FROM

IMMIGRANT TO INVENTOR

BY

MICHAEL PUPIN

PROFESSOR OF ELECTRO-MECHANICS, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

NEW YORK · LONDON

1949

Copyright, 1922, 1923, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Printed in the United States of America

Published September, 1923

Reprinted November, 1928; January, March, 1924

July, 1924

TO THE MEMORY OF

MY MOTHER

Looking back over the development of this volume throughout the year or more during which I have been writing it, it seems to me that I cannot better express the end I have had in view than to repeat here what I wrote at the beginning of Chapter XI:

“The main object of my narrative was, and still is, to describe the rise of idealism in American science, and particularly in physical sciences and the related industries. I was a witness to this gradual development; everything that I have described so far was an attempt to qualify as a witness whose testimony has competence and weight. But there are many other American scientists whose opinions in this matter have more competence and weight than my opinion has. Why, then, should a scientist who started his career as a Serbian immigrant speak of the idealism in American science when there are so many native-born American scientists who know more about this subject than I do? Those who have read my narrative so far can answer this question. I shall only point out now that there are certain psychological elements in the question which justify me in the belief that occasionally an immigrant can see things which escape the attention of the native. Seeing is believing; let him speak who has the faith, provided that he has a message to deliver.”

Michael Pupin.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | What I Brought to America | 1 |

| II. | The Hardships of a Greenhorn | 43 |

| III. | The End of the Apprenticeship as Greenhorn | 72 |

| IV. | From Greenhorn to Citizenship and College Degree | 100 |

| V. | First Journey to Idvor in Eleven Years | 138 |

| VI. | Studies at the University of Cambridge | 167 |

| VII. | End of Studies at the University of Cambridge | 192 |

| VIII. | Studies at the University of Berlin | 218 |

| IX. | End of Studies at the University of Berlin | 247 |

| X. | The First Period of My Academic Career at Columbia University | 279 |

| XI. | The Rise of Idealism in American Science | 311 |

| XII. | The National Research Council | 349 |

| Index | 389 | |

| Michael Pupin | Frontispiece |

| Pupin’s Birthplace | FACING PAGE 4 |

| The Old Monument on Staro Selo | 4 |

| Olympiada Pupin, Mother of Michael Pupin | 10 |

| The Village Church in Idvor | 36 |

| Nassau Hall, Princeton University | 68 |

| An Early View of Cooper Union | 74 |

| Men of Progress—American Inventors | 78 |

| Photograph of Pupin Taken in 1883 | 136 |

| Joseph Henry | 204 |

| John Tyndall | 204 |

| Michael Faraday | 220 |

| Herman von Helmholtz | 232 |

| The Hertzian Oscillator | page 265 |

| Henry Augustus Rowland | 290 |

| James Clerk Maxwell | 290 |

| Electrical Discharges Representing Two Types of Solar Coronæ | 294 |

| Solar Corona of 1922 | 294 |

| Sir J. J. Thomson | 306 |

| Wilhelm Konrad Rœntgen | 306 |

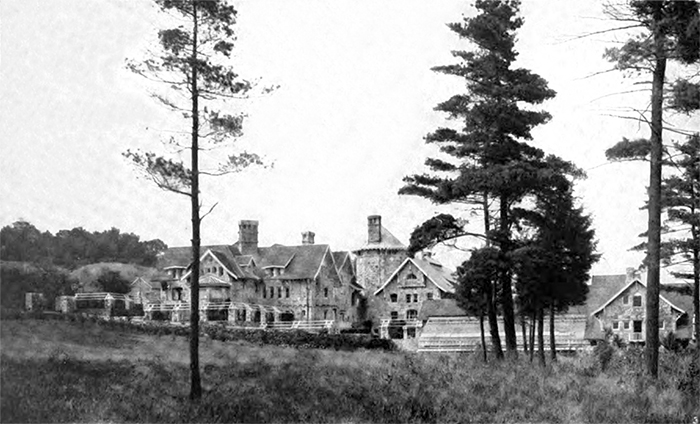

| Pupin’s Residence at Norfolk, Conn. | 328 |

| Dr. George Ellery Hale, Honorary Chairman of the National Research Council | 372 |

| The National Research Council Building, Washington, D. C. | 372 |

| Facsimile of Letter from President Harding | page 386 |

When I landed at Castle Garden, forty-eight years ago, I had only five cents in my pocket. Had I brought five hundred dollars, instead of five cents, my immediate career in the new, and to me a perfectly strange, land would have been the same. A young immigrant such as I was then does not begin his career until he has spent all the money which he has brought with him. I brought five cents, and immediately spent it upon a piece of prune pie, which turned out to be a bogus prune pie. It contained nothing but pits of prunes. If I had brought five hundred dollars, it would have taken me a little longer to spend it, mostly upon bogus things, but the struggle which awaited me would have been the same in each case. It is no handicap to a boy immigrant to land here penniless; it is not a handicap to any boy to be penniless when he strikes out for an independent career, provided that he has the stamina to stand the hardships that may be in store for him.

A thorough training in the arts and crafts and a sturdy physique capable of standing the hardships of strenuous labor do entitle the immigrant to special considerations. But what has a young and penniless immigrant to offer who has had no training in any of the arts or crafts and does not know the language of the land? Apparently2 nothing, and if the present standards had prevailed forty-eight years ago I should have been deported. There are, however, certain things which a young immigrant may bring to this country that are far more precious than any of the things which the present immigration laws prescribe. Did I bring any of these things with me when I landed at Castle Garden in 1874? I shall try to answer this question in the following brief story of my life prior to my landing in this country.

Idvor is my native town; but the disclosure of this fact discloses very little, because Idvor cannot be found on any map. It is a little village off the highway in the province of Banat, formerly belonging to Austria-Hungary, but now an important part of the kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. At the Paris peace conference, in 1919, the Rumanians claimed this province; they claimed it in vain. They could not overcome the fact that the population of Banat is Serb, and particularly of that part of Banat where Idvor is located. President Wilson and Mr. Lansing knew me personally, and when they were informed by the Yugoslav delegates in Paris that I was a native of Banat, the Rumanian arguments lost much of their plausibility. No other nationality except the Serb has ever lived in Idvor. The inhabitants of Idvor were always peasants; most of them were illiterate in my boyhood days. My father and mother could neither read nor write. The question arises now: What could a penniless boy of fifteen, born and bred under such conditions, bring to America, which under any conceivable immigration laws would entitle him to land? But I was confident that I was so desirable an acquisition to America that I should be allowed to land, and I was somewhat surprised that people made no fuss over me when I landed.

The Serbs of Idvor from time immemorial always considered themselves the brothers of the Serbs of Serbia,3 who are only a few gunshots away from Idvor on the south side of the Danube. The Avala Mountain, near Belgrade in Serbia, can easily be seen from Idvor on every clear day. This blue and, to me at that time, mysterious-looking peak seemed always like a reminder to the Serbs of Banat that the Serbs of Serbia were keeping an eye of affectionate watchfulness upon them.

When I was a boy Idvor belonged to the so-called military frontier of Austria. A bit of interesting history is attached to this name. Up to the beginning of the eighteenth century the Austrian Empire was harassed by Turkish invasions. At periodically recurring intervals Turkish armies would cross her southern frontier, formed by the Rivers Danube and Sava, and penetrate into the interior provinces. Toward the end of the seventeenth century they advanced as far as Vienna, and would have become a serious menace to the whole of Europe if the Polish king Sobiesky had not come to the rescue of Vienna. It was at that time that Emperor Leopold I, of Austria, invited Charnoyevich, the Serb Patriarch of Pech, in old Serbia, to move with thirty-five thousand picked families of old Serbia into the Austrian territory north of the Danube and the Sava Rivers, to become its guardians. For three hundred years these Serbs had been fighting the Turks and had acquired great skill in this kind of warfare. In 1690 the Patriarch with these picked families moved into Austria and settled in a narrow strip of territory on the northern banks of these two rivers. They organized what was known later as the military frontier of Austria. 1690 is, according to tradition, the date when my native village Idvor was founded, but not quite on its present site. The original site is a very small plateau a little to the north of the present site.

Banat is a perfectly level plain, but near the village of Idvor the River Tamish has dug out a miniature canyon, and on the plateau of one of the promontories of this4 canyon was the old site of Idvor. It is connected to the new site by a narrow neck. The old site was selected because it offered many strategical advantages of defense against the invading Turk. The first settlers of the old village lived in subterranean houses which could not be seen at a distance by the approaching enemy. Remnants of these subterranean houses were still in existence when I was a schoolboy in the village of Idvor, over fifty years ago. The location of the original church was marked by a little column built of bricks and bearing a cross. In a recess on the side of the column was the image of St. Mary with the Christ Child, illuminated by a burning wick immersed in oil. The legend was that this flame was never allowed to go out, and that a religious procession by the good people of Idvor to the old monument was sure to avert any calamity, like pestilence or drought, that might be threatening the village. I took part in many of these processions to the old deserted village, and felt every time that I was standing upon sacred ground; sacred because of the Christian blood shed there during the struggles of the Christian Serbs of Idvor against the Turkish invaders. Every visit to the old village site refreshed the memories of the heroic traditions of which the village people were extremely proud. They were poor in worldly goods, those simple peasant folk of Idvor, but they were rich in memories of their ancient traditions.

As I look back upon my childhood days in the village of Idvor, I feel that the cultivation of old traditions was the principal element in the spiritual life of the village people. The knowledge of these traditions was necessary and sufficient to them, in order to understand their position in the world and in the Austrian Empire. When my people moved into Austria under Patriarch Charnoyevich and settled in the military frontier, they had a definite agreement with Emperor Leopold I. It was recorded in an Austrian state document called Privilegia. According to5 this ancient document the Serbs of the military frontier were to enjoy a spiritual, economic, and political autonomy. Lands granted to them were their own property. In our village we maintained our own schools and our own churches, and each village elected its own local administration. Its head was the Knez, or chief, usually a sturdy peasant. My father was a Knez several times. The bishops and the people elected their own spiritual and political heads, that is, the Patriarch and the Voyvoda (governor). We were free and independent peasant landlords. In return for these privileges, the people obligated themselves to render military service for the defense of the southern frontiers of the empire against the invading Turks. They had helped to drive the Turks across the Danube, under the supreme command of Prince Eugene of Savoy, in the beginning of the eighteenth century. After the emperor had discovered the splendid fighting qualities of the Serbs of the military frontier, he managed to extend the original terms of the Privilegia so as to make it obligatory upon the military frontiersmen to defend the empire against any and every enemy. Subsequently the Serbs of the military frontier of Austria defended Empress Maria Theresa against Frederick the Great; they defended Emperor Francis against Napoleon; they defended Emperor Ferdinand against the rebellious Hungarians in 1848 and 1849; and in 1859 and 1866 they defended Austria against Italy. The military exploits of the men of Idvor during these wars supplied material for the traditions of Idvor, which were recorded in many tales and stirring songs. Reading and writing did not flourish in Idvor in those days, but poetry did.

Faithful to the old customs of the Serb race, the people of Idvor held during the long winter evenings their neighborhood gatherings, and as a boy I attended many of them at my father’s house. The older men would sit6 around the warm stove on a bench which was a part of the stove and made of the same material, usually soft brick plastered over and whitewashed. They smoked and talked and looked like old senators, self-appointed guardians of all the wisdom of Idvor. At the feet of the old men were middle-aged men, seated upon low stools, each with a basket in front of him, into which he peeled the yellow kernels from the seasoned ears of corn, and this kept him busy during the evening. The older women were seated on little stools along the wall; they would be spinning wool, flax, or hemp. The young women would be sewing or knitting. I, a favorite child of my mother, was allowed to sit alongside of her and listen to the words of wisdom and words of fiction dropping from the mouths of the old men and sometimes also from the mouths of the middle-aged and younger men, when the old men gave them permission to speak. At intervals the young women would sing a song having some relation to the last tale. For instance, when one of the old men had finished a tale about Karageorge and his historic struggles against the Turks, the women would follow with a song describing a brave Voyvoda of Karageorge, named Hayduk Velyko, who with a small band of Serbians defended Negotin against a great Turkish army under Moula Pasha. This gallant band, as the song describes them, reminds one of the little band of Greeks at Thermopylæ.

Some of the old men present at these gatherings had taken part in the Napoleonic wars, and they remembered well also the stories which they had heard from their fathers relating to the wars of Austria against Frederick the Great during the eighteenth century. The middle-aged men had participated in the fighting during the Hungarian revolution, and the younger men had just gone through the campaigns in Italy in 1859 and 1866. One of the old men had taken part in the battle of Aspern,7 when Austria defeated Napoleon. He had received a high imperial decoration for bravery, and was very proud of it. He also had gone to Russia with an Austrian division during Napoleon’s campaign of 1812. His name was Baba Batikin, and in the estimation of the village people he was a seer and a prophet, because of his wonderful memory and his extraordinary power of description. His diction was that of a guslar (Serbian minstrel). He not only described vividly what went on in Austria and in Russia during the Napoleonic wars in which he himself participated, but he would also thrill his hearers by tales relating to the Austrian campaigns against Frederick the Great, which his father upon his return from the battle-fields of Silesia had related to him. I remember quite well his stories relating to Karageorge of Serbia, whom he had known personally. He called him the great Vozhd, or leader of the Serbian peasants, and never grew weary of describing his heroic struggles against the Turks in the beginning of the nineteenth century. These tales about Karageorge were always received at the neighborhood gatherings with more enthusiasm than any other of his stirring narratives. Toward the end of the evening Baba Batikin would recite some of the old Serbian ballads, many of which he knew by heart. During these recitations his thin and wrinkled face would light up; it was the face of a seer, as I remember it, and I can see now his bald head with a wonderful brow, towering over bushy eyebrows through which the light of his deep-set eyes would shine like the light of the moon through the needles of an aged pine. It was from him that the good people of Idvor learned the history of the Serb race from the battle of the field of Kossovo in 1389 down to Karageorge. He kept alive the old Serb traditions in the village of Idvor. He was my first and my best teacher in history.

The younger men told tales relating to Austrian campaigns8 in Italy, glorifying the deeds of valor of the men of Idvor in these campaigns. The battle of Custozza in 1866, in which the military frontiersmen nearly annihilated the Italian armies, received a great deal of attention, because the men who described it had participated in it, and had just returned from Italy. But I remember that every one of those men was full of praise of Garibaldi, the leader of the Italian people in their struggles for freedom. They called him the Karageorge of Italy. I remember also that in my father’s house, in which these winter-evening gatherings took place, there was a colored picture of Garibaldi with his red shirt and a plumed hat. The picture was hung up alongside of the Ikona, the picture of our patron saint; on the other side of the Ikona was the picture of the Czar of Russia, who only a few years before had emancipated the Russian serfs. In the same room and hanging in a very conspicuous place all by itself was a picture of Karageorge, the leader of the Serbian revolution. The picture of the Austrian emperor was not there after 1869!

The Serb ballads recited by Baba Batikin glorified the great national hero, Prince Marko, whose combats were the combats of a strong man in defense of the weak and of the oppressed. Marko, although a prince of royal blood, never fought for conquest of territory. According to the guslar, Prince Marko was a true champion of right and justice. At that time the Civil War in America had just come to a close, and the name of Lincoln, whenever mentioned by Baba Batikin, suggested an American Prince Marko. The impressions which I carried away from these neighborhood gatherings were a spiritual food which nourished in my young mind the sentiment that the noblest thing in this world is the struggle for right, justice, and freedom. It was the love of freedom and of right and justice which made the Serbs of the military frontier desert their ancestral homes in old Serbia and9 move into Austria, where they gladly consented to live in subterranean houses and crawl like woodchucks under the ground as long as they could enjoy the blessings of political freedom.

The military frontiersmen had their freedom guaranteed to them by the Privilegia, and, in exchange for their freedom, they were always ready to fight for the Emperor of Austria on any battle-field. Loyalty to the emperor was the cardinal virtue of the military frontiersmen. It was that loyalty which overcame their admiration for Garibaldi in 1866; hence the Austrian victory at Custozza. The Emperor of Austria as a guardian of their freedom received a place of honor in the selected class of men like Prince Marko, Karageorge, Czar Alexander the Liberator, Lincoln, and Garibaldi. These were the names recorded in the Hall of Fame of Idvor. When, however, the emperor, in 1869, dissolved the military frontier and delivered its people to the Hungarians, the military frontiersmen felt that they were betrayed by the emperor, who had broken his faith to them recorded in the Privilegia. I remember my father saying to me one day: “Thou shalt never be a soldier in the emperor’s army. The emperor has broken his word; the emperor is a traitor in the eyes of the military frontiersmen. We despise the man who is not true to his word.” This is the reason why the picture of the Emperor of Austria was not allowed a place in my father’s house after 1869.

As I look back upon those days I feel, as I always felt, that this treacherous act of the Austrian emperor in 1869 was the beginning of the end of the Austrian Empire. It was the beginning of nationalism in the realm of Emperor Francis Joseph of Hapsburg. The love of the people for the country in which they lived began to languish and finally died. When that love dies, the country10 also must die. This was the lesson which I learned from the illiterate peasants of Idvor.

My teacher in the village school never succeeded in making upon my mind that profound impression which was made upon it by the men at the neighborhood gatherings. They were men who had gone out into the world and taken an active part in the struggles of the world. Reading, writing, and arithmetic appeared to me like instruments of torture which the teacher, who, in my opinion at that time, knew nothing of the world, had invented in order to interfere as much as possible with my freedom, particularly when I had an important engagement with my chums and playmates. But my mother soon convinced me that I was wrong. She could neither read nor write, and she told me that she always felt that she was blind, in spite of the clear vision of her eyes. So blind, indeed, that, as she expressed it, she did not dare venture into the world much beyond the confines of my native village. This was as far as I remember now the mode of reasoning which she would address to me: “My boy, if you wish to go out into the world about which you hear so much at the neighborhood gatherings, you must provide yourself with another pair of eyes; the eyes of reading and writing. There is so much wonderful knowledge and learning in the world which you cannot get unless you can read and write. Knowledge is the golden ladder over which we climb to heaven; knowledge is the light which illuminates our path through this life and leads to a future life of everlasting glory.” She was a very pious woman, and had a rare knowledge of both the Old and the New Testaments. The Psalms were her favorite recitations. She knew also the lives of saints. St. Sava was her favorite saint. She was the first to make me understand the story of the life of this wonderful Serb. This, briefly stated, was the story which she told me: Sava was the youngest son of the Serb Zhupan11 Nemanya. At an early age he renounced his royal titles and retired to a monastery on Mount Athos and devoted many years to study and meditation. He then returned to his native land, in the beginning of the thirteenth century, and became the first Serbian archbishop and founded an autonomous Serbian church. He also organized public schools in his father’s realm, where Serbian boys and girls had an opportunity to learn how to read and write. Thus he opened the eyes of the Serbian people, and the people in grateful recognition of these great services called him St. Sava the Educator, and praised forever his saintly name and memory. Seven hundred years had passed since St. Sava’s time, but not one of them had passed without a memorial celebration dedicated to him in every town and in every home where a Serb lived.

This was a revelation to me. Like every schoolboy, I attended, of course, every year in January, the celebrations of St. Sava’s day. On these occasions we unruly boys made fun of the big boy who in a trembling and awkward voice was reciting something about St. Sava, which the teacher had written out for him. After this recitation, the teacher, with a funny nasal twang, would do his best to supplement in a badly articulated speech what he had written out for the big boy, and finally the drowsy-looking priest would wind up with a sermon bristling with archaic Slavonic church expressions, which to us unruly boys sounded like awkward attempts of a Slovak mouse-trap dealer to speak Serbian. Our giggling merriment then reached a climax, and so my mischievous chums never gave me a chance to catch the real meaning of the ceremonies on St. Sava’s day. My mother’s story of St. Sava and the way in which she told it made the image of St. Sava appear before me for the first time in the light of a saint who glorified the value of books and of the art of writing. I understood then why mother placed such value upon reading and writing. I vowed to devote myself to both, even if that should make it necessary to neglect my12 chums and playmates, and soon I convinced my mother that in reading and writing I could do at least as well as any boy. The teacher observed the change; he was astonished, and actually believed that a miracle had occurred. My mother believed in miracles, and told the teacher that the spirit of St. Sava was guiding me. One day she told him in my presence that in a dream she saw St. Sava lay his hands upon my head, and then turning to her say: “Daughter Piada, your boy will soon outgrow the village school of Idvor. Let him then go out into the world, where he can find more brain food for his hungry head.” Next year the teacher selected me to make the recitation on St. Sava’s day, and he wrote out the speech for me. My mother amended and amplified it and made me rehearse it for her over and over again. On St. Sava’s day the first public speech of my life was delivered by me. The success was overwhelming. My chums, the unruly boys, did not giggle; on the contrary, they looked interested, and that encouraged me much. The people said to each other that even old Baba Batikin could not have done much better. My mother cried for joy; my teacher shook his head, and the priest looked puzzled, and they both admitted that I had outgrown the village school of Idvor.

At the end of that year my mother prevailed upon my father to send me to a higher school in the town of Panchevo, on the Tamish River, about fifteen miles south of Idvor, quite near the point where the Tamish flows into the Danube. There I found teachers whose learning made a deep impression upon me, particularly their learning in natural science, a subject entirely unknown in Idvor. There I heard for the first time that an American named Franklin, operating with a kite and a key, had discovered that lightning was a passage of an electrical spark between clouds, and that thunder was due to the sudden13 expansion of the atmosphere heated by the passage of the electrical spark. The story was illustrated by an actual frictional electrical machine. This information thrilled me; it was so novel and so simple, I thought, and so contrary to all my previous notions. During my visit home I eagerly took the first opportunity to describe this new knowledge to my father and his peasant friends, who were seated in front of our house and were enjoying their Sunday-afternoon talks. I suddenly observed that my father and his friends looked at each other in utter astonishment. They seemed to ask each other the question: “What heresy may this be which this impudent brat is disclosing to us?” And then my father, glaring at me, asked whether I had forgotten that he had told me on so many occasions that thunder was due to the rumbling of St. Elijah’s car as he drove across the heavens, and whether I thought that this American Franklin, who played with kites like an idle boy, knew more than the wisest men of Idvor. I always had a great respect for my father’s opinions, but on that occasion I could not help smiling with a smile of ill-concealed irony which angered him. When I saw the flame of anger in his big black eyes I jumped and ran for safety. During supper my father, whose anger had cooled considerably, described to my mother the heresy which I was preaching on that afternoon. My mother observed that nowhere in the Holy Scriptures could he find support of the St. Elijah legend, and that it was quite possible that the American Franklin was right and that the St. Elijah legend was wrong. In matters of correct interpretation of ancient authorities my father was always ready to abide by the decisions of my mother, and so father and I became reconciled again. My mother’s admission of the possibility that the American Franklin might, after all, be wiser than all the wise men of Idvor, and my father’s silent consent, aroused in me a keen interest in America. Lincoln and Franklin14 were two names with which my early ideas of America were associated.

During those school-days in Panchevo I passed my summer vacation in my native village. Idvor, just like the rest of Banat, lives principally from agriculture, and during harvest-time it is as busy as a beehive. Old and young, man and beast, concentrate all their efforts upon the harvest operations. But nobody is busier than the Serbian ox. He is the most loyal and effective servant of the Serb peasant everywhere, and particularly in Banat. He does all the ploughing in the spring, and he hauls the seasoned grain from the distant fertile fields to the threshing-grounds in the village when the harvesting season is on. The commencement of the threshing operations marks the end of the strenuous efforts of the good old ox; his summer vacation begins, and he is sent to pasture-lands to feed and to rest and to prepare himself for autumn hauling of the yellow corn and for the autumn ploughing of the fields. The village boys who are not big enough to render much help on the threshing-grounds are assigned to the task of watching over the grazing oxen during their summer vacation. The school vacation of the boys coincided with the vacation of the good old ox. Several summers I passed in that interesting occupation. These were my only summer schools, and they were the most interesting schools that I ever attended.

The oxen of the village were divided into herds of about fifty head, and each herd was guarded by a squad of some twelve boys from families owning the oxen in the herd. Each squad was under the command of a young man who was an experienced herdsman. To watch a herd of fifty oxen was not an easy task. In daytime the job was easy, because the heat of the summer sun and the torments of the ever-busy fly made the oxen hug the shade of the trees, where they rested awaiting the cooler hours of the day. At night, however, the task was much more difficult. Being15 forced to hug the shade of the trees during daytime, the oxen would get but little enjoyment of the pasture, and so when the night arrived they were quite hungry and eagerly searched for the best of feed.

I must mention now that the pasture-lands of my native village lay alongside of territory of a score of square miles which in some years were all planted in corn. During the months of August and September these vast corn-fields were like deep forests. Not far from Idvor and to the east of the corn-fields was a Rumanian settlement which was notorious for its cattle-thieves. The trick of these thieves was to hide in the corn-fields at night and to wait until some cattle strayed into these fields, when they would drive them away and hide them somewhere in their own corn-fields on the other side of their own village. To prevent the herd from straying into the corn-fields at night was a great task, for the performance of which the boys had to be trained in daytime by their experienced leader. It goes without saying that each day we boys first worked off our superfluous energy in wrestling, swimming, hockey, and other strenuous games, and then settled down to the training in the arts of a herdsman which we had to practise at night. One of these arts was signalling through the ground. Each boy had a knife with a long wooden handle. This knife was stuck deep into the ground. A sound was made by striking against the wooden handle, and the boys, lying down and pressing their ears close to the ground, had to estimate the direction and the distance of the origin of sound. Practice made us quite expert in this form of signalling. We knew at that time that the sound travelled through the ground far better than through the air, and that a hard and solid ground transmitted sound much better than the ploughed-up ground. We knew, therefore, that the sound produced this way near the edge of the pasture-land could not be heard in the soft ground16 of the corn-fields stretching along the edge. A Rumanian cattle-thief, hidden at night in the corn-fields, could not hear our ground signals and could not locate us. Kos, the Slovenian, my teacher and interpreter of physical phenomena, could not explain this, and I doubt very much whether the average physicist of Europe at that time could have explained it. It is the basis of a discovery which I made about twenty-five years after my novel experiences in that herdsmen’s summer school in Idvor.

On perfectly clear and quiescent summer nights on the plains of my native Banat, the stars are intensely bright and the sky looks black by contrast. “Thy hair is as black as the sky of a summer midnight” is a favorite saying of a Serbian lover to his lady-love. On such nights we could not see our grazing oxen when they were more than a few score of feet from us, but we could hear them if we pressed our ears close to the ground and listened. On such nights we boys had our work cut out for us. We were placed along a definite line at distances of some twenty yards apart. This was the dead-line, which separated the pasture-lands from the corn-field territory. The motto of the French at Verdun was: “They shall not pass!” This was our motto, too, and it referred equally to our friends, the oxen, and to our enemies, the Rumanian cattle-thieves. Our knife-blades were deep in the ground and our ears were pressed against the handles. We could hear every step of the roaming oxen and even their grazing operations when they were sufficiently near to the dead-line. We knew that these grazing operations were regulated by the time of the night, and this we estimated by the position of certain constellations like Orion and the Pleiades. The positions of the evening star and of the morning star also were closely observed. Venus was our white star and Mars was called the red star. The Dipper, the north star, and the milky way were our compass.17 We knew also that when in the dead of the night we could hear the faint sound of the church-bell of the Rumanian settlement about four miles to the east of us, then there was a breeze from the corn-fields to the pasture-lands, and that it carried the sweet perfume of the young corn to the hungry oxen, inviting them to the rich banquet-table of the corn-fields. On such nights our vigilance was redoubled. We were then all eyes and ears. Our ears were closely pressed to the ground and our eyes were riveted upon the stars above.

The light of the stars, the sound of the grazing oxen, and the faint strokes of the distant church-bell were messages of caution which on those dark summer nights guided our vigilance over the precious herd. These messages appealed to us like the loving words of a friendly power, without whose aid we were helpless. They were the only signs of the world’s existence which dominated our consciousness as, enveloped in the darkness of night and surrounded by countless burning stars, we guarded the safety of our oxen. The rest of the world had gone out of existence; it began to reappear in our consciousness when the early dawn announced what we boys felt to be the divine command, “Let there be light,” and the sun heralded by long white streamers began to approach the eastern sky, and the earth gradually appeared as if by an act of creation. Every one of those mornings of fifty years ago appeared to us herdsmen to be witnessing the creation of the world—a world at first of friendly sound and light messages which made us boys feel that a divine power was protecting us and our herd, and then a real terrestrial world, when the rising sun had separated the hostile mysteries of night from the friendly realities of the day.

Sound and light became thus associated in my early modes of thought with the divine method of speech and18 communication, and this belief was strengthened by my mother, who quoted the words of St. John: “In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God.”

I believed also that David, some of whose Psalms, under the instruction of my mother, I knew by heart, and who in his youth was a shepherd, expressed my thoughts in his nineteenth Psalm:

Then, there is no Serb boy who has not heard that beautiful Russian song by Lyermontoff, the great Russian poet, which says:

Lyermontoff was a son of the Russian plains. He saw the same burning stars in the blackness of a summer midnight sky which I saw. He felt the same thrill which David felt and through his Psalms transmitted to me during those watchful nights of fifty years ago. I pity the city-bred boy who has never felt the mysterious force of that heavenly thrill.

Sound and light being associated in my young mind of fifty years ago with divine operations by means of which man communicates with man, beast with beast, stars with stars, and man with his Creator, it is obvious that I meditated much about the nature of sound and of light. I still believe that these modes of communication are the fundamental operations in the physical universe and I am still meditating about their nature. My teachers in Panchevo rendered some assistance in solving many of the puzzles which I met in the course of these19 meditations. Kos, my Slovenian teacher, who was the first to tell me the story of Franklin and his kite, was a great help. He soon convinced me that sound was a vibration of bodies. This explanation agreed with the Serbian figure of speech which says:

I also felt the quivering air whenever during my term of service as guardian of the oxen I tried my skill at the Serbian flute. Few things excited my interest more than the operations of the Serbian bagpiper as he forced the air from his sheepskin bellows and made it sing by regulating its passage through the pipes. The operations which the bagpiper called adjustment and tuning of the bagpipes commanded my closest attention. I never dreamed then that a score of years later I should do a similar operation with an electrical circuit. I called it “electrical tuning,” a term which has been generally adopted in wireless telegraphy. But nobody knows that the operation as well as the name were first suggested to me by the Serbian bagpiper, some twenty years before I made the invention in 1892.

Skipping over several sections of my story, I will say now that twenty years after my invention of electrical tuning a pupil of mine, Major Armstrong, discovered the electrical vacuum-tube oscillator, which promises to revolutionize wireless telegraphy and telephony. A similar invention, but a little earlier, was made by another pupil of mine, Mr. Vreeland. Both these inventions in their mode of operation remind me much of the operation of Serbian bagpipes. Perhaps some of those thrills which the Serbian bagpiper stirred up in me in my early youth were transferred to my pupils, Armstrong and Vreeland.

I was less successful in solving my puzzles concerning the nature of light. Kos, the Slovenian, my first guide20 and teacher in the study of physical phenomena, told me the story that a wise man of Greece with the name of Aristotle believed that light originates in the eye, which throws out feelers to the surrounding objects, and that through these feelers we see the objects, just as we feel them by our sense of touch. This view did not agree with the popular saying often heard in Idvor: “Pick your grapes before sunrise, before the thirsty sunbeams have drunk up their cooling dew.” Nor did it agree with Bishop Nyegosh, the greatest of Serbian poets, who says:

The verse from Nyegosh I obtained from a Serbian poet, who was an arch-priest, a protoyeray, and who was my religious teacher in Panchevo. His name, Vasa Zhivkovich, I shall never forget, because it is sweet music to my ears on account of the memories of affectionate friendship he cherished for me.

According to this popular belief a beam of light has an individual existence just like that of the melodious string under the guslar’s bow. But neither the poet, nor the wise men of Idvor, nor Kos the Slovenian, ever mentioned that a beam of light ever quivered, and if it does not quiver like a vibrating body how can the sun, the moon, and the stars proclaim the glory of God, and how can, according to David, their voice be heard wherever there are speech and language? These questions Kos would not answer. No wonder! Nobody to-day can give a completely satisfactory answer to questions relating to radiation of light. Kos was non-committal and did not seem to attach much importance to the authorities which I quoted; namely, the Serbian poet Nyegosh, the wise sayings of Idvor, and the Psalms of David. Nevertheless, he was greatly interested in my childlike inquiries and always encouraged me to go on with my21 puzzling questions. Once he invited me to his house, and there I found that several of his colleagues were present. One of them was my friend the poet-priest, and another was a Hungarian Lutheran preacher who spoke Serbian well and was famous in Panchevo because of his great eloquence. They both engaged me in conversation and showed a lively interest in my summer vacation experiences as herdsman’s assistant. The puzzling questions about light which I addressed to Kos, and the fact that Kos would not answer, amused them. My knowledge of the Bible and of the Psalms impressed them much, and they asked me quite a number of questions concerning my mother. Then they suggested that I might be transferred from the school in Panchevo to the famous schools of Prague in Bohemia, if my father and mother did not object to my going so far away from home. When I suggested that my parents could not afford to support me in a great place like Prague, they assured me that this difficulty might be fixed up. I promised to consult my parents during the approaching Christmas vacation. I did, but found my father irresistibly opposed to it. Fate, however, decreed otherwise.

The history of Banat records a great event for the early spring of 1872, the spring succeeding the Christmas when my father and mother agreed to disagree upon the proposition that I go to Prague. Svetozar Miletich, the great nationalist leader of the Serbs in Austria-Hungary, visited Panchevo, and the people prepared a torchlight procession for him. This procession was to be a protest of Panchevo and of the whole of Banat against the emperor’s treachery of 1869. My father had protested long before by excluding the emperor’s picture from our house. That visit of Miletich marks the beginning of a new political era in Banat, the era of nationalism. The schoolboys of Panchevo turned out in great numbers, and I was one of them, proud to become one of the torch-bearers. We22 shouted ourselves hoarse whenever Miletich in his fiery speech denounced the emperor for his ingratitude to the military frontiersmen as well as to all the Serbs of Voyvodina. Remembering my father’s words on the occasion mentioned above, I did not hesitate to shout in the name of the schoolboys present in the procession: “We’ll never serve in Francis Joseph’s army!” My chums responded with: “Long five the Prince of Serbia!” The Hungarian officials took careful notes of the whole proceeding, and a few days later I was informed that Panchevo was not a proper place for an ill-mannered peasant boy like me, and that I should pack up and return to Idvor. Kos, the Slovenian, and protoyeray Zhivkovich interfered, and I was permitted to stay.

On the first of May, following, our school celebrated the May-day festival. The Serb youngsters in the school, who worshipped Miletich and his nationalism, prepared a Serbian flag for the festival march. The other boys, mostly Germans, Rumanians, and Hungarians, carried the Austrian yellow-black standard. The nationalist group among the youngsters stormed the bearer of the yellow-black standard, and I was caught in the scrimmage with the Austrian flag under my feet. Expulsion from school stared me in the face. Again protoyeray Zhivkovich came to my defense and, thanks to his high official position and to my high standing in school, I was allowed to continue with my class until the end of the school year, after promising that I would not associate with revolutionary boys who showed an inclination to storm the Austrian flag. The matter did not end there, however. In response to an invitation from the protoyeray, father and mother came to Panchevo to a conference, which resulted in a triumph for my mother. It was decided that I bid good-by to Panchevo, a hotbed of nationalism, and go to Prague. The protoyeray and his23 congregation promised assistance if the financial burden attached to my schooling in Prague should prove too heavy for my parents.

When the day for the departure for Prague arrived, my mother had everything ready for my long journey, a journey of nearly two days on a Danube steamboat to Budapest, and one day by rail from Budapest to Prague. Two multicolored bags made of a beautifully colored web of wool contained my belongings: one my linen, the other my provisions, consisting of a whole roast goose and a big loaf of white bread. The only suit of clothes which I had I wore on my back, and my sisters told me that it was very stylish and made me look like a city-bred boy. To tone down somewhat this misleading appearance and to provide a warm covering during my journey for the cold autumn evenings and nights, I wore a long yellow overcoat of sheepskin trimmed with black wool and embroidered along the border with black and red arabesque figures. A black sheepskin cap gave the finishing touch and marked me as a real son of Idvor. When I said good-by to father and mother on the steamboat landing I expected, of course, that my mother would cry, and she did; but to my great surprise I noticed two big tears roll down my father’s cheeks. He was a stern and unemotional person, a splendid type of the heroic age, and when for the first time in my life I saw a tear in his luminous eyes I broke down and sobbed, and felt embarrassed when I saw that the steamboat passengers were taking a sympathetic interest in my parting from father and mother. A group of big boys on the boat took me up and offered to help me to orient myself on the boat; they were theological students returning to the famous seminary at Karlovci, the seat of the Serb Patriarch. I confided to them that I was going to the schools of Prague, that I never had gone from home farther than Panchevo, that I had never seen a big steamboat or a railroad-train,24 and that my journey gave me some anxiety because I could not speak Hungarian and had some difficulty in handling the limited German vocabulary which I learned in Panchevo. Presently we saw a great church-tower in the distance, and they told me that it was the cathedral of Karlovci, and that near the cathedral was the palace of his holiness, the Patriarch. It was at this place that the Turks begged for peace in 1699, having been defeated with the aid of the military frontiersmen. Beyond Karlovci, they pointed out, was the mountain of Frushka Gora, famous in Serbian poetry. This was the first time I saw a mountain at close range. One historical scene crowded upon another, and I had some difficulty to take them all in even with the friendly assistance of my theological acquaintances. When Karlovci was reached and my theological friends left the boat, I felt quite lonesome. I returned to my multicolored bags, and as I looked upon them and remembered that mother had made them I felt that a part, at least, of my honey-hearted home was so near me, and that consoled me.

I noticed that lunch was being served to people who had ordered it, and I thought of the roast goose which mother had packed away in my multicolored bag. I reached for the bag, but, alas! the goose was gone. A fellow passenger, who sat near me, assured me that he saw one of the young theologians carry the goose away while the other theologians engaged me in conversation, and not knowing to whom the bags belonged, he thought nothing of the incident. Besides, how could any one suspect a student of theology? “Shades of St. Sava,” said I, “what kind of orthodoxy will these future apostles of your faith preach to the Serbs of Banat?” “Ah, my boy,” said an elderly lady who heard my exclamation, “do not curse them; they did it just out of innocent mischief. This experience will be worth many a roast goose25 to you; it will teach you that in a world of strangers you must always keep one eye on what you have and with the other eye look out for things that you do not have.” She was a most sympathetic peasant woman, who probably had seen my dramatic parting with father and mother on the steamboat landing. I took her advice, and during the rest of my journey I never lost sight of my multicolored bags and of my yellow sheepskin coat.

The sight of Budapest, as the boat approached it on the following day, nearly took my breath away. At the neighborhood gatherings in Idvor I had heard many a story about the splendor of the emperor’s palace on the top of the mountain at Buda, and about the wonders of a bridge suspended in air across the Danube and connecting Buda with Pest. Many legends were told in Idvor concerning these wonderful things. But what I saw with my own eyes from the deck of that steamboat surpassed all my expectations. I was overawed, and for a moment I should have been glad to turn back and retrace my journey to Idvor. The world outside of Idvor seemed too big and too complicated for me. But as soon as I landed my courage returned. With the yellow sheepskin coat on my back, the black sheepskin cap on my head, and the multicolored bags firmly grasped in my hands, I started out to find the railroad-station. A husky Serb passed by and, attracted by my sheepskin coat and cap and the multicolored bags, suddenly stopped and addressed me in Serbian. He lived in Budapest, he said, and his glad eye and hand assured me that a sincere friend was speaking to me. He helped me with the bags and stayed with me until he deposited me in the train that was to take me to Prague. He cautioned me that at about four o’clock in the morning my train would reach Gaenserndorf (Goosetown), and that there I should get out and get another train which would take me to Prague.26 The name of this town brought back to memory my goose which had disappeared at Karlovci, and gloomy forebodings disturbed my mind and made me a little anxious.

This was the first railroad-train that I had ever seen. It disappointed me; the legendary speed of trains about which I had heard so much in Idvor was not there. When the whistle blew and the conductor shouted “Fertig!” (Ready!), I shut my eyes and waited anxiously, expecting to be shot forward at a tremendous speed. But the train started leisurely and, to my great disappointment, never reached the speeds which I expected. It was a cold October night; the third-class compartment had only one other passenger, a fat Hungarian whom I could not understand, although he tried his best to engage me in a conversation. My sheepskin coat and cap made me feel warm and comfortable; I fell asleep, and never woke up until the rough conductor pulled me off my seat and ordered me out.

“Vienna, last stop,” he shouted.

“But I was going to Prague,” I said.

“Then you should have changed at Gaenserndorf, you idiot!” answered the conductor, with the usual politeness of Austrian officials when they see a Serb before them. “But why didn’t you wake me up at Gaenserndorf?” I protested. He flared up and made a gesture as if about to box my ears, but suddenly he changed his mind and substituted a verbal thrust at my pride. “You little fool of a Serbian swineherd, do you expect an imperial official to assist you in your lazy habits you sleepy mutton-head?”

“Excuse me,” I said with an air of wounded pride, “I am not a Serbian swineherd; I am a son of a brave military frontiersman, and I am going to the famous schools of Prague.”

He softened, and told me that I should have to go back27 to Gaenserndorf after paying my fare to that place and back. When I informed him that I had no money for extra travelling expenses, he beckoned to me to come along, and after a while we stood in the presence of what I thought to be a very great official. He had a lot of gold braid on his collar and sleeves and on his cap, and he looked as stern and as serious as if the cares of the whole empire rested upon his shoulders.

“Take off your cap, you ill-mannered peasant! Don’t you know how to behave in the presence of your superiors?” he blurted out, addressing me. I dropped my multicolored bags, took off my yellow sheepskin coat in order to cover the bags, and then took off my black sheepskin cap, and saluted him in the regular fashion of a military frontiersman. I thought that he might be the emperor himself and, if so, I wondered if he had ever heard of my trampling upon his yellow-black flag at that May-day festival in Panchevo. Finally, I screwed up my courage and apologized by saying:

“Your gracious Majesty will pardon my apparent lack of respect to my superiors, but this is to me a world of strangers, and the anxiety about my belongings kept my hands busy with the bags and prevented me from taking off my cap when I approached your serene Highness.” I noticed that several persons within hearing distance were somewhat amused by this interview, and particularly an elderly looking couple, a lady and a gentleman:

“Why should you feel anxious about your bags?” said the great official. “You are not in the savage Balkans, the home of thieves; you are in Vienna, the residence of his Majesty, the Emperor of Austria-Hungary.”

“Yes,” said I, “but two days ago my roast goose was stolen from one of these bags within his Majesty’s realm, and my father told me that all the rights and privileges of the Voyvodina and of the military frontier were stolen right here in this very Vienna.”

28 “Ah, you little rebel, do you expect that this sort of talk will get you a free transportation from Gaenserndorf to Vienna and back again? Restrain your rebellious tongue or I will give you a free transportation back to your military frontier, where rebels like you ought to be behind lock and key.”

At this juncture the elderly looking couple engaged him in conversation, and after a while the gold-braided mogul informed me that my ticket from Vienna to Prague by the short route was paid for, and that I should proceed. The rude conductor, who had called me a Serbian swineherd a little while before, led me to the train and ushered me politely into a first-class compartment. Presently the elderly looking couple entered and greeted me in a most friendly, almost affectionate, manner. They encouraged me to take off my sheepskin coat and make myself comfortable, and assured me that my bags would be perfectly safe.

Their German speech had a strange accent, and their manner and appearance were entirely different from anything that I had ever seen before. But they inspired confidence. Feeling hungry, I took my loaf of snowy-white bread out of my bag, and with my herdsman’s knife with a long wooden handle I cut off two slices and offered them to my new friends. “Please, take it,” said I; “it was prepared by my mother’s hands for my long journey.” They accepted my hospitality and ate the bread and pronounced it excellent, the best bread they had ever tasted. I told them how it was made by mixing leaf-lard and milk with the finest wheat flour, and when I informed them that I knew a great deal about cooking and that I had learned it by watching my mother, the lady appeared greatly pleased. The gentleman, her husband, asked me questions about farming and taking care of animals, which I answered readily, quoting my father as29 my authority. “You had two splendid teachers, your father and your mother,” they said; “do you expect to find better teachers in Prague?” I told them briefly what had sent me to Prague, mentioning particularly that some people thought that I had outgrown the schools not only of my native village but also of Panchevo, but that in reality the main reason was because the Hungarian officials did not want me in Panchevo on account of my showing a strong inclination to develop into a rebellious nationalist. My new friends gave each other a significant look and said something in a language which I did not understand. They told me that it was English, and added that they were from America.

“America!” said I, quivering with emotion. “Then you must know a lot about Benjamin Franklin and his kite, and about Lincoln, the American Prince Marko.”

This exclamation of mine surprised them greatly and furnished the topic for a lively conversation of several hours, until the train had reached Prague. It was conducted in broken German, but we understood each other perfectly. I told them of my experience with Franklin’s theory of lightning, and of its clash with my father’s St. Elijah legend, and answered many of their questions relating to my calling Lincoln an American Prince Marko. I quoted from several Serbian ballads relating to Prince Marko which I had learned from Baba Batikin, and at their urgent request described with much detail the neighborhood gatherings in Idvor. They returned the compliment by telling me stories of Benjamin Franklin, of Lincoln, and of America, and urged me to read “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” a translation of which I discovered some time afterward. When the train reached Prague they insisted that I be their guest at their Prague hotel, called the Blue Star, for a day, at least, until I found my friends in Prague. I gladly accepted, and spent a delightful evening with them. The sweetness of their disposition30 was an unfathomable riddle to me. The riddle, however, was solved several years later.

I mentioned above that the first sight of Budapest nearly took my breath away. The first view of Prague filled me with a strange religious fervor. The ancient gates, surmounted by towers with wonderful stone carvings and inscriptions; the lofty domes, crowning mediæval cathedrals, the portals of which were bristling with beautiful images of saints; the historic public buildings, each of which told a story of the old glories of Bohemia’s kingdom; the ancient stone bridge across the Moldava River, supporting statues of Christian martyrs; the royal palace on the hill of Hradchin, which seemed to rise way up above the clouds—all these, and many other wonderful things, made me feel that it was places like Prague which St. Sava visited when he deserted his royal parents and went to the end of the world to seek new knowledge. I saw then why the protoyeray of Panchevo had suggested that I go to Prague; I even began to suspect that he expected the influence of Prague to turn my attention to theology. I think now that it would have done so if it had not been for that unpleasant goose incident at Karlovci. Besides, there was another influence at Prague, which was more powerful than any other influence in the Austrian Empire at that time.

The sights of Prague interested me more than its famous schools, which I was to enter and delayed entering. But finally I was enrolled, and the boys in the school scrutinized me with a puzzled expression, as if they could not make out what country or clime I came from. When they found out that I hailed from the Serb military frontier, all uncertainty vanished, and I knew exactly where I stood. The German boys became very cold, the Czech boys greeted me in their own tongue and hugged me31 when by my Serbian answer I proved not only that I understood them but also that I expected them to understand my Serbian greeting. They were all nationalists to the core and did their best to make me join their ranks, which, after some reluctance, I finally did. I showed them then two letters from protoyeray Zhivkovich introducing me to Rieger and to Palacky, the great apostles of Panslavism and of nationalism in Bohemia. From that day on I was one of their young revolutionary set, and henceforth school lessons looked tame and lost most of their charm to me.

The German victory in France two years prior to that time, resulting as it did in the creation of a united Germany, had encouraged Teutonism to run riot wherever it met a current opposing it, as it did in Prague. Nationalism in Bohemia was a reaction against Austrian Teutonism in those days, just as it was a reaction against Magyarism in Voyvodina and in the military frontier. Hardly a day passed without serious clashes between the Czech nationalist boys and their German classmates. That which made my stay in Panchevo impossible met me in Prague in an even more violent form. Loyal to the traditions of the Serbian military frontiersmen, I liked nothing better than a good fight, and I had the physique and the practice, gained in the pasturelands of Idvor, to lick any German boy of my age or even older. The German pupils feared me, and the German teachers condemned what they called my revolutionary tendencies, and threatened to send me back to Idvor. As time went on, I began to wish that they would expel me and give me a good excuse to return to Idvor. I missed the wide horizon of the plains of Banat in the narrow streets of Prague. My little bedroom in a garret, the only living quarters that I could afford, was a sad contrast to my mode of life on the endless plains of Banat, where for32 six weeks each summer I had lived under the wide canopy of heaven, watching the grazing oxen, gazing upon the countless stars at night, and listening to the sweet strains of the Serbian flute. The people I met on the streets were puffed up with Teutonic pride or with official arrogance; they had none of the gentle manliness and friendliness of the military frontiersmen. The teachers looked to me more like Austrian gendarmes than like sympathetic friends. They cared more for my sentiments toward the emperor and for my ideas about nationalism than for my ideas relating to God and his beautiful world of life and light. Not one of them reminded me of Kos, the Slovenian, or of protoyeray Zhivkovich in Panchevo. Race antagonism was at that time the ruling passion. If it had not been for the affectionate regard which the Czech boys and their parents had for me I should have felt most lonesome; from Banat to Prague was too sudden a change for me.

Another circumstance I must mention now which helped to brace me up. I delivered, after many months of delay, my letters of introduction to Rieger and to Palacky. I saw their pictures, I read about them, and finally I heard them address huge nationalist meetings. They were great men, I thought, and I could not screw up sufficient courage to call on them, as the protoyeray wished me to do, and waste their precious time on my account. But when I received a letter from the protoyeray in Panchevo asking why I had not delivered the letters of introduction he had given me, I made the calls. Rieger looked like my father: dark, stern, reserved, powerful of physique, with a wonderful luminosity in his eyes. He gave me coffee and cake, consuming a generous supply of them himself. When I kissed his hand, bidding him good-by, he gave me a florin for pocket-money, patted me on the cheek, and assured me that I could easily come33 up to the protoyeray’s expectations and surprise my teachers if I would only spend more time on my books and less on my nationalist chums. This suggestion and indirect advice made me very thoughtful. Palacky was a gentle, smooth-faced, old gentleman, who looked to me then as if he knew everything that men had ever known, and that much study had made him pale and delicate. He was much interested in my description of the life and customs of my native village, and when I mentioned St. Sava, he drew a parallel between this saint and Yan Huss, the great Czech patriot and divine, who was burned at the stake in 1415 at Constance because he demanded a national democratic church in Bohemia. He gave me a book in which I could read all about Huss and the Hussite wars and about the one-eyed Zhizhka, the great Hussite general. He gave me no coffee nor cake, probably because his health did not permit him to indulge in eatables between meals, but assured me of assistance if I should ever need it. I eagerly read the book about Yan Huss and the Hussite wars, and became a more enthusiastic nationalist than ever before. I felt that Rieger’s influence pulled me in one direction, and that Palacky encouraged me to persist in the opposite direction which I had selected under the influence of the spirit of Czech nationalism.

In my letters to my elder sisters, which they read to father and mother, I described with much detail the beauties and wonders of Prague, my receptions and talks with Rieger and Palacky, and elaborated much the parallel between St. Sava and Yan Huss to which Palacky had drawn my attention, and which I expected would please my mother; but I never mentioned Rieger’s advice that I stick to books and leave the nationalist propaganda of the boys alone. I never during my whole year’s stay in Prague sent a report home on my school work, because I never did more than just enough to prevent my dropping34 to the lower grade. My mother and the protoyeray in Panchevo expected immeasurably more. Hence, I never complained about the smallness of the allowance which my parents could give me, and, therefore, they did not appeal to my Panchevo friends for the additional help which they had promised. I felt that I had no right to make such an appeal, because I did not devote myself entirely to the work for which I was sent to Prague.

While debating with myself whether to follow Rieger’s advice and leave nationalism in the hands of more experienced people and devote myself to my lessons only, an event occurred which was the turning-point in my life. I received a letter from my sister informing me that my father had died suddenly after a very brief illness. She told me also that my father had had a premonition that he would die soon and never see me again when, a year before, he bade me good-by on the steamboat landing. I understood then the meaning of the tears which on that day of parting I had seen roll down his cheeks for the first time in my life. I immediately informed my mother that I wanted to return to Idvor and help her take care of my father’s land. But she would not listen, and insisted that I stay in Prague, where I was seeing and learning so many wonderful things. I knew quite well what a heavy burden my schooling would be to her, and my school record did not entitle me to expect the protoyeray to make his promise of assistance good. I decided to find a way of relieving my mother of any further burdens so far as I was concerned.

One day I saw on the last page of an illustrated paper an advertisement of the Hamburg-American line, offering steerage transportation from Hamburg to New York for twenty-eight florins. I thought of my mellow-hearted American friends of the year before who bought a first-class35 railroad-ticket for me from Vienna to Prague, and decided on the spot to try my fortune in the land of Franklin and Lincoln as soon as I could save up and otherwise scrape up money enough to carry me from Prague to New York. My books, my watch, my clothes, including the yellow sheepskin coat and the black sheepskin cap, were all sold to make up the sum necessary for travelling expenses. I started out with just one suit of clothes on my back and a few changes of linen, and a red Turkish fez which nobody would buy. And why should anybody going to New York bother about warm clothes? Was not New York much farther south than Panchevo, and does not America suggest a hot climate when one thinks of the pictures of naked Indians so often seen? These thoughts consoled me when I parted with my sheepskin coat. At length I came to Hamburg, ready to embark but with no money to buy a mattress and a blanket for my bunk in the steerage. Several days later my ship, the Westphalia, sailed—on the twelfth day of March, 1874. My mother received several days later my letter, mailed in Hamburg, telling her in most affectionate terms that, in my opinion, I had outgrown the school, the teachers, and the educational methods of Prague, and was about to depart for the land of Franklin and Lincoln, where the wisdom of people was beyond anything that even St. Sava had ever known. I assured her that with her blessing and God’s help I should certainly succeed, and promised that I would soon return rich in rare knowledge and in honors. The letter was dictated by the rosiest optimism that I could invent. Several months later I found to my great delight that my mother had accepted cheerfully this rosy view of my unexpected enterprise.

The ship sailed with a full complement of steerage passengers, mostly Germans. As we glided along the36 River Elbe the emigrants were all on deck, watching the land as it gradually vanished from our sight. Presently the famous German emigrant song rang through the air, and with a heavy heart I took in the words of its refrain:

I did not wait for the completion of the song, but turned in, and in my bare bunk I sought to drown my sadness in a flood of tears. Idvor, with its sunny fields, vineyards, and orchards; with its grazing herds of cattle and flocks of sheep; with its beautiful church-spire and the solemn ringing of church-bells; with its merry boys and girls dancing to the tune of the Serbian bagpipes the Kolo on the village green—Idvor, with all the familiar scenes that I had ever seen there, appeared before my tearful eyes, and in the midst of them I saw my mother listening to my sister reading slowly the letter which I had sent to her from Hamburg. Every one of these scenes seemed to start a new shower of tears, which finally cleared the oppressiveness of my spiritual atmosphere. I thought that I could hear my mother say to my sister: “God bless him for his affectionate letter. May the spirit of St. Sava guide him in the land beyond the seas! I know that he will make good his promises.” Sadness deserted me then and I felt strong again.

He who has never crossed the stormy Atlantic during the month of March in the crowded steerage of an immigrant ship does not know what hardships are. I bless the stars that the immigration laws were different then than they are now, otherwise I should not be among the living. To stand the great hardships of a stormy sea when the rosy picture of the promised land is before your mind’s eye is a severe test for any boy’s nerve and physical stamina; but to face the same hardships as a deported and37 penniless immigrant with no cheering prospect in sight is too much for any person, unless that person is entirely devoid of every finer sensibility. Many a night I spent on the deck of that immigrant ship hugging the warm smoke-stack and adjusting my position so as to avoid the force of the gale and the sharpness of its icy chilliness. All I had was the light suit of clothes which I carried on my back. Everything else I had converted into money with which to cover my transportation expenses. There was nothing left to pay for a blanket and mattress for my steerage bunk. I could not rest there during the cold nights of March without much shivering and unbearable discomfort. If it had not been for the warm smoke-stack I should have died of cold. At first I had to fight for my place there in the daytime, but when the immigrants understood that I had no warm clothing they did not disturb me any longer. I often thought of my yellow sheepskin coat and the black sheepskin cap, and understood more clearly than ever my mother’s far-sightedness when she provided that coat and cap for my long journeys. A blast of the everlasting gales had carried away my hat, and a Turkish fez such as the Serbs of Bosnia wear was the only head-gear I had. It was providential that I had not succeeded in selling it in Prague. Most of my fellow emigrants thought that I was a Turk and cared little about my discomforts. But, nevertheless, I felt quite brave and strong in the daytime; at night, however, when, standing alone alongside of the smoke-stack, I beheld through the howling darkness the white rims of the mountain-high waves speeding on like maddened dragons toward the tumbling ship, my heart sank low. It was my implicit trust in God and in his regard for my mother’s prayers which enabled me to overcome my fear and bravely face the horrors of the angry seas.

On the fourteenth day, early in the morning, the flat coast-line of Long Island hove in sight. Nobody in the38 motley crowd of excited immigrants was more happy to see the promised land than I was. It was a clear, mild, and sunny March morning, and as we approached New York Harbor the warm sun-rays seemed to thaw out the chilliness which I had accumulated in my body by continuous exposure to the wintry blasts of the North Atlantic. I felt like a new person, and saw in every new scene presented by the New World as the ship moved into it a new promise that I should be welcome. Life and activity kept blossoming out all along the ship’s course, and seemed to reach full bloom as we entered New York Harbor. The scene which was then unfolded before my eyes was most novel and bewildering. The first impressions of Budapest and of Prague seemed like pale-faced images of the grand realities which New York Harbor disclosed before my eager eyes. A countless multitude of boats lined each shore of the vast river; all kinds of craft ploughed hurriedly in every direction through the waters of the bay; great masses of people crowded the numerous ferry-boats, and gave me the impression that one crowd was just about as anxious to reach one shore of the huge metropolis as the other was to reach the other shore; they all must have had some important thing to do, I thought. The city on each side of the shore seemed to throb with activity. I did not distinguish between New York and Jersey City. Hundreds of other spots like the one I beheld, I thought, must be scattered over the vast territories of the United States, and in these seething pots of human action there must be some one activity, I was certain, which needed me. This gave me courage. The talk which I had listened to during two weeks on the immigrant ship was rather discouraging, I thought. One immigrant was bragging about his long experience as a cabinetmaker, and informed his audience that cabinetmakers were in great demand in America; another one was telling long tales about his39 skill as a mechanician; a third one was spinning out long yarns about the fabulous agricultural successes of his relatives out West, who had invited him to come there and join them; a fourth confided to the gaping crowd that his brother, who was anxiously waiting for him, had a most prosperous bank in some rich mining-camp in Nevada where people never saw any money except silver and gold and hardly ever a coin smaller than a dollar; a fifth one, who had been in America before, told us in a rather top-lofty way that no matter who you were or what you knew or what you had you would be a greenhorn when you landed in the New World, and a greenhorn has to serve his apprenticeship before he can establish his claim to any recognition. He admitted, however, that immigrants with a previous practical training, or strong pull through relatives and friends, had a shorter apprenticeship. I had no practical training, and I had no relatives nor friends nor even acquaintances in the New World. I had nothing of any immediate value to offer to the land I was about to enter. That thought had discouraged me as I listened to the talks of the immigrants; but the activity which New York Harbor presented to my eager eyes on that sunny March day was most encouraging.

Presently the ship passed by Castle Garden, and I heard some one say: “There is the Gate to America.” An hour or so later we all stood at the gate. The immigrant ship, Westphalia, landed at Hoboken and a tug took us to Castle Garden. We were carefully examined and cross-examined, and when my turn came the examining officials shook their heads and seemed to find me wanting. I confessed that I had only five cents in my pocket and had no relatives here, and that I knew of nobody in this country except Franklin, Lincoln, and Harriet Beecher St owe, whose “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” I had read in a translation. One of the officials, who had40 one leg only, and walked with a crutch, seemed much impressed by this remark, and looking very kindly into my eyes and with a merry twinkle in his eye he said in German: “You showed good taste when you picked your American acquaintances.” I learned later that he was a Swiss who had served in the Union army during the Civil War. I confessed also to the examining officials that I had no training in the arts and crafts, but that I was anxious to learn, and that this desire had brought me to America. In answer to the question why I had not stayed at home or in Prague to learn instead of wandering across the sea with so little on my back and nothing in my pocket, I said that the Hungarian and Austrian authorities had formed a strong prejudice against me on account of my sympathies with people, and particularly with my father, who objected to being cheated out of their ancient rights and privileges which the emperor had guaranteed to them for services which they had been rendering to him loyally for nearly two hundred years. I spoke with feeling, and I felt that I made an impression upon the examiners, who did not look to me like officials such as I was accustomed to see in Austria-Hungary. They had no gold and silver braid and no superior airs but looked very much like ordinary civilian mortals. That gave me courage and confidence, and I spoke frankly and fearlessly, believing firmly that I was addressing human beings who had a heart which was not held in bondage by cast-iron rules invented by their superiors in authority. The Swiss veteran who walked on crutches, having lost one of his legs in the Civil War, was particularly attentive while I was being cross-examined, and nodded approvingly whenever I scored a point with my answers. He whispered something to the other officials, and they finally informed me that I could pass on, and I was conducted promptly to the Labor Bureau of Castle Garden. My Swiss friend looked me up a little later and41 informed me that the examiners had made an exception in my favor and admitted me, and that I must look sharp and find a job as soon as possible.