Frontispiece.

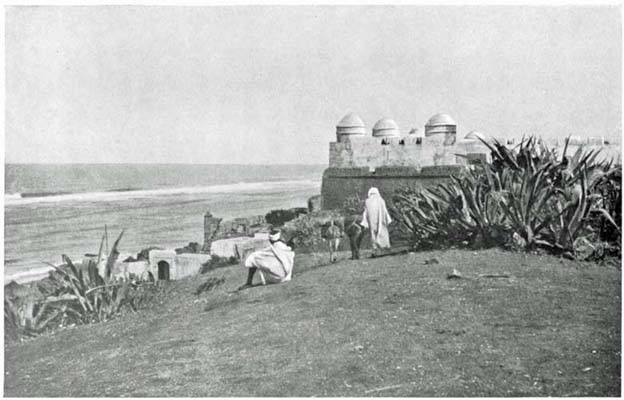

A SAINT HOUSE.

THE

PASSING OF MOROCCO

BY

FREDERICK MOORE

AUTHOR OF ‘THE BALKAN TRAIL’

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAP

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN, AND COMPANY

1908

TO

CHARLES TOWNSEND COPELAND

For several years I had been watching Morocco as a man who follows the profession of ‘Special Correspondent’ always watches a place that promises exciting ‘copy.’ For many years trouble had been brewing there. On the Algerian frontier tribes were almost constantly at odds with the French; in the towns the Moors would now and then assault and sometimes kill a European; round about Tangier a brigand named Raisuli repeatedly captured Englishmen and other foreigners for the sake of ransom; and among the Moors themselves hardly a tribe was not at war with some other tribe or with the Sultan. It was not, however, till July of last year that events assumed sufficient[viii] importance to make it worth the while of a correspondent to go to Morocco. Then, as fortune would have it, when the news came that several Frenchmen had been killed at Casablanca and a few days later that the town had been bombarded by French cruisers, I was far away in my own country. It was ill-luck not to be in London, five days nearer the trouble, for it was evident that this, at last, was the beginning of a long, tedious, sometimes unclean business, that would end eventually—if German interest could be worn out—in the French domination of all North Africa west of Tripoli.

Sailing by the first fast steamer out of New York I came to London, and though late obtained a commission from the Westminster Gazette. From here I went first to Tangier, viâ Gibraltar; then on to Casablanca, where I saw the destruction of an Arab camp and also witnessed the shooting of a party of prisoners; I visited Laraiche against my will in a little ‘Scorpion’ steamer[ix] that put in there; and finally spent some weeks at Rabat, the war capital, after Abdul Aziz with his extraordinary following had come there from Fez.

Of these brief travels, covering all told a period of but three months, and of events that are passing in the Moorish Empire this little book is a record.

Six letters to the Westminster Gazette (forming parts of Chapters I., IV., VI., XIV., XV., and XVI.) are reprinted with the kind permission of the Editor.

I have to thank Messrs. Forwood Bros., the Mersey Steamship Company, for permission to reproduce the picture which appears on the cover.

March 15, 1908.

[x]

[xi]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | vii-ix | |

| I. | Out of Gibraltar | 1 |

| II. | Nights on a Roof | 12 |

| III. | Dead Men and Dogs | 30 |

| IV. | With the Foreign Legion | 38 |

| V. | No Quarter | 52 |

| VI. | The Holy War | 59 |

| VII. | Forced Marches | 71 |

| VIII. | Tangier | 79 |

| IX. | Raisuli Protected by Great Britain | 95 |

| X. | Down the Coast | 102 |

| XI. | At Rabat | 111 |

| XII. | The Pirate City of Salli | 129 |

| XIII. | Many Wives | 139 |

| XIV. | God Save the Sultan! | 147 |

| XV. | Many Sultans | 157 |

| XVI. | The British in Morocco | 173 |

[xii]

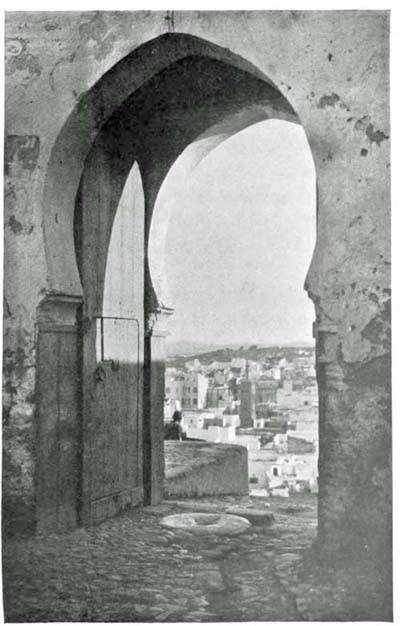

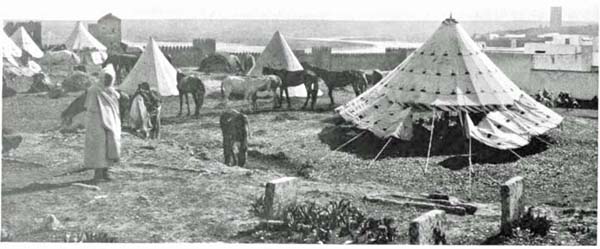

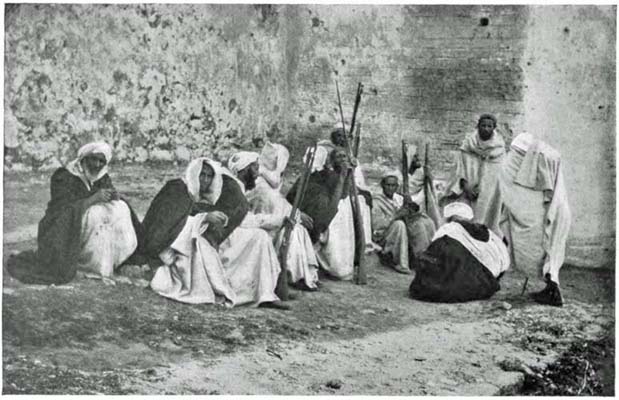

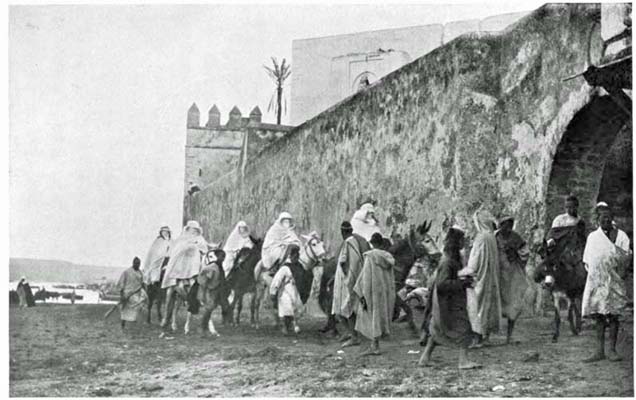

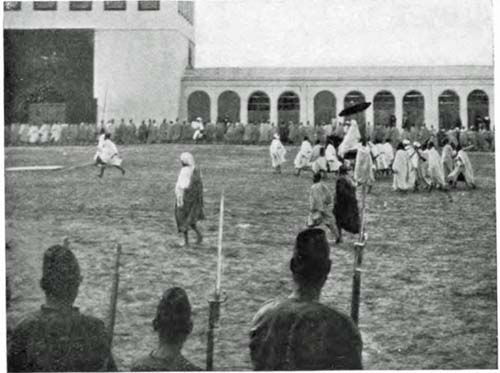

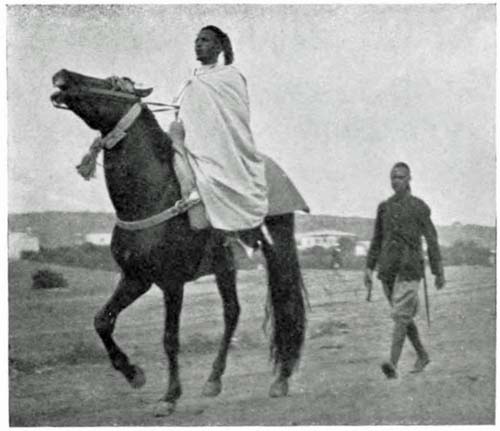

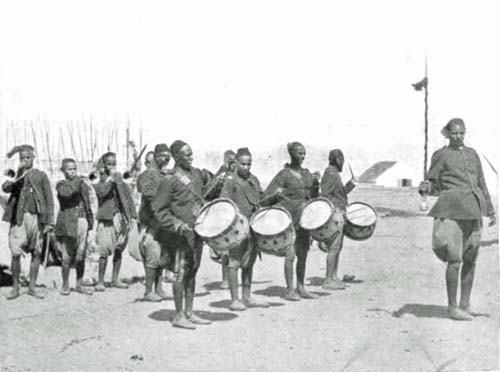

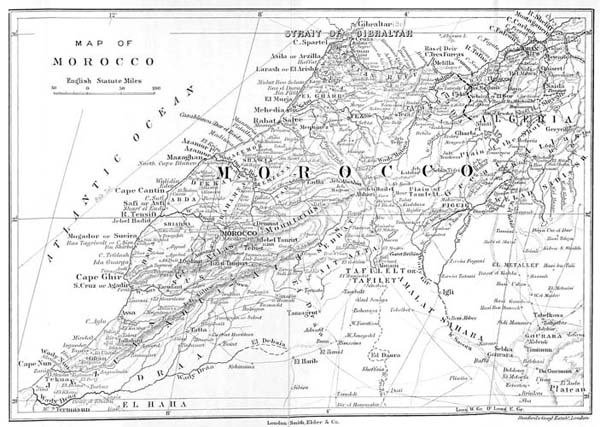

| A Saint House | Frontispiece | |

| Tangier Through the Kasbah Gate | To face page 10 | |

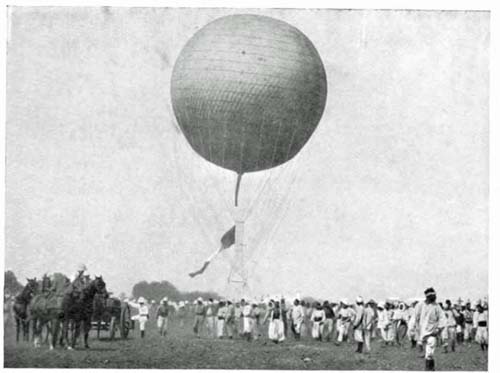

| The French War Balloon | } | ” 38 |

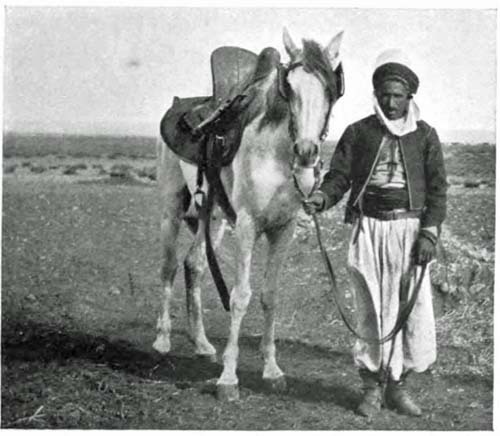

| An Algerian Spahi | ||

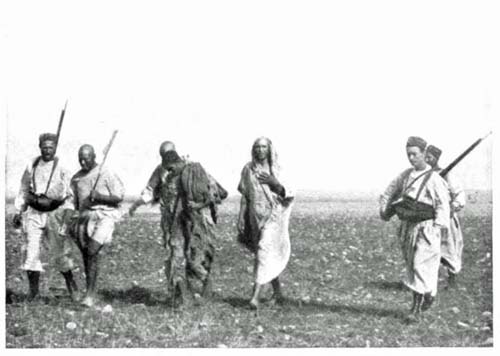

| Arab Prisoners With a White Flag | } | ” 60 |

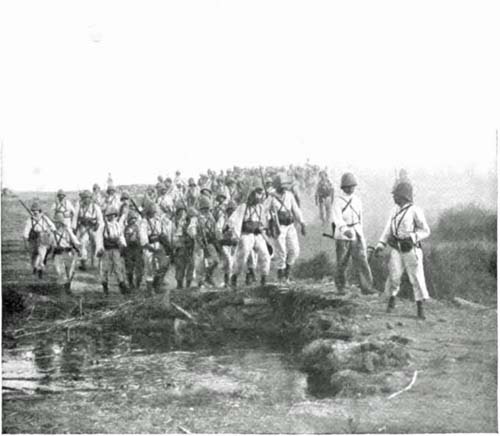

| A Column of the Foreign Legion | ||

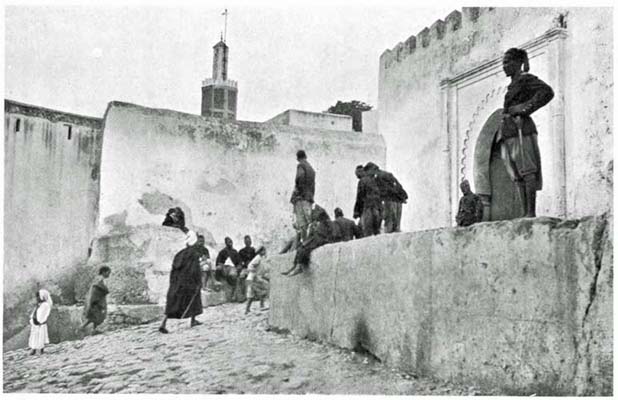

| On the Citadel, Tangier | ” 80 | |

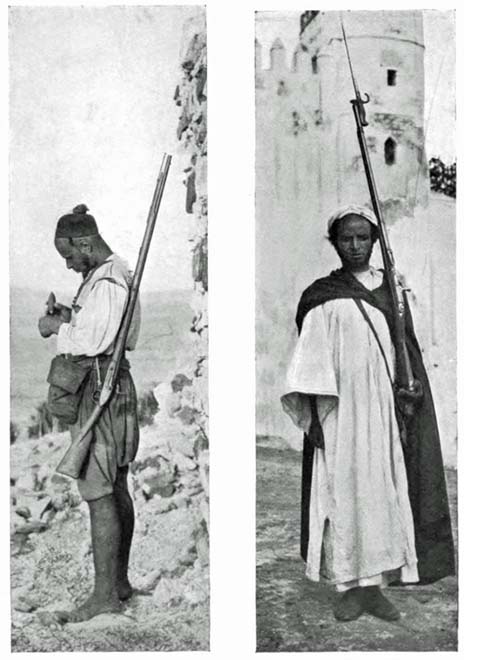

| A Riff Tribesman | } | ” 96 |

| A Maghzen Soldier | ||

| The Castle at Laraiche | ” 104 | |

| A Camp Outside the Walls of Rabat | ” 126 | |

| Shawia Tribesmen | ” 136 | |

| A Few of the Sultan’s Wives | ” 144 | |

| Chained Neck To Neck: Recruits For the Sultan’s Army | } | ” 154 |

| Abdul Aziz Entering His Palace | ||

| A Princely Kaid | } | ” 162 |

| The Royal Band | ||

| Map of Morocco | ” 188 |

THE PASSING OF MOROCCO

It was in August, 1907, one Tuesday morning, that I landed from a P. & O. steamer at Gibraltar. I had not been there before but I knew what to expect. From a distance of many miles we had seen the Rock towering above the town and dwarfing the big, smoking men-of-war that lay at anchor at its base. Ashore was to be seen ‘Tommy Atkins,’ just as one sees him in England, walking round with a little cane or standing stiff with bayonet fixed before a tall kennel, beside him, as if for protection, a ‘Bobbie.’[2] The Englishman is everywhere in evidence, always to be recognised, if not otherwise, by his stride—which no one native to these parts could imitate. The Spaniard of the Rock (whom the British calls contemptuously ‘Scorpion’) is inclined to be polite and even gracious, though he struggles against his nature in an attempt to appear ‘like English.’ Moors from over the strait pass through the town and leisurely observe, without envying, the Nasrani power, then pass on again, seeming always to say: ‘No, this is not my country; I am Moslem.’ Gibraltar is thoroughly British. Even the Jews, sometimes in long black gaberdines, seem foreign to the place. And though on the plastered walls of Spanish houses are often to be seen announcements of bull fights at Cordova and Seville, the big advertisements everywhere are of such well-known British goods as ‘Tatcho’ and ‘Dewar’s.’

I have had some wonderful views of the Rock of Gibraltar while crossing on clear[3] days from Tangier, and these I shall never forget, but I think I should not like the town. No one associates with the Spaniards, I am told, and the other Europeans, I imagine, are like fish out of water. They seem to be of but two minds: those longing to get back to England, and those who never expect to live at home again. Most of the latter live and trade down the Moorish coast, and come to ‘Gib’ on holidays once or twice a year, to buy some clothes, to see a play, to have a ‘spree.’ Of course they are not ‘received’ by the others, those who long for England, who are ‘exclusive’ and deign to meet with only folk who come from home. In the old days, when the Europeans in Morocco were very few, it was not unusual for the lonesome exile to take down the coast with him from ‘Gib’ a woman who was ‘not of the marrying brand.’ She kept his house and sometimes bore him children. Usually after a while he married her, but in some instances not till the children had[4] grown and the sons in turn began to go to Gibraltar.

My first stop at the Rock was for only an hour, for I was anxious to get on to Tangier, and the little ‘Scorpion’ steamer that plied between the ports, the Gibel Dursa, sailed that Tuesday morning at eleven o’clock. I seemed to be the only cabin passenger, but on the deck were many Oriental folk and low-caste Spaniards, not uninteresting fellow-travellers. Though the characters of the North African and the South Spaniard are said to be alike, in appearance there could be no greater contrast, the one lean and long-faced, the other round-headed and anxious always to be fat. Neither are they at all alike in style of dress, and I had occasion to observe a peculiar difference in their code of manners. I had brought aboard a quantity of fresh figs and pears, more than I could eat, and I offered some to a hungry-looking Spaniard, who watched me longingly; but he declined. On the other hand a miserable[5] Arab to whom I passed them at once accepted and salaamed, though he told me by signs that he was not accustomed to the sea and had eaten nothing since he left Algiers. As I moved away, leaving some figs behind, I kept an eye over my shoulder, and saw the Spaniard pounce upon them.

The conductor, or, as he would like to be dignified, the purser, of the ship, necessarily a linguist, was a long, thin creature, sprung at the knees and sunk at the stomach. He was of some outcast breed of Moslem. Pock-marked and disfigured with several scars, his appearance would have been repulsive were it not grotesque. None of his features seemed to fit. His lips were plainly negro, his nose Arabian, his ears like those of an elephant; I could not see his eyes, covered with huge goggles, black enough to pale his yellow face. Nor was this creature dressed in the costume of any particular race. In place of the covering Moorish jeleba he wore a white duck coat with many pockets. Stockings[6] covered his calves, leaving only his knees, like those of a Scot, visible below full bloomers of dark-green calico. On his feet were boots instead of slippers. Of course this man was noisy; no such mongrel could be quiet. He argued with the Arabs and fussed with the Spaniards, speaking to each in their own language. On spying me he came across the ship at a jump, grabbed my hand and shook it warmly. He was past-master at the art of identification. Though all my clothes including my hat and shoes had come from England—and I had not spoken a word—he said at once, ‘You ’Merican man,’ adding, ‘No many ’Merican come Tangier now; ’fraid Jehad’—religious war.

‘Ah, you speak English,’ I said.

‘Yes, me speak Englis’ vera well: been ’Merica long time—Chicago, New’leans, San ’Frisco, Balt’more, N’York’ (he pronounced this last like a native). ‘Me been Barnum’s Circus.’

‘Were you the menagerie?’

[7]The fellow was insulted. ‘No,’ he replied indignantly, ‘me was freak.’

Later when I had made my peace with him by means of a sixpence I asked to be allowed to take his picture, at which he was much flattered and put himself to the trouble of donning a clean coat; though, in order that no other Mohammedan should see and vilify him, he would consent to pose only on the upper-deck.

Sailing from under the cloud about Gibraltar the skies cleared rapidly, and in less than half-an-hour the yellow hills of the shore across the strait shone brilliantly against a clear blue sky. There was no mistaking this bit of the Orient. For an hour we coasted through the deep green waters. Before another had passed a bleak stretch of sand, as from the Sahara, came down to the sea; and there beyond, where the yellow hills began again, was the city of Tangier, the outpost of the East. A mass of square, almost windowless houses, blue and white,[8] climbing in irregular steps, much like the ‘Giant’s Causeway,’ to the walls of the ancient Kasbah, with here and there a square green minaret or a towering palm.

We dropped anchor between a Spanish gunboat and the six-funnelled cruiser Jeanne d’Arc, amid a throng of small boats rowed by Moors in coloured bloomers, their legs and faces black and white and shades between. While careful to keep company with my luggage, I managed at the same time to embark in the first boat, along with the mongrel in the goggles and a veiled woman with three children, as well as others. Standing to row and pushing their oars, the bare-legged boatmen took us rapidly towards the landing—then to stop within a yard of the pier and for a quarter of an hour haggle over fares. Three reals Moorish was all they could extort from the Spaniards, and this was the proper tariff; but from me two pesetas, three times as much, was exacted. I protested, and got the explanation, through the man of[9] many tongues, that this was the regulation charge for ‘landing’ Americans. In this country, he added from his own full knowledge, the rich are required to pay double where the poor cannot. While the Spaniards, the freak and I climbed up the steps to the pier, several boatmen, summoned from the quay, came wading out and took the woman and her children on their backs, landing them beyond the gate where pier-charges of a real are paid.

At the head of the pier a rickety shed of present-day construction, supported by an ancient, crumbling wall, is the custom-house. Not in anticipation of difficulty here, but as a matter of precaution, I had stuffed into my pockets (knowing that my person could not be searched) my revolver and a few books; and to hide these I wore a great-coat and sweltered in it. Perhaps from my appearance the cloaked Moors, instead of realising the true reason, only considered me less mad than the average of my kind. At any rate they ‘passed’ me bag and baggage[10] with a most superficial examination and not the suggestion that backsheesh would be acceptable.

But on another day I had a curious experience at this same custom-house. A new kodak having followed me from London was held for duty, which should be, according to treaty, ten per cent. ad valorem. It was in no good humour that after an hour’s wrangling I was finally led into a room with a long rough table at the back and four spectacled, grey-bearded Moors in white kaftans and turbans seated behind.

‘How much?’ I asked and a Frenchman translated.

‘Four dollars,’ came the reply.

‘The thing is only worth four pounds twenty dollars; I’ll give you one dollar.’

‘Make it three—three dollars, Hassani.’

‘No, one.’

‘Make it two—two dollars Spanish.’

This being the right tax, I paid. But I was not to get my goods yet; what was my name?

TANGIER THROUGH THE KASBAH GATE.

[11]‘Moore.’

‘No, your name.’

‘I presented my card.’

‘Moore!’ A laugh went down the turbaned line.

A writer on the East has said of the Moors that they are the Puritans of Islam, and the first glimpse of Morocco will attest the truth of this. Not a Moor has laid aside the jeleba and the corresponding headgear, turban or fez. In the streets of Tangier—of all Moorish towns the most ‘contaminated’ with Christians—there is not a tramway or a hackney cab. Not a railway penetrates the country anywhere, not a telegraph, nor is there a postal service. Except for the discredited Sultan (whose ways have precipitated the disruption of the Empire) not a Moor has tried the improvements of Europe. It seems extraordinary that such a country should be the ‘Farthest West of Islam’ and should face the Rock of Gibraltar.

I did not stop long on this occasion at Tangier, because, from a newspaper point of view, Casablanca was a place of more immediate interest. The night before I sailed there arrived an old Harvard friend travelling for pleasure, and he proposed to accompany me. Johnny Weare was a young man to all appearances accustomed to good living, and friends of an evening—easy to acquire at Tangier—advised him to take a supply of food. But I unwisely protested and dissuaded John, and we went down laden with little unnecessary luggage, travelling by a French torpedo-boat conveying despatches.

[13]Here I must break my story in order to make it complete, and anticipate our arrival at Casablanca with an account of how the French army happened to be lodged in this Moorish town. In 1906 a French company obtained a contract from the Moorish Government to construct a harbour at Casablanca; and beginning work they found it expedient, in order to bring up the necessary stone and gravel, to lay a narrow-gauge railway to a quarry a few miles down the coast. In those Mohammedan countries where the dead are protected from ‘Infidel’ tread the fact that the tracks bordered close on a cemetery, in fact passed over several graves, would have been cause perhaps for a conflict; but this—though enemies of France have tried to proclaim it—was not a serious matter in Morocco, where the Moslems are done with their dead when they bury them and anyone may walk on the graves. The French were opposed solely because they were Christian invaders to whom the Sultan[14] had ‘sold out.’ They had bought the High Shereef with their machines and their money, but the tribes did not intend to tolerate them.

After many threats the Arabs of the country came to town one market-day prepared for war. Gathering the local Moors, including those labouring on the railway, they surrounded and killed in brutal fashion, with sticks and knives and the butts of guns, the engineer of the locomotive and eight other French and Italian workmen. The French cruiser Galilée was despatched to the scene, and arriving two days later lay in harbour apparently awaiting instructions from home. By this delay the Moors, though quiet, were encouraged, hourly becoming more convinced that if the French could land they would have done so. They were thoroughly confident, as their resistance demonstrated, when, after three days, a hundred marines were put ashore. As the marines passed through the ‘Water Port’ they were fired[15] upon by a single Moor, and thereupon they shot at every cloaked man that showed his head on their march of half-a-mile to the French consulate. At the sound of rifles the Galilée began bombarding the Moslem quarters of the town; and the stupid Moorish garrison, with guns perhaps brought out of Spain, essayed to reply, and lasted for about ten minutes.

But the landing force of the French was altogether too small to do more than protect the French consulate and neighbouring European houses. Town Moors and Arabs turned out to kill and rape and loot, as they do whenever opportunity offers, and for three days they plundered the places of Europeans and Jews and at last fought among themselves for the spoils until driven from the town by reinforcements of French and Spanish troops.

The fighting and the shells from French ships had laid many bodies in the streets and had wrecked many houses and some[16] mosques. Certain Moors, less ignorant of the French power, had asked the French to spare the mosques and the ‘Saint Houses,’ domed tombs of dead shereefs, and when the fighting began the Arabs, seeing these places were untouched, concluded, of course, that the protection came from Allah, until they entered them and drew the French fire.

Casablanca, or, as the Arabs call it, Dar el Baida, ‘White House,’ was a desolate-looking place when we arrived three weeks after the bombardment. Hardly a male Moor was to be seen. The whole Moslem population, with the exception of a few men of wealth who enjoy European protection, and some servants of consulates, had deserted the town and had not yet begun to return. Jews in black caps and baggy trousers were the only labourers, and they worked with a will recovering damaged property at good pay, and grinning at their good fortune. In the attack the Moors had driven them to the[17] boats, but now the Moors themselves had had to go. Native Spaniards did the lighter work.

A Spaniard and a Jewish boy took our luggage to an hotel, of which all the rooms were already occupied, even to the bathroom and the wine closet, as the long zinc tub in the courtyard, filled with bottles, testified. The proprietor told us that for ten francs a day we might have the dining-room to sleep in, but on investigation we decided to hunt further. Speaking Spanish with a grand manner, for he was a cavalier fellow, the hotel-keeper then informed us through an interpreter that he wanted to do what he could for us because he too was an American. The explanation (for which we asked) was that in New York he had a brother whom he had once visited for a few months, and that at that time, ‘to favour an American gentleman,’ he had taken out naturalisation papers and voted for the mayor.

But this man’s breach of the law in New[18] York was his mildest sin, as we came later to hear. He had many robberies to his credit and a murder or two. For his latest crime he was now wanted by the French consul and military authorities, but being an American citizen they could not lay hold of him except with the consent of the American consul, who happened to be a German, and, disliking the French, would let them do nothing that he could help. Rodrigues (this was the name of the Spanish caballero) had defended his place against the Arab attack with the aid only of his servants. The little arsenal which he kept (he was a fancier of good guns and pistols) had been of splendid service. It is said that when the fight was over forty dead Moors lay before the hotel door, half-a-dozen horses were in Rodrigues’s stable, and bundles of plunder in his yard. It was a case of looting the looters. On tinned foods taken from the shops of other Europeans (whom he had plundered when the Arabs were gone from the town)[19] he was now feeding the host of newspaper correspondents who crowded his establishment. But we were not to be looted likewise by this genial fellow-countryman, and our salvation lay at hand as we bade him au revoir.

Leaving the Hôtel Américain we turned into the main street, and proceeding towards the Hôtel Continental came upon a party of French officers, who had just hailed and were shaking hands with a man unmistakably either English or American. Beside him, even in their military uniforms the Frenchmen were insignificant. The other man was tall and splendid and brave, as the writer of Western fiction would say. He wore a khaki jacket, white duck riding trousers, English leggings, and a cowboy hat; and over one shoulder were slung a rifle, a kodak, and a water-bottle. To lend reality to the figure—he was dusty, and his collar was undone; and as we passed the group we heard him tell the Frenchmen he had just returned[20] from the ‘outer lines.’ How often had we seen the picture of this man, the war correspondent of fiction and of kodak advertisements!

Both Weare and I were glad to meet the old familiar friend in the flesh and wanted to speak to him, but we refrained for fear he might be English and might resent American effrontery. As we passed him, however, we noticed his name across the flat side of the water-bottle. In big, bold letters was the inscription: ‘Captain Squall, Special War Correspondent of “The Morning Press.”’ This was characteristic of Squall, as we came to know; neither ‘special correspondent’ nor ‘war correspondent’ was a sufficient title for him; he must be ‘special war correspondent.’

We had heard of Squall at Tangier and thought we could stop and speak to him, and accordingly waited a moment till he had left the Frenchmen. ‘How-do-you-do, Captain?’ I said. ‘I have an introduction to[21] you in my bag from the correspondent of your paper at Tangier.’

‘You’re an American,’ was the Captain’s first remark, not a very novel observation; ‘I’ve been in America a good deal myself.’ He adjusted a monocle and explained with customary originality that he had one bad eye. ‘What do you think of my “stuff” in the Press?’ was his next remark.

‘A little personal, isn’t it? I read that despatch about your being unable to get any washing done at the hotel because of scarcity of water, and your leaving it for that reason.’

‘Yes, that’s what the British public like to read, personal touches, don’t you think?’

‘Where are you living now? We have to find a place.’

‘Come with me. You know the Americans were always very hospitable to me, and I like to have a chance to do them a good turn. I’m living on a roof and getting my own grub. You know I’m an old campaigner—I mean to say, I’ve been in South[22] Africa, and on the Canadian border, and I got my chest smashed in by a Russian in the Japanese war,—I mean a hand to hand conflict, you know, using the butts of our guns.’

‘Were you a correspondent out there?’

‘No, I was fighting for the Japs; I’m a soldier of fortune, you know.’

‘But the Japanese Government did not allow Europeans to enlist.’

‘I was the only one they would enlist; I mean to say, my father had some influence with the Japanese minister in London.’

‘But you’re very young; how old are you?’

‘Well, I don’t like to say; I mean there’s a reason I can’t tell my age,—I mean, I went to South Africa when I was sixteen; you see that’s under age for military service in the British Army.’ The Captain waited a moment, then started off again. ‘I’ve got medals from five campaigns.’

‘I’d like to see them.’

Indifferently he opened his jacket.

[23]‘There are six,’ I remarked.

‘Oh, that’s not a campaign medal; that’s a medal of the Legion of Frontiersmen. I mean to say, I was one of the organisers of that.’

Weare and I recognised the type. There are many of them abroad and some wear little American flags. But, of course, to us they are more grotesque when they affect the monocle. We knew Squall would not be insulted if we turned the conversation to the matter of most interest to us at that moment.

‘For my part,’ said Weare, ‘I could do well with something to eat just now. One doesn’t eat much on a torpedo-boat.’

With the prospects of our companionship—for Squall was boycotted by most of the correspondents—he led us away to his roof to get us a meal; and, for what the town provided, a good meal he served us. He did his own cooking, but he did it because he liked to cook,—he meant to say, he had[24] money coming to him from the sale of a motor-car in London, and he had just lost fifteen or twenty thousand pounds—the exact amount did not matter either to us or to him.

For a fortnight, till an old American resident of Casablanca invited us to his house, we suffered Squall. We three slept on the roof while a decrepit, dirty Spaniard, the owner of the place, slept below. It was a modest, one-storey house, built in Moorish style. There were rooms on four sides of a paved courtyard, under a slab in the centre of which was the customary well. Overhead a covering of glass, now much broken, was intended to keep out the rain. The place had been looted by the Moors, who took away the few things of any value and destroyed the rest, leaving the room littered with torn clothes and bedding and broken furniture, if I might dignify the stuff by these names; nor had the old man (whose family had escaped to Tangier) cleared out any place but the kitchen and the courtyard.

[25]There was a little slave boy whose master had been killed, and who now served a ‘Mister Peto’ and came to us for water every day. As our old Spaniard would not keep the place clean and saved all the food that we left from meals (which filled the place with flies) we hired the boy for a peseta, about a franc, a day to keep it clean. He was to get nothing at all if he allowed in more than twenty-five flies, and for one day he worked well and got the money. But the reason of his success was the presence all that day of one or the other of us engaged at writing, protecting him from the wrath of the old man, who resented being deprived of both stench and flies. The next day when we returned from the French camp there was no more black boy, and we never saw him again, nor could we ascertain from the old man what had happened to him. Thereafter we never drew a bucket of drinking water from the well without the fear of bringing up a piece of poor ‘Sandy.’

[26]As candles were scarce and bad we went to bed early. Weare and I generally retiring first. We climbed the rickety, ladder-like stairs and walked round the glass square over the courtyard to the side of the roof where cooling breezes blew from the Atlantic. There undressing, we rolled our clothes in tight bundles and put them under our heads for pillows. To lie on we had only sacking, for our rain-coats had to be used as covering to keep off the heavy dews of the early morning. Only Squall had a hammock.

Before retiring every evening Squall had the task of examining and testing his weapons, of which he had enough for us all. A ‘Webley’ and ‘Colt’ were not sufficient, he must also bring to the roof his rifle, on the butt of which were fourteen notches, one for each Moor he had shot. He clanked up the steps like Long John, the pirate, coming from ‘below,’ in ‘Treasure Island.’ When he had got into the hammock, lying comfortably on revolvers and cartridge belts, his[27] gun within reach against the wall, he would begin to talk. ‘You chaps think I bring all these “shooting-irons” up here because I’m afraid of something. Only look at what I’ve been through. I’ve got over being afraid. The reason I bring them all up with me is that I don’t want them stolen,—I mean to say there isn’t any lock on the door, you know.’

‘Go to sleep, Squall.’

‘I mean you chaps haven’t got any business talking about me being afraid.’

‘Can’t you tell us about it at breakfast, Squall?’

One night Squall wanted to borrow a knife; his, he said, was not very sharp. He had been out ‘on the lines’ that day, and he wanted it, he explained, to put another notch in his gun.

Sometimes a patrol would pass in the night, and we would hear the three pistols and the gun click. Once the gun went off.

At daybreak we would rouse old Squall[28] to go and make coffee, and while he was thus employed we were entertained by the occupants of a ‘kraal’ (I can think of no better description) next door. In a little, low hut, built of reeds and brush, directly under our roof, lived a dusky mother and her daughter. The one (I imagine) was a widow, the other an unmarried though mature maid. They were among the score of Moors who had not fled, and there being no men of their own race about they were not afraid to show their faces to us. The mother was a hag, but the younger woman was splendid, big and broad-shouldered, with a deep chest. Her colour was that of an Eastern gipsy, bronze as if sunburned, with a slight red in her cheeks; she was black-haired, and she always wore a flower. From her lower lip to her chin was a double line tattooed in blue, and about her ankles and arms, likewise tattooed, were broad blue bangles, one above her elbow. The clothes that she wore, though of common cotton,[29] were brilliant in colour, generally bright green or blue or orange-yellow, sometimes a combination; they were not made into garments but rather draped about her, as is the way in Morocco, and held together with gaudy metal ornaments. Two bare feet, slippered in red, and one bare arm and shoulder were always visible. While this younger woman cooked in the open yard, and the old crone lean and haggard watched, they would look up from their kettle from time to time and speak to us in language we could not understand. We threw them small coins and they offered us tea. But we did not visit the ladies, to run the risk, perhaps, of dissipating an illusion.

‘Coffee, you chaps,’ sounded from below, and we went down to breakfast with good old ‘Blood-stained Bill.’

Though at times unpleasant, it is always interesting to come upon the scene of a recent battle. Casablanca had been a battlefield of unusual order. The fight that had taken place was not large or momentous, but it had peculiarities of its own, and it left some curious wreckage. Windowless Moorish houses with low arched doors now lay open, the corners knocked off or vast holes rent in the side, and any man might enter. Several ‘Saint Houses’ were also shattered, and a mosque near the Water Port had been deserted to the ‘infidels.’ The French guns had done great damage, but how could they have missed their mark at a range of less[31] than a mile! A section of the town had taken fire and burned. One cluster of dry brush kraals had gone up like so much paper and was now a heap of fine ash rising like desert sand to every breeze. Another quarter of a considerable area was untouched by fire, though not by the hand of the Arab; and what he had left of pots and pans and other poor utensils the Spaniard and Jew had gathered after his departure. At the time that we came poking through the quarter only a tom-tom, and that of inferior clay with a broken drum, was to be found. Hut after hut we entered through mazes of twisting alleys, the gates down everywhere or wide ajar; and we found in every case a heap of rags picked over half-a-dozen times, a heap of earthenware broken to bits by the Moors in order that no one else might profit. So silent was this quarter, once the living place of half the Moorish population, that the shimmering of the sun upon the roofs seemed almost audible. Twice we came upon Algerians[32] of the French army, in one case two men, in the other a single stalwart ‘Tirailleur.’ We came to a street of wooden huts a little higher than the kraals, the sok or market-place of the neighbourhood. Invariably the doors had been barricaded, and invariably holes hacked with axes had been made to let in the arm, or, if the shop was more than four feet square, the body of the looter. In front of the holes were little heaps of things discarded and smashed. What fiends these Moors and Arabs are, in all their mad haste to have taken the time to destroy what they did not want or what they could not carry off! They had hurried about the streets robbing each others’ bodies and dressing themselves, hot as the season was, in all the clothes they could crowd on, shedding ragged garments when they came to newer ones, always taking the trouble to destroy the old. And I have heard that in collecting women they acted much in the same way, leaving one woman for another, ‘going partners,’ one[33] man guarding while the other gathered, driving the women off at last like cattle, for women among Mohammedans have a definite market value.

Though the bodies were now removed from the streets it was evident from the stench that some still lay amongst the wreckage. Flies, great blue things, buzzed everywhere, rising in swarms as we passed, to settle again on the wasted sugar or the filthy rubbish and the clots of blood. Emaciated cats and swollen dogs roused from sleep and slunk away noiselessly at our approach. One dog, as we entered a house through a hole torn by a shell, rose and gave one loud bark, but, seeming to frighten himself, he then backed before us, viciously showing his teeth, though growling almost inaudibly. Evidently he belonged to the house. At the fall of night these dogs—I often watched them—would pass in packs, silently like jackals, out to the fields beyond the French and Spanish camps, where the bigger battles had taken[34] place and where a dead Moor or a French artillery horse dried by the sun lay here and there unburied.

The return of the Moors to the wrecks of their homes began about the time of our arrival. At first there came in only two or three wretched-looking creatures, bare-footed and bare-headed, clad usually in a single shirt which dragged about their dirty legs, robbed of everything, in some cases even their wives gone. As the Arabs of the country sought in every way, even to the extent of shooting them, to prevent their surrender, they were compelled to run the gauntlet at night; and often at night the flashes of the Arabs’ guns could be seen from the camp of the French. The miserable Moors who got away lay most of the night in little groups outside the wire entanglements till their white flag, generally the tail of a shirt, was seen by the soldiers at daybreak. The Moors who thus surrendered, after being searched for weapons, were taken for examination[35] to the office of the general’s staff, a square brush hut in the centre of the French camp, where, under a row of fig trees, they awaited their turns. Some Jews among them, refugees from the troubled villages round about, were careful in even this their day to keep a distance from the elect of Mohammed, remaining out in the blinding sun till a soldier of ‘the Legion’ told them also to get into the shade. The Jews were given bread by their sympathisers, and they went in first to be questioned because their examination was not so rigorous as that through which the Moors were put—humble pie this for the Moors!

When a Moor entered the commander’s office he prostrated himself, as he would do usually only to his Sultan or some holy man of his creed; however, he was ordered to rise and go squat in a corner. An officer who spoke Arabic—and sometimes carried a riding-crop—drew up a chair, sat over him and put him through an inquisition;[36] and if he showed the slightest insolence a blow or two across the head soon quelled his spirit. When the examination was over, however, and the Moor had been sufficiently humiliated, the French were lenient enough. The man’s name was recorded and he was then permitted to return to his home and to resume his trade in peace. He received sometimes a pass, and, if he could do so in the teeth of his watchful countrymen outside the barriers, he went back into the interior to fetch such of his women folk as were safe. But every idle Moor was taken from the streets and made to work as it is not in his belief that he should—though he was fed and paid a pittance for his labour. Medical attention was to be had, though the Mohammedan would not ordinarily avail himself of the Nazarene remedies.

I should say the French were just, even kindly, to the Moors who surrendered without arms but to those taken in battle they showed no mercy. The French army returning[37] from an engagement never brought in prisoners, and neither men nor officers kept the fact a secret that those they took they slaughtered.

The French spread terror in the districts round about, and after they began to penetrate the country and leave in their wake a trail of death and desolation, the leaders of several tribes near to Casablanca came in to sue for peace. These were picturesque men with bushed black hair sticking out sometimes six inches in front of their ears. The older of them and those less poorly off came on mules, the youth on horses. They saw General Drude and the French consul, and went away again to discuss with the other tribesmen the terms that could be had: no arms within ten miles of Casablanca and protection of caravans bound hither. But soon it came to be known that the sorties of the French were limited to a zone apparently of fifteen kilomètres, and the spirit of the Arabs rose and they became again defiant.

It was to see the war balloon go up that I planned with a youthful wag of a Scot to rise at five o’clock one morning and walk out to the French lines before breakfast. He came to the roof and got me up, and we passed through the ruined streets, over the fallen bricks and mortar, to the outer gate, the Bab-el-Sok. Arriving in the open, the balloon appeared to us already, to our surprise, high in the air; and on the straight road that divided the French camp we noticed a thick, lifting cloud of brown dust. Lengthening our stride we pushed on as fast as the heavy sand would allow, passing the camp and overtaking the trail of dust just as the last cavalry troop of the picturesque French army turned out through an opening in the wire entanglements which guarded the town. General Drude did not inform correspondents when he proposed an attack.

THE FRENCH WAR BALLOON.

AN ALGERIAN SPAHI.

[39]Spread out in front of us on the bare, rolling country was a moving body of men forming a more or less regular rectangle, of which the front and rear were the short ends, about half as long as the sides. The outer lines were marked by companies of infantry, bloomered Tirailleurs and the Foreign Legion, marching in open order, often single file, with parallel lines at the front and vital points. Within the rectangle travelled the field artillery, three sections of two guns each; a mountain battery, carried dismantled on mules; a troop of Algerian cavalry; the general and his staff; and a brigade of the Red Cross. Outside the main body, flung a mile to the front and far off either wing, scattered detachments of[40] Goumiers, in flowing robes, served as scouts. Already three of them on the sky-line, by the position of their horses, signalled that the way was clear.

This little army, counting in its ranks Germans, Arabs, and negroes, as well as native Frenchmen, numbered all told less than three thousand men. It had got into fighting formation under shelter of a battery and two short flanking lines of infantry lodged on the first ridge; and passing through the wire entanglements the various detachments had found their positions without a halt. The force, even though small, was well handled, and the men were keen for the advance. Of course they were thoroughly confident; they might have been recklessly so but for the controlling hand of the cautious general.

Finding ourselves at a rear corner of the block we set our speed at about double that of the columns of the troops and took a general direction diagonally towards a[41] section of the artillery, now kicking up a pretty dust as it dragged through the ploughed fields. Overtaking the guns we slogged on with them for a mile or more, advising the officers not to waste their camera films, as they seemed inclined to do, before the morning clouds disappeared.

The helmets of the artillerymen and Légionnaires hid their faces and made them look like British soldiers; and this was disappointing, to find that the only French troops in the army had left behind in camp the little red caps that give them the appearance of belonging to the time of the French Revolution.

Though inside us we carried no breakfast, neither were we laden with doughy bread and heavy water-bottles, to say nothing of rifles; and after a short breathing spell and a ride on the guns we were soon able to say au revoir to the battery and to press on ahead. Our eagerness to ascertain the object of the movement led[42] us towards the general’s staff; but we did not get there. The little man with the big moustache spied us at some distance and sent an officer to say that correspondents should keep back with the hospital corps. Thinking perhaps it would be best not to argue this point, we thanked the officer, sent our compliments to Monsieur le Général Drude, and dropped back till the artillery hid us from his view, grateful that he had not sent an orderly with us.

It was only four miles out from Casablanca, as the front line came to the crest of the second rise, that the firing began. About half a mile ahead of us we saw the forward guns go galloping up the slope and swing into position; and a minute later two screeching shells went flying into the distance. A battery to the left was going rapidly to the front, and, keeping an eye on the general, we made over to it and passed to the far side, to be out of his view. It happened that by so doing we also took the shelter of[43] the battery from a feeble Moorish fire, and our apparent anxiety brought down upon us the chaff of the soldiers. But we did not offer to explain. With this battery we went forward to the firing line; and as soon as the guns were in action, the Scot, forgetting the fight in the interest of his own mission, began dodging in and out among the busy artillerists, snapping pictures of them in action. Though the men kept to their work, several of the officers had time to pose for a picture, and one smart-looking young fellow on horseback rode over from the other battery to draw up before the camera. All went well till the general, stealing a march on us, came up behind on foot. I do not know exactly what he said, as I do not catch French shouted rapidly, but I shall not forget the picture he made. Standing with his legs apart, his arms shaking in the air, his cap on the back of his head, the little man in khaki not only frightened us with his rage but made liars of his officers. The same men who had posed[44] for us now turned upon us in a most outrageous manner. Some of them, I am sure, used ‘cuss’ words, which fortunately not understanding we did not have to resent; several called us imbeciles, and one threatened to put us under arrest.

‘There,’ said the Scot as the general turned his wrath upon his officers, ‘that will make a splendid picture, “A Critical Moment on the Battlefield; General Drude foaming at his Staff.” Won’t you ask them to pose a minute?’

We moved back a hundred yards, taking the shelter of a battered Saint House, and began to barter with some soldiers for something to eat. For three cigarettes apiece four of them were willing to part with a two-inch cube of stringy meat and a slab of soggy brown bread, with a cupful of water. As we sat at breakfast with these fellows their officers got out kodaks and photographed the group, perhaps desiring to show the contrast of civilians in Panama hats beside[45] their bloomered, fezzed Algerians. With still a hunk of bread to be masticated we had to rise and go forward. All of the army ahead of us moved off and the reserves took up a position on the ridge the cannon had just occupied. As soon as the general took his departure we began to look about for some protecting line of men or mules, but there were none following him. The rectangle had divided into two squares, and we were with the second, which would remain where it was. The object of this manœuvre was to entice the Moors into the breach, they thinking to cut off the first square and to be caught between the two. But the Moors had had their lesson at this game three weeks before.

Realising soon that we were with the passive force we resolved to overtake the Foreign Legion, now actively engaged, and accordingly set out across the valley after them for a two-mile chase. A caravan track led down through gullies and trailed in and[46] out, round earth mounds and ‘Saint Houses,’ often cutting us off from the view of both forces at the same time, and once hiding from us even the balloon. Crossing a trodden grain-field to shorten our distance we came upon three Arabs, dead or dying, a dead horse, and the scatterings of a shell. A lean old brown man, with a thin white beard and a shaven head, lay naked, with eyes and mouth wide open to the sun, arms and legs flung apart, a gash in his stomach, and a bullet wound with a powder stain between the eyes. His companions, still wearing their long cotton shirts and resting on their arms, might have been feigning sleep; so, as a matter of precaution we walked round them at a distance. It came to me that this was fool business to have started after the general and I said so. ‘Human nature,’ replied the Scot; ‘we have been trying to avoid the general all morning, now we wished we had him.’ We talked of going back but came to the conclusion that it was as far back[47] as it was forward, and went on to a knoll, where four guns had taken up a position and were blazing away as fast as their gunners could load them.

Of course our independence of General Drude revived as we got to a place of more or less security, and we swung away from him towards the right flank. Choosing a good point from which to watch the engagement, we saluted the captain of a line of Algerians and lay down among the men. Below us, in plain view, not a quarter of a mile away, was the camp of the Moors, about four hundred tents, ragged and black with dirt, some of them old circular army tents, but mostly patched coverings of sacking such as are to be seen all over Morocco. It was to destroy this camp, discovered by the balloon, that the French army had come out, and we had managed to come over the knoll at the moment that the first flames were applied to it. Just beyond the camp the squalid village of Taddert, beneath a cluster[48] of holy tombs, a place of pilgrimage, was already afire.

The Moors at Taddert had evidently been taken by surprise. They left most of their possessions behind in the camp, getting away with only their horses and their guns. A soldier of the Foreign Legion came back driving three undersized donkeys, and carrying several short, pot-like Moorish drums. We spoke to him and he told us that they had taken seven prisoners and had shot them.

The Arabs hung about the hills, keeping constantly on the move to avoid shells. Organisation among them seemed totally lacking and ammunition was evidently scarce. Once in a while a horseman or a group of two or three would come furiously charging down to within a mile of the guns and, turning to retire again, would send a wild shot or two in our direction. Wherever a group of more than three appeared, a shell burst over their heads and scattered their frightened horses, sometimes riderless. The fight was entirely[49] one-sided, yet the French general seemed unwilling to risk a close engagement that might cost the lives of many of his men.

After an hour my companion, though under fire for the first time, became, as he put it, ‘exceedingly bored,’ and lying down on the ground as if for a nap, asked me to wake him ‘if the Moors should come within photographing distance.’ I suggested that he might have a look at them with a pair of glasses and that he might borrow those of a young officer who had just come up.

‘Monsoor,’ he said, rising and saluting the officer, ‘Permettez moi à user votre binoculaires, s’il vous plaît?’

‘You want to look through my glasses?—certainly,’ came the reply. ‘There, you see that shot; it is meant for those Moroccans converging on the sky-line. There, it explodes. It got four of them. It was well aimed. These are splendid guns we have. No other country has such guns. I should say many of the Moors are killed to-day.[50] Not less than three hundred. What is that? Give me my things! Pardon, it is only les Goumiers. They look like Moroccans but of course we must not shoot them!’

The energetic Scot interrupted. ‘I should like to see your men fire a volley so that I might get a picture; my paper wants scenes of the fighting about Casablanca.’

‘Perhaps I can do so in a few minutes, if you stay by me.’

The general passed within a few yards, and, ignoring us, went back to the ambulance brigade to see a wounded man of the Foreign Legion. We followed him and took his photograph as he shook hands with the trooper on the litter.

‘Good picture,’ I said.

‘Rotten,’ said the Scot. ‘They’ll think in London that I got Drude to pose; the wounded chap hadn’t a bloodstain on him and he smoked a cigarette.’

We had not long to wait, however, before[51] an example of real misery came to our view. A Goumier covered with blood, riding a staggering wounded horse, brought in a Moor without a stitch of clothes, tied by a red sash to his saddle. Captor, captive, and horse fell to the ground almost together. The Goumier had been shot in the chest, and expired while his fellow horsemen relieved him of his purple cloak and his turban and gave him water. The Moor (who had been taken in the fire at Taddert) was a mass of burns from head to foot. On one hand nothing remained but stumps of fingers, and loose charred flesh hung down from his legs. Well might the French have shot this creature; but they bound up his wounds.

At one o’clock the Arab camp was a mass of smouldering rags, while Taddert blazed from every corner. The day’s work was done. Long parallel lines of men marching single file in open order trailed over the stony ground back towards the white walled city.

On the next excursion with the French I happened to see the shooting of six prisoners. We set out from camp as usual at early morning and moved up the coast for a distance of eight miles, with the object of examining a well which in former dry seasons supplied Casablanca with water and was now no doubt supplying the Arabs round about. By marching in close formation and keeping always down in the slopes between hills we managed to get to the well and to swing a troop of Goumiers round it without being noticed by a party of thirteen Moors, of whom only three were properly mounted.

The unlucky thirteen had no earthly[53] chance. The Goumiers swept down upon them, killing seven, and taking prisoners the remaining six. As I was marching with the artillery at the time, I missed this little engagement, and my first knowledge of it was when the prisoners trailed by me on foot: six tall, gaunt, brown men, bare-legged, and three of them bare-headed, none clad in more than a dirty cotton shirt that dragged to his knees. They moved in quick, frightened steps, keeping close to one another and obeying their captors implicitly. Allah had deserted them and their souls were as water. The Goumiers, fellow Mohammedans and devout—I have seen them pray—followed on tight-reined ponies, riding erect in high desert saddles, their coloured kaftans thrown back from their sword-arms—brown men these too, with small black eyes and huge noses. French soldiers of the Foreign Legion drove three undersized asses, carrying immense pack-saddles of straw and sacking meant to pad their skinny backs and to keep[54] a rider’s feet from trailing ground. They were too small to be worth halter or bridle, and the soldiers prodded them on with short, pointed sticks, that brought to my mind Stevenson’s ‘Travels with a Donkey.’ One of the Frenchmen brought along a gun, a long-barrelled Arab flintlock, an antiquated thing safer to face than to fire. Besides this, I was told, one of the prisoners had carried a bayonet fastened with a hemp string to the end of a stick; the others seem to have been unarmed. They were indeed a poor bag.

Without the least idea that such prisoners would be shot, I did not follow to their summary trial, but moved, instead, over to a spring, where some artillerists were watering their horses, while a dozen sporting tortoises stirred the mud. The gunners had bread and water, while I had none. Bread and water are heavy on campaign, and a few cigarettes I had found were good barter. My cigarettes were distributed and we were just beginning our breakfast, when a man standing[55] up called our attention to the Goumiers coming our way again with the Moors. They were walking in the same order, the prisoners first in a close group, moving quickly on foot, not venturing to look back, the Goumiers, probably twenty, riding steady on hard bits.

‘Pour les tuer,’ said a soldier, smiling; ‘Pour les tuer,’ repeated the others, looking at me to see if I smiled.

I shook my head in pity, for the doomed men were ignorant, pitiable creatures.

A hundred yards beyond us were a clump of dwarfed trees and some patches of dry grass, like an oasis among the rolling, almost barren, hills; and for this spot the Moors were headed. Mechanically I went on eating, undecided whether to follow, for I did not want to see the thing at close range. I thought the Moors would be lined up in the usual fashion, their sentence delivered, and a moment given them for prayer. But suddenly, while their backs were turned, just as they set foot upon the dry grass, quickly a[56] dozen shots rang out almost in a volley, then came a straggling fire of single shots. The single shots were from a pistol, as an officer passed among the dying men and put a bullet into the brain of each.

A young Englishman, the Reuter correspondent, rode over to me from the other side and asked what I thought. It seemed to me, I said, rather brutal that they were not told they were to die.

‘I don’t know,’ said the Englishman. ‘I should say that was considerate. But the thing isn’t nice; it isn’t necessary.’

The Goumiers set fire to the grass about the bodies, and soon the smoke and smell, brought over on a light Atlantic breeze, caused us to move away.

Across the dusty, shimmering plains signal fires began to send up columns of smoke, warning the Arabs beyond of our approach. But we were going no further.

There is no censorship of news in[57] England, but the English press often decides what is good for the public to know and what it should suppress. In my opinion the above affair, reported to the London papers by their own correspondents, who were witnesses, should have been published. But the papers either did not publish the despatches, or else, as in the case of the Times and the Telegraph, which I saw, they gave the incident only the briefest notice, and placed it in a more or less obscure position in the paper. This, on the part of the London editors, was no doubt in deference to the British entente with France. The question arises in my mind, however, whether a paper purporting to supply the news has any right to suppress important news that is legitimate.

The shooting of prisoners continued until I left Morocco; and I am of the opinion that it goes on still. The French did not hide the fact; as I have said, any of the officers would tell you that they took no prisoners in[58] arms. The Arabs opposing them, they pointed out, were murderers who had looted Casablanca, attempted to slaughter the European residents, and failing, had turned upon each other to fight not only for plunder but for wives. What would have happened to the European women, the Frenchmen asked, had the consulates not sustained the siege? What happens to French soldiers who are captured? They argued also that drastic methods brought submission more quickly.

When the Shawia tribesmen made their first attacks upon the French at Casablanca they were thoroughly confident of their own prowess and of the protection of Allah. They had often, before the coming of the French, called the attention of Europeans to the fact that salutes of foreign men-of-war entering port were not nearly so loud as the replies from their own antiquated guns—always charged with a double load of powder for the sake of making noise. But they have come to realise now that Christian ships and Christian armies have bigger guns than those with which they salute, and the news that Allah, whatever may be His reason, is[60] not on the side of the noisy guns has spread over a good part of Morocco.

The Arabs now seldom try close quarters with the French, except when surrounded or when the French force is very small and they are numerous; and as I have indicated before, their defence is most ineffective. One morning on a march towards Mediuna I sat for an hour with the Algerians, under the war balloon, watching quietly an absurd attack of the tribesmen. From the crest of a hill, behind which they were lodged, they would ride down furiously to within half a mile of us, and turning to go back at the same mad pace, discharge a gun, without taking aim, at the balloon, their special irritation. It was all picturesque, but like the gallant charge of the brave Bulgarian in ‘Arms and the Man,’ entirely ridiculous. If the Algerians had been firing at the time, not one of them would have got back over their hill.

ARAB PRISONERS WITH A WHITE FLAG.

A COLUMN OF THE FOREIGN LEGION.

The reports in the London papers of[61] serious resistance on the part of the Moors are seldom borne out by facts. Most of the despatches, passing through excitable Paris, begin with startling adjectives and end with ‘Six men wounded.’ Here, for instance, are the first and the last paragraphs of the Paris despatch describing the first taking of Settat, which is over forty miles inland and among the homes of the Shawia tribesmen. It is headed:

‘At eight a.m. yesterday the French columns opened battle in the Settat Pass. The enemy offered a stubborn resistance, but was finally repulsed, after a fight lasting until midnight. Settat was occupied and Muley Rechid’s camp destroyed.

‘There were several casualties on the French side.... The enemy’s losses were very heavy. The fight has produced a great impression among the tribes.’

The Arab losses under the fire of the[62] French 75-millimètre guns and the fusillade of the Foreign Legion and the Algerians, many of them sharpshooters, are usually heavy where the Arabs attempt a serious resistance. I should say it would average a loss on the part of the Moors of fifty dead to one French soldier wounded. Moreover, when a Moor is badly wounded he dies, for the Moors know nothing of medicine, and the only remedies of which they will avail themselves are bits of paper with prayers upon them, written by shereefs; these they swallow or tie about a wound while praying at the shrine of some departed saint. It has seemed to me a wanton slaughter of these ignorant creatures, but if the French did not mow them down, the fools would say they could not, and would thank some saint for their salvation.

The arms of the Arabs are often of the most ineffective sort, many of them, indeed, made by hand in Morocco. While I was with the French army on one occasion we[63] found on a dead Moor (and it is no wonder he was dead) a modern rifle, of which the barrel had been cut off, evidently with a cold chisel, to the length of a carbine. The muzzle, being bent out of shape and twisted, naturally threw the first charge back into the face of the Moor who fired it. I have seen bayonets tied on sticks, and other equally absurd weapons.

There are in Morocco many Winchester and other modern rifles, apart from those with which the Sultan’s army is equipped. Gun-running has long been a profitable occupation amongst unscrupulous Europeans of the coast towns, the very people for whose protection the French invasion is inspired. A man of my own nationality told me that for years he got for Winchesters that cost him 3l. as much as 6l. and 8l. The authorities, suspecting him on one occasion, put a Jew to ascertain how he got the rifles in. Suspecting the Jew, the American informed him confidentially, ‘as a friend,’ that[64] he brought in the guns in barrels of oil. In a few weeks five barrels of oil and sixteen boxes of provisions arrived at —— in one steamer. The American went down to the custom-house, grinned graciously, and asked for his oil, which the Moors proceeded to examine.

‘No, no,’ said the American.

The Moors insisted.

The American asked them to wait till the afternoon, which they consented to do; and after a superficial examination of one of the provision boxes, a load of forty rifles, the butts and barrels in separate boxes, covered with cans of sardines, tea, sugar, etc., went up to the store of the American.

It was more profitable to run in guns that would bring 8l., perhaps more, than to run in 8l. worth of cartridges, and after the Moors had secured modern rifles they found great difficulty in obtaining ammunition, which for its scarcity became very dear. For that reason many of them[65] have given up the European gun and have gone back to the old flintlock, made in Morocco, cheaper and more easily provided with powder and ball.

Ammunition is too expensive for the poverty-stricken Moor to waste much of it on target practice, and when he does indulge in this vain amusement it is always before spectators, servants and men too poor to possess guns; and in order to make an impression on the underlings—for a Moor is vain—he places the target close enough to hit. The Moor seldom shoots at a target more than twenty yards off.

Even the Sultan is economical with ammunition. It is never supplied to the Imperial Army—for the reason that soldiers would sell it—except just prior to a fight. It is told in Morocco that when Kaid Maclean began to organise the army of Abdul Aziz he was informed that he might dress the soldiers as he pleased—up to his time they were a rabble crew without uniforms—but[66] that he need not teach them to shoot. Nor have they since been taught to shoot.

I am of opinion that the French army under General d’Amade, soon to number 12,000 or 13,000 men, could penetrate to any corner of Morocco with facility, maintaining at the same time unassailable communication with their base. A body of the Foreign Legion three hundred strong could cut their way across Morocco. With 60,000 men the French can occupy, hold, and effectively police—as policing goes in North Africa—the entire petty empire. Such an army in time could make the roads safe for Arabs and Berbers as well as for Europeans, punishing severely, as the French have learned to do, any tribe that dares continue its marauding practices and any brigand who essays to capture Europeans; and as for the rest, the safety of life and property within the towns and among members of the same tribes, the instinct of self-preservation[67] among the Moors themselves is sufficient. There is no danger for the French in Morocco.

Nevertheless, their task is not an easy one. Conservatism at home and fear of some foreign protest has kept them from penetrating the country, as they must, in order to subdue it. So far they have made their power felt but locally, and though they have slain wantonly thousands of Moors, their position to-day is to all practical purposes the same as it was after the first engagements about Casablanca. For four months General Drude held Casablanca, with tribes defeated but unconquered all about him. With the new year General Drude retired and General d’Amade took his place, and the district of operations was extended inland for a distance of fifty miles. But beyond that there are again many untaught tribes ranging over a vast territory.

If the French, from fear of Germany, do not intend to occupy all Morocco I can see[68] for them no alternative but to recognise Mulai el Hafid, who as Sultan of the interior is inspiring the tribesmen to war. Hafid’s position, though criminal from our point of view, is undeniably strong.

On proclaiming himself sultan, he sought to win the support of the country by promising a Government like that of former sultans, one that cut off heads, quelled rebellions, and kept the tribes united and effective against the Christians. This was the message that his criers spread throughout the land; and the people, told that the French had come as conquerors, gave their allegiance to him who promised to save them. Hafid’s attitude towards the European Powers was by no means so defiant as he professed to his people. Emissaries were sent from Marakesh to London and Berlin to plead for recognition, but were received officially at neither capital. He then tried threats, and at last, in January, declared the Jehad, or Holy War. But that he really contemplated[69] provoking a serious anti-Christian, or even anti-French, uprising could hardly be conceived of so intelligent a man; and hard after the news of this came an assuring message—unsolicited, of course—to the Legations at Tangier that his object was only to unite the people in his cause against his brother. Later, when one of his m’hallas took part in a battle against the French he sent apologies to them.

The Moors, the country over, have heard of the disasters to the Shawia tribes, at any rate, of the fighting. Knowing the hopelessness of combating the French successfully, the towns of the coast are willing to leave their future in the diplomatic hands of Abdul Aziz, in spite of their distaste for him and his submission to the Christians. Those of the interior, however, many of whom have never seen a European, have a horror of the French such as we should have of Turks, and they will probably fight an invasion with all their feeble force.

[70]Because of the harsh yet feeble policy of the French, the trouble in Morocco, picturesque and having many comic opera elements, will drag on its bloody course yet many months.

The French Army is an interesting institution at this moment, when it is known that the Navy of France ranks only as that of a second-class Power and it is thought her military organisation is little better. I am not in a position to make comparisons, knowing little of the great armies of Europe, nor is the detachment of troops in Morocco, numbering at this writing hardly 8,000 men, a sufficient proportion of the army of France to allow one to form much of an opinion. But some observations that were of interest to me may also interest others.

The French forces in Morocco represent[72] the best that the colonies of France produce in the way of fighting men. European as well as African troops are from the stations of Algeria, a colony near enough to France to partake of her civilisation yet sufficiently far away to escape conservatism and the so-called modern movements with which the home country is afflicted. If there are weaklings, socialists, and anarchists among the troops they are in the Foreign Legion, absorbed and suppressed by the ‘gentlemen rankers.’ The Army is made up of many elements. Besides ordinary Algerians, it includes Arabs from the Sahara and negroes who came originally perhaps as slaves from the Soudan; besides Frenchmen, there are in the famous Foreign Legion—that corps that asks no questions—Germans, Bulgarians, Italians, Russians, and even a few Englishmen. The main body of the Army is composed of Algerians proper, Mohammedans, who speak, or at least understand, French. They are officered by Frenchmen,[73] who wear the same uniforms as their men: the red fezzes and the baggy white bloomers in the case of infantry, the red Zouave uniform and boots in the cavalry. These Algerians, of course, are regular soldiers, subjected to ordinary military discipline, but there are too the Goumiers, or Goums, of the desert, employed in irregular corps for scout duty and as cavalry, and they, I understand, are exempt from camp regulations and restrictions except such as are imposed by their own leaders. And in the last month similar troops have been organised from the tribesmen of the conquered Shawia districts near to Casablanca.

Algerians and Goumiers, Europeans and Africans, camp all together in the same ground, their respective cantonments separated only by company ‘streets.’ The various commands march side by side and co-operate as if they were all of one nationality, a thing which to me, as an American, knowing that such conditions[74] could not obtain in an American army, speaks wonders for the French democracy.

A good deal of small gambling goes on in the French camps, or rather just outside them; but this seems to be the army’s only considerable vice. Drunkenness and disorder seem to be exceedingly rare. I cannot imagine a more abstemious body of men. Of course conditions in the campaign in which the French are now engaged are all favourable to discipline; there is the stimulus of an active enemy, and yet the men are never overworked, except on occasional long marches, when they are inspired and encouraged to test their endurance.

The marching power of the French infantryman is extraordinary. Carrying two days’ rations and a portion of a ‘dog tent’ (which fits to a companion’s portion), he will ‘slog’ nearly fifty miles in a day and a night. I remember one tremendous march. The army left camp one morning at three o’clock, cavalry, artillery, a hospital staff, Tirailleurs[75] and Légionnaires, about 3,000 men, and marched out fifteen miles to a m’halla, or Moorish camp, beyond Mediuna. For more than two hours they fought the Arabs, finally destroying the camp; and then returned, reaching Casablanca shortly before five o’clock in the afternoon. I did not accompany the army on this occasion, but went out to meet it coming back, curious to see how the men would appear. The Algerians showed distress the least, hardly a dozen of them taking the assistance of their comrades, and many, though covered with dust, so little affected by fatigue that they could jest with me about my fresh appearance. When their officers, about a mile out, gave orders to halt, then to form in fours to march into camp in order, they were equal to the part. But the Foreign Legion obeyed only the first command, that to halt, and it was a significant look they returned for the command of the youthful officer who passed down the line on a strong horse.

[76]A still longer march was made by a larger force of this same army in January, after General d’Amade had taken command. Pushing into the interior from Casablanca to Settat, they covered forty-eight miles in twenty-five hours, marching almost entirely through rough country without roads, or at best by roads that were little more than camel tracks. Proceeding at three miles an hour, the infantry must have done sixteen hours’ actual walking. Moreover, on arriving at Settat the army immediately engaged the m’halla of Mulai Rachid. Good marching is a prized tradition with the French, and in this one thing, if in nothing else, the army of France excels.

It has been stated by men who have some knowledge of Moslems, that the French in Morocco are liable to start that long-threatened avalanche, the general rising of Pan-Islam. The first Mohammedans to join the Moors in the Holy War, it is said, will be the Algerians. But my own knowledge[77] of Moslem countries leads me to argue otherwise. Since the French have been in Morocco, now more than six months, there have been less than a hundred desertions from the ranks of the Algerians; while a significant fact on the other side is the enlistment in the French ranks, in the manner of Goumiers, of Shawia tribesmen who have been defeated by them.

It has been from the Foreign Legion that desertions are frequent. Taking their leave overnight, the deserters, generally three or four together, make their way straight into the Arab country, usually to the north, with a view to reaching Rabat. In almost every case the deserters are Germans, and the Moors permit them to pass, for they understand that German Nasrani and French Nasrani hate each other as cordially as do Arab Moslems and Berber Moslems. Nevertheless, even though the deserters are Germans, it is asking too much of the Moor to spare them their packs as well as their[78] lives. I have seen one man come into Rabat dressed only in a shirt, another, followed by many Arab boys, wearing a loin-cloth and a helmet.

The French consul at Rabat makes no effort to apprehend these men; but they are usually taken into custody by the German consul and sent back to their own country in German ships, to serve unexpired terms in the army they deserted in the first place.

To see Morocco from another side—for we had looked upon the country so far only from behind French guns—we started up the coast on a little ‘Scorpion’ steamer, billed to stop at Rabat. But this unfriendly city is not to be approached every day in the year, even by so small a craft as ours, with its captain from Gibraltar knowing all the Moorish ports. A heavy sea, threatening to roll on against the shores for many days, decided the skipper to postpone his stop and to push on north to Tangier; and we, though sleeping on the open deck, agreed to the change of destination, for we had seen all too little of ‘the Eye of Morocco.’

[80]Tangier is a city outside, so to speak, of this mediæval country. It seems like a show place left for the tourist, always persistent though satisfied with a glimpse. Men from within the country come out to this fair to trade, and others, while following still their ancient dress and customs, are content to reside here; yet it is no longer, they will tell you, truly Morocco. There is no mella where the Jews must keep themselves; Spaniards and outcasts from other Mediterranean countries have come to stay here permanently and may quarter where they please, and there is a great hotel by the water, with little houses in front where Christians, men and women, go to take off their strange headgear and some of their clothes, then to rush into the waves. Truly Tangier is defiled. Franciscan monks clang noisy bells, drowning the voice of the muezzin on the Grand Mosque; the hated telegraph runs into the city from under the sea; an infidel—a Frenchman, of them all—sits the day long in the custom-house and takes one-half the money; and no true Moslem may say anything to all of this.

ON THE CITADEL. TANGIER.

[81]Still there are compensations. The Christian may build big ships and guns that shoot straighter than do Moslem guns, but he is not so wise. He works all day like an animal, and when he gets much money he comes to Tangier with it, and true believers, who live in cool gardens and smoke hasheesh, make him pay five times for everything he buys. He is mad, the Nazarene.

Seated at a modern French or Spanish table at a café on the Soko Chico, the Christian is beset by youthful bootblacks and donkey drivers; and older Moors in better dress come up to tell in whispers of the charms of a Moorish dance—‘genuine Moroccan, a Moorish lady, a beautiful Moorish lady’—that can be seen at a quiet place for ten pesetas Spanish. One of them, confident of catching us, presents a[82] testimonial; and with difficulty we reserve our smile at its contents:

‘Mohammed Ben Tarah, worthy descendant of the Prophet, is a first-class guide to shops which pay him a commission on what you buy. He will take you also to see a Moorish dance, thoroughly indecent, well imitated, for all I know, by a fat Jewish woman. He has an exaggerated idea of his superficial knowledge of the English language, and as a prevaricator of the truth he worthily upholds the reputation of his race.’ (Signed.)

The Soko Chico of Tangier, though an unwholesome place, is thoroughly interesting. About the width of the Strand and half the length of Downing Street—that is, in American, half a block long-it is large enough, as spaces go in Morocco, to be called a market and to be used as such. From early morn until midnight the ‘Little Sok’ is crowded with petty merchants, whose stock of edibles, brought on platters or in little handcarts,[83] could be bought for a Spanish dollar. Mightily they shout their wares, five hundred ‘hawkers’ in a space of half as many feet. The noise is terrific. The cry of horsemen for passage, the brawl of endless arguments, the clatter of small coins in the hands of money-changers, and the strains of the band at the ‘Grand Café,’ struggling to make audible selections from an opera; all these together create an infernal din. The Soko Chico, where the post-offices of the Powers alternate with European cafés, is, of all Morocco, the place where East and West come into closest touch. The Arab woman, veiled, sits cross-legged in the centre of the road, selling to Moslems bread of semolina, and the foreign consul, seated at a café table, sips his glass of absinthe. Occasionally a horseman with long, bushed hair, goes by towards the kasbah, followed a moment later by the English colonel, who lives on the Marshan and wears a helmet. A score of tourists gather at the café tables in the afternoon, and as many couriers, with[84] brown, knotty, big-veined legs, always bare, squat against the walls of the various foreign post-offices, resting till the last moment before beginning their long, perilous, all-night runs. Jews who dress in gaberdines listen to Jews in European clothes, telling them about America.