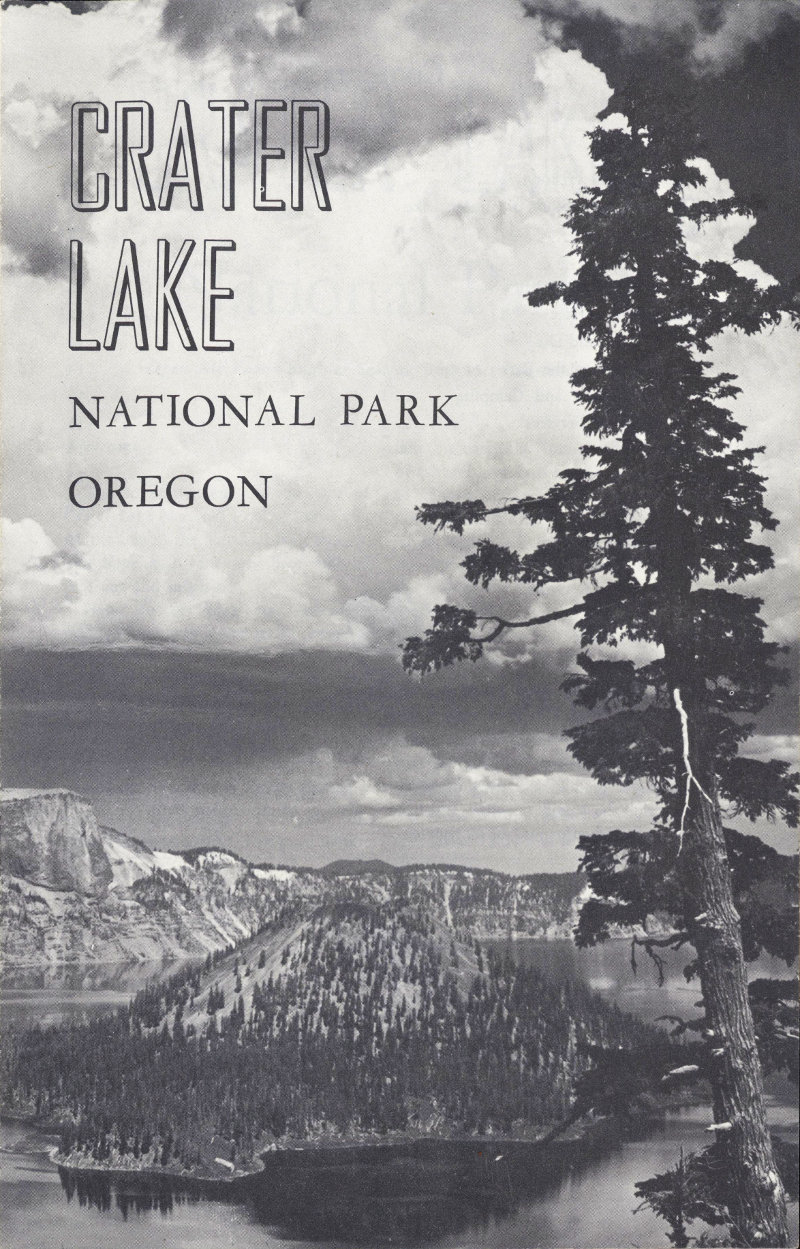

Cover: Wizard Island. Llao Rock in the background.

The National Park System, of which this park is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people.

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Fred A. Seaton, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, Conrad L. Wirth, Director

Open All Year—Regular Season, June 15 to September 15

The superintendent and the staff of Crater Lake National Park welcome you to this area of the National Park System. We hope that your stay here will be pleasant and inspiring.

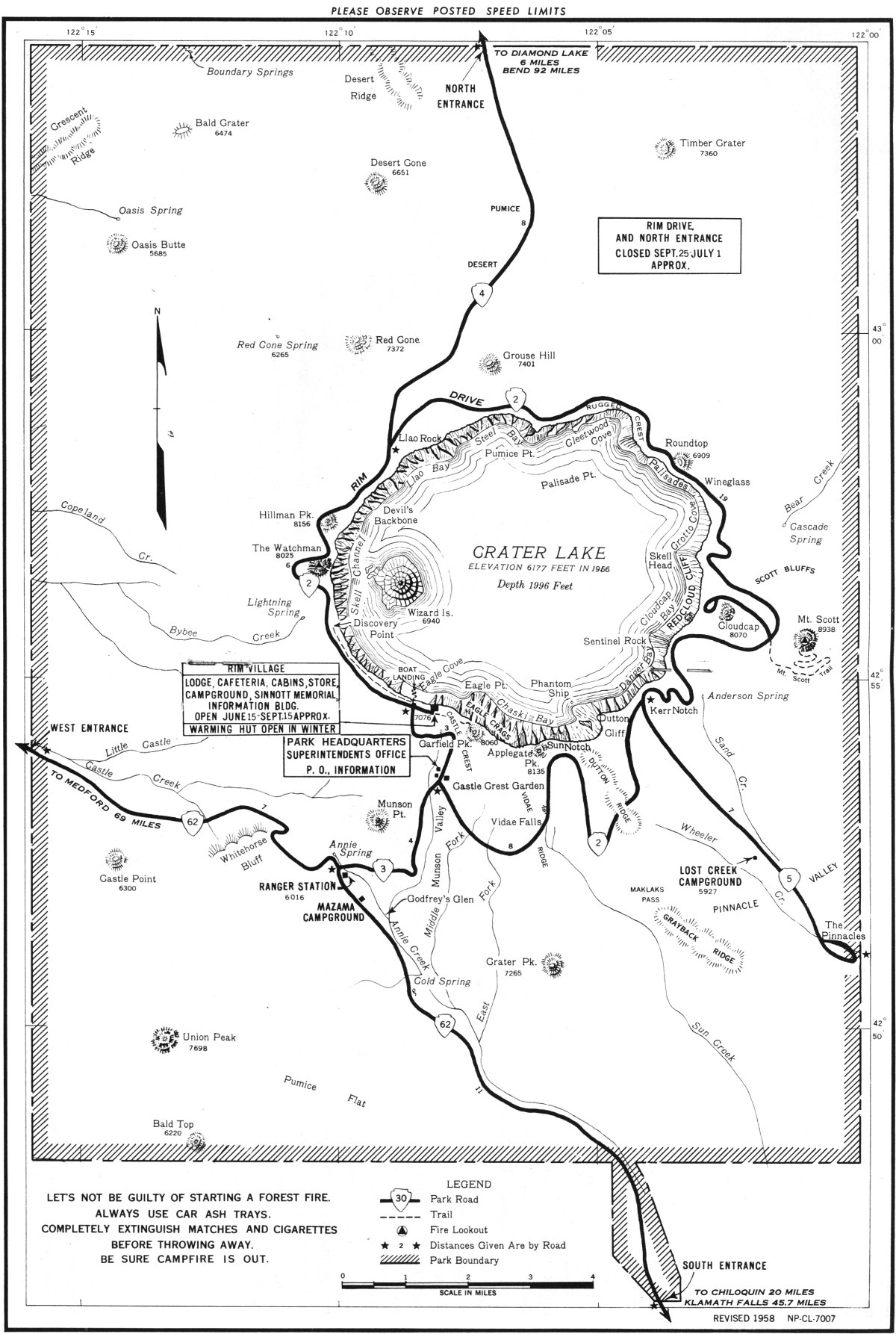

Here in this park you encounter beauty—beauty in a wonderful combination of form and substance and sparking color—great curving walls of rock and sand, green spires of fir and hemlock, and the brilliant reflections of Crater Lake. All this is a part of a remarkable volcanic story.

On this spot, a few thousand years ago, stood the mighty 12,000-foot volcano, Mount Mazama. This great mountain discharged a tremendous quantity of ash and lava, causing the mountaintop to collapse, and creating a caldera, which now contains the unbelievably blue Crater Lake. It is the central feature of this 250-square-mile National Park on the crest of the Cascade Range in southern Oregon.

A major charm of Crater Lake is that the whole lake and its setting can be taken in by the eye at one time. Yet its size is impressive. The lake is about 20 square miles in area, 6 miles wide, and has 20 miles of shoreline. The surrounding cliffs rise as much as 2,000 feet to the uneven crater rim which averages about 7,000 feet in elevation.

It is dangerous for you to get near wild animals though they may appear tame. Some have become accustomed to humans, but they still are wild and may seriously injure you if you approach them. Regulations prohibiting feeding, teasing, touching, or molesting wild animals are enforced for your safety.

The Klamath Indians knew of, but seldom visited Crater Lake. They regarded the lake and the mountain as the battleground of the gods. The lake was discovered on June 12, 1853, by John Wesley Hillman, a young prospector leading a party in search of a rumored “Lost Cabin Mine.” Having failed in their efforts, Hillman and his party returned to Jacksonville, a mining camp in the Rogue River Valley, and reported their discovery which they had named Deep Blue Lake.

On October 21, 1862, Chauncey Nye, leading a party of prospectors from eastern Oregon to Jacksonville, happened upon the lake. Thinking that they had made a discovery, they named it Blue Lake. A third “discovery” was made on August 1, 1865, by two soldiers stationed at Fort Klamath, who called it Lake Majesty. In 1869 this name was changed to Crater Lake by visitors from Jacksonville.

Before 1885 Crater Lake had few visitors and was not widely known. On August 15 of that year William Gladstone Steel, after 15 years of effort to get to the lake, stood for the first time on its rim. Inspired by its beauty, Steel conceived the idea of preserving it as a National Park. For 17 years, with much personal sacrifice, he devoted time and energy to this end. Success was realized when the park was established on May 22, 1902, with W. F. Arant as its first superintendent. Steel continued to devote his life to development of the park, serving as its second superintendent and later as park commissioner, which office he held until his death in 1934.

The slope, which you ascend to view the lake, and the caldera wall rising 500 to 2,000 feet above the water, are remnants of Mount Mazama.

In comparatively recent geologic time, numerous volcanic peaks were formed near the western edge of a vast lava plateau covering parts of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, and California. These are the Cascade Range, of which Mount Mazama was one of the commanding peaks. It was built by successive lava flows with some accumulation of volcanic ash. The cone thus formed was modified by streams and glaciers which carved valleys in its sides and deposited rock debris on its flanks. The layered character and different formations of the mountain are now clearly exposed in numerous places within the caldera wall.

In addition to broad surface flows, it is common for molten lava to be squeezed into cracks, or fissures, that develop in a volcano. Such filling results in dikes, or walls, frequently harder than the enclosing rock. At Crater Lake the destruction of the mountain and subsequent erosion have exposed numerous dikes in the wall, of which the Devil’s Backbone on the west wall is an outstanding example.

In the layers forming the crater wall there is evidence of the action of water. In some places this is shown by the cutting of valleys; in others, by the accumulation of water-carried gravel and boulders.

Glacial ice, carrying sand, pebbles, and boulders, scratches and polishes rock surfaces over which it moves. Glacial polish and thick beds of glacial debris are common around the mountain. They occur on the surface rock and between earlier layers, showing that glaciers existed at various stages in the history of the mountain.

U-shaped valleys, such as Kerr Notch, Sun Notch, and Munson Valley on the southeast slope of Mount Mazama, are evidence of glaciation. The lava flow which formed Llao Rock filled an ancient glacial notch.

Many geologists have concluded that the basin occupied by the lake resulted from the collapse and subsidence of the volcanic cone of Mount Mazama. This explanation was first proposed by J. S. Diller, of the United States Geological Survey, who considered that the support of the summit was weakened by drainage of great quantities of molten rock through subterranean cracks. The pit thus formed grew progressively larger in all directions, as is indicated by the broken edges exposed around its rim today. Extensive study by Prof. Howel Williams, of the University of California, led him to practically the same conclusion.

In his delightful, popular, and scientifically accurate book, Crater Lake, The Story of Its Origin, Williams describes great quantities of pumice extending more than 80 miles northeast of Mount Mazama. This pumice was blown from the mountain in a catastrophic event and carried northeastward by the prevailing winds. Analysis shows that this is material derived from the heart of the volcano and not finely divided fragments of the original mountain walls.

Following this eruption, the crater is believed literally to have boiled over, pouring out great quantities of frothy material as a series of glowing avalanches. These avalanches must have traveled at a terrific speed down the valleys, for those to the south and west did not begin to deposit their load until they had reached a distance of 4 to 5 miles. The greater quantity flowed down the mountain to the south and southwest for distances up to 35 miles from the source. The total volume of the ejected lava was about 5 cubic miles. It is believed that an additional 1.5 cubic miles of old rock were carried away at the same time.

Accompanying these eruptions, which occurred within the past 7,000 years, cracks developed in the flanks of the mountain so that the top collapsed, being engulfed in the void produced by the ejection of the pumice and lava and the withdrawal of 10 cubic miles of molten rock into swarms of cracks that probably opened parallel to the axis of the Cascade Range. Thus was formed the great pit that was to become Crater Lake.

By projecting the slopes of the mountain remnant upward, conforming to the slopes of similar volcanoes, it has been estimated that approximately 17 cubic miles of the upper part of ancient Mount Mazama was destroyed by the collapse.

After the destruction of the peak, volcanic activity within the caldera produced Wizard Island and perhaps other cones. These cones rise above a relatively flat floor, the lowest part of which is almost 2,000 feet below the surface of the present lake.

Hillman Peak—Highest Point on Rim of Crater Lake

The water of Crater Lake comes from rain and snow. The average annual precipitation is 69 inches. The lake has no inlet and no outlet, except seepage. Evaporation, seepage, and precipitation are in a state of relative balance which maintains an approximately constant water level. In 1957, the lake level was the highest recorded since 1908. There is an annual variation of from 1 to 3 feet, the level being highest in spring and lowest in autumn.

The deep blue of the lake is believed to be caused chiefly by the scattering of sunlight in water of exceptional depth and clearness, the blue rays of sunlight being bent back upward, rays of other colors being absorbed.

There are about 60 kinds, of which the golden-mantled ground squirrels are among the most conspicuous. They resemble large chipmunks but have stockier bodies, shorter tails and no stripes on their heads. On each side there is a broad, white stripe sandwiched between two dark stripes. Two species of true chipmunks with striped heads also are numerous. The small, tree-inhabiting chickaree, dark brown above and whitish below, is common; and the porcupine is frequently seen. It is advisable to enjoy these and all other small mammals without actual contact because occasionally they carry diseases which can become serious if transmitted to humans.

The large fat-bodied marmot (a mountain woodchuck) lives in high rocky places and on roadsides. The plaintive bleating “yenk, yenk” of the tiny “rock rabbit” (cony) issues from crevices in the talus. Snowshoe hares, brown in summer and white in winter, are sparingly present around forest clearings, such as at the south and east entrances.

Martens are rather common; they are slim brown animals somewhat like large minks but they can climb trees like squirrels. Less often seen are weasels, badgers, minks, red foxes, and coyotes. The gray fox, bobcat, and mountain lion (cougar) are rare.

American black bears are fairly common and may be encountered in many parts of the park. Usually they are black, but many shades of brown also occur, just as hair color varies among people. Do not let bears get close to you. Many people have been painfully clawed when these animals have lost their natural fear of man and have learned to beg for food. DO NOT FEED THE BEARS! Feeding them is unlawful, and violating this regulation seriously endangers other park visitors by encouraging the bears to beg.

The comparatively small and dark “black-tailed” deer of the Pacific Coast is the most common form, particularly on the west side of the park. The larger, lighter-colored mule deer occurs around meadows on the east side of the park, including Rim Drive.

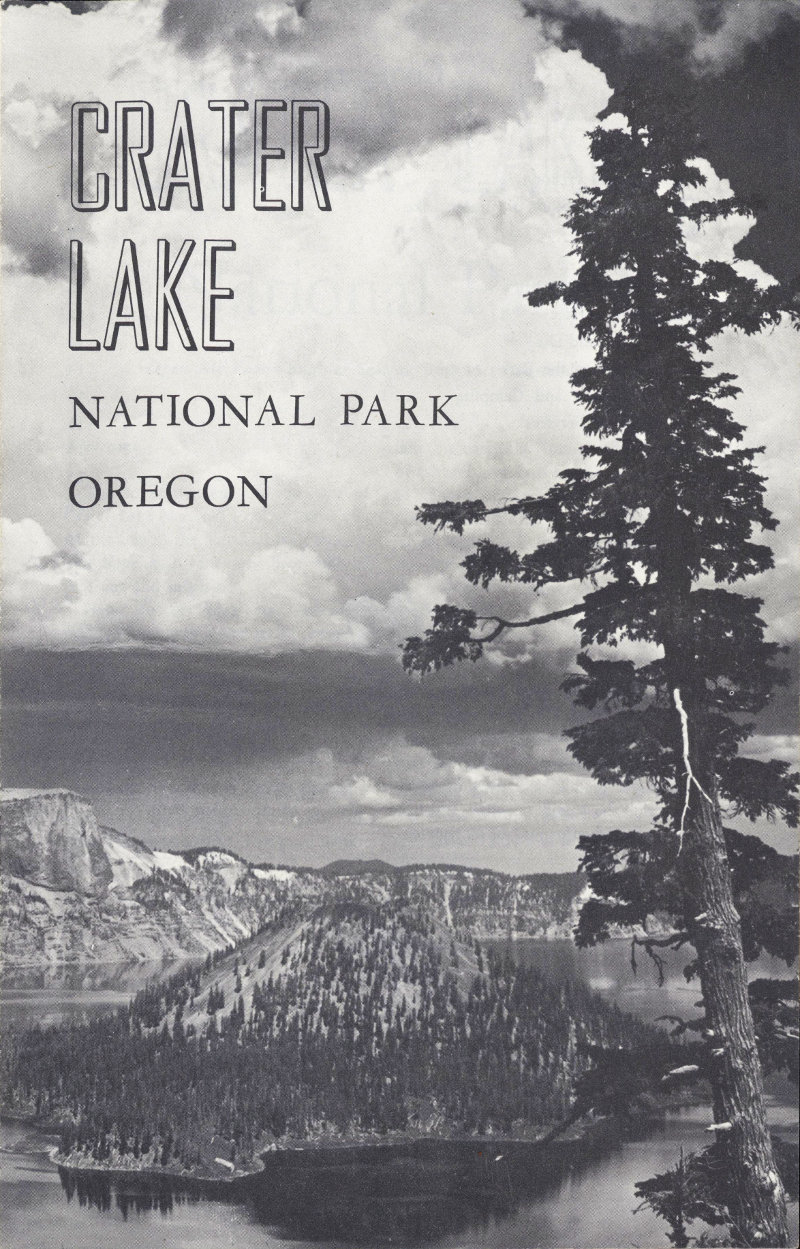

LET’S NOT BE GUILTY OF STARTING A FOREST FIRE.

ALWAYS USE CAR ASH TRAYS.

COMPLETELY EXTINGUISH MATCHES AND CIGARETTES BEFORE THROWING AWAY.

BE SURE CAMPFIRE IS OUT.

More than 120 kinds of birds have been recorded. On the rim, the harsh-voiced Clark’s nutcracker is the most conspicuous. It is a little larger and more heavily built than a jay and has a long sharp bill. The bird’s overall color is light gray, the wings are black with a large white patch, and the tail is conspicuously white with black central tail feathers. Two jays are also numerous at times on the rim, the dark-blue Steller’s jay which has a long, blackish crest, and the uncrested gray jay (“camp robber”) which has a short bill, a dark patch on the back of the head, a white crown, and whitish underparts.

Eagle Crags have furnished nesting places for both the golden and American eagles which sometimes may be seen flying over the lake. Llao Rock is the home of falcons. Double-crested cormorants may perch on the “masts” of the Phantom Ship, and California gulls are seen regularly on the lake. The sooty grouse inhabits the fir forests from which its ventriloquial booming call issues in the spring. Several species of ducks and geese use the lake during migration, and the Barrow’s golden-eye and merganser nest there occasionally.

Other species most likely to be observed are the horned owl, red-tailed hawk, sparrow hawk, nighthawk, rufous hummingbird, olive-sided flycatcher, raven, mountain chickadee, red-breasted nuthatch, dipper (along streams and on the lake shore), robin, hermit thrush, russet-backed thrush, mountain bluebird, golden-crowned kinglet, Audubon warbler, western tanager, evening grosbeak, Cassin purple finch, rosy finch (vicinity of snow banks), pine siskin, Oregon junco, chipping sparrow, and fox sparrow.

The virgin forests and wildflower meadows mantling the slopes, which one ascends to view Crater Lake, are outstanding attractions enhancing the scenic value of the lake. Scattered through the forests of predominantly cone-bearing trees are a few broad-leaved species. Colorful meadows of alpine wildflowers are found around numerous springs which form the sources of many creeks on the outer slope of the mountain.

Plants characteristic of four zones of vegetation are found within the park, yielding over 570 species of ferns and flowering plants. Patches of Douglas-firs, typical of the humid division of the upper Transition Zone, occur in the region of the park lying on the western slope of the Cascade Range. The semi-humid division of the zone, characterized by the ponderosa pines, largest trees in the park, may be found at the south entrance of the park. Associated with it are sugar pines, white firs, and western white pines. Above the Transition is the Canadian Zone in which occur lodgepole pines, Shasta red firs, alpine firs, and mountain hemlocks.

In the rim area around Crater Lake, Hudsonian Zone species are found. These include mountain hemlocks (the most predominant trees in the park), alpine firs, Shasta red firs, and whitebark pines. Stunted whitebark pines predominate on the slopes of Mount Scott, the summit being in the Alpine-Arctic Zone.

During July and August, you will find Nature’s colorful displays of alpine wildflowers on the road between park headquarters and Rim Village and along the trails on the crater rim. These displays change with each week of the short flowering season.

Phantom Ship. Applegate and Garfield Peaks are reflected in Crater Lake.

Castle Crest Wildflower Garden, near park headquarters, is one of the most attractive and ideal places for viewing and studying Crater Lake flora. Throughout the summer, you may study the exhibits of fresh flowers displayed at the Information Building in the Rim Village.

During the summer, daily interpretive service is scheduled by the National Park Service. Informal talks are given at Sinnott Memorial, and evening programs are held in the Community House, both in Rim Village. Field trips start from the Information Building on the rim just west of the lodge. Rim Drive bus trips begin at the lodge. Boat trips, when in operation, start at the foot of the Lake (Crater Wall) Trail.

Programs of current interpretive activities are posted at several places in the park.

The Sinnott Memorial, with its broad terrace overlooking the lake, serves as an orientation point. It is located close to the lodge and the Rim Campground. Pictorial displays in the exhibit room portray artists’ conceptions of the varying moods of the lake. Field glasses and a large relief map of the region are located on the terrace.

Many spectacular views may be had from numerous observation points along this road which encircles the caldera.

This symmetrical cinder cone, towering some 760 feet above the surface of the lake, is reached by boat. A trail leads from the shore to the crater, which is approximately 90 feet deep and 300 feet in diameter.

Rising about 160 feet above the waters of the lake, this island resembles a ship under sail. The best views of the Phantom Ship are obtained from the launches and from Kerr Notch along the Rim Drive.

A 1.7-mile trail, east of the lodge, leads to Garfield Peak. From its summit, elevation 8,060 feet, there is a magnificent view of the lake and surrounding region.

This peak, on the west rim, may be reached by a half-mile trail from the rim road. A rare panorama of the park and surrounding country may be viewed from the fire lookout, 8,025 feet above sea level and about 1,850 feet above the lake.

On the east rim, and rising to an elevation of more than 8,000 feet, Cloudcap provides an excellent observation point.

East of Cloudcap is Mount Scott, the highest point in the park, reaching an altitude of 8,938 feet. Its summit, on which there is a fire-lookout station, is accessible by a 2.5-mile trail from Rim Drive.

In Wheeler Creek, near the east boundary of the park, are slender spires of pumice. Some of the needles are 200 feet high. In Sand Creek Canyon and Godfrey’s Glen, in Annie Creek Canyon, there are other spires and fluted columns carved out of the soft volcanic material by water erosion.

Hillman Peak, 13 8,156 feet, is the highest point on the rim, rising nearly 2,000 feet above the lake. Palisade Point, Kerr Notch, and the Wineglass are low points on the rim, being slightly more than 500 feet above the lake.

Natural ski run cut by old rock slide.

Besides the longer hikes mentioned in preceding paragraphs, there are delightful short walks, such as along Discovery Point Trail on the rim, and through Castle Crest Wildflower Gardens.

Those who desire information about other interesting places in the park and vicinity are invited to inquire at park headquarters or the Information Building.

Angling amid the scenic beauty of Crater Lake is an experience long to be remembered. No fish were native to Crater Lake; the first planting of rainbow trout was made in 1888 by William G. Steel. In recent years only rainbow trout and sockeye (kokanee) salmon have been planted. Trolling has proved to be the most successful method of fishing. The daily limit is 10 fish per person. From about mid-July to Labor Day, rowboats are available. Shore fishing usually may be enjoyed from the latter part of June until late September, depending on weather conditions. No license is needed to fish in Crater Lake. Possession or use of fish as bait is not allowed.

Since the park is open the year round, you may enjoy Crater Lake’s fantasy of snowy splendor and participate in winter sports. 14 Two trails from the Rim Village to park headquarters are maintained for skiers in winter. Professional ski meets are discouraged and amateur sports encouraged.

There are no overnight accommodations in the park from about September 15 to June 15, but warming-room facilities are provided at Rim Village.

The west and south entrance roads to the Rim Village area are open to motor travel. You should be well supplied with gasoline and oil, as they are not available in the park in winter. Tire chains, tow rope, and shovel are necessary accessories.

Rangers are on duty to render service all year.

The Southern Pacific Railroad, several airlines, and bus lines serve Medford, Klamath Falls, and Grants Pass, Oreg. Pacific Trailways buses, operating on daily schedules through the park, connect with points north and south from about June 15 to September 15.

Paved State highways connect with the park road system at all entrances. State Route 62 connects the west entrance of the park, through Medford, with U.S. 99, 199, and 101. It also leads from the south entrance to U.S. 97. From the north entrance, connection is made with U.S. 97 via State Route 230. The roads through the west and south entrances to the rim are maintained as all-year roads. The north entrance road and Rim Drive are closed approximately September 25 to July 1 depending on snow conditions.

Rim Village (900 feet above the lake) includes the lodge, sleeping cabins, cafeteria, store, campground, picnic area, Community House, Information Building, and Sinnott Memorial. The lake is accessible by trail from Rim Village.

which include sleeping cabins and single and double rooms at the lodge, are available from about June 15 to September 15. Information regarding rates may be obtained from the Crater Lake National Park Company (winter address, Box 968, Spokane, Wash.; summer, Crater Lake, Oreg.). It is imperative that reservations be made well in advance and be accompanied by a deposit and a request for confirmation of availability.

There are dining-room facilities in the lodge. The cafeteria, which is near the campground and cabins, is open from 7 a. m. to 8:30 p. m.

There are three main campgrounds open from about July 1 to September 30. Mazama Campground, near the junction of the south and west entrance roads, and Rim Campground, close to Rim Village, have fireplaces, tables, water and flush toilets. Lost Creek Campground in the southeast part of the park and 12 miles from park headquarters, has fireplaces, tables, and water, but toilets are most primitive.

Camping is limited to 30 days. No reservations for campsites can be made.

A number of trips are made daily, during the summer, by launch from the boatlanding at the foot of the lake trail to Wizard Island. Private boats are not permitted on the lake, but rowboats may be hired at the boatlanding.

One of the popular attractions is the 2½-hour launch trip around the lake, leaving the boatlanding at 9 o’clock each morning during the boating season. A naturalist accompanies this trip. Boating services are provided by the Crater Lake National Park Company.

The post office and long-distance telephone and telegraph services are located in the administration building at park headquarters. The post office address is Crater Lake, Oreg. Guests of the Crater Lake National Park Company should have mail addressed in care of Crater Lake Lodge to insure prompt delivery.

A gasoline station is maintained during summer on the road near park headquarters. No storage or repair facilities, however, are available within the park. In case of accident or mechanical failure, towing service must be obtained from outside the park.

Time and place of church services are posted in the lodge, information building, and cafeteria.

Mission 66 is a program designed to be completed by 1966 which will assure the maximum protection of the scenic, scientific, wilderness, and historic resources of the National Park System in such ways and by such means as will make them available for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.

Crater Lake National Park is administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. A superintendent is in immediate charge of the park, with offices in the administrative center, 3 miles from Rim Village. Communications regarding the park should be addressed to the Superintendent, Crater Lake National Park, Crater Lake, Oreg., during the summer and to Box 672, Medford, Oreg., from October to June.

PARK RANGERS AND NATURALISTS

Park rangers are the protective force of the park. They are on duty to enforce park regulations, and to help and advise you. Consult them if you are in any difficulty.

Park naturalists are here to help you understand the park. They, too, welcome your observations and your inquiries.

Park regulations are designed for the protection of the natural features and for your comfort and convenience. The following synopsis is for your guidance:

Fires. Light carefully and only in designated campgrounds. Extinguish completely before leaving camp, even for a temporary absence. Do not guess your fire is out—KNOW IT. One spark may start a forest fire, destroy the beauty of the park, and endanger many lives. Throwing burning materials from car windows constitutes a fire threat and is unlawful in most western States.

Camps. Use designated campgrounds and keep them clean. Burn combustible rubbish on campfires, and place other refuse of all kinds in garbage cans or pits provided for the purpose. Only down material may be used as firewood.

Trash. Do not throw paper, lunch refuse, or other trash over the rim, on walks, trails, roads, or elsewhere. Carry until you can burn in camp or place in receptacle.

Trees, Flowers, and Animals. The destruction, injury, disturbance, or removal in any way of trees, flowers, birds, or animals is prohibited in order that everyone may enjoy the beauties of nature.

Noises. Please do not be noisy in camp before 6 a. m. and after 10 p. m. Many people come to the park for rest.

Automobiles. Drive carefully. Speeds limits, which vary for different sections of the park, are posted.

Pets. When not in an automobile, dogs, cats, and other pets must be on leash or otherwise under physical restrictive control at all times. They are not permitted in the lodge, in the dining room, the store, other public buildings or on any of the trails.

Warning About Bears and Deer. Do not feed, touch, tease, or molest the bears and deer. Bears will enter or break into automobiles if food that they can smell is left inside. They will also rob your camp of unprotected food supplies.

Fishing. Open season: Streams, June 15-September 10; Crater Lake, when trail is open. The limit is 10 fish per day for each person fishing. No fishing license is necessary. Possession of bait fish, or the use thereof as bait, is not allowed.

Accidents. Report all accidents and injuries as soon as possible to the ranger office at park headquarters.

Complete rules and regulations are available at park headquarters.

Automobile, housetrailer, and motorcycle permit fees are collected at entrance stations. When vehicles enter at times when entrance stations are unattended, it is necessary that the permit be obtained before leaving the park and be shown upon reentry. The fees applicable to the park are not listed herein because they are subject to change, but they may be obtained in advance of a visit by addressing a request to the superintendent.

All national park fees are deposited as revenue in the U. S. Treasury; they offset, in part, appropriations made for operating and maintaining the National Park System.

Revised 1958

U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1958—O-458046