HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS

IN LINCOLNSHIRE

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON . BOMBAY . CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK . BOSTON . CHICAGO

DALLAS . SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

Boston.

Highways and Byways

IN

Lincolnshire

BY

WILLINGHAM FRANKLIN RAWNSLEY

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

FREDERICK L. GRIGGS

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1914

COPYRIGHT

All writers make use of the labours of their predecessors. This is inevitable, and a custom as old as time. As Mr. Rudyard Kipling sings:—

In writing this book I have made use of all the sources that I could lay under contribution, and especially I have relied for help on “Murray’s Handbook,” edited by the Rev. G. E. Jeans, and the Journals of the associated Architectural Societies. I have recorded in the course of the volume my thanks to a few kind helpers, and to these I must add the name of Mr. A. R. Corns of the Lincoln Library, for his kindness in allowing me the use of many books on various subjects, and on several occasions, which have been of the utmost service to me. My best thanks, also, are due to my cousin, Mr. Preston Rawnsley, for his chapter on the Foxhounds of Lincolnshire. That the book owes much to the pencil of Mr. Griggs is obvious; his illustrations need no praise of mine but speak for themselves. The drawing given on p. 254 is by Mrs. Rawnsley.

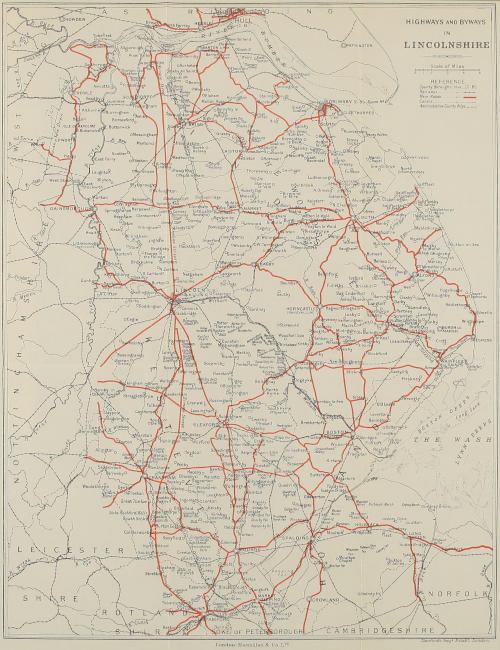

I have perhaps taken the title “Highways and Byways” more literally than has usually been done by writers in this interesting series, and in endeavouring to describe the county and its ways I have followed the course of all the main roads radiating from each large town, noticing most of the places through or near which they pass, and also pointing out some of the more picturesque byways, and describing the lie of the[viii] country. But I have all along supposed the tourist to be travelling by motor, and have accordingly said very little about Footpaths. This in a mountainous country would be entirely wrong, but Lincolnshire as a whole is not a pedestrian’s county. It is, however, a land of constantly occurring magnificent views, a land of hill as well as plain, and, as I hope the book will show, beyond all others a county teeming with splendid churches. I may add that, thanks to that modern devourer of time and space—the ubiquitous motor car—I have been able personally to visit almost everything I have described, a thing which in so large a county would, without such mercurial aid, have involved a much longer time for the doing. Even so, no one can be more conscious than I am that the book falls far short of what, with such a theme, was possible.

W. F. R.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| INTRODUCTORY | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| STAMFORD | 7 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| STAMFORD TO BOURNE | 18 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| ROADS FROM BOURNE | 28 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| SOUTH-WEST LINCOLNSHIRE | 39 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| GRANTHAM | 52 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| ROADS FROM GRANTHAM | 64[x] |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| SLEAFORD | 76 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| LINCOLN CATHEDRAL | 91 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| PAULINUS AND HUGH OF LINCOLN | 112 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| LINCOLN CITY | 120 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| ROADS FROM LINCOLN, WEST AND EAST | 137 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| ROADS SOUTH FROM LINCOLN | 148 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| PLACES OF NOTE NEAR LINCOLN | 165 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| HERMITAGES AND HOSPITALS | 178 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| ROADS NORTH FROM LINCOLN | 182 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| GAINSBOROUGH AND THE NORTH-WEST | 195[xi] |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| THE ISLE OF AXHOLME | 208 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| GRIMSBY AND THE NORTH-EAST | 215 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| CAISTOR | 228 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| LOUTH | 239 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| ANGLO-SAXON, NORMAN AND MEDIÆVAL ART | 251 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| ROADS FROM LOUTH, NORTH AND WEST | 262 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| LINCOLNSHIRE BYWAYS | 278 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| THE BOLLES FAMILY | 285 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| THE MARSH CHURCHES OF EAST LINDSEY | 290 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| LINCOLNSHIRE FOLKSONG | 296[xii] |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| MARSH CHURCHES OF SOUTH LINDSEY | 305 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| WAINFLEET TO SPILSBY | 323 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| SPILSBY AND NEIGHBOURHOOD | 333 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| SOMERSBY AND THE TENNYSONS | 343 |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| ROADS FROM SPILSBY | 358 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| SCRIVELSBY AND TATTERSHALL | 372 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| BARDNEY ABBEY | 390 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| HOLLAND FEN | 400 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| THE FEN CHURCHES—NORTHERN DIVISION | 409 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | |

| ST. BOTOLPH’S TOWN (BOSTON) | 425[xiii] |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII | |

| SPALDING AND THE CHURCHES NORTH OF IT | 441 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX | |

| CHURCHES OF HOLLAND | 463 |

| CHAPTER XL | |

| THE BLACK DEATH | 480 |

| CHAPTER XLI | |

| CROYLAND | 483 |

| CHAPTER XLII | |

| LINCOLNSHIRE FOXHOUNDS | 493 |

| APPENDIX I | |

| SAMUEL WESLEY’S EPITAPH | 499 |

| APPENDIX II | |

| DR. WM. STUKELEY | 500 |

| APPENDIX III | |

| A LOWLAND PEASANT POET | 501 |

| PAGE | |

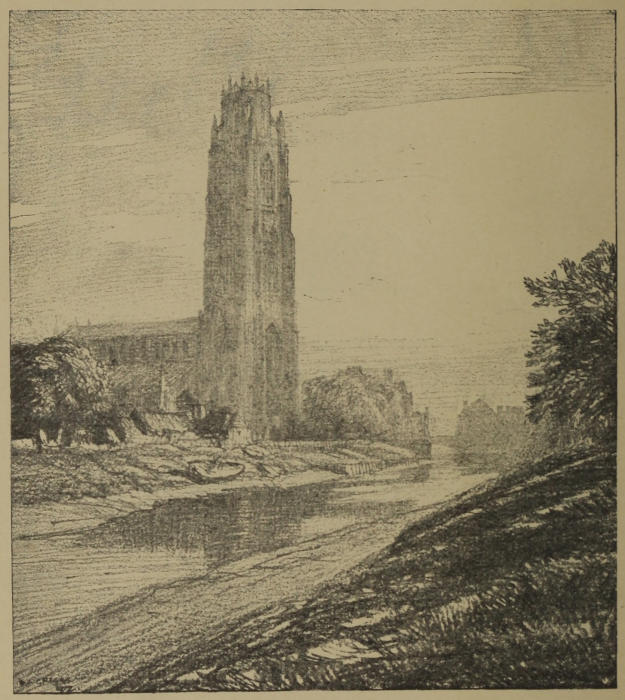

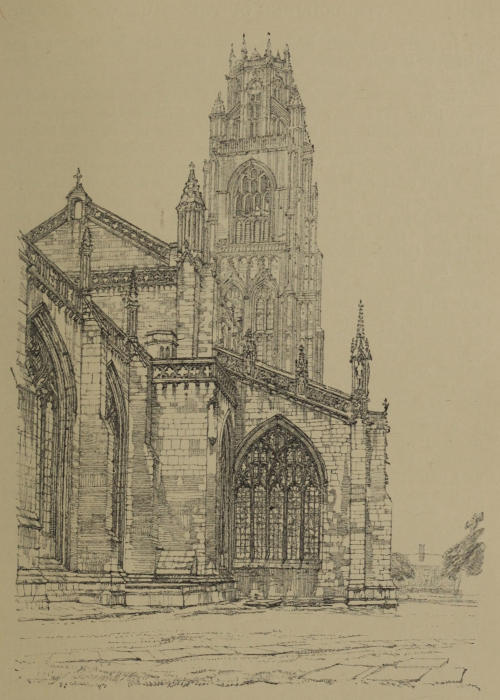

| BOSTON | Frontispiece |

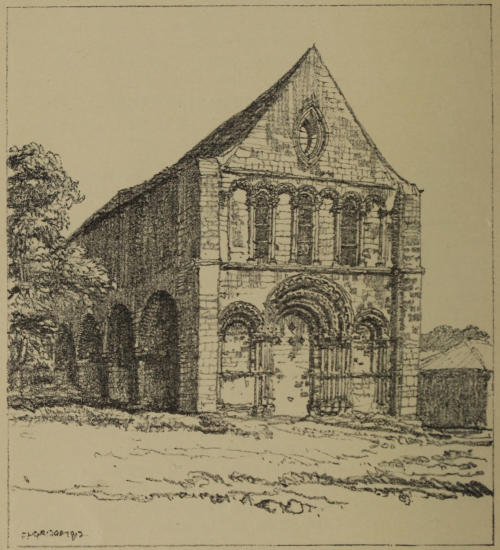

| ST. LEONARD’S PRIORY, STAMFORD | 8 |

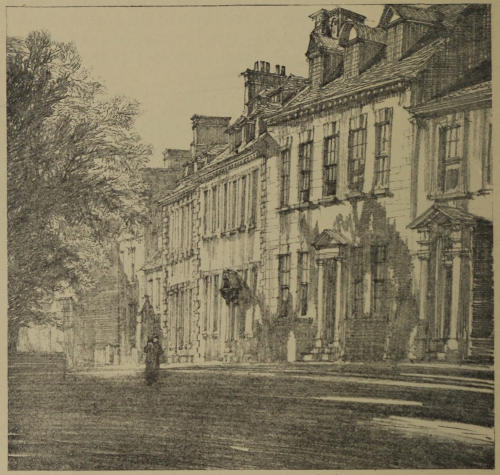

| ST. GEORGE’S SQUARE, STAMFORD | 10 |

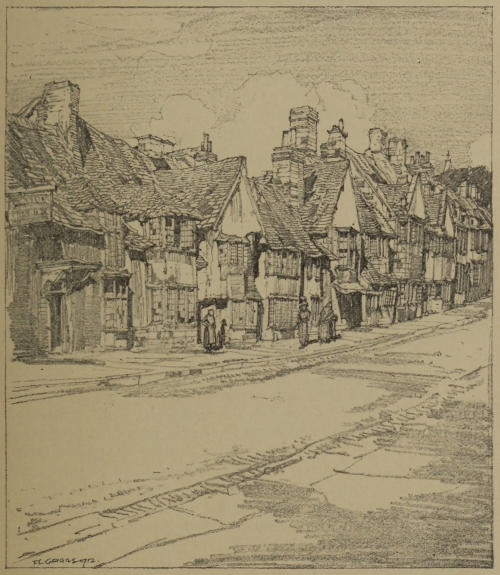

| ST. MARY’S STREET, STAMFORD | 11 |

| ST. PAUL’S STREET, STAMFORD | 13 |

| ST. PETER’S HILL, STAMFORD | 15 |

| STAMFORD FROM FREEMAN’S CLOSE | 17 |

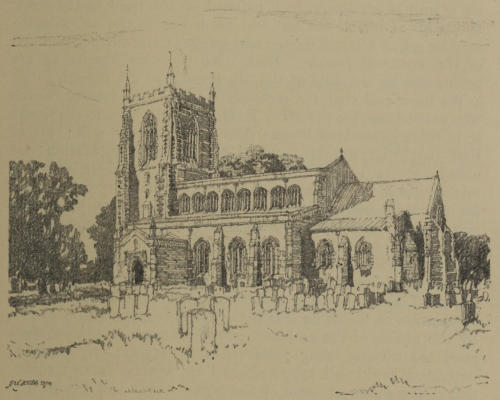

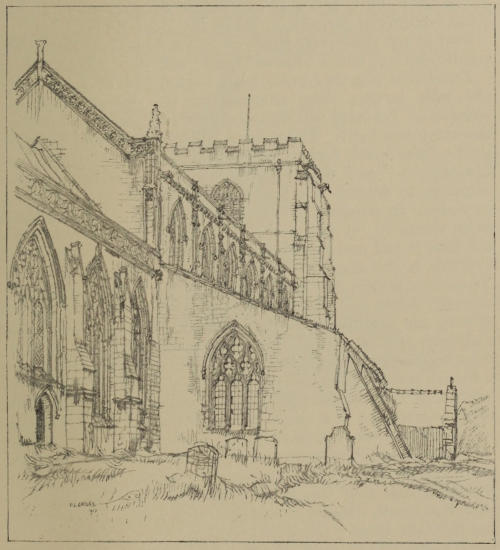

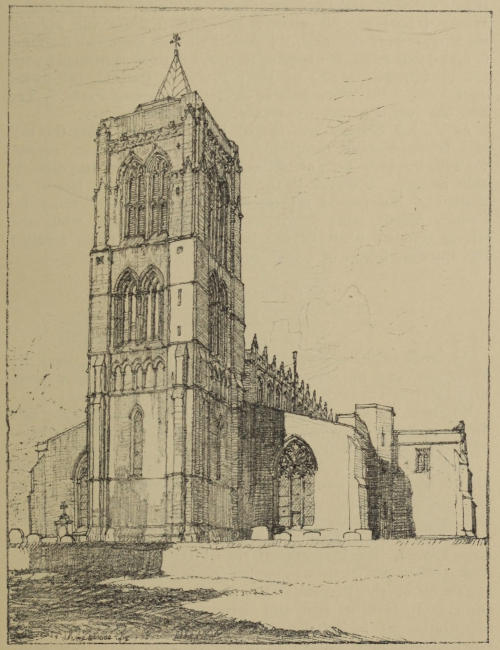

| BOURNE ABBEY CHURCH | 24 |

| THE STATION HOUSE, BOURNE | 26 |

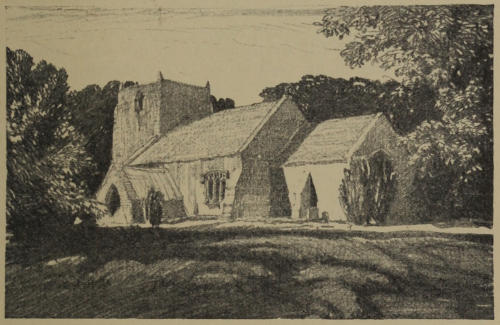

| SEMPRINGHAM | 36 |

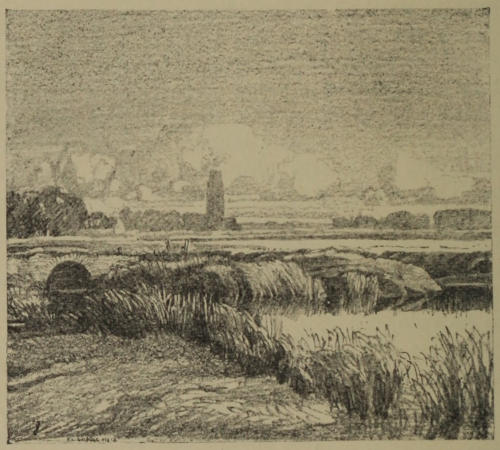

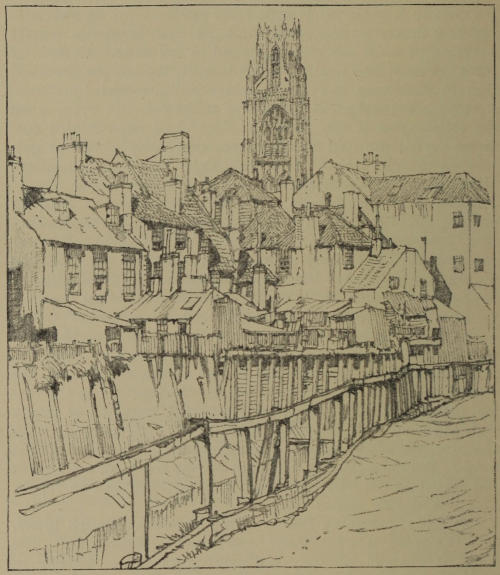

| THE WITHAM, BOSTON | 45 |

| THE ANGEL INN, GRANTHAM | 56 |

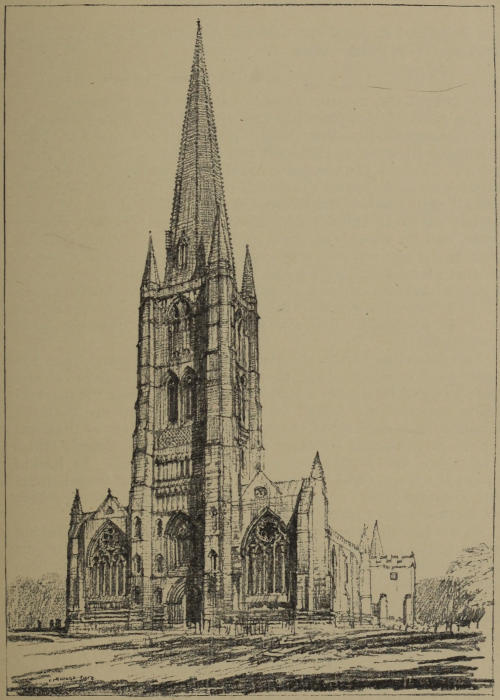

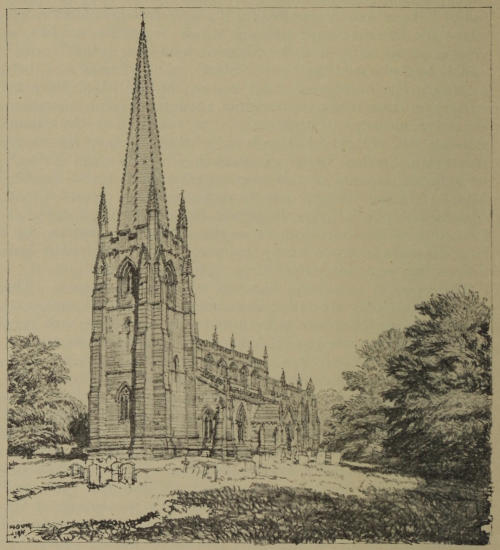

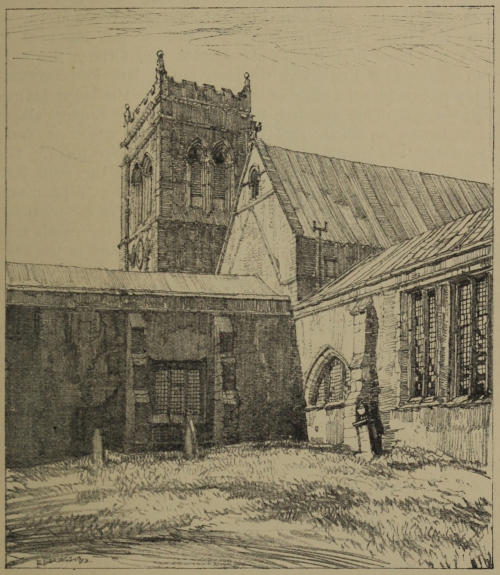

| GRANTHAM CHURCH | 61 |

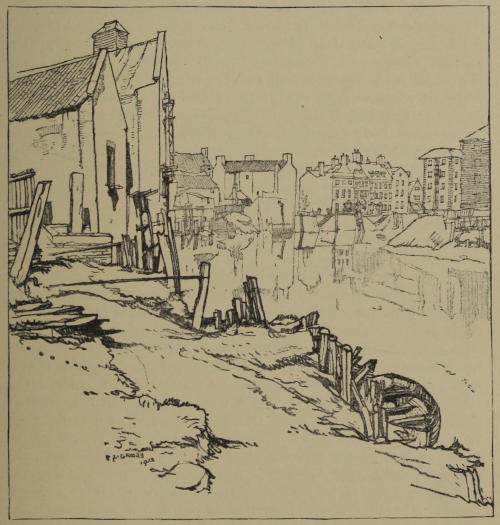

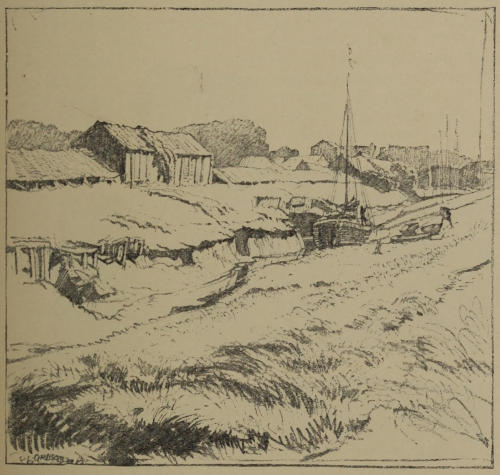

| WITHAM-SIDE, BOSTON | 66 |

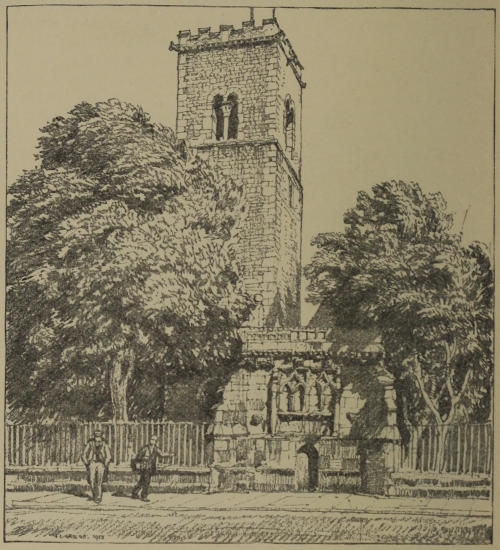

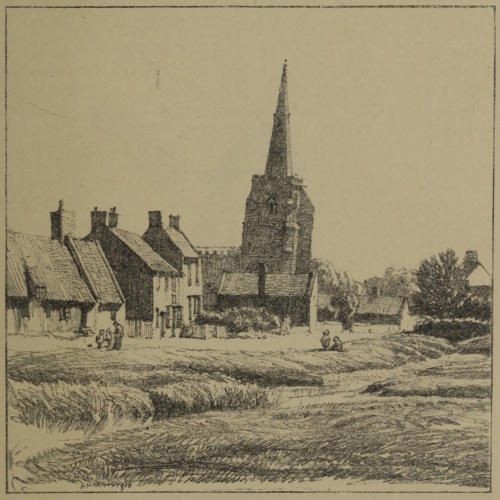

| HOUGH-ON-THE-HILL | 72 |

| NORTH TRANSEPT, ST. DENIS’S CHURCH, SLEAFORD | 78 |

| HECKINGTON CHURCH | 81 |

| GREAT HALE | 84 |

| HELPRINGHAM | 86 |

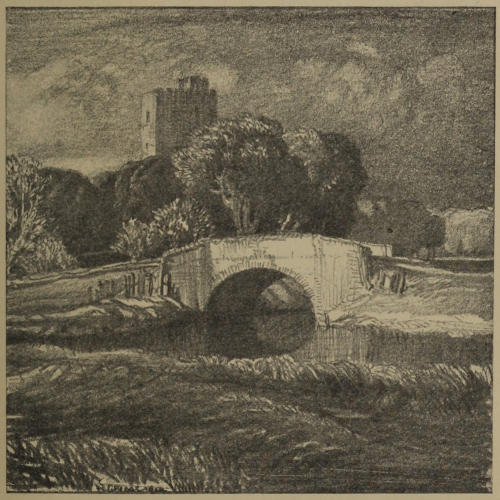

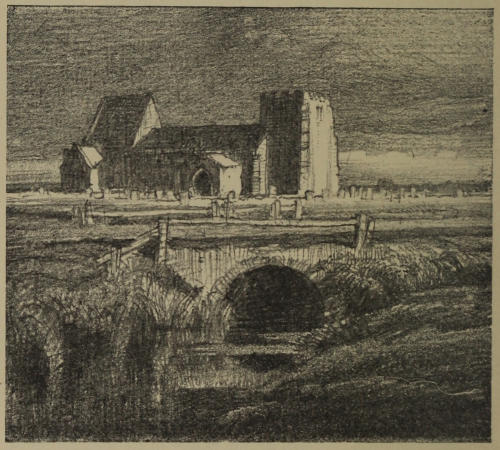

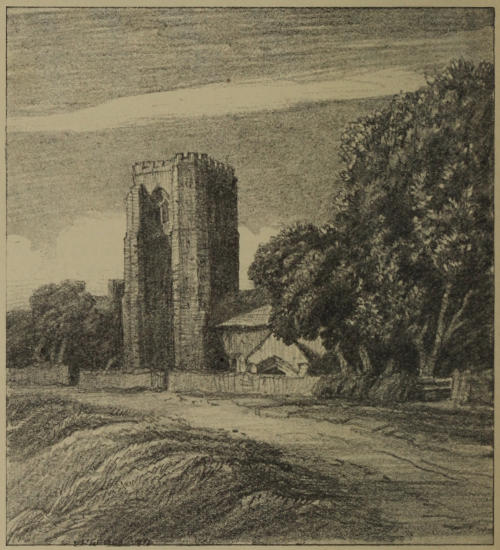

| SOUTH KYME | 88 |

| SOUTH KYME CHURCH | 89 |

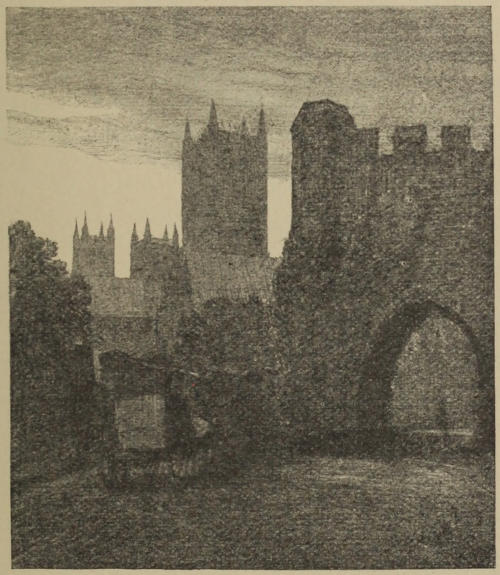

| NEWPORT ARCH, LINCOLN | 92 |

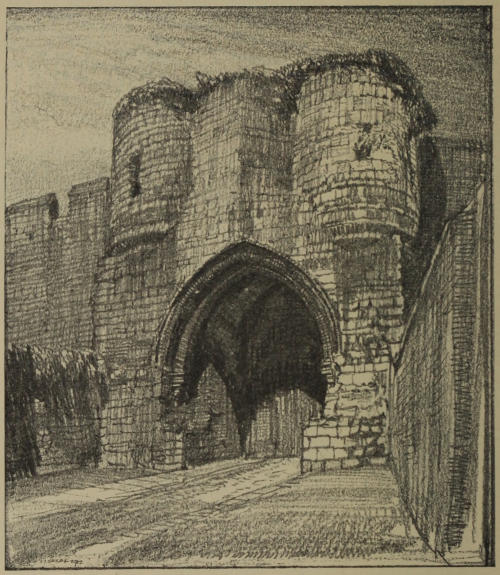

| GATEWAY OF LINCOLN CASTLE | 94 |

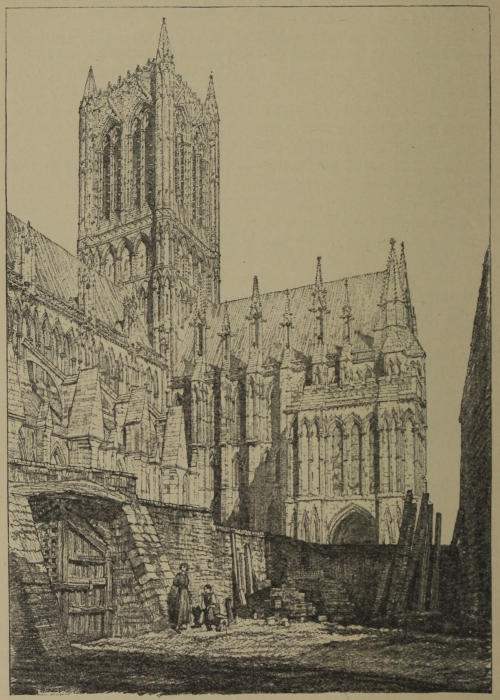

| THE ROOD TOWER AND SOUTH TRANSEPT, LINCOLN | 100 |

| POTTERGATE, LINCOLN | 110[xvi] |

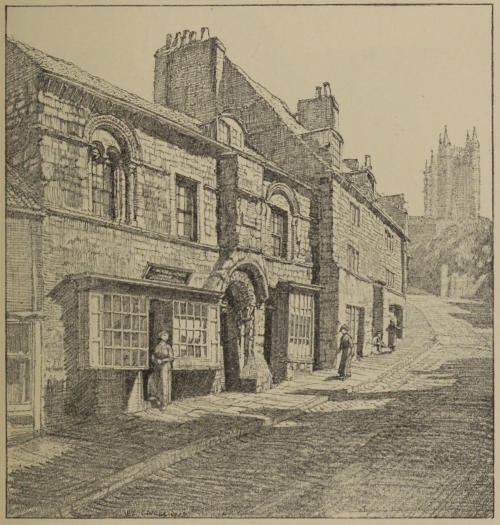

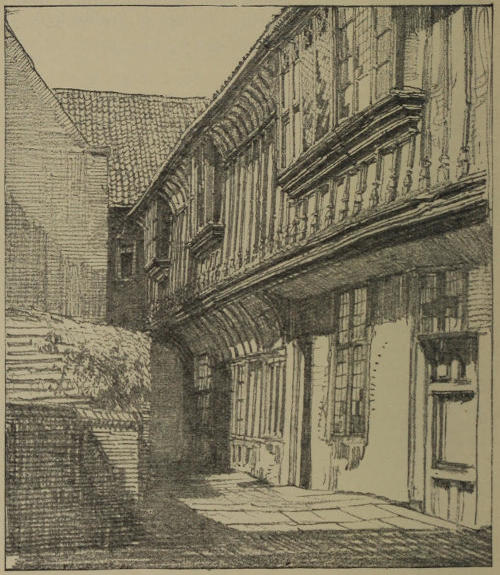

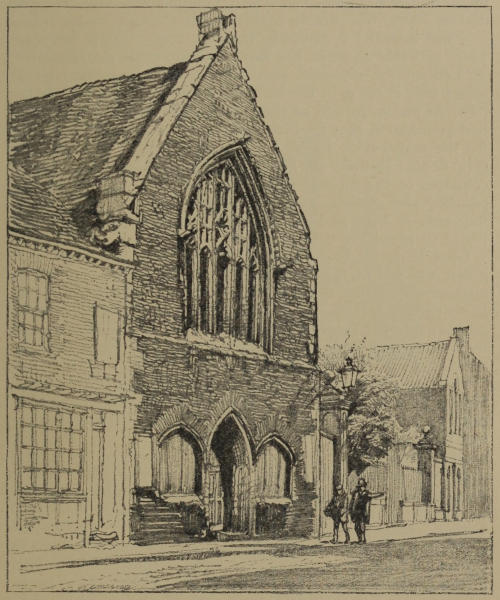

| ST. MARY’S GUILD, LINCOLN | 118 |

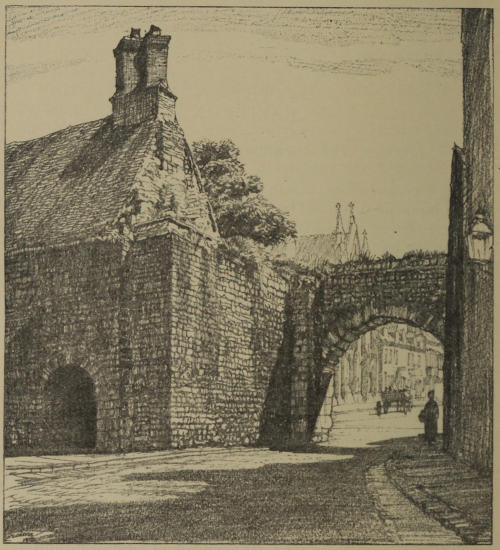

| THE POTTERGATE ARCH, LINCOLN | 121 |

| THE JEW’S HOUSE, LINCOLN | 123 |

| REMAINS OF THE WHITEFRIARS’ PRIORY, LINCOLN | 124 |

| ST. MARY’S GUILD AND ST. PETER’S AT GOWTS, LINCOLN | 125 |

| ST. BENEDICT’S CHURCH, LINCOLN | 127 |

| ST. MARY-LE-WIGFORD, LINCOLN | 128 |

| THE STONEBOW, LINCOLN | 130 |

| OLD INLAND REVENUE OFFICE, LINCOLN | 132 |

| JAMES STREET, LINCOLN | 133 |

| THORNGATE, LINCOLN | 135 |

| LINCOLN FROM THE WITHAM | 138 |

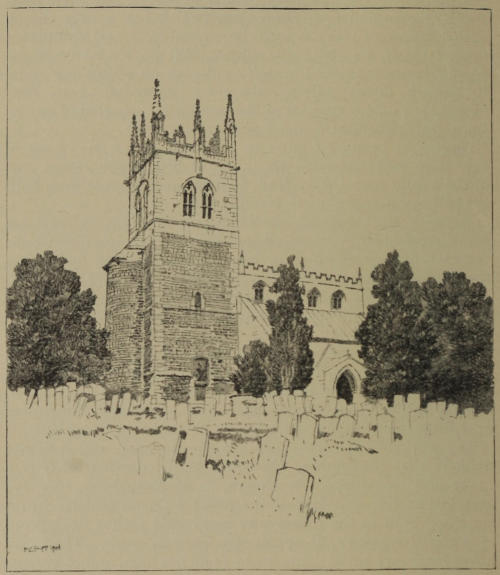

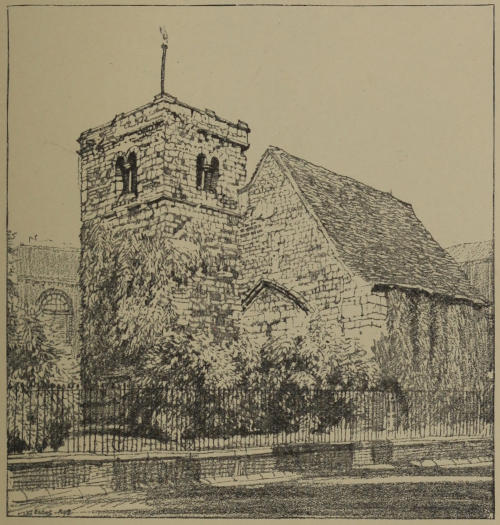

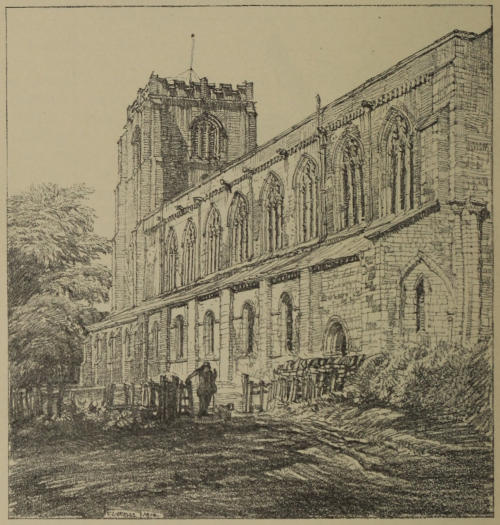

| STOW CHURCH | 142 |

| BRANT BROUGHTON | 152 |

| THE ERMINE STREET AT TEMPLE BRUER | 154 |

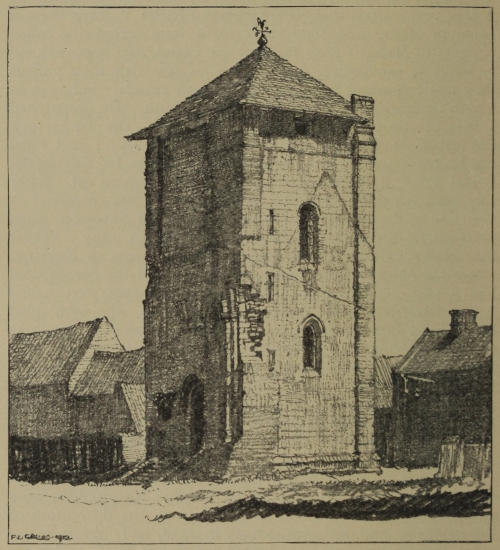

| TEMPLE BRUER TOWER | 158 |

| NAVENBY | 163 |

| WYKEHAM CHAPEL, NEAR SPALDING | 180 |

| THE AVON AT BARTON-ON-HUMBER | 189 |

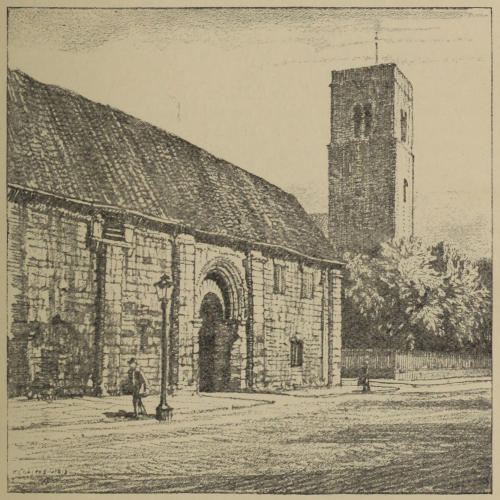

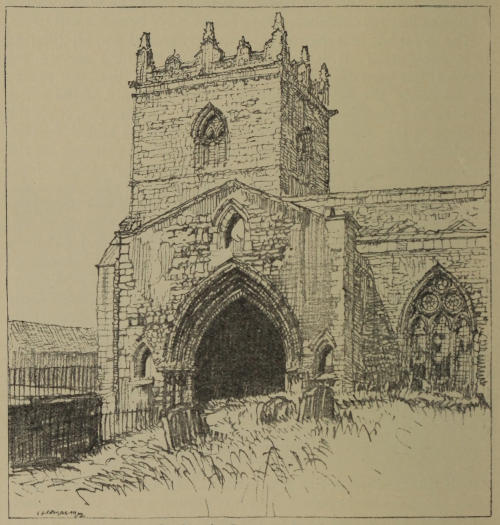

| ST. PETER’S, BARTON-ON-HUMBER | 190 |

| ST. MARY’S, BARTON-ON-HUMBER | 192 |

| NORTH SIDE, OLD HALL, GAINSBOROUGH | 202 |

| SOUTH SIDE, OLD HALL, GAINSBOROUGH | 203 |

| GAINSBOROUGH CHURCH | 205 |

| GREAT GOXHILL PRIORY | 218 |

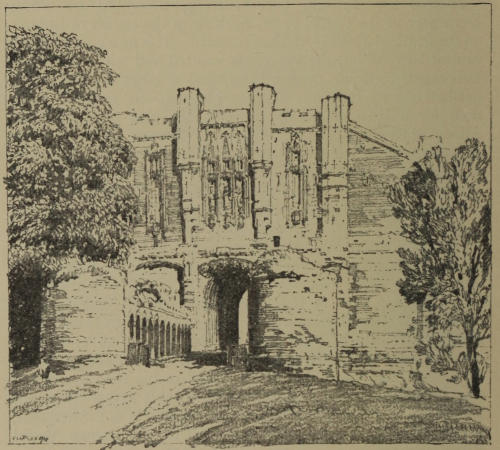

| THORNTON ABBEY GATEWAY | 220 |

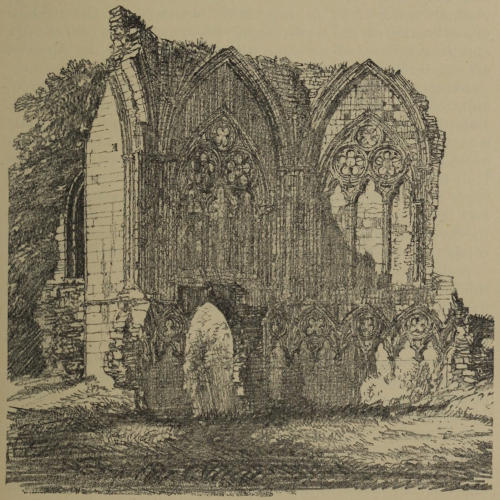

| REMAINS OF CHAPTER HOUSE, THORNTON ABBEY | 221 |

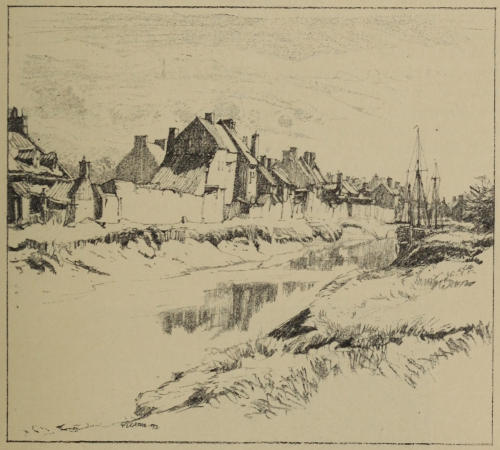

| THE WELLAND, NEAR FULNEY, SPALDING | 237 |

| THORNTON ABBEY GATEWAY | 238 |

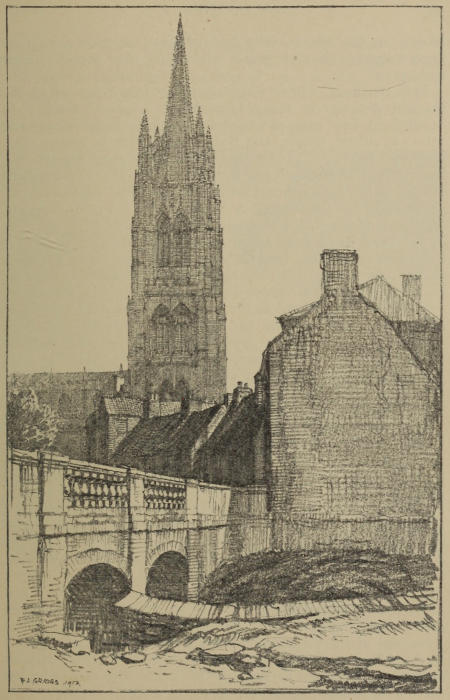

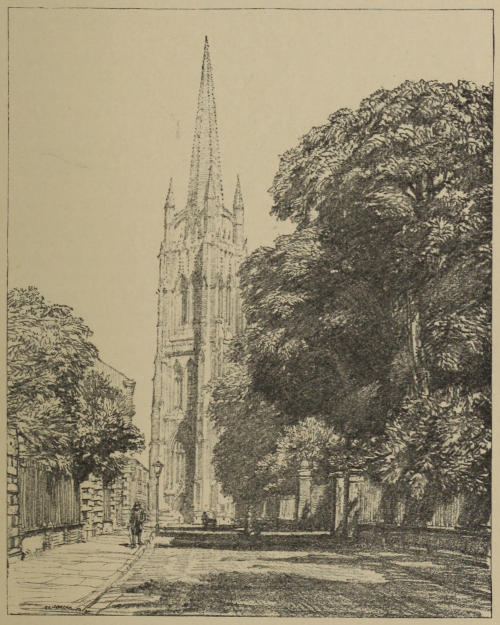

| BRIDGE STREET, LOUTH | 241 |

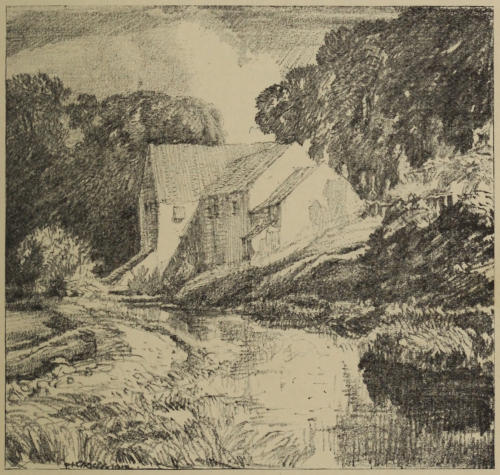

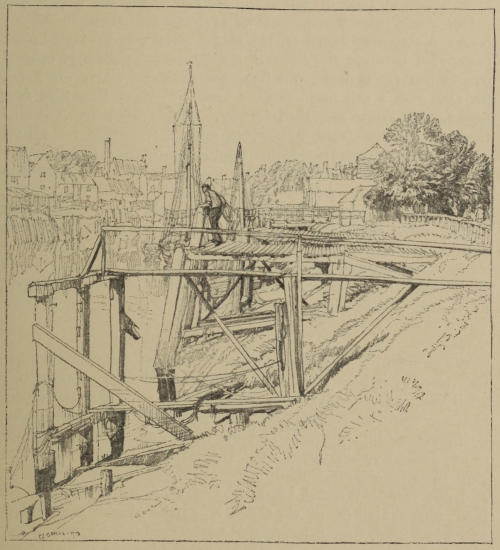

| HUBBARD’S MILL, LOUTH | 243 |

| THE LUD AT LOUTH | 246 |

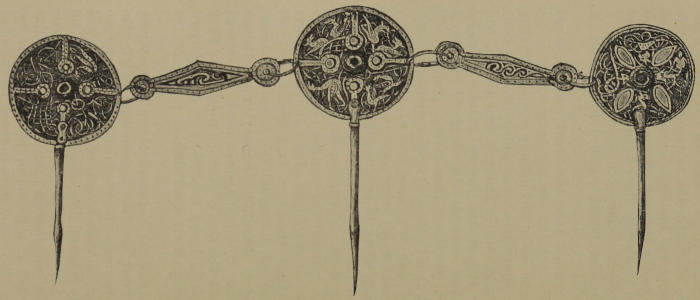

| ANCIENT SAXON ORNAMENT FOUND IN 1826 IN CLEANING OUT THE WITHAM, NEAR THE VILLAGE OF FISKERTON, FOUR MILES EAST OF LINCOLN. DRAWN BY MRS. RAWNSLEY | 254 |

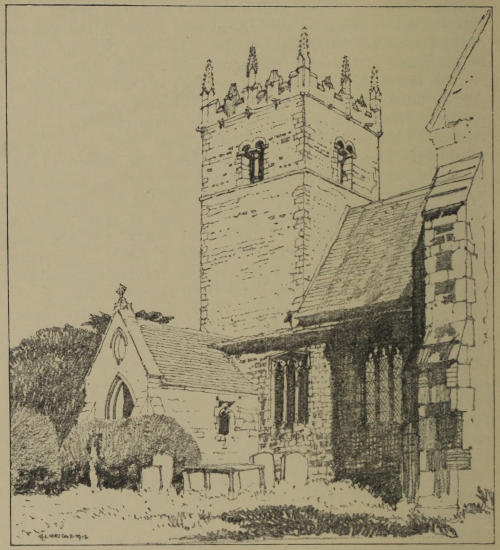

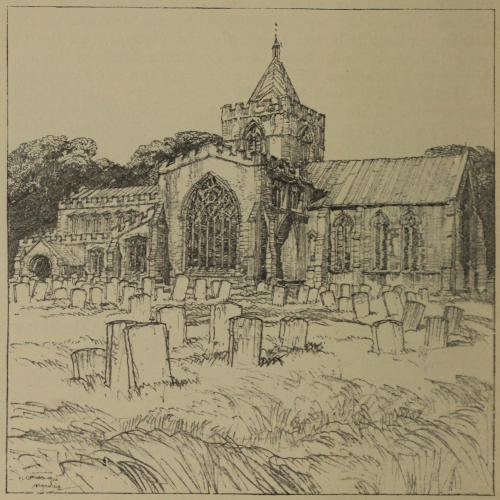

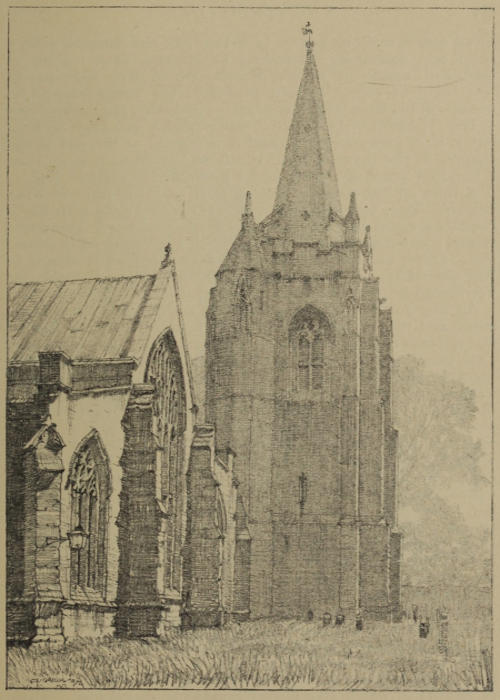

| CLEE CHURCH | 266[xvii] |

| WESTGATE, LOUTH | 275 |

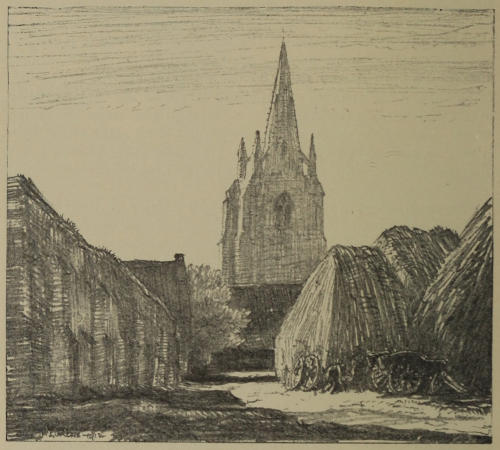

| MANBY | 279 |

| MABLETHORPE CHURCH | 292 |

| SOUTHEND, BOSTON | 297 |

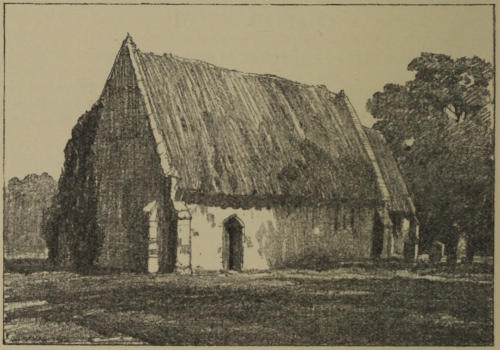

| MARKBY CHURCH | 306 |

| ADDLETHORPE AND INGOLDMELLS | 308 |

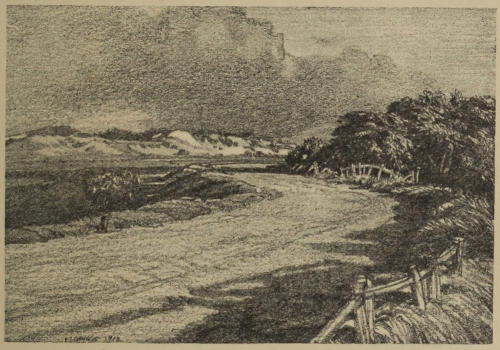

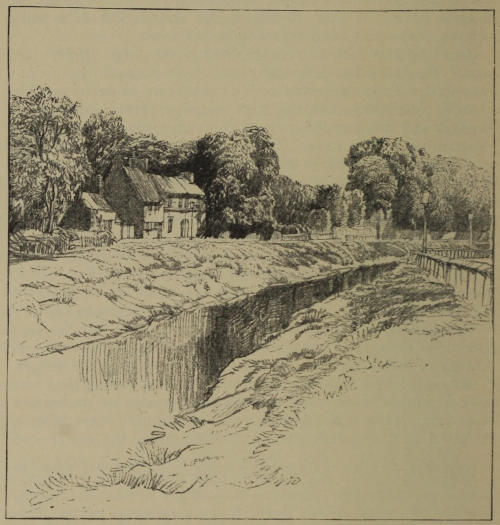

| THE ROMAN BANK AT WINTHORPE | 311 |

| BRIDGE OVER THE HOLLOW-GATE | 330 |

| HALTON CHURCH | 331 |

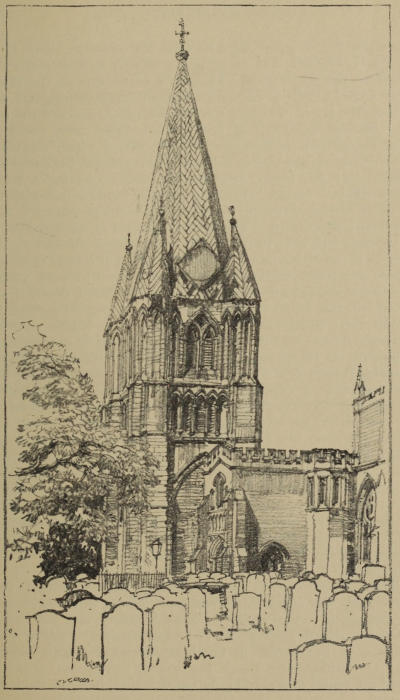

| SOMERSBY CHURCH | 341 |

| TENNYSON’S HOME, SOMERSBY | 351 |

| LITTLE STEEPING | 357 |

| SIBSEY | 362 |

| CONINGSBY | 369 |

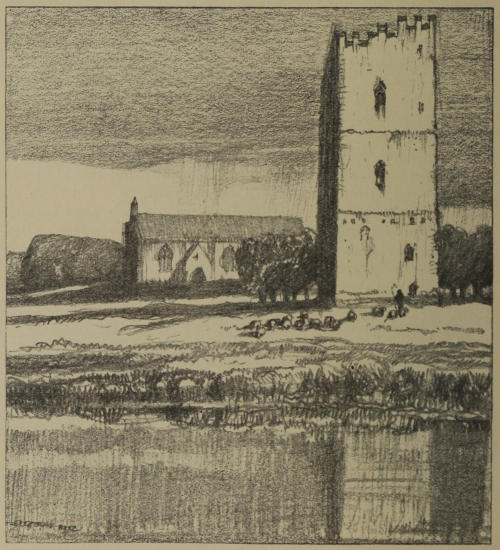

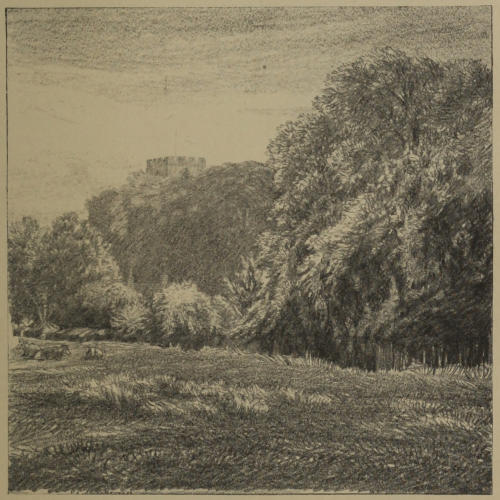

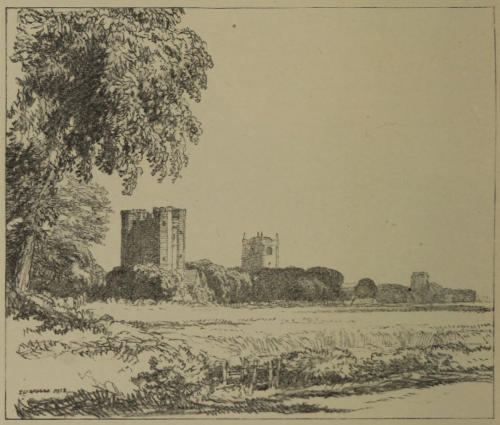

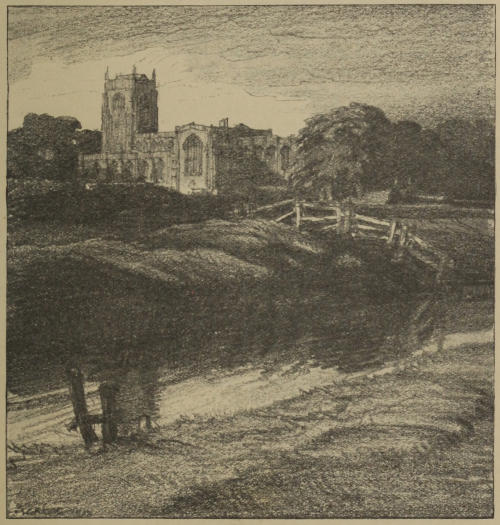

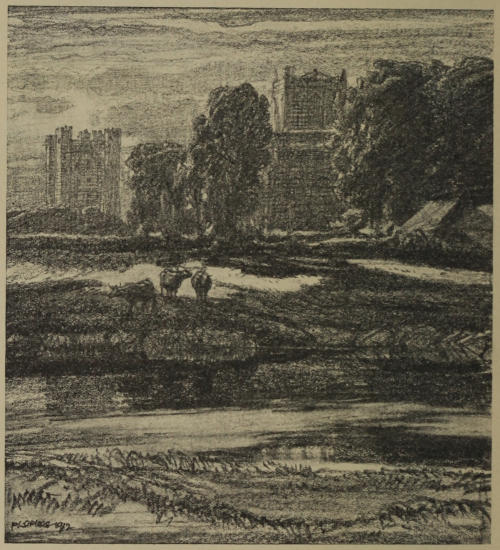

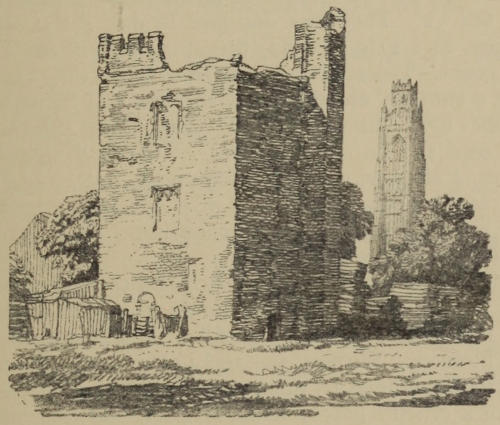

| TATTERSHALL AND CONINGSBY | 370 |

| TATTERSHALL CHURCH | 371 |

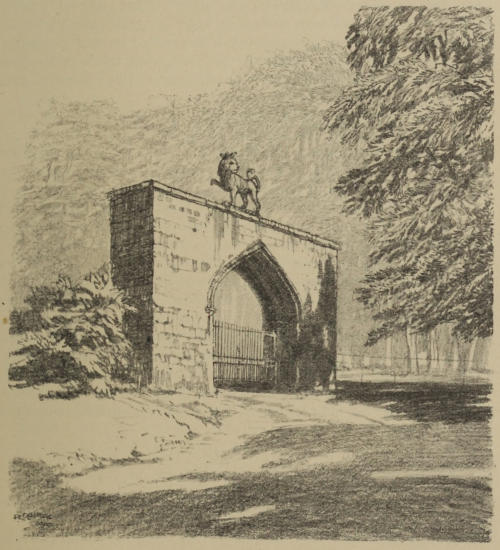

| THE LION GATE AT SCRIVELSBY | 373 |

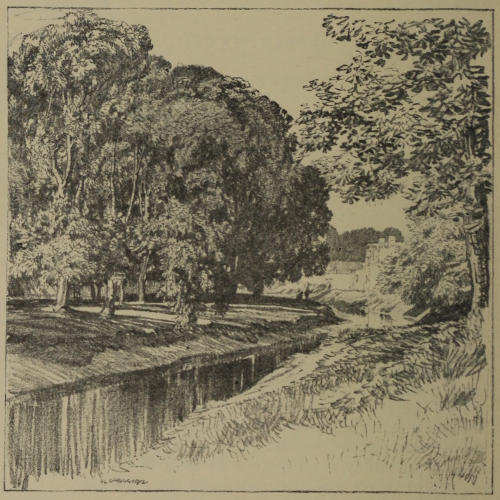

| TATTERSHALL CHURCH AND THE BAIN | 381 |

| TATTERSHALL CHURCH AND CASTLE | 386 |

| TATTERSHALL CHURCH WINDOWS | 388 |

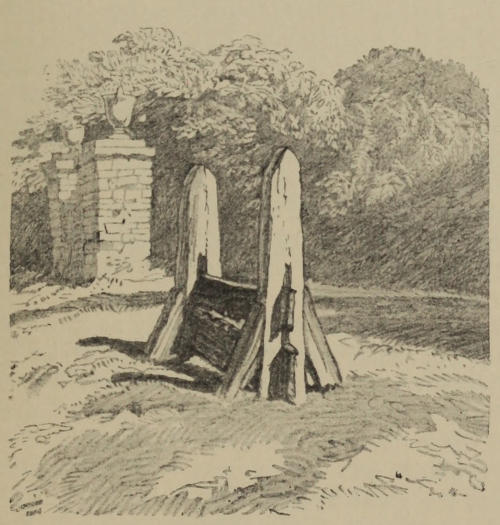

| SCRIVELSBY STOCKS | 389 |

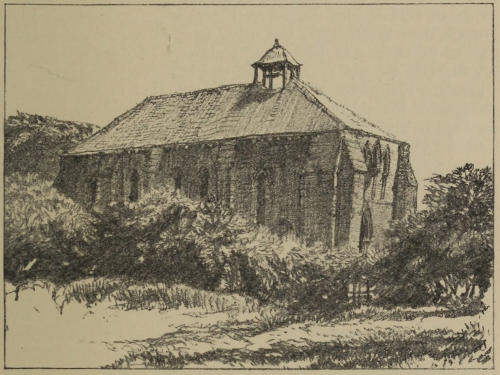

| KIRKSTEAD CHAPEL | 391 |

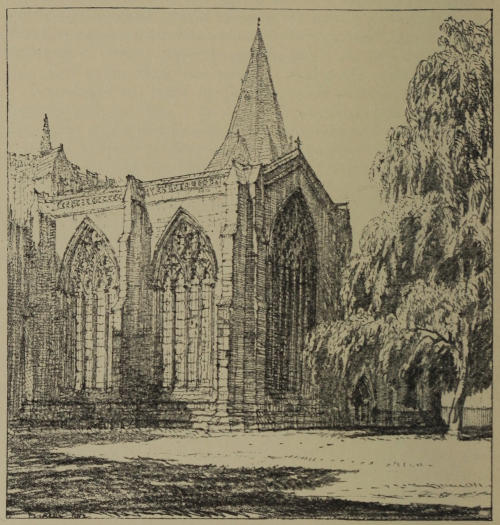

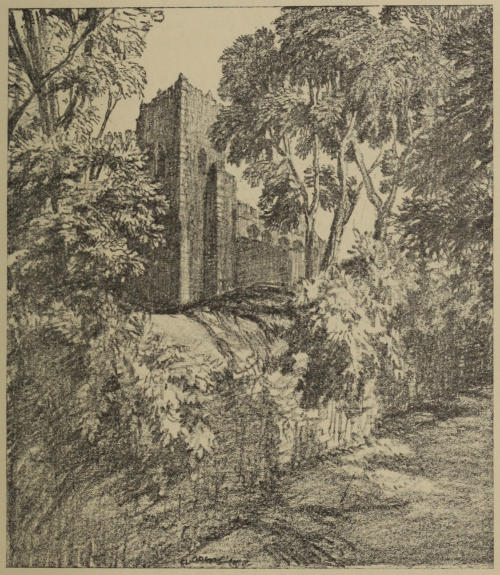

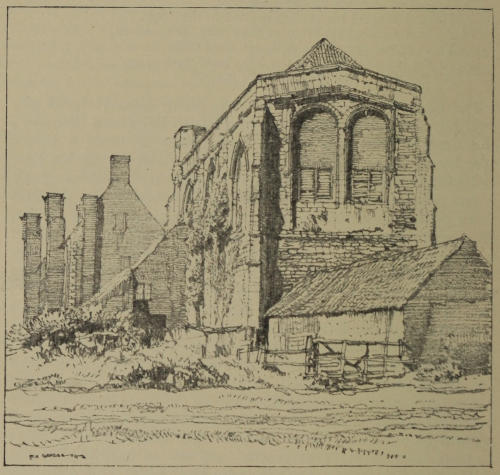

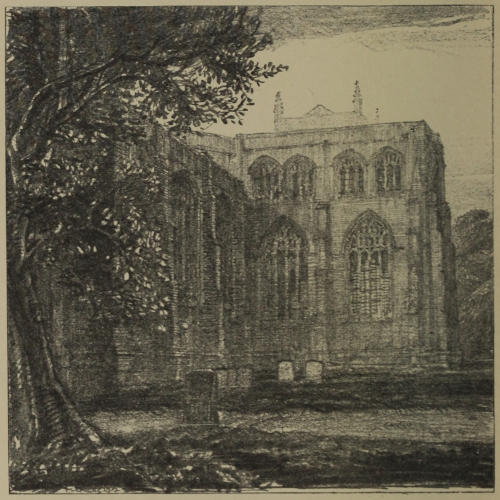

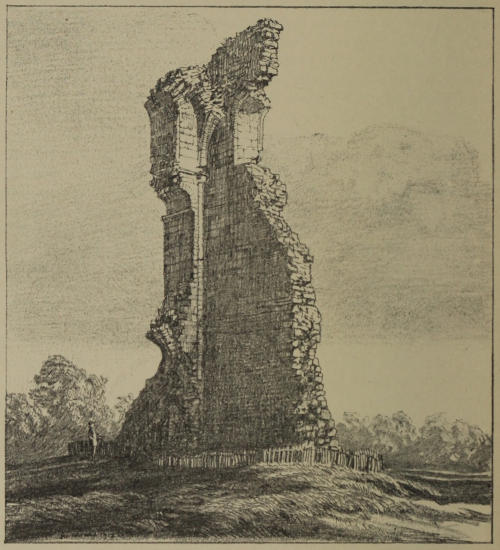

| REMAINS OF KIRKSTEAD ABBEY CHURCH | 396 |

| KIRKSTEAD CHAPEL, WEST END | 398 |

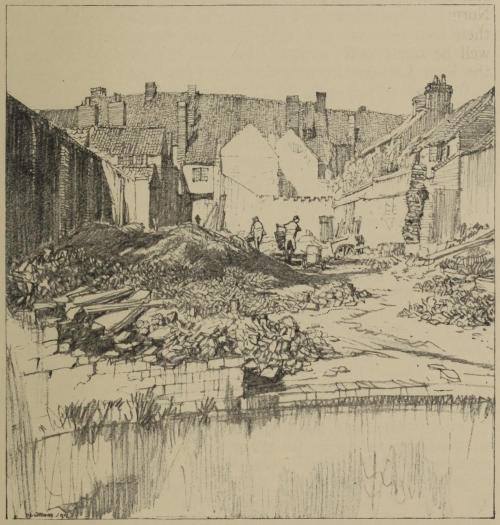

| DARLOW’S YARD, SLEAFORD | 403 |

| LEAKE CHURCH | 415 |

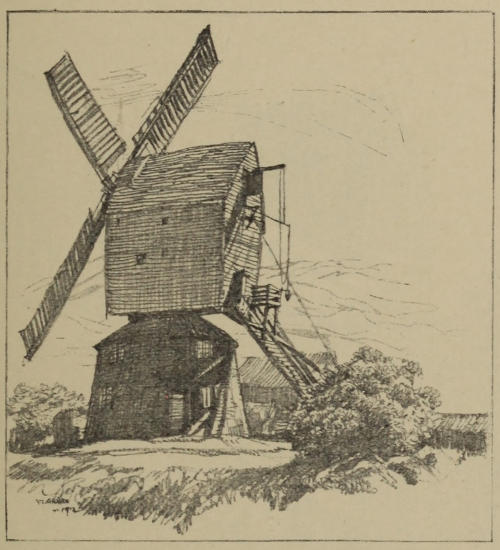

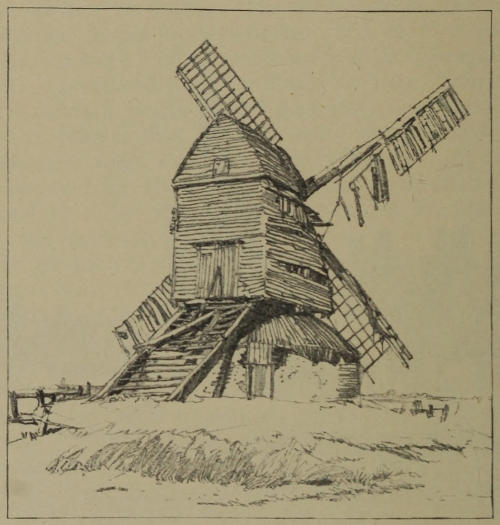

| LEVERTON WINDMILL | 417 |

| FRIESTON PRIORY CHURCH | 418 |

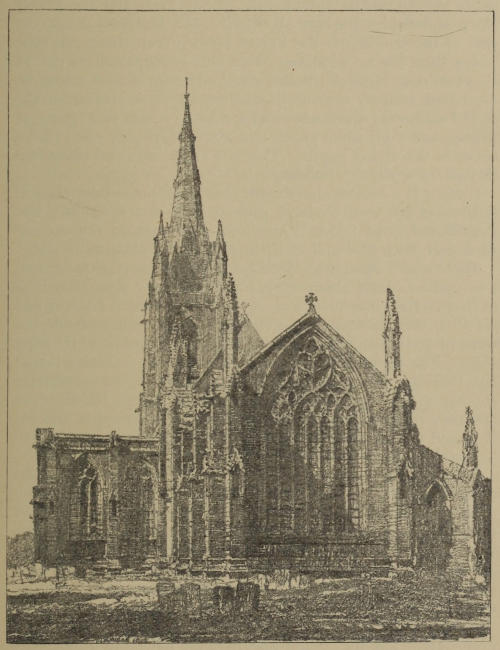

| BOSTON CHURCH FROM THE N.E. | 421 |

| BOSTON STUMP | 424 |

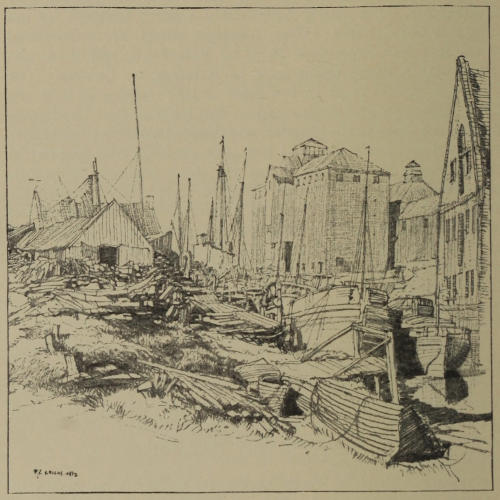

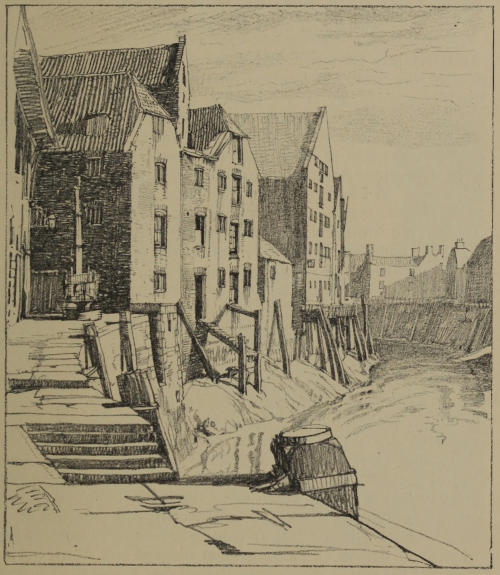

| CUSTOM HOUSE QUAY, BOSTON | 427 |

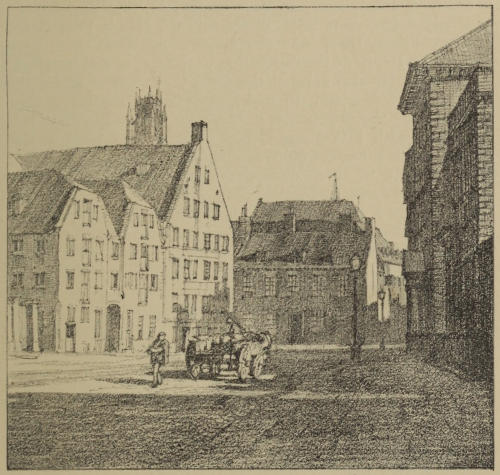

| SOUTH SQUARE, BOSTON | 429 |

| SPAIN LANE, BOSTON | 431 |

| THE HAVEN, BOSTON | 436 |

| THE GUILDHALL, BOSTON | 437 |

| HUSSEY’S TOWER, BOSTON | 439[xviii] |

| THE WELLAND AT COWBIT ROAD, SPALDING | 442 |

| THE WELLAND AT HIGH STREET, SPALDING | 443 |

| AYSCOUGH FEE HALL GARDENS, SPALDING | 445 |

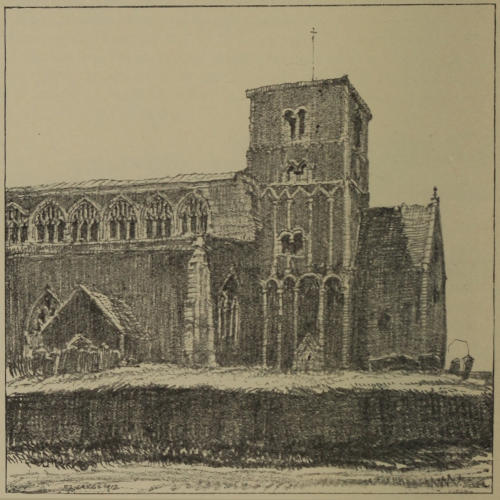

| SPALDING CHURCH FROM THE S.E. | 447 |

| N. SIDE, SPALDING CHURCH | 449 |

| PINCHBECK | 450 |

| SURFLEET | 453 |

| SURFLEET WINDMILL | 454 |

| THE WELLAND AT MARSH ROAD, SPALDING | 458 |

| ALGARKIRK | 460 |

| AT FULNEY | 462 |

| WHAPLODE CHURCH | 467 |

| FLEET CHURCH | 469 |

| GEDNEY CHURCH | 471 |

| LONG SUTTON CHURCH | 473 |

| GEDNEY, FROM FLEET | 482 |

| COWBIT CHURCH | 484 |

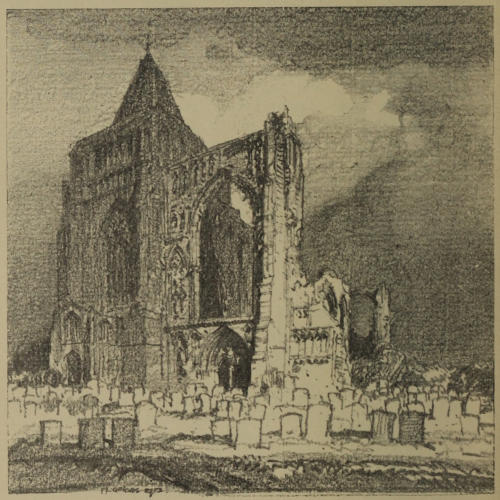

| CROYLAND ABBEY | 488 |

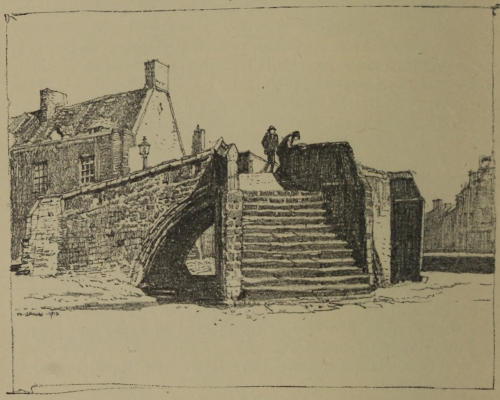

| CROYLAND BRIDGE | 490 |

| MAP | At end Volume |

In dealing with a county which measures seventy-five miles by forty-five, it will be best to assume that the tourist has either some form of “cycle” or, better still, a motor car. The railway helps one less in this than in most counties, as it naturally runs on the flat and unpicturesque portions, and also skirts the boundaries, and seldom attempts to pierce into the heart of the Wolds. Probably it would not be much good to the tourist if it did, as he would have to spend much of his time in tunnels which always come where there should be most to see, as on the Louth and Lincoln line between Withcal and South Willingham. As it is, the only bit of railway by which a person could gather that Lincolnshire was anything but an ugly county is that between Lincoln and Grantham.

But that it is a county with a great deal of beauty will be, I am sure, admitted by those who follow up the routes described in the following pages. They will find that it is a county famous for wide views, for wonderful sunsets, for hills and picturesque hollows; and full, too, of the human interest which clings round old buildings, and the uplifting pleasure which its many splendid specimens of architecture have power to bestow.

At the outset the reader must identify himself so far with the people of Lincolnshire as to make himself at home in the universally accepted meanings of certain words and expressions which he will hear constantly recurring. He will soon come to know that ‘siver’ means however, that ‘slaäpe’ means slippery, that ‘unheppen,’ a fine old word (—unhelpen), means awkward, that ‘owry’ or ‘howry’ means dirty; but, having learnt this, he must not conclude that the word ‘strange’ in ‘straänge an’ owry weather’ means anything unfamiliar. ‘Straänge’—perhaps the commonest adverbial epithet in general use in Lincolnshire—e.g. “you’ve bin a straänge long while coming” only means very. But besides common conversational expressions he will have to note that the well-known substantives ‘Marsh’ and ‘Fen’ bear in Lincolnshire a special meaning, neither of them now denoting bog or wet impassable places. The Fens are the rich flat corn lands, once perpetually flooded, but now drained and tilled; the divisions between field and field being mostly ditches, small or big, and all full of water; the soil is deep vegetable mould, fine, and free from stones, hardly to be excelled for both corn and roots; while the Marsh is nearly all pasture land, stiffer in nature, and producing such rich grass that the beasts can grow fat upon it without other food. Here, too, the fields are divided by ditches or “dykes” and the sea wind blows over them with untiring energy, for the Marsh is all next the coast, being a belt averaging seven or eight miles in width, and reaching from the Wash to the Humber.

From this belt the Romans, by means of a long embankment, excluded the waters of the sea; and Nature’s sand-dunes, aided by the works of man in places, keep up the Roman tradition. Even before the Roman bank was made, the Marsh differed from the Fen, in that the waters which used to cover the fens were fed by the river floods and the waters from the hills, and it was not, except occasionally and along the course of a tidal river, liable to inundation from the sea; whereas the Marsh was its natural prey. Of course both Marsh and Fen are all level. But the third portion of the county is of quite a different character, and immediately you get into it all the usual ideas about Lincolnshire being a flat, ugly county vanish, and as this upland country extends over most of the northern half of the county, viz., from Spilsby to the Humber on the[3] eastern side and from Grantham to the Humber on the western, it is obvious that no one can claim to know Lincolnshire who does not know the long lines of the Wolds, which are two long spines of upland running north and south, with flat land on either side of them.

These, back-bones of the county, though seldom reaching 500 feet, come to their highest point of 530 between Walesby and Stainton-le-Vale, a valley set upon a hill over which a line would pass drawn from Grimsby to Market Rasen. The hilly Wold region is about the same width as the level Marsh belt, averaging eight miles, but north of Caistor this narrows. There are no great streams from these Wolds, the most notable being the long brook whose parent branches run from Stainton-in-the-Vale and “Roman hole” near Thoresway, and uniting at Hatcliffe go out to the sea with the Louth River “Lud,” the two streams joining at Tetney lock.

North of Caistor the Wolds not only narrow, but drop by Barnetby-le-Wold to 150 feet, and allow the railway lines from Barton-on-Humber, New Holland and Grimsby to pass through to Brigg. This, however, is only a ‘pass,’ as the chalk ridge rises again near Elsham, and at Saxby attains a height of 330 feet, whence it maintains itself at never less than 200 feet, right up to Ferriby-on-the-Humber. These Elsham and Saxby Wolds are but two miles across.

Naturally this Wold region with the villages situated in its folds or on its fringes is the pretty part of the county, though the Marsh with its extended views, its magnificent sunsets and cloud effects,

its splendid cattle and its interesting flora, its long sand-dunes covered with stout-growing grasses, sea holly and orange-berried buckthorn, and finally its magnificent sands, is full of a peculiar charm; and then there are its splendid churches; not so grand as the fen churches it is true, but so nobly planned and so unexpectedly full of beautiful old carved woodwork.

West of these Wolds is a belt of Fen-land lying between them and the ridge or ‘cliff’ on which the great Roman Ermine Street runs north from Lincoln in a bee line for over thirty miles to the Humber near Winteringham, only four miles west of the end of the Wolds already mentioned at South Ferriby.

The high ridge of the Lincoln Wold is very narrow, a regular ‘Hogs back’ and broken down into a lower altitude between Blyborough and Kirton-in-Lindsey, and lower again a little further north near Scawby and still more a few miles further on where the railway goes through the pass between Appleby Station and Scunthorpe.

From here a second ridge is developed parallel with the Lincoln Wold, and between the Wold and the Trent, the ground rising from Bottesford to Scunthorpe, reaching a height of 220 feet on the east bank of the Trent near Burton-on-Stather and thence descending by Alkborough to the Humber at Whitton. The Trent which, roughly speaking, from Newark, and actually from North Clifton to the Humber, bounds the county on the west, runs through a low country of but little interest, overlooked for miles from the height which is crowned by Lincoln Minster. Only the Isle of Axholme lies outside of the river westwards.

The towns of Gainsborough towards the north, and Stamford at the extreme south guard this western boundary. Beyond the Minster the Lincoln Wold continues south through the Sleaford division of Kesteven to Grantham, but in a modified form, rising into stiff hills only to the north-east and south-west of Grantham, and thence passing out of the county into Leicestershire. A glance at a good map will show that the ridge along which the Ermine Street and the highway from Lincoln to Grantham run for seventeen miles, as far, that is, as Ancaster, is not a wide one; but drops to the flats more gently east of the Ermine Street than it does to the west of the Grantham road. From Sleaford, where five railway lines converge, that which goes west passes through a natural break in the ridge by Ancaster, the place from which, next after the “Barnack rag,” all the best stone of the churches of Lincolnshire has always been quarried. South of Ancaster the area of high ground is much wider, extending east and west from the western boundary of the county to the road which runs from Sleaford to Bourne and Stamford.

Such being the main features of the county, it will be as well to lay down a sort of itinerary showing the direction in which we will proceed and the towns which we propose to visit as we go.

Entering the county from the south, at Stamford, we will make for Sleaford. These are the two towns which give their[5] names to the divisions of South and North Kesteven. Grantham lies off to the west, about midway between the two. As this is the most important town in the division of Kesteven, after taking some of the various roads which radiate from Sleaford we will make Grantham our centre, then leave South Kesteven for Sleaford again, and thence going on north we shall reach Lincoln just over the North Kesteven boundary, and so continue to Gainsborough and Brigg, from which the west and north divisions of Lindsey are named. From each of the towns we have mentioned we shall trace the roads which lead from them in all directions; and then, after entering the Isle of Axholme and touching the Humber at Barton and the North Sea at Cleethorpes and Grimsby, we shall turn south to the Louth and Horncastle (in other words the east and south) divisions of Lindsey, and, so going down the east coast, we shall, after visiting Alford and Spilsby, both in South Lindsey, arrive at Boston and then at Spalding, both in the “parts of Holland,” and finally pass out of the county near the ancient abbey of Croyland.

By this itinerary we shall journey all round the huge county, going up, roughly speaking, on the west and returning by the east; and shall see, not only how it is divided into the political “parts” of Kesteven, Lindsey and Holland, but also note as we go the characteristics of the land and its three component elements of Fen, Wold and Marsh.

We have seen that the Wolds, starting from the Humber, run in two parallel ridges; that on the west side of the county reaching the whole way from north to south, but that on the east only going half the way and ending abruptly at West Keal, near Spilsby.

All that lies east of the road running from Lincoln by Sleaford and Bourne to Stamford, and south of a line drawn from Lincoln to Wainfleet is “Fen,” and includes the southern portion of South Lindsey, the eastern half of Kesteven, and the whole of Holland.

In this Fen country great houses are scarce. But the great monasteries clung to the Fens and they were mainly responsible for the creation of the truly magnificent Fen churches which are most notably grouped in the neighbourhood of Boston, Sleaford and Spalding. In writing of the Fens, therefore, the churches are the chief things to be noticed, and this is largely,[6] though not so entirely, the case in the Marsh district also. Hence I have ventured to describe these Lincolnshire churches of the Marsh and Fen at greater length than might at first sight seem warrantable.

It would make it easier to follow these descriptions if the reader were first to master the dates and main characteristics of the different periods of architecture and their order of sequence. Thus, roughly speaking, we may assign each style to one century, though of course the style and the century were not in any case exactly coterminous.

| 11th | Century | Norman | ⎫ | With round arches. |

| 12th | ” | Transition | ⎭ | |

| 13th | ” | Early English (E.E.) | ⎫ | With pointed arches. |

| 14th | ” | Decorated (Dec.) | ⎬ | |

| 15th | ” | Perpendicular (Perp.) | ⎭ |

The North Road—Churches—Browne’s Hospital—Brasenose College—Daniel Lambert—Burghley House and “The Peasant Countess.”

The Great Northern line, after leaving Peterborough, enters the county at Tallington, five miles east of Stamford. Stamford is eighty-nine miles north of London, and forty miles south of Lincoln. Few towns in England are more interesting, none more picturesque. The Romans with their important station of Durobrivæ at Castor, and another still nearer at Great Casterton, had no need to occupy Stamford in force, though they doubtless guarded the ford where the Ermine Street crossed the Welland, and possibly paved the water-way, whence arose the name Stane-ford. The river here divides the counties of Lincoln and Northamptonshire, and on the north-west of the town a little bit of Rutland runs up, but over three-quarters of the town is in our county. The Saxons always considered it an important town, and as early as 664 mention is made in a charter of Wulfhere, King of Mercia, of “that part of Staunforde beyond the bridge,” so the town was already on both sides of the river. Later again, in Domesday Book, the King’s borough of Stamford is noticed as paying tax for the army, navy and Danegelt, also it is described as “having six wards, five in Lincolnshire and one in Hamptonshire, but all pay customs and dues alike, except the last in which the Abbot of Burgh (Peterborough) had and hath Gabell and toll.”

This early bridge was no doubt a pack-horse bridge, and an arch on the west side of St. Mary’s Hill still bears the name of Packhorse Arch.

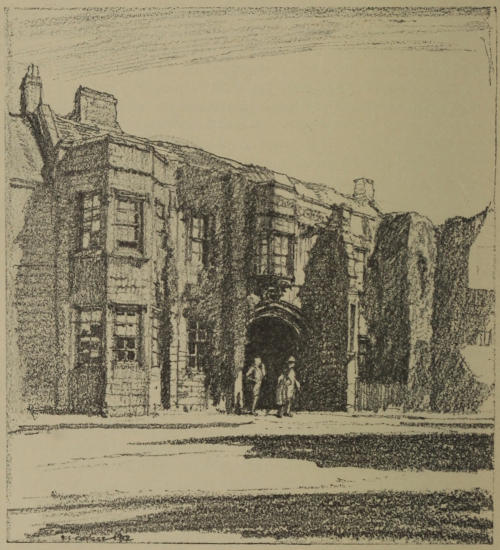

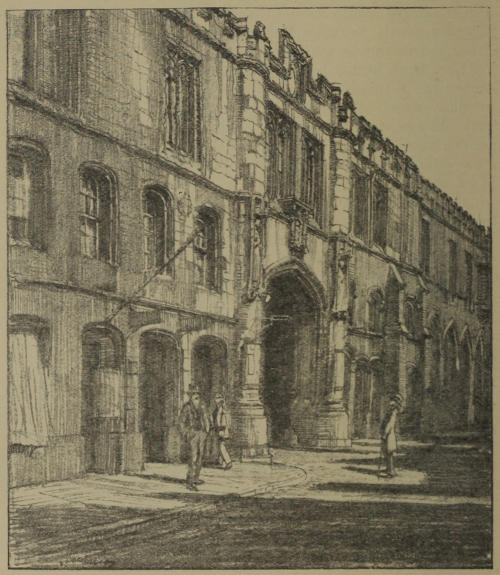

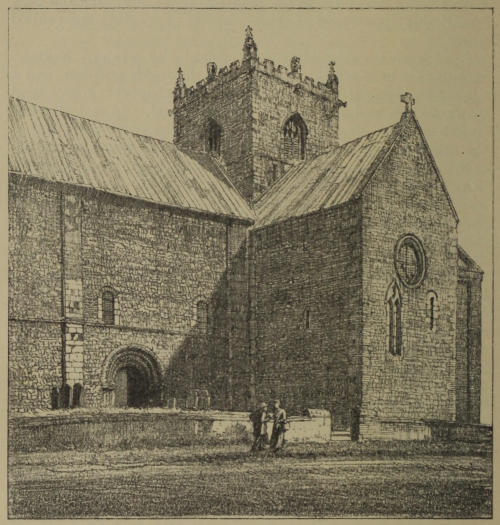

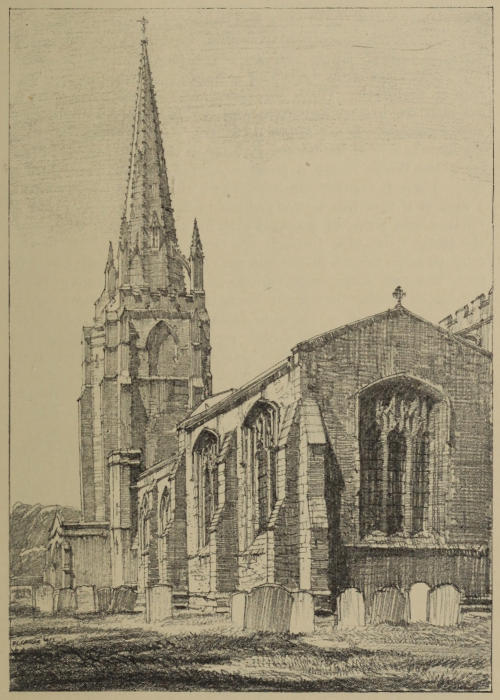

St. Leonard’s Priory, Stamford.

St. Leonard’s Priory is the oldest building in the neighbourhood. After Oswy, King of Northumbria, had defeated Penda, the pagan King of Mercia, he gave the government of this part of the conquered province to Penda’s son Pæda, and gave land in Stamford to his son’s tutor, Wilfrid, and here, in 658, Wilfrid built the priory of St. Leonard which he bestowed on his monastery at Lindisfarne, and when the monks removed thence to Durham it became a cell of the priory of Durham. Doubtless the building was destroyed by the Danes, but it was refounded[9] in 1082 by the Conqueror and William of Carilef, the then Bishop of Durham.

The Danish marauders ravaged the country, but were met at Stamford by a stout resistance from Saxons and Britons combined; but in the end they beat the Saxons and nearly destroyed Stamford in 870. A few years later, when, after the peace of Wedmore, Alfred the Great gave terms to Guthrum on condition that he kept away to the north of the Watling Street, the five towns of Stamford, Leicester, Nottingham, Derby and Lincoln were left to the Danes for strongholds; of these Lincoln then, as now, was the chief.

The early importance of Stamford may be gauged by the facts that Parliament was convened there more than once in the fourteenth century, and several Councils of War and of State held there. One of these was called by Pope Boniface IX. to suppress the doctrines of Wyclif. There, too, a large number of nobles met to devise some check on King John, who was often in the neighbourhood either at Kingscliffe, in Rockingham Forest, or at Stamford itself—and from thence they marched to Runnymede.

The town was on the Great North Road, so that kings, when moving up and down their realm, naturally stopped there. A good road also went east and west, hence, just outside the town gate on the road leading west towards Geddington and Northampton, a cross (the third) was set up in memory of the halting of Queen Eleanor’s funeral procession in 1293 on its way from Harby near Lincoln to Westminster.

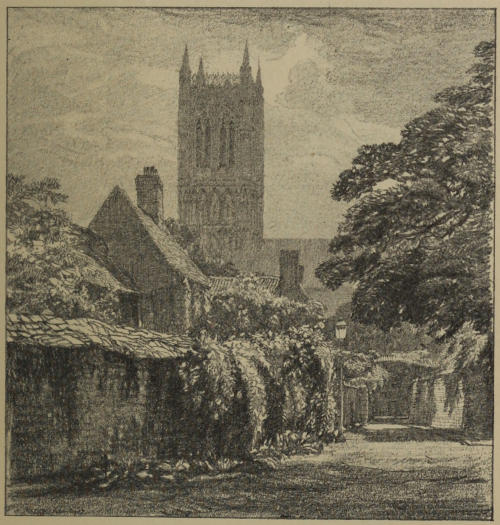

St. George’s Square, Stamford.

There was a castle near the ford in the tenth century, and Danes and Saxons alternately held it until the Norman Conquest. The city, like the ancient Thebes, had a wall with seven gates besides posterns, one of which still exists in the garden of 9, Barn Hill, the house in which Alderman Wolph hid Charles I. on his last visit to Stamford in 1646. Most of the buildings which once made Stamford so very remarkable were the work of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and as they comprised fifteen churches, six priories, with hospitals, schools and almshouses in corresponding numbers, the town must have presented a beautiful appearance, more especially so because the stone used in all these buildings, public and private, is of such exceptionally good character, being from the neighbouring quarries of Barnack, Ketton and Clipsham. But much of this glory of stone building[10] and Gothic architecture was destroyed in the year 1461; and for this reason. It happened that, just as Henry III. had given it to his son Edward I. on his marriage with Eleanor of Castile in 1254, so, in 1363, Edward III. gave the castle and manor of Stamford to his son Edmund of Langley, Duke of York; this, by attaching the town to the Yorkist cause, when Lincolnshire was mostly Lancastrian, brought about its destruction, for after the battle of St. Alban’s in 1461, the Lancastrians under Sir Andrew Trollope utterly devastated the town, destroying everything, and, though some of the churches were rebuilt, the town never recovered its former magnificence. It still looks beautiful with its six churches, its many fragments of arch or wall and several fine old almshouses which were built subsequently,[11] but it lost either then or at the dissolution more than double of what it has managed to retain. Ten years later the courage shown by the men of Stamford at the battle of Empingham or “Bloody Oaks” close by, on the North Road, where the Lancastrians were defeated, caused Edward IV. to grant permission for the royal lions to be placed on the civic shield of Stamford, side by side with the arms of Earl Warren. He had had the manorial rights of Stamford given to him by King John in 1206, and he is said to have given the butchers a field in which to keep a bull to be baited annually on November 13, and the barbarous practice of “bull running” in the streets was actually kept up till 1839, and then only abolished with difficulty.

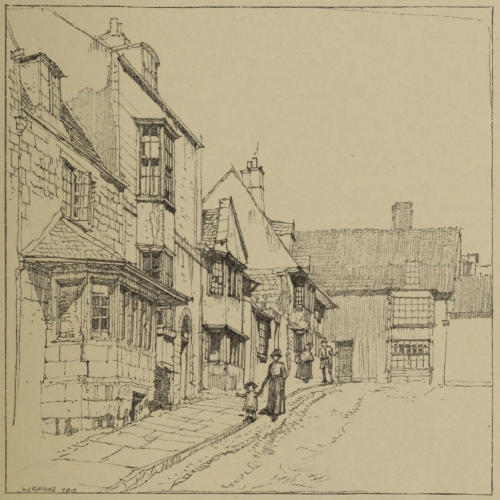

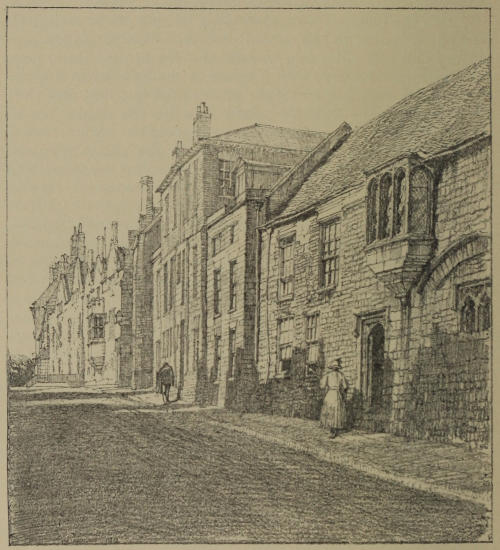

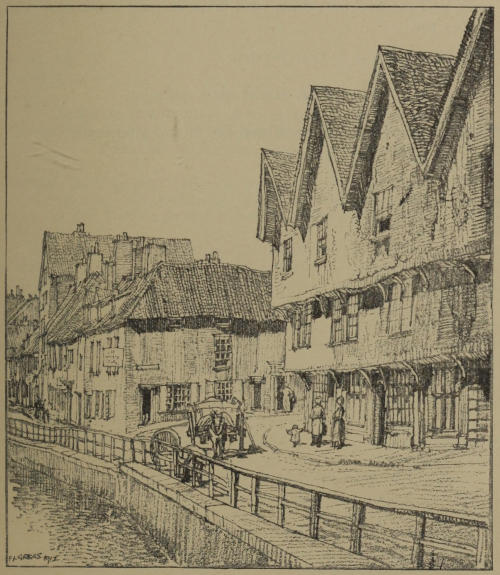

St. Mary’s Street, Stamford.

St. Paul’s Street, Stamford.

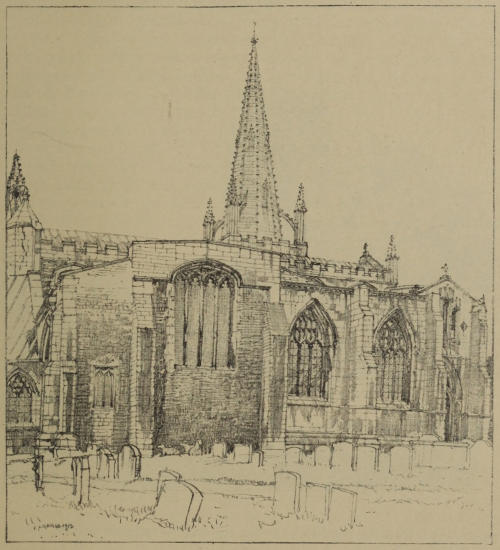

Of the six churches, St. Mary’s and All Saints have spires. St. Mary’s, on a hill which slopes to the river, is a fine arcaded Early English tower with a broach spire of later date, but full of beautiful work in statue and canopy, very much resembling that at Ketton in Rutland. There are three curious round panels with interlaced work over the porch, and a rich altar tomb with very lofty canopy that commemorates Sir David Phillips and his wife. They had served Margaret Countess of Richmond, the mother of Henry VII., who resided at Collyweston close by. The body of the church is rather crowded together and not easy to view. In this respect All Saints, with its turrets, pinnacles and graceful spire, and its double belfry lights under one hood moulding as at Grantham, has the advantage. Moreover the North Road goes up past it, and the market place gives plenty of space all round it. Inside, the arcade columns are cylindrical and plain on the north, but clustered on the south side, with foliated capitals. This church is rich in brasses, chiefly of the great wool-merchant family of Browne, one of whom, William, founded a magnificent hospital and enlarged the church, and in all probability built the handsome spire; he was buried in 1489. The other churches all have square towers, that of St. John’s Church is over the last bay of the north aisle, and at the last bay of the south aisle is a porch. The whole construction is excellent, pillars tall, roof rich and windows graceful, and it once was filled with exceptionally fine stained glass. St. George’s Church, being rebuilt with fragments of other destroyed churches, shows a curious mixture of octagonal and cylindrical work in the same pillars. St. Michael’s and St. Martin’s are the other two, of which the latter is across the water in what is called Stamford Baron, it is the burial place of the Cecils and it is not far from the imposing gateway into Burghley Park. This church and park, with the splendid house designed by John Thorpe for the great William Cecil in 1565, are all in the diocese of Peterborough, and the county of Northampton. We shall have to recall the church when we speak of the beautiful windows which Lord Exeter was allowed by the Fortescue family to take from the Collegiate Church of Tattershall, and which are now in St. Martin’s, where they are extremely badly set with bands of modern glass interrupting the old. Another remnant of a church stands on the north-west of the town, St. Paul’s. This[13] ruin was made over as early as the sixteenth century for use as a schoolroom for Radcliffe’s Grammar School. Schools, hospitals or almshouses once abounded in Stamford, where the latter are often called Callises, being the benefactions of the great wool merchants of the Staple of Calais. The chief of all these, and one which is still in use, is Browne’s Hospital, founded in 1480 by a Stamford merchant who had been six times Mayor, for a Warden, a Confrater, ten poor men, and two poor[14] women. It had a long dormitory hall, with central passage from which the brethren’s rooms opened on either side, and, at one end, beyond a carved screen, is the chapel with tall windows, stalls and carved bench-ends, and a granite alms box. An audit room is above the hall or dormitory, with good glass, and Browne’s own house, with large gateway to admit the wool-wagons, adjoined the chapel. It was partly rebuilt with new accommodation in 1870; the cloister and hall and chapel remain as they were. One more thing must be noted. In the north-west and near the old St. Paul’s Church schoolroom is a beautiful Early English gateway, which is all that remains of Brasenose College. The history is a curious one. Violent town and gown quarrels resulting even in murders, at Oxford in 1260, had caused several students to migrate to Northampton, where Henry III. directed the mayor to give them every accommodation; but in 1266, probably for reasons connected with civil strife, the license was revoked, and, whilst many returned to Oxford, many preferred to go further, and so came to Stamford, a place known to be well supplied with halls and requisites for learning. Here they were joined in 1333 by a further body of Oxford men who were involved in a dispute between the northern and southern scholars, the former complaining that they were unjustly excluded from Merton College Fellowships. The Durham Monastery took their side and doubtless offered them shelter at their priory of St. Leonard’s, Stamford. Then, as other bodies of University seceders kept joining them, they thought seriously of setting up a University, and petitioned King Edward III. to be allowed to remain under his protection at Stamford. But the Universities petitioned against them, and the King ordered the Sheriff of Lincolnshire to turn them out, promising them redress when they were back in Oxford. Those who refused were punished by confiscation of goods and fines, and the two Universities passed Statutes imposing an oath on all freshmen that they would not read or attend lectures at Stamford. In 1292 Robert Luttrell of Irnham gave a manor and the parish church of St. Peter, near Stamford, to the priory at Sempringham, being “desirous to increase the numbers of the convent and that it might ever have scholars at Stamford studying divinity and philosophy.” This refers to Sempringham Hall, one of the earliest buildings of Stamford University.

St. Peter’s Hill, Stamford.

A glance at a plan of the town would show that it is exactly[15] like a maze, no street runs on right through it in any direction, and, for a stranger, it is incredibly difficult to find a way out. To the south-west, and all along the eastern edge on the river-meadows outside the walls, were large enclosures belonging to the different Friaries, on either side of the road to St. Leonard’s Priory. No town has lost more by the constant depredations of successive attacking forces; first the Danes, then the Wars of the Roses, then the dissolution of the religious houses, then the Civil War, ending with a visit from Cromwell in his most truculent mood, fresh from the mischief done by his soldiers in and around Croyland and Peterborough. But, even now, its grey stone buildings, its well-chosen site, its river, its neighbouring[16] hills and wooded park, make it a town more than ordinarily attractive. Of distinguished natives, we need only mention the great Lord Burleigh, who served with distinction through four reigns, and Archdeacon Johnson, the founder of the Oakham and Uppingham Schools and hospitals in 1584, though Uppingham as it now is, was the creation of a far greater man, the famous Edward Thring, a pioneer of modern educational methods, in the last half of the nineteenth century. Archbishop Laud, who is so persistently mentioned as having been once Vicar of St. Martin’s, Stamford, was never there; his vicarage was Stanford-on-Avon. But undoubtedly Stamford’s greatest man in one sense was Daniel Lambert, whose monument, in St. Martin’s churchyard, date 1809, speaks of his “personal greatness” and tells us that he weighed 52 stone 11 lbs., adding “N.B. the stone of 14 lb.” The writer once, when a schoolboy, went with another to see his clothes, which were shown at the Daniel Lambert Inn; and, when the two stood back to back, the armhole of his spacious waistcoat was slipped over their heads and fell loosely round them to the ground.

This enormous personage must not be confounded with another Daniel Lambert, who was Lord Mayor and Member for the City of London in Walpole’s time, about 1740.

It is quite a matter of regret that “Burleigh House near Stamford town” is outside the county boundary. Of all the great houses in England, it always strikes me as being the most satisfying and altogether the finest, and a fitting memorial of the great Lincolnshire man William Cecil, who, after serving in the two previous reigns, was Elizabeth’s chief Minister for forty years. “The Lord of Burleigh” of Tennyson’s poem lived two centuries later, but he, too, with “the peasant Countess” lived eventually in the great house. Lady Dorothy Nevill, in My Own Times published in 1912, gives a clear account of the facts commemorated in the poem. She tells us that Henry Cecil, tenth Earl of Exeter, before he came into the title was divorced from his wife in 1791, owing to her misconduct; being almost broken-hearted he retired to a village in Shropshire, called Bolas Magna, where he worked as a farm servant to one Hoggins who had a mill. Tennyson makes him more picturesquely “a landscape painter.” He often looked in at the vicarage and had a mug of ale with the servants, who[17] called him “Gentleman Harry.” The clergyman, Mr. Dickenson, became interested in him, and often talked with him, and used to invite him to smoke an evening pipe with him in the study. Mr. Hoggins had a daughter Sarah, the beauty of Bolas, and they became lovers. With the clergyman’s aid Cecil, not without difficulty, persuaded Hoggins to allow the marriage, which took place at St. Mildred’s, Bread Street, October 30th, 1791, his broken heart having mended fairly quickly. He was now forty years of age, and before the marriage he had told Dickenson who he was. For two years they lived in a small farm, when, from a Shrewsbury paper, “Mr. Cecil” learnt that he had succeeded his uncle in the title and the possession of Burleigh House and estate. Thither in due course he took his bride. Her picture is on the wall, but she did not live long.

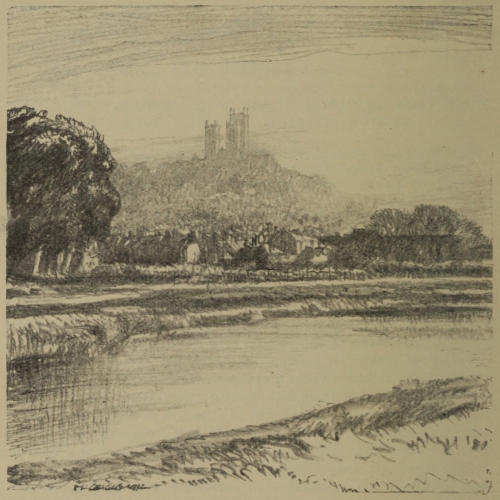

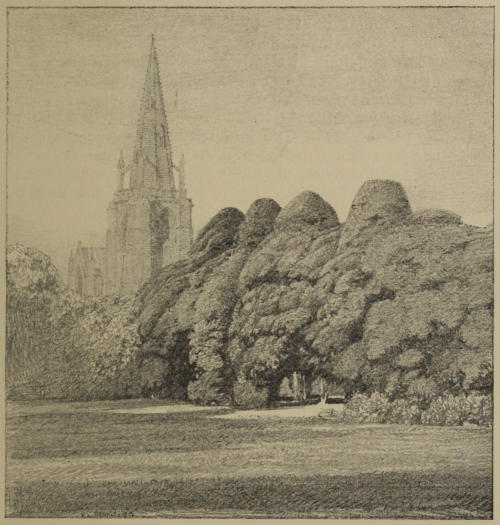

Stamford from Freeman’s Close.

Tickencote—“Bloody Oaks”—Holywell—Tallington—Barholm—Greatford—Witham-on-the-Hill—Dr. Willis—West Deeping—Market Deeping—Deeping-St.-James—Richard de Rulos—Braceborough—Bourne.

Of the eight roads which run to Stamford, the Great North Road which here coincides with the Roman Ermine Street is the chief; and this enters from the south through Northamptonshire and goes out by the street called “Scotgate” in a north-westerly direction through Rutland. It leaves Lincolnshire at Great or Bridge Casterton on the river Gwash; one mile further it passes the celebrated church of Tickencote nestling in a hollow to the left, where the wonderful Norman chancel arch of five orders outdoes even the work at Iffley near Oxford, and the wooden effigy of a knight reminds one of that of Robert Duke of Normandy at Gloucester. Tickencote is the home of the Wingfields, and the villagers in 1471 were near enough to hear “the Shouts of war” when the Lincolnshire Lancastrians fled from the fight on Loosecoat Field after a slaughter which is commemorated on the map by the name “Bloody Oaks.” Further on, the road passes Stretton, ‘the village on the street,’ whence a lane to the right takes you to the famed Clipsham quarries just on the Rutland side of the boundary, and over it to the beautiful residence of Colonel Birch Reynardson at Holywell. Very soon now the Ermine Street, after doing its ten miles in Rutland, passes by “Morkery Wood” back into Lincolnshire.

The only Stamford Road which is all the time in our county is the eastern road through Market Deeping to Spalding, this[19] soon after leaving Stamford passes near Uffington Hall, built in 1688 by Robert Bertie, son of Montague, second Earl of Lindsey, he whose father fell at Edgehill. On the northern outskirt of the parish Lord Kesteven has a fine Elizabethan house called Casewick Hall. Round each house is a well-timbered park, and at Uffington Hall the approach is by a fine avenue of limes. At Tallington, where the road crosses the Great Northern line, the church, like several in the neighbourhood, has some Saxon as well as Norman work, and the original Sanctus bell still hangs in a cot surmounting the east end of the nave. It is dedicated to St. Lawrence.

South Lincolnshire seems to have been rather rich in Saxon churches, and two of the best existing towers of that period at Barnack and Wittering in Northamptonshire are within three miles of Stamford, one on either side of the Great North Road.

Barholm Church, near Tallington, has some extremely massive Norman arches and a fine door with diapered tympanum. The tower was restored in the last year of Charles I., and no one seems to have been more surprised than the churchwarden or parson or mason of the time, for we find carved on it these lines:—

An old Hall adds to the interest of the place, and another charming old building is Mr. Peacock’s Elizabethan house in the next parish of Greatford, or, as it should be spelt, Gretford or Gritford, the grit or gravel ford of the river Glen, just as Stamford should be Stanford or Staneford, the stone-paved ford of the Welland. Gretford Church is remarkable if only for the unusual position of the tower as a south transept, a similar thing being seen at Witham-on-the-Hill, four miles off, in Rutland. Five of the bells there are re-casts of some which once hung in Peterborough Cathedral, and the fifth has the date 1831 and a curious inscription. General Johnson I used to see when I was a boy at Uppingham; he was the patron of the school, and the one man among the governors of the school who was always a friend to her famous headmaster, Edward Thring. But why he wrote the last line of this inscription I can’t conceive:—

To return to Gretford. In the north transept is a square opening, in the sill of which is a curious hollow all carved with foliage, resembling one in the chancel at East Kirkby, near Spilsby, where it is supposed to have been a sort of alms dish for votive offerings. Here, too, is a bust by Nollekens of a man who had a considerable reputation in his time, and who occupied more than one house in this neighbourhood and built a private asylum at Shillingthorpe near Braceborough for his patients, a distinguished clientèle who used to drive their teams all about the neighbourhood; this was Dr. F. Willis, the mad-doctor who attended George III. But these are all ‘side shows,’ and we must get back to Tallington. The road from here goes through West Deeping, which, like the manor of Market Deeping, belonged to the Wakes. Here we find a good font with eight shields of arms, that of the Wakes being one, and an almost unique old low chancel screen of stone, the surmounting woodwork has gone and the west face is filled in with poor modern mosaic. Within three miles the Bourne-and-Peterborough road crosses the Stamford-and-Spalding road at Market Deeping, where there is a large church, once attached to Croyland, and a most interesting old house used as the rectory. This was the refectory of a priory, and has fine roof timbers. The manor passed through Joan, daughter of Margaret Wake, to the Black Prince. Two miles further, the grand old priory church of Deeping-St.-James lies a mile to the left. This was attached as a cell to Thorney Abbey in 1139, by the same Baldwin FitzGilbert who had founded Bourne Abbey. A diversion of a couple of miles northwards would bring us to a fine tower and spire at Langtoft, once a dependency of Medehamstead[1] Abbey at Peterborough, together with which it was ruthlessly destroyed by Swegen in 1013. On the roof timbers are some beautifully carved figures of angels, and carved heads project from the nave pillars. The south chantry is a large one, with[21] three arches opening into the chancel, and has several interesting features. Amongst these is a handsome aumbry, which may have been used as an Easter sepulchre. The south chantry opens from the chancel with three arches, and has some good carving and a piscina with a finely constructed canopy. There is a monument to Elizabeth Moulesworth, 1648, and a brass plate on the tomb of Sarah, wife of Bernard Walcot, has this pretty inscription:—

At Scamblesby, between Louth and Horncastle, is another pathetic inscription on a wife’s tomb:—

To Margaret Coppinger wife of Francis Thorndike 1629.

Dilectissimæ conjugi Mæstissimus maritorum Franciscus

Thorndike.

L.(apidem) M.(armoreum) P.(osuit)

The old manor house of the Hyde family is at the north end of the village. The road for the next ten miles over Deeping Fen is uninteresting as a road can be. But this will be amply made up for in another chapter when we shape our eastward course from Spalding to Holbeach and Gedney.

In Deeping Fen between Bourne, Spalding, Crowland and Market Deeping there is about fifty square miles of fine fat land, and Marrat tells us that as early as the reign of Edward the Confessor, Egelric, the Bishop of Durham, who, having been once a monk at Peterborough, knew the value of the land, in order to develop the district, made a cord road of timber and gravel all the way from Deeping to Spalding. The province then belonged to the Lords of Brunne or Bourne. In Norman times Richard De Rulos, Chamberlain of the Conqueror, married the daughter of Hugh de Evermue, Lord of Deeping. Their only daughter married Baldwin FitzGilbert, and his daughter and heiress married Hugh de Wake, who managed the forest of Kesteven for Henry III., which forest reached to the bridge at Market Deeping. Richard De Rulos, who was the father of all Lincolnshire farmers, aided by Ingulphus, Abbot of Croyland,[22] set himself to enclose and drain the fen land, to till the soil or convert it into pasture and to breed cattle. He banked out the Welland which used to flood the fen every year, whence it got its name of Deeping or the deep meadows, and on the bank he set up tenements with gardens attached, which were the beginnings of Market Deeping. He further enlarged St. Guthlac’s chapel into a church, and then planted another little colony at Deeping-St.-James, where his son-in-law, who carried on his activities, built the priory. De Rulos was in fact a model landlord, and the result was that the men of Deeping, like Jeshuron, “waxed fat and kicked,” and the abbots of Croyland had endless contests with them for the next 300 years for constant trespass and damage. Probably this was the reason why the Wakes set up a castle close by Deeping, but on the Northampton side of the Welland at Maxey, which was inhabited later by Lady Margaret, Countess of Richmond, the mother of Henry VII., who, in addition to all her educational benefactions, was also a capital farmer and an active member of the Commissioners of Sewers.

We must now get back to Stamford. Even the road which goes due north to Bourne soon finds itself outside the county; for Stamford is placed on a mere tongue or long pointed nose of land belonging to Lincolnshire, in what is aptly termed the Wapentake of ‘Ness.’ However, after four miles in Rutland, it passes the four cross railroads at Essendine Junction, and soon after re-crosses the boundary near Carlby. Essendine Church consists simply of a Norman nave and chancel. Here, a little to the right lies Braceborough Spa, where water gushes from the limestone at the rate of a million and a half gallons daily. This is a great district for curative springs. There is one five miles to the west at Holywell which, with its stream and lake and finely timbered grounds, is one of the beauty spots of Lincolnshire, and at the same distance to the north are the strong springs of Bourne. We hear of a chalybeate spring “continually boiling” or gushing up, for it was not hot, near the church at Billingborough, and another at Stoke Rochford, each place a good ten miles from Bourne and in opposite directions. Great Ponton too, near Stoke Rochford, is said to “abound in Springs of pure water rising out of the rock and running into the river Witham.” The church at Braceborough had a fine brass once to Thomas De Wasteneys, who died of the Black Death in 1349.[23] After Carlby there is little of interest on the road itself till it tops the hill beyond Toft whence, on an autumn day, a grand view opens out across the fens to the Wash and to Boston on the north-east, and the panorama sweeps southward past Spalding to the time-honoured abbey of Croyland, and on again to the long grey pile of Peterborough Minster, once islands in a trackless fen (the impenetrable refuge of the warlike and unconquered Gervii or fenmen), but now a level plain of cornland covered, as far as eye can see, with the richest crops imaginable. A little further north we reach the Colsterworth road, and turning east, enter the old town of Bourne, now only notable as the junction of the Great Northern and Midland Railways. Since 1893 the inhabitants have used an “e” at the end of the name to distinguish it from Bourn in Cambridgeshire. Near the castle hill is a strong spring called “Peter’s Pool,” or Bournwell-head, the water of which runs through the town and is copious enough to furnish a water supply for Spalding. This castle, mentioned by Ingulphus in his history of Croyland Abbey, existed in the eleventh century; possibly the Romans had a fort here to guard both the ‘Carr Dyke’ which passes by the east side of the town, and also the King’s Street, a Roman road which, splitting off from the Ermine Street at Castor, runs through Bourne due north to Sleaford. There was an outer moat enclosing eight acres, and an inner moat of one acre, inside which “on a mount of earth cast up with mene’s hands” stood the castle, once the stronghold of the Wakes. To-day a maze of grassy mounds alone attests the site, amongst which the “Bourn or Brunne gushes out in a strong clear stream.” Marrat in his “History of Lincolnshire” tells us that as early as 870 Morchar, Lord of Brun, fell fighting at the battle of Threekingham. Two hundred years later we have “Hereward the Wake” living at Bourn, and in the twelfth century “Hugh De Wac” married Emma, daughter and heir of Baldwin FitzGilbert, who led some of King Stephen’s forces in the battle of Lincoln and refused to desert his king. Hugh founded the abbey of Bourn in 1138 on the site of an older building of the eighth or ninth century.

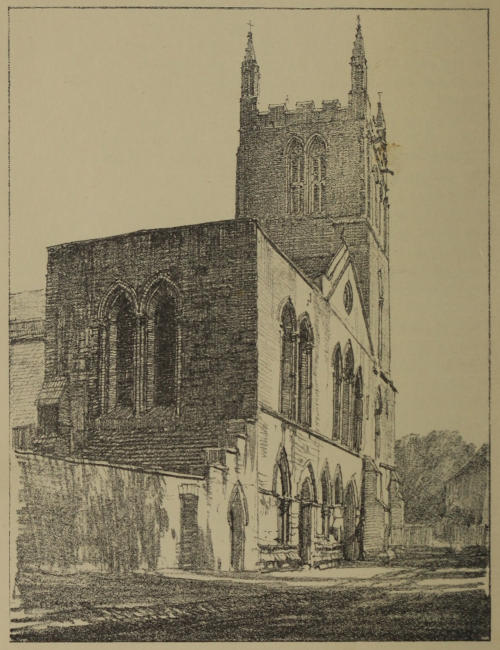

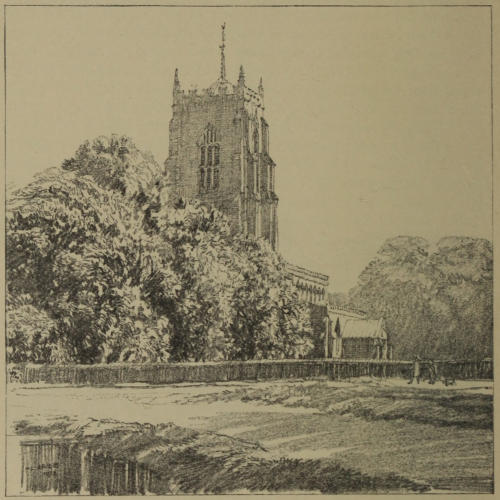

Bourne Abbey Church.

Six generations later, Margaret de Wake married Edmund Plantagenet of Woodstock, Earl of Kent, the sixth son of Edward I., and their daughter, born 1328, was Joan, the Fair Maid of Kent, who was finally married to Edward the Black[24] Prince. Their son was the unfortunate Richard II., and through them the manor of Bourn, which is said to have been bestowed on Baldwin, Count of Brienne, by William Rufus, passed back to the Crown. Hereward is supposed to have been buried in the abbey in which only a little of the early building remains.[25] Certainly he was one of Bourn’s famous natives, Cecil Lord Burleigh, the great Lord Treasurer, being another, of whom it was said that “his very enemies sorrowed for his death.” Job Hartop, born 1550, who sailed with Sir John Hawkins and spent ten years in the galleys, and thirteen more in a Spanish prison, but came at last safe home to Bourn, deserves honourable mention, and Worth, the Parisian costumier, was also a native who has made himself a name; but one of the most noteworthy of all Bourn’s residents was Robert Manning, born at Malton, and canon of the Gilbertine Priory of Six Hills. He is best known as Robert de Brunne, from his long residence in Bourn, where he wrote his “Chronicle of the History of England.” This is a Saxon or English metrical version of Wace’s Norman-French translation of the “Chronicles of Geoffrey of Monmouth,” and of Peter Langtoft’s “History of England,” which was also written in French. This work he finished in 1338, on the 200th anniversary of the founding of the abbey; and in 1303, when he was appointed “Magister” in Bourn Abbey, he wrote his “Handlynge of Sin,” also a translation from the French, in the preface to which he has the following lines:—

Robert was a translator and no original composer, but he was the first after Layamon, the Worcestershire monk who lived just before him, to write English in its present form. Chaucer followed him, then Spenser, after which all was easy. But he was, according to Freeman, the pioneer who created standard[26] English by giving the language of the natives a literary expression.

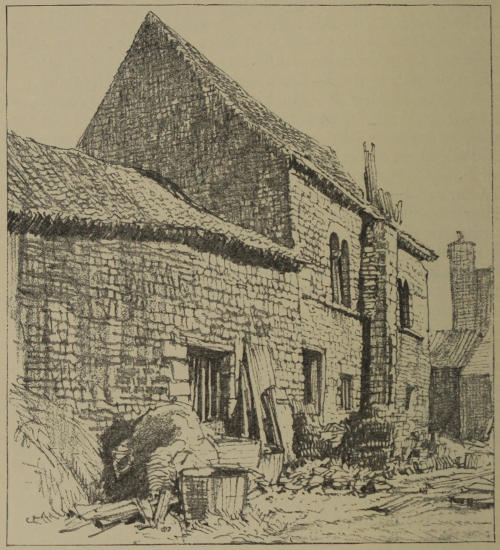

The Station House, Bourne.

It is difficult to see the abbey church, it is so hemmed in by buildings, and it never seems to have been completed. At the west end is some very massive work. In the churchyard there is a curious epitaph on Thomas Tye, a blacksmith, the first six lines of which are also found on a gravestone in Haltham churchyard near Horncastle:—

There is a charming old grey stone grammar school, possibly the very building in which Robert De Brunne taught when “Magister” at the abbey at the beginning of the fourteenth century. The station-master’s house, called “Red Hall,” is a picturesque Elizabethan brick building once the home of the Roman Catholic leader, Sir John Thimbleby, and afterwards of the Digbys. Sir Everard Digby, whose fine monument is in Stoke Dry Church near Uppingham, was born here. Another house is called “Cavalry House” because Thomas Rawnsley, great grandfather of the writer, was living there when he raised at his own expense and drilled a troop of “Light Horse Rangers” at the time when Buonaparte threatened to invade England. Lady Heathcote, whose husband commanded them, gave him a handsome silver goblet in 1808, in recognition of his services. He died in 1826, and in the spandrils of the north arcade in Bourne Abbey Church are memorial tablets to him and to his wife Deborah (Hardwicke) “and six of their children who died infants.”

The Carr Dyke—Thurlby—Edenham—Grimsthorpe Castle—King’s Street—Swinstead—Stow Green—Folkingham—Haydor—Silk Willoughby—Rippingale—Billingborough—Horbling—Sempringham and the Gilbertines.

Bourne itself is in the fen, just off the Lincolnshire limestone. From it the railways run to all the four points of the compass, but it is only on the west, towards Nottingham, that any cutting was needed. Due north and south runs the old Roman road, keeping just along the eastern edge of the Wold; parallel with it, and never far off, the railway line keeps on the level fen by Billingborough and Sleaford to Lincoln, a distance of five-and-thirty miles, and all the way the whole of the land to the east right up to the coast is one huge tract of flat fenland scored with dykes, with only few roads, but with railways fairly frequent, running in absolute straight lines for miles, and with constant level crossings.

One road which goes south from Bourne is interesting because it goes along by the ‘Carr Dyke,’ that great engineering work of the Romans, which served to catch the water from the hills and drain it off so as to prevent the flooding of the fens. Rennie greatly admired it, and adopted the same principle in laying out his great “Catchwater” drain, affectionately spoken of by the men in the fens as ‘the owd Catch.’ The Carr Dyke was a canal fifty-six miles long and fifty feet wide, with broad, flat banks, and connected the Nene at Peterborough with the Witham at Washingborough near Lincoln. From Washingborough southwards to Martin it is difficult to trace, but it is visible at Walcot, thence it passed by Billinghay and north[29] Kyme through Heckington Fen, east of Horbling and Billingborough and the Great Northern Railway line to Bourne. Two miles south of this we come to the best preserved bit of it in the parish of Thurlby, or Thoroldby, once a Northman now a Lincolnshire name. The “Bourne Eau” now crosses it and empties into the River Glen, which itself joins the Welland at Stamford.

Thurlby Church stands only a few yards from the ‘Carr Dyke,’ it is full of interesting work, and is curiously dedicated to St. Firmin, a bishop of Amiens, of Spanish birth. He was sent as a missionary to Gaul, where he converted the Roman prefect, Faustinian. He was martyred, when bishop, in 303, by order of Diocletian. The son of Faustinian was his godson, and was baptized with his name of Firmin, and he, too, eventually became Bishop of Amiens. Part of the church is pre-Norman and even exhibits “long and short” work. The Norman arcades have massive piers and cushion capitals. In the transepts are Early English arcades and squints, and there is a canopied piscina and a font of very unusual design. There is also an old ladder with handrail as in some of the Marsh churches, leading to the belfry. Three miles south is Baston, where there is a Saxon churchyard in a field. Hence the road continues to Market Deeping on the Welland, which is here the southern boundary of the county, and thence to Deeping-St.-James and Peterborough. Deeping-St.-James has a grand priory church, which was founded by Baldwin Fitz-Gilbert as a cell to Thorney Abbey in 1136, the year after he had founded Bourne Abbey. It contains effigies of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Shameful to say a fountain near the church was erected in 1819 by mutilating and using the material of a fine village cross. Peakirk, with its little chapel of St. Pega, and Northborough and Woodcroft, both with remarkable houses built of the good gray stone of the neighbourhood, Woodcroft being a perfect specimen of a fortified dwelling-house, though near, are in the county of Northants.

The Corby-Colsterworth-and-Grantham Road leaves Bourne on the west and, passing through Bourne Wood at about four miles’ distance, reaches Edenham. On the west front of the church tower, at a height of forty feet, is the brass of an archbishop. Inside the church are two stones, one being the figure of a lady and the other being part of an ancient cross, both carved with very early interlaced work. The chancel is a[30] museum of monuments of the Bertie family, the Dukes of Ancaster, continued from the earliest series at Spilsby of the Willoughby D’Eresbys, and beginning with Robert Bertie,[2] eleventh Lord Willoughby and first Earl of Lindsey, who fell at Edgehill while leading the Lincolnshire regiment, 1642. The present Earls of Lindsey and Uffington are descended from Lord Albemarle Bertie, fifth son of Robert, third Earl of Lindsey, who has a huge monument here, dated 1738, adorned with no less than seven marble busts.

Two fine altar tombs of the fourteenth century, with effigies of knight and lady, seem to be treated somewhat negligently, being thrust away together at the entrance. The nave pillars are very lofty, but the whole church has a bare and disappointing appearance from the plainness of the architecture, and the ugly coat of yellow wash, both on walls and pillars, and the badness of the stained glass.

On the north wall of the chancel and reaching to the roof there is a very lofty monument, with life-size effigy to the first Duke of Ancaster, 1723. East of this, one to the second duke with a marble cupid holding a big medallion of his duchess, Jane Brownlow, 1741, and on the south wall are equally huge memorials. In the family pew we hailed with relief a very good alabaster tablet with white marble medallion of the late Lady Willoughby “Clementina Elizabeth wife of the first Baron Aveland, Baroness Willoughby d’Eresby in her own right, joint hereditary Lord Chamberlain of England,” 1888.

The font is transition Norman, the cylindrical bowl surrounded by eight columns not detached, and a circle of arcading consisting of two Norman arches between each column springing from the capitals of the pillars.

The magnificent set of gold Communion plate was presented by the Willoughby family. It is of French, Spanish, and Italian workmanship. Humby church has also a fine gold service, presented by Lady Brownlow in 1682. It gives one pleasure to find good cedar trees and yews growing in the churchyard.

Grimsthorpe Castle is a mile beyond Edenham. The park,[31] the finest in the county, in which are herds of both fallow and red deer, is very large, and full of old oaks and hawthorns; the latter in winter are quite green with the amount of mistletoe which grows on them. The lake covers one hundred acres. The house is a vast building and contains a magnificent hall 110 feet long, with a double staircase at either end, and rising to the full height of the roof. In the state dining-room is the Gobelin tapestry which came to the Duke of Suffolk by his marriage with Mary, the widow of Louis XII. of France. Here, too, are several Coronation chairs, the perquisites of the Hereditary Grand Chamberlain. The Willoughby d’Eresby family have discharged this office ever since 1630 in virtue of descent from Alberic De Vere, Earl of Oxford, Grand Chamberlain to Henry I., but in 1779, on the death of the fourth Duke of Ancaster, the office was adjudged to be the right of both his sisters, from which time the Willoughby family have held it conjointly with the Earl of Carrington and the Marquis of Cholmondeley. Among the pictures are several Holbeins. The manor of Grimsthorpe was granted to William, the ninth Lord Willoughby, by Henry VIII. on his marriage with Mary de Salinas, a Spanish lady in attendance on Katharine of Aragon, and it was their daughter Katherine who became Duchess of Suffolk and afterwards married Richard Bertie.

Just outside Grimsthorpe Park is the village of Swinstead, in whose church is a large monument to the last Duke of Ancaster, 1809, and an effigy of one of the numerous thirteenth century crusaders. Somehow one never looks on the four crusades of that century as at all up to the mark in interest and importance of the first and third under Godfrey de Bouillon and Cœur de Lion in the eleventh and twelfth centuries; as for the second (St. Bernard’s) that was nothing but a wretched muddle all through.

Two miles further on is Corby, where the market cross remains, but not the market. The station on the Great Northern main line is about five miles east of Woolsthorpe, Sir Isaac Newton’s birthplace and early home.

I think the most remarkable of the Bourne roads is the Roman “Kings Street,” which starts for the north and, after passing on the right the fine cruciform church of Morton and then the graceful spire of Hacconby, a name of unmistakable Danish origin, sends first an offshoot to the right to pass through the fens to[32] Heckington, and three or four miles further on another to the left to run on the higher ground to Folkingham, whilst it keeps on its own rigidly straight course to the Roman station on the ford of the river Slea, passing through no villages all the way, and only one other Roman station which guarded a smaller ford at Threckingham.

This place is popularly supposed to be named from the three Danish kings who fell in the battle at Stow Green, between Threckingham and Billingborough, in 870; but the fine recumbent figures of Judge Lambert de Treckingham, 1300, and a lady of the same family, and the fact that the Threckingham family lived here in the fourteenth century points to a less romantic origin of the name. The names of the Victors, Earl Algar and Morcar, or Morkere, Lord of Bourne, survive in ‘Algarkirk’ and ‘Morkery Wood’ in South Wytham.

Stow Green had one of the earliest chartered fairs in the kingdom. It was held in the open, away from any habitation. Like Tan Hill near Avebury, and St. Anne de Palue in Brittany, and Stonehenge, all originally were probably assembling-places for fire-worship, for tan = fire.

But as we go to-day from Bourne to Sleaford, we shall not use the Roman road for more than the first six miles, but take then the off-shoot to the left, and passing Aslackby, where, in the twelfth century, as at Temple-Bruer, the Templars had one of their round churches, afterwards given to the Hospitallers, come to the little town of Folkingham, which had been granted by the Conqueror to Gilbert de Gaunt or Ghent, Earl of Lincoln.

He was the nephew of Queen Matilda, and on none of his followers, except Odo Bishop of Bayeux, did the Conqueror bestow his favours with a more liberal hand; for we read that he gave him 172 Lordships of which 113 were in Lincolnshire. He made his seat at Folkingham, but, having lands in Yorkshire, he was a benefactor to St. Mary’s Abbey, York, at the same time that he restored and endowed Bardney Abbey after its destruction by the Danes under Inguar and Hubba.

The wide street seems to have been laid out for more people than now frequent it. The church is spacious and lofty, with a fine roof and singularly rich oak screen and pulpit, into which the rood screen doorway opens. It was well restored about eighty years ago, by the rector, the Rev. T. H. Rawnsley, who was far ahead of his time in the reverend spirit with which he handled[33] old architecture. The neighbouring church of Walcot has a fine fourteenth century oak chest, similar to one at Hacconby. Three and a half miles further on we come to Osbournby, with a quite remarkable number of old carved bench-ends and some beautiful canopied Sedilia. Another Danish village, Aswardby—originally, I suppose, Asgarby, one can fancy a hero called ‘Asgard the Dane’ but hardly Asward—has a fine house and park, sold by one of the Sleaford Carr family to Sir Francis Whichcote in 1723.

Four miles west of Aswardby is the village of Haydor (Norse, heide = heath). Here, in the north aisle of the church, which has a tall tower and spire, is some very good stained glass. It was given by Geoffrey le Scrope, who was Prebend of Haydor 1325 to 1380, and much resembles the fine glass in York Minster, which was put in in 1338. In this parish is the old manor of Culverthorpe, belonging to the Houblon family. It has a very fine drawing-room and staircase and a painted ceiling.

We must now come back to the Sleaford road which, a couple of miles beyond Aswardby Park, turns sharp to the right for Silk-Willoughby, or Silkby cum Willoughby. Here we have a really beautiful church, with finely proportioned tower and spire of the Decorated period. The Norman font is interesting and the old carved bench-ends, and so is the large base of a wayside cross in the village, with bold representations of the four Evangelists, each occupying the whole of one side. Three miles further we reach Sleaford.

One of the features of the county is the number of roads it has running north and south in the same direction as the Wolds. The Roman road generally goes straightest, though at times the railway line, as for instance between Bourne and Spalding, or between Boston and Burgh, takes an absolute bee line which outdoes even the Romans.

We saw that the two roads going north from Bourne sloped off right and left of the “Kings Street.” That on the left or western side keeps a parallel course to Sleaford, but that on the right, after reaching Horbling, diverges still further to the east and makes for Heckington. These two places are situated about six miles apart, and it is through the Horbling and Heckington fens that the only two roads which run east and west in all South Lincolnshire make their way. They both start from the Grantham and Lincoln Road at Grantham and at[34] Honington, the former crossing the “Kings Street” at Threckingham, and thence to Horbling fen, the latter passing by Sleaford and Heckington. Both of these roads curve towards one another when they have passed the fens, and, uniting near Swineshead, make for Boston and the Wash. The whole of the land in South Lincolnshire slopes from west to east, falling between Grantham and Boston about 440 feet, but really this fall takes place almost entirely in the first third of the way on the western side of “The Roman Street” which was cleverly laid out on the Fen-side fringe of the higher ground. The road from Bourne to Heckington East of the “Street” is absolutely on the fen level and the railway goes parallel to it, between the road and the Roman ‘Carr Dyke.’ Thus we have a Roman road, a Roman canal, two modern roads and a railway, all running side by side to the north.

The Heckington road, after leaving the “Street,” passes through Dunsby and Dowsby, where there is an old Elizabethan house once inhabited by the Burrell family. Rippingale lies off to the left between the two and has in its church a rood screen canopy but no screen, which is very rare, and a large number of old monuments from the thirteenth century onwards, the oldest being two thirteenth century knights in chain mail of the family of Gobaud, who lived at the Hall, now the merest ruin, where they were succeeded by the Bowet, Marmion, Haslewood and Brownlow families. An effigy of a deacon with the open book of the Gospels has this unusual inscription, “Ici git Hwe Geboed le palmer le fils Jhoan Geboed. Millᵒ 446 Prees pur le alme.” It is interesting to find here a fifteenth century monument to a Roger de Quincey. Was he, I wonder, an ancestor of the famous opium eater? There is in the pavement a Marmion slab of 1505. The register records the death in July, 1815, of “the Lincolnshire Giantess” Anne Hardy, aged 16, height 7 ft. 2 in. The Brownlow family emigrated hence to Belton near Grantham. They had another Manor House at Great Humby, which is just half-way between Rippingale and Belton, of which the little brick-built domestic chapel now serves as a church. As we go on we notice that the whole of the land eastwards is a desolate and dreary fen, which extends from the Welland in the south to the Witham near Lincoln. Of this Fenland, the Witham, when it turns southwards, forms the eastern boundary, and alongside of it goes the Lincoln and[35] Boston railway, while the line from Bourne viâ Sleaford and on to Lincoln forms the western boundary. I use the term ‘fen’ in the Lincolnshire sense for an endless flat stretch of black corn-land without tree or hedge, and intersected by straight-cut dykes or drains in long parallels. This is the winter aspect; in autumn, when the wind blows over the miles of ripened corn, the picture is a very different one.

It is curious that on the Roman road line all the way from the Welland to the Humber so few villages are found, whilst on the roads which skirt the very edge of the fen from Bourne to Heckington and then north again from Sleaford to Lincoln, villages abound.

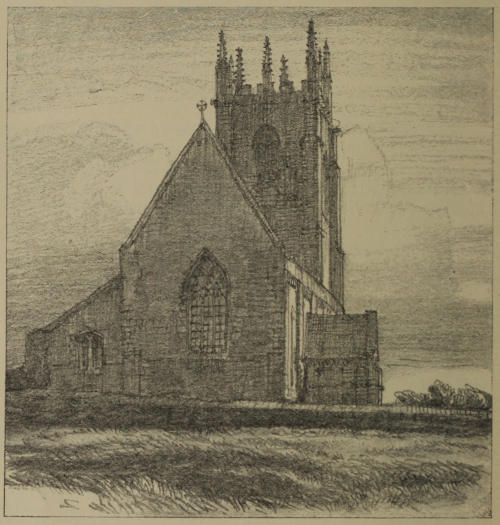

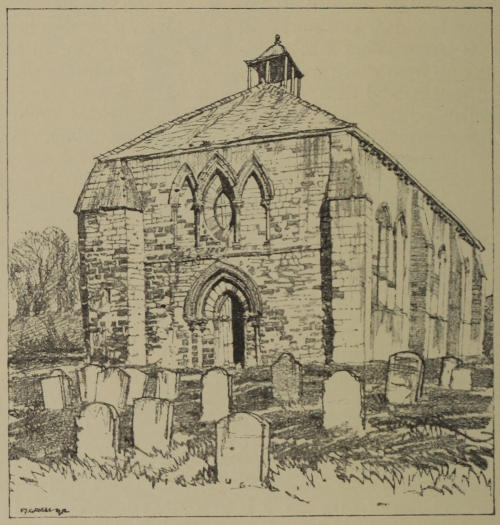

Sempringham.

I once walked with an Undergraduate friend on a winter’s day from Uppingham to Boston, about 57 miles, the road led pleasantly at first through Normanton, Exton and Grimsthorpe Parks, in the last of which the mistletoe was at its best; but when we got off the high ground and came to Dunsby and Dowsby the only pleasure was the walking, and as we reached Billingborough and Horbling, about 30 miles on our way, and had still more than twenty to trudge and in a very uninviting country, snow began to fall, and then the pleasure went out of the walking. By the time we reached Boston it was four inches deep. It had been very heavy going for the last fourteen miles, and never were people more glad to come to the end of their journey. Neither of us ever felt any great desire to visit that bit of Lincolnshire again; and yet, under less untoward circumstances, there would have been something to stop for at Billingborough with its lofty spire, its fine gable-crosses, and great west window, and at the still older small cruciform church at Horbling, exhibiting work of every period but Saxon, but most of which, owing to bad foundations, has had to be at different times taken down and rebuilt. It contains a fine fourteenth century monument to the De la Maine family. Even more interesting would it have been to see the remains of the famous priory church at Sempringham, a mile and a half south of Billingborough, for Sempringham was the birthplace of a remarkable Englishman. Gilbert, eldest son of a Norman knight and heir to a large estate, was born in 1083; he was deformed, but possessing both wit and courage he travelled on the Continent. Later in life he was Chaplain to Bishop Alexander of Lincoln, who built Sleaford Castle in 1137, and Rector of Sempringham, and Torrington,[36] near Wragby. Being both wealthy and devoted to the church, he, with the Bishop’s approval, applied in the year 1148 to Pope Eugenius III. for a licence to found a religious house to receive both men and women; this was granted him, and so he became the founder of the only pure English order of monks and nuns, called after him, the Gilbertines. Eugenius III. suffered a good deal at the hands of the Italians, who at that time were led by Arnold of Brescia, the patriotic disciple of Abelard, insomuch that he was constrained to live at Viterbo, Rome not being a safe place for him; but he seems to have thought rather well of the English, for he it was who picked out[37] the monk, Nicolas Breakspeare, from St. Alban’s Abbey and promoted him to be Papal legate at the Court of Denmark, which led eventually to his becoming Pope Adrian IV., the only Englishman who ever reached that dignity. The elevation does not seem to have improved his character, as his abominable cruelty to the above-mentioned Arnold of Brescia indicates. Eugenius, however, is not responsible for this, and at Gilbert’s request he instituted a new order in which monks following the rules of St. Augustine were to live under the same roof with nuns following the rules of St. Benedict. Their distinctive dress was a black cassock with a white hood, and the canons wore beards. What possible good Gilbert thought could come of this new departure it is difficult to guess. Nowadays we have some duplicate public schools where boys and girls are taught together and eat and play together, and it is not unlikely that the girls gain something of stability from this, and that their presence has a useful and far-reaching effect upon the boys, besides that obvious one which is conveyed in the old line

but these monks and nuns never saw one another except at some very occasional service in chapel; even at Mass, though they might hear each other’s voices in the canticles, they were parted by a wall and invisible to each other, and as they thus had no communication with one another they might, one would think, have just as well been in separate buildings. Gilbert thought otherwise. He was a great educator, and especially had given much thought to the education of women, at all events he believed that the plan worked well, for he increased his houses to the number of thirteen, which held 1,500 nuns and 700 canons. Most of these were in Lincolnshire, and all were dissolved by Henry VIII. Gilbert was certainly both pious and wise, and being a clever man, when Bishop Alexander moved his Cistercians from Haverholme Priory to Louth Park Abbey, because they suffered so much at Haverholme from rheumatism, and handed over the priory, a chilly gift, to the Gilbertines, their founder managed to keep his Order there in excellent health. He harboured, as we know, Thomas à Becket there in 1164, and got into trouble with Henry II. for doing so. He was over 80 then, but he survived it and lived on for another five and twenty years, visiting occasionally his other homes at Lincoln,[38] Alvingham, Bolington, Sixhills, North Ormsby, Catley, Tunstal and Newstead, and died in 1189 at the age of 106. Thirteen years later he was canonised by Pope Innocent III., and his remains transferred to Lincoln Minster, where he became known as St. Gilbert of Sempringham. Part of the nave of his priory at Sempringham is now the Parish Church; it stands on a hill three-quarters of a mile from Pointon, where is the vicarage and the few houses which form the village. Much of the old Norman work was unhappily pulled down in 1788, but a doorway richly carved and an old door with good iron scroll-work is still there. At the time of the dissolution the priory, which was a valuable one, being worth £359 12s. 6d., equal to £3,000 nowadays, was given to Lord Clinton. Campden, 300 years ago, spoke of “Sempringham now famous for the beautiful house built by Edward Baron Clinton, afterwards Earl of Lincoln,” the same man to whom Edward VI. granted Tattershall. Of this nothing is left but the garden wall, and Marrat, writing in 1815, says: “At this time the church stands alone, and there are but five houses in the parish, which are two miles from the church and in the fen.”

The Glen—Burton Coggles—Wilsthorpe—The Eden—Verdant Green—Irnham Manor and Church—The Luttrell Tomb—Walcot—Somerby—Ropsley—Castle Bytham—The Witham—Colsterworth—The Newton Chapel—Sir Isaac Newton—Stoke Rochford—Great Ponton—Boothby Bagnell—A Norman House.

I have said that the whole of the county south of Lincoln slopes from west to east, the slope for the first few miles being pretty sharp. The only exception to the rule is in the tract on the west of the county, which lies north of the Grantham and Nottingham road, between the Grantham to Lincoln ridge and the western boundary of the county. This tract is simply the flat wide-spread valley of the Rivers Brant and Witham, which all slopes gently to the north. North Lincolnshire rivers run to the Humber; these are the Ancholme and the Trent; but there is a peculiarity about the rivers in South Lincolnshire; for though the Welland runs a consistent course eastward to the Wash, and is joined not far from its mouth by the River Glen, that river and the Witham each run very devious courses before they find the Eastern Sea. The Glen flowing first to the south then to the north and north-east, the Witham flowing first to the north and then to the south with an easterly trend to Boston Haven.

Both these streams are of considerable length, the course of the Glen measured without its windings being five and thirty miles, and that of the Witham as much again.

All the other streams which go from the ridge drain eastwards into the fens, and they effectually kept the fens under[40] water until the Romans cut the Carr Dyke, intercepting the water from the hills and taking it into the river.