*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 66768 ***

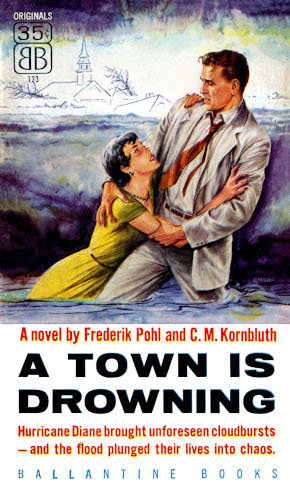

A TOWN IS DROWNING

by

FREDERIK POHL

and

C. M. KORNBLUTH

BALLANTINE BOOKS

NEW YORK

This is an original novel—not a reprint—

published by Ballantine Books, Inc.

© 1955 by Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 55-12407

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

BALLANTINE BOOKS, INC.

404 Fifth Avenue, New York 18, N. Y.

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any

evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

By Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth

Contemporary Novel

A TOWN IS DROWNING

Science Fiction

THE SPACE MERCHANTS

SEARCH THE SKY

GLADIATOR-AT-LAW

TORN FROM TODAY'S HEADLINES

This novel takes you right into the heart of the new flood country,

the Northeast United States which had generally been free of hurricanes

and attendant floods. Now disaster has struck, more than once—terrible

and grim.

Although this novel will give you an accurate and brilliantly

vivid picture of what it's like to live through a flood, even more

importantly it will show you what the people are like who fought the

catastrophe and how those who survived are still fighting. In the

persons of Starkman the burgess, Groff the dynamic young executive,

Sharon the shrewd opportunist, Mrs. Goudeket, the resort owner, and

others, you will meet and understand the varying human elements that

the flood unleashed and intensified. Through it all you will sense a

growing feeling of pride—that despite the selfishness of some, the

people of the town met the terrible onslaught with courage and a sense

of mutual help.

Already well known for their superb science fiction, Frederik Pohl and

C. M. Kornbluth demonstrate here their equal power in the realistic

contemporary novel.

CHAPTER ONE

The man in the filling station was clearly of two minds about it, but

finally he buttoned up his raincoat and pulled on his hat and came out

to Mickey Groff's car. "Sorry to make you come out in the rain like

this," Groff said. "Fill it up, will you?"

He rolled up the window and picked out the least soaked wad of Kleenex

to wipe the mist off the inside of the windshield. The car radio

stopped playing show tunes and began to talk about freezer food plans.

Groff snapped it off and leaned back to watch the turning dials on the

gas pump. By the time the man had put back the cap and sloshed around

to the window Groff had the exact change ready in his hand. "How far is

it to Hebertown?"

"Five miles," the attendant said, and went inside without counting the

money. As Groff pulled out he saw the lights go out on the pumps and

the big sign overhead.

You couldn't blame him, he thought; there weren't enough cars out in

this rain to make it worth while. He had been lucky to find even one

station open.

It was nearly impossible to see the road, no matter how hard the

windshield wipers worked. Rain was spraying in somehow; all the windows

were closed tight, but Groff could feel the thin mist on his face. He

rolled around a long, downgrade curve, and when he touched the brake

for a moment there was a queasy slipping sensation; the rain was coming

down faster than it could flow off the highway.

Foolish to drive all the way to Hebertown, Groff reflected; but the

only alternative, actually, was to take a bus. The railroads didn't

bother much with this little out-of-the-way corner of the state. And

that was something to keep firmly in mind when he talked to the burgess

the next morning, he reminded himself. An industry-hungry town could

make you some tempting offers; there was a firm promise of a tax break

and bank credit, and the suggestion that maybe a suitable factory

building could be turned over to you for nearly nothing at all. But you

had to keep freight differentials in mind too; and what about labor

supply? Well, no; he crossed that off. That was the whole point of the

burgess's cooperative attitude; Hebertown had plenty of available labor

ten months of the year, it was only when the vacationers came up from

New York and the other big cities that local unemployment and the state

of the local tax rolls ceased to be a problem. Still, what about that?

Were you supposed to close down in the months of July and August?

He shifted in his seat, forcing himself to lean back—it did no good

to peer into the rain—and tried to relax. Mickey Groff was a big man

and not used to sitting. It gave him a cramped, unwelcome feeling of

confinement.

There was a light ahead; it turned out to be a store with a neon sign

that said Sam's Grocery, but it gave Groff enough help to let him

pick up his speed to nearly thirty-five miles an hour. He had been

nearly an hour covering the last twenty miles, he saw irritably. Of

course, it didn't matter—it meant just one hour less to spend sitting

in the lobby of the Heber House, since there wasn't a thing he could do

until the next morning in this rain. But why did he have to pick this

particular Thursday to come up?

He passed the store, and at once the road was invisible in front of him

again. He tramped on the brake, slipped and skidded, and straightened

out. That was foolish, he told himself. He carefully slowed as the road

curved again....

Not enough. It was the other car's fault, of course; he saw the lights

raging at him down the middle of the road and automatically pulled over

quickly. At once he felt the sidewise slip and sway of the skid, but

it was too late to do anything about it.

It could have been worse. Thank God there was a good wide shoulder

right there. The only thing was, he seemed to be stuck in the mud.

Mickey Groff wasn't much of a waiter. There wasn't a showdog's chance

of a car stopping to help him, of course—even if one came by, they'd

hardly be able to see him. Anyway, Sam's Grocery couldn't be more than

a quarter of a mile back along the road, and from there he could phone

for a wrecker—or at worst, if the wreckers had their own problems on

a night like this, for a cab to get him into Hebertown. Once the rain

stopped, it wouldn't be much of a problem to get pulled out of the mud.

He almost changed his mind when he stepped out into the rain, but by

the time he had locked the car door behind him it was too late—it was

hard to imagine how he could get any wetter than he was. Mickey Groff

had heard of rain coming down in sheets, but he had never experienced

it before. This was something beyond all expectations; in ten seconds

he was wet to the skin, in a minute he was drenched as a Channel

swimmer. There was wind with the rain, too; part of the time it came

swiping at him from the side, stinging into his eyes, infiltrating his

ears, slipping up the cuffs of his sodden sleeves. By the time he got

around the curve in the road he was shaking with chill.

After ten minutes of staggering through the storm he wondered why he

couldn't see the lights of the store. Then he saw why, and it was like

a fist under the heart; the lights were out. There was the store just

ahead, but the neon was black, the windows were black, there was only

the faintest suggestion of a glimmer at the edges of the glass.

He went stumbling across a little gravel parking lot with water

sloshing around his shoes and banged on the door. Then he saw that

there was a light in the back of the store; it was a candle. He tried

the door handle and it opened.

Inside, the noise of the rain changed and dulled; instead of a

slashing at his ears it was a drumming overhead. A man came out of a

storeroom at the back, carrying a gasoline lantern, and the whole store

brightened and began to look more normal.

"Oh," said Mickey Groff. "Your power's out. I thought maybe you were

closing up."

The man said sourly, "I might as well be. Jesus, did you ever see

weather like this in your life? I been here—"

"Have you got a phone?" Groff interrupted.

"Phone's out too."

Groff sluiced some of the water off his face and hair. "Well," he

said. Somehow it hadn't occurred to him that the phones might not be

working. There wasn't much sense in going back to the car again; he

knew a mudded-in wheel when he saw one. You could push blankets and

boards under those rear wheels all night and the mud would just swallow

up what the wheels didn't slide right off. "Maybe you can help me,"

he said. "I'm stuck in the mud down the road and I've got to get into

Hebertown."

The grocer glanced at him appraisingly and then bent to adjust the

flame on the gasoline lantern. "I'm all alone here," he mentioned.

Mickey Groff waited.

"I hate to close up before time," the grocer said virtuously. "I'd like

to help you out—You stuck bad?"

"Pretty bad. Anyway, I can't rock it out. I was hoping to call a tow

truck from Hebertown."

"I got a pickup truck with four-wheel drive," the grocer said

thoughtfully. "You're welcome to wait here till I close if you want to.

Wouldn't be more than a couple of—"

"How about ten bucks if you do it now?"

The grocer's eyes flickered, but he shook his head. "You don't know

the people around here," he complained. "They wait till I'm just ready

to close, and bingo, two-three cars come zooming up. Milk for Junior,

catfood for the cat, coffee, they gotta have coffee, they wouldn't

bother me if it wasn't so jeezly important. Sit down and wait, mister.

It's only—" He squinted at the advertising clock above his door,

shadowed from the flare of the pressure lamp by a stack of tall cans on

a top shelf—"It's only half an hour."

Mickey Groff thought of lying to the man, giving him a story about a

medical emergency or a big deal with a deadline, something he couldn't

decently brush off for the sake of two or three catfood customers.

Then, because he didn't like to lie, he shrugged, made a disgusted

grimace at himself in the near-dark and sat down in a spindle-back

chair to wait out the thirty minutes. He knew what the trouble was;

it was the old thing. He had been born, apparently, geared up about

twenty-five per cent faster than most people. This was very handy in

some ways; he was a Rising Young Businessman at thirty and pretty soon

now he'd be a Rising Young Industrialist. His picture had been printed

in Nation's Business along with eleven other promising youngsters

who owned their own plants, and one day it would appear alone. He knew

it and he knew it would be due to his built-in overgearing. But that

didn't make it any easier to sit and wait for the catfood customers.

The storekeeper—as most people did—sensed his mood. "Like to look at

the paper?" he asked, and handed him an eight-page sheet. It was the

latest—yesterday's—issue of the Hebertown Weekly Times. Groff had

studied the last four issues preceding it, as well as those of a dozen

other country papers, trying to get the feel of the communities they

served. On one of those communities he would soon have to stake his

play for the jump from forty employees to a hundred.

He held the paper up to the lamplight and read the main headline,

covering the three right columns. The chair crashed behind him as he

snapped to his feet. "God damn it to hell!" he said.

The storekeeper backed away, scared. "What's the matter, mister?"

"Sorry," Groff said. "I didn't mean you. I just thought of something I

forgot to do."

Which was a lie. He forced himself to set up the chair again, sat

down and reread the headline, pulses hammering at his temples. BORO

MAY GRANT SWANSCOMB MILL TO CHESBRO AT NOMINAL RENT; MOVE HAILED AS

EMPLOYMENT BOOM; OLD PLANT TO BE USED AS WAREHOUSE.

The former Swanscomb Mill was the building he had his eye on as the

shell for his projected new factory. It was ideal. It was empty

and unwanted by anybody since Swanscomb had moved south; it was

a low-maintenance brick shell with plenty of adjoining room for

expansion; it was solidly built and able to support his machine tools;

it had its own siding and a loading deck for trucks. And somebody

else, by incredible coincidence, was after it too. The pounding pulses

subsided and he steadied himself to read the story. It was one column

down the right and it was strangely uninformative. It led off: "Civic

leaders today hailed the announcement that Arthur Chesbro hopes to

secure the old Swanscomb Mill from the Borough as a warehouse for the

storage of materials and supplies." It didn't say who the civic leaders

were. It went on to recapitulate the familiar history of the plant. It

concluded by quoting Arthur Chesbro as hoping that at least a dozen

local citizens would be employed as warehousemen in the plant.

A car's headlights outside turned the streaming store window into a

sheet of refracted yellow glare. A woman bustled in and peered about

uncertainly in the gloom. The storekeeper yes-ma'amed her and she

apologized for coming so late, the rain was so terrible she could

barely crawl, and could she have three cans of catfood?

The storekeeper gave her the cans, and when he closed the door behind

her—rain drove in during the brief moment and drenched a square yard

of floor—turned to Groff and said: "What did I tell you?"

"Who's this Arthur Chesbro?" Groff demanded. "The one in the paper."

"Chesbro? A big wheel over in the next county. Justice of the Peace.

Owns business buildings; couple of radio stations; the newspaper, I

don't know the name. I just get copies of the Weekly Times; they send

them so I can check my ads. Every week I take one. You look on page

seven, tell me what you think of it."

Groff yanked the paper open, looked at the grocer's little ad on page

seven and said: "You're Sam Zehedi? Syrian?"

The man looked gratified. "How'd you know?"

"A couple of your boys used to work for me. Damn fine millwrights."

"That's us!" Sam Zehedi said. "You give a Syrian a busted machine and

a wrench, he'll have it going in five minutes. We're a civilized,

Christian people. We been Christian a lot longer than the French or

the Germans. And you know what some dumb people called me when I first

bought the store? An Ay-rab. A heathen Ay-rab."

"They'll learn." Groff shrugged. He studied the newspaper story.

So this Chesbro was interested in newspapers. It looked, it very

definitely looked, as though he might have a piece of the Hebertown

Weekly Times in his pocket; the story was pure propaganda.

Sam Zehedi went on: "Oh, they're learning. It's been five years now,

and I didn't let any grass grow under my feet. I'm a respected man

in this community, mister. You don't hear any Ay-rab talk any more,

except maybe from some of the summer people. Jews—they're bitter about

Ay-rabs, but then somebody sets them straight. I guess I'm the first

Syrian boy around here except for peddlers going through in the old

days the way they used to. It's like being a pioneer. Or a missionary."

He glanced at the clock. "What the hell," he said, "I don't think

anybody else is coming in this rain. I'll get the truck started and

pull her around the front, then you can hop right in and I'll lock up,

then we'll go tow you out."

"Fine," Groff said. "I appreciate it very much." The storekeeper

disappeared in the back; a door slammed and over the drumming rain

Groff heard a truck engine roar into life. Zehedi gunned it and held it

for a minute and then took off, swinging the pickup around in front.

Groff dashed for the cab when the door swung open and vaulted in. His

speed hadn't helped him a bit; he was wet all over again from his brief

exposure.

Zehedi got out on his side, sensibly swathed in a slicker, put out the

lantern in the store and locked up. He climbed back into the cab and

had to raise his voice to be heard above the rain beating on the top.

"Well, here we go, mister. About how far?"

"Quarter of a mile, maybe."

"We'll get you there." He put the truck in gear and crawled away from

the store, feeding the gas lightly. "My tires are pretty good," he

said. "I'd hate to start spinning my wheels, though." They crawled up

the long, gentle grade into the driving torrents.

"Notice my store's located at the foot of the hill?" he chattered. "I

picked it partly for that. People have time to see the sign, not like a

flat straightaway where they go whizzing past fast as they can."

Groff cranked down the window and stuck his head out. He couldn't be

wetter and he wasn't perfectly sure that through the rain-streaked

window his ditched car would be visible. The headlights seemed to bore

yellow cones through the teeming rain without illuminating anything

outside their sharp margins. The drops battered at his face and hair;

he pulled his head in feeling a little stunned. The violence of this

storm—he had a vague feeling that it couldn't go on without something

giving. What, he didn't know.

Headlights stabbed at their eyes from the rear-view mirror. Behind them

a horn howled and out of the darkness behind plunged a shape. Zehedi

gasped and twitched his wheel to the right. The car from behind zoomed

past them, cut into the right lane again and roared on; its taillights

soon were dim and then disappeared.

"Crazy idiot!" the storekeeper gasped, appalled. "He could have wrecked

us! He must have been going fifty! In this!"

Groff twisted in the seat and stared through the rear window. There

were headlights, far back but coming up fast. And the headlights went

out as he watched, with a glimmer....

He knew suddenly what had given. Even a city man, born and bred in city

safety, could recognize the signs.

"Step on it," he said to the storekeeper swiftly. "Floodwater behind

us. Get us to the top of the hill. Fast."

Zehedi didn't argue or hesitate. Few people argued or hesitated when

Groff used that tone of voice. Quickly and steadily he stepped on the

gas. They whirled around the curve where Groff's car stood empty and

past it. It was a long, straight upgrade from there. Either the rain

had slackened off a little or Zehedi was more worried about what was

behind them than about the rain; they roared up the hill, accelerating

all the way, and only stopped when they saw another car parked by the

side of the road, lights on and windshield wipers flapping, and a man

leaning out of the opened door, staring back.

It was the car that had passed them. Zehedi recklessly stopped

alongside him, making it a tight squeeze in case another car wanted to

get by. The other driver misinterpreted the move.

"Jesus!" he said. "That's a good idea! Keep them from getting past into

that. Jesus!"

He was in a flap, Groff observed. It wasn't surprising. "Flood?" he

called. But he knew the answer.

"Flood? Christ a-mighty, the whole goddam Atlantic Ocean's down there.

I was trying to pass a lousy milk tank truck for five miles—they

ought to widen this road, you get stuck behind a truck on these hills

and—anyway, I finally got past him, and all of a sudden I hear him

blowing his horn like a son of a bitch and I turn around and—" The

man choked. "Jesus!" he said again. "That lousy little creek. This time

of year, half the time it's practically dry. And here's the whole creek

jumping up out of the ground at me. I stepped on the gas and got the

hell out of there." He peered back nervously, as though the creek might

still be following, though they were easily two hundred feet up. "You

haven't seen that milk truck, have you?"

It would be a long time, Groff was absolutely sure, before anybody saw

that milk truck again.

Zehedi leaned across him. "Hey, mister. You think there was much damage

down there? I own the store back there—you know, Sam's Grocery, down

at the foot of the hill."

The man laughed. It sounded very nervous. "Not any more you don't," he

said.

CHAPTER TWO

If you had smoothed out the crumpled paper to look at the ad, you would

have read:

GOUDEKET'S GREEN ACRES

Your happy vacation hideaway, tucked away in the heart of the majestic

Shawanganunks. Golf! Tennis! Riding! Swimming (Two Pools)! Moonlight

dancing! That grand Goudeket Cuisine (Dietary Laws Observed)! Under

personal direction of Mrs. S. Goudeket.

However, you would have had trouble smoothing it out, because it was

soaked; it had been thrown in the middle of both of Goudeket's Green

Acres by a dissatisfied customer, raging at the malicious trick Mrs.

Goudeket had played on her by causing it to rain for three consecutive

days.

Mrs. Goudeket, wearing a set smile that was ghastly even in the

candlelight, moved among her guests. She was arch and gay with some

of them, apologetic and sympathetic with others, as circumstances

indicated; but in her heart she was torn between rage and fear. Now

it rains! For two months not a drop, so the grass is dying and the

dug well for the swimming pools goes dry, and the guests complain,

complain, complain, it's hotter than Avenue A, Mrs. Goudeket, and

couldn't you air-condition a little, Mrs. Goudeket, and frankly, Mrs.

Goudeket, what I wouldn't give to be back in our apartment on Eastern

Parkway right now, we always get a breeze from the ocean. And now it

comes down pouring, almost all of last week, and now it starts again

so hard the lights go out and the phone goes out, and there's a hundred

and sixty-five guests looking for something to do.

She told herself pridefully: Thank God Mr. Goudeket didn't have to put

up with this.

Not that he could have handled it; he would have retreated to his

room with a stack of Zionist journals, written letters to friends in

Palestine, wistful letters saying that maybe next year they'd have

enough for a winter cruise—

There had never been enough for a winter cruise; Mrs. Goudeket had

efficiently seen to that. First things first. A new roof before a

winter cruise to visit Palestine, new pine paneling in the recreation

room, things you could lay your hand on. And Goudeket's Green Acres

grew. Because of her.

But she had been kind and reasonable. She had let him send a hundred

dollars a year for planting orange groves. She had never argued when he

talked about retiring some day and going to Palestine—he always called

it that, even after it was Israel—to live. She could have argued;

she could have told him plenty. That this is America, that here you

don't retire and doze in the sun, here you drive hard and get big.

Dave Wax came half-trotting through the dim rooms looking for her.

He started to call to her, changed his mind and came close before he

half-whispered. "It's the telephone, Mrs. Goudeket. It's working again!"

"Ah!" she exclaimed. "Why are you keeping it a secret? It's good news,

let's tell everybody—they can use a little good news. You see—"

She turned to the nearest couple—"they've fixed the telephone lines

already. I bet they'll have the electricity on in ten minutes, you wait

and see. Did you call up, Dave?"

"Call who, Mrs. Goudeket?"

"The electric company, Dave!" He shook his head. "Go call them! No,

wait—better I'll call them myself." Let him talk to the guests a

while, she told herself grimly. Perhaps when the lights were on again

and things were back in their normal swing she would want to talk to

her guests again. Or perhaps, she thought, hurrying across the dark and

deserted entrance lobby, she would go up in her room and lock the door

and pull the covers over her head, as she wanted to about once an hour

from May through September of every year since Mr. Goudeket died.

The phone was working all right, but it wasn't working well. Mrs.

Goudeket got the Hebertown operator and asked for the number of the

power company's repair service, but there was so long a wait after

that, filled with scratchings and squeals on the wire, that she began

to think something had gone wrong. She pulled out the jack and tried

again on another line.

All it took was waiting, it turned out. While she waited Mrs. Goudeket

had plenty of time to think of the meaning of the long wait to get

connected with the repair service. Not that that was any surprise,

actually, because she had been through storms before in the majestic

Shawanganunks; but always before it had been maybe a quick, violent

thunderstorm coming up after a hot spell, and it was a lark for the

guests because it was a change, or maybe a violent autumn storm when

only a handful remained. But here were a hundred and sixty-five who had

been penned in the hotel for days already and....

"Hello, hello?" She tried to hear the scratchy voice at the other end.

"Can you hear me? This is Mrs. S. Goudeket, from Goudeket's Green

Acres."

The scratchy voice was trying to say something, but she couldn't hear;

evidently, though, they could hear her so she went right on: "Our

electricity is off. Can you hear me? Our electricity has been off

for two hours. They fixed the phone lines, why can't you people fix

the power lines?" More scratchy sounds. Mrs. Goudeket listened to

them—first casually, out of politeness, then very, very hard. Then

there was a click.

Mrs. Goudeket looked thoughtfully at the switchboard for a moment.

This is new, she thought. Her mind was cold and alert; she knew she

could not afford rage. The electric company here is not a good company,

not like the wonderful Consolidated Edison in New York City. Here they

overcharge you—by mistake, they say—and here the meter readers are

underpaid and insolent, even with good customers like me. Their repair

men are unshaven and lazy and when they finally get to you they stretch

out a job forever so they don't have to hurry on to the next. But this

is new, this hanging up. I'm no fool, not after thirty years in the

resort business; I know their phone girls are under orders to kid the

customers along, promise anything, not to hang up.

Something must be happening, something bad.

She walked slowly into the lobby, with a mechanical smile for each

sullenly accusing guest. At the cigar stand she told little Mr. Semmel:

"A pack of cigarettes. Any kind."

He raised his eyebrows and passed one over. As she clumsily tore open

the pack, extracted one and lit it he began to grumble: "Some hotel.

Some light-and-power company. By now I should be getting the overnight

lines for Monmouth, Hialeah and Sportsman's, by now I should have

booked two hundred dollars on tomorrow. Believe me, Mrs. Goudeket, this

is my last year at Green Acres. This kind of thing doesn't happen up at

New Hampshire Notch; I don't pay good money for the concession so this

kind of thing happens."

A fattish, red-faced man bulged up to the counter, breathing whiskey

at them. That's a Young Married, Mrs. Goudeket thought with distaste;

that's what I have to take at this place because I can't get enough

nice young people. "Sammy," the red-faced man complained hoarsely,

"isn't the damn ticker working yet? I've got fifty bucks I have to

play. You're busting my system to hell."

Mr. Semmel said politely: "I'll see, Mr. Babin." He opened the plywood

door behind the stand, looked into the little room where the teletype

horse ticker stood, and closed the door again. "I'm sorry, Mr. Babin,"

he said, with a look at Mrs. Goudeket. "I think the wire's okay, but

you got to have power to run the machine and there isn't any power. If

it comes on later maybe I can phone Chicago for a repeat—if there's

time before midnight."

"Nuts," Babin said, and headed through the candlelit gloom for the bar.

"You see?" Mr. Semmel hissed, in a hate-filled whisper. "You see what

you're costing me? Never again, Mrs. Goudeket!"

She wandered off, preoccupied. Semmel was a nobody, a clerk hired by

the big brokers, in spite of his pretensions. But if the brokers, in

their cold and analytical way, did decide at the end of the season

that Goudeket's Green Acres didn't handle enough to make the operation

worth their while, next year nobody would come around and bid for the

horse-book concession. And it was the concession that pushed the resort

over the line between red and black ink.

You had to make money and you had to grow. Mr. Goudeket had never

understood that. Orange trees were all very well, but since 1926 she

had been the driver, the doer, the builder. And Mr. Goudeket had never

got to Palestine after all, which showed that dreaming got you nowhere.

She felt a guilty twinge. One year they could have made the cruise.

One year there had been nothing urgent, which is a miraculous year

in the resort business. She had put the money aside as a reserve and

said nothing about it, and poor Mr. Goudeket couldn't understand a

financial statement. The guests loved him, his Zionist connections had

been valuable, though he never suspected it, and he had been a fine

all-around handyman since the days in the Brighton Beach boarding

house; he had saved them thousands of dollars with his clever hands and

brought in thousands of dollars with his connections. But grow? He had

never understood. And so he never got to see Palestine? What of it,

anyway? And again Mrs. Goudeket felt the guilty twinge.

She peered into the bar; it was doing a good business by candlelight.

Her Young Marrieds—she grimaced—were getting drunk early. Dave Wax

was on a barstool with an on-the-rocks glass in front of him; he was

telling one of his stories.

"Dave," she said softly, "when you've finished your drink why don't you

give a little show for the people outside?"

The comedian theatrically gulped from his glass and told his barmates

loudly: "I love this dear lady. Just like my mother, she is. Just like

my mother—always hollering, 'Get to work, ya bum!'"

He pranced out, grinning, on the tide of half-drunk laughter. She

watched him from the bar for a minute; he went looping through the room

loudly announcing a one-man show by that star of stage, screen, TV and

radio, Dave Wax, also available for weddings and bar mitzvahs, call

Murray Hill 3-41798805427—it went trailing on and on and on as he led

them to circle him around the piano. He pounded out the introductory

chords of his "Nervous in the Service" routine, which was very funny

and not too dirty; from there she hoped he'd go into a community sing;

that would calm the people down.

She went to the switchboard again and snapped the toggle for the

outside line. Try the electric company, get some kind of a real promise

out of them, maybe bully her way through to the Load Dispatcher, a

really responsible person, not like their phone girls.

"Hello," she said. "Operator, hello?" The line wasn't stone-cold dead,

but it wasn't buzzing with the reassuring familiarity of the dial

tone. A delusive droning kept encouraging her to try; mechanically

she switched off and on again, asked for the operator, tried dialing

various service numbers. As she went through the motions she thought

abstractedly that something had to work; the horse-book concession

was absolutely vital. She'd always known she should have an auxiliary

generator, paid for God knows how, so the teletype could be kept

going—but what good was a teletype with power and no line in? It was

dawning on her that the place was cut off from the outside world, that

the wires were down and would stay down for hours.

Radios? The radio must be saying something. There was a little station

in Hebertown that played nothing but records and news a couple of times

a day from the Weekly Times office. Junk like who's in the hospital,

the borough council meeting, "want ads of the air," traffic things.

They'd know what this rain was doing, they'd have an estimate from

the power and phone companies of the damage to the lines and when

they'd be back in service.

The radio would tell her everything she needed to know; then a calm

announcement to the guests and everybody would go to bed cheerfully,

rather enjoying the excitement....

But little Mrs. Fiedler came up and she had her portable radio in her

hand, weighing her down like a suitcase; it wasn't one of those little

pocket jobs but a substantial long-range outfit. Little Mrs. Fiedler

made something of a nuisance of herself when she played it beside the

swimming pool—highbrow music from New York City stations.

"Could you get me an outside line, Mrs. Goudeket?" she said. "I want to

call my mother in New York so she won't worry."

"Worry? About somebody at Goudeket's Green Acres?" the old woman

kidded. "She should have such worries. But I'm sorry, the phone's out

again. I don't know for how long. But why should she worry?"

"There was a news broadcast from New York, there's a flood up in

Richardstown. Of course that's a hundred miles away, but to my mother,

the mountains are the mountains."

"Ah. Richardstown. Mrs. Fiedler, did you try the local station? Let's

go into my office and see what they have to say."

But even the big, powerful portable failed to pick up the local

station. Mrs. Goudeket refused to think of what that might mean.

Alone again, she realized that she'd have to send somebody out into

that terrible rain, send them to town, the Times office or any other

phone they could reach. She had to know what was coming next. Send who?

Not the bartender; he was the most valuable man on the premises right

now. Dave Wax was next, and the kitchen help couldn't be spared. Dick

McCue, the "golf pro"—nineteen years old, doubling in trumpet—where

was he? He should be in the social hall backing up Dave Wax, keeping

the people busy, keeping their minds off—whatever it was. Where was

he?

And then she thought, distastefully, of exactly whom she'd have to

send. Sharon Froman, she called herself, and in the wild week before

opening she had let Sharon Froman foist herself on Green Acres as a

"publicity director"—just room, board, ten a week for the season. At

first Sharon Froman had actually worked; she had written good stories

that actually appeared, not cut too badly, in the issues of the New

York Post which also carried Green Acres advertisements; maybe she

had even got them a couple of guests. That lasted for about ten days,

and then Sharon Froman had slowly withdrawn from any hotel activity

except eating; when you passed her room at any time of the day or night

you were as likely as not to hear the muffled thudding of a noiseless

portable. When Mrs. Goudeket barged in or met her in the dining room

and asked how the publicity stories were coming, Sharon Froman would

smile vaguely, teasingly, and say something that didn't, after you

stopped to think of it, make sense. "I think I've got a very dynamic

program lined up, Mrs. Goudeket, and I'm polishing the rough spots."

Black-haired, square-jawed, near-sighted, in her early thirties, a

persuasive talker—Mrs. Goudeket was the living proof of that—groomed

either to perfection or not at all, maybe five feet six, easily twenty

pounds overweight. Sharon Froman. The perfect expendable to go out and

learn the score. Mrs. Goudeket started grimly up the steps. You better

be feeling good and dynamic, Miss Sharon Froman, she thought, nerving

herself for a battle. I got some real rough spots for you to polish now.

In the bat's nest that that sneaking old hag Goudeket called a room,

Miss Sharon Froman was lovingly recopying chapter one of Her Novel.

Her only light was a candle socketed in the sticky neck of an empty

Southern Comfort bottle, and the flame flickered and turned blue

regularly as the wind swept through the closed windows. What a shack,

thought Miss Sharon Froman, not in anger but in judgment.

But it had its compensations. She could see the jacket copy for the

novel now: "Spraddled Evening is an odd book, written at odd times

in odd places. Begun in a shabby trailer outside a Mississippi Army

camp—" She grimaced, remembering how perfectly foul Ritchie had been

when she'd had story conferences with Don while Ritchie was restricted

to the post—"it was shaped and polished by turns in the club car of a

transcontinental train, a cold-water flat in the East Bronx, a luxury

resort hotel and a Jersey fishing village, reaching its evocative

climax while Miss Froman was—" Well, that you would have to wait and

see, thought Miss Froman, taking page 2 out of the typewriter. But the

end was almost in sight. The first chapter set the tone for the whole

book; and now that that was nearly perfect it was only a dash to the

finish line.

She lit a cigarette from the candle before she put page three into

the typewriter. Page three was the one that would do Hesch in the

eye. He'd be sure to recognize the savagely drawn, feudal-minded pants

presser if he read it—and he'd be goddam sure to read it, if he had to

hock the watch she'd given him to get the price. Sixty bucks that watch

had cost out of her share of his Christmas bonus, and it was the only

decent thing he owned. "So why doesn't he sell it," she demanded of the

wind, "if he's so broke he can't keep up the alimony?"

She knew as soon as she heard the knock on the door that it was Mrs.

Goudeket. The chapter went into the bulging file under the bed; the

half-page beginning on the story about Dick McCue went into the

typewriter, using the paper bail so Old Bat-Ears wouldn't hear the

ratchet clicking. "Come in, please," she called, with just the proper

annoyance at being interrupted.

She glanced coldly at her employer.

Mrs. Goudeket sat down without waiting to be asked; those stairs were

getting steeper every day. "Sharon, honey," she wheezed, "I want you to

do me a favor. Frankly, I'm a little worried."

Sharon listened with minimal courtesy. Unbelievable, she thought to

herself, now the old harpy expected her to go driving out in this crazy

rain to find out if it was really raining. So suppose she got into

Hebertown, what could she find out? The lines were down? They knew

that. And what else could there conceivably be?

Since it was a point of principle, she knew what she had to say.

"I'm sorry, Mrs. Goudeket," she said gently. "It just isn't my job."

Besides, the season was practically over; so let Old Bat-Ears fire her.

"Aw, Sharon," wheedled Mrs. Goudeket. "Who else have I got? Believe me,

it's not for me, it's for all of us. Suppose—"

"No."

"No!" shrilled Mrs. Goudeket. "I feed you the whole summer, for what?

One little thing I want you to do, and what do I get? Listen here,

young lady, I'm telling you for the last time—" It went on for ten

minutes, during which Mrs. Goudeket quite forgot to worry about the

storm.

She was still breathing hard when she appeared at the door of the Game

Room and signaled imperiously to Dick McCue.

"You got to drive me into Hebertown," she ordered.

"But Mrs. Goudeket!" He nodded back at the room, where a couple of

sullen guests were doggedly putting golf balls into a tumbler. "I got a

contest going. Dave said I had to help out; he said—"

"This is more important," Mrs. Goudeket said firmly. "You think I like

going myself? God knows what the guests will think, so don't tell them.

Let them look."

"All right, Mrs. Goudeket. I'll tell you what, I'll go get the car and

meet you at the kitchen entrance. Just the two of us going?"

Mrs. Goudeket smiled frostily. "Three," she said. "Miss Froman is

leaving us."

CHAPTER THREE

The burgess of Hebertown wasn't having any luck with his call to the

weather bureau. Because he was the burgess, he had got his own line to

the central office back in service; but the central office was having a

hell of a time getting through to any point outside.

If he had got through, he wouldn't have had much luck either, because

there were plenty of lines down, but practically all the ones that were

left were trying to get onto the same three instruments in the bureau's

outer office.

The chief of bureau was talking into one of them, kept open with a

direct line to the nearest Civil Defense filter center: "Charley?

Here's the latest. No chance of the rain stopping for at least several

hours, that's the big thing. Some places it's hitting an inch an hour.

There's all that wet air that Diane pulled in from the Atlantic, and

now the winds have pushed it up; when it gets cold the water has to

come out. How much?" He blinked at the phone; he had been in that

office for seventeen hours and, he suddenly remembered, he'd never got

around to having lunch sent up. "Call it ten inches, average through

the area affected. What?" He sat up straight. "Now listen, Charley!

I've busted forecasts and I've admitted it; but you can't hang this one

on me—"

The station duty forecaster, on the phone next to him, was saying:

"Sure, we're sticking by our forecast. Go ahead and print it. Flood

damage? No, I can't give you anything; not our line. Please, won't you

read the forecast? We said heavy rain. We said prospect of danger from

flooding because the soil is saturated—no room for the rain to soak

in, it has to run off somewhere. The only thing we didn't say was

'positively.'" He hung up, but didn't take his hand off the phone; it

would ring again in seconds. It didn't much matter what they printed,

of course; the newspaper that had been on the wire was in a town that

had grown rich from the two rivers that joined in its heart, and the

forecaster had his own feelings about what those two rivers might do.

He took his other hand off the clipboard and found he had crumpled

their copy for the last forecast into a ball. He tossed it in the

basket, hardly hearing his chief shouting into the phone next to him;

it didn't matter, he knew it by heart now anyhow, but as the phone rang

again, he made a dive and recovered the forecast. He smoothed it out

carefully. It might, he suddenly realized, be very important indeed,

over the next weeks and months when the investigating commissions and

legislative committees began sniffing through the debris.

Mrs. Chesbro came smiling into the burgess's office. "Excuse me," she

said. "I knocked, but you were busy on the phone—"

"Not very," said the burgess, slamming the instrument down. Now he

couldn't even get the central office again. "What can I do for you?"

He didn't know the woman. She was expensively dressed; the burgess,

whose wife read Vogue, realized that her flat-heeled leather shoes,

her matching waterproof tweed coat and cap, her neat leather gloves all

were imported and expensive. For the rest, she was a small blonde in

her twenties with a careful, conciliatory look on her face.

"I'm Mrs. Arthur Chesbro," she said. "Arthur and I drove over from

Summit to see you. Arthur let me off and then he decided he'd better

move the car to a little higher ground, the top of that little shopping

street you have, Sullivan Street, isn't it? After General Sullivan, I

suppose? And he'll be right along and then you two can get on with your

little talk."

The burgess looked at her vaguely, her chatter only half comprehended.

If she had been a man he would have said something like: "I'm sorry

but I'm tied up now; write me a letter and we'll make an appointment."

Since she was a woman his old-fashioned notions ruled that out.

"I didn't expect Mr. Chesbro," he began. "I've got so much on my

mind right now with the rain—" He noted with wry amusement that

he had started to say "flood" and changed the word. Civic pride or

superstition?—"that I don't think this is the best time for a meeting.

Could you go and head him off, Mrs. Chesbro? It can't be urgent."

"Arthur thinks it is," she said. "A man phoned him from New York that

this Mickey Groff is on his way and Arthur swore around the house for

fifteen minutes and then told me to get out the car and, well, here I

am." She could ask for a favor and keep her dignity. "I'm sure it won't

take more than a minute. Arthur says it's all cut and dried."

Chief Brayer came in without knocking. His black slicker streamed and

his mustache was limp. "Henry," he said to the burgess, "I make it

twelve feet and rising at the Sullivan Street bridge. In thirty-five

it was only eight feet and in thirty-nine it was only nine and a half.

What's going on down in the Hollow, God only knows. Anyway, I'd better

get down there with all the boys. All right?"

"Sure, Red. Get on down. Send somebody to my place in a car with a

trailer hitch; have 'em tow my boat down to the Hollow. It's all set up

on the trailer in the garage, ready to go." He grinned wryly. "I was

thinking I might take Bess up to Cayuga for a day on the water."

Mrs. Chesbro looked on blankly.

"Great," the chief said. "It's got a good spotlight, too. We'll need

that. If you don't mind a suggestion, Henry, I'd turn out the fire

department and have them standing by. You may need some able-bodied men

in a hurry. Twelve feet and rising—" He hurried from the office.

"Excuse me," the burgess said to Mrs. Chesbro, and tried the

interphone on his desk. It worked; so far the main to the north end of

the borough had not been flooded and shorted out.

"Fire chief," said the interphone.

"This is Henry, Chief. Red Brayer thinks, and I agree, that you should

sound the general alarm for the volunteers, that they should be

standing by in the engine house with their cars parked in the square.

The Hollow's filling up fast—at least it must be; the water's twelve

feet and rising at the bridge."

"Right, Henry. That all?"

"For the present, yes," the burgess sighed. He clicked the box off.

Immediately he heard the klaxon on top of the building hoot three

longs, then pause and hoot again and then again. It was the Emergency

Muster signal, and it would galvanize fifty men scattered throughout

the borough into dropping whatever they were doing, tearing to their

cars and speeding to the borough hall, or more exactly to its ground

floor left wing where the fire department—two LaFrance pumpers, one

ancient and one beautifully new, two full-time employees, the chief and

the driver—were housed. He hoped they wouldn't be too disappointed

when they found they'd be on a boring standby.

And now, he thought, he really ought to get out and drive around

on a tour of inspection. There wasn't any point to sticking in the

office with the phone out and the firemen and police already committed

to action. He had hoped for some usefulness out of the local radio

station, but it was silent, had been for an hour. The news of the

Hollow explained that; the transmitter tower, a modest spire, was

planted in a marshy field down that way. It had something to do with a

good ground, he had been told once, so they had a good ground and they

were now bugged out the one time they'd be able to do a public service

beyond broadcasting damnfool hillbilly music.

He was reaching for his raincoat, to the dismay of Mrs. Chesbro, when

a big man came in. The burgess recognized him as her husband, the

redoubtable Arthur Chesbro of Summit. He had, quite consciously, had

as little to do with Arthur Chesbro as possible, but there was an

irreducible minimum of contact with the man that couldn't be avoided.

He was all over the place in Summit, a closely neighboring borough, and

he had feelers out through the entire area. You heard of his interest

in this and that—bankrolling a resort, buying a professional building

a county away and turning it over fast, snapping up timber rights

to a farmer's woodlot and turning them over to a firm from over the

state line; snatching an FCC television construction permit from under

the nose of heavy competition and then not building the station after

all for mysterious and profitable reasons. He was a leading citizen,

the burgess supposed, but he had nevertheless carefully avoided him

whenever possible. He was not really sure why, but once after a couple

of bourbons with Chief Brayer he had told the chief that he thought

Arthur Chesbro suffered from a case of moral and ethical halitosis.

Physically, Chesbro was a picture of success, rather soaked and winded

success at the moment, having hiked in the rain from Sullivan Street

and climbed the steep stairs to the burgess's second-floor office.

He grasped the burgess's automatically extended hand with a firm and

manly grip. "It's good to see you again, Henry," he intoned. "How's

Bess?"

"Fine, thanks."

"And that boy of yours in medical school?"

"Fine—uh, Arthur." He thought resignedly that you have to go along

with these characters. And maybe, for God's sake, Chesbro actually did

remember Bess and did remember hearing about Ted and actually did wish

them well. Maybe.

"I see you've met my wife, Henry. Well, it looks like quite a nasty

downpour, doesn't it?"

Now he's talking about the weather, for God's sake, to put me at my

ease and get the conversation going on a topic of universal interest.

Always start by talking about the weather; nobody's so shy or so stupid

that he can't think of something to say about the weather. Well, sir,

this time the maxim was going to backfire in Arthur Chesbro's red face.

"Glad you mentioned that, Arthur," the burgess said briskly. "I'm

leaving now. I'm afraid we're in for something worse than we got in

thirty-five and thirty-nine, and I'm going to cruise around and have

a look-see. I don't know why you came to see me on a dirty night like

this, but if you can't put it in a nutshell it'll have to wait."

Arthur Chesbro was disconcerted. "Didn't you see the story in the paper

yesterday, Henry?"

"I've been mighty busy," the burgess apologized, getting into his

raincoat.

"Well, it said, roughly—well, never mind the story. What I want to do

is take the old Swanscomb Mill off the borough's hands and put a tidy

rental into the communal pocket—and hire a few of your local people."

"Sounds fine," the burgess said. He started for the door. "But there's

a fellow with a plant in Brooklyn who's interested too. I understood

he's coming out to see us about it, but I suppose this weather'll hold

him up. I think we'd better table this matter until I hear from him and

have a chance to compare the offers. Now, if you'll excuse me—"

"I never thought," said Chesbro flatly, "that I'd see a neighbor

selling out to foreign interests when he has a bid from a local man."

The burgess took his hand off the doorknob and looked at Chesbro

steadily up and down. "I don't like your language worth a damn,"

he said. "I'd give you a lecture on manners if I didn't have more

important things to do. You can find your way out, can't you?"

Chesbro's eyes dropped, but the burgess thought he could read a look of

calculation on his face. "Sorry," he said. "By the way, my car is just

up the hill. Can I help out?"

"Well," said the burgess, and thought. Might as well save climbing all

the way up West Street—and you couldn't brush off a man who was trying

to do you a favor, just because you thought he stank. "Obliged," he

said. "If you'll drop me at my house I'll pick up my own car."

He waited with Mrs. Chesbro while her husband dashed through the rain.

She didn't talk, which the burgess approved, and once when he met her

eye she gave him a tired smile. The burgess judged that she was onto

her husband, and seldom had anything to smile about.

For that matter, what did anyone have to smile about? The burgess

looked over his borough and hardly heard Artie Chesbro chattering

beside him. The street lamps at the bottom of West Street were out.

One of the big elms that framed the post office was trailing a pair

of enormous branches, broken-winged, across the street; they had to

detour far to the left to pass it. Well, there wouldn't be much traffic

tonight—and you couldn't tell, maybe he'd be lucky and the whole tree

would have to come down; and then they could get on with widening West

Street and the hell with the Garden Club.

They went up over the West Street hill and down the other side.

"—don't know if you've considered the importance of warehousing

facilities in attracting industry," Chesbro was saying in his ear. "War

plants? Sure. They're a dime a dozen, Henry, and they come and fold up

and then where are you? But you take a town that's got a reputation for

good, low-cost—"

The burgess felt entirely too surrounded by Chesbros, with Artie

babbling on one side and the wife, silent on the other. Then they

turned into Sycamore. The burgess leaned forward. Funny, he could

hardly see the highway junction at the bottom of the hill. They rolled

down at forty or so, and then everything happened at once. Something

jumped up out of the pavement ahead of them. "Watch out!" yelled the

burgess. "Jesus!" cried Artie Chesbro, slamming on the brakes and

skidding. It looked like a figure, some crazy kind of figure hard to

make out in the rain, that suddenly started to get up in the middle of

the road; it humped itself and flopped back, and then leaped high in

the air, higher than the roof of the car.

Mrs. Chesbro laughed out loud, nervously.

"Busted water pipe!" cried Artie Chesbro. "Look, Henry, it's a whole

fountain!"

It was a fountain, all right, but it wasn't anything broken. The

burgess swallowed hard. Not in '35, not even in '39, had the storm

sewers backed up hard enough and fast enough to send their manhole lids

flying into the air.

CHAPTER FOUR

Dick McCue started off like a jet pilot. "What's the hurry?" Mrs.

Goudeket demanded. "Better go slow and we'll get there." She was

feeling uneasier than ever; because though she had heard the rain

pounding on the house, and seen the rain sluicing down the windows, she

hadn't felt the rain until that two-yard dash from the door to the

station wagon that had wet her to the skin.

"Sure, Mrs. Goudeket," he said cheerfully, and slowed down—briefly.

Fast, slow—he could drive that blacktop road down to the highway

in his sleep. This was what he liked; something happening. He never

would have taken the agency's offer of this job if he'd known it would

involve running putting contests for rained-in guests who blamed it

all on him. Girls, dances, a chance to sharpen up his game for the

all-important Inter-Collegiate Medalist next year—the agency had made

it sound pretty great. Of course, he had a lot to offer, too—his

maidenhead, for instance, as far as the world of golf was concerned;

now he was definitely and permanently a pro, and some of the doors in

golfing were forever closed to him. Maybe he should have held out for

more money. But what was the difference; Dick McCue knew well enough

that his game wasn't going to support him all his life; he had a good,

powerful drive and a touch with the putter, but everything between the

tee and the cup was hard work. It made him a splendid golf pro for Mrs.

Goudeket's guests, most of whose future golfing would be either on a

driving range or on one of those miniature courses that were coming

back, but that was as far as his talents went. Dick McCue didn't kid

himself—or anyway, not about his golf.

Mrs. Goudeket cried out and clutched his arm. "Look! Four hundred

dollars worth of topsoil!" But it wasn't four hundred dollars worth of

topsoil any more; it was a lake. She looked at it incredulously. She

remembered distinctly what it had looked like when she and Mr. Goudeket

had taken possession of Goudeket's Green Acres, formerly known as

Holiday Hacienda: It had been a muddy cow pasture, rutted and gullied.

It had taken three days with a bulldozer before they could start

putting the topsoil on—

Mrs. Goudeket swallowed, as she considered where the four hundred

dollars for the next batch of topsoil might be coming from. From the

back seat Sharon Froman called sharply: "Watch yourself, Dick!"

"I see him," McCue said, slowing down. A battered pickup truck was

wallowing around their entrance road, trying to turn around. The driver

was being meticulously careful about staying off the shoulders, which

made it a long process, but finally he got turned around and pulled

over. As the station wagon drew close he leaned out and yelled: "This

ain't the road to Hebertown, is it?"

Dick McCue leaned over his employer to roll the window down and yell

back: "No! You have to turn left at the road, then the second right,

left at the bridge—Look, just follow me." He barely got his head out

of the window before Mrs. Goudeket rolled it up again.

"Follow him! Jeez, I ought to have an airplane!"

Mickey Groff said, "We ought to be nearly there by now. Does it look

familiar?"

"Nothing looks familiar," Sam Zehedi complained, trying to keep the

lights of the station wagon in sight. He stole a look at the dashboard.

Forty-two miles they'd come! Backtracking where the bridge was washed

out, taking a shortcut that had turned out impassable, getting lost on

the country roads down toward the river—forty-two miles, and they'd

started out three miles from town. There was a mile marker right in

front of the store....

No, not any more there wasn't. Sam Zehedi got a sudden cramp in his

belly thinking about it. The important thing was whether the insurance

covered it or not. He had the impression that he was covered for

everything from artillery fire by the Argentine army to glacier damage;

but that was a long time ago when he signed that check for the policy,

and he couldn't remember what it said about floods. Of course, he told

himself valiantly, that guy in the car was nuts; the store couldn't

have been just washed away. It was just that it was so dark and you

couldn't see through the rain from as close as you dared to get in the

car. Probably there was water in it, sure—but was that so bad? Look

at those people in Missouri and places like that, they go through this

every year.

He thought of the new freezer, not yet paid for, and moaned.

Mickey Groff snapped: "Are you sick? Want me to drive?"

Sam Zehedi swallowed hard. "I'm okay," he said. And he concentrated on

the twin red lights ahead of him, the beating raindrops that slipped

into the cones of the headlights and out again faster than the eye

could follow. He concentrated on the feel of the gas pedal, feeding the

gas delicately. You're driving, he told himself. So drive and don't

worry.

But in less than five minutes he humbly asked Groff, "You know anything

about insurance?"

"Some," Groff said reluctantly. He could guess what was coming.

"Well, to tell you the truth I don't remember what my policy on the

store was like. Fire, of course, and extended coverage. That means

water damage, doesn't it?"

"I'm afraid not," Groff told him, feeling rotten. "Under some special

circumstances, yes—but what's back there, no. If it were primarily

windstorm damage with water damage secondary—for instance, if wind

tore your roof off and rain ruined your stock, you could collect. But

nobody's covered against—flood."

The word was out in the open at last. Zehedi choked back a sob. You're

driving. So drive.

But in less than five minutes he found himself railing to Groff that it

wasn't fair, that he'd lost five years of work, that he would have been

ready to look for a wife in another three years, a good old-fashioned

girl from the New York or Detroit colonies of Syrians, somebody who

could cook the old-country food—God, how sick he was of hamburgers and

soda pop, sometimes he looked at a hamburger when he thought he was

hungry and just put it down and walked away with a pain in his belly.

"So why," he asked indignantly, a little hysterically, "didn't I stay

in the colony and eat my mother's cooking? I'll tell you why. Because

I wanted to be my own boss, I wanted to be a pioneer, it's no good

crowding into the big cities and working for other people. In this

country you have to make money to be respected, nobody respects you if

you're just a working stiff all your life. So I saved and I bought that

place through a broker and I've been slaving for five years, eating the

lousy food and thinking about broiled lamb I'm going to eat every day

when I find a wife, and then...."

He subsided and the rain drummed down.

They're an emotional people, Mickey Groff thought automatically, and

then cursed himself. Damned fool! Here you are thirty years old and

you're babbling stereotypes to save yourself the trouble of thinking.

Why the hell shouldn't he be emotional with his store washed away? I

seem to remember that when Zimmerman slipped the old knife between your

ribs with the trick specially printed discount sheet and cost you forty

thousand dollars you didn't have, forty thousand dollars for him and

Brody to spend on likker and wimmen, forty thousand dollars you might

have air-conditioned the plant with for better productivity and fewer

rejects, you weren't exactly philosophical about it. Your screams,

in fact, were allegedly heard as far west as Council Buffs, Iowa. So

less guff, please, about any "they," who exist only in your head, being

emotional, or stingy, or stoical, or vindictive or, for that matter,

generous and good-hearted. Take 'em as they come, one by one, for what

they show they are.

Zehedi was under control again. He said; "That guy's driving too fast."

"Watch out!" Mrs. Goudeket yelled at Dick McCue. "Watch out!" The white

posts that marked the sharp left curve loomed big, too big, in front of

them. McCue twisted the wheel and stepped on the brake pedal hard and

fast. It was nightmarish to feel the rear of the car swivel around; it

was uncanny to see the road passing in front of him, defying all his

experience of perhaps a hundred thousand miles in a driver's seat. The

white center line flashed across his vision and then headlights glared

into his eyes; it was the truck that had been following them. The skid

continued for an interminable few seconds more; Sharon Froman was

screaming in the back seat. The rear of the car jolted down and McCue

and Mrs. Goudeket were thrown back against the seat as the front of

the car nosed up; metal crunched behind them. Then it all seemed to be

over. McCue took a deep breath, turned off the ignition and waited for

Mrs. Goudeket to skin him alive verbally.

She said, panting with relief: "I'm sorry I yelled at you, Dick. It

must have made you nervous so that happened."

He could have kissed her, hairy mole and all.

"If I'd been driving—" Sharon began coolly from the back.

"If your aunt had you-know-whats she'd be your uncle," said Mrs.

Goudeket tartly. "No remarks are required from you, Miss Elegant

Loafer." Sharon laughed.

"Both wheels in the drainage ditch," McCue diagnosed, "and we seem to

be hung up on the transmission."

"Can you get us out?" Mrs. Goudeket asked.

"No. But that truck's stopped. I guess we can get a ride."

Sam Zehedi laid his truck alongside the ditched sedan and got out.

"Anybody hurt?" he called.

"We're okay, thank God," Mrs. Goudeket told him shakily. "But my driver

tells me the car is through. Could you maybe give us a lift into

Hebertown? We'll be okay from there."

Mickey Groff got out—soaked again!—and surveyed them. "You two ladies

can fit in the cab with Mr. Zehedi here. The gentleman and I will ride

in the back."

"Will you take these, please?" Sharon said, opening the rear door. "Put

them in the back. Careful, that's a typewriter. And very careful with

that one—it's manuscript. And these two are just clothes."

Groff wrenched open the double rear doors of the truck and put the

four pieces of luggage inside. In the darkness there were crates and

cartons. At least they'd be able to sit up instead of crouching on

a metal floor. As the driver of the ditched car passed before the

headlights he saw he was surprisingly young and obviously shaken by the

accident. "Get in," he said. "It might be worse."

Mrs. Goudeket, puffing, pulled herself up the high running board of the

truck and slid in beside Zehedi. Sharon followed, and slammed the door.

The truck moved cautiously off.

In the dark rear of the truck Groff and McCue had found milk crates to

sit on. "You all right?" Groff asked the young man. "Didn't bump your

head or anything?"

"It wasn't that kind of stop," McCue said. He began to laugh. "I'm from

Springfield, Ohio," he said between chuckles.

"Damned if I see the joke, fella."

"Well, mister, in Springfield, Ohio, damn near every spring, the little

old Springfield river that runs through town begins to rise and rise.

After a week of this it spills over the banks and the sandbags they

put up every time at the last minute and downtown Springfield is a

lake. Then everybody swears and gets the canoes and rowboats out of the

garage and goes boating glumly around until the water subsides. Well,

mister, I came east to college because I was tired of Springfield and

its foolish floods, and I run into this mess!"

Through the windows of the double door Groff saw they were passing a

small frame building with gas pumps in front. It was dark. "Cigarette?"

Groff asked steadily. He didn't want to encourage the kid's

near-hysteria.

"No, thanks. But the difference is, in Springfield it's slow and steady

and this is happening fast. And when it happens fast, sooner or later

a crest comes along and then it isn't one of those years when you just

go boating around; it's one of the years when you head for the goddam

hills, and fast."

"Then you think we're going to have a flood crest?"

"Hell, yes. Thirty, forty feet of water smashing down through the

valley. And when it comes, mister, we'd better not be there. Because

those things don't leave much behind."

They were stopping. "Now what the hell," said Mickey Groff.

There was a scratching at the double doors, and one of the women from

the ditched car climbed in. "Grand Central," she called. "Change for

the downtown local. Follow the green lights for the shuttle to Times

Square."

"You're cheerful enough, Sharon," the kid told her. "What's the matter?"

"Why, it's nothing at all. We're just out of gas, nothing else." She

turned to Mickey Groff. "Mr. Zehedi's compliments, sir, and would you

like to help him scout up some petrol?"

They found the blacked-out gas station after squelching for a couple of

interminable minutes through the sopping night.

"I thought I had plenty of gas. How'd I know we'd be driving all over

the valley? You said just a quarter of a mile down the road and—"

"Shut up and let's see if we can get in," Groff ordered. Zehedi's

whining was getting on his nerves.

There wasn't a soul in the station. Not even a night light. Probably

no power, Groff thought. That meant no burglar alarms in case they

couldn't find an unlocked window—though hell, he thought wryly,

wouldn't it be nice if a State Police car did come screeching up?

"Up you go," he told Zehedi, clasping his hands to receive the toe of

Zehedi's foot.

"Locked," reported Zehedi after a moment.

"Break it open. With your elbow. Try not to cut an artery. Then when

you get inside see if—" He jerked his head aside as glass tinkled

around him.

"Sorry," apologized Zehedi.

Groff heaved and got him through the window and went back to the front

door to wait. He hoped to God Zehedi would be able to unlock something

from the inside. They would never get the women through that upper

window, and he didn't want to have to break the front door. They would

need every bit of shelter they could get.

Zehedi appeared, tried the front door from the inside (you idiot,

didn't you see the padlock? Groff thought sourly), and made shadowy

gestures toward the rear. He was yelling something, but you couldn't

hear a gunshot in the crashing rain. Groff got the general idea in any

case, and stumbled around to the back. Zehedi let him in.

The grocer was all keyed up. "That looks like a fuse box," he

chattered. "Didn't see a switch for the pump motors, but it ought to be

right around there someplace, wouldn't you say? And there're some soda

bottles in case we can't find a gallon jug. All we have to do—"

"Go get the others, Sam," Groff ordered. He took his fingers off the

light switch he had been trying, though he had known what the results

would be ahead of time. "No electricity, you see? So the gas will just

have to stay in the pumps for a while."

He closed the door behind the grocer and looked over their refuge.

It wasn't much of a filling station—a couple of pumps out in front,

an ice chest full of soft-drink bottles and a little serving counter

inside. They had come in through a sort of storeroom, and there was the

chance that there might be something useful in there, but it had looked

like nothing more promising than the usual collection of old newspapers

and three-legged chairs. There was a rickety stair to, presumably, a

couple more storerooms.

Groff made thrifty inventory of what was on and behind the serving

counter. A coffeemaker—no good. No power, though a cup of good hot

coffee would have helped a lot. Easily a dozen cardboard boxes which,

opened, proved to contain peanut-butter-and-cheese crackers and

Orioles. Candy bars and bags of peanuts beyond their utmost powers of

consumption—they might get rickets, but they wouldn't starve. But

water, though—the place didn't seem to have any.

Scratch water. They could get by on the soft drinks, or if worse came

to worst, there certainly was much more water than they needed right

outside.

A telephone! He looked through all his pockets without coming up with

anything smaller than a quarter; he slipped the quarter into the slot

and there was a mellow bong to acknowledge it. There was nothing else.

He held the receiver to his ears for a good two minutes, but the line

was dead.

And then he found the greatest treasure of all, a box of stubby

short candles, under the serving counter. Evidently power failures

were not unheard of around here—something, Groff reminded himself

automatically, to keep in mind when he talked to the burgess tomorrow.

If he talked to the burgess tomorrow. There was something there that

would need thinking about, too, but the thing to do right now was

locate some matches. His own, of course, were more than merely wet—the

striking surface had soaked right off them. But there was a cigarette

machine, and fortunately a mechanical, not an electrically operated,

one.

By the time Sam got back with the others Groff was busy by candlelight,

trying to brace a Coca-Cola easel display to cover the window they had

broken. Sharon Froman was hugging the briefcase full of manuscript.

You don't last thirty years in the resort business unless you know how

to take your mind off your troubles. Mrs. Goudeket, sipping delicately

from a quart bottle of black cherry soda, chattered gaily: "Soda pop!

Three years I haven't had a drop of soda pop. Now don't tell on me,

Dick. If Dr. Postal ever finds out, he'll kill me next time he comes to

the hotel—" She choked on a swallow of the soda.

Dick McCue sat on one of the counter stools, sneering at the spectacle

Sharon Froman was making of herself over that Mickey Groff. All the

same, he admitted to himself, it was a real championship performance.

She hadn't had two minutes alone with him, but McCue was willing to

bet she could tell to a nickel how much a transistor manufacturer, in

process of expansion from forty employees to a hundred, was likely to

have in the bank. And there wasn't a chance in the world that this

Groff knew what she was doing. This was the no-nonsense Sharon, the

hard-working first-week-of-the-season Sharon, who was right by Groff's

side when he needed a hand, who didn't ask foolish questions, who kept

calm and ready. And to think that as late as Monday night, sneaking

back to his own room, he had begun to think—

Sharon and the manufacturer came in from the storeroom with another

load of newspapers and dumped them. "All right," said Groff, "I guess

that's all we'll need. They won't be very comfortable, but maybe

somebody'll come by before morning."

"I don't expect to sleep much anyhow," said Sharon cheerfully. She

tapped Zehedi on the shoulder. "Move your feet a little, will you, Sam?"

The grocer started. He picked his feet up so she could spread the

newspapers, and when she was through she had to remind him he could put

them down again. Five years down the drain. Five more years of hot dogs

and that muddy water they call coffee. I'll be thirty-five years old,

and still three or four years to go—

Everybody felt it at once.

"The wind?" ventured Mrs. Goudeket. They stared at each other; the

building seemed to be vibrating slightly.

Dick McCue, suddenly white, stumbled across the floor and pressed his

face to the door.

"Take a look!" he yelled. "That ain't wind!"

Even in the blackness, they could see the river that had been a road

outside, the comb of current around the gas pumps, the surging water

that lapped at the door.

CHAPTER FIVE

An air watcher, it doesn't matter which one of the thousands he was,

stepped from the hospital elevator at the third, and top floor. He went

through a door marked NO ADMITTANCE and climbed iron stairs to the

roof. It was black and drizzling; he hoped the rain wouldn't get worse,

at least not during his tour of duty. He had heard on a news broadcast

that west of his area there were cloudbursts.

He was tired from a long day at his appliance store on Broad Street and

he was a little sorry he had signed up for this Ground Observer Corps

thing, but everybody in Rotary was taking a shift so he felt he had

to go along. He threaded his way around the invisible obstacles that

studded the hospital roof and groped at the black-out curtain of the

shack.

It was dry and bright inside the little cubicle, but somewhat crowded.

The man he was relieving yawned, looked at the clock—so he was two

minutes late!—and said: "Howdy. Ready to go?"

"Sure. Everything quiet?"

"Yeah. CMA Flight 24 was early and south of their course, so I phoned

in for the hell of it. Coffee's hot."

"Maybe later. Well, I relieve you."

The man passed over the night glasses and went yawning through the