This cover image is placed in the public domain.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Lives of Fair and Gallant Ladies. Vol 1, by Seigneur De Brantôme

Title: Lives of Fair and Gallant Ladies. Vol 1

Author: Seigneur De Brantôme

Release Date: December 27, 2021 [eBook #67025]

Language: English

Produced by: Chris Curnow, Quentin Campbell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Lives of

Fair and Gallant Ladies

VOLUME I

By

The Seigneur De Brantôme

TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL

VOLUME I

The Alexandrian Society, Inc.

London and New York

1922

Copyright, 1922, by

THE ALEXANDRIAN SOCIETY, Inc.

printed in the united states of america

This work is strictly limited to twelve hundred and fifty numbered sets, which are for sale only to subscribers. The type has been distributed on publication and no more will be printed.

Copy No. ....

[v]

This very fine and accurate translation of The Lives of Fair and Gallant Ladies was made by Mr. A. R. Allinson and because of its merit must be considered one of the great English translations, equalling in every quality those of the 16th and 17th centuries. The text of Brantôme’s great work is given practically complete in these volumes and the only modifications are based upon good taste and not on any fearful prudery. A few of Brantôme’s examples that illustrate his points belong more in a treatise on abnormal pathology than in a book of literary or historical interest and value, so nothing of any value is lost by omitting them. The rare charm, shrewd wisdom, amusing anecdote, literary merit and historical and social information will be appreciated by intelligent readers.

The cover design used on this book was made by C. O. Czeschka.

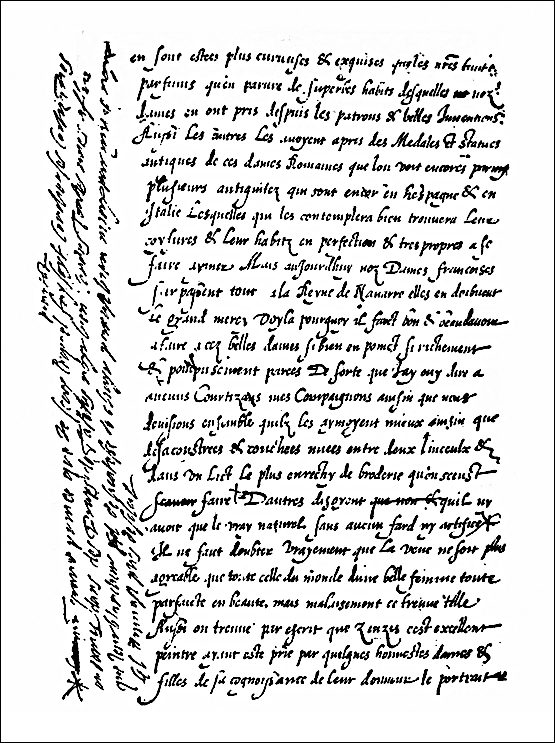

BRANTÔME’S HANDWRITING.

(From a fac-simile page of the manuscript

Recueil des Dames. Biblio. Nat: Mss. Nouv. fses.

No. 20-474, folio 163.)]

[vii]

SON AND BROTHER OF OUR FRENCH KINGS[1*]

My Gracious Lord,

Seeing how you have full often done me the honour at Court to converse with me in great privity of sundry jests and merry tales, the which are so familiar and ready with you they may well be said to grow apace before men’s very eyes in your Lordship’s mouth, so great your wit is and so keen and subtile, and your speech the same, and right eloquent to boot,—for this cause have I set me to indite these discourses, such as they be, to the best of my poor ability, to the end that in this wise some of them may please you, making the time to pass lightly and reminding you of me in your conversations, wherewith erstwhile you have honoured me as much as any gentleman of all the Court.

To you then, my Lord, do I dedicate this present book, and do beseech you fortify the same with your name and authority, till that I may find leisure to attend to discourses of a more serious content. Of such I pray you note one in especial, the which I have all but finished,[viii] wherein I do deduce a comparison of six great Princes and Captains that be to-day abroad in this our Christendom, to wit: the King Henri III. your brother, Your Highness’ self, the King of Navarre your brother-in-law, the Duc de Guise, the Duc de Maine, and the Prince of Parma, making record for each one of you of your noblest deeds of valour and high emprize, of your excellencies and exploits, the full tale and complement whereof I do resign to others better qualified than I to indite the same.

Meanwhile, My Lord, I do beseech God to bless you always more and more in your greatness, happiness and nobility.

And I am for all time

Your very humble and very obedient subject and very loving servant.

BOURDEILLE.[2]

[ix]

I had already dedicated this second Part of my Discourses on Women to the aforesaid my Gracious Lord d’Alençon, the while he yet lived,—seeing how he oft did me the honour to be my friend and to converse very privily with me, and was ever right curious to be informed of mirthful tales. Wherefore, albeit his generous and valorous and most noble body hath fallen on the field of honour, I have not thought good for that to recall my erstwhile dedication; but I do repeat and renew the same to his illustrious ashes and noble spirit, of the valorousness whereof and of his great deeds and high achievements I do treat in their turn among those of the other great Princes and Captains. For of a truth he was indeed a great Prince and a great Captain, if such an one there was ever,—the more so considering he is dead so untimeously.

Enough of such serious themes; let us discourse a while of merrier matters.

[xi]

|

PAGE |

Historical Note. By Henri Vigneau |

xiii |

FIRST DISCOURSE |

|

Of Ladies Which Do Make Love, and Their Husbands Cuckolds |

3 |

SECOND DISCOURSE |

|

On the Question Which Doth Give the More Content in Love, Whether Touching, Seeing, or Speaking |

213 |

1. Of the Sense of Touch in Love |

215 |

2. Of the Power of Speech in Love |

226 |

3. Of the Power of Sight in Love |

233 |

THIRD DISCOURSE |

|

Concerning the Beauty of a Fine Leg, and the Virtue the Same Doth Possess |

273 |

FOURTH DISCOURSE |

|

Concerning Old Dames as Fond to Practise Love as Ever the Young Ones Be |

293 |

Bibliography |

341 |

Appendix A. Brantôme, by Arthur Tilley |

345 |

Appendix B. Brantôme, by George Saintsbury |

351 |

Notes |

355 |

[xiii]

Pierre de Bourdeille, Abbé de Brantôme et d’André, Vicomte de Bourdeille, was born in Périgord, in 1527, in the reign of François I. He early took up the career of arms, serving under his friend François de Guise, Duke of Lorraine, as his Captain, the same who was killed before Orleans by Poltrot de Méré. Afterwards he came up to Court, and was Gentleman of the Bedchamber under Charles IX., who showed him much favour. On the King’s death he retired to his estates, where he composed his Works. These are: Vies des hommes illustres et des grands capitaines françois; Vies des grands capitaines étrangers; Vies des dames illustres; Vies des dames galantes; Anecdotes touchant le duel; and Rodomontades et jurements des Espagnols.—All that really concerns us here is the Vies des dames galantes. It is especially from this point of view that we propose to speak of Pierre de Bourdeille, known almost exclusively to posterity under the name of Brantôme. As to his Essays in the manner of Plutarch, these do not come into our purview at all. Besides which, I am of opinion, it is in this book that Brantôme appears under his most characteristic aspect, and that it is here we may best learn to know and appreciate his genius.

[xiv]

A gentleman of family, acknowledged and treated as kinsman by Queen Margot, wife of Henry IV., living habitually in the society of the most famous men of his time, a contemporary of Rabelais, Marot and Ronsard, a sincere but unbigoted Catholic, a man of exceptional literary endowments, Brantôme is one of the happiest representatives of the French mind in the XVIth Century.

It is the period of the Renaissance,—the days when Europe resounds with the fame of our gallant King Francis I. and his deeds of prowess in love and war, the days when Titian and Primaticcio were leaving behind on French palace walls immortal traces of their genius, when Jean Goujon was carving his admirable figures round the fountains of the Louvre and across its front, when Rabelais was uttering his stupendous guffaw, that was the Comedy of all human life, when Marot and Ronsard were writing their graceful stanzas, when the fair “Marguerite des Marguerites,”—the Queenly Pearl of Pearls,—was telling her delightful tales of love and adventure in the Heptameron.—Then comes the death of Francis I. His son mounts the throne. Protestantism makes serious progress in France, and Montgomery precipitates the succession of Francis II. This last wears the crown for one year only, succumbing to a fatal inflammation of the ears. Then it is Mary Stuart leaves France for ever, and with streaming eyes, as she watches the beloved shores where she has been Queen of France fade out of sight, sings sad and slow:

Adieu, plaisant pays de France!

And now we find seated on the throne of France a young Monarch of a strange, wild, unattractive exterior.[xv] His eye is pale, colourless and shifty, seeming to be void of all expression. He trusts no man, and has no real assurance of his power as Sovereign; he looks long and suspiciously at those about him before speaking, rarely bestows his confidence and believes himself constantly surrounded by spies. ’Tis a nervous, timid child,—’tis Charles IX. History treats him with an extreme severity; and the “St. Bartholomew” has thrown a lurid light over this unhappy Prince’s figure. He allowed the massacres on the fatal nights of the 24th and 25th of August, and even shot down the flying Protestants from his palace roof. Without going into the interminable discussions of historians as to this last alleged fact, which is as strongly denied by some authorities as it is maintained by others, I am not one of those who say hard things of Charles IX. It is more a sentiment of pity I feel for him,—this monarch who loved Brantôme and Marot, and who protected Henri IV. against Catherine de Medici. I see him surrounded by brothers whom he had learned to distrust. The Duc d’Alençon is on the spot, a legitimate object of detestation by reason of the subterranean intrigues he is for ever hatching against his person; while his other brother Henri (afterwards Henri III.), Catherine’s favourite son, is in Poland, kept sedulously informed of every variation in the Prince’s always feeble health, waiting impatiently for the hour when he must hurry back to France to secure the crown he covets. Then his sister’s vicious outbreaks are a source of constant pain and anxiety to him; and last but not least there is his mother Catherine de Medici, an incubus that crushed out his very life-breath. He cannot forget the tortures his brother Francis suffered from his mysterious[xvi] malady, and his premature death after a single year’s reign.

Catherine hated Mary Stuart, his young Queen, whose only fault was to have exaggerated in herself all the frailties together with all the physical perfections of a woman; and dreadful words had been whispered with bated breath about the Queen Mother. An Italian, deprived of all power while her husband lived, insulted by a proud and beautiful favourite, yet knowing herself well fitted for command, she had brought up her children with ideas of respect and submission to her will they were never able to throw off. The ill-will she bore her daughter-in-law was the cause of all those accusations History has listened to over readily. But Charles, a nervous, affectionate child, whose natural impulses however had been chilled by his mother’s influence and the indifference of his father Henri II., was thrown back on himself, and grew up timid, suspicious and morose. The frantic love of Francis for his fascinating Queen, the cold dignity of Catherine in face of slights and cruel mortifications, her bitter disappointment during her eldest son’s reign, her Italian origin (held then even more than now to imply an implacable determination to avenge all injuries), her indifference to the sudden and appalling death of the young King, the insinuations of her enemies,—all combined to make a profound impression on Charles, giving a furtive and, if we may say so, a haggard bent to his character. Presently, seated on the throne of France, Huguenots and Catholics all about him, exposed to the insults and pretensions of the Guise faction on the one hand and that of Coligny on the other, dragged now this way now that between the two, yet all the while instinctively[xvii] drawn toward the Catholic side by ancestral faith and his mother’s counsels no less than by reasons of state, Charles signed the fatal order authorizing the Massacre of the Saint Bartholomew.

Was the young King’s action justifiable or no? It is no business of ours to discuss the question here; but much may be alleged in his excuse. Again whether he did actually fire on the terrified Protestants from the Louvre is a point vehemently debated,—but one it in no way concerns us here to decide. There is no doubt however that, dating from those two terrible nights, a steady decline declared itself in his health and vitality. In no long time he died; and his brother Henri, Duke of Anjou and King of Poland, duly warned of his approaching end, arrived in hot haste to take over the crown to which he was next in succession.

This period of political and religious ferment was no less the period par excellence of gallantry. In its characteristics it bears considerable resemblance to the days of the Empire. At both epochs love was quick, fierce and violent. Hurry was the mark of the times. In the midst of these everlasting struggles between Huguenot and Catholic, who could be sure of to-morrow? So men made it a point to indulge no attachment that was too serious,—for them love was become a mere question of choice and quantity; while women avoided a grand passion with a fervour worthy of a better cause. If ever a deep and earnest passion does show itself, it is an exception, an anomaly; if we find a woman stabbing her faithless husband to death on catching him in the arms of another, let us not for an instant suppose ’tis the fierce stirring[xviii] of a loving heart which in the frenzy of its jealousy avenges the wrong it has suffered,—to die presently of sorrow and remorse, or at the least to suffer long and sorely. This act of daring,—so carefully recorded by the chroniclers of the time,—is only the effect of strong self-love cruelly wounded. But powerful as this feeling may be, it would scarcely be adequate to explain so energetic an act, if we did not remember how frequently ladies in the XVIth Century were exposed to scenes of bloodshed. The dagger and the sword were as familiar to their eyes as the needle; and Brantôme has devoted a whole Discourse,—his Fifth, to courageous dames, and seems positively to scorn weak and timid women! How opposite is this to the sentiment of the present day, where one of the charms of womanhood is held to consist in her having nothing in common with man and being for ever in need of his protection. A few isolated cases then excepted, there existed between men and women nothing better than what Chamfort has wittily defined as “l’échange de deux fantaisies et le contact de deux épidermes,”—in other words gallantry pure and simple.

This then was the atmosphere our Author breathed. His life offers nothing specially striking in the way of incident. No need for me to take him from the arms of his nurse, to follow each of his steps through life and piously close his eyes in death. He served his time without special distinction or applause at the Court of Charles IX. In all he did, he showed so modest a reserve that, but for his Works, his very existence would have remained unknown. He is not like Bussy-Rabutin, the incidents of whose wild and wicked life filled and defaced a big book, or like Tallemant, whose diary, if diary it[xix] can be called, was written day by day and recounted each day’s exploits. Brantôme’s life and work leave little trace of his own personality, beyond the impression of a genial, smiling, witty man of the world. I will be as plain and discreet as himself, and will make no effort to separate the Author from his book.

Brantôme possesses one of those happy, gentle, well ordered natures, which systematically avoid every form of excess and exaggeration. His book Des Dames Galantes is from beginning to end a protest against immoderate passion. It is above all a work of taste. Its seven Discourses are devoted exclusively to stories of love and passion, yet a man must be straightlaced indeed to feel any sort of repulsion. Another extraordinary merit! in spite of the monotony of the subject matter, everlastingly the same, the reader’s attention never flags, and one tale read, he is irresistibly drawn on to make acquaintance with the next.

Such praise, I am aware, is very high; and especially when we possess such masterpieces in this genre as the Tales of Boccaccio, of Pietro Aretino, some of those of Ariosto, those of Voltaire, the short stories of Tallemant des Réaux and the indiscretions of the Histoire amoureuse des Gaules. I name only the most familiar examples. Of course all these works do not offer a complete resemblance to the Vies des Dames Galantes, but they all belong to the same race and family. I propose to say a few passing words of each of these productions.

The most remarkable among all these chroniclers of the frailties of the female heart is undoubtedly Boccaccio. Pietro Aretino has done himself an irreparable wrong by writing in such a vein that no decent man dare confess[xx] to having read him. Ariosto is a story-teller only by the way, but then he is worthy of all imitation. The Heptameron is a collection of stories the chief value of which consists in a sensibility and charming grace that never fail. Tallemant tells a tale of gallantry between two daintily worded sentiments. Voltaire in this as in all departments shows an incontestable superiority of wit and verve. There is nothing new in La Fontaine; ’tis always the same wondrous charm, so simple in appearance, so deep in reality. As to Bussy, a man of the world and a gentleman, but vicious, spiteful and envious, his Histoire amoureuse is his revenge on mankind, a deliberate publication of extravagant personalities flavoured with wit.

Boccaccio, to say nothing of his striking originality, possesses other merits of the very highest order. The sorrows of unhappy love are told with genuine pathos, while lovers’ wiles and the punishments they meet with at once raise a smile and provoke a resolve to profit by such valuable lessons. True Dioneo’s quaint narratives are not precisely fit for ladies’ ears; yet so daintily are they recounted, the most risqué episodes so cleverly sketched in, it is impossible to accuse them of indelicacy. An entire absence of bitterness, a genial indulgence for human weakness, a hearty admiration of women and a doctrine of genial complaisance as the only possible philosophy of life, these are the qualities that make the Decameron the masterpiece of this kind of composition.

Brantôme has not the same preponderating influence in literature that Boccaccio possesses, but he comes next after him. The “Lives of Gallant Ladies” are not, any more than the Novelli, inventions pure and simple; they[xxi] are anecdotes, reminiscences. The great merit of these Tales of Boccaccio is the same as that of Balzac’s Novels or Molière’s Comedies,—to fix a character, to define a phase of manners in the life of the Author’s day; in a word to create by induction and analogy a living being, hitherto unnoticed by every-day observers, but instantly recognized as lifelike. This is the true spirit of assimilation and generalisation,—the work of genius. Well! as for Brantôme, he is a man of talent and wit, not genius. We claim no more; genius is not so common as might be supposed, if we hearkened to all the acclamations daily raised round sundry statues,—but plaster after all, however cunningly contrived to look like bronze.

Brantôme’s fame is already firmly established. To live for two centuries and a half without boring his readers; above all to be a book that scholars, men of sober learning and of literary taste, still read in these latter days, is a success worthy of some earnest thought. This chronicle of gallantry, this collection, as the Author himself describes it, of happy tricks played on each other by men and women, possesses a quite exquisite flavour of youth and freshness,—the whole told with a good nature, a verve, an unconventionality, that are inexpressibly charming. You feel the characters living and breathing through the delicate, pliant style. You see the very glance of a woman’s eye; you hear her ardent, or cunningly alluring, words. For such as can read with a heart unstirred, the book is a series of delicious surprises.

Strong predispositions, nay! positive prejudices, stand in the way of the proper appreciation of our Author. Such is the Puritanism of language and prudery of manners in our day, it would seem prima facie an impossible[xxii] task to popularize Brantôme. By common agreement we speak of the esprit français as distinguished from the esprit gaulois, the latter term being used to denote a something more frank and outspoken. I heartily wish the division were a true one; for I can never forget I belong to this mighty Nineteenth Century. But for my own part, on a careful consideration of the facts, I should make a triple rather than a twofold classification. There would be the esprit gaulois, the esprit français, not the spirit of the age one atom, I must be allowed to observe, and thirdly a certain spirit of curling-irons and kid gloves and varnished boots, a sort of bastard, a cross between French and English, equally shocked at Tristram Shandy and the Physiologie du Mariage as coarse and immoral productions. This is our spirit, if spirit we have.

The two first types have a real and positive value; but the third is the sole and only one nowadays permitted or current as legal tender,—the others are much too outspoken. Well! I will hold my tongue, and mind my own business. An epoch is a mighty ugly customer to come to blows with. I remember Him of Galilee.

The genius of Rabelais was all instinct with this same esprit gaulois—a big, bold, virile spirit, breaking out in resounding guffaws, and crude, outspoken verities, equally unable and unwilling to soften down or gloss over anything, innocent of every species of periphrasis and affectation. It is genius in a merry mood rising above the petty conventionalities of speech,—often reminding us of Molière under like circumstances. Let fools be shocked, if they please; sensible men are ashamed only in presence of positive immorality and deliberate[xxiii] vice. The esprit gaulois is the spirit of primitive man going straight to its end, regardless of fetter or law. The esprit français is equally natural; but then it has acquired a certain degree of civilisation. It has less width of scope; it has learned the little concessions men are bound to make one another, having associated longer with them. It has left hodden grey, and taken to the silken doublet and cap of velvet, and rubs elbows with men of rank. It has lost nothing of its good sense and good temper; but it feels no longer bound in every case to blurt its thought right out; already it leaves something to be guessed at. It is all a question of civilisation and surroundings. But above and beyond this, it must be allowed to be conditioned by the essential distinction between genius and talent. The former does what it likes, ’tis lord and master; the latter is, by its very nature, a creature of compromise.

Brantôme possesses all the verve and brightness of a genuine Frenchman. All the conditions of life are highly favourable for him; he is rich and noble, while intelligence and wit are stamped on his very face. He wins his first spurs under François de Guise, whose protégé he is; when he has had enough of war, he comes to Court. There he receives the most flattering of receptions, every Catholic Noble extending him the hand of good fellowship. His family connections are such, that on the very steps of the throne is a voice ready to call him cousin, and a charming woman’s lips to smile on him with favour. ’Tis a good start; henceforth it is for his moral and intellectual qualities to achieve the career so auspiciously begun.

As I have said already, Brantôme is the finished type of a Frenchman of quality. Well taught and witty, brave[xxiv] and enterprising, capable of appreciating honesty and worth whether in thought or deed, instinctively hating tyrants and tyrannical violence, and avoiding them like the plague, blessing the happy day on which his mother gave him birth, light-hearted and sceptical, he unites in himself everything that makes life go easy. Be sure no over-bearing passion will ever disturb the serenity of his existence. He has too much good sense to let his happiness depend on the chimerical figments of the imagination, and too much real courtesy ever to reproach a woman with her frailties. The world and all its ways seem good to him. In very truth, he is not far from Pangloss’s conclusion,—Pangloss, the perfect type of what a man must be so as never to suffer,—“Well! well! all is for the best in this best of possible worlds.” If woman deceive, she offers so many compensations in other ways that ’tis a hundred times better to have her as she is than not at all. Men are sinners; again most true, as an abstract proposition, but if only we know how to regulate our conduct judiciously, their sinful spite will never touch us. Easy to see how, with this bent of character and these convictions, Brantôme was certain to find friendly faces wherever he went. The favourable impression his person and position had produced, his good sense completed.

The King took delight in the society of this finished gentleman with his easy and agreeable manners. In the midst of the numberless vexations he was surrounded by, one of his greatest distractions was the gay, lively conversation of this noble lord, from whom he had nothing to fear in the way of hostile speech or angry words. The Duc d’Alençon was another intimate, who putting aside[xxv] for a moment his schemes of ambition, would hear and tell tales of love and intrigue, laughing the louder in proportion to the audacity and success of the trick played by the heroine. And so it was with all; the result being that Brantôme quickly acquired the repute of being the wittiest man in France. All men and all parties were on friendly terms with him. The Huguenots forgot he was a Catholic, and made an ally of him. Without religious fanaticism or personal ambition, honoured and sought after by the great, yet quite unspoiled and always simple-hearted and good-natured, equally free from prejudice and pride, he conciliated the good will of all. Throughout the whole of Brantôme’s career, we never hear of his making a single enemy; and be it remembered he lived in the very hottest of the storm and stress, political and religious, of the Sixteenth Century. Let us add to complete our characterisation, a quite incalculable merit,—a discretion such as cannot be found even in the annals of Chivalry, a period indeed when lovers were only too fond of making a show of their ladies’ favours. This is the one and only point where Brantôme is inconsistent with the true French type of character, mostly as eager to declare the fair inamorata’s name as to appreciate the proofs of love she may have given.

Francis I. is but just dead, we must remember. His reign has been called the Renaissance, and not without good reason. Under him begins that light, graceful bearing, that elegance of manner, that politeness of address, which henceforth will make continuous advances to greater and greater refinement. Rabelais is the last expression of that old, unsoftened and unmitigated French speech, from which at a later date Matthieu Regnier will[xxvi] occasionally borrow one of his picturesque phrases. In the same reign costume first becomes dainty. Men’s minds grow finical like their dress; and a new mode of expression was imperatively required to match the new elegance of living. The change was effected almost without effort; ’twas a mere question of external sensibility. The body, now habituated to silk and velvet, grows more sensitive and delicate, and intellect and language follow suit. The correspondence was inevitable. So much for the mental revolution. As for the moral side, manners gained in frankness no doubt; but otherwise things were neither better nor worse than before. It has always seemed to us a strange proceeding, to take a particular period of History, as writers so often will, and declare,—‘At this epoch morals were more relaxed than ever before or since.’

Now under Francis I., and by his example, manners acquired a happy freedom, an unstudied ease, his Courtiers were sure to turn to good advantage. A King is always king of the fashion. Judging by the two celebrated lines[3] he wrote one day on a pane in one of the windows at the Castle of Chambord, Francis I., a Prince of wit and a true Frenchman, could discover no better way of punishing women for their fickleness and frivolity than that of copying their example. Every pretty woman stirred a longing to possess in the ample and facile heart of this Royal Don Juan. They were easy and happy loves,—without remorse and without bitterness, and never deformed with tears. So far did he push his rights as a Sovereign, that there is said to have been at least one instance of rivalry between him and his own[xxvii] son. He died, as he had lived, a lover,—and a victim to love.

Under Henri II., Diane de Poitiers is the most prominent figure on the stage; following the gallant leadership of the King’s mistress, the Court continues the same mode of life and type of manners which distinguished the preceding reign.

Of the reign of Francis II., we need only speak en passant. During the short while he and Mary Stuart were exhausting the joys of a brief married life, there was no time for further change.

But now we come to a far more noteworthy and important period. While the Queen Mother and the Guises are silently preparing their coup d’état; while the Huguenots, light-hearted and unsuspecting, are dancing and making merry in the halls of the Louvre; while Catholics join them in merry feasts at the taverns then in vogue, and ladies allow no party spirit to intrude in their love affairs; while the Pré-aux-Clercs is the meeting-ground where men of honour settle their quarrels, and the happy man, the man who receives the most caressing marks of female favour, is he that has killed most, at a time like this the wits are keen and the spirit as reckless as the courage. With such a code of morals it was a difficult matter for any serious sentiment to survive. Women soon began to feel the same scorn of life that men professed. The strongest were falling day by day, and emotion and sensibility could not but be blunted. Then think of the crowd of eager candidates to seize the vacant reins of Government, and the steeple-chase existence of those days becomes intelligible and even excusable.

In all this movement Brantôme was necessarily[xxviii] involved, but he kept invariably in the back-ground, in a convenient semi-obscurity. But we must by no means assume that this prudence on the Vicomte de Bourdeille’s part proceeded from any lack of energy; this would be doing him a quite undeserved injustice. He had given proofs of his courage; and Abbé as he was, his sword on hip spoke as proudly as the most doughty ruffler’s. But a man of peace, he avoided provoking quarrels; he was a good Catholic, and Religion has always discountenanced the shedding of blood.

The best proof of the position he was able to win at Court is this Book of Fair and Gallant Ladies which has come down to us as its result. Amid all the gay and boisterous fêtes of the time, and the thousand lights of the Louvre, men and women both smiled graciously on our Author. His perfect discretion was perhaps his chief merit in the eyes of all these love-sick swains and garrulous young noodles. The instant a lover received an assignation from his fair one, his joy ran over in noisy fanfaronnades. A happy man is brim full of good-fellowship, and eager for a confidant. Well! if at that moment the gallant Abbé chanced to pass, what more natural than for the fortunate gentleman to seize and buttonhole him? Then he would recount his incomparable good fortune, adding a hundred piquant details, and drunk with his own babbling, enumerate one after the other the most minute particulars of his intrigue, ending by letting out the name of the husband at whose expense he had been enjoying himself. Love is so simple-minded and so charmingly selfish! Every lover seriously thinks each casual acquaintance must of course sympathise actively in his feelings. A bosom friend he must have!—no matter[xxix] who, if only he can tell him, always of course under formal promise of concealment, the secret he should have kept locked in his own bosom. Nor should we look over harshly on this weakness; too much happiness, no less than too much unhappiness, will stifle the bosom that cannot throw off any of its load upon another. ’Tis the world-old story of the reeds and the secret that must be told. Self-expansion is a natural craving; without it, men grow misanthropes and die of an aneurism of the heart.

This brings us to the book of the Dames galantes. When eventually he retired to his estates, Brantôme took up the pen as a relief to his ennui. Among all the works he composed, this one must certainly have pleased him best, because it so exactly corresponds with his own character and ways of thought. But to write these lives of Gallant Ladies was an enterprise not without its dangers. A volume of anecdotes of the sort cannot be written without there being considerable risk in the process of falling into the coarse and commonplace vulgarities that surround such a subject. Style, wit, philosophy, gaiety, all in a degree seldom met with, were indispensable for success; yet Brantôme has succeeded. This book, of the Vies des Dames galantes, offers a close analogy with another celebrated study in the same genre, viz., Balzac’s Physiologie du mariage. Both works deal with the same subject, the ways and wiles of women, married, widow and maid, under the varying conditions of, (1) the Sixteenth Century, and (2) the Present Day. But the mode of treatment is different; an this difference made Brantôme’s task a harder one than the modern Author’s. His short stories of a dozen lines, each revealing woman in[xxx] one of those secret and confidential situations only open to the eye of husband or lover, might easily be displeasing, or worse still tiresome. Brantôme has avoided all these shoals and shallows. Each little tale has its own interest, always fresh and bright.

Moreover a lofty morality runs through the narratives. At first sight the word morality may seem a joke applied to such matters; but it is easy to disconcert the scoffer merely by asking him to read our Author. To support my contention, there is no need to quote any particular story or stories; all alike have their charm, and the work must be perused in its entirety to appreciate the truth of the high praise I give it. Every reader, on finally closing the book, cannot but feel a genuine enthusiasm. The delicate wit of the whole recital passes imagination. On every page we meet some physical trait or some moral remark that rivets the attention. The author puts his hand on some curiosity or perversity, and instantly stops to examine it; while at the same time the propriety of his tone allures the most sedate reader. The discussion of each point, in which the pros and cons are always balanced one against the other in the wittiest and most thorough manner, is interesting to the highest degree. In one word the book is a code and compendium of Love. All is classified, studied, analysed; each argument is supported by an appropriate anecdote,—an example,—a Life.

The mere arrangement of the contents displays consummate skill. The Author has divided his Vies des Dames galantes into seven Discourses, as follows:

In the First, he treats “Of ladies which do make love, and their husbands cuckolds;”

[xxxi]

In the Second, he expatiates “On the question which doth give the more content in love, whether touching, seeing or speaking;”

In the Third, he speaks “Concerning the Beauty of a fine leg, and the virtue the same doth possess;”

In the Fourth, he discourses “Concerning old dames as fond to practise love as ever the young ones be;”

In the Fifth, he tells “How Fair and honourable ladies do love brave and valiant men, and brave men courageous women;”

In the Sixth, he teaches, “How we should never speak ill of ladies,—and of the consequences of so doing;”

In the Seventh, he asks, “Concerning married women, widows and maids—which of these be better than the other to love.”

This list of subjects, displaying as it does, all the leading ideas of the book, leaves me little to add. I have no call to go into a detailed appreciation of the Work under its manifold aspects as a gallery of portraits; my task was merely to judge of its general physiognomy and explain its raisin d’être; and this I have attempted to do.

I will only add by way of conclusion a few words to show the especial esteem we should feel for Brantôme on this ground, that his works contain nothing to corrupt good morals. Each narrative is told simply and straightforwardly, for what it is worth. The author neither embellishes nor exaggerates. Moreover the species of corollary he clinches it with is a philosophical and physiological deduction of the happiest and most apposite kind in the great majority of instances,—some witty and[xxxii] ingenious remark that never offends either against good sense or good taste. If now and again the reader is tempted to shy, he should in justice put this down to the diction of the time, which had not yet adopted that tone of arrogant virtue it nowadays affects. Then there was a large number of words in former days which connoted nothing worse than something ridiculous and absurd.

Then as to beauty of language, we must go roundabout ways to reach many a point they marched straight to in old days. Brantôme at any rate is a purist of style,—one of the most striking and most correct writers I have ever read. It is a great and genuine discovery readers will make, if they do not know him already; if they do, they will be renewing acquaintance with an old friend, at once witty and delightful. In either case, ’tis a piece of luck not to be despised.

H. VIGNEAU.

LIVES OF FAIR AND

GALLANT LADIES

[3]

Of Ladies which do make Love, and their Husbands cuckolds.[4]

1.

Seeing ’tis the ladies have laid the foundation of all cuckoldry, and how ’tis they which do make all men cuckolds, I have thought it good to include this First Discourse in my present Book of Fair Ladies,—albeit that I shall have occasion to speak therein as much of men as of women. I know right well I am taking up a great work, and one I should never get done withal, if that I did insist on full completeness of the same. For of a truth not all the paper in the Records Office of Paris would hold in writing the half of the histories of folk in this case, whether women or men. Yet will I set down what I can; and when I can no more, I will e’en give my pen—to the devil, or mayhap to some good fellow-comrade, which shall carry on the tale.

Furthermore must I crave indulgence if in this Discourse I keep not due order and alignment, for indeed so great is the multitude of men and women so situate, and[4] so manifold and divers their condition, that I know not any Commander and Master of War so skilled as that he could range the same in proper rank and meet array.

Following therefore of mine own fantasy, will I speak of them in such fashion as pleaseth me,—now in this present month of April, the which bringeth round once more the very season and open time of cuckoos; I mean the cuckoos that perch on trees, for of the other sort are to be found and seen enough and to spare in all months and seasons of the year.

Now of this sort of cuckolds, there be many of divers kinds, but of all sorts the worst and that which the ladies fear above all others, doth consist of those wild, fierce, tricky, ill-conditioned, malicious, cruel and suspicious husbands, who strike, torture and kill, some for true cause, others for no true reason at all, so mad and furious doth the very least suspicion in the world make them. With such all dealings are very carefully to be shunned, both by their wives and by the lovers of the same. Natheless have I known ladies and their lovers which did make no account of them; for they were just as ill-minded as the others, and the ladies were bold and reckless, to such a degree that if their cavaliers chanced to fail of courage, themselves would supply them enough and to spare for both. The more so that in proportion as any emprise is dangerous and difficult, ought it to be undertaken in a bold and high spirit. On the contrary I have known other ladies of the sort who had no heart at all or ambition to adventure high endeavours; but cared for naught but their low pleasures, even as the proverb hath it: base of heart as an harlot.

Myself knew an honourable lady,[5*] and a great one, who[5] a good opportunity offering to have enjoyment of her lover, when this latter did object to her the incommodity that would ensue supposing the husband, who was not far off, to discover it, made no more ado but left him on the spot, deeming him no doughty lover, for that he said nay to her urgent desire. For indeed this is what an amorous dame, whenas the ardour and frenzy of desire would fain be satisfied, but her lover will not or cannot content her straightway, by reason of sundry lets and hindrances, doth hate and indignantly abominate above all else.

Needs must we commend this lady for her doughtiness, and many another of her kidney, who fear naught, if only they may content their passions, albeit therein they run more risks and dangers than any soldier or sailor doth in the most hazardous perils of field or sea.

A Spanish dame, escorted one day by a gallant cavalier through the rooms of the King’s Palace and happening to pass by a particular dark and secret recess, the gentleman, piquing himself on his respect for women and his Spanish discretion, saith to her: Señora, buen lugar, si no fuera vuessa merced (A good place, my lady, if it were another than your ladyship). To this the lady merely answered the very same words back again, Si, buen lugar, si no fuera vuessa merced (Yes, Sir, a good place, if it were another than your lordship). Thus did she imply his cowardliness, and rebuke the same, for that he had not taken of her in so good a place what she did wish and desire to lose, as another and a bolder man would have done in like case. For the which cause she did thereupon altogether pretermit her former love for him, and left him incontinently.

[6]

I have heard tell of a very fair and honourable lady, who did make assignation with her lover, only on condition he should not touch her (nor come to extremities at all). This the other accomplished, tarrying all night long in great ecstasy, temptation and continence; and thereat was the lady so grateful that some while after she did give him full gratification, alleging for reason that she had been fain to prove his love in accomplishing the task she had laid upon him. Wherefore she did love him much thereafter, and afforded him opportunity to do quite other feats than this one,—verily one of the hardest sort to succeed in.

Some there be will commend his discretion,—or timidity, if you had rather call it so,—others not. For myself I refer the question to such as may debate the point on this side or on that according to their several humours and predispositions.

I knew once a lady, and one of no low degree, who having made an assignation with her lover to come and stay with her one night, he hied him thither all ready, in shirt only, to do his duty. But, seeing it was in winter-tide, he was so sorely a-cold on the way, that he could accomplish naught, and thought of no other thing but to get heat again. Whereat the lady did loathe the caitiff, and would have no more of him.

Another lady, discoursing of love with a gentleman, he said to her among other matters that if he were with her, he would undertake to do his devoir six times in one night, so greatly would her beauty edge him on. “You boast most high prowess,” said she; “I make you assignation therefore” for such and such a night. Nor did she fail to keep tryst at the time agreed; but lo! to his[7] undoing, he was assailed by so sad a convulsion, that he could by no means accomplish his devoir so much as once even. Whereupon the fair lady said to him, “What! are you good for naught at all? Well, then! begone out of my bed. I did never lend it you, like a bed at an inn, to take your ease forsooth therein and rest yourself. Therefore, I say, begone!” Thus did she drive him forth, and thereafter did make great mock of him, hating the recreant worse than the plague.

This last gentleman would have been happy enough, if only he had been of the complexion of the great Baraud,[6*] Protonotary and Almoner to King Francis, for whenas he lay with the Court-ladies, he would even reach the round dozen at the least, and yet next morning he would say right humbly, “I pray you, Madam, make excuse that I have not done better, but I took physic yesterday.” I have myself known him of later years, when he was called Captain Baraud, a Gascon, and had quitted the lawyer’s robe. He has recounted to me, at my asking, his amours, and that name by name.

As he waxed older, this masculine vigour and power somewhat failed him. Moreover he was now poor, albeit he had had good pickings, the which his prowess had gotten him; yet had he squandered it all, and was now set to compounding and distilling essences. “But verily,” he would say, “if only I could now, so well as once I could in my younger days, I should be in better case, and should guide my gear better than I have done.”

During the famous War of the League, an honourable gentleman, and a right brave and valiant soldier, having left the place whereof he was Governor to go to the wars, could not on his return arrive in garrison before nightfall,[8] and so betook himself to the house of a fair and very honourable and noble widow, who straight invited him to stay the night within doors. This he gladly consented to do, for he was exceeding weary. After making him good cheer at supper, she gives him her own chamber and bed, seeing that all the other bed-chambers were dismantled by reason of the War, and their furniture,—and she had good and fair plenishing,—under lock and key. Herself meanwhile withdraws to her closet, where she had a day-bed in use.

The gentleman, after several times refusing this bed and bed-chamber, was constrained by the good lady’s prayers to take it. Then so soon as he was laid down therein and asleep most soundly, lo! the lady slips in softly and lays herself down beside him in the bed without his being ware of aught all the night long, so aweary was he and heavily asleep. There lay he till broad daylight, when the lady, drawing away from him, as the sleeper began to awake, said, “You have not slept without company; for I would not yield you up the whole of my bed, so have I enjoyed the one half thereof as well as ever you have the other. You have lost a chance you will never have again.”

The gentleman, cursing and railing for spite of his wasted opportunity (’twere enough to make a man hang himself), was fain to stay her and beg her over. But no such thing! On the contrary, she was sorely displeased at him for not having contented her as she would have had him do, for of a truth she had not come thither for only one poor embrace,—as the saying hath it, one embrace is only the salad of a feast. She loved the plural[9] number better than the singular, as do many worthy dames.

Herein they differ from a certain very fair and honourable lady I once knew, who on one occasion having made assignation with her lover to come and stay with her, in a twinkling he did accomplish three good embraces with her. But thereafter, he wishing to do a fourth and make his number yet complete, she did urge him with prayers and commands to get up and retire. He, as fresh as at first, would fain renew the combat, and doth promise he would fight furiously all that night long till dawn of day, declaring that for so little as had gone by, his vigour was in no wise diminished. But she did reply: “Be satisfied I have recognized your doughtiness and good dispositions. They are right fair and good, and at a better time and place I shall know very well how to take better advantage of them than at this present. For naught but some small illhap is lacking for you and me to be discovered. Farewell then till a better and more secure occasion, and then right freely will I put you to the great battle, and not to such a trifling encounter as this.”

Many dames there be would not have shown this much prudency, but intoxicate with pleasure, seeing they had the enemy already on the field, would have had him fight till dawn of day.

The same honourable lady which I spake of before these last, was of such a gallant humour that when the caprice was on her, she had never a thought or fear of her husband, albeit he was a ready swordsman and quick at offence. Natheless hath she alway been so fortunate as that neither she nor her lovers have ever run serious risks of their lives or come near being surprised, by dint[10] of careful posting of guards and good and watchful sentinels.

Still it behoves not ladies to trust too much to this, for one unlucky moment is all that is needed to ruin all,—as happened some while since to a certain brave and valiant gentleman[7] who was massacred on his way to see his mistress by the treachery and contrivance of the lady herself, the which her husband made her devise against him. Alas! if he had not entertained so high a presumption of his own worth and valour as he rightly did, he would have kept better guard, and would never have fallen,—more’s the pity! A capital example, verily, not to trust over much to amorous dames, who to escape the cruel hand of their husbands, do play such a game as these order them, as did the lady in this case, who saved her own life,—at the sacrifice of her lover’s.

Other husbands there be who kill the lady and the lover both together as I have heard it told of a very great lady whose husband was jealous of her, not for any offence he had certain knowledge of, but out of mere suspiciousness and mistaken zeal of love. He did his wife to death with poison and wasting sickness,—a grievous thing and an exceeding sad, after having first slain the lover, a good and honourable man, declaring that the sacrifice was fairer and more agreeable to kill the bull first, and the cow afterwards.

This same Prince was more cruel to his wife than he was later to one of his daughters, the which he had married to a great Prince, though not so great an one as himself was, he being indeed a monarch in all but name.

It fell out to this fickle dame to be gotten with child by another than her husband, who was at the time busied[11] afar in some War. Presently, having been brought to bed of a fine child, she wist not to what Saint to make appeal, if not to her father; so to him she did reveal all by the mouth of a gentleman she had trust in, whom she sent to him. No sooner had he hearkened to his confidence than he did send and charge her husband that, for his life, he should beware to make no essay against that of his daughter, else would he do the same against his, and make him the poorest Prince in Christendom, the which he was well able to accomplish. Moreover he did despatch for his daughter a galley with a meet escort to fetch to him the child and its nurse, and providing a good house and livelihood, had the boy nourished and brought up right well. But when after some space of time the father came to die, thereupon the husband put her to death and so did punish her for her faithlessness at last.

I have heard tell of another husband who did to death the lover before the eyes of his wife, causing him to languish in long pain, to the end she might die in a martyr’s agony to see the lingering death of him she had so loved and had held within her arms.

Yet another great nobleman did kill his wife openly before the whole Court.[8] For the space of fifteen years he had granted the same all liberty, and had been for long while well aware of her ill ways, having many a time and oft remonstrated thereat and admonished her. However at the last a sudden caprice took him (’tis said at the instance of a great Prince, his master), and on a certain morning he did visit her as she still lay abed, but on the point of rising. Then, after lying with her, and after sporting and making much mirth together, he did give her four or five dagger thrusts. This done, he bade a[12] servant finish her, and after had her laid on a litter, and carried openly before all the Court to his own house, to be there buried. He would fain have done the like to her paramours; but so would he have had overmuch on his hands, for that she had had so many they might have made a small army.

I have heard speak likewise of a certain brave and valiant Captain,[9] who conceiving some suspicion of his wife, went straight to her without more ado and strangled her himself with his own hands, in her white girdle. Thereafter he had her buried with all due honour, and himself was present at her obsequies in mourning weeds and of a very sad countenance, the which mourning he did continue for many a long day,—verily a noble satisfaction to the poor lady, as if a fine funeral could bring her to life again! Moreover he did the same by a damosel which had been in waiting on his wife and had aided and abetted her in her naughtiness. Nor yet did he die without issue by this same wife, for he had of her a gallant son, one of the bravest and foremost soldiers of his country, who by virtue of his worth and emprise did reach great honour as having served his Kings and masters right well.

I have heard likewise of a nobleman in Italy which also slew his wife, not being able to catch her gallant who had escaped into France. But it is said he slew her, not so much because of her sin,—for that he had been ware of for a long time, how she indulged in loose love and took no heed for aught else,—as in order to wed another lady of whom he was enamoured.

Now this is why it is very perilous to assail and attack an armed and defended spot,—not but that there be as[13] many of this sort assailed and right well assailed as of unarmed and undefended ones, yea! and assailed victoriously to boot. For an example whereof, I know of one that was as well armed and championed as any in all the world. Yet, was there a certain gentleman, in sooth a most brave and valiant soldier, who was fain to hanker after the same; nay! he was not content with this, but must needs pride himself thereon and bruit his success abroad. But it was scarce any time at all before he was incontinently killed by men appointed to that end, without otherwise causing scandal, and without the lady’s suffering aught therefrom. Yet was she for long while in sore fear and anguish of spirit, seeing that she was then with child and firmly believing that after her bringing to bed, the which she would full fain have seen put off for an hundred years, she would meet the like fate. But the husband showed himself a good and merciful man,—though of a truth he was one of the keenest swordsmen in all the world,—and freely pardoned her; and nothing else came of it, albeit divers of them that had been her servants were in no small affright. However the one victim paid for all. And so the lady, recognizing the goodness and graciousness of such an husband, gave but very little cause for suspicion thereafter, for that she joined herself to the ranks of the more wise and virtuous dames of that day.

It fell out very different not many years since in the Kingdom of Naples to Donna Maria d’Avalos, one of the fair Princesses of that land and married to the Prince of Venusia, who was enamoured of the Count d’Andriane, likewise one of the noble Princes of the country. So being both of them come together to enjoy their passion,[14] and the husband having discovered it,—by means whereof I could render an account, but the tale would be over long,—having insooth surprised them there together, had the twain of them slain by men appointed thereto. In such wise that next morning the fair and noble pair, unhappy beings, were seen lying stretched out and exposed to public view on the pavement in front of the house door, all dead and cold, in sight of all passers-by, who could not but weep and lament over their piteous lot.

Now there were kinsfolk of the said lady, thus done to death, who were exceeding grieved and greatly angered thereat, so that they were right eager to avenge the same by death and murder, as the law of that country doth allow. But for as much as she had been slain by base-born varlets and slaves who deserved not to have their hands stained with so good and noble blood, they were for making this point alone the ground of their resentment and for this seeking satisfaction from the husband, whether by way of justice or otherwise,—but not so, if he had struck the blow with his own hand. For that had been a different case, not so imperatively calling for satisfaction.

Truly an odd idea and a most foolish quibble have we here! Whereon I make appeal to our great orators and wise lawyers, that they tell me this: which act is the more monstrous, for a man to kill his wife with his own hand, the which hath so oftentimes loved and caressed her, or by that of a base-born slave? In truth there are many good arguments to be alleged on the point; but I will refrain me from adducing of them, for fear they prove over weak and silly in comparison of those of such great folk.

[15]

I have heard tell that the Viceroy, hearing of the plot that was toward, did warn the lover thereof, and the lady to boot. But their destiny would have it so; this was to be the issue, and no other, of their so delightsome loves.

This lady was daughter of Don Carlo d’Avalos,[10*] second brother of the Marquis di Pescaïra, to whom if any had played a like trick in any of his love matters wherewith I am acquaint, be sure he would have been dead this many a long day.

I once knew an husband, which coming home from abroad and having gone long without sleeping with his wife, did arrive with mind made up and glad heart to do so with her presently, and having good pleasure thereof. But arriving by night, he did hear by his little spy, how that she was accompanied by her lover in the bed. Thereupon did he straight lay hand on sword, and knocked at the door; the which being opened, he entered in resolved to kill her. After first of all hunting for the gallant, who had escaped by the window, he came near to his wife to kill her; but it so happened she was on this occasion so becomingly tricked out, so featly dressed in her night attire and her fair white shift, and so gaily decked (bear in mind she had taken all this pretty pains with herself the better to please her lover), that he had never found her so much to his taste. Then she, falling at his knees, in her shift as she was, and grovelling on the ground, did ask his forgiveness with such fair and gentle words, the which insooth she knew right well how to set forth, that raising her up and seeing her so fair and of so gracious mien, he felt his heart stir within him, and dropping his sword,—for that he had had no enjoyment for many a day and was anhungered therefor, which likely enough[16] did stir the lady too at nature’s prompting,—he forgave her and took and kissed her, and put her back to bed again, and in a twinkling lay down with her, after shutting to the door again. And the fair lady did content him so well by her gentle ways and pretty cajoleries,—be sure she forgat not any one of them all,—that eventually the next morning they were found better friends than ever, and never was so much loving and caressing between them before. As was the case likewise with King Menelaus, that poor cuckold, the which did ever by the space of ten or twelve years threaten his wife Helen that he would kill her, if ever he could put hands upon her, and even did tell her so, calling from the foot of Troy’s wall to her on the top thereof. Yet, Troy well taken, and she fallen into his power, so ravished was he with her beauty that he forgave her all, and did love and fondle her in better sort than ever.

So much then for these savage husbands that from lions turn into butterflies. But no easy thing is it for any to get deliverance like her whose case we now tell.

A lady, young, fair and noble, in the reign of King Francis I., married to a great Lord of France, of as noble a house as is any to be found, did escape otherwise, and in more pious fashion, than the last named. For, whether it were she had given some cause for suspicion to her husband, or that he was overtaken by a fit of distrust or sudden anger, he came at her sword in hand for to kill her. But she bethought herself instantly to make a vow to the glorious Virgin Mary, and to promise she would to pay her said vow, if only she would save her life, at her chapel of Loretto at St. Jean des Mauverets, in the country of Anjou. And so soon as ever she had made[17] this vow in her own mind, lo! the said Lord did fall to the ground, and his sword slipped from out his hand. Then presently, rising up again as if awaking from a dream, he did ask his wife to what Saint she had recommended herself to escape out of this peril. She told him it was to the Blessed Virgin, in her afore-named Chapel, and how she had promised to visit the holy place. Whereupon he said to her: “Go thither then, and fulfil your vow,”—the which she did, and hung up there a picture recording the story, together with sundry large and fair votive offerings of wax, such as of yore were customary for this purpose, the which were there to be seen for long time after. Verily a fortunate vow, and a right happy and unexpected escape,—as is further set forth in the Chronicles of Anjou.[11]

2.

I have heard say how King Francis[12] once was fain to go to bed with a lady of his Court whom he loved. He found her husband sword in fist ready to kill him; but the King straightway did put his own to his throat, and did charge him, on his life, to do him no hurt, but if he should do him the least ill in the world, how that he would kill him on the spot, or else have his head cut off. So for that night did he send him forth the house, and took his place. The said lady was very fortunate to have found so good a champion and protector of her person, for never after durst the husband to say one word of complaint, and so left her to do as she well pleased.

I have heard tell how that not this lady alone, but[18] many another beside, did win suchlike safeguard and protection from the King. As many folk do in War-time to save their lands, putting of the King’s cognizance over their doors, even so do these ladies put the countersign of their monarchs inside and out their bodies; whereby their husbands dare not afterward say one word of reproach, who but for this would have given them incontinently to the edge of the sword.

I have known yet other ladies, favoured in this wise by kings and great princes, who did so carry their passports everywhere. Natheless were there some of them, whose husbands, albeit not daring to use cold steel to them, did yet have resort to divers poisons and secret ways of death, making pretence these were catarrhs, or apoplexy and sudden death. Verily such husbands are odious,—so to see their fair wives lying by their side, sickening and dying a slow death day after day, and do deserve death far worse than their dames. Others again do them to death between four walls, in perpetual imprisonment. Of such we have instances in sundry ancient Chronicles of France; and myself have known a great nobleman of France, the which did thus slay his wife, who was a very fair and honourable lady,—and this by judgement of the Courts, taking an infatuate delight in having by this means his cuckoldry publicly declared.

Among husbands of this mad and savage temper under cuckoldry, old men hold the first place, who distrusting their own vigour and heat of body, and bent on making sure of their wives’ virtue, even when they have been so foolish as to marry young and beautiful ones, so jealous and suspicious are they of the same (as well by reason of their natural disposition as of their former doings[19] in this sort, the which they have either done themselves of yore or seen done by others), that they lead the unhappy creatures so miserable a life that scarce could Purgatory itself be in any wise more cruel.

The Spanish proverb saith: El diablo sabe mucho, porque es viejo, “The devil knoweth much, because he is old”; and in like sort these old men, by reason of their age and erstwhile habitudes, know full many things. Thus are they greatly to be blamed on this point, for seeing they cannot satisfy their wives, why do they go about to marry them at all? Likewise are the women, being so fair and young, very wrong to marry old men under temptation of wealth, thinking they will enjoy the same after their death, the which they do await from hour to hour. And meanwhile do they make good cheer with young gallants whom they make friends of, for the which some of them do suffer sorely.

I have heard speak of one who, being surprised in the act, her husband, an old man, did give her a certain poison whereby she lay sick for more than a year, and grew dry as a stick. And the husband would go oft to see her, and took delight in that her sickness, and made mirth thereat, declaring she had gotten her deserts.

Yet another her husband shut her up in a room, and put her on bread and water, and very oft would he make her strip stark naked and whip her his fill, taking no pity on that fair naked flesh, and feeling no compunction thereat. And truly this is the worst of them, for seeing they be void of natural heat, and as little subject to temptation as a marble statue, no beauty doth stir their compassion, but they satiate their rage with cruel martyrdoms; whereas if that they were younger, they would[20] take their satisfaction on their victim’s fair naked body, and so forget and forgive, as I have told of in a previous place.

This is why it is ill to marry suchlike ill-conditioned old men; for of a truth, albeit their sight is failing and coming to naught from old age, yet have they always enough to spy out and see the tricks their young wives may play them.

Even so have I heard speak of a great lady who was used to say that never a Saturday was without sun, never a beautiful woman without amours, and never an old man without his being jealous; and indeed everything goeth for the enfeeblement of his vigour.

This is why a great Prince whom I know was wont to say: that he would fain be like the lion, the which, grow he as old as he may, doth never get white; or the monkey, which, the more he performeth, the more he hath desire to perform; or the dog, for the older he waxeth, the bigger doth he become; or else the stag, forasmuch as the more aged he is, the better can he accomplish his duty, and the does will resort more willingly to him than to the younger members of the herd.

And indeed, to speak frankly, as I have heard a great personage of rank say likewise, what reason is there, or what power hath the husband so great that he may and ought to kill his wife, seeing he hath none such from God, neither by His law nor yet His holy Gospel, but only to put her away? He saith naught therein of murder, and bloodshedding, naught of death, tortures or imprisonment, of poisons or cruelties. Ah! but our Lord Jesus Christ did well admonish us that great wrong was in these fashions of doing and these murders, and that He did hardly[21] or not at all approve thereof, whenas they brought to Him the poor woman accused of adultery, for that He might pronounce her doom and punishment. He said only to them, writing with His finger on the ground: “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her,”—the which not one of them all durst do, feeling themselves touched to the quick by so wise and gentle a rebuke.

Our Creator was for teaching us all not to be so lightly ready to condemn folk and put them to death, even on this count, well knowing the weakness of our human Nature, and the violent errors some do commit against it. For such an one doth cause his wife to be put to death, who is more an adulterer than she, while others again often have their wives slain though innocent, being aweary of them and desiring to take other fresh ones. How many such there be! Yet doth Saint Augustine say that the adulterous man is as much to be punished as the woman.

I have heard speak of a very great Prince, and of high place in the world, who suspecting his wife of false love with a certain gallant cavalier, had him assassinated as he came forth by night from his Palace, and afterward the lady.[13*] A little while before, this latter at a Tourney that was held at Court, after fixedly gazing at her lover who did manage his horse right gracefully, said suddenly: “Great Lord! how well he doth ride!” “Yea!” was the unexpected answer, “but he rides too high an horse”; and in short time after was he poisoned by means of certain perfumes or by some draught he swallowed by way of the mouth.

I knew a Lord of a good house who did kill his wife, the which was very fair and of good family and lineage,[22] poisoning her by her private parts, without her being ware of it, so subtle and cunningly compounded was the said poison. This did he in order to marry a great lady who before had been wife to a Prince, without the influence and protection of whose friends he was in sad case, exposed to imprisonment and danger. However as his ill-luck would have it, he did not marry her after all, but was disappointed therein and brought into very evil repute, and ill looked at by all men and honourable ladies.

I have seen high personages greatly blame our old-time Kings, such as Louis X. (le Hutin, the Obstinate)[14*] and Charles the Fair, for that they did to death their wives,—the one Marguérite, daughter of Robert Duke of Burgundy, the other Blanche, daughter of Othelin Count of Burgundy, casting up against them their adulteries. So did they have them cruelly done to death within the four walls of the Château-Gaillard, as did likewise the Comte de Foix to Jeanne d’Arthoys. Wherein was not so much guilt or such heinous crimes as they would have had men to believe; but the truth is the said monarchs were aweary of their wives, and so did bring up against them these fine charges, and after did marry others.

As in yet another case, did King Henry of England have his wife put to death and beheaded, to wit Anne Boleyn, in order to marry another, for that he was a monarch very ready to shed blood and quick to change his wives. Were it not better that they should divorce them, according to God’s word, than thus cruelly cause them to be slain? But no! they must needs ever have fresh meat these folk, who are fain to sit at table apart without inviting any to share with them, or else to have new and fresh wives to bring them gear after that they[23] have wasted that of their first spouses, or else have not gotten of these enough to satisfy them. Thus did Baldwyn,[15] second King of Jerusalem, who making it to be believed of his first wife that she had played him false, did put her away, in order to take a daughter of the Duke of Malyterne,[15] because she had a large sum of money for dowry, whereof he stood in sore need. This is to be read in the History of the Holy Land.[15] Truly it well becomes these Princes to alter the Law of God and invent a new one, to the end they may make away with their unhappy wives!

King Louis VII. (Le Jeune, the Young)[15] did not precisely so in regard to Leonore, duchesse d’Acquitaine, who being suspected of adultery, mayhap falsely, during his voyaging in Syria, was repudiated by him on his sole authority, without appealing to the law of other men, framed as it is and practised more by might than by right or reason. Whereby he did win greater reputation than the other Kings named above, and the name of good, while the others were called wicked, cruel and tyrannical, forasmuch as he had in his soul some traces of remorse and truth. And this forsooth is to live a Christian life! Why! the heathen Romans themselves did for the most part herein behave more Christianly; and above all sundry of their Emperors, of whom the more part were subject to be cuckolds, and their wives exceeding lustful and whorish. Yet cruel as they were, we read of many who did rid themselves of their wives more by divorces than by murders such as we that are Christians do commit.

Julius Caesar did no further hurt to his wife Pompeia, but only divorced her, who had done adultery with Publius[24] Clodius, a young and handsome Roman nobleman. For being madly in love with her, and she with him, he did spy out the opportunity when one day she was performing a sacrifice in her house, to which only women were admitted. So he did dress himself as a girl, for as yet had he no beard on chin, and joining in the singing and playing of instruments and so passing muster, had leisure to do that he would with his mistress. However, being presently recognized, he was driven forth and brought to trial, but by dint of bribery and influence was acquitted, and no more came of the thing.

Cicero expended his Latin in vain in a fine speech he did deliver against him.[16*] True it is that Caesar, wishful of convincing the public who would have him deem his wife innocent, did reply that he desired his bed not alone to be unstained with guilt, but free from all suspicion. This was well enough by way of so satisfying the world; but in his soul he knew right well what the thing meant, his wife being thus found with her lover. Little doubt she had given him the assignation and opportunity; for herein, when the woman doth wish and desire it, no need for the lover to trouble his head to devise means and occasions; for verily will she find more in an hour than all the rest of us men together would be able to contrive in an hundred years. As saith a certain lady of rank of mine acquaintance, who doth declare to her lover: “Only do you find means to make me wish to come, and never fear! I will find ways enough.”

Caesar moreover knew right well the measure of these matters, for himself was a very great debauchee, and was known by the title of the cock for all hens. Many a husband did he make cuckold in his city, as witness the nickname[25] given him by his soldiers at his Triumph in the verse they did sing thereat: Romani, servate uxores; moechum adducimus calvum.

(Romans, look well to your wives, for we bring you the bald-headed fornicator, who will debauch ’em every one.)

See then how that Caesar by this wise and cunning answer he made about his wife, did shake himself free of bearing himself the name of cuckold, the which he made so many others to endure. But in his heart, he knew for all that how that he was galled to the quick.

3.

Octavius Caesar[17] likewise did put away his wife Scribonia for the sake of his own lecherousness, without other cause, though at the same time without doing her any other hurt, albeit she had good excuse to make him cuckold, by reason of an infinity of ladies that he had relations with. Indeed before their husbands’ very faces he would openly lead them away from table at those banquets he was used to give them; then presently, after doing his will with them, would send them back again with hair dishevelled and disordered, and red ears,—a sure sign of what they had been at! Not that myself did ever elsewhere hear tell of this last as a distinctive mark whereby to discover such doings; a red face for a certainty have I heard so spoken of, but red ears never. So he did gain the repute of being exceeding lecherous, and even Mark Antony reproached him therewith; but he was used to excuse himself, saying he did not so much[26] go with these ladies for mere wantonness, as thereby to discover more easily the secrets of their husbands, whom he did distrust.

I have known not a few great men and others, which have done after the same sort and have sought after ladies with this same object, wherein they have had good hap. Indeed I could name sundry which have adopted this good device; for good it is, as yielding a twofold pleasure. In this wise was Catiline’s conspiracy discovered by the means of a courtesan.

The same Octavius was once seriously minded to put to death his daughter Julia, wife of Agrippa, for that she had been a notorious harlot, and had wrought great shame to him,—for verily sometimes daughters do bring more dishonour on their fathers than wives on their husbands. Still he did nothing more than banish her the country, and deprive of the use of wine and the wearing of fine clothing, compelling her to wear poor folk’s dress, by way of signal punishment, as also of the society of men. And this is in sooth a sore deprivation for women of this kidney, to rob them of the two last named gratifications!

Another Emperor, and very cruel tyrant, Caligula,[18] did suspect that his wife, Livia Hostilia, had by stealth cheated him of sundry of her favours, and bestowed the same on her first husband, Caius Piso, from whom he had taken her away by force. This last was still alive, and was deemed to have received of her some pleasure and gratification of her fair body, the while the Emperor was away on a journey. Yet did he not indulge his usual cruelty toward her, but only banished her from him, two[27] years after he had first taken her from her husband Piso and married her.

He did the same to Tullia Paulina, whom he had taken from her husband Caius Memmius. He exiled her and that was all, but in this case with the express prohibition to have naught to do at all with the gentle art of love, neither with any other men nor yet with her husband—truly a cruel and rigorous order so far as the last was concerned!

I have heard speak of a Christian Prince, and a great one, who laid the same prohibition on a lady whom he affected, and on her husband likewise, by no means to touch her, so jealous was he of her favours.

Claudius,[19] son of Drusus Germanicus, merely put away his wife Plautia Urgulanilla, for having shown herself a most notorious harlot, and what is worse, for that he had heard how she had made an attempt upon his life. Yet cruel as he was, though surely these two reasons were enough to lead him to put her to death, he was content with divorce only.