The Project Gutenberg eBook of Turquois mosaic art in ancient Mexico, by Marshall H. Saville

Title: Turquois mosaic art in ancient Mexico

Author: Marshall H. Saville

Release Date: December 27, 2021 [eBook #67027]

Language: English

Produced by: Alan Thompson, Charlene Taylor, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg ix]

CONTRIBUTIONS

FROM THE

MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

HEYE FOUNDATION

VOLUME VI

TURQUOIS MOSAIC ART

IN ANCIENT MEXICO

BY

MARSHALL H. SAVILLE

NEW YORK

MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

HEYE FOUNDATION

1922

CONDÉ NAST PRESS GREENWICH, CONN.

TO

GEORGE GUSTAV HEYE

In appreciation of his long-continued interest in all

that pertains to the study of the aboriginal race of

America, which has reached fruition in the opening of the

Museum of the American Indian

Heye Foundation

this volume is dedicated by the author and the

staff of the Museum

The writer has undertaken the present study of Mexican Turquois Mosaics in honor of the approaching opening to the public of the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, the only institution devoted exclusively to the study of the aboriginal American peoples ever established; and the proximate International Congress of Americanists to be held at Rio de Janeiro this summer. Owing to lack of time it has been impossible to obtain new photographic illustrations of all the specimens of mosaic-work in European museums, but the author desires to express his thanks to T. A. Joyce, Esq., for his courtesy in furnishing photographs of the examples in the British Museum. To Dr. Franz Heger, of the State Natural History Museum, Vienna, we are under deep obligations for photographs and description of the interesting Xolotl figure preserved in that Museum. Dr. S. K. Lothrop has kindly had photographs made of the objects of this class in the Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum in Rome, and has made certain valuable observations concerning them. To Drs. A. M. Tozzer and H. J. Spinden special acknowledgment is due for their generous permission to illustrate the mosaics from Chichen Itza, thus anticipating their own description of the objects in the work now being prepared regarding one of the most important discoveries ever made in ancient America. The fine drawings are from the pen of William Baake, and the beautiful plates represent the best efforts of the Heliotype Company. Finally must be acknowledged the characteristic generosity of one of the trustees of the Museum, James B. Ford, Esq., who has made it possible for us to publish this paper, and to whom the Museum is indebted for its acquisition of the precious collection of Mexican mosaics which are now described for the first time.

[Pg xi]

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| Preface | ix |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Earliest Historical Accounts of Turquois Mosaic in Mexico |

3 |

| The Grijalva Expedition, 1518 | 3 |

| Loot obtained by Cortés, 1519-1525 | 8 |

| Tribute of Mosaic Paid to the Aztec Rulers | 22 |

| Source of Turquois | 27 |

| The Aztec Lapidaries and Their Work | 29 |

| Objects Decorated with Mosaic | 40 |

| Existing Specimens of Mosaic | 47 |

| Minor Examples | 48 |

| Chichen Itza Specimens | 55 |

| Major Examples | 59 |

| Helmet | 60 |

| Masks | 60 |

| Skull Masks | 67 |

| Shields | 68 |

| Ear-plug | 79 |

| Animal Figures | 80 |

| God Figure | 82 |

| Knife Handles | 82 |

| Human Femur Musical Instrument | 84 |

| Conclusion | 86 |

| Notes | 92 |

| List of Works Describing Mexican Mosaics | 103 |

[Pg xii]

[Pg xiii]

ILLUSTRATIONS

Plates

| PAGE | ||

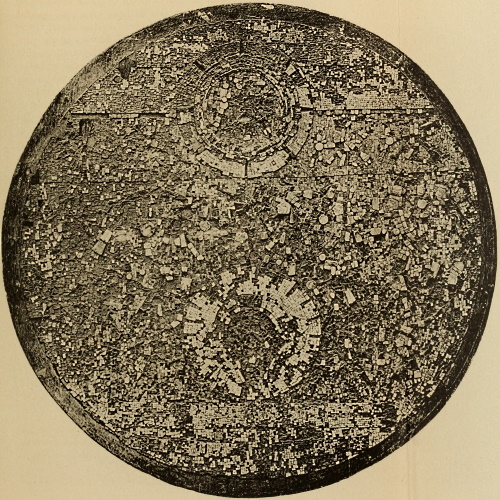

| I. | Wooden shield with turquois mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

Frontispiece |

| II. | Stone idol with mosaic decoration National Museum, Mexico |

22 |

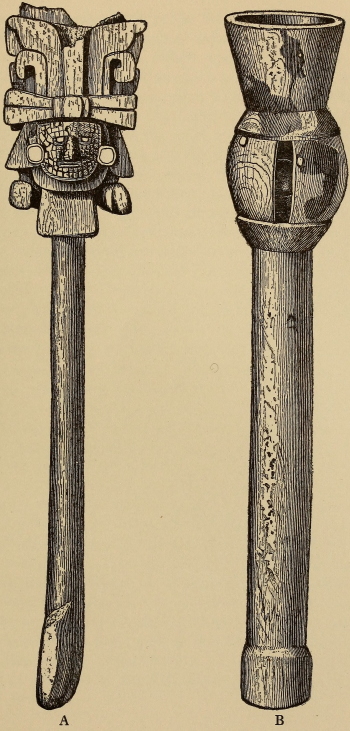

| III. | a, Wooden staff with turquois mosaic decoration, from Sacred cenote, ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan Peabody Museum, Cambridge |

|

| b, Wooden rattle with turquois mosaic decoration, from Sacred cenote, ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan Peabody Museum, Cambridge |

22 | |

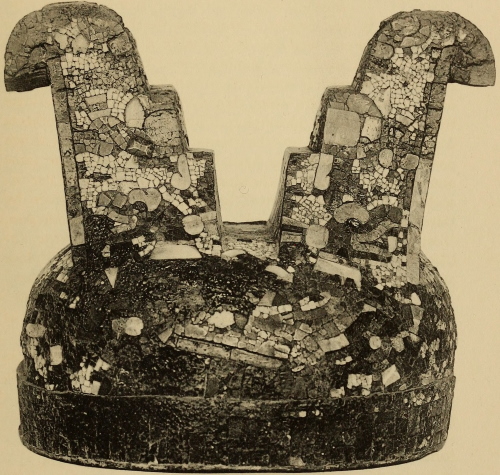

| IV. | Wooden helmet with mosaic decoration British Museum, London |

24 |

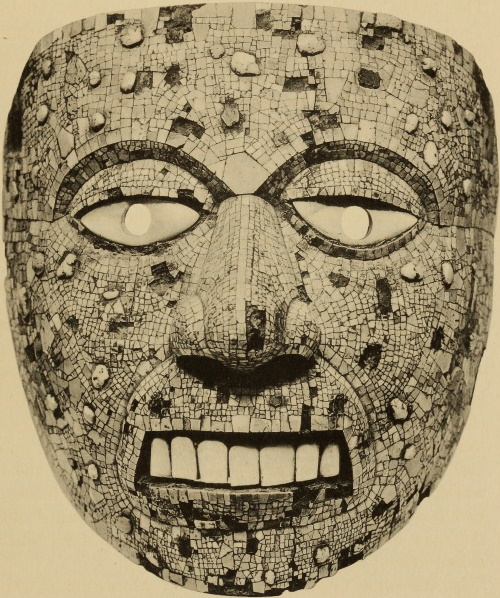

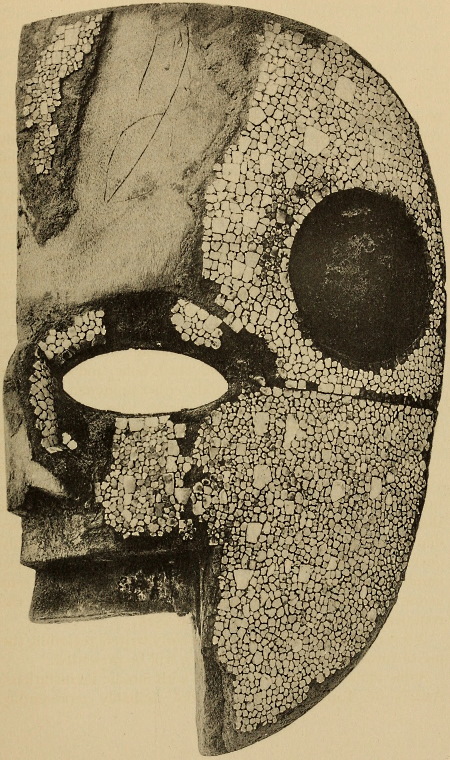

| V. | Wooden mask with turquois mosaic decoration British Museum, London |

26 |

| VI. | Wooden mask with turquois mosaic decoration British Museum, London |

28 |

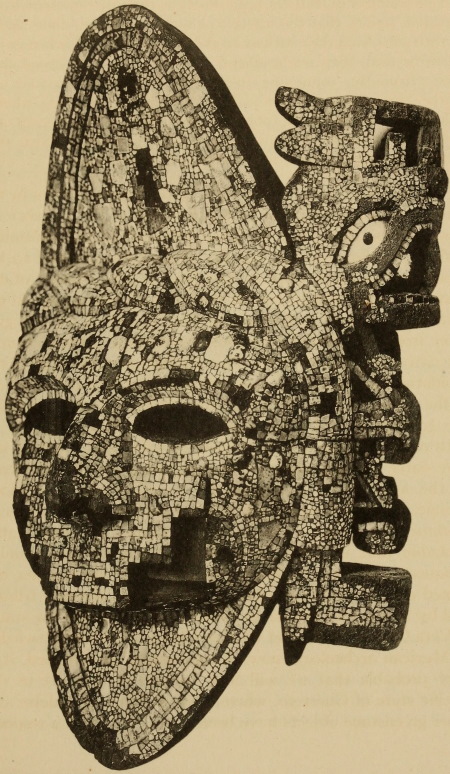

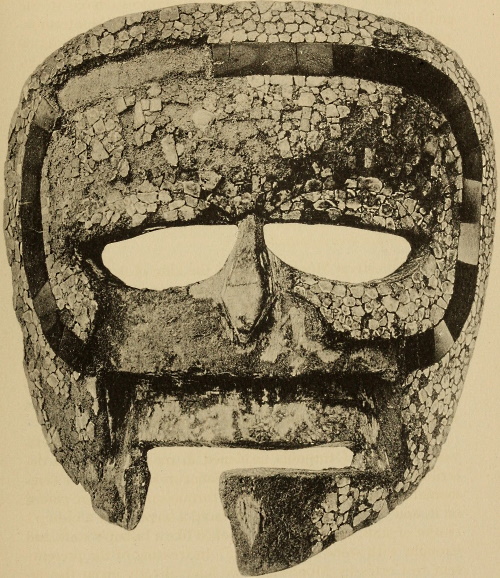

| VII. | Wooden mask with turquois mosaic decoration Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum, Rome |

30 |

| VIII. | Wooden mask with turquois mosaic decoration Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum, Rome |

32 |

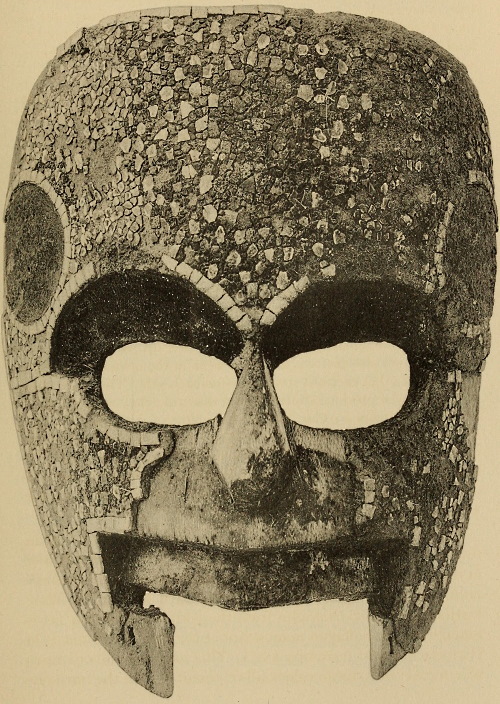

| IX. | Wooden mask with turquois mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

34 |

| X. | Wooden mask with turquois mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

36[Pg xiv] |

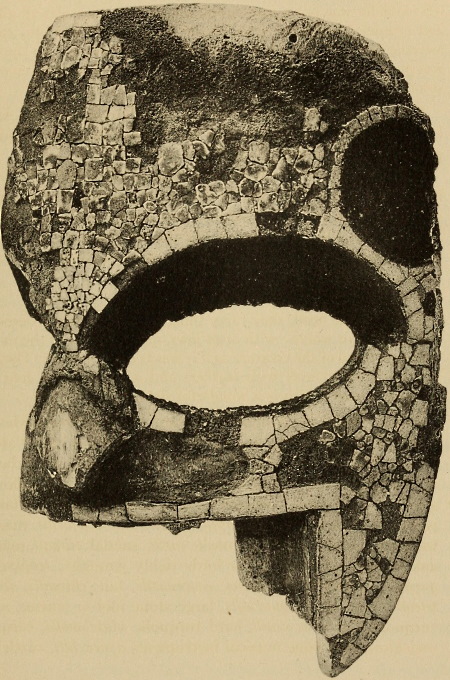

| XI. | Wooden mask (fragment) with turquois mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

38 |

| XII. | Wooden mask (fragment) with turquois mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

40 |

| XIII. | Wooden mask with mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

42 |

| XIV. | Wooden mask with mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

44 |

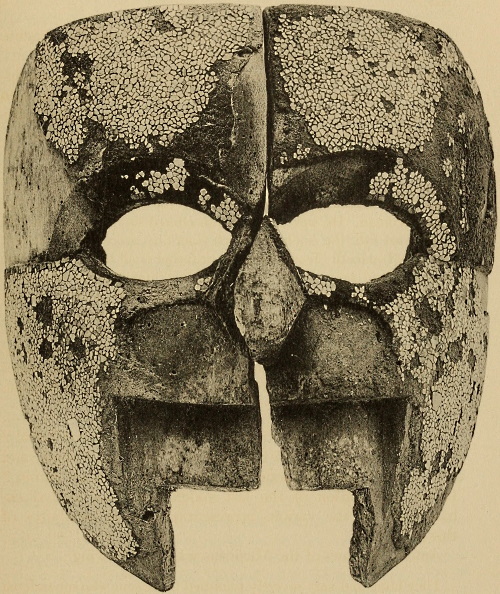

| XV. | Wooden mask (fragment) with mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

46 |

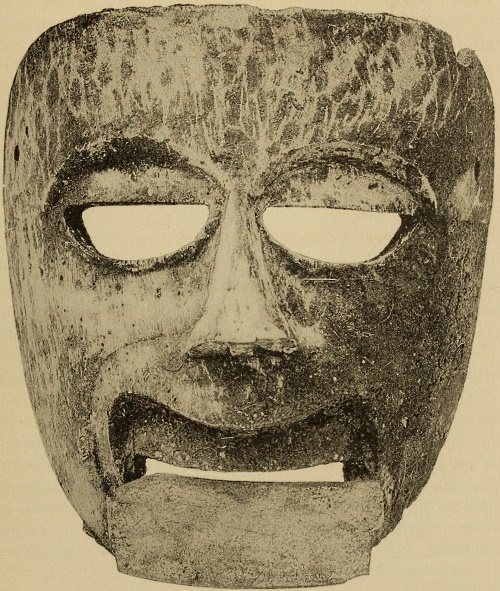

| XVI. | Wooden mask formerly covered with mosaic decoration Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

48 |

| XVII. | Wooden mask with turquois mosaic decoration, from Honduras Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

50 |

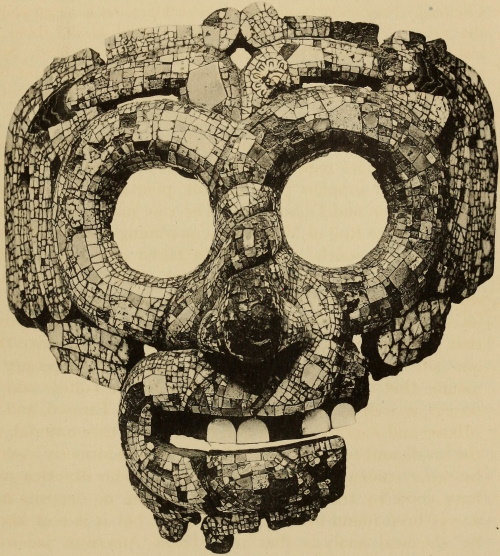

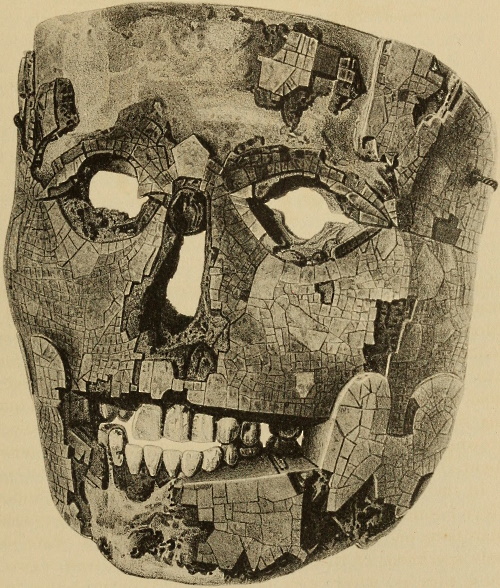

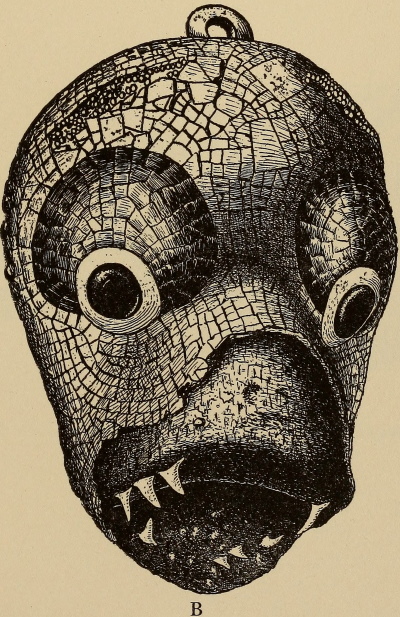

| XVIII. | Skull mask with mosaic decoration Ethnographical Museum, Berlin |

52 |

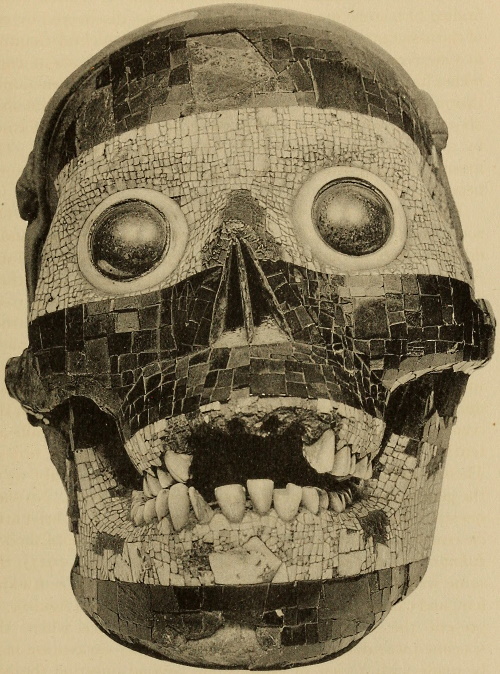

| XIX. | Skull mask with mosaic decoration British Museum, London |

54 |

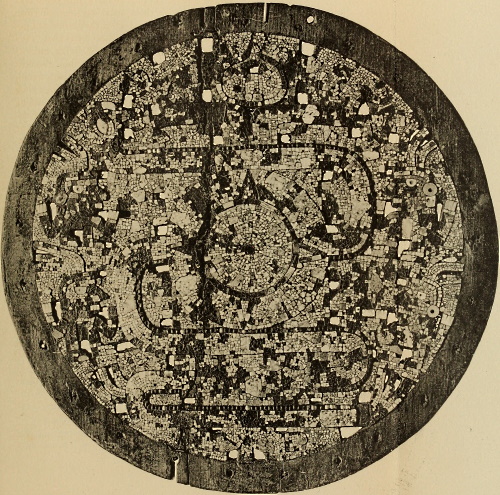

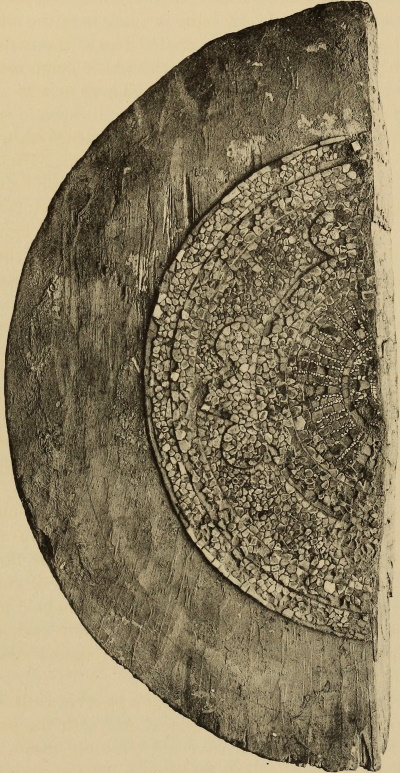

| XX. | Wooden shield with turquois mosaic decoration British Museum, London |

56 |

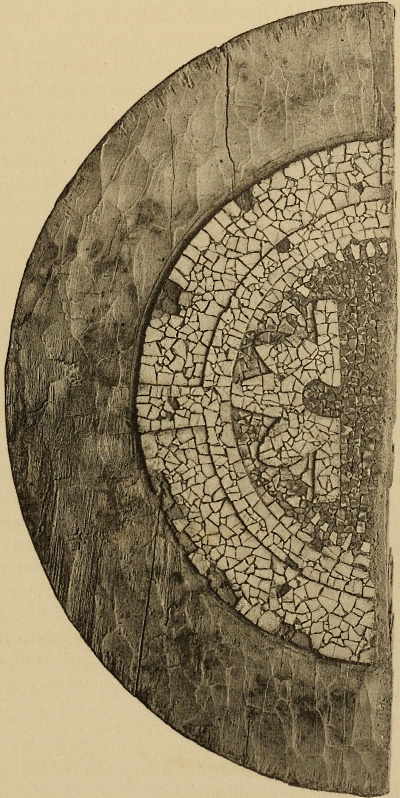

| XXI. | Wooden shield with turquois mosaic decoration State Natural History Museum, Vienna |

58 |

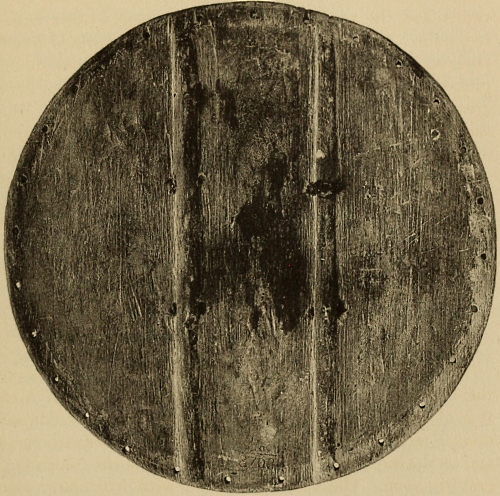

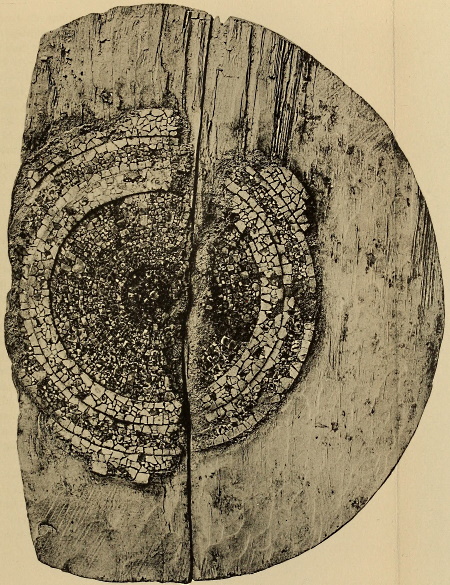

| XXII. | Back of wooden shield illustrated in Pl. I. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

60[Pg xv] |

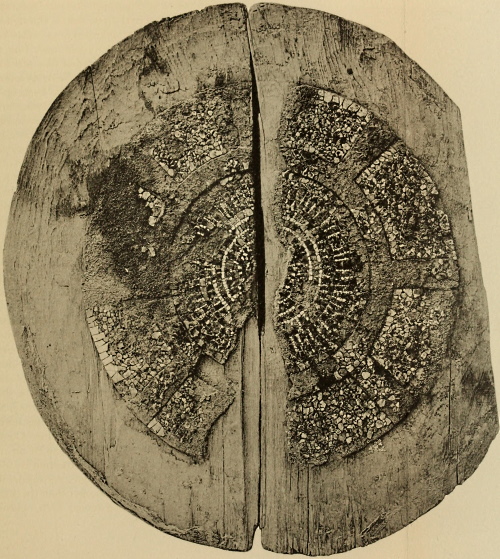

| XXIII. | Wooden shield with mosaic decoration. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

62 |

| XXIV. | Wooden shield with mosaic decoration. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

64 |

| XXV. | Wooden shield (fragment) with mosaic decoration. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

66 |

| XXVI. | Wooden shield (fragment) with mosaic decoration. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

68 |

| XXVII. | Wooden shield (fragment) with mosaic decoration. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

70 |

| XXVIII. | Wooden shield (fragment) with mosaic decoration. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

72 |

| XXIX. | Wooden shield (fragment) with mosaic decoration. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

74 |

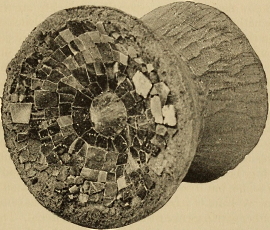

| XXX. | Wooden ear-plug with mosaic decoration. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York |

76 |

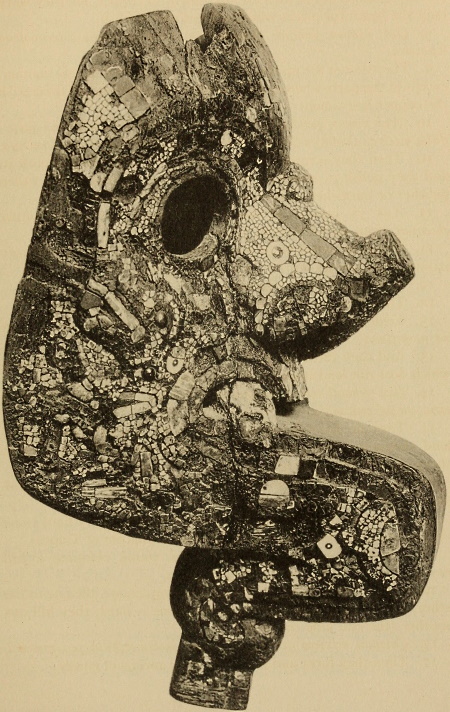

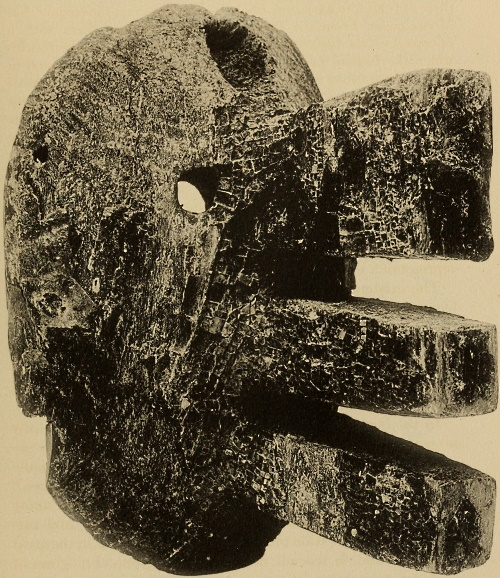

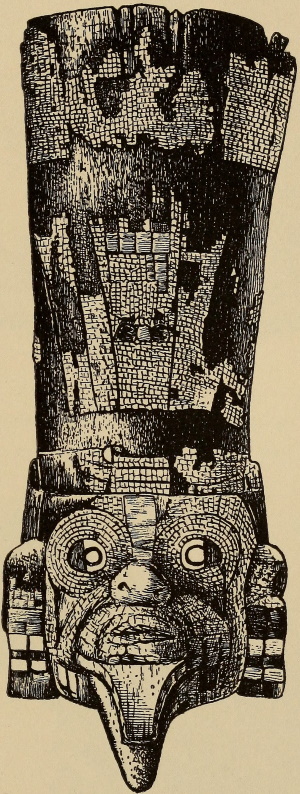

| XXXI. | Wooden head with head-piece, with mosaic decoration. National Museum, Copenhagen |

78 |

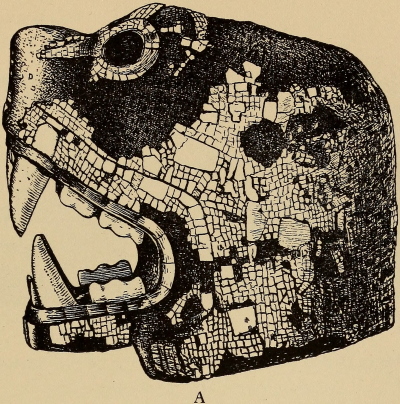

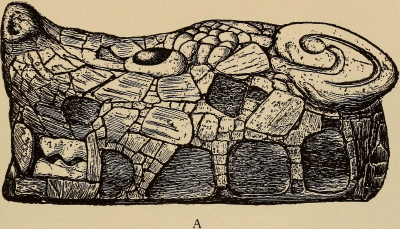

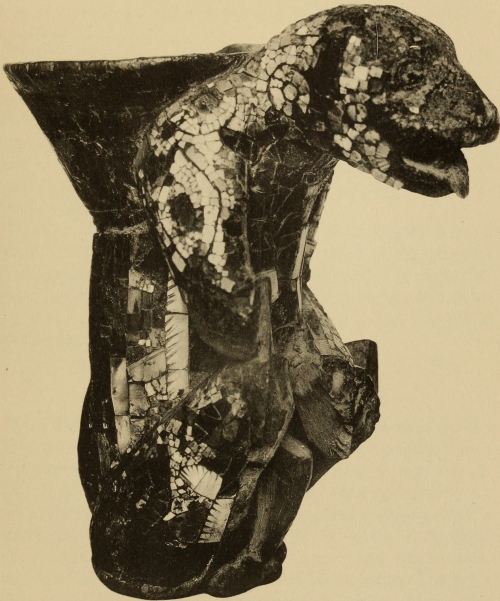

| XXXII. | a, Wooden jaguar head with mosaic decoration. Ethnographical Museum, Berlin |

|

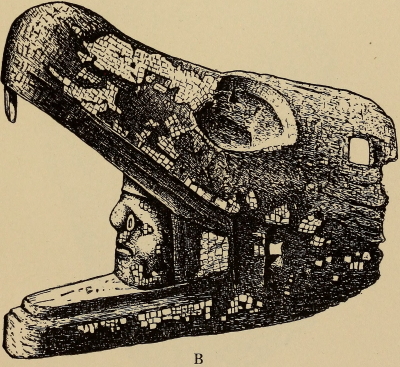

| b, Wooden head of animal and human face in jaws with mosaic decoration. National Museum, Copenhagen |

78 | |

| XXXIII. | a, Wooden head of animal with mosaic decoration. State Natural History Museum, Vienna |

|

| b, Wooden head of monkey with mosaic decoration. British Museum, London |

78[Pg xvi] | |

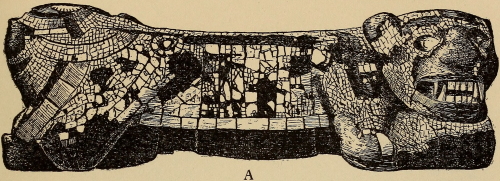

| XXXIV. | a, Wooden two-headed jaguar figure with mosaic decoration. Ethnographical Museum, Berlin |

|

| b, Wooden bird’s head with mosaic decoration. Museum, Gotha |

78 | |

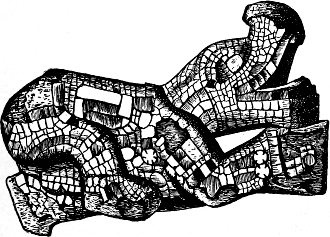

| XXXV. | Wooden animal figure on haunches with mosaic decoration. British Museum, London |

78 |

| XXXVI. | Wooden double-headed snake figure with mosaic decoration. British Museum, London |

80 |

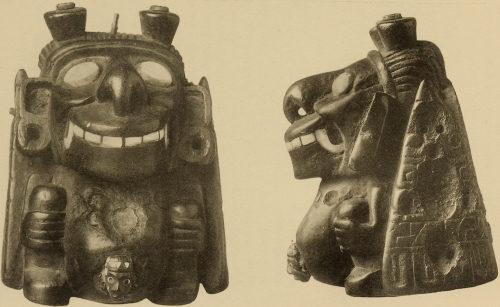

| XXXVII. | Wooden figure of Xolotl god with mosaic decoration. State Natural History Museum, Vienna |

80 |

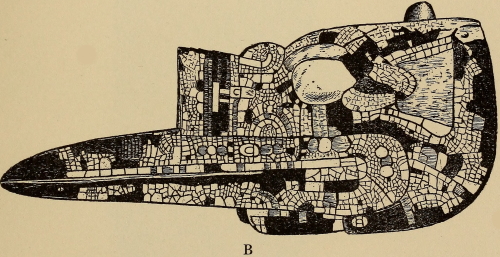

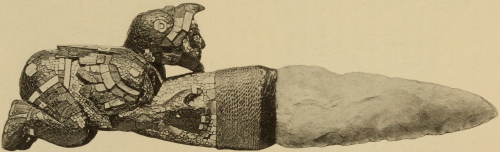

| XXXVIII. | Flint knife with wooden handle with mosaic decoration. British Museum, London |

82 |

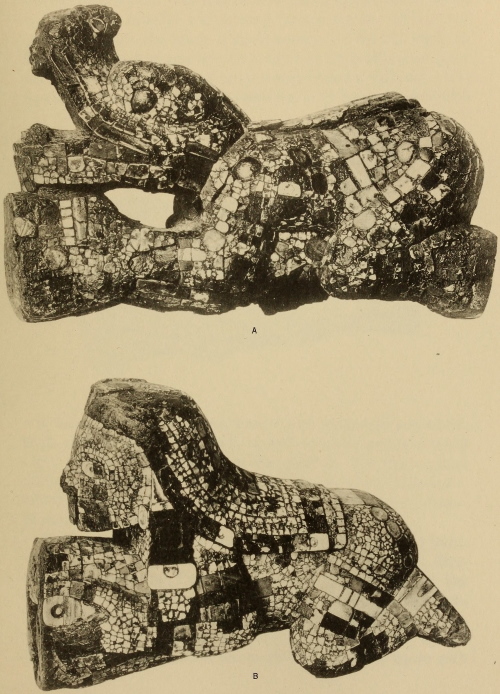

| XXXIX. | a, Wooden knife handle with mosaic decoration. Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum, Rome |

|

| b, Wooden knife handle with mosaic decoration. Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum, Rome |

82 | |

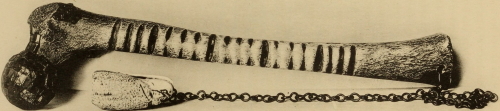

| XL. | Human femur musical instrument with mosaic decoration. Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum, Rome |

84 |

Text Figures

| 1. | Bowl filled with turquois. After Tribute Roll of Montezuma |

24 |

| 2. | Ten masks of turquois. After Tribute Roll of Montezuma |

24 |

| 3. | Small bag filled with turquois. After Tribute Roll of Montezuma |

25 |

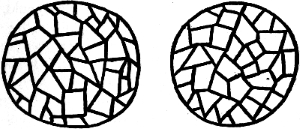

| 4. | Shields with turquois mosaic decoration. After Tribute Roll of Montezuma |

25 |

| 5. | Serpent scepter with turquois mosaic decoration. After Sahagun, manuscript of the Real Palacio, Madrid |

43[Pg xvii] |

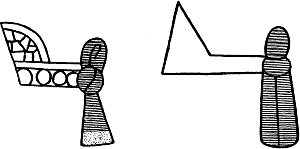

| 6. | a, Gold crown with turquois mosaic decoration. After Sahagun, manuscript of the Real Palacio, Madrid |

|

| b, Gold crown. After Tribute Roll of Montezuma | 45 | |

| 7. | Pottery disc with hematite mosaic decoration, from Cuilapa, Oaxaca. American Museum of Natural History, New York |

51 |

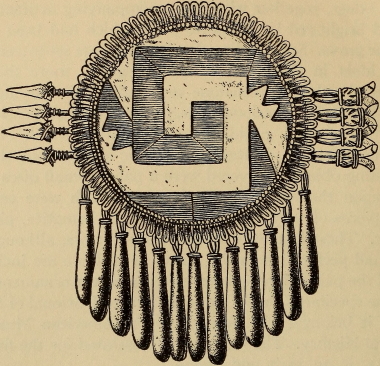

| 8. | Gold shield breast ornament with turquois mosaic decoration, from Yanhuitlan, Oaxaca. National Museum, Mexico |

52 |

| 9. | Wooden object (fragment) with turquois mosaic decoration, from Sacred cenote, ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. Peabody Museum, Cambridge |

57 |

| 10. | Wooden object (fragment) with turquois mosaic decoration, from Sacred cenote, ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. Peabody Museum, Cambridge |

57 |

| 11. | Rattle of the god Xipe Totec. After Sahagun, manuscript of the Real Palacio, Madrid |

58 |

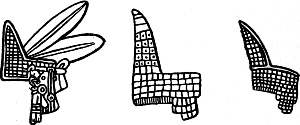

| 12. | a, b, c, Crowns with mosaic decoration, from sculptured wall, Temple of the Jaguars, ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. After Maudslay |

58 |

| 13. | Mask with mosaic decoration, from sculptured wall, Temple of the Jaguars, ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. After Maudslay |

59 |

| 14. | Mask with mosaic decoration, from sculptured wall, Temple of the Jaguars, ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. After Maudslay |

59 |

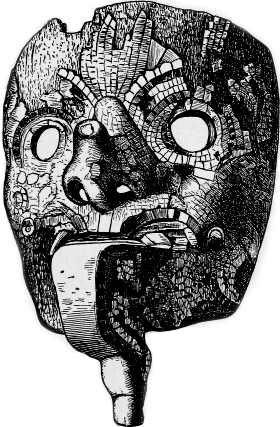

| 15. | Mask of wood with turquois mosaic decoration. Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum, Rome. After Pigorini |

63 |

| 16. | God Paynal with shield decorated with turquois mosaic. After Sahagun, manuscript of the Real Palacio, Madrid |

70 |

| 17. | God Paynal with shield decorated with turquois mosaic. After Sahagun, Florentine manuscript |

70[Pg xviii] |

| 18. | Glyphs of the town of Culhuacan. After Codex Telleriano Remensis |

74 |

| 19. | Knife handle of wood with turquois mosaic decoration. Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum, Rome. After Pigorini |

83 |

[Pg 1]

TURQUOIS MOSAIC ART IN ANCIENT MEXICO

By MARSHALL H. SAVILLE

ONE of the tragedies of the discovery of the New World was the abrupt and summary blotting out of the flourishing and still advancing civilization of the Aztec and other Mexican tribes. Had their complete conquest and subjection been delayed a few decades they in all probability would have developed a written phonetic language. Their intellectual abilities are evidenced by a study of the intricate calendar system, and the picture and hieroglyphic records which survive. The triumphs of their architectural attainments are well known, and may be investigated in the numerous monuments and buildings in the ruined cities scattered throughout Mexico. They had made notable strides toward civilization in certain of the minor fine arts. Ignorant of glass and of glazed pottery, they nevertheless developed the ceramic art to a high degree of excellence. Their inventive genius and technical skill were manifest in their goldsmith’s art.[1]

Without the knowledge of iron, in the working of hard precious and semi-precious stones into idols and personal ornaments, their craftsmanship was equal to that of the best lapidaries of Europe at the beginning of the sixteenth century. In the lapidarian art they had advanced so far as to fashion and adorn many objects with designs, both geometric and realistic, in stone mosaic, employing turquois chiefly for this purpose, but also making use of other stones—marcasite and shell. But the supreme esthetic achievement of the Aztecs was the production of a class of mosaics in which they used tiny bits of colored feathers instead of stones in making the designs.[Pg 2] This unique art was employed in adorning objects for personal use, for warfare, or for priestly ceremonies. The patterns were produced by applying the tiny bits of feathers with glue either directly on wood or on wooden objects covered with skin or with native paper. From descriptions of feather mosaics in the writings of early chroniclers, and from a study of the handful of specimens which have escaped the ravages of time, it is evident that this art reached the highest artistic level attained by any of the aboriginal tribes of America.

We will not enter into a discussion of feather mosaics at this time, but will consider primarily the parallel art of turquois mosaic. Aside from the numerous historical notices contained in the early chronicles and in the inventories of the loot of the Aztecs sent to Europe by Cortés, there is little of this art upon which to base a careful study that has survived. It is one of the most interesting and highly developed arts of ancient America, but it was practised by only a few tribes. Apart from the Mexican region where turquois mosaic was most highly developed, excellent examples have been found with other ancient remains of the Pueblos of Arizona and New Mexico, and incrusted objects have also been found with ancient burials on the coast of Peru, indicating a somewhat similar technique though far less skill in application. The materials usually employed in Mexico were turquois, jadeite, malachite, quartz, beryl, garnet, obsidian, marcasite, gold, bits of red and other colored shell, and nacre. The base upon which the incrustation was laid was wood, stone, gold, shell, pottery, and possibly leather and native paper, the mosaic being held in place by means of a tenacious vegetal pitch or gum, or a kind of cement.

[Pg 3]

The Grijalva Expedition, 1518

The first knowledge received by Europeans of the existence of turquois mosaic objects among the Mexicans was by members of the expedition sent out from Cuba by the governor, Diego Velásquez, during the spring of 1518, under the command of Juan de Grijalva. After reaching the shores of Yucatan near the island of Cozumel, the party coasted the Yucatan peninsula, reaching the territory of the present State of Campeche, which had been discovered the previous year by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba. Proceeding westward along unknown lands, they reached a great river in the State of Tabasco, to which the name of the commandant was given, and it is still known as Rio de Grijalva. Here, according to some accounts, the expedition obtained the first specimens of turquois mosaic. We shall consider this point later. Leaving the Rio de Grijalva they went westward and arrived at the site of the present city of Vera Cruz, where they obtained by barter with the Indians a considerable treasure, including some objects of turquois mosaic, which Grijalva decided to send immediately to the governor in Cuba with a report of his discoveries up to that time. Consequently, on June 24, 1518, one of Grijalva’s captains, Pedro de Alvarado, set out on the return voyage to Fernandina (Cuba), while Grijalva himself continued the exploration of the eastern coast of Mexico.

The provenience of the treasure obtained by Grijalva on this first expedition of discovery to the coasts of Tabasco and Vera Cruz in 1518 is not at all clear from the accounts of this voyage in the writings both of the eye-witnesses themselves and of those who shortly afterward wrote of the conquest from the reports of the participants in the events. It has been[Pg 4] generally assumed that Grijalva obtained mosaic objects from the Indians of Tabasco; this is specifically stated by both Oviedo and Gomara, who recorded detailed accounts of the Grijalva expedition. The account by Oviedo[2] is even more extended and valuable than the narrations of the eye-witnesses, namely, Juan Díaz[3] the chaplain, and the redoubtable Bernal Díaz. Oviedo states that his account is from the report forwarded to the King of Spain by the governor Velásquez, who sent out the expedition from Cuba. Gomara, who for a time was chaplain of Cortés in Spain, never visited the New World, but had access to the various reports sent to Spain regarding the conquest.

Unfortunately in the writings of the eye-witnesses no detailed descriptive lists are to be found relating just what pieces of mosaic-work were obtained by Grijalva from the Mayan Indians of Tabasco and the people of the coast of the present State of Vera Cruz. The extended account given by Oviedo recites the voyage from day to day and the character of various objects received from the Tabasco Indians, followed by the list of specimens obtained from the Mexican Indians near the Isla de Sacrificios, Vera Cruz. We will quote from these lists later. Gomara’s list is quite extended. In the first part of his Historia de las Indias he describes various articles procured by Grijalva from the Indians at the mouth of the river in Tabasco, to which his name was applied, followed in turn by the inventory of objects obtained at San Juan de Ulua, Vera Cruz. In the second part of his history, the Conquista de Mexico, he gives only a single long inventory of the barter obtained, as he says, “from the Indians of Potonchan [Tabasco], San Juan de Ulua, and other places of that coast.” It seems highly probable, however, that such interesting and valuable loot must have been accompanied with an inventory when it was sent to Spain late in 1518 or early in 1519 by Governor Velásquez. Oviedo mentions seeing the things, apparently in Barcelona, in May 1519. It is possible that both Oviedo and Gomara may have had access to such an inventory, or if not,[Pg 5] they wrote their own descriptions of the objects after seeing them.

Bernal Díaz, who accompanied both Grijalva and Cortés to Mexico, wrote his history nearly fifty years after the stirring events of the discovery and conquest. He was a prejudiced writer, and seems to have been largely animated in his old age to tell the story of the conquest primarily to refute many of the statements of Gomara. Bernal Díaz writes bluntly at the very outset of his invaluable history, which he calls the “True History,” that he speaks “here in reply to all that has been said and written by persons who themselves knowing nothing, have received no true account from others of what really took place, but who nevertheless now put forward any statements that happen to suit their fancy.” While not describing the treasure obtained by Grijalva, he mentions “some gold jewels some (of which) were diadems and others were in the shape of ducks like those of Castile, and other jewels like lizards, and three necklaces of hollow beads, and other articles of gold not of much value, for they were not worth more than two hundred pesos.”[4] These he states were obtained from the Indians of Potonchan. For some reason he apparently was not greatly impressed either by the technical excellence or by the esthetic beauty of the objects procured by barter from the vicinity of the present city of Vera Cruz; he simply writes that the Spaniards were engaged for six days in trading with the Indians and got more than sixteen thousand dollars’ worth of jewelry of low-grade gold worked into various forms. He then says: “This must be the gold which the historians Gomara, Yllescas, and Jovio say was given by the natives of Tabasco, and they have written it down as though it were true, although it is well known to eye-witnesses that there is no gold in the province of the Rio de Grijalva or anywhere near it, and very few jewels.”[5] Torquemada wrote in later years to the same effect.

In none of the accounts by the participants of this expedition are mosaic pieces specifically mentioned. The chaplain[Pg 6] of Grijalva’s fleet, Juan Díaz, states merely that they were given “a mask of gold beautifully wrought, and a little figure of a man with a little mask of gold, and a crown of gold beads with other jewels and stone of various colors.” This report was first printed in Venice, March 3, 1520, appearing in Italian as an appendix to the Itinerario of Ludovico de Varthema.

An anonymous independent relation in Italian of this voyage seems to have been printed at Venice in the same year under the title Littera Mãdata della Insula de Cuba, etc., the copy in the Marciana Library, Venice, being the only one known. From a photostat copy of the Italian we are able to present a translation of the mention of these objects, somewhat similar to that given by Juan Díaz. The Littera Mãdata states that the Spaniards obtained “a mask of gold, and the figure of a man all of gold, seemingly of the age of twelve, and a fan of gold, and other jewels of divers colors.”[6]

Another anonymous early printed report, in Latin, without date or place of printing, affords practically the same information as that contained in the Itinerario of Juan Díaz and in the Littera Mãdata.[7]

The earliest printed information regarding the Grijalva voyage in which mosaic objects are specifically noted is in Peter Martyr’s De Nvper Sub D. Carolo Repertis Insulis, printed in Basle in 1521. In speaking of the valuable objects obtained by Grijalva in Coluacan (Vera Cruz), and sent to Spain, he mentions that “the cacique brought a small golden statue of a man, also a gold fan, and a mask beautifully wrought and decorated with stones.”[8] It will be observed that these objects correspond with those mentioned in the reports noted above, only that Peter Martyr speaks of the decoration of the mask with stones. With the exception of this note by Peter Martyr, who saw the objects in Spain, there is, as we have said, no special statement regarding mosaic-work to be found in the earliest known printed accounts of the Grijalva voyage. In 1535 the great work of Oviedo was first published, and here we find the following itemized description of pieces of mosaic-work,[Pg 7] said to have been obtained from the Indians of Potonchan, Tabasco.[9]

Another mask covered from the nostrils upward with well set mosaic-work of stones resembling turquoises, and from the nostrils downward with a thin plate of hammered gold.

Another mask resembling the first, but the stones were placed from the eyes upward, and below them there were thin plates of beaten gold over wood, the ears being of turquois mosaic-work.

Another mask made with bands or rods of wood, two of the strips being covered with mosaic-work, and the remaining other three with thin beaten gold.

A thin disc with a figure of a cemi or devil, covered above with beaten gold-leaf, and in other parts were scattered some stones.

A tablet of wood like the headstall of a horse in armor, covered over with thin gold-leaf, with some strips of black stones well set between the gold.

The head of a dog covered with stones, and very well made.

From Ulua in Vera Cruz these mosaic pieces are noted:

Two masks of small stones like turquois set over wood like mosaic, with some spangles of gold in the ears.

Two guariques of blue stones set in gold, each having eight pendants of the same.

A mask of stone mosaic-work.

In the work of Gomara, printed in 1553, appears also an extended account of this barter.[10]

Seler[11] and Lehmann[12] believe that most of the mosaic objects “apparently came from the eastern provinces, i.e., Tabasco.” Relying on the authority of both Oviedo and Gomara, Lehmann further uses in his discussion the original Nahuatl text of Sahagun in the Florentine manuscript copied and translated by Seler. In this section of Sahagun’s work relating to the attributes of the Mexican deities occurs the paragraph, “In jtlatquj Quetzalcoatl coa-xaiacatl xiuhticatl achivalli, quetzalapanecaiotl,” which Lehmann renders, “The Quetzalcoatl dress, the snake-mask with turquois work, the feather ornament of the people of Quetzalapan (Tabasco).”[13][Pg 8] But there is no mention in early chronicles or on early maps of any town in this region bearing the name Quetzalapan, and Torquemada in giving an account of some of the wars of Montezuma writes that “during the twelfth year of his reign (which was in 1514), his armies set out for the land of the Chichimecas, and entered the Huaxteca, subduing those of Quetzalapan.”[14] Other places bearing the name Quetzalapan were in the present states of Morelos, Guerrero, and Colima.[15] In recounting the episode of the conquest of this town, Clavijero writes explicitly that “Montezuma sent out an army in 1512 to the north against the Quetzalapanecas and conquered them with but little loss.”[16] Hence the place mentioned by Sahagun would seem to have been in Vera Cruz, and probably the region of Huaxteca or Cuexteca, for the Aztecs had considerable communication with this territory.

Loot Obtained by Cortés, 1519-1525

But the treasures of native art secured by the Grijalva expedition were insignificant by comparison with the enormously valuable loot obtained the next year (1519) by Cortés. It is not necessary in this study of Mexican mosaics to enter into the details of the expedition which set out from Cuba to follow the discoveries of Grijalva and which resulted in the conquest of Mexico. This has been done many times, but in the main most weight is given to the writings of the Spanish participants and to the early chroniclers. We have already studied in considerable detail the accounts of the art objects sent to Spain by Cortés, as contained in these early writings, and especially the inventories which accompanied the shipments of objects sent to Europe by the conqueror. Let us quote here merely what we wrote in presenting a summary of the events that occurred when Cortés first landed on the coast of Vera Cruz.

After the arrival of the Spaniards on the coast of Vera Cruz, the Indians were not long in ignorance of the consuming thirst of the conquerors for gold. In order to placate the formidable strangers[Pg 9] with childlike confidence that by giving them their wish the invasion of his dominions would be averted, Montezuma sent rich presents to Cortés through Tendile (Teuhtlile), governor of Cuetlaxtla (the modern Cotastla), which was then subject to the Aztecs. When all this treasure thus brought together was ready to be sent to Spain, with the report of the voyage, an inventory or list of the objects was drawn up and despatched with two special messengers, Alonso Portocarrero and Francisco de Montejo, who were charged to deliver the treasure to the King. These valuable gifts have been briefly described by several members of the expedition who saw them before they left Mexico, and on their receipt in Spain they were described by various other chroniclers.

From the inventory, which we translated, we select the items relating to objects ornamented with stone mosaic.

Item: two collars of gold and stone mosaic-work (precious stones)....

Another item: a box of a large piece of feather-work lined with leather, the colors seeming like martens, and fastened and placed in the said piece, and in the center (is) a large disc of gold, which weighed sixty ounces of gold, and a piece of blue stone mosaic-work a little reddish, and at the end of the piece another piece of colored feather-work that hangs from it.

Item: a miter of blue stone mosaic-work with the figure of monsters in the center of it, and lined with leather which seems in its colors to be that of martens, with a small (piece) of feather-work which is, as the one mentioned above, of this said miter.

Item: ... a scepter of stone mosaic-work with two rings of gold, and the rest of feather-work.

Item: an armlet of stone mosaic-work....

Item: a mirror placed in a piece of blue and red stone mosaic-work, with feather-work stuck to it, and two strips of leather stuck to it....

Item: some leggings of blue stone mosaic-work, lined with leather, of which the colors seem like martens; on each one of them (there are) fifteen gold bells.

Item: two colored (pieces of) feather-work which are for two (pieces of) head armor of stone mosaic-work....

[Pg 10]

More: two guariques (ear ornaments) of blue stone mosaic-work, which are to be put in the head of the big crocodile.

More: another head armor of blue stone mosaic-work with twenty gold bells which hang pendent at the border, with two strings of beads which are above each bell, and two guariques of wood with two plates of gold.

Item: another head armor of blue stone mosaic-work with twenty-five gold bells, and two beads of gold above each bell, that hang around it with some guariques of wood with plates of gold, and a bird of green plumage with the feet, beak, and eyes of gold.

Moreover: sixteen shields of stone mosaic-work with their colored feather-work hanging from the edge of them, and wide-angled slab with stone mosaic-work with its colored feather-work, and in the center of the said slab, made of stone mosaic-work, a cross of a wheel which is lined with leather, which has the color of martens.

Again: a scepter of red stone mosaic-work, made like a snake, with its head, teeth, and eyes (made) from what appears to be mother-of-pearl, and the hilt is adorned with the skin of a spotted animal, and below the said hilt hang six pieces of small feather-work.

Item: a piece of colored feather-work which the lords of this land are wont to put on their heads, and from it hang two ear-ornaments of stone mosaic-work with two bells and two beads of gold, and above a feather-work of wide green feathers, and below hang some white, long hairs.[17]

Peter Martyr, who saw the specimens in Spain shortly after they arrived, speaks of “certain miters beset with precious stones of divers colors, among which some are blue, like unto sapphires.” Also “two helmets garnished with precious stones of a whitish blue color: one of these is edged with bells and plates of gold, and under every bell two knobs of gold. The other, beside the stones wherewith it is covered, is likewise edged with XXV golden bells and knobs: and hath on the crest, a green bird with the feet, bill, and eyes of gold.”[18]

Las Casas describes “a helmet of plates of gold, and little bells hanging (from it), and on it stones like emeralds.” Also “many shields made of certain thin and very white rods, intermingled[Pg 11] with feathers and discs of gold and silver, and some very small pearls, like misshapen pearls.”[19]

These are some of the statements of early Spaniards. Let us now consider what the Indians have said about the treasure given by Montezuma to Cortés at that time. Our best source of information is the great Historia composed by Fray Bernardino de Sahagun, who spent many years in the valley of Mexico gathering information at first-hand from intelligent Indians. This was shortly after the conquest when the natives still retained vivid recollections of the fall of their country. Without this work the history of ancient Mexico, and of the customs and traditions of the Indians, could not be written.

We must not lose sight of the fact that Montezuma, for a number of reasons which we need not relate here, expected the “second coming” of the culture-hero Quetzalcoatl, the great beneficent god of the Aztecs. This myth was one of the several causes that led to the comparatively easy conquest of a numerous and warlike people by the Spaniards. We have translated several chapters of Sahagun’s Historia relating to the first coming of the Christians to the coast of Mexico, which contain a description of some of the gifts sent by Montezuma to Cortés, while he still believed the Spanish conqueror to be the great god Quetzalcoatl. It is really a report transmitted to us from the Aztecs, and is a most fascinating chapter of the history of the conquest of Mexico.[20]

Chapter II. Of the first (Spanish) ships which arrived at this land said to have been those of Juan de Grijalva.

The first time that ships appeared on the coast of New Spain, the captains of Montezuma, who were called calpixques, who were near the coast, at once went to see what it was that had come, never having seen ships; one of whom was the calpixque of Cuextecatl, named Pinotl: other calpixques went with him, one of whom, named Yaotzin, lived in the town of Mictlanquauhtla, another named Teozinzocatl resided in the town of Teociniocan, another named Cuitlalpitoc was not a calpixque but the servant of one of these calpixques, and principalejos, and another principalejo named[Pg 12] Tentlil. These went to see what the thing was, and carried some things to sell under pretence, so as to see what the thing was: they carried some rich mantles which only Montezuma, and no other (person), wore, nor had permission to wear: they entered canoes and went to the ships, saying amongst themselves, “We are here to guard this coast; it is right that we should know for a certainty what this is, in order to carry accurate news to Montezuma.” They entered at once the canoes and commenced to paddle to the ships, and when they arrived near the vessels and saw the Spaniards, all kissed the prows of the ships, in sign of adoration, thinking that it was the god Quetzalcoatl that had returned, which god, as appears in the history, was already expected. Then the Spaniards spoke and said: “Who are you? Whence have you come? From where are you?” Those who came in the canoes responded, “We have come from Mexico.” The Spaniards said, “If it is true that you are Mexicans, tell us what is the name of the Lord of Mexico.” They replied, “Our Lord, he is called Montezuma,” and then they presented all of those rich mantles which they had brought to him who went as general of those ships, who was, as is said, Grijalva, and the Spaniards gave to the Indians some glass beads, some green and others yellow, and the Indians when they saw them were very much astonished and esteemed them greatly, and then they (the Spaniards) dismissed the Indians, saying, “Now we return to Castile, and will soon return and will (then) go to Mexico.” The Indians returned to land and soon departed for Mexico, where they arrived in a day and a night, to give the news of what they had seen to Montezuma, and they brought to him the beads which had been given them by the Spaniards, and spoke to him (Montezuma) as follows: “Our Lord, we are deserving of death; hear what we have seen, and what we have done. Thou hast placed us on guard at the seashore; we have seen some gods on the sea, and went to receive them, and give them various rich mantles; look at these beads that they gave us, saying to us, ‘Is it true that you are Mexicans? Look at these beads, give them to Montezuma, that he may know of us.’” And they told him all that had happened when they were with those (people) on the sea in the ships. Montezuma responded: “You have come tired and worn out; go and rest. I have received this (news) in secret, and command you not to say anything whatever about what has happened.”

[Pg 13]Chapter III. Of what Montezuma disposed after he heard the news from those who saw the first (Spanish) ships.

As soon as he (Montezuma) heard the news from those who had come from the seashore, he ordered to be called at once the highest chief of those who were called Cuextecatl, and the others who had come with the message, and ordered them to place guards and lookouts in all the farms along the shores of the sea, the one called Naulitlantoztlan, and the other Mictlanquactla, so that they might see when those ships returned, and at once give a report. The calpixques and captains then left, and at once ordered the placing of lookouts on the said farms, and Montezuma then summoned the most confidential of his chieftains and communicated to them the news which had arrived, and showed them the glass beads which the messengers had brought, and said, “It seems to me that they are precious stones; take great care of them in the wardrobe that none of them be lost, and if any are lost, those who have charge of the wardrobe will have to pay.” One year hence, in the year thirteen rabbit, those who were on guard saw ships on the sea, and at once came with great speed to give notice to Montezuma. As soon as he had heard the news, Montezuma despatched men for the reception of Quetzalcoatl, because he thought that it was him who came, because they expected him daily, and as he had received news that Quetzalcoatl had gone by sea toward the east, and the ships came from the eastward, for this (reason) they thought that it was he: he sent five of his chief lords to receive him and to present to him a great present, which he sent. Of those who went the most prominent one was called Yallizchan, the second in rank Tepuztecatl, the third Tizaoa, the fourth Vevtecatl, and the fifth Veicaznecatlheca.

Chapter IV. What Montezuma ordered when he learned the second time that the Spaniards had returned, this was D. Hernando Cortés.

To the above mentioned (messengers) Montezuma spoke, and said, “Look, it has been said that our Lord Quetzalcoatl has arrived; go and receive him and listen to what he may say to you with great attention; see to it that you do not forget anything of what he may say; see here these jewels which you are to present to him in my behalf, and which are all the priestly ornaments that belong to him.” First a mask wrought in a mosaic of turquois; this mask had[Pg 14] wrought in the same stones a doubled and twisted snake, the fold of which was the beak of the nose; then the tail was parted from the head, and the head with part of the body came over one eye so that it formed an eyebrow, and the tail with a part of the body went over the other eye, to form the other eyebrow. This mask was inserted on a high and big crown full of rich feathers, long and very beautiful, so that on placing the crown on the head, the mask was placed over the face: it had for a (central) jewel a medallion of gold, round and wide: it was tied with nine strings of precious stones, which, placed around the neck, covered the shoulders and the whole breast: they carried also a large shield bordered with precious stones with bands of gold which went from the top to the bottom of it, and other bands of pearls crossing over the gold bands from the top to bottom of it, and in the spaces left by these bands, which were like the meshes of a net, were placed zapitos (little toads) of gold. This shield had edgings in the lower part; there was attached on the same shield a banner which came out from the handle of the shield, made of rich feathers: it also had a big medallion made of mosaic-work which was fastened and girded around the loins: they carried also strings of precious stones with gold bells placed in between the stones to be tied to the ankles: they carried also a bishop’s staff all decorated with turquois mosaic-work, and the crook of it was like the head of a snake turned around or coiled. They also carried sandals (cotaras) such as great lords were accustomed to wear. They also carried the ornaments or finery with which Tezcatlipoca was adorned, which was a head-piece made of rich feathers which hung down on the back almost to the waist, and was strewn all over with stars of gold. They carried also ear-ornaments of gold: they had hanging from them little gold bells and strings of little white and beautiful sea-shells. From these strings hung a piece of leather like a plastron (peto), and it was carried tied in such a manner that it covered the breast down to the waist: this plastron had strewn on it and hanging from it many little shells. They carried also a corselet of painted white cloth; the lower border of this corselet was edged with white feathers in three strips all around the border: they also carried a rich mantle the cloth of which was a light blue, and embroidered all over with many designs of a very fine blue: this mantle was worn around the waist, the (four) corners tied to the body: over this mantle was worn a medallion of turquois [work] attached to the body[Pg 15] over the loins: they also carried strings of gold bells to tie around the ankles, and also white sandals (cotaras) like those the lords are wont to wear. They also carried the ornaments and decorations of the god Tlalocantecutli, which were, a mask with its feather-work, and a banner like the one above mentioned: also wide ear-ornaments of chalchivitl with snakes of chalchivites inside: and also a corselet painted with green designs, and strings or collar of precious stones, and also a medallion with which they girded the loins, like the one above described, with a rich mantle, with which they girded themselves like the one described above, and golden bells to place on the feet, and the staff like the one above described. Other ornaments which they carried were also of the same Quetzalcoatl, a miter of tiger-skin, and hanging from the miter a hood of raven’s feathers: the miter also had a large chalchivitl rounded at the end, and also round ear-ornaments of turquois mosaic with a hook of gold called ecacozcatl, and a rich mantle with which he girded himself, and some gold bells for the feet, and a shield which had in the center a round plate of gold, which shield was bordered with rich feathers. From the lower part of the shield came out a sash of rich feathers in the shape of the one above described: it had a staff wrought in turquois mosaic, and its crook was set with rich stones or conspicuous pearls. They also had on top of it all some sandals (cotaras), such as the lords were accustomed to wear. All these things were brought by the messengers and presented, as they say, to D. Hernando Cortés. Many other things they presented to him which are not written about, such as a miter of gold made like a periwinkle with edging of rich feathers which hung over the shoulders, and another plain miter of gold and other jewels of gold which are not written about. All these things were placed in hampers (petacas), and upon taking leave from Montezuma he said to them, “Go and worship in my name the god who comes, and say to him we have been sent here by your servant Montezuma: these things which we bring have been sent by him, for you have come to your dwelling, which is Mexico.” These messengers set out on the road at once, and arrived at the seaside, and there took canoes [cañas, undoubtedly canoas was written], and arrived at a place called Xicalanco: from there they took other canoes with all their clothes, and reached the ships, and then those of the ships asked them, “Who are you, and whence have you come?” And those of the canoes answered, “We come from Mexico.” And[Pg 16] those of the ships said to them, “Perchance you are not from Mexico, but falsely say you are from Mexico and deceive us.” And upon this they took and gave (bartered?), until they were satisfied on both sides, and they tied the canoe to the ship, and a ladder was let down, by which they climbed up to the ship and came to where D. Hernando Cortés was.

Chapter V. Of what happened when the messengers of Montezuma entered the ship of D. Hernando Cortés.

They commenced to climb up to the ship on the ladders, and brought the presents that Montezuma had commanded them to carry. When they were in front of the captain D. Hernando Cortés, all kissed the ground [deck] in his presence, and spoke in this wise: “May the god whom we come to adore in the name of his servant Montezuma, who for him rules and governs the city of Mexico, know, and who says that the god has come after much hardship.” And at once they took out the ornaments they had brought, and placed them in front of the captain D. Hernando Cortés, adorning him with them, placing first the crown and mask which has been described above, and all the other things: they put around his neck the collars of (precious) stones with the jewels of gold which they had brought, and put on his left arm the shield above described, and all the other things were placed in front of him in the order they were accustomed to put their presents. The captain said, “Is there something more?” And they said to him, “We have not brought anything else than these things that are here.” The captain at once ordered them to be tied, and ordered shots of artillery fired, and the messengers who were tied hand and foot, when they heard the thunder of the bombardment, fell on the floor like dead, and the Spaniards lifted them from the floor, and gave them wine to drink, with which they strengthened them and revived them. After this captain D. Hernando Cortés said to them, through the interpreter: “Listen to what I say to you. I have been told that the Mexicans are valiant men, that they are great conquerors and great warriors, and are very skillful at arms: they tell me that one Mexican alone is enough to conquer from ten to twenty of his enemies. I wish to prove whether this is true, and whether you are so strong as I have been told.” Then he ordered swords and shields to be given them that they might fight with as many Spaniards, so that he might see[Pg 17] who might win, and the Mexicans then said to captain Cortés, “May it please your grace to listen to our excuse, for we are not able to do what you command, and it is because our Lord Montezuma has sent us to do nothing else than to salute you and give you this present, we cannot do anything else, nor are we able to do what you order us, for if we did we should offend our Lord Montezuma, and he would order us killed.” And the captain responded: “You will have to do by all means what I say. I have to see what kind of men you are, for over yonder in our country we have been told that you are very courageous men: arm yourselves with these arms and be ready that we encounter one another tomorrow on the (battle) field.

Chapter VI. Of how the messengers of Montezuma returned to Mexico with the report of what they had seen.

After what has been related was done, they took leave of the captain, and entered their canoes, and commenced to go toward the land, paddling with great speed, and saying to one another, “There are valiant men; let us exert ourselves to paddle before anything happens.” They arrived very quickly at the town of Xicalanco, and there they ate and rested a little, and then they got into their canoes again, and paddling with great speed they arrived at the town called Tecpantlayacac, and from there began to journey by land, running with great speed, and they reached the town called Cuetlaxtla: there they ate and rested a little, and those of the town begged them that they should rest at least a day, but they responded that they could not, because they had to go with great speed to make known to Montezuma what they had seen, very new things, and never before seen nor heard of, of which no one else could speak about: and so traveling with great speed by night and day, they arrived in Mexico by night.”

In the accounts of the vast treasure secured by Cortés from Montezuma before his untimely death, there is to be found no specific mention or description of objects decorated with stone mosaic. Much of the treasure secured in the final sack of Tenochtitlan (Mexico) was lost. The “empire” of the Aztecs was completely subjugated in 1521. From that time, and up to 1525, Cortés sent to Europe at various intervals great quantities[Pg 18] of loot, gathered as tribute from the stores of the Indians, accompanied with inventories, a number of which have been published. From these inventories we select the following items which clearly relate to stone mosaic objects.

Report of the Feather-work and Jewels sent to Spain to be distributed to the following Churches and Monasteries and Special Persons. [Without date.]

For the Lord Bishop of Burgos

Item: something like a staff (crosier) of stone mosaic-work of many colors, for him (the Bishop).

Copy of the Register of the Gold, Jewels, and other Things which are to go to Spain in the Ship Santa María de la Rábida, its Master (being) Juan Baptista. (The year 1522.)

This report contains a register of much treasure sent in one of the several ships which left Mexico in June, 1522, in charge of the treasurer Julian Alderete, and Alonso Dávila and Antonio de Quiñones, proctors. The register contains statements of the monetary value of certain treasure registered by various persons, among whom we find one Juan de Rivera, who carried treasure for himself, Cortés, and other persons named in the inventory; but none of the articles is described. In the margin of the report are notes stating that a considerable portion remained in the Azores. In another inventory, from which we shall quote later, are descriptions of certain pieces, jewels, and feather-work that remained in the Azores in charge of the above-named proctors. According to Peter Martyr the greater part of this treasure was destined for the King of Spain, but it never reached him, for the vessel, which with the others had put into the Azores to escape French pirates, was captured later by these corsairs and the rich spoils of the Aztecs went to augment the treasure of Francis I.

The ship Santa María de la Rábida seems to have arrived in Sevilla in November, 1522, and Peter Martyr saw the treasure that it brought and interviewed Juan de Rivera at[Pg 19] length concerning the people and country of New Spain. The account which he wrote, based on a view of the wonderful objects and what Rivera had told him, comprises an entire book in the Fifth Decade of his De Orbe Novo, first printed in 1530. It contains a mass of valuable and generally trustworthy information, gleaned not only at first hand from Rivera, but also from a young native Mexican whom Rivera had brought to Spain as a slave and servant. This account supplies certain information describing the treasure, which is missing in the inventory. The report is so interesting that we quote what Peter Martyr writes about some of the objects of stone mosaic-work which Rivera displayed.[21]

We have been particularly delighted with two mirrors of exceptional beauty: the first was bordered with a circle of gold, one palm in circumference, and set in green wood; the other was similar. Ribera states that there is stone found in these countries, which makes excellent mirrors when polished; and we admit that none of our mirrors more faithfully reflect the human face.

We also admire the artistically made masks. The superstructure is of wood, covered over with stones, so artistically and perfectly joined together that it is impossible to detect their lines of junction, with the fingernail. They seem to the naked eye to be one single stone, of the kind used in making their mirrors. The ears of the mask are of gold, and from one temple to another extend two green lines of emeralds; two other saffron colored lines start from the half-opened mouth, in which bone teeth are visible; in each jaw two natural teeth protrude between the lips. These masks are placed upon the faces of the gods, whenever the sovereign is ill, not to be removed until he either recovers or dies.

Peter Martyr gives us details regarding the King’s share of the loot brought by the Santa María de la Rábida, writing as follows:

Without mentioning the royal fifth, that ship brings the treasure which is composed of a part of what Cortés amassed, at the cost of risks and dangers, and the share belonging to his principal lieutenant: they offer it all in homage to their King. Ribera has been instructed to present to the Emperor in his master’s [Cortés’] name the[Pg 20] gifts he sends, while the others will be presented in the name of their colleagues by the officers who, as I have said, remained behind at the Azores.... The treasure destined for the Emperor is on board the vessel which has not yet arrived: but it is said that it amounts to 32,000 ducats of smelted gold in the form of bars. Were all the rings, jewels, shields, helmets, and other ornaments now smelted, the total would amount to 150,000 ducats. The report has spread, I know not how, that French pirates are on the watch for these ships: may they come safely in.

As we have stated, the ships were captured and the treasure was irretrievably lost to the Spaniards. An inventory of the treasure, preserved in Spain, reads:

Statement of Pieces, Jewels, and Feather-work sent from New Spain for His Majesty, and that Remained in the Azores in the Charge of Alonso Dávila and Antonio Quiñones. [Without date.]

Statement of the pieces, jewels, and feather-work that are sent to Their Majesties in the following boxes:

A shield with blue stone mosaic-work with its rim of gold.

A shield of stone mosaic-work, with a rim of blue and red feathers.

A shield of stone mosaic-work, the casco (crown) of feathers and the clasps of gold, and on the rim some long green feathers.

A shield of stone mosaic-work and confas (shells) with some pendants on the rim, of large and small gold bells.

Report of the Objects of Gold that are Packed in a Box for His Majesty which are Sent in Care of Diego de Soto. [Without date.]

A face of gold with the features of stone mosaic-work.

A face of tiger-skin [sic] with two ear-ornaments of gold and stone mosaic-work.

Report of the Things Carried by Diego de Soto from the Governor in Addition to what he Carries Listed in a Notebook of Certain Sheets of Paper for His Majesty. [Without date.]

A large shield with some moons of stone mosaic-work and with much gold.

Two stone mosaic-work shields.

The final inventory from which we extract items relating to stone mosaic-work objects is dated 1525. It is:

[Pg 21]

Report of the Gold, Silver, Jewels, and Other Things that the Proctors of New Spain Carry to His Majesty. (Year of 1525.)

A large head of a duck of blue stone mosaic-work.

Two pieces of gold, such as the natives of these parts wear in their ears with some red and blue stones, weighing altogether ten pesos.

A bracelet with four greenstones set in gold like the hoof of a stag. Not weighed.

Another bracelet of gold with ten pieces like azicates, and two claws of greenstone set in gold.

An armlet of tiger-skin with four greenstones and four small bars of gold of little weight.

A shell like a venerica set in gold with a greenstone in the center.

A large shell set in gold with a face of greenstone, with some blue and yellow little stones around the neck.

A butterfly of gold with the wings of venera, and the body and head of greenstone.

Two veneras, one purple and the other yellow, each one respectively with greenstones in the center and other blue ones around it, set in gold.

Another white venera, set in gold, having some blue and red eyes, the one inserted in the other.

A monster of gold with some greenstone mosaic-work in the belly, weighing altogether eleven pesos.

A poniard (or jewel broncha) of white shell set in gold, weighing altogether thirty-seven pesos, five tomins.

A butterfly of shell, of fancy work, set in gold, weighing altogether eleven pesos, six tomins.[22]

[Pg 22]

Mosaic objects, and especially the raw material for their manufacture, formed a part of the annual tribute paid by some of the coast provinces of ancient Mexico to the Aztec kings of Tenochtitlan. We have the pictorial representation of some of the objects of such tribute in an important native book or codex, painted in colors on maguey fiber paper, known as the Tribute Roll of Montezuma. This original codex was at one time in the famous Boturini collection, and is now one of the treasured possessions of the Museo Nacional in the City of Mexico. It lacks, however, several leaves which were abstracted about a century ago, and which came into possession of Joel R. Poinsett, who had been American Minister to Mexico, and who presented them to the American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia in 1830, where they now are. On the pages have been written explanations of the pictures and figures in both Nahuatl and Spanish. “The Nahuatl words look as if made by a pencil, style, or short brush similar to that used in delineating the figures, and with a sepia-like preparation; while the Spanish ones have evidently been made with an ink containing iron, and an instrument which disturbed the gloss of the paper, as is shown by its penetration to fibres adjacent, giving the lines a sort of hazy margin occasionally.”[23]

Some time between the years 1534 and 1550, Don Antonio de Mendoza, the first Viceroy of Mexico, during this period, had the Indians prepare for the Emperor Charles V, a book on European paper, containing a pictorial account, in colors, of some things relating to the history and life of the natives of the Mexican plateau. It was painted in three sections, the first being a chronological record of the Aztec kings and their conquests, the third relating to the habits and customs of the natives and especially of the education of Mexican youth.

PL. II

STONE IDOL: THE GODDESS COATLICUE, WITH MOSAIC DECORATION

NATIONAL MUSEUM, MEXICO

PL. III

STAFF AND RATTLE OF WOOD WITH MOSAIC DECORATION

PEABODY MUSEUM, CAMBRIDGE

[Pg 23]

The second part was a copy of the Tribute Roll above referred to. These pictures were given to other Indians for the interpretation of their import, which was written down in the Nahuatl language, and another person, well versed in both the Indian and Spanish languages, made a translation into Spanish, which was incorporated in the book. It was then despatched to Spain, probably about the year 1549, but the vessel was captured by French pirates, and the book came into the hands of the French geographer, André Thevet, in 1553. After Thevet’s death it was purchased, about the year 1584, by Richard Hakluyt, at that time chaplain to the English Ambassador to France. Hakluyt bequeathed the volume to Samuel Purchas, who published it, without colors, with an English translation of the text, in Purchas His Pilgrimes, London, 1625. The English text was translated into French and accompanied with the plates was published by Melchisedec Thevenot in his Relations des Divers Voyages, in 1663. The codex ultimately became the property of Selden, and with some other original Mexican codices later became a part of the Bodleian Library at Oxford, where it is now preserved. In 1831, Lord Kingsborough issued it for the first time in colors, together with a new and more accurate English rendering of the Spanish text, in his monumental work on the Antiquities of Mexico.

The Tribute Roll was published by Archbishop Lorenzana in Mexico in 1770, in his edition of the Cartas de Cortés, the drawing, uncolored, being traced in a very inferior manner from the original in Mexico. Finally, Dr. Antonio Peñafiel included a beautiful colored facsimile of the Tribute Roll in his work, Monumentos del Arte Mexicano Antiguo, published in Berlin in 1890, the missing leaves, in Philadelphia, being reproduced from a very poor drawing of the codex on European paper, probably executed for Boturini. These leaves were published in exact facsimile in 1892, with an article entitled, The Tribute Roll of Montezuma, edited by Dr. D. G. Brinton and Henry Phillips, in vol. XVII of the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society.

[Pg 24]

Fig. 1

On plate XVIII (we refer to the Peñafiel edition), in the second section of the plate, among other objects of tribute is a small bowl containing pieces of cut turquois (see fig. 1). In the explanation given by Purchas, this item is described as “a little panne full of Turkes stones,” and in the Kingsborough text it has been translated “a little vessel of small turquois stones.” On the plate published by Lorenzana is the caption, “Matlauac Rosilla con q. se tiñe azul.” The word matlauac is probably a corruption of the Nahuatl word matlaltic, meaning ‘blue,’ but the rest of the sentence in Spanish is confused, for rosilla means ‘reddish,’ and con q. se tiñe azul, ‘with which they dyed blue,’ seems to indicate that the phrase is incomplete. Accompanying the objects depicted as tributes are the hieroglyphs of the towns which paid them. These glyphs have been interpreted in the same manner in all of the reproductions of the codex, but we use the spelling adopted by Peñafiel, in preference to that given by Purchas or by Kingsborough. They are: (1) Quiyauhtecpan, “temple of rain or of its deities” Tlaloc or Chalchiuhtlicue; (2) Olinalan, “place of earthquakes;” (3) Cuauhtecomatlan, “place of tecomates;” (4) Cualac, “place of good drinkable water;” (5) Ichcatlan, “cotton-plantation;” (6) Xala, “sandy ground.” These places are given in the explanation as being “cities of warm provinces.”

Fig. 2

In the third section of the same plate (XVIII) are the objects shown in figs. 2 and 3. Peñafiel writes of fig. 2 as “ten little figures worked in turquois.” Only one object painted blue is depicted, the number ten being indicated by the ten dots. That masks form this tribute is clearly evident; in Purchas the description is “tenne halfe faces of rich blew Turkey stones,” and in Kingsborough, “likewise 10 middling sized masks of rich blue stones like turquois.”

PL. IV

HELMET OF WOOD WITH MOSAIC DECORATION

BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON

[Pg 25]

Fig. 3

The second item in this section (fig. 3) is described by Peñafiel as “a small bag of the same stones.” Kingsborough’s statement is, “a large bag of the said blue stones,” while in Purchas the translation reads, “a great trusse full of the said Turkey stones.” On the bag which is painted blue, with two red vertical bands, is the Aztecan hieroglyph for stone, tetl. The towns whence this tribute was exacted are: (1) Yoaltepec, “place consecrated to the deity of the night;” (2) Ehaucalco, “in the place of tanning;” (3) Tzilacapan, “river of chilacayotes;” (4) Patlanalan, “place where parrots abound;” (5) Ixicayan, “where the water comes down;” (6) Ichcaatoyac, “river of cotton.” These cities are of the warm provinces.

Fig. 4

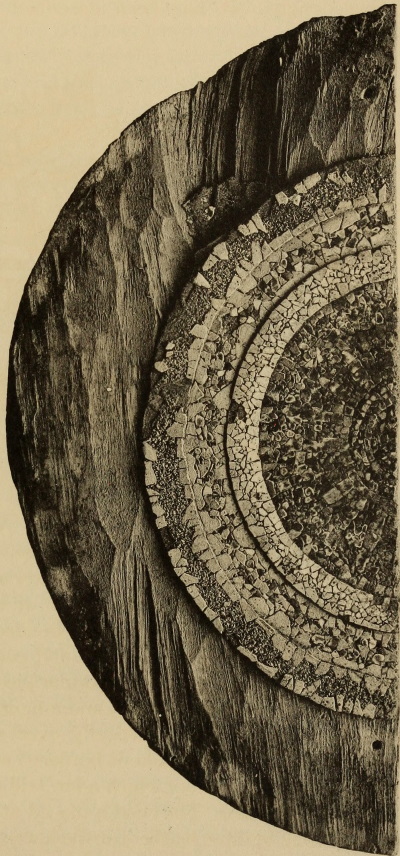

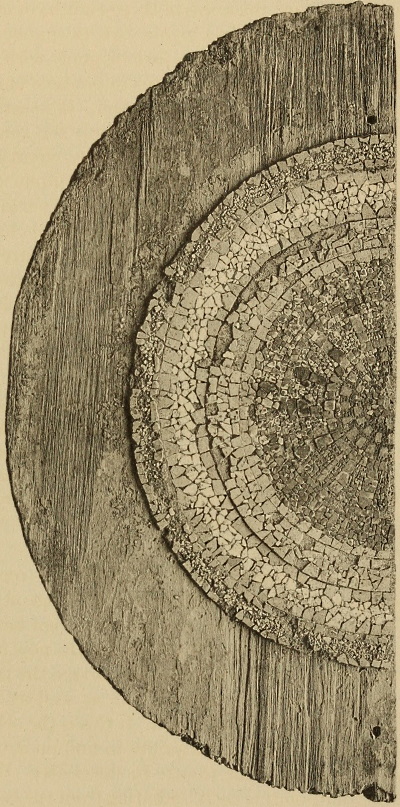

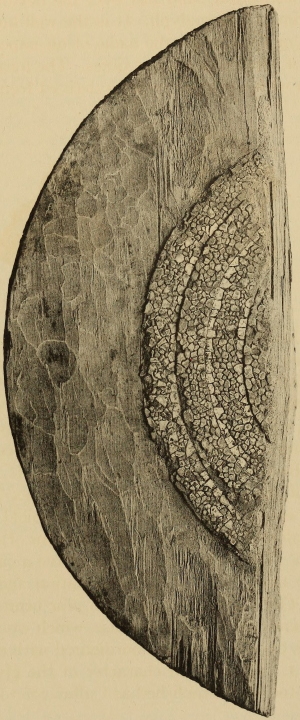

The only finished objects of mosaic-work in the Tribute Roll are on plate XXXII. This is one of the leaves of the original codex in Philadelphia, and we have traced fig. 4 from this original. They are described by Purchas as “two pieces like platters decked or garnished with rich Turkey stones.” Kingsborough mentions them as “two pieces like salvers ornamented or set with rich turquoise stones.” Lorenzana has correctly printed the legend which we find reproduced in the Philadelphia publication of this leaf; it is “Ontetl xiuhtetl,” followed by the Spanish, “turquesas o piedras finas.” Ontetl is Nahuatl for “two,” and xiuhtetl, or xiuitl tetl, “turquois stone.” The mosaic character of these two pieces is graphically represented by the ancient artist. The towns paying the tribute illustrated on this sheet are as follows: (1) Tochpan, or Tuchpan, “over the rabbit;”[Pg 26] (2) Tlaltizapan, “place situated over chalk;” (3) Cihuateopan, “in the temple of Cihuacoatl;” (4) Papantla, “place of the priests;” (5) Ocelotepec, “place of the ocelot;” (6) Mihuapan, “river of the ears of corn;” (7) Mictlan, “place of rest.”

In the Crónica of Tezozomoc is an account of the campaign of the Aztecan king Ahuitzotl into southern Mexico in 1497. The towns of Xuchtlan, Amaxtlan, Izhuatlan, Miahuatla, Tecuantepec, and Xolotlan, in the region of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, had revolted against him. After the complete rout of the rebellious Indians, it was related by Tezozomoc that “the kind of arms carried by the coast people was very rich, so much so that the undisciplined soldiers began to strip the bodies of the dead of the very rich feather-work pieces called quetzalmanalli, and from their military ornaments remove a round emerald like a mirror which sparkled in its perfection, called xiuhtezcatl. Others of the dead carried on the back of their arms that which was called yacazcuil, outside of fine gold, and in the nose they wore stones; others (wore) gold, and the shield which they carried had a very rich greenstone in the center, and around it a decoration of very fine stones set in (mosaic-work), said shield being called xiuhchimal.” Those who remained after the slaughter came to Ahuitzotl, saying: “Our Lords, let us speak. We will give our tribute of all that is produced and yielded on these coasts, which will be chalchihuitl of all kinds and colors, and other small stones called teoxihuitl (turquois) for setting in very rich objects [mosaic], and feathers of the richest sort brought forth in the whole world, very handsome birds, the feathers of which are called xiuhtototl, tlaquechol, tzinitzcan, and zacuan; tanned skins of the tiger (ocelot), lions (puma), and great wolves, and other stones veined with many divers colors.”[24]

In the same Crónica we read that Montezuma, who succeeded Ahuitzotl after his death in 1502, received a royal tribute from his vassals in Xaltepec, a coast town of Tehuantepec, among which were “broad collars [sic] for the ankles, strewn with gold grains and very rich stone mosaic-work.”[25]

PL. V

MASK OF WOOD WITH MOSAIC DECORATION

BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON

[Pg 27]

The source of the considerable quantity of turquois used in Mexico in pre-Spanish times for personal ornaments and mosaic incrustation is still an unsolved problem. Thus far no prehistoric workings have been found in Mexico. Only recently turquois has been discovered at the silver mines at Bonanza, Zacatecas, but Dr. Kunz, who has called our attention to this, writes that he has no information regarding prehistoric workings there.[26] In the extensive bibliography on the geology of Mexico by Aguilar y Santillan[27] we find only a single entry for turquois, that being the study of Mexican mosaics in Rome by Pigorini.[28] Pogue[29] writes that there are no important turquois deposits that do not show signs of prehistoric exploitation, and he is also of the opinion that it is very difficult to trace the source of the turquois used by the Indians of ancient Mexico and Central America. Pogue’s conclusion is that “as no occurrence at all adequate as an important source has been discovered south of the present Mexican boundary, it therefore seems probable that the Aztecs and allied peoples, through trade with tribes to the north, obtained supplies of turquois from the Cerrillos hills [New Mexico] and perhaps other localities of the Southwest.”

Sahagun is the only early chronicler who affords information concerning this point. He writes explicitly that “the Toltecs had discovered the mine of precious stones in Mexico, called xiuitl, which are turquoises, which mine, according to the ancients, was in a hill called Xiuhtzone, close to the town of Tepotzotlan [State of Hidalgo].” We will quote other statements by Sahagun concerning turquois:

The turquois occurs in mines. There are some mines whence more or less fine stones are obtained. Some are bright, clear, and transparent; while others are not.... Teoxiuitl is called turquois of the gods. No one has a right to possess or use it, but always it[Pg 28] must be offered or devoted to a deity. It is a fine stone without any blemish and quite brilliant. It is rare and comes from a distance. There are some that are round and resemble a hazelnut cut in two. These are called xiuhtomolli.... There is another stone, used medicinally, called xiuhtomoltetl, which is green and white, and very beautiful. Its moistened scrapings are good for feebleness and nausea. It is brought from Guatemala and Soconusco [State of Chiapas]. They make beads strung in necklaces for hanging around the neck.... There are other stones, called xixitl; these are low-grade turquoises, flawed and spotted, and are not hard. Some of them are square, and others are of various shapes, and they work with them the mosaic, making crosses, images, and other pieces.[30]

If we are to credit Sahagun, turquois was worked not only in the immediate region of the central Mexican plateau, but they received supplies from distant points, and specifically from Chiapas and Guatemala. The raw material mentioned in the Tribute Roll of Montezuma as coming from coast towns and from the south, must also be taken into consideration. Hence, notwithstanding the present lack of information respecting the localities where turquois is to be found in situ in central and southern Mexico, we cannot reject the opinion that ultimately ancient workings will be found at more than one site in Mexico. We do not believe it necessary to assume that the source of supply of both the Toltecs and the Aztecs, as well as of other tribes, such as the Tarasco, and the Mixtec and Zapotec, which also made use of this material, was the far-distant region of New Mexico. It was formerly asserted by some students that the jadeite of Middle America must have come by trade from China,[31] because no deposits have as yet been found in the former region; but it is now known by chemical analysis that the Middle American jadeite is distinct from that of Asia. In fact, the writer has long held that not alone in one, but in at least five, different localities, jadeite will in time be discovered.[32]

PL. VI

MASK OF WOOD WITH MOSAIC DECORATION

BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON

[Pg 29]

The development of the art of the lapidaries and mosaic-workers, like that of the goldsmiths, is attributed by Sahagun to the Toltecs, under the beneficent influence of Quetzalcoatl, the culture hero god. In treating of the pre-Aztec people called Tultecas, or people of Tollan or Tula, by Sahagun, he states that they were very skilful in all that pertained to the fine arts. He writes:

The Tultecas were careful and thorough artificers, like those of Flanders at the present time, because they were skilful and neat in whatsoever they put their hands to; everything (they did) was very good, elaborate, and graceful, as for example, the houses that they erected, which were very beautiful, and richly ornamented inside with certain kinds of precious stones of a green color as a coating (to the walls), and the others which were not so adorned were very smooth, and worth seeing, and the stone of which they were fashioned appeared like a thing of mosaic.... They also knew and worked pearls, amber, and amethyst, and all manner of precious stones, which they made into jewelry.[33]

We find another statement to the effect that—

The lapidary is very well taught, and painstaking in his craft, a judge of good stones, which, for working, they take off the rough part and bring together or cement with others very delicately with bitumen or wax, in order to make mosaic-work.[34]

In the pictorial section of the Florentine manuscript of Sahagun,[35] in the Codex Mendoza,[36] and in the Mappe Tlotzin,[37] are pictures delineating artisans engaged in various crafts, such as weavers, painters, carpenters (wood-carvers), stone carvers, lapidaries, goldsmiths, and feather-mosaic workers, yet we find no actual representation of turquois-mosaic workers. In the third section of the Codex Mendoza appears a picture of a father teaching his son the secrets of the lapidary’s art. The interpreter of the codex writes:

[Pg 30]

The trades of a carpenter, jeweler (lapidary), painter, goldsmith, and embroiderer of feathers, accordingly as they are represented and declared, signify that the masters of such arts taught these trades to their sons from their earliest boyhood, in order that, when grown up to be men, they might attend to their trades and spend their time virtuously, counseling them that idleness is the root and mother of vices, as well as of evil-speaking and tale-bearing, whence followed drunkenness and robberies, and other dangerous vices, and setting before their imaginations many other grounds of alarm, that hence they might submit to be diligent in everything.

The elaborate series of pictures of the various crafts in the Florentine manuscript of Sahagun (laminas liv to lxiv) includes those that show in detail the work of the goldsmiths and the feather-workers; but the illustrations devoted to the lapidaries we are unable to correlate, in the absence of the text, with the Nahuatl text of the Sahagun manuscript in the Real Academia de la Historia in Madrid, which we will give later from the study by Dr. Seler containing a translation of the native text into French. This description of the work of the lapidaries informs us only concerning the working and polishing of the stones. Unlike the other accounts by Sahagun regarding the goldsmiths and the feather-workers, which enlighten us with respect to the details of these two fine arts, he does not here enter into any description concerning the delicate work of the artists who fashioned the beautiful pieces of stone mosaic. Although such work was turned out by the Aztecan workmen, as we have already demonstrated, it seems highly probable that in times immediately preceding the Spanish conquest, the Aztecan kings Ahuitzotl and Montezuma obtained a considerable number of such objects through tribute and by barter with the tribes living in what are now the states of Vera Cruz, Oaxaca, and western Chiapas. As our knowledge of Mexican archeology, now all too meager, is extended, it is very probable that we will find vestiges of this art in the Pacific state of Guerrero, where great numbers of jadeite and other greenstone objects have been discovered, with a respectable[Pg 31] number of specimens indicating the high artistic skill of the indigenes of that section. We may also hope to find relics of this art in the area of Matlaltzincan culture to the north of the valley of Mexico, and also in the field of Tarascan culture in the states of Michoacan and Jalisco, for, as will be related, mosaic specimens have been recovered from ancient ruins as far north as the State of Zacatecas.

PL. VII

MASK OF WOOD WITH MOSAIC DECORATION

PREHISTORIC AND ETHNOGRAPHIC MUSEUM, ROME

Sahagun’s account (chap. II) of the work of the lapidaries we herewith append, with the Nahuatl text and a translation of the French rendering by Seler.[38]

1. In tlateque tulteca ynic quitequi yn yztac tehuilotl yoan tlapaltehuilotl yoan chalchiuitl yoan quetzalitztli ynica teoxalli yoan tlaquauac tepuztli.

1. The lapidary artisans cut rock-crystal, amethyst, emerald, both common and precious, by means of emery and with an instrument of tempered copper:

2. Auh ynic quichiqui tecpatl tlatetzotzontli.

2. And they scraped it by means of cutting flint.

3. Auh ynic quicoyonia ynic quimamali teputztlacopintli.

3. And they dug it out (hollowed) and drilled it by means of a little tube of copper.

4. Niman yhuian quixteca quipetlaua quitemetzhuia, auh yn yc quicencaua.

4. And then they faceted it very carefully; they burnished (polished) it and gave it the final luster.

5. Ytech quahuitl yn quipetlaua ynic pepetlaca, ynic motonameyotia ynic tlanextia.

5. They polished it set in wood, so that it comes to be very brilliant, shining, glossy.

6. Anoço quetzalotlatl ynitech quilau ynic quicencaua ynic quiyecchiua yn intultecayo tlatecque.

6. Or they polish it mounted in bamboo, and the lapidaries finish it thus, and conclude their work.

7. Auh çannoiuhqui yn tlapaltehuilotl ynic mochiua ynic mocencaua.

7. And in the same manner they work and smooth amethyst.

8. Achtopa quimoleua quihuipeua teputztica yn tlatecque yn tulteca ynic yyoca quitlatlalia yn qualli motquitica tlapaltic yn itaqui.

[Pg 32]

8. In the first place the lapidary artisans break into pieces the amethyst and crush it with an instrument of copper, for they work only the beautiful pieces which are entirely reddish.

9. Çan niman yuhqui tlatlalia yn campa monequiz quimoleua tepuztica.

9. They do not set up the precious stones named in this manner, except in the parts where it is necessary, when they break them with the copper instrument.

10. Auh niman quichiqui quixteca yoan quitemetzhuia yoan quipetlaua ytech quahuitl yn tlapetlaualoni ynic quiyectilia ynic quicencaua.

10. Then they scrape it, and they facet it, and they smooth it, and they polish it, mounted in wood, set on the instrument called polisher or burnisher, and they manufacture and finish it.

11. Auh yn yehoatl yn moteneua eztecpatl ca cenca tlaquauac chicauac camo ma vel motequi ynica teoxalli.

11. The stone called blood silex (heliotrope) is very hard and very strong, and they do not cut it well with emery.

12. Çaçan motlatlapana motehuia.

12. They break it and they cut it up in any kind of way.

13. Yoan motepehuilia yn itepetlayo yn amo qualli, yn amo uel no mopetlaua.

13. And they throw away the vein-stone, the useless stone, that which does not lend itself readily to polishing.

14. Çan yehoatl mocui motemolia yn qualli, yn vel mopetlaua yn eztic, yn uel cuicuiltic.

14. They do not take or seek except the beautiful pieces that lend themselves to good polishing, the red-banded, that permit themselves to be well cut.

15. Michiqui atica yoan ytech tetl cenca tlaquauac vnpa uallauh yn matlatzinco.

15. They rub them with water and mounted in a very hard stone that comes from the country of Matlatzinca [district of Toluca].

16. Ypampa ca uel monoma namiqui, yniuh chicauac tecpatl noyuh chicauac yn tetl, ynic monepanmictia.

16. And because these two stones are companions, the one to the other, as the silex is very hard, so the stone is hard, they kill one another (the one kills the other).

17. Çatepan mixteca yca teoxalli yoan motemetzhuia yca ezmellil.

17. Then they facet and polish them by means of emery.

[Pg 33]

18. Auh çatepan yc mocencaua yc mopetlaua, yn quetzalotlatl.

18. And they finish and polish them with bamboo.

19. Ynic quicuecueyotza quitonameyomaca.