By

J. FRANK HANLY

Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham

New York: Eaton and Mains

Copyright, 1912,

By Jennings and Graham

Mr. Chairman and Gentlemen of the Indiana-Vicksburg Monument Commission:

To you this is no new stage. Its remotest confines were once familiar. You looked upon it, front and rear. You stood before its footlights. You knew its comedy—its tragedy. You had honorable and distinguished cast in the great drama that gave it fame in every land beneath the sun and place in the country’s every annal—a drama real as human life in tensest mood—in which every character was a hero, every actor a patriot, and 10 every word a deed—a drama, the memory of which is enduring, fadeless, and the scenes of which take form and color even now and rise before you vivid as a living picture. How clear the outline is:

Time: The Nation’s natal day, forty-five years ago.

Place: This historic field; yon majestic river; that heroic city there—a beleaguered fortress, girdled with these hills.

Scene: The river’s broad expanse; Admiral Porter’s fleet—grim engines of war, with giant guns and floating batteries, facing deep-mouthed and frowning cannon on terraced heights; the intrepid Army of the Tennessee, with camp and equipage, occupying 11 a line of investment twelve miles in length, with sap and mine, battery and rifle pit, marking a progress that would not be stayed, fronting a system of detached works, redans, lunets, and redoubts on every height or commanding point, with raised field works connected with rifle pits, numerous gullies and ravines, nature’s defenses, impassable to troops; all in all more impregnable than Sevastopol; with here and there ensanguined areas where brave men met death in wild, mad charge against redoubt and bastion; or fell, in the delirium of frenzied struggle, on parapets, where torn and ragged battle flags borne by valorous arms, leaped and fluttered for a moment 12 amid cannon’s smoke and muskets’ glare, only to fall from nerveless hands, lost in the chagrin and grief of repulse, crushing and disastrous.

Denouement: Fortifications sapped and mined! A city wrecked, subdued by want! An army in capitulation! A mighty host, surrendered! Flags furled! Arms stacked! One hundred and seventy-two captured cannon! Sixty thousand rifles taken! Twenty-nine thousand four hundred and ninety-one men prisoners of war—hungry, emaciated, broken, dejected men, worn by sleepless vigil, the ordeal of war, the alarm of siege—men who suffered and endured, but would not yield till dire distress compelled—men whose gallant valor 13 challenges admiration and respect, and gives them equal claim to fame with their invincible captors, whose iron grip and ever-tightening hold they could not break! Victory complete and splendid! And over all—river, field, and city—where crash of musketry, roar of cannon, scream of shell, and all the tumultuous din of war had reigned—the hush and awe of silence, unbroken by cheer or shout or cry of exultation!

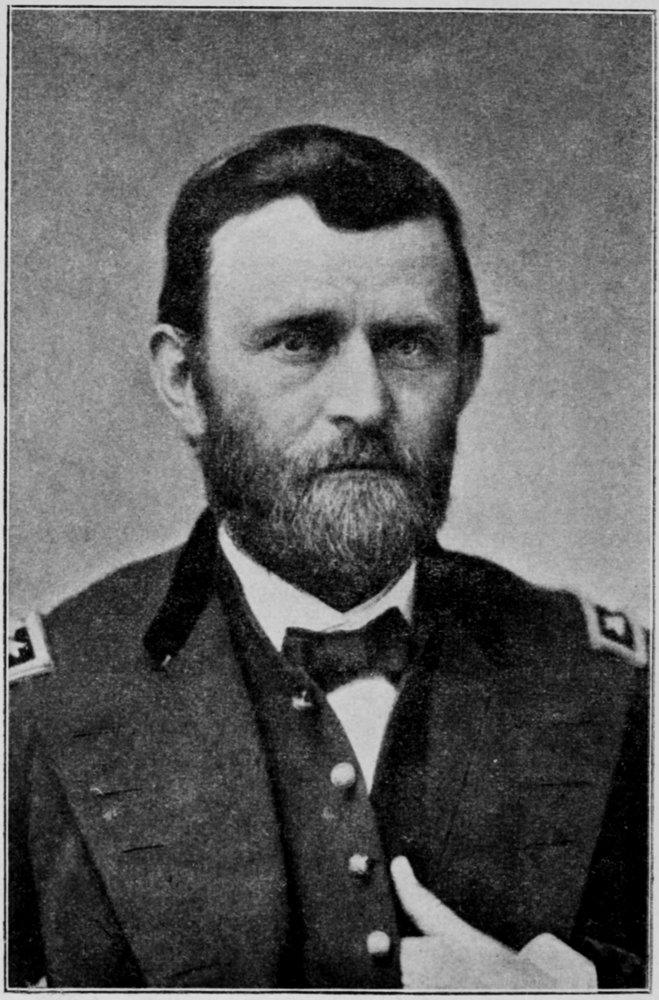

Result: The fall of Port Hudson, an impregnable fortress, two hundred and fifty miles below; the disenthrallment of the Mississippi—unvexed by war, its waters free to seek the sea in peace; the bisecting of the Confederacy—cut in two—severed 14 completely—its doom decreed—its fate forever sealed—all thereafter dying in its defense going hopeless and in vain to sacrificial altars; the establishment of the Union’s indissolubility—its power made manifest East and West—faith in its ultimate triumph, though the pathway led through toil and blood, became assured—the Nation saw the end, distant but sure—it found itself and it found a man, and that man had found himself, and had found others, too—Sherman, McPherson, Logan, Hovey, Osterhaus, McGinnis—a quiet, silent man, of grim determination, who “looked upon side movements as a waste of time”—a man of immovable purpose, who went 15 to his object unswerving as a bullet—a man of sublime courage, who wanted “on the same side of the river with the enemy”—a man of calm confidence, who relied upon himself and the disciplined, hardy men who followed him, who, under him, knew no defeat and who were unwilling to learn what it was—a man who knew the trade of war, its science and its rules, but who dared ignore its long-accepted axioms when occasion required; who, when he could not protect his communications with his base without delay and the diminution of his force, could cut loose from all communications and have no base, though moving in the heart of the enemy’s country—a 16 man of daring brilliancy, who could fight in detail a force superior in the aggregate to his own and defeat in turn its scattered fragments before they could consolidate—who had no rear, whose every side was front—who knew that “time was worth more than re-enforcements,” and that delay only gave “the enemy time to re-enforce and fortify”—whose strategy, celerity, and rapidity of movement threw confusion into the councils of opposing generals, in a land strange to him and filled with his enemies—a land with which they were familiar and where every denizen was an ally—a man who could keep two governments guessing for weeks both as to his purpose 17 and his whereabouts—who could refuse to obey an order that had been so long in transmission as to be obsolete when it reached him, and ride away to victory and to fame—whose blows fell so thick and hard and fast that his foe had neither time nor rest nor food nor sleep—a man who was gentle and considerate enough when his foes surrendered to forbid his men to cheer lest they should wound the sensibilities of their captives—who, in the hour of supreme and final triumph, could speak for peace and give back to his captured countrymen their horses that crops might be put in and cultivated.

Time, place, scene, denouement, 18 and result, taken together, and all in all, have no parallel in all the six thousand years of human history.

It was, therefore, inevitable and in accord with man’s nobler self, that this spot—the place where the great drama was staged and played—should become hallowed ground to those who struggled here to retain or to possess it; that it should be held forever sacred by the Blue and the Gray—the victors and the vanquished—by the Blue because of what was won, by the Gray because of what was lost—by both because of heroic effort and devoted sacrifice made and endured; because of the new national life begun, the 19 new birth of freedom had, through their spilled blood.

Vicksburg was the most important point in the Confederacy and its retention the most essential thing to the defense of the Confederacy. After the safety of Washington, its capture was the first necessity of the Federal Government. It commanded the Mississippi River, and “the valley of the Mississippi is America.” The control of this great central artery of the continent was necessary to the perpetuation of the Confederacy and indispensable to the preservation of the Union. To lose it was death to the one. To gain it was life to the other. The campaign for its capture was, therefore, 20 the most important enterprise of the Civil War. Its importance was understood and appreciated by the authorities at both capitals, and no one in authority in either capital understood it more clearly or appreciated it more fully than the commanders of the two opposing armies—Grant and Pemberton. Both knew the stake and its value and both were conscious that the fight to possess it by the one and to retain it by the other would be waged to the last extremity. And each was resolved that the great issue should be with him. They commanded armies equally brave and well disciplined, efficiently officered, and equally devoted to them 21 and to the respective cause for which they fought.

Strength of position, natural and artificial, was with Pemberton. His task was defensive—to hold what he had. Grant’s was offensive—to possess what he did not have. But the initiative was with him, and to genius that itself is an advantage.

Pemberton knew the ground—the scene of the campaign. Its every natural adaptation of advantage or defense was to him as a thing ingrained in his consciousness and every denizen of the country about him was the friend of his army and his cause.

Grant was in a strange land, without accurate knowledge of its topography 22 or of its natural difficulties of approach or opportunities of defense, and concerning which such knowledge could be acquired only by the exercise of infinite patience, by unremitting toil, and constant investigation. Its inhabitants looked upon him as an invader come to despoil their country—to lay waste their homes. Among them all, his army had no friend, his cause no advocate.

But, while position and natural advantage was with Pemberton, the ability to command armies, the genius of concentration, to decide quickly and accurately, to design with daring boldness and to execute with celerity and rapidity; the tenacity 23 of purpose that, come what will, can not be bent or turned aside, and the grim determination that rises in some men—God’s chosen few—supreme above every let or hindrance—were with Grant. And it was this ability to command, more than all other things, that finally enabled him to wrest the great prize from the hands of Pemberton and the Confederacy, and give it into the keeping of the Union.

The campaign was Grant’s—his alone—in conception and in execution, from the beginning to the end. Its details his government did not know. For a time even its immediate object was unknown in Washington. 24 Its design was without successful military precedent. His most trusted general was opposed to it. But Grant saw and understood. The day he crossed his army at Bruinsburg he was “born again.” He caught a vision that inspired him. He was transformed. There came to him a confidence that thenceforth was never shaken—a faith in which there was no flaw. Less than two years before he had doubtfully asked himself whether he could hope ever to command a division, and if so, whether he could command it successfully. Now he knew he could command an army; that he could plan campaigns, and that he could execute them with high skill and 25 matchless vigor. He had found himself.

General Banks, with a substantial force, was at Port Hudson, two hundred and fifty miles down the river. The two armies were expected by the authorities at Washington to co-operate with each other in an attack upon Pittsburg or Port Hudson. Grant had heard from Banks that he could not come to him at Grand Gulf for weeks. Instantly his purpose crystallized. His resolve was made. He would not go to Banks at Port Hudson nor would he wait for him at Grand Gulf. Waiting meant delay. Delay meant strengthened fortifications and a re-enforced enemy. He would move 26 independently of Banks. His army was inferior in numbers to the aggregate forces of the enemy, but he would invade Mississippi, fight and defeat whatever force he found east of Vicksburg, and invest that city from the rear. And he would not wait a day. He would move at once. He would go now—go swiftly to Jackson, destroy or drive away any force in that direction, and then turn upon Pemberton and drive him into Vicksburg. He would keep his own army a compact force—“round as a cannon ball,” and he would fight and defeat the enemy in detail before his forces could be concentrated. The concept was worthy of Napoleon in his best 27 moments. It was remarkably brilliant, audaciously daring. It was the turning point in Grant’s career—a momentous hour, big with destiny for him, his army, and his country. In its chalice was Vicksburg—Chattanooga—Spotsylvania—Appomattox—national solidarity—and deathless personal fame. The decision was made without excitement, without a tremor of the pulse, in the calmness of conscious power. John Hay fancifully compares his action at this time “to that of the wild bee in the Western woods, who, rising to the clear air, flies for a moment in a circle, and then darts with the speed of a rifle bullet to its destination.”

A long-established and universally accepted axiom of war—one that ought in no case to be violated—required any great body of troops moving against an enemy to go forward only from an established base of supplies, which, together with the communications thereto, should be carefully covered and guarded as the one thing upon which the life of the movement depended. The idea of supporting a moving column in the enemy’s country from the country itself was regarded as impractical and perilous, if not actually impossible. The movement he had determined upon would uncover his base and imperil his communications. Defeat meant irremediable 29 failure and disgrace. The hazard seemed so great, and the proposal so contrary to all the accepted maxims of war and military precedents, that Sherman, seeing the danger, urged Grant “to stop all troops till the army is partially supplied with wagons, and then act as quickly as possible, for this road will be jammed as sure as life.”

Grant knew the difficulty and the peril, but he was not afraid. He knew the military and the political need of the country. He knew his officers. He knew the army he commanded. And, knowing all, he assumed the responsibility and took the hazard; cut loose from his base, severed his communications, went 30 where there was no way, and left a path that will shine while history lasts.

Having decided his course, he telegraphed the government at Washington: “I shall not bring my troops into this place (Grand Gulf), but immediately follow the enemy, and if all promises as favorably as it does now, not stop until Vicksburg is in our possession.” Here was the first and the only intimation of his purpose given the government. The execution of his purpose was immediately begun and pressed with personal energy, attention, and vigor without parallel in the life of a commanding general of an army. Sherman, who of all men had the best 31 opportunity to know and was best qualified to weigh the extent and character of his work, declares: “No commanding general of an army ever gave more of his personal attention to detail, or wrote so many of his own orders, reports, or letters. I still retain many of his letters and notes in his own handwriting, prescribing the route of march of divisions and detachments, specifying the amount of food and tools to be carried along.”

Washburn wrote: “On this whole march of five days he has had neither a horse nor an orderly or servant, a blanket or overcoat, or clean shirt or even a sword. His entire baggage consists of a tooth brush.”

John Hay says of him: “All his faculties seemed sharpened by the emergency. There was nothing too large for him to grasp; nothing small enough for him to overlook.” He gave “direction to generals, sea-captains, quartermasters, commissaries, for every incident of the opening of the campaign, then mounted his horse and rode to his troops.” And then, for three weeks, in quick and dazzling succession, came staggering, stunning blows, one after the other—Raymond—Jackson—Champion’s Hill—The Big Black—until he stood with his army at the very gates of Vicksburg!

The government, hearing that he had left Grand Gulf for the interior 33 of Mississippi without supplies or provision for communication with his base, telegraphed him in concern and alarm to turn back and join Banks at Port Hudson. The despatch reached him days after at the Big Black Bridge, while the battle there was in progress. The message was handed him. He read it; said it came too late, that Halleck would not give it now if he knew his position. As he spoke the cheering of his soldiers could be heard. Looking up he saw Lawler, in his shirt sleeves, leading a charge upon the enemy, in sight of the messenger who bore the despatch. Wheeling his horse, he rode away to victory and to Vicksburg, leaving the officer 34 to ruminate as long as he liked upon the obsolete message he had brought.

I have spoken much of Grant. There is reason that I should. No campaign of the war is so insolubly linked with the personality of the commanding general as the Vicksburg campaign.

For three weeks he was the Army of the Tennessee. He dominated it absolutely. His personality, with its vigor and its action, was in all, through all, over all. His corps and divisions were commanded by great men, but, with a single exception, they were loyal and devoted and reflected his will, and sought the achievement of his purpose in every act and movement. During these 35 days Sherman was his right arm, McPherson his left, and neither ever failed him. The whole army, officers and men, caught his spirit and shared his indomitable purpose. Nothing could daunt it or turn it aside. There was no service it did not perform, no need it did not meet. It had capacity for everything. Grant justly said: “There is nothing which men are called upon to do, mechanical or professional, that accomplished adepts can not be found for the duty required in almost every regiment. Volunteers can be found in the ranks and among the commanding officers to meet any call.” Every obstacle was overcome; every difficulty surmounted. When bridges were 36 burned, new ones were built in a night, or the streams forded. In every event the light of the morning found his soldiers on the same side of the river with the enemy. If rains descended and floods came, they marched on though the roads were afloat with water. They fought and marched, endured and toiled, but they did not complain or even murmur. They, as well as their officers, understood the value of the stake for which they struggled. They knew they were marching and fighting and toiling under the eye of a great commander, one who knew where he was going and how to go; that there was no hardship which he did not share, no task from which 37 he shrunk. Weary from much marching, they marched on; worn from frequent fighting, they fought on; all but exhausted from incessant toil, they toiled on, in a hot climate, exposed to all sorts of weather, through trying and terrible ordeals, watching by night and by day, until they stood in front of the rifle pits and of the batteries of the city, and even here they would not be content until they were led in assault upon the enemy’s works and had stood upon their parapets in a vain but glorious struggle for their possession.

What a story it is! How it stirs the blood! How it inspires to love of country! How it impels to high endeavor! And what a valorous foe 38 they met! They were, and are, thank God, our countrymen—besiegers and besieged. In their veins flowed kindred blood—blood that leaps and burns in ours to-day. They differed. Differed until at last the parliament of debate was closed, and then, like men, they fought their differences out, in open war—on the field of battle—sealing the settlement with their blood and giving the world a new concept of human valor.

There were wounds. There was suffering. There was heartache. There were asperities. There was death. There was bereavement. These were inevitable. But there was a nobility about it all, that, 39 seen through the intervening years, silences discord, softens hate, and makes forgiveness easy. To-day we laugh and weep together. Wounds are healed; asperities are forgotten; the past is remembered without bitterness; glory hovers like a benediction over this immortal field and guards with solemn round the bivouac of all the dead, giving no heed to the garb they wore. Their greatness is the legacy of all—the heritage of the Nation. Reconciliation has come with influences soft and holy. The birds build nests in yonder cannon. The songs of school children fill the air.

Indiana has come to Mississippi to dedicate monuments erected by 40 her to the memory of her soldiers, living and dead, who struggled here; but she comes with malice toward none, with love for all. With you, sir, the Governor of this Commonwealth, and with your people she would pour her tribute of tears upon these mounds where sleep sixteen thousand of our uncommon common dead. Her troops were here with Grant. One of her regiments, the 6th, sought out the way for the army beyond the river yonder. They were the “entering wedge.” They were in every battle. At Champion’s Hill, Hovey’s division bore for hours the battle’s brunt. Fighting under the eye of the great general himself, they captured a battery, 41 lost it, and recaptured it, and at night slept upon the field wet with their blood.

This gray-haired general here (General McGinnis) was with them. He is a member of the commission that erected these granite tributes, and has in charge these ceremonies. He has come to lend the benediction of his presence to this occasion, and to look again upon the ground where so many dramatic and tragic scenes were enacted—scenes in which he had honorable share—scenes that were burned into the very fiber of his young manhood’s memory, and which he would not forget if he could. His days have been long lengthened. We are glad and grateful 42 that he is here. His associates on the commission were here; and so were these battle-scarred veterans standing here round about you. They give character and purpose to this occasion and a benediction to this service. Through them and their comrades, and the great Army in Gray with whom they contended, both we and you are beginning to understand the message and the meaning of the war. They have taught us charity and forgiveness. We are coming “to know one another better, to love one another more.” Here upon these hills and heights was lighted the torch of a national life, that to-day is blessing, enlightening, and enriching the peoples 43 of the earth. Our prayer—a prayer in which we are sure your hearts are joined with ours—is, that this mighty Nation, grown great and powerful, may know war no more, forever; that it may walk uprightly, deal justly with its own people and with all nations; that its purpose may be hallowed, its deeds ennobled, its glory sanctified, by the memories of the crucible through which it came, and that in the future if war must come, its sword may be drawn only in Freedom’s cause, and that its soldiery in such case may acquit themselves as nobly as did those who struggled here.

Mr. Chairman and Gentlemen of 44 the Commission, in the name of the State of Indiana and on her behalf, I accept these splendid monuments and these markers you have erected and which you have so eloquently tendered me, and in the name of the State and on behalf of her people, Captain Rigby, I now present them to you, as the representative of the National Government, and give them through you into its keeping, to be held and kept forever as a sacred trust—a reminder to the countless thousands that in the gathering years may look upon them, of the share Indiana had in the great campaign that ended here July 4, 1863.