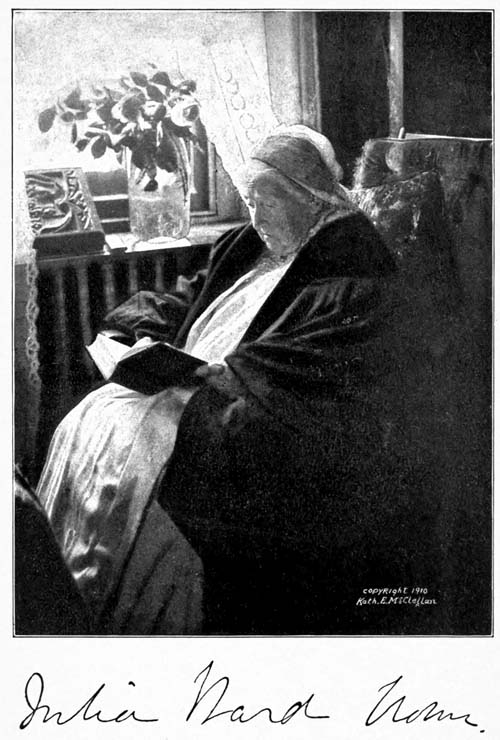

Julia Ward Howe.

From her last photograph, taken at Smith College a fortnight before her death

BY

FLORENCE HOWE HALL

DAUGHTER OF JULIA WARD HOWE

HARPER & BROTHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Story of the Battle Hymn of the Republic

Copyright, 1916, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

Published October, 1916

The author wishes to express her cordial thanks to Messrs. Houghton & Mifflin for their courtesy in allowing her to quote a number of passages from the Reminiscences of Julia Ward Howe (published by them in 1899) and several from Julia Ward Howe (published by them in 1916).

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Anti-slavery Prelude to the Great Tragedy of the Civil War | 3 |

| II. | The Crime against Kansas | 21 |

| III. | Mrs. Howe Visits the Army of the Potomac | 38 |

| IV. | “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” | 49 |

| V. | The Army Takes It Up | 64 |

| VI. | Notable Occasions Where It Has Been Sung | 73 |

| VII. | How and Where the Author Recited It | 88 |

| VIII. | Tributes to “The Battle Hymn” | 96 |

| IX. | Mrs. Howe’s Lesser Poems of the Civil War | 107 |

| X. | Mrs. Howe’s Love of Freedom an Inheritance | 121 |

THE STORY OF

“THE BATTLE HYMN OF

THE REPUBLIC”

The encroachments of the slave power on Northern soil—Green Peace, the home of Julia Ward Howe, a center of anti-slavery activity—She assists her husband, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, in editing the Commonwealth—He is made chairman of the Vigilance Committee—Slave concealed at Green Peace—Charles Sumner is struck down in the United States Senate.

THE “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “the crimson flower of battle,” bloomed in a single night. It sprang from the very soil of the conflict, in the midst of the Civil War. Yet the plant which produced it was of slow growth, with roots reaching far back into the past.

In order to understand how this song of our[4] nation sprang into sudden being we must study that stormy past—the prelude of the Civil War. How greatly it affected my mother we shall see from her own record, as well as from the story of the events that touched her so nearly. My own memory of them dates back to childhood’s days. Yet they moved and stirred my soul as few things have done in a long life.

Therefore I have striven to give to the present generation some idea of the fervor and ferment, the exaltation of spirit, that prevailed at that epoch among the soldiers of a great cause, especially as I saw it in our household.

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with his heel.

So many years have elapsed since the evil monster of slavery was done to death that we sometimes forget its awful power in the middle of the last century. The fathers of the Republic believed that it would soon perish. They forbade its entrance into the Territories and were careful to make no mention of it in the Constitution.

The invention of the cotton-gin changed the whole situation. It was found that slave labor could be used with profit in the cultivation of the cotton crop. But slave labor with its wasteful[5] methods exhausted the soil. Slavery could only be made profitable by constantly increasing its area. Hence, the Southern leaders departed from the policy of the fathers of the Republic. Instead of allowing slavery to die out, they determined to make it perpetual. Instead of keeping it within the limits prescribed by the ancient law of the land, they resolved to extend it.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 gave the first extension of slavery, opening the great Territory of Missouri to the embrace of the serpent. The fugitive-slave law was signed in 1850. Before this time the return of runaway negroes had been an uncertain obligation. The new law took away from State magistrates the decision in cases of this sort and gave it to United States Commissioners. It imposed penalties on rescues and denied a jury trial to black men arrested as fugitives, thus greatly endangering the liberties of free negroes. The Dred Scott decision (see page 10), denying that negroes could be citizens, was made in 1854. In 1856 the Missouri Compromise was repealed by the Kansas and Nebraska law.[1] Additional[6] territory was thrown open to the sinister institution which now threatened to become like the great Midgard snake, holding our country in its suffocating embrace, as that creature of fable surrounded the earth. It was necessary to fling off the deadly coils of slavery if we were to endure as a free nation.

The first step was to arouse the sleeping conscience of the people. For the South was not alone in wishing there should be no interference with their “peculiar institution.” The North was long supine and dreaded any new movement that might interfere with trade and national prosperity. I can well remember my father’s pointing this out to his children, and inveighing against the selfishness of the merchants as a class. Alas! it was a Northern man, Stephen A. Douglas, who was the father of the Kansas and Nebraska bill.

“The trumpet note of Garrison” had sounded, some years before this time, the first note of anti-slavery protest. But the Garrisonian abolitionists did not seek to carry the question into politics. Indeed, they held it to be wrong to vote under the Federal Constitution, “A league with death and a covenant with hell,” as they called it. Whittier,[7] the Quaker poet, took a more practical view than his fellow-abolitionists and advocated the use of the ballot-box.

When the encroachments of the slave power began to threaten seriously free institutions throughout the country, thinking men at the North saw that the time for political action had come. There were several early organizations which preceded the formation of the Republican party—the Liberty party, Conscience Whigs, Free-soilers, as they were called. My father belonged to the two latter, and I can well remember that my elder sister and I were nicknamed at school, “Little Free-Dirters.”

The election of Charles Sumner to the United States Senate was an important victory for the anti-slavery men. Dr. Howe, as his most intimate friend, worked hard to secure it. Yet we see by my father’s letters that he groaned in spirit at the necessity of the political dickering which he hated.

Women in those days neither spoke in public nor took part in political affairs. But it may be guessed that my mother was deeply interested in all that was going on in the world of affairs, and under her own roof, too, for our house at South[8] Boston became one of the centers of activity of the anti-slavery agitation.

My father (who was some seventeen years older than his wife) well understood the power of the press. He had employed it to good effect in his work for the blind, the insane, and others. Hence he became actively interested in the management of the Commonwealth, an anti-slavery newspaper, and with my mother’s help edited it for an entire winter. They began work together every morning, he preparing the political articles, and she the literary ones. Burning words were sent forth from the quiet precincts of “Green Peace.” My mother had thus named the homestead, lying in its lovely garden, when she came there early in her married life. Little did she then dream that the repeal of the Missouri Compromise would disturb its serene repose some ten years later.

The agitation had not yet become so strong as greatly to affect the children of the household. We played about the garden as usual and knew little of the Commonwealth undertaking, save as it brought some delightful juveniles to the editorial sanctum. The little Howes highly approved of this by-product of journalism!

Our mother’s pen had been used before this time[9] to help the cause of the slave. As early as 1848 she contributed a poem to The Liberty Bell, an annual edited by Mrs. Maria Norton Chapman and sold at the anti-slavery bazars. “In my first published volume, Passion Flowers, appeared some lines ‘On the Death of the Slave Lewis,’ which were wrung from my indignant heart by a story—alas! too common in those days—of murderous outrage committed by a master against his human chattel” (Recollections of the Anti-Slavery Struggle, Julia Ward Howe).

Another method of arousing the conscience of the nation was through the public platform. My father and his friends were anxious to present the great question in a perfectly fair way. So a series of lectures was given in Tremont Temple, where the speakers were alternately the most prominent advocates of slavery at the South and its most strenuous opponents at the North. Senator Toombs, of Georgia, and General Houston, of Texas, were among the former.

It was, probably, at this lecture course that my father exercised his office as chairman in an unusual way. In those days it was the custom to open the meeting with prayer, and some of the contemporary clergymen were very long-winded.[10] Dr. Howe informed each reverend gentleman beforehand that at the end of five minutes he should pull the latter’s coat-tail. The divines were in such dread of this gentle admonition that they invariably wound up the prayer within the allotted time.

At this time no criticism of the “peculiar institution” was allowed at the South. Northerners traveling there were often asked for their opinion of it, but any unfavorable comment evoked displeasure. Indeed, a friend of ours, a Northern woman teaching in Louisiana, was called to book because in his presence she spoke of one of the slaves as a “man.” A negro, she was informed, was not a man, and must never be so called. “Boy” was the proper term to use. This was a logical inference from Judge Taney’s famous Dred Scott decision—viz., that “such persons,” i. e., negroes, “were not included among the people” in the words of the Declaration of Independence, and could not in any respect be considered as citizens. Yet, to quote Abraham Lincoln again, “Judge Curtis, in his dissenting opinion, shows that in five of the then thirteen States—to wit, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina—free negroes were voters, and in[11] proportion to their numbers had the same part in making the Constitution that the white people had.”

Events now began to move with ever-increasing rapidity. The scenes of the stirring prelude to the Civil War grew ever more stormy. Men became more and more wrought up as the relentless purpose of the Southern leaders was gradually revealed. The deadly serpent of slavery became a hydra-headed monster, striking north, east, and west. The hunting of fugitive slaves took on a sinister activity in the Northern “border” States; at the national capital the attempts to muzzle free speech culminated in the striking down of Charles Sumner in the Senate Chamber itself; in Kansas the “border ruffians” strove to inaugurate a reign of terror, and succeeded in bringing on a local conflict which was the true opening of the Civil War.

The men who combated the dragon of slavery—the Siegfrieds of that day—fought him in all these directions. In Boston Dr. Howe was among the first to organize resistance to the rendition of fugitive slaves. An escaped negro was kidnapped there in 1846. This was four years before the passage by Congress of the fugitive-slave law made[12] it the duty (!) of the Free States to return runaway negroes to slavery. My father called a meeting of protest at Faneuil Hall. He was the chief speaker and “every sentence was a sword-thrust” (T. W. Higginson’s account). I give a brief extract from his address:

“The peculiar institution which has so long been brooding over the country like an incubus has at length spread abroad its murky wings and has covered us with its benumbing shadow. It has silenced the pulpit, it has muffled the press; its influence is everywhere.... Court Street can find no way of escape for the poor slave. State Street, that drank the blood of the martyrs of liberty—State Street is deaf to the cry of the oppressed slave; the port of Boston that has been shut up by a tyrant king as the dangerous haunt of free-men—the port of Boston has been opened to the slave-trader; for God’s sake, Mr. Chairman, let us keep Faneuil Hall free!”

Charles Sumner, Wendell Phillips, and Theodore Parker also spoke. John Quincy Adams presided at the meeting.

The meeting resulted in the formation of a vigilance committee of forty, with my father as chairman. This continued its work until the[13] hunting of fugitives ceased in Boston. Secrecy necessarily characterized its proceedings. An undated note from Dr. Howe to Theodore Parker gives us a hint of them:

[2]Dear T. P.—Write me a note by bearer. Tell him merely whether I am wanted to-night; if I am he will act accordingly about bringing my wagon.

I could bring any one here and keep him secret a week and no person except Mrs. H. and myself would know it.

Yours,

Chev.[3]

This letter raises an interesting question. Were fugitives concealed, unknown to us children, in our house? It is quite possible, for both our parents could keep a secret. I remember a young white girl who was so hidden from her drunken father until other arrangements could be made for her. I remember also a negro girl, hardly more than a child, who was secreted beneath the roof of Green Peace. Her mistress had brought her to Boston as a servant. Since she was not a runaway, the provisions of the odious fugitive-slave[14] law did not apply to her. Here at least we could cry:

My father applied to the courts and in due process of time Martha was declared free—so long as she remained on Northern soil. It may be guessed that she did not care to return to the South!

The feeling of the community was strongly opposed to taking part in slave-hunts. Yankee ingenuity often found a way to escape this odious task, and yet keep within the letter of the law.

A certain United States marshal thus explained his proceedings:

“Why, I never have any trouble about runaway slaves. If I hear that one has come to Boston I just go up to Nigger Hill [a part of Joy Street] and say to them, ‘Do you know of any runaway slaves about here?’ And they never do!”

This was a somewhat unique way of giving notice to the friends of the fugitive that the officers of the law were after him.

If he could only escape over the border into free Canada he was safe. According to the English law no slave could remain such on British soil.[15] The moment he “shook the Lion’s paw” he became free. Our law in these United States is founded on the English Common Law. Alas! the pro-slavery party succeeded in overthrowing it. No wonder that Senator Toombs, of Georgia, boasted that he would call the roll of his slaves under the shadow of Bunker Hill Monument. The fugitive-slave law gave him the power to do this, and thus make our boasted freedom of the soil only an empty mockery.

The vigilance committee did its work well, and for some time no runaway slaves were captured in Boston. One poor wretch was finally caught. My mother thus describes the event:

“At last a colored fugitive, Anthony Burns by name, was captured and held subject to the demands of his owner. The day of his rendition was a memorable one in Boston. The courthouse was surrounded by chains and guarded with cannon. The streets were thronged with angry faces. Emblems of mourning hung from several business and newspaper offices. With a show of military force the fugitive was marched through the streets. No rescue was attempted at this time, although one had been planned for an earlier date. The ordinance was executed; Burns was[16] delivered to his master. But the act once consummated in broad daylight could never be repeated” (from Julia Ward Howe’s Recollections of the Anti-Slavery Struggle).

So great was the public indignation against the judge who had allowed himself to be the instrument of the Federal Government in the return of Burns to slavery that he was removed from office. Shortly afterward he left Boston and went to live in Washington.

The attempts to enforce the fugitive-slave law at the East failed, as they were bound to fail. The efforts to muzzle free speech at the national capital were more successful for a time.

The task of Charles Sumner in upholding the principles of freedom in the United States Senate was colossal. For long he stood almost alone, “A voice crying in the wilderness, make straight the paths of the Lord.” Fortunately he was endowed by nature with a commanding figure and presence and a wonderful voice that fitted him perfectly for his great task. My mother thus described him:

“He was majestic in person, habitually reserved and rather distant in manner, but sometimes unbent to a smile in which the real geniality of his soul seemed to shed itself abroad. His voice was[17] ringing and melodious, his gestures somewhat constrained, his whole manner, like his matter, weighty and full of dignity.”

As an old and intimate friend, my father sometimes urged him to greater haste in his task of combating slavery at the national capital. Thus Charles Sumner writes to him from Washington, February 1, 1854:

Dear Howe—Do not be impatient with me. I am doing all that I can. This great wickedness disturbs my sleep, my rest, my appetite. Much is to be done, of which the world knows nothing, in rallying an opposition. It has been said by others, that but for Chase and Sumner this Bill would have been rushed through at once, even without debate. Douglas himself told me that our opposition was the only sincere opposition he had to encounter. But this is not true. There are others here who are in earnest.

My longing is to rally the country against the Bill[4] and I desire to let others come forward and broaden our front.

Our Legislature ought to speak unanimously. Our people should revive the old report and resolutions of 1820.[5]

At present our first wish is delay, that the country may be aroused.

“Would that night or Blücher had come!”

God bless you always!

C. S.

[18]In the fateful spring of 1856 Dr. and Mrs. Howe were in Washington. They saw both Charles Sumner and Preston Brooks. My mother has given us pictures of the two men as she then saw them:

“Charles Sumner looked up and, seeing me in the gallery, greeted me with a smile of recognition. I shall never forget the beauty of that smile. It seemed to me to illuminate the whole precinct with a silvery radiance. There was in it all the innocence of his sweet and noble nature.”[6]

“At Willard’s Hotel I observed at a table near our own a typical Southerner of that time, handsome, but with a reckless and defiant expression of countenance which struck me unpleasantly. This was Preston Brooks, of South Carolina.”[7]

During one of his visits to the Howes, Sumner said:

“I shall soon deliver a speech in the Senate which will occasion a good deal of excitement. It will not surprise me if people leave their seats and show signs of unusual disturbance.”

My mother comments thus:

[19]

“At the moment I did not give much heed to his words, but they came back to me, not much later, with the force of prophecy. For Mr. Sumner did make this speech, and though at the moment nothing was done against him, the would-be assassin only waited for a more convenient season to spring upon his victim and to maim him for life. Choosing a moment when Mr. Sumner’s immediate friends were not in the Senate Chamber, Brooks of South Carolina, armed with a cane of india-rubber, attacked him in the rear, knocking him from his seat with one blow, and beating him about the head until he lay bleeding and senseless upon the floor. Although the partisans of the South openly applauded this deed, its cowardly brutality was really repudiated by all who had any sense of honor, without geographical distinction. The blow, fatal to Sumner’s health, was still more fatal to the cause it was meant to serve, and even to the man who dealt it. Within one year his murderous hand was paralyzed in death, and Sumner, after hanging long between life and death, stood once more erect, with the aureole of martyrdom on his brow, and with the dear-bought glory of his scars a more potent witness for the truth than ever. His place[20] in the Senate remained for a time eloquently empty.”[8]

Hon. Miles Taylor, of Louisiana, defended in the Senate the attack on Sumner. A part of his speech makes curious reading:

“If this new dogma” (the evil of slavery) “should be received by the American people with favor, it can only be when all respect for revelation ... has been utterly swept away by such a flood of irreligion and foul philosophy as never before set in.”

Border ruffians from Missouri carry Kansas elections with pistol and bowie-knife. They prevent peaceable Free State emigrants from entering the national territory—Dr. Howe carries out aid from New England—Clergymen and Sharp’s rifles—Mrs. Howe’s indignant verses—She opens the door for John Brown, the hero of the war in Kansas—Gov. Andrew, Theodore Parker, Charles Sumner—The attack on Fort Sumter—“The death-blow of slavery.”

THESE assaults by the serpent of slavery on the free institutions of the North and East were dangerous enough, yet, like other evils, they brought their own remedies with them. Such an open attack on free speech as that on Sumner was sure to be resented, while the forcible carrying-off of fugitive slaves under the shadow of old Faneuil Hall aroused a degree of wrath that even the pro-slavery leaders saw was ominous.

“The crime against Kansas” was still more alarming because it threatened to turn a free Territory into a slave State. In 1854 the Kansas and Nebraska bill had been passed, repealing the[22] Missouri Compromise and exposing a vast area of virgin soil to the encroachments of the “peculiar institution.”

The Free-soil men were speedily on the alert. During that same year of 1854 two Massachusetts colonies were sent out to Kansas, others going later.

But the leaders of the slave power had no intention of allowing men from the free States to settle peacefully in Kansas. They had repealed the Missouri Compromise with the express purpose of gaining a new slave State, and this was to be accomplished by whatever means were necessary.

It was an easy matter to send men from Missouri into the adjacent Territory of Kansas—to vote there and then to return to their homes across the Mississippi.

The New York Herald of April 20, 1855, published the following letter from a correspondent in Brunswick, Missouri:

From five to seven thousand men started from Missouri to attend the election, some to remove, but the most to return to their families, with an intention, if they liked the Territory, to make it their permanent abode at the earliest moment practicable. But they intended to vote.... Indeed, every county furnished its quota; and when they set out it[23] looked like an army.... They were armed.... Fifteen hundred wore on their hats bunches of hemp. They were resolved if a tyrant attempted to trample upon the rights of the sovereign people to hang him.

It will be noted that “the rights of the sovereign people” were to go to the ballot-box not in their own, but in another State. These “border ruffians” took possession of the polls and carried the first election with pistol and bowie-knife.

The pro-slavery leaders strove to drive out the colonists from the free States and to prevent additional emigrants from entering the Territory. A campaign of frightfulness was inaugurated—with the usual result.

Governor Geary of Kansas, although a pro-slavery official himself, wrote (Dec. 22, 1856) that he heartily despised the abolitionists, but that “The persecutions of the Free State men here were not exceeded by those of the early Christians.”

My father was deeply interested in the colonization of Kansas and in the struggle for freedom within its borders. He helped in 1854 to organize the “New England Emigrant Aid Company” which assisted parties of settlers to go to the Territory. In 1856 matters began to look very dark for the colonists from the free States. “Dr.[24] Howe was stirred to his highest activity by the news from Kansas and by the brutal assault on Charles Sumner” (F. B. Sanborn). With others he called and organized the Faneuil Hall meeting. He was made chairman of its committee, and at once sent two thousand dollars to St. Louis for use in Kansas. This prompt action had an important effect on the discouraged settlers. Soon afterward he started for Kansas to give further aid to the colonists.

“I have traversed the whole length of the State of Iowa on horseback or in a cart, sleeping in said cart or in worse lodgings, among dirty men on the floor of dirty huts. We have organized a pretty good line of communication between our base and the corps of emigrants who have now advanced into the Territory of Nebraska. Everything depends upon the success of the attempt to break through the cordon infernale which Missouri has drawn across the northern frontier of Kansas.”[9]

In another letter he writes:

The boats on the river are beset by spies and ruffians, are hauled up at various places and thoroughly searched for anti-slavery men.

[25]He thus describes the emigrants:[10]

Camp of the Emigration, Nebraska Territory,

July 29, ’56.

The emigration is indeed a noble one; sturdy, industrious, temperate, resolute men.... I wish our friends in the East could know the character and behavior of these emigrants. They are and have been for two weeks encamped out upon these vast prairies in their tents and waggons waiting patiently for the signal to move, exhausting all peaceful resources and negotiations before resorting to force.

There is no liquor in the whole camp; no smoking, no swearing, no irregularity. They drink cold water, live mostly on mush and rice and the simplest, cheapest fare. They have instruction for the little children; they have Sunday-schools, prayer-meetings, and are altogether a most sober and earnest community. Most of the loafers have dropped off. The Wisconsin company, about one hundred, give a tone to all the others. I could give you a picture of the drunken, rollicking ruffians who oppose this emigration—but you know it. Will the North allow such an emigration to be shut out of the National Territory by such brigands?

In another letter he tells us that among the emigrants were thirty-eight women and children—grandfathers and grandmothers, too, journeying with their live stock in carts drawn by oxen to the promised land.

[26]He says nothing of danger to himself, but Hon. Andrew D. White tells us that “Dr. Howe had braved death again and again while aiding the Free State men against the pro-slavery myrmidons of Kansas.”

The strength of the movement may be judged from the fact that during this year (1856) the people of Massachusetts sent one hundred thousand dollars in money, clothing, and arms to help the Free State colonists. This money did not come from the radicals only, but from “Hunkers,” as they were then called—i. e., conservative and well-to-do citizens. My father wrote: “People pay readily here for Sharp’s rifles. One lady offered me one hundred dollars the other day, and to-day a clergyman offered me one hundred dollars.”

My mother was greatly moved by these tragic events—the assault on Sumner and the civil war in Kansas. In Words for the Hour—a volume of her poems published in 1857—we find a record of her just indignation. In the “Sermon of Spring” she describes Kansas as:

This poem, which is a long one, contains a tribute to Sumner, as do also “Tremont Temple,” “The Senator’s Return,” and “An Hour in the Senate.” I give a brief extract from the last named:

[28]In the same volume are verses entitled “Slave Eloquence” and “Slave Suicide.”

How did the children of the household feel during this period of “Sturm und Drang”? To the older ones, at least, it was a most exciting time. While we did not by any means know of all that was going on, we felt very strongly the electric current of indignation that thrilled through our home, as well as the stir of action. My father early taught us to love freedom and to hate slavery. He gave us, in brief, clear outline, the story of the aggressions of the slave power. We knew of the iniquity of the Dred Scott decision before we were in our teens. Child that I was, I was greatly moved when he repeated Lowell’s well-known lines:

My father had always something of the soldier about him—a quick, active step, gallant bearing, and a voice tender, yet strong, “A voice to lead a regiment.” This was the natural consequence of his early experiences in the Greek War of Independence,[29] when he served some seven years as surgeon, soldier, and—most important of all—almoner of America’s bounty to the peaceful population. The latter would have perished of starvation save for the supplies sent out in response to Dr. Howe’s appeals to his countrymen. The greater part of his life was devoted to the healing arts of the good physician. Yet the portraits of him, taken during the tremendous struggle of the anti-slavery period, show a sternness not visible in his younger nor yet in his later days.

In her poem “A Rough Sketch” my mother described him as he seemed to her at this time:

Charles Sumner came often to Green Peace when he was in Boston. We children greatly admired him. He seemed to us, and doubtless to others, a species of superman. I can hardly think of those days without the organ accompaniment of his voice—deeper than the depths, round and full. When our friend was stricken down in the Senate, great was our youthful indignation. Many were[30] the arguments held with our mates at school and dancing-school, often the children of the “Hunker” class. They sought to justify the attack, and we replied with the testimony of an eye-witness to the scene (Henry Wilson, afterward Vice-President of the United States) and the fact that a colleague of Brooks stood, waving a pistol[11] in each hand, to prevent any interference in behalf of Sumner. We had heard about the cruel “Mochsa” with which his back was burned in the hope of cure, and we lamented his sufferings.

John A. Andrew, afterward the War Governor of the State, was another intimate of our household, a great friend of both our parents. Genial and merry, as a rule, he yet could be sternly eloquent in the denunciation of slavery.

Indeed, it was a speech of this nature which first brought him into prominence. In the Massachusetts Legislature of 1858 the most striking figure was that of Caleb Cushing. He had been Attorney-General in President Franklin Pierce’s Cabinet and was one of the ablest lawyers in the United States. When all were silent before his[31] oratory and no one felt equal to opposing this master of debate, Andrew, a young advocate, was moved, like another David, to attack his Goliath. In a speech of great eloquence he vindicated the action of the Governor and the Legislature in removing from office the judge who had sent Anthony Burns back into slavery and thus outraged the conscience of the Bay State. As a lawyer he sustained his opinion by legal precedents.

“When he took his seat there was a storm of applause. The House was wild with excitement. Some members cried for joy; others cheered, waved their handkerchiefs, and threw whatever they could find into the air.”[12]

And so, like David, he won not only the battle of the day, but the leadership of his people in the stormy times that soon followed.

When a box of copperhead snakes was sent to our beloved Governor we were again indignant. (Political opponents had not then learned to send gifts of bombs.)

From Kansas itself Martin F. Conway came to us, full of fiery zeal for the Free State cause, although born south of Mason and Dixon’s line.

[32]He later represented the young State in Congress. Samuel Downer and George L. Stearns we often saw; both were very active in the anti-slavery cause. The latter was remarkable for a very long and beautiful beard, brown and soft, like a woman’s hair and reaching to his waist.

We heard burning words about the duty of Massachusetts during these assaults of the slave power. Could she endure them, or should she not rather seek to withdraw from the Union?

These words sound strangely to us now, but it must be remembered that in the fifties we had seen our fair Bay State made an annex to slave territory. Men might well ask one another, “Can the Commonwealth of Massachusetts endure the disgrace of having slave-hunts within her borders?” “The Irrepressible Conflict” had come. When the pro-slavery leaders forced the fugitive-slave law through Congress they struck a blow at the life of the nation as deadly as that of Fort Sumter. The latter was the inevitable sequel of the former.

We saw often at Green Peace another intimate friend of our parents—Theodore Parker, the famous preacher and reformer. As he wore spectacles and was prematurely bald, he did not leave upon our childish minds the impression of grandeur[33] inseparably connected with Charles Sumner. Yet the splendid dome of his head gave evidence of his great intellect, while his blue eyes looked kindly and often merrily at us. Having no children of his own, he would have liked to adopt our youngest sister, could our parents have been persuaded to part with her.

Theodore Parker advocated the anti-slavery cause with great eloquence in the pulpit. He also belonged to my father’s vigilance committee and harbored fugitive slaves in his own home. To one couple of runaway negroes he presented a Bible and a sword—after marrying them legally—a thing not always done in the day of slavery. My father succeeded in sending away from Boston the man who attempted to carry them back to the South, and William and Ellen Croft found freedom in England.

Theodore Parker’s sermons had a powerful influence on his great congregation, of which my mother was for some time a member. In one of her tributes to him she tells us how he drew them all toward the light of a better day and prepared them also for “the war of blood and iron.”

“I found that it was by the spirit of the higher humanity that he brought his hearers into sympathy with all reforms and with the better society[34] that should ripen out of them. Freedom for black and white, opportunity for man and woman, the logic of conscience and the logic of progress—this was the discipline of his pulpit.... Before its [the Civil War’s] first trumpet blast blew his great heart had ceased to beat. But a great body of us remembered his prophecy and his strategy and might have cried, as did Walt Whitman at a later date, ‘O captain, my captain!’”[13]

Rev. James Freeman Clarke, our pastor for many years, was among those whose visits gave pleasure and inspiration as well to our household. He did not hesitate to preach anti-slavery doctrines, unpopular as they were, from his pulpit. My mother says of him at this time:

“In the agitated period which preceded the Civil War and in that which followed it he in his modest pulpit became one of the leaders, not of his own flock alone, but of the community to which he belonged. I can imagine few things more instructive and desirable than was his preaching in those troublous times, so full of unanswered question and unreconciled discord.”[14]

Her beloved minister was among those who[35] accompanied my mother on the visit to the army which inspired “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” This was written to the tune of:

“Old Ossawotamie Brown” was the true hero of the bloody little war in Kansas, where the Free State men finally prevailed, though many lives were lost. He has been called “Savior of Kansas and Liberator of the Slave.” He came at least once to Green Peace. My mother has described her meeting with him. My father had told her some time previously about a man who “seemed to intend to devote his life to the redemption of the colored race from slavery, even as Christ had willingly offered His life for the salvation of mankind.” One day he reminded her of the person so described, and added: “That man will call here this afternoon. You will receive him. His name is John Brown.”...

Later, my mother wrote of this meeting:

“At the expected time I heard the bell ring, and, on answering it, beheld a middle-aged, middle-sized man, with hair and beard of amber color streaked with gray. He looked a Puritan of the[36] Puritans, forceful, concentrated, and self-contained. We had a brief interview, of which I only remember my great gratification at meeting one of whom I had heard so good an account. I saw him once again at Dr. Howe’s office, and then heard no more of him for some time.”[15]

Elsewhere she has written apropos of his raid at Harper’s Ferry:

“None of us could exactly approve an act so revolutionary in its character, yet the great-hearted attempt enlisted our sympathies very strongly. The weeks of John Brown’s imprisonment were very sad ones, and the day of his death was one of general mourning in New England.”[16]

With the election of Lincoln we seemed to come to smoother times. We young people certainly did not realize that we were on the brink of civil war, although friends who had visited the South warned us of the preparations going on there. If there should be any struggle, it would be a brief one, people said.

Suddenly, like a flash of lightning out of a clear sky, came the firing on Sumter. My father came triumphantly into the nursery and called out to his children: “Sumter has been fired upon![37] That’s the death-blow of slavery.” Little did he or we realize how long and terrible the conflict would be. But he knew that the serpent had received its death-wound. All through the long and terrible war he cheered my mother by his unyielding belief in the ultimate success of our arms.

So the prelude ended and the greater tragedy began. The conflict of ideas, the most soul-stirring period of our history, passed into the conflict of arms. In the midst of its agony the steadfast soul of a woman saw the presage of victory and gave the message, a message never to be forgotten, to her people and to the world.

The Civil War breaks out—Dr. Howe is appointed a member of the Sanitary Commission—Mrs. Howe accompanies him to Washington—She makes her maiden speech to a Massachusetts regiment—She sees the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps—She visits the army and her carriage is involved in a military movement—She is surrounded by “Burnished rows of steel.”

“THE years between 1850 and 1857, eventful as they were, appear to me almost a period of play when compared with the time of trial which was to follow. It might have been likened to the tuning of instruments before some great musical solemnity. The theme was already suggested, but of its wild and terrible development who could have had any foreknowledge?”

In her Reminiscences my mother thus compares the Civil War and its prelude. Again she says of the former:

“Its cruel fangs fastened upon the very heart of Boston and took from us our best and bravest. From many a stately mansion father or son went[39] forth, followed by weeping, to be brought back for bitterer sorrow.”

Mercifully she was spared this last. My father was too old for military service and no longer in vigorous health, being in his sixtieth year when the war broke out; my eldest brother was just thirteen years of age. Nevertheless she was brought into close touch with the activities of the great struggle from the beginning.

On the day when the news of the attack on Fort Sumter was received Dr. Howe wrote to Governor Andrew, offering his services:

“Since they will have it so—in the name of God, Amen! Now let all the governors and chief men of the people see to it that war shall not cease until emancipation is secure. If I can be of any use, anywhere, in any capacity (save that of spy), command me.”[17]

With what swiftness the “Great War Governor of Massachusetts” acted at this time is matter of history. Two days after the President issued a call for troops, three regiments started for Washington. Massachusetts was thus the first State to come to the aid of the Union—the first, alas! to have her sons struck down and slain.

[40]Governor Andrew was glad to avail himself of Dr. Howe’s offer of aid. The latter’s early experiences in Greece made his help and counsel valuable both to the State and to the nation. Gen. Winfield Scott, Commander-in-Chief of the Army, and Governor Andrew requested him, on May 2, 1861, to make a sanitary survey of the Massachusetts troops in the field at and near the national capital. Before the end of the month the Sanitary Commission was created, Dr. Howe being one of the original members appointed by Abraham Lincoln.

Governor Andrew was almost overwhelmed with the manifold cares and duties of his office. Our house was one of the places where he took refuge when he greatly needed rest. He was obliged to give up going to church early in the war because many people followed him there, importuning him with requests of all sorts.

Thus the questions of the Civil War were brought urgently to my mother’s mind in her own home, just as those of the anti-slavery period had been a year or two before.

To quote her Reminiscences again:

“The record of our State during the war was a proud one. The repeated calls for men and for[41] money were always promptly and generously answered. And this promptness was greatly forwarded by the energy and patriotic vigilance of the Governor. I heard much of this at the time, especially from my husband, who was greatly attached to the Governor and who himself took an intense interest in all the operations of the war.... I seemed to live in and along with the war, while it was in progress, and to follow all its ups and downs, its good and ill fortune with these two brave men, Dr. Howe and Governor Andrew. Neither of them for a moment doubted the final result of the struggle, but both they and I were often very sad and much discouraged.”

Governor Andrew was often summoned to Washington. Dr. Howe’s duties as a member of the Sanitary Commission also took him there. Thus it happened that my mother went to the national capital in their company in the late autumn of 1861. Mrs. Andrew, the Governor’s wife, Rev. James Freeman Clarke, and Mr. and Mrs. Edwin P. Whipple were also of the party.

As they drew near Washington they saw ominous signs of the dangers encompassing the city. Mrs. Howe noticed little groups of armed men sitting near a fire—pickets guarding the railroad,[42] her husband told her. For the Confederate Army was not far off, the Army of the Potomac lying like a steel girdle about Washington, to protect it.

This was my mother’s first glimpse of the Union Army which later made such a deep impression upon her mind and heart. I have always fancied, though she does not say so, that some of the vivid images of the “Battle Hymn” were suggested by the scenes of this journey.

Arrived at Washington, the party established themselves at Willard’s Hotel. Evidences of the war were to be seen on all sides. Soldiers on horseback galloped about the streets, while ambulances with four horses passed by the windows and sometimes stopped before the hotel itself. Near at hand, my mother saw “The ghastly advertisement of an agency for embalming and forwarding the bodies of those who had fallen in the[43] fight or who had perished by fever.”[18] In the vicinity of this establishment was the office of the New York Herald.

Governor Andrew and Dr. Howe were busy with their official duties; indeed, the former was under such a tremendous pressure of work and care that he died soon after the close of the war. The latter “carried his restless energy and indomitable will from camp to hospital, from battle-field to bureau.” His reports and letters show how deeply he was troubled by the lack of proper sanitation among the troops.

My mother again came in touch with the Army, visiting the camps and hospitals in the company of Mr. Clarke and the Rev. William Henry Channing. It need hardly be said that these excursions were made in no spirit of idle curiosity.

In ordinary times she would not look at a cut finger if she could help it. I remember her telling us of one dreadful woman who asked to be shown the worst wound in the hospital. As a result this morbid person was so overcome with the horror of it that the surgeon was obliged to leave his patient and attend to the visitor, while she went from one fainting fit into another!

[44]Up to this time my mother had never spoken in public. It was from the Army of the Potomac that she first received the inspiration to do so. In company with her party of friends she had made “a reconnoitering expedition,” visiting, among other places, the headquarters of Col. William B. Greene, of the First Massachusetts Heavy Artillery. The colonel, who was an old friend, warmly welcomed his visitors. Soon he said to my mother, “Mrs. Howe, you must speak to my men.” What did he see in her face that prompted him to make such a startling request?

It must be remembered that in 1861 the women of our country were, with some notable exceptions, entirely unaccustomed to speaking in public. A few suffragists and anti-slavery leaders addressed audiences, but my mother had not at this time joined their ranks.

Yet she doubtless then possessed, although she did not know it, the power of thus expressing herself. Colonel Greene must have read in her face something of the emotion which poured itself out in the “Battle Hymn.” He must have known, too, that she had already written stirring verses. So he not only asked, but[45] insisted that she should address the men under his command.

“Feeling my utter inability to do this, I ran away and tried to hide myself in one of the hospital tents. Colonel Greene twice found me and brought me back to his piazza, where at last I stood and told as well as I could how glad I was to meet the brave defenders of our cause and how constantly they were in my thoughts.”[19]

I fear there is no record of this, her maiden speech.

Throughout her long life church-going was a comfort, one might almost say a delight, to her. During this visit to Washington, where the weeks brought so many sad sights, she had the pleasure of listening on Sunday to the Rev. William Henry Channing. Love of his native land induced him to leave his pulpit in England and to return to this country in her hour of darkness and danger.

My mother tells us that this nephew of the great Dr. Channing was heir to the latter’s spiritual distinction and deeply stirred by enthusiasm in a noble cause. “On Sundays his voice rang out, clear and musical as a bell, within the walls of the Unitarian church”[20]—her own church. Thus she[46] listened both in Washington and in Boston, her home city, to men who were patriots as well as priests.

As she tells the story, one sees how almost all the circumstances of her environment tended to promote her love of country and to stir the emotions of her deeply religious nature. It was by no accident that the national song which bears her name is a hymn. Written at that time and amid those surroundings, it could not have been anything else.

Among her cherished memories of this visit was an interview with Abraham Lincoln, arranged for the party by Governor Andrew. “I remember well the sad expression of Mr. Lincoln’s deep blue eyes, the only feature of his face which could be called other than plain.... The President was laboring at this time under a terrible pressure of doubt and anxiety.”[21]

The culminating event of her stay in Washington was the visit to the Army of the Potomac on the occasion of a review of troops. As the writing of the “Battle Hymn” was the immediate result of the memorable experiences of that day, I shall defer their consideration till the next chapter.

[47]I have thus sketched briefly the train of events and experiences both before and during the Civil War which led up to the composition of this national hymn. The seed had lain germinating for years—at the last it sprang suddenly into being. My mother’s mind often worked in this way. It had a strongly philosophic tendency which made her think long and study deeply. But she possessed, also, the fervor of the poet. Her mental processes were often extremely rapid, especially under the stress of strong emotion. She herself thought the quick action of her mind was due to her red-haired temperament. The two opposing characteristics of her intellect, deliberation and speed, were perhaps the result of the mixed strains of her blood inherited from English and French ancestors.

The student of her life will note a number of sudden inspirations, or visions, as we may call them. Before these we can usually trace a long period of meditation and reflection. Her peace crusade, her conversion to the cause of woman suffrage, her dream of a golden time when men and women should work together for the betterment of the world, were all of this description.

The “Battle Hymn” was the most notable of[48] these inspirations. In her Recollections of the Anti-Slavery Struggle she ascribes its composition to two causes—the religion of humanity and the passion of patriotism. The former was a plant of slow growth. In her tribute to Theodore Parker,[22] she tells us how this developed under his preaching, and how he prepared his hearers for the war of blood and iron that soon followed.

My mother had long cherished love for her country, but it burned more intensely when the war came, bursting into sudden flame after that memorable day with the soldiers.

“When the war broke out, the passion of patriotism lent its color to the religion of humanity in my own mind, as in many others, and a moment came in which I could say:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!

—and the echo which my words awoke in many hearts made me sure that many other people had seen it also.”[23]

“The crimson flower of battle blooms” in a single night—The vision in the gray morning twilight—It is written down in the half-darkness on her husband’s official paper of the U. S. Sanitary Commission—How it was published in the Atlantic Monthly and the price paid for it—The John Brown air derived from a camp-meeting hymn—The simple story in her own words.

OVER and over again, so many times that she lost count of them, was my mother asked to describe the circumstances under which she composed “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Fortunately she wrote them down, so that we are able to give “the simple story” in her own words.

The following account is taken in part from her Reminiscences and in part from the leaflet printed in honor of her seventieth birthday, May 27, 1889, by the New England Woman’s Club. She was president of this association for about forty years:

“I distinctly remember that a feeling of discouragement came over me as I drew near the city of Washington. I thought of the women of my[50] acquaintance whose sons or husbands were fighting our great battle; the women themselves serving in the hospitals or busying themselves with the work of the Sanitary Commission. My husband, as already said, was beyond the age of military service, my eldest son but a stripling; my youngest was a child of not more than two years. I could not leave my nursery to follow the march of our armies, neither had I the practical deftness which the preparing and packing of sanitary stores demanded. Something seemed to say to me, ‘You would be glad to serve, but you cannot help any one; you have nothing to give, and there is nothing for you to do.’ Yet, because of my sincere desire, a word was given me to say which did strengthen the hearts of those who fought in the field and of those who languished in prison.

“In the late autumn of the year 1861 I visited the national capital with my husband, Dr. Howe, and a party of friends, among whom were Governor and Mrs. Andrew, Mr. and Mrs. E. P. Whipple, and my dear pastor, Rev. James Freeman Clarke.

“The journey was one of vivid, even romantic, interest. We were about to see the grim Demon of War face to face, and long before we[51] reached the city his presence made itself felt in the blaze of fires along the road, where sat or stood our pickets, guarding the road on which we traveled.

“One day we drove out to attend a review of troops, appointed to take place at some distance from the city. In the carriage with me were James Freeman Clarke and Mr. and Mrs. Whipple. The day was fine, and everything promised well, but a sudden surprise on the part of the enemy interrupted the proceedings before they were well begun. A small body of our men had been surrounded and cut off from their companions, re-enforcements were sent to their assistance, and the expected pageant was necessarily given up. The troops who were to have taken part in it were ordered back to their quarters, and we also turned our horses’ heads homeward.

“For a long distance the foot soldiers nearly filled the road. They were before and behind, and we were obliged to drive very slowly. We presently began to sing some of the well-known songs of the war, and among them:

‘John Brown’s body lies a-moldering in the grave.’

This seemed to please the soldiers, who cried, ‘Good for you,’ and themselves took up the strain.[52] Mr. Clarke said to me, ‘You ought to write some new words to that tune.’ I replied that I had often wished to do so.

“In spite of the excitement of the day I went to bed and slept as usual, but awoke next morning in the gray of the early dawn, and to my astonishment found that the wished-for lines were arranging themselves in my brain. I lay quite still until the last verse had completed itself in my thoughts, then hastily arose, saying to myself, ‘I shall lose this if I don’t write it down immediately.’ I searched for a sheet of paper and an old stump of a pen which I had had the night before and began to scrawl the lines almost without looking, as I had learned to do by often scratching down verses in the darkened room where my little children were sleeping. Having completed this, I lay down again and fell asleep, but not without feeling that something of importance had happened to me.”

It will be noted that the first draft of the “Battle Hymn” was written on the back of a sheet of the letter-paper of the Sanitary Commission on which her husband was then serving. Mr. A. J. Bloor, the assistant secretary of that body, has called attention to this. His account[53] of the eventful day is given at the close of this chapter.

My mother gave the original draft of the “Battle Hymn” to her friend, Mrs. Edwin P. Whipple, “who begged it of me, years ago.” Hence below the letter-heading:

Sanitary Commission, Washington, D. C.

Treasury Building

1861

we find the inscription

WILLARD’S HOTEL

Julia W. Howe

to

Charlotte B. Whipple

The draft remained for many years in the possession of the latter, until it was sent to Messrs. Houghton & Mifflin, in order to have a facsimile made for the Reminiscences.

Mr. and Mrs. Whipple were among the familiar friends of our household in those days. The former achieved brilliant successes both as a writer and as a lecturer. He was greatly interested in the anti-slavery agitation; “His eloquent voice was raised more than once in the cause of human[54] freedom.” The younger members of our family remember him best for his ready and delightful wit. The fact that he was decidedly homely seemed to give additional point to his funny sayings. Mrs. Whipple was as handsome as her husband was plain—sweet-tempered and sympathetic, yet not wanting in firmness.

Before publishing the poem the author made a number of changes, all of which are, as I think, improvements. The last verse, which is an anticlimax, was cut out altogether.

We find from her letters that she hesitated to allow the publication of the original draft of the “Battle Hymn”[24] because it contained this final verse. She did not consider it equal to the rest of the poem.[25] After consulting other literary people, in her usual painstaking way, she decided to have the first draft published.[26] It will be noted that in the first verse “vintage” has been substituted for “wine press.” The first line of the third verse read originally,

I have read a burning gospel writ in fiery rows of steel.

[55]The later version,

I have read a fiery gospel, writ in burnished rows of steel:

brings out more clearly the image of the long lines of bayonets as they glittered in her sight on that autumn afternoon. In the fourth verse the second line was somewhat vague in the first draft,

He has waked the earth’s dull bosom with a high ecstatic beat,

The allusion was probably to the marching feet of the armed multitude. The new version,

He is sifting out the hearts of men before his judgment-seat:

is more direct and simple, hence accords better with the deeply religious tone of the poem.

In the last stanza,

In the whiteness of the lilies he was born across the sea,

now reads,

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

A number of people have asked the meaning of this line. The allusion is evidently to the lilies carried by the angel, in pictures of the annunciation to the Virgin, these flowers being the emblem of purity.

[56]The original version of the second line read,

With a glory in his bosom that shines out on you and me,

The present words,

Transfigures you and me,

give us a clearer and more beautiful image. The passion of the poem seems, indeed, to lift on high and glorify our poor humanity.

It is interesting to note that my mother associated with her husband the line,

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

Not long before her death, new buildings were erected at Watertown, Massachusetts, for the Perkins Institution for the Blind, founded and administered for more than forty years by Dr. Howe. His son-in-law, Michael Anagnos, ably continued the work during thirty more years.

When we were talking about a suitable inscription in memory of the latter, I suggested to my mother the use of this line. The answer was, “No, that is for your father.”

The original draft of the “Battle Hymn” is dated November, 1861; it was published in the Atlantic Monthly for February, 1862. The verses were[57] printed on the first page, being thus given the place of honor. According to the custom of that day, no name was signed to them. James T. Fields was then editor of the magazine. My mother consulted him with regard to a name for the poem. It was he, as I think, who christened it “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The price paid for it was five dollars. But the true price of it was a very different thing, not to be computed in terms of money. It brought its author name and fame throughout the civilized world, in addition to the love and honor of her countrymen. As she grew older and the spiritual beauty of her life and thought shone out more and more clearly, the affection in which she was held deepened into something akin to veneration.

The “Battle Hymn” soon found its way from the pages of the Atlantic Monthly into the newspapers, thence to army hymn-books and broadsides. It has been printed over and over again, in a great variety of forms, sometimes with the picture of the author, as in the Perry prints. A white silk handkerchief now in my possession bears the line,

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord

worked in red embroidery silk.

[58]My mother was called upon to copy the poem times without number. While she was very willing to write a line or even, upon occasion, a verse or two, she objected very decidedly, especially in her later years, to copying the whole poem. Always responsive to the requests of the autograph fiend, she felt that so much should not be asked of her. For it naturally took time and trouble to make the fair copy that came up to her standard. It was with some difficulty that I persuaded her to send a promised copy to Edmund Clarence Stedman, for his collection.

“But mamma, you said you would write it out for him.”

With a roguish twinkle, she replied, “Yes, but I did not say when.”

However, the verses were duly executed and sent to the banker-poet.

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” has been translated into Spanish, Italian, Armenian, and doubtless other languages. New tunes have been composed for it, but they have failed of acceptance. My mother dearly loved music and was a trained musician, hence her choice of a tune was no haphazard selection. She wrote her poem to the “John Brown” air and they cannot be divorced.

[59]I have been so fortunate as to secure from Franklin B. Sanborn an account of the origin of the words and music of the “John Brown” song. Mr. Sanborn, biographer of Thoreau, John Brown, and others, is the last survivor of the brilliant group of writers belonging to the golden age of New England literature.

Concord, Mass., 1916.

Dear Mrs. Hall—I investigated quite thoroughly the air to which the original John Brown folk song was set;...

I happened to be in Boston the day that Fletcher Webster’s regiment (the 12th Mass. Volunteers) came up from Fort Warren, landed on Long Wharf, and marched up State Street past the old State House, on their way to take the train for the Front, in the summer of 1861. As they came along, a quartette, of which Capt. Howard Jenkins, then a sergeant in this regiment, was a tenor voice, was singing something sonorous, which I had never heard. I asked my college friend Jacobsen, of Baltimore, who stood near me, “What are they singing?” He replied, “That boy on the sidewalk is selling copies.” I approached him and bought a handbill which, without the music, contained the rude words of the John Brown song, which I then heard for the first time, but listened to a thousand times afterward during the progress of the emancipating Civil War—before they were superseded by Mrs. Howe’s inspired lines, which now take their place almost everywhere.

The chorus was borne by the marching soldiers, who had[60] practised it in their drills at the Fort; indeed, it had been adapted from a camp-meeting hymn to a marching song, for which it is admirably fitted, by the bandmaster of Col. Webster’s regiment, and afterward revised by Dodworth’s military band, then the best in the country. It was this thrilling music, with its resounding religious chorus, which Mrs. Howe, in company with our Massachusetts Governor Andrew, heard near the Potomac, the next November, in the evening camps that encircled Washington.

Yours ever,

F. B. Sanborn.

The following account of Mrs. Howe’s visit to Washington and of the circumstances connected with the writing of the “Battle Hymn” was written by Mr. A. J. Bloor, assistant secretary of the U. S. Sanitary Commission:

“JULIA WARD HOWE

“It was the writer’s privilege to be introduced early in the Civil War to Julia Ward Howe, the author of ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic,’ and now, through the fullness of her days, the dean of American literature, though recognized long ago as having employed her high gift of utterance not merely as the magnet to attract to herself an advantageous celebrity, but paramountly as the instrument for the righting of[61] wrong and the amelioration of the current conditions of humanity.

“I was presented to Mrs. Howe by her husband, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, a companion of Lord Byron in aiding the Greeks to throw off the yoke of the Turks, and the philanthropist who opened the gates of hope to the famous Laura Bridgman, born blind, deaf, and dumb. Dr. Howe invented various processes by which he rescued her from her living tomb, as he subsequently did others born to similar deprivations, and he was careful to leave on record such exhaustive and clear statements as to his methods that, after his decease, the track was well illumined wherein later any well-doer for other victims in like case might open to them, through their single physical sense of touch, the doors leading to all earthly knowledge so far stored in letters....

“Dr. Howe, on the outbreak of the Civil War, consented to serve as a member of the U. S. Sanitary Commission, a volunteer organization of influential Union men, springing from a central association in New York City for the relief of the forces serving in the war, and consisting of a few Union ladies, one of whom, Miss Louisa Lee Schuyler, suggested the formation of a similar but[62] larger and wider-spread body of men, representing the Union sentiment of the whole North, into which her own society should be merged as one of—so it turned out—many branches.

“Such a body was accordingly enrolled and, with Dr. Bellows, a prominent Unitarian clergyman of the day, as its president, was appointed a commission, by President Lincoln, as a quasi Bureau of the War Department, to complement the appliances and work of the Government’s Medical Bureau and Commissariat, which, at the sudden outbreak of the war, were very deficient.

“Of this commission I was the assistant secretary, with headquarters at its central office in Washington.... On the occasion of General McClellan’s first great review of the Army of the Potomac—numbering at that time about seventy thousand men—at Upton’s Hill, in Virginia, not far from the enemy’s lines, Dr. Howe asked me to accompany him thither on horseback to see it, which I did. Mrs. Howe had preceded us, with several friends, by carriage, and it was there, in the midst of the blare and glitter and bedizened simulacra of actual and abhorrent warfare, that he did me the honor of presenting me to his wife, then known, outside her private circle, only as[63] the author of a book of charming lyrical essays; but for years since recognized, and doubtless, in the future, will be adjudged, the inspired creator of a war song which for rapt outlook, reverent mysticism, and stateliness of expression, as well as for more widely appreciated patriotic ardor, has more claim, in my estimation, to be styled a hymn than not a few that swell the pages of some of our hymnals. I have always thought it an honor even for the Sanitary Commission with all its noble work of help to the nation in its straits, and of mercy to the suffering, that Julia Ward Howe’s ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic’ should have been written on paper headed ‘U. S. Sanitary Commission,’ as may be seen by a facsimile of it in her delightful volume of reminiscences. It seems a pity that Mrs. Howe, an accomplished musical composer in private, as well as a poet in public, should not herself have set the air for her own words in that famous utterance of insight, enthusiasm, and prophecy.”

Gloom in Libby Prison, July 6, 1863—The victory of Gettysburg—Chaplain McCabe sings “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord”—Five hundred voices take up the chorus—The “Battle Hymn” at the national capital—The great throng shout, sing, and weep—Abraham Lincoln listens with a strange glory on his face—The army takes up the song.

“THE Battle Hymn of the Republic” was inspired by the tremendous issues of the war, as they were brought vividly to the poet’s mind by the sight of the Union Army.

My mother had seen all that she describes—she had been a part of the great procession of “burnished rows of steel” when her carriage was surrounded by the Army. She had heard the soldiers singing:

Old John Brown who had

Died to make men free,

whose spirit the army knew to be with them!

[65]All this sank deeply into the heart of the poet. The soul of the Army took possession of her. The song which she wrote down in the gray twilight of that autumn morning voiced the highest aspirations of the soldiers, of the whole people. Hence, when the armies of freedom heard it, they at once hailed it as their own. My mother writes in her Reminiscences:

“The poem, which was soon after published in the Atlantic Monthly, was somewhat praised on its appearance, but the vicissitudes of the war so engrossed public attention that small heed was taken of literary matters. I knew, and was content to know, that the poem soon found its way to the camps, as I heard from time to time of its being sung in chorus by the soldiers.”

This was the beginning, but the interest increased as the “Battle Hymn” became more and more widely known, until it grew to be one of the leading lyrics of the war. It was “sung, chanted, recited, and used in exhortation and prayer on the eve of battle.” “It was the word of the hour, and the Union armies marched to its swing.”

The “singing chaplain”—Rev. Charles Cardwell McCabe of the 122d Ohio Regiment of[66] Volunteers, did much to popularize this war lyric. Reading it in the Atlantic Monthly, he was so charmed with the lines that he committed them to memory before arising from his chair. A year or so later, while attending the wounded men of his regiment, after the battle of Winchester (June, 1863), he was taken prisoner and carried to Libby Prison. Here he was a living benediction to the prisoners. Deeply religious by nature and blest with a cheerful, happy disposition, he kept up the spirits of his companions, ministering alike to their bodily and spiritual needs. Thus he begged three bath-tubs for them, an inestimable treasure, even though these had to serve the needs of six hundred men. Books, too, he procured for them, for the prisoners at this time comprised a notable company of men—doctors, teachers, editors, merchants, lawyers. “We bought books when we needed bread,” the chaplain tells us.

With the music of his wonderful voice he was wont to dispel the gloom that often settled upon the inmates of the prison. Many stories are told of its power, pathos, and magnetism. Whenever the dwellers in old Libby felt depression settling upon their spirits they would call out, “Chaplain, sing us a song.” Then “The heavy load[67] that oppressed us all seemed as by magic to be lifted.”

[27]July 6, 1863, was a dark day for the prisoners. They were required to cast lots for the selection of two captains who were to be executed. These officers were taken to the dungeon below and told to prepare for death. Then the remaining men huddled together discussing the situation. The Confederate forces were marching north, and a terrible battle had been fought. Grant was striving to capture Vicksburg, the key to the Mississippi, with what result they did not know. The Richmond newspapers brought tidings of disaster to the Union armies. In startling head-lines the prisoners read: “Meade defeated at Gettysburg.” “The Northern Army fleeing to the mountains.” “Grant repulsed at Vicksburg.” “The campaign closed in disaster.”

A pall deeper and darker than death settled upon the Union prisoners. The poor, emaciated fellows broke down and cried like babies. They lost all hope. “We had not enough strength left to curse God and die,” as one of them said later.

“By and by ‘Old Ben,’ a negro servant, slipped[68] in among them under pretense of doing some work about the prison; concealed under his coat was a later edition of the paper, on which the ink was scarcely dry. He looked around upon the prostrate host, and called out, ‘Great news in de papers.’ If you have never seen a resurrection, you could not tell what happened. We sprang to our feet and snatched the papers from his hands. Some one struck a light and held aloft a dim candle. By its light we read these head-lines:

‘Lee is defeated! His pontoons are swept away! The Potomac is over its banks! The whole North is up in arms and sweeping down upon him!’

“The revulsion of feeling was almost too great to endure. The boys went crazy with joy. They saw the beginning of the end.” Chaplain McCabe sprang upon a box and began to sing:

“Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord—”

and the five hundred voices sang the chorus, “Glory, Glory, Hallelujah,” as men never sang before. The old negro rolled upon the floor in spasms of joy. I must not forget to add that the two captains were not executed, after all.

Chaplain McCabe remained in Libby Prison[69] until October, 1863, when an attack of typhoid fever nearly cost him his life. As soon as his health would permit, he resumed his labors in behalf of the Army, this time as a delegate of the United States Christian Commission. His deep religious feeling, of which patriotism was an integral part, had a great influence among the soldiers. Wherever he went he took the “Battle Hymn” with him. “He sang it to the soldiers in camp and field and hospital; he sang it in school-houses and churches; he sang it at camp-meetings, political gatherings, and the Christian Commission assemblies, and all the Northland took it up.”[28]

As he wrote the author:

“I have sung it a thousand times since and shall continue to sing it as long as I live. No hymn has ever stirred the nation’s heart like ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic.’”

I must not forget to say that the singing chaplain made excellent use of this war lyric to raise funds for the work among the soldiers. With his matchless voice he sang thousands of dollars out of the people’s pockets into the treasury of the Christian Commission.

On February 2, 1864, a meeting in the interests[70] of the Christian Commission was held in the hall of the House of Representatives at Washington. Hannibal Hamlin, Vice-President of the United States, presided. Abraham Lincoln was present, and an immense audience filled the hall. Various noted men spoke; then Chaplain McCabe made a short speech and, “by request,” sang the “Battle Hymn.” The effect on the great throng was magical. “Men and women sprang to their feet and wept and shouted and sang, as the chaplain led them in that glorious ‘Battle Hymn’; they saw Abraham Lincoln’s tear-stained face light up with a strange glory as he cried out, ‘Sing it again!’ and McCabe and all the multitude sang it again.”[29]

Doubtless many Grand Army posts have among their records stories of the inspiring influence of this song in times of trouble or danger. Such an anecdote was related at the Western home of Mrs. Caroline M. Severance, where Acker Post had been invited to meet my mother:

“Capt. Isaac Mahan affectingly described a certain march on a winter midnight through eastern Tennessee. The troops had been for days without enough clothing, without enough food.[71] They were cold and wet that stormy night, hungry, weary, discouraged, morose. But some one soldier began, in courageous tones, to sing ‘Mine eyes have seen—’ Before the phrase was finished a hundred more voices were heard about the hopeful singer. Another hundred more distant and then another followed until, far to the front and away to the rear, above the splashing tramp of the army through the mud, above the rattle of the horsemen, the rumble of the guns, the creaking of the wagons, and the shouts of the drivers, there echoed, louder and softer, as the rain and wind-gusts varied, the cheerful, dauntless invocation of the ‘Battle Hymn.’ It was heard as if a heavenly ally were descending with a song of succor, and thereafter the wet, aching marchers thought less that night of their wretched selves, thought more of their cause, their families, their country.”

Mr. A. J. Bloor, assistant secretary of the United States Sanitary Commission, has given us some vivid pictures of the soldiers as they sang the hymn:

“Time and again, around the camp-fires scattered at night over some open field, when the Army of the Potomac—or a portion of it—was on[72] the march, have I heard the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic’—generally, however, the first verse only, but in endless repetition—sung in unison by hundreds of voices—occasions more impressive than that of any oratorio sung by any musical troupe in some great assembly-room. And I remember how, one night in the small hours, returning to Washington from the front, by Government steamer up the Potomac, with a party of ‘San. Com.’ colleagues and Army officers, mostly surgeons, we found our horses awaiting us at the Seventh Street dock; and how, mounting them, we galloped all the long distance to our quarters, singing the ‘Battle Hymn’—this time the whole of it—at the top of our voices.”

By great crowds in the street after Union victories in the Civil War—On the downfall of Boss Croker—At Memorial Day celebrations from the Atlantic to the Pacific—At the Chicago convention where the General Federation of Women’s Clubs indorsed woman suffrage—At Brown University and Smith College when Mrs. Howe received the degree of LL.D.

“THE Battle Hymn of the Republic” has been sung and recited thousands of times, by all sorts of people under widely varying circumstances, yet the key-note of it is most fitly struck when men and women are lifted out of themselves by the power of strong emotion. In times of danger and of thanksgiving the “Battle Hymn” is now, as it was in the ’sixties, the fitting vehicle for the expression of national feeling. Indeed, it has been so used in other countries as well as in our own. In my mother’s journal the entry often occurs, “They sang my ‘Battle Hymn.’” Usually she makes no comment.

[74]It would, of course, be impossible and it might be tedious to rehearse all the notable occasions where this national song has been given. Yet many of them have been so full of interest as to demand a place in the story of the “Battle Hymn.” The record would be incomplete without them. I give a few which will serve as samples.

In New York City there was a good deal of disloyal sentiment during the Civil War. Here the draft riots took place in the summer of 1863, when the guns from the battle of Gettysburg were rushed to the metropolis. Here the cannon, their wheels still deeply incrusted with mud, were drawn up, a grim reminder to the rioters of the actual meaning of war. To these the sight of a uniform was odious. My husband, David Prescott Hall, then a young lad returning from a summer camping trip, was chased through the streets by some excited individuals. As he had a knapsack on his back, they mistook him for a soldier.