Title: The Last Duchess of Belgarde

TRIMOUSETTE.

The

Last Duchess

of Belgarde

By

Molly Elliot Seawell

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

NEW YORK MCMVIII

Copyright, 1908, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Published June, 1908

TO

THE DEAR MEMORY OF

HENRIETTA

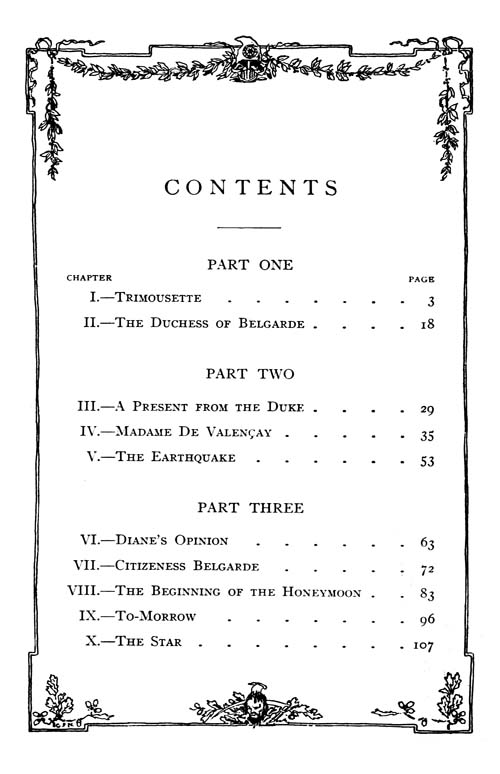

| PART ONE | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | Trimousette | 3 |

| II.— | The Duchess of Belgarde | 18 |

| PART TWO | ||

| III.— | A Present from the Duke | 29 |

| IV.— | Madame De Valençay | 35 |

| V.— | The Earthquake | 53 |

| PART THREE | ||

| VI.— | Diane’s Opinion | 63 |

| VII.— | Citizeness Belgarde | 72 |

| VIII.— | The Beginning of the Honeymoon | 83 |

| XIX.— | To-Morrow | 96 |

| X.— | The Star | 107 |

IN the great, green old garden of Madame, the Countess of Floramour, sat her granddaughter, little Mademoiselle Trimousette, wondering when she was to be married and to whom. Such an enterprise was afoot, and even then being arranged, but nobody, so far, had condescended to give Trimousette any of the particulars. She was stitching demurely at her tambour frame, while in her lap lay an open volume of Ronsard. Every now and then her rosy[4] lips murmured the delicious verses of the poet. A very pale, quiet little person was Mademoiselle Trimousette, with a pair of tragic black eyes, and something in her air so soft, so pensive, so appealing, that it almost made up for the beauty she lacked. Although the only granddaughter of the rich, the highly born and the redoubtable Countess of Floramour, little Trimousette was the very soul of humility, and in her linen gown and straw hat might have passed for a shepherdess of Arcady.

A clump of gnarled and twisted rose trees made a niche for her small white figure on the garden bench. To one side was the yew alley, where the clipped hedge met overhead, making the alley dark even in the May noontime. Before Trimousette stood, in a little open space, a cracked sundial, on which could still be made out in worn letters the legend:

[5]This sounded very sad to little sixteen-year-old Trimousette; shadows passed and re-passed; but men, passing once, passed forever. She sighed, and then her young heart turned away to sweeter, brighter things as she again took up her tambour frame. She knew the motto on the sundial well, did little Trimousette, but it always made her sad, from the time she first spelled it out in her childish days. However, her heart refused to give it more than one little sigh to-day, as she turned again to her embroidery and to her love dream. If only she was to be married to the Duke of Belgarde—that splendid, daredevil duke, whom she had once seen face to face, and to whom she had yielded her innocent heart and all her glowing imagination! Her grandmother, the old countess, who was frightfully pious, probably would not let little Trimousette marry the duke, not even if he asked her; the Duke of Belgarde could not, by any stretch of the imagination, be called a pious person. But[6] Trimousette believed firmly that all the wild duke needed to make him a model of propriety was a little tender remonstrance and perhaps a kiss or two— Here Trimousette held her embroidery frame up to her eyes to hide the hot blushes that leaped into her pale cheeks.

Presently came striding along the garden path the fierce old Countess of Floramour, as tall as a bean pole, and with a voice like an auctioneer.

“It is all arranged,” she said to little Trimousette, “and you are to be married to the Duke of Belgarde.”

The blood dropped out of Trimousette’s face, like water dashed from a vase. She had risen when she saw the old countess approaching. Everybody rose when the old countess approached, for she was a martinet to the backbone. The volume of Ronsard fell out of Trimousette’s lap, and Madame de Floramour pounced upon it.

“Reading poetry, indeed!” she cried indignantly;[7] “precious little use will you find for poetry when you are a duchess. You will be visiting morning, noon, and night, until you can hardly stand upon your legs, and receiving visits until your head swims, or going to balls and routs when you should be in bed, and trailing after their Majesties until you are ready to drop, and racking your brain for compliments to frowsy old women and doddering old men, and doing everything you don’t want to do—that’s being a duchess. Still, it is a fine thing to be a duchess.”

Dark-eyed Trimousette scarcely heard anything of this; her ear had caught only the words—“the Duke of Belgarde”—and she was dazzled and stunned with the splendid vision that rose before her like magic at the speaking of the winged words. Nevertheless, she managed to gasp out:

“And when am I to be married, grandmamma?”

“When you see my coach with six horses[8] drive into the courtyard, miss—then you are to be married, and not before.”

With this the old countess stalked off, and Trimousette fell into a rapturous dream, her head resting upon her hand. So motionless was she that a pair of bluebirds, still in their honeymoon, cooed and chirped almost at her feet. The world held but one object for Trimousette at that moment—the Duke of Belgarde. She knew his first name—Fernand—and her lips involuntarily moved as if speaking it. A heavenly glow seemed to envelop the old garden, the sundial with its melancholy motto, the dark yew walk, bathing them in a golden glory. Before her dreamy eyes returned the vision of the day she had seen the Duke of Belgarde, and had laid her innocent, trembling heart at his feet, just as a subject bows before his king, without waiting to be told. It was exactly a year ago, on a May day, and it was close by the Tuileries gardens. Madame de Floramour’s great coach[9] was drawn up, waiting to see King Louis the Sixteenth and Queen Marie Antoinette pass to some great ceremony at Notre Dame. The duke in a gorgeous riding dress, and superbly horsed, was among the courtiers, and on seeing a certain beautiful lady, Madame de Valençay, he dismounted, and stood uncovered talking with her, the sun gleaming upon his powdered hair, and making his sword hilt shine as a single jewel. How well Trimousette remembered Madame de Valençay’s glorious blonde beauty! She seemed, in her pale violet satin robe that matched the color of her eyes, a part of the splendid pageant of earth and sky that day. At the first sight of her a sudden, sharp, jealous pain rent Trimousette’s little heart. Instantly she realized that she was small and pale, and her gown was dull in color. The duke scarcely saw her, as he left Madame de Valençay’s side long enough to speak to the old countess. Trimousette, making herself as small as possible in the corner of the coach,[10] was, as usual, completely swamped by Madame de Floramour’s enormous hoop, tremendous hat and feathers, and voluminous fan. The old lady, who had a fierce virtue which she would not have hesitated to cram down the throat of the King himself, was lecturing the duke upon the sin of gaming, to which he was addicted, along with several other mortal sins. He listened with laughing, impenitent eyes, and grinning delightfully, swore he would make public confession of his sins and lead a life thereafter as innocent as that of the daisies of the field. Behind him, while he was talking, shone the lovely, fair face of Madame de Valençay, all dimpling with smiles.

Not the least notice did the duke take of little Trimousette until, the old countess preparing to alight and walk about while waiting for their Majesties, Trimousette stepped timidly out of the coach after her. One vagrant glance of the duke’s fell upon Trimousette’s[11] little, little feet, encased in beautiful red-heeled shoes, and, as he turned away with a low bow and a sweep of his hat, Trimousette’s quick ear heard him say to a companion standing by: “What charming little feet!”

From that day Trimousette’s innocent head had been full of this adorable, impudent scapegrace of a duke. She did not, like older and wiser women, try to put him out of her mind, but cherished her idyl, as young things will; only, he seemed too far above her and beyond her. And the beautiful Madame de Valençay was certainly better suited to so splendid a being as the Duke of Belgarde than a small creature like herself, so Trimousette thought. But she had not read the story of Cinderella for nothing—and small feet had carried the day in that case over beauty in all its pride.

The duke divided the empire of Trimousette’s soul with her brother, Count Victor[12] of Floramour, who was an edition in small of the Duke of Belgarde, whom he ardently admired and earnestly copied, especially in his debts. Count Victor had succeeded in piling up quite a respectable number of obligations, but unlike the Duke of Belgarde, who feared nobody, Victor was in mortal terror of his grandmother, the old countess. She held the reins tight over her grandson as over everybody else, and gave him about enough of an allowance to keep him in silk stockings. Being an officer of the Queen’s Musketeers, Victor had a great many opportunities to spend money, which he alleged was a solemn duty he owed her Majesty, the Queen. This was devoutly believed by Trimousette, but the old countess scoffed at it. Trimousette had determined, if she made a rich marriage, she would ask her husband to pay Victor’s debts, even if they were so much as a thousand louis d’ors—and now—ah, sweet delight!—she was to be married to the finest,[13] the most beautiful duke in the world, who no doubt was as rich as he was grand. The thought of Madame de Valençay disturbed Trimousette a little, but she believed if she was very sweet and loving with the duke, and sang him pretty little songs, and always wore enchanting red-heeled shoes, he would soon forget Madame de Valençay.

The duke had more than one splendid château, but Trimousette had heard of the small old castle of Boury, on the coast of Brittany, where the duke was born. Thither Trimousette decided they would go directly they were married; for, of course, the duke—or Fernand, as Trimousette already called him in her thoughts—would ask her where she wished to go. In her day dream she saw the place—an old stone fortalice, perched on the brown Breton rocks, with a garden of hardy shrubs and flowers, straying almost to the cliff, and seagulls clanging overhead in the sharp blue air. There would Trimousette and[14] her duke live like their Majesties at the Little Trianon, where the Count d’Artois milked the cow, and Queen Marie Antoinette herself skimmed the cream from the milk pails. The Queen, too, always wore a linen gown and a straw hat when she was at the Little Trianon, and Trimousette would dress in the same way at Boury.

While all these idle, sweet fancies floated through her mind, like white butterflies dancing in the sun, she glanced up and saw Victor coming toward her. Victor did not march across the flower beds like the old countess, but slinked along through the yew alley, in the dull green light that brooded upon it even at noontide. He was like Trimousette, only ten times handsomer, and gave indications of having seen a good deal of life. To-day, it was plain he had been up all night. He was unshaven, his hat had lost its jaunty cock, his waistcoat was wine-stained, and the lace on his sleeves had been badly damaged in[15] a romp with some very gay ladies about four o’clock that morning.

Victor beckoned to Trimousette, and she rose and went into the cool, dark alley with him where they were quite secure from observation. Then, taking Trimousette’s hand, he kissed it gallantly.

“So you want to be a duchess, my little sister,” he said, laughing, yet kindly. “I hope you will be happy, but don’t get any nonsense in your romantic head about you and Belgarde living like a pair of blue pigeons in an almond tree. Belgarde is a gay dog if ever I saw one. We were together last night—and look!” Victor showed his tattered ruffles and battered hat, and touched his unshaven chin. “We went to a little supper together, which began at midnight, and is just over now within the hour.”

Trimousette firmly believed that she would be able to cure her duke of his taste for such suppers, but she was too timid to put her belief[16] in words. She said, however, after a blushing pause:

“One thing I mean to ask the duke as soon as we are married, and that is for some money to pay your debts, dear Victor.”

At that Victor sat down on the ground and laughed until he cried.

“You are as innocent as the birds upon the bushes, my little duchess,” he said. “Belgarde pay my debts! He cannot pay his own.”

“But yours cannot be so very large,” urged Trimousette earnestly. “If it were even as much as a thousand louis d’ors, I should ask the duke to give it to me, and if he loved me—”

She paused with downcast eyes, and Victor stopped laughing and looked at her with pity. What an innocent, affectionate, guileless child she was, and what a lesson lay before her!

“My debts amount to a good deal more than a thousand louis d’ors,” he responded, smiling in spite of himself at Trimousette’s[17] simplicity. “You will have a good many thousands of louis d’ors at your command, my little duchess, but you will need them all yourself; for Belgarde will have his wife finely dressed, and your hotel and equipages must be suitable to your rank.”

“I shall always be able to spare a little for you, Victor,” answered Trimousette, looking at him with adoring eyes.

“Belgarde will not mind the money; he is a free-handed, generous fellow, as brave as my sword. But you must not try to domesticate him, you must become gay like himself. Belgarde told me on our way home just now that everything had been arranged, and that he meant to treat you well. I answered, if he did not, I would run him through the body; and so I will.”

At which Trimousette was frightened half to death, and replied:

“Then if he treats me ill, I will never let you know anything about it.”

NEVER was a bride less burdened with the details of her marriage than was Mademoiselle Trimousette. Her grandmother arranged the settlements, provided the trousseau, and did not even let Trimousette see the marriage presents, which the duke sent in a couple of large hampers, until the day before the wedding.

The duke did not take the trouble to see his little bride in advance of the formal betrothal, which took place the week after Trimousette[19] had sat and stitched by the old sundial in the garden. The betrothal ceremony took place in the grandest of all of the grand saloons in the hotel of Madame de Floramour. Everything was done in splendor, and the bride herself, for the first time in her life, was expensively dressed and wore jewels. When she entered the grand saloon on Victor’s arm, her eyes were downcast, and she felt as if she were under some enchanting spell. She saw nothing but her adorable duke, with his laughing eyes, and dashing figure, and slim, sinewy hands over which fell lace ruffles.

The duke glanced at his bride with good-humored indifference. She was too young, too unformed to reveal what she might yet become, but she looked so gentle, so unresisting, that she appeared to be a very suitable duchess for a duke who took his pleasure wherever he found it. The only thing he noticed especially about her were her dainty[20] feet, in little white satin shoes, and her black eyes, hidden under her downcast lids. He recognized the melancholy glory of her eyes, but thought them too tragic for everyday use. Personally, he much preferred Madame de Valençay’s blue orbs, languid, yet sparkling. That charming lady was present, and appeared in nowise chagrined. Shortly before the betrothal, she had suggested to the duke that she should put the Count de Valençay out of the way, in order to make a vacancy in his shoes for the duke; de Valençay was always ailing, and could easily be made a little more so. The duke declined the proposition, as every other man has done to whom it has been made since the dawn of time. But he had assured Madame de Valençay that neither a husband nor a wife counted in an all-consuming passion such as theirs, and she believed him. The future duchess pleased Madame de Valençay quite as much as Trimousette pleased the duke. Surely, that small,[21] timid, almost voiceless creature ought not and should not stand in the way of two determined lovers like the Duke of Belgarde and Madame de Valençay.

Few persons present took any more notice of the young bride than did the prospective bridegroom. The betrothal ceremony was soon over and then a great dinner was served, at which the future Duchess of Belgarde sat next the duke at table. Amid the crowd of merry faces, the cheerful noise and commotion of a betrothal dinner, the lights and the flowers, Trimousette saw only the duke’s handsome, laughing, careless face, and heard only his ringing voice. She was so quiet and still during it all that it touched the duke a little, although he had frankly determined in advance he would not trouble himself very much about his future duchess. He was impelled, however, by a certain careless kindness, which was a part of his nature, to pay her a few small compliments. The blood[22] rushed to Trimousette’s face and she raised her black eyes to his with an expression of adoration at once desperate and shy, so that the duke privately resolved not to encourage her to fall in love with him any more than she was already. Nothing was more inconvenient, thought the duke, than a wife who is in love with her husband, except perhaps a husband who is in love with his wife.

The next night the wedding was celebrated. First there was a great supper and ball preceding the ceremony, which took place at midnight, according to the fashion of the age, at Notre Dame. It was a very grand wedding indeed. The King and Queen were represented, and half the old nobility of France was present. In fact, there was so much of rank and grandeur that the bride was as nearly insignificant as a bride could well be. Her costume was very gorgeous; she blazed with jewels, which came from she knew not[23] where, and she was attended by six young ladies of the highest rank, whom she had never before seen. When Trimousette entered the first of the magnificent saloons, her eyes timidly traveled over the splendors before her. Some of the great rooms were devoted to cards, others to dancing, where an orchestra of twenty-four violins played, after the manner of the orchestra of Louis the Fourteenth, at whose court Madame de Floramour had been a shining light. In another huge hall a superb supper was served by a hundred liveried lackeys, wearing wedding favors.

But the only familiar faces the little bride saw were her brother Victor’s and her grandmother’s iron countenance, grimly resplendent under a towering headdress of diamonds and red feathers. Yes, there was another face she knew well, though she had seen it but twice—the lovely rosy-lipped Madame de Valençay. Trimousette, for all her outward[24] timidity, had a shy and silent courage, which appeared when least expected. She did not really fear Madame de Valençay, with all her wit and beauty, for love is the universal conqueror. So thought simple Trimousette. The duke was quite civil to his bride, and she mistook his civility for the beginnings of love, and thought him more adorable than ever.

Half an hour before midnight a great string of coaches, with running footmen carrying torches, started for the Cathedral of Notre Dame, where the Archbishop of Paris, with the assistance of a whole batch of cardinals, was to perform the marriage ceremony. The night, radiant and rose-scented, was the loveliest of June nights. The crowds along the streets hustled and pushed and scrambled good-naturedly to get a sight of the young bride. All agreed that she was not half handsome enough for the beautiful, superb Duke of Belgarde, and such, indeed, was the bride’s[25] own opinion. The duke was in the gayest spirits. The more he saw of his bride, the better she seemed suited to him. She was certainly the meekest, most inoffensive creature on earth, and if only she would not insist on making love to him, it would be an ideal marriage—for the Duke of Belgarde. He congratulated himself that he had not yielded to the seductions of Madame de Valençay when that spirited and fascinating lady had offered to put her husband out of the way to please the duke.

The wedding train, as it swept up the great aisle of Notre Dame, blazed with splendor. In it was the Count d’Artois, who not only milked the cow charmingly at the Little Trianon, but danced adorably on the tight rope. The main altar of the old Cathedral, with its thousands of candles, sparkled like a single jewel. The huge organ thundered under the echoing arches, and the great bells in the towers clashed out joyfully their wedding[26] music to the quiet stars in the heavens. The melody, the beauty, the glory of it all found an echo in the tender, simple heart of the new Duchess of Belgarde.

[28]

INSTEAD of a honeymoon at Boury, the old Breton castle on the cliffs over the sounding seas, where the salt spray upon the crumbling towers, the Duke and Duchess of Belgarde had a racketing time at the Château de Belgarde. This was a great palace of a place in the neighborhood of Versailles. There was incessant dancing, dining, and merry-making for three whole weeks, and the meek, silent little bride grew so tired she could scarcely[30] stand upon her pretty feet. Madame de Valençay was much in evidence, and was easily the loveliest of all the lovely women at the Château de Belgarde. A vague uneasiness came into the heart of the little duchess whenever she looked upon this beautiful blue-eyed creature always radiantly dressed. Trimousette, however, still believed that she could soon make her duke fall as deeply in love with herself as she was irretrievably in love with him. He was certainly kind to her, so thought Trimousette with deep delight in her innocent heart. She did not observe that the duke’s kindness to her was exactly like his kindness to his faithful hound, Diane, who had broken both her forelegs in his service, and though unable to hunt, limped about after him with the desperate devotion of that most sentimental of all creatures except a woman—a dog. The duke did, indeed, show a sort of protective instinct toward his silent, shy, black-eyed young wife, and she noticed[31] that Madame de Valençay was more civil to her when the duke was by than when he was not. But it must be admitted that the Duchess of Belgarde was shamefully bullied in her own house from the day of her marriage by Madame de Valençay. Trimousette bore it with the quiet, wordless courage which enabled her to bear many things in silence, and she continued to mistake her husband’s casual good will for the beginnings of love in its infancy. One day, less than a month after her marriage, came the awakening. The duchess saw a jeweler from Paris at the door of the duke’s room. The duke was holding in his hand a blue, heart-shaped locket with diamonds in it.

“I will take this,” he said, “for one hundred louis.”

He did not see his duchess who was passing a little to the back of him. A palpitating joy shot through Trimousette’s heart. What were all the jewels and laces and furs and[32] silks in her marriage presents from the duke compared to that charming little jeweled heart, which he was choosing for her! The duke thrust the trinket in his breast, dismissed the man, and then turning, for the first time saw his duchess walking along the broad, bright corridor, flooded with the glow of the summer morning. As he was going the same way, he walked after Trimousette, and like a gentleman he uttered some little phrase of compliment. In all honesty, he preferred her as his wife a million times more than Madame de Valençay, whom he could have married, if only he had agreed to have the present incumbent put out of the way. A submissive person was what the duke particularly desired for a wife, and he had got one.

The little duchess’s heart beat so with joy when her husband joined her that she was almost suffocated, and could only say “Yes” and “No” when the duke talked to her. He[33] was obliged to admit, however, after a few minutes of this, as they passed through the long, sunlit corridor out upon the gay terrace, that his bride had not much conversational power. And standing on the terrace, surrounded by gentlemen, was Madame de Valençay, entertaining them all with the most amusing badinage, and every word sparkled. She seemed to embody the very spirit of the rosy morn with her shining eyes, her ringing voice, her gown of a jocund yellow.

Nevertheless, for Trimousette this trifling attention of the duke toward her filled her soul with rapture. There was a great ball that night at the château, and she dressed herself for it with gayety of heart in a very unbecoming gown selected for her by her fierce old grandmother. Her innocent, hidden hope and pleasure lasted until she entered the ballroom to receive her guests. There, amid the jewels sparkling upon Madame de Valençay’s breast, lay the little blue enameled heart.

[34]Something as near resentment as Trimousette could feel stirred within her, and her dark eyes grew sombre. She had a sudden illumination. Never more would she mistake the duke’s careless kindness for the beginnings of love. But with the illumination of her mind rose up that latent, still, wordless courage which enabled her to bear almost unbearable things without one sign of pain. She was but a girl of seventeen, this injured wife, this insulted duchess; she knew nothing of retaliation, she only knew how to suffer silently and with dignity. No one, not even her brother Victor, should know of the cruel affront put upon her in the first month of her marriage. She forced herself to talk and even to smile, and Victor, who was afraid that Trimousette would never look or speak or walk or act as a great duchess should, began to have some hopes of her.

THE gayety and racketing went on during the whole year at one place or another—the Château de Belgarde, other châteaus, Paris and Versailles. Trimousette saw Madame de Valençay oftener than any other woman of her acquaintance. Madame de Valençay was fairly polite, but in her eyes and smile lurked a kind of insolence which the reticent young duchess understood quite well, but of which she made not the slightest sign. She had no[36] more liberty and not much more money as Duchess of Belgarde than when she lived in her grandmother’s house as a little demoiselle. There was much to buy and to give, and besides, ever since King Louis the Sixteenth called the States General together, the peasants had refused to pay their rents and even their taxes, and the work people demanded their money with threats and curses. So far from having a thousand louis d’ors with which to pay Victor’s debts, the poor little duchess had only managed, by skimping and saving in her own personal expenses, to scrape together three hundred louis—and it was so little she was ashamed to offer it to Victor.

A year after her marriage Trimousette disappointed and offended the duke very much by bringing into the world a daughter. A son would have been welcomed; but a girl—well, the poor little thing, as if knowing she was not wanted by anyone except her young[37] mother, soon wailed her life away. Trimousette grieved as one whose heart was broken, and wore nothing but black. This still more annoyed the duke, but on this point alone Trimousette showed a slight obstinacy. The duke wished her to go about, to visit Versailles, to be seen at the theatre. The young duchess humbly obeyed these instructions, but not in the spirit the duke desired. Trimousette’s heart, poor lonely captive, beat against its prison bars, and made its melancholy cry a little heard; then grew silent.

She led a life singularly lonely for a great lady who received twice in the week, and who went to a ball nearly every night. Her grandmother thought she had done enough in marrying Trimousette off to one of the greatest dukes in France, and gave herself up to sermons, taking no more thought of her granddaughter. Victor had his own amusements, as became an officer of the Queen’s Musketeers and a gay dog. Only the poor,[38] broken-legged hound Diane seemed to seek Trimousette’s company, and together the two creatures who loved the duke listened for his footsteps, and hung timidly upon his words.

But there was so great a noise of other things in Paris that private woes were not much heeded. It was impossible for a lady to walk without molestation upon the streets full of turbulent people, and it was actually dangerous to drive about in a ducal coach. The pavements were thronged by hungry creatures, both men and women, with menacing eyes, and threatening, yelling voices, who had been known to scream and flout ladies in their carriages, and to drag gentlemen from their horses and maltreat them. Once Madame de Valençay, seeing Trimousette preparing to go forth somewhat unwillingly in her coach, hinted that perhaps the duchess was afraid.

“Not in the least, madame,” answered Trimousette quietly. “Perhaps you will join me[39] in my coach and drive with me to the Palais Royal.”

Madame de Valençay was so stunned by this proposal that she accepted it, the duke standing by and wondering if his taciturn young duchess had not lost her wits.

The two ladies were assisted into the coach, which set off toward the Palais Royal. It was about seven in the evening when the work of the day was over and the streets were fullest of these ragged, starving beings who had found voice at last, and shouted out the story of their rags, their hunger, their misery, and their determination to punish somebody for it. The splendid coach and six of the Duchess of Belgarde was like showing a red rag to a bull. The mob surrounded it, hooting and screaming, and wrenched the whips from the hands of the coachmen and postilions, and the canes from the three footmen hanging on behind. Madame de Valençay, who had started out laughing and defiant,[40] grew pale and then frightened, and when a wretched woman, with the glare of famine in her eyes, dragged the coach door open and tore the ribbons from Madame de Valençay’s hat, that lady fell to whimpering and almost fainting with terror. Not so little Trimousette. It had been complained of her often that she was too silent and impassive, and she remained so now, giving no sign whatever of fear or uneasiness. She even smiled with a faint contempt at Madame de Valençay’s terrors, and refused to give orders for the coachman to return to the Hôtel de Belgarde until they had made the circuit of the Palais Royal. When they returned, the duke was awaiting them in the courtyard of the hotel. He was wondering what would be the next miracle. Madame de Valençay had been so terribly scared that she could not disguise it, and clamored to have not only the duke, but all the men servants in the hotel to escort her home. She looked a wreck, did this beautiful,[41] gayly gowned lady, with her hat in fragments, her fan broken, her clothes almost torn off her by the furious, yelling, laughing crowd of women in the streets. Not so Trimousette, in her sedate black gown, better suited to eighty than eighteen.

“I was not at all frightened,” she said to the duke, and if she had not been so shy, she would have told him all about it. The coachmen and footmen did this, however, and slyly, after the manner of their kind, brought the duchess’s calm courage into contrast with Madame de Valençay’s undignified screams and pleadings.

The duke, who was insensible to fear himself, expected courage in women, and was secretly disgusted with Madame de Valençay. Besides, like most ladies of her sort, she was beginning to hound the duke with what she called her love. It had grown more insistent since his marriage to the quiet little Trimousette, who appeared not to know there was[42] such a thing as faithlessness in the world. The duke chafed a little under Madame de Valençay’s shameless pursuit of him. Not being a courageous woman she did not venture into the streets when the people became turbulent; but they were not always turbulent, the poor, starving people. Although herself often afraid to go out, Madame de Valençay did not mind sending out her running footmen, and the Duke of Belgarde could scarcely leave his own door without a lackey in Madame de Valençay’s livery poking a scented pink note at him. The duke ground his teeth, and dimly recognized that his friend, as he called her, harassed and worried him, and indeed hen-pecked him more in two weeks than his pale, quiet little duchess had done in the whole two years of their married life. Nevertheless, Madame de Valençay’s glorious and vivid beauty enchanted him, and made him sometimes forget Trimousette’s very existence. He even forgot to compliment her little feet,[43] which Trimousette still, with a faint, foolish hope in her heart, dressed in charming little shoes, the only patch of coquetry or vanity about her.

The people, meanwhile, were growing more and more unruly, and at last one day a mob of dressmakers, washerwomen, cooks, and the like, headed by a tall, red-faced laundress, almost as fierce as the old Countess of Floramour, began a round of domiciliary visits to persons who owed them money. They went to many hotels, including that of Madame de Valençay, who ordered all the doors to be double locked, and ran up to her bedroom, where she remained cowering and terrified, but unable to escape the menaces and shouts of the crowd of haggard, savage women in the courtyard, demanding their money to keep their children from starving. They got nothing, however.

Next, they visited the old Countess of Floramour, who came down boldly enough to[44] them, but gave them a sermon instead of money. She exhorted them to live by Bible texts, and was indignant when the big red-faced laundress replied that they could neither eat nor wear the Bible. Thence the riotous women invaded the courtyard of the splendid Hôtel de Belgarde. They had grown more noisy and the dames de compagnie of the duchess begged her not to go down to them. But Trimousette was of all things least a coward, and taking from her escritoire the little bag of gold she had saved up to pay Victor’s debts, descended the grand staircase into the sunny courtyard, where the mob clamored and abused the powdered and silk-stockinged footmen. Something in the aspect of this pale, soft-eyed little duchess in her black gown, her hair tied with a black ribbon, moved the wild hearts of these savage women, and her voice, trembling and embarrassed, made them keep quiet in order to hear her.

“It is all I have,” she said, blushing and[45] stammering as she handed the bag to the big red laundress; “it is only a little more than three hundred louis, and is not enough to pay you. If I had any more, I would be glad to give it to you.”

The crowd of women looked at her in surprise; she was the first great lady they had visited so far who had given them a franc. The fierce laundress became almost civil when she took the bag from Trimousette’s hands.

“We ask for our money, for we are starving. My little child died last week because I have not for a year past had money enough to give her good food. What do you think of that, madame?” she cried, her red face suddenly growing pale and fiercer.

“My little child died last year,” answered Trimousette, looking at the woman before her with the kinship of motherhood; and then covering her face with her hands, she burst into weeping.

The mob was hungry and savage and[46] ragged and hated duchesses in general, but at the sight of the tears of this black-robed, pale young girl they remained silent. The washerwoman wiped her eyes with her apron, laid her hand on the arm of the weeping duchess, and said roughly:

“It is like this with all of us, we women, duchesses and washerwomen alike. Every one of us has a little pair of wooden shoes, or a cap, or something that belonged to a dead child. But ours died because we could not buy them enough to eat.”

The little duchess wept again at this, but presently drying her eyes, she said:

“I will do all I can to pay you.”

Trimousette did not think it necessary to mention this adventure to the duke. She did not see him every day even when he was in Paris, and besides, when she tried to tell him things, she always grew frightened and the words died upon her lips. The servants, however, told the duke of it when he came home[47] in the evening. He had spent most of the intervening time trying to quiet Madame de Valençay, who was in paroxysms of terror. The duke grew every day more bored by his friend, and concluded to spend the evening at home, in order to escape Madame de Valençay and her scoundrelly running footmen, who watched his comings and goings as if he were a criminal.

For the third or fourth time since his marriage he sought, of his own free will, his wife’s society. She spent her evenings in a little room on the ground floor of the Hôtel de Belgarde which opened upon the garden. When Trimousette heard the duke’s knock, she thought it was Victor’s and ran to open the door. The sight of her husband disconcerted her so that she stopped and hesitated awkwardly, quite unlike Madame de Valençay, who could not be awkward if she tried.

Diane, the broken-legged hound, who was[48] Trimousette’s constant companion, licked the duke’s hand, and gave a soft whine of delight. Trimousette, whose heart fluttered whenever she saw her husband, was undemonstrative and inarticulate. The duke, after politely greeting his duchess, and patting Diane’s head, walked to the fireplace, where a little blaze crackled. The time was September, and there was an autumn sharpness in the air.

“I am afraid you were alarmed to-day by that mob of wretched women,” said the duke presently, as he warmed his hands at the fire, the mantel mirror reflecting his handsome face and figure.

“No,” replied Trimousette timidly, “I was not frightened.”

The duke stroked his chin reflectively. Silent women like his duchess were sometimes preferable to those who shrieked and screamed at the least provocation, like his friend Madame de Valençay.

Having said so much Trimousette picked[49] up her embroidery frame and, seating herself, began to embroider. The duke, looking at her, congratulated himself that she had lost the habit of blushing and starting every time he spoke to her, which, for a while after his marriage, made him apprehend that she might fall in love with him and that would have been excessively annoying. Meanwhile, Trimousette’s heart was palpitating faintly, and her black eyes were cast down because she was too embarrassed to look up.

“I think,” said the duke, “it would be as well to go to the Château de Belgarde a little earlier this year.”

He was thinking that he must get away for a time from Madame de Valençay’s cursed running footmen perpetually chasing him with her pink notes. Trimousette felt a sudden access of courage, which nerved her to say, almost boldly:

“Would it not be pleasanter to go to Boury?”

[50]“That little dungeon in Brittany!” cried the duke, laughing.

“But it is so quiet and peaceful there,” continued Trimousette, blushing at her own boldness. “I think I—I—should like to go to Boury.”

It was the first time since their marriage that she had ever proffered a request; and the duke, like most imperial masters, was sometimes capable of a generous action. Besides, it occurred to him that Madame de Valençay would scarcely follow him to Boury.

All at once, while the duke stood hesitating, the duchess’s shyness vanished for one brief moment, and she became positively eloquent.

“I know all about it,” she said, clasping her hands eagerly; “it is by the sea, and there is a garden running to the cliffs, with plants so hardy that even the fierce sea winds cannot kill them. And there are beautiful woods and fields, and you—I—we could read in the mornings, and in the afternoons you could go[51] out with your fowling piece, and in the evenings—” She stopped, trembling and quite unable to put into words the enchanting dream that rose before her. The quiet evenings tête-à-tête with the duke, he reading perhaps—he sometimes read the works of Monsieur Voltaire and Monsieur Rousseau. And she would sit by working at her tambour frame, with Diane, her faithful friend and sympathizer, at her feet. The vision that hovered in Trimousette’s mind was not reflected in the duke’s. He only saw that his quiet little duchess wished very much to go to Boury, and had made the longest and boldest speech he had ever heard from her lips.

“Then, madame,” he cried, “I will consider what you say. At all events, we will leave Paris, and possibly we may dwell, like a pair of turtle doves in a cage, for the space of a week at Boury.”

When the duke went out, banging the door after him, Trimousette actually danced about[52] the room in her joy and triumph. She would have him at the little country place all to herself, and for one whole week. There would be no brazen intrusion of Madame de Valençay, and perhaps—perhaps the duke might forget her; and then would come true that dream of the honeymoon—for Trimousette had never had a honeymoon.

THIS rosy vision of Boury with her duke lasted Trimousette just twenty-four hours. The duke, on reflection, concluded that Boury was too far away from Paris, where all was tumult and uncertainty. It was not too far away from Madame de Valençay, of whom the duke was now almost weary, but for him to go to Brittany might look as if he were running away from their Majesties, who were in very great danger. So, the next evening, the duke again[54] came into Trimousette’s little room and told her it was not Boury to which they would go, but Belgarde, near to Versailles. He even condescended to give his reasons. Trimousette listened with a mute, unmoved face. She was so used to disappointments that she took them without protest. Of course, she thought the real reason was Madame de Valençay, and when the duke left the room, she went and looked at herself in the mirror.

“No, Trimousette,” she said to herself, “you are not pretty; your eyes are dark, and you have long, soft, black hair, and little feet. But that is not beauty. Nor is the love of the most splendid duke in France for you, although you may be his wife.”

The duke invited a great party to spend the week at the château, and the little duchess went soberly through her duties as hostess. Everybody said she was much too quiet, which was true. Others said she had no feeling, which was ridiculously false.

[55]The party was very gay. The world was rapidly turning upside down. Nobody had any money, the black clouds and red lightnings and earthquake shocks were bewildering men’s minds, so the only thing to do was to laugh, to dance, to sing.

That is what the company at the Château de Belgarde did, the duke leading all the wild spirits in the party.

The one comfort the little duchess had was that her brother Victor was among the roysterers. He was ever kind to her, but like her husband, a trifle careless. Victor was working night and day at a little play, to be produced in the private theatre at Belgarde. It was meant to shadow forth the final triumph of the aristocracy over the people, who were making themselves to be seen and heard and felt at every turn. The play was to be produced on the night before the party broke up.

Now, it was the fixed and grim determination[56] of the duke that Madame de Valençay should not track him to Belgarde, to worry him. But the lady was too clever for him. He could not prevent her from visiting a neighboring château, and coming over with a large party to spend the day at Belgarde, as country neighbors do everywhere.

Never had Madame de Valençay looked more deliciously seductive than on that day. She might have sat for one of Botticelli’s nymphs in her soft wine draperies without a hoop, being in the country, her long fair hair in curls about her shoulders, and wearing a hat crowned with roses.

In contrast to this dazzling creature was the pale little duchess sombrely dressed, her silence, which verged on awkwardness, placing her at the greatest disadvantage beside the brilliant, rippling talk of Madame de Valençay and her laughter like the music of a fountain.

In one thing only did the duchess carry off[57] the palm. Madame de Valençay, like a peacock, was all beauty except her feet, which were large and ill-shaped. The duchess’s small, arched feet looked smaller than ever in the dainty black shoes with black silk stockings which she wore.

Trimousette had shown no sign of chagrin when Madame de Valençay arrived with a merry party, all laughing and chattering like so many birds in spring. It was a part of her reticent pride to make no complaint, to show no uneasiness. The duke was furiously angry with Madame de Valençay for hunting him down, but she was so beautiful, she tripped up and down the terrace with such airy grace, she was so wickedly merry at his expense, that, manlike, he forgave her.

This week, which Trimousette had pictured to herself as so charming, turned out to be one of the most trying of her life. She scarcely saw her duke except in the evening when the saloons were full of persons, and[58] there was much fiddling and dancing. Nor did she see much more of Victor, who was keen about his play. The very last evening of all it was produced and was a huge success. By some sort of hocus-pocus, Madame de Valençay had forced herself into the cast, and made a divinely beautiful marquise, to whom the duke, as a soldier of fortune, made violent love and made it well, too, his duchess looking on with a face composed, almost dull. Victor himself was disguised most bewitchingly as a ragpicker, and in his character denounced the aristocracy furiously, to the uproarious delight of his audience.

It was the most amusing thing in the world, and all the fine ladies and gentlemen nearly died of laughing at it. The heart of the young duchess alone did not respond to this ridicule of the earthquakes and the storm clouds. She remembered the words of the washerwomen and the cooks, and the strange glare in their eyes and their pinched faces.

[59]The gayety of the party lasted until midnight, when the ball after the play and the supper was nearly over. Then a messenger, pale and breathless with hard riding from Paris, arrived on a spent horse, and told how the people had gone to Versailles and had carried the king and queen and their children and Madame Elizabeth off to Paris. How the king, foolish and shamefaced, had appeared on the balcony of the Tuileries with the red cap of liberty on his head, and how the royal people were no better than prisoners in that palace, and that Paris had gone mad.

There were no cowards among this party at the Château of Belgarde except Madame de Valençay. Much as she loved the duke, she loved her own skin better, and privately resolved to seek shelter in England until the shower was over, not knowing it to be the deluge.

The duke, who had not a drop of coward’s blood in him, started for Paris at daylight.[60] He took his duchess with him, not that he particularly cared for her society, but because it did not enter his rash head that anybody should be afraid of anything. So to Paris they went, and on the next night the duke was visited by a deputation of rapscallions calling themselves the National Guard, thrust into a wretched hackney coach with a ruffian on each side of him, and cast into the prison of the Temple as a conspirator against the liberties of the people.

[61]

IT was one thing to catch the Duke of Belgarde and another thing to keep him. Exactly one week from the night of his arrest and imprisonment he was once more at large, and all through the courage, resource, and seductive powers of his quiet, sombre-eyed, shrinking young wife. Trimousette under a sharp spur became articulate, and the latent vast energy and spirit she possessed was instantly developed by blows and hammerings as sparks are struck from[64] the dull black flint. The night of the duke’s arrest Trimousette shed not one tear on parting with the man she loved. The duke thought her rather insensate and would have relished a few tears from her. Nevertheless, Trimousette straightway set her wits, which were not inconsiderable, to work in order to help her husband. She determined to see him. Dressing herself in her simplest gown, for she accorded best with the note of simplicity, and going straight to Marat, the most hideous and abominable of men, she sweetly and calmly asked him to permit her to see her husband for one half hour to settle some family affairs. Marat thought he had never seen a simpler, more democratic young person than this little duchess. He was very artfully flattered by Trimousette, who had little or no experience in that line, but who being all a woman, succeeded admirably at the first attempt. Marat, admiring Trimousette’s large black eyes, agreed to do what he could. These eyes, usually[65] so tragic, assumed a smiling and brilliant expression as soon as Trimousette was brought face to face with danger. Within twenty-four hours after her meeting with Marat, she was admitted to an interview with her husband in the prison of the Temple.

Of course she was searched on entering and leaving the prison. It was an ordeal which brought most great ladies to tears and reproaches, but Trimousette bore it with something that savored both of dignity and coquetry, and actually smiled when the ruffians who searched her complimented her charming little feet. They did not observe, around the bottom of her petticoat, yards and yards of flat silk braid, which made really a good strong rope, nor did they discover, hidden in her thick black hair, some gold pieces. When she was admitted to the cell of the duke, he was the most surprised man in Paris, and more so still when Trimousette, having suddenly found a very eloquent tongue, laid[66] before him a clever plan of escape, along with all the braid she was ripping off her petticoat and the money out of her hair. The duke thought he knew women—certainly he had seen a great deal of them ever since he was a pretty page at the court of Louis the Fifteenth. But he had not been much in the way of knowing true love, nor the magic which it works in the heart of a woman.

He gazed at his wife with something like admiration for the first time, and was very gallant to her, kissing her hand. Trimousette did not now mistake gallantry for love. She had grown wise upon disappointments. She remained a short half hour, and then proudly, for all her humility, would not wait to be notified, but left her husband’s cell, bidding him good-by again without a tear. Certainly the duke shed no tears. He was deeply grateful to his wife and profoundly astonished at the new attitude she assumed. Immediately he[67] busied himself with the schemes for his escape planned by his wife.

Three nights later, just before daylight, he dropped out of his prison window into the garden of the Temple, and scampered off, the sentry very obligingly turning his back until the duke was well out of sight.

Great was the hue and cry raised after the Duke of Belgarde. No suspicion attached to his little duchess, who was then on her way to the small castle on the Breton coast. True, she had seen the duke, but those who knew about these things, or thought they did, declared that she was too timid, too silent, too young to assist in the bold plan of escape which had freed her husband.

Trimousette arrived at Boury under instructions from the duke to remain there until she should get further directions from him. She reckoned upon remaining a month; and stayed three years and a half.

Never in the same space of time had so[68] much happened in any country as in France from 1789 to 1794. The old order that had lasted a thousand years was engulfed, and black chaos reigned. The little duchess in the old stone castle by the sea heard the reverberating thunders, and felt the earth rocking under her feet, and saw the crashing wreck of monarchy. She stirred not, having been told to remain tranquilly at Boury until her lord should send her word otherwise. The duke was in the thick of the tumult and was in danger every hour of the day and night. He was sometimes a fugitive for his life; again he appeared boldly in Paris and defied arrest. He was not one of those who would have saved poor Louis the Sixteenth and Marie Antoinette by flight. On the contrary, being of inextinguishable courage, he advised using the strong hand, and would have had Louis the Sixteenth show something of the spirit of Henry the Fourth. The thing which Fernand, Duke of Belgarde, hated most was[69] cowardice, and through this was he absolved from the spell of Madame de Valençay. She had fled to England and never ceased importuning the duke by letter to run away from France. The duke on reading these letters would dash them under foot and trample upon them in his fury. Nor would he answer them, considering himself insulted by them. This did not keep Madame de Valençay from writing them, because, unlike Trimousette, she was without pride.

The duke made the handsomest possible thanks to his duchess for her share in his escape, and really meant to show his appreciation of the fact that she was the only woman who had ever helped him and never bothered him. But too much was happening; rivers of blood were flowing everywhere, and only those things which were insistent made any impression on the duke, and Trimousette was the least insistent person on earth.

Nothing more unlike the sweet dream which[70] Trimousette had planned for Boury could be imagined than the life she led there for more than three years. She was quite alone, except for her dame de compagnie, a sour old lady of whom Trimousette was mortally afraid. True, she had with her Diane, the broken-legged hound, now blind and scarcely able to creep at Trimousette’s heel when the two walked together upon the rocky shore at sunset to dream of the absent one. For Trimousette felt sure Diane dreamed of her beautiful, brilliant master. In the long evenings spent in the gloomy old saloon Trimousette would take in her hands Diane’s trembling paws and whisper:

“Diane, do you think he ever remembers us? Do you think he will ever send for us?”

And Diane would give a melancholy whine, indicating that she did not believe the duke ever would. Sure enough the duke did not send for either his wife or his dog, and poor Diane, weary of waiting, at last lay down[71] quietly one night by Trimousette’s bed and was found dead next morning.

Trimousette felt more alone than ever in her life when the poor lame dog was dead. Soon after, she got news that Madame de Floramour had died of chagrin at the disasters and irreligion into which France was plunged; and last—ah, cruel stroke!—Victor fell fighting gallantly in La Vendée.

The young duchess bore these blows in patience and silence. The duke managed to contrive a letter of sympathy to his duchess when the soul of Victor de Floramour was called away. The letter was very ill-spelled and ill-written, for the duke’s accomplishments were those of Henry the Fourth—he could drink, he could fight, and he could be gallant to the ladies, but he could not write, although he could think excellently well. Trimousette treasured this rude scrawl. It was the nearest to a love letter she had ever received from any man.

IN the long days and months and years Trimousette spent at Boury she was forced to employ herself. She had no great taste for books beyond books of poetry, but she practiced on the cracked harpsichord which had belonged to the duke’s mother, and she developed a pretty little voice in which she sang to herself songs of love and longing. One day, during the winter of 1794, Trimousette got some news from Paris. Queen Marie Antoinette had[73] followed King Louis to the guillotine, and the Duke of Belgarde was once more in the prison of the Temple. He got there by one of the few acts of stupidity he ever committed in his life. He had slipped into Paris after the execution of Queen Marie Antoinette, determined to save the little Dauphin if the wit of man and the sacrifice of many lives could contrive it. Then came in the stupidity. This duke, who could do everything superlatively well except to write and spell, undertook to pass himself off as a schoolmaster! Moreover, he wore a shabby brocade coat, the last remnant of his wardrobe. Robespierre and St. Just then had France by the throat and were wolfishly devouring her children. It did not take them long to discover that this schoolmaster who could not spell was Fernand, Duke of Belgarde, and they promptly clapped him into prison. For those unfortunates imprisoned by these two men there was but one exit and that was in the arms of Madame Guillotine, who[74] held a well-attended court at sunset every day in the Place de la Révolution.

Within a fortnight Trimousette heard this grim news of her husband. It was February, the ground was covered with snow, and for a duchess to go to Paris was like putting one’s head in the lion’s mouth. All this was urged upon Trimousette by her dame de compagnie. It had no more effect upon her than the soft falling snow upon the Breton rocks. Before midnight on the day she heard the heartbreaking news Trimousette was on her way to Paris. She was not in her own ducal traveling chariot, but in the common diligence, for this inexperienced creature seemed gifted with a kind of prescience, nay, a genius of common sense, which stood her in place of actual knowledge of the world. She traveled as Madame Belgarde, wisely dropping the de, and absolutely alone, refusing even to take a maid.

Three days afterwards, on a March morning,[75] Robespierre, the apostle of murder, had just finished arraying himself in the sky-blue coat and cream-colored breeches which he loved, when a lady was announced in the anteroom. Robespierre loved the society of ladies, and one of the privileges of his position as chief murderer was the sight of dainty women prostrate before him, begging and imploring him for the lives of their husbands, fathers, or sons.

The lady in this case neither prostrated herself, nor begged, nor implored. She was quite calm and self-possessed, and although not beautiful had fine black eyes. After making Robespierre a charming curtsey, she said, smiling:

“Citizen Robespierre, I am Citizeness Belgarde, once known as the Duchess of Belgarde, and I have come to ask that I be admitted to share the imprisonment of my husband, once Duke of Belgarde.”

Robespierre, who dearly loved a duchess,[76] motioned Trimousette to be seated, then said in his croaking voice after a moment:

“There is no doubt your husband has conspired against the liberties of the people, and the only way in which those liberties can be secured is by the death of all those who would have destroyed liberty, like that tyrant Louis Capet.”

Now, thought Robespierre, she will begin to sob and beg for her husband’s life. But not so. Trimousette reflected a moment, and then said, softly and clearly:

“The killing of his Most Christian Majesty and of the blessed Queen Marie Antoinette was barbarous murder.”

Robespierre started violently. No man, much less a woman, had dared before to say so much to him. He looked with scowling green eyes at Trimousette composed and even smiling slightly.

“The National Assembly long since decreed the death of all who should advance[77] such treason,” he said, as soon as he could catch breath.

“So I supposed,” replied Trimousette; “but if I can but be allowed in my husband’s prison——”

A light leaped into her black eyes as she spoke. Robespierre, stroking his chin, regarded her critically. How would she go to the guillotine? Probably quite quietly, without making the least outcry of resistance.

“Now, Citizen Robespierre,” said Trimousette, rising and coming toward him, “surely, you cannot refuse the request of a lady. I came to you not only because you have all power, but because I knew you to be gallant—a gentleman, in short.”

So said the most sincere of women glancing at Robespierre with a look dangerously near to coquetry as well as flattery, and nobody had ever suspected this taciturn woman of being either a coquette or a flatterer. Yet, being a woman, she could be both[78] coquette and flatterer for the man she loved. What perjuries will women commit for love! Robespierre reflected and Trimousette smiled. He spoke and she answered him with soft, insinuating words; and at last she got out of him the written commitment, charging her, too, with conspiring against the liberties of the people, and condemning her to be imprisoned with her husband, Citizen Fernand Belgarde, in the prison of the Temple.

Trimousette almost laughed aloud with joy when this grim document was made out, and again gave Robespierre a bewitching little curtsey, such as the most finished coquette might have done. She climbed joyfully into the dirty cab with the dirtier gendarmes who were to deliver her to the jailers in the Temple.

It was a mild March afternoon when he who had once been Duke of Belgarde sat at his prison window, looking down into the dreary old garden of the Temple. The window was semicircular, reaching from the floor[79] half way to the low ceiling, and gave not much of sun or even light. The duke was thinking, strangely enough, of his duchess. She was a good little thing; shy, but not a born coward like the Valençay woman—nay, somewhat indifferent to danger and, for a woman, averse from shrieking and screaming, but timid in her attitude toward life. She had certainly showed some ingenuity in forwarding his escape three years and a half ago. The duke had made up his mind upon his arrest that there was not much chance of a duke and peer of France escaping the guillotine, and so quite coolly accepted the certainty that his name would soon be in the list which was posted up every morning, of those for whom the tumbrils would wait at seven o’clock in the evening. As his inexpertness with the pen had got him into his present plight, the duke determined to remedy that defect in his education. He had on his incarceration gravely explained to the turnkey that[80] there might not be much use for writing in purgatory, where he declared all gentlemen went—the revolutionists going to eternal punishment, and the ladies to heaven. Nevertheless, he meant to improve his handwriting. On this March afternoon the duke, seated at a rickety table, was busy practicing his new accomplishment of writing, when he heard the door of his cell open behind him. He did not turn his head. This Citizen Belgarde was a disdainful fellow, and never saw his jailers until they stood before him. In spite of this, and perhaps because of it, he was a favorite with turnkey Duval, who often frankly expressed his regret that the day was not far off when Citizen Belgarde would be started in a tumbril on his way to the Place de la Révolution.

Trimousette, standing just within the door, which was closed behind her, had a good look at her duke—as good, that is, as her fast-beating heart would permit to her yearning[81] tear-filled eyes. Upon his profile, clearly silhouetted against the window’s dim light, she saw the pallor of a prisoner. He still wore his shabby brocade coat and an embroidered waistcoat, but both were threadbare and dingy. His hair, long and curling, was tied with a black ribbon to distinguish him from the cropped heads which the revolutionists affected. But his eyes, the eyes of a fighter, were undaunted, and his mouth still knew how to smile. The Duke of Belgarde considered that he had lost the game of life, and the only thing left was to pay like a gentleman. As Trimousette watched, he threw down his pen, pushed his chair back, cocked his feet upon the table, and began to whistle quite jovially “Vive Henri Quatre.”

Still he had not looked toward her, and Trimousette’s courage, having brought her alone in night and storm from Brittany, and strongly sustained her when she went to see Robespierre of the green eyes and croaking voice,[82] and got herself condemned to prison upon a capital charge—could not carry her the yard or two between her and her soul’s desire.

But then the duke turned, recognized her, rose, and, obeying a sudden impulse, opened his arms to her. True, he would have rejoiced to see a dog, even broken-legged Diane, anything which was connected with the splendid dream of the past. Yet was the duke actually glad to see the only woman who could love him without worrying him.

Trimousette did not fly into his arms. Poor soul, even at that moment rose the undying instinct of womanhood not to yield too quickly. The duke came forward and, by the same impulse, swept her into his arms. At once, in the twinkling of an eye, love was born within him, and he kissed her as a lover for the first time in their married life. A glory, as of the morning, rose before Trimousette’s eyes. She had lost all, even her life was a forfeit, but she had gained all—her husband’s love.

PRESENTLY the first agitation was past, and Trimousette told, as if it were the simplest thing in the world, the story of her journey alone by diligence from the Breton coast to Paris, and how she forced her way into Robespierre’s presence and had wrung from him the boon of being with her husband.

“But let us not deceive ourselves,” said the duke gently, still holding her to his breast. “I shall not escape from the Temple this[84] time. No man has ever got away from this prison twice. I am destined to follow his Majesty the King and her Majesty the Queen to the guillotine.”

He expected that Trimousette would faint or shriek when he said this, but she looked at him with calm eyes and answered in a soft, unbroken voice:

“So it may be, but Robespierre has promised me that when you leave the prison I shall go with you.”

The duke held her a little way from him and studied her reflectively. Yes, it was better so. In a flash had been revealed to him the height and depth of her adoration. What would be her fate if left alone among those howling wolves who now ravened France? He would have taken with him any creature that he loved, as he would have saved a bullet for that creature if he had been surrounded and overwhelmed by savages, whose blood thirst must be appeased.

[85]“Well, then,” continued Trimousette, still smiling and composed, “let us here await God’s will.”

“And that of the National Assembly,” grimly replied the duke, who had not become either pious or forgiving under the shadow of the guillotine, but, like most men, was the same in all circumstances. Some, however, mistake fear for repentance—not so Fernand, Duke of Belgarde.

There was but one chair, one bed, one table in the room, and when the turnkey brought the duke’s supper, there was only one cup, one plate, and no spoon or knife at all. To the turnkey’s surprise, Citizen and Citizeness Belgarde made merry at this. Trimousette was to have a little cell opening into the duke’s, but when the rusty door was forced wide, there was nothing but the bare walls and floor. The duke, assuming an air of authority as if he were giving orders to a lackey at the Château de Belgarde, directed the turnkey to[86] bring what was necessary for the comfort of the Duchess of Belgarde, and the turnkey, appreciating the joke, grinned and winked at the duke. Then the duchess, in her sweet, complaisant manner, said to him:

“Pray, take no offense at the Duke of Belgarde. He is not yet used to being in prison. But do me the favor, please, kind sir, to give me at least a bed to sleep upon and a chair to sit in. Not so good as your wife has at home, perhaps, but I shall be easily satisfied.”

The turnkey Duval went, and returned after a few minutes to say that not only might the duchess have a bed and a chair and a table, but he would even get an old counterpane and hang it up as a curtain between the cells. This was luxury undreamed of by Trimousette, and she overwhelmed Duval with pretty thanks. The turnkey of his own accord put up the bed and placed the chair and table which all prisoners were allowed, and,[87] having himself a taste for luxury, actually laid a piece of carpet by the side of the bed and put a coarse cover on the table.

This prison supper was the first time the Duke and Duchess of Belgarde had ever supped together alone with each other. They felt a furtive and secret joy at being together, for the duke had been steadily falling in love with his wife ever since she appeared in his cell an hour before. He noticed a new expression in her black eyes, an expression of hope and even of joy. Trimousette, with a woman’s keenness, knew she was on the road to her kingdom—her husband’s heart. It was so odd that it was almost comical, the way the duke examined his wife. She certainly had beautiful eyes, and a slim figure, and although dressed in the simplest manner, as became a lady who traveled alone, Trimousette had not forgotten her solitary piece of coquetry—her delicious little shoes. Also, she had suddenly found her tongue, and talked to her husband so[88] freely and even gayly that he was astounded. Was this the silent, shy, awkward girl he had married so many years ago and who had seemed to be growing shyer, more silent, more awkward every year? He was so surprised, so pleased, so touched, that he scarcely knew what to make of it. The sky was still alight when their supper was over, and Trimousette produced some needlework which she had been allowed to bring into the prison. She was very artful, was this artless Trimousette, and not meaning to thrust her company on her husband, retired to her own little cell. There a charming surprise awaited her. The turnkey, over whom Trimousette had thrown a spell of enchantment, had placed upon her table a pot containing a geranium with ten leaves and two brilliant scarlet blossoms. Trimousette, after admiring her treasure, sat down upon her one chair and began to stitch diligently by the fading light. She was ever a good needlewoman. Most prisoners, as soon[89] as they were incarcerated, begged for pen, ink, and paper, to write to their friends, and to begin their struggle to get out of prison. Not so Trimousette. She had no one to write to, and particularly did not wish to get out of prison.

As she sat sewing, she heard the duke moving restlessly about in the next cell, beyond the ragged curtain. A mysterious smile came into Trimousette’s eyes and upon her lips; her husband was uneasy without her; he must come and seek her—oh, rapturous thought! Presently, the duke knocked quite timidly at the side of the door. It might have been Trimousette herself, the knock was so gentle; and when Trimousette softly bade him enter, he said, quite shamefacedly:

“I have never been lonely in this place before, for my thoughts, although painful enough, always kept me busy. But I have grown very lonely without you in the last five minutes. May I enter?”

[90]In that hour began Trimousette’s long-delayed honeymoon.

Trimousette, being by nature orderly and the duke philosophic, they regulated their lives as if they expected to die of old age in the prison of the Temple. The duke had never before had much leisure for reading, his time having been chiefly taken up with war and the ladies, nor had he felt the need of any proficiency in writing until he became the guest of the Revolution. His newly found accomplishment with the pen revealed to him a gift which neither he nor anyone else ever suspected in him. He could write verses, very pretty verses, all addressed to Trimousette. These she set to music and sang in a sweet little voice. Some of these songs were quite gay and coquettish, and Trimousette sang them gayly and coquettishly. Thus was the kingdom of poetry and song opened to them and they entered it hand in hand. When they sat together at the rude table in the purple[91] April nights, the duke teaching Trimousette his verses and she singing them softly to him, they gazed with rapture into each other’s eyes, and wondered how they could ever have lived apart.

They had no watch or clock and no means of telling the time except by the prison bells, until the duke contrived, with a wooden peg driven into the bare table, a rude sundial. They would not put upon it the motto of the sundial in the old garden where Trimousette had first dreamed of the duke; it was too sad. The duke suggested the old, old one, “Only the happy hours I mark,” but Trimousette shook her head.

“Are not all our hours happy when we are together?” she asked, and her husband for answer caught her to his breast.

“I know another motto,” she whispered; “it is on the sundial on the broken terrace at Boury, ‘’Tis always morning somewhere in the world.’”

[92]The duke therefore etched, with a piece of a nail out of his shoe, this motto upon the table, and Trimousette said it meant that when they made their journey some evening to the Place de la Révolution, they would close their eyes for a few minutes and open them upon the Eternal Morning. She had many sweet superstitions, but behind them lay a noble courage and faith itself.

Trimousette was not always employed with poetry and music, however, but devised for herself many graceful and feminine employments, the duke watching her meanwhile with great delight. In the mornings she, like a good housewife, would sew with diligence, and patched and mended the duke beautifully. Her own wardrobe contained but two gowns, a black one, which she wore every day, and a white one, which she saved carefully for a certain great occasion likely to arrive any day; for although she and her duke lived in their two cells with love and peace, neither of them[93] expected release except by the road which led to the guillotine in the Place de la Révolution. Robespierre had promised it, and in these matters he never broke his word. They faced the future with a composure which amazed themselves. The duke had the courage of a soldier who is always ready to answer the last roll call; Trimousette’s simple and sublime faith would have made her walk to the stake as calmly as to the guillotine.

It must not be supposed, however, that a man with red blood in him like Fernand, Duke of Belgarde, could see a new, sweet life of love opening before him, and then could always bring himself to resignation. He said little when these moods, like slaves in revolt, possessed him. At such times he would rise from his bed in the night, grinding his teeth and quivering with a dumb rage, and walk stealthily like a cunning madman, up and down, up and down, his narrow cell. Trimousette waking, would rise, and going to[94] him in the darkness, gently recall him to his manhood, his fortitude, his heart of a soldier, and then with the earnestness of an angel and the simplicity of a child, she would tell him of the strange certainty she felt that they would not be separated even in the passage of the abyss called death. The duke, listening to her, and feeling the soft clasp of her arm about his neck, would find something like repose descend upon his tumultuous soul. At least, they would go together—that much of comfort was theirs. But it was only at times that this mood came upon the duke. Soldier-like, he had always looked upon death as an incident, and the only really important thing about it was how the thing could be done with the greatest ease and dignity.

“And surely,” Trimousette would say, drawing up her slight figure and showing the pride that was always alive, but secret in her heart, “to die for one’s loyalty is a very good way for the Duke and Duchess of Belgarde[95] to make their exit.” Let no one feel sorry for Trimousette. She had passed through the Gate of Tears forever, and was already in that Garden of All Delight, which men call Perfect Love.

EVERY day at noon the prisoners walked for an hour in the garden and courtyard of the Temple. They were quite cheerful, and sometimes even gay. Madame Guillotine was grown familiar to their thoughts. They paid each other compliments upon their courage, and made little jokes on very grim subjects. The honeymoon of the Duke and Duchess of Belgarde amused, but also touched their fellow prisoners. Among these was a pretty boy of sixteen,[97] the Vicomte d’Aronda. His father had died, as had Victor, Count of Floramour, gallantly fighting in La Vendée. His mother and sister had perished in the embrace of Madame Guillotine. The boy alone remained. He felt himself every inch a man, and showed more than a man’s courage. He was immensely captivated by the Duke of Belgarde’s dashing air, which he still retained in spite of his patched coat and shabby hat, and when the duke introduced the little vicomte to Trimousette, the boy fell, if possible, more in love with her than with the duke. Every day during their hour of exercise in the garden he watched for them, and his boyish face reddened with pleasure when they would ask him to join them on their promenade up and down the broken flags. It diverted the duke to pretend to be jealous of so gallant a fellow as the little vicomte, and the boy himself, half bashful and half saucy, was charmed with the notion of being treated as a gay dog. Neither[98] the duke nor Trimousette ever spoke to the boy of the fate that lay before him, as well as themselves, for he was so young—but sixteen years old—and the soul is not full fledged at sixteen. One day, however, the lad himself broached the subject.

“You see, madame and monsieur,” he said, quite serenely, “all the men of my line have known how to die, whether in their beds of old age, or falling from their horses in battle, and I, too, know how to die. I shall be perfectly easy, and not let the villains who execute me see that I care anything about it. My mother died as bravely as the Queen herself; so did my sister, only twenty years old; and I shall not disgrace them. But I should like very much to go the same day with you. It would seem quite lonely to walk in this garden without you.”

When he said this, a woman’s passion of pity for the boy overwhelmed Trimousette. She felt nothing like pity for her own fate or[99] that of the man she loved; they had entered into Paradise before their time, that was all. But the boy was too young to have had even a glimpse of that Paradise. At least he would go in his white-souled youth, and this thought comforted Trimousette.