*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 65978 ***

Transcriber’s Note: images outlined in blue (like this note is)

are clickable for a larger version.

[i]

CHAMPIONS OF THE FLEET

[ii]

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

- FAMOUS FIGHTERS OF THE FLEET.

- THE ENEMY AT TRAFALGAR.

- THE ROMANCE OF THE KING’S NAVY.

- ETC. ETC.

CHAMPIONS THEN AND NOW: THE VICTORY AND THE DREADNOUGHT

Both ships, and the submarine alongside the “Victory,” are shown

on the same scale. The picture is reproduced by kind permission

of the Proprietors of the “Illustrated London News.” Photos by

Stephen Cribb, Southsea.

[iii]

CHAMPIONS

OF THE FLEET

CAPTAINS AND MEN-OF-WAR

AND DAYS THAT HELPED TO

MAKE THE EMPIRE

BY EDWARD FRASER

WITH 19 ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON: JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY MCMVIII

[iv]

WM. BRENDON AND SON, LTD., PRINTERS, PLYMOUTH

These tales of the navy of the fighting

days of old are to some extent, it may

seem, cruises in rather out-of-the-way

waters. At the same time, they may

claim present-day associations that should render

them not out of place just now. How and why, for

instance, the world-famous name Dreadnought came

into the Royal Navy is a story of interest on its own

account that ought to be timely. With that also is

told something of what our Dreadnoughts of old did

under fire in the fighting days of history: with

Drake; against the Armada; with Sir Walter

Raleigh; against De Ruyter and the Dutchmen;

at La Hogue; how one gave the sobriquet “Old

Dreadnought” to the famous Boscawen; how Nelson’s

uncle and patron Maurice Suckling captained

the same ship in battle; of Collingwood in the

Dreadnought; and of the Dreadnought at Trafalgar.

We get, too, a passing glance at certain of the

“points” of our mighty battleship the Dreadnought

of the present hour. Again, in the year

that has seen the name of Clive recalled to the

memory of his countrymen by an ex-Viceroy of[vi]

India in connection with the hundred and fiftieth

anniversary of Plassey, what the navy did for Clive

at the most critical moment of his fortunes, how

without its active support on the field of battle Clive

would have been powerless, the forgotten, or certainly

little appreciated, part that the navy took in the

founding of our Indian empire—should be of interest

to English readers. This year again sees a new

Téméraire, one of our “improved Dreadnoughts,”

added to the Royal Navy. The fine story of how

the never-to-be-forgotten name Téméraire—immortalized

alike by Turner and by Trafalgar—first came

to appear on the roll of the British fleet is told here.

And it should be of interest to recall certain incidental

matters concerning the old Victory herself:

among others the circumstances in which she came

to be built and was safely sent afloat in spite of

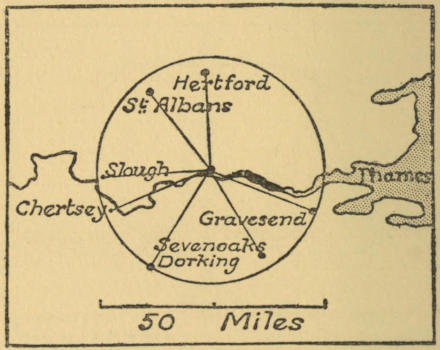

expected incendiarism; where too those who fought

on board at Trafalgar came from, and how many

representatives each of our counties had with Nelson

in his last fight. Such are some of the matters dealt

with in these pages, which of themselves should

afford entertainment and help also to make this book

useful.

E. F.

| CHAPTER |

|

PAGE |

| I. |

Our Dreadnoughts:—Their Name and

Battle Record |

1 |

| II. |

“Kent Claims the First Blow” |

52 |

| III. |

The Avengers of the Black Hole:—What the

Navy did for Clive |

77 |

| IV. |

Boscawen’s Battle:—The Taking of the

Téméraire |

126 |

| V. |

Hawke’s Finest Prize:—How the Formidable

Changed her Flag |

141 |

| VI. |

When the Victory First Joined the

Fleet:—How they Built the Victory at Chatham |

160 |

| VII. |

On Valentine’s Night in Frigate Bay |

191 |

| VIII. |

The Pageant of the Donegal:—A

Memory of ’98 |

208 |

| IX. |

On Board our Flagships at Trafalgar:—Captain

Hardy and those who Manned the Victory—Under Fire with

Collingwood—“Old Ironsides” and the Third in Command |

222 |

[viii]

| Champions then and now: the Victory

and the Dreadnought |

Frontispiece |

| Both ships, and the submarine alongside the

Victory, are shown on the same scale. The picture is

reproduced by kind permission of the proprietors of the

Illustrated London News. Photos by Stephen Cribb,

Southsea. |

|

Facing page |

| Our first Dreadnought |

10 |

| From a contemporary print kindly lent by Mr.

Wentworth Huyshe. The Dreadnought is shown as she

appeared when serving in the “Ship Money” Fleet of Charles

the First—circ. 1637. |

| “Old Dreadnought’s” Dreadnought |

28 |

| From the original drawing made in 1740 for the

official dockyard model. Now in the Author’s collection. |

| The Red-Letter Day of Nelson’s Calendar.

How the Dreadnought led the Attack on the 21st of October,

1757 |

34 |

| Painted by Swaine. Engraved and Published in 1760. |

| When George the Third was King. Officers

at Afternoon Tea Ashore |

38 |

| Thomas Rowlandson. 1786. |

| Manning the Fleet in 1779. A Warm Corner

for the Press Gang |

38 |

| James Gillray. October 15th, 1779. |

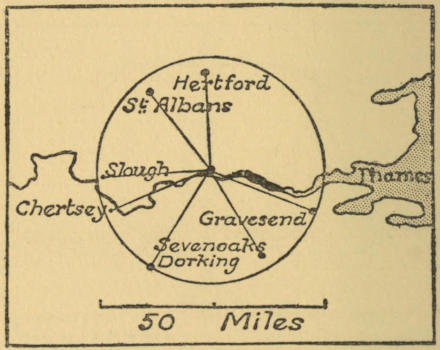

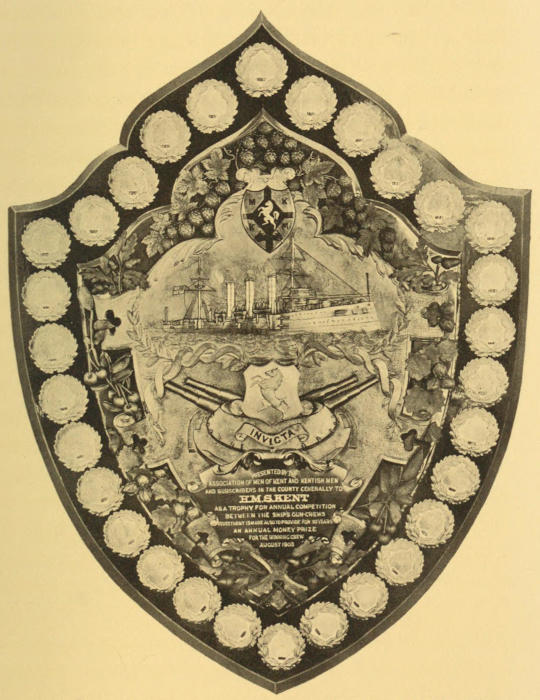

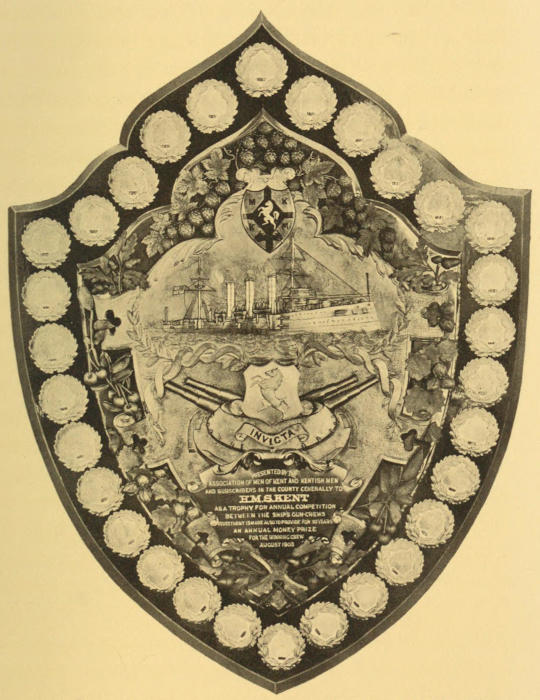

| The County and its Ship. The Kent

Trophy Challenge Shield |

54 |

| From a photograph kindly lent by the designers

and manufacturers of the trophy, Messrs. George Kenning &

Son, Goldsmiths, Little Britain and Aldersgate Street, London.

[x] |

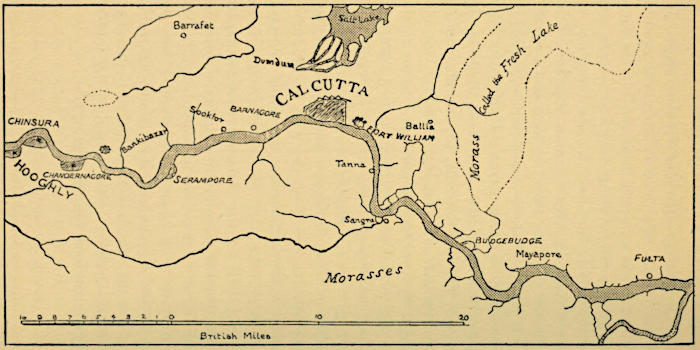

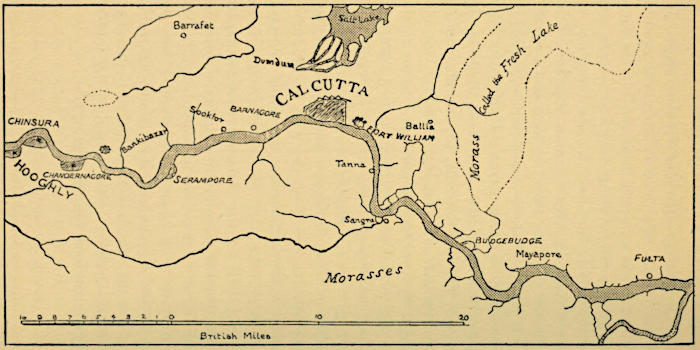

| The Scene of the Operations under Admiral

Watson and Clive |

76 |

| From Major James Rennell’s “Bengal Atlas,”

published in 1781. Reproduced by the courtesy of the Royal

Geographical Society. |

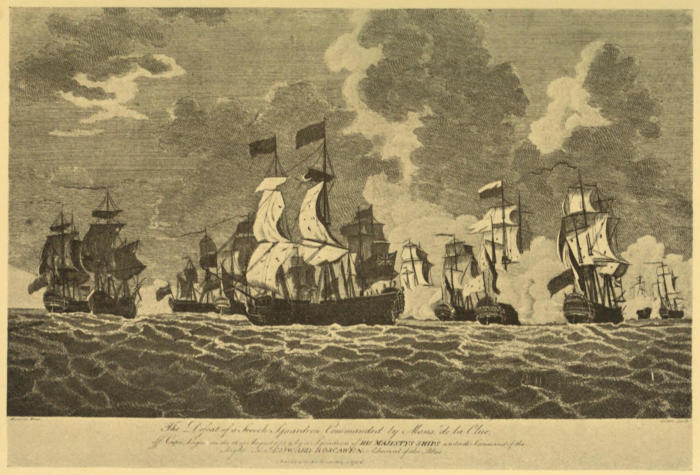

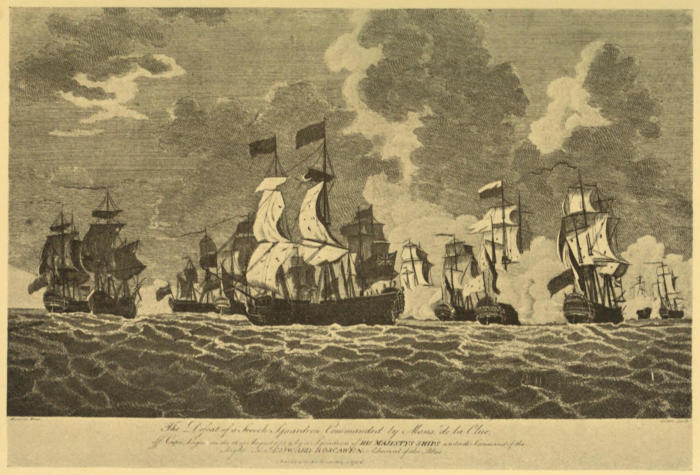

| Admiral Boscawen’s Victory |

136 |

| In the foreground to the right is seen the

Warspite attacking the Téméraire. Boscawen’s

flagship, the Namur, is in the centre flying the Admiral’s

Blue Flag at the main, and at the fore the red battle-flag, the

“Bloody Flag” of the Old Navy. Painted by Swaine. Engraved and

published in 1760. |

| Hawke’s Victory in Quiberon Bay |

152 |

| The picture shows the Royal George (in the

centre) sinking the Superbe, and the Formidable

(immediately beyond the Superbe and in the background)

lowering her colours to the Resolution (the ship coming

up astern of the Royal George). Painted by Swaine. Engraved

and published in 1760. |

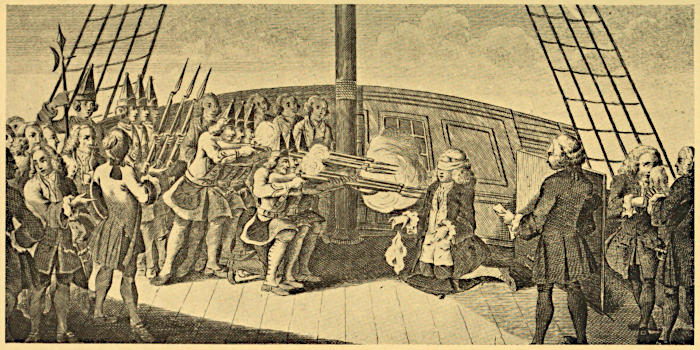

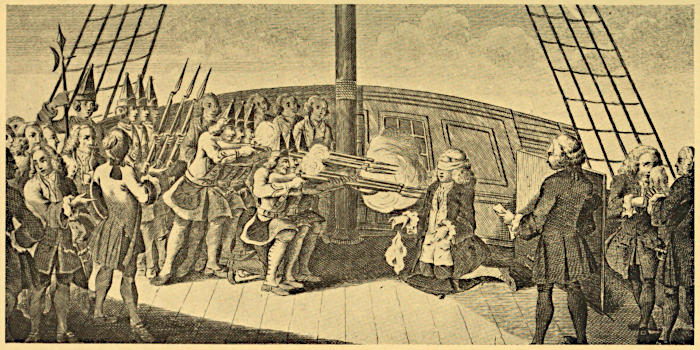

| The Execution of Admiral Byng |

164 |

| From a contemporary print. |

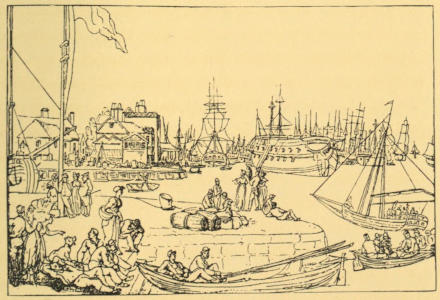

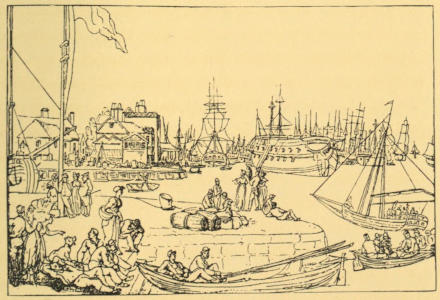

| Portsmouth in the Year that the Victory

joined the Fleet |

170 |

| From a contemporary print. |

| At Portsmouth Point |

176 |

| Thomas Rowlandson. |

| In Portsmouth Harbour |

176 |

| Thomas Rowlandson. |

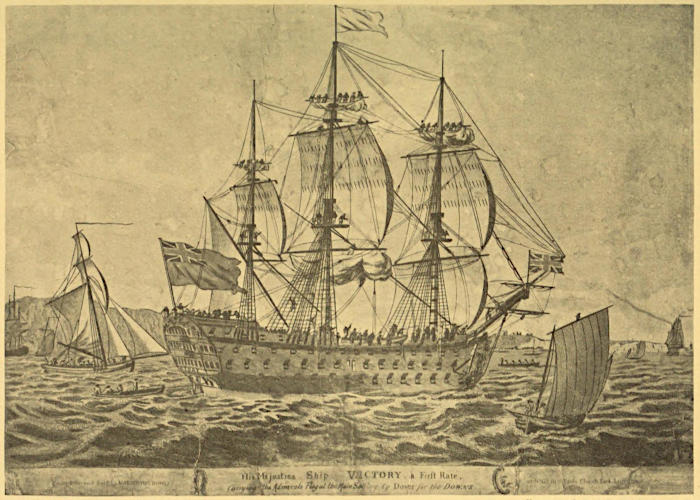

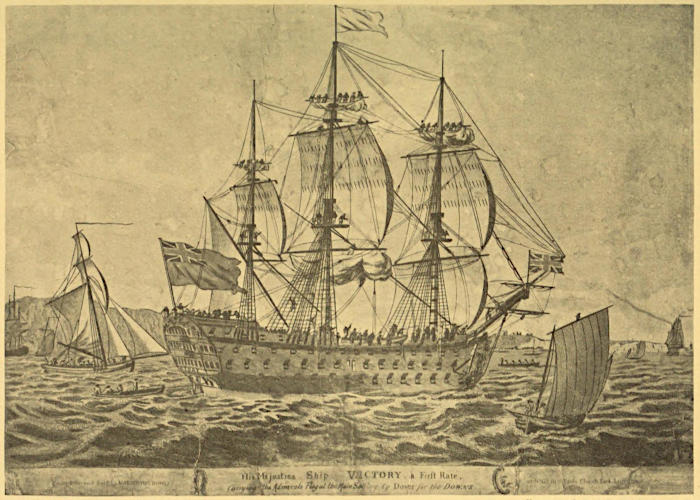

| The Victory on her First Cruise |

186 |

| Drawn by Captain Robert Elliot,

R.N. Engraved and Published in 1780. |

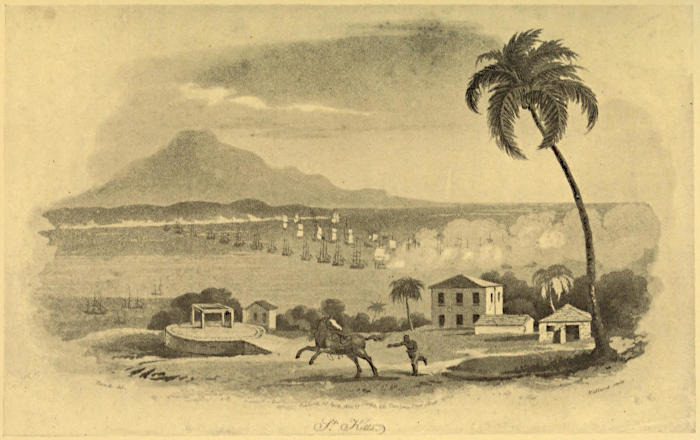

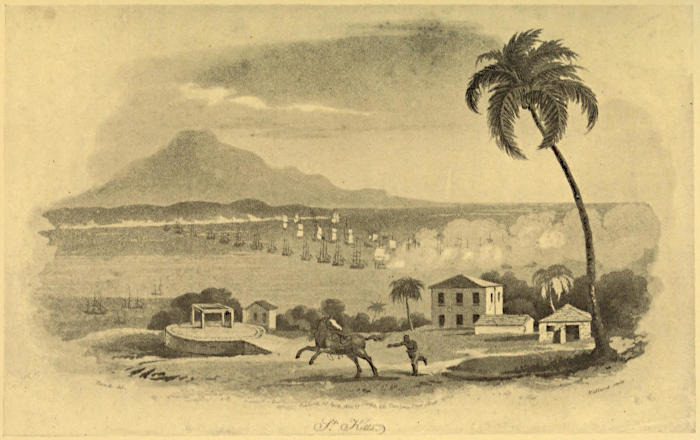

| The First Fight in Frigate Bay, St. Kitts |

198 |

| Admiral Sir Samuel Hood’s squadron of 22 ships (at

anchor) beating off De Grasse’s opening attack with 28 ships (shown

coming into the bay under full sail) at 2.30 p.m. on January 25th,

1782. Drawn by N. Pocock, “from a sketch made by a gentleman who

happened at the time to be on a visit at a friend’s, on a height

between Basse Terre and Old Road.” |

| Our First Donegal |

212 |

| The captured French line-of-battle ship Hoche,

being towed by the Doris, 36, Lord Ranelagh, into Lough Swilly.

Drawn by N. Pocock, from a sketch made from the Robust

by Captain R. Williams of the Marines. |

| [xi]

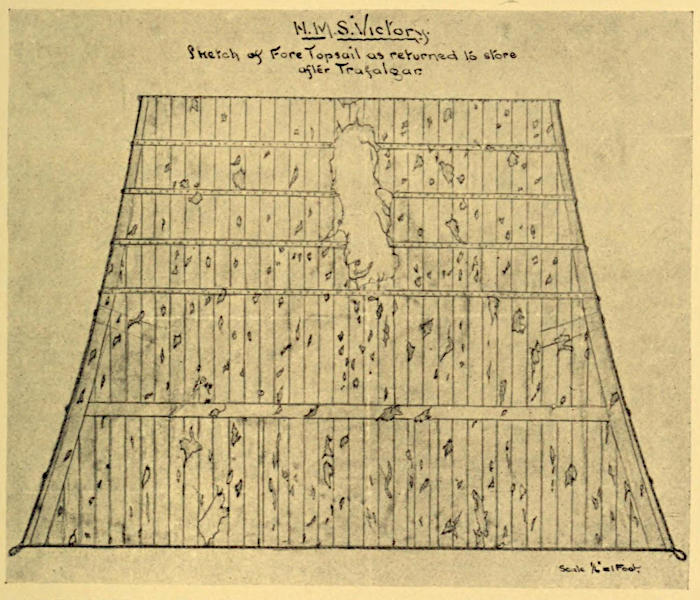

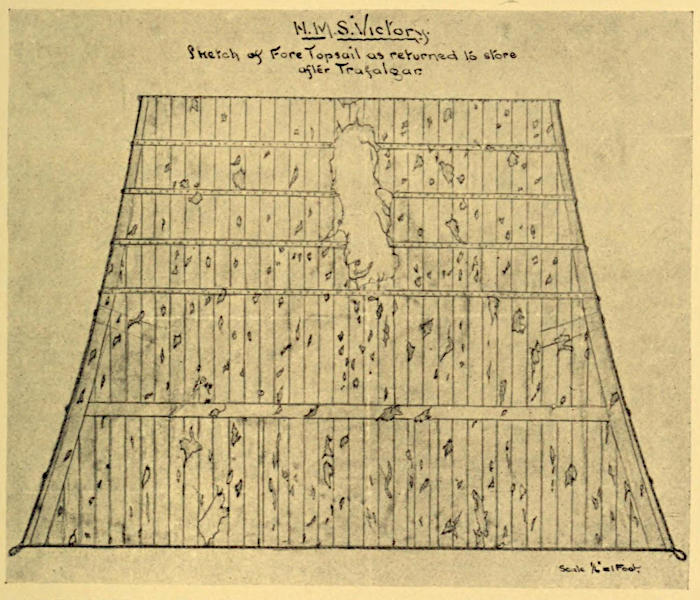

Reproduction of the Official Drawing

of the Victory’s foretopsail after Trafalgar as Returned into Store

at Chatham Dockyard in March, 1806 |

228 |

| Trafalgar—12 noon: as Sketched on the Spot by

a French Officer |

252 |

| From a photograph of the original sepia drawing now

in the possession of a descendant of Captain Lucas of the Redoutable. |

CHAMPIONS

OF THE FLEET

To the fame of your name

When the storm has ceased to blow;

When the fiery fight is heard no more,

And the storm has ceased to blow.

[1]

I

OUR DREADNOUGHTS:—

THEIR NAME AND BATTLE RECORD

A name through all the world renown’d,

A name that rouses as a trumpet sound.

The “Massacre of Saint Bartholomew’s

Day”—on the 24th of August, 1572—was

directly the cause of the coming into

existence of our first Dreadnought.

Startled and horrified at the terrible news, as the

details of the ghastly story crossed the channel,

Queen Elizabeth replied by instantly calling the

forces of England to arms. John Hawkins, at the

head of twenty ships of war, was sent to cruise off

the Azores. The rest of the fleet was ordered to mobilize

and be ready to concentrate in the Downs. Instructions were

issued for the beacons to be watched.

The militia were ordered to muster and march to the

coast. A subsidy was sent over to the Protestants[2]

in Holland, and a rush of volunteers followed to

join those from England already in the field.

Huguenot refugees in this country were given leave

to fit out vessels to help their co-religionists at

La Rochelle. Four men-of-war for the Royal Navy

were ordered to be laid down forthwith. They comprised

the most important effort in shipbuilding

that England had made for ten years.

To facilitate rapidity of building, the work on the

four vessels was divided between the two chief

master-shipwrights—or, as we should say, naval

constructors—of the day: two ships to Matthew

Baker, two ships to Peter Pett. Both men were at

the top of their profession. Peter Pett was a distinguished

member of the great family of naval shipwrights,

whose fame has come down to our own

times. Baker, who was also of a family of naval

shipwrights of repute, was considered by many of

the naval officers of the day as the better man.

“Mr. Baker,” wrote one, “for his skill and surpassing

grounded knowledge in the building of the

ships advantageable to all purposes hath not in any

nation his equal.” Pett and Baker were keen

business rivals, and their rivalry came into play on

the present occasion.

The names of the new ships were announced in due

course, and represented Her Majesty’s mood on the

occasion. She herself selected and appointed them

with intention. It was Queen Elizabeth’s way to

give her ships “telling” names. “The choice of

energetic names for the ships of her Royal Navy,”[3]

it has been said, “was one of the means employed

by the heroic and politic Elizabeth to infuse her

own dauntless spirit into the hearts of her subjects,

and to show to Europe at large how little she

dreaded the mightiest armaments of her enemies.”

More than that, however, needs to be said. As

a rule, in the cases of her bigger ships, the Queen

chose names that carried, in addition, an underlying

meaning, that bore direct allusion to some national

event of the hour. According to one who lived at

the time, writing about the first ship launched by

the Queen, to which, in accordance with old custom,

the sovereign’s name was given: “The great

Shipp called the Elizabeth Jonas was so named by

Her Grace in remembrance of her owne delyverance

from the furye of her Enemys, from which in one

respect she was no less myraculously preserved

than was the prophet Jonas from the Belly of the

whale.” In like manner our first Victory and our

first Triumph were given those ever famous names,

in the first place, of set intention to commemorate

the historic double-event of the year in which they

both joined the Queen’s fleet. The Aid, or Ayde,

another Elizabethan man-of-war, was so called to

commemorate Elizabeth’s first expedition to help

the Huguenots of Normandy in their forlorn hope

struggle for liberty of conscience, which was just

setting out when the Aid went off the stocks. Our

first Revenge, of immortal renown, did not receive

that name at haphazard in the year of Don John of

Austria’s insolent threat to invade England and[4]

depose Elizabeth by force of arms. Our first

Repulse was appointed that name—extant to this

day in the Royal Navy for one of our older battleships—in

memory of the defeat of the Spanish

Armada:—Dieu Repulse was the earlier form of the

name as the Queen gave it. And to take at random

two other names from the list, it was to commemorate

the same overthrow of the arch-enemy of

England in those times that Queen Elizabeth chose the

names Defiance and Warspite—in curious reference,

this latter name, to an incident during the fighting

with the Armada—for two others of her men-of-war.

It was of set purpose that Queen Elizabeth, in the

year of the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew, chose

the name Dreadnought for one of her ships of war.

The intentions of the Catholic League towards

England were an open secret in every council chamber

of Europe. The papal Bull, excommunicating

and deposing Elizabeth, had been nailed on the

doors of Lambeth Palace. It was at their disposal.

Alva’s butcheries in the Netherlands were fresh in

the recollection of the world, and the memory of

other dark doings came still more closely home to

our own people; how Englishmen had been “seized

in Spain and the New World to linger amidst the

tortures of the Inquisition or to die by its fires.”

Burghley and Walsingham, and others as well, had

fully understood the menace for England and the

warning of Lepanto only two years before. Their

secret agents had supplied them with a copy of

De Spes’ confidential report to Alva and King[5]

Philip to the effect that the ports of England were

poorly fortified, and that only eleven at most of

Queen Elizabeth’s twenty ships of war were worth

taking into account. They had not forgotten what

had happened three years before, when, under the

guise of an escort for the new Queen of Spain from

Flanders to the Tagus, an extremely formidable

Spanish fleet, fully equipped for war, had come

north and lain for some weeks in the Scheldt, acting

throughout in a very suspicious way. That was

a twelvemonth before Lepanto. Now the situation

seemed even more menacing for England. The

Queen’s so-called Agreement with Spain, lately

come to, for practical purposes was hardly worth the

paper it was drafted on. There was Mary Stuart

and her partizans to be reckoned with also; the

restless intriguing of the Roman Catholics all over

England; open rebellion in Ireland. What might

not the consequences of the Paris massacre involve

in the near future? It was at such a moment that

the name Dreadnought was first appointed to an

English man-of-war, and the Queen’s choice in the

circumstances partook of the nature almost of an

Act of State, specially designed to express the temper

of the nation. In the same spirit of exalted

patriotism in which, at a later day, Elizabeth, from

Tilbury camp, with proud scorn bade King Philip

and the Prince of Parma and all other enemies

of the realm do their worst, the great Queen, of her

own royal will and pleasure, named for the Royal

Navy its first Dreadnought.

[6]

Swiftsure was the name given to the second ship of

the set. “Swift-suer” was the way the Queen Elizabeth

spelled it—“Swift-pursuer,” that is—not an inappropriate

name for the sister ship of a Dreadnought.

The pair were intended as ships of the line, to use a

later day term. The other two ships of the group

were smaller vessels of the light cruiser class of the

period, intended for service as scouts, as the “eyes

and ears of the fleet” at sea. Their names were the

Achates and the Handmaid, expressive names both

in their way.

Matthew Baker’s men had the Dreadnought and

Handmaid to build; Pett’s men the Swiftsure and

the Achates. They all started work within three

weeks, and Pett’s men won the race by just a month.

The Swiftsure and the Achates were both sent afloat

on the 11th of October, 1573; the Dreadnought and

the Handmaid on the 10th of the following month.

An Arctic explorer of those times, whose name lives

on our maps—the man, indeed, who named the North

Cape for us, Captain Stephen Borough (or Borogh,

as he himself usually wrote it), one of “ye foure

Principall Masters in Ordinarye of ye Queene’s

Maᵗⁱᵉˢ Navye Royall,” by special appointment also

the Master of the Victory, and a son of North Devon

in her proudest day—had naval charge and supervision

over the building of the Dreadnought and the

other ships at Deptford. He lodged meanwhile

at Ratcliffe, across the river, and his “traveylinge

chardges,” with the waterman’s receipt for rowing him

to and fro on his weekly visits of inspection, signed[7]

“Richard Williams of Ratcliff, Whyrryman,” is

still in existence.

The marshmen and labourers at the dockyard

began their digging, “working upon ye opening of

ye dockhedde for ye launchynge,” during the first

days of November. That was the first of the preliminaries,

necessitated by the primitive arrangements

of those times. The dock at Deptford in

which the timbers of the Dreadnought were put

together was of the crudest type: practically an

oblong excavation in the river bank, the sides and

inner end of which were shored up and kept from

falling in by wooden planks. The outer end, or

river end, was closed and sealed when a ship was

inside by a water-tight dam of brushwood-faggots,

clay, and stones filled in and rammed down between

the overlapping double gates of the dock. An

“ingyn to drawe water owte of ye dokke,” worked by

relays of labourers, pumped out the water inside the

dock after it was closed. Before the dock could be

re-opened the stones, faggots, etc. of the “tamping”

or stopping had to be dug up and removed.

Then at low water the gates would be swung back,

and the water from the river flow in as the tide rose

for the launch or float-out of the ship into the

river.

On board the Dreadnought, meanwhile, the finishing

touches were being put by the contractors’ workmen—Thomas

Hodges, of “Parris Garden,” and

Thomas Wells, of Chatham, and their men seeing to

the ironwork fittings, “ye workmanshipp and making[8]

of lockes and boltes, keyes and haidges [sic] for ij

newe cabbons, as also for hookes, and stockelockes,

porthaidges [sic], revetts and countre-revetts, shuttynges

with rings, greate dufftayles and divers

other necessaries”; joiners sent by “Jullyan

Richards of London, widdow,” who had a contract

for certain other fittings; other joiners from Lewys

Stocker, also of London, seeing to “ye sellynges

[sic] and formysling ye cabbins and makyng casements

for windows, seelings, awmeryes [sic], cupboards,

settes, bedsteddes, formes, stools, trisstelles,

tables,” etc. “for her Grace’s newe shippe ye

Dreadnaughte.” Hard by, alongside Deptford creek,

were lying the masts for the ship, ready to be put in

place after she was afloat; with “toppes greate and

small, mayne-tops, ffore-toppe, mizzen-toppe, and

toppe-galantes;” besides barge loads from Richard

Pope, of “Ereth,” of “gravaille for ye ballistynge

of hur highness Shipe called ye Dreadnaughte at iiijᵈ

every time.” Prest-master Thomas Woodcot was

meanwhile hard at work elsewhere, “travailling

about the presting of marynnars within the River of

Theames for ye Launchynge and Rigging of Hur

highnes’ ij newe shippes at Deptfordstraund [sic] by

the space of viii daies at iijs iiijd per diem.”

The future “nucleus crew” of the Dreadnought,

who were to act as ship-keepers on board when the

ship went round to moor with the rest of the fleet

laid up in the Medway, had been warned to be at

Deptford by the morning of the 10th of November.

They were drawn apparently from the ships lying[9]

off Gillingham, just below Chatham, or “Jillingham

Ordinarie”—the “Fleet Reserve,” as we say nowadays—and

numbered, all told, ten men and a boy.

These were the names of our original “Dreadnoughts”

of three hundred and thirty-three years

ago, and their quarterly pay, according to “The

Accompte as well Ordinarie as Extraordinarie of

Benjamin Gonson, Treasurer of ye Quene’s Majestie’s

Maryn cawses,” 1574, a quaint, bulky, ponderous,

parchment covered volume, of massive proportions,

laced with faded green silk, and bound with leather

straps, now well worn and in parts frayed nearly

away:

THE “DREADNAUGHTE.”

| MARYNERS. |

|

|

| Robarte Baxster, boteson:—xij wekes vj daies |

xxxvijˢ |

vjᵈ |

| Richard Boureman, cooke: xij wekes vj daies |

xxixˢ |

vᵈ |

| John Awsten: xij wekes vj daies |

xxjˢ |

vᵈ |

| Nicholas Francton: xij wekes vj daies |

xxjˢ |

vᵈ |

| Christofer Parr, gromett: xij wekes vj daies |

xxjˢ |

jᵈ |

| Henry Osbourne: xij wekes vj daies |

xxjˢ |

vᵈ |

| James Laske: xij wekes vj daies |

xxjˢ |

vᵈ |

| Richard Shutt: xij wekes vj daies |

xxjˢ |

vᵈ |

| Robartt Woodnaughtt: xij wekes vj daies |

xxjˢ |

vᵈ |

| William Appleford: xij wekes vj daies |

xxjˢ |

vᵈ |

| John Huntt, master gonner: xij wekes vj daies |

xxxijˢ |

ijᵈ |

This is what the Dreadnought looked like as she

lay in the dock on the Tuesday morning that saw the

ship take the water. Imagine a solid-looking heavily-timbered

hull, round bowed, with long, raking forward

prow or beak, reaching out some ten or twelve

yards ahead of the actual vessel, and with at the

after-end a lofty towering poop with shallow overhanging[10]

balustraded gallery. Amidships the vessel

is of a width equal to nearly a third of her length.

From the “greate beaste,” the figure-head—a

dragon—“gilded and laid with fine gold,” representing

one of the supporters of the Queen’s arms,

set up on the tip of the beak, away aft to the stern

gallery is a distance of, over all, about a hundred and

twenty feet. The body of the hull itself has a keel

length of some eighty feet—from rudder post to

fore-foot. Along the water-line the bends are all

tarred over, with varnished side planking above,

tough oak timber from the Crown lands of the

Sussex Weald by Horsham. The topsides above

are varnished to the bulwarks, where a touch of

colour shows; ornamental carved and painted work

in royal Tudor green and white, laid on in

“colours of oil” and garnished with Her Majesty’s

family badges in gold, and with here and there, on

the balustrades of the quarter-rails and stern gallery,

an additional touch of red. On the stern, “painted

in oils,” are the arms of England, with the Lion and

the Dragon, the Queen’s royal supporters, and

below, on a scroll, Her Majesty’s motto, Semper

Eadem.

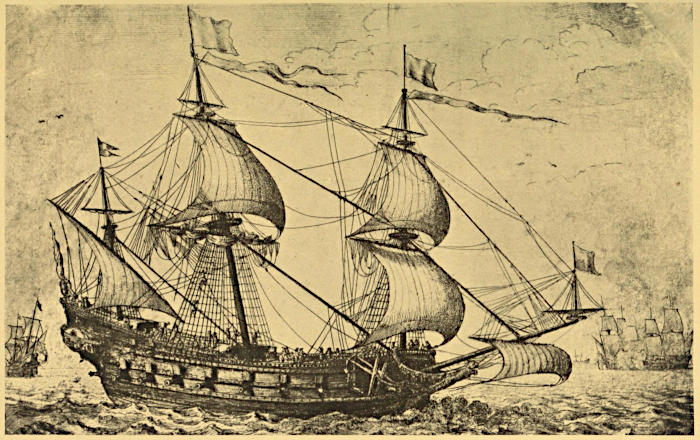

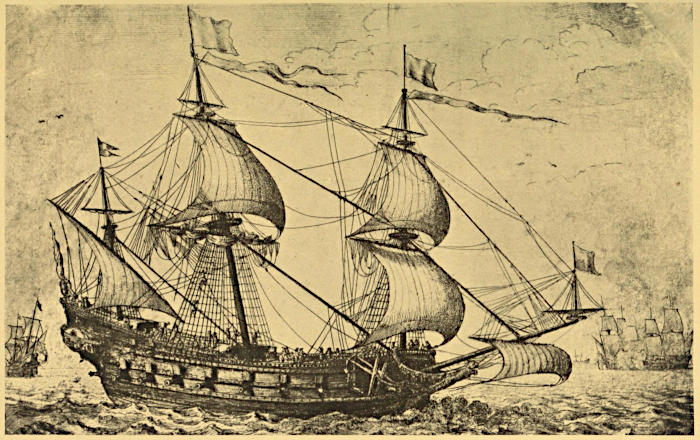

OUR FIRST DREADNOUGHT

From a Contemporary Print kindly lent by Mr. Wentworth Huyshe.

(The “Dreadnought” is shown as she appeared when serving in the

“Ship Money” Fleet of Charles the First:—circ. 1637).

These are other things about the ship that would

strike the Deptford visitor of that day. The square-headed

forecastle is low and squat in appearance,

compared with the piled-up, narrow poop right aft,

looking over from which a foreign visitor to the

Queen’s fleet once declared that “it made one

shudder to look downwards.” The bottom of the[11]

ship is coated with “tallow and rosin mingled with

pitch.” The square-cut, wide portholes, out of which

the guns will point when they are on board—the

Tower lighters will bring them down for mounting in

a week or two—were the idea, they say in the yard,

of Master Shipwright Baker’s father, old James

Baker, many years ago King Harry’s shipwright,

improving on the original French style. It was old

Baker too, they say, who “first adapted English

ships to carry heavy guns.” The Reformers wanted

to send the old man to the stake for “being in

the possession of some forbidden books”; but King

Harry could not afford to let them burn England’s

best naval architect even for the benefit of Protestantism.

The Dreadnought’s gun-ports should open some

four feet clear of the water. People have not forgotten

the horror of the Mary Rose; what happened

to her; how she came to go down one summer’s day

at Spithead. The waist bulwarks of the Dreadnought,

if she swims as she ought, will be some

twenty feet above the water-line. Nearly four hundred

tons in burden is our new man-of-war—five

tons heavier than the Swiftsure, than which ship too

she is six feet longer, though the pair reckon as

sister ships. Upwards of six thousand pounds out

of Queen Elizabeth’s treasury (about £30,000 at present

day value) will have been the cost of the Dreadnought

when she leaves Deptford dockyard.

We will go on board for a brief look round the

Dreadnought within. As we enter the ship we note[12]

how both the half-deck and the fore and aft castles

are loopholed for both arrow-fire and musketry, so as

to sweep the waist should an enemy board and get

a footing amidships. Some of the lighter guns

would be able to help. The heavier guns are mostly

on the broadside, and are mounted on the decks

below in a double tier. The Dreadnought altogether

carries forty-two guns. Sixteen of them are heavy

guns: two “cannon-periers” of six-inch bore, hard

hitters, firing twenty-four pounder stone shot; four

“culverins,” seventeen and a half pounders, twelve

feet long and five and half inches in the bore, firing

iron shot, and able to throw a ball upwards of

three miles—“random shot.” There are also ten

“demi-culverins,” nine-pounders, firing four and a

half inch iron shot. The lighter guns are six

“sakers,” pieces nine feet long (five-pounders, of

three and a half inch bore) and two “fawcons”

(three-pounders). The heavier guns are all muzzle-loaders.

Distributed over the upper decks are

eighteen breech-loading guns, for fighting at

close quarters and rapid firing: “port-pieces,”

“fowlers,” and “bases,” as they are called. They

are on swivel mountings, and fire stone and iron

shot.

All told, the Dreadnought’s armament weighs

thirty-two tons. The guns are from Master Ralphe

Hogge, “the Queen’s gunstone maker, and gunfounder

to the Council.” They are of Sussex iron,

from Master Hogge’s own foundry at Buxted. At

this moment they are waiting at the Tower, together[13]

with the Dreadnought’s supplies of iron shot and

cannon balls of Kentish ragstone from Her Majesty’s

quarries at Maidstone, stacked “in ye Bynns upon

ye Tower Wharfe each side Traitor’s Gate.”

When the Dreadnought goes into battle she will

carry some two hundred officers and men all told:

a hundred and thirty “maryners”—“Able men for

topyard, helme and lead,” and “gromets,” or boys

and “Fresh men”; with twenty gunners and

fifty soldiers. To keep her at sea will cost the

Queen £303. 6s. 8d. a month for sea-wages and

victualling. Three weeks provisions and water is

the most that the ship can stow, owing to the space

wanted for the ballast, the cables for the four anchors,

and the ammunition and sea stores. That is why

victualling ships have to attend Her Majesty’s fleets

on service outside the Narrow Seas. The “cook

room,” of bricks and iron and paving stones, is in

the hold over the ballast. Two more notes may be

made as we return on deck and quit the ship. The

captain’s cabin, opening on the gallery aft, is neatly

wainscoted and garnished with green and white

chintz, and with curtains of darnix hung at the

latticed cabin windows. There are three boats for

the Dreadnought: the “great boat,” which tows

astern at all times, the cock-boat and the skiff, both

of which stow inboard. John Clerk, “of Redryffe,

Shipwrighte,” built the “great boat,” being paid

£24, in the terms of his bill, “For the Workmanshipp

and makeinge of a new Boate for her Highness’

Shipp, the Dreadnought; conteyninge xi foote[14]

Di. in lengthe; ix foote Di. in Breadthe; and iij

foote ij inches in Depthe.—By agrement.”

A brave show should our gallant Dreadnought

make when she goes forth to war, with her varnished

sides and rows of frowning guns and painted top-armours

(the handiwork, according to his bill, of

Master Coteley, of Deptford), and all her wide

spreading sails set (“John Hawkins, Esquire, of

London,” supplied these), and at the masthead,

high above all, her flag of St. George of white

Dowlas canvas with a blood-red cross of cloth

sewn on.

The appointed day has come, and the time for the

sending afloat and formal naming of the Dreadnought:

Tuesday afternoon, the 10th of November,

1573.

The ship lies ready for launching at the appointed

moment, having been duly “struck” upon the launching

ways a day or two before, under the supervision

of Master Baker himself, in the dock where she has

been building; shored up on either side, and with

the lifting screws and “crabs” prepared to heave her

off. The dockhead has been dug out and finally

cleared at low tide on Monday, leaving the double

gates free and in order, ready to be swung back and

opened as soon as the tide begins to make on

Tuesday morning.

We will imagine ourselves on the spot at the time

and looking on at what took place. It is possible to[15]

do so, thanks to a manuscript left by Phineas Pett,

Peter’s son and successor at Deptford royal yard.

All is ready for the day’s proceedings by a little

after noon, when the important personages taking

part at the launch, “by commandement of ye officers

of Her Grace’s Maryn Causys,” and the invited

guests and superior officials of the dockyard assemble

for a light refection of cake and wine in the

Master Shipwright’s “lodging,” preliminary to the

ceremony.

Who named the Dreadnought on that day? Unfortunately

that one detail is not mentioned in any

existing record, and the Navy Office book for the year,

where the name would certainly have been found, together

with the honorarium or fee, paid according to

custom, is missing. Most probably it was Captain

Stephen Borough himself, and we may imagine him

there, apparelled for the day in crimson velvet and

gold lace, in the full uniform of one entitled to wear

“Her Maᵗⁱᵉˢ cote of ordinarie.” His rank and

standing as one of the “Principall Masters of the

Queen’s Maᵗⁱᵉˢ Navie in Ordinarie” qualified him for

performance of so dignified a duty. The Principal

Masters were often deputed by the Lord High

Admiral to preside on his behalf at the launches of

men-of-war and perform the name-giving ceremony.

While the high officers are having their refreshments

in Master Shipwright Baker’s lodging, Boatswain

Baxster and the assistant shipwrights are

stationing the men on board and at the launching

tackles. The customary “musicke” then makes its[16]

appearance, “a noyse of trumpetts and drums,” who

post themselves on the poop and the forecastle of

the ship. Next, a “standing cup” of silver-gilt,

filled to the brim with Malmsey of the best, is set up

on a pedestal fixed prominently on the poop, and the

Queen’s colours are hoisted on board, together with

the flag of St. George. At the same time pennons

and streamers of Tudor green and white, and

decorated with royal emblems and badges, are

ranged here and there along the ship’s sides and on

the forecastle.

All is ready ere long, and then, forthwith,

word is sent to Master Shipwright Baker and the

gentlemen of the company. Forthwith the procession

forms itself and sets out in stately fashion to go

on board.

With his grey hair unbonneted

The old sea-captain comes;

Behind him march the halberdiers,

Before him sound the drums.

So escorted and attended the personage of the

hour paces his way forth and proceeds on board the

new ship, passing along the decks and ascending to

the poop where the company group themselves

according to precedence, near by the glittering silver-gilt

wine cup. Master Shipwright Baker then gives

the signal, and Boatswain Baxster’s whistle shrills

out. At once the gangs of men standing ready

at the crabs and windlasses heave taut, and a

moment later, as the ship begins her first movement

outwards, the trumpets and drums sound forth. So,

at a leisurely rate at the outset, gliding off foot by[17]

foot into deeper water, the new man-of-war hauls

gradually out and clears past the dock gates till well

into the stream. The anchor is then let go and she

brings up. Now it is for Captain Borough—allowing

it to have been he—to do his part.

Stans procul in prorâ, pateram tenet extaque salsos

Porricit in fluctus ac vina liquentia fundit.

The trumpets and drums cease as the “Principall

Master” steps forward and takes up his position

beside the standing cup. He raises the gleaming

cup on high so that all around may see. Then, amid

universal silence, he proclaims, in a clear resonant

voice that every one may hear: “By commandment

of Her Grace, whom God preserve, I name this ship

the Dreadnought! God save the Queen!” As the

Lord High Admiral’s representative utters the last

word, he drinks from the cup, and a moment after

ceremoniously pours out a portion of the wine upon

the deck. The next moment, with a wide sweep

of the arm, he heaves the standing cup, with a little

wine left in it, into the river—a sacrifice, as it were,

on behalf of the bride newly-wedded to the sea, or

that the Queen’s cup might never be put to base

uses—perhaps, indeed, as a sort of propitiatory act.

So it was done, says Master Phineas Pett, “according

to the ancient custom and ceremony performed

at such times.” Again there is a blare of trumpets

and a ruffle from the drums, with cheers afloat and

ashore for Her Grace, and hearty congratulations to

Master Matthew Baker on the occasion. After

that the Dreadnought is formally inspected between[18]

decks and below, and the crew’s health is drunk by

the high officers in ship’s beer—sure to be of a good

brew on a launching day.

By the time that all is over the ship has been warped

back alongside the shore again, and the company

adjourn thereupon to wind up the day’s proceedings

with a good old English dinner, given to the Master

Shipwright and the officials of the yard at the Lord

High Admiral’s expense.

Such is a passing glimpse of the memorable scene—as

far as one may venture to reconstruct it—on

“Dreadnought Day” at Deptford Royal Dockyard,

that Tuesday afternoon, in Tudor times, three hundred

and thirty-three years ago. It is hard to fancy

such doings, at Deptford of all places, now. Oxen

and sheep for the London meat market nowadays

stand penned in lairs on the site of the filled-in

dock whence the Dreadnought was floated out—the

same dock whence the Armada Victory had preceded

her, whence Grenville’s Revenge followed her.

Master Shipwright Baker’s lodging is nowadays

a cattle drovers’ drinking bar. The old-time navy

buildings—their origin even now easily recognisable,

at any rate externally—serve as slaughterhouses,

and so forth, among which rough butcher

lads, reeking of the shambles, jostle daily to and

fro. On every side is bustle and clatter and

hustling, the rumbling of Smithfield meat vans

over the old-time cobble stones, the jargon of

Yankee bullock-men, the bleating of sheep under

sentence of death. Strange and hard is the fate that[19]

in these material times of ours has overtaken what was

once the premier Royal Dockyard of England, this

former temple, so to speak, of the guardian deity of

our sea-girt realm:

This ruined shrine

Whence worship ne’er shall rise again:—

The owl and bat inhabit here

The snake nests in the altar stone,

The sacred vessels moulder near—

The image of the god is gone!

Fallen indeed from its high estate of former days

is the ancient royal establishment of “Navy-building

town.” Where bluff King Hal used to walk and

talk with Matthew Baker’s father, “old honest Jem”;

where our sixth Edward paid a long-remembered

visit, to be “banketted” (as the royal spelling has

it) and see two men-of-war go off the ways; where

Elizabeth knighted Francis Drake, and James and

Charles rode down in state on many a gala day;

where Cromwell paid his second naval visit—his

“grandees” attending him, and escort of clanking

Ironsides—to see the vindictively named Naseby take

the water; where our second Charles liked to saunter

on occasion with Rupert at his side, and chattering

Pepys and John Evelyn in his train; where James

the Second, dull and morose of mood, for the sands

of his monarchy were already running out, paid his

last historic visit one gloomy autumn afternoon of

1688; where brave old Benbow liked best to spend

the mornings of his half-pay life on shore, and

Captain Cook set out on his last voyage; where

George the Third drove down with Queen Charlotte[20]

to do honour to the naming of a Prince of Wales

man-of-war; where, too, Royalty of our own time

has more than once visited—is now “a market for

the landing, sale, and slaughtering of foreign cattle.”

The glory has departed—the image of the god is

gone!

The Dreadnought and Swiftsure and the two

smaller ships were masted and rigged and completed

for service during November and the early

days of December, after which, with the help of a

hundred and fifty extra hands, “prested in ye river

of Theames for ye transportyngs about,” they set off

on the twentieth of the month to join the fleet lying

“in ordinary” in the Medway—an eight days’ voyage

as it proved, owing to squally weather and an east

wind. The Queen was to have seen the Dreadnought

and her squadron pass the palace at Greenwich and

salute the royal standard with cannon and a display

of masthead flags, as was the Tudor naval usage

when the sovereign was in residence, but there had

been a domestic misadventure at Placentia just a few

days before. While talking with her maids of

honour one afternoon, one of the Queen’s ladies—“the

Mother of the Maids”—had suddenly dropped

dead in the royal presence, and the Court had hastily

removed to Whitehall. So the Dreadnought had no

royal standard to salute. Three days after Christmas

the Deptford squadron took up their moorings

in “Jillingham water.”

[21]

“Powerful vessels ... with little tophamper and

very light, which is a great advantage for close

quarters and with much artillery, the heavy pieces

being close to the water,” reported, in a confidential

letter now in the royal archives at Simancas, one of

the King of Spain’s agents in England who saw the

Dreadnought and Swiftsure not long after they had

joined the Medway fleet. So too, indeed, some of

King Philip’s sailors were destined to find out for

themselves.

The Dons, indeed, were destined to taste something

of the Dreadnought’s quality more than once;

beginning with the memorable event of the “Singeing

of the King of Spain’s Beard.” There, Drake’s

right-hand man on many a battle day, commanded

the Dreadnought, Captain Thomas Fenner, a sturdy

son of Sussex and a seaman who knew his business.

How thoroughly Drake—“fiend incarnate; his

name Tartarean, unfit for Christian lips; Draco—a

dragon, a serpent, emblem of Diabolus; Satanas

himself”—did his work among the Spaniards at

Cadiz, burning eighteen of their finest royal galleons,

and carrying off six more in spite of fireships and

all the shooting of the Spanish batteries, is history.

The Dreadnought, after experiencing a narrow

escape from shipwreck off Cape Finisterre at the

outset of her cruise, took her full share of what

fighting there was. She was present, too, at the

second act of the drama, which took place off the[22]

Tagus with so fatal a sequel for the hapless Commander-in-Chief

designate of the Armada, the

Marquis de Santa Cruz—the “Iron Marquis,”

“Thunderbolt of War,” the real Hero of Lepanto,

by reputation the ablest sea-officer the world had

yet seen. First, the news that his flagship and the

finest fighting galleons of his own picked squadron—all

named, too, after the most helpful among the

Blessed Saints of the Calendar—together with his

best transports and victuallers, had been boarded

and taken and sacrilegiously set ablaze to, burned

to the water’s edge, one after the other, by those

“accursed English Lutheran dogs.” Worse still.

To be then defied to his face, he, Spain’s “Captain-General

of the Ocean”; to be audaciously challenged

to come out and fight and have his revenge then

and there—Drake and the Dreadnought and the rest

openly waiting for him—in the offing. The shame

of the disaster was enough to kill the haughty

Hidalgo, to make him fall sick and turn his face

to the wall and die, without Philip’s espionage

and unworthy insults goading him to the grave.

The Dreadnought had a hand in shaping the destinies

of England, for, in the words of the Spanish popular

saying, “to the Iron Marquis succeeded the Golden

Duke,” whose hopeless incompetence gave England

every chance in the next year’s fighting.

In the opening encounter with the Spanish

Armada that July Sunday afternoon of 1588, no

ship of all the Queen’s fleet bore herself better than

did the Dreadnought. Captain George Beeston, of an[23]

ancient Surrey family, held command on board the

Dreadnought. He was a veteran officer of the

Queen’s fleet—more than twenty-five years had gone

by since he first trod the quarter-deck as a captain.

Leading in among the enemy, after the first hour of

long-range firing between the English van and the

Spanish rear had brought both sides to closer

quarters, the Dreadnought with the ships that followed

Drake’s flagship the Revenge, for nearly three hours

fought first with one and then with another of the

most powerful of the Spanish rear-guard ships.

After that, forcing their way among the Spaniards

as they gave back and began to crowd on their

main body, she had a sharp set-to with the big

galleons, led by Juan Martinez de Recalde, perhaps

the best seaman in all King Philip’s navy, commander

of the rear-division of the Armada. On

the Santa Ana and her consorts the Revenge and

Dreadnought and the rest made a spirited attack,

pushing Recalde so hard that eventually Medina

Sidonia himself, the Spanish Admiral, had to turn

back and come to the rescue with every ship at his

disposal. It was enough; Drake and his men had

played their part. Before Medina Sidonia’s advance

in force, the Revenge and Dreadnought left the Santa

Ana, and with the rest of the attacking English

van drew off. They had done an excellent day’s

work.

There was harder work for the Dreadnought in the

great battle of Tuesday off Portland Bill. First

came the fierce brush in the morning, when Drake[24]

and Lord Howard and the leaders of the English

fleet, after a daring attempt to work in between the

Spanish fleet and the Dorset coast, had to tack at

the last moment, baffled for want of sea room, and

were closed with by the enemy in the act of going

about. On came the galleons exultantly, their crews

shouting and cheering, amid a blare of trumpets and

ruffle of drums, in full confidence to run down and sink

the lighter built English vessels. It was a moment

of extreme peril:—but at the very last, suddenly, the

fortune of the day changed. As the Spaniards

seemed to be upon them the wind shifted, the

English sails filled, ship by ship and all together,

and then stretching out with bowsprits pointing seaward,

the Revenge, Victory, Ark Royal, Dreadnought,

and the others safely cleared the enemy, pouring in

so fierce a fire as they passed that the Spanish ships

had to sheer off. This was the first fight of the

day. Later, when the wind, going round with the

sun, shifted again and gave Drake and Howard the

weather gage, came on the most desperate encounter

with the Armada that our ships had yet seen. Lord

Howard in the Ark Royal and Drake in the Revenge,

with the Dreadnought, the Lion, the Victory, and the

Mary Rose near at hand, driving ahead before the

wind, pushed into the thick of the Spanish main

body, and attacked the enemy, in a long and furious

battle that lasted until the afternoon sun was nearing

the horizon.

A third day of battle was yet to come—Thursday’s

hot fight off the back of the Isle Wight, and here[25]

again the Dreadnought took her full share of what

was done, until the long summer day drew to its

close and the Armada “gathered in a roundel,”

sullenly stood off eastward, proposing to fight no

more until the coast of Flanders had been made.

Next morning the Dreadnought’s captain was

summoned on board Lord Howard’s flagship, the

Ark Royal. He returned “Sir George,” knighted

by the Lord High Admiral on the quarter-deck, in

the presence of the enemy.

Sunday night saw the fireship attack, so disastrous

to the Armada, and next morning followed the

crowning victory of the week’s campaign, the great

fight off Gravelines of Monday, the 29th of July, “the

great battle which, more distinctly perhaps than any

battle of modern times, has moulded the history of

Europe—the battle which curbed the gigantic power

of Spain, which shattered the Spanish prestige and

established the basis of England’s empire.” Here

the Dreadnought distinguished herself again, fighting

in the thick of the fray from eight in the morning to

four in the afternoon, within pistol-shot of the enemy

most of the time.

From six till nearly eight the ships of Drake’s

squadron had to bear the brunt of the fight, with, for

antagonists, Medina Sidonia himself and his chief

captains, who had gathered to stand by their admiral.

Trying to rally the Armada after the panic of the

night, this gallant band had at first, from before daybreak,

anchored in a group, to act as rear-guard to

the Spanish fleet, firing signal guns to stop their[26]

flying consorts, and sending pinnaces to order the

fugitives back. Then Hawkins in the Victory, with the

Dreadnought, the Mary Rose, and Swallow, and other

ships unnamed, came up and struck in. Now

moving ahead through her own smoke to plunge into

the mêlée and come to the rescue of some hard-pressed

consort, now working tack for tack parallel with and

firing salvo after salvo at short range into some towering

galleon or huge water-centipede-like galleass—so

the hours of that eventful forenoon wore through

on the Dreadnought’s powder-begrimed decks. “Sir

George Beeston behaved himself valiantly,” records

the official Relation of Proceedings, drawn up for the

Lord High Admiral. In vain did the most formidable

of the Spanish galleons try to close and board.

Ship after ship was forced back with shattered

bulwarks and splintered sides, and with their

scuppers spouting blood, after each English broadside,

as the round shot crashed in among the masses

of Spanish soldiery, packed on board the galleons

as closely almost as they could stand.

More Spaniards joined their admiral as Sidonia

passed north, the Spanish rear and centre squadrons

forming together a long straggling array, among

the ships of which, from nine to after one o’clock,

the Revenge, Victory, Dreadnought, Triumph, Ark

Royal, and the rest charged through and through

fighting both broadsides. Shortly after two o’clock,

the English ships passed on, pressing forward to

overtake the Spanish van group of galleons. By

four o’clock the battle was won, but firing went on[27]

till nearly six, “when every man was weary with

labour, and our cartridges spent and our ammunition

wasted” (i.e. used up).

Once more the Dreadnought followed the fortunes

of Drake’s flag to battle; again, too, as Captain

Fenner’s ship. In the year after the Armada she

had her part in escorting the Corunna expedition,

the “counter-Armada,” designed to beat up the

quarters of the enemy at home and attempt the

wresting of Portugal from the Spanish yoke. A

landing party of “Dreadnoughts” fought ashore.

Led by Drake and the general of the soldiers, Sir

John Norris, they drove the Spaniards before them.

“Unto every volly flying round their ears,” says

old Stow, “the generall, turning his face towards the

enemie would bow and vale his bonnet, saying ‘I

thank you, Sir! I thank you, Sir!’ to the great

admiration of all his campe and of Generall Drake.”

The wine vaults of Corunna, however, interposed on

behalf of Spain. Soldiers and sailors alike broke in

and got drunk, and all that could be done after that

was to reship the men and write the campaign down

a failure.

In the attack on Brest in 1594, when Sir Martin

Frobisher met his death, the Dreadnought had her

share. Two years after that she fought with Essex

and Raleigh in the grand attack on Cadiz—this time

as one of the picked ships of Sir Walter Raleigh’s

own “inshore squadron.” She sailed with Sir

Walter again after that in the celebrated “Islands

Voyage”; and then the curtain rings down on the[28]

memorable days of the story of the Dreadnought

of the Great Queen’s fleet. The old ship lasted

afloat (after an expensive rebuild in James the First’s

reign) until the time of the Civil War. She figured

in the interim in the Rochelle Expedition and also in

one of Charles the First’s Ship-money fleets. The

Dreadnought of St. Bartholomew’s Day and Matthew

Baker made her last cruise of all in the year of

Marston Moor.

Six Dreadnoughts in all have flown the pennant

since England’s Armada Dreadnought passed

away.

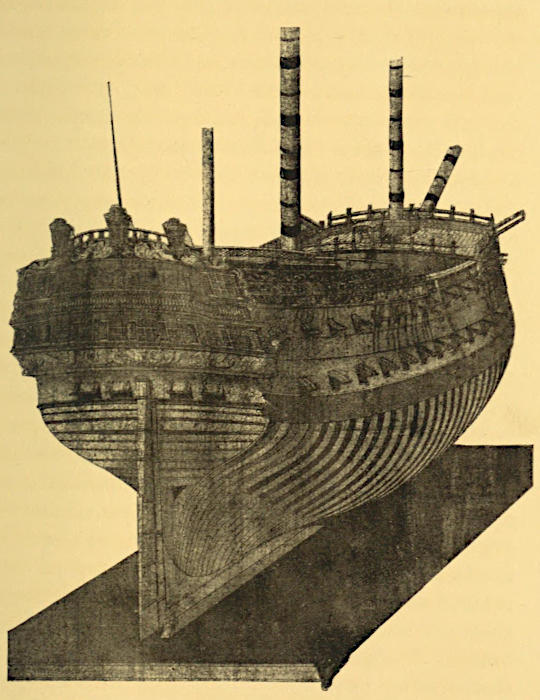

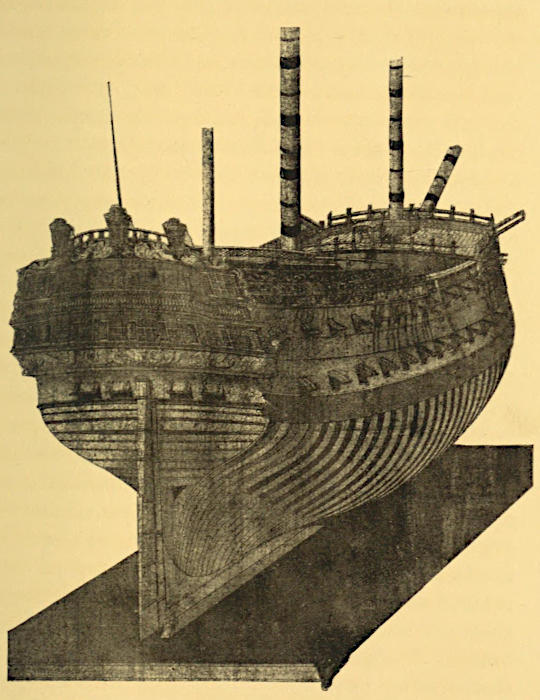

“OLD DREADNOUGHT’S” DREADNOUGHT

From the original drawing made in 1740 for the official dockyard

model. Now in the Author’s Collection.

Charles the Second’s Dreadnought was our second

man-of-war of the name. Originally the Torrington,

one of Cromwell’s frigates, and named, after the

Puritan usage, to commemorate a Roundhead victory

over the hapless Cavaliers, Restoration Year saw the

ship renamed Dreadnought, under which style she

rendered the State good service for many a long

year to come. In that time the Dreadnought fought,

always with credit, in no fewer than seven fleet

battles. She was with the Duke of York when he

beat Opdam off Lowestoft in 1665; with Monk,

Duke of Albemarle, and Prince Rupert in the “Four

Days’ Fight” of 1666; at the defeat of De Ruyter in

the St. James’s Day Fight of the same year. Solebay,

in the Third Dutch War, was another of our second

Dreadnought’s notable days, and also Prince Rupert’s

three drawn battles with De Ruyter off the Banks[29]

of Flanders in 1673. Worn out with thirty-six

years’ service (reckoning from the day that the Torrington

first took the water), the Dreadnought had

set forth to meet the famous French corsair, Jean

Bart, in the North Sea, when, one stormy October

night of 1690, she foundered off the South Foreland.

Happily, the boats of her squadron had time to

rescue those on board.

Our fourth Dreadnought, William the Third’s ship,

fought the French at Barfleur and La Hogue, and

after that did good service down to the Peace

of Ryswick as a Channel cruiser and in charge

of convoys. She served all through “Queen Anne’s

War,” by chance only missing Benbow’s last fight.

Later, the Dreadnought was with the elder Byng—Lord

Torrington—at the battle off Cape Passaro, in

the Straits of Messina, in 1718, where one, if not

two, Spaniards lowered their colours to her. The

Dreadnought on that occasion formed one of Captain

Walton’s detached squadron, whose exploit history

has kept on record, thanks to Captain Walton’s

dispatch to the admiral, as set forth in the popular

version of it: “Sir, we have taken all the ships

on the coast, the number as per margin.” Of that

dispatch more will be said elsewhere.[1] The Dreadnought

ended her days in George the Second’s reign,

at the close of the war sometimes spoken of as

“The War of Jenkins’ Ear.”

Two Dreadnought officers, Sir Edward Spragge,

who captained our second Dreadnought in the “Four[30]

Days’ Fight,” and Sir Charles Wager, a very famous

admiral in his day, First Lieutenant of our third

Dreadnought in the year before La Hogue, have

monuments in Westminster Abbey.

Boscawen’s Dreadnought comes next, a sixty-gun

ship built in the year 1742. She was the first ship

of the line that Boscawen had the command of, and

she gave him his sobriquet in the Navy, “Old Dreadnought,”

the name of his ship just hitting off the

tough old salt’s chief characteristic—absolute

fearlessness. An incident that occurred on board the

Dreadnought while Boscawen commanded the ship

gave the sobriquet vogue. It is, too, a fine sample of

what Carlyle calls “two o’clock in the morning

courage.”

It was in the year 1744, when we were at war with

both France and Spain, one night when the Dreadnought

was cruising in the channel. The officer of

the watch, the story goes, came down after midnight

to Captain Boscawen’s cabin and awoke him,

saying, “Sir, there are two large ships which look

like Frenchmen bearing down on us; what are we to

do?” “Do?” answered Boscawen, turning out of

his cot and going on deck in his nightshirt, “Do?

why, d⸺ ’em; fight ’em!” The fight did not

come off, however, as the suspicious strangers disappeared.

On board Boscawen’s Dreadnought it was that,

fourteen years later, Nelson’s uncle, Maurice Suckling,

who got Nelson his first appointment in the Royal

Navy, and under whose command the boy Nelson[31]

first went to sea, made his mark as a post-captain.

It was in the West Indies in 1757, the year in

which Byng was shot, and the day was the 21st of

October.

The Dreadnought with two consorts met seven

French men-of-war, four of them individually bigger

and more heavily gunned ships than ours, and the

other three powerful frigates, and gave them a sound

thrashing.

The news was received in England with exceptional

gratification as the first sign of the turn of the

tide since Byng’s defeat off Minorca. That was one

thing about it that stamped the event in popular

memory. A second memorable thing was the incident,

according to the popular story, of the

“Half Minute Council of War” that preceded the

fight.

The three British ships were the Augusta, Captain

Forrest; the Dreadnought, Captain Maurice Suckling;

and the Edinburgh, Captain Langdon. The three

had been sent by the admiral at Jamaica to cruise off

Cape François, in order to intercept a large French

homeward merchant convoy reported to be weakly

guarded. The available French naval force on the station

was believed to be too weak to face our little squadron.

But, unknown to Admiral Cotes at Port Royal,

fresh men-of-war had just arrived from France purposely

to see the convoy home. In the result, when our

three ships arrived off Cape François, seven French

ships stood out to meet them. In spite of the odds

the British three held on their course.

[32]

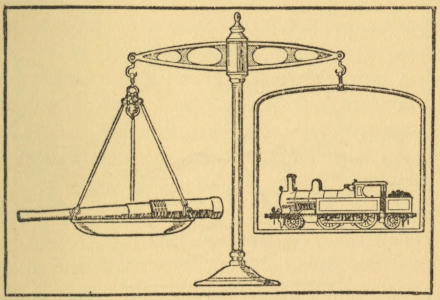

These were the forces on either side, in ships and

men:—

| British Line of Battle. |

| Dreadnought |

60 |

guns |

Capt. Suckling |

375 |

men |

| Augusta |

60 |

” |

Capt. Forrest |

390 |

” |

|

| Edinburgh |

64 |

” |

Capt. Langdon |

467 |

” |

|

|

184 |

guns. |

|

1232 |

men. |

| French Line of Battle. |

| La Sauvage |

30 |

guns |

|

206 |

men |

| L’Intrépide (Commodore) |

74 |

” |

|

900 |

” |

| L’Opiniâtre |

64 |

” |

|

640 |

” |

| Le Greenwich (formerly British) |

50 |

” |

|

400 |

” |

| La Licorne |

30 |

” |

|

200 |

” |

| Le Sceptre |

74 |

” |

|

750 |

” |

| L’Outarde |

44 |

” |

|

350 |

” |

|

366 |

guns. |

|

3446 |

men. |

Directly the French came in sight the senior

officer, Captain Forrest of the Augusta, signalled

to the other two captains to come on board for a

council of war. They came, and, the story goes,

arrived alongside the Augusta together and mounted

the ship’s side together. As they stepped on to the

Augusta’s gangway, Captain Forrest, it is related,

addressed the two officers in these terms: “Gentlemen,

you see the enemy are out; shall we engage

them?” “By all means,” said Captain Suckling. “It

would be a pity to disappoint them,” said Captain

Langdon. “Very well, then,” replied Forrest;

“will you gentlemen go back to your ships and

clear for action?” The two captains bowed, and[33]

turned and withdrew without having, as it was said,

actually set foot on the senior officer’s quarter-deck.

Within three-quarters of an hour they were in

action, the Dreadnought leading in and attacking

the French headmost ship as the squadrons closed.

Captain Suckling opened the fight by throwing the

Dreadnought right across the bows of the Intrépide,

a 74, and much the bigger ship, forcing her to sheer

off to port to avoid being raked.

Backed up by the Augusta and the Edinburgh,

the Dreadnought was able to overwhelm the French

commodore with her fire, and force the crippled

Intrépide back on the next ship, the Opiniâtre.

That vessel in turn backed into the fourth French

ship, and she into another, the Sceptre. The four

big ships of the enemy were accounted for. Our

three ships seized the opportunity. Well in hand

themselves, they pounded away, broadside after

broadside, into the hapless Frenchmen, who were

too much occupied in trying to disentangle themselves

to do more than make a feeble and ineffective

reply. By the time that they got clear the British

squadron had so far got the upper hand that the

French drew off, leaving the British squadron

masters of the field. All of our three ships suffered

severely, the Dreadnought most of all.

In Nelson’s lifetime the day was always observed

by the family at Burnham Thorpe with

special festivities, and Nelson himself often called

it, it is on record, “the happiest day of the year.”

More than that too, Nelson himself more than once[34]

half playfully expressed his conviction that he too

might some time fight a battle on another 21st of

October, and make the day for the family even more

of a red-letter day. As a fact, during the last three

weeks of his life on board the Victory off Cadiz, in

October, 1805, Nelson, with a prescience that the event

justified, used these words both to Captain Hardy

and to Dr. Beatty the surgeon of the flagship:

“The 21st of October will be our day!”

Captain Maurice Suckling’s “Dreadnought” sword

was bequeathed to Nelson and was ever kept by him

as his most treasured possession. He always wore

it in battle, it is said; notably at St. Vincent, when

he boarded and took the two great Spanish ships the

San Nicolas and the San Josef; and his right hand

was grasping it when the grape shot shattered his

arm at Teneriffe.

The Dreadnought of Boscawen and Maurice

Suckling ended her days at perhaps England’s

darkest hour of national trial—at the time of the

American War. She was doing harbour duty at

Portsmouth at the time, as a guard and receiving

ship.

At no period, perhaps in all our history did the

future and the prospects of the British Empire seem

so absolutely hopeless. We were fighting for existence

against France and Spain, the two chief maritime

Powers of Europe; and at the same time the

vitality of the nation was being sapped by the never-ceasing

struggle with the American colonists, now in

its seventh year. Holland had added herself to our[35]

foes; Russia and the Baltic Powers were banded

together in a league of “armed neutrality,” and

stood by sullen and menacing. That, however, was

not the worst. The price of naval impotence had to

be paid. Great Britain was no longer mistress of

the sea. She had lost command of the sea, and

was drinking the bitter cup of consequent humiliation

to the dregs.

THE RED-LETTER DAY OF NELSON’S CALENDAR. HOW THE

DREADNOUGHT LED THE ATTACK ON THE 21st OF OCTOBER, 1757

| “Edinburgh.” |

“Augusta.” |

|

“Dreadnought.” |

Painted by Swaine. Engraved and Published in 1760.

It was the direct outcome of party politics and

short sighted naval retrenchments in time of peace,

pandering to the clamour of ministerial supporters

in the House of Commons. The printed Debates

and Journals of the House between 1773 and 1781

are extant, as are also the summaries of the Gentleman’s

Magazine, for those who care to learn what

passed.

Out-matched and out-classed at every point, the

British fleet found itself held in check all the world

over. Colony after colony was wrested from us, or

had to be let go, while our squadrons in distant seas

had not strength enough to do better than fight

drawn battles.[2] Gibraltar, closely beset by sea and

land, was still holding out, but no man dared

prophesy what news of the great fortress might not[36]

arrive next. Minorca, England’s other Mediterranean

possession, had to surrender. The enemy

were masters of the island, after driving the garrison

into their last defences at St. Philip’s Castle.

Nearer home, Ireland, in the enjoyment of Home

Rule, was using the hour of Great Britain’s difficulty

as her opportunity for demanding practical independence,

with eighty thousand Irish volunteers under

arms to back up the threats of the Dublin Parliament.

The Channel Fleet, though reinforced with every

ship it was possible to find crews for, held the

Channel practically on sufferance. Once it had to

retreat before the enemy and seek refuge at Spithead.

On another occasion the enemy were on the

point of attacking it in Torbay with such preponderance

of force that overwhelming disaster must have

befallen it. Fortunately for England the French

and Spanish admirals disagreed at the last moment

and turned back.

Hanging in a frame on the walls of the Musée de

Marine at the Louvre the English visitor to Paris

to-day may see a draft original “State,” giving the

official details of the divisions and brigades and the

ships to escort them, of one of the French armies

which was to be thrown across into England. It

was no empty menace, and for three years the

beacons along our south and east coasts had to be

watched nightly; while camps of soldiers, horse and

foot and artillery—the few regulars that had not

been sent off to America—with all the militia regiments[37]

in the kingdom, extended all the way round,

at points, from Caithness to Cornwall. To safeguard

London there were camps of from eight to

ten battalions each, mostly militia, at Coxheath,

near Maidstone, at Dartford, at Warley, at Danbury

in Essex, and at Tiptree Heath. To secure

the colliery shipping of the Tyne two militia battalions

were under canvas near Gateshead. A camp

at Dunbar and Haddington watched over Edinburgh.

The West Country was guarded by a big

camp of fifteen militia battalions at Roborough,

near Plymouth, with an outlying camp on Buckland

Down, near Tavistock. To prevent the enemy

making use of Torbay, Berry Head was fortified,

the ruins of the old Roman camp of Vespasian’s

legionaries there being utilized to build two twenty-four

pounder batteries overlooking the passage into

the bay. Every town almost throughout England

had its “Armed Association” or “Fencibles,”

volunteers, the men of which, by special permission

from the Archbishop of Canterbury, drilled after

church time every Sunday.

The effect on the oversea commerce of the

country, penalized by excessive insurance rates,

was calamitous. From 25 to 30 per cent premium

was paid at Lloyds on cargoes from Bristol, Liverpool,

and Glasgow to New York (still in British

hands); and 20 per cent to the West Indies. As

to the reality of the risk. On one occasion the

enemy captured an Indiaman fleet bodily off

Madeira, only eight vessels out of sixty-three escaping,[38]

with a loss to Great Britain of a million and

a half sterling, including £300,000 in specie. We

have, indeed, at this moment a daily reminder of

the disaster. One of the unfortunate underwriters

was a Mr. John Walter. His whole fortune swept

away, he took to journalism, and the Times newspaper

was the result. Home waters were hardly

more secure. Rather than pay the excessive extra

premium demanded for the voyage up Channel,

London merchants had their goods unladen at

Bristol, and carried in light flat-bottomed craft

called “runners,” built specially for the traffic, up

the Severn to Gloucester, thence to be carted across

to Lechlade for conveyance to their destination by

barge down the Thames. At the same time the

North Sea packets from Edinburgh (Grangemouth)

to London refused all passengers who would not undertake

to assist in the defence of the vessel in emergency.

Printed notices were pasted up at the wharves

announcing that no Quakers would be carried.

To such a pass had the loss of her supremacy at

sea reduced Great Britain in the closing year of our

fourth Dreadnought’s career.

Our fifth Dreadnought fought at Trafalgar. She

was a 98-gun ship, one of the same set as the

famous “fighting” Téméraire. The newspapers of

the day made a good deal of her launch, which

took place at Portsmouth Dockyard, on Saturday,

the 13th of June, 1801. Here is an extract from one

account:—

“At about twelve o’clock this fine ship, which has[39]

been thirteen years upon the stocks, was launched

from the dockyard with all the naval splendour that

could possibly be given to aid the grandeur and

interest of the spectacle. She was decorated with

an Ensign, Jack, Union, and the Imperial Standard,

and had the marine band playing the distinguished

martial pieces of ‘God save the King,’ ‘Rule Britannia,’

etc. etc. A prodigious concourse of persons,

to the amount, as is supposed, of at least 10,000,

assembled, and were highly delighted by the magnificence

of the ship and the beautiful manner in which

she entered the watery element. But what afforded

great satisfaction was, that, in the passage of this

immense fabric from the stocks, not a single accident

happened. She was christened by Commissioner Sir

Charles Saxton, who, as usual, broke a bottle of wine

over her stem. Her complement of guns is to be 98,

and she has the following significant emblem at her

head; viz.—a lion couchant on a scroll containing

the imperial arms as emblazoned on the Standard.

This is remarkably well timed and adapted to her as

being the first man-of-war launched since the Union

of the British Isles.”

WHEN GEORGE THE THIRD WAS KING. OFFICERS AT AFTERNOON TEA ASHORE.

Thomas Rowlandson. 1786.

MANNING THE FLEET IN 1779. A WARM CORNER FOR THE PRESS GANG.

James Gillray. Oct. 15, 1779.

For twelve months before Trafalgar, the Dreadnought

was Collingwood’s flagship in the Channel

Fleet. Collingwood passed most of the time cruising

on blockade duty in the Bay of Biscay, where

he used to spend his nights pacing on deck to and

fro restlessly, expecting the enemy at any moment,

and snatching intervals of sleep lying down on a

gun-carriage on the quarter-deck. Collingwood[40]

only changed from her into the bigger Royal

Sovereign ten days before the battle. Under the

eye of the former captain of our first Excellent

man-of-war, the Dreadnought’s men had been trained

to fire three broadsides in one minute and a half—a

gunnery record for that day.

At Trafalgar the Dreadnought fought as one of the

ships in Collingwood’s line, and did the best with

what opportunity came her way.

“This quiet old Dreadnought” wrote Dickens of

his visit to the ship in her last years, “whose fighting

days are all over—sans guns, sans shot, sans

shells, sans everything—did fight at Trafalgar under

Captain Conn—did figure as one of the hindmost

ships in the column which Collingwood led—went

into action about two in the afternoon, and captured

the San Juan in fifteen minutes.”

While fighting the San Juan—the San Juan Nepomuceno,

a Spanish seventy-four—the Dreadnought

had to keep off two other Spaniards and a Frenchman

at the same time; Admiral Gravina’s flagship,

the Principe de Asturias, of 112 guns, and the San

Justo and Indomptable, two seventy-fours. The San

Juan in the end proved an easy prize, for she had

been already severely mauled by some of Collingwood’s

leading ships. On being run alongside of

she gave in quickly. Without staying to take

possession, the Dreadnought pushed on to close

with the big Principe de Asturias, and gave her

several broadsides, one shot from which mortally

wounded Admiral Gravina. The Spanish three-decker,[41]

however, managed to disengage, and made

off, to lead the escaping ships in their flight for

Cadiz. Thus the Dreadnought was baulked of her

big prize.

It was the Trafalgar Dreadnought that gave the

name to that great international institution, the

Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital, at Greenwich.

This, of course, was long after Trafalgar, for the

“wooden whopper of the Thames,” as Dickens

called the old three-decker in her old age, did not

make her appearance off Greenwich until a quarter

of a century later. The fine old veteran of “Eighteen

Hundred and War Time,” lasted until 1857,

and to the end they preserved on board as the

special relic of interest, “a piece of glass from a

cabin skylight scrawled over, with somebody’s

diamond ring, with the names of those officers who

were in her at Trafalgar.” Another old three-decker

replaced the Trafalgar ship until 1870, when the

institution was removed on shore. At Chatham

to-day, in the dockyard museum, visitors may see

the Dreadnought’s bell which was on board the old

ship during the battle, and was removed from her

when the Dreadnought was broken up. Yet another

memento of the Trafalgar Dreadnought exists in the

Eton eight-oar Dreadnought, one of the “Lower

Boats,” and so-called originally, together with the

boat that bears the name Victory, in honour of Nelson

and Trafalgar.

Our sixth Dreadnought is a still existing ironclad

turret-ship, mounting four 38-ton muzzle loaders,[42]

launched in 1875. She is a ship of 10,820 tons, and

cost to complete for sea £619,739. She served for

ten years—from 1884 to 1894—in the Mediterranean,

and after that as a coast-guard ship in Bantry Bay.

Paid off finally in 1905, the Dreadnought now lies

at her last moorings in the Kyles of Bute, awaiting

the final day of all for her naval career, and the

auctioneer’s hammer.

To conclude with a flying glance at our mighty

battleship, the Dreadnought of to-day, the seventh

bearer of the name until now, and as all the

world knows by far the most powerful man-of-war

that has ever sailed the seas. She is the biggest

and the heaviest and the fastest and the hardest-hitting

vessel that any navy as yet has seen afloat.

And more than that. The Dreadnought has been

so built as to be practically unsinkable by mine or

torpedo; while at the same time her tremendous

battery of ten 12-in. guns—huge cannon, each forty-five

feet long—makes her absolutely irresistible in

battle against all comers; a match for any two—probably

any three—of the biggest battleships in foreign

navies afloat at the present hour.

These are some of the “points”—some of the

leading features—of this grim mastodonte de mer

of ours, His Majesty’s battleship, the Dreadnought.

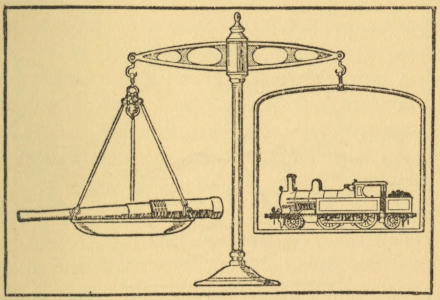

With her coal, ammunition, and sea stores on board,

the Dreadnought weighs—or displaces in equivalent

bulk of sea water, according to the present-day

method of reckoning the size of men-of-war—17,800

tons.

[43]

Put the Dreadnought bodily inside St. Paul’s and

she would fill the whole nave and chancel of the

Cathedral from reredos to the Western doors. Her

length would take up the whole of one side of Trafalgar

Square. Her width would exactly fill Northumberland

Avenue, leaving only some half-dozen

inches between the house fronts on either side and

the outside of the hull. Two Victorys and a frigate

of Nelson’s day, fully manned and rigged, could be packed

away within the Dreadnought’s hull.

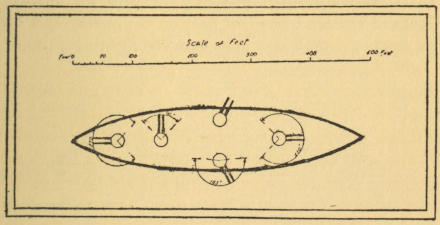

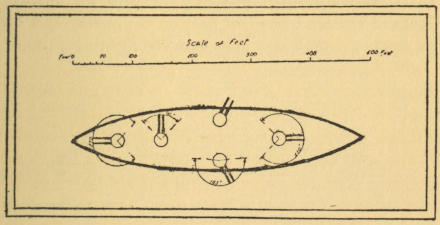

[Our Dreadnought of to-day: deck-plan

to scale; showing the disposition of the 12-in. 58-ton turret-guns

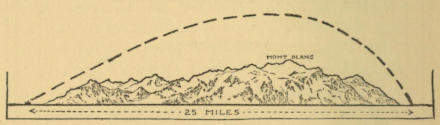

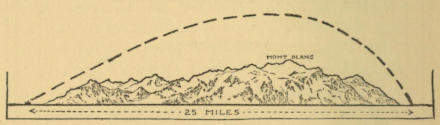

and their arcs of training. (Bows to the right.)][3]

Measured from end to end, from bows to stern,