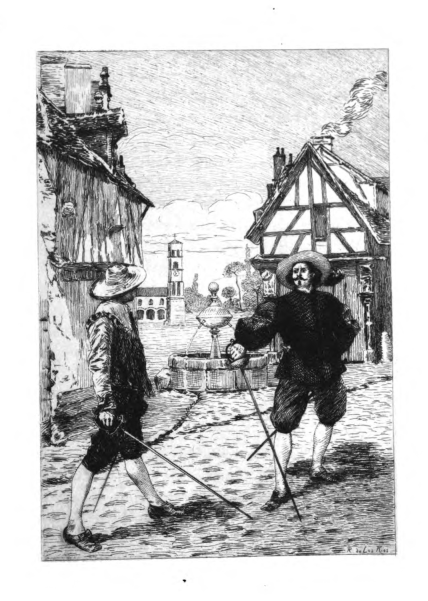

Don Alphonso and Baron Steinbach

ALAIN RENÉ LE SAGE

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY TOBIAS SMOLLETT

PRECEDED BY

A BIOGRAPHICAL AND CRITICAL NOTICE OF LE SAGE

BY GEORGE SAINTSBURY

With Twelve Original Etchings by R. de Los Rios

IN THREE VOLUMES—VOL. II.

LONDON

J. C. NIMMO AND BAIN

14, KING WILLIAM STREET, STRAND, W.C.

NEW YORK: SCRIBNER, WELFORD & CO.

1881

CONTENTS OF VOL. II.

BOOK THE FOURTH—CONTINUED.

Gil Blas leaves his Place, and goes into the Service of Don Gonzales Pacheco.

The Marchioness of Chaves; her Character, and that of her Company.

An Incident which parted Gil Blas and the Marchioness of Chaves. The subsequent Destination of the Former.

The History of Don Alphonso and the fair Seraphina.

The old Hermit turns out an extraordinary Genius, and Gil Blas finds himself among his former Acquaintance.

BOOK THE FIFTH

History of Don Raphael

Don Raphael's Consultation with his Company, and their Adventures as they were preparing to leave the Wood.

BOOK THE SIXTH.

The Fate of Gil Blas and his Companions after they took Leave of the Count de Polan. One of Ambrose's notable Contrivances, set off by the Manner of its Execution.

The Determination of Don Alphonso and Gil Blas, after this Adventure.

An unfortunate Occurrence, which terminated to the high Delight of Don Alphonso. Gil Blas meets with an Adventure, which places him all at once in a very superior Situation.

BOOK THE SEVENTH.

The tender Attachment between Gil Blas and Dame Lorenza Zephora.

What happened to Gil Blas after his Retreat from the Castle of Leyva, showing that those who are crossed in Love are not always the most miserable of Mankind.

Gil Blas becomes the Archbishop's Favorite, and the Channel of all his Favors.

The Archbishop is afflicted with a Stroke of Apoplexy. How Gil Blas gets into a Dilemma, and how he gets out.

The Course which Gil Blas took after the Archbishop had given him his Dismissal. His accidental Meeting with the Licentiate who was so deeply in his Debt; and a Picture of Gratitude in the Person of a Parson.

Gil Blas goes to the Play at Grenada. His Surprise at seeing one of the Actresses, and what happened thereupon.

Laura's Story

The Reception of Gil Blas among the Players at Grenada; and another old Acquaintance picked up in the Green-room.

An extraordinary Companion at Supper, and an Account of their Conversation.

The Marquis dc Marialva gives a Commission to Gil Blas. That faithful Secretary acquits himself of it as shall be related.

A Thunderbolt to Gil Blas

Gil Blas takes Lodgings in a ready-furnished House. He gets acquainted with Captain Chinchilla. That Officer's Character and Business at Madrid.

Gil Blas comes across his dear Friend Fabricio at Court. Great Ecstasy on both Sides. They adjourn together and compare Notes; but their Conversation is too curious to be anticipated.

Fabricio finds a Situation for Gil Blas in the Establishment of Count Galiano, a Sicilian Nobleman.

The Employment of Gil Blas in Don Galiano's Household.

An Accident happens to the Count de Galiano's Monkey; his Lordship's Affliction on that Occasion. The Illness of Gil Blas, and its Consequences.

BOOK THE EIGHTH.

Gil Blas scrapes an Acquaintance of some Value, and finds wherewithal to make him Amends for the Count de Galiano's Ingratitude. Don Valerio de Luna's Story.

Gil Blas is introduced to the Duke of Lerma, who admits him among the Number of his Secretaries, and requires a Specimen of his Talents, with which he is well satisfied.

All is not Gold that glitters. Some Uneasiness resulting from the Discovery of that Principle in Philosophy, and its practical Application to existing Circumstances.

Gil Blas becomes a Favorite with the Duke of Lerma, and the Confidant of an important Secret.

The Joys, the Honors, and the Miseries of a Court Life in the Person of Gil Blas.

Gil Blas gives the Duke of Lerma a Hint of his wretched Condition. That Minister deals with him accordingly.

A good Use made of the fifteen hundred Ducats. A first Introduction to the Trade of Office, and an Account of the Profit accruing therefrom.

HISTORY OF GIL BLAS OF SANTILLANE.

GIL BLAS LEAVES HIS PLACE AND GOES INTO THE SERVICE OF DON GONZALES PACHECO.

Three weeks after marriage, my mistress bethought herself of rewarding the services I had rendered her. She made me a present of a hundred pistoles, telling me at the same time: Gil Blas, my good fellow, it is not that I mean to turn you away, for you have my free leave to stay here as long as you please; but my husband has an uncle, Don Gonzales Pacheco, who wants you very much for a valet-de-chambre. I have given you so excellent a character, that he would let me have no peace till I consented to part with you. He is a very worthy old nobleman, so that you will be quite in your element in his family.

I thanked Aurora for all her kindness, and, as my occupation was over about her, I so much the more readily accepted the post that offered, as it was merely a transfer from one branch of the Pachecos to another. One morning, therefore, I called on the illustrious Don Gonzales with a message from the bride. He ought at least to have overslept himself, for he was in bed at near noon. When I went into his chamber, a page had just brought him a basin of soup, which he was taking. The dotard cherished his whiskers, or rather tortured them with curling-papers; though his eyes were sunk in their sockets, his complexion pale, and his visage emaciated. This was one of those old codgers who have been a little whimsical or so in their youth, and have made poor amends for their freedoms by the discretion of their riper age. His reception of me was affable enough, with an assurance that if my attachment to him kept pace with my fidelity to his niece, my condition should not be worse than that of my fellows. I promised to place him in my late mistress's shoes, and became the working partner in a new firm.

A new firm it undoubtedly was, and heaven knows we had a strange head of the house. The resurrection of Lazarus was an ordinary event compared to his getting up. Imagine to yourself a long bag of dry bones, a mere skeleton, a dissection, an anatomy of a man; a study in osteology! As for the legs, three or four pair of stockings, one over the other, had no room to make any figure upon them. In addition to the foregoing, this mummy before death was asthmatic, and therefore obliged to divide the little breath he had between his cough and his loquacity. He breakfasted on chocolate. On the strength of that refreshment, he ventured to call for pen, ink, and paper, and to write a short note, which he sealed and sent to its address by the page who had administered the broth. But this henceforth will be your office, my good lad, said he, as he turned his haggard eyes upon me; all my little concerns will be in your hands, and especially those in which Donna Euphrasia takes an interest. That lady is an enchanting young creature, with whom I am distractedly in love, and by whom, though I say it who should not say it, I am met with all the mutual ardor of inextinguishable and unutterable passion.

Heaven defend us! thought I within myself: good now! if this old antidote to rapture can fancy himself an object on which the fair should waste their sweets, is it any wonder that among our young folks each fancies himself the Adonis, for whom every Venus pines? Gil Blas, pursued he with a chuckle, this very day will I take you to this abode of pleasure: it is my house of call almost every evening for a bit of supper. You will be quite petrified at her modest appearance, and the rigid propriety of her behavior. Far from taking after those little wanton vagrants, who are hey-go mad after striplings, and give themselves up to the fascinations of exterior appearance, she has a proper insight into things, staid, ripe, and judicious: what she wants is the bonâ fide spirit and discretion of a man; a lover who has served an apprenticeship to his trade, in preference to all the flashy fellows of the modern school. This is but an epitome of the panegyric, which the noble duke Don Gonzales pronounced upon his mistress. He burdened himself with the task of proving her a compendium of all human perfection; but the lecture was little calculated for the conviction of the hearer. I had attended an experimental course among the actresses; and had always found that the elderly candidates had been plucked in their amours. Yet, as a matter of courtesy, it was impossible not to put on the semblance of giving implicit credit to my master's veracity; I even added chivalry to courtesy, and threw down my glove on Euphrasia's penetration and the correctness of her taste. My impudence went the length of asserting, that it was impossible for her to have selected a better-provided crony. The grown-up simpleton was not aware, that I was fumigating his nostrils at the expense of his addled brain; on the contrary, he bristled at my praises: so true is it, that a flatterer may play what game he likes against the pigeons of high life! They let you look over their hand, and then wonder that you beat them.

The old crawler, having scribbled through his billet-doux, restrained the luxuriance of a straggling hair or two with his tweezers; then bathed his eyes in the nostrum of some perfumer to give them a brilliancy which their natural gum would have eclipsed. His ears were to be picked and washed, and his hands to be cleansed from the effects of his other ablutions; and the labors of the toilet were to be closed, by pencilling every remaining hair in the disforested domain of his whiskers, pericranium, and eyebrows. No old dowager, with a purse to buy a second husband, ever took more pains to assure herself by the cultivation of her charms, that the person, and not the fortune, should be the object of attraction. The assassin stab of time was parried by the quart and tierce of art. Just as he had done making himself up, in came another old fogram of his acquaintance, by name the Count of Asumar. This genius made no secret of his gray locks; leaned upon a stick, and seemed to plume himself on his venerable age, instead of wishing to appear in the heyday of his prime. Signor Pacheco, said he as he came in, I am come to take pot-luck with you to-day. You are always welcome, count, rejoined my master. No sooner said than done! they embraced with a thousand grimaces, took their seats opposite to one another, and began chatting till dinner was served.

Their conversation turned at first upon a bull-feast which had taken place a few days before. They talked about the cavaliers, and who among them had displayed most dexterity and vigor; whereupon the old count, like another Nestor, whom present events furnish with a topic of expatiating on the past, said, with a deep-drawn sigh: Alas! where will you meet with men, nowadays, fit to hold a candle to my contemporaries? The public diversions are a mere bauble, to what they were when I was a young man. I could not help chuckling in my sleeve at my good lord of Asumar's whim; for he did not stop at the handiwork of human invention. Would you believe it? At table, when the fruit was brought in, at the sight of some very fine peaches, this ungrateful consumer of the earth's produce exclaimed: In my time, the peaches were of a much larger size than they are now; but nature sinks lower and lower from day to day. If that is the case, said Don Gonzales with a sneer, Adam's hot-house fruit must have been of a most unwieldy circumference.

The count of Asumar staid till quite evening with my master, who had no sooner got rid of him, than he sallied forth with me in his train. We went to Euphrasia's, who lived within a stone's throw of our house, and found her lodged in a style of the first elegance. She was tastefully dressed, and for the youthfulness of her air might have been taken to be in her teens, though thirty bonny summers at least had poured their harvests in her lap. She had often been reckoned pretty, and her wit was exquisite. Neither was she one of your brazen-faced jilts, with nothing but flimsy balderdash in their talk, and a libertine forwardness in their manners: here was modesty of carriage as well as propriety of discourse; and she threw out her little sallies in the most exquisite manner, without seeming to aspire beyond natural good sense. O heaven! said I, is it possible that a creature of so virtuous a stamp by nature should have abandoned herself to vicious courses for a livelihood? I had taken it for granted, that all women of light character carried the mark of the beast upon their foreheads. It was a surprise therefore to see such apparent rectitude of conduct; neither did it occur to me that these hacks for all customers could go at any pace, and assume the polish of well-bred society, to impose upon their cullies of the higher ranks. What if a lively petulance should be the order of the day? they are lively and petulant. Should modesty take its turn in the round of fashion, nothing can exceed their outward show of prudent and delicate reserve. They play the comedy of love in many masks; and are the prude, the coquette, or the virago, as they fall in with the quiz, the coxcomb, or the bully.

Don Gonzales was a gentleman and a man of taste; he could not stomach those beauties who call a spade, a spade. Such were not for his market; the rites of Venus must be consummated in the temple of Vesta. Euphrasia had got up her part accordingly, and proved by her performance that there is no comedy like that of real life. I left my master, like another Numa with his Egeria, and went down into a hall, where whom should fortune throw in my way but an old abigail, whom I had formerly known as maid-of-all-work to an actress? The recognition was mutual. So! well met once more, Signor Gil Blas, said she. Then you have turned off Arsenia, just as I have parted with Constance. Yes, truly, answered I, it is a long while ago since I went away, and exchanged her service for that of a very different lady. Neither the theatre nor the people about it are to my taste. I gave myself my own discharge, without condescending to the slightest explanation with Arsenia. You were perfectly in the right, replied the new-found abigail, called Beatrice. That was pretty much my method of proceeding with Constance. One morning early, I gave in my accounts with a very sulky air; she took them from me in moody silence, and we parted in a sort of well-bred dudgeon.

I am quite delighted, said I, that we have met again, where we need not be ashamed of our employers. Donna Euphrasia looks for all the world like a woman of fashion, and I am much deceived if she has not reputation too. You are too clear-sighted to be deceived, answered the old appendage to sin. She is of a good family; and as for her temper, I can assure you it is unparalleled for evenness and sweetness. None of your termagant mistresses, never to be pleased, but always grumbling and scolding about everything, making the house ring with their clack, and fretting poor servants to a thread, whose places, in short, are a hell upon earth! I have not in all this time heard her raise her voice on any occasion whatever. When things happen not to be done exactly in her way, she sets them to rights without any anger, nor does any of that bad language escape her lips, of which some high-spirited ladies are so liberal. My master, too, rejoined I, is very mild in his disposition; the very milk of human kindness; and in this respect we are, between ourselves, much better off than when we lived among the actresses. A thousand times better, replied Beatrice; my life used to be all bustle and distraction; but this place is an actual hermitage. Not a creature darkens our doors but this excellent Don Gonzales. You will be my only helpmate in my solitude, and my lot is but too greatly blessed. For this long time have I cherished an affection for you: and many a time and oft have I begrudged that Laura the felicity of engrossing you for her sweetheart; but in the end I hope to be even with her. If I cannot boast of youth and beauty like hers, to balance the account, I detest coquetry, and have all the constancy as well as affection of a turtle-dove.

As honest Beatrice was one of those ladies who are obliged to hawk their wares, and cheapen themselves for want of cheapeners in the market, I was happily shielded from any temptation to break the commandments. Nevertheless, it might not have been prudent to let her see in what contempt her charms were held: for which reason I forced my natural politeness so far, as to talk to her in a style not to cut off all hope of my more serious advances. I flattered myself then, that I had found favor in the eyes of an old dresser to the stage: but pride was destined to have a fall, even on so humble an occasion. The domestic trickster did not sharpen her allurements from any longing for my pretty person; her design in subduing me to the little soft god was to enlist me for the purposes of her mistress, to whom she had sworn so passive an obedience, that she would have sold her eternal self to the old chapman, who first set up the trade of sin, rather than have disappointed her slightest wishes. My vain conceit was sufficiently evident on the very next morning, when I carried an Ovidian letter from my master to Euphrasia. The lady gave me an affable reception, and made a thousand pretty speeches, echoed from the practised lips of her chambermaid. The expression of my countenance was peculiarly interesting to the one: but that within which passeth show was the flattering theme of the other. According to their account, the fortunate Don Gonzales had picked up a treasure. In short, my praises ran so high, that I began to think worse of myself than I had ever done in the whole course of my life. Their motive was sufficiently obvious; but I was determined to play at diamond cut diamond. The simper of a simpleton is no bad countermine to the attack of a sharper. These ladies under favor were of the latter description, and they soon began to open their batteries.

Hark you, Gil Blas! said Euphrasia; fortune declares in your favor if you do not balk her. Let us put our heads together, my good friend. Don Gonzales is old, and a good deal shaken in constitution; so that a very little fever, in the hands of a very great doctor, would carry him to a better place. Let us take time by the forelock, and ply our arts so busily as to secure to me the largest slice of his effects. If I prosper, you shall not starve, I promise you; and my bare word is a better security than all the deeds and conveyances of all the lawyers in Madrid. Madam, answered I, you have but to command me. Give me my commission on your muster-roll, and you shall have no reason to complain either of my cowardice or contumacy. So be it then, replied she. You must watch your master, and bring me an account of all his comings and goings. When you are chatting together in his more familiar moments, never fail to lead the conversation on the subject of our sex; and then by an artful, but seemingly natural transition, take occasion to say all the good you can invent of me. Ring Euphrasia in his ears till all the house reëchoes. I would counsel you besides to keep a wary eye on all that passes in the Pacheco family. If you catch any relation of Don Gonzales sneaking about him, with a design on the inheritance, bring me word instantly: that is all you have to do, and trust me for sinking, burning, and destroying him in less than no time. I have ferreted out the weak side of all your master's relations long ago; they are each of them to be made ridiculous in some shape or other; so that the nephews and cousins, after sitting to me for their portraits, are already turned with their faces to the wall.

It was evident by these instructions, with many more to the same time and tune, that Euphrasia was one of those ladies whose partialities all lean to the side of elderly inamoratos, with more money than wit. Not long before, Don Gonzales, who could refuse nothing to the tender passion, had sold an estate; and she pocketed the cash. Not a day passed but she got some little personal remembrance out of him; and besides all this, a corner of his will was the ultimate object of her speculation. I affected to engage hand over head in their infamous plot; and if I must confess all without mental reservation, it was almost a moot point, on my return home, on which side of the cause I should take a brief. There was on either a profitable alternative; whether to join in fleecing my master, or to merit his gratitude by rescuing him from the plunderers. Conscience, however, seemed to have some little concern in the determination; it was quite ridiculous to choose the by-path of villany, when there was a better toll to be taken on the highway of honesty. Besides, Euphrasia had dealt too much in generals; an arithmetical definition of so much for so much has more meaning in it than "all the wealth of the Indies;" and to this shrewd reflection, perhaps, was owing my uncorrupted probity. Thus did I resolve to signalize my zeal in the service of Don Gonzales, in the persuasion that if I was lucky enough to disgust the worshipper by befouling his idol, it would turn to very good account. On a statement of debtor and creditor between the right and the wrong side of the action, the money balance was visibly in favor of virtue, not to mention the delights of a fair and irreproachable character.

If vice so often assumes the semblance of its contrary, why should not hypocrisy now and then change sides for variety? I held myself up to Euphrasia for a thorough swindler. She was dupe enough to believe that I was incessantly talking of her to my master; and thereupon I wove a tissue of frippery and falsehood, which imposed on her for sterling truth. She had so completely given herself up to my insinuations, as to believe me her convert, her disciple, her confederate. The better still to carry on this fraud upon fraud, I affected to languish for Beatrice: and she, in ecstasy at her age to see a young fellow at her skirts, did not much trouble herself about my sincerity, if I did but play my part with vigor and address. When we were in the presence of our princesses, my master in the parlor and myself in the kitchen, the effect was that of two different pictures, but of the same school. Don Gonzales, dry as touchwood, with all its inflammability, and nothing but its smother, seemed a fitter subject for extreme unction than for amorous parley; while my little pet, in proportion to the violence of my flame, niggled, nudged, toyed, and romped, like a school-girl in vacation; and no wonder she knew her lesson so pat, for the old coquette had been upwards of forty years in the form. She had finished her studies under certain professors of gallantry, whose art of pleasing becomes the more critical by practice; till they die under the accumulated experience of two or three generations.

It was not enough for me to go every evening with my master to Euphrasia's: it was sometimes my lounge even in daytime. But let me pop my head in at what hour I would, that forbidden creature man was never there, nor even a woman of any description, that might not be just as easily expressed as understood. There was not the least loop-hole for a paramour!—a circumstance not a little perplexing to one who could not readily believe, that so pretty a bale of goods could submit to a strict monopoly, by such a dealer as Don Gonzales. This opinion undoubtedly was formed on a near acquaintance with female nature, as will be apparent in the sequel; for the fair Euphrasia, while waiting for my master's translation, fortified herself with patience in the arms of a lover, with some little fellow-feeling for the frailties of her age.

One morning I was carrying, according to custom, a note to this peerless pattern of perfection. There certainly were, or I was not standing in the room, the feet of a man ensconced behind the tapestry. Out slunk I, just as if I had no eyes in my head; yet, though such a discovery was nothing but what might have been expected, neither was the piper to be paid out of my pocket; my feelings were a good deal staggered at the breach of faith. Ah, traitress! exclaimed I, with virtuous indignation, abandoned Euphrasia! Not satisfied to humbug a silly old gentleman with a tale of love, you share his property in your person with another, and add profligacy to dissimulation! But to be sure, on afterthoughts, I was but a greenhorn when I took on so for such a trivial occurrence! It was rather a subject for mirth than for moral reflection, and perfectly justified by the way of the world; the languid, embargoed commerce of my master's amorous moments had need be filliped by a trade in some more merchantable wares. At all events it would have been better to have held my tongue, than to have laid hold on such an opportunity of playing the faithful servant. But instead of tempering my zeal with discretion, nothing would serve the turn but taking up the wrongs of Don Gonzales in the spirit of chivalry. On this high principle, I made a circumstantial report of what I had seen, with the addition of the attempt made by Euphrasia to seduce me from my good faith. I gave it in her own words without the least reserve, and put him in the way of knowing all that was to be known of his mistress. He was struck all in a heap by my intelligence, and a faint flash of indignation on his faded cheek seemed to give security that the lady's infidelity would not go unpunished. Enough, Gil Blas, said he; I am infinitely obliged by your attachment to my service, and your probity is very acceptable to me. I will go to Euphrasia this very moment. I will overwhelm her with reproaches, and break at once with the ungrateful creature. With these words, he actually bent his way to the subject of his anger, and dispensed with my attendance, from the kind motive of sparing me the awkwardness which my presence during their explanation would have occasioned to my feelings.

I longed for my master's return with all the impatience of an interested person. There could not be a doubt but that with his strong grounds of complaint, he would return completely disentangled from the snares of his nymph. In this thought I extolled and magnified myself for my good deed. What could be more flattering than the thanks of the kindred who were naturally to inherit after Don Gonzales, when they should be informed that their relative was no longer the puppet of a figure-dance so hostile to their interests? It was not to be supposed but that such a friend would be remembered, and that my merits would at last be distinguished from those of other serving-men, who are usually more disposed to encourage their masters in licentiousness, than to draw them off to habits of decency. I was always of an aspiring temper, and thought to have passed for the Joseph or the Scipio of the servants' hall; but so fascinating an idea was only to be indulged for an hour or two. The founder of my fortunes came home. My friend, said he, I have had a very sharp brush with Euphrasia. She insists on it that you have trumped up a cock-and-bull story. If their word is to be taken, you are no better than an impostor, a hireling in the pay of my nephews, for whose sake you have set all your wits at work to bring about a quarrel between her and me. I have seen the real tears, made of water, run down in floods from her poor dear eyes. She has vowed to me as solemnly as if I had been her confessor, that she never made any overtures to you in her life, and that she does not know what man is. Beatrice, who seems a simple, innocent sort of girl, is exactly in the same story, so that I could not but believe them and be pacified, whether I would or no.

How then, sir? interrupted I, in accents of undissembled sorrow, do you question my sincerity? Do you distrust .... No, my good lad, interrupted he again in his turn; I will do you ample justice. I do not suspect you of being in league with my nephews. I am satisfied that all you have done has been for my good, and own myself much obliged to you for it; but appearances are apt to mislead, so that perhaps you did not see in reality what you took it into your head that you saw; and in that case, only consider yourself how offensive your charge must be to Euphrasia. Yet, let that be as it will, she is a creature whom I cannot help loving in spite of my senses; so that the sacrifice she demands must be made, and that sacrifice is no less than your dismission. I lament it very much, my poor dear Gil Blas, and if that will be any satisfaction to you, my consent was wrung from me most unwillingly; but there was no saying nay. With one thing, however, you may comfort yourself, you shall not be sent away with empty pockets. Nay, more, I mean to turn you over to a lady of my acquaintance, where you will live to your liking.

I was not a little mortified to find all my noble acts and motives end in my own confusion. I gave a left-handed blessing to Euphrasia, and wept over the weakness of Don Gonzales, to be so foolishly infatuated by her. The kind-hearted old gentleman felt within himself that in turning me adrift at the peremptory demand of his mistress, he was not performing the most manly action of his life. For this reason, as a set-off against his hen-pecked cowardice, and that I might the more easily swallow this bitter dose, he gave me fifty ducats, and took me with him next morning to the Marchioness of Chaves, telling that lady before my face, that I was a young man of unexceptionably good character, and very high in his good graces, but that as certain family reasons prevented him from continuing me on his own establishment, he should esteem it as a favor if she would take me on hers. After such an introduction, I was retained at once as her appendage, and found myself, I scarcely knew how, established in another household.

THE MARCHIONESS OF CHAVES: HER CHARACTER, AND THAT OF HER COMPANY.

The Marchioness of Chaves was a widow of five and thirty, tall, handsome, and well-proportioned. She enjoyed an income of ten thousand ducats, without the encumbrance of a nursery. I never met with a lady of fewer words, nor one of a more solemn aspect. Yet this exterior did not prevent her from being set up as the cleverest woman in all Madrid. Her great assemblies, attended by people of the first quality, and by men of letters who made a coffee-house of her apartments, contributed perhaps more than anything she said to give her the reputation she had acquired. But this is a point on which it is not my province to decide. I have only to relate as her historian, that her name carried with it the idea of superior genius, and that her house was called, to distinguish it from the ordinary societies in town, The Fashionable Institution for Literature, Taste, and Science.

In point of fact, not a day passed, but there were readings there, sometimes of dramatic pieces, and sometimes in other branches of poetry. But the subjects were always selected from the graver muses; wit and humor were held in the most sovereign contempt. Comedy, however spirited; a novel, however pointed in its satire or ingenious in its fable, such light productions as these were treated as weak efforts of the brain, without the slightest claim to patronage; whereas, on the contrary, the most microscopical work in the serious style, whether ode, pastoral, or sonnet, was trumpeted to the skies as the most illustrious effort of a learned and poetical age. It not unfrequently fell out, that the public reversed the decrees of this chancery for genius: nay, they had sometimes the gross ill-breeding to hiss the very pieces which had been sanctioned by this court of criticism.

I was chief manager of the establishment, and my office consisted in getting the drawing-room ready to receive the company, in setting the chairs in order for the gentlemen, and the sofas for the ladies; after which, I took my station on the landing-place to bawl out the names of the visitors as they came up stairs, and usher them into the circle. The first day, an old piece of family furniture, who was stationed by my side in the ante-chamber, gave me their description with some humor, after I had shown them into the room. His name was Andrew Molina. He had a good deal of mother's wit, with a flowing vein of satire, much gravity of sarcasm, and a happy knack at hitting off characters. The first comer was a bishop. I roared out his lordship's name, and as soon as he was gone in, my nomenclator told me—That prelate is a very curious gentleman. He has some little influence at court, but wants to persuade the world that he has a great deal. He presses his service on every soul he comes near, and then leaves them completely in the lurch. One day he met with a gentleman in the presence chamber who bowed to him. He laid hold of him, and squeezing his hand, assured him, with an inundation of civilities, that he was altogether devoted to his lordship. For goodness sake, do not spare me; I shall not die in my bed without having first found an opportunity of making you my debtor. The gentleman returned his thanks with all becoming expressions of gratitude, and when they were at some distance from one another, the obsequious churchman said to one of his attendants in waiting, I ought to know that man; I have some floating, indistinct idea of having seen him somewhere.

Next after the bishop, came the son of a grandee. When I had introduced him into my lady's room, This nobleman, said Molina, is also an original in his way. You are to take notice that he often pays a visit, for the express purpose of talking over some urgent business with the friend on whom he calls, and goes away again without once thinking on the topic he came solely to discuss. But, added my showman on the sight of two ladies, here are Donna Angela de Penafiel and Donna Margaretta de Montalvan. This pair have not a feature of resemblance to each other. Donna Margaretta prides herself on her philosophical acquirements; she will hold her head as high as the most learned head among the doctors of Salamanca, nor will the wisdom of her conceit ever give up the point to the best reasons they can render. As for Donna Angela, she does not affect the learned lady though she has taken no unsuccessful pains in the improvement of her mind. Her manner of talking is rational and proper, her ideas are novel and ingenious, expressed in polite, significant, and natural terms. This latter portrait is delightful, said I to Molina; but the other, in my opinion, is scarcely to be tolerated in the softer sex. Not over bearable indeed! replied he with a sneer: even in men it does but expose them to the lash of satire. The good marchioness herself, our honored lady, continued he, she too has a sort of a philosophical looseness. There will be fine chopping of logic there to-day! God grant the mysteries of religion may not be invaded by these disputants.

As he was finishing this last sentence, in came a withered bit of mortality, with a grave and crabbed look. My companion showed him no mercy. This fellow, said he, is one of those pompous, unbending spirits, who think to pass for men of profound genius, under favor of a few commonplaces extracted out of Seneca; yet they are but shallow coxcombs when one comes to examine them narrowly. Then followed in the train a spruce figure, with tolerable person and address, to say nothing of a troubled air and manner, which always supposes a plentiful stock of self-sufficiency. I inquired who this was. A dramatic poet! said Molina. He has manufactured a hundred thousand verses in his time, which never brought him in the value of a groat; but as a set-off against his metrical failure, he has feathered his nest very warmly by six lines of humble prose: you will wonder by what magic touch a fortune could be made...

And so I did; but a confounded noise upon the staircase put verse and prose completely out of my head. Good again! exclaimed my informer; here is the licentiate Campanario. He is his own harbinger before ever he makes his appearance. He sets out from the very street door in a continued volley of conversation, and you hear how the alarm is kept up till he makes his retreat. In good sooth, the vaulted roof reëchoed with the organ of the thundering licentiate, who at length exhibited the case in which the pipes were contained. He brought a bachelor of his acquaintance by way of accompaniment, and there was not a sotto voce passage during the whole visit. Signor Campanario, said I to Molina, is to all appearance a man of very fine conversation. Yes, replied my sage instructor, the gentleman has his lucky hits, and a sort of quaintness that might pass for humor; he does very well in a mixed company. But the worst of it is, that incessant talking is one of his most pardonable errors. He is a little too apt to borrow from himself; and as those who are behind the scenes are not to be dazzled by the tinsel of the property-man, so we know how to separate a certain volubility and buffoonery of manner from sterling wit and sense. The greater part of his good things would be thought very bad ones, if submitted, without their concomitant grimaces, to the ordeal of a jest book.

Other groups passed before us, and Molina touched them with his wand. The marchioness, too, came in for a magic rap over the knuckles. Our lady patroness, said he, is better than might be expected for a female philosopher. She is not dainty in her likings; and bating a whim or two, it is no hard matter to give her satisfaction. Wits and women of quality seldom approach so near the atmosphere of good sense; and for passion, she scarcely knows what it is. Play and gallantry are equally in her black books: dear conversation is her first and sole delight. To lead such a life would be little better than penance to the common run of ladies. Molina's character of my mistress established her at once in my good graces. And yet, in the course of a few days, I could not help suspecting that, though not dainty in her likings, she knew what passion was, and that a foul copy of gallantry delighted her more than the fairest conversation.

One morning, during the mysteries of the toilet, there presented himself to my notice a little fellow of forty, forbidding in his aspect, more filthy if possible than Pedro de Moya the book-worm, and verging in no marketable measure towards deformity, he told me he wanted to speak with my lady marchioness. On whose business? quoth I. On my own, quoth he, somewhat snappishly. Tell her I am the gentleman; ... she will understand you; ... about whom she was talking yesterday with Donna Anna de Velasco. I went before him into my lady's apartment, and gave in his name. The marchioness all at once shrieked out her satisfaction, and ordered me to show him in. It was not courtesy enough to point to a chair, and bid him sit down: but the attendants, forsooth, her own maids about her person, were to withdraw, so that the little hunchback, with better luck than falls to the lot of many a taller man, had the field entirely to himself, as lord paramount. As for the girls and myself, we could not help tittering a little at this uncouthly concerted duet, which lasted nearly an hour: when my patroness dismissed his little lordship, with such a profusion of farewells and God-be-with-you's, as sufficiently evinced her thankfulness for the entertainment she had received.

The conversation had, in fact, been so edifying, that in the afternoon she seized a private opportunity of whispering in my ear, Gil Blas, when the short gentleman comes again, you may show him up the back stairs; there is no need of parading him along a line of staring servants. I did as I was ordered. When this epitome of humanity knocked at the door, and that hour was no farther off than the next morning, we threaded all the by-passages to the place of assignation. I played the same modest part two or three times in the very innocence of my soul, without the most distant guess that the material system could form any part of their philosophy. But that hound-like snuff at an ill construction, with which the devil has armed the noses of the most charitable, put me on the scent of a very whimsical game, and I concluded either that the marchioness had an odd taste, or that crookback courted her as proxy to a better man.

Faith and troth, thought I, with all the impertinence of a hasty opinion, if my mistress really likes a handsome fellow behind the curtain, all is well; I forgive her her sins: but if she is stark mad for such a monkey as this, to say the truth, there will be little mercy for her on male or female tongues. But how foully did I defame my honored patroness! The genius of magic had perched herself upon the little conjurer's protuberant shoulder; and his skill having been puffed off to the marchioness, who was just the right food for such jugglers and their tricks, she held private conferences with him. Under his tuition she was to command wealth and treasure, to build castles in the air, to remove from place to place in an instant, to reveal future events, to tell what is done in far countries, to call the dead out of their graves, and terrify the world with many miracles. Seriously, and to give him his deserts, the scoundrel lived on the folly of the public; and it has been confidently asserted, that ladies of fashion have not in all ages and countries been exempt from the credulity of their inferiors.

AN INCIDENT THAT PARTED GIL BLAS AND THE MARCHIONESS OF CHAVES. THE SUBSEQUENT DESTINATION OF THE FORMER.

For six months I lived with the Marchioness of Chaves, and, as it must be admitted, on the fat of the land. But fate, who thrusts footmen as well as heroes into the world, with herself tied about their necks, gave me a jog to be gone, and swore that I should stay no longer in that family or in Madrid. The adventure by which this decree was announced shall be the subject of the ensuing narrative.

In my mistress's female squad there was a nymph named Portia. To say nothing of her youth and beauty, it was her meek demeanor and good repute that captivated me, who had yet to learn that none but the brave deserves the fair. The marchioness's secretary, as proud as a prime minister, and as jealous as the Grand Turk, was caught in the same trap as myself. No sooner did he cast an unlucky squint at my advances, than, without waiting to see how Portia might chance to fancy them, he determined pell-mell to have a tilt with me. To forward this ghostly enterprise, he gave me an appointment one morning in a place sadly impervious to all seasonable interruption. Yet as he was a little go-by-the-ground, scarcely up to my shoulders, and apparently of feeble frame, he did not look like a very dangerous antagonist; so away I went with some little courage to the appointed spot. Thinking to come off with flying colors, I anticipated the effect of my bravery on the heart of Portia; but as it turned out, I was gathering my laurels before they had budded. The little secretary, who had been practising for two or three years at the fencing-school, disarmed me like a very baby, and holding the point of his sword up to my throat, Prepare thyself, said he, to balance thine accounts with this world, and open a correspondence with the next, or give me thy rascally word to leave the Marchioness of Chaves this very day, and never more to think of my Portia. I gave him my rascally word, and was honest enough not to think of breaking it. There was an awkwardness in showing my face before the servants of the family, after having been worsted; and especially before the high and mighty princess who had been the theme of our tournament. I only returned home to get together my baggage and wages, and on that very day set off towards Toledo, with a purse pretty well lined, and a knapsack at my back with my wardrobe and movables. Though my rascally word was not given to abandon the purlieus of Madrid, I considered it as a matter of delicacy to disappear, at least for a few seasons. My resolution was to make the tour of Spain, and to halt first at one town and then at another. My ready money, thought I, will carry me a good way: I shall not call about me very prodigally. When my stock is exhausted, I can but go into service again. A lad of my versatility will find places in plenty, whenever it may be convenient to look out for them.

It was particularly my wish to see Toledo: and I got thither after three days' journey. My quarters were at a respectable house of entertainment, where I was taken for a gentleman of some figure, under favor of my best clothes, in which I did not fail to bedizen myself. With the pick-tooth carelessness of a lounger, the affectation of a puppy, and the pertness of a wit, it remained with me to dictate the terms of an arrangement with some very pretty women who infested that neighborhood; but, as a hint had been given me that the pocket was the high road to their good graces, my amorous enthusiasm was a little flattered, and, as it was no part of my plan to domesticate myself in any one place, after having seen all the lions at Toledo, I started one morning with the dawn, and took the road to Cuença, intending to go to Arragon. On the second day I went into an inn which stood open to receive me by the road side. Just as I was beginning to recruit the carnal department of my nature, in came a party belonging to the Holy Brotherhood. These gentlemen called for wine, and set in for a drinking bout. Over their cups they were conning the description of a young man, whom they had orders to arrest. The spark, said one of them, is not above three and twenty: he has long black hair, is well grown, with an aquiline nose, and rides a bay horse.

I heard their talk without seeming to be a listener; and, in fact, did not trouble my head much about it. They remained in their quarters, and I pursued my journey. Scarcely had I gone a quarter of a mile, before I met a young gentleman on horseback, as personable as need be, and mounted as described by the officers. Faith and troth, thought I within myself, this is the very identical man. Black hair and an aquiline nose! One cannot help doing a good office when it comes in one's way. Sir, said I, give me leave to ask you whether you have not some disagreeable business on your hands? The young man, without returning any answer, looked at me from head to foot, and seemed startled at my question. I assured him it was not wanton curiosity that induced me to address him. He was satisfied of that when I related all I had heard at the inn. My unknown benefactor, said he, I will not deny to you that I have reason to believe myself actually the person of whom the officers are in quest; therefore I shall take another road to avoid them. In my opinion, answered I, it would be better to look out for a spot where you may be in safety, and under shelter from a storm which is brewing, and will soon pour down upon our heads. Without loss of time we discovered and made for a row of trees, forming a natural avenue, which led us to the foot of a mountain, where we found a hermitage.

There was a large and deep grotto which time had worn away into the heart of the rock; and the hand of man had added a rude front built of pebbles and shell-work, covered all over with turf. The adjacent grounds were strewed with a thousand sorts of flowers, which scattered their perfume; and one was pleased to see, hard by the grotto, a small fissure in the mountain, whence a spring rippled with a tinkling noise, and poured its pellucid stream along the meadow. At the entrance of this solitary abode stood a venerable hermit, seemingly weighed down with years. He supported himself with one hand upon a staff, and held a rosary of large beads with the other, composed of at least twenty rows. His head was almost lost in a brown woollen cap with long ears; and his beard, whiter than snow, swept down in aged majesty to his waist. We advanced towards him. Father, said I, is it your pleasure to allow us shelter from the threatening storm? Come in, my sons, replied the hermit, after examining me attentively; this hermitage is at your service, to occupy it during pleasure. As for your horse, added he, pointing to the court-yard of his mansion, he will be very well off there. My companion disposed of the animal accordingly, and we followed the old man into the grotto.

No sooner had we got in than a heavy rain fell, with a terrific storm of thunder and lightning. The hermit threw himself upon his knees before a consecrated image, fastened to the wall, and we followed the example of our host. Our devotions ceased with the subsiding of the storm; but as the rain continued, though with diminished violence, and night was not far distant, the old man said to us, My sons, you had better not pursue your journey in such weather, unless your affairs are pressing. We answered with one consent, that we had nothing to hinder us from staying there, but the fear of incommoding him; but that if there was room for us in the hermitage, we would thank him for a night's lodging. You may have it without inconvenience, answered the hermit, at least the inconvenience will be all your own. Your accommodation will be rough, and your meal such as a recluse has to offer.

With this cordial welcome to a homely board, the holy personage seated us at a little table, and set before us a few vegetables, a crust of bread, and a pitcher of water. My sons, resumed he, you behold my ordinary fare, but to-day I will make a feast in hospitality towards you. So saying, he fetched a little cheese and some nuts, which he threw down upon the table. The young man, whose appetite was not keen, felt but little tempted by his entertainment. I perceive, said the hermit to him, that you are accustomed to better tables than mine, or rather that sensuality has vitiated your natural relish. I have been in the world like you. The utmost ingenuity of the culinary art, whether to stimulate or soothe the palate, was exerted by turns for my gratification. But since I have lived in solitude, my taste has recovered its simplicity. Now, vegetables, fruit, and milk, are my greatest dainties; in a word, I keep an antediluvian table.

While he was haranguing after this fashion, the young man fell into a deep musing. The hermit was aware of his inattention. My son, said he, something weighs upon your spirits. May we not be informed what disturbs you? Open your heart to me. Curiosity is not my motive for questioning you, but charity, and a desire to be of service. I am at a time of life to give advice, and you perhaps are under circumstances to stand in need of it. Yes, father, replied the gentleman with a sigh, I doubtless do stand in need of it, and will follow yours, since you are so good as to offer it; I cannot suppose there is any risk in unbosoming myself to a man like you. No, my son, said the old man, you have nothing to fear, it is under more stately roofs that confidences are betrayed. On this assurance the cavalier began his story.

THE HISTORY OF DON ALPHONSO AND THE FAIR SERAPHINA.

I will attempt no disguise from you, my venerable friend, nor from this gentleman who completes my audience. After the generosity of his conduct towards me, I should be in the wrong to distrust him. You shall know my misfortunes from their beginning. I am a native of Madrid, and came into the world mysteriously. An officer of the German guard, Baron Steinbach by name, returning home one evening, espied a bundle of fair linen at the foot of his staircase. He took it up and carried it to his wife's apartment, where it turned out to be a new-born infant, wrapped up in very handsome swaddling-clothes, with a note containing an assurance that it belonged to persons of condition, who would come forward and own it at some future period; and the further information that it had been baptized by the name of Alphonso. I was that unfortunate stranger in the world, and this is all that I know about myself. Whether honor or profligacy was the motive of the exposure, the helpless child was equally the victim; whether my unhappy mother wanted to get rid of me, to conceal an habitual course of scandalous amours, or whether she had made a single deviation from the path of virtue with a faithless lover, and had been obliged to protect her fame at the expense of nature and the maternal feelings.

However this might be, the baron and his wife were touched by my destitute condition, and resolved, as they had no children of their own, to bring me up under the name of Don Alphonso. As I grew in years and stature their attachment to me strengthened. My manners, genteel before strangers and affectionate towards them, were the theme of their fondest panegyric. In short, they loved me as if I had been their own. Masters of every description were provided for me. My education became their leading object; and far from waiting impatiently till my parents should come forward, they seemed, on the contrary, to wish that my birth might always remain a mystery. As soon as the Baron thought me old enough to bear arms, he sent me into the service. With my ensign's commission, a genteel and suitable equipment was provided for me; and, the more effectually to animate me in the career of glory, my patron pointed out that the path of honor was open to every adventurer, and that the renown of a warrior would be so much the more creditable to me, as I should owe it to none but myself. At the same time he laid open to me the circumstances of my birth, which he had hitherto concealed. As I had passed for his son in Madrid, and had actually thought myself so, it must be owned that this communication gave me some uneasiness. I could not then, nor can I even now, think of it without a sense of shame. In proportion as the innate feelings of a gentleman bear testimony to the birth of one, am I mortified at being rejected and renounced by the unnatural authors of my being.

I went to serve in the Low Countries, but peace was concluded in a short time; and Spain finding herself without assailants, though not without assassins, I returned to Madrid, where I received fresh marks of affection from the Baron and his wife. Rather more than two months after my return, a little page came into my room one morning, and presented me with a note couched nearly in the following terms: "I am neither ugly nor crooked, and yet you often see me at my window without the tribute of a glance. This conduct is little in unison with the spirit of your physiognomy, and so far stings me to revenge that I will make you love me if possible."

On the perusal of this epistle, there could be no doubt but it came from a widow, by name Leonora, who lived opposite our house, and had the character of a very great coquette. Hereupon I examined my little messenger, who had a mind to be on the reserve at first, but a ducat in hand opened the flood-gates of his intelligence. He even took charge of an answer to his mistress, confessing my guilt, and intimating that its punishment was far advanced.

I was not insensible to a conquest even of this kind. For the rest of the day, home and my window-seat were the grand attraction; and the lady seemed to have fallen in love with her window-seat too. I made signals. She returned them; and on the very next day sent me word by her little Mercury, that if I would be in the street on the following night between eleven and twelve, I might converse with her at a window on the ground floor. Though I did not feel myself very much captivated by so coming on a kind of widow, it was impossible not to send such an answer as if I was; and a sort of amorous curiosity made me as impatient as if I had really been in love. In the dusk of the evening, I went sauntering up and down the Prado till the hour of assignation. Before I could get to my appointment, a man mounted on a fine horse alighted near me, and coming up with a peremptory air, Sir, said he, are not you the son of Baron Steinbach? I answered in the affirmative. You are the person then, resumed he, who were to meet Leonora at her window to-night? I have seen her letters and your answers; her page has put them into my hands, and I have followed you this evening from your own house hither, to let you know you have a rival whose pride is not a little wounded at a competition with yourself in an affair of the heart. It would be unnecessary to say more. We are in a retired place; let us therefore draw, unless, to avoid the chastisement in store for you, you will give me your word to break off all connection with Leonora. Sacrifice in my favor all your hopes and interest, or your life must be the forfeit. It had been better, said I, to have insured my generosity by good manners, than to extort my compliance by menaces. I might have granted to your request what I must refuse to this insolent demand.

Don Alphonso and Baron Steinbach

Well then, resumed he, tying up his horse and preparing for the encounter, let us settle our dispute like men. Little could a person of my condition have stomached the debasement of a request, to a man of your quality. Nine out of ten in my rank would, under such circumstances, have taken their revenge on terms of less honor but more safety. I felt myself exasperated at this last insinuation, so that, seeing he had already drawn his sword, mine did not linger in the scabbard. We fell on one another with so much fury, that the engagement did not last long. Whether his attack was made with too much heat, or my skill in fencing was superior, he soon received a mortal wound. He staggered, and dropped dead upon the spot. In such a situation, having no alternative but an immediate escape, I mounted the horse of my antagonist, and went off in the direction of Toledo. There was no venturing to return to Baron Steinbach's, since, besides the danger of the attempt, the narrative of my adventure from my own mouth would only afflict him the more, so that nothing was so eligible as an immediate decampment from Madrid.

Chewing the cud of my own melancholy reflection, I travelled onwards the remainder of the night and all the next morning. But about noon it became necessary to stop, both for the sake of my horse and to avoid the insupportable fierceness of the mid-day heat. I staid in a village till sunset, and then, intending to reach Toledo without drawing bit, went on my way. I had already got two leagues beyond Illescas, when, about midnight, a storm like that of to-day overtook me as I was jogging along the road. There was a garden wall at some little distance, and I rode up to it. For want of any more commodious shelter, my horse's station and my own were arranged, as comfortably as circumstances would admit, near the door of a summer-house at the end of the wall, with a balcony over it. Leaning against the door, I discovered it to be open, owing, as I thought, to the negligence of the servants. Having dismounted, less from curiosity than for the sake of a better standing, as the rain had been very troublesome under the balcony, I went into the lower part of the summer-house, leading my horse by the bridle.

My amusement during the storm was in reconnoitring my quarters; and though I had nothing to form an opinion by, but the lurid gleams of the lightning, it was very evident that such a house must belong to some family above the common. I was waiting anxiously till the rain abated, to set forward again on my journey; but a great light at a distance made me change my purpose. Leaving my horse in the summer-house, with the precaution of fastening the door, I made for the light, in the assurance that they were not all gone to bed in the house, and with the intention of requesting a lodging for the night. After crossing several walks, I came to a saloon, and here, too, the door was left open. On my entrance, from the magnificence so handsomely displayed by the light of a fine crystal lustre, it was easy to conclude that this must be the residence of some illustrious nobleman. The pavement was of marble, the wainscot richly carved and gilt, the proportions of architecture tastefully preserved, and the ceiling evidently adorned by the masterpieces of the first artists in fresco. But what particularly engaged my attention, was a great number of busts, and those of Spanish heroes, supported on jasper pedestals, and ranged round the saloon. There was opportunity enough for examining all this splendor, since there was not even a foot-fall, nor the shadow of any one gliding along the passage, though my ears and eyes were incessantly on the watch for some inhabitant of this fairy desert.

On one side of the saloon there was a door ajar; by pushing it a little wider open, I discovered a range of apartments, with a light only in the farthest. What is to be done now? thought I within myself. Shall I go back, or take the liberty of marching forward, even to that chamber? To be sure, it was obvious that the most prudent step would be to make good my retreat; but curiosity was not to be repelled, or rather, to speak more truly, my star was in its ascendant. Advancing boldly from room to room, at length I reached that where the light was. It was a wax taper on a marble slab, in a magnificent candlestick. The first object that caught my eye was the gay furniture of this summer abode; but soon afterwards, casting a look towards a bed, of which the curtains were half undrawn on account of the heat, an object arrested my attention, which engrossed it with the deepest interest. A young lady, in spite of the thunderclaps which had been pealing round her, was sleeping there, motionless and undisturbed. I approached her very gently, and by the light of the taper I had seized, a complexion and features the most dazzling were submitted to my gaze. My spirits were all afloat at the discovery. A sensation of transport and delight came over me; but however my feelings might harass my own heart, my conviction of her high birth checked every presumptuous hope, and awe obtained a complete victory over desire. While I was drinking in floods of adoration at the shrine of her beauty, the goddess of my homage awoke.

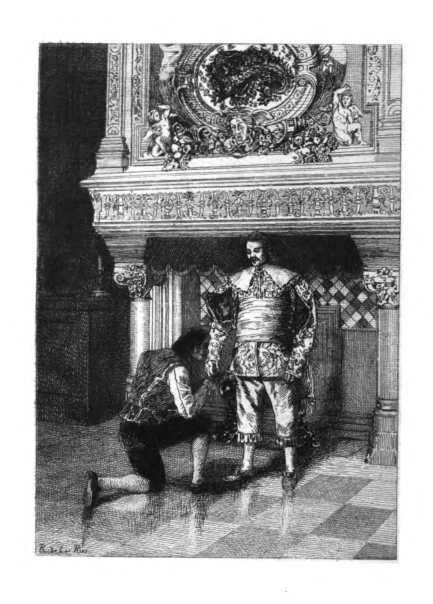

You may well suppose her consternation, at seeing a man, an utter stranger, in her bed-chamber, and at midnight. She was terrified at this strange appearance, and uttered a loud shriek. I did my best to restore her composure, and throwing myself on my knees in the humblest posture, Madam, said I, fear nothing. My business here is not to hurt you. I was going on, but her alarm was so great that she was incapable of hearing my excuses. She called her women with a most vehement importunity, and as she could get no answer, she threw over her a thin night-gown at the foot of the bed, rushed rapidly out of the room, and darted into the apartments I had crossed, still calling her female establishment about her, as well as a younger sister whom she had under her care. I looked for nothing less than a posse of strapping footmen who were likely, without hearing my defence, to execute summary justice on so audacious a culprit; but by good luck, at least for me, her cries were to no purpose; they only roused an old domestic, who would have been but a sorry knight had any ravisher or magician invaded her repose. Nevertheless, assuming somewhat of courage from his presence, she asked me haughtily who I was, by what inlet and to what purpose I had presumptuously gained admission into her house. I began then to enter on my exculpation, and had no sooner declared that the open door of the summer-house in the garden had invited my entrance, than she exclaimed, as if thunderstruck, Just heaven! what an idea darts across my mind!

As she uttered these words, she caught at the wax light on the table; then ran through all the apartments one after another, without finding either her attendants or her sister. She remarked, too, that all their personals and wardrobe were carried off. With such a comment on her hasty suspicions, she came up to me, and said, in the hurried accent of suspense and perturbation, Traitor! add not hypocrisy to your other crimes. Chance has not brought you hither. You are in the train of Don Ferdinand de Leyva, and are an accomplice in his guilt. But hope not to escape; there are still people enough about me to secure you. Madam, said I, do not confound me with your enemies. Don Ferdinand de Leyva is a stranger to me; I do not even know who you are. You see before you an outcast, whom an affair of honor has compelled to fly from Madrid; and I swear by whatever is most sacred among men, that had not a storm overtaken me, I should never have set my foot over your threshold. Entertain, then, a more favorable opinion of me. So far from suspecting me for an accomplice in any plot against you, believe me ready to enlist in your defence, and to revenge your wrongs. These last words, and still more the sincere tone in which they were delivered, convinced the lady of my innocence, and she seemed no longer to look on me as her enemy; but if her anger abated, it was only that her grief might sway more absolutely. She began weeping most bitterly. Her tears called forth my sympathy, and my affliction was scarcely less poignant than her own, though the cause of this contagious sorrow was still to be ascertained. Yet it was not enough to mingle my tears with hers; in my impatience to become her defender and avenger, an impulse of terrific fury came over me. Madam, exclaimed I, what outrage have you sustained? Let me know it, and your injuries are mine. Would you have me hunt out Don Ferdinand, and stab him to the heart? Only tell me on whom your justice would fall, and they shall suffer. You have only to give the word. Whatever dangers, whatever certain evils may be attendant on the execution of your orders, the unknown, whom you thought to be in league with your enemies, will brave them all in your cause.

This enraptured devotion surprised the lady, and stopped the flowing of her tears. Ah! sir, said she, forgive this suspicion, and attribute it to the blindness of my cruel fate. A nobility of sentiment like this speaks at once to the heart of Seraphina; and while it undeceives, makes me the less repine at a stranger being witness of an affront offered to my family. Yes, I own my error, and revolt not, unknown as you are, from your proffered aid. But the death of Don Ferdinand is not what I require. Well, then, madam, resumed I, of what nature are the services you would enjoin me? Sir, replied Seraphina, the ground of my complaint is this. Don Ferdinand de Leyva is enamoured of my sister Julia, whom he met with by accident at Toledo, where we for the most part reside. Three months since, he asked her in marriage of the Count de Polan, my father, who refused his consent on account of an old grudge subsisting between the families. My sister is not yet fifteen; she must have been indiscreet enough to follow the evil counsels of my woman, whom Don Ferdinand has doubtless bribed; and this daring ruffian, advertised of our being alone at our country-house, has taken the opportunity of carrying off Julia. At least I should like to know what hiding-place he has chosen to deposit her in, that my father and my brother, who have been these two months at Madrid, may take their measures accordingly. For heaven's sake, added she, give yourself the trouble of examining the neighborhood of Toledo, an act so heinous cannot escape detection, and my family will owe you a debt of everlasting gratitude. The lady was little aware how unseasonable an employment she was thrusting upon me. My escape from Castile could not be too soon effected; and yet how should such a reflection ever enter into her head, when it was completely superseded in mine by a more powerful suggestion? Delighted at finding myself important to the most lovely creature in the universe, I caught at the commission with eagerness, and promised to acquit myself of it with equal zeal and industry. In fact, I did not wait for daybreak, to go about fulfilling my engagement. A hasty leave of Seraphina gave me occasion to beg her pardon for the alarm I had caused her, and to assure her that she should speedily hear somewhat of my adventure. I went out as I came in, but so wrapped up in admiration of the lady, that it was palpable I was completely caught. My sense of this truth was the more confirmed by the eagerness with which I embarked in her cause, and by the romantic, gayly-colored bubbles which my passion blew. It struck my fancy that Seraphina, though engrossed by her affliction, had remarked the hasty birth of my love, without being displeased at the discovery. I even flattered myself that if I could furnish her with any certain intelligence of her sister, and the business should terminate in any degree to her satisfaction, my part in it would be remembered to my advantage.

Don Alphonso broke the thread of his discourse at this passage, and said to our aged host, I beg your pardon, father, if the fulness of my passion should lead me to dilate too long upon particulars, wearisome and uninteresting to a stranger. No, my son, replied the hermit, such particulars are not wearisome: I am interested to know the state and progress of your passion for the young lady you are speaking of; my counsels will be influenced by the minute detail you are giving me.

With my fancy heated by these seductive images, resumed the young man, I was two days hunting after Julia's ravisher: but in vain were all the inquiries that could be made; by no means I could devise was the least trace of him to be discovered. Deeply mortified at the unsuccessful issue of my search, I bent my steps back to Seraphina, whom I pictured to myself as overwhelmed with uneasiness. Yet she was in better spirits than might have been expected. She informed me that her success had been better than mine; for she had learned how her sister was disposed of. She had received a letter from Don Ferdinand himself, importing that after being privately married to Julia, he had placed her in a convent at Toledo. I have sent his letter to my father, pursued Seraphina; I hope the affair may be adjusted amicably, and that a solemn marriage will soon extinguish the feuds which have so long kept our respective families at variance.

When the lady had thus informed me of her sister's fate, she began making an apology for the trouble she had given me, as well as the danger into which she might imprudently have thrown me, by engaging my services in pursuit of a ravisher, without recollecting what I had told her, that an affair of honor had been the occasion of my flight. Her excuses were couched in such flattering terms, as to convert her very oversight into an obligation. As rest was desirable for me after my journey, she conducted me into the saloon, where we sat down together. She wore an undress gown of white taffety with black stripes, and a little hat of the same materials with black feathers; which gave me reason to suppose that she might be a widow. But she looked so young, that I scarcely knew what to think of it.

If I was all impatient to get at her history, she was not less so to know who I was. She besought me to acquaint her with my name, not doubting, as she kindly expressed it, by my noble air, and still more by the generous pity which had made me enter so warmly into her interests, that I belonged to some considerable family. The question was not a little perplexing. My color came and went, my agitation was extreme: and I must own that, with less repugnance to the meanness of a falsehood than to the acknowledgment of a disgraceful truth, I answered that I was the son of Baron Steinbach, an officer of the German guard. Tell me, likewise, resumed the lady, why you left Madrid. Before you answer my question, I will insure you all my father's credit, as well as that of my brother Don Gaspard. It is the least mark of gratitude I can bestow on a gentleman who, for my service, has neglected the preservation even of his own life. Without further hesitation, I acquainted her with all the circumstances of my rencounter: she laid the whole blame on my deceased antagonist, and engaged to interest all her family in my favor.

When I had satisfied her curiosity, it seemed not unreasonable to plead in favor of my own. I inquired whether she was maid, wife, or widow. It is three years, answered she, since my father made me marry Don Diego de Lara; and I have been a widow these fifteen months. Madam, said I, by what misfortune were your wedded joys so soon interrupted? I am going to inform you, sir, resumed the lady, in return for the confidence you have reposed in me.

Don Diego de Lara was a very elegant and accomplished gentleman: but, though his affection for me was extreme, and every day was witness to some attempt at giving me pleasure, such as the most impassioned and most tender lover puts in practice to win the smile of her he loves; though he had a thousand estimable qualities, my heart was untouched by all his merit. Love is not always the offspring either of assiduity or desert. Alas! we are often captivated at first sight by we know not whom, nor why, nor how. To love, then, was not in my power. More disconcerted than gratified by his repeated offices of tenderness, which I received with a forced courtesy, but without real pleasure, if I accused myself in secret of ingratitude, I still thought myself an object as much of pity as of censure. To his unhappiness and my own, his delicacy more than kept pace with his affection. Not an action or a speech of mine, but he unravelled all its hidden motives, and fathomed all my thoughts, almost before they arose. The inmost recesses of my heart were laid open to his penetration. He complained without ceasing of my indifference; and esteemed himself only so much the more unfortunate in not being able to please me, as he was well assured that no rival stood in his way; for I was scarcely sixteen years old; and, before he paid his addresses to me, he had tampered with my woman, who had assured him that no one had hitherto attracted my attention. Yes, Seraphina, he would often say, I could have been contented that you had preferred some other to myself, and that there were no more fatal cause of your insensibility. My attentions and your own principles would get the better of such a juvenile prepossession; but I despair of triumphing over your coldness, since your heart is impenetrable to all the love I have lavished on you. Wearied with the repetition of the same strain, I told him that instead of disturbing his repose and mine by this excess of delicacy, he would do better in trusting to the effects of time. In fact, at my age, I could not be expected to enter into the refinements of so sentimental a passion; and Don Diego should have waited, as I warned him, for a riper period and more staid reflection. But, finding that a whole year had elapsed, and that he was no forwarder in my favor than on the first day, he lost all patience, or rather, his brain became distracted. Affecting to have important business at court, he took his leave, and went to serve as a volunteer in the Low Countries; where he soon found in the chances of war what he went to seek, the termination of his sufferings and of his life.

After the lady had finished her recital, her husband's uncommon character became the topic of our discourse. We were interrupted by the arrival of a courier, charged with a letter for Seraphina from the Count de Polan. She begged my permission to read it; and as she went on, I observed her to grow pale, and to become dreadfully agitated. When she had finished, she raised her eyes upward, heaved a long sigh, and her face was in a moment bathed with her tears. Her sorrow sat heavily on my feelings. My spirits were greatly disturbed; and, as if it were a forewarning of the blow impending over my head, a death-like shudder crept through my frame, and my faculties were all benumbed. Madam, said I, in accents half choked with apprehension, may I ask of what dire events that letter brings the tidings? Take it, sir, answered Seraphina most dolefully, while she held out the letter to me. Read for yourself what my father has written. Alas! you are but too deeply concerned in the contents.

At these words, which made my blood run cold, I took the letter with a trembling hand, and found in it the following intelligence: "Your brother, Don Gaspard, fought yesterday at the Prado. He received a small sword wound, of which he died this day; and declared before he breathed his last that his antagonist was the son of Baron Steinbach, an officer of the German guard. As misfortunes never come alone, the murderer has eluded my vengeance by flight; but wherever he may have concealed himself, no pains shall be spared to hunt him out. I am going to write to the magistrates all round the country, who will not fail to take him into custody, if he passes through any of the towns in their jurisdiction, and by the notices I am going to circulate, I hope to cut off his retreat in the country or at the seaports.—THE COUNT DE POLAN."

Conceive into what a ferment this letter threw all my thoughts. I remained for some moments motionless and without the power of speech. In the midst of my confusion, I too plainly saw the destructive bearing of Don Gaspard's death on the passion I had imbibed. My despair was unbounded at the thought. I threw myself at Seraphina's feet, and offering her my naked sword, Madam, said I, spare the Count de Polan the necessity of seeking farther for a man who might possibly withdraw himself from his resentment. Be yourself the avenger of your brother: offer up his murderer as the victim of your own hand: now, strike the blow. Let this very weapon, which terminated his life, cut short the sad remnant of his adversary's days. Sir, answered Seraphina, a little softened by my behavior, I loved Don Gaspard, so that though you killed him in fair and manly hostility, and though he brought his death upon himself, you may rest assured that I take up my father's quarrel. Yes, Don Alphonso, I am your decided enemy, and will do against you all that the ties of blood and friendship require at my hands. But I will not take advantage of your evil star: in vain has it delivered you into my grasp: if honor arms me against you, the same sentiment forbids to pursue a cowardly revenge. The rights of hospitality must be inviolable, and I will not repay such service as you have rendered me with the treachery of an assassin. Fly! make your escape, if you can, from our pursuit and from the rigor of the laws, and save your forfeit life from the dangers that beset it.