(Original cover)

(Original cover)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dotted gray underline.

(Original cover)

(Original cover)

BY

WILLIAM HOWARD RUSSELL.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

BRADBURY AND EVANS, 11, BOUVERIE STREET.

1863.

[The right of Translation is reserved.]

LONDON:

BRADBURY AND EVANS, PRINTERS, WHITEFRIARS

TO

RICHARD QUAIN, M.D.,

These Volumes are Dedicated

IN TESTIMONY

OF

THE REGARD AND GRATITUDE

OF

THE AUTHOR.

A book which needs apologies ought never to have been written. This is a canon of criticism so universally accepted, that authors have abstained of late days from attempting to disarm hostility by confessions of weakness, and are almost afraid to say a prefatory word to the gentle reader.

It is not to plead in mitigation of punishment or make an appeal ad misericordiam, I break through the ordinary practice, but by way of introduction and explanation to those who may read these volumes, I may remark that they consist for the most part of extracts from the diaries and note-books which I assiduously kept whilst I was in the United States, as records of the events and impressions of the hour. I have been obliged to omit many passages which might cause pain or injury to individuals still living in the midst of a civil war, but the spirit of the original is preserved as far as possible, and I would entreat my readers to attribute the frequent use of the personal[vi] pronoun and personal references to the nature of the sources from which the work is derived, rather than to the vanity of the author.

Had the pages been literally transcribed, without omitting a word, the fate of one whose task it was to sift the true from the false and to avoid error in statements of fact, in a country remarkable for the extraordinary fertility with which the unreal is produced, would have excited some commiseration; but though there is much extenuated in these pages, there is not, I believe, aught set down in malice. My aim has been to retain so much relating to events passing under my eyes, or to persons who have become famous in this great struggle, as may prove interesting at present, though they did not at the time always appear in their just proportions of littleness or magnitude.

During my sojourn in the States, many stars of the first order have risen out of space or fallen into the outer darkness. The watching, trustful, millions have hailed with delight or witnessed with terror the advent of a shining planet or a splendid comet, which a little observation has resolved into watery nebulæ. In the Southern hemisphere, Bragg and Beauregard have given place to Lee and Jackson. In the North M‘Dowell has faded away before M‘Clellan, who having been put for a short season in eclipse by Pope, only to culminate with increased effulgence, has finally paled[vii] away before Burnside. The heroes of yesterday are the martyrs or outcasts of to-day, and no American general needs a slave behind him in the triumphal chariot to remind him that he is a mortal. Had I foreseen such rapid whirls in the wheel of fortune I might have taken more note of the men who were below, but my business was not to speculate but to describe.

The day I landed at Norfolk, a tall lean man, ill-dressed, in a slouching hat and wrinkled clothes, stood, with his arms folded and legs wide apart, against the wall of the hotel looking on the ground. One of the waiters told me it was “Professor Jackson,” and I have been plagued by suspicions that in refusing an introduction which was offered to me, I missed an opportunity of making the acquaintance of the man of the stonewalls of Winchester. But, on the whole, I have been fortunate in meeting many of the soldiers and statesmen who have distinguished themselves in this unhappy war.

Although I have never for one moment seen reason to change the opinion I expressed in the first letter I wrote from the States, that the Union as it was could never be restored, I am satisfied the Free States of the North will retain and gain great advantages by the struggle, if they will only set themselves at work to accomplish their destiny, nor lose their time in[viii] sighing over vanished empire or indulging in abortive dreams of conquest and schemes of vengeance; but my readers need not expect from me any dissertations on the present or future of the great republics, which have been so loosely united by the Federal band, nor any description of the political system, social life, manners or customs of the people, beyond those which may be incidentally gathered from these pages.

It has been my fate to see Americans under their most unfavourable aspect; with all their national feelings, as well as the vices of our common humanity, exaggerated and developed by the terrible agonies of a civil war, and the throes of political revolution. Instead of the hum of industry, I heard the noise of cannon through the land. Society convulsed by cruel passions and apprehensions, and shattered by violence, presented its broken angles to the stranger, and I can readily conceive that the America I saw, was no more like the country of which her people boast so loudly, than the St. Lawrence when the ice breaks up, hurrying onwards the rugged drift and its snowy crust of crags, with hoarse roar, and crashing with irresistible force and fury to the sea, resembles the calm flow of the stately river on a summer’s day.

The swarming communities and happy homes of the New England States—the most complete exhibition of the best results of the American system—it was denied[ix] me to witness; but if I was deprived of the gratification of worshipping the frigid intellectualism of Boston, I saw the effects in the field, among the men I met, of the teachings and theories of the political, moral, and religious professors, who are the chiefs of that universal Yankee nation, as they delight to call themselves, and there recognised the radical differences which must sever them for ever from a true union with the Southern States.

The contest, of which no man can predict the end or result, still rages, but notwithstanding the darkness and clouds which rest upon the scene, I place so much reliance on the innate good qualities of the great nations which are settled on the Continent of North America, as to believe they will be all the better for the sweet uses of adversity; learning to live in peace with their neighbours, adapting their institutions to their necessities, and working out, not in their old arrogance and insolence—mistaking material prosperity for good government—but in fear and trembling, the experiment on which they have cast so much discredit, and the glorious career which misfortune and folly can arrest but for a time.

W. H. RUSSELL.

London, December 8, 1862.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Departure from Cork—The Atlantic in March—Fellow-passengers—American politics and parties—The Irish in New York—Approach to New York | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Arrival at New York—Custom-house—General impressions as to North and South—Street in New York—Hotel—Breakfast—American women and men—Visit to Mr. Bancroft—Street-railways | 10 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| “St. Patrick’s day” in New York—Public dinner—American Constitution—General topics of conversation—Public estimate of the Government—Evening party at Mons. B——’s | 22 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Streets and shops in New York—Literature—A funeral—Dinner at Mr. H——’s—Dinner at Mr. Bancroft’s—Political and social features—Literary breakfast: Heenan and Sayers | 34 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Off to the railway station—Railway carriages—Philadelphia—Washington—Willard’s Hotel—Mr. Seward—North and South—The “State Department” at Washington—President Lincoln—Dinner at Mr. Seward’s | 43 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A state dinner at Mr. Abraham Lincoln’s—Mrs. Lincoln—The Cabinet Ministers—A newspaper correspondent—Good Friday at Washington | 60 |

| CHAPTER VII.[xii] | |

| Barbers’ shops—Place-hunting—The Navy Yard—Dinner at Lord Lyons’—Estimate of Washington among his countrymen—Washington’s house and tomb—The Southern Commissioners—Dinner with the Southern Commissioners—Feeling towards England among the Southerners—Animosity between North and South | 73 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| New York Press—Rumours as to the Southerners—Visit to the Smithsonian Institute—Pythons—Evening at Mr. Seward’s—Rough draft of official dispatch to Lord J. Russell—Estimate of its effect in Europe—The attitude of Virginia | 99 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Dinner at General Scott’s—Anecdotes of General Scott’s early life—The startling dispatch—Insecurity of the capital | 105 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Preparations for war at Charleston—My own departure for the Southern States—Arrival at Baltimore—Commencement of hostilities at Fort Sumter—Bombardment of the fort—General feeling as to North and South—Slavery—First impressions of the city of Baltimore—Departure by steamer | 111 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Scenes on board an American steamer—The Merrimac—Irish sailors in America—Norfolk—A telegram on Sunday: news from the seat of war—American “chaff” and our Jack tars | 117 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Portsmouth—Railway journey through the forest—The great Dismal Swamp—American newspapers—Cattle on the line—Negro labour—On through the pine forest—The Confederate flag—Goldsborough: popular excitement—Weldon—Wilmington—The Vigilance Committee | 126 |

| CHAPTER XIII.[xiii] | |

| Sketches round Wilmington—Public opinion—Approach to Charleston and Fort Sumter—Introduction to General Beauregard—Ex-Governor Manning—Conversation on the chances of the war—“King Cotton” and England—Visit to Fort Sumter—Market-place at Charleston | 138 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Southern Volunteers—Unpopularity of the Press—Charleston—Fort Sumter—Morris’ Island—Anti-union enthusiasm—Anecdote of Colonel Wigfall—Interior view of the fort—North versus South | 146 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Slaves, their masters and mistresses—Hotels—Attempted boat-journey to Fort Moultrie—Excitement at Charleston against New York—Preparations for war—General Beauregard—Southern opinion as to the policy of the North, and estimate of the effect of the war on England, through the cotton market—Aristocratic feeling in the South | 162 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Charleston: the Market-place—Irishmen at Charleston—Governor Pickens: his political economy and theories—Newspaper offices and counting-houses—Rumours as to the war policy of the South | 173 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Visit to a plantation; hospitable reception—By steamer to Georgetown—Description of the town—A country mansion—Masters and slaves—Slave diet—Humming-birds—Land irrigation—Negro quarters—Back to Georgetown | 180 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Climate of the Southern States—General Beauregard—Risks of the post-office—Hatred of New England—By railway to Sea Island plantation—Sporting in South Carolina—An hour on board a canoe in the dark | 195 |

| CHAPTER XIX.[xiv] | |

| Domestic negroes—Negro oarsmen—Off to the fishing-grounds—The devil-fish—Bad sport—The drum-fish—Negro quarters—Want of drainage—Thievish propensities of the blacks—A Southern estimate of Southerners | 204 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| By railway to Savannah—Description of the city—Rumours of the last few days—State of affairs at Washington—Preparations for war—Cemetery of Bonaventure—Road made of oyster shells—Appropriate features of the cemetery—The Tatnall family—Dinner-party at Mr. Green’s—Feeling in Georgia against the North | 216 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| The river at Savannah—Commodore Tatnall—Fort Pulaski—Want of a fleet to the Southerners—Strong feeling of the women—Slavery considered in its results—Cotton and Georgia—Off for Montgomery—The Bishop of Georgia—The Bible and slavery—Macon—Dislike of United States’ gold | 225 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Slave-pens: negroes on sale or hire—Popular feeling as to secession—Beauregard and speech-making—Arrival at Montgomery—Bad hotel accommodation—Knights of the Golden Circle—Reflections on slavery—Slave auction—The Legislative Assembly—A “live chattel” knocked down—Rumours from the North (true and false) and prospects of war | 234 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Proclamation of war—Jefferson Davis—Interview with the President of the Confederacy—Passport and safe-conduct—Messrs. Wigfall, Walker, and Benjamin—Privateering and letters of marque—A reception at Jefferson Davis’s—Dinner at Mr. Benjamin’s | 248 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Mr. Wigfall on the Confederacy—Intended departure from the South—Northern apathy and Southern activity—Future prospects of the Union—South Carolina and cotton—The theory of slavery—Indifference at New York—Departure from Montgomery | 258 |

| CHAPTER XXV.[xv] | |

| The River Alabama—Voyage by steamer—Selma—Our captain and his slaves—“Running” slaves—Negro views of happiness—Mobile—Hotel—The city—Mr. Forsyth | 265 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Visit to Forts Gaines and Morgan—War to the knife the cry of the South—The “State” and the “States”—Bay of Mobile—The forts and their inmates—Opinions as to an attack on Washington—Rumours of actual war | 277 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Pensacola and Fort Pickens—Neutrals and their friends—Coasting—Sharks—The blockading fleet—The stars and stripes, and stars and bars—Domestic feuds caused by the war—Captain Adams and General Bragg—Interior of Fort Pickens | 284 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Bitters before breakfast—An old Crimean acquaintance—Earthworks and batteries—Estimate of cannons—Magazines—Hospitality—English and American introductions and leave-takings—Fort Pickens: its interior—Return towards Mobile—Pursued by a strange sail—Running the blockade—Landing at Mobile | 303 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Judge Campbell—Dr. Nott—Slavery—Departure for New Orleans—Down the river—Fear of cruisers—Approach to New Orleans—Duelling—Streets of New Orleans—Unhealthiness of the city—Public opinion as to the war—Happy and contented negroes | 325 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| The first blow struck—The St. Charles Hotel—Invasion of Virginia by the Federals—Death of Col. Ellsworth—Evening at Mr. Slidell’s—Public comments on the war—Richmond the capital of the Confederacy—Military preparations—General society—Jewish element—Visit to a battle-field of 1815 | 338 |

| CHAPTER XXXI.[xvi] | |

| Carrying arms—New Orleans jail—Desperate characters—Executions—Female maniacs and prisoners—The river and levee—Climate of New Orleans—Population—General distress—Pressure of the blockade—Money—Philosophy of abstract rights—The doctrine of State Rights—Theoretical defect in the constitution | 353 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Up the Mississippi—Free negroes and English policy—Monotony of the river scenery—Visit to M. Roman—Slave quarters—A slave-dance—Slave-children—Negro hospital—General opinion—Confidence in Jefferson Davis | 366 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Ride through the maize-fields—Sugar plantation; negroes at work—Use of the lash—Feeling towards France—Silence of the country—Negroes and dogs—Theory of slavery—Physical formation of the negro—The defence of slavery—The masses for negro souls—Convent of the Sacré Cœur—Ferry-house—A large landowner | 378 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Negroes—Sugar-cane plantations—The negro and cheap labour—Mortality of blacks and whites—Irish labour in Louisiana—A sugar-house—Negro children—Want of education—Negro diet—Negro hospital—Spirits in the morning—Breakfast—More slaves—Creole planters | 391 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| War-rumours, and military movements—Governor Manning’s slave plantations—Fortunes made by slave-labour—Frogs for the table—The forest—Cotton and sugar—A thunderstorm | 405 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| Visit to Mr. M‘Call’s plantation—Irish and Spaniards—The planter—A Southern sporting man—The creoles—Leave Houmas—Donaldsonville—Description of the city—Baton Rouge—Steamer to Natchez—Southern feeling; faith in Jefferson Davis—Rise and progress of prosperity for the planters—Ultimate issue of the war to both North and South | 410 |

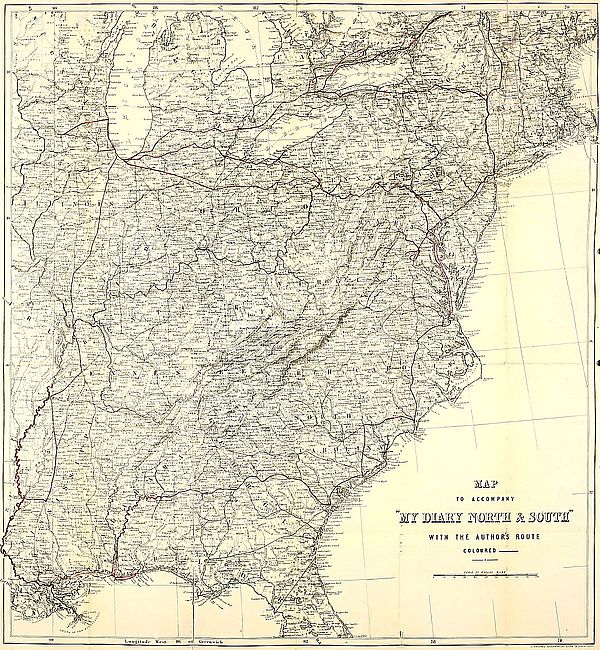

click here for larger image.

click here for larger image.

Departure from Cork.—The Atlantic in March—Fellow-passengers—American politics and parties—The Irish in New York—Approach to New York.

On the evening of 3rd March, 1861, I was transferred from the little steam-tender, which plies between Cork and the anchorage of the Cunard steamers at the entrance of the harbour, to the deck of the good steamship Arabia, Captain Stone; and at nightfall we were breasting the long rolling waves of the Atlantic.

The voyage across the Atlantic has been done by so many able hands, that it would be superfluous to describe mine, though it is certain no one passage ever resembled another, and no crew or set of passengers in one ship were ever identical with those in any other. For thirteen days the Atlantic followed its usual course in the month of March, and was true to the traditions which affix to it in that month the character of violence and moody changes, from bad to worse and back again. The wind was sometimes dead against us, and then the infelix Arabia with iron energy set to work, storming great Malakhofs of water, which rose above her like the side[2] of some sward-coated hill crested with snow-drifts; and having gained the summit, and settled for an instant among the hissing sea-horses, ran plunging headlong down to the encounter of another wave, and thus went battling on with heart of fire and breath of flame—igneus est ollis vigor—hour after hour.

The traveller for pleasure had better avoid the Atlantic in the month of March. The wind was sometimes with us, and then the sensations of the passengers and the conduct of the ship were pretty much as they had been during the adverse breezes before, varied by the performance of a very violent “yawing” from side to side, and certain squashings of the paddle-boxes into the yeasty waters, which now ran a race with us and each other, as if bent on chasing us down, and rolling their boarding parties with foaming crests down on our decks. The boss, which we represented in the stormy shield around us, still moved on; day by day our microcosm shifted its position in the ever-advancing circle of which it was the centre, with all around and within it ever undergoing a sea change.

The Americans on board were, of course, the most interesting passengers to one like myself, who was going out to visit the great Republic under very peculiar circumstances. There was, first, Major Garnett, a Virginian, who was going back to his State to follow her fortunes. He was an officer of the regular army of the United States, who had served with distinction in Mexico; an accomplished, well-read man; reserved, and rather gloomy; full of the doctrine of States’ Rights, and animated with a considerable feeling of contempt for the New Englanders, and with the strongest prejudices in favour of the institution of slavery. He laughed[3] to scorn the doctrine that all men are born equal in the sense of all men having equal rights. Some were born to be slaves—some to be labourers in the lower strata above the slaves—others to follow useful mechanical arts—the rest were born to rule and to own their fellow-men. There was next a young Carolinian, who had left his post as attaché at St. Petersburgh to return to his State: thus, in all probability, avoiding the inevitable supercession which awaited him at the hands of the new Government at Washington. He represented, in an intensified form, all the Virginian’s opinions, and held that Mr. Calhoun’s interpretation of the Constitution was incontrovertibly right. There were difficulties in the way of State sovereignty, he confessed; but they were only in detail—the principle was unassailable.

To Mr. Mitchell, South Carolina represented a power quite sufficient to meet all the Northern States in arms. “The North will attempt to blockade our coast,” said he; “and in that case, the South must march to the attack by land, and will probably act in Virginia.” “But if the North attempts to do more than institute a blockade?—for instance, if their fleet attack your seaport towns, and land men to occupy them?” “Oh, in that case, we are quite certain of beating them.” Mr. Julian Mitchell was indignant at the idea of submitting to the rule of a “rail-splitter,” and of such men as Seward and Cameron. “No gentleman could tolerate such a Government.”

An American family from Nashville, consisting of a lady and her son and daughter, were warm advocates of a “gentlemanly” government, and derided the Yankees with great bitterness. But they were by no means[4] as ready to encounter the evils of war, or to break up the Union, as the South Carolinian or the Virginian; and in that respect they represented, I was told, the negative feelings of the Border States, which are disposed to a temporising, moderate course of action, most distasteful to the passionate seceders.

There were also two Louisiana sugar-planters on board—one owning 500 slaves, the other rich in some thousands of acres; they seemed to care very little for the political aspects of the question of Secession, and regarded it merely in reference to its bearing on the sugar crop, and the security of slave property. Secession was regarded by them as a very extreme and violent measure, to which the State had resorted with reluctance; but it was obvious, at the same time, that, in event of a general secession of the Slave States from the North, Louisiana could neither have maintained her connection with the North, nor have stood in isolation from her sister States.

All these, and some others who were fellow-passengers, might be termed Americans—pur sang. Garnett belonged to a very old family in Virginia. Mitchell came from a stock of several generations’ residence in South Carolina. The Tennessee family were, in speech and thought, types of what Europeans consider true Americans to be. Now take the other side. First there was an exceedingly intelligent, well-informed young merchant of New York—nephew of an English county Member, known for his wealth, liberality, and munificence. Educated at a university in the Northern States, he had lived a good deal in England, and was returning to his father from a course of book-keeping in the house of his uncle’s firm in Liverpool. His[5] father and uncle were born near Coleraine, and he had just been to see the humble dwelling, close to the Giant’s Causeway, which sheltered their youth, and where their race was cradled. In the war of 1812, the brothers were about sailing in a privateer fitted out to prey against the British, when accident fixed one of them in Liverpool, where he founded the house which has grown so greatly with the development of trade between New York and Lancashire, whilst the other settled in the States. Without being violent in tone, the young Northerner was very resolute in temper, and determined to do all which lay in his power to prevent the “glorious Union” being broken up.

The “Union” has thus founded on two continents a family of princely wealth, whose originals had probably fought with bitterness in their early youth against the union of Great Britain and Ireland. But did Mr. Brown, or the other Americans who shared his views, unreservedly approve of American institutions, and consider them faultless? By no means. The New Yorkers especially were eloquent on the evils of the suffrage, and of the licence of the Press in their own city; and displayed much irritation on the subject of naturalisation. The Irish were useful, in their way, making roads and working hard, for there were few Americans who condescended to manual labour, or who could not make far more money in higher kinds of work; but it was absurd to give the Irish votes which they used to destroy the influence of native-born citizens, and to sustain a corporation and local bodies of unsurpassable turpitude, corruption, and inefficiency.

Another young merchant, a college friend of the former, was just returning from a tour in Europe with[6] his amiable sister. His father was the son of an Irish immigrant, but he did not at all differ from the other gentlemen of his city in the estimate in which he held the Irish element; and though he had no strong bias one way or other, he was quite resolved to support the abstraction called the Union, and its representative fact—the Federal Government. Thus the agriculturist and the trader—the grower of raw produce and the merchant who dealt in it—were at opposite sides of the question—wide apart as the Northern and Southern Poles. They sat apart, ate apart, talked apart—two distinct nations, with intense antipathies on the part of the South, which was active and aggressive in all its demonstrations.

The Southerners have got a strange charge de plus against the Irish. It appears that the regular army of the United States is mainly composed of Irish and Germans; very few Americans indeed being low enough, or martially disposed enough, to “take the shilling.” In case of a conflict, which these gentlemen think inevitable, “low Irish mercenaries would,” they say, “be pitted against the gentlemen of the South, and the best blood in the States would be spilled by fellows whose lives are worth nothing whatever.” Poor Paddy is regarded as a mere working machine, fit, at best, to serve against Choctaws and Seminoles. His facility of reproduction has to compensate for the waste which is caused by the development in his unhappy head of the organs of combativeness and destructiveness. Certainly, if the war is to be carried on by the United States’ regulars, the Southern States will soon dispose of them, for they do not number 20,000 men, and their officers are not much in love with the new[7] Government. But can it come to War? Mr. Mitchell assures me I shall see some “pretty tall fighting.”

The most vehement Northerners in the steamer are Germans, who are going to the States for the first time, or returning there. They have become satisfied, no doubt, by long process of reasoning, that there is some anomaly in the condition of a country which calls itself the land of liberty, and is at the same time the potent palladium of serfdom and human chattelry. When they are not sea-sick, which is seldom, the Teutons rise up in all the might of their misery and dirt, and, making spasmodic efforts to smoke, blurt out between the puffs, or in moody intervals, sundry remarks on American politics. “These are the swine,” quoth Garnett, “who are swept out of German gutters as too foul for them, and who come over to the States and presume to control the fate and the wishes of our people. In their own country they proved they were incapable of either earning a living, or exercising the duties of citizenship; and they seek in our country a licence denied them in their own, and the means of living which they could not acquire anywhere else.”

And for myself I may truly say this, that no man ever set foot on the soil of the United States with a stronger and sincerer desire to ascertain and to tell the truth, as it appeared to him. I had no theories to uphold, no prejudices to subserve, no interests to advance, no instructions to fulfil; I was a free agent, bound to communicate to the powerful organ of public opinion I represented, my own daily impressions of the men, scenes, and actions around me, without fear, favour, or affection of or for anything but that which seemed to me to be the truth. As to the questions which[8] were distracting the States, my mind was a tabula rasa, or, rather, tabula non scripta. I felt indisposed to view with favour a rebellion against one of the established and recognised governments of the world, which, though not friendly to Great Britain, nor opposed to slavery, was without, so far as I could see, any legitimate cause of revolt, or any injury or grievance, perpetrated or imminent, assailed by States still less friendly to us, which the slave States, pure and simple, certainly were and probably are. At the same time, I knew that these were grounds which I could justly take, whilst they would not be tenable by an American, who is by the theory on which he revolted from us and created his own system of government, bound to recognise the principle that the discontent of the popular majority with its rulers, is ample ground and justification for revolution.

It was on the morning of the fourteenth day that the shores of New York loomed through the drift of a cold wintry sea, leaden-grey and comfortless, and in a little time more the coast, covered with snow, rose in sight. Towards the afternoon the sun came out and brightened the waters and the sails of the pretty trim schooners and coasters which were dancing around us. How different the graceful, tautly-rigged, clean, white-sailed vessels from the round-sterned, lumpish billyboys and nondescripts of the eastern coast of our isle! Presently there came bowling down towards us a lively little schooner-yacht, very like the once famed “America,” brightly painted in green, sails dazzling white, lofty ponderous masts, no tops. As she came nearer, we saw she was crowded with men in chimney-pot black hats, and coats, and the like—perhaps a party of citizens on pleasure, cold as[9] the day was. Nothing of the kind. The craft was our pilot-boat, and the hats and coats belonged to the hardy mariners who act as guides to the port of New York. Their boat was lowered, and was soon under our mainchains; and a chimney-pot hat having duly come over the side, delivered a mass of newspapers to the captain, which were distributed among the eager passengers, when each at once became the centre of a spell-bound circle.

Arrival at New York—Custom-house—General impressions as to North and South—Street in New York—Hotel—Breakfast—American women and men—Visit to Mr. Bancroft—Street-railways.

The entrance to New York, as it was seen by us on 16th March, is not remarkable for beauty or picturesque scenery, and I incurred the ire of several passengers, because I could not consistently say it was very pretty. It was difficult to distinguish through the snow the villas and country houses, which are said to be so charming in summer. But beyond these rose a forest of masts close by a low shore of brick houses and blue roofs, above the level of which again spires of churches and domes and cupolas announced a great city. On our left, at the narrowest part of the entrance, there was a very powerful case-mated work of fine close stone, in three tiers, something like Fort Paul at Sebastopol, built close to the water’s edge, and armed on all the faces—apparently a tetragon with bastions. Extensive works were going on at the ground above it, which rises rapidly from the water to a height of more than a hundred feet, and the rudiments of an extensive work and heavily armed earthen parapets could be seen from the channel. On the right hand, crossing its fire with that of the batteries and works on our left, there was another[11] regular stone fort with fortified enceinte, and higher up the channel, as it widens to the city on the same side, I could make out a smaller fort on the water’s edge. The situation of the city renders it susceptible of powerful defence from the sea-side, and even now it would be hazardous to run the gauntlet of the batteries unless in powerful iron-clad ships favoured by wind and tide, which could hold the place at their mercy. Against a wooden fleet New York is now all but secure, save under exceptional circumstances in favour of the assailants.

It was dark as the steamer hauled up alongside the wharf on the New Jersey side of the river; but ere the sun set I could form some idea of the activity and industry of the people from the enormous ferry-boats moving backwards and forwards like arks on the water, impelled by the great walking-beam engines, the crowded stream full of merchantmen, steamers, and small craft, the smoke of the factories, the tall chimneys—the net-work of boats and rafts—all the evidences of commercial life in full development. What a swarming, eager crowd on the quay-wall! what a wonderful ragged regiment of labourers and porters, hailing us in broken or Hibernianized English! “These are all Irish and Germans,” anxiously explained a New Yorker. “I’ll bet fifty dollars there’s not a native-born American among them.”

With Anglo-Saxon disregard of official insignia, American Custom House officers dress very much like their British brethren, without any sign of authority as faint as even the brass button and crown, so that the stranger is somewhat uneasy when he sees unauthorised-looking people taking liberties with his plunder, especially[12] after the admonitions he has received on board ship to look sharp about his things as soon as he lands. I was provided with an introduction to one of the principal officers, and he facilitated my egress, and at last I was bundled out through a gate into a dark alley, ankle deep in melted snow and mud, where I was at once engaged in a brisk encounter with my Irish porter-hood, and, after a long struggle, succeeded in stowing my effects in and about a remarkable specimen of the hackney-coach of the last century, very high in the axle, and weak in the springs, which plashed down towards the river through a crowd of men shouting out, “You haven’t paid me yet, yer honour. You haven’t given anything to your own man that’s been waiting here the last six months for your honour!” “I’m the man that put the lugidge up, sir,” &c., &c. The coach darted on board a great steam ferry-boat, which had on deck a number of similar vehicles, and omnibuses, and the gliding, shifting lights, and the deep, strong breathing of the engine, told me I was moving and afloat before I was otherwise aware of it. A few minutes brought us over to the lights on the New York side—a jerk or two up a steep incline—and we were rattling over a most abominable pavement, plunging into mud-holes, squashing through snow-heaps in ill-lighted, narrow streets of low, mean-looking, wooden houses, of which an unusual proportion appeared to be lager-bier saloons, whisky-shops, oyster-houses, and billiard and smoking establishments.

The crowd on the pavement were very much what a stranger would be likely to see in a very bad part of London, Antwerp, or Hamburg, with a dash of the[13] noisy exuberance which proceeds from the high animal spirits that defy police regulations and are superior to police force, called “rowdyism.” The drive was long and tortuous; but by degrees the character of the thoroughfares and streets improved. At last we turned into a wide street with very tall houses, alternating with far humbler erections, blazing with lights, gay with shop-windows, thronged in spite of the mud with well-dressed people, and pervaded by strings of omnibuses—Oxford Street was nothing to it for length. At intervals there towered up a block of brickwork and stucco with long rows of windows lighted up tier above tier, and a swarming crowd passing in and out of the portals, which were recognised as the barrack-like glory of American civilisation—a Broadway monster hotel. More oyster-shops, lager-bier saloons, concert-rooms of astounding denominations, with external decorations very much in the style of the booths at Bartholomew Fair—churches, restaurants, confectioners, private-houses! again another series—they cannot go on expanding for ever. The coach at last drives into a large square, and lands me at the Clarendon Hotel.

Whilst I was crossing the sea, the President’s Inaugural Message, the composition of which is generally attributed to Mr. Seward, had been delivered, and had reached Europe, and the causes which were at work in destroying the cohesion of the Union, had acquired greater strength and violence.

Whatever force “the declaration of causes which induced the Secession of South Carolina” might have for Carolinians, it could not influence a foreigner who knew nothing at all of the rights, sovereignty, and[14] individual independence of a state, which, however, had no right to make war or peace, to coin money, or enter into treaty obligations with any other country. The South Carolinian was nothing to us, quoad South Carolina—he was merely a citizen of the United States, and we knew no more of him in any other capacity than a French authority would know of a British subject as a Yorkshireman or a Munsterman.

But the moving force of revolution is neither reason nor justice—it is most frequently passion—it is often interest. The American, when he seeks to prove that the Southern States have no right to revolt from a confederacy of states created by revolt, has by the principles on which he justifies his own revolution, placed between himself and the European a great gulf in the level of argument. According to the deeds and words of Americans, it is difficult to see why South Carolina should not use the rights claimed for each of the thirteen colonies, “to alter and abolish a form of government when it becomes destructive of the ends for which it is established, and to institute a new one.” And the people must be left to decide the question as regards their own government for themselves, or the principle is worthless. The arguments, however, which are now going on are fast tending towards the ultima ratio regum. At present I find public attention is concentrated on the two Federal forts, Pickens and Sumter, called after two officers of the revolutionary armies in the old war. As Alabama and South Carolina have gone out, they now demand the possession of these forts, as of the soil of their several states and attached to their sovereignty. On the other hand, the Government of Mr. Lincoln considers it has no right to give up[15] any thing belonging to the Federal Government, but evidently desires to temporize and evade any decision which might precipitate an attack on the forts by the batteries and forces prepared to act against them. There is not sufficient garrison in either for an adequate defence, and the difficulty of procuring supplies is very great. Under the circumstances every one is asking what the Government is going to do? The Southern people have declared they will resist any attempt to supply or reinforce the garrisons, and in Charleston, at least, have shown they mean to keep their word. It is a strange situation. The Federal Government, afraid to speak, and unable to act, is leaving its soldiers to do as they please. In some instances, officers of rank, such as General Twiggs, have surrendered everything to the State authorities, and the treachery and secession of many officers in the army and navy no doubt paralyze and intimidate the civilians at the head of affairs.

Sunday, 17th March.—The first thing I saw this morning, after a vision of a waiter pretending to brush my clothes with a feeble twitch composed of fine fibre had vanished, was a procession of men, forty or fifty perhaps, preceded by a small band (by no excess of compliment can I say, of music), trudging through the cold and slush two and two: they wore shamrocks, or the best resemblance thereto which the American soil can produce, in their hats, and green silk sashes emblazoned with crownless harp upon their coats, but it needed not these insignia to tell they were Irishmen, and their solemn mien indicated that they were going to mass. It was agreeable to see them so well-clad and respectable-looking, though occasional hats seemed as if they had[16] just recovered from severe contusions, and others had the picturesque irregularity of outline now and then observable in the old country. The aspect of the street was irregular, and its abnormal look was increased by the air of the passers-by, who at that hour were domestics—very finely dressed negroes, Irish, or German. The coloured ladies made most elaborate toilettes, and as they held up their broad crinolines over the mud looked not unlike double-stemmed mushrooms. “They’re concayted poor craythures them niggirs, male and faymale,” was the remark of the waiter as he saw me watching them. “There seem to be no sparrows in the streets,” said I. “Sparras!” he exclaimed; “and then how did you think a little baste of a sparra could fly across the ochean?” I felt rather ashamed of myself.

And so down-stairs where there was a table d’hôte room, with great long tables covered with cloths, plates, and breakfast apparatus, and a smaller room inside, to which I was directed by one of the white-jacketted waiters. Breakfast over, visitors began to drop in. At the “office” of the hotel, as it is styled, there is a tray of blank cards and a big pencil, whereby the cardless man who is visiting is enabled to send you his name and title. There is a comfortable “reception-room,” in which he can remain and read the papers, if you are engaged, so that there is little chance of your ultimately escaping him. And, indeed, not one of those who came had any but most hospitable intents.

Out of doors the weather was not tempting. The snow lay in irregular layers and discoloured mounds along the streets, and the gutters gorged with “snow-bree” flooded the broken pavement. But after a time the[17] crowds began to issue from the churches, and it was announced as the necessity of the day, that we were to walk up and down the Fifth Avenue and look at each other. This is the west-end of London—its Belgravia and Grosvenoria represented in one long street, with offshoots of inferior dignity at right angles to it. Some of the houses are handsome, but the greater number have a compressed, squeezed-up aspect, which arises from the compulsory narrowness of frontage in proportion to the height of the building, and all of them are bright and new, as if they were just finished to order,—a most astonishing proof of the rapid development of the city. As the hall-door is made an important feature in the residence, the front parlour is generally a narrow, lanky apartment, struggling for existence between the hall and the partition of the next house. The outer door, which is always provided with fine carved panels and mouldings, is of some rich varnished wood, and looks much better than our painted doors. It is generously thrown open so as to show an inner door with curtains and plate glass. The windows, which are double on account of the climate, are frequently of plate glass also. Some of the doors are on the same level as the street, with a basement story beneath; others are approached by flights of steps, the basement for servants having the entrance below the steps, and this, I believe, is the old Dutch fashion, and the name of “stoop” is still retained for it.

No liveried servants are to be seen about the streets, the doorways, or the area-steps. Black faces in gaudy caps, or an unmistakeable “Biddy” in crinoline are their substitutes. The chief charm of the street was the living ornature which moved up and down the[18] trottoirs. The costumes of Paris, adapted to the severity of this wintry weather, were draped round pretty, graceful figures which, if wanting somewhat in that rounded fulness of the Medicean Venus, or in height, were svelte and well poised. The French boot has been driven off the field by the Balmoral, better suited to the snow; and one must at once admit—all prejudices notwithstanding—that the American woman is not only well shod and well gloved, but that she has no reason to fear comparisons in foot or hand with any daughter of Eve, except, perhaps, the Hindoo.

The great and most frequent fault of the stranger in any land is that of generalising from a few facts. Every one must feel there are “pretty days” and “ugly days” in the world, and that his experience on the one would lead him to conclusions very different from that to which he would arrive on the other. To-day I am quite satisfied that if the American women are deficient in stature and in that which makes us say, “There is a fine woman,” they are easy, well formed, and full of grace and prettiness. Admitting a certain pallor—which the Russians, by-the-bye, were wont to admire so much that they took vinegar to produce it—the face is not only pretty, but sometimes of extraordinary beauty, the features fine, delicate, well defined. Ruby lips, indeed, are seldom to be seen, but now and then the flashing of snowy-white evenly-set ivory teeth dispels the delusion that the Americans are—though the excellence of their dentists be granted—naturally ill provided with what they take so much pains, by eating bon-bons and confectionery, to deprive of their purity and colour.

My friend R——, with whom I was walking, knew every one in the Fifth Avenue, and we worked our way through a succession of small talk nearly as far as the end of the street which runs out among divers places in the State of New York, through a débris of unfinished conceptions in masonry. The abrupt transition of the city into the country is not unfavourable to an idea that the Fifth Avenue might have been transported from some great workshop, where it had been built to order by a despot, and dropped among the Red men: indeed, the immense growth of New York in this direction, although far inferior to that of many parts of London, is remarkable as the work of eighteen or twenty years, and is rendered more conspicuous by being developed in this elongated street, and its contingents. I was introduced to many persons to-day, and was only once or twice asked how I liked New York; perhaps I anticipated the question by expressing my high opinion of the Fifth Avenue. Those to whom I spoke had generally something to say in reference to the troubled condition of the country, but it was principally of a self-complacent nature. “I suppose, sir, you are rather surprised, coming from Europe, to find us so quiet here in New York: we are a peculiar people, and you don’t understand us in Europe.”

In the afternoon I called on Mr. Bancroft, formerly minister to England, whose work on America must be rather rudely interrupted by this crisis. Anything with an “ex” to it in America is of little weight—ex-presidents are nobodies, though they have had the advantage, during their four years’ tenure of office, of being prayed for as long as they live. So it is of ex-ministers,[20] whom nobody prays for at all. Mr. Bancroft conversed for some time on the aspect of affairs, but he appeared to be unable to arrive at any settled conclusion, except that the republic, though in danger, was the most stable and beneficial form of government in the world, and that as a Government it had no power to coerce the people of the South or to save itself from the danger. I was indeed astonished to hear from him and others so much philosophical abstract reasoning as to the right of seceding, or, what is next to it, the want of any power in the Government to prevent it.

Returning home in order to dress for dinner, I got into a street-railway-car, a long low omnibus drawn by horses over a strada ferrata in the middle of the street. It was filled with people of all classes, and at every crossing some one or other rang the bell, and the driver stopped to let out or to take in passengers, whereby the unoffending traveller became possessed of much snow-droppings and mud on boots and clothing. I found that by far a greater inconvenience caused by these street-railways was the destruction of all comfort or rapidity in ordinary carriages.

I dined with a New York banker, who gave such a dinner as bankers generally give all over the world. He is a man still young, very kindly, hospitable, well-informed, with a most charming household—an American by theory, an Englishman in instincts and tastes—educated in Europe, and sprung from British stock. Considering the enormous interests he has at stake, I was astonished to perceive how calmly he spoke of the impending troubles. His friends, all men of position in New York society, had the same dilettante tone, and were as little anxious for the future, or excited by[21] the present, as a party of savants chronicling the movements of a “magnetic storm.”

On going back to the hotel, I heard that Judge Daly and some gentlemen had called to request that I would dine with the Friendly Society of St. Patrick to-morrow at Astor House. In what is called “the bar,” I met several gentlemen, one of whom said, “the majority of the people of New York, and all the respectable people, were disgusted at the election of such a fellow as Lincoln to be President, and would back the Southern States, if it came to a split.”

“St. Patrick’s day” in New York—Public dinner—American Constitution—General topics of conversation—Public estimate of the Government—Evening party at Mons. B——’s.

Monday, 18th.—“St. Patrick’s day in the morning” being on the 17th, was kept by the Irish to-day. In the early morning the sounds of drumming, fifing, and bugling came with the hot water and my Irish attendant into the room. He told me: “We’ll have a pretty nice day for it. The weather’s often agin us on St. Patrick’s day.” At the angle of the square outside I saw a company of volunteers assembling. They wore bear-skin caps, some turned brown, and rusty green coatees, with white facings and cross-belts, a good deal of gold-lace and heavy worsted epaulettes, and were armed with ordinary muskets, some of them with flintlocks. Over their heads floated a green and gold flag with mystic emblems, and a harp and sunbeams. A gentleman, with an imperfect seat on horseback, which justified a suspicion that he was not to the manner born of Squire or Squireen, with much difficulty was getting them into line, and endangering his personal safety by a large infantry-sword, the hilt of which was complicated with the bridle of his charger in some inexplicable manner. This gentleman was the officer in command of the martial body, who were gathering[23] to do honour to the festival of the old country, and the din and clamour in the streets, the strains of music, and the tramp of feet outside announced that similar associations were on their way to the rendezvous. The waiters in the hotel, all of whom were Irish, had on their best, and wore an air of pleased importance. Many of their countrymen outside on the pavement exhibited very large decorations, plates of metal, and badges attached to broad ribands over their left breasts.

After breakfast I struggled with a friend through the crowd which thronged Union Square. Bless them! They were all Irish, judging from speech, and gesture, and look; for the most part decently dressed, and comfortable, evidently bent on enjoying the day in spite of the cold, and proud of the privilege of interrupting all the trade of the principal streets, in which the Yankees most do congregate, for the day. They were on the door-steps, and on the pavement men, women, and children, admiring the big policemen—many of them compatriots—and they swarmed at the corners, cheering popular town-councillors or local celebrities. Broadway was equally full. Flags were flying from the windows and steeples—and on the cold breeze came the hammering of drums, and the blasts of many wind instruments. The display, such as it was, partook of a military character, though not much more formidable in that sense than the march of the Trades Unions, or of Temperance Societies. Imagine Broadway lined for the long miles of its course by spectators mostly Hibernian, and the great gaudy stars and stripes, or as one of the Secession journals I see styles it, the “Sanguinary United States Gridiron”—waving in all[24] directions, whilst up its centre in the mud march the children of Erin.

First came the acting Brigadier-General and his staff, escorted by 40 lancers, very ill-dressed, and worse mounted; horses dirty, accoutrements in the same condition, bits, bridles, and buttons rusty and tarnished; uniforms ill-fitting, and badly put on. But the red flags and the show pleased the crowd, and they cheered “bould Nugent” right loudly. A band followed, some members of which had been evidently “smiling” with each other; and next marched a body of drummers in military uniform, rattling away in the French fashion. Here comes the 69th N. Y. State Militia Regiment—the battalion which would not turn out when the Prince of Wales was in New York, and whose Colonel, Corcoran, is still under court martial for his refusal. Well, the Prince had no loss, and the Colonel may have had other besides political reasons for his dislike to parade his men.

The regiment turned out, I should think, only 200 or 220 men, fine fellows enough, but not in the least like soldiers or militia. The United States uniform which most of the military bodies wore, consists of a blue tunic and trousers, and a kepi-like cap, with “U. S.” in front for undress. In full dress the officers wear large gold epaulettes, and officers and men a bandit-sort of felt hat looped up at one side, and decorated with a plume of black-ostrich feathers and silk cords. The absence of facings, and the want of something to finish off the collar and cuffs, render the tunic very bald and unsightly. Another band closed the rear of the 69th, and to eke out the military show, which in all was less than 1,200 men, some companies were borrowed from[25] another regiment of State Militia, and a troop of very poor cavalry cleared the way for the Napper-Tandy Artillery, which actually had three whole guns with them! It was strange to dwell on some of the names of the societies which followed. For instance, there were the “Dungannon Volunteers of ’82,” prepared of course to vindicate the famous declaration that none should make laws for Ireland, but the Queen, Lords, and Commons of Ireland! Every honest Catholic among them ignorant of the fact that the Volunteers of ’82 were all Protestants. Then there was the “Sarsfield Guard!” One cannot conceive anything more hateful to the fiery high-spirited cavalier, than the republican form of Government, which these poor Irishmen are, they think, so fond of. A good deal of what passes for national sentiment, is in reality dislike to England and religious animosity.

It was much more interesting to see the long string of Benevolent, Friendly and Provident Societies, with bands, numbering many thousands, all decently clad, and marching in order with banners, insignia, badges and ribands, and the Irish flag flying alongside the “stars and stripes.” I cannot congratulate them on the taste or good effect of their accessories—on their symbolical standards, and ridiculous old harpers, carried on stages in “bardic costume,” very like artificial white wigs and white cotton dressing-gowns, but the actual good done by these societies, is, I am told, very great, and their charity would cover far greater sins than incorrectness of dress, and a proneness to “piper’s playing on the national bagpipes.” The various societies mustered upwards of 10,000 men, some of them uniformed and armed,[26] others dressed in quaint garments, and all as noisy as music and talking could make them. The Americans appeared to regard the whole thing very much as an ancient Roman might have looked on the Saturnalia; but Paddy was in the ascendant, and could not be openly trifled with.

The crowds remained in the streets long after the procession had passed, and I saw various pickpockets captured by the big policemen, and conveyed to appropriate receptacles. “Was there any man of eminence in that procession,” I asked. “No; a few small local politicians, some wealthy store-keepers, and beer-saloon owners perhaps; but the mass were of the small bourgeoisie. Such a man as Mr. O’Conor, who may be considered at the head of the New York bar for instance, would not take part in it.”

In the evening I went, according to invitation, to the Astor House—a large hotel, with a front like a railway terminus, in the Americo-Classical style, with great Doric columns and portico, and found, to my surprise, that the friendly party was to be a great public dinner. The halls were filled with the company, few or none in evening dress; and in a few minutes I was presented to at least twenty-four gentlemen, whose names I did not even hear. The use of badges, medals, and ribands, might, at first, lead a stranger to believe he was in very distinguished military society; but he would soon learn that these insignia were the decorations of benevolent or convivial associations. There is a latent taste for these things in spite of pure republicanism. At the dinner there were Americans of Dutch and English descent, some “Yankees,” one or two Englishmen, Scotchmen, and Welshmen.[27] The chairman, Judge Daly, was indeed a true son of the soil, and his speeches were full of good humour, fluency, and wit; but his greatest effect was produced by the exhibition of a tuft of shamrocks in a flower pot, which had been sent from Ireland for the occasion. This is done annually, but, like the miracle of St. Januarius, it never loses its effect, and always touches the heart.

I confess it was to some extent curiosity to observe the sentiment of the meeting, and a desire to see how Irishmen were affected by the change in their climate, which led me to the room. I came away regretting deeply that so many natives of the British Isles should be animated with a hostile feeling towards England, and that no statesman has yet arisen who can devise a panacea for the evils of these passionate and unmeaning differences between races and religions. Their strong antipathy is not diminished by the impossibility of gratifying it. They live in hope, and certainly the existence of these feelings is not only troublesome to American statesmen, but mischievous to the Irish themselves, inasmuch as they are rendered with unusual readiness the victims of agitators or political intriguers. The Irish element, as it is called, is much regarded in voting times, by suffraging bishops and others; at other times, it is left to its work and its toil—Mr. Seward and Bishop Hughes are supposed to be its present masters. Undoubtedly the mass of those I saw to-day were better clad than they would have been if they remained at home. As I said in the speech which I was forced to make much against my will, by the gentle violence of my companions, never had I seen so many good hats[28] and coats in an assemblage of Irishmen in any other part of the world.

March 19. The morning newspapers contain reports of last night’s speeches which are amusing in one respect, at all events, as affording specimens of the different versions which may be given of the same matter. A “citizen” who was kind enough to come in to shave me, paid me some easy compliments, in the manner of the “Barber of Seville,” on what he termed the “oration” of the night before, and then proceeded to give his notions of the merits and defects of the American Constitution. “He did not care much about the Franchise—it was given to too many he thought. A man must be five years resident in New York before he is admitted to the privileges of voting. When an emigrant arrived, a paper was delivered to him to certify the fact, which he produced after a lapse of five years, when he might be registered as a voter; if he omitted the process of registration, he could however vote if identified by two householders, and a low lot,” observed the barber, “they are—Irish and such like. I don’t want any of their votes.”

In the afternoon a number of gentlemen called, and made the kindest offers of service; letters of introduction to all parts of the States; facilities of every description—all tendered with frankness.

I was astonished to find little sympathy and no respect for the newly installed Government. They were regarded as obscure or undistinguished men. I alluded to the circumstance that one of the journals continued to speak of “The President” in the most contemptuous manner, and to designate him as the great “Rail-Splitter.”[29] “Oh yes,” said the gentleman with whom I was conversing, “that must strike you as a strange way of mentioning the Chief Magistrate of our great Republic, but the fact is, no one minds what the man writes of any one, his game is to abuse every respectable man in the country in order to take his revenge on them for his social exclusion, and at the same time to please the ignorant masses who delight in vituperation and scandal.”

In the evening, dining again with my friend the banker, I had a favourable opportunity of hearing more of the special pleading which is brought to bear on the solution of the gravest political questions. It would seem as if a council of physicians were wrangling with each other over abstract dogmas respecting life and health, whilst their patient was struggling in the agonies of death before them! In the comfortable and well-appointed house wherein I met several men of position, acquirements, and natural sagacity, there was not the smallest evidence of uneasiness on account of circumstances which, to the eye of a stranger, betokened an awful crisis, if not the impending dissolution of society itself. Stranger still, the acts which are bringing about such a calamity are not regarded with disfavour, or, at least, are not considered unjustifiable.

Among the guests were the Hon. Horatio Seymour, a former Governor of the State of New York; Mr. Tylden, an acute lawyer; and Mr. Bancroft; the result left on my mind by their conversation and arguments was that, according to the Constitution, the Government could not employ force to prevent secession, or to compel States which had seceded by the will of the[30] people to acknowledge the Federal power. In fact, according to them, the Federal Government was the mere machine put forward by a Society of Sovereign States, as a common instrument for certain ministerial acts, more particularly those which affected the external relations of the Confederation. I do not think that any of the guests sought to turn the channel of talk upon politics, but the occasion offered itself to Mr. Horatio Seymour to give me his views of the Constitution of the United States, and by degrees the theme spread over the table. I had bought the “Constitution” for three cents in Broadway in the forenoon, and had read it carefully, but I could not find that it was self-expounding; it referred itself to the Supreme Court, but what was to support the Supreme Court in a contest with armed power, either of Government or people? There was not a man who maintained the Government had any power to coerce the people of a State, or to force a State to remain in the Union, or under the action of the Federal Government; in other words, the symbol of power at Washington is not at all analogous to that which represents an established Government in other countries. Quid prosunt leges sine armis? Although they admitted the Southern leaders had meditated “the treason against the Union” years ago, they could not bring themselves to allow their old opponents, the Republicans now in power, to dispose of the armed force of the Union against their brother democrats in the Southern States.

Mr. Seymour is a man of compromise, but his views go farther than those which were entertained by his party ten years ago. Although secession would[31] produce revolution, it was, nevertheless, “a right,” founded on abstract principles, which could scarcely be abrogated consistently with due regard to the original compact. One of the company made a remark which was true enough, I dare say. We were talking of the difficulty of relieving Fort Sumter—an infallible topic just now. “If the British or any foreign power were threatening the fort,” said he, “our Government would find means of relieving it fast enough.” In fact, the Federal Government is groping in the dark; and whilst its friends are telling it to advance boldly, there are myriad voices shrieking out in its ears, “If you put out a foot you are lost.” There is neither army nor navy available, and the ministers have no machinery of rewards, and means of intrigue, or modes of gaining adherents known to European administrations. The democrats behold with silent satisfaction the troubles into which the republican triumph has plunged the country, and are not at all disposed to extricate them. The most notable way of impeding their efforts is to knock them down with the “Constitution” every time they rise to the surface and begin to swim out.

New York society, however, is easy in its mind just now, and the upper world of millionaire merchants, bankers, contractors, and great traders are glad that the vulgar republicans are suffering for their success. Not a man there but resented the influence given by universal suffrage to the mob of the city, and complained of the intolerable effects of their ascendancy—of the corruption of the municipal bodies, the venality of electors and elected, and the abuse, waste, and profligate outlay of the public funds. Of these there were many illustrations given to me, garnished with[32] historiettes of some of the civic dignitaries, and of their coadjutors in the press; but it did not require proof that universal suffrage in a city of which perhaps three-fourths of the voters were born abroad or of foreign parents, and of whom many were the scum swept off the seethings of European populations, must work most injuriously on property and capital. I confess it is to be much wondered at that the consequences are not more evil; but no doubt the time is coming when the mischief can no longer be borne, and a social reform and revolution must be inevitable.

Within only a very few hundreds of yards from the house and picture-gallery of Mons. B——, the representative of European millions, are the hovels and lodgings of his equals in political power. This evening I visited the house of Mons. B——, where his wife had a reception, to which nearly the whole of the party went. When a man looks at a suit of armour made to order by the first blacksmith in Europe, he observes that the finish of the joints and hinges is much higher than in the old iron clothes of the former time. Possibly the metal is better, and the chasings and garniture as good as the work of Milan, but the observer is not for a moment led to imagine that the fabric has stood proof of blows, or that it smacks of ancient watch-fire. If he were asked why it is so, he could not tell; any more perhaps than he could define exactly the difference between the lustrous, highly-jewelled, well-greaved Achaian of New York and the very less effective and showy creature who will in every society over the world pass muster as a gentleman. Here was an elegant house—I use the word in its real meaning—with pretty statues, rich carpets, handsome furniture, and a gallery of[33] charming Meissoniers and genre pieces; the saloons admirably lighted—a fair fine large suite, filled with the prettiest women in the most delightful toilettes, with a proper fringe of young men, orderly, neat, and well turned-out, fretting against the usual advanced posts of turbaned and jewelled dowagers, and provided with every accessory to make the whole good society; for there was wit, sense, intelligence, vivacity; and yet there was something wanting—not in host or hostess, or company, or house—where was it?—which was conspicuous by its absence. Mr. Bancroft was kind enough to introduce me to the most lovely faces and figures, and so far enabled me to judge that nothing could be more beautiful, easy, or natural than the womanhood or girlhood of New York. It is prettiness rather than fineness; regular, intelligent, wax-like faces, graceful little figures; none of the grandiose Roman type which Von Raumer recognised in London, as in the Holy City, a quarter of a century ago. Natheless, the young men of New York ought to be thankful and grateful, and try to be worthy of it. Late in the evening I saw these same young men, Novi Eboracenses, at their club, dicing for drinks and oathing for nothing, and all very friendly and hospitable.

The club-house is remarkable as the mansion of a happy man who invented or patented a waterproof hat-lining, whereby he built a sort of Sallustian villa, with a central court-yard, à l’Alhambra, with fountains and flowers, now passed away to the New York Club. Here was Pratt’s, or the defunct Fielding, or the old C. C. C.’s in disregard of time and regard of drinks—and nothing more.

Streets and shops in New York—Literature—A funeral—Dinner at Mr. H——’s—Dinner at Mr. Bancroft’s—Political and social features—Literary breakfast; Heenan and Sayers.

March 20th.—The papers are still full of Sumter and Pickens. The reports that they are or are not to be relieved are stated and contradicted in each paper without any regard to individual consistency. The “Tribune” has an article on my speech at the St. Patrick’s dinner, to which it is pleased to assign reasons and motives which the speaker, at all events, never had in making it.

Received several begging letters, some of them apparently with only too much of the stamp of reality about their tales of disappointment, distress, and suffering. In the afternoon went down Broadway, which was crowded, notwithstanding the piles of blackened snow by the kerbstones, and the sloughs of mud, and half frozen pools at the crossings. Visited several large stores or shops—some rival the best establishments in Paris or London in richness and in value, and far exceed them in size and splendour of exterior. Some on Broadway, built of marble, or of fine cut stone, cost from 6000l. to 8000l. a year in mere rent. Here, from the base to the fourth or fifth story, are piled collections of all the world can[35] produce, often in excess of all possible requirements of the country; indeed I was told that the United States have always imported more goods than they could pay for. Jewellers’ shops are not numerous, but there are two in Broadway which have splendid collections of jewels, and of workmanship in gold and silver, displayed to the greatest advantage in fine apartments decorated with black marble, statuary, and plate glass.

New York has certainly all the air of a “nouveau riche.” There is about it an utter absence of any appearance of a grandfather—one does not see even such evidences of eccentric taste as are afforded in Paris and London, by the existence of shops where the old families of a country cast off their “exuviæ” which are sought by the new, that they may persuade the world they are old; there is no curiosity shop, not to speak of a Wardour Street, and such efforts as are made to supply the deficiency reveal an enormous amount of ignorance or of bad taste. The new arts, however, flourish; the plague of photography has spread through all the corners of the city, and the shop-windows glare with flagrant displays of the most tawdry art. In some of the large book-sellers’ shops—Appleton’s for example—are striking proofs of the activity of the American press, if not of the vigour and originality of the American intellect. I passed down long rows of shelves laden with the works of European authors, for the most part, oh shame! stolen and translated into American type without the smallest compunction or scruple, and without the least intention of ever yielding the most pitiful deodand to the authors. Mr. Appleton sells no less[36] than one million and a half of Webster’s spelling books a year; his tables are covered with a flood of pamphlets, some for, others against coercion; some for, others opposed to slavery,—but when I asked for a single solid, substantial work on the present difficulty, I was told there was not one published worth a cent. With such men as Audubon and Wilson in natural history, Prescott and Motley in history, Washington Irving and Cooper in fiction, Longfellow and Edgar Poe in poetry, even Bryant and the respectabilities in rhyme, and Emerson as essayist, there is no reason why New York should be a paltry imitation of Leipsig, without the good faith of Tauchnitz.

I dined with a litterateur well known in England to many people a year or two ago—sprightly, loquacious, and well-informed, if neither witty nor profound—now a Southern man with Southern proclivities, as Americans say; once a Southern man with such strong anti-slavery convictions, that his expression of them in an English quarterly had secured him the hostility of his own people—one of the emanations of American literary life for which their own country finds no fitting receiver. As the best proof of his sincerity, he has just now abandoned his connection with one of the New York papers on the republican side, because he believed that the course of the journal was dictated by anti-Southern fanaticism. He is, in fact, persuaded that there will be a civil war, and that the South will have much of the right on its side in the contest. At his rooms were Mons. B——, Dr. Gwin, a Californian ex-senator, Mr. Barlow, and several of the leading men of a certain clique in New York. The Americans complain, or assert, that we do not[37] understand them, and I confess the reproach, or statement, was felt to be well founded by myself at all events, when I heard it declared and admitted that “if Mons. Belmont had not gone to the Charleston Convention, the present crisis would never have occurred.”

March 22nd.—A snow-storm worthy of Moscow or Riga flew through New York all day, depositing more food for the mud. I paid a visit to Mr. Horace Greeley, and had a long conversation with him. He expressed great pleasure at the intelligence that I was going to visit the Southern States. “Be sure you examine the slave-pens. They will be afraid to refuse you, and you can tell the truth.” As the capital and the South form the chief attractions at present, I am preparing to escape from “the divine calm” and snows of New York. I was recommended to visit many places before I left New York, principally hospitals and prisons. Sing-Sing, the state penitentiary, is “claimed,” as the Americans say, to be the first “institution” of its kind in the world. Time presses, however, and Sing-Sing is a long way off. I am told a system of torture prevails there for hardened or obdurate offenders—torture by dropping cold water on them, torture by thumb-screws, and the like—rather opposed to the views of prison philanthropists in modern days.

March 23rd.—It is announced positively that the authorities in Pensacola and Charleston have refused to allow any further supplies to be sent to Fort Pickens, the United States fleet in the Gulf, and to Fort Sumter. Everywhere the Southern leaders are forcing on a solution with decision and energy, whilst the Government appears to be helplessly drifting with the current[38] of events, having neither bow nor stern, neither keel nor deck, neither rudder, compass, sails, or steam. Mr. Seward has declined to receive or hold any intercourse with the three gentlemen called Southern Commissioners, who repaired to Washington accredited by the Government and Congress of the Seceding States now sitting at Montgomery, so that there is no channel of mediation or means of adjustment left open. I hear, indeed, that Government is secretly preparing what force it can to strengthen the garrison at Pickens, and to reinforce Sumter at any hazard; but that its want of men, ships, and money compels it to temporise, lest the Southern authorities should forestall their designs by a vigorous attack on the enfeebled forts.

There is, in reality, very little done by New York to support or encourage the Government in any decided policy, and the journals are more engaged now in abusing each other, and in small party aggressive warfare, than in the performance of the duties of a patriotic press, whose mission at such a time is beyond all question the resignation of little differences for the sake of the whole country, and an entire devotion to its safety, honour, and integrity. But the New York people must have their intellectual drams every morning, and it matters little what the course of Government may be, so long as the aristocratic democrat can be amused by ridicule of the Great Rail Splitter, or a vivid portraiture of Mr. Horace Greeley’s old coat, hat, breeches, and umbrella. The coarsest personalities are read with gusto, and attacks of a kind which would not have been admitted into the “Age” or “Satirist” in their worst days, form the staple[39] leading articles of one or two of the most largely circulated journals in the city. “Slang” in its worst Americanised form is freely used in sensation headings and leaders, and a class of advertisements which are not allowed to appear in respectable English papers, have possession of columns of the principal newspapers, few, indeed, excluding them. It is strange, too, to see in journals which profess to represent the civilisation and intelligence of the most enlightened and highly educated people on the face of the earth, advertisements of sorcerers, wizards, and fortune-tellers by the score—“wonderful clairvoyants,” “the seventh child of a seventh child,” “mesmeristic necromancers,” and the like, who can tell your thoughts as soon as you enter the room, can secure the affections you prize, give lucky numbers in lotteries, and make everybody’s fortunes but their own. Then there are the most impudent quack programmes—very doubtful “personals” addressed to “the young lady with black hair and blue eyes, who got out of the omnibus at the corner of 7th Street”—appeals by “a lady about to be confined” to any “respectable person who is desirous of adopting a child:” all rather curious reading for a stranger, or for a family.