The National Gallery of Art belongs to all the people of the United States of America. Established by a joint resolution of Congress, it is supported by public appropriation. The Board of Trustees consists of four public servants, ex officio, and five private citizens. Chairman of the Board is the Chief Justice of the United States. Under the policies set by the Board, the Gallery assembles and maintains a collection of paintings, sculpture, and the graphic arts, representative of the best in the artistic heritage of America and Europe. Supported in its daily operations by Federal funds, the Gallery is entirely dependent on the generosity of private citizens for the works of art in its collections.

Funds for the construction of the original building were provided by The A. W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust. During the 1920s, Mr. Mellon began to collect with the intention of forming a national gallery of art in Washington. His collection was given to the nation in 1937, the year of his death. In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt accepted the completed Gallery on behalf of the people of the United States of America.

Architect for the National Gallery was John Russell Pope, who also designed the Jefferson Memorial and other outstanding public buildings in Washington. The building is one of the largest marble structures in the world, measuring 780 feet in length and containing more than 500,000 square feet of interior floor space. The exterior is of rose-white Tennessee marble. The columns in the Rotunda were quarried in Tuscany, Italy. Green marble from Vermont and gray marble from Tennessee were used for the floor of the Rotunda. The interior walls are of Alabama Rockwood stone, Indiana limestone, and Italian travertine. The entire building is air-conditioned and humidity-controlled throughout the year to maintain the optimum atmospheric conditions for the works of art it contains.

The original building is no longer large enough to accommodate the Gallery’s acquisitions and interpretive art programs. A second building, presently under construction, will house new exhibition galleries and a Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts. The two buildings will be connected by a plaza above ground and by a concourse of public service areas, including a new café/buffet, below. The new construction has been made possible by generous gifts from Mr. Paul Mellon, the late Ailsa Mellon Bruce, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

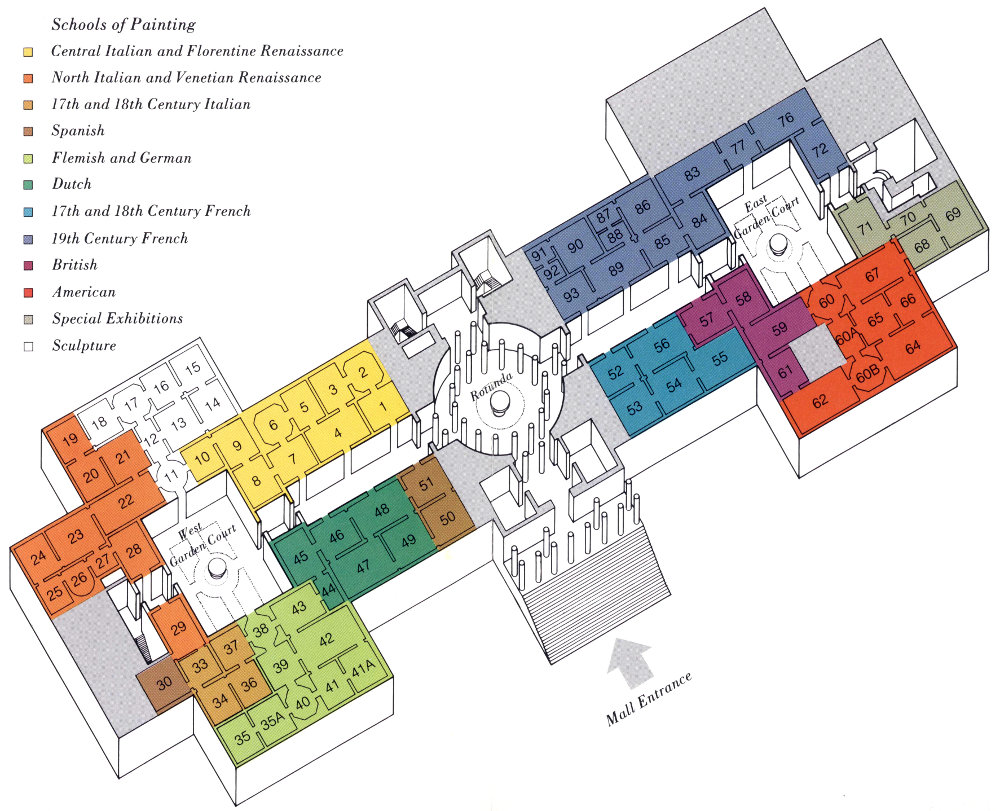

| 3 | Florentine and Central Italian Art |

| 6 | Venetian and North Italian Art |

| 8 | Italian Art of the 17th and 18th Centuries |

| 10 | Flemish and German Art |

| 13 | Dutch Art |

| 15 | Spanish Art |

| 16 | French Art of the 17th, 18th, and Early 19th Centuries |

| 19 | British Art |

| 21 | American Art |

| 24 | French Art of the 19th Century |

| 28 | 20th-Century Art |

| 30 | Decorative Arts |

| 30 | Prints and Drawings |

| 31 | Index of American Design |

Owing to changes in installation, certain works of art listed in this brochure may not always be on view. For up-to-date information, please inquire at the information desks.

The paintings and sculpture given by the founder, Andrew W. Mellon, comprising works by the greatest masters from the thirteenth to the nineteenth century, have formed a nucleus of high quality around which the collection has grown. Indeed, in making his gift Mr. Mellon had expressed the hope that the newly established National Gallery would attract gifts from other collectors, so that these works of art might be enjoyed by all and would be a lasting contribution to the cultural life of the nation.

Mr. Mellon’s hope that others would carry on the work was realized, even before the Gallery opened, by the action of Samuel H. Kress, who gave to the nation his great collection of paintings and sculptures of the Italian schools ranging from the thirteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Enlarging and enriching the Kress Collection on subsequent occasions, Samuel H. Kress and his brother Rush H. Kress made the National Gallery outstanding for its representation of Italian art and also added a distinguished group of French eighteenth-century canvases and sculpture and fine examples of early German paintings, as well as works of first importance from other schools.

In 1942 Joseph E. Widener gave the famous collection of painting, sculpture, and decorative arts formed by him and his father P.A.B. Widener. Chester Dale, besides making numerous gifts during his lifetime, bequeathed his extensive collection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century French paintings to the Gallery. Ailsa Mellon Bruce also bequeathed her collection of French paintings to the Gallery and, in addition, generously provided funds for the purchase of many old master paintings, including the Leonardo da Vinci. Lessing J. Rosenwald has given over 20,000 prints and drawings.

In addition, more than 325 other donors have generously added to the collections of the National Gallery of Art.

ROTUNDA: Attributed to Adriaen de Vries, Mercury, cast probably c. 1603-1613

The vigorous movement, muscular lines, and above all the grace and lightness of the bronze figure capture in this Mercury the fleeting presence of an ancient god. Protector of the forlorn and travel weary, patron of shepherds, merchants, wayfarers, and even thieves fleeing the law, Mercury was the bearer of news and tidings for the gods of mythology. He was known by his winged feet, a 3 traveler’s cap with wings, and his herald’s staff, a caduceus, perhaps given him by Apollo, who had the power of healing. The design of Mercury’s caduceus with its two serpents intertwined has been traditionally associated with medicine and is the adopted symbol of the medical profession. This masterful piece was probably made by Adriaen de Vries, a Dutch artist trained in Italy, and was modeled after a Mercury completed twenty years earlier by Giovanni Bologna.

Because the Church defined much of the social and cultural structure of medieval life, Christian themes predominated as the subject matter for the arts of the period. In the National Gallery collections, works created in Florence, Siena, Rome, and Central Italy show the range of skills and styles prevalent in painting as it progressed from the highly religious art of the Middle Ages to the more secular art of the Renaissance.

The usual technique for medieval religious art was egg tempera on wood panels covered with a fine bone plaster, called gesso. Egg yolk mixed with powdered pigments was applied to the gesso surface resulting in pictures characterized by bright colors and clear outer contours. To recall the radiant light of the heavenly kingdom and to heighten the patterns typifying this art, the artist often used gold-leafed grounds as well.

By the late fifteenth century, tempera gave way to oil paints that dried more slowly, permitting the artist subtle modulations in his color and allowing him to create realistic atmospheric effects. As the Renaissance progressed, artists combined a renewed interest in nature, analytical science, and classical humanism with the recently developed techniques in media to bring about a corresponding realism in art.

GALLERY 1: Byzantine School, Enthroned Madonna and Child, 13th century

A medieval walled city is transformed into a throne by this imaginative, unknown artist to symbolize the dominance of Christ and Mary, Queen of Heaven, over the celestial city. To symbolize Christ’s rule on earth as well, the artist included, in the rondels, images of angels bearing orbs and scepters. So typical of the art of the Byzantine Empire, this painting is an icon, or holy image, and reflects within its composition a fusion of ancient Roman and medieval Oriental styles. A feeling for classical solidity shows in the faces, which are modeled with cast shadows to suggest three-dimensional forms, whereas a Near Eastern love of decoration accounts for the flattened drapery patterns and their dazzling highlights. The Enthroned Madonna and Child and another large Byzantine icon of the same subject, also in this room, are among the earliest paintings in the collection.

GALLERY 3: Duccio, The Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew, painted between 1308 and 1311

Called to be “fishers of men,” the brothers Peter and Andrew pause in their labors at the persuasive words of Christ. In him, their future as apostles, or teachers, and the future of mankind hang momentarily suspended—like the net in their hands. This panel is part of an altarpiece commissioned for the high altar of the Cathedral in Siena and called the Maestà (“majesty”) because its central theme was the Virgin splendidly enthroned with angels and saints. The purpose of this piece, like so many medieval paintings, was to teach, and Duccio arranged bright colors in simple shapes so that the story could easily be recognized.

GALLERY 4: Fra Angelico and Fra Filippi Lippi, The Adoration of the Magi, painted c. 1445

Painted by two monks (Fra means “friar”), this important painting fuses the concerns and techniques of medieval and Renaissance artists. The tapestrylike lawn, the decorative bright colors, and the inverted perspective of the shed are elements common to medieval art. The realistic rendering of birds and animals, the weight and volume given the kneeling Magi in the foreground, and the classically inspired nude figures at the distant left reflect the new-found interest of the Renaissance in both classical antiquity and the external world. The colorful, festive mood of the painting, moreover, is emphasized by the bustling throngs of people arriving to worship the Christ Child.

GALLERY 4: Andrea del Castagno, The Youthful David, painted c. 1450

Not simply a work of art, this painted leather shield reflects the uniquely nationalistic consciousness of the Florentine city-state. As a public image carried in parades and ceremonies, its function was to symbolize the Florentine struggle for freedom and, as a gruesome depiction of victory against oppression, to warn all potential enemies of Florence. On the shield, both main episodes of the Old Testament story appear concurrently: David takes aim with his sling, while the giant’s head lies already severed at his feet. The effective, although awkward, foreshortening of the upraised arm and the sharply delineated veins and muscles attest to Castagno’s Renaissance interest in the realistic rendition of perspective and anatomy.

GALLERY 6: Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci, painted c. 1480

With precise draftsmanship and an infinitely subtle manipulation of light and shadow, Leonardo captures the character of a young Florentine noblewoman of the fifteenth century. In her eyes he has drawn a look of intelligence; in her bearing and the set of her mouth, there is a sense of determination and conviction. Punning on the name of his sitter, the artist has framed her head with a juniper bush—ginepro in Italian—and decorated the back of the panel with a juniper sprig. Commissioned just after he completed an apprenticeship with Verrocchio, this early work is the only painting in the Western hemisphere accepted by scholars as indisputably by Leonardo, one of the true geniuses of the Renaissance.

GALLERY 8: Raphael, The Alba Madonna, painted c. 1510

The solidity and serenity of the figures derive from the forms and poses seen in ancient Roman sculpture and from the art of Raphael’s contemporaries, Leonardo and Michelangelo. The equilibrium and stability of the grouping provides not only a freshness and majesty suitable for the religious moment but also a source of contrast to the subtle but painful implications of the reed cross held by the two children. Named for the Spanish Dukes of Alba who once owned it, the Alba Madonna is one of five paintings by Raphael in the National Gallery of Art.

The splendor of Venetian art reflects the city’s prosperity during its years as a major Mediterranean port. Typical of Venetian lavishness is The Feast of the Gods (gallery 22) by Giovanni Bellini, Renaissance artist and teacher of Giorgione and Titian. This huge painting draws from the fantasies of mythology, turning a Venetian picnic into a feast for gods.

Aware of the subtle reflections of light and shadow playing in the 7 misty air over the lagoons of Venice, sixteenth-century artists such as Titian, Veronese (gallery 28), and Tintoretto (gallery 29) strove to capture the illusion of surface texture and tangible atmosphere through their paints. Because oils blended easily together and because one could thicken these paints with pigments, artists soon established a more flexible technique. At the same time, they abandoned rigid wood panels for canvas supports, which allowed larger, lighter pictures. These innovations, combined with worldly subjects, soon had a significant impact on the rest of Europe.

GALLERY 21: Giorgione, The Adoration of the Shepherds, painted c. 1510

Dominated by a placid landscape bathed in the half-light of dawn, Giorgione’s composition focuses on the small group placed off-center in the foreground. Rendering the Holy Family in luminous colors, the artist has silhouetted them against the dark mouth of a cave, a traditional nativity setting borrowed from Byzantine art that here reflects the strong cultural ties between the city-state of Venice and the empire to the east. This composition, one of the very few existing paintings by the master, demonstrates Giorgione’s mastery of color and control of mood, elements which helped him to achieve fame during his short life of thirty-three years.

WEST SCULPTURE HALL: Jacopo Sansovino, Venus Anadyomene, cast c. 1527-1530

One of the rare, life-sized bronzes of the Renaissance now in the United States, the Venus Anadyomene is of unparalleled elegance. While the softness of the modeled forms and the vertical sweep of the curving silhouette invest the nude with a heightened grace, her twisting pose invites the viewer to move around the statue, following the fluid line of her encircling arms. Shown holding a seashell, a reflection of Venus’ birth from the sea, this statue is appropriately entitled anadyomene, “rising from the waters.” The artist, Jacopo 8 Sansovino, was trained in Florence and Rome. Moving to Venice in 1527, this major high Renaissance sculptor and architect designed or remodeled many important private and public buildings including several palaces and the Library of Saint Mark.

GALLERY 28. Titian, Doge Andrea Gritti, painted c. 1535/1540

Typically Venetian was Titian’s method of starting with a dark preparatory ground, then building up the forms with thin layers of oil paint. Choosing the pose that best focuses our attention, Titian has captured his sitter’s restless vitality in the turn of the doge’s head and the penetrating glance. By accentuating the size and grasp of the hand and the bulk of the body beneath the sumptuous ceremonial robes, the artist has drawn a massive and commanding presence befitting this renowned admiral and doge, or duke of Venice. As seen here, the figure seems to emerge quite powerfully from the shadow, and the predominant hues of red and yellow have a rich, smoldering quality.

The baroque period began around 1600, when the Church was engaged in a movement to curb the spreading of the Protestant Reformation. To appeal to the large numbers of ambivalent Christians torn between the two theologies, the Catholic clergy commissioned and supported a realistic but dramatic art designed to involve the populace in the teachings and the authority of the Church. Indeed, so appealing was the baroque style that it was quickly adapted to the worldly subjects of the secular arts. Representative of the Counter-Reformation era is Gian Lorenzo Bernini, an enormously successful and influential architect and sculptor. As world trade shifted to the Atlantic nations, however, Italy’s economic position declined, and by the eighteenth century many Italian painters had 9 to search for commissions elsewhere in Europe. Through their travels, decorative painters and muralists, such as Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, soon established an international style filled with brilliant colors and virtuoso brushwork.

LOBBY A: Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Monsignor Francesco Barberini, carved c. 1624/1625

A masterful example of the immediacy of baroque art, this bust of the uncle of Matteo Barberini, who became Pope Urban VIII, captures the textural qualities of living flesh. Through Bernini’s virtuosity, the highly polished forehead gives the illusion of glossy skin, whereas the starched fabric has been left with a rough, light-absorbing surface. To create a thoughtful expression, Bernini has exaggerated the depth of the eye sockets, casting deep shadows. Such a convincing portrayal of aging flesh and stern character—commissioned by the pope as a tribute to his uncle—is all the more impressive since Bernini had never seen the long-dead Francesco Barberini. The bee on the pedestal is the emblem of the Barberini, a wealthy Roman family.

GALLERY 33: Orazio Gentileschi, The Lute Player, painted c. 1610

The most casual elements of this intimate portrait of human activity combine to create a masterful composition of complex and dynamic parts. The pose of the girl, shown with arm and head poised as she tunes her lute, generates a feeling of sustained movement. The intricate still life fading into shadowy depths at the left is in deliberate contrast to the brightly lit costume and solid figure of the lute player. The combination of abrupt spotlighting and suggested deep space was characteristic of baroque painting in seventeenth-century Rome, and Gentileschi, an international court artist, transmitted this robust style to Genoa, Paris, and London.

GALLERY 36: Giovanni Paolo Panini, The Interior of the Pantheon, painted c. 1740

In an era of travel, when men and women of wealth toured the continent as part of their education, factual renderings of interiors and cityscapes became important souvenirs. A major attraction on the Grand Tour during the eighteenth century was Rome; and in Rome, the Pantheon, a circular temple built in the second century. Converted to a Christian church, it became the burial spot of Renaissance authors and artists, such as Raphael, and has proved the source of inspiration for many later structures, including the central rotunda of the National Gallery. Panini was the greatest view painter in Rome during the 1700s, although his precise manner of painting was paralleled by his Venetian contemporaries, Canaletto and Guardi.

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, northern European art was caught up by the same spirit of empirical inquiry and technical innovation that predominated in Italy during this period. Northern art, however, reflects neither the influence of classical art nor the development of a single-point perspective that are the hallmarks of the Italian Renaissance. Rather, Netherlandish artists such as Jan van Eyck achieved mastery in the new technique of oil painting. The use of oil on wood panel permitted an extraordinary increase in the depth and richness of color, which, in turn, was coupled with the tradition of minute, craftsmanly detail established in late medieval manuscript illumination.

Around 1500, Italian humanism and Renaissance science had a discernable effect upon northern European painting. Albrecht Dürer (gallery 35A) and Francois Clouet (gallery 41) both profited from their exposure to Italian art. The Renaissance influence carried over into the work of Rubens in the seventeenth century despite the religious and political upheaval of the Reformation which affected so 11 much European art of the mid-1500s. Catholic Flanders, the home of Rubens, remained relatively untouched by the changing times and maintained a continuity of political and economic ties to the Spanish monarchy. Rubens, who drew heavily from the work of earlier Italian masters, at the same time developed a baroque preference for large-scale canvases and bravura brushwork, transmitting this style to his associate van Dyck.

GALLERY 39: Jan van Eyck, The Annunciation, painted c. 1425/1430

The sacred setting of a medieval church provides the backdrop to van Eyck’s interpretation of the Annunciation. The archangel Gabriel, dressed in jewels and rich fabrics, greets Mary: “Hail Mary, full of grace.” The simply gowned young virgin lifts her hands in wonder and replies, “Behold the handmaiden of the Lord.” The two Latin phrases (Mary’s is written upside-down) reinforce the contrast and balance between these two important figures: Gabriel in his sumptuous attire and with wings in rainbow colors stands slightly in front in a partially turned position, whereas Mary in her subdued glory sits slightly behind the angel and faces forward. Following the established tradition of the story, van Eyck added a lily, symbol of purity, and a dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit. He also decorated the floor tiles with Old Testament scenes prefiguring the life and triumph of Christ—Samson destroys the Philistine temple and David slays Goliath. This subtle integration of religious history into the background of the painting is indicative of the late medieval belief that objects of the external world are imbued with religious symbolism.

GALLERY 35A: Mathis Grünewald, The Small Crucifixion, painted c. 1510

One of the few surviving paintings by Grünewald, this crucifixion amply displays the emotional power of this German Renaissance artist. Set against a sky darkened by an eclipse of the sun, the scarred and haggard body of Christ makes the scene painfully and physically immediate. With the agonized gesture of the hands, the ragged loincloth, the dislocated shoulders, and twisted feet, little remains to soften the tension of the painting; rather, the artist emphasizes the human suffering necessary for Christ to redeem mankind. Painted on the eve of the Protestant Reformation, this panel reflects the growing insistence in northern Europe upon the reality and importance of private religious experiences.

GALLERY 41A: Peter Paul Rubens, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, painted c. 1615

Scholar, collector, diplomat, and one of the finest artists of his century, Rubens was famed for the boundless enthusiasm and technical wizardry of his paintings. This monumental piece was executed early in Rubens’ career. Its impact depends not only upon its large scale but also upon the baroque combination of the theatrical—the dramatic lighting and Daniel’s expressive pose—with a convincing realism—the lifelike postures and superbly rendered lions’ fur.

GALLERY 42: Sir Anthony van Dyck, Queen Henrietta Maria with Her Dwarf, painted probably in 1633

Painted in London, this depiction of Henrietta Maria, wife of Britain’s Charles I and sister of France’s Louis XIII, is a prime example of the baroque “Grand Manner” portrait. Analysis of character is sacrificed in favor of a stately and essentially flattering mode of presentation; the glittering crown, for example, recalls Henrietta Maria’s station as a queen and the sumptuous fabrics declare her wealth. The large size of the canvas and the lack of expression on the queen’s face are both devices that engender a mood of aloof formality and grandeur; animation and warmth are limited 13 to the minor figures of the dwarf Geoffrey Hudson, who was to become a trusted ambassador, and his pet monkey Pug. With seventeen paintings by van Dyck, the National Gallery has one of the finest and most representative collections of portraits by this master.

The United Netherlands was founded in 1609 as a Protestant nation following bitter wars of liberation from Catholic Spain. The combination of excellent seaports, a powerful navy, and strong mercantile interests made Holland a flourishing economic center. Dutch patrons, predominantly Calvinist and middle class, demanded not religious or mythological pictures, but landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and genres, or scenes of daily life. Their demands were met by an ever-increasing number of Dutch artists who, perhaps in response to a burgeoning and competitive market, specialized in a single type of subject. Thus Frans Hals was famed for his portraits, Kalf for his still lifes, and Ruisdael and Hobbema for their landscapes. The one exception was Rembrandt, whose penetrating insight into the human condition and whose superb technical facility enabled him to explore successfully a variety of subjects. Holland’s artistic boom was soon ended, however, for as quickly as it arose, the economic and artistic Golden Age declined during the last years of the seventeenth century.

GALLERY 44: Jan Vermeer, A Woman Weighing Gold, painted c. 1657

One aspect of Vermeer’s genius was his ability to create a poetry of the obvious, to transmute a mundane scene into an evocative moment. In what appears at first to be a simple depiction of a woman holding a pair of scales, a framed painting of the Last Judgment included on the back wall of the scene suggests a more serious, allegorical meaning. Weighing the souls of mankind serves as a point of comparison to the woman weighing her worldly possessions. Vermeer’s incomparable sensitivity in rendering effects 14 of light can be seen in the careful modulation of the cool, muted daylight that fills the room. Especially striking are the touches of pure white paint that highlight the fur collar and the pearls on the table. The stable, geometric gridwork formed by the table, picture frame, and window reinforce the calm and serious mood.

GALLERY 44: Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Vase of Flowers, painted c. 1645

This still life reveals more than a study of inanimate objects positioned in light and shadow; it also betrays the artist’s interest in the lively microcosmic worlds unnoticed in our daily life. Using more than twenty varieties of blossoms, including roses, tulips, morning-glories, and candytuft, de Heem weaves the blooms, overflowing in the insect-inhabited shadows, into the arrangement of sunlit flowers thriving in the central area of the painting. Since none of the flowers bloom concurrently, the artist portrayed them either from illustrations in botanical texts or from his own studies made during different times of the year. Such interest in the cycle of the seasons and the transience of life, as reflected in this symbolic bouquet, is frequently seen in Dutch flower painting.

GALLERY 47: Aelbert Cuyp, The Maas at Dordrecht, painted c. 1660

Cuyp was a marine and landscape painter, noted for his delicate atmospheric effects. A major portion of this composition is taken up by the sky, which is painted in translucent washes of thinned oils. The scene, bathed in the gentle golden light of early morning, shows the Maas River and, at the left, the unfinished church tower of Cuyp’s home city of Dordrecht. The fleet of boats on the left, arranged on the diagonal, serves both to create deep space and to contrast with the single massive ship on the right. As cannons salute in the middle distance, a figure in a vivid red, black, and white uniform prepares to board ship.

GALLERY 48: Rembrandt, Self-Portrait, dated 1659

The some sixty self-portraits painted by Rembrandt during his long career form a unique visual autobiography. In early life, he was Amsterdam’s leading portraitist and narrative painter and a wealthy man. Later, ravaged by bankruptcy and personal misfortunes, Rembrandt became increasingly introspective. In this self-portrait, painted when he was fifty-three, all but the essential forms are concealed in shadow. Light appears to emanate from the face itself, although the eyes are veiled in a mysterious half-shadow. Rembrandt’s technical genius enabled him to create subtle nuances even within a restricted range of color; the golden light glistening from his forehead merges with the blue-gray at the temples. All of Rembrandt’s painterly skill was used, ultimately, to confront us with a candid self-appraisal that neither flatters nor disparages. (The National Gallery has a wide range of Rembrandt paintings in galleries 45 and 48.)

Imported by the royal courts or commissioned by the Church, foreign artists dominated the arts of Spain during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Juan de Flandes, a Flemish painter (galleries 38 and 39), served the court of Ferdinand and Isabella, and El Greco (gallery 30), a Greek who studied in Venice and Rome, settled and worked in Toledo. By the 1600s, Spain had become an economic and cultural force in Europe, her power sustained in large part by the wealth of her vast American colonies. Seville was then the artistic capital of Spain; Zurbarán, Valdés Leal, Murillo, who founded an academy there in 1660, and Velázquez all worked in Seville. After moving to Madrid, Velázquez served Philip IV as court painter and director of the royal museum. The greatest Spanish artist of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was Francisco de Goya, who was court portraitist to a succession of corrupt monarchs and French conquerors. It should not be forgotten, too, that the twentieth-century artist Pablo Picasso (gallery 76) was first active in Barcelona before emigrating to France.

GALLERY 30: El Greco, Laocoön, painted c. 1610

Unnatural color, particularly in the weightless, elongated figures, combines with a mannered representation of landscape in this unearthly vision from Homeric legend. Shown is the priest Laocoön, who, with his sons, is attacked and destroyed by serpents for having offended the gods during the course of the Trojan War. Beyond the wooden horse lies the city of Troy, a distant and stormy image based on the artist’s adopted city of Toledo. Born in Greece, Domenikos Theotokopoulos was nicknamed El Greco, “the Greek,” when he moved to Spain in 1576.

GALLERY 50: Francisco de Goya, Señora Sabasa García, painted c. 1806 or 1807

Acutely sensitive to the ignorance, hypocrisy, and cruelty in all levels of society, Goya often worked in a satirical mode to capture the realities of war and the tyranny and decadence of court life. Yet, in depicting the niece of a high-ranking government official, the artist has given us a marvelously direct and sympathetic portrait. The innate, peculiarly Spanish sense of pride and self-discipline is evident in Sabasa García’s aristocratic posture and bold, unflinching gaze. Equally direct is Goya’s manner of painting, which captures the rough texture of the shawl as well as the gossamer quality of the mantilla lace. The result is a portrait of great intensity heightened by feminine beauty.

Troubled by the Catholic-Huguenot wars and civil wars of the previous century, seventeenth-century France followed a course of aggression against foreign monarchies and of consolidation within 17 the French state. Most heavily supported by the royal court, French artists were sent to Rome to study the arts of the Italian Renaissance and classical antiquity; some, like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin (gallery 52), chose to remain in Italy. In Paris, an Academy, which rapidly became the ruling body for French art, was established in 1648. To enhance the brilliance of his reign in the latter part of the century, Louis XIV sponsored a ceremonial art—more idealistic than realistic in style—and built near Paris the largest palace in Europe, Versailles. The fountains in the National Gallery’s East and West Garden Courts once stood in the gardens of Versailles and still bear traces of the lavish gold leaf that originally covered them.

Under Louis XV and Louis XVI in the eighteenth century, French society became more relaxed and informal. Most apparent in the decorative arts, the move to a lighter, more graceful style affected painting as well. The new style, rococo, was first developed by Watteau (galleries 53 and 54), who used a carefree delicacy, pastel colors, and gracefully curving lines. After the French Revolution of 1789, a school of neoclassical artists dominated painting, using themes of patriotic heroism and stressing severe beauty of line and firm modeling, over light and color.

GALLERY 44: Georges de La Tour, The Repentant Magdalen, c. 1640

Within the melancholy darkness of this painting, the dim light reveals emblems of the vanity and brevity of life: a skull, book, and mirror. Eliminating unnecessary detail, La Tour makes us focus on the inward, spiritual aspect of his themes, through monumental shapes and a nearly abstract geometry of forms. Mary Magdalen’s fingers touching the skull, for instance, are emphasized in stark angularity against the light from the hidden flame. Like Vermeer, La Tour is a rediscovery of recent years. Although highly respected in his lifetime, La Tour slipped into obscurity, and only thirty-eight of his paintings survive today. A court painter to Louis XIII, La Tour was noted for his “nocturnes,” which generate a mood of isolation by their dense shadows that envelop the composition.

GALLERY 52: Claude Lorrain, The Judgment of Paris, painted 1645/1646

In a landscape of such serenity and beauty as this, the figures almost play a secondary role. The perfectly blue sky with light cloud formations enhances the golden tones of the foreground; the distant Trojan citadel on the right balances the figures at the near left, where three goddesses gather round the Prince of Troy, Paris. Chosen to judge the women on their beauty, Paris is bribed by Venus, here accompanied by her son Cupid, and accepts her aid in abducting Helen, Queen of Sparta. Claude’s vision of this episode, which eventually touched off the Trojan War, is a fine example of his ability both to ennoble and to idealize nature, and it was this mode of painting which was to dominate European landscape painting for the next two centuries.

EAST SCULPTURE HALL: Jean-Louis Lemoyne, Diana, dated 1724

Girlish and slightly awkward, her skirts disheveled by the breeze, Diana is shown as though embarking on a woodland jaunt. The turning figure of the goddess, the poised, expectant look of her dog, and the lightness of her simple drapery lend a sense of buoyancy and delicacy to the ponderous weight of the marble. Lemoyne’s surviving masterpiece, this statue formed part of a group executed by several eighteenth-century French sculptors for the gardens of the Château de la Muette at Marly, a royal retreat and hunting lodge near Paris. This sculptural series helped to generate a new interest in graceful vitality, replacing the earlier ideals of serene monumentality in European statuary.

GALLERY 55: Jean-Honoré Fragonard, A Young Girl Reading, painted c. 1776

The delicate rococo style of the 1700s culminates in the work of Fragonard, court painter to Louis XVI. Indeed, an intimate portrayal such as this typifies rococo taste. Stabilized only by the straight wall and armrest, curving lines wind through the composition. Fragonard’s fascination with the irregular extends to the positioning of the girl’s hand and the boneless curl of her little finger, to the interlacings of her hair ribbons and the bows on her gown. The radiant golden quality of the light and the frothy texture of the paint add to the picture’s sensuous warmth.

GALLERY 56: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, dated 1812

Sensitive to the political aspirations of his sitter, David has here chosen an activity, a time, and a setting that subtly but pointedly illuminate the tenacity and drive of the conqueror Napoleon. With the clock pointing to 4:13 and with candles guttering, Napoleon is presumably rising from a night of work; his dress uniform is wrinkled and his face unshaven. The study is littered with symbols of power, the sword alluding to Napoleon’s military conquests and the scroll on the desk representing the Napoleonic Code, still the basis of French law. The crisp silhouettes and dark colors typify the neoclassical style that followed the French Revolution of 1789.

The history of sixteenth-century England was characterized by unstable, often short-lived alliances made with her several continental neighbors. No wonder then that the influx and influence of foreign artists during this and the following century reflects the diversity of political ties between England and Europe. In the 1500s, the German Hans Holbein the Younger (gallery 40) was court artist to Henry VIII soon after that monarch’s audacious break with the Church, and in the 1600s the Fleming, Anthony van Dyck (galleries 42 and 43), was in the employ of Charles I.

In the eighteenth century, however, when England became a leading maritime and industrial nation under George III and George IV, a large group of native British painters emerged, and in 1768 the Royal Academy was founded in London. The portraitists were led by Sir Joshua Reynolds, first president of the Royal Academy, and Thomas Gainsborough, noted for his virtuoso brushwork. Among their contemporaries and followers were Romney, Hoppner, Raeburn and Lawrence. In the early 1800s, England produced two landscapists who achieved international reputations. Constable was basically a realist in his study of scenes in natural light; Turner, however, was a romantic who interpreted the moods of nature.

GALLERY 59: Thomas Gainsborough, Mrs. Richard Brinsley Sheridan, painted probably 1785/1786

With a feeling for theatricality, Gainsborough interplays the frail figure of a young woman and the powerful mood of nature to establish a perfect setting for this celebrated actress and wife of the playwright and politician Sheridan. Born Elizabeth Linley, she was Gainsborough’s lifelong friend. A motif common to the eighteenth century, the Age of Enlightenment, was the use of nature and an informal pose to achieve unaffected simplicity. In this portrait, however, early signs of romanticism are clearly seen in the dramatic quality of the blowing trees and windswept figure contrasted with the calm features of the finely modeled face. Gainsborough normally painted under candlelight to give a glow and flickering liveliness to his sitters and sometimes used six-foot-long brushes to avoid finicky detailing.

GALLERY 57: Joseph Mallord William Turner, Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Moonlight, painted probably in 1835

Turner’s exaggerated rendition of moonlight was criticized by conservatives when this night scene on the River Tyne was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1835. Cutting through the center of the painting, the arched curve of brilliant light transforms the reality of a gritty industrial scene into 21 an appealingly romantic seascape and brings the world of man into accord with nature. Through the misty English air and against the thinly painted sky, the moon shimmers forth as a disk of thick white paint.

Established as a subculture of the mother country, the American colonies looked to England for leadership in the arts. Ambitious painters, finding no opportunity for formal training in the colonies, went to study in Europe. Benjamin West, a Pennsylvania Quaker, after three years in Italy, in 1763 established himself in London, where he achieved such renown that he became History Painter to King George III and was later appointed second president of the Royal Academy of Arts. Until after the Civil War, the best training was still abroad, but usually the American students returned to the United States, where a growing urban society with more leisure was providing a market for works of art.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, many untrained artists, working in the cities but more often traveling about the countryside, provided naïve or primitive pictures for the ever-increasing middle classes. Up to this time the artist had been mainly a portraitist; but with the invention of the camera in 1839 he had to shift his emphasis, and by mid-century America had a thriving school of landscape painters, whose works fed a national pride in the great wild terrain of the New World. After the Civil War, however, these landscapes also appealed to a populace seeking relief in the ideal world of a quiet countryside away from the humdrum of dirty cities that were springing up everywhere, the result of the Industrial Revolution.

Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer were the great turn-of-the-century artists. They portrayed American life and scenery with straightforward candor. Their example has been carried on by some modern American artists who, fascinated with the urban growth of the 1900s, have emphasized the vitality of city life. These include painters such as Henri, Bellows, and Sloan. More recently abstract art has been in the forefront of American painting.

GALLERY 64: John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark, dated 1778

Unusual in European art, the sense of immediacy in this rescue scene was an American innovation, and it assured Copley’s reputation in Britain while furthering the importance of realism in narrative painting. The successful merchant and former English sailor Brook Watson commissioned the young American artist, who had settled in London, to depict an adventure that occurred in the sailor’s youth. Watson had been attacked by a shark while swimming in Havana, Cuba, in 1749. Using a fresh approach, Copley recaptured the horror of that event by lending vivid emotions to the rescuers—cowardice, fear, compassion—and by catching the helpless fright of the boy.

GALLERY 60B: Gilbert Stuart, The Skater, painted in 1782

Artist and subject, while breaking from the first posing session for this portrait, took to the fresh air and exercise of skating on the frozen Serpentine in London’s Hyde Park. The sport gave Stuart a novel idea, which he translated with a free-spirited freshness and vigor. Commissioned by Mr. William Grant, this, Stuart’s first full-length portrait, was a triumph at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1782. Unlike West, under whom he studied, and Copley, another American artist, Gilbert Stuart eventually returned to the United States, achieving further fame with his innumerable portraits of George Washington. Painted in 1795, the famous portrait in gallery 62 is believed to be his first life study of the president.

GALLERY 60: Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Childhood, dated 1842

One of the earliest American landscapists, Thomas Cole produced imaginary, symbolic scenes as well as glorified panoramas of native wilderness. In the first of four fantasies, Childhood, a baby’s ship of life, steered by a guardian angel, floats at the source of a river toward a promising dawn. In the other three pictures completing The Voyage of Life series, Youth sets off on a meandering stream, striving toward a castle in the clouds, while Manhood weathers a storm on a tumultuous river and Old Age drifts into a quiet ocean where heavenly messengers wait to receive him.

GALLERY 66: Edward Hicks, The Cornell Farm, dated 1848

After an 1848 Pennsylvania agricultural fair, James Cornell commissioned this record of his prize-winning livestock and acreage. In addition to carefully detailing each cow, horse, pig, sheep, and building, the artist Edward Hicks has also emphasized the decorative patterning of the group. This so-called naïve piece does not present a sophisticated rendering of anatomy or landscape, but it does present a study in contrast between the rhythmic row of animals and the geometric background. Lacking formal artistic schooling, Hicks was a sign and coach painter, who did pictures as a sideline or as favors for friends.

GALLERY 67: James McNeill Whistler, The White Girl (Symphony in White, No. 1), dated 1862

Painted in Paris, this canvas caused a scandal at an 1863 exhibition. The lack of personality in the face infuriated critics; they failed to realize that this was not intended as a portrait. Whistler, an American expatriate, was exercising his artistic theories by exploring a single tone—white. The starched cuffs, striped sleeves, cambric skirt, brocade curtain, and fur rug create a “Symphony in White,” as Whistler once titled this work. The fullness of the girl’s lips, the thick richness of her chestnut hair, and her wide blue eyes, 24 however, mark a subtle but uneasy contrast to the purity of the white color. This tension is carried further by the presence of the bearskin and the garish flowers wilting on the floor, symbolic, perhaps, of a bestiality of nature and an innocence lost. To emphasize the color relationships around this woman, his mistress Joanna Hiffernan, Whistler flattened the space and avoided strong lights and shadows.

GALLERY 68: George Bellows, Both Members of This Club, painted in 1909

When public boxing was illegal in New York, fights were held in private clubs with fighters elected as members for only the night of the match. The black boxer may be Joe Gans, lightweight champion from 1901 to 1908; his opponent has not been identified. Once a professional athlete himself, George Bellows understood the violence of the sport. Brutality is conveyed by the angular lines of the fighters’ bodies, the boldly slashing brushwork, and the lurid glare of spotlights within the gloomy arena.

French art during the second half of the 1800s is noted for its innovation and its diversity. Yet, although the paintings produced during this period differ in their visual effects, the artists of these works were all largely concerned with the same problem: how to treat nature and how to define reality. Thus, in reaction to the neoclassicists, who stressed line and color, and the romantics, who favored lush hues, exotic or unusual subject matter, and emotionalism, the realists sought to paint only what was before them, free from embellishment. Other artists such as Monet and Renoir concentrated 25 upon recording the fleeting and subtle color impressions created by changes in sunlight. Because their technique was rapid and sketchy, these latter artists gave less attention to studiously modeled form, and their paintings, although “realistic” in their rendition of light and space, do not have the solid, tangible qualities so evident in Academic painting. (The Gallery’s collections are particularly comprehensive in the works of Manet, Renoir, and Degas. Included also is Mary Cassatt, the only American who exhibited with the impressionists.) Still other artists rejected impressionism’s concern with transitory moments in order to express either their intuitive reactions to the natural world or their personalized interpretation of the physical laws that order appearances. Reality was redefined by these artists, such as Gauguin, van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Cézanne, who were known as post-impressionists. It was their work which prepared the way for twentieth-century expressionism and abstraction.

GALLERY 93: Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Forest of Fontainebleau, painted c. 1830

Amid the controversies of nineteenth-century French art criticism, Corot was a transitional figure. Popular with conservative patrons, he was also a champion of the younger, radical painters. This scene in a forest near Paris is composed of traditional elements: the overlapping planes of light and dark foliage and a deep perspective established by the path of light and space running through the painting’s center. Corot’s treatment of light, studied directly from nature, is quite modern, however, as he exactly captures the harsh glare and heavy shadow caused by strong sun.

GALLERY 83: Edouard Manet, Gare Saint-Lazare, dated 1873

Overlooking Paris’ Saint-Lazare railroad yards, this sun-drenched scene is the first major picture Manet executed out-of-doors. Though influenced by his friends, the impressionists Monet and Renoir, Manet’s disciplined temperament rejected impressionism’s less structured effects. The rigid lines of the iron fence, for example, act as a foil for the figures’ curves. The little girl, whose interest lies on the rail yards behind, forms a subtle tension with the woman who gazes out at the viewer. The color scheme, with its reversal of colors, serves both to unify the pattern and to underscore the separation of the two figures: the full womanly figure is dressed in blue accented with white, whereas the childish figure is in white accented with blue.

GALLERY 90: Auguste Renoir, A Girl with a Watering Can, dated 1876

Wanting to capture the dazzling colors found in strong sunlight, the impressionist painter Renoir intensified the natural hues of reality to a greater vibrancy on canvas. The green of the grass depicted here is more intense in hue than that which one might expect to find in nature, and the gravel path sparkles like gems. In calculating the juxtaposition of color, the artist placed pale blue-green shadows on the child’s face to heighten her rosy complexion. In addition, the blurred impressionist brushstrokes create the effect of shimmering sunlight dissolving form and detail. Once in response to criticism about his work, Renoir said, “There are enough things to bore us in life without our making more of them.”

GALLERY 86: Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, West Facade, dated 1894

Monet, a founder of impressionism, became obsessed with the variations with natural light. From 1892 to 1895, he recorded in a series of paintings a medieval French cathedral as it appeared at different times of day or under different weather conditions. In over thirty canvases of Rouen Cathedral, Monet’s analyses of light on the cathedral’s surfaces resulted in iridescent colors and thick paint textures that are visually sensational 27 yet highly naturalistic. Here, in early morning, the church shimmers lavender and violet, the stone of the upper portions glowing in the rich red-orange of the rising sun. Another from the Rouen series, showing the church in the yellow-white heat of the afternoon, is also in this room.

GALLERY 85: Edgar Degas, Four Dancers, painted c. 1899

One of Degas’ own favorite works, this, his last major oil painting, has a chalky texture reminiscent of the pastels he frequently used. Studying the strong patterns in Japanese prints as well as the snapshot effects of photography, this superb draftsman often designed his paintings with an angled point of view or created an off-center balance, cutting off figures by the frame edge. With the increasing abstraction of his late style, Degas here used a black outline which not only separates the gestures of the dancers but also accents their red apparel, intensifying the theatrical effect.

GALLERY 85: Paul Cézanne, Still Life, painted c. 1894

Most evident in this painting is the tension between what is, on the one hand, a rendition of nature and, on the other, Cézanne’s deliberate organization of the shapes into a rhythm of forms. The swirls and eddies of the blue drapery are reflected in the curves of the apples, peppermint bottle, white linen, and carafe. At the same time, horizontal or vertical lines dominate along the edge of the table, the molding of the back wall, and the neck of the bottle, creating a linear grid that offsets and balances the curving lines. The blue-green tonality, in addition to the geometric patterning, further demonstrates the artist’s intent to visually organize and unify. Indeed, for the sake of unity, Cézanne has even distorted the carafe by swelling it out on one side, pulling it deeper into the folds of the fabric.

Flattened shapes, strong outlines, unmodulated hues, and pronounced pigment textures have been among the central devices of many twentieth-century painters. Artists have often abandoned the direct imitation of reality, preferring instead to work through complex problems of pictorial design to express human feelings. A tremendous diversity of artistic styles has resulted, emerging in tempo with the rapid changes of modern society and technology. The National Gallery’s present collection of modern art concentrates on the French school prior to World War I, the period when Paris was the cultural center of Europe.

With the opening of the East Building, the National Gallery will have increased space for the display of contemporary art.

GALLERY 76: Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltimbanques, painted in 1905

Obsessed in 1905 with the theme of the circus, Picasso sought the company of performers not only as potential subjects for his paintings but also as companions. Their agility and grace delighted him; their gypsy lives intrigued him, as did their professional pursuit of the fine art of illusion. The circus family in this painting is assembled in a lonely landscape devoid of any living thing. Their static poses suggest that each member, caught up in reverie, is unaware of the others. A sense of equilibrium is maintained, however, in the compact shape of the five figures at the left balanced against the single figure in the right foreground. The pastel tints of red, violet, and blue, moreover, create an aura of elegiac melancholy. Although Picasso has abandoned the predominantly blue palette of his earlier, more pensive work, the Family of Saltimbanques still exudes a feeling of pathos and isolation. (The thirteen paintings by Picasso in the National Gallery represent the major phases within the first half of Picasso’s career.)

GALLERY 76: Georges Braque, Still Life: Le Jour, dated 1929

Although common, everyday items, the objects in this painting are not shown in an everyday arrangement. Rather, through a precise, rational manipulation of shapes, the artist has so structured the objects as to arrive at a fresh understanding of their reality. The pitcher and the wineglass, for example, are each shown as an overview of the rim (presenting one angle of vision) and a profile view of the object’s body (presenting a second angle of vision); these and other aspects of the objects are combined to reveal a new, but nonetheless accurate, perception of the object. And, as Braque intended, it is this flattened perception that, throughout the composition, constantly reminds us of the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Braque’s geometric compositions—which to outraged critics were nothing more than “cubes”—were one aspect of a style known as cubism which developed shortly after the turn of the century.

WEST STAIR HALL: Salvador Dali, The Sacrament of the Last Supper, dated 1955

Known neither for his Christian themes nor for simplicity of organization, Dali has in this painting moved away from the surrealism that preoccupied him during his earlier years. The composition of the Last Supper is clearly defined in two main planes: foreground action and background scenery. The placement of the figures is symmetrical with a mirror-image repetition of the same figures from one side of the painting to the other. The men, their faces hidden, are more the idealized participants in a timeless Eucharist than specific men of a specific time and place. The strange translucent enclosure—a geometrical dodecahedron—is meant to be understood as part earthly, part celestial. The enigma of this intellectual and complex painting centers finally in the all-embracing arms—symbolic of the heavens and of the creator, who is seen as youthful rather than patriarchal but whose face is hidden.

As objects for daily use, the decorative arts allow a close insight into cultures of the past. Among its holdings, the National Gallery has an extensive collection of European furniture, tapestries, and ceramics from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as well as medieval church vessels and Renaissance jewelry. In addition, there is a fine selection of eighteenth-century French furniture—including many pieces signed by cabinetmakers to Louis XV and Louis XVI and, of historic interest, the writing table used by Queen Marie Antoinette while she was imprisoned three years during the French Revolution (gallery 55). The Gallery also contains a large collection of Chinese porcelains, including porcelains from the Ch’ing Dynasty of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Until the East Building is completed, only a few selected works can be placed on exhibition in the galleries.

The collection of prints and drawings at the National Gallery contains about fifty thousand examples from the fifteenth century to the present time. Included are drawings by Dürer, Rembrandt, Rubens, and Blake, as well as a wide range of prints by the major graphic artists of the Western World. The National Gallery’s collection incorporates an extremely fine selection of early Northern woodcuts and engravings and one of the most important groups of eighteenth-century French prints, drawings, and book illustrations outside of France. There is also an excellent group of early manuscript illuminations.

Visitors may examine prints and drawings not on exhibition by appointment with a curator in the Department of Graphic Arts.

The Index of American Design is a collection of watercolor renderings of objects of popular art in the United States from before 1700 until about 1900. The renderings represent American ceramics, furniture, woodcarving, glassware, metalwork, tools and utensils, textiles, costumes, and other types of American craftsmanship. There are some seventeen thousand renderings and about five hundred photographs. These are available for study, by appointment. The works themselves may be loaned to organizations for exhibition outside the Gallery.

The National Gallery is open to the public every day in the year except Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. Admission is free at all times.

Regular: Weekdays, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Sundays, 12 noon to 9 p.m.

Summer: During the summer months the regular hours are extended to 9 p.m. Dates for the beginning and termination of evening hours are announced on Gallery information boards and in the Gallery’s monthly Calendar of Events.

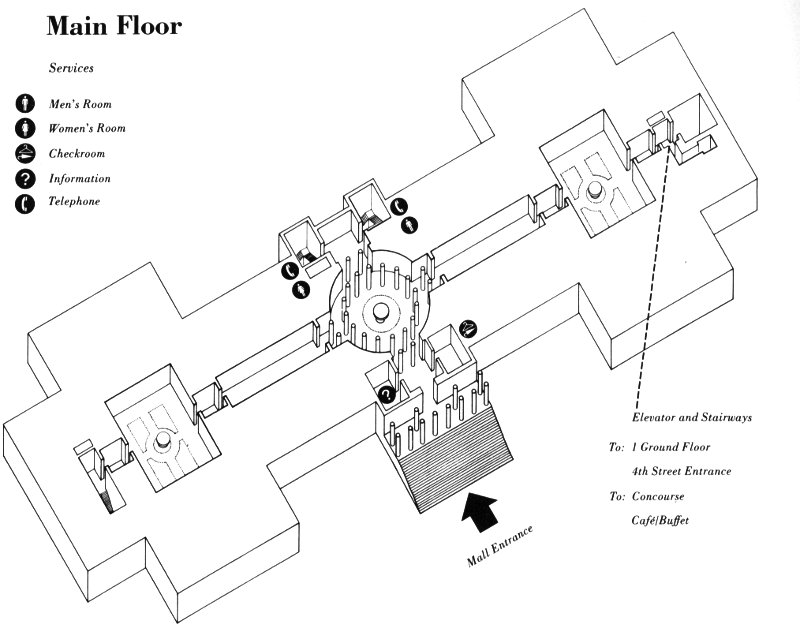

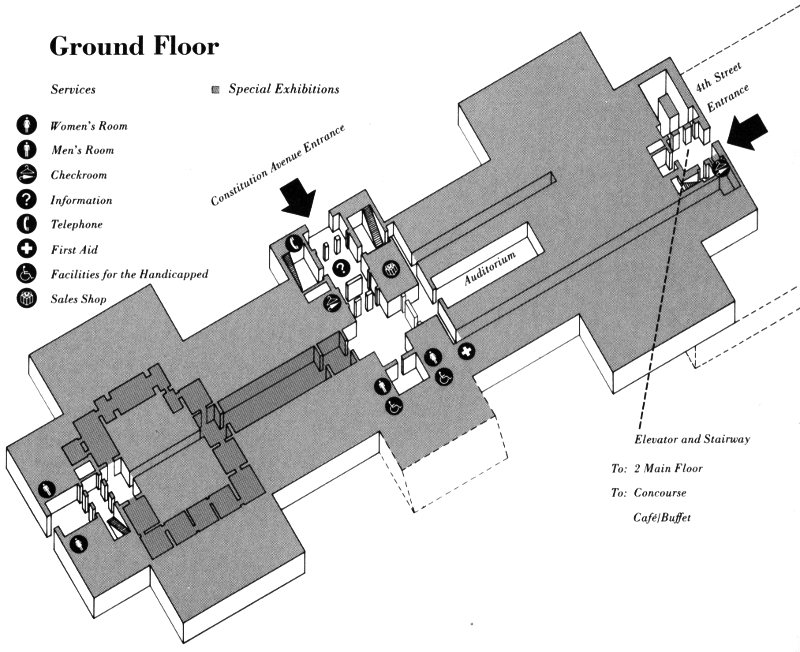

There are two art information desks: one at the Constitution Avenue entrance on the Ground Floor; and the other at the Mall entrance near the Rotunda on the Main Floor.

Free checking service is provided near the entrances. All parcels, briefcases, and umbrellas must be checked.

Reproductions and catalogues of the collections are sold in the publications salesroom on the Ground Floor near the Constitution Avenue entrance. Books and catalogues, postcards, color reproductions, framed reproductions, original color slides, recordings, portfolios, sculpture reproductions (including jewelry), note folders, and other publications are available.

Gallery talks and free tours of the collection are given by the Education Department.

An Introductory Tour, lasting about 50 minutes, covers the Gallery’s highlights. It is offered at 11 a.m. and 3 p.m., Monday through Saturday, and at 5 p.m. on Sunday.

The Tour of the Week, lasting about 50 minutes, concentrates on a specific topic or on a special exhibition. It is given at 1 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday, and at 2:30 p.m. on Sunday.

The Painting of the Week, a 15-minute gallery talk on a single picture in the collection, is scheduled at noon and 2 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday, and at 3:30 and 6 p.m. on Sunday.

Special appointments for groups of 15 or more people can be arranged by applying to the Education Department at least two weeks in advance.

Recorded tours, one offering a selection of the Director’s choice of paintings and another discussing works in various galleries, may be rented for nominal fees.

Lectures by visiting art authorities, and occasionally by members of the Gallery staff, are given at 4 p.m. on Sunday afternoons in the Auditorium.

The subjects are often grouped to form a series treating a single aspect of art history. Admission is free and no reservations are required. The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, a special series commissioned by the National Gallery, which are subsequently published in book form, take place during the spring.

Free films on art are presented on a varying schedule. For further information on tours, lectures, and films, consult the Gallery’s Calendar of Events.

Free concerts are given in the East Garden Court every Sunday evening at 7 p.m. (with the exception of the summer period from late June to late September). Concerts are given either by guest artists or by the National Gallery of Art Orchestra under the direction of Richard Bales. The programs, with intermission talks or interviews by the Gallery staff, are broadcast live over WGMS-AM (570) and FM (103.5). Seats, which are not reserved, are available after 6 p.m.

The monthly Calendar of Events listing special exhibitions, lectures, concerts, and films at the National Gallery of Art will be sent to you regularly, free of charge, if you fill out an application at either information desk.

A variety of educational materials suitable for schools, colleges, and libraries can be borrowed from the Gallery. Color slide programs, with accompanying audio cassettes, texts, and study prints, cover a wide range of subjects. A number of films, including “Art in the Western World” and “The American Vision,” are available. All material is lent free of charge except for return postage. For information, apply to the office of the Extension Service.

Slides of the Gallery’s collection are available as loans to organizations, schools, and colleges without charge. For information, apply to the slide library in the Education Department.

Photography for personal purposes, with or without flash, but not with a tripod, is permitted throughout the Gallery unless signs in a particular area indicate to the contrary. Application for permission to use a tripod should be made to the Photographic Services Office, Monday through Friday, exclusive of legal holidays.

Easels and stools are provided without charge for those individuals who have secured permission to copy works of art in the Gallery. Application for permits should be made at the Registrar’s Office. Letters of reference and examples of work are required before permission to copy may be granted. No special permission is required for sketching without easels if only nonliquid materials, such as pencil, ballpoint pen, or crayon, are used.

The café/buffet is open every day of the year except Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. It is located at the Concourse level and may be reached from the Main Floor via the East Garden Court and East Lobby or from the 4th Street Plaza.

Regular hours: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. on weekdays and Saturdays, and 1 p.m. to 7 p.m. Sundays.

Summer hours: During the period when the Gallery is open until 9 p.m., the café/buffet remains open until 7:30 p.m. on weekdays and Saturdays. Sunday hours are 1 p.m. to 7 p.m.

Two lounges are provided for smoking: the smoking room on the Ground Floor and the Founder’s Room on the Main Floor near the Rotunda. Smoking is also permitted in the café/buffet but is strictly prohibited in all halls and exhibition galleries.

Restrooms are located on the Ground Floor, at the top of each staircase near the Rotunda on the Main Floor, and at the Concourse level.

An emergency room, under the supervision of a trained nurse, is available for first-aid treatment in case of accident or sudden illness. It is located on the Ground Floor near the entrance to the Auditorium. The guards will direct visitors to this room on request.

Strollers for small children and wheelchairs are available from the guards at both entrances without charge. Attendants for pushing wheelchairs are not available.

Pay-station telephone booths are on the Ground Floor near the stairways, on the Main Floor near the Rotunda, and at the Concourse level.

The guards are under orders not to permit visitors to touch the paintings or sculpture under any circumstances. Fountain pens with fluid ink may not be used in the galleries. Smoking is forbidden in the exhibition areas.

Flowers and plants in the courts are grown in the National Gallery’s greenhouses and are changed frequently by the Gallery’s horticultural staff. There are special floral displays at Christmas and Easter in both the Garden Courts and the Rotunda.

Board of Trustees

The Chief Justice of the United States, Chairman

The Secretary of State

The Secretary of the Treasury

The Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

Paul Mellon

John Hay Whitney

Franklin D. Murphy

Carlisle H. Humelsine

John R. Stevenson

Officers and Staff

President: Paul Mellon

Vice President: John Hay Whitney

Director: J. Carter Brown

Assistant To the Director for Music: Richard Bales

Assistant To the Director for National Programs: W. Howard Adams

Assistant To the Director for Public Information: Katherine Warwick

Assistant To the Director for Special Events: Robert L. Pell

Construction Manager: Hurley F. Offenbacher

Planning Consultant: David Scott

Assistant Director/Chief Curator: Charles Parkhurst

Curators:

American Painting: William P. Campbell

Dutch and Flemish Painting: Arthur Wheelock

French Painting: David E. Rust

Graphic Arts: Andrew C. Robison

Italian Painting, Northern and Later: Sheldon Grossman

Italian Painting, Early: David Alan Brown

Northern European Painting To 1700: John Hand

Sculpture: Douglas Lewis, Jr.

Spanish Painting: Anna M. Voris

Twentieth-century Art: E. A. Carmean, Jr.

Curator of Education: Margaret I. Bouton

Head, Extension Program Development: Joseph J. Reis

Head, Art Information Service: Elise V. H. Ferber

Chief Librarian: J. M. Edelstein

Editor: Theodore S. Amussen

Head Conservator: Victor C. B. Covey

Chief, Design and Installation: Gaillard F. Ravenel

Chief, Exhibitions, Loans and Registration: Jack C. Spinx

Registrar: Peter Davidock

Head Photographer: William J. Sumits

Treasurer: Lloyd D. Hayes

Assistant Treasurer: James W. Woodard

Administrator: Joseph G. English

Assistant Administrator: George W. Riggs

Personnel Officer: Jeremiah J. Barrett

Secretary and General Counsel: Robert Amory, Jr.

The Board of Trustees has full power to accept gifts, bequests, or devises of works of art, money, or other personal or real property, and either absolutely or in trust. Gifts and donations to the National Gallery of Art are deductible for Federal income tax purposes within the limits provided by law, and are welcomed in amounts of any size.

★U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1976 O—207-802

Main Floor

Schools of Painting

Central Italian and Florentine Renaissance

North Italian and Venetian Renaissance

17th and 18th Century Italian

Spanish

Flemish and German

Dutch

17th and 18th Century French

19th Century French

British

American

Special Exhibitions

Sculpture

West Garden Court

Rotunda

East Garden Court

Mall Entrance