Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

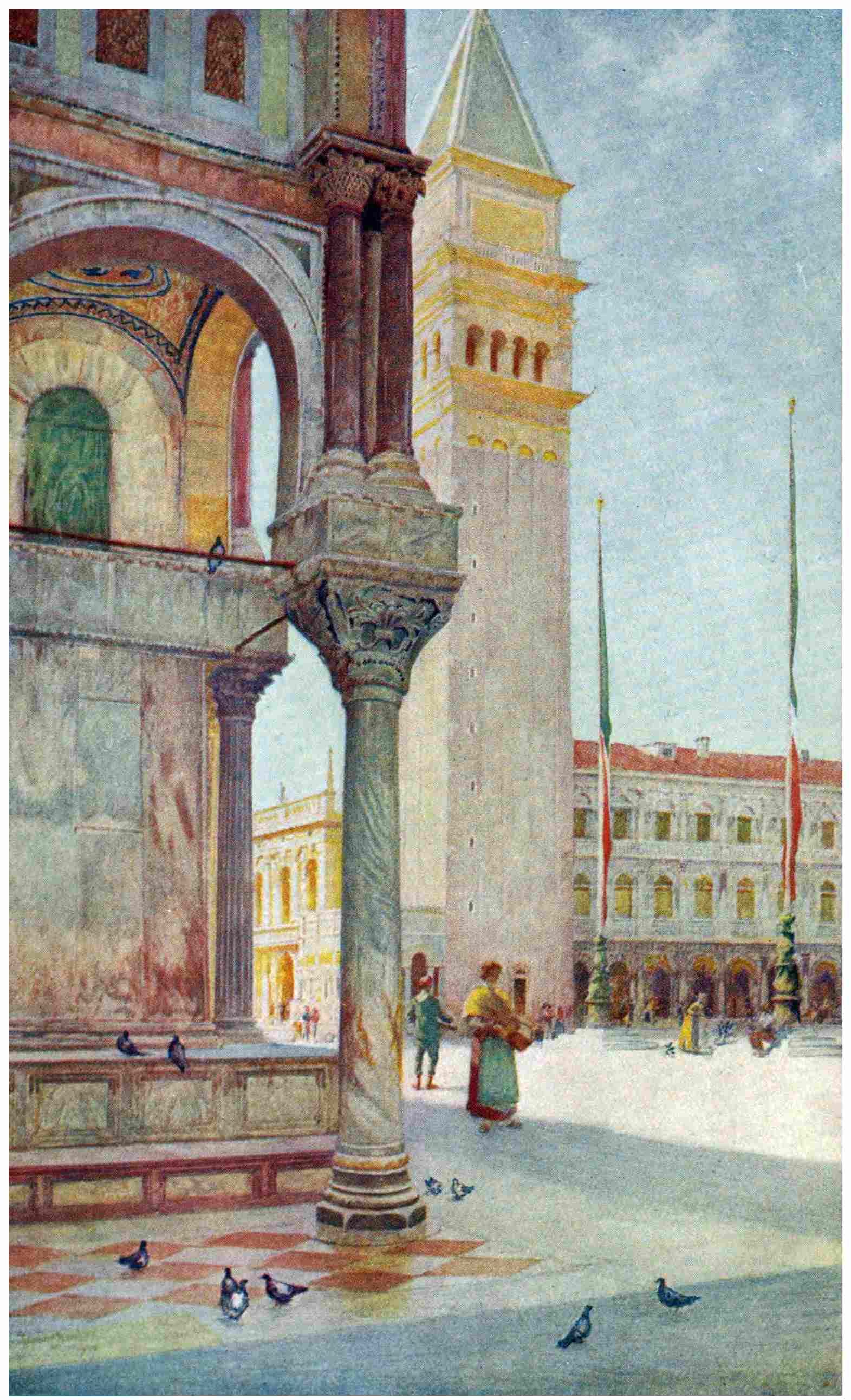

THE CAMPANILE.

VENICE

BY

BERYL DE SÉLINCOURT

AND

MAY STURGE HENDERSON

ILLUSTRATED BY

REGINALD BARRATT

OF THE ROYAL WATER-COLOR

SOCIETY

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1907

Copyright, 1907,

By Dodd, Mead and Company

Published, October, 1907

| Page | |

| I | |

| Introductory | 1 |

| II | |

| Phantoms of the Lagoons | 16 |

| III | |

| The Nuptials of Venice | 54 |

| IV | |

| Venice in Festival | 74 |

| V | |

| A Merchant of Venice | 98 |

| VI | |

| Venice of Crusade and Pilgrimage | 124 |

| VII | |

| Two Venetian Statues | 160 |

| VIII | |

| Venetian Waterways (Part I) | 187 |

| IX | |

| Venetian Waterways (Part II) | 253 |

| X | |

| Artists of the Venetian Renaissance | 275 |

| XI | |

| The Soul that Endures | 317 |

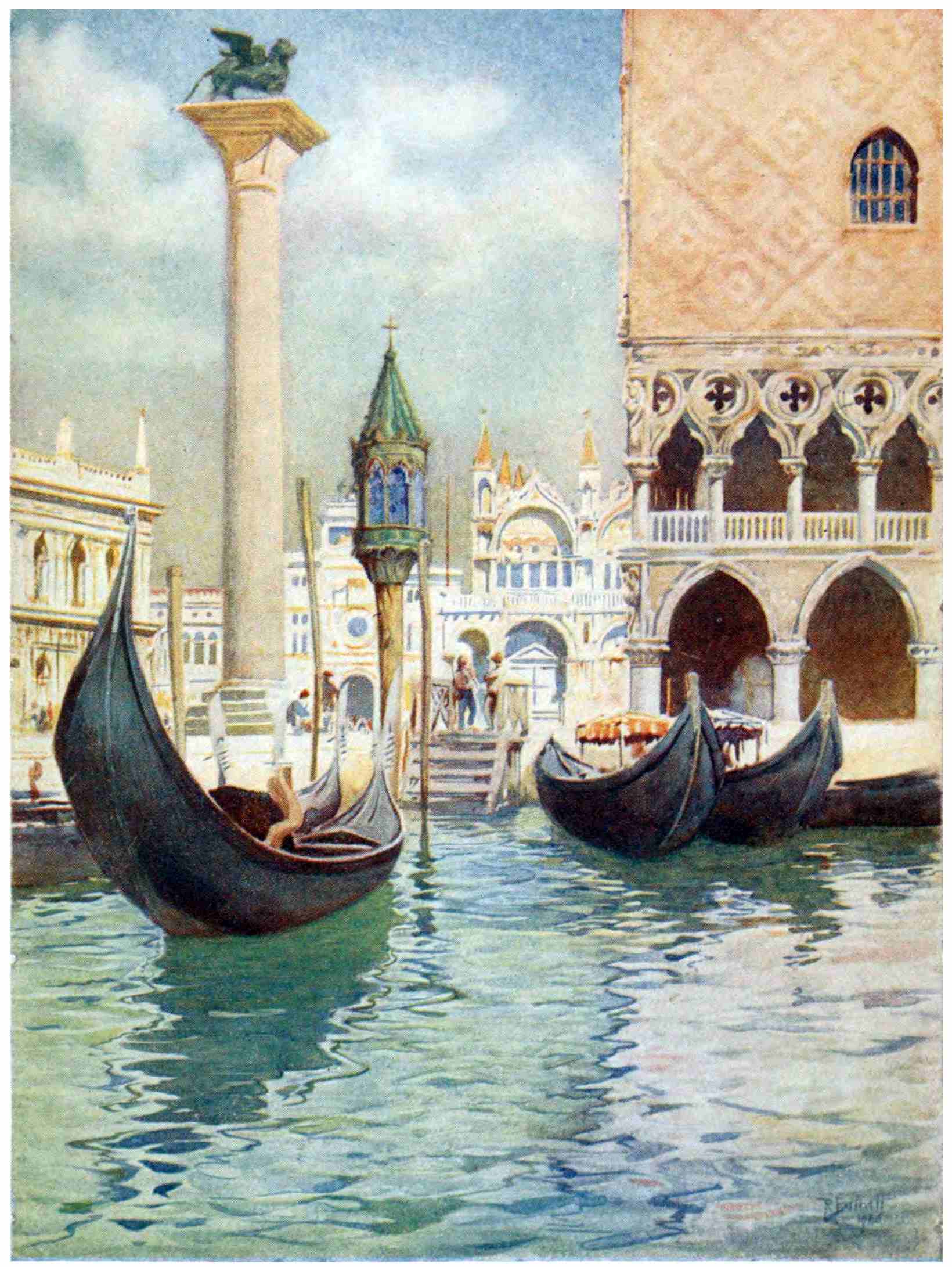

| The Campanile | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

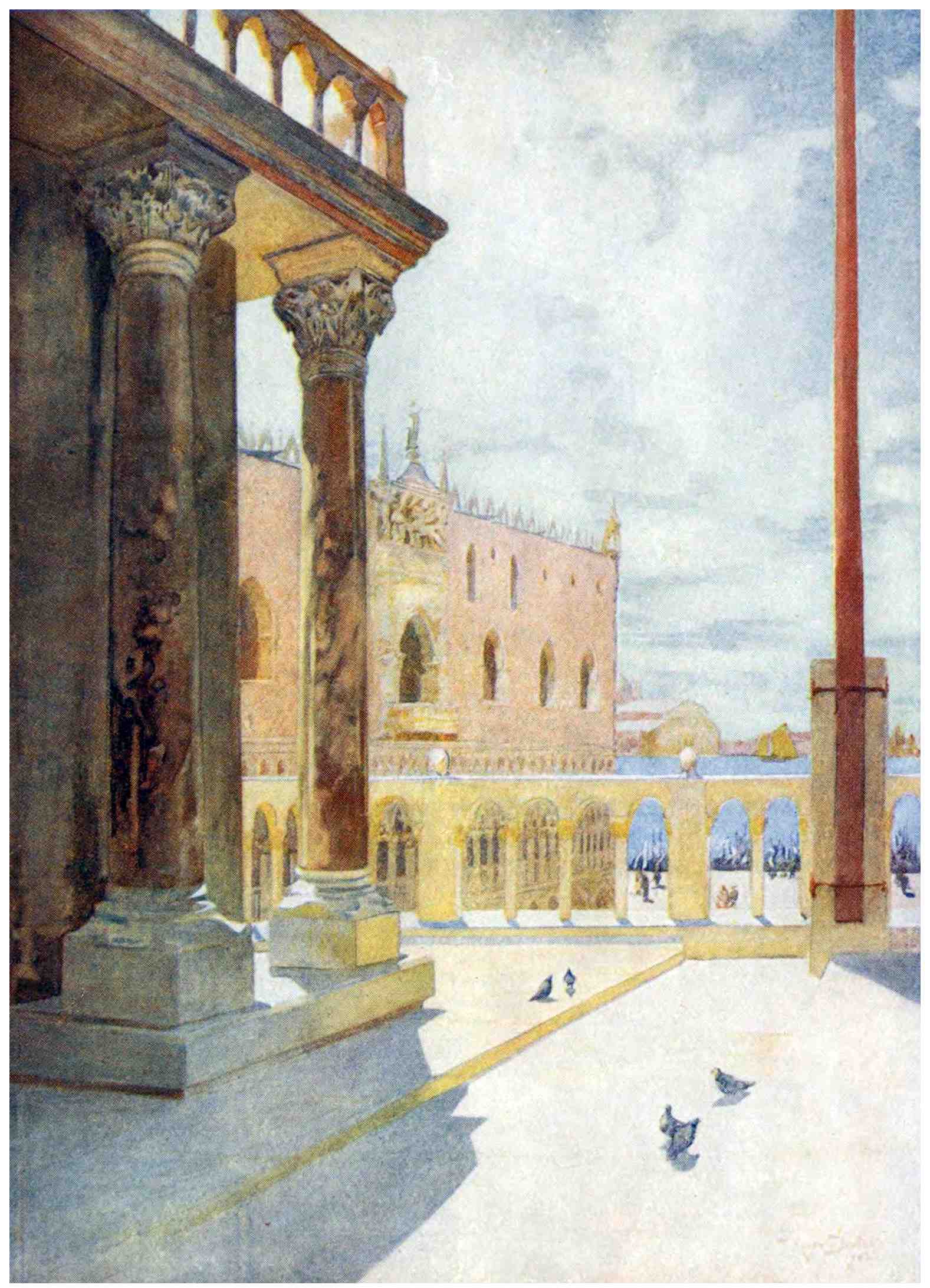

| View from the Gallery of San Marco | 7 |

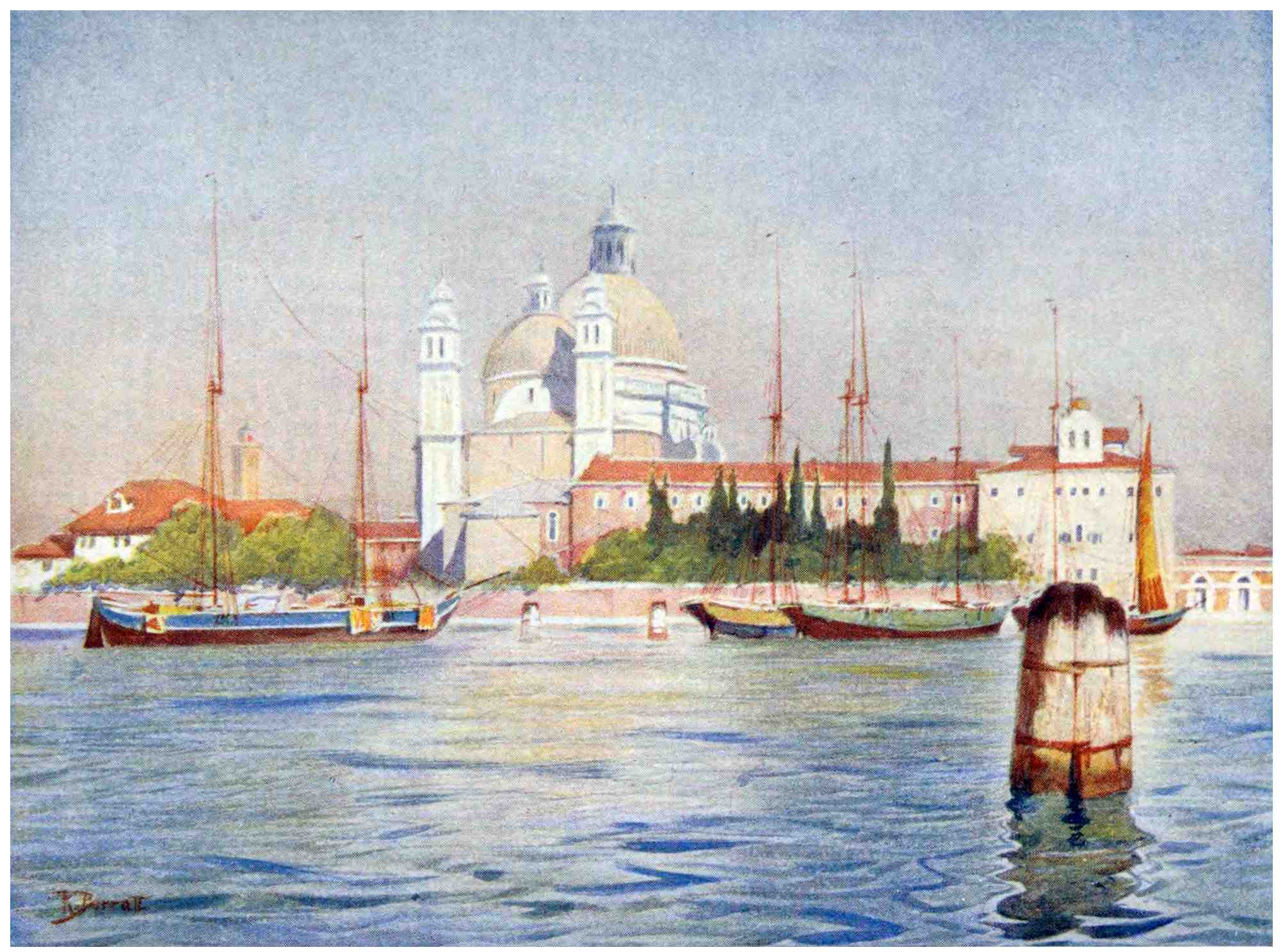

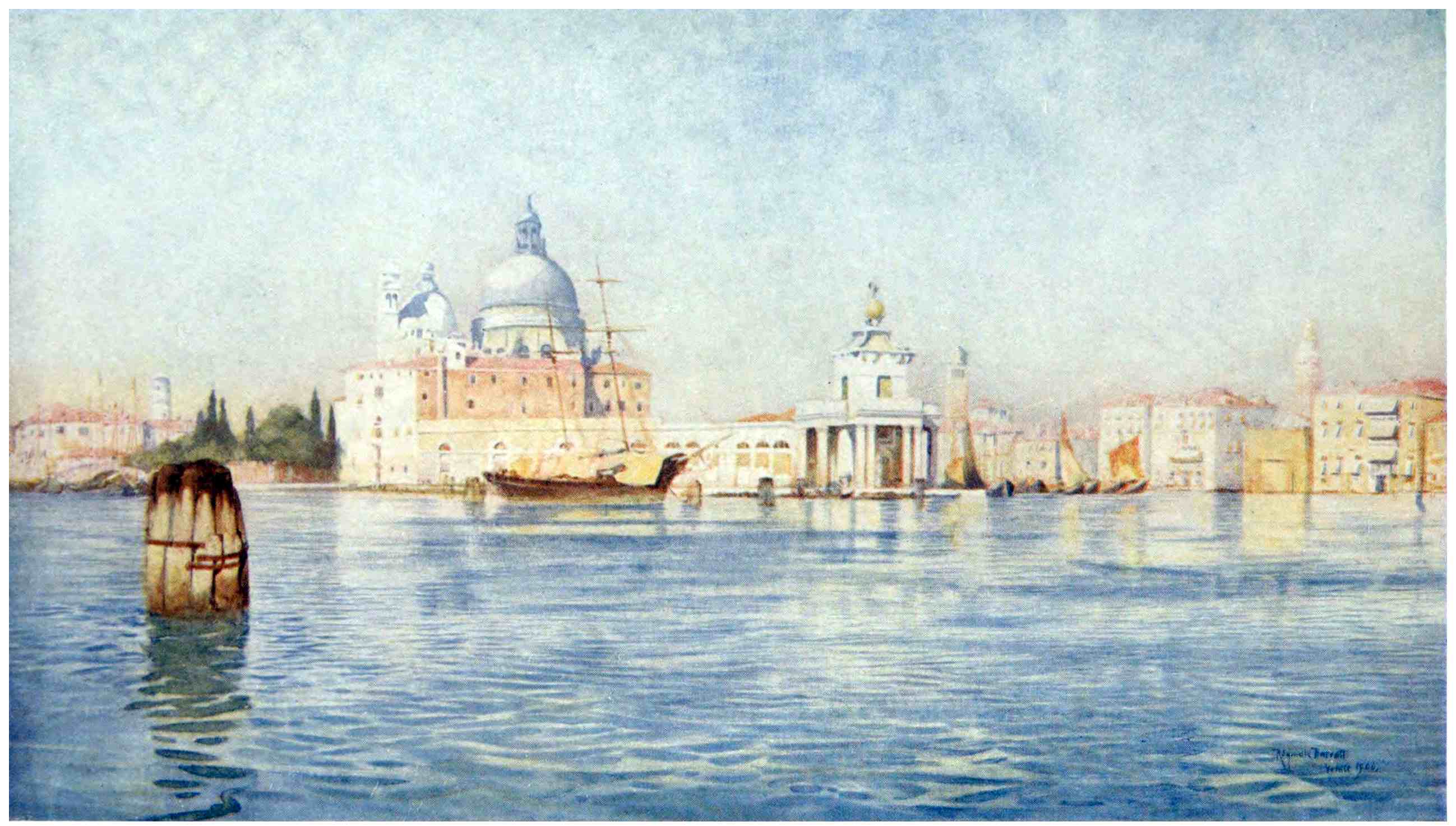

| Santa Maria della Salute | 23 |

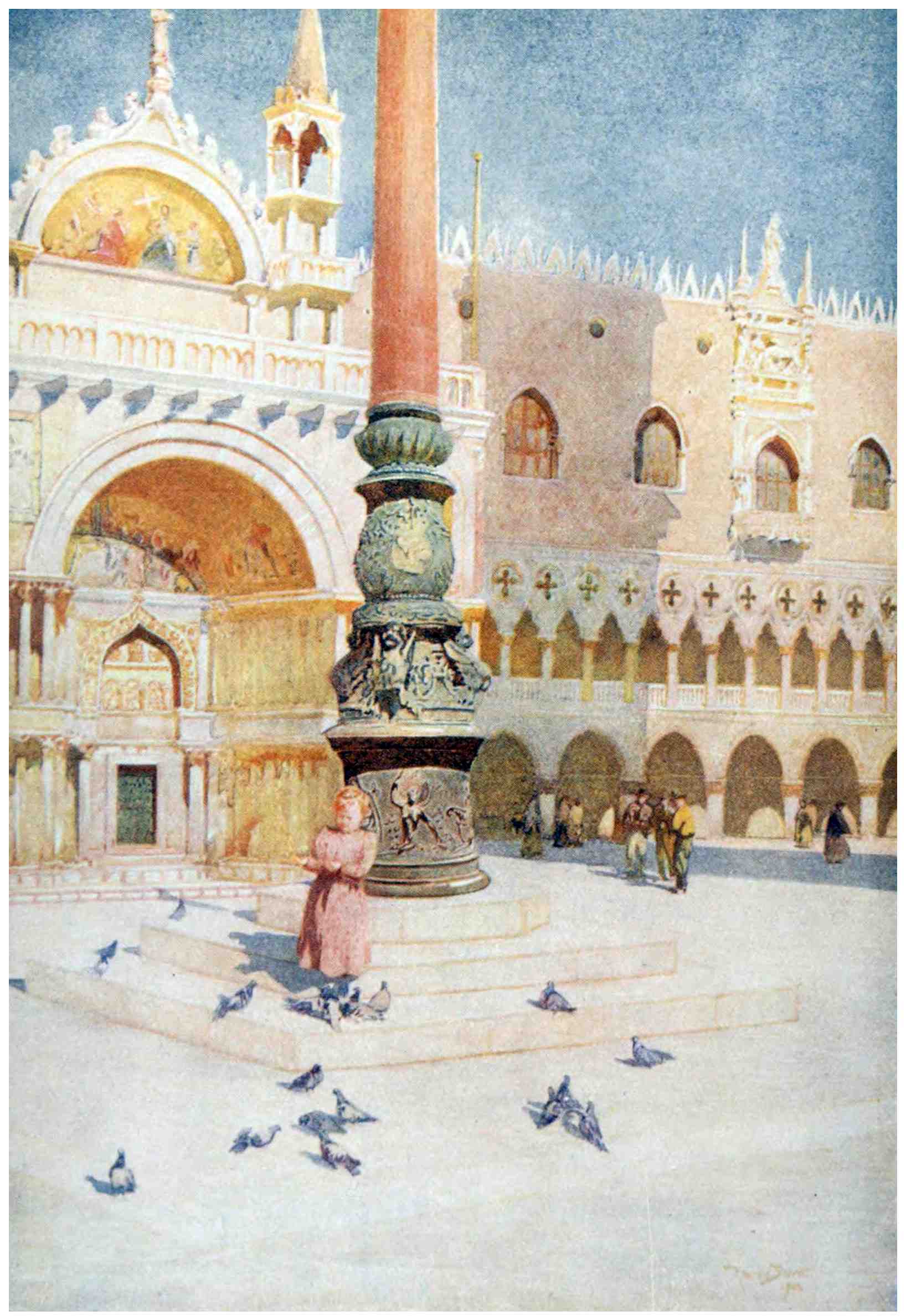

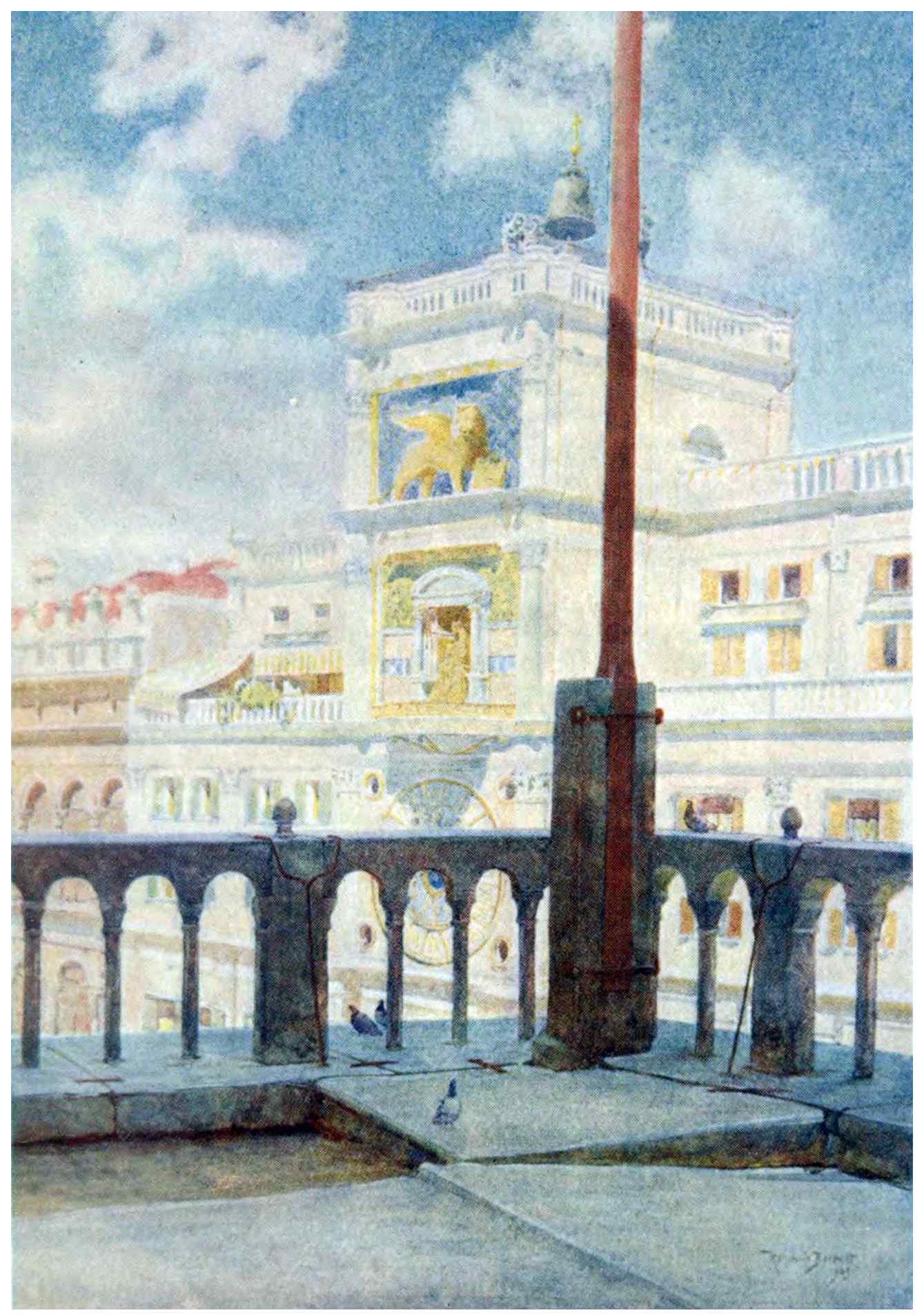

| The Clock Tower | 37 |

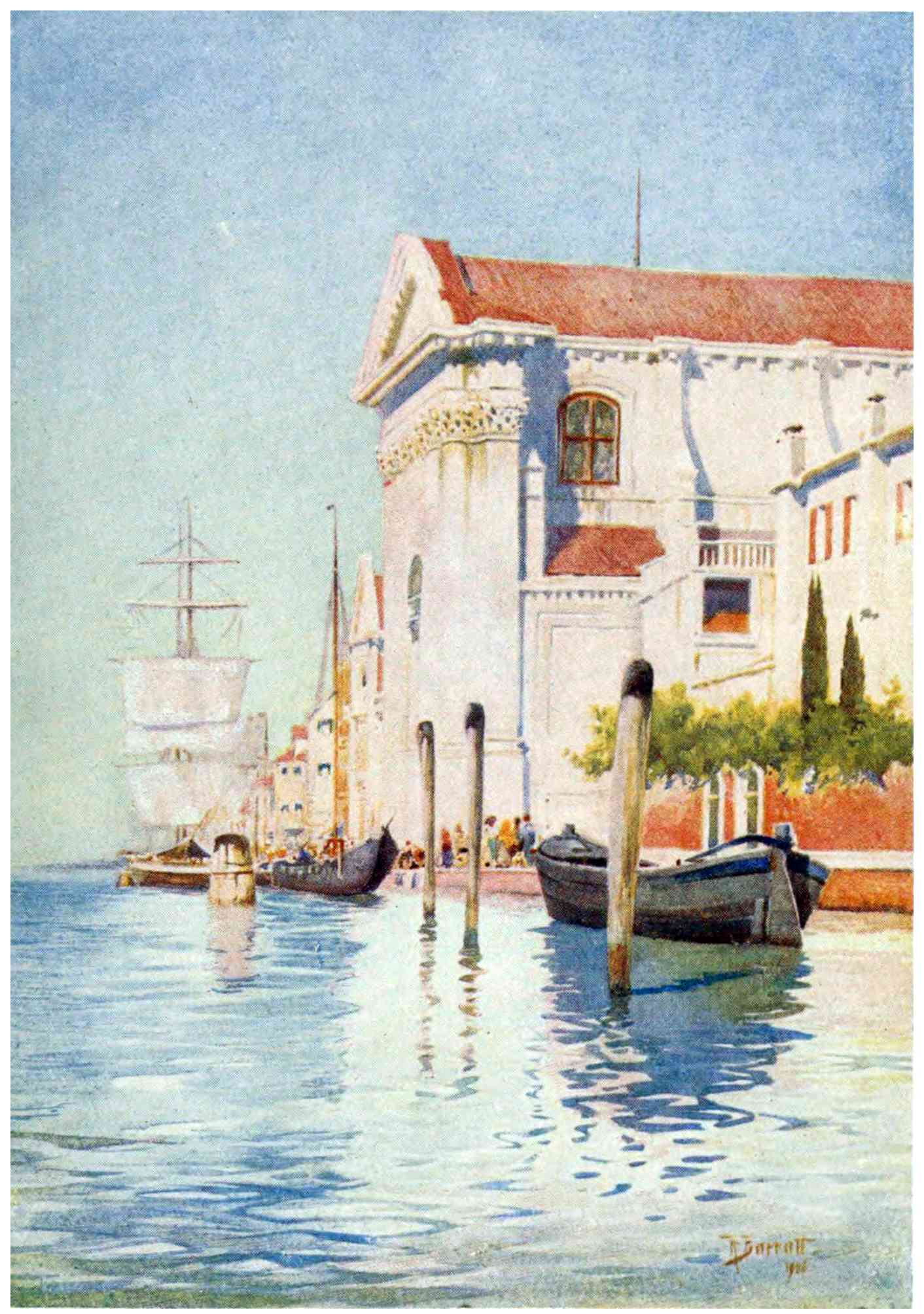

| Riva Degli Schiavoni | 57 |

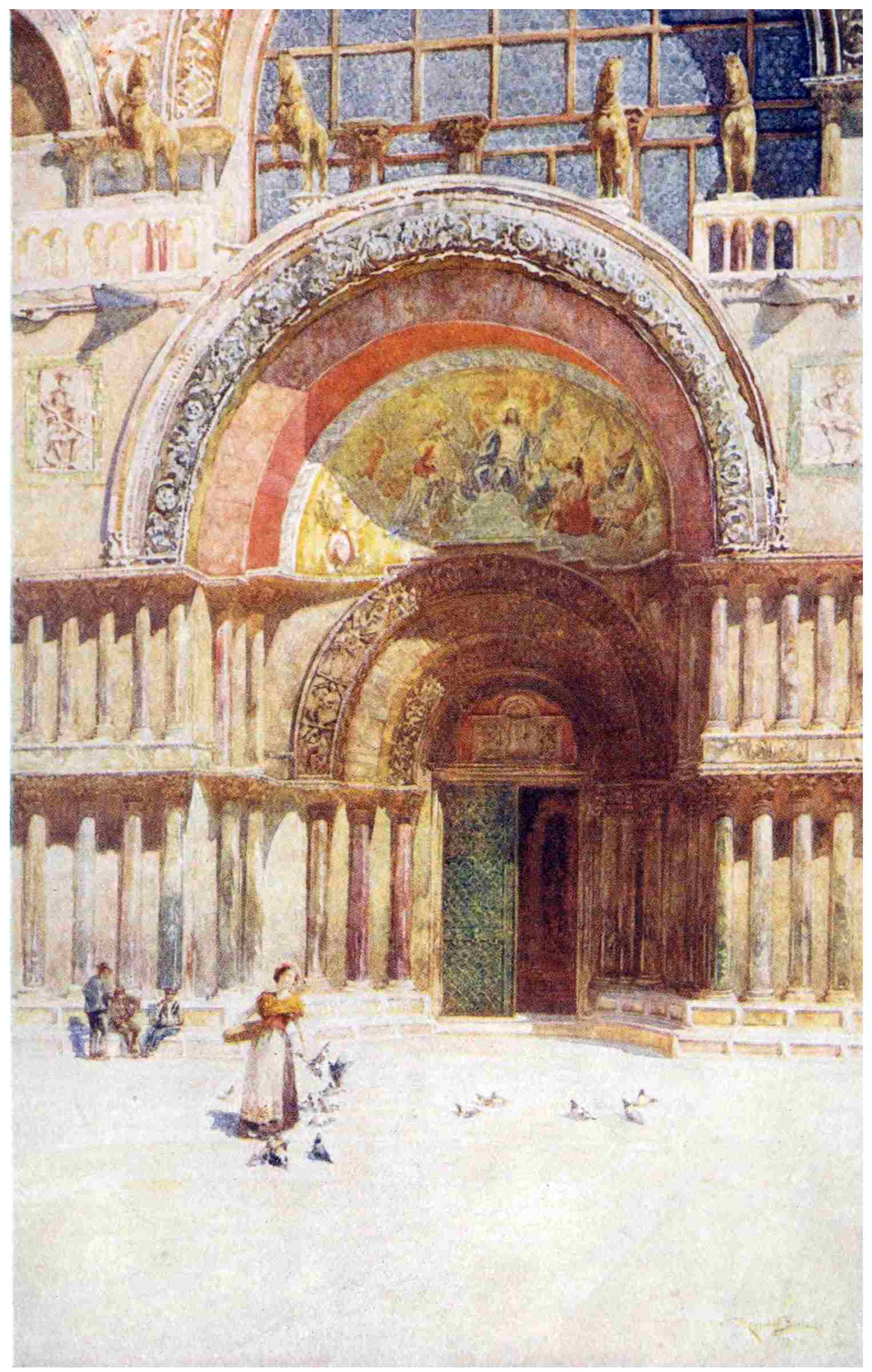

| The Doorway of San Marco | 71 |

| View from Cà d’Oro | 81 |

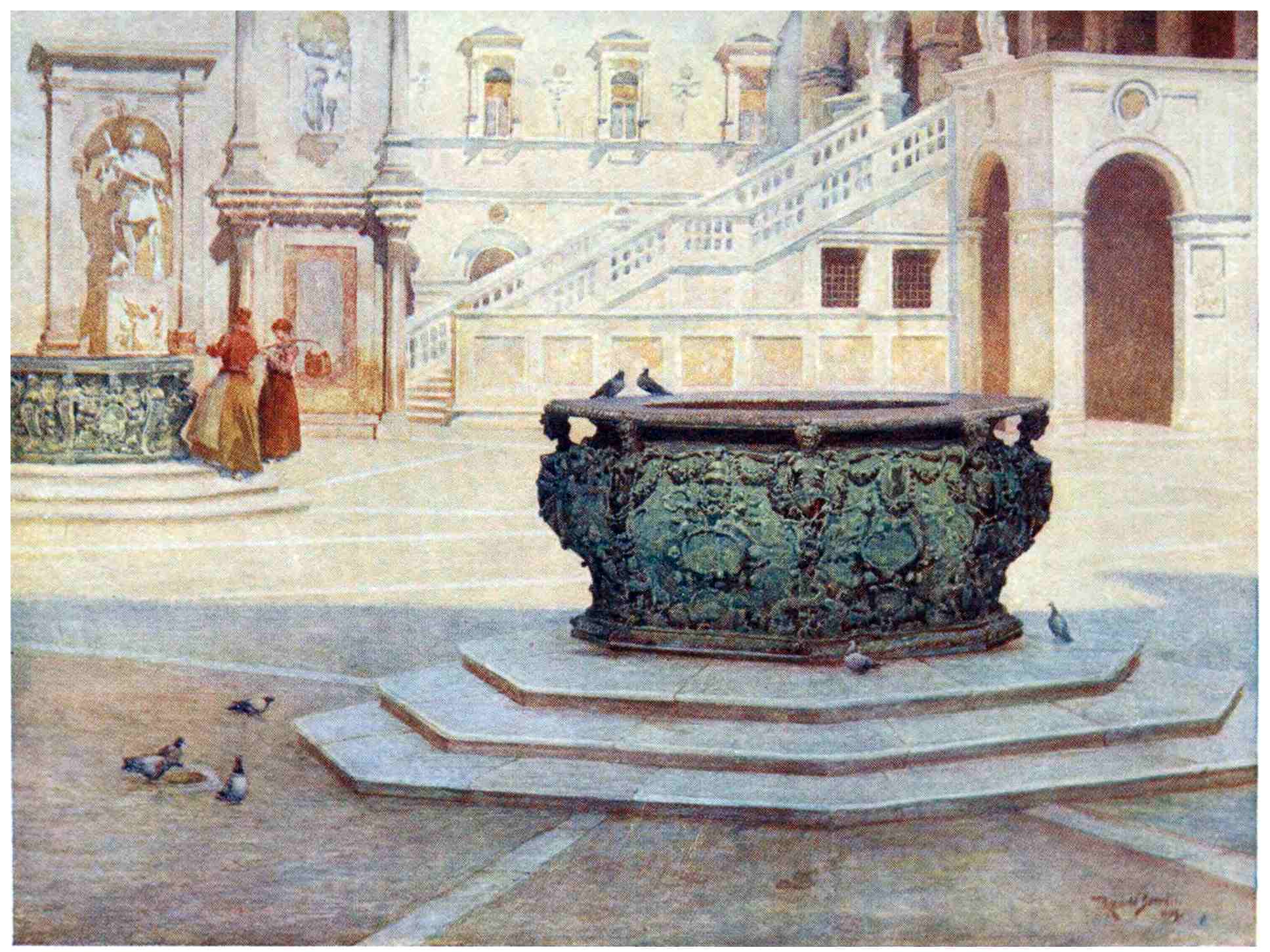

| Courtyard of the Palazzo Ducale | 91 |

| San Giorgio | 107 |

| The Dogana | 119 |

| The Shadow of the Campanile | 127 |

| The Clock Tower from Gallery of San Marco | 137 |

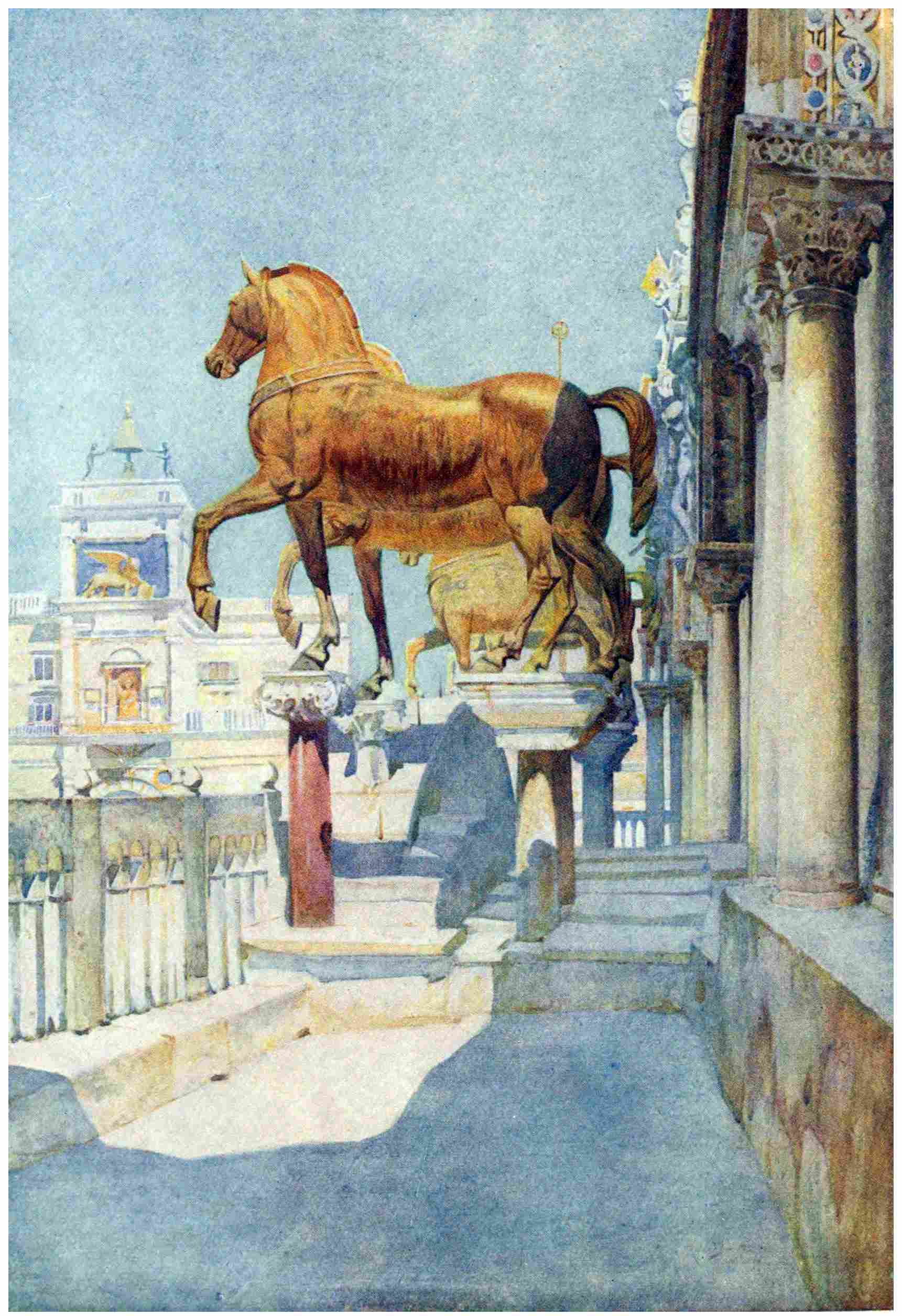

| The Horses of San Marco, looking South | 147 |

| The Horses of San Marco, looking North | 155 |

| In the Piazza | 175 |

| View on the Grand Canal from San Angelo | 189 |

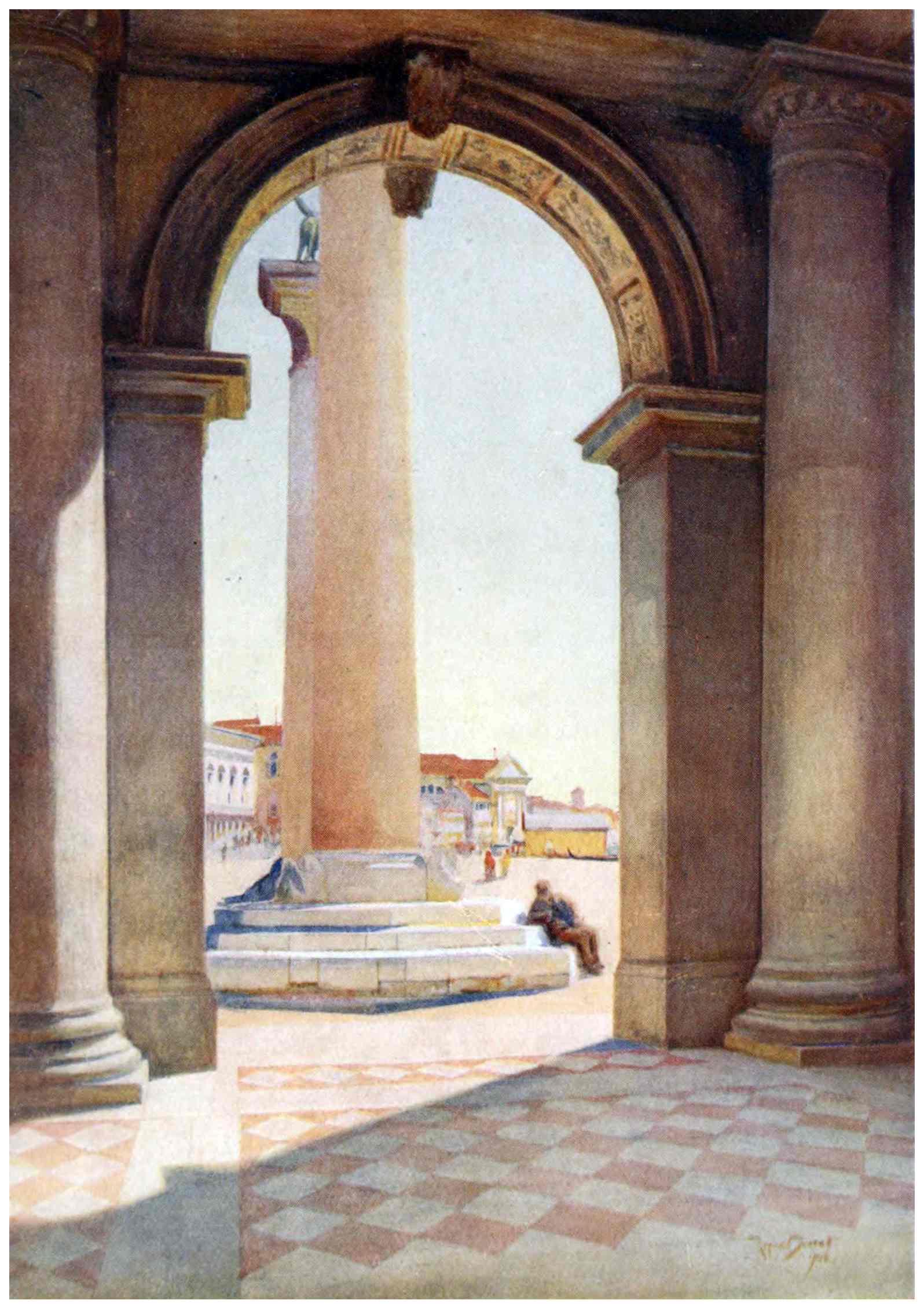

| Piazzetta, The Library | 195 |

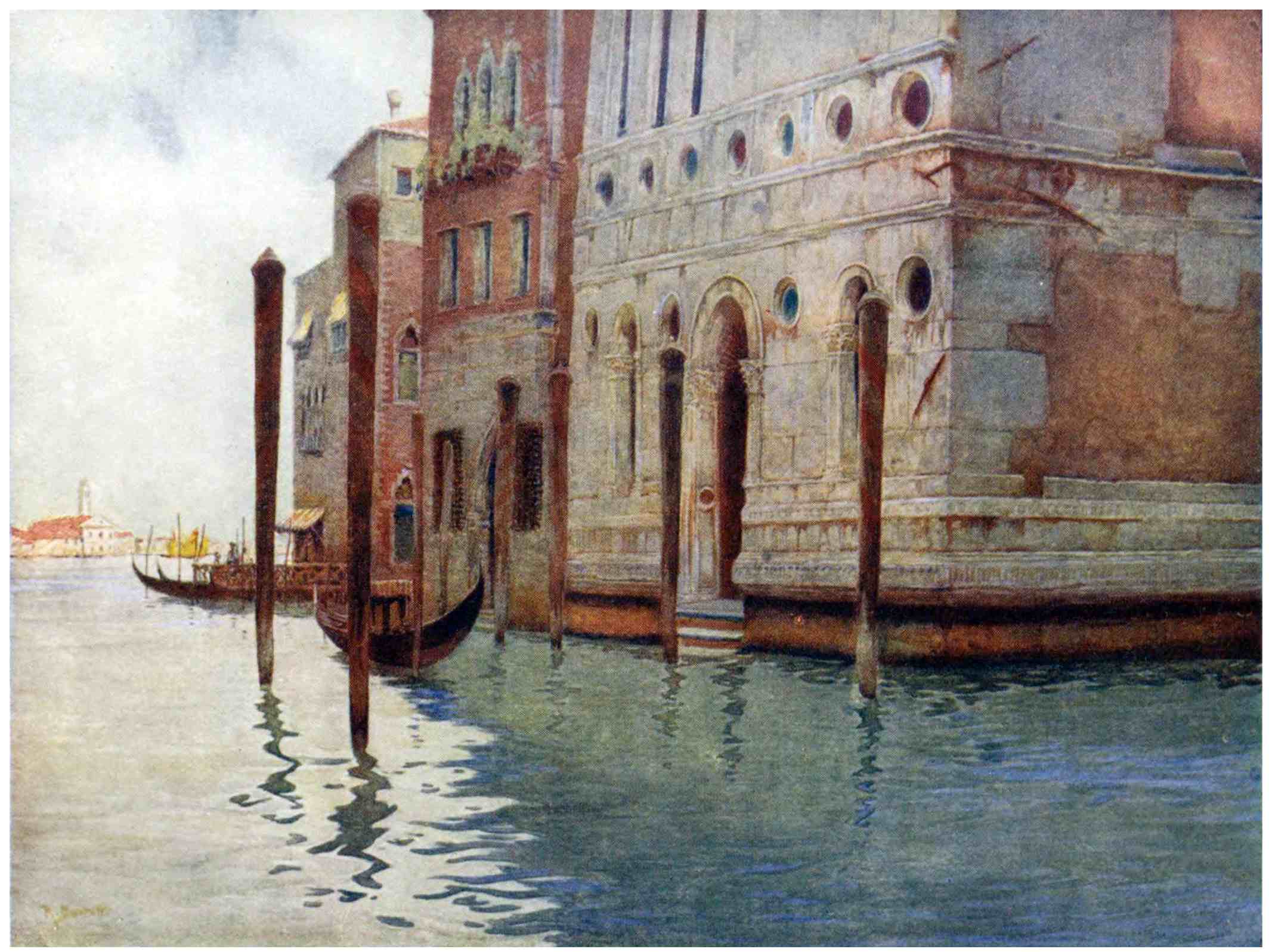

| Corner of the Palazzo Dario | 201 |

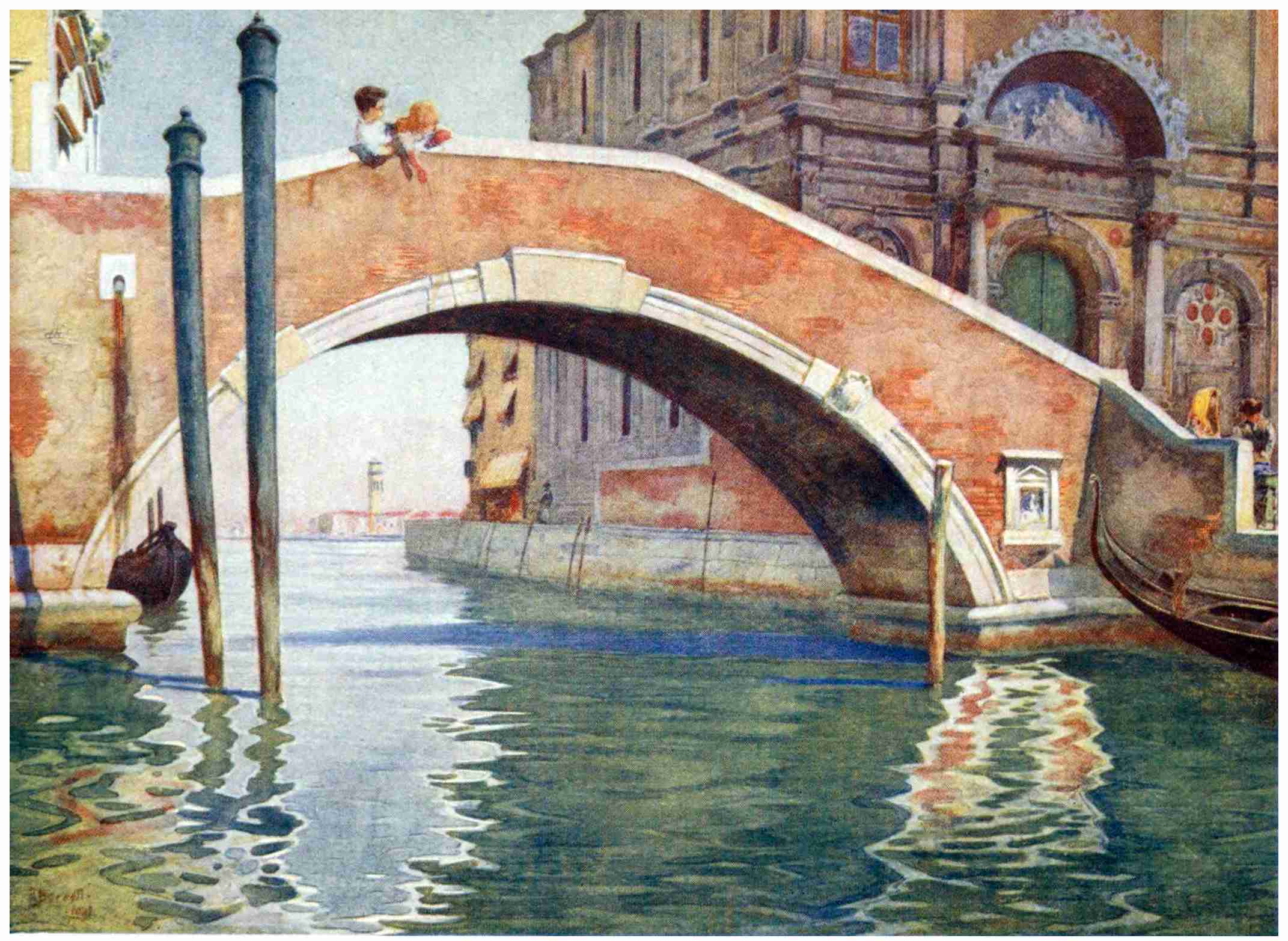

| A Venetian Bridge | 219 |

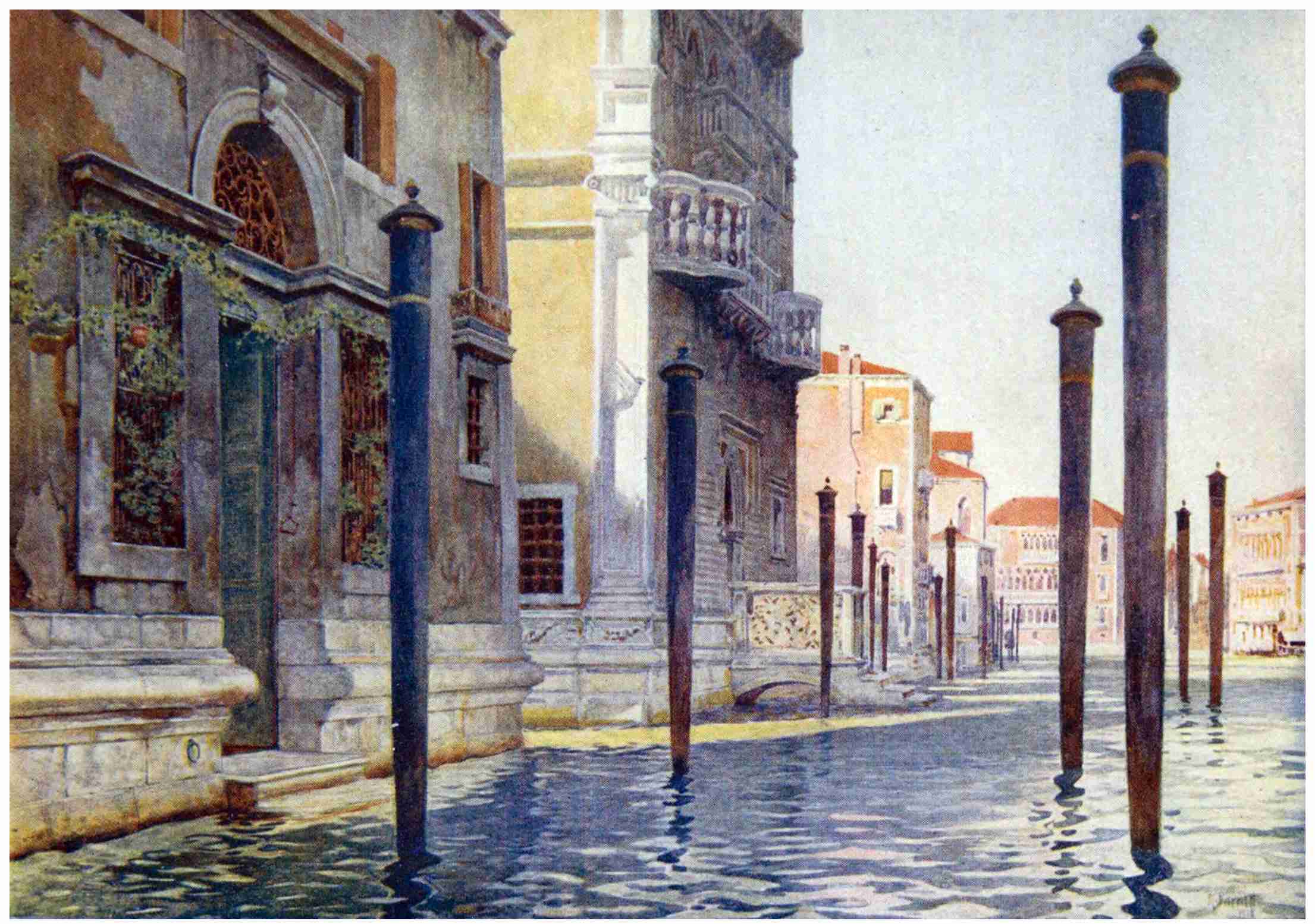

| Palazzo Sanudo | 231 |

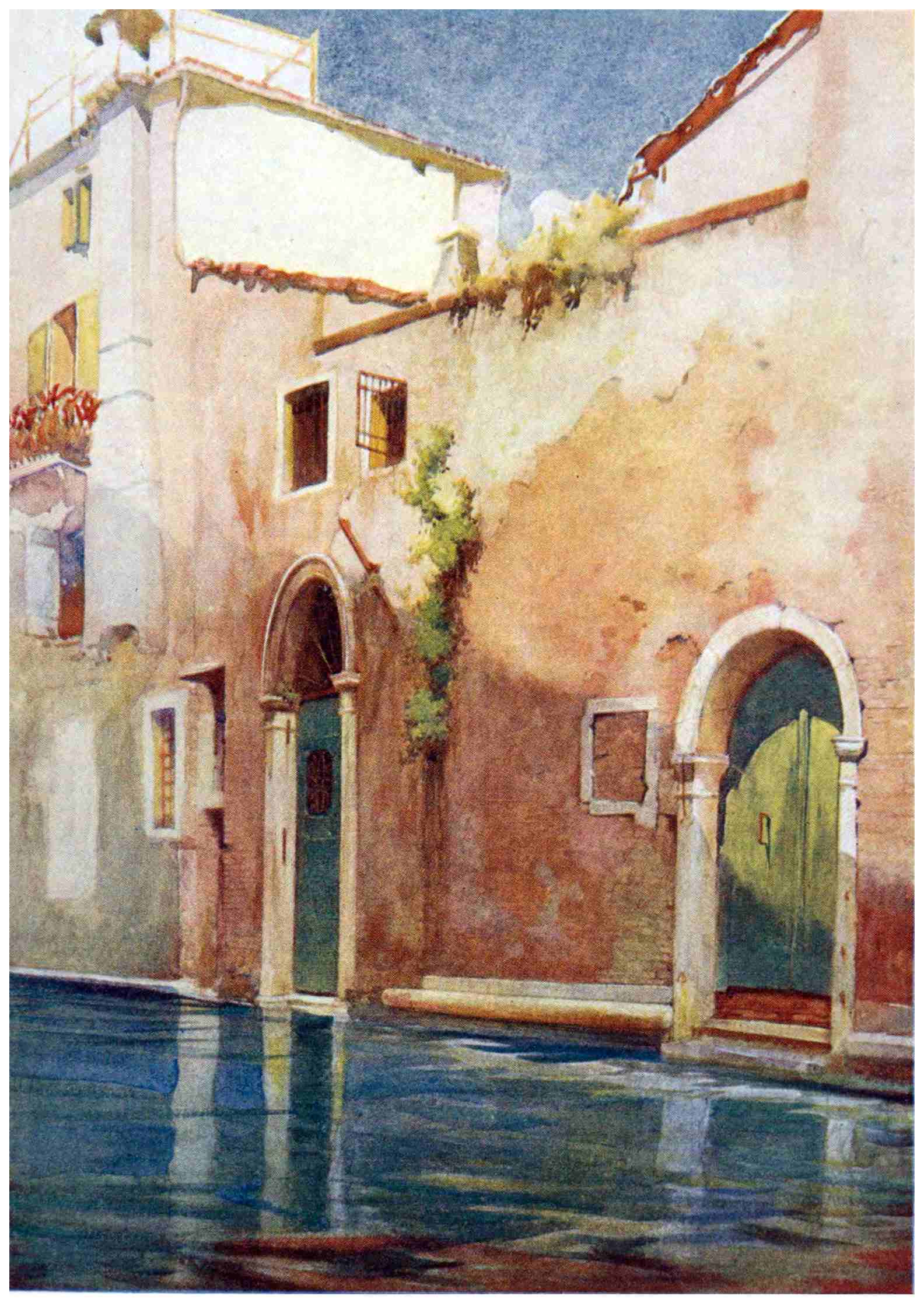

| A Side Canal | 241 |

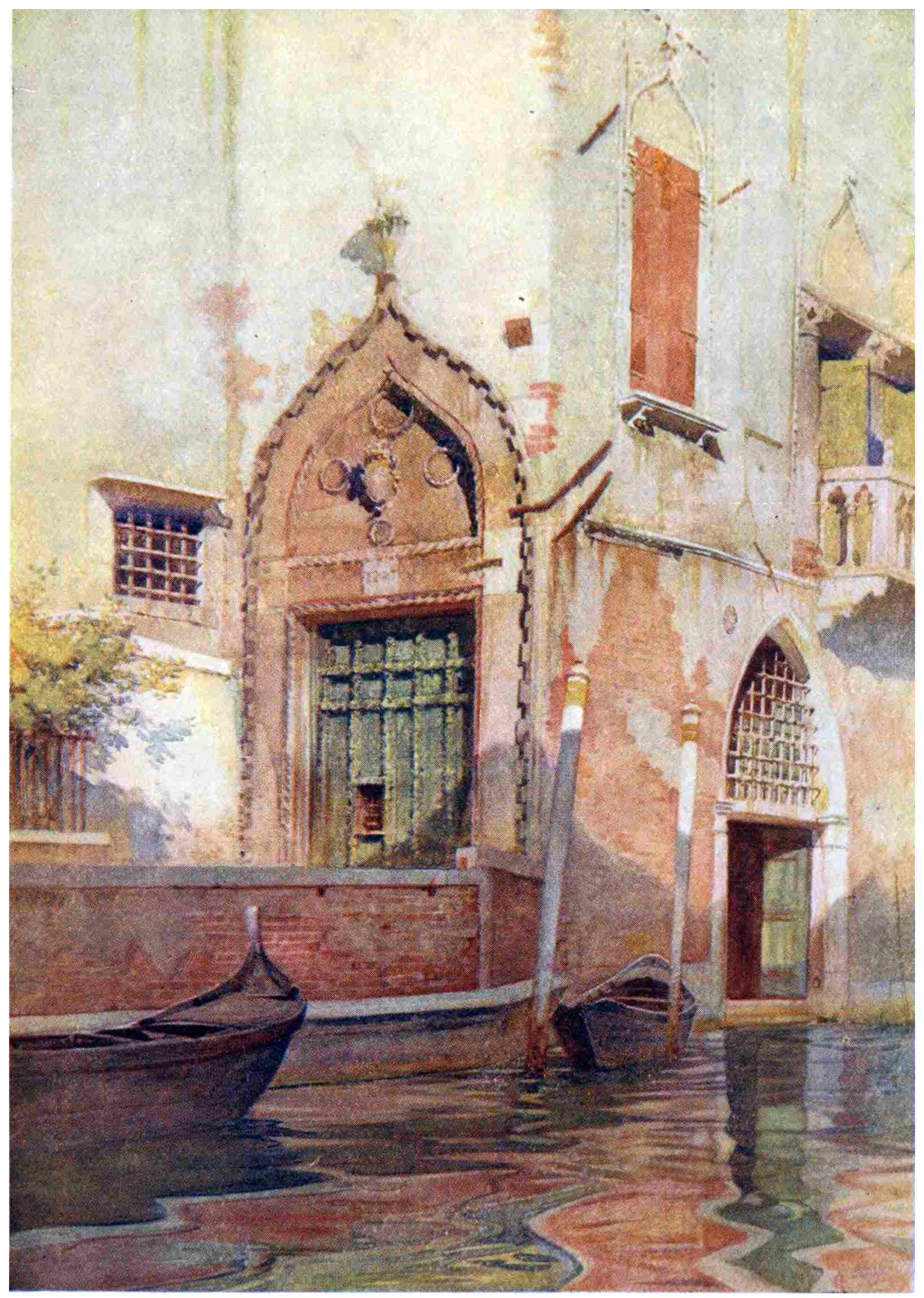

| The Gondoliers’ Shrine | 247 |

| Entrance of the Grand Canal | 257 |

| View on the Grand Canal | 269 |

| Palazzo Rezzonico | 281 |

| Towards the Rialto San Angelo | 291 |

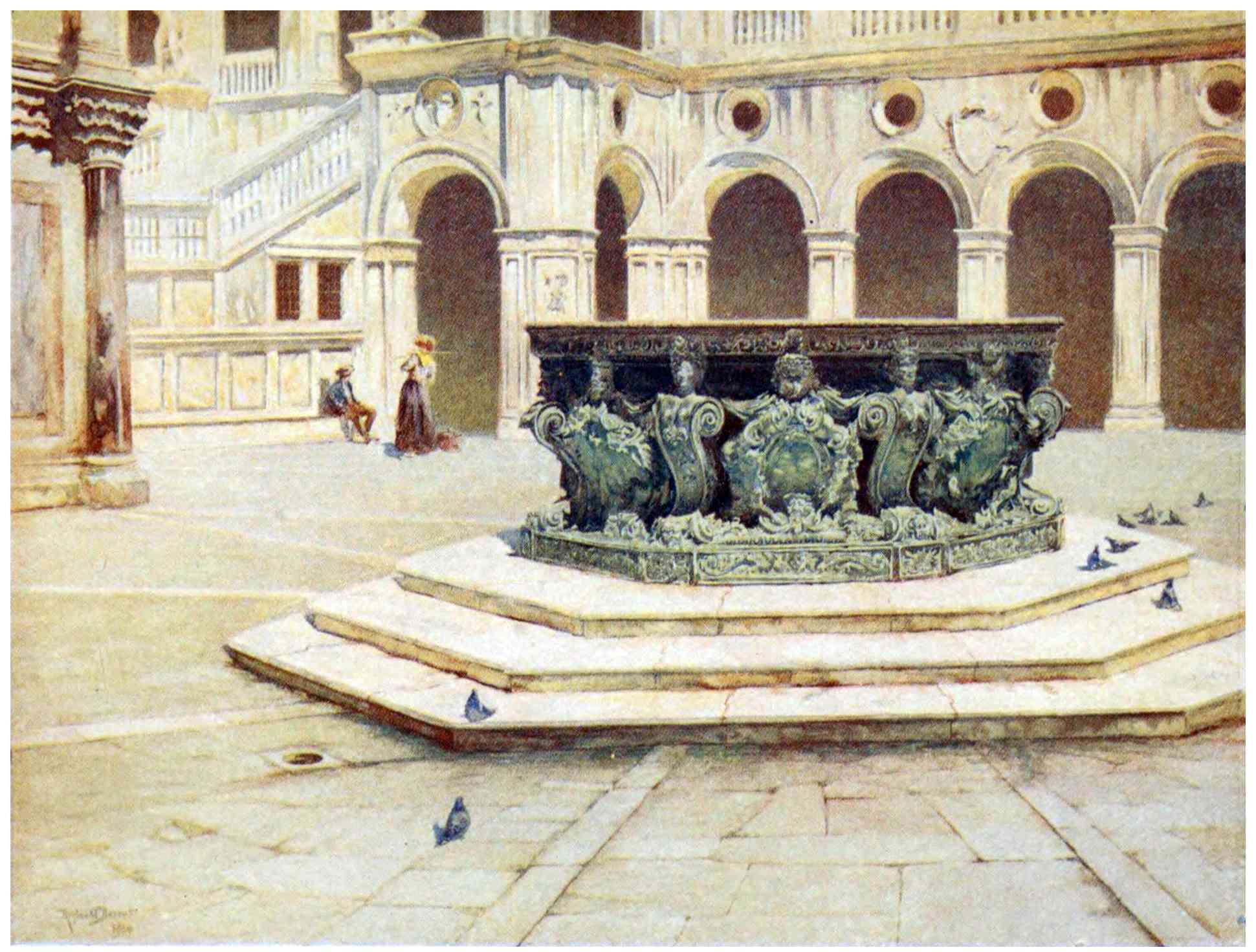

| Bronze Well-Head by Alberghetti—The Courtyard of Palazzo Ducale | 305 |

| Evening in the Piazzetta | 313 |

| A Palace Door | 323 |

| Zattere | 331 |

1

“Venice herself is poetry, and creates a poet out of the dullest clay.” It was a poet who spoke, and his clay was instinct with the breath of genius. But it is true that Venice lends wings to duller clay; it has been her fate to make poets of many who were not so before—a responsibility that entails loss on her as well as gain.

She has lived—she has loved and suffered and created; and the echoes of her creation are with us still; the pulse of the life which once she knew continues to throb behind the loud and insistent present. The story of Venice has been often written; the Bride of the Adriatic, in her decay as in her youthful and her mature beauty, has been the beloved of many men. “Wo betide the wretch,” cries Landor through the mouth of Machiavelli, “who desecrates and humiliates her; she may fall, but she shall rise again.” Venice even then had passed her zenith; the path she2 had entered, though blazing with a glory which had not attended on her dawn of life, was yet a path of decline, the resplendent, dazzling path of the setting sun. And now a second Attilla, as Napoleon vaunted himself, has descended upon her. She has been desecrated, but she has never been dethroned. She could not, if she would, take the ring off her finger. No hand of man, however potent, can destroy that once consummated union, however the stranger and her traitor sons may abase her from within.

It is to her own domain, embraced by her mutable yet eternally faithful ocean-lover, that we must still go to see the relics of her pomp. The old sternness has passed from her face, that compelling sovereignty which gave her rank among the greatest potentates of the Middle Age; her features, portrayed by these latter days, are mellowed; a veil of golden haze softens the bold outlines of that imperious countenance. We are sometimes tempted to forget that the cup held by the enchanter, Venice, was filled once with no dream-inducing liquor, but with a strong potion to fire the nerves of heroes. Viewing Venice in her greater days, it is impossible to make that separation between the artist and the man of action so deadly to action and to art. The portraits of3 the Venetian masters, supreme among the portraits of the world, could only have been produced by men who beyond the divine perception of form and colour were endowed with a profound understanding and divination of human character. The pictures of Gentile Bellini, of Carpaccio, of Mansueti, are a gallery of portraits of stern, strong, capable, self-confident men; and Giovanni Bellini, who turned from secular themes to concentrate his energy on the portrayal of the Madonna and Child, endowed her with a strength and solemn pathos which only Giotto could rival, combined with a luminous richness of colour in which perhaps he has no rival at all.

No mystics have sprung from Venice. Her sons have been artists of life, not dreamers, though the sea, that great weaver of dreams, has been ever around them. Or rather it is truer to say that the dreamers of Venice have also been men of action; strong, capable and intensely practical. They have not turned their back on the practice of life; they have loved it in all its forms. Even when they speak through the medium of allegory, of symbols, the art of Carpaccio and of Tintoretto is a supreme record of the interests of the greatest Venetians in the actions of everything living in this wonderful world, and in particular—they are not ashamed4 to own it—in their supremely wonderful city of Venice. There are dreamers among those crowds of Carpaccio, of Gentile Bellini; but their hands can grasp the weapons and the tools of earth; their heads and hearts can wrestle with the problems and passions of earth. Compare them with the dreamers of Perugino’s school: you feel at once that a gulf lies between them; the fabric of their dream is of another substance. The great Venetians are giants; like the sea’s, their embrace is vast and powerful, endowed also with the gentleness of strength. The history of Venetian greatness in art, in politics, in theology, is the history of men who have accepted life and strenuously devoted themselves to mastering its laws. They were not iconoclasts, because they were not idolaters: the faculties of temperance and restraint are apparent in their very enthusiasms. Venice did not fall because she loved life too well, but because she had lost the secret of living. Pride became to her more beautiful than truth, and finally more worshipful than beauty.

Much has, with truth, been said about the destruction of Venice. Even in those who have not known her as she was, who in presence of her wealth remaining are unconscious of the greatness of her loss, there constantly stirs indignant sorrow5 at the childish wantonness of her inhabitants, which loves to destroy and asks only a newer and brighter plaything. But much persists that is indestructible; and though Venice has become a spectacle for strangers, for those who are her lovers the old spirit lingers still near the form it once so gloriously inhabited, wakened into being, perchance, by a motion, an echo, a light upon the waters, and once wakened never again lost or out of mind. Does not the silent swiftness of the Ten still haunt the sandolo of the water police, as it steals in the darkness with unlighted lamp under the shadow of larger craft moored beside the fondamenta, visible only when it crosses the path of a light from house or garden? It is in her water that Venice eternally lives; it is thus that we think always of her image—elusive, unfathomable, though plumbed so often by no novice hand. It is the wonder of Venice within her waters which justifies the renewal of the old attempt to reconstruct certain aspects of a career which has been a challenge to the world, a mystery on which it has never grown weary of speculating. And as the light falling from a new angle on familiar features may reveal some grace hidden heretofore in shadow or unobserved, so, perchance, the vision of Venice may be renewed or kindled through the medium of a new personality.

6

Venice is inexhaustible, and it is from her waters that her mine of wealth is drawn. They give her wings; without them she would be fettered like other cities of the land. But Venice with her waters is never dead. The sun may fall with cruel blankness on calle, piazza and fondamenta, but nothing can kill the water; it is always mobile, always alive. Imagine the thoroughfare of an inland city on such a day as is portrayed in Manet’s Grand Canal de Venise; heart and eye would curse the sunshine. But in the luminous truth of Manet’s picture, as in Venice herself, the heat quivers and lives. Above ground, blue sky beating down on blue canal, on the sleepy midday motion of the gondolas, on the brilliant blue of the striped gondola posts, which appear to stagger into the water; and under the surface, the secret of Venice, the region where reflections lurk, where the long wavering lines are carried on in the deep, cool, liquid life below. When Venice is weary, what should she do but dive into the water as all her children do? If we look down, when we can look up no longer, still she is there; a city more shadowy but not less real, her elements all dissolved that at our pleasure we may build them again;

7

9

And if in the middle day we realise this priceless dowry of Venice, it is in the twilight of morning or evening that her treasury is unlocked and she invites us to enter. Turner’s Approach to Venice is a vision, a dream, but not more divinely lovely than the reality of Venice in these hours, even as she appears to duller eyes. Pass down the Grand Canal in the twilight of an August evening, the full moon already high and pouring a lustre from her pale green halo on the broad sweeping path of the Canal. The noble curves of the houses to west and south shut out the light; day is past, the reign of night has begun. Then cross to the Zattere: you pass into another day. A full tide flows from east to west, blue and swelling like the sea, dyed in the west a shining orange Where the Euganean hills rise in clear soft outline against the afterglow, while to the east the moon has laid her silver bridle upon the dim waters. Cross to the Giudecca and pass along the narrow, crowded quay into the old palace, which in that deserted corner shows one dim lamp to the canal. The great hall opens at the further end on a bowery garden where a fountain drips in the darkness and the cicalas begin their piping. Mount the winding stair, past the kitchen and the great key-shaped reception room, and look out over the city—across10 the whole sweep of the magnificent Giudecca Canal and the basin of San Marco. The orange glow is fading and the Euganean hills are dying into the night, while near at hand one great golden star is setting behind the Church of the Redentore, and the moon shines with full brilliance upon the swaying waters, upon the Ducal Palace and the churches of the Zattere, with the Salute as their chief. The night of Venice has begun; she has put on her jewels and is blazing with light. At the back of the house, where the lagoons lie in the shimmering moonlight, is a silent waste of waters under the stars, broken only by the lights of the islands. This also is Venice, this mystery of moonlit water no less than the radiance of the city. And it is possible to come still nearer to the lagoon. Passing along a dark rio little changed from the past, we may cross a bridge into one of the wonderful gardens for which the Giudecca is famous. The families of the Silvi, Barbolini and Istoili, banished in the ninth century for stirring up tumult in the Republic, when at last they were recalled by intercession of Emperor Ludovico, inhabited this island of Spinalunga or Giudecca and laid out gardens there. This one seems made for the night. The moonlight streams through the vine pergolas which cross it in every direction,11 lights the broad leaves of the banana tree and the dome of the Salute behind the dark cypress-spire, and stars the grass with shining petals. The night is full of the scent of haystacks built along the edge of the lagoon, beside the green terrace which runs the length of the water-wall. Then, as darkness deepens, we leave to the cicalas their moonlit paradise, and glide once more into the Grand Canal. It is at this hour, more than at any other, that, sweeping round the curves of that marvellous waterway, it possesses us as an idea, a presence that is not to be put by, so compelling, so vitally creative, is its beauty. Truly Venice is poetry, and would create a poet out of the dullest clay.

Every one will remember that a few years ago an enterprising man of business attempted with sublime self-confidence to transfer Venice to London, to enclose her within the walls of a great exhibition. Many of us delighted in the miniature market of Rialto, in gliding through the narrow waterways, in the cry of the gondoliers, and the sound of violin and song across the water. But one gift in the portion of Venice was forgotten, a gift which she shares indeed with other cities, but which she alone can put out to interest and increase a thousandfold. The sky is the roof of all the world, but Venice alone is paved with sky; and12 the streets of Venice with no sky above them are like the wings of the butterfly without the sun. Tintoret and Turner saw Venice as the offspring of sky and water: that is the spirit in which they have portrayed her; that is the essence of her life. It has penetrated everything she has created of enduring beauty. Go into San Marco and look down at what your feet are treading. Venice, whose streets are paved with sky, must in her church also have sky beneath her feet. It is impossible to imagine a more wonderful pavement than the undulating marbles of San Marco; its rich and varied colours bound together with the rarest inspiration; orient gems captured and imprisoned and constantly lit with new and vivid beauty from the domes above. The floor of San Marco is one of the glories of Venice—of the world; and it is surely peculiarly expressive of the inspiration which worked in Venice in the days of her creative life. San Marco, indeed, in its superb and dazzling harmonies of colour, is almost the only living representative of the Venice of pomegranate and gold which created the Cà d’Oro, of the City of Carpaccio and Gentile Bellini, whose cornice-mouldings were interwoven with glittering golden thread, while every side canal gave back a glow of colour from richly-tinted walls.13 The banners of the Lion in the Piazza no longer wave in solemn splendour of crimson and gold above a pavement of pale luminous red; in their place the tricolour of Italy flaunts over colourless uniformity. The gold is fading from the Palace of the Doges, and only in a few rare nooks, such as the Scuola of the Shoemakers in the Campo San Tomà, do we find the original colours of an old relief linger in delicate gradation over window or door.

Day after day some intimate treasure is torn from the heart of Venice. Since Ruskin wrote, one leaf after another has been cut from the Missal which “once lay open upon the waves, miraculous, like St. Cuthbert’s book, a golden legend on countless leaves.” Those leaves are numbered now. Year by year some familiar object disappears from bridge or doorway, to be labelled and hoarded in a distant museum among aliens and exiles like itself. And here, in Venice itself, a sentiment of distress, the fastidio of the Italians, comes over us as we ponder upon the sculptured relics in the cortile of the Museo Civico. What meaning have they here? It is atmosphere that they need—the natural surroundings that would explain and vivify their forms. Many also of the Venetian churches are despoiled, and their14 paintings hung side by side with alien subjects in a light they were never intended to bear. The Austrian had less power to hurt Venice than she herself possesses. In those of her sons who understand her malady there flows an undercurrent of deep sadness, as if day by day they watched the ebbing of a life in which all their hope and all their love had root. They cannot sever themselves from Venice: they cannot save her. Venice pretending to share in the vulgar life of to-day, Venice recklessly discarding one glory after another for the poor exchange of coin, still has a power over us not wielded by the inland cities of Italy, happier in the untroubled beauty of their decay. For, as you are turning with sorrow from some fresh sign of pitiless destruction, of a sudden she will flash upon you a new facet of her magic stone, will draw you spell-bound to her waters and weave once more that diaphanous web of radiant mystery:

Each of us, face to face with Venice, has a new question to ask of her, and, as he alone framed the question, the answer will be given to him alone. Every stone has not yielded up its secret: in some15 there may still be a mark yet unperceived beneath the dust. Here and there in her manuscript there may lurk between the lines a word for the skilled or the fortunate. Venice is not yet dumb: every day and every night the sun and moon and star make music in her that has not yet been heard: with patience and love we may redeem here and there a chord of those divine musicians, or at least a tone which shall make her harmony more full.

16

We have called them the phantoms of the lagoons, those islands that lie like shadows among the silver waters; for it is in this likeness that they appear to us of the city—strangely mirrored, remote, a group of clustering spirits, whose common halo is the sea. They are a choir of spirits, yet each has a mute music of its own, and accosting them one by one—slowly and in the silence entering into their life—we may come to know and love the several members of this company of the blest, till our senses grow alive to their harmony as they sing together, sometimes in the clear, cold light of the spreading dawn, sometimes in the evening twilight—when peak after peak is lit with the flame of sacrifice and, in the Titanic memory of the sunset cloud, the great fire lit on earth burns up with solemn flames into the sky.

All the languors, the fierce passions, of Venice, her vitality and her mysticism, are mirrored in the lagoons; there is no pulse of Venice that does not17 beat in them; in swift sequence, as in a lighter element, they reflect the phases of her being. And the islands of the lagoons are, as it were, the footsteps of young Venice. As she was passing into her kingdom, she set her feet here and there among the waters, and where she trod a life was born. Her roots are far back in the past, far up upon the mainland, where still remain some fragments of the giant growth, which, grafted in the lagoons, was to expand there into a new fulness of beauty and life. It is as if the genius that conceived Jesolo, Torcello, the Madonna of San Donato, had undergone a sea-change as it moved towards the Adriatic, as if some vision had passed before it and shaken it, as if the immutable had felt the first touch of mutability—had been endowed with a new sense born of the ebb and flow of ocean tides. In Malamocco she stepped too near the sea, and left behind the mystery of a city submerged; but no one can receive into his mind the peerless blue and green of the open water beyond the Lido, with the foam upon it, or the sound of its incessant sweep against the shore, without feeling that the spirit that had thus embraced the sea had received a new pulse into her being—a nerve of desire, of expansion, of motion, which her mountain infinitudes had not18 inspired. And with the new life came new dreams to Venice, dreams she was not slow to realise, and into them were woven materials for which we should seek in vain among the islands, except in so far as the reflex of her later activities fell also upon them. The Madonna of San Donato is the goddess of the lagoons; and if there are children of Venice who creep also for blessing and for protection to the borders of her dusky garment, they are but few. The mystic beauty of that Madonna was not the beauty that inspired Venice when she built upon the seas. The robe of her divinity was more akin to the dazzling incomparable blue of the bay that lies within the curve of the Schiavoni, as we may see it from the Palazzo Ducale on a morning of sunshine and east wind; that indomitable intensity of colour, unveiled, resplendent, filled to the brim with the whole radiance and strength and glory of the day—that is the girdle of Venice, the cup she drank of in her strength. But it is clear that she had bowed to a new dominion: with the ocean she wedded the world.

The lagoons are full of mysteries of light; they are a veritable treasure ground of illusion. They are not one expanse of water over which the light broods with equable influence; they form a region19 of various circles, as it were, of various degrees of remoteness or tangibility. Almost one feels that each circle must be inhabited by a spirit appropriate to itself, and that a common language could not be between them, so sharp are the limits set by the play of light. On an early autumn morning when the sky is clear and the sun streams full and level upon the clear blue expanse that separates Venice and Mestre, we seem to have a firm foothold on this dancing water. It is a substantial glory; but as our eye flits on from jewel to jewel in the clear blue paving, a sudden line is drawn beyond which it may not pass. The rich flood of vital colour has its bound, and beyond it lies a region bathed in light so intense that even colour is refined into a mystic whiteness—a mirror of crystal, devoid of substance, infinitely remote; and above it, suspended in that lucent unearthly atmosphere, hover the towers of Torcello and Burano, like a mirage of the desert, midway between the water and the sky. They hang there in completest isolation, yet with a precise definition, a startling clearness of contour. There is no vestige of other buildings or of the earth on which they stand, only the dome and campanile of Murano, the leaning spire of Burano and Mazzorbo’s lightning-blasted tower, their reflections distinctly mirrored in a luminous20 medium, half mist, half water. There is an immense awe in the vision of these phantoms, caught up into a region where the happy radiant colour dares not play; and yet not veiled—clearer in what they choose to reveal than the near city strong and splendid in the unreserve of the young day, but so unearthly, so magical, that our morning spirits scarcely dare accost them. What boat shall navigate that shining nothingness that divides them from our brave and brilliant water?

Venice, indeed, at times falls under the phantom spell. In those mornings of late autumn when the duel between the sun and the scirocco seems as if it could not end till day is done and night calls up her reinforcements of mist, Venice is herself the ghost, her goblet brimming with a liquor that seems the drink of death, a perilous, grey, steely vapour. One only of her islands looms out of the enfolding, foggy blanket: it is San Michele, the island of the dead. On such a morning we may visit this abode of shadows, not at this hour more strange, more ghostly, than the city. To-day a veil is hung upon the hard, bare outline of its boundary wall, which in sunny weather is a glaring eye-sore as you travel towards Murano over the lagoon. Here, in the cloisters where once Fra Mauro dreamed and studied his famous Mappamondo,21 there is nothing to terrify the spirit on this morning of the mist. The black and tinsel drapings, the strange, unprofitable records of devotion and bereavement, the panoply of death—all these are veiled, and only the wild grasses glisten with their dewdrops on the graves of the very poor, or autumn leaves and flowers gleam from less humble graves, while the cypresses raise their solemn spires into the faintly dawning blue. But the cemetery island of San Michele together with the islands of the Giudecca and San Giorgio Maggiore, of San Pietro di Castello and Sant’ Elena, with many lesser islands close to Venice, have become absorbed for us in the life of the city itself. Their bells and hers sound together; we see them as one with her, and from them look out to the wider lagoon, where the remoter islands, the true phantoms, wander. Many of those near to Venice have had their vicissitudes, their sometime glorious past, their pomp and solemn festival. But, bit by bit, it has been stolen from them, and the treasures which once they stored have been destroyed or gathered into the city. Now they serve only as shelters for those whose life is done—as places of repose for the dead or for the sick in mind and body. One only has passed from humble service into a fuller and happier present. San Lazzaro, once the shelter22 of lepers from the East, has become under the Armenian Benedictines a haunt of active, cultured life. It has a living industry, printing the ancient trade of Venice, and is in daily commerce with the East.

Torcello is a città morta, but scarcely a cemetery or a ruin. Relics of a past older than even Torcello has known are gathered into the humble urn of her museum; beside it stands abandoned, but not in ruins, the group of the cathedral buildings and the vast secular campanile; beyond this there is nothing but the soil—the golden gardens of vine and pomegranate, the fields of maize and artichokes between their narrow canals. The intervening period has entirely vanished; it is like a dream. The page of populous palatial Torcello has been blotted out as if it had had no existence. No vestige remains of the churches which in the old maps flourished along the chief canal, of the names which in the documents have no unsubstantial sound. None now can remember the time when the spoiler was busy among the ruined palaces; he too has passed into the shadows, and the very stones of Torcello are scattered far and wide. There is something mysterious in this complete wiping out of a page of history, so that not time only, but even the mourners of time have disappeared. There is something unique in the isolation2524 of the cathedral and the campanile, rising thus out of the far past—this mighty masonry alone among the herbs of the field. Of her great history Torcello brings only the first page and the last, the duomo, the peasants’ houses and the thatch shelters of their boats. Wandering along the grassy paths beside the vineyards, the pomegranates, the golden thorn bushes of Torcello, we seem in a sleepy pastoral land where the sun always shines. Torcello seems ripe, rich ground for a new life rather than the cemetery of an old; and we may feed the fancy as we will, for she does not refuse her doom; she has no hard contrasts of the old and new.

The few natives whom foreign gold supports upon this island of malaria, have their chief haunts in the cathedral campo, keeping guard over the treasures of the past. For here upon the campo stands the urn where Torcello keeps the ashes of her ancestors—strange relics of old Altinum, pathetic household gods, forks and spoons and safety-pins, keys and necklaces, lamps and broken plates and vases, chains and girdles and mighty bracelets, some of delicate and some of coarser make, with more ambitious works of mosaic and relief, Greek and Roman and Oriental. There is little in all; yet as we stand here in the museum,26 looking out through the sunny window on the hazy autumn gold of earth and the shimmering water beyond, this little speaks eloquently to the mind. Even to Torcello, the aged, these things are ancestral; their life was in the old Altinum when Torcello lay still undreamed-of in the womb of time. Climb the campanile, and you will wonder no more at the passing of the city at its feet; it is so mighty, so self-contained and now so voiceless with any tongue that earth can hear and understand; almost it seems as if that iron clapper, lying mute below the bell, were symbol of Torcello’s farewell to the busy populous world that needs the call to prayer. The great tower is given up to mighty musings, and we upon its summit speculate no more on the forgotten Middle Age; we are content in the golden earth beneath our feet, in the soft dreamy azure of the encircling lagoon, where in the low tide the deep tracks wind and writhe like glistening water-snakes, or lie, like the faint transparent veining of a leaf, upon that smooth expanse of interchanging marsh and water, the uncertain dominion over which Torcello towers. For the campanile, in its vast simplicity of structure, its loneliness, its duration, is of kin with those great sentinels of the desert in which the Egyptians embodied their27 giant dreams of power. It is here that the soul of Torcello still abides, to dream out upon the mystery of day and night to the mountains and the city and the sea. And even if the sunlight is rich and jubilant in the yellow fields below, where the autumn has such fitting habitation, it spreads upon the waters a broad path of silver that gleams mysteriously like moonlight upon the distant spaces of the ocean shield, waking points of light out of the immense surrounding dimness. And it is most of all in the deep night that the gulf of the centuries may be bridged. The monotonous piping of the cicalas rises even to this height in the darkness, but no other sound is heard. It is a strangely moving, melancholy landscape, half hidden, half revealed, still holding in its patient, silent heart the tragic sorrows, the hopes and shattered longings, the courageous struggle of the past ages, the fierce cry of desolation, the flames of cities doomed to destruction in the darkness of night, and their ruins outspread beneath the unsparing sun. It has lain now so long deserted, a presence from which the stream of life has flowed away, carrying with it all the agitations of joy and sorrow, that among the fluctuating marshes the key for its deciphering has been lost.

28

As we have said, whole pages are torn from the history of Torcello. Fragments only remain. But here and there is a word or two that may be gathered into a sentence. If we approach the island from the east, by the waterway between Sant’ Erasmo and Tre Porti instead of by the narrow channels of the inner lagoon, we may receive some impression of the relation it once bore to the mainland. We may see how Torcello stands as the entrance of the lagoon north of Venice, the last outpost of the mainland, the first-fruits of a new career—recognise that she was once through the Portus Torcellus in closest touch with the high seas. In the ninth century it was one Rustico of Torcello who combined with Buono of Malamocco to carry the bones of St. Mark from Alexandria to Venice. In 1268 Torcello is specially mentioned by da Canale among the “Contrees, que armerent lor navie, et vindrent a lor signor Mesire Laurens Teuple (Lorenzo Tiepolo) li haut Dus de Venise, et a Madame la Duchoise” on the occasion of Tiepolo’s election. Torcello contributed three galleys completely equipped for the Genoese war, and in 1463 sent one hundred crossbowmen in the service of the Republic against Trieste.

What is left of this city, which shared the early29 glory if not the later pomp of Venice? Where are her palaces, her gardens, her bridges, her waterways? Where are her piazzas and calles and fondamentas, her churches and rich convents? We pass their names in the old chronicles: Piazza del Duomo, Rio Campo di San Giovanni, Fondamenta dei Borgognoni, Calle Santa Margherita, Fondamenta Bobizo, Ponte di Chà Delfino, Ponte de Pino, and the rest. Many of these were of very old foundation: their stones and traces of their construction have been discovered from time to time under the mud of the canals. In the poor houses of the peasants traces still remain of original windows, cornices and pillars; the main canal is still spanned by the beautiful ruined bridge of the Diavolo. But for the rest the grass piazza with its little group of buildings, its museum flanked by the cathedral, is the sole echo, itself no more than an echo of the past.

When Altinum and her neighbouring cities roused themselves from the crushing desolation of conquest which had driven them forth to the remote borders of the mainland, they began to desire to live anew in the lagoons. There is no reason to question Dandolo’s statement that Torcello and the group of surrounding islands, Burano, Mazzorbo, Constanziana, Amoriana and30 Ammiana, were named from the gates of Altinum—a pathetic attempt to perpetuate the ruined city. Nuovo Altino was indeed the name for Torcello, and when the terror of invasion had momentarily passed, the fugitives ventured back to the mainland, and brought down to the soft-soiled island the stones of their ancient city. Torcello was built from the stones of Altinum; her very stones were veterans, the stamp of old times was upon them, the stamp of thoughts that were often sealed for those men of a later day who built them anew into their temples. The steps up to the pulpit in the duomo are perhaps the most striking instance of this ingrafting of the old upon the new, the naïve earnestness, perhaps the urgent haste and need of builders who did not fear to set an old pagan relief to do service in this temple of their Christian God. There are various theories as to the meaning of the wonderful relief which forms the base of the pulpit stair, cut like its companion slabs to meet the requirements of the stair without regard to its individual existence. We cannot help pausing before it; for it is unique among the monuments of the estuary, so unique that it seems incredible it should have been the work of those late Greek artists who executed the wonderful beasts and birds of the sanctuary screen.31 On the right is a woman’s figure, of Egyptian rather than Greek or Roman mould, standing with averted face and head resting on her arms, in melancholy thought. Beside her a man, like her resigned and meditative in attitude, but not yet with the resignation of despair, raises his left arm as if to ward off a blow. The blow is dealt left-handed by one who in his right hand holds a pair of scales and advances swiftly on winged wheels. He, again, is met in his advance by a fourth figure whom we only see in part, his right side having been almost completely cut away. He is fronting us, however—his feet planted firmly on the ground, his right hand folded on his breast, while with his left he grasps the forelock of the impetuous figure of the winged wheels and balances. Thanks to the happy discovery by Professor Cattaneo of part of the fragment missing to the design, we know that a woman’s figure stood beyond him, holding in her left hand a palm and in her right a crown which she raises to the stalwart conqueror’s head. It is a simple but daring and most spirited composition. It seems to belong to a far remoter past than that of the earliest building of Torcello. Professor Cattaneo explains it as an allegory of the passage of Time, who on his winged wheels has already passed one man by,32 as he stands stroking his beard, while tears and sorrow await him in the form of the woman on his right in mourning guise and posture; the stalwart man on the left is he who faces Time and takes him by the forelock, and for him the crown and palm of victory are in waiting. But Professor Cattaneo seems to give a needlessly limited significance to the idea of Time. It is to him the Time which God offers to man that he may do what is just and combat his own evil passions; this seems to him to be expressed by the scales and the stick he grasps in his hand. Perhaps it is enough to think merely of the club as that with which a more familiar Time is wont to deal back-handed blows at those who are so idle or so sluggish as to let him pass. At any rate the men of Torcello could comprehend this language of the rough stone. What matter if the oracles were dumb? Which of them had not wept to see the face of Time averted, which of them had not felt the weight of his backward blow? And yet this symbol of old Time must have been mute to them before the great solemn Madonna in the dusky, golden circle of the apse; she looks beyond all fortunes and vicissitudes of man. How should they dare to pray to her? Worship they may, and rise with strength to contend with Time and33 conquer him, with a weapon to face the mystery of life; but they meet here no smile of comfort, no companionable grace. To those men who dreamed this figure, to us who look upon her and worship, the dominion of Time is a forgotten thing; we ask no pity for our human woes; they have passed, they have crumbled: she gives us a better gift than pity, insight into the hidden things of life and of art; she wings with hope, if with stern hope, our dream of beauty. The mosaics on the west wall of the cathedral have the same stern character, with less of beauty than the Madonna of the apse: the great angels on either side the weird central Christ in the upper division have a strangely oriental effect. They might be Indian gods. They hold the Christian symbols, but with how abstracted, how remote a gaze they look out from their aureoles! They are at one with the noble simplicity and strength and greatness of the spirit of the building they adorn. Somehow they seem to us the oldest thing within it; we begin to be drawn by them into mysteries older than the caves of Greece whence the pillars of this duomo came; we begin to share their watch over a vast desert where all the faiths and imaginings of men may move and mingle, and find a common altar under the dome of the evening sky.

34

Greater than Torcello, and still maintaining, as near neighbour to Venice, something of its old activities, Murano lives, none the less, a phantom life. We would choose, as a fitting atmosphere for Murano, a day of delicate lights and pale, lucent water, with faint fine tints within the water and the sky: a day of the falling year, not expectant, only acceptant, pausing in the dim quiet of its decay. Even the hot sunshine, though it irradiates the features of Murano, cannot penetrate to that spent heart. The marvellous fascination of its Grand Canal, with its swift and unaccustomed current of blue waters, cannot draw us from the sadness, or disperse the spectral melancholy which invades the spirit and surrounds it as an atmosphere. The sun infects the dirty children with a desire to shine, and prompts somersaults for a soldino; but the weary women, the old, crouching men, still creep about the fondamenta impervious to his rays. Murano is not less disinherited, not less phantasmal, because the daylight comes to pierce the semblance of her life. It is strangely invasive and possessing, this sentiment of a life outlived, a body whose soul is fled. The long vine gardens that spread to the lagoon, dispossessed, but still apparently doing service and rich in vegetables and fruit, seem as if they would persuade35 us of their reality; but their walls are ruined, their ways are low and narrow; it was not thus they looked when Bembo and Navagero paced here in an earthly paradise, a haunt of nymphs and demigods. The living population of Murano seems to have fallen under the same spell. If we bestow on them more than a cursory glance as we pass along the fondamenta, we seem to detect in their faces an indescribable sense of weariness and sorrow and decay. There seem many old among them, and on the young toil and privation have already laid their hand. The strange habitual chant of priest and women and young girls, going up from tired nerveless throats in the twilight of San Pietro Martire, seemed a symbol of the voice of Murano, melancholy, mechanical, the phantom of a voice—an echo struck with the hand or by a breath of wind from a fallen instrument, an instrument that has lost its virtue and its ring, an instrument unstrung. We have seen Murano in festa. She can pay her tribute to free Italy. Ponte Lungo was hung with lamps, and the desolate campi had their share in the illumination. In the very piazza of San Donato a hawker was winding elastic strings of golden treacle, while women and children in gay dresses hurried to and fro. In another square,36 under the clock tower, a demagogue addressed the crowd excitedly: there was plentiful noise, plentiful determination to enjoy. The campanile looked down and wondered. O Roma o morte. Had it been Rome then and not death? Rome and freedom, freedom to destroy the historic and the old? It was a grand triumph, a triumph justly commemorated, and yet the conquerors themselves might grieve over the Italy of to-day. Mazzini, we know, struck a note of melancholy out of that proud exultation. Italy, if she lives, lives among ruins, and for the most part she is careless of her decay.

Murano, like Torcello, is bound by one glorious link with her Byzantine past, and this one of the noblest monuments, not of the lagoons only, but of all Italy; simple, stern, august. San Donato has not, indeed, gone unscathed by time, nor by modernity. The wonders of its pavement are becoming blackened and obscured; holes are being worn in it, missing cubes leave gaps in the design. In winter it is constantly flooded by high tide, and even in other seasons the damp is ruining a pavement which rivals, if it does not surpass, that of San Marco. It is impossible to describe the beauty of the designs, the exquisite harmonics of its precious marbles, porphyry and verd-antique, Verona, serpentine and marmo greco,39 with noble masses of colour among the smaller fragments, and a most precious gem of chalcedony, which, if we may believe the poor old sacristan, whose complaints concerning his precious floor wake no response, an English visitor would have wished to steal. The sacristan can show to all who will lament with him the ruin wrought by sacrilegious man. But no profane hand has dared to raise itself against the Madonna of the apse. This Madonna of San Donato is even grander, more august, than that other who in Torcello conquers Time, and surely it is not without reason that we have called her the goddess of the lagoons. In perfect aloofness and secrecy she stands, but with luminous revelation in her strangely significant eyes; her white hands uplifted, her white face shining out of the darkness, the long, straight folds of her dark robe worked with gold, her feet resting, it seems, upon a golden fire. The gaze of this marvellous Madonna seems to comprehend the world. She is a sphinx who holds the key of every mystery. In her presence we are overcome by the impulse to kneel and worship. She is not, like many Byzantine Madonnas, grotesque, forbidding in her immensity, in her aloofness; for even while she rebukes and subdues our littleness of soul, she draws all our senses as a being of absolute,40 inexplicable beauty. She holds us rapt and will not let us go. The memory of the Duomo of San Donato is concentrated in the single magical figure of her Madonna, leaning in benediction from the golden apse.

Murano is full of corners where Gothic and Byzantine have combined to beautify portico, pillar and arch. In the Asilo dei Vecchii are two of the most ancient fireplaces known in Venice, and at Venice fireplaces were very early in use. One is a deep square hollowed in the wall, and furnished with doors that shut upon it like a panelling, while two little windows, as usual, open out behind. The other projects into the room, with sloping roof and little seats within on either side. Murano, it is well known, was the pleasure-ground of the Venetians in happier days; it was here that the men of the Great Republic had their gardens elect for solace and for beauty. But with the Republic Murano fell; the patrimonies of the patricians were scattered—gradually their palaces were snatched away, piece by piece, and fell into irrecoverable ruin. One only now retains some image of its former splendour, the famous Cà da Mula, upon the fine sweep of the Grand Canal. The Madonna of San Donato has looked down on the spoliation of her temple; she still looks on its41 slow decay. She has shared the proud sorrows of the campanile; in colloquy through the night what may he not have told of the passing of Murano? They have little, these solemn guardians of the past, in common with the exuberant Renaissance, but perhaps a common fate, the unifying hand of Time, may have bound their spirits in a confraternity of grief. The heart of the old campanile would be stirred with pity for the fate of those deserted palaces, the sublime Madonna would turn an eye not of scorn but of sorrow on the fading forms of those radiant women, so splendid on the frescoed palace fronts, so alluring in the smooth mirror of the canal. The work of the spoiler, so far as it was a work of violence, of a human spoiler, is done; but the slower work of nature still proceeds.

Long before Murano became a Venetian pleasure-ground, she had been famous for her painters, for her ships, for her furnaces. Like Torcello, she sent vessels to the triumph of the Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo, and she was conspicuous among the others, as da Canale says: “For you must know that those of Murano had on their vessels living cocks, so that they might be known and whence they came.” Molmenti thinks that Carpaccio himself belonged to a shipbuilding family of Murano, and this is the more interesting in view of42 the frequency and detail of shipping operations in his pictures. Murano was indeed the birthplace of Venetian art, and the riches of its furnaces glow in the garments of those early painters, Vivarini, Andrea and Quirico. From the end of the eleventh century the glass works had begun to flourish; by the thirteenth the industry was transferred wholly to Murano. The legend runs that a certain Cristoforo Briani, hearing from Marco Polo of the monopoly of agates, chalcedony and other precious stones on the coast of Guiana, set about imitating them. With Domenico Miotto to help him he succeeded, and the latter carried the art to still greater perfection, which resulted at last in the imitation of the pearl. In 1528 Andrea Vidoare received a special mariegola or charter for the fame of his wonderful pearls, polished and variegated by him to a degree unknown before. In the middle of the fifteenth century the first crystals came from the furnaces, and the following century was the golden period of the art—a period coinciding with the greatest patrician glory of the island. Murano still burns with its secular fire, winning from the old world its secrets, the old, wise world that worshipped fire, to fuse them once more in its crucible for the wonder of the new; secrets of crystal, pearl and ruby, and of the blue of the deepest ocean43 depths or the impenetrable night sky, imprisoning them in those transparent cenotaphs in forms of infinite harmony and grace. And it is not only in the revival of ancient memories and forgotten mysteries that the furnaces of Murano play their part; they contribute also to the present renewal of Venice: for it is here that the units of the mosaicist’s art are made. In Murano is laid the foundation-stone of its success—the quality of the colour, the depth and richness of the gold. The period of decadence in the Venetian arts is accurately reflected in its mosaics; with the decadence of conception we note also the decadence of colour. Those hard blatant tones that characterise the late mosaics of San Marco are records, too permanent, alas! of a time when the furnaces had lost their cunning, or rather when the master minds were blunted and the secret of the ancient colourists allowed to lie unquestioned under the dust of time.

There is a humbler department of the glass works which we must not pass by. It lies away from the furnaces devoted to rare and subtle texture and design, behind San Pietro Martire, among the gardens: a manufactory of common glass for daily use, tumblers and water-bottles and other humble ware. Here there is the swift operation of machinery, at least among the coarser glasses,44 and a noise of the very inferno with countless sweating fiends—little black-faced grinning boys, grateful for a package full of grapes or juicy figs; there is little mystery in the production of this coarser glass, or rather few of the obvious accessories of mystery, the delicate slow fashioning, the infusion of colours. Instead, the constant noise of machinery, deafening and exhausting in its incessant motion, though even here the reign of machinery is limited: the finer tumblers must go a longer journey to be filed by a slower, more gradual process, the direct handiwork of man. There is an upper circle to which we gladly pass from this inferno, almost a paradise if we contrast it with the turmoil and heat below; to reach it we pass by the troughs of grey sand which all day men are trampling with the soles of their bare feet, to mould into fit temper for the furnace. The floor of the room above is covered and the walls lined with strange creations of cold, grey earth, fashioned by hand, roll after roll of clay, ungainly forms to be inhabited by fire. This upper attic, with its company of mute grey moulds, opens out upon the vineyards of Murano, with water shimmering through the long golden alleys, and the city visible beyond. The gardens of the Palazzo da Mula and of San Cipriano are beside45 us. The bustle of the new world has invaded the peaceful seclusion of a spot once sacred to the student aristocracy of Venice.

For this island, famed for so glorious an industry, was beloved and honoured by the noblest of Venetian names, Trifone Gabriele and Pietro Bembo and Andrea Navagero. Here Navagero founded one of the first botanic gardens of Europe—“a terrestrial paradise, a place of nymphs and demigods”; here Gabriele wandered for hours under the thick vine pergola walled with jessamine against the sun. And it was not only as a temporary pleasure-ground that they loved Murano: they clung to it as their resting-place in death. Bernardo Giustiniani desired to be buried by his palace, at the foot of Ponte Lungo, and Andrea Navagero in the church of San Martino in the same quarter where his house was built. Murano was honoured by at least one royal guest. It was here that Henry III of France, on his passage through Venice from Polonia, was given his first lodging, and the palace which witnessed the first transports of this rapturous monarch, the palace of Bartolomeo Capello, still exists, close beside the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, at the extreme western point of the city. It would thus form the most convenient landing-place, besides commanding46 a view of extreme beauty; to the left, the fine torrent-like sweep of the chief canal, with the noble Cà da Mula a little lower on the opposite bank and its gardens immediately over the water; Venice filling the horizon clear across the lagoon, where the south curve of Murano ends to-day in a meadow of rough grass and fragrant herbs; to the right the Convent of the Angeli, leading on the eye across the lagoon to the mainland and the distant mountains beyond. Traces of fresco remain on the outer walls of the palazzo, and the upper hall still stretches through the whole breadth of the house. It is on the balcony of this central hall that Henry must have stood when he appeared before dinner to gratify the crowds on the fondamenta and in the boats below. The view of Venice in the evening light is exquisitely lovely, with the lagoon spread like a mirror to reflect the delicate opaline of the sunset sky. In this hall hung with cloth of gold and cremosine, and perhaps with the colours of Veronese, looking over a paradise of gardens and water to the immortal city, Henry kept his court, received the legates from the Pope and said a thousand graceful things about His Holiness, rejoiced the natives by his noble bearing, his perfumed gloves, his frank pleasure in their tribute, his decision to go on foot to the47 Angeli to morning Mass. Thus was he initiated to the magical city and its enchantments by that wise providence of the Venetians, who made their islands always stepping-stones, outer courts of the central shrine, where their pilgrim must pause awhile to shake the dust of the mainland off his feet, that the spell might permeate his being and fill his senses with desire.

The fondamenta below Henry’s palace, leading to the church of the Angeli, is one of the most desolate in Murano; the wide green campo of the cemetery which opens from it is deserted and bare, save for a few fowls that humbly commemorate the proud old shield. The dirt of the children is indescribable, as they press close begging a soldino. But their dirt is dearer to them. A bargain for a washed face, even when the reward rings cheerily on the pavement, brings no response but laughter and surprise. We are reminded by contrast of the tribute of Andrea Calmo, a popular poet of the sixteenth century:

48

(And I wish so well to that Murano, that to tell you the sober truth I am thinking of selling my takings and coming there to live more healthily. The gardens there are so full of olive trees, and the canal so clear and clean, the houses so beautiful and so airy, with so many fair creatures that it seems a place of joy stamped by the Lord God.) Beside the Cà da Mula, hidden among some outbuildings, from which it has in the last years been partially released, is one of Murano’s finest treasures, the convent front of San Cipriano, which in the ninth century, when Malamocco was on the point of submersion, was brought here by order of Ordelafo Faliero. Andrea Dandolo dates the building from 881; it was rebuilt in 1109 and restored in 1605, and its exquisite façade, still bearing the stamp of several ages, freed somewhat from the earth about its base, stands up nobly from the tangled garden around it. The central arch is outlined with the finest Byzantine tracery lined with Gothic, surrounded once with coloured marbles of which only fragments now remain, and above this is a frieze of the best Roman of the Renaissance: slender columns, some Byzantine, some Gothic, adorn it on either side, and fantastic Byzantine symbols are sculptured in the stone discs that are embedded in the walls between the arches49 of the cloister. A campanula on the ruined wall to the left of the arch stands out clear and pale against the brick building behind, where once the cloister opened out, an exquisite harmony of lavender and rose. Fragmentary though it is, this façade of the famous monastery is one of the most precious relics of the islands of the lagoons.

There is an island where we cannot think of death, where decay dare not come; though the water plants smell faint upon its shores, and the cypresses that clothe it rise black against the sky. It is the island that sheltered one of the most joyful spirits that has ever walked the world, the island where the larks once sang in such prolonged impulsive harmony of joy that the sound of their singing has never passed away; it may seem to lie silent as a veil upon the water, but the tremor of the sunshine will waken it to renewed harmonics of delight—San Francesco del Deserto. We rejoice to think that the Poverello set foot in the lagoons, that he left here in the lonely waters the blossom of his love. St. Francis of the Desert can wake no thoughts of melancholy, and indeed this is no deserted place, nor in the morning of his coming, after the night of storm, can it have seemed a place of desolation; for nothing is more wonderful, more prodigally50 full of the mysterious rapture of life, than the flowing in of day upon the lagoons after the tumult of rain and hurricane. They say that St. Francis, coming from the Holy Land on a Venetian ship, was driven by the storm to cast anchor near Torcello; that as he prayed, the storm subsided, and a great calm fell on the lagoon. Then as the Poverello set foot upon this cypress-covered shore, the sun came out—the sun of the early summer dawn—and shone through the dripping branches of the cypresses, covering them with glistening crystals, and shone on the damp feathered creatures among the branches and on the larks among the reedy grass, and as he shone a choir of voices woke in the lonely island and a chorus of welcome burst from ten thousand throats. And the sun shone in the heart of St. Francis also, and it overflowed with joy; and St. Francis said to his companion, “The little birds, our brothers, praise their Creator with joy; and we also as we walk in the midst of them—let us sing the praises of God.” And then as St. Bonaventura relates the legend, the birds sang so clamorously on the branches that St. Francis had to entreat their silence till he had sung the Lauds; but we may read another story if we will, and say that the dewy matin song of the birds was not so51 clamorous as to disturb the quiet morning gladness of the Poverello, that they sang together in the dawn. San Francesco del Deserto is not an island of sorrow. In the little convent inhabited still by a few quiet Franciscans, the narrow gloomy corner is to be seen which they name St. Francis’s bed: in the convent garden there rises a stone memorial round the tree that flowered from the Saint’s planted staff. We know these familiar symbols of the Franciscan convents: the brothers cling to them as to some fragmentary testament that their eyes can read and their hand grasp when the living spirit has fled away; everywhere among the mountain or the valley solitudes where St. Francis dwelt, the same dark relics of that luminous spirit are to be found, the story even of birds banished for ever by the command of that prince of singers, as if his own voice chanting eternal litanies could be his sole delight. They are strange stories; we pass them by, and go out to find the Poverello where the cones of the cypresses gleam silver-grey against the blue. His spirit has taken happy root among the waters of the lagoons; a new joy and glory is added to the mountains as they rise in the calm dawn, clear and luminous from the departing rain cloud; there is joy and peace in the raised grass walk between the cypress trees; the island is52 indeed a place of life and not of death for those who have felt the suffering and the joy of love, and who worship beauty in their hearts.

There are still solitudes in the desert of the lagoon where some of us have dreamed of beginning a new day. In the hour when the last gold has faded from the sun-path—when those dancing gems he flings to leap and sport upon the water have been slowly gathered in, when the churches and palaces of the city are folded under one soft clinging veil, which softens the outline that it does not obscure, when Torcello and Burano lean in pallid solitude above the level disc of the marsh, and the Lido lies like a sea-serpent coiled on itself, its spires reflected in the motionless mirror far south to Chioggia—they steal out, these island phantoms, faint, alluring, upon the still mosaic of the lagoon, like black pearls in that shell-like surface of tenderest azure and rose. Shall we not dare to wander among those lovely paths, those dimly burning gems? None visits them, unless it be the golden stars and the dreaming lover of Endymion: their roof is the broad rainbow spread above them by the setting sun. They seem sometimes to welcome53 a spirit that should come and dwell among them silently; one that should tread them with loving reverence and quiet hope, seeking to set free the fantasies with which earth has stored it, but which no power of earth may help it to disburden.

54

Until the fall of the Venetian Republic the rite of the Sporalizio del Mare, the wedding of Venice with the sea, continued to be celebrated annually at the feast of the Ascension. Long after the fruits of the espousal had been gathered, when its renewal had become no more than a ceremonious display, there stirred a pulse of present life in the embrace; and in a sense, the significance of the ceremony never can be lost while one stone remains upon another in the city of the sea.

For the earliest celebration of the nuptials there was need of no golden Bucintoro, no feast of red wine and chestnuts, no damask roses in a silver cup, not so much as a ring to seal the bond. For it was no vaunt of sovereignty; it was a humble oblation, a prayer to the Creator that His creature might be calm and tranquil to all who travelled over it, an oblation to the creature that it might be pleased to assist the gracious and pacific work of its Creator. The regal ceremony of later times55 was inaugurated by the Doge Pietro Orseolo II who, having largely increased the sea dominion of Venice and made himself lord of the Adriatic, welded his achievement into the fabric of the state by the ceremony of the espousal. The ring was not introduced till the year 1177, when Pope Alexander III, being present at the festival, bestowed it on the Doge, as token of the papal sanction of the ceremony, with the words, “Receive it as pledge of the sovereignty that you and your successors shall maintain over the sea.” But the true importance of the festival, whether in its primitive form or in its later elaboration, is the development of Venetian policy which it signified—a development which, for the purposes of this chapter, will best be considered in relation to events separated by nearly two centuries, but united in their acknowledgment of the growing importance of Venice on the waters. The first is Pietro Orseolo’s Dalmatian campaign, followed in 1001 by the secret visit of the German Emperor Otho III, and the second the famous concordat of Pope Alexander III and the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, concluded under the auspices of Venetian statecraft in 1177.

Pietro Orseolo II appears as one of the most potent interpreters of the Venetian spirit. He combined qualities which enabled him to gather56 together the threads which the genius of Venice and the exigencies of her position were weaving, and to fashion from them a substantial web on which her industry might operate. He was a soldier, a great statesman and a patriot. All the subtlety, all the ambition, all the dreams of glory with which his potent and spacious mind was endowed, were at his country’s service, and the material in which he had to work was plastic to his touch. Venice lay midway between the kingdoms of the East and West, and from the earliest times this fact had determined her importance: she might rise to greatness or she might be annihilated; she could not be ignored. The Venice of Orseolo was instinct with vitality and teeming with energies, but she was divided against herself. The foundations of her greatness were already laid, but her general aim and tendency were not determined. She was in need of a leader of commanding mind and capacious imagination, who could envisage her future, and who should possess the power of inspiring others with confidence in his dreams. Such a man was Pietro Orseolo II. Venice had been threatened with destruction by the division of the two interests which, interwoven, were the basis of her power. Before the final settlement at Rialto she had been torn hither59 and thither by the factions of the East and West, the party favouring Constantinople and the party favouring the Frankish King; and at any moment still the Doge’s policy might be wrecked by the rivalries of the two parties, if he proved lacking in insight or capacity for uniting in his service the interests of both.

For some time Dalmatia had been a thorn in the side of Venice, a refuge for the disloyal, and, through the agency of the hordes of pirates infesting the coast, a real menace to her commerce. Venice had attempted to purchase immunity from the pirates by payment of an annual indemnity. Orseolo decided at once to put an end to this payment, but he realised that the price of the decision was a foothold in Dalmatia that would need to be obtained by force of arms. For this end it was necessary to secure harmony within the city itself, and, knowing this, he exercised his powers to obtain approval of his expedition from the authorities of East and of West, from the Emperors of Germany and Byzantium. He was successful in this, and circumstances combined further to aid his designs. The Croatians and Narentines, by wreaking on Northern Dalmatia their anger at the loss of the Venetian indemnity, had prepared the minds of the Dalmatians to look on the prospect60 of Venetian supremacy as one of release rather than of subjugation. It is said that they even went so far as to send a message to Orseolo encouraging his coming. Their province was nominally under the Emperor of Byzantium, but their overlord had decided to look favourably on a means of securing peace and safe passage to his province at so small an expense to himself. Orseolo set sail on Ascension Day, after a service in the Cathedral of Olivolo (now San Pietro di Castello), fortified by the good will of East and of West, and the united acclamations of all parties in Venice. Pride and vigorous hope must have swelled the hearts of these warriors. It was summer, and their songs must have travelled across the dazzling blue of the great basin of St. Mark, and echoed and re-echoed far out on the crystal waters of the lagoon. Triumph was anticipated, and triumph was their portion. Orseolo’s expedition was little less than a triumphal progress; the coast towns of Dalmatia from Zara to Ragusa rendered him their homage. A new and immensely rich province was acquired by Venice, and the title of Duke of Dalmatia accorded to himself.

Soon after Orseolo’s return from this campaign, Venice, unknown to herself, was to receive the homage of one of the emperors she had made it61 her business to propitiate. There is something that stirs the imagination in this secret visit of Otho III to the Doge. According to the ingenuous account of John the Deacon, Venetian ambassador at the Emperor’s court, it was merely one of those visits of princely compliment which the age knew so well how to contrive, and loved so well to recount—a visit in disguise for humility or greater freedom, like that of St. Louis to Brother Giles at Perugia, where host and guest embrace in fellowship too deep for words. The Emperor, John the Deacon tells us, was overcome with admiration of Orseolo’s achievements in Dalmatia, and filled with longing to see so great a man, and the chronicler was despatched to Venice to arrange a meeting. The Doge, while acknowledging the compliment of Otho’s message, could not believe in its reality, and consequently kept his own counsel about it—“tacitus sibi in corde servabat.” However, when Otho on his travels had come down to Ravenna for Lent, John the Deacon was again despatched, and this time from Doge to Emperor.

It was ultimately arranged that after the Easter celebration Otho with a handful of followers should repair, under pretext of a “spring-cure,” to the abbey of Santa Maria in the isle of Pomposa62 at the mouth of the Po. He pretended to be taking up his quarters here for several days, but at nightfall he secretly embarked in a small boat prepared by John the Deacon, and set sail with him and six followers for Venice. All that night and all the following day the little boat battled with the tempest, and the storm was still unabated the next evening, when it put in at the island of San Servolo and found itself harboured at last in the waters of St. Mark. Venice knew nothing of this arrival; her royal guest had taken her unawares, and her waterways had prepared him no welcome. We may picture the anxiety of Orseolo, alone with the secret of his expected guest, on the island of San Servolo. The journey may well have been perilous for so small a boat even within the sheltering wall of the Lido, and we may imagine his relief when it could at last be descried beating towards the island through the tempestuous waters of the lagoon. In impenetrable night, concealed from one another’s eyes by the thick darkness, Emperor and Doge embraced. Otho was invited to rest for an hour or two at the convent of San Zaccaria, but he repaired before dawn to the Ducal Palace and the lodging made ready for him in the eastern tower. There is a fascination in attempting to imagine63 the two sovereigns moving amid the shadows of Venetian night, in thinking of the Emperor watching from the vantage of his tower for daybreak over the city. There are wonders to be seen from this eastern aspect, but after the discomfort of his voyage to Venice the royal captive may well have felt a longing for a sight of the city from within. It is all rather like a children’s game—Orseolo’s feigned first meeting with an embassy from Otho, his inquiry as to the Emperor’s health and whereabouts, and the public dinner with the ambassadors. Venice is robbed of a pageant, and one most dear to her, the fêting of a royal guest; the guest is deprived of all festivities beyond a christening of the Doge’s daughter; yet the pleasurable excitement of John the chronicler communicates itself and disarms our criticism; and it is not till gifts have been offered and refused—“ne quis cupiditatis et non Sancti Marci tuæque dilectionis causa me hac venisse asserat”—till tears and kisses have been exchanged, and the Emperor, this time preceding his companions by a day, has set sail once more for the island of Pomposa, that we break from the spell of the chronicler and begin to cavil at the strange conditions of the visit.

Modern historians have laid a probing hand on64 the sentimentality of John the Deacon’s tale; they do not doubt the kisses or the tears, but the unparalleled eccentricity of secrecy seems to demand an urgent motive. Why this strange coyness of the Emperor? Might he not have thought more to honour Venice and her Doge by coming with imperial pomp than by stealing in and out of the triumphant city like a thief in the night? And why did the persons concerned make public boast of the success of their freak immediately after its occurrence? For John tells us that when three days had passed, the people were assembled by the Doge at his palace to hear of his achievement, “and praised no less the faith of the Emperor than the skill of their leader.” The probable solution of the various enigmas rather rudely shatters the romance. Gfrörer lays on Orseolo the responsibility of the incognito, attributing it partly to a memory of the fate that overtook the Candiani’s personal relations with an imperial house, partly to his desire to treat with the Emperor unobserved. He recalls point by point the precautions taken by Orseolo to preclude Otho from contact with other Venetians, and comes to the conclusion that in those private interviews in the tower the “eternal dreamer” was feasted on the milk and honey of promises, food of which65 no third person could have been allowed to partake. “What lies,” he exclaims, “were invented, what assurances vouchsafed of the most unbounded devotion to imperial projects in general and the longed-for reconstitution of the Roman Empire in particular! Never was prince so shamefully abused as Otho III at Venice.” It is not necessary to abandon our belief in Otho’s personal feelings for the Doge, augmented by Orseolo’s recent campaign, to realise that there must have been another side to the picture. Gulled the royal guest in all probability was, but there is little doubt that he had an axe of his own to be ground on this visit to Venice—that the journey had for its aim something beyond his delectation in a sight of the Doge and his obeisance to the Lion. For the furtherance of his schemes of empire Otho needed a fleet. He had, Gfrörer tells us, “an admiral already in view for it. Nothing was wanted but cables, anchors, equipments; in short there were not even ships, nor the necessary money, and above all, there were no sailors. I believe that Otho III undertook the journey to Venice precisely to procure for himself these necessary trifles. Who knows how many times already he had urged the Doge to hasten his sending of the long-promised fleet; but in place of ships66 nothing had yet come but letters or embassies carrying specious excuses.” If the historian’s motivisation is accurate, Otho must have found, like so many after him, Venice more capable of exercising persuasion than of submitting to it. For our uses, however, the original or the revised versions of the tale serve the same purpose. As an act of spontaneous homage or an act of practical policy, the visit of Otho, full as it is of speculative possibilities, was an imperial tribute to the position Orseolo had given to Venice, an imperial recognition of her progress towards supremacy in the Adriatic.

Orseolo’s achievement and the rite which symbolised it were confirmed two centuries later when, in the spring and summer of 1177, Venice was the meeting place of Pope Alexander III and the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Tradition has woven a curious romance round the fact of the Pope’s sojourn in Venice before the coming of the Emperor. By a manipulation of various episodes, he is brought as a fugitive to creep among the tortuous by-ways of the city, sleeping on the bare ground, and going forward as chance might direct till he is received as a chaplain—or, to enhance the thrill of agony, as a scullion—in the convent of Santa Maria della Carità, and after some67 months have elapsed is brought to the notice of the Doge, when a transformation scene of the Cinderella type is effected. It is inevitable that melodramatic touches should have been added to so important an episode, and the accounts of the manner of Alexander’s arrival and his bearing in Venice are many and varied. None the less, it is clear that splendour and not secrecy, ceremony not intimacy, are the general colouring of the event. Frederick had shown himself disposed to make peace and to accept the mediation of Venice, and in the early days of the Pope’s visit the Venetians had acted as counsellors, pending the agreement as to a meeting place. Significant terms are used by the chroniclers to account for the ultimate choice, and the note which they strike is repeated again and again in the chorus of praise that throughout the centuries was to wait upon Venice. “Pope and Emperor sent forth their mandates to divers parts of the world, that Archbishops, Bishops, Abbots, Ecclesiastics and secular Princes should repair to Venice; for Venice is safe for all, fertile and abounding in supplies, and the people quiet and peace-loving.” Secure among the lagoons, Venice is aloof from the disturbances of the mainland cities, and though her inhabitants are proved warriors they are peaceable citizens. Many of the68 glories of Gentile Bellini’s Procession of the Cross would be present in the procession in which the Doge and the magnates of Venice formally conducted Alexander III to the city—patriarch, bishops, clergy, and finally the Pope himself, all in their festival robes. Ecclesiastical and secular princes of Germany, France, England, Spain, Hungary and the whole of Italy were crowding to Venice. The occasion gave scope for her fascinations, and they were exerted. No opportunity for display was neglected; ceremony was heaped upon ceremony.

For over a fortnight Venice was the centre of correspondence daily renewed between Emperor and Pope, of embassies hastening to and fro, of endless postponements and uncertainties. The Pope retires for a few days to Ferrara; then he is back again to be received as before. But Venice, the indomitable, is secure of her will, and preparations for the coming of the Emperor are growing apace. In July the Doge’s son is despatched to meet the royal guest at Ravenna and conduct him to Venice by way of Chioggia. No tempests disturbed his arrival. He was conducted in triumph up the lagoon by the galleys of “honest men” and Cardinals who had gone forth to Chioggia to meet him. Slowly the islands of the Lido would69 unfold themselves to his eyes, Pellestrina in shining curves, Malamocco with its long reaches of bare shore and reeds. The group clustered round Venice itself—San Servolo, La Grazia, San Lazzaro, Poveglia—would be green and smiling then, living islands, not desolated as now for the most part by magazine or asylum. San Nicolo del Lido welcomed the guest, and he was borne thence on the ducal boat to the city and landed at the Riva. Through the acclamations of an “unheard-of multitude” his way was made to San Marco, where the Pope in all his robes, amid a throng of gorgeous ecclesiastics and laymen, was waiting on the threshold. As he passed out of the brilliant and garish day into the solemn mosaiced glory of San Marco and moved to the high altar between Pope and Doge singing a Te Deum, “while all gave thanks to God, rejoicing and exulting and weeping,” even an emperor and a Barbarossa may well have surrendered his pride. Even we, spectators removed by time, find ourselves exalted on the tide of colour and of sound, and crying to the Venetians, with the strangers who thronged in their streets, “Blessed are ye, that so great a peace has been able to be established in the midst of you! This shall be a memorial to your name for ever.” Peace was secured and Venice had accomplished70 her task. She had devoted the subtleties of her statecraft to its performance, but perhaps the splendour of this hour in San Marco was her crowning achievement. She asked the recognition of a Pope, and she brought the temporal sovereign to his side in a church which is one of the wonders of Christendom. She polished and gilded every detail of her worldly magnificence, and poured it as an oblation at the altar. Her reinforcements to the cause of Alexander III were drawn from far back in the ages, from the inspiration of the men who had fashioned her temple; and may there not be some deeper signification than merely that of Frederick’s stubbornness in the “Not to thee, but to St. Peter,” traditionally attributed to him as he prostrated himself at his enemy’s feet?

To Venice there remained, beside the praise of all Christendom, many tangible tokens of the events of the summer. Emperor and Pope vied with each other in evincing their gratitude. Alexander formally sanctioned and confirmed the title of Venice as sovereign and queen of the Adriatic, and bestowed on the Doge a consecrated ring for use at the Nuptials. And henceforth the ceremony at San Nicolo del Lido, the place of arrival and departure for the high seas and for Dalmatia and the East, was increased in magnificence. No trace73 now remains of the church where the rites were performed; but the grassy squares of San Nicolo and the wooded slopes of its canal, looking on one side to the city, on the other to the sea, are beautiful still. The ocean calls to the lagoon, and the calm waters of the lagoon sway themselves in answer; while, outside the Lido, line beyond line of snowy-crested waves, ever advancing, bear in to Venice, Bride of the Adriatic, the will of the high sea.

74