*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 66861 ***

[Transcriber's Notes:]

This volume is the continuation of volume 1,

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/65306

These modifications are intended to provide continuity of the

text for ease of searching and reading.

1. To avoid breaks in the narrative, page numbers (shown in curly

brackets "{123}") are usually placed between paragraphs. In this

case the page number is preceded and followed by an empty line.

2. If a paragraph is exceptionally long, the page number is

placed at the nearest sentence break on its own line, but

without surrounding empty lines.

3. Blocks of unrelated text are moved to a nearby break

between subjects.

5. Use of em dashes and other means of space saving are replaced

with spaces and newlines.

6. Subjects are arranged thusly:

Main titles are at the left margin, in all upper case

(as in the original) and are preceded by an empty line.

Subtitles (if any) are indented three spaces and

immediately follow the main title.

Text of the article (if any) follows the list of subtitles (if

any) and is preceded with an empty line and indented three

spaces.

References to other articles in this work are in all upper case

(as in the original) and indented six spaces. They usually

begin with "See", "Also" or "Also in".

Citations of works outside this book are indented six spaces

and in italics, as in the original. The bibliography in Volume

1, APPENDIX F on page xxi provides additional details,

including URLs of available internet versions.

----------Subject: End----------

indicates the end of a long group of subheadings or other

large block.

[End Transcriber's Notes.]

-----------------------------------------------------------

HISTORY FOR READY REFERENCE

FROM THE BEST HISTORIANS, BIOGRAPHERS, SPECIALISTS

THEIR OWN WORDS IN A COMPLETE SYSTEM OF HISTORY

FOR ALL USES, EXTENDING TO ALL COUNTRIES AND SUBJECTS,

AND REPRESENTING FOR BOTH READERS AND STUDENTS THE BETTER AND

NEWER LITERATURE OF HISTORY IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

BY J.N.LARNED

WITH NUMEROUS HISTORICAL MAPS FROM ORIGINAL STUDIES

AND DRAWINGS BY ALAN C. REILEY

IN FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME II-EL DORADO TO GREAVES

SPRINGFIELD, MASS.

THE C. A. NICHOLS CO., PUBLISHERS

MDCCCXCV

COPYRIGHT, 1894.

BY J. N. LARNED.

The Riversider Press, Cambridge, Mass, U. S. A.

Printed by H. O. Houghton & Company.

LIST OF MAPS.

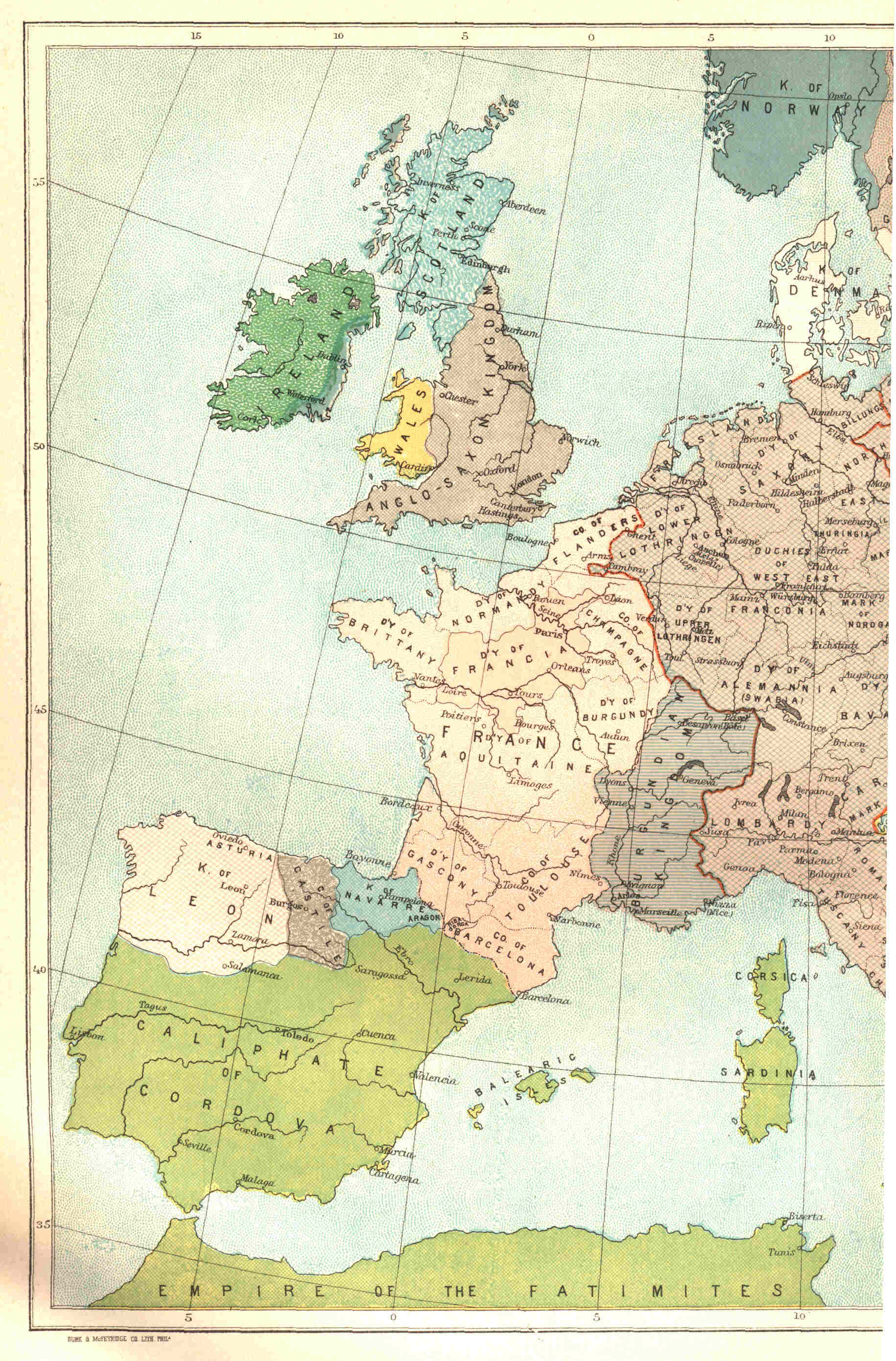

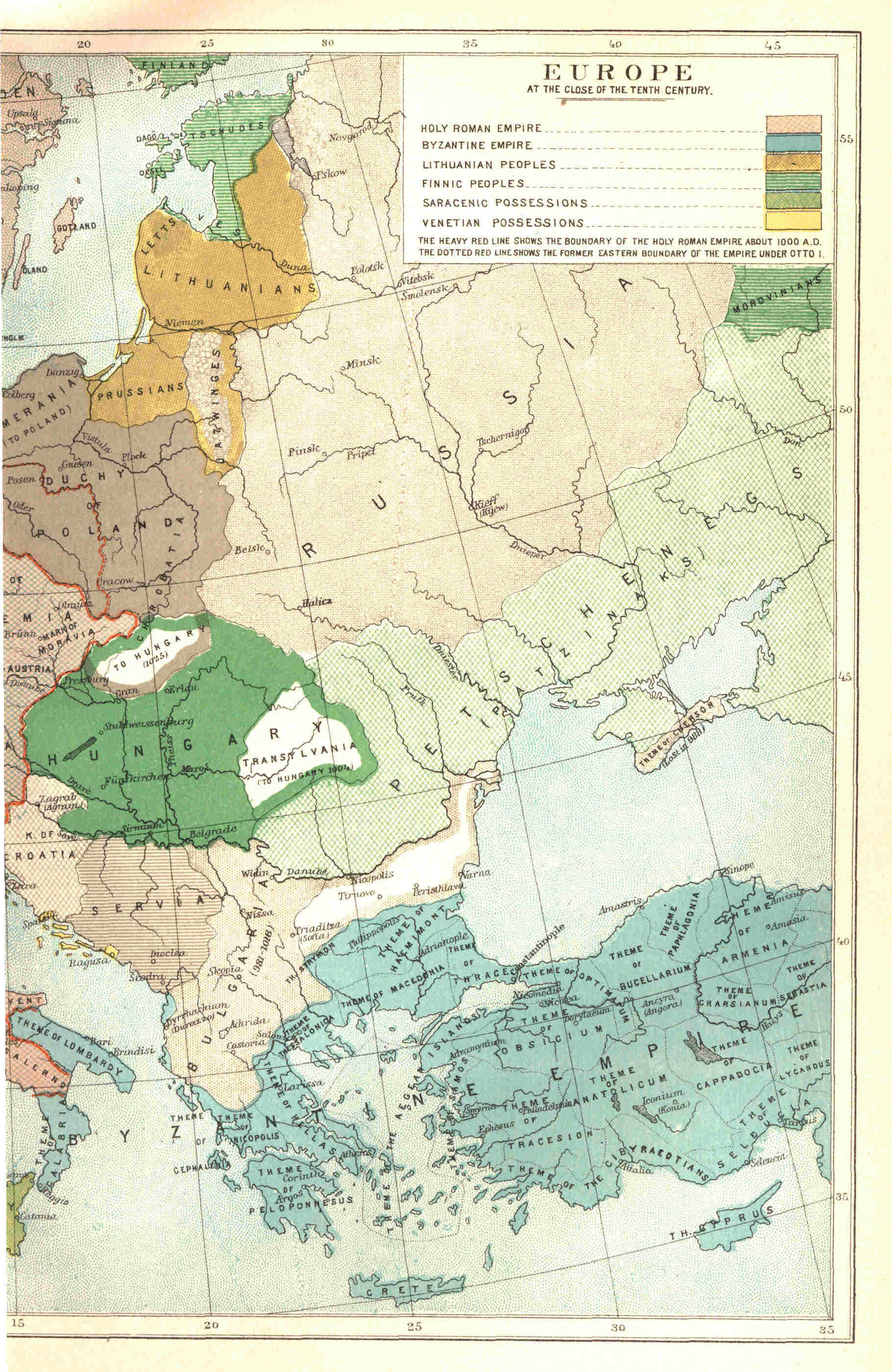

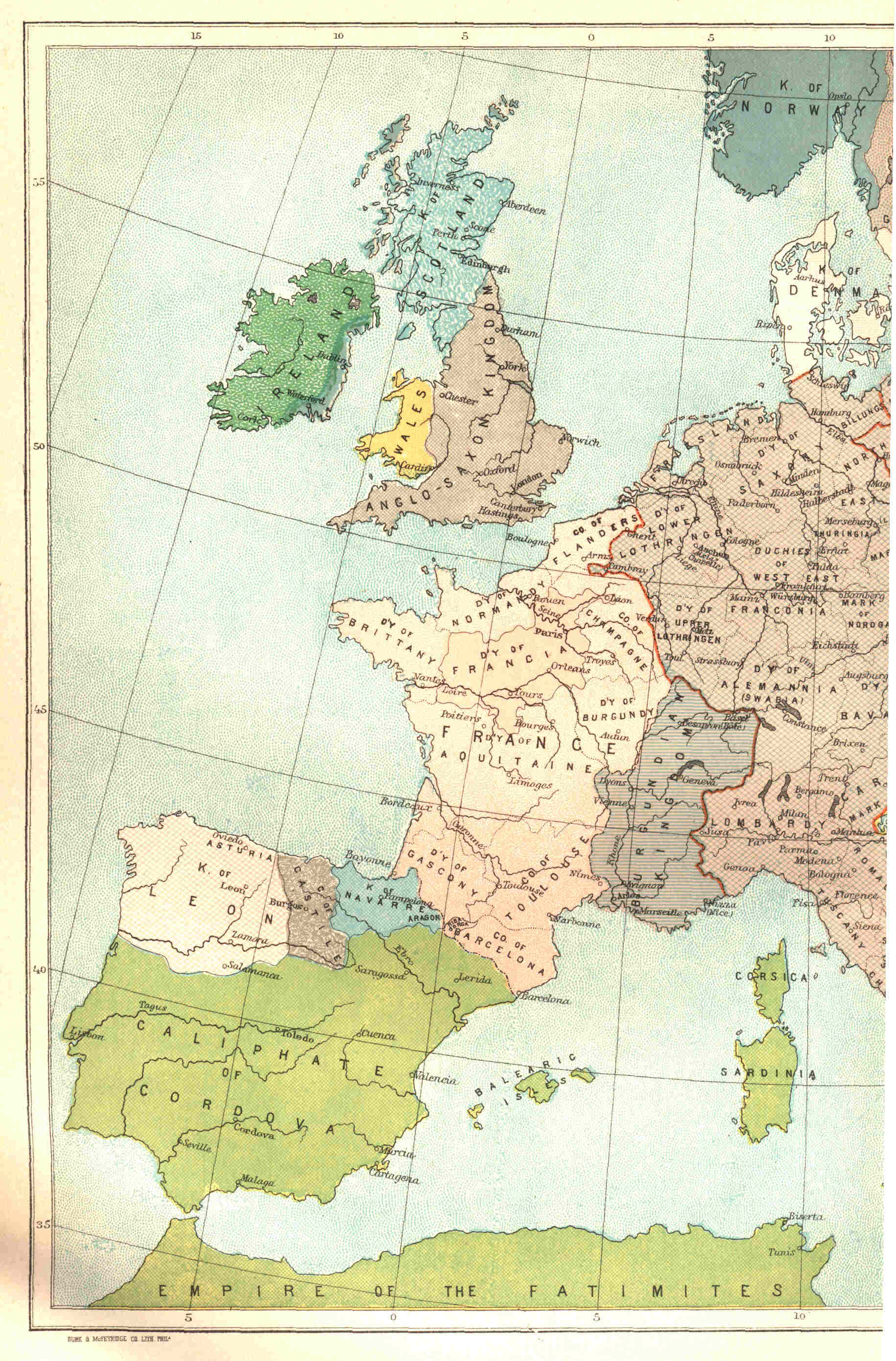

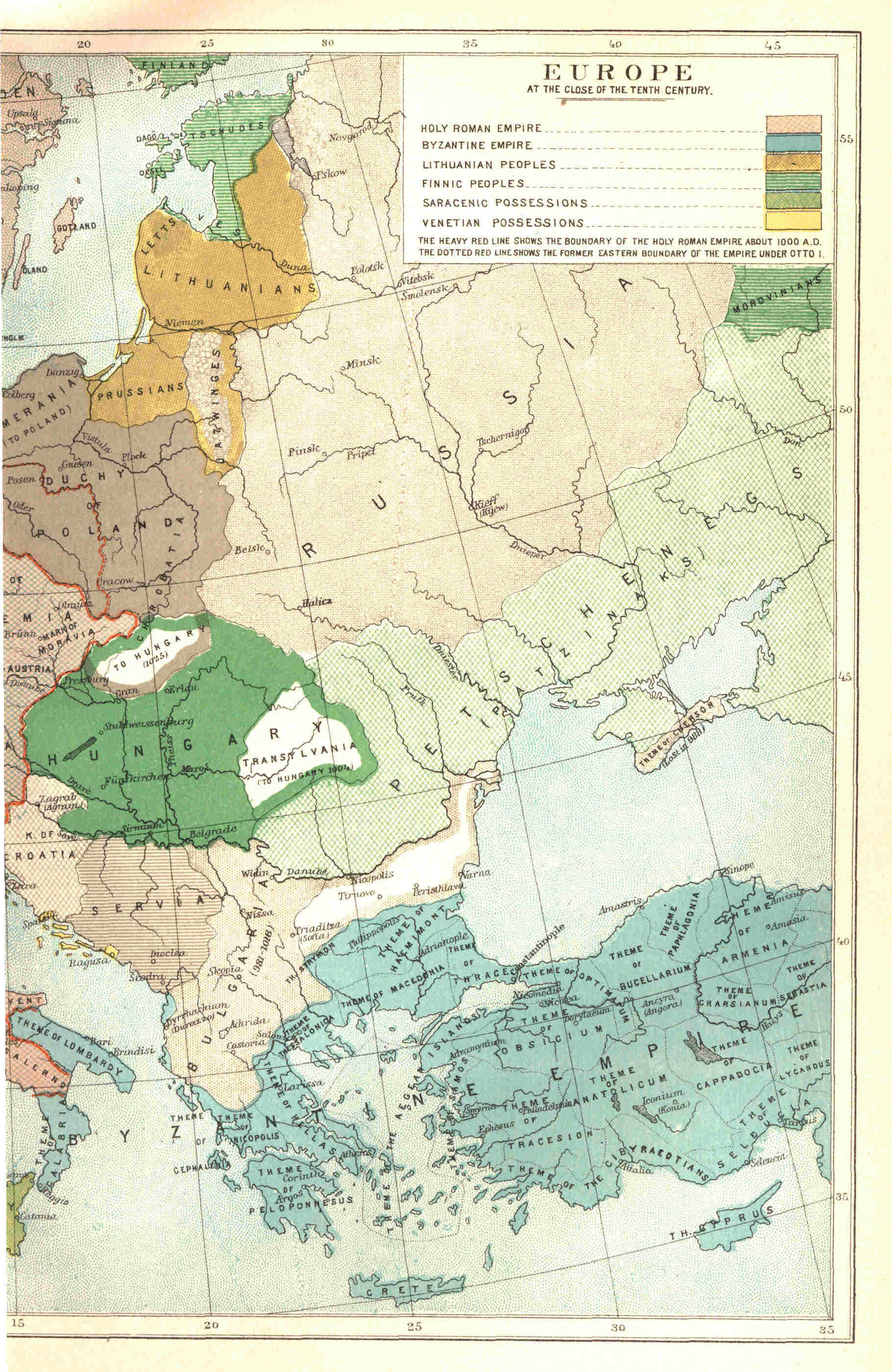

Map of Europe at the close of the Tenth Century, ... To follow page 1020

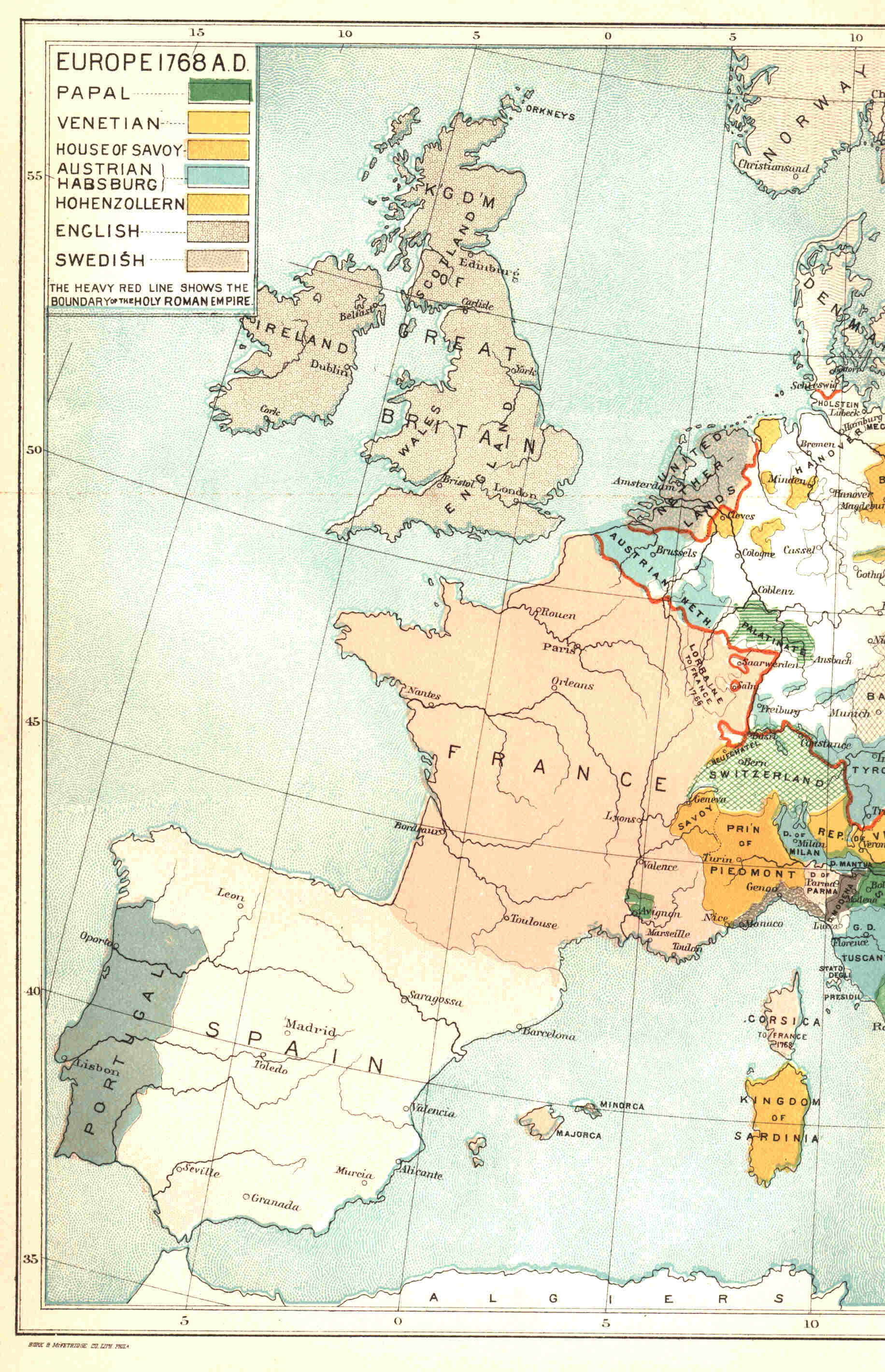

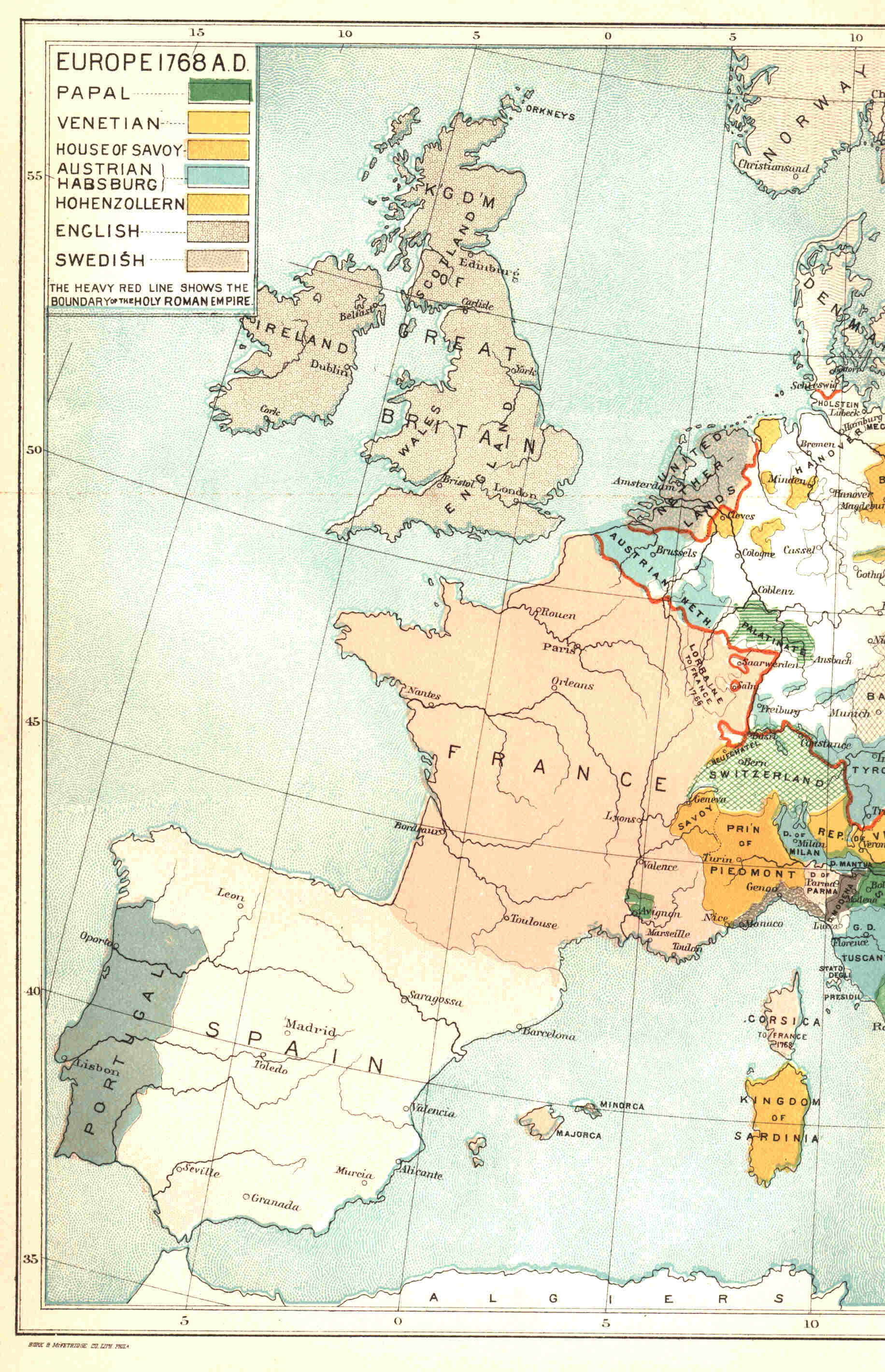

Map of Europe in 1768, ... To follow page 1086

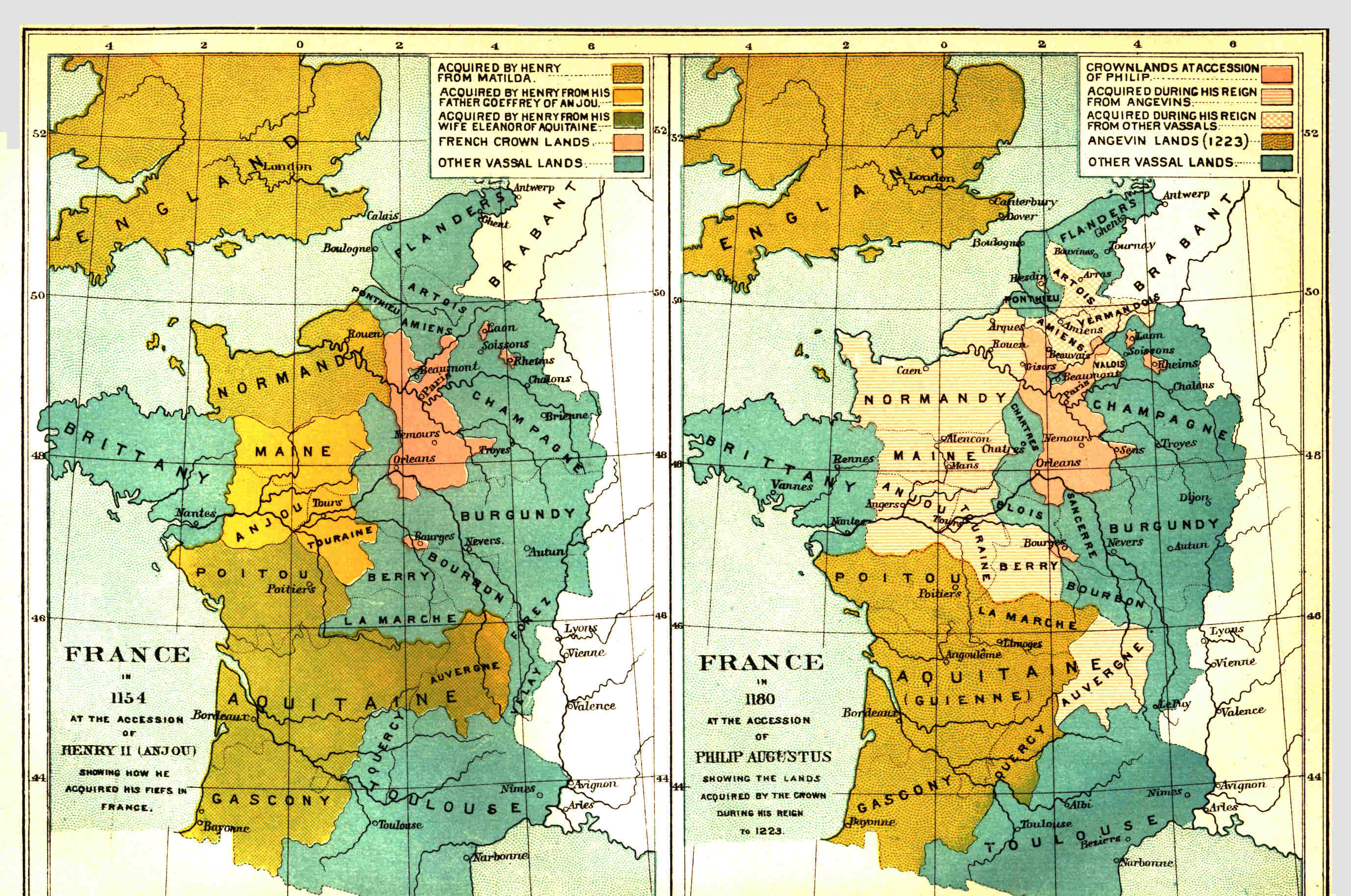

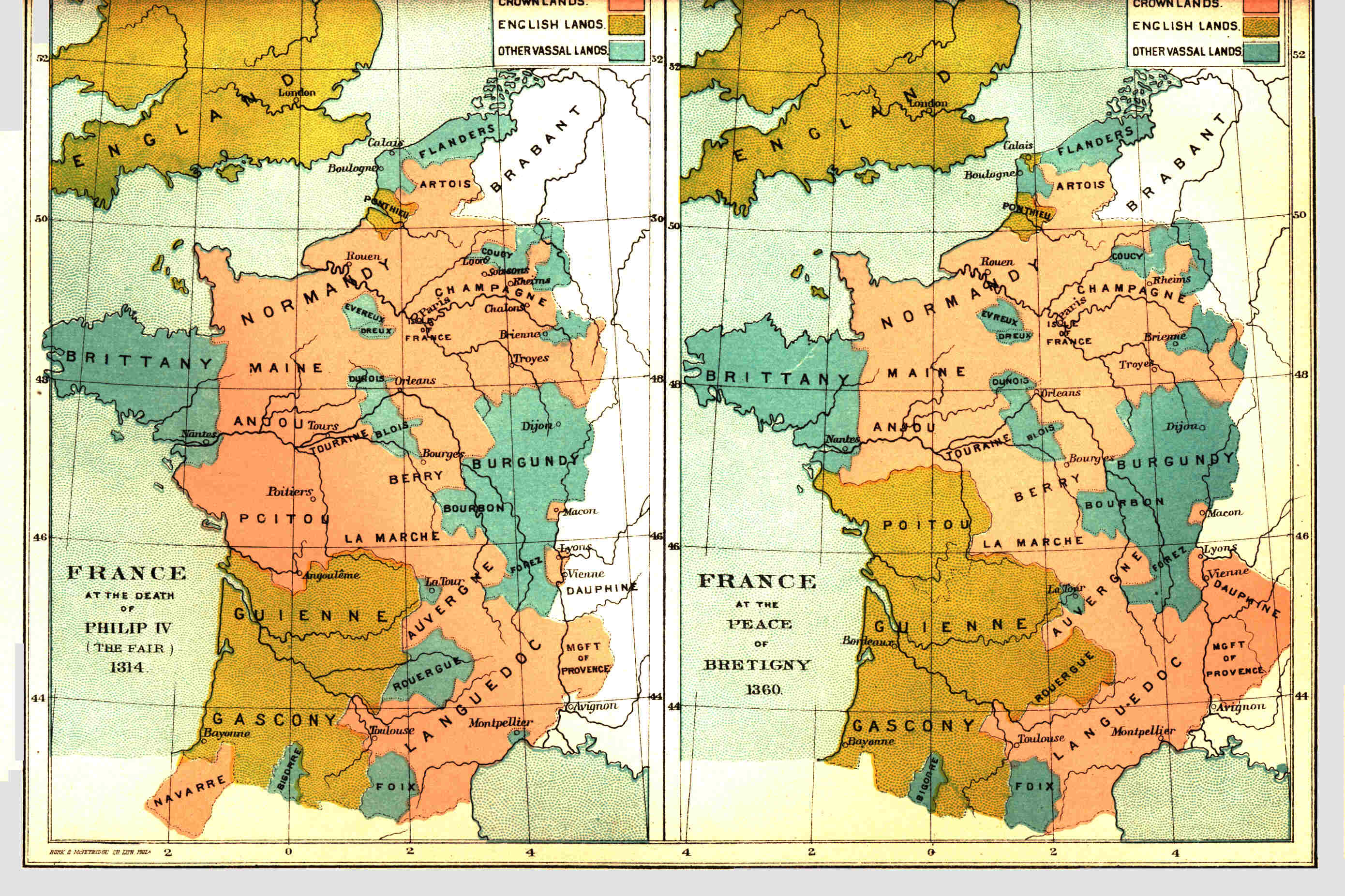

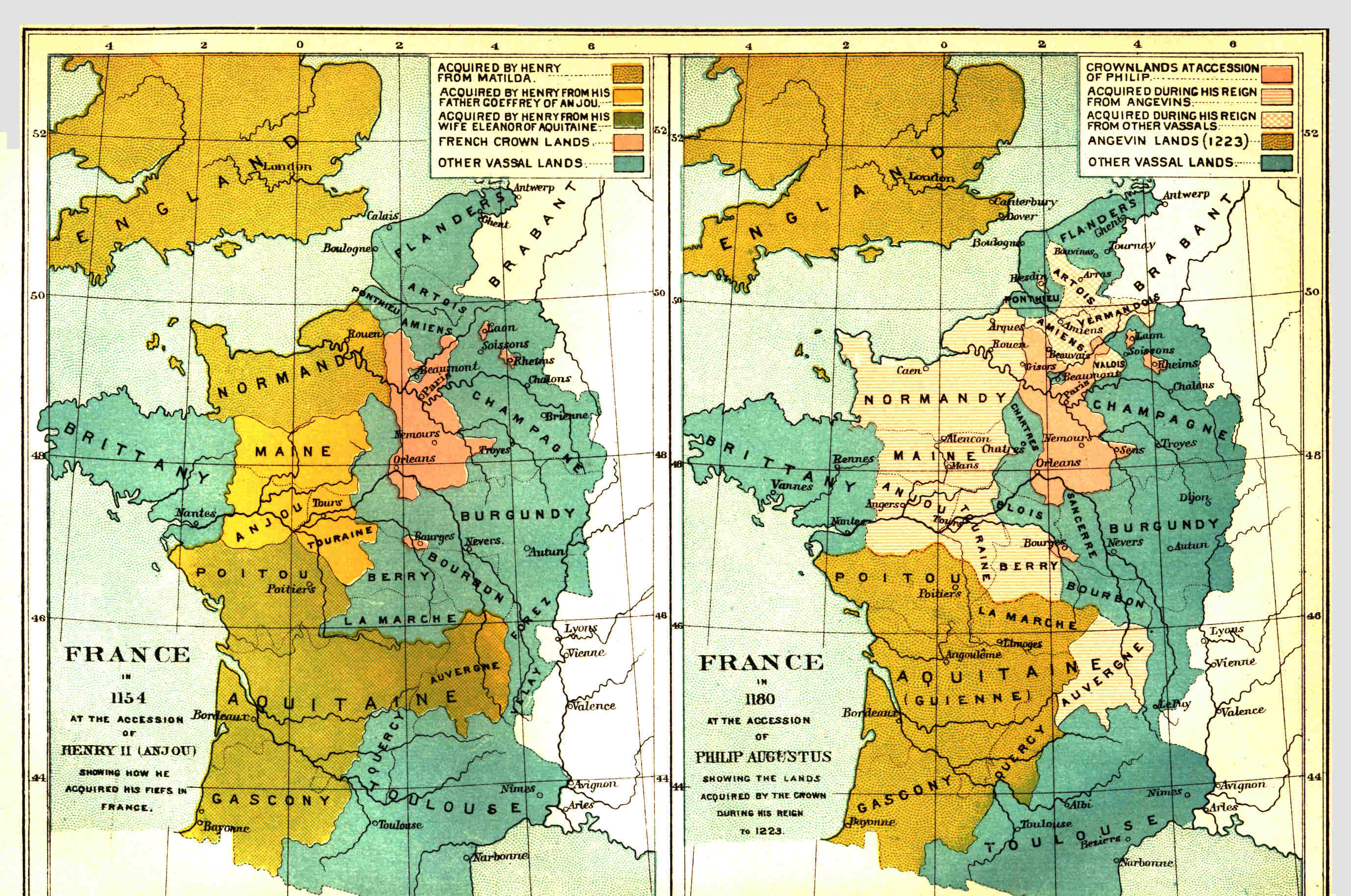

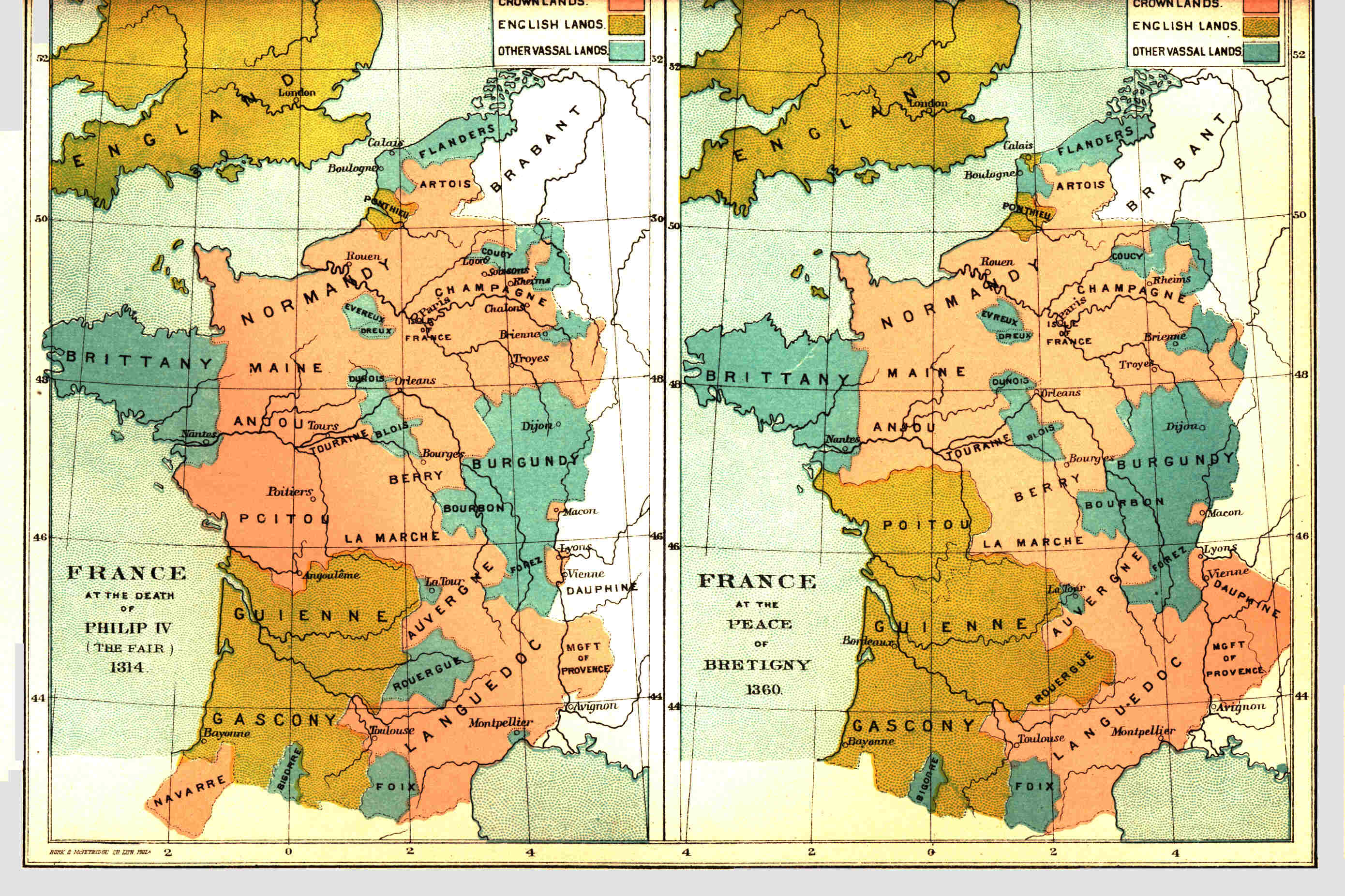

Four maps of France,

A. D. 1154, 1180, 1814 and 1860, ... To follow page 1168

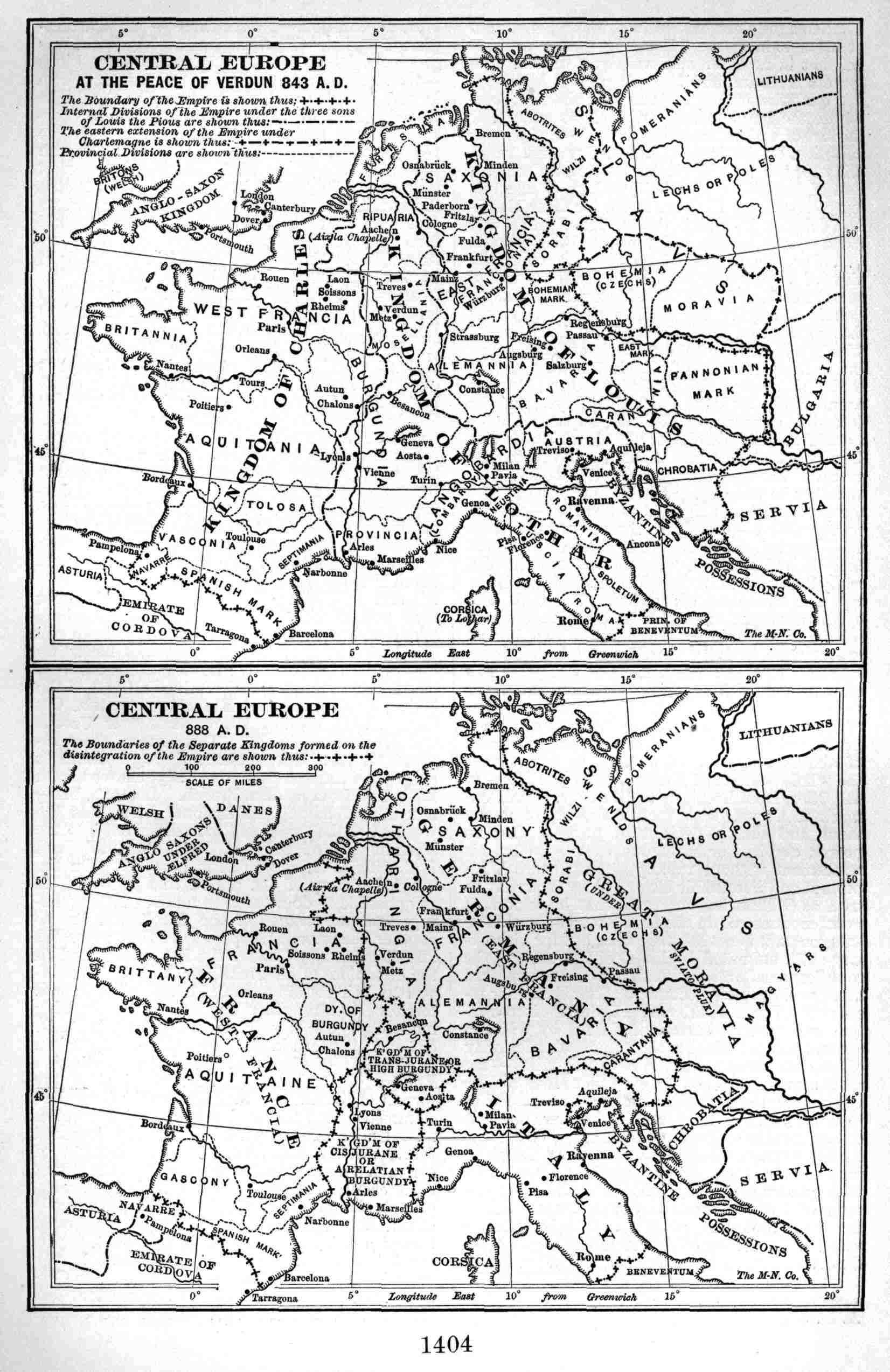

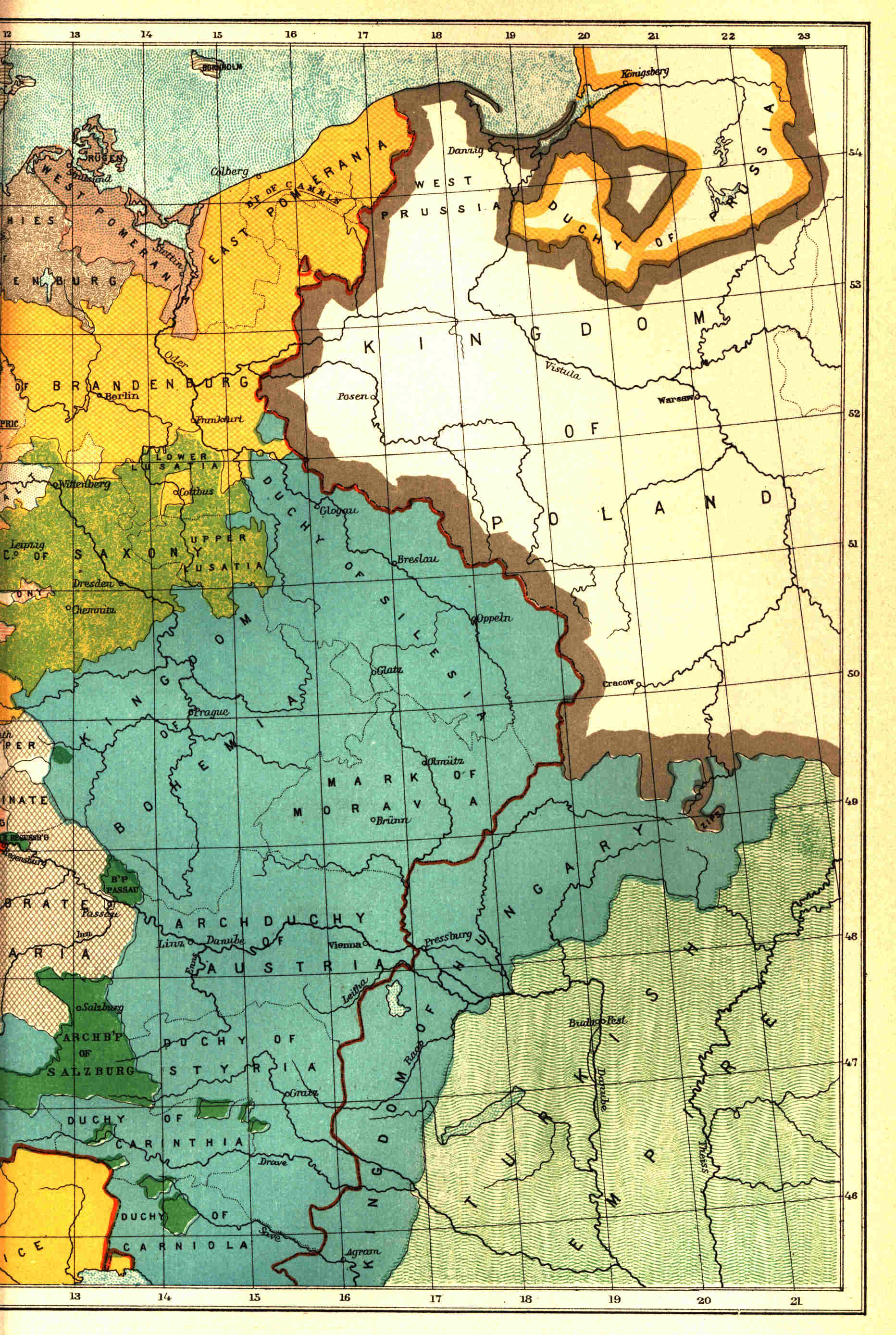

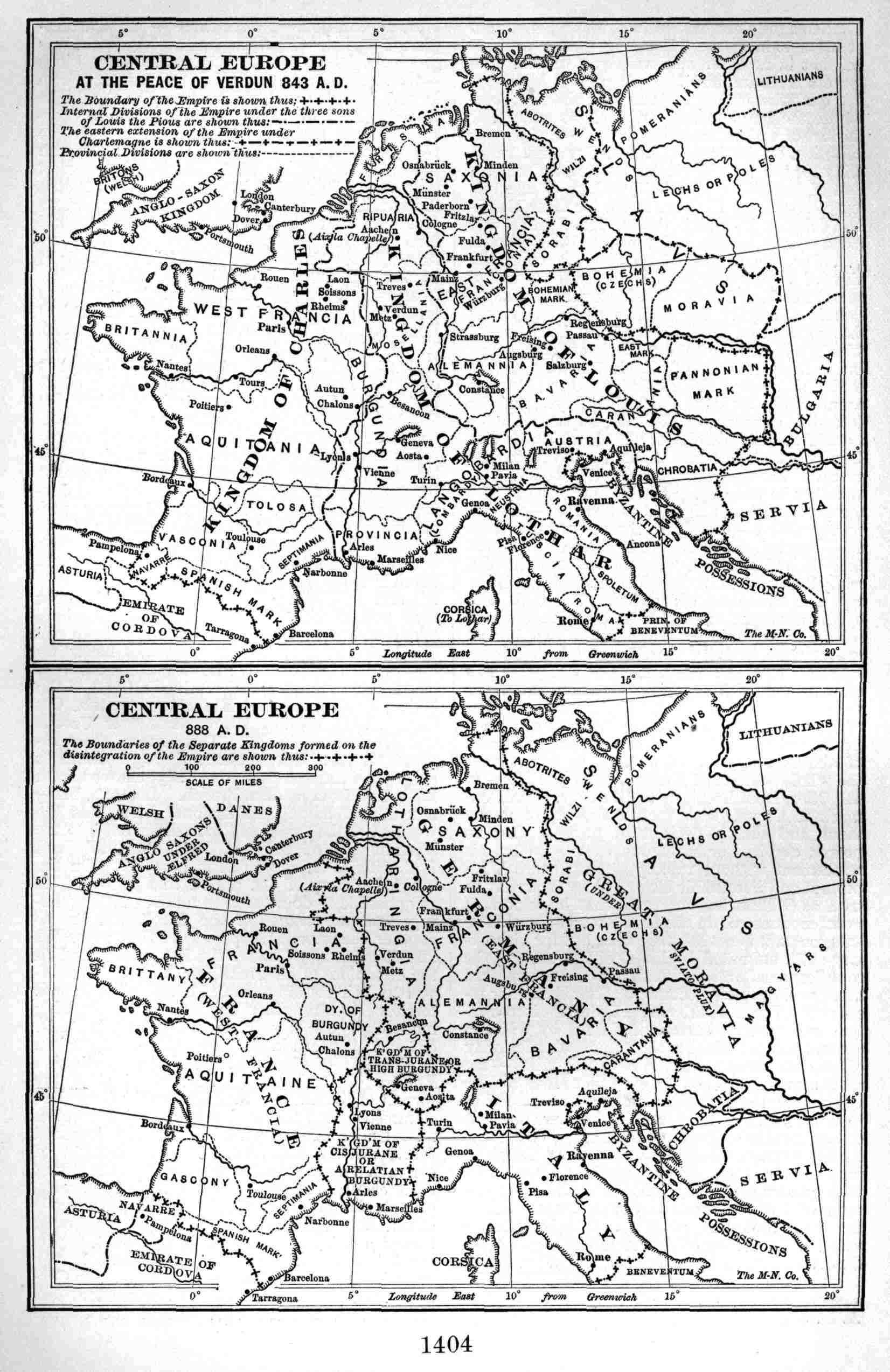

Two maps of Central Europe, A. D. 848 and 888, ... On page 1404

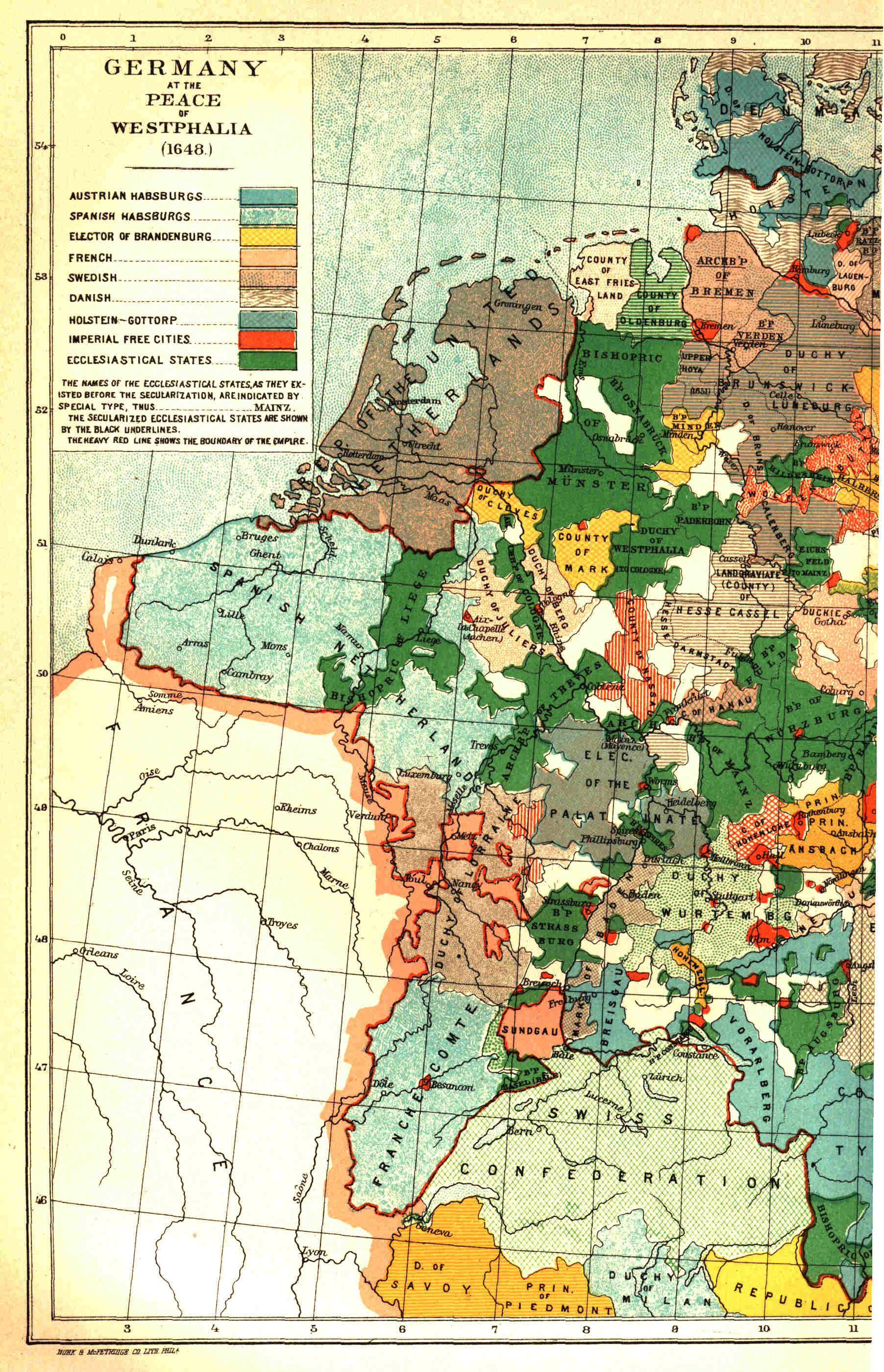

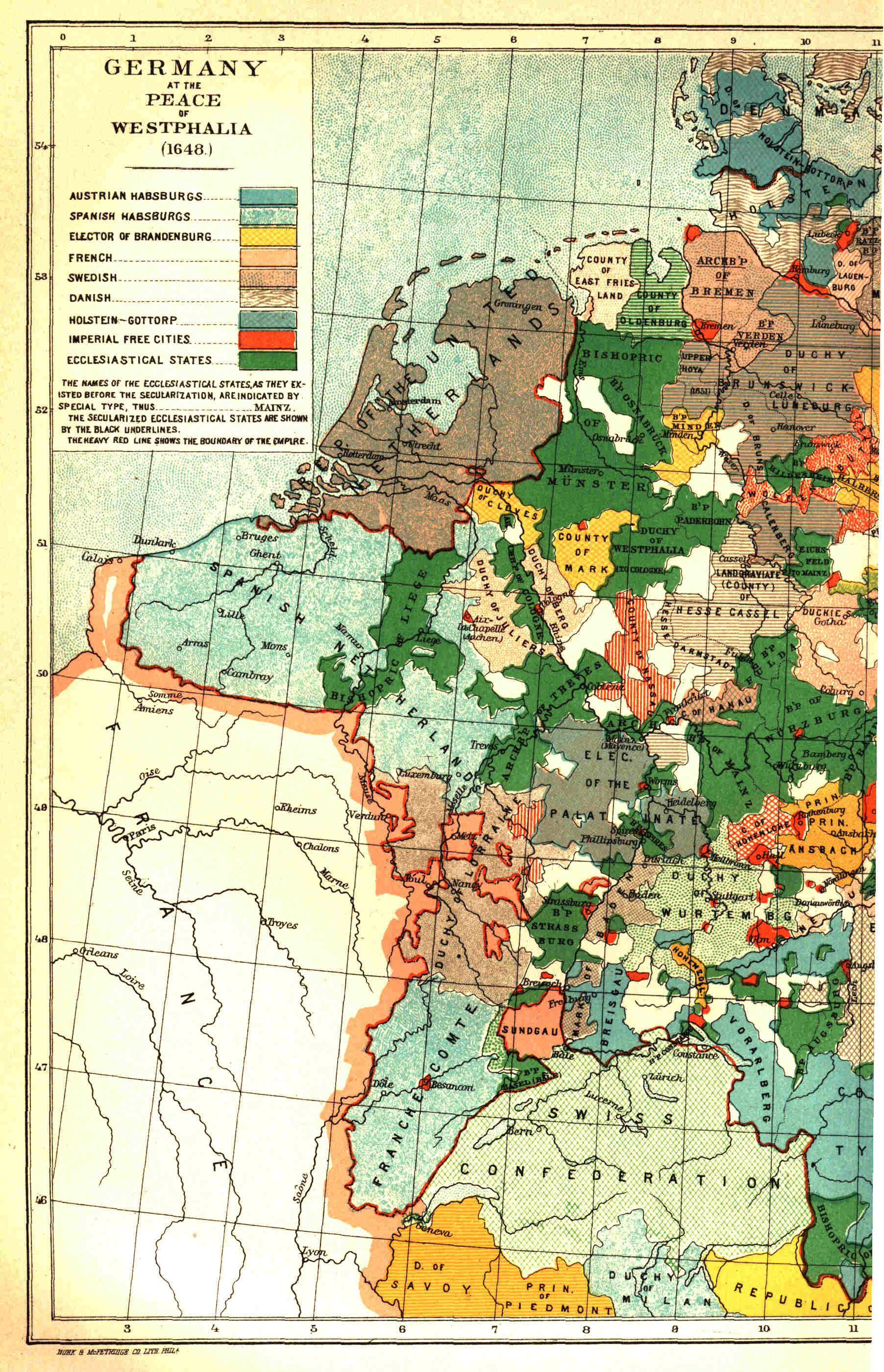

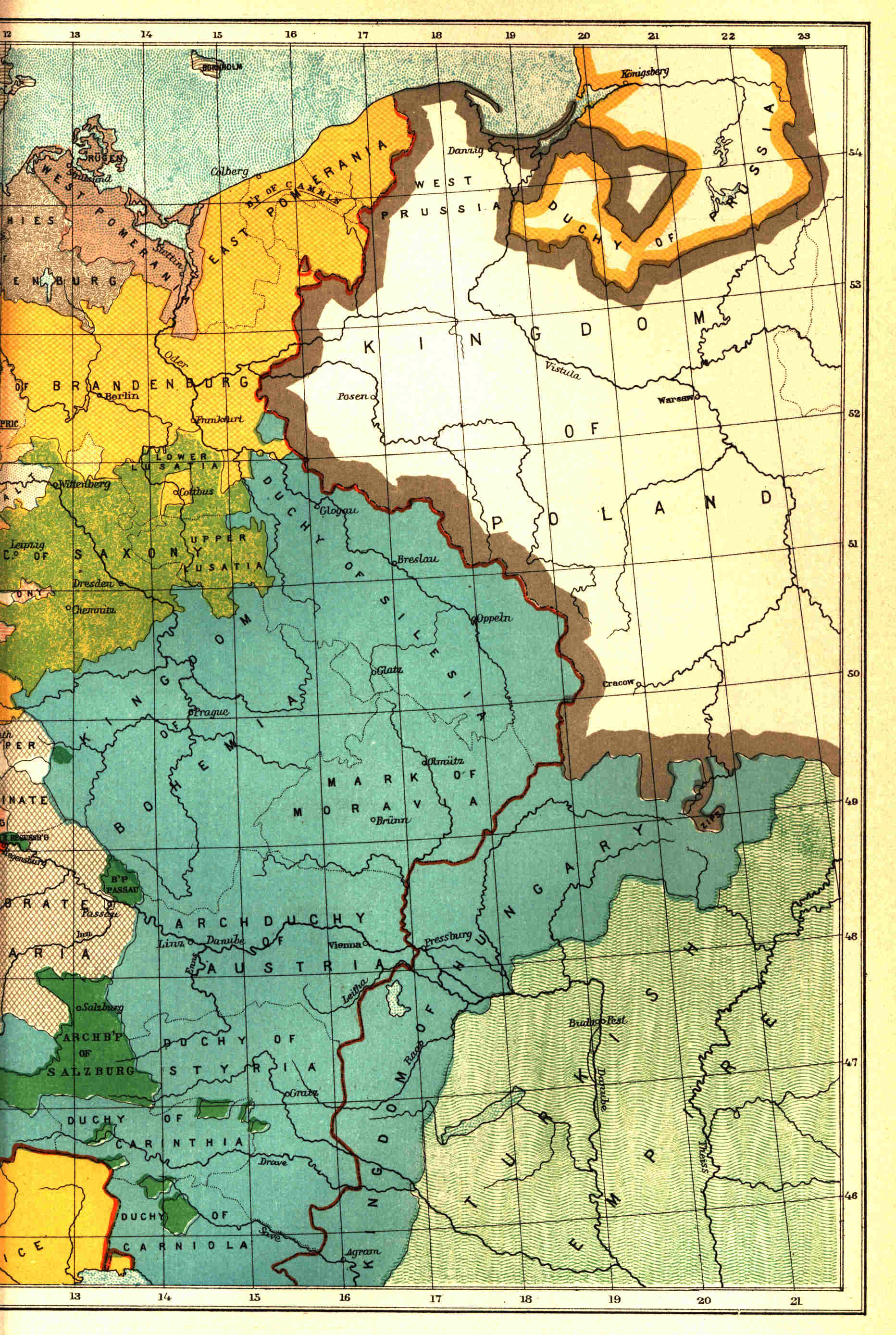

Map of Germany at the Peace of Westphalia, ... To follow page 1486

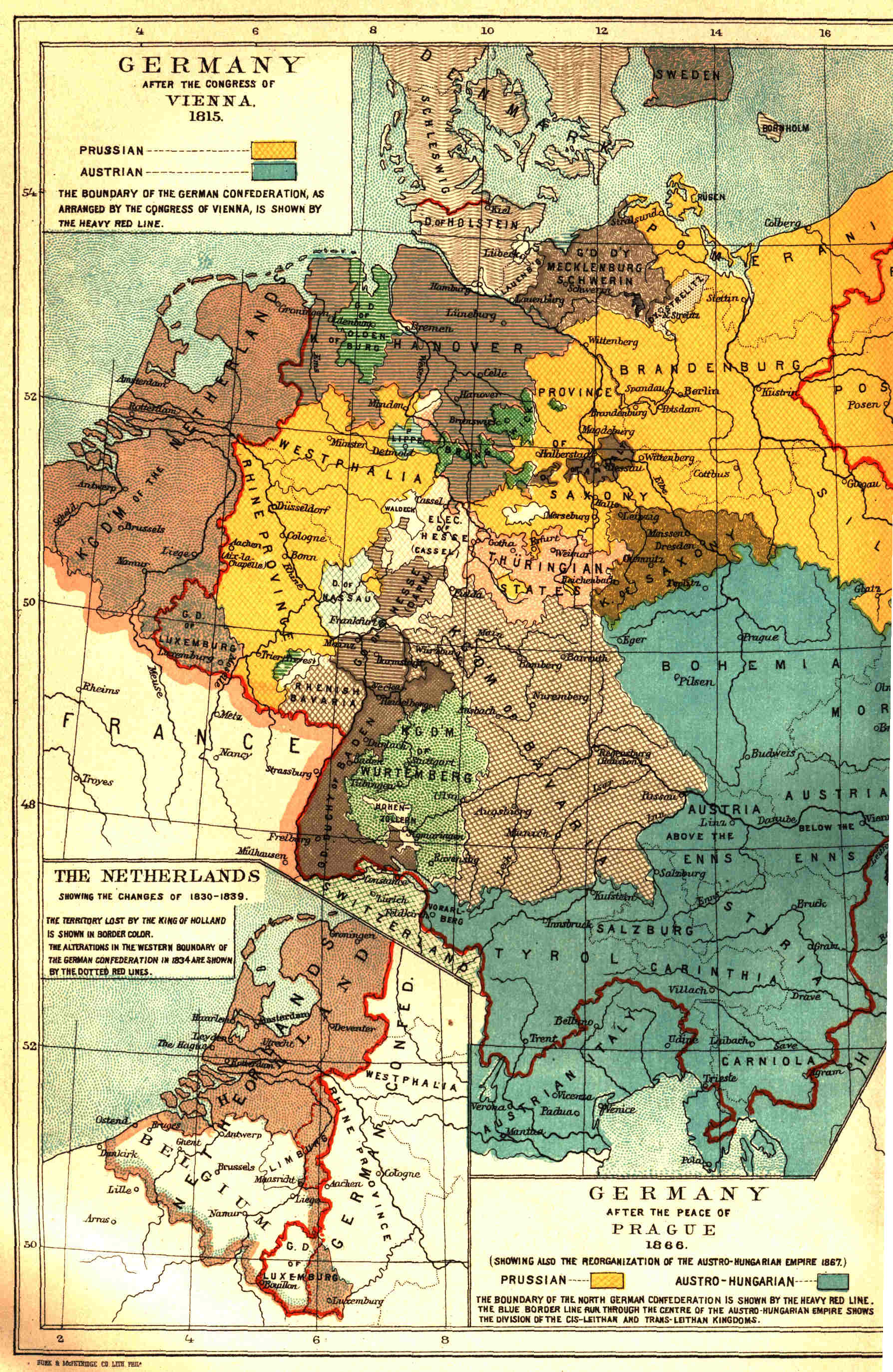

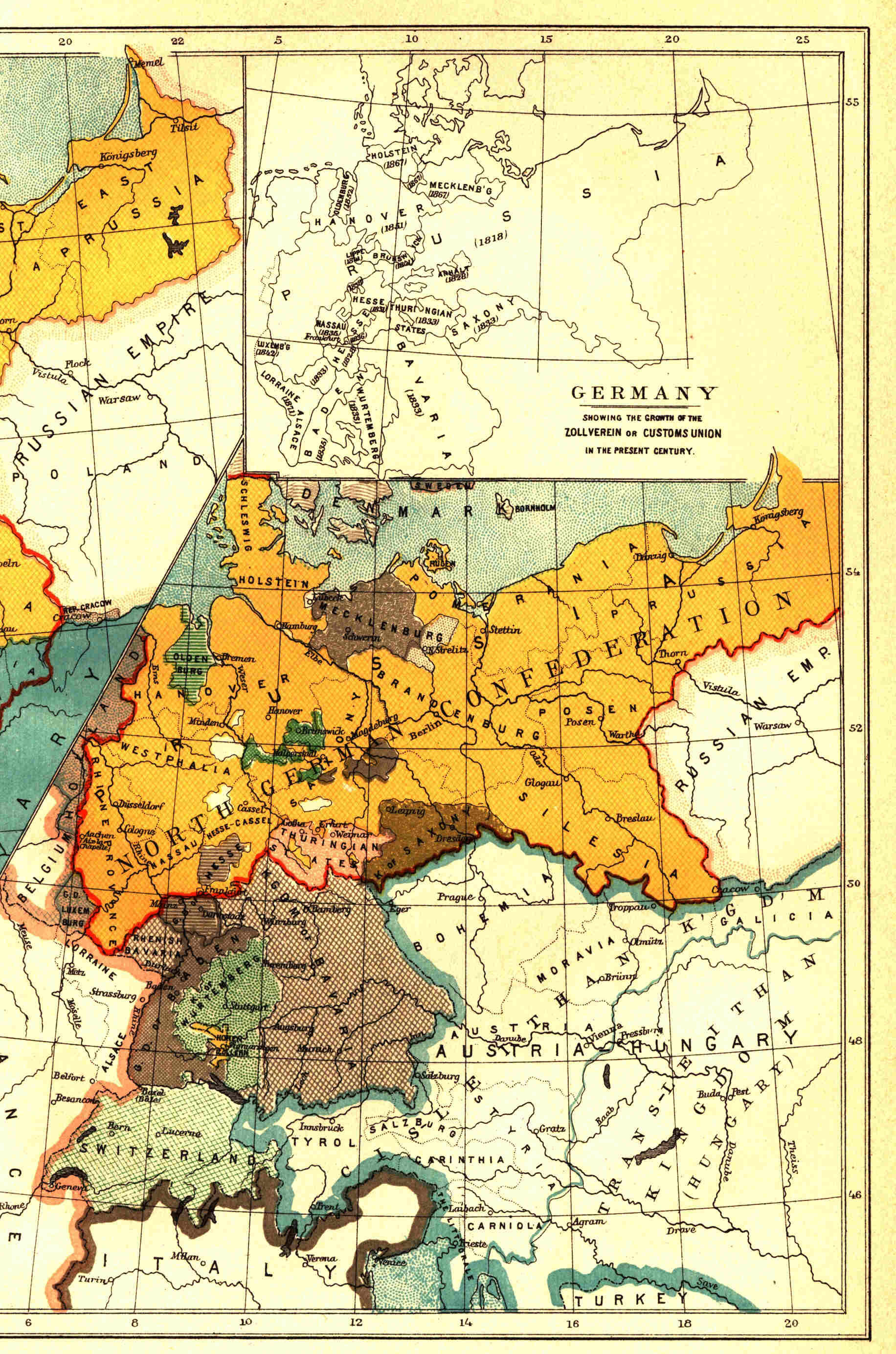

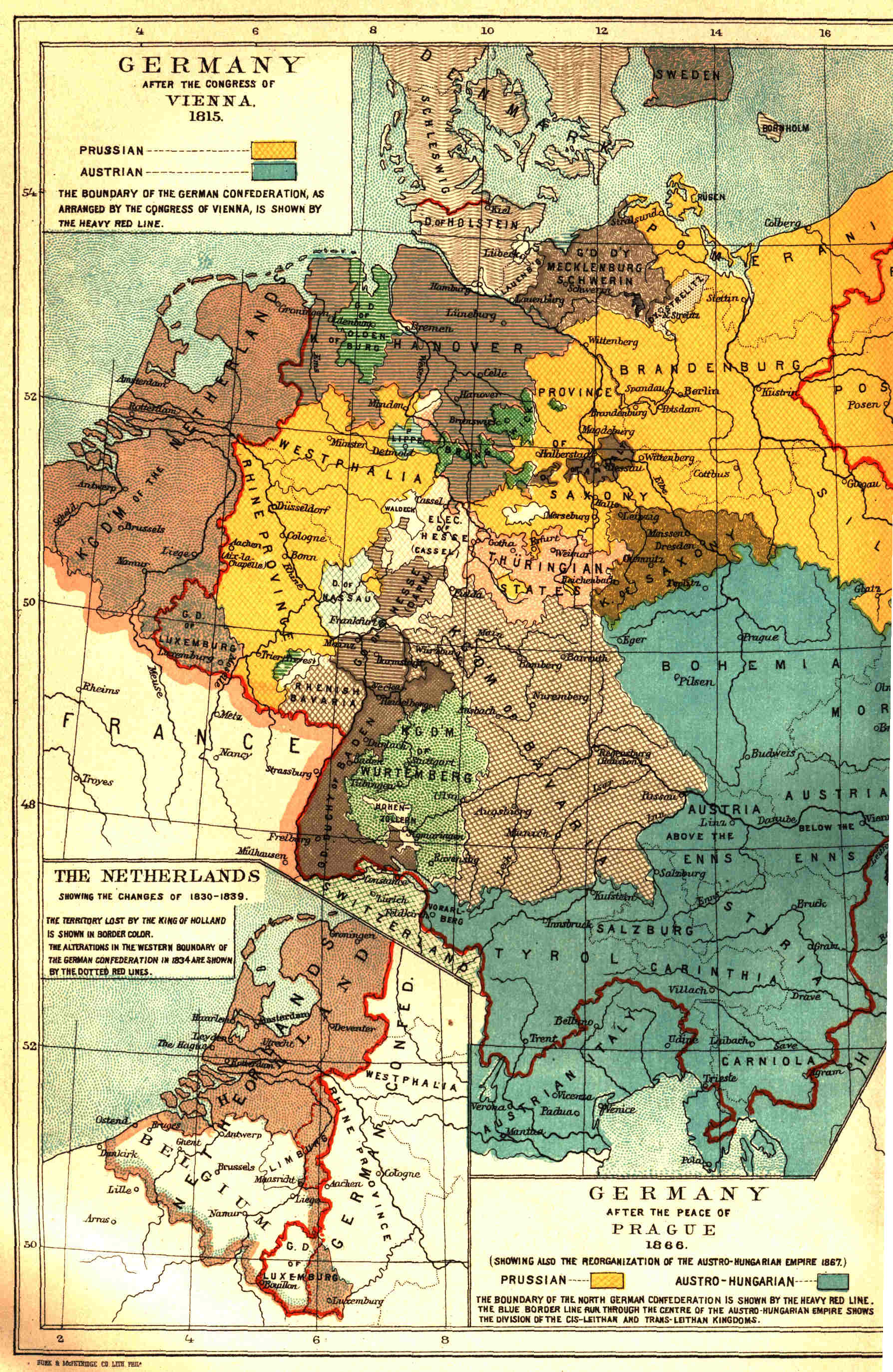

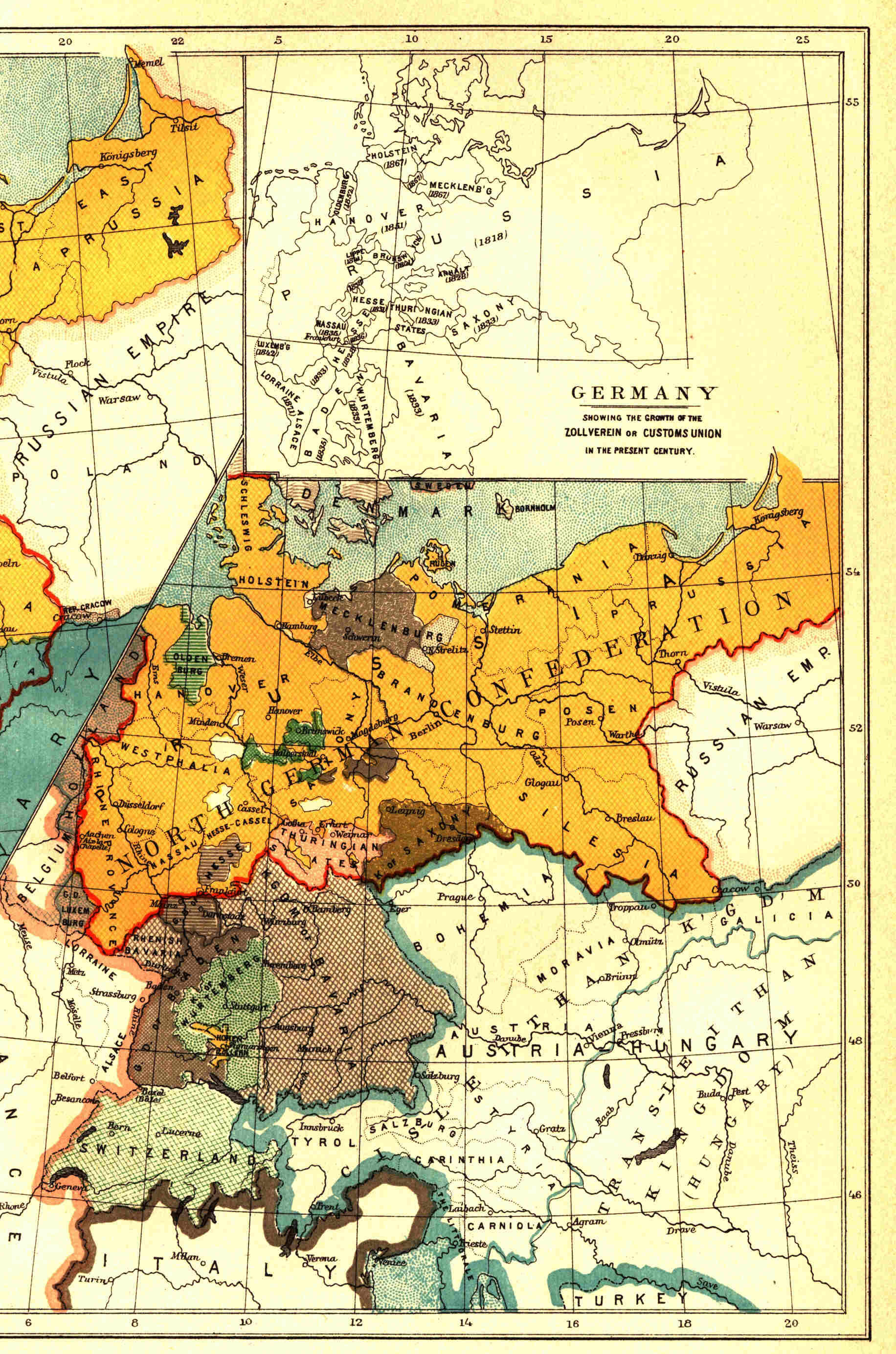

Maps of Germany, A. D. 1815 and 1866;

of the Netherlands, 1880-1889; and

of the Zollverein, ... To follow page 1540

LOGICAL OUTLINES, IN COLORS.

English history, ... To follow page 730

French history, ... To follow page 1158

German history, ... To follow page 1428

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLES.

The Fifth Century, ... On page 1433

The Sixth Century, ... On page 1434

{769}

EL DORADO,

The quest of.

"When the Spaniards had conquered and pillaged the civilized

empires on the table lands of Mexico, Bogota, and Peru, they

began to look round for new scenes of conquest, new sources of

wealth; the wildest rumours were received as facts, and the

forests and savannas, extending for thousands of square miles

to the eastward of the cordilleras of the Andes, were covered,

in imagination, with populous kingdoms, and cities filled with

gold. The story of El Dorado, of a priest or king smeared with

oil and then coated with gold dust, probably originated in a

custom which prevailed among the civilized Indians of the

plateau of Bogota; but El Dorado was placed, by the credulous

adventurers, in a golden city amidst the impenetrable forests

of the centre of South America, and, as search after search

failed, his position was moved further and further to the

eastward, in the direction of Guiana. El Dorado, the phantom

god of gold and silver, appeared in many forms. ... The

settlers at Quito and in Northern Peru talked of the golden

empire of the Omaguas, while those in Cuzco and Charcas dreamt

of the wealthy cities of Paytiti and Enim, on the banks of a

lake far away, to the eastward of the Andes. These romantic

fables, so firmly believed in those old days led to the

exploration of vast tracts of country, by the fearless

adventurers of the sixteenth century, portions of which have

never been traversed since, even to this day. The most famous

searches after El Dorado were undertaken from the coast of

Venezuela, and the most daring leaders of these wild

adventures were German knights."

C. R. Markham,

Introduction to Simon's Account of the

Expedition of Ursua and Aguirre

(Hakluyt Society 1861).

"There were, along the whole coast of the Spanish Main,

rumours of an inland country which abounded with gold. These

rumours undoubtedly related to the kingdoms of Bogota and

Tunja, now the Nuevo Reyno de Granada. Belalcazar, who was in

quest of this country from Quito, Federman, who came from

Venezuela, and Gonzalo Ximenez de Quesada, who sought it by

way of the River Madalena, and who effected its conquest, met

here. But in these countries also there were rumours of a rich

land at a distance; similar accounts prevailed in Peru; in

Peru they related to the Nuevo Reyno, there they related to

Peru; and thus adventurers from both sides were allured to

continue the pursuit after the game was taken. An imaginary

kingdom was soon shaped out as the object of their quest, and

stories concerning it were not more easily invented than

believed. It was said that a younger brother of Atabalipa

fled, after the destruction of the Incas, took with him the

main part of their treasures, and founded a greater empire

than that of which his family had been deprived. Sometimes the

imaginary Emperor was called the Great Paytite, sometimes the

Great Moxo, sometimes the Enim or Great Paru. An impostor at

Lima affirmed that he had been in his capital, the city of

Manoa, where not fewer than 3,000 workmen were employed in the

silversmiths' street; he even produced a map of the country,

in which he had marked a hill of gold, another of silver, and

a third of salt. ... This imaginary kingdom obtained the name

of El Dorado from the fashion of its Lord, which has the merit

of being in savage costume. His body was anointed every

morning with a certain fragrant gum of great price, and gold

dust was then blown upon him, through a tube, till he was

covered with it: the whole was washed off at night. This the

barbarian thought a more magnificent and costly attire than

could be afforded by any other potentate in the world, and

hence the Spaniards called him El Dorado, or the Gilded One. A

history of all the expeditions which were undertaken for the

conquest of his kingdom would form a volume not less

interesting than extraordinary."

R. Southey,

History of Brazil,

volume 1, chapter 12.

The most tragical and thrilling of the stories of the seekers

after El Dorado is that which Mr. Markham introduces in the

quotation above, and which Southey has told with full details

in The Expedition of Orsua; and the Crimes of Aguirre.

The most famous of the expeditions were those in which Sir

Walter Raleigh engaged, and two of which he personally led--in

1595, and in 1617-18. Released from his long imprisonment in

the Tower to undertake the latter, he returned from it, broken

and shamed, to be sent to the scaffold as a victim sacrificed

to the malignant resentment of Spain. How far Raleigh shared

in the delusion of his age respecting El Dorado, and how far

he made use of it merely to promote a great scheme for the

"expansion of England," are questions that will probably

remain forever in dispute.

Sir Walter Raleigh,

Discoverie of the Large, Rich and

Beautiful Empire of Guiana

(Hakluyt Society 1848).

ALSO IN:

J. A. Van Heuvel,

El Dorado.

E. Edwards,

Life of Raleigh,

volume 1, chapters 10 and 25.

P. F. Tytler,

Life of Raleigh,

chapters 3 and 6.

E. Gosse,

Raleigh,

chapters 4 and 9.

A. F. Bandelier,

The gilded man.

ELECTORAL COLLEGE, The Germanic:

Its rise and constitution.

Its secularization and extinction.

See GERMANY: A. D. 1125-1152,

and 1347-1493;

also, 1801-1803,

and 1805-1806.

ELECTORAL COMMISSION, The.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1876-1877.

ELECTORS,

Presidential, of the United States of America.

See PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.

ELECTRICAL DISCOVERY AND INVENTION.

"Electricity, through its etymology at least, traces its

lineage back to Homeric times. In the Odyssey reference is

made to the 'necklace hung with bits of amber' presented by

the Phœnician traders to the Queen of Syra. Amber was highly

prized by the ancients, having been extensively used as an

ornamental gem, and many curious theories were suggested as to

its origin. Some of these, although mythical, were singularly

near the truth, and it is an interesting coincidence that in

the well-known myth concerning the ill-fated and rash youth

who so narrowly escaped wrecking the solar chariot and the

terrestrial sphere, amber, the first known source of

electricity, and the thunder-bolts of Jupiter are linked

together. It is not unlikely that this substance was indebted,

for some of the romance that clung to it through ages, to the

fact that when rubbed it attracts light bodies. This property

it was known to possess in the earliest times: it is the one

single experiment in electricity which has come down to us

from the remotest antiquity. ... The power of certain fishes,

notably what is known as the 'torpedo,' to produce

electricity, was known at an early period, and was commented

on by Pliny and Aristotle.

{770}

... Up to the sixteenth [century] there seems to have been no

attempt to study electrical phenomena in a really scientific

manner. Isolated facts which almost thrust themselves upon

observers, were noted, and, in common with a host of other

natural phenomena, were permitted to stand alone, with no

attempt at classification, generalization, or examination

through experiment. ... Dr. Gilbert can justly be called the

creator of the science of electricity and magnetism. His

experiments were prodigious in number, and many of his

conclusions were correct and lasting. To him we are indebted

for the name 'electricity,' which he bestowed upon the power

or property which amber exhibited in attracting light bodies,

borrowing the name from the substance itself, in order to

define one of its attributes. ... This application of

experiment to the study of electricity, begun by Gilbert three

hundred years ago, was industriously pursued by those who came

after him, and the next two centuries witnessed a rapid

development of science. Among the earlier students of this

period were the English philosopher, Robert Boyle, and the

celebrated burgomaster of Magdeburg, Otto von Guericke. The

latter first noted the sound and light accompanying electrical

excitation. These were afterwards independently discovered by

Dr. Wall, an Englishman, who made the somewhat prophetic

observation, 'This light and crackling seems in some degree to

represent thunder and lightning.' Sir Isaac Newton made a few

experiments in electricity, which he exhibited to the Royal

Society. ... Francis Hawksbee was an active and useful

contributor to experimental investigation, and he also called

attention to the resemblance between the electric spark and

lightning. The most ardent student of electricity in the early

years of the eighteenth century was Stephen Gray. He performed

a multitude of experiments, nearly all of which added

something to the rapidly accumulating stock of knowledge, but

doubtless his most important contribution was his discovery of

the distinction between conductors and non-conductors. ...

Some of Gray's papers fell into the hands of Dufay, an officer

of the French army, who, after several years' service, had

resigned his post to devote himself to scientific pursuits.

... His most important discovery was the existence of two

distinct species of electricity, which he named 'vitreous' and

'resinous.' ... A very important advance was made in 1745 in

the invention of the Leyden jar or phial. As has so many times

happened in the history of scientific discovery, it seems

tolerably certain that this interesting device was hit upon by

at least three persons, working independently of each other.

One Cuneus, a monk named Kleist, and Professor Muschenbroeck,

of Leyden, are all accredited with the discovery. ... Sir

William Watson perfected it by adding the outside metallic

coating, and was by its aid enabled to fire gunpowder and

other inflammables."

T. C. Mendenhall,

A Century of Electricity,

chapter 1.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1745-1747.

Franklin's identification of Electricity with Lightning.

"In 1745 Mr. Peter Collinson of the Royal Society sent a

[Leyden] jar to the Library Society of Philadelphia, with

instructions how to use it. This fell into the hands of

Benjamin Franklin, who at once began a series of electrical

experiments. On March 28, 1747, Franklin began his famous

letters to Collinson. ... In these letters he propounded the

single-fluid theory of electricity, and referred all electric

phenomena to its accumulation in bodies in quantities more

than their natural share, or to its being withdrawn from them

so as to leave them minus their proper portion." Meantime,

numerous experiments with the Leyden jar had convinced

Franklin of the identity of lightning and electricity, and he

set about the demonstration of the fact. "The account given by

Dr. Stuber of Philadelphia, an intimate personal friend of

Franklin, and published in one of the earliest editions of the

works of the great philosopher, is as follows:--'The plan

which he had originally proposed was to erect on some high

tower, or other elevated place, a sentry-box, from which

should rise a pointed iron rod, insulated by being fixed in a

cake of resin. Electrified clouds passing over this would, he

conceived, impart to it a portion of their electricity, which

would be rendered evident to the senses by sparks being

emitted when a key, a knuckle, or other conductor was

presented to it. Philadelphia at this time offered no

opportunity of trying an experiment of this kind. Whilst

Franklin was waiting for the erection of a spire, it occurred

to him that he might have more ready access to the region of

clouds by means of a common kite. He prepared one by attaching

two cross-sticks to a silk handkerchief, which would not

suffer so much from the rain as paper. To his upright stick

was fixed an iron point. The string was, as usual, of hemp,

except the lower end, which was silk. Where the hempen string

terminated, a key was fastened. With this apparatus, on the

appearance of a thunder-gust approaching, he went into the

common, accompanied by his son, to whom alone he communicated

his intentions, well knowing the ridicule which, too generally

for the interest of science, awaits unsuccessful experiments in

philosophy. He placed himself under a shed to avoid the rain.

His kite was raised. A thunder-cloud passed over it. No signs

of electricity appeared. He almost despaired of success, when

suddenly he observed the loose fibres of his string move

toward an erect position. He now pressed his knuckle to the

key, and received a strong spark. How exquisite must his

sensations have been at this moment! On his experiment

depended the fate of his theory. Doubt and despair had begun

to prevail, when the fact was ascertained in so clear a

manner, that even the most incredulous could no longer

withhold their assent. Repeated sparks were drawn from the

key, a phial was charged, a shock given, and all the

experiments made which are usually performed with

electricity.' And thus the identity of lightning and

electricity was proved. ... Franklin's proposition to erect

lightning rods which would convey the lightning to the ground,

and so protect the buildings to which they were attached, found

abundant opponents. ... Nevertheless, public opinion became

settled ... that they did protect buildings. ... Then the

philosophers raised a new controversy as to whether the

conductors should be blunt or pointed; Franklin, Cavendish,

and Watson advocating points, and Wilson blunt ends. ... The

logic of experiment, however, showed the advantage of pointed

conductors; and people persisted then in preferring them, as

they have done ever since."

{771}

P. Benjamin,

The Age of Electricity,

chapter 3.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1753-1820.

The beginnings of the Electric Telegraph.

"The first actual suggestion of an electric telegraph was made

in an anonymous letter published in the Scots Magazine at

Edinburgh, February 17th, 1753. The letter is initialed 'C.

M.,' and many attempts have been made to discover the author's

identity. ... The suggestions made in this letter were that a

set of twenty-six wires should be stretched upon insulated

supports between the two places which it was desired to put in

connection, and at each end of every wire a metallic ball was

to be suspended, having under it a letter of the alphabet

inscribed upon a piece of paper. ... The message was to be

read off at the receiving station by observing the letters

which were successively attracted by their corresponding

balls, as soon as the wires attached to the latter received a

charge from the distant conductor. In 1787 Monsieur Lomond, of

Paris, made the very important step of reducing the twenty-six

wires to one, and indicating the different letters by various

combinations of simple movements of an indicator, consisting

of a pith-ball suspended by means of a thread from a conductor

in contact with the wire. ... In the year 1790 Chappe, the

inventor of the semaphore, or optico-mechanical telegraph,

which was in practical use previous to the introduction of the

electric telegraph, devised a means of communication,

consisting of two clocks regulated so that the second hands

moved in unison, and pointed at the same instant to the same

figures. ... In the early form of the apparatus, the exact

moment at which the observer at the receiving station should

read off the figure to which the hand pointed was indicated by

means of a sound signal produced by the primitive method of

striking a copper stew pan, but the inventor soon adopted the

plan of giving electrical signals instead of sound signals.

... In 1795 Don Francisco Salva ... suggested ... that instead

of twenty-six wires being used, one for each letter, six or

eight wires· only should be employed, each charged by a Leyden

jar, and that different letters should be formed by means of

various combinations of signals from these. ... Mr.

(afterwards Sir Francis) Ronalds ... took up the subject of

telegraphy in the year 1816, and published an account of his

experiments in 1823," based on the same idea as that of

Chappe. ... "Ronalds drew up a sort of telegraphic code by

which words, and sometimes even complete sentences, could be

transmitted by only three discharges. ... Ronalds completely

proved the practicability of his plan, not only on [a] short

underground line, .... but also upon an overhead line some

eight miles in length, constructed by carrying a telegraph

wire backwards and forwards over a wooden frame-work erected

in his garden at Hammersmith. ... The first attempt to employ

voltaic electricity in telegraphy was made by Don Francisco

Salva, whose frictional telegraph has already been referred

to. On the 14th of May, 1800, Salva read a paper on 'Galvanism

and its application to Telegraphy' before the Academy of Sciences

at Barcelona, in which he described a number of experiments

which he had made in telegraphing over a line some 310 metres

in length. ... A few years later he applied the then recent

discovery of the Voltaic pile to the same purpose, the

liberation of bubbles of gas by the decomposition of water at

the receiving station being the method adopted for indicating

the passage of the signals. A telegraph of a very similar

character was devised by Sömmering, and described in a paper

communicated by the inventor to the Munich Academy of Sciences

in 1809. Sömmering used a set of thirty-five wires corresponding

to the twenty-five letters of the German alphabet and the ten

numerals. ... Oersted's discovery of the action of the

electric current upon a suspended magnetic needle provided a

new and much more hopeful method of applying the electric

current to telegraphy. The great French astronomer Laplace

appears to have been the first to suggest this application of

Oersted's discovery, and he was followed shortly afterwards by

Ampere, who in the year 1820 read a paper before the Paris

Academy of Sciences."

G. W. De Tunzelmann,

Electricity in Modern Life,

chapter 9.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1786-1800.

Discoveries of Galvani and Volta.

"The fundamental experiment which led to the discovery of

dynamical electricity [1786] is due to Galvani, professor of

anatomy in Bologna. Occupied with investigations on the

influence of electricity on the nervous excitability of

animals, and especially of the frog, he observed that when the

lumbar nerves of a dead frog were connected with the crural

muscles by a metallic circuit, the latter became briskly

contracted. ... Galvani had some time before observed that the

electricity of machines produced in dead frogs analogous

contractions, and he attributed the phenomena first described

to an electricity inherent in the animal. He assumed that this

electricity, which he called vital fluid, passed from the

nerves to the muscles by the metallic arc, and was thus the

cause of contraction. This theory met with great support,

especially among physiologists, but it was not without

opponents. The most considerable of these was Alexander Volta,

professor of physics in Pavia. Galvani's attention had been

exclusively devoted to the nerves and muscles of the frog;

Volta's was directed upon the connecting metal. Resting on the

observation, which Galvani had also made, that the contraction

is more energetic when the connecting arc is composed of two

metals than where there is only one, Volta attributed to the

metals the active part in the phenomenon of contraction. He

assumed that the disengagement of electricity was due to their

contact, and that the animal parts only officiated as

conductors, and at the same time as a very sensitive

electroscope. By means of the then recently invented

electroscope, Volta devised several modes of showing the

disengagement of electricity on the contact of metals. ... A

memorable controversy arose between Galvani and Volta. The

latter was led to give greater extension to his contact

theory, and propounded the principle that when two

heterogeneous substances are placed in contact, one of them

always assumes the positive and the other the negative

electrical condition. In this form Volta's theory obtained the

assent of the principal philosophers of his time."

A. Ganot,

Elementary Treatise on Physics;

translated by Atkinson, book 10, chapter 1.

Volta's theory, however, though somewhat misleading, did not

prevent his making what was probably the greatest step in the

science up to this time, in the invention (about 1800) of the

Voltaic pile, the first generator of electrical energy by

chemical means, and the forerunner of the vast number of types

of the modern "battery."

{772}

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1810-1890.

The Arc light.

"The earliest instance of applying Electricity to the

production of light was in 1810, by Sir Humphrey Davy, who

found that when the points of two carbon rods whose other ends

were connected by wires with a powerful primary battery were

brought into contact, and then drawn a little way apart, the

Electric current still continued to jump across the gap,

forming what is now termed an Electric Arc. ... Various

contrivances have been devised for automatically regulating

the position of the two carbons. As early as 1847, a lamp was

patented by Staite, in which the carbon rods were fed together

by clockwork. ... Similar devices were produced by Foucault

and others, but the first really successful arc lamp was

Serrin's, patented in 1857, which has not only itself survived

until the present day, but has had its main features

reproduced in many other lamps. ... The Jablochkoff Candle

(1876), in which the arc was formed between the ends of a pair

of carbon rods placed side by side, and separated by a layer of

insulating material, which slowly consumed as the carbons

burnt down, did good service in accustoming the public to the

new illuminant. Since then the inventions by Brush,

Thomson-Houston, and others have done much to bring about its

adoption for lighting large rooms, streets, and spaces out of

doors."

J. B. Verity,

Electricity up to Date for Light, Power, and Traction,

chapter 3.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1820-1825.

Oersted, Ampere, and the discovery of the Electro-Magnet.

"There is little chance ... that the discoverer of the magnet,

or the discoverer and inventor of the magnetic needle, will

ever be known by name, or that even the locality and date of

the discovery will ever be determined [see COMPASS]. ... The

magnet and magnetism received their first scientific treatment

at the hands of Dr. Gilbert. During the two centuries

succeeding the publication of his work, the science of

magnetism was much cultivated. ... The development of the

science went along parallel with that of the science of

electricity ... although the latter was more fruitful in novel

discoveries and unexpected applications than the former. It is

not to be imagined that the many close resemblances of the two

classes of phenomena were allowed to pass unnoticed. ... There

was enough resemblance to suggest an intimate relation; and

the connecting link was sought for by many eminent

philosophers during the last years of the eighteenth and the

earlier years of the present century."

T. C. Mendenhall,

A Century of Electricity,

chapter 3.

"The effect which an electric current, flowing in a wire, can

exercise upon a neighbouring compass needle was discovered by

Oersted in 1820. This first announcement of the possession of

magnetic properties by an electric current was followed

speedily by the researches of Ampere, Arago, Davy, and by the

devices of several other experimenters, including De la Rive's

floating battery and coil, Schweigger's multiplier, Cumming's

galvanometer, Faraday's apparatus for rotation of a permanent

magnet, Marsh's vibrating pendulum and Barlow's rotating

star-wheel. But it was not until 1825 that the electromagnet

was invented. Arago announced, on 25th September 1820, that a

copper wire uniting the poles of a voltaic cell, and

consequently traversed by an electric current, could attract

iron filings to itself laterally. In the same communication he

described how he had succeeded in communicating permanent

magnetism to steel needles laid at right angles to the copper

wire, and how, on showing this experiment to Ampere, the

latter had suggested that the magnetizing action would be more

intense if for the straight copper wire there were substituted

one wrapped in a helix, in the centre of which the steel

needle might be placed. This suggestion was at once carried

out by the two philosophers. 'A copper wire wound in a helix

was terminated by two rectilinear portions which could be

adapted, at will, to the opposite poles of a powerful

horizontal voltaic pile; a steel needle wrapped up in paper

was introduced into the helix.' 'Now, after some minutes'

sojourn in the helix, the steel needle had received a

sufficiently strong dose of magnetism.' Arago then wound upon

a little glass tube some short helices, each about 2¼ inches

long, coiled alternately right-handedly and left-handedly, and

found that on introducing into the glass tube a steel wire, he

was able to produce 'consequent poles' at the places where the

winding was reversed. Ampère, on October 23rd, 1820, read a

memoir, claiming that these facts confirmed his theory of

magnetic actions. Davy had, also, in 1820, surrounded with

temporary coils of wire the steel needles upon which he was

experimenting, and had shown that the flow of electricity

around the coil could confer magnetic power upon the steel

needles. ... The electromagnet, in the form which can first

claim recognition ... was devised by William Sturgeon, and is

described by him in the paper which he contributed to the

Society of Arts in 1825."

S. P. Thompson,

The Electromagnet,

chapter 1.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1825-1874.

The Perfected Telegraph.

"The European philosophers kept on groping. At the end of five

years [after Oersted's discovery], one of them reached an

obstacle which he made up his mind was so entirely

insurmountable, that it rendered the electric telegraph an

impossibility for all future time. This was [1825] Mr. Peter

Barlow, fellow of the Royal Society, who had encountered the

question whether the lengthening of the conducting wire would

produce any effect in diminishing the energy of the current

transmitted, and had undertaken to resolve the problem. ... 'I

found [he said] such a considerable diminution with only 200

feet of wire as at once to convince me of the impracticability

of the scheme.' ... The year following the announcement of

Barlow's conclusions, a young graduate of the Albany (N. Y.)

Academy--by name Joseph Henry--was appointed to the

professorship of mathematics in that institution. Henry there

began the series of scientific investigations which is now

historic. ... Up to that time, electro-magnets had been made

with a single coil of naked wire wound spirally around the

core, with large intervals between the strands. The core was

insulated as a whole: the wire was not insulated at all.

Professor Schweigger, who had previously invented the

multiplying galvanometer, had covered his wires with silk.

Henry followed this idea, and, instead of a single coil of

wire, used several. ... Barlow had said that the gentle

current of the galvanic battery became so weakened, after

traversing 200 feet of wire, that it was idle to consider the

possibility of making it pass over even a mile of conductor

and then affect a magnet.

{773}

Henry's reply was to point out that the trouble lay in the way

Barlow's magnet was made. ... Make the magnet so that the

diminished current will exercise its full effect. Instead of

using one short coil, through which the current can easily

slip, and do nothing, make a coil of many turns; that

increases the magnetic field: make it of fine wire, and of

higher resistance. And then, to prove the truth of his

discovery, Henry put up the first electro-magnetic telegraph

ever constructed. In the academy at Albany, in 1831, he

suspended 1,060 feet of bell-wire, with a battery at one end

and one of his magnets at the other; and he made the magnet

attract and release its armature. The armature struck a bell,

and so made the signals. Annihilating distance in this way was

only one part of Henry's discovery. He had also found, that,

to obtain the greatest dynamic effect close at hand, the

battery should be composed of a very few cells of large

surface, combined with a coil or coils of short coarse wire

around the magnet,--conditions just the reverse of those

necessary when the magnet was to be worked at a distance. Now,

he argued, suppose the magnet with the coarse short coil, and

the large-surface battery, be put at the receiving station;

and the current coming over the line be used simply to make

and break the circuit of that local battery. ... This is the

principle of the telegraphic 'relay.' In 1835 Henry worked a

telegraph-line in that way at Princeton. And thus the

electro-magnetic telegraph was completely invented and

demonstrated. There was nothing left to do, but to put up the

posts, string the lines, and attach the instruments."

P. Benjamin,

The Age of Electricity,

chapter 11.

"At last we leave the territory of theory and experiment and

come to that of practice. 'The merit of inventing the modern

telegraph, and applying it on a large scale for public use,

is, beyond all question, due to Professor Morse of the United

States.' So writes Sir David Brewster, and the best

authorities on the question substantially agree with him. ...

Leaving for future consideration Morse's telegraph, which was

not introduced until five years after the time when he was

impressed with the notion of its feasibility, we may mention

the telegraph of Gauss and Weber of Göttingen. In 1833, they

erected a telegraphic wire between the Astronomical and

Magnetical Observatory of Göttingen, and the Physical Cabinet

of the University, for the purpose of carrying intelligence

from the one locality to the other. To these great

philosophers, however, rather the theory than the practice of

Electric Telegraphy was indebted. Their apparatus was so

improved as to be almost a new invention by Steinheil of

Munich, who, in 1837 ... succeeded in sending a current from

one end to the other of a wire 36,000 feet in length, the

action of which caused two needles to vibrate from side to

side, and strike a bell at each movement. To Steinheil the

honour is due of having discovered the important and

extraordinary fact that the earth might be used as a part of

the circuit of an electric current. The introduction of the

Electric Telegraph into England dates from the same year as

that in which Steinheil's experiments took place. William

Fothergill Cooke, a gentleman who held a commission in the

Indian army, returned from India on leave of absence, and

afterwards, because of his bad health, resigned his

commission, and went to Heidelberg to study anatomy. In 1836,

Professor Mönke, of Heidelberg, exhibited an

electro-telegraphic experiment, 'in which electric currents,

passing along a conducting wire, conveyed signals to a distant

station by the deflexion of a magnetic needle enclosed in

Schweigger's galvanometer or multiplier.' ... Cooke was so

struck with this experiment, that he immediately resolved to

apply it to purposes of higher utility than the illustration

of a lecture. ... In a short time he produced two telegraphs

of different construction. When his plans were completed, he

came to England, and in February, 1837, having consulted

Faraday and Dr. Roget on the construction of the

electric-magnet employed in a part of his apparatus, the

latter gentleman advised him to apply to Professor Wheatstone.

... The result of the meeting of Cooke and Wheatstone was that

they resolved to unite their several discoveries; and in the

month of May 1837, they took out their first patent 'for

improvements in giving signals and sounding alarms in distant

places by means of electric currents transmitted through

metallic circuits.' ... By-and-by, as might probably have been

anticipated, difficulties arose between Cooke and Wheatstone,

as to whom the main credit of introducing the Electric

Telegraph into England was due. Mr. Cooke accused Wheatstone

(with a certain amount of justice, it should seem) of entirely

ignoring his claims; and in doing so Mr. Cooke appears to have

rather exaggerated his own services. Most will readily agree

to the wise words of Mr. Sabine: "It was once a popular

fallacy in England that Messrs. Cooke and Wheatstone were the

original inventors of the Electric Telegraph. The Electric

Telegraph had, properly speaking, no inventor; it grew up as

we have seen little by little."

H. J. Nicoll,

Great Movements,

pages 424-429.

"In the latter part of the year 1832, Samuel F. B. Morse, an

American artist, while on a voyage from France to the United

States, conceived the idea of an electromagnetic telegraph

which should consist of the following parts, viz: A single

circuit of conductors from some suitable generator of

electricity; a system of signs, consisting of dots or points

and spaces to represent numerals; a method of causing the

electricity to mark or imprint these signs upon a strip or

ribbon of paper by the mechanical action of an electro-magnet

operating upon the paper by means of a lever, armed at one end

with a pen or pencil; and a method of moving the paper ribbon

at a uniform rate by means of clock-work to receive the

characters. ... In the autumn of the year 1835 he constructed

the first rude working model of his invention. ... The first

public exhibition ... was on the 2d of September, 1837, on

which occasion the marking was successfully effected through

one third of a mile of wire. Immediately afterwards a

recording instrument was constructed ... which was

subsequently employed upon the first experimental line between

Washington and Baltimore. This line was constructed in 1843-44

under an appropriation by Congress, and was completed by May

of the latter year. On the 27th of that month the first

despatch was transmitted from Washington to Baltimore. ... The

experimental line was originally constructed with two wires,

as Morse was not at that time acquainted with the discovery of

Steinheil, that the earth might be used to complete the circuit.

{774}

Accident, however, soon demonstrated this fact. ... The

following year (1845) telegraph lines began to be built over

other routes. ... In October, 1851, a convention of deputies

from the German States of Austria, Prussia, Bavaria,

Würtemberg and Saxony, met at Vienna, for the purpose of

establishing a common and uniform telegraphic system, under

the name of the German-Austrian Telegraph Union. The various

systems of telegraphy then in use were subjected to the most

thorough examination and discussion. The convention decided

with great unanimity that the Morse system was practically far

superior to all others, and it was accordingly adopted. Prof.

Steinheil, although himself ... the inventor of a telegraphic

system, with a magnanimity that does him high honor, strongly

urged upon the convention the adoption of the American

system." ... The first of the printing telegraphs was patented

in the United States by Royal E. House, in 1846. The Hughes

printing telegraph, a remarkable piece of mechanism, was

patented by David E. Hughes, of Kentucky, in 1855. A system

known as the automatic method, in which the signals

representing letters are transmitted over the line through the

instrumentality of mechanism, was originated by Alexander Bain

of Edinburgh, whose first patents were taken out in 1846. An

autographic telegraph, transmitting despatches in the

reproduced hand-writing of the sender, was brought out in

1850, by F. C. Bakewell, of London. The same result was

afterwards accomplished with variations of method by Charles

Cros, of Paris, Abbé Caseli, of Florence, and others; but none

of these inventions has been extensively used. "The

possibility of making use of a single wire for the

simultaneous transmission of two or more communications seems

to have first suggested itself to Moses G. Farmer, of Boston,

about the year 1852." The problem was first solved with

partial success by Dr. Gintl, on the line between Prague and

Vienna, in 1853, but more perfectly by Carl Frischen, of

Hanover, in the following year. Other inventors followed in

the same field, among them Thomas A. Edison, of New Jersey,

who was led by his experiments finally, in 1874 to devise a

system "which was destined to furnish the basis of the first

practical solution of the curious and interesting problem of

quadruplex telegraphy."

G. B. Prescott,

Electricity and the Electric Telegraph,

chapter 29-40.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1831-1872.

Dynamo

Electrical Machines, and Electric Motors.

"The discovery of induction by Faraday, in 1831, gave rise to

the construction of magneto-electro machines. The first of

such machines that was ever made was probably a machine that

never came into practical use, the description of which was

given in a letter, signed 'P. M.,' and directed to Faraday,

published in the Philosophical Magazine of 2nd August, 1832.

We learn from this description that the essential parts of

this machine were six horse-shoe magnets attached to a disc,

which rotated in front of six coils of wire wound on bobbins."

Sept. 3rd, 1832, Pixii constructed a machine in which a single

horse-shoe magnet was made to rotate before two soft iron

cores, wound with wire. In this machine he introduced the

commutator, an essential element in all modern continuous

current machines. "Almost at the same time, Ritchie, Saxton,

and Clarke constructed similar machines. Clarke's is the best

known, and is still popular in the small and portable

'medical' machines so commonly sold. ... A larger machine

[was] constructed by Stöhrer (1843), on the same plan as

Clarke's, but with six coils instead of two, and three

compound magnets instead of one. ... The machines, constructed

by Nollet (1849) and Shepard (1856) had still more magnets and

coils. Shepard's machine was modified by Van Malderen, and was

called the Alliance machine. ... Dr. Werner Siemens, while

considering how the inducing effect of the magnet can be most

thoroughly utilised, and how to arrange the coils in the most

efficient manner for this purpose, was led in 1857 to devise

the cylindrical armature. ... Sinsteden in 1851 pointed out

that the current of the generator may itself be utilised to

excite the magnetism of the field magnets. ... Wilde [in 1863]

carried out this suggestion by using a small steel permanent

magnet and larger electro magnets. ... The next great

improvement of these machines arose from the discovery of what

may be called the dynamo-electric principle. This principle

may be stated as follows:--For the generation of currents by

magneto-electric induction it is not necessary that the

machine should be furnished with permanent magnets; the

residual or temporary magnetism of soft iron quickly rotating

is sufficient for the purpose. ... In 1867 the principle was

clearly enunciated and used simultaneously, but independently,

by Siemens and by Wheatstone. ... It was in February, 1867,

that Dr. C. W. Siemens' classical paper on the conversion of

dynamical into electrical energy without the aid of permanent

magnetism was read before the Royal Society. Strangely enough,

the discovery of the same principle was enunciated at the same

meeting of the Society by Sir Charles Wheatstone. ... The

starting-point of a great improvement in dynamo-electric

machines, was the discovery by Pacinotti of the ring armature

... in 1860. ... Gramme, in 1871, modified the ring armature,

and constructed the first machine, in which he made use of the

Gramme ring and the dynamic principle. In 1872,

Hefner-Alteneck, of the firm of Siemens and Halske,

constructed a machine in which the Gramme ring is replaced by

a drum armature, that is to say, by a cylinder round which

wire is wound. ... Either the Pacinotti-Gramme ring armature,

or the Hefner-Alteneck drum armature, is now adopted by nearly

all constructors of dynamo-electric machines, the parts

varying of course in minor details." The history of the dynamo

since has been one of a gradual perfection of parts, resulting

in the production of a great number of types, which can not

here even be mentioned.

A. R. von Urbanitzky,

Electricity in the Service of Man,

pages 227-242.

S. P. Thompson,

Dynamo Electrical Machines.

ELECTRICITY:

Electric Motors.

It has been known for forty years that every form of electric

motor which operated on the principle of mutual mechanical

force between a magnet and a conducting wire or coil could

also be made to act as a generator of induced currents by the

reverse operation of producing the motion mechanically. And

when, starting from the researches of Siemens, Wilde, Nollet,

Holmes and Gramme, the modern forms of magneto-electric and

dynamo-electric machines began to come into commercial use, it

was discovered that any one of the modern machines designed as

a generator of currents constituted a far more efficient

electric motor than any of the previous forms which had been

designed specially as motors.

{775}

It required no new discovery of the law of reversibility to

enable the electrician to understand this; but to convince the

world required actual experiment."

A. Guillemin, Electricity and Magnetism,

part 2, chapter 10, section 3.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1835-1889.

The Electric Railway.

"Thomas Davenport, a poor blacksmith of Brandon, Vt.,

constructed what might be termed the first electric railway.

The invention was crude and of little practical value, but the

idea was there. In 1835 he exhibited in Springfield,

Massachusetts, a small model electric engine running upon a

circular track, the circuit being furnished by primary

batteries carried in the car. Three years later, Robert

Davidson, of Aberdeen, Scotland, began his experiments in this

direction. ... He constructed quite a powerful motor, which

was mounted upon a truck. Forty battery cells, carried on the

car, furnished power to propel the motor. The battery elements

were composed of amalgamated zinc and iron plates, the

exciting liquid being dilute sulphuric acid. This locomotive

was run successfully on several steam railroads in Scotland,

the speed attained was four miles an hour, but this machine

was afterwards destroyed by some malicious person or persons

while it was being taken home to Aberdeen. In 1849 Moses

Farmer exhibited an electric engine which drew a small car

containing two persons. In 1851, Dr. Charles Grafton Page, of

Salem, Massachusetts, perfected an electric engine of

considerable power. On April 29 of that year the engine was

attached to a car and a trip was made from Washington to

Bladensburg, over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad track. The

highest speed attained was nineteen miles an hour. The

electric power was furnished by one hundred Grove cells

carried on the engine. ... The same year, Thomas Hall, of

Boston, Mass., built a small electric locomotive called the

Volta. The current was furnished by two Grove battery cells

which were conducted to the rails, thence through the wheels

of the locomotive to the motor. This was the first instance of

the current being supplied to the motor on a locomotive from a

stationary source. It was exhibited at the Charitable

Mechanics fair by him in 1860. ... In 1879, Messrs. Siemen and

Halske, of Berlin, constructed and operated an electric

railway at the Industrial Exposition. A third rail placed in

the centre of the two outer rails, supplied the current, which

was taken up into the motor through a sliding contact under

the locomotive. ... In 1880 Thomas A. Edison constructed an

experimental road near his laboratory in Menlo Park, N. J. The

power from the locomotive was transferred to the car by belts

running to and from the shafts of each. The current was taken

from and returned through the rails. Early in the year of 1881

the Lichterfelde, Germany, electric railway was put into

operation. It is a third rail system and is still running at

the present time. This may be said to be the first commercial

electric railway constructed. In 1883 the Daft Electric

Company equipped and operated quite successfully an electric

system on the Saratoga & Mt. McGregor Railroad, at Saratoga,

N. Y." During the next five or six years numerous electric

railroads, more or less experimental, were built." October 31,

1888, the Council Bluffs & Omaha Railway and Bridge Company

was first operated by electricity, they using the

Thomson-Houston system. The same year the Thomson-Houston Co.

equipped the Highland Division of the Lynn & Boston Horse

Railway at Lynn, Massachusetts. Horse railways now began to be

equipped with electricity all over the world, and especially

in the United States. In February, 1889, the Thomson-Houston

Electric Co. had equipped the line from Bowdoin Square,

Boston, to Harvard Square, Cambridge, of the West End Railway

with electricity and operated twenty cars, since which time it

has increased its electrical apparatus, until now it is the

largest electric railway line in the world."

E. Trevert,

Electric Railway Engineering,

appendix A.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1841-1880.

The Incandescent Electric Light.

"While the arc lamp is well adapted for lighting large areas

requiring a powerful, diffused light, similar to sunlight, and

hence is suitable for outdoor illumination, and for workshops,

stores, public buildings, and factories, especially those

where colored fabrics are produced, its use in ordinary

dwellings, or for a desk light in offices, is impractical, a

softer, steadier, and more economical light being required.

Various attempts to modify the arc-light by combining it with

the incandescent were made in the earlier stages of electric

lighting. ... The first strictly incandescent lamp was

invented in 1841 by Frederick de Molyens of Cheltenham,

England, and was constructed on the simple principle of the

incandescence produced by the high resistance of a platinum

wire to the passage of the electric current. In 1849 Petrie

employed iridium for the same purpose, also alloys of iridium

and platinum, and iridium and carbon. In 1845 J. W. Starr of

Cincinnati first proposed the use of carbon, and, associated

with King, his English agent, produced, through the financial

aid of the philanthropist Peabody, an incandescent lamp. ...

In all these early experiments, the battery was the source of

electric supply; and the comparatively small current required

for the incandescent light as compared with that required for

the arc light, was an argument in favor of the former. ...

Still, no substantial progress was made with either system

till the invention of the dynamo resulted in the practical

development of both systems, that of the incandescent

following that of the arc. Among the first to make

incandescent lighting a practical success were Sawyer and Man

of New York, and Edison. For a long time, Edison experimented

with platinum, using fine platinum wire coiled into a spiral,

so as to concentrate the heat, and produce incandescence; the

same current producing only a red heat when the wire, whether

of platinum or other metal, is stretched out. ... Failing to

obtain satisfactory results from platinum, Edison turned his

attention to carbon, the superiority of which as an

incandescent illuminant had already been demonstrated; but its

rapid consumption, as shown by the Reynier and similar lamps,

being unfavorable to its use as compared with the durability

of platinum and iridium, the problem was, to secure the

superior illumination of the carbon, and reduce or prevent its

consumption. As this consumption was due chiefly to oxidation,

it was questionable whether the superior illumination were not

due to the same cause, and whether, if the carbon were inclosed

in a glass globe, from which oxygen was eliminated, the same

illumination could be obtained.

{776}

Another difficulty of equal magnitude was to obtain a

sufficiently perfect vacuum, and maintain it in a hermetically

sealed globe inclosing the carbon, and at the same time

maintain electric connection with the generator through the

glass by a metal conductor, subject to expansion and

contraction different from that of the glass, by the change of

temperature due to the passage of the electric current. Sawyer

and Man attempted to solve this problem by filling the globe

with nitrogen, thus preventing combustion by eliminating the

oxygen. ... The results obtained by this method, which at one

time attracted a great deal of attention, were not

sufficiently satisfactory to become practical; and Edison and

others gave their preference to the vacuum method, and sought

to overcome the difficulties connected with it. The invention

of the mercurial air pump, with its subsequent improvements,

made it possible to obtain a sufficiently perfect vacuum, and

the difficulty of introducing the current into the interior of

the globe was overcome by imbedding a fine platinum wire in

the glass, connecting the inclosed carbon with the external

circuit; the expansion and contraction of the platinum not

differing sufficiently from that of the glass, in so fine a

wire, as to impair the vacuum. ... The carbons made by Edison

under his first patent in 1879, were obtained from brown paper

or cardboard. ... They were very fragile and short-lived, and

consequently were soon abandoned. In 1880 he patented the

process which, with some modifications, he still adheres to.

In this process he uses filaments of bamboo, which are taken

from the interior, fibrous portion of the plant."

P. Atkinson,

Elements of Electric Lighting,

chapter 8.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1854-1866.

The Atlantic Cable.

"Cyrus Field ... established a company in America (in 1854),

which ... obtained the right of landing cables in Newfoundland

for fifty years. Soundings were made in 1856 between Ireland

and Newfoundland, showing a maximum depth of 4,400 metres.

Having succeeded after several attempts in laying a cable

between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, Field founded the

Atlantic Telegraph Company in England. ... The length of the

... cable [used] was 4,000 kilometres, and was carried by the

two ships Agamemnon and Niagara. The distance between the two

stations on the coasts was 2,640 kilometres. The laying of the

cable commenced on the 7th of August, 1857, at Valentia

(Ireland); on the third day the cable broke at a depth of

3,660 metres, and the expedition had to return. A second

expedition was sent in 1858; the two ships met each other

half-way, the ends of the cable were joined, and the lowering

of it commenced in both directions; 149 kilometres were thus

lowered, when a fault in the cable was discovered. It had,

therefore, to be brought on board again, and was broken during

the process. After it had been repaired, and when 476

kilometres had been already laid, another fault was

discovered, which caused another breakage; this time it was

impossible to repair it, and the expedition was again

unsuccessful, and had to return. In spite of the repeated

failures, two ships were again sent out in the same year, and

this time one end of the cable was landed in Ireland, and the

other at Newfoundland. The length of the sunk cable was 3,745

kilometres. Field's first telegram was sent on the 7th of

August, from America to Ireland. The insulation of the cable,

however, became more defective every day, and failed

altogether on the 1st of September. From the experience

obtained, it was concluded that it was possible to lay a

trans-Atlantic cable, and the company, after consulting a

number of professional men, again set to work. ... The Great

Eastern was employed in laying this cable. This ship, which is

211 metres long, 25 metres broad, and 16 metres in height,

carried a crew of 500 men, of which 120 were electricians and

engineers, 179 mechanics and stokers, and 115 sailors. The

management of all affairs relating to the laying of the cable

was entrusted to Canning. The coast cable was laid on the 21st

of July, and the end of it was connected with the Atlantic

cable on the 23rd. After 1,326 kilometres had been laid, a

fault was discovered, an iron wire was found stuck right

across the cable, and Canning considered the mischief to have

been done with a malevolent purpose. On the 2nd of August,

2,196 kilometres of cable were sunk, when another fault was

discovered. While the cable was being repaired it broke, and

attempts to recover it at the time were all unsuccessful; in

consequence of this the Great Eastern had to return without

having completed the task. A new company, the Anglo-American

Telegraph Company, was formed in 1866, and at once entrusted

Messrs. Glass, Elliott and Company with the construction of a

new cable of 3,000 kilometres. Different arrangements were

made for the outer envelope of the cable, and the Great

Eastern was once more equipped to give effect to the

experiments which had just been made. The new expedition was

not only to lay a new cable, but also to take up the end of

the old one, and join it to a new piece, and thus obtain a

second telegraph line. The sinking again commenced in Ireland

on the 13th of July, 1866, and it was finished on the 27th. On

the 4th of August, 1866, the Trans-Atlantic Telegraph Line was

declared open."

A. R. von Urbanitzky,

Electricity in the Service of Man,

pages 767-768.

ELECTRICITY: A. D. 1876-1892.

The Telephone.

"The first and simplest of all magnetic telephones is the Bell

Telephone." In "the first form of this instrument, constructed

by Professor Graham Bell, in 1876 ... a harp of steel rods was

attached to the poles of a permanent magnet. ... When we sing

into a piano, certain of the strings of the instrument are set

in vibration sympathetically by the action of the voice with

different degrees of amplitude, and a sound, which is an

approximation to the vowel uttered, is produced from the

piano. Theory shows that, had the piano a much larger number

of strings to the octave, the vowel sounds would be perfectly

reproduced. It was upon this principle that Bell constructed

his first telephone. The expense of constructing such an

apparatus, however, deterred Bell from making the attempt, and

he sought to simplify the apparatus before proceeding further in

this direction. After many experiments with more, or less

unsatisfactory results, he constructed the instrument ...

which he exhibited at Philadelphia in 1876. In this apparatus,

the transmitter was formed by an electro-magnet, through which

a current flowed, and a membrane, made of gold-beater's skin,

on which was placed as a sort of armature, a piece of soft

iron, which thus vibrated in front of the electro-magnet when

the membrane was thrown into sonorous vibration.

{777}

... It is quite clear that when we speak into a Bell

transmitter only a small fraction of the energy of the

sonorous vibrations of the voice can be converted into

electric currents, and that these currents must be extremely

weak. Edison applied himself to discover some means by which

he could increase the strength of these currents. Elisha Gray

had proposed to use the variation of resistance of a fine

platinum wire attached to a diaphragm dipping into water, and

hoped that the variation of extent of surface in contact would

so vary the strength of current as to reproduce sonorous

vibrations; but there is no record of this experiment having

been tried. Edison proposed to utilise the fact that the

resistance of carbon varied under pressure. He had

independently discovered this peculiarity of carbon, but it

had been previously described by Du Moncel. ... The first

carbon transmitter was constructed in 1878 by Edison."

W. H. Preece, and J. Maier,

The Telephone,

chapter 3-4.

In a pamphlet distributed at the Columbian Exposition,

Chicago, 1893, entitled "Exhibit of the American Bell

Telephone Co.," the following statements are made: "At the

Centennial Exposition, in Philadelphia, in 1876, was given the

first general public exhibition of the telephone by its

inventor, Alexander Graham Bell. To-day, seventeen years

later, more than half a million instruments are in daily use

in the United States alone, six hundred million talks by

telephone are held every year, and the human voice is carried

over a distance of twelve hundred miles without loss of sound

or syllable. The first use of the telephone for business

purposes was over a single wire connecting only two

telephones. At once the need of general inter-communication

made itself felt. In the cities and larger towns exchanges

were established and all the subscribers to any one exchange

were enabled to talk to one another through a central office.

Means were then devised to connect two or more exchanges by

trunk lines, thus affording means of communication between all

the subscribers of all the exchanges so connected. This work

has been pushed forward until now have been gathered into what

may be termed one great exchange all the important cities from

Augusta on the east to Milwaukee on the west, and from

Burlington and Buffalo on the north to Washington on the

south, bringing more than one half the people of this country

and a much larger proportion of the business interests, within

talking distance of one another. ... The lines which connect

Chicago with Boston, via New York, are of copper wire of extra

size. It is about one sixth of an inch in diameter, and weighs

435 pounds to the mile. Hence each circuit contains 1,044,000

pounds of copper. ... In the United States there are over a

quarter of a million exchange subscribers, and ... these make

use of the telephone to carry on 600,000,000 conversations

annually. There is hardly a city or town of 5,000 inhabitants

that has not its Telephone Exchange, and these are so knit

together by connecting lines that intercommunication is

constant." The number of telephones in use in the United

States, on the 20th of December in each year since the first

introduction, is given as follows;

1877, 5,187;

1878, 17,567;

1879, 52,517;

1880, 123,380;

1881, 180,592;

1882, 237,728;

1883, 298,580;

1884, 325,574;

1885, 330,040;

1886, 353,518;

1887, 380,277;

1888, 411,511;

1889, 444,861;

1890, 483,790;

1891, 512,407;

1892, 552,720.

----------End: Electricity----------

ELEPHANT, Order of the.

A Danish order of knighthood instituted in 1693 by

King Christian V.

ELEPHANTINE.

See EGYPT: THE OLD EMPIRE AND THE MIDDLE EMPIRE.

ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES, The.

Among the ancient Greeks, "the mysteries were a source of

faith and hope to the initiated, as are the churches of modern

times. Secret doctrines, regarded as holy, and to be kept with

inviolable fidelity, were handed down in these brotherhoods,

and no doubt were fondly believed to contain a saving grace by

those who were admitted, amidst solemn and imposing rites,

under the veil of midnight, to hear the tenets of the ancient

faith, and the promises of blessings to come to those who,

with sincerity of heart and pious trust, took the obligations

upon them. The Eleusinian mysteries were the most imposing and

venerable. Their origin extended back into a mythical

antiquity, and they were among the few forms of Greek worship

which were under the superintendence of hereditary

priesthoods. Thirlwall thinks that 'they were the remains of a

worship which preceded the rise of the Hellenic mythology and

its attendant rites, grounded on a view of Nature less

fanciful, more earnest, and better fitted to awaken both

philosophical thought and religious feeling.' This conclusion

is still further confirmed by the moral and religious tone of

the poets,--such as Æschylus,--whose ideas on justice, sin and

retribution are as solemn and elevated as those of a Hebrew

prophet. The secrets, whatever they were, were never revealed

in express terms; but Isocrates uses some remarkable

expressions, when speaking of their importance to the

condition of man. 'Those who are initiated,' says he

'entertain sweeter hopes of eternal life'; and how could this

be the case, unless there were imparted at Eleusis the

doctrine of eternal life, and some idea of its state and

circumstances more compatible with an elevated conception of

the Deity and of the human soul than the vague and shadowy

images which haunted the popular mind. The Eleusinian

communion embraced the most eminent men from every part of

Greece,--statesmen, poets, philosophers, and generals; and

when Greece became a part of the Roman Empire, the greatest

minds of Rome drew instruction and consolation from its

doctrines. The ceremonies of initiation--which took place

every year in the early autumn, a beautiful season in

Attica--were a splendid ritual, attracting visitors from every

part of the world. The processions moving from Athens to

Eleusis over the Sacred Way, sometimes numbered twenty or

thirty thousand people, and the exciting scenes were well

calculated to leave a durable impression on susceptible minds.

... The formula of the dismissal, after the initiation was

over, consisted in the mysterious words 'konx,' 'ompax'; and

this is the only Eleusinian secret that has illuminated the

world from the recesses of the temple of Demeter and

Persephone. But it is a striking illustration of the value

attached to these rites and doctrines, that, in moments of

extremest peril--as of impending shipwreck, or massacre by a

victorious enemy,--men asked one another, 'Are you initiated?'

as if this were the anchor of their hopes for another life."

{778}

C. C. Felton,

Greece, Ancient and Modern,

chapter 2, lecture 10.

"The Eleusinian mysteries continued to be celebrated during

the whole of the second half of the fourth century, till they

were put an end to by the destruction of the temple at

Eleusis, and by the devastation of Greece in the invasion of

the Goths under Alaric in 395."

See GOTHS: A. D. 395.

W. Smith,

Note to Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,

chapter 25.

ALSO IN:

R. Brown,

The Great Dionysiak Myth,

chapter 6, section. 2.

J. J. I. von Dollinger,

The Gentile and the Jew,

book 3 (volume 1).

See, also, ELEUSIS.

ELEUSIS.

Eleusis was originally one of the twelve confederate townships

into which Attica was said to have been divided before the

time of Theseus. It "was advantageously situated [about

fourteen miles Northwest of Athens] on a height, at a small

distance from the shore of an extensive bay, to which there is

access only through narrow channels, at the two extremities of

the island of Salamis: its position was important, as

commanding the shortest and most level route by land from

Athens to the Isthmus by the pass which leads at the foot of

Mount Cerata along the shore to Megara. ... Eleusis was built

at the eastern end of a low rocky hill, which lies parallel to

the sea-shore. ... The eastern extremity of the hill was

levelled artificially for the reception of the Hierum of Ceres

and the other sacred buildings. Above these are the traces of an

Acropolis. A triangular space of about 500 yards each side,

lying between the hill and the shore, was occupied by the town

of Eleusis. ... To those who approached Eleusis from Athens,

the sacred buildings standing on the eastern extremity of the

height concealed the greater part of the town, and on a nearer

approach presented a succession of magnificent objects, well

calculated to heighten the solemn grandeur of the ceremonies

and the awe and reverence of the Mystæ in their initiation.

... In the plurality of enclosures, in the magnificence of the

pylæ or gateways, in the absence of any general symmetry of

plan, in the small auxiliary temples, we recognize a great

resemblance between the sacred buildings of Eleusis and the

Egyptian Hiera of Thebes and Philæ. And this resemblance is

the more remarkable, as the Demeter of Attica was the Isis of

Egypt. We cannot suppose, however, that the plan of all these

buildings was even thought of when the worship of Ceres was

established at Eleusis. They were the progressive creation of

successive ages. ... Under the Roman Empire ... it was

fashionable among the higher order of Romans to pass some time

at Athens in the study of philosophy and to be initiated in

the Eleusinian mysteries. Hence Eleusis became at that time

one of the most frequented places in Greece; and perhaps it

was never so populous as under the emperors of the first two

centuries of our æra. During the two following centuries, its

mysteries were the chief support of declining polytheism, and

almost the only remaining bond of national union among the

Greeks; but at length the destructive visit of the Goths in

the year 396, the extinction of paganism and the ruin of

maritime commerce, left Eleusis deprived of every source of

prosperity, except those which are inseparable from its

fertile plain, its noble bay, and its position on the road

from Attica to the Isthmus. ... The village still preserves

the ancient name, no further altered than is customary in

Romaic conversions."

W. M. Leake,

Topography of Athens;

volume 2: The Demi, section 5.

ELGIN, Lord.

The Indian administration of.

See INDIA: A. D. 1862-1876.

ELIS.

Elis was an ancient Greek state, occupying the country on the

western coast of Peloponnesus, adjoining Arcadia, and between

Messenia at the south and Achaia on the north. It was noted

for the fertility of its soil and the rich yield of its

fisheries. But Elis owed greater importance to the inclusion

within its territory of the sacred ground of Olympia, where

the celebration of the most famous festival of Zeus came to be

established at an early time. The Elians had acquired Olympia

by conquest of the city and territory of Pisa, to which it

originally belonged, and the presidency of the Olympic games

was always disputed with them by the latter. Elis was the

close ally of Sparta down to the year B. C. 421, when a bitter

quarrel arose between them, and Elis suffered heavily in the

wars which ensued. It was afterwards at war with the

Arcadians, and joined the Ætolian League against the Achaian

League. The city of Elis was one of the most splendid in

Greece; but little now remains, even of ruins, to indicate its

departed glories.

See, also, OLYMPIC GAMES.

ELISII, The.

See LYGIANS.

ELIZABETH,

Czarina of Russia, A. D. 1741-1761..

Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia, and the Thirty Years War.

See GERMANY: A. D. 1618-1620; 1620; 1621-1623;

1631-1632, and 1648.

Elizabeth, Queen of England, A. D. 1558-1603.

Elizabeth Farnese, Queen of Spain.

See ITALY: A. D. 1715-1735; and

SPAIN: A. D. 1713-1725, and 1726-1731.

ELIZABETH, N. J.

The first settlement of.

See NEW JERSEY: A. D. 1664-1667.

ELK HORN, OR PEA RIDGE, Battle of.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1862 (JANUARY-MARCH: MISSOURI-ARKANSAS).

ELKWATER, OR CHEAT SUMMIT, Battle of.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1861 (AUGUST-DECEMBER: WEST VIRGINIA).

ELLANDUM, Battle of.

Decisive victory of Ecgberht, the West Saxon king, over the

Mercians, A. D. 823.

ELLEBRI, The.

See IRELAND, TRIBES OF EARLY CELTIC INHABITANTS.

ELLENBOROUGH, Lord, The Indian administration of.

See INDIA: A. D. 1836-1845.

ELLSWORTH, Colonel, The death of.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1861 (MAY: VIRGINIA).

ELMET.

A small kingdom of the Britons which was swallowed up in the

English kingdom of Northumbria early in the seventh century.

It answered, roughly speaking, to the present West-Riding of

Yorkshire. ... Leeds "preserves the name of Loidis, by which

Elmet seems also to have been known."

J. R. Green, The Making of England, page 254.

ELMIRA, N. Y. (then Newtown).

General Sullivan's Battle with the Senecas.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1779 (AUGUST-SEPTEMBER).

ELSASS.

See ALSACE.

ELTEKEH, Battle of.

A victory won by the Assyrian, Sennacherib, over the

Egyptians, before the disaster befell his army which is

related in 2 Kings xix. 35. Sennacherib's own account of the

battle has been found among the Assyrian records.

{779}

A. H. Sayce,

Fresh Light from the Ancient Monuments,

chapter 6.

ELUSATES, The.

See AQUITAINE, TRIBES OF ANCIENT.

ELVIRA, Battle of(1319).

See SPAIN: A. D. 1273-1460.

ELY, The Camp of Refuge at.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1069-1071.

ELYMAIS.

See ELAM.

ELYMEIA.

See MACEDONIA.

ELYMIANS, The.

See SICILY: EARLY INHABITANTS.

ELYSIAN FIELDS.

See CANARY ISLANDS.

ELZEVIRS.

See PRINTING: A. D. 1617-1680.

EMANCIPATION, Catholic.

See IRELAND: A. D. 1811-1829.

EMANCIPATION, Compensated;

Proposal of President Lincoln.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1862 (MARCH).

EMANCIPATION, Prussian Edict of.

See GERMANY: A. D. 1807-1808.

EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATIONS,

President Lincoln's.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1862 (SEPTEMBER), and 1863 (JANUARY).

EMANUEL,

King of Portugal, A. D. 1495-1521.

Emanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, A. D. 1553-1580.

EMBARGO OF 1807, The American.