Liberty Tract. No. 2.

FACTS FOR THE PEOPLE

OF THE

FREE STATES.

NEW YORK:

PUBLISHED BY WILLIAM HARNED,

FOR THE

AMERICAN AND FOREIGN ANTI-SLAVERY SOCIETY,

22 Spruce Street.

$1 PER 100, $8 PER 1000.

Liberty Tract. No. 2.

NEW YORK:

PUBLISHED BY WILLIAM HARNED,

FOR THE

AMERICAN AND FOREIGN ANTI-SLAVERY SOCIETY,

22 Spruce Street.

$1 PER 100, $8 PER 1000.

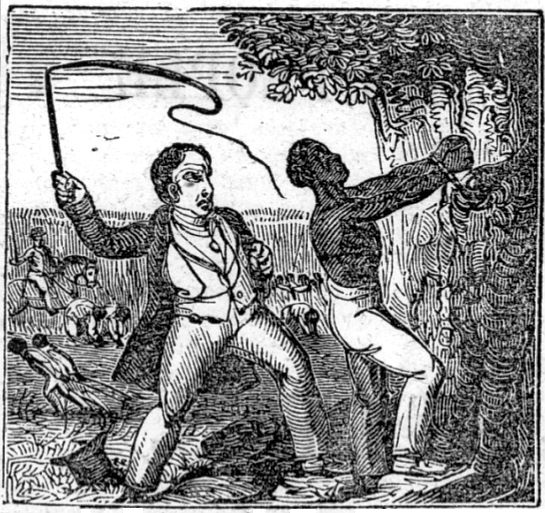

The Abbeville (S. C.) Banner states, that two of Gov. McDuffie’s slaves were killed on Friday, Feb. 13th, by two other slaves, acting in the capacity of drivers! They were killed by what the law terms “moderate correction!”

In June, 1846, the Baltimore Sun gave an account of a woman who “jumped out of the window of the place in which her owner had confined her, and immediately took the nearest route to throw herself into the water.” She was rescued. But, says the Sun, “Upon being taken upon the deck of the vessel, she begged the by-standers to let her drown herself, stating, that she would 'sooner be dead, than go back again to be beaten as she had been!’”

A correspondent of the Philadelphia Inquirer, July 25, 1846, wrote from Richmond, as follows:—“An unpleasant occurrence took place in this city yesterday. A man, who has a number of negroes in his employment, was proceeding, for a slight offence, to punish one of them by whipping, when the poor wretch, knowing his master’s unmerciful nature, implored that he might be hung at once, instead of whipped. This of course would not answer, and on tying the negro’s hands behind him in the usual manner, the employer went into another room to procure a cowhide, when the negro, taking advantage of his master’s absence, rushed from the room, jumped into the river, and was drowned.”

In June, 1846, the New Orleans Commercial Times said—“We learn that a few days since a negro man, belonging to Captain Newport, of East Baton Rouge, while closely pursued by the dogs of Mr. Roark, of this Parish, ascended a tree and hung himself. Mr. Roark, with Captain Newport’s son-in-law and overseer, were in pursuit of a runaway slave. They did not know that this negro was out, and were surprised upon their arrival, a few minutes in the rear of the dogs, to find him suspended by his neck, with his feet dangling only a foot or two from the earth. Every effort was made to restore animation, but without success, although on their coming up the body was still warm. The act was one, it would seem, of resolute predetermination, as the slave was well provided with cords, which he made use of to perpetrate his suicidal purpose.”

The Palmyra (Mo.) Courier, in August, 1846, says:—“We understand that a gentleman, living in Macon county, while out hunting with his rifle, last week, came suddenly upon two fugitive slaves, who gave him battle. He shot one, and split the other’s skull with the barrel of his gun. He then started for home, but before reaching it he met a man in the road, who inquired if he had seen or heard of two runaway negroes—describing them. The gentleman replied, that he had just killed two, and related the circumstance. On proceeding to the spot, the stranger identified them as his slaves.”

The following is from the Washington (Pa.) Patriot of 1846: “We learn that a few days ago, a fugitive slave from Maryland was pursued and overtaken in Somerset county, in this State by a man named Holland, a wagoner from Ohio, who was tempted to the task by the reward offered, $150. When they reached McCarty’s tavern the slave attempted to escape, but was caught by Holland while in the act of climbing a fence. The slave drew a long knife, which he had concealed about his person, and plunged it into Holland’s heart, causing his death instantly. He made good his escape, immediately pursued by the people of the neighborhood, who at nightfall, had surrounded him, but in the darkness of the night he eluded their vigilance, and is now beyond their reach.”

The Hon. J. R. Giddings, in a speech in the House of Representatives, at Washington, Feb. 18, 1846, said—“In regard to arresting slaves, we [of the free States] owe no duties to the master; on the contrary, all our sympathies, our feelings, and our moral duties, beyond what I have stated, are with the slave. We will neither arrest him for the master, nor will we assist the master in making such arrest. I am aware that the third clause of the second section of the first article of the Constitution was once believed, by some, to impose upon the people of these free States the duty of arresting fugitive slaves. But it is now judicially settled that no such obligation rests upon us. Indeed a proposition to impose upon us such a duty, at the time of framing the Constitution, was rejected, without a division, by the Convention. We, therefore, leave the master to arrest the slave if he can; and we leave the slave to defend himself against the master if he can. We do not interfere between them. The slave possesses as perfect a right to defend his person and his liberty against the master as any citizen of our State. Our laws protect him against every other person, except the master or his agent, but they leave him to protect himself against them. If he, while defending himself, slays the master, our laws do not interfere to punish him in any way, further than they would any other person who should slay a man in actual self-defence. The laws of the slave State cannot reach him, nor is there any law, of God or man, that condemns him. On the contrary, our reason, our judgment, our humanity approves the act; and we admire the courage and firmness with which he defends the ”inalienable rights with which the God of Nature has endowed him.“ We regard him as a hero worthy of imitation; and we place his name in the same category with that of Madison Washington, who, on board the Creole, boldly maintained his God-given rights, against those inhuman pirates who were carrying him and his fellow-servants to a worse than savage slave-market.”

Another Slave Suicide. “The slave of a farmer in an adjoining county, (Jefferson,) having been jumped upon and stamped by his master, with spurs on, so as to cruelly lacerate his face as well as his body, he was found, next morning, in an adjacent pond or stream of water—having tied a stone to his own neck, (as it is said,) and plunged in, for the successful purpose of drowning himself, under the feelings of desperation caused by the fiendish treatment of his master!”—Balt. Sat. Visiter, Aug., 1846.

| No. | Name. | Native State. | Born. | Installed into office. | Age at that time. | Years in the office. | Died. | Age at his death. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Geo. Washington | Virginia | 1732 | 1789 | 57 | 8 | Dec. 14, 1799 | 68 |

| 2. | John Adams | Mass. | 1735 | 1796 | 62 | 4 | July 4, 1826 | 91 |

| 3. | Thos. Jefferson | Virginia | 1743 | 1801 | 52 | 8 | July 4, 1826 | 83 |

| 4. | James Madison | Virginia | 1751 | 1809 | 58 | 8 | June 28, 1836 | 85 |

| 5. | James Monroe | Virginia | 1758 | 1817 | 58 | 8 | July 4, 1831 | 72 |

| 6. | John Q. Adams | Mass. | 1767 | 1825 | 58 | 4 | ||

| 7. | Andrew Jackson | Virginia | 1767 | 1829 | 62 | 8 | June 8, 1845 | 78 |

| 8. | M. Van Buren | N. York | 1782 | 1837 | 55 | 4 | ||

| 9. | Wm. H. Harrison | Virginia | 1773 | 1841 | 68 | — | April 4, 1841 | 68 |

| 10. | John Tyler | Virginia | 1790 | 1841 | 51 | 4 | ||

| 11. | James K. Polk | N. Car. | 1795 | 1845 | 49 |

George Washington.—“I never mean, unless some particular circumstance should compel me to it, to possess another slave by purchase: it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by which slavery in this country may be abolished by law.”—Letter to John F. Mercer.

“There is not a man living, who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it (Slavery); but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that is, by the legislative authority; and this, as far as my suffrage will go, will not be wanting.”—Letter to Robert Morris.

John Adams.—“Great is truth—great is liberty—great is humanity; and they must and will prevail.”

Thomas Jefferson.—“The rightful power of all legislation is to declare and enforce only our NATURAL RIGHTS AND DUTIES, and take none of them from us. No man has a natural right to commit aggressions on the equal rights of another, and this is ALL from which the law ought to restrain him. Every man is under a natural duty of contributing to the necessities of society, and this is all the law should enforce upon him. When the laws have declared and enforced all this, they have fulfilled their functions.”—“The idea is quite unfounded, that on entering into society, we give up any natural right.”

“The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions; the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. * * And with what execration should the statesman be loaded, who, permitting one-half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the others, transforms those into despots, and these into enemies, destroys the morals of the one part, and the love of country of the other. For, if a slave can have a country in this world, it must be any other in preference to that in which he is born to live and labor for another. * * And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people, that these liberties are the gift of God; that they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; and that his justice cannot sleep forever. * * When the measure of the slaves’ tears shall be full; when their tears shall have involved heaven itself in darkness; doubtless a God of justice will awaken to their distress, and by diffusing light and liberality among their oppressors, or, at length by his exterminating thunder, manifest his attention to things of the world, and that they are not left to the guidance of blind fatality.”—Notes on Virginia.

James Madison.—“It seemed now to be pretty well understood, that the real difference of interests lay, not between the large and small, but between the Northern and Southern States. The institution of slavery, and its consequences, formed the line of discrimination.”—Speech in the Convention for the formation of the Federal Constitution.

James Monroe.—“We have found that this evil (slavery) has preyed upon the very vitals of the Union; and has been prejudicial to all the States in which it has existed.”—Speech in the Virginia Convention.

John Q. Adams.—“Nay, I may go further, and insist that that (the slave) representation has ever been, in fact, the ruling power of this government. The history of the Union has afforded a continual proof that this representation of property, which they enjoy, has secured to the slaveholding States the control of the national policy, and, almost without exception, the possession of the highest executive office of the Union.”—Speech in Congress, Feb. 4, 1833.

“Fellow citizens: The numbers of freemen constituting your nation are much greater than those of the slaveholding States, bond and free. You have at least three-fifths of the whole population of the Union. Your influence on the legislation and the administration of the government ought to be in proportion of three to two. But how stands the fact? * * * By means of the double representation, the minority command the whole, and a knot of slaveholders give the law and prescribe the policy of the country.”—Speech at North Bridgewater, Nov. 6, 1844.

James K. Polk.—On the 12th of May, 1841, a resolution was introduced in Congress, to the effect, “That the President of the United States be requested to renew, and to prosecute, from time to time, such negotiations with the several maritime powers of Europe and America, as he may deem expedient for the effectual abolition of the African Slave Trade, and its ultimate denunciation as piracy under the law of nations, by the consent of the civilized world.” The vote on this resolution was 118 ayes and 32 nays; James K. Polk voting in the negative. (Cong. Deb. vol. 7., p. 850). Mr. Polk, since occupying the presidency, has pardoned two individuals, convicted in the courts of having been engaged in this trade.

Of the fourteen presidential terms, now expired since the formation of the government, eleven have been filled by slaveholders, one by a “Northern man with Southern principles,” and only two by Northern men. The present incumbent is a slaveholder, sworn fully to do his utmost to uphold, and even extend the abomination; and most terribly he is fulfilling his vow, in the surrender of free territory in Oregon, and in a war of conquest for slavery in Mexico, at a cost of millions of dollars and thousands of lives. By holding the Presidency, slavery controls the cabinet, the diplomacy, the army, and the navy of the country. The power that controls the Presidency controls the nation. No Northern President has been allowed to serve more than one term.

The President exercises much of his power by and with the Senate. The Vice President is, ex-officio, President of the Senate. As such, he has the casting vote in all questions before that body. For the last twenty years, with one exception, he has been a slaveholder. From the adoption of the Constitution up to June 1842, there were 76 elections, in the Senate, of President pro. tem. Of these the slave States had 60 and the free States 16. Most of the 16 were in the earlier periods of the government. Mr. Southard was elected in 1842. Previous to that, no Northern man had received the appointment for thirty years! so careful were the slaveholders to watch their interests by securing the casting vote.

For a long series of years the Senate has been equally divided between the free and the slave States. In this condition of it, it was a great point with the slaveholders to secure the casting vote of the Vice Presidency, and right carefully have they done it. This vote is of less importance now, since, by the admission of Texas, the balance of power is broken up, and “The Valley of Rascals,” on any tie vote, now rules the Senate and the nation.

The Office of Secretary of State is the most important of any, perhaps, in the cabinet of the President. As it is the duty of this officer to direct the correspondence with foreign courts, instruct our foreign ministers, negotiate treaties, &c.; his station is second only, in importance, to that of the Presidency itself. Of the 15, who had filled this office up to 1845, the slave States have had 10; the free States 5. The whole number of officers in this department at Washington, in 1846, is 86. Of these Virginia has 6 and the District of Columbia 45.

In 1846, there are, at Washington, 98 officers in this department. Of these, the District of Columbia has 49—exactly one half, and Virginia and Maryland have the balance.

The free States generally have furnished the seamen and the soldiers; the men to do the fighting and endure the hard knocks, but slavery has taken care to furnish Southern men for officers. Thus, of 1054 naval officers, New England has only 172; of the 68 commanders, New England has only 11; of the 328 lieutenants, New England has only 59; of the 562 midshipmen, New England has only 82; and New England owns nearly half the tonnage of the country. Of all the officers in the navy in 1844, whether in service or waiting orders, Pennsylvania, with a free population more than double that of Virginia, had but 177, while Virginia had 224. In 1842, under Mr. Upshur, of 191 naval appointments, the slave States had 117; the free States only 73.

The greatest opposition to cheap postage is from the South. The reason is obvious. As multitudes of their Post-routes do not pay for themselves, they must be paid for, through a system of high postage, by the North, or be given up. Thus in 1842, the deficit in the Post Office department from the slave States was $571,000, while the excess over the expenditures in the free States was $600,000. This went of course to make up the deficiency of the South. So that in 1842 alone the North paid all its own postage, and $571,000 of postage for the South. Nor was this all. The whole number of miles of mail transportation for 1842, was 34,835,991, at an expense of $3,087,796. Of these miles, the mail was carried 20,331,461, at a cost of $1,508,413, in the free States; and 14,504,530 miles, at a cost of $1,579,383 in the slave States; that is, it cost $70,970 more to carry the mail in the slave States than in the free, while it ran 5,826,931 miles less. Under the new system, from official returns, presenting a comparative view of the postage received at forty-two offices, North and South, during the third quarter of 1844 and 1845, it appears that while the falling off at the offices in the free States has not been one third, that at the offices in the slave States has been more than one half.

That most of the “spoils” of office, in these departments go to the slaveholders is well known. The following is the Diplomatic Agency of 1846.

Full Ministers. To Great Britain, Louis McLane; France, William R. King; Spain, Romulus M. Saunders; Turkey, Dabney S. Carr; Mexico, John Slidell; Brazil, Henry A. Wise;—all from slave States; and Russia, R. I. Ingersoll from Connecticut.

Charges. Austria, William A. Stiles; Holland, Auguste Davezac; Belgium, Thomas G. Glenson; The two Sicilies, William H. Polk; Sardinia, Robert Wickliffe; Portugal, Abraham Rencher; Venezuela, Benjamin G. Shields; Buenos Ayres, George Harris; Chili, William Crump, all from the slave states, and from the free States only Denmark, William W. Irwin; Sweden, H. W. Ellsworth; Central America, B. W. Bidlack; and Peru, A. G. Jewett.

Thus, of the seven full ministers six are from the slave States; and of the thirteen Charges, nine are from the same; and the four given to Northern men[7] are among the most insignificant governments in the world. And this favoritism of the South has been the policy for years. The civil and consular agencies are dispensed with a like injustice to the free States. The following, prepared by Prof. Cleveland, gives the number of persons employed in 1845, in these several agencies, from a few States, with their salaries, and the number of free white inhabitants in the same.

| Free States. | Free Pop. | Persons | Salaries | Slave States | Free Pop. | Persons | Salaries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York, | 2,378,890 | 37 | $ 63,250 | Virginia, | 740,968 | 114 | $200,395 |

| Pennsylvania, | 1,676,115 | 90 | 123,790 | Maryland, | 318,204 | 133 | 170,305 |

| Massachusetts, | 729,030 | 43 | 86,215 | Dist. Colum., | 30,657 | 99 | 77,455 |

| Ohio, | 1,502,122 | 6 | 4,400 | Kentucky, | 590,253 | 7 | 34,150 |

During the twenty years, ending in 1832, there were six presidential elections. In these, the South cast 608 electoral votes, but only 41 of them for Northern candidates. During the twenty years, ending in 1835, there were five presidential elections, in which the South cast 515 electoral votes, only 11 of which were for Northern candidates.

In the presidential election of 1844, thirteen free States had 161 electors, and gave 1,890,884 votes—one elector to 11,739 votes; while twelve slave States had 105 electors and gave 798,848 votes—one elector to 6,608 votes. In other terms; six slave State votes counted as much in choice of President and Vice President as eleven free State votes. In the same election, Michigan had 5 electors and gave 56,222 votes, or one elector to 11,244 votes; while Louisiana had 6 electors and gave 26,865 votes, or one elector to 4,447 votes—that is, four slaveholding Louisiana votes were equal to eleven free Michigan votes.

The present number of the House of Representatives, including Texas is 228. Of these 21 represent slave property. In fixing the ratio of representation, after the last census, the House adopted that of 50,179. This would have given a House of 306 members, and the free States a majority of 68. But a small majority is more easily managed than a large. The Senate rejected that ratio and sent back the bill with the ratio of 70,680. This reduced the House to 223 and brought down the majority of the free States to the more manageable number of 47. The effect of the odd number, 680, was to deprive the four great States of the north, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio, of one member each, with no corresponding disadvantage to any slave State. Of this proceeding, even the correspondent of the New York Herald said,—“The Senate apportionment has robbed the North of at least one quarter of its practical influence in the Union, when regarded in its full extent; and the members of the free States who voted for it, have thus surrendered the rights of their constituents, and violated their trusts.”

The Speaker of the House has the appointment of all committees, and of course exerts an immense influence in this, as well as other ways, in the legislation of the country. During 31 of the 34 years, from 1811 to 1845, the speakers were all slaveholders.

The Supreme Court of the United States is the court of highest appeal in the nation. Its decision on all questions coming before it is final. Of the 30 judges of this court, the slave States have had 17; the free States 13. The circuits and salaries are still more unequal and unjust. Vermont, Connecticut, and New York, with 42 representatives in Congress, and a free population of over three millions, constitute but one circuit; while Alabama and Louisiana, with but 11 representatives and a free population of but half a million, consti[8]tute another. So of other circuits. Louisiana, with a free population of 183,959, has one judge at a salary of $3,000; Ohio, with a population of 1,519,461, more than eight times as great as that of Louisiana, has only one judge, at a salary of $1,000: that is, with eight times as many people to do business for, he receives one-third as much pay. Arkansas, with a free population of 77,639, has one judge at a salary of $2,000; New Hampshire, with a population of 284,573, has but one judge, at a salary of $1,000. Mississippi, with a free population of 180,440, has one judge, at a salary of $2,500; Indiana, with a population of 685,863, has but one judge, at a salary of $1,000—that is, two-fifths as much pay for doing more than three times the work!

The Surplus Revenue, distributed by the Act of 1836, amounted to 37,468,859 dollars. The slaveholders managed to have it distributed, not, as it should have been, on the basis of free population, but that of federal representation. Thereby the South, with a free population of 3,823,289, received $16,058,082,85, while the North, with a free population of 7,008,451, received but $21,410,777,12. So that for each inhabitant of the free North, there was received but $3,06; while for each free person in the South, there was received $4,20; or $1,14 more for each free person in the South, than for each free person in the North. The South, by this operation alone, received for her slave representation in Congress, $4,358,549!

In this war,—New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania,—seven States—furnished 172,436 troops and were paid for services, $61,971,167. Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia—six States—furnished 59,335 troops, and received $52,438,130. In other terms, the Northern States furnished about three times the number of troops and received less than one fifth more pay. In particular States the inequality was far greater.

The Slaveholders envied the commercial prosperity of the North, and, to crush it, decreed the war of 1812, under the pretence of defending “free trade and sailor’s rights;” and one hundred and thirty-seven millions of dollars were wasted in its prosecution, and $200,000,000 more were lost on sea and land by Northern merchants and farmers, and then, leaving “free trade and sailor’s rights” where they were before, they made peace, and demanded a National Bank and Protective Tariff. And in the prosecution of the war, says Alvan Stewart, Esq, (Address to Abolitionists Aug. 1846)—“The South placed Major General Smyth at Buffalo, a slaveholding lawyer of Virginia; Major General Winder, a slaveholding lawyer of Maryland, at Forty Mile Creek, on the side of Lake Ontario; Major General Wilkinson, a Louisiana slaveholder, at the Cedars and Rapids of the St. Lawrence; and Major General Wade Hampton, the great sugar boiler of Louisiana, and the largest slaveholder in the United States, (having over 5000 crushed human beings bowing to this monster and tyrant), was located at Burlington, Vermont, four slaveholding Generals with their four armies, were stretched out on our northern frontier, not to take Canada, but to prevent its being taken, by the men of New England and New York, in 1812, '13 and '14; lest we should make some six or eight free States from Canada, if conquered. This was treason against Northern interests, blood and honor. This horrid revelation could have been proved by General John Armstrong, then Secretary of War, after he and Mr. Madison quarreled.”

While Florida was in possession of Spain it furnished an asylum for slaves escaping from the contiguous States. It was therefore bought, at the dictation[9] of the slaveholders, at an expense of $5,000,000. For the same purpose, and at the same dictation the late Florida War was waged, and the native Indian exiled. Of this, the Hon. J. R. Giddings, 1845, said,—“They (the army) captured 460 negroes, who were adjudged slaves by staff officers of the army, to whom the duty was assigned, and who delivered them over to interminable bondage. [See House Doc. 52, 3d Sess. 27th Congress.] We have no means by which we can determine the number of lives sacrificed in that war; but it may be safely asserted, that the capture of each slave cost the lives of two white men, and at least $80,000 in cash, the most of which was drawn from the pockets of the people of the free States. The whole expense of the war is estimated at $40,000,000. The moral guilt incurred, and the sacrifice of national character cannot be estimated. Perhaps I ought to add, on the authority of Gen. Jessup, that bloodhounds were also purchased to act as auxiliaries to our army, and that bloodhounds, and soldiers, and officers, marched together under the star-spangled banner, in pursuit of the panting fugitives who had fled from Southern oppression. [House Doc. 125, 3d Sess. 25th Congress.] And blood hounds, and soldiers, and officers were paid for from the avails of Northern industry; while our people were not permitted to petition their servants to be relieved from such degradation.” One R. Fitzpatrick was employed to get the blood hounds. He obtained thirty-three, and the cost, including expenses of bringing to Florida, was $5000. The removal of the Indians from the several slave States was merely to make room for slavery; and it has cost at least $50,000,000, and of all these millions the North has had to pay the largest share.

Everybody knows that Texas was annexed and that the war is waged to extend and strengthen Slavery. The cost of these measures is yet to be ascertained. There is little doubt that it will exceed rather than fall short of one hundred millions.

The South originated the Bank and the Tariff. When they ceased to work for its interests, the South abolished both. The sums filched from the North by these changes of national polity and by Southern bankrupts, seem almost incredible. $27,000,000, of the capital of the United States Bank was sunk at the South. $500,000,000, it is estimated, would not more than meet the losses of the North, in sixty years, from Southern bankruptcy. In fine, there is no end to these burdens—this side-wise plunder of the free, by those whose entire life is a wholesale plunder of the Slave. How long will freemen bear it?

The following is the conclusion of an advertisement in the Savannah Republican of March 23, 1845:—

“Also, at the same time and place, the following negro slaves, to wit: Charles, Peggy, Antonet, Davy, September, Maria, Jenny, and Isaac, levied as the property of Henry T. Hall, to satisfy a mortgage fi. fa., issued out of the Supreme Court, in favor of the Board of Directors of the Theological Seminary of the Synod of South Carolina and Georgia, vs. said Henry T. Hall. Conditions, Cash.

C. O’NEAL, Sheriff M. C.“

A runaway slave, in 1841, assigned the following as his reason for not communing with the church to which he belonged at the South. “The church,” said he, “had silver furniture for the administration of the Lord’s Supper, to procure which, they sold my brother! and I could not bear the feelings it produced, to go forward and receive the sacrament from the vessels which were the purchase of my brother’s blood.”

The Rev. J. Cable, of Indiana, May 20, 1846, in a letter to the Mercer Luminary, says:—“I have lived eight years in a slave State, (Va.)—received my Theological education at the Union Theological Seminary, near Hampden Sydney College. Those who know anything about slavery, know the worst kind is jobbing slavery—that is, the hiring out of slaves from year to year, while the master is not present to protect them. It is the interest of the one who hires them, to get the worth of his money of them, and the loss is the master’s if they die. What shocked me more than anything else, was the church engaged in this jobbing of slaves. The college church which I attended, and which was attended by all the students of Hampden Sydney College and Union Theological Seminary, held slaves enough to pay their pastor, Mr. Stanton, ONE THOUSAND DOLLARS a year, of which the church members did not pay a cent (so I understood it). The slaves, who had been left to the church by some pious mother in Israel, had increased so as to be a large and still increasing fund. These were hired out on Christmas day of each year, the day in which they celebrate the birth of our blessed Savior, to the highest bidder. These worked hard the whole year to pay the pastor his $1000 a year, and it was left to the caprice of their employers whether they ever heard one sermon for which they toiled hard the whole year to procure. This was the church in which the professors of the seminary and the college often officiated. Since the abolitionists have made so much noise about the connection of the church with slavery, the Rev. Elisha Balenter informed me the church had sold this property and put the money in other stock. There were four churches near the college church, that were in the same situation with this, when I was in that country, that supported the pastor, in whole or in part, in the same way, viz: Cumberland church, John Kirkpatrick, pastor; Briny church, William Plummer, pastor, (since Dr. P. of Richmond;) Buffalo church, Mr. Cochran, pastor; Pisga church, near the peaks of Otter, J. Mitchell, pastor.”

At the great Convention, at Cincinnati, in June 1845, Mr. Needham of Louisville, Ky., said:—“Sir, in 1844, a Methodist preacher, with regular license and certificate, was placed in the Louisville jail, as a slave on sale. He preached in the jail sermons which would have done credit to any white preacher of the town. He kept a little memorandum in his pocket, in which he marked the number of persons hopefully converted under his preaching. I represented his case to leading Methodists in Louisville, and showed them a copy of his papers which I had taken. Not one of them visited him in his prison. He said he forgave those who had imprisoned him and were about to sell him. He was sold down the river, which was the last time I saw him.”

March 28, 1843, in a public address at Cincinnati, the Rev. Edward Smith, True Wesleyan, of Pittsburgh, stated that he had lived in slave states thirty-two years; and, speaking of a certain D. D. of his acquaintance, he adds:—“He was a slaveholder, and a severe one, too, and often, with his own hands, he applied the cowhide to the naked backs of his slaves. On one occasion, a woman that served in the house, committed, on Sabbath morning, an offence of too great magnitude to go unpunished until Monday morning. The Dr. took his woman into the cellar, and as is usual in such cases, stripped her from her waist up, and then applied the lash. The woman writhed and winced under each stroke, and cried, 'Oh Lord! Oh Lord!! OH LORD!!!’ The Doctor[11] stopped, and his hands fell to his side as though struck with palsy, gazed on the woman with astonishment, and thus addressed her, (the congregation must pardon me for repeating his words), 'Hush, you b—h, will you take the name of the Lord in vain on the Sabbath day?’ When he had stopped the woman from the gross profanity of crying to God on the Sabbath day, he finished whipping her, and then went and essayed to preach that gospel to his congregation, which proclaims liberty to the captive and the opening of the prison doors to them who are bound.”

“We are about to make an announcement,” says the True American, “which must sound very strange to those whose field of observation is unlike our own: The greatest impediment to the success of the Anti-Slavery movement in the slave States is, the opposition to it of those men who profess to have been commissioned by high Heaven to go abroad and use their efforts for the mitigation of human misery and the extirpation of human wrong! This assertion, which appears so monstrous, will not surprise any one who lives among slaveholders. Our conviction of its truth has been confirmed by extensive observation.”

Archbishop Potter. Some of our wise ones will have it that doulos means slave. Archbishop Potter, than whom no man was more learned in Grecian antiquities, in his work on them, published years ago, says, chap. 10, “Slaves, as long as they were under the government of a master, were called oiketdi; but after their freedom was granted them, they were douloi, not being like the former, a part of their master’s estate, but only obliged to some grateful acknowledgments and small services, such as were required of the Metoikoi, to whom they were in some few things inferior.”

The Younger Edwards, (Pastor of a church in New Haven, and afterwards President of Union College)—“Every man who cannot show, that his negro hath by his voluntary conduct, forfeited his liberty, is obligated immediately to manumit him. And to hold [such an one] in a state of slavery, is to be every day guilty of robbing him of his liberty, or of man-stealing—and fifty years from this time (1791) it will be as shameful for a man to hold a negro slave, as to be guilty of common robbery or theft.”

Dr. Adam Clarke. “Among Christians slavery is an enormity, and a crime for which perdition has scarcely an adequate state of punishment.”

Rev. Albert Barnes. “From the whole train of reasoning which I have pursued, I trust it will not be considered as improper to regard it as a position clearly demonstrated, that the fair influence of the Christian religion would everywhere abolish slavery. Let its principles be acted out; let its maxims prevail and rule in the hearts of all men, and the system, in the language of the Princeton Repertory, 'would SPEEDILY come to an end.’ In what way this is to be brought about, and in what manner the influence of the church may be made to bear upon it, are points on which there may be differences of opinion. But there is one method which is obvious, and which, if everywhere practised, would certainly lead to this result. It is, for the Christian church to cease all connection with slavery.”

Rev. S. H. Cox, D. D. “The cause of human rights is only the converse of the cause of human duties; and how pious, or how orthodox, or how heroic, I should like to know, is he, for whose higher evangelical refinement of sensibility, this subject of righteousness is too 'delicate’ to be theologized into our ethics, our creed, or our prayers? Away with such nauseating and hypocritical affectation, in high places, and low ones, too.”—Letter to S. J. May, Auburn, May 5, 1835.

PUBLICATION OFFICE,

AND

FREE READING ROOM;

NO. 22 SPRUCE STREET,

(3rd door east of Nassau Street,)

NEW YORK.

William Harned, Publishing Agent of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, invites the attention of the friends of the cause in every part of the country, to the new Depository and Publishing Office, which is centrally and pleasantly located, and designed to afford every attainable facility for promoting the great objects of the Society.

THE AMERICAN AND FOREIGN ANTI-SLAVERY REPORTER, edited by Rev. A. A. Phelps, is published monthly, at 50 cents per annum, with a material reduction to those who take several copies.

The Reading Room, free to all, is furnished with files of all the Anti-Slavery papers and periodicals published in this country; together with a good selection of religious, literary, and political papers. It is also intended to establish an extensive Library of all works on the subject of Slavery, so far as they can be obtained.

A Depository for the sale of Anti-Slavery Publications has been established; from which it is intended that all the standard works on Slavery may be obtained, at wholesale and retail. In addition to such of the publications of the American Anti-Slavery Society as are yet in print, we have now on sale the following new and popular works, viz.:—

---> Address all orders for the Reporter, Books, &c. postpaid, to

WILLIAM HARNED, 5 Spruce Street, New York.