FALCON

BOOKS

BOOKS

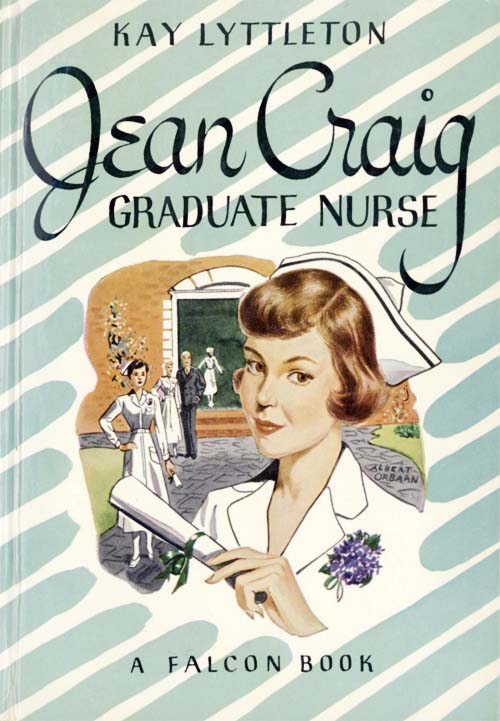

Jean Craig, Graduate Nurse

By Kay Lyttleton

As Jean Craig finished her training and prepared for graduation, illness struck—first in her own family, and later in epidemics that swept the village of Elmhurst. It was with a deep feeling of satisfaction that Jean was able to give trained and efficient aid at the hospital. It was with equal satisfaction that she watched romance blossom between Dr. Benson, the fresh young intern, and Eileen Gordon, the new Supervisor of Nurses, and discovered that her sister Kit was practically engaged. But the joy of the family reached a new peak when Doris, the youngest daughter, won a music scholarship. Jean Craig, Graduate Nurse is another heartwarming and happy story about the Craigs of Elmhurst.

OTHER JEAN CRAIG BOOKS

JEAN CRAIG,

GRADUATE NURSE

by KAY LYTTLETON

THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

CLEVELAND AND NEW YORK

FALCON BOOKS

are published by THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

2231 WEST 110th STREET · CLEVELAND 2 · OHIO

WP 8·50

COPYRIGHT 1950

BY THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

| 1. | Illness Strikes! | 9 |

| 2. | A Villain Unmasked | 21 |

| 3. | Fresh As Paint! | 30 |

| 4. | Emergency Operation | 42 |

| 5. | April Wedding | 52 |

| 6. | Dr. Benson Confesses | 62 |

| 7. | Ralph Returns from Europe | 73 |

| 8. | Jean and Ralph Discuss Their Future | 80 |

| 9. | Polio Claims a Victim | 89 |

| 10. | Kit at the Capital | 99 |

| 11. | Kit and Frank | 113 |

| 12. | An All Night Vigil | 122 |

| 13. | The Doctor’s Dilemma | 133 |

| 14. | Mercyville | 145 |

| 15. | Graduation! | 158 |

| 16. | Double Triumph | 166 |

| 17. | Judge Ellis Is Trapped | 174 |

| 18. | Just Among Girls | 184 |

| 19. | Elmhurst vs. Mercyville | 194 |

| 20. | Sweethearts’ Dance | 205 |

| 21. | Summer’s End | 212 |

JEAN CRAIG,

GRADUATE NURSE

The small village of Elmhurst, Connecticut, was enjoying a balmy early spring. The March winds were soft breezes coaxing the New England earth to life again.

Night had settled after a long twilight, and gay sounds could be heard coming from the nurses’ quarters at the Gallup Memorial Clinic. The clinic, now almost two years old, was the pride of the community. Before it was built, Dr. Gallup, gentle, wise and able physician, had tended the sick, brought babies into the world and guarded the health of the community with constant vigilance.

Like the noble man he was, Dr. Gallup refused to retire from active practice until he had helped to provide for the future medical care of his beloved patients. And because the town loved and respected him, they backed him solidly. Together the people of Elmhurst created the Gallup Memorial Clinic. And now, the white clapboard house which had once belonged to a wealthy native was a small but efficient combination hospital and clinic for the community.

[10] Dr. Edward Barsch, eminent surgeon, had come down from Boston to serve as head of the clinic. His staff was small but competent, and he had managed to open an accredited nursing course.

It wouldn’t be long before the first class of nurses would graduate. Standing high in the class, Jean Craig, one of the very first girls interested in the clinic, was looking eagerly toward the summer day when she would win her cap.

But tonight there was no thought of graduation. The nurses were planning a party. For there was a wedding in the offing, and the excited girls were wrapping presents and prettying themselves for Ethel Simpson’s wedding shower.

Ethel had come down from Boston with Dr. Barsch to act as supervisor of nurses. As is told in Jean Craig, Nurse, Jean and her classmates had been taught and guided by the lovely, competent girl through their year and a half of training. They had also laughed and cried with her during her courtship and subsequent engagement to Dr. Ted Loring, staff pediatrician. And now they were planning many gay and exciting parties to celebrate the coming wedding.

The party was to be held at the Craig farmhouse just outside of town. And while the girls were getting ready, Mrs. Craig was making a final inspection of her home. When she was satisfied with the preparations, she threw open the front door of the farmhouse and took a deep breath of the fresh spring air.

[11] It would be a happy spring, Mrs. Craig thought. Each year that passed seemed to push the war and the hardships that followed farther back in the shadowy memories of the family. Here in this simple village they had found peace and happiness.

She smiled as she thought of her family. It was truly growing up. Jean, her oldest daughter, was an adult. In a few months she would be twenty-one. It was exciting to have an adult daughter, Mrs. Craig thought fondly. Jean would be old enough to vote. She would be a registered nurse, and lastly, but most important of all, she would soon be a bride herself.

Five years ago, when the Craig family had moved to Elmhurst to forget the misery of the war years, Jean had met Ralph MacRae, a handsome young Canadian boy from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Jean Craig Grows Up tells how Ralph sold his Elmhurst farm to the Craig family, and lost his heart to Jean in the bargain.

Next came Kit. Mrs. Craig smiled in spite of herself as she thought of her nineteen-year-old impetuous daughter. Kit was the family scholar. She had been sent to Hope College in Delphi, Wisconsin, by a crotchety old uncle, and she had endeared herself to the elderly scholar by turning into a scholar, herself. The tale of Kit’s entrance to Hope College is told in Jean Craig Finds Romance. Mrs. Craig chuckled as she remembered how Kit and Uncle Bart had stumbled upon a secret while they were examining an ancient Egyptian mummy case, and how the money awarded12 to Uncle Bart was now providing her daughter with the chance for her education. Although Kit was many miles away from her family, Mrs. Craig could almost feel the vitality of her daughter halfway across the continent.

Doris was the youngest daughter. Mrs. Craig thought of her sweet, pretty seventeen-year-old with tenderness. Doris was shy. In her demure way, she often made her mother think of girls of generations past. There was something almost old-fashioned about the feminine child. But Doris was also very talented. Right now, while Mrs. Craig waited for the guests to arrive, she could hear Doris softly playing a Debussy etude. The music blended with the soft evening air and made the atmosphere nearly perfect.

As Mrs. Craig thought of her son, Tommy, her mood changed. No one could think of fifteen-year-old Tommy without smiling in amusement. Tommy was all boy. His head was full of eager projects, and his legs were long and still awkward. But he was a businessman, too. His chickens had provided him with enough money for spending and for a good start on his future college education. During the years that Mr. Craig had been invalided after the war, Tommy had been the man of the family. But though he knew the value of a dollar and the rich returns for hard work, there was mischief and play in the boy. Baseball season was just around the corner, and[13] this, to Tommy, was as important as the money he was putting away for the future.

Mrs. Craig frowned suddenly. She was thinking of Jack, the Craigs’ adopted son. Several years before, the homeless waif had found his way to the Craig’s home and into all their hearts, and he had never left. Jack was now thirteen. Two years ago, Mr. Craig had formally adopted the boy, and he was now as truly a member of the family as any of the other children. But Mrs. Craig was worried about him. Perhaps he was growing too fast. For the past month, Jack had been listless and pale. His appetite was poor ... a sure sign that something was wrong.

As she fretted about Jack, Jean came out on the porch and slipped her arm around her mother’s waist. She was wearing a simple, pale blue party dress which set off her sparkling eyes and curly brown hair.

“Everything’s ready,” she said. “Doris and Becky have organized the whole party. And whatever are you baking in the kitchen? I can hardly wait to find out!”

Mrs. Craig squeezed her daughter’s hand. “I wonder if we’ve ever tried to have any sort of party in this house without Becky’s help,” she mused.

Jean laughed. “Aunt Becky would be positively insulted if you didn’t ask for her help, and you know it,” she answered.

“Aunt Becky would be lost without the Craig family[14] to look after, you mean,” Mrs. Craig laughed. “Ever since she urged us to come to Elmhurst in the first place, she’s been watching over us like a mother hen.”

Jean giggled. “I would give anything to be at the hospital now. Did I tell you that the doctors have taken over for the nurses tonight? So that the girls could all come to the shower. I can just see Dr. Daley and Dr. Jenkins running to answer patients’ calls.”

“It was lovely of them to volunteer,” Mrs. Craig said.

Jean nodded. “Oh, they’re all like that. I guess you have to cooperate if you have such a small hospital. Oh golly,” she sighed, “the wedding makes me want to cry.”

“I know how much you miss Ralph, dear,” Mrs. Craig answered. “Just a few more weeks and he’ll be back again.”

“He’s in Norway now. Did I tell you, Mother?” Jean asked.

Mrs. Craig laughed. “Yes, dear. You told me. In fact, you read me his last letter.”

Jean blushed. “That’s right. I guess I’ve told you a hundred times.”

Mrs. Craig smiled. “I think it’s wonderful that you want to talk about Ralph so much.”

Doris came out on the porch and breathed deeply of the fresh air. “What a night for a party!” she exclaimed. “It’s just about perfect!”

“Where’s Becky?” Mrs. Craig asked.

[15] “Oh, she went upstairs to see Jack for a minute.”

Mrs. Craig sighed. “Has Jack gone to bed? So early?”

Jean turned around to face her mother. “I thought he and Tommy were going over to Billy Ellis’s for the night.”

Mrs. Craig shook her head. “Tommy went, but Jack said he didn’t feel well.”

Doris sat down on the porch swing. “Becky went up to give him a tonic. She said something about springtime and sulphur and molasses....”

“And sulphur and molasses never hurt anyone,” Aunt Becky said as she came out to join them. “I tell you, you have to get winter out of a growing boy’s bones. The way that youngster has been mizzering around lately just proves it. When he passed up the chance to spend the night with us, I knew something was wrong.”

“Is Jack in bed, Becky?” Mrs. Craig asked.

“Yes, he is. He’s just plumb tuckered out. No wonder. He didn’t eat enough supper to keep a bird alive.”

Mrs. Craig said, “I’ll go up to him in a few minutes. After the guests arrive.”

Just then a car turned into the Craig driveway. Doris stood up. “Here they come. Don’t forget, Mother, Becky. This is a surprise party.”

The car door opened and Hedda and Ingeborg hopped out. The student nurses ran up the steps while[16] Ethel switched off the ignition and headlights and climbed out after them.

“Evening, Mrs. Craig, everyone,” the girls called as they came up to the porch.

“Good evening, girls,” Mrs. Craig replied, grasping their hands. “Ethel, dear, you look lovely this evening.”

Ethel slipped off her white wool jacket and displayed her silver-green party dress. She whirled around. “See the skirt,” she laughed. “Ted helped me pick this out.”

“He has lovely taste, then,” Mrs. Craig said.

“For a man,” Hedda added. “It’s simply gorgeous.”

Ethel smiled as she thought of her fiance. “You know, it’s wonderful,” she said softly. “I haven’t any father or mother to help me prepare for the wedding, so I have a fiance who can be so helpful and wonderful in these things!”

Mrs. Craig smiled fondly at the girl. “Well,” she said briskly, “let’s go inside.”

The girls drifted into the living room. Doris sat down at the piano and began to play a popular tune. They all grouped around her and began to sing as Mrs. Craig slipped out to the kitchen.

Jean heard sputtering and backfiring in the driveway. “Here come Helen and Eileen,” she cried.

In a few minutes, the two girls appeared in the doorway. “Old Bessy made it up your hill,” Eileen giggled. “There’s life in the old rattletrap yet.”

[17] “How’re the doctors making out over at the clinic?” Ingeborg asked.

Helen chuckled. “Oh, just fine. Can you imagine Dr. Jenkins making formula for the babies? He certainly looked fussed and awkward.”

“Wait till Ted’s bachelor dinner,” Jean teased. “Then I suppose we’ll have to do all their work.”

“Dr. Barsch is at the desk,” Helen continued. “Any calls tonight are going to be answered by St. Peter himself,” she said irreverently.

Lucy Peckham and Sally Hancock came in the door just as Mrs. Craig brought in a large bushel basket decorated with white and gold paper. The basket was heaped with shower gifts for Ethel.

“Here you are, my dear,” Mrs. Craig said. “And you know we all wish you great happiness with every gift.”

Tears glistened in Ethel’s eyes as she looked at the basket.

“I sort of knew it would be a shower,” she admitted. “But I never had a basketful of presents before in my life. You just shouldn’t have done it!”

Doris started to play the Wedding March, and the girls clustered around Ethel as she slowly opened her presents. Mrs. Craig waited till the first gift was opened, and then she slipped out into the hall. As she started up the stairs, the door opened, and Mr. Craig and Ted Loring came in.

She turned around and came down to greet her[18] husband and the young doctor. “Why, Ted,” she said fondly, “how nice to see you!” She smiled at her husband.

“Ted and I have some things to talk over, Marge,” Mr. Craig explained. “We thought tonight would be a fine time.”

“Then you didn’t come to join the party?”

Ted stared at her in mock horror. “Heaven forbid!” he exclaimed. He peeked through the entranceway into the living room. “They do look lovely, don’t they?”

Mr. Craig smiled at the sight of the radiant girls. “Yes, they do,” he agreed. “Now Marge, if you’ll excuse us, I’ll just take this young man into the study.”

“Oh, of course,” Mrs. Craig said. “I’m on my way upstairs. I’ll bring you some hot chocolate later, if you like.”

They both smiled and nodded as she went upstairs.

“Come in, Ted,” Mr. Craig said, opening the door to his study. They sat down in comfortable chairs and pulled out their pipes.

Mr. Craig smiled disarmingly at the boy. “You might call this a trial run for me, son,” he said.

“I don’t understand, sir,” Ted replied, lighting his pipe.

Mr. Craig leaned back and stared out of the window. “I guess you know that our daughter will be getting married pretty soon. When young MacRae comes back[19] from Europe, probably. I guess he’ll want a few words with me beforehand. So I thought I’d ... well, I’d practice on you.”

Ted nodded. “You don’t know what this means to me, Mr. Craig,” he said warmly. “You and Mrs. Craig have been like a second father and mother to Ethel, and this gesture just about completes the picture.”

Mr. Craig nodded. “Fine girl,” he mused. “I can’t remember knowing any finer girl, as a matter of fact. Well, I guess all young people have to listen to some old man recount the blessings and pitfalls of marriage sooner or later. Your mother is still living, isn’t she, Ted?”

“Yes, sir. She will be here next month for the wedding. She and Ethel have been corresponding for several months, now. Needless to say, Mother is thrilled.”

The older man nodded. “I’m glad to hear that. Now, Ted, I’m in no position to ask you impertinent questions about your bank account or your ideas about marriage or anything else. But I just want to give you a little advice. Advice which I think you can use. In some ways, you and I are very much alike. Before I went into the Army, I was pretty absorbed in my work. Perhaps I knew as much as the average husband and father about what was going on in my family. But it took a war and a serious illness to prove to me that no work in the world is one quarter as important as a man’s wife and children.

[20] “I know what medicine means to you, Ted. I have some idea of the demands it makes on you. But never forget that you will have a wife who will stand beside you and will help you fight whatever battles come along. Just don’t forget to let her help you in the fight....”

Mrs. Craig knocked softly at the door.

“Come in, Marge,” Mr. Craig called. “We could use some hot chocolate.”

“I’m sorry,” Mrs. Craig said as she closed the door behind her. “I didn’t intend to break in on you quite so soon. But, dear, I’m worried. Jack is upstairs in bed. He isn’t feeling at all well.”

Mr. Craig tapped the heel of his pipe in his hand. “Something he ate for supper?”

Mrs. Craig shook her head. “No, it’s a cold, or, well, I don’t exactly know what. He has some fever.”

“How high a fever, Mrs. Craig?” Ted asked.

Mrs. Craig smiled almost apologetically. “Hardly any at all. His temperature registers just over ninety-nine. But he feels so bad. He says he aches all over.”

Ted started for the door. “If you don’t mind, Mrs. Craig, I’m going to take a look at him,” he said.

Jack was lying face down on his cot when Ted and Mr. and Mrs. Craig came into his room. He turned his head with a grimace and looked up at them listlessly. Ted walked quickly over to him and sat down on the floor beside his bed.

“Just let your head down, Jack,” Ted said as Jack tried to look up at his mother and father. “Now tell me where you hurt.”

“All over,” Jack whispered.

Ted nodded. “Does it hurt to talk?”

Jack nodded.

Ted looked up at Mrs. Craig. “How long has he been feeling this way?”

Mrs. Craig said helplessly, “I don’t think it’s ever been this bad. He’s been sort of listless ever since he had a cold last month.”

Ted picked up Jack’s arm gently. He pressed against the elbow. Jack winced.

“What kind of cold was it?” Ted asked.

Mrs. Craig smoothed Jack’s forehead. “Well, he first had the sniffles, and then a sore throat and then a[22] cough. Pretty much like all his colds. Then, a while later, he got another sore throat. He ran some fever.”

“Uh huh,” Ted said, nodding his head.

“Mother, my head aches,” Jack moaned.

Ted sighed and stood up. “Well, we can’t do anything here. If you don’t mind, I’d like to run him over to the clinic and let Dr. Barsch and Dr. Jenkins have a look at him. I came on a social call, and I don’t even have a stethoscope with me.”

Mrs. Craig straightened up. “Is it serious, Ted?” she asked.

Ted hesitated and then nodded. “It might be, Mrs. Craig,” he said. He picked up Jack’s wrist and looked at it. “There’s some swelling here. You see?”

Mr. and Mrs. Craig both nodded.

“Well, let’s get him to the hospital,” Ted said. “If we can wrap him up in blankets, we don’t need to bother him with clothes.”

Mrs. Craig picked up Jack’s blankets and wrapped them around the bewildered boy. Ted smiled at him and said, “Cheer up, son. These things happen to the best of us. We probably won’t keep you at the clinic very long.”

Mrs. Craig started for the door. “I’ll get my coat,” she said.

Mr. Craig caught her arm. “Let me take the boy over, Marge,” he said. “The girls will need you for their party.”

Mrs. Craig whirled around. “I can’t leave him now!”[23] she cried. “My boy is sick, and I’m going to stay with him!”

Mr. Craig put his arm around his distraught wife. “Of course, dear,” he said. “And please don’t worry.”

“Get your car ready,” Mrs. Craig said to Ted. “Mr. Craig can carry him downstairs. We’ll be ready when you are.”

Mrs. Craig ran downstairs and took her coat from the hall closet. She looked into the living room where the party was in full swing. After a minute she caught Jean’s eye.

“Jean,” she said softly, as her daughter came to the doorway. “Jack is sick, and Ted and I are going over to the clinic with him. Don’t tell the others. I don’t want to break up their fun. But you’ll have to manage without me.”

Jean gasped. “Oh, Mother! I’ll go over with you!” she cried.

“No, dear,” Mrs. Craig said firmly. “You stay with your guests. I’ll call you as soon as we know anything.”

Mr. Craig bundled Jack into the car, and Mrs. Craig and Ted started off with him toward town. Ted drove slowly, avoiding the bumps in the country road. Mrs. Craig supported Jack tenderly, trying to brace him against the swaying of the car. She noticed that Ted was scowling angrily, and she suddenly felt cold with fright. As if he could sense her terror, Ted reached over and patted her hand.

“I think everything’s going to be all right, Mrs.[24] Craig,” he said reassuringly.

Dr. Barsch was at the desk when they came into the hospital. Ted exchanged a few words with him. The head doctor nodded gravely and came over to Mrs. Craig and the boy.

“So you’ve caught yourself a bug, Jack,” Dr. Barsch said. “Well, let’s get you upstairs, and Dr. Jenkins and I’ll go over you, and see just what is the matter. If Dr. Loring will take over at the desk, I’ll have an orderly take you right up.”

“May I go, too, Doctor?” Mrs. Craig asked.

Dr. Barsch hesitated, and then Mrs. Craig said, “No, I’ll wait here. I shouldn’t have asked. I’m sorry.”

Dr. Barsch nodded. “It’s all right, Mrs. Craig. I know you’re worried. I’ll let you see Jack as soon as I can.”

After the orderly had taken Jack upstairs, Ted sat down behind the desk facing Mrs. Craig, who paced nervously back and forth.

“Please sit down, Mrs. Craig,” he begged her. “You’ll just wear yourself out.”

Mrs. Craig smiled and sat down in an easy chair across the desk from Ted. “I must seem like a foolish mother hen,” she said apologetically.

Ted looked at her in wonder. “I wish there were more mothers in the world like you. Some of the mothers I’ve seen wouldn’t be this anxious about their own children, let alone an adopted son.”

Mrs. Craig thought a moment. “I wonder why people don’t understand,” she said softly. “Jack is every[25] bit as much my own child as if I had given birth to him.”

Ted nodded. “Of course I’ve always thought of him as your own, because he’s been with you as long as I’ve known you. But I’ve often wondered, Mrs. Craig, why you and Mr. Craig adopted another child. I mean, when your family is as large as it is.”

Mrs. Craig smiled softly as she remembered Jack when he first came to her house. “We didn’t exactly adopt Jack. He adopted us. He turned up one day looking for work. When he was just a bit of a thing. His mother was dead. And his father!” she made a face as she remembered the distasteful man. “He was frightful! He dragged that mite of a child along with him on box cars! He ... he rode the rails, I think the expression is. And then he found that Jack was too much of a nuisance, thank God! And he dumped him off at Elmhurst.”

“You mean he ran away from his own son?”

Mrs. Craig nodded. “And so Jack came to us. Then, just about two years ago, his father turned up again. I suppose that was fortunate, too. He wanted Jack back. You see, Jack and Tommy make quite a bit of money from their chickens. So he wanted Jack’s money. Mr. Craig made a settlement with him, and he gave us permission to adopt Jack. So, you see, Jack is our very own child. And that dreadful man has no claim to him, whatsoever!”

Ted smiled. “Jack was lucky,” he said quietly.

“And so were we. I can’t imagine how, but that[26] boy, brought up in filth and horrible conditions, was as fine a boy as you can imagine. Right from the very start. Oh, Ted, if anything happened to Jack, we’d be lost!”

Ted smiled again. “Nothing will happen, Mrs. Craig,” he reassured her.

“What ... what do you think it is?” she asked timidly.

Ted hesitated. “I don’t know, of course,” he said.

“You mean, you don’t want to tell me?” she asked.

He drew a long breath. “Very well,” he said. “I’m afraid it may be rheumatic fever.”

Mrs. Craig drew a long sigh of relief. “Oh, good heavens. And here I’ve been really worried. I was so afraid of polio. I know it isn’t the right season for polio, but you don’t know how a mother worries about such things!”

Ted ran his hand through his hair. “I don’t think you understand, Mrs. Craig. Do you know what rheumatic fever is?”

Mrs. Craig shook her head. “A sort of rheumatism, isn’t it? That would explain the aching and the tiredness and swelling of the joints.”

Ted sighed. “It’s a type of rheumatism, all right. But compared to rheumatic fever, polio is a pink tea party.”

Mrs. Craig gasped. “Oh, no!” she cried.

Ted drummed his fingers against the desk. “I don’t mean to under-rate the seriousness of polio. But almost always polio can be diagnosed ... at least the mother[27] knows the child is really sick. But this mean villain of a germ which Jack may have is one of the slickest criminals of the medical world. Rheumatic fever doesn’t cripple outwardly ... doesn’t disfigure a person the way polio does. But it can cripple and kill.”

Mrs. Craig caught Ted’s hand. “Oh, Ted!” she cried.

Ted covered her hand with his. “Now, it’s not going to kill Jack. I can promise you that.” He ran his fingers through his hair again. “But you have no idea how many youngsters contract the disease and no one ever knows it.”

“How does it work, Ted?” she asked.

“It usually starts in the form of a strep throat. You remember you told me Jack had not one but two sore throats with his cold? Probably he caught the infection while his resistance was low from his cold. Then, after a while, the throat heals and the patient is presumably well. Only he doesn’t really feel good. He hasn’t much appetite. He’s listless. He aches in the joints. He isn’t exactly sick, but he isn’t well, either. Lots of people ignore these symptoms. So the strep then attacks the heart. If the patient is lucky, after that, he manages to fight off the infection, or arrest it, and survives with a badly damaged heart.”

Mrs. Craig covered her mouth with her hand. “And if the patient isn’t lucky?” she asked.

Ted shook his head. “Let’s not talk about it any more,” he said.

“You mean, he dies?”

Ted nodded. “But you must remember this. Jack[28] doesn’t fit either case. Thanks to you, we’ve caught the villain. Jack’s going to have help in his fight.”

Dr. Jenkins came down into the lobby and nodded to them. “I think we’ve found the root of the trouble,” he said calmly.

Mrs. Craig shook her head as if to fight off a bad dream. “Dr. Jenkins,” she said slowly, “your specialty is heart trouble, isn’t it?”

Dr. Jenkins smiled. “Of course I’m just past my internship, Mrs. Craig. Someday I hope to be a heart specialist, though. But for right now, I’d like to call in a specialist from Boston. We want to be very sure to do exactly the right things.”

Ted looked at the other doctor. “I was right, Fred?” he asked.

Dr. Jenkins nodded. “And if Mrs. Craig wants to see Jack now....”

“Oh, please!” Mrs. Craig cried. “Ted, will you call Mr. Craig and tell him? But please don’t let him tell the girls till the party is over.”

Jack was lying flat on his back in a small single room near the pediatric ward. He managed a grin as Mrs. Craig came into the room.

“Jeepers, you should see all the things they did to me,” he said as gaily as he could. “Mother, it sorta makes a guy feel important with a couple of doctors fussing over him.”

Mrs. Craig knelt beside his bed. “All right, baby, everything is going to be fine.”

[29] Jack grimaced. “I’m not a baby,” he protested weakly. “They gave me some aspirin and stuff. My head doesn’t ache so much. Hey, will you ask Tommy if he ever had a car—cardio—you know what I mean?”

“A cardiograph? I’m sure Tommy never had one. You’ll be able to tell him all about it in a few days,” Mrs. Craig smiled.

“They gave me a pill. I feel sorta dopey. But don’t hang around all night or anything, because I’m gonna be okay.”

Mrs. Craig caressed his forehead gently. “Of course you are, Jack.”

Jack dozed off. But as he relaxed, a spasm of pain hit him, and he cried, “Mother!” Too near to sleep to act like a man any longer, he whimpered like a young child. Mrs. Craig stroked his black hair tenderly.

Dr. Barsch appeared in the doorway. “I think he’s asleep, Mrs. Craig. If you want to stay here tonight, there is a room next to this one....”

“Is it all right if I stay right with him?” she asked. “I’m not very sleepy.”

Dr. Barsch came in and sat down beside the bed. “You’re a wonderful woman, Mrs. Craig,” he said softly. “This boy is so lucky. And what a boy he is! The exam we gave him wasn’t very pleasant for him. He’s in a lot of pain. But he joked and grinned and ...” he turned his head away a little. “I don’t know. Sometimes a youngster like this can make one proud to be part of the human race!”

Billy Ellis and Buzzy Hancock dashed up the driveway to the porch of the Craigs’ farmhouse. Tommy was sitting on the porch swing jotting down figures in his account book when his pals joined him. They jumped up on the porch, and Billy cuffed Buzzy playfully as they sat down on the swing.

“Hey, take it easy, you guys,” Tommy said. “I’m trying to add up my accounts. I want to give Jack an exact report of how much money we made while he was gone.”

Billy stretched his long legs out in front of him. His voice, which wavered between soprano and baritone, was full of sympathy as he said, “Jeepers, what a break! The poor little guy’s going to miss all the fun this summer.”

Tommy looked at his two closest pals. Billy, Judge Ellis’s son and Aunt Becky’s stepson, was a few months younger than he. Ever since the Craigs had come to Elmhurst, both Billy and Sally Hancock’s young brother, Buzzy, had been involved in every project Tommy and Jack had undertaken.

He shut his book. Stretching lazily, he said, “I[31] guess it’s up to us to see he has as much fun as possible. It’s a real tough break for the ball team, though. I don’t know where we’re going to get a good shortstop now that Jack’s out for the season.”

“Can we see him soon?” Buzzy asked.

Tommy shook his head. “Mom says no company for a while. He’s coming home this afternoon, but you guys can’t see him for some time.”

Billy sighed. “Seems to me there isn’t any use in being sick. It isn’t any fun no matter which way you look at it. What’s the guy going to do with his time?”

“Oh, read, I guess. And study. He’s going to have a tutor, Mom said,” Tommy answered.

Buzzy whistled. “You mean he’s gotta have school work? Jeepers! That’s terrible!”

Tommy shrugged. “It would be worse if he had to stay back a term in school.”

“Yeah, I guess so,” Buzzy said thoughtfully. “But about what we guys can do. You think about it, Tommy. Let us know, won’t you?”

Tommy stood up. “Will do,” he said. “And listen, you guys, one more thing. Mom said those letters you wrote were just about the nicest things you could have done for him. Keep it up, will you?”

Doris came out to the porch. “Tommy, have you seen Mother?” she asked.

“Sure. Mom’s upstairs getting ready to go over to get Jack. What’s up?”

“Where’s Dad?”

[32] Tommy stared at her. “At the office, of course. Where else?”

Doris giggled at herself. “I guess I got so used to having Dad around the house that I forgot he does go to work regularly now.” She pulled a letter from her pocket. “It’s from Kit,” she told him.

“From Kit? Hey, let’s see it!” Tommy cried.

Doris put it back in her pocket. “It’s to Mother and Dad,” she said severely.

Tommy shrugged. “Come on, gang,” he cried. “Let’s get some cookies.”

The boys disappeared into the kitchen, and Doris went upstairs.

“Mother!” she called. “Letter from Kit!”

Mrs. Craig was putting on her hat when Doris came into her room. She smiled at her daughter and held out her hand. “Good news, I hope,” she smiled, taking the envelope.

“Kit’s news is always good,” Doris said. “College seems to agree with her.”

Mrs. Craig hastily scanned the note, nodding and then frowning as she read. “Kit has spring fever,” she decided as she folded the letter and slipped it back into the envelope. “Claims she’s bored with life.” She smiled to herself. “But after her trip to Washington, I think she’ll feel better.”

“What trip to Washington?” Doris asked.

Mrs. Craig grinned at the thought. “Kit has been elected president of the Hope College Historical Society,[33] you know, dear. There’s a large history convention in Washington after classes let out in June. There will be girls and boys from all over the country.”

Doris grinned. “And of course there will be Frank Howard in Washington.”

Mrs. Craig sighed. “I think that’s what’s wrong with Kit. I think she misses Frank more than she will admit.”

Doris sat down on her mother’s bed. “Do you think Kit will marry Frank, Mother?”

“Good heavens!” Mrs. Craig exclaimed. “How should I know? They are very close friends ... and they have been for several years.”

“Ever since Kit caught Frank in the berry patches,” Doris giggled. It was typical of Kit that she should have trapped the bright young entomologist in an effort to catch a berry thief. A bantering friendship had grown out of this episode, and lately there had been sure signs that the friendship between Kit and Frank was ripening into affection.

Mrs. Craig powdered her nose. “Do you want to ride with me to the hospital, Doris?”

“Yes, I’d like to,” Doris said. “I want to talk to you about something, anyway.”

On the way over to the clinic, Doris said, “There’s a sort of contest at school, Mother. A music contest.”

Mrs. Craig smiled. “That’s nice, dear,” she said. “Are you going to enter it?”

Doris frowned slightly. “That’s what I wanted to[34] talk to you about. It’s for a scholarship to a music school. I don’t know whether I want to try for it or not.”

Mrs. Craig stared at her. “But good heavens, why not? What school is it?”

“Timothy College in North Carolina. It’s very small—all music, you know. It’s awfully far away, too. And with Jean getting married and Kit away at school, well, I don’t know whether I want to leave home or not.”

Mrs. Craig slowed down the car. “Let’s talk about this with your father. But, dear, I think you should at least try out. It would be a shame to let your talent go to waste.”

Doris hesitated. Then she said, “But Mother, I don’t want to go away! I’m not like Jean and Kit. I’d just like to stay right here in Elmhurst forever and ever. I like it at home.”

Mrs. Craig tapped the steering wheel with her fingers. “Doris, I want you to enter that contest. Why shouldn’t you have the right to go away to school? We were able to send Jean to New York for a year of Art School,” she said, referring to Jean’s experiences which are recounted in Jean Craig in New York. “Then Kit won herself the chance to go to Hope College. Now, it’s your turn.”

“But Mother....” Doris began.

Mrs. Craig shook her head. “I don’t know very much about art or music, my dear,” she interrupted, “but your father and I have always felt that you were[35] extremely talented. Frankly, I’ve always felt that you were the most talented of all my daughters. Jean is a good artist. Competent, I think she calls herself. But she has no illusions about being a great artist. I think perhaps you have the ability to develop into a fine musician.”

Doris shook her head. “Oh, golly,” she said, “I just don’t want to go through what Jean and Kit have gone through.”

“What do you mean?” Mrs. Craig asked, surprised.

“You know. You get yourself all ready to do something important in this life, and then you fall in love with some man and want to get married. Look how mixed up Jean was. And look at Kit now. She’s going to college and has even talked about doing graduate work. But you and I know she’s mad about Frank Howard and that she’ll probably just get married.”

Mrs. Craig repressed a smile. “Darling, you don’t just get married,” she said gently. “Both Jean and Kit are much better prepared to become good wives because they did develop their talents. I think you should do the same.”

Doris sighed. “Maybe so,” she agreed. “Oh, golly! I’m selfish! I know you’re worrying about Jack and his homecoming. It’ll be so good to have him home again!”

Jack was waiting when they arrived at the hospital. Jean and Sally Hancock were in his room gathering his few belongings. Mrs. Craig shook her head as[36] she saw the thin, pale boy lying on the bed. His black eyes seemed even larger than usual, but they were no longer dull and glassy. They sparkled when they saw Mrs. Craig.

“Oh, Mother!” he cried. “I thought you’d never get here! Golly, but I’m tired of this room. Not that they haven’t been swell here, though. Dr. Jenkins and Dr. Caulfield from Boston have been here almost all the time. They talked a lot to me.”

“That’s fine, dear,” Mrs. Craig said briskly.

“But, gee, I sure missed Tommy. And the hens. Tommy doesn’t know how to keep track of all those hens. I ... I don’t know what he’s gonna do, now that I can’t help him.”

Jean patted Jack’s shoulder. “You’re learning young that no man is indispensable to his business.”

He looked up at her. “Huh?” he said.

They all laughed. “Jean means that business has to go on no matter what happens,” Mrs. Craig said, smiling. “And it usually does. Billy Ellis and Buzzy Hancock were over this morning. They want to see you as soon as you can have company.”

“Yeah, I know,” Jack said. “They wrote me. Jeepers, what a swell gang they are! Those dumb letters! They made me laugh till I hurt!”

Ted Loring brought in a wheel chair. “Here’s your chair, my lord,” he called from the doorway. “Oh, good morning, Mrs. Craig. You’re looking fine this morning. I’m going to ride over with you and help[37] get our patient back to bed, if that’s all right with you.”

Mrs. Craig smiled. “That’s very thoughtful, Ted. Mr. Craig is in town this morning, and we could use a strong back.”

Ted grinned. “I heard about Mr. Craig’s new position. I think it’s swell. We need an architect around this town, although I sort of like these old New England designs.”

Mrs. Craig smiled. “He’s glad to be back at work, too.”

“I found out about it from Dr. Daley,” Ted explained. “I guess you know he kept a pretty close eye on Mr. Craig while he was working on the veterans’ houses. A nervous breakdown is nothing to fool around with. But Dr. Daley seems to think he’s now in fine shape.”

Jean tucked a robe around Jack’s legs as they started out of the room. “Take good care of him, Mother,” she said. “I’ll be home for dinner tonight, you know.”

Jean watched the small procession move slowly down the hall. Then she pulled her sketchbook from her pocket and began thumbing through it.

“Hi, gorgeous!”

Jean turned around to see Gerald Benson, the new intern, coming down the hall. “Oh, good morning, Dr. Benson,” she said. She started to pass him, but he blocked her path.

“I’ve just been having a lecture on the glories of[38] one Miss Jean Craig,” Dr. Benson said. “They sure go for you around here.”

Jean stared at him in surprise. “Whatever are you talking about?”

He shrugged. “I was ambling through the lobby with Dr. Barsch this noon and just happened to comment on the painting over the mantel down there. And the good doctor ups and tells me that you did it!”

Jean giggled. “I’m afraid I did,” she admitted. “It’s not so glorious, though,” she added.

“It’s good enough. I didn’t know you were an artist.”

Jean smiled. “I’m not. Not really. I studied for a year in New York. And I like to paint for pleasure. As a matter of fact, I’m hoping to do something with my art work combined with medicine.”

Dr. Benson whistled. “You mean surgical art? That’s a tough field.”

Jean grinned. “I know it is. But Dr. Barsch has encouraged me to try my hand at it. I guess starting just about any time now, he’s going to give me practice sketching operations here. As a matter of fact, I was just going through my sketchbook. I’m working on anatomical drawings from books now so I’ll be better at doing real life sketches.”

Dr. Benson put his hands on his hips. “Did you donate that painting to the clinic as your contribution?”

Jean smiled again. “Well, not exactly,” she admitted. “You see, when the hospital first opened, Ted Loring[39] and I had a long talk about clinics and things. And he gave me the idea, sort of. He said a clinic was a place where people exercised cooperation, ingenuity and hard work. So I put the idea down on canvas. You know, the man and woman and child joining hands in a field of grain. And then, of all things, Dr. Loring swiped it! He donated it!”

Dr. Benson smiled wryly. “It sounds like a motto he might make up.”

“What’s the matter with it?” Jean demanded.

“Let’s go out tonight, and I’ll tell you,” Dr. Benson said.

She smiled at him. “I’m sorry, Dr. Benson, but I can’t.”

“But you’re off tonight. I saw the schedules.”

Jean smiled. “But I thought you knew. I’m engaged. I’m not free to accept dates. I’m sure one of the other girls....”

“You mean you’re turning me down just because you’ve got a ring? I hear your man is in Europe. That’s pretty far away. And a pretty little girl like you shouldn’t be sitting home nights, just because—”

Jean brushed past him. “I’m sorry,” she said shortly.

Dr. Benson grabbed her arm. “Now wait, honey. Don’t get sore. I mean, what’s the harm? I’m not asking you to break your engagement. I just wanted to have some fun. You look as if you could use some yourself.”

Jean pulled free. “I’m sorry, Dr. Benson,” she said[40] stiffly. “I’m very busy just now.”

The intern watched her walk down the hall. “Okay, sweetheart,” he said, “I’ll try again sometime. You’ll get lonely before too long.”

Jean marched into the students’ lounge and slammed the door behind her. Eileen Gordon was lying on the couch reading a magazine. She looked up as Jean came in.

“Why, Jean, what’s the matter?” she asked, looking at Jean’s angry face. “Didn’t Jack get off all right?” Eileen sat up and closed her magazine.

Jean sat down in an easy chair. “Oh, yes. Mother came for him just now. Ted was sweet. He went home with them to help her get Jack settled in bed at home.”

“Well, then, what’s wrong?” Eileen asked.

“Oh, nothing really, I guess. Only that new Dr. Benson asked me for a date.”

Eileen sniffed. “Oh, is that all?” she asked. “Well, don’t worry about it. He won’t ask you again.”

Jean stared at her. “Why?” she asked.

Eileen shrugged. “He asked me for a date when he first came here. I was busy and told him so, and he hasn’t bothered me since.”

Jean shook her head. “It’s the principle of the thing,” she said.

“Maybe he didn’t know you’re engaged.”

“He knew, all right. He knew that Ralph is abroad, too. He said I might be lonely.”

[41] Eileen scowled. “So that’s the way he is! Well, that settles Dr. Benson as far as I’m concerned. So he’d try to steal someone’s girl when the someone isn’t around to fight for her.”

Jean laughed as she opened a coke. “Don’t be too hard on him. He wasn’t exactly trying to steal me. He just asked to take me out.”

Eileen grimaced. “I know the type. You know, Jean, I’ve been around hospitals a long time. And I’ve known a lot of doctors. They aren’t all like Ted and Dr. Barsch and the rest of them here. Sometimes they get pretty cynical. Yep, I know Dr. Benson’s type, all right!”

The following night Jean was on duty. She had just come up from early supper when she was called into Dr. Barsch’s office.

“Miss Craig,” Dr. Barsch said briskly, “I haven’t much time to explain, but if you will get your sketch pad, I want you to try to do a drawing of an operation I’m about to perform. The little DuPrez boy is coming in immediately. Acute appendicitis. Loring says we can’t wait. I’ve already called the staff.”

Jean gasped. “You mean, you want me to go right in there and do a drawing?” she asked.

Dr. Barsch nodded. “You can’t learn surgical art any better way. I don’t expect to be able to use your sketch, but I want you to have the practice.”

“Then you won’t use me to assist you?” she asked.

Dr. Barsch frowned impatiently. “Naturally not. Now, please hurry. Get your materials, and I’ll see you upstairs.”

Jean hurried to her room and snatched up her sketch pad and pencils. She ran down the hall towards the operating room and went into the small[43] lavatory to scrub. Two women were scouring the room, and Helen Pierce was sterilizing instruments. When Jean had finished scrubbing, Helen helped her with her gloves and mask.

“This is a real emergency,” Helen muttered as she checked her instruments. “They always wait till the last minute before they call the doctor.”

“Will it be a dangerous operation?” Jean asked.

Helen shrugged. “That depends. Usually an appendectomy is a snap. That is, easy for the patient. But it can be ticklish if the appendix is ready to break open.”

Dr. Barsch and Ted came in to scrub up. The girls worked in silence, and the only sound was that of the rushing water in the lavatory. Dr. Henry, the anesthetician, bustled in and, after scrubbing, came over to the sterilizer and peeked in.

“I can’t use ether, Miss Pierce,” he said. “You should know that.” He grunted. “And if we could use a complete anesthetic, I’d choose sodium pentothal. But this will have to be a local block. The child undoubtedly has eaten today.”

Helen nodded and went over to the cabinet. Carefully she selected an injection syringe with her tongs and dropped it into the sterilizer. Dr. Henry checked his supply of anesthetic, nodded, and rubbed his gloved hands together briskly.

Jean frowned. “Why can’t you use ether, Dr. Henry?” she asked.

[44] The portly, middle-aged anesthetician turned around to face her. “Some people get very sick when we put them out. Particles of food or liquid are apt to catch in their lungs. They haven’t the control of their reflexes that people who are awake do. There’s always the danger of a patient choking to death.”

“Then the child will be conscious?” Jean asked. “He’ll know what’s going on? I know we’ve used that frequently for adults, but won’t it be difficult with a child?”

Ted laughed. “He won’t know much. We already have him so groggy with sedatives that he doesn’t know what’s going on.”

Dr. Barsch frowned impatiently. “What’s keeping them? Every minute we lose gives us less of a chance.”

As he spoke, the small patient was wheeled into the operating room. Jean’s heart went out to the tiny, white figure lying on the table. His eyes were dulled, and his body was partially relaxed. But his face was a study in fear.

Dr. Barsch stepped over to the table. “All right, son,” he said gently. “I’m going to put a curtain right over your middle. You know what you’re going to feel?”

Gene DuPrez shook his head, and he gazed pleadingly at Dr. Barsch.

“Ever been to the dentist?”

The boy nodded.

“And did he poke a needle into your gum so it[45] wouldn’t hurt when he drilled into your tooth?” Dr. Barsch asked.

Gene nodded solemnly. Sally, who had come in with the boy, and Helen turned him over on his side and bent his legs up to meet his chest.

“Well, we’re going to do the same thing now. We’re only going to hurt you enough to make you say, ‘ouch’.”

Gene interrupted Dr. Barsch by saying, “Ouch!”

“That’s it, Gene,” Dr. Barsch said. “You’re going to feel something else, now. Your toes will get all numb. Then your legs, and then your tummy. Now, I have a feather, and I’m going to tickle your tummy. You tell me when you can’t feel it any longer.”

Sally drew the curtain across the boy’s abdomen so that he couldn’t see below his chest. Then she took her station by Gene’s head. Smiling down at him, she tousled his hair. “Feel kind of sleepy, don’t you?” she asked.

“It still tickles,” Gene murmured.

On the other side of the curtain, Dr. Barsch had made the incision. He smiled and silently gave thanks for the anesthetic which made a deep abdominal wound feel like a tickle. But his smile disappeared when he reached the appendix.

“Oh, brother!” Ted said, shaking his head. Jean glanced at the open wound and began to sketch rapidly.

“Here’s one we caught just in time,” Dr. Barsch[46] sighed. He spoke so low that Gene couldn’t hear him. “Look at that appendix. I’ll be lucky if I can get it out without breaking it. When, in heaven’s name, did you first see this boy?” he asked Ted.

Ted bit his lip. “Ten minutes before we came over. I didn’t even stop to do a blood count on him. Let’s not talk about it. I get cold shivers up and down my back when I think of how close his mother came to giving him something for his stomach ache instead of calling a doctor.”

Jean shuddered at the thought.

“It still tickles, doctor,” Gene said in a piping voice. “I’ll tell you when it stops.”

Jean grinned as she bent over her sketch.

“Something just stopped her,” Ted continued. “She called me instead. A hunch, she said.”

“God loves His small creatures,” Dr. Barsch replied. “All right, here we go.” He lifted the swollen appendix from the wound with great care. With a sigh of relief, he placed it carefully in a receptacle on the table. The distended organ broke as he laid it down.

“Ye Gods!” Ted said, turning white. “That’s the closest one I’ve ever seen!”

Dr. Barsch grinned as he started to sew up the incision. “It’s all over now, doctor. Gene, does it still tickle?”

“A little bit,” the boy answered. “Not much.”

“Good boy!” Dr. Barsch said. He finished his sewing and nodded. “What about now?”

[47] “I don’t feel anything now,” Gene admitted. “You going to cut into my stomach now?” his face became tense with fear. Sally rubbed his forehead and grinned.

“Too bad, Gene,” she said. “You missed the show.”

Gene stared up at her. “What?” he asked.

Dr. Barsch dressed the wound and pulled the curtain aside. “How do you feel?” he asked.

“I’m ... I’m a little scared,” Gene admitted.

Dr. Barsch laughed. “We just played a dirty trick on you, son. Your operation’s all over.”

Sally gave the patient an injection, and he relaxed again.

“You’re going to sleep for a while now. And when you wake up, you’ll be back in your room with a sore tummy.”

Gene relaxed and slipped off to sleep as Sally and Helen wheeled him down the corridor.

Dr. Barsch slipped off his gloves and glanced at the broken appendix. He shook his head. “Get that to the lab right away,” he said. “Miss Hancock can take it down when she gets back. Miss Craig, you come on down to my office with me. I want to take a look at that sketch.”

When they reached Dr. Barsch’s office, Jean laid her sketch pad on the desk for Dr. Barsch to see. He picked it up and nodded.

“Sit down, Miss Craig. Dr. Loring will be down in a minute. I want him to have a look at this, too. Then we’ll get some coffee. I could use some.”

[48] Jean smiled. “I’ll go down to the kitchen and get some while we’re waiting,” she offered. “You must be tired.”

Dr. Barsch waved his hand. “Sit down. The coffee can wait.” He tapped the sketch with his forefinger and looked at it thoughtfully for a moment. Then he searched among the papers on his desk for a letter. Finding it, he nodded his head as he read it over.

“I think maybe we’ve found a way to put your talents to practical use, Miss Craig,” he said slowly.

Jean jumped up. “Really?” she cried. “But how? I mean, I’m so far from ready to do anything useful with my art. Surgical art is such a specialized and highly skilled profession!”

The doctor nodded gravely. “Yes, it most certainly is,” he said thoughtfully. “And of course the sketch you did for us just now is still rather amateurish. But I was right about you, I think. It shows a great deal of promise.”

Jean grinned with pleasure. “Thank you, Doctor,” she said.

Dr. Barsch picked up the letter again. “I’ve been in touch with a medical publisher about you. You see, whenever they hear of a promising young artist who knows something about medicine, they leap at the chance to sign him—or her—up. It doesn’t happen often. Not often enough, that an artist is also interested in medicine.”

Jean clasped her hands together. “You mean, some publisher wants me to do drawings for him?”

[49] Dr. Barsch laughed. “Not so fast, young lady. No, their offer isn’t quite that spectacular.” He rubbed his hands together. “But in a sense, I suppose maybe the offer is in its way more spectacular. You see, they want you to take more art courses.”

“But ...” Jean began.

The doctor held up his hand. “Wait till I finish,” he said. “I think it can all be figured out quite simply. You will finish your nurse’s training this summer. And then, as I understand it, you are thinking about being married.”

Jean hesitated. “Of course no definite date has been set yet.”

Dr. Barsch stroked his chin. “Well, let’s assume that the wedding will take place soon after your graduation. When you reach Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, you can begin a correspondence course in art, can’t you?”

Jean grinned. “I had sort of planned to continue studying art after Ralph and I were married.” She looked down. “You see, I don’t want to forget my skills just because I’m being married.”

The doctor grinned. “Fine! Fine!” he said. “Then my little plan can be worked. This publishing company is prepared to award you a sort of scholarship so that you can take the course. In return, you will have to make arrangements with a hospital near your home in Saskatchewan to attend their operations and do sketching for the company when you have completed the course.”

Jean thought a moment. “There is a small hospital[50] near Ralph’s ranch,” she said. “Ralph has told me about it. Certainly I could make arrangements with them to sketch at their operations.”

Dr. Barsch nodded. “Of course I’ll help you arrange things. I think maybe if they realize you’re a student of mine, there won’t be much trouble with the details.”

“Someone open the door,” Ted called from outside. “I’ve got coffee for everyone.”

Jean went over to the door. Ted brought in the tray and set it on the desk.

“You should have let me get it,” Jean cried.

Ted smiled. “Division of labor, my child. Dr. Barsch operates, you sketch and I just stand around. So I’m elected coffee boy.”

“Take a look at Miss Craig’s sketch, Loring,” Dr. Barsch said, handing him the pad. “I think it’s pretty fair.”

“That’s high praise, coming from you,” Ted laughed. He looked at it carefully. “Uh huh,” he said, nodding. “It looks swell. Jeannie, you could make a career out of doing this.”

Jean laughed. “Dr. Barsch and I have just been discussing that.”

“But of course you’re off to the altar, and there’s the end of a beautiful career,” Ted said dolefully.

“Oh, no!” Jean cried.

Dr. Barsch smiled slyly. “Sounds to me as if you are against marriage, Dr. Loring. I suppose Miss Simpson realizes this?”

[51] Ted blushed. “Oh, marriage is all right,” he protested.

Dr. Barsch lit his pipe. “Marriage is all right. Hm,” he said playfully. “I’ve a notion to tell Miss Simpson how enthusiastic you are about the institution of wedlock. You and your city ways! Moon and pussyfoot around and steal the best doggoned Supervisor of Nurses I ever had! All right, indeed!”

Ted shifted painfully. “Oh, I’m very much in favor of marriage, doctor....”

“That’s good to hear,” Dr. Barsch said.

“It’s just that Jean draws so well....”

“And Miss Simpson makes such a good Supervisor,” Dr. Barsch added.

Ted squirmed. “I’m sorry,” he said. “You can’t have her back!” He looked at Jean’s and Dr. Barsch’s faces. They were grinning.

“Dr. Barsch, you shouldn’t tease him so,” Jean said lightly. “Isn’t it all right to tell him about the plan?”

Dr. Barsch puffed at his pipe. “Of course, my dear.”

Breathlessly, Jean repeated Dr. Barsch’s plans for her to Ted. The young doctor nodded and clapped his hands together in agreement.

“Marvelous idea, Jeannie,” he said. “I think Ralph will like the idea, too.”

Ethel’s and Ted’s wedding was scheduled for April eighteenth. The first two weeks of the month were dreary and rainy. The skies above Elmhurst were constantly gray, and the countryside looked bleak and unpromising after the long winter. Tempers were short at the clinic. The season of spring colds was on, and Jean felt a great depression as she tended her duties as an upperclass nurse. Because of the shortage of graduate nurses at the hospital, Jean and her classmates were used almost as regular nurses. Jean had to attend courses in chemistry, biology and dietetics along with her regular duties, and as the spring term got under way, she was now in charge of the pediatric ward.

A whole procession of youngsters flooded both the doctors’ offices and the hospital wards. And Jean’s days were full of bathing youngsters, trying to put dosages of penicillin and sulpha into unwilling small mouths, taking temperatures and pulses of the squirming children. She tried to study at night after writing her daily letter to Ralph, but often she would steal[53] back into the ward to hold the hand of a tiny, miserable patient lonely for his mother. Jean found solace in the quiet ward at night. The children were calmer, there were no adults about, and she couldn’t see the dreadful, gloomy sky.

Ordinarily, Jean would have welcomed the chance to work so closely with Ted, whose capacity as pediatrician kept him closely in touch with the ward. But Ted was cross and nervous. For hours at a time, he swabbed throats and sprayed sniffly noses and tried to reason with mothers weary of the winter and of housefuls of pent-up children.

The radio forecasts were always the same: showers.

“April showers,” Jean remarked one day bitterly as she gazed up at the sky which was sending down its interminable drizzly rain. “If these are showers, let me know when one stops and the next one starts, someone!”

Only Ethel and Jack seemed to retain their high spirits. Ethel was too excited about her wedding even to notice the weather. And Jack, bedridden already a month, had drawn from some inner source a courage and even temper which amazed everyone around him. Although Jack knew that he would be in bed for many months, he never seemed to be depressed. He made a full life for himself within his tiny room. Although he wasn’t allowed many visitors, he soon fell into a routine which occupied his mind, but which didn’t excite him too much.

[54] But just when everyone decided that it would never stop raining, the sun came out. The sky was blue with fluffy white clouds, and spring had come to Elmhurst. Trees which had been barren two weeks before were now covered with soft green buds. The whole countryside softened with new-growing greenery. The river ran with vigorous energy to carry its extra burden to the ocean, and the air smelled clean, as if the heavens had spent two energetic weeks in spring housecleaning.

The day of Ethel’s wedding was cool and clear. The ceremony was to be held in the Craigs’ parlor, and the whole family was busy making final preparations.

Doris was singing “Brightly Dawns Our Wedding Day” from the Mikado as she dusted the living room furniture for the third time. Jean arranged the wedding presents on the dining room table for everyone to see. She sighed gently as she laid out the sterling silver which Mrs. Loring had given her son and daughter-to-be. And she smiled in satisfied anticipation as she arranged the kitchen equipment which had been the contribution of the nurses at the shower. She handled the linens and china with loving care.

Mrs. Craig ran downstairs and popped her head into the dining room.

“Time to get dressed, dear. I want you to be ready so you can help me with the bride. Oh, dear,” she sighed, “where is that girl?”

“Ethel?” Jean asked. “I suppose she’s still at the[55] hospital. If I know Ethel, she’s probably making a long list of instructions to leave behind her.” She sighed. “Oh, Mother,” she cried, “all these lovely things! And you should see that terrible little apartment they’re going to have to put them in! Darn it, anyhow! Why couldn’t Ted have been a veteran? Then he could have one of the houses Dad designed for the veterans’ project. Now, where on earth will they put all these things in that stuffy little place?”

Mrs. Craig smiled knowingly. “Never mind, dear. Ethel can store things here if she wants to, till she has a better place. Now hurry, Jean. With everyone dressing here, we have to hustle.”

Jean obediently went upstairs. Mrs. Craig went in to send Doris up to dress, muttering, “Ethel should have come to breakfast as I told her to. She probably didn’t eat a thing.”

As she spoke, Ethel came in the front door. Mrs. Craig stretched out both hands to her, and Ethel grabbed them. She attempted to smile.

“I’m sorry I couldn’t make it for breakfast, Mrs. Craig,” she said. “But there were just a few things I wanted to take care of at the hospital before I left.”

Jean bent over the upstairs railing and called down, “What did I tell you, Mother?”

Mrs. Craig smiled in despair. “Oh, child, this is your wedding day! Now, let’s get you upstairs and into your finery.”

Suddenly Ethel burst into tears. Mrs. Craig put her[56] arms around her and drew her over to a chair.

“I ... I don’t want to get married,” Ethel cried. “I ... well, I just don’t want to get married!”

Mrs. Craig smiled knowingly and patted the girl on the shoulder. “I know, my dear. I know just how you feel....”

“They’re so short-handed over at the hospital. They can’t spare any nurses,” Ethel sobbed. “I just can’t get married now! There are too many things to do!”

Suddenly her eyes brightened. “Do you think Ted would understand if we called the wedding off? I mean, just till I finish everything that has to be done at the hospital?”

Mr. Craig came into the front hall together with Aunt Becky. He stopped at the sight of Ethel’s tearful face and stared at her in alarm.

“Great heavens!” he exclaimed. “Tears on your wedding day?”

Becky elbowed him out of the way and came over to Ethel. “Oh, run along with you, man,” she snapped at the bewildered Mr. Craig. “There isn’t a girl alive who doesn’t get plumb nervous at the thought of her wedding day!” She turned to Ethel. “Now, now, child,” she said, “you just have a good cry, and....”

Mr. Craig interrupted Becky with a loud laugh. He threw back his head and roared. “If you think you’re nervous, my girl,” he said, “you should see Ted, now. When I stopped in to see him, his poor mother was trying to help him dress. Ted was hopping around on one foot like a scared chicken....”

[57] Mrs. Craig touched her husband’s arm. “All right, dear,” she said, “now run along and get yourself dressed.”

As Mr. Craig went upstairs, whistling, Ethel composed herself and smiled at the two women.

“Poor Ted,” she grinned. “He’s so helpless. And of course he’s scared! He needs someone to look after him.” She glanced at her watch. “Good heavens!” she cried, “I’d better hurry and dress! Mrs. Craig, where is my gown?”

Mrs. Craig smiled. “Your clothes are up in Jean’s room, dear. Doris and Jean are waiting to help you. I’ll be up, myself, in a few minutes.”

Ethel threw her arms around Mrs. Craig’s neck and hugged her. “How can Ted and I ever thank you for what you are doing for us?”

“Humph!” Becky snorted. “Now, scat, girl. And Marge, you come out with me to the kitchen. I want to unload my basket.” She shook the overflowing basket of last-minute additions to the party food which she was carrying.

Ethel nearly collided with Tommy on the stairway.

“Hi, beautiful,” Tommy said, grinning. “I hereby swear my eternal devotion to you on your wedding day.”

Ethel laughed. “You idiot! Whatever do you mean?”

Tommy shook his head. “Only for you. For you only, I say, would I struggle into this!” And he waved a stiff collar under her nose. “That is, outside of the immediate family.”

[58] As Tommy reached the bottom of the stairs, still muttering about his collar, the front door flew open, and Ted, followed by a distraught Mrs. Loring, came dashing into the hall. Ted confronted Tommy, his face twisted in wrath.

“Tommy, where’s your father?” he demanded.

Tommy stared at the bridegroom.

“Now, now, dear,” Ted’s mother clutched at his arm, “don’t upset everyone, now. Calm yourself!”

Ted turned to face his mother. “But you know this means the wedding’s off! How can a man get married when...?”

“Huh?” said Tommy.

“The apartment! The furniture! Gone! Everything’s gone! I’ve been robbed! The apartment wasn’t much, but it was a place to live, and Ethel and I picked out all our furniture and had it sent to that place. Now it’s gone!”

Mrs. Loring took Ted’s hand. “Now listen, son,” she said, “there must be an explanation. People don’t run off with a houseful of furniture.”

“Well, hello, Mrs. Loring,” he said, shaking her hand. “And Ted. I’m afraid I have to do the honors. The women are all upstairs dressing.”

Mrs. Loring smiled wryly. “Mr. Craig, forgive this ridiculous son of mine. We would have come over at the proper time when everything was ready. But Ted has some fool notion that he’s been robbed.”

[59] Mr. Craig chuckled. “If Ted didn’t come crashing into a party, I would know there was something wrong. Did he ever tell you about the first time we met?”

Mrs. Loring smiled as if she knew her son’s habits. “I can imagine the entrance he made was spectacular,” she said.

Mr. Craig laughed at the memory. “It certainly was. We gave a large barn dance to celebrate the building of the clinic. Dr. Gallup was in the midst of introducing Dr. Barsch to the community when, bang! The lights all went out. Seems as if Ted had come in and tripped over the light cords.”

Mrs. Loring laughed despairingly. “Oh, Ted,” she sighed. “I’m afraid you had a typical introduction to my son,” she said to Mr. Craig.

“Mother!” Ted cried, “how can you stand around swapping tales with Mr. Craig when I’ve been robbed?”

Mr. Craig looked at Ted gravely. “Suppose you start from the beginning and tell me the whole story.”

“Well, sir, I went over to see the apartment this morning to check on last minute details, you know. The landlady told me that she didn’t have an apartment for me! I told her that was ridiculous and that I’d already paid my first month’s rent and that I had a whole apartment full of furniture moved in not two days ago. She showed me the apartment and there wasn’t a stick of it ... there wasn’t anything in it! Then she handed me back my money!” Ted’s[60] face became redder.

Mr. Craig began to chuckle. “How much rent did she want for those three rooms?”

Ted glowered. “Sixty-five a month.”

“Sixty-five a month is a little high for children just setting up housekeeping. I tell you what, Ted. There’s no point in upsetting your wedding by keeping it from you any longer. You see, for forty-five a month, you can have a regular house.”

Ted stared at Mr. Craig. “I don’t understand, sir,” he said.

Mr. Craig smiled. “Mrs. Craig and I went over to see your apartment a week or so ago. Frankly, Mrs. Craig didn’t think much of it. So we decided to move you out. It just happens I have a house for rent. In the housing project that I designed. It’s been open for four days, only, and they’re pretty nice little houses. The builders gave me one as a sort of bonus, and I want to rent it, of course. Perhaps it was presumptuous of me....”

Ted gasped. “This ... this is a miracle. But it’s too much! We couldn’t possibly accept it!”

Mr. Craig shook his head. “Mrs. Craig and I are very anxious to see you two settled nicely. If you won’t do it for yourself, do it for Ethel.” He handed Ted a set of keys. “Here you are, son. You’ll find your furniture at this address.”

Mrs. Loring sat down. “I don’t know what to say, Mr. Craig,” she murmured.

[61] Ted sat down and stared at the keys in his hand. Mr. Craig patted him on the shoulder and turned to his son. “Hey, Tommy,” he called. “Come here, and I’ll fix your collar.”

Only the members of the Craig family even suspected that Ethel had shed tears less than an hour before the ceremony. When she came down the stairs on Dr. Barsch’s arm, she was the perfect picture of a radiant bride. The wedding was held in the front parlor with the family and hospital staff in attendance. It was a regular old-fashioned wedding, and the fragrance of roses and lilacs filled the parlor as the minister read the time-revered words. And from the silent congregation came the sound of muffled sobs—not from the happy Mrs. Craig, who beamed on the beautiful bride, nor from Mrs. Loring, who smiled at her new daughter with contented pride, but from Jean, who suddenly felt the tragic loneliness of a girl whose beloved is many, many miles away.

Ethel and Ted had gone on a short tour of New England for their honeymoon. The routine of the hospital resumed, and Eileen Gordon became official Supervisor of Nurses. Jean was amused at the comparison of the two girls. For Eileen had taken over Ethel’s classes, and Jean and the other girls soon realized that Eileen was every bit as devoted to her profession as Ethel had been. Eileen was a bit different from Ethel in that she was new at handling girls. But there was no question about the fact that she knew her business. And she was friendly and helpful, so the students became used to her brusque manner in class and on the floor.

Jean, Sally, Hedda, Lucy Peckham and Ingeborg were all in dietetics class when Eileen took over the class for the first time. The new Supervisor was plainly nervous, and the students smiled encouragingly at her as she opened the notebook which Ethel had left for her.

Eileen toyed with a pencil as she scanned Ethel’s notes. “You all know, or should know, by this time,”[63] she said, “the importance of a balanced diet.” She smiled at the class. “I’m rather hoping that one of you will plan to specialize in dietetics, because we will be needing a good one for our own kitchen. But we all have to know about diet ... in fact, every human being should know about it.” She stopped, realizing that she was being too repetitious and long-winded.

“Let’s start with the three major groups of foods. Miss Peckham, will you please name them?”

Lucy smiled and said, “The three major classifications of foods are fats, carbohydrates and proteins.”

Eileen nodded. “And who can tell me what a calory is?”

The class groaned in mock despair. Counting calories was an unpleasant job which some of them occasionally had to do.

“Something we could do without,” Sally said flippantly.

Eileen laughed with the rest of the class. “As a woman, I agree with you, Miss Hancock,” she said. “But as a nurse, I have to send you to the foot of the class.” She looked about the classroom. “Miss Craig, will you tell Miss Hancock what a calory is and why she couldn’t possibly get along without it?”

Jean laughed. “A calory is a unit of heat ... or, in the case of food which provides fuel, weight. And Sally would have to have calories or give up eating altogether.”

[64] Eileen nodded as the rest of the class tittered. “Can anyone name foods which do not have calories?”

The class thought. Lucy raised her hand. “Coffee doesn’t have any calories,” she said.

Eileen frowned a little and nodded. “Strictly speaking, I think you can’t exactly call coffee a food. It’s actually a drug ... or, at least, its main function is that of a drug.”

“How about salt?” Hedda asked.

“That’s right,” Eileen said. “But of course no pure minerals have calories. The function of the mineral is not to provide body heat.” She flipped a page. “Now let’s talk about diets and people. Can someone name three special categories of people needing different diets?”

Jean held up her hand. “Adults, children and expectant mothers.”

Eileen nodded. “Very good. Any more?”

Sally raised her hand. “Sick people have to have lots of different diets, depending on what’s the matter with them. And an office worker needs different food from the food needed by a laborer.”

Eileen hesitated. “You’re right about the first category, but don’t forget that all people need the same basic foods, no matter what they do.”

“All except Dr. Benson,” Lucy muttered under her breath. “He eats people. He’s a wolf!”

Eileen caught part of Lucy’s remark and blushed fiery red. She hesitated a moment and then decided[65] to pass on to something else. For the rest of the hour, the class discussed the essentials of a balanced diet. And when Eileen dismissed them, the class adjourned for a few minutes in the lounge before they returned to duty.

They all helped themselves to cokes from the machine in the lounge and relaxed. Sally giggled as she opened her coke bottle. “That was a lovely remark you made in class, Lucy,” she said. “Eileen heard you, too.”

Lucy made a face. “I don’t care. She feels the same way we all do.”

Jean looked questioningly at Lucy. “I didn’t know you knew Dr. Benson that well.”

Sally giggled. “Haven’t you heard? Lucy had a date with the man himself last night.”

“Really?” Jean asked.

Sally nodded. “Lucy and I made a bargain that the first one he would ask yesterday to go out would date him. Just to see if his bark was as bad as his bite. So he asked Lucy, and Lucy is forthwith ready to make her report to the clan.”

Lucy took a drink of her coke. “It wasn’t bad at all,” she confessed. “In fact, I would have been quite flattered by all the lovely words. That is, I would have been if my name had been Jean.”

“What on earth are you talking about, Lucy?” Jean asked.

“Such a crush on you our Dr. Benson has! He[66] talked on and on about you till I almost got insulted.”

The door opened and Eileen came in. “Okay if I join you?” she asked.

“Come on in,” Sally answered. “We’re having a time roasting Dr. Benson. Lucy went out with him last night.”

“So that’s what was behind the remark you made in class,” Eileen said. “Well, how was it?”

“We went to a movie,” Lucy continued. “Then the dear doctor started to make a play for poor little me....”

“Oh, goodness, Lucy!” Eileen interrupted. “You aren’t actually telling them all about your date!”

“She went out with him on a sort of a dare,” Sally explained.

Eileen shook her head. “Even so,” she said, “it doesn’t seem right to talk about it. It’s sort of unkind, don’t you think?”

Sally grinned. “He has it coming. You know perfectly well he’s been chasing everyone in sight ever since he got here. The perfect redhead, disposition and all.”

Jean shook her head. “I think Eileen’s right,” she said.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake!” Sally cried. “Now all at once Dr. Benson is perfectly okay, and we aren’t to betray his confidences.”

Eileen smiled. “He’s stupid in lots of ways. But he is a good doctor, and he’s awfully young, after all. Maybe he’s never been away from home before.”

[67] Sally shrugged. “Well, if you feel so tenderly towards him, why don’t you go out with him, yourself?”

Eileen chuckled. “Never! He’s not my type, in the first place.”

Jean laughed and put down her coke bottle. “I’m on duty, so I’d better get back to work. I’m glad you had such a lovely time, Lucy.” She stretched and yawned. “Well, so long, gang,” she said.

She hurried down the hall of the second floor to look at the call sheet. Each day after lunch, the students were assigned to special duties for the day, and Jean wanted to check on her assignment. She frowned as she saw her name opposite that of Dr. Benson. Then she grinned sheepishly and shrugged her shoulders. As long as he was on duty, Dr. Benson would be professional and mannerly. Jean determined that she would be as pleasant as she could be to the young man.

Dr. Benson was making routine checks in the contagious ward when Jean found him. He seemed very grave as he examined his patients. Jean noted with satisfaction that he made very thorough checks on each one. He didn’t even seem to notice Jean as he worked. Quietly and efficiently she followed him from patient to patient, making notes on each chart.

“Well, that’s that,” Dr. Benson finally said as he finished examining his last patient. “Thanks, gorgeous.”

Jean smiled in spite of herself. “Anything else, Doctor?” she asked.

Dr. Benson ran his fingers through his red hair.[68] “I guess not. Not now, anyway. But tell me something, beautiful? How did I make out with Lucy last night?”

Jean blushed and looked up at him questioningly. “I don’t have any idea,” she asked. “Why?”

Dr. Benson grinned wryly. Jean noticed that he had a dimple near his mouth. “That’s not a straight answer, and you know it, Miss Craig,” he said. “I know I was up for discussion today. Well, did you all approve of my technique?”

Jean instantly felt a warm surge of feeling for the doctor. He was actually pathetic. He sensed her reaction and waved his hand as if to brush it off.

“Forget it,” he said brusquely. “My ears are still burning from a dressing down I got this morning from Dr. Barsch. I’m still shaky on making out reports. Well, we all have to learn....” His voice trailed off, and he grinned. “What’s new with the boy friend, cutie?” he asked.

“Ralph’s fine,” Jean answered. “He’ll be back next week.”

“I wonder if he knows what a lucky guy he is,” Dr. Benson said. “To have a girl waiting for him ... you know, having someone he cares for thinking so much of him. Oh well, skip it. This is just a bad day.”

“I know how to make out reports,” Jean said. “Let me help you with yours.”

Dr. Benson stared at her. “You want to help me[69] after the way I’ve acted towards you? The other nurses treat me as if I were poison!”

Dr. Barsch came down the hall. He smiled affectionately at Jean and nodded to Dr. Benson.

“I’m sorry if I was a bit rough this morning, Doctor,” he said gravely. “Sometimes I forget how complicated these reports can be till one becomes used to them.”