Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Cover created by Transcriber and placed into the Public Domain.

Other notes will be found at the end of this eBook.

The World of

Flying Saucers

A SCIENTIFIC EXAMINATION OF A

MAJOR MYTH OF THE SPACE AGE

Donald H. Menzel

AND

Lyle G. Boyd

DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC., GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 63-12989

Copyright © 1963 by Donald H. Menzel and Lyle G. Boyd

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America

vii

To Fred L. Whipple, whose studies have added much to our knowledge of meteors—which have furnished more than their share of UFOs.

| PREFACE | xiii |

| I. THE SAUCER WORLDS | 1 |

| UFO Reports and the Air Force—The Scientist’s View—The Question of “Evidence”—Various Types of UFO—Descriptions of UFOs—A “Baedeker’s Guide” to Saucerdom | |

| II. LO! | 13 |

| Arnold’s Nine Disks—The Great Shaver Mystery—The Maury Island Fragments—Science Fiction Adopts the Saucers—Mirage or Wave Clouds? | |

| III. AIR-BORNE UFOS: BALLOONS TO BUBBLES | 31 |

| The Mantell Tragedy—A Probable Solution of the Mantell Case—A Radiosonde over Virginia—Skyhook and Pibal UFOs—The Guantánamo “Dogfight”—The Wallops Island UFO—Weather Balloons and Saucers—Plastic UFOs and the “Stack of Coins”—Jets and Contrails—The Killian Case— ... And Kites and Soap Bubbles | |

| IV. THE SPANGLED HEAV’NS: STARS AND PLANETS | 60 |

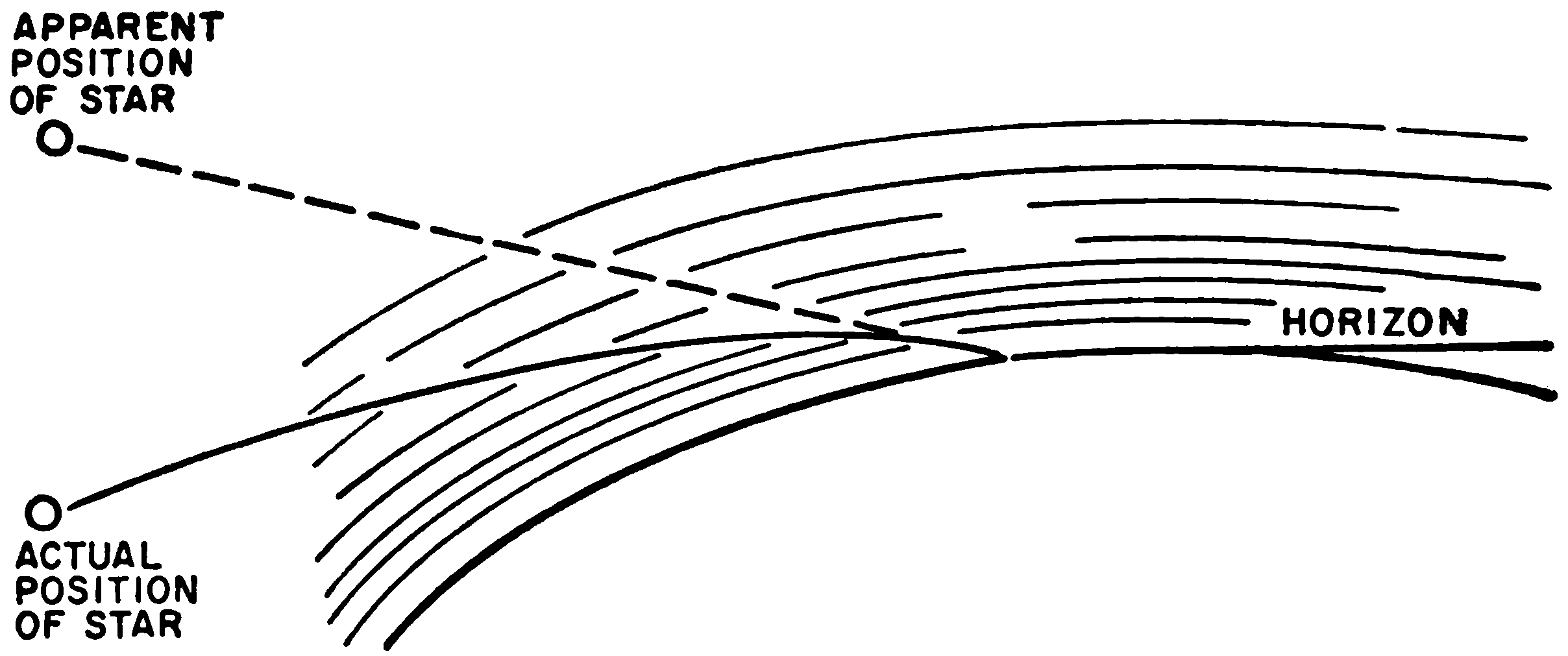

| A Mirage of Sirius—Earth’s Distorting Atmosphere—The “Whipping Girl” of Saucerdom—The Ryan Case—Venus as a Morning Star—Venus as an Evening Star—The Rotating Lights of Japan—UFOs and the Opposition of Mars—The Gorman “Dogfight”—Only a Balloon?—Jupiter through a Jet Trailviii | |

| V. OUT OF THE SKY: METEORS AND FIREBALLS | 88 |

| Stones from Heaven—Meteor Streams and Showers—The Green Fireballs—Meteors in the Records—Fallacies about Meteors—Facts about Meteors—Unusual Fireballs—Great Meteor Processions—The Chiles-Whitted Sighting—Other Flaming UFOs | |

| VI. LIVING LIGHTS | 118 |

| The Luminous Owls of Norfolk—Things That Glow in the Dark—Sea Gulls as UFOs—The Lubbock Lights—The Lubbock Pictures—Other Winged UFOs—The Tremonton Movies | |

| VII. PANIC | 133 |

| Growth of a Panic—The Scoutmaster’s UFO—Monster in West Virginia—The Panel of Civilian Scientists | |

| VIII. PHANTOMS ON RADAR | 145 |

| Radar as a Reporter—The Principle of Radar—Weather and Radar Echoes—The Kinross Case—The “Invasion” of Washington, D.C.—Radar Experiments in Washington—“Simultaneous” Radar-Visual Reports—“Ghosts” and “Angels” on Radar—The Rapid City Sighting | |

| IX. E-M AND G-FIELDS IN UFO-LAND | 172 |

| Stormy Weather in Texas—The Phenomenon of Ball Lightning—E-M and Non-E-M Saucers—The Saturnian Visitors—Surveillance by Flying Eggs—Saucerdom’s Miraculous Electromagnetic Force—Effects and Causes—“G-Fields” and UFO Propulsion—The G-Field Myth—Electricity, Magnetism, and Gravity | |

| X. CONTACT! | 198 |

| Earthlings and Extraterrestrials—The “Contactees”—Adamski’s Travels—Photography and the UFO—The Isle of Lovers Hoax—The Trindade Island Saucer—The Brazilian Naval Ministry—The Icarai Submarine Hunting Club—The Trindade Photographs—Project Ozma | |

| XI. ANGEL HAIR, PANCAKES, ETC. | 219 |

| Angel Hair and Spiders—Other Varieties of Angel Hair—The Wisconsin Pancakes—The Moon Bridge—“Pieces of Saucers”—Silver Rain in Brazil—Other Mysterious Fragmentsix | |

| XII. SPECIAL EFFECTS | 238 |

| The Role of Unusual Coincidence—The Problem of Unknown Lights—Michigan’s Flying Bird Cage—UFOs from Reflections—Sundogs in Utah and France—Bright Spots on Films—Unfamiliar Lights on Planes—Inversions in California—The Chesapeake Bay Case—A Possible Explanation of the Nash-Fortenberry Disks—Other UFOs in “Stack” Formation—The Tombaugh Rectangles | |

| XIII. INVESTIGATORS: AIR FORCE AND CIVILIAN | 271 |

| Official Study of UFOs—Civilian Saucer Groups—NICAP—The “Conspiracy” Fantasy-UFO at Sheffield Lake, Ohio—“The Fitzgerald Report”—The Open Mind | |

| APPENDIX | 291 |

| INDEX | 295 |

x

xi

PLATE I: a, The Seattle Times. b, A Shell Photo

PLATE II: a, Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. b, Wide World Photo

PLATE III: a, Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. b, Gilberto Vazquez, El Imparcial, San Juan, Puerto Rico

PLATE IV: a, Wide World Photo. b, Wide World Photo. c, David Atlas, Air Force Cambridge Research Center, Bedford, Massachusetts

PLATE V: a, Bernd T. Matthias and Solomon J. Buchsbaum, Bell Telephone Laboratories. b, Dr. John C. Jensen, Nebraska Wesleyan University

PLATE VI: a, United Press Photo. b, United Press Photo

PLATE VII: a, C. L. Johnson. b, Mrs. William Felton Barrett

PLATE VIII: a, United Press Photo. b, Wide World Photo

Figure 18. Courtesy True, The Man’s Magazine. Copyright 1952, Fawcett Publications, Inc.

Drawings by Cushing and Nevell

xiii

Both as scientists and as devotees of science fiction, we have long been interested in space travel. When reports of unidentified flying objects began to increase in the years between 1947 and 1952, one of us (D.H.M.) collected and studied the limited information available about the sightings. He soon concluded (with a slight feeling of disappointment!) that the flying saucers were not vehicles from other worlds but were only mundane objects and events of various kinds, some of them commonplace, some familiar chiefly to meteorologists, physicists, and astronomers.

At a conference with Air Force officials in Washington in April 1952, he presented his idea that planetary mirages, sundogs, reflections, and other astronomical, atmospheric, and optical phenomena probably accounted for a large percentage of the mysterious UFOs. This suggestion met with strong skepticism from some of the conferees who at that time were sympathetic to the interplanetary hypothesis and were, of course, better acquainted with military than with physical science. Other conferees, however, wished to consider and test the theories offered. Proof obviously required a knowledge of all the facts of a given sighting, facts that often were not available to the public. The Air Force therefore granted access to the file of UFO cases. At the same time, since many of the cases were then classified as secret, the Air Force imposed the condition that security regulations must be strictly observed.

D.H.M. was then preparing a book to present his explanations of flying saucers. Acceptance of the Air Force offer, with the accompanying restriction, would have prevented his publishing analyses based on material in the files. It would also have hindered any future public discussion of the UFO problem. For these reasons he felt compelled to decline the opportunity.

In the spring of 1959 as we began planning the present book, wexiv again requested permission to study the Air Force records of UFO sightings. This time the officials generously opened their files to us without restriction. Thus we have been able to include detailed studies of particular incidents, to give the explanations found for most of them by Air Force investigators, to explain the causes of some hitherto unsolved cases, and to suggest highly probable solutions for several classic “Unknowns.”

To discuss each one of the thousands of unidentified flying objects reported during the last fifteen years is obviously impossible. We have therefore chosen to describe the common types of sighting and to analyze some of the representative and most interesting cases in each category. In general we have avoided using the names of the persons involved; but when the names are well known to the flying-saucer public and have previously appeared in print, we have felt no obligation to disguise them.

Many persons have contributed to the material in this book. Members of the United States Air Force have generously helped us to collect the basic facts, and have shown amazing patience in answering hundreds of small questions of detail. In particular, we wish to thank Col. Philip G. Evans, Col. Edward H. Wynn, Lt. Col. William T. Coleman, Lt. Col. Robert J. Friend, Lt. Col. Lawrence J. Tacker, Major Carl R. Hart, and Sgt. David Moody.

Others who have helped us in various ways include Dr. Isaac Asimov, Mr. Carleton Atherton, Miss C. M. Botley, Mr. Wilfred J. Chambers, Mr. Albert M. Chop, Dr. Leon Davidson, Mr. Charles W. Dean, Mr. John F. Gifford, Mr. Richard Hall, Mr. Theodore Hieatt, Prof. Seymour B. Hess, Prof. J. Allen Hynek, Dr. Luigi G. Jacchia, Mr. Craig L. Johnson, Dr. Urner Liddell, Mr. Oscar Main, Prof. Charles A. Maney, Dr. Richard E. McCrosky, Mr. John W. McLellan, Capt. William B. Nash, Dr. Thornton W. Page, Dr. Vernon G. Plank, the late Dr. H. P. Robertson, Dr. Donald H. Robey, Dr. Carl Sagan, Dr. Clyde W. Tombaugh, Mr. John Walkin, Prof. Fred L. Whipple, and Mr. John G. Wolbach.

D.H.M.

L.G.B.

xv

1

Thousands of reports of “flying saucers,” “unidentified flying objects,” or “UFOs” have appeared in print during the last fifteen years. Although most of the things seen have later been explained as unusual but normal phenomena, some enthusiasts continue to regard them as mysterious, and thus help perpetuate the myth that the “saucers” are actually spaceships from other planets, busily carrying out a patrol of the earth.

This saucer myth owes an unacknowledged debt to Charles Fort, a talented reporter, writer, and self-appointed gadfly of science. With a strong curiosity about the world of nature but without training in the disciplines of research, Fort liked to challenge scientists in general and astronomers in particular with tales of “impossible” happenings culled from books of folklore, old journals, and newspapers. He mistrusted orthodox knowledge because, he believed, it smugly damned to oblivion all reports of marvels that it could not explain: pyrogenic persons; rains of fish, frogs, and stones; accounts of telepathy, teleportation, the vanishing of human beings, luminous objects in the sky. Although he never claimed that he believed the stories himself, Fort enjoyed collecting them and before his death in 1932 had completed four volumes of these anecdotes.

Science-fiction writers have found an inexhaustible mine of ideas in The Book of the Damned, New Lands, Lo!, and Wild Talents, which also provide the chief elements of the saucer myth:

“Unknown, luminous things, or beings, have often been seen, sometimes close to this earth, and sometimes high in the sky. It may be that some of them were living things that occasionally come from somewhere else in our existence, but that others were lights on the vessels of explorers, or voyagers, from somewhere else.”2[I-1] These extraterrestrials may have been in communication with earthmen for many years, Fort suggested, and they may sometimes kidnap and carry away human beings.

Most flying-saucer reports have come from reliable citizens who have seen something extraordinary, something they do not understand. Genuinely puzzled, they often report the incident to the nearest Air Force base. The evaluation of such cases is the responsibility of the United States Air Force. Since the beginning of the saucer scare in 1947, the chief investigating agency has been that at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio, and has borne a succession of names—Project Sign, Project Grudge, Project Blue Book, and the Aerial Phenomena Group of the Aerospace Technical Intelligence Center, usually known as ATIC. Until recently this group operated under the jurisdiction of the Assistant Chief of Staff, Intelligence. On July 1, 1961, it was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Air Force Systems Command. To simplify discussion in this book, however, the group that investigates unidentified aerial phenomena is generally referred to as ATIC.

In military parlance the phrase “unidentified flying object,” abbreviated as UFO, is used to indicate any air-borne phenomenon that fails to identify itself to, or to be identified by, trained witnesses on the ground or in the air who are using visual or radar methods of observation. Created in the early days of the saucer era, the term UFO is unfortunately misleading because it seems to imply that the unknown is a solid material object. Many of them are not. The more dramatic phrase “flying saucer” is similarly misleading because not all the unknowns are shaped like a saucer, and not all of them are flying. Since no one has been able to devise a more accurate brief term that will apply to all reports in this category, both “UFO” and “flying saucer” have remained in common use.

Air Force investigators and scientists have been able to account for almost every reported “spaceship” as the result of failure to identify some natural phenomenon. Some were the product of delusion or deliberate hoaxes. A few remain technically “Unknown”3 because, although the probable explanation is obvious, too few facts are available to permit a positive identification. No such report suggests the possibility that interplanetary craft are cruising in our skies.

If a spaceship from another planet should ever visit the earth, no one would be more eager to acknowledge it than our government officials and our scientists. All governments would feel their responsibility to protect the human race if necessary, and to establish diplomatic relations with the alien race if possible. The scientists would want to study, analyze, and try to understand the nature of both the ship and its occupants.

Many persons, sincerely believing that flying saucers do exist, berate the investigator who denies their reality and characterize him as stupid, willfully obtuse, or intellectually dishonest because he does not accept the saucer reports at face value but weighs them by the same methods most of us use in weighing evidence in everyday life. When told there’s a horse in the bathtub, for example, the sensible man realizes that the alleged visitation, while not impossible, is extremely improbable. Therefore he does not immediately begin speculating on the color of the horse, where it might have come from, what its purpose may be, and whether it will wreck the bathroom. Instead he adopts the scientific method and first goes to find out whether the horse is really there.

Like Fort, some flying-saucer believers are consciously or unconsciously antagonistic to the scientific method and resent its restrictions as a child objects to discipline. Suggesting that a strictly logical approach deprives us of valuable truths about the nature of the universe, and bluntly asserting that present-day physicists and astronomers have closed their minds to the possibility of new knowledge, these enthusiasts imply that we should require less rigorous proof for the reality of saucers than for other types of physical phenomena.

Because so many amateur investigators have misunderstood, misrepresented, and condemned the scientists’ attitude, the authors of this book (asking the indulgence of their colleagues) will briefly4 outline the principles a researcher ordinarily applies to the study of any new problem—the nature of radioactivity, the cause of a disease, or the origin of flying saucers.

Most physicists, chemists, biologists, and astronomers will agree that life in some form probably exists in other parts of the galaxy. These other life forms, if they exist, may or may not have a kind of intelligence similar to our own; if they have, we might or might not be able to recognize it. Such speculations, while fascinating, lie entirely in the realm of theory. They are not facts and do not provide the slightest support to the often stated corollary that intelligent creatures do live on other planets and frequently visit the earth.

In approaching the spacecraft hypothesis, the scientist asks first: What facts are we trying to account for? And second: Does the spacecraft theory account for these facts better than the normal explanations that are already available? After studying hundreds of UFO reports, however, he concludes that much of the startling “proof” that saucers are spacecraft is merely inference. Of the established facts, none requires a new theory to account for it; and no evidence exists that even faintly suggests, to the expert, that interplanetary visitors are involved.

In the study of UFO phenomena this question of “evidence” is crucial. The careful investigator tries always to distinguish sharply between an observed fact, which is evidence, and an interpretation of that fact, which is not evidence no matter how reasonable it may seem.

As a simple analogy, consider this situation: A man is sitting in his living room late at night; the rest of the family have gone to bed. Suddenly he is startled by a loud noise somewhere upstairs. Trying to account for the noise, he thinks of various possible causes—a burglar, the “settling” of the house, a mouse in the wall, someone dropping a shoe, the wind rattling a door, the sonic boom from a distant plane. If, without having further information, he decides that any one of these is the true cause, he is accepting a guess as though it were a fact. The real cause of the noise may be one of5 these or it may be something else that he hasn’t even thought of.

Amateur investigators of UFOs publish many reports which they characterize as absolute proof that spaceships exist. The expert, analyzing the same reports, finds no proof at all because the actual facts and the interpretations of the witnesses are hopelessly confused. An early UFO case provides a typical example.

According to Air Force records[I-2], on the morning of December 6, 1952, a B-29 bomber was over the Gulf of Mexico returning from a training mission. At 5:25 A.M. the student radar operator, using an uncalibrated set, observed four bright blips (radar jargon for bright spots on a radarscope; such a spot indicates the presence of an object reflecting the radar pulses, but does not reveal the nature or shape of the object). The blips were apparently returns from objects about twenty miles away, in no specific group, which rapidly moved off the scope. Similar groups of fast-moving blips appeared at intervals during a period of about five minutes, and appeared also on two auxiliary radarscopes. After the first set was calibrated, the blips reappeared; none was observed after 5:35 A.M. From the radar data estimates of size and distance were made; calculations based on these estimates indicated a probable speed of 5000 to 9000 miles an hour. During the ten-minute period two visual observations were made, lasting about three seconds, which bore no obvious relation to the radar observations: at the right of the plane one crewman saw a single blue-white streak going from front to rear under the wing, and another crewman saw two flashes of blue-white light.

An explanation of the incident was not found immediately, and ATIC at first classified it as an Unknown. Some saucer enthusiasts interpreted the facts to mean that several groups of saucers had been in the area, machines flying so fast that they were visible only as blue-white streaks, whose presence was confirmed by radar. These conclusions were merely deductions from fact, not observed facts. The radarscope is not a camera and does not, at least at present, picture the shape or physical structure of the phenomenon it reports; it shows only spots of light that change position and size. Similarly, the blue-white streaks were mere flashes of light without size or shape.

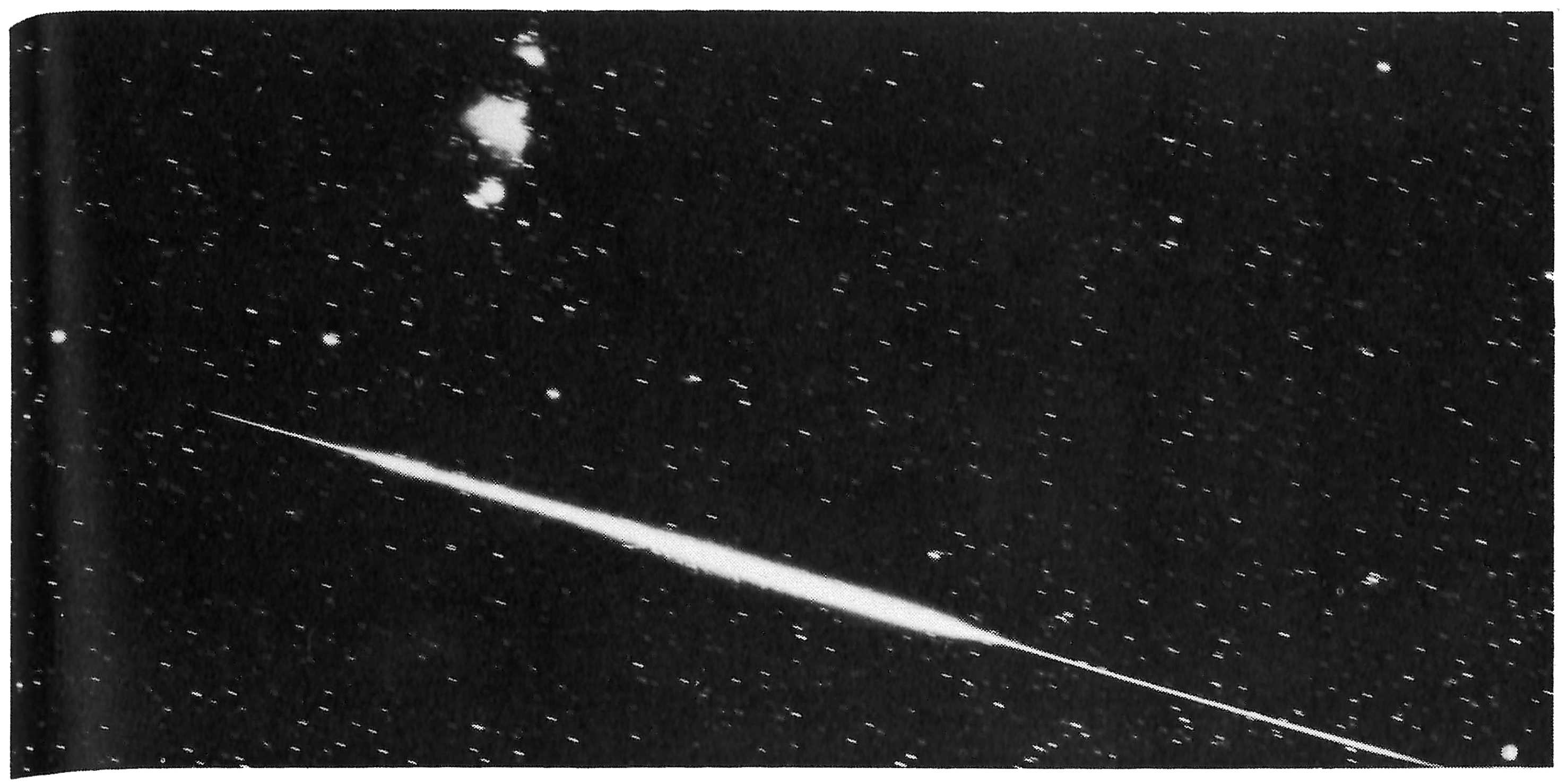

In a later study of the evidence, the Air Force experts recognized this incident as one of false targets on radar (see Chapter VIII).6 The radar phantoms may have been caused by beacon returns triggered by another radar; by variations in the atmosphere; or, if “ducting” conditions existed, by reflections from objects that were far beyond the normal range of the radar set. The blue-white flashes had no relation to the radar returns and were probably meteors; the date corresponded with the beginning of the annual Geminid shower (see Chapter V).

This Gulf of Mexico incident is neither complicated nor puzzling. We mention it chiefly to illustrate why the saucer enthusiasts so often disagree with the conclusions reached by the Air Force experts. The amateur assumes that the instrument operated faultlessly and detected a solid object; he uses these assumptions to interpret the data, uses the interpretation as fact, and by this “bootstrap” process deludes himself into thinking he has proved what he assumed in the first place.

A biologist trying to identify a group of unusual animals which are said to represent a new species begins by collecting all possible information about their appearance and behavior. After he has determined their typical size, shape, color, mode of reproduction, manner of locomotion, etc., he compares these characteristics with those of animals of known species and eventually classifies the strange specimens. In a similar way the professional investigator of UFO phenomena begins by asking the question: What is a typical unidentified flying object?

The published reports comprise a heterogeneous collection of facts, fiction, and guesses. The investigator must first separate and discard accounts that are obvious hoaxes or delusions. There are many of these. The remaining material he divides into two classes. The first includes statements made by competent, careful witnesses, describing what they have seen and heard—for example, “I saw a brilliant light moving swiftly without sound.” The second class includes statements of opinion or belief about the thing seen—for example, “The strange light obviously was controlled by intelligence.” Putting aside this second class of material for the time being, he7 looks at the information in the first and immediately faces an awkward conclusion: apparently no “typical” flying saucer exists.

No two reports describe exactly the same kind of UFO. There are dozens of types of saucers, resembling each other as little as turnips do comets. Hoping to find some consistent pattern, the investigator opens his notebook and starts listing the data.

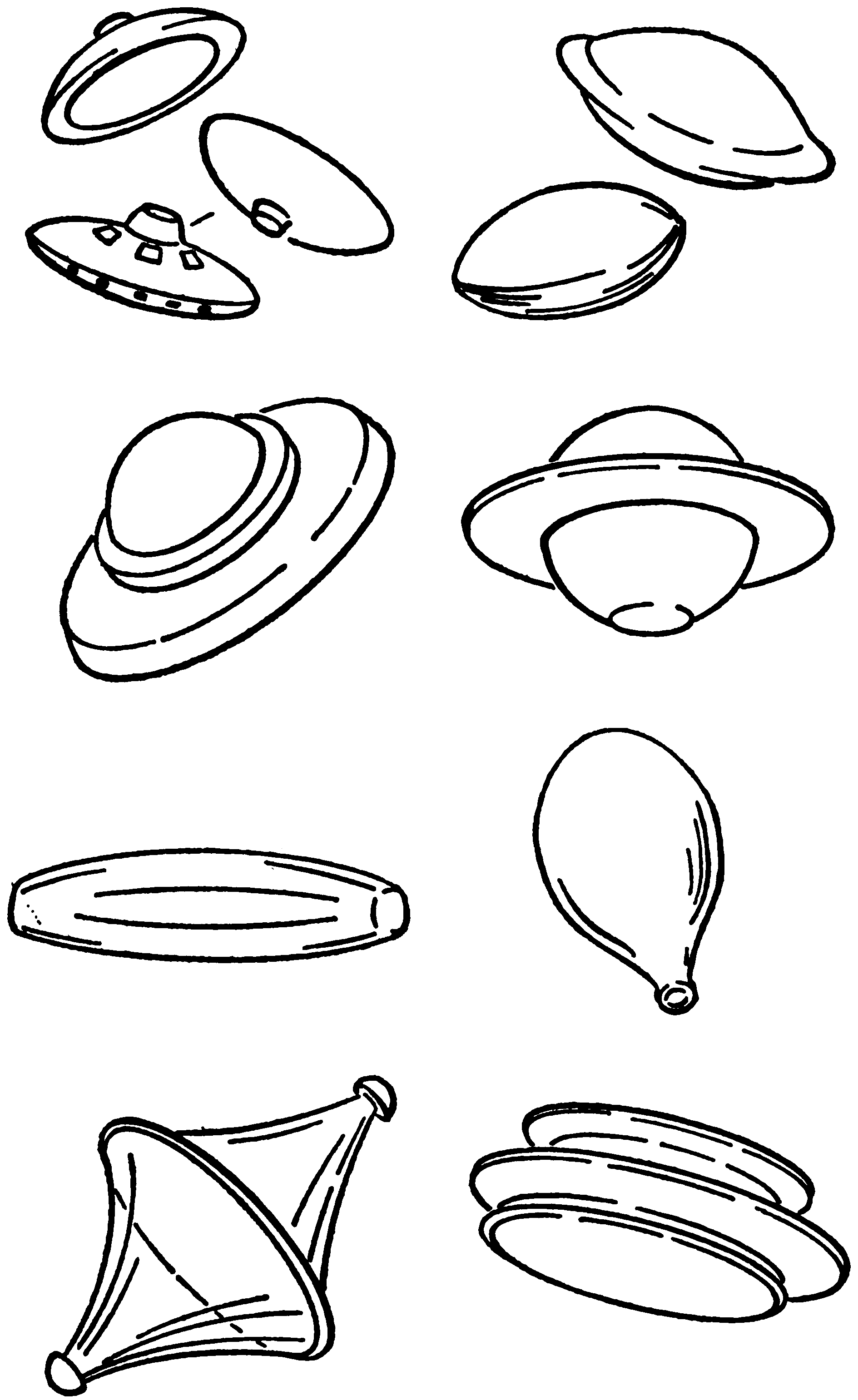

Shape—The flying saucer varies greatly in shape (see Figure 1). At different times and places it may be a circular disk like a saucer, often with a small protrusion in the center like the knob on a tea-kettle lid; elliptical or bean-shaped like a flattened sphere; a circular base supporting a dome-like superstructure; a sphere surrounded by a central platform, like Saturn in its rings; long and thin like a cigar; a tapered sphere like a teardrop; spindle-shaped, with or without knobs on the ends; or a double- or triple-decked form like a stack of plates.

Size—The saucer varies greatly in size. Estimated diameters range from 20 or 30 feet to several thousand. While under observation it may instantaneously increase or decrease in size.

Color—The saucer varies greatly in color. It may be white, black, gray, red, blue, green, pink, yellow, silver; may be luminous or dull; may be a solid color; may be circled by a central band of different color; may display flashing lights of various colors. It may change color or luminosity while being observed.

Motion—The saucer displays a wide variety of motions. It may travel very slowly; very fast, approaching the speed of light; at jet speed; at meteoric speed; may hover motionless over one place. At any speed it can instantaneously change velocity and direction of motion—can move horizontally, vertically, toward the observer, away from the observer, in a straight path, a zigzag, a spiral. Like the Cheshire cat, it can vanish instantly or slowly fade away.

Means of propulsion—Unknown. Some saucers move in complete silence; others produce noises: a hiss, a whistle, a roar, a thunderclap, or a detonation like a sonic boom.

Incidence—Saucers may appear at any hour of the day or night,9 but they appear most frequently in the hours before and after sunset, and before and after sunrise. Their numbers may suddenly increase at certain places and certain times. The objects can appear singly, in random groups, in groups showing a geometrical pattern. A single object may split and multiply into a group, or a group may merge into one. Saucers almost always appear in the air, rarely on the earth’s surface or in bodies of water. They almost never come within touching distance of the observer. The length of their stay varies greatly, from about two seconds to two or three hours.

Structure—Unknown. A saucer may be visible or invisible to the observer; visible to the human eye but not to the camera or radar; visible to the camera or radar but not to the eye. Some obey the laws of gravity and inertia, others do not.

Purpose—Unknown. No officials in the government, the press, the churches, or the universities have received any attempt at communication. No saucer has produced intelligible visible, audible, or radio signals.

Long before finishing this tabulation the investigator realizes that he is not dealing with one thing but with many. No single phenomenon could possibly display such infinite variety. However, before he starts trying to classify the descriptions and to explain them, he takes a look at the second class of material—the conclusions offered by saucer enthusiasts. Leaving the realm of observation for that of interpretation, he is suddenly catapulted into a world of fantasy.

One of the commonest themes in science fiction is that of parallel universes—a number of nearly identical worlds coexisting in alternate space-time continua. Occasionally, at a vulnerable spot, the barrier between two of these worlds will dissolve so that they overlap near the point of contact. After such an accident a man may find himself unhappily living two lives at once, identical in some ways but so different in others that if one is real, the other cannot be. Until the break is repaired and the incompatible worlds are safely separated once more, the man exists in a state of desperate confusion and performs agonizing mental acrobatics, trying to maintain10 a foothold in both worlds until he can decide which one is valid.

From the “damned” phenomena collected by Charles Fort, plus the legends of Atlantis, Mu, and Lemuria, flying-saucer addicts have constructed a multiplicity of such alternate worlds. Although they differ in minor ways, all are in direct conflict with the real world known to science. Let us ignore, for the moment, the descriptions given by the “contactees” (Chapter X) and consider only the beliefs and/or theories offered by serious proponents of the interplanetary theory and publicized by writers such as Donald E. Keyhoe[I-3, I-4, I-5] Aimé Michel[I-6], and Morris K. Jessup[I-7]. A “Baedeker’s Guide” to saucerdom based solely on statements and speculations in the books published by these investigators would portray a fantastic universe:[A]

[A] Following common practice in scientific discussion, we originally included the specific sources of important and/or controversial ideas described in this book and, for maximum accuracy, often used the original phrasing of the several authors involved. In this and certain other sections, however, we have been forced to abandon the more scholarly method of presentation because one author (Major Donald E. Keyhoe) refused permission to quote from his works.

“In saucerdom, alien spacecraft continually visit the earth and have done so for centuries. Constructed and controlled by intelligent extraterrestrial beings, the craft perhaps come from secret bases on artificial earth satellites; on the moon; on Mars; on Venus; on Jupiter; perhaps on the planets supposed to be orbiting the binary stars 61 Cygni and 70 Ophiuchi; or from planets supposed to be in orbit around the stars Tau Ceti and Epsilon Eridani, about eleven light-years distant from earth. Radio transmitters serving as beacons for space navigation may exist on both Venus and Jupiter.

“These spacecraft can perform maneuvers that, on earth, are possible only for rays of light. They fly at speeds of many thousands of miles an hour, can reverse direction instantaneously at any speed, ascend or descend vertically, and hover motionless in the air. They accomplish these feats perhaps by using the power of cosmic rays and by generating and manipulating artificial gravitational fields, which they could also use to prevent the transmission of sound waves and to become invisible.

“The extraterrestrial visitors may be explorers sent to study the earth, descendants of a race living thousands of light-years away11 from the solar system. They may be the ancestors of the human race, which itself is a remnant of a colony established on earth thousands of years ago and then abandoned. More than 300,000 years ago the inhabitants of earth had found the secret of space travel, and human beings mapped the earth by an aerial survey at least 5000 years ago. It is also possible that these craft come not from space but from time; they may be earthmen of the future who have traveled backward through time to explore their own past.

“The purpose of these visitors is still unknown. They shun close contact with human beings, rarely if ever land their ships, and never allow close-up photographs, perhaps because they are afraid of human savagery or are afraid of starting a panic. Nevertheless they attempt to signal to earthmen in various ways: they have caused the production of gigantic letters of the alphabet [U and Z] on earth radarscopes; from a material that radiates light they have built an enormous letter W, spanning more than 1000 miles on the surface of Mars; they have sent out wireless signals in Morse code to represent the letter S. They may occasionally abduct earthmen in order to use them as language teachers.

“Although these visitors are probably not hostile to human beings, they often manifest their presence in destructive ways. They cause many airplane crashes; seize and carry off ships, human beings, and airplanes; destroy flocks of birds; interfere with the operation of radio, TV, gasoline and electric motors; pelt the earth with rocks, metal, and strange organic substances; create loud noises and detonations; damage the windshields of cars; set fire to highways; hurl various types of missiles; drop chunks of ice; cause storms; and cause radioactive rain.

“One of the most peculiar features of saucerdom is the role played by government officials and scientists who, knowing the space visitors are real, yet deny their existence and unite in a gigantic conspiracy to deceive the public.”

These excerpts from a hypothetical Baedeker have summarized the ideas publicized by the most literate and most persuasive advocates of the saucer theory. The chapters that follow will examine certain flying-saucer cases. As the discussion continues and is able to account for specific UFOs in terms of normal physical phenomena,12 these anarchistic worlds of saucerdom will gradually dissolve and merge with reality as we know it—a world that holds many mysteries but is still subject to the laws of nature.

[I-1] Fort, Charles. Lo! New York: Claude H. Kendall, 1931.

[I-2] Air Force Files.

[I-3] Keyhoe, D. E. The Flying Saucer Conspiracy. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1955.

[I-4] —— Flying Saucers from Outer Space. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1953.

[I-5] —— Flying Saucers: Top Secret. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1960.

[I-6] Michel, A. The Truth about Flying Saucers. New York: Criterion Books, Inc., 1956.

[I-7] Jessup, M. K. The Case for the UFO. New York: Citadel Press, 1955.

13

The overture to the Flying Saucer opera took place in the summer of 1947, presenting the main themes that were to develop with fantastic variations during the fifteen-year-long drama that followed: mysterious apparitions in the sky, alleged interplanetary visitors, government investigators, growing public excitement, civilians who zealously encouraged the hysteria, and, as a climax, an elaborate hoax that produced material “evidence” to prove the existence of spaceships.

The first man to report a flying saucer was a veteran pilot named Kenneth Arnold, representative of a fire-control equipment firm in Boise, Idaho. On the afternoon of June 24 Arnold was flying a private plane on his way from Chehalis to Yakima, Washington. Above the Cascade Mountains at about 9200 feet, he noticed a series of bright flashes in the sky off to his left. Looking for the cause, he saw what appeared to be a formation of peculiar aircraft approaching Mount Rainier at fantastic speed. There were nine very bright, disk-shaped objects which he estimated to be twenty to twenty-five miles away, forty-five to fifty feet long, and traveling at a speed of almost 1700 miles an hour. Talking with a reporter that evening, Arnold said that the objects “flew like a saucer would if you skipped it across the water.” In a later report to Air Force Intelligence he stated: “They flew very close to the mountaintops, directly south to southeast down the hogback of the range, flying like geese in a diagonal, chainlike line, as if they were linked together.... They14 were flat like a piepan and so shiny they reflected the sun like a mirror.”[II-1]

Newspapers all over the country picked up the story and printed it under headlines describing flying pies, flying piepans, and flying saucers. Alert to the possibility that the objects might have been a new type of aircraft of Russian origin, investigators from Military Intelligence interviewed Arnold and officials from Air Technical Intelligence requested a report.

No one doubted Arnold’s word. He was an experienced pilot, a respected citizen, and a careful observer. Nevertheless his description showed some inconsistencies that made it difficult to decide what the nine disks really were. If they had actually been forty-five or fifty feet long, they must have been much closer than he thought; objects that size would not have been visible at a distance of twenty to twenty-five miles. However, if the estimated distance was correct, then in order to be visible the objects must have been much larger, at least 210 feet long. One of the estimates must be wrong—but which one? Until that question was settled, the computed speed was meaningless, since to estimate the velocity of a moving object an observer must know either its true distance or its true size. Even after a careful study, Air Force investigators could not identify the disks; they might have been clouds, a mirage, or some kind of aircraft, but no definite answer was possible from the evidence available.

Predictably, after so much publicity, a rash of similar sightings broke out all over the country and continued for the rest of the summer. During the hot months of the “silly season,” newspapers are traditionally hospitable to tales of barnyard freaks, sea serpents, and man-bitten dogs. Such stories were now shoved aside as people in every state began to report unorthodox objects sailing through the sky—flying disks, flying dimes, flying ice-cream cones, flying shoe heels, and flying hubcaps. Seeing saucers became a national pastime, but Arnold, who had reported the strange objects in all good faith, resented the implied ridicule. Deluged with telephone calls and mail, he resolved to keep silent in the future even if he should happen to see a ten-story building flying through the air.

In spite of the publicity, the flying-saucer scare would probably have died with the first frost of autumn but for the efforts of a15 talented writer, editor, and publisher of science fiction, Raymond A. Palmer. Among the many letters Arnold received was one from Palmer, then editor of Amazing Stories. Tired of being laughed at, Arnold found the tone of “sincere interest” so appealing that he answered the letter[II-2]. After a second letter a week later, he changed his mind about keeping silent and agreed to sell his story for publication.

Under the title, “I Did See the Flying Disks,” the article appeared in the first issue of a new magazine, Fate, which published “true stories of the strange, the unusual, the unknown.”[II-3] Although Arnold was not a professional writer, he had the assistance of an expert and produced a vivid, clearly written story—Palmer had had unusual experience in helping fledgling authors tell their tales. Interesting differences between Arnold’s original statements and those in the magazine version demonstrate how much he must have owed to editorial help. Without it, he might not have included certain colorful details that he had apparently overlooked earlier. In his original reports, for example, he said that he had at first supposed the disks to be some type of experimental aircraft; in the magazine version he added that, even at the time, the objects had given him “an eerie feeling.” In the intervening months he had also remembered more about their shape (see Figure 2). He no longer described them as saucerlike, flat and shiny like piepans. Instead, a drawing based on his revised account shows an object like the crescent moon with a sharp protrusion on the inner, concave side and a dark, mottled circle marking the center of the top surface. Furthermore, he told the readers of Fate, one object had been darker than the others and of a slightly different form—a detail he had forgotten to mention to reporters, to military officials, to his friends, or even to his wife.

Arnold had never been much of a reader and was not a science-fiction fan, but his interests were obviously widening. The next two issues of Fate carried other articles under his name. Palmer’s growing influence is suggested by the titles: “Are Space Visitors Here?”[II-4] and “Phantom Lights of Nevada.”[II-5]

16

Ray Palmer lays claim to being “the first flying saucer investigator”[II-6], although he frankly admits his debt to the writings of Charles Fort. Any full account of the saucer era must include the names of other enthusiasts such as Adamski, Bethurum, Scully, Cramp, Keyhoe, Jessup, Michel, and Wilkins, but none merits so much credit for keeping the saucers flying as does Palmer. He not only opened the pages of his magazines to the first saucer reports but also, in the beginning, paid the witnesses for their stories.

In 1947 Palmer was the editor of Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures, two of the great magazines of science fiction in which stories of spaceships and interplanetary travel have long been commonplace. For several years he had been hinting to readers of these magazines that alien spaceships might actually be cruising in our skies, but Fate was the first magazine that seriously promoted the idea. No man was better qualified to glimpse the dramatic possibilities of flying saucers. Born in Wisconsin in 1910, Palmer had17 begun reading Amazing Stories soon after it started publication in 1926. Turning to writing, he showed the remarkable persistence that has characterized his life. Although he received 100 rejections before he sold his second story, he stubbornly kept on until he not only achieved success as an author but also, in 1938, became managing editor of Amazing Stories for the Ziff-Davis Publishing Company. Under Palmer’s guidance, “... the entertainment side of science fiction took over.... Gone were the ponderous styles, the verbiage, the highly technical explanations of what mattered little in the first place. The stories took on pace and excitement, the characters in them were faced with human problems, the dialogue was realistic....”[II-7]

Alert to the tastes of his readers, Palmer carried the magazine to new heights. Many science-fiction fans (including the present authors) still remember that golden age around 1940 when Amazing came out every month with 146 pages full of startling, fantastic, wonderful stories of how life might be on other worlds and in other galaxies.

In January 1944 began the publishing drama that for a time changed the direction of Amazing and heralded the advent of flying saucers. The “Discussions” department that month included a letter captioned “An Ancient Language?” which introduced what came to be known both as the Great Shaver Mystery and the Great Shaver Hoax. Signed “S. Shaver,” the letter began:

“Sirs: Am sending you this in hopes you will insert in an issue to keep it from dying with me. It would arouse a lot of discussion.”[II-8]

It did indeed. The letter announced the discovery that words and syllables of the ancient Atlantean language still exist in English today; hence the legends of Atlantis must be true and a “wiser race than modern man” must once have existed on the earth.

Richard Sharpe Shaver was then living in Barto, Pennsylvania, and operated a welding machine in a war plant. In writing to thank the editor for publishing his letter, he enclosed a manuscript called “Warning to Future Man” which purported to give his memories of life in the fabled continent of Lemuria. The information had been preserved in “thought records” hidden in secret caves. By “telaug,” a kind of audio-visual telepathy, he had begun to remember18 his forgotten past when, through the noise of his welding machine, he heard voices. After visiting Shaver and probing his “memories,” Palmer bought the story. He didn’t like the way it was written, however, so he rewrote it, added material that expanded it to three times its original length[II-9], changed the title to “I Remember Lemuria,” and started advertising it well in advance of publication as a true story:

“Twelve thousand years ago the Lemurians and the Atlanteans disappeared from the Earth. Where and why did they go?”[II-10] This story would show that Newton and Einstein were all wrong, Palmer promised, and would reveal new concepts of gravity, the nature of matter, and the foundation for physical mathematics.

Thus began the controversy that rocked the world of science fiction. Since Palmer has affirmed that “Flying saucers are a part of the Shaver Mystery—integrally so”[II-11], we turn to the old files of Amazing Stories to trace their development.

The first of the Shaver series, “I Remember Lemuria” appeared in March 1945[II-12], along with “Mantong, The Language of Lemuria,” an article signed by both Shaver and Palmer, and other stories followed quickly in succeeding issues of Amazing. The basic themes were shopworn—a jumble of Fortean ideas, Plato’s fables, and mystic science—but when brightened by Palmer’s magic pencil, they seemed fresh and exciting: The earth had an ancient past, now forgotten. The lost continents of Atlantis, Lemuria, and Mu had been colonized many thousands of years ago by superior beings from another planet who could travel through space by utilizing forces unknown to present-day earthmen. Eventually these noble aliens had been forced to abandon the earth to escape evil radiations coming from our sun, but they had left descendants who still lived on earth in concealment in great subterranean cities that could be entered through certain caves. The underground dwellers in the hidden world had retained all the secret powers of their ancestors. They could communicate by thought transference, could speak to earthmen by mental “voices,” and could travel on beams of light because they understood the true nature of gravity and magnetism. These creatures were divided into two opposing groups, one good and one evil. The dero (detrimental robots) were the bad guys and they caused all the unexplained accidents and misfortunes that happen19 to human beings. The tero (integrative robots) were the good guys; they warned earthmen of danger and tried to protect them from the destructive forces of the dero.

Reader response to these fantasies was phenomenal. Fan mail zoomed from 40 or 50 to 2500 letters a month[II-13], and the magazine’s circulation increased by some 50,000. As the records of “racial memory” continued to appear, connoisseurs of good science fiction began to cry “Hoax!” but their protests had no effect. Thousands of new readers were buying the magazine and many of them were beginning to recall and report “memories” of their own. Since the “Discussions” columns could not take care of so many letters, Palmer opened a new department, “Report from the Forgotten Past”[II-14], and urged the readers to send in their personal experiences with the hidden world. Did they ever hear strange voices? Receive mysterious messages through the air? Suspect that they were being affected by strange rays? Feel that they had been put on earth for some special mission? Have dreams that they could not explain? Have a strong urge to explore caves? Have memories of other lives? The editor was eager to learn of all such incidents. Through the Shaver stories, Palmer was already promoting the idea that interplanetary craft do visit the earth:

“There are many mysteries of the past that have intrigued investigators to an almost unbearable point.... What were the glories of Babylon? What truth is there in the Chinese legend of being the people of the Moon, and of coming to Earth in rocket ships? What was the mystery metal of the Lemurians, orichalcum? What was the secret of their airships that walked on beams of light?”[II-12]

When one correspondent informed him that space travel was possible “if one travels through curves but not through angles,” Palmer replied, “Your editor is sincere—and he’d like to know everything you know.... For instance, please explain this space-travel business—about curves and not angles.”[II-15]

For more than three years the columns of Amazing continued to assert, not as fiction but as fact, that interplanetary travel is a present reality and that the laws of physics are not valid. In a mystic mumbo jumbo the readers were told that the velocity of light, for example, was not the ultimate speed:

“Light speed is due to ‘escape velocity’ on the sun, which is not20 large. This speed is a constant to our measurement because the friction of exd, which fills all space, holds down any increase unless there is more impetus. The escape velocity of light from a vaster sun than ours is higher, but once again exd slows the light speed down to its constant by friction, so that when it reaches the vicinity of our sun, no appreciable difference is to be noted. A body can travel at many times the exd constant, under additional impetus, such as rocket explosions. A ship whose weight is reduced to a very little by reverse gravity beam can attain a great speed with a very small rocket.”[II-12]

Devotees of reasonable science fiction (who include many leading scientists) were writing angrily to Palmer, protesting that the Shaver hoax had gone too far, but their letters seemed only to amuse him:

“There have been some odd reactions, one of them being a promise by a fan group to ‘expose’ our ‘hoax’ (which was a compliment, by the way, because it was termed the ‘biggest ever attempted in modern science fiction history’). We are waiting for this expose, [sic] with interest—because we are curious to know how a hoax which is not a hoax can be exposed as a hoax. We realize that a lot of our readers find it difficult to believe that we ourselves believe one single word of what Mr. Shaver tells us in his stories, but we’ll keep on presenting the evidence as it comes in, and you can judge for yourself.”[II-14]

Readers continued to object and many stopped buying the magazine, but Palmer persisted with ambiguous hints that spaceships were really here. A full year before the first flying-saucer report he wrote:

“If you don’t think space ships visit the earth regularly, as in this story [‘Cult of the Witch Queen’], then the files of Charles Fort and your editor’s own files are something you should see.... And if you think responsible parties in world governments are ignorant of the fact of space ships visiting earth, you just don’t think the way we do.”[II-16]

In succeeding months he became more and more explicit. In September 1946 he told one correspondent, “As for space ships, ... personally we believe these ships do visit the earth. You, or any observer, would be inclined to call it something else if you did see one.”[II-15] In the spring of 1947 he replied to a reader who asked21 for concrete evidence that Shaver’s stories were true: “... the mystery is not just ‘are there caves with dero and tero in them?’ but it has to do with space ships, other inhabited worlds, and so on.”[II-17]

In June 1947, the month the first flying saucers were reported, the issue of Amazing Stories was an addict’s dream[II-18]. The cover featured “The Shaver Mystery, the Most Sensational True Story Ever Told”; the four stories, 90,000 words, were all under the byline of Richard S. Shaver. The entire magazine—editorial comments, discussion columns, and most of the feature articles—was devoted to the supernatural world of Shaver.

But the end was near. Amazing published its last Shaver story, “Gods of Venus,” in the summer of 1948; as far as the magazine was concerned, the mystery was dead.

Who or what killed it? One version says that the publisher, William B. Ziff, ordered the series stopped because so many fans had quit buying the magazine. Palmer himself has given various explanations. He stopped the stories, he said at first, when he realized that such material did not really belong in a fiction magazine. Later he explained that he killed the mystery because he intended to go into publishing for himself and didn’t want to leave his successor to handle “this hot potato.”[II-19] Later still, he implied that publishing the stories was dangerous; that he had learned too much about the “hidden world,” the sinister forces responsible for the plane crash that followed the Tacoma hoax. Said Palmer, “I wanted no more dead men on my hands.”[II-11]

The Maury Island Mystery, a complex and eventually tragic affair, occurred near Tacoma, Washington, less than 100 miles from the place where Arnold had sighted the nine disks. In this mystery, too, Palmer was involved. According to their story, two harbor patrolmen named Harold A. Dahl and Fred L. Crisman on June 31 had observed a group of six flying disks that hovered over their boat near Maury Island and jammed their radio when they tried to notify the authorities. One of the disks had seemed to be disabled, had showered down lavalike metallic fragments that damaged the22 boat and killed the dog on board; the disks had then disappeared but the fragments remained as proof of the visit. The men also claimed to have taken some pictures that showed the six objects but were fogged as though by radiation. Back on shore, they had not telephoned the newspapers nor had they notified any government officials. Instead, they had mailed a box of the fragments to Ray Palmer, to prove that they had actually seen an accident to a flying saucer[II-20].

Crisman was no stranger to Amazing Stories. A science-fiction fan, he apparently had accepted the Shaver stories as literal truth. More than a year before the Maury Island episode he had written to Palmer, warning him that the knowledge contained in the Shaver stories was too dangerous to print. Identifying himself as an ex-Air Force pilot who had flown the Hump, Crisman explained that when he was in Burma, he had been exploring a cave when a dero attacked him with a mysterious ray that made a hole the size of a dime in his arm. Palmer had kept up the correspondence[II-21] and, some months later, received a telephone call from Crisman, then in Texas: for $250, said Crisman, he would descend into a cave and take some actual pictures of the mysterious underground machines that Shaver had described. The result of this offer is not known, but in July 1947 Palmer received another letter from Crisman; he had witnessed an accident to a flying saucer and was sending a box of the fragments as proof[II-22].

Palmer considered buying the story for Fate, but first he asked Arnold, living close to the scene, to investigate the tale. Arnold agreed. Thus the first man to report flying saucers became also a victim of the first flying-saucer hoax.

With an advance of $200 for expenses, Arnold flew to Tacoma and into a nightmare of mystery. The two men were elusive, their story full of discrepancies, their manner evasive. Wondering at first whether the affair was a hoax, Arnold finally attributed the strange behavior of the men to their fear of hostile saucers. Alarmed, he called in the help of Army Intelligence. Two officers arrived from Hamilton Air Force Base, California, and made a careful investigation. They found that Dahl and Crisman were not “harbor patrolmen” but salvagers of floating lumber; their boat was scarcely seaworthy and showed no evidence of major repairs; they couldn’t23 remember what they had done with the pictures they mentioned; and although the saucer accident was supposed to have occurred nearly six weeks earlier, they had never notified the authorities or even mentioned it to a reporter. The only evidence offered for the truth of their tale was the collection of “strange” fragments which were later found to be slag from a local smelter plant. Similar fragments could be found by the ton on Maury Island[II-20].

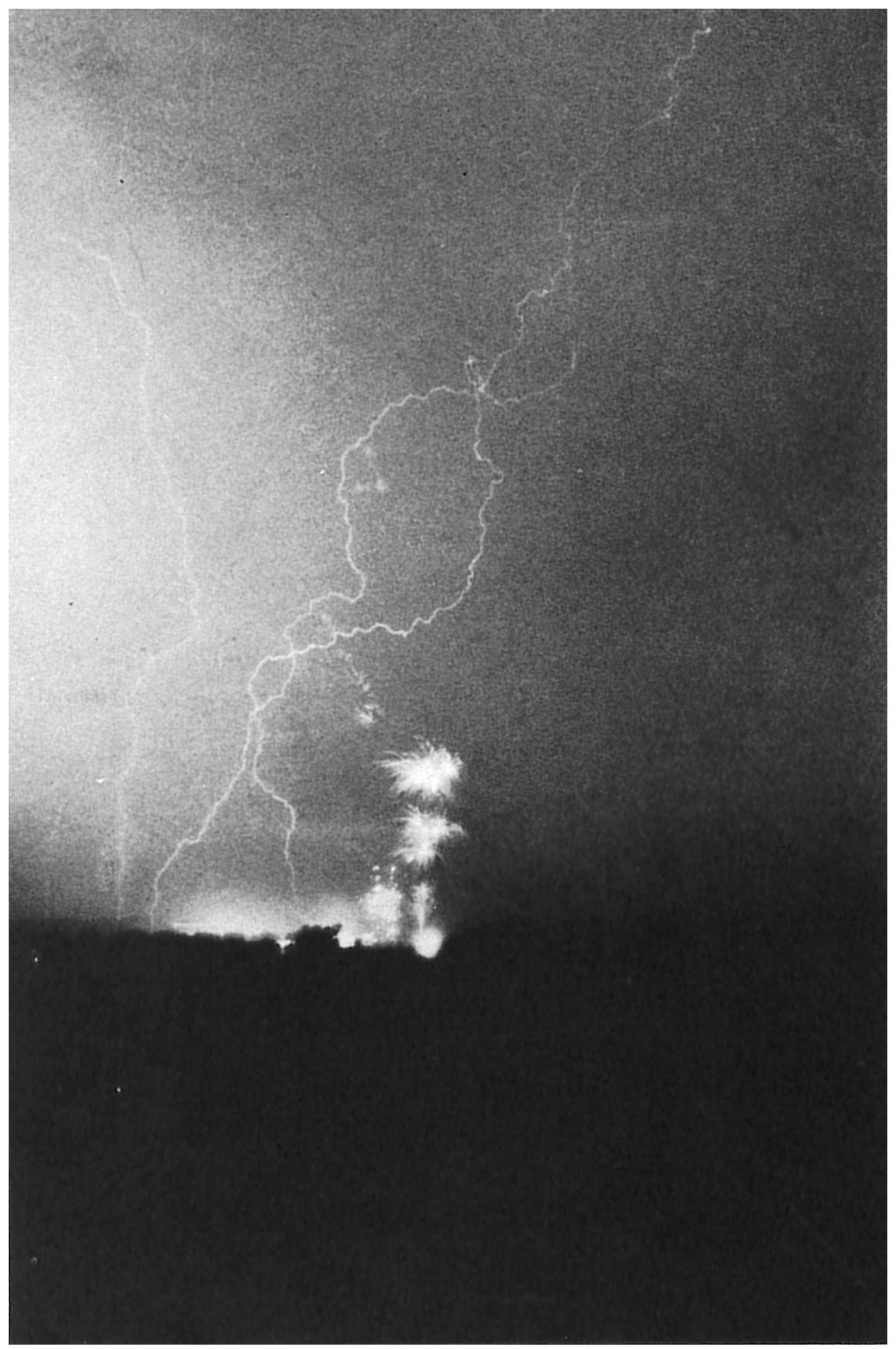

The officers concluded that they had wasted their time on a flagrant hoax, but the bewildered Arnold insisted that they take some of the fragments for analysis. Unhappily, on the way back to the base the plane crashed and although two passengers parachuted to safety, both officers were killed. At once fantastic rumors sprang up: that the Tacoma “disks” had been spaceships, and that the beings who operated the craft had been forced to arrange the plane crash so that no one could analyze the fragments of their disabled spaceship. Arnold himself seemed to believe that the crash had resulted from extraplanetary sabotage, but investigation showed a more ordinary cause. A burned exhaust stack had set the left wing afire; the blazing wing had then broken from the fuselage and torn off the plane’s tail.

For a time government officials considered placing a charge of fraud against the two men who had started the unhappy chain of events. After further questioning, both had admitted that their “sighting” had been a hoax, planned merely to make their story more salable, but when first Arnold and then Military Intelligence had entered the picture, the hoax had simply gotten out of hand. Since the men obviously had never intended the tragic outcome and were not directly responsible for it, the idea of prosecution was abandoned[II-1].

No longer editor of Amazing, Palmer continued to promote the cause of flying saucers in the pages of Fate. During the early nineteen-fifties, the boom years of science fiction, he started other magazines—Search, Mystic Universe, Other Worlds Science Stories. After24 a time, Fate began to concentrate on tales of the mystic and occult, while Other Worlds eventually took over the flying-saucer theme.

Starting as an orthodox magazine of science fiction, Other Worlds flourished until the general slump in the market caused it to suspend publication. Revived after a time, it has undergone several changes of editorial policy reflected in its changing names: Other Worlds Science Stories, Flying Saucers from OTHER WORLDS, FLYING SAUCERS from Other Worlds, Flying Saucers the Magazine of Space Conquest, and, since the spring of 1961 when the magazine became pocket-size, just Flying Saucers. Classic science fiction long ago vanished from its pages and all articles are “true” accounts of flying saucers and similar Fortean incidents.

Flying Saucers is probably unique in modern publishing history. Issued monthly or bimonthly at a price of thirty-five cents, the magazine does not pay its authors because, as the editor explains, “Flying Saucers is not a commercial project.” Published by Palmer Publications, edited by Palmer, containing liberal amounts of editorial comment and at least one article by Palmer, a typical issue in 1960[II-6] contained sixty-six pages and carried a small number of advertisements for telescopes, binoculars, Rosicrucian and similar mystic publications. The remaining ads featured books and magazines issued by Palmer Publications, Amherst, Wisconsin; books issued by Amherst Press, also of Amherst, Wisconsin; Saucerian Books, published under the aegis of Gray Barker, a contributing editor to Flying Saucers. “Austrogen,” described as a face cream or clay for skin ailments, was obtainable from Palmer at a dollar an ounce. Another ad recommended something (the wording does not specify exactly what, perhaps a powder?) that helps make good chili. Readers could buy this too, from Palmer, for a dollar a pound or $3.50 for five pounds. A combination dandruff remover, itch preventer, and restorer of hair color personally recommended by Palmer sold for $5.00 a bottle, number of ounces not specified.

The dandruff remover was also recommended by Kenneth Arnold, whose flying disks had started the saucer epidemic. Arnold was advertising his “World Society of Flying Saucer” which would “hold no meetings, no minutes, no by-laws, no restrictions or regulations, no records outside of actual membership, no presidents, no vice-presidents, no secretary, or board of directors.” For only25 $5.00 those who joined the society would receive twelve issues of Flying Saucers (which if ordered from Palmer Publications would have cost $4.00), plus an official membership card. Arnold also offered for sale a crescent-shaped lapel pin in solid silver, supposedly just like the “original” saucers he had sighted in 1947; and, for the ladies, the saucers in pendant form. The addition of seven-point diamonds was optional.

The magazine has grown smaller, but its main theme is still flying saucers, which until recently have been interpreted as interplanetary vehicles. In December 1959, however,[II-23] Palmer announced in a lead article that flying saucers were not from outer space after all; instead, they came from secret earth bases located under the north and the south poles. The earth is actually shaped like a doughnut, not like a pear, he says, and has openings at both poles where the saucer people reside. Whether they are manned by dero or tero he has not said.

In the autumn of 1962, Arnold entered the arena of politics and was the Republican nominee for lieutenant governor of Idaho, but lost. Shaver became a dairy farmer, a Wisconsin neighbor of Palmer’s, but in science-fiction circles his name will never die. Recently he has been advertising the sale of alleged pre-Deluge and pre-Ice-Age “art stones” described as rare, voluptuous, exciting, and usable as ornaments for wall or mantel, or simply as book ends.

Palmer has now revived the Shaver Mystery and is reprinting the entire series in book form “with the fiction removed,” under the general title of The Hidden World. In advertising the new project he stated, “This magazine concerns flying saucers. Flying saucers are a part of the Shaver mystery—integrally so.” He abandoned the stories in Amazing, he says, not because an outraged publisher insisted, but because he believed the stories to be true. “That is the true motive. I was convinced that not only was there a ‘hidden world,’ but it was one of immense ramification, and the caves of the dero, flying saucers, military espionage, the political science of the world, and even some phases of religion, specifically those of the ‘cult’ variety, were inextricably linked.” In announcing that he intended to end the secrecy that had existed for so long, and to tell the truth after seventeen years of “sugar-coating” the facts, he did not explain exactly why he feels it is safe to publish the “truth” now,26 when it was not safe seventeen years ago. He says only, “... there have been good reasons for the delay—had it been done from the beginning, the pitfalls that would have crushed it could not have been avoided.”[II-11]

At the tenth annual World Science Fiction Convention, held in Chicago in September 1952, fans and fellow editors awarded to Palmer a bronze plaque honoring him as a “son of science fiction,”[II-24] a citation he fully merits. As long as flying saucers continue to make good copy and sell magazines, Palmer will probably keep them soaring—whether their home bases are other planets or polar caves. As one of his colleagues once commented:

“... in these times of drab and unconvincing falsehood, there is still something to be thankful for. A Palmer promotion has the touch of genius. It has zing, sparkle, and true showmanship. It can be spotted a mile away by the bright lights. The thing to do is sit back and enjoy it.”[II-19]

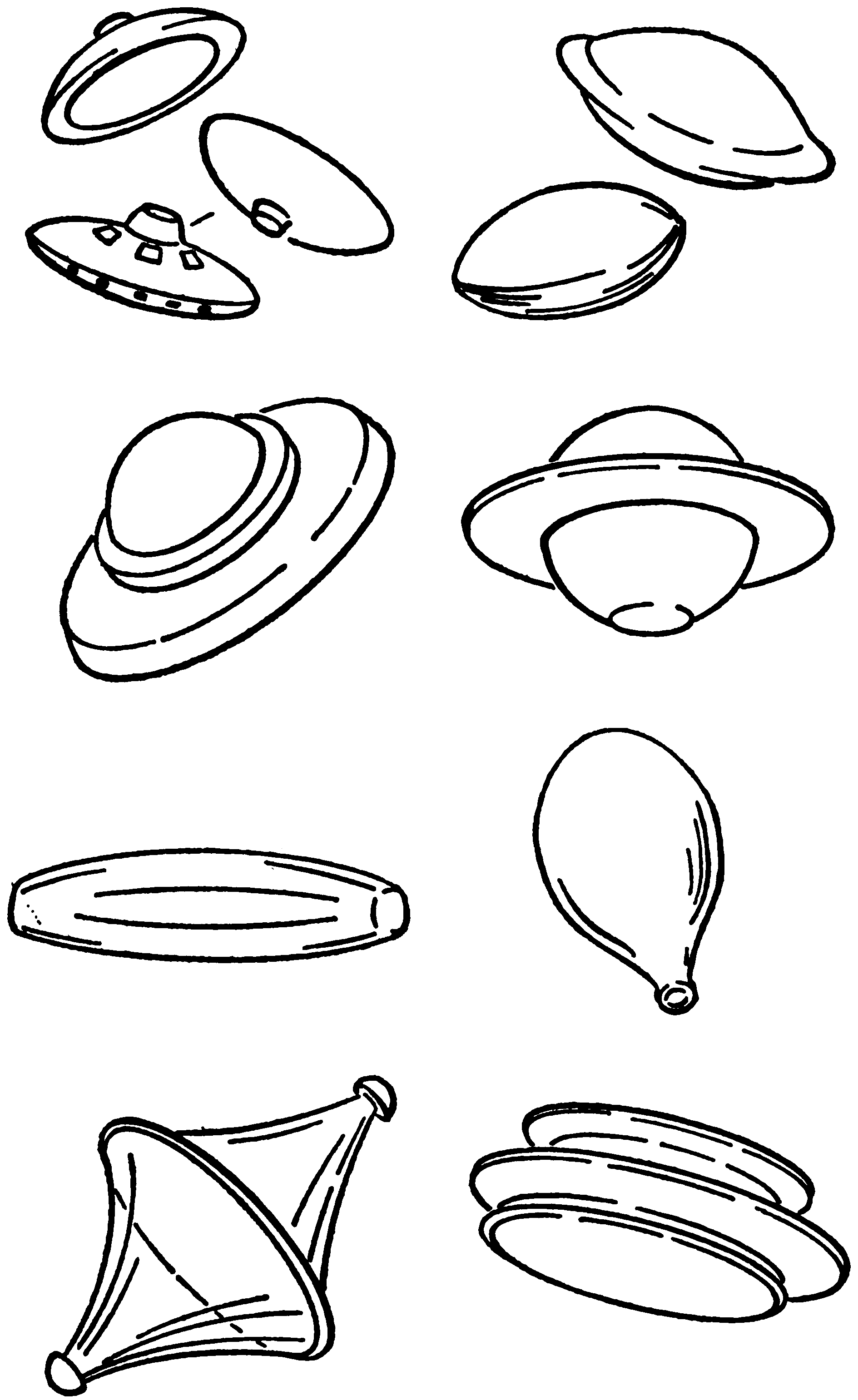

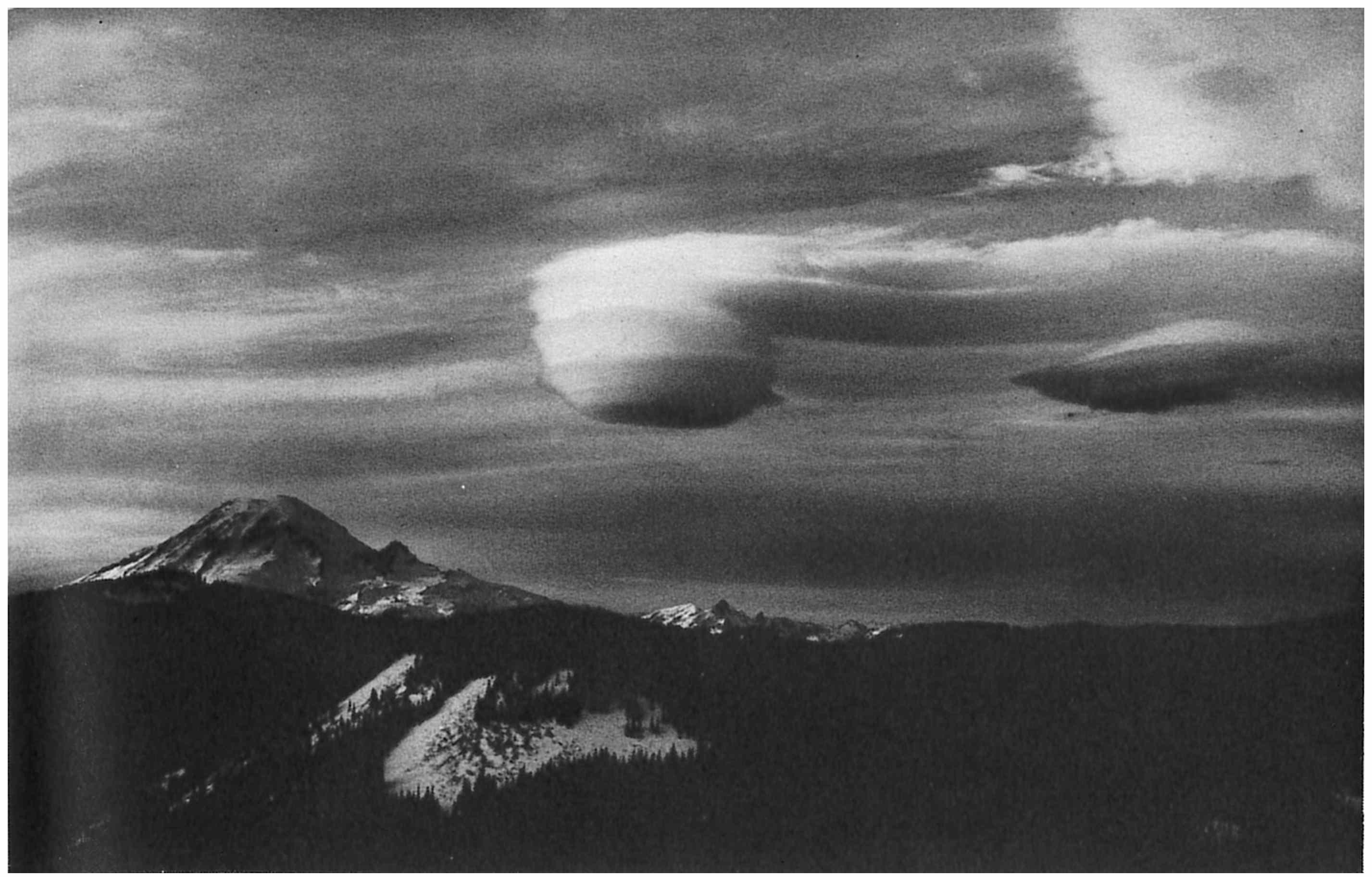

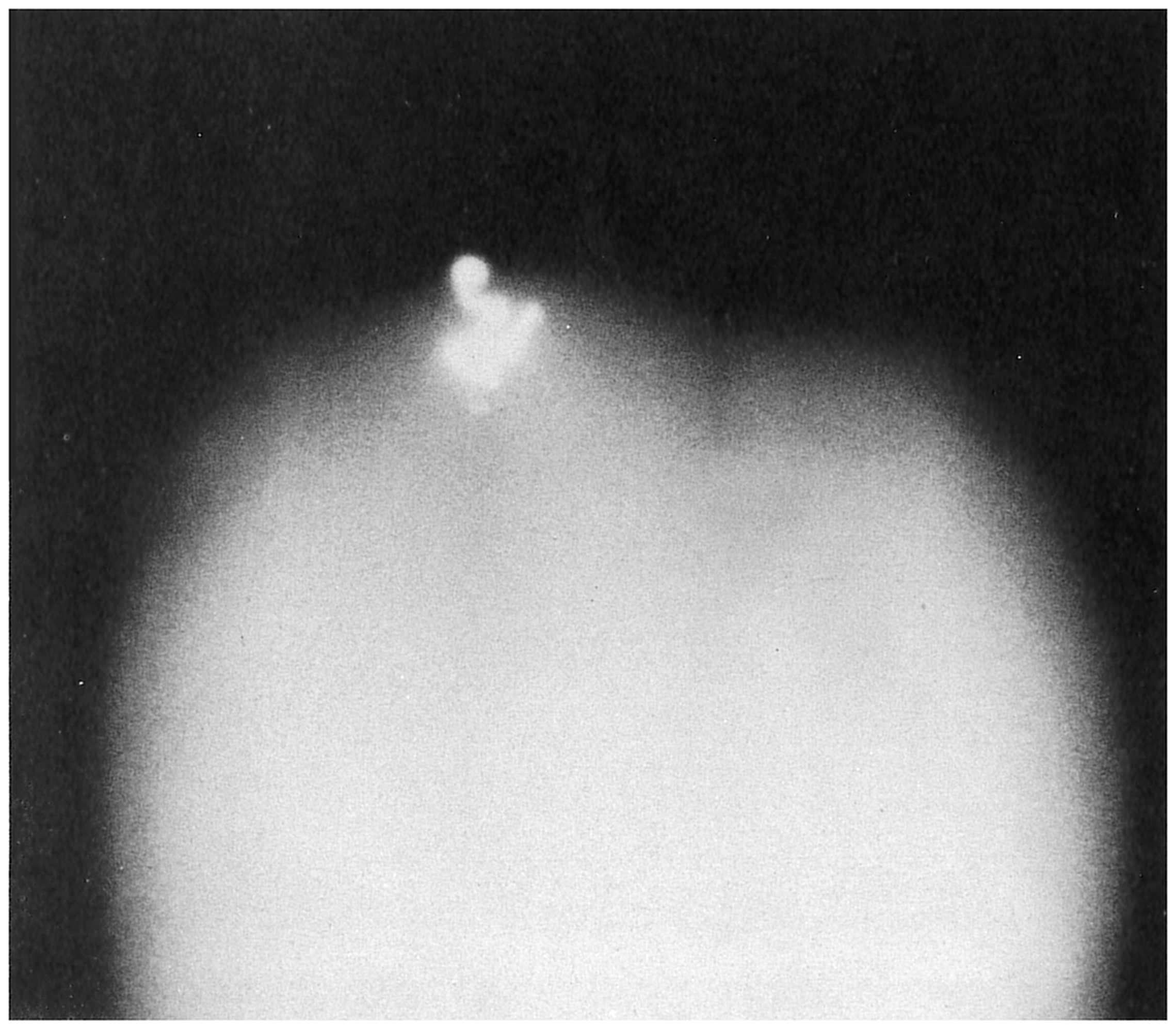

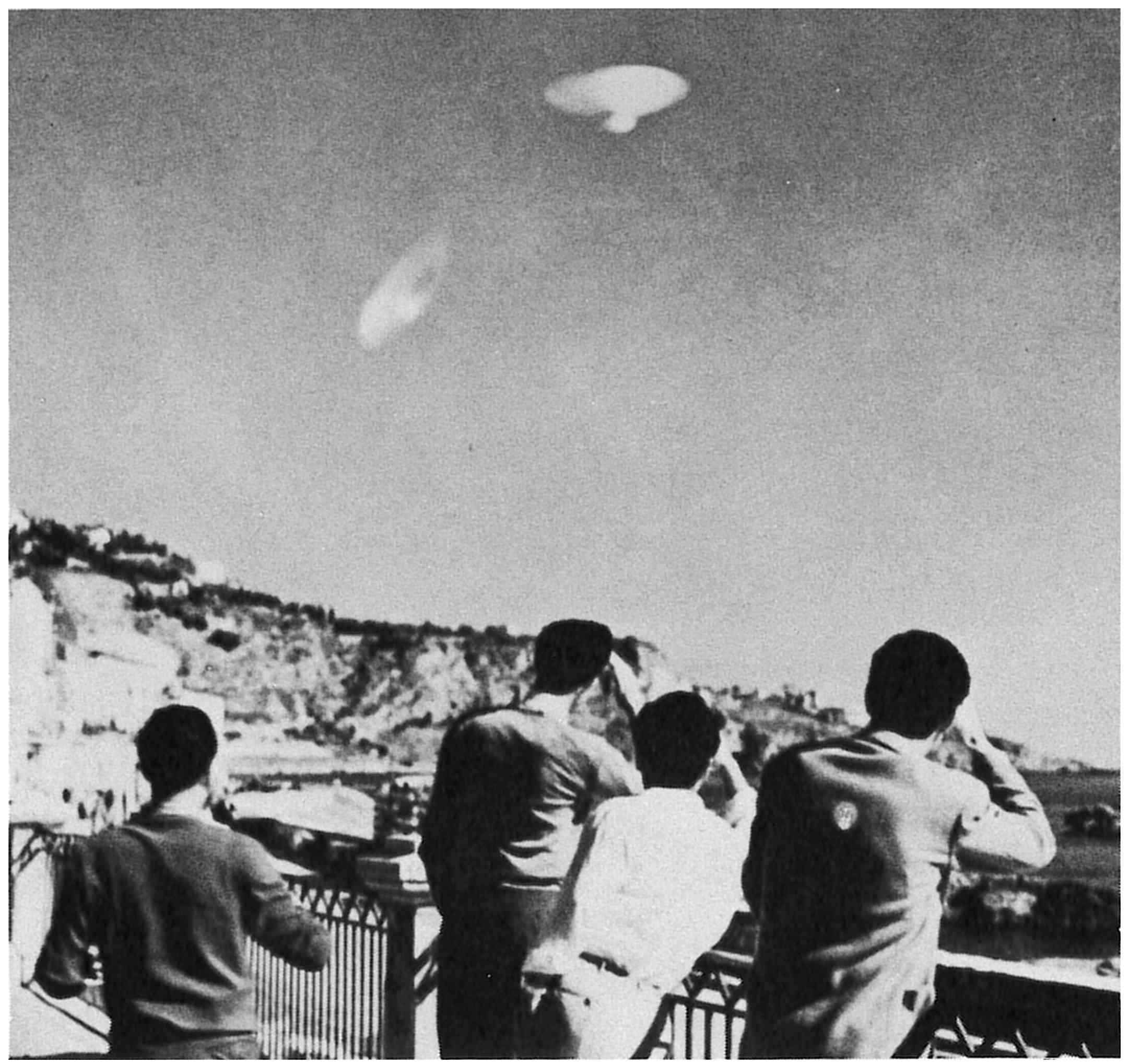

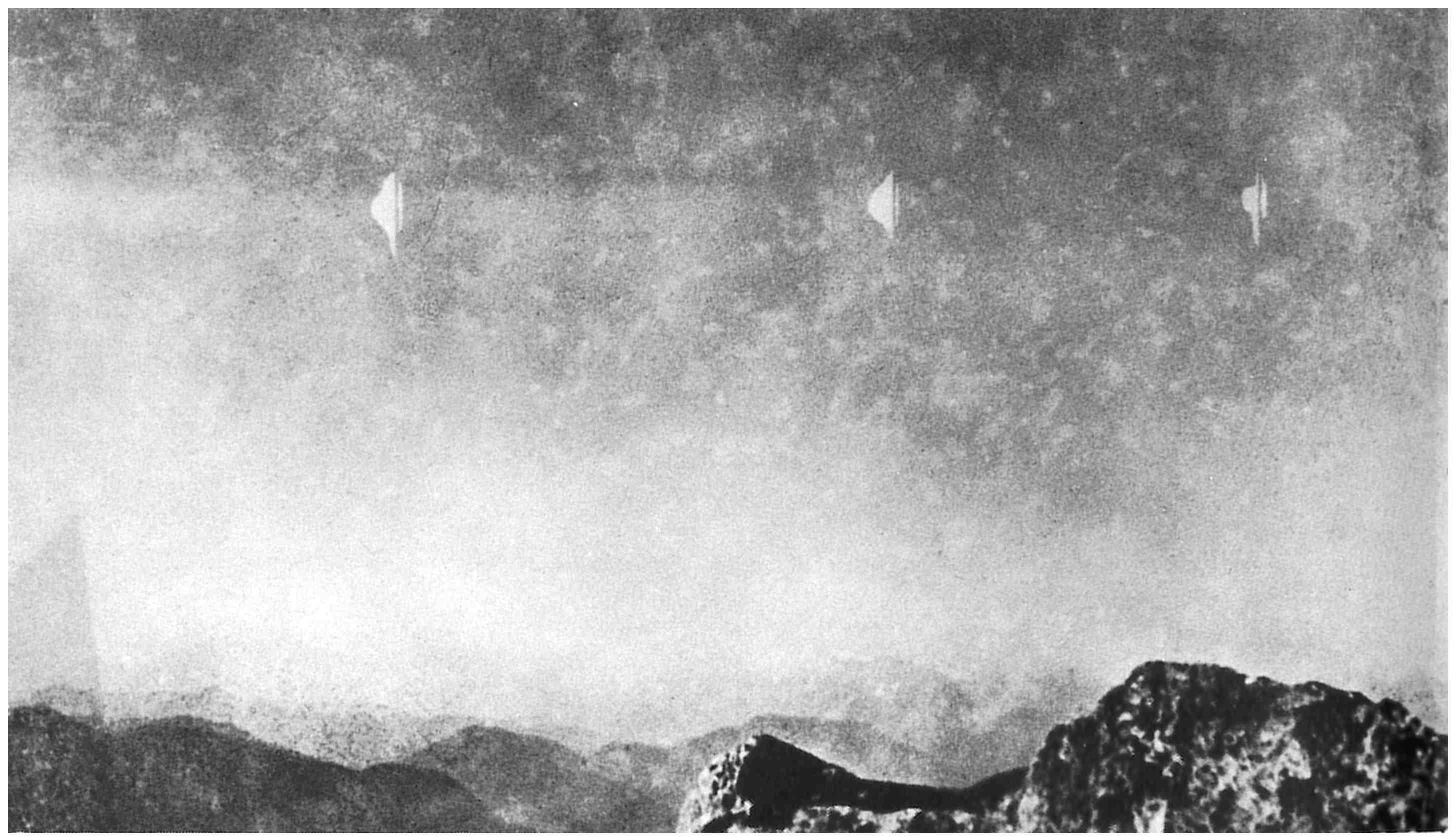

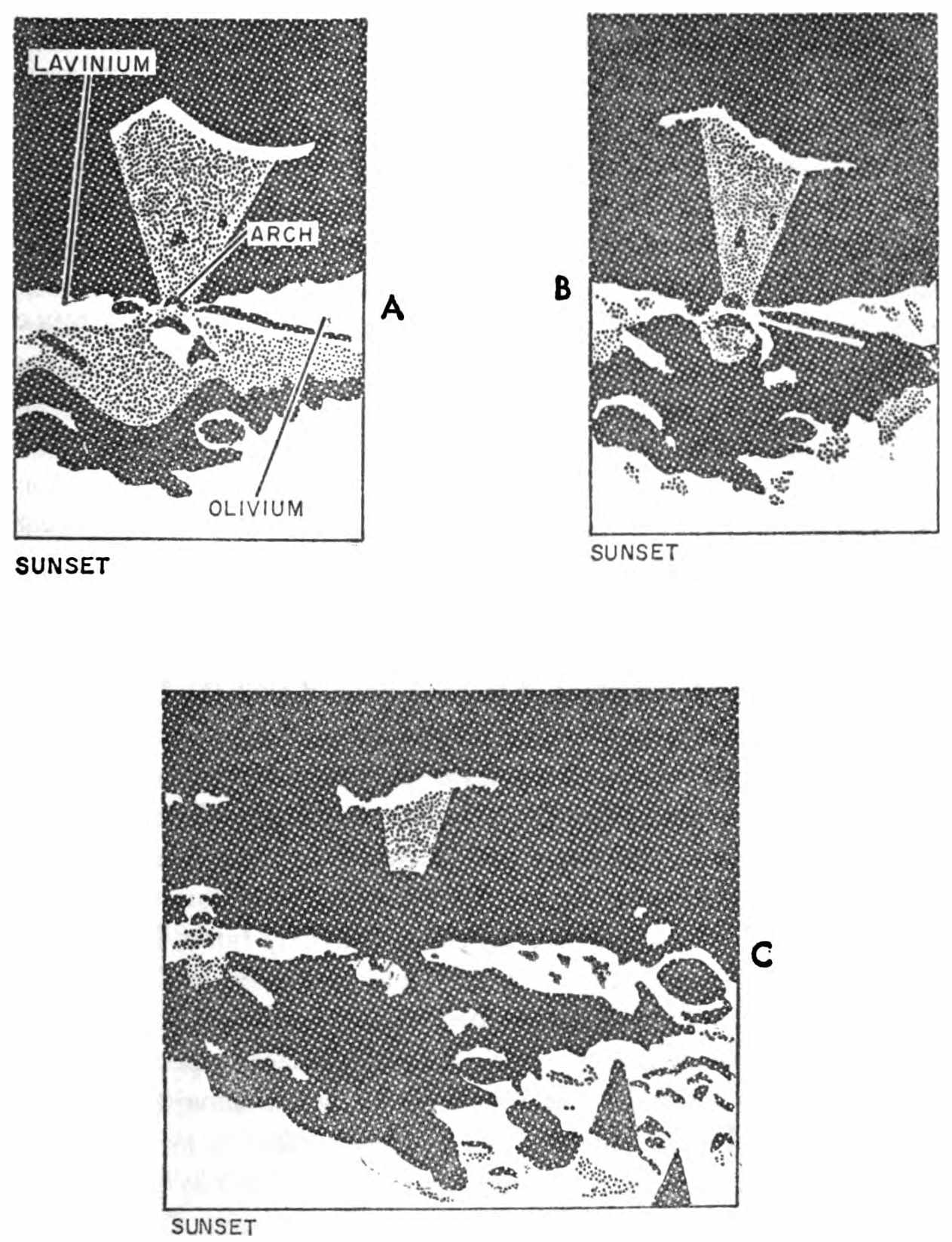

What did Kenneth Arnold actually see, that June afternoon in 1947? No absolutely certain answer is possible after so long a time. The disks were probably a mirage (see Figure 3) in which the peaks of the mountains seemed to float above the mountain chain[II-25]. An alternative but much less probable explanation is that he observed orographic clouds, a type unique to mountainous country, which often appear to stand more or less motionless and can assume dramatic shapes. “Grindstone” clouds, shaped like thick, solid disks (see Plate Ia), are common phenomena in the valleys just east of the Sierra Nevada in California and in the mountainous regions of Washington, Colorado, and New Mexico—areas where flying-saucer reports have tended to concentrate[II-26]. One of the most spectacular types of mountain cloud, it closely resembles the “pile d’assiettes” or “stack of plates” formation in which the cloud assumes a flat, round shape like a plate or a saucer, and two or more are piled together in a neat stack, as in Plate Ib[II-27]. Another picture of a “stack of plates” (which some observers reported as a hovering flying saucer) was made on May 31, 1953, near Jindabyna, Snowy Mountains,27 New South Wales, and reproduced in Weather in November 1954 Plate 47. The cloud formed over a tub-shaped depression in the mountains and remained stationary for more than an hour[II-28].

Such clouds reflect the undulations of lee waves formed in the atmosphere when stable currents of air flow over obstacles such as hills or mountains. An up-and-down wave motion may be impressed upon the air, provided that temperature and wind conditions are suitable. As the air describes its wavelike path, it alternately warms and cools, the warming taking place as it sinks into the wave trough and the cooling as it ascends to the wave crest. If the air is very dry, the undulating current will not be visible to the eye, although the updrafts and downdrafts will readily be felt by aircraft28 that chance to pass through them. On the other hand, if the air before entering the wave is moist enough, the cooling in the wave crest will cause water droplets to condense and a cloud to appear.

In the vicinity of an isolated peak the cloud may assume the form of a cap covering the summit, or it may be displaced slightly downwind and resemble a lens or disk. Not infrequently a series of lenticular clouds will appear, trailing downwind at regular intervals of a few miles. Although these wave clouds are usually stationary, they sometimes move at great speed, especially when the air temperature is changing rapidly.

From a study of a remarkable photograph made in 1956, R. J. Reed of the University of Washington has offered the suggestion that the disks Arnold saw were actually wave clouds in rapid motion.

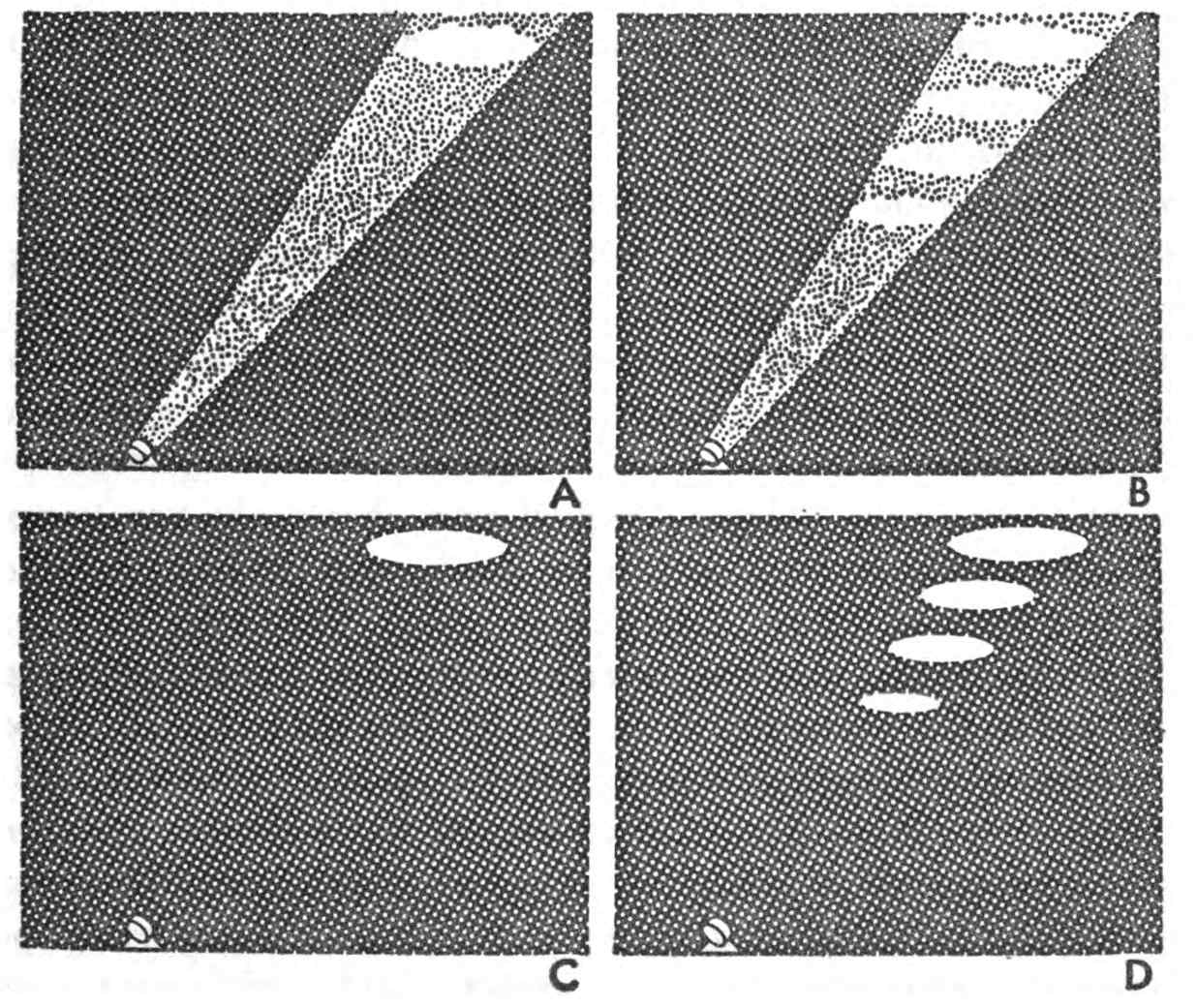

On the afternoon of December 29, 1956, a photographer for the Seattle Times was on top of Pigtail Peak near White Pass, Washington (not far from the area where Arnold’s nine disks had appeared), taking ski pictures for the rotogravure section of the Sunday Times. The weather was beautiful. Down in the pass temperatures hovered near freezing, but the slopes were warmed by sunlight that filtered down through thin cirrus clouds and raised the temperature to a balmy fifty degrees. Just at sunset a strange object suddenly appeared off toward the northeast horizon. Several skiers urged the photographer to take a picture of the “flying saucer,” but since it was still far away and indistinct, he waited. The first object, now followed by a second one, moved rapidly toward Mount Rainier, began to sharpen in outline, and both were soon so clearly visible that he was able to snap his unusual picture. The photograph shows two apparently solid, disklike objects, flattened, brilliantly white but dark at the bottom, apparently linked together by white streamers, skimming toward the mountain peak (Plate Ia).

Recognizing the close resemblance between the objects in the photograph and those Arnold described, Reed made a full analysis of the weather conditions prevailing at the time the picture was taken. From radiosonde data provided by the Seattle-Tacoma Airport, he obtained measurements of the size of the clouds, their height above the mountains, wind directions, and temperature and29 humidity at mountain height and cloud height. Obviously the pattern of weather conditions that prevailed that day was suitable for the formation of saucerlike clouds.

To test the hypothesis that Arnold also had seen such clouds, he then obtained records of the weather data for June 24, 1947, to determine whether atmospheric conditions on the two dates were basically similar. “To be comparable, winds would have to be blowing from the north or northwest in Mr. Arnold’s case since the objects were sighted to the south and southeast of the peak. The air would have to be dry at lower elevations and moisture would have to be spreading in at higher levels. An inspection of the historical maps reveals that, indeed, all these conditions were met.”[II-29]

Reed concludes that, although we can never know for certain, the implication that the Times photographer and Kenneth Arnold viewed essentially the same phenomenon seems “inescapable.” This interesting hypothesis, however, requires the presence of undulating air currents and turbulence great enough to endanger a plane in flight. Since Arnold specifically mentioned the smooth, calm flying, the mirage explanation remains the most probable one.

[II-1] Air Force Files.

[II-2] Arnold, K., and Palmer, R. A. The Coming of the Saucers. Amherst, Wisconsin: privately printed, 1952.

[II-3] Fate, Vol. I, No. 1 (Spring 1948).

[II-4] Fate, Vol. I, No. 2 (Summer 1948).

[II-5] Fate, Vol. I, No. 3 (Fall 1948).

[II-6] Flying Saucers, The Magazine of Space Conquest (June 1960).

[II-7] Amazing Stories, Vol. XXX, No. 4 (April 1956).

[II-8] Amazing Stories, Vol. XVIII, No. 1 (January 1944).

[II-9] Amazing Stories, Vol. XIX, No. 4 (December 1945).

[II-10] Amazing Stories, Vol. XVIII, No. 5 (December 1944).

[II-11] Flying Saucers, The Magazine of Space Conquest (November 1960).

[II-12] Amazing Stories, Vol. XIX, No. 1 (March 1945).

[II-13] Palmer, R. A. “An Open Letter to Paul Fairman,” Other Worlds Science Stories (June 1952), pp. 151–56.

[II-14] Amazing Stories, Vol. XIX, No. 3 (September 1945).

[II-15] Amazing Stories, Vol. XX, No. 6 (September 1946).

[II-16] Amazing Stories, Vol. XX, No. 4 (July 1946).

[II-17] Amazing Stories, Vol. XXI, No. 2 (February 1947).

[II-18] Amazing Stories, Vol. XXI, No. 6 (June 1947).

[II-19] Fairman, P. W. “Personalities in Science Fiction,” If (May 1952), pp. 63–67.

[II-20] Ruppelt, E. J. The Report on Unidentified Flying Objects. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1956.

30

[II-21] Flying Saucers, The Magazine of Space Conquest (December 1958).

[II-22] Flying Saucers from Other Worlds (June 1957).

[II-23] Flying Saucers, The Magazine of Space Conquest (December 1959).

[II-24] Other Worlds (July 1953).

[II-25] Tacker, L. J. Flying Saucers and the U. S. Air Force. Princeton, N.J.: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1960.

[II-26] Ives, R. L. “Areas of Occurrence of ‘Grindstone’ Clouds,” Weatherwise, Vol. XI (1958), p. 201.

[II-27] Scorer, R. S. “Lee Waves in the Atmosphere,” Scientific American, Vol. CCIV (1961), p. 124.

[II-28] Kraus, E. B. “Flying Saucer?” Weather (November 1954).

[II-29] Reed, R. J. “Flying Saucers over Mount Rainier,” Weatherwise, Vol. XI (1958), p. 43.

31

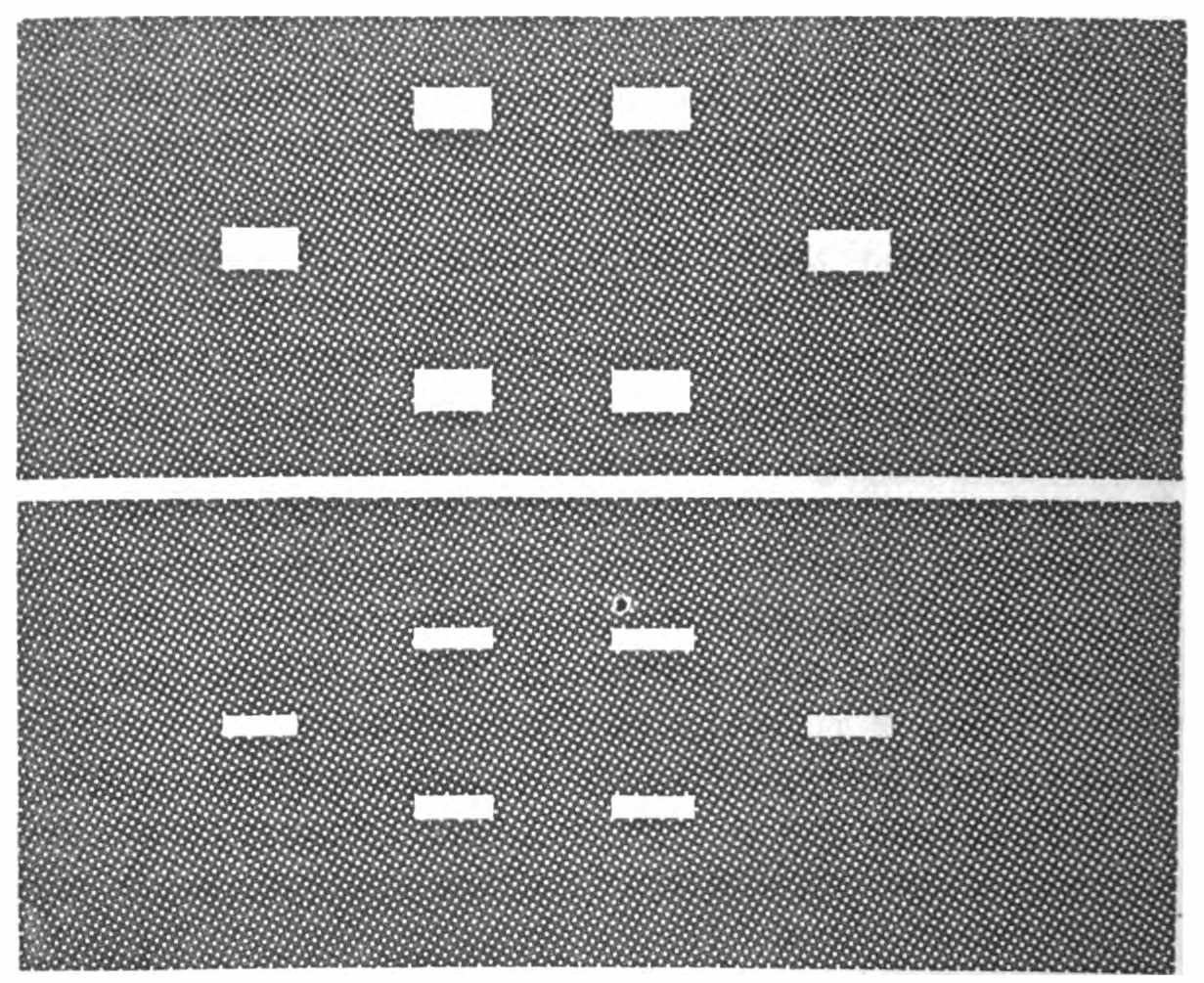

In the year 1948 the “Skyhook” balloons were an official secret. These giant plastic bags, shaped something like a teardrop, a hundred feet and more in diameter, were part of a classified research project sponsored by the United States Navy, and few except the researchers and technicians involved knew of their existence. Carrying cases of heavy instruments, the balloons were launched from various Air Force bases to collect information about the atmosphere high above the earth, the winds in the stratosphere, and the incidence of cosmic rays. Soaring upward, they traveled in courses determined by the winds and changed in direction and speed as they shifted from one wind stream to another. Even at heights of 60,000 feet these objects with their highly reflecting surfaces could be seen from the ground (see Figure 4). Such balloons were especially noticeable against dark-blue skies, which are much more common in the western United States than in the eastern areas. They could reach heights of 100,000 feet, higher than our planes could go. Once considered as a means for collecting information for Military Intelligence, a task later assumed by the U-2 jets, they could travel across the entire continent and even across the oceans. If the plastic skin developed a leak, the resulting loss of gas altered both the appearance and the behavior of the balloon; if the leak became great enough the balloon shriveled and eventually fell to the earth. At high altitudes where the cold was extreme, the skin might become brittle and the balloon would burst into fragments to be dispersed by the winds and vanish.

Although these balloons were sometimes visible at distances of fifty or sixty miles and were very conspicuous, officially they did not exist until 1950 when Dr. Urner Liddel of the Office of Naval33 Research released the facts behind the Skyhook balloon program. He pointed out then that the balloons had given rise to many reports of flying saucers. If the Skyhook project had been public knowledge in 1948 and if information about their launching and movements had not been a matter of security, a courageous pilot might still be alive today and the infant flying-saucer myth would have died long ago. There can be little question that Captain Mantell crashed in trying to intercept a Skyhook balloon, an object he had never heard of.

The basic facts of the Mantell case, the second of the “classic”[B] UFO sightings, are familiar to all who have studied flying-saucer phenomena[III-1, p. 51]. Early on the afternoon of January 7, 1948, the Kentucky State Highway Patrol received a large number of calls from the towns of Maysville, Owensboro, and Irvington, reporting a strange object moving west at high speed. Alerted by the police, officials at Godman Air Force Base, near Ft. Knox, began looking for the unknown craft. They soon located the object but could not identify it. Watching it through binoculars, various observers described its shape as circular, like a teardrop, or rounded and tapered like a parachute or an ice-cream cone. At about 2:30 P.M. (all times in this account are E.S.T.), as they were discussing the object, a flight of four P-51 planes approached the base from the south. Led by Captain Thomas Mantell, the planes were being ferried from Marietta Air Base, Georgia, to Standiford Field near Louisville. The tower operator at Godman thereupon radioed Captain Mantell for assistance:

[B] A “classic” in the literature of flying saucers is a particularly dramatic UFO incident whose specific cause has not yet been found or, if found, cannot be absolutely proved from the evidence available. Lacking a completely airtight explanation, official investigators classify the case as Unknown. Saucer fans classify it as proof that flying saucers exist.

“We have an object out south of Godman here that we are unable to identify and we would like to know if you have gas enough and if so could you take a look for us if you will.”

34

The ferry had been planned as a low-level flight and none of the planes had been serviced with oxygen. Captain Mantell, a combat pilot in World War II, nevertheless agreed to help out: “Roger. I have the gas and I will take a look for you if you will give me the correct heading and any information you have on locating the object.”

The talk between Godman tower and Captain Mantell was not recorded and transmission was sometimes garbled. Although many persons heard the exchange of remarks during the next critical minutes and agreed on the general content, no two remembered exactly the same words; therefore the official reports[III-2] represent only the best possible reconstruction of the conversation that took place.

One plane, short of fuel, continued on to Louisville. The other three circled and began to climb. At about 2:45 Mantell notified the tower that he was at about 15,000 feet: “I have an object in sight above and ahead of me, and it appears to be moving at about half my speed or approximately 180 miles an hour.” One of his wing men said: “What the hell are we looking for?” When Godman asked Mantell to describe the object, he said: “It appears to be a metallic object, or possibly a reflection of sun from a metallic object, and it is of tremendous size. I’m going to 20,000 feet.”

The other two pilots, who had seen nothing and were alarmed at flying so high without oxygen, leveled off at 15,000 feet. Mantell was then above 22,000 feet and still climbing. In ship-to-ship conversation he said that he would go to 25,000 feet for about ten minutes, then come down. When all further attempts to call Mantell went unanswered, the other pilots discontinued the search and went on to their base; although one returned after refueling and equipping himself with a mask and oxygen, he found nothing in the area.

At about 3:15 Mantell radioed that the object was “directly ahead of me and slightly above, and is now moving at about my speed or better. I am trying to close in for a better look.” He did not call again. Less than an hour later searchers found the crashed plane. Mantell was dead. His shattered watch had stopped at 3:18.

During the period of search, ground observers at Godman Field35 had been able to watch the UFO, gradually diminishing in size, and about 3:50 it disappeared from view. Within a few minutes, however, observers farther south in Kentucky and Tennessee were reporting an unknown object in the sky.

A hundred rumors sprang up immediately after the tragedy: that the UFO was a Russian missile; was a weird machine from outer space that had deliberately or accidentally knocked the plane out of the air when it got too close; that Captain Mantell’s body was riddled with bullets; that the plane had completely disintegrated before striking the ground; that the wreckage was radioactive.

Investigators rushed in to find the cause of the fatal crash and brought confusion with them. Some facts could be quickly established. There were no bullet wounds. The plane had not burned on impact and was not radioactive. The left wing had come off while in the air and landed 100 feet from the main crash area. Parts of the plane were scattered on a line north to south within six tenths of a mile of the central wreckage. The emergency canopy lock was in place and apparently no attempt had been made to release it. The throttle was set at one fourth open, mixture control at “Idle cut-off,” and prop control at “Full increase r.p.m.”

From this evidence investigators concluded that because of lack of oxygen Mantell had lost consciousness at about 25,000 feet, while his plane continued to climb to about 30,000 feet; leveling off, it then began a gradual turn to the left because of engine torque, and went into a spiraling dive that produced a speed and a structural stress greater than the plane could stand—the plane was “red-lined” (Air Force jargon for the limit of safety) at 525 mph. Pilots who have flown the P-51 in combat conditions have agreed with this conclusion and have suggested that, as the plane fell, Mantell may have regained consciousness, realized what was happening, pulled the throttle back and tried to pull back on the control, thus producing a stress so great that the wing was torn off and the plane then fell vertically.

As an immediate result of this tragic accident, Air Force officials recommended that all pilots be briefed again on the use of oxygen and the effects of lack of oxygen. New orders were issued; that no pilot go above 12,000 feet without oxygen under any circumstances;36 that no aircraft be cleared for cross-country flight unless it had been serviced with oxygen; that classes in the use of oxygen start immediately for all pilots and crew members; that all aircraft be equipped with oxygen; and that all pilots carry mask, helmet, goggles, and gloves on all flights.

The cause of the crash was known. But investigators had still to solve the problem: what was the unknown object that Mantell had been chasing?

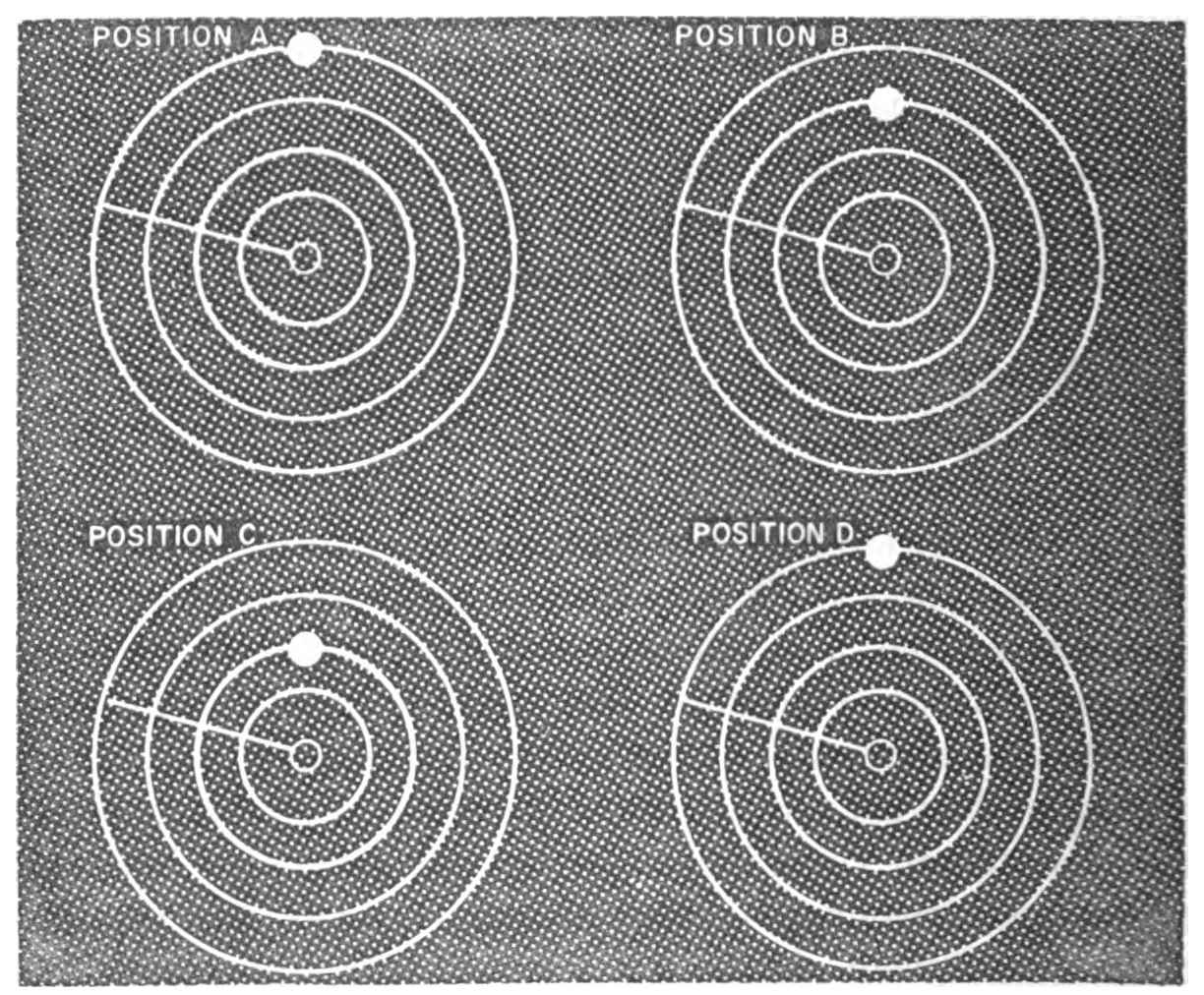

An Air Force official had announced to the press that the unknown had been the planet Venus. This explanation, while not impossible, was not very probable. The position of Venus that afternoon had indeed been very close to that of the unknown object. But with a stellar magnitude of -3.4, less than half its maximum brilliance, in the daylight sky the planet would have been visible, if at all, only as an exceedingly small, bright point of light. Furthermore this answer did not fit the pattern of sightings. The accompanying map (see Figure 5) of the Ohio-Kentucky-Tennessee region illustrates the succession of events:

37

1:15 P.M., Maysville, Kentucky. Strange object sighted moving west.

1:35 P.M., Owensboro and Irvington, Kentucky. Circular object sighted, 250 to 300 feet in diameter, moving west.

Shortly before 1:45 P.M., Godman Air Force Base, Kentucky. Circular or parachute-shaped object sighted; in view for about two hours, slowly moving south.

4:00 P.M., Madisonville, Kentucky. Strange object; through binoculars identified as a balloon.

4:45 P.M., Nashville, Tennessee. Strange object sighted; through binoculars identified as a balloon.

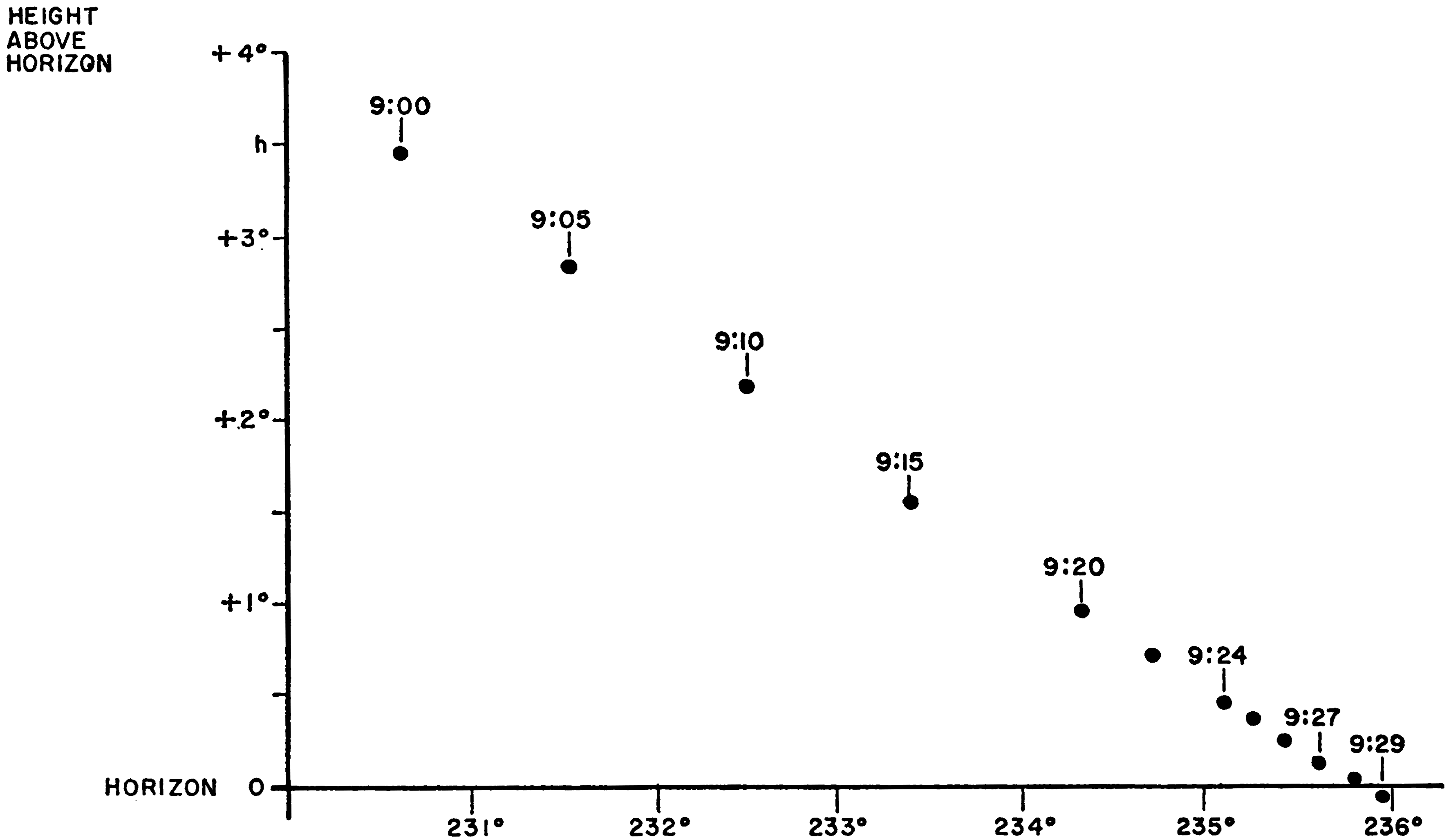

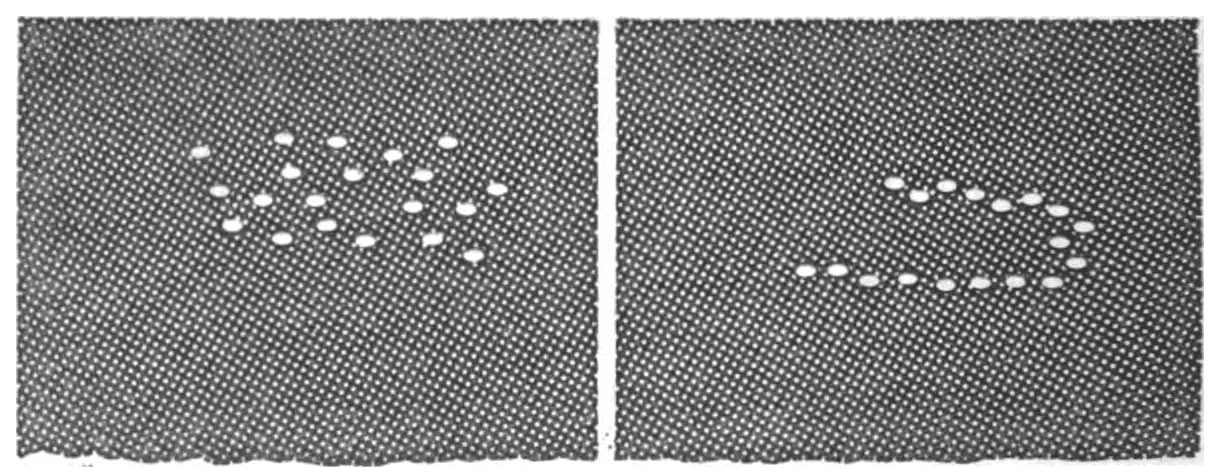

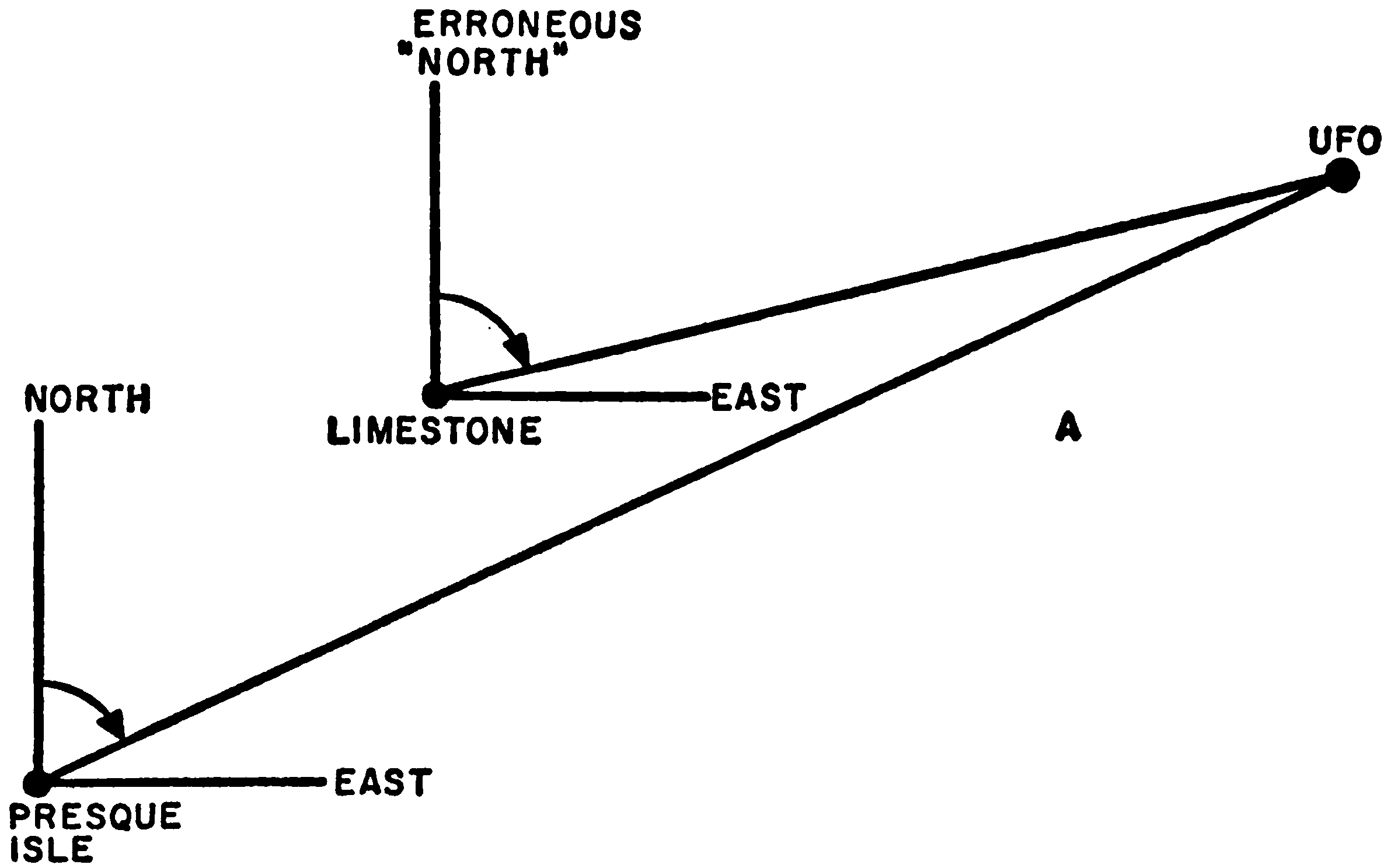

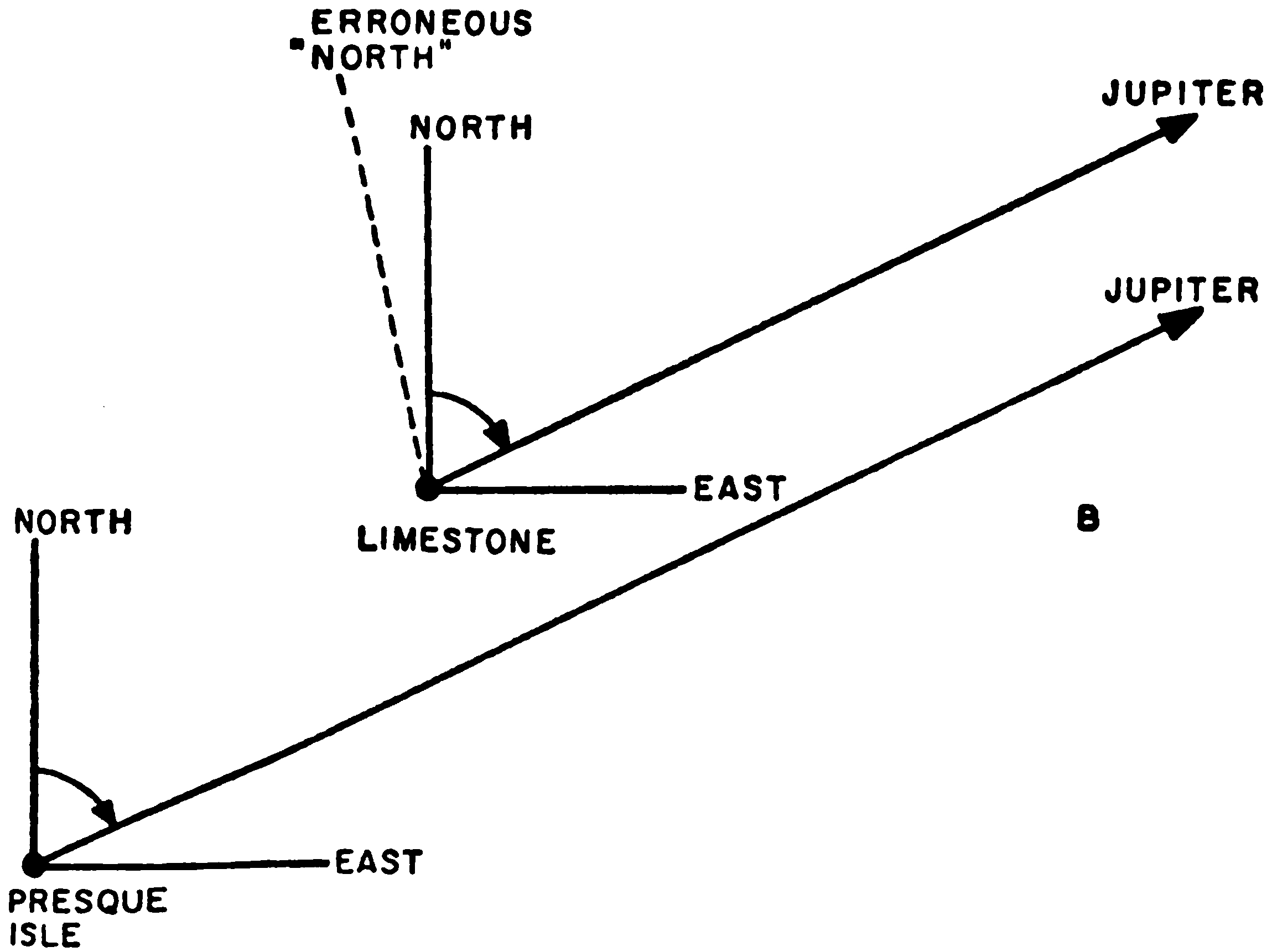

5:00 P.M., Lockbourne Air Force Base, Columbus, Ohio. Round glowing amber object sighted on southwest horizon in horizontal flight; in view about twenty minutes, then disappeared below the horizon.