PENMANSHIP

Teaching and

Supervision

Teaching and

Supervision

BY

LETA SEVERANCE HILES

Supervisor of Penmanship

Long Beach, California

Jesse Ray Miller

3474 UNIVERSITY AVENUE

LOS ANGELES

Copyright 1924, by Jesse Ray Miller

FIRST PRINTING

APRIL, 1924

Printed in the United States of America

Press of Jesse Ray Miller

Los Angeles

| CHAPTER | ||

| I | The Penmanship Problem | 9 |

| The Commercial Factor—The Educational Factor—Educational Value. | ||

| II | Fundamentals Concerned in the Problem | 15 |

| Physical Training Phase—Correct Posture—Correct Movement—Visualization of Letter Forms—Practice—Application of the Correct Habits to Daily Requirements. | ||

| III | The Generally Accepted Solution: Muscular Movement | 43 |

| Conservation of Health a Prime Factor in the Solution—Economy of Time a Result of the Solution. | ||

| IV | Preparation of the Teacher | 51 |

| The Technique of the Subject—The Ability to Secure Results—The Penmanship Perspective. | ||

| V | Suitable Equipment and Materials | 61 |

| Text—Blackboard and the Use of It—Paper—Folders—Pencil—Pen—Penholder—Blotter—Ink—Economy in the Use of Material. | ||

| VI | Some Workable Suggestions | 72 |

| How to Study—How to Move and Slant the Paper—Blackboard Work of the Pupils—Name Cards—Figures—Alphabet—Endurance Tests—Objectives in Good Writing Habits—Progress Lesson—Segregation—Line Quality—Samples—Preparation for the regular Visit of the Supervisor—Counting—Use of the Timepiece—Awards—Use of Standard Penmanship Tests. | ||

| VII | Suggestions for the Grades, Junior and Senior High Schools | 85 |

| A General Not a Specific Plan—First Grade—Second Grade—Third Grade—Fourth Grade—Fifth Grade—Sixth Grade—Seventh Grade—Eighth Grade—Junior High School—Senior High School. | ||

| VIII | Supervision and the Penmanship Supervisor | 113 |

| Supervision in the Past—Function of the Supervisor—Leadership a Prime Qualification—Personality a Necessary Qualification—Broad Preparation Indispensable to the Supervisor—Continual Preparation Essential—Rating—The Best Qualified Supervisor. | ||

| Bibliography | 123 | |

| Index | 126 | |

Reading, writing, and arithmetic have for long been looked upon as the fundamentals in education. And in very truth they are. Altogether too little attention has been given the expression of thought involved in the study of any school subject whether such expression takes the form of oral or written language. In fact, many failures in school and misunderstandings in actual life are due to inability to properly interpret text, read intelligently, or speak correctly.

No small part of this entire problem, especially when applied to grade pupils, is the mechanical or penmanship side. Everywhere there is criticism, on the part of teachers and parents, of the quality of the pupils’ writing. In many instances the process is a slow and laborious one. The bodily positions assumed by pupils during the operation of writing are harmful. The effort frequently results in an illegible scrawl. Too often, little or no attention is given penmanship in the grades and consequently boys and girls go through life laboring under a serious handicap.

In the following pages an attempt is made to bring definitely and concisely before educators[8] the fundamental facts necessary to secure legibility and rapidity in penmanship, without causing strain of eye or cramp of hand. The treatment of the subject is simple and direct. The discussion of the problem of penmanship is followed by a consideration of the essentials necessary to the establishment of a habit that shall result in good penmanship. The materials necessary are taken up in detail. The teacher’s preparation is dwelt upon. Workable suggestions are given a place. One chapter deals with the minimum requirements for all and the closing chapter discusses supervision.

The entire work is based upon an extended experience with pupils and teachers. Every suggestion and direction has been worked out in actual practice. The volume has been prepared in response to continued requests from teachers, principals, and superintendents who desire explicit directions that can be used to supplement any system of muscular movement penmanship.

The author wishes to express her gratitude to the hundreds of teachers, scattered throughout several states in the Union, to whom she has had the privilege of offering instruction and from whom helpful suggestions have come.

L. S. H.

[9]

We are living in a practical age. Every institution of worth points to the truth of this statement. Of every plan advanced the query comes, “Will it stand a practical test?” We are constantly experimenting with, and adopting, new methods, and those in force today may be displaced tomorrow as being behind the spirit of the time. It is only natural that the commercialization of penmanship should take place.

When a business man is asked what qualification counts most in employing clerks he is very apt to say, “Other things being equal, the good writer gets the place.” Henry Clews, the Wall Street banker, frankly states that the beginning of his successful career may be traced to good penmanship.

A letter of application for a position is not judged by school room standards, but by business standards. These two sets of standards should[10] be in harmony. An educator of authority finds that “there is little contention as to the function the child is to serve when he becomes part of the world in which he shall eventually find himself. Our methods as practiced however, would hardly be recognized as having any foundation in the thought for future citizenship.” Think of the vast army of boys and girls who leave the elementary school at an early age to earn a livelihood. These should be given the best practical equipment.

To be sure, there are those who cite instances of great men whose handwriting is almost unreadable, and argue that point in favor of allowing all public school pupils to be poor writers. Common sense teaches us that it is unwise to burden ourselves with an unnecessary handicap.

Others will say that it is not worth while, as every one will use a typewriter upon entering the commercial world. Only a certain proportion will enter the world of commerce, and a majority of those who do enter tell us that they have as much work to do with pen or pencil as on the typewriter.

The initial drafts of the majority of all important documents are usually written with the pen. We have the word of many an author that an attempt[11] to dictate the first draft results disastrously to the content of the manuscript. We therefore infer that in matters of importance the use of the mechanical device is not conducive to the best composition. The typewriter is of great convenience after the first draft has been revised.

Again, would it not be vastly worth while, even for school purposes alone, to learn rapid, easy and legible hand-writing, since a majority of pupils spend nine years in the elementary and junior high schools? A good percentage finish high school and many pursue a college career for four years. What an asset good easy writing is in school and college! Every pupil owes it as a duty to himself and to his instructors to express himself legibly on paper.

Finally, while its worth cannot be fully estimated, good writing is eagerly sought and its possessor finds it ever a ready servant and valued friend. We should strive for usable knowledge. In McMurray’s How To Study we learn that “It is a part of one’s work as a student, therefore, to plan to turn one’s knowledge to some account; to plan not alone to sell it for money, but to use it in various ways in daily life.”

[12]

Perhaps the most widely recognized educational value of good penmanship would come under the head of utility. Pleasing angles, graceful curves, uniformity, and clear strong lines appeal alike to all. From the attitude taken by many educational folk, relegating this subject in the curriculum to the background, we might think that they prefer illegible writing. Yet frequently these are the very persons who are heard to complain the loudest and longest over poorly written test papers and unreadable letters from friends.

Muscular movement penmanship may be utilized to advantage in school and out. In the first place it saves the pupils’ time and physical energy in execution and the teachers’ time and energy in interpreting. In the second place it is most emphatically demanded by the world that many of these pupils will enter upon leaving school. Parents draw their conclusions, many times, regarding the quality of work in the school largely from the appearance of written work.

Pupils who have persistently followed the drill until it has influenced their actual writing will soon realize their power: here is the evidence on paper, the measure of the effort put forth. They[13] have conquered both mentally and physically. Will not the confidence established in their own ability be of value to them in mastering other subjects? What gives more pleasure, self-respect and encouragement to persevere than the conscious knowledge of skill? This consciousness of power and skill is a tremendous educational force and one that should receive constant recognition with reference to penmanship.

Many are the pupils who have great difficulty in gaining book lore, but who find the manual arts attractive. To such the consciousness that they can do even one thing well is a powerful inducement toward the mastery of something less attractive.

Pupils learn before they finish the elementary school that proper conventions must be observed in order to preserve social order and relations. When these conventions are overlooked to a great extent in writing, pupils are not gaining the most that the subject has to teach them. When irregularities become noticeable a check should be placed; otherwise the habit will become strong enough to be of great hindrance in later life. In no subject can a tendency to tear down conventions be discovered more easily than in penmanship and nowhere can we better impress upon pupils[14] the desirability of obeying, to a reasonable degree, the conventional lines which all social beings are bound to recognize.

Who cannot recall at least one “bad boy” who has been completely reformed by some one of the manual arts? Muscular movement penmanship has many such to its credit. Teachers and supervisors are called upon quite as much to reform as to form and inform.

[15]

Pupils who are apt at athletics will easily recognize the purpose of muscular movement penmanship. They will draw upon former experiences in the field or gymnasium and compare the value of relaxation, good posture, rhythm, and continuity of movement. They will recognize that the same laws of control govern Indian club swinging, field sports, and penmanship. They will appreciate the fact that to obtain good results with the pen they must follow with military precision the directions of the leader. Interest will be doubled when pupils really find themselves. Many pupils obey the laws of correlation naturally, and through their athletics they gain control of the muscular adjustment that operates in the process of writing.

Adult learners of muscular movement frequently have more difficulty in relaxing completely[16] than do younger pupils. Often with adults the habit of bodily relaxation has not been developed along with other habits, and therefore muscular tension prevails. A leading criticism on Americans is that we never relax.

James says: “It is your relaxed and easy worker who is in no hurry and quite thoughtless most of the while of consequences who is your efficient worker; and tension and anxiety, present and future, all mixed up together in our mind at once, are the surest drags upon steady progress.”

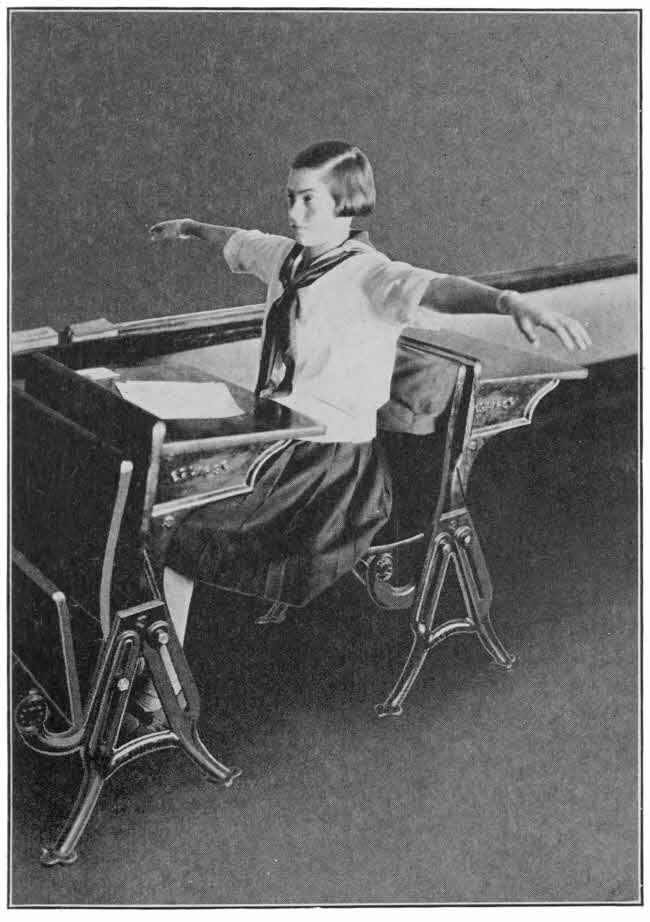

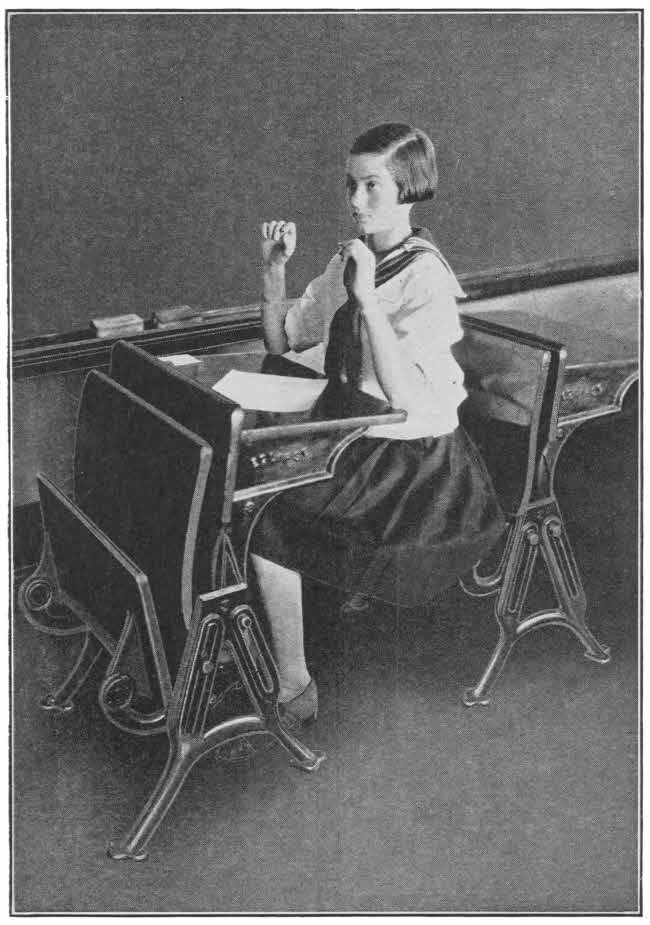

At Attention

Relaxation

Ready to Assume Correct Position of Arms, Hands, Pen and Paper

The mind must be concentrated upon the relaxation of the muscles in order to get the best results. As writing is feeling passed through thought and fixed in form, it is very important in writing that the mind help make the muscles to make movements, just as it helps them to relax. By putting the muscles in a workable condition at the beginning of each lesson, great improvement in muscular response will be observed. Muscular relaxation must be considered seriously if we would make real progress in muscular training. We all know how cramped and tremulous the letters are when they are written by a hand that is under nervous tension. The nerves must be at ease, the pen must rest lightly in the hand in order to obtain the best results. Teachers[17] who have not the ability to relax themselves, cannot hope to lead the class to do so. The tone of voice used in giving directions, whether musical or strident, has to do with inducing relaxation. The following plan has proven of value in the class room:

1. Pupils sit erect in seats, stretch arms out even with the shoulders, feet on the floor, heads erect, while the teacher counts softly to ten, with the pupils; at ten, drop the arms to the sides. Repeat six times. A practiced eye will soon see whose arms are tense. Ask pupils to become as limber as they would in skating, jumping, dancing, horseback riding or swimming.

2. Pupils sit erect in seats, bend forward from the hips, raise arms over the desk, and six inches from the desk, make a square turn at the elbow, count ten slowly, drop the arms on the desk; repeat six times.

3. Pupils sit erect, bend from the hips, both elbows on the lower corners of the desk, relax, dropping the forearm on the desk; repeat six times.

4. Retaining position in paragraph 3 let pupils roll the muscle below the elbow in a circular manner to a soft musical count, from one to ten. Eyes should be first directed toward the arm, then[18] away from it, toward the ceiling. By following the last suggestion, it is observed that pupils relax unconsciously. All of this drill will be of no value unless pupils are able to retain a relaxed condition of the muscles while the writing instrument is in use. Let them take the handle end of the pen, and prepare for this circular motion before making it.

5. It will be necessary for the teacher to spend a few minutes at the beginning of every lesson with one or more relaxing exercises during the first months of each school year, and later if found necessary. It is advisable to break the lesson with relaxation exercises if it is observed that pupils are becoming keyed-up through effort.

6. Rhythm and regularity of movement are essential. Pupils’ counting aloud relieves the tension. It may be necessary to lay the pens down once or twice, for a few seconds each time, during the lesson. Ability to control the writing arm comes in proportion to our ability to relax the controlling muscles. Control in the matter of penmanship is a vital educational factor. Says a well known authority: “Could the school teach effectively the lesson of self control, we need have little fear of the results when the product of the system is thrown upon the currents of the world.[19] What is the most important attribute of man as a moral being? May we not answer, the faculty of self control? This it is which forms a chief distinction between the human being and the brute.”

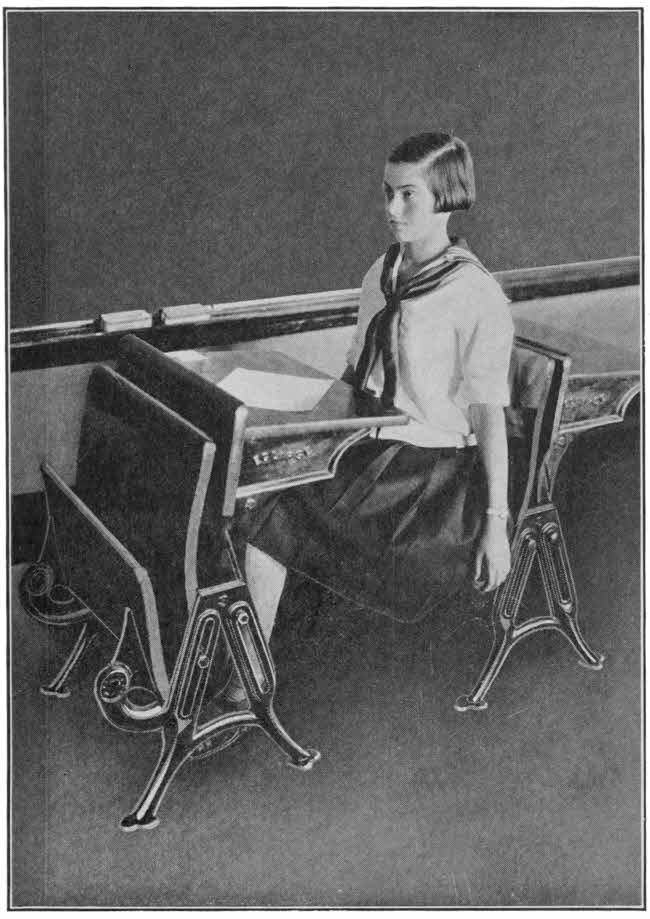

Correct posture while writing is an essential; first, from the standpoint of health, and again, that we may have free play of the writing muscles. Proper seating has an important place here. The desk should be sufficiently high from the seat, so that, when a pupil is seated and with both arms on the desk, the shoulders should not be raised. If the desk is too low, pupils will bend in the shoulders instead of from the hips and the chest will be compressed and the spine contorted.

No doubt many cases of spinal trouble are a direct result of improper seating and unhealthful posture during school hours. Pupils frequently bend the neck and strain the nerves and muscles uselessly. The hint, “Heads up” is often a sufficient reminder and will serve to correct this ungraceful and harmful habit. By sitting almost square in front of the desk, circulation is not impeded in any way and relaxation will result more[20] easily. The body supports itself, and must not touch the desk. The eyes should be fourteen inches from the paper. In order to be comfortable, the feet must touch the floor. It is within the province of the manual training department to provide wooden footstools of simple construction for the small pupils who must sit at large desks.

With the feet on the floor, body erect, ready to bend from the hips, chest high, arms hanging at the sides in a relaxed manner, we are ready for the next step. By placing the elbows at, or near the lower corner of the desk, raising forearms, then relaxing and dropping to the desk, the pupils are impressed with the idea that they must keep the cushionlike muscle on the desk. The elbows may extend beyond the edge of the desk, perhaps an inch, if this adds to the comfort of the writer. There should be a right angle turn at the elbow.

Drill on correct posture should be given frequently until acquired, several times during a lesson, in fact, while learning. Too many liberties with these rules will cause trouble later when the next step is to be accomplished.

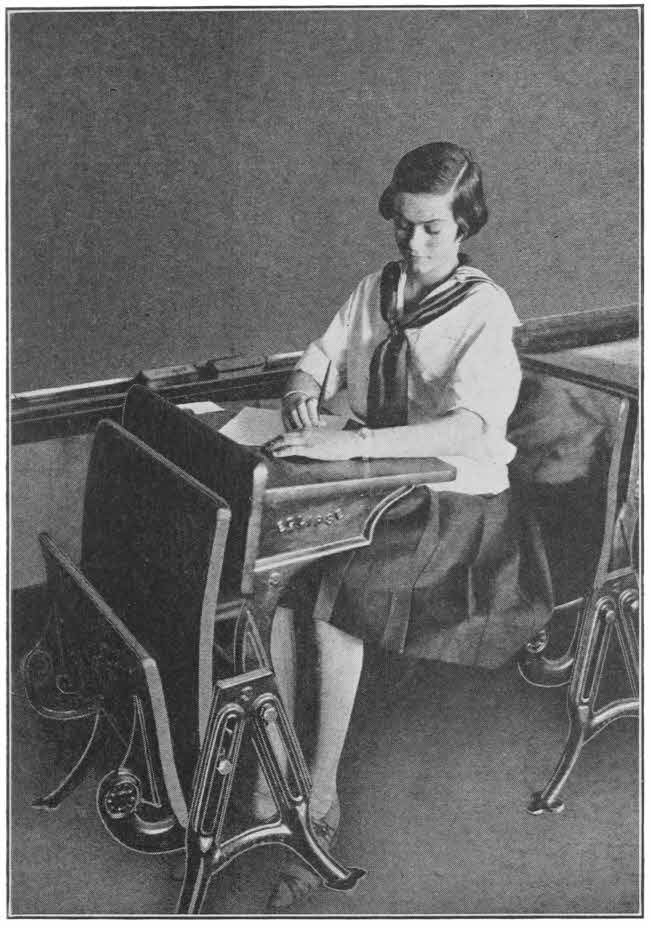

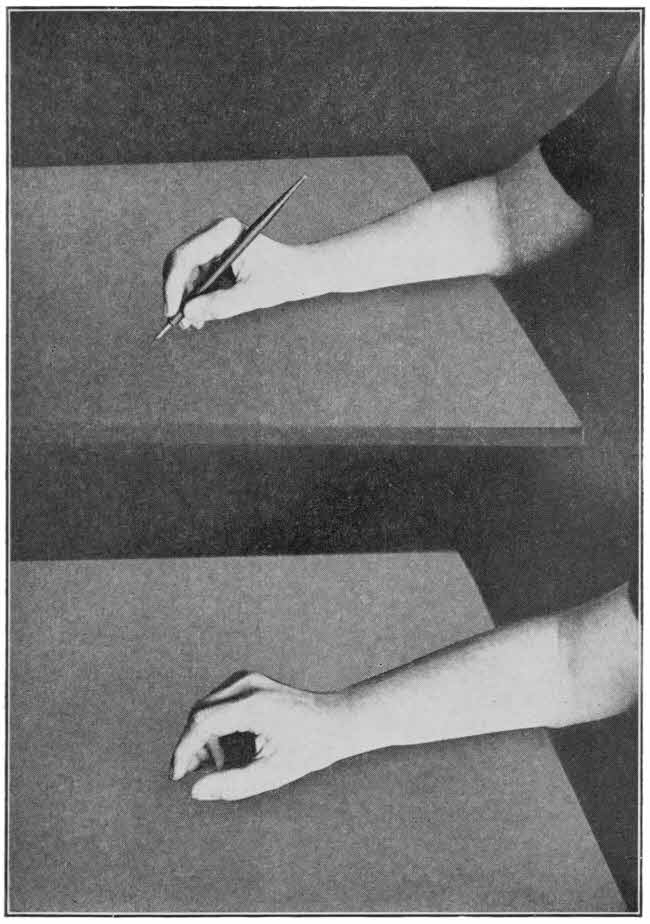

Ready for Work

With the forearms on the desk, close the right hand; open and close several times; with the right hand half open, the tips and nails of the[21] third and little fingers touch the desk. The knuckles of the thumb and three fingers should be in sight. Every joint is bent a trifle in correct position of the hand. The two points of contact then are a large portion of the under forearm and the tops and nails of the third and little fingers. The wrist should be kept straight and free from the paper. The side of the hand must not touch the paper. Slip a card under the side of the hand to test this point. The muscles that hold the third and little finger in correct positions need to be strengthened. Pupils are apt to straighten the fingers and bring about a tension or go to the other extreme and curl the third and little fingers into the palm of the hand and glide on the knuckle joints. Both positions strain the ligaments and bear away from, instead of toward, good control. It is most important that a beginner should watch the position of the hand. Other mistakes may be rectified gradually, but correct position of the hand must be established at once.

The penholder is held by the thumb and first and second finger, touching the second finger near the root of the nail. The first finger joints are bent slightly. The first finger rests on the penholder at least an inch from the point of the pen. The thumb joint is also bent. The penholder may[22] cross above or below the knuckle joint of the first finger. The penholder should point half way between the shoulder and the elbow. Keep the penpoint on the paper squarely, wearing both nibs equally.

Ready for Action

Ready for Penholding

In Comprehensive Physical Culture, we find this valuable suggestion: “In sitting it is necessary to hold the chest up; to guard against bending forward at the waist line, for this contracts the chest, cramps the lungs and stomach, and often produces dyspepsia. In sitting, if one wishes to bend, the movement should be from the hips, but never from the waist; the knees should never be crossed, for this position, besides being inelegant and ungraceful, often leads to paralysis by diverting the blood from the leg through pressure. The one rule to be observed by the woman who seeks to be healthy and graceful is to keep the chest active; it should never be relaxed; holding this part of the body constantly erect gives real poise to the carriage and strength to the muscles. A fine bearing is of great advantage, for it has a significance which people intuitively recognize and respect; the person who comes before us chest raised and head erect inspires confidence. Other things being equal, the person who elevates the chest constantly is more self-respecting than the one who habitually depresses it.”

[23]

Pupils must be taught that a line is the product of the motion used; “that the motion preceding the contact of the pen to the paper must be in the direction of the line to be made, and that some letters being more complex than others, less speed should be used.” For example, the straight stroke exercise is essential as a beginning step in movement application because it not only stretches the muscles, but correctly done it teaches direction. Movement that prepares for the straight stroke exercise is best obtained by taking correct position and pushing the first finger to and from the center of the chest with the third and fourth finger nails gliding on the desk and forming a movable rest. The wrist must be kept free at this time, and the forearm moves on the cushionlike muscle below the elbow. We base the direction or slant of down strokes in letters later upon this straight stroke exercise. If the ovals, the next exercise in order, take an incorrect slant at any time, return to the practice of the straight strokes as a corrective means toward the proper slant.

Pupils must know that the direction of movement is one of the chief essentials, and that before[24] they can possess ability to produce properly proportioned forms they must develop their movement in the proper direction. They must be led to understand that the mere free and easy action of the arm in any direction is not necessarily a movement that can be used in writing.

To insure against too slow a movement it will be necessary to use some measure for time. Counting is a good means of regulating the movement; it keeps the class working enthusiastically together, and gives an idea of how fast to practice. One count should be given for each down stroke. The count, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 20; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 30, etc., to one hundred is advised for straight strokes and ovals. All pupils counting in concert with the teacher at the rate of about two hundred down strokes per minute is effective, as the oral count relieves the muscular tension that is apt to prevail at this time. Insist that every arm move from the shoulder and that each pupil feel correct movement and observe his own arm. It is advisable to use the watch, and time pupils daily on a part of all drill work. If the count be too rapid, nervous spasmodic movements will result; if too slow, the fingers or wrist joint will be apt to act, and finger movement will be the result. A[25] steady rhythmic beat is essential, to tone down the speed of the nervous and erratic and inspire the slow ones into more rapid response.

There is a subtle influence in the sprightly musical count as well as in the conversational count, such as “round, round, round,” or “light, light, light,” to induce proper width to a narrow oval, or lightness to a heavy line. A mistake that is fatal to early progress is frequently made by allowing pupils to take the pen in hand to write before automatic movement is gained. Much drill on relaxation and study of the writing machine and attention to rhythm work at the correct speed is necessary at the beginning of each lesson, to make for automatism. Sufficient speed to discourage finger and induce muscular movement must be insisted upon at all times.

At this point it will be observed that pupils vary in regard to their ability in the use of free movement. The group plan meets this difficulty very successfully. Some allowance must be made for new pupils, those habitually irregular, and for the slow pupils in rooms where children have not been segregated for ability.

When all is done that can be done by the class plan to make pupils understand relaxation, posture, and motive power, we find that there will[26] still be some who have not made sufficient progress to advance. The important question is, when are these pupils going to have an opportunity to learn? How can encouragement be offered to those who have done well, and at the same time continue repetition of what is necessary with those who have accomplished but little?

The group plan is advised by many successful teachers. Assign pupils who have done well and who can practice in the right way to seats at the left of the room (“A” group) as the teacher faces the class, it being understood that those who prove themselves unworthy of being in the “A” group will have a place in the “B” group. After the segregation is complete and the plan under way it will be well to keep a check on the “A” group; some pupils forget quickly when left to themselves, while it develops independence and pride in others. The “B” group will occupy the rows to the right of the teacher as she faces the pupils, and by stepping to the extreme right side for the survey every hand may be seen while at work. The members of the “B” group understand that they are there because they need special help, and will be promoted as soon as they learn the lessons already mastered by the “A” group. At the beginning of every lesson a careful[27] but brief review will be necessary of the points that the “B” group is expected to learn. The entire class should give attention at this time.

The “B” group is still preparing with the handle end of the pen while the “A” group will be actually making lines. Economy of time should be studied, or the period will be wasted; both groups must be kept busy all the time. The same count will answer for both divisions. Occasionally it will be well to give the “A” group a certain amount of work to accomplish and to note if it is done within the right time limit. They are to compare carefully with their models and also to work for improvement in the product without special instruction. The “B” group will not make so many exercises but their posture and movement will be growing stronger every lesson. In order that they may not become discouraged, it is well to let them make some of the exercises each day but the greater part of the time should be given over to rapid changes of relaxation, posture and movement until these essentials are thoroughly ingrained. The “B” group will be greatly helped by working at the board, to the same count that the “A” group uses at the seats. Once during the lesson allow the “B” group to rest and watch the “A” group work. The pupils[28] in the “B” group will not cover as much subject matter as will the “A” since it is composed of the new pupils and those who have the greatest difficulties. No pupil should be promoted to the “A” group until he assumes correct posture in all written work and can make ovals, straight strokes and short words with correct movement. He must prove his ability as an independent worker and show reasonably good results in order to be considered an “A” pupil.

It has been said, “The three arts of education are seeing, reading, thinking. The boy who learns to see is awakened; the boy who learns to read is enriched; the boy who learns to think is emancipated.” Why does not an artist always make a desirable and pleasing picture? Perhaps it is because he does not see the subject correctly or to advantage, or perhaps he has not mastered all the mechanical difficulties. It is for the teacher to decide whether all has been done that can be done to assist the pupils to see the model letter form correctly. Perhaps there exist mechanical difficulties in posture and movement that prevent a free execution of the letter form that may exist in the mind.

[29]

Pupils should understand that they are to educate the head and hand together. Concentration on correct forms goes hand in hand with practice. Some pupils have greater aptitude than others toward perception of form; it is certain that the hand will not learn to reproduce constantly a form that has not been fully and entirely idealized by the mind. It has been discovered that human beings vary greatly in the completeness, definiteness, and extent of their visual images. Pupils should be impressed through as many sense channels as possible. Some learn through explanations, others through demonstrations at the board, still others by working at the board themselves. Out of this variety of impressions each pupil will find the one that is most lasting for himself. Every penmanship teacher should recognize this principle of multiple impression.

Mental pictures are what we mean when we speak of “noticing” things. We think we are noticing all sorts of things during our waking hours; as a matter of fact, we recognize fewer things than we suppose. Ask a pupil to describe any familiar object and prove this statement. If you point out the various characteristics he will quickly see them, and will be likely in future trials to see them; but if left to himself he would[30] need a great deal of time to become familiar with the main features. Frequent review of model letter forms is necessary, for it keeps our minds fresh and helps to reveal new and hitherto unthought-of aspects. Each view well considered, then put aside, freshens us for the next one. We are thus led to make trials and discover relations which otherwise would remain hidden. Many pupils, for the most part unsuccessful, never get so far as that. Many who fail believe that they have seen all there is to see, take up something else, or do nothing.

Pupils may be led to observe the forms of letters and their common characteristics through variations of common principles. To illustrate: many letters are modifications of the oval exercise, near or remote. In almost every writing system on the market we have four, the O, A, C, and E. Modifications of the straight stroke are more numerous still; then we have letters that show a combination and modification of the two exercises. Pupils should be able to see and describe just which stroke gives slant and character to the letter. There is a striking analogy in the beginning, ending, and width of many of our letters.

Very rarely is the image the exact reproduction of the percept; it differs in distinctness, outline,[31] detail, and sometimes even in most important qualities. Look at the model letter, close the eyes, you will still see the form. Retentive and reproductive powers are at work, while the image is in process of formation. Form perception, and other mental pictures than what we are striving for, are present and act upon and modify present percepts.

Let the room be quiet, so quiet that there is nothing to distract. Require the pupils to lay their heads on the desks, shut their eyes, and rest, not for long, for fear of day dreams. Without allowing them to awake from their playsleep, picture in brief vivid statements, without repetition, or unnecessary detail, the parts of a letter. Raise the heads, open the eyes, take pens and ask pupils to reproduce a picture of the letter just described.

In effective visualization certain conditions must be fulfilled. In the first place the exposure must have lasted for a sufficient length of time, very much as is required in photography. We can gain no mental picture of things where the exposure is too brief.

A careful study of letter forms must engender the habit of observation and knowledge of the difference between accuracy and vagueness. Since penmanship is one of the manual arts it will[32] be executed definitely right or definitely wrong. Chamberlain on the value of manual training says: “The more accurate the work in hand, the less likely is doubt and uncertainty to play a part. In grammar and history a mistake upon the pupil’s part may easily pass unchallenged. The student glides over an error unconsciously or without intent; and even the teacher may not detect the fault. In a word both the teacher and pupil are likely to be deceived. In the shop or in the cooking room it is quite different. Be the box too short, the metal too thick or too thin, the joint too loose, the basket askew, the stitches uneven, or the ingredients improper in proportion, little doubt need enter the pupil’s mind as to the rightness of his work.”

A few years ago Dr. Gulick laid down the following hints on training for the boys in their athletic work in New York City:

1. Always warm up slowly and cool off gradually when finished.

2. Stop practice when you are exhausted.

3. Dress lightly for practice or competition.

4. Practice regularly, a little each day if possible.

[33]

5. Have regular hours for eating and sleeping.

6. Don’t smoke.

To a person who has the correct perspective on the penmanship habit the application of the hints enumerated will seem quite reasonable. To train in any line, one must practice. Repetition is necessary, and the time element essential, as it takes many efforts to accomplish the desired end, good penmanship. The muscles to be trained are large, and the conventional forms are small.

With a little forethought and planning the practice period may be varied, live and interesting. Everyone must learn, sooner or later, that much discipline may be gained by keeping steadily at work not interesting in itself. James says: “We have of late been learning much of the philosophy of tenderness in education; ‘interest’ must be assiduously awakened in everything, difficulties must be smoothed away. Soft pedagogics have taken the place of the old steep and rocky paths to learning. But from this lukewarm air the bracing oxygen of effort is left out. It is nonsense to suppose that every step in education can be interesting.”

Thoughtless practice might much better be left undone. There is no use in trying to excuse careless work to oneself with the thought, “I won’t[34] count this time.” Each careless stroke is being registered though we do not count it; for nothing we ever do, strictly speaking, is ever wholly blotted out. Paths frequently and recently trodden are those that lie most open, and those which may be expected most easily to lead to results.

The first practice may be difficult, for the nervous and muscular systems have a new lesson to learn. The second and third trials will be easier, for the body has begun to recognize what lies before it. The following attempts will steadily become easier. A path means economy in traveling. The muscle should work with a fatalistic steadiness; if so, the result must necessarily be work done in a clean and finished manner.

Ready for Drill

To be concrete, let us presuppose a thirty minute practice period in muscular movement penmanship, under fairly favorable conditions. The desk should be adjusted for physical comfort. The light should come from the left side. Loose sheets of good quality paper eight by ten and one-half inches in size, with three-eighths inch spacing should be furnished. At least two sheets should be placed under the one being used, that the penpoint may be saved extra wear. A fluid ink that flows freely is best. A coarse, flexible pen, blotter, and ink-wiper complete the list of supplies. It[35] is assumed that the adopted manual containing instructions and model letter forms is always on the desk for reference during the practice period.

Our first aim should be to get the mind and muscle into action. To this end at least two hundred two-space straight strokes or the same number of ovals should be made in one minute. Secondly, this will assist in the form building of the letter to be mastered, which let us assume is the capital O. A light smooth line will be obtained by limiting the amount of ink. Make at least two hundred strokes with one dip of ink. Correct speed will be best obtained by requiring the time limit in all drill work. Correct slant should develop as a result of the correct teaching of the straight stroke exercise.

Having done this preliminary drill we are now ready to consider the second point of the lesson, namely, the making of the letter O. The first consideration is the general form. By comparison with the model we find a striking analogy in width and slant, to the form of the oval. The ending stroke and the points that characterize the letter must be observed, and lastly, the size is to be noted. Close the eyes a moment and see if the image is fixed. Prepare to write by using the handle end of the penholder until the right[36] rhythm has been established by counting one, two, for the first O; three, four, for the second O; five, six, for the third O; seven, eight, for the fourth O; nine, ten, for the fifth letter of the group. Five “make believe” letters is the result of this count; we can easily make three groups of five each, across the page. Time consumed will be one minute for sixty to seventy-five letters. When the muscular adjustment is perfected through this preparatory motion, then, and then, only, are the pupils ready to write. Write and compare with the model, time and again. If the letter has been visualized correctly, each child will be able to criticize his own work effectively. Glaring errors should be pointed out first and remedied. Work on this letter might occupy the main portion of the writing lesson for many days before passing to another letter form.

Any class that has been drilled correctly on the ovals, straight strokes and capital O should be able to apply the movement acquired to a short word and this perhaps forms the most important part of the lesson. For example take “Omen,” spelling the letters aloud, capital O-m-e-n. Words so dictated should be executed by junior high school pupils and adults at the rate of at least fifteen to eighteen per minute. This will prevent[37] any possibility of a return to finger movement at this time. Dictation of letters is quite effective with slow pupils. The application of movement to a word, at the close of each lesson, will lead the pupils quite unconsciously into a better movement of all written work. Here they get the help along the lines necessary to steady and modify the movement, and a chance to get into the swing of actual writing without too much thought as regards the content. Such drill serves the same purpose in penmanship that scale practice does in music. The writing of words at the close of each lesson serves as the connecting link between the theoretical drill work and practical writing. Such daily drill work as just suggested at the close of the writing lesson will effectually eliminate the sharp line of demarcation between the drills and “real writing.” In a short time a list of words will be the result, and these with others may be combined into sentences. The supplementary words given should incorporate all the small letters of the alphabet; the one-space letters first, thirteen in all, then the loops above the line, b, f, h, k, and l; loops below the line, g, j, y, and z; and lastly, those irregular in height, p, t, q, and d. A fair allotment of time for the above suggestive plan would be five to ten minutes on[38] ovals and strokes; ten to fifteen minutes on the letter O; and five to ten minutes on the word-practice.

The group plan seems to be the only logical method of reaching all pupils with the instruction necessary to their peculiar needs. The advanced group will be learning to act independently, while the other will be learning basic principles. Friendly criticism and rivalry should be fostered, by comparing the method by which results were obtained. Let one group watch the other work. Let the group watching count for the other and change about. Generally, the entire class work, if any, should be posted, unless it be known that a certain page is posted because of its special merit. Pupils should be taught at the outset that team work in a drill subject is what counts and should take proper pride in good work as a class. Every class will produce a few good writers. In many schools a new lesson is not taken up before seventy-five per cent of the pupils have accomplished the preceding lesson well according to standards previously agreed upon. It is often impossible for all members of a class to attain perfection in penmanship. We do not demand that in other subjects.

[39]

The muscular movement writing habit should become automatic when pupils have developed enough skill through exercises to apply the movement consistently to all written work. The best skilled teachers might give a lesson daily in any grade, but unless the principles inculcated during that lesson are followed conscientiously during the remaining periods of the day the gain will be slight. If time is allotted for practice the result is surely worth applying to all written exercises. The Committee of Fifteen appointed to investigate the coordination of studies in primary and grammar grades propounded the question, “Has penmanship distinct pedagogical value?” The following is one of the best answers: “Penmanship as an art is but pen drawing, as a factor in education it should be taught more frequently in connection with other studies. Both penmanship and drawing suffer much from their isolated position in the school course. We therefore need to teach writing while teaching other subjects and the reverse.”

In grounding the movement application habit we may well follow these maxims:

[40]

First, focalize the attention of the pupils on the habit to be acquired. Teach definitely relaxation, posture, movement, and visualization.

Maxim number two tells us to suffer no exception to occur until the new habit is firmly rooted in our lives.

Number three calls for frequent repetition. We must therefore give daily drill on the points that go to make up the correct writing habit.

Fourthly, “Don’t preach too much.” Lie in wait for the practical opportunities, and get the pupils at once both to think and to act. Such opportunities are never lacking, since so many lessons are conducted through the medium of the pen.

Lastly, keep the faculty of personal effort alive by a little gratuitous exercise every day. After a high degree of perfection has been reached it is maintained only by the follow-up system of daily effort directed toward the retention of the habit.

The habit of movement application demands vigorous and continued effort; the exertion may possibly be so great that the pupil is temporarily more discommoded than by his former habit. If the wise course is pursued the old disability will vanish, a new path will be made in the brain, and application of movement will be established.

[41]

The main problem with every teacher is how to assist pupils in linking up the principles that have been mastered, namely, correct posture, and movement applied to drills and short words with the practical writing. The drill on short words will prove as valuable as any other part of this theory work. By the laws of association, pupils will connect the muscular sensation of the short, rapidly written word, with what is required when a variety of longer words or sentences is dictated.

At the beginning of every lesson in which writing is used as a vehicle for thought, attention to the correct habit will be the means of setting many pupils right, and of increasing from week to week the number of those who do all writing with muscular movement. Finally, all incorrect movement will be eliminated, and we may then return to visualization. A proper balance must be preserved in regard to seeing and doing, or our results will be one sided. When a pupil “finds” himself with reference to the application of movement problem, attention may be almost equally divided between retention of that movement and form building. By the time form is established movement will be second nature, and with a little continuous practice will never be lost.

[42]

It is time to require all written work to be done with muscular movement when pupils can make good two-space ovals, four hundred across an eight inch page, and straight strokes in the same manner; have visualized one capital letter and can make it at the right speed per minute, for example, sixty to eighty O’s per minute; and can write short words such as “men” and “mine” with correct movement, in correct posture, and within the correct space limit. An easy way to begin is to require application to the subjects where the mind is least concerned as to the content, for example, the spelling lesson.

If pupils have been taught to turn the searchlight of investigation on their own habits they will be entirely conscious of the feeling of mastery that takes possession when muscular movement becomes automatic.

Those who have not thus succeeded should look well into the basic principles of relaxation, correct posture, and movement, especially as applied to letters and short words. Study the hand and arm in its preparatory motion while working at the correct speed. Care should be exercised that there be no movements of the joints of the wrist, thumb or fingers. Alternate the preparatory motion with writing until the sensation of mastery prevails.

[43]

Truly, necessity is the mother of invention. At the dawn of the present commercial age, the finger movement and even the slightly improved combined movement were forced to give way to some method more rapidly executed. Whole arm movement also proved inadequate. The method that has made the commercialization of penmanship possible is that of muscular movement. By this method only are the fingers relieved from furnishing the power which should rightly come from the large muscles of the arm. Muscular movement, as applied to writing, is a rotary motion with the large muscles of the forearm for a center while the fingers, though not held rigid, are not permitted any movement of their own. This movement takes place from the shoulder, the pivotal point, with the weight of[44] the arm resting on the desk. Muscular movement method does not emphasize prescribed forms so much as proper method of execution.

It is no special wonder that the leading educators of the day are now investigating penmanship. Changing from the slant to vertical, and now again to the slant, what is the average teacher to conclude? What shall she teach indeed if she is convinced at all regarding any system of penmanship, or is qualified to teach any method?

The person who makes practical use of penmanship, the one who uses it to help him earn his daily bread, points the way. It matters not if he calls it muscular movement or if he ever saw a penmanship teacher. Watch such a person and observe his method. Observation will reveal that practically all use what we term a muscular movement slant method. It takes the practical person only a short time to discover the method that will best conserve energy, economize time, and, above all, lead to writing which will prove readable and attractive. It is a method of such character as fulfills all necessary requirements and thus proves the useful tool.

Because we are a practical people, the public is now looking forward to results from the formal writing lesson. Teachers should expect the same[45] degree of excellence to come from penmanship instruction as from correct teaching of mathematics, history, reading, or any other subject in the curriculum.

It has been remarked many times that commercial schools and business men have put the stamp of approval upon the muscular-movement-slant method rather than upon any other. The reason is obvious. In fact, commercial schools have been the missing link between the oft-times theoretical public school and the actual business world. Commercial schools have found it possible during their short course of six or eight months to give our elementary school pupils an asset that the public schools have failed to bestow in as many years.

With the present day crowded curriculum it has been found necessary to adopt some method by which the time consumed in the preparation of the written lessons might be shortened. Again muscular movement slant method came to the rescue, this time to the elementary school pupils.

There is a certain amount of energy available in the nervous system. Discreet use of this energy is a lesson dearly bought by many. The automatic writing habit conserves energy and prevents diffusion of effort. In writing one’s[46] thoughts, the mind should be occupied only in rendering the thought into correct English. To be truly useful the art of writing must finally be done with the muscles and not with brain energy. That we may save any draught on the intellectual power we should be entirely unconscious of the execution of the forms.

Men are constantly at work in the business world devising schemes whereby energy and time may be economized. Cannot the schools do their share in this great scheme for the betterment of humanity? We should teach pupils an energy-saving manner of expressing themselves upon paper. How much useless nerve force is applied daily by pupils of all ages in forcing the pen along with the fingers in such a way that it is only less painful to the observer than to the performer? Why not try to assist in ending this useless waste of energy in the school world by directing a reasonable amount of energy into the correct channel? How much of our energy is misdirected daily when we should be making it our ally? We should fund and capitalize all energy, and at last live at ease upon the interest. The more details we can hand over to automatism, the more our higher powers of mind will be set free for greater work.

[47]

Children are the nation’s most valuable asset. Vision is the first faculty in order of importance. How can it be best conserved? A proper regard for the future usefulness of the eyes of the pupils requires that a departure be made from the method now prevalent of demanding so much written work. A keen observer who realizes the true nature of a child will postpone the requirement of written language and fine print reading until a time when the more delicate eye muscles are properly developed and able to stand the strain. Muscular movement writing makes conservation of vision possible because it demands first, last and always, correct posture and proper lighting.

Nearsight is frequently brought on by straining the eyes to see objects, and especially small blackboard writing, at a distance. Light shining on the board causes a glare, and when pupils are sitting so that the work on the board is seen at a trying angle the result is harmful to the eye. All work placed on the board during a penmanship demonstration, or at any other time, should be executed large enough and with lines so bold that pupils in the rear of the room may see it plainly without eye strain.

Correct posture while writing precludes a tendency toward curvature of the spine, and also[48] saves the eyes unnecessary strain. Numberless people sit and write more hours than they walk or ride. Who would presume to question the value of correct posture while walking, in its relation to good health? We are painfully inconsistent, when the writing habit is in operation, with regard to many of the laws that make for good health.

Only as we work toward the saving of energy for ourselves and others are we keeping step with the progressives who are teaching conservation from the kitchen to forestry. Surely our aim should be the greatest accomplishment with the least expenditure of energy.

Second only in importance to conserving the health by economizing energy through muscular movement is the time saving element. People who would recoil from ordinary thieving are often guilty of dishonesty of a kind that is closely akin thereto. We joke over our own poor handwriting and moan over that of our friends, yet we would be greatly startled were we actually to compute the number of priceless hours wasted every day by busy people trying to decipher illegible[49] writing. Not only time but temper as well is destroyed. Quite as painful, only less annoying, to the economist of time is the accurately drawn script that we know consumed fully three times as much time as should have been required for its execution.

In many schools we find that the method of executing written lessons is not equal to the need. Then also, we have pupils taking several times as long as should be required for written spelling or composition. Muscular movement will reduce several fold the time necessary for all written work and the benefits will not end there, for better quality in the content will result. The pupil will be left free to dictate and the hand will obey quite unconsciously.

We constantly hear the plea, “We cannot teach writing; we have not the time.” Would it not be well to make some computations at this point? Compare a class or school that uses a good muscular movement, acquired through a formal writing lesson of from twenty to thirty minutes daily, with a class in which penmanship is hit or miss. The latter irregular habit always results in an irregular slant and finger movement. Judge then if it would not be well to teach pupils to save time. We carefully consider how to minimize[50] waste of energy in a machine. Is the human machine of less importance?

Since penmanship is used largely as a vehicle for expression to convey the mental product to others, is it not reasonable that we employ the easiest and speediest method of transportation? It is convenient to be master of a method that can record thought as fast as the mind shapes it. The right method will aid thought, not impede it.

Henry Maxwell, as a workman, began to study the length of time he required to each part of a job. He kept a record and studied it. He then busied himself seeing where he could cut down all unnecessary strokes. He found that on a certain six hour job all but two hours and forty-seven minutes were consumed by bad planning, poor tools, and needless movements. Maxwell, as a master craftsman, is one of the all too rare people who are setting things in order. Everything can be provided more easily as a result of the work of a man like him. He opens up the possibility of leisure through the saving of labor.

Assuming that not more than five or ten minutes were saved by the pupil during each written lesson, think of the total saving per day, per week, per month, not to mention the saving of time to that same man or woman when his school life is over and school of real life begins.

[51]

To fit oneself from year to year for the ever increasingly difficult task of teaching is a serious problem. We are to some extent compensated in a material way; our chief payment, however, is in the consciousness that through newly acquired knowledge our methods are improved, and the reflection is mirrored in the quality of our work. That methods presuppose a knowledge of the subject matter, is necessarily as true in the science of muscular movement penmanship as in other subjects less homely and less practical. The indispensable accompaniment is inspiring instruction suited to the inculcation of the proper habit on the part of the class. Too often we forget that anything that is worth possessing is paid for in strokes of daily effort. By neglecting the necessary concrete labor, by sparing ourselves the daily effort, we are standing in the way of obtaining the desired final results.

[52]

All will agree that results speak. Shall we not then be repaid for our trouble when pupils mirror the reflection of our labor? Having personally mastered the difficulties of the subject, the teacher and supervisors are aware of the pitfalls which await the pupils. Only then do we cease to be theorists and become capable of demonstrating the truth of our methods. Uniformly good results may be obtained in almost any class if proper instructions are followed. If we are not obtaining good results in the product our methods are at fault. Could a teacher without knowledge of reading or of numbers devise suitable methods for presenting reading or numbers? Surely, the teacher cannot teach that which he does not know, be the subject penmanship or astronomy. Neither is the ambitious teacher content with a partial knowledge of any subject. Unless intensive knowledge of a subject obtains, no teacher will be able to follow successfully second hand methods.

It is significant that the Normal Schools require their graduates to qualify in the useful art of practical penmanship. Many teachers have found that the correspondence method is well suited to and fulfills their needs for a complete penmanship training. Universities now offer[53] summer courses in penmanship. Supervisors frequently give weekly drill classes for unqualified teachers upon which attendance is obligatory or optional. It is the regret of many of our best teachers who have been in the service for some years that they did not have opportunity or were not required to qualify in penmanship earlier in their educational career. Unless an inexperienced teacher knows how to teach intuitively, ludicrous blunders will be made. If knowledge be lacking regarding any branch, the quality of the young teacher’s work will be still less desirable. The everlasting how will confront the teacher every day, and each time it will be necessary to find an answer.

It is unfortunate for our schools that so many teachers feel that they can succeed in teaching penmanship without themselves knowing how to write. To know only the first few principles will not be sufficient, though they are not to be underestimated. To complete the structure we must build upon the firm foundation of first principles a crude but proper framework. When this is firmly reinforced, we put on the finishing touches. Many do not get further than the foundation; others stop at the next important stage, the crude product; while others who are persevering work[54] to the end and have the satisfaction of enjoying the beautiful structure complete.

There are few successful teachers who are not good psychologists and who therefore do not know the process by which growth is secured. Knowledge is the cornerstone of the foundation. However it is not enough that we know the subject which we are to teach; we must have the ability to impart knowledge that the self-activity of the pupils may induce growth.

All teachers are not endowed alike with this wonderful gift. It is also a truism that to realize one’s shortcomings in this direction is the first step. If the pupils are not interested, and response cannot be obtained, let us look for the direct cause in the teacher and for the indirect cause in the supervisor. The far seeing teacher will aim to surround the penmanship lesson with the proper atmosphere at the outset. As pupils are more interested in seeing what is done than by abstract explanation, a few skillful and telling strokes at the desk or on the blackboard will serve as a much greater inspiration than for the pupils to come into the room and sit before a[55] model that has been executed while they were out of sight.

Skillful questioning and holding the entire class for answers is of great advantage when visualizing letter forms, and again when criticising and comparing results. The laws of cause and effect operate in penmanship as surely as they operate elsewhere. What is the cause of incorrect slant, a heavy stroke or a careless form? Pupils who know how to think may be put on the right road by being taught to criticize their own work.

It is one thing to impart the knowledge one may possess of correct execution; the obtaining of results is quite another. Many a teacher has been greatly discouraged when a view of the results was obtained because close observation revealed that pupils had not comprehended the idea which the teacher intended to convey. Let us adopt new methods or modify old ones until desirable results are obtained. The pupils are placed under our care that they may have an opportunity to gain some of the knowledge and skill of which we, as teachers, are supposed to be in possession.

The best proof that the imparting has been clear, logical, and effective is in the quality of the[56] results so easily observed in the penmanship class. Every lesson is a new record of what has already been grasped by the pupils or a presentation of something new, or better still, a combination of both. Enthusiasm is one of the most essential points to be gained by the class. It must actually be experienced before it can be imparted to the pupil. If it is not felt by the teacher the next duty is to induce it by look and act.

The unconscious influence of the teacher cannot be measured. With pupils, teachers are more than ideals; they are realities. The personal influence is more lasting than the particular system that is taught. A competent teacher must be the master of the situation. Little inspiration can be created by the timid teacher. Originality, individuality, attractive personality, courage, confidence, ease of manner, firmness, tact, initiative—these are desirable assets for the penmanship leader. Such a leader has a ready following.

A penmanship teacher must balance enthusiasm with tact, system, and resourcefulness, and be ever on the alert to discover the individual needs. Tact plays a very important part in penmanship instruction for by the exercise of it we are led to say and do the right thing at the right time.

True, we get no more out of this subject than[57] we put into it. Let us be more pedagogical in imparting this subject. Let us outline a penmanship lesson as carefully as we would other lessons. The result will justify the labor.

Penmanship is entirely too isolated, and the value of cooperation and correlation are not sufficiently recognized. Young America demonstrated this perfectly when at the beginning of a written spelling test he asked if he should write it with muscular movement or with his “real writin’.” To him the drill that was supposed to make for the correct writing habit had not taken hold. He failed to associate the practice method with practical work. Again, great tact must be exercised in the attempt to correlate the penmanship with other subjects, lest in an unguarded moment a teacher may tire the pupils and thus defeat the much sought-for end.

Colonel Parker says: “The present trend of study, investigation, and discovery in the science of education is toward the correlation and unification of educative subjects and their concentration upon human development. All subjects, means and modes of study are concentrated under[58] this doctrine upon the economization of educative effort.”

Persistence on the part of the teacher is absolutely essential, for pupils will forget and must be constantly reminded. If on all occasions the teacher of English or other subjects will bring a due amount of pressure to bear upon the class during all written recitations and take the proper share of responsibility, good results will be rapidly noted. On the other hand, we should have scant respect for the penmanship teacher who habitually uses poor English and who is not pedagogical in the presentation of the subject.

Since it is common to evaluate subjects in terms of credits, would not a system of daily credits in writing tend to dignify the subject? Would not this react upon the pupil in a desirable way? As the matter now stands in many schools no credit is given to encourage; only complaints are heard when the work is not up to standard.

We do know that all pupils who enter the commercial department of our public schools soon take it for granted that penmanship is a part of their stock in trade. The laws of necessity are plainly followed. These pupils have credits for penmanship.

[59]

In the requirements for good penmanship, consistency should be shown from the lowest to the highest. The closest cooperation from the superintendent down to the first grade teacher is urged. Set a standard, and bring the pupils up to it, as is done in other subjects. One grade teacher may teach well, another poorly or indifferently, and thus the pupils are passed along. The school system where this prevails may be compared to a chain with now and then a weak link. Unless there is unity and cooperation among teachers the subject suffers greatly. The right kind of supervision is helpful, but it cannot accomplish all things. Not infrequently we hear the remark, “I am not the penmanship teacher; Miss So-and-so teaches all the penmanship.” Our “second speech” is too important a matter to be left to one person unaided. Upon whose shoulders shall be placed the responsibility? If a school does remarkably excellent or noticeably poor work in any subject, whose is the reward or the blame?

The proper attitude of the Superintendent and the principal will go far to popularize any subject, penmanship no less than any other. This attitude will be reflected unconsciously upon the teacher, and the pupils will be quick to take the cue.

[60]

How often is the muscular movement writing supervisor told by the boys in particular, “My father writes that way.” The right attitude is established immediately because the boy sees the relation of the school to a practical need. In fact, parental influence is a factor to be reckoned with in penmanship and the thoughtful teacher will do well to inquire into the attitude of the parents toward this useful art. Many times it means leverage for the teacher. In case the pupil is old enough to realize a motive for improving, the influence of the teacher alone may be sufficient. On the other hand, the boy frequently decides to follow the occupation or trade of his father, without regard to capacity or aptitude. Vocational guidance is essential.

In the consideration of this subject, by parents, superintendents, principals, and teachers, let us not forget that we are living in a rapidly changing age, that we should ever be on the alert to study the present day needs, and that an open mind is essential to progress.

[61]

When the conclusion has been reached that some muscular movement system should be followed in order to inculcate the best writing habit, it still remains to select the text. Great care should be taken in this. A satisfactory text should abound in instructions to be read until fully understood, and illustrated with a sufficient number of models to answer all purposes of visualization. The text should be of convenient size; the drills and cuts should be arranged in a logical manner. The instructions should be in such simple language that all pupils can comprehend them. A manual with model forms only for the lower grades would prove very helpful, the teacher supplying the instruction. First grade pupils should write on the blackboard, but only from correct models placed there by the teacher in the presence of the pupils. Many primary grade educators[62] favor no writing in the first grade except such as is taught from the board.

She would be far more than an ordinary teacher who could give a class of pupils (without the help of a text) the pictures in her own mind in a sufficiently clear and vivid manner to result in correctly executed work on the part of the pupil. Surely all reasonable aids should be given pupils in their efforts to learn penmanship. A good text is as much needed in this as in any other subject. We should laugh at the idea of teaching arithmetic or English without the aid of the text; yet many good school people seem to think writing can be absorbed in some mysterious manner from more or less indefinite word pictures and a few blackboard copies done in a more or less skillful manner.

Again we hear of schools that arrogate unto themselves the right to change the author’s plan, or to accept it in part, frequently omitting the most important and vital points. There is no unity and no consistency in this manner of doing things. McMurray’s question and answer along this line is pertinent when he says, “What should be the attitude of the young student toward the authorities that he studies?” The answer is, “Certainly, authors are, as a rule, more mature[63] and far better informed upon the subjects that they discuss than he, otherwise he would not be pursuing them.”

Much may be said for and against the use of the blackboard. At best, it cannot supplant the use of the text. To begin with, the blackboard models are liable to be executed hurriedly and therefore poorly; and again these models, however correct, are not seen by all at the same angle. A slate or glass board is to be preferred. This should be placed low enough for all pupils to reach easily. All wall space, including that between the windows, should be utilized for blackboard. When pupils are copying writing from the board the window shades should be adjusted in such a manner that the pupils’ eyes do not suffer from the glare.

Good blackboard writing on the part of the teacher points its own moral. The teacher has less teaching to do. Pupils imitate almost every school room procedure from the teacher’s dress and mannerisms to her writing. Fortunately it is much easier to write well upon the blackboard than upon paper and no possible excuse can be[64] offered that will cover poor board writing on the part of either teacher or pupil.

Good work on the board serves as an attraction to the subject since the pupils are always interested in seeing the creation of a skillful hand. It is also indispensable in studying the construction of letters and the teacher who can execute freely and rapidly at the board possesses a most valuable asset. When proper visualization has taken place, that is, when the mental photograph has been acquired by exposing the lens of the eye sufficiently long, it is well to erase the model or constructive lines and refer to the models in the text, since these are what the pupil will aim to approach. All work placed upon the board should be in exact harmony with the system in use at the writing hour, since example is more than precept and pupils gain unconsciously by seeing the correct forms before them.

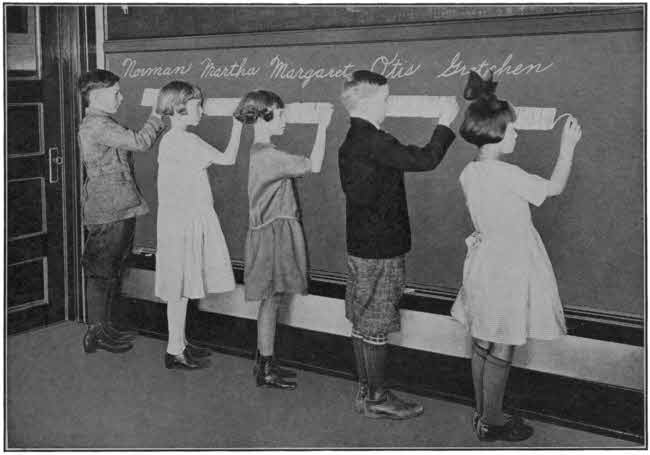

Blackboard Position

Just as we have pictures that exert a correct moral influence hung in the rooms and halls, and mottoes containing beautiful sentiments ever before us, so should we place the correct written forms before the pupil. Again, note the effect of regular written work done in an incorrect manner! Pupils will be very apt to draw the conclusion that the models used during the writing lesson[65] and real work are two different matters. Frequently the grade teacher will apologize to the supervisor for the appearance of the copy. This does not raise her in the estimation of her class, but rather calls their attention to her short-comings. By spending a few minutes daily for a month any teacher may develop such excellent blackboard work that no apologies should be necessary.

Pupils who are discouraged in penmanship will find that good results may be obtained very easily at the board. They must be taught at the outset, however, that the movement at the board and that required at the seat is quite different. Form, rhythm, and slant should be developed first at the board, as these three points are in common. By listening to the teacher’s criticism of blackboard results, pupils will easily become more critical of their own work.

Points to be observed in a blackboard lesson:

1. The teacher should be able to make for each pupil a correct copy in the presence of the class.

2. Pupils should stand with the left side turned slightly toward the board to insure slant writing, and prepare to write as high as the eyes. Make movement for the exercises in the air yet almost touching the copy first, in order to gain correct size and spacing.

[66]

3. All pupils should write to the teacher’s count or dictation. Require much concert work at the board. Keep the lips closed and thus avoid breathing dust from the crayon. Hold the crayon between the thumb, and first and second fingers, allowing the end not in contact with the board to extend toward the center of the palm.

4. Straight strokes and ovals on correct slant will serve as a basis upon which to build all letters and words. Pupils should step along with the work as it is executed on the board, and thus keep correct alignment.

5. Pupils should be taught to do board work carefully, whether it be a writing exercise or regular work. Develop all difficult new drills at the board first. Suppose the class numbers forty; allow twenty to pass to the board for a ten minute period, if twenty minutes is the time allotted for a writing lesson. The groups at the seats should be taught to do the counting for or with the teacher, also to be alert for all errors in posture, slant and form.

6. It is very important that the line should be made strong enough that it may be seen easily from the rear of the room without eye strain. The writing should be large enough to be seen easily from any point in the room.

[67]

7. When erasing use a downward stroke. Lift the eraser on the upward stroke. This allows the dust to drop in the trough; a good signal is, “Erase,” “Lift,” “Erase,” “Lift,” or “Down,” “Lift,” “Down,” “Lift.”

“A workman is known by his tools.” It is as essential that good material be supplied for the penmanship as that any other department be well supplied as regards quality and quantity. Not only should good paper, pencils, pens and ink be used during the formal lessons each day, but in every lesson wherein writing is used to carry on the other work. Permit no scribbling, utilize every line, keep paper in neat folders; thus economize in the right manner, and not by the purchase of poor equipment, which is an irritation to teacher and pupil alike. The difference in cost of good and poor material is slight when compared with the results.

Paper should be of such quality that the pen will not pick up the fiber and cause blots. The proper ruling for penmanship paper is three-eighths of an inch (26 points). Size of letters and space between letters will be more easily developed[68] by the use of the ruling suggested than by the use of unruled paper. Only in upper grades where good work obtains should an attempt be made to use unruled paper for the writing lesson. Size of sheets for lower grades should be not more than six by eight inches. Upper grades may use a sheet eight by ten and one-half inches. Writing on thick tablets should not be permitted. Use loose sheets of paper, always having the top sheet padded by one or two extra ones beneath to save wearing the penpoint needlessly.

Each pupil should have a heavy paper folder in which to keep all writing material. The use of such a folder saves much time in the passing of material.

If pencils are used in the first or second grade they should be large, and cylindrical in form (never octagonal), and of medium soft lead. The writing period should not be taken up with the sharpening of pencils. Erasers should not be allowed. Lead pencils are not at best conducive[69] to movement beyond the ovals and strokes. The use of the cheap tablet, the bane of the teacher’s life, and the poor quality lead pencil do much to hinder application of the correct writing habit in the lower grades.

A coarse, flexible pen (never a fountain or a stub pen) should be used by all teachers of muscular movement writing. Pens are dipped in oil before being boxed; for that reason when taking a new pen it is best to dampen it and remove the oil. Many a blot will be saved by so doing. Dip in the ink until the hole in the pen is partly or entirely filled with ink. When touching to the paper, be sure that both nibs come in contact, and are made to wear evenly. Each pupil should have his own pencil or pen, for sanitary reasons, as well as because no two persons wear a pen in exactly the same manner. After the lesson is ended the pen should be wiped on a penwiper. Removing the ink, which contains acid, will cause the pen to last longer, and a clean pen will do better work than one clogged with sediment. Pupils should never drop the pen to the bottom of the inkwell in order to get ink; this ruins the penpoint[70] and causes unnecessary noise. A good penpoint should last from eight to fourteen hours or longer if properly treated. Inkwells should be filled frequently.

A penholder of wood, or one tipped with cork, is preferred. No learner should be permitted to use a metal tipped penholder. On account of the pressure that must be exerted in order to keep the metal penholder from slipping, proper relaxation of the hand cannot take place. Frequently the metal rusts or is so heavy that the penholder is a burden to the inexperienced.

Each child should be provided with a blotter. It is well to let the ink dry as the pen spreads it on the paper except in case of a blot. Many pupils have the habit of taking the blotter in the hand and of giving the page a series of slaps with it, in quick succession; instead of taking up the ink this merely blurs the page. The correct way is to place the blotter on the line, give it an even pressure, and lift it, never moving it while the pressure is being applied.

[71]

Use the best fluid ink obtainable. Ink made from crystals or powder is less satisfactory. It should be dark blue or black and flow freely. Bottles and inkwells should be kept closed when not in use. If the air is excluded the ink does not thicken. Occasionally water may be added, but great care must be taken in reducing ink that it be not made too thin.

School boards and officials are generally willing to procure good supplies if economy is practiced in the use of them. For the sake of uniformity, and that every child may have an equal chance, it is advisable for the school to furnish all material for writing. Pupils frequently do not use proper discrimination in their purchases, when the matter of supplies is left to them.

Lastly, it is a mistake to think that good results can be obtained with poor material. In building any structure that we hope to last a lifetime we are careful to supply ourselves with the best of material. This principle applies in rearing the penmanship structure.

[72]

Observe the board demonstration. Trace text correctly: Capitals twelve times, words six times and sentences three times, at correct speed. Write at correct speed one-half minute, one minute, or two minutes as required. Compare with models. Test and grade.

How to study capital letters: Height, three-fourths space high; slant, same as strokes; width, wider or narrower than single ovals; beginning stroke, how and where; end stroke, how and where; speed of letter studied; name a variety of counts and select the most pleasing; analogy to other letters; name as many points as can be observed that are peculiar to the letter under discussion.