning by wireless of the Cap Trafalgar’s fate, decided that discretion was the better part of valour and did not approach any nearer.

During the night the Carmania succeeded in getting into touch with the cruiser Bristol, with whom she arranged a rendezvous for the next morning, and under whose care, and afterwards that of the Cornwall, she came to anchor near the Abrolhos Rocks at eight o’clock on the morning of the day after. Here, with the aid of the Cornwall’s engineers, the worst of her holes were patched up, and with what navigating gear she35 could borrow, and in company with the Macedonia, the Carmania set out for Gibraltar at 6 p.m. on September 17th. Well did she deserve, as she did so, the hearty cheers of the Cornwall, and the two accompanying colliers, and those of the old battleship Canopus whom she passed early on the morning of the 19th.

She arrived at Pernambuco on the same afternoon, leaving there Captain Grant’s despatches for the Admiralty, and reached Gibraltar nine days later. Her re-fitting took several months, but she remained as an armed cruiser until May, 1916, when she was again restored to the Cunard Company’s service. Her casualties in this brilliant action amounted to nine killed or dying of wounds, and four severely and twenty-two slightly wounded. There were no Cunarders among the casualties. Besides other honours conferred upon participants in this fight, his Majesty the King decorated Captain Barr with the well deserved Companionship of the Bath, in recognition of his splendid services in what was to prove a unique action of the war at sea.

Twelve months later, on September 15th, 1919, there was an interesting sequel on board the36 Carmania, which had then returned to the Cunard Company’s service. A piece of plate which belonged to Lord Nelson, and was with him at Trafalgar, was presented to the ship in commemoration of her very gallant fight. Twenty-four of these pieces of plate came into the possession of the Navy League who asked the Admiralty to allocate them to various ships. The Carmania was the only merchant vessel to receive this honour. In notifying the Company of the presentation, the General Secretary of the Navy League stated that “the Navy League realises that while every unit of the fleet has rendered service in accordance with the best traditions of the Royal Navy, H.M.S. Carmania has been able to render herself conspicuous amongst her gallant comrades, and in accepting this souvenir, the Navy League trusts that you will recognise it as an expression of gratitude to the glorious fleet of which that ship was so distinguished a representative.”

The veteran Admiral, the Hon. E. R. Fremantle who was present, stated that there never was a single ship action which reflected greater credit, both on the R.N. and on the Mercantile Marine, and more especially on the R.N.R. It had very aptly37 been compared with the fight of the Shannon and the Chesapeake.

Captain Grant was unfortunately unable to be present, but in a letter read at the function he claimed that “this action was the only one throughout the war in which an equal, or as a matter of fact, a slightly inferior vessel annihilated the superior force.... I shall always feel proud of the fact that it was my great good fortune to command a ship in action in which the glorious traditions of the British Navy were upheld by every soul on board.”

Captain Barr, who retired from the Company’s service in 1917, said that the Captain of the Cap Trafalgar put up a very gallant fight. “I do not know his name,” he said, “but he is the only German I would care to meet.”

38

We have confined ourselves so far to the adventures of the Cunard vessels that were used in the early stages of the war for purely combatant purposes. They were, as has been seen, merely a small, though important, fraction of the whole fleet, and indeed the distinction that we have drawn is a somewhat difficult one to maintain. Thus, from acting, as we have shewn, as purely combatant cruisers, the Aquitania, Caronia, Laconia and Carmania passed to different and even more valuable work; and at the same time many other39 Cunard vessels were upon the outbreak of war withdrawn from their usual avocation for more or less militant purposes. We find the Mauretania, for example, originally intended for employment as an armed cruiser, converted into a Troopship in 1915, and from this into a Hospital Ship in 1916, while in 1917 she again became a Transport, fitted with 6-in. guns. In all these capacities she did magnificent work, not without imminent risk of destruction, and it was only by the brilliant seamanship of Commander Dow, one of the Cunard Company’s oldest and most trusted skippers, that she escaped being sunk while plying between England and Mudros, in her role of Troopship. Attacked by a submarine, Commander Dow noticed the wake of the approaching torpedo on his starboard bow, and immediately ordering the helm to be flung hard aport the torpedo was missed by not more than 5 feet, the Mauretania’s great speed fortunately thereafter placing her beyond range of the enemy.

The Franconia and Alaunia were also employed in carrying troops from September, 1914, onwards until both of them were sunk, curiously enough within a few days of one another in October, 1916.40 During this period they carried troops not only from Canada to England, but made several voyages to India and various parts of the Mediterranean. It was while she was on her way from Alexandria to Salonica, though fortunately after she had disembarked 2,700 soldiers, that the Franconia (Captain D. S. Miller), was torpedoed, about 200 miles N.E. of Malta. Twelve of her crew were killed by the explosion. The ship sank fifty minutes after she was hit, the survivors being picked up by H.M. Hospital Ship Dover Castle, whose R.A.M.C. Surgeon, Dr. J. D. Doherty chanced himself to be one of the Cunard Company’s Medical Officers. The Alaunia, again, as it happened, having landed her passengers and mails at Falmouth, after a voyage from New York, was torpedoed on her way to London, about two miles south of the Royal Sovereign Light Vessel. Captain H. M. Benison, in command, hoped to beach the ship, but unfortunately the water gained too rapidly, and the necessary tugs did not arrive in time. Two members of the crew were found to be missing, probably as the result of the explosion, the rest being saved by patrol boats and destroyers and the Alaunia’s own lifeboats.

The Andania, Ascania, Ivernia, and Saxonia, were all for several months used as prison ships in 1915, each of them providing accommodation for nearly 2,000 German prisoners. They were afterwards employed as Transports, both to India and the Mediterranean, the Ivernia, Ascania and Andania, in the end, all being sunk by enemy submarines. These losses represented a heavy sacrifice by the Company, particularly in view of the post-war needs of navigation.

It was on January 27th, 1918, that the Andania was torpedoed without warning, having sailed the day previously from Liverpool, via the North of Ireland, with 51 passengers and mails. Captain J. Marshall, in command, immediately ordered her boats to be lowered with the result that within a quarter of an hour all the passengers and crew were clear of the ship, except the Captain himself, the Chief, First, Second and Third Officers, who made a special request to the Captain to be allowed to remain on board. The manner in which the boats were thus speedily lowered and filled and navigated to positions of safety was an evolution which reflected favourably on the organisation of the ship. Captain Marshall then made an examination42 of the ship and called for volunteers from the nearest boat. The response was immediate and unanimous, and the Chief Engineer, Purser, Wireless Operator, and two Stewards, with two Able Seamen at once returned on board with a fine carelessness to their own safety and rendered valuable assistance in getting out hawsers forward and aft. At half-past two, these men were again ordered to leave the vessel, and, with the occupants of the other boats, were picked up by patrols. Captain Marshall himself and his Chief Officer (Mr. Murdoch) boarded a drifter and stood by the Andania until 4 o’clock in the evening, when they again returned on board to make her fast to a tug which had just arrived, still entertaining the hope that it might be possible to save her. Unhappily their efforts were of no avail, the vessel sinking about half-past seven. Seven lives were unfortunately lost, probably as the result of the explosion.

On the morning of the 28th December, 1916, the Ivernia left Marseilles with a crew of 213, 94 officers and 1,950 troops. Shortly after her departure from Marseilles Captain Turner received orders to proceed 11 miles south of Damietta43 (Malta), but prior to altering course he received further orders to proceed north of Gozo Island (Malta), where the Ivernia’s escort, H.M.S. Camelia (Destroyer), was relieved by H.M.S. Rifleman (Destroyer). On approaching the Adriatic, Captain Turner was instructed not to pass through the danger zone in daylight. As the Ivernia was proceeding she received a signal from the escort that permission had been requested and granted from the Admiralty at Malta to proceed through the danger zone at daybreak.

There was a fresh breeze which accounted for a heavy swell, the morning sun was shining brightly on the starboard side, when Captain Turner observed the wake of a torpedo approaching his vessel, too late to enable him to do anything to avoid it. The torpedo struck the Ivernia on the starboard side, abreast the funnel, and consequently rendered the engines out of commission, owing to the bursting of the steam pipe, by the explosion. This explosion accounted for the loss of 13 stewards and 9 firemen.

Fortunately, at the time, all troops were mustered on deck and were standing by boat stations. The boats were immediately lowered clear of the water.

44

The destroyer Rifleman immediately manœuvred for the purpose of locating the submarine, by which time several of the Ivernia’s boats were in the water. At this juncture an unfortunate incident occurred. The destroyer dashed by the port quarter at full speed without having an opportunity of avoiding a collision with the ship’s lifeboat, containing Chief Engineer Wilson and Dr. Parker, among other members of the crew, the boat sinking immediately. Dr. Parker was picked up but died almost immediately from injuries received. Chief Engineer Wilson was not seen.

Two steam trawlers came alongside the Ivernia, after the destroyer had left with 600 survivors on board, which took the remainder of the Military and Crew, which apparently left only Captain Turner and Second Officer Leggett remaining on board. The Second Officer, however, went round the decks and discovered a soldier on the after deck who had sustained a broken thigh. Two soldiers were immediately ordered aboard for the purpose of assisting in strapping a board to the man’s damaged thigh, he being eventually lowered on to one of the trawlers by means of a bowline, where he was placed in charge of the R.A.M.C.

The Second Officer then went aboard the trawler, later followed by Captain Turner, who first of all made sure that the vessel was sinking.

The trawlers then cruised around among the boats and wreckage picking up survivors.

One of the trawlers unfortunately became disabled owing to the ropes fouling her propellers, which necessitated her being towed by the other.

The trawlers proceeded to Crete, where the survivors were billeted for 14 days, after which time they were taken on board the P. & O. S.S. Kalyan and conveyed to Marseilles, from which port they were sent overland to England.

The Ausonia was another of the fine Cunard vessels which the enemy succeeded in destroying. In February, 1915, she had taken over 2,000 refugees from Belgium to La Pallice, being afterwards employed as a Troopship from February to May, 1916, working to Mediterranean and Indian ports. She was then returned to the Cunard Company’s service, and was sunk on the 30th of May, 1918. Once before, this ship had been struck by a torpedo, off the south coast of Ireland, in June, 1917, while on a voyage from Montreal to Avonmouth. In this case she was fortunately46 salved, and her valuable cargo of food stuffs safely discharged. On the second occasion, while sailing from Liverpool, she was less fortunate. The Ausonia was some 600 miles west of the Irish coast at 5 p.m. on May 30th, when a torpedo struck her, causing a terrific explosion. As her Commander, Captain R. Capper, afterwards said, he saw rafts, ventilators, ladders, and all kinds of wreckage coming down as if from the sky, falling round the after part of the ship. Captain Capper who, at the moment, was at the entrance of his cabin, at once went to the bridge, put the telegraph to ‘Stop’—‘Full Speed Astern’ but received no reply from the Engine Room. All hands were at once ordered to their boat stations, and the wireless operator tapped out the ship’s position on his auxiliary gear. Ten boats were lowered, and, within a quarter of an hour after the ship was struck, they had safely left her. When about a quarter of a mile astern, Captain Capper mustered them together and called the roll. It was then discovered that eight stewards were missing, having been at tea in a room immediately above the part of the ship struck by the torpedo.

Half an hour after the vessel was torpedoed, a periscope was sighted on the port bow, and an enemy submarine came to the surface and fired about 40 shells at the ship, some of these dropping within fifty yards of the boats. After the Ausonia had sunk, the submarine approached the boats, and Captain Capper, who was at the oars was ordered to come alongside. Upon the submarine’s deck several of her crew were lounging, laughing and jeering at the shipwrecked survivors. After enquiring as to the Ausonia’s cargo, the submarine commander ordered the boats to steer in a north-easterly direction; in callous disregard of the peril which confronted the Ausonia’s crew the submarine herself then made off northwards.

Captain Capper gave orders to the officers in charge of the boats that they were to keep together, and endeavour to get into the track of convoys, the weather being fine at the time. Until midnight the boats were successful in remaining in each other’s company, but the wind, having risen in the night, two boats, one of them in charge of the first officer, and the other in charge of the boatswain were, on the following morning, not to be seen. Captain Capper had48 assembled the survivors in seven boats, and he now gave orders to the remaining five that they should make themselves fast together. In this formation, they continued throughout the following day and night, when the ropes began to part. They were also retarding progress and were therefore cast off, the boats, however, still continuing to remain pretty well together.

On Sunday, January 2nd, to add to the misery of their occupants, the weather became bad, heavy rain falling and soaking them all to the skin. On Monday and Tuesday, conditions improved a little, but on Wednesday a storm broke, and by mid-day a heavy sea was running, and a gale blowing from the north-west. The boats were now running before this, with great seas breaking over them and saturating everybody on board. These conditions continued until Friday the 7th, when land was at last sighted, turning out to be Bull Rock. A wise and strict rationing had been enforced, only two biscuits a day and one ounce of water having been allowed for the first two days, and one biscuit and a half and four tablespoons of water the subsequent ration. The crew were approaching the extremities of exhaustion when49 hope of deliverance was awakened in them. Fortunately, on sighting land, the wind fell a little, but it was another fifteen hours before the unhappy survivors were picked up by H.M.S. Zennia, an American Destroyer also assisting. Captain Capper’s boat had only 25 biscuits left together with half a bucketful of water—but one day’s meagre supply when the terrible ordeal ended. The little boats, it was calculated, had covered 900 miles since the Ausonia disappeared before their eyes. Under these conditions the conduct of the Cunarder’s crew was of the highest order, that of the stewardess, Mrs. Edgar, of Orrell Park, Aintree, the only woman on board the vessel, being particularly courageous.

Special mention must also be made of the butcher’s boy, Robinson. At the moment of the explosion, together with the pantry boy, Lister, he was in one of the cooling chambers, and the explosion made it impossible for the two boys to get out. Robinson had several wounds on his hips and thighs, and his left arm was lacerated. Both boys, in addition, had both legs broken above the ankle. Robinson, however, managed to crawl out on both his hands and knees and50 secure a board and place it across the gaping hole in the deck, thus enabling Lister also to reach a place of comparative safety. The two boys then crawled on hands and knees up two sets of ladders to the boat deck, and were placed in the boats. The doctor attended to the boy Robinson’s injuries, as far as was possible, but it was not for 30 hours that Captain Capper was able to transfer him to the boat in which Lister was lying, so that he also might receive medical aid. In spite of their experiences and injuries, both boys remained calm and cheerful, and indeed in high spirits, but it is sad to record that Robinson subsequently succumbed in hospital, as the result of his injuries.

More, however, to Captain Capper than to any one man, was the salvation of the five boat loads due, and it was in recognition of his dogged determination and splendid seamanship that his Majesty the King afterwards bestowed upon him the Distinguished Service Cross.

The Ultonia, in August, 1914, was the means by which some of the old “Contemptibles” were brought from Malta to England, and she then proceeded to India with Territorial troops. She51 was subsequently returned to the Company’s Service and was finally sunk in June, 1917. She was at this time eastward bound, and about 350 miles west from Land’s End. She disappeared in ten minutes, so deadly was the blow she received. Fortunately, she was at the time, being escorted by one of the “Q” boats, by whom her crew was picked up and safely landed the next day at Falmouth, one man unfortunately being killed during the operation of leaving the ship. Captain J. Marshall was in command.

Meanwhile, with their ordinary carrying power thus depleted, the Cunard management had been looking about for reinforcements, and had entered into negotiations with certain other lines for additional vessels. Thus they took over from the Canadian Northern Steamship Company (The Royal Line and The Uranium Steamship Company), the Royal George, and three other vessels, which they re-christened respectively the Folia, Feltria, and Flavia. They also purchased five additional vessels which they re-christened the Vinovia, Valeria, Volodia, Valacia, and Vandalia.

Now during the years 1915 and 1916, merchant shipping, apart from those ships especially chartered52 by the Government, continued under the direction of its various owners. In 1917, however, the Liner Requisitioning Scheme, came into being, and a Shipping Controller was appointed.

Under this scheme all British shipping came under the control of the Government, the object being, in view of the shortage of tonnage caused by the depredations of the submarines, to confine steamers to those trades necessary for providing the Allies with the essential foodstuffs and munitions of war. The greatest percentage of these had, of course, to be obtained from America, and in consequence many steamers which had been trading to other parts of the world, were diverted to the North Atlantic, and placed under the management of the Companies already established on these particular routes. The owners of these transferred steamers were given permission to allot their ships to any of the lines so established, and it came about that the Cunard Company, in addition to their own ships, had the management of a large number of vessels thus diverted. It is estimated, in fact, that the number of additional steamers so handled by the Company, amounted to more than 400. In addition to this, the Company53 managed several prize steamers captured from the enemy and neutral steamers that had been placed at the disposal of the Allies, and it thus happened that the Cunard management found itself in charge of vessels from the Indian, China, South African, and Australian trades, assembled from the ends of the earth in this vital emergency.

Some idea of the magnitude of the work thus carried upon the shoulders of the Cunard management may be gathered from the facts that in one year alone not less than 200 sailings were made from American and Canadian ports, and that over 10,000 tons of cargo were often carried in one steamer.

With the entrance of America into the war, the carrying problem became at once more complicated and greater in bulk; and in its solution the Cunard Company may once more justly be said to have played a major part. Let us consider first its work in the carriage of troops. The Cunard organisation was responsible for the transport during the war of over 900,000 officers and men. This excludes the big total repatriated after the Armistice was signed. When it is remembered that this aggregate is greater than54 the total population of either Liverpool, Manchester or Birmingham; that 900,000 men, marching in column of route in sections of fours would take, without halting, nearly six days to pass a single point, it becomes possible to visualise the immensity of the task represented by these bald figures. When it is further remembered that the total British Expeditionary Force first thrown across the English Channel in August, 1914, was only 80,000; that this was less than one-tenth of the number carried during the war by the Cunard Company; and that the number so carried was equal to not less than one-eighth of the whole British Army at its greatest strength, the nation’s debt to this great Company can be estimated.

Nor was the mere provisioning of these troops while en route a negligible feat of transport. Taking an average voyage as ten days, the food required to feed this number of men amounted to no less than 9,750,000 pounds of meat, 11,250,000 pounds of potatoes, 4,500,000 pounds of vegetables, 9,575,000 loaves of bread, 1,275,000 pounds of jam, 900,000 pounds of tea and coffee, and among other things 900,000 pounds of oatmeal, 600,000 pounds of butter and 127,000 gallons of milk.

55

Vast as these figures are, however, they are dwarfed when we begin to consider what was accomplished during the five years of war in the way of cargo carrying—in the humdrum performance of an unadvertised and often little appreciated service, upon which, fundamentally, our whole war structure rested. Between August, 1914, and November, 1918, 7,314,000 tons of foodstuffs, munitions of war, and general cargo were carried from America and Canada to the British Isles; over 340,000 tons from the British Isles to Italy and the Adriatic; over 500,000 tons from the British Isles to other Mediterranean Ports; nearly 320,000 tons from this country to France; and nearly 60,000 tons from France to this country. In addition to this, huge quantities were also carried westwards from this country, amounting to a total, in the same period, of more than 1,000,000 tons.

Not the least important service rendered in this way was connected with the supply of oil fuel, of which the stocks in this country were seriously depleted—so seriously that at one time they were insufficient to supply the needs of the Navy for more than a few weeks ahead. In this56 predicament the Admiralty, realizing the danger, approached Sir Alfred Booth, Chairman of the Cunard Company, and asked him to put the matter before other leading ship-owners. He readily consented to do so, and all owners running ships in the North Atlantic, at once agreed to take the necessary steps to allow of oil being carried in the double bottoms of their ships, the Cunard Company themselves adapting for this purpose the double bottoms of the Andania, Carmania, Carpathia, Pannonia, Saxonia, Valacia, Vandalia, Valeria, and Vinovia, each of which brought on each voyage to this country, about 2,000 tons of oil. The Cunard Company alone, in a little over a year, thus brought over 100,000 tons of oil across the Atlantic.

During all this time, of course, it must be remembered that the Cunard Company, as throughout the war, plied in a zone particularly exposed to hostile attack by enemy raiders and submarines; and as we have already shown, and shall show again, a very heavy toll of their vessels was taken by hostile torpedoes. How greatly the Cunard steamers were concentrated upon dangerous routes will be seen on reference to57 the map,B which indicates the most important services of Cunard Steamers during the war. Finally, let it be stated that from August, 1914 to November, 1918, without taking into account such outside steamers as were working under the Cunard Company’s direction, its own steamers steamed not less than 3,313,576 miles, with a consumption of 1,785,000 tons of coal. This distance is equivalent to the circum-navigation of the world no less than 132 times.

B This map will be found in the inside front cover of the book.

58