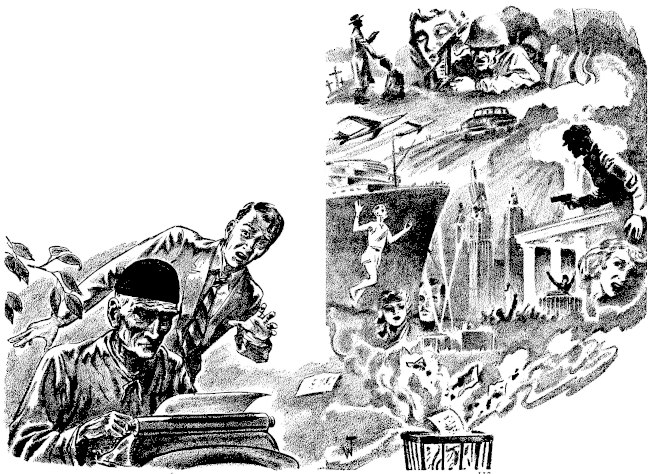

Is Fate a robot typing out the destiny of

the world? Lin knew it was true so with his own

future at stake—he stole a page from history!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

May 1952

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"I'm never going to take my last breath," Lin said with a gloating tone that implied some deep secret. He waited until his remark had had its full dramatic moment, then added, "I'm simply going to take my next to last breath and hold it."

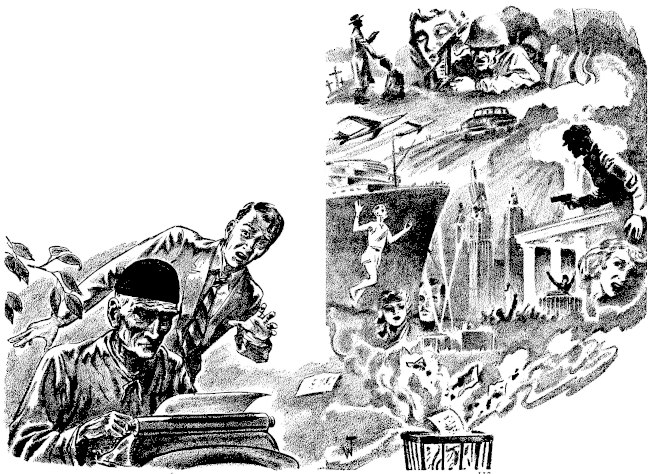

Jerry Myer's voice emerged from the wave of laughter, serious. "But there does often seem to be something predestined about death. Even seemingly accidental death." He shuddered. "There were five hundred and sixty-nine traffic deaths last Labor Day weekend. I wonder how those victims would have felt if they had been told, say, a week before they died? And been unable to avoid it, no matter what they did?"

"Nonsense!" Phil Arnoff said. "What about surgery, serums, and safety devices? They get demonstrable results in saving lives. A man has an enlarged aorta. Ten years ago he would have been a goner. Today he has an operation. They transplant a section of the aorta of a dead person, and he lives another twenty years."

Jerry sighed. "You're getting into a meaningless argument. It could be answered that destiny brought the operation into the realm of actuality to save him because it wasn't his time to die. There's a lot of evidence to support predestination. Some of the oldest of philosophies and religions are based on it. It is written is a concept as old as man."

"And maybe as mistaken as the ancient belief in a god of thunder," Lin scoffed.

"And maybe not," Jerry said. "You read a book. Unless you cheat and look at the ending first it's like life. Unpredictable. But you can skip to the end and see how it will come out, and then start in at the beginning and read with that knowledge. And when you again reach the end it's still the same, because it was already written and unchangeable when you began reading the first page. Sometimes I think real life is like that."

Phil and Lin winked at each other. Then Phil said, "Let's suppose that's true for the moment. Who does the writing?"

Jerry shrugged. "What difference would that make? There's the old tale of the Fates as weavers, weaving a cloth that becomes the events of men's lives as it is woven. And there's another one I heard once, or read someplace...."

"What's that?" Lin prodded.

"I was trying to remember where I got it," Jerry said. "It doesn't matter. The way it goes, Fate is an old man with sightless eyes, sitting at a typewriter, pecking out the events that will happen. Beside him is a wastebasket affair with an eternal flame in it. When the sightless old man finishes one page he yanks it out and drops it in the wastebasket. The flame consumes it, and as it is consumed it becomes the reality of life."

"Say!" Phil said. "That's a darned cute idea. Writing on paper, burning, and in the process of burning it transforms into reality by some strange alchemy. I hope you can remember where you read that."

Lin snorted. "Maybe he wrote it himself and burned the pages as they were finished," he suggested. He glanced at the clock on the wall. His eyes widened in surprise. "I didn't know it was that late," he said, rising. "I've got to get to the city before the bank closes. Have to really step on it."

"Take it easy," Phil called after him. "Don't get killed."

"Nothing to worry about," Lin called back. "If it isn't written it won't happen, you know."

"Don't tempt Fate!" Jerry said warningly.

But Lin was out the door beyond hearing.

The sign read SLOW TO 35. Lin smiled. That was for ordinary cars. His Hudson had a low center of gravity. But he took his foot off the gas and the uphill drag slowed his car to seventy, sixty-five, sixty, then fifty-five as he entered the first bend of the S curve.

The pines were tall right to the edge of the shoulder, hiding what was ahead. It was a bad gamble, he decided, but the dashboard clock told him it was one he would have to take. Twenty-four miles to go yet and in twenty-two minutes. Even fifty-five was going to make him late. He edged up to fifty-eight, leaning his head over so he could see farther around the bend of the two lane highway.

A car was coming toward him. It was over on its side of the pavement, which was well. There was a woman in it. The color and shape of the hat, which was about all he could really see, told him that.

The oncoming car vanished for a moment on the curve. Then it was rushing toward him on the short stretch of straightaway between the two curved sections of the S.

Lin relaxed. There wasn't a thing to worry about. He'd taken the first curve easily. The oncoming car was thirty yards away, then ten. Then—

It was one of those absolutely incredible instants of time. Something had happened to his Hudson. A blowout? A wheel off? Whatever it was, he had veered straight toward the oncoming car.

Instinctively he turned his wheel to get back into his own lane. The car responded by lifting into the air and turning over.

There was a brief, photographic still picture of the other car poised at a crazy angle scant inches in front of him. He could see the girl's features clearly, etched in lines of horror. She was nice looking. Her eyes were wide blue pools, and there were two sharp vertical lines between them.

She looked at him then, accusingly, reproachfully. He shook his head in mute apology and wished he could do it over and go slower.

Quite calmly, though, he knew they would probably both be killed. And it was strange that time could speed up so quickly in the moment before death. Even now, in this instant that hung poised in eternity he could find time left to wonder what had happened. It couldn't have been a tire. All four tires were less than five thousand miles old. It couldn't have been a wheel either.

It could have been something in the road. He had been looking at the female hat behind the windshield of that car and could have missed seeing something on the road.

Forgetting what was in front of him, he started to turn his head to look back.

He blinked his eyes. There was something wrong. It came to him. He had been about to have a head-on collision with another car. He looked down at the ground where he stood. His feet were resting on a well packed dirt path that went forward across the grass and curved behind a clump of large leaved shade trees.

He looked around him. No one was in sight. The place was strange to him. He'd never been here before.

He closed his eyes and thought back. He was quite certain he had been about to be killed in an accident. It couldn't have been a dream. He opened his eyes again and looked about him curiously. This could be a dream. Or was he dead and was this something after life?

There was a test he could make. He tried to remember having reached this point on the path. He turned around and looked back the way it came up the gentle slope of the hill. He couldn't remember having reached this spot at all.

There was another test. He used the edge of his shoe to scrape a line on the path. Then he got down on his haunches and studied the ground. There was no sign of his footsteps. But the ground was well packed.

He straightened up. There was no use just standing here, he decided. So he started walking, the way he had been facing originally.

Suddenly he thought of another test. Stopping, he went through his pockets. Everything was where it should be. His billfold held his identification cards and currency. He studied the currency. It was too perfect in detail to be a figment of a dream.

He shook his head in perplexity. Whatever had happened, it was beyond his grasp. Shoving things back in his pockets he started forward again.

The sky was blue, with billowing white clouds drifting lazily high above the treetops. Ahead there was the sound of water. Shortly he came to a foot bridge that spanned a small and turbulent stream.

The path followed the bank of the stream for a hundred yards, then turned sharply and cut through the woods. The trees seemed to be some kind of Maple. The ground was covered with short cropped meadow, as though cattle had grazed here. But there was no sign of movement anywhere.

But there was. Something small and black was drifting down toward him in the air. He stopped and waited until he could reach out and seize it between his fingers.

It crumpled at his touch. He rubbed it between thumb and finger, examining its texture. It seemed to be a flake of burnt paper, as though someone had tossed a piece of paper in a campfire, and a charred piece of it had floated away on the breeze.

He went forward more eagerly now. Undoubtedly someone was ahead of him. Probably on a picnic. He could find out from them where he was.

And there was a sensible explanation of things now. He had probably been thrown clear of the car and knocked out. That could have lasted for hours while he wandered through the woods.

Of course that was it, he decided with relief. Now all he had to do was find someone and tell them about it, and they would take him back to the scene of the accident.

Ahead through the trees he could see the steep bank of a tableland that rose above the treetops. While he watched, there was a flurry of motion that swept downward from up there. Black flakes that turned and tossed in the breeze. More charred bits of paper. That was obviously where the campfire was.

"Hello up there!" he called. There was no answer. No sound at all.

He broke into a trot, marvelling that he didn't feel groggy or upset. The path turned in toward the steep bank and terminated at the foot of concrete steps that went upward. When he reached them he paused to get his breath, then started up the steps at a more leisurely pace.

They zigzagged up the face of the steep bank, twelve steps to each section.

He paused half way up and looked over the treetops, which sloped gently for several hundred yards, then dropped away. In the far distance was the hazy panorama of a valley with two lakes that were irregular blue splotches on a carpet of greens and browns.

He resumed his upward climb. Finally there was only one more section of steps before the top.

He sighed with relief and paused to look downward, almost regretting that he hadn't chosen to go the other way on the path. He would almost certainly have run into someone before this, going the other way, and then he wouldn't have had all this climb. But.... He shrugged and climbed the last of the steps.

He was on a flat table of jigsaw design, flagstone cemented together. Twenty feet away was a man. The man, his back to him, was seated on a stone bench before a small stone table, intent on something he was doing that was concealed by his back and hunched shoulders.

In the incredible stillness came the staccato click of what sounded exactly like typewriter keys. As Lin watched, the man jerked something. A piece of paper appeared briefly, then was dropped into a wire basket where almost invisible blue flames immediately licked at it and began to consume it.

Blackened bits floated upward and away. And even as they floated over the edge of the table the rapid click of the typewriter began again.

"Hello!" Lin said in good natured greeting.

The head didn't turn. The clack of the typewriter continued without pause.

Lin hesitated a moment, then approached the man slowly, debating whether he should speak to him again or wait until he paused to rest. The man must not be doing so well with his writing, to toss a finished page into the fire so casually.

Lin's lips quirked into a smile. He would sneak up and glance over the man's shoulder and read what he was typing.

As he stole forward he studied what he could see of the man. Instead of conventional attire he was wearing what seemed to be a heavy gray robe. If he had any hair it was concealed under the black skull cap he was wearing. The back of his neck was deeply wrinkled like that of a man well past the prime of life. His ears were well formed, but stuck out a trifle too much. And from the speed at which he was typing he was probably completely unaware of his surroundings.

Lin paused above him and admired the typewriter. It was the most beautiful machine he had ever seen, and electric, he decided as the man's fingers touched a key and the carriage swung back to starting position on a new line.

The type on the paper wasn't standard. In fact, some of it didn't even seem to be ordinary letters, but some strange type of symbols. Others were almost ordinary.

Lin leaned forward cautiously in order to make out what was already typed. He saw only two words that were recognizable. One was force in the middle of the second line. The other was late in the line that had just been written.

It was a foreign language. Lin decided. But the two words he could recognize gave no clue to what language it might be.

The page was finished. The man's hand seized it and jerked it from the machine, dropping it into the flame in the wire wastebasket.

And from some automatic feed a new sheet came into view on the platen, and the man continued his typing, his fingers moving with great rapidity and without letup.

Lin straightened and stepped back a bit so as not to startle the man. He coughed loudly and said, "Hello, there."

The rhythm of the man's typing didn't vary. He gave no indication of having heard.

Slightly annoyed, Lin reached out and tapped him firmly on the shoulder. Still no result.

"Hey there!" Lin shouted, clamping fingers over the man's shoulders and starling to shake him. "Hey!" he started to say again, then his voice died away.

The shoulder under his fingers was unyielding. Too unyielding. His lips took on a stubborn line. He applied force. The shoulder was immovable.

He released it and stared down, mystified. The fingers continued their typing without pause, a blur of movement over the keys.

With abrupt decision Lin stepped around so he could see the man's face. He caught an impression of a lean face, intellectual and relaxed, with firm lips and thin high bridged nose. But these were only vaguely noticed, because his attention was immediately dominated by the man's eyes.

Or lack of eyes, that is. For where his eyes should have been was nothing but tightly closed lids that, from their sunken contours, covered no eyes at all, but only empty sockets.

Experimentally Lin reached out and touched the face. The pale skin was as unyielding as rock. He pressed his finger against the right cheek until his nail bent over. It should have left a mark on any living skin and brought an exclamation of pain from any living person. But it left no perceptible mark, and the man gave no sign of having noticed. And the fingers continued their rapid movement over the typewriter keyboard.

Incredulously Lin reached out and tried to remove the skullcap. It wouldn't budge, and was as unyieldingly hard as the face.

"A robot!" The exclamation escaped Lin's lips in a hoarse whisper. "Or—a statue?"

In desperation he seized one of the man's arms at the elbow and tried to interrupt the smooth flow of movement. All his strength couldn't vary the motion of that arm enough to cause a finger to miss a key on the typewriter.

"Not a millionth of an inch of play in the joints!" he said, marvelling.

For the first time he turned his attention from the figure before him and examined his surroundings. The robot or statue or whatever it was was seated at a spot practically perched on the edge of a cliff that went down much farther than the stairs on the other side. Here there was a sheer drop of at least a thousand feet, and probably more nearly two thousand.

Below, an immense valley stretched out toward the far horizon.

Lin looked out over the valley with a puzzled frown, trying to recall if there were any high mountains in this section of the country. There were hills, but no real mountains. Nothing to compare with this.

"How long have I been unconscious?" he muttered.

His attention jerked back to the typist in time to see another sheet of paper go into the flames. He watched it burn. The flame itself seemed to come out of a round hole in the rock inside the area of the bottom of the wire basket. From its color it was a gas flame. In the dark it would be a bright blue.

His attention turned to the typewriter and the stone table on which it rested. An inscription was embossed on the smooth face of the front of the table.

Lin nodded in grim understanding. This was a statue. But a statue such as never had existed on the Earth he lived in, or it would have been considered the eighth wonder of the world and known to every school child.

An urgency possessed him to seize the next sheet of paper before the flame could get it, and try to read it. He waited while the robot statue typed, and when the hand jerked out the sheet to throw it into the flames, he grabbed it, though part of it tore away and dropped into the flame before he could rescue it.

He examined the texture of the paper. It had the feel of plastic more than paper. He studied the typing. It was sharp and clear, and completely unintelligible.

Or was it unintelligible? He could almost make sense out of the words. Some of the letters that had been strange were taking on a feel of familiarity.

He closed his eyes tightly and shook his head, then opened them and looked again. It did make sense, but the sense was just beyond his reach.

He looked at the figure bent over the typewriter again, and it struck a chord of familiarity somewhere in his mind. He had heard of this statue somewhere....

He remembered now! This statue, or whatever it was, was the embodiment of Fate. It was writing all that was in store for each individual, and when it tossed the sheets that were written on in the flame their burning brought what was written into being, and it happened, somewhere, just as it had been written.

He stared at the fragment of paper he held in his hand, and wondered what was written on it, and what events he was holding up by not tossing the sheet in the flame.

A smile curved his lips. He held it over the basket. By releasing it, it would drop down and burn. Then whatever event he was holding up would happen.

His fingers relaxed. The paper slipped a fraction of an inch. Suddenly he clutched it tightly and drew it to safety. His forehead prickled. Beads of perspiration dampened it. This puzzled him. It was almost as though somewhere in his mind was terrible anxiety. But he was quite calm.

He stared at the torn sheet of paper again, the smile playing about his lips. Slowly and deliberately he folded it and, taking out his billfold, stored it safely away.

He took a last look at the silent robot, the clicking typewriter, then crossed the tablerock to the stairs and went down them to the path.

Again he saw no sign of movement except for the occasional bit of floating charred paper that came from above. He recrossed the stream at the footbridge. He went slower then, looking for the mark he had made in the hard packed path with the edge of his shoe.

He nearly missed it, seeing it only as he stepped over it. Stopping, he turned and looked back the way he had come. Ahead were the broad leaved trees that looked so much like Maples, the path over which he had come.

He started to turn—and the world turned topsy turvy around him. There was the white face of the girl through the windshield of a car, dropping away suddenly and rotating in a mad gyration until the face was upside down, and then was gone past him.

A dull booming sound exploded on his bewildered mind. Wild forces were tossing him about inside the car so rapidly that there was no way to tell which was up and which was down.

As abruptly as it began, it ended. In the dead silence he heard the screech of brakes. He wondered if it was the girl stopping her car to come back, but he didn't turn his head to look.

He was trying to reconcile the sequence of events brought by his senses. It was impossible. He had spent at least two hours walking up that path, watching the robot statue, and walking back down again to where he had first appeared.

Yet, if it had happened at all, it had happened in less than a split second, for events in the collision had taken up at the exact point where they had left off.

He opened his eyes and saw the creamy gloss surface of a ceiling and knew at once he was in a hospital. Without moving his head he let his fingers explore the clean smelling sheets, the hospital bed gown tied around his neck.

A footstep sounded. A nurse looked down at him with a quiet smile. "Feel all right?" she asked.

He dipped his head in an almost imperceptible nod. The nurse went away. There was a swish of wind as the door closed behind her, but he didn't bother to turn his head to look.

After several minutes the swish of the door sounded again. More than one pair of footsteps came toward the bed. Two men, probably doctors, looked down at him.

"How's the patient today?" one of them asked.

"Today?" Lin echoed. "How long have I been here?"

"Almost a week."

It came flooding in. He could remember hours of torturous pain during which he cried for them to put him out of his misery, of at least two terrible nightmarish scenes where he was surrounded by gleaming chrome things, and the awful odor of ether.

"I remember now," he said weakly. "Will—will I live?"

"If you'd asked us that yesterday we'd have said no," the doctor said, "but—" He shrugged.

"How badly am I hurt?" Lin asked the doctors.

"Pretty badly," one of them said with grave frankness. "Broken back. Severed spine. If you live you'll never walk again."

"But I probably won't live?" Lin said.

The doctors didn't reply.

"The girl," Lin said, "the one who was driving the other car? Was she hurt?"

"Yes. Pretty badly. But she'll live."

"What's her name?"

The two doctors looked at each other. One of them said, "I believe she gave her name as Dorothy Lake."

"Tell me, what was it that caused my car to go out of control?" Lin asked suddenly.

"I can tell you that," one of the doctors said. "The mechanic reported that your tierod, the rod that connects the front wheels together so they stay in line, had come off one of its moorings."

"Oh." Lin said vaguely. He was beginning to feel strange. The memory of that interlude atop the mountain had come back. He was remembering that bit of paper he had snatched from the flames. But of course there was nothing in that.... "Are my things here?" he asked abruptly. "My billfold?"

"Yes," the nurse said. "Your billfold is in the drawer here."

"Get it," Lin said.

She opened the drawer and brought out the billfold.

"Open it and see if there's a folded piece of paper that's torn off on one corner," he demanded.

He watched while she explored the contents. He recognized the texture of the paper as it came to view. "That's it!" he said tensely. "Give it to me!"

He tried to lift an arm. He had to be content with taking it in his fingers while his elbows rested on the bed. With shaking fingers he opened it, and saw the typing that was so different from ordinary typing.

His fingers no longer shook. He folded the sheet of paper and handed it back. "Don't put it back in my billfold," he said. "I want you to take that down to the hospital office and have them put it in an envelope and lock it in the safe. Do you understand? I want that taken care of as though it were worth a million dollars. I don't want anything to happen to it. Do you understand?"

"Y-yes," she said. "I'll do that."

Lin watched her leave the room, then turned with a grin to the doctors.

"I'll live," he said confidently. "I'll live. Nothing can kill me now—so long as that sheet of paper remains intact."

He didn't mind at all the way the two men looked at each other with lifted eyebrows.

The door swished open. The nurse came in. "There's a man down in the waiting room who wants to see you, Mr. Grant," she said. "He gave his name as Hugo Fairchild."

Lin frowned. "You sure he wants to see me?" he asked. "I don't know anyone by that name."

"Yes, it's you," the nurse said. "I told him you weren't in any shape to see any visitors, but he said he would take only a moment of your time."

"All right," Lin sighed. "Send him up, but make sure he doesn't stay any longer than that."

Lin examined the man the nurse brought in. He was of medium height and of ordinary appearance. A type that wouldn't attract a second glance on the street or anywhere else.

"I'm Hugo Fairchild," the man said. "You're Lin Grant."

"That's right," Lin said.

Fairchild looked down at Lin for a moment, then said abruptly, "I'll come straight to the point. You have a piece of paper that doesn't belong to you. I've come to get it."

Lin's eyes narrowed. "How did you know about it, and why do you want it?"

"There's no need to ask questions," Fairchild said. "I'm here to get that piece of paper. It's of no importance to you."

"You can't have it," Lin said.

Fairchild looked around quickly. "We're alone," he said rapidly. "I could knock you out with one blow of my fist. If you won't make any outcry I'll just take it out of your billfold and leave."

Lin watched, grinning, as Fairchild opened the drawer and took out the billfold and searched it swiftly. When he saw it wasn't there he tossed the billfold back in the drawer and looked grimly at Lin. "Where is it?"

"You think I don't know the value of that bit of paper?" Lin said. "You'll never get it. But you interest me. How did you get here? You know what I mean."

"Look, Lin Grant," Fairchild said. "I'm desperate. I have to have that paper. It means nothing to you. Please let me have it."

"Means nothing to me?" Lin said, his voice soft and mocking. "If I hadn't snatched that paper from the fire I would be dead right now. You know that. And so long as I keep it nothing can ever kill me. That's why you'll never get it."

"You're insane," Fairchild said. "How could a mere piece of paper have that power? It has no meaning whatever. The writing on it is merely nonsense."

"Then why are you so interested in getting it to put into the flame?" Lin said. "If you hadn't shown up I might in time have rationalized my memories some way and torn the thing up. But not now. Your coming after it convinces me I'm right. You'll never get it!"

"If I don't," Fairchild said, tight-lipped, "you'll regret every minute you keep it. You're wrong about it. It has nothing to do with you at all." His voice became pleading. "Give it to me and I promise you that you will recover completely as though you were never in a wreck. The doctors can tell you how much of a miracle that will be."

Lin shook his head. "There's more to this than mere superstition or fantastic miracles," he said. "I'll never give up that paper until I know what it means and what it's all about. I know, I should have died. I don't have anything to lose, whatever I do. So I'm keeping it."

"You'll regret it," Fairchild said. He turned abruptly to the door just as the nurse came in. "I was just going," he said calmly.

That night Lin slept, and in the morning when he awakened a nurse was bringing in his breakfast tray. "Good morning!" she said brightly.

Lin yawned and stretched a vague, "Mornin'" coming from his wide open mouth.

The nurse placed the tray where he could reach it easily, and started to leave the room. At the door she stopped abruptly and gasped, then turned and looked at him. She opened her lips to say something, thought better of it and hurried out.

Less than five minutes later she returned with one of the doctors. She was saying, "He did. I saw him with my own eyes," as she opened the door.

"Good morning, Lin," the doctor said. "The nurse tells me she saw you pull your legs up without touching them. Of course she's wrong."

Lin looked at his knees where they pushed the blankets up, a startled expression on his face. "So I did," he whispered in amazement. And he moved his legs again.

"That's impossible!" the doctor said sharply.

"So it is," Lin said, grinning. "I must have established a telepathic bridge across the severed nerves."

"That's impossible too," the doctor said, but his first surprise was wearing off. He came to the bed and pulled down the blankets, and stood there watching Lin move his legs. "Better take it easy until we check with fluoroscopy," he warned. "There's something mighty funny here. I examined the X-ray plates myself. The spinal break was unmistakable!"

Half an hour later Lin was relaxed on the table in the X-ray lab, while a full half dozen doctors studied him through the fluoroscope screen and all talked at once, with every once in a while one of them going to an illuminated plate and tracing what was quite obviously a wide gap in a spinal column.

"I think I could walk without any trouble if you'd let me get up," Lin remarked.

"Good heavens no!" one doctor gasped.

"I don't see why not," another said. "If we had nothing to go on but what we see now you'd agree nothing's wrong with him. Why not let him try?"

There were uneasy mutterings that gradually drifted into a majority opinion that he should try. The technician moved the fluoroscope screen out of the way.

Lin sat up, swiveled gently ninety degrees and lowered his legs over the edge of the table. Cautiously he eased his feet to the floor. Even more cautiously he let his weight gradually settle on them. While the doctors watched without seeming to breathe, he stood up and took a timid step, a more bold one, and then walked several steps and turned around, coming back to the table.

"Feels perfectly natural," he said. "I guess you'll have to admit you were wrong about that spinal cord break."

"But we weren't wrong!" It was the doctor who had had charge of Lin in the first place. "The X-rays prove it!"

"Are you sure they weren't mixed up with those of some other patient?" another doctor suggested.

"Find me another patient in this hospital who has a spinal break half an inch wide and I'll—I'll—"

"Eat him?" Lin suggested.

"Yes. I'll eat him. Gladly. There was definitely no error. A miracle is more possible than those X-ray plates getting mixed up."

"Does this fix me up then?" Lin asked. "Can I leave the hospital?"

"Not for another two or three days under any circumstances," his doctor said. "Personally I think we should put you on display. Permanently. The first proven miracle in two thousand years. Or more! But we'd like you to remain long enough for us to make sure this isn't some freak happening that will undo itself. And also to give us time to get used to the fact that you can walk."

"Okay," Lin said. "I'd just as soon stay another couple of days anyway. Can I go back to my room and have another breakfast? I didn't get a chance to finish my first one."

As soon as he was alone in his room he went to the window and peeked out. Below was the street, and to the left he could see the sidewalk that led to the main entrance of the hospital.

Across the street were office buildings, and after a moment he found what he had half expected to find. Hugo Fairchild was standing on the sidewalk watching the entrance of the hospital.

"You should stay in bed."

Lin whirled at the sound of the voice, then relaxed with a relieved sigh. It was the doctor.

"Okay, doc," he growled. He went and sat on the edge of the bed.

A twisted smile curved the doctor's lips. "You know," he said, "you aren't the only miracle that happened in this hospital today."

Lin blinked. "Don't tell me Dorothy Lake, the girl in that other car, is the other one!"

"How did you know?" the doctor said. "Yes, it was she. Five fractured ribs and a broken right arm. And a severe laceration on the cheek. And not a sign of them now."

"Where is she?" Lin demanded. "I've got to see her."

"I wish I knew what was going on," the doctor said. He studied Lin silently. "I'll ask Miss Lake if she will see you."

Lin lay down and tried to relax while the doctor was gone, but his eyes didn't leave the door. It was over an hour before the nurse came in with a robe and the information that "Miss Lake wants to see you."

He followed her the full length of the hallway. She opened the door for him. He went past her into the room, and saw the face he had seen through the windshield.

"I'll leave you alone for ten minutes," the nurse said.

"Hello," Dorothy Lake said nervously.

Lin saw that she was afraid. "Hello," he said. "You don't need to be afraid of me. I won't eat you. As a matter of fact, I'm awfully sorry I ran into you. If there's anything I can do.... I'll pay the hospital bill of course...."

"I'm not afraid of you," she said. "It's the way I woke up this morning with nothing wrong with me. It scares me. I don't know what to make of it."

Lin started to say something and thought better of it.

"And there's something else," Dorothy went on. "It's the man that insisted on seeing me yesterday. He demanded that I give him a paper I was supposed to have. He wouldn't believe me when I told him I didn't know anything about it."

"Was his name Hugo Fairchild?" Lin asked.

"Yes!"

"I see it all now," Lin said grimly. "Your fate was written on that slip of paper too."

"My fate?" Dorothy said, bewildered.

"And he made us get well so we would have to leave the hospital," Lin went on. "When we leave he'll get us and take it away from me."

Dorothy laughed nervously. "Don't leave it there. I think I'm really insane. The things that are happening can't happen. That's a good test of insanity isn't it?"

"Don't be silly," Lin said. "When a thing happens it can happen, no matter how impossible it may seem. Let me tell you what happened to cause all this."

"Please do," she said. "I'm sure it can't be any more impossible than my bones healing up and a bad cut on my cheek vanishing overnight without even leaving a scar."

"You think not?" Lin said grimly. "Then listen to this. You remember when we were about to hit? A fraction of a second before the crash? At that precise instant when you were staring at me reproachfully I suddenly found myself in—I don't know where it was, but I know it wasn't on this earth. I followed a path up to a high tablerock overlooking an immense valley, and there on that high perch was a statue."

"A statue?" Dorothy echoed.

"Don't interrupt," Lin said. "You can't possibly understand. I don't myself. So just listen to what happened and what I think it means. It was a moving statue. Like a robot, in a way. But it was more than that. I'm sure of that now. It was, in some way, a god. The god of Fate. It was typing on a typewriter of some sort that had an automatic feed to supply a new sheet of paper every time the old one was yanked out. And beside the typewriter was a wastebasket sort of thing with a flame burning at the bottom. This statue would fill a sheet of paper with typing and then yank it out and drop it in the basket, and it would instantly burn. And I know now that the very process of burning that sheet of paper made reality out of whatever was written on it. And to cut a long story short, I yanked a sheet of paper out of the statue's fingers just as it was about to be dropped into the flame."

"But—" Dorothy said weakly.

"That piece of paper," Lin said firmly, "was our fate. Yours and mine. On it was written that we were to die in that accident. And until that paper is returned to that place and burned in the flame, we cannot die!"

She was looking at him queerly now.

"You think I'm crazy?" Lin said. "Hugo Fairchild came to get that paper didn't he? And I have it. Fairchild's waiting outside the hospital for me—or you—to come out with it, too. I saw him from my room."

"How...." Dorothy said weakly. "How did you get over into that—that other world?"

"I don't know," Lin said. "I just did, that's all."

"Then ... then Hugo Fairchild is from this other world?"

"It's obvious, isn't it?" Lin said.

"But it's too late for it to do him any good now, isn't it?" she persisted. "The accident is over. We weren't killed."

Lin shook his head slowly. "It isn't too late, or he wouldn't want it. Don't you see? We, you and I, can't die until he gets it. That's why he wants it. Since it's written on it that we died in that crash, the moment it burns we'll be back where we were when I snatched that paper from the flames, and we'll die in that accident. Then all this, our being in the hospital and all, will never have happened!"

It was the next day. Dorothy had come to Lin's room. She was peeking out the window at Fairchild down on the sidewalk.

"What will we do, Lin?" she asked, turning to him. "We can't hope to fight him. He must have supernatural powers, or he couldn't have caused us to recover so miraculously."

"I don't know," Lin said. "We'll have to sneak out the back way or something. We have to leave tomorrow, you know. Or—Look, he's after the paper and you don't have it. It's me he wants. I'll leave first, with that paper. Then you'll be free and can forget about it."

"I still can't believe it," Dorothy said. "If it weren't for the fact that my ribs were definitely broken, and I saw that nasty cut on my cheek...."

"You know there's no other explanation," Lin said.

"But how could writing on a piece of paper form reality?" she objected. "It just can't!"

"But it does," Lin said. "What is reality? Scientists have been trying to find out since time began. There could be different kinds of reality. Ours could be subject to the minds of beings on another plane of it. This robot could sit there and write out things that happen, and make them happen here. It has to be that."

"I know," Dorothy said. "It has to be that, even if it doesn't seem possible."

She left the window and went to a chair and sat down.

"Lin," she said. "If he gets that paper we both die. I'm going with you. I couldn't stand going out alone and not knowing when he gets it."

"Nonsense," Lin said. "He won't get it. You can forget about it."

"What if he never gets it?" Dorothy asked.

"Then we'd live forever." Lin grinned. "Maybe that's why he has to get it back."

"Suppose," Dorothy said. "Suppose—don't think I'm silly, but suppose we destroyed it on this plane. Then it could never go into that flame."

"I don't know," Lin frowned. "Maybe any flame would make it happen. It would be an awful risk to take."

"We wouldn't have to burn it," she said. "We could tear it into little bits and let the wind carry them away, one at a time."

"I'll have the nurse get it," Lin said.

When the nurse brought it Dorothy examined it eagerly, trying to read what was typed on it. A light of excitement danced in her bright blue eyes. Finally she held it in a position to tear it.

"Shall I?" she said.

Lin nodded. She hesitated a moment, dramatically, then abruptly pulled her hands in a shearing movement that should have torn it easily.

It didn't.

"Here, let me do it," Lin said.

He took it and tried to tear it, without success. He grunted, and exerted every ounce of strength. It remained intact.

"That's funny," he said. "It tore easily when I grabbed it from Fate."

"Let's burn a little corner of it and see what happens," Dorothy suggested.

Lin went to the bedside stand and got his lighter. He held the flame to one corner of the sheet of paper. A minute went by, two minutes. The paper refused to burn or even char.

"Huh!" Lin said, snapping his lighter shut. "Well, it's a cinch that scissors will cut it. I'll ask the nurse to bring us a pair."

Ten minutes later he was trying to cut it, without success. It would bend between the blades of the scissors, or stop them from coming together at all. But it wouldn't cut.

"It's indestructible on this plane of existence," Dorothy said. "Now I believe you, Lin."

"I'm glad you do," Lin said dryly. "So now it's clear what I should do. My job is to hide this someplace where Hugo Fairchild can never find it. You can go your way and forget about it."

Dorothy shook her head. "No," she said. "I'm going with you. We'll face this together. I—I couldn't stand the suspense of wondering when Fairchild would catch up with you and get it."

"You'd get used to it," Lin said. "After all, everyone has to die sometime, and no one spends much time worrying about when it will come."

"But this isn't the same," Dorothy said stubbornly. "That man is after it, and when he gets it we'll die. I'm sticking with you—and that piece of paper."

Lin went to the window and peeked out. Fairchild was still in sight, watching the main entrance of the hospital.

"Okay," he said, turning back to Dorothy. "Go to your room and put on your street clothes. We're going to leave now. We'll sneak out the back way."

Lin watched the door close, then went to work. Folding the piece of paper several times until it was a compact square, he taped it to his side under his left armpit where it couldn't be noticed.

He dressed swiftly, wrote a hurried note informing the hospital he wasn't sneaking out to avoid paying his bill. He left the note on the bed in plain sight and started toward the door. Just as he reached it he remembered Dorothy's hospital bill. He went back and added a P.S. for the hospital to put her on his bill.

Opening the door, he peeked out. A nurse was in the hall. He watched her until she went into a room, then slipped out and hurried toward the stairs.

He was grinning to himself. Dorothy wouldn't have had time yet to get dressed. And he had no intention of waiting for her. It would be too dangerous. She would find him gone. She would be unable to find him. And eventually she would take up her life where it had left off. In time she would forget him and think the whole thing a dream. That was the best way.

He passed people on the stairway without meeting anyone who would recognize him. In the basement the risk was greater. There were dozens of people. But no one stopped him as he hurried toward the exit. They considered him just a visitor, he reflected.

The critical moment was just ahead of him now. A hundred questions were tormenting him. How had Fairchild known which hospital he was in? How had Fairchild known it was he who had stolen that paper?

He shrugged the questions off. There was no way of knowing now. If Fairchild had powers that would enable him to discern that he was sneaking out the back way and be there waiting for him, he'd just have to make the best of it.

At the exit he paused and peeked out. There was a wide concrete driveway. An ambulance was parked there. No one was in sight.

He opened the door boldly and stepped out. He started along the driveway with an appearance of casual unconcern, as though he were a visitor taking a shortcut.

"Not so fast, Lin!"

He turned quickly. Dorothy was half running to catch up with him. He felt his pulse leap and somehow couldn't feel anger.

Dorothy smiled knowingly at him. "I figured you'd try to escape alone," she said. "So I hurried."

"Well, it was an idea," Lin said. "Come on. We've got to put distance between us and Fairchild before he discovers we're gone."

They reached the driveway exit. It was on a sidestreet from the main entrance. Fairchild wasn't in sight.

"Where'll we go?" Dorothy asked nervously.

"How about my apartment?" Lin said. "We can stay there months at a time without going outside."

She gasped, then saw that he was laughing at her with his eyes. "I'll have you know ..." she said angrily.

"Know what?" Lin prompted.

"Let's go some place," she said. "We can't just stand here."

"There's a taxi," Lin said, taking her hand and pulling her after him into the street. In the taxi he gave the driver directions. "First National Bank down on Center Street," he said. "Wait there. We're going to the airport from the bank." And to Dorothy in a lower voice, "We'll put some real distance between us and Fairchild. After that you can go your way and I'll go mine."

"If that's what you want," she said. She broke suddenly. "Oh, Lin. I don't know what I want. I don't want to leave you. I'm afraid. Or maybe I'm not. I don't know. It's all a rotten mess. Why couldn't we have met normally so that if—" She bit her lip and turned away.

The taxi hummed along for several blocks while they were silent. When Lin spoke his voice was low and serious. "Maybe I feel that way too," he said. "But—you know what's wrong with it? We're running away. It's like being an escaped criminal with a death sentence hanging over you."

"But it needn't be!" she said, laying her hand on his arm. "The police aren't after us or anything like that. We've given this Fairchild the slip now. All we have to do is go away somewhere and he'll never find us."

"He'll be looking," Lin said, "and we'll wake up every morning with the knowledge that this may be the day he finds us." He turned and looked through the rear window of the taxi. "Actually I'm surprised we gave him the slip. I can't understand it."

"You feel that way?" Dorothy said with a shaky laugh. "I do too. He found us in the hospital. I keep thinking he just knows things. You know what I mean."

"He didn't know which one of us took that paper," Lin said. He frowned. "But he knew it was one of us. He must know what's on it. He has supernatural powers, too. Look how he fixed us up."

He looked through the back window again. When he straightened he fixed his eyes on Dorothy's face.

"Dorothy," he said, "maybe nothing can stop him from getting that paper back soon. It may be hours or days. But—would you marry me and make the most of it until...?"

She began twisting her fingers together nervously. "I—I don't know what to say," she hesitated. "It seems so wrong in a way. I don't mean wrong. Unfair. That's it. Unfair to—to both of us. Like we were doing this whether we love each other or not. It doesn't give whatever love we could have had a chance."

Lin stared at her a moment. "Then let's turn around and go back and give it to him," he said quietly.

"Let's—let's—" Suddenly she was in his arms, her face buried in his collar, her body trembling. She lifted her head until her cheek rested against his. Her voice was a whisper in his ear. "Let's—get married."

"Boy, have you two got it!" Phil Arnoff said. "You get me on the phone and tell me to rush to town, and you can't wait five minutes. What's the matter? Afraid you'll fall out of love if you don't plunge?"

"We wouldn't have waited for you to get here," Lin said, "only we have to have a witness, they said when we got the license." He looked pleadingly at Dorothy. "Please, honey. Let's skip the church. You don't have to be married in one do you?"

"It's got to be a church," she said. "That's the one thing I've always been certain of."

"Why not?" Phil said. "There's a dozen churches that exist on weddings. Don't even have a congregation. Just weddings. One of 'em ought to have a vacant ten minutes today."

They found a phone booth and Lin began making calls. The third number was answered by a man with an Irish brogue who blessed them for their eagerness and agreed to perform the ceremony at once.

"Hah!" Lin said when he hung up. "We'd have got along without you okay, Phil. Reverend O'Hara said he has a witness on hand all the time for couples like us."

"I'll trail along anyway," Phil grinned, "What is the rush though? How long have you two known each other?"

"We ran into each other a few days ago," Dorothy said, taking Lin's hand and leading him toward the sidewalk.

Phil followed them and noted silently the way they glanced anxiously about when they were out in the open, as though afraid of being seen by someone.

Lin flagged a cruising taxi again. The three of them piled into it and Lin gave the address of the church.

Phil broke the silence after a few blocks. "I'm being nosey, I know. But you two were obviously looking to see if you were being followed. Why don't you tell old uncle Phil about it? Huh?"

"About what?" Lin said, turning innocent eyes on him.

"Nothing," Phil said. "Only, sometimes three heads are better than one. If you two, or one of you, is in trouble, maybe I could be of help if I knew what to look out for."

"I doubt it," Lin grunted. "In fact, if we told you you wouldn't believe it, so skip it."

"So it is trouble," Phil murmured. "I thought so." He grunted. "Count me in on it. What is it. Bank robbery?"

"Worse than that," Dorothy said. "But let's forget it. I want to relish every minute of my wedding."

"Just like a woman," Phil said, lifting his eyes upward. "My wedding, she says."

The taxi chose that moment to pull to the curb and stop. Outside was a small and picturesque church.

"Go on in and get things started," Phil said. "I'll pay the driver."

"Tell him to wait," Lin said. "This shouldn't take more than ten minutes." He took Dorothy by the hand and led her toward the entrance. Phil grinned at the taxi driver and shrugged.

"As best man I get to kiss the bride first," Phil said fifteen minutes later.

Lin jumped, startled. "Huh uh!" he exclaimed. "I've never kissed her yet myself!" He put his arms around her and kissed her lingeringly.

She pulled away from his embrace finally, one hand trying to keep her hat on her head, murmuring, "It's about time!" But the bright lights in her eyes said that it was worth waiting for.

"Bless you, my children," the minister said, smiling.

"Oh yes, how much do I owe you?" Lin said. Realizing his mistake he hurriedly took out his billfold and handed the man a twenty dollar bill. He turned to Dorothy, not waiting for the thanks he expected.

Phil correctly interpreted the minister's dismayed look and slipped him another ten. "He doesn't realize the overhead ate that up," he whispered. "He doesn't get married very often."

"Oh, I see," Reverend O'Hara whispered.

Phil hurried after Lin and Dorothy, catching up with them just outside the front entrance.

"Now," he said grimly as they got into the taxi again, "you want to be alone. My price for leaving you alone is for us to go somewhere first and have a drink or two—which you would anyway—and listen while you tell me what's behind all this rush." He looked sidelong at Dorothy and chuckled. "Surely it wasn't a race with the stork! Or is the hospital our next stop?"

"Of course not!" Dorothy said indignantly. "We just came from there this morning."

"Then this was...?" Phil said, half seriously.

"Not what you think," Lin said. "There's the Shangri-La ahead. We can have a couple of drinks there and something to eat. And we'll tell you all about it, though you won't believe a word."

It was almost two hours later. And four drinks later. "So you see why," Lin was saying while Phil stared at them with round eyes, "we don't know how long we have. Maybe—" He looked anxiously toward the gloom of the entrance across the room. "He could walk in during the next minute. I can't see why he doesn't. I know he knows where we are. I feel it."

"And you have this paper taped to your side under your shirt?" Phil said. "Let me see it."

"No!" Dorothy said.

"I've known Phil most of my life," Lin said. "He's all right. Anyway, you know the thing's indestructible on this plane."

Dorothy hesitated, then reluctantly nodded her agreement. Lin yanked the folded paper from under his shirt.

Phil took it, unfolded it curiously, and frowned at the strange typewritten characters on it.

"You say it's indestructible?" he asked after a moment.

"We tried to tear it, to burn it, and to cut it with the scissors," Lin said. "All it does is bend."

Phil tried to tear it, cautiously at first, then exerting every ounce of strength in his fingers. He gave up and examined the paper with a new respect in his eyes. "I almost think I believe your tall tale," he said musingly.

He dipped a finger in his cocktail and rubbed it over the characters on the paper. Though they became wet they didn't blur or fade.

He took out his lighter and touched the corner of the paper to the flame. When it didn't char he touched it again and let the flame play on one corner for a moment, then touched the corner with his fingers.

"Just warm," he grunted. He began folding the paper up the way it had been. "Of course there's one way I could help you," he said slowly. "You could let me keep this. I could hide it where even you wouldn't know how to find it. That way when this character catches up with you it's out of your hands."

"That's an idea," Lin said. "But we would know you had it. Maybe he could worm it out of us and then he'd be after you. And it wouldn't be your life that hung in the balance."

"True enough," Phil said. He cupped the folded paper in his hand, closing his fingers over it. "There's one or two points I'm not clear on, Lin. You say you grabbed it when it was still in Fate's fingers, and that's when that part tore off? You were able to tear it then. Why can't you now?"

"I don't know," Lin said. "Things are different over there, I guess. It burns over there, too, remember. In that flame."

"Yes, I know," Phil said. "I just—"

A terrified gasp from Dorothy interrupted what he had been about to say. Her eyes were wide and round, and fixed on the entrance across the room.

"Fairchild!" Lin gasped.

Phil turned his head and glanced briefly at the man who stood there surveying the occupants of the room. He got swiftly to his feet just as Fairchild saw them and started toward them.

"Well, goodbye, kids," he said casually. But his broad wink warned them to let him escape with the paper that was still hidden in the palm of his hand.

"Give me back—" Lin blurted. But Phil was hurrying toward the entrance, passing Hugo Fairchild. Lin sighed in relief as Phil made it to the door and vanished.

"Well, well," Fairchild said. "I finally tracked you two down. So you're married now." He slid into the seat Phil had occupied.

"Yes, we're married," Lin said coldly. "And we want to be alone."

"I don't doubt that," Fairchild said. "I don't doubt it at all. I sympathize with you, but I have my job to do, you know."

"I'll bet you sympathize with us," Dorothy said worriedly.

"But I do, really," Fairchild said. "And to prove it I'm going to make you a nice offer. I don't have to, but I can, and I will. Give me the paper and I'll promise not to toss it into the Flame for a whole year. That will give you a year of happiness. It won't do any harm in the long run, because the instant that paper is consumed everything goes right back to the instant of the crash, and world events go on as they should have in the first place. But I'll stick to my bargain. If you give me the paper without trouble."

"But we don't have it!" Dorothy blurted.

"You don't?" Fairchild exclaimed. His eyes widened in sudden comprehension. "That fellow...." He half rose and looked toward the exit. He glanced back at their faces and saw that he had guessed right. Waiting for no more he leaped across the room, bumping into a waiter and causing him to spill a tray of drinks. Then he was out the door before anyone could stop him.

"I hope Phil had sense enough to get far away, and quick," Lin groaned. "Come on, Dorothy, let's see." He dropped enough money on the table to take care of the check and, taking her arm, hurried after Fairchild.

Twenty feet away a crowd had gathered about a central point. They ran to the crowd and pushed their way toward its center. Dorothy gasped and Lin tensed at what they saw.

Phil was getting slowly to his feet, nursing a large bruise under one eye with gentle fingers.

"The other guy just vanished!" someone said unbelieving. "I saw him! He just vanished in thin air where he was standing!"

"Did he get it?" Lin said, helping Phil to his feet.

Phil nodded, then muttered, "Let's get away from here. I think I need another drink."

Lin's legs were suddenly watery. Dorothy's lip was trembling.

"A drink," Lin said dully, then, determinedly, "Yes, a drink." He took Dorothy's arm in his fingers. "Come on, honey. Maybe we'll have time."

"A drink?" Dorothy said shrilly. "We're going to be dead in another minute and all you want is time enough to have a drink?"

"That isn't it at all," Lin said. "Let's get off the street."

He guided her firmly through the crowd, Phil following in their wake. They went back into the Shangri-La once more and back to their table where their unfinished drinks still rested.

"I'm sorry you took what I said the wrong way," Lin said. "Believe me—"

"It's all right, darling," Dorothy said. "I know you didn't mean it that way. It's just that, well, we haven't had a chance together...." Her lips started to tremble again, then she was smiling bravely.

"That's the girl," Phil said.

"You should talk," Lin growled. "You aren't going to die."

"Let's drink to that, or something," Phil said. "I need one, and I'm sure you both do too."

They drank solemnly. Lin and Dorothy were looking into each other's eyes as they drank.

"I wish—" Lin choked.

"I know," Dorothy said. She leaned across the table and Lin kissed her.

"Cigarette?" Phil asked, holding out his pack. They each took one and he lit them with his lighter.

"Three on a match," Dorothy said nervously. "I guess it's all right this time though. The conclusion is foregone."

"Wonder how long it will take," Lin said, sucking in the smoke hungrily.

"That's another thing," Phil said. "That other time you took that long walk and got the paper and walked back to where you started from, and it all happened in less than an instant."

"That's right," Lin said. "He should be...."

"As a matter of fact," Phil said, "I think he should. So it worked after all. I'd really hoped it would. Or maybe ... but I think it worked."

"What worked?" Lin and Dorothy demanded together.

"He must have tossed that paper into the flame by now, unless he read what was on it," Phil said. He spread his hands apologetically. "You see I knew this couldn't go on forever. The only way to fight the supernatural is to outsmart it, I figured. So I wrote on it. Simple as that. I bore down good too so that if the ink came off, the writing would still be creased in good. On the theory that whatever was on that paper would come true when it got burned."

"What did you write?" Again Lin and Dorothy spoke in unison.

"I didn't have time for anything involved," Phil apologized. "I rather expected him to be after me before I could go far."

"What did you write?"

"Just one word," Phil said, "Cancelled."

"Cancelled?" Lin and Dorothy echoed dumbly, then, comprehendingly, "Cancelled!"

"Sure," Phil said. "That way when it was burned it wouldn't do anything. They'll have to start over on you."

They stared at him wordlessly.

"It must have been burned by now," he added weakly. "So my scheme worked."

They turned their heads and looked into each other's eyes. Two ghostly windshields obscured their vision. The tables and people about them faded, to be replaced by ghostly pines, a more solid concrete highway.

They stared into each other's eyes, knowing all that had been, feeling it slip away.

But abruptly it vanished and they were looking at each other across the table while a waiter asked them if they wanted another drink. For a long second their minds hovered in that other stream of time before the realization came that it was over and they were safe.

"Another?" Lin said. "Yes. Sure. You want one, Dorothy?"

She nodded and watched the waiter's back as he hurried away.

"You two look as if you'd seen a ghost," Phil said. "I would almost swear that paper reached the flame a second ago."

Dorothy turned to him. "It did," she said. "And I don't know whether to be happy about it or—never forgive you."

"Why?" Phil asked.

She looked at Lin, her eyes soft and luminous. Her hand reached out and nestled in his.

"Well," she said, "it seems to me the least you could have done while you had the opportunity was write on it for us to live forever!"

She laughed nervously.

Lin flicked the ash off the end of his cigarette and grinned at her. "That would have been tempting Fate!" he said....