Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this text, and is in the public domain.

© Major Hamilton Maxwell

© Underwood and Underwood

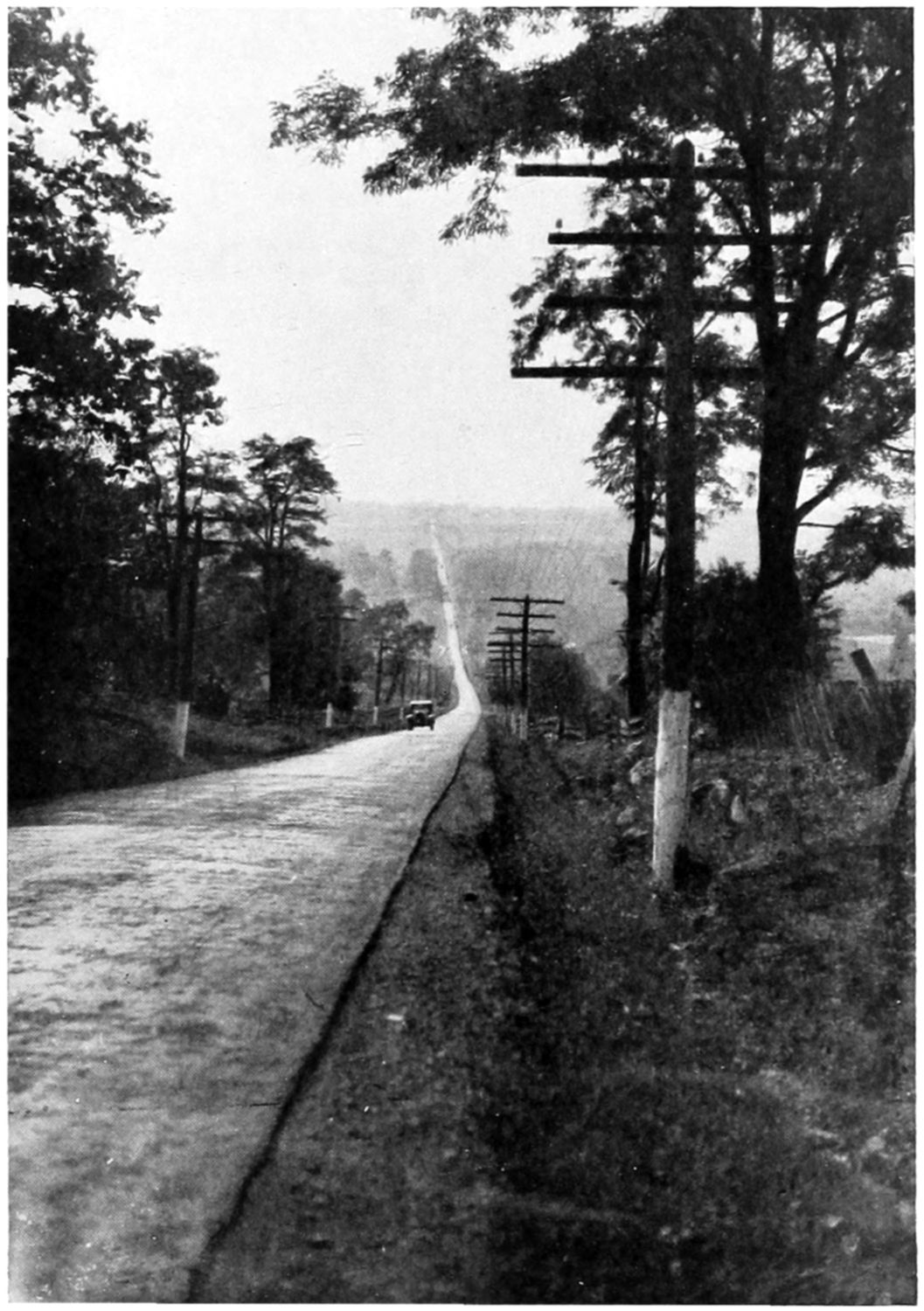

STORM KING HIGHWAY

A Great Engineering Project Along the Hudson between Cornwall and West Point, N. Y.

HIGHWAYS

AND

HIGHWAY TRANSPORTATION

BY

GEORGE R. CHATBURN, A.M., C.E.

Professor of Applied Mechanics and Machine Design

Lecturer on Highway Engineering

The University of Nebraska

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright 1923, by

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

[v]

The following pages on Highways and Highway Transportation do not pretend to be an exhaustive treatise on the subject, but rather a glimpse of the vast development of the humble road and its office as an agency for transportation. Possibly the grandeur of the mountains is best appreciated by one who lives among them, who climbs their acclivitous heights, who daily experiences their power and majesty, and measures their magnitude by grim muscular exertion. But, even so, it would be foolish to contend that he who gets his information from the seat of a Pullman car receives no benefit from the hasty glimpse, or, that his imagination is not quickened and cultured by the experience. In writing this book, then, I have had constantly in mind the myriads of people who have not the time, and possibly not the facilities, to search the pages of the literature of the past for the origin and development, or to work out their present importance, of our amplification of roads and of road uses. It is felt that many of these people laudably desire a conversational knowledge of the origin, evolution and present status of highway transportation, even though it be glimpsed by a very rapid passage through a very large subject.

The primary objects have therefore been, to sketch briefly and simply the development of the transportation systems of the United States, to indicate their importance and mutual relations, to present some practical methods used in the operation of highway transport and to make occasional suggestions for the betterment of the road as a usable machine for the benefit and pleasure of mankind.

Any observations made or conclusions drawn are purely personal. I entered into and have carried on the work entirely unbiased. I am not financially or otherwise, except academically, interested in any firm or company whose[vi] business has to do with transportation either directly as a carrier, or indirectly as a manufacturer of the instruments or accessories to transportation, nor does any of my living come from societies or foundations organized as propagandists for any particular forms of transportation, or transportation materials or equipment. I have no admiration for the man who hopes to see the steam and electric railways put out of business or even caused to run at a loss by the automobile, motor express or motor bus. Neither have I any plaudits for the man who would arrest the growth of the new forms of transportation by drastic legal enactments and excessive taxation in order to preserve the old. I believe there is room and need in the United States for all forms of transportation, and that each can thrive in its respective field just as do wheat and corn but none will thrive if they attempt to occupy the same field at the same time.

The text is naturally divided into two parts—the development of highways and their use. The first part treats of the relation of transportation to civilization generally, explaining briefly how the two have grown together like children at school, how each has helped the other, and how the meter of one is the measure of the other.

Leaving the old world there is sketched all too briefly the development in the United States of transportation facilities from the coastal and natural waterways, from the pack and trail, used by the aborigine and early settlers, through the treks of the pioneers, the periods of canal digging, the toll road competition, and the railway frenzy, to the advent of the modern road with the coming of the bicycle and automobile and their wonderful accelerative impulse.

The effects of State and Federal aid upon the road conditions of the country are fully treated as is also the planning of highway systems.

Automotive transportation for business and pleasure including rural motor express and bus lines, and their effect on production and marketing are described and discussed.

[vii]

In the chapters on highway accidents and highway aids to traffic, attention is called to many types of accidents, including railway crossing accidents, with suggestions for their mitigation. Here also are given the most recent practical rules for the regulation of traffic in both city and country.

A chapter is devoted to the esthetics of the highway, a subject just coming to the attention of road men who have heretofore been mostly concerned with distances, grades, widths and surfaces, which, by the way, are frequently mentioned in the text. As in all building construction the first appeal was made to material things and their relation to the pocket-book, while the last and most enduring appeal is spiritualistic and is made to the pleasures of the imagination.

The same idea of making the road a means of catering to the preservative and pleasure instincts of man is considered in the final chapter on aids and attractions to traffic and travel. Safety and warning devices are discussed as such, while comforts and conveniences are means for luring the average citizen to the highway, to the camps and parks, for the broadening effect upon his character, the health of his body, and the enlightenment of his soul.

Thus we close a most hurried journey from the very beginning of roads to their modern far superior yet very imperfect attainments. The main thought throughout has been the road as a usable agency in the economic and entertaining phases of life. Each equally important to the wealth, health, and happiness of our people. The mind easily travels ahead to a time when separate roads will be devoted to the two great ends of business and pleasure. Then the flight of fancy passes on to still another period of time and sees the highways made inoperative and superfluous, overgrown by weeds and grass, for the argosies of business and pleasure have taken to the air.

George Richard Chatburn.

Lincoln, Nebraska

March 9, 1923.

[ix]

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Transportation a Measure of Civilization | 1 |

| Stages of Civilization: Direct Appropriation; Pastoral; Agricultural — Manorial and Feudal Systems; Handicraft — Merchant Guilds, Effect upon Trade, Domestic System, Government Control, Agriculture; Industrial — Building of Canals, Smelting Iron, Invention of Steam Engine, Railways Developed. Some Historical Roads and their Influence: Early Highways — Asiatic, Greek, Roman, Pre-Historic American. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Transportation Development in the United States: Early Trails and Roads | 34 |

| First Settlements near Coast. Birch Bark Canoe, Meagerness of Roads. Settlement follows Waterways. Portages. Lines of Travel — Through Alleghanies, from the North, Boone’s Trace or the Wilderness Road, Calk’s Diary. Explorations — Marquette, Lewis and Clark, Fur Companies. Western Trails — Oregon, Salt Lake, Later California, Santa Fé, Gila and Spanish. Turnpike Roads, Wagon Road Neglect, National Participation — Cumberland Road. Early Inns. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Waterways and Canals | 70 |

| Coastal, Inlets, Rivers, Creeks. Canals — Europe, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Other States; Passenger Traffic on; Prosperity and Desuetude. Ship Canals: Sault Ste. Marie, Cape Cod, Panama — Inducements for, Early Schemes, Routes — Tehauntepec, Nicaragua, Others; French Participation — DeLesseps’ Grant, Company Organized; Other Promotion Schemes; Indignation in the[x] United States against Foreign Building Canal; DeLesseps begins Work; Clayton-Bulwer Treaty; Hay and Pauncefote Treaty; Commission Reports Favorably on Nicaraguan Route; French Company Bankrupt; Colombian Congress Refuses to Sell to the United States Control of the Canal Strip; Panamanian Revolution — Roosevelt’s Part in Revolution; United States Secures Control of Canal Strip, Colombia Protests; Construction of Canal Begun; Description of Canal, Canal Traffic. River Transportation: Small Boats, Pole Boats, Large Boats, Rafts. Steamboat: Construction, Mississippi River Traffic, New Orleans Levee, Mississippi Steamboats and Steamboating; Steamboat Fares. Government Attitude toward River Improvement. John Fitch Granted a Right in New Jersey; Calhoun’s Activities, Monroe’s Attitude. National Aid for Internal Improvements. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

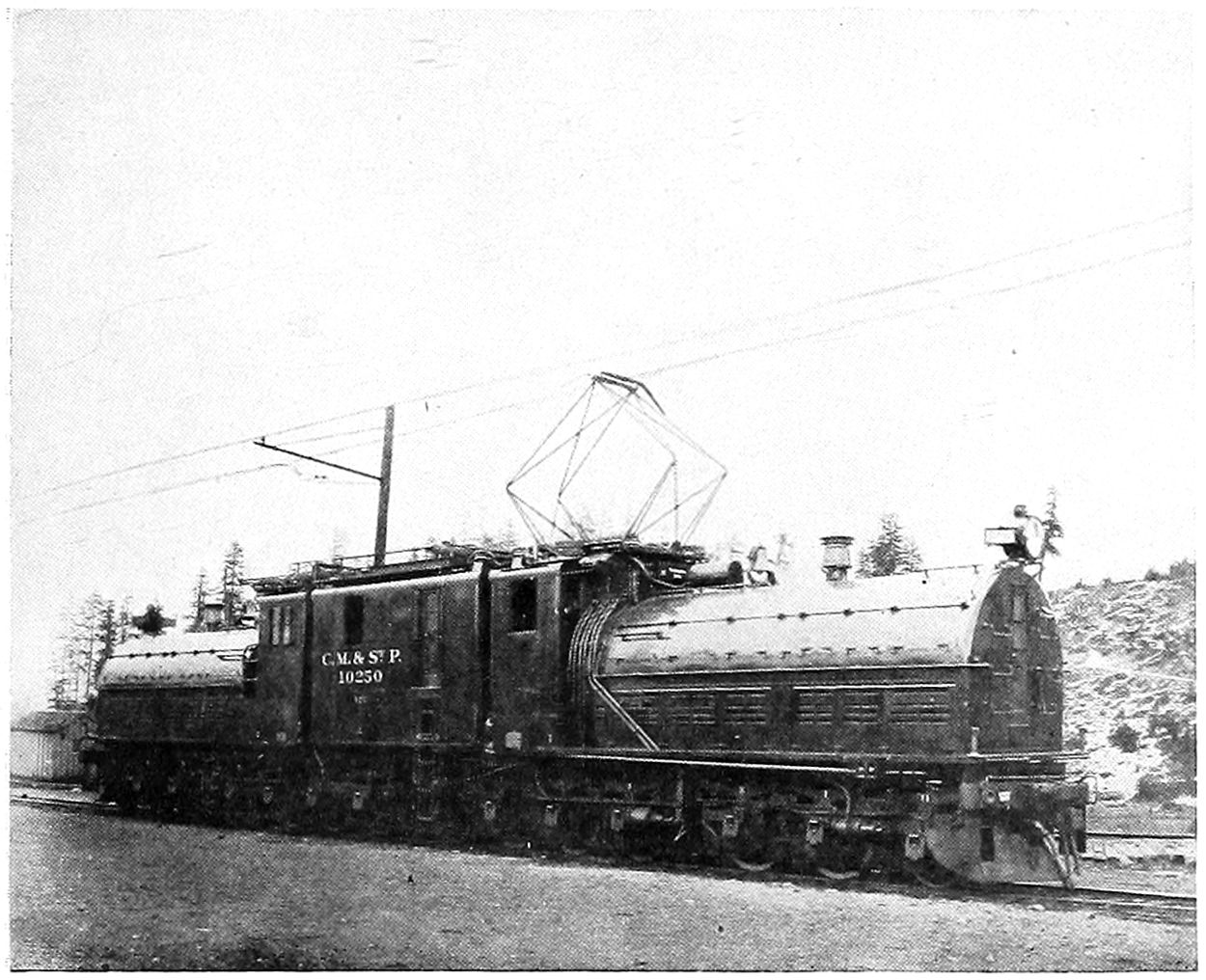

| Railroads | 99 |

| Origin and Early Development. Optimism of Promoters. Early Locomotives. First Chartered Railroad — Charleston and Hamburg, First Passenger Car on Baltimore and Ohio, New York Central, Camden and Amboy, New England Roads, West of Alleghanies, in the South. Rapid Growth in Railway Mileage. Call for Government Aid. Land Grants. Pacific Roads — Congressional Discussion, Compromise Bills, Construction of Pacific Roads, Crédit Mobilier. Era of Railway Consolidation — Typical Consolidations, Methods of Consolidating. Mechanical Development: Rails, Freight Cars, Locomotives, Gauge, Telegraph, Signals. The Evolution of the Sleeping Car. Street Car Service. Electric Traction — Origin, Development. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Modern Wagon Road | 126 |

| Neglect and Desuetude of Wagon Roads, 1830-1890. Laying out and Working Roads, Statutory Width of Roads. Influence of Bicycle for Better Roads: Origin of Bicycle, Development, Ordinary, Safety, Cycling Boom, Organization of Wheel Clubs, Propaganda for Good Roads, Prevalence of Poor Roads, Comments by Writers. Good[xi] Roads Associations; League of American Wheelmen, National Highway Commission, Col. Pope’s Propaganda, Bills Introduced in Congress. Office of Public Roads Inquiry: Duties and Limitations, Cooperation with Good Roads Organizations, National Good Roads Association — Good Roads Trains, Object Lesson Roads, Policy Discontinued, Duties and Scope of Office of Public Roads Widened and Name Changed — Educational Work, Research, Administration of Federal Aid. Rural Free Delivery of Mail: Origin, Development, Advantages. State Aid: Origin — New Jersey, Salient Features, Difficulties of Getting it Enacted; Massachusetts; Other States; State Bonds for State Aid. Federal Aid; Enactment of Law, Provisions, Appropriation, Administration, Additional Appropriations. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Interrelation between Highway and Other Kinds of Transportation | 159 |

| Classification of Transportation. Railroads have not always Acted Honorably. Quantity Production and Division of Labor Applied to Railway Transportation, to Motor Transport. Automobiles Cutting into Railway Earnings, Babson’s Prediction. Effect of Motor Competition on Interurban Trolley Lines, on Street Car Lines, Taxicabs and Jitneys, Buses, Trackless Trolleys. Guaranteeing Earnings of Street Car Companies, Legitimate Fields of Transportation Agencies. Length of Haul for Economic Trucking. Reduction of Rates and Expenses. Carving out New Fields. Still Room for all Kinds of Transportation. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Automotive Transportation | 181 |

| Defined, Radical Changes to be Expected. Business Passenger Traffic: Jitney and Taxicab, Motor Bus — Qualifications, Fares, Competition with Street Cars, Cross-country Service, Carriers of School Children, Transfer between Depots. Pleasure Passenger Traffic: An Influence in the Purchase of Automobiles, Pleasurable Effect of Automobile Riding, Recreational and Pathological Benefits of Motoring, Cost of Motoring. Freight Traffic: Cost and[xii] Time Factors, Motor Trucks and Congested Districts, Time Devoted to Loading and Unloading, Depots, Warehouses, Devices, Removable Bodies, Sectional Containers, Store to Door Delivery, Mass Loading. Devices Connected with the Truck. Devices Separate, Special Types of Bodies. Traffic between Towns: Economic Distance, Licenses and Insurance, State Regulation without Competition, Development of State Regulation. Motor Bus Traffic: Buses, Rates, Future of Motor Bus and Other Types of Transportation. To and from the Farm: Importance of Farm Trucking, Arguments in Favor of, Cost of Trucking, Diversified Farming, Intensive Farming, Live Stock. Trucking, Benefits to the Farmer, Economy of Farm Trucking, Parcel Post Service and the Farm, Rural Express, Milk Trucks, Convenience to the Farmer, Purchasing a Truck. Terminal Facilities: Advantages. Social Aspect of Motor Transportation: Effect on Merchandising, Housing, Unification of Society, Standard of Living, Size of Farms, Salesmen, Hotels, City and Country Stores. Consolidated Rural Schools: The Public School and Patriotism, Peace, Changing Concepts of Public Schools. Rural Mail Delivery. Automobile and Health: As a Form of Exercise, Effect on Styles; Medical Science; Sanitary Effects — Mosquitoes, Flies. The Automobile and Crime: Bootlegging, Robbery, Vandalism. Types of Automobile Transportation. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Planning Highway Systems: Selection of Road Types | 222 |

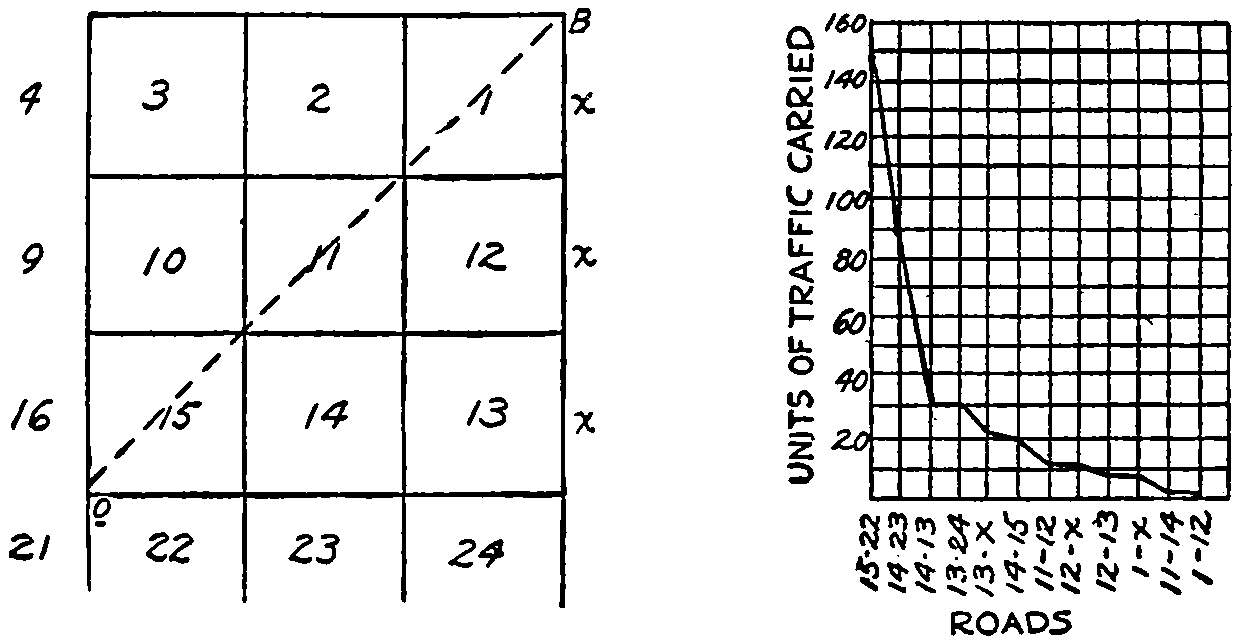

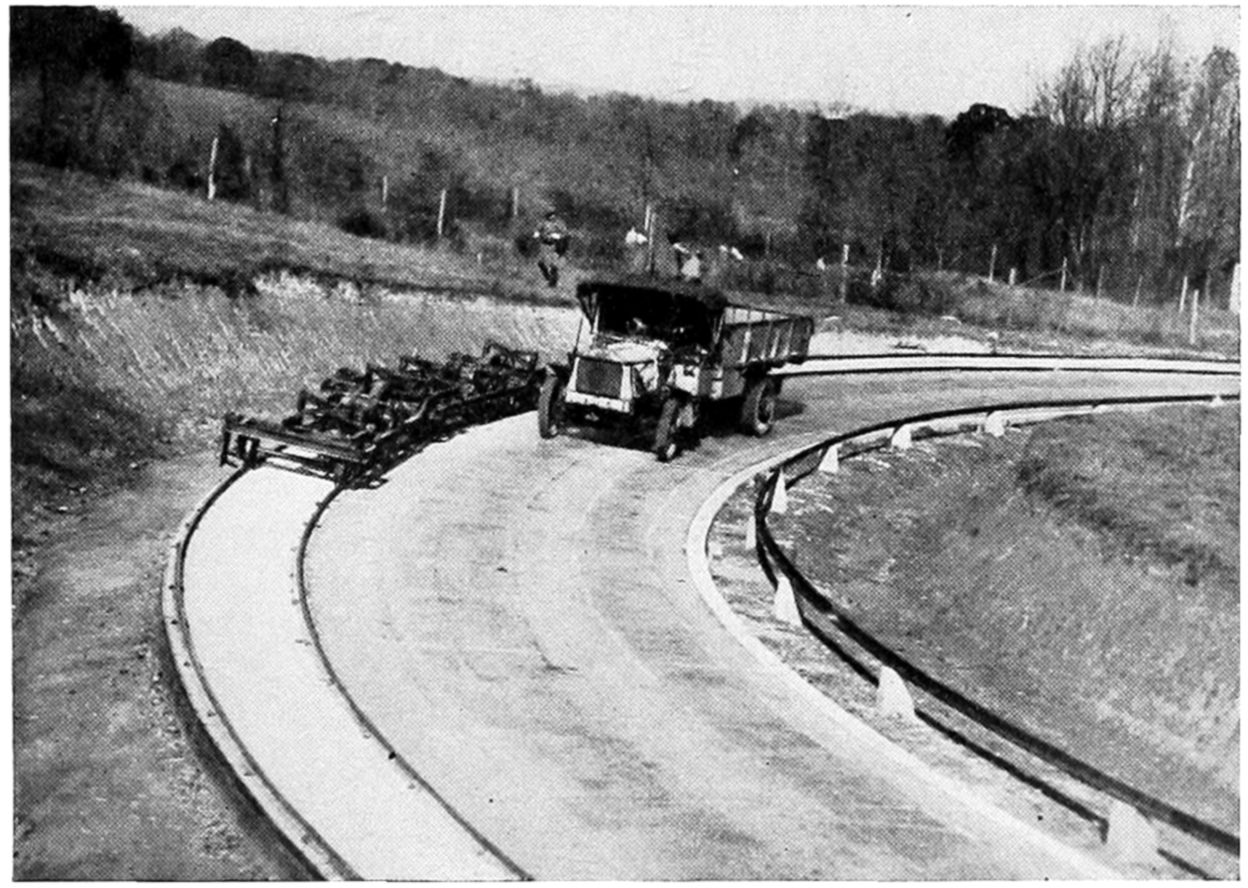

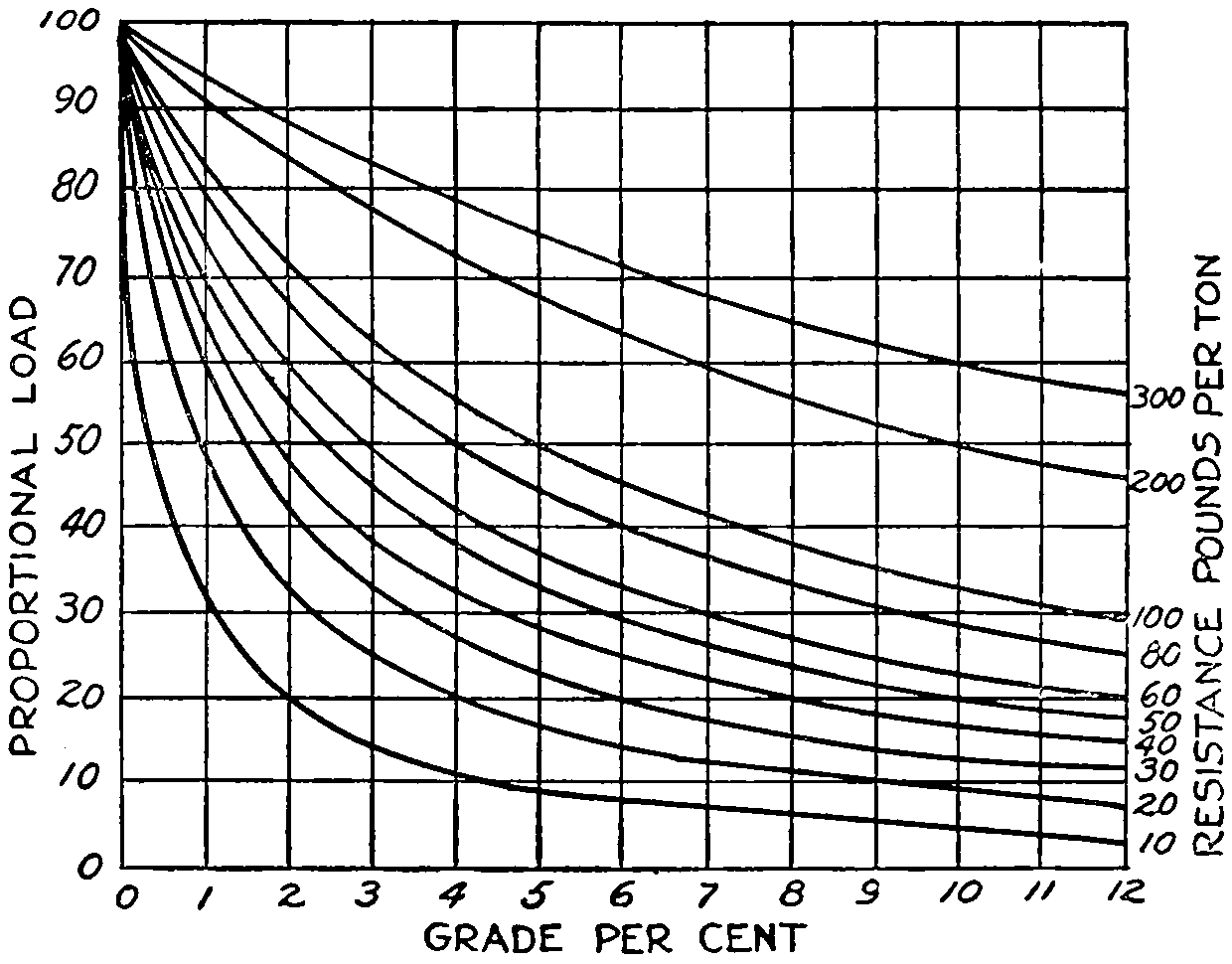

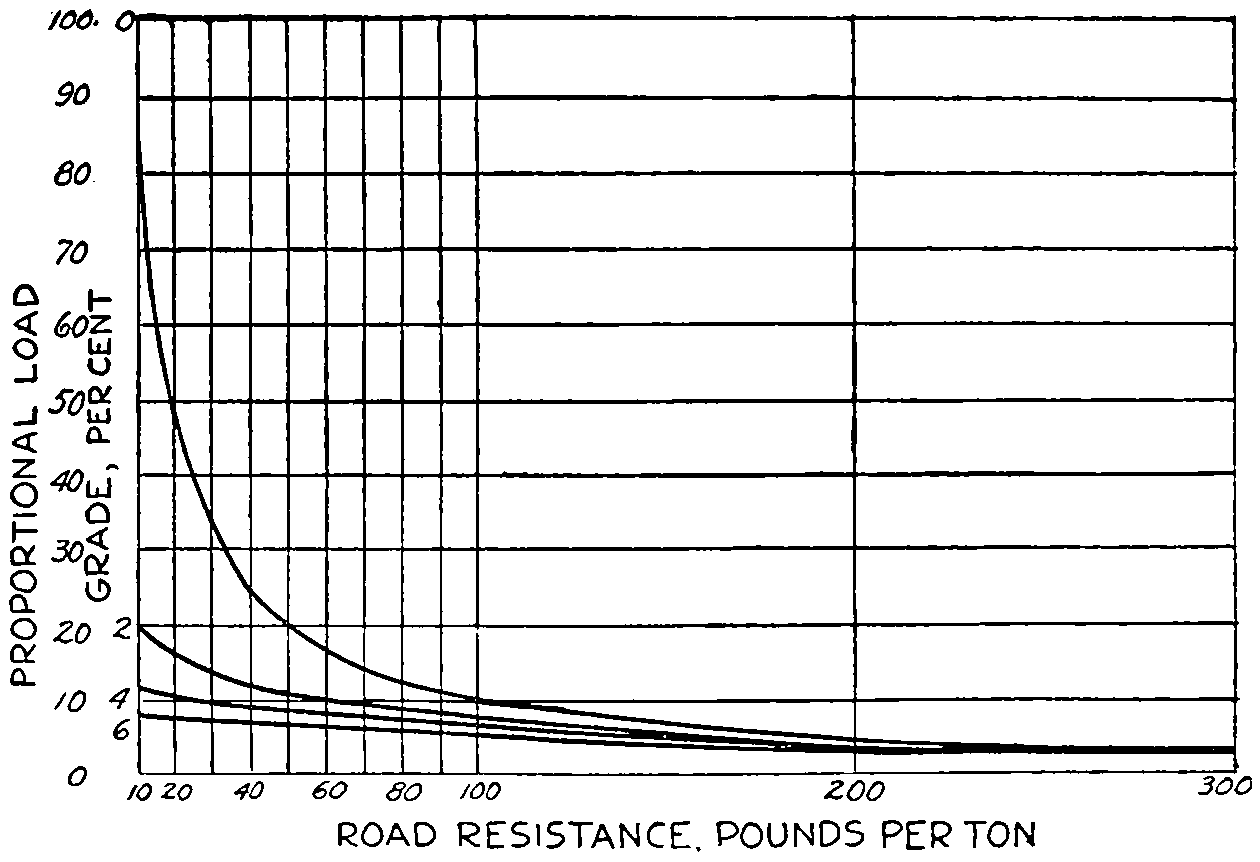

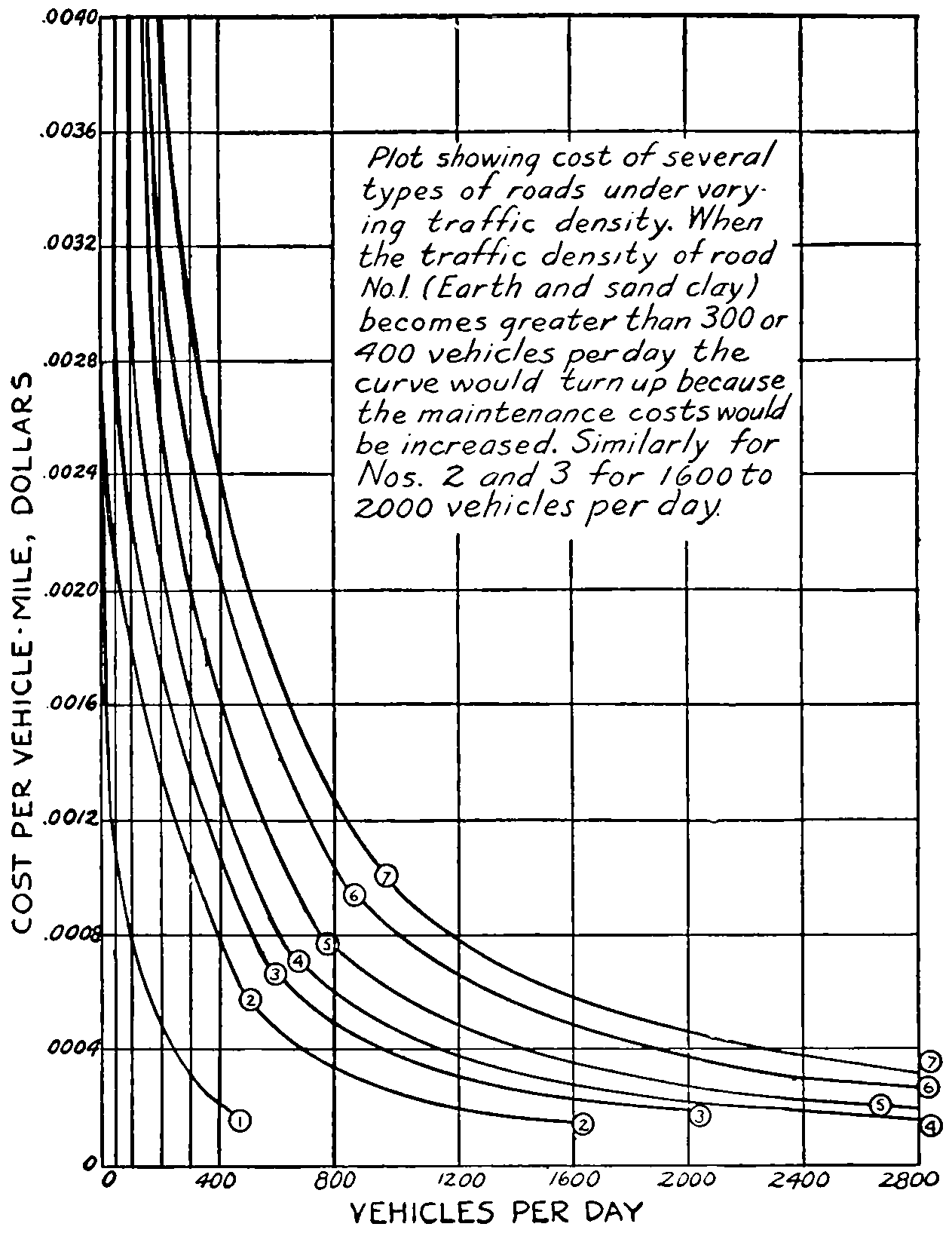

| Object of a Road. Road Classification: Agricultural. Recreational, Commercial, Military. Problem of the Road Planner: Economy, Accommodation, Utilizing Existing Roads. Essentials to be Considered: Ruling Points, Branch Lines and Detours, Alternate Routes, Existing Highways and City Streets, Vested Rights, Widening Roads and Streets, Railroads, Trolley Lines, etc., Bridges, Culverts, Drainage, etc., Ruling Grades, Esthetics. Motor Transport Efficiency Outline, Highway System Unit: Arguments in Favor of National System — Eliminates Sectional Differences, Gives Continuous Roads, Military Roads, Benefits of Example. State Systems — Benefits. Procedure of Laying out a Road System: Commission, Determining Factors, Maps, Tentative System, Reconnaisance Survey — What Shown, How[xiii] Taken, Instruments; Hearings — Object; Final Location — Considerations, Traffic Census Advisable. Financial Considerations: First Cost, Upkeep, Traffic Census: Affects Location, Type of Road, Grades, Width, Foundations. Making a Traffic Census: Variation of Traffic — Number of Counting Days, Hours Each Day, Weights, Observer’s Cards, Both Way Count, Weather, Stations — Location of. Classification of Traffic: Object, Maximum Loads, Effect of Heavy Loads, Influence Units of Traffic — British, French, Other Countries, Maryland, Massachusetts, Borough of Brooklyn; Suggested Form of Traffic Sheet — New Jersey. Destructive Factors: Density of Traffic, Weight of Vehicles, Impact, Speed, Wrinkling, Sprung and Unsprung Weight, Tires, Pleasure Cars and Light Traffic to be Considered. Other Methods of Estimating the Amount of Traffic: Area Served, Tonnage Arising. Distribution of Traffic over Township Roads. Selection of a Suitable Type of Road. Taxpayers Allowed to Assist in Selection, Engineers to Suggest. Ideal Road: Qualities of — Low First Cost, Durability — Materials and Design, Resistance to Traction and Tractive Force — Horse, Truck, Speed, Temperature, Roughness, Width of Tire, Diameter of Wheel, Table of Resistances; Resistance Due to Grade — Formulas, Coefficient, Available Engine Effort; Slipperiness — Type of Pavement, Climatic Conditions; Sanitariness — Definition, Effect of Type of Road; Noisiness; Acceptability. Some Types of Roads and their Qualities: Earth, Sand-clay, Gravel, Macadam, Bituminous Macadam, Bituminous Concrete, Brick, Concrete, Creosoted Wood Block, Asphalt Block, Sheet Asphalt, Other Types. Comparison of Roads — Specimen Tables. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

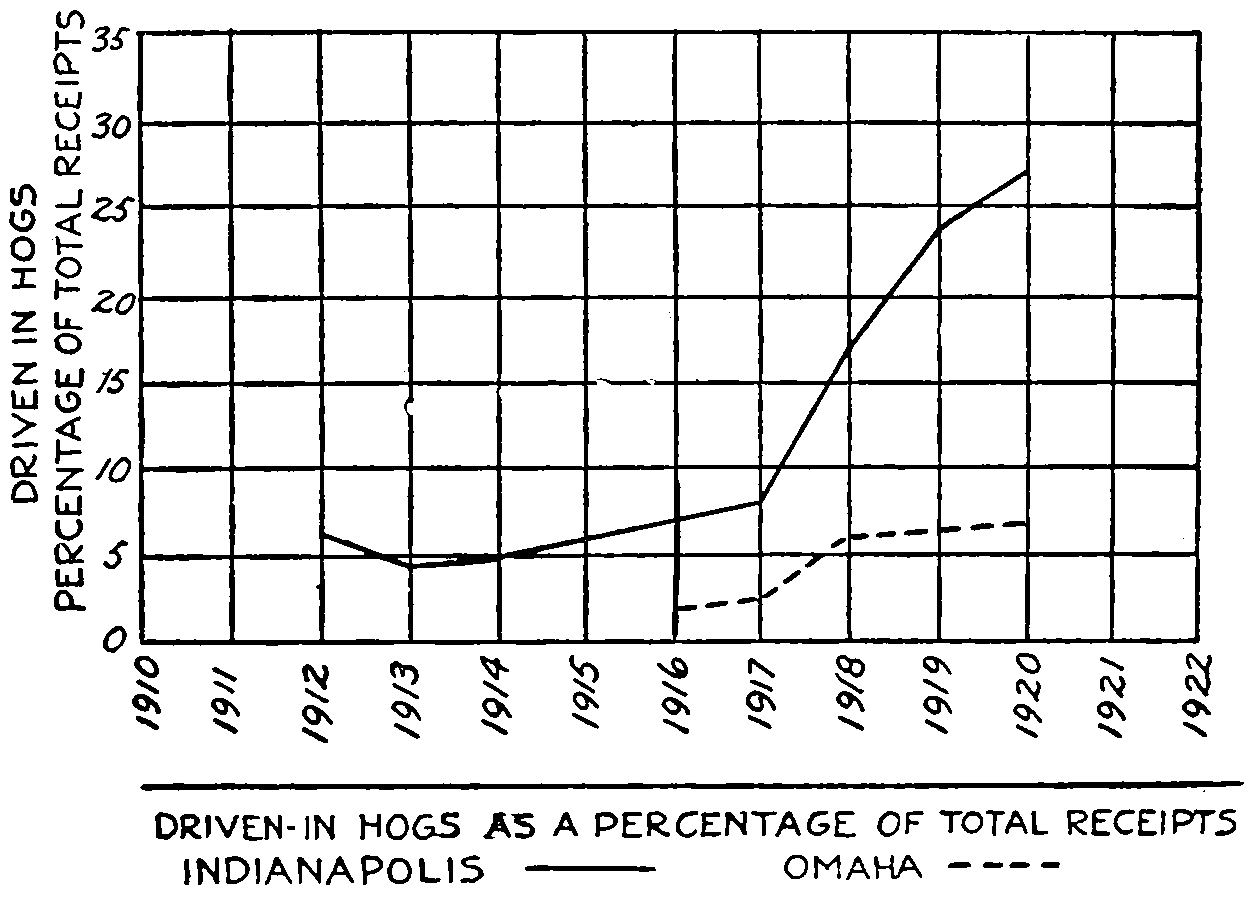

| Effect of Ease and Cost of Transportation on Production and Marketing | 273 |

| Production Defined, Productive Activities — Change of Form, Change of Place, Change of Time. Nature and Labor. Capital — Stored up Labor. Marketing — Wholesaling and Retailing. Grain Exchanges; Defined, Object, Commission Merchant, Dealing in Futures — Hedging. Cooperative Marketing: Advantages. Local Grain Merchant — Financing Movement of Crops. Elements Entering into the Cost of Marketing. Transportation from[xiv] Farm to Local Market. Cost of Production, Effect of Good Roads upon, Intensive Farming, Fruit Farming, Long Haul Transportation. Stock Marketing: Changing Character of Stock Raising, Distance of Economic Hauling by Team and by Truck, Effect of Truck Hauling on Number of Hogs Marketed. Seasonal Effect. Stock Merchant — Local, Shrinkage, Dairying. Poultry. Forestry: Logging and Lumbering, Forest Management, Use of Truck and Trailer, At Saw Mill, Log Loader, in Lumber Yards, Mining. Factory Products. From Factory to Retailer. Terminal Charges Eliminated. Construction. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Financing Highways and Highway Transportation Lines | 306 |

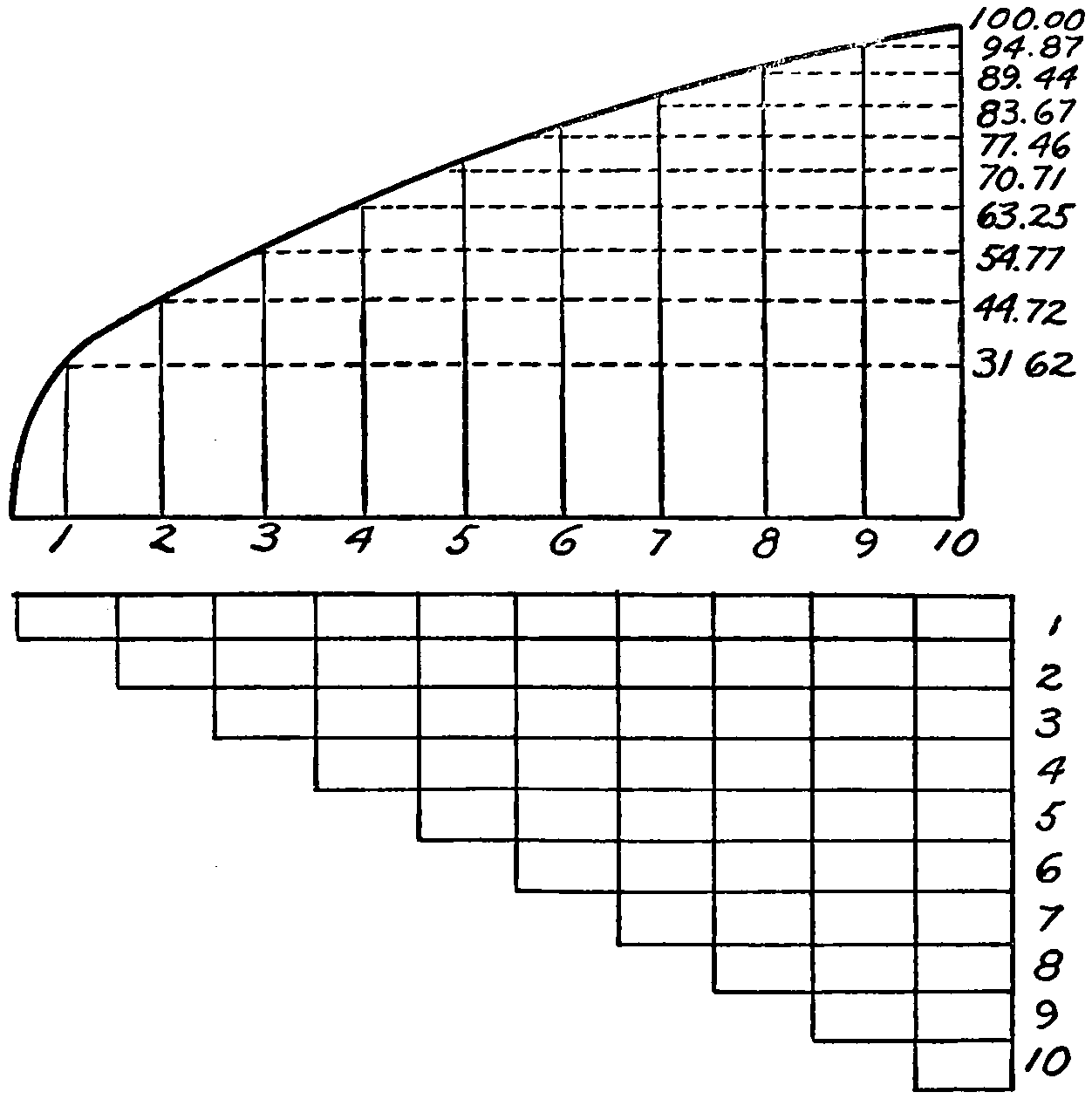

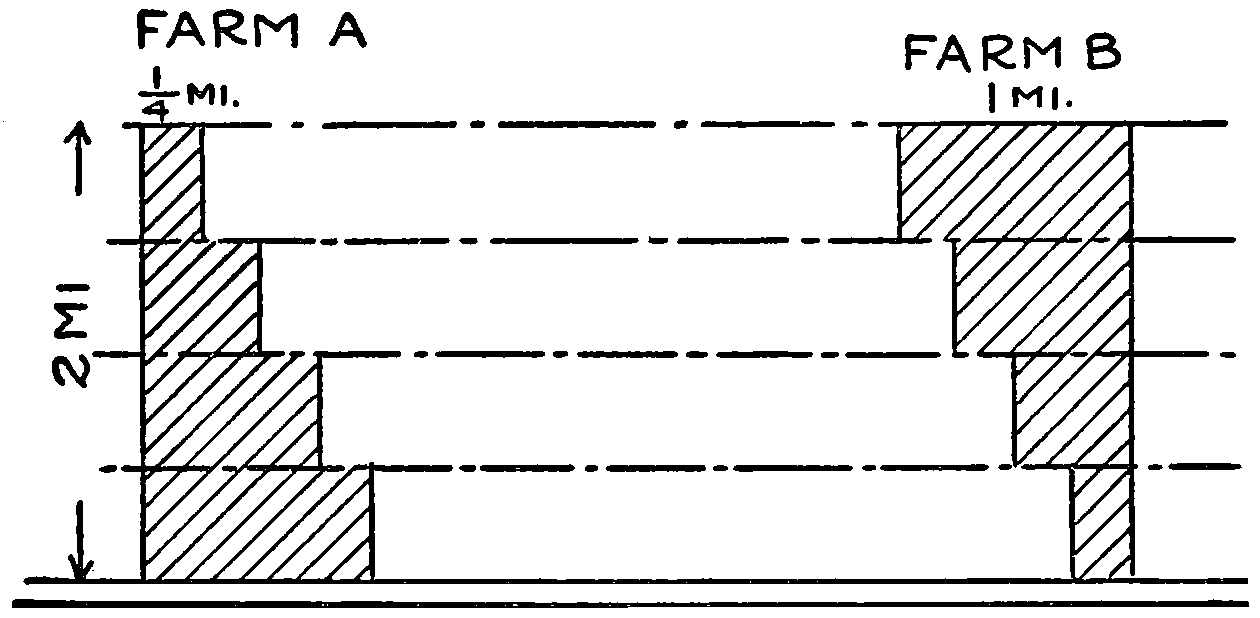

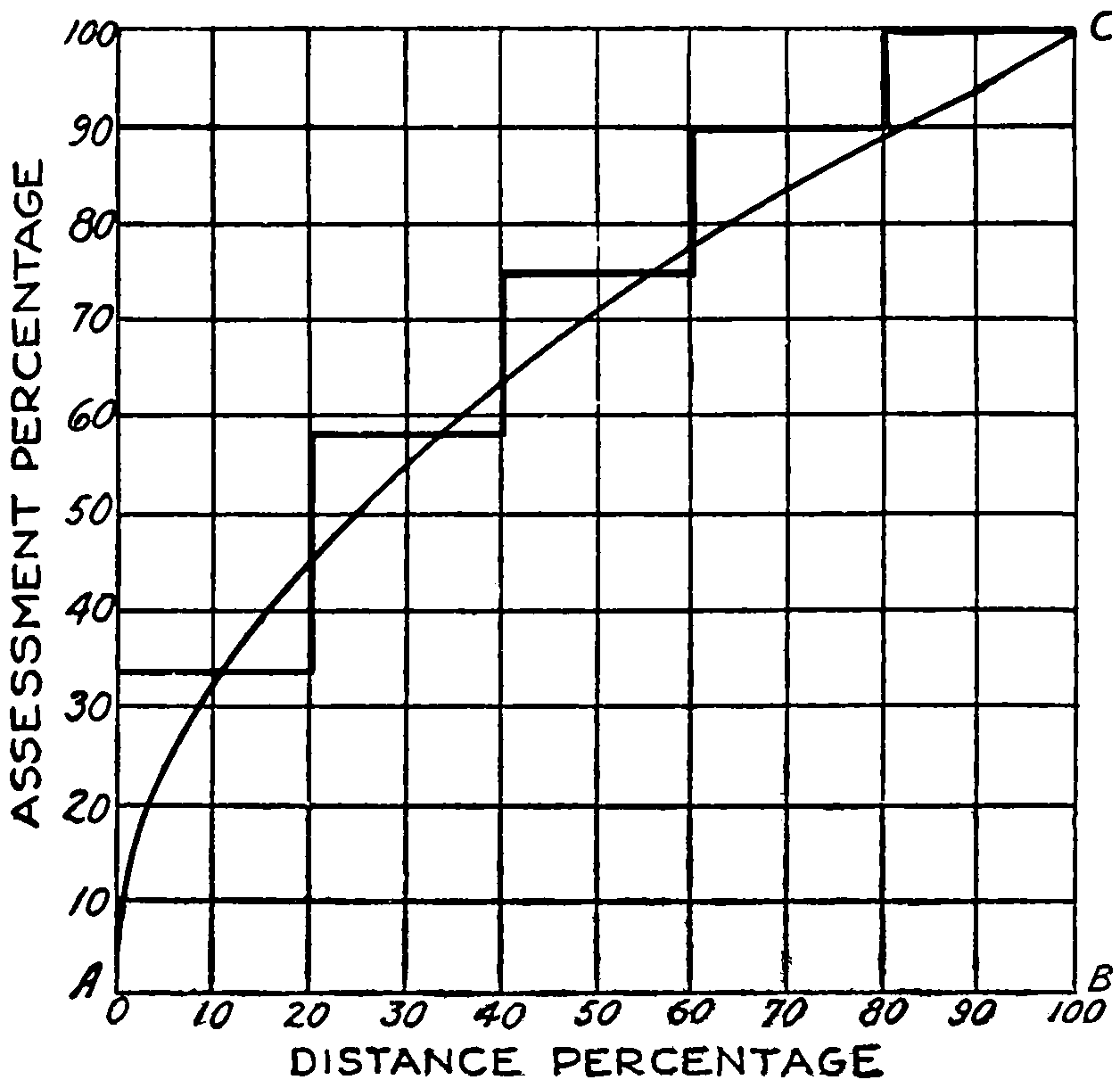

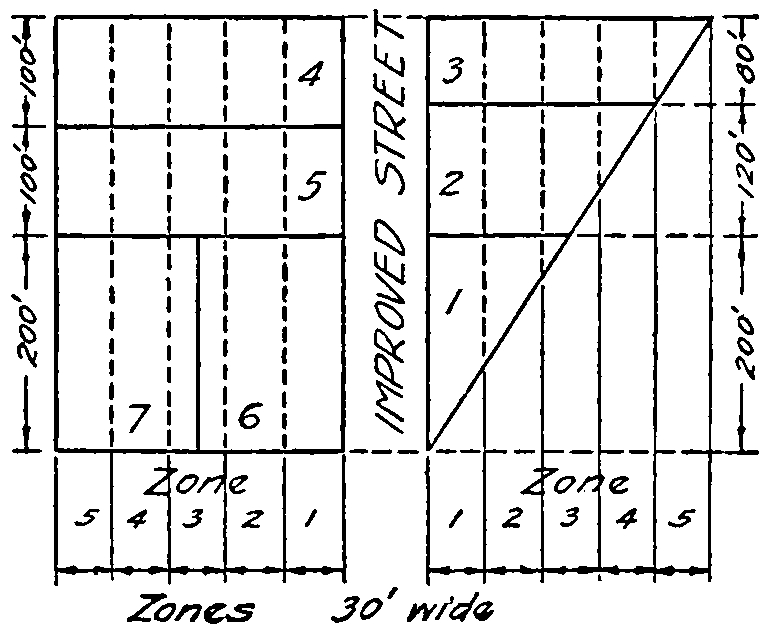

| Origin and Reasons for Road Work. Working out Road Tax Abolished. Private Financing, Public Financing. Taxation: Tax Defined, Classified. Direct Taxes — Levied Uniformly. Indirect Taxes: Defined, Classes of, Special Taxes, How Levied, Benefits Decrease with Distance, Petitioning Influence — Curve of, Concrete Illustration. Zone Weights: How Determined, Plots and Tables. Frontage: Defined, Calculation, Illustrative Example. Unequal Zones and Irregular Lots — Concrete Illustration. Another Method of Apportioning Assessments. Rule for Assessment. Miscellaneous Sources of Revenue: Public Service Corporations, Bus and Truck Lines, Municipal Sale of Water, Gas, Electricity, Ice, Coal. Public Ownership of Transportation and other Necessary Utilities. Bonds: Sinking Fund, Serial, Annuity, Comparison of Costs. Term of Bonds. Stocks and Bonds. National and State Aid. Present Status of Federal Aid. Matching Federal Aid Dollars. Financing Highway Transportation: Individual, Partnership, Corporation. Public Ownership — When Advisable. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Highway Accidents and their Mitigation | 351 |

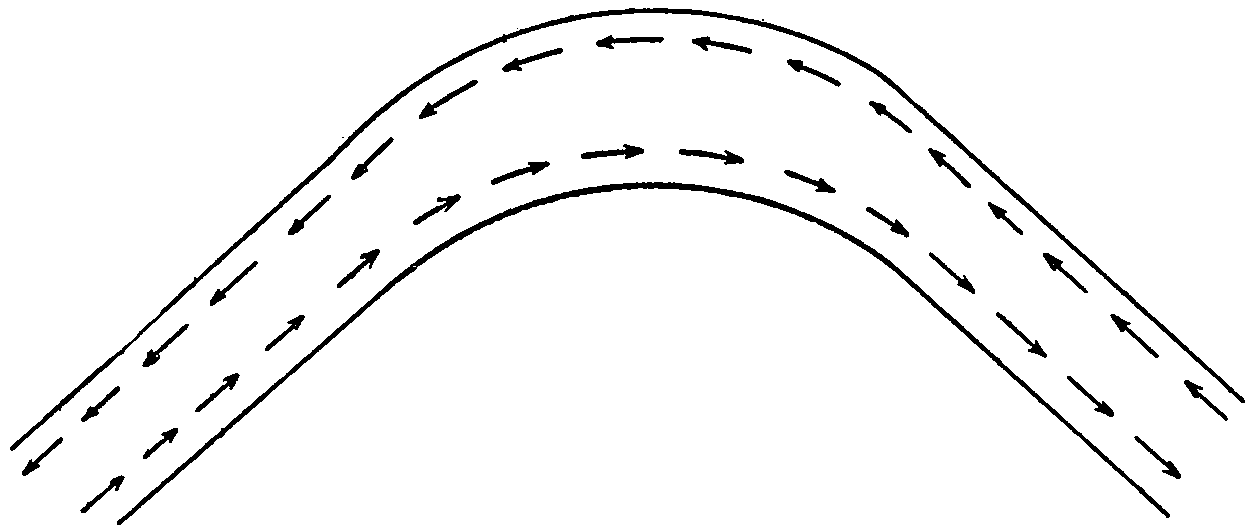

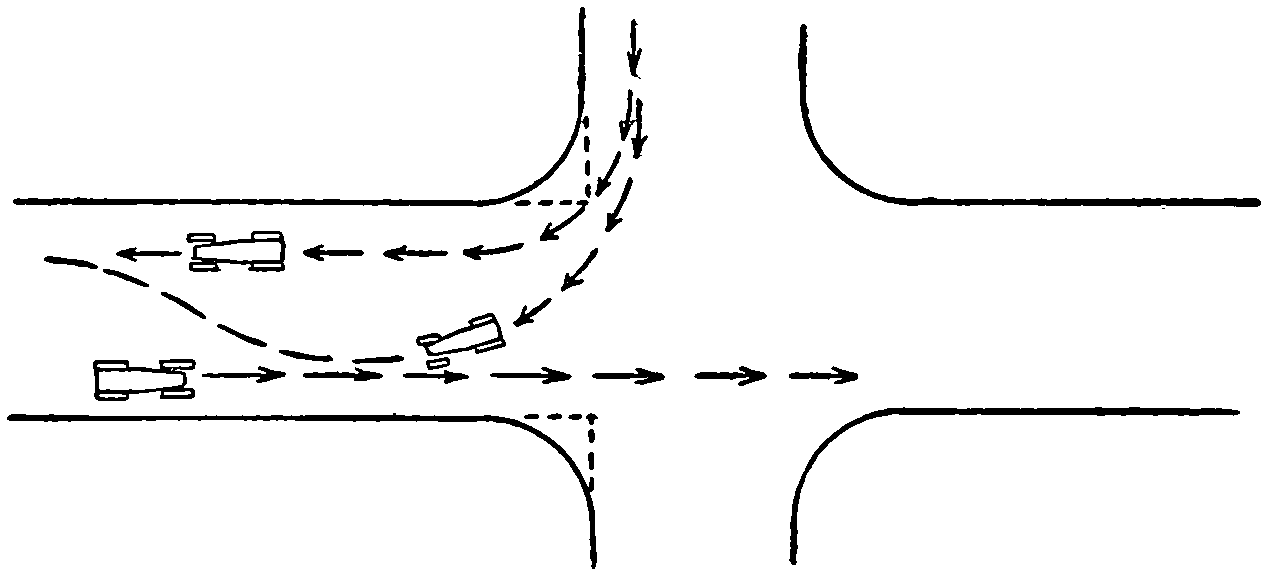

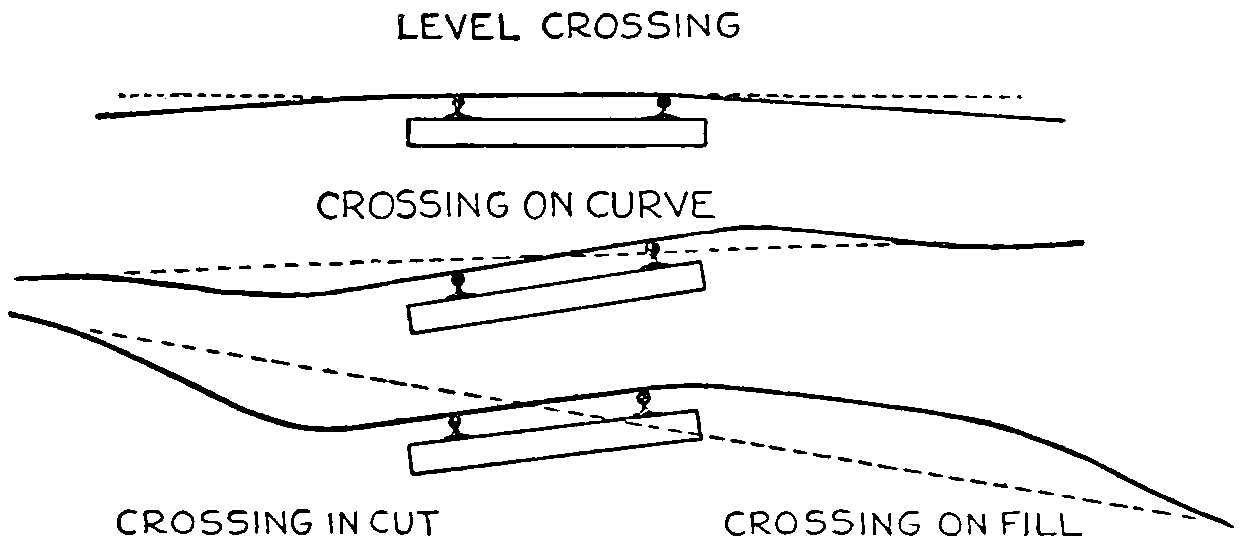

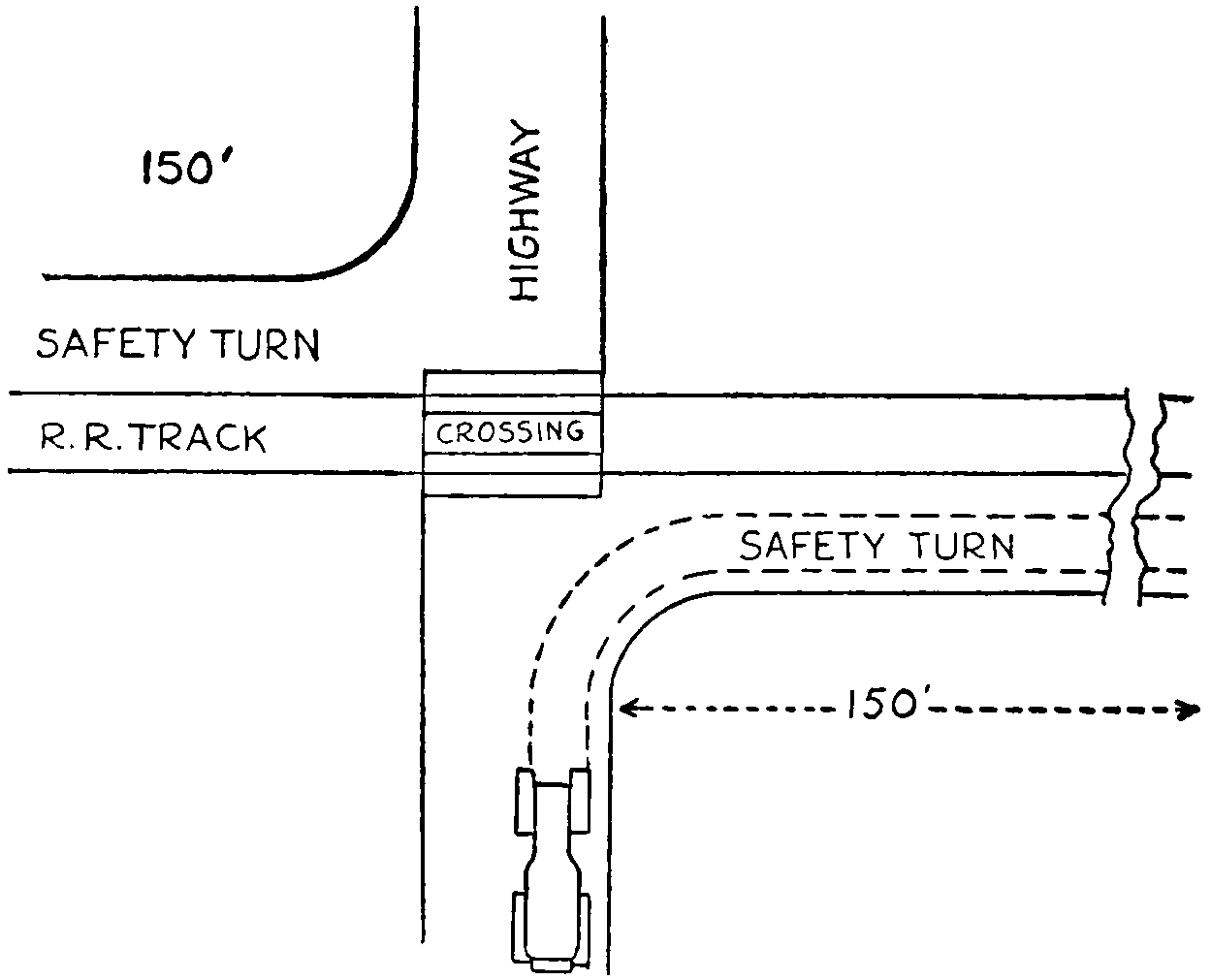

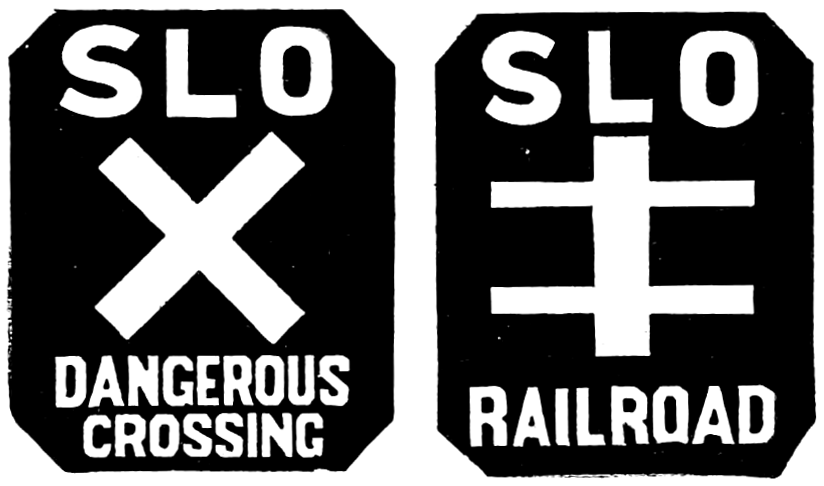

| Accidents Result of Disorder, Codes to Prevent, Automobile Accidents Lead in Number. Causes: The Driver — Mentally or Physically Unfit, Ignorant, Indifferent, Reckless; Driving and Operating: Recklessness, Speeding, Around Sharp Turns, Passing Cars. Horns. Stopping Cars on[xv] Grades, in Streets, etc., Backing. Other Forms of Carelessness. The Car: Skidding, Brakes, Flexibility, Steering and Turning Ability, Lights, Unlighted Vehicles, Speedometer. Bad Roads: Slipperiness — High Crowns, Embankments and Guard Rails, Super-elevation — Rule for, Clear Vision, Curves, Bridges and Culverts. Railway Crossing Accidents: Prevalency, Elimination of Crossings — Cost, Automobile Drivers Careless — Observations, Methods of Mitigation; Bridge Clearance. Pedestrians — Jay-walkers, Obstacles that Obscure Vision, Pedestrians on Country Roads, Slow Going Vehicles, Bicycles. Road and Traffic Regulations: Development of, Council of National Defense Code, Education Necessary. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

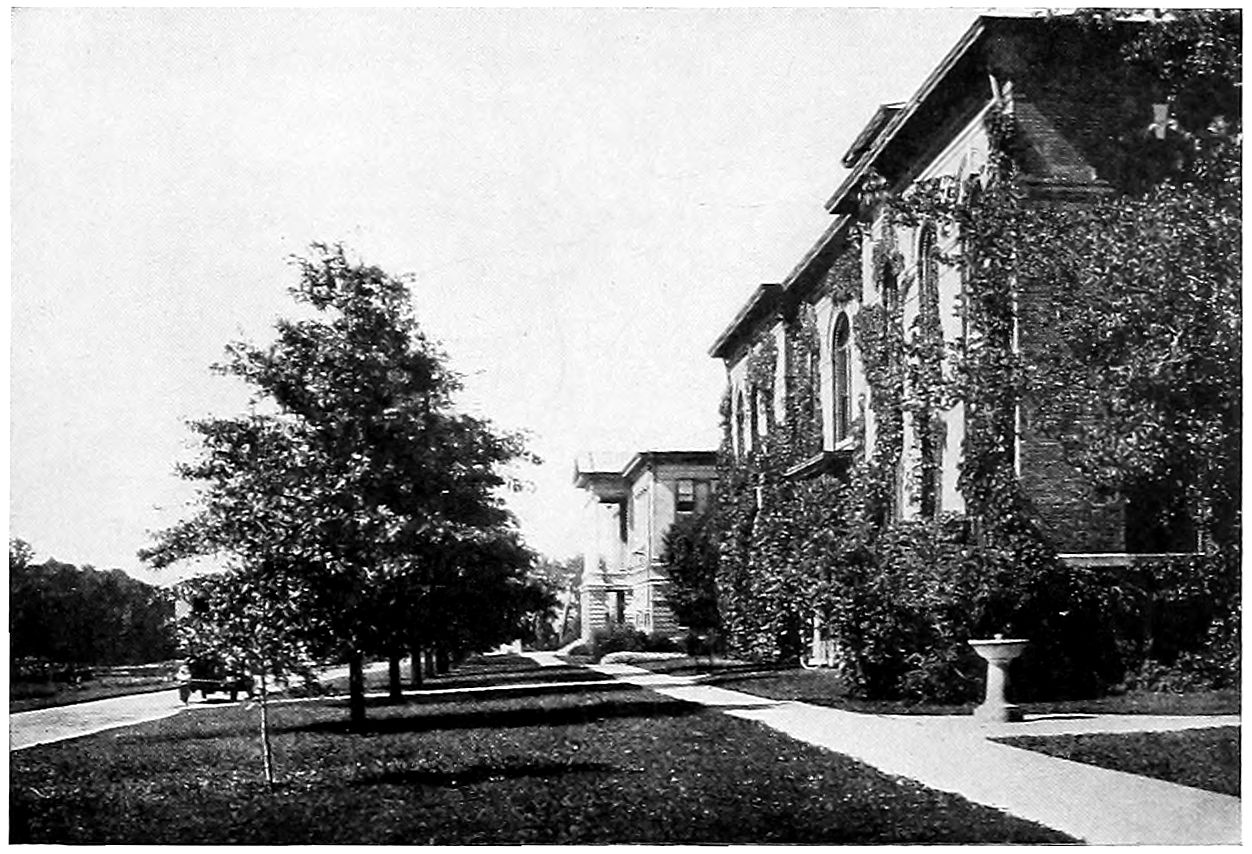

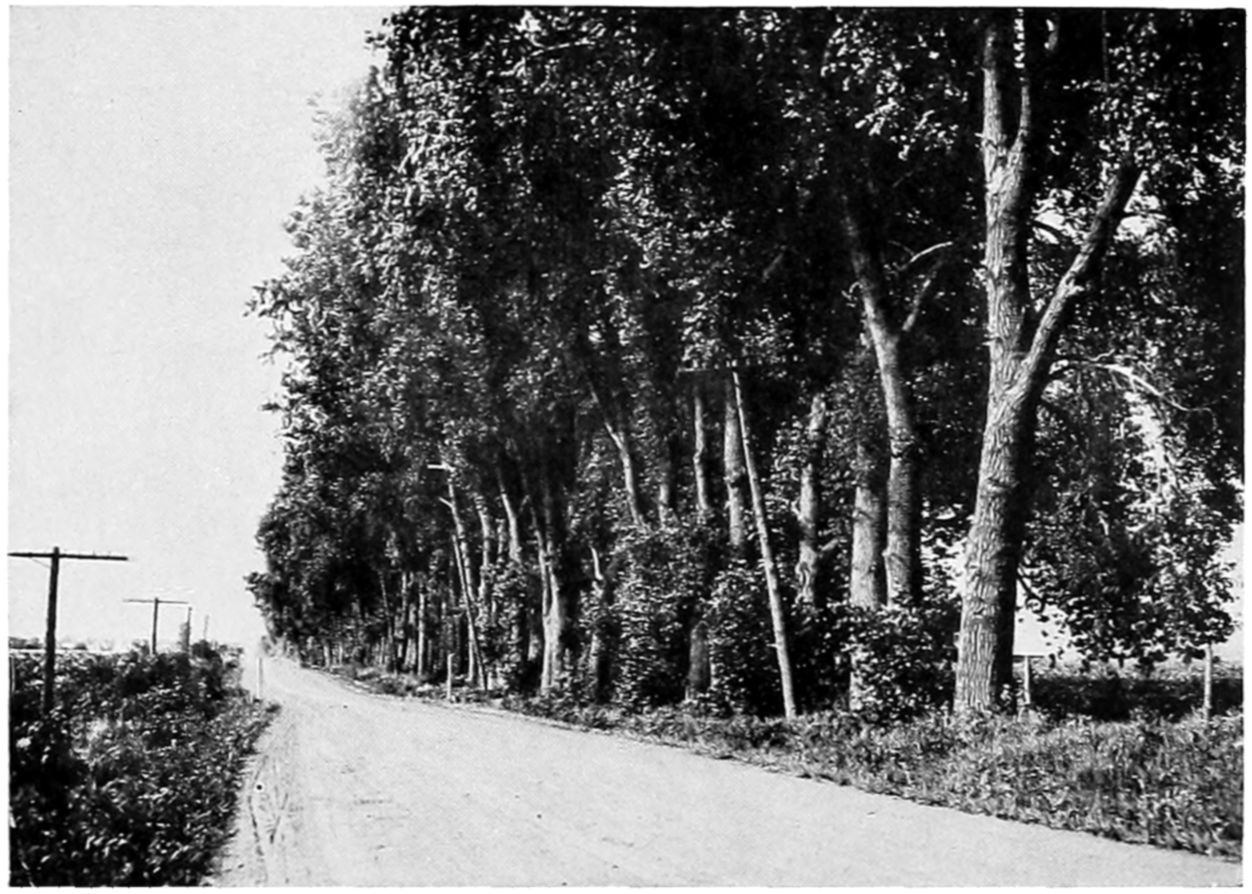

| Highway Esthetics | 382 |

| Indispensable Elements of Architecture — Stability, Utility, Beauty. Esthetic Sense — Applied to Roads, to Landscape Gardening. Styles — Natural and Formal. Application to Roads. Varieties of Road and Street Trees — List; Shrubs — List; Climbers — List. Semi-formal Style. Telephone and other Poles, the Ideal Section, Legislation Necessary. Local Conditions Determine Planting. | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Aids and Attractions to Traffic and Travel | 418 |

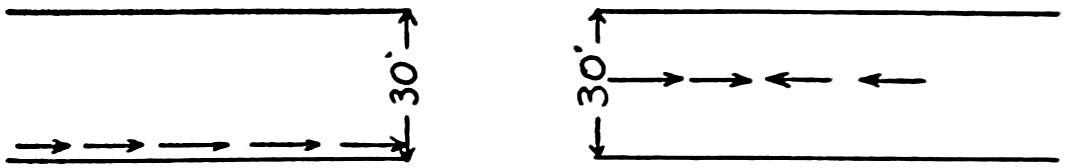

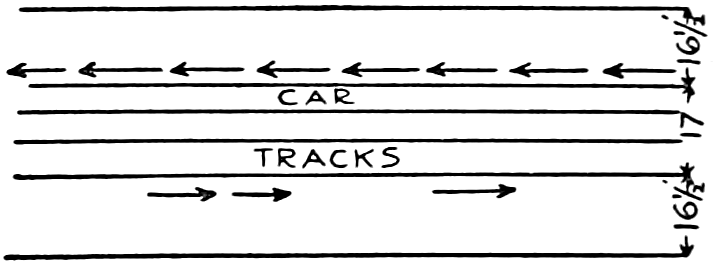

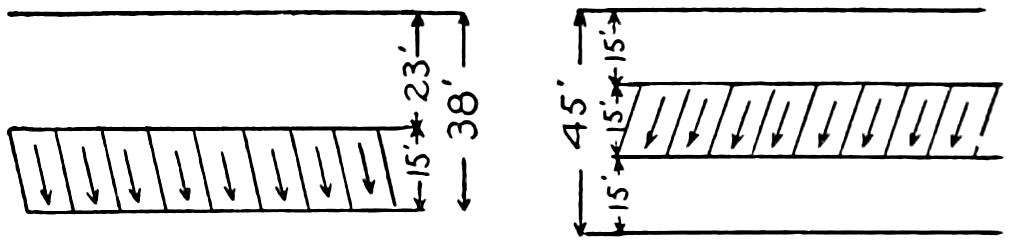

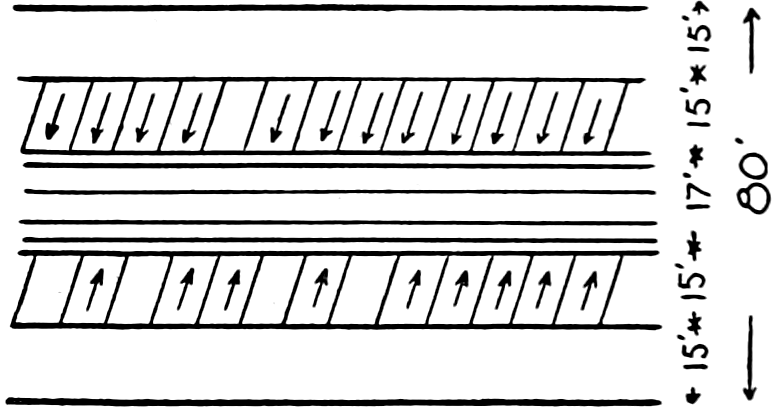

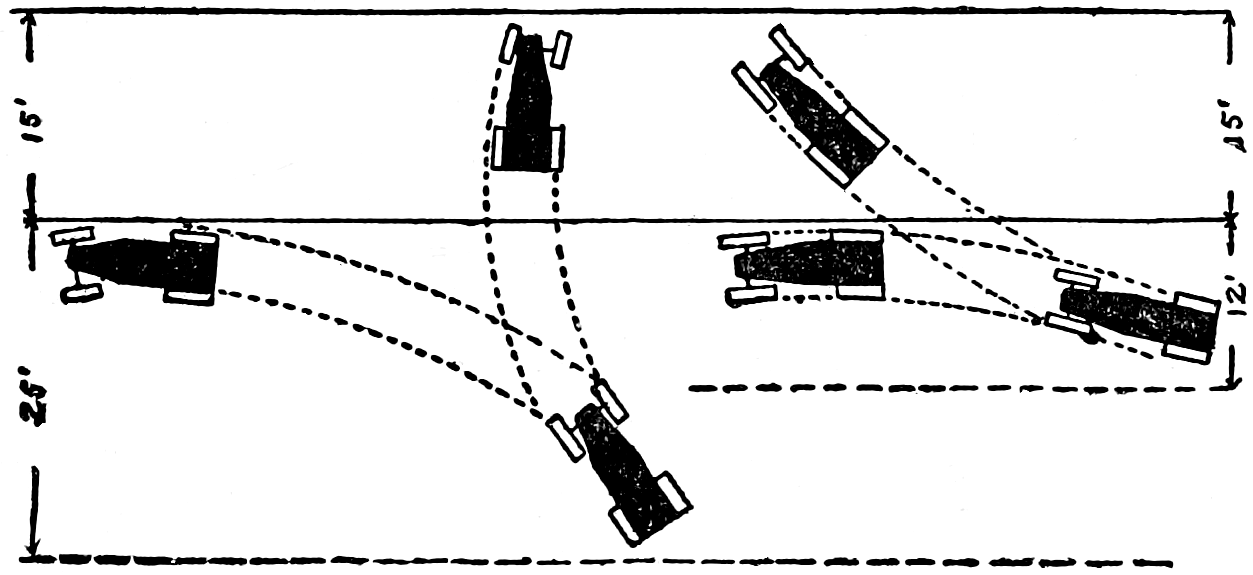

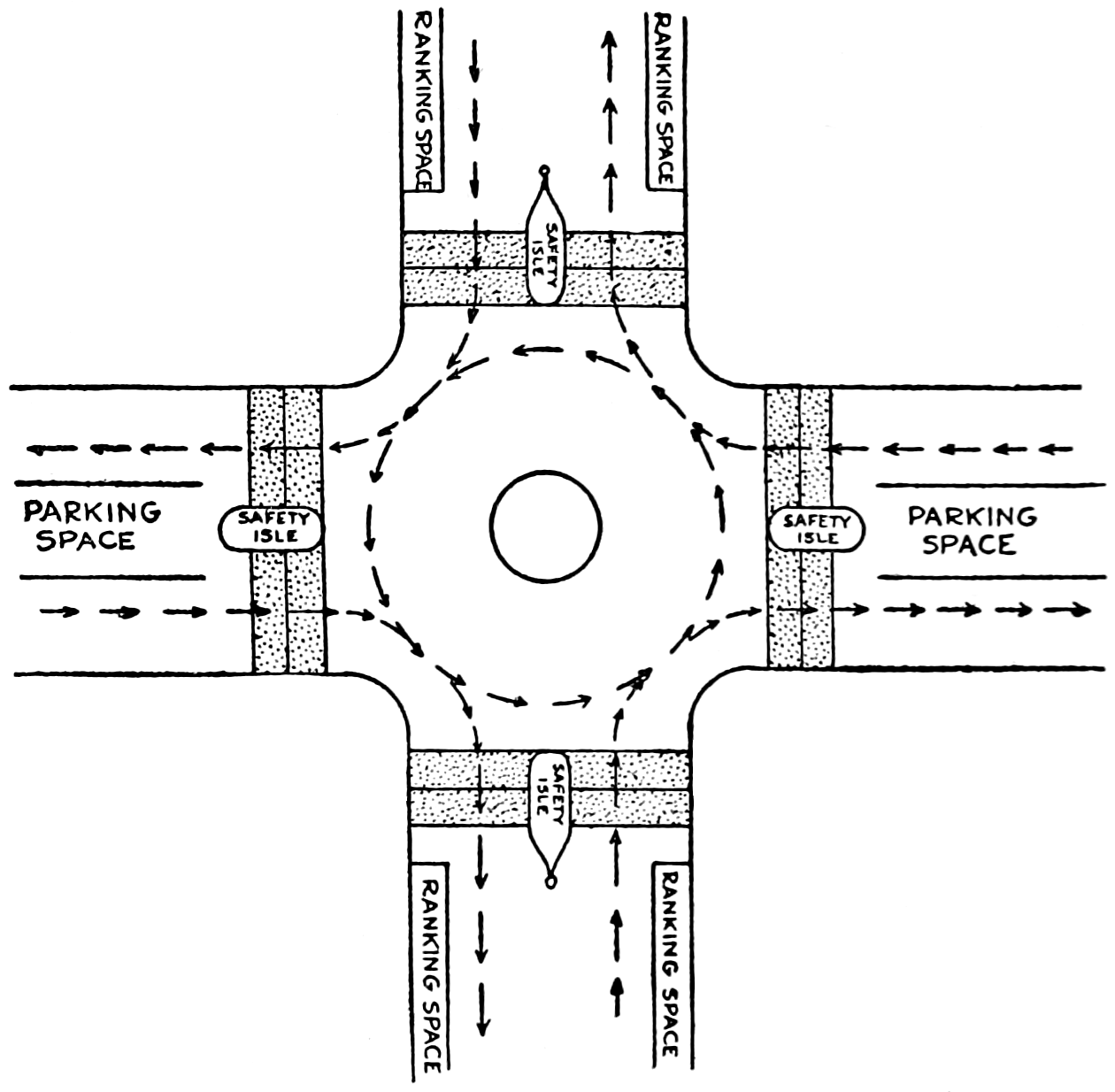

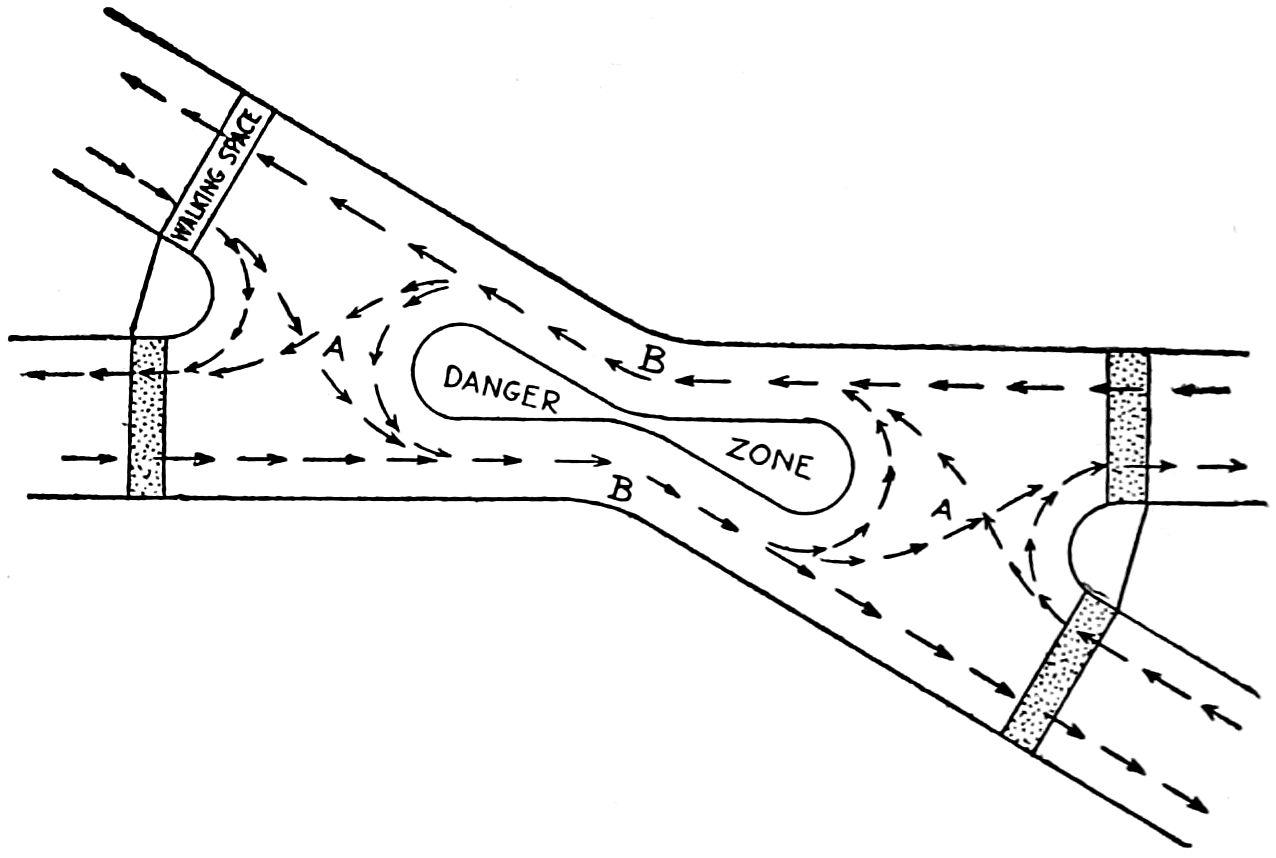

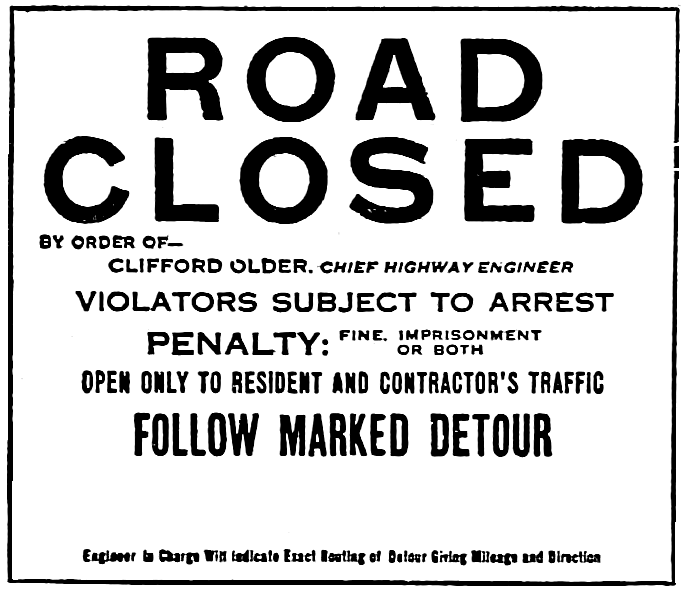

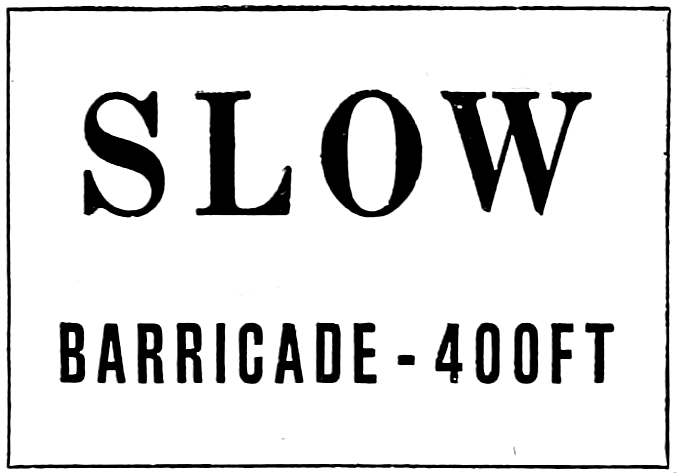

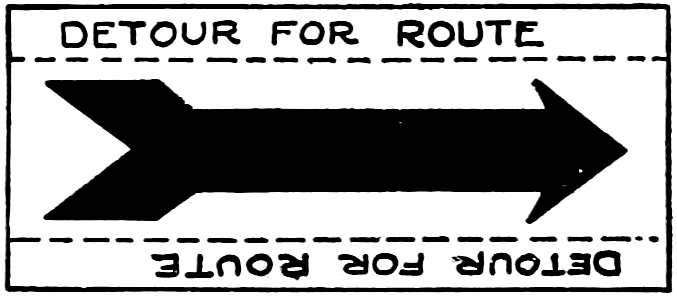

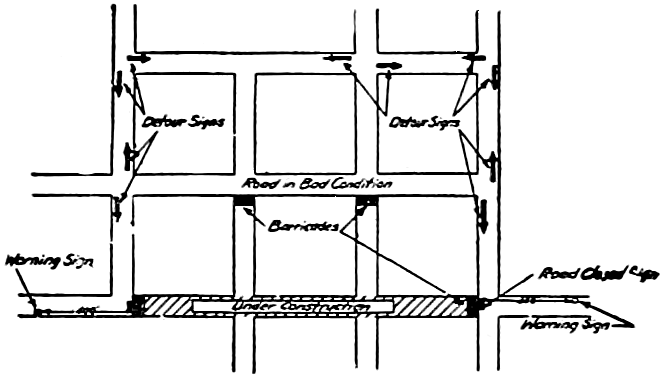

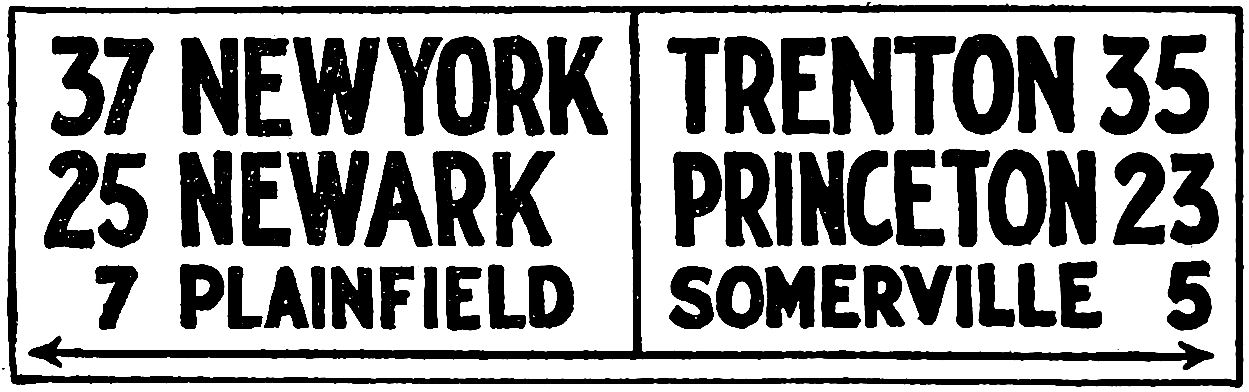

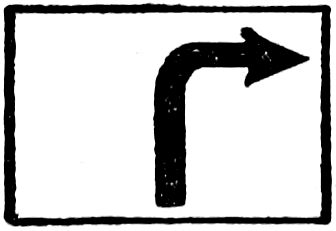

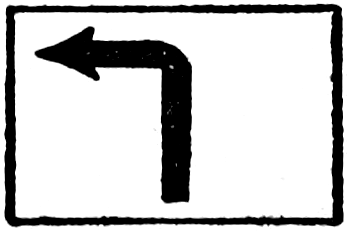

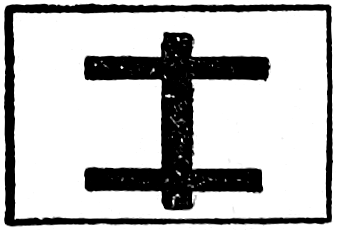

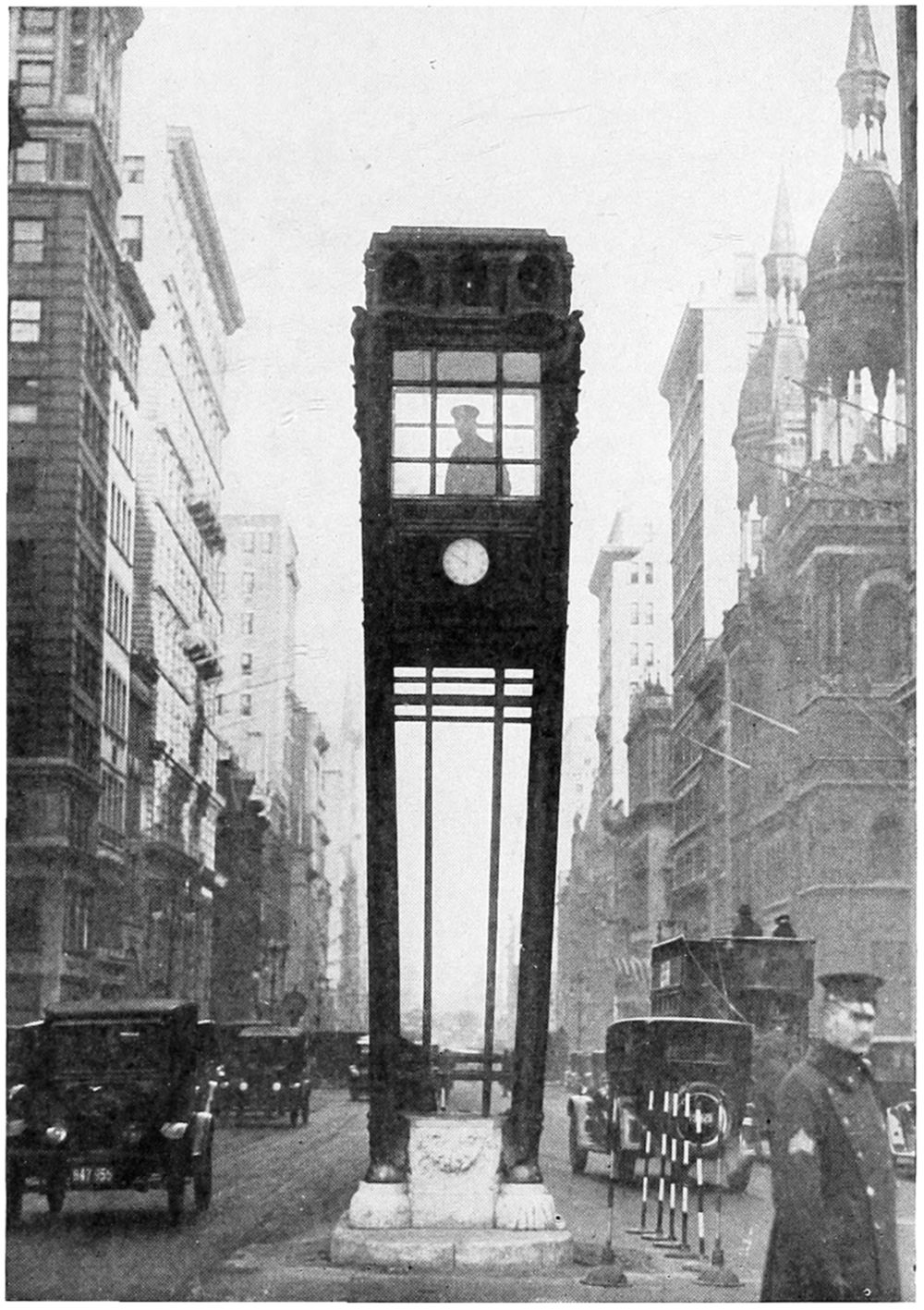

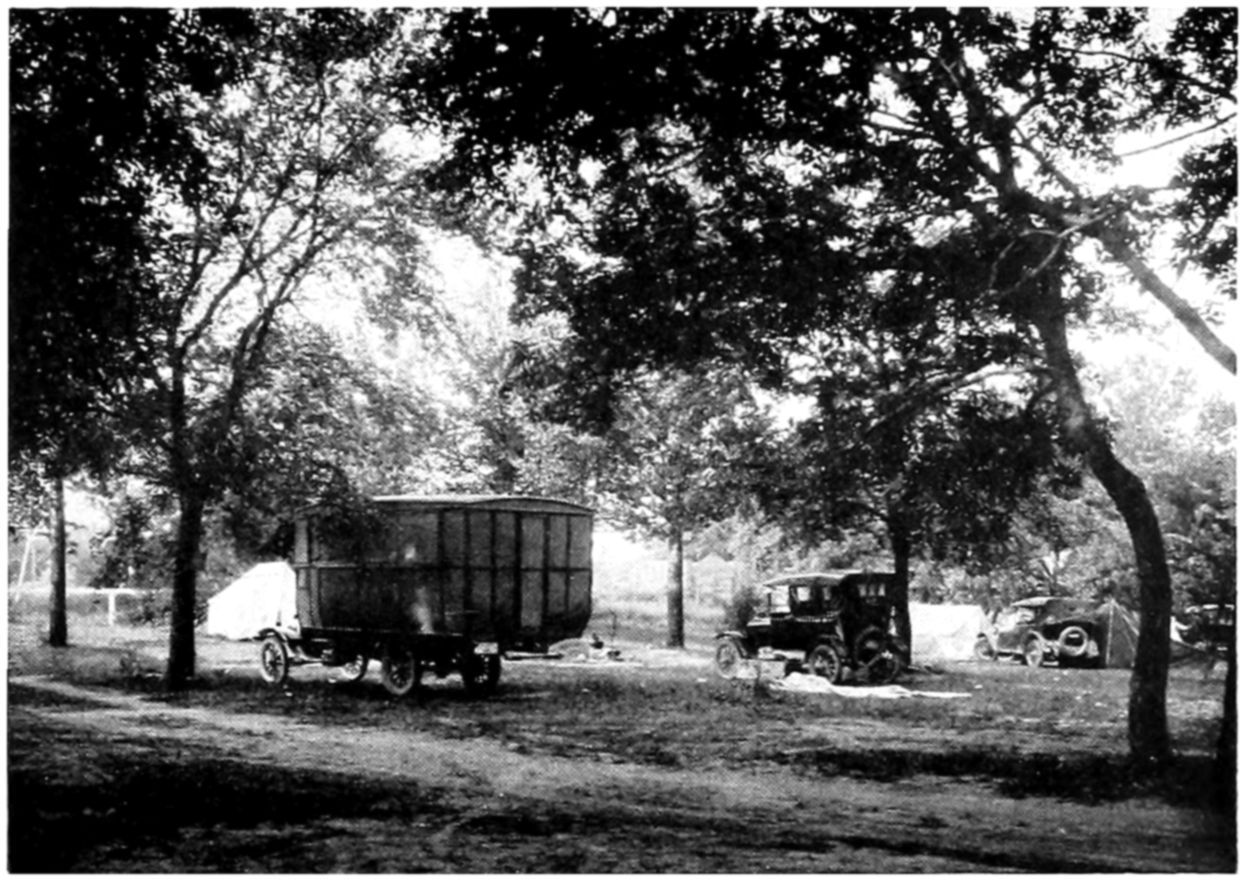

| Pleasure Riding — Extent, Advantages to a Community to Have Tourists Pass through, Ranking and Parking, Parking Spaces a Convenience to Motorists — Space for and Angle of Parking, Location of Parking Spaces, One Way and Rotary Traffic, Opera House Traffic, Public Garages — Several Story Garages. Terminal Stations — Omaha, Poughkeepsie, Elsewhere. Gas, Air and Water Stations, Named and Numbered Roads; Marks, Signs and Guides — Distance and Direction Signs, Letters and Colors, Warning Signs, Map Signs, Detour Signs, Location of Detour Markers, Dummy Cop, Semaphores, Signal Lights and Colors, Road and Street Lighting, City Traffic Lighting, Traffic Officer, Semaphore and Towers. Touring: Prevalency and Pleasures of, Camping — Grounds, Caravans, and Equipment. Camp Sites, Hotels, Parks, Information Bureaus and Agencies. | |

| Index | 465 |

[xvii]

| 1. | Storm King Highway | Frontispiece | ||

| A Great Engineering Project Along the Hudson between Cornwall and West Point, N. Y. | ||||

| PAGE | ||||

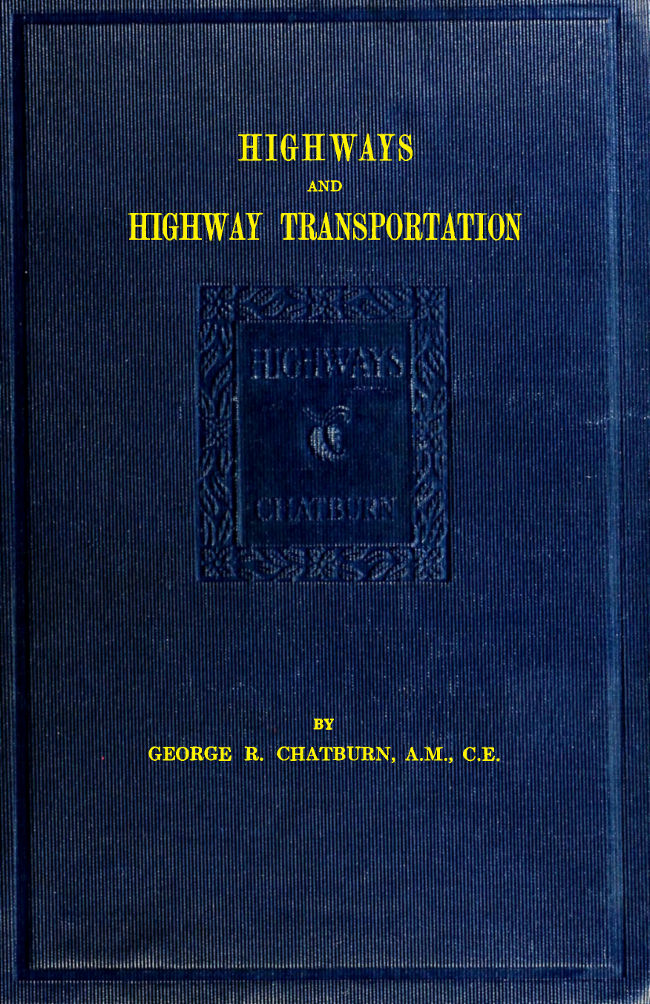

| 2. | The Appian Way | 22 | ||

| Showing the original Paving Stones laid 300 B.C. | ||||

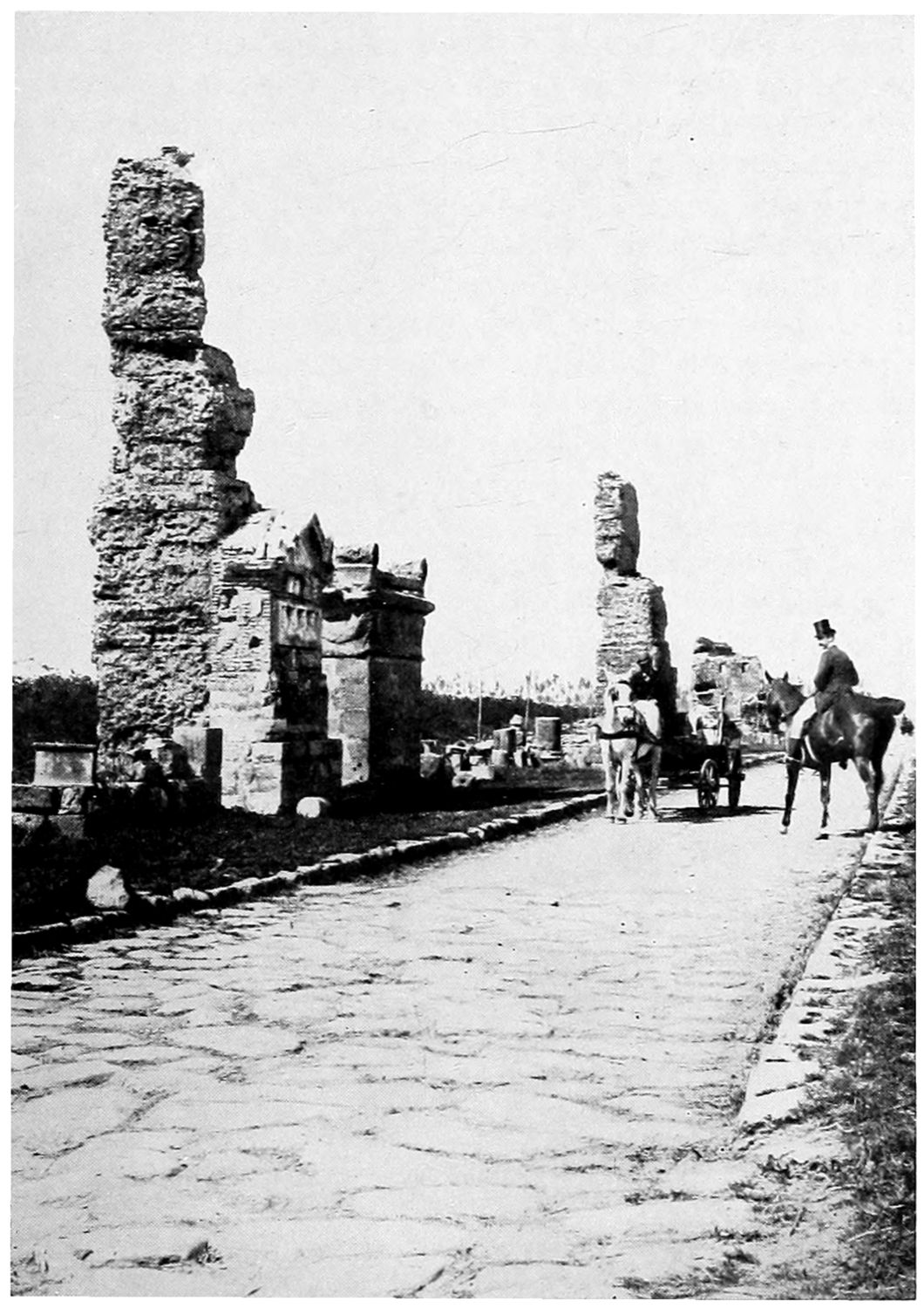

| 3. | Map of Italy | 24 | ||

| Showing Some of the Twenty or More Roads that Radiated from Rome. | ||||

| 4. | Map of Roman Roads in England | 26 | ||

| (After Jackman: “Development of Transportation in Modern England.”) | ||||

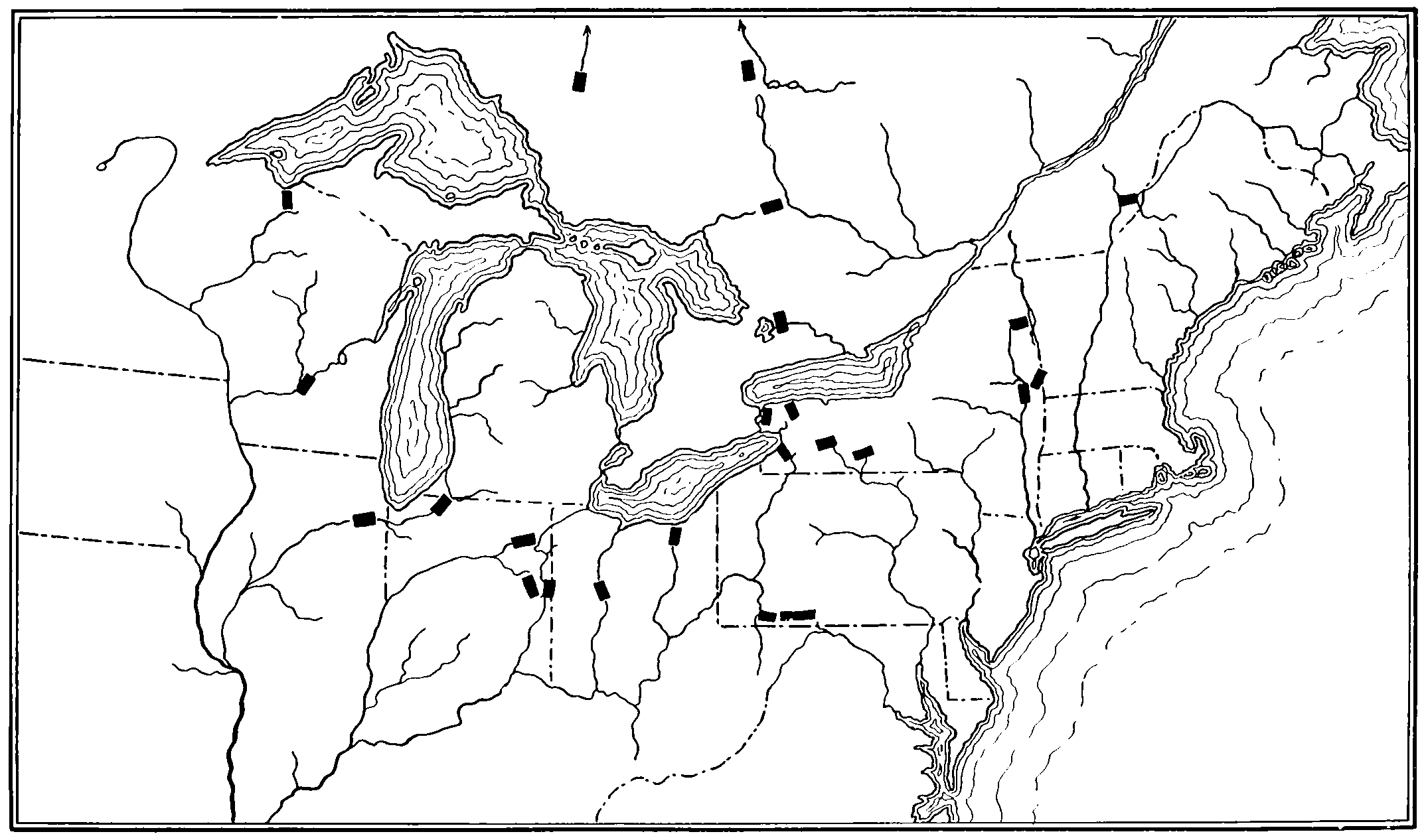

| 5. | Map of the North-Eastern Portion of the United States | 36 | ||

| Showing the Location of Well-known Portages. There Were Other Portages Wherever Two Water Courses Came Near to Each Other. (See Farrand: “American Nation,” Vol. I, and Thwaites, Ib. Vol. VII.) | ||||

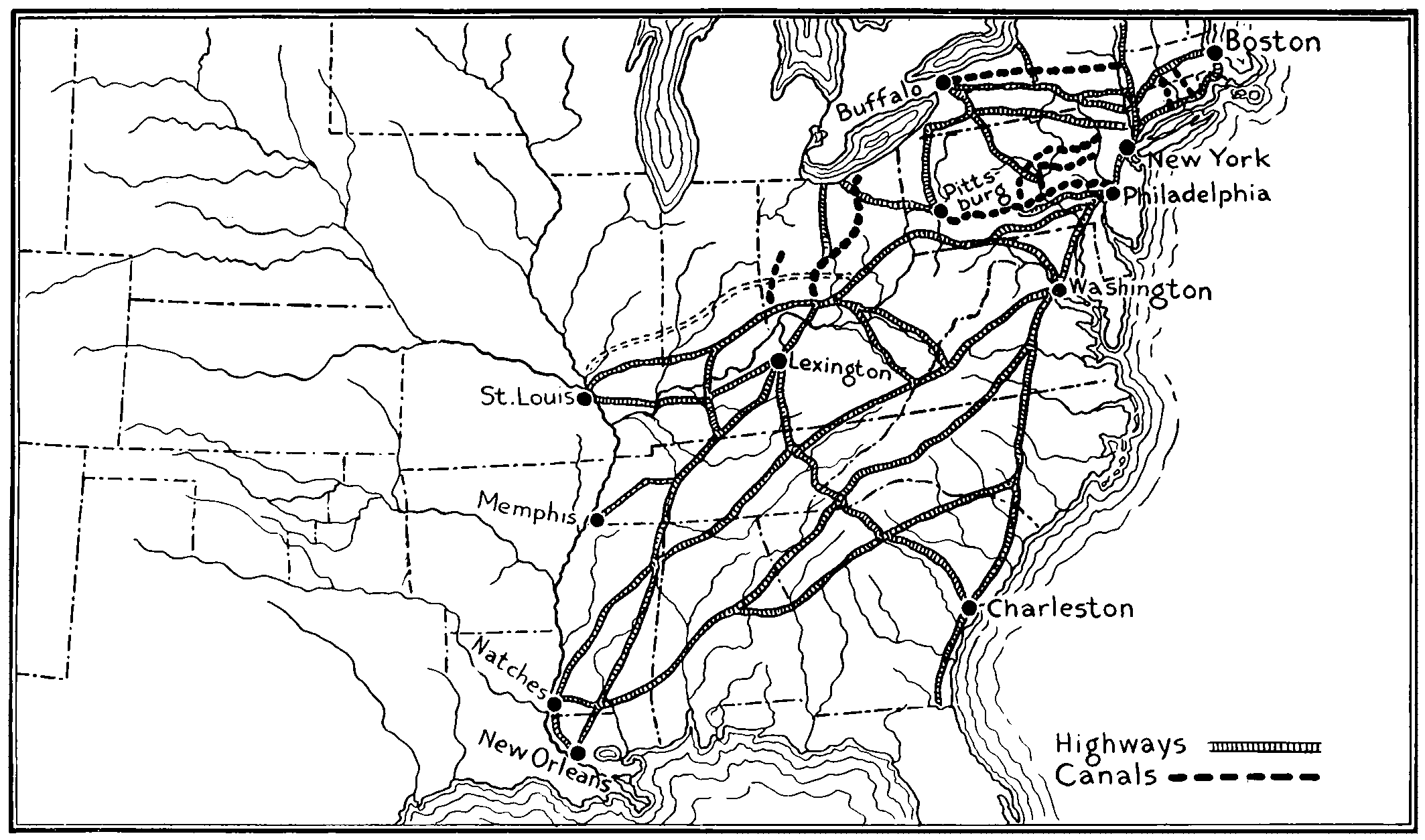

| 6. | Map | 42 | ||

| Showing Main Highways and Waterways in the United States about 1830. When the Railroads Entered the Industrial Arena, the Country Was Being Covered With a Net Work of Highways. (Based on Tanner’s Map of 1825 and Turner in “American Nation,” Vol. XIV.) | ||||

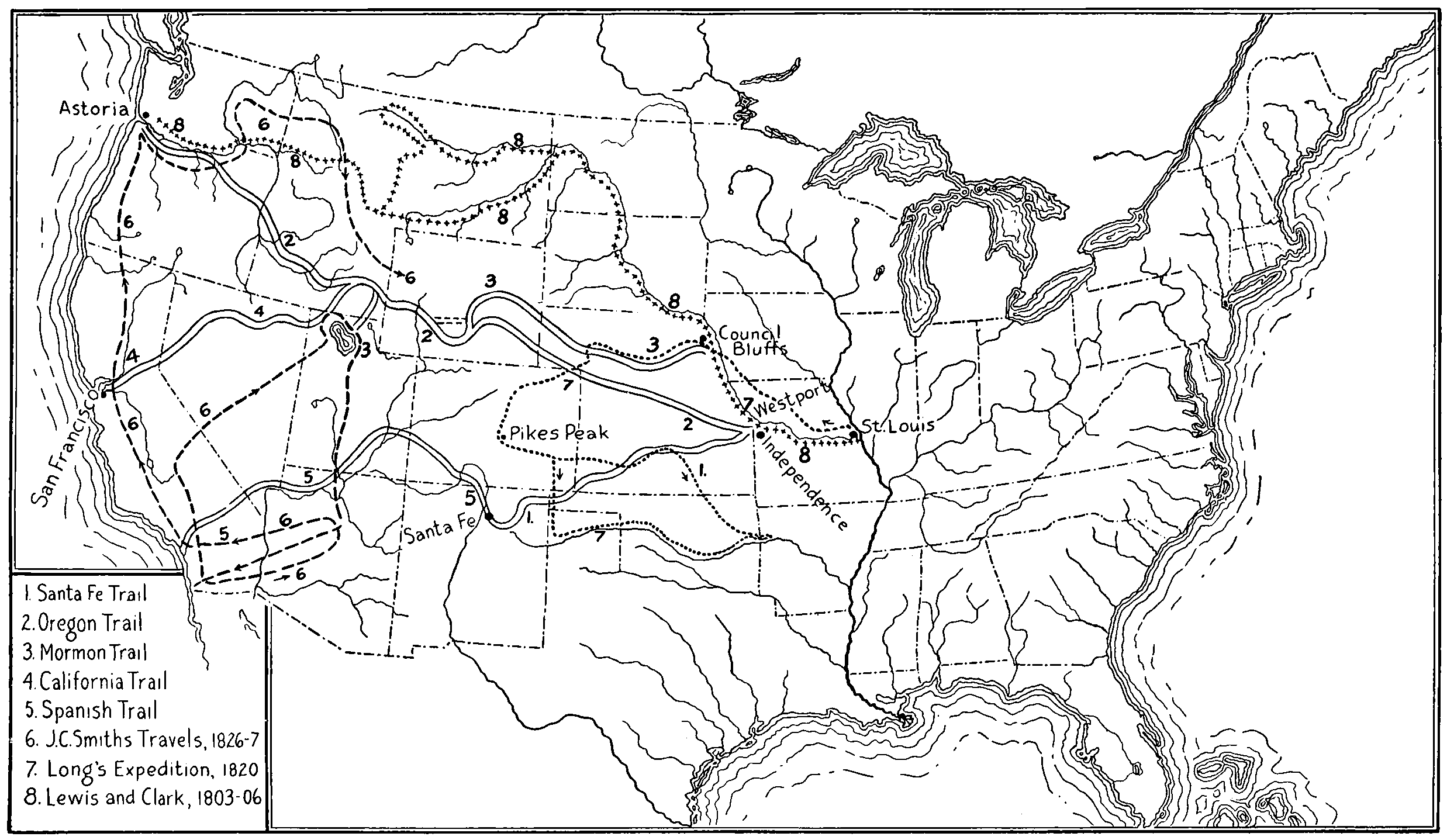

| 7. | Map | 54 | ||

| Showing Transcontinental Trails in the United States. | ||||

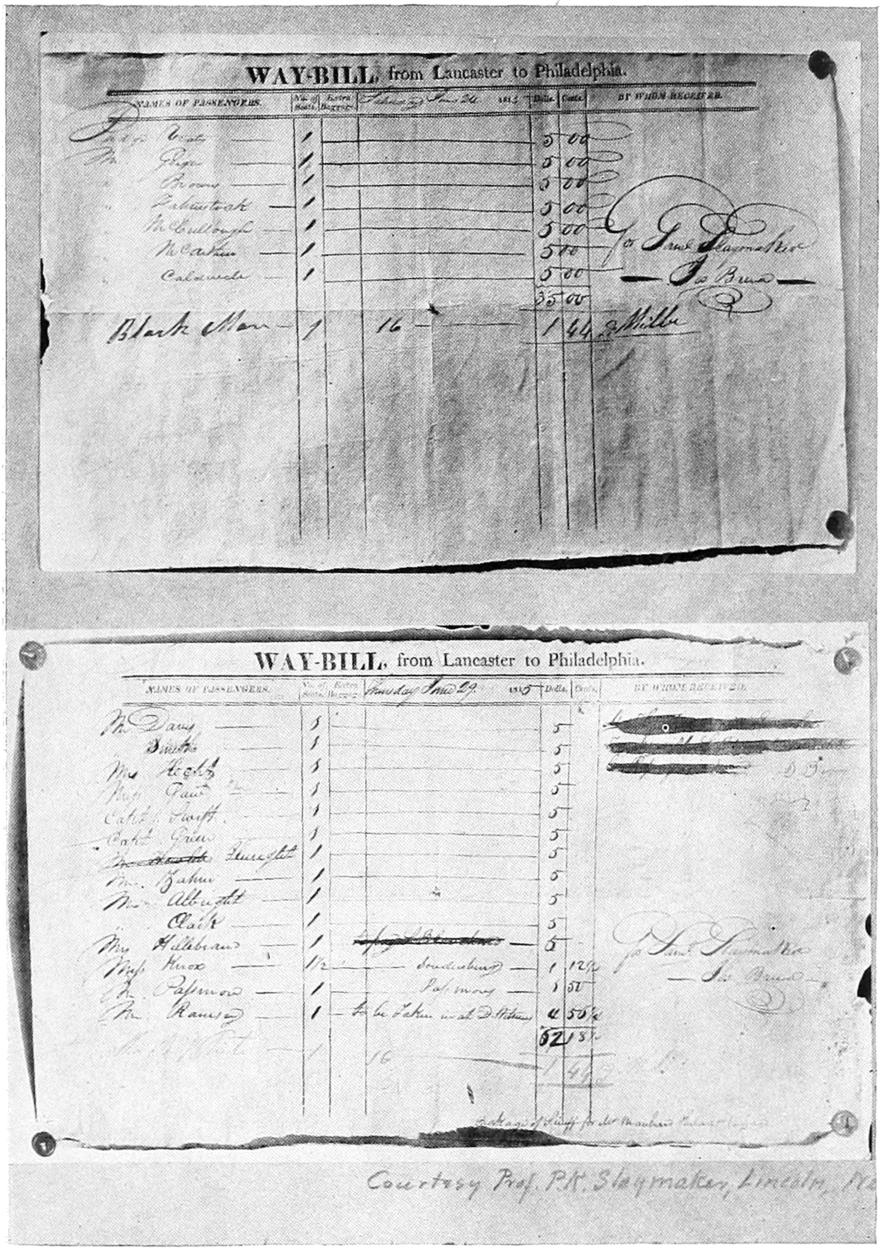

| 8. | Way Bill | 66 | ||

| Used on the Slaymaker Stage Line from Lancaster to Philadelphia, 1815. (Courtesy of Prof. P. K. Slaymaker, Lincoln, Nebr.) | ||||

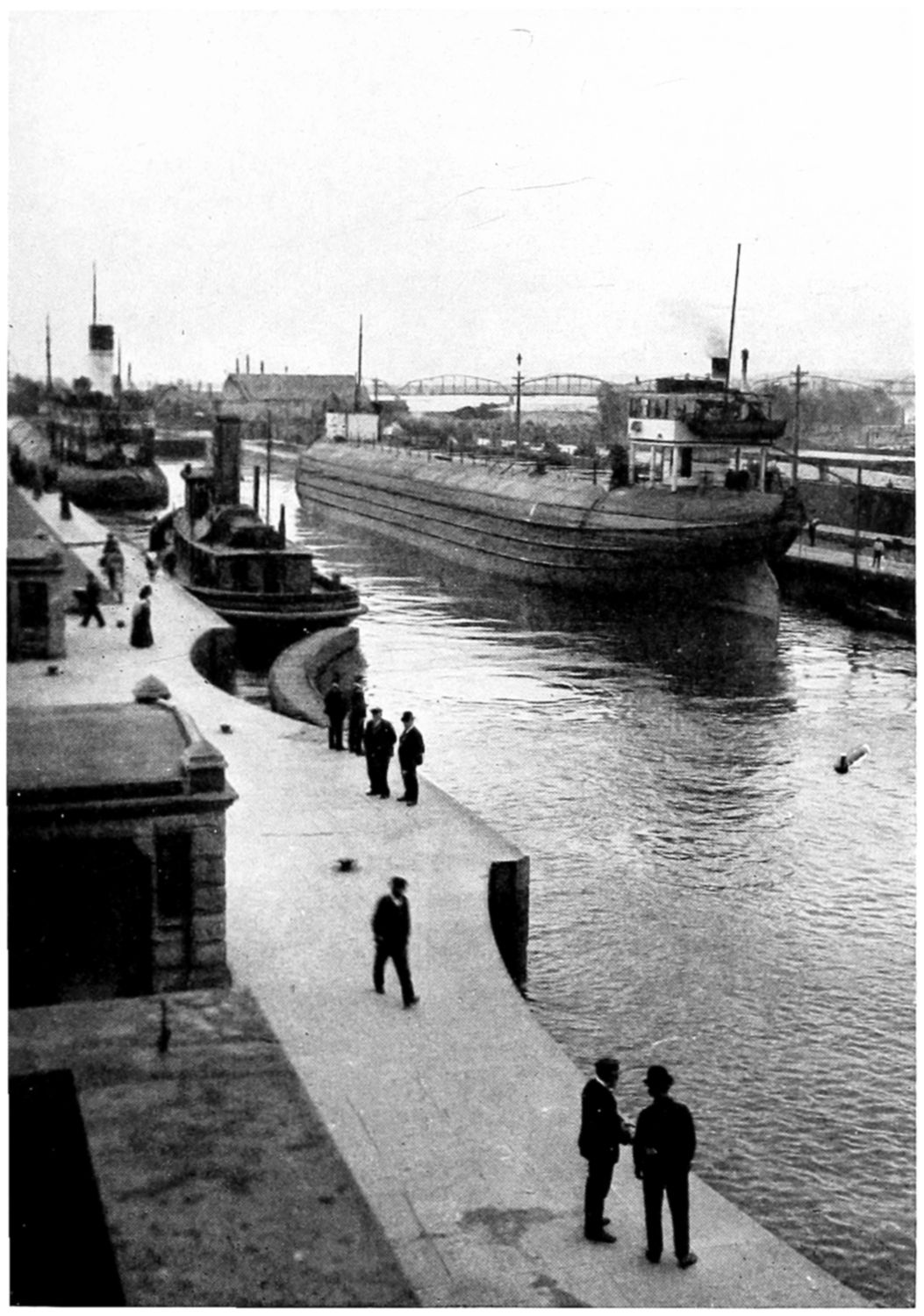

| 9. | The Sault Ste. Marie Canal | 76 | ||

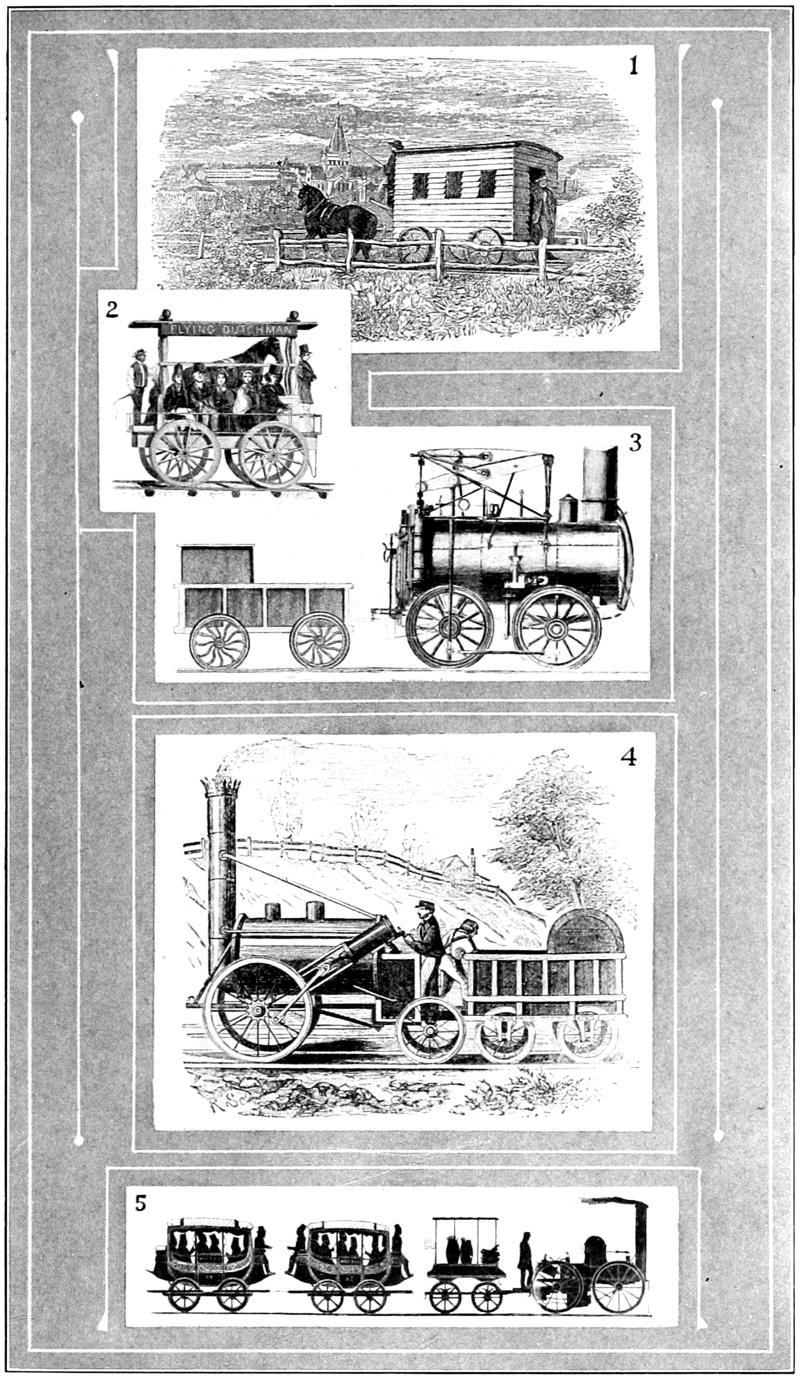

| 10. | The Evolution of the Railway Train[xviii] | 102 | ||

|

||||

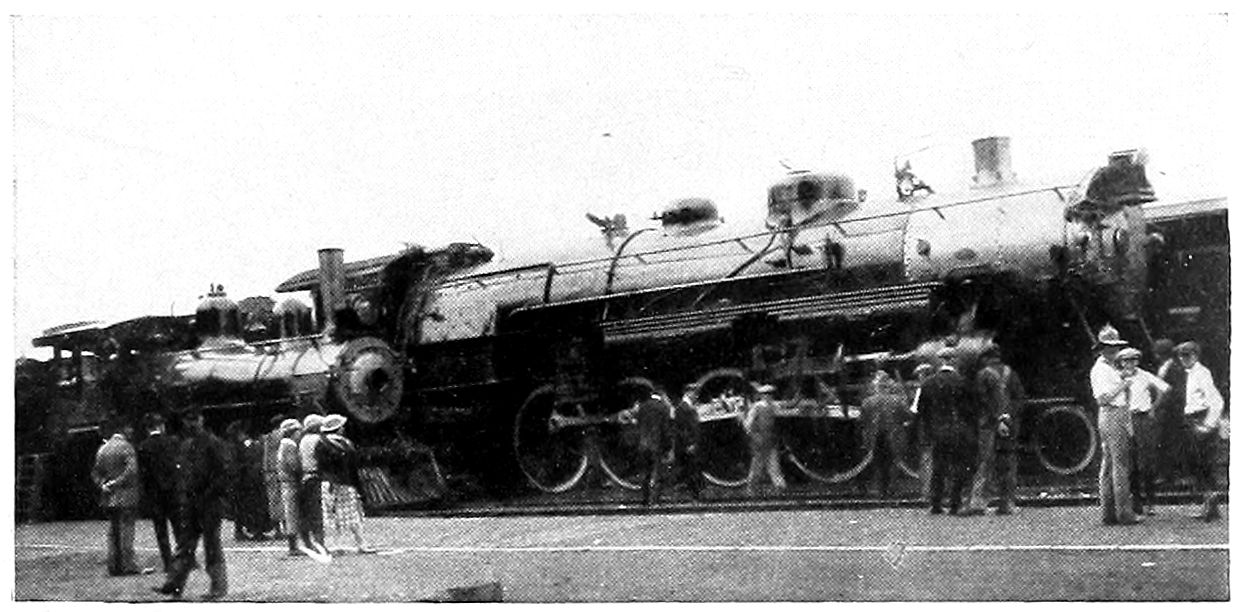

| 11. | Modern Locomotives | 120 | ||

|

||||

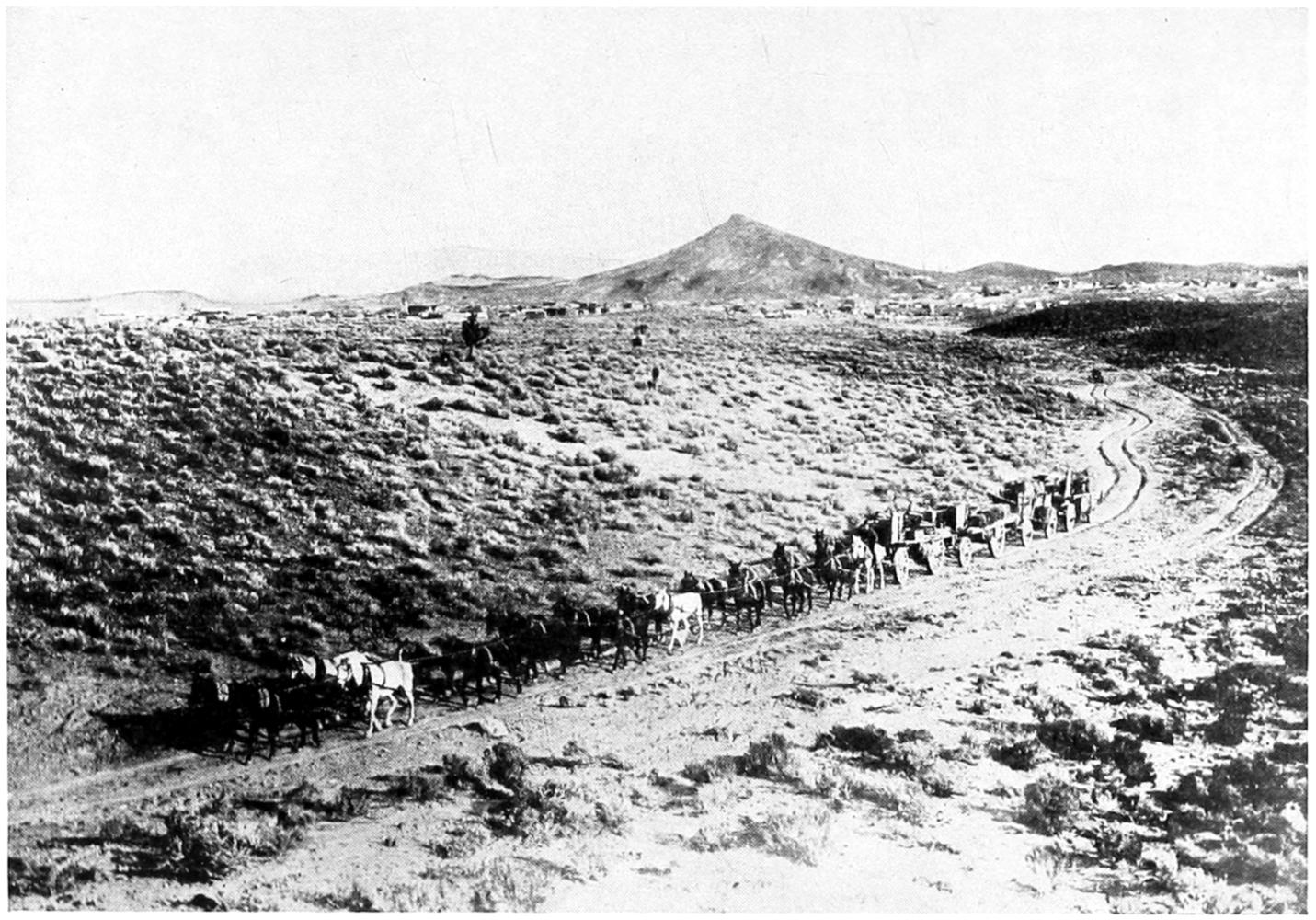

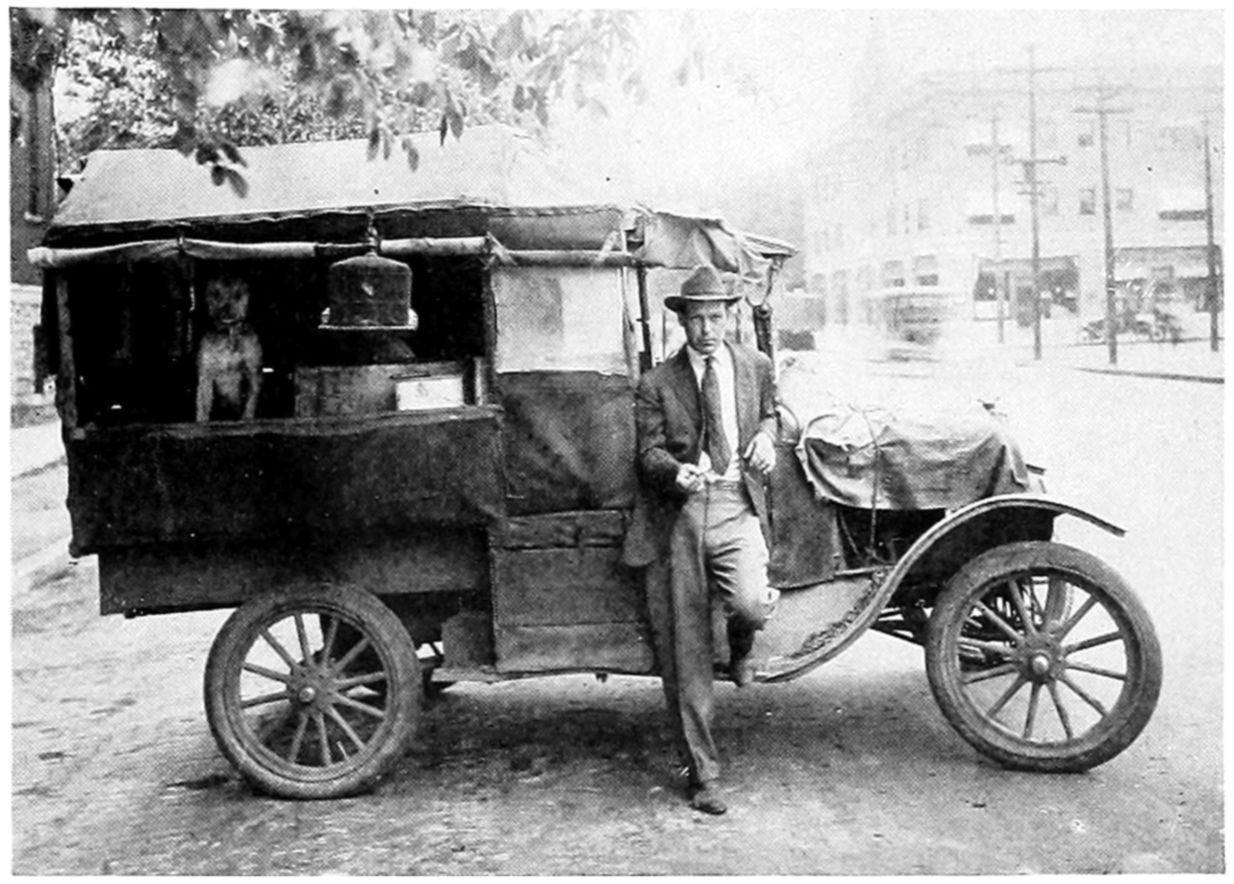

| 12. | Transportation Across Death Valley | 126 | ||

| A Picturesque Method of Earlier Days. | ||||

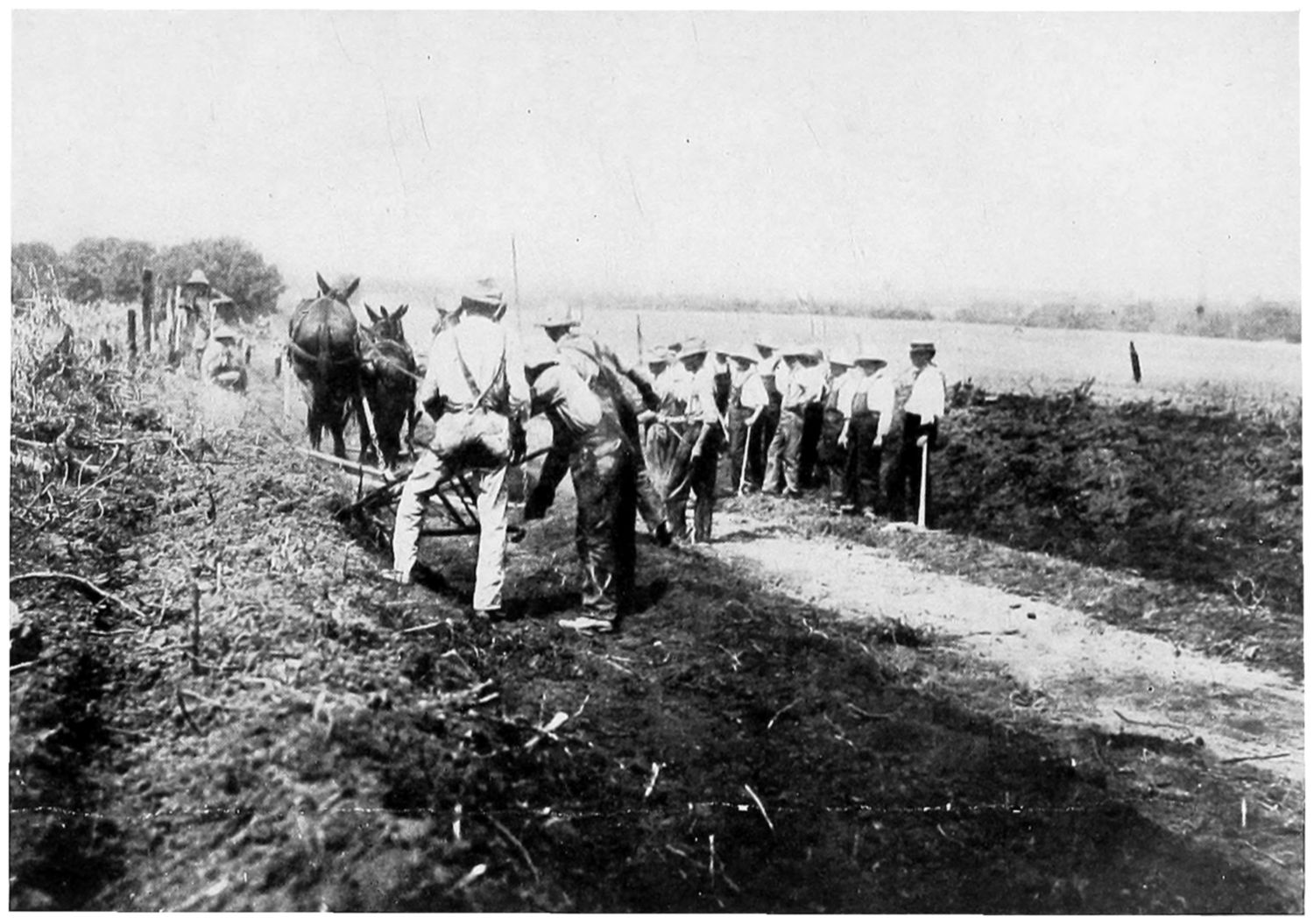

| 13. | Good Roads Day in Jackson County, Mo. | 132 | ||

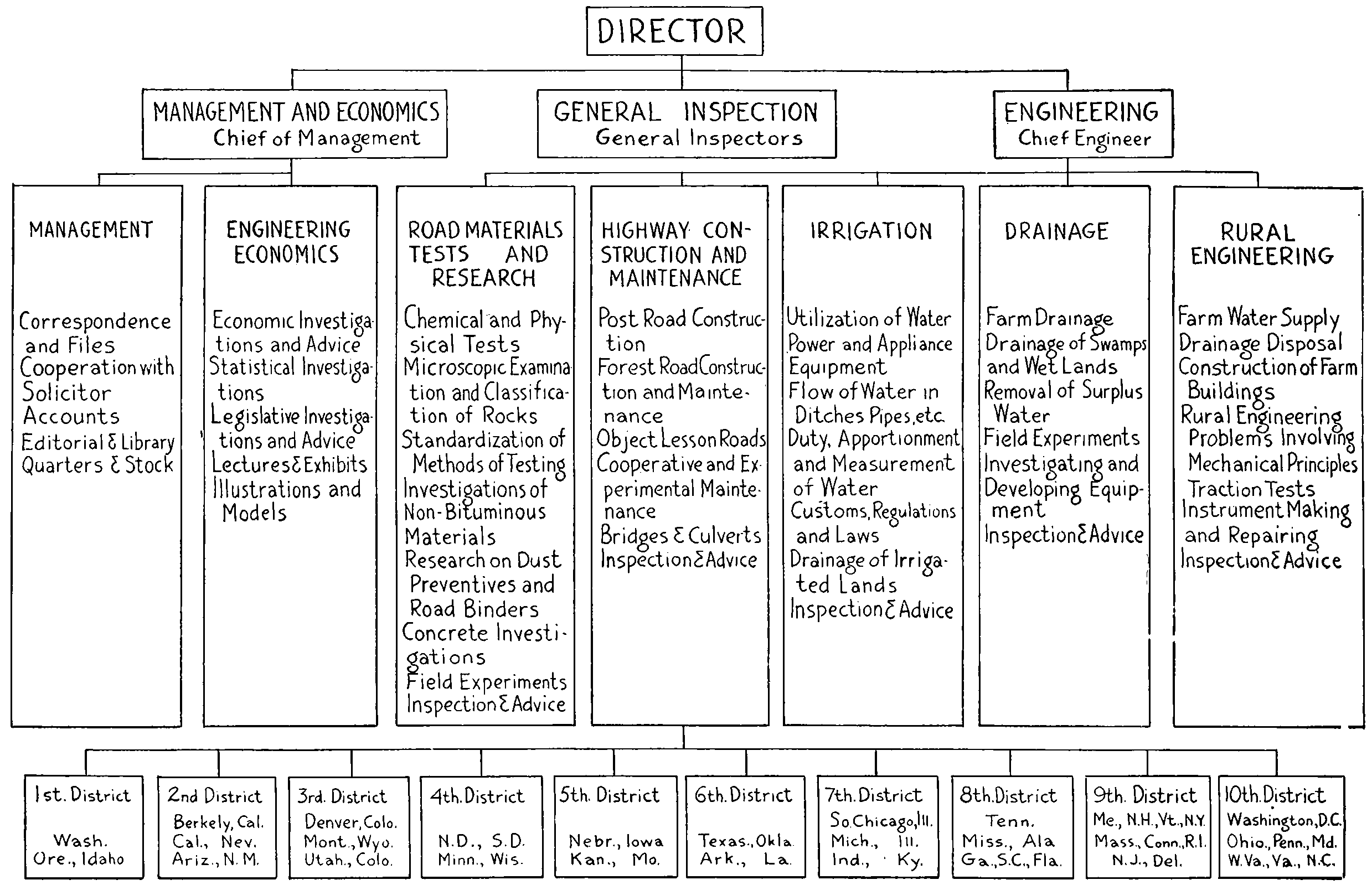

| 14. | Chart of the Organization of the U. S. Bureau of Public Roads and Rural Engineering, 1917 | 142 | ||

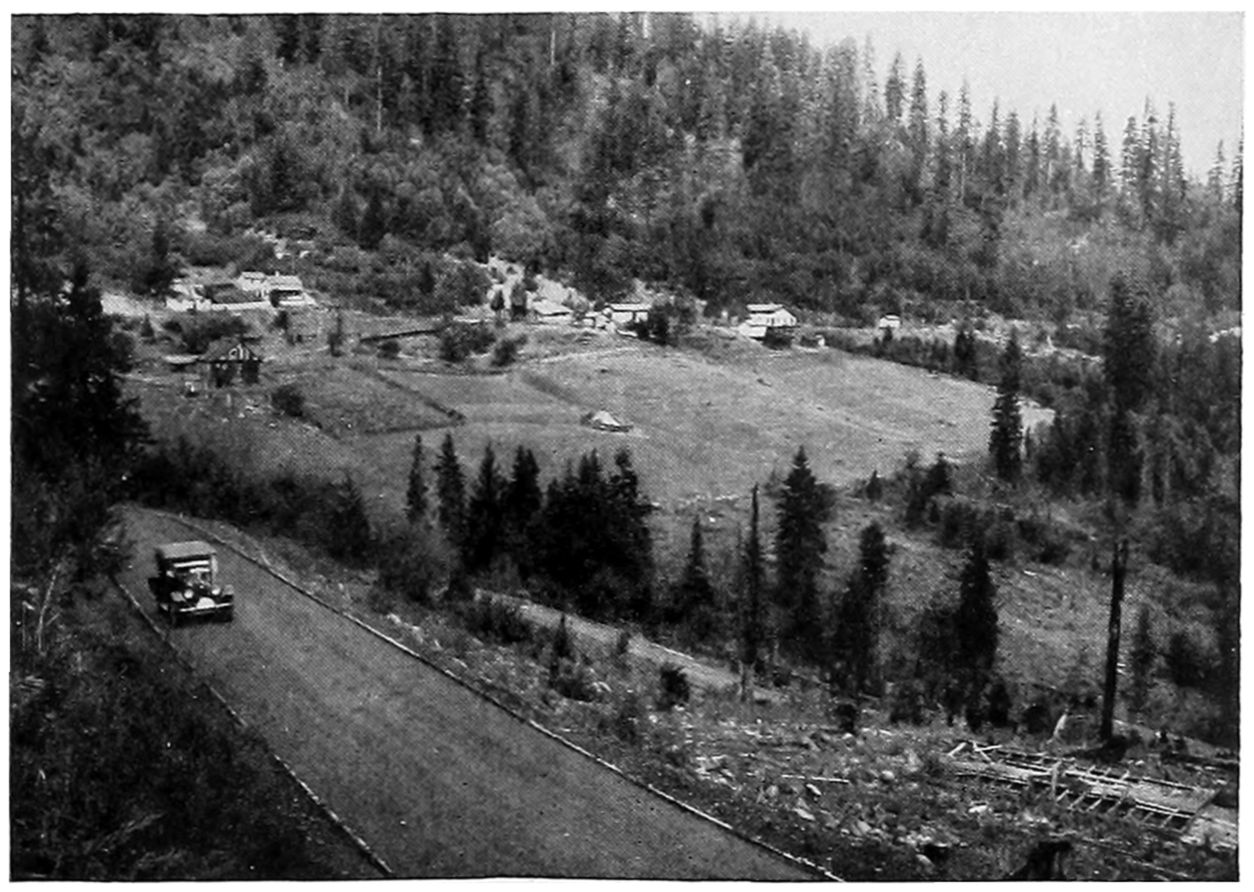

| 15. | Hard Surface Highway in Oregon | 146 | ||

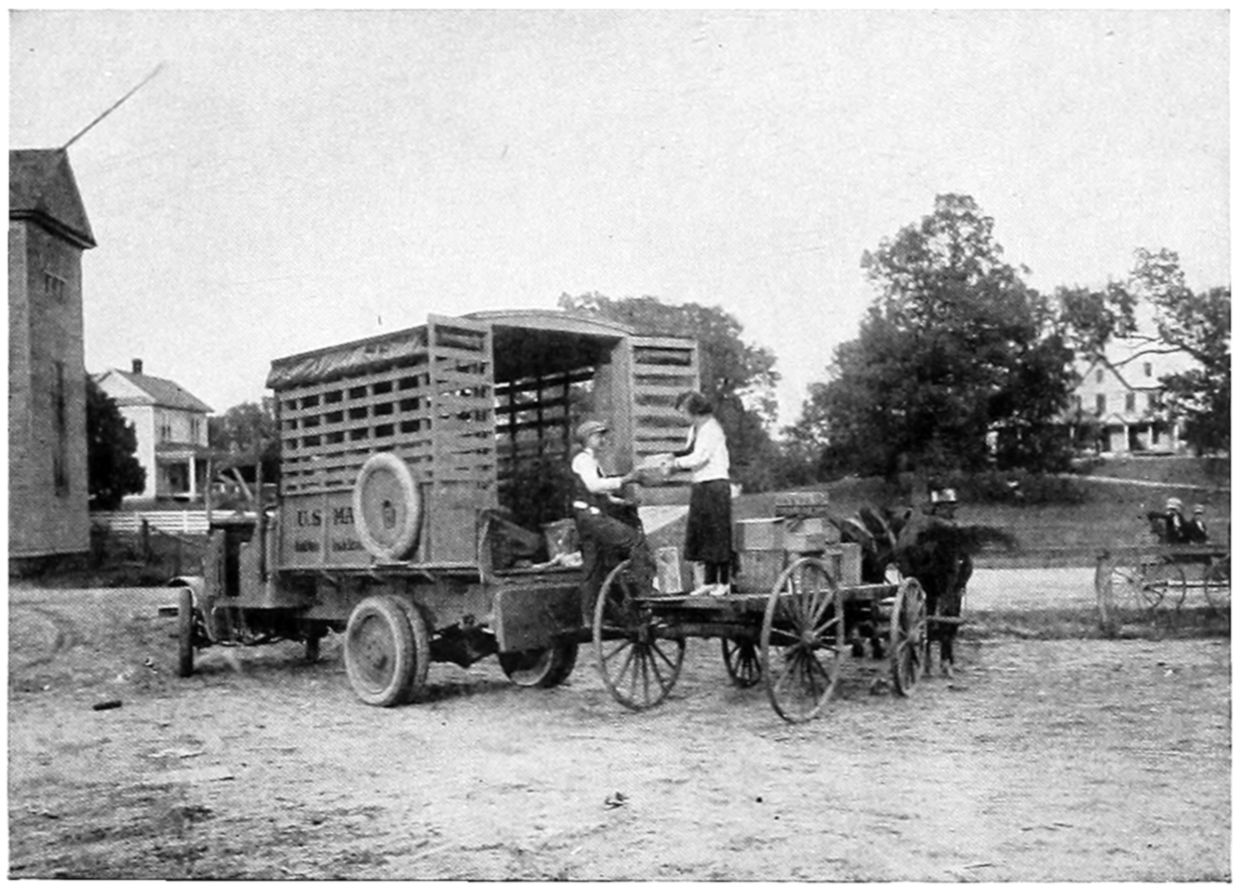

| 16. | A Farmer’s Wife Meeting the Postal Truck | 146 | ||

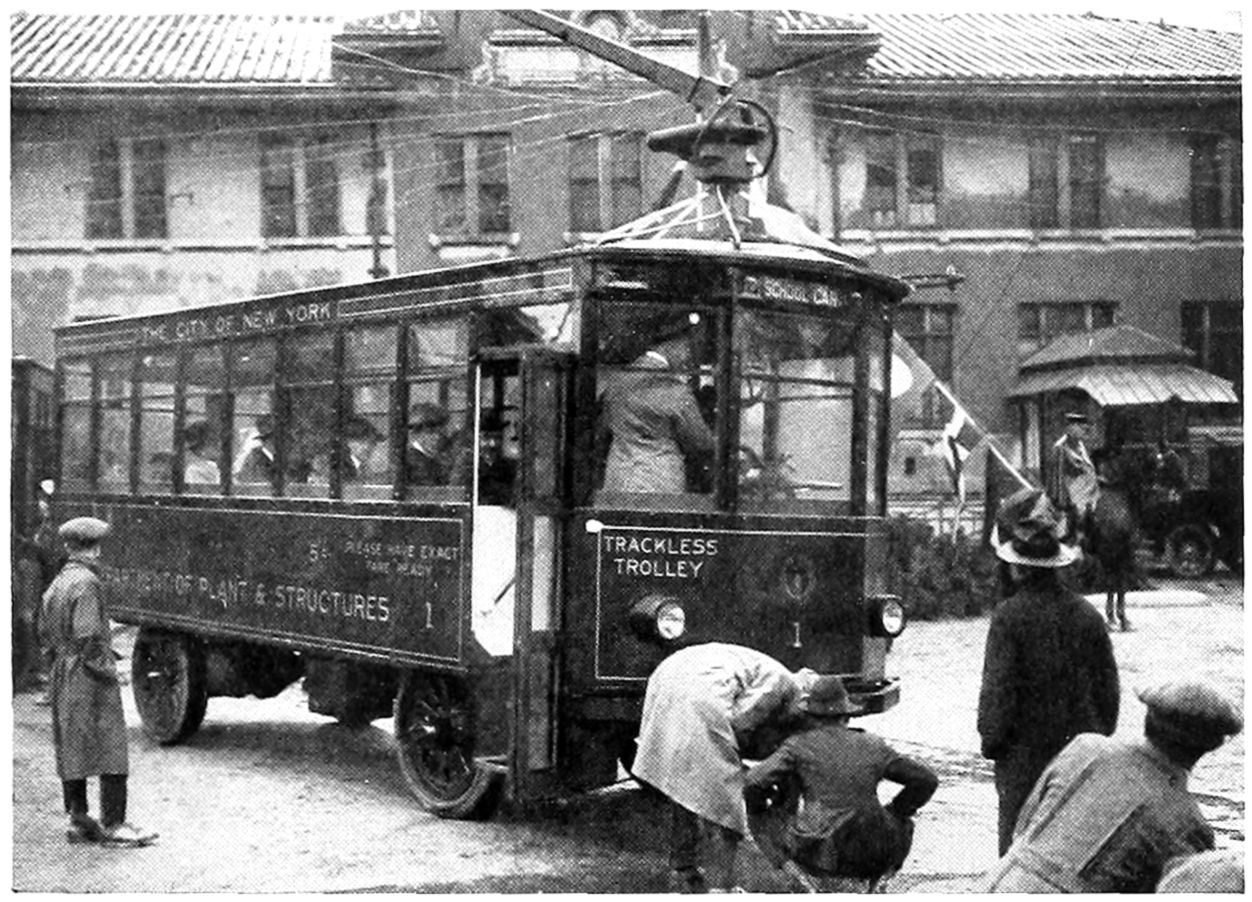

| 17. | Trackless Trolley Operated on Staten Island, N. Y. | 166 | ||

| 18. | Motor or Rail-Car | 166 | ||

| Showing the Gasoline Locomotive and Trailer, Operated by the Chicago & Great Western R. R. | ||||

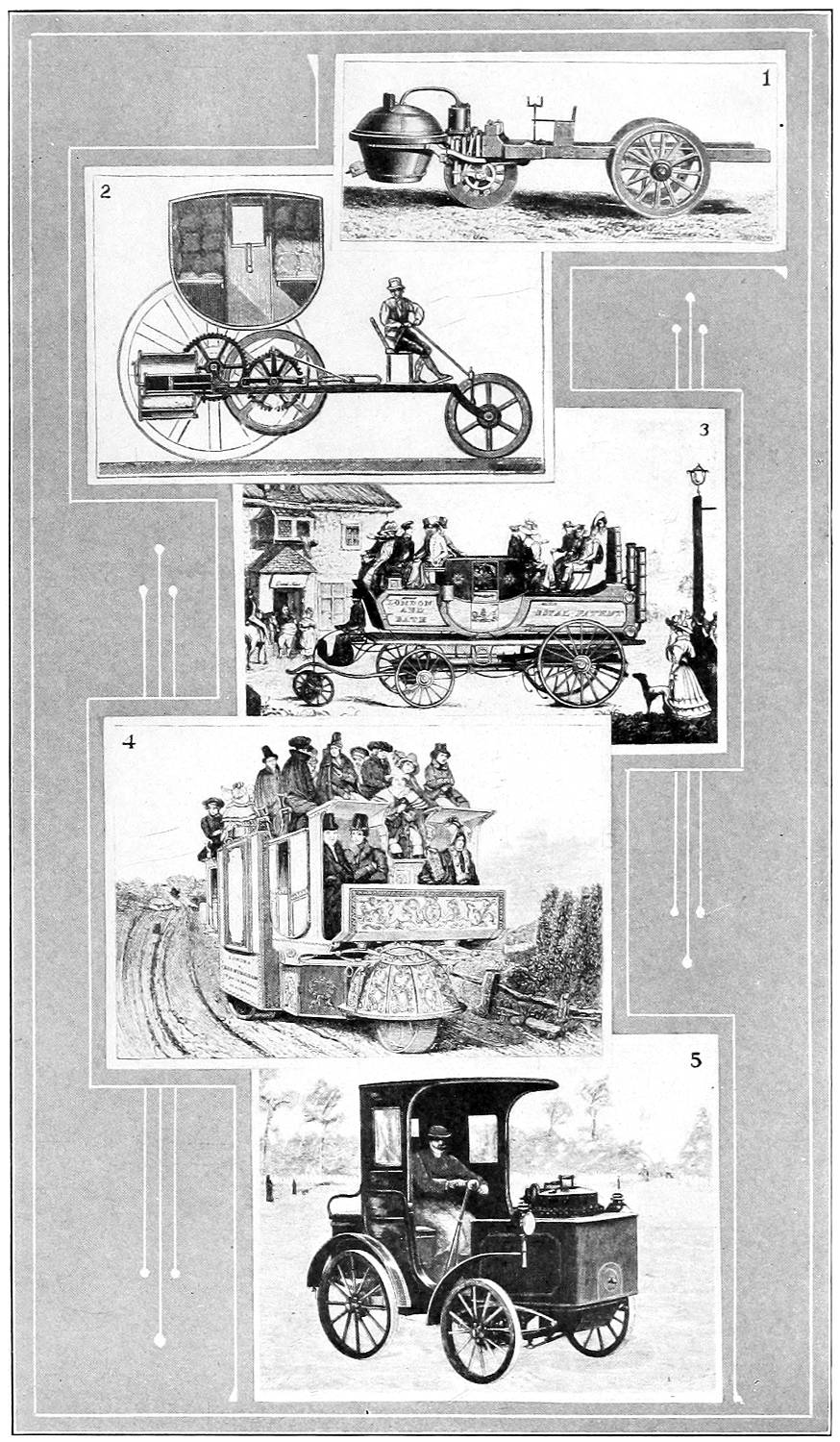

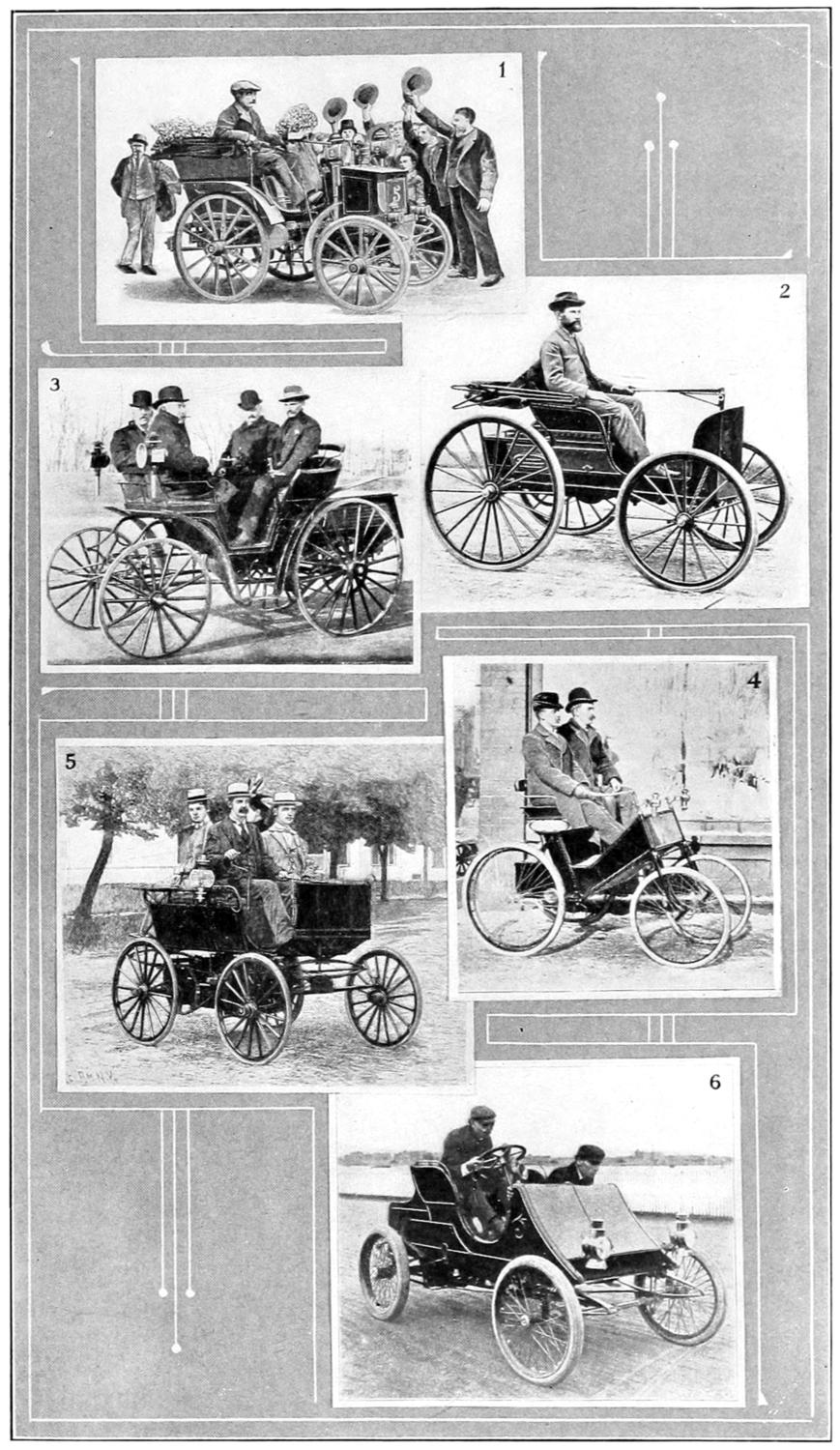

| 19. | The Evolution of the Steam Automobile | 182 | ||

|

||||

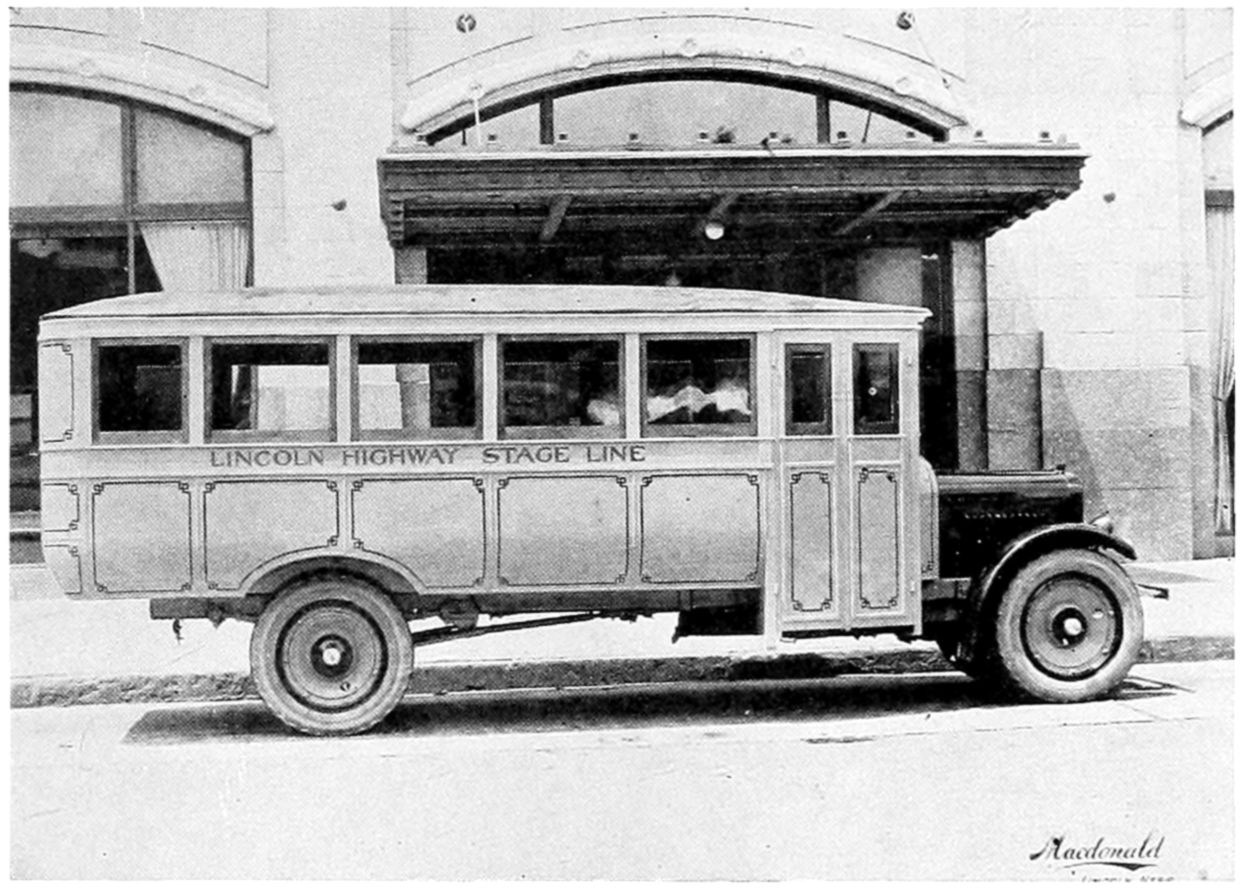

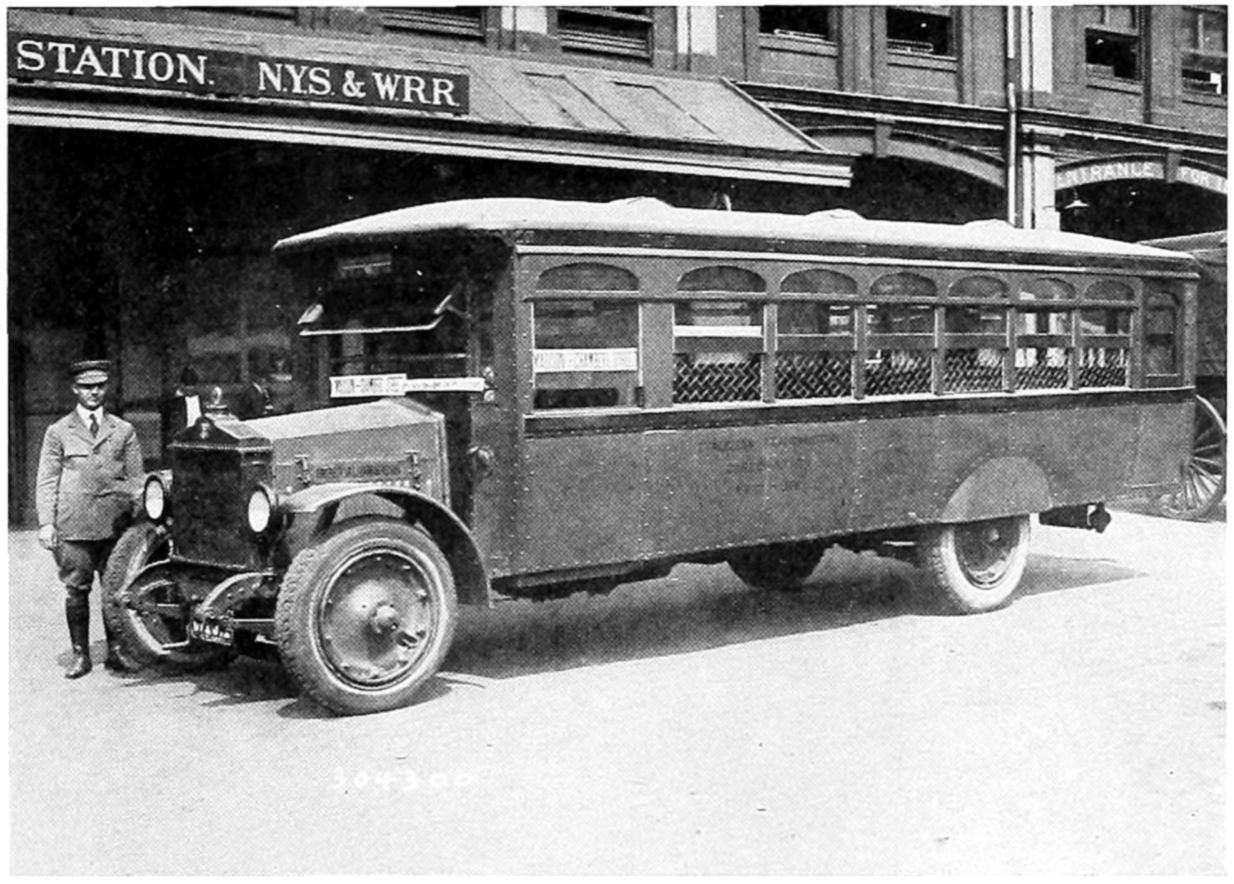

| 20. | A Modern Rural Passenger Bus | 184 | ||

| 21. | A New York City “Stepless” Bus[xix] | 184 | ||

| It Has an Emergency Door, with Wire Window Guards, and will Seat 30 Persons. | ||||

| 22. | The Evolution of the Gasoline Motor Car | 188 | ||

|

||||

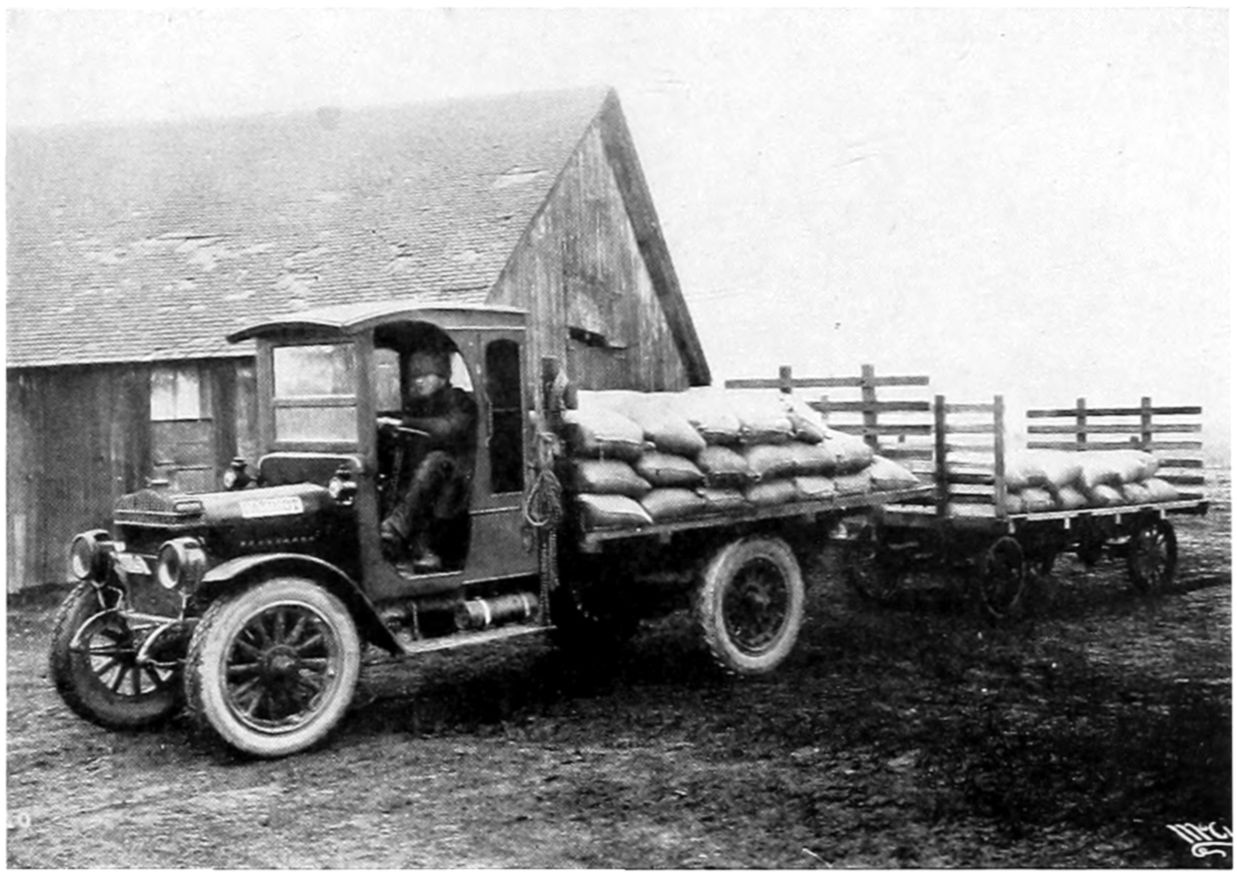

| 23. | Hauling Beans by Motor Truck and Trailer | 200 | ||

| Sacramento Valley, Calif. | ||||

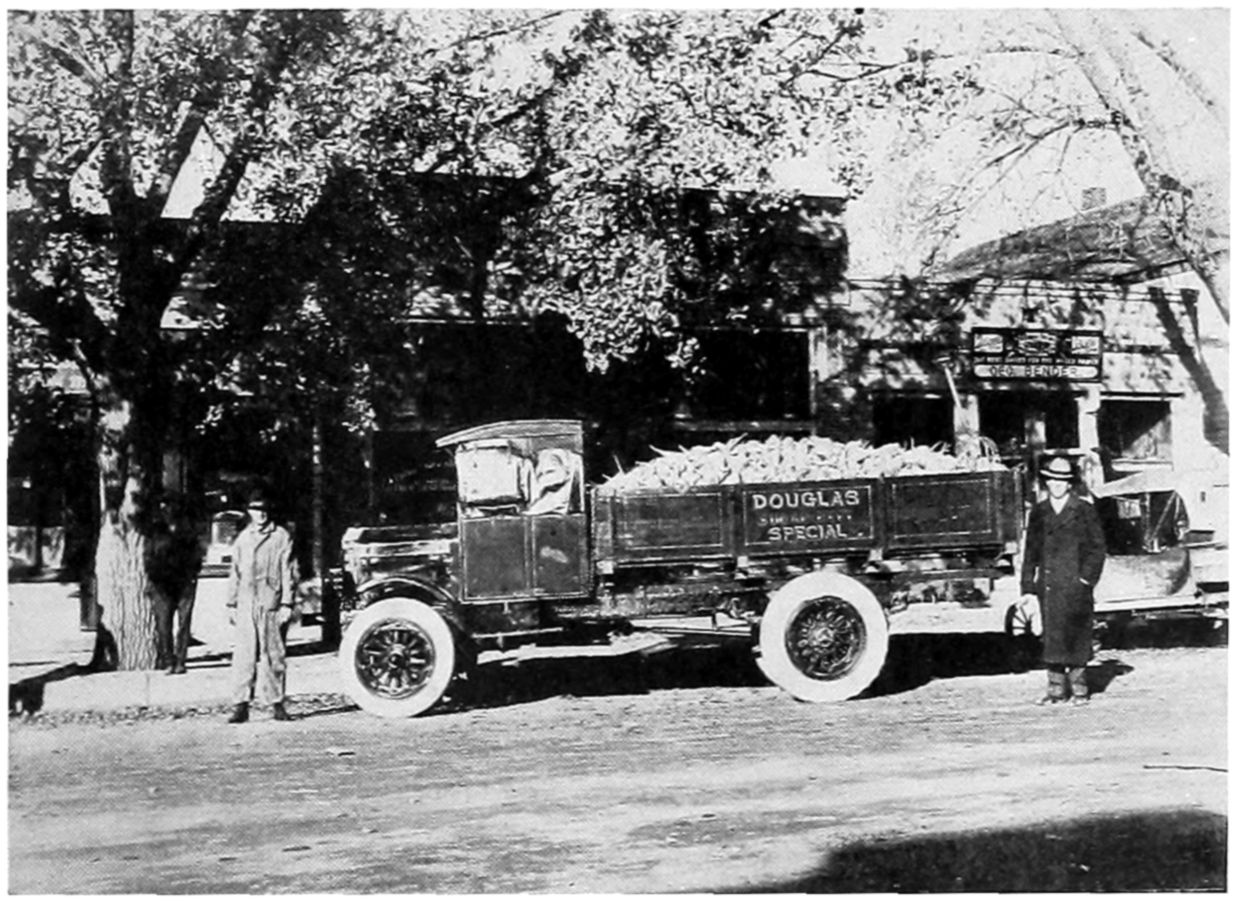

| 24. | Hauling Sugar Beets to Market in a Motor Truck | 200 | ||

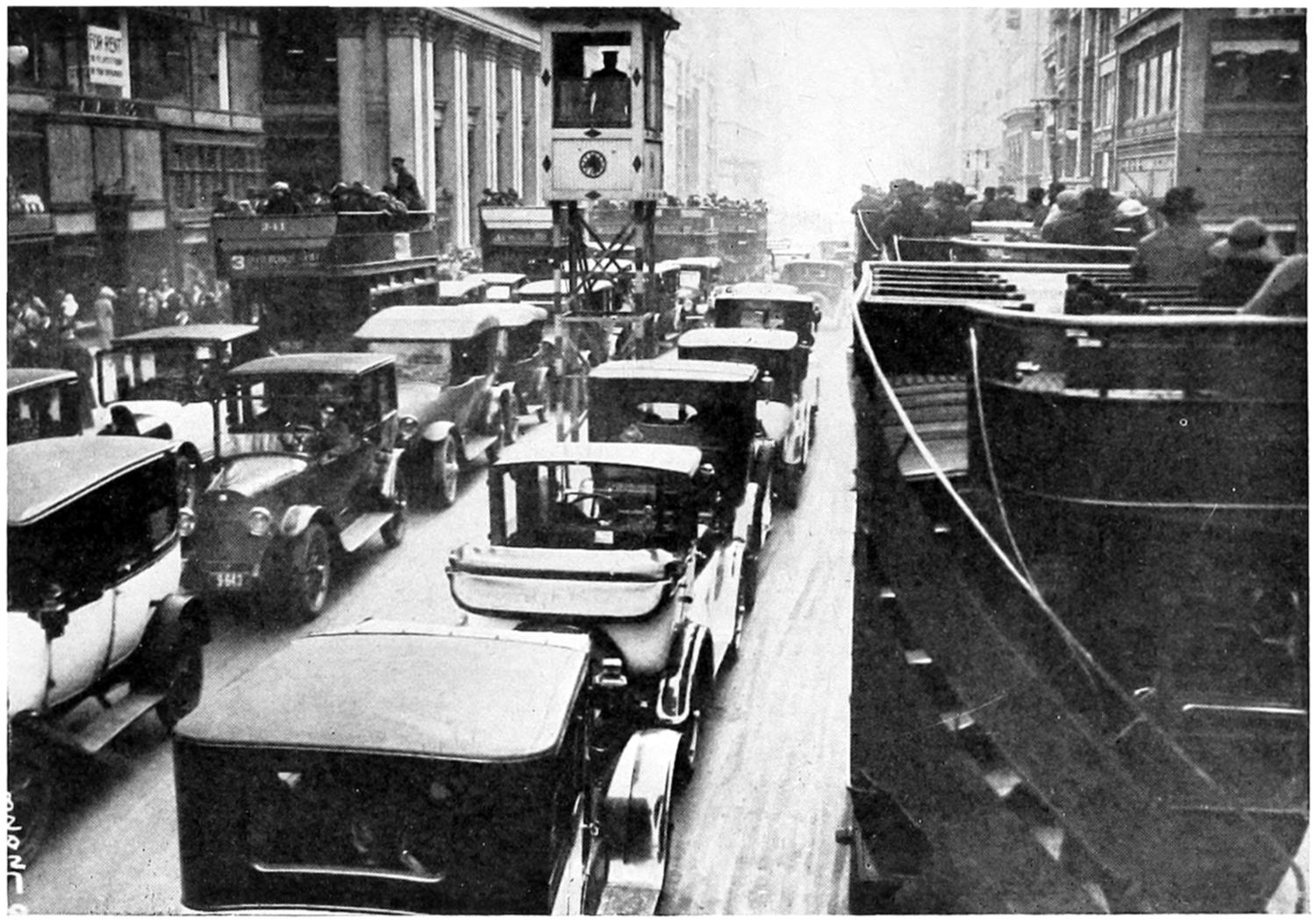

| 25. | Traffic on Fifth Avenue, New York City | 234 | ||

| 26. | Giving a Macadam Road an Application of Tarvia Binder | 254 | ||

| This is Followed by a Coat of Screenings and then the Road is Rolled Again. | ||||

| 27. | A Road of Mixed Asphalt and Concrete Being Tested Out | 254 | ||

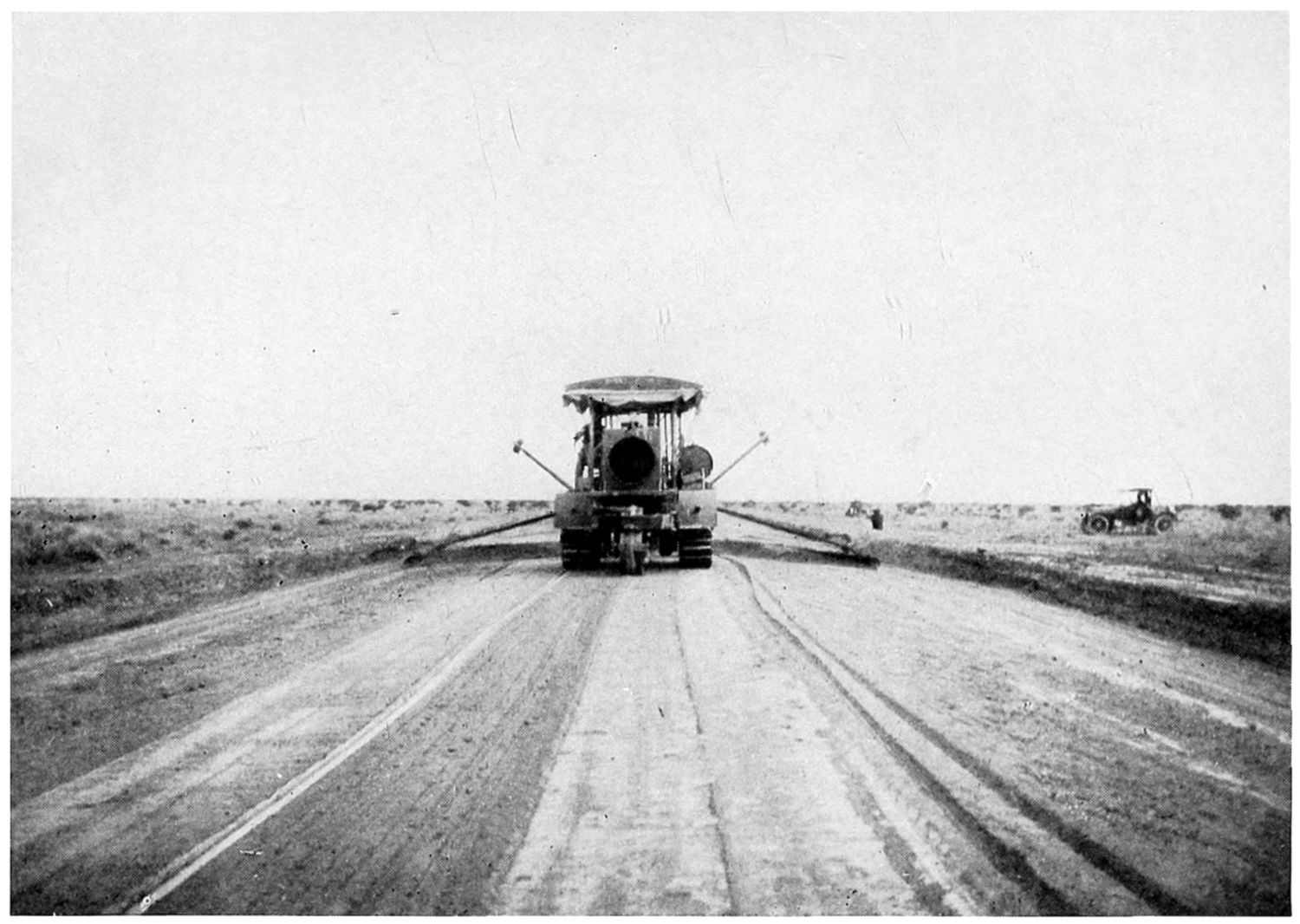

| 28. | Crowning a Dirt Road in California with Tractor Drawn Grader | 263 | ||

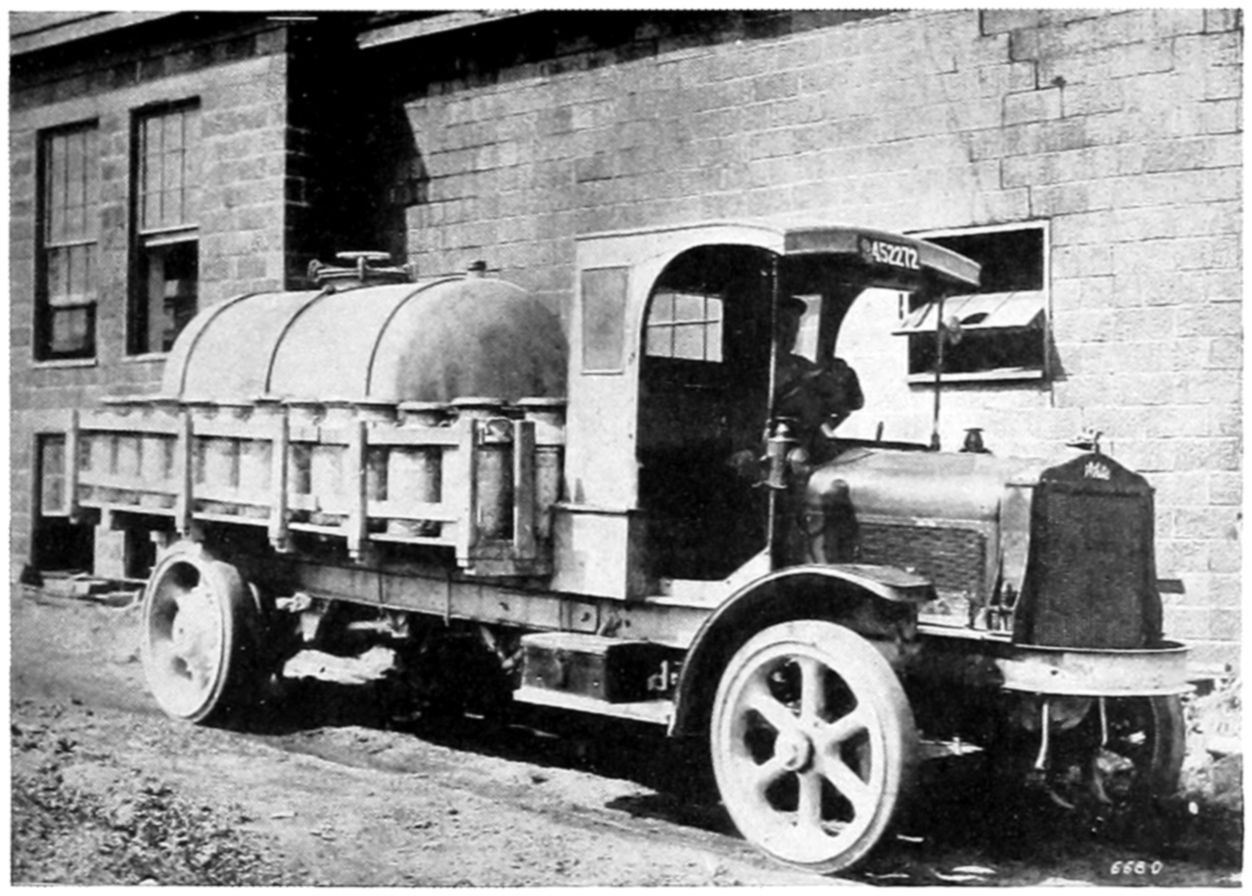

| 29. | A Milk Truck Equipped with both Cans and Tank | 296 | ||

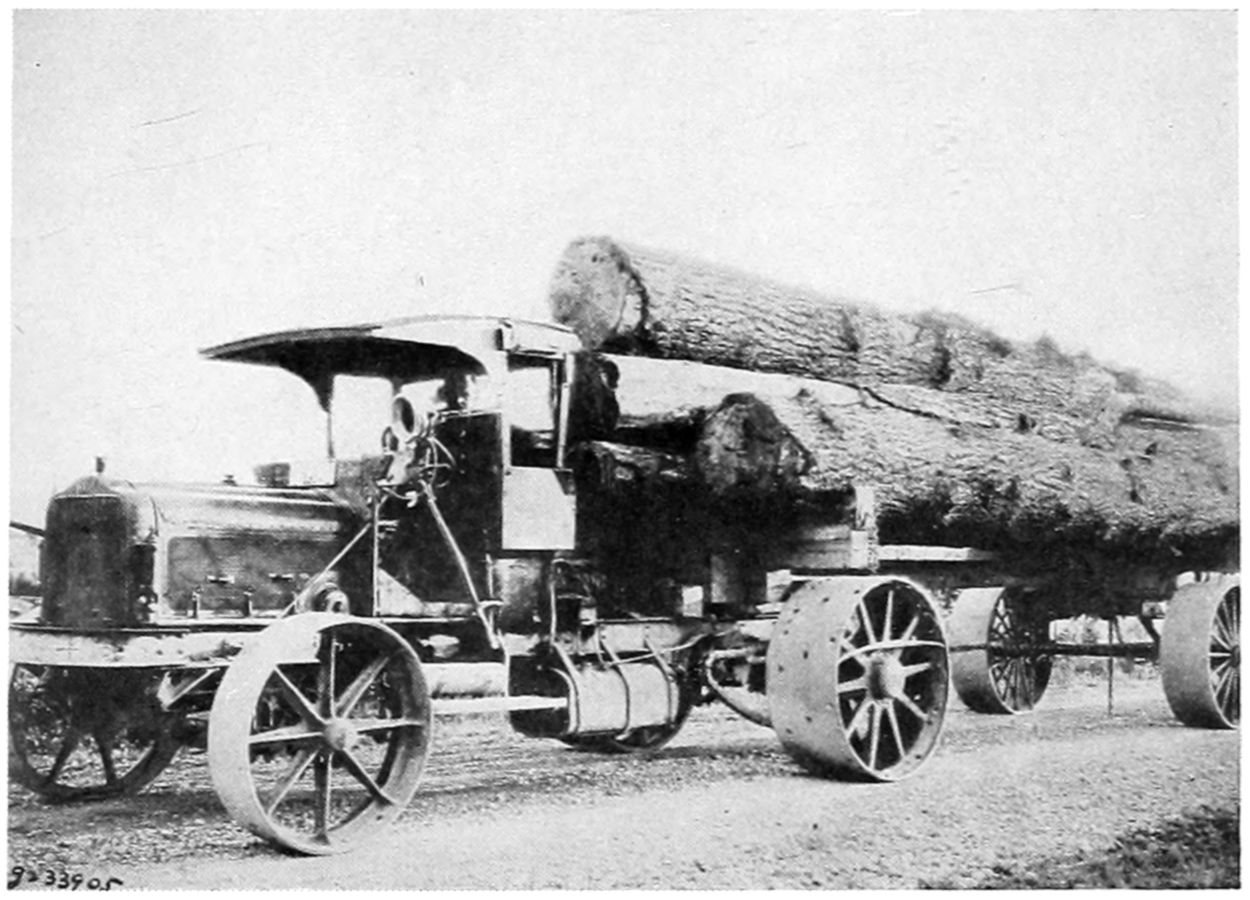

| 30. | A Lumber Log Truck Used in the Northwest | 296 | ||

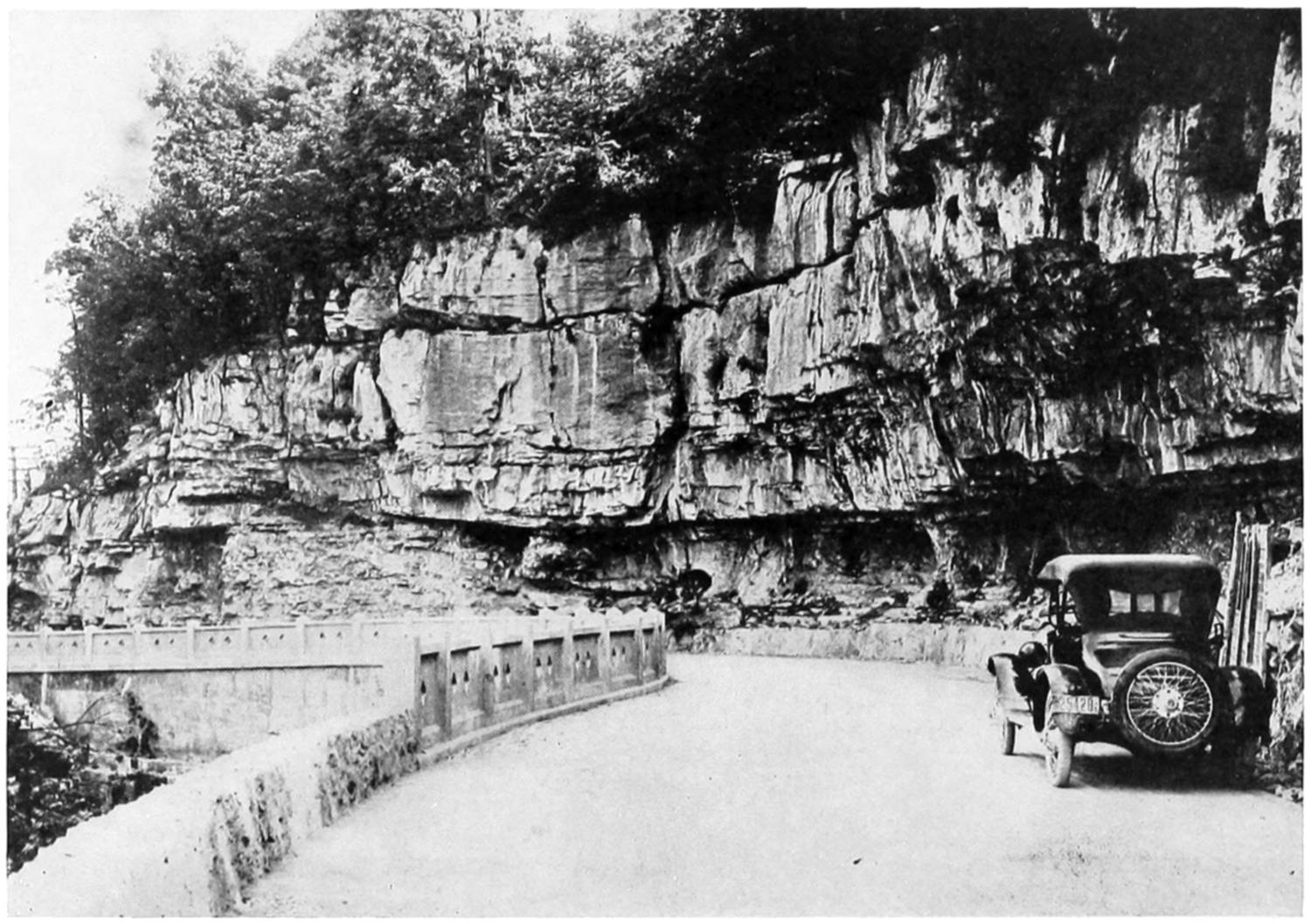

| 31. | A National Highway in the Mountains of Maryland | 332 | ||

| 32. | A Dangerous Curve Made Safe by an Artistic Concrete Wall | 364 | ||

| The Tennessee State Highway at Lookout Mountain, Built of Cemented Concrete. | ||||

| 33. | Pin Oak Street Trees | 388 | ||

| About 15 Years Old on Land that Was Once Considered to be a part of the “Great American Desert.” | ||||

| 34. | A Cottonwood Wind Break | 388 | ||

| Formerly very Common in the Prairie Region. | ||||

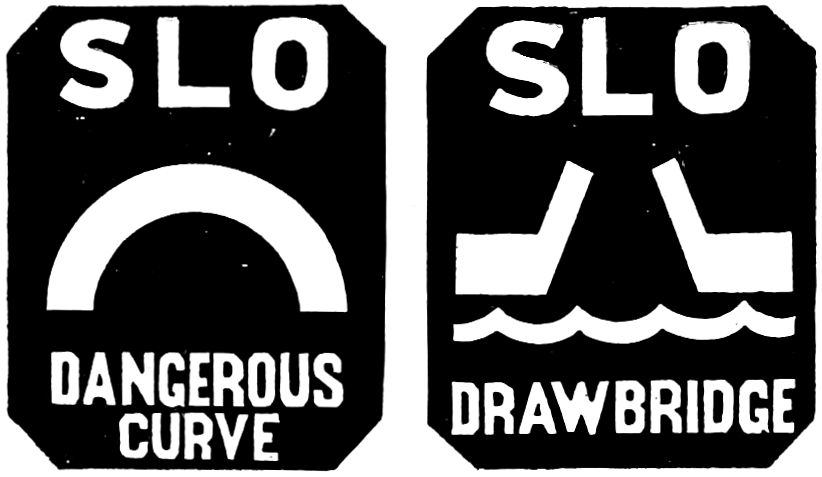

| 35. | Warning and Direction Signs Used in the State of Illinois | 434 | ||

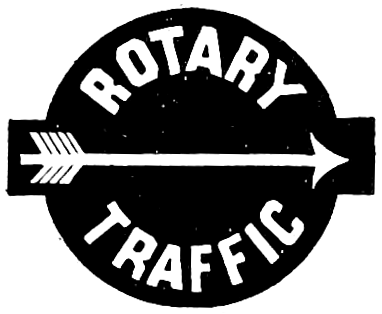

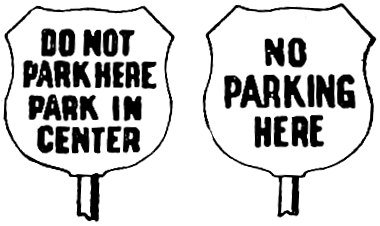

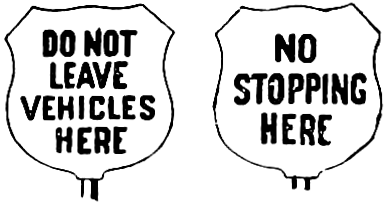

| 36. | Traffic Guides[xx] | 442 | ||

| (From Eno’s “The Science of Highway Traffic Regulation.”) | ||||

| 37. | New York City Traffic Guides | 444 | ||

| “In November, 1903, one hundred blue and white enameled signs, directing slow-moving vehicles to keep near the right-hand curb, were put in use in New York. These were probably the first traffic regulation signs ever used.” (From Eno’s “The Science of Highway Traffic Regulation.”) | ||||

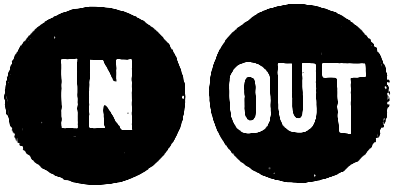

| 38. | Traffic Tower on Fifth Avenue, New York City | 446 | ||

| 39. | Camping Ground and Caravan | 458 | ||

| 40. | A Gipsying Touring Caravan | 458 | ||

[1]

HIGHWAYS AND HIGHWAY TRANSPORTATION

As the several peoples inhabiting the earth have progressed from barbarism through the different stages of civilization, the transportation occasioned by their wants and desires has kept a close pace. By a study of the transportation—travel, movement of goods and commodities—and the means and facilities for its accomplishment, the relative civilization of any people, their rank and position may be accurately surveyed, graduated, and estimated. The highways of a nation, whether they be of the land or sea, or both, are most vital elements in its progress and could almost as well as transportation be considered the measuring rod of civilization.

—Sociologists differ as to what constitute the several stages of civilization. One might trace the development of man through literature, another through art, another through government; others consider his economic activities the more fundamental factors. The most widely used economic classification, according to Ely,[1] is based upon the increasing power of man over nature and consists of (1) Direct Appropriation,[2] (2) The Pastoral Stage, (3) The Agricultural Stage, (4) The Handicraft Stage, and (5) The Industrial Stage. These stages are well illustrated in English history. The stage of direct appropriation corresponding to the prehistoric period and up to 54 B.C., when the Romans overran the island of Britain; the Pastoral stage from this time to the invasion by William the Conqueror, 1066; the Agricultural up to about the discovery of America, when a great impetus was given to travel and discovery; the stage of Handicraft, from 1500 to the invention of the steam engine and its application to manufacture at the beginning of the eighteenth century; the Industrial stage, to the present time. While these stages necessarily overlap each other considerably, it will be seen that as one declines the next is ushered in with some radical change in government or in economic or industrial condition. The present day—immediately following as it does the Great World War, out of which have issued many scientific discoveries and inventions, notably those advancing the theory and practice of air navigation, with many potential possibilities in new lines of transportation; and the setting forth of an idea which is capable of leading to a better understanding or even a confederation of nations and altering all forms of national government—may be the beginning of a new stage of civilization.

—This stage covers the whole course of prehistoric man from the time the first ape stood erect some 500,000 years ago[2] through the stone, bronze, and iron ages to the age of literature and art. During these long years civilization traveled far, for the least cultured savages observed have advanced not only away beyond the highest of the lower animals but also beyond the lowest intellectual estate of which human beings may be supposed capable of subsisting. And from the lowest to the highest of these tribes are shown traits varying as greatly in degree as from one stage in the above classification to another. The Indians at the time of the[3] discovery of America and the three centuries following, and many of the tribes of Africa during the explorations of Livingstone and Stanley, were and still are in this stage and hence have been subjected to scientific study and investigation. Their governments while variable are of the primitive types. Ordinarily a chief autocratically rules because of hereditary influence. Little is manufactured, planting is scarcely known; by hunting, fishing, and collecting nature’s products of wild seeds and roots is a subsistence obtained often with long, arduous, and dangerous labor. Efficiency, as we understand that term to-day, is very low, and the number of persons that a given area can support is few. No one can predict but what to-morrow he may have to go hungry or suffer cold from the inclemency of the weather, for his store of food is nil or small, his shelter rudimentary and clothing scanty. Note the hardships of the party of Henry M. Stanley during his expedition across the African wilderness in quest of Emin Pasha.[3] Notwithstanding Stanley’s men were possessed of firearms and edged tools and carried some provisions with them, and were traversing a country teeming with vegetable and animal life, many times they were on the verge of starvation. The number of the natives in these wildernesses are no doubt kept low because of the extreme difficulties of procuring the necessities of life.

The barbarian requires less, of course, than the civilized man; he is satisfied with mere subsistence. He is improvident and relies upon picking up his needs from day to day as a robin picks worms from the grass. Cannibalism often exists, for the sacredness of human life has not yet been established, although magic and crude religious rites are seldom missing. While private personal property is recognized and retained by personal prowess, the ownership of land is absent. Coöperation of the crudest sort only is found; division of labor consists largely in having the females perform the work of planting, cultivating, carrying[4] burdens—when these are attempted at all—cooking and caring for the children in the crudest fashion, leaving to the men the work of hunting, fishing, and fighting. Each tribe is self-sufficient and consists of a chief with a few followers bound together loosely for the purposes of protection from other tribes. Exchange, barter, and trade is at its lowest ebb; consequently transportation is practically unnecessary, and roadways except mere trails do not exist.

—In the process of evolution certain animals undoubtedly were domesticated and used for food. Whether or not this domestication preceded or followed primitive agriculture or “hoe culture,” is not important, as the pastoral stage of culture evidently lies between the hunting and the farming stages. The written history of mankind indicates that this stage largely prevailed among the earlier Hebrew, Greek, and Teutonic races. A private ownership in cattle and herds was recognized, but the necessity of moving about with the flocks precluded fixed habitations, although large areas were claimed and held or endeavored to be held from trespass thereon by neighboring tribes. A given area would thus support a much larger number of people than in the preceding stage. A small amount of trading or bartering was carried on and consequently some transportation was required, but road building as such was little known. Rivers and coast waters for canoes and dugouts were no doubt early taken advantage of by the aborigines of bordering territories. But since there is so little division of labor, so little of barter and exchange, commerce was not developed much during this stage.

—The growing and storage of crops, increased by the use of animal power, greatly changed the economic and social conditions of man. It made possible and profitable the living in fixed habitations, even in communities, and this brought out the needs of rules of government. But even yet each family provided without the assistance of others for practically all its own needs. In planting, reaping, threshing, grinding the meal and[5] cooking, the family became the unit. No great division of labor was yet evident, consequently exchange, barter, and transportation still remained low. Ownership of land was necessary if a family was to cultivate the same land year after year. This meant definite rules and laws and consequently the development of governments. Ownership of herds and land brought wealth and a certain distinction in the community. Slavery, which had no doubt existed to some extent in the pastoral stage, here, because it greatly increased wealth, grew immensely. Large families likewise meant more workmen and greater wealth, distinction, and leisure, hence polygamy and polyandry often existed. As the evolution continued there was a trend toward handicraft and the division of labor; the products of one place began to be exchanged for the products of other places. This necessitated some forms of transportation, meager though they might be, and trails between communities.

—In England and on the continent during the later years of this stage there were developed the manorial or feudal forms of government. The people lived largely in villages each controlled by a lord or earl (eorl) and to whom in return for his protection, the use of land, and other favors, they were bound to return to him service in the cultivation of his land and in waging war when called upon to do so. The lords in turn held their allegiance to the king. Some handicraftsmen were among the retainers but they were so few that they did not form an important part of the village, neither was there a great deal of travel or transportation. The manor instead of the family was the unit, and it was almost self-sufficient. The land was allotted in small tracts and tilled in the manner designated by the lord. Each person raised barley, oats, peas, and lentils sufficient for his own needs. Variation in crops was little practiced. Much land at distances from the manor was still devoted to herds and flocks.

However, toward the later part of this stage, the feudal system began to break down. There were more free-holders[6] and free-tenants, living upon the land they cultivated according to their own ideas. Wheat, rye, flax, and root crops were assuming greater importance. This variety in farming and the larger fields cultivated by the individual naturally increased the products to be sold or exchanged and hence increased transportation. People who had devoted only so much of their time to spinning and weaving as was necessary to supply their own family needs, were beginning to do more, selling the excess and purchasing from others things not grown or manufactured by themselves. Thus were developed towns as centers of trade; money as a medium of exchange assumed greater importance; and a division of labor brought into being and increased the social standing of trades and professions. Thus was ushered in the Handicraft Stage of civilization.

—In England this stage lasted through approximately five centuries, from 1200 to 1700. The merging of one period into another came about so gradually that a definite date can hardly be designated, and the time is so long that undoubtedly many changes occurred in the economic activities as well as in the government and literature of the people.

While it is probable that merchants, middlemen who bought from one person and sold to another, had thrived throughout the earlier civilizations of Asia, Africa, and Europe, and even extended their trade to Britain, merchandising held a comparatively minor position in England until the twelfth century, when merchants became very prominent, so much so that combinations or guilds were formed by them in all the large towns for the purpose of protecting and controlling the conduct of business and, to some extent, of maintaining a monopolistic control of the trade in their particular businesses. A guild was an association or fraternity of persons engaged in the same line of business. It differed from a trade-union in that the guild was an association of masters and employees, whereas the trade-union is an association of employees only.

Many of the merchant guilds grew wealthy and strong;[7] they obtained Royal Charters from the Crown either by direct payment or by an arrangement to pay a special tax, or secured recognition in the borough charters. By authority of these they were endowed with certain privileges such as: (a) limiting the number of their own members and the number who could participate in any line of merchandising; (b) entering into secret price agreements and trade arrangements; (c) controlling the import and export of wares; (d) the establishing of a court which had absolute jurisdiction over its members and others not members engaged in the same line of business. This court “could settle trade disputes, discipline its apprentices with the whip if necessary, could imprison its journeymen who struck work, and could fine its master members who acted against its rules. And, finally, the members of the company were forbidden to appeal to any other court unless their own court failed to obtain justice for them.”[4] Moreover, the meeting together for social enjoyment, feasting, and worship; the helping one another in sickness and poverty; and uniting together for the pursuit of some common cause, naturally brought about very close and fraternal relations.

—Craftsmen of like occupations joined together in guilds also and they, too, became not only numerous but very influential. They regulated their own internal affairs and specified how many apprentices might be entered, and under what circumstances a man might become a journeyman or master craftsman. Numerous other guilds, social and religious, were extant throughout Europe.

—The merchant guilds and the craft-guilds materially affected the production and trade of the community and country. The merchants of Phoenicia and later of Greece and Rome are said to have visited the British Isles to secure tin and copper. The great merchant guilds outfitted adventures to the ends of the then known[8] world to secure the goods—whether they were silks, spices, furs or grain—in which they dealt. They were instrumental in the passage of laws encouraging and securing commerce. They themselves regulated the quality of goods dealt in. For example the Goldsmiths’ Guild of London required that all silver and gold-plate and jewelry manufactured within three miles of London should be brought to the guild hall for inspection. If it did not come up to the specified standard it was ordered remelted; if it did it received the “Hall Mark” that anyone purchasing it might be assured of its quality. It is said the guilds were so punctilious in the matter of quality that “Made in England” goods received in the markets of the world a standing of the highest rank; a reputation that never entirely disappeared, and as a consequence English uprightness of character became proverbial.

—All this made necessary the building of ships and harbors, and the improvement of internal highways of trade, and these in turn stimulated manufacture which as yet was carried on by hand. The family instead of the town or guild became the unit; apprentices were entered and kept, usually, as members of the family and worked along side the sons and daughters of the master. As these grew to manhood their pay, beginning with mere keep, was gradually increased with their work and responsibility until at the end of seven years they were fitted to go forth as journeymen and later themselves became masters. The work was done at or near the master’s home. The raw material was usually received from a middleman, to whom was returned the finished product; the middleman disposed of it to the merchant who in turn sold it to the consumer.

This corresponds rather closely to what is called the “sweat shop” method of the present time. Goods in a raw or a semi-raw state are received by the workman from the “manufacturer” and carried home; the workman performs, with the help of his family, certain specified operations and upon the return of the goods is paid for his work.[9] Or in agriculture, to the contract method, whereby specified products such as sugar beets, sweet-corn, peas, beans, tomatoes, fruits, and other products for manufacture, canning, preserving, or pickling in a factory, are raised by the farmer and sold to the manufacturer at a previously agreed-upon contract price. Under the guild plan the manufacturer or importer sold usually to the ultimate consumer. So the economic system was gradually growing more complex, and the interdependence of man upon man more pronounced.

The older agricultural procedure had not entirely disappeared. Most families cultivated land, and raised more or less stock and poultry, but performed the work of manufacturing as a side line, as at present in the Middle West farmers make grain and stock raising their main industry with dairying, vegetable gardening, poultry, and eggs as mere adjuncts, although these latter often bring in about as much money as the former. Defoe[5] describes these methods (1724-1726) as follows:

[The land] was divided into small inclosures from two acres to six or seven each, seldom more; every three or four pieces of land had a house belonging to them ... hardly an house standing out of a speaking distance from another.... We could see at every house a tenter, and on almost every tenter a piece of cloth or kersie or shaloon.... At every considerable house was a manufactury.... Every clothier keeps one horse, at least, to carry his manufactures to the market, and everyone generally keeps a cow or two or more for his family. By this means the small pieces of inclosed land about each house are occupied, for they scarce sow corn enough to feed their poultry.... The houses are full of lusty fellows, some at the dye-vat, some at the looms, others dressing the cloths, the women or children carding or spinning, being all employed, from the youngest to the oldest.

—The numerous guilds reached their zenith during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and then gradually diminished in importance. Some of them, however, still remain active in London. During the[10] recent World War several were engaged in welfare work. Guilds in France were destroyed or lapsed into desuetude during the revolution, 1791-1815. Those of Spain and Portugal likewise during the revolutionary years of 1833-40; of Austria and Germany in 1859-60 and of Italy in 1864. Guilds, as known in Europe, never found a substantial lodging in the United States.

The functions of the guilds were gradually taken over by the government, which seemed later to be a better and more satisfactory medium to control labor, trade, and commerce. Laws were enacted in England to regulate the entering of apprentices, to force able bodied men to serve as agricultural laborers in case of need, and to work the roads annually. Justices of the Peace were given authority to settle disputes and regulate wages. Foreign trade was by laws and Royal Grants encouraged; likewise immigration of artisans to introduce new industries, the establishment of foreign colonies and the development of banking and insurance. Almshouses were built and poor laws enacted to care for the old and indigent. The public roads were still very poor but a beginning was made for their betterment. Macaulay, in writing of the State of England in 1685,[6] has considerable to say regarding the condition of the highways. Speaking of the lack of homogeneity among the people he says:

There was not then the intercourse which now exists between the two classes. [The Londoner and the rustic Englishman.] Only very great men were in the habit of dividing the year between town and country. Few esquires came to the capital thrice in their lives. [And again], The chief cause which made the fusion of the different elements of society so imperfect was the extreme difficulty found in passing from place to place. Of all inventions, the alphabet and the printing press alone excepted, those inventions which abridge distance have done most for the civilization of our species. Every improvement of the means of locomotion benefits mankind morally and intellectually as well as materially, and not only facilitates the interchange of the various productions of nature and art, but tends to remove[11] national and provincial antipathies, and to bind together all the branches of the great human family.

[Further on], It was by the highways that both travellers and goods generally passed from place to place; and those highways appear to have been far worse than might have been expected from the degree of wealth and civilization which the nation had even then attained.

The degree of civilization attained was no doubt due to other things than the public roads. Sea transportation brought to England the products of the world. Coast transportation was well developed and river and canal transportation had well begun. Macaulay states that

One chief cause of the badness of the roads seems to have been the defective state of the law. Every parish was bound to repair the highways which passed through it. The peasantry were forced to give their gratuitous labor six days in the year.... That a route connecting two great towns, which have a large and thriving trade with each other, should be maintained at the cost of the rural population scattered between them, is obviously unjust.

This sounds like modern arguments against paving rural roads and charging the cost to the abutting property, and is evidently one good reason for state and national aid.

However, transportation and travel continued to improve. On the main roads “waggons” were employed to transport goods and stage coaches for people, while pack animals and riding horses were used on less frequented trails and roads. Four and six horses were necessary to pull a carriage or a coach “because with a smaller number there was great danger of sticking fast in the mire.” A diligence ran between London and Oxford in two days, but in 1669 it was announced that the “Flying Coach would perform the whole journey between sunrise and sunset.” The heads of the university after solemn deliberation gave consent and the experiment proved successful. The rival university at Cambridge, not to be outdone, set up a diligence to run from Cambridge to London in one day. Soon flying coaches were carrying passengers to other points. Posts were established for the change of horses and longer[12] distances essayed. This mode of traveling was extolled by contemporaneous writers “as far superior to any similar vehicles ever known in the world.” It is not to be thought that these advances in rapid transportation were without objectors. According to Macaulay,

It was vehemently argued that this mode of conveyance would be fatal to the breed of horses and to the noble art of horsemanship; that the Thames, which had long been an important nursery of seamen, would cease to be the chief thoroughfare from London up to Windsor and down to Gravesend; that saddlers and spurriers would be ruined by hundreds; that numerous inns, at which mounted travelers had been in the habit of stopping, would be deserted, and would no longer pay any rent; that the new carriages were too hot in summer and too cold in winter; that the passengers were grievously annoyed by invalids and crying children; that the coach sometimes reached the inn so late that it was impossible to get supper, and sometimes started so early that it was impossible to get breakfast.

Objections of this character have been made against every innovation and advancement in travel and transportation to the present day when the air-plane is beginning to attract notice as an economic vehicle. Laws were then demanded and passed, as they are now, to regulate power and speed, accommodations and rates, and multifarious other things which might affect the privileges or profits of those interested in older methods, as well as laws for the protection and safety of the general public.

—It might be thought that the agriculture of the preceding stage of development might wane. But not so; with the division of labor and improved transportation and marketing facilities agriculture received a great impetus. Larger tracts were farmed by the individual. Growing crops and stock became more of a business and from the lords of the manor was evolved the landed aristocracy of the country. To be sure, there were holders who cultivated their own soil, but much was held upon leaseholds for short or long periods. Many still lived in the villages where “commons” were laid out for the pasturage of the few cows each family needed for its own milk.[13] Farms were divided by hedges into fields or closes, the amount of land depending upon the rent. The “Book of Surveying,” by Fitzherbert, 1539, gives reasons for such closes and explains the manner of laying them out so that they shall be most convenient and together. The following is a specimen of his style:

Now every husband hath sixe severall closes whereof iii. be for corne, the fourthe for his leyse, the fyfthe for his commen pastures, and the sixte for his haye; and in wynter time there is but one occupied with corne, and then hath the husbande other fyue to occupy tyll lent come, and then he that hath his falowe felde, his ley felde, and his pasture felde al sommer, and when he hath mowen his medowe then he hath his medowe grounde, soo that if he hath any weyke catel that wold be amended, or dyvers maner of catel, he may put them in any close he wyll, the which is a great advantage; and if all should lye commen, then wolde the edyche of the corne feldes and the aftermath of all the medowes be eaten in X or XII dayes. And the rych men that hath moche catel wold have the advantage, and the poore man can have no helpe nor relefe in wynter when he hath most nede; ... and if any of his thre closes that he hath for his corne be worn or ware bare, then he may breke and plowe up his close that he had for his layse, or the close that he had for his commen pasture, or bothe, and sowe them with corne and let the other lye for a time, and so shall he have always reist grounds, the which will bear moche corne, with lytel donge; and also he shall have a great profyte of the wod in the hedges when it is growen; and not only these profytes and advantages aforesaid but he shall save moche more than al these, for by reason of these closes he shall save meate drinke, and wages of a shepherde, the wages of the heerdmen, and the wages of the swineherde, the which may fortune to be as chargeable as all his holle rent; and also his corne shall be better saved from eatings or destroying with catel.

Later the system of crop rotation came into vogue resulting in great improvement in the fertility of the soil.

In the same author’s “Book of Husbandry,” 1534, are described farm tools and their uses. There are explanations to show where a “horse plow” is better and where an “oxen plow.” It indicates that beans, peas, wheat, barley, and oats are common crops, and that some vegetables and root-crops were coming into use. Wheat was[14] probably sowed after plowing up a pasture or “fallowe” field, for he observes,

the greater clottes (clods) the better wheate, for the clottes kepe the wheate warm all wynter; and at march they will melte and breake and fae in many small peces, the which is a new donynge and refreshynge of the corne.

The industries and arts of transportation continued to develop: ocean craft, especially, became more numerous and more efficient. Learning and art grew in harmony as the intercourse of the peoples of the country and of the world increased.

—This stage of economical civilization, while brought about gradually through many years as factories and special work shops came into existence, was nevertheless greatly accelerated by the inventions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The invention of the canal lock (it is a disputed question whether in Holland or in Italy) in the fourteenth century had made practicable the building of many canals throughout Europe, one of the largest across France connecting the Bay of Biscay with the Mediterranean Sea. However, the building of important commercial canals began in England with the Bridgewater Canal from Worsley to Manchester, completed in 1767. Green[7] tells us that the main roads which lasted fairly well through the middle ages had broken down under the increased production of the eighteenth century. That the new lines of trades lay along “mere country lanes”; that much of the woolen trade had to be carried on long trains of pack animals at a large cost; that transportation “in the case of heavier goods such as coal distribution was almost impracticable save along the greater rivers.” In fact coal was ordinarily referred to as “sea coal” because it was brought to most ports by water routes. The Duke of Bridgewater and a young engineer[15] of the name of Brindley solved the problem of transportation for the time being by beginning the great network of canals which later covered England to the extent of more than 3000 miles. Too great praise cannot be given to the engineers and constructors of these canals. Brindley considered canals not as adjuncts of rivers and bays, on the contrary “rivers were only meant,” he said, “to feed canals.” He carried this canal by means of an aqueduct over the river to Manchester, thus bringing the coal to a new thriving manufacturing city. Green further says (Paragraph 1528)

To English trade the canal opened up the richest of all markets, the market of England itself. Every part of the country was practically thrown open to the manufacturer; and the impulse which was given by this facility of carriage was at once felt in a vast development of production. But such a development would have been impossible had not the discovery of this new mode of distribution been accompanied by the discovery of a new productive force. In the coal which lay beneath her soil England possessed a store of force which had hitherto remained almost useless.

Not the least were the new methods of smelting iron with coal instead of wood, which changed the whole aspect of the iron trade and which made Great Britain for many years the workshop of the world. Lead, copper, and tin were also mined and smelted by the use of coal. The great advance of the “industrial revolution” did not come until Watt’s improvements upon the steam engines of Newcomen, Cawley, and Savery, which were themselves improvements over earlier inventions of Papin, della Porta, and Worcester, made practicable the transfer of energy stored up in coal to the movement of machinery. He changed the steam engine from a clumsy, wasteful, inefficient machine into a workable apparatus little differing from the reciprocating steam engines of the present. Up until the successful operation of the turbine engine, the principal advances upon Watt’s engine were mere details, though often of great importance. For instance the boilers for the generation of steam were improved;[16] the enlarged application of the principle of expansion, developing better cut-off mechanisms and governors, to more economical construction due to better facilities and better knowledge of materials and their properties; and to the application of the steam engine in locomotives to propel transportation cars.

Watt’s claims and specifications for patents from 1769 to 1784 cover such inventions as:

1. Methods of keeping the cylinder or steam vessel hot by covering it with wood or other slow heat-conducting materials, by surrounding it with steam or other heated bodies, and by suffering no water or other substance colder than steam to touch it.

2. By condensing the steam in vessels entirely distinct from the cylinder, called condensers, which are to be kept cool.

3. By drawing out of the condenser all uncondensed vapors or gases by means of an air pump.

4. The use of the expansion force of steam directly against the cylinder.

5. The double-acting engine and the conversion of the reciprocating motion into a circular motion.[8]

6. Throttle valve with governor and gear for operating the same, parallel motion for opening and closing the valves, and indicator.

These inventions not only made it possible to replace hand-labor often with machines, but made it possible to construct machines much more rapidly and to make them in every way more convenient.

Improvement in the arts of spinning and weaving caused the textile establishments and population of north England to go forward by leaps and bounds.

Previous to the invention of the “fly shuttle” in 1733 by John Kay of Bury, the weaver had to throw the shuttle through the warp by hand. Weaving became much more[17] rapid; also by having several shuttles with different-colored yarn stripes and checks could be woven into the cloth. Since weaving had been made quicker and easier there came a demand for more yarn. Three separate inventions satisfied this, viz., James Hargreaves of Blackburn invented his “jenny” about 1767, by which eight threads could be spun at once. At the same time Richard Arkwright, a barber of Preston, invented and developed the throstle spinning frame (1769-1775). Samuel Crompton, about 1775, invented his spinning “mule,” which seemed to combine the good principles of the others. Power was applied to spinning about 1785 and then it was weaving that needed accelerating. To Cartwright in 1784 is ascribed the honor of inventing the power loom. Other inventions for both spinning and weaving have made almost automatic the running of thousands of spindles and hundreds of looms in a single factory.

—With power manufacturing and increased production due to the adoption of improved factory systems came still greater demand for transportation. Tramways had already been laid in 1676 for transporting coal from the mines to the sea. The rails were first made of scantling laid in the wheel ruts, then of straight rails of oak on which “one horse would draw from four or five chaldrons of coal.” Later (1765) cast-iron trammels 5 feet long by 4 inches wide were nailed to the wooden rails. These trammels collected dust, therefore in 1789 Jessop laid down at Loughborough cast-iron edge-rails and put a flanged wheel on the waggon. The rails were also placed on chairs and sleepers (ties), the first instance of this method. The distance apart of the rails was 4 feet 81⁄2 inches, what is now known as “standard gauge.” The success of these coal roads suggested tramways for freight and for passenger transportation between the larger towns. The canals had become congested with much traffic; it is said that notwithstanding there were three between Liverpool and Manchester the merchandise passing “did not average more than[18] 1200 tons daily.” The average rate of carriage was 18s. ($4.37) per ton, and the average time of transit on the 50 miles of canal was thirty-six hours. The conveyance of passengers by the improved coach roads, was, for then, quite rapid but rather expensive.

Some experimental locomotives had been made and used in the mining regions. Their success led to the building of others. The Stockton and Darlington Railway opened in September, 1825, by a train of thirty-four vehicles, making a gross load of 90 tons, drawn by one engine driven by George Stephenson, with a signal man on horseback in advance. The train made at times as high as 15 miles per hour. The rail used weighed 28 pounds per yard. This road was intended entirely for freight but the demand of the people to ride was so pressing that a passenger coach to carry six inside and fifteen to twenty outside was put on to make the round trip in two hours at a fare of one shilling.

When the bill passed for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1826 Stephenson was appointed engineer in charge at a salary of $5000 per year. This road made a great impression on the national mind, no little enhanced by the competition of locomotives at its completion in 1829, resulting in the victory of Stephenson’s engine the “Rocket.” It made the then astonishing speed of 35 miles per hour and proved conclusively the practicability of railway locomotion.

To follow the progress of industry during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries would require volumes. More has probably been accomplished, not without evils at times, than in the whole preceding history of the world. And as no small part of these accomplishments are the means and amount of travel and traffic and associated developments and organization made necessary by the vast industries which now supply the world’s wants, once more it may be asserted that the civilization of the world can be measured by its transportation.

—In the[19] brief survey of the stages through which ordinarily a civilization passes note has frequently been made that as the world progresses so does the necessary transportation increase and improve in character. It is not contended that civilization follows the improvement of transportation, although that is no doubt sometimes the case, but that the state of transportation follows up and down with the state of civilization. Very likely the same could be truthfully said of other elements of civilization such as literature, art, religion, and government. Or even if there be applied Guizot’s three tests of a civilized people: “First, they review their pledges and honor; second, they reverence and pursue the beautiful in painting, architecture, and literature; third, they exhibit sympathy in reform toward the poor, the weak and the unfortunate,” it will be found that those nations most progressed in traffic and travel will rank highest in these tests.

—To return to some of the important earlier highways. All evidence seems to indicate that civilization had its origin in western Asia. Early history speaks of the civilization and culture of Arabia and Egypt, of Assyria and Persia. Coeval with these civilizations were trade and commerce. Great caravans of camels traversed the sandy highway with their accompanying merchants carrying many products of many lands—frankincense and myrrh from Arabia; cloths and carpets from Babylon and Sardis; shawls from Cashmere; leather from Cordavan and Morocco; tin, copper, gold, and silver utensils from Phœnicia; pearls from the Far East; and grain and other agricultural products nourished and grown by the beneficence of the great mother Nile. The extensive civilizations of these countries are handed down stingily by cuneiform inscriptions on clay tablets scattered here and there among the ruins of their ancient towns and villages, or inscribed upon granite mountain sides as historical memoranda for future generations. Even Holy Writ says little about roads and highways, but that they were known is evident from the few references made. Those things which are commonplace[20] often receive least attention by writers. In Isaiah, 35:8, may be read: “And a highway shall be there, and a way, and it shall be called the way of holyness ... the wayfaring men, though fools, shall not err therein.” And again, Isa. 40:3-4, “The voice of him that cryeth in the wilderness, prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low: and the crooked shall be made straight and the rough places plain.” These would certainly indicate that in Isaiah’s time there were both travelers and roads marked and graded. Isaiah in other places shows that he, if not himself a road builder, is familiar with that process: Isa. 57:14, “And shall say, cast ye up, cast ye up, prepare the way take up the stumbling block out of the way of my people.” Isa. 62:10, “Prepare ye the way of the people; cast up, cast up the highway; gather out the stones; lift up a standard for the people.” Also Jeremiah likens the path of the wicked to an ungraded road. Jeremiah 18:15, “Because my people have forgotten me, they have burned incense to vanity, they have caused them to stumble in their ways from the ancient paths, to walk in paths, in a way not cast up.”

The trade along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean and across Palestine and the great Arabian deserts to Persia, to Babylonia, and possibly to India was evidently of importance to the fluctuating destinies of Egypt and Assyria, and later of Greece, Rome, and Turkey; so much so, that many wars were waged for the control of the great highway over which it passed. Palestine became a territory of importance. It is said Jerusalem has suffered some three score sieges, most of them because she dominated this highway, being at or near the confluence of its forks reaching east into the deserts, north toward the straits over which a crossing could be made into Europe, and southward to Egypt. Egypt and Assyria fought for its control; Greece and Rome in turn came into possession of it; Turkey and the Mohammedans for centuries monopolized it; and the[21] recent great World War was no doubt accentuated by the cupidity of Germany to control a long line of transportation through Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Turkey, Mesopotamia to Persia, Baluchistan and India.[9]

Alexander the Great overran the East, besieged Tyre, and converted an island into an isthmus in order to secure and hold control of the highway and the rich bounty imagined to be at its farther end. “Babylon is a ruin, a stately and solitary group of palms marks where Memphis stood, jackals slake their thirst in the waters of the sacred lake by the hall of a thousand columns at Thebes, but the road that formed the nexus between these vanished civilizations remains after the winds of four millenniums have sighed themselves to silence over the graves of its forgotten architects and engineers.”[10]

But the Greater Greece, built up by the personality and sword of Alexander the Great, fell, largely, because of the lack of roads. The very name of Alexander was sufficient to subdue city after city, but as soon as his personal influence was at an end the cities fell apart. Here was a wonderful opportunity. With magnificent natural-made waterways, with innumerable safe harbors what a chance for commerce, for trade with the entire world. The islands of the Aegean Sea were stepping stones to Asia Minor; Macedonia furnished an open route for the Bosphorus and Dardanelles; Thrace led to those fertile lands surrounding the Black Sea and extending away to the Caspian and joining once more with empire already conquered. On the west there was close at hand the islands of, and land bordering, the Adriatic, the great Italian boot, and Sicily where new civilizations were ready to rise and take on Greek culture for the mere offering. It would seem as[22] though Greece ought to have become the fostering mother of world colonization, but the different parts of Greece proper, where the real mental ability lay, were separated by lack of roads from each other. Athens was potentially nearer to the Black Sea than to Sparta; Corinth was nearer Sicily than to Macedonia. The many Grecian tribes were distinct, having different laws, customs and manners. Intercourse, which could have been brought about had there been interconnecting roads, was necessary to weld the people into a homogeneous mass. Sparta and Athens, less than an hour apart by modern air-plane, because of the mountains, roadless and almost pathless between them, barriers which they failed to surmount, developed different forms of civilization, different thought, habits, and tastes. To Athens the world owes an everlasting debt for masterpieces in poetry, oratory, architecture, and sculpture. “There was no Spartan sculpture, no Laconian painter, no Lacedaemonian poet.” The lack of intercommunication caused differences in language, in customs, in ideals, and in manners, making of Greece a heterogeneous conglomeration of tribes where internecine strife was ever present, and no strong centralized government could exist. Lucky for the best of the Greek civilization that it would be carried to the ends of the world by the roads of a young giant which was arising in the west.

—The roads in Rome bore such a prominent part in the civilization that they could not be entirely overlooked by contemporaneous writers. The roads are often described as military roads because they were primarily planned to transport soldiers quickly and easily to any desirable part of the empire. But no doubt the greatness of Rome was due more to the traffic in goods and people brought to and taken away from her precincts by these roads than to military prowess. Her roads were the arteries and veins through which the life blood of the nation pulsated; were the sensory and motive nerves which fetched and carried intelligence, which prompted action. She received and she disseminated. She was the hub of the universe, her roads the spokes radiating to and holding together the limits of her vast domain.

© Underwood and Underwood

THE APPIAN WAY

Showing the original Paving Stones laid 300 B.C.

[23]

How many roads Rome built it is difficult to state, for they were found in all parts of the empire. Some, as those in Italy, were very carefully and substantially built; others less so, grading down to mere trails in the hintermost districts. The Via Egnatia, which was one of the important provincial roads, is said by Strabo to have been regularly laid out and marked by milestones from Dyrrhacium, (Durazzo) on the coast of the Adriatic across from the heel of Italy’s boot through Thessalonica (Saloniki) and Philippi to Cypselus on the Hebnis and later to the Hellespont, for Cicero speaks of “that military way of ours which connects us with the Hellespont.” This road became historic as the scene of the conflict between the friends and enemies of the decaying Roman republic. Brutus and Cassius on the one hand here in 42 B.C., met the forces of Antony and Octavius. There tradition states the ghost of the dead Caesar met Brutus, and as a matter of fact, the “liberators” were cut to pieces in two engagements. Brutus and Cassius, believing the cause of the republic lost, both committed suicide, and the Roman world was soon thereafter in the hands of two masters—Antony in the East and Octavius in the West. Three centuries later this road became the leading highway to Byzantium (Constantinople), the great city founded by Constantine, impregnable in its rocky seclusion, dominating the waterway to the Black Sea and the rich agricultural land beyond.

Some twenty of these roads, more if their branches be counted, concentrated at the Eternal City and passed through her several gates. Rome could sit on her seven hills and by means of these roads rule the world. Among the most important of these were the Via Appia, Via Flaminia and Via Aemilia, Via Aurelia, Via Ostiensis, and Via Latina. One peculiarity of these Roman roads was their straightness, passing almost in a direct line between determining points. Another, to which is due their[24] durability, was their massiveness. Their general construction may be described as follows: The line of direction having been laid out trenches were made along each side defining the width, which was from 13 to 17 feet. The loose earth between was excavated to secure a firm foundation and the road was then filled or graded up to the required height with good material, sometimes as high as 20 feet. The pavement usually consisted of a layer of small stones; then a layer of broken stones cemented with lime mortar; then a layer of broken fragments of brick and pottery incorporated with clay and lime; and finally a mixture of gravel and lime or a floor of hard flat stones cut into rectangular slabs or irregular polygons fitted nicely together. The whole was frequently 4 feet thick. Along the road milestones were erected, some of them quite elaborate with carved names and dates. Near the arch of Septimus Severus in the Roman Forum still remains a portion of the “Golden Milestone,” a gilded pillar erected by Augustus, on which were carved the names of roads and lengths similar to a modern guide post. Some of these roads were used hundreds of years until they fell into neglect after Rome had been invaded by the northern barbarians. From a statement of Procopinus, the Appian Way, construction begun 312 B.C., was in good condition 800 years later, and he describes it as broad enough for two carriages to pass each other. It was made of stones brought from some distant quarry and so fitted to each other (over some 2 feet of gravel) that they seemed to be thus formed by nature, rather than cemented by art. He adds that notwithstanding the traffic of so many ages the stones were not displaced, nor had they lost their original smoothness. The papal government excavated, repaired, and reopened that road as far as Albano and it is still being used as a highway.

MAP OF ITALY

Showing some of the twenty or more roads that radiated from Rome

[25]

The Flaminian Way extended from Rome to Ariminum and thence was carried under the name Via Aemilia through Parma, and Placentia across to Spain. While not so much traffic passed over it, because the West was sparsely settled, as over the Appian Way, it nevertheless was a worthy rival. The Aurelian Way followed up the coast through Etruria and furnished another highway to Spain and Gaul. The Ostien highway connected Rome with a splendid harbor at the mouth of the Tiber. But the Appian Way was rightly the most famous of all; it was the earliest made, it was perhaps the longest paved road, and it carried the greatest amount of traffic. The road was built by Appius Claudius Caecus—then a Roman Censor, afterwards a Consul, from whom it takes its name—to Capua, a distance of 142 miles. Later it was extended across the Apennine Mountains through Beneventum, Venusia, and Tarentum, to Brundisium, a port on the Adriatic Sea, in the heel of the boot, a total distance of 350 miles. The improvements of Appius were begun in the year 312 B.C., and carried out at least as far as Capua. Livy speaks of a road over part of this way some thirty-five years earlier. A portion outside the walls was paved with lava (silex) in 189 B.C., and during the reign of Trajan (A.D. 98-117) the Via Appia was paved from Capua to Brundisium (Niebuhr). From Brundisium (Brindis) traffic could be carried by ship to Dyrrhacium and thence over the Via Egnatio to Macedonia and the Bosphorus; or along the coast to the Grecian towns, to the cities of the Far East and to Egypt. Many are the references to the noted highway in literature; Milton, in “Paradise Regained,” book four, bids us to watch flocking to the city, enriched with spoils, proconsuls, embassies, legions, in “various habits on the Appian road.”

“What a cosmopolitan throng must have graced that highway in the first century,” says Dr. Carroll.[11] “Thick-lipped Ethiopians with rings in noses and ears, swarthy-browed turbaned Mesopotamians, haughty Parthians, burnoosed Arabs still worshiping their polygods, hook-nosed Hebrews, carven with the humility of the despised[26] rich, Greek Pedagogues and Rhetors and Tutors, togaed senators, white-clad vestals with modest faces, and painted harlots with amber hair. Lictors clearing the way with rods for some purple clad dignitary of Nero’s court and carrying the fasces and the ax; street merchants and hawkers of small wares, slaves scantily clad, stark bemuscled gladiators, Cives and Peregrini, citizens and strangers, displaying, in varying degree, arrogance and curiosity; long yellow-haired Germans, their faces smeared with ocher and their yellow hair with oil; kilted soldiers with long spears and short broad swords; beggars (the lazzaroni of that bygone age), pathetically sullen or volubly mendicant in the sunshine lecticae; couches carried by bearers containing pampered nobles or high-born ladies; the cisium and the rhoda meritoria; the carriage and the hack of that time crossing each other’s path in the narrow road; children naked and joyous; merchants on caparisoned asses; the swinging columns of the legionaries; brown, straight-featured Egyptians. For part of the distance a canal runs parallel and travelers have their choice to take the pavement or to ride in state on painted barges dragged by mules; on the pavement a Pontifex in his robes of office and Augurs exchanging cynical smiles; the rattle of chariot wheels and some haggard-eyed noble, redolent from the warm and scented bath, with flower-crowned brow, drives in furious guise along the Appian Way, while barbarian and Scythian, bond and free, yield the way before him.”

MAP OF ROMAN ROADS IN ENGLAND

(After Jackman: “Development of Transportation in Modern England.”)

[27]

Davis[12] tells us that the Roman road system after it had become a network over Italy began to spread over the whole Empire. That admirable highways were built by peaceful legionaries for commercial purposes—and that even to-day in North Africa and in the wilds of Asia Minor where travelers seldom penetrate may be found the Roman road with its hard stones laid on a solid foundation. He further states that as a consequence of these roads commerce expanded by leaps and bounds. A great trade passing down the Red Sea sprang up with India, reaching to the coast of Ceylon, returning with pearls, rare tapestries, and spices. Another set penetrated Arabia for much-desired incense, or unto the heart of Africa for ivory. Also with such merchandising there came a money system with banks, checks and bonds rivaling those of the present day. The bridges are an important part of any road. Those across the Tiber in Rome were regarded as sacred. They were cared for by a special body of Priests called pontifaces (bridge-makers). The name Pontifex Maximus was borne by the High Priest and became a designation for the emperor; it is now applied to the Pope as the highest authority in the papal or pontifical state.

—When America was discovered it was sparsely settled with tribes of semi-civilized peoples. The ordinary aborigine was in the hunting and fishing stage, just beginning to cultivate crops. True, tribes claimed regions and attempted by force to keep other tribes from trespassing thereon. They had no literature save perhaps a few rough diagrams or drawings. There was no trade or commerce and consequently no roads except mere trails. Their methods of transportation consisted in walking or in paddling canoes. In the making and operating of canoes and of weapons of warfare and of the chase they were most advanced.

In many parts of the country there had been a civilization, but so long ago no very authentic knowledge of its character can be predicated upon the mounds, utensils, and other evidence now remaining. The Mound Builders and the Cliff Dwellers are as yet to us unknown peoples.