The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Proof of the Pudding, by Meredith Nicholson

Title: The Proof of the Pudding

Author: Meredith Nicholson

Illustrator: C. H. Taffs

Release Date: September 20, 2021 [eBook #66354]

Language: English

Produced by: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE PROOF OF THE

PUDDING

BY

MEREDITH NICHOLSON

With Illustrations

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1916

COPYRIGHT, 1915 AND 1916, BY THE RED BOOK CORPORATION

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY MEREDITH NICHOLSON

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published May 1916

By Meredith Nicholson

THE PROOF OF THE PUDDING. Illustrated.

THE POET. Illustrated.

OTHERWISE PHYLLIS. With frontispiece in color.

THE PROVINCIAL AMERICAN AND OTHER PAPERS.

A HOOSIER CHRONICLE. With illustrations.

THE SIEGE OF THE SEVEN SUITORS. With illustrations.

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston and New York

TO

CARLETON B. McCULLOCH

| I. | A Young Lady of Moods | 1 |

| II. | The Affairs of Mrs. Copeland | 20 |

| III. | Mr. Farley becomes Explicit | 39 |

| IV. | Nan and Billy’s Wife | 57 |

| V. | A Collector of Facts | 68 |

| VI. | An Error of Judgment | 87 |

| VII. | Welcome Callers | 99 |

| VIII. | Mrs. Copeland’s Good Fortune | 113 |

| IX. | A Narrow Escape | 124 |

| X. | The Ambitions of Mr. Amidon | 136 |

| XI. | Canoeing | 151 |

| XII. | Last Wills and Testaments | 165 |

| XIII. | A Kinney Lark and its Consequences | 175 |

| XIV. | Bills Payable | 194 |

| XV. | Fate and Billy Copeland | 208 |

| XVI. | An Abrupt Ending | 226 |

| XVII. | Shadows | 243 |

| XVIII. | Nan against Nan | 256 |

| XIX. | Not according to Law | 263 |

| XX. | The Copeland-Farley Cellar | 275 |

| XXI. | A Solvent House | 283 |

| XXII. | Null and Void | 292[viii] |

| XXIII. | In Trust | 301 |

| XXIV. | “I never stopped loving him!” | 317 |

| XXV. | Copeland’s Unknown Benefactor | 327 |

| XXVI. | Jerry’s Dark Days | 337 |

| XXVII. | “Just helping; just being kind!” | 354 |

| “Now we’re in for it!” said Nan uncomfortably | Frontispiece |

| “A very charming person—a little devilish, but keen and amusing” | 26 |

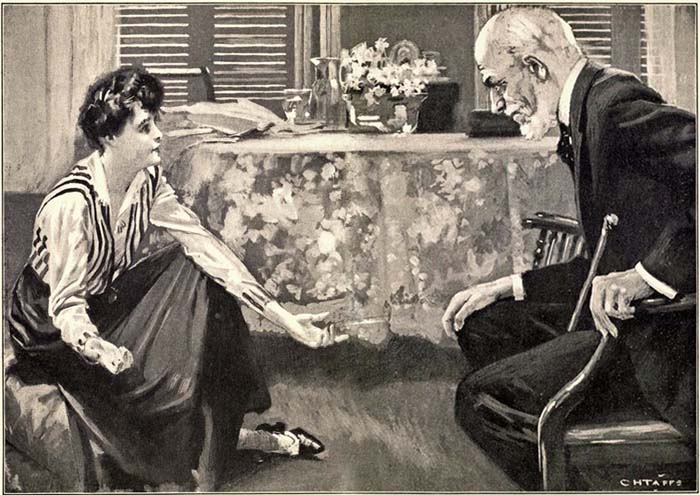

| “Oh, I had one glass; nobody had more, I think; there was some kind of mineral water besides. It was all very simple” | 44 |

| Nan experienced suddenly a disturbing sense of her inferiority to this woman | 62 |

| “I’m not losing anything; and besides, I’m having a mighty good time” | 66 |

| The furtive touch of his hand seemed to establish an understanding between them that they were spectators, not participants in the revel | 188 |

| The touch of her wet cheek thrilled him | 372 |

From drawings by C. H. Taffs

THE PROOF OF THE

PUDDING

It was three o’clock, but the luncheon the Kinneys were giving at the Country Club had survived the passing of less leisurely patrons and now dominated the house. The negro waiters, having served all the food and drink prescribed, perched on the railing of the veranda outside the dining-room, ready to offer further liquids if they should be demanded. Such demands had not been infrequent during the two hours that had intervened since the party sat down, as a row of empty champagne bottles in the club pantry testified. The negroes watched with discreet grins the antics of a girl of twenty-two who seemed to be the center of interest. She had been entertaining the company with a variety of impersonations of local characters, rising and moving about for the better display of her powers of mimicry. Hand-clapping and cries of “Go on!” followed each of these performances.

She concluded an imitation of the head waiter—a pompous individual who had viewed this impiety with mixed emotions—and sank exhausted[2] into her chair amid boisterous laughter. The flush in her cheeks was not wholly attributable to the heat of the June day, and the eagerness with which she gulped a glass of champagne one of the men handed her suggested a familiar acquaintance with that beverage.

“Now, Nan, give us Daddy Farley. Do old Uncle Tim cussing the doctor—put it all in—that’s a good little Nan!”

“Go to it, Nan; we’ve got to have it!” cried Mrs. Kinney.

“I think it will kill me to hear it again,” protested Billy Copeland, who was refilling the girl’s glass; “but I’d be glad to die laughing. It’s the funniest stunt you ever did.”

The girl’s arms hung limp, and she sat, a crumpled, dejected figure, glancing about frowningly with dull eyes.

“I’m all in; there’s nothing doing,” she replied tamely.

“Oh, come along, Nan. We’ll go for a spin in the country right afterwards,” said Mrs. Kinney—who had just confided to a guest from Pittsburg, for whom the party was given, that Nan’s imitation of Daddy Farley abusing his doctor was the killingest thing ever, and that she just must hear it.

Their importunities were renewed to the accompaniment of much thumping of the table, and suddenly the girl sprang to her feet. She seemed[3] immediately transformed as she began a minute representation of the gait and speech of an old man.

“You ignorant blackguard! you common, low piece of swine-meat! How dare you come day after day to torture me with your filthy nostrums! You’ve poured enough dope into me to float a battleship and given me pills enough to sink it, and here I am limpin’ around like a spavined horse, and no more chance o’gettin’ out o’ here again than I have of goin’ to heaven! What’s that! You got the cheek to offer to give up the case! Just like you to want to turn me over to some other pirate and keep me movin’ till the undertaker comes along and hangs out the crape! There’s been a dozen o’ you flutterin’ in here like hungry sparrows lookin’ for worms. You don’t see anything in my old carcass but worm-food! Hi, you! What you up to now? Oh, Lord, don’t leave me! Come back here; come back here, I say! Oh, my damned legs! How long you say I’d better take that poison you sent up here yesterday? Well, all right”—meekly—“I guess I’ll try it. Where’s that nurse gone? You better tell her again about the treatment. She forgets it half the time; tell her to double the dose. If I’ve got to die, I want to die full o’ poison to make it easier for the embalmer. I guess you’re all right, doc; but you’re slow, mighty damned slow. Hi, Nan, you grinnin’ little fool, who told you to come in here? Oh, Lord! Oh, my poor legs! Oh,[4] for God’s sake, doctor, do something for me—do something for me!”

She tottered toward her chair, imaginably the bed from which the old man had risen, and glanced at her audience indifferently, as they broke into hilarious applause. The vulgarity of the exhibition was mitigated somewhat by her amazing success in sinking herself in another personality. They all knew that the man she was imitating was her foster-father and benefactor; that he had rescued her from obscure, hopeless poverty, educated her and given her his name; and that but for his benevolence they never would have known or heard of her; but this clearly was not a company that was fastidious in such matters. The exhibition of her cleverness had been highly diverting. They waved their napkins and demanded more.

She continued to survey them coldly, standing by her chair and absently biting her lip. Then she turned with an air of disdain and moved among the tables to the nearest door with languid deliberation. They watched her dully, mystified. This possibly was a prelude to some further contribution to the hour’s entertainment, and they craned their necks to follow her, expecting that at any moment she would turn back.

The screen door banged harshly upon her exit. She crossed the veranda, ran down the steps toward the canal that lay a little below the clubhouse, and hurried away as though anxious to escape pursuit[5] or questioning. She came presently to the river, pressed through a tangle of briars and threw herself down on the bank under a majestic sycamore.

A woodpecker drummed upon a dead limb of the tree, and a kingfisher looked down at her wonderingly. She lay perfectly quiet with her face buried in the grass. Hers was not a happy frame of mind. Torn with contrition, she yielded herself to the luxury of self-scorn. She had no intention of returning immediately to the clubhouse, and she was infinitely relieved that none of her late companions had followed her. She wished that she might never see them again. Then her mood changed and she sat up, flung aside her hat, dipped her handkerchief in the river and held it to her burning face.

“You little fool, you silly little fool!” she said, addressing her reflection in the water. She spoke as though quoting, which was indeed exactly what she was doing. It was just such endearing terms that her foster-father applied to her in his frequent fits of anger.

Then she stretched herself at ease with her hands clasped under her head and stared at the sky. Beneath the cloud of loosened black hair that her various exertions had shaken free, her violet eyes were fine and expressive. Her face was slender, with dimples near the corners of her mouth: a sensitive face, still fresh and girlish. Her fairness was that of her type—a type markedly Irish. The wet handkerchief that had brought away a faint blotch of scarlet[6] from her rather full lips had left them still red with the sufficient color of youthful health. Lying relaxed for half an hour, watching the lazily drifting white clouds, she became tranquillized. Her eyes lost their restlessness as she gazed dreamily at the heavens.

The soft splash of oars caused her to lift her head guardedly and glance out upon the river. A young man was deftly urging a cedar skiff toward a huge elm that had been uprooted by a spring storm and lay with half its trunk submerged. He jumped out and tied the skiff to a convenient limb and then, standing on the trunk, adjusted a rod and line and began amusing himself by dropping a brilliant fly here and there on the rippling surface. It was inconceivable that any one should imagine that fish were to be wooed and won in this part of the stream; even Nan knew better than that. But failures apparently did not diminish the pleasure the fisherman found in his occupation.

He was small and compactly made and wore white flannel trousers, canvas shoes, and a pink shirt with a four-in-hand to match. He moved about freely on the log to give variety to his experiments; he was indeed much nimbler with his feet than with his hands, for his whipping of the stream lacked the sophistication of skilled fly-casting. He lighted a cigarette without abating his efforts, and commented audibly upon his stupidity when a too-vigorous twist of the wrist sent the fly into a sapling,[7] from which he extricated it with the greatest difficulty.

He was not of her world, Nan reflected, peering at him through the fringing willows. She knew most of the young gentlemen who attended dances or played tennis and golf at the Country Club, and he was not of their species. Once in making a long cast his foot slipped, and he capered wildly while regaining his balance, fell astraddle of the log, and one shoe shipped water. He glanced about to make sure this misfortune had not been observed, shook the water out of his shoe and lighted a fresh cigarette.

She admired the dexterity with which he held the rod under his arm, manipulated the “makings” and had the little cylinder burning in a jiffy and hanging to his lip—a fashion of carrying a cigarette not affected by the young gentlemen she knew. It was just a little rakish; but he was, she surmised, a rather rakish young man. A gray cap tilted over one ear exaggerated his youthful appearance; his countenance was still round and boyish, though she judged him to be older than herself.

The patience and industry with which he plied the rod were admirable: though there was not the slightest probability that a fish would snap at the fly, he continued his futile casting with the utmost zeal and good humor. His sinewy arms were white—which, being interpreted, meant that their exposure to the sun had not been as constant as might[8] be expected of one who was lord of his own time and devoted to athletics. She was wondering whether he intended to continue his exercise indefinitely, when his efforts to extricate the fly from a tangle of water-grass freed it unexpectedly, and the line described a semicircle and caught a limb of the sycamore under which she was lying.

His vigorous tugs only tightened it the more, and she began speculating as to whether she should rise and loosen it or await his own solution of the difficulty. If it became necessary for him to leave the fallen tree to effect a rescue, he must find her hiding-place; and her dignity, she argued, would suffer if she allowed him to discover that she had been watching him. He now began moving toward the bank with the becoming air of determination that had attended his practice with the rod. She rose quickly, jumped up and caught the bough that held the fly, and tore it loose with a handful of leaves.

“Lordy!” he exclaimed, staring hard. “Did you buy a ticket for this show, or did you stroll in on a rain-check?”

“Oh, I was here first; but it isn’t my river!” she replied easily. “They don’t seem to be biting very well,” she added consolingly.

“Biting? Well, I should say not! There hasn’t been a minnow in this river since the Indians left. I’m just practicing.”

“You’ve done a lot of it,” said Nan, looking[9] about for her hat and picking it up as an earnest of her immediate departure.

He dropped his rod and walked toward her guardedly and with an assumed carelessness, his hands in his pockets.

“That’s one good thing about fly-fishing,” he observed detainingly; “you don’t need to bother about the fish so long as there’s plenty of water.”

He noted the handkerchief that she had spread on a bush to dry, and eyed her with appreciation as she thrust the pins through her hat.

“Country Club?” he asked casually.

She nodded affirmatively, glancing toward the red roof of the clubhouse, and brushed the bits of bark and earth from her skirt. If he meant to annoy her with further conversation, it might be just as well to make it clear that the club afforded an easily accessible refuge.

“Excuse me, but you’re Miss Farley,—yes? It’s kind o’ funny,” he continued, still lounging toward her, “but I remember you away back when we were both kids—my name being Amidon—Jeremiah A., late of good old Perry County on La Belle Rivière—and I’ve seen you lots o’ times downtown. I’m connected in a minor capacity with the well-known house of Copeland-Farley Company, drugs, wholesale only—naturally sort o’ take an interest in the family.”

It was still wholly possible for her to walk away without replying; and yet his slangy speech amused[10] her, and his manner was deferential. She remembered the Amidons from her childhood at Belleville, on the Ohio, and she even vaguely remembered the boy this young man must have been. Within three yards of her he paused, as though to reassure her that he was not disposed to presume upon an acquaintance that rested flimsily upon knowledge that might have awakened unwelcome memories; and seeing that she hesitated, he remarked:—

“A good deal has happened since you sat in front of me in the public school down there. I guess a good deal has happened to both of us.”

This was too intimate for immediate acceptance; but she would at least show him that whatever changes might have taken place in their affairs, she was not a snob.

“You are Jerry; the other Amidon boy was Obadiah. I remember him because the name always seemed so funny.”

“You’re playing safe! Obey died when he was ten—poor little kid! Scarlet fever. That was right after the flood you floated away on.”

She murmured her regret at the death of his brother. It was, however, still a delicate question just how much weight should be given to these slight ties of their common youth.

The disagreeable connotations of his introduction—the southward-looking vista that led back to the poverty and squalor to which she was born—were rather rosily obscured by the atmosphere[11] of assured blitheness he exhaled. He seemed to imply that both had put Belleville behind them and that there was nothing surprising in this meeting under happier conditions. He was a clean-cut, well-knit, resolute young fellow. His brownish hair was combed back from his forehead with an onion-skin smoothness; indeed, he imparted a general impression of smoothness. His gray eyes expressed a juvenile innocence; his occasional smile was a slow, reluctant grin that disclosed white, even teeth. A self-confident young fellow, a trifle fresh, and yet with an unobtrusive freshness that was not displeasing, Nan thought, as she continued to observe and appraise him.

“I broke away from the home-plate when I was sixteen,” he went on, “about four years after you pulled out; and I’ve been engaged in commercial pursuits in this very town ever since. Arrived in a freight-car,” he amplified cheerfully, as though she were entitled to all the facts. “Got a job with the aforesaid well-known jobbing house. Began by sweeping out, and now I swing a sample-case down the lower Wabash. Oh, not vulgarly rich! but I manage to get my laundry out every Saturday night.”

“You travel for the house, do you?” she asked with a frown of perplexity.

“That’s calling it by a large name; but I can’t deny that your words give me pleasure. They’re just trying me out; it’s up to me to make good.[12] I’ve seen you in the office now and then; but you never knew me.”

“If I ever saw you, I didn’t know you, of course,” she said with unaffected sincerity; “if I had, I should have spoken to you.”

“Oh, I never worried about that! But of course it would be all right if you didn’t want to remember me. I was an ugly little one-gallus kid with a frowsy head and freckled face. I shouldn’t expect you to remember me for my youthful beauty; but you saved me from starvation once; I sat on your fence and watched you eat a large red apple, and traded you my only agate—it was an imitation—for the core.”

She laughed, declaring that she could never have been so grasping, and he decided that she was a good fellow. Her manner of ignoring the social chasm that yawned between members of the fashionable Country Club and the Little Ripple Club farther down the river, to which young men who invaded the lower Wabash with sample-cases were acceptable, was wholly in her favor. Her parents had been much poorer than his own: his father had been a teamster; hers had been a common day laborer and a poor stick at that. And recurring to the maternal line, her mother had without shame added to the uncertain family income by taking in washing. His mother, on the other hand, had canned her own fruit and been active in the affairs of the First M.E. Church, serving on committees[13] with the wives of men who owned stores and were therefore of Belleville’s aristocracy; she had even been invited to the parsonage to supper.

If Nan Corrigan’s parents had not perished in an Ohio River flood, and if Timothy Farley, serving on a flood sufferers’ relief committee, had not rescued her from a shanty that was about to topple over by the angry waters, Nan Farley would not be standing there in expensive raiment talking to Jerry Amidon. These facts were not to be ignored and she was conscious of no wish to ignore them.

“I’ve been fortunate, of course,” she said, as though condensing an answer to many questions.

“I guess there’s a good deal in luck,” he replied easily. “If one of our best tie-hoppers hadn’t got killed in a trolley smash-up, I might never have got a chance to try the road. I’d probably have been doing Old Masters with the marking-pot around the shipping-room to the end of time.”

His way of putting things amused her, and her smile heightened his admiration of her dimples.

“I suppose you’re going fishing when you learn how to manage the fly?” she asked, willing to prolong the talk now that they had disposed of the past.

“You never spoke truer words! It’s this way,” he continued confidentially: “When I see a fellow doing something I don’t know how to do, my heart-action isn’t good till I learn the trick. It used to make me sick to have to watch ’em marking boxes[14] at the store, and I began getting down at six A.M. to practice, so when a chance came along I’d be ready to handle the brush. And camping once over Sunday a few miles down this romantic stretch of sandbars, I saw a chap hook a bass with a hand-made fly instead of a worm, and I’ve been waiting until returning prosperity gave me the price of a box of those toys to try it myself. And here you’ve caught me in the act. But don’t give me away to the sports up there.” He indicated the clubhouse with a jerk of the head. “It might injure my credit on the street.”

“Oh, I’ll not give you away!” she replied in his own key. “But did the man you saw catch the fish that time ever enter more fully into your life? I should think he ought to have known how highly you approved of him.”

“Well, I got acquainted with him after that, and he’s taken quite a shine to me, if I may say it which shouldn’t. The name being Eaton—John Cecil—lawyer by trade.”

Her face expressed surprise; then she laughed merrily.

“He’s never taken a shine to me; I think he disapproves of me. If he doesn’t”—she frowned—“he ought to!”

“Oh, nothing like that!” he declared with his peculiar slangy intonation. “He isn’t half as frosty as he looks; he’s the greatest ever; says he believes he could have made something out of me if he’d[15] caught me sooner. He works at it occasionally, anyway; trying to purify my grammar—a hard job; says my slang is picturesque and useful for commercial purposes, but little adapted to the politer demands of the drawing-room. You know how Cecil talks? He’s a grand talker—sort o’ guys you, and you can’t get mad.”

“I’ve noticed that,” said Nan, with a rueful smile. “You ought to be proud that he takes an interest in you. I suppose it’s your sense of humor; he’s strong for that.”

This compliment, ventured cautiously, clearly pleased Amidon. He stooped, picked up a pebble and sent it skimming over the water.

“He says a sense of humor is essential to one who gropes for the philosophy of life—his very words. I don’t know what it means, but he says if I’m good and quit opening all my remarks with ‘Listen,’ he’ll elucidate some day.”

Her curiosity was aroused. The social conjunction of John Cecil Eaton and Jeremiah A. Amidon was bewildering.

“He’s not in the habit of wasting time on people he doesn’t like—me, for example,” she remarked, lifting her handkerchief from the bush and shaking it out. “I suppose you met him in a business way?”

“Not much! Politics! I room in his ward, and we met in the Fourth Ward Democratic Club. He tried to smash the Machine in the primary last spring, and I helped clean him up—some job, I[16] can tell you! But he’s a good loser, and he says it’s his duty to win me over to the Cause of Righteousness. Cecil’s a thinker, all right. He says thought isn’t regarded as highly nowadays as it used to be; says my feet are well trained now, and I ought to begin using my head. He always wears that solemn front, and you never know when to laugh. Just toys with his funny whiskers and never blinks. Says he tries his jokes on me before he springs ’em at the University Club. I just let him string me; in fact, I’ve got to; he says I need his chastening hand. Gave me a copy of the Bible, Christmas, and told me to learn the Ten Commandments; said they were going out of fashion pretty fast, and he thought I could build up a reputation for being eccentric by living up to ’em. Says if Moses had made eleven, he couldn’t have improved on the job any. Queer way of talking religion, but Cecil’s different, any way you look at him.”

These revelations as to John Cecil Eaton’s admiration for the Ten Commandments, coming from Amidon, were surprising, but not so puzzling as the evident fact that Eaton found Copeland-Farley’s young commercial traveler worth cultivating. Amidon was quick to see that he rose in Nan’s estimation by reason of Eaton’s friendly interest.

“Well, I never get on with him,” she confessed, willing to sacrifice herself that Amidon might plume himself the more upon Eaton’s partiality.

“Lord, I don’t understand him!” Amidon protested.[17] “If I was smart enough to do that, I wouldn’t be working for eighteen per. I guess he just gets lonesome sometimes and looks me up to have somebody to talk to—not that anybody wouldn’t be tickled to hear him, but he says he finds in me a certain raciness and tang of the Hoosier soil—whatever that means. He took me over to the Art Institute last Sunday and gave me a lecture on the pictures, and me not understanding any more than if he’d been talking Chinese. Introduced me to a Frenchman fresh from Paris and told him my ideals were distinctly post-impressionistic. Then we bumped into a college professor, and he made me talk so the guy could note the mellow flavor of my idiom. Can you beat that? Cecil says the hostility of the social classes to each other is preposterous. Got me to take him to a dance the freight-handlers were throwing. It was funny, but they all warmed to him like flies to a leaky sugar-barrel. Wore his evening clothes, white vest and all, and he was the only guy there in an ironed shirt! I thought they’d sure kill him; but not on your life!”

The John Cecil Eaton thus limned was not the austere person Nan knew. Her Eaton was a sedate gentleman who made cryptic remarks to her at parties and was known to be exceedingly conservative in social matters. Amidon, she surmised, was far too keen to subject himself unwillingly to Eaton’s caustic humor, nor was Eaton a man to[18] trouble himself with any one unless he received an adequate return.

“I must be going back,” she said, glancing at her watch. Her casual manner of consulting the pretty trinket on her wrist charmed him. He was pleased with himself that he had been able to carry through an interview with so superior a person.

He had never been more at ease in his most brilliant conversations with the prettiest stenographer in the drug house, whose sole aim in life seemed to be to “call him down” for his freshness. Lunch-counter girls, shop-girls, attractive motion-picture cashiers, were an alluring target for his wit, and the more cruelly they snubbed him the more intensely he admired them. But the stimulus of these adventures was not comparable to the exaltation he experienced from this encounter with Nan Farley. If she had pretended not to remember him he would have hated her cordially; as it was, he liked her immensely. Though she lacked the pert “come-back” of girls behind desks and counters, he felt, nevertheless, that she would give a good account of herself in like positions if exposed to the bold raillery of commercial travelers. He was humble before her kindness. She turned away, hesitated an instant, then took a step toward him and put out her hand. There was something of appeal in the look she gave him as their hands touched—the vaguest hint of an appeal. Her eyes narrowed for an instant with the intentness of her gaze as she searched his face for—sympathy,[19] understanding, confidence. Then she withdrew her hand quickly, aware that his admiration was expressing itself with disconcerting frankness in his friendly gray eyes.

“It’s been nice to see you again,” she said softly. “Good luck!”

“Good luck to you, Miss Farley; I hope to meet you again sometime.”

“Thank you; I hope so too.”

She nodded brightly and moved off along the path toward the clubhouse. He felt absently for his book of cigarette-papers as he reviewed what she had said and what he had said.

He did not resume his whipping of the river, but restored his rod to its case and turned slowly downstream, not neglecting to lift his eyes to the clubhouse as he drifted by.

In a quiet corner of the club veranda Fanny Copeland and John Cecil Eaton had been conscious of the noisy gayety of Mrs. Kinney’s party, and they observed Nan Farley’s hurried exit and disappearance.

“Nan doesn’t seem to be responding to encores,” Eaton remarked. “She’s gone off to sulk—bored, probably; prefers to be alone, poor kid! It’s outrageous the way those people use her.”

“They have to be amused,” replied Mrs. Copeland, “and I’ve heard that Nan can be very funny.”

“There are all kinds of fun,” Eaton assented dryly. “She’s been taking off Uncle Tim again. I don’t see that he’s getting anything for his money—that is, assuming that she gets his money.”

“If she doesn’t,” said Mrs. Copeland quickly, “she won’t be the only person that’s disappointed.”

Eaton lifted his eyes toward a stretch of woodland beyond the river and regarded it fixedly. Then his gaze reverted to her.

“You think Billy wants to get back the money he paid Farley for the drug business?” he asked, in a colorless, indifferent tone that was habitual.

John Cecil Eaton was nearing the end of his[21] thirties—tall, lean, with a closely trimmed black beard. He was dressed for the links, and his waiting caddy was guarding his bag in the distance and incidentally experimenting at clock golf. Eaton’s long fingers were clasped round his head in such manner as to set his cap awry. One was conscious of the deliberate gaze of his eyes; his drawling voice and dry humor suggested a man of leisurely habits. He specialized in patent law—that is to say, having a small but certain income, he was able to discriminate in his choice of cases, and he accepted only those that particularly interested him. He had been educated as a mechanical engineer, and the law was an afterthought. His years at Exeter and the Tech, prolonged by his law course at Harvard, had quickened his speech and modified its Hoosier flavor. He passed for an Eastern man with strangers. He was the fourth of his name in the community, and it was a name, distinguished in war and peace, that was well sprinkled through the pages of Indiana history. Though the Eatons had rendered public service in conspicuous instances they had never been money-makers, and when John heard of the high prices attained by Washington Street property in the early years of the twentieth century he reflected that if his father and grandfather had been a little more sanguine as to the city’s future he might have been the richest man in town.

Eaton’s interests were not all confined to his[22] profession. He read prodigiously in many fields; he observed politics closely and was president of a club that debated economic and social questions; he was the best fly-fisherman in the State. His occasional efforts to improve the tone of local politics greatly amused his friends, who could not see why a man who might have been pardoned for looking enviously upon a seat in the United States Senate should subject himself to the indignity of a defeat for the city council. To the men he lunched with daily at the University Club his interest in municipal affairs was only another of his eccentricities. He had never married, but was still carried hopefully on the list of eligibles. By general consent he was the best dinner man in town—a guest who could be relied upon to keep the talk going and make a favorable impression on pilgrims from abroad.

Mrs. Copeland’s ironic smile at his last remark had lingered. Their eyes met glancingly; then the gaze of both fell upon the distant treetops. Theirs was an old friendship that rendered unnecessary the filling in of gaps. Eaton was thinking less concretely of her reference to Billy Copeland’s designs upon the Farley money than of the abstract fact that a divorced woman might sit upon a club veranda and hear her former spouse’s voice raised in joyous exclamation within, and even revert without visible emotion to the possibility of his remarrying.

Times and standards had changed. This was no[23] longer the sober capital it had been, where every one went to church, and particular merit might be acquired by attending prayer-meeting. It was a very different place from what it had been in days well within Eaton’s recollection, before the bobtail mule cars yielded to the trolley, or the automobile drove out the sober-going phaëtons and station-wagons that had satisfied the native longing for grandeur. The roster of the Country Club bore testimony of the passing of the old order. The membership committee no longer concerned itself with the ancestry or reputation for sobriety of applicants, or their place of worship, or whether their grandfathers had come to town before the burning of the Morrison Opera House, or even the later conflagration that consumed the Academy of Music. You might speak of late arrivals like the Kinneys with all the scorn you pleased, but they had been recognized by everybody but a few ultra-conservatives; and if Bob Kinney was something of a sport or his wife’s New York clothes were a trifle daring for the local taste, such criticisms did not weigh heavily as against the handsome villa in which these same Kinneys had established themselves in the new residential area on the river bluff. Curiosity is a stern foe of snobbishness; and when Mrs. Kinney seemed so “sweet” and had given a thousand dollars to the new Girls’ Club, besides endowing a children’s room in the Presbyterian Hospital, many very proper and dignified matrons[24] felt fully justified in crossing the Rubicon (otherwise White River) for an inspection of Mrs. Kinney’s new house. Eaton had accepted such things in a philosophic spirit, just as he accepted Kinney’s retainer to safeguard the patents on the devices that made Kinney’s cement the best on the market and the only brand that would take the finish and tint of tile or marble.

“It seems to be understood that they’re waiting for Farley to die so they can be married comfortably,” Eaton remarked. “But Farley’s a tough old hickory knot. He’s capable of hanging on just to spite them.”

“He was always very kind to me. I saw a good deal of him and his wife after I came here. He was proud of the business and anxious that Billy should carry it on and keep developing it.”

“I always liked the steamboating period of Farley’s life,” said Eaton, ignoring this frank reference to her former husband, in which he thought he detected a trace of wistfulness; “and he’s told me a good deal about it at times. It was much more picturesque than his wholesale-drugging. He never quite got over his river days—he’s always been the second mate, bullying the roustabouts.”

“He never forgot how to swear,” Mrs. Copeland laughed. “He does it adorably.”

“There was never anything like him when he’s well heated,” Eaton continued. “He never means anything—it’s just his natural way of talking.[25] His customers rather liked it on the whole—expected him to commit them to the fiery pit every time they came to town and dropped in to see him. When he got stung in a trade—which wasn’t often—he’d go into his room and lock the door and curse himself for an hour or two and then go out and raise somebody’s wages. A character—a real person, old Uncle Tim!”

The thought of the retired merchant seemed to give Eaton pleasure; a smile played furtively about his lips.

“Then it must have been his wife who used to lure him to church every Sunday morning.”

“Not a bit of it! It was the old man himself. He had a superstitious feeling that business would go badly if he cut church. He never swore on Sundays, but made up for it Monday mornings. He’s always been a generous backer of foreign missionaries on the theory that by Christianizing the heathen we’re widening the market for American commerce. We’ve had worse men than Farley. I suppose he never told a lie or did an underhanded thing through all the years he was in business. And all he has to leave behind him is his half million or more—and Nan.”

“And Nan,” Mrs. Copeland repeated with a shrug of her shoulders. “I suppose Mr. Farley knows what’s up. He’s too shrewd not to know. Clever as Nan is, she could hardly pull the wool over his eyes.”

[26]“She’s much too clever not to know she can’t fool him; but he’s immensely fond of her, just as his wife was. And we’ve got to admit that Nan is a very charming person—a little devilish, but keen and amusing. She’s too good for that crowd she’s running with—no doubt of that! If Uncle Tim thought she meant to marry Billy, he would take pains to see that she didn’t.”

“You mean he wouldn’t leave her the money?” she asked in a lower tone. “I suppose he’d have to.”

Eaton shook his head.

“He’s under no obligation to give it all to Nan. If he thought there was any chance of her marrying Billy—”

“She’s been led to believe that it would all be hers. The Farleys educated her and brought her up in a way to encourage the belief. It would be cruel to disappoint her; he wouldn’t have any right to cut her off,” Mrs. Copeland concluded with feeling.

“It might be less cruel to cut her off than to let her have it all and go on the way she’s started. She came about ten years too late upon the scene. It’s only within a few years that a party like we’ve listened to in there would have been possible in this town. If Nan had reached her twentieth year a decade ago, she’d have been the demurest of little girls, and there would have been no question of her marrying a man who had divorced his wife merely to be free to appropriate her.”

“A VERY CHARMING PERSON—A LITTLE DEVILISH,

BUT KEEN AND AMUSING”

[27]Mrs. Copeland opened and closed her eyes quickly several times. No other man of her acquaintance would have dared to speak of her personal affairs in this blunt fashion. Eaton had referred to the divorce that had severed her ties with Copeland quite as though she were not an interested party to that transaction. He now went a step further, and the color deepened in her face as he said:—

“I don’t understand why you didn’t resist his suit. I’ve never said this to you before, and it’s too late to be proffering advice, but you oughtn’t to have let it go as you did. Billy’s whole conduct was perfectly contemptible.”

“There was no sense in making a fight if he wanted to quit. The law couldn’t widen the breach; it was there anyhow, from the first moment I knew what was in his mind.”

“He acted like a scoundrel,” persisted Eaton in his cool, even tones; “it was base, rotten, damnable!”

“If you mean”—she hesitated and frowned—“if you mean that he let the impression get abroad that I was at fault—that it was I who had become interested elsewhere—it’s only just to say that I never thought Billy did that. I don’t believe now that he did it.”

He was aware that he had ventured far toward the red lamps of danger. This matter of her personal honor was too delicate for veranda discussion;[28] in fact, it was not a matter that he had any right to refer to even remotely at any time or place.

“Of course, unpleasant things were said,” she added. “I suppose they’re always bound to be. Manning was his friend, not mine.”

Eaton received this impassively, which was his way of receiving most things.

“By keeping out of the way, that gentleman proved that he couldn’t have been any friend of yours. If he’d been a gentleman or even a man—”

She broke in upon him quietly, bending toward him with tense eagerness.

“He offered to: I have never told that to any one, but I don’t want you to be unfair even to him. My mistake was that I meekly followed Billy when he began running with the new crowd. I knew I was boring him, and I thought if I took up with the Kinneys and the people they were training with, he might get tired of them after a while and we could go on as we had begun. But I hadn’t reckoned with Nan. I allowed myself to be put in competition with a girl of twenty—which is a foolish thing for a woman of thirty-five to do.”

She carried lightly the thirty-five years to which she confessed, but sometimes, in unguarded moments, a startled, pained look stole into her brown eyes, as though at the remembrance of a blow that might repeat itself. There was a patch of white in her hair just at one side of her forehead. Its effect was to contribute to her natural air of distinction.[29] She was of medium height and her trim figure retained its girlish lines. Her face and hands were tanned brown, and the color was becoming. She wore to-day a blue skirt and a plain blouse, with a soft collar opened at the throat. She had walked to the clubhouse from her home, a mile distant, and her meeting with Eaton had been purely incidental. After her divorce she had established herself as a dairy farmer on twenty acres of land that she had inherited from her father, a banker in one of the smaller county seats, who had been specially interested in dairying and had encouraged her interest in the diversion he made profitable. To please him she had taken a course in dairying at the State Agricultural School and knew the business in all its practical aspects. Copeland had first seen her at a winter resort in Florida where she had gone with her father in his last illness, and their common ties with Indiana had made it easily possible for him to cultivate her better acquaintance later at home. Billy Copeland was an attractive young fellow with good prospects; his social experience was much ampler than hers, and the marriage seemed to her friends an advantageous one. When after ten years she found herself free, she rose from the ruins of her domestic happiness determined to live her life in the way that pleased her best. She shrank from adjusting herself to a new groove in town; the plight of the divorced woman was still, in this community, not wholly comfortable. There was little consolation[30] in the sympathy of friends—though she had many; and even the general attitude, that Copeland’s conduct was utterly indefensible, did not help greatly. She realized perfectly that in following Copeland’s lead unprotestingly when he caught step with the quicker social pace set by the Kinneys,—a name that stood as a synonym for noiser functions and heavier libations than the community had tolerated,—she had estranged many who were affronted by the violence with which the town was becoming kinneyized.

Two years had passed and her broken wings again beat the air with something of their early rhythm. The pathos of her isolation was more apparent to her old friends in town than to herself. Whether she had dropped out of the Kinney crowd, or whether it was more properly an ejectment, there was all the more reason why women who had regarded the intrusions of that set with horror should manifest their confidence in her. If she had been poor, a divorcée lodged in a boarding-house and in need of practical aid, she might have suffered from neglect; but having an assured small income which her investment in the dairy farm in no wise jeopardized, it was rather the thing to look in on her occasionally. Young girls in particular thought her handsome and interesting-looking, and risked their mothers’ displeasure by going to see her. And there were women who sought her out merely to emphasize their disapproval of Copeland and the[31] scandal of his divorce, which they felt to be an affront to the community’s dignity in a man whose father had been of the old order of decent, law-abiding, home-keeping, church-going citizens. They admired the courage and dignity with which she met misfortune and addressed herself uncomplainingly to the business of fashioning a new life.

“I’ve been keeping you from your game,” she said, rising abruptly; “and I must be getting home.”

They walked down the veranda toward the entrance and reached the door at a moment when Copeland, who had been keeping company with a tall glass in the rathskeller below, waiting impatiently for Nan’s return, lounged out.

He stopped short with a slightly challenging air. Eaton bowed and tugged at the visor of his cap. Copeland lifted his straw hat and muttered a good-afternoon that was intended for one or both as they chose to take it. Mrs. Copeland glanced at him without making any sign; she did not speak to Eaton again, but as they parted near the first tee and she started across the links toward the highway, she nodded quickly and smiled a forlorn little smile that haunted him for some time afterward.

Half an hour later, standing erect after successfully negotiating a difficult putt, he said, under his breath:—

“By George! She’s still in love with him!”

He glanced around to make sure no one had overheard him, and crossed to the next tee with a look of deep perplexity on his face.

[32]Nan, having returned to the clubhouse, sauntered down the veranda toward Copeland, wearing a demure air she had practiced for his benefit. Her indifference to his annoyance at her long absence added to his vexation.

“Well, what have you been up to?” he demanded irritably. “The others skipped long ago.”

“Oh, I was tired and went down to the river to rest. I’m going home now.”

“You can’t go home; Grace expects us to stop at her house; they’ll all be there in half an hour.”

“Sorry, but I must skip. You run along like a good boy, and I’ll hop on the trolley. I must be home by five, and I’ll just about make it.”

“That’s not treating Grace right, to say nothing of me!” he expostulated. “I’m getting sick of all this dodging and ducking. I’m coming up to the house to-morrow and have it out with Farley.”

“You’re a nice boy, Billy, but you’re not going to do anything foolish,” she replied.

He found the kindness of this—even its note of fondness—unsatisfying. He read into it a skepticism that was not flattering.

“We’ve been fooling long enough about this; we’ve got to announce our engagement and be done with it.”

“But, Billy, we’re not engaged! We’re just the best of friends. Why should we stir up a big fuss by getting engaged?”

“What’s got into you, anyhow!” he exclaimed,[33] eyeing her angrily. “This talk about not being engaged doesn’t go! I’m getting tired of all this nonsense—being kicked about and held off when I’ve staked everything I’ve got on you.”

“You mean,” she said steadily, “that you divorced your wife, thinking I would marry you; and now you’re angry because I’m not in a hurry about it, and don’t want to trouble papa, who has been kinder to me than anybody else ever was—”

“For God’s sake, don’t cry here! We’ve been talked about enough; I don’t understand what’s got into you to-day.”

“I just mean to be sensible, that’s all. We’ve had some mighty fine times, and you’ve been nice to me; but there’s no hurry about getting married—”

“No hurry!” He stared at her, unable in his impotent rage to deal with the situation as he thought it deserved. “Look here, Nan, I can stand a lot of this Irish temperament of yours, but you’re playing it a little too far.”

“My Irish temperament!” she repeated poutingly. “Well, I guess the Irish is there all right; I don’t know about the temperamental part of it. A good many people call it something very different.”

“When am I going to see you again?” he demanded roughly.

“How should I know! You see me now and you don’t like me. You’d better go downtown and do[34] some work, Billy; that’s what I should prescribe for you. And you’ve got to cut out the drink; it’s getting too big a hold on you. I’m going to quit, too.”

Standing near the entrance, they had been obliged to acknowledge the greetings of a number of new arrivals. It was manifestly no place for a prolonged serious discussion of their future. Mrs. Harrington, whose husband’s bank, the Phœnix National, was the soundest in the State, climbed the steps from her motor without seeing Nan and her companion. Until Farley retired, the Copeland-Farley account was carried by the Phœnix; when Billy Copeland took the helm he transferred it to the Western, as likely to grant a more generous credit.

Copeland flushed angrily at the slight; Nan bit her lip.

“I’m off!” she said. “Be a good boy. I’ll see you again in a day or two. And for Heaven’s sake, don’t call me on the telephone; papa has an extension in his room, you know, and hears everything. Tell Grace I’m sorry—”

“Let me run you into town; I can set you down somewhere near home. The trolleys are hot and dusty. Besides, I want to talk to you; I’ve got a lot to say to you.”

“Not to-day, Billy. Good-bye!”

Eaton found Nan waiting for him at the fourth green.

[35]“I was praying for a mascot, and here you are,” he remarked affably. “I can’t fail to turn in a good card. Glad to see you’ve taken up walking; there’s nothing like it—particularly on a humid afternoon.”

“Sorry to disappoint you, but I hope to catch the four-thirty for town. What are my chances?”

“Excellent, if you don’t waste more than ten minutes on me. You’ve never given me more than five up to date. How is Mr. Farley?”

“He’s been very comfortable for a week; really quite like himself. You’d better come and see him.”

“I meant to drop in often all winter, but was afraid of boring him.”

“You’re one of the few that couldn’t do that. He likes to talk to you. You don’t bother him with questions about his health—a sure way of pleasing him.”

“A rare man, Farley. Wiser than serpents, and stimulating. I’ve learned a good deal from him.”

They reached his ball, that had accommodatingly effected a good lie, and after viewing it with approval he glanced at Nan and remarked:—

“You’d better urge me to come to see you, too. It’s just occurred to me that it might be well for us to know each other better. I may flatter myself; but—”

“That’s the nicest thing I’ve heard to-day! Please come soon.”

[36]“Thank you, Nan; I shall certainly do that.”

“I met a friend of yours a while ago,” she said, “who pronounced you the greatest living man.”

“Ah! A gentleman, of course; I identify him at once; he’s the only person alive I fool to that extent—Jeremiah A. Amidon! I can’t imagine why he hasn’t mentioned his acquaintance with you. I shall chide him for this.”

He viewed her in his quizzical fashion through the thick-lensed spectacles he used for golfing. In his ordinary occupations these gave place to eyeglasses that twinkled with a sharp, hard brightness, as though bent upon obscuring the kindness that lay behind them.

“I hadn’t seen him lately—not since I was a child. We used to be neighbors when we were children, and he was a very, very naughty boy.”

“I dare say he was,” Eaton remarked, with his air of thinking of something else. “I suppose you didn’t find him at all backward in bringing himself to your notice. Shyness isn’t his dominant trait.”

“On the other hand, he was rather diffident and wholly polite. I thought his manners did you credit—for he said you had been coaching him.”

“He must be chidden; his use of my name in that connection is utterly unwarranted. He was one of Mrs. Kinney’s party, I suppose,—very interesting. I’m glad they have taken him up!”

He was watching, with the quick eagerness that[37] made him so disconcerting a companion, the passing of a motor toward the clubhouse, but she understood perfectly that this utterance had been with ironic intent. She laughed softly.

“How funny you are! I wish I weren’t afraid of you.”

“I’ve made a careful study of the phobias, and there is nothing in the best authorities to justify a fear of me. I’m as tame as buttered toast.”

“Well, it’s clear Mr. Amidon isn’t afraid of you!”

“I’m relieved—infinitely; I’m in mortal terror of him. He’s fixed standards of conduct for me that make me nervous. I’m afraid the young scoundrel will catch me with my visor down some day; then smash goes his poor idol. I’m glad you spoke of him; if he wasn’t at your luncheon—a guess you scorned to notice—I suppose you met by chance, the usual way.”

“It was just like that,” she laughed. “Very much so!”

“H’m! I warn you against accepting the attentions of just any young man who strolls up the river. A girl of your years must be discreet. Your early knowledge of Mr. Amidon in the loved spots your infancy knew won’t save you. You’d better refer all such matters to me. Pleasant as this is, you’re going to miss your car if you don’t rustle. And Harrington’s bawling his head off trying to fore me away. Good-bye!”

[38]With a neat stroke he landed his ball on the green and ran after it to raise the blockade. When Nan had halted the car and climbed into the vestibule, she waved her hand, a salute which he returned gallantly with a sweep of his cap.

The Farleys had lived for twenty years in an old-fashioned square brick house surrounded by maples. The lower floor comprised a parlor, sitting-room, and dining-room, with a library on the side. The library had been Farley’s den, where he smoked his pipe and read his newspapers. The bookcases that lined the walls had rarely been opened; they contained the “Waverley Novels,” Dickens’s “Works” complete, and a wide range of miscellaneous fiction, including “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” most of Mark Twain, Tourgée’s novel of Reconstruction, “A Fool’s Errand,” Helen Hunt Jackson’s “Ramona,” and a number of Mrs. A. D. T. Whitney’s stories for girls—these latter reminiscent of Nan’s girlhood. The brown volumes of “Messages and Papers of the Presidents” were massed on the bottom shelves invincibly with half a dozen “Reports” of the State Geological Survey. The doors of the black-walnut bookcases were warped so that the contents were accessible only after patient tugging. Half the books were upside-down—and had been since the last house-cleaning. The room presented an inhospitable front to literature, and the other arts fared no better elsewhere in the house. A steel[40] engraving of the Parthenon on the dining-room wall confronted a crude print of the Jane E. Newcomb, an Ohio River packet on which Farley had been second mate—and an efficient one—in ’69-’70.

Mrs. Farley had established in her household the Southwestern custom of abating the heat by keeping the outer shutters closed through the middle of the day, and the negro servants who still continued in charge had not changed her system in this or in any other important particular. Nan had not lacked instruction in the domestic arts; in her school vacations she had been thoroughly drilled by Mrs. Farley. Cleanliness in its traditional relationship to godliness had been deeply impressed upon her; and she had been taught to sew, knit, and crochet. She knew how to cook after the plain fashion to which Mrs. Farley’s tastes and experience limited her; she had belonged to an embroidery class formed to give occupation to one of Mrs. Farley’s friends who had fallen upon evil times; and Nan had been the aptest of pupils.

But Nan had never been equal to the task of initiating changes in the Farley household, with its regular order of sweepings, scrubbings, and dustings; its special days for baking, its inexorable rotation in meats and vegetables for the table. And if she had needed justification she would have given as her excuse Farley’s long acceptance of his wife’s domestic routine, and the fear of displeasing him by altering it. The colored cook’s husband did the[41] heavier indoor cleaning and maintained the yard; and the dining-room and the upper floor were cared for by a colored woman. Hardly any one employed a black second girl, and Nan would have changed the color scheme in this particular and substituted a neatly capped and aproned white girl of the type that opened the door of her friends’ houses, but the present incumbent was a niece of the cook and not to be eliminated without rending the entire domestic fabric.

Nan reached home a few minutes after five. She ran upstairs and found Farley in his room, bending over a table by the window playing solitaire. The trained nurse who had been in the house for a year appeared at the door and withdrew. Nan crossed the room and laid a hand on Farley’s shoulder. He had nearly finished the game, and she remained quietly watching his tremulous hands shifting the cards until he leaned back with a little grunt of satisfaction at the end. He put up his hand to hers and drew her round so that he could look at her.

“Still wearing that fool hat! Take it off and sit down here and talk to me.”

His small, round head was thickly covered with stiff white hair, though his square-cut beard had whitened unevenly and still showed traces of brown. While he lay in the chair with a pathetic inertness, his eyes moved about restlessly, and his bleached, gnarled fingers were never wholly quiet.

[42]“Let’s see what you’ve been up to to-day?” he asked.

“Mamie Pembroke’s; she was having a luncheon for her cousin.”

“Just girls, I suppose?” he asked indifferently. “You must have had a lot to eat to be gone all this time.”

“Well, we went for a motor run afterward and stopped at the Country Club on the way back.”

“More to eat, I suppose. My God! everybody seems able to eat but me! I told that fool doctor awhile ago I was goin’ to shoot him if he didn’t cut off this gruel he’s feedin’ me. You can lay in corn’ beef and cabbage for to-morrow; I’m goin’ to eat a barrel of it, too. If I can get hold of some real food for a week, I’ll get out of this. I understand they’ve got Bill Harrington playin’ golf. My God! he’s two years older than I am and sits on his job every day. If I’d never knuckled under to the doctors, I’d be a well man!” The wind rustling the maple by the nearest window attracted his attention. “Open that blind, and let the air in. Things have come to a nice pass when a man with my constitution can be shut up in a dark room without air enough to keep him alive.”

It was necessary to lift the wire screen before the shutters could be opened, and he watched her intently as she obeyed him quickly and quietly.

“Been to luncheon, have you?” he remarked as she sat down. “Well, eatin’ your meals outside[43] doesn’t save me any money. Those damned niggers cook just as much as if they had a regiment in the house. What did they give you to eat at the Pembrokes’—the usual bird-food rubbish?”

Before his illness he had scrupulously reserved his profanity for business uses; and it was only when his pain grew intolerable or the slow action of his doctor’s remedies roused him to fury that he had recourse to strong language. He allowed her to change the position of his footstool, which had slipped away from him, and grunted his appreciation as he stretched his long, bony figure more comfortably.

“Well, go on and tell me what you had to eat.”

It seemed best to meet this demand in a spirit of lightness. Having lied once, it might be well to vary her recital by resorting to the truth, and she counted off on her fingers, with the mockery that he had always seemed to like, the items of food that had really constituted Mrs. Kinney’s luncheon.

“Grape-fruit, broiled chicken, asparagus, potatoes baked in their jackets and sprinkled with red pepper, the way you like them; romaine salad, ice-cream and cake—just plain sponge cake—coffee. Nothing so very sumptuous about that, papa.”

It had always been “papa” and “mamma” since her adoption. When she came home from a boarding-school near Philadelphia where she had spent two years, her attempts to change the provincial “poppa” and “momma” to the French pronunciation[44] had been promptly thwarted. Farley hated anything that seemed “high-falutin’”; and having grown used to being called “poppa,” his heart was as flint against the impious substitution.

“Of course there were no cocktails or champagne. Not at the Pembrokes’! If all the women around here were like Mrs. Pembroke, we wouldn’t have nice little girls like you swillin’ liquor; nor these sap-headed boys that trot with you girls stewin’ their worthless little brains in gin. What do you think these cigarette-smokin’ swine are goin’ to do! Do you hear of ’em doin’ any work? Is there one of ’em that’s worth a dollar a week? My God! between you girls runnin’ around half-naked and these worthless young cubs plantin’ their weak, wobbly little chins against cocktails all night, things have come to a nice pass. Well, why don’t you go on and tell me who was at your party? Here I am, lyin’ here waitin’ for the pallbearers to carry me out, and never hearin’ a thing, and you sit there deaf and dumb! Who was at that party?”

“Well, poppa, there were just seven girls, counting me: Mary Waterman, Minnie Briskett, Marian Doane, and Libby Davis, and Mamie and her guest—a cousin from Louisville. Of course, there was nothing to drink but claret cup, with sprigs of mint in the glasses.”

“OH, I HAD ONE GLASS; NOBODY HAD MORE, I THINK; THERE WAS SOME

KIND OF MINERAL WATER BESIDES. IT WAS ALL VERY SIMPLE”

[45]“So the Pembrokes are comin’ to it, are they? They’ve got to have something that looks like liquor—well, they’ll be passin’ the cocktails before long. Claret cup dressed up like juleps; and how much did you get of it?”

“Oh, I had one glass; nobody had more, I think; there was some kind of mineral water besides. It was all very simple.”

“Just a simple little luncheon, was it? Well, I suppose it’s not too simple to get into the newspapers. Nobody can put an extra plate on the table now without the papers have to print it.”

He had never quizzed her like this, and his reference to the newspaper alarmed her. His usual custom was to ask her what she had been doing and whom she had seen and then change the subject in the midst of her answer. If he had laid a trap for her she had gone too far to retreat; and while she had lied to him before, she had managed it more discreetly. She had escaped detection so long that she believed herself immune from discovery.

He began tugging at a newspaper that had been hidden under his wrapper, and her heart throbbed violently as he opened it and thrust it toward her. It was the afternoon paper, folded back to the personal and society items.

“Just read that aloud to me, will you? I may have been mistaken. Maybe I didn’t get it straight. Go ahead, now, and read it—read it slow.”

She knew without looking what it was; the reading was exacted merely to add to her discomfiture. The newspaper was delivered punctually at four o’clock every afternoon, so that before she left the[46] Country Club he had known just where she had been and the names of her companions. She read in a low, monotonous tone:—

“‘Mrs. Robert Smiley Kinney entertained at luncheon at the Country Club to-day for Mrs. Ridgeley P. Farwell, of Pittsburg, who is her house guest. The decorations were in pink. Those who enjoyed Mrs. Kinney’s hospitality were Mr. and Mrs. Frederic Towlesley, Miss Nancy Farley, Miss Edith Saxby, Mr. George K. Pickard, and Mr. William B. Copeland.’”

She refolded the paper and placed it on the table beside him. Instead of the violent lashing for which she had steeled herself, he spoke her name very kindly and gently, with even a lingering caress.

“I lied to you papa,” she faltered; “but I didn’t mean to see him again. I—”

“Let’s be square about this,” he said, bending forward and clasping his fingers over his knees. “You promised me a year ago that you’d not meet or see Copeland; I didn’t ask you to drop Mrs. Kinney, for I don’t think she’s a particularly bad woman; she’s only a fool, and we’ve got to be charitable in dealin’ with fools. You can’t ever tell when you’re not one yourself; that means me as well as you, Nan. Now, about that worthless whelp, Copeland! I want the whole truth—no more little lies or big ones. You know that piece of carrion wouldn’t dare come to this house, and yet you sneak away and meet him and leave me to find[47] it out by accident! Now, I want the God’s truth; just what does all this mean?”

His quiet tone was weighted with the dignity, the simple righteousness, that lay in him. She could have met more courageously a violent tirade than his subdued demand. She was conscious that he had controlled himself with difficulty; throughout the interview his wrath had flashed like heat-lightning on far horizons, but he had kept himself well in hand. He was outraged, but he was hurt, troubled, perplexed by her conduct. The adoption of Nan had marked a high altitude in the married life of the Farleys, and they had lavished upon her the pent love of their childlessness. The very manner in which she had been flung upon their protection made her advent in their household something of an adventure, broadening their narrowing vistas and bringing a welcome cheer to their monotonous existence. They had felt it to be a duty, but one that would repay them a thousand-fold in happiness.

Farley patiently awaited her explanation—an explanation she dared not make. She must satisfy him, if at all, by evasions and further lies.

“Mrs. Kinney made a point of my coming; she was always very nice to me, and I haven’t been seeing her,—honestly I haven’t,—and I was afraid she’d be offended if I refused to go. And I didn’t know Mr. Copeland would be there. The luncheon was in the big dining-room, where everybody could see us. I didn’t see any more of him[48] than of anybody else. In fact, I got tired and ran away—down to the river and was there by myself for an hour before I came home on the trolley. When I got back to the clubhouse, they had all gone motoring and I didn’t see them again.”

“Left you there, did they? Well, Copeland waited for you, didn’t he?”

“Yes,” she admitted quickly. “But I saw him only a minute on the veranda and told him I was coming home. He understands perfectly that you don’t want me to see him.”

“H’m! I should hope he did! All that crowd understand it, don’t they? They’ve been puttin’ you in his way, haven’t they,—tryin’ to fix up something between you and that loafer! Look here, Nan, I’m not dead yet! I’m goin’ to live a long time, and if these fool doctors have been tellin’ you I’m done for, they’ve lied. And if Copeland thinks my money’s goin’ to drop into his lap, he’s waitin’ under the wrong tree. Never a cent! What you got to say to that?”

“I don’t think he ever thought of it; it’s only because you don’t like him that you imagine he wants to marry me. I tell you now that I have never had any idea of marrying him. And as for your money—it isn’t my fault that you brought me here! You don’t have to give me a cent; I don’t want it; I won’t take it! I was only a poor, ignorant little nobody, anyhow, and you’ve been disappointed in me from the start. I’ve never pleased[49] you, no matter how hard I’ve tried. But I’ve done the best I could, and I’m sorry if I’ve hurt you. I never told you an untruth before,” she ran on glibly; “and I wouldn’t to-day if I hadn’t guessed that you knew where I’d been and were trying to trick me into lying. You don’t love me any more, papa; I know that; and I’m going away—”

Her histrionic talents, employed so successfully in imitating him in his fury, for the pleasure of Mrs. Kinney’s guests, were diverted now to self-martyrization to the accompaniment of tears. She had been closer to him than to his wife: what Mrs. Farley denied in the way of indulgences he had usually yielded. He had liked her liveliness, her keen wit, the amusing cajoleries with which she played upon him. The remote Irish in his blood had been responsive to the fresher strain in her.

“For God’s sake, stop bawlin’!” he growled. “So you admit you lied, do you? Thought I had laid a trap for you, eh?”

It was difficult for him to realize that she was twenty-two and quite old enough to be held accountable for her sins. Her appeal to tears had always found him weak, but her declaration that she had suspected a trap when he began to quiz her was a trifle too daring to pass unchallenged. He repeated his demand that she sit up and stop crying.

“We may as well go through with this, Nan. I want to know what kind of an arrangement you[50] have with Copeland. Are you in love with that fellow?”

“No!”

“Have you promised to marry him?”

“No!”

“Then why are you goin’ places where you expect to see him?”

“I’ve explained that, papa,” she replied with more assurance, finding that he did not debate her answers. “I didn’t like to refuse Mrs. Kinney when I’d been refusing so many of her invitations. She asked me a while ago to come to her house to spend a week; and a little before that she wanted me to go on a trip with them, but you were sick and I knew you didn’t like her, anyhow, so I refused. You’ve got the wrong idea about her, papa,” she continued ingratiatingly. “She’s really very nice. The fact that she hasn’t been here long is against her with some of the older women, but that’s just snobbishness. I always thought you hated the snobbishness of some of these people who have lived here always and are snippy to anybody else.”

He was conscious that she was eluding him, and he gripped his hands with a sudden resolution not to be thwarted.

“I don’t care a damn about the Kinneys; I’m talkin’ about you and Copeland,” he rasped impatiently.

“Very well, papa; I’ve told you all there is to know about that—”

[51]“I don’t care what you say ‘about that,’” he mocked; “that worthless scoundrel seems to have an evil fascination for you. I don’t understand it; a decent young girl like you and a whiskey-soaked, loafin’, gamblin’ degenerate, who shook his wife—a fine woman—to be free to trail after you! That slimy wharf-rat has the fool idea that I took advantage of him when I sold him my interest in the store—and just to show you what a fool he is I’ll tell you that I sold him my interest at a tenth less than I could have got from three other people—did it, so help me God, out of sheer good feelin’, because he’s the son of a father who’d given me a hand up, and I thought because he was a fool I wouldn’t be just fair with him—I’d be generous! I did that for Sam Copeland’s sake.

“That was four years ago, and I hadn’t much idea then that he’d make good. He’s already cashed in everything Sam left him but the store. And I’ve still got his notes for twenty-five thousand dollars—twenty-five thousand, mind you!—that he’d like damned well to cancel by marryin’ you. A man nearly forty years old, who gambles and soaks himself in cocktails and runs after a feather-head like you while the business his father and I made the best in the State goes plumb to hell! Now, you listen to what I’m sayin’: if you want to marry him, you do it,—you go ahead and do it now, for if you wait for me to die, you’ll find he[52] won’t be so anxious; there ain’t goin’ to be anything to marry you for!”

His voice that had been firm and strong at the beginning of this long speech sank to a hoarse whisper, but he cleared his throat and uttered his last words with sharp distinctness.

“I never meant to; I never had any idea of marrying him,” she said. “And I’ve never thought of the money. You can do what you like with it.”

“Well, a man can’t take his money with him to the graveyard, but he can tie a pretty long string to it; and it’s my duty to protect you as long as I can. I’d hoped you’d be married and settled before I went. Your mamma and I used to talk of that; you’d got a pretty tight grip on us; it couldn’t have been stronger if you’d been our own; and I don’t want anything to spoil this, Nan. I want you to be a good woman—not one of these high-flyin’, drinkin’ kind, that heads for the divorce court, but decent and steady. Now, I guess that’s about all.”

She stood beside him for a moment, smoothing his hair. Then she knelt, as though from an accession of feeling, and took his hands.

“I’m so sorry, papa! I never mean to hurt you; but I know I do; I know I must have troubled mamma, too, a very great deal. And you’ve both been so good to me! And I want to show you I appreciate it. And please don’t talk of the money any more or of my marrying anybody. I don’t want the money; I’m not going to marry: I want[53] us to live on just as we have been. You’ve been cooped up too long, but you’re so much better now you’ll soon be able to travel.”

“No; there’s no more travel for me; I’ll be glad to hang on as I am. There’s nothing in this change idea. About a year more’s all I count on, and then you can throw me on the scrap-heap.”

She protested that there were many more comfortable years ahead of him; the doctors had said so. At the mention of doctors his anger flared again, but for an instant only. It was a question whether he had been mollified by her assurances or whether the peace that now reigned was attributable to his satisfaction with the plans he had devised to protect her from fortune-hunters.

She hated scenes and trouble of any kind, and peace or even a truce was worth having at any price. She had grown so accustomed to the bright, smooth surfaces of life as to be impatient of the rough, unburnished edges. It was not wholly Nan’s fault that she had reached womanhood selfish and willful. In their ignorance and anxiety to do as well by her as their neighbors did by their daughters, there had been no bounds to the Farleys’ indulgence.

“I’m going to have dinner up here with you,” she said cheerfully, after an interval. “I’m tired of eating alone downstairs with Miss Rankin; her white cap gets on my nerves.”

She satisfied herself that this plan pleased him,[54] and ran downstairs whistling—then was up again in her room, where he heard her quick step, the opening and closing of drawers.

She faced him across the small table in the plainest of white frocks, with her hair arranged in a simple fashion he had once commended. She told stories—anecdotes she had gathered while dressing, from the back pages of “Life.” He was himself a capital story-teller, though at the age when a man repeats, and she listened to tales of his steamboating days that she had heard for years and could have told better herself.

Soon a thunder-shower cooled the air, and made necessary the closing of windows, with a resulting domestic intimacy. The atmosphere was redolent of forgiveness on his part, of a wish to please on hers.

At nine o’clock, when she had finished reading some chapters from “Life on the Mississippi,”—a book that he kept in his room,—and Miss Rankin appeared to put him to bed, he begged half an hour more. He hadn’t felt so well for a year, he declared.

“Look here, Nan,” he remarked, when the nurse had retired after a grudging acquiescence, “I don’t want you to feel I’m hard on you. I guess I talk pretty rough sometimes, but I don’t mean to. But I worry about you—what’s goin’ to happen to you after I’m gone. I wish I’d gone first, so mamma could have looked after you. You know we set a lot by you. If I’m hard on you, I don’t mean—”

[55]She flung herself down beside him and clasped his face in her hands.

“You dear old fraud!—there can’t be any trouble between you and me, and as for your leaving me—why, that’s a long, long time ahead. And you can’t tell! I might go first—I have all kinds of queer symptoms—honestly, I do! And the doctor made me stop dancing last winter because my heart was going jigglety. Please let’s be good friends and cheerful as we always have been, and I’ll never, never tell you any fibs any more!”

She saw that her nearness, the touch of her hands, her supple young body pressed against his worn knees, were freeing the remotest springs of affection in his tired heart.

Nan wanted to be good—“good” in the sense of the word that had expressed the simple piety of her foster-mother. She had the conscience of her temperament and from childhood had often been miserable over the smallest infractions of discipline. Her last words with Copeland on the club veranda had not left her happy. It had been in her mind for some time that she must break with Billy. She had never been able to convince herself that she loved him. She had liked his admiration, and had over-valued it as coming from a man much older than herself; one who, moreover, stood to her as a protagonist of the gay world. No one but Billy Copeland gave suppers for visiting actors and actresses or chartered a fleet of canoes for a thousand-dollar[56] picnic up the river. It was because he was different and amusing and made love to her with an ardor her nature craved that she had so readily lent herself to the efforts of the Kinneys to throw them together.

Being loved by Copeland, a divorced man rated “fast,” had all the more piquancy for Nan as affording a relief from the life of the staid, colorless household in which she had been reared. There were those who, without being snobs, looked down just a little upon a girl who was merely an adopted child to whom her foster-parents gave only a shadowy background. The Farleys were substantial and respectable, but they were not an “old family.” She was conscious of this, and the knowledge had made her the least bit rebellious and the more ready to surrender to the blandishments of the Kinneys, who were even more under the ban.

As she undressed and crept wearily into bed, she pondered these things, and the thought of them did not increase her happiness.

Farley improved as the summer gained headway. He became astonishingly better, and his doctor prescribed an automobile in the hope that a daily airing would exercise a beneficent effect upon his temper. Farley detested automobiles and had told Nan frequently that they were used only by fools and bankrupts. A neighbor who failed in business that spring had been one of the first men in town to fall a victim to the motor craze, and Farley had noted with grim delight that three automobiles were named among the bankrupt’s assets.

When the idea of investing in a machine took hold of him, he went into the subject with his characteristic thoroughness. He had Nan buy all the magazines and cut from them the automobile advertisements and he sent for his friends to pump them as to their knowledge of various cars. Then he commissioned a mechanical engineer to buy him a machine that could climb any hill in the State, and that was free of the frailties and imperfections of which his friends complained.

Farley manifested a childlike joy in his new plaything; he declared that he would have a negro[58] chauffeur. It would be like old steamboat times, he said, to go “sailin’ around with a nigger to cuss.”