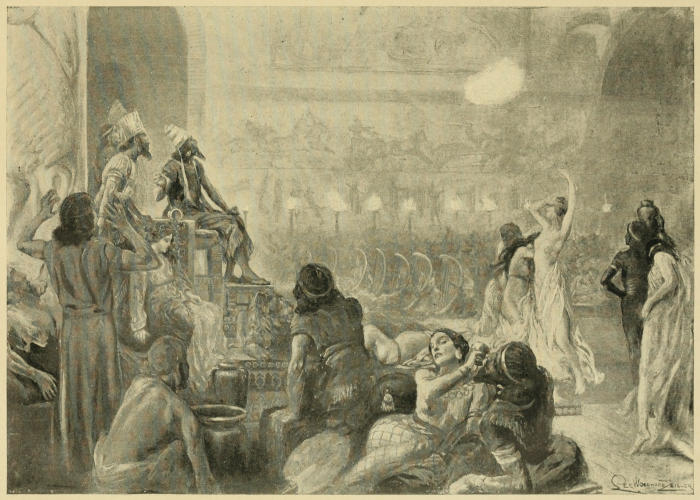

“The poet sang a marvellous song, full of all the flowery flatteries of the East, praising the princess.”

BELSHAZZAR

A TALE OF THE

FALL OF BABYLON

BY

WILLIAM STEARNS DAVIS

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

LEE WOODWARD ZIGLER

DECORATIONS BY

J.E. LAUB.

NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & CO.

1902

COPYRIGHT, 1901, 1902,

BY JOHN WANAMAKER.

COPYRIGHT, 1902,

BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY.

PUBLISHED JUNE, 1902.

NORWOOD PRESS

J. S. CUSHING & CO.—BERWICK & SMITH

NORWOOD MASS. U.S.A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Babylon the Great | 1 |

| II. | Belshazzar the King | 14 |

| III. | The Yoke of the Chaldees | 31 |

| IV. | Ruth | 48 |

| V. | The Temple of Nabu | 60 |

| VI. | The Glory of the Chaldees | 75 |

| VII. | The Spell of the Maskim | 97 |

| VIII. | The Harem of the King | 117 |

| IX. | The King of the Bow | 131 |

| X. | Bel accuses | 154 |

| XI. | Nabu defies the King | 167 |

| XII. | The Wise Gudea prospers | 181 |

| XIII. | Gudea fares on a Journey | 196 |

| XIV. | Belshazzar chooses his Path | 212 |

| XV. | Daniel delivers a Message | 229 |

| XVI. | The Procession of Bel | 245[vi] |

| XVII. | Bel totters | 264 |

| XVIII. | Avil-Marduk gives Counsel | 283 |

| XIX. | Cyrus, Father of the People | 297 |

| XX. | Belshazzar’s Guests forsake him | 310 |

| XXI. | Belshazzar pursues in Vain | 325 |

| XXII. | The King and the Father | 342 |

| XXIII. | Belshazzar secures his Prey | 354 |

| XXIV. | The Warning of Jehovah | 370 |

| XXV. | Nabu betrays Bel-Marduk | 387 |

| XXVI. | The Fulfilment of Jehovah | 397 |

| XXVII. | “Bel is dead” | 412 |

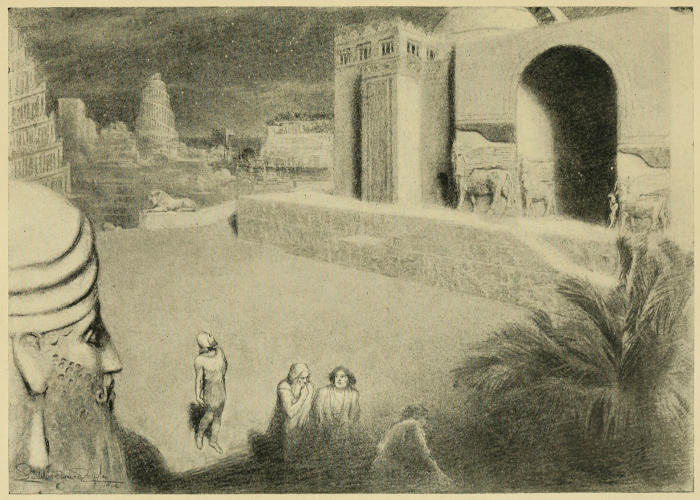

| “The poet sang a marvellous song, full of all the flowery flatteries of the East, praising the princess” (page 82) | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

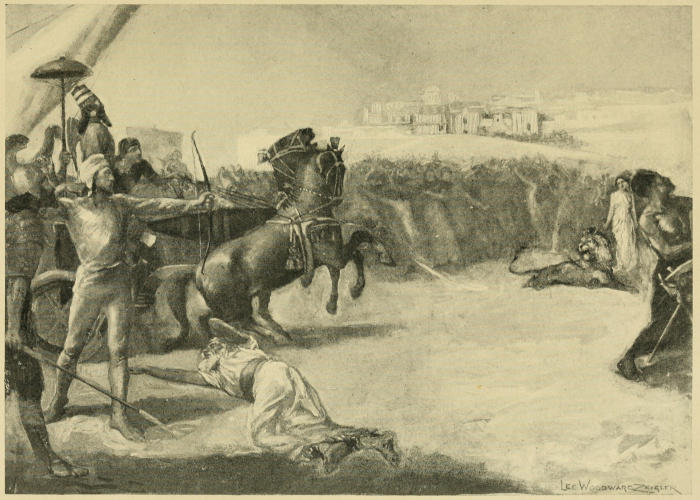

| “Darius had proved his title, ‘King of the Bow’” | 24 |

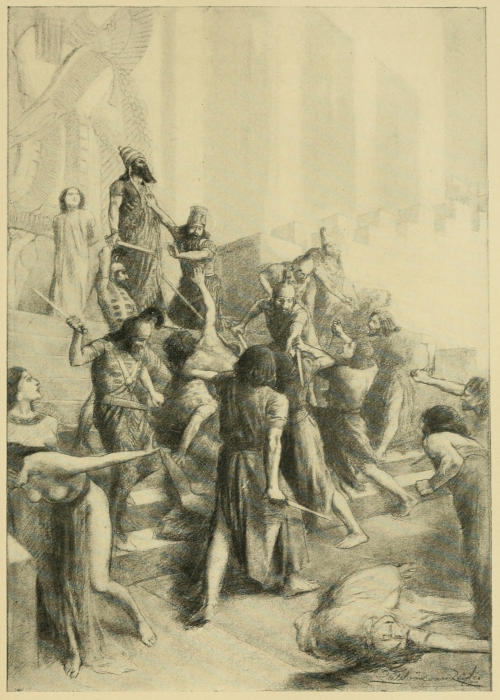

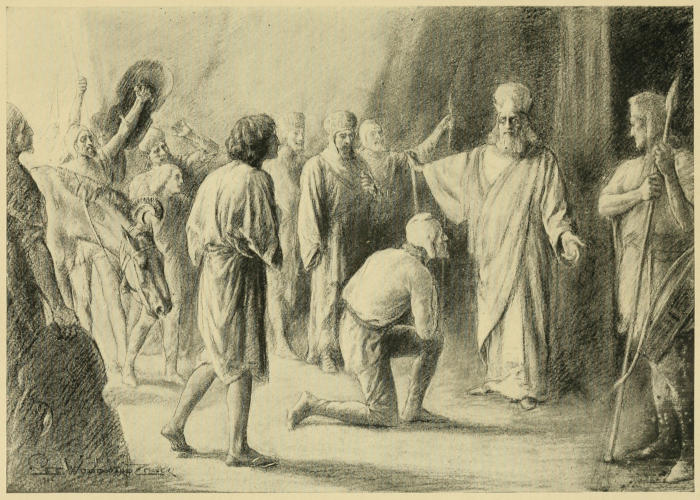

| “Isaiah plucked him roughly by the robe. ‘Make your feet wings, or I will aid you’” | 104 |

| “All the Persian’s skill could not save his horse” | 150 |

| “They did not know the lion spirit within the king, that made him as steeled against fear as against mercy” | 272 |

| “The starlight touched something that glittered—a soldier’s helmet” | 318 |

| “‘Here is only the king; within your father waits’” | 348 |

| “They saw terror flash across the king’s face as he looked upward” | 386 |

On a certain day in the month Airu, by men of after days styled April, a bireme was speeding down the river Euphrates. Her swarthy Phœnician crew were bending to the double tier of oars that rose flashing from the tawny current; while the flute-player, perched upon the upcurved prow, was piping ever quicker, hastening the stroke, and at times stopping the music to cry lustily, “Faster, and faster yet! Thirty furlongs to Babylon now, and cool Helbon wine in the king’s cellars!” Whereupon all would answer with a loud, “Ha!”; and make the bireme leap on like a very sea-horse. Under the purple awning above the poop, others were scanning the flying waves, and counting the little mud villages[2] dotting the river-banks. A monotonous landscape;—the stream, the sky, and between only a broad green ribbon, broken by clumps of tassel-like date palms and the brown thatched hamlets. Four persons were on the poop, not counting as many ebony-skinned eunuchs who squatted silently behind their masters. Just as the flute-player blew his quickest, a young man of five and twenty rose from the scarlet cushions of his cedar couch, yawned, and stretched his muscular arms.

“So we approach Babylon?” he remarked in Chaldee, though with a marked Persian accent. And Hanno the ship-captain, a wiry, intelligent Phœnician in Babylonian service, answered:—

“It is true, my Lord Darius; in another ‘double-hour’ we are inside the water-gate of Nimitti-Bel.”

The first speaker tossed his head petulantly: “Praised be Ahura the Great, this river voyage closes! I am utterly weary of this hill-less country. Surely the Chaldees have forgotten that God created green mountain slopes, and ravines, and cloud-loved summits.”

Hanno shrugged his shoulders.

“True; yet this valley is the garden of the earth. The Nile boasts no fairer vineyards nor greater yield of corn-land. He who possesses here a farm has a treasure better than a king’s. Gold is scattered; the river yields eternal riches. Four thousand years, the tablets tell, has the river been a mine of things more precious than gems. And we[3] approach Babylon, rarest casket in all this vast treasure-house.”

“All men praise Babylon!” quoth the Persian lightly, yet frowning downward.

“Yes, by Astarte! I have seen India and the Tin Isles, the chief wonders of the world. Yet my heart beats quicker now. A hundred strokes brings us to the first view of the mistress of cities.”

But Darius did not answer—only scowled in silence at the foam-eddy under the flying stern. As he stood, a stranger could have noted that his tight leathern dress set off a figure short, but supple as a roe’s, with the muscles of a leopard. Fire sparkled in his steel-blue eyes; the smile on his lips, from under his curling, fair beard, was frank and winsome. His crisp blond hair and high forehead were pressed by a gray felt cap, and upon his untanned jacket hung his sole ornament, a belt of gold chains, whence dangled a short sword in an agate sheath. Here was a man of power, the first glance told.

After no short silence the young man turned to his companions. Upon one of the couches lounged a handsome elderly nobleman, dressed in a flowing white and purple robe, and with a felt cap like Darius’s; on the next a lady, clad also in the loose “Median” mantle, beneath which peeped low boots of crimson leather. But her face and shoulders were quite hidden by an Indian muslin veil. Without speaking, Darius stood beside her for so long a time[4] that she broke the silence in their own musical Persian:—

“My prince, you grow dumb as a mute. Does this piping desert breeze waft all your thoughts after it? By Mithra! Pharnaces”—with a nod to the old nobleman—“has been a wittier travelling companion.”

And, as if to gain a better view, the lady lowered the veil, showing a face very white, save as the blood of health crimsoned behind it, and deep-blue eyes, and hair bound by a gold circlet, though not more golden than the unruly tresses it confined. The lines of her face were soft; but despite the banter on her lips none was in her eyes. Upon her breast burned a single great topaz, such as only kings’ daughters wear.

There was no levity in Darius’s voice when he answered:—

“Princess Atossa, you do well to mock me. Let Ahura grant forgetfulness of that night in the gardens at Ecbatana, when we stood together, and heard the thrushes sing and the fountains tinkle, and said that which He alone may hear. And now we near Babylon, where Belshazzar will hail you as his bride. In Babylon they will proclaim you ‘Lady of the Chaldees,’ and I Darius, son of Hystaspes, must obey Cyrus, your father—must deliver you up, as pledge of peace betwixt Persia and Babylon; must sit at your marriage feast”—with a pause—“must return[5] to Susa, and forget Atossa, daughter of the Great King.”

The lady drew back the veil and answered softly: “Cyrus is King; his word is law and is right. Is he not called ‘the father of his people’?”

“Yes, verily, more a father to his people than to his friends,” was the bitter reply. “In my despair when you were promised to the Babylonian I went to him, and he professed great sorrow for us both. But ‘he were unworthy to rule if he set the joy of a daughter and a friend above the peace of his kingdom.’ Then he bade me ask any boon I wished, saving your hand; I should have it, though it be ten satrapies. And I asked this—‘to go as the envoy that should deliver you to Belshazzar.’ He resisted long, saying I made the parting more bitter; but I was steadfast. And now”—hesitating again—“we are close to Babylon.”

Atossa only looked away, and repeated, “Better to have parted in Susa! We should be learning a little how to forget.”

Darius had no answer, but Hanno, who could not hear her, cried from the steering oar, “Look, my lords and my lady! Babylon!” He was pointing southward.

The river bent sharply. Just above the topmost plumes of the palms on the promontory thus formed hung a glitter as of fire, pendent against the cloudless blue.

“Flame!” exclaimed Darius, shaken out of his black mood.

“Gold!” answered Hanno, smiling; “the crest of the queen of ziggurats, the uppermost shrine of Bel-Marduk, the greatest temple-tower of the twenty in Babylon.” And Darius, fresh from the splendours of Susa, marvelled, for he knew the wondrous shining was still a great way off.

But even without this bright day-beacon they would have known they approached the city. The shores were still level as the stream, but the palm-groves grew denser. They saw great cedars and tamarisks, blossoming shrubs, strange exotic trees in pleasant gardens, and the splendour of wide beds of flowers. Tiny canals drained away inland. The villages were larger, and beyond them scattered white-walled, rambling farm-houses. They saw dirty-fleeced sheep and long-horned kine; and presently Hanno pointed out a file of brown camels swaying along the river road—a Syrian caravan, doubtless, just safe across the great desert.

But never in her mountain home had Atossa seen a sight like that upon the river. For the Euphrates seemed turned to life. Clumsy barges loaded with cattle were working with long sweeps against the current; skiffs loaded with kitchen produce were drifting southward; and especially huge rafts, planks upborne by inflated skins, and carrying building-stone and brick, were creeping down-stream towards Babylon. In and out sculled little wicker boats,[7] mere baskets, water-tight, which bore a goodly cargo. And, as the bireme swept onward, the boatman gave many a hail of good omen. “Marduk favour you! Samas shine on you!” While others, who guessed the royal passenger, shouted, “Istar shed gladness on the great lady Atossa!”

So for the moment the young Persians forgot all cares, admiring river and land. All the time the tower of Bel shone with growing radiance. They could see its lower terraces. Around it other ziggurats, nearly as high, seemed springing into being, their cone-shaped piles of terraces glowing with the glazed brickwork,—gold, silver, scarlet, blue,—and about them rose masses of walls and buildings, stretching along the southern horizon almost as far as the eye could traverse.

Hanno stood smiling again at the wonderment of the Persians.

“Babylon the Great!” he would cry. “Babylon that endures forever!”

And truly Darius and Atossa thought his praise too faint, as they saw those ramparts springing up to heaven, worthy to be accounted the handiwork of the gods.

“Do you say now,” asked Hanno, “that the Chaldees have forgotten the hills? Elsewhere the gods make the mountains; in Babylonia men vie with the lords of heaven! You can see yonder the green feathers of the trees in the Hanging Gardens. The great Nebuchadnezzar once wedded Amytis the[8] Mede, who wept for her native uplands. In fifteen days, such was her husband’s love and might, he reared for her this mountain upon arches, and covered it with every fruit and tree. And this paradise shall be yours, O Lady Atossa!”

“Verily,” cried Darius, half bitterly, “on this earth you will enjoy the delights of Ahura’s Garo-nmana, ‘the Abode of Song.’”

But Atossa, shuddering, answered, “Not so; in Garo-nmana there is no such word as ‘farewell.’” And for a moment her eyes went back to the river. But now Hanno was thundering to his men to back water. A crimson pennant was being dipped on the staff before an ample country house by the river bank, and as the Phœnicians stroked slowly backward, a six-oared barge shot out towards the bireme. Behind the white liveries of the rowers one could see two figures sitting in the stern, and Hanno, with his hawk’s eyes, cried again, “I am not deceived. The ‘civil-minister’ Daniel and the chief of the eunuchs, Mermaza, are coming aboard, as escort of honour, before we reach the city.”

Darius appeared puzzled. “Daniel?” he asked. “That is not a Babylonian name.”

“You are right. His official name is Belteshazzar, but he is by birth a Jew; one from the petty kingdom Nebuchadnezzar destroyed. He has held very high office in these parts. All men honour him, for he is justice and faithfulness itself. The priests hate him because he clings to the worship of his native[9] god Jehovah; but the government continues him, old as he is, as ‘Rabsaris,’ the ‘civil-minister.’ His popularity strengthens the dynasty.”

“And the eunuch with him?”

The captain laughed significantly. “There must be like pretty serpents at Cyrus’s court. He was born a Greek. Men say he is soft-voiced and soft-mannered, yet with a brain sharp enough to outwit Ea, god of wisdom. But he is nothing to dread; never will dog run more obediently at your heels than will he.”

The boat was near. The two figures in the stern rose, and the elder hailed, “God favour you, Hanno! Is the Lady Atossa aboard?”

“May Baal multiply your years! She is here and the Lords Darius and Pharnaces.”

Then, while the boat drew alongside, the younger of the strangers, who was beringed and coiffured in half-feminine fashion, burst into a flowery oration, praising every god and goddess for the safety of the princess, for the sight of whose face the King Belshazzar waited impatient as the hungering lion. The need of clambering upon the bireme cut short the flow of his eloquence. Darius had only good-natured indifference for the eunuch, who was, as Hanno said, quite one of his kind—handsome, according to a vulgar mould, rouged, pomaded, and dressed in a close-fitting robe of blue, skilfully embroidered with red rosettes; gold in his ears, gold chains about his neck, gold on his white sandals;[10] the whole adorned with a smile of such imperturbable sweetness that Darius wondered if he were a god, and so removed above mortal hate and grief.

But the Jew was far otherwise. The Persians saw a man of quite seventy, yet still unbowed by his years, his hair and beard white as the wave-spray; in his dark eyes a fire; strength, candour, and wisdom written on his sharp Semitic features. His dress was the plainest—a white woollen robe that fell with hardly a fold, a simple leathern girdle, around the feet a fringe of green tassels. He was barefoot, his hair was neatly dressed, but he wore no fillet. Upon his breast hung his badge of office, a cylinder seal of carved jasper, bored through the centre for the scarlet neck-cord.

Daniel had salaamed respectfully; Mermaza brushed his purple fillet on the very deck. The salutations once over, Darius began with a question:—

“And is it true, the report we heard at Sippar, that my Lord Nabonidus, the father of my Lord Belshazzar, has been so grievously stricken with madness that he can never hope to be made whole, and that his son must rule for him, as though he were dead?”

Daniel’s answer came slowly, as if he were treading on delicate ground. “The rumour is too true. So it has pleased the All-Powerful. Nabonidus is hopelessly mad, the chiefs of the Chaldeans declare. He lies in his palace at Tema. Belshazzar has, seven[11] days since, as the saying is, ‘taken the hands of Bel,’ and become sole Lord of Babylon.”

“And I trust, with Ahura’s grace,” replied the prince formally, “soon to stand before him, and in my master’s name wish his reign all manner of prosperity.”

Then, when the ceremonies of greeting were ended, formality fled, and the talk drifted to the wonders of the approaching city.

“And was it your own villa that your boat left?” asked Darius; to which the minister answered affably: “My own. As Hanno may have told, I am by birth a Jew; yet our God has blessed me in this land of captivity. I possess a passing estate; it will be a fair marriage portion to my daughter.”

“Your daughter? Does God refuse a son?” A shiver and sigh seemed to sweep over Daniel at the question.

“I had three sons. All perished in the conspiracy when the young king Labashi-Marduk fell. They are in Abraham’s bosom. Now, in my evening, Jehovah sends me one ewe lamb, Ruth, who now waits for me in Babylon. But alas! her mother is dead.”

“Ahura pity you, good father,” protested the Persian, thrilling in sympathy; “in Persia there is no greater woe than to lack a son. You have much to mourn.”

But the other answered steadily, “And much to rejoice over.” Then, raising his head, he pointed forward.[12] “See! We are before the great water-gate of the outer wall. The king waits in his yacht inside the barrier. We are sighted from the walls; they raise flags and parade the garrison in honour of the daughter of Cyrus.”

Darius gazed not forward, but upward; for though not yet within the fortifications, the walls of brown brick lowered above his head like beetling mountains. The mast of the bireme was dwarfed as it stood against the bulwark. Steep and sheer reared the wall; a precipice, so high that Darius could well believe Hanno’s tale that the city folk boasted its height two hundred cubits. At intervals square flanking towers jutted and rose yet higher, faced with tiles of bright blue and vermilion; and behind this “rampart of the gods” rose a second, even loftier; while Daniel professed that inside of this ran still a third, not so high, yet nigh impregnable. As the current swept them nearer they saw the water-gates, ponderous cages of bronze, hung from the towers by ingenious chainwork, ready to drop in a twinkling, and seal all ingress to the “Lady of Kingdoms.”

Then, while Darius looked, suddenly the sun flashed on the armour of many soldiers pacing the airy parapets. He heard the bray of trumpets, the clangor of kettle-drums, the tinkling of harps, and soft flutes breathing; while, as the vessel sped between the guardian towers, a great shower of blossoms rained upon her deck, of rose, lily, scarlet pomegranate; and a cheer out-thundered “Hail,[13] Atossa! Hail, Queen of Akkad! Hail, Lady of Babylon!”

Daniel knelt at the princess’s feet. “My sovereign,” said he, with courtly grace, “behold your city and your slaves. We have passed the water-gate of Nimitti-Bel; before us lies the inner barrier of Imgur-Bel. Except Belshazzar order otherwise, your wish is law to all Babylon and Chaldea.”

And at sight of this might and glory, Atossa forgot for a moment her father and the love of Darius. “Yes, by Mithra!” cried she in awe, “this city is built, not by man, but by God Most High.”

But Daniel, while he rose, answered softly, as if to himself, “No, not by God. Blood and violence have builded it. And Imgur-Bel and Nimitti-Bel shall be helpless guardians when Jehovah’s will is otherwise.”

Another shout from Hanno, and Daniel cut short his soliloquy.

“My lady,” said the Jew, in a changed tone, “the royal galley comes to greet us. Prepare to meet Belshazzar.”

While Hanno’s bireme glided betwixt the portals of Nimitti-Bel, a yet more magnificent galley had been flying up-stream to meet her. On the poop, where the polished teak and ivory glittered, stood a group of officers, in array glorious as the orb of Samas. Here stood Sirusur, the Tartan, commander of the host; here Bilsandan, the Rabsaki, grand vizier; here, proudest of all, Avil-Marduk, whose gray goatskin across his shoulders proclaimed him chief priest of Bel,[1] highest pontiff of the kingdom. Tall, handsome men were they all, worthy rulers of the city of cities. But at their centre was no less a person than Belshazzar himself, sovereign lord of “Sumer and Akkad,” as myriads hailed him. The monarch sat while his ministers stood round him; yet even on his gold-plated chair Belshazzar seemed nearly as tall as they. The royal dress differed from that of the nobles’ only as the embroideries on the close-fitting robes blazed with more than common splendour, and the gems on the necklet[15] would have drained the revenues of a petty kingdom. Upon the carefully curled hair perched the royal tiara, white and blue, threaded with gold, cone-shaped, but the top slightly flattened. There was majesty and force stamped upon his aquiline features; force—and it might be passion—glittered in his dark eye, and shone from the white teeth half hid by the thick black beard. In brief, no diadem was needed to proclaim Belshazzar lord.

Avil-Marduk, a gaunt, haughty man, with a strident voice, was speaking to Sirusur, while the eunuchs behind the king flapped their ostrich fans to keep the flies away from majesty.

“I would give much,” quoth he, “to know how long Cyrus will remain blind. We must dissemble to the envoys; chatter peace. By Istar! I wish the Egyptian treaty were signed! Pharaoh’s envoy is timorous as a wild deer.”

Sirusur laughed dryly. “I have less fear. There are two envoys—Pharnaces, an old nobleman, but the chief is the young Prince Darius. They say his eyes are only for hunts and arrow-heads, after these Persian barbarians’ fashion. We will give him a great fête, and show all courtesy. He will return to Susa dazzled, and tell Cyrus that Belshazzar is friendly as his own son.”

“Nevertheless,” answered Avil, cautiously, “be guarded. The Persians forgive twelve murders sooner than one lie. If Darius dreams we ask the marriage treaty but to gain time for an Egyptian[16] alliance and war—”he broke off—“then, my gallant Tartan, you may have chance to prove your valour.”

Sirusur shrugged his shoulder. “The power of Cyrus is great. Media and Lydia were both swallowed by him; but Babylon, Bel grant, shall prove over large in his maw!”

“The ship of the princess approaches,” announced Bilsandan. And even Belshazzar arose as the vessel of Hanno swept alongside. The king stepped to the bulwarks, the purple parasol of royalty held above his head by a ready nobleman. The nimble Phœnicians lashed the two vessels together, and laid a railed gangway between. Of the Persians Atossa crossed first, followed by her eunuchs; and as she knelt at the king’s feet, she unveiled. Her face was very pale, but marvellously fair in the eyes of the Chaldeans, accustomed to the darker beauty of their own race.

Belshazzar spoke to her, his voice deep, melodious, penetrating. “Rise, daughter of Cyrus. Istar grant that the white rose of Persia shall bud with new beauty in the gardens of Chaldea!”

Atossa stood with downcast eyes. “I am content to find grace in the sight of my lord,” was all she said. Then Darius followed, bowed himself before the king, and delivered the good wishes of his master, to which Belshazzar made friendly reply. After these compliments were ended, and the Babylonians had salaamed before Atossa, Belshazzar commanded[17] the Persians to sit beside him, and affably pointed out each new building as they entered the city.

“Before us, on the left, rises the citadel of Nebuchadnezzar; yonder flashes the brass of the great Gate of Istar; beside the mighty ziggurat of Bel rises that, scarce smaller, of his consort Beltis. These brick quays on either bank extend ten furlongs, yet do not suffice for the shipping. The high walls to the right are of the royal palace, a city in itself, and the forest of the Hanging Gardens is close by. Though all the rest of Babylon were taken,” Belshazzar spoke proudly, “a host might rage against the palace in vain.”

Darius could only wonder and gaze. The quays were a forest of masts. The houses that crowded the water-front rose three and four stories high, and were flat-roofed, walled with plastered wicker brightly painted. The windows were very small, and all the buildings were closely thrust together.

“By Ahura!” cried the Persian, “do your people forget the smell of pure air?”

To which Belshazzar answered, laughing: “If one would live in Babylon, one must pay his price. Happy the man so rich as to possess a little garden in the midst of the city. As you go south, you find vineyards and country houses inside the walls.”

“Verily,” declared Darius, “better a reed hut in the forest, and good hunting, than a thousand talents and life in Babylon!”

The frankness and good nature of the Persian[18] seemed contagious. Belshazzar laughed again, heartily.

“Now, by Marduk! you will never covet my kingdom. Tell me, do you love to follow the lion?”

The prince’s eyes flashed fire. “What are the joys of Ahura’s paradise without a lion hunt before the feasting? Understand, O king, that the name men call me by in Persia is the ‘King of the Bow,’ for I boast that I have no peer in archery.”

“Then, by Nergal, lord of the hunting,” swore the monarch, “you shall face the fiercest lions and wild bulls in my preserves in the marshes! And I will learn if a Persian can conquer a king of Babylon in the chase.”

“Excellent,” exclaimed the Persian. “Babylon and Persia are at peace; they shall test their might on the lord of beasts. And if I am not Cyrus’s self, next to him there is none other of my nation that calls me vassal.”

But now the water-gate of Imgur-Bel was passed, and while on the left the cone of Bel-Marduk lifted its series of diminishing terraces to a dizzy height, on the right spread the royal palace, a vast structure, surrounded by a dense park, and all girded by a wall. On the river side the buildings closely abutted the shores, rising from a lofty brick-faced embankment, themselves of brick, but splendid with the gilding on the battlements, with the sculptured winged bulls that flanked the many portals, and the bright enamel upon the brickwork. Out of the masses of walls sprang[19] castellated towers crowned with gaudy flags, and toward the centre reared a ziggurat, the private temple of the king.

For an instant Darius was at Atossa’s side as she gazed, and no one watched them.

“This is the dwelling of Belshazzar,” said he softly, “a great king. Joy to be his wife.” But the lady shivered behind her veil.

“He is a great king, but they will never call him, like Cyrus, ‘the father of his people.’”

“You will soon forget Persia, happy as mistress in this wondrous city.”

“When I have lived ten thousand years I shall forget—perhaps.” Then she added very softly, “I am afraid of Belshazzar; his lips drop praise, his heart is cold and hard as the northern ice. I shall always dread him.”

“You wrong the king,” Darius vainly strove to speak lightly; “the ways of Babylon are not those of Persia. But there will come a day when you will feel that the Chaldees are your own people. Belshazzar is a splendid man; he will delight to honour you.”

But Atossa only held down her head, and answered in a whisper Darius might not hear.

They had no time for more. A vast multitude was upon the embankment before the palace—white-robed priests, garlanded priestesses, the glittering body-guard, all manner of city folk. A shout of welcome drifted over the river.

“Hail, King Belshazzar! Hail, Lady Atossa! May your years exceed those of Khasisadra the Ancient!” Then, amid tinkling harps, many voices raised the hymn of praise to Marduk, the conductor of the royal bride:—

The royal galley headed toward the landing. The great orchestra of eunuchs and playing-girls raised a prodigious din; yet all their music was drowned by the shoutings of the people. The staid citizens brandished their long walking-staffs, and cheered till the heavens seemed near cracking. But a large corps of the body-guard had cleared a portion of the royal quay, and the party disembarked between two files of soldiers. Close to the landing waited the chariots—the six-spoked wheels all glistening with the gilding, more gilding on the panels of the body, the pole, and the harness, and jewels and silver bells braided into the manes of the prancing bay Elamites. For Atossa was ready a four-wheeled coach, adorned as richly as the chariots, drawn by two sleek gray mules, and with a closed body, that the daughter of Cyrus might rest on her cushions within, undisturbed by the vulgar ken. Belshazzar ceremoniously waited upon the princess, till Mermaza closed the door upon her. Then the[21] king beckoned to Darius to mount one of the chariots, while he leaped himself into another. “To the palace,” was the royal command; but just as the charioteers upraised their lashes, the steeds commenced to plunge and rear almost beyond control.

Along the brick-paved terrace tugged several lumbering wains, for which great and small made way. As the wagons approached, a low rumble proceeded from them, which set all the chariot horses prancing, and the women and timid burghers uttered low cries and began to mutter incantations. The eyes of Darius commenced to sparkle. The meaning of that rumble he knew right well.

“Lions?” demanded he of his chariot-driver.

“Yes, lord,” the man answered, scarce reining the horses, “twelve bull-lions just taken, being sent to Kutha for the king’s preserves.”

The Persian’s nostrils dilated like a charger scenting battle. And as if in answer to his half-breathed prayer, lo! one of the oxen, stung by the goad and fretted by the roarings, commenced to shake his yoke, halting obstinately, and lifting a full-voiced bellow. Instantly his mates answered; the lions’ thunders doubled; the wagon-train was halted.

Belshazzar called fiercely to the chief wagoner, “Quiet instantly, or fifty stripes!”

His voice was drowned in the roar. The teams were so near now that one could look into the cages, and see the great beasts pent up behind the stout wooden bars; bars that seemed all too frail at this[22] moment, as lion after lion, frightened and enraged by the din of the oxen, the multitude, and his own fellows, began to claw at the bars, digging out huge splinters with tooth and talon, and roaring louder, ever louder.

Belshazzar’s voice sounded now above all the noise. “Clear away this rabble!” he was ordering Sirusur, “Master of the Host.” “The man who sent the lion-train this way shall face me to-night. Silence the beasts, and get off with them!”

But not the lord of Babylon and all his guards could still those oxen and their maddened freight.

Sirusur did as bidden. His men pushed on the crowd with their sword-scabbards, but truth to tell the press was so close, and the exits from the quay so cramped, the soldiers could accomplish little. The panic was spreading swiftly enough, however. The goads on the oxen had only driven them into deeper obstinacy.

“Look! In Nergal’s name, look!” cried Darius’s charioteer; and before the prince’s half-terrified, half-exulting eyes he saw the lion within the nearest cage leaping to and fro, trebly maddened now by all the growing tumult. The wagon swayed on its wheels. The wooden bars gave a crash every instant.

“Three more leaps and he is free!” the prince was shouting, transported by his excitement.

“Danger! The wagon topples!” was the howl of the people, and at last they began to give way indeed.

Sirusur, having abandoned his hopeless effort to restore order and silence, hurried men to form before the chariots, while others ran to aid the despairing drivers. Late—the unruly oxen strained their chains. Darius saw the heavy cage totter, fall—a crash, a murk of dust, a noise that thrilled the stoutest, hard wood giving way under harder talons and teeth, then a roar of triumph. Out of the dust he saw a kingly lion bounding, in all his panoply of tawny mane. As the beast leaped, drivers and soldiers sped back like leaves before a gale. The multitude was shrinking, trampling.

“The lion! The lion! Loose! Escape!”

Belshazzar’s curse was heard above all else. “Take him alive, or, by Marduk, you are all flayed!” Some guardsmen sprang forward, but the lion, crafty brute, did not fling himself against those breasts of steel. There were bowmen present, but the king stayed their arrows. “Not a shaft. Better ten killed than have him butchered!” The soldiers stood impotent, while the lion ran with low bounds straight into the helpless crowd, that recoiled as at the touch of fire. Belshazzar was in a towering rage. “Nets and hot irons from the palace!” he thundered. “Impalement to all if he escapes!”

The people were screaming, panic-struck; priests were trampling down women; the noise grew indescribable. The other lions dashed against their cages. The brute ran like a great cat down the lane opened through the multitude. A moment, and[24] he would have broken clear and ranged the streets. But from his own side Darius heard a cry of mortal fear.

“Jehovah, have mercy! Ruth! My daughter!”

In the next chariot stood Daniel, covering his face with his hands. The Persian glanced toward the lion. In the centre of the lane, before the escaping monster, stood a white-clad girl, terrified, shivering, her eyes upon the lion, fascinated by his gaze, held helpless as a dove before the snake. How she came there, what fate ordained that she alone of those thousands should be left to confront the monster, that was no time to know. But present she was, and before her the lion. The whole scene passed in less time than the telling. The beast had instantly forgotten his own perils. Keepers, soldiers, multitude, all ignored. He seemed again in his forest—fair prey! That was all he knew!

The lion sank low upon the earth, and crept by little leaps nearer, nearer. The charming fire in the eyeballs Darius saw not, but he saw the red, lolling tongue, the bristling mane, the great tail undulating at the tip, the paws fit to crush an ox. Daniel was turning away his face.

“Arrows, O king! Shoot! My only one!” pleaded he; but Belshazzar flung back, “What is a maid beside a royal lion! Too far—no bow can carry!”

“Darius had proved his title, ‘King of the Bow.’”

Many an archer’s fingers tightened around his bow, but the king’s eye was on them. Not a shaft[25] flew. There was a moment’s silence, lions and oxen hushed. A low moan seemed rising from the people. The lion had covered twenty of the thirty paces betwixt him and his prey. The maid was quaking, yet her feet seemed turned to stone. Belshazzar stood in his car, no god more splendid, more merciless.

“Pity me, O king!” was Daniel’s last appeal. He had leaped down, and grovelled as a worm before the royal car.

“Too late,” came the answer, “only Bel’s bolt now can save!” What joy to the king to see those lithe limbs in the monster’s clutch! But a great cry had broken from Darius.

“No, in the name of Ahura the merciful!” Few saw him, bounding from his chariot, pluck bow and quiver from a soldier. The lion coiled his limbs for the final leap; men saw his body spring as a stone from a catapult; heard a twitter of a bow, and right at the bound the shaft entered the shoulder, cunningly sped. A roar of dying agony, the body dashed upon the pavement at the girl’s feet. No second shaft needed—a twitch, a great bestial groan. Darius had proved his title, “King of the Bow.”

But Belshazzar, who had seen the shot but not the archer, blazed out in blind fury, “As Marduk rules, who shot? Impale him!”

Darius stepped beside the royal chariot; his pose was very haughty. “My lord,” said he, “I give proof we Persians are fair huntsmen.”

Belshazzar’s hand went to his sword-hilt, but Darius met the flame in his eyes unflinchingly. By a great effort the king controlled himself, but did not risk speech. The drivers had mastered the oxen, the lions grew still. The people were shouting in delight, “Glory to Nergal! The Persian is peer to the hero Gilgamesh!”

Daniel was kissing Darius’s shoes, his voice too choked for thanks. But a young man with a forceful, frank face, a manly form, dressed like Daniel, very simply, came and kissed, not the shoes, but the dust at Darius’s feet.

“For life I am your slave, O prince! You have saved me my betrothed!” Then he ran among the people to lead away the girl. Belshazzar ventured to speak.

“How now, Daniel?” ignoring Darius. “By Nergal, your wench has been the death of an African lion! Why here? You keep her locked at home, safe as a gold talent. I have never seen her.”

“She was with Isaiah, her betrothed. In the crowd they were swept asunder. The king saw the rest.”

Belshazzar was still raging.

“Yes, verily. A rare bull-lion sacrificed for a slip of a wench like her!” Then to the eunuchs: “Run, bring the lass to me. Rare treasure she must prove to make her more precious than the lion.”

Darius saw a fresh cloud on the old Jew’s face.[27] In a moment Isaiah and the maid were before the king. Very young and fragile seemed the Jewess. The blood had not returned to the smooth brown cheeks. Her black hair was scattered in little curls, for veil and fillet had been torn away. She looked about with great, scared eyes, and all could see her tremble. She started to kneel before the king, but Belshazzar, regarding her, gave a mighty laugh.

“Good, by Istar! So this is your treasure, Daniel? Not the Egibi bankers possess a greater, you doubtless swear. Stand up, my maid. Bel never made those eyes to stare upon that dusty road. Closer. Look at me, and I vow I will forgive you the lion. There are more in the marshes, but only one daughter of Daniel!”

“Look up, child; his Majesty bids you,” the old Hebrew was saying, but his face was very grave. Ruth raised her great eyes; her lips moved, as if in some answer, but no sound came. Belshazzar smiled down upon her from his car. Atossa was to be his queen, but when was a king of Babylon denied a maid that was pleasant to his eyes? He turned to Darius.

“Now, by every god, I thank you, Persian. I was about to curse, but your archery saved one beside whom Istar’s self must flush in shame. Well are you named ‘King of the Bow.’”

Then he gazed again upon the maid. “Mermaza,” he commanded, “put the girl in a chariot, and take her to the palace harem. Give her dresses and[28] jewels like the sun. Do you, Daniel, draw five talents from the treasury. Not enough? Ten then. Fair payment for a daughter—ha!”

Daniel was on his knees before the king. “Mercy! Hear me, my lord. If ever, by faithfulness serving you and your fathers, I gather some store of gratitude—”

Belshazzar cut him short. “Now does Anu, lord of the air, topple down heaven? What father says to a king, ‘Mercy. Give back my daughter’? Oh, presumption! No more, or you forfeit the money.”

“The money,” groaned Daniel, “the price of my daughter? Kiss the earth, Ruth; and you, Isaiah, entreat the king to forbear!”

Belshazzar turned his back. “Fool,” he cried, “the money is truly forfeit! Away with her, Mermaza. Great mercy I leave the Jew his life.”

But Darius deliberately thrust himself before the king, and looked him in the face. “My lord,” he said soberly, “if to any, the girl belongs to me. I saved her and restore her to her father.”

“You beard me thus, Persian, barbarian!” broke forth Belshazzar, again in his wrath. The prince answered him very slowly:—

“Your Majesty, in me you see the ‘eyes and ears’ of Cyrus, lord of the Aryans. What if I report in Susa, ‘On the day I delivered Atossa to Belshazzar, he, before her own eyes, showed his esteem for her by haling to his harem a maid chance sent him on[29] the streets’? Would such a tale knit the alliance firmer?”

Avil-Marduk was beside the king in the chariot, and he whispered in the royal ear, “Risk nothing. Dismiss the maid; the eunuchs can watch for her and secure her quietly.”

Belshazzar was again calm. His passion was swift; he subdued it more swiftly. “Son of Hystaspes,” said he, with easy candour, “I am a man of sudden moods. The maid pleased me; but, by Istar, I did not think to insult the princess. Let the Jews go in peace, and to heal their hurts let the treasurer weigh to each a talent. The Jewess shall sleep safe as a goddess’s image in the temple. I swear it, on the word of a king of Babylon. Enough, and now to the palace.”

Darius was received with stately hospitality at the palace. He was told the arrangements made for Belshazzar’s bride. The king would give her a great betrothal feast at the Hanging Gardens, but could not wed her for one year; for before marriage she must be taught the religious duties of a queen of Babylon. Darius paced the open terrace of the palace that evening. Below him and all about lay the city of the Chaldees, fair as a vision of heaven, with the white moon riding above the tower of Bel. But the beauty of the city brought no joy. Into the hands of what manner of man had Atossa fallen? The desire of[30] Belshazzar to sacrifice the maiden for the beast, followed by the outburst of carnal passion—how unlike this king to Cyrus, whom the meanest Persian loved! At last, when it had grown very dark, Darius looked about him. No one was near. He lifted his hands toward the starry sky.

“Verily this Babylon is a city of wickedness, and most evil of all is its cruel king. But I am young. I am strong. Belshazzar shall not possess Atossa for one year. And in that year a brave man may do much—much. Help Thou me, Ahura-Mazda, Lord God of my fathers!”

Near the meeting of the great Nana-Sakipat Street with Ai-Bur-Schabu Street stood the banking-house of the “Sons of Egibi.” The long bridge of floats across the river was close by, and in and out the portals of the wide river-gate poured a constant stream of veiled ladies, with their guardian eunuchs, intent on shopping, of donkey boys, carters, pedlers, and priests. Under the shade of the great stone bull guarding one side of the entrance, the district judge was sitting on his stool, listening to noisy litigants; from the brass founder’s shop opposite rose the clang of hammers; and under his open booth descended a stairway to Nur-Samas’s beer-house, by which many went down and few ascended, for it was hard to recollect one’s cares while over the drinking-pots.

The Egibis’ office, like all the other shops, was a room open to all comers, nearly level with the way, without door or window, but made cool by the green awning stretched across the street in front, and the shadow cast by the high houses opposite. In the office many young clerks were on their stools,[32] each busily writing on the frames of damp clay in their laps with a wedge-headed stylus. Itti-Marduk, present head of this the greatest banking-house of Babylon, was a plainly dressed, quiet-speaking man; and only the great rubies in his earrings and the rare Arabian pomade on his hair told that he could hold up his head before any lord of Chaldea saving Belshazzar himself. At this moment he was entertaining no less a client than Avil-Marduk, the chief priest, who came in company with his boon companion, the priest Neriglissor, as did all the city at one or another time, to ask an advance from the omnipotent broker. As for Itti, he was angling his fish after his manner, keeping up a constant stream of polite small talk, sending out a lad to bring perfumed water to bathe his noble guests’ feet, and yet making it plain all the while that current rates of interest were exceedingly heavy.

“Alas!” the worthy banker was bewailing, “that I must speak of shekels and manehs before friends, but what with heavy remittances I must send to agents in Erech, with the farmers all calling for funds to pay their help for the coming season, and a heavy loan to be placed by his Majesty to complete the fortifications of Borsippa, I have been put to straits to raise so much as a talent; and were you any other than yourself, my dear high priest, I fear I could do nothing for you.”

“Yet I swear by Samas,” protested the pontiff, with a wry face at the loan-contract before him,[33] “you have enough in your caskets to build us poor priests of Bel a new ziggurat.”

“A new ziggurat!” protested the banker; “am I like Ea, able to see all hidden riches? I declare to you that what with the rumour that the tribes in the southern marshes around Teredon are restless, money becomes as scarce as snow in midsummer. Ramman forbid that anything come of the report! It will wither all credit!” So at last, with many protests from Avil, the contract was signed, and stored away in a stout earthen jar, in the strong room of the cellar, where lay countless jugs of account books. And Itti, to make his guest forget that he had just bargained to pay “twelve shekels on the maneh,”[2] inquired genially if the recent taking of the omens had chanced to be fortunate. He was met by blank faces both from Avil and his chariot comrade, the toothless old “anointer of Bel,” Neriglissor.

“The omens are direful,” began the latter, in a horrified whisper.

“Hush!” admonished the chief priest, “a state secret. To breathe it on the streets would send corn to a famine price.”

The banker had pricked up his ears. “I am not curious in matters of state; Marduk forbid! Yet if in confidence I were told anything—”

Neriglissor was only too ready to begin. “The Persians,” he whispered, “the Persians! Barbarous dogs! Faugh! I sicken thinking of the strong[34] Median nard the daughter of Cyrus smeared on her hair!”

Itti smiled benevolently. “What Persian can have the delicate taste of a Babylonian? Yet you have not told the omen.”

Neriglissor’s voice sank yet lower. “These Persians are friends to the Jews, that race of blasphemers. Each nation worships the same demon, though the Jews style him Jehovah, the Persians Ahura-Mazda. Long have the pious foreseen that unless these unbelievers were kept out of Babylon the gods would be angry. Yesterday this Atossa comes to Babylon to be his Majesty’s queen. Thus we are about to strike hands with the foes of the gods, as if it were not enough to continue the old scoffer Daniel in office. And this morning follows the omen.”

Itti was bending over that not a word might escape. Neriglissor continued, “As Iln-ciya, the chief prophet, and I stood by the temple gate, a band of street dogs, all unawares, strayed past, and entered the enclosure.”

Itti started as he sat, forgot his manehs, and began to mutter an invocation to Ramman, while his lips twitched. “Impossible!” was all he could gasp.

“Too true,” put in Avil, solemnly. “You know the ancient oracle,” and he rolled out the formula:—

We brought the news to the king. He is all anxiety. There will be a special council and consulting of the oracles. We trust, by laying extra burdens on these stubborn Jews, we can in some measure avert the wrath of heaven. Yet this is a fearful portent, just as his Majesty is about to marry a Persian.”

Itti was still shaking his head, when an increased din rising from the street warned Avil that there would be no passing at present for his chariot.

“Way! way!” a squad of spearmen were bawling, forcing back the traffickers to either side. The banker and his guests stared forth curiously.

“Way! way!” the shout grew louder, and behind sounded a creaking and a rumbling. The chief priest glanced toward the gate.

“The new stone bull,” commented he, “comes from Karkhemish. They landed it above the bridge; now they drag it to the old palace of Nabupolassar, which the king is repairing.”

“Then the Jews,” remarked Itti shrewdly, “are already being rewarded for their impiety. Has not the labour gang been taken from their nation?”

“You are right,” said Avil, “they will fast learn that to keep clear of forced labour they must go to the ziggurat and the grove of Istar.”

“Strange people,” declared Itti, “so steadfast to their helpless god!”

“If Marduk gives me life,” swore Avil, “I will bend their stiff necks. His Majesty promises the indulgence of former reigns shall end forever.”

The rumbling in the streets drowned further words. Long before the bull came in sight appeared four long lines of panting men, naked save for loincloths, dusty, sullen. Each man tugged at a short cord, made fast in turn to one of the four heavy cables stretching far behind them. At times the march would come to dead halt; then every back would bend, and at a shout from the rear the hundreds would pull as one, and start forward with a jerk. The laggards were spurred on by the prick of the lances of the spearmen outside the lines, or felt the staffs of the overseers who walked between the cables. Young boys ran in and out with water jars, and now and then a weary wretch would drop from the line to gulp down a draught, and run back to his toil. So the long snake wound down the street, groaning, panting, cursing. Behind this thundered the bull. The stone monster was upon a boat-shaped sledge, itself the height of a man. Busy hands laid rollers before it. To steady its mass, men ran beside, holding taut the cords fixed to the tips of the huge wings. On the front of the sledge stood the guard’s captain, bellowing orders through a speaking trumpet. The bull reared above him to thrice his height. Last of all came many toiling from behind, with heavy wooden levers.

“Ah, noble Avil,” called the guard’s captain, familiarly, “who would say the chief priest makes way for Igas-Ramman, captain of a fifty?”

And Avil, recognizing a friend, called back,[37] “Beware, or I beg your head of the king! Make the Jews give full service.”

“They shall, by Nabu!” And Igas trumpeted, “Faster now! Wings of eagles! Feet of hares, or your backs smart!”

The overseers’ blows doubled, the bull swayed as it leaped forward, but suddenly Igas cursed. “Now, by the Maskim, foul genii of the deep, what is this? Down again, worthless ox!”

An old man had fallen from line. Overcome by weariness he lay on the stone slabs while the strokes of the overseers’ staffs made him writhe. Rise he could not. Neriglissor recognized him.

“A Jew named Abiathar, a great blasphemer of Marduk. Ha! Smite again, again!”

Igas leaped into the throng, waving a terrific Ethiopian whip of rhinoceros hide. At the second blow blood reddened the flags. The Hebrew groaned, tried vainly to rise.

“Beast,” raged Igas, swinging again, “you shall indeed be taught not to lag!”

The great whip whisked on high, but just as it fell, a heavy hand sent the captain sprawling. Young Isaiah stood above the prostrate Igas, his eyes burning with righteous wrath, his form erect.

“Coward! You will not strike twice a man of your own age!”

The spearmen stood blinking at Isaiah in sheer astonishment. Igas crawled to his feet; rage choked the curses in his throat, then flowed forth a torrent[38] of imprecations. In his wrath he forgot even to call for help.

“Beetle!” howled he, bounding on Isaiah. But the Jew had caught the whip, lashed it across the guards captain’s shoulders, and raised a smarting welt. Then at last all leaped on the intruder, but he laid about as seven, till a stroke of a cudgel dashed the whip from his grasp; he was carried off his feet, overpowered, and gripped fast. Around the motionless bull a tumultuous crowd was swelling, when a squad of red-robed “street-wardens” hastened up to arrest the peace-breakers.

“High treason against the king!” Igas was screeching. “His head off before sunset!” But the police rescued Isaiah from the spearmen, and their chief urged:—

“Softly, excellent captain, he must be tried before the judge.”

“A Jew! A Jew!” shouted many. “Away with him! Strike! Kill!”

The multitude seemed growing riotous, and ready to attack the police, when a new band of runners commenced forcing a passage.

“Way! way! for the noble Persian Darius and the Vizier Bilsandan!” was the cry; but to the astonishment of those in the banking-house, they saw the young envoy leap from his chariot and plunge before his escort into the crowd. Dashing back the mob with sturdy blows from his scabbard, he was in an instant beside the Jew. For a moment[39] few recognized him. Igas thrust at him with a lance, a quick thrust, yet more quickly had Darius unsheathed, and struck off the spear-head. “Treason! Rebellion! A plot!” shouted a hundred. The police endeavoured to arrest the new offender.

“Death to the Jews!” rang the yell, as many hands were outstretched. But the Persian had released Isaiah, and thrust a cudgel in his hands. His own sword shone very bright.

“Guard my back!” commanded he, and braced himself. The crowd cut him off from his escort.

Avil cried vainly across the deafening tumult.

“Hold, on your lives! Will you murder the Persian envoy?”

There was a rush, a struggle; those thrust against Darius shrank back howling, all save two, who had tasted his short sword.

In the respite following, Bilsandan had forced himself to the envoy’s side. Mere sight of the vizier was enough to enforce quiet.

“Peace, dogs!” thundered Bilsandan. “Why this tumult?”

Darius had sheathed his sword, but looked about smiling. Joy to show these city folk the edge of Aryan steel!

“I struck only in self-defence,” quoth he to the vizier. “You saw the cruelty of this scorpion. Isaiah deserves reward for avenging the old man. I will mention the evil deed of this captain to the king. We Persians hold that he who reveres[40] not the gray head will still less reverence the crown.”

Igas was falling on his knees before Darius. Well he knew Belshazzar would snuff out his life so cheaply to humour the envoy of Cyrus, if only Darius asked it. But the Persian laughed good-naturedly, forced him to swear he would pay old Abiathar two manehs, for salve to his stripes, and the king should hear nothing about it. As for Isaiah, spearmen and police were glad to leave him at liberty. They bore the two wounded away. Darius was about to return to the chariot in which Bilsandan had been driving him about the city, but gave Isaiah a last word. “By Mithra, I love you, Jew! You are like myself, swift as a thunderbolt, striking first and taking counsel later.”

“Jehovah bless you again, my prince!” cried the other. “How may I repay? They would have taken my life.”

So Darius was gone. The bull lumbered on its way. Isaiah alone remained to help home the wretched Abiathar. As he bargained with a carter to take the old man to his home on the Arachtu Canal, Avil-Marduk called from the banking-house: “Praise Bel, Hebrew, you are not on the way to execution! Be advised. I love men of your spirit. Enter our service at the ziggurat, and, by Istar, you may wear the goatskin in my place some day!”

Isaiah held up his head haughtily. “I would[41] indeed enter the service of a god—not of Bel-Marduk, but of Jehovah. I am a Jew, my lord.”

Avil smiled patronizingly. “Excellent youth, you are too wise to think I do not set your wish at true value. No offence, but where does Jehovah rule to-day? Fifty years long we have used the dishes from His temple at your village of Jerusalem, in our own worship of Bel-Marduk. Your god is helpless or forsakes you; no shame to forsake Him.”

Isaiah bowed respectfully. “Your lordship, we gain little by debate,” replied he.

“Nevertheless,” quoth Avil, blandly, “I am grieved to see a young man of your fair parts throw his opportunities away. Be led by me; what do you owe Jehovah? Bel-Marduk will prove a more liberal patron. You are Jew only in name, your birth and breeding have been in this Babylon. To her gods you should owe your fealty. Believe me, I speak as a friend—”

Isaiah straightened himself haughtily.

“My Lord Avil, do not think Jehovah is like your Bel, the god of one city, of one nation. For from the east to the gates of the sun in the west is His government. And all the peoples are subject unto Him, though the most part know it not.”

The high priest’s lip curled a little scornfully. “Truly,” flew his answer, “Jehovah displays His omnipotence in strange ways,—to let the one nation that affects to serve Him languish in captivity.”

“I fear many words of mine will not make your lordship understand,” replied Isaiah; and he bowed again and was gone. Those in the banking-house looked at one another.

“Sad that so promising a youth must cast himself away in fanatical devotion to his helpless god,” commented Itti the banker. “Yet he only imitates his father, Shadrach, the late royal minister.”

“Young as he is,” responded Avil, “he is already a power amongst his countrymen. He has the reputation of being a prophet of their Jehovah, and many treat him with high respect. Nevertheless, if he is not better counselled soon, he will find his head in danger, unless the king stops his ears to my warnings.”

Isaiah walked beside Abiathar as the cart rumbled homeward. The old Jew was all groans and moans.

“Ah, woe!” he was bewailing, “is this to be the reward of the Lord God for remembering Him, and keeping away from the ziggurat! Stripes and forced labour and insult! Speak as you will, good Isaiah, you who have the civil-minister to protect you from all harm; it is easy for you to toss out brave words. You are passing rich; we are poor, and all the stripes crack over our shoulders!”

“Hush!” admonished the younger Jew, severely; “my perils are great as yours, did you but know them. It is for our sins this trouble is visited upon us. Our fathers have forgotten Jehovah, and is He[43] not now visiting their sins upon us, unto the third and fourth generation, even as says His Law?”

“I do not know,” replied the other, moodily; “I only know that a little oil and fruit offered now and then to Sin or Samas would cure many aching backs!”

Isaiah did not answer him. In truth, there was very little to reply. He walked beside the wagon until Abiathar was safe at his little house by the Western Canal. Then he left him, and went in the bitterness of his spirit to the palace of Daniel, near the Gate of Beltis in the inner city.

Like all Babylonian gentlemen, the civil-minister had an extensive establishment, though the exterior was gloomy and windowless. When Isaiah had entered the narrow gate he found himself in a spacious court, surrounded by a two-story veranda, upborne on palm trunks. In the court were ferns, flowers, and a little fountain; an awning covered the opening toward the sky. In a farther corner maid-servants were pounding grain and sitting over their embroidery.

Isaiah entered unceremoniously; but just at the inner door of the farther side of the court he came on Daniel himself, dressed in his whitest robe, and surrounded by several servants, as if about to set forth in his chariot.

“My father!” And the younger Hebrew fell on his knees while the other’s hand outstretched in blessing.

“The peace of Jehovah cover you, my son,” declared the old man. Yet when Isaiah had risen, he was startled at the anxiety written on the other’s face. He knew it was no light thing that could shake the civil-minister out of his wonted calm.

“As Jehovah lives,” adjured the younger Jew, “what has befallen? Where are you going? You do not commonly ride abroad in the heat of the day.”

“I have urgent need of going to Borsippa to see my good friend Imbi-Ilu, high priest of Nabu, on a private matter.” The effort to speak lightly was so evident that Isaiah’s fears were only doubled.

The minister turned to the others.

“Tell Absalom to hasten with harnessing the chariots,” commanded Daniel. The servants took the hint and withdrew. Their master cast a searching glance about the courtyard, to make sure that no others were in easy earshot.

“Listen.” His speech sank to a whisper. “I am in sore anxiety concerning the safety of Ruth.”

“Of Ruth!” Isaiah’s grave face grew dark as the thunder-cloud. “How? Who threatens?”

Daniel spoke yet lower. “This day I have received a message from friends in the palace, that the king still remembers her beauty, and desires her. His promise to Darius was a lie, to appease the envoy for the moment. I dare not doubt that some attempt will be made by Mermaza, or by others of his spawn, to carry away the girl at the first convenient[45] opportunity. She must not sally abroad, however much she may desire it. I do not know how great is the immediate danger, but there is nought to be risked. On this account I am going to Borsippa without delay.”

“Then as our God rewardeth evil for evil, so will I reward the king!” Isaiah had turned livid with his wrath. “I will slay Belshazzar with my own hand, and then let them kill me with slow tortures.”

Daniel smiled despite his heavy heart.

“Small gain would that be to our people. The fury of the Babylonians would grow sixfold. If the yoke is hard to bear now, what then?”

“Yet will Belshazzar truly break his promise?” demanded Isaiah, plucking at the last straw of hope.

“Promise?” Daniel laughed grimly. “He will break ten thousand oaths, when they stand betwixt him and a passion. Avil-Marduk urges him each day to ruin me and mine, as a lesson to the rest of our people. The Jews are to be driven like sheep to the ziggurat, and forced to blaspheme Jehovah. Alas! When I think of the plight of our nation, the dangers of a few of us seem but as the first whisperings of a mighty storm! If no succour comes, Ruth and you and I are utterly undone; and our people will forget its God, as He in His just wrath seems to have forgotten them.”

“And is there no hope?” groaned Isaiah in his despair.

Before Daniel could answer, a sweet girlish voice[46] sounded, singing from the upper casement, over the court. The two men stood in silence.

“It is the song of Ruth,” said Daniel, as in dreamy melancholy. “She has waited you for long. Blessed is she; to her Jehovah thus far is kind. She does not know her danger. The ‘Song of Songs’ is ever in her mouth, in these days of her love. You must go to her.”

“Let all Belshazzar’s sword-hands take her from me!” was Isaiah’s rash boast. But then he asked more calmly: “And why do you, my father, go to Borsippa? You have not told.”

“To ask Imbi-Ilu if he will give sanctuary in the temple of Nabu to Ruth, if worst comes to worst. Bitter expedient!—a daughter of Judah sheltered in the house of idols! Such is the only shift.”

“But Imbi could not guard her always, if the king’s mind is fixed. And what of our nation, of the peril of great apostasy? Ah!” Isaiah lifted his hand toward heaven. “I am not wrong. I must kill Belshazzar; then if we die, we die not unavenged!”

Daniel quieted him with a touch.

“Do not anger God with unholy rashness. All is[47] not yet lost. I have still my position as ‘civil-minister,’ and though the Babylonians may rage against our people, they reverence me still. My word and name are yet a power in Babylon. Even the king will hesitate to strike me too openly. And if the worst does come, let them know I have yet a weapon that may shake Belshazzar on his throne.”

“What mean you? For Jehovah’s sake, declare!”

Daniel smiled sadly at the impetuosity of the younger man.

“No, not now. Fifty years long have I served the kings of the Chaldees, and betrayed none of their secrets. I keep fealty as long as I may; yet the time for casting it off may be near at hand. The Lord grant I may not be driven thus to bay—”

“The chariot waits, my lord,” interrupted a servant. And Daniel gathered his robe about him, to depart.

“Remain with Ruth until I return,” was his last injunction; “the king will hardly wax so bold as to go to extremities to-day. But till Belshazzar lies dead, or Jehovah creates in him a new heart, we must not cease to guard her.”

The chariot of the “civil-minister” clattered away, and Isaiah stood for a long time in gloomy revery. Ever since Nabonidus had been thrust from power, the condition of the Hebrews had been growing steadily more miserable. Belshazzar was in all things guided by Avil-Marduk, and the high pontiff’s rage against the Jehovah worship of the exiles was nothing new. Shadrach, Isaiah’s father, had been a fellow-minister with Daniel, but the liberal sway of Nebuchadnezzar was long since past. Isaiah saw himself shut out of every office, so long as he clung to the God of his people. Amongst his fellow-Hebrews Isaiah had passed as a prophet; in moments of ecstasy he had poured forth burning words,—of encouragement to the faithful, of threatenings to the oppressor, of promised restoration to that dear Jerusalem he had seen only in his dreams. But at this moment the dreams seemed shadowy indeed. The events of the day had darkened him utterly; and, crowding upon Avil’s scarce veiled threat, came the tidings of the king’s unholy lusting after Ruth! The young man’s heart[49] was sickened. How could he sit with smiling face, and listen to his love, and her merry nothings? The task was seemingly impossible, when the sweet voice sounded again from the casement. “Ah! my wandering swallow, why linger? Up quickly! Say something to make me glad. I am exceeding vexed with my father.”

Merry or sad, the young man waited no second bidding. He sped up the narrow stairway by the side of the court, and reached the upper veranda. Here a sort of balcony, overhanging the yard, had been walled with curtains of blue Egyptian stuffs, and behind had been set a tall loom, its frame half filled with a web of bright wools, where a brilliant rug was unfolding under skilful fingers. Two dark-eyed Arabian girls were aiding their mistress; but at sight of Isaiah, the red thread shook from her lap, and she flew twittering into his arms. Then like two birds they cooed together, their eyes talking faster than their lips; and at last—for all things lovely must find end—Isaiah was in his accustomed seat, a cushioned footstool beside the loom, and there he could sit and chatter while the broad web grew.

But Ruth was in no mood for small talk. Her little lips were wrinkled in a pout, the cast of her eye was sulky. And while she wrought over the loom, her fountain of wrath was emptied.

“Were I not an obedient daughter of Israel, I should say unholy things of my good father. Surely Jehovah forsakes us and suffers him to wax mad!”

“Daniel mad? He has the sagest head in all Babylon. Fie, little owlet!”

“Either he is mad or worse. There!” the red-thonged sandals over the small feet stamped angrily, “I will tell all, though it be a sin to revile a parent.”

“Verily, for you to be wroth with your father must spring from no slight cause!” protested Isaiah, feebly attempting to smile.

“Is it not sufficient that I must be kept precious as a finch in his cage?—never suffered to go forth to any of the fêtes at the palace, veiled always, when I sally abroad, and guarded as if I were a prisoner about to make escape?”

“Old tales, Ruth,”—Isaiah strove to speak lightly; then more gravely, “Was the last time we sallied forth, and met the lion and the king, so joyous that you wish it repeated daily?”

He saw her shudder, and her mouth twitched, as he recalled that scene; but she was too thoroughly filled with wrath even to let that memory turn her.

“Not so—let my father send fifty servants about me, and wrap my face in twoscore veils! But now I am made utter prisoner. Yesterday I visited the bazaars with Gedeliah, our body-servant; and in the jeweller’s shop of Binzurbasna by the Gate of Istar I saw an armlet that fitted my eye as water its cup. I had no money, but last night my father gave me more than the price. To-day Gedeliah starts at dawn with a letter to Kisch. Later I say, ‘Father, I will take[51] another servant and go and buy the armlet.’ He makes all manner of objections to my going. ‘Let the serving-man go; do you remain.’ ‘No,’ answered I, ‘only Gedeliah and I can tell which is the armlet; if I wait, it is sold.’ I beseech exceedingly, whereupon he says, after his firm manner: ‘Peace, Ruth; I know what is well for you. You shall not go to-day.’ Then he summons his chariot, and departs to Borsippa. Have I no cause for anger?”

Isaiah did not reply immediately; and she returned to the charge. “Speak,—are you so jealous that no man may set eyes on the hem of my mantle? Speak!” And she snapped her bright eyes before his.

“Your father is a wise man,” began Isaiah, cautiously; “assuredly he had reasons.”

“Which clearly you agree in?” pressed she, sharply.

“I said not that; though, were he to tell, no doubt they would seem sufficient.”

“He has not told them? What passed then so slyly, when you stood together?”

Isaiah had boasted that in a city where the clever liar was deemed the sage, he had been wont to speak truly; but he found himself close to equivocation.

“We spoke of the increasing power of Avil. Your father grows anxious.”

“And was not my name mentioned once, twice?”

Ruth had turned from the loom, and was looking Isaiah in the face.

“You did wrong to eavesdrop,” he faltered, nigh desperately, for falsehood tripped hardest off his tongue when those soft eyes were on him.

“No answer,” she challenged, lowering her head till her curls almost brushed his cheek. “Speak! Why did you use my name?”

“You must have confidence in us,” began Isaiah, putting on manly austerity, “to believe that whatever we said was only for your good.”

A tart retort was tingling on her tongue, when a voice from the court interrupted. “Ho! Is the young master Isaiah above?”

It was the old porter’s call; the other responded instantly.

“Since my Lord Daniel is away,” went on the porter, “will my young master come down at once? His friend, the guardsman Zerubbabel, is here, and demands instant speech of weighty matters.”

Isaiah was down the stairs by leaps. In the court he met a young man of about his own age, comely and erect, dressed in the short mantle of a soldier off duty.

“Where is my Lord Daniel?” was his quick demand; he was breathless with running.

“Has none told? Gone to Borsippa.”

“Jehovah God have mercy!”

Isaiah caught his friend by the arm.

“Hold, Zerubbabel; gain breath, and speak to the point. Your wits are all scattered on the road behind!”

The guardsman took a deep breath.

“Be a man, Isaiah,” he admonished, as if speaking sorely against his will; “I have a heavy piece of news for you.”

“Touching Ruth?”

Zerubbabel nodded. “You have heard that the king had designs on her. Did you know Mermaza was to make an attempt on her this very night?”

His voice had risen, despite Isaiah’s warning “Hush!” They heard a little cry on the balcony above—a louder scream. Isaiah clapped his hands to his face. “The Lord spare her now!—she has heard it!”

The next instant Ruth was beside them. She was trembling; her hand quivered in her lover’s while he held it, yet it seemed as much in anger as in dread, though her face had blanched to the whiteness of a summer’s cloud.

“Tell me all! All! Do you think me too weak to bear?” was her plea, turning her great eyes from the soldier to Isaiah and back again. “What danger waits?”

The young prophet’s voice grew very calm.

“Beloved, blessing and bane come from the Lord God alike. He can do nothing ill. Let us listen to Zerubbabel.”

The guardsman’s speech came falteringly,—no joy to chase the gladness from those bright eyes.

“Daughter of Daniel, I know that your father reproaches me for having conformed to the Babylonish[54] worship, and taken service on the royal guard; but, believe me, my heart is still faithful to Jehovah. At no small peril have I come here, to warn you. You, O Isaiah, have not been without an inkling; but did you know that Belshazzar has given his royal signet to Mermaza, chief of the eunuchs, commanding him—”

Before he could utter another word, a bitter cry had burst from Ruth: “Would God I had been unborn, or died while yet a speechless child, than win the love of Belshazzar. For the love of the king is tenfold more cruel than his hate. Slay me; slay now, rather than let the eunuchs lay hands on me!” So she cried in her sudden agony; and what might Isaiah say to comfort her? She could only feel the muscles of his arms grow hard as iron, as she leaned against his breast.

“Fear not,” he answered, with that confidence born of a touch and a thrill that can make the weakling giant strong; “were Belshazzar seven times the king he is, he shall never do you harm.”

“So be it!” quoth Zerubbabel, gravely, “yet the proof is close at hand. It is as I said. Mermaza has received an order, signed by the royal signet, authorizing him to take Ruth, the daughter of Daniel, when there may be ‘convenient opportunity’—which is to say, when no disturbance will arise likely to hamper Avil-Marduk and his plots.”

“How know you this?” demanded Isaiah, almost fiercely.

“One of the eunuchs, whose life Daniel had once begged of Nabonidus, told me. I more than fear that my visit to this house has been observed, and will be laid up against me.”

“And what hinders the ‘profoundly-to-be-reverenced’ chief eunuch from coming this moment, with his Majesty’s ring and order, and carrying away the maid perforce? Does not Belshazzar command all the sword-hands in Babylon?” pressed Isaiah, in cutting irony.

Zerubbabel smiled bitterly. “Even a king must know some restraints. He has passed his word to Darius, the Persian envoy, that the maid shall not be touched. What if Darius heard of the kidnapping! Would he trust Belshazzar’s professions of friendship longer? And Daniel is popular with the city folk. Enter his house at mid-day, and let some outcry rise,—behold! there is a riot in the streets.”

“Therefore the attempt will be made this evening, when all is quiet?”

Zerubbabel bowed gloomily. “You have said.”

Isaiah shot one glance at the shadow cast by the tall “time-staff” set in the centre of the courtyard.

“It lacks three hours of sundown. There is yet time!” he cried.

But Ruth had suddenly steadied herself, and looked from one young man to the other. Her voice was very shrill.

“Who am I to make you rush into peril for my poor sake? If you hide me from the king, his fury[56] will turn against you, and against my father. How can you save me? Go to Mermaza. Tell him he may take me when he wills. I can endure all rather than ruin those I love.”

She stood before her lover with head erect, eyes flashing. The glory of a great sacrifice had sent the colour crimsoning through her cheeks. If beautiful before, how much more beautiful now, in the sight of her betrothed! Had she counted the cost of her word? No, doubtless; but for the moment she was the girl no more, but the strong woman ready to dare and to do all.

But Isaiah answered her with a sternness never shown by him to her till now: “Peace! You know not what you say. What profit is my life, with you sent to a living death in Belshazzar’s impure clutch? There is but one thing left.”

“Away! Leave me!” she implored, new agony chasing across her face. “Is it not enough that I should be victim? Those who cross Belshazzar’s path are seekers for death.”

“Peace!” repeated Isaiah, and not ungently he thrust his hand across her mouth. “Must the whole house hear us? You, Zerubbabel, indeed, begone. You can only add to your peril, not aid.”

The guardsman hesitated. “If I can do aught—” he began.

“Avoid suspicion,” commanded Isaiah; “if you learn of anything new plotted, forewarn. In so doing you prove truest friend.”

“The Lord God keep you, dear lady,” protested the guardsman, kissing her robe; “believe me, I am your and your father’s friend, though men say I bow down to Bel-Marduk.”

He had vanished; and Isaiah looked upon Ruth, and Ruth back to Isaiah. The peril had broken upon her so suddenly that she was yet numbed. She had not realized all she had to fear, and the ordeal awaiting. But if her lover realized, he proved his anguish by act, not word.

“Ruth,” spoke he, “your father knew the king had not forgotten you, though that the deed was planned so soon was hid. He has ridden to Borsippa to see if Imbi-Ilu will shelter you at the temple of Nabu. If we await his return, it will be too late. The shadows are falling already. You must quit this house without delay.”

“I am ready,” she answered, but she spoke mechanically, not knowing what she said.

Old Simeon, the porter, had approached, his honest face all anxiety for his betters. “My mistress is in trouble? Zerubbabel brought ill news?” he ventured, not presuming more. But Isaiah ordered sharply:—

“Let the closed carriage be made ready at once.”

“The closed carriage? For the mistress? My Lord Daniel commanded—” hesitated the worthy; but Isaiah’s tone grew peremptory. “Daniel’s commands weigh nothing now. Were he here, he would order the same. No questions; hasten.”

The stern ring in the young man’s voice ended all parley. Simeon shuffled away to rouse the stable grooms, and Isaiah turned once more to Ruth.

“Beloved, we must drive to Borsippa at once. Take what clothes you need, nothing else. No tarrying. Each instant is worth a talent.”

“And this house? The room of my mother? The thousand things of my glad life—all left behind?”

The tears would come again. Ruth was weeping now—bitterly, but not from dread of Belshazzar. Events had raced too fast these last few moments to leave room for the greatest griefs or fears.

“Trust that Jehovah will send you back to them, in the fulness of His mercy. He is more pitiful than even Daniel your father.”

She did as bidden; in the turmoil of emotions, at least some sorrows were spared her. The maid-servants stared at their mistress, as she flew about her well-loved chambers. The little bundle was soon ready,—so little! And so many girlish delights and trinkets all left behind. Isaiah’s voice was summoning her. The carriage was waiting in the yard. Daniel had not taken his swift pair of black Arabs in the chariot, and for these Isaiah thanked his God!

Ruth darted one glance about the court—the well-known balcony, the drapery hiding the loom, the swallows flitting in and out of the eaves, a thousand dear and homely things, so familiar she had forgotten[59] how much she loved them—one last sight; when could she see them again?

“The servants,—my friends,—I must say farewell,” she pleaded; but Isaiah shook his head.

“You must leave with as little commotion as possible. The Most High grant we have not tarried too long!” He lifted her almost perforce, and thrust her upon the soft cushions inside the carriage. She heard him tying the door to the wicker body, to secure against sudden and unfriendly opening. The only light that came to her was from the little latticed window in the roof, through which she could see only sky. She heard Isaiah leap upon the driver’s platform, in front, beside Abner, one of the stoutest and trustiest of her father’s serving-men. The courtyard gate creaked open. The carriage rumbled forth. “Abner,” sounded Isaiah’s voice, “if ever you drove with speed, drive now. To Borsippa, to the temple of Nabu!”