BEING

A Standard Work on Composition

and Oratory

CONTAINING

RULES FOR EXPRESSING WRITTEN THOUGHT IN A CORRECT AND ELEGANT

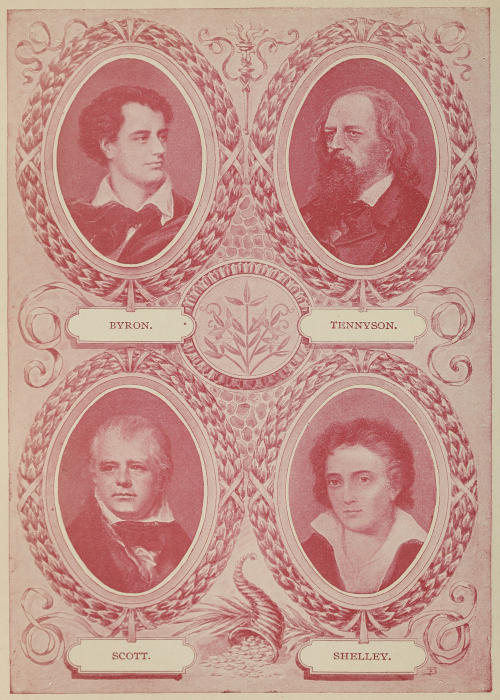

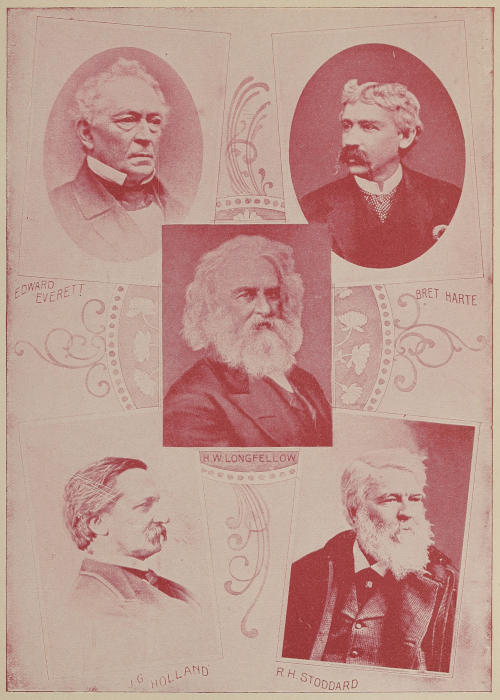

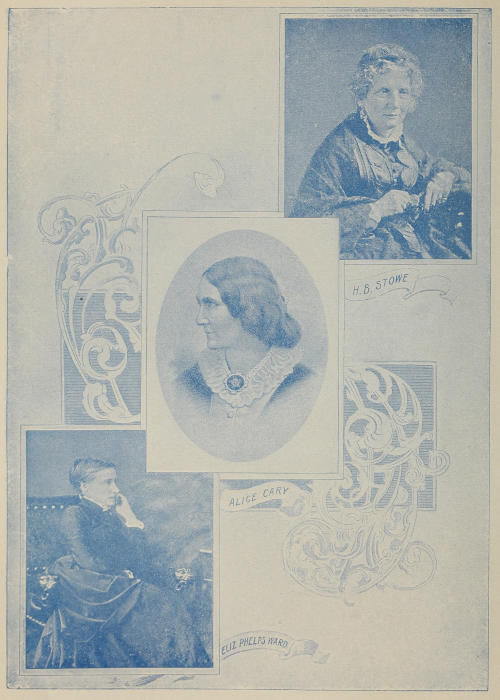

MANNER; MODEL SELECTIONS FROM THE MOST FAMOUS AUTHORS;

SUBJECTS FOR COMPOSITIONS AND HOW TO TREAT THEM; USE

OF ILLUSTRATIONS; DESCRIPTIVE, PATHETIC AND

HUMOROUS WRITINGS, ETC., ETC.

TOGETHER WITH A

Peerless Collection of Readings and Recitations,

Including Programmes for Special

Occasions

FROM AUTHORS OF WORLD-WIDE RENOWN, FOR PUBLIC SCHOOLS, ACADEMIES,

COLLEGES, LODGES, SUNDAY-SCHOOL AND

SOCIAL ENTERTAINMENTS

THE WHOLE FORMING AN

UNRIVALED SELF-EDUCATOR FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

by Henry Davenport Northrop

Author of “Delsarte Manual of Oratory,” “Golden Gleanings of Poetry, Prose and Song,” etc., etc.

Embellished with a Galaxy of Charming Engravings

NATIONAL PUBLISHING CO.

239, 241, 243 South American St.

Philadelphia

ENTERED ACCORDING TO ACT OF CONGRESS, IN THE YEAR 1901, BY

D. Z. HOWELL

IN THE OFFICE OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS, AT WASHINGTON, D. C., U. S. A.

Millions of young people in America are being educated, and hence there is a very great demand for a Standard Work showing how to express written thought in the most elegant manner and how to read and recite in a way that insures the greatest success. To meet this enormous demand is the aim of this volume.

Part I.—How to Write a Composition.—The treatment of this subject is masterly and thorough, and is so fascinating that the study becomes a delight. Rules and examples are furnished for the right choice of words, for constructing sentences, for punctuation, for acquiring an elegant style of composition, for writing essays and letters, what authors should be read, etc. The directions given are all right to the point and are easily put into practice.

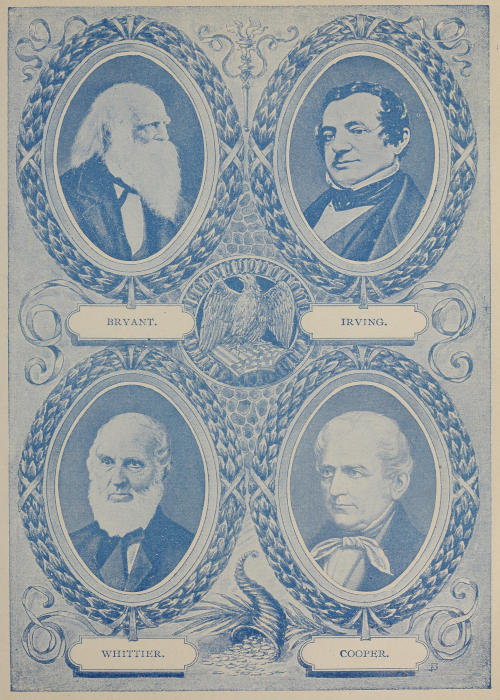

The work contains a complete list of synonyms, or words of similar meaning, and more than 500 choice subjects for compositions, which are admirably suited to persons of all ages. These are followed by a charming collection of Masterpieces of Composition by such world-renowned authors as Emerson, Hawthorne, George Eliot, Lord Macaulay, Washington Irving, C. H. Spurgeon, Sarah J. Lippincott, Mrs. Stowe and many others.

These grand specimens of composition bear the stamp of the most brilliant genius. They are very suggestive and helpful. They inspire the reader to the noblest efforts, and teach the truth of Bulwer Lytton’s well-known saying that “The pen is mightier than the sword.”

Part II.—Readings and Recitations.—The second part of this incomparable work is no less valuable, and a candid perusal will convince you that it contains the largest and best collection of recitations ever brought together in one volume. These are of every variety and description. Be careful to notice that every one of these selections, which are from the writings of the world’s best authors, is especially adapted for reading and reciting. This is something which cannot be said of any similar work.

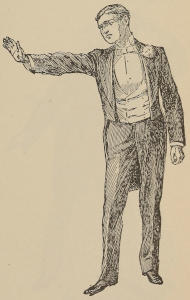

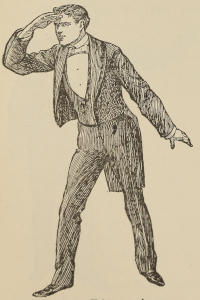

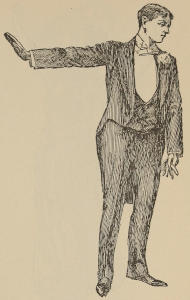

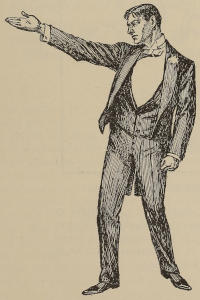

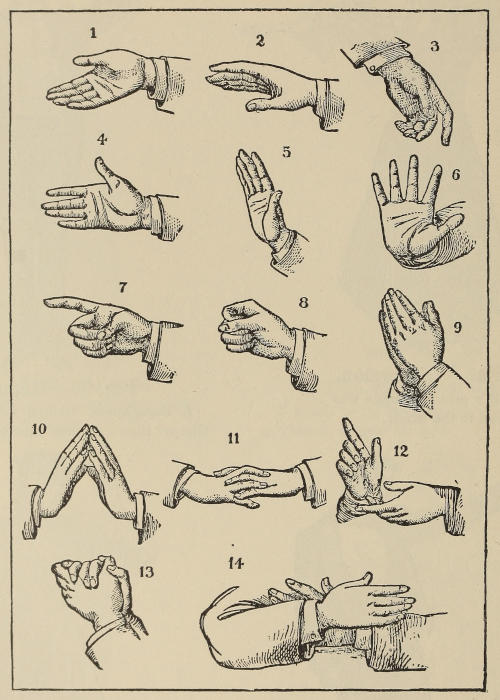

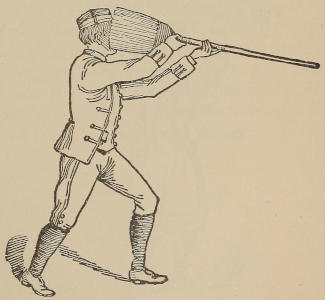

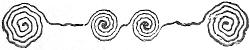

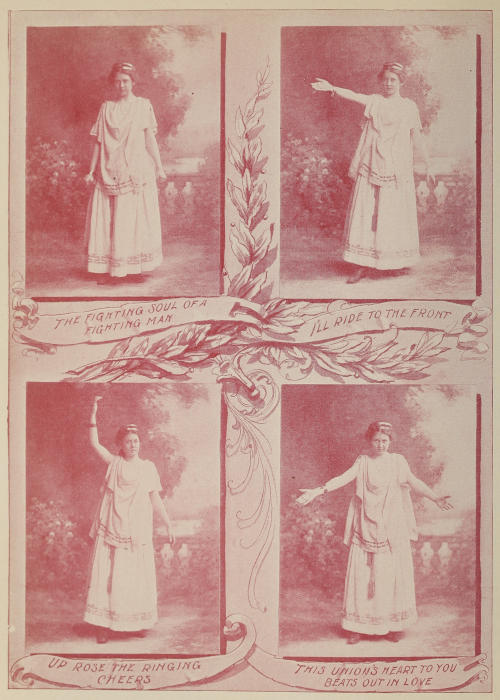

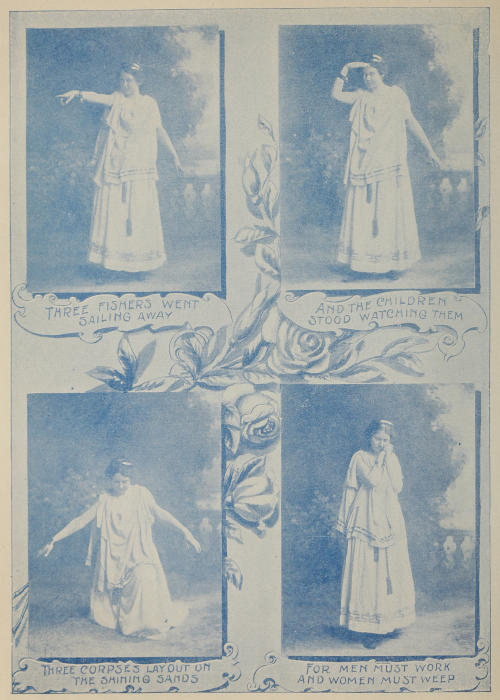

All the Typical Gestures used in Reciting are shown by choice engravings, and the reader has in reality the best kind of teacher right before him. The different attitudes, facial expressions and gestures are both instructive and charming. These are followed by Recitations with Lesson Talks. Full directions are given for reciting the various pieces, and this is done by taking each paragraph or verse of the selection and pointing out the gestures, tone of voice, emphasis, etc., required to render it most effectively. The Lesson Talks render most valuable service to all who are studying the grand art of oratory.

The next section of this masterly volume contains Recitations with Music.[iv] This is a choice collection of readings which are rendered most effective by accompaniments of music, enabling the reader by the use of the voice or some musical instrument to entrance his audience.

These charming selections are followed by a superb collection of Patriotic Recitations which celebrate the grand victories of our army and navy in the Philippines and West Indies. These incomparable pieces are all aglow with patriotic fervor and are eagerly sought by all elocutionists.

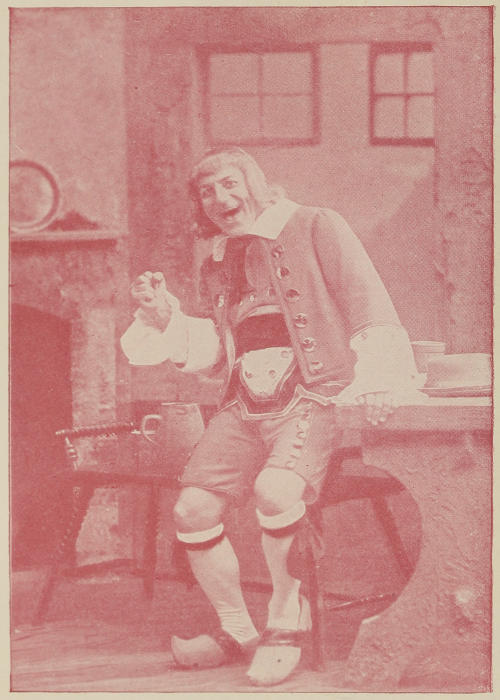

There is space here only to mention the different parts of this delightful volume, such as Descriptive and Dramatic Recitations; Orations by Famous Orators; a peerless collection of Humorous and Pathetic Recitations, and Recitations for Children and Sunday Schools.

Parents are charmed with this volume because it furnishes what the little folks want and is a self-educator for the young. It marks a new era in book publishing.

Part III.—Programmes for Special Occasions.—These have been prepared with the greatest care in order to meet a very urgent demand. The work contains Programmes for Fourth of July; Christmas Entertainments; Washington’s Birthday; Decoration Day; Thanksgiving Day; Arbor Day; Public School and Parlor Entertainments; Harvest Home; Flower Day, etc. Beautiful Selections for Special Occasions are contained in no other work, and these alone insure this very attractive volume an enormous sale.

Dialogues, Tableaux, etc.—Added to the Rich Contents already described is a Charming Collection of Dialogues and Tableaux for public and private entertainments. These are humorous, pithy, teach important lessons and are thoroughly enjoyed by everybody.

In many places the winter lyceum is an institution; we find it not only in academies, and normal schools, but very frequently the people in a district or town organize a debating society and discuss the popular questions of the day. The benefit thus derived cannot be estimated. In the last part of this volume will be found by-laws for those who wish to conduct lyceums, together with a choice selection of subjects for debate.

Thus it is seen that this is a very comprehensive work. Not only is it carefully prepared, not only does it set a very high standard of excellence in composition and elocution, but it is a work peculiarly fitted to the wants of millions of young people throughout our country. The writer of this is free to say that such a work as this would have been of inestimable value to him while obtaining an education. All wise parents who wish to make the best provision for educating their children should understand that they have in this volume such a teacher in composition and oratory as has never before been offered to the public.

| PART I.—HOW TO WRITE A COMPOSITION. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Treatment of the Subject | 18 | |

| Right Choice of Words | 19 | |

| Obscure Sentences | 19 | |

| Write Exactly what You Mean | 20 | |

| What You Should Read | 21 | |

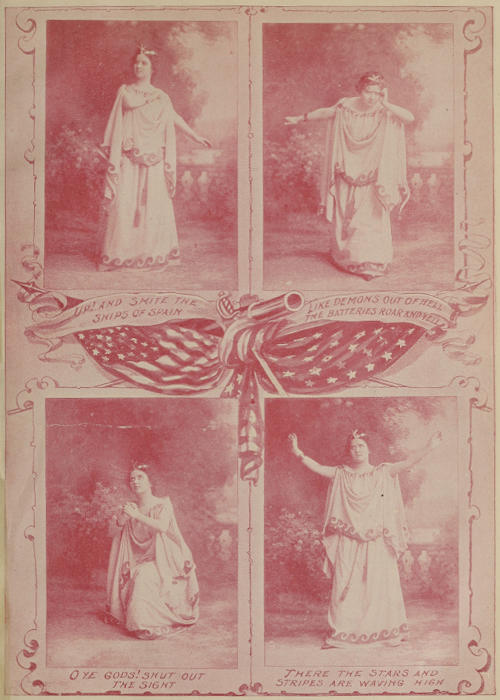

| Our Great Writers | 21 | |

| Learning to Think | 22 | |

| How to Acquire a Captivating Style | 23 | |

| Make Your Composition Attractive | 24 | |

| The Choice of Language | 25 | |

| Faults in Writing | 26 | |

| Putting Words into Sentences | 27 | |

| Suit the Word to the Thought | 28 | |

| An Amusing Exercise | 29 | |

| Errors to be Avoided | 30 | |

| Exercises in Composition | 32 | |

| Subject and Predicate | 32 | |

| Practice in Simple Sentences | 34 | |

| Sentences Combined | 36 | |

| Punctuation | 39 | |

| The Full Stop | 39 | |

| The Note of Interrogation | 40 | |

| The Comma | 40 | |

| The Semi-colon | 42 | |

| Quotation Marks | 43 | |

| The Note of Exclamation | 43 | |

| Exercises in Easy Narratives | 46 | |

| Short Stories to be Written from Memory | 47 | |

| Outlines to be Turned into Narratives | 50 | |

| Stories in Verse to be Turned into Prose | 51 | |

| Three Fishers Went Sailing | 51 | |

| The Sands of Dee | 52 | |

| The Way to Win | 52 | |

| Press On | 52 | |

| The Dying Warrior | 52 | |

| The Boy that Laughs | 53 | |

| The Cat’s Bath | 53 | |

| The Beggar Man | 53 | |

| The Shower Bath | 54 | |

| Queen Mary’s Return to Scotland | 54 | |

| The Eagle and Serpent | 54 | |

| Ask and Have | 55 | |

| What Was His Creed? | 55 | |

| The Old Reaper | 55 | |

| The Gallant Sailboat | 55 | |

| Wooing | 56 | |

| Miss Laugh and Miss Fret | 56 | |

| Monterey | 56 | |

| A Woman’s Watch | 57 | |

| Love Lightens Labor | 57 | |

| Abou Ben Adhem | 57 | |

| Essays to be Written from Outlines | 58 | |

| Easy Subjects for Compositions | 61 | |

| Use of Illustrations | 62 | |

| Examples of Apt Illustrations | 63 | |

| Examples of Faulty Illustrations | 63 | |

| How to Compose and Write Letters | 64 | |

| Examples of Letters | 65 | |

| Notes of Invitation | 65 | |

| Letters of Congratulation | 66 | |

| Love Letters | 66 | |

| Outlines to be Expanded into Letters | 66 | |

| SPECIMENS OF ELEGANT COMPOSITION. | ||

| Getting the Right Start | J. G. Holland | 67 |

| Dinah, the Methodist | George Eliot | 69 |

| Godfrey and Dunstan | George Eliot | 70 |

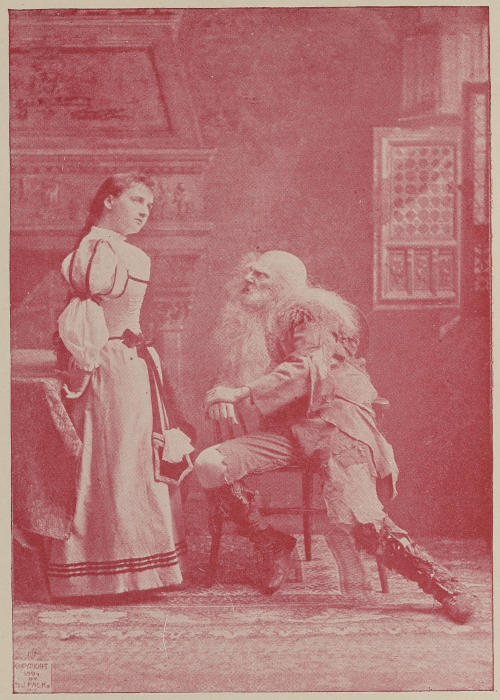

| Rip Van Winkle | Washington Irving | 72 |

| Puritans of the Sixteenth Century | Lord Macaulay | 73 |

| On being in Time | C. H. Spurgeon | 75 |

| John Ploughman’s Talk on Home | C. H. Spurgeon | 76 |

| Pearl and her Mother | Nathaniel Hawthorne | 78 |

| Candace’s Opinions | Mrs. H. B. Stowe | 80 |

| Midsummer in the Valley of the Rhine | Geo. Meredith | 81 |

| Power of Natural Beauty | R. W. Emerson | 82 |

| SUBJECTS FOR COMPOSITIONS. | ||

| Historical Subjects | 84 | |

| Biographical Subjects | 85 | |

| Subjects for Narration and Description | 86 | |

| Popular Proverbs | 87 | |

| Subjects to be Expounded | 87 | |

| Subjects for Argument | 89 | |

| Subjects for Comparison | 89 | |

| Miscellaneous Subjects | 90 | |

| Synonyms and Antonyms | 91 | |

| Noms de Plume of Authors | 111[vi] | |

| PART II.—READINGS AND RECITATIONS. | ||

| How to Read and Recite | 113 | |

| Cultivation of the Voice | 113 | |

| Distinct Enunciation | 113 | |

| Emphasis | 114 | |

| Pauses | 114 | |

| Gestures | 114 | |

| The Magnetic Speaker | 114 | |

| Self-Command | 114 | |

| Typical Gestures for Reading and Reciting | 115 | |

| Malediction | 115 | |

| Designating | 115 | |

| Silence | 115 | |

| Repulsion | 115 | |

| Declaring | 116 | |

| Announcing | 116 | |

| Discerning | 116 | |

| Invocation | 117 | |

| Presenting or Receiving | 117 | |

| Horror | 117 | |

| Exaltation | 117 | |

| Secrecy | 117 | |

| Wonderment | 118 | |

| Indecision | 118 | |

| Grief | 118 | |

| Gladness | 118 | |

| Signalling | 119 | |

| Tender Rejection | 119 | |

| Protecting—Soothing | 119 | |

| Anguish | 119 | |

| Awe—Appeal | 120 | |

| Meditation | 120 | |

| Defiance | 120 | |

| Denying—Rejecting | 120 | |

| Dispersion | 121 | |

| Remorse | 121 | |

| Accusation | 121 | |

| Revealing | 121 | |

| Correct Positions of the Hands | 122 | |

| RECITATIONS WITH LESSON TALKS. | ||

| Song of Our Soldiers at Santiago | D. G. Adee | 123 |

| Lesson Talk | 123 | |

| The Victor of Marengo | 124 | |

| Lesson Talk | 125 | |

| The Wedding Fee | 125 | |

| Lesson Talk | 126 | |

| The Statue in Clay | 127 | |

| Lesson Talk | 127 | |

| The Puzzled Boy | 128 | |

| Lesson Talk | 128 | |

| RECITATIONS WITH MUSIC. | ||

| Twickenham Ferry | 129 | |

| Grandmother’s Chair | John Read | 130 |

| Put Your Shoulder to the Wheel | H. Clifton | 131 |

| A Brighter Day is Coming | Ellen Burnside | 132 |

| Katie’s Love Letter | Lady Dufferin | 132 |

| Dost Thou Love Me, Sister Ruth? | John Parry | 133 |

| Two Little Rogues | Mrs. A. M. Diaz | 134 |

| Arkansaw Pete’s Adventure | 135 | |

| PATRIOTIC RECITATIONS. | ||

| The Beat of the Drum at Daybreak | Michael O’Connor | 137 |

| The Cavalry Charge | 137 | |

| Great Naval Battle at Santiago | Admiral W. S. Schley | 138 |

| Hobson’s Daring Deed | 139 | |

| General Wheeler at Santiago | J. L. Gordon | 140 |

| The Flag Goes By | 140 | |

| In Manila Bay | Chas. Wadsworth, Jr. | 141 |

| My Soldier Boy | 142 | |

| The Yankees in Battle | Captain R. D. Evans | 142 |

| The Banner Betsey Made | T. C. Harbaugh | 143 |

| Our Flag | Chas. F. Alsop | 144 |

| That Starry Flag of Ours | 144 | |

| The Negro Soldier | B. M. Channing | 145 |

| Deeds of Valor at Santiago | Clinton Scollard | 145 |

| A Race for Dear Life | 146 | |

| Patriotism of American Women | T. Buchanan Read | 147 |

| Our Country’s Call | Richard Barry | 147 |

| The Story of Seventy-Six | W. C. Bryant | 148 |

| The Roll Call | 148 | |

| The Battle-Field | W. C Bryant | 149 |

| The Sinking of the Merrimac | 150 | |

| The Stars and Stripes | 151 | |

| Rodney’s Ride | 152 | |

| A Spool of Thread | Sophia E. Eastman | 153 |

| The Young Patriot, Abraham Lincoln | 154 | |

| Columbia | Joel Barlow | 155 |

| Captain Molly at Monmouth | William Collins | 156 |

| Douglas to the Populace of Stirling | Sir Walter Scott | 157[vii] |

| Our Country | W. G. Peabodie | 157 |

| McIlrath of Malaté | John J. Rooney | 158 |

| After the Battle | 159 | |

| Great Naval Battle of Manila | 160 | |

| Sinking of the Ships | W. B. Collison | 161 |

| Perry’s Celebrated Victory on Lake Erie | 163 | |

| Capture of Quebec | James D. McCabe | 164 |

| Little Jean | Lillie E. Barr | 165 |

| Defeat of General Braddock | James D. McCabe | 166 |

| DESCRIPTIVE AND DRAMATIC RECITATIONS. | ||

| Quick! Man the Life Boat | 167 | |

| Beautiful Hands | J. Whitcomb Riley | 167 |

| The Burning Ship | 168 | |

| The Unknown Speaker | 169 | |

| Child Lost | 171 | |

| The Captain and the Fireman | W. B. Collison | 172 |

| The Face on the Floor | H. Antoine D’Arcy | 173 |

| The Engineer’s Story | Eugene J. Hall | 174 |

| Jim | James Whitcomb Riley | 175 |

| Queen Vashti’s Lament | John Reade | 176 |

| The Skeleton’s Story | 177 | |

| The Lady and the Earl | 179 | |

| My Vesper Song | 180 | |

| The Volunteer Organist | S. W. Foss | 180 |

| Comin’ thro’ the Rye | Robert Burns | 181 |

| Joan of Arc | Clare S. McKinley | 181 |

| The Vulture of the Alps | 183 | |

| The Old-fashioned Girl | Tom Hall | 184 |

| Nathan Hale, the Martyr Spy | I. H. Brown | 184 |

| The Future | Rudyard Kipling | 186 |

| The Power of Habit | John B. Gough | 186 |

| Died on Duty | 187 | |

| My Friend the Cricket and I | Lillie E. Barr | 188 |

| The Snowstorm | 188 | |

| Parrhasius and the Captive | N. P. Willis | 189 |

| The Ninety-third off Cape Verde | 190 | |

| A Felon’s Cell | 191 | |

| The Battle of Waterloo | Victor Hugo | 192 |

| A Pin | Ella Wheeler Wilcox | 194 |

| A Relenting Mob | Lucy H. Hooper | 195 |

| The Black Horse and His Rider | Chas. Sheppard | 196 |

| The Unfinished Letter | 198 | |

| Legend of the Organ Builder | Julius C. R. Dorr | 198 |

| Caught in the Quicksand | Victor Hugo | 200 |

| The Little Quaker Sinner | Lucy L. Montgomery | 201 |

| The Tell-tale Heart | Edgar Allan Poe | 202 |

| The Little Match Girl | Hans Andersen | 203 |

| The Monk’s Vision | 205 | |

| The Boat Race | 205 | |

| Phillips of Pelhamville | Alexander Anderson | 207 |

| Poor Little Jim | 208 | |

| ORATIONS BY FAMOUS ORATORS. | ||

| True Moral Courage | Henry Clay | 209 |

| The Struggle for Liberty | Josiah Quincy | 210 |

| Centennial Oration | Henry Armitt Brown | 211 |

| Speech of Shrewsbury before Queen Elizabeth | F. Von Schiller | 212 |

| Prospects of the Republic | Edward Everett | 212 |

| The People Always Conquer | Edward Everett | 213 |

| Survivors of Bunker Hill | Daniel Webster | 214 |

| South Carolina and Massachusetts | Daniel Webster | 215 |

| Eulogium on South Carolina | Robert T. Hayne | 216 |

| Character of Washington | Wendell Phillips | 217 |

| National Monument to Washington | Robert C. Winthrop | 218 |

| The New Woman | Frances E. Willard | 219 |

| An Appeal for Liberty | Joseph Story | 220 |

| True Source of Freedom | Edwin H. Chapin | 220 |

| Appeal to Young Men | Lyman Beecher | 221 |

| The Pilgrims | Chauncey M. Depew | 222 |

| Patriotism a Reality | Thomas Meagher | 223 |

| The Glory of Athens | Lord Macaulay | 224 |

| The Irish Church | William E. Gladstone | 225 |

| Appeal to the Hungarians | Louis Kossuth | 226 |

| The Tyrant Verres Denounced | Cicero | 227 |

| HUMOROUS RECITATIONS. | ||

| Bill’s in Trouble | 229 | |

| “Spacially Jim” | 229 | |

| The Marriage Ceremony | 230 | |

| Blasted Hopes | 230 | |

| Tim Murphy Makes a Few Remarks | 231 | |

| Passing of the Horse | 231 | |

| A School-Day | W. F. McSparran | 232 |

| The Bicycle and the Pup | 233 | |

| The Puzzled Census Taker | 233 | |

| It Made a Difference | 233 | |

| Bridget O’Flannagan on Christian Science and Cockroaches | M. Bourchier | 234 |

| Conversational | 235 | |

| Wanted, A Minister’s Wife | 235 | |

| How a Married Man Sews on a Button | J. M. Bailey | 236[viii] |

| The Dutchman’s Serenade | 236 | |

| Biddy’s Troubles | 237 | |

| The Inventor’s Wife | Mrs. E. T. Corbett | 238 |

| Miss Edith Helps Things Along | Bret Harte | 239 |

| The Man Who Has All Diseases at Once | Dr. Valentine | 240 |

| The School-Ma’am’s Courting | Florence Pyatt | 240 |

| The Dutchman’s Snake | 241 | |

| No Kiss | 243 | |

| The Lisping Lover | 243 | |

| Larry O’Dee | W. W. Fink | 243 |

| How Paderewski Plays the Piano | 244 | |

| The Freckled-Faced Girl | 244 | |

| When Girls Wore Calico | Hattie Whitney | 245 |

| A Winning Company | 246 | |

| The Bravest Sailor | Ella Wheeler Wilcox | 246 |

| How She Was Consoled | 247 | |

| That Hired Girl | 247 | |

| What Sambo Says | 248 | |

| The Irish Sleigh Ride | 248 | |

| Jane Jones | Ben King | 249 |

| De Ole Plantation Mule | 249 | |

| Adam Never Was a Boy | T. C. Harbaugh | 250 |

| A Remarkable Case of S’posin | 251 | |

| My Parrot | Emma H. Webb | 252 |

| Bakin and Greens | 252 | |

| Hunting a Mouse | Joshua Jenkins | 253 |

| The Village Sewing Society | 254 | |

| Signs and Omens | 255 | |

| The Ghost | 255 | |

| A Big Mistake | 256 | |

| The Duel | Eugene Field | 258 |

| Playing Jokes on a Guide | Mark Twain | 258 |

| A Parody | 260 | |

| Man’s Devotion | Parmenas Hill | 261 |

| Aunt Polly’s “George Washington” | 261 | |

| Mine Vamily | Yawcob Strauss | 263 |

| At the Garden Gate | 264 | |

| The Minister’s Call | 264 | |

| Led by a Calf | 265 | |

| Tom Goldy’s Little Joke | 266 | |

| How Hezekiah Stole the Spoons | 266 | |

| Two Kinds of Polliwogs | Augusta Moore | 268 |

| The Best Sewing Machine | 268 | |

| How They Said Good Night | 269 | |

| Josiar’s Courting | 270 | |

| PATHETIC RECITATIONS. | ||

| Play Softly, Boys | Teresa O’Hare | 271 |

| In the Baggage Coach Ahead | 272 | |

| The Musing One | S. E. Kiser | 272 |

| In Memoriam | Thomas R. Gregory | 273 |

| The Dying Newsboy | Mrs. Emily Thornton | 273 |

| Coals of Fire | 274 | |

| Dirge of the Drums | Ralph Alton | 275 |

| The Old Dog’s Death Postponed | Chas. E. Baer | 275 |

| The Fallen Hero | Minna Irving | 276 |

| The Soldier’s Wife | Elliott Flower | 276 |

| “Break the News Gently” | 277 | |

| On the Other Train | 277 | |

| Some Twenty Years Ago | Stephen Marsell | 279 |

| Only a Soldier | 280 | |

| The Pilgrim Fathers | 280 | |

| Master Johnny’s Next-Door Neighbor | Bret Harte | 281 |

| Stonewall Jackson’s Death | Paul M. Russell | 282 |

| The Story of Nell | Robert Buchanan | 284 |

| Little Nan | 285 | |

| One of the Little Ones | G. L. Catlin | 285 |

| The Drunkard’s Daughter | Eugene J. Hall | 286 |

| The Beautiful | 287 | |

| Trouble in the Amen Corner | C. T. Harbaugh | 288 |

| Little Mag’s Victory | Geo. L. Catlin | 289 |

| Life’s Battle | Wayne Parsons | 290 |

| The Lost Kiss | J. Whitcomb Riley | 290 |

| Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots | Lamartine | 291 |

| Over the Range | J. Harrison Mills | 292 |

| The Story of Crazy Nell | Joseph Whitten | 292 |

| Little Sallie’s Wish | 293 | |

| Drowned Among the Lilies | E. E. Rexford | 294 |

| The Fate of Charlotte Corday | C. S. McKinley | 294 |

| The Little Voyager | Mrs. M. L. Bayne | 295 |

| The Dream of Aldarin | George Lippard | 296 |

| In the Mining Town | Rose H. Thorpe | 297 |

| Tommy’s Prayer | I. F. Nichols | 298 |

| Robby and Ruth | Louisa S. Upham | 300 |

| RECITATIONS FOR CHILDREN. | ||

| Two Little Maidens | Agnes Carr | 301 |

| The Way to Succeed | 301 | |

| When Pa Begins to Shave | Harry D. Robins | 301 |

| A Boy’s View | 302 | |

| Mammy’s Churning Song | E. A. Oldham | 302 |

| The Twenty Frogs | 303 | |

| Only a Bird | Mary Morrison | 303 |

| The Way to Do It | Mary Mapes Dodge | 303 |

| We Must All Scratch | 304 | |

| Kitty at School | Kate Hulmer | 304 |

| A Fellow’s Mother | Margaret E. Sangster | 305 |

| The Story Katie Told | 305[ix] | |

| A Little Rogue | 306 | |

| Mattie’s Wants and Wishes | Grace Gordon | 306 |

| Won’t and Will | 307 | |

| Willie’s Breeches | Etta G. Saulsbury | 307 |

| Little Dora’s Soliloquy | 307 | |

| The Squirrel’s Lesson | 308 | |

| Little Kitty | 308 | |

| Labor Song | 309 | |

| What Baby Said | 310 | |

| One Little Act | 311 | |

| The Little Orator | Thaddeus M. Harris | 311 |

| A Gentleman | Margaret E. Sangster | 312 |

| Babies and Kittens | L. M. Hadley | 312 |

| A Dissatisfied Chicken | A. G. Waters | 312 |

| The Little Torment | 313 | |

| The Reason Why | 313 | |

| A Child’s Reasoning | 314 | |

| A Swell Dinner | 314 | |

| Little Jack | Eugene J. Hall | 314 |

| A Story of an Apple | Sydney Dayre | 315 |

| Idle Ben | 315 | |

| Baby Alice’s Rain | John Hay Furness | 316 |

| Give Us Little Boys a Chance | 316 | |

| Puss in the Oven | 316 | |

| What Was It? | Sydney Dayre | 317 |

| The Cobbler’s Secret | 317 | |

| A Sad Case | Clara D. Bates | 318 |

| The Heir Apparent | 318 | |

| An Egg a Chicken | 319 | |

| One of God’s Little Heroes | Margaret J. Preston | 320 |

| What the Cows were Doing | 320 | |

| Mamma’s Help | 320 | |

| How Two Birdies Kept House | 321 | |

| Why He Wouldn’t Die | 321 | |

| The Sick Dolly | 322 | |

| Days of the Week | Mary Ely Page | 322 |

| Popping Corn | 323 | |

| How the Farmer Works | 323 | |

| The Birds’ Picnic | 324 | |

| A Very Smart Dog | 324 | |

| Opportunity | 325 | |

| The Little Leaves’ Journey | 325 | |

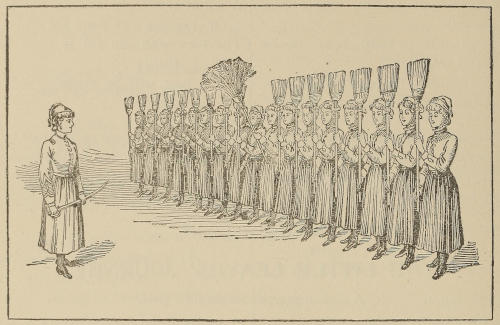

| The Broom Drill | 325 | |

| RECITATIONS FOR SUNDAY-SCHOOLS. | ||

| Little Servants | 332 | |

| Willie and the Birds | 332 | |

| A Child’s Prayer | 332 | |

| God Loves Me | 332 | |

| The Unfinished Prayer | 333 | |

| Seeds of Kindness | 333 | |

| A Lot of Don’ts | E. C. Rook | 333 |

| Little Willie and the Apple | 334 | |

| The Child’s Prayer | Mary A. P. Humphrey | 334 |

| “Mayn’t I Be a Boy?” | 335 | |

| Give Your Best | Adelaide A. Proctor | 335 |

| The Birds | Myra A. Shattuck | 335 |

| “Come Unto Me” | 336 | |

| There is a Teetotaler | 337 | |

| An Appeal for Beneficence | 337 | |

| Address of Welcome to a New Pastor | 337 | |

| Address of Welcome to a New Superintendent | 338 | |

| Opening Address for a Sunday-school Exhibition | 338 | |

| Closing Address for a Sunday-school Exhibition | 338 | |

| Presentation Address to a Pastor | 339 | |

| Presentation Address to a Teacher | 339 | |

| Presentation Address to a Superintendent | 339 | |

| Address of Welcome After Illness | 340 | |

| Welcome to a Pastor | May Hatheway | 340 |

| PART III.—PROGRAMMES FOR SPECIAL OCCASIONS. | ||

| Programme No. 1 for Fourth of July | 341 | |

| “America” | 341 | |

| The Fourth of July | Chas. Sprague | 341 |

| The Vow of Washington | J. G. Whittier | 342 |

| The Little Mayflower | Edward Everett | 343 |

| O Land of a Million Brave Soldiers | 343 | |

| To the Ladies | 344 | |

| Programme No. 2 for Fourth of July | 344 | |

| God Bless our Native Land | 344 | |

| Our Natal Day | Will Carleton | 345 |

| The Banner of the Sea | Homer Green | 346 |

| What America Has Done for the World | G. C. Verplanck | 346 |

| Stand Up for Liberty | Robert Treat Paine | 347 |

| Off with Your Hat as the Flag Goes By | H. C. Bunner | 348 |

| Programme for Christmas Entertainment | 349 | |

| Ring, O Bells, in Gladness | Alice J. Cleator | 349 |

| A Letter to Santa Claus | 349 | |

| Christmas in All the Lands | G. A. Brown | 349 |

| Santa Claus on the Train | Henry C. Walsh | 350 |

| The Waifs | Margaret Deland | 351 |

| Welcome Santa Claus | 351 | |

| Santa Claus and the Mouse | Emilie Poulsson | 351 |

| What Ted Found in His Stocking | 352 | |

| Programme for Decoration Day | 353 | |

| The Meaning of the Day | 353 | |

| Exercise for Fifteen Pupils | 353[x] | |

| Decoration Day | J. Whitcomb Riley | 354 |

| Acrostic | 355 | |

| Origin of Memorial Day | 355 | |

| Strew with Flowers the Soldier’s Grave | J. W. Dunbar | 355 |

| Our Nation’s Patriots | 356 | |

| Programme for Washington’s Birthday | 357 | |

| Washington Enigma | 357 | |

| Washington’s Day | 357 | |

| A Little Boy’s Hatchet Story | 357 | |

| Maxims of Washington | 358 | |

| Once More We Celebrate | Alice J. Cleator | 358 |

| The Father of His Country | 358 | |

| February Twenty-Second | Joy Allison | 359 |

| A True Soldier | Alice J. Cleator | 359 |

| Washington’s Life | 360 | |

| Birthday of Washington | George Howland | 360 |

| Programme for Arbor Day | 361 | |

| We Have Come with Joyful Greeting | 361 | |

| Arbor Day | 361 | |

| Quotations | 361 | |

| What Do We Plant When We Plant a Tree? | Henry Abbey | 362 |

| Wedding of the Palm and Pine | 363 | |

| Origin of Arbor Day | 363 | |

| Value of Our Forests | 364 | |

| Up From the Smiling Earth | Edna D. Proctor | 364 |

| The Trees | 364 | |

| Programme for A Harvest Home | 365 | |

| Through the Golden Summertime | 365 | |

| A Sermon in Rhyme | 365 | |

| Farmer John | J. T. Trowbridge | 366 |

| The Husbandman | John Sterling | 366 |

| The Nobility of Labor | Orville Dewey | 367 |

| The Corn Song | J. G. Whittier | 367 |

| Great God! Our Heartfelt Thanks | W. D. Gallagher | 367 |

| Programme for Lyceum or Parlor Entertainment | 368 | |

| Salutatory Address | 368 | |

| Mrs. Piper | Marian Douglass | 369 |

| Colloquy—True Bravery | 370 | |

| Reverie in Church | George A. Baker | 371 |

| The Spanish-American War | President McKinley | 372 |

| A Cook of the Period | 372 | |

| Song—Bee-Hive Town | 373 | |

| Programme for Thanksgiving | 373 | |

| Honor the Mayflower’s Band | 373 | |

| What am I Thankful For? | 374 | |

| The Pumpkin | J. G. Whittier | 374 |

| What Matters the Cold Wind’s Blast? | 374 | |

| Outside and In | 375 | |

| The Laboring Classes | Hugh Legare | 375 |

| A Thanksgiving | Lucy Larcom | 376 |

| Song—The Pilgrims | 376 | |

| Programme for Flower Day | 377 | |

| Let Us With Nature Sing | 377 | |

| The Poppy and Mignonette | 377 | |

| Flower Quotations | 377 | |

| When Winter O’er the Hills Afar | 378 | |

| Flowers | Lydia M. Child | 378 |

| The Foolish Harebell | George MacDonald | 378 |

| Questions About Flowers | 379 | |

| Pansies | Mary A. McClelland | 379 |

| Plant Song | Nellie M. Brown | 380 |

| We Would Hail Thee, Joyous Summer | 380 | |

| Summer-Time | H. W. Longfellow | 380 |

| The Last Rose of Summer | Thomas Moore | 381 |

| DIALOGUES FOR SCHOOLS AND LYCEUMS. | ||

| In Want of a Servant | Clara Augusta | 382 |

| The Unwelcome Guest | H. Elliot McBride | 386 |

| Aunty Puzzled | 388 | |

| The Poor Little Rich Boy | Mrs. Adrian Kraal | 390 |

| An Entirely Different Matter | 391 | |

| The Gossips | 392 | |

| Farmer Hanks Wants a Divorce | 393 | |

| Taking the Census | 397 | |

| Elder Sniffles’ Courtship | F. M. Whitcher | 400 |

| The Matrimonial Advertisement | 403 | |

| Mrs. Malaprop and Captain Absolute | R. B. Sheridan | 407 |

| Winning a Widow | 410 | |

| MISCELLANEOUS DIALOGUES AND DRAMAS | 411 | |

| CONSTITUTION AND BY-LAWS FOR LYCEUMS | 443 | |

| SUBJECTS FOR DEBATE BY LYCEUMS | 446 | |

| TABLEAUX FOR PUBLIC ENTERTAINMENTS | 447 | |

The correct and pleasing expression of one’s thoughts in writing is an accomplishment of the highest order. To have little or no ability in the art of composition is a great misfortune.

Who is willing to incur the disgrace and mortification of being unable to write a graceful and interesting letter, or an essay worthy to be read by intelligent persons? What an air of importance belongs to the young scholar, or older student, who can pen a production excellent in thought and beautiful in language! Such a gifted individual becomes almost a hero or heroine.

When I was a pupil in one of our public schools the day most dreaded by all of the scholars was “composition day.” What to write about, and how to do it, were the most vexatious of all questions. Probably nine-tenths of the pupils would rather have mastered the hardest lessons, or taken a sound whipping, than to attempt to write one paragraph of a composition on any subject.

While some persons have a natural faculty for putting their thoughts into words, a much larger number of others are compelled to confess that it is a difficult undertaking, and they are never able to satisfy themselves with their written productions.

Let it be some encouragement to you to reflect that many who are considered excellent writers labored in the beginning under serious difficulties, yet, being resolved to master them, they finally achieved the most gratifying success. When Napoleon was told it would be impossible for his army to cross the bridge at Lodi, he replied, “There is no such word as impossible,” and over the bridge his army went. Resolve that you will succeed, and carry out this good resolution by close application and diligent practice. “Labor conquers all things.”

Study carefully the lessons contained in the following pages. They will be of great benefit, as they show you what to do and how to do it.

These lessons are quite simple at first, and are followed by others that are more advanced. All of them have been carefully prepared for the purpose of furnishing just such helps as you need. You can study them by yourself; if you can obtain the assistance of a competent teacher, so much the better. I predict that you will be surprised at the rapid progress you are making. Perhaps you will become fascinated with your study; at least, it is to be hoped you will, and become enthusiastic in your noble work.

Be content to take one step at a time. Do not get the mistaken impression that you[18] will be able to write a good composition before you have learned how to do it. Many persons are too eager to achieve success immediately, without patient and earnest endeavor to overcome all difficulties.

Choose a subject for your composition that is adapted to your capacity. You cannot write on a subject that you know nothing about. Having selected your theme, think upon it, and, if possible, read what others have written about it, not for the purpose of stealing their thoughts, but to stimulate your own, and store your mind with information. Then you will be able to express in writing what you know.

The principal reason why many persons make such hard work of the art of composition is that they have so few thoughts, and consequently so little to say, upon the subjects they endeavor to treat. The same rule must be followed in writing a composition as in building a house—you must first get your materials.

I said something about stealing the thoughts of others, but must qualify this by saying that while you are learning to write, you are quite at liberty in your practice to make use of the thoughts of others, writing them from memory after you have read a page or a paragraph from some standard author. It is better that you should remember only a part of the language employed by the writer whose thoughts you are reproducing, using as far as possible words of your own, yet in each instance wherein you remember his language you need not hesitate to use it. Such an exercise is a valuable aid to all who wish to perfect themselves in the delightful art of composition.

Take any writer of good English—J. G. Holland, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Irving, Cooper, or the articles in our best magazines—and read half a page twice or thrice; close the book, and write, in your own words, what you have read; borrowing, nevertheless, from the author so much as you can remember. Compare what you have written with the original, sentence by sentence, and word by word, and observe how far you have fallen short of the skilful author.

You will thus not only find out your own faults, but you will discover where they lie, and how they may be mended. Repeat the lesson with the same passages twice or thrice, if your memory is not filled with the words of the author, and observe, at each trial, the progress you have made, not merely by comparison with the original, but by comparison with the previous exercises.

Do this day after day, changing your author for the purpose of varying the style, and continue to do so long after you have passed on to the second and more advanced stages of your training. Preserve all your exercises, and occasionally compare the latest with the earliest, and so ascertain what progress you have made.

Give especial attention to the words, which, to my mind, are of greater importance than the sentences. Take your nouns first, and compare them with the nouns used by your author. You will probably find your words to be very much bigger than his, more sounding, more far-fetched, more classical, or more poetical. All young writers and speakers fancy that they cannot sufficiently revel in fine words. Comparison with the great masters of English will rebuke this pomposity of inexperience, and chasten and improve your style.

You will discover, to your surprise, that our best writers eschew big words and do not aim to dazzle their readers with fine words. Where there is a choice, they prefer[19] the pure, plain, simple English noun—the name by which the thing is known to everybody, and which, therefore, is instantly understood by all readers. These great authors call a spade “a spade;” only small scribblers term it “an implement of husbandry.” If there is a choice of names, good writers prefer the one best known, while an inexperienced writer is apt to select the most uncommon.

The example of the masters of the English tongue should teach you that commonness (if I may be allowed to coin a word to express that for which I can find no precise equivalent) and vulgarity are not the same in substance. Vulgarity is shown in assumption and affectation of language quite as much as in dress and manners, and it is never vulgar to be natural. Your object is to be understood. To be successful, you must write and talk in a language that everybody can understand; and such is the natural vigor, picturesqueness and music of our tongue, that you could not possess yourself of a more powerful or effective instrument for expression.

It is well for you to be assured that while, by this choice of plain English for the embodying of your thoughts, you secure the ears of ordinary people, you will at the same time please the most highly educated and refined. The words that have won the applause of a political meeting are equally successful in securing a hearing in Congress, provided that the thoughts expressed and the manner of their expression be adapted to the changed audience.

Then for the sentences. Look closely at their construction, comparing it with that of your author; I mean, note how you have put your words together. The placing of words is next in importance to the choice of them. The best writers preserve the natural order of thought. They sedulously shun obscurities and perplexities. They avoid long and involved sentences. Their rule is, that one sentence should express one thought, and they will not venture on the introduction of two or three thoughts, if they can help it.

Undoubtedly this is extremely difficult—sometimes impossible. If you want to qualify an assertion, you must do so on the instant; but the rule should never be forgotten, that a long and involved sentence is to be avoided, wherever it is practicable to do so.

Another lesson you will doubtless learn from the comparison of your composition with that of your model author. You will see a wonderful number of adjectives in your own writing, and very few in his. It is the besetting sin of young writers to indulge in adjectives, and precisely as a man gains experience do his adjectives diminish in number. It seems to be supposed by all unpracticed scribblers that the multiplication of epithets gives force. The nouns are never left to speak for themselves.

It is curious to take up any newspaper and read the paragraphs of news, to open the books of nine-tenths of our authors of the third and downward ranks. You will rarely see a noun standing alone, without one or more adjectives prefixed. Be assured that this is a mistake. An adjective should never be used unless it is essential to correct description. As a general rule adjectives add little strength to the noun they are set to prop, and a multiplication of them is always enfeebling. The vast majority of nouns convey to the mind a much more accurate picture of the thing they signify than you can possibly paint by attaching epithets to them.

Yet do not push to the extreme what has just been said. Adjectives are a very important part of language, and we could not well do without them. You do not need to say a “flowing river;” every river flows, but you might wish to say a “swollen river,” and you could not convey the idea you desire to express without using the adjective “swollen.” What I wish to caution you against is the needless multiplication of adjectives, which only serve to overload and weaken the expression of your thought.

When you have repeated your lesson many times, and find that you can write with some approach to the purity of your author, you should attempt an original composition. In the beginning it would be prudent, perhaps, to borrow the ideas, but to put them into your own language. The difficulty of this consists in the tendency of the mind to mistake memory for invention, and thus, unconsciously to copy the language as well as the thoughts of the author.

The best way to avoid this is to translate poetry into prose; to take, for instance, a page of narrative in verse and relate the same story in plain prose; or to peruse a page of didactic poetry, and set down the argument in a plain, unpoetical fashion. This will make you familiar with the art of composition, only to be acquired by practice; and the advantage, at this early stage of your education in the arts of writing and speaking, of putting into proper language the thoughts of others rather than your own is, that you are better able to discover your faults. Your fatherly love for your own ideas is such that you are really incompetent to form a judgment of their worth, or of the correctness of the language in which they are embodied.

The critics witness this hallucination every day. Books continually come to them, written by men who are not mad, who probably are sufficiently sensible in the ordinary business of life, who see clearly enough the faults of other books, who would have laughed aloud over the same pages, if placed in their hands by another writer, but who, nevertheless, are utterly unable to recognize the absurdities of their own handiwork. The reader is surprised that any man of common intelligence could indite such a maze of nonsense where the right word is never to be found in its right place, and this with such utter unconsciousness of incapacity on the part of the author.

Still more is he amazed that, even if a sensible man could so write, a sane man could read that composition in print, and not with shame throw it into the fire. But the explanation is, that the writer knew what he intended to say; his mind is full of that, and he reads from the manuscript or the type, not so much what is there set down, as what was already floating in his own mind. To criticise yourself you must, to some extent, forget yourself. This is impracticable to many persons, and, lest it may be so with you, I advise you to begin by putting the thoughts of others into your own language, before you attempt to give formal expression to your own thoughts.

You must habitually place your thoughts upon paper—first, that you may do so rapidly; and, secondly, that you may do so correctly. When you come to write your reflections, you will be surprised to find how loose and inaccurate the most vivid of them have been, what terrible flaws there are in your best arguments.

You are thus enabled to correct them, and to compare the matured sentence with the rude conception of it. You are thus trained to weigh your words and assure yourself[21] that they precisely embody the idea you desire to convey. You can trace uncouthness in the sentences, and dislocations of thought, of which you had not been conscious before. It is far better to learn your lesson thus upon paper, which you can throw into the fire unknown to any human being, than to be taught it by readers who are not always very lenient critics and are quick to detect any faults that appear in your production.

Having accustomed yourself to express, in plain words, and in clear, precise and straightforward sentences, the ideas of others, you should proceed to express your own thoughts in the same fashion. You will now see more distinctly the advantage of having first studied composition by the process I have recommended, for you are in a condition to discover the deficiencies in the flow of your own ideas. You will be surprised to find, when you come to put them into words, how many of your thoughts were shapeless, hazy and dreamy, slipping from your grasp when you try to seize them, resolving themselves, like the witches in Macbeth,

Thus, after you have learned how to write, you will need a good deal of education before you will learn what to write. I cannot much assist you in this part of the business. Two words convey the whole lesson—Read and think. What should you read? Everything. What think about? All subjects that present themselves. The writer and orator must be a man of very varied knowledge. Indeed, for all the purposes of practical life, you cannot know too much. No learning is quite useless. But a speaker, especially if an advocate, cannot anticipate the subjects on which he may be required to talk. Law is the least part of his discourse. For once that he is called upon to argue a point of law, he is compelled to treat matters of fact twenty times.

And the range of topics is very wide; it embraces science and art, history and philosophy; above all, the knowledge of human nature that teaches how the mind he addresses is to be convinced and persuaded, and how a willing ear is to be won to his discourse. No limited range of reading will suffice for so large a requirement. The elements of the sciences must be mastered; the foundations of philosophy must be learned; the principles of art must be acquired; the broad facts of history must be stamped upon the memory; poetry and fiction must not be slighted or neglected.

You must cultivate frequent and intimate intercourse with the genius of all ages and of all countries, not merely as standards by which to measure your own progress, or as fountains from which you may draw unlimited ideas for your own use, but because they are peculiarly suggestive. This is the characteristic of genius, that, conveying one thought to the reader’s mind, it kindles in him many other thoughts. The value of this to speaker and writer will be obvious to you.

Never, therefore, permit a day to pass without reading more or less—if it be but a single page—from some one of our great writers. Besides the service I have described in the multiplication of your ideas, it will render you the scarcely lesser service of preserving purity of style and language, and preventing[22] you from falling into the conventional affectations and slang of social dialogue.

For the same reason, without reference to any higher motive, but simply to fill our mind with the purest English, read daily some portion of the Bible; for which exercise there is another reason also, that its phraseology is more familiar to all kinds of audiences than any other, is more readily understood, and, therefore, is more sufficient in securing their attention.

Your reading will thus consist of three kinds: reading for knowledge, by which I mean the storing of your memory with facts; reading for thoughts, by which I mean the ideas and reflections that set your own mind thinking; and reading the words, by which I mean the best language in which the best authors have clothed their thoughts. And these three classes of reading should be pursued together daily, more or less as you can, for they are needful each to the others, and neither can be neglected without injury to the rest.

So also you must make it a business to think. You will probably say that you are always thinking when you are not doing anything, and often when you are busiest. True, the mind is active, but wandering, vaguely from topic to topic. You are not in reality thinking out anything; indeed, you cannot be sure that your thoughts have a shape until you try to express them in words. Nevertheless you must think before you can write or speak, and you should cultivate a habit of thinking at all appropriate seasons.

But do not misunderstand this suggestion. I do not design advising you to set yourself a-thinking, as you would take up a book to read at the intervals of business, or as a part of a course of self-training; for such attempts would probably begin with wandering fancies and end in a comfortable nap. It is a fact worth noting, that few persons can think continuously while the body is at perfect rest. The time for thinking is when you are kept awake by some slight and almost mechanical muscular exercise, and the mind is not busily attracted by external subjects of attention.

Thus walking, angling, gardening, and other rural pursuits are pre-eminently the seasons for thought, and you should cultivate a habit of thinking during those exercises, so needful for health of body and for fruitfulness of mind. Then it is that you should submit whatever subject you desire to treat to careful review, turning it on all sides, and inside out, marshalling the facts connected with it, trying what may be said for or against every view of it, recalling what you may have read about it, and finally thinking what you could say upon it that had not been said before, or how you could put old views of it into new shapes.

Perhaps the best way to accomplish this will be to imagine yourself writing upon it, or making a speech upon it, and to think what in such case you would say; I do not mean in what words you would express yourself, but what you would discourse about; what ideas you would put forth; to what thoughts you would give utterance.

At the beginning of this exercise you will find your reflections extremely vague and disconnected; you will range from theme to theme, and mere flights of fancy will be substituted for steady, continuous thought. But persevere day by day, and that which was in the beginning an effort will soon grow into a habit, and you will pass few moments of your working life in which, when not occupied from without, your mind will not be usefully employed within itself.

Having attained this habit of thinking, let[23] it be a rule with you, before you write or speak on any subject, to employ your thoughts upon it in the manner I have described. Go a-fishing. Take a walk. Weed your garden. Sweep, dust, do any sewing that needs to be done. While so occupied, think. It will be hard if your own intelligence cannot suggest to you how the subject should be treated, in what order of argument, with what illustrations, and with what new aspects of it, the original product of your own genius.

At all events this is certain, that without preliminary reflection you cannot hope to deal with any subject to your own satisfaction, or to the profit or pleasure of others. If you neglect these precautions, you can never be more than a wind-bag, uttering words that, however grandly they may roll, convey no thoughts. There is hope for ignorance; there is none for emptiness.

To sum up these rules and suggestions: To become a writer or an orator, you must fill your mind with knowledge by reading and observation, and educate it to the creation of thoughts by cultivating a habit of reflection. There is no limit to the knowledge that will be desirable and useful; it should include something of natural science, much of history, and still more of human nature. The latter must be your study, for it is with this that the writer and speaker has to deal.

Remember, that no amount of antiquarian, or historical, or scientific, or literary lore will make a writer or orator, without intimate acquaintance with the ways of the world about him, with the tastes, sentiments, passions, emotions, and modes of thought of the men and women of the age in which he lives, and whose minds it is his business to instruct and sway.

You must think, that you may have thoughts to convey; and read, that you may have words wherewith to express your thoughts correctly and gracefully. But something more than this is required to qualify you to write or speak. You must have a style. I will endeavor to explain what I mean by that.

As every man has a manner of his own, differing from the manner of every other man, so has every mind its own fashion of communicating with other minds. This manner of expressing thought is style, and therefore may style be described as the features of the mind displayed in its communications with other minds; as manner is the external feature exhibited in personal communication.

But though style is the gift of nature, it is nevertheless to be cultivated; only in a sense different from that commonly understood by the word cultivation.

Many elaborate treatises have been written on style, and the subject usually occupies a prominent place in all books on composition and oratory. It is usual with teachers to urge emphatically the importance of cultivating style, and to prescribe ingenious recipes for its production. All these proceed upon the assumption that style is something artificial, capable of being taught, and which may and should be learned by the student, like spelling or grammar.

But, if the definition of style which I have submitted to you is right, these elaborate trainings are a needless labor; probably a positive mischief. I do not design to say a style may not be taught to you; but it will be the style of some other man, and not your own; and, not being your own, it will no[24] more fit your mind than a second-hand suit of clothes, bought without measurement at a pawn-shop, would fit your body, and your appearance in it would be as ungainly.

But you must not gather from this that you are not to concern yourself about style, that it may be left to take care of itself, and that you will require only to write or speak as untrained nature prompts. I say that you must cultivate style; but I say also that the style to be cultivated must be your own, and not the style of another.

The majority of those who have written upon the subject recommend you to study the styles of the great writers of the English language, with a view to acquiring their accomplishment. So I say—study them, by all means; but not for the purpose of imitation, not with a view to acquire their manner, but to learn their language, to see how they have embodied their thoughts in words, to discover the manifold graces with which they have invested the expression of their thoughts, so as to surround the act of communicating information, or kindling emotion, with the various attractions and charms of art.

Cultivate style; but instead of laboring to acquire the style of your model, it should be your most constant endeavor to avoid it. The greatest danger to which you are exposed is that of falling into an imitation of the manner of some favorite author, whom you have studied for the sake of learning a style, which, if you did learn it, would be unbecoming to you, because it is not your own. That which in him was manner becomes in you mannerism; you but dress yourself in his clothes, and imagine that you are like him, while you are no more like than is the valet to his master whose cast-off coat he is wearing.

There are some authors whose manner is so infectious that it is extremely difficult not to catch it. Hawthorne is one of these; it requires an effort not to fall into his formula of speech. But your protection against this danger must be an ever-present conviction that your own style will be the best for you, be it ever so bad or good. You must strive to be yourself, to think for yourself, to speak in your own manner; then, what you say and your style of saying it will be in perfect accord, and the pleasure to those who read or listen will not be disturbed by a sense of impropriety and unfitness.

Nevertheless, I repeat, you should cultivate your own style, not by changing it into some other person’s style, but by striving to preserve its individuality, while decorating it with all the graces of art. Nature gives the style, for your style is yourself; but the decorations are slowly and laboriously acquired by diligent study, and, above all, by long and patient practice. There are but two methods of attaining to this accomplishment—contemplation of the best productions of art, and continuous toil in the exercise of it.

I assume that, by the process I have already described, you have acquired a tolerably quick flow of ideas, a ready command of words, and ability to construct grammatical sentences; all that now remains to you is to learn to use this knowledge that the result may be presented in the most attractive shape to those whom you address. I am unable to give you many practical hints towards this, because it is not a thing to be acquired by formal rules, in a few lessons and by a set course of study; it is the product of very wide and long-continued gleanings from a countless variety of sources; but, above all, it is taught by experience.

If you compare your compositions at intervals of six months, you will see the progress[25] you have made. You began with a multitude of words, with big nouns and bigger adjectives, a perfect firework of epithets, a tendency to call everything by something else than its proper name, and the more you admired your own ingenuity the more you thought it must be admired by others. If you had a good idea, you were pretty sure to dilute it by expansion, supposing the while that you were improving by amplifying it. You indulged in small flights of poetry (in prose), not always in appropriate places, and you were tolerably sure to go off into rhapsody, and to mistake fine words for eloquence. This is the juvenile style; and is not peculiar to yourself—it is the common fault of all young writers.

But the cure for it may be hastened by judicious self-treatment. In addition to the study of good authors, to cultivate your taste, you may mend your style by a process of pruning, after the following fashion. Having finished your composition, or a section of it, lay it aside, and do not look at it again for a week, during which interval other labors will have engaged your thoughts. You will then be in a condition to revise it with an approach to critical impartiality, and so you will begin to learn the wholesome art of blotting. Go through it slowly, pen in hand, weighing every word, and asking yourself, “What did I intend to say? How can I say it in the briefest and plainest English?”

Compare with the plain answer you return to this question the form in which you had tried to express the same meaning in the writing before you, and at each word further ask yourself, “Does this word precisely convey my thought? Is it the aptest word? Is it a necessary word? Would my meaning be fully expressed without it?” If it is not the best, change it for a better. If it is superfluous, ruthlessly strike it out.

The work will be painful at first—you will sacrifice with a sigh so many flourishes of fancy, so many figures of speech, of whose birth you were proud. Nay, at the beginning, and for a long time afterwards, your courage will fail you, and many a cherished phrase will be spared by your relenting pen. But be persistent, and you will triumph at last. Be not content with one act of erasure. Read the manuscript again, and, seeing how much it is improved, you will be inclined to blot a little more. Lay it aside for a month, and then read again, and blot again as before. Be severe toward yourself.

Simplicity is the crowning achievement of judgment and good taste. It is of very slow growth in the greatest minds; by the multitude it is never acquired. The gradual progress towards it can be curiously traced in the works of the great masters of English composition, wheresoever the injudicious zeal of admirers has given to the world the juvenile writings which their own better taste had suffered to pass into oblivion. Lord Macaulay was an instance of this. Compare his latest with his earliest compositions, as collected in the posthumous volume of his “Remains,” and the growth of improvement will be manifest.

Yet, at first thought, nothing appears to be easier to remember, and to act upon, than the rule, “Say what you want to say in the fewest words that will express your meaning clearly; and let those words be the plainest, the most common (not vulgar), and the most intelligible to the greatest number of persons.” It is certain that a beginner will adopt[26] the very reverse of this. He will say what he has to say in the greatest number of words he can devise, and those words will be the most artificial and uncommon his memory can recall. As he advances, he will learn to drop these long phrases and big words; he will gradually contract his language to the limit of his thoughts, and he will discover, after long experience, that he was never so feeble as when he flattered himself that he was most forcible.

I have dwelt upon this subject with repetitions that may be deemed almost wearisome, because affectations and conceits are the besetting sin of modern composition, and the vice is growing and spreading. The literature of our periodicals teems with it; the magazines are infected by it almost as much as the newspapers, which have been always famous for it.

Instead of an endeavor to write plainly, the express purpose of the writers in the periodicals is to write as obscurely as possible; they make it a rule never to call anything by its proper name, never to say anything directly in plain English, never to express their true meaning. They delight to say something quite different in appearance from that which they purpose to say, requiring the reader to translate it, if he can, and, if he cannot, leaving him in a state of bewilderment, or wholly uninformed.

Worse models you could not find than those presented to you by the newspapers and periodicals; yet are you so beset by them that it is extremely difficult not to catch the infection. Reading day by day compositions teeming with bad taste, and especially where the style floods you with its conceits and affectations, you unconsciously fall into the same vile habit, and incessant vigilance is required to restore you to sound, vigorous, manly, and wholesome English. I cannot recommend to you a better plan for counteracting the inevitable mischief than the daily reading of portions of some of our best writers of English, specimens of which you will find near the close of the First Part of this volume. We learn more by example than in any other way, and a careful perusal of these choice specimens of writing from the works of the most celebrated authors will greatly aid you.

You will soon learn to appreciate the power and beauty of those simple sentences compared with the forcible feebleness of some, and the spasmodic efforts and mountebank contortions of others, that meet your eye when you turn over the pages of magazine or newspaper. I do not say that you will at once become reconciled to plain English, after being accustomed to the tinsel and tin trumpets of too many modern writers; but you will gradually come to like it more and more; you will return to it with greater zest year by year; and, having thoroughly learned to love it, you will strive to follow the example of the authors who have written it.

And this practice of daily reading the writings of one of the great masters of the English tongue should never be abandoned. So long as you have occasion to write or speak, let it be held by you almost as a duty. And here I would suggest that you should read them aloud; for there is no doubt that the words, entering at once by the eye and the ear, are more sharply impressed upon the mind than when perused silently.

Moreover, when reading aloud you read more slowly; the full meaning of each word must be understood, that you may give the right expression to it, and the ear catches the general structure of the sentences more perfectly. Nor will this occupy much time.[27] There is no need to devote to it more than a few minutes every day. Two or three pages thus read daily will suffice to preserve the purity of your taste.

Your first care in composition will be, of course, to express yourself grammatically. This is partly habit, partly teaching. If those with whom a child is brought up talk grammatically, he will do likewise, from mere imitation; but he will learn quite as readily anything ungrammatical to which his ears may be accustomed; and, as the most fortunate of us mingle in childhood with servants and other persons not always observant of number, gender, mood, and tense, and as even they who have enjoyed the best education lapse, in familiar talk, into occasional defiance of grammar, which could not be avoided without pedantry, you will find the study of grammar necessary to you under any circumstances. Your ear will teach you a great deal, and you may usually trust to it as a guide; but sometimes occasions arise when you are puzzled to determine which is the correct form of expression, and in such cases there is safety only in reference to the rule.

Fortunately our public schools and academies give much attention to the study of grammar. The very first evidence that a person is well educated is the ability to speak correctly. If you were to say, “I paid big prices for them pictures,” or, “Her photographs always flatters her,” or, “His fund of jokes and stories make him a pleasant companion,” or, “He buys the paper for you and I”—if you were guilty of committing such gross errors against good grammar, or scores of others that might be mentioned, your chances for obtaining a standing in polite society would be very slim. Educated persons would at once rank you as an ignorant boor, and their treatment of you would be suggestive of weather below zero. Do not “murder the King’s English.”

Having pointed out the importance of correct grammar and the right choice of language, I wish now to furnish you with some practical suggestions for the construction of sentences. Remember that a good thought often suffers from a weak and faulty expression of it.

Your sentences will certainly shape themselves after the structure of your own mind. If your thoughts are vivid and definite, so will be your language; if dreamy and hazy, so will your composition be obscure. Your speech, whether oral or written, can be but the expression of yourself; and what you are, that speech will be.

Remember, then, that you cannot materially change the substantial character of your writing; but you may much improve the form of it by the observance of two or three general rules.

In the first place, be sure you have something to say. This may appear to you a very unnecessary precaution; for who, you will ask, having nothing to say, desires to write or to speak? I do not doubt that you have often felt as if your brain was teeming with thoughts too big for words; but when you came to seize them, for the purpose of putting them into words, you have found them evading your grasp and melting into the air. They were not thoughts at all, but fancies—shadows which you had mistaken for substances, and whose vagueness you would never have detected, had you not sought to embody them in language. Hence you will need to be assured that you have thoughts to express, before you try to express them.

And how to do this? By asking yourself, when you take up the pen, what it is you intend to say, and answering yourself as you best can, without caring for the form of expression. If it is only a vague and mystical idea, conceived in cloudland, you will try in vain to put it into any form of words, however rude. If, however, it is a definite thought, proceed at once to set it down in words and fix it upon paper.

The expression of a precise and definite thought is not difficult. Words will follow the thought; indeed, they usually accompany it, because it is almost impossible to think unless the thought is clothed in words. So closely are ideas and language linked by habit, that very few minds are capable of contemplating them apart, insomuch that it may be safely asserted of all intellects, save the highest, that if they are unable to express their ideas, it is because the ideas are incapable of expression—because they are vague and hazy.

For the present purpose it will suffice that you put upon paper the substance of what you desire to say, in terms as rude as you please, the object being simply to measure your thoughts. If you cannot express them, do not attribute your failure to the weakness of language, but to the dreaminess of your ideas, and therefore banish them without mercy, and direct your mind to some more definite object for its contemplations. If you succeed in putting your ideas into words, be they ever so rude, you will have learned the first, the most difficult, and the most important lesson in the art of writing.

The second is far easier. Having thoughts, and having embodied those thoughts in unpolished phrase, your next task will be to present them in the most attractive form. To secure the attention of those to whom you desire to communicate your thoughts, it is not enough that you utter them in any words that come uppermost; you must express them in the best words, and in the most graceful sentences, so that they may be read with pleasure, or at least without offending the taste.

Your first care in the choice of words will be that they shall express precisely your meaning. Words are used so loosely in society that the same word will often be found to convey half a dozen different ideas to as many auditors. Even where there is not a conflict of meanings in the same word, there is usually a choice of words having meanings sufficiently alike to be used indiscriminately, without subjecting the user to a charge of positive error. But the cultivated taste is shown in the selection of such as express the most delicate shades of difference.

Therefore, it is not enough to have abundance of words; you must learn the precise meaning of each word, and in what it differs from other words supposed to be synonymous; and then you must select that which most exactly conveys the thought you are seeking to embody. There is but one way to fill your mind with words, and that is, to read the best authors, and to acquire an accurate knowledge of the precise meaning of their words—by parsing as you read.

By the practice of parsing, I intend very nearly the process so called at schools, only limiting the exercise to the definitions of the principal words. As thus: take, for instance the sentence that immediately precedes this,—ask yourself what is the meaning of “practice,” of “parsing,” of “process,” and such like. Write the answer to each, that you may be assured that your definition is distinct. Compare it with the definitions of the same word in the dictionaries, and observe[29] the various senses in which it has been used.

You will thus learn also the words that have the same, or nearly the same, meaning—a large vocabulary of which is necessary to composition, for frequent repetition of the same word, especially in the same sentence, is an inelegance, if not a positive error. Compare your definition with that of the authorities, and your use of the word with the uses of it cited in the dictionary, and you will thus measure your own progress in the science of words.

This useful exercise may be made extremely amusing as well as instructive, if friends, having a like desire for self-improvement, will join you in the practice of it; and I can assure you that an evening will be thus spent pleasantly as well as profitably. You may make a merry game of it—a game of speculation. Given a word; each one of the company in turn writes his definition of it; Webster’s Dictionary, or some other, is then referred to, and that which comes nearest the authentic definition wins the honor or the prize; it may be a sweepstakes carried off by him whose definition hits the mark the most nearly.

But, whether in company or alone, you should not omit the frequent practice of this exercise, for none will impart such a power of accurate expression and supply such an abundance of apt words wherein to embody the delicate hues and various shadings of thought.

So with sentences, or the combination of words. Much skill is required for their construction. They must convey your meaning accurately, and as far as possible in the natural order of thought, and yet they must not be complex, involved, verbose, stiff, ungainly, or full of repetitions. They must be brief, but not curt; explicit, but not verbose. Here, again, good taste must be your guide, rather than rules which teachers propound, but which the pupil never follows.

Not only does every style require its own construction of a sentence, but almost every combination of thought will demand a different shape in the sentence by which it is conveyed. A standard sentence, like a standard style, is a pedantic absurdity; and, if you would avoid it, you must not try to write by rule, though you may refer to rules in order to find out your faults after you have written.

Lastly, inasmuch as your design is, not only to influence, but to please, it will be necessary for you to cultivate what may be termed the graces of composition. It is not enough that you instruct the minds of your readers; you must gratify their taste, and win their attention, giving pleasure in the very process of imparting information. Hence you must make choice of words that convey no coarse meanings, and excite no disagreeable associations. You are not to sacrifice expression to elegance; but so, likewise, you are not to be content with a word or a sentence if it is offensive or unpleasing, merely because it best expresses your meaning.

The precise boundary between refinement and rudeness cannot be defined; your own cultivated taste must tell you the point at which power or explicitness is to be preferred to delicacy. One more caution I would impress upon you, that you pause and give careful consideration to it before you permit a coarse expression, on account of its correctness, to pass your critical review when you revise your manuscript, and again when you read the proof, if ever you rush into print.

And much might be said also about the music of speech. Your words and sentences[30] must be musical. They must not come harshly from the tongue, if uttered, or grate upon the ear, if heard. There is a rhythm in words which should be observed in all composition, written or oral. The perception of it is a natural gift, but it may be much cultivated and improved by reading the works of the great masters of English, especially of the best poets—the most excellent of all in this wonderful melody of words being Longfellow and Tennyson. Perusal of their works will show you what you should strive to attain in this respect, even though it may not enable you fully to accomplish the object of your endeavor. Aim at the sun and you will shoot high.

The faculty for writing varies in various persons. Some write easily, some laboriously; words flow from some pens without effort, others produce them slowly; composition seems to come naturally to a few, and a few never can learn it, toil after it as they may. But whatever the natural power, of this be certain, that good writing cannot be accomplished without study and painstaking practice. Facility is far from being a proof of excellence. Many of the finest works in our language were written slowly and painfully; the words changed again and again, and the structure of the sentences carefully cast and recast.

There is a fatal facility that runs “in one weak, washy, everlasting flood,” that is more hopeless than any slowness or slovenliness. If you find your pen galloping over the paper, take it as a warning of a fault to be shunned; stay your hand, pause, reflect, read what you have written; see what are the thoughts you have set down, and resolutely try to condense them. There is no more wearisome process than to write the same thing over again; nevertheless it is a most efficient teaching. Your endeavor should be to say the same things, but to say them in a different form; to condense your thoughts, and express them in fewer words.

Compare this second effort with the first, and you will at once measure your improvement. You cannot now do better than repeat this lesson twice; rewrite, still bearing steadily in mind your object, which is, to say what you desire to utter in words the most apt and in the briefest form consistent with intelligibility and grace. Having done this, take your last copy and strike out pitilessly every superfluous word, substitute a vigorous or expressive word for a weak one, sacrifice the adjectives without remorse, and, when this work is done, rewrite the whole, as amended.

And, if you would see what you have gained by this laborious but effective process, compare the completed essay with the first draft of it, and you will recognize the superiority of careful composition over facile scribbling. You will be fortunate if you thus acquire a mastery of condensation, and can succeed in putting the reins upon that fatal facility of words, before it has grown into an unconquerable habit.

Simplicity is the charm of writing, as of speech; therefore, cultivate it with care. It is not the natural manner of expression, or, at least, there grows with great rapidity in all of us a tendency to an ornamental style of talking and writing. As soon as the child emerges from the imperfect phraseology of his first letters to papa, he sets himself earnestly to the task of trying to disguise what he has to say in some other words than such as plainly express his meaning and nothing more. To him it seems an object of ambition—a[31] feat to be proud of—to go by the most indirect paths, instead of the straight way, and it is a triumph to give the person he addresses the task of interpreting his language, to find the true meaning lying under the apparent meaning.

Circumlocution is not the invention of refinement and civilization, but the vice of the uncultivated; it prevails the most with the young in years and in minds that never attain maturity. It is a characteristic of the savage. You cannot too much school yourself to avoid this tendency, if it has not already seized you, as is most probable, or to banish it, if infected by it.

If you have any doubt of your condition in this respect, your better course will be to consult some judicious friend, conscious of the evil and competent to criticism. Submit to him some of your compositions, asking him to tell you candidly what are their faults, and especially what are the circumlocutions in them, and how the same thought might have been better, because more simply and plainly, expressed. Having studied his corrections, rewrite the article, striving to avoid those faults.

Submit this again to your friendly censor, and, if many faults are found still to linger, apply yourself to the labor of repetition once more. Repeat this process with new writings, until you produce them in a shape that requires few blottings, and, having thus learned what to shun, you may venture on self-reliance.