TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

THE WORKS OF

WINTHROP PACKARD

WOODLAND PATHS

WILD PASTURES

WOOD WANDERINGS

WILDWOOD WAYS

Each illustrated by Charles Copeland

12mo. Ornamental cloth, gilt top, each volume $1.20 net; by mail, $1.28

These four volumes together constitute “The New England Year” series, dealing, in the order given, with the four seasons. Sold separately.

FLORIDA TRAILS

As seen from Jacksonville to Key West, and from November to April, inclusive

Illustrated from photographs by the author and others

8vo. Ornamental cloth, gilt top, boxed, $3.00 net; by mail, $3.25

LITERARY PILGRIMAGES OF A NATURALIST

Visits to the haunts of Whittier, Emerson, Hawthorne, Celia Thaxter, Webster, Aldrich, and others

Illustrated from photographs by the author and others

12mo. Ornamental cloth, gilt top, boxed, $2.00 net; by mail, $2.20

SMALL, MAYNARD AND COMPANY

Publishers Boston

LITERARY PILGRIMAGES

OF

A NATURALIST

BY

WINTHROP PACKARD

Author of “Florida Trails,” “Wild Pastures,”

“Wood Wanderings,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE

AUTHOR AND OTHERS

BOSTON

SMALL, MAYNARD, AND COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1911

By Small, Maynard, and Company

(INCORPORATED)

Entered at Stationers’ Hall

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

TO THE MEMORY

OF

CLARENCE H. BERRY

A Schoolmaster of Long Ago

THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

The author wishes to express his thanks to the editors of the “Boston Evening Transcript” for permission to reprint in this volume matter which was originally contributed to its columns.

[Pg ix]

| Chapter | Page | ||

| I. | In Old Marshfield | 1 | |

| II. | At Whittier’s Birthplace | 15 | |

| III. | In Old Ponkapoag | 30 | |

| IV. | At the Isles of Shoals | 44 | |

| V. | Thoreau’s Walden | 60 | |

| VI. | On the First Trail of the Pilgrims | 75 | |

| VII. | In Old Concord | 90 | |

| VIII. | The Old Oaken Bucket | 104 | |

| IX. | In Old Newburyport | 118 | |

| X. | Plymouth Mayflowers | 135 | |

| XI. | Old Salem Town | 148 | |

| XII. | Vermont Maple Sugar | 164 | |

| XIII. | Nature’s Memorial Day | 183 | |

| XIV. | Birds of Chocorua | 197 | |

| Index | 213 | ||

[x]

[xi]

| Page | ||

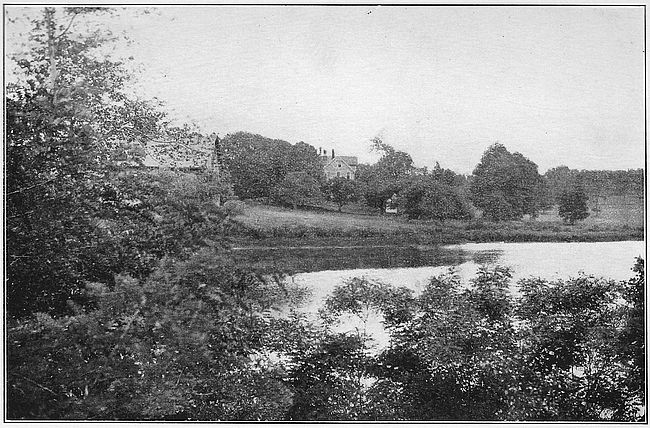

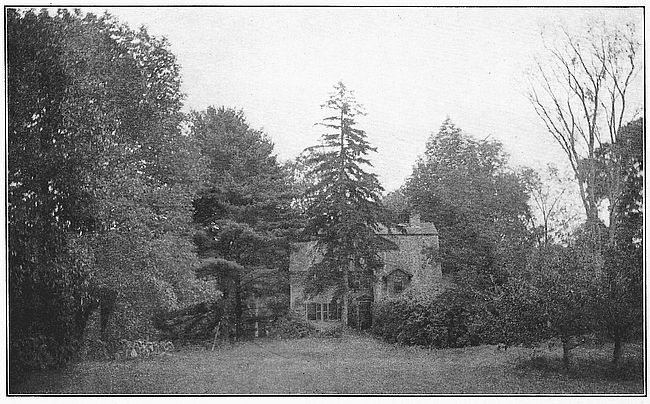

| “No wonder Daniel Webster, wandering southward over the hills in search of a country home, chose this as his abiding-place.” See page 2 | Frontispiece | |

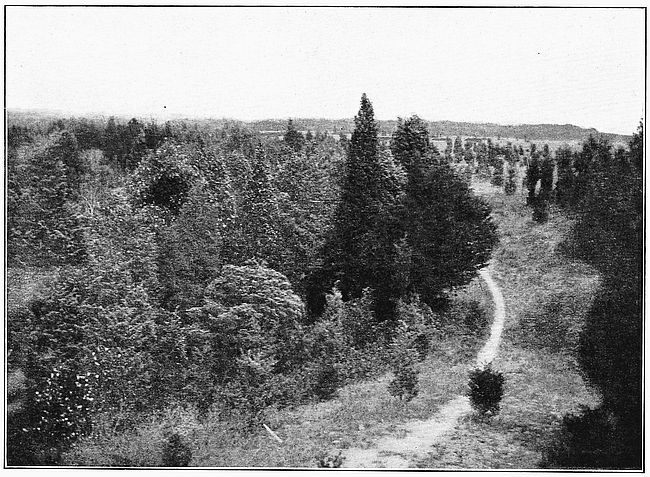

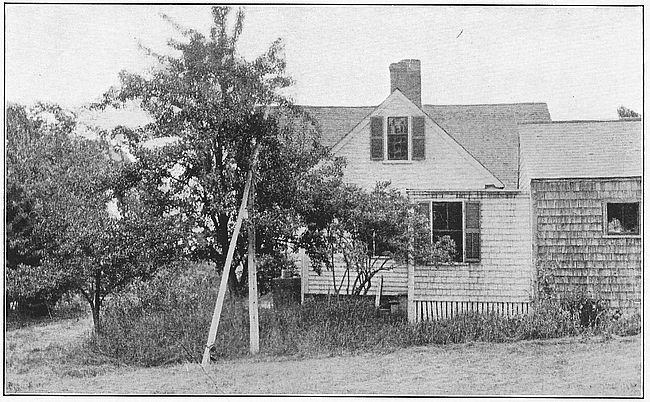

| “Telling the pearls on this rosary of a path one is led beyond the homestead.” | 12 | |

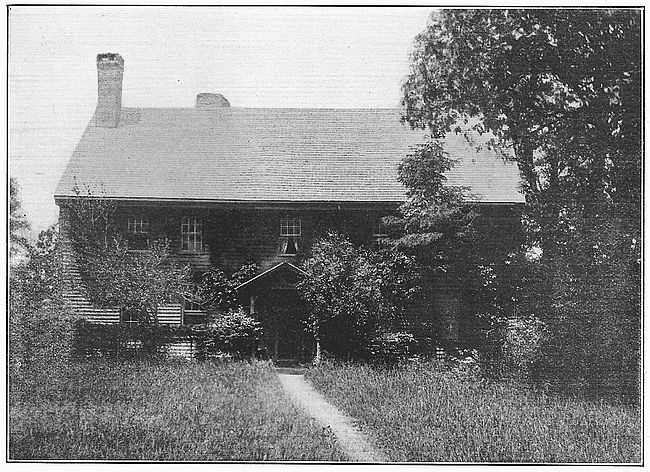

| “Within this wide circle, with the house its core, and the hearth its shrine, revolved the homely, cheerful, whole-hearted life of the farm.” | 22 | |

| “Watching the crane and pendant trammels grow black against the blaze.” See page 18 | 28 | |

| A corner of the room in which Whittier was born | 28 | |

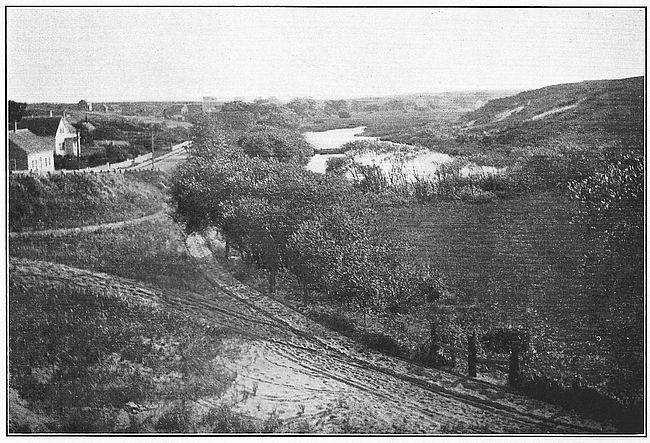

| “The study where Aldrich wrote some of his daintiest verse looks forth upon a sweet valley.” | 30 | |

| “The study window in what was ‘The Bemis Place’ of the elder days of Ponkapoag.” See page 35 | 36 | |

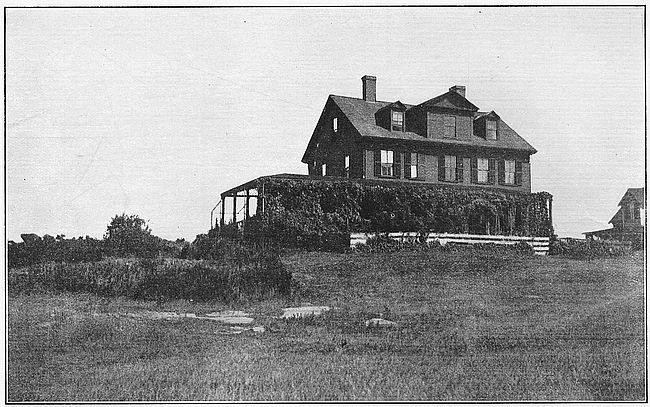

| Celia Thaxter’s home at the Isles of Shoals | 44 | |

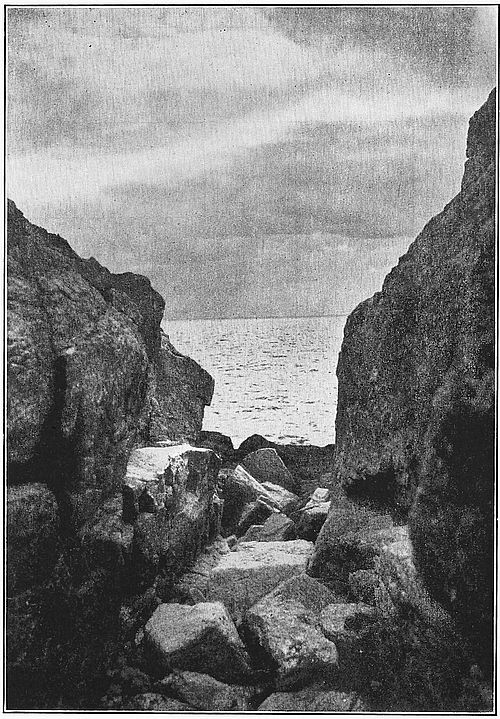

| “Chasms down which you may walk to the tide between sheer cliffs.” | 50 | |

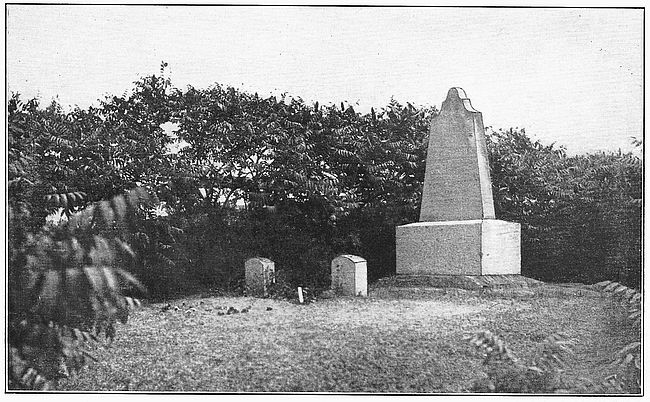

| “Up to the smooth turf on this knoll crowd all the pasture shrubs that she loved.” | 58 | |

| “Here is the cairn erected to his memory, to which with doffed hat you may well add a stone.” See page 65 | 66 | |

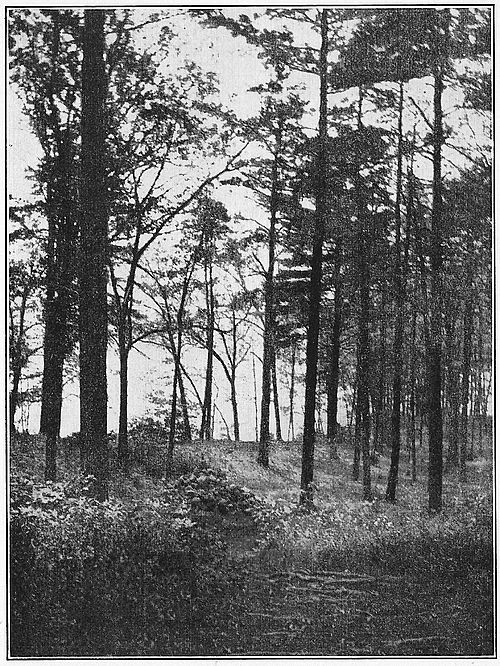

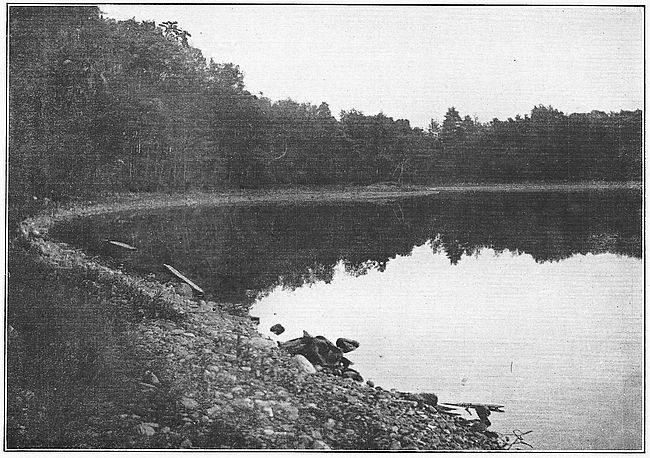

| “Walden is Walden still, very much as Thoreau painted it.” | 70 | |

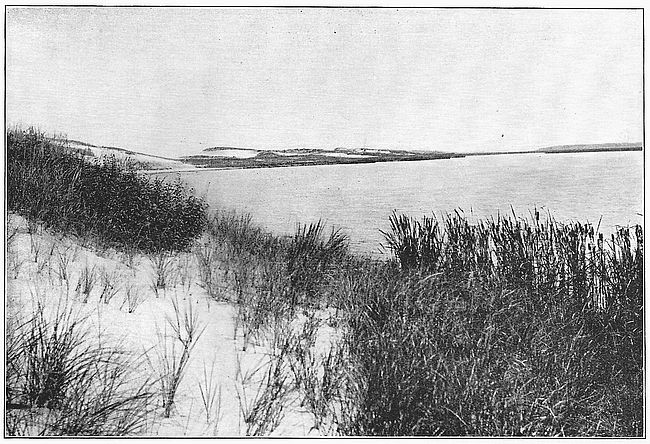

| “Pilgrim Lake,” where that first washing was done by the Pilgrim mothers | 78 | |

| “That little creek that blocked the way of doughty Myles Standish and his men, sending them inland on a detour.” See page 85 [xii] | 86 | |

| “Here in a volley was the summing up of the nature of the heroes that had grown up, quite literally, in the Concord soil.” See page 93 | 92 | |

| “Hither, too, came Hawthorne, to tramp the woods as did the others, and feel as did they, the divine afflatus.” | 98 | |

| “The water from the old well cooled the throat of his memory, and sparkled to the eye of it as he recalled the dripping bucket.” | 114 | |

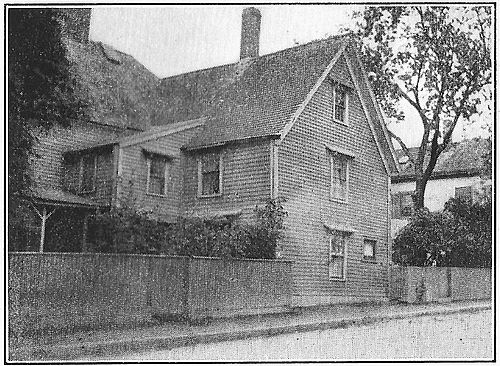

| The Newburyport home of Joshua Coffin, the early friend and teacher of Whittier | 126 | |

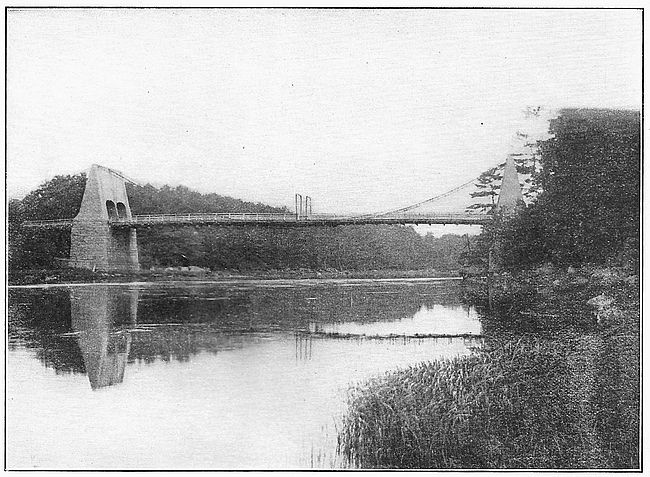

| “Down river to the old chain bridge the rough rocks of the New Hampshire hills come to get a taste of salt.” See page 129 | 130 | |

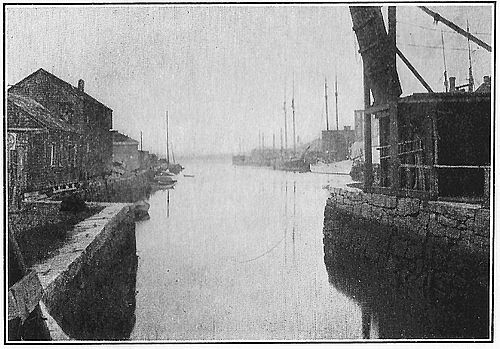

| One angle of “The House of the Seven Gables.” | 150 | |

| “A Salem dock of the old sea-faring days.” | 150 | |

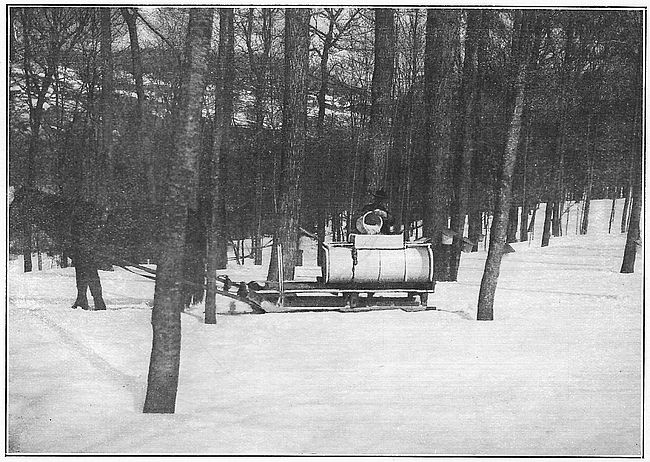

| “The only sound was the crunch of soft snow and the splash of sap within the barrel.” See page 171 | 172 | |

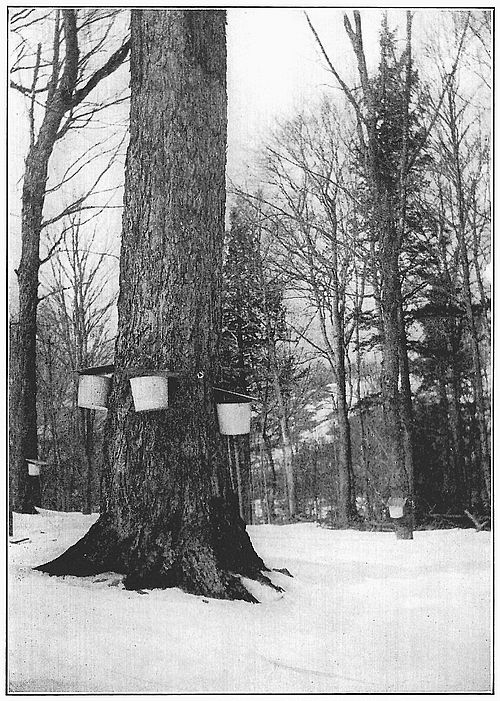

| “But here is a sweetness that the tree almost bursts to deliver.” | 178 | |

| “The farmhouse where Bolles lived and loved the woods and all that therein lived with him.” See page 197 | 198 | |

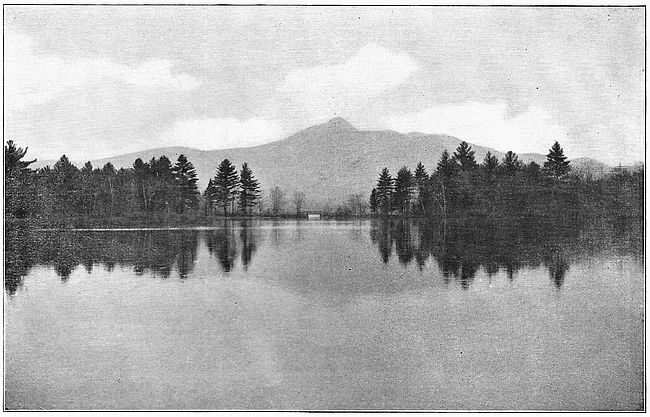

| Nightfall on Chocorua Lake | 208 |

LITERARY PILGRIMAGES

OF A NATURALIST

[Pg 1]

LITERARY PILGRIMAGES OF

A NATURALIST

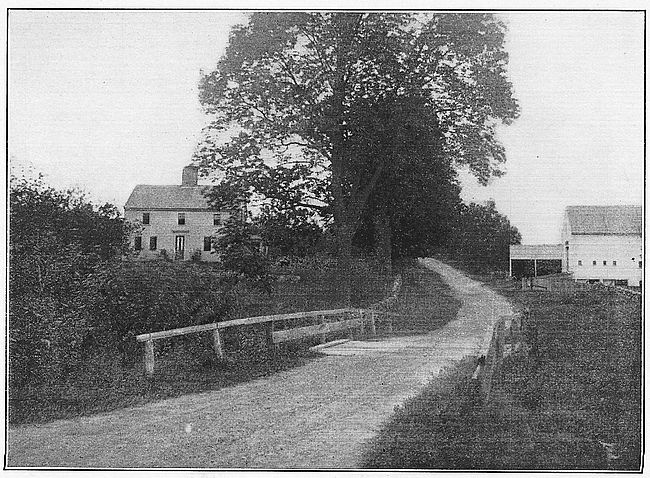

Glimpses of the Country about the Daniel Webster Place

Down in Marshfield early morning brings to the roadside troops of blue-eyed chicory blooms, shy memories of fair Pilgrim children who once trod these ways. They do not stay long with the wanderer, these early morning blooms. The turmoil and heat of the mid-summer day close them, but the dreams they bring ramble with the roads in happy freedom from all care among drumlins and kames, vanishing in the flooding heat of some wood-enclosed pasture corner to spring laughingly back again as the way tops a hill and gives a glimpse of the purple velvet of the sea. No wonder Peregrine White, the first fair-skinned child born in New England, strayed from[2] the boundaries of Plymouth and chose his home here. No wonder Daniel Webster, New England’s most vivid great man, wandering southward over the hills in search of a country home two centuries later, fixed upon the spot just below Black Mount, looking down upon Green Harbor marshes and the sea, and chose this for his abiding-place.

The statesman and orator, whose words still ring across the years to us, with the trumpet sounding in them even from the printed page, may well have breathed inspiration for them from the winds that come from seaward across the aromatic marshes. There is cool truthfulness in these winds, and understanding of the depths, and the salty, wild flavor of the untamed marsh gives them a tang of primal vitality. Breasting them at mid-day from under the wilt of summer heat you seem to drink air rather than to breathe it, and find intoxication in the draught. I never heard a robin sing in mid-flight, soaring upward like a skylark, till I came to this bit of sweet New England country. The east wind drifted in to him as he sat on a treetop caroling, and he spread his[3] wings to it and fluttered upward, pouring out round notes of melody as he went. Webster’s most famous speeches were composed while he tramped these hills and marshes and sailed the blue velvet of the outlying sea, and their richest phrases soar as they sing, even as did the robin.

You may come to Black Mount with its panoramic view of the Webster farm, the surrounding pastures and marshes and the little Pilgrim cemetery where he lies buried, from either the Marshfield railway station or that of Green Harbor, both a mile or more away by road. A better route lay for me through the woods by paths flecked with sunlight and dappled with shadow, paths which the Pilgrims’ descendants first sought out and which are as fair to-day to our feet as they were to theirs. One can easily fancy Peregrine and his wife picking berries along here on days when the farm work allowed them freedom, the children frolicking about with them and eating or spilling half they picked, as the children do on these hills now. Voices and laughter rang through the woods as I passed, and there is small blame to the pickers if they do eat the berries as[4] fast as they pick them. They never taste quite so good as on this direct route from producer to consumer. Along this path you may have your choice of varieties as you go, from the pale blue ones that grow so very near the earth on their tiny bushes that they seem the salt of it, giving the day its zest, through the low-bush-blacks, crisp with seeds and aromatic in flavor as if smoked with the incense of the sweet-fern, to those other black ones that grow on the high bushes and rightfully take the name of huckleberry. The soil of these sandy hills may be thin and not worth farming, but it produces fruit whose quality puts to shame the product of well-cultivated gardens. The good bishop of England who once said, “Doubtless God could have produced a better berry than the strawberry, but doubtless He never did,” never ate blueberries from the bush in a New England pasture.

From the summit of Black Mount the grassy hill slopes sharply beneath your feet to the road and beyond this to the home acres of the Webster place, the roof tree far below you and the house snuggling among the trees that the great statesman[5] loved, many of which he planted. A little farther on stands a great barn with huge mows and the big hay doors front and rear always hospitably open to the scores of barn swallows that build on the beams up next the roof. In no barn have I found quite so many swallows at home. At every vantage point on a beam, wherever a corner of a timber or a locking pin protrudes to give a support, nests have been built, generation following generation till some of the structures are curious, deep, inverted mud pyramids, topped with straw and grass and lined with feathers, downy beds for the clamorous young. I can think of no finer picture of rural peace than such a barn as this, the cool wind sighing gently through the wide doors, the beams stretching across the cavernous space above dotted with the gray nests, the air full of the friendly, homey twittering of the birds, some resting and preening their feathers on the beams, others swinging in amazing flight down and out through the doors to skim the grass of the neighboring fields and marshes for food, then flashing back again to the hungry nestlings. Such barns grow fewer year by year here in[6] eastern Massachusetts, and the pleasant intimacy of the barn swallows is but a happy recollection in the mind of many of us, more is the pity. It is worth a trip to Marshfield just to foregather with such a colony.

Eastward again the eye passes over wide mowing fields, rough pastures and hills clad with short, brown grass and red cedars, the thousand-tree orchard of Baldwin apples which Webster planted, the tiny Pilgrim cemetery on a little hillock where he lies buried among the pioneers of the place, the brown-green marshes flecked with the silver of the full tide, to the deep, velvety blue rim of the sea, which sweeps in its splendid curve uninterrupted from north to south. Behind your back is the rich green of Massachusetts woodland, beneath your feet this landscape of pasture, field and marsh, scarcely changed since Webster’s day, changed but little indeed since the days of Peregrine White and his pioneer neighbors, and rimming it round the deep sapphire romance of the sea. Across this blue romance of sea the winds of the world, fresh and vital with brine, come to woo you on your way. They croon in your ears[7] the strange sagas that the blood of no wanderer can resist, and you know something of the lure that led the vikings of old ever onward to new shores as you plunge down the grassy slope to meet them. The stately beauty of the home place may thrall you for a while beneath the trees and the friendly great barn try to lull you to contentment with the cradle songs of the swallows, but the marsh adds its wild, free tang to the muted trumpets which these east winds blow in your ears, and so you fare onward through a country of enchantment, toward the ocean.

Webster’s well house, where still the ancient spring flows, cool and clear, gave me a drink as I went by. The dyke which borders his cranberry bog and separates it from a tiny pond where white pond lilies floated and perfumed the air, gave further progress eastward, and soon I passed naturally into an old, old path which led me purposefully in the desired direction. Without looking for it I had found the footpath way which rambles from the farm across country to Green Harbor, where the statesman kept his boats, a path without doubt often trodden by his feet in[8] seaward excursions. He could have found no pleasanter way. The pastures which lie between upland and marsh in this region are covered with a wild, free growth of shrub and vine which no herds, however ravenous, can keep down. The best that the cattle can do with them is to beat paths through the lush tangle along which wild grasses find room to work upward toward the light and add to the browse. Here the greenbrier grows greener and more briery than anywhere else that I know, and the staghorn sumac emulates it in vigor of growth if not in convolutions. In places these reach almost the dignity of young trees, and the pinnate leaves spread a wide, fern-like shade as I walked beneath the antler-like branches. The staghorn sumac is surely rightly named. Its antlers are covered now with an exquisite, deep, soft velvet which clothes them to the leafbud tips and along the very petioles of the leaves. Now it is a clear green which with later growth will become purple and pass into brown, the promise of autumn showing now in a slight purple tinge on the sun-ripened petioles of the older leaves. This soft fuzz clothes the[9] crowded, conical heads of bloom also, heads that are of the same sweet pink as the petals of the wild roses which grow near by as you may see if you will hold one up against the other. But the pink of the wild rose seems flat against that of the sumac, for it has only a smooth surface on which to show itself, while that of the sumac is full of soft, shadowy withdrawals and shows a yellow background in the interstices of the blossom spike.

Skirting this jungle so aromatic with scent of sassafras and bayberry, perfumed with wild rose and azalea, pulsing with the flight of unseen birds in its cool depth and echoing with their song, the path crosses a brook that gently chuckles to itself over its escape from the monotony of a big mowing field to the salt freedom of the marsh, then suddenly breasts the steep northern side of a drumlin. Here the press of toiling feet has been supplemented by the wash of torrential rains till the narrow way becomes a miniature chasm in places, worn down in the gravel among great red cedars, hoary with age and lichens. To know the slow growth of a red cedar and to calculate the[10] age of these by dividing their present bulk with the slight increase that each year brings is to place the birth of these trees far back in the centuries. Not one hundred years will account for it, nor two, and I am quite sure that these trees were growing where they now stand when Peregrine White’s mother first embarked on the Mayflower at Southampton. Webster’s path may have gone through them then, and no one knows how long before, for it is worn deep not only on the steep hillsides where the rains have helped it but in level reaches beyond where only the passing and re-passing of feet through centuries would have done it. It was as direct a route from the hills to the mouth of Cut River at Green Harbor before the white man’s time as after, and if I am not mistaken the red men trod it long before the first ship’s keel furrowed Plymouth Bay.

As I topped the rise I found myself in a hilltop pasture a half-mile long which covers the rest of the hill. Once it was a cultivated field, and the corn-hills of the last planter still show in spots, these, like the rest of it, now overgrown with close-set grass and crisp reindeer lichen. The[11] patriarchal cedars I had left behind, old men of their tribe sitting solemn and motionless in council. Here I had come upon a vast but scattered concourse of young people, lithe and slender folk who seemed to stroll gayly all about the place. Here were plumed youths and debonair maidens regarding one another, family groups, mothers with children at the knee and other little folk in the very attitude of playing romping games. But there were tinier folk than these, too small to be real cedars, gamboling among the others, as if underworld sprites also in cedar guise had come forth to join the festivities. Nowhere else have I seen such a merry concourse of cedars as on the long top of this hill that some Pilgrim father first cleared for a cornfield two centuries and a half ago. Here and there little groups of wee wild rose shrubs seemed to dance up and scatter perfume about their feet in tribute, then stand motionless like diffident children, finger in mouth, stolid and uncommunicative. Hilltops are often lonely, but this one could never be. It gladdens with its quaint fancies. Through a veritable picnic of young cedars I tramped down the eastward[12] slope to the dusty road that leads on to Green Harbor and the slumbrous uproar of the surf.

Telling the pearls on this rosary of a path in the homeward direction one is led beyond the homestead and on, by a slenderer, less trodden way to the old Pilgrim cemetery where the great man lies buried among the pioneers of the neighborhood, Peregrine White, the Winslows, and a host of others whose fame has not gone so far perhaps, but those names may be written in the final domesday book in letters as large as his. Nor does any storied monument recite the deeds of the statesman or bear his name higher than that of his fellows. A simple slab with the name only stands above the mound beneath which he lies, and in the side of this mound a woodchuck has his burrow, seeming to emphasize by his presence the cosy friendliness of the little spot. It is a hillock, just a little way from the house, just a little way from the big orchard which Webster loved so well, surrounded by pasture and cranberry bog and with the marsh drawing lovingly up to it on one side. Over this marsh comes [13]the free salt air of the sea, but a little more gently to the lowly hillock than to the summit of Black Mount. Because of this loitering gentleness it has time to drop among the lingerers there all the wild aromas and soft perfumes of the marsh and pasture and bring all the soothing sounds of life to ears that for all I know hear them dreamily and approve. Quail, the first I have heard in New England for a long time, whistled cheerily one to another from nearby thickets. Nor did these seem fearful of man. One whistled as a wagon rattled by his hiding place on the dusty winding road, and held his perch beneath a berry bush till I approached so near that I could hear the full inflection of the soft note with which he prefixed his “bob white,” see the swell of his white throat and the tilt of his head as he sent forth the call. A pair of mourning doves crooned in the old apple orchard and flew on whistling wings as I approached too near. I have heard heartache in the tones of these birds, but here their mourning seemed only the gentle sorrow of a mother’s tones as she soothes a weary child, a mourning that voiced love and sympathy rather than pain. On[14] a tree nearby a great-crested flycatcher sat and seemed to say to himself, “grief, grief.” These were the only notes of sorrow that the place held. All else in sky and field, marsh and hillside, seemed to thrill with a gentle optimism, and the hillock itself rested amidst this in a patriarchal peace and simplicity that became it well. Memory of this gentle peace and simplicity lingers long and runs like a tender refrain through the harmony of fragrant, vivid life that marks this lovely section of old Marshfield.

[15]

The Homestead two Centuries Old and the Unspoiled Country about it

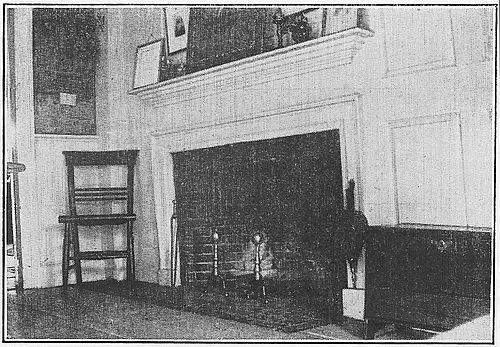

They lighted a fire for me in Whittier’s fireplace. The day had been one of wilting July heat and sun glare till storm clouds from the New Hampshire hills brought sudden cool winds and black shadows. Twilight settled down in the wide, ancient living-room, bringing brooding darkness and mystery. The little light that came through the tiny, lilac-shaded windows seemed to half reveal ghosts of legends and romance, wrapped in darkness, slipping indistinctly from the black cavern of the fireplace, standing close before it and hiding it, and gathering in formless groups in the corners of the room. They whispered and the leaves on the trees outside rustled the tale, while echoes of warlock warfare rumbled in the sky above and witch fires flared. A witches’ twilight had come down the Merrimac and[16] brought under its blanket shades of all the mountain legends that had in times past trooped to the mind of the poet as he sat there with sensitive soul a-quiver to their touch, photographing them in black and white for the minds of all men forever. From the fireplace stalked Mogg Megone and the powwows of his tribe, bringing with them all the dusky people of the weird stories of his day. The wind wailed their lone songs outside, and in its deep throat the aged chimney mumbled to itself old, old tales of night and darkness.

Then a slender flame slipped upward from the hearth, showing the form of the caretaker faintly shadowed and edged with light against the black background, and if I saw not her but the outline of Whittier’s mother bending to light the fire and drive from the minds of the children the fancies of the dusk it must have been because the witches’ twilight still held the room under its spell. Between the fore and back logs the brush of hemlock and of pine crackled and sent incense across the gloom to me, and with the leap of the flame all the weird shadows wavered into the corner and vanished. In their stead trooped up-river the[17] cheery hearthside stories of the English settlers, sturdy tales and rough perhaps but with the glow of the hearth log flickering gleefully through them. The gusts drew whirling sparks upward, and in its deep throat the chimney, no longer aged but stout and strong with vigorous work to do, guffawed in cheerful content. The dancing firelight sent gleams of quiet laughter over the face of Whittier himself, that before had looked so grimly from the frame over his ancient desk, and the room glowed with homey hospitality. If there were shades there they were golden ones of gentle maids and rollicking boys that we knew and loved so well, and though without the window opposite the fireplace and right through the shading lilac bushes a ghostly replica of the fireplace with its flickering flames appeared and vanished and reappeared, there was nothing sinister in its uncanniness, for

Stormbound if not snowbound I sat for an hour by the hearth that was the heart of a home for[18] two hundred years, watching the crane and pendent trammels show black against the blaze, seeing the Turk’s heads on the andirons glow, reading by the firelight verses which the poet wrote in that same home room, and when the storm passed and I could go forth to his brook and his fields and hills it could not fail to be with something of his love for them in my heart. Some critic, whose visit must have been shortened by homesick memories of a steam-heated flat, has said that Whittier’s birthplace is lonely and that its loneliness had its effect on his life and work. But how could such a place be lonely to a man who was born there? Here was the great living-room with its hearth, where the life of the home centered. Without was the wonderful rolling country with all its majesty of hill, whence he saw the crystal mountains to north and the blue lure of the sea to eastward, with all its gentle delights of ravines where brooks laughed, and meadows and swamps where they slipped peacefully along, mirroring the sky, watering all wild flowers and offering refuge to all wild creatures. Within this wide circle, with the house its core and the hearth its shrine,[19] revolved the homely, cheerful, whole-hearted life of the farm. What chance for loneliness was there?

After the shower had passed I climbed the gentle slope of the hill back of the house, traversing the old garden where grow the plants that came over with pioneers from England, hollyhocks and sweet william, old-time poppies, marjoram and London pride, dear to every housewife’s heart in the good old days when to wrest a farm from the forest and build a home on it was still an ambition for which a free-born New Englander need feel no shame. The witchery of the hour had not been for the hearthside alone. The sooth of the rain had been for the hearts of these also, and the joy of their answering delight made all the fresh air sweet and kindly so far as the gentle winds blew. The perfume of an old-time garden after rain is made up of gracious memories. Wherever chance has taken their seeds or care has transported their roots a thousand generations of sweet-hearted, home-keeping mothers have tended these plants and loved their flowers and the very leaves and stalks on which[20] they grew. The caress of the rain brings from each leaf and petal but the aromatic essence of such lives, welling within and flowing forth again through the unnumbered years.

Out of homely love of the hearth, out of wild Indian legends that flowed down the Merrimac and English folk lore that flowered over seas and blew westward with a sniff of the brine in it, Whittier made his poems. But not out of these was born their greatness. That was distilled from his own fiber where it grew out of the rugged, honest, fearless life of generations whose home shrine had been that glowing hearth, whose love and tenderness welled within and overflowed like the scent of the old-time garden. To such a house and such a hearth sweetness climbs and nestles. To stand on the old door stone was to be greeted with dreams of meadows and lush fields, for wild mint has left the brookside and come shyly to the very door sill to toss its aroma to all comers. A spirit of the meadows that the barefoot boy loved thus dwells ever by his door and none may enter without its benediction. There is something Quakerlike in the wild mint, that[21] dwells apart, unnoticed and wearing no flaunting colors, yet is so dearly fragrant and yields its sweetness most when bruised.

A stone’s toss from the door I found his brook, its music muted by the summer drought so that you must bend the ear close to hear its song. With the foam brimming on its lip in spring the brook roars good fellowship, a stein song in which its brothers over nearby ridges join, filled with the potency which March brews from snow-steeped woods. Now, its March madness long passed, repentant and shriven by the kindly sun, it slips, a pure-souled hermit, from pool to pool, each pool so clear that in it the sky rests content, while water striders mark changing constellations on its surface. The pools are silent, only beneath the stones the passing water chirps to itself a little cheerful song which the vireos in the trees overhead faintly imitate. The trees love the brook’s version best, for they bend their heads low to listen to it, beech and maple, white oak and red, yellow birch and white birch and black birch, hemlock and pine, dappling the pools with shade and interlocking arms across the glen in which[22] the brook flows. In the dapple of shadow and sunlight beneath them ferns of high and low degree, royal and lady, cinnamon, interrupted and hay-scented, wade in the shallows and caress the deeps with their arching fronds. The blue flags that waved beside the water a month ago are gone, leaving only green pennants to mark their camp site for another year; and it is well that it is thus marked, else it were lost, for in the very brook bottom where the March flood crashed along have come to usurp it those tender annuals, the jewel weeds. Their stems almost transparent, their oval leaves so dark a green that it seems as if some of the dancing shadows found rest in them, they press in close groups into all shallow places and lean over the edges of the clear pools to admire the gold pendants that tinkle in their ears.

With these through the grassy shallows climb true forget-me-nots, slenderest of brookside wanderers, each blue bloom a tiny turquoise for the setting of the jewel-weeds’ gold. Thus shaded and carpeted the little ravine wanders down from the hills, and the brook goes with it, as if hand in hand, bringing to its side all sprightly life, a place [23]filled with boyhood fancies and echoes of boyhood laughter. A chewink, singing on a treetop up the slope, voiced this feeling. Someone has called the chewink the tambourine bird. His song makes the name a deserved one. It consists of one clear, melodious call and then an ecstatic tinkling as of a tambourine skillfully shaken and dripping joyous notes. Always before the chewink’s song has been without words to me. This one sang so clearly “Whittier; ting-a-ling-a-ling” that I knew the bird and his ancestors had made the glen home since the boyhood of the poet, learning to sing the name that rang oftenest through the tinkle of the brook.

You begin to climb Job’s Hill right from the glen, passing from beneath its trees to stone-walled mowing fields where rudbeckias dance in the morning wind, their yellow sunbonnets flapping and flaring about homely black faces. I fancy these fields were white with ox-eye daisies in the spring. They are yellow now with the sunbonnets of these jolly wenches. It is like getting from Alabama to New England to step over the last wall which divides the fields of the[24] hill’s shoulder from its summit, which is a close-cropped cow pasture. Here the winds of all the world blow keen and free and you may look north to the crystal hills of New Hampshire whence come their strength. Eastward under the sun lies the pale rim of the sea. Kenoza Lake opens two wide blue eyes at your feet, and all along beneath you roll bare, round-topped hills sloping down to dark woods and scattered fields, as unspoiled by man as in Whittier’s days. The making of farms does not spoil the beauty of a country; it adds to it. It is the making of cities that spells havoc and desolation. Through the pasture, up the steep slopes to the summit of Job’s Hill, that seems so bare at first glimpse, climb all the lovely pasture things to revel in the free winds. Foremost of these is the steeplebush, prim Puritan of the open wold, erect, trying to be just drab and green and precise, but blushing to the top of his steeple because the pink wild roses have insisted on dancing with him up the hill, their cheeks rosy with the wind, their arms twined round one another at first, then round him as well. Somehow this bachelor bush which would be so austere reminds[25] one of the Quaker youth at the academy, surrounded by those rosy maidens of the world’s people, one of whom we suspect he loved, yet could no more tell it than can the steeplebush acknowledge how sweet is the companionship of the wild rose and how he hopes it may go on forever. Stray red cedars stroll about the lower slopes and climb gravely, while juniper, in close-set prickly clumps, seems to follow their leadership. The canny, chancy thistle holds its rosy pompons up to the bumble-bees, that fairly burrow in them for their Scotch honey, and the mullein would be even more erect and more Quakerly drab than the steeplebush if it could. It is erect and gray, but just as it means to look its grimmest dancing whorls of yellow sunshine blossom up its stalk in spirals, the last one fairly taking flight from the tip. Among all these strays the yarrow, whose aroma is as much a New England odor as that of sweet-fern or bayberry. The aromatic incense of this herb follows you up the hill and seems to bring the pungent presence of the poet himself.

Job’s steepest hillside drops you in one long swoop to the road which leads through woodland[26] windings to the haunted bridge over Country Brook. The way itself is haunted by woodland fragrance and chant of birds innumerable, and in the freshness of the morning after the shower it seemed as if built new. The world is apt to be this way after rain. Yet if the vivid morning sun and exhilarating north wind had driven all ghosts away there had been necromancy at work. All the day before the blossoms on the staghorn sumac had been of that velvety pink that rivals the wild rose. Over night they had turned a warm, rich red. Autumn brings this richer, more stable color to the sumac blooms as they ripen toward seed time, but it does not do it in July, over night. The pukwudgies had been at work, painting with the rain, filling the sumac heads with it till they hung heavy. The water had massed the tiny pubescence of the blooms till pink had deepened into red and autumn had seemed to come for the sumacs in a night. It took the sun and the wind all day to dry them out and bring back the witchery of pink that the necromancy of the rain had banished. But the spell was not altogether broken, nor will it be till autumn has worked its[27] will with the world about Country Brook. Out of the birches the fresh wind threshed here and there yellow leaves that fluttered like colias butterflies before it. There and here among the sumacs hung a crimson leaf, more vivid in its color than the blossoms or the berries could ever be, and as in the woodland all news flashes from shrub to shrub and from creature to creature, so it seemed as in the hint of autumn, first born, a simulacrum merely, in the wet sumac heads, had gone by birch leaf messengers to all distances. Along the way flashed out of invisibility the yellow of tall goldenrod heads and the blue and white of the earliest asters and, once materialized, remained.

August may bring vivid heat and wilting humidity if it will. The witches’ twilight had brought down the Merrimac from the far north the flavor of autumn which is later to follow in full force, nor will it wholly leave us again. The ghostliest thing about Country Brook was a sound which seemed to come up it from the cool depths of the woods into which it flows, a soft breathing sigh, now regular, now intermittent, as if a spirit[28] of the woodland slept peacefully for a little, then gasped with troubled dreams. Seeking to discover this ghost I found a little way along the road from the bridge a broad grassy avenue that led with a certain majesty in its sweep as if to some woodland castle whose people were so light-footed that they wore no paths in their broad green avenue. Yet after all it led me only to a wide meadow where the sighing I had heard was that of the grass going to sleep under the magic passes of a mower’s scythe. No clatter of mowing machine was here, just the swish of a scythe such as the meadow has heard yearly since the pioneers came. There were deer tracks here along the margin of Country Brook, and all the gentle wild life of woods and meadows seemed to pass freely, without care or fear.

And so I found all the country about the Whittier homestead an epitome of the free, cheerful, country life of the New England of a century ago. They lighted a fire for me in Whittier’s fireplace—and as the rose glow on the walls of the old living-room brought back the hearth-cheer of bygone years, as the witches, daintily making [29]tea without under the lilac bush, brought the romance and legend of the olden time to the threshold, so the crackling draft of the fire up the deep throat of the chimney seemed to draw in to the place the free, hearty, farming, wood-loving life of the men of the earlier centuries out of which the poet drew what was best in him, to be given out in unforgettable verse to us all. If such a place was ever lonely it was that gentle and desirable loneliness which great souls love.

[30]

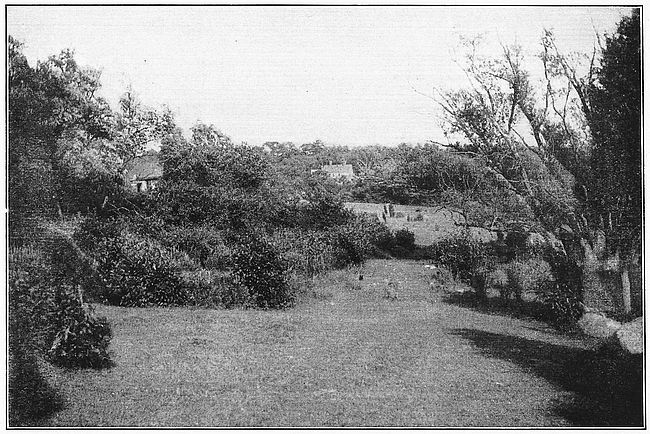

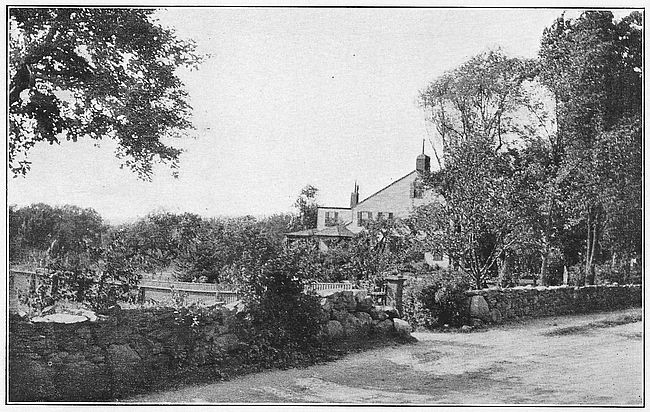

Glimpses from a Study Window of Thomas Bailey Aldrich

The study where Thomas Bailey Aldrich wrote some of his daintiest verse looks forth upon a sweet valley. Down this valley prattle clear-eyed brooks that meet and grow, and water lush meadows filled with all lovely things of summer, while low woods beyond set a dark green line against the sunsets. Looking toward these of a day when rosy mists tangle the sun’s rays and anon let them slip in arrow flight earthward, we have pictured for us how

Wherever written, this and a hundred other dainty things seem to flock into the tiny valley upon which he looked from the study window of [31]his later life in what was then the quaint old village of Ponkapoag, as if the flowers of fancy to which he gave wings still hovered there. At nightfall it is easy along these meadows to

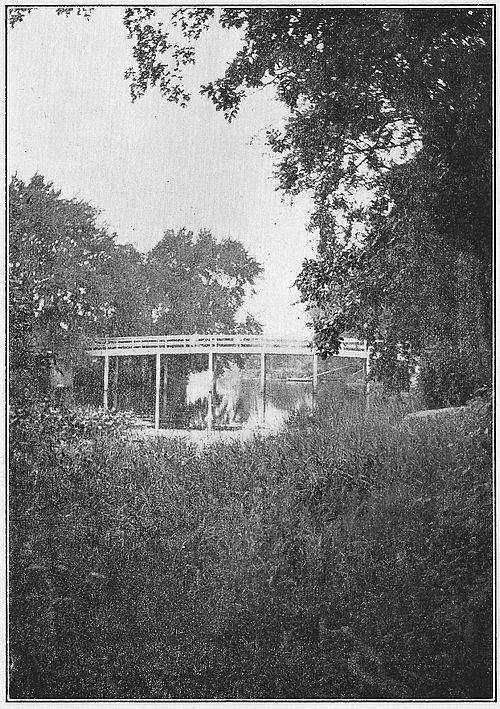

The quaint old Ponkapoag of not so very many years ago is changing fast. The trolley car passes and re-passes in what was once its one street. The real estate man has come and modern houses grow up over night, almost, in the empty spaces over the old stone walls, while in the surrounding pastures and woodland appear the mansions of those who seek large estates not too far from the city. Suburban life begins to crowd Ponkapoag and the little self-centered country village of the genuine New England type passes. Most, however, of the sturdy old houses of a century or more ago remain and much of the beauty of the country round about them. On Sundays and holidays Ponkapoag Pond teems with an uproarious holiday crowd, but on weekdays one may still enjoy its beauty unmolested,[32] hear the blackbird’s music tinkle along the bogs, and see the pond lily, the pure white spirit of Miantowonah, sit on the water. On such days Ponkapoag Pond, “the spring bubbling from red earth,” seems still to belong as much to the Indians, whose favorite fishing ground it was, as to us latter-day usurpers, and the outlook across it to the dusky loom of Blue Hill is as wild now as it was in their day.

From the north-facing window of the poet’s study you may see the hill again, with all its beauty of color which changes with the whim of the day. At dawn of a clear morning it looms blue-black against the rosy deep of the sky. At noon it looms still but friendly and green, so near that the eye may pick out the shape of each tree that feathers the jutting crags. At noon of such a day Ponkapoag hill with its houses bowered in green seems a part of it, the half mile of intervening space making no impression on the eye. As the sun sinks a haze rises from the rich farming land which lies level between the two hills. The spirit on slender ropes of mist is at work, and through this vapory amethyst the larger hill withdraws into[33] soft colors of blue that grow violet purple with the coming of dusk below and the rosy afterglow of reflected sunset in the sky above. Captain John Smith named the range “The Cheviot Hills” in recollection of old England, but all the countryside named it Blue Hill because of the changing wonder of its coloring, which is a constant delight to the eye. On stormy days when gray northeasters send torn clouds, fragrant with the tonic smell of the brine, whirling over it, the hill looms misty and vague, as if it might well be a mountain scores of miles distant, instead of the single mile it is along the straight road. On such days all the wild sea myths and northland sagas seem to be blown in over the hill barrier and trail down from the skirts of the clouds into the secluded peace of Ponkapoag valley. Hence, to those who dream, come sea longings.

Infinite variance of changing moods has the hill which lifts such abrupt crags above the Ponkapoag plain. At times the poet may have seen it as it was one day not long ago, when a great thunderstorm, born of the sweltering, blue haze of a fiercely hot July day, swept across it. On that day the hill withdrew itself into the menacing black sky, looming against it, then vanishing, becoming part of a night like that of the apocalypse, in which hung the observatory and the higher houses of Ponkapoag hill “as glaring as our sins on judgment day.” The storm in which the miracle of “The Legend of Ara-Cœli” was wrought could not have been blacker than the sky, nor the face of the monk, when he saw the toes of the bambino beneath the door, whiter than gleamed those houses. The weirder, greater things of nature loom often through the poems of the man who looked upon such scenes from the study window in what was[35] “The Bemis Place” of the elder days of Ponkapoag village. It seems as if all the lighter, sweeter fancies that laugh or slip, tear in eye, through his verse, whirled like rose petals on summer winds or danced like butterflies into the little valley on which the westward study windows looked. Through this, right in the foreground, flows Ponkapoag brook, and on it falls slowly into decay an ancient mill, a relic of the early days of the village. The old dam no longer restrains the water which gurgles along the stones below it, humming to itself a quatrain which never was meant for it, but which voices the fate of the shallow mill pond, which has been empty for so many long years that it is no longer a pond but a tiny meadow in which cattle cool their feet and feed contentedly. Here the spendthrift brook sings contentedly:

In the meadow and along the brookside blooms to-day the Habenaria psycodes, the smaller purple-fringed[36] orchid, its dainty petal-mist rising like flower steam of an August noon, a shy child of woodland bogs, which often runs away out into the open meadow to hear the blackbirds sing. This year I have not found the larger fringed orchid, the Habenaria fimbriata, which comes to the meadow less often, a flower which one might fancy the mother of the other, coming to lead the truant home again to the seclusion of the woodland shadows. In all the fairy nooks of this valley ferns spring up like vagrant, delicate fancies that are real while you hold them in close contemplation, yet vanish into the green of the surroundings, as the form of a poet’s thought fades when you take your eye from the printed page, though the thought itself lingers long in your memory. In the shallow meadow that was once the tiny pond stands, shoulder high to the feeding cattle, a solid, serried phalanx of the tall sagittaria, its heart-shaped, lanceolate, pointed leaves aiming this way and that, as if to fend it with keen tips from the eager browsers. These wade through it indeed, but do not feed on it, plunging their heads deep amoung the spear points to gather the tender [37]herbage beneath. While I watched them two of these, half-grown Holstein heifers, bounded friskily to the hard turf of the cedar-guarded pasture above and raced in a satyr-like romp over the close turf and among the cedars for a time. It was as if they knew that Corydon had just vanished up that roadside in Arcady in pursuit of the maiden that the Pilgrim described to him, and the valley was free from all supervision for a time. The white spikes of bloom on the water-plantain nodded to let them pass, and nodded again as if they too knew why the satyrs frisked and on what errand the shepherd had gone.

Daintiest of embodied thoughts which flit along this sequestered valley are the butterflies. This is their feasting time of year, for now the milkweed blooms hang crowded umbels of sticky sweetness that no honey-loving insect can resist. Commonest of these by the brookside is Asclepias cornuti with its large pale leaves and its dull greenish-purplish flowers. It is rather odd that out of the same brook water and the salts and humus in the black earth through which it flows one plant should grow these dull, heavy, loutish flowers,[38] while just beside it, perhaps, the Habenaria psycodes gets its misty delicacy of purple bloom from the same source. With plants as with people it is not that on which we feed nor the spot on which we stand that counts in the final moulding of character. Some subtle essence, some fire of spirit within the orchid makes its bloom. Some grosser ideal within the milkweed matures in the dull, sticky umbels. Thus within the town, attending the same schools, and fed by the same butcher and baker, one boy grows up a poet and another a yokel. Even in the same family you may see it, for the milkweeds are not all alike. Along the dry hillsides the Asclepias tuberosa gives us bright orange flowers, exudes little if any stickiness, and even gets a better name from the botanist, being called the butterfly-weed.

But however gross and homely the milkweed blooms the butterflies find rich pasturage there and sip and cling till they fairly fall off in satiety. Winging to the milkweed out of the chestnut and maple shade of the deep wood comes Papilio turnus, striped tigerwise with rich yellow and black. Out of the long saw-edged grass that grows long[39] in the meadow and bows before the wind as do fields of grain sails Argynnis cybele, the great spangled fritillary, the fulvous glory of his broad wings spangled beneath with silver, as if he carried his coin of a fairy realm with him wherever he goes. Over the very pine tops soars the monarch, his rich dark red and black borne on wings that are the strongest in butterfly flight. These three, most conspicuous sprites in the meadow tangle, give rich coloring and the poetry of motion as they bear down upon the milkweed blooms, to leave them no more save for short flights taken merely to secure a better strategic position on the umbels, till they are cloyed with the rich nectar, and smeared with the sticky exudation which the plant puts out on the blooms for purposes of its own. I fancy the butterflies are vexed and indignant at this stickiness which smears their legs and makes yellow pollen masses cling to them when, satiated and lazy, they next take flight. Yet the whole is cleverly arranged. On the smeared legs as they sail away cling pollen masses which the insect is not likely to get rid of till it lights on another head of bloom, very likely one of some distant[40] plant. There the sticky masses cling closer to the quaint horns which each bloom protrudes from behind the anthers, there to drop pollen grains on the stigma and insure the cross-fertilization of the flower. Thus unwittingly butterfly and bee as they sail about the sun-steeped meadow suffer discomfort for their own good, insuring vigorous crops of milkweed for another summer, for themselves or their descendants.

With these comes the smaller, Colias philodice, the sulphur, bringing with him the very gold of the sunlight. Colias philodice has many changes. Sometimes the black margins of his wings are missing and his gold melts into the sunshine and vanishes before your eyes. Another may come that is white instead of gold, a wan ghost of a colias that seems born of the mist instead of the sunshine and to vanish into nothing when he flies away, as mist does. Sometimes the colias flies up into the wood and lights, and as I come to the spot where I think I saw him stop I find nothing but a single bloom of the golden gerardia which now slips from glade to glade all along where the hardwood growth comes down to meet the meadow[41] grasses. The gerardia might very well explain all this if it would, but it is born close-mouthed. If you will look at the yellow buds which later open into the golden bells into which the bumble-bees love to scramble, bumbling as they go, you will see how tightly their lips are pressed together. No word can you get from these by the most insistent questioning, and even when they open it is easy to see that they have learned that silence is golden.

The Baltimore butterfly, wearing Lord Baltimore’s colors of orange and black, is a common visitant to these meadows, too. He loves to tipple the lees of the milkweed blooms, but he does not frequent the meadow for that. It is because along its shoreward edges where the cool water oozes from black mud grows his home plant, the turtle-head. On this he was born and to it he goes for the housing and feeding of his children. Like Gerardia flava, Chelone glabra is close-mouthed, but its silence is a wan white one which only blushes pink with embarrassment when questioned, but yields no reply. You cannot learn any mysteries of the meadow from these.

[42]

Palest and most ghostlike of all flowers that one finds as he climbs from the meadow to the woods beyond is that of the Monotropa uniflora, or Indian pipe. Round about it its cousins, the pyrola and the pipsissewa, grow green leaves and show waxy white or flesh-pink blossoms. The only color in the Indian pipe is that of the yellow stamens, which shrink in a close circle within the wax-white bloom that stands on a scaly, wax-white stem. A very ghost of a flower is this, nor may we account for its ghostliness. When, long ago, Miantowonah fled to drown her grief in the lake and later rise from it the spirit of a flower which is the regal white pond lily that scatters incense all along the borders of Ponkapoag Pond, her Indian lover followed, too late to prevent the sacrifice. Did he drop his peace pipe in the race through the wood, and did this ghost flower spring from the spot, a faintly fragrant, almost transparent ghostly reminder of it? If so, it has passed into no legend.

Coming back through the meadow, with its butterfly sprites of fancy dancing among the flowers, I find one which always seems a reminder of the poet’s work at its daintiest and best. That[43] is the bloom of the wild caraway. Here is a mist of delicate thought which speaks to you with lace-like beauty. Nor does the closest inspection reveal any fault. The bloom appeals as a delightful bit of sentiment, at first glance. It is only as you examine it minutely that you marvel at its exquisite workmanship. However carefully you pick it to pieces you find each part perfect and as admirable in its ingenuity as in its appeal to the imagination. And after you have done this you pass on, touched with the white purity of it and bearing far a gentle, aromatic pungency which is the essence of the parent stem that bore the bloom.

[44]

The Island and the Garden which Celia Thaxter Loved

The poppies that grow in Celia Thaxter’s garden nod bright heads in welcome to all who come. It is as if the sunny presence of their mistress dwelt always in the spot, finding voice in these blooms which are so delicate, yet so regnant in spirit. To these all the other flowers which speak of the homely virtues, marigolds and red geraniums, coreopsis and pinks and love-in-a-mist, seem subordinate at first approach, though they occupy the bulk of the garden, which seems to epitomize the life of the mistress who tended it so long. There is no square of it without its rich aroma of love and womanliness, yet it is the vivid personality of the poppies, flowers for dreams, which touches first the comer from the outside world.

Round about the garden lies Appledore, the largest of the Isles of Shoals, rocked gently on [45]the bosom of blue seas, its margin flashing with beryl and pearl where rocks and breakers touch, its rounded ridges white and green again with the granite of which it is built and the verdure with which it is clothed. Over it all bends the blue of the summer sky, and as you look up to this from the little garden it seems to lean lovingly upon the hill which is the island’s highest part, heaven so near that the scent of the flowers may easily pass to it by way of the little winding path. To climb this path yourself is to find the sky not so near after all. Standing on the summit, you realize first the depth of its great dome and the wide sweep of sea that rims the islands round. Here are but gray ledges that rise out of an immensity which dwarfs them. Far to the north and west is a thin, blue line of land that lifts in the farthest distance the peaks of the White Mountains. All else is but a vast expanse of sea that seems as if it might rise in a storm and overwhelm these rocks that it has washed so white and smooth. Somewhere to the eastward of our coast lies, they tell us, the lost Atlantis, submerged beneath this great sweep of blue that smiles beryl[46] and laughs pearl-white in wave crests. Who knows but this granite dome of Appledore on which we seem to loom so high in air is the westernmost peak of the vanished continent? We are but seventy-five feet above the sea’s surface. It must be the thought of its depths that gives us the feeling of being upon a mountain peak. For all that, this height and distance so make us dominate the other islands that they seem but ledges, wave-washed reefs in comparison, and one wonders how such of them as have buildings on them hold them during the sweep of winter gales and full-moon tides.

In the smile of summer it is easy to forget this. It is but a step from the rough rocks of the island to the dense verdure of its shrubbery. At first one wonders where the soil came from that nourishes herb and shrub in such profusion. Here among the gray granite grow most of the beauties of any shore-sheltered New England pasture. Here is elder showing white, lace-like blooms, bayberry and staghorn sumac each striving to overtop the other, wild cherry and shadbush, and beneath and around these low-bush black huckleberries, raspberries[47] and blackberries, the last two blessing the tangle with fruit. Among the grasses grow yarrow, St. John’s-wort, mullein, toad-flax, cranes-bill, evening primrose and other herbs, while Virginia creeper and fragrant clematis make many a spot a bower of climbing vines. Not only do all these familiar pasture folk grow here, but in many instances they seem to grow with a luxuriance that exceeds that of their favorite shore locations. Their tangle makes passage difficult except by established paths, and the road which circumnavigates the island is cut almost as much through the compacted shrubbery as through the rough rocks along the tops of the cliffs. Rainfall collects in the hollows of the granite in some places and makes miniature marshes, and in one spot a tiny pond which is big enough to supply ice to the islanders, filling to the brim with the winter rains and in some winters freezing pretty nearly solid. In August this pond, which is high in the middle of the island, is dry, its bottom green with rushes and its sides rampant with the spears of the blue flag.

Often in the tiny valleys in the heart of the island, surrounded by its dense shrubbery, you lose sight[48] of the sea, but you cannot forget it. However still the day, you can hear the deep breathing of the tides, sighing as they sleep, and a mystical murmur running through the swish of the breakers, that is the song of the deep sea waves, riding steadily in shore, ruffled but in no wise impeded by the west winds that vainly press them in the contrary direction. However rich the perfume of the clematis the wind brings with it the cool, soothing odor that is born of wild gardens deep in the brine and loosed with nascent oxygen as the curling wave crushes to a smother of white foam. It may be that the breathing of this nascent oxygen and the unknown life-giving principles in this deep sea odor gives the plants of Appledore their vigor and luxuriance of growth. Certainly it would not seem to be the soil that does it. Down on the westward shore of the island, in an angle of the white granite, where there was but a thin crevice for its roots and no sign of humus, I found a single yarrow growing. Its leaves were so luxuriant, yet delicate, so fern-like and beautiful, such feathery fronds of soft, rich green as to make one, though knowing it but yarrow, yet[49] half believe it a tropic fern by some strange chance transplanted to the rugged ledges of the lonely island. With something in the air, and perhaps in the granite, that makes this common roadside plant develop such luxuriance, it is no wonder that other common pasture folk, goldenrod and aster, morning glory and wild parsnip, and a dozen others, growing in abundant soil in the tiny levels and hollows, are taller and fuller of leaf and petal than elsewhere. In the richness and beauty of the yarrow leaves growing in the very hollow of the granite’s hand, as in the height and splendor of the Shirley poppies in the little garden, one seems to find a parallel to Celia Thaxter, whose own character, nurtured on the same sea air, sheltered in the hollow hand of the same granite, grew equally rich and beautiful.

All Appledore, indeed all the Isles of Shoals are built of this rock, which is white in the distance, but which near to shows silver fleckings of mica that flash in the sun. Through the granite run narrow veins of quartz that is as hard as flint, but that has scattered among its crystals also a silvering of these mica flecks[50] which are in strange contrast to the tiny pin points of a softer, darker rock which one finds evenly sprinkled through the white. This dark rock softens to wind and weather first and leaves these white cliffs honeycombed with the tiniest of fissures, so that they are as rough to the hand as sandpaper. Dykes of trap run through the island, and as this rock too is softer than its casing the winds and waves of centuries have worn it away, leaving chasms down which you may walk to the tide, between the sheer cliffs. One such chasm runs quite across Appledore from east to west near the northern end of the island, almost cutting off a round dome of granite from its fellow rock. The soil lies rich in this narrow hollow between ledges, and many things grow in it, lush with leaves and beautiful with bloom. Here the shadbush had already ripened its fruit. Here the island’s one apple tree grows vigorously, though it dares not lift its head above the level of the rocks against which it snuggles, lest the zero gales of winter nip it off. Crowding round it grow wild cherry and wild rose, elder and sumac and huckleberry and chokeberry, all eager [51]to fend it from rough winds in that friendliness which seems, like foliage, to flourish in the place. Here is a soft turf of grass in which grow violets and dandelions, both spring and fall, and plantain, cinquefoil and evening primrose have come to make the place homelike. If rough winds blow here rougher rocks fend them off, and though they may whistle over the tops of these in the little valley between there is quiet, and floods of sunshine gather and well up till the place is full.

This tiny valley dips toward the sea at the west and broadens to a meadow where I fancy the islanders have at some time grown cranberries, for a few plants remain. For the most part, however, this meadow is set thick with the green spears of the bog rushes which grow so close together that there is little room for anything else. To crush your way in among these is to pass through a very forest of dark green lances whose tips stretch upward to stab your chin, yet burst into bloom from the sides near these tips, as if the full life within them which could not be restrained yet which finds no outlet in leaves, exploded in a lance pennant of olive-brown beauty.[52] A Maryland yellow-throat whose nest stands empty in the grass on the borders of this little, lance-serried marsh fluttered and chirped and clung among these rushes and from the top of a near-by bayberry shrub a song sparrow trilled a note or two, despite the fact that it is moulting time and few birds have the heart to sing in dishabille. Nightfall brought no sound of frog voices from this little marsh, yet I cannot fancy it in spring without a hyla or two to pipe flute notes from its margin. Near this I found the one ophidian of the island, a beautiful, slender, graceful green snake, little more than a foot long. This lovely little creature feeds on crickets and insect larvæ and is the very gentlest snake that ever crawled. Jarred by my footfall in the grass he glided away among the tangle, trusting to his coloration, which is a perfect grass green, to hide him, which it soon did. If Appledore must have its serpent no sweeter-natured nor lovelier variety could be found. If modern Eves sit upon the rocks of moonlight nights and listen to this one’s promptings one can scarcely blame them.

Under the eaves and under the verandas of the[53] houses are the nests of barn swallows, gray mud stippled up against a rafter, the fast-growing young almost crowding one another out. So gently familiar are these birds, and so little afraid of people, that one has built a nest under the frequented piazza of the big hotel, and the parent birds flit back and forth unconcerned by the rows of guests that often take chairs and watch the nestlings for long periods. Not only do the parents feed their young while thus watched by crowds but a few feet away, but they fly in under the veranda and capture food right over the heads of the promenaders with equal freedom from fear. Barn swallows are usually friendly, confiding birds. They seem here to have caught the sense of protection and safety which comes to all on the little island, and become even more fearless. It is much the same way with the tree swallows, which, having no hollow trees, build in bird boxes all about. These already have young in flight. Standing on the cliffs you see their steel blue backs as they swirl with the little waves in and out among the rockweed at low tide, seeking their food very close to land or water.[54] Often the young sit on some safe pinnacle and are fed there, the old bird flashing up, twittering, delivering a message and a mouthful at the same time, then flashing away again, whirling and wheeling, never beyond call of the eager fledgling. Often the fledgling soars into space, hardly to be distinguished then from the older bird, and twitters back and forth near the parent. Then when the latter comes with a mouthful the former simply poises fluttering while the old bird dashes up, twitters and feeds, and is off again in the flash of an eye, so fleet of motion, so agile of turn, that it puzzles the watcher to follow the course of flight.

At the bottom of the tide the rocks over which the tree swallows swirl with the waves are a golden olive with the sun-touched tips of the carrageen. Higher up the boulders lift their heads with the air-celled rockweed falling all about them like wet hair. Some of these tresses hang down in golden luxuriance, others are dark, almost black, as if blondes and brunettes were to be found among tide rocks as among men. Between these rocks are still pools of brine where mussels and[55] crabs wait the deliverance of the full sea and kelp waves its long, dark-olive, ruffle-margined banners. Down among these with the ear close to the smooth, undulating surface you may catch the eerie plaint of the whistling buoy off the channel some miles to landward, telling its loneliness in recurrent moans.

Up on the rocks again in the bright sunlight, one finds the land birds numerous, chief among which are the song sparrows. In the secluded peace of the place these also, evidently making their summer home here and nesting in the shrubbery that is all about, have lost most of their fear of man and will approach very near to gather crumbs about your feet. A small flock of robins goes by, stopping a moment to feed, then taking wing again as if practising for that southward migration which will begin before very long. Olive-sided flycatchers, already working toward the sun, flit to catch flies and light alternately almost as if playing leapfrog from bush to bush. So far as I have observed, the olive-sided flycatchers do most of their migrating thus, hippety-hop from perch to perch, with a fly well caught[56] at every hop and well swallowed at every perch. A kingbird sat haughtily, as if mounted, on a stub, monarch of all he surveyed, now and then giving his piercing little cry and sailing out to the destruction of a moth or beetle, then sailing leisurely back again. A lone gull fished and cried lonesomely in the surf, and a few pairs of sandpipers slipped with twinkling feet along the rocks, feeding in the moist path of the receding wave and lifting on long, slender wings to safety at the crash of the next one. These were the only day birds to be found of a pleasant day at Appledore. Monarch butterflies were plentiful, migrants these over the seven miles or more of sea between the island and the mainland. A few cabbage butterflies fluttered white wings over the Cruciferæ which grow in the vegetable gardens of the place. The cabbage butterflies may well be natives, and so might that other which danced away so rapidly that I could not be sure of him, though I am confident that he was either a hunter’s butterfly or an angle-wing. Yet these, too, may have come from the mainland on a still day or with the wind right and not too[57] strong, such extraordinary distances do these seemingly frail and impotent insects cover sometimes. Honey bees from hives ashore make a regular business of flying to the islands and back laden with honey. Students of bees ordinarily give them a range of two and a half to four miles, yet these Appledore bees must come at least seven miles and probably ten for their harvesting.

At nightfall three great blue herons came flapping out from the mainland to fish among the kelp and rockweed of the outlying reefs. All along the western horizon the soft blue line of land began to melt into the steel blue of the sea that the sunset fire seemed then to temper to a violet hardness. The southwest wind had blown the sky full of blowsy cumulus clouds that were touched with fire from the setting sun, yet in the main had the color of the steel sea, as if they were the flaked dross from its melting. Then the sun for a moment burned through the thin blue line of land and set the sea ablaze with a gentle radiance of crimson and gold that slipped along the level miles and wrapped the blessed isles in its arms, radiant arms that unclasped themselves in[58] a moment, lifted above the islands in benediction and then passed. The poppies in Celia Thaxter’s garden folded their two inner petals like slim hands, clasped in prayer, lifted trustfully to the sky.

A little way from the garden that she loved and tended so long is Celia Thaxter’s grave, on a knoll to which the sky bends so gently that it seems as if you might step off into it. Up to the smooth turf of this knoll crowd all the pasture shrubs that she loved, sheltering it from the wind on three sides and letting the sun smile in upon it all day long without hindrance. The sumacs come nearest as if they were the very guard of honor, but close behind them press the wild roses, the St. John’s-wort, the evening primroses and even the shy white clover slipping in between the others, very close to the ground, and tossing soft perfumes out over the brown grass. On the grave itself someone in loving remembrance scatters the petals of red geranium, which seems of all things the home-loving, home-keeping flower. The poppies are for poets’ dreams which write themselves in the dancing morning wind, [59]clasp hands in prayer at sunset, and flutter away. Red geraniums seem born of the fireside where home has been since fire first came down out of heaven. Dreams and hearthfire both were dear to the sweet lady of Appledore, and both flowers commemorate her there.

[60]

A Survey of the Pond and its Surroundings

He who would know Thoreau’s Walden will do well to bathe in it. His first plunge may well be in Thoreau’s story of the pond and his life on its bank, and when he comes dripping from this and puts on the garments of everyday life he still must feel a little of the glow of the fire with which this alchemist of the woods transmuted all things, showing us how rough granite, hard iron and base lead are gold. Thoreau lived on the borders of the little clear pond but two years. He knew it in the flesh for just his short life. But his spirit had birth in something akin to its pure, profound waters and dwells above them now for all centuries.

The next plunge should be in the waters themselves, and only thus shall you learn to the full what a miracle the pond is. Here is a crater of[61] glacier-crushed granite, out of which never came smoke nor lava, only a white fire from unexplored depths, a fire of cool austerity which burns the dross out of all that may be put into it. There is no inflowing stream. Its waters well up from a mysterious source within the very earth. Their outflow is equally invisible. In their going they leap spirit-like along the golden stairs which the sun lets down to them and pass up for the building of rainbows, their white light breaking in its mystical seven colors, a visible ecstasy to all who watch the heavens. To plunge in these waters at dawn is to feel this cool fire thrill through the marrow of your bones, and only by total immersion shall you know to the full its purity.

Coming to such a flight with Eos through the dusky solemnity of the trees of the western bank, I saw the pond silvered beneath its tense level with the frosty scintillations of the stars that had shone into it all night. It was as if their radiance had but penetrated the water-tension film of the surface and collected just beneath it, making a white mirror which my plunge shattered into a thousand[62] prisms of scintillant light. The dancing night winds had shaken all the rich odors from the white clethra blooms that grow all about the pond’s rim and stored them along its surface, and to swim out toward the center was to enter a sweetly perfumed bath. The forest to eastward, full of black density, as it was, could not bar out the rose of the morning from the sight. Instead it stood in a silhouetted fretting against it and let its glow shine through a million tiny windows of the day, blossoming again in the ripples ahead. Here was a moving picture of the blooming and vanishing of pink meadow-flowers, flashing a brief life upon the film, vanishing and growing again. The cinematograph is nothing new. Walden has operated it for those who will swim toward the dawn in its waters since the centuries began. In our theaters we are but tawdry imitators of its film productions.

Chin deep in its middle you begin to feel that you know the pond. In a sense you are its eye and look upon the world as it does. Day breaks for the swimmer as it does for Walden, and the flash of the sun above the wood to eastward warms[63] you both with the same sudden sweep of its August fire. In the same sense you are the pond’s ear and hear as it does. The morning rustle of the trees, shaking the dusk from their boughs, comes to you as a clear ecstasy, and you think you can hear the wan tinkling of the invisible feet of fairy mists as they leap sunward from the surface and vanish in the day. Over the wood comes the intermittent pulse of Concord waking, and by fainter reverberations the pond knows that Lincoln and more distant villages are astir. Then the first train of the day crashes by the southern margin and stuns the tympanum with a vast avalanche of uproar.

To plunge beneath the surface and escape this is to learn the real color of the pond. From without, on the banks, this varies. Oftenest it is a dull, clear green like that of alexandrite, a chrysoberyl gem from the mines of Ceylon and the Ural mountains. You see this best from the higher points of the hills along the borders and at certain angles of the sun the green shows red reflections and tints of blue as does the gem. If, swimming in the center, you will tip up as a duck[64] does and go head foremost with open eyes into the depths, you will see none of this color. There with all the influences of reflection and refraction eliminated you find yourself moving through an infinitely soft blue that is semi-opaque merely because a million generations of use has fitted the human eye for seeing details through air only. Yet the perception of color remains. Hold your breath desperately and swim as far down as you may and there is no change. The color has all the softness and gentle beauty of the turquoise. In certain lights among the Florida Keys I have seen this sweetest, gentlest of blues in the Gulf Stream, but in no other water.

To turn and look at yourself in this water is to have another surprise. Already it seems as if the mystic fires of its depths had begun to inform you with a pure whiteness that should be akin to nobility of soul, and as you step forth on the shore mayhap this quality, passing subtly to the blood and brain, lingers for a while, and in the clear fire of renewed vitality you feel that the morning has indeed brought back to you the heroic age.

[65]

To come to Walden at mid-day, even with Thoreau’s account of it in the back of your head, is not at first to be impressed with the clear spirituality of its waters nor their depth. Here, you say, is the path from Concord, lightly worn by the spring of his tread, clumsily rutted by the heavy footsteps of many who follow, having indeed hitched their wagon to a star. Here is the cairn erected in his memory, to which with doffed hat you may well add a stone from the pond shore. And here is the pond itself, a gem of silvered water set among low, wooded hills. Your eye may well catch first a sight of the driftwood on the shore, of which there is much and think it makes the place untidy and wish that the Concord selectmen might have it removed. But the thought which this first mid-day glimpse stirs soon passes from you and standing on the very brink you realize the limpidity of the water and the spirit of dignity and peace which prevails over all. The world grows up around many shrines of its great ones and so changes the environment that you go away sorry that you came, wishing that you had let the place live in your imagination as it[66] was in its heroic age, rather than as it has since degenerated.

Walden is Walden still, very much as Thoreau painted it. No chimney smoke rises in view from its shore. No picnic pavilion disturbs its outline or jangle of trolley echoes within its spaces. The woods grow tall all about it, and if they are more frequented by men than in his day and less by wild creatures the casual visitor need hardly know the difference. The pond was low when he wrote of Walden. So it is now and the same stones with which it was “walled-in” then pave the wide margins to-day. You may walk all around it on this crushed granite and note the sparkle of plentiful mica in the pebbles. Near the beach where he took his morning swim is the tiny meadow which in the years of high water is a cove to be fished in. You may throw a stone across this meadow cove and in any direction save at its narrow entrance from the pond you will hit tall woods that in dense array lean lovingly over it and give it cool shadows except when the sun is high. Between the tall trees and the meadow grasses grows the clethra, its white spikes of perfume [67]seeming to make a lace collar all about the place. In the bottom of this meadow grows much thoroughwort, which is a plain, homely weed to the passing glance, not considered fit for a garden nor thought to beautify a roadside as do so many fairer pasture blooms. Yet its gray-white heads add a soft friendliness to the coarse meadow grasses and give delicacy to the whole place, seeming to invite invasion and preparing the invader to find the more fragile flowers of the Gerardia tenuifolia that nestles beneath it, its pink bells set by some fairy bell-ringer of the dawn with mute throats open toward the sky. The little enclosure is as deep as a well, stoned in by forest walls, and is beloved of the argynnis butterflies whose spangled underwings shine with the same silver as the mica along the pond shore. Meadowsweet and a half dozen other August flowers warm their heads in the sun and cool their feet in the shadows of this same meadow, but the thoroughwort seems to possess it most and to have a feeling of rightful ownership as if it were Thoreau’s own plant. All about the pond you will find it blossoming in the same way, standing bravely out from[68] the wood with its feet among the close-set stones. Always before thoroughwort has seemed to me coarse and unattractive. Here it seems to belong and to give and take a certain beauty of virility and appropriateness. Perhaps it is because with it came so often the fond fragrance of the white alders and the soft, rose-pink beauty of the gerardia bells. In many places the stones of the beach are set so close together and have so little soil beneath them that nothing can grow, yet in others the plucky, bright-faced hedge hyssop has crept into the interstices among them and made a carpet pattern of soft green that is all flecked with the golden yellow of their blooms. And all behind these rise the woods, oak and chestnut, maple and scattered pines, whose plumed tops seem like the war-bonnets of Indian chiefs, standing guard over the homely, beautiful, simple, mysterious little pond which seems to excite love and reverence in the hearts of all who remain long on its banks.

The hills climb abruptly from the brink of Walden on all sides. The woods climb the hills and top their summits with half-century-old[69] growth that yearly adds to its girth and stature.

Nor, one fancies, need these trees again fear the sweep of the woodchopper’s axe. The spirit of reverence for its shores, which through the one-time hermit of Walden has spread to us all, should prevent that. For now the pond is much as Thoreau remembered it had been in his boyhood, walled in by dense forests, a place of echoes. Your spoken word comes back to you from this shore and from that, refined and made more sonorous, as if the wood gods would fain teach you oratory and had taken your phrase into their own mouths and put it forth again as an example. To your ears it comes again sweetened with the gentle essences of juniper, birch and sassafras, rich with the melodies taught to bare boughs by winter winds. In the haze of the August noon these other shores are distant to the eye. The sight must swim a long way through the quivering air to reach one or the other. The hearing, thanks to the kindly offices of the wood gods, leaps the space at a bound.

The kingfisher seems as much a familiar of the[70] place as the echoes. Like them he flies back and forth from shore to shore till you wonder whether he is trying to keep pace with them or whether he is the embodiment of one that does not need to be set going by a word but has volition of its own. The kingfisher’s voice hardly seems to belong at Walden, it is so harsh and unlovely. Even in this very school of sweet echoes it has learned neither modulation nor singing quality. Far different is the gentle peet-weet of the sandpipers which precede you along shore in scalloped flight. Something of the bright sweetness of the hedge hyssop strolls along the moist stones of the margin with them, as if the two became yearly more and more related. Each fall I think the olive-fuscous backs of these little birds get just a little more of a golden tinge from this continual neighboring with the equally gentle, friendly Gratiola aurea. If in return some fine summer the hedge hyssop should blossom into twittering song no one need be terribly surprised.