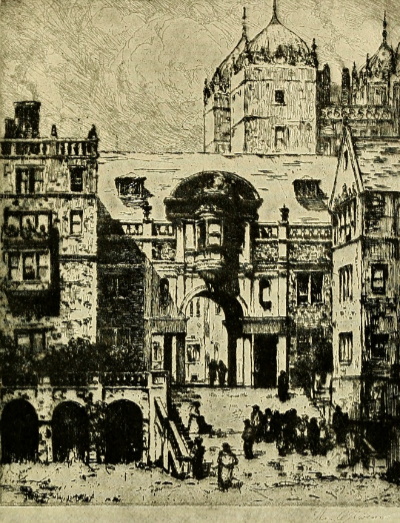

The Chapel at West Point as seen from an Entrance to the Area of the Cadet Barracks

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Chapel at West Point as seen from an Entrance to the Area of the Cadet Barracks

WHY GO TO COLLEGE

BY

CLAYTON SEDGWICK COOPER

Author of “College Men and the Bible”

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1912

Copyright, 1912, by

The Century Co.

Published, October, 1912

WITH GRATEFUL REMEMBRANCE

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO MY

COLLEGE TEACHER AND FRIEND

E. BENJAMIN ANDREWS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| I | General Characteristics | 3 | |

| II | Education à la Carte | 51 | |

| III | The College Campus | 93 | |

| IV | Reasons for Going to College | 135 | |

| V | The College Man and the World | 173 | |

| Index | 203 |

| The Chapel at West Point as seen from an Entrance to the Area of the Cadet Barracks | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

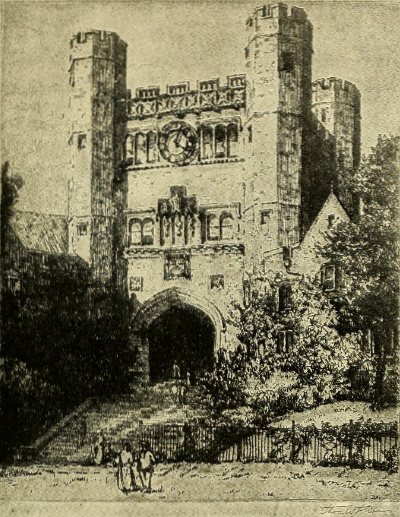

| Old South Middle, Yale University | 8 |

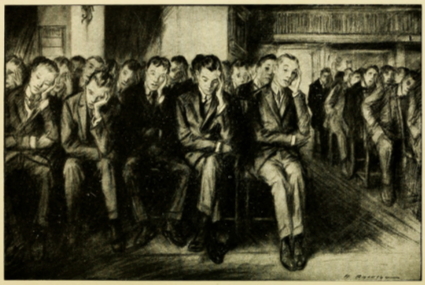

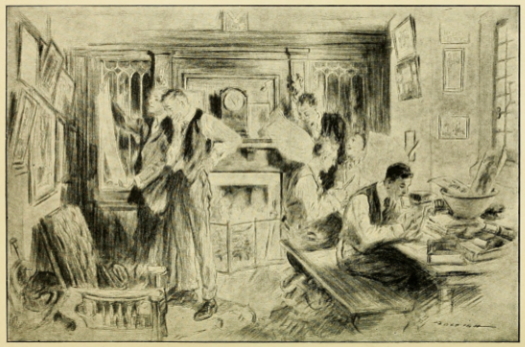

| A Protest against Prosiness | 21 |

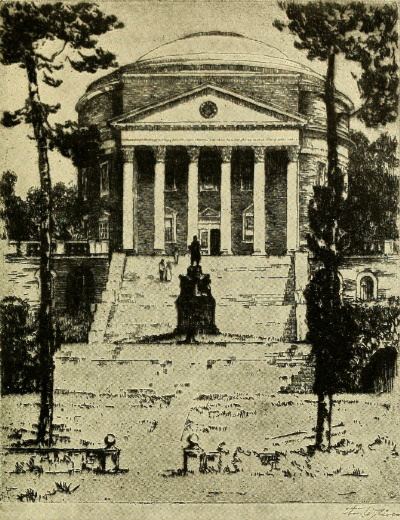

| University Hall, University of Michigan | 37 |

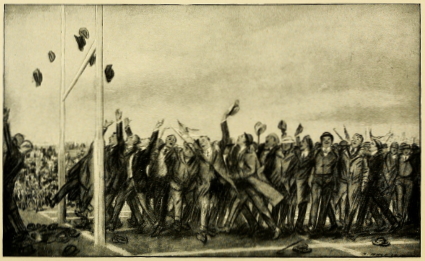

| The Serpentine Dance after a Foot-ball Game | 45 |

| Johnston Gate from the Yard, Harvard University | 55 |

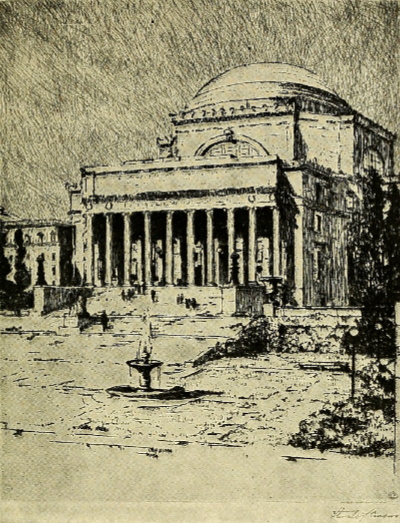

| The Library, Columbia University | 66 |

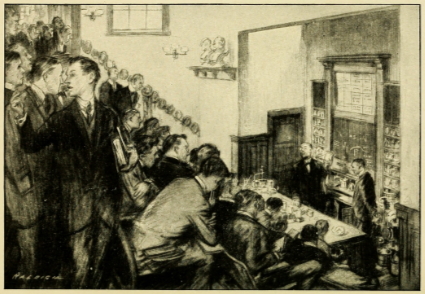

| A Popular Professor of Chemistry and his Crowded Lecture-Room | 80 |

| Student Waiters in the Dining-Hall of an American College | 97 |

| Amateur College Theatricals | 112 |

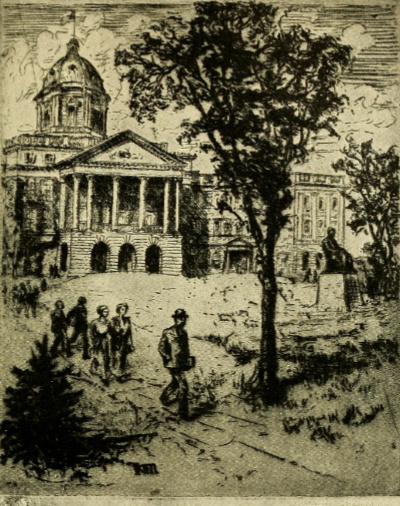

| The Main Hall, University of Wisconsin | 122 |

| Blair Arch, Princeton University | 143 |

| Editors of the Harvard Lampoon making up the “Dummy” of a Number | 154 |

| The Library and the Thomas Jefferson Statue, University of Virginia | 164 |

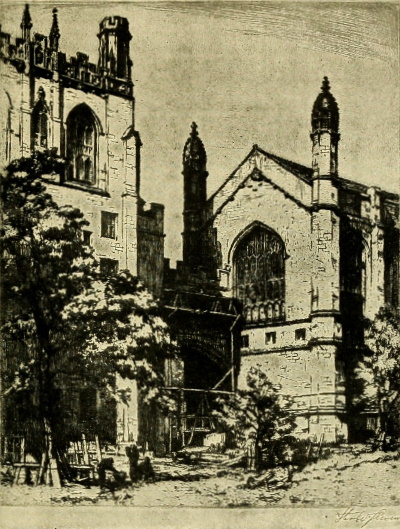

| Harper Memorial Building and the Law Building, University of Chicago | 178 |

| The Arch between the Dormitory Quadrangle and the Triangle, University of Pennsylvania | 192 |

The characteristics of a college course demanded by our American undergraduates is determined by two things; first, by the character of the man who is to be educated, and second, by the kind of world in which the man is to live and work. Without these two factors vividly and practically in mind, all plans for courses of study, recreation, teaching, or methods of social and religious betterment are theoretical and uncertain.

After ten years of travel among American college men, studying educational tendencies in not less than seven hundred diverse institutions in various parts of the United States and Canada, it is my deep conviction that the chief need of our North American Educational system is to focus attention upon the individual student rather than upon his environment, either in the curriculum or in the college buildings.

A few great teachers in every worthy North American institution who know and love the boys, have always been and doubtless will continue[xii] to be the secret of the power of our schools and colleges. There are indications that our present educational system involving vast endowments will be increasingly directed to the end of engaging as teachers the greatest men of the time, men of great heart as well as of great brain who will live with students, truly caring for them as well as teaching them. We shall thus come nearer to solving the problem of preparing young men for leadership and useful citizenship.

That this is the sensible and general demand of graduates is easily discovered by asking any college alumnus to state the strongest and most abiding impression left by his college training. Of one hundred graduates whom I asked the concrete question, “What do you consider to be the most valuable thing in your college course?”—eighty-six said, substantially: “Personal contact with a great teacher.”

Clayton Sedgwick Cooper.

March 12th, 1912.

Colleges, in like manner, have their indispensable office,—to teach elements. But they can only highly serve us when they aim not to drill, but to create; when they gather from far every ray of various genius to their hospitable halls, and by the concentrated fires, set the hearts of their youth on flame. Thought and knowledge are natures in which apparatus and pretension avail nothing. Gowns and pecuniary foundations, though of towns of gold, can never countervail the least sentence or syllable of wit. Forget this, and our American colleges will recede in their public importance, whilst they grow richer every year.

Emerson.

The American college was recently defined by one of our public men as a “place where an extra clever boy may go and still amount to something.”

This is indeed faint praise both for our institutions of higher learning and for our undergraduates; but judging from certain presentations of student life, we may infer that it represents a sentiment more or less common and wide-spread. Our institutions are criticized for their tendency toward practical and progressive education; for the views of their professors; for their success in securing gifts of wealth, which some people think ought to go in other directions; and for the lack of seriousness or the dissipation of the students themselves. Even with many persons who have not developed any definite or extreme opinions[4] concerning American undergraduate life, the college is often viewed in the light in which Matthew Arnold said certain people regarded Oxford:

Beautiful city! so venerable, so lovely, so unravaged by the fierce intellectual life of our century, so serene! There are our young barbarians, all at play!

Indeed, to people of the outside world, the American undergraduate presents an enigma. He appears to be not exactly a boy, certainly not a man, an interesting species, a kind of “Exhibit X,” permitted because he is customary; as Carlyle might say, a creature “run by galvanism and possessed by the devil.”

The mystifying part of this lies in the fact that the college man seems determined to keep up this illusion of his partial or total depravity. He reveals no unchastened eagerness to be thought good. Indeed, he usually “plays up” his desperate wickedness. He revels in his unmitigated lawlessness, he basks in the glory of fooling folks. As Owen Johnson describes Dink Stover, he seems to possess a “diabolical imagination.” He chuckles exuberantly as he reads in the papers of his picturesque public[5] appearances: of the janitor’s cow hoisted into the chapel belfry; of the statue of the sedate founder of the college painted red on the campus; of the good townspeople selecting their gates from a pile of property erected on the college green; or as in graphic cartoons he sees himself returning from foot-ball victories, accompanied by a few hundred other young hooligans, marching wildly through the streets and cars to the martial strain,

In other words, the American student is partly responsible for the attitude of town toward gown. He endeavors in every possible way to conceal his real identity. He positively refuses to be accurately photographed or to reveal real seriousness about anything. He is the last person to be held up and examined as to his interior moral decorations. He would appear to take no thought for the morrow, but to be drifting along upon a glorious tide of indolence or exuberant play. He would make you believe that to him life is just a great frolic, a long, huge joke, an unconditioned holiday.[6] The wild young heart of him enjoys the shock, the offense, the startled pang, which his restless escapades engender in the stunned and unsympathetic multitude.

This perversity of the American undergraduate is as fascinating to the student of his real character as it is baffling to a chance beholder, for the American collegian is not the most obvious thing in the world. He is not discovered by a superficial glance, and surely not by the sweeping accusations of uninformed theoretical critics who have never lived on a college campus, but have gained their information in second-hand fashion from question-naires or from newspaper-accounts of the youthful escapades of students.

We must find out what the undergraduate really means by his whimsicalities and picturesque attitudinizing. We must find out what he is thinking about, what he reads, what he admires. He seems to live in two distinct worlds, and his inner life is securely shut off from his outer life. If we would learn the college student, we must catch him off guard, away from the “fellows,” with his intimate friend, in the chapter-house, or in his own quiet[7] room, where he has no reputation for devilment to live up to. For college life is not epitomized in a story of athletic records or curriculum catalogues. The actual student is not read up in a Baedeker. His spirit is caught by hints and flashes; it is felt as an inspiration, a commingled and mystic intimacy of work and play, not fixed, but passing quickly through hours unsaddened by the cares and burdens of the world—

It is with such sympathetic imagination that the most profitable approach can be made to the American undergraduate. To see him as he really is, one needs to follow him into his laboratory or lecture-room, where he engages with genuine enthusiasm in those labors through which he expresses his temperament, his inmost ideals, his life’s choice. Indeed, to one who knows that to sympathize is to learn, the soul windows of this inarticulate, immature, and intangible personality will sometimes be flung wide. On some long, vague walk[8] at night beneath the stars, when the great deeps of his life’s loyalties are suddenly broken up, one will discover the motive of the undergraduate, and below specious attempts at concealment, the self-absorbed, graceful, winsome spirit. Here one is held by the subtle charm of youth lost in a sense of its own significance, moving about in a mysterious paradise all his own, “full of dumb emotion, undefined longing, and with a deep sense of the romantic possibilities of life.”

Old South Middle, Yale University

In this portrait one sees the real drift of American undergraduate life—the life that engaged last year in North American institutions of higher learning 349,566 young men, among whom were many of America’s choicest sons. Thousands of American and Canadian fathers and mothers, some for reasons of culture, others for social prestige, still others for revenue only, are ambitious to keep these students in the college world. Many of these parents, whose hard-working lives have always spelled duty, choose each year to beat their way against rigid economy, penury, and bitter loss, that their sons may possess what they themselves never had, a college education. And[9-11] when we have found, below all his boyish pranks, dissimulations, and masqueradings, the true undergraduate, we may also discern some of the pervasive influences which are to-day shaping life upon this Western Continent; for the undergraduate is a true glass to give back to the nation its own image.

Early in this search for the predominant traits of the college man one is sure to find a passion for reality. “We stand for him because he is the real thing,” is the answer which I received from a student at the University of Wisconsin when I asked the reason for the amazing popularity of a certain undergraduate.

The American college man worships at the shrine of reality. He likes elemental things. Titles, conventions, ceremonies, creeds—all these for him are forms of things merely. To him

The strain of the real, like the red stripe in[12] the official English cordage, runs through the student’s entire existence. His sense of “squareness” is highly developed. To be sure, in the classroom he often tries to conceal the weakness of his defenses with extraordinary genius by “bluffing,” but this attitude is as much for the sake of art as for dishonesty. The hypocrite is an unutterable abomination in his eyes. He would almost prefer outright criminality to pious affectation. Sham heroics and mock sublimity are specially odious to him. The undergraduate is still sufficiently unsophisticated to believe that things should be what they seem to be: at least his entire inclination and desire is to see men and things as they are.

This passion for reality is revealed in the student’s love of brevity and directness. He abhors vagueness and long-windedness. His speeches do not begin with description of natural scenery; he plunges at once into his subject.

A story is told at New Haven concerning a preacher who, shortly before he was to address the students in the chapel, asked the president of the university whether the time for his address[13] would be limited. The president replied, “Oh, no; speak as long as you like, but there is a tradition here at Yale chapel that no souls are saved after twenty minutes.”

The preacher who holds his sermon in an hour’s grip rarely holds students. The college man is a keen discerner between rhetoric and ideas. No decisions are more prompt or more generally correct than his. He knows immediately what he likes. You catch him or you lose him quickly; he never dangles on the hook. The American student is peculiarly inclined to follow living lines. He is not afraid of life. While usually he is free from affectation, he is nevertheless impelled by the urgent enthusiasm of youth, and demands immediate fulfilment of his dreams. His life is not “pitched to some far-off note,” but is based upon the everlasting now. He inhabits a miniature world, in which he helps to form a public opinion, which, though circumscribed, is impartial and sane. No justice is more equal than that meted out by undergraduates at those institutions where a student committee has charge of discipline and honor-systems. A child of reality and modernity, he is economical of his[14] praise, trenchant and often remorseless in his criticisms and censures, for as yet he has not learned to be insincere and socially diplomatic. This penchant for reality emerges in the platform of a successful college athlete in a New England institution who, when he was elected to leadership in one of the college organizations, called together his men and gave them two stern rules:

First, stop apologizing! Second, do a lot of work, and don’t talk much about it!

The undergraduate’s worship of reality is also shown in his admiration of naturalness. The modern student has relegated into the background the stilted elocutionary and oratorical contests of forty years ago because those exercises were unnatural. The chair of elocution in an American college of to-day is a declining institution. Last year in one of our universities of one thousand students the course in oratory was regularly attended by three.

The instructor in rhetorical exercises in a college to-day usually sympathizes with the remarks[15] of one Professor Washington Value, the French teacher of dancing at New Haven when that polite accomplishment was a part of college education. At one time when he was unusually ill-treated by his exuberant pupils, he exclaimed in a frenzy of Gallic fervor: “Gentlemen, if ze Lord vere to come down from heaven, and say, ‘Mr. Washington Value, vill you be dancing mast’ at Yale Collège, or vill you be étairnally dam’?’ I would say to Him—‘’Sieur, eef eet ees all ze sem to you, I vill be étairnally dam’.’” The weekly lecture in oratory usually furnishes an excellent chance for relaxation and horseplay. A college man said to me recently: “I wouldn’t cut that hour for anything. It is as good as a circus.”

The student prefers the language of naturalness. He is keen for scientific and athletic exercises, in part at least because they are actual and direct approaches to reality. His college slang, while often superabundant and absurd, is for the sake of brevity, directness, and vivid expression. The perfect Elizabethan phrases of the accomplished rhetorician are listened to with enduring respect, but the stumbling and broken sentences of the college athlete in a[16] student mass-meeting set a college audience wild with enthusiasm and applause.

Henry Drummond was perhaps the most truly popular speaker to students of the last generation. A chief reason for this popularity consisted in his perfect naturalness, his absolute freedom from pose and affectation. I listened to one of his first addresses in this country, when he spoke to Harvard students in Appleton Chapel in 1893. His general subject was “Evolution.” The hall was packed with Harvard undergraduates. Collegians had come also from other New England institutions to see and to hear the man who had won the loving homage of the students of two continents. As he rose to speak, the audience sat in almost breathless stillness. Men were wondering what important scientific word would first fall from the lips of this renowned Glasgow professor. He stood for a moment with one hand in his pocket, then leaned upon the desk, and, with that fine, contagious smile which so often lighted his face, he looked about at the windows, and drawled out in his quaint Scotch, “Isn’t it rather hot here?” The collegians broke into an applause that lasted for[17] minutes, then stopped, began again, and fairly shook the chapel. It was applause for the natural man. By the telegraphy of humanness he had established his kinship with them. Thereafter he was like one of them; and probably no man has ever received more complete loyalty from American undergraduates.

Furthermore, the college man’s love of reality is kept in balance by his humorous tendencies. His keen humor is part of him. It rises from him spontaneously on all occasions in a kind of genial effervescence. He seems to have an inherent antagonism to dolefulness and long-facedness. His life is always breaking into a laugh. He is looking for the breeziness, the delight, the wild joy of living. Every phenomenon moves him to a smiling mood. Recently I rode in a trolley-car with some collegians, and could not but notice how every object in the country-side, every vehicle, every group of men and women, would draw from them some humorous sally, while the other passengers looked on in good-natured, sophisticated[18] amusement or contempt. The whole student mood is as light and warm and invigorating as summer sunshine. He lives in a period when

Rarely does one find revengefulness or sullen hatred in the American undergraduate. When a man with these traits is discovered in college, it is usually a sign that he does not belong with collegians. His place is elsewhere, and he is usually shown the way thither by both professors and students. Heinrich Heine said he forgave his enemies, but not until they were dead. The student forgives and usually forgets the next day. The sense of humor is a real influence toward this attitude of mind, for the student blots out his resentment by making either himself or his antagonist appear ridiculous.

He has acquired the fine art of laughing both at himself and with himself. A story is told of a cadet at a military school who committed some more or less trivial offense which reacted upon a number of his classmates to the extent[19] that, because of it, several cadets were forced to perform disciplinary sentinel duty. It was decided that the young offender should be forthwith taken out on the campus, and ordered to kiss all the trees, posts, telegraph-poles, and, in fact, every free object on the parade-ground. The humorous spectacle presented was sufficient compensation to sweep quite out of the hearts of his classmates any possible ill feeling.

The faculty song, the refrain of which is

and is indulged in by many undergraduate students, usually covers all the sins and foibles of the instructors. One or two rounds of this song, with the distinguished faculty members as audience, is often found sufficient to clear the atmosphere of any unpleasantness existing between professors and students.

Not long ago, in an institution in the Middle West, this common tendency to wit and humor came out when a very precise professor lectured vigorously against athletics, showing their deleterious effect upon academic exercises.[20] The following day the college paper gave on the front page, as though quoted from the professor’s remarks, “Don’t let your studies interfere with your education.”

The student’s humor is original and pointed. Not long ago I saw a very dignified youth solemnly measuring the walks around Boston Common with a codfish, keeping accurate account of the number of codfish lengths embraced in this ancient and honorable inclosure. His labors were made interesting by a gallery of collegians, who followed him with explosions of laughter and appropriate remarks.

Not long ago in a large university, during an exceedingly long and prosy sermon of the wearisome type which seems always to be coming to an end with the next paragraph, the students exhibited their impatience by leaning their heads over on their left hands. Just as it seemed sure that the near-sighted preacher was about to conclude, he took a long breath and said, “Let us now turn to the other side of the character of Saint Paul,” whereupon, suiting the action to the word, every student in the chapel shifted his position so as to rest his head wearily upon the other hand.

A Protest against Prosiness

I have often been asked by people who only see the student in such playful and humorous moods, “Is the American college man really religious?” The answer must be decidedly in the affirmative. The college boy—with the manner of young men somewhat ashamed of their emotions—does not want to talk much about his religion, but this does not prove that he does not possess the feeling or the foundation of religion. In fact, at present there is a deep current of seriousness and religious feeling running through the college life of America. The honored and influential students in undergraduate circles are taking a stand for the things most worth while in academic life.

The undergraduate’s religious life is not usually of the traditional order; in fact it is more often unconventional, unceremonious, and expressed in terms and acts germane to student environment. College men do not, for example, crowd into the church prayer-meetings in the local college town. As some one has expressed it, “You cannot swing religion into[24] college men, prayer-meeting-end-to.” When the student applies to people such words as “holy,” “saintly,” or “pious,” he is not intending to be complimentary. Furthermore, he does not frequent meetings “in derogation of strong drink.” His songs, also, are not usually devotional hymns, and his conversation would seldom suggest that he was a promoter of benevolent enterprises.

Yet the undergraduate is truly religious. Some of the things which seem at first sight quite out of the realm of the religious are indications of this tendency quite as much as compulsory attendance upon chapel exercises. Dr. Henry van Dyke has said that the college man’s songs and yells are his prayers. He is not the first one who has felt this in listening to Princeton seniors on the steps of Nassau Hall singing that thrilling hymn of loyalty, “Old Nassau.”

I have stood for an entire evening with crowds of students about a piano as they sang with a depth of feeling more readily felt than described. As a rule there was little conversing except a suggestion of a popular song, a plantation melody, or some stirring hymn.[25] One feels at such times, however, that the thoughts of the men are not as idle as their actions imply. As one student expressed it in a college fraternity recently, “When we sing like that, I always keep up a lot of thinking.”

Moreover, if we consider the college community from a strictly conventional or religious point of view, the present-day undergraduates do not suffer either in comparison with college men of other days, or with other sections of modern life. The reports of the last year give sixty out of every one hundred undergraduates as members of churches. One in every seven men in the American colleges last season was in voluntary attendance upon the Bible classes in connection with the College Young Men’s Christian Association.

The religious tendencies of the American undergraduates are also reflected in their participation in the modern missionary crusades both at home and abroad. Twenty-five years ago the entire gifts of North American institutions for the support of missions in foreign lands was less than $10,000. Last year the students and alumni of Yale University alone gave $15,000 for the support of the Yale Mission[26] in China, while $131,000 represented the gifts of North American colleges to the mission cause in other countries. The missionary interests of students on this continent are furthermore revealed in the fact that 11,838 men were studying modern missions in weekly student mission study classes during the college season of 1909-10. At Washington and Lee University there were more college men studying missions in 1910 than were doing so in the whole United States and Canada sixteen years ago.

During the last ten years 4338 college graduates have gone to foreign lands from North America to give their lives in unselfish service to people less fortunate than themselves. Six hundred of these sailed in 1910 to fill positions in foreign mission ports in the Levant, India, China, Japan, Korea, Africa, Australia, and South America.

Furthermore, the standards of morals and conduct among the American undergraduates are perceptibly higher than they were fifty[27] years ago. There is a very real tendency in the line of doing away with such celebrations as have been connected with drinking and immoralities. To be sure, one will always find students who are often worse for their bacchic associations, and one must always keep in mind that the college is on earth and not in heaven; but a comparison of student customs to-day with those of fifty years ago gives cause for encouragement. Even in the early part of the nineteenth century we find conditions that did not reflect high honor upon the sobriety of students; for example, in the year 1814 we find Washington Irving and James K. Paulding depicting the usual sights about college inns in the poem entitled “The Lay of the Scottish Fiddle.” The following is an extract:

There has probably never been a time in our colleges when such scenes were less popular than they are to-day. Indeed, it is doubtful whether the American college man was ever more seriously interested in the moral, social, and religious uplift of his times. One of his cardinal ambitions is really to serve his generation worthily both in private and in public. In fact, we are inclined to believe that serviceableness is to-day the watchword of American college religion. This religion is not turned so much toward the individual as in former days. It is more socialized ethics. The undergraduate is keenly sensitive to the calls of modern society. Any one who is skeptical on this point may well examine the biographies in social, political, and religious contemporaneous history.[29] In a recent editorial in one of our weeklies it was humorously stated that “Whenever you see an enthusiastic person running nowadays to commit arson in the temple of privilege, trace it back, and ten to one you will come against a college.” President Taft and a majority of the members of his Cabinet are college-trained men. The reform movements, social, political, economic, and religious, not only in the West, but also in the Levant, India, and the Far East, are being led very largely by college graduates, who are not merely reactionaries in these national enterprises, but are in a very true sense “trumpets that sing to battle” in a time of constructive transformation and progress.

Undoubtedly one of the reasons which helps to account for the lack of knowledge on the part of outsiders concerning the revival in college seriousness is found in the fact that the play life of American undergraduates has become a prominent factor in our educational institutions.[30] Indeed, there is a general impression among certain college teachers and among outside spectators of college life that students have lost their heads in their devotion to intercollegiate athletics. And it is not strange that such opinions should exist.

A dignified father visits his son at college. He is introduced to “the fellows in the house,” and at once is appalled by the awestruck way with which his boy narrates, in such technical terms as still further stagger the fond parent, the miraculous methods and devices practised by a crack short-distance runner or a base-ball star or the famous tackle of the year. When in an impressive silence the father is allowed the unspeakable honor of being introduced to the captain of the foot-ball team, the autocrat of the undergraduate world, the real object of college education becomes increasingly a tangle in the father’s mind. As a plain business man with droll humor expressed his feelings recently, after escaping from a dozen or more collegians who had been talking athletics to him, “I felt like a merchant marine without ammunition, being fired into by a pirate ship until I should surrender.”

Whatever the undergraduate may be, it is certain that to-day he is no “absent-minded, spectacled, slatternly, owlish don.” His interest in the present-day world, and especially the athletic world, is acute and general. Whether he lives on the “Gold Coast” at Harvard or in a college boarding-house in Montana, in his athletic loyalties he belongs to the same fraternity. To the average undergraduates, athletics seem often to have the sanctity of an institution. Artemus Ward said concerning the Civil War that he would willingly sacrifice all his wife’s relatives for the sake of the cause. Some such feeling seems to dominate the American collegian.

Because of such athletic tendencies, the college student has been the recipient of the disapprobation of a certain type of onlookers in general, and of many college faculties in particular.

President Lowell of Harvard, in advocating competitive scholarship, in a Phi Beta Kappa address at Columbia University, said, “By free[32] use of competition, athletics has beaten scholarship out of sight in the estimation of the community at large, and in the regard of the student bodies.” Woodrow Wilson pays his respects to student athleticism by sententiously remarking, “So far as colleges go, the side-shows have swallowed up the circus, and we in the main tent do not know what is going on.”

Professor Edwin E. Slosson, who spent somewhat over a year traveling among fourteen of the large universities, utters a jeremiad on college athletics. He found “that athletic contests do not promote friendly feeling and mutual respect between the colleges, but quite the contrary; that they attract an undesirable set of students; that they lower the standard of honor and honesty; that they corrupt faculties and officials; that they cultivate the mob mind; that they divert the attention of the students from their proper work; and pervert the ends of education.” And all these cumulative calamities arrive, according to Professor Slosson, because of the grand stand, because people are watching foot-ball games and competitive athletics. The professor would have no objection to a few athletes playing foot-ball on the desert[33] of Idaho or in the fastnesses of the Maine woods, provided no one was looking. “If there is nobody watching, they will not hurt themselves much and others not at all,” he concedes.

In fact, such argument appeals to the average collegian with about the same degree of weight as the remark of the Irishman who was chased by a mad bull. The Irishman ran until out of breath, with the bull directly behind him; then a sudden thought struck him, and he said to himself: “What a fool I am! I am running the same way this bull is running. I would be all right if I were only running the other way.”

It will doubtless be conceded by fair-minded persons generally that in many institutions of North America athletics are being over-emphasized, even as in some institutions practical and scientific education is emphasized at the expense of liberal training. It is difficult, however, to generalize concerning either of these subjects. Opinion and judgment vary almost[34] as widely as does the point of view from which persons note college conditions. A keen professor of one of the universities where athletics too largely usurped the time and attention of students, justifiably summed up the situation by saying:

The man who is trying to acquire intellectual experience is regarded as abnormal (a “greasy grind” is the elegant phrase, symptomatic at once of student vulgarity, ignorance, and stupidity), and intellectual eminence falls under suspicion as “bad form.” The student body is too much obsessed of the “campus-celebrity” type,—a decent-enough fellow, as a rule, but, equally as a rule, a veritable Goth. That any group claiming the title students should thus minimize intellectual superiority indicates an extraordinary condition of topsyturvydom.

During the last twelve months, however, I have talked with several hundred persons, including college presidents, professors, alumni, and fathers and mothers in twenty-five States and provinces of North America in relation to this question. While occasionally a college professor as well as parent or a friend of a particular student has waxed eloquent in dispraise[35-37] of athletics, by far the larger majority of these representative witnesses have said that in their particular region athletic exercises among students were not over-emphasized.

University Hall, University of Michigan

Yet it is evident that college athletics in America to-day are too generally limited to a few students who perform for the benefit of the rest. It is also apparent that certain riotous and bacchanalian exercises which attend base-ball and foot-ball victories have been very discouraging features to those who are interested in student morality. In another chapter I shall treat at some length of these and other influences which are directly inimical to the making of such leadership as the nation has a right to demand of our educated men. In this connection, however, I wish to throw some light upon the student side of the athletic problem, a point of view too often overlooked by writers upon this subject.

In the first place, it needs to be appreciated that student athletics in some form or other have absorbed a considerable amount of attention of collegians in American institutions for over half a century. Fifty years ago, even, we find foot-ball a fast and furious conflict between[38] classes. If we can judge by ancient records, these conflicts were often quite as bloody in those days as at present. An old graduate said recently that, compared with the titanic struggles of his day, modern foot-ball is only a wretched sort of parlor pastime. In those days the faculty took a hand in the battle, and a historical account of a New England college depicts in immortal verse the story of the way in which a divinity professor charged physically into the bloody savagery of the foot-ball struggle of the class of ’58.

It will be impossible to fully represent the values of athletics as a deterrent to the dissolute wanderings and immoralities common in former times. Neither can one dwell upon the real apotheosis of good health and robust strength that regular physical training has brought to the youth of the country through the advent of college gymnasiums and indoor and outdoor athletic exercises. Much also[39] might be said in favor of athletics, especially foot-ball, because of the fact that such exercises emphasize discipline, which, outside of West Point and Annapolis, is lamentably lacking in this country both in the school and in the family. While there is much need to engage a larger number of students in general athletic exercises, it is nevertheless true that even though a few boys play at foot-ball or base-ball, all of the students who look on imbibe the idea that it is only the man who trains hard who succeeds.

There is, too, a feeling among those who know intimately the real values of college play life, when wholesale denunciations are made of undergraduate athletics, that it is possible for one outside of college walls or even for one of the faculty to produce all the facts with accuracy, and yet to fail in catching the life of the undergraduate at play. Inextricably associated with college athletics is a composite and intangible thing known as “college spirit.” It is something which defies analysis and exposition, which, when taken apart and classified, is not; yet it makes distinctive the life and atmosphere of every great seat of learning, and is[40] closely linked not only with classrooms, but also with such events as occur on the great athletic grand stands, upon fields of physical contest in the sight of the college colors, where episodes and aims are mighty, and about which historical loyalties cling much as the old soldier’s memories are entwined with the flag he has cheered and followed. While we are quoting from Phi Beta Kappa orators, let us quote from another, a contemporary of Longfellow, Horace Bushnell, whom Henry M. Alden has called, next to Emerson, the most original American thinker of his day. In his oration before the Phi Beta Kappa Society of Harvard sixty years ago, Dr. Bushnell said that all work was for an end, while play was an end in itself; that play was the highest exercise and chief end of man.

It is this exercise of play which somehow gets down into the very blood of the American undergraduate and becomes a permanently valuable influence in the making of the man and the citizen. It is difficult exactly to define the spirit of this play life, but one who has really entered into American college athletic events will understand it—the spirit of college tradition[41] in songs and cheers sweeping across the vast, brilliant throng of vivacious and spell-bound youth; the vision of that fluttering scene of color and gaiety in the June or October sunshine; the temporary freedom of a thousand exuberant undergraduates; pretty girls vying with their escorts in loyalty to the colors they wear; the old “grad,” forgetting himself in the spirit of the game, springing from his seat and throwing his hat in the air in the ebullition of returning youth; the mercurial crowd as it demands fair play; the sudden inarticulate silences; the spontaneous outbursts; the disapprobation at mean or abject tricks,—or that unforgettable sensation that comes as one sees the vast zigzagging lines of hundreds of students, with hands holding one another’s shoulders in the wild serpentine dance, finally throwing their caps over the goal in a great sweep of victory. One joins unconsciously with these happy spirits in this grotesque hilarity as they march about the stadium with their original and laughable pranks, in a blissful forgetfulness, for the moment at least, that there is any such thing in existence as cuneiform inscriptions and the mysteries of spherical trigonometry.[42] Is there any son of an American college who has really entered into such life as this who does not look back lingeringly to his undergraduate days, grateful not only for the instruction and the teachers he knew, but also for those childish outbursts of pride and idealism when the deepest, poignant loyalties caught up his spirit in unforgettable scenes:

Ah! happy days! Once more who would not be a boy?

A friend of mine had a son who had been planning for a long time to go to Yale. Shortly before he was to enter college he went with his father to see a foot-ball game between Yale and Princeton. On this particular occasion Yale vanquished the orange and black in a decisive victory. After the game the Yale men were marching off with their mighty shouts of triumph. The Princeton students collected in the middle of the foot-ball-field, and before singing “Old Nassau,” they cheered with even greater vigor than they had cheered at any time during the game, and this time not for Princeton, but for Yale. The sons of Eli came back from their celebration and stopped[43-45] to listen and to applaud. As the mighty tiger yell was going up from hundreds of Princetonian throats, and as the Princeton men followed their cheers by singing the Yale “Boolah,” the young man who stood by his father, looked on in silence, indeed, with inexpressible admiration. Suddenly he turned to his father and said: “Father, I have changed my mind. I want to go to Princeton.”

The Serpentine Dance after a Foot-ball Game

Such events are associated (in the minds of undergraduates) not only with the physical, but with the spiritual, with the ideal. The struggle on the athletic-field has meaning not simply to a few men who take part, but to every student on the side-lines, while the pulsating hundreds who sing and cheer their team to victory think only of the real effort of their college to produce successful achievement.

Standing beneath a tree near Soldiers’ Field at Cambridge, with undergraduates by the hundred eager in their athletic sports on one side, and the ancient roofs of Harvard on the other, there is a simple marble shaft which bears the names of the men whom the field commemorates, while below these names are written Emerson’s[46] words, chosen for this purpose by Lowell:

Not only upon the shields of our American universities do we find “veritas”; in spirit at least it is also clearly written across the face of the entire college life of our times. Gentlemanliness, open-mindedness, originality, honor, patriotism, truth—these are increasingly found in both the serious pursuits and the play life of our American undergraduates. The department in which these ideals are sought is not so important as the certainty that the student is forming such ideals of thoroughness and perfection. This search for truth and reality may bring to our undergraduates unrest or doubt or arduous toil. They may search for their answer in the lecture-room, on the parade-ground, in the hurlyburly of college comradeships, in the competitive life of college contests, or even in the hard, self-effacing labors[47] of the student who works his way through college. While, indeed, it may seem to many that the highest wisdom and the finest culture still linger, one must believe that the main tendencies in the life of American undergraduates are toward the discovery of and devotion to the highest truth—the truth of nature and the truth of God.

“If I were to return to college, I should take nothing that was practical,” remarked a recent college graduate. This attitude reveals by contrast a somewhat wide-spread tendency of opinion toward practical and progressive studies.

At a public gathering not long since, the president of a great State institution in the Middle West said that he believed within another decade every course in the institution of which he was the head would be intended simply to fit men to earn a livelihood. A cultivated disciple of quiet and delightful studies who overheard this remark was heard to say almost in a groan, “If I thought that was true of American education generally, I should want to die.”

An even more significant note of warning against merely bread-and-butter studies comes[52] from Amherst College, where the class of 1885 recently presented to the governing board the radical plan of abolishing entirely the degree of bachelor of science, with the purpose of building up a strictly classical course for a limited number of students admitted to college only by competitive examinations. The plan provides for the raising of a fund to meet any deficiency caused by the temporary loss of students and also for the increase of teachers’ salaries. The general idea in the mind of the Amherst committee is expressed as follows:

The proposition for which Amherst stands is that preparation for some particular part of life does not make better citizens than “preparation for the whole of it”; that because a man can “function in society” as a craftsman in some trade or technical work, he is not thereby made a better leader; that we have already too much of that statesmanship marked by ability “to further some dominant social interest,” and too little of that which is “aware of a world moralized by principle, steadied and cleared of many an evil thing by true and catholic reflection and just feeling, a world not of interest, but of ideas.” Amherst upholds the proposition that for statesmen, leaders of public thought, for literature, indeed for all work which demands culture and breadth of view, nothing can take[53-55] the place of the classical education; that the duty of institutions of higher education is not wholly performed when the youth of the country are passed from the high schools to the universities to be “vocationalized,” but that there is a most important work to be performed by an institution which stands outside this straight line to pecuniary reward; that there is room for at least one great classical college, and we believe for many such.

Johnston Gate from the Yard, Harvard University

These opinions are impressive. No one can visit widely our American colleges without feeling the appropriateness of such warnings and demands. A story is told of the president of a college praying in chapel for the prosperity of his school and all new and “inferior” institutions. The prayer would seem to have been answered in the last decade, which marks the marvelous growth of modern technical institutions in America. This growth has been specially pronounced in the great State universities and in the institutions fitted to train men in practical education.

Dr. William R. Harper is quoted as saying shortly before his death that “no matter how[56] liberally the private institution might be endowed, the heritage of the future, at least in the West, is to be the State university.” An ex-president of a State university has given the following indication of ten years of advance in attendance of students at fifteen State universities in comparison with attendance at fifteen representative Eastern colleges and universities:

| 1896-97 | 1906-07 | |

| State universities | 16,414 | 34,770 |

| Increase 112% | ||

| Eastern institutions | 18,331 | 28,631 |

| Increase 56% |

Almost any one of our great universities at present has many times the wealth, equipment, and students of all of our colleges fifty years ago. Our American agricultural and mechanical colleges, the greater number of which have arisen within ten years, now enroll more than 25,000 students. In 1850 there were only eight non-professional graduate students in the United States. In 1876, when Johns Hopkins opened, there were 400 such students. There are now at least 10,000 students of this class, and every year finds an additional number[57] of our larger institutions including graduate courses preparing for practical vocations, with many of them adding facilities for graduate study during the summer.

The following more concrete comparison by Professor E. E. Slosson reveals the manner in which the new State institutions are rapidly meeting the demands of modern times for technical and professional education; for the chief progress in these institutions has been not in the old-fashioned culture studies, but in special departments, including well-nigh everything from engineering and dairying to music and ceramics:

| Total | Annual | Total | Average | |

| Annual | Appropriation | Instructing | Expenditure | |

| Institutions. | Income. | for Salaries | Staff in | for Instruction |

| of Instructing | University. | per Student. | ||

| Staff. | ||||

| Columbia University | $1,675,000 | $1,145,000 | 559 | $280 |

| Harvard University | 1,827,789 | 841,970 | 573 | 209 |

| University of Chicago | 1,304,000 | 699,000 | 291 | 137 |

| University of Michigan | 1,078,000 | 536,000 | 285 | 125 |

| Yale University | 1,088,921 | 524,577 | 365 | 158 |

| Cornell University | 1,082,513 | 510,931 | 507 | 140 |

| University of Illinois | 1,200,000 | 491,675 | 414 | 136 |

| University of Wisconsin | 998,634 | 489,810 | 297 | 157 |

| University of Pennsylvania | 589,226 | 433,311 | 375 | 117 |

| University of California | 844,000 | 408,000 | 350 | 136 |

| Stanford University | 850,000 | 365,000 | 136 | 230 |

| Princeton University | 442,232 | 308,650 | 163 | 235 |

| University of Minnesota | 515,000 | 263,000 | 303 | 66 |

| Johns Hopkins University | 311,870 | 211,013 | 172 | 324 |

This sudden and enormous advance in the pursuit of technical studies, which have made the State universities formidable rivals to our older, privately endowed institutions, has aroused uncertainty as to the real object of collegiate training. Modern commercialism, which has said that you must touch liberal studies, if at all, in a utilitarian way, has swept in a mighty current through our American universities. The undergraduate is feeling increasingly the pressure of the outside modern world—the world not of values, but of dollars. The sense of strain, of rush, and of anxiety which generally pervades our business, our public and our professional life, has pervaded the atmosphere in which men should be taught first of all to think and to grow.

The present tendency of students is to feel that any form of education that does not associate itself directly with some form of practical and significant action is artificial, unreal, and undesirable. Last winter I visited an institution on the Pacific coast where literary[59] studies were considered, among certain classes of students, as not only unpractical, but almost unmanly. As a result of such drift in educational sentiment, the American undergraduate is in danger of getting prepared for an emergency rather than for life. He is losing,

The student leads his life noisily and hurriedly. He scarcely takes time to see it all plainly without dust and confusion. There is all about him a blurred sense of motion and duties. His culture lies upon him in lumps. He does not allow it time to impress him. College is a bewildering episode rather than a place of clear vision.

It is far easier to turn out of our colleges mechanical experts than it is to create men who are thoughtful, men who know themselves and the world. The value of the modern man to society does not depend upon his ability to do[60] always the same thing that everybody else is doing. College men should be fitted to make public sentiment as well as to follow it. The educated leader should be in advance of his period. Independence born of thoughtfulness and self-control should mark his thought and decision. The world looks to him for assistance in vigorously resisting those deteriorating influences which would commercialize intellect, coarsen ideas, and dilute true culture. His hours of insight and vision in the world of art, ideas, letters, and moral discipline should assist him to will aright when high vision is blurred by the duties of the common day. His clearer conception of highest truth should lead him to hope when other men despair. Our colleges should train men who will be “trumpets that sing to battle” against all complacency, indifference, and social wrong.

When a student, however, puts his profession of medicine or engineering before that of responsible leadership in social, political, moral, and industrial life, he ceases to be a real factor in the modern world. We already have a thousand men who can make money to one man who can think and make other men think. We[61] have a thousand followers to one genuine leader who incorporates in his own mind and heart a high point of view and the ability to present it in an attractive way. It is one thing for an undergraduate to go out from his institution expert in electrical science; it is quite another thing for him to so truly discover the spirit of life itself, as to be able to harmonize his expert ability with the broader and deeper life of the age in which he lives.

The present undergraduate often fails lamentably at this very point. He frequently reminds one of the remark of an old gentleman to an old lady whom I saw at a backwoods railway-station in Oregon watching a small white dog chasing with great zeal an express-train which had surged past the station. The old lady, turning to her companion, said eagerly, “Do you think he will catch it?” The old man answered, “I am wondering what he will do with the blamed thing if he does catch it.” The college undergraduate likewise is often uncertain about what he is to do with his profession beyond making a living with it. Our colleges, with their technical training, should give the conviction that a physician in a[62] community is more than a medical practitioner. His success as a physician brings with it an obligation of interest and leadership in all of the social, civic, and philanthropic movements of the town or city in which he works. He should discover in college that he is to be more than a doctor; that he is to be also a man and a citizen. In the last analysis, for real success it is not a question whether a man is a great engineer or a great electrician or a great surgeon; it is the question of individual character.

The pressing inquiry, then, for all undergraduate training is, Are we giving to our boys the kind of education which will fill their future life with meaning? A man must live with himself. He must be a good companion for himself. A college graduate, whatever his specialty, should be able to spend an evening apart from the crowd. The theater, the automobile, the lobster-palace, were never intended to be the chief end of collegiate education. A college course should give the undergraduate tastes, temperament, and habits of reading. A graduate who studies to be a specialist in any line needs also the education which will give him depth, background, and the historical[63] significance of civilization and life in general.

A lady at a dinner-party was making desperate attempts to interest in her conversation a certain business man who had been introduced to her as a graduate of a prominent university. She talked to him of books, education, theater, races, pictures, society, and out-of-door life. All of her efforts were futile. Finally he said, “Try me on leather; that’s my line.” This college graduate lost something important in his incompetency for general and intelligent conversation. His loss was more tragic, however, as a representative of the so-called college-educated classes, exponents of specialistic training, who have become materially successful, but who are without those personal resources necessary for their own enjoyment and profit, and who find themselves utterly inadequate for guidance or incentive to their fellowmen.

The system of elective studies which now widely characterizes the training in our higher educational institutions has made it increasingly[64] difficult for the college man to secure a clear idea of a college course and the comprehensive training which is his due. In many institutions the whole curriculum is in a state of unstable equilibrium. The endeavor to follow the demands of the times and the desire to secure patrons and students, have often brought to both the faculty and the undergraduate an uncertainty as to the true meaning of the college. Even in freshman and sophomore years the arrangement of studies is often left to the choice of the immature student. In one of our oldest universities there is at present only one prescribed course of study. For the rest, the students are allowed to choose at their own sweet will, and their choice, while dictated by a variety of motives, is influenced in no small degree by the preponderance of emphasis, both in buildings and faculty, upon technical education. Students are left to flounder about in their selection of courses, guided neither by curriculum nor life purpose. Recently I asked twenty-six students why they chose their studies. Sixteen of them gave monetary or practical reasons; six answered that the studies chosen furnished the line of least resistance as[65] far as preparation was concerned; and only four had in mind comprehensive culture and preparation for life.

I sympathize with the educator who said recently:

Is it not time that we stop asking indulgence for learning and proclaim its sovereignty? Is it not time that we remind the college men of this country that they have no right to any distinctive place in any community unless they can show it by intellectual achievement? that if a university is a place for distinction at all, it must be distinguished by conquest of mind?

While these tendencies threaten, instead of criticizing too severely our universities and our undergraduates, we should strive first to find the reason for these modern scientific and practical lines of work; and second, to suggest, if possible, definite ways by which a truer harmony in educational studies may be brought about.

The rapid extension of natural-physical science in the last fifty years has had much to do with the change of accent in American education.[66] This change of emphasis has effected a distinct transformation in the curriculum, in the college teacher and in the student ideal.

Should one care to get one’s fingers dusty with ancient documents, one might turn to an old leaflet in the files of the library at Columbia, dated November 2, 1853. It is the report of the trustees of Columbia College upon the establishment of a university system. Among other things this report outlines, in accordance with the ideas of the trustees, “the mission of the college.”

The Library, Columbia University

This mission is, “to direct and superintend the mental and moral culture. The design of a college is to make perfect the human intellect in all its parts and functions; by means of a thorough training of all the intellectual faculties, to obtain their full development; and by the proper guidance of the moral functions, to direct them to a proper exertion. To form the mind, in short, is the high design of education as sought in a College Course.” The report hereupon proceeds to note that unfortunately this sentiment, “manifest and just” though it be, “does not meet with universal sympathy or acquiescence.” On the contrary, the demand[67-69] for what is termed progressive knowledge ... and for fuller instruction in what are called the useful and practical sciences, is at variance with this fundamental idea. The public generally, unaccustomed to look upon the mind except in connection with the body, and to regard it as a machine for promoting the pleasures, the conveniences, or the comforts of the latter, will not be satisfied with a system of education in which they are unable to perceive the direct connection between the knowledge imparted and the bodily advantages to be gained. The committee therefore “think that while they would retain the system having in view the most perfect intellectual training, they might devise parallel courses, having this design at the foundation, but still adapted to meet the popular demand.”

We have here one of the early indications of “parallel courses” in one of our institutions of higher learning as a concession to popular demands. But this concession at Columbia was made before the immense extension and development of modern natural, physical, and industrial science. Education or culture in the early fifties was something easy to define. It[70] included logic, literature, oratory, conic sections, and religion. Since that date, however, the American undergraduate has discovered modern research work at the German university. Cecil Rhodes has opened Oxford for American students with his “golden key.” The American student has been called upon to match with his technical ability the enormous and rapid development of a new material civilization, and educational institutions take color from the social and political media in which they exist. In fact, it cannot be easily estimated how real or how comprehensive a factor the college graduate has been in guiding and shaping this practical and progressive awakening.

The American undergraduate is more than ever before contemporaneous with all that is real and important in modern existence. He is filled with enthusiasm for civic and social and religious investigation and improvement. With self-reliant courage he works his way through college, tutoring, waiting on table, and performing other real services. He debates with zeal economics, immigration, and labor questions. Indeed, the modern American university[71] is taking increasingly firmer hold upon the life of the nation. The college graduate of fifty years ago was more or less a thing apart. If he was strong in his literary studies, he was also weak in his attachment to life itself, where education really has its working arena. In comparison with him, the student to-day spends a greater proportion of his time in the study of political science. One feels the limitation of the modern undergraduate especially in the sweep of his literary knowledge, and in his acquaintance with abstract thought, art, and poetry. But when we see student and professor working together on our American farms, bringing about a new and higher type of rural life; when we find our mechanical engineers not only in the mountains and on the Western prairies, but in the heart of India or inland China or South Africa, building there their bridges and railroad tunnels according to the ideas seen in the vision of their new practical educational training, we are bound to ask whether the modern undergraduate is not truly interested in the deep aim of all true scholarship, namely, the spiritual and concrete construction of life by means of ideas made real.[72] Ambassador Bryce’s opinion of the American universities carries weight, and of them he has said:

If I may venture to state the impression which the American universities have made upon me, I will say that while of all the institutions of the country they are those of which the American speaks most modestly, and indeed deprecatingly, they are those which seem to be at this moment making the swiftest progress, and to have the brightest promise for the future. They are supplying exactly those things which European cities have hitherto found lacking to America; and they are contributing to her political as well as to her contemplative life elements of inestimable worth.

But since undergraduate training must deal not simply with the theory of education, but also with the imperative demands and conditions of a new time, there must be discovered practical ways by which our undergraduates may save their literary ideals at the same time that they enlarge their practical and progressive knowledge; means by which they may discover literary, historical, linguistic, and philosophical values without losing their mathematics and their physical and material sciences.

To the end, therefore, of making cultural studies as strong, attractive, and profitable to our undergraduates as practical and scientific training, our institutions should train men of large caliber to teach English and belles-lettres. They should discover great teachers and inspiring personalities.

President Gilman of Johns Hopkins University took as his motto, “Men before buildings.” The subject of securing great teachers for students is perhaps the most vital topic which can be considered, since from the point of view of undergraduates a professor, whether teaching civil engineering or Greek, is invariably influential because of what he is personally.

In a large university which I recently visited I was told that there were three thousand students and five hundred instructors and professors, an average of a professor to every six students. Upon asking several of the undergraduates how many professors they knew personally, I was somewhat astounded to find that[74] less than a dozen of these six hundred teachers came into personal contact with the students outside of the classes. One graduate told me that he had not been in the home of more than three professors during his college course.

There are undoubtedly reasons for this lack of association between the professors and the undergraduates. In a large university, the demand upon the teacher for more work than he should rightfully undertake, the ever-increasing interest of the student in college affairs, with many other influences, are constantly presented as difficulties in the way of the teacher’s close relationship with the student. But the important point in this association between student and professor is that in many cases the professor has nothing vital and individual to give the undergraduate when he meets him. In too many cases he is a dry and weary man, living his life in books rather than in men. A. C. Benson has described a Cambridge don in terms that at times we fear fit some college professors of our own land. He sits “like a moulting condor in a corner, or wanders seeking a receptacle for his information.” The American college teacher has too[75] often been chosen simply because of his scholarship. Our institutions of learning have been obsessed with the mere value of the degree of doctor of philosophy. As a consequence, many a young professor is scholarly and expert in his knowledge of his subject, but utterly without ability to impart it with interest. He lacks driving force as well as guiding and regulating force. He seems at times without the capacity for real feeling. He is not alive to the issues of the time in which he lives. He starts his subject a century behind the point of view in which his scholars are interested. Too often, alas! he misses the chief opportunity of a college teacher in not becoming friendly with his undergraduates; for there is no comradeship like the comradeship of letters, the comradeship of knowledge, the comradeship of those whose lives are united in the higher aims of serious education.

Letters have never lacked their fascination when they have been embodied in the thought and personalities of great teachers. Albert Harkness, with his face aglow with literary enthusiasm, reading “Prometheus Bound,” in his lecture-room in the old University Hall at[76] Providence, is one of the unfading memories of my undergraduate days. When Tennyson said, “I am sending my son not to Marlborough, but to Bradley, the great teacher,” it was not a subject he had in mind, but a personality. In one institution which I visit, virtually the entire undergraduate body elects botany. A student said to me one day, “We do not care especially for botany, but we would elect anything to be under Dr. ——.” Not long ago, attending a college dinner at the University of Minnesota, I heard a professor at my side lamenting the tendency to irreverence on the part of American college men. While we were speaking, ex-President Northrop came into the room, and the entire crowd of students were on their feet in an instant, cheering their beloved president. One of the undergraduates closed his remarks by saying that the deepest impression of his college days had occurred in the chapel when their honored president prayed; and he quoted the following verse:

The classroom presentation of the college professor is also highly important. Many a subject is spoiled for a student because of the pedantic, priggish, or solemn manner of the teacher. Many a teacher is devoted to his subject and painstaking, but his lack of knowledge as to the use of incident, epigram, and enticing speech in presenting his subject, prevents his popularity and power as a teacher. Woodrow Wilson says that he had been teaching for twenty years before he discovered that the students forgot his facts, but remembered his stories. We realize that tables of population, weights, and measures, temperatures, birth-rates, and dimensions, are at times necessary, but these should be used in the classroom with moderation.

Too often a teacher takes for granted that he has an uninteresting subject, and therefore gives up the task of making it attractive. A[78] professor of mathematics, endeavoring to evade the obligation for good teaching, gave to a professor of chemistry, whose lecture-room was always crowded with interested students, the following reason for the unpopularity of his subject: “The trouble with mathematics is that nothing ever happens. If, when an equation is solved, it would blow up or give off a bad odor, I should get as many students as you.” The real reason, however, was deeper than the nature of his subject. It lay in the nature of the man. He did not have the power to bring his subject into vital contact with reality and with the life of his students.

The lecture plan also handicaps many a teacher in this important task of getting near the student and drawing him out. The seminar of our larger universities and graduate schools help much in individualizing the students. Students may be talked to death. They themselves often want to talk. An undergraduate in the South, after hearing a professor who was without terminal facilities, told me the old story of Josh Billings, who defined a bore as a man who talked so much about[79] himself that you couldn’t talk about yourself.

In many institutions the students also are forced to take too many lectures. Their minds become jaded. Thinking is the last thing they have power to do in the lecture-room. There is little desire or opportunity for intellectual reaction; as one professor of a Western university humorously remarked:

They do not listen, however attentive or orderly they may be. The bell rings, and a troop of tired-looking boys, followed perhaps by a larger number of meek-eyed girls, file into the classroom, sit down, remove the expressions from their faces, open their note-books on the broad chair-arms, and receive. It is about as inspiring an audience as a room full of phonographs holding up their brass trumpets.

The most discouraging moments of my college days occurred during the lecture hours of history, not because I did not have a natural bent for history, but because the professor made the topic, for me, uninteresting. My mind became a blank almost as soon as I entered the classroom. Lecture days in history covered me with a darkness beyond that which[80] I had ever imagined could emanate from the world of fallen spirits. My powers went into eclipse. There seemed to be a kind of automatic cut-off between my brains and my note-book. My only source of comfort consisted in the fact that my miseries had companionship. In some examinations, I remember, only a small remnant of the class succeeded in satisfying the demands of our scholarly teacher.

I can only remember flashes and hints of a long, solemn, student face, shrouded with whiskers, bending with piercing eye over books which seemed only slightly less dry than a remainder biscuit, droning, in “hark-from-the-tombs-a-doleful-sound” incantation, words, which to our vagrant attention were just words, belonging to remote centuries, while about me my companions shivered audibly, waiting to be called up. The professor was called a great student of history. He might have been. We gladly admitted this: it was the chief compliment we could pay him. As a teacher and inspirer of boys, however, he was a good example of the way to make history impregnable.

A Popular Professor of Chemistry and his Crowded Lecture-Room

I hold in memory, also, another professor[81-83] who taught history. He was seldom called a professor. The students called him “Benny.” There was a kind of lingering affection in our voices as we spoke his name. His lecture-room was always crowded. No student ever went to sleep, no student became so frightened that he lost his wits, no student ever took himself too seriously. There was an element of humor and humanness which was constantly kindled by this great, manly teacher and which fired at frequent intervals every student heart. His illustrations were not confined to Horatius on the bridge, Garibaldi promising his soldiers disaster and death, or Luther at Worms. He attached history to modern themes. His historical situations were described not in the terms of tedious systems, but in the personalities of great men. We somehow felt that he himself was greater than anything he said; that he himself was a great man. He found interest in the life of college as well as in the work of college. He talked about the last foot-ball game and the reason why the college was defeated and the lessons that men should draw from their failure. The value of his remarks was enhanced by the fact that most[84] of the men had seen him on the running-track in the gymnasium, or on the front row of the grand stand, cheering patriotically with both voice and arms. I remember how he used to add driving power to our awakening resolves and ambitions. We were quite likely to forget that we were learning history. To-day at alumni dinners the mere mention of the name “Benny” brings an enthusiasm which the most eloquent speech of any other man seems incapable of invoking. Here was a man who also taught history; but the man was more than his book, he was more than his subject: he was the light and the blood of it, and the glory of that theme still brightens the path of every one of those hundreds of students who caught a new and radiant vision of the march of events in the light of a great man’s eyes. It was of such teachers that Emerson must have been thinking when he said, “There is no history, only biography,” and again, “An institution is but the lengthened shadow of a man.”

It is of such men that other college graduates think to-day, even as Matthew Arnold thought of Jowett at Balliol:

But how are we to train such teachers for our undergraduates? This is no child’s task. It is the matchless opportunity of the college; it is the crying need of our times. A large proportion of undergraduates in college lecture-rooms are virtually untouched in either their feelings or their intellects by the ministry of the church. Whatever the ministry may have been in our father’s times, it is not to-day significant or effective in imparting its message to students. The fact is periodically demonstrated by test questions of teachers to their students concerning the Bible, English literature, and church history. I have recently visited a dozen of the leading preparatory schools whose headmasters and teachers quite invariably unite in lamenting the inadequacy of the Sunday-schools and of religious training in the home. Indeed, many students go up to our best preparatory schools in almost a[86] heathenish condition as regards religion and Christian knowledge. It is the day and time of the teacher’s ministry in both secondary schools and in colleges. No pulpit in our day is more far-reaching and decisive than the desk of the college teacher. The college professor who does not forget that he is first a man, then a professor, and who can get past the friendship of books and knowledge to a genuine friendship with students, can be the highest force in our present day civilization. But the teacher says: “I am only a teacher of literature, or of chemistry, or of engineering, or of bridge-building. I am not an evangelist or a moral reformer, or a promoter of polite accomplishments or of social service.” Much of this is true also of the great teachers of history. Yet somehow these men found in their specialty the door through which they entered into the very hearts and lives of their school-boys.

A short time ago at the University of Iowa I had the opportunity of meeting at luncheon thirty members of the faculty. The subject for discussion was: “What can the professor do really to assist students at the University of Iowa in discovering the values worth while[87] in college life?” Approximately one-half of the teachers for various reasons prayed to be excused from the discussion. I was specially interested in the answers of the other men—among whom were the men, according to student testimony, who had a real hold upon the university life. One man was of the department of chemistry. He was prominent in student activities. When he was introduced, a student said, “There is no man more truly liked in the university than Professor ——.” As he talked, we felt that, while he might be a good teacher of chemistry, his department was chiefly important in giving him a point of departure from which he could go forth to interest himself in the life of young men. After the conference he said to me: “If professors want influence with students, let them appear at debates, at athletic games, and at student mass-meetings; let them show real interest in undergraduate activities of all sorts, even at personal sacrifice.”

Another professor was a teacher of English. He was not interested in athletics or in the religious life of the students so much as in revealing to students in the classroom as well as[88] outside the classroom the charm of literary things. That was his message—his individual message to his college. His life-work was more than presenting the evolution of the English novel: it was a mission to students to secure on their part habits of reading and a taste for genuine literature which in after years would be to many the most priceless reward of their college days. It is not necessary that two college teachers should present the same truth in the same way, but when college professors and instructors, presidents, deans, and tutors, realize that teaching to-day as in former days is a calling, not simply a means of livelihood, and that every man who holds any such position must somehow discover how to reach personally at least a small circle of students, then our colleges will not longer be defined as “knowledge shops,” but as the homes of those inspirations and friendships, those ideals and incitements, which make life more than meat and the body than raiment.

While the drift of our modern life in the outside world may be toward technical and scientific education, the drift in college is still toward the great teacher—the man of thought-provoking[89] power and of spiritual capacity; sincere and genuine both in scholarship and manhood, of whom one can speak, as Carlyle spoke of Schiller, “a high ministering servant at Truth’s altar, and bore him worthily of the [90]office he held.”

Rudyard Kipling speaks of four street corners of four great cities where a man may stand and see pass everybody of note in the world. There are likewise vantage-points in our American colleges from which one may discover not only the influential undergraduate types, but also the real life of their environment. One of these places is the college campus.