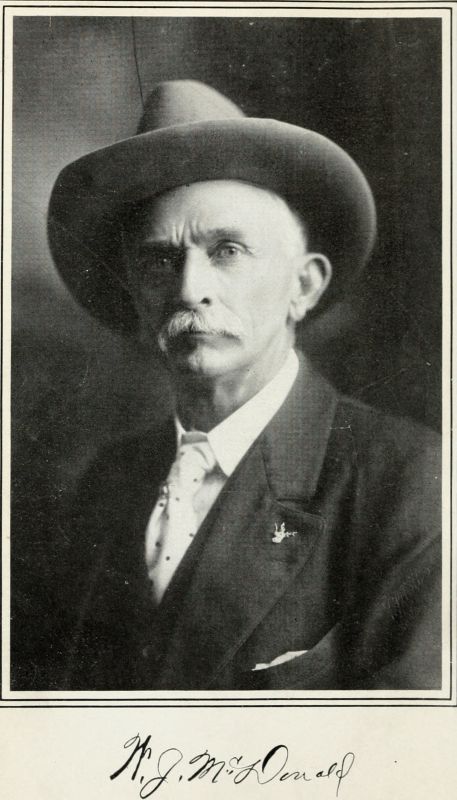

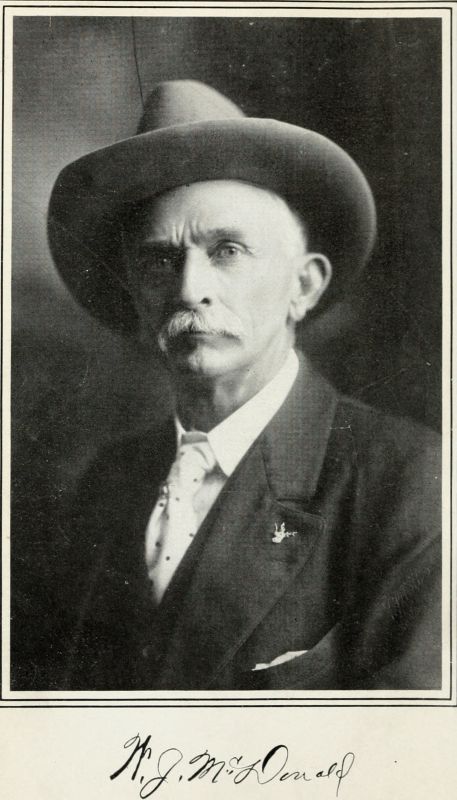

W.J. McDonald

CAPTAIN BILL McDONALD

TEXAS RANGER

A Story of Frontier Reform

BY

ALBERT BIGELOW PAINE

Author of "Th: Nast—His Period and His Pictures," etc., etc.

With Introductory Letter by Theodore Roosevelt

"No man in the wrong can stand up

against a fellow that's in the right

and keeps on a-comin'."

Bill McDonald's Creed.

SPECIAL SUBSCRIPTION EDITION

Made by J.J. Little & Ives Co.

New York, 1909

Copyright, 1909, by

WILLIAM J. McDONALD

To

EDWARD M. HOUSE

WITHOUT WHOSE ENDURING

FRIENDSHIP, WISE COUNSEL

AND ACTIVE INTEREST THIS

BOOK WOULD NEVER HAVE

BEEN WRITTEN

CONTENTS

| Page | ||

| Foreword: | A letter from Theodore Roosevelt | 11 |

| I.— | Introducing "Captain Bill" | 13 |

| II.— | An Old-Time Mississippi Childhood | |

| The kind of education for a young Ranger. Presence of mind early manifested | 16 | |

| III.— | Emigration and Adventure | |

| A boy at the head of a household. Meeting the "Devil and his wife." An early reform | 21 | |

| IV.— | The Making of a Texan | |

| Reconstruction and "treason." "Dave" Culberson to the rescue. Education, marriage and politics | 26 | |

| V.— | The Beginning of Reform | |

| Subduing a bad man. First official appointment. A deputy who did things. "Bill" McDonald and "Jim" Hogg | 33 | |

| VI.— | Into the Wilderness | |

| A New Business in a New Land. A "Sand-lapper" shows his "sand" | 43 | |

| VII.— | Commercial Ventures and Adventures | |

| Bill McDonald's method of collecting a bill; and his method of handling bad men | 48 | |

| VIII.— | Reforming the Wilderness | |

| The kind of men to be reformed. Early reforms in Quanah. Bad men meet their match | 55 | |

| IX.— | Getting Even with the Brooken Gang | |

| The Brooken Gang don't wait for callers. One hundred and twenty-seven years' sentence for an outlaw | 65 | |

| X.— | New Tactics in No-Man's Land | |

| A man with a buck-board. Holding up a bad gang single-handed | 69 | |

| XI.— | Redeeming No-Man's Land | |

| Bill McDonald and Lon Burson gather in the bad men. "No man in the wrong can stand up against a fellow that's in the right and keeps on a-comin'" | 78 | |

| XII.— | Some of the Difficulties of Reform | |

| "Frontier" law and practice. Caught in a Norther in No-Man's Land | 87 | |

| XIII.— | Captain Bill as a Tree-Man | |

| The lost drove of Lazarus. A pilgrim on a "paint-hoss." A new way of getting information in the "Strip" | 95 | |

| XIV.— | The Day for "Deliveries" | |

| The tree-man turns officer, and single-handed wipes out a bad gang | 106 | |

| XV.— | Cleaning Up the Strip | |

| Deputy Bill gets "stood off," but makes good. Bill Cook and "Skeeter," "A hell of a court to plead guilty in!" | 115 | |

| XVI.— | Texas Ranger Service and Its Origin | |

| The massacre of Fort Parker; Cynthia Ann Parker's capture. Rangers and what they are for. Their characteristics and their requirements | 126 | |

| XVII.— | Captain of Company B, Ranger Force | |

| Capture of Dan and Bob Campbell. Recommendations for a Ranger Captain. Governor "Jim" Hogg appoints his old friend on the strength of them | 136 | |

| XVIII.— | An Exciting Indian Campaign | |

| First service as Ranger Captain. Biggest Indian scare on record | 145 | |

| XIX.— | A Bit of Farming and Politics | |

| Captain Bill and his goats. The "car-shed" convention | 149 | |

| XX.— | Taming the Pan-handle | |

| The difference between cowboys and "bad men." How Captain Bill made cow-stealing unpopular | 154 | |

| XXI.— | The Battle with Matthews | |

| What happened to a man who had decided to kill Bill McDonald | 165 | |

| XXII.— | What Happened to Beckham | |

| An outlaw raid and a Ranger battle. Joe Beckham ends his career | 176 | |

| XXIII.— | A Medal for Speed | |

| Captain Bill outruns a criminal and wins a gold medal | 179 | |

| XXIV.— | Captain Bill in Mexico | |

| Mexican thieves try to hold up Captain Bill and get a surprise. Mexican police make the same attempt with the same result. President Diaz tries to enlist him | 182 | |

| XXV.— | A New Style in the Pan-handle | |

| Charles A. Culberson pays a tribute to Ranger marksmanship. Captain Bill in a "plug" hat | 189 | |

| XXVI.— | Preventing a Prize-Fight | |

| The Fitzsimmons-Maher fight that didn't come off at El Paso, and why. Captain Bill "takes up" for a Chinaman | 194 | |

| XXVII.— | The Wichita Falls Bank Robbery and Murder | |

| Kid Lewis and his gang take advantage of the absence of the Rangers. They make a bad calculation and come to grief. Good examples of Bill McDonald's single-handed work, and nerve | 199 | |

| XXVIII.— | Captain Bill as a Peace-maker | |

| He attends certain strikes and riots alone with satisfactory results. Goes to Thurber and disperses a mob | 214 | |

| XXIX.— | The Buzzard's Water-Hole Gang | |

| The Murder Society of San Saba and what happened to it after the Rangers arrived | 221 | |

| XXX.— | Quieting a Texas Feud | |

| The Reece-Townsend trouble, and how the factions were once dismissed by Captain Bill McDonald | 243 | |

| XXXI.— | The Trans-Cedar Mystery | |

| The lynching of the Humphreys and what happened to the lynchers | 250 | |

| XXXII.— | Other Mobs and Riots | |

| Rangers at Orange and at Port Arthur. Five against four hundred | 260 | |

| XXXIII.— | Other Work in East Texas | |

| Districts which even a Ranger finds hopeless. The Touchstone murder. The confession of Ab Angle | 265 | |

| XXXIV.— | A Wolf-Hunt with the President | |

| Captain Bill sees the President through Texas and accompanies him on the "best time of his life." Quanah Parker tells stories to the hunters | 273 | |

| XXXV.— | The Conditt Murder Mystery | |

| A terrible crime at Edna, Texas. Monk Gibson's arrest and escape. The greatest man-hunt in history. | 290 | |

| XXXVI.— | The Death of Rhoda McDonald | |

| The end of a noble woman's life. Her letter of good-by | 304 | |

| XXXVII.— | The Conditt Mystery Solved | |

| Captain Bill as a "sleuth." The tell-tale handprint. A Ranger captain's theories established | 308 | |

| XXXVIII.— | The Brownsville Episode: An Event of National Importance | |

| The Twenty-fifth Infantry's midnight raid | 315 | |

| XXXIX.— | Captain Bill on the Scene | |

| The situation at Brownsville. Rangers McDonald and McCauley defy the U.S. army. Captain Bill holds a court of inquiry | 323 | |

| XL.— | What Finally Happened at Brownsville | |

| How State officials failed to support the men who quieted disorder and located crime | 341 | |

| XLI.— | The Battle on the Rio Grande | |

| Assassination of Judge Stanley Welch. A Rio Grande election. Captain Bill ordered to the scene. An ambush; a surprise, and an inquest. Captain Bill's last battle. | 357 | |

| XLII.— | The End of Rangering and a New Appointment | |

| State Revenue Agent of Texas. The "Full Rendition" Bill enforced. A great battle for Tax Reform, and a bloodless triumph | 373 | |

| XLIII.— | Conclusion | |

| Captain Bill McDonald of Texas—what he has been and what he is to-day | 388 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

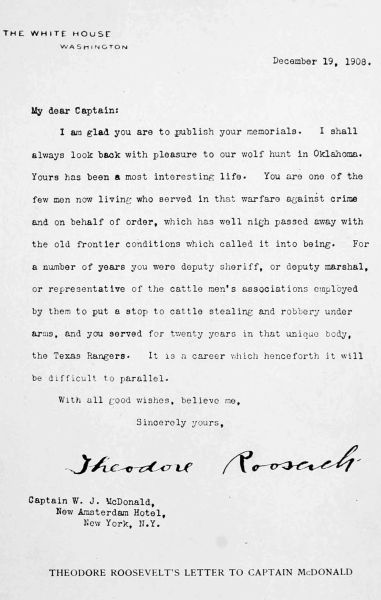

THEODORE ROOSEVELT'S LETTER TO CAPTAIN McDONALD

A Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Captain McDonald

The White House,

Washington.

December 19, 1908.

My dear Captain: I am glad you are to publish your memorials. I shall always look back with pleasure to our wolf-hunt in Oklahoma. Yours has been a most interesting life. You are one of the few men now living who served in that warfare against crime and on behalf of order, which has well-nigh passed away with the old frontier conditions which called it into being. For a number of years you were deputy sheriff, or deputy marshal, or representative of the cattlemen's associations, employed by them to put a stop to cattle stealing and robbery under arms, and you served for twenty years in that unique body, the Texas Rangers. It is a career which henceforth it will be difficult to parallel.

With all good wishes, believe me,

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt.

CAPTAIN BILL McDONALD, TEXAS RANGER

Introducing "Captain Bill"

Captain Bill McDonald is a name that in Texas and the districts lying adjacent thereto makes the pulse of a good citizen, and the feet of an outlaw, move quicker. Its owner is a man of fifty-six, drawn out long and lean like a buckskin thong, with the endurance and constitution of the same.

In repose, Captain Bill is mild of manner; his speech is a gentle vernacular, his eyes are like the summer sky. I have never seen him in action, but I am told that then his voice becomes sharp and imperative, that his eyes turn into points of gray which pierce the offender through.

Two other features bespeak this man's character and career: his ears and his nose—the former, alert and extended—the ears of the wild creature, the hunter; the latter of that stately Roman architecture which goes with conquest, because it signifies courage, resolution and the peerless gift of command.

His nerves are of that quiet and steady sort which belong to a tombstone and he does not disturb them with tobacco or stimulants of any kind—not even with tea and coffee. In explanation, he once said:

"Well, you see, sometimes I have to be about two-fifths of a second quicker than the other fellow, and a little quiver, then, might be fatal."

Incidentally, it may be added that Captain Bill—they love to call him that in Texas—is ranked as the best all-round rapid-fire marksman in the State, and for the "other fellow" to begin shooting is believed to be equivalent to suicide. Add to these various attributes a heart in which tenderness, strict honesty and an overwhelming regard for duty prevail, and you have in full, Captain William Jesse McDonald, formerly Deputy Sheriff, Deputy U.S. Marshal and Ranger Captain, now State Revenue Agent of Texas.

It is the story of this man that we shall undertake to tell. During his twenty-five years or more of service in the field, he reduced those once lawless districts known as the Pan-handle, No-man's Land, and, incidentally, Texas at large to a condition of such proper behavior that nowhere in this country is life and property safer than in the very localities where only a few years ago the cow-thief and the train-robber reigned supreme. Their species have become scarce and "hard to catch" there now, and the skittish officials who used to shield them have been trained to "stand hitched." The story of a[Pg 15] reform like that is worth the telling, for it is the unwritten history of a territory so vast that if moved to the Atlantic seaboard it would extend from New York to Chicago, from Lake Erie to the Gulf of Mexico—its area equal to that of France and England combined, with Wales, Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland thrown in, for good measure. Furthermore, it is the story of a man who, in making that history, faced death almost daily, often under those supreme conditions when the slightest hesitancy—the twitch of a muscle or the bat of an eyelid—a "little quiver," as he put it—would have been fatal; it is the story of a man who time and again charged into the last retreat of armed and desperate murderers and brought them out hand-cuffed, the living ones, of course; it is the story of a man who, according to Major Blocksom, in his report of the Brownsville troubles in 1906, would "Charge hell with a bucket of water." In a word, it is the story of a man who has done things, who is still doing them, and whose kind is passing away forever.

An Old Time Mississippi Childhood

THE KIND OF AN EDUCATION FOR A YOUNG RANGER. PRESENCE OF MIND EARLY MANIFESTED

In those days when the Mississippi planter was only something less than a feudal baron, with slaves and wide domain and vested rights; with horses, hounds and the long chase after fox and good red deer; with horn and flagon and high home wassail in the hall—in those days was born William Jesse McDonald, September 28th, 1852. His father, Enoch McDonald, was the planter of the feudal type—fearless, fond of the chase, the owner of wide acres and half a hundred slaves—while his grandfather, of the clan McDonald on its native heath, was a step nearer in the backward line to some old laird who led his men in roistering hunt or bloody fray amid the green hills and in dim glens of Scotland.

That was good blood, and from his mother, who was a Durham—Eunice Durham—the little chap that was one day to be a leader on his own account, inherited as a clear a strain. The feudal hall in Mississippi, however, was a big old plantation[Pg 17] house, built of hewn logs and riven boards, with woods and cotton-fields on every hand; with cabins for the slaves and outbuildings of every sort. That was in Kemper County, over near the Alabama line, with DeKalb, the county-seat, about twenty miles away.

It was a peculiar childhood that little "Bill Jess" McDonald had. It was full of such things as the home-coming of the hunters with a deer or a fox—sometimes (and these were grand occasions) even with a bear. Then there were wonderful ball-games played by the Bogue Chita and Mucklilutia Indians; exciting shooting-matches and horse races; long fishing and swimming days with companions black and white, and the ever recurring chase, with the blood-hounds, of some runaway slave. There was not much book-schooling in a semi-barbaric childhood such as that. There was a school-house, of course, which was used for a church and gatherings of any sort, and sometimes the children had lessons there. But the Kemper County teaching of that day was mainly to ride well, to shoot at sight, and to act quickly in the face of danger. That was the proper education for the boy who was one day to make the Texas Pan-handle and No-man's land his hunting ground, with men for his quarry.

Presence of mind he had as a gift, and it was early manifested. There was a lake not far away where fishing and swimming went on almost continuously during the summer days, and sometimes[Pg 18] the small swimmers would muddy the water near the shore and then catch the fish in their hands. They were doing this one day when Bill Jess was heard to announce excitedly:

"I've got him, boys! I've got him! You can't beat mine!" at the same instant swinging his catch high for them to see.

That was a correct statement. They couldn't beat his catch and they didn't want to. What they wanted to do was to get out of his neighborhood without any unnecessary delay, for the thing he held up to view was an immense deadly moccasin, grasped with both hands by the neck, the rest of it curling instantly around the lower arm. His hold was so tight and so near its head that the snake could not bite him, but the problem was to turn it loose. His friends were all ashore and at a safe distance. He did not lose his head, however, but wading ashore himself he invited them one after another to unwind that snake. Nobody cared for the job and he told them in turn and collectively what he thought of them. Then he offered the honor to a little slave boy on attractive terms.

"Alec," he said, "ef you-all don't come an' unwind this heah snake, I'll beat you-all to death an' cut off yo' ears an' skin you alive and give yo' carcass to the buzzards."

Those were the days when a little slave-boy could not resist an earnest entreaty of that sort from the son of the household, and Jim came forward, his[Pg 19] face gray with gratitude, and taking hold gingerly he unwound a yard or so of water-moccasin from Bill Jess, who, with the last coil, flung his prize to the ground, where it was quickly killed, it being well-nigh choked to death already.

But even the great gift of presence of mind will sometimes balk at unfamiliar dangers. It was about this time that the Civil War broke out, and Enoch McDonald enlisted a company to defend the Southern cause. The little boy left behind was heart-broken. His father was his hero, and when by and by the news came that the soldiers were encamped at Meridian—a railway station about fifty miles distant—the lad made up his mind to join them. He set out alone afoot and being used to finding his way in unfamiliar places he made the journey with no great difficulty, eating and sleeping where opportunity afforded. He arrived at Meridian one morning, and began to look over the ground and to make a few inquiries as to his father's headquarters. There was a busy place, where a lot of supplies were being unloaded from what appeared to be little houses on wheels. They were freight cars, but Bill Jess didn't know it. He had never seen a railroad before, and he followed along the track with increasing interest till he reached the engine, which he thought must be the most wonderful and beautiful thing ever created. Then suddenly it let off steam, the bell rang and the air was split by a screaming whistle. It was too sudden and too strange for his[Pg 20] gift to work. The son of all the McDonald's and of a gallant soldier set out for the horizon, never pausing until halted by the sentry of his father's camp.

He was permitted to enter, and was directed to the drill ground, where his father, who had been promoted for bravery to the rank of Major, was superintending certain maneuvers. The little boy in his eagerness ran directly into the midst of things, and Major McDonald, suddenly seeing him, was startled into the conclusion that some dire calamity had befallen his family and only Bill Jess had escaped to tell the tale. Half sliding, half falling he dropped from his horse to learn the truth. Then gratefully he lifted the lad up behind him and continued the drill. Eunice McDonald was only a day or two behind Bill Jess, for her instinct told her where the boy had gone. They remained a few days in camp and then bade their soldier good-bye. They never saw him again, for he was killed at the battle of Corinth, October 3d, 1862, charging a breastworks at the head of his regiment, his face to the enemy, as a soldier should die.[1] The boy, Bill Jess, ten years old, went after his father's effects, which included two horses, both wounded. These he brought home, but his soldier father had been buried on the field, where he fell.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Col. Rogers of Texas was killed in the same charge; Major McDonald and Col. Rogers fell side by side, within a few feet of the works.

Emigration and Adventure

A BOY AT THE HEAD OF A HOUSEHOLD. MEETING "THE DEVIL AND HIS WIFE." AN EARLY REFORM

The boy of ten was now the head of the household. He had his mother and sister, and most of the negroes still remained; but he was the "man of the house" and was mature before his time. Except in the matter of strength, he was a man's equal—he could do whatever a man could do. Already he was a crack shot, and at the age of twelve he hunted deer, and killed them, alone. Long before, even during his father's first absence, he had followed runaway slaves with the blood-hounds and without other assistance had captured them and marched them back to the plantation. It was not a child's work, and we may not approve of it to-day, but we must confess that it constituted a special training for the part he was to play in after years.

The war ended at last, and with it the McDonald fortune. Slaves and cotton were gone. Only a remnant of land, then worthless, remained. Eunice McDonald, widowed, with two children—her home left desolate by the ravages of war—knew not which way to turn. A bachelor brother with his face set[Pg 22] Texasward offered to make a home for her in the new land. She accepted the offer, and in 1866 they reached east Texas and settled in Rusk County, near Henderson, the county-seat. Here the brother and sister made an effort to retrieve their broken fortunes, with moderate success. All the family worked hard, and young McDonald, now in his fifteenth year and really a man in achievements, did a man's part on the farm, attending school a portion of the year. His uncle permitted him to earn some money for himself by cutting wood and hauling it to the village, and a part of this money he laid away. Such leisure as he had, he spent in following the hounds, and presently, even as a boy, became famous for his marksmanship. Coon hunting was perhaps his favorite diversion, and frequently with his dogs he threaded the dark woods all night, alone.

But he had not as yet achieved that perfect fearlessness which distinguished him in later years, and there is still another instance recorded where his presence of mind failed to work. This latter is a curious circumstance, indeed, and should be investigated, perhaps, by the Society of Psychical Research.

He had been out on one of his long night tramps and was very tired next evening when his work was done. Coming in, he threw himself down on a lounge in the hallway and was soon sound asleep. By and by his mother came along and wakened him.

"It's bed-time, Bill Jess," she said.

He got up, walked out toward the gate, and she supposed he was awake. When he really awoke, he was a mile from there, leaning on the gate of one Jasper Smith, the father of two young ladies whom Bill Jess was in the habit of visiting. Realizing where he was, and what might happen to him if discovered just there, he set out for home down the wide public road, when suddenly a little way ahead he saw two objects perched on the top of the rail fence. At first he thought they were two men, and was not disturbed; then all at once they had left the top of that fence and in the wink of an eye, lit in the road directly in front of him.

"It was the devil and his wife," McDonald declared. "They had horns and tails, exactly like all the pictures of the devil I ever saw. Of course it might have been the devil and his brother; anyway they belonged to that family. I got by those things. I didn't debate a minute, but went home as fast as my legs could carry me, emptying my pockets as I ran, which I had always heard the darkeys say would keep off witches. There was a short way home by the graveyard, but I didn't take it. I kept to the big road, and when I did get home, I didn't wait to go around to the door, but went right in the open window where my mother was. She said that I had imagined everything, but I hadn't. There was no imagination about it."

Curiously enough, soon after this happened a[Pg 24] little flock of school-children passing near the same rail fence in daylight, saw something that scared them so badly that some of them fainted. But by this time Bill Jess had gathered himself, and taking his gun he loaded it heavily and went devil hunting. However, without success.

In spite of this slight lapse, young McDonald probably considered himself a man, now. We have seen that he was already calling on the young ladies, and in the locality where he lived an ability to drink whiskey was regarded as another manly achievement. There was a small still-house located not far from his home, and he got into the habit of visiting it and of tasting the output. One day he tasted too much and did not return either in good season or condition. When his mother prepared to administer punishment, he pulled away from her and stated that he would not take a whipping. But Eunice McDonald was not one to condone such rebellion. She put away the rod and bided her time. One night when Bill Jess was fast asleep she wrapped and pinned him securely in a sheet and laid on such a thrashing as gave him a permanent distaste both for liquor and disobedience.

At another time it was attentions paid to a young lady that got him into difficulties. The young lady was the sister of his school teacher, and the latter did not approve of anything resembling attachment between the two. One day the young wooer wrote a letter in school, and passing it down the line it[Pg 25] unluckily fell under the eye of the teacher, who captured and read it, forthwith.

"I'll settle with you at recess, sir," he said, nailing Bill Jess to the seat with his eye.

Bill Jess didn't care to have him settle. He was willing to let the account run right along, and to knock off the interest. He decided not to wait. The teacher had his back to the board, working out something hard, when Bill Jess went away. He didn't rush wildly. He didn't even run—not exactly—but he lost no time, tip-toeing out of there. Neither did he go home. He'd gone home once in disgrace, and he remembered what had happened. Eunice McDonald's combination of sheet and horse-whip offered no fresh inducements in that direction. He walked twenty miles to a saw-mill and got a job. Then, by and by, everything blew over; everybody was sorry, and he returned home to forgiveness and safety. A cyclone hit the school-house for some reason or other about this time and demolished it, Bill Jess being raked out of the debris undamaged in any particular. Perhaps this was vindication.

The Making of a Texan

RECONSTRUCTION AND "TREASON." "DAVE" CULBERSON TO THE RESCUE. EDUCATION, MARRIAGE AND POLITICS

But though still a boy in years, being not more than sixteen, his youth really came to an end now. It was the period of Reconstruction in the South—a time of obnoxious enforcements on the one hand, and rebellious bitterness on the other, with general lawlessness in the back settlements. The military dominated the towns and there were continuous misunderstandings between the still resentful conquered and the aggressive and sometimes insolent conquerors. Young McDonald, with the memory of his hero father, shot dead while leading his regiment against these men in blue, was in no frame of mind to submit to any indignity, real or fancied, at their hands. It happened just at this time that one Colonel Greene, a relative of the McDonalds, was murdered by negroes, who, being arrested, confessed the killing, stating that they had mistaken Greene for a mule-buyer supposed to have a large sum of money. The men were lodged in jail, but it was believed that under the "carpet-bag" military[Pg 27] law then prevailing they would escape punishment. In later years, young McDonald was to become one of the most strenuous defenders of official procedure—one of the bitterest opponents of lynch-law the State of Texas has ever known; but he was hot-blooded in 'sixty-eight, and the situation was not one to develop moral principles. When, therefore, a mob formed and took the negroes out of jail and hanged them, there is no record of Bill Jesse having distinguished himself in their defense as he certainly would have done in later years. Indeed, it is likely that if he did not help pull a rope that night it was only because the rope was fully occupied with other willing hands.

Of course the military descended on Henderson and set in to discipline it for this concerted lawlessness. The townspeople as a whole, and the relatives of Colonel Greene in particular, resented this occupation. Charley Greene, a brother of the murdered man, in company with Bill Jess, presently got into trouble with some soldiers who were deporting themselves in a manner considered offensive, and the result was a running fight with the military in the lead. The soldiers made for their quarters in the court-house. It would have been proper to leave them alone, then—to retire flushed with victory, as the books say, and satisfied. But Greene could not rest. He persuaded Bill Jess to stay with him, and they rode up and down in front of the court-house, occasionally taking a shot at the windows, to punctu[Pg 28]ate their challenge to warfare. Finally Greene decided that they could charge the court-house and capture it. He primed himself with liquor for the onset, and refused to heed his companion's advice to abandon the campaign. The two ascended the court-house stairs, at last, with pistols cocked. Greene had one in each hand and, with them, shoved open the double doors at the head of the stairs. That was another mistake. The soldiers were "laying for him" just inside, and in an instant later his arms were pinioned, and he was a prisoner. The doors swung to, then, and Bill Jess stood outside, wondering whether he ought to charge to the rescue, wait there and be captured, or retire in good order. With that gift of logic and rare presence of mind which would one day make him famous, he decided to get out of there. He had a plan for organizing a rescue party, and did in fact get a crowd together, but in the meantime, under cover of rain and darkness, the soldiers had taken their prisoner from Henderson and he was well on the way to Jefferson, where there was a stockade. No attempt was made at the time to arrest young McDonald, though soldiers frequently loitered about his home premises, and with these he had many collisions, usually coming off victorious. He was strong, wiry and fearless, and he had then, as always, that piercing eye and a manner of going straight at things without flutter or hesitation.

Still, he was laying up trouble for himself, for[Pg 29] Greene's court-martial was coming off, and Bill Jess, who went over to see if he could be of any assistance, was promptly arrested while nosing about the stockade, and landed with his relative on the inside. This was a serious matter. The boy realized that it was, as soon as the gates closed behind him. He realized it still more forcibly when a few days later he and Greene were led into the court-house for military trial, and he took a look at the men who were to prosecute him for aiding in the crime of treason. Nor was he reassured when one of the lawyers present announced that he would "defend that boy's case." For there was nothing inspiring about this champion's appearance. Nothing about him except his generosity seemed worth while. He wore ill-fitting home-spun clothes, smoked a common clay pipe and his long hair straggled down over his forehead. His shirt collar was carelessly unbuttoned, and his trousers, too short for him, revealed common home-knit yarn socks. Moreover, his eyes were half-closed and he had a general air of sleepy indifference which did not disappear until it came his turn to take part in the proceedings. Then suddenly the sleepy eyes became alive, the shaggy hair was tossed back, the clay pipe was laid on the table, and Dave Culberson, afterward known as an eminent lawyer and statesman, arose and made such a plea in behalf of the boy whose father had died at Corinth, and whose mother and sister relied on him to-day for protection, that only one[Pg 30] verdict remained in the minds of his hearers when he closed. Bill Jess was acquitted, but his relative, Charley Greene, was less fortunate. He remained in a Northern prison several years before he was finally released. Dave Culberson afterward represented his district in Congress, and the boy he defended eventually served the son, Charles A. Culberson—then Governor—now, in 1909, United States Senator from Texas.

It is likely that this bit of experience with hot-headed lawlessness, and the result thereof, proved of immense value to young McDonald. From that time forward we find him a peace-maker, a queller of disturbances, a separator of combatants, even at great personal risk. He had never been a seeker after trouble and he seemed now to develop a natural talent for preserving the peace. Wherever guns are drawn, and they were drawn pretty frequently and upon small provocation in that day and locality, he stepped in without hesitation and the would-be slayers were disarmed by what seemed a veritable sleight-of-hand. In 1871, when he was nineteen years old, he decided to follow a commercial life, and with the money saved from the sale of the wood he had cut and hauled, he took a course in Soule's Commercial College, at New Orleans, graduating in 1872. Penmanship came easy to him, and upon his return to Henderson he taught a writing class. Within the year he was able to establish a small store in connection with the ferry at Brown's[Pg 31] Bluff on the Sabine River, between Henderson and Longview. Here, with his ferry assistant he kept bachelor's hall, not the most congenial existence, perhaps, for one with his natural leaning toward female society. At all events, he gave it up, by and by, and after a brief sojourn in Longview established himself in Wood County, at Mineola, then a newly established and busy railway terminus. This was in 1875, and his venture was a success. Soon he was considered the leading grocer of the town.

It was during this period that McDonald made the acquaintance of James S. Hogg, who in later life, as Governor of Texas, was to confer his most useful official appointment—that of Ranger Captain, thus enabling him to do much of the work which has identified his name with the State's constructive history. Hogg, then a young man, was Justice of the Peace at the county-seat, Quitman, a few miles distant from Mineola, and was also conducting a paper there. He bought his groceries of McDonald, and the account ran along in a go-as-you-please sort of a way. They were good friends, and courted together, and it was through Hogg that young McDonald met Miss Rhoda Isabel Carter, a young woman with fine nerve and force of character—just the girl for a Texas regulator's wife. And such, in due season, she was to become, for he married her in January, 1876. His friendship for Hogg continued for some time after that, but came to a[Pg 32] sudden end, one day, when Hogg, who had been elected County Attorney, with characteristic conscientiousness prosecuted McDonald and others for carrying concealed weapons—McDonald's possession of such a weapon having been revealed through his aiding in the capture of a gang of boisterous disturbers of the peace. McDonald rose and defended his own case, declaring he had quit business to do his duty as a good citizen, and that he would stay in jail the balance of his days before he would pay a fine.

With his usual frank fearlessness he said some hard things to Hogg in the presence of the court, and though discharged, the two were estranged for a considerable period. Then a truce was patched up, but only for a time. Both were sharply interested in politics and on opposing sides in the congressional convention. They were near coming to blows over their differences, and were only separated by the intervention of friends. It is not pleasant to record this of these two worthy men, but after all they were only human beings, and young, and then the sequel makes it still further worth while.

The Beginning of Reform

SUBDUING A BAD MAN. FIRST OFFICIAL APPOINTMENT. A DEPUTY WHO DID THINGS. "BILL" MCDONALD AND "JIM" HOGG

But now came Bill McDonald's first official appointment and service. Living just outside of Mineola was a man named Golden, alias George Gordon, of hard character, and the owner of several bulldogs, similarly endowed. Man and dogs became a menace to travel in that neighborhood, as they lived near a public road and were allowed at large. The man was particularly quarrelsome and ugly and was said to have killed several more or less inoffensive persons. He always carried arms—the customary pistol, and a bowie knife—the latter worn in a scabbard "down his back." He was an expert at throwing this weapon, and altogether a terror to the community. Bill McDonald would naturally resent the domination of a man like Gordon, and when one day the latter came to town with one of his unruly bulldogs, and the dog set upon and injured McDonald's prized pointer, there was trouble, active and immediate. McDonald's reputation as a[Pg 34] good man to let alone was already established at Mineola. He was known as a capable marksman—fearless, resolute and very sudden. When, therefore, he produced a six-shooter for the avowed purpose of killing the bulldog, its master, who, like every bully by trade, was a coward at heart, interceded humbly for the dog's life, promising to take the animal home and leave him there. McDonald agreed to the arrangement, but for the benefit of the community at large he promptly applied to Sheriff Pete Dowell for a commission as deputy, in order that in future he might restrain officially the obnoxious Gordon and others of his kind. The commission was promptly conferred, and thus Bill Jess McDonald, quietly and without any special manifest, stepped into the ranks of Texas official regulators, where, in one capacity or another, he was to serve so long and well.

But, however quiet his enlistment, his service was to be of another sort. Those were not quiet days, and the officer who set out to enforce the law was apt to become a busy person. Gordon very soon appeared again in Mineola, and after investing in a good deal of bad whisky, went on the war-path, flourishing a six-shooter and giving out the information that nobody could arrest him. He was in the very midst of a militant harangue when Deputy McDonald suddenly appeared on the scene, and before Gordon could gather himself, he was, by some magic "twist of the wrist," disarmed, arrested and on the[Pg 35] way to the calaboose. He demurred and resisted, but slept that night behind lock and bars. Next morning he refused breakfast and demanded release. Deputy McDonald left him in a mixed condition of reflection and profanity, returning at noon to find him sober, subdued and hungry. Upon promise of good behavior for the future, he was taken before a justice, where he pled guilty and paid a fine. Then he took his place as the first example of a long line of wonderful cures set down to Captain Bill McDonald's credit, to-day; for he gave little trouble after that and remained mostly in retirement, to be set upon, at last, by his own dogs, who inflicted terrible wounds. His death soon afterward was thought to be the result of this attack.

But the Gordon experience was mild enough, after all, compared with the many which followed, and is only set down because it marks the beginning of a career. Indeed, an episode of larger proportions was already under way. In the timber lying adjacent to Mineola, some three hundred tie-cutters were encamped, supplying cross-ties for the I. & G.N. road. They were a drinking, lawless lot, and on Saturday nights the Mineola streets were filled with riot and disorder. The city marshal, George Reeves, and Deputy McDonald had on several occasions made arrests and such enforcement of the law had been regarded by the tie-gang as an affront to all. They sent word to the officers, at last, that they would be on hand in full force, on the following Saturday, and[Pg 36] that the calaboose might as well go out of commission, so far as they were concerned.

Saturday night came, and according to promise the tie-cutters were on the street, numerous and noisy. McDonald and Reeves were among them, keeping a general lookout for trouble, not always together. The saloons were full, presently, and the men getting constantly more noisy and quarrelsome. Seeing a commotion at the rear of a cheap hotel where a number of the men had gathered, McDonald went over there, and found Reeves surrounded. Without hesitation he shoved a way through, with his pistol, until he stood by Reeves's side. Reeves had arrested a man, and a general riot was imminent. The prisoner was very drunk and disorderly and demanding that he be allowed to go to his room before accompanying the officer. Of course the whole intention was to precipitate a general fight, during which the officers were to be pummeled and battered to a jelly. Catching the drift of matters, McDonald said:

"All right, take him to his room, if he's got one. I'll take care of this crowd."

There was something in the business-like confidence of that statement which impressed the crowd. And then he had such a handy way of holding a six-shooter. Nobody quite wanted to die first, and Reeves started for the back entrance of the hotel with his man. As they entered the door the fellow reeled against the casing and fell to the ground.[Pg 37] Then a general stampede started, for it was called out that Reeves had struck him. McDonald said:

"Stop you fellers! The fool fell down. I'll shoot the first man that interferes!"

That was another discouraging statement from a man who had a habit of keeping his word. It seemed to the crowd that an officer like that didn't play fair. He didn't argue at all. Somebody was likely to get hurt, if they didn't get that gun away from him. Movements to this end were started here and there, but they didn't get near enough to the chief actor to be effective. Finally when Reeves and his prisoner set out for the calaboose, the crowd moved in that direction, timing their steps to a chorus of threats and profanity. Reeves and McDonald made no reply until they arrived at the lockup; then, the disturbers being there handy, the officers began gathering them in, a dozen at a time. It was a genuine surprise-party for the tie-men. They were too much astonished for any concerted movement, and when invited at the points of those guns to step inside and make themselves at home, they did not have the bad taste to refuse.

"Step in, gentlemen; always room for one more," might have been the form of the invitation, but it wasn't. It was a Bill McDonald invitation and it was full of compliments and promises that burnt holes wherever they hit anything. The calaboose was full in a brief time and a box-car on a nearby switch was used as an annex. By the time it was[Pg 38] full, there were no more disturbers. The outer edges had melted away. The woods were full of them. The turbulent tie-men of Texas were sober and sensible by Monday morning and allowed to go, under promise of good behavior, and upon payment of adequate fines.

Mineola suddenly became a moral town. Amusements of the old sort languished. Drunk or sober, it was humiliating to flourish a gun, only to be suddenly disarmed and marched to the calaboose by a man who acted as if he thought he was gun-proof. It was hard to understand—it was supernatural. It was better to go to the next town to nourish the gun.

But by this time Deputy Bill Jess was not satisfied with the quiet life. He had found his proper vocation—that of active enforcement of the law—and he was moved to pursue it in remoter places. A certain desperate outlaw, a white man by the name of Jim Bean, had committed crimes in Smith County, whence he had escaped to Kansas. There he had killed a city marshal and returned once more to Smith County, which adjoins Wood on the south. The officers of Smith County had surprised Jim Bean and his brother Ed, at a small station where they had gone to rob some freight cars, but the two men had handled their revolvers so desperately that they had been allowed to escape, and pursuit of them had been abandoned.

This was the kind of game that Deputy Bill always enjoyed hunting. It was worth while. He[Pg 39] made frequent still-hunts along the Sabine River, the dividing line between Wood and Smith, hoping to locate his quarry on the side of his jurisdiction. Perhaps the men knew of these excursions and remained safely, as they believed, on the other side. At last, however, the temptation to cross the line became too strong for a hunter like Bill Jess. The impulse of the Ranger was already upon him. He crossed the Sabine River into Smith, with his Winchester on his saddle, and became an official poacher. The river bottom was overgrown in places with tall cane-brake, and he had reason to believe that the Beans were hiding, and storing their loot, in the dense growth. He had heard a rumor, too, that a certain family of swamp-dwellers (negroes) were in league with the men, and, reflecting on the matter, he concluded to visit this house, both for the purpose of investigation, and to borrow a shot-gun, which he thought might be more useful, in a man-chase through a thick cane-brake swamp, than his rifle. Arriving at the suspected house, he told in his mildest manner a tale of a wounded deer not far away, and borrowed a shot-gun, as well as the information that the men and dogs of the place were in the brakes. He now began a careful still-hunt for his game, and presently came full upon Jim Bean, who was on a horse, with a shot-gun, guarding some stolen hogs. Bean was a great burly creature, more animal than man, from having lived and slept so long in the woods and brakes. He had been shot at[Pg 40] many times, and had been desperately wounded, but such was his natural vitality, and so hardened was he by exposure that it seemed impossible to kill him.

Before Bean could move, now, Deputy McDonald had him covered and commanded him to get off his horse or he would shoot him dead. Bean obeyed and McDonald threw his own leg over his saddle and slid to the ground, still covering Bean with his gun. Suddenly Bean made a dash for a large tree, turning to shoot just as he reached this cover. McDonald was too quick, however, and let go with two loads of buckshot, which struck Bean in several places, knocking him down. He then made off in the direction of a slough, toward thick hiding. The shot-gun was a muzzle loader and before McDonald could get it charged again he heard somebody coming through the brush. It was Ed Bean and some negroes. He was ready for them by the time they came in sight, and throwing his gun to position he commanded them to halt. Instead of doing so they turned and disappeared in the direction from which they had come. McDonald now mounted his horse and started in pursuit of the wounded Jim Bean. He found where he had crossed the slough, and presently came to the desperado's gun, which had been thrown away in his hurry. Blood-stains made the trail easy to follow. Soon a powder-horn and then a pair of boots lay in the path of flight. McDonald followed six miles to a cabin occupied by negroes. Bean was not in the cabin, but barefoot[Pg 41] prints led into the woods. The man-hunter followed them and finally overtook their owner. It was not Bean. The officer had been tricked—Bean had escaped while his pursuer had been following this false lead. It was dark, now, and further search was hopeless. Next morning the outlaws had vanished from the country. They never returned and were heard of no more until some time after, when news came from Wise County that both the Bean brothers had been killed, resisting arrest.

While this episode did not turn out altogether successfully, inasmuch as the game got away, it had a better result in that it effected a complete reconciliation between McDonald and his old, and what was to be his lifetime friend, James S. Hogg. Certain jealous officials were bent upon making trouble for the young deputy for overstepping his authority by working outside of his own county, and especially for shooting a man in attempting an illegal arrest. McDonald held that the conditions justified his act, and was going to make his fight on that ground. But it never came to a fight, for when the matter was brought to the notice of the grand jury, Hogg, by this time District Attorney, went before that body, and regardless of the old animosity between McDonald and himself, and of the fact that they were not yet on speaking terms, declared that if the jury found an indictment against the deputy for so worthy an undertaking as that which, irregular or not, had resulted in ridding the country of a gang[Pg 42] of outlaws, he would nolle pros the case—in other words, he would refuse to prosecute.

When McDonald heard of this, he went to his old friend at once.

"Jim," he said, "you're a gentleman, and I know I want to act right. Let's not be enemies any more." And they never were.

Ten years later, Jim Hogg, as Governor of Texas, would make it possible for Bill McDonald to bring down criminals in any county of that mighty State. But this is further along in our story.

Into the Wilderness

A NEW BUSINESS IN A NEW LAND. A "SAND-LAPPER" SHOWS HIS SAND

Hard times came on in Mineola. Railroad building was at an end; crops failed; men who had bought goods on long credit could not pay. "Bill" McDonald, as he was now usually called, had been one to carry long lines of credit for his customers, and he was hurt accordingly. He gave up business, at last, and in 1883 invested in cattle whatever remained to him, and set his steps further westward where there was free grass. He headed toward Wichita County, which was almost an unknown land in that day, driving his cattle before him, his young wife at his side, both eager to begin a new life in a new land.

To drive cattle across the wild Texas prairies, twenty-five years ago, was an experience worth while. There were no fences, no boundaries and few roads. Settlers were far between. The climate in any season was likely to be mild; the air was pure and stimulating; society, such as it was, had not many conventions.

Yet, few and fundamental as were the conditions, they were of a sort to develop sudden situations, and[Pg 44] one had to be ready to face them fairly and firmly or write himself down as unfit for the wild free life of the range. The grass was free, but there were always those who wanted to form a trust of its vast areas and make trespassers of the smaller men. McDonald had scarcely located his herd and pitched his tent when two of these magnates notified him that he had better move. It was a bluff, of course, and the man who had been deputy sheriff for half a dozen years and purified a bad community was the wrong man to use it on. He asked in that quiet way of his, to let him have a look at their titles, and when they could not produce them, he added that he thought he'd stay where he was. They began to tell him of some of the things that were likely to happen if he did that, but he did not seem impressed by the information. He repeated that he would stay where he was, and that anyone who did not wish to be in his neighborhood had his permission to move on, to other free grass. Perhaps they looked him over a bit more carefully, then, and noticed the peculiarity of his nose and of his eyes, and the handy and casual way he had of picking off the heads of rattlesnakes and such things, with a six-shooter, while he talked. At all events they did not refer to the matter again and even cultivated his friendship. In a neighborhood where cattle thieves were beginning to be troublesome a man like that would be handy to have around. They were to have an example presently of his willingness and ability to[Pg 45] defend the rights of ownership—a small example, but convincing.

It was no easy matter to keep a herd intact in those days. In a land of free grass, where the cost of cattle was chiefly the expense of herding, it was not likely that the moral title to the cattle themselves would be very highly regarded, especially where brands had been obliterated, or where a few strays mingled with a larger herd. The outlaw pure and simple was bad enough, but to the newcomer with a small bunch of "cows" (cattle, regardless of gender), the vast roaming herd, guarded by a veritable army of punchers whose respect for any law was small enough, was an even greater menace. McDonald knew of these conditions, and when, soon after his arrival, some of his cattle strayed away, he set out to inspect the surrounding herds. After riding some distance he came upon a large drove, evidently on its way to market. It was about noon and the men were "rounding-in" for dinner. McDonald started to address a herder, when the man turned abruptly and started off. McDonald immediately began looking through the cattle, whereupon the herder wheeled.

"What do you want in there?" he asked roughly.

"I was looking for hobbled horses," was the easy reply. The puncher made some surly comment and rode away.

McDonald, presently satisfied that his stray cattle were not with that portion of the drove, continued[Pg 46] his search further along and came up with the "chuck-wagon" where dinner was being prepared. Cow-men are hospitable and the foreman invited him to dismount and join them. He did so, and a little later the surly puncher came in, giving the camp guest anything but a friendly look. In the course of the meal the visitor was asked where he was from.

"Mineola," he said, "Wood County." The surly herder spoke up.

"These d—d sand-lappers (east-Texans) are getting too thick out here."

McDonald set down his coffee.

"The d—d skunks and prairie dogs are already too thick," he said.

An instant later the puncher had out his pistol, but the sand-lapper was still quicker. The puncher was covered before he could bring his weapon to bear. McDonald said:

"Turn it loose! Drop it!"

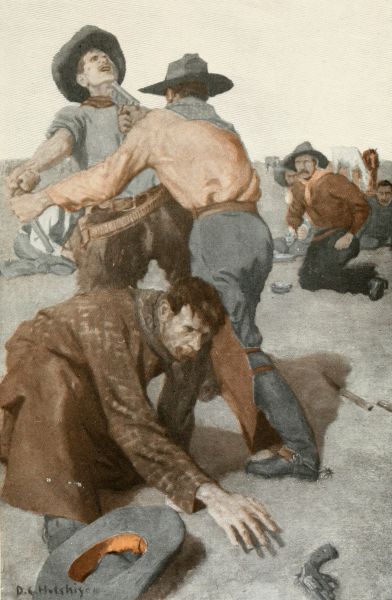

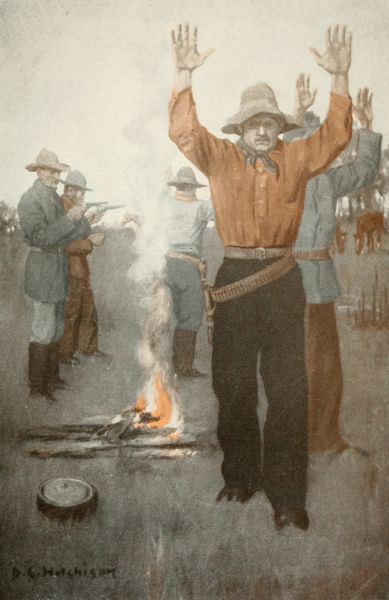

INTRODUCING REFORM IN THE WILDERNESS.

"He was disarmed with amazing suddenness."

The herder still clutched the weapon which he was afraid to raise. The sand-lapper stepped nearer to him, and with a sudden movement rapped him smartly on the head with the heavy barrel of his six-shooter. It was a thing that as a deputy he had done often, and it was always effective. The puncher dropped his gun. One of his comrades sprang to his assistance, but was covered and disarmed with amazing suddenness. The foreman interfered, now, and the beginner of the disturbance[Pg 47] was led away to a brook to have his head bathed and bandaged; whereupon the sand-lapper quietly finished his dinner, thanked his host, continued the search for his missing stock, and when he had found them, set out for home. Meeting a group of punchers among which was his surly friend with a now bandaged head, he expected further trouble. Nothing happened. The sand-lapper and his missing cows had the right of way.

Commercial Ventures and Adventures

BILL MCDONALD'S METHOD OF COLLECTING A BILL; AND HIS METHOD OF HANDLING BAD MEN

The inclination to commercial enterprise still survived. At the end of a year McDonald sold his cattle and invested in the lumber business at Wichita Falls—another railway terminus, dropped down in the prairie, with a population of about two thousand, at that time. A little later he established a branch business at Harrold when the railway reached that point. Two big lumber yards were already established at Wichita Falls, and the competition was strenuous. It was a brief experience for McDonald, for he presently yearned for the freer life of the range, and soon abandoned commerce, once more, for cattle—this time for good. Yet the experience was not without valuable return, inasmuch as it established for him in Wichita Falls, quickly and permanently, a reputation of a useful kind in a country where law and order are likely to be of an elemental, go-as-you-please sort. It happened in this wise:

There was a merchant in Baylor County, Texas, to whom Lumberman McDonald sold a good bill, on time. The account ran along, until one day the[Pg 49] county judge of Baylor, one Melvin, dropped in and stated that he had called to settle the amount for his neighbor. He gave his own check for it and McDonald supposed the matter had ended. A few days later the bank returned Melvin's check as worthless. Evidently the quiet unobtrusive life which Bill Jess had been living as a lumber merchant had given the impression that he was an inoffensive person who would pocket a loss rather than make trouble, especially with a county judge, who added to his official prestige the reputation of being a very bad man from "far up Bitter Creek." However, this impression was a mistake. McDonald ascertained that his customer had really sent the money by Melvin, to pay his bill, and considered what he ought to do. Morally, perhaps legally, he could have demanded payment a second time, on the ground that the said customer, being acquainted with Melvin, should have selected a more reliable messenger. But that was not the Bill McDonald way. What he did was to write to Melvin, demanding an explanation; adding in pretty positive terms that he expected immediate settlement. No reply came and a second and a third letter followed, each getting more definite as to phrase. Then one day Melvin and certain henchmen from Baylor appeared on the streets of Wichita Falls. McDonald who had heard of their arrival, suddenly confronted Melvin and delivered himself in whatever terms and emphasis as he had on hand at the moment. Melvin[Pg 50] withdrew, gathered his clans and laid for McDonald in a saloon where the latter had to pass. Though previously warned of the ambush, McDonald did pass, with the result that next morning Melvin settled his bill in full, paid for a glass door that he had broken, and a fine and costs amounting to sixty-five dollars, for carrying concealed weapons. What really happened to Melvin is best told in Bill Jess's own testimony when that same morning he had, himself, been summoned to answer a charge for carrying concealed weapons, disturbing the peace, and for assault—said action being the result of Melvin's judicial pull. Arriving at the court-room the prosecuting attorney asked McDonald if he had a lawyer.

"No," he said, "I don't need anybody to defend me for knocking that scoundrel over. I'll attend to my own case, whatever is necessary."

The attorney then stated the charge to the court. Bill Jess waited until he was through and then asked permission to speak.

"Your honor," he said, rising, "I'm a busy man with no time to be fooling around this way with men who give bogus checks and steal horses and such like, but if your honor will spare about a minute I'll tell the court what happened." He then gave a history of the lumber transaction, and added the sequel, as follows:

"When I wrote him as strong a letter as I could frame up, and as would go through the mail, he[Pg 51] came down with a crowd of what he thought was fighting men, and I met him and tried like a gentleman to persuade him to settle up and to convince him what a dad-blamed rascal he was; which he pled guilty to, and didn't deny. Then he gathers his feeble bunch of fighters together, arms them up with six-shooters and corrals them in Bill Holly's saloon, that I had to pass, going home. I met Johnny Hammond who tried to persuade me not to take that street—said those fellows were up there and I'd better go in some other direction. I said I wasn't in the habit of going out of my way for such cattle, and proceeded on up the street. When I got in front of Bill Holly's, Melvin and his warriors stepped out. Melvin wanted an explanation of my former remarks, and I gave it to him and added some more which I would not like to mention in the presence of the court. Then he pulled out a big white-handled forty-five six-shooter, but being a little slow with it, I grabbed it by the barrel and hit him with my fist two or three times, which kind of jarred him loose from his gun. Then I gave him a rap on the head with it and knocked him through Bill Holly's glass-front door, into the saloon. His pals pulled their guns, but I covered them with the one I took away from Melvin and they nearly broke the furniture to pieces getting out of there. I didn't see any more of any of them until next morning. Then I looked up the bunch and got a check in full, with interest, from Melvin, and made him pay[Pg 52] Bill Holly five dollars for his glass door. So far as carrying a gun is concerned, I had one, and I got another from this fellow here who had pulled it on me. I took it away from him and hit him with it, and I have the same here in my possession now, to turn over to the Court."

Bill Jess reached down somewhere and drawing forth the big white handled six-shooter, laid it down in front of the court. Then suddenly turning upon Melvin who was present, he looked him straight through.

"Melvin, is not all I have told the Court true?" he demanded.

Melvin found himself unable to tell anything but the truth, just then.

"Yes, sir," he said, quite meekly.

McDonald was discharged and Melvin paid a fine as before noted. Following this incident came another which solidified Bill McDonald's reputation for nerve, in Wichita Falls. Bill Holly, the aforementioned—whose name in another part of the State had been Buck Holly, which he forgot when he left East Texas, after getting into a mix-up, during which the other man died—one day absorbed an overdose of his own stock-in-trade and set forth to shoot up the town. He went afoot and let go at things generally, emptying the streets and bringing business to a standstill. The city marshal was organizing a posse to take him, and summoned McDonald, when McDonald said:

"Give me the key to the calaboose, and the' won't be no need of a posse."

He took the key in one hand and a six-shooter in the other; marched up to where Holly was practicing on front-doors and hardware signs; struck the gun close up under the nose of the disturber, and with his quick magic, disarmed him and set out with him for the lockup. Holly begged and pleaded and was finally locked in a room in the hotel. He broke a window before morning and promptly paid for it by McDonald's request. He made a fairly quiet citizen during the remainder of McDonald's stay in Wichita Falls.

Removing to Hardeman County was the only thing that saved Bill McDonald from being drafted into official service where he was. Law abiding citizens with his gifts are scarce enough anywhere, and they were needed in the cattle districts of Texas. There was not much law in those parts, none at all outside of the towns. In the countries bordering on Indian Territory and up through the Pan-handle a man had to "stand pat" whatever his hand, and hold his own by strength of arm and quickness of trigger. Cow thieves and cut-throats abounded. Officials often worked in accord with them, or were afraid to prosecute. The man who would neither co-operate with outlaws nor condone their offences was already on the ground and would presently be in the field. It was a wide field and a fruitful one and the harvest was ripe for the gathering.

Hardeman County was a tough locality in the early eighties. It had lately been organized, and the settlers were cow-men, cowboys and gamblers—lawless enough, themselves—and another element, which pretended to be these things, but in reality consisted of outlaws, pure and simple. The latter lived chiefly off of the herds, driving off horses and cattle and hiding them in remote and inaccessible places. Often cattle were butchered; their hides, which were marked with brand and ear-marks were destroyed to avoid identification, and the meat was sold. Men who did these things were known well enough, but went unapprehended for the reasons named. In certain sections of the Territory itself and in No-man's Land (a piece of disputed ground lying to the north of the Pan-handle, now a part of Oklahoma) matters were even worse. In these places there was hardly a semblance of law. Certainly the need of active reform—of an official crusader, without fear and above reproach—was both wide and vociferous.

Reforming the Wilderness

THE KIND OF MEN TO BE REFORMED. EARLY REFORMS IN QUANAH. BAD MEN MEET THEIR MATCH

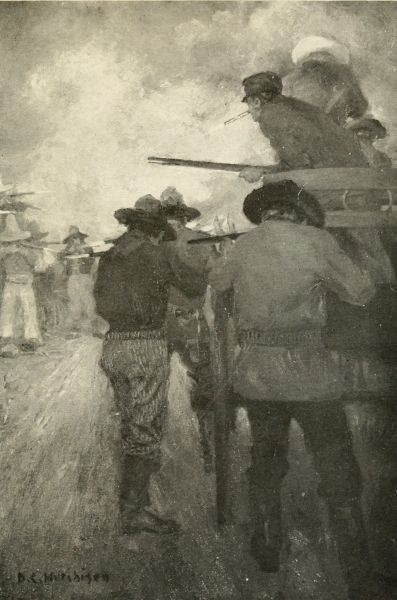

It was in 1885 that Bill McDonald disposed of his lumber interests in Wichita Falls and at Harrold, reinvested in cattle and set out once more for the still farther west. He had filed on some school-land on Wanderer's Creek in Hardeman County, about four miles from where the town of Quanah now stands, and in the heart of what was then the wilderness. Somewhat previous to this, McDonald, whose reputation as a man of nerve had traveled to Harrold, was one night called upon by Ranger Lieutenant Sam Platt to assist in handling a gang of outlaws, known as the Brooken Band, that infested the neighborhood. The Brookens had ridden into Harrold and were running things in pretty much their own way. Platt and McDonald promptly bore down upon them and a running fight ensued as the Brookens retreated. About one hundred shots were fired altogether, but it was dark and the range was too great for accuracy. Nothing was accomplished, but the event marked the beginning of a warfare between Bill McDonald and a band of[Pg 56] cut-throats, the end of which would be history. It was soon after this first skirmish that McDonald sold out his lumber business and set out for his Hardeman County ranch. As on his former migration he drove his cattle to the new land, and after the first hard day's drive, camped at nightfall in a pleasant spot where grass was plentiful and water handy. It seemed a good place, and man and beast gladly halted for food and rest.

But next morning there was trouble. When preparations for an early start were under headway, it was suddenly discovered that four of the best horses and a fine Newfoundland dog were missing. Investigation of the surrounding country was made, and two of the horses were found astray, evidently having broken loose from their captors. It was further discovered that the Brooken Band had a rendezvous in what was known as the Cedar-brakes, a stretch of rough country, densely covered with scrubby cedar, located about twelve miles to the south westward. McDonald naturally felt that it was again his "move" in the Brooken game, but it did not seem expedient to stop the journey with the herd and undertake the move, just then, so biding his time he pushed on, to his land on Wanderer's Creek, where he established his ranch, fenced his property, built a habitation for himself and the wife who was always ready to follow him into the wilderness; then he rode over to Margaret, at that time the county-seat, and asked Sheriff Jim Alley—a[Pg 57] good man with his hands over full—to appoint him deputy that he might begin the work which clearly must be done in that country before it could become a proper habitation for law abiding citizens. The commission was readily granted, and from that appointment dates "that tired feeling" which the bad men of Texas began to have when they heard the sound of Bill McDonald's name.

Another word as to the kind of men with which an officer in those days had to deal. They were not ordinary malefactors, but choice selections from the world at large. "What was your name before you came to Texas?" was a common inquiry in those earlier days, and it was often added that a man could go to Texas when he couldn't go anywhere else. It was such a big State, with so many remote fastnesses, so many easy escapes across the borders. It was the natural last resort of men who could not live elsewhere with safety or profit. There is a story of a man arrested in Texas in those days for some misdemeanor, who was advised by his lawyer to leave the State without delay.

"But where shall I go?" asked the troubled offender, "I'm in Texas, now."

They were the men who had borne other names before they came to Texas and who were "in Texas, now," because they could not live elsewhere and keep off of the scaffold, that Bill McDonald undertook to exterminate. He was willing to undertake the task single handed, if necessary, and in reality[Pg 58] did much of his work in that manner, as we shall see.

With his commission in his pocket Bill Jess was not long in getting down to his favorite employment, that of man-hunting. He began quietly, for he wanted to identify some of the men nearer at hand who were in one way and another connected with the Cedar-brakes gang. Bill Brooken, a notorious outlaw, was the head of the band, and his brother Bood was one of its chief members. The Brookens were wanted not only for cattle stealing, but for train-robbing and murder, as well. A certain Bull Turner was one of their victims. Turner was said to have been one of the Brooken gang at an earlier time, but had abandoned that way of life and made an effort to become a decent citizen. The gang believed he had given information, and somewhat later when he was driving across the country with a prominent stockman—a Hebrew named Lazarus—the Brookens and half a dozen of their followers suddenly dashed out of a roadside concealment and began firing. Turner was instantly killed, and Lazarus fell over the dash-board in a wild effort to get behind something. The frightened horses, one of them wounded in the foot, ran madly all the way to town with Lazarus still clinging to the whiffletrees. He received no injury, but acquired a scare which was permanent.

With the assistance of Sheriff Alley—also short a horse, through the industries of the Brooken gang[Pg 59]—and one Pat Wolforth, who was acquainted with certain of the silent partners of the outlaws and stood ready to give information, several arrests were made, presently, and trouble filled the air.

Threatening letters now began to come to the new deputy, warning him against further procedure—promising him death and torture of many varieties if he did not suspend operations. Such letters always stimulated Bill McDonald to renewed enterprise. He redoubled his efforts and brought in offenders of various kinds almost daily. Cattle stealers began to migrate to other counties. Their friends and beneficiaries grew nervous.

Meantime, the railroad had reached Hardeman and the town of Quanah—named for Chief Quanah Parker, son of the historic Cynthia Ann Parker—had sprung up. It was the typical tough place and certain bad men still at large came there to proclaim vengeance and to "lay" for the men who were making them trouble. Among these disturbers was one John Davidson of Wilbarger County, on the borders of which the Cedar-brakes gang was located. Davidson was reputed to have killed several men and was believed to be an accessory of the Brooken Band, but was thus far not positively identified, and remained unapprehended. He did not hesitate, however, to boast of his always being armed and ready for men like Bill McDonald, and especially for Pat Wolforth who was getting good friends and neighbors into trouble.

Davidson appeared presently on the streets of Quanah, flourishing his fire-arms and making his boasts. McDonald suddenly arrived on the scene, and without any parley whatever stepped quickly up to Davidson and disarmed him so suddenly that the terror of Wilbarger stood dazed, and did not recover himself until he was half way to the office of justice, where he paid a fine. It was an unusual proceeding. It was unprecedented. The customary thing was a noisy warfare of words, followed by a general shooting, with the bad man in possession when the smoke had cleared away. This new method was prosaic. Davidson couldn't understand it at all. He tried it again the next week, with the same result. He kept on trying it, and each time settled for his amusement with a fine. Why he did not kill somebody he couldn't understand. He never seemed to get in action before Bill McDonald had his gun and was marching him to the "Captain's Office." Finally he got himself appointed Deputy Sheriff of Wilbarger and came triumphantly to Quanah, with his commission, which he believed would entitle him to carry arms. Met suddenly, as usual, by McDonald and promptly disarmed, he flourished his commission.

"That's all right, Bill McDonald, but I'm fixed for you this time. Give me back that gun."

McDonald said:

"Your commission won't do you much good up here. If Sheriff Barker wants to appoint a man[Pg 61] that throws in with thieves, all right. But in Hardeman County we don't have to recognize him."

There was never such a stubborn man, Davidson decided, as that fool deputy, Bill McDonald. He decided to wait until McDonald should be absent, and then have it out with Wolforth. When the time came, Davidson brought a gang along with him and they followed Wolforth about with pestering remarks, until their victim suddenly grew tired of the annoyance, and opened fire. This was unexpected and the gang retired for reorganization. Then some rangers, quartered at Quanah, appeared on the scene, and Wolforth was put under arrest. He was taken before a justice, who fixed his bond at a thousand dollars, which he was unable to raise, because of the dread in which Davidson and his crowd were held. It was just about this moment that Deputy McDonald returned, and the Rangers delivered Wolforth into his hands.

"What's the matter, Pat?" McDonald asked.

His co-worker explained how he had fired on the Davidson gang, though without damage to anybody.

"And they put you under a thousand dollar bond for it?" commented Deputy Bill.

"Yes."

"Well, they ought to have made it a good deal heavier for your not being a better shot. Never mind, I'll fill your bond all right," and this McDonald did, immediately.

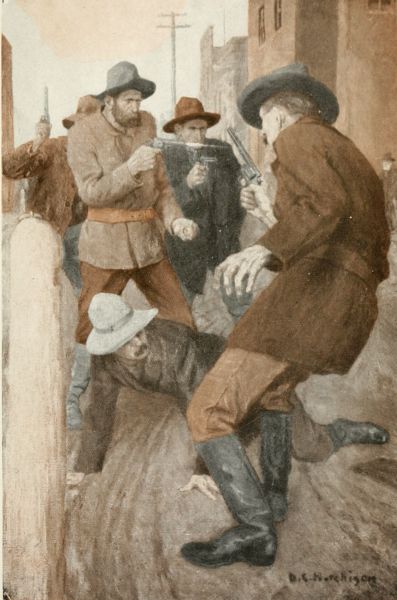

The Davidson crowd was still in town, and far[Pg 62] from satisfied. Davidson felt that he had support enough now to tackle even that hard-headed McDonald, and he enlisted a big butcher named Williams to stir up the mess. The gang armed themselves with long butcher knives from Williams' shop and started out to hunt up their victim. They located him in a saloon where troubles of various kinds were likely to originate and the presence of an officer was desirable. Big Bill Williams, the butcher, entered first and coming near to McDonald, slightly bumped against him. Not wishing trouble, McDonald walked away, followed by Williams who bumped against him again. Deputy Bill then walked to the other side of the room, which was unoccupied, and when Williams and his crowd started to follow, he warned them not to come any closer. At this a number of cow-men who were present saw the trouble and stepped in, and Williams and his crowd worked toward the door. Outside, the disturbers gave vent to their animosity for McDonald in violent language and opprobrious names. Suddenly McDonald himself stepped out among them and seeing a piece of scantling about four feet long lying by the door, he seized it and as Williams started toward him he gave the big butcher a lick across the face with it that flattened his features and put a habitual crook in his nose. The crowd thought Williams was killed and his supporters began to get out of the way of the scantling. But McDonald dropped it and had out his guns in a moment.

"Halt!" he said, "every one of you. Hold up there!" Then to the Rangers who at that moment appeared on the scene, "Search those men for weapons."

Search was made and the long butcher knives, intended for McDonald, came to light. A knife of the same kind was found on Williams.

"Now get a doctor quick," commanded McDonald, "that fellow looks like he's pretty badly hurt."

A doctor was found and Williams was removed. McDonald's wife, then stopping at a nearby hotel, had been an interested, not to say excited, spectator of the proceedings, and now called down a few words of encouragement and approval. Somewhat later, word was brought to Deputy Bill that what was left of the Davidson and Williams crowd had collected in Tip McDowell's saloon, where a brother of Williams tended bar, and these were declaring war to the death. McDonald promptly went down there and entered, with a revolver in each hand. The crowd of would-be assassins, about a dozen or so, took one look and made a break for the back window, climbing over chairs, counters and billiard tables—some of them almost tearing the bar down in an effort to get behind it. Deputy Bill held enough of them with the persuasion of his two six-shooters to give them some useful information in the matter of running a town like Quanah and the surrounding country, as long as he was in office.

"You thieves that have been trying to run over this country, and stealing cattle and shooting the town up," he said, "from now on are going to stop it. And you fellows like Bill Williams that are selling stolen beef, are going to stop that, too. If any one of you sells a pound of beef hereafter without showing me the hide and the brand-marks, you'll go behind the bars and I'll put you there."

There was something about the tone of that brief address that made it sink in, and from that time forward when beef was brought to Quanah the hide came with it, and they would wake up Deputy Bill McDonald to show it to him as early as three o'clock in the morning.

As for Davidson, he now became an officer of the law, in reality. Satisfied, no doubt, that the Cedar-brakes gang was doomed, he came to McDonald and offered to guide him to the den of the Brookens if McDonald would cause to be dismissed certain indictments which had been lodged against him. McDonald consulted Sheriff Barker of Wilbarger and the arrangement was made. Davidson then ascertained when his former business associates would be at their headquarters in the brakes, and the raid was planned accordingly.

Getting even with the Brooken Gang

THE BROOKENS DON'T WAIT FOR CALLERS. ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-SEVEN YEARS SENTENCE FOR AN OUTLAW

The brakes of the Big Wichita made an ideal cover for outlaws engaged in the industry of stealing cattle and horses. There were plenty of grass and water there and the ground was so densely covered with scrub cedar as to afford any number of hiding places. Moreover, there were deep gulches and canyons that made travel dangerous to those not familiar with the region. The place was remote and not often molested.

Everything being arranged, the raiders set out—Sheriff Barker of Wilbarger, in charge—the party including two Rangers from Quanah. On drawing near the locality, Barker proposed that all but two men should halt, several hundred yards from the stronghold—a dug-out occupied by the gang when at home. To this, Deputy Bill strenuously objected. He wanted to charge forthwith, believing always in a surprise attack. Barker, however, being in his own county, was in command and was for more gradual tactics. He added that McDonald's big white hat would attract attention before they could[Pg 66] get near enough to charge. Two men were therefore sent to reconnoiter and report. The rest lay in hiding. Presently peering through the trees they saw two other men ride up to the dug-out and go in. Deputy Bill was all excitement.

"There they are now," he said, "let's get down there and get them."

Again he was overruled. In a few minutes a number of men issued from the dug-out, mounted horses and rode away. The first two had been scouts, and had given warning. At the same moment Barker's two men came running back with the information that the Brookens were getting away.

"Of course they're getting away," said McDonald. "Do you suppose they are going to wait and hold an afternoon tea when we arrive?"

Accompanied by one of the Rangers, he started in pursuit of the outlaws, but it was impossible to follow far in that dense unfamiliar place. Returning to the dug-out they were rejoiced to find Sheriff Alley's horse, so something was accomplished, though the expedition as a whole had failed, through over-caution.